Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Justinian II." to "Kells"

Author: Various

Release date: September 25, 2012 [eBook #40863]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

JUSTINIAN II., Rhinotmetus (669-711), East Roman emperor 685-695 and 704-711, succeeded his father Constantine IV., at the age of sixteen. His reign was unhappy both at home and abroad. After a successful invasion he made a truce with the Arabs, which admitted them to the joint possession of Armenia, Iberia and Cyprus, while by removing 12,000 Christian Maronites from their native Lebanon, he gave the Arabs a command over Asia Minor of which they took advantage in 692 by conquering all Armenia. In 688 Justinian decisively defeated the Bulgarians. Meanwhile the bitter dissensions caused in the Church by the emperor, his bloody persecution of the Manichaeans, and the rapacity with which, through his creatures Stephanus and Theodatus, he extorted the means of gratifying his sumptuous tastes and his mania for erecting costly buildings, drove his subjects into rebellion. In 695 they rose under Leontius, and, after cutting off the emperor’s nose (whence his surname), banished him to Cherson in the Crimea. Leontius, after a reign of three years, was in turn dethroned and imprisoned by Tiberius Absimarus, who next assumed the purple. Justinian meanwhile had escaped from Cherson and married Theodora, sister of Busirus, khan of the Khazars. Compelled, however, by the intrigues of Tiberius, to quit his new home, he fled to Terbelis, king of the Bulgarians. With an army of 15,000 horsemen Justinian suddenly pounced upon Constantinople, slew his rivals Leontius and Tiberius, with thousands of their partisans, and once more ascended the throne in 704. His second reign was marked by an unsuccessful war against Terbelis, by Arab victories in Asia Minor, by devastating expeditions sent against his own cities of Ravenna and Cherson, where he inflicted horrible punishment upon the disaffected nobles and refugees, and by the same cruel rapacity towards his subjects. Conspiracies again broke out: Bardanes, surnamed Philippicus, assumed the purple, and Justinian, the last of the house of Heraclius, was assassinated in Asia Minor, December 711.

See E. Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (ed. Bury, 1896), v. 179-183; J. B. Bury, The Later Roman Empire (1889), ii. 320-330, 358-367.

JUSTIN MARTYR, one of the earliest and ablest Christian apologists, was born about 100 at Flavia Neapolis (anc. Sichem), now Nablus, in Palestinian Syria (Samaria). His parents, according to his own account, were Pagans (Dial. c. Tryph. 28). He describes the course of his religious development in the introduction to the dialogue with the Jew Trypho, in which he relates how chance intercourse with an aged stranger brought him to know the truth. Though this narrative is a mixture of truth and fiction, it may be said with certainty that a thorough study of the philosophy of Peripatetics and Pythagoreans, Stoics and Platonists, brought home to Justin the conviction that true knowledge was not to be found in them. On the other hand, he came to look upon the Old Testament prophets as approved by their antiquity, sanctity, mystery and prophecies to be interpreters of the truth. To this, as he tells us in another place (Apol. ii. 12), must be added the deep impression produced upon him by the life and death of Christ. His conversion apparently took place at Ephesus; there, at any rate, he places his decisive interview with the old man, and there he had those discussions with Jews and converts to Judaism, the results of which he in later years set down in his Dialogue. After his conversion he retained his philosopher’s cloak (Euseb., Hist. Eccl. iv. 11. 8), the distinctive badge of the wandering professional teacher of philosophy, and went about from place to place discussing the truths of Christianity in the hope of bringing educated Pagans, as he himself had been brought, through philosophy to Christ. In Rome he made a fairly long stay, giving lectures in a class-room of his own, though not without opposition from his fellow-teachers. Among his opponents was the Cynic Crescentius (Apol. ii. 13). Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. iv. 16. 7-8) concludes somewhat hastily, from the statement of Justin and his disciple Tatian (Orat. ad Graec. 19), that the accusation of Justin before the authorities, which led to his death, was due to Crescentius. But we know, from the undoubtedly genuine Acta SS Justini et sociorum, that Justin suffered the death of a martyr under the prefect Rusticus between 163 and 167.

To form an opinion of Justin as a Christian and theologian, we must turn to his Apology and to the Dialogue with the Jew Trypho, for the authenticity of all other extant works attributed to him is disputed with good reason. The Apology—it is more correct to speak of one Apology than of two, for the second is only a continuation of the first, and dependent upon it—was written in Rome about 150. In the first part Justin defends his fellow-believers against the charge of atheism and hostility to the state. He then draws a positive demonstration of the truth of his religion from the effects of the new faith, and especially from the excellence of its moral teaching, and concludes with a comparison of Christian and Pagan doctrines, in which the latter are set down with naïve confidence as the work of demons. As the main support of his proof of the truth of Christianity appears his detailed demonstration that the prophecies of the old dispensation, which are older than the Pagan poets and philosophers, have found their fulfilment in Christianity. A third part shows, from the practices of their religious worship, that the Christians had in truth dedicated themselves to God. The whole closes with an appeal to the princes, with a reference to the edict issued by Hadrian in favour of the Christians. In the so-called Second Apology, Justin takes occasion from the trial of a Christian recently held in Rome to argue that the innocence of the Christians was proved by the very persecutions.

Even as a Christian Justin always remained a philosopher. By his conscious recognition of the Greek philosophy as a preparation for the truths of the Christian religion, he appears as the first and most distinguished in the long list of those who have endeavoured to reconcile Christian with non-Christian culture. Christianity consists for him in the doctrines, guaranteed by the manifestation of the Logos in the person of Christ, of God, righteousness and immortality, truths which have been to a certain extent foreshadowed in the monotheistic religious philosophies. In this process the conviction of the reconciliation of the sinner with God, of the salvation of the world and the individual through Christ, fell into the background before the vindication of supernatural truths intellectually conceived. Thus Justin may give the impression of having 603 rationalized Christianity, and of not having given it its full value as a religion of salvation. It must not, however, be forgotten that Justin is here speaking as the apologist of Christianity to an educated Pagan public, on whose philosophical view of life he had to base his arguments, and from whom he could not expect an intimate comprehension of the religious position of Christians. That he himself had a thorough comprehension of it he showed in the Dialogue with the Jew Trypho. Here, where he had to deal with the Judaism that believed in a Messiah, he was far better able to do justice to Christianity as a revelation; and so we find that the arguments of this work are much more completely in harmony with primitive Christian theology than those of the Apology. He also displays in this work a considerable knowledge of the Rabbinical writings and a skilful polemical method which was surpassed by none of the later anti-Jewish writers.

Justin is a most valuable authority for the life of the Christian Church in the middle of the 2nd century. While we have elsewhere no connected account of this, Justin’s Apology contains a few paragraphs (61 seq.), which give a vivid description of the public worship of the Church and its method of celebrating the sacraments (Baptism and the Eucharist). And from this it is clear that though, as a theologian, Justin wished to go his own way, as a believing Christian he was ready to make his standpoint that of the Church and its baptismal confession of faith. His works are also of great value for the history of the New Testament writings. He knows of no canon of the New Testament, i.e. no fixed and inclusive collection of the apostolic writings. His sources for the teachings of Jesus are the “Memoirs of the Apostles,” by which are probably to be understood the Synoptic Gospels (without the Gospel according to St John), which, according to his account, were read along with the prophetic writings at the public services. From his writings we derive the impression of an amiable personality, who is honestly at pains to arrive at an understanding with his opponents. As a theologian, he is of wide sympathies; as a writer, he is often diffuse and somewhat dull. There are not many traces of any particular literary influence of his writings upon the Christian Church, and this need not surprise us. The Church as a whole took but little interest in apologetics and polemics, nay, had at times even an instinctive feeling that in these controversies that which she held holy might easily suffer loss. Thus Justin’s writings were not much read, and at the present time both the Apology and the Dialogue are preserved in but a single MS. (cod. Paris, 450, A.D. 1364).

