Title: The wolf-cub

a novel of Spain

Author: Patrick Casey

Terence Casey

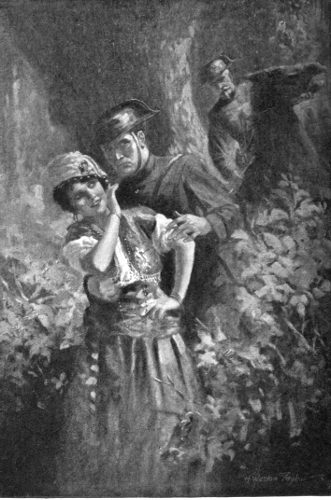

Illustrator: Henry Weston Taylor

Release date: October 21, 2012 [eBook #41126]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander, Mary Meehan, The Internet Archive

(TIA) and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

WITH FRONTISPIECE BY

H. WESTON TAYLOR

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY

1918

Copyright, 1918,

By Patrick and Terence Casey

All rights reserved

Published, January, 1918

When Jacinto Quesada was yet a very little Spaniard, his father kissed him upon both cheeks and upon the brow, and went away on an enterprise of forlorn desperation.

On a great rock at the brink of the village Jacinto Quesada stood with his weeping mother, and together they watched the somber-faced mountaineer hurry down the mountainside. He was bound for that hot, sandy No Man's Land which lies between the British outpost, Gibraltar, and sunburned, haggard, tragic Spain. The two dogs, Pepe and Lenchito, went with him. They were pointers, retrievers. For months they had been trained in the work they were to do. In all Spain there were no more likely dogs for smuggling contraband.

The village, where Jacinto Quesada lived with his peasant mother, was but a short way below the snow-line in the wild Sierra Nevada. Behind it the Picacho de la Veleta lifted its craggy head; off to the northeast bulked snowy old "Muley Hassan" Cerro de Mulhacen, the highest peak of the peninsula; and all about were the bleak spires of lesser mountains, boulder-strewn defiles, moaning dark gorges. The village was called Minas de la Sierra.

The mother took the little Jacinto by the hand and led him to the village chapel. She knelt before the dingy altar a long time. Then she lit a blessed candle and prayed again. And then she handed the wick dipped in oil to Jacinto and said:

"Light a candle for thy father, tiny one."

"But why should I light a candle for our Juanito, mamacita?"

"It is that Our Lady of the Sorrows and the Great Pity will not let him be killed by the men of the Guardia Civil!"

"Men do not kill unless they hate. Do the men of the Guardia Civil hate, then, the pobre padre of me and the sweet husband of thee, mamacita?"

"It is not the hate, child! The men of the Guardia Civil kill any breaker of the laws they discover guilty-handed. It is the way they keep the peace of Spain."

"But our Juanito is not a lawbreaker, little mother. He is no lagarto, no lizard, no sly tricky one. He is an honest man."

"Hush, nino! There are no honest men left in Spain. They all have starved to death. Thy father has become a contrabandista And if it be the will of the good God, and if Pepe and Lenchito be shrewd to skulk through the shadows of night and swift to run past the policemen on watch, we will have sausages and garbanzos to eat, and those little legs of thine will not be the puny reeds they are now. Ojala! they will be round and pudgy with fat!"

The men of Minas de la Sierra were all woodchoppers and manzanilleros—gatherers of the white-flowered manzanilla. Their fathers had been woodchoppers and manzanilleros before them. But too persistently and too long, altogether too long, had the trees been cut down and the manzanilla harvested. The mountains had grown sterile, barren, bald. Not so many cords of Spanish pine were sledded down the mountain slopes as on a time; not so many men burdened beneath great loads of manzanilla went down into the city of Granada to sell in the market place that which was worth good silver pesetas.

There are no deer in the Sierra Nevada—neither red, fallow, nor roe. There are no wild boar. There is only the Spanish ibex. And what poor serrano can provision his good wife and his cabana full of lusty brats by hunting the Spanish ibex? He has but one weapon—the ancient muzzle-loading smooth-bore. And the ibex speeds like a chill glacial wind across the snow fields and craggy solitudes, and only a man armed with a cordite repeater can hope to bring him down.

Soon descended the mountains only men who had turned their backs upon Minas de la Sierra and who thought to leave behind forever the bleak peaks and the wind-swept gorges and the implacable hunger. Out of every ten only one crawled back, beaten and bruised by the savage Spanish cities and the savage Spanish plains. With those of Minas de la Sierra who could not tear themselves away from their native rocks, these broken-hearted ones continued on and with them slowly starved.

It was not the will of the good God that Jacinto Quesada should have fat pudgy legs by reason of his father's endeavors. Shrewd were the dogs, Pepe and Lenchito, but they were not so shrewd as were the Spanish police. Came a pale and stuttering arriero, a muleteer, up to the village one day. To Jacinto Quesada's mother he brought tragic news.

The men of the Guardia Civil had discovered poor Juanito as he was unbuckling a packet of Cuban cigars from the throat of the dog Lenchito; they had walked him out behind a sand dune; they had made him dig a grave. Then they had shot down Lenchito; then they had shot down Juan Quesada. And then the dog and the man were kicked together into the one grave and sand piled on top of them both.

But make no mistake, mi señor caballero reader! The men of the Guardia Civil are not abominations of cruelty. They are not monsters, brutal and depraved. Quita! no.

There are twenty-five thousand men in the Guardia Civil; twenty thousand foot and five thousand cavalry. By twos, eternally by twos, they go through Spain, exterminating crime wherever crime shows its fanged and evil head.

Every Spaniard is potentially a criminal. An empty belly goads him into lawlessness; his very nature greases his wayward feet. The Spaniard is by nature sullen, irascible, insolently independent, lawless. He is more African than European. Prick a Spaniard and a vindictive Moor bleeds.

Then, whether it be his famishing hunger or lawless passion which has caused him to rise above the law, the Spaniard, his crime writ in red, flees from the police. Spain is a country of uncouth wilds. There are the desolate high steppes and the savage mountains; there are the tawny despoblados, which are uninhabitated wastes; there are the marismas, which are labyrinthine everglades where whole regiments may lie concealed.

But also, in Spain, there are railroads and telegraphs, and a most efficient constabulary, the Guardia Civil. And, were it not for Caciquismo, all evil-doers would be speedily apprehended by the Guardia Civil, tried under the alcaldes, and incarcerated in the Carcel de la Corte or the Presidio of Ceuta.

Caciquismo is not a tangible thing. It is a secret and sinister influence. It is not the Tammany of New York; it is not the Camorra of Naples. Yet it resembles both these corrupt edifices in its special Spanish way. Its instruments are prime ministers and muleteers, members of the cortes and bullfighters, hidalgos and low-caste Gitanos.

A cacique may be only the mayor of a tiny hamlet; again, he may be privy councilor to the king. Yet high or low, he is but one of the many tentacles of a gigantic octopus which lays its clammy shadow athwart the land.

It is well known that Tammany, for reasons political or otherwise, protected criminals. Well, even as did Tammany, so does Caciquismo. A Spanish criminal may be captured, tried before a magistrate and all; but if he be one in good standing with the caciques, never is he sent to the Carcel de la Corte or Ceuta. The invisible eight arms of the gigantic octopus uncoil and reach out, the thousand ducts along those arms open to spew a flood of favors and gold, and magistrate and prosecutor are bought and paid for, and the men of the Civil Guard who cannot be bought, who are incorruptible, are in the Spanish courts betrayed!

Therefore, the men of the Guardia Civil are most high-handed and cruel. The criminal caught in the deed never reaches the Spanish jail. He is shot down on the spot. Bigots for justice are the men of the Guardia Civil!

Carajo! but there was wailing in Minas de la Sierra when came the news of Juan Quesada's death. So many men had gone away and been murdered by the police, and so few were left! Women who had been made widows in the selfsame way as Jacinto Quesada's mother came to the hut and sought to comfort her. But she would not be comforted. For three days she lay on the earthen floor of her hut and beat her hands and her head against the dust. Then she commenced vomiting and swooning like one sick unto death.

They thought it was the cholera. The cholera was forever scaling the high mountains and skulking into the village in the night. A man of the village went for the doctor, Don Jaime de Torreblanca y Moncada. He lived but a few miles from Granada, and the man had to go all down the hills to summon him.

Torreblanca y Moncada was what is called a "hard man." He was a grandee by birth and breeding, a hidalgo of the old granite-jawed, eagle-stern and eagle-haughty Spanish sort—the Cortes y Monroy sort, the Hernan de Soto sort. He worshipped his ancient name, his high hidalgo blood. His personal honor was to him more precious than life, more sacred than a sacrament, inviolable, consecrated.

