THE ASSAULT

THE ASSAULT

Germany Before the Outbreak and

England in War-Time

A Personal Narrative

By

FREDERIC WILLIAM WILE

Author of "Men Around the Kaiser"

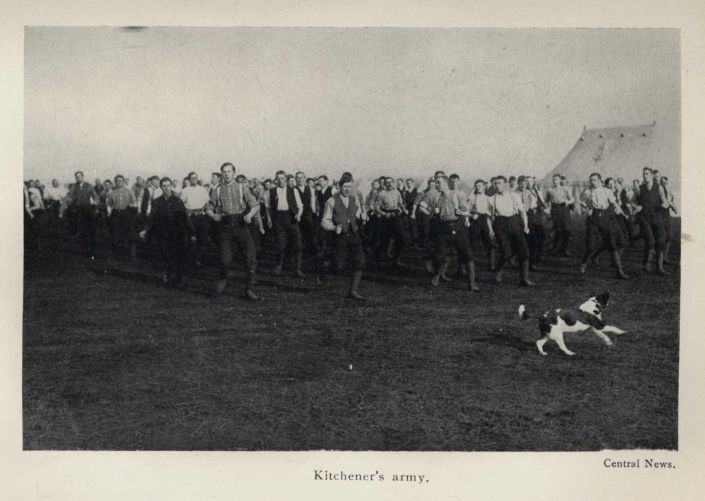

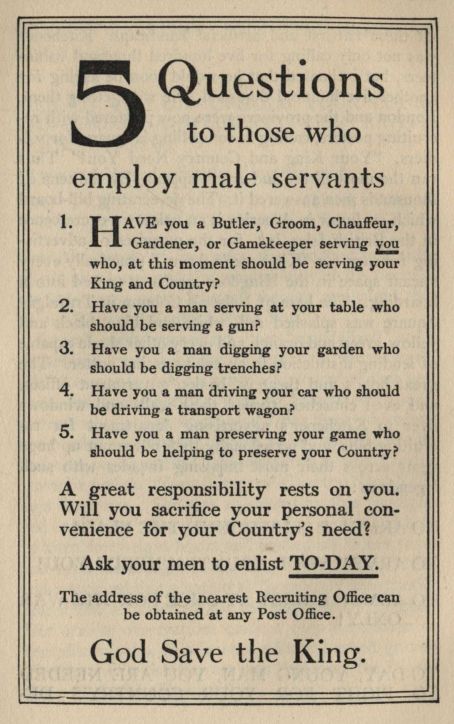

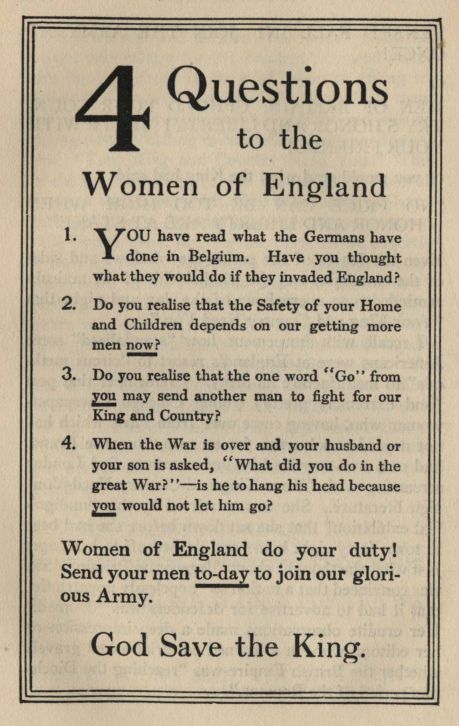

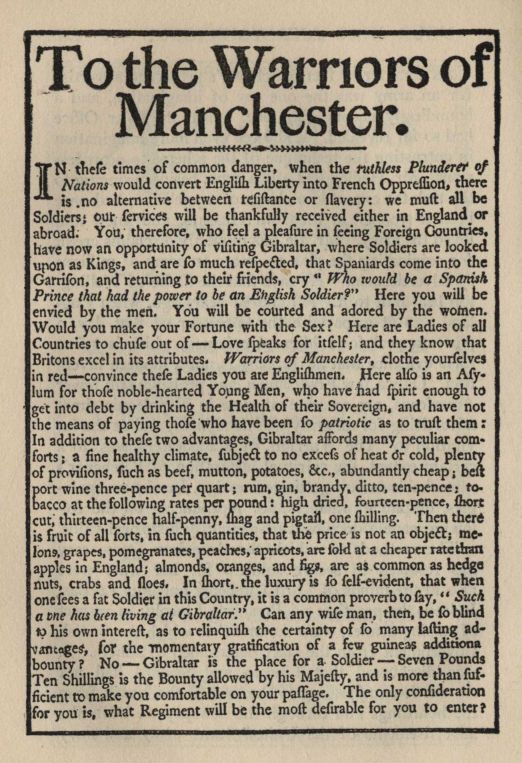

ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS AND FACSIMILES OF

DOCUMENTS AND CARTOONS

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT 1916

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

To

AMBASSADOR AND MRS. GERARD

LIFE-SAVERS

IN GRATITUDE

INTRODUCTION

This is not a "war book." It has not been my privilege at any stage of the Great Blood-Letting to come into close contact with the spectacular clash and din of the fray. Abler pens than mine, many of them wielded by the "neutral" hands of American colleagues, are immortalizing the terrible, yet irresistibly fascinating, scenes of this most stupendous drama. But every drama has its scenario and its prologue and its behind-the-curtain scenes--none ever written was so rich in these preliminaries and accessories as is Europe's epic. To have witnessed and lived through some of these was vouchsafed me; and to take American readers with me down the line of the past year's recollections and impressions is the sole object of this unpretentious effort. History, Carlyle said, was some one's record of personal experiences. To such experiences, as far as possible, the pages of this book are confined.

