Riverside Edition

THE

COMPLETE WORKS OF NATHANIEL

HAWTHORNE, WITH INTRODUCTORY

NOTES BY GEORGE PARSONS

LATHROP

AND ILLUSTRATED WITH

Etchings by Blum, Church, Dielman, Gifford, Shirlaw,

and Turner

IN THIRTEEN VOLUMES

VOLUME XII.

Title: The Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Appendix to Volume XII: Tales, Sketches, and other Papers by Nathaniel Hawthorne with a Biographical Sketch by George Parsons Lathrop

Author: George Parsons Lathrop

Release date: August 18, 2012 [eBook #40529]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jana Srna, Eleni Christofaki, Richard Lammers,

Eric Eldred and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

This text is an appendix to volume 12 of a 13-volume set of the complete works of Nathaniel Hawthorne entitled:

The Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, with Introductory Notes by George Parsons Lathrop and illustrated with Etchings by Blum, Church, Dielman, Gifford, Shirlaw, and Turner in Thirteen Volumes, Volume XII.

Tales, Sketches, and other Papers by Nathaniel Hawthorne with a Biographical Sketch by George Parsons Lathrop.

BOSTON HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY New York: 11 East Seventeenth Street The Riverside Press, Cambridge 1883.

Some illustrations of this work have been moved from the original sequence to enable the contents to continue without interruption. The original page numbering has been retained. Punctuation inconsistencies have been silently corrected. A list of other corrections made can be found at the end of the book.

Riverside Edition

THE

COMPLETE WORKS OF NATHANIEL

HAWTHORNE, WITH INTRODUCTORY

NOTES BY GEORGE PARSONS

LATHROP

AND ILLUSTRATED WITH

Etchings by Blum, Church, Dielman, Gifford, Shirlaw,

and Turner

IN THIRTEEN VOLUMES

VOLUME XII.

TALES, SKETCHES, AND OTHER

PAPERS

BY

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

BY

GEORGE PARSONS LATHROP

BOSTON

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

New York: 11 East Seventeenth Street

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1883

Copyright, 1850, 1852, 1862, 1864, and 1876,

By NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, TICKNOR & FIELDS, AND

JAMES R. OSGOOD & CO.

Copyright, 1878,

By ROSE HAWTHORNE LATHROP.

Copyright, 1883,

By HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

All rights reserved.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge:

Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton & Co.

The lives of great men are written gradually. It often takes as long to construct a true biography as it took the person who is the subject of it to complete his career; and when the work is done, it is found to consist of many volumes, produced by a variety of authors. We receive views from different observers, and by putting them together are able to form our own estimate. What the man really was not even himself could know; much less can we. Hence all that we accomplish, in any case, is to approximate to the reality. While we flatter ourselves that we have imprinted on our minds an exact image of the individual, we actually secure nothing but a typical likeness. This likeness, however, is amplified and strengthened by successive efforts to paint a correct portrait. If the faces of people belonging to several generations of a family be photographed upon one plate, they combine to form a single distinct countenance, which shows a general resemblance to them all: in somewhat the same way, every sketch of a distinguished man helps to fix the lines of that typical semblance of him which is all that the world can hope to preserve.

This principle applies to the case of Hawthorne, notwithstanding that the details of his career are comparatively few, and must be marshalled in much the same way each time that it is attempted to review them. The veritable history of his life would be the history of his mental development, recording, like Wordsworth's "Prelude," the growth of a poet's mind; and on glancing back over it he too might have said, in Wordsworth's phrases:—

But a record of that kind, except where an autobiography exists, can be had only by indirect means. We must resort to tracing the outward facts of the life, and must try to infer the interior relations.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on the Fourth of July, 1804, at Salem, Massachusetts, in a house numbered twenty-one, Union Street. The house is still standing, although somewhat reduced in size and still more reduced in circumstances. The character of the neighborhood has declined very much since the period when Hawthorne involuntarily became a resident there. As the building stands to-day it makes the impression simply of an exceedingly plain, exceedingly old-fashioned, solid, comfortable abode, which in its prime 443must have been regarded as proof of a sufficient but modest prosperity on the part of the occupant. It is clapboarded, is two stories high, and has a gambrel roof, immediately beneath which is a large garret that doubtless served the boy-child well as a place for play and a stimulant for the sense of mystery. A single massive chimney, rising from the centre, emphasizes by its style the antiquity of the building, and has the air of holding it together. The cobble-stoned street in front is narrow, and although it runs from the house towards the water-side, where once an extensive commerce was carried on, and debouches not far from the Custom House where Hawthorne in middle life found plenty of occupation as Surveyor, it is now silent and deserted.

He was the second of three children born to Nathaniel Hathorne, sea-captain, and Elizabeth Clarke Manning. The eldest was Elizabeth Manning Hathorne, who came into the world March 7, 1802; the last was Maria Louisa, born January 9, 1808, and lost in the steamer Henry Clay, which was burned on the Hudson River, July 27, 1852. Elizabeth survived all the members of the family, dying on the 1st of January, 1883, when almost eighty-one years old, at Montserrat, a hamlet in the township of Beverly, near Salem. In early manhood, certainly at about the time when he began to publish, the young Nathaniel changed the spelling of his surname to Hawthorne; an alteration also adopted by his sisters. This is believed to have been merely a return to a mode of spelling practised by the English progenitors of the line, although none of the American ancestors had sanctioned it.

"The fact that he was born in Salem," writes Dr. George B. Loring, who knew him as a fellow-townsman, 444"may not amount to much to other people, but it amounted to a great deal to him. The sturdy and defiant spirit of his progenitor, who first landed on these shores, found a congenial abode among the people of Naumkeag, after having vainly endeavored to accommodate itself to the more imposing ecclesiasticism of Winthrop and his colony at Trimountain, and of Endicott at his new home. He was a stern Separatist ... but he was also a warrior, a politician, a legal adviser, a merchant, an orator with persuasive speech.... He had great powers of mind and body, and forms a conspicuous figure in that imposing and heroic group which stands around the cradle of New England. The generations of the family that followed took active and prominent part in the manly adventures which marked our entire colonial period.... It was among the family traditions gathered from the Indian wars, the tragic and awful spectre of the witchcraft delusion, the wild life of the privateer, that he [Nathaniel] first saw the light."