When a young man, he had married a woman of race and beauty. She had run off with a Gypsy picador. Don Jaime had put a Manchegan knife down his boot and set off after them, vowing to follow them to the end of the earth even, and to kill them both. But the train, in which the guilty ones fled, had not reached Jaen when it was wrecked, and they both were crushed out of all semblance to two sinful lovers.

With composure and reserve, Don Jaime heard the news. He did not even laugh harshly or curse God for robbing him of his revenge. Only grim, quiet and morose, he returned to his dishonored house and to his baby daughter that had been robbed, sacrileged, and orphaned.

He was quite a rememberable-looking man. His hair had whitened quickly in the years that followed; his skin, from exposure to wind and weather, was a deep swarth; and his eyes were gray. Not many Spaniards have gray eyes. The eyes of Torreblanca y Moncada were a clear, cold, agate gray. All in all, there was about his appearance, especially the long aquiline nose, the stony eyes and pointed white beard, something which seemed to harken back to the days of ruffs and ready swords—the days of the terrible Spanish infantry, the Armada, the Bigotes, the "bearded men" the Conquistadores.

The mountaineers of Minas de la Sierra knew fear of him and awe. For them he had only a contemptuous eye and a bitter smile and a harsh imperious way. They said he had a granite boulder for a heart. But he was very tender with the sick.

He was the sort of physician who looks upon his business of serving the ailing as a sacred commission from on high. He was like one who had taken Holy Orders with his doctor's degree. No Jesuit was more slave to his oaths; no Jesuit worked with more zeal for God and the Society than did Don Jaime for Humanity and Science. The most poverty-abased labrador, the most filthy beggar, had but to summon him, and he would arise from his table or his bed and ride across Spain to him who needed healing.

He was the only physician who would journey up the mountains to Minas de la Sierra. It mattered not to him that there were long climbing miles of perilous goat-paths along howling gorges; it mattered not to him that the mountaineers never had money to pay him his just due. He was indeed a "hard man," haughty as Satanas, and grim and dour. But even as his personal honor was to him more precious than life, so was his physician's honor a covenant with Jehovah, tyrannical and imperious to command him.

The old men of Minas were sitting under the cork-oak in the center of the village when the hidalgo doctor came out of the hut of the sick woman.

"Is it not the great illness, Don Jaime?" asked one of the old men, old Castro. He was thinking of the dread cholera.

"No. She is merely sick with despair."

"Ah, that is the great illness of Spain! All Spain is sick with despair!"

"Carajo! but you are right, my father!" answered the Senor Doctor in his bitter way. "Spain despairs. And why not? Spain famishes. There is no food for honest men to eat. And men turn dishonest, thinking by crime to appease their gnawing bellies. They became contrabandistas, salteadores de camino, abigeos, ladrones. And the men of the Guardia Civil take them out on the mountainside and murder them.

"Our forefathers," he philosophized, "were refugees from the fall of Troy. Black was their national color; black for their lost cause. They should put a black stripe with the red and yellow stripes of our modern Spanish flag. A black stripe for despair."

"Bueno, Don Jaime!" said the old men. One added:

"We have not studied at Salamanca like you, but we know what we know. Every night the hungry children cry themselves to sleep. Our own porridge bowls are never full. We have seen our sons grow desperate. We have seen them one by one go away. There was Benito, my youngest. He became a contrabandista, and the Civil Guard murdered him. There was Adolpho, the son of my sister Teresa. He also went the same way. There was Santiago Reyes and Mateo Pacheco and Ignacio Parral. And now follows Juan Quesada."

"What would you?" asked the Senor Doctor, with sudden brutality. "The Guardia Civil must keep the peace of Spain. And Spaniards must steal to live. It is dog eat dog. It will always be dog eat dog while men are Spaniards and Spaniards starve."

He turned abruptly away and entered once more the hut of Jacinto Quesada's mother. When he came out again, he said to the women clustered about the door:

"She is forever kissing the child Jacinto and moaning, 'My poor Jacintito! What will become of thee, thou pale tiny one? My poor, poor Jacintito!'

"It is better that he should be taken away from her until she is herself again. His presence here only deepens her despair. I will carry him with me down the mountain to my casa outside Granada and keep him there for a time. I have not much—what Spaniard is rich?—but he will be fed well; he will be given the same food as is given my own daughter, Felicidad."

"Ah, Don Jaime, you have the heart of gold!" cried one woman, her eyes moist and tender.

"The Mother of God reward you, and mend your broken heart, proud Torreblanca y Moncada!" cried another. And the others would have burst out in a full litany of praises, had not the Senor Doctor fiercely said:

"Don't stand there making the monkey of me, you mountain jades! Quita de ahi! Pronto! Get the peasants' brat into his jacket and alpagartas, and wrap him warmly in his shawl. I desire to get out of this accursed hole as quick as possible. It smells bad, and I itch. The place is lousy!"

In the great harsh fist of the hidalgo doctor Jacinto Quesada, who was then ten years old, put his little trembling hand and went down the mountains, and entered a new world.

The casa of Don Jaime was large, decayed, dingy, and full of lizards that lived between the crumbling adobe bricks. But it seemed to Jacinto Quesada a sumptuous palace. Besides the hidalgo doctor, there lived in the sumptuous palace two old servants and a pretty little girl with golden hair and legs round and pudgy as would have been the legs of Jacinto, had his father lived and prospered.

In the great rooms that were so bare with poverty, the two children played together. The eyes of the little Jacinto, alert to see all in this new strangeness, had noted a peculiar thing. One day he said to Felicidad:

"Do you love your father, the Senor Doctor?"

The child knuckled her brow.

"It is not the love," she said thoughtfully. "Don Jaime is a very grand and haughty hidalgo; it is not his desire that I should love him. But I fear him much!"

Came a day when Felicidad was very naughty. She tore leaves from the huge old sheepskin-bound books in the great gloomy library, and cut them into paper dolls. It was Don Jaime's one delight to read and reread, in the long hot afternoons, those yellow-leaved, richly illuminated ancient volumes. Pedro, one of the old servants, informed the doctor of Felicidad's naughtiness. The doctor's face went ashy; he shook all over with rage. He brought out a short whip of horsehide, a quirta such as vaqueros use. With the quirta he lashed Felicidad's legs and back unmercifully.

Her screams drove like knives into little Jacinto Quesada's heart. He was but ten years old and he was much afraid of the terrible hidalgo. But as the whip pitilessly descended again and again, and Felicidad screamed and writhed in agony, a hot anger welled up in him; he became desperate as only a child becomes desperate; he went mad.

Screaming himself, he charged at the doctor and tore at his trousers with his finger nails, and tried to leap up and upon him. The quirta rose again and fell upon his head. Then he caught at the doctor's wrist and sunk his teeth into it. With bulldog tenacity he hung on, until he was beaten into insensibility, and his jaws forced open.

Strangely, Don Jaime conceived a sort of liking for Jacinto Quesada after that. He took to calling him The Little Wolf of the Mountains. It became his wont to greet Jacinto, when he stumbled across him in the great bare house, with a look of savage admiration and the words:

"Ah, here is the wolf-cub! And how are the fangs to-day, hungry scrawny one?"

Upon a time, Don Jaime, his hand still in bandages, discovered Jacinto alone in the dusky library, bent over a quaint old account of the battles and triumphs of the swineherd Pizarro.

"When did you learn to read, son of a mangy she-wolf?" asked the doctor in great surprise.

"When I was but five. My mother taught me letters. She is a woman of honest birth and of education," answered Jacinto proudly. "When she was a child, she was sent to the convent of Santa Ursola in Granada."

"And what do you think of this swashbuckler, Pizarro? He robbed the Indians of their golden suns and chalices and their silver bars, without morality and without ruth, did he not? But—do you think him cruel?"

The boy nodded his head slowly. Then with the oldish quaintness of a book-bitten child, he explained:

"I do think him cruel, mi senor don. But he would not have been Pizarro had he been soft-handed and pitiful. He led three hundred and fifty Spanish caballeros and four thousand Indians deep into the cordilleras. About him were the millions of the Inca Empire. If he had been less brave, less strong, less cruel, those many Peruvians would have swirled about him like the waters of an ocean, and engulfed him and his poor few Conquistadores. But he knew how to be most cruel. That was why he conquered. That was why he was altogether the great captain!"

