WHG Kingston

"The School Friends"

"Nothing New"

Story 1--Chapter I.

STORY I—THE SCHOOL FRIENDS; NOTHING NEW.

Lance Loughton and Emery Dulman were brought up together at Elmerston Grammar-School. They were both in the upper or sixth form; but Lance was nearly at the head, while Emery was at the bottom, of the form. They were general favourites, though for different causes. Lance was decidedly best liked by the masters. He was steady, persevering, and studious, besides being generous, kind-hearted, and brave—ever ready to defend the weak against the strong, while he would never allow a little boy to be bullied by a big one if he could help it. Emery had talents, but they were more showy than solid. He was good-natured and full of life and spirits, and having plenty of money, spent it freely. He was, however, easily led, and had in consequence done many foolish things, which got him into trouble, though he managed, on the whole, to maintain a tolerably good character.

Lance and Emery were on friendly terms; and Lance, who thought he saw good qualities in his companion, would gladly have won his confidence, but Emery did not like what he called Lance’s lectures, and there was very little or no interchange of thought between them. Without it real friendship can scarcely be said to exist. They were, however, looked upon as school friends, and certainly Lance would at all times have been ready to do a friendly act for Emery.

Emery was somewhat of a fine gentleman in his way. His father was a tradesman in the place, and wished his son to assist him in his business, but Emery often spoke of entering the army or one of the liberal professions. He therefore considered himself equal to those whose fathers held a higher social grade than his own. His father’s style of life encouraged him in this. Mr Dulman had a handsome house, and gave dinners and parties; and at elections took a leading part, and entertained the proposed member and his friends, and indeed sometimes talked of entering Parliament himself, and altogether did a good deal to excite the envy of his less successful fellow-townsmen.

Emery constantly invited Lance to his house, and was really flattered when he came; for Lance’s father, who had died when he was very young, was a lieutenant in the navy; and his widowed mother, though left with only her pension to depend on, was a lady by birth and education. Lance, however, very frequently refused Emery’s pressing invitations.

“I never met such a stay-at-home fellow as you are,” exclaimed the latter, when on one occasion Lance had declined attending a gay party Mr and Mrs Dulman were about to give. “We shall have half the neighbourhood present—Mr Perkins, our member, and I don’t know how many other grandees—and we want some young fellows like you, who can dance and do the polite. Mother says I must get you, for we don’t know what to do for proper partners for the young ladies.”

“I should have been happy to make myself useful,” answered Lance, laughing; “but I am no great dancer, and my poor mother is so unwell that I cannot leave her.”

“Oh, she has got little Maddie Hayward to look after her, so I will come and get her to let you off.”

“I beg that you will not make the attempt,” answered Lance, more gravely than he had hitherto spoken. “My mother is seriously ill; besides I have work to do, and any time I can spare I must devote to her.”

“Oh, but a little gaiety will do you good, and you can cheer her up with an account of the party,” persisted Emery.

Lance was, however, firm, and he returned in a thoughtful mood to his humble little cottage in the outskirts of the town.

A sweet fair face met him at the jessamine-covered porch—that of a girl three or four years younger than himself. It would not have been surprising had he preferred her society to that of the fine ladies his friend had spoken of, though he certainly was not conscious that this had in any degree influenced him.

Madelene Hayward was indeed a lovely young creature, sweet-tempered and good as she was beautiful. She was the orphan child of a distant relative of Lieutenant Loughton. Having been left, when still an infant, utterly destitute, she had been adopted by the kind-hearted officer at his wife’s earnest wish, and brought up as their daughter, although their own scanty means might have excused them in the eyes of the world had they declined the responsibility.

Mrs Loughton had devoted herself to Maddie’s education, and the young girl repaid her with the most tender love. Some time before this Mrs Loughton’s old servant had married, and Maddie had persuaded her not to engage another in her place, consenting only that a woman should come in to light the fires and do the rougher work which she was less able to perform. While Mrs Loughton was well, she herself attending to what was necessary, Maddie’s duties were not very heavy, but since her illness they had of necessity much increased.

Though she tried not to let Lance discover how hard she worked, he knew that her attendance on his mother must occupy the chief part of her time. His aim was therefore to relieve her as much as possible. Where there is a will there is a way. He soon learned to clean his shoes, and purchasing needles and thread and worsted, to mend his clothes and darn his socks; and Maddie was surprised to find one morning that his bed was made and his room set to rights, when she was sure that Dame Judkin had not gone into it. She found him out at last, and reproachfully asked why he had not given her his torn coat to mend, and a pair of socks which she had discovered darned in a curious fashion.

“I wanted to try if I could not do it,” he answered, smiling. “Just look at that sleeve—I defy it to tear again in the same place.”

“Perhaps so, but as every one can see that there has been a rent, I shall be accused of being a very bad tailoress, and I am afraid you will find an uncomfortable lump in the heel of your socks. Do, dear Lance, bring the next pair requiring mending to me, and I will find time to dam them.”

Few could fail to admire Madelene Hayward.

“How is our mother?” asked Lance, taking her hand, as he found her waiting for him in the porch of their little cottage.

“She has at last dropped off to sleep; but she has been in much pain all the day,” answered Maddie. “And, O Lance! I sometimes fear that she will not recover. Yet our lives are in God’s hands, and we can together pray, if He thinks fit, that hers may be preserved for our sakes—I cannot say for her own, as I am sure, resting on the merits of Him who died for sinners, she is ready to go hence to enjoy that happiness He has prepared for those who love Him.”

“But, Maddie, do you really think mother is so ill?” asked Lance, with an anxious look. “I know that when she is taken, the change to her must be a blessed one; but, Maddie, what would become of you?”

He spoke in a tone which showed the grief which Madelene’s announcement had caused him.

“I have not thought about myself,” she answered quietly. “My wish was to prepare you for what I dread may occur, and to ask you to join your prayer with mine that God will in His mercy allow her to remain longer with us. He can do all things, and the prayer of faith availeth much.”

“I am sure it does,” said Lance. “I will pray with you. I have too often prayed as a matter of form, but now I can pray from the bottom of my heart.”

The young people lifted up their hearts and voices as they stood together, hand in hand, in the porch, which was hid by a high hedge from the passers-by.

They noiselessly entered the cottage. Mrs Loughton was still sleeping. Perhaps even then Lance realised the fact that Maddie was more to him than any other being on earth, and he mentally resolved to exert all his energies to procure the means of supporting her, should she be deprived of her present guardian.

They sat together in silence lest their voices might awaken Mrs Loughton. Maddie had resumed her work, while Lance had placed his books on the table; but his eyes scarcely rested on them—he was thinking of the future.

Mrs Loughton at length awoke. She appeared revived by her sleep, the most tranquil she had enjoyed for many a day. After this, to the joy of Maddie and her son, she rapidly got better, and with thankful hearts they saw her restored to comparative health.

Lance had no foolish pride, but he had refrained from asking any of his schoolfellows, especially those who, like Emery, lived in fine houses, to enter his mother’s humble cottage. One day, however, Emery overtook him as he was returning from home. On reaching the cottage, his companion pulled out his watch, observing that it was tea-time, and saying in an off-hand way, “I daresay your mother will give me a cup, for I am fearfully thirsty.”

Lance, without downright rudeness, could not refuse to ask him in.

The widow received her guest with the courtesy of a lady, though, more acquainted with the world than her son, she saw defects in the manners of his companion which he had not discovered. She was not pleased, either, with the undisguised admiration Emery bestowed on Maddie, and was very glad when Lance, bringing out his books, observed, “Now, old fellow, I have got to study, and you ought to be doing the same, and though I don’t want to turn you out, you will excuse me if I set to work.”

Maddie got up to remove the tea-things, and Mrs Loughton took her work; so that Emery, finding that the young lady was not likely to listen to his fine speeches, at length, greatly to their relief, wished them good evening.

Story 1--Chapter II.

Emery had certainly not received the slightest encouragement to pay another visit to his schoolfellow’s abode. He, however, fancied himself desperately smitten with the beauty of Madelene Hayward, and after this very frequently sauntered by the cottage, or whenever he could make an excuse to accompany Lance, he walked with him towards his home, in the hopes of being again invited in. Lance, however, sturdily refused to understand his hints, and managed, generally without churlishness, to get rid of him.

