Title: In League with Israel: A Tale of the Chattanooga Conference

Author: Annie F. Johnston

Release date: August 20, 2012 [eBook #40527]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, Emmy, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org). Music was transcribed by Linda Cantoni.

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/inleaguewithisra00johniala |

What Paul was to the Gentiles, may you, the Young Apostle of our Church, become to the Jews. Surely, not as the priest or the Levite have you so long passed them by "on the other side."

Haply, being a messenger on the King's business, which requires haste, you have never noticed their need. But the world sees, and, re-reading an old parable, cries out: "Who is thy neighbor? Is it not even Israel also, in thy midst?"

| Page. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Rabbi's Protégé, | 7 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| On to Chattanooga, | 23 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| The Sunrise Service on "Lookout," | 43 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| An Epworth Jew, | 65 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| "Trust," | 86 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| Two Turnings in Bethany's Lane, | 105 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| Judge Hallam's Daughter, Stenographer, | 115 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| [6]A Kindling Interest, | 130 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| A Junior takes It in Hand, | 145 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| The Deaconess's Story, | 163 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| "Yom Kippur," | 186 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| Dr. Trent, | 199 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| A Little Prodigal, | 220 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Herzenruhe, | 241 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| On Christmas Eve, | 261 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| A "Watch-night" Consecration, | 275 |

—————————— | |

Silent Keys, | 297 |

He was reading aloud in Hebrew, and his deep voice filled the room with its musical intonations: "Praise Him, ye heavens of heavens, and ye waters that be above the heavens."

He raised his head and glanced out toward the western sky. A star or two twinkled through the fading afterglow. Pushing the book aside, he walked to the open window and looked up.

There was a noise of children playing on the pavement below, and the rumbling of an electric[8] car in the next street. A whiff from a passing cigar floated up to him, and the shrill whistle of a newsboy with the evening paper.

But Abraham at the door of his tent, Moses in the Midian desert, Elijah by the brook Cherith, were no more apart from the world than this old rabbi at this moment.

He saw only the star. He heard only the inward voice of adoration, as he stood in silent communion with the God of his fathers.

His strong, rugged features and white beard suggested the line of patriarchs so forcibly, that had a robe and sandals been substituted for the broadcloth suit he wore, the likeness would have been complete.

He stood there a long time, with his lips moving silently; then suddenly, as if his unspoken homage demanded voice, he caught up his violin. Forty years of companionship had made it a part of himself.

The depth of his being that could find no expression in words, poured itself out in the passionately reverent tones of his violin.

In such exalted moods as this it was no earthly instrument of music. It became to him a veritable Jacob's ladder, on which he heard[9] the voices of the angels ascending and descending, and on whose trembling rounds he climbed to touch the Infinite.

There was a quick step on the stairs, and a heavy tread along the upper hall. Then the portiere was pushed aside and a voice of the world brought the rhapsody to a close.

"Where are you, Uncle Ezra? It is too dark to see, but your fiddle says that you are at home."

"Ah, David, my boy, come in and strike a light. I wondered why you were so late."

"I was out on my wheel," answered the young man. "Cycling is warm work this time of year."

He lighted the gas and threw himself lazily down among the pile of cushions on the couch.

"I had a letter from Marta to-day."

"And what does the little sister have to say?" answered the rabbi, noticing a frown deepening on David's forehead. "I suppose her vacation has commenced, and she will soon be on her way home again."

"No," answered David, with a still deeper frown. "She has changed all her plans, and wants me to change mine, just to suit the Herrick[10] family. She has gone to Chattanooga with them, and they are up on Lookout Mountain. She wants me to meet her there and spend part of the summer with her. She grows more infatuated with Frances Herrick every day. You know they have been inseparable friends since they first started to kindergarten."

"Why did she go down there without consulting you?" asked the old man impatiently. "You should be both father and mother to her, now that neither of your parents is living. I wish I were really your uncle and hers, that I might have some authority. You must be more careful of her, my boy. She should spend this summer with you at home, instead of with strangers in a hotel."

"But, Uncle Ezra," protested David, quick to excuse the little sister, who was the only one in the world related to him by family ties, "at home there is nobody but the housekeeper. Mrs. Herrick is with the girls now, and the major will join them next week. Marta is just like one of the family, and I have encouraged the intimacy, because I felt that Mrs. Herrick gives her the motherly care she needs. Besides, Marta and Frances are so congenial in every way that[11] they find their greatest happiness together. I tell them they are as bad as Ruth and Naomi. It is a case of 'where thou goest I will go,' etc."

"Heaven forbid!" exclaimed the rabbi, fervently. "Do you remember that the rest of that declaration is, 'Thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God?' David, my son, I tell you there is great danger of the child's being led away from the faith. Your father and hers was my dearest friend. I have loved you children like my own. You must heed my warning, and discourage such intimacy with a Gentile family, especially when it includes such an agreeable member as that young Albert Herrick."

"Why, he is only a boy, Uncle Ezra."

"Yes, but he is older than Marta, and they are thrown constantly together."

David looked down at the carpet, and began absently tracing a pattern with his foot. He was thinking of the little sixteen-year-old sister. The seven years' difference in their ages gave him a fatherly feeling for her. He could not bear the thought of interfering seriously with her pleasure, yet he could not ignore the old man's warning.

Rabbi Barthold had been his tutor in both[12] languages and music. Aside from a few years at college, all that he knew had been learned under the old man's wise supervision.

"Ezra, my friend," said the elder David, when he lay dying, "take my child and make him a man after your own pattern. I know your noble soul. Give his the same strength and sweetness. We are so greedy for the fleshpots of Egypt, that we forget to satisfy the soul hunger. But you will teach the little fellow higher things."

Later, when the end had almost come, his hand groped out feebly towards the child, who had been brought to his bedside.

"Never mind about the shekels, little David," he said in a hoarse, broken whisper. "But clean hands and a pure heart—that's all that counts when you're in your coffin."

The child's eyes grew wide with wonder as a paroxysm of pain contracted the beloved face. He was led quickly away, but those words were never forgotten.

The rabbi was thinking of them now as he studied the handsome features of the young fellow before him.

It was a strong face, but refinement and[13] gentleness showed in every line. There was something so boyish and frank, also, in its expression, that a tender smile moved the rabbi's lips. "Clean hands and a pure heart," he said fondly to himself. "He has them. Ah, my David, if thou couldst but see how thy little one has grown, not only in stature, but in soul-life, in ideals, thou would'st be satisfied."

"Well," he said aloud, as the young man left his seat and began to walk up and down the room with his hands in his pockets, "what are you going to do?"

"I scarcely know," was the hesitating answer. "It would not be wise to send for Marta to come home, for the reason you suggest, and I have no other to offer her."

"Then go to her!" the rabbi exclaimed. "You need not tell her that you have any fear of her being influenced by Gentile society—but never for a moment let her forget that she is a Jewess. Kindle her pride in her race. Teach her loyalty to her people, and love for all that is Hebrew."

"But my Hudson Bay trip?" David suggested.

"That can wait. The Tennessee mountains[14] will give you as good a summer outing as you need, and you can play guardian angel for Marta while you take it."

David laughed, and took another turn across the room. Then he paused beside the table, and picked up a newspaper.

"I wonder what connections the trains make now," he said. "There used to be a long wait at a dismal old junction." He glanced hastily over the time-table.

"Why, look here!" he exclaimed. "Here is a cheap excursion to Chattanooga this next week. I could afford to run down and see Marta, anyhow. Maybe I could persuade her to come back with me, if I promised to take her to Hudson Bay with me."

"What kind of an excursion?" asked the rabbi.

"Epworth League, it says here, whatever that may be. It seems to be some sort of an international convention, and says to apply to Frank B. Marion for particulars."

"Marion," repeated the rabbi, thoughtfully. "O, then it is a Methodist affair. He is not only the head and shoulders of that big Church on Garrison Avenue, but hands and feet as well,[15] judging by the way he works for it. I wish my congregation would take a few lessons from him."

