"And so as Tiny Tim observed, God bless us every one!"

"And so as Tiny Tim observed, God bless us every one!"Charles Dickens

Title: Dickens and His Illustrators

Author: Frederic George Kitton

Release date: August 4, 2012 [eBook #40410]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Pat McCoy, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive).

[Pg i]

[Pg ii]

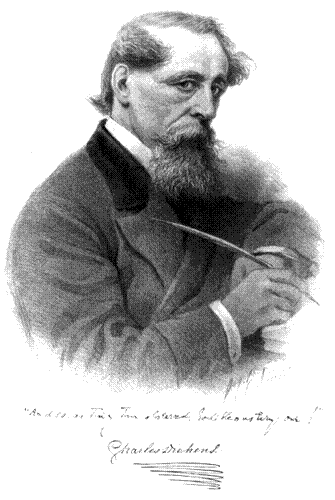

Plate I

CHARLES DICKENS

From a scarce Lithograph by

SOL. EYTINGE, Junr.

"And so as Tiny Tim observed, God bless us every one!"

"And so as Tiny Tim observed, God bless us every one!"This Portrait was published during the Novelist's last visit to America (1867-68), by Fields, Osgood & Co., of Boston, their advertisement describing it as "an Authentic Portrait of Charles Dickens, drawn on stone by S. Eytinge, Jr., whose Illustrations of Dickens's Novels have been so popular." The late Mr. J. R. Osgood did not recall any actual sitting for the Portrait, but remembers that Eytinge often saw Dickens while making the drawing. The impression from which the present reproduction was made is particularly interesting on account of the quotation from "A Christmas Carol" in the autograph of Dickens.

Lent by Mr. Stuart M. Samuel.

[Pg iii]

[Pg iv]

BY

FREDERIC G. KITTON

AUTHOR OF "CHARLES DICKENS BY PEN AND PENCIL," ETC.

WITH TWENTY-TWO PORTRAITS AND FACSIMILES OF

SEVENTY ORIGINAL DRAWINGS NOW REPRODUCED

FOR THE FIRST TIME

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

GEORGE REDWAY

1899

[Pg v]

[Pg vi]

TO

CHARLES DICKENS'S DAUGHTER

KATE PERUGINI

THESE NOTES UPON THE ILLUSTRATIONS

TO HER FATHER'S WRITINGS

are respectfully dedicated

BY THE AUTHOR

In the matter of pictorial embellishment, the writings of Charles Dickens may be regarded as occupying a unique position. The original issues alone present a remarkable array of illustrations; and when we remember the innumerable engravings specially prepared for subsequent editions, as well as for independent publication, we are fain to confess that, in this respect at least, the works of "Boz" take precedence of those of any other novelist. These designs, too, are of particular interest, inasmuch as they are representative of nearly every branch of the art of the book-illustrator; both the pencil of the draughtsman and the needle of the etcher have been requisitioned, while the brush of the painter has depicted for us many striking scenes culled from the pages of Dickens.

The evolution of a successful picture, as exhibited by means of preparatory sketches, is eminently instructive to the student of Art. The present volume should therefore appeal not merely to the Dickens Collector, but to all who appreciate the artistic value of tentative studies wrought for a special purpose. The absolute facsimiles, here given for the first time, enable us to obtain an insight into the methods adopted by the designers in developing their conceptions, those methods being further manifested by the aid of correspondence which, happily, is still extant.

Referring to Dickens's intercourse with his Illustrators, Forster significantly observes that the artists certainly had not an easy time with him. The Novelist's requirements were exacting even beyond what is[Pg viii] ordinary between author and illustrator; for he was apt (as he himself admitted) "to build up temples in his mind not always makeable with hands." While resenting the notion that Dickens ever received from any artist "the inspiration he was always striving to give," his biographer assures us that, so far as the illustrations are concerned, he had rarely anything but disappointments,—a declaration which apparently substantiates the statement (made on good authority) that the Novelist would have preferred his books to remain unadorned by the artist's pencil. That the vast majority of his readers approved of such embellishment cannot be questioned, for the genius of Cruikshank and "Phiz" has done much to impart reality to the persons imagined by Dickens. We are perhaps even more indebted to the excellent illustrations than to the Author's descriptions for the ability to realise the outward presentments of Pickwick, Fagin, Micawber, and a host of other characters, simply because the material eye absorbs impressions more readily than the mental eye.

That Dickens's association with his Illustrators was something more than mere coadjutorship is evidenced both in Forster's "Life" and in the published "Letters." From these sources we derive much information tending to prove the existence of a warm friendship subsisting between Author and Artists; indeed, the latter (with two or three exceptions) were privileged to enjoy the close personal intimacy of Dickens and his family circle. Recalling the fact that the Novelist not unfrequently availed himself of the traits and idiosyncrasies of his familiars, it seems somewhat strange that in the whole range of his creations we fail to discover a single attempt at the portraiture of an artist; for those dilettanti wielders of the brush, Miss La Creevy and Henry Gowan, can scarcely be included under that denomination.

[Pg ix]During the earlier part of this century the illustrators of books seldom, if ever, resorted to the use of the living model. Such experts as Cruikshank, Seymour, "Phiz," Maclise, Doyle, and Leech were no exceptions to this rule; but at the beginning of the sixties there arose a new "school" of designers and draughtsmen, prominent among them being Leighton, Millais, Walker, and Sandys. Those popular Royal Academicians, Mr. Marcus Stone and Mr. Luke Fildes (the illustrators respectively of "Our Mutual Friend" and "Edwin Drood"), are almost the only surviving members of that confraternity; they, however, speedily relinquished black-and-white Art in order to devote their attention to the more fascinating pursuit of painting. While admitting the technical superiority of many of the illustrations in the later editions of Dickens's works (such as those by Frederick Barnard and Charles Green), the collector and bibliophile claim for the designs in the original issue an interest which is lacking in subsequent editions; that is to say, they possess the charm of association—a charm that far outweighs possible artistic defects and conventions; for, be it remembered, these designs were produced under the direct influence and authorisation of Dickens, and by artists who worked hand in hand with the great romancer himself.

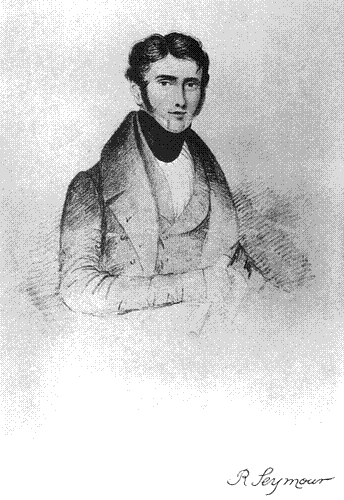

It is averred that "Phiz," who rightly retains the premier position among Dickens's Illustrators, placed very little value upon his tentative drawings, which, as soon as they had served their purpose, were either thrown upon the fire or given away incontinently to those who had the foresight to ask for them. Fortunately, the recipients were discriminating enough to treasure these pencillings, many of them having since been transferred to the portfolios of collectors. For the privilege of reproducing interesting examples I am indebted to Her Grace the[Pg x] Duchess of St. Albans, Mr. J. F. Dexter, Mr. M. H. Spielmann, Mr. W. H. Lever, Messrs. Robson & Co., the Committee of Nottingham Castle Museum, and others. I am especially grateful to Mr. Augustin Daly, of New York, for so generously permitting me to photograph the famous "Pickwick" drawings by Seymour, together with a hitherto unpublished portrait of that artist. The portrait of Dickens forming the frontispiece to this volume is reproduced from a unique impression of a very scarce lithograph in the possession of Mr. Stuart M. Samuel.

In order to give an effect of continuity to my Notes, I have lightly sketched the career of each Artist, introducing in chronological sequence the facts relating to his designs for Dickens. In several cases, the proof-sheets of these chapters have been revised by the representatives of the Artists to whom they refer, and for valued aid in this direction my cordial thanks are due to the Rev. A. J. Buss, Mr. Field Stanfield, Mr. A. H. Palmer, and Mr. F. W. W. Topham. Those of Dickens's Illustrators who are still with us have furnished me with much information, and have kindly expressed their approval of what I have written concerning them. I therefore avail myself of this opportunity of tendering my sincere thanks, for assistance thus rendered, to Mr. Marcus Stone, R.A., Mr. Luke Fildes, R.A., Mr. W. P. Frith, R.A., and Sir John Tenniel, R.I., whose mark of approbation naturally imparts a special value to the present record. I am still further indebted to Mr. Stone and Mr. Fildes for the loan of a number of their original drawings and sketches for Dickens, which have not hitherto been published.

Owing to the circumstance that many of the so-called "Extra" Illustrations are now extremely rare, my list of them could never have been compiled but for advantages afforded me by collectors, in[Pg xi] allowing me to have access to their Dickensiana. The kind offices of Mr. W. R. Hughes, Mr. Thomas Wilson, Mr. W. T. Pevier, and Mr. W. T. Spencer are gratefully acknowledged in this connection, as well as those of Mr. Dudley Tenney of New York, who has rendered me signal service in respect of American Illustrations.

To Forster's "Life of Dickens" and to the published "Letters" I am naturally beholden for information not otherwise procurable, while certain interesting details concerning "Phiz's" drawings and etchings are quoted from Mr. D. C. Thomson's "Life and Labours of Hablôt K. Browne," which is more extended in its general scope than my previously-issued Memoir of the artist.

I am privileged to associate the names of Miss Hogarth and Mrs. Perugini with this account of Charles Dickens and his collaborateurs; to the former I am obliged for permission to print some of the Novelist's correspondence which has never previously been made public, while the latter has favoured me with the loan of photographic portraits. Finally, I must express my indebtedness for much valuable aid to George Cattermole's daughter, Mrs. Edward Franks, the "cousin" to whom the Novelist alluded in a letter to her father dated February 26, 1841, and to whose "clear blue eyes" he desired to be commended.