Emery, however, met Maddie one day when out walking alone, and with a self-assurance of which no gentleman would have been guilty, in spite of her evident annoyance, accompanied her till just before she arrived at home.

Lance felt more angry than he had ever before been when he heard what had occurred, and the next day cautioned Emery not to repeat the offence, telling him very plainly that his mother did not wish to see him again at her cottage.

Emery, who stood somewhat in awe of Lance, looked foolish; but trying to conceal his vexation, muttered a sort of apology, and walked hurriedly away.

Emery had some time before made the acquaintance of a person who had for a year or so been residing at Elmerston, where he had acted as one of the inferior agents in the last election contest. Sass Gange had been a seaman. He was a long-tongued fellow, with an assumed sedate manner, which gained him the credit of being a respectable man.

Sass having been employed by Mr Dulman, Emery became acquainted with him, and he had ever since taken pains to gain the confidence of the lad, with considerable success. Emery always found himself a welcome guest at Sass Gange’s lodgings, when the old sailor was wont to indulge him in a pipe of tobacco and a glass of ale, while he spun long yarns about his adventures at sea.

After leaving Lance, Emery made his way to Sass Gange’s lodgings.

“What is up now, Master Emery?” asked the old sailor as the lad threw himself into an arm-chair before the fire. “You look out of sorts somehow.”

“With good reason too, I should think,” exclaimed Emery. “I have taken it into my head to admire a beautiful young creature; and though my father is rolling in wealth, and I suppose I shall come in for a good share of it one of these days, I have just been told that I must keep away from the house, and if they had their will, never see her again.”

“Well, take a blow, lad, and it will calm your spirits, and we will then talk the matter over,” said old Sass, handing a pipe which he had just charged, and filling up a tumbler with ale.

“Now tell me all about it.”

Emery gave his own version of what had just occurred.

“Don’t be cast down, Master Emery,” said old Sass, “I will help you if I can. I have no reason to love that young Loughton, and he is at the bottom of it, depend upon that. If she was his sister, he would not be so very particular; but that’s not what I was going to say. I once served under Lieutenant Loughton, and, thanks to him, my back more than once got a scoring which it has not forgotten yet. I vowed vengeance, but had no opportunity of getting it; and as the lieutenant is gone, why, I shall have a pleasure in paying the son what I owed the father. We must bide our time, though; but it will come if we are on the watch, depend upon that.”

Emery, instead of being shocked at these remarks, listened to them eagerly.

The rest of the conversation need not be repeated.

“I must go now,” said Emery, “for we have a grand party at our house to-night, and I must be at home in time to dress.”

Mr Dulman’s party was the grandest he had ever given. The member for the borough with all his family was there, and he had persuaded a number of his friends to come and honour Mr Dulman, by whose means he had gained his election. All the magnates of the town were also present, so that Elmerston had never before seen a more brilliant assemblage.

Mr Dulman exerted himself to the utmost to make the party go off well, and poor Mrs Dulman did her best, though she always felt overwhelmed with the responsibilities of the new position in which she was placed, and awed by the great people. Emery, though not a bad-looking young man, felt too much abashed to appear to advantage, in spite of his off-hand manner among his ordinary associates; and though he made many efforts to do the polite to his father’s guests, he as often failed from awkwardness, and would have felt much happier smoking his pipe and drinking beer with old Sass.

During the evening, as Mr Dulman went into the hall, a letter was put into his hand by a messenger who had been waiting to see him. He retired to a corner to read it. His usually ruddy countenance turned deadly pale. He hurriedly thrust it into his pocket.

“I will attend to the matter to-morrow,” he said, in as firm a voice as he could command. “It’s impossible to do so now.”

He went to the supper-room, and rapidly drinking off three or four glasses of wine, hastened back to his guests. Many of them, however, remarked his agitated and absent manner, while some of his acquaintances observed that old Dulman had been over-fortifying himself for his arduous duties.

As soon as his guests were gone he shut himself up in his room, and spent the remainder of the night, with the fatal letter before him, making calculations. Before the rest of the family were up he had left the house, and was off by the first train to London.

The next day it was whispered that Mr Dulman, who was known to have speculated largely in railway shares, was ruined. People said that he had only love of ostentation to thank for what had occurred, and few pitied him.

His fine house and furniture were sold, but his estate did not yield a penny in the pound.

Ashamed of again showing his face at Elmerston, he sailed for Australia, leaving his wife and younger children living in a mean cottage in the neighbourhood, a small allowance having been made to them by the creditors, while Emery was sent to seek his fortune in London.

About the same time Sass Gange, for reasons best known to himself, finding it convenient to leave the town, went up also to London, where, with the character of a highly respectable and confidential man, through the influence of some of his political friends, he obtained a situation as porter in the large West End draper’s establishment of Messrs Padman and Co. Sass was not a man to allow his talents to remain under a bushel. By means of his persuasive eloquence, he soon induced the confiding Mr Padman to place the most unbounded confidence in his honesty and devoted attention to business. When the cash received during the day was sent to the bank by one of the clerks, Sass was invariably ordered to follow, to be ready to assist him should he be waylaid by pickpockets, and to see that he faithfully deposited the amount as directed. Sass did not know how much was carried, but he guessed that at times it must be a considerable sum.

Story 1--Chapter III.

Sass Gange had been for some time in the employment of Messrs Padman, when one day as he entered the shop he saw behind the counter his former Elmerston acquaintance, Emery Dulman, busily engaged in serving a customer. Emery did not recognise him, nor did he just then wish to be recognised, so he passed quickly on to deliver the parcels he had just brought in. He observed, however, that Emery was even better dressed than usual—that he wore a fashionably-cut black suit, a neck-cloth of snowy whiteness, a gold ring on his finger, and a somewhat large gold watch-chain, ostentatiously exhibited. As he was repassing, Emery looked up, when Sass gave him an almost unperceived wink, and turning away his head, hurried on.

“I hope that he will have the sense not to tell any one that we are acquainted,” he thought. “I must let him know where I live, and he will soon be coming to have a talk over old times.”

Sass might have been pretty sure that Emery was not likely to tell any one that they were acquainted; indeed, that young gentleman’s chief pleasure was boasting to his new associates of his highly-connected and fashionable friends, and bewailing the hard fate which had compelled him to become a draper’s assistant. Some were inclined in consequence to treat him with respect, but many of the older hands laughed at his folly, and having discovered who his father was, observed that he was fortunate in obtaining so good a situation in a business for which he ought to be well suited.

Sass soon found an opportunity of letting Emery know where he lived, and the next day received a visit from him, when the usual pipe and ale were prepared for his entertainment.

“Curious that we should meet again, Master Emery, in this big city,” observed Sass. “We all have our ‘ups and downs,’ and you have had one of the ‘downs’ lately, so it appears. Well, I have had them in my time. I never told you that I got my education, such as it is, at Elmerston Grammar-School, and I might have been a steady-going burgess, with pink cheeks and a fat paunch, if I had stuck to business. But I had no fancy for that sort of life; so one morning, taking French leave of school, and father and mother, and brothers and sisters, I went off to sea. When I came back some years afterwards, all who were likely to care for me were dead or scattered; so I set off again, and knocked about in all parts of the world till about two or three years ago, when, having a little money in my pocket, and thinking I should like a spell on shore, I found my way back to the old place. I made myself useful, as you know, to the grandees; and as I did not wish to go to sea again just then, one of them got me this situation. Though I can’t say it’s much to my taste, I intend to stick to it as long as it suits me.”

“I don’t see anything very tempting in the life you have led,” observed Emery.

“I have not told you much about its pleasures, the curious countries I have visited, and the strange adventures I have met with,” answered Sass. “For my part, I would not have missed them on any account.” “When you come to hear about them, you will have a fancy for setting off too, or I am much mistaken. With a young companion like you I should not mind taking another trip, and enjoying myself for a few years more afloat, instead of leading the dull life you and I are doomed to in London.”

Such was the style of conversation with which the old rogue entertained his credulous young guest. The adventures he described were highly entertaining, garnished as they were by his fertile imagination, and Emery began to wonder how he could consent to remain on shore when so delightful an existence might be led by going off to sea.