When first he discovered Jacinto in his library, Don Jaime had been of the mind to send him bundling, and to lock the door between the peasant boy and his precious old books. Now he turned about abruptly, said "Humph!" and went thoughtfully away.

At last, came an arriero to take Jacinto Quesada back to Minas de la Sierra. She stood beside the mule upon which Jacinto mounted, the golden-haired little Felicidad, and held up her small fat hands for him to kiss. The hidalgo doctor watched his departure from the dark of the doorway. He looked after the great dust-cloud on the brown road for a long time.

"The Little Wolf!" he muttered in his morose way. "He was as famished for knowledge as he was for food. He would have gone blind if he lingered in my library much longer. To see him rip the entrails out of Bernal Diaz's 'Cortes' and the Lives of Balboa, De Soto, Coronado—what a joy! He has eyes of gold for seeing things clearly—for seeing beyond good and evil. And he has a heart of fire, he has gusto, that Spanish boy! Pizarro was cruel, but he was great, he was magnificent, because he was cruel! What a Spanish answer!

"Por los Clavos de Cristo! he will go far, that mountain brat! He will be a great realist and philosopher like Cervantes. Or he will be a great dramatist like Lope de Vega. Or a great poet or statesman. Or a great captain like the Conquistadores whose lives he studied with such gusto and whose strength he analyzed with such clear-sightedness!"

Then Don Jaime smiled very bitterly. For the moment he had forgotten that his Jacinto Quesada had been born a Spaniard of the people. He swore a vile oath.

"But no, he will be none of those things!" he said. "Cascaras! I am becoming an old driveling fool."

Don Jaime knew that God smiles sardonically upon the Spaniard of the people who seeks to rise in the world. He knew that, just as the United States is a country of unlimited opportunities, just so is Spain a country of opportunities limited and few. The Spaniard of the people, strong with heart and gusto, has but two careers open to him. By those two careers and those two careers only, can your ambitious Iberian attain to fame and fortune, and stand greatly above his countrymen.

"He will become a bullfighter, perhaps!" said Don Jaime.

Every man and boy in Spain is an aficionado, a bullfight "fan," a frantic bullfight "bug." The successful bullfighter, be he matador, or murderer of bulls, or only a peon of the cuadrilla, is given rich food with which to garnish his belly; he learns how gold feels when it is minted into money; his photographs are purchased by romantic señoritas; and wherever he goes, he is followed by crowds of tattered street urchins who studiously and hopefully ape his swagger. The whole universe salves and butters him with admiration and envy; and he, the popular picador or the distinguished espada, is in many ways more truly a king of Spain than is Alfonso the King. Jacinto Quesada, he of the heart of fire and the great gusto, might become a bullfighter.

But suddenly Don Jaime remembered that the little Jacinto was a boy of the desolate mountains. He could never see the great bullfights of the cities of the plains, those great bullfights so golden with glamor. Hence never would be waked in him the ambition to become a bullfighter.

"Ea pucs!" said Don Jaime with grimness. "Well, then! There is naught for my Jacinto to do but to become a bandolero!"

The bandolero sells no photographs of himself; he goes houseless in the wind and rain; he bites upon gold coins but rarely; he is hunted persistently by the Spanish police. And yet, from day to day, his deeds have their place in the Hispanic newspapers; he is the hero of a thousand household stories and ballads; the people give him the fat of the countryside to eat; the people love him more even than once they loved that greatest of all bullfighters, the negro Frascuelo!

"Quita!" exclaimed Don Jaime, chuckling. "God forbid!" It had struck him that he might live to the day when people would say in his hearing: "Jacinto Quesada? Ah, he is good, he is brave, he is like the very God Himself. Watch over him in the mountains, Mary, Queen of Angels! and protect him from the Guardia Civil and from treachery!" And he, Torreblanca y Moncada, the prophet who, years before, had seen his vision, would laugh and they would wonder why he laughed.

A bandolero is a Spanish highwayman, a Spanish Dick Turpin, a Spanish Robin Hood. He is a man of a type altogether extinct in countries less backward than Spain. In Spain the type has persisted for five hundred years and still continues to persist. In Spain the type is obstinate, ineradicable.

José Maria was a Spanish bandolero. Diego Corrientes, he who was loved by a duchess, was a Spanish bandolero. And Spanish bandoleros were Visco el Borje, Agua-Dulce, Joaquin Camargo, nicknamed El Vivillo, and Pernales, the blond beast of prey. The bandolero is the blight of Spain. But countries that have been exploited by Spaniards are also affected with the Spanish blight. A bandolero of Mexico is Zapata. And a Mexican bandolero is Pancho Villa, too.

One wintry gloaming of Jacinto Quesada's thirteenth year, there entered Minas de la Sierra, a ruddy-haired, blue-eyed, burly man on horseback. He was clad in weather-worn corduroys; a week's golden stubble was on his broad, sunburned face; and his body smelled sourly of sweat. He guided his horse with his knees and heels. In both hands he held half-raised a Mauser carbine.

The horse halted under the cork-oak, but the man did not dismount. He sat looking slowly from right to left, from left to right, along the village street. Presently he shouted:

"Hola, mis paisanos! Why do you not come out to greet me?"

With trembling and hesitation they came forth from their doorways. They were like so many wary brown lizards stealing out from their rocks. They formed a tongue-tied ring about the quiet horseman and eyed him with awe.

"I desire food," said he shortly.

"It is our wish to serve you, maestro," said Antonio Villarobledo, speaking for the rest. "You shall have the best of our poor lean store."

Then spoke up Carlos Machado, a showy and presumptuous man.

"Come to my house with me. I have a stew of lentils!"

"But I have a puchero!" another bid. "Come with me, Gran Caballero."

Suddenly a woman who had been hiding in her doorway ran out into the street, crying shrilly:

"Do not listen to these selfish stingy Moors, maestro! Come with me—I will kill a pullet for you, the last of my lot! Come with me, I beg you, caballerete! To ask you to be my guest, I have the supreme right. My husband was the last man of the village to be murdered by the Guardia Civil!"

Carlos Machado and certain others turned wrathful faces toward Juan Quesada's widow. But she had, indeed, the supreme right, and they dared make no objection when the corduroy-clad cabalgador said most heartily:

"Well spoken, woman! I will go with you. Your husband shall not have been murdered in vain and your pullet lived to no good purpose!"

Then he laughed in the faces of the others and said with sudden imperiousness:

"Bring your lentils and your puchero to the widow's casa, mis paisanos! My appetite is the most gorgeous appetite in Spain, and all you have will not be too much for me. Besides you will do well to fat me up, you Spaniards!"

He dismounted and followed Jacinto Quesada's mother, giving instructions to certain of the villagers as to how they should water and fodder his horse.

When his mother went out on the mountainside to catch and to kill the last surviving chicken, Jacinto Quesada went with her both to lend her a hand and to ask her a question. She held the pullet to the block and Jacinto raised the axe. Then, the axe poised aloft, Jacinto asked:

"Who is this rough burly man to whom the people do such honor?"

"He is the great Pernales!"

The axe descended; blood spattered the faces of the two; the head of the pullet lay free from the body and still; the body flapped about in a manner outrageous and vile. Said Jacinto, after a moment:

"Pernales, the bandolero?"

"Si, si! Pernales, the bandolero, him hunted forever by the men of the Guardia Civil!"

"But why do not the men of the Guardia Civil murder him as they murdered our poor Juanito?"

"Art thou a dullard, child! Thy father was a mere contrabandista. Thy father wished only to be left undisturbed by the police. He was a coward at heart as are most Spaniards who turn dishonest that they might eat. He suffered himself to be captured without a struggle; there was no murder in his bowels!"

She swept on with true Latin eloquence and fervor:

"But this Pernales! The men of the Guardia Civil fear Pernales as they do not fear men of your poor father's sort. He is muscled like a leopard; he is long of arm; he is deep-loined; and the strength of him is like the strength of the first Spaniard, Hispanus, the son of Hercules. But there is more to him than mere body strength! He is possessed of a strength above body strength, a strength beyond body strength. He is strong in his soul!

"He is strong to live; he is strong to conquer; he is strong to make men die. The bandoleros are all like that. They are arrogant, imperious, absolute. They are like our ancestors, the Cristinos Viejos, the Old Rusty Christians, they who eradicated the Moors from Spain. They are like our ancestors, the Celtiberians, they who bathed in the urine of horses that they might grow hard and muscular, they who asked for no quarter in battle and who gave none.

