Title: The Ranche on the Oxhide: A Story of Boys' and Girls' Life on the Frontier

Author: Henry Inman

Illustrator: Charles B. Hudson

Release date: August 24, 2012 [eBook #40574]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, Emmy, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Ranche on the Oxhide, by Henry Inman, Illustrated by Charles Bradford Hudson

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/rancheonoxhidest00inma |

In the execution of its purpose to give educational value and moral worth to the recreational activities of the boyhood of America, the leaders of the Boy Scout Movement quickly learned that to effectively carry out its program, the boy must be influenced not only in his out-of-door life but also in the diversions of his other leisure moments. It is at such times that the boy is captured by the tales of daring enterprises and adventurous good times. What now is needful is not that his taste should be thwarted but trained. There should constantly be presented to him the books the boy likes best, yet always the books that will be best for the boy. As a matter of fact, however, the boy's taste is being constantly vitiated and exploited by the great mass of cheap juvenile literature.

To help anxiously concerned parents and educators to meet this grave peril, the Library Commission of the Boy Scouts of America has been organised. EVERY BOY'S LIBRARY is the result of their labors. All the books chosen have been approved by them. The Commission is composed of the following members: George F. Bowerman, Librarian, Public Library of the District of Columbia, Washington, D. C.; Harrison W. Graver, Librarian, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Claude G. Leland, Superintendent, Bureau of Libraries, Board of Education, New York City: Edward F. Stevens, Librarian, Pratt Institute Free Library, Brooklyn, New York; together with the Editorial Board of our Movement William D. Murray, George D. Pratt and Frank Presbrey, with Franklin K. Mathiews, Chief Scout Librarian, as Secretary.

In selecting the books, the Commission has chosen only such as are of interest to boys, the first twenty-five being either works of fiction or stirring stories of adventurous experiences. In later lists, books of a more serious sort will be included. It is hoped that as many as twenty-five may be added to the Library each year.

Thanks are due the several publishers who have helped to inaugurate this new department of our work. Without their co-operation in making available for popular priced editions some of the best books ever published for boys, the promotion of EVERY BOY'S LIBRARY would have been impossible.

We wish, too, to express our heartiest gratitude to the Library Commission, who, without compensation, have placed their vast experience and immense resources at the service of our Movement.

The Commission invites suggestions as to future books to be included in the Library. Librarians, teachers, parents, and all others interested in welfare work for boys, can render a unique service by forwarding to National Headquarters lists of such books as in their judgment would be suitable for EVERY BOY'S LIBRARY.

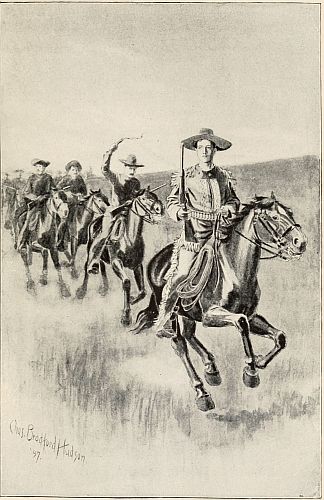

"The most indescribable antics were gone through."

"The most indescribable antics were gone through."In 1865-66, immigrants began to rush into the new state of Kansas which had just been admitted into the Union. A large majority of the early settlers were old soldiers who had served faithfully during the war for the preservation of their country. To these veterans the Government, by Act of Congress, made certain concessions, whereby they could take up "claims" of a hundred and sixty acres of the public land under easier regulations than other citizens who had not helped their country in the hour of her extreme danger.

Many of them, however, were forced to go out on the extreme frontier, as the eastern portion of the state was already well settled. On the remote border several tribes of Indians, notably the Cheyennes, Kiowas, Comanches, and Arapahoes, still held almost undisputed possession, and they were violently opposed to the white man's encroachment upon their ancestral hunting-grounds, from which he drove away the big game upon which they depended for the subsistence of themselves and their families. Consequently, these savages became very hostile as they witnessed, day after day, the arrival of hundreds of white settlers who squatted on the best land, felled the trees on the margin of the streams to build their log-cabins, and ploughed up the ground to plant crops.

Late in the fall of 1866, Robert Thompson, a veteran of one of the Vermont regiments, having read in his village newspaper such glowing accounts of the advantages offered by Kansas to the immigrant, decided to leave his ancestral homestead among the barren hills of the Green Mountain State, and take up a claim in the far West. The family, consisting of father, mother,[3] Joseph, Robert, Gertrude, and Kate, after a journey by railroad and steamboat without incident worth recording, arrived at Leavenworth on the Missouri River, the general rendezvous in those early days for all who intended to cross the great plains, through which a railroad was then an idle dream. In that rough, but busy town, Mr. Thompson purchased two six-mule teams, two white-covered wagons called "prairie schooners," together with sufficient provisions to last a month, by which time he thought he should find a suitable location on the vast plains whither he was going.

A few cooking-utensils of the simplest character, together with a double-barrelled shot-gun and a Spencer rifle, constituted the entire outfit necessary for their lonely trip of perhaps three hundred miles, before they could hope to find unoccupied land on which to settle.

One Monday morning, bright and early, the teams pulled out of the town, Mr. Thompson driving in the lead, and Joe, who was the elder of the boys, in the other. Gertrude rode with her father and mother, and Kate and Rob with their brother Joe. Their course ran over the[4] broad trail to the Rocky Mountains, on which were then hauled by government caravans, all the supplies for the military posts in the Indian country.

Their route for the first two weeks passed through deep forests extending for a long distance from the bank of the great river. The whole family were charmed with the new and strange scenes they passed as they rode slowly on day after day, scenes so different in their details from those to which they had been used in the staid old region they had left so far behind them. The boys and girls, particularly, were in a constant state of excitement. They marvelled at the immense trees as they passed through groups of great elms and giant cottonwoods. The gnarled trunks were vine-covered clear to their topmost branches by the magnificent Virginia creeper, or woodbine, as it is called, the most beautiful of the American ivies, and which grows in its greatest luxuriance west of the Missouri River. On the ends of the huge limbs of the lofty trees as they branched over the trail, the red squirrels sat, peeping saucily at the travellers as they drove under them, and the blue[5] jay, the noisiest of birds, screeched as he darted like lightning through the dark foliage. The blue jay is the shark of the air; he kills, without any discrimination, all the young fledglings he can find in their nests while their parents are absent. Although his plumage is magnificent in its cerulean hue as the sun glints upon it, and he has a very sweet note when sitting quietly on the limbs of the oak, which he loves, yet his awful screaming as he flies—and he is ever on the wing—is far from pleasant to ears not trained to listen to his harsh voice.

Occasionally a gaunt, hungry wolf—they are always hungry—would skulk out of the timber and then run across the trail, with his tail wrapped closely between his legs. He would just show a mouth full of great white teeth for a moment, as he sneaked cowardly off, the rattle of the wagons having, perhaps, disturbed his slumbers on some ledge of rock near the road.

Prairie chickens, or pinnated grouse, were seen in large flocks as soon as the open country was reached. They were far from wild in those days; you could approach near enough always to get a good shot at them, for civilization was to them[6] almost as strange an experience as it was to those beasts and birds on Robinson Crusoe's island. Joe was already quite proficient with the shot-gun, and he often handed the lines to Rob, and stopping the team, got out and walked ahead of the wagons to stalk a flock of the beautiful game, which had been frightened away from their feeding-ground by the rattle of the teams. For a long time grouse was a part of every meal until the party became really tired of them. Mrs. Thompson was a famous cook, and they were served up in a variety of ways, but the favorite style of all the family was to have them broiled before the camp-fire on peeled willow twigs. Rob always regarded it as part of his duty to procure these twigs, as he was the handiest with a jack-knife or hatchet.

The weeks passed pleasantly for the children, but the old folks were becoming very anxious to settle somewhere, for the winter, as they thought, would soon be coming on. They did not know then that that season in Kansas is usually short, and that the three or four months preceding it is the most delightful time of the whole year. So after travelling nearly two months on the[7] broad trail to the mountains, examining a piece of land here and another there, they camped early one afternoon on the bank of Oxhide Creek, in what is now Ellsworth County, and so delighted were they all with the charming spot, that they made up their minds to seek no further.

