Title: A System of Midwifery

Author: Edward Rigby

Release date: September 3, 2012 [eBook #40654]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (http://archive.org/details/americana)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A System of Midwifery, by Edward Rigby

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/systemidwifer00rigb |

Lea & Blanchard have lately published.

NEW REMEDIES,

The Method of Preparing and Administering them;

THEIR EFFECTS

UPON THE

HEALTHY AND DISEASED ECONOMY, &c. &c.

BY ROBLEY DUNGLISON, M. D.

Professor of the Institutes of Medicine and Materia Medica in

Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia; Attending

Physician to the Philadelphia Hospital, &c.

THIRD EDITION BROUGHT UP TO 1841.

IN ONE VOLUME.

A NEW EDITION

Completely Revised, with Numerous Additions and Improvements,

OF

DUNGLISON’S DICTIONARY

OF

MEDICAL SCIENCE AND LITERATURE:

CONTAINING

A concise account of the various Subjects and Terms, with a vocabulary of Synonymes in different languages, and formulæ for various officinal and empirical preparations, &c.

IN ONE ROYAL 8vo. VOLUME.

A Fourth Edition Improved and Modified, of

DUNGLISON’S

HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY:

ILLUSTRATED WITH NUMEROUS ENGRAVINGS.

IN TWO VOLUMES, OCTAVO.

Brought up to the present day.

A PRACTICAL TREATISE

ON THE

HUMAN TEETH:

Showing the causes of their destruction and the means of their preservation. By Wm. Robertson: with plates. First American, from the second London edition. In one volume.

OUTLINES

OF A

COURSE OF LECTURES, ON MEDICAL JURISPRUDENCE.

BY THOMAS STEWART TRAILL, M. D.

From the Second Edinburgh Edition,

WITH AMERICAN NOTES AND ADDITIONS.

ARNOTT’S ELEMENTS OF PHYSICS.

Complete in One Volume.

A new edition of Elements of Physics, or Natural Philosophy, general and medical, written for universal use, in plain or non-technical language, and containing New Disquisitions and Practical Suggestions, comprised in five parts: 1st. Somatology, Statics and Dynamics. 2d. Mechanics. 3d. Pneumatics, Hydraulics, and Acoustics. 4th. Heat and Light. 5th. Animal and Medical Physics. Complete in one volume. By Neil Arnott, M. D., of the Royal College of Physicians. A new edition, revised and corrected from the last English edition, with additions, by Isaac Hays, M. D.

THE NINTH BRIDGEWATER TREATISE.

A FRAGMENT,

BY

CHARLES BABBAGE, ESQ.

From the Second London Edition.

IN ONE VOLUME, 8vo.

A New Edition with Supplementary Notes, and Additional Plates; of BUCKLAND’S GEOLOGY AND MINERALOGY, considered with reference to Natural Theology; from the last London Edition with nearly one hundred Maps and Plates.

PROFESSOR GIBSON’S RAMBLES IN EUROPE, in 1839:—Containing Sketches of Prominent Surgeons, Physicians, Medical Schools, Hospitals, &c. &c. In One Volume.

AN ATLAS OF PLATES, illustrative of the Principles and Practice of Obstetric Medicine and Surgery, with descriptive Letter Press, by Francis H. Ramsbotham. This will form a large super royal volume, with over One Hundred lithographic plates—to be ready in November.

THE PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE of MEDICINE, By Professor Dunglison in 2 vols. 8vo. This work will be ready the approaching fall.

THE LIBRARY OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE. Edited by Tweedie, is now complete in five volumes, royal octavo, handsomely bound in leather, to match. The different volumes may be had separate, bound in extra cloth.

BY

EDWARD RIGBY, M. D.,

PHYSICIAN TO THE GENERAL LYING-IN HOSPITAL, LECTURER ON MIDWIFERY,

AT ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL, ETC. ETC.

A

SYSTEM

OF

MIDWIFERY.

WITH NUMEROUS WOOD CUTS.

BY

EDWARD RIGBY, M. D.,

PHYSICIAN TO THE GENERAL LYING-IN HOSPITAL, LECTURER ON MIDWIFERY,

AT ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL, ETC. ETC.

WITH NOTES AND ADDITIONAL ILLUSTRATIONS.

Philadelphia:

LEA & BLANCHARD.

1841.

Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1841, by Lea &

Blanchard, in the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

GRIGGS & CO., PRINTERS.

This System of Midwifery, complete in itself, was published in London, as a part of Dr. Tweedie’s “Library of Medicine.” The first series of the Library, that on “Practical Medicine,” recently completed, has been received with extraordinary favour on both sides of the Atlantic, and the character of the publication is fully sustained in the present contribution by Dr. Rigby, and will secure for it additional patronage.

The late Professor Dewees, into whose hands this volume was placed, a few weeks before his death, in returning it, expressed the most favourable opinion of its merits; and the judgment of such high authority renders it supererogatory to add a word farther of commendation.

It is only necessary for the editor to say that the production of the author is so complete as to have rendered his labour a light one. He has restricted himself mainly to such additions and references as he conceived would render the work more useful to American practitioners. The object of the publication being to present the most condensed view of each subject, he believed it to be inexpedient to depart from the plan by making extensive additions, and entering into the discussion of controversial points, most of which are of minor practical importance.

CONTENTS.

| Introduction, | Page 13 |

| PART I. | |

| THE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF UTERO-GESTATION. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE PELVIS. | |

| Ossa innominata.—Sacrum.—Coccyx.—Distinction between the male and female pelvis.—Diameters of the pelvis.—Pelvis before puberty.—Axes.—Inclination, | 15 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| FEMALE ORGANS OF GENERATION. | |

| Internal and external.—Ovaria.—Ovum.—Corpus luteum.—Fallopian tubes.—Uterus.—Vagina.—Hymen.—Clitoris.—Nymphæ.—Labia, | 22 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

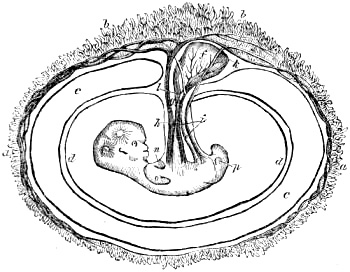

| DEVELOPMENT OF THE OVUM. | |

| Membrana decidua.—Chorion.—Amnion.—Placenta.—Umbilical cord.—Embryo.—Fœtal circulation, | 48 |

| PART II. | |

| NATURAL PREGNANCY AND ITS DEVIATIONS. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| SIGNS OF PREGNANCY. | |

| Difficulty and importance of the subject.—Diagnosis in the early months.—Auscultation.—Changes in the vascular and nervous systems.—Morning sickness.—Changes [Pg 6]in the appearance of the skin.—Cessation of the menses.—Areola.—Sensation of the child’s movements.—“Quickening.”—Auscultation.—Uterine souffle.—Sound of the fœtal heart.—Funic souffle.—Sound produced by the movements of the fœtus.—Ballottement.—State of the urine.—Violet appearance of the mucous membrane of the vagina.—Cases of doubtful pregnancy.—Diagnosis of twin pregnancy, | 80 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| TREATMENT OF PREGNANCY. | |

| Sympathetic affections of the stomach during pregnancy.—Morning sickness.—Constipation.—Flatulence.—Colicky pains.—Headach.—Spasmodic cough.—Palpitation.—Toothach.—Diarrhœa.—Pruritus pupendi.—Salivation, | 101 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| SIGNS OF THE DEATH OF THE FŒTUS. | |

| Difficulty of the subject.—Signs before labour.—Motion of the fœtus.—Sound of the fœtal heart.—Uterine souffle.—Signs during labour where the head presents—where the face, the nates, the arm, or the cord, present.—Fetid liquor amnii.—Discharge of meconium, | 107 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| MOLE PREGNANCY. | |

| Nature and origin.—Varieties.—Diagnostic symptoms.—Treatment, | 112 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| EXTRA-UTERINE PREGNANCY. | |

| Tubarian, ovarian, and ventral pregnancy.—Pregnancy in the substance of the uterus, | 117 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| RETROVERSION OF THE UTERUS. | |

| History.—Causes.—Symptoms.—Diagnosis.—Treatment.—Spontaneous terminations, | 126 |

| [Pg 7] | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| DURATION OF PREGNANCY, | 136 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| PREMATURE EXPULSION OF THE FŒTUS. | |

| Abortion.—Miscarriage.—Premature labour.—Causes.—Symptoms.—Prophylactic measures.—Effects of repeated abortion.—Treatment, | 141 |

| PART III. | |

| EUTOCIA, OR NATURAL PARTURITION. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| STAGES OF LABOUR. | |

| Preparatory stage.—Precursory symptoms.—First contractions.—Action of the pains.—Auscultation during the pains.—Effect of the pains upon the pulse.—Symptoms to be observed during and between the pains.—Character of a true pain.—Formation of the bag of liquor amnii.—Rigour at the end of the first stage.—Show.—Duration of the first stage.—Description of the second stage.—Straining pains.—Dilatation of the perineum.—Expulsion of the child.—Third stage.—Expulsion of the placenta.—Twins, | 156 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| TREATMENT OF NATURAL LABOUR. | |