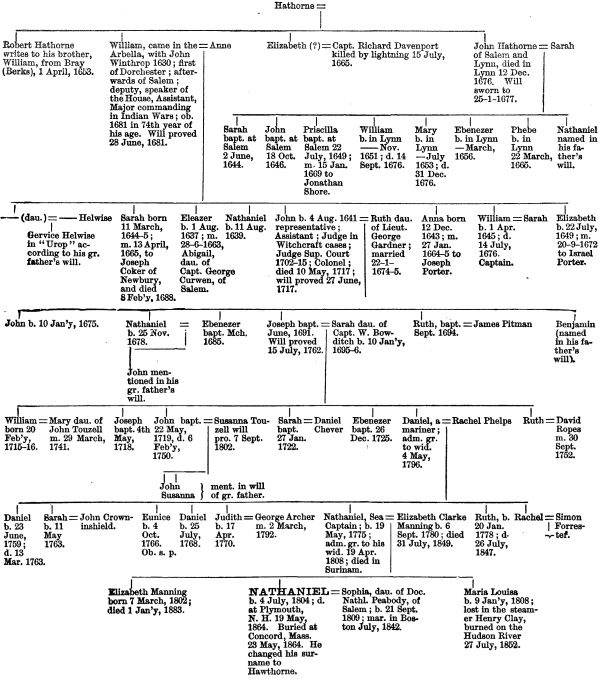

The progenitor here referred to is William Hathorne, who came to America with John Winthrop in 1630. He had grants of land in Dorchester, but was considered so desirable a citizen that the town of Salem offered him other lands if he would settle there; which he did. It has not been ascertained from what place William Hathorne originally came. His elder brother Robert is known to have written to him in 1653 from the village of Bray, in Berkshire, England; but Nathaniel Hawthorne says in the "American Note-Books" that William was a younger brother of a family having for its seat a place called Wigcastle, in Wiltshire. He became, however, a person of note and of great usefulness in the community with which 445he cast his lot, in the new England. Hathorne Street in Salem perpetuates his name to-day, as Lathrop Street does that of Captain Thomas Lathrop, who commanded one of the companies of Essex militia, when John Hathorne was quartermaster of the forces; Thomas Lathrop, who marched his men to Deerfield in 1675, to protect frontier inhabitants from the Indians, and perished with his whole troop, in the massacre at Bloody Brook. The year after that, William Hathorne also took the field against the Indians, in Maine, and conducted a highly successful campaign there, under great hardships. He had been the captain of the first military organization in Salem, and rose to be major. He served for a number of years as deputy in the Great and General Court; was a tax-collector, a magistrate, and a bold advocate of colonial self-government. Although opposed to religious persecution, as a magistrate he inflicted cruelties on the Quakers, causing a woman on one occasion to be whipped through Salem, Boston, and Dedham. "The figure of that first ancestor," Hawthorne wrote in "The Custom House," "invested by family tradition with a dim and dusky grandeur, was present to my boyish imagination as far back as I can remember;" so that it is by no means idle to reckon the history of his own family as among the important elements influencing the bent of his genius. John, the son of William, was likewise a public character; he, too, became a representative, a member of the Governor's council, a magistrate and a military officer, and saw active service as a soldier in the expedition which he headed against St. John, in 1696. But he is chiefly remembered as the judge who presided over the witchcraft trials and displayed great harshness and bigotry 448in his treatment of the prisoners. His descendants did not retain the position in public affairs which had been held by his father and himself; and for the most part they were sea-faring men. One of them, indeed, Daniel—the grandfather of Nathaniel—figured as a privateer captain in the Revolution, fighting one battle with a British troop-ship off the coast of Portugal, in which he was wounded; but the rest led the obscure though hardy and semi-romantic lives of maritime traders sailing to Africa, India, or Brazil. The privateersman had among his eight children three boys, one of whom, Nathaniel, was the father of the author, and died of fever in Surinam, in the spring of 1808, at the age of thirty-three.

HATHORNE FAMILY OF SALEM, MASSACHUSETTS.446

| Hathorne = | |||||||||||||||||

| Robert Hathorne writes to his brother, William, from Bray (Berks), 1 April, 1653. | William, came in the Arbella, with John Winthrop 1630; first of Dorchester; afterwards of Salem; deputy, speaker of the House, Assistant, Major commanding in Indian Wars; ob. 1681 in 74th year of his age. Will proved 28 June, 1681. | = Anne | Elizabeth (?) = Capt. Richard Davenport killed by lightning 15 July, 1665. | John Hathorne of Salem and Lynn, died in Lynn 12 Dec. 1676. Will sworn to 25-1-1677. | = Sarah | ||||||||||||

| Sarah bapt. at Salem 2 June, 1644. | |||||||||||||||||

| John bapt. at Salem 18 Oct. 1646. | |||||||||||||||||

| Priscilla bapt. at Salem 22 July, 1649; m. 15 Jan. 1669 to Jonathan Shore. | |||||||||||||||||

| William b. in Lynn —— Nov. 1651; d. 14 Sept. 1676. | |||||||||||||||||

| Mary b. in Lynn —— July 1653; d. 31 Dec. 1676. | |||||||||||||||||

| Ebenezer b. in Lynn —— March, 1656. | |||||||||||||||||

| Phebe b. in Lynn 22 March, 1665. | |||||||||||||||||

| Nathaniel named in his father's will. | |||||||||||||||||

| — (dau.) | = — Helwise | Sarah born 11 March, 1644-5; m. 13 April, 1665, to Joseph Coker of Newbury, and died 3 Feb'y, 1688. | Eleazer b. 1 Aug. 1637; m. 28-6-1663, Abigail, dau. of Capt. George Curwen, of Salem. | Nathaniel b. 11 Aug. 1639. | John b. 4 Aug. 1641 representative; Assistant; Judge in Witchcraft cases; Judge Sup. Court 1702-15; Colonel; died 10 May, 1717; will proved 27 June, 1717. | = Ruth dau. of Lieut. George Gardner; married 22-1-1674-5. | Anna born 12 Dec. 1643; m. 27 Jan. 1664-5 to Joseph Porter. | William b. 1 Apr. 1645; d. 14 July, 1676. Captain. = Sarah | Elizabeth b. 22 July, 1649; m. 20-9-1672 to Israel Porter. | ||||||||

| Gervice Helwise in "Urop" according to his gr. father's will. | |||||||||||||||||

| 447 | |||||||||||||||||

| John b. 10 Jan'y 1675. | Nathaniel b. 25 Nov. 1678. = | Ebenezer bapt. Mch. 1685. | Joseph bapt. June, 1691. Will proved 15 July, 1762. | = Sara dau. of Capt. W. Bowditch b. 10 Jan'y, 1695-6. | Ruth, bapt. Sept. 1694. = James Pitman | Benjamin (named in his father's will). | |||||||||||

| John mentioned in his gr. father's will. | |||||||||||||||||

| William born 20 Feb'y, 1715-1716. = Mary dau. of John Touzell m. 29 March, 1741. | Joseph bapt. 4th May, 1718. | John bapt. 22 May, 1719, d. 6 Feb'y, 1750. | = Susanna Touzell will pro. 7 Sept. 1802. | Sarah bapt. 27 Jan. 1722. = Daniel Chever | Ebenezer bapt. 26 Dec. 1725. | Daniel, a mariner; adm. gr. to wid. 4 May, 1796. | = Rachel Phelps | Ruth = David Ropes m. 30 Sept. 1752. | |||||||||

| John, Susanna } ment. in will of gr. father. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Daniel b. 23 June, 1759; d. 13 Mar. 1763. | Sarah b. 11 May 1763. = John Crowninshield. | Eunice b. 4 Oct. 1766. Ob. s. p. | Daniel b. 25 July, 1768. | Judith b. 17 Apr. 1770. = George Archer m. 2 March, 1792. | Nathaniel, Sea Captain; b. 19 May, 1775; adm. gr. to his wid. 19 Apr. 1808; died in Surinam. | = Elizabeth Clarke Manning b. 6 Sept. 1780; died 31 July, 1849. | Ruth b. 20 Jan. 1778; d. 26 July, 1847. | Rachel | = Simon Forrester. | ||||||||

| —— | |||||||||||||||||

| Elizabeth Manning born 7 March, 1802; died 1 Jan'y, 1883. | NATHANIEL b. 4 July, 1804; d. at Plymouth, N. H. 19 May, 1864. Buried at Concord, Mass. 23 May, 1864. He changed his surname to Hawthorne. | = Sophia, dau. of Doc. Nathl. Peabody, of Salem; b. 21 Sept. 1809; mar. in Boston July, 1842. | Maria Louisa b. 9 Jan'y, 1808; lost in the steamer Henry Clay, burned on the Hudson River 27 July, 1852. | ||||||||||||||

The founders of the American branch were men of independent character, proud, active, energetic, capable of extreme sternness and endowed with passionate natures, no doubt. But they were men of affairs; they touched the world on the practical side, and, even during the decline of the family fortunes, continued to do so. All at once, in the personality of the younger Nathaniel Hawthorne, this energy which persisted in them reversed its direction, and found a new outlet through the channel of literary expression. We must suppose that he included among his own characteristics all those of his predecessors; their innate force, their endurance, their capacity for impassioned feeling; but in him these elements were fused by a finer prevailing quality, and held in firm balance by his rare temperament. This must be borne in mind, if we would understand the conjunction of opposite traits in him. It was one of his principles to guard against being run away with by his imagination, and to cultivate in practical affairs what he called "a morose common sense." 449There has been attributed to him by some of those who knew him a certain good-humored gruffness, which might be explained as a heritage from the self-assertive vitality of his ancestors. While at Liverpool he wrote to one of his intimates in this country, and in doing so made reference to another acquaintance as a "wretch," to be away from whom made exile endurable. The letter passed into the hands of the acquaintance thus stigmatized long after Hawthorne was in his grave; but he declared himself to be in no wise disturbed by it, because he knew that the remark was not meant seriously, being only one of the occasional explosions of a "sea-dog" forcefulness, which had come into the writer's blood from his skipper forefathers. Hawthorne had, in fact, parted on friendly terms from the gentleman of whom he thus wrote. On the other hand we have the traits of sensitiveness, great delicacy, reserve and reverie, drawn from both his father and his mother. Captain Hathorne had been a man of fine presence, handsome, kindly, and rather silent; a reader, likewise; and his son's resemblance to him was so marked that a strange sailor stopped Hawthorne on the steps of the Salem Custom House, many years afterward, to ask him if he were not a son or nephew of the Captain, whom he had known.