"A man to be a bandolero must have entrails of iron. This Pernales is of the right guts. He likes nothing better than to meet a policeman alone in the hills and to fight him to the death. The men of the Guardia Civil would capture and slay him if they could; but when they come up to him on the high road, he turns and gives battle with laughter and taunt, with ardor, strength, desperation, and ferocity! Never does he hesitate or falter when comes the supreme moment—the moment when his weakness says 'Be merciful!' and his strength says 'Kill thou, Pernales!'"

His mother sped into the house, but Jacinto stood by the dripping block, immersed in thought.

Presently Jacinto Quesada sat on his little stool in the far corner of the great fireplace and watched the bandolero eat. What huge teeth he had and how white they were! Over each mouthful the whole broad face worked, the lips and cheeks making a dozen grimaces, the jaws snapping and grinding.

Every little while, the bandolero mumbled from a full mouth some question. He seemed much interested in the murdered Juanito. But it was almost as though he considered poor Juanito's death a humorous mishap; at certain of the widow's remarks he laughed roughly, and his laughter stormed through the cabana like a wind through one of the boulder-strewn passes overhead.

An hour later he was astride his horse again and riding down the goat-path that dropped away from Minas de la Sierra and wound through the lower gorges. It is never the habit of the bandolero to linger in a pueblo or village longer than a very short time; most sensational and brief and furtive are his visits.

There was a fat and brilliant moon, that night. It was as though a snow had fallen, the heads and shoulders of the mountains were so white. Down into the dark moaning gorges, one could see a great distance.

Pernales walked his horse very slowly, for the path led along the sheer of a precipice. But while he kept a vigilant eye on the way ahead, ready to throw himself toward the wall of the gorge should the nag stumble on a loose stone, or shy from the path, and plunge screaming into nothingness, Pernales continually cast wary quick glances toward the crags and boulders overhead, and continually bent his ear back the way he had come. It was almost as though he feared an ambush in that lonely perilous place. It was almost as if, at any moment, he expected men of the Guardia Civil to rise from behind every rock, and the command of the Guardia Civil to sound in his ears:

"Alto a la Guardia Civil!"

He rounded a great rock that threatened to tear from its moorings down into the winding gorge below. Abruptly he halted his horse and his carbine came up. A long tense hush. Then suddenly he exploded:

"Who are you that stands beside the way?"

Came the answer in a child's thin voice:

"Jacinto Quesada!"

Minas de la Sierra was a long distance above and far back in the sierras. With great surprise the bandolero recognized the child to whom he had waved a hand and called a laughing "á Dios" some time before.

"Are you alone?" The carbine still threatened.

"See for yourself, maestro! But I am altogether alone."

The bandolero rode nearer. When the horse shouldered up, the little Jacinto was compelled to squeeze into the very crevices of the rock wall, so narrow was the path.

From his lofty seat on the big, rawboned black horse, Pernales looked down at the son of the widow Quesada and measured, with his eyes, the boy's extreme youthfulness and preposterous lack of strength and size. Jacinto was only thirteen years old.

What he saw altogether reassured Pernales. His blue eyes twinkled; he smiled; he grinned, his lips working and twitching; and at last he broke out in a frank and free burst of laughter.

"Cascaras!" he roared, between guffaws. "How came you here, lively little one? Have you the sharp hoofs of the ibex to gallop you from crag to crag, across gorges and gargantas and all? Or have you the griffon vulture's wings that you may fly over mountains? You are no real flesh and blood child! You are a sprite, a—"

Jacinto Quesada, imperious with a great desire, brushed his bantering words aside. Trembling with eagerness, he cried:

"Take me with you, Pernales! I would be a bandolero, too! Lift me up behind you on your horse, and I will go with you through Spain and be your compañero and your dorado—your golden one, your trustworthy one! Take me with you, please, please, Pernales!"

The bandolero did not credit his own ears. He was too astounded to laugh.

"Hola!" he gasped. "What is this now? You, my chicken, would be a bandolero! And you came all the way down here to recruit with me! Por los Clavos de Cristo!"

Then soberly and slyly, for he was beginning to see good fun in the little fellow:

"But do you not know that it is a rule, a convention, of us good bandoleros to ride alone? Solitary and single-handed, we are safer and stronger than if a troop of cabalgadores surrounded us. There is no one so swift and slippery and elusive as a bandolero who rides alone, and no one so free from fear of treachery—he trusts no man and no man he dreads."

"True. You understand your business, I see," said Jacinto Quesada.

He was only thirteen; yet he spoke slowly, with deliberation and discernment and a great air of mannish profundity. He had got something from Don Jaime's books, this mountaineer's bantling!

"But there are times," he qualified, "when even the most superb bandolero needs assistance in some serious and signal business. Have you not yourself a dorado, a camarada, who rides with you on your greater crimes, the Nino de Arahal? Certain folk have told me of the Nino; they said he shared the glory of those enterprises which made imperative a show of numbers and strength; do not tell me these folk lied! I had hoped to dispossess this camarada and dorado of yours, this Nino de Arahal, and to attain to the envied place down from which I threw him headlong!

"But the Nino," he added, arrogating to himself judicial authority—"let us forget him! Za! he is only an insignificant frog! Your wish to ride unhindered and alone, of that I would speak! Maestro, when I become your dorado, we will ride together always, for we will commit only imposing and glorious crimes!"

Said Pernales softly:

"But how would you dispossess the Nino de Arahal?"

"I would pit against the huge gorilla's head of the Little One of Arahal, my head of gold for thinking quick thoughts and audacious ones. I would displace him and replace him by my natural superiority of brain. But if that were not enough—Carajo! I would lock knives with him, I would lunge and slash and rip and stab with my navaja, while he tore and stabbed and slashed and lunged with his, until one or the other of us gushed out his life through his wounds and was dead!"

Then it was that Pernales laughed so that the very canyon roared and rang. He rolled back his head; he clapped his hands to his stomach; he opened his mouth to its widest stretch; and he guffawed so tremendously that the horse beneath him staggered and almost overbalanced from the wall. He was Olympian in his laughter.

And why not laugh? Did he not see in his mind's eye the gigantic ruffian nicknamed the Nino de Arahal locked with this stripling, this barefoot child, this suckling babe? Za! The Nino would make ten of him! Zape! The Nino would swallow him at a mouthful! It was preposterous! It was so funny, he cared not a peseta if he laughed himself to death!

But suddenly, through his laughter, slid Jacinto Quesada's low-toned words:

"But if he were altogether too huge and brawny for me to murder in open combat, then I would murder him in some hidden, treacherous way. Treachery is the strength of the weak who are yet strong. If there be no other way, the superior brain resorts to treachery for the superior brain is invincible. While I am still weak of body, I will not disdain to use treachery!

"And, man, man, I warn you! Do not continue to laugh at me! You have laughed quite enough at me, Pernales! Cease laughing this instant! Quick! Straighten your face, or Porvida! the Manchegan knife I have with me, I will use on your horse. I will rip open his belly; and he, with you upon him, will go bounding off the path and fall head over heels down into the abyss!"

Instantly Pernales sobered. His face set into an emotionless mask; his teeth clenched together with an audible click; his eyes became hard as blue bright pebbles. Without seeming to do so, he looked down at the child's hands; and true! there was in those hands a huge, flat-bladed dagger, a dagger of La Mancha. The child was turning it over and over, and studying it with a pensive interest.

Deep within himself, Pernales laughed ironically at his own discomfiture. He could not use the carbine. Without chancing the great risk of sending his horse recoiling and reeling off the path, he could not strike down the child with a blow of his fist! And the child had but to turn aside his gun or dodge his hard fist, and crouch out of harm's way beneath the horse's barrel. Then might he strike up with the dagger, and the horse would make the breakneck plunge as surely as he would scream when stabbed.

"Jacinto Quesada," said Pernales bitterly, "you have caught Pernales in a pretty deadfall! Use your knife; then go for the Guardia Civil and guide a brace of policemen to where my body lies on the bottom of the gorge, and there awaits you the money offered for my head! Cascaras! I judged you altogether too superficially; I was too contemptuous!"

Quietly Jacinto Quesada put the Manchegan knife back in his belt.

"I forbear to strike," said he, "since you have confessed your fault. Now, soberly and with due respect, give me your answer. Will you take me with you?"

A gleam of admiration lit the eye of Pernales.

"Jacinto Quesada," he said, "you are no child. You have shown resolution, force, finality; you are altogether masculine, altogether varonil; you are a man! Therefore, as one man to another, I say: No, I cannot take you with me!"

Pernales now was very serious.