"Is he very tall, with a short, brown beard, and blue eyes, and a habit of shaking hands with everybody?" asked David. "I believe I know the man. I met him on the cars last fall. He's lively company. I've a notion to hunt him up, and find what's going on."

"Telephone out to Hillhollow that you will not be at home to-night," said the rabbi, "and stay in the city with me. If you conclude to go to Chattanooga next week, I have much to say to you before taking leave of you for the summer."

"Very well," consented David. "I'll go down town immediately, and see if I can find this Mr. Marion. What is his business, do you know?"

"A wholesale shoe merchant, I believe. He is in that big new building next to Cohen's furniture-store, on Duke Street. But you'll not find him Wednesday night. They have Church in the middle of the week, and he is one of the few Christians whose life is as loud as his profession."

David smiled a little bitterly. "Then I shall certainly cultivate his acquaintance for the purpose of studying such a rara avis. It has never been my lot to know a Christian who measured up to his creed."

"Do not grow cynical, my lad," answered the old man, gently. "I have made you a dreamer like myself. I have kept you in an atmosphere of high ideals. I have led you into the companionship of all that was heroic in the past, and held you apart as much as possible from the sordid selfishness of the age. O, I grow sick at heart sometimes when I stroll through the great centers of trade, watching the fierce struggle of humanity as they snatch the bread from other mouths to feed their own.

"You remember our Hebrew word for teach comes from tooth, and means to make sharp like a tooth. Sometimes I think that primitive idea has become the popular view of education in this day. Anything that will fit a man to bite and cut his way through this hungry wolf-pack is what is sought after, no matter how many of his kind are trampled under foot in the struggle. I am almost afraid for you to step down from the place where I have kept you. When you[17] are thrown with men who care for nothing but material things, who would barter not only their birthrights but their souls for a mess of pottage, I am afraid you will lose faith in humanity."

"That is quite likely, Uncle Ezra."

"Aye, but I would not have it so, David. The world is certainly growing a little less savage, and in every nature smolders some spark, however small, of the eternal good. No matter how we have fallen, we still bear the imprint of the Creator, in whose likeness we were first fashioned."

Rabbi Barthold had been right in calling himself a dreamer. The ability to live apart from his surroundings, had been his greatest comfort. Because of it, the rigor of extreme poverty that surrounded his early life had not touched his heart with its baneful chill. He had gone through the world a happy optimist.

He had been trained according to the most strictly orthodox system of Judaism. But even its severe pressure had failed to confine him to the limits of such a narrow mold.

He was still a dreamer. In the new world he had cast aside the shackles of tradition for the larger liberty of the Reformed Jew.

Now in his serene old age, surrounded by luxuries, he still lived apart in a world of music and literature.

His congregation, broken loose from the old moorings, drifted dangerously away towards radicalism, but he stood firm in the belief that the "chosen people" would finally triumph over all error, and found much comfort in the thought.

David took out his watch. "It is after eight o'clock," he said. "Probably if I walk down Garrison Avenue, I may meet Mr. Marion coming from Church. I'll be back soon."

People were beginning to file out of the side entrance that led to the prayer-meeting room, by the time he reached the church.

"Is Mr. Frank Marion in here?" he asked of the colored janitor, who was standing in the doorway.

"Yes, sah!" was the emphatic response. "He sut'n'y is, sah! He am always the fust to come, an' the last to depaht."

"Why, good evening, Mr. Herschel," exclaimed a pleasant voice.

David turned quickly to lift his hat. An elderly lady was coming down the steps with[19] two young girls. She came up to him with a smile, and held out her hand.

"I have not seen you since you came back from college," she said, cordially; "but I never lose my interest in any of Rob's playmates."

"Thank you, Mrs. Bond," he replied, with his hat still in his hand.

As she passed on, a swift rush of recollection brought back the big attic where he had passed many a rainy day with Rob Bond. He recalled with something of the old boyish pleasure a certain jar on their pantry shelf, where the most delicious ginger-snaps were always to be found.

But the next moment the smile left his lips, as an exclamation of one of the girls was carried back to him. It was made in an undertone, but the still evening air transmitted it with startling distinctness.

"Why, Auntie, he's a Jew! I didn't think you would shake hands with a Jew!"

He could not hear Mrs. Bond's reply. He drew himself up haughtily. Then the indignant flash died out of his eyes. After all, why should he, with the princely blood of Israel in his veins, care for the callow prejudices of a little school-girl?

A crowd of people passed out, laughing and talking. Then he saw Mr. Marion come into the vestibule with several boys, just as the janitor began to extinguish the lights.

He turned to David with a hearty smile and a strong hand-clasp, recognizing him instantly.

"How are you, brother?" he asked. He spoke with a slight Southern accent. Somehow, David felt forcibly that it was not merely as a matter of habit that Frank Marion called him brother. Such a warm, personal interest seemed to speak through the friendly blue eyes looking so honestly into his own, that he was half-way persuaded to go to Chattanooga with him before a word had been said on the subject. They walked several blocks together up the avenue, discussing the excursion. Then Mr. Marion stopped at the gate of an old-fashioned residence, built some distance back from the street.

"I have a message to deliver to Miss Hallam, a cousin of mine," he said. "If you will wait a moment, I'll go with you over to the office."

The front door stood open, and the hall-lamp sent a flood of yellow light streaming out into the warm, June darkness.

In response to Mr. Marion's knock, there was a flutter of a white dress in the hall, and the next instant the massive old doorway framed a picture that the young Jew never forgot. It was Bethany Hallam. The light seemed to make a halo of her golden hair, and to illuminate her dress and the sweet upturned face with such an ethereal whiteness that David was reminded of a Psyche in Parian marble.

"Who is she?" he exclaimed, as Mr. Marion rejoined him. "One never sees a face like that outside of some artist's conception. It is too spirituelle for this planet, but too sad for any other."

"She is Judge Hallam's daughter," Mr. Marion responded. "He died last fall, and Bethany is grieving herself to death. I have at last persuaded her to go to Chattanooga with us. She needs to have her thoughts turned into another channel, and I hope this trip will accomplish that purpose."

"I knew the Judge," said David. "I met him a number of times after I was admitted to the bar."

"O, I didn't know you were a lawyer," said Mr. Marion.

"Yes, I expect to begin practicing here after vacation," he answered.

"Well, I am going to begin my practice right now," said Mr. Marion, laughing, "and plead my case to such purpose that you will be persuaded to take this Chattanooga trip." He slipped his arm through David's, and drew him around the corner toward his store.

"O, we were so afraid you were not coming, Mrs. Marion," cried an impulsive young girl, just in front of David. "It would have been such a disappointment. Isn't she just the dearest thing in the world?" she rattled on to her companion, as Mrs. Marion passed out of hearing.

"Well, if she hasn't got Bethany Hallam with her! Of all people to go on an excursion, it seems to me she would be the very last."

"Why?" asked the other girl. As that was the question uppermost in David's mind, he listened with interest for the answer.

"O, she seems so different from other people. Her father always used to treat her as if she were made of a little finer clay than ordinary mortals. When she traveled, it was always in a private car. When she went to lectures or concerts, they always had the best seats in the house. All her teachers taught her at home except one. She went to the conservatory for her drawing lessons, but a maid came with her in the morning, and her father drove by for her at noon."

As he listened, David's eyes had followed the tall, graceful girl who was now seating herself by Mrs. Marion.

Every movement, as well as every detail of her traveling dress, impressed him with a sense of her refinement and culture. He noticed that she was all in black. A thin veil drawn over her face partially concealed its delicate pallor; but her soft, light hair, drawn up under the little black hat she wore, seemed sunnier than ever by contrast.

"Isn't she beautiful?" sighed David's talkative[25] neighbor. "I used to wish I could change places with her, especially the year when she went abroad to study art; but I wouldn't now for anything in the world."

"Why?" asked her companion again, and David mentally echoed her interrogation.

