Title: Portage Paths: The Keys of the Continent

Author: Archer Butler Hulbert

Release date: October 26, 2012 [eBook #41179]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note: Obvious errors in spelling and punctuation have been corrected except for narratives and letters included in this text. Footnotes have been moved to the end of the text body. Also images have been moved from the middle of a paragraph to the closest paragraph break, causing missing page numbers for those image pages and blank pages in this ebook.

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

CLEVELAND, OHIO

1903

COPYRIGHT, 1903

BY

The Arthur H. Clark Company

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | 9 | |

Part I: Portage Paths | ||

| I. | Nature and Use of Portages | 15 |

| II. | The Evolution of Portages | 51 |

Part II: A Catalogue of American Portages | ||

| I. | Introductory | 85 |

| II. | New England and Canadian Portages | 94 |

| III. | New York Portages | 122 |

| IV. | Portages to the Mississippi Basin | 151 |

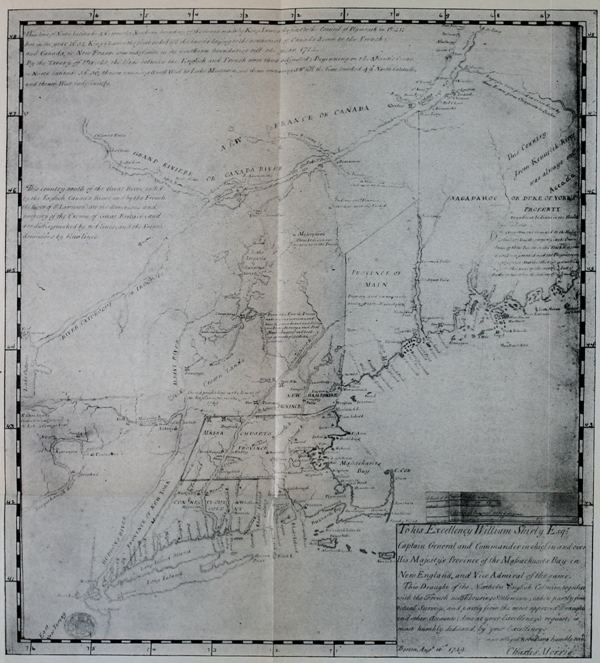

| I. | The Morris Map of 1749: Northern English Colonies | 55 |

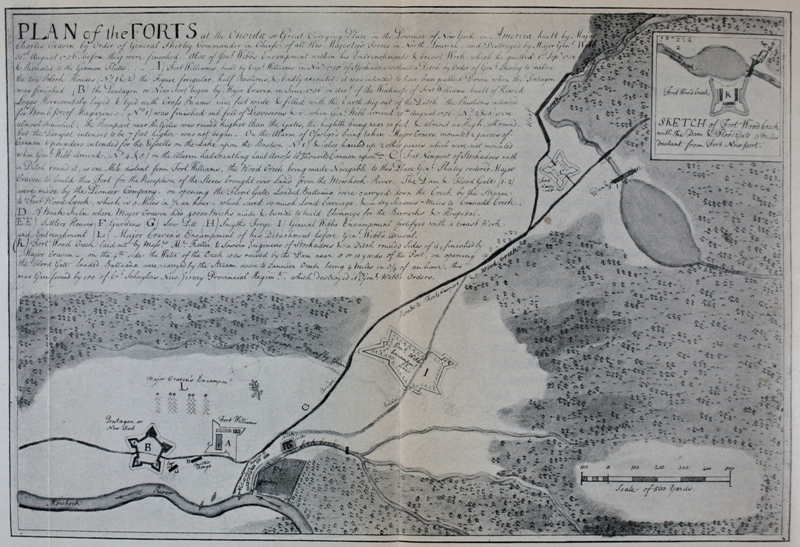

| II. | The Old Oneida Portage in 1756 (Rome, New York) | 142 |

The little portage pathways which connected the heads of our rivers and lakes or offered the voyageur a thoroughfare around the cataracts and rapids of our rivers were, as the subtitle of this volume suggests, the “Keys of the Continent” a century or so ago. The forts, chapels, trading stations, treaty houses, council fires, boundary stones, camp grounds, and villages located at these strategic points all prove this. The study of these routes brings one at once face to face with old-time problems from a point of view almost never otherwise gained. The newness and value of reviewing historic movements from the standpoint of highways is strikingly emphasized in the case of portage paths. While studying them, one seems to rise on heights of ground like those these pathways spanned—and from that altitude, gazing backward, to get a better perspective of the[Pg 10] military and social movements which made these little roads historic.

The difficulty of treating such a broad subject in a single monograph must be apparent. Portages are found wherever lakes or rivers lie, and our subject is therefore as broad as the continent. It is obvious that in a limited space it is possible to treat only of portages most used and best known—which most influenced our history. These are practically included in the territory lying south of the Great Lakes between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mississippi River. Historically, too, we are taken back to the early days of our history when America was coextensive with the continent, for the important portages were those binding the St. Lawrence with the rivers of New England, and the tributaries of the Great Lakes with those of the Mississippi.

It has seemed most profitable to divide the subject into two parts: in the first, under the specific title of “Portage Paths” is given a description of these routes, their nature, use, and evolution. The second part is devoted to a “Catalogue of American Portages,” and in it are included[Pg 11] extracts from the studies of students who have given the subject of portages their attention, showing style of treatment, methods of investigation and research, and results of field-work. Among these Dr. Wm. F. Ganong’s Historic Sites in the Province of New Brunswick and Elbert J. Benton’s The Wabash Trade Route are commanding examples of critical, scholarly field-work and specific historical analysis. Professor Justin H. Smith’s impressive monograph on Arnold’s Battle with the Wilderness, and Secretary George A. Baker’s The St. Joseph-Kankakee Portage are illustrations of what could and should be done in many score of cases throughout the United States. To Sylvester’s Northern New York and Dr. H. C. Taylor’s The Old Portage Road the author is likewise indebted. The author has attempted to make good in some degree the astonishing lack of material concerning the famous Oneida Portage in New York, a subject which calls loudly for earnest and minute study—for this portage path at Rome, New York, with the exception of Niagara, was the most important west of the Hudson River. A plea for the study[Pg 12] of the subject of portages and the marking of historic sites occupies the concluding pages.

A. B. H.

Marietta, Ohio, May 22, 1903.

There may be no better way to introduce the subject of the famous old portages of America, than to ask the reader to walk, in fancy, along what may be called a “Backbone of America”—that watershed which runs from the North Atlantic seaboard to the valley of the Mississippi River. It will prove a long, rough, circuitous journey, but at the end the traveler will realize the meaning of the word “portage,” which in our day has almost been forgotten in common parlance, and will understand what it meant in the long ago, when old men dreamed dreams and young men saw visions which will never be dreamed or seen again in human history. As we start westward from New Brunswick and until we reach the sweeping tides of the Mississippi we shall see, on the right hand and on the left, the gleaming lakes[Pg 16] or half-hidden brooks and rivulets which flow northward to the St. Lawrence or the Great Lakes, or southward to the Atlantic Ocean or the Gulf of Mexico. On the high ground between the heads of these water-courses our path lies.

For the greater portion of our journey we shall find neither road nor pathway; here we shall climb and follow long, ragged mountain crests, well nigh inaccessible, in some spots never trod by human foot save the wandering hunter’s; there we shall drop down to a lower level and find that on our watershed run roads, canals, and railways. At many points in our journey we shall find a perfect network of modern routes of travel, converging perhaps on a teeming city which owes its growth and prosperity to its geographical situation at a strategic point on the watershed we are following. And where we find the largest population and the greatest activity today, just there, we may rest assured, human activity was equally noticeable in the old days.

As we pass along we must bear in mind the story of days gone by, as well as the[Pg 17] geography which so much influenced it. It is to the earliest days of our country’s history that our attention is attracted—to the days when the French came to the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes, and sought to know and possess the interior of the continent, to which each shining tributary of the northern water system offered a passage way. Passing the question how and why New France was founded on the St. Lawrence, it is enough for us to know she was there before the seventeenth century dawned, and that her fearless voyageurs, undaunted by the rushing tides of that great stream, were pushing on to a conquest of the temperate empire which lay to the southward. Here in treacherous eddies, the foaming rapids, and the mighty current of that river, they were soon taught the woodland art of canoeing, by the most savage of masters; and in canoes the traders, trappers, missionaries, explorers, hunters, and pioneers were soon stemming the current of every stream that flowed from the south.