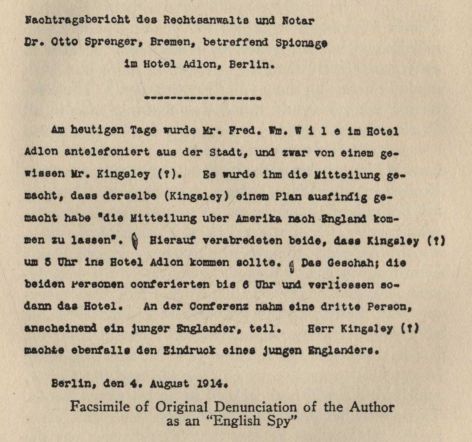

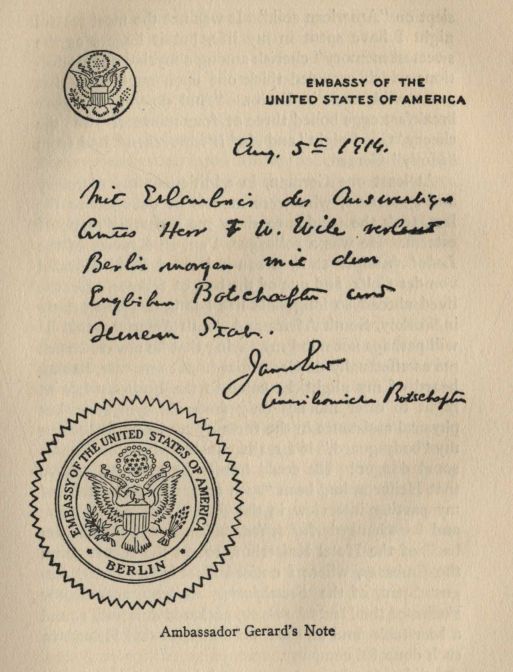

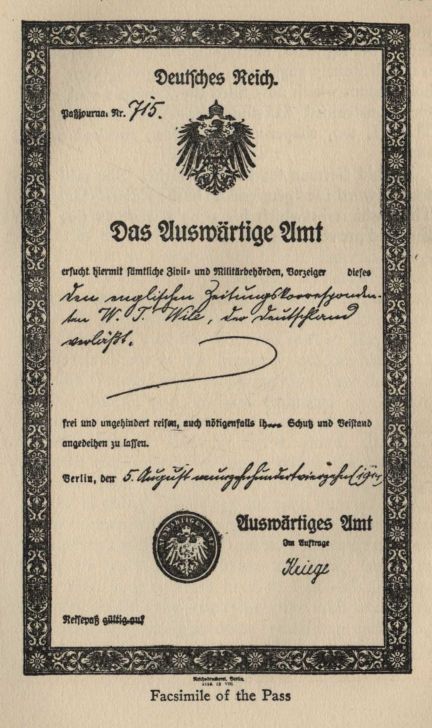

For thirteen years to the week--I have always had a respectful horror of thirteen--I was a resident of Berlin. During the first five years of that period my identity was clear: I was the representative in Germany of an American newspaper, the Chicago Daily News. But in 1906 I became an international complication, for it was then I joined the staff of the London Daily Mail, which converted my status into that of an American serving British journalistic interests in Germany. It was not long afterward that welcome opportunity presented itself to renew home professional ties in connection with my British work, and for several years prior to the outbreak of the war I carried the credentials of Berlin correspondent of the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune. They were on my person, with my United States passport, the night of August 4, 1914, when the Kaiser's police arrested me as an "English spy."

I feel it necessary to introduce so highly personal a narrative with these details in order to make plain, at the outset, that it is the narrative of an American born and bred. My proudest boast during ten years' association with Great Britain's premier newspaper organization was that I never lost my Americanism. My English editor, on the occasion of my earliest physical conflict with the Mailed Fist in Berlin, doubtless recalls taking me to task for invoking the protection of the United States Embassy, just as my British colleagues, concerned in the same imbroglio, had invoked the aid of their Embassy. Of the reams I have written for the Daily Mail in my day, I never sent it anything which sprang more sincerely from the heart than the message to its editor that I had not renounced allegiance to my country when I pledged my professional services to a British newspaper.