"To be my dorado, it is not enough that you have a full-grown soul. You must have a full-grown body; and your body is still the puny, soft-boned body of a child. If you rode away with me, you of the weak body, your strong soul might be sacrificed to the Nino de Arahal or the Guardia Civil. And that—God forbid!

"Let us look at this matter like two sensible Moors. Don Eduardo Miura, let us suppose, has a young fighting bull of extraordinary promise. At the Tentaderos (the breeders' private bullfight, when the young bulls are ranked according to their merit as fighting animals), this youngster shows superb courage and astounding ferocity. But he is only two years old; and five years old must be the age of Don Eduardo's animals before he exhibits them in the Plaza de Toros. Does Don Eduardo make an exception of this unique bull, does he allow him because of his astounding ferocity to have a premature début in the bull-ring? Name of God, no! Not even if he be as magnificent with meat as the most mature seven-year-old!

"Jacinto Quesada, quickly I have grown to love your strong soul—I have grown to love your strong soul too much. And that is why I say, I cannot take you with me. No! Porvida, no! But, if you are resentful, use your knife and send me whirling down into the gorge. Proceed! I care not a peseta what you do."

Jacinto Quesada stood motionless as a rock, thinking deeply. Something in the boy's downcast attitude moved Pernales to pity.

"Do not despair, my fire-hearted, arrogante little man," he said presently. "I have said no; this time my no is absolute; but I shall not say no to you, should I pass this way again when you are more fully grown. Some day, I promise you, I shall again pass this way, and then if you are still of the mind to be my dorado, you may join out with me and we will murder the men of the Guardia Civil together, two sworn compañeros. Meanwhile, grow brawny, grow brave, grow high-handed. There will always be room in Spain for haughty resolute ones like you!"

"I accept the promise given," said Jacinto Quesada. "And I do not ask you to swear to return for me—a word is enough between men. Now, knowing you will come back, I will compose myself and wait. A child is impetuous and fretful; a man is implacable yet patient."

"Son of the widow Quesada," returned Pernales magnificently, "on the promise given and taken, let us strike hands! With a handshake, like two true Spaniards, we will bind the bargain."

Jacinto Quesada took his hand off the hilt of his Manchegan navaja and gripped claws with the bandolero. A certain note of solemnity thrilled through the moment.

The bandolero started on.

"Go thou with God, compañero!" said Jacinto Quesada.

"Grow big, grow strong, thou!" said the great Pernales.

Jacinto Quesada grew bigger, stronger. But he suffered more with ambition than with growing pains. Ambition is the seed of greatness, but the seed cannot germinate and bourgeon without giving agony and labor to the soil in which it is nurtured.

Pernales did not again pass that way. Three months had not intervened, since the promise to return had been given, when the great bandolero was murdered for the reward by a Gallego on a lonely hill-road in the Asturias—shot through the head at forty yards.

Now, if never could Jacinto Quesada ride with Pernales, then by the Life! he would ride alone.

When at last he attained to manhood, he went down the mountains, stole a carbine and a horse, and became a bandolero errant and free.

He had hands of gold, that fire-hearted Spanish boy, for sticking up a troop of caballeros and their ladies out for a merienda or a bull-baiting on the parched plains about Madrid. And he had hands of gold for sticking up a diligence full of notables in the savage defiles of the Sierra de Guadalupe or the Sierra de Gredos or the Sierra de Guadarrama. And he had courage and originality. Why, he was still a mere novice as a bandolero, an apprentice hand, a novillero, when he took it into that round, young, handsome and arrogant Spanish head of his to way-lay and loot the Seville-to-Madrid Express!

Spanish highwaymen, you must know, are not in the habit of holding up passenger trains. To way-lay a lone muleteer in the mountains, to halt and rob a party of itinerant guitarists and dancers, or to pillage the hacienda of a rich rural cattle breeder are the conventional things to do. But to hold up the Seville-to-Madrid—it is unthinkable, it is not the will of God! Spanish highwaymen prefer to do less spectacular deeds and to live to see their grandchildren.

In the province of Ciudad Real, the Seville-to-Madrid Express crosses the river Zancura by means of a safe and modern steel cantilever bridge built by Le Brun, a French engineer. And a half hour before it reaches this steel bridge, the Seville-to-Madrid crosses another bridge, a bridge over a small tributary of the Zancura which is dry three fourths of the year. This bridge is not of steel; it is timbered. It was never built by Le Brun; it is flimsy, weather-worn, and liable to give under any unusual strain. It is called the Arroyo Seco Bridge.

Here, where the Arroyo Seco lies like a great brown gutter across the world, are the high parameras of La Mancha. There are no more desolate and lonely uplands in all Spain. Swarthy, sun-scorched and thirsty, they torture the eye with dusty dun distances and prone dun lines. You would think it an altogether unlikely place for a bandolero to stage a hold-up.

And here, a hundred yards below the Arroyo Seco bridge and close beside the railroad track, waited Jacinto Quesada one hot, dry, windless afternoon. He was seated upon a small sleek mouse-colored Manchegan pony. He wore corduroy leggins, a sheepskin zamarra, and a Cordovan sombrero that had once been white. His dress was that of the typical Manchegan herdsman. He looked like any one of the hundred or more vaqueros who lived the wild lonely life of the cattle country roundabout.

The Seville-to-Madrid showed in the southwest. Like a somber black snake it crawled slowly forward—like a black snake laggard and heavy after a great dinner of mice.

Spanish passenger trains are altogether unlike American passenger trains, for American passenger trains eat up distances like the brazen cars of old Northern gods. The passenger trains of Spain are most deliberate and slow. They halt for ten minutes at every wayside station, for no better reason than to allow the passengers to alight, unlimber their legs, and smoke the eternal cigarette. They are the very crawling snails of the earth!

Of course, the Seville-to-Madrid was an express, a through train. But you may be sure she was no fast train except when viewed through Spanish eyes. At fifteen miles the hour, morosely it crawled on. It neared the waiting Jacinto Quesada and, fearful of the flimsy wooden bridge beyond, slackened its pace to a painful glacier-slow flow.

As the wheezing locomotive lumbered up, Jacinto Quesada, with knees and one hand, held the shuddering pony motionless beside the track. The other hand he raised aloft. Pointedly, his eyes turned to that upraised hand; then to the locomotive's cab; then significantly, to the upflung hand once again.

The engine driver, one arm extended to the throttle, a blue-smoking cigarette between his lips, leaned far out the cab and looked down at the uplifted hand of Jacinto Quesada. In that significantly uplifted hand of Jacinto Quesada was an unlighted cigarette.

Now, an American engineer would have passed unheeding by, with perhaps a curse for Jacinto Quesada as an arrant fool. Again, a French engineer might have called back: "It is a pleasure!" and thrown down a paper of matches. For, as it was plain to see, Jacinto Quesada was requesting, in pantomime, a spark to ignite his hopelessly dead slim cylinder of tobacco.

But the Spanish engine driver did neither of those two things. It is not that the Iberians are not as polite as the French; they are more polite and altogether more ceremonious. Know you that in Spain, and also in Mexico, it is considered something of an insult to proffer a man matches when he requests a light of you and you yourself are smoking. It is as though you consider him socially beneath you, when you proffer him matches.

The locomotive lumbered by. But the engine driver crowded forward on his seat; his arms worked; the whistle shrieked. And the train groaned and jolted, roared and banged to a full stop.

Passengers telescoped themselves out of windows, some knocked all a-scramble by the sudden halt, others pale and frightened. Those heads that protruded from fortunate windows saw the engine driver clamber down from his high turret, a lighted cigarette in his hand. And they saw spur forward to meet him, the dusty vaquero, in his mouth a cigarette that was dead.

The vaquero flung himself from his pony. He and the engine driver drew together. A hand of each met, became entwined. Their heads leaned close, the cigarettes between their teeth touching ends.

Suddenly the engine driver staggered away from the vaquero, his jaw dropping, his cigarette falling unheeded to the ground. A huge long-barrelled revolver in the hand of the vaquero was nuzzling his umbilicus.

"Aupa!" shouted the vaquero harshly. "Up!"

Prodding his belly persistently, the vaquero followed him back, step by step. The engine driver was suddenly enlightened. It was all a piece of herdsmen's buffoonery, a monstrous practical joke!

"Benito!" he roared, addressing his stoker in the cab above. "Benito, look down! Here is a vaquero who thinks himself a salteador de camino, a bandolero like the poor dead Pernales or that new man, Jacinto Quesada! Por los Clavos de Cristo! what a fool's idea!"