His mother belonged to an excellent family, the Mannings, of English stock, settled in Salem and Ipswich ever since 1680, and still well represented in the former place. She, too, was a very reserved person; had a stately, aristocratic manner; is remembered as possessing a peculiar and striking beauty. Her education was of that simple, austere, but judicious and perfected kind that—without taking any 450very wide range—gave to New England women in the earlier part of this century a sedate freedom and a cultivated judgment, which all the assumed improvements in pedagogy and the general relations of men and women since then have hardly surpassed. She was a pious woman, a sincere and devoted wife, a mother whose teachings could not fail to impress upon her children a bias towards the best things in life. Nathaniel's sister Elizabeth, although a recluse to the end of her days, and wholly unknown to the public, gave in her own case evidence indisputable of the fine influences which had moulded her own childhood and that of her brother. She showed a quiet, unspoiled, and ardent love of Nature, and was to the last not only an assiduous reader of books but also a very discriminating one. The range of her reading was very wide, but she never made any more display of it than Hawthorne did of his. An intuitive judgment of character was hers, which was really startling at times: merely from the perusal of a book or the inspection of a portrait, she would arrive at accurate estimates of character which revealed a power of facile and comprehensive insight; and her letters, even in old age, flowed spontaneously into utterance of the same finished kind that distinguished Nathaniel Hawthorne's epistolary style. How fresh and various, too, was her interest in the affairs of the world! For many years she had not gone farther from her secluded abode in a farm-house at Montserrat, than to Beverly or Salem; yet I remember that, only six months before her death, she wrote a letter to her niece, a large part of which was devoted to the campaign of the English in Egypt, then progressing: with a lively and clear comprehension she discussed the 451difficulties of the situation, and expressed the utmost concern for the success of the English army, at the same time that she laughed at herself for displaying, as an old woman, so much anxiety about the matter. Now, a mother who could bring up her daughter in such a way as to make all this possible and natural, must be given much credit for her share in developing an illustrious son. Let us not forget that it was to his mother that Goethe owed in good measure the foundation of his greatness. Mrs. Hathorne had large, very luminous gray eyes, which were reproduced in her son's; so that, on both sides, his parentage entitled him to the impressive personal appearance which distinguished him. In mature life he became somewhat estranged from her, but their mutual love was presumably suspended only for a time, and he was with her at her death, in 1849. She lived long enough to see him famous as the author of "Twice-Told Tales"; but "The Scarlet Letter" had not been written when she died.

She, as well as her husband, was one of a family of eight brothers and sisters; these were the children of Richard Manning. Two of the brothers, Richard and Robert, were living in Salem when she was left a widow; Robert being eminent in New England at that time as a horticulturist. She was without resources, other than her husband's earnings, and Robert undertook to provide for her. Accordingly, she removed with her young family to the Manning homestead on Herbert Street, the next street east of Union Street, where Nathaniel was born. This homestead stood upon a piece of land running through to Union Street, and adjoining the garden attached to Hawthorne's birthplace. At that time Dr. Nathaniel Peabody, 452a physician, occupied a house in a brick block on the opposite side of Union Street; and there in 1809, September 21st, was born his daughter, Sophia A. Peabody, who afterwards became Hawthorne's wife. Her birthplace, therefore, was but a few rods distant from that of her future husband. Sophia Peabody's eldest sister, Mary, who married Horace Mann, noted as an educator and an abolitionist, remembers the child Nathaniel, who was then about five years old. He used to make his appearance in the garden of the Herbert Street mansion, running and dancing about there at play, a vivacious, golden-haired boy. The next oldest sister, who was the first of this family to make the acquaintance of the young author some thirty years later on, was Miss Elizabeth P. Peabody, who has taken an important part in developing the Kindergarten in America. There were plenty of books in the Manning house, and Nathaniel very soon got at them. Among the authors whom he earliest came to know were Shakespeare, Milton, Pope, Thomson, and Rousseau. The "Castle of Indolence" was one of his favorite volumes. Subsequently, he read the whole of the "Newgate Calendar," and became intensely absorbed in Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress," which undoubtedly left very deep impressions upon him, traceable in the various allusions to it scattered through his works. He also made himself familiar with Spenser's "Faërie Queen," Froissart's "Chronicles," and Clarendon's "History of the Rebellion."

"Being a healthy boy, with strong out-of-door instincts planted in him by inheritance from his sea-faring sire, it might have been that he would not have been brought so early to an intimacy with books, but for an accident similar to that which played a part in 453the boyhoods of Scott and Dickens. When he was nine years old, he was struck on the foot by a ball, and made seriously lame. The earliest fragment of his writing now extant is a letter to his uncle Robert Manning, at that time in Raymond, Maine, written from Salem, December 9, 1813. It announces that the foot is no better, and that a new doctor is to be sent for. 'Maybe,' the boy writes, 'he will do me some good, for Dr. B—— has not, and I don't know as Dr. K—— will.' He adds that it is now four weeks since he has been to school, 'and I don't know but it will be four weeks longer.'... But the trouble was destined to last much longer than even the young seer had projected his gaze. There was some threat of deformity, and it was not until he was nearly twelve that he became quite well. Meantime, his kind schoolmaster, Dr. Worcester, ... came to hear him his lessons at home. The good pedagogue does not figure after this in Hawthorne's history; but a copy of Worcester's Dictionary still exists and is in present use, which bears in a tremulous writing on the fly-leaf the legend: 'Nathaniel Hawthorne Esq., with the respects of J. E. Worcester.' For a long time, in the worst of his lameness, the gentle boy was forced to lie prostrate, and choosing the floor for his couch, he would read there all day long. He was extremely fond of cats—a taste which he kept through life; and during this illness, forced to odd resorts for amusement, he knitted a pair of socks for the cat who reigned in the household at the time. When tired of reading, he constructed houses of books for the same feline pet, building walls for her to leap, and perhaps erecting triumphal arches for her to pass under."[1]

The lexicographer, Dr. Worcester, was then living at Salem in charge of a school, which he kept for a few years; and it was with him that Hawthorne was carrying on his primary studies. He also went to dancing-school, was fond of fishing as well as of taking long walks, and doubtless engaged in the sundry occupations and sports, neither more nor less extraordinary than these, common to lads of his age. He already displayed a tendency towards dry humor. As he brought home from school frequent reports of having had a bout at fisticuffs with another pupil named John Knights, his sister Elizabeth asked him: "Why do you fight with John Knights so often?" "I can't help it," he answered: "John Knights is a boy of very quarrelsome disposition."

But all this time an interior growth, of which we can have no direct account, was proceeding in his mind. The loss of the father whom he had had so little chance to see and know and be fondled by, no doubt produced a profound effect upon him. While still a very young child he would rouse himself from long broodings, to exclaim with an impressive shaking of the head: "There, mother! I is going away to sea some time; and I'll never come back again!" The thought of that absent one, whose barque had glided out of Salem harbor bound upon a terrestrial voyage, but had carried him softly away to the unseen world, must have been incessantly with the boy; and it would naturally melt into what he heard of the strange, shadowy history of his ancestors, and mix itself with the ever-present hush of settled grief in his mother's dwelling, and blend with his unconscious observations of the old town in which he lived. Salem then was much younger in time, but much older to the eye, than 455it is now. In "Alice Doane's Appeal" he has sketched a rapid bird's-eye view of it as it appeared to him when he was a young man. Describing his approach with his sisters to Witch Hill, he says: "We ... began to ascend a hill which at a distance, by its dark slope and the even line of its summit, resembled a green rampart along the road; ... but, strange to tell, though the whole slope and summit were of a peculiarly deep green, scarce a blade of grass was visible from the base upward. This deceitful verdure was occasioned by a plentiful crop of 'wood-wax,' which wears the same dark and gloomy green throughout the summer, except at one short period, when it puts forth a profusion of yellow blossoms. At that season, to a distant spectator the hill appears absolutely overlaid with gold, or covered with a glory of sunshine even under a clouded sky." This wood-wax, it may be said, is a weed which grows nowhere but in Essex County, and, having been native in England, was undoubtedly brought over by the Pilgrims. He goes on: "There are few such prospects of town and village, woodland and cultivated field, steeples and country-seats, as we beheld from this unhappy spot.... Before us lay our native town, extending from the foot of the hill to the harbor, level as a chess-board, embraced by two arms of the sea, and filling the whole peninsula with a close assemblage of wooden roofs, overtopped by many a spire and intermixed with frequent heaps of verdure.... Retaining these portions of the scene, and also the peaceful glory and tender gloom of the declining sun, we threw in imagination a deep veil of forest over the land, and pictured a few scattered villages here and there and this old town itself a village, as when the prince of Hell bore sway there. The idea thus 456gained of its former aspect, its quaint edifices standing far apart with peaked roofs and projecting stories, and its single meeting-house pointing up a tall spire in the midst; the vision, in short, of the town in 1692, served to introduce a wondrous tale." There were in fact several old houses of the kind here described still extant during Hawthorne's boyhood, and he went every Sunday to service in the First Church, in whose congregation his forefathers had held a pew for a hundred and seventy years. It is easy to see how some of the materials for "The House of the Seven Gables" and "The Scarlet Letter" were already depositing themselves in the form of indelible recollections and suggestions taken from his surroundings.