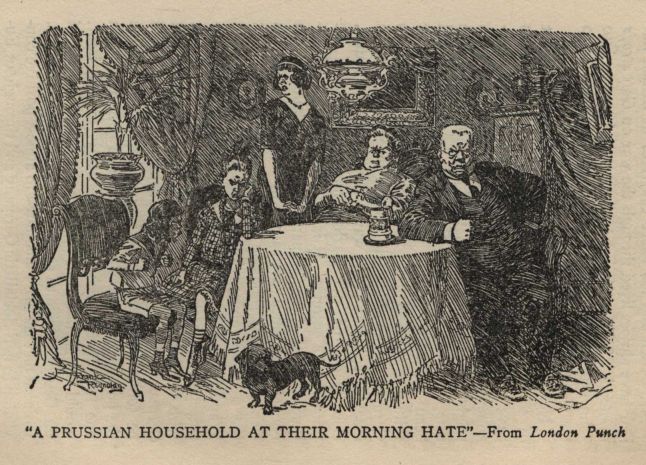

I have no higher aspiration, as far as this volume is concerned, than that critics of it, hostile or friendly, may pronounce it "pro-Ally" from start to finish. I shall survive even the charge that it is "pro-English." I mean it to be all of that, as I have tried to breathe sincerity into every line of it. But I shall not feel inclined to accept without protest an accusation that the book is "anti-German." It is true that I regard this essentially a German-made, or rather a Prussian-made, war, and that I hold Prussian militarism and militarists solely responsible for plunging the world into this unending bath of blood and tears. It is true that I wish to see Germany beaten. I wish her beaten for the Allies' sake and for my own country's sake. A victorious Germany would be a menace to international liberty and become automatically a threat to the happiness and freedom of the United States. My years in Germany taught me that. But I cherish no scintilla of hatred or animosity toward the German people as individuals, who will be the real victims of the war. I saw them with my own eyes literally dragged into the fight against their will, fears and judgment. I know from their own lips that they considered it a cruelly unnecessary war and did not want it. They were joyful and prosperous a year and a half ago--never more so. They craved a continuance of the simple blessings of peace, unless their tearful protestations in the fateful month preceding the drawing of their mighty sword were the plaints of a race of hypocrites, and I do not think the percentage of hypocrisy higher in Germany, man for man, than elsewhere in the world. The German's Gott strafe England cult, for example, is no revelation to any man who has lived among them. Their hatred for Perfidious Albion has long been vigorous and purposeful.

During the war I have lived in Germany, England and the United States--a week of it in Berlin, three months at different periods in America, and the rest of the time in London. My observations of Germany have not been confined to the six and a half days the Prussian police permitted me to tarry in their midst, for my work in London has dealt almost exclusively with day-by-day examination of that weird production which will be known to history as the German war-time Press. I am quite sure the perspective of the life and times of the Kaiser's people in their "great hour" was clearer from the vantage-ground of a newspaper desk near the Thames embankment than it could possibly have been had it been my lot to view the Fatherland at war as an observer writing, under the hypnotic influence of mass-suggestion, of Germany from within.

Though I deal with Britain in war-time, no pretense is made of treating so vast a subject except by way of fleeting impressions. Indeed, nothing but snap-shots of British life are possible at the moment, so kaleidoscopic are its developments and vagaries. I am conscious that the pictures I have drawn are, therefore, superficial, but no portrayal of a people in a state of flux could well be otherwise. Although the concluding chapters were written in October, conditions now (in mid-December) have altered vitally in many directions. Sir John French no longer commands the British Army in France and Flanders. Serbia has gone the way of Belgium. Gallipoli has been abandoned. The Coalition Government, established at the end of May, is widely considered a failure at the end of December. The Man in the Street, that oracle of all-wisdom in these Isles, is asking whether the war can be won without still another, and more sweeping, change of National leadership.

I hope my British friends, and particularly my professional colleagues of ten years' standing, will not find my snap-shots too under-exposed. The camera was in pro-British hands every minute of the time. If the pictures appear indistinct, I trust the photography will at least not be criticized as in any respect due to lack of sympathy with the British cause.

F. W. W.

London, December 20, 1915.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

New Introductory Chapter

HOW EUROPE VIEWS AMERICAN INTERVENTION

It will hardly be possible for any faithful chronicler of that transcendent event to record that America's entry into the war set embattled Europe by the ears. The most such a historian can say of the impression created in Allied countries is that the abandonment of our neutrality toward the "natural foe to liberty" produced profound satisfaction but nothing in the way of a staggering sensation. Even in Germany and among her vassals, declaration of war by the United States failed to provoke consternation, although it was received in a spirit of nonchalance which was more studied than real. The Damoclean sword of Washington had hung so long in the mid-air of indecision that when the blow fell its effect was to a large extent lost upon beneficiary and victim alike. The peoples who became our Allies were gratified; the Germans mortified. But our leap into the arena stained with nearly three years of combatant blood was so belated that it seemed bereft of the power to plunge either our friends into paroxysms of enthusiasm or our enemies into the depths of despair.

I am speaking exclusively of the first impressions generated by President Wilson's call to arms. In Allied Europe, as well as Germanic Europe, opinion is changing, now that the words of April are merging into the deeds of midsummer. Still different emotions will fire the breasts of both our comrades-in-arms and of the common foe when the full magnitude of American intervention dawns upon their reluctant consciousness. As yet the illimitable import of America's "coming in" is only faintly realized. Europe's attitude toward the new belligerent is too strongly intrenched in decade-old disbelief in the existence of American idealism and in gross ignorance of our actual potentialities for war, spiritual as well as physical, to be lightly abandoned. We shall have to win our spurs. There is at this writing no inclination whatever to present them to us on trust.