Emery, however, had not got over his fancy for trying to assume the airs of a fine gentleman. On Sundays, though he went with his employer’s family and the rest of the young men in the establishment to church, as soon as dinner was over it was his delight to saunter out into the Park, and loll over the railings round the drive with a gold-headed cane in his hand, watching the gay people as they drove past in their carriages. Occasionally he would lift his hat as if returning a bow from a lady, or he waved his hand as if recognising a gentleman acquaintance. Some might have considered him only foolish; but he was undoubtedly acting a lie, and trying to deceive those around him. He was besides wasting time given for higher purposes.

Unhappily, not only such as he, but many others waste time, without for a moment considering their guilt, and that they will some day be called to account for the way in which every moment of their lives has been spent.

In time Emery formed a number of acquaintances, mostly silly lads like himself, and inclined to consider him a remarkably fine fellow; several were vicious, and they, as vicious people always wish to make others like themselves, tried to induce him to accompany them to see something, as they called it, of London life. He at first feebly declined, but at length yielded; and though such scenes, it must be said to his credit, were not to his taste, he was over-persuaded again and again, and soon found that the greater part of his wages were spent at theatres, dancing-rooms, and other places to which he and his companions resorted. His employer, finding that he was out late at night, spoke to him on the subject. He excused himself with a falsehood, saying that he had gone to visit a friend of his father’s, who had just come up to town, promising that he would not again break through the rules of the establishment. After this he was very exact in his conduct, and again, in consequence, rose in the estimation of his employer. He had, indeed, an attraction to keep him at home. Mr Padman possessed a daughter, a pretty, good-humoured young lady; and though she was considerably older than Emery, he took it into his head that she was not insensible to his personal appearance and gentlemanly manners. Whenever he had an opportunity, he offered his services to attend on her; and as he made himself useful, and he was quiet and well-behaved, they were frequently accepted, while Miss Madelene Hayward was, happily perhaps, soon forgotten.

Thus a year or more went by. Poor Emery might under proper guidance have become a useful member of society, as all people are who do their duty in the station of life for which they are fitted; but he wanted what no one can do without—right religious and moral principles.

Story 1--Chapter IV.

Mr Dulman did not fall alone. The bank at Elmerston, which had made him large advances, got into difficulties, and though its credit was bolstered up for some time, it ultimately failed, and many of the people in the place suffered. Among others of small means who had cause to mourn the wicked extravagance and folly of their ambitious townsman, was Mrs Loughton. Some cursed him in their hearts, loudly exclaiming against his extravagance, which had brought ruin on themselves and their families. Mrs Loughton bore her loss meekly. The sum of which she had been deprived she had saved up, by often depriving herself of necessaries, to assist in starting her dear Lance in life. This was indeed a great trial. Lance entreated her not to mourn on his account. He was not even aware that she had saved so much money, and only regretted that she should not have it to benefit herself and Maddie. He had for long determined to go forth into the world, trusting, with God’s help, to his own industry and perseverance to make his way. He was ready to take any situation which offered, or to do anything which was thought advisable. All he desired was to perform his duty in that station of life to which he might be called, and to be able to assist his mother and Maddie. To secure their happiness and comfort was his great aim; for himself; independent of them, he had no ambition. He was aware that talent, such as his master considered he possessed, with honesty, industry, and zeal, must, should he get his foot on the ladder, enable him to rise higher. Still, metaphorically speaking, he was content to secure his position on the ground where he stood, while he refrained from withdrawing his attention, by looking up at the prize at the top.

“By thinking only of the prize, and not duly employing the means to obtain it, many a man has slipped off the ladder, and, crushed by his fall, has failed again to reach it,” the Doctor observed to him one day. “Go on as you propose, my boy, and never trouble yourself about the result; God blesses honest efforts when His assistance is sought. I do not advise you to remain at Elmerston. Seek your fortune in London. You may have a much harder struggle to endure than you would here, but you will come off victorious, and gain ultimately a respectable position.”

Such was the tenor of the remarks of his late master to Lance, during a visit he paid him, after he had left school. His mother agreed with what had been said.

“I should grieve to part with you, Lance; but as I am sure it will be for your advantage, it must be done, and we shall have the happiness of seeing you down here when you can get a holiday.”

“That will indeed be great!” murmured Maddie, who had not before spoken.

She was in the habit of looking at the bright side of things, and thought more of the joyful meeting than of the long, long time they must be separated.

“I will write to your uncle Durrant, and ask him what he can do,” continued Mrs Loughton. “My brother is kind and generous, and though he has a large family, and I fear his salary from the Government office he holds is but small, yet I am sure he will do his utmost to assist you.”

“I ought to be at work without delay, mother,” said Lance; “so pray write as you propose to uncle Durrant.” He cast a glance at Maddie, and added, “I’ll do my best to employ my time profitably while I am at home. You know that I am happier here than I can be anywhere else.”

“Yes,” said Maddie, “I am sure there is no happier place than this.”

The letter to Mr Durrant was written, and while waiting for an answer, Lance spent much of the time not occupied in study in the garden, very frequently with Maddie as his companion. He had from his boyhood been accustomed to cultivate it, and he was anxious to leave it in the most perfect order possible. It was pleasant to sit reading with Maddie by his side, but pleasanter still to be working in the fresh air among sweet flowers, receiving such assistance as she could give, and talking cheerfully all the time.

The expected answer from Mr Durrant came in the course of a few days. “I lost no time in looking for a situation for Lance, and I was able, from the report I received from the Doctor, to speak confidently of him,” he wrote. “I have obtained one in the office of my friend Mr Gaisford, a highly respectable solicitor in the city, who, knowing Lance’s circumstances, will attend to his interests, and advance him according to his deserts.”

“It appears very satisfactory, and we should be truly grateful to your uncle,” observed Mrs Loughton. “You are to go to his house. You will have a long walk into London every day, but that, he says, will be good for you. He does not speak about salary, but as, from what I understand, you are to take up your abode with him, I hope that you will receive sufficient to repay him.”

“I would rather live in a garret on bread and water, than be an expense to my uncle, who can with difficulty support his large family,” observed Lance; “and so I will thankfully take any office where I can get enough to maintain myself, even in the most humble way.”

“Well, well, dear Lance, your uncle and I will settle that,” said Mrs Loughton. “He wishes you to go up the day after to-morrow.”

“So soon?” exclaimed Maddie; “his things will scarcely be ready.”

“I must not delay a day longer than can be helped,” said Lance firmly; “I am eager to begin real work, whatever that may be.”

“You will always do what is right,” said Maddie. “And I will ask Mrs Judkin to come and help me iron your things,” and she ran out of the room, it might possibly have been to hide the tears rising in her eyes.

Maddie was still very young; she had not before parted from Lance, even for a day, and had as yet experienced none of the trials of life. She would have felt the same had Lance been her brother; she scarcely recognised the fact that he was not.

The day of parting came. Mrs Loughton was unable to leave the house. She clasped her boy to her heart, and blessed him, committing him to the charge of One all able and willing to protect those who confide in His love. Maddie, attended by Mrs Judkin, whose husband wheeled his portmanteau, accompanied Lance to the railway station, and her last tender, loving glance still seemed following him long after the train had rushed off along its iron way.

Perhaps now for the first time he realised how completely his future hopes of happiness depended on her. With manly resolution, and firm confidence in the goodness of God, he prepared, as he had often said he would, to do his duty.

He safely reached his uncle’s house, where he received a kindly welcome from his aunt and a number of young cousins. They looked at him approvingly; he was likely to become a favourite with them.

“I think you will get on with Gaisford,” said his uncle after the conclusion of dinner. “He is an honest man, and a Christian, and feels that he has responsibilities which many are not apt to acknowledge. I will say no more about him. You tell me you wish to do your duty; and therefore all I can say to you is, to try and ascertain what that duty is, and to do it.”

At an early hour the next morning Mr Durrant accompanied his nephew to Mr Gaisford’s office. The principal had not arrived. His head clerk scrutinised Lance from under his spectacles for a few seconds. Apparently satisfied, his countenance relaxed.

“We can find work for him,” he observed, after Lance had been duly introduced; “and as you have to be at your office you can leave him here, and the time need not hang heavily on his hand till Mr Gaisford arrives.”

Mr Durrant, promising to call for his nephew on his way home, hurried off.