But these streams found their sources in this highland we are treading. Heedless[Pg 18] of the interruption, these daring men pushed their canoes to the uttermost navigable limit, and then shouldered them and crossed the watershed. Once over the “portage,” and their canoes safely launched, nothing stood between them and the Atlantic Ocean. It is these portage paths for which we shall look as we proceed westward. As we pass, one by one, these slight roadways across the backbone of the continent, whether they be miles in length or only rods, they must speak to us as almost nothing else can, today, of the thousand dreams of conquest entertained by the first Europeans who traversed them, of the thousand hopes that were rising of a New France richer and more glorious than the old.

Advancing westward from the northern Atlantic we find ourselves at once between the headwaters of the St. John River on the south and sparkling Etchemin on the north, and we cross the slight track which joins these important streams. Not many miles on we find ourselves between the Kennebec on the south and the Chaudière on the north, and cross the pathway between[Pg 19] them which has been traversed by tens of thousands until even the passes in the rocks are worn smooth. The valley of the Richelieu heads off the watershed and turns it southwest; we accordingly pass down the Green Mountain range, across the historic path from Otter Creek to the Connecticut, and below Lake George we pass northward across the famous road from the extremity of that lake to the Hudson. Striking northward now we head the Hudson in the Adirondacks and come down upon the strategic watershed between its principal tributary, the Mohawk, and Lake Ontario. The watershed dodges between Wood Creek, which flows northward, and the Mohawk, at Rome, New York, where Fort Stanwix guarded the portage path between these streams. Pressing westward below Seneca Lake and the Genessee, our course takes us north of Lake Chautauqua, where we cross the path over which canoes were borne from Lake Erie to Lake Chautauqua, and, a few miles westward, we cross the portage path from Lake Erie to Rivière aux Bœufs, a tributary of the Allegheny. Pursuing the height of land[Pg 20] westward we skirt the winding valley of the Cuyahoga and at Akron, Ohio, find ourselves crossing the portage between that stream and the Tuscarawas branch of the Muskingum. As we go on, the valley of the Sandusky turns up southward until we pass between its headwaters and just north of the Olentangy branch of the Scioto.

We face north again and look over the low-lying region of the Black Swamp until the Maumee Valley bars our way and we turn south to cross the historic portage near Fort Wayne, Indiana, which connects the Maumee and the Wabash. By a zig-zag course we approach the basin of Lake Michigan and pass deftly on the height of ground between the St. Joseph flowing northward and the Kankakee flowing southward. Here we cross another famous portage path. Circling the extremity of Lake Michigan by a wide margin, our course leads us to a passage way between the Chicago River and the Illinois. Here we find another path. The Wisconsin River basin turns us northward now, and near Madison, Wisconsin, we run between the head of the Fox and the head of the Wis[Pg 21]consin and cross the famed portage path which connected them. Just beyond lies the Mississippi, and if we should wish to avoid it we would be compelled to bear far north among the Canadian lakes.

Thus from the Atlantic coast we have passed to the Mississippi without crossing one single stream of water; but we have crossed at least twelve famous pathways between streams that flow north and south—routes of travel, which, when studied, give us an insight into the story of days long passed which cannot be gained in any other way. Over these paths pushed the first explorers, the men who, first of Europeans, saw the Ohio and Mississippi. Possessing a better knowledge of their routes and their experiences while voyaging in an unknown land, we realize better the impetuosity of their ambition and the meaning of their discoveries to them. We can almost see them hurrying with uplifted eyes over these little paths, tortured by the luring suggestions of the glimmering waterways in the distance. Whether it is that bravest of brave men, La Salle, crossing from Lake Erie to the Allegheny, or Mar[Pg 22]quette striding over the little path to the stream which should carry him to the Mississippi, or Céloron bearing the leaden plates which were to claim the Ohio for France up the difficult path from Lake Erie to Lake Chautauqua, there is no moment in these heroes’ lives more interesting than this. These paths crossed the dividing line between what was known and what was unknown. Here on the high ground, with eyes intent upon the vista below, faint hearts were fired to greater exertions, and dreamers heavy under the dead weight of physical exhaustion again grew hopeful at the camping place on the portage path.

Of all whose ambitions led them over these little paths, none appeal more strongly to us than the daring, patient missionaries who here wore out their lives for the Master. Each portage was known to them, better, perhaps, than to any other class of men. Here they encamped on their pilgrimages, though, from being spots of vantage which excited them onward, they were rather the line of demarcation between the near and the distant fields of service, and all of them full of trial and suffering[Pg 23] and seeming defeat. Nowhere in the North can the heroism of the Catholic missionaries be more plainly read today in any material objects than in the deep-worn, half-forgotten portage paths which lay along their routes. The nobility of their ambitions, compared with those of explorers, traders, and military and civil officials, has ever been conspicuous, but the full measure of their self-sacrifice cannot be realized until we know better the intense physical suffering they here endured. If the study of portage paths results only in a deeper appreciation of the bravery of these black-robed fathers, it will be worth far more than its cost.

In this connection it is proper to make a restriction; portage paths not only joined the heads of streams flowing in opposite directions, but were also land routes between rivers and lakes, between lakes, and even between rivers running in the same direction. They not only connected the Etchemin and St. John, and the Chaudière and Kennebec, but also the St. John and the Kennebec, and the Kennebec and Penobscot. Many portages joined the[Pg 24] lesser lakes; for example, such as Lake Simcoe, lying between Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay, or Lake Chautauqua lying between Lake Erie and the Allegheny River. The most common form of portage, however, was the pathway on a river’s bank around rapids and waterfalls which impeded the voyageur’s way. These were very important on such a turbulent river as the St. Lawrence, and on smaller rivers such as the Scioto or Rivière aux Bœufs which were almost dry in certain places in midsummer.[1] In midwinter, with ice running or blocking the course on small streams, these carrying places were as important as in the dry season.

The clearest pictures preserved for us of travelers on these first highways are, happily, to be found in the letters of the Jesuit missionaries who knew them so well, and whose heroism it were a sin to forget. Without attempting to distinguish the various personalities of these brave men, let us take some descriptions of their routes from their own lips.[Pg 25]

“These places are called portages, inasmuch as one is compelled to transport on his shoulders all the baggage, and even the boat, in order to go and find some other river, or make one’s way around these rapids and Torrents; and it is often necessary to go on for several leagues, loaded down like mules, and climbing mountains and descending into valleys, amid a thousand difficulties and a thousand fears, and among rocks or amid thickets known only to unclean animals.”[2]

“We returned by an entirely different road from that which we had followed when going there. We passed almost continually by torrents, by precipices, and by places that were horrible in every way. In less than five days, we made more than thirty-five portages, some of which were a league and a half long. This means that on these occasions one has to carry on his shoulders his canoe and all his baggage, and with so little food that we were constantly hungry, and almost without strength and vigor. But God is good and it is only[Pg 26] too great a favor to be allowed to consume our lives and our days in his holy service. Moreover, these fatigues and difficulties—the mere recital whereof would have frightened me—did not injure my health.... I hope next Spring to make the same journey and to push still farther toward the North Sea, to find there new tribes and entire new Nations wherein the light of faith has never yet penetrated.”[3]

“On the third day of June, after four Canoes had left us to go and join their families, we made a portage which occupied an entire day spent now in climbing mountains and now in piercing forests. Here we had much difficulty in making our way, for we were all laden as heavily as possible—one carrying the Canoe, another the provisions, and a third what we needed in our commercial transactions. I carried my Chapel and my little store of provisions; there was no one who was not laden and sweating from every pore. We entered, somewhat late, the great river Manikovaganistikov, which the French call rivière Noire [“Black river”], because of its depth.[Pg 27] It is quite as broad as the Seine and as swift as the Rhone. The eleven portages which we had to make there and the numerous currents which it was necessary to overcome by dint of paddling gave us abundant exercise.”[4]