Then to the vaquero. "Don't you know I have no time for horseplay, you silly one, you buffoon, you? You are making yourself liable to arrest!"

"I am the new man, Jacinto Quesada!" said Jacinto Quesada with politeness and reserve. Then, "Aupa, aupa!"

"Jacinto Quesada—Almighty God!" gasped the engine driver. Only he made it, "Todopoderoso Dio!" and he groaned it out slowly.

But with great alacrity he put up his hands.

Then after a moment, stuttering with fright, he commenced objecting.

"But caballerete—but Don Jacinto—"

"What would you?"

"But you cannot hold up the Seville-to-Madrid! No one ever holds up the Seville-to-Madrid! And besides, you are alone!"

"But I am not alone," returned Jacinto Quesada.

Nor was he. Out of the Arroyo Seco, a hundred yards up the track, three men as drab and dusty as he had poked their dishevelled heads.

Shouted Quesada, "Adelante, mis dorados! The stew is ready, approach the bowl! Forward, my golden ones!"

The Golden Ones approached at a run, showing in their hands carbines of no recent fashion. They were rough-bearded fellows of impetuous courage but of little skill or fame; reckless scapegraces whom he had picked up, on the plains and in the mountains, to reinforce him in this most pretentious and uncommon hold-up.

After the consummation of the deed, they would go their ways and he his. Like most Spanish bandoleros en grande, Jacinto Quesada preferred, whenever he could, to keep his heels clean of confederates and coadjutors; he preferred to hold himself aloof and solitary. However, they were his compañeros for the nonce; for the nonce, they were his dorados, his golden, his trustworthy ones.

One of them clambered up into the cab after the fireman, Benito. The rest, under the supervision of Jacinto Quesada, proceeded to turn inside out the Seville-to-Madrid.

Pretentious train robberies are forever much alike. Save that those waylaid and despoiled were Spaniards, and Spaniards are eternally themselves, and their souls glow frankly and incandescently out through their bodies in everything they do, the hold-up of the Seville-to-Madrid was like an American train robbery, like a train robbery anywhere.

The mail coach was first disposed of. Then the highwaymen turned their attention to the passengers. In a jostling, milling, frightened drove on the open plain to the right of the stalled coaches, the passengers were herded by the four taciturn workmanlike bandoleros. Then one by one each passenger was led forward from the rest and searched for money and valuables.

Those who were cowardly, quaked and walked knock-kneed, their mouths stuttering rapid prayers. Those who were courageous but overawed, clenched their teeth in their lips, held their eyes pasted upon the bandoleros, and did silently and with utter obedience that which they were told to do. Those who were weak, wept. Few words were said, yet the faces of all were as a loudly chanted litany of dreads.

Jacinto Quesada took little part in the searching; he left that to his journeymen. He stood aloof, his revolver in hand, his eyes studying pensively, as they were put to the search, the demeanor of the brave and the base.

Many of the herded and driven and robbed wondered at this boy with no vestige of hair on his smooth brown cheeks. They did not know him. They thought Jacinto Quesada, he who had begun making such a great noise through Spain, one of the bearded, black-visaged, older men.

First to be led forward and made to deliver was a traveler for a Barcelona manufactory. Then came two brokers who had been speeding about Spain to make contracts on the grape, olive, orange, and apricot crops. Then came a wine taster, one cork grower, and three cattle breeders; and then a troupe of Gitanos, Gypsy musicians and dancers of the metropolitan cafés. And these having been plucked in their proper sequence, there was led forward a wisp of black-clad nuns.

Jacinto Quesada stepped forward and took off his hat to the nuns. He motioned that they should be brought back to their old places without suffering the sacrilege of search, and he said, "Your pardon, Ladies of God!"

Then was led forward a foreign looking man, a globe-trotter who had been traveling alone. He was big, broad-shouldered, fair-haired and as smooth-shaven as any bullfighter. He was square of face, his jaw was a round resolute knob, and his eyes were blue and hinted of being quick to laugh. Struck by the foreign look of the man, Jacinto Quesada stepped forward once again and, with an air of ingenuous curiosity, asked, "You are a Frenchman, are you not?"

It is a fact that most Spaniards mistake all foreigners for either Frenchmen or Englishmen. And they never can distinguish between persons of the two races.

Answered the outlander, "I am neither, muchacho. I am what you Spaniards call a Yanqui, a Norte Americano."

"Cascaras! You are one of those who gave Spain such a great beating a few years ago and robbed us of Cuba and the Philippines. Thorough and impudent salteadores de camino, you Yanquis seem to me! But sometimes it does a person or a country good to be beaten and robbed. Spain is the better for having had her buttocks soundly spanked; and the Philippines and Cuba—zut! they were ulcers on her flesh, and Spain is sincerely thankful she submitted to the surgeon's knife, now that the thing is done!"

At the philosophical and rather elevated tone of the boy, the American raised his eyebrows in surprise. Yet he had traveled in Spain some months already, and he should have been used to Spanish logic and Spanish eloquence.

The race of the Cristinos Viejos is an old, old race, full of salt and masculinity and knowledge that is not to be acquired in schools. In a country where any peasant will argue or exchange racy jokes with Alfonso and even slap him on the back in the ensuing hurly-burly of merriment, where a hidalgo will eat with his coachman, and a beggar light his cigarette from that of a bishop, how otherwise than the way Jacinto Quesada talked, would a man of the people talk?

So this was the notorious Jacinto Quesada, he whom all Spain had commenced talking about! Smiling a smile of appreciation, the American said:

"I think you are very well right about the recent war. You Spaniards are certainly long on common sense. But you are young to be a philosopher, Don Jacinto."

At least, that was what he tried to say. But he was speaking in Spanish and he was not altogether at home in the idioms of the language. However, Jacinto Quesada got his meaning.

He felt pleased, did Jacinto Quesada, to be called a philosopher. With a smile he remembered the ferocious way of thinking which had caused him, when a child, to seek to be the dorado of the poor dead Pernales—that savage philosophy which had finally moved him to become a bandolero. He was not nearly so impetuous and fiery and bigoted a youngster as then; he was more serene, more Apollonian, more pensively thoughtful.

But the American was speaking. Thinking to be polite and, at the same time, rid his system of a sally typically American in humor, he said, "It is pleasant to meet a Spaniard like you!"

Quesada caught the inference. He smiled, showing his clean white teeth, and returned, "It is pleasant to rob you, senor!"

And he added, struck with surprise that a man could joke while in such an awkward and even perilous position, and startled by his surprise into admiration and wonder:

"To know you, caballero, is to know why your countrymen won the recent war. You are a man of the great bravery; you are as brave as the very God Himself!"

Your American is forever afraid lest he be made the butt of irony and ridicule, the target of satire and sarcasm. His very self-consciousness indicates how vulnerable he is to others' opinions of him; and his extreme reserve is only a cloak worn eternally to mask the weakness. This particular American changed countenance as he had never changed countenance when menaced by the bandoleros' carbines; he went white and cold, his eyes flashed angrily. And sharply, he exploded:

"Why do you say that?"

"Because you do not recoil from the rough touch of my dorados; because your eye fearlessly meets my eye; because you talk without falter and without affected ease; because you act like a man who is a man!" explained Jacinto Quesada with sincerity. And to clinch the argument, he added, Spaniard-like, "I am utterly brave myself. Do you think I cannot recognize men of my own kind?"

The American fidgeted, blushed slightly, and smiled a very rueful smile.

"But why, if I am so very brave," he countered, "did I not rebel and kill some of you when your men herded me out on the prairie with the rest, and then yanked me forward to pick my pockets? There is a Colt's automatic in my hip pocket, but you'll notice I have not used it!"

"A brave man is not necessarily a brave fool like the hidalgo don, Quixote of La Mancha," returned Quesada shortly. "You Americans are a sentimental race."

Then, turning to one of the searchers, he ordered, "Relieve the Yanqui caballero of the pistol that is such a temptation to him, Rafael Perez!"

Presently, eager to have their turns and be done with the necessary formalities, pressed forward a cuadrilla of bullfighters. A few of them wore the ordinary street dress of men of the profession. They would be known anywhere in Spain for bullfighters by their broad, stiff-brimmed, low-crowned black hats and their black, tightly fitting clothes.

The most of them were still in bull-ring costume, however. In the busy months of the Taurine Season, when bullfights are almost daily events and contracts must be fulfilled, the Brethren of the Coleta are kept continually on the jump—rushing precipitantly from town to town, from bull ring to railroad train and straightway again to bull ring—and they have little or no time to change from bull ring costume into street clothes and scarcely more time to spend in eating, sleeping, or doing anything else than murdering bulls. Therefore, it is a habit with bullfighters to railroad everywhere about the peninsula in full ring regalia; and one often sees these athletes speeding, gorgeously clad, over the desert vegas or alighting at the depots of bullfight-crazy towns.

