Title: To Him That Hath

Author: Leroy Scott

Release date: October 26, 2012 [eBook #41180]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

New York

Doubleday, Page & Company

1907

Copyright, 1906, 1907, by Leroy Scott

Copyright, 1907, by Doubleday, Page & Company

Published, July, 1907

All Rights Reserved,

Including that of Translation into Foreign Languages,

Including the Scandinavian

TO THOSE WHOM THE WORLD HAS MADE UGLY

AND WHOSE UGLINESS THE WORLD CANNOT FORGIVE

| I. | An Injustice of God | 1 |

| II. | What David Found in Morton's Closet | 10 |

| III. | The Bargain | 29 |

| I. | David Re-enters the World | 45 |

| II. | A Call from a Neighbour | 56 |

| III. | The Superfluous Man | 68 |

| IV. | An Uninvited Guest | 86 |

| V. | Guest Turns Host | 97 |

| VI. | Tom is Seen at Work | 107 |

| VII. | A New Item in the Bill of Scorn | 117 |

| VIII. | The World's Denial | 123 |

| IX. | The Open Road | 136 |

| I. | The Mayor of Avenue A | 152 |

| II. | The Saving Ledge | 167 |

| III. | A Prophecy | 174 |

| IV. | Puck Masquerades as Cupid | 187 |

| V. | On the Upward Path | 201 |

| VI. | John Rogers | 214 |

| VII. | Hope and Dejection | 226 |

| VIII. | Rogers Makes an Offer | 235 |

| IX. | The Mayor and the Inevitable | 244 |

| X. | A Bad Penny Turns Up | 254 |

| XI. | A Love that Persevered | 262 |

| XII. | Mr. Chambers Takes a Hand | 273 |

| XIII. | The End of the Deal | 282 |

| I. | Helen Gets a New View of Her Father | 298 |

| II. | David Sees the Face of Fortune | 313 |

| III. | Helen's Conscience | 324 |

| IV. | The Ordeal of Kate Morgan | 331 |

| V. | The Command of Love | 343 |

| VI. | Another World | 350 |

| VII. | As Love Apportions | 357 |

| VIII. | A Partial Release | 365 |

| IX. | Father and Daughter | 377 |

| X. | The Beginning of Life | 391 |

| David Aldrich | An author |

| Alexander Chambers | A king of finance |

| Helen Chambers | His daughter |

| Henry Allen | A lawyer with a political future |

| Carl Hoffman | The Mayor of Avenue A |

| Carrie Becker | An admirer of the Mayor |

| William Osborne | A publisher |

| Rev. Joseph Franklin | Director of St. Christopher's Mission |

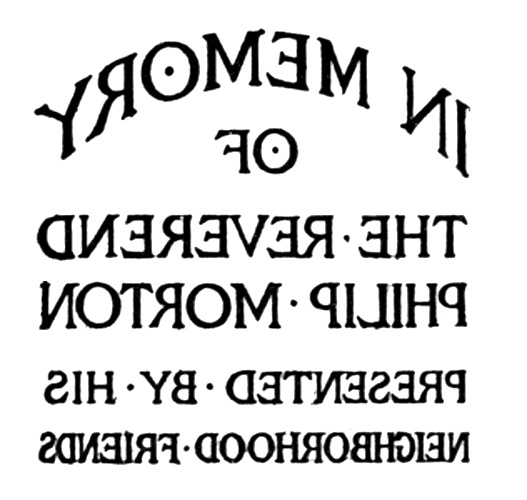

| Rev. Philip Morton | Dead, but a living memory |

| John Rogers | A real estate agent |

| Kate Morgan | A nurse-maid |

| Jimmie Morgan | Her father |

| Tom (last name uncertain) | Whose parents were the street |

| Lillian Drew | Of the sisterhood of Magdalene |

The Reverend Philip Morton, head of St. Christopher's Mission, had often said that, in event of death or serious accident, he wished David Aldrich to be placed in charge of his personal affairs; so when at ten o'clock of a September morning the janitor, at order of the frightened housekeeper, broke into the bath-room and found Morton's body lying white and dead in the tub, the housekeeper's first clear thought was of a telegram to David.

The message came to David while he was doggedly working over a novel that had just come back from a third publisher. He glanced at the telegram, then his tall figure sank back into his chair and he stared at the yellow sheet. Never before had Death struck him so heavy a blow. The wound of his mother's death had been dealt in quick-healing childhood; and though his father, a Western mining engineer, had died but seven years before, David had known him hardly otherwise than as a remotely placed giver of an allowance. Morton had for years been his best friend—latterly almost his only friend. For a space the blow rendered him stupid; then the agony of his personal loss entered him, and wrung him; and then in beside his personal sorrow there crept a sense of the appalling loss of the people about St. Christopher's.

But there was no time for inactive grief. He quickly threw a black suit and a week's linen into a travelling bag, and within an hour after the New York train pulled out of his New Jersey suburb, he paused across the street from St. Christopher's Mission—a chapel of red brick, with a short spire rising above the tenements' flat heads, and adjoining it a four-story club-house in whose windows greened forth boxes of ivy and geraniums. The doors of the chapel stood wide, as they always did for whoso desired to rest or pray, but the doors of the club-house, usually open, were closed against the casual visitor by the ribboned seal of death.

David held his eyes on the fourth-story windows, behind which he knew his friend lay. Minutes passed before he could cross the street and ring the bell. He was admitted into the large hallway, cut with numerous doors leading into club-rooms, and hung with prints of Raphaels, Murillos, Angelicos and other holy master-painters. Overwhelmed though all his senses were, he was at once struck by the emptiness, the silence, of the great house—by its strange childlessness.

As he started up the stairway he saw at its top a tall young woman dressed in black. His mounting steps quickened. "Miss Chambers!" he said.

She came down the stairway with effortless grace, her hand outheld, her subdued smile warm with friendship. He quivered within as he heard his name in her rich voice, as he clasped her hand, as he looked into the sincerity, the dignity, the rare beauty of her face.

There were none of those personal questions with which long-parted friends bridge the chasm of their separation. Death made self trivial. At first they could only breathe awed interjections upon the disaster that so suddenly had fallen. Then David asked the question that had been foremost in his mind for the last two hours:

"What caused his death? I've had only a bare announcement."

She gave him the details. "His doctor told me he had a weak heart," she added. "'In all likelihood,' the doctor said, 'the shock of the cold bath had caused heart failure. Perhaps the seizure itself was fatal; perhaps on the other hand the seizure was recoverable but while helpless he drowned.'

"As soon as I learned of his death I hurried here—I happened to be in town for a few days," she went on, after a moment. "I thought I might possibly be of service. But Bishop Harper has sent a Dr. Thorn, and Mrs. Humphrey told me you were coming, so it seems I can be of no assistance. But if there's anything I can do, please let me know."

David promised. They spoke of the great misfortune to the Mission—which she felt even more keenly than he, for her interest in St. Christopher's had been more active, so was deeper; then she bade him good-bye and continued down the stairway. He followed her with his eyes. This was but the second time he had seen her since her mother's death, six months before; and her beauty, all in black, was still a fresh marvel to him.

When the door had closed upon her, he mounted stairs and passed through hallways, likewise hung with brown prints and opening into club-rooms, till he came to the door of Morton's quarters. Mrs. Humphrey answered his ring, and the housekeeper's swollen eyes flowed fresh grief as she took his hand and led him into the sitting-room, walled with Morton's books.

"The noblest, ablest, kindest man on earth—gone—and only thirty-five!" she said, between her sobs. "Millions might have been called, and no difference; but he was the one man we couldn't spare. And yet God took him!"

The same cry against God's injustice had been springing from David's own grief. Mrs. Humphrey continued her lamentations, but they were soon interrupted by the entrance of a clergyman, of most pronounced clerical cut, whom she introduced as Dr. Thorn. Dr. Thorn explained that Bishop Harper, knowing Morton had no relatives, had sent him to take charge of the funeral arrangements; and he went on to say that if David had any requests, he'd be glad to carry them out. It was a relief to David to be freed of the business details of his friend's funeral. He replied that he had no wishes, and Dr. Thorn withdrew, taking with him Mrs. Humphrey.