"O, because her father is dead now, and everything is so different. Something happened to their property, so there's nothing left but the old home. Then her little brother had such a dreadful fall just after the Judge's death. They thought he would die, too, or be a cripple all his life; but I believe he's better now. He is sort of paralyzed, so he has to stay in a wheel-chair; but the doctor says he is gradually getting over that, and will be all right after awhile. It's a very peculiar case, I've heard. There have only been a few like it. She is studying stenography now, so that she can keep on living in the old home and take care of little Jack."

"Do you know her?" interrupted the interested listener.

"No, not very well. I've always seen her in Church; you know Judge Hallam was one of our best paying members, and rarely missed a[26] Sabbath morning service. But they were very exclusive socially. My easel stood next to hers in the art conservatory one term, and we talked about our work sometimes. She used to remind me of Sir Christopher in 'Tales of a Wayside Inn.' Don't you remember? She had that

Both girls laughed, and then the lively chatter was drowned by the jarring rumble of the train as it puffed slowly out of the depot.

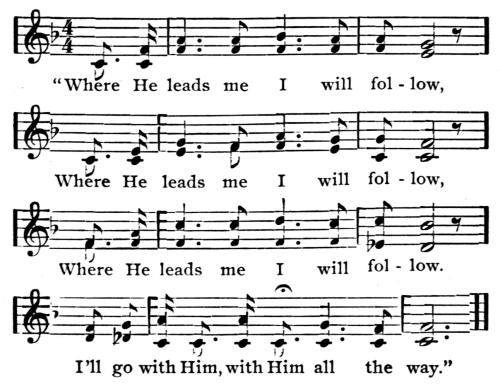

"Any one would know this is a Methodist crowd," said Mrs. Marion laughingly, as a dozen happy young voices began to sing an old revival hymn, and it was caught up all over the car.

"That reminds me," said her husband, reaching into his coat pocket, "I have something here that will prevent any mistake if doubt should arise."

He drew out a little box of ribbon badges and a paper of pins. "Here," he said, "put one[27] on, Ray; we must all show our colors this week. You, too, Bethany."

"O no, Cousin Frank," she protested. "I am not a member of the League."

"That makes no difference," he answered, in his hearty, persistent way. "You ought to be one, and you will be by the time you get back from this conference."

"But, Cousin Frank, I never wore a badge in my life," she insisted. "I have always had the greatest antipathy to such things. It makes one so conspicuous to be branded in that way."

He held out the little white ribbon, threaded with scarlet, and bearing the imprint of the Maltese cross. The light, jesting tone was gone. He was so deeply in earnest that it made her feel uncomfortable.

"Do you know what the colors mean, Bethany?" Then he paused reverently. "The purity and the blood! Surely, you can not refuse to wear those."

He laid the little badge in her lap, and passed down the aisle, distributing the others right and left.

She looked at it in silence a moment, and then pinned it on the lapel of her traveling coat.

"Cousin Ray, did you ever know another such persistent man?" she asked. "How is it that he can always make people go in exactly the opposite way from the one they had intended? When he first planned for me to come on this excursion, I thought it was the most preposterous idea I ever heard of. But he put aside every objection, and overruled every argument I could make. I did not want to come at all, but he planned his campaign like a general, and I had to surrender."

"Tell me how he managed," said Mrs. Marion. "You know I did not get home from Chicago until yesterday morning, and I have been too busy getting ready to come on this excursion to ask him anything."

"When he had urged all the reasons he could think of for my going, but without success, he attacked me in my only vulnerable spot, little Jack. The child has considered Cousin Frank's word law and gospel ever since he joined the Junior League. So, when he was told that my health would be benefited by the trip, and it would arouse me from the despondent, low-spirited state I had fallen into, he gave me no rest until I promised to go. Jack showed generalship,[29] too. He waited until the night of his birthday. I had promised him a little party, but he was so much worse that day, it had to be postponed. I was so sorry for him that I could have promised him almost anything. The little rascal knew it, too. While I was helping him undress, he put his arms around my neck, and began to beg me to go. He told me that he had been praying that I might change my mind. Ever since he has been in the League he has seemed to get so much comfort out of the belief that his prayers are always answered that I couldn't bear to shake his faith. So I promised him."

"The dear little John Wesley," said Mrs. Marion; "you ought to give him the full benefit of his name, Bethany."

"Mamma did intend to, but papa said it was as much too big for him as the huge old-fashioned silver watch that Grandfather Bradford left him. He suggested that both be laid away until he grew up to fit them."

"Who is taking care of him in your absence?" was the next question.

"O, he and Cousin Frank arranged that, too. They sent for his old nurse. She came last[30] night with her little nine-year-old grandson. Just Jack's age, you see; so he will have somebody to make the time pass very quickly."

Mrs. Marion stopped her with an exclamation of surprise. "Well, I wish you'd look at Frank! What will he do next? He is actually pinning an Epworth League badge on that young Jew!"

Bethany turned her head a little to look. "What a fine face he has!" she remarked. "It is almost handsome. He must feel very much out of place among such an aggressive set of Christians. I wonder what he thinks of all these songs?"

Mr. Marion came back smiling. As superintendent of both Sunday-school and Junior League, he had won the love of every one connected with them. His passage through the car, as he distributed the badges, was attended by many laughing remarks and warm handclasps.

There was a happy twinkle in his eyes when he stopped beside his wife's seat. She smiled up at him as he towered above her, and motioned him to take the seat in front of them.

"I'm not going to stay," he said. "I want[31] to bring a young man up here, and introduce him to you. He's having a pretty lonesome time, I'm afraid."

"It must be that Jew," remarked Mrs. Marion. "I know every one else on the car. I don't see that we are called on to entertain him, Frank. He came with us, simply to take advantage of the excursion rates. I should think he would prefer to be let alone. He must have thought it presumptuous in you to pin that badge on him. What did he say when you did it?"

Mr. Marion bent down to make himself heard above the noise of the train.

"I showed him our motto, 'Look up, lift up,' and told him if there was any people in the world who ought to be able to wear such a motto worthily, it was the nation whose Moses had climbed Sinai, and whose tables of stone lifted up the highest standard of morality known to the race of Adam."

Mrs. Marion laughed. "You would make a fine politician," she exclaimed. "You always know just the right chord to touch."

"Cousin Frank," asked Bethany, "how does it happen you have taken such an intense interest in him?"

He dropped into the seat facing theirs, and leaned forward.

"Well, to begin with, he's a fine fellow. I have had several talks with him, and have been wonderfully impressed with his high ideals and views of life. But I am free to confess, had I met him ten years ago, I could not have seen any good traits in him at all. I was blinded by a prejudice that I am unable to account for. It must have been hereditary, for it has existed since my earliest recollection, and entirely without reason, as far as I can see. I somehow felt that I was justified in hating the Jews. I had unconsciously acquired the opinion that they were wholly devoid of the finer sensibilities, that they were gross in their manner of living, and petty and mean in business transactions. I took Fagin and Shylock as fair specimens of the whole race. It was, really, a most unaccountable hatred I had for them. My teeth would actually clinch if I had to sit next to one on a street-car. You may think it strange, but I was not alone in the feeling. I know it to be a fact that there are hundreds and hundreds of Church members to-day that have the same inexplicable antipathy."

Bethany looked up quickly.

"My father's reading and training," she said, "has caused me to have a great admiration and respect for Jews in the abstract. I mean such as the Old Testament heroes and the Maccabees of a later date. But in the concrete, I must say I like to have as little intercourse with them as possible. And as to modern Israelites, all I know of them personally is the almost cringing obsequiousness of a few wealthy merchants with whom I have dealt, and the dirty swarm of repulsive creatures that infest the tenement districts. We used to take a short cut through those streets sometimes in driving to the market. Ugh! It was dreadful!" She gave a little shiver of repugnance at the recollection.

"Yes, I know," he answered. "I had that same feeling the greater part of my life. But ten years ago I spent a summer at Chautauqua, studying the four Gospels. It opened my eyes, Bethany. I got a clearer view of the Christ than I ever had before. I saw how I had been misrepresenting him to the world. The inconsistencies of my life seemed like the lanterns the pirates used to hang on the dangerous cliffs[34] along the coast, that vessels might be wrecked by their misleading light. Do you suppose a Jew could have accepted such a Christ as I represented then? No wonder they fail to recognize their Messiah in the distorted image that is reflected in the lives of his followers."