Lance had at once a draft placed before him to copy. He wrote a clear, bold hand. Mr Brown, the head clerk, watched him for a minute.

“That will do—go on,” he said, and returned to his seat.

The draft was finished just as Mr Gaisford arrived. The clerk took it in his hand, telling Lance to follow him to their principal’s room. While introducing him, he placed it on the table, and withdrew.

Mr Gaisford, a middle-aged man, slightly grey, with a pleasant expression of countenance, having glanced over the paper, turned round and addressed Lance kindly.

“Sit down,” he said. “Your uncle has told me something about you, but I should like to hear more. Where were you at school?”

Lance told him.

“You were the head boy, I understand.”

He then asked what books he had read, and a variety of other questions, to which Lance answered modestly and succinctly. He then handed the paper back to Lance, to give it to Mr Brown, who would find him something more to do.

“This is written as well as it could be,” he observed. “I always like to have my work well done, and I can depend upon your doing it to the best of your ability.”

“That is what I wish to do,” said Lance, taking the paper and bowing as he left the room.

He had plenty of work during the morning. Mr Brown asked him to come out and take a chop with him at one o’clock.

The head clerk was never long absent from the office, as he might be wanted, and he made it a rule never to keep clients waiting longer than he could help.

“Time is money, my young friend,” he observed. “We should never squander other people’s time more than our own.”

Lance worked hard till his uncle arrived just at the usual hour for closing the office. Mr Gaisford had gone away some time before.

“He has done very well, sir,” observed Mr Brown as Mr Durrant entered; “and what is more, I feel sure he will do as well every day he is here.”

He and his uncle walked home together. Mr Durrant told him that his employer promised to give him a salary at once should the head clerk make a favourable report of him.

“That he will do that, I am confident, from what he has said.”

Lance felt very happy, and wrote home in good spirits, giving a satisfactory account of the commencement of his career in London.

He generally accompanied his uncle to and from the office, but he soon learned to find the way by himself. He always went directly there and back, refraining from wandering elsewhere to see the great city which to him was still an unknown land. He was very happy in his new home, and on his return each day he was greeted by his young cousins with shouts of pleasure. Lance was never tired of trying to amuse them.

With intense satisfaction Lance received his first quarter’s salary. He took it immediately to his uncle.

“This should be yours, sir,” he said, “though I fear it is not sufficient to repay you for the expense to which you have been put on my account.”

His uncle smiled.

“I think you must settle that with your aunt; and if she finds her household expenses much increased, you shall pay the difference: to the room you occupy you are welcome.”

Lance received back the greater portion of the sum he placed in his aunt’s hands, and immediately forwarded it to his mother.

The balance from next quarter, however, was somewhat less, as he had to pay for a few articles of clothing. His mother begged that he would not send her any more, as she was sure he would soon require considerable additions to his wardrobe. He, however, resolved to be very economical, and with the assistance of Mr Brown, who knew where everything was to be got the cheapest and best, he found that he still had a fair sum left to forward for the use of the loved ones at Elmerston.

“Pay ready money,” observed his friend the clerk. “Owe no man anything; it’s a golden rule, and assists to give a good digestion in the day, and sound sleep at night.”

Some time after this Mr Gaisford sent for Lance into his room, and put a document into his hand.

“Here, my young friend,” he said, “are your articles. Your mother is a widow with limited means, and has, moreover, not only brought you up well, but supported an orphan relative, so I understand. Such as she has claims on one like me, who am a bachelor with an ample fortune. Such claims I must recognise, for I am sure God does, whatever the rest of the world may think. I say this to set you at your ease about the matter. You have done your duty hitherto, and I am sure you will continue to do it. Your salary will be increased from the commencement of this quarter.”

Lance’s heart was too full to thank his kind benefactor as he wished. He tried to express his gratitude; at all events, Mr Gaisford understood him.

From that time forward it was evident that he rose still more in the estimation of one who was a keen judge of character.

Story 1--Chapter V.

Lance had been more than a year in London, and having been frequently sent with papers to clients in all directions, he learned his way about the City and West End.

During the first autumn vacation, as it was soon after his arrival, he had not gone home. He was looking forward to a visit before the close of the following summer. He kept up, however, a frequent correspondence with his mother and Maddie. His greatest pleasure was receiving their letters.

Mr Brown continued his friend, as at first, and took pains to initiate him into the mysteries of his profession.

He was one evening in the West End, near the Park, having been sent after office hours to a client’s house with the draft of a will. He had performed his commission, and had just left the house, when he encountered a young man, dressed in the height of the fashion, with a gold-headed cane in his hand. The other stopped and looked at him, exclaiming as he did so—

“Upon my word, I believe you are Lance Loughton!” and Lance recognised his former schoolfellow.

“What! Dulman?” he said, unconsciously scanning him from head to foot. “I did not know what had become of you; I thought you were engaged in business somewhere.”

“Hush, hush, my dear fellow! let me ask you not to call me by that odious name. I am Emery Delamere on this side of Temple Bar. I had been sent to call on a lady of fashion about a little affair of my employers, and embraced the opportunity of taking a stroll in the Park, in the hopes of meeting some of my acquaintances. You, I conclude, are bound eastward; so am I. We will proceed together, though I wish you had got rid of a little more of your rustic appearance. And now tell me all about yourself. Where are you? Who are you employed with? What are your prospects?”

As soon as Emery’s rattling tongue would allow him to answer, Lance briefly gave him the information he asked for.

“Very good, better than I had thought, for I am inclined to envy you. At the same time, the dull existence you are compelled to lead would not have suited my taste. However, you were always better adapted to plodding work than I am,” he answered, with a slight degree of envy in his tone. “But I suppose you have managed to see something of London life; if not, let me have the pleasure of initiating you. What do you say, shall we go to the theatre? I have tickets for the Haymarket, but it’s a dull house, I prefer Drury Lane; and though I ought to be in at ten o’clock according to rule, I can easily explain that I was detained by Lady Dorothy, and had to wait for an omnibus.”

“I am much obliged to you for your kind intentions, but I have no wish to go to a theatre, and beg that you will not on my account be late in returning home, and especially that you will not utter a falsehood as your excuse.”

“Falsehood! that’s a good joke,” exclaimed Emery; “you use a harsh term. We should never be able to enjoy ourselves without the privilege of telling a few white lies when necessary, ha! ha! ha! Why, my dear Lance, you seem as ignorant of the world as when you were at Elmerston.”

“I knew the difference between right and wrong, as I do now,” answered Lance gravely, “and I regret to hear you express yourself as you are doing. I was in hopes that the misfortunes you met with would have tended to give you more serious thoughts. Excuse me for saying so, but I speak frankly, as an old friend, and I pray that you may see things in their true light.”

“Really, Lance, you have become graver and more sarcastic than ever,” exclaimed Emery, not liking the tenor of his companion’s remarks. “I only wished to find some amusement for you; and since you don’t wish to be amused, I will not press you further to come with me. I myself do not care about going to the theatre, and will walk home with you as far as our roads run together.”

Lance thanked him, and hoping to be able to speak seriously to him of the sin and folly of the conduct he appeared to be pursuing, agreed to his proposal.

Though Emery would rather have had a better dressed companion, yet recollecting that Lance was a gentleman by birth, he felt some satisfaction in being in his society; for notwithstanding his boastings of the fashionable friends he possessed, he knew perfectly well that none of those whose acquaintance he casually made were real gentlemen.

“You appear to be better off than I am in some respects, Lance,” he observed. “For though I stand high in the opinion of my employer, and, I flatter myself, still higher in that of his daughter, a very charming girl I can assure you, they are not equal in social position to your relatives; and as you know, my desire has always been to move in a good circle, and maintain a high character among the aristocracy.”

Though Lance could not help despising the folly of poor Emery, he felt real compassion for him as he continued to talk this sort of nonsense.