Bibliography.—The editions of Robert Étienne (Stephanus) (1551); H. Sylburg (1593); F. Morel (1615); Prudentius Maranuis (1742) are superseded by J. C. T. Otto, Justini philosophi et martyris opera quae feruntur omnia (3rd ed. 5 vols., Jena, 1876-1881). This edition contains besides the Apologies (vol. i.) and the Dialogue (vol. ii.) the following writings: Speech to the Greeks (Oratio); Address to the Greeks (Cohortatio): On the Monarchy of God; Epistle to Diognetus; Fragments on the Resurrection and other Fragments; Exposition of the True Faith; Epistle to Zenas and Serenus; Refutation of certain Doctrines of Aristotle; Questions and Answers to the Orthodox; Questions of Christians to Pagans; Questions of Pagans to Christians. None of these writings, not even the Cohortatio, which former critics ascribed to Justin, can be attributed to him. The authenticity of the Dialogue has occasionally been disputed, but without reason. For a handy edition of the Apology see G. Krüger, Die Apologien Justins des Märtyrers (3rd ed. Tübingen, 1904). There is a good German translation with a comprehensive commentary by H. Veil (1894). For English translations consult the “Oxford Library of the Fathers” and the “Ante-Nicene Library.” Full information about Justin’s history and views may be had from the following monographs: C. Semisch, Justin der Märtyrer (2 vols., 1840-1842); J. Donaldson, A Critical History of Christian Literature and Doctrine, vol. 2 (1866); C. E. Freppel, St Justin (3rd ed., 1886); Moritz von Engelhardt, Das Christentum Justins des Märtyrers (1878); T. M. Wehofer, Die Apologie Justins des Philosophen und Märtyrers in litterarhistorischer Beziehung zum ersten Male untersucht (1897); Alfred Leonhard Feder, Justins des Märtyrers Lehre von Jesus Christus (1906). On the critical questions raised by the spurious writings consult W. Gaul, Die Abfassungsverhältnisse der pseudo-justinischen Cohortatio ad Graecos (1902); Adolf Harnack, Diodor von Tarsus. Vier pseudo-justinische Schriften als Eigentum Diodors nachgewiesen (1901).

JUTE, a vegetable fibre now occupying a position in the manufacturing scale inferior only to cotton and flax. The term jute appears to have been first used in 1746, when the captain of the “Wake” noted in his log that he had sent on shore “60 bales of gunney with all the jute rope” (New Eng. Dict. s.v.). In 1795 W. Roxburgh sent to the directors of the East India Company a bale of the fibre which he described as “the jute of the natives.” Importations of the substance had been made at earlier times under the name of pāt, an East Indian native term by which the fibre continued to be spoken of in England till the early years of the 19th century, when it was supplanted by the name it now bears. This modern name appears to be derived from jhot or jhout (Sansk. jhat), the vernacular name by which the substance is known in the Cuttack district, where the East India Company had extensive roperies when Roxburgh first used the term.

|

| Fig. 1.—Capsules of Jute Plants. a, Corchorus capsularis; b, C. olitorius. |

The fibre is obtained from two species of Corchorus (nat. ord. Tiliaceae), C. capsularis and C. olitorius, the products of both being so essentially alike that neither in commerce nor agriculture is any distinction made between them. These and various other species of Corchorus are natives of Bengal, where they have been cultivated from very remote times for economic purposes, although there is reason to believe that the cultivation did not originate in the northern parts of India. The two species cultivated for jute fibre are in all respects very similar to each other, except in their fructification and the relatively greater size attained by C. capsularis. They are annual plants from 5 to 10 ft. high, with a cylindrical stalk as thick as a man’s finger, and hardly branching except near the top. The light-green leaves are from 4 to 5 in. long by 1½ in. broad above the base, and taper upward into a fine point; the edges are serrated; the two lower teeth are drawn out into bristle-like points. The small whitish-yellow flowers are produced in clusters of two or three opposite the leaves.

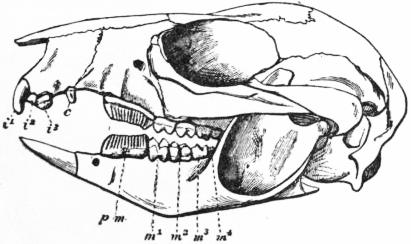

The capsules or seed-pods in the case of C. capsularis are globular, rough and wrinkled, while in C. olitorius they are slender, quill-like cylinders (about 2 in. long), a very marked distinction, as may be noted from fig. 1, in which a and b show the capsules of C. capsularis and C. olitorius respectively. Fig. 2 represents a flowering top of C. olitorius.

Both species are cultivated in India, not only on account 604 of their fibre, but also for the sake of their leaves, which are there extensively used as a pot-herb. The use of C. olitorius for the latter purpose dates from very ancient times, if it may be identified, as some suppose, with the mallows (מלוח) mentioned in Job xxx. 4; hence the name Jew’s mallow. It is certain that the Greeks used this plant as a pot-herb; and by many other nations around the shores of the Mediterranean this use of it was, and is still, common. Throughout Bengal the name by which the plants when used as edible vegetables are recognized is nalitā; when on the other hand they are spoken of as fibre-producers it is generally under the name pāt. The cultivation of C. capsularis is most prevalent in central and eastern Bengal, while in the neighbourhood of Calcutta, where, however, the area under cultivation is limited, C. olitorius is principally grown. The fibre known as China jute or Tien-tsin jute is the product of another plant, Abutilon Avicennae, a member of the Mallow family.

Cultivation and Cropping.—Attempts have been made to grow the jute plant in America, Egypt, Africa and other places, but up to the present the fibre has proved much inferior to that obtained from plants grown in India. Here the cultivation of the plant extends from the Hugli through eastern and northern Bengal. The successful cultivation of the plant demands a hot, moist climate, with a fair amount of rain. Too much rain at the beginning of the season is detrimental to the growth, while a very dry season is disastrous. The climate of eastern and northern Bengal appears to be ideal for the growth of the plant.

The quality of the fibre and the produce per acre depend in a measure on the preparation of the soil. The ground should be ploughed about four times and all weeds removed. The seed is then sown broadcast as in the case of flax. It is only within quite recent years that any attention has been paid to the selection of the seed. The following extract from Capital (Jan. 17, 1907) indicates the new interest taken in it.

“Jute seed experiments are being continued and the report for 1906 has been issued. The object of these experiments is, of course, to obtain a better class of jute seed by growing plants, especially for no other purpose than to obtain their seed. The agricultural department has about 300 maunds (25,000 ℔) of selected seed for distribution this year. The selling price is to be Rs. 10 per maund. The agricultural department of the government of Bengal are now fully alive to the importance of fostering the jute industry by showing conclusively that attention to scientific agriculture will make two maunds of jute grow where only one maund grew before. Let them go on (as they will) till all the ryots are thoroughly indoctrinated into the new system.”

The time of sowing extends from the middle of March to the middle of June, while the reaping, which depends upon the time of sowing and upon the weather, is performed from the end of June to the middle of October. The crop is said to be ready for gathering when the flowers appear; if gathered before, the fibre is weak, while if left until the seed is ripe, the fibre is stronger, but is coarser and lacks the characteristic lustre.

The fibre is separated from the stalks by a process of retting similar to that for flax and hemp. In certain districts of Bengal it is the practice to stack the crop for a few days previous to retting in order to allow the leaves to dry and to drop off the stalks. It is stated that the colour of the fibre is darkened if the leaves are allowed to remain on during the process of retting. It is also thought that the drying of the plants before retting facilitates the separation of the fibre. Any simple operation which improves the colour of the fibre or shortens the operation of retting is worthy of consideration. The benefits to be derived from the above process, however, cannot be great, for the bundles are usually taken direct to the pools and streams. The period necessary for the completion of the retting process varies according to the temperature and to the properties of the water, and may occupy from two days to a month. After the first few days of immersion the stalks are examined daily to test the progress of the retting. When the fibres are easily separated from the stalk, the operation is complete and the bundles should be withdrawn. The following description of the retting of jute is taken from Royle’s Fibrous Plants of India:—

“The proper point being attained, the native operator, standing up to his middle in water, takes as many of the sticks in his hands as he can grasp, and removing a small portion of the bark from the ends next the roots, and grasping them together, he strips off the whole with a little management from end to end, without breaking either stem or fibre. Having prepared a certain quantity into this half state, he next proceeds to wash off: this is done by taking a large handful; swinging it round his head he dashes it repeatedly against the surface of the water, drawing it through towards him, so as to wash off the impurities; then, with a dexterous throw he fans it out on the surface of the water and carefully picks off all remaining black spots. It is now wrung out so as to remove as much water as possible, and then hung up on lines prepared on the spot, to dry in the sun.”