"But they rejected Christ himself when he was among them," ventured Bethany.

"Yes," answered Mr. Marion, "it was like the old story of the man with a muck rake. Do you remember that picture that was shown to Christian at the interpreter's house in 'Pilgrim's Progress?' As a nation, Israel had stooped so much to the gathering of dry traditions, had bent so long over the minute letter of the law, that it could not straighten itself to take the crown held out to it. It could not even lift its eyes to discern that there was a crown just over its head."

"It always made me think of the blind Samson," said Mrs. Marion. "In trying to overthrow something it could not see, spiritually I mean, it pulled down the pillars of prophecy on its own head."

Mr. Marion turned to Bethany again.

"Yes, Israel, as a nation, rejected Christ;[35] but who was it that wrote those wonderful chronicles of the Nazarene? Who was it that went out ablaze with the power of Pentecost to spread the deathless story of the resurrection? Who were the apostles that founded our Church? To whom do we owe our knowledge of God and our hope of redemption, if not to the Jews? We forget, sometimes, that the Savior himself belonged to that race we so reproach."

He was talking so earnestly, he had forgotten his surroundings, until a light touch on his shoulder interrupted him.

"What's the occasion of all this eloquence, Brother Marion?" asked the minister's genial voice.

He turned quickly to smile into the frank, smooth-shaven face bending over him.

"Come, sit down, Dr. Bascom. We're discussing my young friend back there, David Herschel. Have you met him?"

"Yes, I was talking with him a little while ago," answered the minister. "He seems very reserved. Queer, what an intangible barrier seems to arise when we talk to one of that race. I just came in to tell you that Cragmore is in the next car. He got on at the last station."

"What, George Cragmore!" exclaimed Mr. Marion, rising quickly. "I haven't seen him for two years. I'll bring him in here, Ray, after awhile."

"That's the last we'll see of him till lunch-time," said Mrs. Marion, as the door banged behind the two men.

"Frank will never think of us again when he gets to spinning yarns with Mr. Cragmore. I want you to meet him, Bethany. He is one of the most original men I ever heard talk. He's a young minister from the 'auld sod.' They called him the 'wild Irishman' when he first came over, he was so fiery and impetuous. There is enough of the brogue left yet in his speech to spice everything he says. He and Frank are a great deal alike in some things. They are both tall and light-haired. They both have a deep vein of humor and an inordinate love of joking. They are both so terribly in earnest with their Christianity that everybody around them feels the force of it; and when they once settle on a point, they are so tenacious nothing can move them. I often tell Frank he is worse than a snapping-turtle. Tradition says they do let go when it thunders, but nothing[37] will make him let go when his mind is once clinched."

There was a stop of twenty minutes at noon. At the sound of a noisy gong in front of the station restaurant, Mr. Marion came in with his friend. Capacious lunch-baskets were opened out on every side, with the generous abundance of an old-time camp-meeting.

"Where is Herschel?" inquired Mr. Marion. "I intended to ask him to lunch with us."

"I saw him going into the restaurant," replied his wife.

"You must have a talk with him this afternoon, George," said Mr. Marion. "I've been all up and down this train trying to get people to be neighborly. I believe Dr. Bascom is the only one who has spoken to him. They were all having such a good time when I interrupted them, or they didn't know what to say to a Jew, and a dozen different excuses."

"O, Frank, don't get started on that subject again!" exclaimed Mrs. Marion. "Take a sandwich, and forget about it."

Bethany Hallam laughed more than once during the merry luncheon that followed. She could not remember that she had laughed before[38] since her father's death. The young Irishman's ready wit, his droll stories, and odd expressions were irresistible. He seemed a magnet, too, drawing constantly from Frank Marion's inexhaustible supply of fun.

"You have seen only one side of him," remarked Mrs. Marion, when her husband had taken him away to introduce David. "While he was very entertaining, I think he has shown us one of the least attractive phases of his character."

David had felt very much out of place all morning. It was one thing to travel among ordinary Gentiles, as he had always done, and another to be surrounded by those who were constantly bubbling over with religious enthusiasm. He did not object to sitting beside a hot-water tank, he said to himself, but he did object to its boiling over on him.

His neighbors would have been very much surprised could they have known he was studying them with keen insight, and finding much to criticise. Even some of their songs were objectionable to him, their catchy refrains reminding him of some he had heard at colored minstrel shows.

With such an exalted idea of worship as the old rabbi had inculcated in him, it did not seem fitting to approach Deity in song unless through such sonorous utterances as the psalms. Some of these little tinkling, catch-penny tunes seemed profanation.

He ventured to say as much to George Cragmore. He had very unexpectedly found a congenial friend in the young minister. It was not often he met a man so keenly alert to nature, so versed in his favorite literature, or of his same sensitive temperament. He felt himself opening his inner doors as he did to no one else but the rabbi.

A drizzling rain was falling when they began to wind in and out among the mountains of Tennessee, and for miles in their journey a rainbow confronted them at every turn in the road. It crowned every hilltop ahead of them. It reached its shining ladder of light into every valley. It seemed such a prophecy of what awaited them on the mountain beyond, that some one began to sing, "Standing on the Promises."

As the full glory of the rainbow flashed on Cragmore's sight, he stopped abruptly in the middle of a sentence. The expression of his face[40] seemed to transfigure it. When he turned to David, there were tears in his eyes.

"O, the covenants of the Old Testament!" he said, in a low tone, that thrilled David with its intensity of feeling. "The Bethels! The Mizpahs! The Ebenezers! See, it is like a pillar of fire leading us to a veritable land of promise."

Then, with his hand resting on David's knee, he began to talk of the promises of the Bible, till David exclaimed, impulsively: "You make me forget that you are a Christian. You enter into Israel's past even more fully than many of her own sons."

Cragmore thrust out his hand, in his quick, nervous way, with an impetuous gesture.

"Why, man!" he cried, relapsing unconsciously into the broad brogue of his childhood, "we hold sacred with you the heritage of your past. We look up with you to the same God, the Father; we confess a common faith till we stand at the foot of the cross. There is no great barrier between us—only a step—one step farther for you to take, and we stand side by side!"

He laid his hand on David's, and looked into[41] his eyes with an expression of tender pleading as he added:

"O, my friend, if you could only see my Savior as he has revealed himself to me! I pray you may! I do pray you may!"

It was the first time in David's life any one had ever said such a thing to him. He sat back in his corner of the seat, at loss for an answer. It put an end to their conversation for a while. Cragmore felt that his sympathy had carried him to the point of giving offense. He was relieved when Dr. Bascom beckoned him to share his seat.

After a while, as the train sped on into the darkness, the passengers subsided in to sleepy indifference. It seemed hours afterward when Mr. Marion clapped him on the shoulder, saying briskly, "Wake up, old fellow, we are getting into Chattanooga."

"Let us go in with banners flying," said Dr. Bascom. "I understand that every car-full that has come in, from Maine to Mexico, has come singing."

The lights of the city, twinkling through the car-windows, aroused the sleepy passengers with a sense of pleasant anticipations, and when[42] they steamed slowly into the crowded depot, it was as "pilgrims singing in the night."

In the general confusion of the arrival, Mr. Marion lost sight of David.

"It's too bad!" he exclaimed, in a disappointed tone. "I intended to ask him to drive to Missionary Ridge with us to-morrow, and I wanted to introduce him to you, Bethany."

"I'm very glad you didn't have the opportunity, Cousin Frank," she said, as she followed him through the depot gates. "He may be very agreeable, and all that, but he's a Jew, and I don't care to make his acquaintance."

The handle of the umbrella she was carrying came in collision with some one behind her.

"I beg your pardon," she said, turning in her gracious, high-bred way.

The gentleman raised his hat. It was David Herschel. A stylish-looking little school-girl was clinging to his arm, and a gray-bearded man, whom she recognized as Major Herrick, was walking just behind him. They had come down from the mountain to meet him, and take him to Lookout Inn. As their eyes met, Bethany was positive that he had overheard her remark.