In the introduction to the original edition of The Assault, which was completed at the end of 1915, I was un-neutral enough to utter the pious hope that Germany would be beaten. I confessed to the creed that "a victorious Germany would be a menace to international liberty and become automatically a threat to the happiness and freedom of the United States." I said that "my years in Germany taught me that"--years lived in closest contact with Prussian militarism long before it had taken the concrete form of savagery at sea. With that passion for corroboration of his own prejudices and predictions, which is inherent in the average man, and which dominates most writers, I rejoice to feel that our government and country have at length joined in liberty's fray from the identical motives which induced me at the outset to take the only side that it seemed possible for an American to espouse.

Properly to analyze Europe's mentality in respect of the United States' entry into the war we need to bear in mind that for the thirty-two preceding months President Wilson was the riddle of the political universe. Europe had been assured ceaselessly since August, 1914, that America was overwhelmingly and irretrievably pro-Ally, though its confidence in such assertions was shipwrecked when we failed to go to war over the Lusitania incident and was never fully restored. Not even Berlin could reconcile the Washington government's invincible neutrality with the alleged existence of universal counter-sentiment. Europeans are educated to believe that public opinion is the only monarch to whom the American citizenry owns allegiance. They were unable to comprehend a president who so resolutely refused to bow to the people's sovereign will. In its myopic misconception of American conditions, Allied Europe indulged in grotesque misinterpretation of Mr. Wilson's hesitancy and mystic diplomacy. He had been "re-elected by German votes." In London Americans were solemnly asked if the true explanation of his policy did not lie in the fact that he had "a German wife!" It was also mooted that he had "a secret understanding" with Count Bernstorff. The president was this, that and the other thing--everything, in fact, except what he ought to be. No American chief magistrate since Lincoln was ever so magnificently misunderstood, none so incorrigibly maligned.

Thus it was that although the United States' action under President Wilson's sagacious leadership did not fill Europe with either animation or excitement, it nevertheless came as a full-fledged surprise to both sets of belligerents. Briton, Frenchman, Russian and Italian, as well as German, Austrian and Hungarian, each in his own dogmatic way, had long since and definitely made up their minds that America did not mean to fight. Their cocksureness on this cardinal point was not unnaturally supported by the circumstances of President Wilson's re-election on what was commonly understood to be the democratic candidate's paramount campaign issue--his success in keeping the country out of the war. In the two or three days in which Mr. Wilson's fate trembled in the balance of the Electoral College, a London newspaper, venting splenitic feelings long pent up, gratefully acclaimed the premature announcement of Mr. Hughes' triumph as an historic and deserved rebuke of the statesman who was "too proud to fight."

Within a month President Wilson, in his first public utterance since election day, made his "peace-without-victory" address to the Senate. This cryptic deliverance was interpreted in Allied Europe as not only obliterating all possibility of America's entering the war against Germany, but as actually promoting Germany's efforts, launched about the same time, to secure a premature, or "German," peace. There was probably no time during the entire war when feeling against the president and the United States in general ran higher in England and France than during the ensuing weeks. It was not so much what one read in the public prints, for press utterances were restrained if not unqualifiedly friendly, that impelled many an American in London and Paris to seek cover from the withering blast of criticism and impatience to which he now found his country subjected. It was rather the sentiments encountered among Englishmen and Frenchmen in private that supplied the real index to, and revealed the full intensity of, the disappointment and indignation now aroused in Allied lands.

Indelibly impressed upon my memory is the passionate outburst of a dear--and, of course, temperamental--French friend in London. He is a gentleman, a scholar and sincere lover of America, where he found the charming lady who is now his wife. He had retired to a bed of illness in consequence of the climatic iniquities which will forever make it impossible for a Frenchman ever really to like England, and I was paying him a neighborly visit of inquiry. Though I had hoped and intended that the acrimonious topic of America would for once be eliminated from our conversation, I was not to be spared what turned out to be almost the most violent castigation of the United States and all its works under which I could ever remember to have winced. I was left in no doubt that his outpouring of righteous Gallic wrath, though it sprang to a certain degree from temperature as well as temperament, was the voice of France crying out in holy anger with the great but recreant sister republic. Wilson had "surrendered to the Germans and pro-Germans." They were now getting their reward. The president was "playing the Kaiser's peace game." He may not have meant to do so, but that is what his Senate manifesto amounted to, in French estimation. "The Americans care only for their money." So be it. France would not forget. Jamais! Americans would rue the day they had sent back to the White House the man who was now stabbing crucified democracy in the back!

The essential difference between the French and the English is that Frenchmen usually say what they feel, and Englishmen feel what they do not say. Emotions were given to Frenchmen to be expressed; to Englishmen, to be suppressed. Almost identically the same emotions which fired the French soul, as typified by the instance I have just cited, filled British breasts, but owing to the psychic machinery with which his organism is equipped the Englishman was able more successfully to stifle them. The public tone toward the latest manifestation of our "war policy" was punctiliously correct. It was discussed by the great newspapers in terms of polite dismay but almost invariably in good temper. Yet millions of Britons were boiling within, and if wearing their hearts on their sleeves had been "good form," there is little reason to doubt that their ebullitions would have been no less articulate or meaningful than those of my distinguished French friend herein narrated.