Their "claim," as the possession of the public land is called, included a beautiful bend of the little stream which flowed through the one hundred and sixty acres to which they were entitled by being the first to settle on it. They discovered in the very centre of a group of elms and cottonwoods a large spring of deliciously cool water, and the trees which hid it from view were more than a century old. The magnificent pool for untold ages had evidently been a favorite resort of the antelope and buffalo, if one could so judge from the quantity of the bones of those animals that were constantly ploughed up near by when the ground was cultivated. No doubt that the big prairie wolf and the cowardly little coyote hidden in the long grass and underbrush surrounding the spring got many a kid and calf whose incautious mothers had strayed from the protection of the herd to quench their thirst.

The beautiful creek flowed at the base of a range of low, rocky hills, while two miles northward ran a magnificent stretch of level prairie, beyond which ran the Smoky Hill River.

To their ranche, as all homes in the far West are called, the Thompsons gave the name of Errolstrath. It had no special significance; it was so called merely because "Strath" in Scotch means a valley through which a stream meanders. It comported perfectly with the situation of the place, and "Errol" was added as a prefix for euphony's sake. In this picturesque little valley Mr. Thompson, with the assistance of his boys, began at once the construction of a rude but comfortable cabin, fashioned partly out of logs and partly of stone. The house outside gave no hint of the excellence of its interior, or the cosy rooms which a refined taste and culture had felt to be as necessary on the remote frontier as in the thickly settled East. The largest division of the house was an apartment which served as the family sitting-room. In one corner of this, they built diagonally across it, after the Mexican style, an old-fashioned fireplace, patterned like one in the ancestral homestead in Vermont. Up its cavernous[9] throat you could see the sky, and in the summer, when the full moon was at the zenith, a flood of bright light would pour down on the broad hearth. In the winter evenings the family gathered around the great blazing logs, whose yellow flames roared like a tornado as they shot up the chimney. The mother sewed, the girls were engaged with their studies, and the boys either listened to their father as he told of some experience in his own youthful days, played chess, or were busied with some other intellectual amusement.

This large room was also furnished with a small but well-selected library. It was a source of much pleasure to the family, as the country was not settled up very rapidly, and the members were thrown entirely upon their own resources for amusements. The following spring and summer many newcomers arrived and took up the choicest lands in the vicinity, until there were several families within varying distances of Errolstrath. Some were only three miles away, others twelve, but in that region then, all were considered neighbors, no matter how far away.

The children had lots of fun, for the rare sport[10] differed entirely from that which their former home in the old East had furnished. The dense timber which grew by the water of the Oxhide like a fringe, was the home of the lynx, erroneously called the wild cat, squirrels, badgers, and coons. The wolf and the little coyote had their dens in the great ledges of rock that were piled up on the hilly sides of the valley. The great prairie was often black with vast herds of buffalo, or bison, which roamed over its velvety area at certain seasons. The timid antelope, too, graceful as a flower, and gifted with a wonderful curiosity, could be seen for many years after the Thompsons had settled on the creek. They moved in great flocks, frequently numbering a thousand or more, but now, like their immense shaggy congener, the buffalo, through the wantonness of man, they have been almost annihilated.

Joe Thompson, the eldest child, about fourteen, was a rare boy, strongly built, and possessed of a mind that was equal to his well-developed body. He was a born leader, and became one of the most prominent men on the frontier when the troublous times came with the savages, some[11] years after the family had settled on Oxhide Creek. Robert, the second son, was a bright, active, muscular fellow, two years younger than Joe, but he lacked that self-reliance, energy, and coolness in the presence of danger which so strikingly characterized Joe. Gertrude and Kate were respectively ten and seven years old, and were carefully instructed by their estimable mother in all that should be known by a woman whose life was destined, perhaps, to the isolation and hardships of the frontier. They were both taught to cook a dinner, ride horseback, handle a pistol if necessary, or entertain gracefully in the parlor. To employ a metaphor, theirs was a versatility which "could pick up a needle or rive an oak!" In some of her characteristics Gertrude resembled her brother Joe; she was braver and cooler under trying circumstances than Kate, who was more like Rob. Both were rare specimens of noble girlhood, and their life on the ranche, as will be seen, was full of adventure and thrilling experiences.

It may seem strange that a stream should be called Oxhide, but, like the nomenclature of the Indians, the name of every locality out on the[12] great plains is based upon some incident connected with the scene or the individual. As this is a true story, it will not be amiss to tell here why the odd-sounding name was given to the creek on which the Thompsons had settled. Some years before the country was sought after by emigrants, the only travellers through it were the old-time trappers, who caught the various fur-bearing animals on the margins of its waters, and the miner destined for far-off Pike's Peak or California. A party camping there one day, on their way to the Pacific coast, discovered a yoke of oxen, or rather their desiccated hides and skeletons, fastened by their chains to a tree, where they had literally starved to death. It was supposed that they had belonged to some travellers like themselves, on their way to the mines, who had been surprised and murdered by the Indians. The savages must have run off the moment they had finished their bloody work, without ever looking for or finding the poor animals. Thus it was that the stream was given the name of Oxhide, which it bears to this day.

It was quite late in the season, towards the end of October, when the stone and log cabin was completed and ready for occupancy. The family had meanwhile lived in their big tent which they had brought with them from the Missouri River. They had carried in their wagons bedding and blankets, a table and several chairs, enough to suffice until the arrival of their other goods, which had been stored at Leavenworth while they were hunting for a location. At the end of two months after their settlement on the Oxhide, a freight caravan arrived with their things, much of it the old-fashioned furniture from the homestead in Vermont. This caravan was en route to Fort Union, New Mexico, the[14] trail to which military post ran along the bank of the Smoky Hill River, not more than two miles from the ranche.

Joe and Rob were constantly busy helping their father to make matters snug for the winter, building a corral for the cows, a stone stable for the horses, and a chicken house for the fowls, of which they had more than a hundred, Plymouth rocks and white leghorns, the best layers in the world. Up to that time they had not had as much time for sport as they wished for. They had been kept too busy, until long after the cold weather set in, when all the streams were frozen over and the woods were bare and brown.

A near neighbor who had taken a fancy to the bright lads when they first arrived in the country, had given them two fine greyhounds, which they named Bluey and Brutus; the former on account of his color, and the other because they had recently been interested in Shakespeare's play of "Julius Cæsar," which their father had read to them. With these magnificent animals they had lots of fun during the long months of the winter, hunting jack-rabbits, digging[15] coyotes out of their holes in the ledge above the banks of the creek, or fighting lynxes and coons in the timber.

One bright day they were out among the hills with their hounds, which had run far in advance of their young masters, when suddenly the boys' ears were startled by a terrible commotion in a wooded ravine about a hundred yards ahead of them. The dogs were barking furiously, sometimes howling in pain, and they could see the dust flying in great clouds. In a few moments all was still; the turmoil had ceased, a truce evidently having been patched up between the belligerents. The boys hurried on and presently came to a sheltered spot where the timber had been apparently blown down by a small tornado many years before; and there as they came up to it, in a triangle formed by the trunks of three fallen trees, a space about ten feet square, they saw the hounds holding a great lynx at bay! The cat was standing in the apex of the triangle, crowding her body as closely as she could against the timber so that the dogs were unable to attack her without getting a scratch from her sharp claws. Her hair was all bristling up with[16] battle, and the dogs had evidently tried several times to drive her out of her almost impregnable position, but each attempt had ended in themselves being driven back discomfited. As soon as the hounds saw the boys, however, their courage rose, and Bluey, the oldest dog, at an encouraging "Sic 'em!" from Joe, made a sudden dash, caught the ferocious beast by the middle of the back and commenced to shake her with the awful rapidity for which he was noted, and in a few seconds she was dropped dead at Joe's feet.