| State of the bowels.—Form and size of the uterus.—True and spurious pains.—Treatment of spurious pains.—Management of the first stage.—Examination.—Position of the patient during labour.—Prognosis as to the duration of labour.—Diet during labour.—Supporting the perineum.—Treatment of perineal laceration.—Cord round the child’s neck.—Birth of the child, and ligature of the cord.—Importance of ascertaining that the uterus is contracted after labour.—Management of the placenta.—Twins.—Treatment after labour.—Lactation.—Milk fever and abscess.—Excoriated nipples.—Diet during lactation.—Management of lochia.—After-pains, | 169 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| MECHANISM OF PARTURITION. | |

| Cranial presentations—first and second position.—Face presentations—first and second positions.—Nates presentations, | 199 |

| [Pg 8] | |

| PART IV. | |

| MIDWIFERY OPERATIONS. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

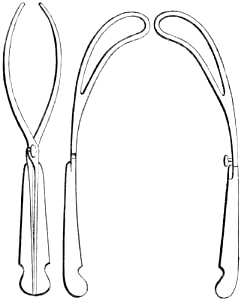

| THE FORCEPS. | |

| Description of the straight and curved forceps.—Mode of action.—Indications.—Rules for applying the forceps.—History of the forceps, | 216 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| TURNING. | |

| Turning.—Indications.—Circumstances most favourable for this operation.—Rules for finding the feet.—Extraction with the feet foremost.—Turning with the nates foremost.—Turning with the head foremost.—History of turning, | 230 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| CÆSAREAN OPERATION. | |

| Indications,—Different modes of performing the operation.—History of the Cæsarean operation, | 243 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| ARTIFICIAL PREMATURE LABOUR. | |

| History of the operation.—Period of pregnancy most favourable for performing it.—Description of the operation, | 250 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

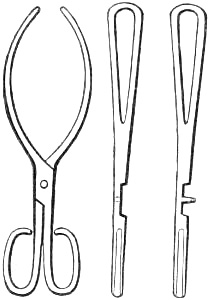

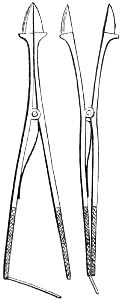

| PERFORATION. | |

| Variety of perforators.—Indications.—Mode of operating.—Extraction.—Crotchet.—Embryulcia, | 256 |

| PART V. | |

| DYSTOCIA, OR ABNORMAL PARTURITION. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| FIRST SPECIES OF DYSTOCIA. | |

| Malposition of the child.—Arm or shoulder the only faulty position of a full-grown [Pg 9]living fœtus.—Causes of malposition.—Diagnosis before and during labour.—Results where no assistance is rendered.—Spontaneous expulsion.—Malposition complicated with deformed pelvis or spasmodically contracted uterus.—Embryulcia.—The prolapsed arm not to be put back or amputated.—Presentation of the arm and head.—Presentation of the hand and feet.—Presentation of the head and feet.—Rupture of the uterus.—Usual seat of laceration.—Causes.—Premonitory symptoms.—Symptoms.—Treatment.—Gastrotomy.—Rupture in the early months of pregnancy, | 264 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| SECOND SPECIES OF DYSTOCIA. | |

| Size and form of the child.—Hydrocephalus.—Cerebral tumours.—Accumulation of fluid and tumours in the chest or abdomen.—Monsters.—Anchylosis of the joints of the fœtus, | 281 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THIRD SPECIES OF DYSTOCIA. | |

| Difficult labour from faulty condition of the parts which belong to the child.—The membranes.—Premature rupture of the membranes.—Liquor amnii.—Umbilical cord.—Knots upon the cord.—Placenta, | 286 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| FOURTH SPECIES OF DYSTOCIA. | |

| Abnormal state of the pelvis.—Equally contracted pelvis.—Unequally contracted pelvis.—Rickets.—Malacosteon, or mollities ossium.—Symptoms of deformed pelvis.—Funnel-shaped pelvis.—Obliquely distorted pelvis.—Exostosis.—Diagnosis of contracted pelvis.—Effects of difficult labour from deformed pelvis.—Fracture of the parietal bone.—Treatment.—Prognosis, | 292 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| FIFTH SPECIES OF DYSTOCIA. Obstructed Labour from a Faulty Condition of the Soft Passages. | |

| Pendulous abdomen.—Rigidity of the os uteri.—Belladonna.—Edges of the os uteri adherent.—Cicatrices and callosities.—Agglutination of the os uteri.—Contracted vagina.—Rigidity from age.—Cicatrices in the vagina.—Hymen.—Fibrous bands.—Perineum.—Varicose and œdematous swellings of the labia and nymphæ.—Tumours.—Distended or prolapsed bladder.—Stone in the bladder, | 308 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| SIXTH SPECIES OF DYSTOCIA. Faulty Labour from a Faulty Condition of the expelling Powers. | |

| I. Where the uterine activity is at fault—functionally or mechanically—from debility—derangement [Pg 10]of the digestive organs—mental affections—the age and temperament of the patient—plethora—rheumatism of the uterus—inflammation of the uterus—stricture of the uterus.—Treatment. II. Where the action of the abdominal and other muscles is at fault.—Faulty state of the expelling powers after the birth of the child.—Hæmorrhage.—Treatment, | 324 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| INVERSION OF THE UTERUS. | |

| Partial and complete.—Causes.—Diagnosis and symptoms.—Treatment.—Chronic inversion.—Extirpation of the uterus, | 345 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| ENCYSTED PLACENTA. | |

| Situation in the uterus.—Adherent placenta.—Prognosis and treatment.—Placenta left in the uterus.—Absorption of retained placenta, | 354 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| PRECIPITATE LABOUR. | |

| Violent uterine action.—Causes.—Deficient resistance.—Effects of precipitate labour.—Rupture of the cord.—Treatment.—Connexion of precipitate labour with mania, | 361 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| PROLAPSUS OF THE UMBILICAL CORD. | |

| Diagnosis.—Causes.—Treatment.—Reposition of the cord, | 368 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| PUERPERAL CONVULSIONS. | |

| Epileptic convulsions with cerebral congestion.—Causes.—Symptoms.—Tetanic species.—Diagnosis of labour during convulsions.—Prophylactic treatment.—Treatment—Bleeding.—Purgatives.—Apoplectic species.—Anæmic convulsions.—Symptoms.—Treatment.—Hysterical convulsions.—Symptoms, | 376 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| PLACENTAL PRESENTATION, OR PLACENTA PRÆVIA. | |

| History.—Dr. Rigby’s division of hæmorrhages before labour into accidental and unavoidable.—Causes.—Symptoms.—Treatment.—Plug.—Turning.—Partial presentation of the placenta.—Treatment, | 393 |

| [Pg 11] | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| PUERPERAL FEVERS. | |

| Nature and varieties of puerperal fever.—Vitiation of the blood.—Different species of puerperal fever.—Puerperal peritonitis.—Symptoms.—Appearances after death.—Treatment.—Uterine phlebitis.—Symptoms.—Appearances after death.—Treatment.—Indications.—False peritonitis.—Treatment.—Gastro-bilious puerperal fevers.—Symptoms.—Appearances after death.—Treatment.—Contagious or adynamic puerperal fevers.—Symptoms.—Appearances after death.—Treatment, | 415 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| PHLEGMATIA DOLENS. | |

| Nature of the disease.—Definition of phlegmatia dolens.—Symptoms.—Duration of the disease.—Connexion with crural phlebitis.—Causes.—Connexion between the phlegmatia dolens of lying-in women and puerperal fever.—Anatomical characters.—Treatment.—Phlegmatia dolens in the unimpregnated state, | 463 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| PUERPERAL MANIA. | |

| Inflammatory or phrenitic form.—Treatment.—Gastro-enteric form.—Treatment.—Adynamic form.—Causes and symptoms.—Treatment, | 473 |

| Index, | 483 |

A SYSTEM OF MIDWIFERY.

By the term Midwifery is understood the knowledge and art of treating a woman and her child during her pregnancy, labour, and the puerperal state. We employ it in this extended sense, because most systematic writers of later times have adopted this arrangement. The terms, Art des Accouchemens of the French, the Ostetricia, and Arte della Parteria, of the Italians and Spaniards, and the Geburtshülfe of the Germans, are restricted to the process of parturition, although they have been and continue to be, used in the same extended sense as that in which we propose to use the term Midwifery.

Although pregnancy and parturition, strictly speaking, are perfectly natural functions, yet they involve such a complication and variety of other processes, and also changes of such extent, that the whole system is rendered more or less subservient to them during the periods of their existence: hence, therefore, their number and variety must ever render them more or less liable to deviations and irregularities of action, which will necessarily be aggravated by the effects of civilized life, and in many instances are productive of derangement in the general economy of the system. Under such circumstances the irritability of the system increases at the expense of its strength and vigour, and not only increases its liability to these derangements, but diminishes its power of resisting their effects.

In order that we may render the nature and treatment of the changes and phenomena, which take place in the human system during the periods above alluded to, more intelligible, we shall take a short anatomico-physiological view of the structure, form, arrangement, and function of the parts and organs which are[Pg 14] more or less directly concerned in these important processes. This will embrace the subject of embryology, a department of physiological knowledge, which, though it has lately been much enriched by valuable discoveries, still affords a rich field of investigation and research.

