Title: True Bear Stories

Author: Joaquin Miller

Author of introduction, etc.: David Starr Jordan

Release date: September 26, 2012 [eBook #40869]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRUE BEAR STORIES

JOAQUIN MILLER

TOGETHER WITH A THRILLING ACCOUNT OF THE

CAPTURE OF THE CELEBRATED

GRIZZLY “MONARCH.”

FULLY ILLUSTRATED.

CHICAGO AND NEW YORK:

RAND, McNALLY & COMPANY,

PUBLISHERS.

Copyright, 1900, by Rand, McNally & Co.

DEDICATED

to

My Dear Little Daughter,

JUANITA MILLER,

FOR WHOSE PLEASURE AND INSTRUCTION I HAVE MANY TIMES

DUG UP THE MOST OF THESE STORIES FROM

OUT THE DAYS OF MY BOYHOOD.

My Bright Young Reader: I was once exactly your own age. Like all boys, I was, from the first, fond of bear stories, and above all, I did not like stories that seemed the least bit untrue. I always preferred a natural and reasonable story and one that would instruct as well as interest. This I think best for us all, and I have acted on this line in compiling these comparatively few bear stories from a long life of action in our mountains and up and down the continent.

As a rule, the modern bear is not a bloody, bad fellow, whatever he may have been in Bible days. You read, almost any circus season, about the killing of his keeper by a lion, a tiger, a panther, or even the dreary old elephant, but you never hear of a tame bear’s hurting anybody.

I suppose you have been told, and believe, that bears will eat boys,

good or bad, if they meet them in the woods. This is not true. On the

contrary, there are several well-authenticated cases, in Germany

mostly, where bears have taken lost children under their protection,

one boy having been[Pg 1]

[Pg 2] reared from the age of four to sixteen by a she

bear without ever seeing the face of man.

I have known several persons to be maimed or killed in battles with bears, but in every case it was not the bear that began the fight, and in all my experience of about half a century I never knew a bear to eat human flesh, as does the tiger and like beasts.

Each branch of the bear family is represented here and each has its characteristics. By noting these as you go along you may learn something not set down in the schoolbooks. For the bear is a shy old hermit and is rarely encountered in his wild state by anyone save the hardy hunter, whose only interest in the event is to secure the skin and carcass.

Of course, now and then, a man of science meets a bear in the woods, but the meeting is of short duration. If the bear does not leave, the man of books does, and so we seldom get his photograph as he really appears in his wild state. The first and only bear I ever saw that seemed to be sitting for his photograph was the swamp, or “sloth,” bear—Ursus Labiatus—found in[Pg 3] the marshes at the mouth of the Mississippi River. You will read of an encounter with him further on.

I know very well that there exists a good deal of bad feeling between boys and bears, particularly on the part of boys. The trouble began, I suppose, about the time when that old she bear destroyed more than forty boys at a single meeting, for poking fun at a good old prophet. And we read that David, when a boy, got very angry at a she bear and slew her single-handed and alone for interfering with his flock. So you see the feud between the boy and bear family is an old one indeed.

But I am bound to say that I have found much that is pathetic, and something that is almost half-human, in this poor, shaggy, shuffling hermit. He doesn’t want much, only the wildest and most worthless parts of the mountains or marshes, where, if you will let him alone, he will let you alone, as a rule. Sometimes, out here in California, he loots a pig-pen, and now and then he gets among the bees. Only last week, a little black bear got his head fast in a bee-hive that had been improvised from a nail-keg, and the bee-farmer killed him with a pitchfork;[Pg 4] but it is only when hungry and far from home that he seriously molests us.

The bear is a wise beast. This is, perhaps, because he never says anything. Next to the giraffe, which you may know never makes any noise or note whatever, notwithstanding the wonderful length of his throat, the bear is the most noiseless of beasts. With his nose to the ground all the time, standing up only now and then to pull a wild plum or pick a bunch of grapes, or knock a man down if he must, he seems to me like some weary old traveler that has missed the right road of life and doesn’t quite know what to do with himself. Ah! if he would only lift up his nose and look about over this beautiful world, as the Indians say the grizzly bear was permitted to do before he disobeyed and got into trouble, an account of which you will find further on, why, the bear might be less a bear.

Stop here and reflect on how much there is in keeping your face well lifted. The pig with his snout to the ground will be forever a pig; the bear will be a bear to the end of his race, because he will not hold up his head in the world; but the horse—look at the horse! However, our business is with the bear now.

| Page | ||

| Introductory Notes | 7 | |

| I. | A Bear on Fire | 13 |

| II. | Music-Loving Bears | 29 |

| III. | My First Grizzly | 36 |

| IV. | Twin Babies | 44 |

| V. | In Swimming with a Bear | 56 |

| VI. | A Fat Little Editor and Three Little Browns | 68 |

| VII. | Treeing a Bear | 76 |

| VIII. | Bill Cross and His Pet Bear | 86 |

| IX. | The Great Grizzly Bear | 96 |

| X. | As a Humorist | 106 |

| XI. | A Grizzly’s Sly Little Joke | 110 |

| XII. | The Grizzly as Fremont Found Him | 112 |

| XIII. | The Bear with Spectacles | 116 |

| XIV. | The Bear-Slayer of San Diego | 129 |

| XV. | Alaskan and Polar Bear | 146 |

| XVI. | Monnehan, The Great Bear-Hunter of Oregon | 156 |

| XVII. | The Bear “Monarch”—How He Was Captured | 166 |

The bear is the most human of all the beasts. He is not the most man-like in anatomy, nor the nearest in the line of evolution. The likeness is rather in his temper and way of doing things and in the vicissitudes of his life. He is a savage, of course, but most men are that—wild members of a wild fauna—and, like wild men, the bear is a clumsy, good-natured blunderer, eating with his fingers in default of a knife, and preferring any day a mouthful of berries to the excitement of a fight.

In this book Joaquin Miller has tried to show us the bear as he is, not the traditional bear of the story-books. In season and out of season, the bear has been represented always the same bear, “as much alike as so many English noblemen in evening dress,” and always as a bloody bear.

Mr. Miller insists that there are bears and bears, as unlike one another in nature and action as so many horses, hogs or goats. This mon—bears are [Pg 8]never cruel. They are generally full of homely, careless kindness, and are very fond of music as well as of honey, blackberries, nuts, fish and other delicacies of the savage feast.

The matter of season affects a bear’s temper and looks as the time of the day affects those of a man.

He goes to bed in the fall, when the fish and berry season is over, fat and happy, with no fight in him. He comes out in spring, just as good-natured, if not so fat. But the hot sun melts him down. His hungry hunt for roots, bugs, ants and small game makes him lean and cross. His claws grow long, his hair is unkempt and he is soon a shaggy ghost of himself, looking “like a second-hand sofa with the stuffing coming out,” and in this out-at-elbows condition he loses his own self-respect.

Mr. Miller has strenuously insisted that bears of the United States are of more than one or two species. In this he has the unqualified support of the latest scientific investigations. Not long ago naturalists were disposed to recognize but three kinds of bear in North America. These are the polar bear, the black bear, and the grizzly bear,[Pg 9] and even the grizzly was thought doubtful, a slight variation of the bear of Europe.

But the careful study of bears’ skulls has changed all that, and our highest authority on bears, Dr. C. Hart Merriam of the Department of Agriculture, now recognizes not less than ten species of bear in the limits of the United States and Alaska.

In his latest paper (1896), a “Preliminary Synopsis of the American Bears,” Dr. Merriam groups these animals as follows:

I. POLAR BEARS.

1. Polar Bear: Thalarctos maritimus Linnaeus. Found on all Arctic shores.

II. BLACK BEARS.

2. Common Black Bear (sometimes brown or cinnamon): Ursus americanus Pallas. Found throughout the United States.

3. Yellow Bear (sometimes black or brown): Ursus luteolus Griffith. Swamps of Louisiana and Texas.

4. Everglade Bear: Ursus floridanus Merriam. Everglades of Florida.

5. Glacier Bear: Ursus emmonsi Dall. About Mount St. Elias.

III. GRIZZLY BEARS.

6. The Grizzly Bear: Ursus horribilis Ord. Found in the western parts of North America.

Under this species are four varieties: the original horribilis, or Rocky Mountain grizzly, from Montana to the Great Basin of Utah; the variety californicus Merriam, the California grizzly, from the Sierra Nevada; variety horriaeus Baird, the Sonora grizzly, from Arizona and the South; and variety alascensis Merriam, the Alaska grizzly, from Alaska.