"It is too late to make any change to-night," said Mrs. Marion, as they left her. "We are only one block further up on this same street. We will try to make some arrangement to-morrow to have you with us."

Bethany followed her hostess into the wide reception-hall. One of the most elegant homes of the South had opened its hospitable doors to receive them. Ten delegates had preceded her, all as tired and travel-stained as herself.

During the introductions, Bethany mentally classified them as the most uninteresting lot of people she had seen in a long time.

"I believe you are the odd one of this party, Miss Hallam," said the hostess, glancing over the assignment cards she held; "so I shall have to ask you to take a very small room. It is[44] one improvised for the occasion; but you will probably be more comfortable here alone than in a larger room with several others."

It had never occurred to Bethany that she might have been asked to share an apartment with some stranger, and she hastened to assure her hostess of her appreciation of the little room, which, though very small indeed compared with the great dimensions of the others, was quite comfortable and attractive.

"I have always been accustomed to being by myself," she said, "and it makes no difference at all if it is so far away from the other sleeping-rooms. I am not at all timid."

Yet, when she had wearily locked her door, she realized that she had never been so entirely alone before in all her life. Home seemed so very far away. Her surroundings were so strange. Her extreme weariness intensified her morbid feeling of loneliness. She remembered such a sensation coming to her one night in mid-ocean, but she had tapped on her state-room wall, and her father had come to her immediately. Now she might call a weary lifetime. No earthly voice could ever reach him.

With a throbbing ache in her throat, and[45] hot tears springing to her eyes, she opened her valise and took out a little photograph case of Russia leather. Four pictured faces looked out at her. She was kneeling before them, with her arms resting on the low dressing-table. As she gazed at them intently, a tear splashed down on her black dress.

"O, it isn't right! It isn't right," she sobbed, passionately, "for God to take everything! It would have been so easy for him to let me keep them. How could he be so cruel? How could he take away all that made my life worth living, and then let little Jack suffer so?"

She laid her head on her arms in a paroxysm of sobbing. Presently she looked up again at her mother's picture. It was a beautiful face, very like her own. It brought back all her happy childhood, that seemed almost glorified now by the remembered halo of its devoted mother-love.

The years had softened that grief, but it all came back to-night with its old-time bitterness.

The next face was little Jack's—a sturdy, wide-awake boy, with mischievous dimples and laughing eyes. But the recollection of all he[46] had suffered since his accident, made her feel that she had lost him also, in a way. The physician had assured her that he would be the same vigorous, romping child again; but she found that hard to believe when she thought of his present helpless condition.

She pressed the next picture to her lips with trembling fingers, and then looked lovingly into the eyes that seemed to answer her gaze with one of steadfast, manly devotion.

"O, it isn't right! It isn't right!" she sobbed again. How it all came back to her—the happy June-time of her engagement!—the summer days when she dreamed of him, the summer twilights when he came. Every detail was burned into her aching memory, from the first bunch of violets he brought her, to the judge's tender smile when she spread out all her bridal array for him to see. Such shimmering lengths of the white, trailing satin; such filmy clouds of the soft, white veil, destined never to touch her fair hair! For there was the telegram, and afterward the darkened room, and the darker hour, when she groped her way to a motionless form, and knelt beside it alone. O, how she had clung to the cold hands, and[47] kissed the unresponsive lips, and turned away in an agony of despair! But as she turned, her father's strong arms were folded about her, and his broken voice whispered comfort.

The dear father! It had been doubly desolate since he had gone, too.

Kneeling there, with her head bowed on her arms, she seemed to face a future that was utterly hopeless. Except that Jack needed her, she felt that there was absolutely no reason why she should go on living.

The ticking of her watch reminded her that it was nearly midnight. In a mechanical way, she got up and began to arrange her hair for the night.

After she had extinguished the light, she pulled aside the curtain, and looked out on the unfamiliar streets.

The moon had come up. In the dim light the crest of old Lookout towered grimly above the horizon. A verse of one of the Psalms passed through her mind: "I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help."

"No," she whispered, bitterly, "there is no help. God doesn't care. He is too far away."

As she went back to the bed, the words of[48] the novice in Muloch's "Benedetta Minelli" came to her:

"I wish I could do that," she thought; "lock myself away with my memories, and not be obliged to keep up this empty pretense of living, just as if nothing were changed. It might not be so hard. How I dread to-morrow, with its crowds of strange faces! O, why did I ever come?"

Next morning, the guests gathered out on the vine-covered piazza to discuss their plans for the day.

There were two theological students from Boston, a young doctor from Texas, and the son of a wealthy Louisiana planter. A Kansas farmer's wife and her sister, a bright little schoolteacher from an Iowa village, and three pretty Georgia girls, completed the party.

Bethany sat a little apart from them, wondering how they could be so greatly interested in such things as the most direct car-line to[49] Missionary Ridge, or the time it would take to "do" the old battle-grounds.

The youngest Georgia girl was about her own age. She had made several attempts to include Bethany in the conversation, but mistaking her reserve and indifference for haughtiness, turned to the Louisiana boy with a remark about unsociable Northerners.

Their frequent laughter reached Bethany, and she wondered, in a dull way, how anybody could be light-hearted enough even to smile in such a world full of heart-aches. Then she remembered that she had laughed herself, the day before, when Mr. Cragmore was with them. It rather puzzled her now to know how she could have done so. Her wakeful night had left her unusually depressed.

An open, two-seated carriage stopped at the gate. Mrs. Marion and George Cragmore were on the back seat. Mr. Marion and Dr. Bascom sat with the driver. Bethany had been waiting for them some time with her hat on, so she went quickly out to meet them. Mr. Cragmore leaped over the wheel to open the gate, and assist her to a seat between himself and Mrs. Marion.

They drove rapidly out towards Missionary Ridge. To Bethany's great relief, neither of her companions seemed in a talkative mood. Mr. Marion, who was an ardent Southerner, had been deep in a political discussion with Dr. Bascom. As they stopped on the winding road, half way up the ridge, to look down into the beautiful valley below, and across to the purple summit of Lookout, Mr. Marion drew a long breath. Then he took off his hat, saying, reverently, "The work of His fingers! What is man, that Thou art mindful of him?" Then, after a long silence: "How insignificant our little differences seem, Bascom, in the sight of these everlasting hills! Let's change the subject."

Mrs. Marion, absorbed in the beauty on every side, did not notice Bethany's continued silence or Cragmore's spasmodic remarks. The fresh air and brisk motion had somewhat aroused Bethany from her apathy. First, she began to be interested in the constantly-changing view, and then she noticed its effect on the erratic man beside her.

From the time they commenced to ascend the ridge he had not spoken to any one directly,[51] but everything he saw seemed to suggest a quotation. He repeated them unconsciously, as if he were all alone; some of them dreamily, some of them with startling force, and all with the slight brogue he spoke so musically.

"Every common bush afire with God," he murmured in an undertone, looking at a dusty wayside weed, with his soul in his eyes.

Bethany thought to herself, afterwards, that if any other man of her acquaintance had kept up such a steady string of disjointed quotations, it would have been ridiculous. She never heard him do it again after that day. It seemed as if the old battle-fields suggested thoughts that could find no adequate expression save in words that immortal pens had made deathless.

The warm odor of ripe peaches floated out to them from grassy orchards, where the trees were bent over with their wealth of velvety, sun-reddened fruit. Seemingly, Cragmore had taken no notice of Bethany's depression when she joined them, or of the soothing effect nature was having on her sore heart. But she knew that he had seen it, when he turned to her abruptly with a quotation that fitted her as well as his first one had the wayside weed. He[52] half sang it, with a tender, wistful smile, as he watched her face.