The separated fibre is then made up into bundles ready for sending to one of the jute presses. The jute is carefully sorted into different qualities, and then each lot is subjected to an enormous hydraulic pressure from which it emerges in the shape of the well-known bales, each weighing 400 ℔.

The crop naturally depends upon the quality of the soil, and upon the attention which the fibre has received in its various stages; the yield per acre varies in different districts. Three bales per acre, or 1200 ℔ is termed a 100% crop, but the usual quantity obtained is about 2.6 bales per acre. Sometimes the crop is stated in lakhs of 100,000 bales each. The crop in 1906 reached nearly 9,000,000 bales, and in 1907 nearly 10,000,000 was reached. The following particulars were issued on the 19th of September 1906 by Messrs. W. F. Souter & Co., Dundee:—

| Year. | Actual acreage. |

Estimated yield (100% equal 3 bales per acre). |

Estimated total crop. Bales. |

Shipment to Europe. | Shipment to America. | Supplies to Indian mills and local consumption. |

Out-turn total crop. Bales. | ||

| Jute. Bales. |

Cuttings. Bales. |

Jute. Bales. |

Cuttings. Bales. | ||||||

| 1901—1st | 2,216,500 | 94% = | 6,250,000 | ||||||

| Final | 2,249,000 | 96% = | 6,500,000 | 3,528,691 | 54,427 | 295,921 | 426,331 | 3,100,000 = | 7,405,370 |

| 1902—1st | 2,200,000 | 80% = | 5,280.000 | ||||||

| Final | 2,200,000 | 80% = | 5,280,000 | 2,773,621 | 39,019 | 230,415 | 207,999 | 2,600,000 = | 5,851,054 |

| 1903—1st | 2,100,000 | 85% = | 5,400,000 | ||||||

| Final | 2,250,000 | 93¾% = | 6,500,000 | 3,161,791 | 59,562 | 329,048 | 236,959 | 3,650,000 = | 7,437,360 |

| 1904—1st | 2,700,000 | 87½% = | 7,100,000 | ||||||

| Final | 2,850,000 | 85% = | 7,400,000 | 2,939,940 | 44,002 | 253,882 | 290,854 | 3,475,782 = | 7,004,460 |

| 1905—1st | 3,163,500 | 87% = | 8,250,000 | ||||||

| Final | 3,145,000 | 87% = | 8,200,000 | 3,483,315 | 63,118 | 347,974 | 245,044 | 4,018,523 = | 8,233,358 |

| Outlying | 200,000 | ||||||||

| Madras | 75,384 | ||||||||

| 1906—1st | 3,271,400 | 87% = | 8,713,000 | ||||||

| Outlying | 67,000 | Madras | 100,000 | ||||||

| Final | 3,336,400 | 8,736,220 | |||||||

| (Outlying Districts and Madras, say 250,000 bales additional) | |||||||||

Estimated consumption of jute 1906-1907.

| In Europe | Bales per annum. | ||

| Scotland | 1,250,000 | ||

| England | 20,000 | ||

| Ireland | 25,000 | ||

| France | 475,000 | ||

| Belgium | 120,000 | ||

| Germany | 750,000 | ||

| Austria and Bohemia | 262,000 | ||

| Norway and Sweden | 62,500 | ||

| Russia | 180,000 | ||

| Holland | 25,000 | ||

| Spain | 90,000 | ||

| Italy | 160,000 | ||

| ——— | 3,419,500 | bales | |

| In America | 600,000 | ||

| ——— | 600,000 | ” | |

| In India— | |||

| Mills | 3,900,000 | ||

| Local | 500,000 | ||

| ———— | 4,400,000 | ” | |

| ——————— | |||

| 8,419,500 | bales | ||

Statistics of consumption of jute, rejections and cuttings.

| Consumption. | 1894. Bales. | 1904. Bales. | 1906. Bales. |

| United Kingdom | 1,200,000 | 1,200,000 | 1,295,000 |

| Continent | 1,100,000 | 1,800,000 | 2,124,500 |

| America | 500,000 | 500,000 | 600,000 |

| Indian mills | 1,500,000 | 2,900,000 | 3,900,000 |

| Local Indian consumption | 500,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 |

| Total jute crop consumption | 4,800,000 | 6,900,000 | 8,419,500 |

A number of experiments in jute cultivation were made during 1906, and the report showed that very encouraging results were obtained from land manured with cow-dung. If more scientific attention be given to the cultivation it is quite possible that what is now considered as 100% yield may be exceeded.

Characteristics.—The characters by which qualities of jute are judged are colour, lustre, softness, strength, length, firmness, uniformity and absence of roots. The best qualities are of a clear whitish-yellow colour, with a fine silky lustre, soft and smooth to the touch, and fine, long and uniform in fibre. When the fibre is intended for goods in the natural colour it is essential that it should be of a light shade and uniform, but if intended for yarns which are to be dyed a dark shade, the colour is not so important. The cultivated plant yields a fibre with a length of from 6 to 10 ft., but in exceptional cases it has been known to reach 14 or 15 ft. in length. The fibre is decidedly inferior to flax and hemp in strength and tenacity; and, owing to a peculiarity in its microscopic structure, by which the walls of the separate cells composing the fibre vary much in thickness at different points, the single strands of fibre are of unequal strength. Recently prepared fibre is always stronger, more lustrous, softer and whiter than such as has been stored for some time—age and exposure rendering it brown in colour and harsh and brittle in quality. Jute, indeed, is much more woody in texture than either flax or hemp, a circumstance which may be easily demonstrated by its behaviour under appropriate reagents; and to that fact is due the change in colour and character it undergoes on exposure to the air. The fibre bleaches with facility, up to a certain point, sufficient to enable it to take brilliant and delicate shades of dye colour, but it is with great difficulty brought to a pure white by bleaching. A very striking and remarkable fact, which has much practical interest, is its highly hygroscopic nature. While in a dry position and atmosphere it may not possess more than 6% of moisture, under damp conditions it will absorb as much as 23%.

Sir G. Watt, in his Dictionary of the Economic Products of India, mentions the following eleven varieties of jute fibre: Serajganji, Narainganji, Desi, Deora, Uttariya, Deswāl, Bākrabadi, Bhatial, Karimginji, Mirganji and Jungipuri. There are several other varieties of minor importance. The first four form the four classes into which the commercial fibre is divided, and they are commonly known as Serajgunge, Naraingunge, Daisee and Dowrah. Serajgunge is a soft fibre, but it is superior in colour, which ranges from white to grey. Naraingunge is a strong fibre, possesses good spinning qualities, and is very suitable for good warp yarns. Its colour, which is not so high as Serajgunge, begins with a cream shade and approaches red at the roots. All the better class yarns are spun from these two kinds. Daisee is similar to Serajgunge in softness, is of good quality and of great length; its drawback is the low colour, and hence it is not so suitable for using in natural colour. It is, however, a valuable fibre for carpet yarns, especially for dark yarns. Dowrah is a strong, harsh and low quality fibre, and is used principally for heavy wefts. Each class is subdivided according to the quality and colour of the material, and each class receives a distinctive mark called a baler’s mark. Thus, the finest fibres may be divided as follows:—

| Superfine | first marks. | |||

| Extra fine | first marks | 1st, 2nd | and 3rd | numbers. |

| Superior | first marks | ” | ” | ” |

| Standard | ” | ” | ” | ” |

| Good | ” | ” | ” | ” |

| Ordinary | ” | ” | ” | ” |

| Good | second marks | ” | ” | ” |

| Ordinary | ” | ” | ” | ” |

The lower qualities are, naturally, divided into fewer varieties.

|

| Fig. 2.—Corchorus olitorius. |

Each baler has his own marks, the fibres of which are guaranteed equal in equality to some standard mark. It would be impossible to give a list of the different marks, for there are hundreds, and new marks are constantly being added. A list of all the principal marks is issued in book form by the Calcutta Jute Baler’s association.