Oppressed by her great sorrow, his mother had shut herself away, after her husband's death, from all society except that of her immediate relatives. This was perhaps not a very extraordinary circumstance, nor one that need be construed as denoting a morbid disposition; but it was one which must have distinctly affected the tone of her son's meditations. In 1818, when he was fourteen years old, she retired to a still deeper seclusion, in Maine; but the occasion of this was simply that her brother Robert, having purchased the seven-mile-square township of Raymond, in that State, had built a house there, intending to found a new home. The year that Hawthorne passed in that spot, amid the breezy life of the forest, fishing and shooting, watching the traits and customs of lumber-men and country-folk, and drinking in the tonic of a companionship with untamed nature, was to him a happy and profitable one. "We are all very well," he wrote thence to his Uncle Robert, in May, 1819: "The fences are all finished, and the garden is laid 457out and planted.... I have shot a partridge and a henhawk, and caught eighteen large trout out of our brook. I am sorry you intend to send me to school again." He had been to the place before, probably for short visits, when his Uncle Richard was staying there, and his memories of it were always agreeable ones. To Mr. James T. Fields, he said in 1863: "I lived in Maine like a bird of the air, so perfect was the freedom I enjoyed. But it was there I first got my cursed habits of solitude." "During the moonlight nights of winter he would skate until midnight all alone upon Sebago Lake, with the deep shadows of the icy hills on either hand. When he found himself far away from his home and weary with the exercise of skating, he would sometimes take refuge in a log-cabin, where half a tree would be burning on the broad hearth. He would sit in the ample chimney, and look at the stars through the great aperture through which the flames went roaring up. 'Ah,' he said, 'how well I recall the summer days, also, when with my gun I roamed through the woods of Maine!'"[2]

Hawthorne at this time had an intention of following the example of his father and grandfather, and going to sea; but this was frustrated by the course of events. His mother, it is probable, would strongly have objected to it. In a boyish journal kept while he was at Raymond he mentions a gentleman having come with a boat to take one or two persons out on "the Great Pond," and adds: "He was kind enough to say that I might go (with my mother's consent), which she gave after much coaxing. Since the loss of my father she dreads to have any one belonging to her go upon the water." And again: "A young man named 458Henry Jackson, Jr., was drowned two days ago, up in Crooked River.... I read one of the Psalms to my mother this morning, and it plainly declares twenty-six times that 'God's mercy endureth forever.'... Mother is sad; says she shall not consent any more to my swimming in the mill-pond with the boys, fearing that in sport my mouth might get kicked open, and then sorrow for a dead son be added to that for a dead father, which she says would break her heart. I love to swim, but I shall not disobey my mother." This same journal, which seems to have laid the basis of his life-long habit of keeping note-books, was begun at the suggestion of Mr. Richard Manning, who gave him a blank-book, with advice that he should use it for recording his thoughts, "as the best means of his securing for mature years command of thought and language." In it were made a number of entries which testify plainly to his keenness of observation both of people and scenery, to his sense of humor and his shrewdness. Here are a few:—

"Swapped pocket-knives with Robinson Cook yesterday. Jacob Dingley says that he cheated me, but I think not, for I cut a fishing-pole this morning and did it well; besides, he is a Quaker, and they never cheat."

"This morning the bucket got off the chain, and dropped back into the well. I wanted to go down on the stones and get it. Mother would not consent, for fear the well might cave in, but hired Samuel Shaw to go down. In the goodness of her heart, she thought the son of old Mrs. Shaw not quite so good as the son of the Widow Hathorne."

Of a trout that he saw caught by some men:—"This trout had a droll-looking hooked nose, and they 459tried to make me believe that, if the line had been in my hands, I should have been obliged to let go, or have been pulled out of the boat. They are men, and have a right to say so. I am a boy, and have a right to think differently."

"We could see the White Hills to the northwest, though Mr. Little said they were eighty miles away; and grand old Rattlesnake to the northeast, in its immense jacket of green oak, looked more inviting than I had ever seen it; while Frye's Island, with its close growth of great trees growing to the very edge of the water, looked like a monstrous green raft, floating to the southeastward. Whichever way the eye turned, something charming appeared."

The mental clearness, the sharpness of vision, and the competence of the language in this early note-book are remarkable, considering the youth and inexperience of the writer; and there is one sketch of "a solemn-faced old horse" at the grist-mill, which exhibits a delightful boyish humor with a dash of pathos in it, and at the same time is the first instance on record of a mild approach by Hawthorne to the writing of fiction:—

"He had brought for his owner some bags of corn to be ground, who, after carrying them into the mill, walked up to Uncle Richard's store, leaving his half-starved animal in the cold wind with nothing to eat, while the corn was being turned into meal. I felt sorry, and, nobody being near, thought it best to have a talk with the old nag, and said, 'Good morning, Mr. Horse, how are you to-day?' 'Good morning, youngster,' said he, just as plain as a horse can speak; and then said, 'I am almost dead, and I wish I was quite. I am hungry, have had no breakfast, and must 460stand here tied by the head while they are grinding the corn, and until master drinks two or three glasses of rum at the store, then drag the meal and him up the Ben Ham Hill home, and am now so weak that I can hardly stand. Oh dear, I am in a bad way;' and the old creature cried. I almost cried myself. Just then the miller went down-stairs to the meal-trough; I heard his feet on the steps, and not thinking much what I was doing, ran into the mill, and, taking the four-quart toll-dish nearly full of corn out of the hopper, carried it out, and poured it into the trough before the horse, and placed the dish back before the miller came up from below. When I got out, the horse was laughing, but he had to eat slowly, because the bits were in his mouth. I told him that I was sorry, but did not know how to take them out, and should not dare to if I did.... At last the horse winked and stuck out his lip ever so far, and then said, 'The last kernel is gone;' then he laughed a little, then shook one ear, then the other; then he shut his eyes. I jumped up and said: 'How do you feel, old fellow; any better?' He opened his eyes, and looking at me kindly answered, 'Very much,' and then blew his nose exceedingly loud, but he did not wipe it. Perhaps he had no wiper. I then asked him if his master whipped him much. He answered, 'Not much lately. He used to till my hide got hardened, but now he has a white-oak goad-stick with an iron brad in its end, with which he jabs my hind-quarters and hurts me awfully.'... The goad with the iron brad was in the wagon, and snatching it out I struck the end against a stone, and the stabber flew into the mill-pond. 'There,' says I, 'old colt,' as I threw the goad back into the wagon, 'he won't harpoon you again with 461that iron.' The poor old brute understood well enough what I said, for I looked him in the eye and spoke horse language."

Mother and uncles could hardly have missed observing in him many tokens of a gifted intelligence and an uncommon individuality. The perception of these, added to Mrs. Hawthorne's dread of the sea, may have led to the decision which was taken to send him to college. In 1819 he went back to Salem, to continue his schooling; and one year later, March 7, 1820, wrote to his mother, who was still at Raymond: "I have left school, and have begun to fit for College, under Benjamin L. Oliver, Lawyer. So you are in great danger of having one learned man in your family.... Shall you want me to be a Minister, Doctor, or Lawyer? A minister I will not be." Miss E. P. Peabody remembers another letter of his, in which he touched the same problem, thus: "I do not want to be a doctor and live by men's diseases, nor a minister to live by their sins, nor a lawyer and live by their quarrels. So I don't see that there is anything left but for me to be an author. How would you like some day to see a whole shelf full of books written by your son, with 'Hathorne's Works' printed on the backs?" There appears to have been but little difficulty for him in settling the problem of his future occupation. During part of August and September he amused himself by writing three numbers of a miniature weekly paper called "The Spectator;" and in October we find that he had been composing poetry and sending it to his sister Elizabeth, who was also exercising herself in verse. At this time he was employed as a clerk, for a part of each day, in the office of another uncle, William Manning, proprietor of a great 462line of stages which then had extensive connections throughout New England; but he did not find the task congenial. "No man," he informed his sister, "can be a poet and a book-keeper at the same time;" from which one infers his distinct belief that literature was his natural vocation. The idea of remaining dependent for four years more on the bounty of his Uncle Robert, who had so generously taken the place of a father in giving him a support and education, oppressed him, and he even contemplated not going to college; but go he finally did, taking up his residence at Bowdoin with the class of 1821.