“Now, Emery,” he said, “we have been schoolfellows, and you will excuse me for speaking freely to you. Would it not be wiser to accept the position in which you are placed, to work on steadily to gain a good name among those with whom you are associated, instead of aping the manners and customs of people who enjoy wealth and undoubtedly belong to a higher social grade than you do. You will be far more respected, even by them, if you are known to be looked up to by those of your own station in life. I speak from experience: I am treated with kindness and attention, not only by all the clerks in the office, and their friends whom I occasionally meet, but by the head clerk himself, not because I am the son of a naval officer, but simply because I work hard, and try to do whatever work is given me as well as possible. Besides, my old friend, we should have a higher motive for all our actions. Remember God sees us; and though we may give our earthly masters eye-service, we cannot deceive Him. Yet we should be influenced by a higher motive than that, not by fear alone, but by love and gratitude to Him who has given us life and health, and all the blessings we enjoy, and the promise of everlasting happiness if we will accept the offer He so graciously makes us, and become reconciled to Him, through faith in the great sacrifice—His Son offered upon the cross for us, His rebellious and disobedient creatures. Pray seek for grace to realise the great fact that we are by nature and conduct rebels, vile and foul—that if trusting to our own strength, we are in the power of our great enemy Satan, who is always trying to lead us astray—and that we have no claim whatever to God’s love and protection while here on earth, or to enjoy the happiness of heaven when we leave this world—that there is but one state of existence for which, if we die in rebellion, we can be fitted, that is, to associate for ever with the fallen angels justly cast out from His glorious presence.”

Lance spoke with deep earnestness, holding Emery lightly by the arm. He might never, he felt, have another opportunity of putting the truth before him.

Emery suddenly snatched his arm away.

“I really don’t like the sort of things you have been saying,” he exclaimed, “and I don’t know what authority you have for talking to me thus. I did not know what you were driving at when you began to talk, or I should not have listened so patiently, I can tell you. I asked you in a friendly way to come and enjoy a little harmless amusement with me, and you in return first give me a grave lecture, such as some one might expect from a Solon, rather than from a lawyer’s clerk, and then preach a sermon, which might be all very well if thundered out by the Archbishop of Canterbury from the pulpit, but really, when uttered by one young fellow to another, is simply ridiculous. I hope, for your sake, that you don’t pester your brother scribes, and that head clerk you speak of, with such balderdash, or favour your principal with an occasional discourse in the same strain. We are old schoolfellows, as you have remarked, so you will not be offended at what I say. Ah! ah! ah! Good evening to you, friend Solon; should we meet again, I hope you will recollect such an address as you have just given me is not to my taste. I have to go south; you go north, I fancy;” and Emery, swinging round his cane, and cocking his hat on one side, sauntered off, whistling a popular street air to show his unconcern.

Lance was too much hurt and astonished at the effect his earnest and faithful remarks had produced to say anything. He stood irresolute for a minute, feeling much inclined to run after Emery, and to entreat him not to take what he had said thus amiss. Just then he saw that his old schoolfellow was joined by another youth of a similar appearance, and the two went into a tobacconist’s together. It would be hopeless, he felt, to attempt saying anything more. He therefore hastened homewards, hoping that he might before long have another opportunity of again speaking seriously to Emery.

Story 1--Chapter VI.

Emery had been sent by his employer on a commission of some importance. On his return he gave a highly satisfactory account of the way he had performed it. He had risen, in consequence of his address and supposed abilities, high in the favour of Mr Padman, who placed perfect confidence in his zeal and honesty. He was always prepared beforehand with a sufficient excuse when he intended to be late out, or to break through any of the rules of the establishment. He was utterly regardless of the truth Lance had put before him, that God at all times sees us, and that those who deceive their fellow-men are sure, misled by Satan, to be discovered at last, and left to the consequences of their sin.

Emery, proud of what he considered his cleverness, and trusting to the confidence Mr Padman placed in him, became bolder in his proceedings. “There was no young man,” he said to himself, “so much thought of as he was;” and believing that Miss Padman also looked on him with a favourable eye, he determined to propose to marry her. He consulted old Sass, who, seeing no reason to doubt his success, advised him to try his chance. If he failed, Sass, knowing his secret, thought that he might take advantage of it. If he succeeded, he himself would certainly benefit by the influence he had gained over the young gentleman. Emery had to wait some time for the desired opportunity of speaking alone to Miss Padman. That young lady, however, did not hold her father’s shopman in the high estimation he had flattered himself. Others had taken care to whisper that Emery was not as correct in his conduct as he professed to be, and she thought her father unwise in placing so much confidence in him. When, therefore, he at length made her an offer, she replied that she considered him very presumptuous, and begged him to understand that she had no more regard for him than for the boy who swept out the shop, or for any one else in the establishment; and having discovered how he deceived her father, she should put Mr Padman on his guard. As the young lady was perfectly cool and decided, Emery had discernment enough to perceive that her decision was final, and as is often the case with weak natures, any better feeling he might have entertained for her was turned into hatred.

As there was no one else to whom he could express his anger and vexation, he called as soon as he could leave the shop on Sass Gange.

“Well, it was a toss up, I thought, from the first, and you have lost,” observed the old man. “However, Master Emery, don’t be cast down, there is as good fish in the sea as out of it. If the girl threatens you, as you say, I would advise you to cut the concern altogether. You will get disrated, depend upon it, and be worse off. Make hay while the sun shines. Now, my lad, I don’t want you to do anything that would get you into trouble, but there is nothing worth having without some risk. You have often said you would like a new sort of life instead of the humdrum counter-jumping work you have got to do. What do you say to making a start for South America or the Pacific? You might lead a jolly life among the natives, with nothing to do and lots of pretty girls to make love to, who would not treat you like Miss Padman, that I can tell you.”

Thus the old sailor ran on, describing in overdrawn colours, with a large admixture of fable, the life he had himself led in his early days. He did not say how he had seen his companions, some murdered, and the rest dying of disease, or that he himself had narrowly escaped with his life.

Emery listened eagerly. He had felt how unsatisfactory was the life he was trying to lead, the constant rebuffs of those into whose society he tried to thrust himself, and the hopelessness of succeeding in his foolish aims, and Satan was of course ready to suggest that he might find far greater enjoyment in something new.

“It will be capital fun!” he exclaimed at last; “but I have spent every shilling of my salary, and am in debt to a pretty considerable amount to some who look upon me as Mr Padman’s future son-in-law, and to others who have taken me to be a young man of fortune; and if I were to sell my whole wardrobe, I don’t suppose it would fetch enough to pay for a good sea outfit and my passage.”

“So I thought,” said Gange; “and as I have a notion that you have been shamefully treated by Miss Padman, if I were you, I would help myself in a way I can suggest to you, and the loss will fall upon her more than on her father, who is an old donkey, and it will do him no harm either. The chances are that he will send you to-morrow to pay the receipts of the shop into the bank, and as business is brisk just now, it’s likely to be a good round sum. I shall be sure to be sent to look after you, to see that no one picks your pockets, or knocks you down, or makes off with it. Now, then will be the time to fill your purse, and have some cash to spare for me. I won’t be very hard on you. To say the truth, I have had a little business of my own on hand, and have made up my mind to cut and run, so you won’t have me here as your friend much longer if you stay. Come, what do you say? a free and independent life, with plenty of money in your pocket; or hanging on here, to be snubbed by Miss Padman, and jeered at by the other fellows at your ill luck. She is sure to tell them, and the chances are there is some one she likes better than you.”

The unhappy youth listened to all the old tempter said, instead of at once seeking for grace to put away temptation and to say, “Get thee behind me, Satan.” He consented to all Sass had proposed.

“That’s right!” said the old sailor, “I like your spirit, my boy; I will help you, depend on me. You had better get your portmanteau packed with all your best things, and just carry it down the first thing in the morning. You can tell the house-porter that you are going away for a day; he will not ask questions, and I will send a man to bring it here.”

All other arrangements were speedily made. Sass had evidently thought the matter over, and Emery was impressed by what he fancied the clever way all risks had been provided against.