The relative prices of the different classes depend upon the crop, upon the demand and upon the quality of the fibre; in 1905 the prices of Daisee jute and First Marks were practically the same, although the former is always considered inferior to the latter. It does not follow that a large crop of jute will result in low prices, for the year 1906-1907 was not only a record one for crops, but also for prices. R. F. C. grade has been as high as £40 per ton, while its lowest recorded price is £12. Similarly the price for First Marks reached £29, 15s. in 1906 as compared with £9, 5s. per ton in 1897. The following table shows a few well-known grades with the average prices during December for the years 1903, 1904, 1905 and 1906.

| Class. | Dec. 1903. | Dec. 1904. | Dec. 1905. | Dec. 1906. | ||||||||

| £ | s. | d. | £ | s. | d. | £ | s. | d. | £ | s. | d. | |

| First marks | 12 | 15 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 15 | 0 | 27 | 15 | 0 |

| Blacks S C C | 11 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 15 | 0 |

| Red S C C | 12 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 17 | 6 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 23 | 15 | 0 |

| Native rejections | 8 | 2 | 6 | — | 14 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 17 | 6 | ||

| S 4 group | — | — | 25 | 10 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| R F block D group | — | — | — | 36 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| R F circle D group | 14 | 10 | 0 | 16 | 15 | 0 | 21 | 10 | 0 | — | ||

| R F D group | 11 | 15 | 0 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 17 | 12 | 6 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| N B green D | 14 | 5 | 0 | — | 21 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Heart T 4 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 0 | 22 | 10 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart T 5 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

| Daisee 2 | 12 | 17 | 6 | — | 18 | 15 | 0 | 25 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Daisee assortment | 12 | 10 | 0 | 14 | 17 | 6 | 18 | 5 | 0 | — | ||

| Mixed cuttings | 4 | 5 | 0 | — | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | ||

Jute Manufacture.—Long before jute came to occupy a prominent place amongst the textile fibres of Europe, it formed 606 the raw material of a large and important industry throughout the regions of Eastern Bengal. The Hindu population made the material up into cordage, paper and cloth, the chief use of the latter being in the manufacture of gunny bags. Indeed, up to 1830-1840 there was little or no competition with hand labour for this class of material. The process of weaving gunnies for bags and other coarse articles by these hand-loom weavers has been described as follows:—

“Seven sticks or chattee weaving-posts, called tanā parā or warp, are fixed upon the ground, occupying the length equal to the measure of the piece to be woven, and a sufficient number of twine or thread is wound on them as warp called tanā. The warp is taken up and removed to the weaving machine. Two pieces of wood are placed at two ends, which are tied to the ohari and okher or roller; they are made fast to the khoti. The belut or treadle is put into the warp; next to that is the sarsul; a thin piece of wood is laid upon the warp, called chupari or regulator. There is no sley used in this, nor is a shuttle necessary; in the room of the latter a stick covered with thread called singa is thrown into the warp as woof, which is beaten in by a piece of plank called beyno, and as the cloth is woven it is wound up to the roller. Next to this is a piece of wood called khetone, which is used for smoothing and regulating the woof; a stick is fastened to the warp to keep the woof straight.”

Gunny cloth is woven of numerous qualities, according to the purpose to which it is devoted. Some kinds are made close and dense in texture, for carrying such seed as poppy or rape and sugar; others less close are used for rice, pulses, and seeds of like size, and coarser and opener kinds again are woven for the outer cover of packages and for the sails of country boats. There is a thin close-woven cloth made and used as garments among the females of the aboriginal tribes near the foot of the Himalayas, and in various localities a cloth of pure jute or of jute mixed with cotton is used as a sheet to sleep on, as well as for wearing purposes. To indicate the variety of uses to which jute is applied, the following quotation may be cited from the official report of Hem Chunder Kerr as applying to Midnapur.

“The articles manufactured from jute are principally (1) gunny bags; (2) string, rope and cord; (3) kampa, a net-like bag for carrying wood or hay on bullocks; (4) chat, a strip of stuff for tying bales of cotton or cloth; (5) dola, a swing on which infants are rocked to sleep; (6) shika, a kind of hanging shelf for little earthen pots, &c.; (7) dulina, a floor-cloth; (8) beera, a small circular stand for wooden plates used particularly in poojahs; (9) painter’s brush and brush for white-washing; (10) ghunsi, a waist-band worn next to the skin; (11) gochh-dari, a hair-band worn by women; (12) mukbar, a net bag used as muzzle for cattle; (13) parchula, false hair worn by players; (14) rakhi-bandhan, a slender arm-band worn at the Rakhi-poornima festival; and (15) dhup, small incense sticks burned at poojahs.”

The fibre began to receive attention in Great Britain towards the close of the 18th century, and early in the 19th century it was spun into yarn and woven into cloth in the town of Abingdon. It is claimed that this was the first British town to manufacture the material. For years small quantities of jute were imported into Great Britain and other European countries and into America, but it was not until the year 1832 that the fibre may be said to have made any great impression in Great Britain. The first really practical experiments with the fibre were made in this year in Chapelshade Works, Dundee, and these experiments proved to be the foundation of an enormous industry. It is interesting to note that the site of Chapelshade Works was in 1907 cleared for the erection of a large new technical college.

In common with practically all new industries progress was slow for a time, but once the value of the fibre and the cloth produced from it had become known the development was more rapid. The pioneers of the work were confronted with many difficulties; most people condemned the fibre and the cloth, many warps were discarded as unfit for weaving, and any attempt to mix the fibre with flax, tow or hemp was considered a form of deception. The real cause of most of these objections was the fact that suitable machinery and methods of treatment had not been developed for preparing yarns from this useful fibre. Warden in his Linen Trade says:—

“For years after its introduction the principal spinners refused to have anything to do with jute, and cloth made of it long retained a tainted reputation. Indeed, it was not until Mr. Rowan got the Dutch government, about 1838, to substitute jute yarns for those made from flax in the manufacture of the coffee bagging for their East Indian possessions, that the jute trade in Dundee got a proper start. That fortunate circumstance gave an impulse to the spinning of the fibre which it never lost, and since that period its progress has been truly astonishing.”

The demand for this class of bagging, which is made from fine hessian yarns, is still great. These fine Rio hessian yarns form an important branch of the Dundee trade, and in some weeks during 1906 as many as 1000 bales were despatched to Brazil, besides numerous quantities to other parts of the world.

For many years Great Britain was the only European country engaged in the manufacture of jute, the great seat being Dundee. Gradually, however, the trade began to extend, and now almost every European country is partly engaged in the trade.

The success of the mechanical method of spinning and weaving of jute in Dundee and district led to the introduction of textile machinery into and around Calcutta. The first mill to be run there by power was started in 1854, while by 1872 three others had been established. In the next ten years no fewer than sixteen new mills were erected and equipped with modern machinery from Great Britain, while in 1907 there were thirty-nine mills engaged in the industry. The expansion of the Indian power trade may be gathered from the following particulars of the number of looms and spindles from 1892 to 1906. In one or two cases the number of spindles is obtained approximately by reckoning twenty spindles per loom, which is about the average for the Indian mills.

| Year. | Looms. | Spindles. |

| 1892-3 | 8,479 | 177,732 |

| 1893-4 | 9,082 | 189,144 |

| 1894-5 | 9,504 | 197,673 |

| 1895-6 | 10,071 | 212,595 |

| 1896-7 | 12,276 | 254,610 |

| 1897-8 | 12,737 | 271,363 |

| 1898-9 | 13,323 | 277,398 |

| 1899-1900 | 14,021 | 293,218 |

| 1900-01 | 15,242 | 315,264 |

| 1901-02 | 16,059 | 329,300 |

| 1902-03 | 17,091 | 350,120 |

| 1904* | 19,901 | 398,020** |

| 1905* | 21,318 | 426,360** |

| 1906* | 26,799 | 520,980** |

* End of calendar year, the remainder being taken to the 31st of March, the end of financial year.

** Approximate number of spindles.

The Calcutta looms are engaged for the most part with a few varieties of the commoner classes of jute fabrics, but the success in this direction has been really remarkable. Dundee, on the other hand, turns out not only the commoner classes of fabrics, but a very large variety of other fabrics. Amongst these may be mentioned the following: Hessian, bagging, tarpaulin, sacking, scrims, Brussels carpets, Wilton carpets, imitation Brussels, and several other types of carpets, rugs and matting, in addition to a large variety of fabrics of which jute forms a part. Calcutta has certainly taken a large part of the trade which Dundee held in its former days, but the continually increasing demands for jute fabrics for new purposes have enabled Dundee to enter new markets and so to take part in the prosperity of the trade.