“But what detracts from this river’s [St. Lawrence] utility is the waterfalls and rapids extending nearly forty leagues,—that is from Montreal to the mouth of Lake Ontario,—there being only the two lakes I have mentioned where navigation is easy. In ascending these rapids it is often necessary to alight from the canoe and walk in the river, whose waters are rather low in such places, especially near the banks. The canoe is grasped with the hand and dragged behind, two men usually sufficing for this.... Occasionally one is obliged to run it ashore, and carry it for some time, one man in front and another behind—the first bearing one end of the canoe on his right shoulder, and the second the other end on his left.”[5]

“Now when these rapids or torrents are[Pg 28] reached, it is necessary to land and carry on the shoulder, through woods or over high and troublesome rocks, all the baggage and the canoes themselves. This is not done without much work; for there are portages of one, two, and three leagues, and for each several trips must be made, no matter how few packages one has.... I kept count of the number of portages, and found that we carried our canoes thirty-five times, and dragged them at least fifty. I sometimes took a hand in helping my Savages; but the bottom of the river is full of stones so sharp that I could not walk long, being barefooted.”[6]

“But the mission of the Hurons lasted more than sixteen years, in a country whither one cannot go with other boats than of bark, which carry at the most only two thousand livres of burden, including the passengers—who are frequently obliged to bear on their shoulders, from four to six miles, along with the boat and the provisions, all the furniture for the journey; for there is not, in the space of more than 700 miles, any inn. For this reason, we have[Pg 29] passed whole years without receiving so much as one letter, either from Europe or from Kebec, and in a total deprivation of every human assistance, even that most necessary for our mysteries and sacraments themselves,—the country having neither wheat nor wine, which are absolutely indispensable for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.”[7]

The following are extracts from the instructions given to missionaries concerning their conduct on the journey from Montreal to the Huron country (1637):

“The Fathers and Brethren whom God shall call to the Holy Mission of the Hurons ought to exercise careful foresight in regard to all the hardships, annoyances, and perils that must be encountered in making this journey.... To conciliate the Savages, you must be careful never to make them wait for you in embarking. You must provide yourself with a tinder box or a burning mirror, or with both, to furnish them fire in the daytime to light their pipes, and in the evening when they have to encamp; these little services win their[Pg 30] hearts.... You must try and eat at daybreak unless you can take your meal with you in the canoe; for the day is very long, if you have to pass it without eating. The Barbarians eat only at Sunrise and Sunset, when they are on their journeys. You must be prompt in embarking and disembarking; and tuck up your gowns so that they will not get wet, and so that you will not carry either water or sand into the canoe. To be properly dressed, you must have your feet and legs bare; while crossing the rapids you can wear your shoes, and, in the long portages, even your leggings.... It is not well to ask many questions, nor should you yield to your desire to learn the language and to make observations on the way; this may be carried too far. You must relieve those in your canoe of this annoyance, especially as you cannot profit much by it during the work.... Each one should be provided with half a gross of awls, two or three dozen little knives called jambettes [pocket-knives], a hundred fishhooks, with some beads of plain and colored glass.... Each one will try, at the portages, to carry[Pg 31] some little thing, according to his strength; however little one carries, it greatly pleases the Savages, if it be only a kettle.... Be careful not to annoy any one in the canoe with your hat; it would be better to take your nightcap. There is no impropriety among the Savages.”[8]

With the foregoing introduction to the subject of portage paths and the nature of the journey over them, their historical importance is next to be noted.

In 1611 Champlain laid the foundation for Montreal, and two years later pushed northwest up the Ottawa River in search of a northwest passageway to the East, but he only reached Isle des Allumettes, the Indian “half-way house” between the St. Lawrence and Lake Huron. Two years later the missionary Le Caron pushed up the same long voyage; following the Ottawa and Mattawan he entered the famous portage to Lake Nipissing which opened the way to “Mer Douce”—Lake Huron. Champlain soon followed Le Caron over the same course and reached Lake Nipissing by the same portage. In his campaign[Pg 32] against the Iroquois in central New York, Champlain also found another route to Lake Huron, by way of Lake Ontario, the Trent, and the Lake Simcoe portage. Champlain’s unfortunate campaigns against the Iroquois were of far-reaching effect; one of the significant results being to drive the French around to Lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior by way of the Lake Nipissing and Lake Simcoe portages.[9] The finding of Lakes Huron and Ontario and the routes to them was the hardy “Champlain’s last and greatest achievement.”

An interpreter of Champlain’s, Etienne Brulé, was the first to push west of “Mer Douce” and bring back descriptions that seem to fit Lake Superior. This was in 1629. Five years later Nicollet drove his canoe through the Straits of Mackinaw, discovered the “Lake of the Illinois”—Lake Michigan—and from Green Bay went up the Fox and crossed the strategic portage to the Wisconsin. He affirmed that[Pg 33] if he had paddled three more days he would have reached the ocean!

Though Lake Erie was known to the French as early as 1640 it was not until 1669 that it was explored or even approximately understood. In September of that year the two men who rank next to Champlain as explorers, La Salle and Joliet, met on the portage between Lake Ontario and Grand River, and discussed the question of what the West contained and how to go there. They had heard of a road to a great river and they both were men to do and dare. They parted. Joliet went to Montreal, having converted the two Sulpitian missionaries Galinée and Dollier to his belief that the western road would be found by passing to the western lakes. They therefore left La Salle and went up through the Strait of Detroit, and Galinée made the first map of the Upper Lakes now in existence.

La Salle on the other hand, believing a story told him by the Senecas, held that the road sought lay to the southwest, and it is practically agreed today that he passed from near Grand River across Lake[Pg 34] Erie southward, and entered the stream which was later known as the Ohio, and passed down this waterway perhaps to the present site of Louisville, Kentucky. If modern scholarship in this case is correct, La Salle was the discoverer of the sweeping Ohio, having come to it over the Lake Erie-Rivière aux Bœufs portage, or the Lake Erie-Chautauqua portage. There is little reason to believe he ascended the Cuyahoga and descended the Tuscarawas and Muskingum as has been feebly asserted. The Ohio, if it was at this time actually discovered by La Salle, remained almost unknown for nearly a century.

In 1672 Frontenac detailed Joliet to make the discovery of the Mississippi and the adventurer went westward to Mackinaw where he met Marquette. The two went down Green Bay, up the Fox, and across the portage to the Wisconsin; on June 17, 1673, they entered the Mississippi River. Returning, they ascended the Illinois and (probably) the Kankakee; crossing the portage to the St. Joseph they were again afloat on Lake Michigan.[Pg 35]

The indomitable La Salle built a vessel of sixty tons on Lake Erie in 1679—the “Griffin,” first craft of her kind “that ever sailed our inland seas above Lake Ontario.” In her La Salle was to sail to near the Mississippi; part of this ship’s cargo comprised anchors and tackling for a boat in which the explorer would descend the Mississippi and reach the West Indies. The “Griffin” was lost, but her builder pushed on undismayed to the valley of the Illinois River. Late in 1679 he built Fort Miamis at the mouth of the St. Joseph, and in December he passed up that river and over the portage to the Kankakee which Joliet and Marquette had traversed six years before. “Passing places soon to become memorable in western annals ... he finally stopped at a point just below the [Peoria] lake and began a fortification. He gave to this fort a name that, better than anything else, marks the desperate condition of his affairs. Hitherto he had refused to believe that the “Griffin” was lost—the vessel that he had strained his resources to build, and freighted with his fortunes.... But as hope of her safety[Pg 36] grew faint, he named his fort Crèvecœur—‘Broken Heart.’”[10]

Leaving here his thirty men under Tonty to build a new boat, and sending Hennepin to the Upper Mississippi, the indomitable hero set out for Canada to secure additional material for his new boat. Ascending the Kankakee he crossed the portage to the western extremity of Lake Erie and passed on through the lakes to Niagara.