It was about at this time, the end of 1916, that an American colleague, Edward Price Bell, of The Chicago Daily News, set forth in the columns of The Times upon a bold adventure--an attempt to persuade captious Britons that, far from desiring to "play the Kaiser's game," President Wilson was actually anxious to make war on Germany, and, indeed, was deliberately, as was his way, proceeding in that direction. It was a risky throw for the doyen of the American press in London, who enjoyed a reputation for sanity and sagacity and who had good reason for desiring to preserve the respect of a community in which his professional lot had been cast for sixteen years. I purpose summarizing the course of Bell's effort to scale the walls of British prejudice because of its immensely symptomatic and psychological interest.

"I believe that Wilson wants to go to war," Bell wrote to The Times on December 23. "I believe that he wants to fight Germany. I believe that he wants Germany to commit herself to a program that would warrant him in asking the American people to enter the conflict." In every allied quarter in Europe, practically without exception, Bell's letter produced a prodigious and contemptuous guffaw. Americans in Europe, any number of them, joined in the gibes. Undismayed, Bell returned to the attack within three days. "America can not keep out of this war unless Germany gives way," he wrote on December 26. "The time may come very soon when President Wilson will be under the necessity of making his appeal to the American nation." The thunderer did not consign Bell's letters to the editorial waste-basket, where most Englishmen believed they belonged, yet it declined, in its scrupulously courteous way, to associate itself with its correspondent's manifestly fantastic and fanatical sophistry. In an editorial comment The Times expressed its reluctance to place any trust in Bell's exposition of the policy "which Mr. Wilson so carefully wraps up." Bell had by this time become a laughing-stock far beyond the confines of the metropolitan area of London. Paris, Petrograd and Rome read his letters and shook with incredulous mirth. The feelings of fellow-Americans toward him began to be tinged with pity.

Yet Bell broke forth afresh on New Year's Day with his third letter to Printing House Square, asserting, roundly, that "America will and can support no peace but an Entente peace." On January 25 The Times printed Bell's fourth letter within five weeks, in which he this time declared unequivocally that "Mr. Wilson's purpose is solely to inform the world what America stands for and what he is willing to ask America, if need be, to fight for."

Germany now proclaimed her new policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. Mr. Gerard was recalled from Berlin and Count Bernstorff received his passports in Washington. Yet Allied faith in America, momentarily revived by these events, took wings once more when it became known that Mr. Wilson's next "step" would be armed neutrality. The editor of The Times, who had been exceptionally tolerant of the pestiferous Bell, imagined now, I fancy, that events had at length put a timely end to the letter-writing energies of the Chicago scribe; for Englishmen, with notably few exceptions, had by this time pretty well "eliminated" America from their calculations. But on February 22, inspired perhaps by the rugged traditions clinging to that date, Bell cleared for action for the fifth time and next day The Times printed him for the fifth time. He wrote: "I will risk the view that we are on the edge of great things in America--things worthy of the country of Washington and Lincoln. America, I feel, is about to fructify internationally--about to make her real contribution to humanity and history." The Times now went so far as to suggest, with characteristic prudence, that Bell's "sagacious and racy letter deserves careful consideration by all who are trying to understand the situation in Washington." Unhappily, there was little evidence in the continued British mistrust of America that The Times' counsel was being taken widely to heart.

On February 27 Bell craved the indulgence of The Times for his sixth, and final, epistle to the skeptics. With what was destined to turn out to be rare prescience and penetration, he now said that Mr. Wilson's delay in coming to grips with Hohenzollernism meant only that "the president wants the public temper so hot throughout America that it will instantly burn to ash any revolutionary unrest or any opposition by the pacifist diehards." Five weeks later the United States and Germany were at war, with the American nation united in fervent support of the president's pronunciamento that the task which demanded the renunciation of our neutrality was one to which "we can dedicate our lives, our fortunes, everything we are and everything we have." The hour of Europe's awakening from its scornful dreams had come.

For several days after Congress, at the president's instigation, voted to "accept the gage of battle," there lay neatly folded up in a certain front room of the American Embassy in London a fine, new American flag. It had been put there for a special purpose--to be hoisted at a psychological moment believed to be imminent. Our people in Grosvenor Gardens, in their hearty, imaginative American way, considered that there might possibly be a "demonstration" in welcome of Britain's latest comrade-in-arms. There were visions of a procession, brass bands and cheering crowds; and the spick and span stars and stripes were to be flung to the glad breeze when the "demonstrators" reached the scene and called for a speech from Ambassador Page on the Embassy balcony. Such things happened when Italy and Roumania "came in." Surely history would not fail to repeat itself in the case of "daughter America." But neither procession, bands, cheers nor crowds ever materialized. After all, we could not expect Englishmen to celebrate in honor of the greatest mistake they had ever made in their lives. That would be something more than un-English. It would be a violation of all the laws of human nature.