Alone, memories of his friend lying in the next room rushed upon him. Morton had been some kind of distant cousin—so distant that the exact fraction of their kinship was beyond computation. After the death of David's mother, Morton's father had stood in place of David's far-absent parent; and Morton himself, though David's senior by hardly ten years, had succeeded to the guardianship on his own father's death nine years before.

This formal relation had grown, with David's growth into manhood, into warmest friendship. David had given Morton the admiring love a younger brother gives his brilliant elder, and had received the affection such as an older brother would give a younger, who was not alone brother but a youth of sympathy and promise. It had been Morton who had insisted that he had a literary future, Morton who had tried to cheer him through his five years of struggling unsuccess. And so the memories and grief that now flooded David were not less keen than if Morton's blood and his had indeed been the same.

After a time David moved to a window and looked out over the geraniums and ivy into the narrow street, with its dingy, red-faced tenements zig-zagged with fire-escapes. His mind slipped back six years to when Morton had taken charge of St. Christopher's, which then occupied merely an old dwelling, and when he, a boy of twenty, had first visited the neighbourhood. The neighbourhood was then a crowded district forgotten by those who called themselves good and just, remembered only by landlords, politicians and saloonkeepers—grimy, quarrelsome, profane, ignorant of how to live. Now decency was here. There was still poverty, but it was a respectable poverty. Men brought home their pay, and fought less often. Shawled wives went less frequently with tin pails to the side entrances of saloons. It was becoming uncommon to hear a child swear.

David's mind ran over the efforts by which this change had been wrought: Morton's forcing the police to close disorderly resorts; his eloquent appeals to the public for fair treatment of such neighbourhoods as his; his unwearied visiting of the sick, and his ready assumption of the troubles of others; his perfect good-fellowship, which made all approach him freely, yet none with disrespectful familiarity; his wonderful sermons, so simple, direct and appealing that there was never an empty seat. He was sympathetic—magnetic—devoted—brilliant. Thus he had won the neighbourhood; not all, for the evil forces he had fought, led by the boss of the ward, held him in bitter enmity. But in three or four hundred families, he was God.

David turned from the window. Mrs. Humphrey had asked if she should not take him in to see Morton, but he had shrunk from having eyes upon him when he entered the presence of his dead friend. He now moved to the door of Morton's chamber, paused chokingly, then stepped into the darkened room. On the bed lay a slender, sheeted figure. For the first moment, awe at the mystery of life rose above all other feelings: Monday he had seen Morton, strangely depressed to be sure, but in his usual health; this was Saturday, and there he lay!

His emotions trembling upon eruption, David crossed slowly to the bed. With fearing hand he drew the sheet from the face, and for a long space gazed down at the fine straight nose, at the deeply-set eyes, and at the high broad forehead, the most splendid he had ever seen, with the soft hair falling away from it against the pillow. Then suddenly he sank to a chair, and his grief broke from him.

Soon his mind began to dwell upon the contrast between Morton and himself—what a great light was this that had been stricken out, what a pitiable candle flame was this left burning. In the presence of these dead powers he felt how small was his literary achievement, how small his chance of future success, how comparatively trivial that success would be even if gained. David had felt to its full the responsibility of life; he had longed, with a keenness that was at times actual physical pain, that his life might count some little what in advancing the general good. But he realised now, as he gazed at the white face on the pillow, that in the field of humanitarianism, as in the field of literature, his achievement was nothing.

He burnt with a sudden rush of shame that he was alive, and he clenched his hands and in tense whispers cried out against the injustice of God in taking so useful a man as Morton and leaving so useless a cumbrance as himself. But this defiance soon passed into a different mood. He slipped to his knees, and a wish sobbed up from his heart that he might change places with the figure on the bed.

This wish was present in his thoughts all that evening and the next two days as he did his share in the sad routine of the funeral arrangements. The service was set for the evening so that the people of the neighbourhood could be present without difficulty or financial loss. At the hour of beginning the chapel was packed to the doors, and David learned afterwards that as large a crowd stood without and that many notables who had come at the appointed time were unable to gain any nearer the chapel than the middle of the street.

Bishop Harper himself was in charge, and about him were gathered the best-known clergymen of his persuasion in the city—a tribute to his friend that quickened both David's pride and grief. Bishop Harper was ordinarily a pompous speaker of sonorous platitudes, ever conscious of his high office. But to-night he had a simple, touching subject; he forgot himself and spoke simply, touchingly. When he used an adjective it was a superlative, and yet the superlative did not seem to reach the height of Morton's worth. Morton was "the most gifted, the most devoted" man of the Bishop's acquaintance, and the other clergymen by their looks showed complete and unjealous approval of all the Bishop's praise.

David's eyes flowed at the tribute paid Morton by his peers. Yet he was moved far more by the inarticulate tribute of the simple people who crowded the chapel. Whatever was good in their lives, Morton had brought them; and now, mixed with their sense of loss, was an unshaped fear of how hard it was going to be to hold fast to that good without his aid. Never before had David seen anything so affecting; and even in after days, when he saw Morton's death with new eyes, the picture of the love and grief of this audience remained with him, unsoiled, as the strongest, sincerest scene he had ever witnessed. The women—factory girls, scrub-women, hard-working wives—wept with their souls in their tears and in their spasmodic moans; and the men—labourers, teamsters, and the like—let the strange tears stream openly down their cheeks, unashamed. The chapel was one great sob, choked down at times, at times stopping the Bishop's words. It was as if they were all orphaned.

All through the service, one cry rose from David's heart, and continued to repeat itself while the audience, and after them the crowd from the street, filed by the open casket—and still rose as, later, he sat with bowed head in a front pew beside the coffin:

"If only I could change places, and give him back to them!"

David was sitting in Morton's study, looking through the six years' accumulation of letters and documents, saving some, destroying others, when he came upon a dusty snap-shot photograph. Hands and eyes were arrested; Morton sank from his mind. Four persons sat in a little sailboat; their faces were wrinkled in sun-smiles; about and beyond them was the broad white blaze of the Sound. The four were Miss Chambers and her mother, Morton and himself.

The day of the photograph ran its course again, hour by hour, in David's mind, and slowly rose other pictures of his acquaintance with Helen Chambers: of their first meeting three years before at a dinner at St. Christopher's Mission; of later meetings at St. Christopher's, where she had a club and where he was a frequent visitor; of the summer passed at St. Christopher's two years before, during the early part of which he, in Morton's stead, had aided her in selecting furnishings for a summer house given by her father for the Mission children; of two weeks at the end of that summer which he and Morton had spent at Myrtle Hill, the Chambers's summer home on the Sound. Since then he had seen her at irregular intervals, and their friendship had deepened with each meeting.

She had interested his mind as no other woman had ever done. She had been bred in the conventions of her class, the top strata of the American aristocracy of wealth; all her friends, save those she had gained at the Mission, belonged in this class; and her life had been lived within her class's boundaries. Given these known quantities, an average social algebraist would have quickly figured out the unknown future to be, a highly desirable marriage, gowning and hatting, tea-drinking, dining, driving, calling, Europe-going, and the similar activities by which women of her class reward God for their creation—and in time, the motherhood of a second generation of her kind.

But there was her character, which by degrees had revealed itself fully to David: her sympathy, her love of truth, a lack of belief in her social superiority, an instinct to look very clearly, very squarely, at things, a courage unconscious that it was courage, that was merely the natural action of her direct spirit—all these dissolved in a most simple, charming personality. It was these qualities (a stronger reprint of her mother's), in one of her position, that made David think her future might possibly be other than that contained in the algebraist's solution—that made him regard her as a potential surprise to her world.

And Helen Chambers had interested not only David's mind. In moments when his courage had been high and his fancy had run riotously free, he had dared dream wild dreams of her. But now, as he gazed at the photograph, he sighed. In place and fortune she was on the level of the highest; he was far below—still only a straggler, obscure, barely keeping alive.