Fort Crèvecœur was plundered and deserted, but La Salle, in the winter of 1681-82 was again dragging his sledges over the portage to the Illinois on his way to the great river which he, first of Europeans, should fully traverse, “but which fate seemed to have decreed that he should never reach.” On the ninth of the following April the brave man stood at last at its mouth, and beside a column bearing the arms of France, a cross and a leaden plate claiming all the territory from which those waters came, he took possession of the richest four million square miles of earth for Louis XIV. “That the Mississippi[Pg 37] Valley was laid open to the eyes of the world by a voyageur who came overland from Canada, and not by a voyageur who ploughed through the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico from Spain, is a fact of far-reaching import. The first Louisiana was the whole valley; this and the Lake-St. Lawrence Basin made up the second New France ... the two blended and supplemented each other geographically....”[11] The second New France was united to Louisiana by hinges; these hinges were the portage paths which joined them.

The importance of these routes of travel did not by any means pass when once the explorers and missionaries had hurried over them and brought back news of the lands to which they led. The economic history of these routes is both interesting and important, and should be considered, perhaps, before reviewing their military significance.

As we have had occasion to notice, straits and portages were famous meeting places. La Salle and Joliet met between Lake Erie[Pg 38] and Lake Ontario; Joliet and Marquette met at Mackinaw. All routes converged on these narrow land and water courses, while on the broad lakes sojourners passed each other at short distances unwittingly. For in the old days of canoes the coming and going routes varied with a thousand circumstances. Of course the traveler’s general rule was to reach quickest waters flowing toward his destination. If he was making for the mouth of the Mississippi from Montreal his best route would be to turn south from Lake Ontario to the first easterly head of the Allegheny River, in preference to pushing further west to the head of any of the other tributaries of the Mississippi. Following the same rule, the route from Quebec to the Kennebec Valley was by way of Moosehead Lake; the return route was by way of the Dead River. A person returning from the “Falls of the Ohio” (Louisville, Kentucky) to Canada would, other things being equal, make for the nearest head of a stream flowing into Lake Erie.

In the case of the Great Lakes, winds and changing water-level soon became[Pg 39] understood and governed travel. Parties journeying from Mackinaw to Illinois or the Mississippi would hold to the western coast of Lake Michigan, for here they were favored by the winds, and proceeded southward by the Fox-Wisconsin portage or the Chicago-Illinois portage. In returning they would, under ordinary circumstances, choose the Kankakee-St. Joseph portage which would obviate the necessity of stemming the Illinois or Wisconsin and crossing Lake Michigan. The more direct route to the head of the Maumee was not discovered or appreciated until later. Thus traffic, on the lakes at least, was not on the bee line that it is today, and thus it was that portage paths and straits were famous meeting-places and camping spots.[12] Straits, in many cases, may be classed with portages; often a portage was necessary only in one direction. On the rivers the same portages were usually the routes of parties ascending and descending, but on such a stream as the St. Lawrence [Pg 40]they were frequently different; descending voyageurs “shot” many rapids about which it was necessary to make a portage when ascending.

As a meeting place the portage must have been anticipated with an interest inconceivable to us who know comparatively nothing of woodland journeying. Eager eyes were often strained to catch first sight across the water of the opening where the portage path entered the woods. And when this opening was lost to the sight of the departing traveler, the last hope of meeting friends had vanished. What this meant in a day when friends were few and far to seek and enemies quite the reverse, it would be difficult even to hint. Even in the good old colonial days in the heart of New England, friends met at the tavern, when a neighbor was to make a little journey on horseback, to drink his health. Pioneers moving from New York City to what is now Utica spent an afternoon previous to starting in prayer with clergymen.[13] What, then, did partings and meetings mean in the earliest days on the Great[Pg 41] Lakes and St. Lawrence—when every rapid was a danger and every wood concealed an enemy?[14] Letters were sometimes left hanging conspicuously on trees at portages.

The social nature of the portage camping ground is illustrated by the meetings—friendly and otherwise—between the Indian retinues of the many travelers who encamped here. When Céloron journeyed from Quebec to the Ohio Valley with his leaden plates, he paused at one of the portages to allow his Indian allies to jollify with certain comrades whom they met here.[15] There are cases where such meetings resulted more seriously than mere drunken sprees.[16]

The meeting-place was also the famous camping ground. To reach the portage path the tired paddler bent every energy as the red sun lay on the horizon. Two landings were thus saved. Here the ground around either end of the path had[Pg 42] been cleared and trodden hard by a thousand campers, and if wood was scarce in the immediate locality there was abundance at no great distance. No one familiar with camping need be told the advantages, natural and artificial, to be found on an old camping ground.

But here it should be noted that the shortest portage between any two bodies of water was rather an arbitrary line, at least theoretically so. It was chosen as a good site, not for staying, but for passing. Usually it traversed some sort of watershed, more or less distinct; on either side low ground, marshes, and swamps were not uncommon. In many instances the length of the portage path varied inversely with the stage of the water. Some portages were a mile long in wet seasons and ten miles long in dry. Where this was true the country through which the path ran was not altogether suitable for camps nor for villages, which the camps on important portages often became. Often, however, the nature of the country was favorable for habitation, and at many portages the camps became permanent. At such points Indian[Pg 43] villages were sometimes found; but as a rule portages were not largely inhabited unless they were defended, and that was not until the era of military occupation.

The portages were frequently used as burying grounds by the Indians, and beside the little paths around the rapids of the river lies the dust of hundreds swept away to their death by the boiling waters. The portages were not infrequently on high, dry ground, favorable for interment.

Here, too, on the portages the toiling missionaries were wont to pause and erect their crosses and altars. In the long journeys back and forth from Quebec to the land of the Hurons, for instance, the portage paths of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence became familiar ground; where one had raised an altar another would be glad to pray. There were silent, holy places on these little roads by which we run noisily today—we who know little of the suffering, the devotion, and the piety of those who first walked and worshiped here.

The missionaries called the Indian trails “Roads of Iron” to suggest the fatigue and suffering endured in their rough jour[Pg 44]neys. If the ordinary trail was a Road of Iron, what of the portage path—which so often led over cliffs and mountain spurs in going around a waterfall or rapid? But these were not the most difficult portages. There were many carrying places which, uniting heads of streams or lakes, ran over high mountains, through the most impenetrable fastnesses—paths fit only for mountain goats. Yet up these rough steeps the missionaries of the Cross, soldiers, and traders forced their way, slipping, sliding, seizing now and again at any object which would offer assistance. Many of these climbs would tax a person free of baggage in this day of cleared fields and hills; fancy the toil of the old-time voyageurs weighed down by canoes, provisions, and baggage, assailed by the clouds of insects which greeted a traveler in the old forests, and perhaps enduring fears of unseen enemies and unknown dangers.

Then there was the stifling heat of the primeval forests. Our present day notion of forests is diametrically opposed to old-time experience. To us, the forest is a popular symbol of restful coolness; former[Pg 45]ly they were exhausting furnaces in the hot season, where horses fell headlong in their tracks and men fainted from fatigue. We wonder sometimes that pioneer armies frequently accomplished only ten or twelve miles a day, sometimes less. But these marches were mostly made in the months of October and November—the dryest months of the year in the Central West—and the stifling heat of the becalmed forest easily explains both slowness and wearing fatigue. It was the heat that all leaders of pioneer armies feared; for heat meant thirst and at this season of the year the ground was very dry. Many a crazed trooper has thrown himself into the first marsh or swamp encountered and has drunk his fill of water as deadly as any bullet.

All this applies with special force to portages, as all know who have essayed mountain climbing in the stifling heat of a windless day. All that marching troops have endured, the brave missionaries and those who came after them suffered on the carrying place with the additional hardship, often, of climbing upward in the heat rather than marching on level ground. When[Pg 46] attempting to gain some idea of the physical effort of old-time traveling, the cost of crossing a difficult portage must be considered as the most expensive in time and strength. The story of Céloron’s climb up from Lake Erie to Lake Chautauqua, Hamilton’s struggle through the beaver dams and shoals of Petite Rivière on the Maumee-Wabash portage route, Arnold’s desperate invasion of Canada over “The Terrible Carrying Place” on the Kennebec-Chaudière route, and the history of the difficulties of the Oneida portage at Rome, New York, present to us pictures of the portages of America that can never fade from our eyes.