The diagnosis and course of healthy pregnancy, and its various diseases, terminating with the subject of healthy parturition and its treatment will form the subject of the succeeding part.

Parturition properly speaking, will come under two separate heads eutocia and dystocia; the one signifying natural or favourable labour, the other, unnatural, faulty, or unfavourable labour.

The concluding part will contain a short account of some of the more important diseases which occur to the female during the first month after parturition.

THE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF UTERO-GESTATION.

THE PELVIS.

Ossa innominata.—Sacrum.—Coccyx.—Distinction between the male and female pelvis.—Diameters of the pelvis.—Pelvis before puberty.—Axes.—Inclination.

The Pelvis, as the frame-work which, in great measure, contains, supports, and protects, the complicated apparatus of the generative organs, first claims our attention; since an accurate knowledge of the form, size, and uses, of its different parts is indispensably necessary, not only to understand the situation of the viscera it contains, but also to form a correct view of the mechanism upon which the process of parturition depends.

This osseous canal or circular archway, consists essentially of three bones, the right and left os innominatum, which form the sides of the arch, with the sacrum between them, acting as a keystone, and supporting the whole weight of the trunk above.

Ossa innominata. The ossa innominata in early life consists of three distinct bones, the iliac or hip bones at the sides, the ischia or lower portion upon which we sit, and the ossa pubis which meet each other anteriorly to form the front part of the pelvis. In the adult these are consolidated into one bone, merely leaving irregular lines and ridges here and there to mark their previous existence.

These bones present several striking points of resemblance with those which belong to the upper extremities, viz. the scapula and clavicle; and in the early stages of development, this similarity is much more distinctly seen: it is remarkable, that although the ischia and ossa pubis are formed later than the ilia, yet they unite with each other much sooner than with the ilia, so that the two consolidated bones bear the same relation to the ilium which is separated from them, that the clavicle does to the scapula: many other points of resemblance between the bones of the shoulder and[Pg 16] pelvis might be noticed if necessary. (Meckel, Anat. vol. ii. p. 239.) The ossa innominata meet each other in front, forming the symphysis pubis, having layers of fibro-cartilage interposed between their extremities, and bound together by ligamentous fibres constituting the ligamentum arcuatum, or annulare ossium pubis, and by which a more rounded appearance is given to the pubic arch. They are united to the sacrum posteriorly, one on each side of it, forming the right and left sacro-iliac symphysis or synchondrosis; this differs in many respects from the symphysis pubis, the cartilaginous coverings of the opposing bones being much thinner, especially those of the ossa innominata; the surfaces are extremely uneven from the deep indentations which each bone presents at this part, locking, as it were, into each other, and thus contributing greatly to increase the firmness of the joint, which is also still farther strengthened by the support of powerful ligaments.

Between the ligamento-and cartilaginous layers which cover the surfaces of the bones at the pubic and sacro-iliac symphyses, a minute collection of synovial fluid may be detected, like that found in the fibro-cartilages between the vertebræ; it serves to lubricate their surfaces, and separates them more or less, thereby increasing the thickness of the intervening cartilaginous structure; and separating also the edges of the bones, to a certain extent, more especially at the symphysis pubis. (Portal, Anat. Méd.) These laminæ of intervening fibro-cartilage are thicker in the female than in the male, although of smaller extent; and this is still more remarkable during pregnancy, this ligamento-cartilaginous structure becoming now more cushiony and elastic, while in the latter months we can easily distinguish blood-vessels ramifying through it, which are branches of the pudic arteries and veins.

Sacrum. The sacrum, which forms the upper and posterior portion of the pelvis, contributes greatly to the general solidity of the whole bony circle. From its wedge-like shape, it is admirably adapted to support the entire weight of the trunk, and acts, as we have before observed, as a kind of keystone to the arch which is formed by the ossa innominata. It is of a triangular shape, being concave before and convex behind. In the fœtus it consists of five distinct pieces of bone separated by intervening layers of cartilage, like the vertebræ of the spinal column, and from their resemblance to those bones they have been called false vertebræ. These cartilages, after a time, gradually disappear; bony matter is deposited in their place; so that by the period of puberty the five sacral vertebræ become united into one solid bone, although they may be distinguished, until an advanced period of life, by the ridges which their edges form.

The upper surface of the sacrum, having to sustain the whole weight of the spinal column, is broad and flat, and corresponds to the lower surface of the last lumbar vertebra. Its anterior surface forms with that of the other mentioned bone a considerable angle,[Pg 17] which projects forwards and more or less downwards towards the symphysis pubis, and is called the promontory of the sacrum. Beneath this point, the sacrum takes a considerable sweep backwards as it descends, gradually advancing again forwards, as we approach its inferior extremity, forming an extensive concavity upon its anterior surface: this is termed the hollow of the sacrum.

Coccyx. The lower end is prolonged by a small bone, called Coccyx or os Coccygis, from its supposed resemblance to a cuckoo’s beak. It usually consists of four, and sometimes (especially in women) of five portions; they are much smaller than the bones of the sacrum, and are very imperfect rudiments of vertebral formation; like these, they are at an early period little else than cartilage, and even when the bones are fully formed, they are united by intermediate cartilage, and thus retain so much mobility upon each other, as well as upon the lower end of the sacrum, as to admit of being forced backwards to the extent of a full inch, thus contributing greatly to increase the capacity of the outlet.

The sacrum not only serves to form the posterior parietes of the pelvis, but by the curve which its lower portion takes forwards, together with the coccyx, it gives a powerful support to the pelvic viscera.

When we take a general view of the bones which collectively form the pelvis, we find that it is evidently divided into two portions—an upper and a lower one. On the Continent these have been called the large and the small pelvis; in Britain we merely speak of the pelvis above or below the brim, the line of demarcation being the linea ilio-pectinea at the sides, the crista of the os pubis in front, and the promontory of the sacrum behind. The alæ of the ilia form a prominent feature in the upper pelvis, and not only afford an attachment for numerous muscles, but furnish a powerful and ample means of protection and support to the pelvic and lower abdominal viscera. In the female pelvis this is remarkably the case, the cavitas iliaca being well expanded and of greater extent than in the male, the crista of the ilium thrown more outwards; hence the distance between the antero-superior processes is much more considerable.

Distinction between the male and female pelvis. At the brim, the female pelvis presents several well-marked points of distinction from that of the male. The male pelvis has a contracted brim of a rounded or rather triangular form, with the promontory of the sacrum considerably projecting; whereas, that of the female is spacious, of an oval shape, and with a slightly prominent sacrum, thus affording more room for the passage of the child through the brim. The cavity of the male pelvis is deep, while in the female pelvis it is shallow, a circumstance which is very strikingly seen in comparing the length of the symphysis pubis in each, that of the male pelvis being nearly double the length of the female. This is an important point of difference as regards parturition, [Pg 18]because in a shallow pelvis, the extent of surface exposed to the pressure of the head will be much less than where it is deep, and hence the resistance to the passage of the child will be proportionably diminished: in confirmation of this, we find that tall women, in whom the pelvis is usually deep, do not, on the whole, bear children so easily as women of middling stature in whom the pelvis is more shallow. The capacious hollow of the sacrum in the female pelvis adds also greatly to the extent of its cavity, and peculiarly adapts it for parturition, the injurious pressure of the head upon the soft linings of the pelvis being thus prevented, and every facility afforded for its quick and easy transit through the cavity. This applies especially to the neck of the bladder, which would almost inevitably suffer in every labour, were it not for the ample hollow of the sacrum relieving the pressure of the head against the anterior portions of the pelvis. The bones of the female pelvis being more slender and delicately formed, the foramina ovalia and sacro-ischiatic notches are wider, and thus add still farther to the capacity of the cavity.

In no part of the pelvis is the difference between the sexes more strongly marked than at the outlet. The spacious and well-rounded arch of the pubes in the female of the slender rami, is a striking contrast to the contracted angular arch of the male pelvis; and the tuberosities of the ischium being much wider apart, the head is enabled to pass under the arch with greater facility, and thus still farther to relieve the anterior of the pelvis from its pressure. The length of the sacro-sciatic ligaments, and the mobility of the coccyx upon the sacrum, by which it can be forced backwards to the extent of an inch by the pressure of the head during labour, not merely serve to distinguish it from the male pelvis, but afford a beautiful instance of design and adaptation.

The greater width of the pubic arch in the female pelvis is seen by comparing its angle with that of the arch in the male pelvis. In the female it has been estimated to form an angle varying between 90° and 100°, whereas in the male it is not more than between 70° and 80°. (Osiander, Handbuch der Embindungs-kunst, cap. iv. p. 58.)

From the greater width of the female pelvis, the acetubula are farther apart, and the great trochanters of the thigh-bones more projecting; hence the greater motion of the hips in the female when she walks, which is still more visible when she runs, for the motion is communicated to the whole trunk, so that each shoulder is turned more or less forwards as the corresponding foot is advanced. The thigh-bones, which are so far apart at their upper extremities, approach each other at the knees, contributing to produce that unsteady gait which is peculiar to the sex. “The woman,” says Mr. John Bell, “even of the most beautiful form, walks with a delicacy and feebleness which we come to acknowledge as a beauty in the weaker sex.” (Bell’s Anat. vol. i.)