7. The Barren Ground Bear: Ursus richardsoni Mayne Reid. A kind of grizzly found about Hudson Bay.

IV. GREAT BROWN BEARS.

8. The Yakutat Bear: Ursus dalli Merriam. From about Mount St. Elias.

9. The Sitka Bear: Ursus sitkensis Merriam. From about Sitka.

10. The Kadiak Bear: Ursus middendorfi Merriam. From Kadiak and the Peninsula of Alaska.

These three bears are even larger than[Pg 11] the grizzly, and the Kadiak Bear is the largest of all the land bears of the world. It prowls about over the moss of the mountains, feeding on berries and fish.

The sea-bear, Callorhinus ursinus, which we call the fur seal, is also a cousin of the bear, having much in common with its bear ancestors of long ago, but neither that nor its relations, the sea-lion and the walrus, are exactly bears to-day.

Of all the real bears, Mr. Miller treats of five in the pages of this little book. All the straight “bear stories” relate to Ursus americanus, as most bear stories in our country do. The grizzly stories treat of Ursus horribilis californicus. The lean bear of the Louisiana swamps is Ursus luteolus, and the Polar Bear is Thalarctos maritimus. The author of the book has tried without intrusion of technicalities to bring the distinctive features of the different bears before the reader and to instruct as well as to interest children and children’s parents in the simple realities of bear life.

Leland Stanford, Jr., University.

TRUE BEAR STORIES.

A BEAR ON FIRE.

It is now more than a quarter of a century since I saw the woods of Mount Shasta in flames, and beasts of all sorts, even serpents, crowded together; but I can never forget, never!

It looked as if we would have a cloudburst that fearful morning. We three were making our way by slow marches from Soda Springs across the south base of Mount Shasta to the Modoc lava beds—two English artists and myself. We had saddle horses, or, rather, two saddle horses and a mule, for our own use. Six Indians, with broad leather or elkskin straps across their foreheads, had been chartered to carry the kits and traps. They were men[Pg 14] of means and leisure, these artists, and were making the trip for the fish, game, scenery and excitement and everything, in fact, that was in the adventure. I was merely their hired guide.

This second morning out, the Indians—poor slaves, perhaps, from the first, certainly not warriors with any spirit in them—began to sulk. They had risen early and kept hovering together and talking, or, rather, making signs in the gloomiest sort of fashion. We had hard work to get them to do anything at all, and even after breakfast was ready they packed up without tasting food.

The air was ugly, for that region—hot, heavy, and without light or life. It was what in some parts of South America they call “earthquake weather.” Even the horses sulked as we mounted; but the mule shot ahead through the brush at once, and this induced the ponies to follow.

The Englishmen thought the Indians and horses were only tired from the day[Pg 15] before, but we soon found the whole force plowing ahead through the dense brush and over fallen timber on a double quick.

Then we heard low, heavy thunder in the heavens. Were they running away from a thunder-storm? The English artists, who had been doing India and had come to love the indolent patience and obedience of the black people, tried to call a halt. No use. I shouted to the Indians in their own tongue. “Tokau! Ki-sa! Kiu!” (Hasten! Quick! Quick!) was all the answer I could get from the red, hot face that was thrown for a moment back over the load and shoulder. So we shot forward. In fact, the horses now refused all regard for the bit, and made their own way through the brush with wondrous skill and speed.

We were flying from fire, not flood! Pitiful what a few years of neglect will do toward destroying a forest! When a lad I had galloped my horse in security and comfort all through this region. It was like a park then. Now it was a dense[Pg 16] tangle of undergrowth and a mass of fallen timber. What a feast for flames! In one of the very old books on America in the British Museum—possibly the very oldest on the subject—the author tells of the park-like appearance of the American forests. He tells his English friends back at home that it is most comfortable to ride to the hounds, “since the Indian squats (squaws) do set fire to the brush and leaves every spring,” etc.

But the “squats” had long since disappeared from the forests of Mount Shasta; and here we were tumbling over and tearing through ten years’ or more of accumulation of logs, brush, leaves, weeds and grass that lay waiting for a sea of fire to roll over all like a mass of lava.

And now the wind blew past and over us. Bits of white ashes sifted down like snow. Surely the sea of fire was coming, coming right on after us! Still there was no sign, save this little sift of ashes, no sound; nothing at all except the trained[Pg 17] sense of the Indians and the terror of the “cattle” (this is what the Englishmen called our horses) to give us warning.

In a short time we struck an arroyo, or canyon, that was nearly free from brush and led steeply down to the cool, deep waters of the McCloud River. Here we found the Indians had thrown their loads and themselves on the ground.

They got up in sulky silence, and, stripping our horses, turned them loose; and then, taking our saddles, they led us hastily up out of the narrow mouth of the arroyo under a little steep stone bluff.

They did not say a word or make any sign, and we were all too breathless and bewildered to either question or protest. The sky was black, and thunder made the woods tremble. We were hardly done wiping the blood and perspiration from our torn hands and faces where we sat when the mule jerked up his head, sniffed, snorted and then plunged headlong into the river and struck out for the deep forest[Pg 18] on the farther bank, followed by the ponies.

The mule is the most traduced of all animals. A single mule has more sense than a whole stableful of horses. You can handle a mule easily if the barn is burning; he keeps his head; but a horse becomes insane. He will rush right into the fire, if allowed to, and you can only handle him, and that with difficulty if he sniffs the fire, by blindfolding him. Trust a mule in case of peril or a panic long before a horse. The brother of Solomon and willful son of David surely had some of the great temple-builder’s wisdom and discernment, for we read that he rode a mule. True, he lost his head and got hung up by the hair, but that is nothing against the mule.

As we turned our eyes from seeing the animals safely over, right there by us and a little behind us, through the willows of the canyon and over the edge of the water, we saw peering and pointing toward the[Pg 19] other side dozens of long black and brown outreaching noses. Elk!

They had come noiselessly, they stood motionless. They did not look back or aside, only straight ahead. We could almost have touched the nearest one. They were large and fat, almost as fat as cows; certainly larger than the ordinary Jersey. The peculiar thing about them was the way, the level way, in which they held their small, long heads—straight out; the huge horns of the males lying far back on their shoulders. And then for the first time I could make out what these horns are for—to part the brush with as they lead through the thicket, and thus save their coarse coats of hair, which is very rotten, and could be torn off in a little time if not thus protected. They are never used to fight with, never; the elk uses only his feet. If on the defense, however, the male elk will throw his nose close to the ground and receive the enemy on his horns.

Suddenly and all together, and perhaps[Pg 20] they had only paused a second, they moved on into the water, led by a bull with a head of horns like a rocking-chair. And his rocking-chair rocked his head under water much of the time. The cold, swift water soon broke the line, only the leader making the bank directly before us, while the others drifted far down and out of sight.

Our artists, meantime, had dug up pencil and pad and begun work. But an Indian jerked the saddles, on which the Englishmen sat, aside, and the work was stopped. Everything was now packed up close under the steep little ledge of rocks. An avalanche of smaller wild animals, mostly deer, was upon us. Many of these had their tongues hanging from their half-opened mouths. They did not attempt to drink, as you would suppose, but slid into the water silently almost as soon as they came. Surely they must have seen us, but certainly they took no notice of us. And such order! No crushing or crowding, as you[Pg 21] see cattle in corrals, aye, as you see people sometimes in the cars.

And now came a torrent of little creeping things: rabbits, rats, squirrels! None of these smaller creatures attempted to cross, but crept along in the willows and brush close to the water.

They loaded down the willows till they bent into the water, and the terrified little creatures floated away without the least bit of noise or confusion. And still the black skies were filled with the solemn boom of thunder. In fact, we had not yet heard any noise of any sort except thunder, not even our own voices. There was something more eloquent in the air now, something more terrible than man or beast, and all things were awed into silence—a profound silence.

And all this time countless creatures, little creatures and big, were crowding the bank on our side or swimming across or floating down, down, down the swift, woodhung waters. Suddenly the stolid leader[Pg 22] of the Indians threw his two naked arms in the air and let them fall, limp and helpless at his side; then he pointed out into the stream, for there embers and living and dead beasts began to drift and sweep down the swift waters from above. The Indians now gathered up the packs and saddles and made a barricade above, for it was clear that many a living thing would now be borne down upon us.