The village of Brunswick, where Bowdoin College is situated, some thirty miles from Raymond, stands on high ground beside the Androscoggin River, which is there crossed by a bridge running zig-zag from bank to bank, resting on various rocky ledges and producing a picturesque effect. The village itself is ranged on two sides of a broad street, which meets the river at right angles, and has a mall in the centre that, in Hawthorne's time, was little more than a swamp. This street, then known as "sixteen-rod road," from its width, continues in a straight line to Casco Bay, only a few miles off; so that the new student was still near the sea and had a good course for his walks. If Harvard fifty and even twenty-five years ago had the look of a rural college, Bowdoin was by comparison an academy in a wilderness. "If this institution," says Hawthorne in "Fanshawe," where he describes it under the name of Harley College, "did not offer all the advantages of elder and prouder seminaries, its deficiencies were compensated to its students by the inculcation of regular habits, and of a deep and awful sense of religion, which seldom deserted them in their 463course through life. The mild and gentle rule ... was more destructive to vice than a sterner sway; and though youth is never without its follies, they have seldom been more harmless than they were here." The local resources for amusement or dissipation must have been very limited, and the demands of the curriculum not very severe. Details of Hawthorne's four years' stay at college are not forthcoming, otherwise than in small quantity. His comrades who survived him never have been able to give any very vivid picture of the life there, or to recall any anecdotes of Hawthorne: the whole episode has slipped away, like a dream from which fragmentary glimpses alone remain. By one of those unaccountable associations with trifles, which outlast more important memories, Professor Calvin Stowe (to whom the authoress of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was afterwards married) remembers seeing Hawthorne, then a member of the class below him, crossing the college-yard one stormy day, attired in a brass-buttoned blue coat, with an umbrella over his head. The wind caught the umbrella and turned it inside out; and what stamped the incident on Professor Stowe's mind was the silent but terrible and consuming wrath with which Hawthorne regarded the implement in its utterly subverted and useless state, as he tried to rearrange it. Incidents of no greater moment and the general effect of his presence seem to have created the belief among his fellows that, beneath the bashful quietude of his exterior, was stored a capability of exerting tremendous force in some form or other. He was seventeen when he entered college,—tall, broad-chested, with clear, lustrous gray eyes,[3] a fresh complexion, 464and long hair: his classmates were so impressed with his masculine beauty, and perhaps with a sense of occult power in him, that they nicknamed him Oberon. Although unusually calm-tempered, however, he was quick to resent disrespectful treatment (as he had been with John Knights), and his vigorous, athletic frame made him a formidable adversary. In the same class with him were Henry W. Longfellow; George Barrell Cheever, since famous as a divine, and destined to make a great stir in Salem by a satire in verse called "Deacon Giles's Distillery," which cost him a thirty days' imprisonment, together with the loss of his pastorate; also John S. C. Abbott, the writer of popular histories; and Horatio Bridge, afterwards Lieutenant in the United States Navy, and now Commander. Bridge and Franklin Pierce, who studied in the class above him, were his most intimate friends. He boarded in a house which had a stairway on the outside, ascending to the second story; he took part, I suppose, in the "rope-pulls" and "hold-ins" between Freshmen and Sophomores, if those customs were practised then; he was fined for card-playing and for neglect of theme; entered the Athenæan Society, which had a library of eight hundred volumes; tried to read Hume's "History of England," but found it "abominably dull," and postponed the attempt; was fond of whittling, and destroyed some of his furniture in gratifying that taste. Such are the insignificant particulars to which we are confined in attempting to form an idea of the externals of his college-life. Pierce was chairman of the Athenæan Society, and also organized a military company, which Hawthorne joined. 465In the Preface to "The Snow-Image" we are given a glimpse of the simple amusements which occupied his leisure: "While we were lads together at a country college, gathering blueberries in study hours under those tall academic pines; or watching the great logs as they tumbled along the current of the Androscoggin; or shooting pigeons and gray squirrels in the woods; or bat-fowling in the summer-twilight; or catching trouts in that shadowy little stream which, I suppose, is still wandering riverward through the forest." He became proficient in Latin. Longfellow was wont to recall how he would rise at recitation, standing slightly sidewise—attitude indicative of his ingrained shyness—and read from the Roman classics translations which had a peculiar elegance and charm. In writing English, too, he won a reputation, and Professor Newman was often so struck with the beauty of his work in this kind that he would read them in the evening to his own family. Professor Packard says: "His themes were written in the sustained, finished style that gives to his mature productions an inimitable charm. The recollection is very distinct of Hawthorne's reluctant step and averted look, when he presented himself at the professor's study and submitted a composition which no man in his class could equal."

Hawthorne always looked back with satisfaction to those simple and placid days. In 1852 he revisited the scene where they were passed, in order to be present at the semi-centennial anniversary of the founding of the college. A letter, from Concord (October 13, 1852), to Lieutenant Bridge, now for the first time published, contains the following reference to that event:—

466 "I meant to have told you about my visit to Brunswick.... Only eight of our classmates were present, and they were a set of dismal old fellows, whose heads looked as if they had been out in a pretty copious shower of snow. The whole intermediate quarter of a century vanished, and it seemed to me as if they had undergone the miserable transformation in the course of a single night—especially as I myself felt just about as young as when I graduated. They flattered me with the assurance that time had touched me tenderly; but alas! they were each a mirror in which I beheld the reflection of my own age. I did not arrive till after the public exercises were nearly over—and very luckily, too, for my praises had been sounded by orator and poet, and of course my blushes would have been quite oppressive."

Hawthorne's rank in his class entitled him to a "part" at Commencement, but the fact that he had not cultivated declamation debarred him from that honor; and so he passed quietly away from the life of Bowdoin and settled down to his career. "I have thought much upon the subject," he wrote to his sister, just before graduation, "and have come to the conclusion that I shall never make a distinguished figure in the world, and all I hope or wish is to plod along with the multitude." But declamation was not essential to his success, which was to be achieved in anything but a declamatory fashion.

In one sense it was all very simple, this childhood and youth and early training of Hawthorne. We can see that the conditions were not complicated and were 467quite homely. But the influence of good literature had been at work upon the excellent mental substance derived from a father who was fond of reading and a mother who had the plain elementary virtues on which so much depends, and great purity of soul. The composure and finish of style which he already had at command on going to college were ripened amid the homely conditions aforesaid: there must have been an atmosphere of culture in his home, unpretentious though the mode of life there was. His sister, as I have mentioned, showed much the same tone, the same commanding ease, in her writing. There existed a dignity, a reserve, an instinctive refinement in this old-fashioned household, which moved its members to appropriate the best means of expression as by natural right. They appear to have treated the most ordinary affairs of life with a quiet stateliness, as if human existence were really a thing to be considered with respect, and with a frank interest that might occasionally even admit of enthusiasm or strong feeling with regard to an experience, although thousands of beings might have passed through it before. Our new horizons, physically enlarged by rapid travel, our omnifarious culture, our passion for obtaining a glaze of cosmopolitanism to cover the common clay from which we are all moulded, do not often yield us anything essentially better than the narrow limits of the little world in which Hawthorne grew up. He was now to go back to Salem, which he once spoke of as being apparently for him "the inevitable centre of the universe;" and the conditions there were not radically altered from what they had been before. We can form an outline of him as he was then, or at most a water-color sketch presenting the fresh hues of youth, 468the strong manly frame of the young graduate, his fine deep-lighted eyes, and sensitively retiring ways. But we have now to imagine the change that took place in him from the recent college Senior to the maturing man; change that gradually transforms him from the visionary outline of that earlier period to a solid reality of flesh and blood, a virile and efficient person who still, while developing, did not lose the delicate sensibility of his young prime.