Bluey first became famous as a shaker several months before his encounter with the lynx. One morning Rob got up very early for some reason, and went into the chicken house, and as soon as he entered it he saw a skunk half hidden under one of the beams of the floor. He did not dare to call Bluey, who was sleeping on a pile of hay a few feet away, for fear the animal would take the alarm and run off. So he quietly went to where the dog was, and lifting him bodily in his arms carried him to the chicken house and held his nose down to the ground so that he could see or smell the skunk. In an instant that skunk[17] was caught up by the neck and the life shaken out of him before he could have possibly realized what was the matter with him.

"By jolly!" said Rob, a favorite ejaculation with him when he was excited, as he saw the cat lying perfectly still where Bluey had dropped him. "I say, Joe, what a set of teeth and a strong neck old Bluey must have to shake anything as he does! Why, if he could take up a man in his jaws, the fellow would stand no more chance of his life than that lynx!"

"The hound," replied Joe, "has a strong jaw and a powerful neck; but he lacks the intelligence of some other breeds. His brain is not nearly as large as that of a Newfoundland, a setter, pointer, or even a poodle. Hounds like Bluey and Brutus run by sight alone; they have no nose, and the moment they cannot see their game they are lost. You have often noticed that, Rob, when a rabbit gets away from them in the long grass or in the corn stalks. They will jump up and down, completely bewildered until they catch sight of the animal again. Now, with the other breed of hounds, they hunt by scent; the moment they get wind of anything[18] they run with their noses close to the ground and commence to howl. The greyhound, on the contrary, makes no noise at all."

Joe skinned the lynx, assisted by Rob, and after throwing the carcass in the ravine where the battle had been fought, slowly walked back to the ranche, followed by the dogs, that kept close to their heels, tired and sore from the struggle just ended.

"Let us give the hide to Gert after we tan it, to put at the side of her bed; you know she is fond of such things," said Rob.

"All right," replied Joe. "We'll do it, and if we have good luck in getting other animals, we'll just fill her room with skins. Won't that be jolly?"

Mr. Thompson had but two teams of horses on the ranche, and they could not often be spared from work, for the mere amusement of the boys. It was a constant source of regret to them that they did not have ponies of their own. On their way home the oft-repeated subject came up again. Both Joe and Rob felt keenly that they were obliged to go where they were sent, or desired to go themselves, on foot. How to obtain the[19] coveted little creatures was a source of continual worry to them.

"I do wish that we had ponies," began Rob for the hundredth time, "so that we could go anywhere in a hurry; don't you, Joe?"

"Father would buy them for us if he felt that he could afford it; and he means to as soon as he can see his way clear. I heard him tell mother so, several times when she wished that we had 'em," replied Joe. "Maybe," continued he, "some band of friendly Indians will come along after a while; it's nearly time for the Pawnees to start out on their annual buffalo hunt. When they come up here, we may be able to trade 'em out of a real nice pair. They are always eager for a 'swap'; so old man Tucker told me the other day, and he is an old Indian trader and fighter. He has lived on the plains and in the mountains for more than forty years; so he knows what he is talking about."

"Golly! couldn't we have lots of fun," he continued, "with old Bluey and Brutus, after jack-rabbits and wolves, if we only had something to ride?"

"Couldn't we, though!" answered Rob. "I tell[20] you, Joe, it's awful hard work to climb over these hills on foot; we can't begin to keep up with the dogs; can't get anywhere in sight of 'em. You know that, and I just bet that we lose lots of game; don't you?"

"Oh! I know it," said Joe; "for the hounds become discouraged when they find themselves so far away from us. Often, when I'm out alone with them, Brutus will come back to hunt me instead of hunting rabbits. Sometimes I can't get him to go on after Bluey; he, the old rascal is more cunning; he gets many a rabbit we never see, and eats it. That is what makes him so much fatter than Brutus, though he does twice as much running. Did you ever think of that, Rob?"

That night when the tired boys went to bed, they little dreamed that they were to have something to ride sooner than their fondest hopes had flattered them, and from an entirely different source than the Indians.

Before the sun's broad disc rose above the Harker Hills next morning, although its rays had already crimsoned the rocky crests of the buttes which bounded the little valley of the[21] Oxhide on the west, Rob had risen without disturbing his brother. He was always an early riser; he loved the calm, beautiful hours that usher in the day, and was the first one of all the family out of bed on the ranche.

He took the tin wash basin from its hook outside of the kitchen door, and started for the spring, only a few yards away, to wash himself. Just as he arrived there, chancing to look towards the hills, he saw that the whole country, upland and bottom alike, was black with buffaloes. In his excitement, he threw down the basin, and ran back to the house as fast as his legs could carry him. He rushed into his father's room, and unceremoniously seizing him by the shoulder, waking him from a sound slumber, shook him, and shouted as loud as he was able:—

"Father, get up! Father, get up! the whole country is alive with buffaloes, and the nearest one is not a quarter of a mile away. Quick! father."

Mr. Thompson roused himself, and instantly got out of bed and dressed himself quicker than he had ever done since he had lived on the ranche. He threw on only clothes enough to[22] cover him, for he had already caught some of his boy's enthusiasm.

He told Rob to go to the closet, bring him a dozen bullets and his powder-flask, while he commenced to wipe out the barrels of his two old-fashioned rifles and the Spencer carbine, that always hung on a set of elk antlers fastened to the wall of his bed-chamber.

As Rob had declared, the whole region was literally dark with a mighty multitude of the great shaggy monsters, grazing quietly toward the east. There were thousands in sight, and for just such a chance Mr. Thompson had been anxiously waiting to get a supply of meat for the family.

Of course, every member of the household got up as soon as Rob had ended his noisy announcement. Hurriedly dressing, they rushed out under a group of trees that grew near the door, and watched Mr. Thompson crawling cautiously round the rocks as he drew nearer and nearer to the yet unconscious herd.

In a few moments he was lost to sight, and almost immediately they saw the herd raise their heads simultaneously. The family then knew that Mr. Thompson had been discovered by the[23] wary animals, for the alarmed buffaloes began their characteristic quick, short gallop, and the boys were fearful that their father had not gotten within range and that there would be no meat for breakfast. But at the instant they were expecting to be disappointed, the loud crack of a rifle echoed through the valley once, twice, then a short silence; three, four times.

As the sound of the discharges died away, they saw their father climb to the summit of the divide, in full view of all, and wave his hat. Then they knew he had been successful, and eagerly watched him as he came slowly down the declivity toward them.

When he had come within hailing distance he cried out that he had killed four fat cows; one for each shot. Then the boys and girls took off their hats, and, vigorously waving them, gave three hearty cheers.

Just beyond the cabin and corral, which latter was surrounded by a stone wall nearly five feet high, was a single hill whose summit was round, and to which had been given the name of Haystack Mound, because at a distance it exactly resembled a haystack. When the buffaloes had[24] started to run eastwardly, this mound cut off some of the animals of the herd, about three hundred in all, the majority going south of it, the smaller number north, which brought them near the house. Seeing the family standing there, they suddenly turned and rushed right over the corral; the gate was open, and a few dashed through it, but the most of them leaped over the wall. The buffalo is not easily stopped by any ordinary obstacle when stampeded; he will go down a precipice, or up a steep hill; madly rushing on to his destruction, in order to get away from the common enemy, man.

Rob saw the buffaloes first as they were turned from their course by the mound, and when they began to rush over the wall of the corral and through its gate, he shouted to Joe:—

"Come, Joe, let's try to shut some of them in; maybe there are calves among them. If there are, we can keep 'em in, for the little ones can never mount that wall on the other side."

Instantly acting on the suggestion, both boys ran as fast as they could to the corral, and succeeded in closing the entrance just as the last of the herd was leaping over the far wall.