The two Englishmen looked one another in the face long and thoughtfully, pulling their feet under them to keep from being trodden on. Then, after another avalanche of creatures of all sorts and sizes, a sort of Noah’s ark this time, one of them said to the other:

“Beastly, you know!”

“Awful beastly, don’t you know!”

As they were talking entirely to themselves and in their own language, I did not trouble myself to call their attention to an enormous yellow rattlesnake which had suddenly and noiselessly slid down,[Pg 23] over the steep little bluff of rocks behind us, into our midst.

But now note this fact—every man there, red or white, saw or felt that huge and noiseless monster the very second she slid among us. For as I looked, even as I first looked, and then turned to see what the others would say or do, they were all looking at the glittering eyes set in that coffin-like head.

The Indians did not move back or seem nearly so much frightened as when they saw the drift of embers and dead beasts in the river before them; but the florid Englishmen turned white! They resolutely arose, thrust their hands in their pockets and stood leaning their backs hard against the steep bluff. Then another snake, long, black and beautiful, swept his supple neck down between them and thrust his red tongue forth—as if a bit of the flames had already reached us.

Fortunately, this particular “wisest of all the beasts of the field,” was not disposed[Pg 24] to tarry. In another second he had swung to the ground and was making a thousand graceful curves in the swift water for the further bank.

The world, even the world of books, seems to know nothing at all about the wonderful snakes that live in the woods. The woods rattlesnake is as large as at least twenty ordinary rattlesnakes; and Indians say it is entirely harmless. The enormous black snake, I know, is entirely without venom. In all my life, spent mostly in the camp, I have seen only three of those monstrous yellow woods rattlesnakes; one in Indiana, one in Oregon and the other on this occasion here on the banks of the McCloud. Such bright eyes! It was hard to stop looking at them.

Meantime a good many bears had come and gone. The bear is a good swimmer, and takes to the water without fear. He is, in truth, quite a fisherman; so much of a fisherman, in fact, that in salmon season here his flesh is unfit for food. The pitiful[Pg 25] part of it all was to see such little creatures as could not swim clinging all up and down and not daring to take to the water.

Unlike his domesticated brother, we saw several wild-cats take to the water promptly. The wild-cat, you must know, has no tail to speak of. But the panther and Californian lion are well equipped in this respect and abhor the water.

I constantly kept an eye over my shoulder at the ledge or little bluff of rocks, expecting to see a whole row of lions and panthers sitting there, almost “cheek by jowl” with my English friends, at any moment. But strangely enough, we saw neither panther nor lion; nor did we see a single grizzly among all the bears that came that way.

We now noticed that one of the Indians had become fascinated or charmed by looking too intently at the enormous serpent in our midst. The snake’s huge, coffin-shaped head, as big as your open palm, was slowly[Pg 26] swaying from side to side. The Indian’s head was doing the same, and their eyes were drawing closer and closer together. Whatever there may be in the Bible story of Eve and the serpent, whether a figure or a fact, who shall say?—but it is certainly, in some sense, true.

An Indian will not kill a rattlesnake. But to break the charm, in this case, they caught their companion by the shoulders and forced him back flat on the ground. And there he lay, crying like a child, the first and only Indian I ever saw cry. And then suddenly boom! boom! boom! as if heaven burst. It began to rain in torrents.

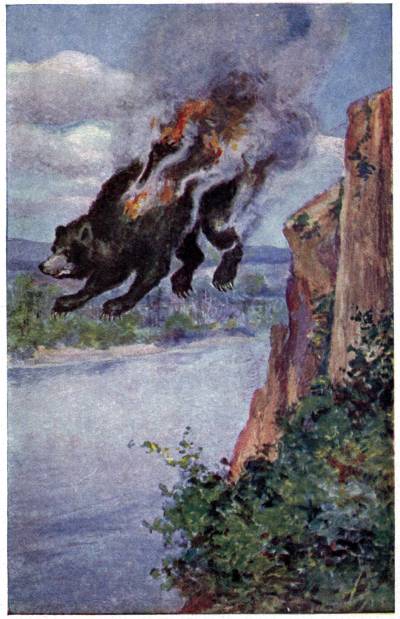

And just then, as we began to breathe freely and feel safe, there came a crash and bump and bang above our heads, and high over our heads from off the ledge behind us! Over our heads like a rocket, in an instant and clear into the water, leaped a huge black bear, a ball of fire! his fat sides in flame. He sank out of sight but soon came up, spun around like a top, dived [Pg 27]again, then again spun around. But he got across, I am glad to say. And this always pleases my little girl, Juanita. He sat there on the bank looking back at us quite a time. Finally he washed his face, like a cat, then quietly went away. The rattlesnake was the last to cross.

Into the water leaped a black bear.—Page 26.

The beautiful yellow beast was not at all disconcerted, but with the serenest dignity lifted her yellow folds, coiled and uncoiled slowly, curved high in the air, arched her glittering neck of gold, widened her body till broad as your two hands, and so slid away over the water to the other side through the wild white rain. The cloudburst put out the fire instantly, showing that, though animals have superhuman foresight, they don’t know everything before the time.

“Beastly! I didn’t get a blawsted sketch, you know.”

“Awful beastly! Neither did I, don’t you know.”

And that was all my English friends[Pg 28] said. The Indians made their moaning and whimpering friend who had been overcome by the snake pull himself together and they swam across and gathered up the “cattle.”

Some men say a bear cannot leap; but I say there are times when a bear can leap like a tiger. This was one of the times.

MUSIC-LOVING BEARS.

No, don’t despise the bear, either in his life or his death. He is a kingly fellow, every inch a king; a curious, monkish, music-loving, roving Robin Hood of his somber woods—a silent monk, who knows a great deal more than he tells. And please don’t go to look at him and sit in judgment on him behind the bars. Put yourself in his place and see how much of manhood or kinghood would be left in you with a muzzle on your mouth, and only enough liberty left to push your nose between two rusty bars and catch the peanut which the good little boy has found to be a bad one and so generously tosses it to the bear.

Of course, the little boy, remembering the experience of about forty other little boys in connection with the late baldheaded Elijah, has a prejudice against the[Pg 30] bear family, but why the full-grown man should so continually persist in caging this shaggy-coated, dignified, kingly and ancient brother of his, I cannot see, unless it is that he knows almost nothing at all of his better nature, his shy, innocent love of a joke, his partiality for music and his imperial disdain of death. And so, with a desire that man may know a little more about this storied and classic creature which, with noiseless and stately tread, has come down to us out of the past, and is as quietly passing away from the face of the earth, these fragmentary facts are set down. But first as to his love of music. A bear loves music better than he loves honey, and that is saying that he loves music better than he loves his life.

We were going to mill, father and I, and Lyte Howard, in Oregon, about forty years ago, with ox-teams, a dozen or two bags of wheat, threshed with a flail and winnowed with a wagon cover, and were camped for the night by the Calipoola River; for it took[Pg 31] two days to reach the mill. Lyte got out his fiddle, keeping his gun, of course, close at hand. Pretty soon the oxen came down, came very close, so close that they almost put their cold, moist noses against the backs of our necks as we sat there on the ox-yokes or reclined in our blankets, around the crackling pine-log fire and listened to the wild, sweet strains that swept up and down and up till the very tree tops seemed to dance and quiver with delight.

Then suddenly father seemed to feel the presence of something or somebody strange, and I felt it, too. But the fiddler felt, heard, saw nothing but the divine, wild melody that made the very pine trees dance and quiver to their tips. Oh, for the pure, wild, sweet, plaintive music once more! the music of “Money Musk,” “Zip Coon,” “Ol’ Dan Tucker” and all the other dear old airs that once made a thousand happy feet keep time on the puncheon floors from Hudson’s bank to the Oregon. But they are no more, now. They have[Pg 32] passed away forever with the Indian, the pioneer, and the music-loving bear. It is strange how a man—I mean the natural man—will feel a presence long before he hears it or sees it. You can always feel the approach of a—but I forget. You are of another generation, a generation that only reads, takes thought at second hand only, if at all, and you would not understand; so let us get forward and not waste time in explaining the unexplainable to you.

Father got up, turned about, put me behind him like, as an animal will its young, and peered back and down through the dense tangle of the deep river bank between two of the huge oxen which had crossed the plains with us to the water’s edge; then he reached around and drew me to him with his left hand, pointing between the oxen sharp down the bank with his right forefinger.