His family having reëstablished themselves in Salem, at the old Herbert Street house, he settled himself with them, and stayed there until December, 1828, meanwhile publishing "Fanshawe" anonymously. They then moved to a smaller house on Dearborn Street, North Salem; but after four years they again took up their abode in the Herbert Street homestead. Hawthorne wrote industriously; first the "Seven Tales of my Native Land," which he burned, and subsequently the sketches and stories which, after appearing in current periodicals, were collected as "Twice-Told Tales." In 1830 he took a carriage trip through parts of Connecticut. "I meet with many marvellous adventures," was a part of his news on this occasion, but they were in reality adventures of a very tame description. He visited New York and New Hampshire and Nantucket, thus extending slightly his knowledge of men and places. A great deal of discursive reading was also accomplished. In 1836 he went to Boston to edit for Mr. S. G. Goodrich "The American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge." It did not turn out to be either useful or entertaining for the editor, who was to be paid but $500 a year for his drudgery, and in fact received only a small part of that sum. Through Goodrich, he became a copious 469contributor to "The Token," in the pages of which his tales first came to be generally known; but he gave up the magazine after a four months' misery of editorship, and sought refuge once more in his native town.

Salem was an isolated place, was not even joined to the outer world by its present link of railroad with Boston, and afforded no very generous diet for a young, vigorous, hungry intellect like that of Hawthorne. Surroundings, however, cannot make a mind, though they may color its processes. He proceeded to extract what he could from the material at hand. "His mode of life at this period was fitted to nurture his imagination, but must have put the endurance of his nerves to the severest test. The statement that for several years 'he never saw the sun' is entirely an error. In summer he was up shortly after sunrise, and would go down to bathe in the sea; but it is true that he seldom chose to walk in the town except at night, and it is said that he was extremely fond of going to fires if they occurred after dark. The morning was chiefly given to study, the afternoon to writing, and in the evening he would take long walks, exploring the coast from Gloucester to Marblehead and Lynn—a range of many miles.... Sometimes he took the day for his rambles, wandering perhaps over Endicott's ancient Orchard Farm and among the antique houses and grassy cellars of old Salem Village, the witchcraft ground; or losing himself among the pines of Montserrat and in the silence of the Great Pastures, or strolling along the beaches to talk with old sailors and fishermen." "He had little communication with even the members of his family. Frequently his meals were brought and left at his locked door, and it was not often that the four inmates of the 470old Herbert Street mansion met in family circle. He never read his stories aloud to his mother and sisters, as might be imagined from the picture which Mr. Fields draws of the young author reciting his new productions to his listening family; though, when they met, he sometimes read older literature to them. It was the custom in this household for the members to remain very much by themselves: the three ladies were perhaps nearly as rigorous recluses as himself; and, speaking of the isolation which reigned among them, Hawthorne once said, 'We do not even live at our house!' But still the presence of this near and gentle element is not to be underrated, as forming a very great compensation in the cold and difficult morning of his life." Of self-reliant mind, accustomed to solitude and fond of reading, it was not strange that they should have fallen into these habits, which, however peculiarly they may strike others, did not necessarily spring from a morbid disposition, and never prevented the Hawthornes from according a kindly reception to their friends.

Nathaniel Hawthorne's own associates were not numerous. There was a good society in the town, for Salem was not, strictly speaking, provincial, but—aided in a degree by the separateness of its situation—retained very much its old independence as a commercial capital. There were people of wealth and cultivation, of good lineage in our simple domestic kind, who made considerable display in their entertainments and were addicted to impressive absences in Paris and London. Among these Hawthorne did not show himself at all. His preference was for individuals who had no pretensions whatever in the social way. Among his friends was one William B. Pike, a carpenter's 471son, who, after acquiring an ordinary public-school education without passing through the higher grades, adopted his father's trade, became a Methodist class-leader, secondly a disciple of Swedenborg, and at length a successful politician, being appointed Collector of the port of Salem by President Pierce. He is described as having "a strongly marked, benignant face, indicative of intelligence and individuality. He was gray at twenty, and always looked older than his years.... He had a keen sense of the ludicrous, a vivid recollection of localities and incidents, a quick apprehension of peculiarities and traits, and was a most graphic and entertaining narrator."[4] As Mr. James has said: "Hawthorne had a democratic strain in his composition, a relish for the common stuff of human nature. He liked to fraternize with plain people, to take them on their own terms." It was the most natural thing in the world for him to fancy such a man as Pike is represented to have been. His Society in college was the one which displayed a democratic tendency; and, in addition to making friends with persons of this stamp, men of some education and much innate "go," he had a taste for loitering in taverns where he could observe character in the rough, without being called upon to take an active share in talk. "Men," we are told, "who did not meddle with him he loved, men who made no demands on him, who offered him the repose of genial companionship. His life-long friends were of this description, and his loyalty to them was chivalrous and fearless, and so generous that when they differed from him on matters of opinion he rose at once above the difference and adhered 472to them for what they really were." Inevitably, such a basis for the selection of companions, coupled with his extreme reserve, subjected him to criticism; but when, in 1835, his former classmate, the Rev. George B. Cheever, was thrown into jail on account of the satirical temperance pamphlet which has already been referred to in this sketch, Hawthorne emerged from his strict privacy, and daily visited the imprisoned clergyman. He showed no especial love for his native place, and in return it never made of him a popular idol. At this initial epoch of his career as an author there probably did not exist that active ill-will which his chapter on the Custom House afterwards engendered; he was in fact too little known to be an object of malice or envy, and his humble friendships could not be made the ground of unfavorable insinuations. The town, however, was not congenial to him, and the profound retirement in which he dwelt, the slow toil with scanty meed of praise or gold, and the long waiting for recognition, doubtless weighed upon and preyed upon him.

To stop at that would be to make a superficial summary. His seclusion was also of the highest utility to him, nay, almost indispensable to his development; for his mind, which seemed to be only creeping, was making long strides of growth in an original direction, unhindered by arbitrary necessities or by factitious influences.

Nevertheless, the process had gone on long enough; and it was well that circumstances now occurred to bring it to a close, to establish new relations, and draw him somewhat farther into the general circle of human movement. Dr. Peabody, who has been spoken of on a preceding page as living on the opposite side 473of Union Street from Hawthorne's birthplace, had, during the vicissitudes of the young author's education and journeys to and fro, changed his residence and gone to Boston. No acquaintance had as yet sprung up between the two families which had been domiciled so near together, but in 1832 the Peabodys returned to Salem; and Miss Elizabeth, who followed in 1836, having been greatly struck by the story of "The Gentle Boy," and excited as to the authorship, set on foot an investigation which resulted in her meeting Hawthorne. It is an evidence of the approachableness, after all, of his secluded family, that Miss Louisa Hawthorne should have received her readily and with graciousness. Miss Peabody, having formerly seen one of Miss Hawthorne's letters, had supposed that she must be the writer of the stories, under shelter of a masculine name. She now learned her mistake. Months passed without any response being made to her advance. But when the first volume of "Twice-Told Tales" was issued, Hawthorne sent it to her with his compliments. Up to this time she had not obtained even a glimpse of him anywhere; and, in acknowledging his gift, she proposed that he should call at her father's house; but although matters had proceeded thus far, and Dr. Peabody lived within three minutes' walk of Herbert Street, Hawthorne still did not come. It was more than a year afterward that she addressed an inquiry to him about a new magazine, and in closing asked him to bring his sisters to call in the evening of the same day. This time he made his appearance, was induced to accept an invitation to another house, and thus was led into beginning a social intercourse which, though not extensive, was unequalled in his previous experience.

About a week after the first call, he came again. Miss Sophia Peabody, who was an invalid, had been unable to appear before, but this time she entered the room; and it was thus that Hawthorne met the lady whom he was to make his wife some two or three years later. She was now about twenty-nine, and younger by five years than Hawthorne. In childhood her health had received a serious shock from the heroic treatment then upheld by physicians, which favored a free use of mercury, so that it became necessary from that time on to nurse her with the utmost care. Many years of invalidism had she suffered, being compelled to stay in a darkened room through long spaces of time, and although a sojourn in Cuba had greatly benefited her, it was believed she could never be quite restored to a normal state of well-being. Despite such serious obstacles, she had gently persisted in reading and study; she drew and painted, and no fear of flippant remark deterred her from attempting even to learn Hebrew. At the same time she was a woman of the most exquisitely natural cultivation conceivable. A temperament inclined like hers, from the beginning, to a sweet equanimity, may have been assisted towards its proper culmination by the habit of patience likely enough to result from the continued endurance of pain; but a serenity so benign and so purely feminine and trustful as that which she not displayed, but spontaneously exhaled, must have rested on a primary and plenary inspiration of goodness. All that she knew or saw sank into her mind and took a place in the interior harmony of it, without ruffling the surface; and all that she thought or uttered seemed to gain a fragrance and a flower-like quality from having sprung thence. Neither were strength of 475character and practical good sense absent from the company of her calm wisdom and refinement. In brief, no fitter mate for Hawthorne could have existed.