The development of the trade with countries outside India from 1828 to 1906 may be seen by the following figures of exports:—

| Average | per year | from | 1828 | to | 1832-33 | 11,800 | cwt. |

| ” | ” | ” | 1833-34 | ” | 1837-38 | 67,483 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1838-39 | ” | 1842-43 | 117,047 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1843-44 | ” | 1847-48 | 234,055 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1848-49 | ” | 1852-53 | 439,850 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1853-54 | ” | 1857-58 | 710,826 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1858-59 | ” | 1862-63 | 969,724 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1863-64 | ” | 1867-68 | 2,628,110 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1868-69 | ” | 1872-73 | 4,858,162 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1873-74 | ” | 1877-78 | 5,362,267 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1878-79 | ” | 1882-83 | 7,274,000 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1883-84 | ” | 1887-88 | 8,223,859 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1888-89 | ” | 1892-93 | 10,372,991 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1893-94 | ” | 1897-98 | 12,084,292 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1898-99 | ” | 1902-03 | 11,959,189 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1903-04 | ” | 1905-06 | 13,693,090 | ” |

The subjoined table shows the extent of the trade from an agricultural, as well as from a manufacturing, point of view. The difference between the production and the exports represents the native consumption, for very little jute is sent overland. The figures are taken to the 31st of March, the end of the Indian financial year.

| Year. | Acres under cultivation. | Production in cwt. | Exports by sea in cwt. |

| 1893 | 2,181,334 | 20,419,000 | 10,537,512 |

| 1894 | 2,230,570 | 17,863,000 | 8,690,133 |

| 1895 | 2,275,335 | 21,944,400 | 12,976,791 |

| 1896 | 2,248,593 | 19,825,000 | 12,266,781 |

| 1897 | 2,215,105 | 20,418,000 | 11,464,356 |

| 1898 | 2,159,908 | 24,425,000 | 15,023,325 |

| 1899 | 1,690,739 | 19,050,000 | 9,864,545 |

| 1900 | 2,070,668 | 19,329,000 | 9,725,245 |

| 1901 | 2,102,236 | 23,307,000 | 12,414,552 |

| 1902 | 2,278,205 | 26,564,000 | 14,755,115 |

| 1903 | 2,142,700 | 23,489,000 | 13,036,486 |

| 1904 | 2,275,050 | 25,861,000 | 13,721,447 |

| 1905 | 2,899,700 | 26,429,000 | 12,875,312 |

| 1906 | 3,181,600 | 29,945,000 | 14,581,307 |

Manufacture.—In their general features the spinning and weaving of jute fabrics do not differ essentially as to machinery and processes from those employed in the manufacture of hemp and heavy flax goods. Owing, however, to the woody and brittle nature of the fibre, it has to undergo a preliminary treatment peculiar to itself. The pioneers of the jute industry, who did not understand this necessity, or rather who did not know how the woody and brittle character of the fibre could be remedied, were greatly perplexed by the difficulties they had to encounter, the fibre spinning badly into a hard, rough and hairy yarn owing to the splitting and breaking of the fibre. This peculiarity of jute, coupled also with the fact that the machinery on which it was first spun, although quite suitable for the stronger and more elastic fibres for which it was designed, required certain modifications to suit it to the weaker jute, was the cause of many annoyances and failures in the early days of the trade.

|

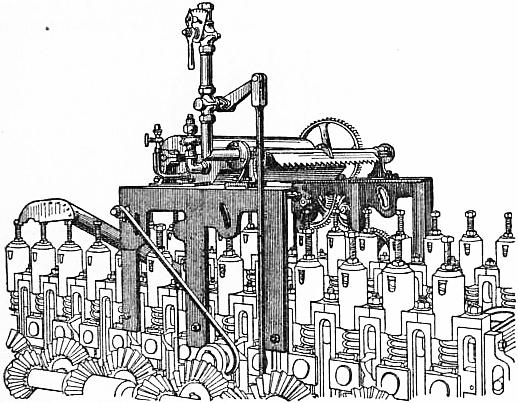

| Fig. 3.—Jute Opener. (The three machines shown in this article are made by Urquhart, Lindsay & Co., Ltd., Dundee.) |

The first process in the manufacture of jute is termed batching. Batch setting is the first part of this operation; it consists of selecting the different kinds or qualities of jute for any predetermined kind of yarn. The number of bales for a batch seldom exceeds twelve, indeed it is generally about six, and of these there may be three, four or even more varieties or marks. The “streaks”1 or “heads” of jute as they come from the bale are in a hard condition in consequence of having been subjected to a high hydraulic pressure during baling; it is therefore necessary to soften them before any further process is entered. The streaks are sometimes partly softened or crushed by means of a steam hammer during the process of opening the bale, then taken to the “strikers-up” where the different varieties are selected and hung on pins, and then taken to the jute softening machine. The more general practice, however, is to employ what is termed a “bale opener,” or “jute crusher.” The essential parts of one type of bale opener are three specially shaped rollers, the peripheries of which contain a number of small knobs. Two of these rollers are supported in the same horizontal plane of the framework, while the third or top roller is kept in close contact by means of weights and springs acting on each end of the arbor. Another type of machine termed the three pair roller jute opener is illustrated in fig. 3. The layers from the different bales are laid upon the feed cloth which carries them up to the rollers, between which the layers are crushed and partly separated. The proximity of the weighted roller or rollers to the fixed ones depends upon the thickness of material passing through the machine. The fibre is delivered by what is called the delivery cloth, and the batcher usually selects small streaks of about 1½ ℔ to 2 ℔ weight each and passes them on to the attendant or feeder of the softening machine. These small streaks are now laid as regularly as possible upon the feed-cloth of the softening machine, a general view of which is shown in fig. 4. The fibre passes between a series of fluted rollers, each pair of which is kept in contact by spiral springs as shown in the figure. The standard number of pairs is sixty-three, but different lengths obtain. There is also a difference in the structure of the flutes, some being straight, and others spiral, and each pair may or may not contain the same number of flutes. The springs allow the top rollers of each pair to rise as the material passes through the machine. Advantage is taken of this slight upward and downward movement of the top rollers to automatically regulate the flow of water and oil upon the material. The apparatus for this function is placed immediately over the 11th and 12th rollers of the softening machine and an idea of its construction may be gathered from fig. 5. In many cases the water and oil are applied by less automatic, but equally effective, means. The main object is to see that the liquids are distributed evenly while the fibre is passing through, and to stop the supply when the machine stops or when no fibre is passing. The uniform moistening of the fibre in this machine facilitates the subsequent operations, indeed the introduction of this preliminary process (originally by hand) constituted the first important step in the practical solution of the difficulties of jute spinning. The relative quantities of oil and water depend upon the quality of the batch. Sometimes both whale and mineral oils are used, but in most cases the whale oil is omitted. About 1 to 1¼ gallons of oil is the usual amount given per bale of 400 ℔ of jute, while the quantity of water per bale varies from 3 to 7 gallons. The delivery attendants remove the streaks, give them a twist to facilitate future handling, and place them on what are termed jute barrows. The streaks are now handed over to the cutters who cut off the roots, and finally the material is allowed to remain for twelve to twenty-four hours to allow the mixture of oil and water to thoroughly spread over the fibre.

|

| Fig. 4.—Jute Softening Machine. |

|

| Fig. 5.—Improved Batching Gear. |

When the moisture has spread sufficiently, the material is taken to the “breaker card,” the first machine in the preparing department. A certain weight of jute, termed a “dollop,” is laid upon the feed cloth for each revolution of the latter. The fibre, which should be arranged on the sheet as evenly as possible, is carried up by the feed cloth and passes between the feed roller and the shell on to the 608 large cylinder. This cylinder, which has a high surface speed, carries part of the fibre towards the workers and strippers; the surface speed of the workers being much slower than that of the cylinder. The pins in the two rollers oppose each other, those of the workers being “back-set,” and this arrangement, combined with the relative angle of the pins, and the difference in the surface speeds of the two rollers, results in part of the fibre being broken and carried round by the worker towards the stripper. This, as its name implies, strips the fibre off the worker, and carries it round to the cylinder. The pins of the stripper and cylinder point in the same direction, but since the surface speed of the cylinder is much greater than the surface speed of the stripper, it follows that the fibre is combed between the two, and that part is carried forward by the cylinder to be reworked. The strippers and workers are in pairs, of which there may be two or more. After passing the last pair of workers and strippers the fibre is carried forward towards the doffing roller, the pins of which are back-set, and the fibre is removed from the cylinder by the doffer, from which it passes between the drawing and pressing rollers into the conductor, and finally between the delivery and pressing rollers into the sliver can. It may be mentioned that more or less breaking takes place between each pair of rollers, the pins of which are opposed, and that combing and drawing out obtains between those rollers with pins pointing in the same direction. The ratio of the surface speeds of the drawing roller and the feed roller is termed the draft:—

| surface speed of drawing roller | = draft. |

| surface speed of feed roller |

In this machine the draft is usually about thirteen.