Yes—he was still only a struggler. He nodded as his mind repeated the sentence. Now and then his manuscripts were accepted—but only now and then. His English was admirable; this he had been told often. But there was a something lacking in almost all he wrote, and this too he had been often told. David had tried to write of the big things, the real things—but of such one cannot write convincingly till he has thought deeply or travelled himself through the deep places. David's trouble was, he did not know life—but no one had told him this. So in his ignorance of the real difficulty, he had thought to conquer his unsuccess by putting forth a greater effort. He had gone out less and less often; he had sat longer and longer at his writing-table; his English had become finer and finer. And his people had grown more hypothetical, more unreal. The faster he ran, the farther away was the goal.

He sighed again. Then his square jaw tightened, his eyes narrowed to grim crescents, his clenched fist lightly pounded the desk; and to a phalanx of imaginary editors he announced with slow defiance:

"Some of these days the whole blamed lot of you will be camping on my door-steps. You just wait!"

He was returning to the sifting of the letters when the bell of the apartment rang. He answered the ring himself, as Mrs. Humphrey was out for the afternoon, and opened the door upon a shabby, wrinkled man with a beery, cunning smile. His manner suggested that he had been there before.

"Is Mr. Morton at home?" the man asked.

"No," David answered shortly, not caring to vouchsafe the information that Morton was in his grave these two days. "But I represent him."

"Then I guess I'll wait."

"He'll not be back."

The man hesitated, then a dirty hand drew an envelope from a torn pocket. "I was to give it only to him, but I guess it'll be all right to leave it with you."

David closed the door, ripped open the envelope, glanced at the note, turned abruptly and re-entered Morton's study, and read the lines again:

"You paid no attention to the warning I sent you last Friday. This is the last time I write. I must get the money to-day, or—you know!

"L. D."

He was clutched with a vague fear. Who was L. D.? And how could money be thus demanded of Morton? His mind was racing away into wild guesses, when he observed there was no street and number on the note. In the same instant it flashed upon him that the note must be investigated, and that the address of its writer was walking away in the person of the old messenger.

He caught his hat, rushed down the stairs, and came upon the old man just outside the club-house entrance.

"I want to see the writer of that note," he said. "Give me the address."

"Do better'n that. I'll go with you. I'm the janitor there."

David was too agitated to refuse the offer. They walked in silence for several paces, then the old man jerked his head toward the club-house and knowingly winked a watery eye.

"Lucky they don't know where you're goin'," he said. "But I'm safe. Safe as a clam!" He reassured David with his beery smile.

The vague dread increased. "What do you mean?"

"Innocent front! Oh, you're a wise one, I see. But you can trust me. I'm safe."

David was silent for several paces. "Who is this man L. D.?"

"This man?" He cackled. "This man! Oh, you'll do!"

David looked away in disgust; the old satyr made him think of the garbage of dissipation. All during their fifteen-minute car ride his indefinite fear changed from one dreadful shape to another. After a short walk the old man led the way into a small apartment house, and up the stairs.

He paused before a door. "Here's your 'man,'" he said, nudging David and giving his dry, throaty little laugh.

"Thanks," said David.

But the guide did not leave. "Ain't you got a dime that's makin' trouble for the rent o' your coin?"

David handed him ten cents. "Safe as a clam," he whispered, and went down the stairs with a cackle about "the man."

David hesitated awhile, with high-beating heart, then knocked at the door. It was opened by a coloured maid.

"Who lives here?" he asked.

"Miss Lillian Drew."

David stepped inside. "Please tell her I'd like to see her. I'm from Mr. Morton."

The maid directed him toward the parlour and went to summon her mistress. At the parlour door David was met with the heavy perfume of violets. The room was showily furnished with gilt, upholstery, vivid hangings, painted bric-a-brac—all with a stiff shop-newness that suggested recently acquired funds. An ash-tray on the gilded centre-table held several cigarette stubs. On the lid of the upright piano was the last song that had pleased Broadway, and on the piano's top stood a large photograph of a man with a shrewd, well-fed face, his derby hat pushed back, his hands in his trousers pockets, a jewelled saddle in his necktie. Across this picture of portly jauntiness was scrawled, "To lovely Lil, from Jack."

David had no more than seated himself upon a surface of blue chrysanthemums and taken in these impressions, when the portieres parted and between them appeared a tall, slender woman in a trained house-gown of pink silk, with pearls in her ears and a handful of rings on her fingers. She looked thirty-five, and had a bold, striking beauty, though it was perhaps a trifle over-accentuated by the pots and pencils of her dressing-table. Possibly her nature had its kindly strain—doubtless she could smile alluringly; but just now her dark eyes gazed at David in hard, challenging suspicion.

David rose. "Is this Miss Drew?"

"You are from Phil Morton?" she asked.

He shivered at the implied familiarity with Morton. "I am."

She crossed to a chair and, as she seated herself, spread her train fan-wise to its full display. Her near presence seemed to uncork new bottles of violet perfume.

"Why didn't he come himself?" she demanded, her quick, brilliant eyes directly upon David.

It was as her note had indicated—she didn't read the papers. Obeying an unformed policy, David refrained from acquainting her with the truth.

"He's not at home. I've come because his affairs are left with me."

Her eyes gleamed. "So he's run away from home!" She sneered, but the sneer could not wholly hide her disappointment. "That won't save him!" She paused an instant. "Well—what're you here for?"

"I told you I represent him."

"You're his lawyer?"

"I'm his friend."

"Well, I'm listening. Go on."

The fear had taken on an almost definite shape. David shrunk from what he was beginning to see. But it was his duty to settle the affair, and settle it he could not without knowing its details. "To begin with, I shall have to ask some information from you," he said with an effort. "Mr. Morton left this matter entirely in my hands, but he told me nothing concerning its nature."

She half closed her eyes, and regarded David intently. "You brought the money?" she asked abruptly.

"No."

"Then he's——" She made a grim cipher with her forefinger, and stood up. "If there's no money, good afternoon!"

David did not rise. He guessed her dismissal to be a bit of play-acting. "Whatever comes to you must come through me," he said, "and you of course realise that nothing can come from me till I understand the situation."

"He understands it. That's enough."

"Oh, very well then. I see you want nothing." David determined to try play-acting himself. He rose. "Let it be good-afternoon."

She stopped him at the portieres, as he had expected. "It's mighty queer, when Morton's been trying hard to keep this thing between himself and me, for him to send a third person here."

"I can't help that," he returned with a show of indifference.

"But how do I know you really represent him?"

"You must take my word for it. Or you can telephone St. Christopher's and ask if David Aldrich is not in charge of his affairs."

She eyed him steadily for a space. "You look on the square," she said abruptly; then she added with an ominous look: "If there's no money, you know what'll happen!"

David shrugged his shoulders. "I told you I know nothing."

She was thoughtfully silent for several minutes. David studied her face, in preparation for the coming conflict. He saw that appeal to her better parts would avail nothing. He could guess that she needed money; it was plainly her nature, when roused, to spare nothing to gain her desire. And if defeated, she could be vindictive, malevolent.

In her inward struggle between caution and desire for money, greed had the assistance of her pride; for a woman living upon her attraction for men, is by nature vain of her conquests. Also, David's physical appearance was an element in the contest. Her quick bold eyes, looking him over, noted that he was tall and straight, square of shoulder, good-looking.

Greed and its allies won. "Well, if you want to know, come back," she said.

David resumed his seat. She stood thinking a moment, then went to a writing-desk. For all his suspense, David was aware she was trying to display her graces and her gown. She rustled to his chair with the unhinged halves of a gold locket in her hand.

"Suppose we begin here," she said, handing him one half of the locket. "Perhaps you'll recognise it—though that was taken in eighty-five."

David did recognise it. It was Lillian Drew at twenty. The face was fresh and spirited, and had in an exceptional measure the sort of beauty admired in the front row of a musical-comedy chorus. It was not a bad face; had the girl's previous ten years been otherwise, the present Lillian Drew would have been a very different woman; but the face showed plainly that she had gone too far for any but an extraordinary power or experience to turn her about. It was bold, striking, luring—a face of strong appeal to man's baser half—telling of a girl who would make advances if the man held back.