At the ends of many of the portage paths were to be found busy out-door work-shops in the old days of pirogues and canoes. The trees nearby and far away stood stark and white against the forest green, having lost their coats of bark; many were fallen, and others were tottering. Here and there were scattered the refuse pieces of bark and wood. The ends of portage paths were famous carpenter shops.[17] There were[Pg 47] humble libraries here, too. It was while wintering on the Chicago portage that Marquette wrote memoirs of his voyages.

In some instances, too, peculiar relics of the old life in the heyday of the canoe have come down to us. The end of the portage path, besides being a camping spot, was the provisioning place. Here food was to be made or to be secured and properly seasoned and packed. At the old French portages stone ovens were erected, in which quantities of bread might be baked before starting on a journey. At either end of the Chautauqua portage between Lake Erie and Lake Chautauqua such little monuments have been discovered. In each case the baking place was a circular piece of masonry of stone laid in strong mortar, three feet in height and three or four feet in diameter.[18]

The portages between many waters crossed important transverse watersheds along which coursed the great landward routes of primeval America. Here at the junction of the greater and lesser paths were[Pg 48] wide, open spaces where many a camp has been raised and struck, where assemblies innumerable have been harangued, where a thousand ambuscades have been laid and sprung.

Portage paths crossed the watersheds which were frequently boundary lines. They also connected river valleys which came to be boundary lines. Consequently these routes of travel became themselves, in several instances, important boundaries. This is illustrated by the line decided upon at the Fort Stanwix Treaty; in several instances the territory of the United States has been bounded by a little portage path—such as that between the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas Rivers in Ohio—which is now quite forgotten. In this instance the little path is still to be identified from the fact that it was a boundary line for such a length of time that the lands on the eastern and western sides were surveyed by different systems. The “Great Carrying Place” between the Hudson and Lake George was one of the boundaries of the first grant of land made by the Mohawks at Saratoga. At the Treaty of Fort McIntosh, 1785, the[Pg 49] western boundary line of the United States included the courses of two portage paths.

As in Maine, of which subsequent mention is to be made, so throughout the continent, portage paths were commonly named from the destinations to which they led; thus they had two names, as is true of highways in general. In certain instances, as in the case of the “Oneida Carrying-place” well-known portages had one general name. To the portages about the rapids on such rivers as the St. Lawrence and Ottawa, descriptive names were given by the French. One was called “Portage de l’Épine,” another “Portage des Roses”—suggestive of the fragrant wild rose which overhung the path to the annoyance of the traveler in spite of its perfume. Another path was known as “Portage Talon.” Perhaps the most fanciful name recorded is “Portage de la Musique”—where the river’s tide boiled noisily over the rocks and reefs, forever chanting the same song. Other names were “Portage des Chats,” “Portage de Joachin,” “Portage de la Roche fendue,” “Portage des Chenes,” “Portage des Galots.” One[Pg 50] path, at least, bore the noble title “Portage d’ Récollets.”[19]

In the Post Office Directory twelve states are today represented by an office bearing the name Portage or Portageville.

From every point of view the portages of America, considered historically, were most important, because by reason of their strategic position they were coigns of vantage for military operations.

Picture the continent at the opening of the culminating phases of the Old French War in 1740-1760. For nearly two centuries military and civil officials, missionaries and traders had been passing to and fro on the Ottawa, St. Lawrence, and Richelieu, through Canada, Illinois, and Louisiana, erecting forts and establishing chapels and trading stations. Little by little the English settlements had crept back into the interior. Ten score of portage paths had been traversed; forts and blockhouses had been built, captured, burned, and rebuilt. Flying parties of French had swooped down into New York, and English and[Pg 52] Dutch had chased them back. Both sides had become more and more acquainted with the geography of the continent, and now, when war was about to begin in earnest, both antagonists leaped forward quickly to seize for once and all the vital spots in the “communications” in the neutral ground between them, where the vanguards had been bickering and fighting for at least a century.

The Richelieu River, Lake Champlain, and the Hudson had offered the founders of Quebec and Montreal the most direct course to the New England settlements. They had learned it well in their campaigns against the Iroquois. The keys of this route were the portage paths between the St. Lawrence and the Richelieu in the north; and the portages between Lakes Champlain and George, and Lake George and the Hudson River in the south. As early as 1664 Jacques de Chambly erected a fort at the foot of the rapids, at Chambly on the Richelieu, at the end of the thirteen-mile portage from La Prarie three miles above Montreal on the St. Lawrence. Two other forts, Fort St. Louis and Fort[Pg 53] Sainte Terese, also guarded the Richelieu River; and at its head, at the foot of Lake Champlain, stood Fort Richelieu.

Later a portage path fifteen miles in length was built from La Prarie (Laprairie) to Fort John (St. Johns), below the “Island of St. Therese.” Ascending Lake Champlain the French quickly perceived the strategic positions of Crown Point and “Carillon”—at the end of the portage from Lake George—where they erected Fort Crown Point in 1727, and Fort Frederick (Ticonderoga) in 1731.

The English on the other hand ascended the Hudson from Albany, and built Fort Ingoldesby at Stillwater in 1709, and Fort Nicholson at Fort Edward in the same year. At the Wood Creek end of the portage another fort was built first named Fort Schuyler, later named Fort Anne. Fort Edward and Fort William Henry were built in 1755.

This chain of forts from Albany to Montreal, guarding the important passageways on land and water, marks the line of what was known as “the Grand Pass from New York to Montreal.” The last struggle[Pg 54] for this line of communication, Johnson’s rebuke to the advancing Dieskau, Abercrombie’s stroke at Fort Ticonderoga, the brilliant Montcalm’s capture of Fort William Henry, and, finally, the wresting of the Champlain Valley from the French by the hitherto defeated English, forms a unique romance which finds its key of action at the portage paths which united the Hudson, Lake George, and Lake Champlain.

Click here for larger image size

The Morris Map of 1749[Showing important portages between the St. Lawrence and New England rivers]

(From the original in the British Museum)

There were other routes into New England, known of old, on which the French had spread terror throughout the North Atlantic slope. They came up the Chaudière and down the Kennebec into Massachusetts’ “Province of Main.” Early in the French and Indian wars Massachusetts began another series of campaigns, to secure again and once for all the Kennebec Valley, building Forts Halifax (1754) and Western (1752) at the head of navigation. At the northern end of the portage between the Kennebec and “Rivière Puante,” on the Morris map of 1749, here presented, we find the Indian village Wanaucok still described as a nest of “Indians in the French interest.” These allies of [Pg 57] the French around the highland portages explain the need of English forts on the Kennebec. The forts of the Connecticut River were largely necessitated by the routes of travel between the heads of its tributaries and the “Rivière St. Francis” and “Otter River.” On the Morris map we read “Indians of St. Francis in league with the French.” The mouth of Otter Creek was near Fort Ticonderoga, and it offered, with a portage to the Connecticut, another route of French aggression. “From this Fort the French make their excursions,” reads the interesting Morris map, “and have this war [1745 seq.] burnt and destroy’d two Forts (Saratoga and Fort Massachusets) and broke up upwards of 30 Settlements.”

The Hudson-Lake George portage marked the most important course from Canada to New York, but there was another route which was fought for earnestly. The French could ascend the St. Lawrence to Lake Ontario and gain access to the entire rear of New York, and by a dozen minor waterways the Hudson again could be reached. The St. Lawrence had long been[Pg 58] an avenue of French exploration and missionary activity. “The route thither (from Quebec up the St. Lawrence to Lake Ontario and Lake Simcoe to Georgian Bay to the land of the Hurons) is very easy, there being only two waterfalls where it is necessary to land and make a portage—a short one at that; and there it would be easy to construct a small redoubt for the purpose of maintaining free communication and of making ourselves masters of this great lake.”[20] Thus the Jesuits “had anticipated by twenty years Frontenac’s plan of building a fort for the control of Lake Ontario.”[21] Fort Frontenac (Kingston, Canada, 1673) guarded the French end of Lake Ontario, while the English ascended the Mohawk and descended the “Onnondaga” (Oswego) to its mouth (Oswego, New York) where they erected Fort Oswego in 1722, which Montcalm captured in 1757.