A bear! two bears! and another coming; one already more than half way across on the great, mossy log that lay above the[Pg 33] deep, sweeping waters of the Calipoola; and Lyte kept on, and the wild, sweet music leaped up and swept through the delighted and dancing boughs above. Then father reached back to the fire and thrust a long, burning bough deeper into the dying embers and the glittering sparks leaped and laughed and danced and swept out and up and up as if to companion with the stars. Then Lyte knew. He did not hear, he did not see, he only felt; but the fiddle forsook his fingers and his chin in a second, and his gun was to his face with the muzzle thrust down between the oxen. And then my father’s gentle hand reached out, lay on that long, black, Kentucky rifle barrel, and it dropped down, slept once more at the fiddler’s side, and again the melodies; and the very stars came down, believe me, to listen, for they never seemed so big and so close by before. The bears sat down on their haunches at last, and one of them kept opening his mouth and putting out his red tongue, as if he really wanted to taste[Pg 34] the music. Every now and then one of them would lift up a paw and gently tap the ground, as if to keep time with the music. And both my papa and Lyte said next day that those bears really wanted to dance.

And that is all there is to say about that, except that my father was the gentlest gentleman I ever knew and his influence must have been boundless; for who ever before heard of any hunter laying down his rifle with a family of fat black bears holding the little snow-white cross on their breasts almost within reach of its muzzle?

The moon came up by and by, and the chin of the weary fiddler sank lower and lower, till all was still. The oxen lay down and ruminated, with their noses nearly against us. Then the coal-black bears melted away before the milk-white moon, and we slept there, with the sweet breath of the cattle, like incense, upon us.

But how does a bear die? Ah, I had forgotten. I must tell you of death, then.[Pg 35] Well, we have different kinds of bears. I know little of the Polar bear, and so say nothing positively of him. I am told, however, that there is not, considering his size, much snap or grit about him; but as for the others, I am free to say that they live and die like gentlemen.

I shall find time, as we go forward, to set down many incidents out of my own experience to prove that the bear is often a humorist, and never by any means a bad fellow.

Judge Highton, odd as it may seem, has left the San Francisco bar for the “bar” of Mount Shasta every season for more than a quarter of a century, and he probably knows more about bears than any other eminently learned man in the world, and Henry Highton will tell you that the bear is a good fellow at home, good all through, a brave, modest, sober old monk.

MY FIRST GRIZZLY.

One of Fremont’s men, Mountain Joe, had taken a fancy to me down in Oregon, and finally, to put three volumes in three lines, I turned up as partner in his Soda Springs ranch on the Sacramento, where the famous Shasta-water is now bottled, I believe. Then the Indians broke out, burned us up and we followed and fought them in Castle rocks, and I was shot down. Then my father came on to watch by my side, where I lay, under protection of soldiers, at the mouth of Shot Creek canyon.

As the manzanita berries began to turn the mountain sides red and the brown pine quills to sift down their perfumed carpets at our feet, I began to feel some strength and wanted to fight, but I had had enough of Indians. I wanted to fight grizzly bears[Pg 37] this time. The fact is, they used to leave tracks in the pack trail every night, and right close about the camp, too, as big as the head of a barrel.

Now father was well up in woodcraft, no man better, but he never fired a gun. Never, in his seventy years of life among savages, did that gentle Quaker, school-master, magistrate and Christian ever fire a gun. But he always allowed me to have my own way as a hunter, and now that I was getting well of my wound he was so glad and grateful that he willingly joined in with the soldiers to help me kill one of these huge bears that had made the big tracks.

Do you know why a beast, a bear of all beasts, is so very much afraid of fire? Well, in the first place, as said before, a bear is a gentleman, in dress as well as address, and so likes a decent coat. If a bear should get his coat singed he would hide away from sight of both man and beast for half a year. But back of his pride is the fact that a fat bear will burn like a candle;[Pg 38] the fire will not stop with the destruction of his coat. And so, mean as it was, in the olden days, when bears were as common in California as cows are now, men used to take advantage of this fear and kindle pine-quill fires in and around his haunts in the head of canyons to drive him out and down and into ambush.

Read two or three chapters here between the lines—lots of plans, preparations, diagrams. I was to hide near camp and wait—to place the crescent of pine-quill fires and all that. Then at twilight they all went out and away on the mountain sides around the head of the canyon, and I hid behind a big rock near by the extinguished camp-fire, with my old muzzle-loading Kentucky rifle, lifting my eyes away up and around to the head of the Manzanita canyon looking for the fires. A light! One, two, three, ten! A sudden crescent of forked flames, and all the fight and impetuosity of a boy of only a dozen years was uppermost, and I wanted a bear!

All alone I waited; got hot, cold, thirsty, cross as a bear and so sick of sitting there that I was about to go to my blankets, for the flames had almost died out on the hills, leaving only a circle of little dots and dying embers, like a fading diadem on the mighty lifted brow of the glorious Manzanita mountain. And now the new moon came, went softly and sweetly by, like a shy, sweet maiden, hiding down, down out of sight.

Crash! His head was thrown back, not over his shoulder, as you may read but never see, but down by his left foot, as he looked around and back up the brown mountain side. He had stumbled, or rather, he had stepped on himself, for a bear gets down hill sadly. If a bear ever gets after you, you had better go hill and go down hill fast. It will make him mad, but that is not your affair. I never saw a bear go down hill in a good humor. What nature meant by making a bear so short in the arms I don’t know.[Pg 40] Indians say he was first a man and walked upright with a club on his shoulder, but sinned and fell. As evidence of this, they show that he can still stand up and fight with his fists when hard pressed, but more of this later on.

This huge brute before me looked almost white in the tawny twilight as he stumbled down through the steep tangle of chaparral into the opening on the stony bar of the river.

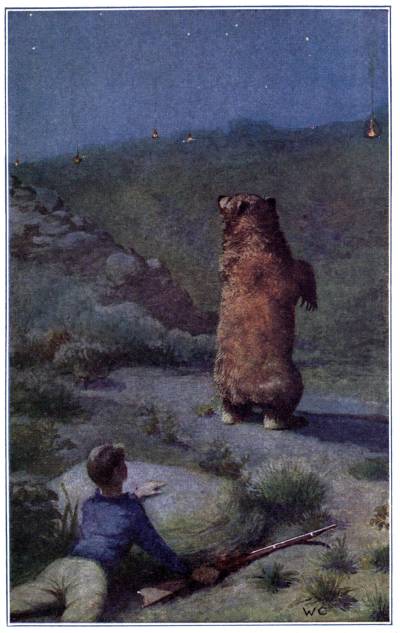

He had evidently been terribly tangled up and disgusted while in the bush and jungle, and now, well out of it, with the foamy, rumbling, roaring Sacramento River only a few rods beyond him, into which he could plunge with his glossy coat, he seemed to want to turn about and shake his huge fists at the crescent of fire in the pine-quills that had driven him down the mountain. He threw his enormous bulk back on his haunches and rose up, and rose up, and rose up! Oh, the majesty of this king of our continent, as he seemed[Pg 41] to still keep rising! Then he turned slowly around on his great hinder feet to look back; he pushed his nose away out, then drew it back, twisted his short, thick neck, like that of a beer-drinking German, and then for a final observation he tiptoed up, threw his high head still higher in the air and wiggled it about and sniffed and sniffed and—bang!

I shot at him from ambush, with his back toward me, shot at his back! For shame! Henry Highton would not have done that; nor, indeed, would I or any other real sportsman do such a thing now; but I must plead the “Baby Act,” and all the facts, and also my sincere penitence, and proceed.

The noble brute did not fall, but let himself down with dignity and came slowly forward. Hugely, ponderously, solemnly, he was coming. And right here, if I should set down what I thought about—where father was, the soldiers, anybody, everybody else, whether I had best just fall on[Pg 42] my face and “play possum” and put in a little prayer or two on the side, like—well, I was going on to say that if I should write all that flashed and surged through my mind in the next three seconds, you would be very tired. I was certain I had not hit the bear at all. As a rule, you can always see the “fur fly,” as hunters put it; only it is not fur, but dust, that flies.