David felt that she waited for praise. "It's a handsome face."

"You're not the first to say so," she returned, proudly.

She let him gaze at the picture a full minute, keenly watching his face for her beauty's effect. Then she continued:

"That is the picture of a girl in Boston. And this"—a jewelled hand gave him the locket's other half—"is a young man in Harvard."

David knew whose likeness was in the locket, yet something snapped sharply within him when he looked upon the boyish face of Morton at twenty-one. It was the snap of suspense. His fear was now certainty.

"She probably wouldn't have suited you"—the tone declared she certainly would—"but Phil Morton certainly had it bad for four or five months."

David forced himself to his duty—to search this relationship to its limits. "And then—he broke it off?" he asked, with a sudden desire to make her smart.

"No man ever threw me down," she returned sharply, her cheeks flushing. "I got tired of him. A woman soon gets tired of a mere boy like that. And he was repenting about a third of the time, and preaching to me about reforming myself. To live with a man like that——it's not living. I dropped him."

"But all this was fifteen years ago," David said, calm by an effort. "What has that to do with your note?"

She sank into a chair before him, and ran the tip of her tongue between her thin lips. She leaned back luxuriously, clasped her be-ringed hands behind her head, and regarded him amusedly from beneath her pencilled eye-lashes.

"A woman comes to New York about four months ago. She was—well, things hadn't been going very well with her. After a month she learns a man is in town she had once—temporarily married. She hasn't heard anything about him for fifteen years. He is a minister, and has a reputation. She has some letters he wrote her while they had been—such good friends. She guesses he would just as soon the letters should not be made public. She has a talk with him; she guessed right.... Now you understand?"

David leaned forward, his face pale. "You mean Morton has been paying you—to keep still?"

She laughed softly. She was enjoying this display of her power. "In the last three months he has paid me the trifling sum of five thousand."

David stared at her.

"And he's going to pay me a lot more, or—the letters!"

His head sank before her bright, triumphant eyes, and he was silent. He was a confusion of thoughts and emotions, amid which only one thought was distinct—to protect Morton if he could. He tried to push all else from his mind and think of this alone.

A minute or more passed. Then he looked up. His face was still pale, but set and hard. "You are mistaken in at least one point," he said.

"And that?"

"About the money you are going to get. There'll be no more."

"Why not?" she asked with amused superiority.

"Because the letters are valueless." He watched her sharply to see the effect of his next words. "Philip Morton was buried two days ago."

Her hands fell from her head and she stood up, suddenly white. "It's a lie!"

"He was buried two days ago," David repeated.

Her colour came back, and she sneered. "It's a lie. You're trying to trick me."

David rose, drew out a handful of clippings he had cut from the newspapers, and silently held them toward her. She glanced at a headline, and her face went pale again. She snatched the clippings, read one half through, then flung them all from her, and abruptly turned about—as David guessed, to hide from him the show of her loss.

In a few moments she wheeled around, wearing a defiant smile. "Then I shall make the letters public!"

"What good will that do you? Think of all those people——"

"What do I care for those people!" she cried. "I'll let them see what their saint was like!"

David stepped squarely before her; his tall form towered above her, his dark eyes gleamed into hers. "You shall do nothing of the kind," he said harshly. "You are going to turn over the letters to me."

She did not give back a step. "Oh, I am, am I!" she sneered. At this close range, penetrating the violet perfume, he caught a new odour—brandy.

"You certainly are! You're guilty of the crime of blackmail. You've confessed it to me, and I have your letter demanding money—there's proof enough. The punishment is years in prison. Give me those letters, or I'll have a policeman here in five minutes."

She was shaken, but she forced another sneer. "To take me to court is the quickest way to make the letters public," she returned. "You're bluffing."

He was, to an extent—but he knew his bluff was a strong one. "If you keep them, you will give them out," he went on grimly. "Between your making them public and going unharmed, and their coming out in the course of the trial that will send you to prison, I choose the latter. Morton is dead; the letters can't hurt him now. And I'd like to see you suffer. The letters, or prison—take your choice!"

She slowly drew back from him, and her look of defiance gave place to fear. She stared without speaking at his square face, fierce with determination—at his roused, dominating masculinity.

"Which is it to be?"

She did not move.

"You choose prison then. Very well. I'll be back in five minutes."

He turned and started to leave the room.

"Wait!"

He looked round and saw a thoroughly frightened face.

"I'll get them."

She passed out through the beflowered portieres, and in a few minutes returned with a packet of yellow letters, which she laid in David's hand.

"These are all?" he demanded.

"Yes."

A more experienced investigator might have detected an unnatural note in her voice that would have prompted a further pursuit of his question; but David was satisfied, and did not mark a cunning look as he passed on.

"Here's another matter," he said threateningly. "If ever a breath of this comes out, I'll know it comes from you, and up you'll go for blackmail. Understand?"

Now that danger was over her boldness began to flow back into her. "I do," she said lightly.

He left her standing amid her crumpled, forgotten train. As he was passing into the hall, she called to him:

"Hold on!"

He turned about.

She looked at him with fear, effrontery, admiration. "You're all right!" she cried. "You're a real man!"

As David came into the street, his masterful bearing fell from him like a loosened garment. There was no disbelieving the prideful revelation of Lillian Drew—and as he walked on he found himself breathing, "Thank God for Philip's death!" Had Philip lived, with that woman dangling him at the precipitous edge of exposure, life would have been only misery and fear—and sooner or later she would have given him a push and over he would have gone. Death comes too late to some men for their best fame, and to some too early. To Philip Morton it had come in the nick of time.

One thought, that at first had been merely a vague wonder, grew greater and greater till it fairly pressed all else from David's mind: where had Philip got the five thousand dollars for which Lillian Drew had sold him three months' silence? David knew that Philip Morton had not a penny of private fortune, only his income as head of the Mission; and that of this income not a dollar had been laid by, so open had been his purse to the hand of distress. He could not have borrowed the money in the usual manner, for he had no security to give; and sums such as this are not blindly loaned with mere friendship as the pawn.

David entered Philip's study with this new dread pulsing through him. It was his duty to his friend to know the truth, and besides, his suspense was too acute to permit remaining in passive ignorance; so he locked the study door and began seeking evidence to dispel or confirm his fear. He took the books from the safe—he remembered the combination from the summer he had spent at the Mission—and turned them through, afraid to look at each new page. But the books dealt only with small sums for incidental expenses; the large bills were paid by cheque from the treasurer of the Board of Trustees. There was nothing here. He looked through the papers in the desk—among them no reference to the money. He scrutinised every page of paper in the safe, except the contents of one locked compartment. No reference. Knowing he would find nothing, he examined Morton's private bank-book: a record of the monthly cheque deposited and numerous small withdrawals—that was all.

And then he picked up a note-book that all the while had been lying on the desk. He began to thumb it through, not with hope of discovering a clue but merely as a routine act of a thorough search. It was half engagement book, half diary. David turned to the page dated with the day of Morton's death, intending to work from there backwards—and upon the page he found this note of an engagement:

"5 P. M.—at Mr. Haddon's office—first fall meeting of Boy's Farm Committee."

He turned slowly back through the leaves of September, August, July, June, finding not a single suggestive record. But this memorandum, on the fifteenth of May, stopped him short:

"Boy's Farm Committee adjourned to-day till fall, as Mr. Chambers and Mr. Haddon go to Europe. Money left in Third National Bank in my name, to pay for farm when formalities of sale are completed."

Instantly David thought of an entry on the first of June recording that, with everything settled save merely the binding formalities, the farmer had suddenly broken off the deal, having had a better offer.

Here was the money, every instinct told David. But the case was not yet proved; the money might be lying in the bank, untouched. He grasped at this chance. There must be a bank-book and cheque-book somewhere, he knew, and as he had searched the office like a pocket, except for the drawer of the safe, he guessed they must be there. After a long hunt for the key to this drawer, he found a bunch of keys in the trousers Morton had worn the day before his death. One of these opened the drawer, and sure enough here were cheque-book and bank-book.