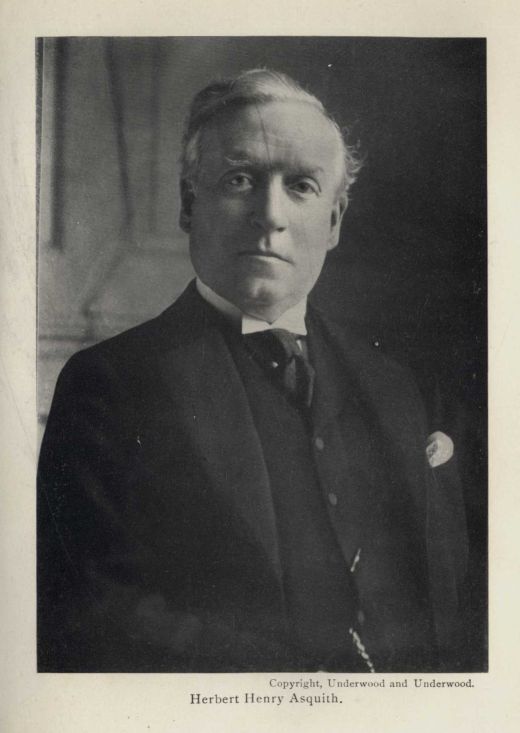

Yet I suppose there was not an American in Great Britain who was not keenly disappointed at the conspicuously undemonstrative character of our welcome into the Allied fold. I must not be understood as minimizing the warmth of either governmental or press utterances evoked by President Wilson's Lincolnesque speech to Congress and the action which so promptly ensued. The sentiments expressed by Mr. Lloyd George, Mr. Asquith, Mr. Bonar Law, Lord Robert Cecil and Lord Bryce, in and out of Parliament, and the thoughts which found vivid expression in the columns of the newspapers of London and the provinces left little to be desired; but eloquent and hearty as they were, their effect upon that all-powerful molder of British public opinion known as the Man in the Street was strangely negligible. I am sure I am not the only American in England who, waiting for words of greeting from British friends and not getting them, was irresistibly constrained to search for the reason. Our chagrin was not lessened by assurances from Paris that "France was going wild with joy"; that the president's speech was being read aloud in the schools and officially placarded on all the hoardings of the republic; that the government buildings were flying the tricolor and "Old Glory" side by side; and that American men were being publicly embraced in the boulevards.

Many Americans found themselves, for reasons never entirely clear to them, the objects of "congratulation." I know of at least one instance in which a very estimable American lady, showered with "congratulations" by British friends on the action of her country, preserved sufficient presence of mind to suggest that she thought "congratulations" were due to the Allies. Another favorite view advanced by vox populi was that America had only "come in" at this late stage of the sanguinary game because "the war was won" and intervention now was "safe" and "cheap." It was not uncommon to be told that our determination to "spend the whole force of the nation" was due to commercial acumen and our desire to safeguard the heavy "investment" we had already made in the Allied cause. Last-ditchers--their name was legion: the Englishmen who refused to believe even yet that America "meant business"--declined to throw their hats into the air and shout until "big words" had become "big deeds." Much more impressive in my own ears seemed the explanation that Britons were not tumultuous in our honor because these days of endless sacrifice--the spring offensive in France was at its height and the nation's best were falling in thousands--were not days for cheering and flag-waving. And, finally, there was that extensive school of thought which had always and sincerely opposed American intervention on the ground that America, as a neutral granary and arsenal, was a more effective Allied asset than a belligerent America which would naturally and necessarily husband its vast resources for its own military requirements.

The story of Germany's state of mind toward America's entry into the lists against her is soon told. The German government and German people looked upon us as all but declared enemies throughout the war. They felt, and repeatedly said, that we were doing them quite as much damage as neutrals as we could possibly inflict in the guise of belligerents. That, indeed, was the argument on which Hindenburg and his fellow-strategists based the "safety" of inaugurating unrestricted submarine warfare and the moral certainty of war with the United States as a result. Not all Germans blithely relegated the prospect of a formally hostile America to the realm of inconsequence. Hindenburg and Ludendorff know nothing about America. But men like Ballin, Gwinner, Rathenau and Dernburg know that the United States, in a famous German idiom, is, indeed, "the land of unlimited possibilities." There can be no manner of doubt that the vision of America's limitless resources harnessed to those of the nations already at war with their country always filled the business giants of the Fatherland with all the terror of a nightmare. But as those elements, both before and during the war, were as a voice crying in the wilderness of Prussian militarism, they were condemned to silence when the dreaded thing became a reality; and the only note that issued forth from Berlin was the "inspired" croak in the government-controlled press that only the expected had happened; that Hindenburg's plans had been made with exact regard for that which had now supervened, and that Germany's irresistible march to victory would not and could not be arrested by anything the Americans could do.

Doubts were universally expressed in America and in Allied Europe as to whether the Kaiser's government would permit President Wilson's crushing indictment of Prussianism to be published in Germany. One heard of picturesque schemes to drop millions of copies of the speech over the German trenches and towns from aeroplanes. In at least one widely-read German newspaper, the Berliner Tageblatt, a Radical-Liberal journal which has not entirely surrendered its old-time independence, the president's speech was printed almost verbatim. In nearly every paper there were adequate extracts. But such effect as they may have been designed to create upon the German body politic--particularly the president's insistence that America's war is with "the Imperial German Government" and not with "the German people"--was nullified by the press bureau's imperious orders to editors to reject Mr. Wilson's "moral clap-trap" as impudent and insolent interference with Germany's domestic concerns. Under the leadership of the celebrated Berlin theologian, Professor Doctor Adolf Harnack, meetings of German scholars and savants were organized for the purpose of giving public expression to the "unanimity and indignation with which the German nation protests against the American president's officious intrusion upon matters which are the affair of the German people and themselves alone." Or words to that effect.