The sliver from the can of the breaker card may be wound into balls, or it may be taken direct to the finisher card. In the latter method from eight to fifteen cans are placed behind the feed rollers, and all the slivers from these cans are united before they emerge from the machine. The main difference between a breaker card and a finisher card is that the latter is fitted with finer pins, that it contains two doffing rollers, and that it usually possesses a greater number of pairs of workers and strippers—a full circular finisher card having four sets.

After the fibre has been thoroughly carded by the above machines, the cans containing the sliver from the finisher card are taken to the first drawing frame. A very common method is to let four slivers run into one sliver at the first drawing, then two slivers from the first drawing are run into one sliver at the second drawing frame. There are several types of drawing frames, e.g. push-bar or slide, rotary, spiral, ring, open-link or chain, the spiral being generally used for the second drawing. All, however, perform the same function, viz., combing out the fibres and thus laying them parallel, and in addition drawing out the sliver. The designation of the machine indicates the particular method in which the gill pins are moved. These pins are much finer than those of the breaker and finisher cards, consequently the fibres are more thoroughly separated. The draft in the first drawing varies from three to five, while that in the second drawing is usually five to seven. It is easy to see that a certain amount of draft, or drawing out of the sliver, is necessary, otherwise the various doublings would cause the sliver to emerge thicker and thicker from each machine. The doublings play a very important part in the appearance of the ultimate rove and yarn, for the chief reason for doubling threads or slivers is to minimize irregularities of thickness and of colour in the material. In an ordinary case, the total doublings in jute from the breaker card to the end of the second drawing is ninety-six: 12 × 4 × 2 = 96; and if the slivers were made thinner and more of them used the ultimate result would naturally be improved.

The final preparing process is that of roving. In this operation there is no doubling of the slivers, but each sliver passes separately through the machine, from the can to the spindle, is drawn out to about eight times its length, and receives a small amount of twist to strengthen it, in order that it may be successfully wound upon the roving bobbin by the flyer. The chief piece of mechanism in the roving frame is the gearing known as the “differential motion.” It works in conjunction with the disk and scroll, the cones, or the expanding pulley, to impart an intermittingly variable speed to the bobbin (each layer of the bobbin has its own particular speed which is constant for the full traverse, but each change of direction of the builder is accompanied by a quick change of speed to the bobbin). It is essential that the bobbin should have such a motion, because the delivery of the sliver and the speed of the flyer are constant for a given size of rove, whereas the layers of rove on the bobbin increase in length as the bobbin fills. In the jute roving frame the bobbin is termed the “follower,” because its revolutions per minute are fewer than those of the flyer. Each layer of rove increases the diameter of the material on the bobbin shank; hence, at the beginning of each layer, the speed of the bobbin must be increased, and kept at this increased speed for the whole traverse from top to bottom or vice versa.

| Let R = the revolutions per second of the flyer; r = the revolutions per second of the bobbin; d = the diameter of bobbin shaft plus the material; L = the length of sliver delivered per second; then (R − r) d·π = L. |

In the above expression R, π and L are constant, therefore as d increases the term (R − r) must decrease; this can happen only when r is increased, that is, when the bobbin revolves quicker. It is easy to see from the above expression that if the bobbin were the “leader” its speed would have to decrease as it filled.

The builder, which receives its motion from the disk and scroll, from the cones, or from the expanding pulley, has also an intermittingly variable speed. It begins at a maximum speed when the bobbin is empty, is constant for each layer, but decreases as the bobbin fills.

The rove yarn is now ready for the spinning frame, where a further draft of about eight is given. The principles of jute spinning are similar to those of dry spinning for flax. For very heavy jute yarns the spinning frame is not used—the desired amount of twist being given at the roving frame.

The count of jute yarn is based upon the weight in pounds of 14,400 yds., such length receiving the name of “spyndle.” The finest yarns weigh 2¾ ℔ to 3 ℔ per spyndle, but the commonest kinds are 7 ℔, 8 ℔, 9 ℔ and 10 ℔ per spyndle. The sizes rise in pounds up to about 20 ℔, then by 2 ℔ up to about 50 ℔ per spyndle, with much larger jumps above this weight. It is not uncommon to find 200 ℔ to 300 ℔ rove yarn, while the weight occasionally reaches 450 ℔ per spyndle. The different sizes of yarn are extensively used in a large variety of fabrics, sometimes alone, sometimes in conjunction with other fibres, e.g. with worsted in the various kinds of carpets, with cotton in tapestries and household cloths, with line and tow yarns for the same fabrics and for paddings, &c., and with wool for horse clothing. The yarns are capable of being dyed brilliant colours, but, unfortunately, the colours are not very fast to light. The fibre can also be prepared to imitate human hair with remarkable closeness, and advantage of this is largely taken in making stage wigs.

For detailed information regarding jute, the cloths made from it and the machinery used, see the following works: Watts’s Dictionary of the Economic Products of India; Royle’s Fibrous Plants of India; Sharp’s Flax, Tow and Jute Spinning; Leggatt’s Jute Spinning; Woodhouse and Milne’s Jute and Linen Weaving; and Woodhouse and Milne’s Textile Design: Pure and Applied.

1 Also in the forms “streek,” “strick” or “strike,” as in Chaucer, Cant. Tales, Prologue 676, where the Pardoner’s hair is compared with a “strike of flax.” The term is also used of a handful of hemp or other fibre, and is one of the many technical applications of “strike” or “streak,” which etymologically are cognate words.

JÜTERBOG, or Güterbog, a town of Germany in the Prussian province of Brandenburg, on the Nuthe, 39 m. S.W. of Berlin, at the junction of the main lines of railway from Berlin to Dresden and Leipzig. Pop. (1900), 7407. The town is surrounded by a medieval wall, with three gateways, and contains two Protestant churches, of which that of St Nicholas (14th century) is remarkable for its three fine aisles. There are also a Roman Catholic church, an old town-hall and a modern school. Jüterbog carries on weaving and spinning both of flax and wool, and trades in the produce of those manufactures and in cattle. Vines are cultivated in the neighbourhood. Jüterbog belonged in the later middle ages to the archbishopric of Magdeburg, passing to electoral Saxony in 1648, and to Prussia in 1815. It was here that a treaty over the succession to the duchy of Jülich was made in March 1611 between Saxony and Brandenburg, and here in November 1644 the Swedes defeated the Imperialists. Two miles S.W. of the town is the battlefield of Dennewitz where the Prussians defeated the French on the 6th of September 1813.

JUTES, the third of the Teutonic nations which invaded Britain in the 5th century, called by Bede Iutae or Iuti (see Britain, Anglo-Saxon). They settled in Kent and the Isle of Wight together with the adjacent parts of Hampshire. In the latter case the national name is said to have survived until Bede’s own time, in the New Forest indeed apparently very much later. In Kent, however, it seems to have soon passed out of use, though there is good reason for believing that the inhabitants of that kingdom were of a different nationality from their neighbours (see Kent, Kingdom of). With regard to the origin of the Jutes, Bede only says that Angulus (Angel) lay between the territories of the Saxons and the Iutae—a statement which points to their identity with the Iuti or Jyder of later times, i.e. the inhabitants of Jutland. Some recent writers have preferred to identify the Jutes with a tribe called Eucii mentioned in a letter from Theodberht to Justinian (Mon. Germ. Hist., Epist. iii., p. 132 seq.) and settled apparently in the neighbourhood of the Franks. But these people may themselves have come from Jutland.