David gazed at these for a full minute before he gained sufficient mastery of himself to open the bank-book. On the first page was this single line:

May 15. By deposit 5,000

This was the only entry, and the fact gave him a moment's hope. He opened the cheque-book—and his hope was gone. Seven stubs recorded that seven cheques had been drawn to "self," four for $500 each, and three for $1,000.

Even amid the chill of horror that now enwrapped him, David clearly understood how Morton had permitted himself to use this fund. Here was a woman with power to destroy, demanding money. Here was money for which account need not be rendered for months. In Morton's situation a man of strong will, of courageous integrity, might have resigned and told the woman to do her worst. But David suddenly saw again Morton's dead face upon the pillow, and he was startled to see that the mouth was small, the chin weak. He now recognised, what he would have recognised before had the fault not been hidden among a thousand virtues, that Morton did not have a strong will. He recognised that a man might have genius and all the virtues, save only courage, and yet fail to carry himself honourably through a crisis that a man of merest mediocrity might have weathered well.

If exposure came—so Temptation must have spoken to Morton—all that he had done for his neighbours would be destroyed, and with it all his power for future service. He could take five hundred dollars, buy the woman's silence, and somehow replace the money before he need account for his trust. But she had demanded more, and more, and more; and once involved, his only safety, and that but temporary, was to go on—with the terror of the day of reckoning before him.

And then, while he sat chilled, David's mind began to add mechanically three things together. First, the engagement Philip had had on the day of his death with the Boys' Farm Committee; at that he would have had to account for the five thousand dollars, and his embezzlement would have been laid open. Second, the certainty of exposure from Lillian Drew, since he had no more money to ward it off. Third, was it not remarkable that Morton's heart trouble, if heart trouble there had been, with fifteen hundred minutes in the day in which to strike, had selected the single minute he spent in his bath?

As David struck the sum of these, there crawled into his heart another awful fear. Would a man who had not had the courage to face the danger of one exposure, have the courage to face a double exposure? Had Morton's death been natural, or——

Sickened, David let his head fall forward upon his arms, folded on the desk—and so he sat, motionless, as twilight, then darkness, crept into the room.

David was still sitting bowed amid appalling darkness, when Mrs. Humphrey knocked and called to him that dinner waited. He had no least desire for food, and as he feared his face might advertise his discoveries to Dr. Thorn and Mrs. Humphrey, he slipped out of the apartment and sent word by the janitor that he would not be in to dinner. For an hour and a half he walked the tenement-cliffed streets, trying to force his distracted mind to deduce the probable consequences of Morton's acts.

At length one result stood forth distinct, inevitable: Morton's death was not going to save his good name. In a few days his embezzlement would be discovered. There would be an investigation as to what he had done with the money. Try as the committee might to keep the matter secret, the embezzlement would leak out and afford sensational copy for the papers. Lillian Drew, out of her malevolence, would manage to triple the scandal with her story; and then someone would climax the two exposures by putting one and one together, as he had done, and deducing that Morton's lamented death was suicide. In a week, perhaps in three days, all New York would know what David knew.

He was re-entering the club-house, shortly after eight o'clock, when the sound of singing in the chapel reminded him that the regular Thursday even prayer-meeting had been turned into a neighbourhood memorial service for Morton. He slipped quietly into the rear of the chapel. It was crowded, as at the funeral. Dr. Thorn, who was temporarily at the head of the Mission, was on the rostrum, but a teamster from the neighbourhood was in charge of the meeting. The order of the service consisted of brief tributes to Morton, brief statements of what he had meant to their lives. As David listened to the testimonies, uncouth in the wording, but splendid in feeling, the speaker sometimes stopped by his own emotion, sometimes by sobbing from the audience—his tears loosened and flowed with theirs.

And then came a change in his view-point. He found himself thinking, not of Morton the individual, Morton his friend, but of Morton in his relation to these people. What great good he had brought them! How dependent they had been upon him, how they now clung to him and were lifted up by his memory! And how they loved him!

But what would they be saying about him a week hence?

The question plunged into David like a knife. He hurried from the chapel and upstairs into Morton's study. Here was the most ghastly of all the consequences of Morton's deeds. What would be the effect on these people of the knowledge he had gained that afternoon? They were not discriminating, could not select the good, discard and forget the evil. He still loved Morton; Morton to him was a man strong and great at ninety-nine points, weak at one. Impregnable at all other points, temptations had assailed his one weakness, conquered him and turned his life into complete disaster. But, David realised, the neighbourhood could not see Morton as he saw him. They could see only the evils of his one point of weakness, see him only as guilty of larger sins than the most sinful of themselves—as a libertine, an embezzler, a suicide.

And they would be helped to this new view by the elements he had fought. How old Boss Grogan would rejoice in Morton's fall—how his one eye would light up, and triumph overspread his veinous, pouched face! How he and his henchmen, victory-sure, would return to their attack on the Mission, going among its people with sneers at Morton and at them!

There was no doubt in David's mind of the effect of all this upon them. The words of a shrivelled old woman who had given tribute in the chapel stayed in his memory. "He has been to me like St. Christopher, what this place is called from," she had quavered. "He holds me in his arms and carries me over the dark waters." Exactly the case with all of them, David thought. Morton, who had lifted them out of darkness, was supporting them over the ferry of life—till a few days ago by his presence among them, now and in the future by the powerful influence in which he had enarmed them. Once they saw their St. Christopher as baser than themselves [and what a picture Grogan would keep before their eyes!], they would call him hypocrite, despise his support and the shore whither he carried them; his strength to save them would be gone, and they would fall back into the darkness out of which they had been gathered.

David's concern was now all for these unsuspecting hundreds mourning and praising Morton in the chapel. Presently, amid the chaos in his mind, one thought assumed definite shape: if the people were kept in ignorance, if Morton were kept pure in their eyes, would not their love for him, the saving influence he had set about them, remain just as potent as though he were in truth unspotted? Yes—without doubt. And then this question asked itself: could they be kept in ignorance? Yes, if the embezzlement could be concealed—for Morton's relations with Lillian Drew and his suicide would come before the public only by being dragged, as it were, by this engine of disgrace.

David's whole mind, his whole being, was suddenly gripped by the thought that by concealing the embezzlement he could save these hundreds of persons from falling back into the abyss. But how conceal it? The answer was ready at his mind's ear: by replacing the money. But where get the money? He had almost nothing himself, for the little fortune from his father with which he had been eking out his meagre earnings was now in its last dollars, and he had hardly a friend in New York. Again the answer was ready: take into the secret some rich man interested in the Mission—he'd gladly furnish the money rather than have St. Christopher's dishonoured.

This idea rapidly shaped itself into a definite plan. At half-past nine David left the study and descended the stairs, with the decision to complete the lesser details of his scheme that night, leaving only the getting of the money for the morrow. The moment he stepped into the never-quiet street, he pressed back into the shadow of the club-house entrance, for out of the chapel was riling the mourning crowd—some of the women crying silently, some of the men having traces of recent tears, all stricken with their heavy loss. Yes, their loss was grievous, but, God helping him, that which was left them they should not lose!—and David gazed upon them till the last was out, with a tingling glow of saviourship.

Half an hour later he was standing before the apartment house he had visited that afternoon. A dull glow through Lillian Drew's shades informed him she was at home; and, glancing through the open basement window into the janitor's apartment, he saw his guide of the afternoon stretched on a shabby lounge. He was not proud of the part he was about to play; but for Lillian Drew to remain in town—danger was in this that must be avoided.

That afternoon he had noticed there was a telephone in the house. He now walked back to a drug store on whose front he had seen the sign of a public telephone. He closed himself in the booth, and soon had Lillian Drew on the wire.

"This is a friend with a tip," he said. "I just happened to overhear a man ask a policeman to come with him to arrest you."

"What was the man like?" came tremulously from the receiver.

David began a faithful description of himself, but before he was half through he heard the receiver at the other end of the wire click into place upon its hook. He returned to where he had a view of the entrance of the apartment house, and almost at once he saw Lillian Drew come hurriedly out. He then walked over to Broadway, asked a policeman to arrest a woman on his complaint, and led the officer to the apartment house.

He rang the janitor's bell, and after a minute it was answered by his "safe" friend. He put on his most ominous look. "Is Lillian Drew in?" he demanded.

"No; she just went out," the janitor answered, glancing in fear at the policeman.

The officer gave him a shove. "Bluffin' don't work on me. You just take us up, you old booze-tank, and we'll have a look around for ourselves."

They searched the flat, followed about by the frightened black maid, but found no Lillian Drew. As they were leaving the house David again directed his ominous look upon the janitor. "Don't you tell her we were here," he ordered; and then he whispered to the policeman, but for the janitor's ears, "I'll get her in the morning."

He walked away with the officer, but quickly returned to his place of observation. He saw the janitor come furtively out and hurry away, and in a little while he saw Lillian Drew enter—and he knew that the janitor, who had summoned her, had told of her narrow escape and of the danger in which she stood.

He wandered about, passing the house from time to time. Toward twelve o'clock, when he again drew near the house, the great van of a storage warehouse was before it, and men were carrying out furniture. Beside the van stood an express wagon in which was a trunk, and coming out of the doorway was a man bearing on his back another trunk, from the end of which dangled a baggage check. As the man staggered across the sidewalk, David stepped behind him, caught the tag and read it by the light that streamed from the entrance. The trunk was checked to Chicago.

Lillian Drew would make no trouble. One part of his plan was completed. Half an hour later David was back in Morton's study, beginning another part of his preparation. To prevent suspicion when the Boys' Farm Committee discovered the replaced money, to make it appear that the drawing of the fund was no more than a business absurdity such as is normally expected from clergymen, David had determined to surround the presence of the money in the safe with the formality of an account. At the head of a slip of paper he wrote, "Cash Account of Boys' Summer Home," and beneath it, copying from the stubs of the cheque-book: "June 7, Drawn from Bank $500"; and beneath this, under their respective dates, the six other amounts. Then at the foot of these he wrote under date of September fifteenth, the day before Morton's death, "Cash on hand, $5,000."

These items he set down in a fair copy of Morton's hand, not a difficult mimicry since their writing was naturally much alike and had a further similarity from their both using stub pens. He wrote with an ink, which he had secured for the purpose on his way home, that immediately after drying was of as dead a black as though it had been on paper for weeks. He put the slip, with the bank-book and cheque-book, into the drawer of the safe. To-morrow the five thousand dollars would go in there with them, and Morton's name, and the people of St. Christopher's, would be secure.

He had not yet disposed of the letters Lillian Drew had given him. He carried the packet into the sitting-room, tore the letters into shreds and heaped them in the grate between the brass andirons. Then he touched a match to the yellow pile, and watched the destroying flames spring from the record of Morton's unholy love—as though they were the red spirit of that passion leaping free. He sat for a long space, the dead hush of sleep about him, gazing at where the heap had been. Only ashes were left by those passionate flames. A symbol of Morton, thus it struck David's fancy. Just so those flames had left of Morton only ashes.

The next morning David had before him the task of getting the money. He had determined to approach Mr. Chambers first, and he was in the great banking house of Alexander Chambers & Company, in Wall Street, as early as he thought he could decently appear there. He was informed that Mr. Chambers had gone out to attend several directors' meetings—not very surprising, since Mr. Chambers was a director in half a hundred companies—and that the time of his return was uncertain, if indeed he returned at all. David went next to the office of Mr. Haddon, treasurer of the Mission and of the Boys' Farm Committee, and one of the Mission's largest givers. Mr. Haddon, he was told, had left the office an hour before for St. Christopher's.

David hurried back to the Mission, wondering what Mr. Haddon's errand there could be, and hoping to catch him before he left. As he was starting up the stairway the janitor stopped him. "Mr. Haddon was asking for you," the janitor said. "And Miss Chambers, too. I think she's in the reception room."

David turned back, walked down the hall and entered the dim reception room. She was sitting in a Flemish oak settle near a window, her hands clasped upon an idle book in her lap, gazing fixedly into vacancy. Her dress of mourning was almost lost in the shadow, and her face alone, softly lighted from between the barely parted dark-green hangings, had distinctness. He paused at the door and gazed long at her. Then he crossed the bare floor.

She rose, gave him her firm, slender hand, and, allowing him half the settle, resumed her seat. Now that he could look directly into her face, he saw there repressed anxiety.

"I came down this morning on an errand about the Flower Guild," she said. "I'm going back to the country this afternoon. I've been waiting to see you because I wanted to tell you something."

She paused. David was conscious that she was making an effort to keep her anxiety out of her voice and manner.

"It's not at all important," she went on. "Just a little matter about Mr. Morton. Oh, it's nothing wrong," she added quickly, noticing that David had suddenly paled. "I'm sure nothing unpleasant is going to develop. But I wanted you to know it, so that if there was any little difficulty, you wouldn't be taken by surprise."

David's pulses stopped. "Yes?" he said. "Yes?"

She had become very white. "It's about the money of the Boys' Farm Committee. Day before yesterday morning Mr. Haddon went to the Third National Bank to arrange for withdrawing the funds he had deposited in Mr. Morton's name. He found—Mr. Morton had withdrawn it."

"Yes?"

"Please remember, I'm sure nothing's wrong. Of course Mr. Haddon acted immediately. He called a meeting of the committee; they decided to make a quiet investigation at once. Father told me about it. So far they haven't found the money, but of course they will. The worst part is, the newspapers have somehow learned that five thousand dollars is missing from the Mission. The sum is not so large, but for it to disappear in connection with a place like this—you can see what a great scandal the papers are scenting? Several reporters were here just a little while ago. I sent them upstairs to Mr. Haddon."

He stared at her dizzily. His plan was come to naught. Morton's shame was about to be trumpeted over the city. The people of St. Christopher's were about to topple back into the abyss.

"What is Mr. Haddon doing upstairs?"

"It occurred to him that possibly Mr. Morton had put the money in the safe in his study. I'm certain the money's there. Mr. Haddon's up in the study with a safe-opening expert."

For a moment David sat muted by the impending disaster. Then he rose. "Come—let's go up!" he said.

They mounted the stairs in silence, and in the corridor leading to Morton's apartment passed half a dozen reporters. David unlocked the apartment with his latch-key, led the way to Morton's study, and pushed open its door. Before the safe sat a heavily spectacled man carefully turning its dial-plate and knob. On one side of him stood Dr. Thorn, his formal features pale, and on the other side gray-haired Mr. Haddon, his hard, lean face, milled with financial wrinkles like a dollar's edge, as expressionless as though he was in the midst of a Wall Street crisis.

Mr. Haddon recognised the presence of David and Helen with a slight nod, but Dr. Thorn stepped to David's side.

"You've heard about it?" he asked in an agitated voice.

"Yes—Miss Chambers told me."

At that moment the safe door swung open. "There you are," said the spectacled man, with a complacent little grunt.

Mr. Haddon dismissed the man and knelt before the safe. Helen and Dr. Thorn leaned over him, and David, still stunned by the suddenness of the catastrophe, looked whitely on from behind them. A minute, and Mr. Haddon's search was over.

He looked about at the others. "It's not here," he said quietly.

A noise at the door caused all to turn in that direction. There stood the reporters. They had edged into the apartment as the safe-expert had gone out.

"Will you gentlemen please wait outside!" requested Mr. Haddon, sharply.

"We've got to hurry to catch the afternoon editions," one spoke up. "Can't you give us the main facts right now? You've got 'em all—I just heard you say the money wasn't here."

"I'll see you in a few minutes," answered Mr. Haddon, and brusquely pressed them before him into the corridor.

When he reëntered the study he looked at them all grimly. "There's absolutely no keeping this from the papers," he said.

"But there must still be another place the money can be!" Helen cried.

"I've investigated every other place," returned Mr. Haddon, in the calm voice of finality. "The safe was the last possibility."

They all three stared at each other. It was Dr. Thorn that spoke the thought of all. "Then the worst we feared—is true?"

Mr. Haddon nodded. "It must be."

David could not speak, nor think—could only lean sickened against the desk. The exposure of Morton—and a thousand times worse, the ruin of St. Christopher's—both inevitable!

"Won't you please look again!" Helen cried, with desperate hope. "Perhaps you overlooked something."

Mr. Haddon knelt once more, and slowly fluttered the pages of the books and scrutinised each scrap of paper. Soon he paused, and studied a slip he had come upon. Then he rose, and David saw at the head of the slip, "Cash Account of Boys' Summer Home." It was the paper he had prepared to hide Morton's embezzlement.

Mr. Haddon's steady eyes took in David and Dr. Thorn. "Could anybody have been in the safe since Mr. Morton's death?"

"It's hardly possible," returned Dr. Thorn. "Mr. Aldrich has been in the study almost constantly."

Mr. Haddon's eyes fastened on David; a quick gleam came into them. David, unnerved as he was, could not keep his face from twitching.

There was a long silence. Then Mr. Haddon asked quietly:

"Could you have been in the safe, Mr. Aldrich?"

David did not recognise whither the question led. "Why, yes," he said mechanically.

Mr. Haddon held out the slip of paper. "According to this memorandum in Mr. Morton's hand, the money was in the safe the day before his death." His eyes screwed into David. "Perhaps you can suggest to us what became of the money."

David stared at him blankly.

"The money—was there—when Morton died!" said Dr. Thorn amazedly. He looked from one man to the other. Then understanding came into his face, and a great relief. "You mean—Mr. Aldrich—took it?"

"I took it!" David repeated stupidly.

He turned slowly to Helen. Her white face, with its wide eyes and parted lips, and the sudden look of fear she held upon him, cleared his head, made him see where he was.

"I did not take the money!" he cried.

"No, of course not," returned Mr. Haddon grimly. "But who did?"

"If I'd taken it, wouldn't I have disappeared? Would I have been such a fool as to have stayed here to be caught?"

"If the thief had run away, that would have fastened the guilt on him at once. To remain here, hoping to throw suspicion on Mr. Morton—this was the cleverest course."

"I did not take the money!" David cried desperately. "It's a lie!"

Helen moved to David's side, and gazed straight into Mr. Haddon's accusing face. Indignation was replacing her astoundment; her cheeks were tingeing with red.

"What, would you condemn a man upon mere guess-work!" she cried. "Merely because the money is not there, is that proof that Mr. Aldrich took it? Do you call this justice, Mr. Haddon?"

Mr. Haddon's look did not alter, and he did not reply. The opinion of womankind he had ever considered negligible.

Helen turned to David and gave him her hand. "I believe you."

He thanked her with a look.

"It must have been Mr. Morton," she said.

Her words first thrilled him. Then suddenly they rang out as a knell. If he threw off the guilt, it must fall on Morton; if Morton were publicly guilty, then the hundreds of the Mission—

Mr. Haddon's hard voice broke in, changeless belief in its tone: "Mr. Aldrich took it."

David looked at Mr. Haddon, looked whitely at Helen. And then the great Thought was conceived, struggled dizzily, painfully, into birth. He stood shivering, awed, before it....

He slowly turned and walked to a window and gazed down into the street, filled with children hurrying home from school. The Thought spoke to him in vivid flashes. He had no relatives, almost no friends. He loved Helen Chambers; but he was nobody and a beggar. He had not done anything—perhaps could never do anything—and even if he did, his work would probably be of little worth. He had wanted his life to be of service; had wanted to sell it, as it were, for the largest good he could perform. Well, here were the people of St. Christopher's toppling over the edge of destruction. Here was his Great Bargain—the chance to sell his life for the highest price.

As to what he had done with the five thousand, which of course he'd be asked—well, an evening of gambling would be a sufficient explanation.

He turned about.

"Well?" said Mr. Haddon.

David avoided Helen's look. He felt himself borne upward to the apex of life.

"Yes ... I took it," he said.

The history of the next four years of David's life is contained in the daily programme of Croton Prison. At six o'clock the rising gong sounded; David rolled out of his iron cot, washed himself at the faucet in his cell, and got into his striped trousers and striped jacket. At six-thirty he lock-stepped, with a long line of fellows, to a breakfast of hash, bread and coffee. At seven he marched to shoe factory or foundry, where he laboured till twelve, when the programme called him to dinner. At one he marched back to work; at half-past five he marched to his cell, where his supper of bread and coffee was thrust in to him through a wicket. He read or paced up and down till nine, when the going out of his light sent him into his iron cot. Multiply this by fifteen hundred and the product is David's prison life.

It would be untruth to say that a sense of the good he was doing sustained a passionate happiness in David through all these years. Moments of exaltation were rare; they were the sun-blooming peaks in an expanse of life that was otherwise low and gloom-hung. David had always understood that prisons in their object were not only punitive—they were reformative. But all his intelligence could not see any strong influence that tended to rouse and strengthen the inmates' better part. Occasional and perfunctory words from chaplains could not do it. Monotonous work, to which they were lock-stepped, from which they were lock-stepped, and which was directed and performed in the lock-step's deadening spirit, this could not do it. Constant silence, while eating, marching, working, could not do it. The removal for a week of a man's light because he had spoken to a neighbour, this could not do it. Nor could a day's or two days' confinement, on the charge of "shamming" when too ill to work, in an utterly black dungeon on a bit of bread and a few swallows of water.

Rather this routine, these rules, enforced unthinkingly, without sympathy, had an opposite energy. David felt himself being made unintelligent—being made hard, bitter, vindictive—felt himself being dehumanised. One day as he sat at dinner with a couple of hundred mates, silent, signalling for food with upraised fingers, a man and woman who were being escorted about the prison by the warden, came into the room. The woman studied for several minutes these first prisoners she had ever seen—then the dumb rows heard her exclaim: "Why look,—they're human!" To David the discovery was hardly less astonishing. He had been forgetting the fact.

Yes, moments of exaltation were rare. More frequent were the dark times when the callousness and stupidity of some of the regulations enraged him, when the weight of all the walls seemed to lie upon his chest—when he frantically felt he must have light and air, or die;—and he cursed his own foolishness, and would have traded the truth to the people of St. Christopher's for his freedom. Prometheus must often have repented his gift of fire. But the momentum of David's resolve carried him through these black stretches; and during his normal prison mood, which was the restless gloom of all caged animals, his mind was in control and held him to his bargain.

But always there was with him a great fear. Was Morton's memory retaining its potency over the people of St. Christopher's? Were they striving to hold to their old ideals, or were they gradually loosening their grip and slipping back into the old easy ways of improvidence and dissipation? Perhaps, even now, they were entirely back, and his four years had paid for nothing. The long day carrying the liquid iron to the moulds would have been easier, the long night in the black cell would have been calmer, had he had assurance that his sacrifice was fulfilling its aim. But never a word came from St. Christopher's through those heavy walls.

And always he thought of Helen Chambers. He could never forget the stare of her white face when he had acknowledged his guilt, how she had first tried to speak, then turned slowly and walked away. The four walls of his mind were hung with that picture; wherever he turned, he saw it. He had wanted to spring after her and whisper his innocence, but there had flashed up a realisation that his plan was feasible only with a perfect secrecy, and to admit one person to his confidence might be to admit the world. Besides, she might not believe him. So, silent, he had let her walk from the room with his guilt.

He often wondered if she ever thought of him. If she did, it was doubtless only to despise him. More likely, he had passed from her mind. Perhaps she was married. That thought wrung him. He tried to still the heavy pain by looking at the impassable gulf that lay between them, and by telling himself it was natural and fitting that she should have married. He wondered what her husband was like, and if she were happy. But the walls were mute.

Long before his release he had decided he should settle in New York. Life would be easiest, he knew, if he were to lose himself in a new part of the world. But St. Christopher's, where four prison years and the balance of his dishonoured life were invested, was in New York; Helen Chambers was in New York. The rest of the world had no like attractions; it could hide him—that was all. But save at first while he was gaining a foothold—and could he not then lose himself among New York's millions?—he did not desire to hide himself.