Emery went home. He felt too nervous to sleep soundly, and rising, lighted a candle and packed up his portmanteau, keeping out his best things, in which to dress in the morning. If questions were asked, he would say that his mother was ill, and that he intended to ask leave to go home in the evening. The thoughts of the sinfulness of the act he was about to commit did not trouble him so much as the fear of possible detection. Still, the plan proposed by Sass was so feasible, and the arrangements he had made so perfect, that he had great hopes all would go right. He thought the matter over and over. Sometimes the remarks made by Lance would force themselves upon him, but he put them away, muttering, “That’s all old women’s nonsense, I am not going to be prevented from doing what I like by such stuff.” Dressing, and putting all the small articles of value he possessed into his pockets, as soon as he thought the porter would be opening the house he carried down his portmanteau, observing to the man as he did so, that he had had a sad letter the previous night, and should be compelled to start for home as soon as he could get leave from Mr Padman. In a short time the porter sent by Sass appeared, and he got it sent off without any questions being asked. He then went back to his room, and afraid of going to bed again with the risk of oversleeping himself, sat down in a chair by his bedside. Not having slept a wink during the night, his head soon dropped on his chest. His dreams were troubled—he felt a fearful pressure round his neck—it seemed that a cap was drawn over his eyes—the murmuring sound of numberless voices rang in his ears—he was standing on the platform at Newgate, the drop was about to fall beneath his feet. He had once witnessed such a scene, and gazed at it with indifference, moving off among the careless throng with the remark “Poor wretch! he has got what he deserved.” Could it be possible that he himself was now standing where he had seen the unhappy culprit launched into eternity. He awoke with a start, and found to his satisfaction that he had been only dreaming. His eyelids were heavy, his eyes bloodshot. He washed his face in cold water, and endeavoured to laugh off the recollection of his dream while he brushed his hair and arranged his cravat. He went down-stairs and joined his companions in the breakfast-room. They rallied him on his rakish look. He talked in his usual affected way, managing, however, to bring in the falsehood he had already uttered about his mother’s illness. It would assist, he hoped, to account for his not returning from the bank.

After a good breakfast he went with apparent diligence to business, waiting with anxious trepidation to be summoned by Mr Padman to convey the money received to the bank. Sometimes, as Lance’s words, and the recollection of his horrid dream, would intrude, he almost hoped that some one else would be selected; then he thought of, his debts, and the consequence of Miss Padman’s communication to her father, and the sneers of his companions, and he resolved to carry out the plan proposed by Sass Gange.

The expected summons came. He received nearly 400 pounds, with the usual directions.

“I need not tell you to be careful, Dulman, and keep out of crowds,” said Mr Padman as he gave him the money.

Emery, buttoning up his coat, replied, with a forced smile, that he need have no fear on that score, though it was with difficulty that he prevented his knees from knocking together as he walked away.

He hastened out of the house. As he expected, before getting far, on looking back, he saw Sass Gange following at his heels. Would it not be safer, after all, to pay the money in? Miss Padman might relent; and should he be captured, the dreadful dream of the morning might be realised. “Pooh! they don’t hang for such things as that,” he said to himself.

Directly afterwards he felt Sass’s hand laid on his shoulder.

“Have you a goodish sum, my lad?” he asked.

“Seldom have had more at one time,” answered Emery.

“Then come along, don’t let us lose the chance.” Sass called a cab, and forced his dupe into it. They drove away to Gange’s lodgings.

He ran in and brought down Emery’s portmanteau, and a sea-bag with his own traps. The cabman was ordered to drive to Euston Square station. Sass had a railway guide; he had been consulting it attentively; they might catch a train starting for Liverpool.

“Is it most in notes or gold?” asked Sass.

“About a third in gold, the rest in bank-notes, with a few cheques,” said Emery.

“Hand me out the gold, then, it will suit me best,” said Sass. “I will be content with that as my share. You can get rid of the notes better than I can.”

Sass promised double fare to the cabman if he would drive faster.

Emery wanted to keep some of the gold for himself, but Sass insisted on having the whole of it. He made Emery pay the fare. They had three minutes to spare.

“You take our tickets,” said Sass, “second class for me, there are no third, and a first for yourself. We had better be separate; and if by any chance we are traced thus far, it will help to put them off the scent.”

Emery having no gold, took out a bank-note for ten pounds. He felt somewhat nervous as the booking-clerk examined it. It was all right, however, and he received his change, and going on to the next shutter took a ticket for his companion.

“All right,” said Gange, “get in, and sit at the further side, and pretend to be sleepy or drunk, only keep your face away from the light. Your portmanteau is ticketed for Liverpool. Good-bye, my lad, till we stop on the road, and I will come and have a look at you.”

Gange disappeared. Off went the train, and Emery’s brain whirled round and round, even faster than the carriage seemed to be moving. He tried not to think, but in vain.

The other seats were filled, but he had not dared to look at his companions. He heard them laughing and talking. A board was opened, and dice rattled, still he did not look up. Cards were produced.

“Will any other gentleman join us?” asked a man sitting opposite to the seat, next to him. He caught Emery’s eye. “Will you, sir,” he added in a bland voice. “We play for very moderate stakes.”

Emery knew something about the game proposed. It would have been better for him had he been ignorant of it altogether. A game of cards would enable him to turn his thoughts from himself. He agreed to play. He knew that he did not play well, but to his surprise he found himself winning. The stakes were doubled. He still won. He thought that his companions were very bad players. Again the stakes were increased, he still occasionally won, but oftener lost. He had soon paid away all his gold, and was compelled to take out one of the notes which he had stolen; that quickly went, and another, and another. He felt irritated, and eager to get back the money he had lost; he had won at first, why should he not again? His companions looked calm and indifferent, as if it mattered very little if the luck turned against them.

When they came to a station, they shut up the board, and put the cards under their railway rugs.

Emery had lost fifty pounds of the stolen money. He felt ready for any desperate deed. Two of the men got out at the next large station. Could he have been certain that the money was in the possession of the remaining man, he would have seized him by the throat, and tried to get it back.

The man kept eyeing him sternly, as if aware of his thoughts. Just before the train started, he also stepped out, carrying the board concealed in his rug.

“You have been a heavy loser, I fear,” said a gentleman in the seat near the door. “I would have warned you had I thought you would have lost so much, but it will be a lesson to you in future. I am convinced, by their movements, that those were regular card-sharpers. It’s too late now, but you may telegraph from the next station to try and stop them.”

As this remark was made, it flashed into Emery’s mind that some one might telegraph to Liverpool to stop him. He scarcely thought about his loss, but dreaded that his agitation might betray him. The gentleman naturally thought it arose from his being cheated of so much money. Emery tried to look unconcerned.

“A mere trifle,” he said, forcing a laugh, “I will try and catch the rogues, though.”

However, when he reached the next station, remembering Sass Gange’s caution, he was afraid to leave his seat.

“I might lose the train,” he said, “and business of importance takes me to Liverpool.”

“As you think fit,” observed the gentleman, “but you will now have little chance of recovering your money.”

Emery was thankful when the train again moved on.

Sass Gange had not appeared at either of the stations.

Liverpool was at length reached. He looked about expecting to see Sass, but he was nowhere to be found. His own portmanteau was in the luggage-van, but the sailor’s bag was not with it.

Where to go he could not tell. His eye caught the name of a hotel. He took a cab and drove to it.

It was too late to change any notes that night; but he determined in the morning, as early as possible, to get rid of those evidences of his guilt. In the meantime, he went to bed utterly miserable.

Story 1--Chapter VII.

Mr Padman became anxious when neither Emery nor Sass Gange returned at the expected time. On sending to the bank he found that no money had been paid in. He made inquiries if they had been seen, and learned that Emery had sent for his portmanteau in the morning. He at once despatched a messenger to Gange’s lodgings. Gange had left with his bag in the afternoon. Mr Padman immediately suspected the truth. He sent to the police, and to each of the railway stations. Lance’s master, Mr Gaisford, was his lawyer. He hurried to consult him as to what other steps it would be advisable to take. Lance was in the room receiving instructions about a draft, and not being told to withdraw, remained. With sincere grief he heard of Emery’s guilt.

“He comes from Elmerston, do you know him?” asked Mr Gaisford, turning to Lance.

“Yes,” said Lance, “he was a schoolfellow, and I saw him but a few days ago. I have also frequently seen the man who is supposed to have accompanied him.”

“If we can find out where they have gone to I will send you down with an officer and a warrant. It will save much trouble, and you will be able at once to identify them, and the sooner they are captured the less money they will have spent.”

The number of the cab happened to consist but of two figures; a fellow-lodger of Sass had remarked it, and heard him order the cabman to drive to Euston Square station. A clue was obtained in the course of a few hours, and a telegraph message sent to stop the fugitives. Before Emery had reached Liverpool, Lance and the officer, having warrants for his and Gange’s apprehension, were on their way.