But this bear was very fat and hot, and so there could have been no dust to fly. After shuffling a few steps forward and straight for the river, he suddenly surged up again, looked all about, just as before, then turned his face to the river and me, the tallest bear that ever tiptoed up and up and up in the Sierras. One, two, three steps—on came the bear! and my gun empty! Then he fell, all at once and all in a heap. No noise, no moaning or groaning at all, no clutching at the ground, as men have seen Indians and even white men do; as if they would hold the earth from passing away—nothing of that sort. He lay[Pg 43] quite still, head down hill, on his left side, gave just one short, quick breath, and then, pulling up his great right paw, he pushed his nose and eyes under it, as if to shut out the light forever, or, maybe, to muffle up his face as when “great Cæsar fell.”

And that was all. I had killed a grizzly bear; nearly as big as the biggest ox.

He threw his enormous bulk back on his haunches, and rose up.—Page 40.

TWIN BABIES.

These twin babies were black. They were black as coal. Indeed, they were blacker than coal, for they glistened in their oily blackness. They were young baby bears; and so exactly alike that no one could, in any way, tell the one from the other. And they were orphans. They had been found at the foot of a small cedar tree on the banks of the Sacramento River, near the now famous Soda Springs, found by a tow-headed boy who was very fond of bears and hunting.

But at the time the twin babies were found Soda Springs was only a wild camp, or way station, on the one and only trail that wound through the woods and up and down mountains for hundreds of miles, connecting the gold fields of California with the pastoral settlements away to the [Pg 45]north in Oregon. But a railroad has now taken the place of that tortuous old packtrail, and you can whisk through these wild and woody mountains, and away on down through Oregon and up through Washington, Montana, Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin and on to Chicago without even once getting out of your car, if you like. Yet such a persistent ride is not probable, for fish, pheasants, deer, elk, and bear still abound here in their ancient haunts, and the temptation to get out and fish or hunt is too great to be resisted.

This place where the baby bears were found was first owned by three men or, rather, by two men and a boy. One of the men was known as Mountain Joe. He had once been a guide in the service of General Fremont, but he was now a drunken fellow and spent most of his time at the trading post, twenty miles down the river. He is now an old man, almost blind, and lives in Oregon City, on a pension received as a soldier of the Mexican war. The[Pg 46] other man’s name was Sil Reese. He, also, is living and famously rich—as rich as he is stingy, and that is saying that he is very rich indeed.

The boy preferred the trees to the house, partly because it was more pleasant and partly because Sil Reese, who had a large nose and used it to talk with constantly, kept grumbling because the boy, who had been wounded in defending the ranch, was not able to work—wash the dishes, make fires and so on, and help in a general and particular way about the so-called “Soda Spring Hotel.” This Sil Reese was certainly a mean man, as has, perhaps, been set down in this sketch before.

The baby bears were found asleep, and alone. How they came to be there, and, above all, how they came to be left long enough alone by their mother for a feeble boy to rush forward at sight of them, catch them up in his arms and escape with them, will always be a wonder. But this one thing is certain, you had about as well[Pg 47] take up two rattlesnakes in your arms as two baby bears, and hope to get off unharmed, if the mother of the young bears is within a mile of you. This boy, however, had not yet learned caution, and he probably was not born with much fear in his make-up. And then he was so lonesome, and this man Reese was so cruel and so cross, with his big nose like a sounding fog-horn, that the boy was glad to get even a bear to love and play with.

They, so far from being frightened or cross, began to root around under his arms and against his breast, like little pigs, for something to eat. Possibly their mother had been killed by hunters, for they were nearly famished. When he got them home, how they did eat! This also made Sil Reese mad. For, although the boy, wounded as he was, managed to shoot down a deer not too far from the house almost every day, and so kept the “hotel” in meat, still it made Reese miserable and envious to see[Pg 48] the boy so happy with his sable and woolly little friends. Reese was simply mean!

Before a month the little black boys began to walk erect, carry stick muskets, wear paper caps, and march up and down before the door of the big log “hotel” like soldiers.

But the cutest trick they learned was that of waiting on the table. With little round caps and short white aprons, the little black boys would stand behind the long bench on which the guests sat at the pine board table and pretend to take orders with all the precision and solemnity of Southern negroes.

Of course, it is to be confessed that they often dropped things, especially if the least bit hot; but remember we had only tin plates and tin or iron dishes of all sorts, so that little damage was done if a dish did happen to fall and rattle down on the earthen floor.

Men came from far and near and often[Pg 49] lingered all day to see these cunning and intelligent creatures perform.

About this time Mountain Joe fought a duel with another mountaineer down at the trading post, and this duel, a bloodless and foolish affair, was all the talk. Why not have the little black fellows fight a duel also? They were surely civilized enough to fight now!

And so, with a very few days’ training, they fought a duel exactly like the one in which poor, drunken old Mountain Joe was engaged; even to the detail of one of them suddenly dropping his stick gun and running away and falling headlong in a prospect hole.

When Joe came home and saw this duel and saw what a fool he had made of himself, he at first was furiously angry. But it made him sober, and he kept sober for half a year. Meantime Reese was mad as ever, more mad, in fact, than ever before. For he could not endure to see the boy have any friends of any kind. Above all, he did[Pg 50] not want Mountain Joe to stay at home or keep sober. He wanted to handle all the money and answer no questions. A drunken man and a boy that he could bully suited him best. Ah, but this man Reese was a mean fellow, as has been said a time or two before.

As winter came on the two blacks were fat as pigs and fully half-grown. Their appetites increased daily, and so did the anger and envy of Mr. Sil Reese.

“They’ll eat us out o’ house and hum,” said the big, towering nose one day, as the snow began to descend and close up the pack trails. And then the stingy man proposed that the blacks should be made to hibernate, as others of their kind. There was a big, hollow log that had been sawed off in joints to make bee gums; and the stingy man insisted that they should be put in there with a tight head, and a pack of hay for a bed, and nailed up till spring to save provisions.

Soon there was an Indian outbreak.[Pg 51] Some one from the ranch, or “hotel,” must go with the company of volunteers that was forming down at the post for a winter campaign. Of course Reese would not go. He wanted Mountain Joe to go and get killed. But Joe was sober now and he wanted to stay and watch Reese.

And that is how it came about that the two black babies were tumbled headlong into a big, black bee gum, or short, hollow log, on a heap of hay, and nailed up for the winter. The boy had to go to the war.

It was late in the spring when the boy, having neglected to get himself killed, to the great disgust of Mr. Sil Reese, rode down and went straight up to the big black bee gum in the back yard. He put his ear to a knothole. Not a sound. He tethered his mule, came back and tried to shake the short, hollow log. Not a sound or sign or movement of any kind. Then he kicked the big black gum with all his might. Nothing. Rushing to the wood-pile, he caught up an ax and in a moment had the whole end[Pg 52] of the big gum caved in, and, to his infinite delight, out rolled the twins!

But they were merely the ghosts of themselves. They had been kept in a month or more too long, and were now so weak and so lean that they could hardly stand on their feet.

“Kill ’em and put ’em out o’ misery,” said Reese, for run from him they really could not, and he came forward and kicked one of them flat down on its face as it was trying hard to stand on its four feet.

The boy had grown some; besides, he was just from the war and was now strong and well. He rushed up in front of Reese, and he must have looked unfriendly, for Sil Reese tried to smile, and then at the same time he turned hastily to go into the house. And when he got fairly turned around, the boy kicked him precisely where he had kicked the bear. And he kicked him hard, so hard that he pitched forward on his face just as the bear had done. He got up quickly, but he did not look back. He[Pg 53] seemed to have something to do in the house.

In a month the babies, big babies now, were sleek and fat. It is amazing how these creatures will eat after a short nap of a few months, like that. And their cunning tricks, now! And their kindness to their master! Ah! their glossy black coats and their brilliant black eyes!

And now three men came. Two of these men were Italians from San Francisco. The third man was also from that city, but he had an amazing big nose and refused to eat bear meat. He thought it was pork.

They took tremendous interest in the big black twins, and stayed all night and till late next day, seeing them perform.

“Seventy-five dollars,” said one big nose to the other big nose, back in a corner where they thought the boy did not hear.

“One hundred and fifty. You see, I’ll have to give my friends fifty each. Yes, it’s true I’ve took care of ’em all winter,[Pg 54] but I ain’t mean, and I’ll only keep fifty of it.”

The boy, bursting with indignation, ran to Mountain Joe with what he had heard. But poor Joe had been sober for a long time, and his eyes fairly danced in delight at having $50 in his own hand and right to spend it down at the post.