Soon after their acquaintance began, she showed him, one evening, a large outline drawing which she had made, to illustrate "The Gentle Boy," and asked him: "Does that look like Ilbrahim?"

Hawthorne, without other demonstration, replied quietly: "Ilbrahim will never look otherwise to me."

The drawing was shown to Washington Allston, who accorded it his praise; and a Miss Burleigh, who was among the earliest admirers of Hawthorne's genius, having offered to pay the cost of an engraving from it, the design was reproduced and printed with a new special edition of the story, accompanied by a Preface, and a Dedication to Miss Sophia Peabody. The three sisters and two brothers who composed the family of Dr. Peabody were strongly imbued with intellectual tastes: nothing of importance in literature, art, or the philosophy of education escaped them, when once it was brought to their notice by the facilities of the time. Miss Sophia was not only well read and a very graceful amateur in the practice of drawing and painting, but evinced furthermore a somewhat remarkable skill in sculpture. About the year 1831, she modelled a bust of Laura Bridgman, the blind girl, who was then a child of twelve years. This portrait not only was said to be a very good likeness, but—although it is marred by a representation of the peculiar band used to protect the eyes of the patient—has considerable artistic value, and attains very nearly to a classic purity of form and treatment. Miss Peabody also executed a medallion portrait, in relief, of Charles Emerson, the brilliant brother of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 476whose great promise was frustrated by his premature death. This medallion was done from memory. The artist had once seen Mr. Emerson while he was lecturing, and was so strongly impressed by his eloquent profile that, on going home, she made a memory-sketch of it in pencil, which supplied a germ for the portrait in clay which she attempted after his death.

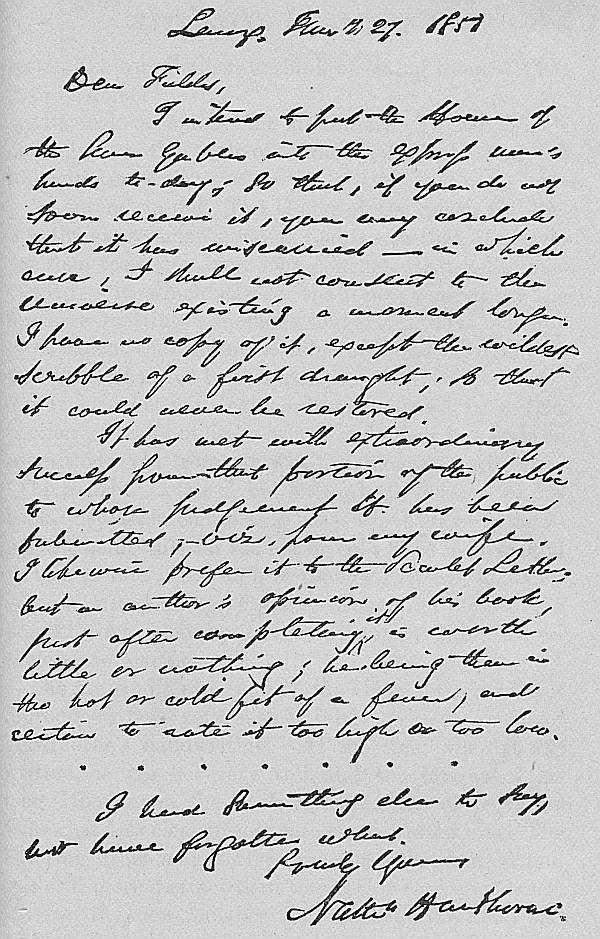

The appearance of the "Twice-Told Tales" in book-form had, like that of the "Gentle Boy" design, been due to the kindness of a friend. In this case it was Lieutenant Bridge who became responsible for the expense; and the volume met with, if not much pecuniary success, a gratifying literary renown. The author sent a copy to Longfellow, who acknowledged it cordially; and then Hawthorne wrote him as follows:—

"By some witchcraft or other—for I really cannot assign any reasonable cause—I have been carried apart from the main current of life, and find it impossible to get back again. Since we last met, which you remember was in Sawtell's room, where you read a farewell poem to the relics of the class—ever since that time I have secluded myself from society; and yet I never meant any such thing nor dreamed what sort of life I was going to lead.... For the last ten years I have not lived, but only dreamed of living....

"As to my literary efforts, I do not think much of them, neither is it worth while to be ashamed of them. They would have been better, I trust, if written under more favorable circumstances."

But Longfellow broke out, as it were, into an exulting cry over them, which echoed from the pages of the next "North American Review."[5] His notice was 477hardly a criticism; it was a eulogy, bristling with the adornment of frequent references to European literature; but it is worth while to recall a few of its sentences.

"When a star rises in the heavens," said Longfellow, "people gaze after it for a season with the naked eye, and with such telescopes as they may find. In the stream of thought, which flows so peacefully deep and clear through this book, we see the bright reflection of a spiritual star, after which men will be prone to gaze 'with the naked eye and with the spy-glasses of criticism.'... To this little work we would say, 'Live ever, sweet, sweet book.' It comes from the hand of a man of genius. Everything about it has the freshness of morning and of May.... The book, though in prose, is nevertheless written by a poet. He looks upon all things in a spirit of love and with lively sympathies. A calm, thoughtful face seems to be looking at you from every page; with now and then a pleasant smile, and now a shade of sadness stealing over its features. Sometimes, though not often, it glares wildly at you, with a strange and painful expression, as, in the German romance, the bronze knocker of the Archivarius Lindhorst makes up faces at the student Anselm.... One of the prominent characteristics of these tales is that they are national in their character. The author has wisely chosen his themes among the traditions of New England.... This is the right material for story. It seems as natural to make tales out of old tumble-down traditions as canes and snuff-boxes out of old steeples, or trees planted by great men."

This hearty utterance of Longfellow's not only was of advantage to the young author publicly, but also 478doubtless threw a bright ray of encouragement into the morning-dusk which was then the pervading atmosphere of his little study, which he termed his "owl's nest." "I have to-day," he wrote back, "received and read with huge delight, your review of 'Hawthorne's Twice-Told Tales.' I frankly own that I was not without hopes that you would do this kind office for the book; though I could not have anticipated how very kindly it would be done. Whether or no the public will agree to the praise which you bestow on me, there are at least five persons who think you the most sagacious critic on earth, viz., my mother and two sisters, my old maiden aunt, and finally the strongest believer of the whole five, my own self. If I doubt the sincerity and earnestness of any of my critics, it shall be of those who censure me. Hard would be the lot of a poor scribbler, if he may not have this privilege."

His pleasant intimacy with the Peabodys went on; the dawn of his new epoch broadened, and he began to see in Miss Sophia Peabody the figure upon which his hopes, his plans for the future converged. Her father's house stood on the edge of the Charter Street Burying-Ground, oldest of the Salem cemeteries. "A three-story wooden house"—thus he has described it—"perhaps a century old, low-studded, with a square front, standing right upon the street, and a small enclosed porch, containing the main entrance, affording a glimpse up and down the street through an oval window on each side: its characteristic was decent respectability, not sinking below the level of the genteel." In his "Note-Books" (July 4, 1837) he speaks of the old graveyard. "A slate gravestone round the borders, to the memory of 'Col. John Hathorne Esq.,' 479who died in 1717. This was the witch-judge. The stone is sunk deep into the earth, and leans forward, and the grass grows very long around it.... Other Hathornes lie buried in a range with him on either side.... It gives strange ideas, to think how convenient to Dr. P——'s family this burial-ground is,—the monuments standing almost within arm's reach of the side-windows of the parlor—and there being a little gate from the back-yard through which we step forth upon those old graves aforesaid. And the tomb of the P—— family is right in front, and close to the gate." Among the other Hathornes interred there are Captain Daniel, the privateersman, and a Mr. John Hathorne, "grandson of the Hon. John Hathorne," who died in 1758. The specification of his grandfather's name, with the prefix, shows that the relentless condemner of witches was still held in honor at Salem, in the middle of the eighteenth century. Dr. Peabody's house and this adjoining burial-ground form the scene of the unfinished "Dolliver Romance," and also supply the setting for the first part of "Dr. Grimshawe's Secret." In the latter we find it pictured with a Rembrandtesque depth of tone:—

"It stood in a shabby by-street and cornered on a graveyard.... Here were old brick tombs with curious sculpture on them, and quaint gravestones, some of which bore puffy little cherubs, and one or two others the effigies of eminent Puritans, wrought out to a button, a fold of the ruff, and a wrinkle of the skull-cap.... Here used to be some specimens of English garden flowers, which could not be accounted for—unless, perhaps, they had sprung from some English maiden's heart, where the intense love of those homely things and regret of them in the foreign 480land, had conspired together to keep their vivifying principle.... Thus rippled and surged with its hundreds of little billows the old graveyard about the house which cornered upon it; it made the street gloomy so that people did not altogether like to pass along the high wooden fence that shut it in; and the old house itself, covering ground which else had been thickly sown with bodies, partook of its dreariness, because it hardly seemed possible that the dead people should not get up out of their graves and steal in to warm themselves at this convenient fireside."