First to come forward was the espada, the dexterous with the sword, the murderer of bulls, the man of death.

Jacinto Quesada took one look at him, then with gusto cried, "Por los Clavos de Cristo! if here is not the great Morales!"

"Seguramente, yes, I am the great Morales!" returned the matador, bowing in acknowledgment of the swift and hearty recognition. He wore pink silk stockings, gold-braided green silk breeches, waistcoat, and jacket, a white ruffled shirt, a crimson tie, and a black cap. He wore the black rosette and ribbons of the matador in his coleta, his queue—that long, thick, and sacred lock of hair all bullfighters wear as the time-honored insignia of their ancient profession.

He was not yet thirty. He was a little below the middle height. He had a long body and short muscular legs. He was all iron and strength. And his brown Andalusian face was the typical young bull fighter's face, boyish, almost effeminate with its mild contours; a face made expressive and pleasing by eyes soft, dark, thick-lashed and very brave; a face that was the easily read table-of-contents of an honest, simple-souled, intrepid man.

Jacinto Quesada's eyes smiled, and his whole face beamed, as he looked at him, for he recognized in this man whom he had long admired because of his splendid courage in the bull ring a kindred spirit.

"And how are the wife and the children, Manuel?" he asked.

"Most excellent in health, thank you, Jacinto! And you? And your family?"

"Superb! But ah, Morales, what would I not give to be watching you killing your bulls in the Seville bull ring at this moment, instead of doing what I am—setting my dogs of ladrones upon you to rob you of your hard-earned money! Say but the word, and you will be exempted from this indignity!"

"A thousand thanks; but no, I would rather not! It is too much honor!"

"Too much honor for you, one of the three bravest men in Spain? You, whom I have ridden fifty miles many times to see give the suerte de matar, the stroke of death! Why, to sit in the sun and watch you perform, I have ventured into Seville in disguise when the men of the Guardia Civil were as thick about the bull ring as flea-bitten curs about a camp of Gitanos; and I have counted the risk nothing!"

"But if I am one of the three bravest men in Spain, as you say, who are the others? Who is the second? Who is the third?"

"The second! Can you not guess?"

"Ah, chispas! yes. Yourself, Jacinto Quesada, of course!"

"And the third?"

The brow of the matador darkened with professional jealousy. Tentatively he asked, "You do not mean the espada, Lagartijo, do you?"

"No; I do not like Lagartijo's ceremoniousness and caution; I like only diestros of the good old charge-and-take-a-chance Sevillian school. I mean that Yanqui traveler over there. He is like us two; he is an iron-boweled man!"

The bullfighter turned around and took a good look at the lone American. Then he slapped his breeches and jacket and invited the bearded salteadores to continue with the search.

After the cuadrilla of bullfighters came a fat gray parish priest; then several tourists from Central and South America; then a pretty flight of rosy and demure young convent girls, bound northward under the vigilant watch of two prim sallow duennas; and then a tall blond man with a straw-colored mustache darkened and stiff with wax.

It was palpable this man was no Spaniard. He was dressed with neatness, even elegance. Strangely, his face looked much older than his lithe athletic body. It was a sharp, clever face, but a peculiar ashy pallor overspread it and, about the mouth, there were hard grim lines. The nose was long, high-bridged, predatory. The eyes were slate-colored, small and bright and furtive. They had a peculiar trick of drooping at the outer corners, a trick that gave him a calculating and rather sinister look.

He had been traveling with his young wife, a very lovely slip of a girl. Her turn was to come next. She stood at the edge of the muster of people, looking after her foreign-looking husband with blue eyes oddly eager rather than anxious. She was a golden-haired girl of the rare Castilian blond type. She seemed made all of gold, ivory, and rose petals. Among all those frightened people, she alone was without fear. As she stood there, looking calmly about her, she seemed altogether the innocent and trustful child; to all appearances she should have been still in some Spanish convent, sequestered and secure—not abroad in the world where there are bandoleros and even men of worse sorts.

Her husband, the foreign-looking man, was about to be put to the search when, aroused by something more than curiosity, Jacinto Quesada stepped forward and asked brusquely, "You are a Frenchman?"

"I am a Frenchman, monseñor."

"And why, Frenchman, do you make signs with your hands to me?"

With good reason Jacinto Quesada asked that question. Ever since he had been singled out for the search, the Frenchman, looking everywhere but at his hands, had been persistently making covert signals with those hands. First he drew two fingers down across his left cheek; then he made certain finger movements very like the word-spelling finger movements of the deaf and dumb; and finally he stroked his throat and Adam's apple with a certain lingering wistful care!

The pale Frenchman looked full at Jacinto Quesada, and suddenly his small slate-colored eyes blazed like sunlight on ice.

"Do you not comprehend of the signs the meaning?" he asked sharply in tolerable Spanish.

"No."

"Nor that which I desire you to understand when I do this thing?"

Impetuously he stepped forward and grasped, with his right hand, the right hand of Jacinto Quesada. What followed seemed only a most ardent handshake. Then he dropped Quesada's hand and stepped back, assuming his old passive pose. And only Quesada knew that there had passed between them another signal—he alone knew that the Frenchman, on gripping his hand, had tapped the wrist of that hand with his index finger twice.

Rumpling his brow, the youthful bandolero consulted with himself for a space. Then, his face clearing, decisively he said:

"No, Frenchman, your signals to me have no meaning. It is, perhaps, that I am not of sufficient knowledge; I am only a poor Moor of Andalusia, you know. But what is the message you wish to convey by your cabalistic signs? I am curious, senor; tell me in honest Spanish and interestedly I shall listen."

The tall blond Frenchman laughed ruefully under his waxed mustache.

"As you do not comprehend my signs," he said, "to explain to you the meaning would do me little good, I fear."

Returned Quesada, somewhat disappointed, "You fear rightly, Frenchman!"

He made a slight gesture of the hand. Two of his dorados seized the Frenchman and proceeded to subject him to a rough overhauling. The Frenchman grimaced with impotent rage and, narrowing his naturally small calculating eyes, watched the searchers' every move with covert anxiety.

Brusque, precipitant, hasty was that search. Very easily might it have been more studied and thorough. But a gold watch, a few Spanish gold and silver peseta pieces, two rings set with diamonds and an emerald scarfpin were taken from him before he was liberated by the searchers. The rings and the scarfpin were not plucked from his hands and necktie; they were found deep in his pockets where he had hidden them, thinking perhaps, to smuggle them past the bandoleros.

At that, the emerald scarfpin was but a very ordinary jimcrack and the diamonds of the two rings, though huge and pretentious, had the dishonest and glassy look of paste imitations. Though but simple Moors, even as they called themselves, the bandoleros were not so ingenuous as to be deceived by them; and they wondered greatly why he had concealed them with such pains. Remarked sarcastically one of the searchers, a certain Ignacio Garcia, addressing Quesada:

"The elegant French rooster has but a thinly lined crop, maestro!"

He grasped the Frenchman's elbow and swung him about-face. Then he gave him a shove toward the group already plucked and gutted, shouting harshly, "Away with you, you false jewel! Pronto!"

The Frenchman hastened to merge himself into the background. Once his face was turned away from the bandoleros, his pebbly eyes sparkled with profound relief; they sparkled with inconcealable joy; and he smiled a superior triumphant smile.

"Who comes next?" asked Jacinto Quesada, without much interest.

"The beautiful young wife of the Frenchman, maestro. She, with the mouth that is a nest for kisses!" And Rafael Perez pointed her out.

"And it please you, you may come forward, Senora Dona!" in a carefully softened voice called Pio Estrada, another of the searchers. Strange, but her youth and beauty and high hidalgo look had moved the man to a ruffian's attempt at courtesy and gentleness.

As she made to step forward, Jacinto Quesada turned his eyes upon the beautiful golden-haired girl and, for the first time, gave her a special and particular scrutiny.

"Hola!" he gasped. "What is this?"

He stepped forward a step, his eyelids narrowed, his eyes gleaming; and he shot toward her a second look, piercing, probing. It was as though he were shocked and aroused, puzzled and confounded. While he looked eagerly and long at her, he muttered:

"What a resemblance! But no—it is not a resemblance. She is she herself!"

He moved slowly towards her as though drawn thence by an irresistible influence. Suddenly he called out a name!