As Rob had surmised, four calves remained inside, too young to follow their mothers over the wall. Both he and Joe were nearly wild with excitement at their luck in having been able to shut the gate in time to corral the baby buffaloes. They were about to rush to the house to tell the rest of the family of their wonderful capture, when Joe chanced to look into the door of the rude shed that was used to shelter the stock in stormy weather, and saw jammed against the farther wall two animals that were too small to be full-grown buffaloes, and too large for calves. It was so dark in the corner where they were that he could not make out at first what kind of animals they had caught. He called Rob, who crawled nearer to where the beasts stood huddled against each other, trembling with fear at their strange quarters.

In another moment, as soon as Rob's eyes became used to the dim light, he came bounding out with the speed of a Comanche Indian on the war-path, and catching Joe by the shoulders was just able to gasp:—

"By jolly, Joe, they're real ponies!"

They were so astonished for a few seconds[26] that they stood paralyzed before they ventured in the shed to take a good look at the little animals. They boldly went in, and the moment the ponies saw the boys they made a break for the outside and vainly attempted to dash over the wall. Their frantic efforts, however, were of no avail; they could not make it: they were regular prisoners, and Rob and Joe were almost out of their senses with delight.

After their excitement had somewhat subsided they went to the house and brought out all the rest of the family to see the cunning little animals. They lost all their interest in the buffalo calves now that their brightest dreams of owning ponies of their own were realized.

The diminutive beasts which the boys had so successfully corralled were sorry-looking animals enough. They were so dirty, thin, angular, and their coats so rough, so filled with sand-burrs and bull-nettles, that it was hard to determine what color they were. All the family made a guess at it. Kate said she thought they were mouse-color, while Gertrude believed they were gray. Joe thought they were brown, and Rob white. Mr. Thompson, however, who knew more[27] about horses than his boys, told them they were bays, but it would take a few days of currying and brushing up to determine which of the family had guessed correctly. There was evidently lots of life in them, for they cavorted around the big corral, prancing like thoroughbreds.

That afternoon, when they had taken care of the buffaloes which Mr. Thompson shot, and had stretched their robes on the corral wall to cure, the ponies were roped by Mr. Thompson, who could handle a lariat with some degree of skill, and halters were put on them. They were nearly of a size, and both of the same color, so they could hardly be distinguished from each other, but on a closer examination it was discovered that one of them had a white spot on his breast. This was the only apparent difference between them, so the boys drew lots to see which should have the one with the white breast. Their father selected two straws, one shorter than the other, and holding them partly concealed so that only their ends showed, told Rob to draw first. He got the longer straw, and so became the owner of the pony with the spot of white on his breast.

In less than two weeks, through kindness and good care, they were changed into clean, sleek, beautiful bays, just as Mr. Thompson had said they would be. In a month the boys could ride them anywhere, and the acme of their happiness was reached.

The animals had strayed from some band of wild horses and had drifted along with the herd of buffaloes, as was not infrequently the case in the early days on the great plains.

The winter, contrary to their expectations, was not a severe one. The family had been used to the long, dreary, cold months of a New England winter, and were agreeably surprised when April arrived with its sunny skies, delicious breezes, and wild flowers covering the prairies.

One morning, when his father was just starting for the little village of Ellsworth, six miles distant, for a load of lumber, Rob asked him to buy some hooks and lines.

"Father," said he, "Oxhide Creek is just full of bull-pouts, perch, cat and buffalo fish. Joe and I want to go fishing to-day, if you return in time."

Mr. Thompson told the boys that he would not forget them, and as he drove off, they took their spades to dig in the garden as their father had directed them to do while he was away.

Both Joe and Rob worked very industriously, anxious to make the time slip away until their father's return, when, if he was satisfied with what they had done, they knew he would let them go fishing.

Just before twelve o'clock Mr. Thompson came back. The boys had worked for more than three hours, but it seemed only one to them, so quickly does time glide along when we are engaged in some healthful labor.

When Mr. Thompson saw how faithfully his boys had worked, he told them, as he handed to each a line and some hooks, they might have the afternoon to themselves and go fishing if they wished to, but must wait until they had taken the lumber off the wagon and eaten their dinner.

The boys were all excitement at the idea of going fishing. When they sat down to dinner they hurried through it, asked to be excused, and went out and unloaded the lumber before their father had done eating.

When they returned to the house and told their father they had unloaded the boards and run the wagon under the shed, he said they might go, but were to be sure to return in time to do the chores.

They took a spade from the tool-shed and an old tomato can their mother had given them, and started for the creek, where in the soft, black soil of its banks they dug for white grubs for bait. They were not very successful, however. They turned over almost as much soil as they had dug in the garden that morning, but found only three or four worms; not enough to take out on their excursion. They were disgusted for a few moments, fearing that they would have to give up their fishing, so stood staring at each other, their faces filled with disappointment.

At last an idea struck Rob. He said:—

"I'll tell you what we'll do, Joe. I read in one of father's books the other day about the Indians out in Oregon catching trout with crayfish. It said that the savages commence to fish far up at the head of the stream, lifting, as they walk down, the flat stones under which the little animals hide themselves. They look like small lobsters,[32] only they are gray instead of green. Then they break them open and use the white meat for bait. The book said they catch more trout in an hour than a white man will in a week with all his flies, bugs, and fancy rigging."

"Let's try 'em for luck," answered Joe. "I don't know whether there are any crayfish in the Oxhide, but we can go and find out; and if there are, I guess cat and perch will bite at 'em as well as trout."

"All right," said Rob, the look of disappointment instantly vanishing from his face as he listened to his brother's suggestion. "But I tell you, Joe," continued he, "we've got to have poles. You go up to that bunch of willows yonder," pointing with the old can he held in his hand, to the bunch of willows growing as thick as rushes on a little island in the creek, about an eighth of a mile from where he stood; "and here, Joe, take my line and hooks, too. Fix yours and mine all ready for us, while I go and hunt for the crayfish. I know where they are; I saw a whole lot crawling in the water near the house the other day."

The two brothers then separated,—Joe, jack-knife[33] in hand, going toward the willows, and Rob to the creek with the tomato can.

As soon as Rob arrived at the bank of the stream, he took off his boots and stockings, rolled his trousers above his knees, tied the can around his neck with a string, and waded in. The creek was not at all deep, and the water as clear as crystal. He could see shoals of perch dart ahead of him, and many bull-pouts rush under the shadow of the bank as he waded toward the island of willows. In the bed of the creek were hundreds of flat rocks; some that he could easily lift, others so large that he could not budge them.

The first stone he turned over had three of the coveted crayfish hidden under its slimy bottom, and excited at his luck, he quickly caught them. So many were there as he lifted stone after stone, that he soon filled the tomato can, and by that time he had arrived at the willows. Joe was anxiously waiting for him with two handsome rods, at least ten feet long, the lines already attached and the hooks nicely fastened to their ends.

"Golly! Rob, you must have had awful good[34] luck," said Joe, as he looked at the can full of struggling crayfish,

"Pshaw!" answered Rob. "Why, Joe, I could have got a bushel of 'em; the Oxhide was just swimming with 'em."

"Let's go to that little lake that was so nice where we went swimming last autumn," suggested Joe. "I know there are lots of cats in there; big ones, too."

"All right, Joe," said Rob, as he commenced to put on his stockings. When he had got his boots on, the two boys walked briskly toward the so-called lake, which was a mere widening of the creek, forming quite a large sheet of water, where they arrived in about seven minutes. It was a very delightful spot. The whole surface of the water was shaded by the gigantic limbs of great elms a hundred years old, growing on its margin, and all around the edge was a heavy mat of buffalo grass, soft as a carpet.

It required only a dozen seconds or so for the boys to unwind their lines, bait the hooks, seat themselves on the cushioned sod, and cast the shining white meat in the water.

There they anxiously waited for results, as the catfish is not game like the trout, but is slow and deliberate in all its movements. The trout rushes at anything that touches the surface of the water, but the catfish carefully investigates whatever comes within reach of its great jaws, before it opens its ugly mouth to take it in.

In a few minutes, Rob felt a tremendous tugging at his line, and in another instant he skilfully landed a large channel cat on the grass at his feet.