See Bede, Hist. Eccles, i. 15, iv. 16.

JUTIGALPA, or Juticalpa, the capital of the department of Jutigalpa in eastern Honduras, on one of the main roads from the Bay of Fonseca to the Atlantic coast, and on a small left-hand tributary of the river Patuca. Pop. (1905), about 18,000. Jutigalpa is the second city of Honduras, being surpassed only by Tegucigalpa. It is the administrative centre of a mountainous region rich in minerals, though mining is rendered difficult by the lack of communications and the unsettled condition of the country. The majority of the inhabitants are Indians or half-castes, engaged in the cultivation of coffee, bananas, tobacco, sugar or cotton.

JUTLAND (Danish Jylland), though embracing several islands as well as a peninsula, may be said to belong to the continental portion of the kingdom of Denmark. The peninsula (Chersonese or Cimbric peninsula of ancient geography) extends northward, from a line between Lübeck and the mouth of the Elbe, for 270 m. to the promontory of the Skaw (Skagen), thus preventing a natural communication directly east and west between the Baltic and North Seas. The northern portion only is Danish, and bears the name Jutland. The southern is German, belonging to Schleswig-Holstein. The peninsula is almost at its narrowest (36 m.) at the frontier, but Jutland has an extreme breadth of 110 m. and the extent from the south-western point (near Ribe) to the Skaw is 180 m. Jutland embraces nine amter (counties), namely, Hjörring, Thisted, Aalborg, Ringkjöbing, Viborg, Randers, Aarhus, Vejle and Ribe. The main watershed of the peninsula lies towards the east coast; therefore such elevated ground as exists is found on the east, while the western slope is gentle and consists of a low sandy plain of slight undulation. The North Sea coast (western) and Skagerrack coast (north-western) consist mainly of a sweeping line of dunes with wide lagoons behind them. In the south the northernmost of the North Frisian Islands (Fanö) is Danish. Towards the north a narrow mouth gives entry to the Limfjord, or Liimfjord, which, wide and ramifying among islands to the west, narrows to the east and pierces through to the Cattegat, thus isolating the counties of Hjörring and Thisted (known together as Vendsyssel). It is, however, bridged at Aalborg, and its depth rarely exceeds 12 ft. The seaward banks of the lagoons are frequently broken in storms, and the narrow channels through them are constantly shifting. The east coast is slightly bolder than the west, and indented with true estuaries and bays. From the south-east the chain of islands forming insular Denmark extends towards Sweden, the strait between Jutland and Fünen having the name of the Little Belt. The low and dangerous coasts, off which the seas are generally very shallow, are efficiently served by a series of lifeboat stations. The western coast region is well compared with the Landes of Gascony. The interior is low. The Varde, Omme, Skjerne, Stor and Karup, sluggish and tortuous streams draining into the western lagoons, rise in and flow through marshes, while the eastern Limfjord is flanked by the swamps known as Vildmose. The only considerable river is the Gudenaa, flowing from S.W. into the Randersfjord (Cattegat), and rising among the picturesque lakes of the county of Aarhus, where the principal elevated ground in the peninsula is found in the Himmelbjerg and adjacent hills (exceeding 500 ft.). The German portion of the peninsula is generally similar to that of western Jutland, the main difference lying in the occurrence of islands (the North Frisian) off the west coast in place of sand-bars and lagoons. Erratic blocks are of frequent occurrence in south Jutland. (For geology, and the general consideration of Jutland in connexion with the whole kingdom, see Denmark.)

Although in ancient times well wooded, the greater portion of the interior of Jutland consisted for centuries of barren drift-sand, which grew nothing but heather; but since 1866, chiefly through the instrumentality of the patriotic Heath association, assisted by annual contributions from the state, a very large proportion of this region has been more or less reclaimed for cultivation. The means adopted are: (i.) the plantation of trees; (ii.) the making of irrigation canals and irrigating meadows; (iii.) exploring for, extracting and transporting loam, a process aided by the construction of short light railways; and (iv.), since 1889, the experimental cultivation of fenny districts. The activity of the association takes the form partly of giving gratuitous advice, partly of experimental attempts, and partly of model works for imitation. The state also makes annual grants directly to owners who are willing to place their plantations under state supervision, for the sale of plants at half price to the poorer peasantry, for making protective or sheltering plantations, and for free transport of marl or loam. The species of timber almost exclusively planted are the red fir (Picea excelsa) and the mountain pine (Pinus montana). This admirable work quickly caused the population to increase at a more rapid rate in the districts where it was practised than in any other part of the Danish kingdom. The counties of Viborg, Ringkjöbing and Ribe cover the principal heath district.

Jutland is well served by railways. Two lines cross the frontier from Germany on the east and west respectively and run northward near the coasts. The eastern touches the ports of Kolding, Fredericia, Vejle, Horsens, Aarhus, Randers, Aalborg on Limfjord, Frederikshavn and Skagen. On the west the only port of first importance is Esbjerg. The line runs past Skjerne, Ringkjöbing, Vemb and Holstebro to Thisted. Both throw off many branches and are connected by lines east and west between Kolding and Esbjerg, Skanderborg and Skjerne, Langaa and Struer on Limfjord via Viborg. Of purely inland towns only Viborg in the midland and Hjörring in the extreme north are of importance.

JUTURNA (older form Diuturna, the lasting), an old Latin divinity, a personification of the never-failing springs. Her original home was on the river Numicius near Lavinium, where there was a spring called after her, supposed to possess healing qualities (whence the old Roman derivation from juvare, to help). Her worship was early transferred to Rome, localized by the Lacus Juturnae near the temple of Vesta, at which Castor and Pollux, after announcing the victory of lake Regillus, were said to have washed the sweat from their horses. At the end of the First Punic War Lutatius Catulus erected a temple in her honour on the Campus Martius, subsequently restored by Augustus. Juturna was associated with two festivals: the Juturnalia on the 11th of January, probably a dedication festival of a temple built by Augustus, and celebrated by the college of the fontani, workmen employed in the construction and maintenance of aqueducts and fountains; and the Volcanalia on the 23rd of August, at which sacrifice was offered to Volcanus, the Nymphs and Juturna, as protectors against outbreaks of fire. In Virgil, Juturna appears as the sister of Turnus (probably owing to the partial similarity of the names), on whom Jupiter, to console her for the loss of her chastity, bestowed immortality and the control of all the lakes and rivers of Latium. For the statement that she was the wife of Janus and mother of Fontus (or Fons), the god of fountains, Arnobius (Adv. gentes iii. 29) is alone responsible.

See Virgil, Aeneid, xii. 139 and Servius ad loc.; Ovid, Fasti, ii. 583-616; Valerius Maximus, i. 8. 1; L. Deubner, “Juturna und die Ausgrabungen auf dem römischen Forum,” in Neue Jahrb. f. das klassische Altertum (1902), p. 370.

JUVENAL (Decimus Junius Juvenalis) (c. 60-140), Roman poet and satirist, was born at Aquinum. Brief accounts of his life, varying considerably in details, are prefixed to different MSS. of the works. But their common original cannot be traced to any competent authority, and some of their statements are intrinsically improbable. According to the version which appears to be the earliest:—

“Juvenal was the son or ward of a wealthy freedman; he practised declamation till middle age, not as a professional teacher, but as an amateur, and made his first essay in satire by writing the lines on Paris, the actor and favourite of Domitian, now found in the seventh satire (lines 90 seq.). Encouraged by their success, he devoted himself diligently to this kind of composition, but refrained for a long time from either publicly reciting or publishing his verses. When at last he did come before the public, his recitations were attended by great crowds and received with the utmost favour. But the lines originally written on Paris, having been inserted in one of his new satires, excited the jealous anger of an actor of the time, who was a favourite of the emperor, and procured the poet’s banishment under the form of a military appointment to the extremity of Egypt. Being then eighty years of age, he died shortly afterwards of grief and vexation.”