And so the two Italians muzzled the big, pretty pets and led them kindly down the trail toward the city, where they were to perform in the streets, the man with the big nose following after the twins on a big white mule.

And what became of the big black twin babies? They are still performing, seem content and happy, sometimes in a circus, sometimes in a garden, sometimes in the street. They are great favorites and have never done harm to anyone.

And what became of Sil Reese? Well, as said before, he still lives, is very rich and very miserable. He met the boy—the boy that was—on the street the other day[Pg 55] and wanted to talk of old times. He told the boy he ought to write something about the old times and put him, Sil Reese, in it. He said, with that same old sounding nose and sickening smile, that he wanted the boy to be sure and put his, Sil Reese’s name, in it so that he could show it to his friends. And the boy has done so.

The boy? You want to know what the boy is doing? Well, in about a second he will be signing his autograph to the bottom of this story about his twin babies.

IN SWIMMING WITH A BEAR.

What made these ugly rows of scars on my left hand?

Well, it might have been buckshot; only it wasn’t. Besides, buckshot would be scattered about, “sort of promiscuous like,” as backwoodsmen say. But these ugly little holes are all in a row, or rather in two rows. Now a wolf might have made these holes with his fine white teeth, or a bear might have done it with his dingy and ugly teeth, long ago. I must here tell you that the teeth of a bear are not nearly so fine as the teeth of a wolf. And the teeth of a lion are the ugliest of them all. They are often broken and bent; and they are always of a dim yellow color. It is from this yellow hue of the lion’s teeth that we have the name of one of the most famous early flowers of May: dent de lion, tooth[Pg 57] of the lion; dandelion. Get down your botany, now, find the Anglo-Asian name of the flower, and fix this fact on your mind before you read further.

I know of three men, all old men now, who have their left hands all covered with scars. One is due to the wolf; the others owe their scars to the red mouths of black bears.

You see, in the old days, out here in California, when the Sierras were full of bold young fellows hunting for gold, quite a number of them had hand-to-hand battles with bears. For when we came out here “the woods were full of ’em.”

Of course, the first thing a man does when he finds himself face to face with a bear that won’t run and he has no gun—and that is always the time when he finds a bear—why, he runs, himself; that is, if the bear will let him.

But it is generally a good deal like the old Crusader who “caught a Tartar” long[Pg 58] ago, when on his way to capture Jerusalem, with Peter the Hermit.

“Come on!” cried Peter to the helmeted and knightly old Crusader, who sat his horse with lance in rest on a hill a little in the rear. “Come on!”

“I can’t! I’ve caught a Tartar.”

“Well, bring him along.”

“He won’t come.”

“Well, then, come without him.”

“He won’t let me.”

And so it often happened in the old days out here. When a man “caught” his bear and didn’t have his gun he had to fight it out hand-to-hand. But fortunately, every man at all times had a knife in his belt. A knife never gets out of order, never “snaps,” and a man in those days always had to have it with him to cut his food, cut brush, “crevice” for gold, and so on.

Oh! it is a grim picture to see a young fellow in his red shirt wheel about, when he can’t run, thrust out his left hand, draw his knife with his right, and so, breast to[Pg 59] breast, with the bear erect, strike and strike and strike to try to reach his heart before his left hand is eaten off to the elbow!

We have five kinds of bears in the Sierras. The “boxer,” the “biter,” the “hugger,” are the most conspicuous. The other two are a sort of “all round” rough and tumble style of fighters.

The grizzly is the boxer. A game old beast he is, too, and would knock down all the John L. Sullivans you could put in the Sierras faster than you could set them up. He is a kingly old fellow and disdains familiarity. Whatever may be said to the contrary, he never “hugs” if he has room to box. In some desperate cases he has been known to bite, but ordinarily he obeys “the rules of the ring.”

The cinnamon bear is a lazy brown brute, about one-half the size of the grizzly. He always insists on being very familiar, if not affectionate. This is the “hugger.”

Next in order comes the big, sleek, black[Pg 60] bear; easily tamed, too lazy to fight, unless forced to it. But when “cornered” he fights well, and, like a lion, bites to the bone.

After this comes the small and quarrelsome black bear with big ears, and a white spot on his breast. I have heard hunters say, but I don’t quite believe it, that he sometimes points to this white spot on his breast as a sort of Free Mason’s sign, as if to say, “Don’t shoot.” Next in order comes the smaller black bear with small ears. He is ubiquitous, as well as omniverous; gets into pig-pens, knocks over your beehives, breaks open your milk-house, eats more than two good-sized hogs ought to eat, and is off for the mountain top before you dream he is about. The first thing you see in the morning, however, will be some muddy tracks on the door steps. For he always comes and snuffles and shuffles and smells about the door in a good-natured sort of way, and leaves his card. The fifth member of the great bear family is not[Pg 61] much bigger than an ordinary dog; but he is numerous, and he, too, is a nuisance.

Dog? Why not set the dog on him? Let me tell you. The California dog is a lazy, degenerate cur. He ought to be put with the extinct animals. He devotes his time and his talent to the flea. Not six months ago I saw a coon, on his way to my fish-pond in the pleasant moonlight, walk within two feet of my dog’s nose and not disturb his slumbers.

We hope that it is impossible ever to have such a thing as hydrophobia in California. But as our dogs are too lazy to bite anything, we have thus far been unable to find out exactly as to that.

This last-named bear has a big head and small body; has a long, sharp nose and longer and sharper teeth than any of the others; he is a natural thief, has low instincts, carries his nose close to the ground, and, wherever possible, makes his road along on the mossy surface of fallen trees in humid forests. He eats fish—dead and[Pg 62] decaying salmon—in such abundance that his flesh is not good in the salmon season.

It was with this last described specimen of the bear family that a precocious old boy who had hired out to some horse drovers, went in swimming years and years ago. The two drovers had camped to recruit and feed their horses on the wild grass and clover that grew at the headwaters of the Sacramento River, close up under the foot of Mount Shasta. A pleasant spot it was, in the pleasant summer weather.

This warm afternoon the two men sauntered leisurely away up Soda Creek to where their horses were grazing belly deep in grass and clover. They were slow to return, and the boy, as all boys will, began to grow restless. He had fished, he had hunted, had diverted himself in a dozen ways, but now he wanted something new. He got it.

A little distance below camp could be seen, through the thick foliage that hung[Pg 63] and swung and bobbed above the swift waters, a long, mossy log that lay far out and far above the cool, swift river.

Why not go down through the trees and go out on that log, take off his clothes, dangle his feet, dance on the moss, do anything, everything that a boy wants to do?

In two minutes the boy was out on the big, long, mossy log, kicking his boots off, and in two minutes more he was dancing up and down on the humid, cool moss, and as naked as the first man, when he was first made.

And it was very pleasant. The great, strong river splashed and dashed and boomed below; above him the long green branches hung dense and luxuriant and almost within reach. Far off and away through their shifting shingle he caught glimpses of the bluest of all blue skies. And a little to the left he saw gleaming in the sun and almost overhead the everlasting snows of Mount Shasta.

Putting his boots and his clothes all[Pg 64] carefully in a heap, that nothing might roll off into the water, he walked, or rather danced on out to where the further end of the great fallen tree lay lodged on a huge boulder in the middle of the swift and surging river. His legs dangled down and he patted his plump thighs with great satisfaction. Then he leaned over and saw some gold and silver trout, then he flopped over and lay down on his breast to get a better look at them. Then he thought he heard something behind him on the other end of the log! He pulled himself together quickly and stood erect, face about. There was a bear! It was one of those mean, sneaking, long-nosed, ant-eating little fellows, it is true, but it was a bear! And a bear is a bear to a boy, no matter about his size, age or character. The boy stood high up. The boy’s bear stood up. And the boy’s hair stood up!

The bear had evidently not seen the boy yet. But it had smelled his boots and clothes, and had got upon his dignity. But[Pg 65] now, dropping down on all fours, with nose close to the mossy butt of the log, it slowly shuffled forward.

That boy was the stillest boy, all this time, that has ever been. Pretty soon the bear reached the clothes. He stopped, sat down, nosed them about as a hog might, and then slowly and lazily got up; but with a singular sort of economy of old clothes, for a bear, he did not push anything off into the river.

What next? Would he come any farther? Would he? Could he? Will he? The long, sharp little nose was once more to the moss and sliding slowly and surely toward the poor boy’s naked shins. Then the boy shivered and settled down, down, down on his haunches, with his little hands clasped till he was all of a heap.