Bethany wondered if her cousin Frank had told him of all she had suffered, or if he had guessed it intuitively. Somehow she felt that he had not been told, but that he had divined it. Yet when they stopped on the Chickamauga battle-field, and she saw him go leaping across the rough fields like an overgrown boy, she thought of her cousin Ray's remark, "They used to call him the wild Irishman," and wondered at the contradictory phases his character presented. She saw him pause and lay his hand reverently on the largest cannon, and then come running back across the furrows with long, awkward jumps.

"What on earth did you do that for, Cragmore?"[53] asked Mr. Marion, in his teasing way. "The idea of keeping us waiting while you were racing across a ten-acre lot to pat an old gun."

"Old gun, is it?" was the laughing answer, yet there was a flash in his eyes that belied the laugh. "Odds, man! it is one of the greatest orators that ever roused a continent. I just wanted to lay my hands on its dumb lips." He waved his arm with an exulting gesture. "Aye, but they spoke in thunder-tones once, the day they spoke freedom to a race."

He did not take his seat in the carriage for a while, but followed at a little distance, ranging the woods on both sides; sometimes plunging into a leafy hollow to examine the bark of an old tree where the shells had plowed deep scars; sometimes dropping on his knees to brush away the leaves from a tiny wild-flower, that any one but a true woodsman would have passed with unseeing eyes. Once he brought a rare specimen up to the carriage to ask its name. He had never seen one like it before. That was the only one he gathered.

"It's a pity to tear them up, when they would wither in just a few hours," he said; "the solitary places are so glad for them."

"He's a queer combination," said Dr. Bascom, as he watched him break a little sprig of cedar from the stump of a battle-broken tree to put in his card-case. "Sometimes he is the veriest clown; at others, a child could not be more artless; and I have seen him a few times when he seemed to be aroused into a spiritual giant. He fairly touched the stars."

Bethany was so tired by the morning's drive that she did not go to the opening services in the big tent that afternoon.

"Well, you missed it!" said Mr. Marion, when he came in after supper, "and so did David Herschel."

"Missed what?" inquired Bethany.

"The mayor's address of welcome, this afternoon. You know he is a Jew. Such a broad, fraternal speech must have been a revelation to a great many of his audience. I tell you, it was fine! You're going to-night, aren't you, Bethany?"

"No," she answered, "I want to save myself for the sunrise prayer-meeting on the mountain to-morrow. I saw the sun come up over the Rigi once. It is a sight worth staying up all night to see."

It was about two o'clock in the morning when they started up the mountain by rail. The cars were crowded. People hung on the straps, swaying back and forth in the aisles, as the train lurched around sudden curves. Notwithstanding the early hour, and the discomfort of their position, they sang all the way up the mountain.

"Cousin Ray," said Bethany, "do tell me how these people can sing so constantly. The last thing I heard last night before I went to sleep was the electric street-car going past the house, with a regular hallelujah chorus on board. Do you suppose they really feel all they sing? How can they keep worked up to such a pitch all the time?"

"You should have been at the tent last night, dear," answered Mrs. Marion. "Then you would have gotten into the secret of it. There is an inspiration in great numbers. The audiences we are having there are said to be the greatest ever gathered south of the Ohio. Our League at home has been doing very faithful work, but I couldn't help wishing last night that every member could have been present. To see ten thousand faces lit up with the same[56] interest and the same hope, to hear the battle-cry, 'All for Christ,' and the Amen that rolled out in response like a volley of ten thousand musketry, would have made them feel like a little, straggling company of soldiers suddenly awakened to the fact that they were not fighting single-handed, but that all that great army were re-enforcing them. More than that, these were only the advance-guard, for over a million young people are enlisted in the same cause. Think of that, Bethany—a million leagued together just in Methodism! Then, when you count with them all the Christian Endeavor forces, and the Baptist Unions, and the King's Daughters and Sons, and the Young Men's Christian Associations, and the Brotherhood of St. Andrew, it looks like the combined power ought to revolutionize the universe in the next decade."

"Then you think it is an inspiration of the crowds that makes them sing all the time," said Bethany.

"By no means!" answered Mrs. Marion. "To be sure, it has something to do with it; but to most of this vast number of young people, their religion is not a sentiment to be fanned into spasmodic flame by some excitement. It[57] is a vital force, that underlies every thought and every act. They will sing at home over their work, and all by themselves, just as heartily as they do here. I remember seeing in Westminster Abbey, one time, the profiles of John and Charles Wesley put side by side on the same medallion. I have thought, since then, it is only a half-hearted sort of Methodism that does not put the spirit of both brothers into its daily life—that does not wing its sermons with its songs."

Hundreds of people had already gathered on the brow of the mountain, waiting the appointed hour. Mr. Marion led the way to a place where nature had formed a great amphitheater of the rocks. They seated themselves on a long, narrow ledge, overlooking the valley. They were above the clouds. Such billows of mist rolled up and hid the sleeping earth below that they seemed to be looking out on a boundless ocean. The world and its petty turmoils were blotted out. There was only this one gray peak raising its solitary head in infinite space. It was still and solemn in the early light. They spoke together almost in whispers.

"I can not believe that any man ever went up into a mountain to pray without feeling himself[58] drawn to a higher spiritual altitude," said Dr. Bascom.

Frank Marion looked around on the assembled crowds, and then said slowly:

"Once a little band of five hundred met the risen Lord on a mountain-side in Galilee, and were sent away with the promise, 'Lo, I am with you alway!' Think what they accomplished, and then think of the thousands here this morning that may go back to the work of the valley with the same promise and the same power! There ought to be a wonderful work accomplished for the Master this year."

Cragmore, who had walked away a little distance from the rest, and was watching the eastern sky, turned to them with his face alight.

"See!" he cried, with the eagerness of a child, and yet with the appreciation of a poet shining in his eyes; "the wings of the morning rising out of the uttermost parts of the sea."

He pointed to the long bars of light spreading like great flaming pinions above the horizon. The dawn had come, bringing a new heaven and a new earth. In the solemn hush of the sunrise, a voice began to sing, "Nearer, my God, to thee."

It was as in the days of the old temple. They had left the outer courts and passed up into an inner sanctuary, where a rolling curtain of cloud seemed to shut them in, till in that high Holy of Holies they stood face to face with the Shekinah of God's presence.

Bethany caught her breath. There had been times before this when, carried along by the impetuous eloquence of some sermon or prayer, every fiber of her being seemed to thrill in response. In her childlike reaching out towards spiritual things, she had had wonderful glimpses of the Fatherhood of God. She had gone to him with every experience of her young life, just as naturally and freely as she had to her earthly father. But when beside the judge's death-bed she pleaded for his life to be spared to her a little longer, and her frenzied appeals met no response, she turned away in rebellious silence. "She would pray no more to a dumb heaven," she said bitterly. Her hope had been vain.

Now, as she listened to songs and prayers and testimony, she began to feel the power that emanated from them,—the power of the Spirit, showing her the Father as she had never known[60] him before: the Father revealed through the Son.

Below, the mists began to roll away until the hidden valley was revealed in all its morning loveliness. But how small it looked from such a height! Moccasin Bend was only a silver thread. The outlying forests dwindled to thickets.

Bethany looked up. The mists began to roll away from her spiritual vision, and she saw her life in relation to the eternities. Self dwindled out of sight. There was no bitterness now, no childish questioning of Divine purposes. The blind Bartimeus by the wayside, hearing the cry, "Jesus of Nazareth passeth by," and, groping his way towards "the Light of the world," was no surer of his dawning vision than Bethany, as she joined silently in the prayer of consecration. She saw not only the glory of the June sunrise; for her the "Sun of righteousness had arisen, with healing in his wings."

People seemed loath to go when the services were over. They gathered in little groups on the mountain-side, or walked leisurely from one point of view to another, drinking in the rare beauty of the morning.

Bethany walked on without speaking. She was a little in advance of the others, and did not notice when the rest of her party were stopped by some acquaintances. Absorbed in her own thoughts, she turned aside at Prospect Point, and walked out to the edge. As she looked down over the railing, the refrain of one of the songs that had been sung so constantly during the last few days, unconsciously rose to her lips. She hummed it softly to herself, over and over, "O, there's sunshine in my soul to-day."