To reach the mouth of the Onondaga, the English crossed the already well-worn[Pg 59] path, the “Oneida Portage” a mile in length, between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek. The strategic position of this path is not shown more clearly than by the number and importance of the military works erected there, Forts Williams (1732), Bull (1737), Newport and famed Stanwix (1758). Throughout the old French War this strip of ground was the scene of bloody battles, massacres, and sieges; and its detailed story—a fascinating one—should be written immediately. The Mohawk end of the portage path forms the main avenue of Rome, New York, and at the center of the little city the site of Fort Stanwix, “a fort which never surrendered,” is appropriately marked. It is the boast of the Romans that from this site the stars and stripes were “first unfurled in battle” August 3, 1777. The flag was made from an officer’s blue camlet cloak and the red petticoat of a soldier’s wife. The white stars and stripes were cut from ammunition bags. The news that Congress, on June 14, had adopted the flag had just reached the inland portage fortress by a batteau from down the Mohawk.[Pg 60]

The granting of the vast area of land on the Ohio River by the King of England to the Ohio Land Company in 1749 brought home to the French the realization that the West was disputed territory, and Governor Galissonière immediately dispatched Céloron de Bienville with a band of two hundred and seventy men to reënforce the French claim to the Ohio Valley. It is an ancient French custom to bury leaden plates at the mouths of rivers as a sign of possession, and Céloron bore a supply of such memorials to bury at the mouths of rivers emptying into the Ohio. Ascending the St. Lawrence the party crossed Lake Ontario to the Niagara River. This strategic portage path around Niagara Falls, which joined Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, used from time immemorial, became important to the French when they secured the mastery of Lake Ontario after the erection of Fort Frontenac. Four years after the English came to Oswego the French erected the first permanent Fort Niagara here in 1726, absolutely controlling all intercourse with the West by way of the Great Lakes. It was the key of the lake[Pg 61] system, and the numerous campaigns of the English projected against Fort Niagara until its capture in 1759 are evidence of its strategic position and the importance of the little worn road it guarded.

Once beyond the Niagara portage Céloron’s attention was turned to the rival routes from Lake Erie to La Belle Rivière. There were at least five passageways well-known to the Indians. Of these the French knew very little, for, having found the Mississippi, they had been less interested in this branch of it. But now that the English were claiming and even settling the land along its half-known shores it was time they were enforcing their claims. So Céloron made for the first portage southward in order to strike the Ohio on its headwaters. This was the Chautauqua Lake portage from Chautauqua Creek—which the French knew as “Rivière aux Pommes”—six miles by land from the present Barcelona, New York, to Lake Chautauqua. From the seventeenth to the twenty-second of July was spent in making the difficult march over what has long been known as the “Old Portage Road.” Bon[Pg 62]nécamps, who accompanied Céloron, wrote: “The road is passably good. The wood through which it is cut resembles our forests in France.”[22]

Céloron went his way, having given great prominence to the Chautauqua portage, indirectly suggesting that it was the most convenient pass from Lake Erie into the disputed Ohio Valley. It remained for another to mark a more practicable course.

Céloron’s report to his governor was thoroughly alarming, and a French force under M. Marin was sent from Montreal in 1752 to fortify the route to the Ohio River and to erect forts to hold that river itself.

After looking over the formidable Chautauqua route, Marin moved along the shore of Lake Erie to “Presque Isle” (Erie, Pennsylvania), where the French had made a settlement as early as 1735. Marin chose to make this twenty-mile portage from Presque Isle to “Rivière aux Bœufs” the armed route of French aggression into the Ohio Valley, in preference to the shorter but more tedious and more uncertain Chau[Pg 63]tauqua pass. At the northern end of the portage he built Fort Presque Isle and at its southern extremity Fort Le Bœuf.[23] The arrival of the French upon the headwaters of the Allegheny will forever be remembered by the new and significant name Washington now gave Rivière aux Bœufs—which the stream still bears—French Creek. Marin, who hurried on down the Allegheny building Forts Machault (Venango) at the junction of Rivière aux Bœufs and the Allegheny, and Duquesne at the junction of Allegheny and Monongahela, should have named the Youghiogheny “English Creek.” When once on the way, the time taken by the French and English to reach the key position of the West—Pittsburg—varied inversely as the length of the portages they had to traverse. It will be remembered that Washington in his first campaign of 1754 explored carefully the Youghiogheny River in the hope that the road he had just opened from the Potomac at Cumberland, Maryland to the “Great Crossings” (Smithfield, Pennsylvania) might[Pg 64] after all be a portage path between Atlantic waters and the Mississippi system. He found the Youghiogheny useless.[24] The English route to the Ohio was practically an all-land route; Braddock received a little help from the Potomac but did not even attempt to use any western river, nor did Forbes in 1758 or Bouquet in 1763. The Monongahela, downward from Redstone Old Fort (Brownsville, Pennsylvania), at the end of Burd’s road, began to be used in the Revolutionary period, and in pioneer days was a famous point of embarcation for western travelers.

On the other hand, the French portage at Presque Isle was the key to their position in the Ohio Valley, for over it came every ounce of ammunition and stores for Fort Duquesne. It was Braddock’s purpose in 1755 to ascend the Allegheny after the capture of Fort Duquesne, raze the forts that guarded this portage path, and then meet Governor Shirley who was marching upon Niagara.[25] With Fort Duquesne captured,[Pg 65] Forts Le Bœuf and Presque Isle razed, and Fort Niagara besieged, the French would have had as little hope of holding the Ohio Valley as the Shenandoah. Nothing could show more plainly the signification of these fortified portages than the campaigns directed against them.

Further west, the Maumee Valley was of early importance to the French because of the two portages which gave them access to the Miami River on the south and the Wabash on the southwest. The use to explorers of the latter portage has been mentioned. Here, near the present site of Maumee City, the first settlement of whites in the limits of the state of Ohio was made about 1679. The city of Fort Wayne, Indiana, marks the Maumee terminus of the important portage to the Wabash River—the modern name carrying the significance of fortification which we are emphasizing. It is to be deplored that the name Fort Stanwix, rather than Rome, is not retained for the city at the Mohawk terminus of the Oneida Portage in New York. Here the French built forts in 1686 and 1749, the latter being surrendered in[Pg 66] 1760. Here General Anthony Wayne built a fortress in 1794 which controlled all traffic over the old pathway as had its predecessors.

Passing further west, two forts, at least, guarded well-known portages: Fort St. Joseph’s (1712), located a little below South Bend, Indiana, guarding the Kankakee- St. Joseph portage; and Fort Winnebago (1829) guarding the Fox-Wisconsin portage. The post Ouiatanon founded on the Wabash in 1720 was the first military establishment within what is now the state of Indiana. It was located eighteen miles (by the river) below the mouth of the Tippecanoe and near the city of Lafayette. Many writers have located this historic site incorrectly—a mistake it is impossible to make when the actual meaning of the post is understood. It guarded the key of the upper Wabash, for this point “was the head of navigation for pirogues and large canoes, and consequently there was a transfer at this place of all merchandize that passed over the Wabash.”[26]

Coming down to the Revolutionary period, the battles fought upon these por[Pg 67]tages and the forts that were built show that these historic paths had lost little of their significance. All the way across the continent from the portage from the Kennebec to Quebec, over which Arnold led his army, to Fallen Timbers on the Maumee, near which Wayne built Fort Wayne, a significant portion of the struggle for a free America took place on portage paths. As in the French War, so in this later struggle, the paths between Lake Champlain and the Hudson and between the Mohawk and Lake Oneida were all-important passageways. Burgoyne was defeated not far from the spot where the French Dieskau was repulsed, and on the Oneida carrying-place, as has been said, the first United States flag was unfurled in battle in 1777. In the West, of course, Niagara never lost its importance, but the remainder of the portages had now lost something of their military significance, as the Revolution in the West was a series of raids and counter-raids on the settlements of the whites in Virginia and Kentucky, and upon the Indians in the valleys of the Muskingum, Scioto, Sandusky, Maumee, and[Pg 68] Wabash. Cross-country land routes were well-worn at this date and few military movements were made which involved portages; such were Hamilton’s capture of Vincennes by way of the Maumee and the Wabash, and Burd’s keel-boat invasion up the Licking River into Kentucky. Savage strokes like those of Robertson and Sevier, Clark at Vincennes, McIntosh, Lewis, Brodhead, Bowman, Crawford, Harmar, St. Clair, and Wayne were distinctively land campaigns.