[Pg 19]These characteristic marks of the female figure, upon which its beauty in great measure depends, are well seen in all great works of art, whether of sculpture or painting. “The ancients,” as Mr. Abernethy has observed, “who had a clear and strong perception of whatever is beautiful or useful in the human figure, and who, perhaps, delicately exaggerated beauty to render it more striking, have represented Venus as measuring one-third more across the hips than the shoulders, whilst, in Apollo, they have reversed these measurements.” (Physiological Lectures.)

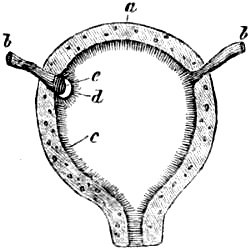

Diameters of the pelvis. It is of the utmost importance to the obstetrician, that he should be thoroughly acquainted with the various dimensions of the female pelvis, for, without this, he can form no correct idea of the manner in which the presenting part of the child passes through its brim, cavity and outlet during labour; indeed, unless he be thoroughly versed in this necessary point of obstetric knowledge, he will remain in almost total ignorance of the whole mechanism of parturition, which must, in great measure, be looked upon as the basis of practical midwifery. The dimensions of the brim cavity and outlet of the pelvis may be given with sufficient correctness for all practical purposes, by measuring three of their diameters,—1. the straight, antero-posterior, or conjugate; 2. the transverse; and 3. the oblique. At the brim they are as follow:—the straight diameter, drawn from the middle of the promontorium sacri to the upper edge of the symphisis pubis, 4·3 inches; the transverse diameter, from the middle of the linea-ilio-pectinea of one ilium to that of the other, 5·4 inches; and the oblique diameter, from one sacro-iliac synchondrosis to the opposite acetabulum, 4·8 inches. The oblique diameters are called right and left, according to the sacro-iliac symphysis from which they are drawn.

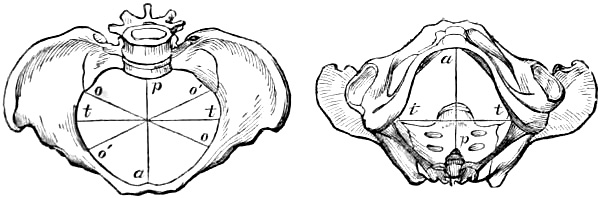

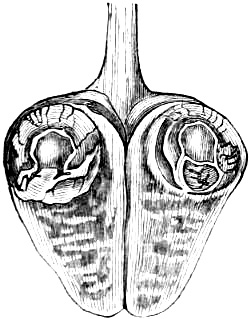

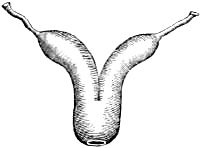

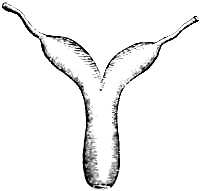

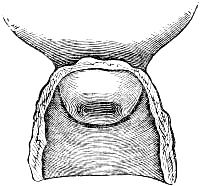

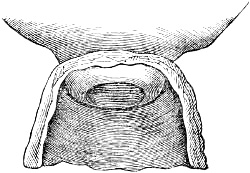

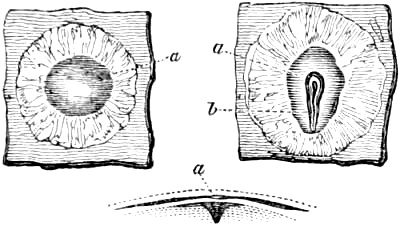

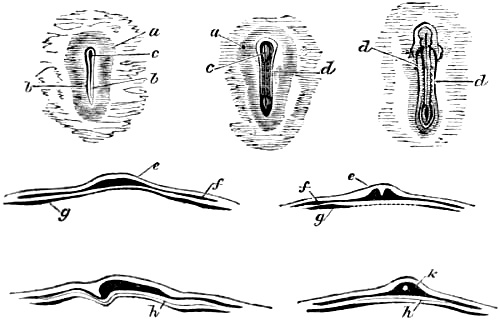

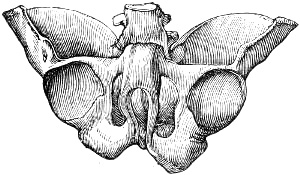

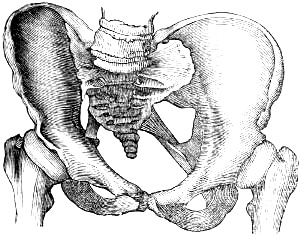

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

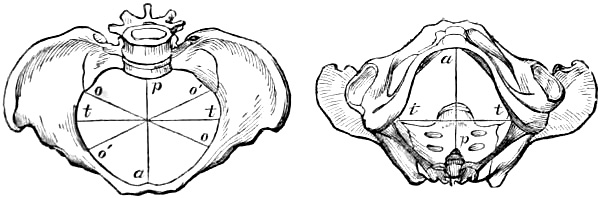

In the annexed representations of the superior and inferior aspects of the female pelvis are shown the three diameters of its brim and outlet; those of the former in fig. 1., and those of the latter in fig. 2. The same letters of reference are used in each figure to indicate the several diameters; thus a p refers to the antero-posterior, t t to the transverse, o o to the right oblique, and o′ o′ to the left oblique diameters.

In fig. 2. the coccyx is represented in situ.

In the cavity these dimensions vary more or less. The straight diameter, measured from the centre of the hollow of the sacrum to that of the symphysis pubis, is 4·8 inches; the transverse, from[Pg 20] the point corresponding to the lower margin of the acetabulum on one side to that of the other, 4·3; and the oblique, drawn from the centre of the free space formed by the sacro-ischiatic notch and ligaments on one side of the foramen ovale of the other, 5·2.

At the inferior aperture or outlet the alteration is still more remarkable. The straight diameter, from the point of the coccyx to the lower edge of the symphysis pubis, measures only 3·8 inches; but from the mobility of the coccyx enabling it to be pushed back during labour to the extent of a whole inch, it is capable of being extended to 4·8 inches. The transverse diameter from one tuberosity of the ischium to the other, measures 4·3 inches: and the oblique, from the middle of the lower edge of the sacro-sciatic ligament of one side, to the point of union between the ischium and descending ramus of the pubes on the other 4·8 inches.

Although these are the proportions of the brim cavity and outlet of the female pelvis in the skeleton state, their real dimensions during life, when the pelvis is thickly lined with muscular and other structures, are very different. The large masses of the psoas magnus and iliacus internus, besides other muscles of inferior size, contribute to alter materially the relations of the pelvic diameters to each other; hence we find that, so far from being the longest, the transverse diameter is one of the shortest, being little more than the antero-posterior. This holds good, especially during labour, because these muscles being thrown into powerful contraction, their bellies swell, and thus tend still farther to diminish its length. The oblique diameters are, in fact, the longest during life, because not only are the parietes of the pelvis at the brim covered by a very thin layer of soft tissues in these directions; but as the extremities of these diameters, in the cavity and outlet, correspond to free spaces which are merely filled up with soft yielding structure, it follows that their length can be somewhat increased when pressure is applied in these directions; the antero-posterior diameter of the outlet can alone be compared with the oblique diameters in this respect, and then only when the coccyx is forced backwards to its full extent by the pressure of the head.

Pelvis before puberty. The proportions of the adult female pelvis are no longer what they were during childhood; before the age of puberty they resemble those of the male pelvis, the brim being contracted and more or less triangular, and the antero-posterior diameter equalling or even exceeding the transverse. Indeed, at a still earlier period, it presents many points of resemblance even to the pelvis of animals; as, however, growth and development advance, and the various changes which constitute puberty take place, the transverse diameters of the brim, cavity,[Pg 21] and outlet increase at the expense of the antero-posterior, until at length, it has assumed the proper proportions of the adult female pelvis.

Axes. Of not less importance is it that the obstetrician should be thoroughly acquainted with the direction which the central line or axis of the entrance and outlet of the pelvis takes. The axis of the superior aperture has been considered to form with the horizon an angle varying between 50° and 60°; this was noticed long ago by Dr. Smellie: “when the body of a woman,” says this valuable author, “is reclined backwards, or half sitting half lying, the brim of the pelvis is horizontal; and an imaginary straight line, descending from the navel, would pass through the middle of the cavity; but in the last month of pregnancy such a line must take its rise from the middle space between the navel and scrobiculus cordis in order to pass through the same point of the pelvis.” (Treatise of Midwifery, book i. chap. i. sect. 2.)

Inclination of the pelvis. The angle which the axis of the superior aperture of the pelvis forms with the horizon, when a woman is in the upright posture, necessarily marks what has been called the inclination of her pelvis, and varies, of course, in proportion to the angle which the above mentioned axis forms. In a tall woman of slender figure, where the different curves of the spinal columns are slight, the inclination of the pelvis is much less than in a short thick set woman, where the spine is much more strongly curved. Where the inclination is slight, the hollow of the sacrum is generally small, and the vulva directed more forwards; where, on the other hand, the pelvis is much inclined, the hollow of the sacrum is generally observed to be deep, and the vulva directed more or less backwards. The axis of the lower aperture or outlet appears to depend, in great measure, on the curve which the lower part of the sacrum takes downwards and forwards; but, as a general rule, we think it will be found to form, more or less, a right angle with the axis of the brim. The greater the angle which the axis of the brim forms with the horizon, the less will be that which the axis of the outlet forms, and vice versâ; or, in other words, the angle with the horizon which the axis of the one forms is inversely to that of the other.