"Look, Joe, look! see what a big one I've caught," said Rob, as he dexterously extracted the hook from the creature's great mouth, and then held the fish at arm's length so that his brother could have a good look at it.

Rob's catch weighed at least four pounds, and no wonder he was delighted at such success, as it showed considerable skill to land a fish of that size.

Joe had not yet had a nibble, and a shade of disappointment began to creep over his face when suddenly, just as he was about to go over to examine his brother's catch more closely, he[36] was nearly jerked off his feet by a tremendous pull at his own line. He recovered himself immediately, and by dint of a hard struggle, hauled in a cat that was almost as big again as that which Rob had caught.

It was Joe's turn to yell now; he held up the big fish as high as he could,—its tail touched the ground even then,—and sung out:—

"I say, Rob, just look at this, will you? Yours is only a minnow alongside of mine. When you go fishing, why don't you catch something like this?"

Unfortunately, at the instant he was so wild with excitement, he stood on the very edge of the bank, and so absorbed was he in the contemplation of the great fish, that his foot slipped and both he and the cat were thrown into the water at the same moment. The cat made a terrible lunge forward when it found itself once more in its native element, and before you could say "Jack Robinson," was out of sight.

If ever disgust was to be seen on a boy's face, that face was Joe Thompson's; he only glanced at the water, did not say a word; his feelings were too sad for utterance.

Rob looked over at his brother and sarcastically said, as he held up his cat and stroked it:—

"I say, Joe, who's got the biggest fish now?"

In an instant he saw that he had touched Joe in a tender spot; he was a very sensitive boy, so Rob quickly added: "Well, never mind, Joe. You remember what mother often says to us, 'There is as good a fish in the sea as was ever caught,' and I'll bet there's just as big cats in here as the one you lost. Try again, Joe, but stand away from the edge of the water with the next one you haul out."

Joe, thus encouraged and comforted, sat down again in his old place, threw his line to try once more, and in the excitement soon forgot his misfortune.

In less than three hours the boys caught more than a dozen apiece, none so large, however, as that which escaped from Joe. It was now nearly six o'clock, the sun was low in the heavens, and as they had as many fish as they could conveniently carry, they decided to go home. Arriving there in a short time, they at once went to work at their chores. Their[38] customary evening's task was to drive the cows into the corral, feed the horses and their own ponies, and bring water from the spring for their mother, so that it should be handy when she rose in the morning.

While Joe and Rob were at their work, their father cleaned some of the fish, which their mother then cooked for supper, and they certainly tasted to the young anglers better than ever did fish before. While at the table they related every little incident that had befallen them on this their first angling expedition in the new country.

After that very successful excursion the brothers sometimes spent whole mornings or portions of the afternoons at some place on the creek or river, when the work on the ranche was not pushing, and so expert did they become with hook and line, that the family was never at a loss for a supply of fish during the proper seasons.

Joe was a close observer of nature, and he very quickly learned the habits of all the animals, birds, and fish that were common to the region where he lived. Being the eldest son, too, he was[39] intrusted with a small but excellent rifle and a shot-gun which his father bought one morning in the village, on the fifteenth anniversary of his birthday. He would get up very early in the morning and with his pony and the hounds have many a lively chase after the little cottontail rabbit or the larger "jack," improperly so called, for it is really the hare. The rabbit burrows in the ground, while the jack-rabbit does not, but makes his nest on the top, in a bunch of grass, or in the holes in the rocky ledges of the bluffs that fringe nearly every stream on the great plains. Out on the open prairies the grouse congregated in large flocks at certain seasons, and in every covert in the woods the quail could be found. Joe had really handled a gun long before he left Vermont, but the superior chance for practice out on the ranche soon made him a magnificent shot; consequently the table at the ranche was never without game if the family desired it.

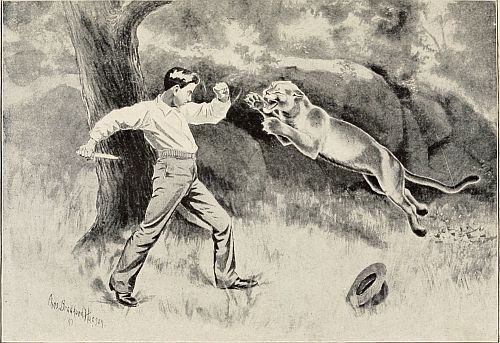

Beside the smaller game I have mentioned, there were immense herds of buffalo and antelope, and in some places in the deep woods was the only long-tailed specimen of the genus felis[40] on the continent,—the cougar, or panther. All the wildcats, so called, are lynxes, with short tails. With one of the first mentioned Joe once had a severe tussle, which nearly proved disastrous to him. It happened in this way.

One afternoon in November shortly after the cabin was finished and the family had moved in, he was out on the range with his father's horse, the Spencer carbine, and about twenty rounds of ammunition. Even at that early stage of his life at Errolstrath he was always careful never to ride far away from home, without taking a gun with him; for he was always sure to see something in the shape of game worth killing for the table; and as its main support in that particular very soon depended on his prowess as a hunter, he was always on the lookout.

Joe had ridden a long way from the cabin. He had really forgotten how far away he was and was becoming very thirsty, for the day had been warm, so he commenced to hunt for water.

He was riding along the bank of the Smoky Hill in the thickest of the timber which grows on its banks, and by certain signs he had studied since he had lived on the ranche, knew[41] that he was near some springs, though he had never been in that vicinity before.

He got off his horse, slipped the loop of the bridle-rein over his left arm, slung the carbine across his right shoulder, and cautiously walked on. There was, of course, no trail or path at the base of the bluffs along which he was travelling, so he stopped at the mouth of every ravine he came to, hoping to find a pool of water, or to discover some hidden spring whose source was high up among the great rocks that towered above his head.

Presently he arrived at a depression in the earth in the bottom of a gully, evidently made by the claws of some animal, for beside those marks were the imprint of foot-tracks. Joe intuitively guessed they were those of a panther, as he had been told by the old trapper, Tucker, that that animal knows by instinct when the water is near the surface, and scratches with his claws until he reaches it. Joe knew, too, that the panther was not a very large one; his footprints were too small; so he did not feel at all alarmed at their sight. On the contrary, boy-like, he was delighted at the idea of a possible tussle with one[42] of the dreadful creatures, and he thought that if he could succeed in killing it he would add another feather to his cap by taking its hide home.

Joe felt himself equal to a possible struggle. He knew that he was fully armed, and at once examined his carbine, took out the knife which he always carried in his belt for skinning, and finding everything in perfect order, he was really anxious to find the animal that had been digging for water only a little while before his arrival at the spot.

A few rods further on, in the same ravine, he saw a little pool of water, evidently clear and cool, and after looking cautiously all around him, dipped the rim of his hat into the pool before him and indulged in a long drink of the delicious fluid. Then after having satisfied his thirst, he stood still for a few moments undecided as to what course he should pursue.

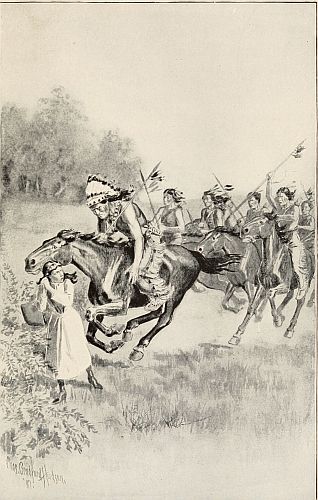

"With one vigorous thrust of his knife he struck the animal's heart."

"With one vigorous thrust of his knife he struck the animal's heart."

He concluded that if he was to remain and fight the panther if the animal made his appearance, it would be best to tie his horse to a sapling a short distance from the pool. After doing this he placed a fresh cartridge in his carbine and[43] walked slowly on, following the beast's tracks, which had grown plainly visible a few paces from the edge of the water, and which soon led him into a rocky cañon.

Joe came in sight of the panther much sooner than he expected. As he was turning the sharp projecting corner of a mass of rocks which formed the walls of a ravine, there was the panther sitting on a shelf of sandstone, not forty feet away from him. He was busy licking his paws cat-fashion, his ears cocked as if listening, and his small green eyes turned toward the intruder, but evidently not much concerned at the sight of his greatest enemy, man.

Joe was rather taken aback at first, but as the brute was only a little over half-grown, and appeared so indifferent to his presence, he uncocked his carbine, which he had a moment before hastily cocked, and both boy and panther stood quietly gazing at each other for ten seconds before either made any demonstration.

Presently the panther rose and turned sideways toward Joe, and edging up toward the top of the ledge, gave vent to a low growl, and showed a beautiful set of long, sharp teeth, evidently[44] intending to let Joe know that he wasn't afraid of him. This movement on the part of the panther somewhat excited Joe, and cocking his carbine again, he deliberately took aim at the place where the heart of the beast should be, as the animal had now turned its left side toward the young hunter. Quick as a flash Joe pulled the trigger, but the ball glancing upward, only grazed the end of the beast's shoulder-blade and shattered it, the panther at the same instant tumbling over on its side. This made Joe yell with delight, for he thought he had killed it at the first shot.

The panther lay on the ground only for about ten seconds when the aspect of affairs for Joe was suddenly changed. The brute staggered to its feet, and, maddened with rage and pain, made for the boy. Although the beast was evidently very lame from the effect of the shot, Joe saw to his amazement that he was far from dead, and for a moment his usual presence of mind forsook him, and he made a bolt for his horse, feeling that the dreadful animal was close to him.

In his fright he dropped his carbine, but in another moment was on his horse, who, on being so unceremoniously mounted, and seeing the[45] panther, gave a wild snort and a desperate kick which sent Joe heels over head to the ground, and then dashed down the trail for home!

Joe was now all alone, on foot, and with nothing but his knife to defend himself from the attack of the panther, who was almost upon him as he got up from the ground after having been so hurriedly tossed from his saddle. Although the panther was lame and bleeding profusely, he waddled along as best he could toward Joe, his mouth wide open and his great jaws covered with froth in his rage. Joe was somewhat bruised by his fall, and seeing very quickly that he could not escape a tussle with the beast, made up his mind that he would fight him to the best of his ability. There was no other chance, for the panther was now upon him, trying to get at him so that he could claw and bite at his leisure. But Joe, who had now gained his normal coolness, turned deliberately, and facing the savage brute, whose hot breath he could feel, with one vigorous thrust of his knife he struck the animal's heart and fortunately killed him instantly.

In the close struggle the panther was so near[46] Joe, that in his death throes, having fallen right on top of the boy, his sharp claws tore the sleeve of his coat off and scratched a goodly piece of flesh from his arms, as with one convulsive shudder the ferocious animal had rolled over dead.

There was never a more delighted boy than Joe, despite his really painful wounds, and rising with some difficulty to his feet, he went back for his carbine, and returned with it to the dead panther. He picked up his knife which had fallen on the ground when the fatal thrust was given, deftly skinned him, suspended the beautiful hide to a limb of a cottonwood tree to keep the wolves from it, and then turned away and followed his trail towards the ranche. Of course, in a little while he began to grow stiff in his arms from the severity of his wounds, and not knowing exactly how far he was from the cabin, he was disturbed, not so much for himself as at the thought that when the riderless horse arrived there it would alarm his parents.

Joe was correct in his conjectures. As the horse dashed up to the stable without his[47] rider, both his father and mother were terribly frightened. They plucked up courage, however, and immediately saddling another horse, led back on his own trail the one Joe had ridden, and soon came up to where Joe was resting at the side of a large spring, and suffering considerably with the pain caused by his wounds.

They all arrived at the cabin by sundown, with the skin of the panther, Joe's father having gone back to the tree where the boy had hung it. That was a red-letter day in Joe's young life. He had to tell again and again how he happened to come on the panther and his awful fight with the enraged creature.

Joe soon recovered under the devoted nursing of his mother; his arm healed nicely, but a good-sized scar was left where the panther had dug its sharp claws into the flesh. The hide was smoke-tanned, and for many years afterward adorned the floor at the foot of his mother's bed.

As the months rolled on, the family, particularly the children, grew more and more delighted with their new home in the wilderness. The boys and girls had an abundance of leisure; for though their father exacted the most prompt obedience, he was not a hard task-master. He allowed his children every indulgence compatible with reason, and only certain portions of the day were devoted to work. They all studied under their father's personal supervision, for no schools had yet been established in the settlement.

For the boys, there were the cows to be driven to and from their pasture, morning and night, and it was their duty to milk them, too. Then the horses were to be fed, and in season[49] they worked in the large garden, on which their father prided himself. The girls helped their mother in every household duty, and relieved her of many cares as she grew older. So the children of Errolstrath Ranche had a good time—a much better time than generally falls to the lot of those families in only moderate circumstances, as were the Thompsons.

Before they had resided on the ranche a year, the boys and girls had become possessed of a variety of pets. Gertrude had a coon; Kate, an antelope; Rob, a prairie dog; and Joe, an elk.

The antelope was caught when young by Joe, and the hounds, Bluey and Brutus, under the following circumstances: Although one of the most timid and swift of all the ruminants on the great plains, it is also one of the most inquisitive. Whenever it sees something with which it is not familiar, its curiosity overpowers its usual fear, and it will approach very near to the object that has excited its attention. Now Joe had learned from old Tucker, the trapper, just how the Indians act, when out hunting the antelope, to draw the herd within[50] range of their arrows. He said that sometimes one or two of the savages would stand on their heads and shake their legs in the air; then again, they would hold up a blanket, no matter what color, and wave it slowly, when the herd, or at least a number from it, would gradually walk toward the Indians who were lying flat on the ground, and thus become easy victims to their swift, unerring arrows.

It was this knowledge of the antelope's prominent characteristic that enabled Joe to secure one for his favorite sister. He was out very early one morning when he noticed a large herd with many kids among it, about half a mile distant. He was well aware that his dogs, swift as they were, would be no match for the beautiful creatures in a trial of speed, so he resolved to resort to the Indian method. Ordering his hounds to lie close, he tied his white handkerchief round his head, and taking off his overalls, he began to move his body slowly backward and forward, at the same time vigorously waving the overalls in the air. In a few moments, just as he expected they would, he had the satisfaction of seeing first one, then[51] another, look up and gaze steadily at the strange object. Presently, about half a dozen of the does with their little ones by their sides, commenced to move cautiously towards him. When they had approached sufficiently near, he started the hounds after them, and after a short, lively chase they caught a fine kid, which, of course, could not keep up with its mother. They captured it without injury, for they had been trained not to mouth their game. As there were a dozen cows on the ranch, there was an abundance of milk, with which Kate used to feed her little pet from a bottle. The pretty creature throve rapidly, and soon became as affectionate as a kitten, following its mistress everywhere like a dog.

The big gray wolf, that ghoul of the great plains, understands full well the inordinate curiosity of the antelope, and knowing that it is impossible for him to catch one of the fleet animals by the employment of his legs alone, he effects by cunning what he could never accomplish by the best efforts of his endurance. The wicked old fellow, when he discovers a bunch of antelopes in the distance, rolls himself into a ball, like[52] a badger, and tumbles about on the grass until some of the deluded animals come near enough for him to spring on them.

Gertrude's coon was caught by both the boys, assisted by Bluey and Brutus. They dug him out of his nest under the roots of a huge elm tree near the cabin, one day in the early springtime, when the warm sun had just begun to thaw him after his winter's hibernation. He was "'cute" and mischievous as he could be, stealing anything on which he could get his tiny paws. Whenever Gertrude called him,—his name was Tom,—he would run to her as fast as he could, jump on her back, and sit on her shoulders for an hour at a time, when she was sewing or doing something which did not require her to move about. He lived on any scraps from the table, always rolling his food in his paws before he ate it.

The prairie dog, the property of Rob, was accidentally captured by Gertrude one morning when she and Kate were out gathering wild flowers. She actually stumbled on him as she stooped to pick a sensitive rose. The little creature had somehow become entangled in the convolutions of the vine, and thus became an easy prey. It[53] fought like a tiger at first, and tried to bite with its sharp teeth everything that came near it. It was soon tamed, however, and became a regular nuisance at times, for it would run under your feet in spite of the many pinches it got by being stepped upon. It tripped up the boys and girls a dozen times a day, as it was allowed the freedom of the house and the dooryard. Gertrude gave it to Rob, who had often expressed a desire to own one, and had failed a hundred times, perhaps, to capture one by drowning it out of its hole.

The elk was given to Joe by old Tucker, and in a short time grew to be as big as a young mule. Joe broke him to harness, and used to drive him hitched to a little cart which his father, with the boy's help, improvised out of an odd pair of wheels and a dry-goods box. He was kept in the corral with the cows and horses, and became very tame, but sometimes attempted to use his sharp front hoofs too freely. He was forbidden the precincts of the dooryard and the house, for he came near cutting Kate in two once, all in play, but too rough a kind of affection for a repetition of it to be allowed.

The wild raspberries grew in great profusion near every ledge of rock in the vicinity of the ranche. About a mile and a half from the house, however, there was a specially favored spot for them, where the vines were more dense and the berries of large size and delicious flavor. In the second week of June, the second year of their residence on the creek, Rob, who had been up the valley herding the cows, reported that evening, upon his return, that the berries were ripe and that there were bushels of them.

The next morning, immediately after breakfast, Gertrude and Kate left the house with a tin bucket each, intending to go up to the ledge and gather raspberries. They were dressed lightly,—Kate in a white muslin skirt, and her sister in a lawn. As the nearest way to the place where the berries were to be found lay by a trail on the other side of the Oxhide the girls crossed it near the cabin, and as there was neither log bridge nor stepping-stones, they took off their shoes and stockings and waded it. After reaching the other side and putting on their shoes and stockings, they wandered slowly through a little flower-bedecked prairie, beyond the margin of[55] timber which fringed the creek, to make a short cut to where the raspberries grew, for the Oxhide made a sweeping curve to the northeast, nearly in the shape of half a circle.

Both loving flowers, they gathered great bunches of the sensitive roses, anemones, and white daisies, growing everywhere in such profusion. This occupation consumed a great deal of time, for they naturally loitered, charmed by so much floral beauty around them. It was fortunate they did, as the sequel will show, and they did not arrive at the ledge of rocks until nearly ten o'clock—more than two hours after they had left home. It was intensely hot, and after gathering their buckets full of the delicious fruit, they sat down on a shelf of the ledge which projected over the creek. They dabbled their bare feet in the stream as it flowed in murmuring rhythm over the rounded white pebbles, while they ate their lunch of cake brought from the ranche, and the red berries so sweet in the wildness of their flavor.

Having satisfied their hunger, Kate said to her sister: "Gert, we ought to fill up our buckets again. If we go home empty-handed,[56] mother will think we have been making pigs of ourselves."

"There's time enough for that yet," replied Gertrude. "This cool water feels so delightful to my feet that I believe I could sit here and dabble in it until dark. Don't you think it's delicious, Kate?"

"Yes," answered Kate, "but I want to get home before dinner, because Joe said that he would go with me down to the village this evening. I am going to ride his pony, and he will ride Rob's."

"Well," said Gertrude, "if we must, we must. Mother loves raspberries so; they are her favorite fruit, you know; and if we did not take her a bucketful back with us, I should never forgive myself, though perhaps she would not say a word."

"Let us commence right now," imploringly said Kate. "I want to get back as soon as I can."

Both girls rose languidly to do as they proposed, but there did not seem to be much energy in their motions. Just as Gertrude had taken her pail from its place in the rocks, their ears were[57] greeted by a low growl, which seemed to come directly from underneath the shelf on which they had been sitting. They looked at each other, and their faces blanched as another snarl and a howl, nearer than before, came to their ears, and both recognized the familiar sound they had so often heard when lying in bed at night, as that of a wolf. Those predatory brutes frequently made their nightly rounds in the vicinity of the corral, trying to get at the young calves, and they might be heard in the timber, watching for a chance to secure some of the fowls shut up in their house of stone near the barn.

Gertrude, who was really very brave under ordinary circumstances, immediately stood still, and looking all around her, she suddenly met the gaze of a large, gaunt she-wolf at whose side were standing six little ones! Generally the wolf, like nearly all other wild animals, will run instantly at the sight of a human being; but the maternal instinct is so wonderful that, when they have young, they will die in defending their offspring from any supposed danger. This instinct was shown in this instance. The fierce animal had crept out of her den at the sound of voices, and[58] believing that her cubs were in jeopardy, she made a frantic dash toward the now thoroughly frightened girls, who hastily scrambled to the summit of the ledge.

Fortunately for them, the wolf is a poor climber, but with a savage bound toward the base of the flat rock on which the girls had a moment before been sitting, she arrived at it the same instant they had succeeded in reaching an elevation of about twelve feet above the level of the water.

Just as Kate, who was not as collected as her sister, was being dragged up by Gertrude, the wolf made a desperate leap and snapped at her with his terrible teeth, but failed. It succeeded, however, in catching her skirt in its ponderous jaws, and tore it completely from her waist, and she, almost feeling the hot breath of the infuriated brute, uttered a loud scream and fell fainting in her sister's arms.

Less than three hundred yards above the ledge of rocks, in a beautiful piece of prairie, Joe was herding the cattle, and Kate's cry, so full of fear, fell piercingly on his ears. He was aware that his sisters were to go berrying that morning,[59] and he also knew that the sound could only come from one of them. He was lying on the grass under the shade of a big elm with the bridle-rein of his pony in his hand. Grasping his rifle, which was at his side, in an instant he had mounted his animal, and digging his heels into its flanks, fairly flew down the creek to where his sisters were held at bay by the wolf. He arrived there in less than three minutes after he heard the scream of alarm, and saw the wolf still persisting in its vain efforts to reach the girls on the summit of the ledge. Gertrude was almost paralyzed with fear, and Kate lay at her feet in the swoon into which the action of the wolf had thrown her.

The enraged beast was too much occupied with the girls to notice that its would-be victims had assistance so near at hand, and Joe, as Gertrude saw her brother's approach, put his finger to his lips, indicating that she must remain perfectly silent. He dismounted in a second, and putting the loop of the reins over his left arm, dropped on one knee, and taking careful aim, sent a ball crashing right through the brain of the wolf, which instantly fell dead in its tracks.

Joe then rushed down to the creek and filled his hat with water. He then climbed hurriedly up to the rocky steep again and threw the water into Kate's face as she still lay prone on the ledge at her sister's feet. Kate soon revived, and after staring around her for a few seconds in a dazed way, she smiled and said:—

"Oh, Joe, you have saved us!" and rising to her feet, forgetful of her wet face, she kissed him half a dozen times.

While his sisters were adjusting their dresses and recovering from their terrible fright, Joe killed the young wolves with the butt of his rifle, and then taking his knife from his belt commenced to skin the old one. It did not require much time to perform the operation, for he had long since become an adept at such work. He then threw the beautiful hide over the withers of his pony, and walked home with his sisters.

Arriving at the cabin, the girls had much to tell about their wonderful experience and lucky escape from the jaws of the wolf, which would certainly have torn them to pieces if it had not been for Joe's timely arrival.

The hide, which was an immense one, was first tacked to the side of the stable, and when dried, Joe smoke-tanned it until it was as soft as a piece of silk. He gave it to Kate as a memento of her awful experience with its former owner. She used it as a rug at the side of her bed, and often said that for a long time whenever she stepped on it, the scene in which it played such an important part was brought vividly to her mind.

The Pawnees and Kaws, tribes of Indians long at peace with the whites, and whose reservations were in the eastern part of the state, frequently made incursions into the buffalo region two hundred miles from their home in the valley of the Neosho, on their annual hunt for their winter's supply of meat. The valley of the Oxhide was one of their favorite camping-grounds, and from thence they radiated in bands to the plains, where the vast herds of the great shaggy animals grazed in the autumn months, on their curious elliptical march from the Yellowstone to the southern border of Texas.