Yet in these, too, the value of the portage routes is most clearly seen, as for instance during the conquest of the northwestern Indians by General Anthony Wayne in 1793-94. The permanent headquarters of Wayne were at Fort Washington (Cincinnati), and temporary headquarters were at Fort Greenville (Greenville, O.) and Fort Defiance (Defiance, O.) The conquest was directed northward up the Great Miami Valley to the heads of the Wabash and Maumee. It was directed against the Indian villages, as was true of Harmar’s and St. Clair’s campaigns before it; and these villages, like so many others, were[Pg 69] located in part at the portages between the Miami, Auglaize, St. Mary, and Wabash. At these places Wayne struck swiftly—building Forts Greenville, Recovery, Adams, and a fort on the headwaters of the Auglaize, the name of which is not known. From these points he made his heroic campaign of 1794 in the valleys of the Maumee, Auglaize and St. Mary. But with the successful prosecution of this campaign General Wayne’s work was not done. The country conquered must be held—the crops destroyed must not be resown—the villages destroyed must not be rebuilt. All this was as important a feat as the victory at Fallen Timber, and much more difficult.

And so, in the months succeeding his victory, Wayne did as valuable work for his country as at any time, and one of the most important of his plans was a movement which looked toward holding the northern portages from the Miami River to the St. Mary and Auglaize. In a letter to the Secretary of War, dated October 17, 1794, at the Miami villages, Wayne observes: “The posts in contemplation at Chillicothe, or[Pg 70] Picque town, on the Miami of the Ohio, at Lormie’s stores, on the north branch, and at the old Tawa town, will reduce the land carriage of dead or heavy articles, at proper seasons, viz: late in the fall, and early in the spring, to thirty-five miles, and in times of freshets, to twenty in place of 175, by the most direct road to Grand Glaize, and 150 to the Miami villages, from fort Washington, on the present route, which will eventually be abandoned, as the one now mentioned will be found the most economical, and surest mode of transport, in time of war, and decidedly so in time of peace.”[27]

From Greenville on the twelfth of November he wrote again:

“As soon as circumstances will admit, the posts contemplated at Picque town, Lormie’s stores, and at the old Tawa towns, at the head of navigation, on Au Glaize river, will be established for the reception, and as the deposites, for stores and supplies, by water carriage, which is now determined to be perfectly practicable, in proper season; I am, therefore, decidedly[Pg 71] of opinion, that this route ought to be totally abandoned, and that adopted, as the most economical, sure, and certain mode of supplying those important posts, at Grand Glaize and the Miami villages, and to facilitate an effective operation towards the Detroit and Sandusky, should that measure eventually be found necessary; add to this, that it would afford a much better chain for the general protection of the frontiers, which, with a block house at the landing place, on the Wabash, eight miles southwest of the post at the Miami villages, [southern end of the Maumee-Wabash portage path on Little River] would give us possession of all the portages between the heads of the navigable waters of the Gulfs of Mexico and St. Lawrence, and serve as a barrier between the different tribes of Indians....”[28] In the treaty of Greenville, signed by the confederated nations and the United States authorities, the reserved tracts indicate the line of policy previously suggested by General Wayne, and the following section emphasizes the strategic meaning of the portages of the[Pg 72] interior of the West: “And the said Indian tribes will allow to the people of the United States, a free passage by land and by water, as one and the other shall be found convenient, through their country, along the chain of posts hereinbefore mentioned; that is to say, from the commencement of the portage aforesaid, at or near Loramie’s store, thence, along said portage to the St. Mary’s, and down the same to fort Wayne, and then down the Miami to lake Erie; again, from the commencement of the portage at or near Loramie’s store, along the portage; from thence to the river Auglaize, and down the same to its junction with the Miami at fort Defiance; again, from the commencement of the portage aforesaid, to Sandusky river and down the same to Sandusky bay and lake Erie, and from Sandusky to the post which shall be taken at or near the foot of the rapids of the Miami of the lake; and from thence to Detroit. Again, from the mouth of Chicago, to the commencement of the portage between that river and the Illinois, and down the Illinois river to the Mississippi; also, from fort Wayne, along the portage foresaid, which[Pg 73] leads to the Wabash and then down the Wabash to the Ohio.”[29]

As a site for forts the old portage paths came to take an important place in the social order of things. In many parts settlements were safe only within the immediate vicinity of a fort. Often they were safe only within the palisade walls of upright logs;[30] and around these interior fortresses the first lands were cleared and the first grain sowed. They were trading posts as well as forts—indeed many of the portage forts were originally only armed trading stations located at the portages because these were common routes of travel. Around them the Indians raised their huts when the semi-annual hunting seasons were over. Thus on the portage, settlements sprang up about the forts to which the military régime had no objection—though such settlements were discouraged equally by those devoted to the earliest fur trade and to missionary expansion.[31] But mili[Pg 74]tary officers found their one hope of retaining the land lay in allying the Indians firmly with them. The attempts of the French so to shift the seats of the Indian tribes in the West that the English could not trade with them or deflect them from French interest forms an interesting chapter in the early rivalry for Indian support.[32] This never appeared more acute than at Fort Duquesne in 1758 when Forbes’s army was approaching and the brave missionary Post was among the Delawares urging them to leave the region about the fort and abandon the French.

These portage forts being, oftentimes, half-way places, were convenient points for conventions and treaties. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) was one of the most important in our national history; other conventions, such as at Fort Watauga (1775), Fort Miami (1791), Greenville (1795), and Portage des Sioux (1815), are instances of important conventions meeting at half-way fortresses on or near the portage passageways.

When the pioneer era of expansion[Pg 75] dawned, these worn paths, in many cases, became filled with the eager throngs hastening westward to occupy the empire beyond the mountains. The roads the armies had cut during the era of military conquest became the main lines of the expansive movement and only the waterways which gave access to the Ohio River or the Great Lakes were of great importance. The two important roadways which served as portages were the Genesee Road from the Mohawk to Buffalo, and Braddock’s Road from Alexandria, Virginia to Brownsville (Redstone Old Fort), Pennsylvania. The heavier freight of later days tended to lengthen the old portages, as each terminus had to be located at a depth of water which would float many hundred-weight. But, as in the old days of canoes, the stage of water still determined the length of portage. Freight sent over the Alleghenies for the lower Ohio River ports of Indiana and Kentucky was shipped at Brownsville if the Monongahela contained a good stage of water; if not, the wagons continued onward to Wheeling with their loads. Old residents at such points as[Pg 76] Rome, New York; Watertown, Pennsylvania; Akron, Ohio; Fort Wayne, Indiana remember vividly the pioneer day of the portages when barrels of salt and flour, every known implement of iron, mill stones, jugs and barrels of liquor, household goods, seeds, and saddles composed the heterogeneous loads that were dragged or rolled or hauled or “packed” over the portages of the West. Strenuous individuals have been known to roll a whiskey barrel halfway across a twenty-mile portage.

With the settling of the country and a new century came a new age of road-building. Travel until now had been on north and south routes—on portage paths, which usually ran north and south between the heads of rivers which flowed north or south, on routes of the buffalo, which the herds had laid on north and south lines during their annual migrations, and on Indian trails which had been worn deep by the nations of the north and those of the south during their immemorial conflicts. The main east and west land routes, such as Forbes’s and Braddock’s, were now to be replaced by well-made thoroughfares. In[Pg 77] the building of certain of these, the dominating influence of water transportation, and, consequently, the strategic routes between them, were considered of utmost importance. This is emphasized strikingly in the building of the Cumberland National Road across the Alleghenies by the United States Government (1806-1818). In the Act passed by Congress enabling the people of Ohio to form a state we read: “That one-twentieth of the net proceeds of the lands lying within said State sold by Congress shall be applied to the laying out and making public roads leading from the navigable waters emptying into the Atlantic, to the Ohio.”[33] The Commissioners appointed according to law by President Jefferson surveyed the territory through which the road should pass and met at Cumberland, Maryland for consultation. In their report of 1806 they said: “In this consultation the governing objects were:

1. Shortness of distance between navigable points on the eastern and western waters.

2. A point on the Monongahela best[Pg 78] calculated to equalize the advantages of this portage in the country within reach of it.