So oblivious was she of all surroundings that she did not hear Frank Marion's quick step behind her. He had come to tell her they were going down the mountain by the incline.

"O, there's sunshine, blessed sunshine!" The words came softly, almost under her breath; but he heard them, and felt with a quick heart-throb that some thing unusual must have occurred to bring any song to her lips.

"O Bethany!" he exclaimed, "do you mean it, child? Has the light come?"

The face that she turned towards him was radiant. She could find no words wherewith to tell him her great happiness, but she laid her[62] hands in his, and the tears sprang to her eyes.

"Thank God! Thank God!" he exclaimed, with a tremor in his strong voice. "It is what I have been praying for. Now you see why I urged you to come. I knew what a mountain-top of transfiguration this would be."

Standing on the outskirts of the crowd, David Herschel had looked around with great curiosity on the gathering thousands. It was only a little distance from the inn, and he had come down hoping to discover the real motive that had brought these people together from such vast distances. He wondered what power their creed contained that could draw them to this meeting at such an early hour.

He had felt as keenly as Cragmore the sublimity of the sunrise. He felt, too, the uplifting power of the old hymn, that song drawn from the experience of Jacob at Bethel, that seemed to lift every heart nearer to the Eternal.

He was deeply stirred as the leader began to speak of the mountain scenes of the Bible, of Abraham's struggles at Moriah, of Horeb's burning bush, of Sinai and Nebo, of Mount Zion with its thousand hallowed memories. So[63] far the young Jew could follow him, but not to the greater heights of the Mountain of Beatitudes, of Calvary, or of Olivet.

He had never heard such prayers as the ones that followed. Although there can be found no sublimer utterances of worship, no humbler confessions of penitence or more lofty conceptions of Jehovah, than are bound in the rituals of Judaism, these simple outpourings of the heart were a revelation to him.

There came again the fulfillment of the deathless words, "And I, if I be lifted up, will draw all men unto me!" O, how the lowly Nazarene was lifted up that morning in that great gathering of his people! How his name was exalted! All up and down old Lookout Mountain, and even across the wide valley of the Tennessee, it was echoed in every song and prayer.

When the testimony service began, David turned from one speaker to another. What had they come so far to tell? From every State in the Union, from Canada, and from foreign shores, they brought only one story—"Behold the Lamb of God!" In spite of himself, the young Jew's heart was strangely drawn[64] to this uplifted Christ. Suddenly he was startled by a ringing voice that cried: "I am a converted Jew. I was brought to Christ by a little girl—a member of the Junior League. I have given up wife, mother, father, sisters, brothers, and fortune, but I have gained so much that I can say from the depths of my soul, 'Take all the world, but give me Jesus.' I have consecrated my life to his service."

David changed his position in order to get a better view of the speaker. He scrutinized him closely. He studied his face, his dress, even his attitude, to determine, if possible, the character of this new witness. He saw a man of medium height, broad forehead, and firm mouth over which drooped a heavy, dark mustache. There was nothing fanatical in the calm face or dignified bearing. His eyes, which were large, dark, and magnetic, met David's with a steady gaze, and seemed to hold them for a moment.

With a lawyer-like instinct, David longed to probe this man with questions. As he went back to the inn, he resolved to hunt up his history, and find what had induced him to turn away from the faith.

"I have just come back from Grant University," she wrote. "Cousin Frank was so interested in the Jew who spoke at the sunrise meeting yesterday, because he said a little Junior League girl had been the means of his conversion, that he arranged for an interview with him. His name is Lessing. Cousin Frank asked me to go with him to take the conversation down in shorthand for the League. I[66] haven't time now to give all the details, but will tell them to you when I come home."

Bethany had been intensely interested in the man's story. They sat out on one of the great porches of the university, with the mountains in sight. They had drawn their chairs aside to a cool, shady corner, where they would not be interrupted by the stream of people constantly passing in and out.

"It is for the children you want my story," he said; "so they must know of my childhood. It was passed in Baltimore. My father was the strictest of orthodox Jews, and I was very faithfully trained in the observances of the law. He taught me Hebrew, and required a rigid adherence to all the customs of the synagogue."

Bethany rapidly transcribed his words, as he told many interesting incidents of his early home life. He had come to Chattanooga for business reasons, married, and opened a store in St. Elmo, at the foot of Mount Lookout. He was very fond of children, and made friends with all who came into the store. There was one little girl, a fair, curly-haired child, who used to come oftener than the others. She grew to love him dearly, and, in her baby fashion,[67] often talked to him of the Junior League, in which she was deeply interested.

Her distress when she discovered that he did not love Christ was pitiful. She insisted so on his going to Church, that one morning he finally consented, just to please her. The sermon worried him all day. It had been announced that the evening service would be a continuation of the same subject. He went at night, and was so impressed with the truth of what he heard, that when the child came for him to go to prayer-meeting with her the next week, he did not refuse.

Towards the close of the service the minister asked if any one present wished to pray for friends. The child knelt down beside Mr. Lessing, and to his great embarrassment began to pray for him. "O Lord, save Brother Lessing!" was all she said, but she repeated it over and over with such anxious earnestness, that it went straight to his heart.

He dropped on his knees beside her, and began praying for himself. It was not long until he was on his feet again, joyfully confessing the Christ he had been taught to despise. In the enthusiasm of this new-found happiness[68] he went home and tried to tell his wife of the Messiah he had accepted, but she indignantly refused to listen. For months she berated and ridiculed him. When she found that not only were tears and arguments of no avail, but that he felt he must consecrate his life to the ministry, she declared she would leave him. He sold the store, and gave her all it brought; and she went back to her family in Florida.

In order to prepare for the ministry he entered the university, working outside of study hours at anything he could find to do. In the meantime he had written to his parents, knowing how greatly they would be distressed, yet hoping their great love would condone the offense.

His father's answer was cold and businesslike. He said that no disgrace could have come to him that could have hurt him so deeply as the infidelity of his trusted son. If he would renounce this false faith for the true faith of his fathers, he would give him forty thousand dollars outright, and also leave him a legacy of the same amount. But should he refuse the offer, he should be to him as a stranger—the[69] doors of both his heart and his house should be forever barred against him.

His mother, with a woman's tact, sent the pictures of all the family, whom he had not seen for several years. Their faces called up so many happy memories of the past that they pleaded more eloquently than words. It was a sweet, loving letter she wrote to her boy, reminding him of all they had been to each other, and begging him for her sake to come back to the old faith. But right at the last she wrote: "If you insist on clinging to this false Christ, whom we have taught you to despise, the heart of your father and of your mother must be closed against you, and you must be thrust out from us forever with our curse upon you."

He knew it was the custom. He had been present once when the awful anathema was hurled at a traitor to the faith, withdrawing every right from the outlaw, living or dead. He knew that his grave would be dug in the Jewish cemetery in Baltimore; that the rabbi would read the rites of burial over his empty coffin, and that henceforth his only part in the family life would be the blot of his disgraceful memory.

He spread the pictures and the letters on the desk before him. A cold perspiration broke out on his forehead, as he realized the hopelessness of the alternative offered him. One by one he took up the photographs of his brothers and sisters, looked at them long and fondly, and laid them aside; then his father's, with its strong, proud face. He put that away, too.

At last he picked up his mother's picture. She looked straight out at him, with such a world of loving tenderness in the smiling eyes, with such trustful devotion, as if she knew he could not resist the appeal, that he turned away his head. The trial seemed greater than he could bear. He was trembling with the force of it. Then he looked again into the dear, patient face, till his eyes grew too dim to see. It was the same old mother who had nursed him, who had loved him, who had borne with his waywardness and forgiven him always. He seemed to feel the soft touch of her lips on his forehead as she bent over to give him a goodnight kiss. All that she had ever done for him came rushing through his memory so overwhelmingly that he broke down utterly, and began to sob like a child. "O, I can't give her[71] up," he groaned. "My dear old mother! I can't grieve her so!"