Meantime the so-called comic press of Germany, which to an extent probably unknown in any other country of the world gives the keynote for popular sentiment, engaged in an orgy of unbridled abuse of President Wilson, the United States and Americans in general. The leitmotif of hundreds of cartoons, caricatures and jokes was that the "American money power" had "dragged" us into the war. Simplicissimus epitomized German thoughts of the moment in a full-page drawing entitled "High Finance Crowning Wilson Autocrat of America by the Grace of Mammon." The president was depicted enthroned upon a dais resting on bulging money-bags and surmounted by a canopy fringed with gold dollars. A crown of shells and cartridges is being placed upon his head by the grinning shade of the late J. Pierpont Morgan. In the background is the filmy outline of George Washington, delivering the farewell address.

Then, of a sudden, German press policy toward the United States underwent a radical change. Silence supplanted abuse. It became so oppressive and so profound as to be eloquent. The purpose of this organized indifference soon became crystal-clear: on the one hand to bolster up German confidence in the innocuousness of American enmity, and, on the other, to slacken the United States' war preparations by committing no "overt act" of word or deed designed to stimulate them. Bernstorff had by this time reached Berlin and there is reason to suspect that his was the crafty hand directing the new policy of ostensible disinterestedness in American belligerency. The arrival of American naval forces in European waters; the inauguration of conscription; the far-reaching preparations for succoring our Allies with money, food and ships; the splendid success of the Liberty Loan; the presence of General Pershing and the headquarters staff of the United States Army in France; the enrollment of nearly ten million young men for military service; our ambitious plans for the air war; the girding up of our loins in every conceivable direction, that we may play a worthy part in the war--all these things have been either deliberately ignored in Germany, by imperious government order, or, when not altogether suppressed from public knowledge, been slurred or glossed over in a way designed to make them appear as harmless or "bluff." Finally, in an "inspired" article which offered sheer affront to the large body of truly patriotic American citizens of German extraction, the Cologne Gazette bade Germans to continue to pin their faith in "our best allies," i.e., the German-Americans, who might be relied upon (quoth the semi-official Watch on the Rhine) to "inject into American public opinion an element of restraint and circumspection which has already often been a cause of embarrassment to Herr Wilson and his English friends." "We may be sure," concluded this impudent homily, "that our compatriots are still at their post."

Events have marched fast since America "came in." In Great Britain and France men of perspicacity are not quite so jubilant over the effects of the Russian revolution as they were three months ago. They realize that the amazing cataclysm which began in Petrograd on March 13 warded off a treacherous peace between Romanoff and Hohenzollern, but also, alas! that it has effectually eliminated Russia as a fighting factor for the purposes of this year's campaign. Englishmen and Frenchmen are only now beginning to comprehend the immeasurable task that confronts New Russia in the erection of a democratic state on the ruins of autocracy while faced by the simultaneous necessity of warring against an enemy in occupation of vast Russian territory.

To-day there is little inclination in London or Paris to underestimate the providential importance of American intervention. The specter of dwindling manpower in both countries is of itself sufficient to cause them to gaze gratefully and longingly toward our untapped reservoir of human sinews. What is happening in chaotic and liberty-dazed Russia forces Englishmen and Frenchmen, however disconcerting to their pride, to acknowledge the absolute indispensability of American support. There are many among them candid enough to admit that democracy's horizon might now be perilously beclouded if the United States had refrained from playing a man's part in the battle of the nations. In Berlin, too, the true import of America's decision is dawning upon government and governed alike.

Our Allies expect us to justify our world-wide reputation for speed and organizing capacity and to transfer our activities from the forum of Demosthenes to the field of Mars. They are impressed by what we have already accomplished--I write on the day when the arrival of the first American army in France, well within three months of our entering the war, is officially announced. But amid our remote isolation from the scene of the conflict, safeguarded by geographical guarantees that its consuming fires can hardly ever sear our own soil, Englishmen and Frenchmen wonder whether we are able to estimate the magnitude of the effort required of us if we are to rise to the majestic zenith of our potentialities. Some of them, seemingly no wiser for their myopia of recent times, are frankly skeptical on that point.

It is our bounden duty, as I am sure it is our unconquerable resolve, to disillusion our Allies. To us has fallen the privilege of proving that our mighty sword has been drawn in earnest and that we shall not sheathe it until America's plighted word is gloriously made good. "Make Good!" Leaping to the tasks which await us on land and sea with that indigenous idiom on their lips, our soldiers and sailors need crave for no more inspiring slogan. Allied Europe expects us--expects us almost anxiously--to "make good."

London, June 28, 1917.

THE ASSAULT

CHAPTER I

THE CURTAIN RAISER

Countess Hannah von Bismarck missed her aim. The beribboned bottle of "German champagne" with which she meant truly well to baptize the newest Hamburg-American leviathan of sixty thousand-odd tons on the placid Saturday afternoon of June 20, 1914, went far wide of its mark. The Kaiser, impetuous and resourceful, came gallantly and instantaneously to the rescue. Grabbing the bottle while it still swung unbroken in midair by the black-white-red silken cord which suspended it from the launching pavilion, Imperial William crashed it with accuracy and propelling power a Marathon javelin-thrower might have envied squarely against the vast bow. The granddaughter of the Iron Chancellor, a bit crestfallen because she had only thrown like any woman exclaimed: "I christen thee, great ship, Bismarck!" and the milky foam of the Schaumwein trickled in rivulets down the nine- or ten-story side of the most Brobdingnagian product which ever sprang from shipwrights' hands. Then, with ten thousand awestruck others gathered there on the Elbe side, I watched the huge steel carcass, released at last from the stocks which had so long held it prisoner, glide and creak majestically down the greasy ways midst our chanting of Deutschland, Deutschland, über Alles. Half a minute later the Bismarck was resting serenely, house-high, on the surface of the murky river five hundred yards away. The Kaiser and Herr Ballin shook hands feelingly, the royal monarch smiling benignly on the shipping king. The military band blared forth Heil Dir im Siegeskranz, and the last fête Hamburg was destined to know for many a troublous month had passed into history.