F. G. KITTON.

St. Albans, September 1898.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | vii |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | xv |

| GEORGE CRUIKSHANK | 1 |

| ROBERT SEYMOUR | 29 |

| ROBERT W. BUSS | 47 |

| HABLÔT K. BROWNE ("PHIZ") | 58 |

| GEORGE CATTERMOLE | 121 |

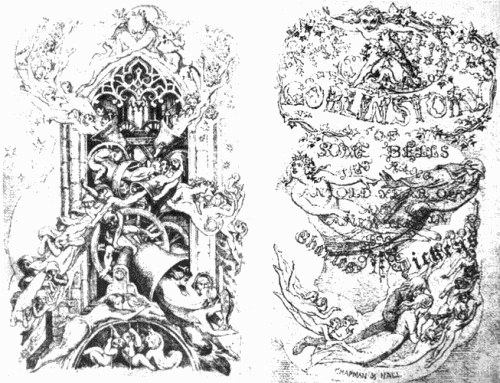

| ILLUSTRATORS OF THE CHRISTMAS BOOKS | 136 |

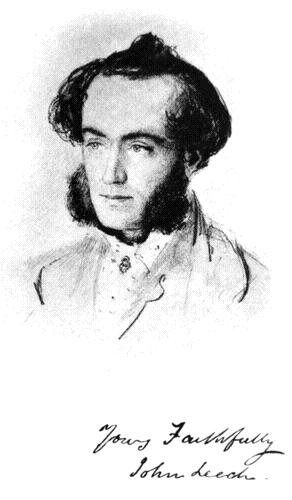

| JOHN LEECH | 138 |

| RICHARD DOYLE | 149 |

| CLARKSON STANFIELD, R.A. | 153 |

| DANIEL MACLISE, R.A. | 161 |

| SIR JOHN TENNIEL | 172 |

| FRANK STONE, A.R.A. | 175 |

| SIR EDWIN LANDSEER, R.A. | 180 |

| SAMUEL PALMER | 182 |

| F. W. TOPHAM | 189 |

| MARCUS STONE, R.A. | 192 |

| LUKE FILDES, R.A. | 204 |

| I. | ILLUSTRATORS OF CHEAP EDITIONS | 219 |

| II. | CONCERNING "EXTRA ILLUSTRATIONS" | 227 |

| III. | DICKENS IN ART | 243 |

| INDEX | 249 |

The Frontispiece Portrait of Charles Dickens was photo-engraved by Mr. E. Gilbert Hester, and the Collotype Plates were prepared and printed by Mr. James Hyatt.

[Pg xvii]

[Pg xviii]

[Pg xix]

[Pg xx]

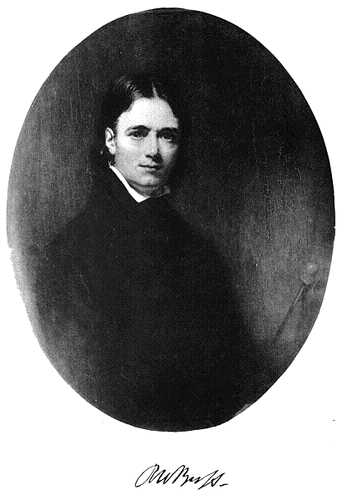

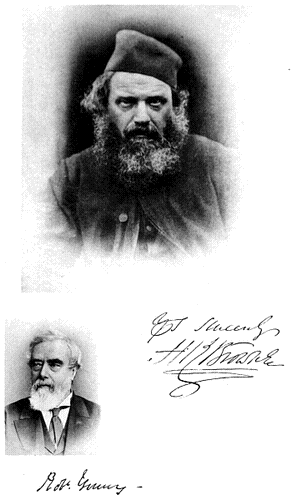

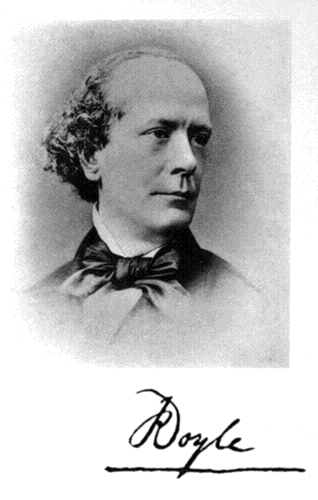

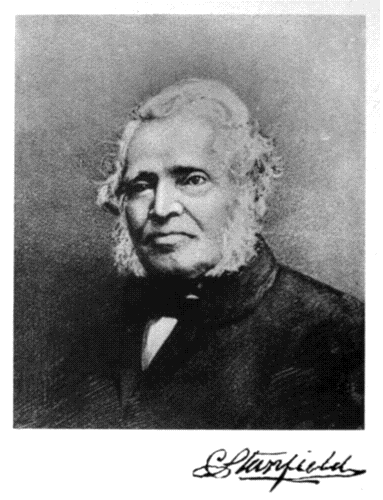

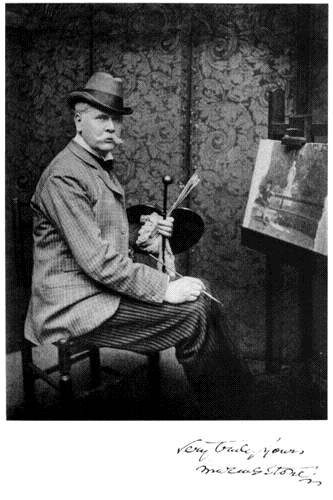

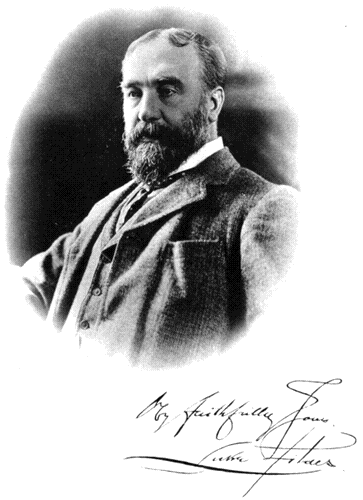

Plate II

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

From the Lithograph by

BAUGNIET

This Portrait is a reproduction of a proof impression, showing the retouching by Cruikshank himself.

First Start in Life—Early Productions—"Sketches by Boz"—Introduction to Dickens—First and Second Series of the "Sketches"—Extra Plates—Additional Designs for the Complete Edition—Portraiture of Artist and Author—Historic Value of Cruikshank's Illustrations—Some Slight Inaccuracies—Frontispiece of the First Cheap Edition—Tentative Sketches and Unused Designs—"Oliver Twist"—Incongruities Detected in a Few of the Plates—Thackeray's Eulogium—Working Tracings and Water-Colour Replicas—Trial Sketches—A Note from Cruikshank to Dickens—Sketches of Bill Sikes in the Condemned Cell—How the Design for "Fagin in the Condemned Cell" was Conceived—A Criticism by Ruskin—The Cancelled Plate—Cruikshank's Claim to the Origin of "Oliver Twist"—Designs for Dickens's Minor Writings in Bentley's Miscellany—"The Lamplighter's Story"—Cruikshank's Last Illustration for Dickens—"Frauds on the Fairies"—The Artist's Remuneration—Death.

The name of George Cruikshank, which stands first in the long and imposing list of Dickens Illustrators, is familiar to every one as that of a pencil humorist of no common calibre, whose genius as a designer and whose marvellous skill as an etcher have evoked enthusiastic praise from John Ruskin and other eminent critics. He undoubtedly inherited his artistic talent from his father, who was not only an etcher and engraver, but (as George himself has recorded) "a first-rate water-colour draughtsman." So experienced an artist was therefore thoroughly capable of training his sons, George and Isaac Robert, for the same profession.

Like most boys, George dreamt of the sea, aspiring to become a second Captain Cook; but, happily, the death of his father compelled him to take up seriously the work of designing, in order that he might assist in maintaining his mother and sister. His first start[Pg 2] in life originated in a publisher seeing some of his sketches, which indicated such unusual talent that he was immediately engaged to illustrate children's books, songs, and other cheap literature peculiar to the period. Then the young artist essayed the more profitable arena of political caricaturing, distinctly making his mark as a satirist Realising at this time his imperfections as a draughtsman, he determined to acquire the art of drawing with correctness, entering the Royal Academy as a student; but, finding it difficult to work on pedantic lines, his resolution soon waned, and, after one course of study, he left the place for a short interval of—forty years! Although he never became the learned artist, nor was able to draw with academic accuracy, he wielded his pencil with a facility and vigour that delighted all beholders, and this deftness, combined with a remarkable sense of humour and satire, speedily brought him commissions from every quarter.

It was as a book-illustrator that George Cruikshank undoubtedly excelled, and some idea of his industry in this direction (during a period of eighty years of his busy life) may be obtained from G. C. Reid's comprehensive catalogue of his works, where we find enumerated more than five thousand illustrations on paper, wood, copper, and steel. This, however, by no means exhausts the list, for the artist survived the publication of the catalogue several years, and was "in harness" to the end of his long career. If the works described by Mr. Reid be supplemented by the profusion of original sketches and ideas for his finished designs, the number of Cruikshank's productions may be estimated at about fifteen thousand!

Before his introduction to Charles Dickens in 1836, the versatile artist had adorned several volumes, which, but for his striking illustrations, would probably have enjoyed but a brief popularity. His etchings and drawings on wood are invariably executed in an exceedingly delicate manner, at the same time preserving a breadth of effect unequalled by any aquafortiste of his day. "Only those who know the difficulties of etching," observes Mr. P. G. Hamerton, "can[Pg 3] appreciate the power that lies behind his unpretending skill; there is never, in his most admirable plates, the trace of a vain effort."

Sketches by Boz, 1833-36.Dickens's clever descriptions of "every-day life and every-day people" were originally printed in the Monthly Magazine, the Evening Chronicle and the Morning Chronicle, Bell's Life in London, and "The Library of Fiction," and subsequently appeared in a collected form under the general title of "Sketches by Boz." Early in 1836 Dickens sold the entire copyright of the "Sketches" to John Macrone, of St. James's Square, who published a selection therefrom in two duodecimo volumes, with illustrations by George Cruikshank. It was at this time that Charles Dickens first met the artist, who was his senior by about a score of years, and already in the enjoyment of an established reputation as a book-illustrator. That the youthful author, as well as his publisher, realised the value of Cruikshank's co-operation is manifested in the Preface to the "Sketches," where Dickens, after appropriately comparing the issue of his first book to the launching of a pilot balloon, observes: "Unlike the generality of pilot balloons which carry no car, in this one it is very possible for a man to embark, not only himself, but all his hopes of future fame, and all his chances of future success. Entertaining no inconsiderable feeling of trepidation at the idea of making so perilous a voyage in so frail a machine, alone and unaccompanied, the author was naturally desirous to secure the assistance and companionship of some well-known individual, who had frequently contributed to the success, though his well-known reputation rendered it impossible for him ever to have shared the hazard, of similar undertakings. To whom, as possessing this requisite in an eminent degree, could he apply but to George Cruikshank? The application was readily heard and at once acceded to; this is their first voyage in company, but it may not be the last." Each of the two volumes contains eight illustrations, and it may justly be said of these little vignettes that they are among the[Pg 4] artist's most successful efforts with the needle. Although highly popular from the beginning, the "Sketches" were now received with even greater fervour, and several editions were speedily called for. As the late Mr. G. A. Sala contended, the coadjutorship of so experienced a draughtsman as George Cruikshank, who knew London and London life "better than the majority of Sunday-school children know their Catechism," was of real importance to the young reporter of the Morning Chronicle, with whose baptismal name (be it remembered) his readers and admirers were as yet unacquainted.