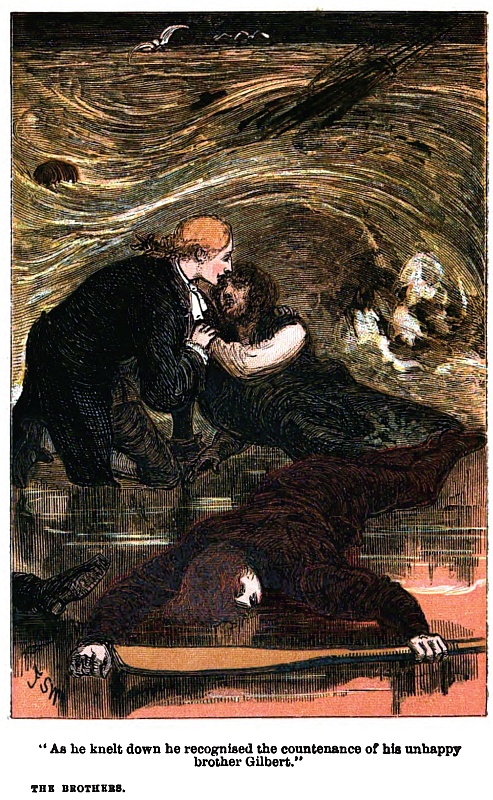

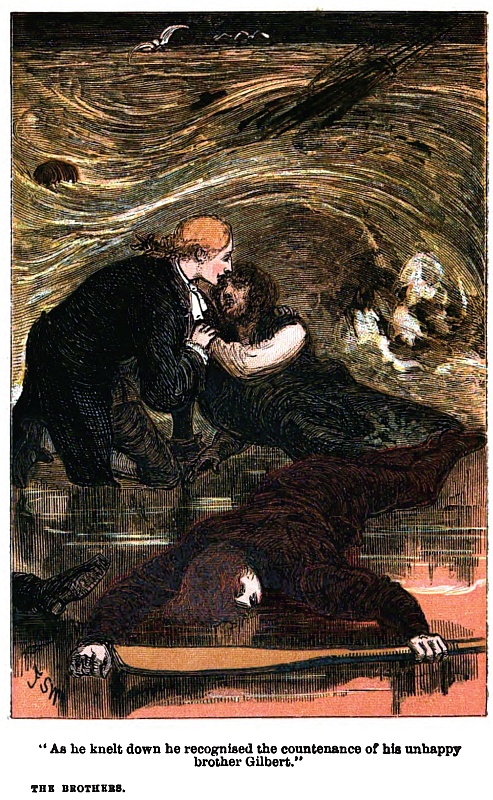

The cunning old sailor, however, having obtained all the gold as his share, had quitted the train and gone off to Hull, leaving his unhappy dupe to follow his own devices. The Liverpool police being on the look-out for an old man and a young one allowed Emery to pass, though not altogether unnoticed; and when Lance and the London officer arrived, the latter, suspecting the true state of the case, inquired if a young man of Emery’s appearance had arrived alone. The hotel which he had driven to was at once discovered, and he was still in bed when the officer, followed by Lance, entered the room. He awoke as the door opened. As the officer, turning to Lance, asked, “Is that the man?” Emery gazed at Lance with a look of the most abject terror, unable to utter a word.

“Yes, I am sorry to say he is Emery Dulman,” said Lance, his voice choking with emotion.

The usual form of arrest was gone through. The officer examined his clothes, and found the pocket-book with the remainder of the stolen notes.

“Is this your doing, Lance?” asked Emery, at length making an effort to speak.

“No, it is not; I wish that I could have prevented you from committing the crime, and I am anxious, to serve you as far as I have the power,” answered Lance; “I advise you to confess everything, and to restore the money to your employer.”

The unhappy youth was allowed to dress, and while at breakfast told Lance everything that had occurred. Of Sass Gange he could say nothing, except that he believed he had entered a second-class carriage.

The wretched Emery, instead of enjoying the liberty and pleasure he had anticipated, as he sat waiting for the train, with his hands between his knees and his head bent down, looked the very picture of misery and despair.

“I have been befooled and deceived by every one—right and left!” he murmured, evidently wishing to throw blame on others rather than to condemn himself. “Mr Padman shouldn’t have given the money to me to carry to the bank, and he ought to have known what an old rascal that Sass Gange is. To think that the villain should have played me so scurvy a trick, and have gone off and left me in the lurch! Then to have lost so much money to these cheating card-sharpers. I expected only to meet gentlemen in a first-class carriage. I would punish them for robbing me if I could catch them—that I would, and they would deserve it! And now to have you, Lance, whom I looked upon as a friend, ferret me out and assist to hand me over to prison, and for what you can tell to the contrary, to the hangman’s noose, if the matter is proved against me. I wish that I was dead, that I do. If I had a pistol, I’d shoot myself, and get the affair settled at once!” he exclaimed, jumping up and dashing his fists against his forehead.

Lance did his utmost to calm the unhappy youth. “My poor Emery, Satan has duped you as he dupes all those who listen to his agents, or to the evil suggestions of their own wicked hearts. ‘All our hearts are deceitful, and desperately wicked above all things,’ the Bible tells us. Notwithstanding which, had you sought for strength from God’s Holy Spirit, you would assuredly have resisted the temptations thrown in your way. I have ever been your friend, and I wish to remain so. You remember the line in our Latin Grammar—‘A true friend is tried in a doubtful matter.’ As a friend, I rejoice that through God’s mercy you have been arrested in the downward course you had commenced. It must have led to your utter destruction. Think what you would have become old Sass Gange as your counsellor and guide. You will have much that is painful to go through—from that you cannot escape; but thank our loving Father in heaven for it. Far better is it to suffer a light affliction here for a short season, than to be eternally cast out. Never—let me entreat you—again utter the impious threat of rushing into the presence of your Maker; but turn to Him with a penitent heart, seeking forgiveness for all your sins through the one only way He has appointed—faith in our crucified Saviour: and oh! believe me, He will not deny you, for He has promised to receive all who thus come to Him. He has said, ‘Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.’ Text upon text I might bring forward to prove God’s readiness to forgive the greatest of sinners. Trust Him. Throw yourself upon His mercy. Do not fear what man can do to you. Submit willingly to any punishment the just laws of our country may demand you should suffer. Not that imprisonment or any other punishment you may receive can atone for the sin you have committed in God’s sight—not if you were to refund every farthing of the sum you stole. As the blood of Jesus Christ cleanseth from all sin, so through that precious blood alone can the slightest as well as the deepest shade of sin be washed away. I say this now, Emery, in case I should be prevented from speaking again to you on the subject. Reflect, too, on the condition in which you would have been placed had you committed this crime a few years ago, for then an ignominious death on the scaffold would have been your inevitable doom, and bless God that you will now be spared to prove the sincerity of your repentance in some new sphere of life.”

Happy would it be for criminals if they had, when placed as Emery Dulman now was, faithful friends like Lance Loughton to speak to them. Emery now and then, as Lance was addressing him, looked up, but again turned aside his head with an expression of scorn on his lips. Lance, however, was too true a Christian, and too sincerely desirous of benefiting his former acquaintance, to be defeated in his efforts to do so. Again and again he spoke to him so lovingly and gently that at length Emery burst into tears. “I wish that I had listened to you long ago, when you warned me of my folly, and it would not have come to this,” he exclaimed. “I will plead guilty at once, and throw myself on the mercy of my employer whom I have robbed.”

“I do not know whether he will be inclined to treat you mercifully. It may be considered necessary, as a warning to others, to punish you severely,” answered Lance. “But, my dear Emery, I am very sure that our Father in heaven, whom you have far more grievously offended, will, if you come to Him in His own appointed way, through faith in the Great Sacrifice, with sincere repentance, not only abundantly pardon you, but will inflict no punishment, because the punishment justly your due has been already borne by the Just and Holy One when He died on the Cross for sinners.”

The officer, looking at his watch, interrupted Lance by saying that it was time to start. Emery was conveyed to the station, and in a short time they were on their way back to London.

The officer made inquiries at the different stations, and at length discovered the one at which Gange had left the train. He sent to London for another officer to follow on his track.