All that morning he clung to her picture, sometimes walking the floor in his agony, sometimes falling on his knees to pray. "God in heaven have pity," he cried. "That a man should have to choose between his mother and his Christ!" At last he rose, and, with one more long look at the picture, laid it reverently away with shaking hands. He had surrendered everything.

He did not tell all this to his sympathizing listeners. They could read part of the pathos of that struggle in his face, part in the voice that trembled occasionally, despite his strong effort to control it.

Frank Marion's thoughts went back to his own gentle mother in the old homestead among the green hills of Kentucky. As he thought of the great pillar of strength her unfaltering faith had been to him, of how from boyhood it had upheld and comforted and encouraged him, of how much he had always depended upon her love and her prayers, his sympathies were stirred to their depths. He reached out and took Lessing's hand in his strong grasp.

"God help you, brother!" he said, fervently.

Bethany turned her head aside, and looked away into the hazy distances. She knew what it meant to feel the breaking of every tie that bound her best beloved to her. She knew what it was to have only pictured faces to look into, and lay away with the pain of passionate longing. The question flashed into her mind, could she have made the voluntary surrender that he had made? She put it from her with a throb of shame that she was glad that she had not been so tested.

Some acquaintance of Mr. Marion, passing down the steps, recognized him, and called back:

"What time does your speech come on the program, Frank? I understand you are to hold forth to-day."

Mr. Marion hastily excused himself for a moment, to speak to his friend.

Bethany sat silent, thinking intently, while she drew unmeaning dots and dashes over the cover of her note-book.

Mr. Lessing turned to her abruptly. "Did you ever speak to a Jew about your Savior?" he asked, with such startling directness, that Bethany was confused.

"No," she said, hesitatingly.

"Why?" he asked.

He was looking at her with a penetrating gaze that seemed to read her thoughts.

"Really," she answered, "I have never considered the question. I am not very well acquainted with any, for one reason; besides, I would have felt that I was treading on forbidden grounds to speak to a Jew about religion. They have always seemed to me to be so intrenched in their beliefs, so proof against argument, that it would be both a useless and thankless undertaking."

"They may seem invulnerable to arguments," he answered, "but nobody is proof against a warm, personal interest. Ah, Miss Hallam, it seems a terrible thing to me. The Church will make sacrifices, will cross the seas, will overcome almost any obstacle to send the gospel to China or to Africa, anywhere but to the Jews at their elbows. O, of course, I know there are a few Hebrew missions, scattered here and there through the large cities, and a few earnest souls are devoting their entire energy to the work. But suppose every Christian in the country became an evangel to the little[74] community of Jews within the radius of his influence. Suppose a practical, prayerful, individual effort were made to show them Christ, with the same zeal you expend in sending 'the old story' to the Hottentots. What would be the result? O, if I had waited for a grown person to speak to me about it, I might have waited until the day of my death. I was restless. I was dissatisfied. I felt that I needed something more than my creed could give me. For what is Judaism now? I read an answer not long ago: 'A religion of sacrifice, to which, for eighteen centuries, no sacrifice has been possible; a religion of the Passover and the Day of Atonement, on which, for well-nigh two millenniums, no lamb has been slain and no atonement offered; a sacerdotal religion, with only the shadow of a priesthood; a religion of a temple which has no temple more; its altar is quenched, its ashes scattered, no longer kindling any enthusiasm, nor kindled by any hope.'[A] No man ever took me by the hand and told me about the peace I have now. No man ever shared with me his hope, or pointed out the way for me to find it. If it had not been for the[75] blessed guiding influence of a little child, my hungry heart might still be crying out unsatisfied."

He went on to repeat several conversations he had had with men of his own race, to show her how this indifference of Christians was reckoned against them as a glaring inconsistency by the Jews. Almost as if some one had spoken the words to her, she seemed to hear the condemnation, "I was a hungered, and ye gave me no meat. I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink. I was a stranger, and ye took me not in. Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these my brethren, ye did it not to me."

Strange as it may seem, Bethany's interpretation of that Scripture had always been in a temporal sense. More than once, when a child, she had watched her mother feed some poor beggar, with the virtuous feeling that that condemnation could not apply to the Hallam family. But now Lessing's impassioned appeal had awakened a different thought. Who so hungered as those who, reaching out for bread, grasped either the stones of a formal ritualism or the abandoned hope of prophecy unfulfilled? Who such "strangers within the gates" of the[76] nations as this race without a country? From the brick-kilns of Pharaoh to the willows of Babylon, from the Ghetto of Rome to the fagot-fires along the Rhine, from Spanish cruelties to English extortions, they had been driven—exiles and aliens. The New World had welcomed them. The New World had opened all its avenues to them. Only from the door of Christian society had they turned away, saying, "I was a stranger, and ye took me not in."

In the pause that followed, Bethany's heart went out in an earnest prayer: "O God, in the great day of thy judgment, let not that condemnation be mine. Only send me some opportunity, show me some way whereby I may lead even one of the least among them to the world's Redeemer!"

Mr. Marion came back from his interview, looking at his watch as he did so. It was so near time for services to begin at the tent, that he did not resume his seat.

"We may never meet again, Mr. Lessing," said Bethany, holding out her hand as she bade him good-bye. "So I want to tell you before I go, what an impression this conversation has made upon me. It has aroused an earnest desire[77] to be the means of carrying the hope that comforts me, to some one among your people."

"You will succeed," he said, looking into her earnest upturned face. Then he added softly, in Hebrew, the old benediction of an olden day—"Peace be unto you."

All that day, after the sunrise meeting, David Herschel had been with Major Herrick, going over the battle-fields, and listening to personal reminiscences of desperate engagements. A monument was to be erected on the spot where nearly all the major's men had fallen in one of the most hotly-contested battles of the war. He had come down to help locate the place.

"It's a very different reception they are giving us now," remarked the major, as they drove through the city.

Epworth League colors were flying in all directions. Every street gleamed with the white and red banners of the North, crossed with the white and gold of the South.

"Chattanooga is entertaining her guests royally; people of every denomination, and of no faith at all, are vying with each other to show the kindliest hospitality. We are missing[78] it by being at the hotel. I told Mrs. Herrick and the girls I would meet them at the tent this evening. Will you come, too?"

"No, thank you," replied David, "my curiosity was satisfied this morning. I'll go on up to the inn. I have a letter to write."

The major laughed.

"It's a letter that has to be written every day, isn't it?" he said, banteringly. "Well, I can sympathize with you, my boy. I was young myself once. Conferences aren't to be taken into account at all when a billet-doux needs answering."

The next day David kept Marta with him as much as possible. He could see that she was becoming greatly interested, and catching much of Albert Herrick's enthusiasm. The boy was a great League worker, and attended every meeting.

David took Marta a long walk over the mountain paths. They sat on the wide, vine-hung veranda of the inn, and read together. Then, as it was their Sabbath, he took her up to his room, and read some of the ritual of the day, trying to arouse in her some interest for the old customs of their childhood.

To his great dismay, he found that she had drifted away from him. She was not the yielding child she had been, whom he had been able to influence with a word.

She showed a disposition to question and contend, that annoyed him. The rabbi was right. She had been left too long among contaminating influences.

It was with a feeling of relief that he woke Sunday morning to hear the rain beating violently against the windows. He was glad on her account that the storm would prevent them going down into the city. But toward evening the sun came out, and Frances Herrick began to insist on going down to the night service in the tent.

"It is the last one there will be!" she exclaimed. "I wouldn't miss it for anything."

"Neither would I," responded Marta. "There is something so inspiring in all that great chorus of voices."

When David found that his sister really intended to go, notwithstanding his remonstrances, and that the family were waiting for her in the hall below, he made no further protest,[80] but surprised her by taking his hat, and tucking her hand in his arm.

"Then I will go with you, little sister," he said. "I want to have as much of your company as possible during my short visit."

Albert Herrick, who was waiting for her at the foot of the stairs, divined David's purpose in keeping his sister so close. He lifted his eyebrows slightly as he turned to take his mother's wraps, leaving Frances to follow with the major.

The tent was crowded when they reached it. They succeeded with great difficulty in obtaining several chairs in one of the aisles.