During the following year (1837) Macrone published a Second Series of the "Sketches" in one volume, uniform in size and character with its predecessors, and containing ten etchings by Cruikshank; for the second edition of this extra volume two additional illustrations were done, viz., "The Last Cab-Driver" and "May-day in the Evening."[1] It was at this time that Dickens repurchased from Macrone the entire copyright of the "Sketches," and arranged with Chapman & Hall for a complete edition, to be issued in shilling monthly parts, octavo size, the first number appearing in November of that year. The completed work contained all the Cruikshank plates (except that entitled "The Free and Easy," which, for some unexplained reason, was cancelled) and the following new subjects: "The Parish Engine," "The Broker's Man," "Our Next-door Neighbours," "Early Coaches," "Public Dinners," "The Gin-Shop," "Making a Night of It," "The Boarding-House," "The Tuggses at Ramsgate," "The Steam Excursion," "Mrs. Joseph Porter," and "Mr. Watkins Tottle."

Cruikshank also produced a design for the pink wrapper enclosing each of the twenty monthly parts; this was engraved on wood by John Jackson, the original drawing (adapted from one the artist had previously made for Macrone) being now in the possession of Mr. William Wright, of Paris. The subject of the frontispiece is the same as that of the title-page in the Second Series. The alteration in the size of the illustrations for this cheap edition necessitated larger plates, so that the artist was compelled to re-etch his designs. These reproductions, although on an extended scale, were executed with even a greater degree of finish, and contain more "colour" than those in the first issue; but the general treatment of the smaller etchings is more pleasing by reason of the superior freedom of line therein displayed. As might be anticipated, a comparison of the two sets of illustrations discloses certain slight variations, which are especially noticeable in the following plates: "Greenwich Fair;" musicians and male dancer added on left. "Election for Beadle;" three more children belonging to Mr. Bung's family on right, and two more of Mr. Spruggins's family on left, thus making up the full complement in each case. "The First of May" (originally entitled "May-day in the Evening"); the drummer on the left, in the first edition, looks straight before him, while in the octavo edition he turns his face towards the girl with the parasol. "London Recreations;" in the larger design the small child on the right is stooping to reach a ball, which is not shown in the earlier plate.

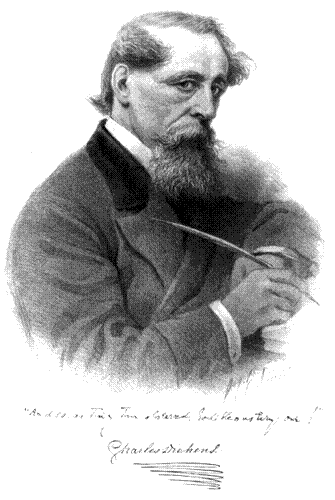

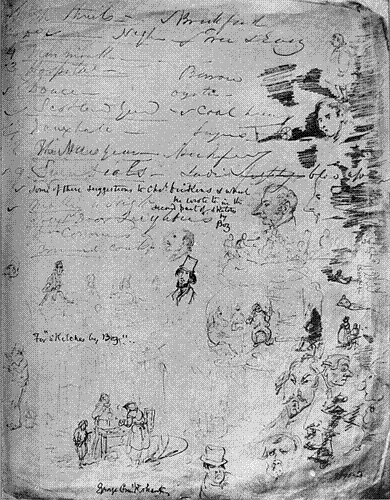

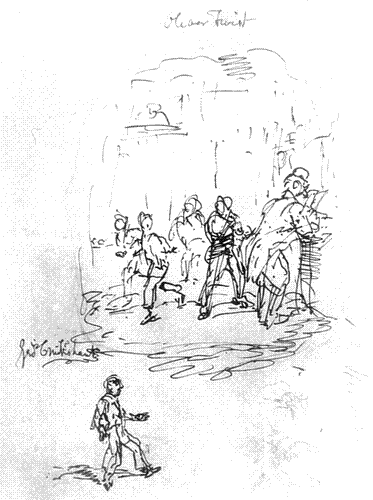

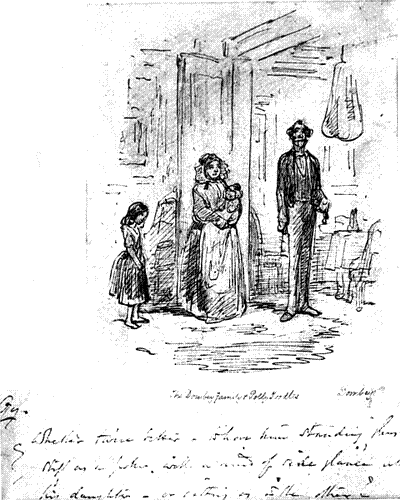

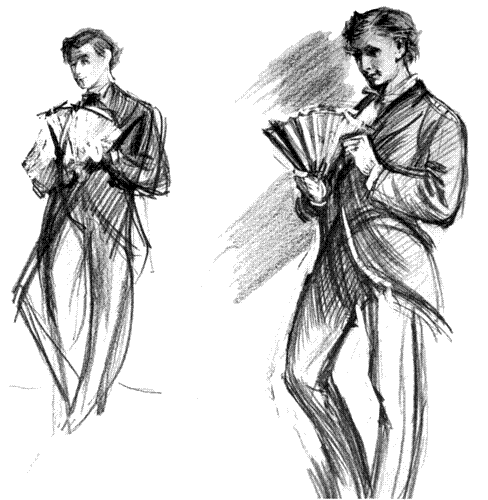

Plate III

"JEMIMA EVANS"

Facsimile of Unused Designs for "Sketches by Boz" by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

Additional interest is imparted to some of the etchings in "Sketches by Boz" owing to the introduction by the artist of portraits of Charles Dickens and himself, there being no less than five delineations of the face and figure of the youthful "Boz" as he then appeared. In the title-page of the Second Series (as well as in the reproduction of it in the octavo edition), the identity of the two individuals waving flags in the car of the balloon has been pointed out by Cruikshank, who wrote on the original pencil-sketch, "The parties going up in the balloon are intended for the author and the artist,"—which may be considered a necessary explanation, as the likenesses are not very apparent.

In the plates entitled "Early Coaches," "A Pickpocket in

Custody," and "Making a Night of It," Cruikshank has similarly[Pg 5]

[Pg 6]

attempted to portray his own lineaments and those of Dickens; he

was more successful, however, in the illustration to "Public Dinners,"

where the presentments of himself and the novelist, as stewards

carrying official wands, are more life-like. There exist, by the way,

several seriously-attempted portraits of Dickens by Cruikshank, concerning

the earliest of which it is related that author and artist were

members of a club of literary men known during its brief existence as

"The Hook and Eye Club," and that at one of their nightly meetings

Dickens was seated in an arm-chair conversing, when Cruikshank

exclaimed, "Sit still, Charley, while I take your portrait!" This

impromptu sketch, now the property of Colonel Hamilton, has been

etched by F. W. Pailthorpe, and a similar drawing is included in

the Cruikshank Collection at South Kensington. Among other contemporary

portrait-studies (executed in pencil and slightly tinted in

colour) is one bearing the following inscription in the artist's autograph:

"Charles Dickens, Author of Sketches by Boz, the Pickwick Papers,

&c., &c., &c.,"—an admission that seems to dispose of Cruikshank's

subsequent claim to the authorship of "Pickwick."

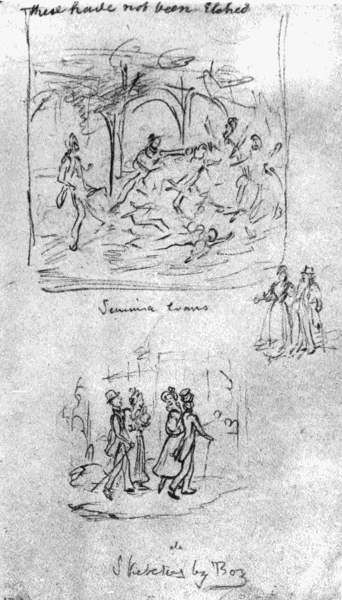

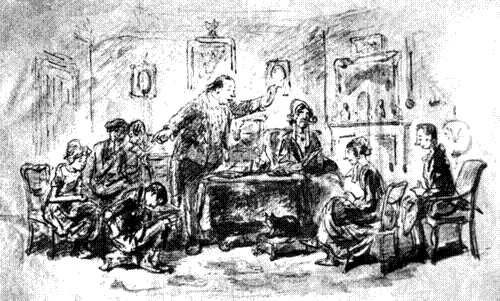

Plate IV

"THE FOUR MISS WILLISES"

Facsimile of an Unused Design for "Sketches by Boz" by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

It has been remarked that Cruikshank was so accurate in the rendering of details that future antiquaries will rely upon his plates as authoritative in matters of architecture, costume, &c. For example, in the etching of "The Last Cab-Driver," he has depicted an obsolete form of cabriolet, the driver being seated over the right wheel; and in that of "The Parish Engine" we may discover what kind of public fire-extinguisher was then in use—a very primitive implement in comparison with the modern "steamer." In the latter plate, by the way, we behold the typical beadle of the period, who afterwards figured as Bumble in "Oliver Twist." Apropos of this etching, Mr. Frederick Wedmore points out (in Temple Bar, April 1878) that it is "an excellent example of Cruikshank's eye for picturesque line and texture in some of the commonest objects that met him in his walks: the brickwork of the house, for instance, prettily indicated, the woodwork of the outside shutters, and the window, on which various lights are pleasantly broken. I know no artist," he continues, "so alive as Cruikshank to the pretty sedateness of Georgian architecture. Then, too, there is the girl with basket on arm, a figure not quite ungraceful in line and gesture. She might have been much better if Cruikshank had ever made himself that accurate draughtsman of the figure which he hardly essayed to be, and she and all her fellows—it is only fair to remember—might have been better, again, had the artist who designed her done his finest work in a happier period of English dress." Mr. Wedmore alludes to another etching in "Sketches by Boz" as being "perhaps the best of all in Cruikshank as proof of that sensitive eye for what is picturesque and characteristic in every-day London. It is called 'The Streets, Morning,' the design somewhat empty of 'subject,' only a comfortable sweep who does not go up the chimney, and a wretched boy who does, are standing at a stall taking coffee, which a woman, with pattens striking on pavement and head tied up close in a handkerchief, serves to the scanty comers in the early morning light. A lamp-post rises behind her; the closed shutters of the baker are opposite; the public-house of the Rising Sun has not yet opened its doors; at some house-corner further off a solitary figure lounges homeless; beyond, pleasant light morning shadows cross the cool grey of the untrodden street; a church tower and spire rise in the delicate distance, where the turn of the road hides the further habitations of the sleeping town."