The consideration of the various deviations, as to size and form, from the natural proportions which the female pelvis occasionally presents, belongs, more strictly speaking, to that species of faulty labour which arises from these conditions. We, therefore, refer to the fourth species of dystocia, viz. Dystocia Pelvica, where the different pelvic anormalities are described.

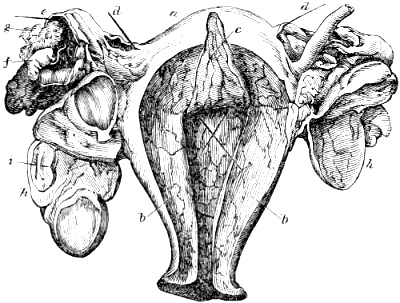

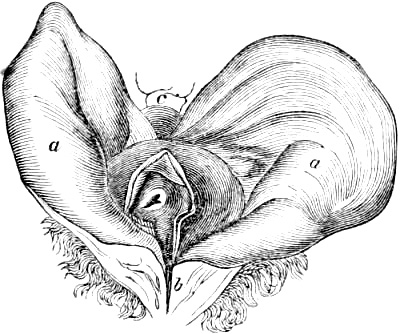

FEMALE ORGANS OF GENERATION.

Internal and external.—Ovaria.—Ovum.—Corpus luteum.—Fallopian tubes.—Uterus.—Vagina.—Hymen.—Clitoris.—Nymphæ.—Labia.

The female organs of generation have been usually classed by the English authors under the two heads of internal and external; a similar arrangement has also been followed by the Continental writers, but with the advantage of using distinctive terms which are more expressive of their peculiar functions, viz. the formative and copulative organs. Under the first are included the ovaria, Fallopian tubes, and uterus: under the second, the vagina and external parts. We propose to give a short description of these in the unimpregnated state, and then to describe the changes which they present during pregnancy, labour, and the puerperal condition. In point of situation and arrangement they bear a considerable resemblance to the generative organs in the male, being situated at the lower portion of the trunk, and arranged in symmetrical order, so that they either occur in pairs, one on each side the median line of the body, or singly, being equally divided by it throughout their whole length. Although there is in many points considerable difference between the male and female organs, still there is sufficient resemblance to entitle them to be considered as being formed upon the same fundamental type, a resemblance which is seen still more strikingly in the early periods of fœtal life. They differ essentially from all the other organs of the system, being in activity during a portion of a woman’s life only, and then only at intervals.

Ovaria. The ovaries are situated in the upper part of the cavity of the pelvis, one on each side, near to the uterus, to which they are merely attached by a ligament (the ligamentum ovarii) which is a portion of that duplicature of the peritoneum which connects the uterus to the pelvis, and is known by the name of ligamentum latum, or broad ligament.

They are of an oval figure; their anterior and posterior surface is convex, the superior margin is also convex, while their lower edge is straight or somewhat concave: towards their inner and outer extremities they become thinner.

Their external surface in the virgin state is usually smooth, but in[Pg 23] advanced age they become uneven and shrivelled; when fully developed they are about an inch and a half in length: their greatest breadth, which is at that portion of the ovary which is farthest from the uterus, is half an inch; their thickness is somewhat less.

The ovaries are supplied with blood by the spermatic arteries, which are of course considerably shorter in the female; they pass between the two layers of the broad ligament to the ovarium, assuming there a beautifully convoluted arrangement, very similar to the convoluted arteries of the testis. These vessels traverse the ovary nearly in parallel lines, forming numerous minute twigs, which have an irregular knotty appearance from their tortuous condition, and appear to be chiefly distributed to the Graafian vesicles. The external covering of the ovaries is formed by peritoneum, which here receives the name of Inducium; it envelopes the parenchymatous tissue of the gland called stroma, which is a dense laminar cellular tissue of a reddish colour; its external portion which is in contact with and firmly adherent to the indusium, is condensed into a species of covering of a firm structure and whitish colour, and is called the tunica albuginea of the ovary. In the substance of the stroma are embedded a number of vesicles of various sizes, which, although previously described by Vesalius and Fallopius, have been called Graafian vesicles, after De Graaf. These do not commonly become visible until the seventh year, from which period they gradually enlarge until puberty, when the ovaries increase in size, become softer and more vascular, and one or two of these vesicles may be observed to be larger, more developed, and projecting considerably from the surface of the gland.

The proper capsule of the Graafian vesicle is composed of two layers. The outer is formed of dense cellular tissue, in which are ramified many blood vessels; the inner layer is thicker, softer, and more opaque than the preceding, to which it is closely united, and from which it receives vascular twigs.

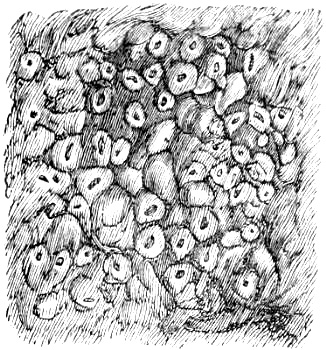

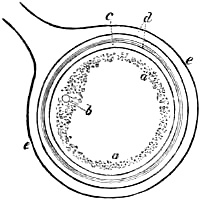

Ovum. The contained part or nucleus of the vesicle of De Graaf consists of, first, a granulary membrane, enclosing, secondly, a coagulable granular fluid; thirdly, connected with the granulary membrane on one side is a circular mass or disc of granulary matter, in the centre of which is embedded, fourthly, the ovum.

This disc, called by Baer the proligerous disc, presents in its centre on the side towards the interior of the vesicle, a small rounded prominence, called the cumulus, and on the opposite[Pg 24] side a small cup-like cavity hollowed out in the cumulus. The cavity is for the reception of the ovum.[1]

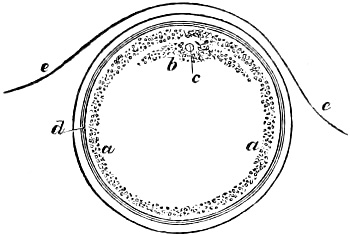

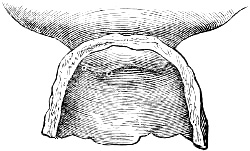

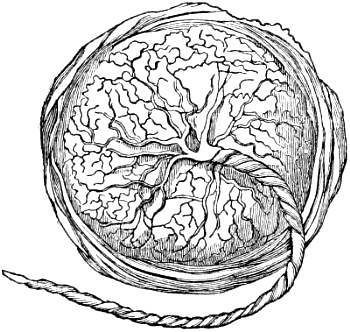

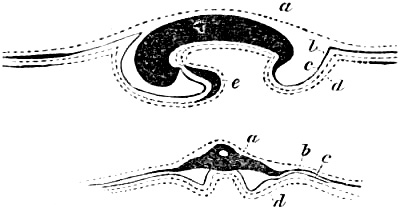

Diagram of a section of the Graafian Vesicle and its contents, showing the situation of the Ovum.

a The granulary membrane. b The proligerous disc. c Ovum. d The inner and outer walls of the Graafian vesicle. e Indusium of the ovary. From T. W. Jones.

From the very minute size of the human ovum, and the difficulty of detecting it, the existence of this little corpuscule was not satisfactorily ascertained until modern times. Although De Graaf had observed ova in the Fallopian tube so early as 1668, which fact had been confirmed by the researches of Dr. Haighton and Mr. Cruickshank, still, as no traces of such ova had been discovered in the Graafian vesicle, and as it was evident that the Graafian vesicle, from its size, &c. could not pass along the Fallopian tube, it was concluded that the inner surface of the vesicle was a species of glandular structure which secreted the fluid with which it was filled, and which was analogous to the semen of the male testicle; hence, in former times, the ovaries were known by the name of testes muliebres. The celebrated anatomist Steno[2] first pointed out the analogy between these organs and the ovaries of the fish tribe: this view was afterwards supported by De Graaf,[3] and they have since continued to retain the name of ovaries.

To Professor von Baer, now of St. Petersburg, is due the merit of having first pointed out the distance of the ovum in the Graafian vesicle, and of thus putting beyond all doubt the accuracy of De Graaf’s observations, as well as those of Dr. Haighton and Mr. Cruickshank.

Corpus luteum. Upon impregnation taking place, one or more[Pg 25] of the most prominent Graafian vesicles begins to show marks of considerable vascularity, both in its external capsule and in the surrounding stroma of the ovary. The vesicle swells, and at length bursts, discharging its contents into the funnel-shaped extremity of the Fallopian tube, which firmly grasps the ovary at this point by means of its fimbriæ.

These changes begin to take place immediately after impregnation; the inner lining of the vesicle, which Professor von Baer considers to be a mucous membrane, appears to undergo a rapid development, much more so than the external capsule which contains it. It is, therefore, thrown into a number of corrugations by which the cavity of the vesicle is greatly diminished; it becomes much thicker, and assumes a yellow colour. As its growth proceeds, the cavity of the vesicle becomes still farther contracted, until being unable longer to retain its contents, it bursts and discharges them as above described.