"Felicidad!"

On the barren, windless plain to the right of the stalled carriages, they were all gathered, the bandoleros with their carbines, the travelers so like a herd of cattle in a rodeo. Those passengers, already searched and robbed, were in a separate group; they were sequestered from those not yet searched and made to deliver. No sound came across the everlasting flats but the low incessant chitter of the desert-loving wheatears, little fuzzy fat birds that live among the mimosa and the thorny acacia and the stunted ilex of that ugly and desolate Manchega veldt. Out from the main drove of passengers moved bravely the golden-haired girl. And then, a name was called, and the windless air became suddenly electric with drama.

The Frenchman's young wife moved forward, seemingly unaware of Jacinto Quesada's call, of his now devouring gaze. Well, suddenly and all on the moment, she turned about-face and started swiftly for the stalled train!

It was altogether unexpected. She was not the first of her sex to be singled out for the search; she had seen nuns and convent maids and even Gitanas treated by the bandoleros with a respect and courtesy that amounted almost to reverence; and yet, at the last instant, alarm and trepidation had overcome her, it seemed. She was hysterical, perhaps; almost insane with terror.

Be that as it may, her unexpected and erratic performance caused an echoing panic to sweep over the other passengers. Even the bandoleros felt the contagion. Cursing excitedly, two of them started to pursue the golden-haired girl, while the third, Rafael Perez, standing near Quesada, raised his carbine and screamed hoarsely:

"Come back here, you outrageous minx!"

The crowd, momentarily free from the dread of the bandoleros, had commenced an insensate shouting and milling. Now, had Perez fired off the carbine, the whole hold-up might have ended then and there for the bandoleros in an inglorious headlong rout. The passengers, already out of thrall to the salteadores, would have risen in tumultuous, uncontrollable fury at this firing on a defenseless woman.

But Jacinto Quesada rose to the crisis and saved the situation. Excited though he was, he sprung toward Perez, tore the carbine from his hands and, pointing it at the crowd, shouted imperiously to his men:

"Back, you fools, to your stations! Guard these people. Shoot any that break away! And don't mind the girl! I'll bring her back—I, and no one else!"

Presto! and the bandoleros were back in their old positions, their carbines sweeping the crowd. The imminent danger of stampede was dissipated. The discipline of dread again prevailed.

Handing the carbine back to Perez, Jacinto Quesada started after the girl. She had fled without aim, without purpose, he thought, like a frightened doe that cares not where she flees so long as she flees from the huntsmen. Her panicky flight would do little good, however; a sort of trap was the stalled train, not a refuge and sanctuary.

The girl was just about to open the door of one of the third-class coaches and fling herself therein when, all at once, she cast back a look, first at her tall blond mustached husband, then at Quesada. Strangely, her glances seemed to have become preposterously mixed. It was a look of dread and loathing she threw back toward her husband; and a look of entreaty and beseeching she sent toward the pursuing bandolero!

With his long mountaineer's legs, Jacinto Quesada sprinted to the train. Hardly had the door of the third-class carriage closed behind the golden-haired girl than he was at that door. Open he flung it and in he burst.

"Felicidad! Felicidad, querida mia, my darling! It is I, Jacinto—Jacinto Quesada! You have naught to fear from me. And if you had told me that he, the Frenchman, was your husband, I would not have robbed him. Porvida! everything taken already shall be given him back. And as for you, dear Felicidad—"

She had backed herself against the door opposite. Now she came forward swiftly, her face paling and flushing, her lip a-quiver. It was not as though she were glad with sudden recognition: it was as though she were terribly agitated by some deadly fear. She said, in a dry expressionless tone:

"I heard your name mentioned by some passenger as we were bundled from the train, Jacinto, and ah! how grateful to God I was when I first saw you, almost half an hour ago, standing among those ruffianly ladrones! I remembered the time you saved me from my father's quirta—and I needed you so much more, now!

"All this long, long afternoon I prayed that something would happen—anything, anything! God of my soul! how I prayed! But even after I discovered you and realized that, for our childhood's sake, you would protect me, it took all my courage and strength to flee from the crowd and conceal myself here, where I could speak to you and not be spied upon or suspected by that evil, that terrible man!"

Almost in a whisper were her words spoken, but they crashed upon Jacinto Quesada's brain like exploding, detonating shells. He reeled back, overwhelmed, staggered, knocked all to pieces. He gasped:

"Por los Clavos de Cristo! what is all this?"

"Ah, Maria purissima! He does not understand! But all, I shall tell him!"—and swiftly, precipitantly, the girl went on:

"This Frenchman. He calls himself Jacques Ferou. He was the only one that was kind to me and even until two hours ago, I thought I loved him. We were to be married in Madrid to-night—but now—"

"Then he is not already your husband! Carajo! I thought—"

"No; we but eloped this morning. And now, I would not continue on with him; I would turn back! I am afraid—afraid!"

"But tell me all from the beginning. Your words turn my brain to a stew!"

Jacinto Quesada had known Felicidad's father, Don Jaime de Torreblanca y Moncada; he had lived in the great, cold, dingy house near Granada; he had tasted the secluded, lonely life of Felicidad. Therefore, she had but to say a few sketchy rapid sentences and he comprehended the beginning of everything.

"Of late years, my father has become gradually poorer, Jacinto," she said.

Quesada nodded his head understandingly. Don Jaime had never refused his physician's services to the poverty-stricken and wretched; and the poverty-stricken and wretched were always becoming sick; and the poverty-stricken and wretched seldom paid. Small wonder that Don Jaime's fortunes had fallen into decay!

"My father had no money put by to keep him in his old age; but he always said he would sell those old beloved books of his when he became incapacitated, by age, for a physician's arduous toils, or when bitter necessity pressed him hard. You must know, Jacinto, that father's ancient, yellow-leafed books are worth much, much money."

She went on to explain. Learned men, famous men—some of them scholarly descendants of noble families, others erudite plebeians with the right to affix a dozen initials after their names—were always coming to Don Jaime's house from the University of Salamanca and the Museo Provincial of Seville to examine those books and to write historical treatises and critiques from them. And it was not unusual to find one of these bookworms, these bibliophiles, these hombres del todo aficionado á los libros, making eager hints to purchase such of the precious dingy tomes as they considered within their means.

Some of the books had been possessed by Don Jaime's family for hundreds of years; others he had come by through his godfather who was a famous Spanish historian and very rich; and still others he had himself discovered when doctoring ruined hidalgo families and the monks of poverty-gutted monasteries; and he had taken these finds in place of monetary fees. Naturally enough, therefore, he hated to part with any of this great treasure in books.

Fearing an old age of stony poverty, however, Don Jaime at last made up his mind to put the books on sale. The money he might receive from marketing the books he planned to invest in Argentine bonds. Three months gone, he wrote to two great houses that deal in rare and valuable books; the one in London, the other in Paris.

Posthaste, two months since, came to the house outside Granada, the buyer for the London firm. In far-away cold London, they had heard of Don Jaime's collection, for there was not another collection of its like outside of Spain. For two weeks the London book-buyer lived in the casa with Don Jaime and Felicidad, cataloguing and pricing the books. Some of the old quaint authors he rejected as of little worth, but others he called "glorious Golcondas" and offered Don Jaime such a sum for them that he was amazed, astounded. He had not expected to receive so much money for the whole aggregate and total of his collection.

"Three weeks ago, after paying my father a fortune in bank notes," continued the girl, "the English book-buyer, Senor Havelock Moore-Ingraham, went away, and with him, borne by a caravan of ten mules, went the cream and richness of my father's library.

"Then came to our house this Jacques Ferou. He said he had been sent by the Paris house to whom my father had written. My father told him that he was too late to bid, that all the books of value had been sold.

"At that Jacques Ferou became very downcast; he said that his firm would be much put out when they learned he had allowed the English company to bag the hares while he played the laggard. And he begged very earnestly for permission to look through the books, which had not been purchased, in the hope that the English agent had overlooked a few volumes of value, volumes that he might buy in order to save his face."

Don Jaime gave him permission so to do. For almost a month he lived in the great dusky lonely house. When he was not in the library poring over the yellowed tomes, he wandered through the house, seeking sight of Felicidad. When she had her daily "hour of balcony", he would leave the casa and stand watching her from across the road, "playing the bear" in a very serious and devoted manner.

"I had never had a novio before," explained Felicidad, "and his eyes were so kind and sympathetic! It was very lonely in the great house with just my father and the old whining Pedro and the old childish Teresa. And he treated me with such consideration and reverence!