It may be hypercritical to resent, on the score of inaccuracy, an

occasional oversight on the part of Cruikshank; but it is nevertheless

interesting to note that in the plate entitled "Election for Beadle,"

Cruikshank has omitted from the inscription on Spruggins's placard

a reference to "the twins," the introduction of which caused that

candidate to become temporarily a favourite with the electors; in

"Horatio Sparkins," the "dropsical" figure of seven (see label on

right) is followed by a little "1/2d." instead of the diminutive "3/4d."

mentioned in the text; in "The Pawnbroker's Shop" it will be

observed that the words "Money Lent" on the glass door should[Pg 7]

[Pg 8]

appear reversed, so as to be read from the outside; while in the

etching illustrating "Private Theatres," the artist has forgotten to

include the "two dirty men with the corked countenances," who are

specially referred to in the "Sketch."

The first cheap edition of "Sketches by Boz," issued by Chapman & Hall in 1850, contained a new frontispiece, drawn on wood by Cruikshank, representing Mr. Gabriel Parsons being released from the kitchen chimney,—an incident in "Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle."

George Cruikshank not unfrequently essayed several "trial" designs before he succeeded in realising to his satisfaction the subject he aimed at portraying. Some of these are extremely slight pencil notes—"first ideas," hastily made as soon as conceived—while others were subjected to greater elaboration, and differing but slightly, perhaps, from the etchings; on certain drawings are marginal memoranda—such as studies of heads, expressions, and attitudes—which are valuable as showing how the finished pictures were evolved. The majority of the designs are executed in pencil, while a few are drawn with pen-and-ink; occasionally one may meet with a sketch in which the effect is broadly washed in with sepia or indian-ink, and, more rarely still, with a drawing charmingly and delicately wrought in water-colours. Besides original sketches, the collection at the South Kensington Museum contains a series of working tracings, by means of which the artist transferred his subjects to the plates. There are no less than three different suggestions for the frontispiece of the first cheap edition of "Sketches by Boz," together with various renderings of the design for the wrapper of the first complete edition, in which the word "Boz" in the title constitutes a conspicuous feature, being formed of the three letters superimposed, while disposed about them are several of the prominent characters. Probably the most interesting in this collection is a sheet of slight sketches signed by the artist, although they are merely tentative jottings for his etchings. One of these pencillings (an unused subject) represents a [Pg 9]man proposing a toast at a dinner-table, doubtless intended as an illustration for "Public Dinners"; and here, too, are marginal studies of heads—including one of a Bill Sikes type—together with a significant note (apparently of a later date) in the autograph of Cruikshank, which reads thus: "Some of these suggestions to Chas. Dickens, and which he wrote to in the second part of 'Sketches by Boz'!"

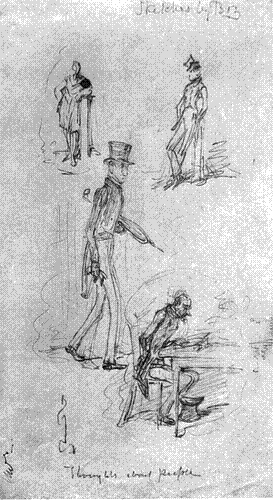

Plate V

"THOUGHTS ABOUT PEOPLE"

Facsimile of an Unused Design for "Sketches by Boz" by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

A large number of studies for "Sketches by Boz" may also be seen in the Print Room of the British Museum, many of which are very slight. In some instances we find the same subject rendered in different ways, and it is worthy of note that a few of these designs were never etched; among the most remarkable of the unused sketches is a rough drawing for the wrapper of the monthly parts (octavo edition), with ostensible portraits of author and artist introduced. This collection includes "first ideas" for "Thoughts about People," "Hackney Coaches," "The Broker's Man," &c., and a careful examination shows that the sketches for the plates illustrating "Seven Dials" and "The Pickpocket in Custody" are entitled by the artist "Fight of the Amazons" and "The Hospital Patient" respectively. In one of the trial sketches for "The Last Cabman," the horse is represented as having fallen to the ground, the passenger being violently ejected from the vehicle.

Oliver Twist, 1837-39.On August 22, 1836, Charles Dickens entered into an agreement with Richard Bentley to edit a new monthly magazine called Bentley's Miscellany, and to furnish that periodical with a serial tale. George Cruikshank's services as illustrator were also retained, and his design for the wrapper inspired Maginn to indite, for "The Bentley Ballads," the "Song of the Cover," whence this characteristic verse is quoted:—

The first number of the Miscellany was issued in January 1837, and in February appeared the initial chapter of the editor's story, entitled "Oliver Twist, or, the Parish Boy's Progress," which was continued in succeeding numbers until its completion in March 1839, with etchings by Cruikshank.

The dramatic character of this stirring romance of low London life afforded the artist unusual scope for the display of his talent; indeed, his powerful pencil was far more suited to the theme than that of any of his contemporaries. The principal scenes in the novel proved most attractive to him, and he fairly revelled in delineating the tragic episodes associated with the career of Fagin and Sikes. These twenty-four etchings are on the same scale as those in the first collected edition of the "Sketches," but they are broader and more effective in treatment. In October 1838,—that is, about five months before completion in the Miscellany,—the entire story was issued by Chapman & Hall in three volumes post octavo, and there can be no doubt that its remarkable success was brought about in no small measure by Cruikshank's inimitable pictures. Nearly eight years later (in January 1846) a cheaper edition, containing all the illustrations, was commenced in ten monthly parts, demy octavo, and subsequently published in one volume by Bradbury & Evans. On the cover for the monthly numbers Cruikshank has portrayed eleven of the leading incidents in the story, some of the subjects being entirely new, while others are practically a repetition of the etched designs. The plates in this edition, having suffered from previous wear-and-tear, were subjected to a general touching-up, as a comparison with the earlier issue clearly indicates, such reparation (carried out by an engraver named Findlay, much to Cruikshank's annoyance) being especially noticeable in cases where "tones" have been added to wall-backgrounds and other parts of the designs. Apart from actual proof impressions, the "Oliver Twist" etchings are naturally to be found in their best state in Bentley's Miscellany, where they are seen in their pristine beauty. In some of the plates it will be observed that Cruikshank has introduced "roulette" (or dotted) work with excellent effect, although, of course, this disqualifies them as examples of pure etching. The first cheap edition of "Oliver Twist," issued in 1850 by Chapman & Hall, contains a frontispiece only by George Cruikshank, representing Mr. Bumble and Oliver in Mrs. Mann's parlour, as described in the second chapter.

Plate VI

"THE PARISH ENGINE"

Facsimile of the Original Drawing for the First Octavo Edition of

"Sketches by Boz" by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

It has been said that Cruikshank could not draw a pretty woman.

At any rate, he neglected his opportunity in "Oliver Twist," for he

fails in so depicting Rose Maylie, while his portrayal of Nancy is particularly

ugly and repelling, whereas she certainly possessed physical

charms not unfrequently found in women of her class. Although the

artist has imparted too venerable an appearance to the Artful Dodger,

he has seized in a wonderful manner the characteristics of criminal

types in his rendering of Fagin and Bill Sikes. In many of Cruikshank's

etchings the accessories are very àpropos, and sometimes not

without a touch of quiet humour. For example, in the plate representing

Oliver recovering from the fever, there is seen over the

chimney-piece a picture of the Good Samaritan, in allusion to Mr.

Brownlow's benevolent intentions with respect to the invalid orphan;

while in that depicting Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney taking tea,

may be noticed the significant figure of Paul Pry on the mantelshelf.

Some of the designs are marked by slight incongruities, which,

however, do not detract from their interest. In the etching "Oliver

Plucks up a Spirit," it will be observed that the small round table

which the persecuted lad overthrows during his desperate attack

upon Noah Claypole could not possibly assume, by such accidental

means, the inverted position as here shown. In the plate entitled

"The Evidence Destroyed," the lantern (according to the text) should[Pg 11]

[Pg 12]

have been lowered into the dark well, but doubtless the error was

intentional on the part of the artist, in order to secure effect; in

"Mr. Fagin and his Pupil Recovering Nancy," the girl is represented

as being exceedingly robust, whereas she was really "so reduced with

watching and privation as hardly to be recognised as the same Nancy."

Again, in the illustration depicting Sikes attempting to destroy his

dog, we see in the distance the dome of St. Paul's, while, as a matter

of fact, the desperate ruffian had not reached a point so near the

metropolis when he thought of drowning the faithful animal.[2] In

"The Last Chance," where the robber contemplates dropping from

the roof of Fagin's house to escape his pursuers, the rope (described

in the letterpress as being thirty-four feet long) is barely half that

length, and could never have extended to the ground; while the dog,

who lay concealed until his master had tumbled off the parapet, must

have been distinctly visible to all observers if he stood so prominently

on the ridge-tiles as here indicated. The latter etching is one

of the most fascinating of the series, for here Cruikshank has realised

every feature of the dramatic scene,—the harassed expression on

the evil face of the hunted criminal, the squalid tenements half

shrouded by approaching darkness, the excitement of the people

crowding the windows of the opposite houses; indeed, the tragic

and repulsive element in the picture constitutes a remarkable effort

on the part of the artist.