He tried to pray, but somehow or another, all he could think of as he sat there crouched down with all his clothes off was:

But all this could not last. The bear was almost on him in half a minute, although he did not lift his nose six inches till almost within reach of the boy’s toes. Then the surprised bear suddenly stood up and began to look the boy in the face. As the terrified youth sprang up, he thrust out his left hand as a guard and struck the brute with all his might between the eyes with the other. But the left hand lodged in the two rows of sharp teeth and the boy and bear rolled into the river together.

But they were together only an instant. The bear, of course, could not breathe with his mouth open in the water, and so had to let go. Instinctively, or perhaps because his course lay in that direction, the bear struck out, swimming “dog fashion,” for the farther shore. And as the boy certainly had no urgent business on that side of the river he did not follow, but kept very still, clinging to the moss on the big boulder till the bear had shaken the water from his coat and disappeared in the thicket.

Then the boy, pale and trembling from fright and the loss of blood, climbed up the broken end of the log, got his clothes, struggled into them as he ran, and so reached camp.

And he had not yelled! He tied up his hand in a piece of old flour sack, all by himself, for the men had not yet got back; and he didn’t whimper! And what became of the boy? you ask.

The boy grew up as all energetic boys do; for there seems to be a sort of special providence for such boys.

And where is he now?

Out in California, trapping bear in the winter and planting olive trees in their season.

And do I know him?

Yes, pretty well, almost as well as any old fellow can know himself.

A FAT LITTLE EDITOR AND THREE LITTLE “BROWNS.”

Mount Sinai, Heart of the Sierras—this place is one mile east and a little less than one mile perpendicular from the hot, dusty and dismal little railroad town down on the rocky banks of the foaming and tumbling Sacramento River. Some of the old miners are down there still—still working on the desolate old rocky bars with rockers. They have been there, some of them, for more than thirty years. A few of them have little orchards, or vineyards, on the steep, overhanging hills, but there is no home life, no white women to speak of, as yet. The battered and gray old miners are poor, lonely and discouraged, but they are honest, stout-hearted still, and of a much higher type than those that hang about the towns. It is hot down on the river—too[Pg 69] hot, almost, to tell the truth. Even here under Mount Shasta, in her sheets of eternal snow, the mercury is at par.

This Mount Sinai is not a town; it is a great spring of cold water that leaps from the high, rocky front of a mountain which we have located as a summer home in the Sierras—myself and a few other scribes of California.

This is the great bear land. One of our party, a simple-hearted and honest city editor, who was admitted into our little mountain colony because of his boundless good nature and native goodness, had never seen a bear before he came here. City editors do not, as a rule, ever know much about bears. This little city editor is baldheaded, bow-legged, plain to a degree. And maybe that is why he is so good. “Give me fat men,” said Caesar.

But give me plain men for good men, any time. Pretty women are to be preferred; but pretty men? Bah! I must get on with the bear, however, and make a long story[Pg 70] a short story. We found our fat, bent-legged editor from the city fairly broiling in the little railroad town, away down at the bottom of the hill in the yellow golden fields of the Sacramento; and he was so limp and so lazy that we had to lay hold of him and get him out of the heat and up into the heart of the Sierras by main force.

Only one hour of climbing and we got up to where the little mountain streams come tumbling out of snow-banks on every side. The Sacramento, away down below and almost under us, from here looks dwindled to a brawling brook; a foamy white thread twisting about the boulders as big as meeting houses, plunging forward, white with fear, as if glad to get away—as if there was a bear back there where it came from. We did not register. No, indeed. This place here on Square Creek, among the clouds, where the water bursts in a torrent from the living rock, we have named Mount Sinai. We own the whole place for one mile square—the tall[Pg 71] pine trees, the lovely pine-wood houses; all, all. We proposed to hunt and fish, for food. But we had some bread, some bacon, lots of coffee and sugar. And so, whipping out our hooks and lines, we set off with the editor up a little mountain brook, and in less than an hour were far up among the fields of eternal snow, and finely loaded with trout.

What a bed of pine quills! What long and delicious cones for a camp fire! Some of those sugar-pine cones are as long as your arm. One of them alone will make a lofty pyramid of flame and illuminate the scene for half a mile about. I threw myself on my back and kicked up my heels. I kicked care square in the face. Oh, what freedom! How we would rest after dinner here! Of course we could not all rest or sleep at the same time. One of us would have to keep a pine cone burning all the time. Bears are not very numerous out here; but the California lion is both numerous and large here. The wild-cat, too, is[Pg 72] no friend to the tourist. But we were not tourists. The land was and is ours. We would and all could defend our own.

The sun was going down. Glorious! The shades of night were coming up out of the gorges below and audaciously pursuing the dying sun. Not a sound. Not a sign of man or of beast. We were scattered all up and down the hill.

Crash! Something came tearing down the creek through the brush! The fat and simple-hearted editor, who had been dressing the homeopathic dose of trout, which inexperience had marked as his own, sprang up from the bank of the tumbling little stream above us and stood at his full height. His stout little knees for the first time smote together. I was a good way below him on the steep hillside. A brother editor was slicing bacon on a piece of reversed pine bark close by.

“Fall down,” I cried, “fall flat down on your face.”

It was a small she bear, and she was very[Pg 73] thin and very hungry, with cubs at her heels, and she wanted that fat little city editor’s fish. I know it would take volumes to convince you that I really meant for the bear to pass by him and come after me and my friend with both fish and bacon, and so, with half a line, I assert this truth and pass on. Nor was I in any peril in appropriating the little brown bear to myself. Any man who knows what he is about is as safe with a bear on a steep hillside as is the best bull-fighter in any arena. No bear can keep his footing on a steep hillside, much less fight. And whenever an Indian is in peril he always takes down hill till he comes to a steep plane, and then lets the bear almost overtake him, when he suddenly steps aside and either knifes the bear to the heart or lets the open-mouthed beast go on down the hill, heels over head.

The fat editor turned his face toward me, and it was pale. “What! Lie down and be eaten up while you lie there and[Pg 74] kick up your heels and enjoy yourself? Never. We will die together!” he shouted.

He started for me as fast as his short legs would allow. The bear struck at him with her long, rattling claws. He landed far below me, and when he got up he hardly knew where he was or what he was. His clothes were in shreds, the back and bottom parts of them. The bear caught at his trout and was gone in an instant back with her two little cubs, and a moment later the little family had dined and was away, over the hill. She was a cinnamon bear, not much bigger than a big, yellow dog, and almost as lean and mean and hungry as any wolf could possibly be. We helped our inexperienced little friend slowly down to camp, forgetting all about the bacon and the fish till we came to the little board house, where we had coffee. Of course the editor could not go to the table now. He leaned, or rather sat, against a pine, drank copious cups of coffee and watched the stars, while I heaped up great[Pg 75] piles of leaves and built a big fire, and so night rolled by in all her starry splendor as the men slept soundly all about beneath the lordly pines. But alas for the fat little editor; he did not like the scenery, and he would not stay. We saw him to the station on his way back to his little sanctum. He said he was satisfied. He had seen the “bar.” His last words were, as he pulled himself close together in a modest corner in the car and smiled feebly: “Say, boys, you won’t let it get in the papers, will you?”

TREEING A BEAR.

Away back in the “fifties” bears were as numerous on the banks of the Willamette River, in Oregon, as are hogs in the hickory woods of Kentucky in nut time, and that is saying that bears were mighty plenty in Oregon about forty years ago.

You see, after the missionaries established their great cattle ranches in Oregon and gathered the Indians from the wilderness and set them to work and fed them on beef and bread, the bears had it all their own way, till they literally overran the land. And this gave a great chance for sport to the sons of missionaries and the sons of new settlers “where rolls the Oregon.”

And it was not perilous sport, either, for the grizzly was rarely encountered[Pg 77] here. His home was further to the south. Neither was the large and clumsy cinnamon bear abundant on the banks of the beautiful Willamette in those dear old days, when you might ride from sun to sun, belly deep in wild flowers, and never see a house. But the small black bear, as indicated before, was on deck in great force, at all times and in nearly all places.

It was the custom in those days for boys to take this bear with the lasso, usually on horseback.