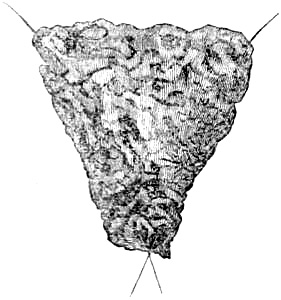

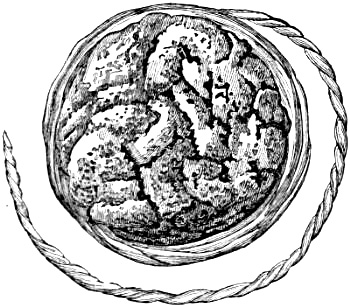

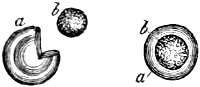

The remains of the ruptured vesicle form a round glandular yellow coloured body, called corpus luteum: it projects considerably from the surface of the ovary, attaining the size of a small mulberry. In the middle of this projection there is a little irregular and generally triangular depression or indentation, which is the opening through which the ovum was discharged from the Graafian vesicle: this after a short time closes, forming a little cicatrix on the surface of the ovary.

“Upon slitting the ovarium at this part, the corpus luteum appears a round body, of a very distinct nature from the rest of the ovarium. Sometimes it is oblong or oval, but more generally round. Its centre is white, with some degree of transparency; the rest of its substance has a yellowish cast, is very vascular, tender and friable, like glandular flesh. Its larger vessels cling round its circumference, and these send their smaller branches inwards through its substance: a few of these larger vessels are situated at the cicatrix or indentation on the outer surface of the ovarium, and are there so little covered as to give that part the appearance of being bloody when seen at a little distance.”[4] Upon making a section[Pg 26] of a corpus luteum, we observe that its cavity has an angular form, from which, as from a centre, white lines radiate to the circumference of the vesicle; an appearance which is evidently produced by the corrugation of the inner membrane of the vesicle, as above alluded to. To a similar cause we may also attribute the lobular appearance, which the structure of the corpus luteum presents when a section is made of it. The number of these corpora lutea corresponds exactly with the number of newly formed ova. Meckel, after having examined no less than two hundred pregnant animals of the class mammalia, found that the number of corpora lutea corresponded exactly with that of the young produced. “When there is only one child,” says Dr. W. Hunter, “there is only one corpus luteum, and two in the case of twins. I have had opportunities of examining the ovaria with care in several cases of twins, and always found two corpora lutea. In some of these cases there were two distinct corpora lutea in one ovarium, in others there was a distinct corpus luteum in each ovarium.”

A Graafian vesicle cannot be converted into a corpus luteum except by actual and effective sexual intercourse; and the strange and discrepant accounts which have every now and then been published, even by authors of considerable repute, of corpora lutea having been found in the ovaries of virgin and even newly-born animals merely prove that the true characteristics of the corpus luteum were not sufficiently known. The irregular cysts, cavities, or deposites of whitish or yellowish structure which are frequently found in the ovary, independent of impregnation, and which have been improperly enough called virgin corpora lutea, present points of difference so marked that they can scarcely be mistaken by an experienced eye. The angular cavity opening externally, the stellated, radiated, cicatrix-like appearance, which a section of the corpus luteum presents, its soft and delicate structure as described by Dr. Hunter, and above all its vascularity, and the facility with which its vessels can be injected from the general tissue of the ovary, are characters only found in a true corpus luteum. Virgin corpora lutea frequently occur under circumstances of disease, especially those of a tubercular character. They frequently appear as distinct cysts, the walls of which are semi-cartilagenous; at other times they seem to be nothing more than a coagulum of blood: they seldom project much from the ovary, and in no instance have they the peculiar structure of the corpus luteum, nor the external cicatrix, nor are they capable of being injected.

After awhile the cavity of the corpus luteum contracts, and the opening into it closes. The surrounding stroma loses its vascularity, the prominence at this part of the ovary gradually subsides, and the ovary returns to its former size. The periods[Pg 27] at which these changes take place vary, but with the exception of those first mentioned they proceed slowly whilst pregnancy lasts, after which time, now that the increased activity of the pelvic circulation peculiar to that period has ceased, they advance more rapidly.

“If an examination be made within the first three or four months after conception, we shall, I believe, always find the cavity still existing, and of such a size as to be capable of containing a grain of wheat at least, and very often of much greater dimensions: this cavity is surrounded by a strong white cyst (the inner coat of the Graafian vesicle,) and as gestation proceeds the opposite parts of this approximate, and at length close together, by which the cavity is completely obliterated, and in its place there remains an irregular white line, whose form is best expressed by calling it radiated or stelliform.”[5] Dr. Montgomery adds, “I am unable to state exactly at what period the central cavity disappears, or closes up to form the stellated line. I think I have invariably found it existing up to the end of the fourth month. I have one specimen in which it was closed in the fifth month, and another in which it was open in the sixth: later than this I never found it.”

When pregnancy is over, the corpus luteum gradually diminishes and disappears. Dr. Montgomery states that “the exact period of its total disappearance I am unable to state, but I have found it distinctly visible so late as at the end of five months after delivery at the full time, but not beyond this period.” Hence it will be seen that in a few months after the termination of pregnancy, all traces of the corpus luteum are lost, and that, therefore, it will be impossible to decide as to how frequently impregnation has taken place, merely by examining the ovaries, as has been supposed. There is also another point to which Dr. Montgomery has alluded, which is well worthy of notice: in mentioning the fact that a vesicle may contain two ova, and thus a woman be delivered of twins, and yet there be but one corpus luteum, he observes that “the presence of a corpus luteum does not prove that a woman has borne a child, although it would be a decided proof that she has been impregnated, and had conceived, because it is quite obvious that the ovum, after its vivification, may be, from a great variety of causes, blighted and destroyed, long before the fœtus has acquired any distinct form.[Pg 28] It may have been converted into a mole or hydatids: thus, however paradoxical it may at first sight appear, it is nevertheless obviously true, that a woman may conceive and yet not become truly with child, a fact already alluded to, as noticed by Harvey; but the converse will not hold good. I believe no one ever found a fœtus in utero without a corpus luteum in the ovary; and that the truth of Haller’s carollary, ‘nullus unquam conceptus est absque corpore luteo’ remains undisputed.”

During childhood, the ovaries present a perfectly smooth surface, and their structure appears to be homogeneous, consisting of a dense cellular tissue. About the seventh year, the first traces of the Graafian vesicles make their appearance; as the period of puberty approaches, the whole gland enlarges, becomes softer and more vascular; the Graafian vesicles are more numerous, and generally one or two will be found larger and more prominent than the rest. After repeated impregnations, and especially towards that time of life when the catamenia are about to disappear, the ovary becomes more or less flabby and corrugated, and at a still more advanced age presents a shrivelled appearance.

The ovaries are liable to inflammation and its consequences, more especially abscess, general enlargement, and induration: the malignant changes of structure, viz. cephaloma, hæmatoma, and cancer, rarely have their origin in the ovaries, but extend to these organs from the adjacent parts. Lipomatous or fatty tumours are occasionally met with, containing hair, rudiments of teeth, &c. Cysts not unfrequently occur in the ovaries, and attain a very considerable size; they are simple or compound, sometimes consisting of several cysts one within the other, and distended with fluids, which vary considerably in their character. These tumours come under the general head of Ovarian Dropsy. The ovaries are also liable to many remarkable morbid changes in the puerperal state, such as softening and complete disorganization, the natural structure of the organ being entirely broken down and converted into a bloody pulpy mass; in some cases the whole gland is apparently dissolved away, so as scarcely to leave a trace of its previous existence.

Fallopian tubes. The Fallopian tubes, which act as excretory ducts to the ovaries, take their course through the upper portion of the broad ligaments, running from without inwards, towards the superior margin of the uterus, the ovaries being situated behind and somewhat above them. They are somewhat contorted, and are considerably more dilated at their abdominal extremity where they are unattached, than where they are connected to the uterus, being as much as from three to four lines at the former point; whereas, at the latter, they are not more than half a line.

Their abdominal extremity, which is like the mouth of a funnel,[Pg 29] has its edge strongly fimbriated, and has hence been called the morsus diaboli. Their other extremity opens into the cavity of the uterus at the angle which the fundus forms with its sides, and the whole of the tube is about five inches.

The Fallopian tubes receive their external covering from the peritoneum, which becomes connected at their open extremity with the membrane which lines them. Between the external and internal membrane is the proper tissue of the tubes, and which, except in very muscular subjects, seldom display the fibrous structure; still, nevertheless, two layers of fibres have been observed—an outer or longitudinal, and an inner or circular layer. The Fallopian tubes are lined with mucous membrane, forming numerous longitudinal rugæ. The canal is not pervious during the early months of fœtal life, the abdominal extremity being closed and rounded; this appears to open about the fourth month. The canal is relatively larger, the younger the embryo is, and may, therefore, be easily demonstrated at this time.