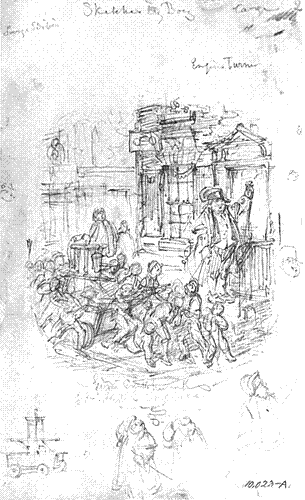

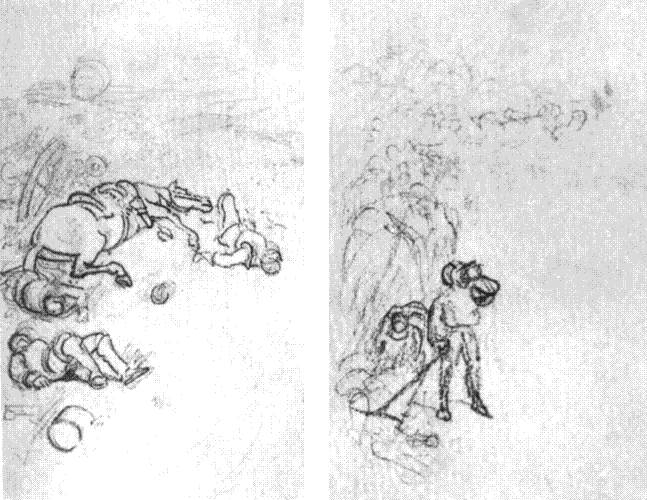

Plate VII

STUDIES FOR SCENES AND CHARACTERS IN "SKETCHES BY BOZ"

Facsimile of the Original Sketches by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

In the centre of the sheet the Artist has written: "Some of these suggestions to Chas. Dickens, and which he wrote to in the second part of 'Sketches by Boz.'"

In considering the story as a whole, it is difficult to say how much of the powerful impression we are conscious of may be due to the illustrator. In his famous eulogy on Cruikshank, Thackeray remarked: "We are not at all disposed to undervalue the works and genius of Mr. Dickens, and we are sure that he would admit as readily as any man the wonderful assistance that he has derived from the artist who has given us portraits of his ideal personages, and made [Pg 13]them familiar to all the world. Once seen, these figures remain impressed on the memory, which otherwise would have had no hold upon them, and the Jew and Bumble, and the heroes and heroines of the Boz Sketches, become personal acquaintances with each of us. O that Hogarth could have illustrated Fielding in the same way! and fixed down on paper those grand figures of Parson Adams, and Squire Allworthy, and the great Jonathan Wild." Again, with more especial reference to the "Oliver Twist" designs, the kindly "Michael Angelo Titmarsh" wrote: "The sausage scene at Fagin's; Nancy seizing the boy; that capital piece of humour, Mr. Bumble's courtship, which is even better in Cruikshank's version than in Boz's exquisite account of the interview; Sykes's[3] farewell to his dog; and the Jew—the dreadful Jew—that Cruikshank drew! What a fine touching picture of melancholy desolation is that of Sykes and the dog! The poor cur is not too well drawn, the landscape is stiff and formal; but in this case the faults, if faults they be, of execution rather add to than diminish the effect of the picture; it has a strange, wild, dreary, broken-hearted look; we fancy we see the landscape as it must have appeared to Sykes, when ghastly and with bloodshot eyes he looked at it. As for the Jew in the dungeon, let us say nothing of it—what can we say to describe it?"

The complete set of twenty-four working tracings of the original designs for "Oliver Twist," some of which exhibit variations from the finished etchings, realised £140 at Sotheby's in March 1892. Water-colour replicas of all the subjects were prepared by Cruikshank in 1866 for Mr. F. W. Cosens, which the artist supplemented by thirteen smaller drawings and a humorous title-page, the entire series being reproduced in colour for an edition de luxe of "Oliver Twist," published by Chapman & Hall in 1894. The Cruikshank Collections in the British and South Kensington Museums include many of the artist's sketches and "first ideas" for the "Oliver Twist" [Pg 14]plates, as well as a number of the matured designs. Here are several trial sketches for the monthly wrapper of the first octavo edition, executed in pencil with slight washes of sepia added; the original drawings for "Rose Maylie and Oliver" (known to collectors as the "Fireside" plate, to which reference will presently be made), and for "Mr. Bumble Degraded in the Eyes of the Paupers" (with marginal sketches), the title of which is appended in Dickens's autograph, where, instead of "the eyes," the word "presence" was originally written. Here, also, we find the first sketch of Noah Claypole enjoying an oyster-supper, with the following query written by the artist: "Dr. Dickens, 'Title' wanted—will any of these do? Yours, G. Ck." The proposed titles are then given, thus: "Mr. Claypole Astonishing Mr. Bumble and 'the Natives';" "Mr. Claypole Indulging;" "Mr. Claypole as he Appeared when his Master was Out,"—the latter being adopted. On the back of a pen-and-ink drawing of "Oliver's Reception by Fagin and the Boys," Cruikshank suggested a different title, viz., "Oliver Introduced to the Old Gentleman by Jack Dawkins." A beautiful little water-colour drawing of the subject, entitled "Oliver Introduced to the Respectable Old Gentleman," is in the Print Room of the British Museum, where we may also discover a portrait of Oliver himself—a profile study of the head as seen in the drawing now referred to. On the back of a sketch of Mr. Brownlow at the bookstall (for the plate entitled "Oliver Amazed at the Dodger's Mode of 'Going to Work'") is the rough draft of an unsigned note in the autograph of Cruikshank, evidently addressed to Dickens:—

"Thursday Eg., June 15, '37.

"My dear Sir,—Can you let me have a subject for the second Plate? The first is in progress. By the way, would you like to see the Drawing? I can spare it for an hour or two if you will send for it."

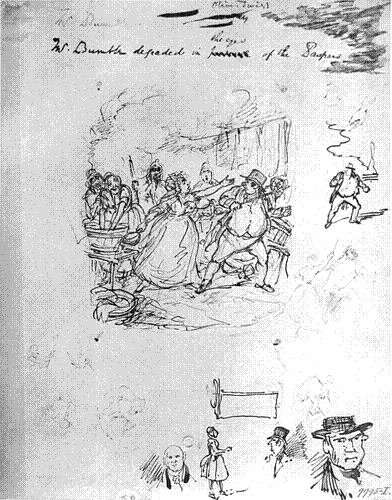

Plate VIII

"MR. BUMBLE DEGRADED IN THE EYES OF THE

PAUPERS"

Facsimile of the Original Sketch for "Oliver Twist" by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

The Inscription above the Sketch is in the Autograph of Dickens.

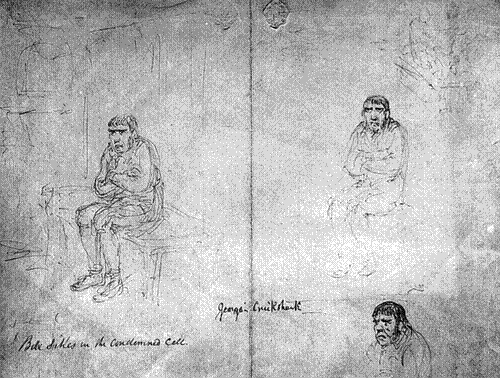

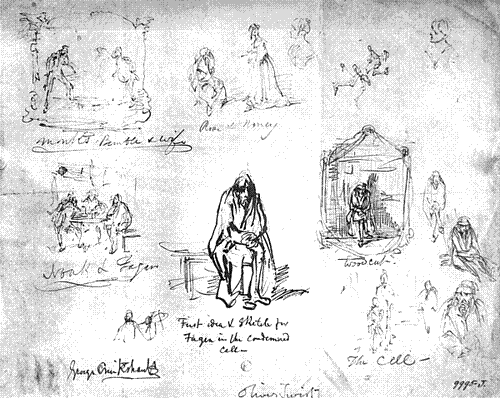

I am enabled to reproduce in facsimile a very interesting sheet of sketches for prominent characters in "Oliver Twist," containing no less than five studies of Fagin, including the "first idea" for the famous etching of the Jew in the condemned cell. Still more noteworthy are four studies of Bill Sikes in the condemned cell, evidently made early in the progress of the book, thus seeming to indicate that the artist conjectured this would be the fate of the burglar instead of the Jew; or is it possible that the existence of these studies may be considered as a corroboration of his assertion (in a letter to the Times, presently to be quoted) that he, and not Dickens, must be credited with the idea of putting either Sikes or Fagin in the cell?

Concerning Cruikshank's powerful conception of Fagin in the

condemned cell ("the immortal Fagin of 'Oliver Twist,'" as

Thackeray styled him), it is related by Mr. George Hodder (in

"Memories of my Time") that when the great George brought forth

this picture, where the Jew is seen biting his finger-nails and suffering

the tortures of remorse and chagrin, Horace Mayhew took an opportunity

of asking him by what mental process he had conceived such an

extraordinary notion; and his answer was, that he had been labouring

at the subject for several days, but had not succeeded in getting the

effect he desired. At length, beginning to think the task was almost

hopeless, he was sitting up in bed one morning, with his hand

covering his chin and the tips of his fingers between his lips, the

whole attitude expressive of disappointment and despair, when he

saw his face in a cheval-glass which stood on the floor opposite

to him. "That's it!" he involuntarily exclaimed; "that's just the

expression I want!" and by this accidental process the picture was

formed in his mind. Many years afterwards Cruikshank declared

this statement to be absurd, and when interrogated by Mr. Austin

Dobson, who met the artist at Mr. Frederick Locker's house in 1877,

he said he had never been perplexed about the matter, but attributed

the story to the fact that, not being satisfied whether the knuckles

should be raised or depressed, he had made studies of his own hand

in a glass, and illustrated his account by putting his hand to his

mouth, looking, with his hooked nose, wonderfully like the character[Pg 15]

[Pg 16]

he was speaking of. Respecting another illustration in the story,

where "The Jew and Morris Bolter begin to Understand each Other,"

Professor Ruskin observes that it is "the intensest rendering of

vulgarity, absolute and utter," with which he is acquainted.

The latter portion of "Oliver Twist" was written in anticipation of the magazine, in order that the complete story might be promptly launched in volume form. The illustrations for the final chapters had consequently to be produced simultaneously and with all possible speed, so that the artist had no time to submit his designs to Dickens. One of these plates, viz., "Rose Maylie and Oliver," depicted a scene in the new home of the Rev. Harry Maylie; he, his wife, and mother, are seated by the fire, while Oliver stands by Rose Maylie's side. When Dickens first saw this etching he so strongly disapproved of it that the plate was forthwith cancelled and another design substituted; but, the book being then on the eve of publication, it was impossible to prevent a small number of impressions of this illustration being circulated, and copies of the work containing the scarce "Fireside" plate are therefore eagerly sought after by collectors. Dickens, in expressing to Cruikshank his disapprobation of this etching, undoubtedly realised the delicacy of the situation, in the possibility of injuring the susceptibilities of the artist, as the following carefully-worded intimation testifies:—

"I returned suddenly to town yesterday afternoon, to look at the latter pages of 'Oliver Twist' before it was delivered to the booksellers, when I saw the majority of the plates in the last volume for the first time.

"With reference to the last one—Rose Maylie and Oliver—without entering into the question of great haste, or any other cause, which may have led to its being what it is, I am quite sure there can be little difference of opinion between us with respect to the result. May I ask you whether you will object to designing this plate afresh, and doing so at once, in order that as few impressions as possible of the present one may go forth?

"I feel confident you know me too well to feel hurt by this enquiry, and, with equal confidence in you, I have lost no time in preferring it."

Plate IX

"MR. CLAYPOLE AS HE APPEARED WHEN HIS

MASTER WAS OUT"

Facsimile of the Original Sketch for "Oliver Twist" by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

The Inscriptions are in the Autograph of the Artist.

It seems, however, that Cruikshank did not immediately proceed to carry out the author's wish, but endeavoured to improve the plate by retouching and adding further tints by means of stippling, &c. In the South Kensington Collection there is an early proof of the etching in which the shadow tints are washed in with a brush, and the fact that these alterations were subsequently carried out is established by the existence of a unique impression of the plate in its second state. This proof was probably submitted to Dickens and again rejected, for no impressions having the stippled additions are known to have been published. The substituted design, bearing the same title as the suppressed one, does not much excel it in point of interest, as the artist himself readily admitted; it represents Rose Maylie and Oliver standing in front of the tablet put up in the church to the memory of Oliver's mother, this etching appearing in Bentley's Miscellany and in all but the earliest copies of the book. The substituted plate (like many others in the volume) was afterwards considerably "touched up," for it will be noticed that in the earlier impressions Rose's dress is light in tone, while subsequently it was changed to black.

A very circumstantial story relative to Cruikshank's connection

with "Oliver Twist" was published in a Transatlantic journal

called The Round Table, and reprinted immediately after Dickens's

death in a biography of the novelist by Dr. Shelton Mackenzie,

who avers that he had been informed that Dickens intended to

locate Oliver in Kent, and to introduce hop-picking and other picturesque

features of the county he knew so well: that the author

changed his purpose, and brought the boy to London: and further,

that for such important alterations in the plot Cruikshank was

responsible. But the more remarkable portion of this narrative

is Dr. Mackenzie's account of his visit to Cruikshank in 1847,[Pg 17]

[Pg 18]

at the artist's house in Myddleton Terrace, Pentonville, concerning

which he writes:—

"I had to wait while he was finishing an etching, for which a printer's boy was waiting. To while away the time, I gladly complied with his suggestion that I should look over a portfolio crowded with etchings, proofs, and drawings, which lay upon the sofa. Among these, carelessly tied together in a wrap of brown paper, was a series of some twenty-five to thirty drawings, very carefully finished, through most of which were carried the now well-known portraits of Fagin, Bill Sikes and his dog, Nancy, the Artful Dodger, and Master Charles Bates—all well known to the readers of 'Oliver Twist'—and many others who were not introduced. There was no mistake about it, and when Cruikshank turned round, his work finished, I said as much. He told me that it had long been in his mind to show the life of a London thief by a series of drawings, engraved by himself, in which, without a single line of letterpress, the story would be strikingly and clearly told. 'Dickens,' he continued, 'dropped in here one day just as you have done, and, while waiting until I could speak with him, took up that identical portfolio and ferreted out that bundle of drawings. When he came to that one which represents Fagin in the condemned cell, he silently studied it for half-an-hour, and told me that he was tempted to change the whole plot of his story; not to carry Oliver Twist through adventures in the country, but to take him up into the thieves' den in London, show what their life was, and bring Oliver safely through it without sin or shame. I consented to let him write up to as many of the designs as he thought would suit his purpose; and that was the way in which Fagin, Sikes, and Nancy were created. My drawings suggested them, rather than his strong individuality suggested my drawings."

Plate X

"OLIVER AMAZED AT THE DODGER'S MODE

OF 'GOING TO WORK'"

Facsimile of the First Sketch for the Etching by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

Forster naturally characterises this story as a deliberate untruth, related with "a minute conscientiousness and particularity of detail that might have raised the reputation of Sir Benjamin Backbite himself," and points out that the artist's version, as here narrated, is completely refuted by Dickens's letter to Cruikshank, which unquestionably proves that the closing illustrations had not even been seen by the novelist until the book was ready for publication. Cruikshank, on reading in the Times a criticism of Forster's biography, in which this charge against Dickens was commented upon, at once indited the following letter to that journal, where it appeared on December 30, 1871:—

"To the Editor of 'The Times.'

"Sir,—As my name is mentioned in the second notice of Mr. John Forster's 'Life of Charles Dickens,' in your paper of the 26th inst., in connection with a statement made by an American gentleman (Dr. Shelton Mackenzie) respecting the origin of 'Oliver Twist,' I shall be obliged if you will allow me to give some explanation upon this subject. For some time past I have been preparing a work for publication, in which I intend to give an account of the origin of 'Oliver Twist,' and I now not only deeply regret the sudden and unexpected decease of Mr. Charles Dickens, but regret also that my proposed work was not published during his life-time. I should not now have brought this matter forward, but as Dr. Mackenzie states that he got the information from me, and as Mr. Forster declares his statement to be a falsehood, to which, in fact, he would apply a word of three letters, I feel called upon, not only to defend the Doctor, but myself also from such a gross imputation. Dr. Mackenzie has confused some circumstances with respect to Mr. Dickens looking over some drawings and sketches in my studio, but there is no doubt whatever that I did tell this gentleman that I was the originator of the story of 'Oliver Twist,' as I have told very many others who may have spoken to me on the subject, and which facts I now beg permission to repeat in the columns of the Times, for the information of Mr. Forster and the public generally.

"When Bentley's Miscellany was first started, it was arranged that[Pg 19]

[Pg 20] Charles Dickens should write a serial in it, and which was to be illustrated by me; and in a conversation with him as to what the subject should be for the first serial, I suggested to Mr. Dickens that he should write the life of a London boy, and strongly advised him to do this, assuring him that I would furnish him with the subject and supply him with all the characters, which my large experience of London life would enable me to do."My idea was to raise a boy from a most humble position up to a high and respectable one—in fact, to illustrate one of those cases of common occurrence, where men of humble origin, by natural ability, industry, honest and honourable conduct, raise themselves to first-class positions in Society. And as I wished particularly to bring the habits and manners of the thieves of London before the public (and this for a most important purpose, which I shall explain one of these days), I suggested that the poor boy should fall among thieves, but that his honesty and natural good disposition should enable him to pass through this ordeal without contamination; and after I had fully described the full-grown thieves (the Bill Sykeses) and their female companions, also the young thieves (the Artful Dodgers) and the receivers of stolen goods, Mr. Dickens agreed to act on my suggestion, and the work was commenced, but we differed as to what sort of boy the hero should be. Mr. Dickens wanted rather a queer kind of chap, and, although this was contrary to my original idea, I complied with his request, feeling that it would not be right to dictate too much to the writer of the story, and then appeared 'Oliver Asking for More;' but it so happened just about this time that an inquiry was being made in the parish of St. James's, Westminster, as to the cause of the death of some of the workhouse children who had been 'farmed out,' and in which inquiry my late friend Joseph Pettigrew (surgeon to the Dukes of Kent and Sussex) came forward on the part of the poor children, and by his interference was mainly the cause of saving the lives of many of these poor little creatures. I called the attention of Mr. Dickens to this inquiry, and said that [Pg 21]if he took up this matter, his doing so might help to save many a poor child from injury and death; and I earnestly begged of him to let me make Oliver a nice pretty little boy, and if we so represented him, the public—and particularly the ladies—would be sure to take a greater interest in him, and the work would then be a certain success. Mr. Dickens agreed to that request, and I need not add here that my prophecy was fulfilled: and if any one will take the trouble to look at my representations of 'Oliver,' they will see that the appearance of the boy is altered after the two first illustrations, and, by a reference to the records of St. James's parish, and to the date of the publication of the Miscellany, they will see that both dates tally, and therefore support my statement.

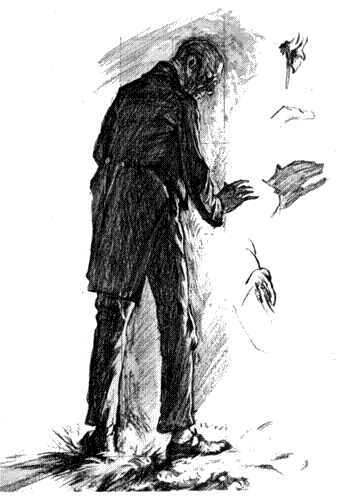

Plate XI

STUDIES FOR BILL SIKES, NANCY, AND THE ARTFUL DODGER

Facsimile of Original Sketches by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANKLent by Messrs. Robson & Co.

"I had, a long time previously to this, directed Mr. Dickens's attention to Field Lane, Holborn Hill, wherein resided many thieves and receivers of stolen goods, and it was suggested that one of these receivers, a Jew, should be introduced into the story; and upon one occasion Mr. Dickens and Mr. Harrison Ainsworth called upon me at my house in Myddleton Terrace, Pentonville, and in course of conversation I then and there described and performed the character of one of these Jew receivers, whom I had long had my eye upon; and this was the origin of 'Fagin.'

"Some time after this, Mr. Ainsworth said to me one day, 'I was so much struck with your description of that Jew to Mr. Dickens, that I think you and I could do something together,' which notion of Mr. Ainsworth's, as most people are aware, was afterwards carried out in various works. Long before 'Oliver Twist' was ever thought of, I had, by permission of the city authorities, made a sketch of one of the condemned cells in Newgate prison; and as I had a great object in letting the public see what sort of places these cells were, and how they were furnished, and also to show a wretched condemned criminal therein, I thought it desirable to introduce such a subject into this work; but I had the greatest difficulty to get Mr. Dickens to allow me to carry out my wishes in this respect; but I said I[Pg 22] must have either what is called a Christian or what is called a Jew in a condemned cell, and therefore it must be 'Bill Sikes' or 'Fagin;' at length he allowed me to exhibit the latter.

"Without going further into particulars, I think it will be allowed from what I have stated that I am the originator of 'Oliver Twist,' and that all the principal characters are mine; but I was much disappointed by Mr. Dickens not fully carrying out my first suggestion.

"I must here mention that nearly all the designs were made from conversation and mutual suggestion upon each subject, and that I never saw any manuscript of Mr. Dickens until the work was nearly finished, and the letter of Mr. Dickens which Mr. Forster mentions only refers to the last etching—done in great haste—no proper time being allowed, and of a subject without any interest; in fact, there was not anything in the latter part of the manuscript that would suggest an illustration; but to oblige Mr. Dickens I did my best to produce another etching, working hard day and night, but when done, what is it? Why, merely a lady and a boy standing inside of a church looking at a stone wall!

"Mr. Dickens named all the characters in this work himself, but before he had commenced writing the story he told me that he had heard an omnibus conductor mention some one as Oliver Twist, which name, he said, he would give the boy, as he thought it would answer his purpose. I wanted the boy to have a very different name, such as Frank Foundling or Frank Steadfast; but I think the word Twist proves to a certain extent that the boy he was going to employ for his purpose was a very different sort of boy from the one introduced and recommended to him by, Sir, your obedient servant,

George Cruikshank.

"Hampstead Road, December 29, 1871."

Plate XII

STUDIES FOR

BILL SIKES IN THE CONDEMNED CELL

Facsimile of Original Sketches by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

In 1872 Cruikshank issued a pamphlet entitled "The Artist and the Author, a Statement of Facts," where he positively asserted that not only was he the actual originator of "Oliver Twist," but also [Pg 23]of many of Harrison Ainsworth's weird romances; that these authors "wrote up to his suggestions and designs," just as Combe did with regard to "Dr. Syntax" and Rowlandson's previously-executed illustrations. In another published letter, dated more than a year prior to that printed in the Times, the artist emphatically declared that the greater part of the second volume of "Sketches by Boz" was written from his hints and suggestions, and he significantly added, "I am preparing to publish an explanation of the reason why I did not illustrate the whole of Mr. Dickens's writings, and this explanation will not at all redound to his credit." Indeed, so thoroughly was he imbued with this conviction, that on April 20, 1874, in responding to a vote of thanks accorded him by the Mayor of Manchester for an address on Intemperance, he reiterated his statement relative to the origin of "Oliver Twist." The Mayor having referred to the artist's designs in Dickens's novels, Cruikshank intimated that the only work of the novelist he had illustrated was "Sketches by Boz"; his worship remarked, "You forget 'Oliver Twist,'" whereupon Cruikshank replied, "That came out of my own brain. I wanted Dickens to write me a work, but he did not do it in the way I wished. I assure you I went and made a sketch of the condemned cell many years before that work was published. I wanted a scene a few hours before strangulation, and Dickens said he did not like it, and I said he must have a Jew or a Christian in the cell. Dickens said, 'Do as you like,' and I put Fagin, the Jew, into the cell. Dickens behaved in an extraordinary way to me, and I believe it had a little effect on his mind. He was a most powerful opponent to Teetotalism, and he described us as 'old hogs.'"[4]

Unfortunately for Cruikshank's claim to the origin of "Oliver Twist," he allowed more than thirty years to elapse before making it public. When questioned on this point he would say that ever since [Pg 24]these works were published, and even when they were in progress, he had in private society, when conversing upon such matters, always explained that the original ideas and characters of these works emanated from him! Mr. Harrison Ainsworth has recorded that Dickens was so worried by Cruikshank putting forward suggestions that he resolved to send him only printed proofs for illustration. In a letter to Forster (January 1838) the novelist wrote, alluding to the severity of his labours: "I have not done the 'Young Gentleman,' nor written the preface to 'Grimaldi,' nor thought of 'Oliver Twist,' or even supplied a subject for the plate," the latter intimation sufficiently indicating that Dickens was more directly concerned in the selection of suitable themes for illustration than Cruikshank would have us believe. The author of "Sketches by Boz" abundantly testified in those remarkable papers that his eyes, like Cruikshank's, had penetrated the mysteries of London; indeed, we find in the "Sketches" all the material for the story of poor Oliver, where it is more artistically and dramatically treated. It is not improbable, of course, that from Cruikshank's familiarity with life in the Great City he was enabled to offer useful hints to the young writer, and even perhaps to make suggestions respecting particular characters; but this constitutes a very unimportant share in the production of a literary work. To what extent the interchange between artist and author was carried can never be satisfactorily determined; but of this there can be no doubt, that Cruikshank's habit of exaggeration, combined with his eagerness in over-estimating the effect of his work, led him (as Mr. Blanchard Jerrold remarks) "into injudicious statements or over-statements," which were sometimes provocative of much unpleasant controversy. It is, however, no exaggeration to say that the pencil of George Cruikshank was as admirable in its power of delineating character as was the mighty pen of Charles Dickens, and that in the success and popularity of "Oliver Twist" they may claim an equal share.

Plate XIII

"FAGIN IN THE CONDEMNED CELL"

Facsimile of a Trial Sketch by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

[Pg 25]Minor Writings in "Bentley's Miscellany." Certain humorous pieces written by Dickens for Richard Bentley were also illustrated by Cruikshank. The first paper, entitled "Public Life of Mr. Tulrumble, once Mayor of Mudfog" (published in January 1837), contains an etching of Ned[5] Twigger in the kitchen of Mudfog Hall, and the next contribution, purporting to be a "Full Report of the Second Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything" (September, 1838) is embellished with a very ludicrous illustration, entitled "Automaton Police Office and Real Offenders, from the model exhibited before Section B of the Mudfog Association." This design depicts the interior of a police-court in which all the officials are automatic—an ingenious rendering of the idea propounded by Mr. Coppernose to the President and members of the Association. To the second paper the artist also supplied a woodcut portrait of "The Tyrant Sowster," of whom he made no less than six studies before he succeeded in producing a satisfactory presentment of Mudfog's "active and intelligent" beadle.

In his juvenile days Dickens wrote a farce entitled "The Lamplighter," which, owing to its non-acceptance by the theatrical management for whom it was composed, he converted into an amusing tale called "The Lamplighter's Story." This constituted his share in a collection of light essays and other papers gratuitously supplied by well-known authors, and issued in volume form under the title of "The Pic Nic Papers," for the benefit of the widow of Macrone, Dickens's first publisher. The work, edited by Dickens, was launched by Henry Colborn in 1841, in three volumes, with fourteen illustrations by Cruikshank, "Phiz," and other artists. The first volume opened with "The Lamplighter's Story," for which Cruikshank provided an etching entitled "The Philosopher's Stone," the subject represented being the unexpected explosion of Tom Grig's [Pg 26]crucible. This was the last illustration executed by the artist for Dickens's writings,[6] and it may be added that some impressions of the plate were issued in proof state "before letters," but these are exceedingly rare. Although for many years afterwards they continued fast friends, it may be (as Mr. Graham Everitt conjectures) that Cruikshank found it impossible to co-operate any longer with so exacting an employer of artistic labour as Charles Dickens, who remonstrated, with some show of reason, that he was the best judge of what he required pictorially,—an argument, however, which did not suit the independent spirit of the artist. Of his genius Dickens was ever a warm admirer, and remarking upon the exclusion of so able a draughtsman from the honours of the Royal Academy, because, forsooth! his works were not produced in certain mediums, the novelist pertinently asks: "Will no Associates be found upon its books one of these days, the labours of whose oil and brushes will have sunk into the profoundest obscurity, when many pencil-marks of Mr. Cruikshank and Mr. Leech will be still fresh in half the houses in the land?"

It will be remembered that George Cruikshank published a version of the Fairy Tales, converting them into stories somewhat resembling Temperance tracts. Dickens was greatly incensed, and, half-playfully and half-seriously, protested against such alterations of the beautiful little romances, this re-writing them "according to Total Abstinence, Peace Society, and Bloomer principles, and expressly for their propagation;" in an article published in Household Words, October 1, 1853, entitled "Frauds on the Fairies," the novelist enunciates his opinions on the subject, and gives the story of Cinderella as it might be "edited" by a gentleman with a "mission." This elicited a reply from Cruikshank (in a short-lived magazine bearing his name, and launched by him in 1854), which took the form of "A Letter from Hop-o'-my-Thumb to Charles Dickens, Esq.," commencing with "Right Trusty, Well-Beloved, Much-Read, and Admired Sir," the artist contending that he was justified in altering "a common fairy-tale" when his sole object was to remove objectionable passages, and, in their stead, to inculcate moral principles. There is no doubt, however, that Dickens's rebuke seriously affected the sale of the Fairy Library.

Plate XIV

FIRST IDEA AND SKETCH FOR

"FAGIN IN THE CONDEMNED CELL"

And Various Studies for Scenes and Characters in "Oliver Twist"

Facsimile of Original Drawings by

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

In 1847 Dickens instituted a series of theatrical entertainments

for certain charitable objects, the distinguished artists and writers

who formed the goodly company of amateur actors including George

Cruikshank. On one occasion they made a tour in the provinces,

giving performances at several important towns, and on the conclusion

of this "splendid strolling" Dickens wrote an amusing little jeu

d'esprit in the form of a history of the trip, adopting for the purpose

the phraseology of Mrs. Gamp. It was to be a new "Piljian's

Projiss," with illustrations by the artist-members; but, for some

reason, it was destined never to appear in the manner intended by

its projector. Forster has printed all that was ever written of the

little jest, where we find a humorous description of Cruikshank in

Mrs. Gamp's vernacular: "I was drove about like a brute animal

and almost worritted into fits, when a gentleman with a large shirt-collar

and a hook nose, and a eye like one of Mr. Sweedlepipe's

hawks, and long locks of hair, and wiskers that I wouldn't have no

lady as I was engaged to meet suddenly a turning round a corner,

for any sum of money you could offer me, says, laughing, 'Halloa,

Mrs. Gamp, what are you up to?' I didn't know him from a man

(except by his clothes); but I says faintly, 'If you're a Christian

man, show me where to get a second-cladge ticket for Manjester,

and have me put in a carriage, or I shall drop!' Which he kindly

did, in a cheerful kind of a way, skipping about in the strangest

manner as ever I see, making all kinds of actions, and looking and

vinking at me from under the brim of his hat (which was a good

deal turned up), to that extent, that I should have thought he meant[Pg 27]

[Pg 28]

something but for being so flurried as not to have no thoughts at

all until I was put in a carriage...." When Mrs. Gamp was

informed, in a whisper, that the gentleman who assisted her into the

carriage was "George," she replied, "What George, sir? I don't

know no George." "The great George, ma'am—the Crookshanks,"

was the explanation. Whereupon Mrs. Gamp continues: "If you'll

believe me, Mrs. Harris, I turns my head, and see the wery man

a making picturs of me on his thumb-nail at the winder!" The

artist took part in several plays under Dickens's management, but,

although it is not recorded that he created great sensation as an

actor, it seems evident that his impersonations met with the

approval of the novelist, who was a thorough martinet in Thespian

matters.

That George Cruikshank was by no means a prosperous man is perhaps explained by the fact that he never was highly remunerated for his work. "Time was," wrote Thackeray, "when for a picture with thirty heads in it he was paid three guineas—a poor week's pittance, truly, and a dire week's labour!" The late Mr. Sala declared that for an illustrative etching on a plate, octavo size, George never received more than twenty-five pounds, and had been paid as low as ten,—that he had often drawn "a charming little vignette on wood" for a guinea. On February 1, 1878, this remarkable designer and etcher—the most skilled book-illustrator of his day—passed painlessly away at his house in Hampstead Road, having attained the ripe old age of eighty-five. His remains were interred at Kensal Green, but were ultimately removed to the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral, where a bust by Adams perpetuates his memory.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A set of the twenty-eight etchings, proofs before letters (First and Second Series), realised £30 at Sotheby's in 1889. Lithographic replicas of the plates in the Second Series were published in Calcutta in 1837.

[2] In a large water-colour replica of this subject, signed "George Cruikshank, Octr. 14th, 1873, in my 82nd year," the artist stated that the landscape represented the old Pentonville fields, north of London.

[3] The name of Sikes is frequently thus mis-spelt. It is odd that Dickens himself first wrote it "Sykes," as may be seen in the original manuscript of the story.

[4] This is, doubtless, a reference to an article by Dickens entitled "Whole Hogs," which appeared in Household Words, August 23, 1851, protesting against the extreme views of the Temperance party.

[5] In the original title on the plate, Ned Twigger's Christian name is incorrectly given as Tom.

[6] Cruikshank designed the illustrations for the "Memoirs of Grimaldi," 1838, but this work was merely edited by Dickens, and therefore does not come within the scope of the present volume.

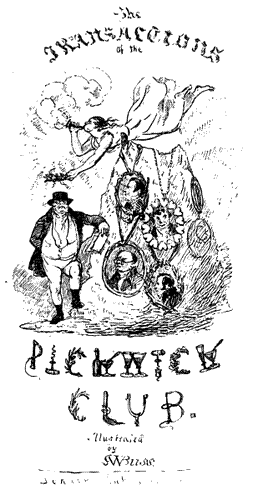

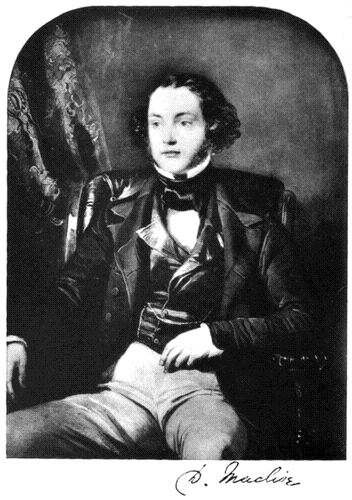

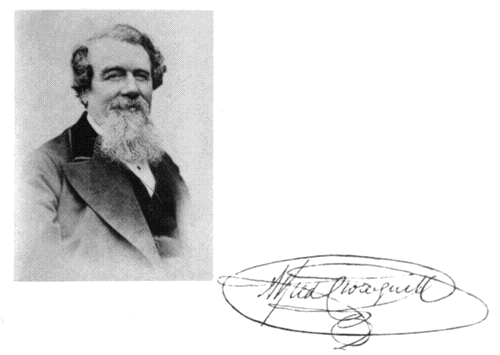

Plate XV

ROBERT SEYMOUR

From an Unpublished Drawing by

TAYLOR

Lent by Mr. Augustin Daly.

Early Years—A Taste for High Art—Drawings on Wood for Figaro and Bell's Life in London—Essays the Art of Etching—Designs for "Maxims and Hints for an Angler"—Proposes to Publish a Book of Humorous Sporting Subjects—A "Club of Cockney Sportsmen"—Charles Whitehead and Charles Dickens—The Inception of "The Pickwick Papers"—Seymour's Illustrations—The Artist Succumbs to Overwork—Suicide of Seymour—Dickens's Tribute—Seymour's Last Drawing for "Pickwick"—"The Dying Clown"—His Original Designs—Seymour's Conception of Mr. Pickwick—Letter from Dickens to the Artist—"First Ideas" and Unused Sketches—A Valuable Collection—Scarcity of Seymour's "Pickwick" Plates—Design for the Wrapper of the Monthly Parts—Mrs. Seymour's Account of the Origin of "The Pickwick Papers"—An Absurd Claim Refuted—"The Library of Fiction"—Seymour's Illustrations for "The Tuggses at Ramsgate."

Concerning the artist who was primarily engaged in the illustration of "Pickwick," very little has been recorded, owing perhaps to the fact that his career, which terminated so tragically and so prematurely, was brief and uneventful. The following particulars of his life and labours, culled from various sources, will, I trust, enable the reader to appreciate Robert Seymour's true position respecting his connection with Charles Dickens's immortal work.

Born "in or near London" in 1798, Robert Seymour indicated at a very early age a decided taste for drawing, whereupon his father, Henry Seymour, a Somerset gentleman, apprenticed him to a skilful pattern-draughtsman named Vaughan, of Duke Street, Smithfield.[7] Although this occupation was most uncongenial to young Seymour, it caused him to adopt a neat style of drawing which ultimately proved of much utility. He aspired to a higher branch of Art than [Pg 30]that involved in the delineation of patterns for calico-printers; but for a time he remained with Vaughan, pleasantly varying the monotony of his daily routine by producing miniature portraits of friends who consented to sit to him, receiving in return a modest though welcome remuneration. Still cherishing an inclination towards "High Art," he and a colleague named Work (significant patronymic!) deserted Vaughan, and, renting a room at the top of the old tower at Canonbury, they purchased a number of plaster-casts, lay-figures, &c., from which the two juvenile enthusiasts began to study with great assiduity. In Seymour's case tangible results were speedily forthcoming, for he presently painted a picture of unusually large dimensions, quaintly described by his fellow-student as containing representations of "the Giant of the Brocken, the Skeleton Hunt, the Casting of Bullets, and a full meal of all the German horrors eagerly swallowed by the public of that day." This remarkable canvas was, it seems, a really creditable work, and found a place on the walls of a gallery in Baker Street Baazar. Seymour, like many other ambitious young artists possessing more talent than pence, quickly realised the sad fact that, though the pursuit was in itself a very agreeable one, it meant penury to the painter unless he owned a private fortune or commanded the purse-strings of rich patrons. The artist's widow afterwards declared that he invariably sold his pictures direct from the easel; but there is no doubt that with him "High Art" proved a financial failure, and he reluctantly turned his attention to the more lucrative (if less attractive) occupation of designing on wood, for which he was peculiarly fitted by his previous practice in clean, precise draughtsmanship during that probationary period in Vaughan's workshop.

Seymour was endowed by Nature with a keen sense of the ludicrous, and this, aided by a knowledge of drawing, enabled him to execute designs of so humorous a character that his productions were immediately welcomed by the proprietors of such publications as Figaro and Bell's Life in London, to which were thus given a[Pg 31] vitality and a popularity they did not previously possess. Although at first the recompense was but scanty, hardly sufficient, indeed, to procure the necessaries of life, yet Robert Seymour felt it was the beginning of what might eventually resolve itself into a fairly remunerative vocation. His talent speedily brought him profitable commissions for more serious publications, while his pencil was simultaneously employed in sketching and drawing amusing incidents, especially such as related to fishing and shooting,—forms of sport which constituted his favourite recreation. Living at this time in the then rural suburb of Islington, he had many opportunities of observing the methods of Cockney sportsmen, who were wont to wander thither on Sundays and holidays, and whose inexperience with rod and gun gave rise to many absurdities and comic fiascos, thus affording the young artist abundant material for humorous designs.

Until 1827, Seymour confined his labours to drawing for the wood-engravers. He now essayed the art of etching upon plates of steel or copper, simulating the style and manner of George Cruikshank; he even ventured to affix the nom de plume of "Shortshanks" to his early caricatures, until he received a remonstrance from the famous George himself. Having attained some proficiency in both etching and lithography, he determined to make practical use of his experience, and in 1833 designed a series of twelve lithographic plates for a new edition of a work entitled "Maxims and Hints for an Angler," in which the humours of the piscatorial art were excellently rendered; he also executed a number of similar designs portraying, with laughable effect, the adventures and misadventures of the very "counter-jumpers" whose ways and habits came under his keen, observant eye. These amusing pictures, drawn on stone with pen-and-ink, and published as a collection of "Sketches by Seymour," achieved an immense popularity, and were chiefly the means of rendering his name generally familiar.