3. A point on the Ohio river most capable of combining certainty of navigation with road accommodation; embracing, in this estimate, remote points westwardly, as well as present and probable population on the north and south.

4. Best mode of diffusing benefits with least distance of road.”

In their choice of Cumberland as the eastern terminus for this national road the question of portage entered largely into consideration: “... it was found that a high range of mountains, called Dan’s, stretching across from Gwynn’s to the Potomac, above this point, precluded the opportunity of extending a route from this point in a proper direction, and left no alternative but passing by Gwynn’s; the distance from Cumberland to Gwynn’s being upward of a mile less than from the upper point, which lies ten miles by water above Cumberland, the Commissioners were not permitted to hesitate in preferring a point which shortens the portage, as well as the Potomac navigation.[Pg 79]”

After outlining the route of the road, the Commissioners summed up matters as follows: “... it will lay about twenty-four and a half miles in Maryland, seventy-five and a half in Pennsylvania, and twelve miles in Virginia; ... this route ... has a capacity at least equal to any other in extending advantages of a highway; and at the same time establishes the shortest portage between the points already navigated, and on the way accommodates other and nearer points to which navigation may be extended, and still shorten the portage.... Under these circumstances the portage may be thus stated:

“From Cumberland to Monongahela, sixty-six and one-half miles. From Cumberland to a point in measure with Connelsville, on the Youghiogeny river, fifty-one and one-half miles. From Cumberland to a point in measure with the lower end of the falls of the Youghiogeny, which will lie two miles north of the public road, forty-three miles. From Cumberland to the intersection of the route with the Youghiogeny river, thirty-four miles.... The point which this route locates, at the[Pg 80] west foot of Laurel Hill, having cleared the whole of the Alleghany mountain, is so situated as to extend the advantages of an easy way through the great barrier, with more equal justice to the best parts of the country between Laurel Hill and the Ohio. Lines from this point to Pittsburg and Morgantown, diverging nearly at the same angle, open upon equal terms to all parts of the western country that can make use of this portage; and which may include the settlements from Pittsburg up Big Beaver, to the Connecticut reserve, on Lake Erie, as well as those on the southern borders of the Ohio and all the intermediate country.”

Thus it is clear that our one great national turnpike was, in reality, a portage path. Upon this same general principle many of our first highways were built, in an era when inland water navigation, on canal and river, was considered the secret of commercial prosperity.

With the building of canals, the ancient portages again became prominent because of geographical position; in every state the portage paths marked the summit levels.[Pg 81] In the cases of such important works as the Erie Canal and the Ohio Canal the portages between the Mohawk and Wood Creek in New York and between the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas in Ohio were of vital importance. In many instances, at the points where the old portages mark the spots of least elevation, two canals are found converging from three or four valleys.

It is quite impossible for us to realize the importance attached to the portage routes in days when steam navigation and locomotion were not dreamed of. This is suggested by the clause of the famous Ordinance of 1787 in which they were again declared to be “common highways forever free.” Washington’s serious study of this subject is exceedingly interesting—not less so because many of his plans which seemed to many idle dreaming were completely realized not long after his death.[34]

With the advent of the era of railway building, and as the number of the shining rails increase yearly at these geographical centers, the strategic nature of the portage routes has been and is still being strongly[Pg 82] emphasized. Engineering art is now defying nature everywhere, and daring feats of bridge-building are daily accomplished; but the old routes and passes still remain the most practicable, and in the long run pay best. In spite of the fact that tunnels can go wherever money dictates, and bridges can be swung across the most baffling chasms, at the same time the fiercest struggles for rights of way (outside the cities) are being waged today for the portage paths first trod by the Indian.

As introductory to the description of the more noted American portages, it will be advantageous to present them at a bird’s-eye view in the form of a comparative chart stating the names and termini of each, with a remark concerning its specific function:[Pg 86]

| Portage Route. | Water Termini. | Remarks. |

| St. Johns—St. Lawrence. | Grand River—Wagan. | This and the two following are important land passes in the water route up the St. Johns to Canada. |

| Same. | Touladi—Trois Pistoles. | |

| Same. | Ashberish—Trois Pistoles. | |

| Same. | Temiscouata—Rivière du Loup. | Route of present post road between same points.[Pg 87] |

| Same. | St. Francis—Lake Pohenegamook, to head of La Fourche branch of Rivière du Loup. | Short but difficult portage. |

| Same. | Black River—Ouelle. | Morris Map describes this as an express route. |

| Same. | North-West Branch of St. John River—Rivière du Sud. | “Grand Portage.” |

| Same. | Lake Etchemin route. | Route of Etchemin Indians to Quebec.[Pg 88] |

| Kennebec—St. Lawrence. | Rivière des Loups—Moosehead Lake—Rivière Chaudière. | Probably the most practicable route from Quebec up the Chaudière and over the divide into the Kennebec River. |

| Same. | Dead River—Chaudière (“The Terrible Carrying-place”). | Probably the most practicable route from the south by way of the Kennebec to Quebec. Arnold’s route. |

| Connecticut—St. Francis. | Same. | Important Indian route from Canada into New Hampshire.[Pg 89] |

| Connecticut—Lake Champlain. | Otter Creek—Black(?) River. | Route from French ports on Lake Champlain to the Connecticut Valley. |

| Hudson—Lake Champlain. | Hudson—Lake George. | The “Grand Pass” from the Hudson Valley toward Canada. Followed by Dieskau, Johnson, Montcalm, Abercrombie and Burgoyne.[Pg 90] |

| Same. | Hudson—Wood Creek—Lake George. | Portage to Fort Ann. |

| St. Lawrence—Lake Champlain. | St. Lawrence—Richelieu. | Last portage in the “Grand Pass” from New York to Montreal. |

| Hudson—Lake Ontario. | Mohawk—Wood Creek (feeder of Lake Oneida). | Strategic portage in the route from Albany and New York to Oswego and Niagara. |

| Mohawk—Susquehanna. | Mohawk—Lake Otsego. | Route from Central New York to Pennsylvania.[Pg 91] |

| Niagara. | Portage around Niagara Falls. | Another route around Niagara Falls was by portage from western extremity of Lake Ontario to Grand River. |

| Chautauqua. | Chautauqua Creek—Chautauqua Lake. | Céloron’s Route to the Ohio. |

| Lake Erie—Allegheny. | Lake Erie—French Creek. | Marin’s Route to Fort Duquesne. |

| Ohio River—Lake Erie. | Cuyahoga—Tuscarawas. | Route from Muskingum to Lake Erie.[Pg 92] |

| Same. | Scioto—Sandusky. | |

| Same. | Miami—Auglaize and St. Mary. | Céloron’s return route from the Ohio to Lake Erie. |

| Wabash—Lake Erie. | Maumee—St. Mary—Little River (“Petite Rivière.”) | “The Wabash—Maumee Trade Route.” |

| Wabash—Lake Michigan. | Wabash—St. Joseph. | |

| Illinois—Lake Michigan. | Kankakee—St. Joseph. | |

| Illinois—Lake Michigan. | Des Plaines—Illinois.[Pg 93] | |

| Mississippi—Lake Michigan. | Pigeon River—Lake of the Woods. | Direct route from Georgian Bay and Lake Michigan to the Mississippi. |

| Lake Superior—Hudson Bay. | Green Bay—Fox-Wisconsin. | “The Grand Portage.” |

The territory lying between the St. Lawrence River and the Atlantic seaboard offers an unexcelled field for the study of portage paths and their part in the history of the continent. The student of this branch of archæology finds at his disposal the admirable studies of Dr. William F. Ganong, which cover an important portion of this field.[35] From these studies (the best published account) the following general statements concerning Indian routes of travel are very enlightening: