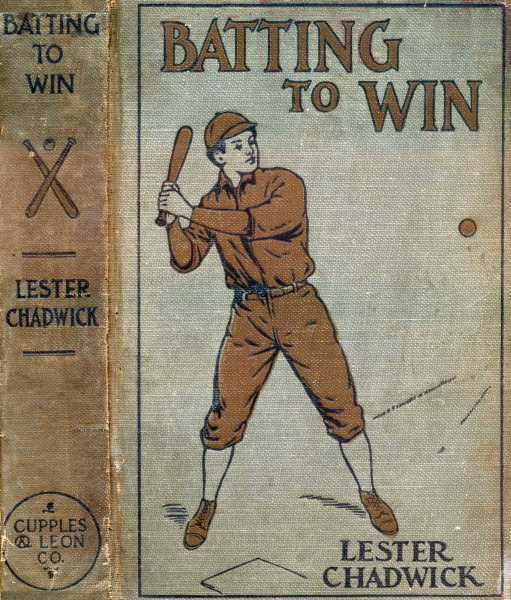

Title: Batting to Win: A Story of College Baseball

Author: Lester Chadwick

Release date: October 28, 2012 [eBook #41206]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A Story of College Baseball

BY

AUTHOR OF “THE RIVAL PITCHERS,” “A QUARTER-BACK’S PLUCK,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

BOOKS BY LESTER CHADWICK

THE COLLEGE SPORTS SERIES

12mo. Illustrated

THE RIVAL PITCHERS

A Story of College Baseball

A QUARTER-BACK’S PLUCK

A Story of College Football

BATTING TO WIN

A Story of College Baseball

(Other Volumes in preparation)

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY NEW YORK

Copyright, 1911, by

Cupples & Leon Company

Batting to Win

Printed in U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | A Strange Message | 1 |

| II | Sid Is Caught | 16 |

| III | Miss Mabel Harrison | 27 |

| IV | Electing a Manager | 41 |

| V | Randall Against Boxer | 59 |

| VI | The Accusation | 75 |

| VII | Getting Back at “Pitchfork” | 84 |

| VIII | The Envelope | 92 |

| IX | A Clash | 100 |

| X | Sid Is Spiked | 105 |

| XI | A Joke on the Proctor | 114 |

| XII | Planning a Picnic | 122 |

| XIII | A Sporty Companion | 131 |

| XIV | “Mind Your Own Business!” | 140 |

| XV | An Unexpected Defense | 146 |

| XVI | A Serious Charge | 152 |

| XVII | Sid Keeps Silent | 157 |

| XVIII | Bascome Gives a Dinner | 163 |

| XIX | Fairview and Randall | 170 |

| XX | Randall Scores First | 176 |

| XXI | Randall in the Tenth | 183 |

| XXII | Sid Despairs | 195 |

| XXIII | Financial Difficulties | 202 |

| XXIV | Pitchfork’s Tall Hat | 209 |

| XXV | A Petition | 219 |

| XXVI | Tom Stops a Hot One | 226 |

| XXVII | Gloomy Days | 233 |

| XXVIII | A Freshman Plot | 239 |

| XXIX | The Sophomore Dinner | 246 |

| XXX | Tom’s Last Appeal | 255 |

| XXXI | The Ban Lifted | 265 |

| XXXII | A Perilous Crossing | 275 |

| XXXIII | The Championship Game | 284 |

| XXXIV | Batting to Win | 295 |

| HE SLAMMED IT OUT FOR A THREE-BASE HIT. |

| “MR. ZANE WOULD LIKE TO SEE YOU, MR. HENDERSON.” |

| HE LEAPED INTO THE AIR AND WITH HIS BARE HAND CAUGHT THE HORSEHIDE. |

| “BAT TO WIN! IT ALL DEPENDS ON YOU!” |

Sid Henderson arose from the depths of an antiquated easy chair, not without some effort, for the operation caused the piece of furniture to creak and groan, while from the thick cushions a cloud of dust arose, making a sort of haze about the student lamp, and forcing two other occupants of the college room to sneeze.

“Oh, I say, Sid!” expostulated Tom Parsons, “give a fellow notice, will you, when you’re going to liberate a colony of sneeze germs. I—er—ah! kerchoo! Hoo! Boo!” and he made a dive for his pocket handkerchief.

“Yes,” added Phil Clinton, as he coughed protestingly. “What do you want to get up for and disturb everything, when Tom and I were so nice and quiet? Why can’t you sit still and enjoy a good think once in a while? Besides, do you want to give that chair spinal meningitis or lumbago?[2] Our old armchair, that has stuck to us, through thick and thin, for better and for worse—mostly worse, I guess. I say——”

“I came near sticking to it, myself,” remarked Sidney Henderson, otherwise known as, and called, Sid. “It’s like getting out of the middle of a featherbed to leave it. And say, it does act as if it was going to pieces every time one gets in or out of it,” he added, making a critical inspection of the chair.

“Then why do you want to get in or out?” asked Phil, closing a book, over which he had made a pretense of studying. “Why do you do it, I ask? You may consider that I have moved the previous question, and answer,” he went on. “How about it, Tom?”

“The gentleman is out of order,” decided Tom, a tall, good-looking lad, with the bronzed skin of an athlete, summer and fall, barely dimmed by the enforced idleness of winter. “Sid, you are most decidedly out of order—I think I’m going to sneeze again,” and he held up a protesting hand. “No, I’m not, either,” he continued. “False alarm. My, what a lot of dust! But, go ahead, Sid, answer the gentleman’s query.”

“Gentleman?” repeated the lad, who had arisen from the easy chair, and there was a questioning note in his voice.

“Here! Here! Save that for the amateur[3] theatricals!” cautioned Tom, looking about for something to throw at his chum. “Why did you get up? Answer!”

“I wanted to see if it had stopped raining,” announced Sid, as he moved over toward one of the two windows in the rather small living room and study, occupied by the three chums, who were completing their sophomore year at Randall College. “Seems to me it’s slacking up some.”

“Slacking up some!” exclaimed Tom.

“Stopped raining!” echoed Phil. “Listen to it! Cats and dogs, to say nothing of little puppies, aren’t in it. It’s a regular deluge. Listen to it!”

He held up his hand. Above the fussy ticking of a small alarm clock, which seemed to contain a six-cylindered voice in a one-cylindered body, and which timepiece was resting at a dangerous angle on a pile of books, there sounded the patter of rain on the windows and the tin gutter outside.

“Rain, rain, nothing but rain!” grumbled Phil. “We haven’t had a decent day for baseball practice in two weeks. I’m sick of the inside cage, and the smell of tan bark. I want to get into the open, with the green grass of the outfield to fall on.”

“Well, this weather is good for making the grass grow,” observed Tom, as he got up from his chair, and joined Sid at the window, down[4] which rain drops were chasing each other as if in glee at the anguish of mind they were causing the three youths.

“Aren’t you anxious to begin twirling the horsehide?” asked Sid. “I should think you’d lose some speed, having only the cage to practice in, Tom.”

“I am, but I guess we’ll get some decent weather soon. This can’t last forever.”

“It’s in a fair way to,” grumbled Phil.

“It would be a nice night if it didn’t rain,” came from Sid musingly, as he turned back to the old easy chair, “which remark,” he added, “is one a little boy made in the midst of a driving storm, when he met his Sunday-school teacher, and wanted to say something, but didn’t know what.”

“Your apology is accepted,” murmured Tom. “I don’t know what you fellows are going to do, but I’m going to sew up a rip in my pitcher’s glove. I think maybe if I do the weather man will get a hunch on himself, and hand us out a sample of a nice day for us to select from.”

“Nice nothing!” was what Phil growled, but with the activity of Tom in getting out his glove, and searching for needle and thread, there came a change of atmosphere in the room. The rain came down as insistently, and the wind lashed[5] the drops against the panes, but there was an air of relief among the chums.

“I’ve got to fix a rip in my own glove,” murmured Sid. “Guess I might as well get at it,” and he noted Tom threading a needle.

“And I’ve got to do a little more boning on this trigonometry,” added Phil, as, with a sigh, he opened the despised book.

For a time there was silence in the apartment, while the rain on the windows played a tattoo, more or less gentle, as the wind whipped the drops; the timepiece fussed away, as if reminding its hearers that time and tide waited for no man, and that 99-cent alarm clocks were especially exacting in the matter. Occasionally Sid shifted his position in the big chair, to which he had returned, each movement bringing out a cloud of dust, and protests from his chums.

The room was typical of the three lads who occupied it. At the beginning of their friendship, and their joint occupation of a study, they had agreed that each was to be allowed one side of the apartment to decorate as he saw fit. The fourth side of this particular room was broken by two windows, and not of much use, while one of the other walls contained the door, and this one Sid had chosen, for the simple reason that his fancy did not run to such things as did Tom’s[6] and Phil’s, and he required less space for his ornaments.

Sid was rather an odd character, somewhat quiet, much given to study, and to delving after the odd and unusual. One of his fads was biology, and another, allied to it, nature study. He would tramp all day for a sight of some comparatively rare bird, nesting; or walk many miles to get a picture of a fox, or a ground-hog, just as it darted into its burrow. In consequence Sid’s taste did not run to gay flags and banners of the college colors, worked by the fair hands of pretty girls, nor did he care to collect the pictures of the aforesaid girls, and stick them up on his wall. He had one print which he prized, a representation of a football scrimmage, and this occupied the place of honor.

As for Tom and Phil, the more adornments they had the better they liked it, though I must do them the credit to say that they only had one place of honor for one girl’s photograph at a time. But they sometimes changed girls. Then, on their side, were more or less fancy pictures—scenes, mottoes, and what not. Much of the ornamentation had been given them by young lady friends.

Of course the old chair and an older sofa, together with the alarm clock, which had been handed down from student to student until the[7] mind of Randallites ran not to the contrary, were the chief other things in the apartment, aside from the occupants thereof. Each lad had a desk, and a bureau or chiffonier, or “Chauffeur” as Holly Cross used to dub them. These articles of furniture were more or less in confusion. Neckties, handkerchiefs, collars and cuffs were piled in a seemingly inextricable, if not artistic, confusion. Nor could much else be expected in a room where three chums made a habit of indiscriminately borrowing each other’s articles of wearing apparel, provided they came any where near fitting.

On the floor was a much worn rug, which Phil had bought at auction at an almost prohibitive price, under the delusion that it was a rare Oriental. Learning to the contrary he and his chums had decided to keep it, since, old and dirty as it was, they argued that it saved them the worriment of cleaning their feet when they came in.

Then there were three neat, white, iron beds—neat because they were made up fresh every day, and there was a dormitory rule against having them in disorder. Otherwise they would have suffered the fate of the walls, the rug or the couch and easy chair. Altogether it was a fairly typical student apartment, and it was occupied, as I hope my readers will believe, by three of the finest chaps it has been my lot to write about; and it is in[8] this room that my story opens, with the three lads busily engaged in one way or another.

“Oh, I say! Hang it all!” burst out Sid finally. “How in the mischief do you shove a needle through this leather, Tom? It won’t seem to go, for me.”

“You should use a thimble,” observed Tom. “Nothing like ’em, son.”

“Thimble!” cried Sid scornfully. “Do you take me for an old maid? Where did you ever learn to use a thimble?” and he walked over to where Tom was making an exceedingly neat job of mending his glove.

“Oh, I picked it up,” responded the pitcher of the Randall ’varsity nine. “Comes in handy when your foot goes through your socks.”

“Yes, and that’s what they do pretty frequently these days,” added Phil. “If you haven’t anything to do, Tom, I wish you’d get busy on some of my footwear. I just got a batch back from the laundry, and I’m blessed if out of the ten pairs of socks I can get one whole pair.”

“I’ll look ’em over,” promised the pitcher. “There, that’s as good as new; in fact better, for it fits my hand,” and he held up and gazed critically at the mended glove. “Where’s yours, Sid?” he went on. “I’ll mend it for you.”

Silence was the atmosphere of the apartment for a few minutes—that is comparative silence,[9] though the pushing of Tom’s needle through the leather, squeaking as he forced it, mingled with the ticking of the clock.

“I guess we can count on a good nine this year,” observed Tom judicially, apropos of the glove repairing.

“It’s up to you, cap,” remarked Sid, for Tom had been elected to that coveted honor.

“You mean it’s up to you fellows,” retorted the pitcher-captain. “I want some good batters, that’s what I want. It’s all right enough to have a team that can hold down Boxer Hall and Fairview Institute, but you can’t win games by shutting out the other fellows. Runs are what count, and to get runs you’ve got to bat to win.”

“Listen to the oracle!” mocked Phil, but with no malice in his voice. “You want to do better than three hundred with the stick, Sid.”

“Physician, heal thyself!” quoted Tom, smiling. “I think we will have a good——”

He was interrupted by the sound of footsteps coming along the corridor. Instinctively the three lads started, then, as a glance at the clock showed that they were not burning lights beyond the prescribed hour, there was a breath of relief.

“Who’s coming?” asked Tom.

“Woodhouse, Bricktop or some of the royal family,” was Phil’s opinion.

“No,” remarked Sid quietly, and there was[10] that in his voice which made his chums look curiously at him, for it seemed as if he expected some one. A moment later there came a rap on the door, and then, with a seeming knowledge of the nerve-racking effect this always has on college students, a voice added:

“I’m Wallops, the messenger. I have a note for Mr. Henderson.”

“For me?” and there was a startled query in Sid’s voice, as he went to the door.

Outside the portal stood a diminutive figure—Wallops—the college messenger, so christened in ages gone by—perhaps because of the chastisements inflicted on him. At any rate Wallops he was, and Wallops he remained.

“A message for me?” repeated Sid. “Where from?”

“Dunno. Feller brought it, and said it was for you,” and, handing the youth an envelope, the messenger departed.

Sid took out the note, and rapidly scanned it.

“See him blush!” exclaimed Phil. “Think of it, Tom, Sid Henderson, the old anchorite, the petrified misogynist, getting notes from a girl.”

“Yes,” added Tom. “Why don’t you sport her photograph, old man?” and he glanced at several pictures of pretty girls that adorned the sides of the room claimed by Phil and himself.

Sid did not answer. He read the note through[11] again, and then began to tear it into bits. The pieces he thrust into his pocket, but one fluttered, unnoticed, to the floor.

“I’ve got to go out, fellows,” he announced in a curiously quiet voice.

“Out—on a night like this?” cried Tom. “You’re crazy. Listen to the rain! It’s pouring.”

“I can’t help it,” was the answer, as the lad began delving among his things for a raincoat.

“You’re crazy!” burst out Phil. “Can’t you wait until to-morrow to see her, old sport? My, but you’ve got ’em bad for a fellow who wouldn’t look at a girl all winter!”

“It isn’t a girl,” and Sid’s voice was still oddly calm. “I’ve got to go, that’s all—don’t bother me—you chaps.”

There was such a sudden snap to the last words—something so different from Sid’s usual gentle manner—that Phil and Tom looked at each other in surprise. Then, as if realizing what he had said, Sid added:

“It’s something I can’t talk about—just yet. I’ve got to go—I promised—that’s all. I’ll be back soon—I guess.”

“How about Proc. Zane?” asked Tom, for the proctor of Randall College was very strict.

“I’ll have to chance it,” replied Sid. “I’ve got about two hours yet, before locking-up time, and[12] if I get caught—well my reputation’s pretty good,” and he laughed uneasily.

This was not the Sid that Tom and Phil—his closest chums—had known for the last three terms. It was a different Sid, and the note he received, and had so quickly destroyed, seemed to have worked the change in him. Slowly he drew on his raincoat and took up an umbrella. He paused a moment in the doorway. The rain was coming down harder than ever.

“So long,” said Sid, as he stepped into the corridor. He almost collided with another youth on the point of entering, and the newcomer exclaimed:

“Say, fellows! I’ve got great news! Baseball news! I know this is a rotten night to talk diamond conversation, but listen. There’s been a new trophy offered for the championship of the Tonoka Lake League! Just heard of it. Dr. Churchill told me. Some old geezer that did some endowing for the college years ago, had a spasm of virtue recently and is now taking an interest in sports. It’s a peach of a gold loving cup, and say——”

“Come on in, Holly,” invited Tom, “Holly” being about all that Holman Cross was ever called. “Come on in,” went on Tom, “and chew it all over for us. Say, it’s great! A gold loving[13] cup! We must lick the pants off Boxer and Fairview now!”

Holly started to enter the room, Phil and Tom reaching out and clasping his hands.

“Where are you bound for?” asked Holly, looking at Sid, attired in the raincoat.

“I’ve got to go out,” was the hesitating answer.

“Wait until you hear the news,” invited Holly. “It’s great! It will be the baseball sensation of the year, Sid.”

“No—no—sorry, but I’ve got to go. I’ll be back—soon—I guess. I’ve—I’ve got to go,” and breaking away from the detaining hand of Holly, the strangely-acting boy turned down the corridor, leaving his roommates, and the newcomer, to stare curiously after him.

“Whatever has gotten into old Sid?” inquired Holly.

“Search us,” answered Phil. “He got a note a little while ago; seemed quite put out about it, tore it up and then tore out, just as you saw.”

“A note, eh?” mused Holly, as he threw himself full length on a rickety old sofa, much patched fore and aft with retaining boards—a sofa that was a fit companion for the ancient chair. It creaked and groaned under the substantial bulk of Holly.

“Easy!” cautioned Phil. “Do you want to wreck our most cherished possession?”

“Anyone who can wreck this would be a wonder,” retorted Holly, as he looked over the edge, and saw the boards that had been nailed on to repair a bad fracture. “Hello!” he exclaimed a moment later, as he picked up from the floor a scrap of paper. “You fellows are getting most uncommon untidy. First you know Proc. Zane will have you up on the carpet. You should keep your scraps of paper picked up.”

“We didn’t put that there,” declared Tom. “That must be part of the note Sid tore up.”

Idly Holly turned the bit of paper over. It was blank on one side, but, at the sight of the reverse the athlete uttered a cry.

“I say, fellows, look here!” he said.

He held the paper scrap out for their inspection. It needed but a glance to see that it bore but one word, though there were pen tracings of parts of other words on the edges. But the word that stood plainly out was “trouble,” and it appeared to be the end of a sentence, for a period followed it.

“Trouble,” mused Holly.

“Trouble,” repeated Phil. “I wonder if that means Sid is going to get into trouble?” and his voice took a curious turn.

“Trouble,” added Tom, the last of the trio to[15] use the word. “Certainly something is up or Sid wouldn’t act the way he did. I wonder——”

“It isn’t any of our affair,” spoke Holly softly, “that is unless Sid wants our help, of course. I guess we shouldn’t have looked at this. It’s like reading another chap’s letters.”

“We couldn’t help it,” decided Phil. “Go ahead, Holly. Tell us about the trophy. Sid may be back soon.”

“All right, here goes,” and wiggling into a more comfortable position on the sofa, an operation fraught with much anxiety on the part of Phil and Tom, Holly launched into a description of the loving cup. But, unconsciously perhaps, he still held in his hand that scrap of paper—the paper with that one word on—“trouble.”

“It’s this way,” began Holly, as he crossed one leg over, and clasped his hands under his recumbent head. “Randall has been looking up in athletics lately. Since we did so well last season on the diamond, and won the championship at football, some of the old grads and men who have such ‘oodles’ of money that they don’t know what to do with it, have a kindlier feeling for the old college. It’s that which brought about the presentation of the loving cup trophy, or, rather the offer of it to the winner of the baseball championship of the Tonoka Lake League. The cup will be worth winning, so the doctor says.”

“How’d he come to tell you?” asked Phil.

“I happened to go to his study to consult him about some of my studies——” began Holly.

“Yes you did!” exclaimed Tom disbelievingly.

“You went there because Proc. Zane made you!” declared Phil.

“Well, no matter, if you can’t take a gentleman’s[17] word for it,” said Holly, with an assumed injured air. “Anyhow, I was in the doctor’s office, and he had just received a letter from some old grad, honorary degree man, offering the gold cup. Doc asked me if I thought the boys would like to play for it. Has to be won two out of three times before any college can keep it. I told him we’d play for it with bells on!”

“Of course!” agreed Tom and Phil.

“Now, about the team for this spring?” resumed Holly. “You’re captain, Tom, but we’ve got to elect a manager soon, and we’d better begin talking about it,” and then the trio launched into a rapid-fire talk on baseball and matters of the diamond.

The three youths were sophomores in Randall College, a well-known institution located near the town of Haddonfield, in one of our Middle Western States. The college proper was on the shore of Sunny River, not far from Lake Tonoka; and within comparative short distance of Randall were two other colleges. One was Boxer Hall, and the other Fairview Institute—the latter a co-educational institution. The three, together with some other near-by colleges and schools, formed what was called the Tonoka Lake Athletic League, and there were championship games of baseball, football, tennis, hockey, golf, and other forms of sport.

Those of you who have read the previous volumes of this “College Sports Series” need little if any introduction to the characters who have held the stage in my opening chapter. Others may care for a formal introduction, which I am happy to give them.

In the first book, called “The Rival Pitchers,” there was told of the efforts Tom Parsons made to gain the place as “twirler” on the ’varsity nine. Tom was a farmer’s son, in moderate circumstances, and had come to Randall from Northville. Almost at once he got into conflict with Fred Langridge, a rich student, who was manager of the ’varsity ball nine, and also its pitcher, and who resented Tom’s efforts to “make” the nine. After much snubbing on the part of Langridge, and not a few unpleasant experiences Tom got his chance. Eventually he supplanted Langridge, who would not train properly, and who smoked, drank and gambled, thinking himself a “sport.”

Tom soon became one of the most liked of the sporting crowd, and the especial friend of Phil Clinton and Sidney Henderson, with whom he had roomed for the last term. The three were now called the “inseparables.” In the first book several thrilling games were told of, also how Randall won the championship after a hard struggle with Boxer and Fairview, in which[19] games Tom Parsons fairly “pitched his head off,” to quote Holly Cross, who was an expert on diamond slang. Langridge did his best to injure Tom, and nearly succeeded, but the pitcher had many friends, besides his two special chums, among them being Holly Cross, Bricktop Molloy, Billy or “Dutch” Housenlager, who was full of horseplay, “Snail” Looper, so called from his ability to move with exceeding slowness, and his liking for night prowlings.

Then there was Pete Backus, known as “Grasshopper,” from his desire, but inability, to shine as a high and broad distance jumper; “Bean” Perkins, a “shouter” much depended on in games, when he led the cheering; Dan Woodhouse, called Kindlings, and Jerry and Joe Jackson, known as the “Jersey Twins.”

Of course, Tom and his two chums had many other friends whom you will meet from time to time. Sufficient to say that he “made good” in the eyes of the coach, Mr. Leighton, and was booked not only to pitch on the ’varsity again, but he had been elected captain, just before the present story opens.

Phil Clinton was the hero of my second volume, a story of college football, entitled “A Quarter Back’s Pluck.” Phil was named for quarter back on the ’varsity eleven, but, for a time it looked as if he would be out of the most[20] important games. His mother was very ill in Florida, in danger of death from a delicate operation, and Phil, and his sister Ruth Clinton (who attended Fairview Institute) were under a great nervous strain.

Langridge, seeing that Tom was beyond his vengeance, tried his tricks on Phil. Together with Garvey Gerhart, a freshman, Langridge planned to keep Phil out of an important game. They “doctored” a bottle of liniment he used, but this trick failed. Then they planned to send him, just before an important contest, a telegram, stating that his mother was dying. They figured that he would not play and that Randall would lose the contest—both Gerhart and Langridge being willing to thus play the traitor to be revenged on the coach and captain of the eleven.

But, with characteristic pluck, Phil went into the game, stuffing the fake telegram in his pocket, and playing like a Trojan, even though he believed his mother was dying. It was pluck personified. After aiding his fellows to win the championship, Phil hurried off the field, to go to Florida to his mother. Then, for the first time, he learned that the message he had received was a “fake”—for his mother was on the road to recovery as stated in a telegram his sister Ruth had received.

Of course the trick Langridge and Gerhart played was found out, and they both left Randall[21] quietly, so that the name of the college might not be disgraced.

But though Tom, Phil, Sid and their chums lived a strenuous life when sports were in the ascendency, that does not mean that they had no time for the lighter side of life. There were girls at Fairview—pretty girls and many of them. One, in particular—Madge Tyler—seemed to fit Tom’s fancy, and he and she grew to be very friendly. Perhaps that was because Tom had rather supplanted Langridge in the eyes of Miss Tyler, who had been to many affairs with him, before she knew his true character. Then there was Ruth Clinton, Phil’s sister. After meeting her Tom was rather wavering in his attachment toward Miss Tyler, but matters straightened themselves out, for Phil and Miss Tyler seemed to “hit it off,” to once more quote Holly Cross, though for a time there was a little coldness between Tom and Phil on this same girl question. When this story opens, however, Tom considered himself cheated if he did not see Ruth at least twice a week, and as for Phil, he and Miss Tyler—but there, I’m not going to be needlessly cruel.

To complete the description of life at Randall I might mention that Dr. Albertus Churchill, sometimes called “Moses,” was the venerable and well-beloved head of the institution, and that as much as he was revered so much was Mr. Andrew[22] Zane, the proctor, disliked; for, be it known, the proctor did not always take fair advantage of the youths, and he was fond of having them “upon the carpet,” or, in other words, before Dr. Churchill for admonition about certain infractions of the rules. Another character, little liked, was Professor Emerson Tines, dubbed “pitchfork,” by his enemies, and they were legion.

I believe that is all—no, to give you a complete picture of life at Randall I must mention that Sidney Henderson, the third member of the “inseparables” was a woman hater—a misogynist—an anchorite—a dub—almost anything along that line that his chums could think to call him. He abhorred young ladies—or he thought he did—and he and Tom and Phil were continually at variance on this question, and that of having girls’ photographs in the common study. But of that more later.

With Holly stretched out on the old sofa, and Phil and Tom in various tangled attitudes in chairs—Phil in the depths of the ancient one—the talk of baseball progressed.

“Yes, we must have an election for manager soon,” conceded Tom. “But first I want to see what sort of a team I’m going to have. We need outdoor practice, but if this rotten weather keeps up——”

“Hark! I think I hear the rain stopping,” exclaimed Phil.

“Stop nothing,” declared Holly. “It’s only catching its breath for another deluge.” And it did seem so, for, presently, there came a louder patter than ever, of drops on the tin gutter.

“Well, guess I’d better be moving,” announced Holly, after another spasm of talk. “What time is it by your town clock, anyhow?” and he shied a book at the alarm timepiece so that the face of it would be slewed around in his direction, giving him a peep at it without obliging him to get up.

“Here! What are you trying to do?” demanded Tom. “Do you want to break the works, and stop it?”

“Impossible, my dear boy,” said Holly lazily. “Just turn it around for me, will you, like a good fellow. I don’t see how I missed it. I must practice throwing, or I won’t be any good when the ball season opens. Give me another shot?” and he raised a second volume.

“Quit!” cried Tom, interposing his arm in front of the fussy little clock.

“That calls us to our morning duties,” added Phil, adding in a sing-song voice: “Oh, vandal, spare that clock, touch not a single hand, for surely it doth keep the time the worst in all the land.”

“Fierce,” announced Holly, closing his eyes and pretending to breathe hard. “It tells you how much longer you can sleep in the morning, I guess you mean,” he went on. “The three of you were late for chapel this a. m.”

“That’s because Sid monkeyed with the regulator,” insisted Tom. “He thought he could improve it. But, say, it is getting late. Nearly ten.”

“And Sid isn’t back yet,” went on Phil.

“My bedtime, anyhow,” came from Holly, as he slid from the sofa, and glided from the room. “So long. Sid wants to look out or he’ll be caught. Proc. Zane has a new book, and he wants to get some of the sporting crowd down in it. See you in the dewy morn, gents,” and he was gone.

“Sid is late,” murmured Tom, as he began to prepare for bed. “Shall we leave a light for him?”

“Nope. Too risky,” decided Phil. “No use of us all being hauled up. But maybe he’s back, and is in some of the rooms. He’s got ten minutes yet.”

But the ten minutes passed, and ten more, and Sid did not come back. Meanwhile Tom and Phil had “doused their glim,” and were in bed, but not asleep. Somehow there was an uneasy[25] feeling worrying them both. They could not understand Sid’s action in going off so suddenly, and so mysteriously—especially as there was a danger of being caught out after hours. And, as Sid was working for honors, to be caught too often meant the danger of losing that for which he had worked so hard.

“I can’t understand——” began Tom, in a low voice, when from the chapel clock, the hour of eleven boomed out.

“Hush!” exclaimed Phil.

Some one was coming along the corridor—two persons to judge by the footsteps.

“Is that Sid?” whispered Tom.

Phil did not answer. A moment later the door opened, and in the light that streamed from a lamp in the corridor, Sid could be seen entering. Behind him stood Proctor Zane.

“You will report to Dr. Churchill directly after chapel in the morning,” the proctor said, in his hard, cold voice. “You were out an hour after closing time, Mr. Henderson.”

“Very well, sir,” answered Sid quietly, as he closed the door, and listened to Mr. Zane walking down the corridor.

“Caught?” asked Tom, though there was no need of the query.

“Sure,” replied Sid shortly.

“Where were you?” asked Phil, sitting up in bed, and trying to peer through the darkness toward his unfortunate chum.

“Out,” was the answer, which was none at all.

“Humph!” grunted Tom. Then, suddenly: “You must have been hitting it up, Sid. I thought you didn’t smoke. Been trying it for the first time?”

“I haven’t been smoking!” came the answer, in evident surprise.

“Your clothes smell as if you’d been at the smoker of the Gamma Sig fraternity,” declared Tom.

“Oh, shut up, and let a fellow alone; can’t you?” burst out Sid, and he threw his shoes savagely into the corner of the room. Neither Tom nor Phil replied, but they were doing a great deal of thinking. They could not fathom Sid’s manner—he had never acted that way before. What could be the matter? It was some time before they learned Sid’s secret, and the keeping of it involved Sid in no small difficulties, and nearly cost the college the baseball championship.

Neither Tom nor Phil made any reference, the following morning, to the incident of the night before. As usual, none of the boys got up when the warning of the alarm clock summoned them, for they always allowed half an hour for its persistent habit of running fast. As it was, it happened to be correct on this occasion, and they were barely in time for chapel, Tom having to adjust his necktie on the race across the campus.

“Well, what’s on for to-day?” asked Phil, as, with Tom and Sid, he strolled from the chapel after service.

“Baseball practice this afternoon,” decided Tom, for the rain had stopped.

“It’ll be pretty sloppy,” observed Phil dubiously.

“Wear rubbers,” advised the captain. “The fellows need some fresh air, and they’re going to get it. Be on hand, Sid?”

“Sure. Now I’ve got to get a disagreeable job over with. Me for the doctor’s office,” and that was his only reference to the punishment meted out to him. He was required to do the usual number of lines of Latin prose, which was not hard for him, as he was a good scholar. Tom and Sid went to their lectures, the captain, on the way, calling to the various members of the team to be on hand at the diamond in the afternoon.

Sid accomplished his sentence of punishment in the room, and after dinner the three chums, with a motley crowd of players, and lovers of the great game, moved over the campus toward the diamond.

“Done anything about a manager?” asked Holly Cross, as he tightened his belt and began tossing up a grass-stained ball.

“Not yet,” replied Tom. “There’s time enough. I want to get the fellows in some kind of shape. We won’t play a game for a month yet—that is any except practice ones, and we don’t need a manager to arrange for them. Whom have you fellows in mind?”

“Ed Kerr,” spoke Holly promptly. “He knows the game from A to Z.”

“I thought he was going to play,” came quickly from Tom. “We need him on the nine.”

“He isn’t going to play this season,” went on[29] Holly. “I heard him say so. He wants to save himself for football, and he says he can’t risk going in for both. He’d make a good manager.”

“Fine!” agreed Tom, Sid and Phil.

“Yes, but did you hear the latest?” asked Snail Looper, gliding along, almost like the reptile he was christened after.

“What?” demanded several.

“There’s talk of Ford Fenton for manager,” went on Snail.

“What, Ford!” cried Tom. “He’d be giving us nothing all the while but ‘my uncle says this’ and ‘my uncle used to do it that way’! No Ford for mine, though I like the chap fairly well.”

“Same here,” agreed Phil. “We can stand him, but not his uncle,” for, be it known, Ford Fenton, one of the sophomore students, was the nephew of a man who had been a celebrated coach at Randall in the years gone by. Ford believed in keeping his memory green, and on every possible, and some impossible, occasions he would preface his remarks with “My Uncle says” and then go on and tell something. It got on the nerves of his fellows, and they “rigged” him unmercifully about it, but Fenton could not seem to take the hint. His uncle was a source of pride to him, but it is doubtful if the former coach knew how his reputation suffered at the hands of his indiscrete youthful relative.

“Who told you Fenton had a chance for manager?” asked Sid Henderson.

“Why, Bert Bascome is his press agent.”

“Bascome, the freshman?” Phil wanted to know, and Snail Looper nodded.

“Guess he didn’t get all the hazing that was coming to him last fall,” remarked Tom. “We’ll have to tackle him again. Kerr is the only logical candidate for manager, if he isn’t going to play.”

“That’s right,” came in a chorus, as the lads kept on toward the diamond.

Tom was doing some hard thinking. It was a new responsibility for him—to run the team—and he wanted a manager on whom he could depend. If there was a contest over the place, as seemed likely from what Snail Looper had said, it would mean perhaps a dividing of interests, and lack of support for the team. He did not like the prospect, but he knew better than to tell his worries to the players now. At present he wanted to get them into some kind of shape, after a winter of comparative idleness.

“Here comes Mr. Leighton,” observed Phil, as a young, and pleasant-faced gentleman was seen strolling toward the diamond. “Everybody work hard now—no sloppy work.”

“That’s right,” assented Tom. “Fellows, what I want most to bring out this season,” he[31] went on, “is some good hitting. Good batting wins games, other things being equal. We’ve got to bat to win.”

“You needn’t talk,” put in Dutch Housenlager, coming up then, and, with his usual horse play trying to trip Tom. “You are the worst hitter on the team.”

“I know it,” admitted Tom good naturedly, as he gave Dutch a welt on the chest, which made that worthy gasp. “My strong point isn’t batting, and I know it. I can pitch a little, perhaps——”

“You’re there with the goods when it comes to twirling,” called out Holly Cross.

“Well, then, I’m going to depend on you fellows for the stick work,” went on Tom. “But let’s get down to business. The ground isn’t so wet.”

“Well, boys, let’s see what we can do,” proposed the coach, and presently balls were being pitched and batted to and fro, grounders were being picked up by Bricktop Molloy, who excelled in his position of shortstop, while Jerry and Joe Jackson, the Jersey twins, with Phil Clinton, who on this occasion filled, respectively, the positions of right, left and center field were catching high flies.

“Now for a practice game,” proposed Tom. “I want to see if I have any of my curves left.”

Two scrub nines were soon picked out, and a game was gotten under way. It was “ragged and sloppy” as Holly Cross said, but it served to warm up the lads, and to bring out strong and weak points, which was the object sought.

The team, of which Tom was just then the temporary captain, won by a small margin, and then followed some coaching instructions from Mr. Leighton.

“That will do for to-day,” he said. “Be at it again to-morrow, and we’ll soon be in shape.”

The players and their admirers—lads who had not made the team—strolled off the diamond. Tom, walking along with Phil and Sid, suddenly put his hand in his pocket.

“Just my luck!” he exclaimed.

“What’s the matter?” asked Phil.

“I’m broke,” was the answer, “and I want to get a new shirt. Phil, lend me a couple of dollars. I’ll get my check from dad to-morrow.”

“I’m in the same boat, old man,” was the rueful reply. “Tackle Sid here, I saw him with a bunch of money yesterday. He can’t have spent it all since, for he isn’t in love.”

“Just the thing,” assented Tom. “Fork over a couple of bones, Sid. I’ll let you have it directly.”

“I—er—I’m sorry,” fairly stammered the second baseman, for that was the position Tom[33] had picked out for his chum, “I haven’t but fifty cents until I get my allowance, or until——” and he stopped suddenly.

“Wow!” cried Phil. “You must have slathered it away last night then, when you were out, for I saw you with a bundle——”

Then he stopped, for he saw a queer look come over Sid’s face. The second baseman blushed, and was about to make reply, when Phil remarked:

“I beg your pardon, Sid. I hadn’t any right to make that crack. Of course I—er—you understand—er—I——”

“That’s all right,” said Sid quickly. “I was a little flush yesterday, but I had a sudden demand on me, Tom, and——”

“Don’t mention it!” interrupted Tom. “I dare say I can get trusted at Ballman’s for a shirt. I’m going out to-night, or I wouldn’t need a clean one, and my duds haven’t come back from the laundry.”

“I didn’t know my sister was going out to-night,” fired Phil, for Tom had been rather “rushing” Ruth Clinton of late, “rushing” being the college term for accompanying a young lady to functions.

“I guess she doesn’t have to ask you,” retorted the captain. “But I understood you and Miss Tyler——”

“Speak of trolley cars, and you’ll hear the gong,” put in Sid suddenly. “I believe your two affinities are now approaching.”

“By Jove, he’s right!” exclaimed Phil, looking across the green campus. “There’s Ruth, and Madge Tyler is with her. I didn’t know Ruth was coming over from Fairview.”

“And they’ve got a friend with them—there are three girls,” said Tom quickly. “Sid, you’re right in it. There’s one for you.”

“Not on your life!” cried the tall and good-looking second baseman. “I’ve got an important engagement,” and he would have fled had not Tom and Phil seized and held him, despite his struggles, until Miss Ruth Clinton, Miss Madge Tyler and the third young lady approached. Whereat, seeing that his struggle to escape was futile, as well as undignified, Sid gave it up.

“Hello, Ruth!” cried Phil good-naturedly to his sister, but his eyes sought those of Madge Tyler. “How’d you get here?”

“Trolley,” was the demure answer. “I’m going to the Phi Beta theatrical with Mr. Parsons to-night, and I thought I’d save him the trouble of coming for me. Madge and I are staying in Haddonfield with friends of Miss Harrison.”

“Good!” cried Tom, as he moved closer to Phil’s pretty sister, while, somehow, Phil and Madge seemed to drift together.

“Oh, I almost forgot, you don’t know Mabel, do you, boys?” asked Madge, with a merry laugh. “Miss Mabel Harrison. Mabel, allow me to present to you Tom Parsons, champion pitcher of the Randall ’varsity nine; Phil Clinton, who made such a good showing on the gridiron last year, he’s Ruth’s brother, you know, and——” she paused as she turned to Sid Henderson, who was moving about uncomfortably.

“Sid Henderson, the only and original misogynist of Randall college,” finished Tom, with a mischievous laugh. “He is the only one in captivity, but will eat from your hand.”

“I’ll fix you for that,” growled Sid in Tom’s ear, but the girls laughed, as did Phil and the captain, and the introductions were completed. Miss Harrison proved to be an exceptionally pretty and vivacious girl, a fit companion for Ruth and Madge. She was fond of sport, as she soon announced, and Phil and Tom warmed to her at once.

As might have been expected, Tom walked along with Ruth, Phil with Miss Tyler, and that left Sid nothing to do but to stroll at the side of Miss Harrison.

“So you play ball, too,” she began as an opener, looking at his uniform.

“Yes—er—that is I play at it, sometimes,” floundered Sid, conscious of a big green grass[36] stain on one leg, where he had fallen in reaching for a high fly.

“Isn’t it great!” went on the girl, her blue eyes flashing as she glanced up at Sid. Somehow the lad’s heart was beating strangely.

“It’s the only game—except football,” he conceded. “Do you play—I—er—I mean—of course——”

“Oh, I just love football!” she cried. “I hope our team wins the championship this year!”

“Your team?” and Sid was plainly puzzled.

“Well, I mean the boys of Fairview—I attend there you know.”

“I didn’t know it, but I’m glad to,” spoke Sid, wondering why he never before thought blue eyes pretty. “Do you live at the college?”

“Oh, yes; but you see I happened to come to Haddonfield to stay over night with relatives, and when I found Madge and Ruth were going to a little affair here to-night, I asked them to stay with me. It’s such a jaunt back to the college.”

“Indeed it is,” agreed Sid. “You and Miss Tyler and Miss Clinton are great friends, I judge,” he went on, wondering what his next sentence would be.

“Indeed we are. Aren’t they perfectly sweet girls?”

“Fine!” exclaimed Sid with such enthusiasm[37] that his companion looked at him in some surprise, her flashing eyes completing the work already begun by their first glance.

“I thought you didn’t care for—that is—was that true what Mr. Parsons accused you of?” Miss Harrison asked. “Is a misogynist a very savage creature?” she went on demurely.

“That’s all rot—I beg your pardon—they were rigging you—I—er—I mean—Oh, I say, Miss Harrison, are you going to the Phi Beta racket to-night—I mean the theatricals to-night?” and poor Sid floundered in deeper and deeper.

“No,” answered the girl, “I’m not going.”

“Why not?” asked Sid desperately.

“Because I haven’t been asked, I suppose,” and she laughed merrily.

“Then would you mind—that is—I have two tickets—but I didn’t expect to go. Now, if you would——”

“Oh, Mr. Henderson, don’t go on my account!”

“Oh, it isn’t on your account—I mean—that is—Oh, wouldn’t you like to go?” and he seemed in great distress.

“I should love to,” she almost whispered.

“Then will you—that is would you—er—that is——”

“Of course I will,” answered Mabel, taking pity on her companion’s embarrassment. “Won’t[38] it be lovely, with Madge and Ruth, and her brother and Mr. Parsons. We’ll be quite a party.”

“It’ll be immense!” declared Sid with great conviction. Thereafter he seemed to find it easier to keep the conversation going.

The little group came to the end of the campus. Phil, Tom, Madge and Ruth waited for Sid and Mabel.

“Well, we’ll see you girls to-night,” said Tom, for he and his chum were anxious to get to their room and “tog up.” Then he added: “It’s a pity Miss Harrison isn’t going. If I had thought——”

“Miss Harrison is going!” cried Sid with sudden energy.

“What?” cried Tom and Phil together. Then, realizing that it might embarrass the girl, Tom added:

“Fine! We’ll all go together. Come on, Sid, and get some of the outfield mud scraped away.”

The girls waved laughing farewells, and Sid, rather awkwardly, shook hands with Miss Harrison.

“What’s the matter, old chap?” asked Tom of him, when they were beyond hearing distance of the girls. “Are you afraid you’ll never see her again?”

“Shut up!” cried Sid.

“Wonders will never cease,” went on Phil. “To see our old misogynist being led along by a pretty girl! However did you get up the spunk to ask her to go to-night, sport?”

“Shut up!” cried Sid again. “Haven’t I got a right to?”

“Oh, of course!” agreed Tom quickly. “It’s a sign of regeneration, old man. I’m glad to see it! What color are her eyes?”

“Blue,” answered Sid promptly, before he thought.

“Ha! Ha!” laughed Phil and Tom.

“Did you get her photograph?” asked Tom, clinging to Phil, so strenuous was his mirth.

“Say, I’ll punch your head if you don’t quit!” threatened Sid, and then, as he saw Wallops, the messenger, coming toward him, with a letter, there came to Sid’s face a new look—one of fear, his chums thought.

He read the note quickly, and stuffed it into his pocket. Then he turned, and hastened after the three girls.

“Here, what’s up?” demanded Tom, for Sid had acted strangely.

“I can’t go to the theatricals to-night, after all,” was the surprising answer. “I must apologize to Miss Harrison. Will you take her, Tom?”

“Of course,” was the answer, and then, as Sid hastened to make his excuses to the girl who, but[40] a few minutes before, he had asked to accompany him, his two chums looked at each other, and shook their heads. The mystery about Sid was deepening.

Sidney Henderson fairly broke into a run in order to catch up to the three girls. They heard him coming, and turned around, while Tom and Phil, some distance off, were spectators of the scene.

“I say!” burst out poor Sid pantingly, as he came to a halt, “I’m awfully sorry, Miss Harrison, but—er—I can’t take you to the theatricals to-night, after all. I’ve just received bad news.”

“Bad news? Oh, I’m so sorry!” and the blue eyes of the pretty girl, that had been merry and dancing, as she chatted with Ruth and Madge, took on a tender glance.

“Oh, it isn’t that any one is sick, or—er—anything like that,” Sid hastened to add, for he saw that she had misunderstood him. “It’s just that I have received a message—I have got to go away—I—er—I can’t explain, but some one is in trouble, and I—I’m awfully sorry,” he blurted out, feeling that he was making a pretty bad[42] mess of it. “I’ve arranged for Tom Parsons to take you to the theatricals, Miss Harrison.”

“You’ve arranged for Mr. Parsons to take me?” There was no mistaking the anger in her tones. Her blue eyes seemed to flash, and she drew herself up proudly. Madge and Ruth, who had shown some pity and anxiety at Sid’s first words, looked at him curiously.

“Yes, Tom will be very glad to take you,” went on the unfortunate Sid.

“Thank you,” spoke Miss Harrison coldly. “I don’t believe I care to go to the theatricals after all. Come on, girls, or we will be late for tea,” and without another look at Sid she turned aside and walked on.

“Oh, but I say, you know!” burst out the second baseman. “I thought—that is—you see—I can’t possibly take you, as it is, and I thought——”

“It isn’t necessary for anyone to take me!” retorted Miss Harrison coldly. “It’s not at all important, I assure you. Good afternoon, Mr. Henderson,” and she swept away, leaving poor Sid staring after her with bewilderment in his eyes. It was his first attempt at an affair with a maiden, and it had ended most disastrously. He turned back to rejoin his chums.

“Well?” questioned Tom, as Sid came up. “Is[43] it all right? Am I to have the pleasure of two young ladies to-night?”

“No, it’s all wrong!” blurted out Sid. “I can’t understand girls!”

“That’s rich!” cried Phil. “Here you have been despising them all your life, and now, when you do make up to one, and something happens, you say you can’t understand them. No man can, old chap. Look at Tom and me, here, and we’ve had our share of affairs, haven’t we, old sport.”

“Speak for yourself,” replied the pitcher. “But what’s the row, Sid?”

“Hanged if I know. I told her I couldn’t possibly go to-night——”

“Did you tell her why?” interrupted Phil.

“Well, I said I had received word that I had to go away, and—er—well I can’t explain that part of it even to you fellows. I’ve got to go away for a short time, that’s all. It’s fearfully important, of course, or I wouldn’t break a date with a girl. I can’t explain, except that I have to go. I tried to tell her that; and then I said I’d arranged with you to take her, Tom.”

“You what?” cried the amazed pitcher.

“I told her I was going to have you take her.”

“Without asking her whether it would be agreeable to her?”

“Of course. I didn’t suppose that was necessary, as you and Miss Clinton and Miss Tyler were all going together. I just told her you’d take her.”

“Well, of all the chumps!” burst out Phil.

“A double-barreled one!” added Tom.

“Why—what’s wrong?” asked Sid wonderingly.

“Everything,” explained Phil. “You ask a pretty girl—and by the way, Sid, I congratulate you on your choice, for she is decidedly fine looking—but, as I say, you ask a pretty girl to go to some doings, and when you find you can’t go, which is all right, of course, for that often happens, why then, I say, you coolly tell her you have arranged for her escort. You don’t give her a chance to have a word to say in the matter. Why, man alive, it’s just as if you were her guardian, or grandfather, or something like that. A girl likes to have a voice in these matters, you know. My, my, Sid! but you have put your foot in it. You should have gently, very gently, suggested that Tom here would be glad to take her. Instead, you act as though she had to accept your choice. Oh, you doggoned old misogynist, I’m afraid you’re hopeless!”

“Do you suppose she’ll be mad?” asked Sid falteringly.

“Mad? She’ll never speak to you again,” declared[45] Tom, with a carefully-guarded wink at Phil.

“Well, I can’t help it,” spoke Sid mournfully. “I’ve just got to go away, that’s all,” and he hastened on in advance of his companions.

“Don’t stay out too late, and get caught by Proc. Zane again,” cautioned Phil, but Sid did not answer.

Tom and Phil lingered in the gymnasium, whither they went for a shower bath, and when they reached their room, to put on clothes other than sporting ones for supper, Sid was not in the apartment. There was evidence that he had come in, hastily dressed, and had gone out again.

“He’s off,” remarked Tom.

“Yes, and it’s mighty queer business,” remarked Phil. “But come on, we’ll get an early grub, tog up, and go get the girls.”

“What about Miss Harrison?”

“Hanged if I know,” answered Tom. “I’d be glad to take her, of course, but I’m not going to mix up in Sid’s affairs.”

“No, of course not. Well, come on.”

In spite of hearty appetites Tom and Phil did not linger long at the table, and they were soon back in their room, where they began to lay out their dress suits, and to debate over which ties they should wear. Tom had managed to borrow a dress shirt, and so did not have to buy one.

“I say, Phil,” remarked the pitcher, as he almost strangled himself getting a tight fifteen collar to fit on the same size shirt, “doesn’t it strike you as queer about Sid—I mean his chasing off this way so suddenly?”

“It sure does. This is the second time, and each time he scoots off when he’s had a note from some one.”

“Remember when he came back last night, smelling so strong of tobacco?”

“Sure; yet he doesn’t smoke.”

“No, and that’s the funny part of it. Then there’s the fact of him having no money to-day, though he had a roll yesterday.”

There was silence in the small apartment, while the clock ticked on. Tom, somewhat exhausted by his struggle with his collar, sank down on the ancient sofa, a cloud of dust, like incense, arising around him.

“Cæsar’s legions! My clothes will be a sight!” he cried, jumping up, and searching frantically for a whisk broom.

“Easy!” cried Phil, “I just had my tie in the right shape, and you’ve knocked it all squee-gee!” for Tom in his excitement had collided with his chum.

They managed to get dressed after a while—rather a long while.

“Come on,” said Tom, as he took a final look[47] at himself in the glass, for though he was not too much devoted to dress or his own good looks, much adornment of their persons must be excused on the part of the talented pitcher and his chum, on the score of the pretty girls with whom they were to spend the evening.

“I’m ready,” announced Phil. “Shall we leave a light for Sid?”

“I don’t know. No telling when he’ll be in. Do you know, Phil, it seems rotten mean to mention it, and I only do it to see if you have the same idea I have, but I shouldn’t be surprised if old Sid was gambling.”

“Gambling!”

“Yes. Look how he’s sneaked off these last two nights, not saying where he’s going, and acting so funny about it. Then coming in late, all perfumed with tobacco, and getting caught, and not having any money and—and—Oh, well, hang it all! I know it won’t go any further, or I shouldn’t mention it; but doesn’t it look queer?”

Phil did not reply for a moment. He glanced at Tom, as if to fathom his earnestness, and as the two stood there, looking around their common home, marked by the absence of Sid, the fussy little alarm clock seemed to be repeating over and over again the ugly word—“gambler—gambler—gambler.”

“Well?” asked Tom softly.

“I hate to say it, but I’m afraid you’re right,” replied Phil. “Sid, of all chaps, though. It’s fierce!” and then the two went out.

Tom and Phil called at the residence of Miss Harrison’s relatives for Madge and Ruth. Tom tried, tactfully enough, to get Miss Harrison to come to the theatricals with himself and Ruth, but the blue-eyed girl pleaded a headache (always a lady’s privilege), and said she would stay at home. Sid’s name was not mentioned. Then the four young people went off, leaving a rather disconsolate damsel behind.

Sid was in bed when Tom and Phil returned, and he did not say anything, or exhibit any signs of being awake, so they did not disturb him, refraining from even talking in whispers of the jolly time they had had. There was a strong smell of tobacco about Sid’s clothes, but his chums said nothing of this.

The next day Sid was moody and disconsolate. He wrote several letters, tearing them up, one after the other, but finally he seemed to hit on one that pleased him, and went out to mail it. Amid the torn scraps about his desk Phil and Tom could not help seeing several which began variously “My dear Miss Harrison,” “Dear Miss Harrison,” “Dear friend,” and “Esteemed friend.”

“Trying to square himself,” remarked Tom.

“He’s got it bad—poor old Sid,” added Phil. “It will all come out right in the end, I hope.”

But it didn’t seem to for Sid, since in the course of the next week, when he had written again to Miss Harrison asking her to go with him to a dance, he received in return a polite little note, pleading a previous engagement.

“Well,” remarked Tom one afternoon, when he and his crowd of players had thronged out on the diamond, “we’re getting into some kind of shape. Get back there, Dutch, while I try a few curves, and then we’ll have a practice game.”

“And pay particular attention to your batting, fellows,” cautioned Coach Leighton. “It isn’t improving the way it ought, and I hear that Boxer has some good stick-wielders this season.”

“Yes, and they’ve got some one else on their nine, too,” added Bricktop Molloy. “Have ye heard the news, byes?” for sometimes the red-haired shortstop betrayed his genial Irish nature by his brogue.

“No, what is it?” asked Phil.

“Fred Langridge is playing with them.”

“What? Langridge, the bully who used to be here?” cried one student.

“That same,” retorted Bricktop.

“Have they hired him?” inquired Holly Cross.

“No, he’s taking some sort of a course at Boxer Hall, I believe.”

“A course in concentrated meanness, I guess,” suggested Tom, as he thought of the dastardly trick Langridge had tried to play on Phil during the previous term.

“Well, no matter about that,” came from the coach. “You boys want to improve your batting—that’s all. Your field work is fair, and I haven’t anything but praise for our battery.”

“Thanks!” chorused Tom and Dutch Housenlager, making mock bows.

“But get busy, fellows,” went on the coach. “Oh, by the way, captain, what about a manager?”

“Election to-night,” answered Tom quickly. “The notice has been posted. Come on, we’ll have a scrub game. Five innings will be enough. There ought to be——”

“My uncle says——” began a voice from a small knot of non-playing spectators.

“Fenton’s wound up!” cried Dutch, making an attempt to penetrate the crowd and get at the offending nephew of the former coach.

“Can him!” shouted Joe Jackson.

“Put your uncle on ice!” added Pete Backus.

“Leave him out after dark, and Proc. Zane will catch him,” came from Snail Looper.

“Well, I was only going to say,” went on Ford, but such a storm of protesting howls arose that his voice was drowned.

“And that’s the chap they talk of for manager,” said Phil to Tom disgustedly.

“Oh, I guess it’s all talk,” remarked the pitcher. “We will rush Ed Kerr through, and the season will soon start.”

The scrub game began. It was not remarkable for brilliant playing, either in the line of fielding or batting. Tom, though, did some fine work in pitching, and he and Dutch worked together like well-built machines. Tom struck out three men, one after the other, in the second inning, and repeated the trick in the last. Sid Henderson rather surprised the coach by making a safe hit every time he was up, a record no one else approached that day, for Rod Evert, who was doing the “twirling” for the team opposed to Tom’s, was considered a good handler of the horsehide.

“Good work, Henderson,” complimented Mr. Leighton. But Sid did not seem particularly pleased.

“Everybody on hand for the election to-night,” commanded Tom, as the game ended, the pitcher’s team having won by a score of eight to four.

There was a large throng assembled in the gymnasium that evening, for at Randall sports reigned supreme in their seasons, and the annual election of a baseball manager was something of no small importance. For several reasons no manager had been selected at the close of the[52] previous season, when Tom had been unanimously selected as captain, and it now devolved upon the students who were members of the athletic committee to choose one.

As has been explained, among the players themselves, or, rather, among the majority, Ed Kerr, the catcher of the previous season was favored, but, of late there had been activity looking to the choosing of some one else.

There were vague rumors floating about the meeting room, as Tom Parsons went up on the platform, and called the assemblage to order. It was noticed that Bert Bascome, a freshman who was said to be quite wealthy, was the center of a group of excited youths, of whom Ford Fenton was one. Ford had tried for the ’varsity the previous season, had failed, and was once more in line. As for Bascome, he, too, wanted to wear the coveted “R.”

“Politics over there all right,” observed Phil Clinton to Dutch. “Any idea of how strong they are?”

“Don’t believe they can muster ten votes,” was the answer. “We’ll put Ed in all right.”

Tom called for nominations for chairman, and Mr. Leighton, who was in the hall, was promptly chosen, he being acceptable to both sides.

“You all know what we are here for,” began the coach, “and the sooner we get it over with[53] the better, I presume. Nominations for a manager of the ball nine are in order.”

Jerry Jackson was on his feet in an instant.

“Mr. Chairman,” he began.

“Are you speaking for yourself or your brother?” called Dutch.

Bang! went the chairman’s gavel, but there was a laugh at the joke, for Jerry and Joe, the “Jersey twins” were always so much in accord that what one did the other always sanctioned. Yet the query of Dutch seemed to disturb Jerry.

“Mr. Chairman,” he began again. “I wish——”

“Help him along, Joe,” sung out Snail Looper. “Jerry is going to make a wish.”

“Boys, boys,” pleaded the coach.

“My uncle says——” came from Ford Fenton, indiscreetly.

“Sit down!”

“Put him out!”

“Muzzle him!”

“Silence!”

“Get a policeman!”

“Turn the hose on him!”

“Don’t believe he ever had an uncle!”

These were some of the cries that greeted Ford.

Bang! Bang! went the gavel, and order was finally restored, but Fenton did not again venture to address the chair.

“Mr. Chairman,” began Jerry Jackson once more, and this time he secured a hearing, and was recognized. “I wish to place in nomination,” he went on, “a manager who, I am sure, will fulfill the duties in the most acceptable manner; one who knows the game from home plate to third base, who has had large experience, who is a jolly good fellow—who——”

“Who is he?”

“Name him!”

“Don’t be so long-winded about it!”

“Tell us his name!”

“He’s going to name Ford’s uncle!”

Once more the horse-play, led by Dutch, broke out.

Bang! Bang! went Mr. Leighton’s gavel again.

“I nominate Ed Kerr!” sung out Jerry.

“Second it!” came from his brother in a flash.

“Mr. Kerr has been nominated,” spoke the chairman. “Are there any others?”

“Move the nominations be closed,” came from Tom quickly, but, before it could be seconded, Bert Bascome was on his feet. He had a sneering, supercilious air, that was in distinct bad taste, yet he seemed to have a sort of following, as, indeed, any youth in college may have, who is willing to freely spend his money.

“One moment, Mr. Chairman,” began Bascome, and so anxious were the others to hear[55] what was coming that they did not interrupt. “When I came to Randall college,” went on the freshman, with an air as if he had conferred a great favor by his act, “I was given to understand that the spirit of sportsmanship and fair play was a sort of a heritage.”

“So it is!”

“What’s eating you?”

“Who’s the goat?” came the cries. Bert flushed but went on:

“Closing the nominations before more than one name——”

“The nominations have not been closed,” suggested Mr. Leighton.

“Then am I out of order?” inquired Bascome sarcastically. He seemed to know parliamentary law.

“No,” answered the coach. “You must speak to the point, however. Have you a name to place in nomination? Mr. Parsons’ motion was lost for want of a second.”

“I have a name to place in nomination,” went on Bert deliberately, “and in doing so I wish to state that I am actuated by no sense of feeling against Mr. Kerr, whom I do not know. I simply wish to see the spirit of sport well diversified among the students, and——”

“Question! Question!” shouted several.

“Name your man!” demanded others.

“I believe Mr. Kerr is highly esteemed,” continued Bascome, holding his ground well, “and I honor him. I believe, however, that he belongs to a certain crowd, or clique——”

“You’re wrong!” was a general shout.

“Mr. Chairman!” shouted Kerr, springing to his feet, his face strangely white.

“Mr. Bascome has the floor,” spoke Mr. Leighton quietly.

“Name your man!” was the cry from half a score of youths.

“I nominate Ford Fenton for manager!” shouted Bascome, for he saw the rising temper of some of the students.

“Second it,” came from Henry Delfield, who was the closest chum of the rich lad.

“Move the nominations close!” cried Tom quickly, and this time Phil Clinton seconded it. The battle was on.

“Two students have been nominated,” remarked Mr. Leighton, when the usual formalities had been completed. “How will you vote on them, by ballot or——”

“Show of hands!” cried Tom. “We want to see who’s with us and who’s against us,” he added in a whisper to Phil and Sid.

“I demand a written ballot,” called out Bascome.

“We will vote on that,” decided the chairman, and it went overwhelmingly in favor of a show of hands.

“We’ve got ’em!” exulted Tom, when this test had demonstrated how few were with Bascome—a scant score.

A moment later the real voting was under way, by a show of hands, Kerr’s name being voted on first. He had tried to make a speech, but had been induced to keep quiet.

It was as might have been expected. Possibly had the ballot been a secret one more might have voted for Fenton, but some freshmen saw which way the wind was blowing, changing their votes after having declared for a secret ballot, and all of Bascome’s carefully laid plans, and his scheming for several weeks past, to get some sort of control of the nine, came to naught. Fenton received nine votes, and Kerr one hundred and twenty. It was a pitiful showing, and Fenton soon recognized it.

“I move the election of Mr. Kerr be made unanimous!” he cried, and that did more to offset his many references to his uncle than anything else he could have done. Bascome was excitedly whispering to some of his chums, but when Fenton’s motion was put it was carried without a vote in opposition, and Kerr was the unanimous choice.

“Well, I’m glad that’s over,” said Phil with a sigh of relief, as he and his chums drifted from the gymnasium.

“Yes, now we’ll begin to play ball in earnest,” added Tom. “Come on, Sid, I’ll take you and Phil down to Hoffman’s and treat you to some ice cream.”

“I—er—I’m going out this evening,” said Sid, and he blushed a trifle.

“Where, you old dub?” asked Tom, almost before he thought.

“I’m going to call on Miss Harrison,” was the somewhat unexpected answer.

Tom and Phil stood staring at each other as Sid walked on ahead.

“Well, wouldn’t that get your goat?” asked Tom.

“It sure would,” admitted Phil. “He must have made up with her, after all.”

How it came about Sid, of course, would never tell. It was too new and too delightful an experience for him—to actually be paying attentions to some girl—to make it possible to discuss the matter with his chums. Sufficient to say that in the course of two weeks more there was another photograph in the room of the inseparables.

Baseball matters began to occupy more and more attention at Randall. The team was being whipped into shape, and between Tom, Ed Kerr and the coach the lads were beginning to get rid of the uncertainty engendered by a winter of comparative idleness.

“Have you arranged any games yet?” asked[60] Tom of Ed one afternoon, following some sharp practice on the diamond.

“We play Boxer Hall next week,” answered the manager. “And I do hope we win. It means so much at the beginning of the season. How is the team, do you think?”

“Do you mean ours or theirs?”

“Ours, of course.”

“Fine, I should say,” replied Tom.

“You know who’ll pitch against you when we play Boxer, I dare say,” remarked Mr. Leighton, who had joined Tom and Ed.

“No. Who?”

“Your old enemy, Langridge. He’s displaced Dave Ogden, who twirled for them last season. But you’re not frightened, are you?”

“Not a bit of it! If there’s anything that will make our fellows play fierce ball it’s to know that Langridge—the fellow who almost threw our football team—is going to play against them. I couldn’t ask a better tonic. Will they play on our grounds?”

“No, we’ve got to go there. But don’t let that worry you.”

There was sharp practice for the next few days, and Tom and his chums were put through “a course of sprouts” to quote Holly Cross. They did some ragged work, under the eagle eye of the coach, and things began to look bad, but it was[61] only the last remnant of staleness disappearing, for the day before the game there was exhibited a noticeable stiffness, and a confidence that augured well for Randall.

“The batting still leaves something to be desired,” remarked Mr. Leighton, as practice was over for the day. “I have great hopes of Sid Henderson, though.”

“Yes, if——” began Tom.

“If what?” asked the coach quickly.

“If he doesn’t go back on himself,” finished the pitcher, but that was not what he had intended to say. He was thinking of Sid’s queer actions of late—wondering what they portended, and what was the meaning of his chum’s odd absences, for, only the night previous, Sid had gone out, following the receipt of a note, and had come in late, smelling vilely of tobacco. Fortunately he had escaped detection by the proctor, but he offered no explanation, and his manner was disturbed, and not like his usual one.

As for Sid, well might his chums be puzzled about him. He seemed totally to have changed, not only in manner but in his attitude toward Tom and Phil. There was a new look on his face. Several times, of late, since his acquaintance with Miss Harrison, and the reconciliation following his little “de trop faux pas,” as Tom termed it, Sid had been caught day dreaming. Phil or Tom[62] would look up from their studying to see Sid, with a book falling idly from his hands, gazing vacantly into a corner of the room, or looking abstractedly at his side of the wall space, as though calculating just where would be the best spot for a certain girl’s picture.

It was a most enthralling occupation for Sid—this day dreaming. It was a new experience—a deliciously tender and sweet one—for no young man can be any the worse for thinking and dreaming of a fine-charactered girl, albeit one who is amazingly pretty; in fact he is the better for it. In Sid’s case his infatuation had come so suddenly that it was overwhelming. In the past he had either been shy with girls, or had not cared enough for them to be more than decently polite. But now everything was different. Though he had seen her but a few times, he could call to mind instantly the very way in which she turned her head when she addressed him. He could see the slight lifting of the eyebrows as she asked a question, the sparkle that came into the blue eyes, that held a hint of mischief. He could hear her rippling laugh, and he knew in what a tantalizing way a certain ringlet escaped from the coils of her hair, and fell upon her neck.

Often in class the lecturer would suddenly call his name, and Sid would start, for he had sent[63] his thoughts afar, and it required a sort of wireless message to bring them back.

The day of the Boxer game could not have been better. There had been a slight shower in the night, but only sufficient to lay the dust, and it was just cool enough to be delightful. The Randall players and their supporters, including a crowd of enthusiastic “rooters,” a number of substitutes and a mascot, in the shape of a puppy, fantastically attired, made the trip to Boxer Hall in special trolleys, hired stage coaches and some automobiles. Bert Bascome owned an automobile, and he made much of himself in consequence.

There was a big crowd in the grand stands when the Randall players arrived, and they were received with cheers, for the sporting spirit between the two colleges was a generous one.

“My, what a lot of girls!” remarked Tom to Sid and Phil, as the three chums looked over toward the seats, which were a riot of color.

“Yes, all the Fairview students are here to-day,” spoke Phil. “Ruth said she and Miss Tyler were coming.”

“I wonder if——” began Sid, and then he stopped, blushing like a girl.

“Yes, Miss Harrison is coming with them,” replied Phil, with a laugh. “We’ll look ’em up after the game—if we win.”

“Why not, if we lose?” asked Sid quickly.

“I haven’t the nerve, if we let Boxer Hall take the first game of the season from us,” was the reply.

Fast and snappy practice began, and it was somewhat of a revelation to the Randall players to note the quick work on the part of their rivals. In getting around the bases, batting out flies, getting their fingers on high balls and low grounders, Boxer Hall seemed to have improved very much over last year.

“We’ve got our work cut out for us,” remarked Phil in a low voice to his two chums. “Say, Langridge has some speed, too. Look at that!”

The new pitcher of Boxer Hall was throwing to Stoddard, the catcher, and the balls landed in the pocket of the big mitt with a vicious thud.

“Don’t worry. Sid, here, will knock out a couple of home runs,” said Tom. “Won’t you, Sid?”

“I only hope I don’t fan the air. How are his curves?”

“Pretty good, for the first few innings,” answered Tom. “After that you can find ’em easy enough. He wears down—at least he did last year.”

The practice came to an end. The preliminaries were arranged, and, with the privilege of the home team coming last to the bat, Randall[65] went in the initial inning. The two teams were made up as follows:

RANDALL COLLEGE

Sid Henderson, second base.

William Housenlager, catcher.

Phil Clinton, first base.

Tom Parsons, pitcher.

Dan Woodhouse, third base.

Jerry Jackson, right field.

Bob Molloy, shortstop.

Joe Jackson, left field.

Holman Cross, center field.

BOXER HALL

Lynn Ralling, second base.

Hugh McGherity, right field.

Roy Conklin, left field.

Arthur Flood, center field.

George Stoddard, catcher.

Pinkerton Davenport, first base.

Fred Langridge, pitcher.

Bert Hutchin, third base.

Sam Burton, shortstop.

“Now, Sid, show ’em what you can do,” advised Mr. Leighton, as Sid selected a bat, and walked up to the plate. He faced Langridge,[66] and noted the grim and almost angry look in the eyes of the former pitcher on the Randall ’varsity.

“Make him give you a nice one,” called Bean Perkins, who was ready to shout for victory.

A ball came whizzing toward Sid, and so sure was he that he was going to be hit that he dodged back, but he was surprised when it neatly curved out, went over the plate, and the umpire called:

“Strike One!”

There was a howl of protest on the part of the Randall sympathizers, but it died away when Mr. Leighton held up a warning hand.

Sid struck viciously at the next ball, and felt a thrill of joy as he felt the impact, but, as he rushed away toward first he heard the umpire’s call of “Foul; strike!” and he came back.

“Wait for a good one,” counseled Phil, in a low voice. “Make him give you a pretty one.”

Langridge sent in another swift curve and Sid struck at it. Another foul resulted, and he began to wonder what he was up against. The next attempt was a ball, for Langridge threw away out, but Sid saw coming a moment later, what he thought would make at least a pretty one-bagger. He swung viciously at it, but missed it clean, and walked to the bench somewhat chagrined.

Dutch Housenlager, with a smile of confidence,[67] walked up next. He was cool, and Langridge, having struck out Sid, seemed to lose some of his anger. He delivered a good ball—an in-shoot—and Dutch caught it on the end of his bat. It seemed to promise well, but Roy Conklin, out on left field was right under it, and Dutch ingloriously came back from first.

“Now, Phil, line one out!” pleaded Tom, as his chum selected his bat, and Phil struck at the first ball, sending a hot liner right past the shortstop.

Phil got to first, and stole second when Tom came up, making it only by a close margin.

“A home run, Tom,” begged the coach, and Tom nodded with a grim smile on his face. But alas for hopes! He knocked a fly, which the right fielder got without much difficulty, and the first half of the initial inning was over with a goose-egg in the space devoted to Randall.

“Never mind, we’re finding him,” consoled Tom, as he walked to his box.