This was the place in which Hawthorne conducted his courtship; but we ought not to lose sight of the fact that, in the account above quoted, he was writing imaginatively, indulging his fancy, and dwelling on particular points for the sake of heightening the effect. It is not probable that he associated gloomy fantasies with his own experience as it progressed in these surroundings. Here as elsewhere it is important to bear in mind the distinction which Dr. Loring has made: "Throughout life," he declares, "Hawthorne led a twofold existence—a real and a supernatural. As a man, he was the realest of men. From childhood to old age, he had great physical powers. His massive head sat upon a strong and muscular neck, and his chest was broad and capacious. His strength was great; his hand and foot were large and well made.... In walking, he had a firm step and a great stride without effort. In early manhood he had abounding health, a good digestion, a hearty enjoyment of food. His excellent physical condition gave him a placid and even temper, a cheerful spirit. He was a silent man and often a moody one, but never irritable or morose; his organization was too grand for that. He was a 481most delightful companion. In conversation he was never controversial, never authoritative, and never absorbing. In a multitude his silence was oppressive; but with a single companion his talk flowed on sensibly, quietly, and full of wisdom and shrewdness. He discussed books with wonderful acuteness, sometimes with startling power, and with an unexpected verdict, as if Shakespeare were discussing Ben Jonson. He analyzed men, their characters and motives and capacity, with great penetration, impartially if a stranger or an enemy, with the tenderest and most touching justice if a friend. He was fond of the companionship of all who were in sympathy with this real and human side of his life." But there was another side of his being, for which we may adopt the name that Dr. Loring has given it, the "supernatural." It was this which gave him his high distinction. "When he entered upon his work as a writer, he left behind him his other and accustomed personality by which he was known in general intercourse. In this work he allowed no interference, he asked for no aid. He was shy of those whose intellectual power and literary fame might seem to give them a right to enter his sanctuary. In an assembly of illustrious authors and thinkers, he floated, reserved and silent, around the margin in the twilight of the room, and at last vanished into the outer darkness; and when he was gone, Mr. Emerson said of him: 'Hawthorne rides well his horse of the night.' The working of his mind was so sacred and mysterious to him that he was impatient of any attempt at familiarity or even intimacy with the divine power within him. His love of personal solitude was a ruling passion, his intellectual solitude was an overpowering necessity.... Hawthorne said himself 482that his work grew in his brain as it went on, and was beyond his control or direction, for nature was his guide.... I have often thought that he understood his own greatness so imperfectly, that he dared not expose the mystery to others, and that the sacredness of his genius was to him like the sacredness of his love."

And did not Hawthorne write to his betrothed wife?—"Lights and shadows are continually flitting across my inward sky, and I know not whence they come nor whither they go; nor do I inquire too closely into them. It is dangerous to look too minutely into such phenomena." What we may collect and set down of mere fact about his surroundings and his acts relates itself, therefore, mainly to his outwardly real existence, to the mere shell or mask of him, which was all that anybody could behold with the eyes; and as for the interior and ideal existence, it is not likely that we shall securely penetrate very far, where his own impartial and introverted gaze stopped short. It is but a rough method to infer with brusque self-confidence that we may judge from a few words here and there the whole of his thought and feeling. A fair enough notion may be formed as to the status of his post-collegiate life in Salem, from the data we have, but we can do no more than guess at its formative influence upon his genius. And I should be sorry to give an impression that because his courtship went on in the old house by the graveyard, of which he has written so soberly, there was any shadow of melancholy upon that initiatory period of a new happiness. His reflections concerning the spot had to do with his imaginative, or if one choose, his "supernatural," existence; what actually passed there had to do with the 483real and the personal, and with the life of the affections. We may be sure that the meeting of two such perfected spirits, so in harmony one with another, was attended with no qualified degree of joy. If it was calm and reticent, without rush of excitement or exuberant utterance, this was because movement at its acme becomes akin to rest. Let us leave his love in that sanctity which, in his own mind, it shared with his genius.

Picturesquely considered, however,—and the picturesque never goes very deep,—it is certainly interesting to observe that Hawthorne and his wife, both of Salem families, should have been born on opposite sides of the same street, within the sound of a voice; should have gone in separate directions, remaining unaware of each other's existence; and then should finally have met, when well beyond their first youth, in an old house on the borders of the ancient burial-ground in which the ancestors of both reposed, within hail of the spot where both had first seen the light.

When they became engaged, there was opposition to the match on the part of Hawthorne's family, who regarded the seemingly confirmed invalidism of Miss Peabody as an insuperable objection; but this could not be allowed to stand in the way of a union so evidently pointed out by providential circumstance and inherent adaptability in those who were to be the parties to it. The engagement was a long one; but in the interval before her marriage Miss Peabody's health materially improved.

The new turn of affairs of course made Hawthorne impatient to find some employment more immediately productive than that with the pen. He was profoundly dissatisfied, also, with his elimination from the active life of the world. "I am tired of being an ornament!" he said with great emphasis, to a friend. "I want a little piece of land of my own, big enough to stand upon, big enough to be buried in. I want to have something to do with this material world." And, striking his hand vigorously upon a table that stood by: "If I could only make tables," he declared, "I should feel myself more of a man."

President Van Buren had entered on the second year of his term, and Mr. Bancroft, the historian, was Collector of the port of Boston. One evening the latter was speaking, in a circle of whig friends, of the splendid things which the democratic administration was doing for literary men.

"But there's Hawthorne," suggested Miss Elizabeth Peabody, who was present. "You've done nothing for him."

"He won't take anything," was the answer: "he has been offered places."

In fact, Hawthorne's friends in political life, Pierce and Jonathan Cilley, had urged him to enter politics; and at one time he had been offered a post in the West Indies, but refused it because he would not live in a slaveholding community.

"I happen to know," said Miss Peabody, "that he would be very glad of employment."

The result was that a small position in the Boston 485Custom House was soon awarded to the young author. On going down from Salem to inquire about it, he received another and better appointment as weigher and gauger. His friend Pike was installed there at the same time. To Longfellow, Hawthorne wrote in good spirits:—

"I have no reason to doubt my capacity to fulfil the duties; for I don't know what they are. They tell me that a considerable portion of my time will be unoccupied, the which I mean to employ in sketches of my new experience, under some such titles as follows: 'Scenes In Dock,' 'Voyages at Anchor,' 'Nibblings of a Wharf Rat,' 'Trials of a Tide-Waiter,' 'Romance of the Revenue Service,' together with an ethical work in two volumes on the subject of Duties; the first volume to treat of moral duties and the second of duties imposed by the revenue laws, which I begin to consider the most important."

His hopes regarding unoccupied time were not fulfilled; he was unable to write with freedom during his term of service in Boston, and the best result of it for us is contained in those letters, extracts from which Mrs. Hawthorne published in the first volume of the "American Note-Books." The benefit to him lay in the moderate salary of $1,200, from which the cheapness of living at that time and his habitual economy enabled him to lay up something; and in the contact with others which his work involved. He might have saved time for writing if he had chosen; but the wages of the wharf laborers depended on the number of hours they worked, and Hawthorne—true to his instinct of democratic sympathy and of justice—made it a point to reach the wharf at the earliest hour, no matter what the weather might be, solely for the convenience 486of the men. "It pleased me," he says in one of his letters, "to think that I also had a part to act in the material and tangible business of life, and that a portion of all this industry could not have gone on without my presence."