At the period of impregnation, the Fallopian tubes implant themselves by means of their fimbriated extremity upon that part of the ovary where the Graafian vesicle is about to burst; they become remarkably engorged with blood, assuming a deep purple colour, and are now much thicker; the canal enlarges, so that a tolerably-sized probe can be introduced, whereas, at other periods it will scarcely admit a large bristle. The uterine extremity of the tube is closed by a continuation of that pulpy coagulable lymph-like secretion which now lines the cavity of the uterus, forming the membrana decidua of Hunter, and which, especially on the side where the corpus luteum is found, extends into the tube to nearly the distance of an inch. The tubes are now observed to be in a state of distinct peristaltic motion, “like writhing worms,” as Mr. Cruickshank has well expressed it; “the fimbriæ were also black and embraced the ovaria (like fingers laying hold of an object) so closely and so firmly, as to require some force and even slight laceration to disengage them.”[6] From the great degree of vascularity which is observed in the Fallopian tubes at this period, some anatomists have been induced to consider that their proper tissue was vascular, analogous to the corpora cavernosa penis. Besides the peristaltic motion already mentioned, other movements called ciliary have been observed in the Fallopian tubes at this period, consisting of minute portions of mucous membrane moving briskly and whirling round their axis, apparently for the purpose of propelling the ovum.[7]

As pregnancy advances, the Fallopian tubes undergo other changes as respects their situation, which are worthy of notice.[Pg 30] The broad ligaments, in the upper parts of which the Fallopian tubes take their course, are well known to be merely expansions of peritoneum from each side of the uterus, and therefore become gradually unfolded and shorter as the uterus increases in size. “In proportion as the fundus uteri rises upwards and increases in size, the upper part of the broad ligament is so stretched that it clings close to the side of the uterus, so that in reality the broad ligament disappears, no more of it remaining than its very root, viz. its upper and outer corner, where the group of spermatic vessels pass over the iliacs immediately to the side of the uterus. In this state, though the small end of the tube opens in the same part of the uterus as before impregnation, yet the tube has a very different direction. Instead of running outwards in the horizontal direction, it runs downwards, clinging to the side of the uterus. And behind the fimbriæ lies the ovarium, for the same reason clinging close to the side of the uterus.”[8]

Uterus. The uterus is a hollow fibrous viscus situated in the hypogastric region between the bladder and the rectum, below the intestinum ileum and above the vagina, and is by far the largest of the generative organs. It is of a pyriform figure: its upper portion which is the largest is triangular, becoming gradually smaller inferiorly; that portion of it which is above the spot where the Fallopian tubes enter is called the fundus uteri; the lower and cylindrical portion receives the name of cervix; that between the cervix and fundus is called the body of the uterus.

The parietes of the adult uterus are nearly half an inch in their greatest thickness, which is about the middle of the body, the body being slightly thicker than the cervix, which is of a somewhat harder structure. Near the point at which the Fallopian tubes enter the uterus the parietes become thinner, gradually diminishing from four or five to only one line in thickness.

The cavity of the uterus is triangular, its base being directed upwards, the superior angles corresponding to the points where the Fallopian tubes enter it. The cavity of the uterus is so small, owing to the thickness of its parietes, that they are nearly in contact: it is only four lines in breadth; the fundus, which forms the base of the triangle, is convex both internally as well as externally; whereas, the sides which form the body are convex internally, but somewhat concave externally.

The cavity of the uterus is most contracted at the point where the cervix is united to the body, which here forms the os uteri internum; from this point the cervix gradually dilates as far as its middle portion, when it again contracts; its lower extremity terminates in the upper part of the vagina by an anterior and posterior cushion-like projection, of which the posterior is usually[Pg 31] the longest, although from the direction of the uterine axis the anterior is commonly felt lowest in the pelvis. Between these there is a transverse fissure known by the name of os tincæ or os uteri externum, the lips or labia of which are formed by the two above-mentioned prominences. The internal surface of the body of the uterus is smooth, whereas that of the cervix is uneven, forming upon its anterior and posterior wall a number of delicate rugæ diverging obliquely in an arborescent form, and hence called the arbor vitæ. The lips of the os uteri are smooth, except when slight lacerations have taken place during labour.

In the virgin state the uterus is about two inches long, of which the cervix occupies the smaller half: the greatest breadth of the body is sixteen lines; that of the cervix from nine to ten. The uterus which has been impregnated, especially when this has been frequently the case, scarcely ever regains its original dimensions, and the fissure which the os tincæ forms becomes broader from before backwards. The weight of an adult virgin uterus is from seven to eight drachms, but the uterus which has been once impregnated is seldom less than an ounce and a half. It lies between the bladder and rectum, its upper half being covered by peritoneum, which closely adheres to it. In the adult state it is situated entirely in the cavity of the pelvis; the fundus, which is below the upper edge of the symphysis pubis, is turned forwards and upwards, while its mouth is directed downwards and backwards, so that its long axis is nearly parallel to the axis of the superior aperture of the pelvis.

The uterus is connected to the neighbouring parts by several duplicatures of peritoneum, which are continuous with that portion of it which covers the fundus. The most considerable are the broad or lateral ligaments: these arise from the sides of the uterus, which is enclosed between their anterior and posterior layers or laminæ; they proceed transversely outwards towards the sides of the pelvic cavity, which is thus divided into two portions, and are then continued into that portion of the peritoneum which lines the cavity.

The round ligaments arise from the sides of the uterus close beneath and a little anterior to the uterine extremity of the Fallopian tubes. They pass between the two layers of the broad ligaments, behind the umbilical arteries, and before the iliac vessels, in a direction upwards and outwards to the external opening of the inguinal canal; they then make a turn round the epigastric artery downwards, inwards, and forwards, and pass through the abdominal ring, and dividing into numerous fasciculi and fibres are gradually lost in the cellular substance of the mons Veneris and upper portion of the labia. Besides consisting of cellular substance and blood-vessels, the round ligaments contain some very distinct bundles of muscular fibres, of which the upper arise from the external layer of uterine fibres, and the[Pg 32] lower from the inferior edge of the internal oblique muscle, and pass upwards.

Upon a superficial examination, the structure of the uterus would almost seem to be homogeneous, nevertheless a number of reddish yellow strata interspersed with whitish streaks running from behind forwards may be perceived even in the unimpregnated state; between these strata the vessels of the uterus take their course, forming numerous anastomoses.

There is much difference of opinion among anatomists as to the fibrous structure of the uterus. The majority however agree as to the presence of muscular fibres,[9] some considering that they always exist, while others, and by far the greater number, consider them as appearances peculiar to pregnancy: they are, it is true, extremely indistinct in the unimpregnated state, but they are far from being peculiar to pregnancy, as they are frequently developed by any circumstances by which the formative powers of the uterus are excited. Thus in cases where the uterus has been much distended by some anormal growth, its fibres become much developed and distinctly fasciculated. Lobstein observed them very distinctly in a uterus which had been distended to the size of a seven months’ pregnancy by a fatty tumour.

The uterine fibres have been usually considered as fleshy, but they differ from the red fibres of voluntary muscles, in being of a paler colour, flatter, and remarkably interwoven with each other: nevertheless they appear to be really muscular fibres from the powerful contraction with which they expel the fœtus and placenta, and nearly obliterate the cavity of the uterus. In the unimpregnated state they resemble the fibrous coat of an artery, whereas, those of the gravid uterus are more like the fibres of muscle. Most anatomists agree in describing two sets of fibres, viz. longitudinal and transverse. The external layer of fibres appears to form the round ligaments, which seem to have the same relation with them as tendon and muscle. “The fibres arise from the round ligaments, and regularly diverging spread over the fundus until they unite and form the outmost stratum of the muscular substance of the uterus. The round ligaments of the womb have been considered as useful in directing the ascent of the uterus during gestation, so as to throw it before the floating viscera of the abdomen: but in truth it could not ascend differently; and on looking to the connexion of this cord with the fibres of the uterus, we may be led to consider it as performing rather the office of a tendon than that of a ligament.”[10] “On the outer surface and lateral part of the womb, the [Pg 33]muscular fibres run with an appearance of irregularity among the larger blood-vessels, but they are well calculated to constringe the vessels, whenever they are excited to contraction. The substance of the gravid uterus is powerfully and distinctly muscular, but the course of the fibres is less easily described than might be imagined: this is owing to the intricate interweaving of the fibres with each other—an intermixture however which greatly increases the extent of their power in diminishing the cavity of the uterus. After making sections of the substance of the womb in different directions, we have no hesitation in stating that towards the fundus the circular fibres prevail, that towards the orifice the longitudinal fibres are most apparent, and that on the whole, the most general course of the fibres is from the fundus towards the orifice.

“This prevalence of longitudinal fibres is undoubtedly a provision for diminishing the length of the organ, or for drawing the fundus towards the orifice. At the same time these longitudinal fibres must dilate the orifice and draw the lower part of the uterus over the head of the child.

“In making sections of the uterus while it retained its natural muscular contraction, I have been much struck in observing how entirely the blood-vessels were closed and invisible, and how open and distinct the mouths of the cut blood-vessels became when the same portions of the uterus were distended or relaxed. This fact of the natural contraction of the substance of the uterus closing the smallest pore of the vessels, so that no vessels are to be seen, where we nevertheless know that they are large and numerous, demonstrates that a very principal effect of the muscular action of the womb is the constringing of the numerous vessels which supply the placenta, and which must be ruptured when the placenta is separated from the womb.”