Emery was conveyed to prison. He was tried, convicted, and sent to gaol for twelve months’ imprisonment. Old Sass, however, was too cunning to be caught, and got off to sea.

Lance obtained leave frequently to visit his unhappy schoolfellow, who, now left to his own reflections, listened to him attentively when with gentle words he impressed on him the truths he had hitherto derided. Before he left the prison Emery became thoroughly and deeply convinced that he was an utterly lost sinner, and that so he would have been, had he not been guilty of the crime for which he was suffering, or the countless others he had committed which his memory conjured up. Often had he cried, “Lord, be merciful to me a sinner!” That prayer had been heard, and he now knew that God is merciful, and that He has given good proof of His mercy by sending Jesus, the pure and sinless One, to suffer on the cross for every one who will trust to that sufficient atonement which He thus made for sin.

“God as a Sovereign with free grace offers pardon to rebellious man,” said Lance. “He leaves us with loving gratitude to accept it, and if we reject His mercy, justly to suffer the consequence of that rejection, and to be cast out for ever from His presence.”

“I see it!—I understand!—I do accept His gracious offer, and from henceforth, and with the aid of His Holy Spirit, will seek to obey and serve Him,” said Emery. “And I feel thankful that all this has come upon me, for I might never otherwise have learned to know Him in whom I can now place all my trust and love.”

At the end of Emery’s term of imprisonment, with the help of Mr Gaisford, Lance was able to procure him a passage to Australia, where he had in the meantime learned that his father had obtained a situation of trust, and would be able to find employment for his son.

Lance went on as he had begun, and as soon as he was out of his articles his loving and faithful Maddie became his wife, his mother having the happiness of seeing him the partner of his former employer before she was called to her rest.

He heard frequently from Emery, who, ever thankful for the mercies shown him by his heavenly Father, continued with steady industry to labour in the humble situation he had obtained.

A decrepit beggar one day came to Lance’s door with a piteous tale of the miseries he had endured, and Lance, ever ready to relieve distress, visited him at the wretched lodging where a few days afterwards he lay dying. He there learned that the unhappy man was Sass Gange. Lance told him that he knew him. Sass inquired for Emery.

“I’m thankful I did not help to bring him to the gallows,” he murmured. “The way I tempted the lad has laid heavier on my conscience than anything I ever did, and I’ve done a good many things I don’t like to think about.”

Lance endeavoured to place the gospel before the old man, but his heart was hard, his mind dull. In a few days he died.

The End.

Story 2--Chapter I.

STORY II—ALONE ON AN ISLAND.

The Wolf, a letter-of-marque of twenty guns, commanded by Captain Deason, sailing from Liverpool, lay becalmed on the glass-like surface of the Pacific. The sun struck down with intense heat on the deck, compelling the crew to seek such shade as the bulwarks or sails afforded. Some were engaged in mending sails, twisting yarns, knotting, splicing, or in similar occupations; others sat in groups between the guns, talking together in low voices, or lay fast asleep out of sight in the shade. The officers listlessly paced the deck, or stood leaning over the bulwarks, casting their eyes round the horizon in the hopes of seeing signs of a coming breeze. Their countenances betrayed ill-humour and dissatisfaction; and if they spoke to each other, it was in gruff, surly tones. They had had a long course of ill luck, as they called it, having taken no prizes of value. The crew, too, had for some time exhibited a discontented and mutinous spirit, which Captain Deason, from his bad temper, was ill fitted to quell. While he vexed and insulted the officers, they bullied and tyrannised over the men. The crew, though often quarrelling among themselves, were united in the common hatred to their superiors, till that little floating world became a perfect pandemonium.

Among those who paced her deck, anxiously looking out for a breeze, was Humphry Gurton, a fine lad of fifteen, who had joined the Wolf as a midshipman. This was his first trip to sea. He had intended to enter the Navy, but just as he was about to do so his father, a merchant at Liverpool, failed, and, broken-hearted at his losses, soon afterwards died, leaving his wife and only son but scantily provided for.

Tenderly had that wife, though suffering herself from a fatal disease, watched over him in his sickness, and Humphry had often sat by his father’s bedside while his mother was reading from God’s Word, and listened as with tender earnestness she explained the simple plan of salvation to his father. She had shown him from the Bible that all men are by nature sinful, and incapable, by anything they can do, of making themselves fit to enter a pure and holy heaven, however respectable or excellent they may be in the sight of their fellow-men, and that the only way the best of human beings can come to God is by imitating the publican in the parable, and acknowledging themselves worthless, outcast sinners, and seeking to be reconciled to Him according to the one way He has appointed—through a living faith in the all-atoning sacrifice of His dear Son. Humphry had heard his father exclaim, “I believe that Jesus died for me; O Lord, help my unbelief! I have no merits of my own; I trust to Him, and Him alone.” He had witnessed the joy which had lighted up his mother’s countenance as she pressed his father’s hand, and bending down, whispered, “We shall be parted but for a short time; and, oh! may our loving Father grant that this our son may too be brought to love the Saviour, and join us when he is summoned to leave this world of pain and sorrow.”

Humphry had felt very sad; and though he had wept when his father’s eyes were closed in death, and his mother had pressed him—now the only being on earth for whom she desired to live—to her heart, yet the impression he had received had soon worn off.

In a few months after his father died, she too was taken from him, and Humphry was left an orphan.

The kind and pious minister, Mr Faithful, who frequently visited Mrs Gurton during the last weeks of her illness, had promised her to watch over her boy, but he had no legal power. Humphry’s guardian was a worldly man, and finding that there was but a very small sum for his support, was annoyed at the task imposed on him.

Humphry had expressed his wish to go to sea. A lad whose acquaintance he had lately made, Tom Matcham, was just about to join the Wolf, and, persuading him that they should meet with all sorts of adventures, offered to assist him in getting a berth on board her. Humphry’s guardian, to save himself trouble, was perfectly willing to agree to the proposed plan, and, without difficulty, arranged for his being received on board as a midshipman.

“We shall have a jovial life of it, depend upon that!” exclaimed Matcham when the matter was settled. “I intend to enjoy myself. The officers are rather wild blades, but that will suit me all the better.” Harry went to bid farewell to Mr Faithful.

“I pray that God will prosper and protect you, my lad,” he said. “I trust that your young companion is a right principled youth, who will assist you as you will be ready to help him, and that the captain and officers are Christian men.”

“I have not been long enough acquainted with Tom Matcham to know much about him,” answered Humphry. “I very much doubt that the captain and officers are the sort of people you describe. However, I daresay I shall get on very well with them.”

“My dear Humphry,” exclaimed Mr Faithful, “I am deeply grieved to hear that you can give no better account of your future associates. Those who willingly mix with worldly or evil-disposed persons are very sure to suffer. Our constant prayer is that we may be kept out of temptation, and we are mocking God if we willingly throw ourselves into it. I would urge you, if you are not satisfied with the character of those who are to be your companions for so many years, to give up the appointment while there is time. I would accompany you, and endeavour to get your agreement cancelled. It will be better to do so at any cost, rather than run the risk of becoming like them.”

“Oh, I daresay that they are not bad fellows after all!” exclaimed Humphry. “You know I need not do wrong, even though they do.”

The minister sighed. In vain he urged Humphry to consider the matter seriously.

“All I can do, then, my young friend, is to pray for you,” said Mr Faithful, as he wrung Harry’s hand, “and I beg you, as a parting gift, to accept these small books. One is a book above all price, of a size which you may keep in your pocket, and I trust that you will read it as you can make opportunities, even though others may attempt to interrupt you, or to persuade you to leave it neglected in your chest.”

It was a small Testament, and Harry, to please the minister, promised to carry it in his pocket, and to read from it as often as he Could.

Humphry having parted from his friend, went down at once to join the ship.

Next day she sailed. Humphry at first felt shocked at hearing the oaths and foul language used, both by the crew and officers. The captain, who on shore appeared a grave, quiet sort of man, swore louder and oftener than any one. Scarcely an order was issued without an accompaniment of oaths; indeed blasphemy resounded throughout the ship.

Matcham only laughed at Humphry when he expressed his annoyance.

“You will soon get accustomed to it,” he observed. “I confess that I myself was rather astonished when I first heard the sort of thing, but I don’t mind it now a bit.”