We would ride along close to the dense woods that grew by the river bank, and, getting between him and his base of retreat, would, as soon as we sighted a bear feeding out in the open plain, swing our lassos and charge him with whoop and yell. His habit of rearing up and standing erect and looking about to see what was the matter made him an easy prey to the lasso. And then the fun of taking him home through the long, strong grass!

As a rule, he did not show fight when once in the toils of the lasso; but in a few hours, making the best of the situation like a little philosopher, he would lead along like a dog.

There were, of course, exceptions to this exemplary conduct.

On one occasion particularly, Ed Parish, the son of a celebrated missionary, came near losing his life by counting too confidently on the docility of a bear which he had taken with a lasso and was leading home.

His bear suddenly stopped, stood up and began to haul in the rope, hand over hand, just like a sailor. And as the other end of the rope was fastened tightly to the big Spanish pommel of the saddle, why of course the distance between the bear and the horse soon grew perilously short, and Ed Parish slid from his horse’s back and took to the brush, leaving horse and bear to fight it out as best they could.

When he came back, with some boys to[Pg 79] help him, the horse was dead and the bear was gone, having cut the rope with his teeth.

After having lost his horse in this way, poor little Ed Parish had to do his hunting on foot, and, as my people were immigrants and very poor, why we, that is my brother and I, were on foot also. This kept us three boys together a great deal, and many a peculiar adventure we had in those dear days “when all the world was young.”

Ed Parish was nearly always the hero of our achievements, for he was a bold, enterprising fellow, who feared nothing at all. In fact, he finally lost his life from his very great love of adventure. But this is too sad to tell now, and we must be content with the story about how he treed a bear for the present.

We three boys had gone bear hunting up a wooded canyon near his father’s ranch late one warm summer afternoon. Ed had a gun, but, as I said before, my people were very poor, so neither brother nor I as yet[Pg 80] had any other arms or implements than the inseparable lasso.

Ed, who was always the captain in such cases, chose the center of the dense, deep canyon for himself, and, putting my brother on the hillside to his right and myself on the hillside to his left, ordered a simultaneous “Forward march.”

After a time we heard him shoot. Then we heard him shout. Then there was a long silence.

Then suddenly, high and wild, his voice rang out through the tree tops down in the deep canyon.

“Come down! Come quick! I’ve treed a bear! Come and help me catch him; come quick! Oh, Moses! come quick, and—and—and catch him!”

My brother came tearing down the steep hill on his side of the canyon as I descended from my side. We got down about the same time, but the trees in their dense foliage, together with the compact underbrush,[Pg 81] concealed everything. We could see neither bear nor boy.

This Oregon is a damp country, warm and wet; nearly always moist and humid, and so the trees are covered with moss. Long, gray, sweeping moss swings from the broad, drooping boughs of fir and pine and cedar and nearly every bit of sunlight is shut out in these canyons from one year’s end to the other. And it rains here nearly half of the year; and then these densely wooded canyons are as dark as caverns. I know of nothing so grandly gloomy as these dense Oregon woods in this long rainy season.

I laid my ear to the ground after I got a glimpse of my brother on the other side of the canyon, but could hear nothing at all but the beating of my heart.

Suddenly there was a wild yell away up in the dense boughs of a big mossy maple tree that leaned over toward my side of the canyon. I looked and looked with eagerness, but could see nothing whatever.

Then again came the yell from the top of the big leaning maple. Then there was a moment of silence, and then the cry: “Oh, Moses! Why don’t you come, I say, and help me catch him?” By this time I could see the leaves rustling. And I could see the boy rustling, too.

And just behind him was a bear. He had treed the bear, sure enough!

My eyes gradually grew accustomed to the gloom and density, and I now saw the red mouth of the bear amid the green foliage high overhead. The bear had already pulled off one of Ed’s boots and was about making a bootjack of his big red mouth for the other.

“Why don’t you come on, I say, and help me catch him?”

He kicked at the bear, and at the same time hitched himself a little further along up the leaning trunk, and in doing so kicked his remaining boot into the bear’s mouth.

“Oh, Moses, Moses! Why don’t you come? I’ve got a bear, I tell you.”

“Where is it, Ed?” shouted my brother on the other side.

But Ed did not tell him, for he had not yet got his foot from the bear’s mouth, and was now too busy to do anything else but yell and cry “Oh, Moses!”

Then my brother and I shouted out to Ed at the same time. This gave him great courage. He said something like “Confound you!” to the bear, and getting his foot loose without losing the boot he kicked the bear right on the nose. This brought things to a standstill. Ed hitched along a little higher up, and as the leaning trunk of the tree was already bending under his own and the bear’s weight, the infuriated brute did not seem disposed to go further. Besides, as he had been mortally wounded, he was probably growing too weak to do much now.

My brother got to the bottom of the canyon and brought Ed’s gun to where I[Pg 84] stood. But, as we had no powder or bullets, and as Ed could not get them to us, even if he would have been willing to risk our shooting at the bear, it was hard to decide what to do. It was already dusk and we could not stay there all night.

“Boys,” shouted Ed, at last, as he steadied himself in the forks of a leaning and overhanging bough, “I’m going to come down on my laz rope. There, take that end of it, tie your laz ropes to it and scramble up the hill.”

We obeyed him to the letter, and as we did so, he fastened his lasso firmly to the leaning bough and descended like a spider to where we had stood a moment before. We all scrambled up out of the canyon together and as quickly as possible.

When we went back next day to get our ropes we found the bear dead near the root of the old mossy maple. The skin was a splendid one, and Ed insisted that my brother and I should have it, and we gladly accepted it.

My brother, who was older and wiser than I, said that he made us take the skin so that we would not be disposed to tell how he had “treed a bear.” But I trust not, for he was a very generous-hearted fellow. Anyhow, we never told the story while he lived.

BILL CROSS AND HIS PET BEAR.

When my father settled down at the foot of the Oregon Sierras with his little family, long, long years ago, it was about forty miles from our place to the nearest civilized settlement.

People were very scarce in those days, and bears, as said before, were very plenty. We also had wolves, wild-cats, wild cattle, wild hogs, and a good many long-tailed and big-headed yellow Californian lions.

The wild cattle, brought there from Spanish Mexico, next to the bear, were most to be feared. They had long, sharp horns and keen, sharp hoofs. Nature had gradually helped them out in these weapons of defense. They had grown to be slim and trim in body, and were as supple and swift as deer. They were the deadly enemies[Pg 87] of all wild beasts; because all wild beasts devoured their young.

When fat and saucy, in warm summer weather, these cattle would hover along the foothills in bands, hiding in the hollows, and would begin to bellow whenever they saw a bear or a wolf, or even a man or boy, if on foot, crossing the wide valley of grass and blue camas blossoms. Then there would be music! They would start up, with heads and tails in the air, and, broadening out, left and right, they would draw a long bent line, completely shutting off their victim from all approach to the foothills. If the unfortunate victim were a man or boy on foot, he generally made escape up one of the small ash trees that dotted the valley in groves here and there, and the cattle would then soon give up the chase. But if it were a wolf or any other wild beast that could not get up a tree, the case was different. Far away, on the other side of the valley, where dense woods lined the banks of the winding[Pg 88] Willamette river, the wild, bellowing herd would be answered. Out from the edge of the woods would stream, right and left, two long, corresponding, surging lines, bellowing and plunging forward now and then, their heads to the ground, their tails always in the air and their eyes aflame, as if they would set fire to the long gray grass. With the precision and discipline of a well-ordered army, they would close in upon the wild beast, too terrified now to either fight or fly, and, leaping upon him, one after another, with their long, sharp hoofs, he would, in a little time, be crushed into an unrecognizable mass. Not a bone would be left unbroken. It is a mistake to suppose that they ever used their long, sharp horns in attack. These were used only in defense, the same as elk or deer, falling on the knees and receiving the enemy on their horns, much as the Old Guard received the French in the last terrible struggle at Waterloo.

Bill Cross was a “tender foot” at the time[Pg 89] of which I write, and a sailor, at that. Now, the old pilgrims who had dared the plains in those days of ’49, when cowards did not venture and the weak died on the way, had not the greatest respect for the courage or endurance of those who had reached Oregon by ship. But here was this man, a sailor by trade, settling down in the interior of Oregon, and, strangely enough, pretending to know more about everything in general and bears in particular than either my father or any of his boys!

He had taken up a piece of land down in the pretty Camas Valley where the grass grew long and strong and waved in the wind, mobile and beautiful as the mobile sea.