Some of these statements are so much in consonance with the indirect evidence afforded by the satires that they may be a series of conjectures based upon them. The rare passages in which the poet speaks of his own position, as in satires xi. and xiii., indicate that he was in comfortable but moderate circumstances. We should infer also that he was not dependent on any professional occupation, and that he was separated in social station, and probably too by tastes and manners, from the higher class to which Tacitus and Pliny belonged, as he was by character from the new men who rose to wealth by servility under the empire. Juvenal is no organ of the pride and dignity, still less of the urbanity, of the cultivated representatives of the great families of the republic. He is the champion of the more sober virtues and ideas, and perhaps the organ of the rancours and detraction, of an educated but depressed and embittered middle class. He lets us know that he has no leanings to philosophy (xiii. 121) and pours contempt on the serious epic writing of the day (i. 162). The statement that he was a trained and practised declaimer is confirmed both by his own words (i. 16) and by the rhetorical mould in which his thoughts and illustrations are cast. The allusions which fix the dates when his satires first appeared, and the large experience of life which they imply, agree with the statement that he did not come before the world as a professed satirist till after middle age.

The statement that he continued to write satires long before he gave them to the world accords well with the nature of their contents and the elaborate character of their composition, and might almost be inferred from the emphatic but yet guarded statement of Quintilian in his short summary of Roman literature. After speaking of the merits of Lucilius, Horace and Persius as satirists, he adds, “There are, too, in our own day, distinguished writers of satire whose names will be heard of hereafter” (Inst. Or. x. 1, 94). There is no Roman writer of satire who could be mentioned along with those others by so judicious a critic, except Juvenal. The motive which a writer of satire must have had for secrecy under Domitian is sufficiently obvious; and the necessity of concealment and self-suppression thus imposed upon the writer may have permanently affected his whole manner of composition.

So far the original of these lives follows a not improbable tradition. But when we come to the story of the poet’s exile the case is otherwise. The undoubted reference to Juvenal in Sidonius Apollinaris as the victim of the rage of an actor only proves that the original story from which all the varying versions of the lives are derived was generally believed before the middle of the 5th century of our era. If Juvenal was banished at the age of eighty, the author of his banishment could not have been the “enraged actor” in reference to whom the original lines were written, as Paris was put to death in 83, and Juvenal was certainly writing satires long after 100. The satire in which the lines now appear was probably first published soon after the accession of Hadrian, when Juvenal was not an octogenarian but in the maturity of his powers. The cause of the poet’s banishment at that advanced age could not therefore have been either the original composition or the first publication of the lines.

An expression in xv. 45 is quoted as a proof that Juvenal had visited Egypt. He may have done so as an exile or in a military command; but it seems hardly consistent with the importance which the emperors attached to the security of Egypt, or with the concern which they took in the interests of the army, that these conditions were combined at an age so unfit for military employment. If any conjecture is warrantable on so obscure a subject, it is more likely that this temporary disgrace should have been inflicted on the poet by Domitian. Among the many victims of Juvenal’s satire it is only against him and against one of the vilest instruments of his court, the Egyptian Crispinus, that the poet seems to be animated by personal hatred. A sense of wrong suffered at their hands may perhaps have mingled with the detestation which he felt towards them on public grounds. But if he was banished under Domitian, it must have been either before or after 93, at which time, as we learn from an epigram of Martial, Juvenal was in Rome.

More ancient evidence is supplied by an inscription found at Aquinum, recording, so far as it has been deciphered, the dedication of an altar to Ceres by a Iunius Iuvenalis, tribune of the first cohort of Dalmatians, duumvir quinquennalis, and flamen Divi Vespasiani, a provincial magistrate whose functions corresponded to those of the censor at Rome. This Juvenalis may have been the poet, but he may equally well have been a relation. The evidence of the satires does not point to a prolonged absence from the metropolis. They are the product of immediate and intimate familiarity with the life of the great city. An epigram of Martial, written at the time when Juvenal was most vigorously employed in their composition, speaks of him as settled in Rome. He himself hints (iii. 318) that he maintained his connexion with Aquinum, and that he had some special interest in the worship of the “Helvinian Ceres.” Nor is the tribute to the national religion implied by the dedication of the altar to Ceres inconsistent with the beliefs and feelings expressed in the satires. While the fables of mythology are often treated contemptuously or humorously by him, other passages in the satires clearly imply a conformity to, and even a respect for, the observances of the national religion. The evidence as to the military post filled by Juvenal is curious, when taken in connexion with the confused tradition of his exile in a position of military importance. But it cannot be said that the satires bear traces of military experience; the life described in them is rather such as would present itself to the eyes of a civilian.

The only other contemporary evidence which affords a glimpse of Juvenal’s actual life is contained in three epigrams of Martial. Two of these (vii. 24 and 91) were written in the time of Domitian, the third (xii. 18) early in the reign of Trajan, after Martial had retired to his native Bilbilis. The first attests the strong regard which Martial felt for him; but the subject of the epigram seems to hint that Juvenal was not an easy person to get on with. In the second, addressed to Juvenal himself, the epithet facundus is applied to him, equally applicable to his “eloquence” as satirist or rhetorician. In the last Martial imagines his friend wandering about discontentedly through the crowded streets of Rome, and undergoing all the discomforts incident to attendance on the levées of the great. Two lines in the poem suggest that the satirist, who inveighed with just severity against the worst corruptions of Roman morals, was not too rigid a censor of the morals of his friend. Indeed, his intimacy with Martial is a ground for not attributing to him exceptional strictness of life.

The additional information as to the poet’s life and circumstances derivable from the satires themselves is not important. He had enjoyed the training which all educated men received in his day (i. 15); he speaks of his farm in the territory of Tibur 611 (xi. 65), which furnished a young kid and mountain asparagus for a homely dinner to which he invites a friend during the festival of the Megalesia. From the satire in which this invitation is contained we are able to form an idea of the style in which he habitually lived, and to think of him as enjoying a hale and vigorous age (203), and also as a kindly master of a household (159 seq.). The negative evidence afforded in the account of his establishment suggests the inference that, like Lucilius and Horace, Juvenal had no personal experience of either the cares or the softening influence of family life. A comparison of this poem with the invitation of Horace to Torquatus (Ep. i. 5) brings out strongly the differences not in urbanity only but in kindly feeling between the two satirists. Gaston Boissier has drawn from the indications afforded of the career and character of the persons to whom the satires are addressed most unfavourable conclusions as to the social circumstances and associations of Juvenal. If we believe that these were all real people, with whom Juvenal lived in intimacy, we should conclude that he was most unfortunate in his associates, and that his own relations to them were marked rather by outspoken frankness than civility. But they seem to be more “nominis umbrae” than real men; they serve the purpose of enabling the satirist to aim his blows at one particular object instead of declaiming at large. They have none of the individuality and traits of personal character discernible in the persons addressed by Horace in his Satires and Epistles. It is noticeable that, while Juvenal writes of the poets and men of letters of a somewhat earlier time as if they were still living, he makes no reference to his friend Martial or the younger Pliny and Tacitus, who wrote their works during the years of his own literary activity. It is equally noticeable that Juvenal’s name does not appear in Pliny’s letters.

The times at which the satires were given to the world do not in all cases coincide with those at which they were written and to which they immediately refer. Thus the manners and personages of the age of Domitian often supply the material of satiric representation, and are spoken of as if they belonged to the actual life of the present,1 while allusions even in the earliest show that, as a finished literary composition, it belongs to the age of Trajan. The most probable explanation of these discrepancies is that in their present form the satires are the work of the last thirty years of the poet’s life, while the first nine at least may have preserved with little change passages written during his earlier manhood. The combination of the impressions, and, perhaps of the actual compositions, of different periods also explains a certain want of unity and continuity found in some of them.

There is no reason to doubt that the sixteen satires which we possess were given to the world in the order in which we find them, and that they were divided, as they are referred to in the ancient grammarians, into five books. Book I., embracing the first five satires, was written in the freshest vigour of the author’s powers, and is animated with the strongest hatred of Domitian. The publication of this book belongs to the early years of Trajan. The mention of the exile of Marius (49) shows that it was not published before 100. In the second satire, the lines 29 seq.,

| “Qualis erat nuper tragico pollutus adulter Concubitu,” |