He did not care to hide himself because the prison had given him a message, and this message he intended speaking publicly. He had pondered long over society's treatment of the man who breaks its law. That treatment seemed to him absurd, illogical. It would have been laughably grotesque in its deforming incompetence had it not been directed at human beings. It was a treatment bounded on one side by negligence, on the other by severity. It maimed souls, killed souls; it was criminal. David's sense of justice and humanity demanded that he should protest against this great criminal—our prison system. He knew it as prison reformers did not—from the inside. He could speak from his heart. And as soon as he had gained a foothold, he would begin.

At length came the day of his liberation, and he found himself back in New York, twenty dollars, his prison savings, in his pocket, the exhaustion of prison life in his flesh, and in his heart a determination to conquer the world. He knew but one part of New York—the neighbourhood of St. Christopher's Mission—and that part drew him because of his interest in it, and also because he must live cheaply and there life was on a cheap scale. He hesitated to settle in the immediate neighbourhood; but he could settle just without its edge, where he could look on, and perhaps pass unnoticed. He at length found a room on the fifth floor of a dingy tenement, seven or eight blocks from the Mission. The room had a chair, a bed, a promise of weekly change of sheets, and a backyard view composed of clothes-lines, bannered with the block's underwear, and the rear of a solid row of dreary tenements. Five years before the room would have been unbearable; now it was luxury, for it was Freedom.

After paying the first month's rent of five dollars and buying a few dishes, a little gas stove and a small supply of groceries, he had nine dollars left with which to face the world and make it give him place. If he spent twenty cents a day for food, and spent not a cent for other purposes, he could eat for six weeks. But before then rent would again be due. Four weeks he could stand out, no longer; by then he must have won a foothold.

Well, he would do it.

By the time he had made a cupboard out of the soap-box the grocer had given him and had set his room in order, dusk was falling into the gulch-like backyard and the opposite wall was springing into light at a hundred windows. He ate a dinner from his slender store, using his bed as a chair and his chair as a table, and after its signs were cleared away he sat down and gazed across the court into the privacy of five strata of homes. He saw, framed by the windows, collarless men and bare-armed women sitting with their children at table; the odours of a hundred different dinners, entangled into one odour, filled his nostrils; family talk, and the rumble and clatter of the always-crowded streets, came to his ears as a composite murmuring that was an inarticulate summary of life.

But none of these impressions reached his mind; that had slipped away to Helen Chambers. The question that had asked itself ten thousand times repeated itself again: was she married? He tried to tell himself quietly that it was none of his affair, could make no difference to him—but the suspense of four years was not to be strangled by self-restraint. The desire to know the truth, to see her if he could, mounted to an impulse there was no withstanding.

And another oft-asked question also came to him. Was the Mission still a power for good? And this also roused an uncontrollable desire to know the truth. He left his room and set out for St. Christopher's, wondering if he would be recognised. But, though often Morton's guest, he had mixed but little in the affairs of the Mission, and not many from the hard-working neighbourhood had been able to attend his brief trial; so he was known by sight to few, and no one now gave him a second look.

As he came into the old streets, with here and there a little shop that had been owned by one of Morton's followers, and here and there among the passers-by a face that was vaguely familiar, his suspense grew and grew—till, when St. Christopher's loomed before him, it seemed his suspense would almost choke him. He paused across the street in the shadow of a tenement entrance, and stared over at the club-house and at the chapel with its spire rising into the rain-presaging night. Light streamed from the open door of the chapel; on the club-house window-sills were the indistinct shapes of flower-boxes; boys and girls, young men and women, parents, were entering the club-house. Everything seemed just the same. But were the people the same? Had his four years been squandered—or spent to glorious purpose?

He slipped across the street and looked cautiously into the chapel. There were the three rows of pews, the plain pulpit bearing an open Bible, behind which Morton used to preach, the organ at which a stooped girl, a shirt-waist maker, used to play the hymns and lead the congregation's singing—all just as in other days.

The chapel was empty, save the corner of a rear pew in which sat a troubled, poorly-dressed woman, and a gray-haired man whose clerical coat made David guess him to be Morton's successor. The voice of his advice was gentle and persuasive, and when the woman's rising to go revealed his shaven face, David saw that it had strength and kindness, spirit and humility—saw that the man's vigour remained despite his obvious sixty years.

David entered the chapel and approached the director of the Mission. The old man held out his hand. "I'm glad to see you," he said. "Is there anything in which I can serve you?"

David strove for a casual manner, but prison had made him too worn, too nervous, to act a part requiring so much control. "I was just—going by," he stammered, taking the hand. "I used to know the Mission—years ago—when Mr. Morton was here. So I came in."

"Ah, then you knew Mr. Morton!" said the director warmly.

"A—a little."

"Even to know him a little was a great privilege," he said with conviction, admiration. "He was a wonderful man!"

David braced himself for one of the two great questions of his last four years. "Does the neighbourhood still remember him?"

"Just as though he were still here," the director answered, with the enthusiasm an unjealous older brother may feel for the family genius.

"He has left an influence that amounts to a living, inspiring presence. That influence, more than anything I have done, has kept the people just as earnest for truer manhood and womanhood as when he left them. I feel that I am only the assistant. He is still the real head."

David got away as quickly as he could, a mighty, quivering warmth within him. On the other side of the street, he gave a parting glance over his shoulder at the chapel. He stopped short, and stared. While they had talked, the director of the Mission had turned on additional lights, among which had been an arc-light before the great stained-glass window at the street end of the chapel. The window was now a splendid glow of red and blue and purple, and printed upon its colours was this legend:

David stared at the window, weak, dizzy. There was a momentary pang of bitterness that Morton should be so honoured, and he be what he was. Then the glow that had possessed him in the chapel flowed back upon him in even greater warmth. The window seemed to David, in his then mood, to be the perpetuation in glowing colour of Morton's influence. It seemed to throw forth into the street, upon the chance passer-by, the inspiration of Morton's life.

Yes,—his four years had counted!

Half an hour later he took his stand against the shadowed stoop of an empty mansion in Madison Avenue, and gazed across at a great square three-story stone house, with a bulging conservatory running along its left side—the only residence in the block that had re-opened for the autumn. All thought of Morton and the Mission was gone from him. His mind was filled only with the other great fear of his last four years. If she came out of the door he watched, if he glimpsed her beneath a window shade, then probably she still belonged in her father's house—was still unmarried.

A cold drizzle had begun to fall. He drew his head down into his upturned collar, and though his weakened body shivered, he noticed neither the rain nor the protest of his flesh. His whole being was directed at the house across the way. Slow minute followed slow minute. The door did not open, and he saw no one inside the windows. His heart beat as though it would shake his body apart. The sum of four years suspense so weakened him that he could hardly stand. Yet he stood and waited, waited; and he realised more keenly than ever how dear she was to him—though to possess her was beyond his wildest dreams, and perhaps he might not even speak to her again.

At length a nearby steeple called the hour of ten. Presently a carriage began to turn in towards the opposite sidewalk. David, all a-tremble, his great suspense now at its climax, stepped forth from his shadow. The carriage stopped before the Chambers home. He hurried across the street, and a dozen paces away from the carriage he stooped and made pretense of tying his shoe-lace; but all the while his eyes were on the carriage door, which the footman had thrown open. First a man stepped forth, back to David, and raised an umbrella. Who? The next instant David caught the profile. It was Mr. Chambers. After him came an ample, middle-aged woman, brilliantly attired—Mrs. Bosworth, Mr. Chambers's widowed sister, who had been living with him since his wife's death.

A moment later Mr. Chambers was helping a second woman from the carriage. The umbrella cut her face from David's gaze, but there was no mistaking her. So she still lived in the house of her father!

She paused an instant to speak to the footman. For a second a new fear lived in David: might she not come with her father to her father's house, and still be married? But at the second's end the fear was destroyed by the conventional three-word response of the footman. David watched her go up the steps, her face hidden by the umbrella, watched her enter and the door close behind her. Then, collapsed by the vast relief which followed upon his vast suspense, he sank down upon the stoop, and the three words of the footman maintained a thrilling iteration in his ears.

The three words were: "Thank you, Miss."