Every autumn these Indians camped in the timber only about a mile from Errolstrath ranche, and it was very natural that the boys, especially[63] Joe, should often visit their temporary village, as it was decidedly a new sensation for them. The tepees, or lodges, built in a conical shape out of long poles covered with well-tanned buffalo hides, were a never-ending curiosity to Joe. The chief of the band, Yellow Calf, an old man nearly eighty years of age, took a great fancy to Joe from the moment he first saw him. As soon as he became acquainted with his character he called him "White Panther," after the strange nomenclature of the North American savage. The Indians noticed immediately that Joe was different from the majority of white children they had met, and his quickness of motion was the reason they named him as they did. His readiness in acquiring their language, which he almost mastered in a few months, astonished them. Then Joe was always kind and gentle to the band, often bringing food from his mother's table when she could give it to him, especially bread or biscuit, of which old Yellow Calf was inordinately fond. At the suggestion of the chief, the closest warriors of his council took great delight in showing their new boy friend the use of the bow and arrow. They taught him how to prepare the skins of animals[64] he shot; how to make the robe of the buffalo as soft as a doeskin, and they taught him how to trap beaver, otter, and muskrat, in which valuable fur-bearing animals all the streams abounded. Yellow Calf would sit for hours talking with Joe, learning from him all about the strange inventions of the white man, and their uses. He in turn taught the boy the mysteries of the beautiful sign language, so wonderful in its symbolism; and the manner of trailing, so that in a few months he was as well versed in the methods of following an enemy on the warpath as the savages themselves.

The Indians frequently took Joe with them far up the Arkansas valley on their grand hunts after the buffalo. His parents readily gave their consent to his going with his red friends, though he was sometimes absent from home for more than a week. For three seasons the same band of Pawnees had their village on the creek, remaining there during the months of September and October of each year. All that time Joe continued his intimacy with them, and became more perfect in his knowledge of their savage methods. He could follow the blindest trail by[65] day or night, and the signs of the various hostile tribes were as familiar to him as the alphabet.

He had been carefully trained to all this knowledge by the Pawnees, who were the hereditary enemies of the Cheyennes who still claimed sovereignty over the great plains. Once, in fact, when he had been out for a fortnight with his Indian friends on a buffalo hunt, the party was suddenly met by a band of Cheyennes, and, of course, a battle ensued to which Joe was a witness. After the fight that night, when the band camped on the Walnut, he saw the dances of the victorious Pawnees and learned a great deal about savage warfare.

Shortly after the advent of the Pawnees on the Oxhide, and when Joe had established his friendly relations with them, although he could shoot fairly well previously, he now began to take a special delight in hunting. Every moment he could get to himself, he was off in the timber or out on the prairie with his rifle or shot-gun. He never carried these, however, unless he hunted alone, as on many occasions he was accompanied by one or two of the Pawnee boys about his own age whom the band had brought[66] with them; young bucks, not yet old enough to have reached the dignity of warriors. They had to do the work generally assigned to the women, for no squaws were with the band. It is beneath a warrior to do anything but hunt, eat, smoke, and go to war; for idleness is the predominant characteristic of the men of every savage race, and the Pawnees were no exception.

While they were encamped on the Oxhide the warriors scarcely ever left the delightful place except, of course, when summoned by their chief to the hunt. They sat all day in the shadow of their lodges, puffing lazily at their pipes and relating over and over again the stories of their feats in personal encounters with their enemies, the Cheyennes.

The North American Indians are very assiduous in teaching their boys all that becomes a great warrior,—how to ride the wildest horses, and how to hunt and trap every variety of animal used in the domestic economy of their families. The very moment a son is large enough to handle them, bows and arrows are constantly in his hands.

As the Indians had only a few poor rifles,[67] whenever Joe went out with his dusky young companions on a hunt, he, too, took nothing but his bow and arrows which the Pawnees had given him, for he did not want his boy friends to feel his superiority when armed with the white man's weapons. The number of squirrels, rabbits, and game birds he killed in a single day would have astonished a city-bred boy.

The Pawnee warriors, flattered by Joe's preference for their society to that of his white neighbors, made him the very finest bows and arrows of which their skill was capable. They looked forward to the day when he should develop into a great warrior, and hoped, too, that the time would come when, becoming tired of civilization, he would let them adopt him into the tribe. One morning, to the surprise of Joe, the old chief despatched a runner back to the reservation with orders to his squaws to make a complete suit of buckskin for his young white friend. In about two weeks when the messenger returned to the camp with the savage dress, Joe, of course, was delighted with his quaint and really beautiful costume. It was made out of the finest doeskin, elegantly embroidered with beads; the[68] seams of the coat-sleeves and trousers were fringed in the most approved savage fashion, while the moccasins were exquisitely wrought with the quills of the porcupine, gayly colored. There were also given the boy all the adjuncts of a warrior,—a tomahawk, medicine-bag, tobacco-pouch, powder-horn, bullet-sack, flint and steel, and, last of all, a magnificent calumet manufactured of the red stone from the sacred quarry in far-off Minnesota.

Joe had never mentioned to any of the family, not even to Rob, what was in store for him from the Pawnees. To make the surprise greater to the household, when he was ready to put on the new suit, he got one of the warriors to decorate his face in royal savage style, and thus metamorphosed, he walked into the cabin one noon, just as the family were about to sit down to dinner. None of them recognized him, and when he began to talk in the Pawnee language, not a word of which any of them could understand, his father motioned him to take a seat at the table and eat, as he had often done to the real Pawnees on their many visits to the ranche.

At last Joe could contain himself no longer, and he cried out in his exultation over the farce he had enacted: "Father, mother, Rob, and you girls, don't you know me?"

"No!" they all answered simultaneously, but immediately recognizing his voice, now that he spoke English, his mother said that she had never suspected for a moment that the horrid-looking, paint-bedaubed creature before her could be her own child.

Then all had a good laugh over the manner in which Joe had deceived them, but his father insisted that he must go and wash the paint from his face before he thought of sitting down to eat with Christian people; he could allow it in the case of a real savage, because they did not know any better.

Joe was very hungry, for he had been out hunting grouse on the hills all the morning, and was tired, too, so he hastily obeyed his father's injunction. He ran to the spring, and by vigorously rubbing at the various colors, he at last succeeded in getting his face clean. In a few moments he returned to the dining-room looking like himself again, but very stately, by reason of his brand-new[70] suit; and the family could not help staring at and admiring him. Then, when he had taken his place at the table, he was obliged to tell how he had happened to acquire such a fantastic dress, and explain the use of each curious article belonging to it.

Gertrude and Kate both hoped that he would not wear the handsome clothes every day, and his mother suggested that he must never go to the village in such a savage dress. His father said nothing, but evidently regarded his boy with pride.

In reply to the various comments, Joe told the family that he intended to wear the Indian costume only on extraordinary occasions. If ever the Cheyennes, Kiowas, Comanches, or Arapahoes broke out, he would certainly wear it, for when those savages saw him, they would think he was a great warrior, and be careful how they bothered him. The family little thought, as he uttered his playful remarks, how soon that uniform would be worn on a mission fraught with danger to themselves and the whole settlement.

The family had lived on their comfortable ranche on the Oxhide for nearly three years. During the whole of this period the valley had been most happily exempt from any raid by the hostile Indians farther west, who for all that time had made incursions into the sparse settlements not a hundred miles away, devastating the country from Nebraska on the north to the border of Texas on the south.

General Sheridan had been ordered by the Government to the command of the Military Department of the Missouri, with headquarters at Fort Leavenworth. The already famous General Custer with his celebrated regiment, the Seventh United States Cavalry, was stationed[72] at Fort Harker, recently established on the Smoky Hill, about four miles from Errolstrath ranche, so the settlers on the Oxhide, and through the valley, felt comparatively safe from any possible raid by the savages into that region.