“Upon inverting the uterus, and brushing off the decidua, the muscular structure is very distinctly seen: the inner surface of the fundus consists of two sets of fibres, running in concentric circles round the orifices of the Fallopian tubes; these circles at their circumference unite and mingle, making an intricate tissue. Ruysch, I am inclined to believe, saw the circular fibres of one side only; and not adverting to the circumstance of the Fallopian tube opening in the centre of these fibres, which would have proved their lateral position, he described the muscle as seated in the centre of the fundus uteri. This structure of the inner surface of the fundus of the uterus is still adapted to the explanation of Ruysch, which was that they produced contraction and corrugation of the surface of the uterus, which, the placenta, not partaking of, the cohesion of the surface was necessarily broken. Farther, I have observed a set of fibres on the inner surface of the uterus, which are not described: they commence at the centre of the last described muscle, and having a course in some degree[Pg 34] vortiginous, they descend in a broad irregular band towards the orifice of the uterus: these fibres co-operating with the external muscle of the uterus, and with the general mass of fibres in the substance of it, must tend to draw down the fundus in the expulsion of the fœtus, and to draw the orifice and lower segment of the uterus over the child’s head.” (C. Bell, op. cit.)

There are other circumstances which prove the muscularity of the uterus, beyond the mere evidence of its fibres, as seen during pregnancy. “In the quadruped,” as Dr. Hunter observes, “the cat particularly and the rabbit, the muscular action or peristaltic motion of the uterus is as evidently seen as that of the intestines, when the animal is opened immediately after death.” It is also proved by the powerful contraction which it exerts during labour, and “by the thickness of the fibres corresponding with their degree of contraction.” (Ibid.)

The inner surface of the uterus is lined by a smooth or somewhat flocculent membrane of a reddish colour, which is continued superiorly into the Fallopian tubes; inferiorly it becomes the lining membrane of the vagina.

Mucous follicles are only found in the cervix, especially at its lower part: when by chance these become inflamed, the orifice closes, and the follicle becomes more or less distended by a collection of thin fluid. The mucous casts of these follicles have been known by the name of ovula Nabothi, having been mistaken by an old anatomist for Graafian vesicles, which had been detached from the ovary, and conveyed into the cavity of the uterus.

The mucous membrane which lines the cervix uteri is corrugated into a number of rugæ, between which the mucous follicles are chiefly found.

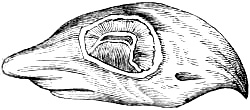

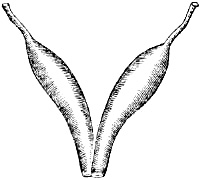

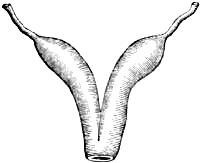

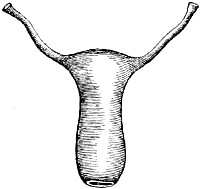

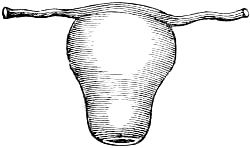

Before quitting this subject, it will be necessary to point out the changes which the uterus presents at different periods of fœtal life, and the great resemblance it has at these periods to the uterus, as it appears in the lower classes of the mammalia. We may, however, observe in the first place, that the uterus is not found to exist as a separate organ until we come to the class mammalia; and even in the lower genera of this class it bears a strong resemblance to the tubular character of the generative organs in the inferior classes of animal life. The nearest to the tubular uterus, and where the transition from the oviduct in birds, &c. to the uterus in mammalia is least distinctly marked, is in the uterus duplex. Although the uterus is double, there is but one vagina into which the two ora uteri open; its low grade of development is marked by the resemblance which each uterus bears to an intestinal tube: there are as yet no traces of a cervix, each os uteri merely forming a simple[Pg 35] opening at the lower end of what is little more than a cylindrical canal. We do not find that thickening at the lower extremity of the uterus which distinguishes the cervix in the higher mammalia. This species of uterus is found among a large portion of the rodentia, and is also occasionally met with as an abnormal formation in the human subject. The next grade of uterine development appears under the form of the uterus bicollis. The double os uteri here ceases to exist, and the division begins a little higher up, so that the two cavities of the uterus communicate for a short space: the ova, however, do not reach the common cavity, but remain each in its separate cornu. In this form of uterus, the os uteri is not only single, but the lower portion is thickened, although it has not yet formed a distinct neck or cervix; it is met with among some of the rodentia, and also certain carnivora.

In the uterus bicorporeus, the union of the cornua is higher up, so that the lower portion is single, while the upper part alone is double, consisting of two strongly curved cornua. This conformation is peculiar to ruminating animals. If two ova be present they are separate from each other, each being contained in its own distinct body or cornu, but a portion of the membranes extends along the common cervix, from one body to the other.

A still higher grade is the uterus bifundalis, where the fundus alone is double, the cornu being formed only by this portion. This formation is observed in the horse, ass, &c.: the common cavity is here the receptacle of the ovum, so that in the unimpregnated state, the cornua appear only as appendices, into which a portion of the membranes extend.

In the uterus biangularis, the double formation has nearly disappeared, except at the fundus, where the uterus imperceptibly passes into the tubes: this is the case among the edentata, and some of the monkey tribes.

The highest grade is the uterus simplex: every trace here of the double form is lost; the fundus no longer forms an acute angle, where it bifurcates into two cornua; but is convex. We now for the first time see the divisions of the uterus into body and cervix distinctly marked.

The human uterus presents a similar variety of forms, as it[Pg 36] gradually rises in the scale of development during the different periods of utero-gestation. It is at first divided into two cornua, and usually continues so to the end of the third month, or even later; the younger the embryo the longer are the cornua, and the more acute the angle which they form; but even after this angle has disappeared, the cornua continue for some time longer.

The uterus is at first of an equal width throughout; it is perfectly smooth and not distinguished from the vagina either internally or externally by any prominence whatever. This change is first observed when the cornua disappear and leave the uterus with a simple cavity. The upper portion is proportionably smaller, the younger the embryo is. The body of the uterus gradually increases, until at the period of puberty it is no longer cylindrical, but pyriform: even in the full-grown fœtus the length of the body is not more than a fourth part of the whole uterus; from the seventh even to the thirteenth year it has only a third, nor does it reach a half until puberty has been fully attained. The os tincæ or os uteri externum first appears as a scarcely perceptible prominence projecting into the vagina; it increases gradually, in size until the latter months of gestation, when the portio vaginalis is relatively much larger than afterwards.

The parietes of the uterus are thin in proportion to the age of the embryo. They are of an equal thickness throughout at first: at the fifth month, the cervix becomes thicker than the upper parts; between five or six years of age, the uterine parietes are nearly of an equal thickness, and remain so until the period of puberty, when the body becomes somewhat thicker than the cervix.

As the function of menstruation with its various derangements will be considered among the diseases of the unimpregnated state, we proceed to consider these changes which the uterus undergoes during pregnancy as well as during and after labour: these are very remarkable both as regards its structure, form, and size.

Shortly after conception, and before we can perceive any traces of the embryo, the uterus becomes softer and somewhat larger, its blood-vessels increased in size, and the fibrous layers of which its parietes are composed looser and more or less separated. The internal surface when minutely examined has a flocculent appearance, and very quickly after conception becomes covered with a whitish paste-like substance, which is secreted from the vessels opening upon it; this pulpy effusion soon becomes firmer and more[Pg 37] dense; it bears a strong analogy to coagulable lymph, and forms a membrane which lines the whole cavity of the uterus, and which in the course of a few weeks (from changes to be mentioned hereafter) crosses the os uteri and thus closes it. The uterine cavity in a short time becomes still farther closed by the canal of the cervix being completely sealed, as it were, by a tough plug of gelatinous matter which is secreted by the glandules of that part.

The structure of the uterus becomes remarkably altered; its fibrous structure is much more apparent; in fact, it is only during pregnancy, or when the uterus has been distended by some anormal growth, that we are able to detect the uterine fibres with any degree of certainty. This has led some anatomists to consider that they are only formed at such periods, a supposition which is not very probable; at any rate they now become very distinct: hence the uterus does not owe its increasing size to mere extension, but it evidently acquires a considerable increase of substance, a fact which is not only proved by examining the contracted uterus after labour at the full period, but also by comparing its weight with that of the unimpregnated organ. The adult virgin uterus weighs about one ounce, whereas the gravid uterus at the full term of pregnancy, when emptied of its contents, weighs at least twenty-four ounces, showing that there has been an actual increment of substance in the proportion of one to twenty-four. Having ascertained this point, it next becomes a question, whether the parietes of the gravid uterus increase in thickness during pregnancy, or whether they become thinner. Meckel, who is one of the greatest modern authorities on these subjects, states that from careful admeasurement of sixteen gravid uteri at different periods of gestation, he finds the parietes become thicker during the first, second, or third months, but after this period they become gradually thinner up to the full time: they are thicker in the upper parts of the uterus, whereas inferiorly they are a third or nearly a half less.

Nothing proves the actual increase of bulk and substance in the uterus more than its appearance when contracted immediately after labour at the full term; it forms a fleshy mass as large as the head of a new-born child, the parietes of which are at least an inch in thickness.