Countess von Bismarck had missed her aim! I wonder if there are not many, like myself, who witnessed the ill-omened launch and who endow it now with a meaning which events of the intervening year have borne out? For, surely, when the Great General Staff at Berlin reviews dispassionately the beginnings of the war, as it some day will do, there will be an absorbingly interesting explanation of how the machine which Moltke, the Organizer of Victory, handed down to an incompetent namesake and nephew missed its aim, too--the winning of the war by a series of short, sharp and staggering blows which should decide the issue in favor of the Germans before the next snow. The argument has been advanced, in vindication of Germany's innocent intentions, that the Hamburg-American line would never have launched the mighty Bismarck if the Fatherland was planning or contemplating war. But the ship was not to have made her maiden transatlantic voyage until April 1, 1915, the centenary of her great patronym's birth. The German Staff expected to dictate a glorious peace long before that time, and might have done so but for Belgium, Joffre, "that contemptible little British army," and other miscalculations. If the Staff, like Countess von Bismarck, had not missed its aim, the Bismarck would have poked her gigantic nose into New York harbor on scheduled time, a mammoth symbol of Germany, the World Power indeed, and fitting incarnation of the new Mistress of the Seas. Who knows but what perhaps grandiose visions of that sort were in the far-seeing Herr Ballin's card-index mind?

The Kaiser customarily visits the Venice of the North on his way to Kiel Week, the yachting festival invented by him to outrival England's Cowes, and the launch of the Bismarck was timed accordingly. From Hamburg the Emperor proceeds aboard the Imperial yacht Hohenzollern up the Elbe to Brunsbüttel for the annual regatta of the North German Yacht Squadron, a club consisting for the most part of Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck patricians with the love of the sea inborn in their Hanseatic veins. There was no variation from the time-honored programme in 1914. William II even adhered to his unfailing practice of delivering an apotheosis of the marine profession at the regatta-dinner of the N.G.Y.S. aboard the Hamburg-American steamer on which Herr Ballin is wont to entertain for Kiel Week a party of two or three hundred German and foreign notables. There was no glimmer of coming events in the guest-list of S.S. Victoria Luise, for it included Mr. John Walter, one of the hereditary proprietors of The Times, and several other distinguished Englishmen soon to be Germany's hated foes.

By that occult agency which determines with diabolical delight the irony of fate, it was ordained that Kiel, 1914, should be the occasion of a spectacular Anglo-German love-feast, with a squadron of British super-dreadnoughts anchored in the midst of the peaceful German Armada as a sign to all the world of the non-explosive warmth of English-German "relations." That, at any rate, was the design of that unfortunately nebulous element in Berlin, headed by Doctor von Bethmann Hollweg, known as the Peace Party; for had certain highly-placed Germans acting under the Imperial Chancellor's inspiration had their way, the British Admiralty yacht Enchantress, the official craft of the First Lord of the Admiralty and actually bearing that dignitary, Mr. Winston Churchill, M.P., would have been convoyed to Kiel by Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender's ironclads. The Kaiser's approval of the Churchill project--as I happen to know--had been sought and secured. Eminent friends of an Anglo-German rapprochement in London had done the necessary log-rolling in England. Matters were regarded in Germany so much of a fait accompli that an anchorage diagram issued by the naval authorities at Kiel only a fortnight before the "Week" indicated the precise spot at which Mr. Churchill and the Enchantress would make fast in the harbor of Kiel Bay.

But Mr. Churchill did not come. I know why. Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz, to whom the half-American enfant terrible of British politics was a pet aversion, did not want him at Kiel. Mr. Churchill's visit might have resulted in some sort of an Anglo-German naval modus vivendi, or otherwise postponed "the Day." The German War Party's plans, so soon to materialize, would have been sadly thrown out of gear by such an untimely event, and von Tirpitz is not the man to brook interference with his programmes. Had not the German Government, under the Grand-Admiral's invincible leadership, persistently rejected the hand of naval peace stretched out by the British Cabinet? Was it not Mr. Churchill's own proposals to which Berlin had repeatedly returned an imperious No? Could Germany afford to run the risk of being cajoled, amid the festive atmosphere of Kiel Week, into concessions which she had hitherto successively withheld? Von Tirpitz said No again. For years he had been saying the same thing on the subject of an armaments understanding with Britain. He said No to Prince Bülow when the fourth Chancellor suggested the advisability of moderating a German naval policy certain to lead to conflict with Great Britain. He said No to Doctor von Bethmann Hollweg when Bülow's successor timorously suggested from time to time, as he did, the foolhardiness of a programme which meant, in an historic phrase of Bülow's, "pressure and counter-pressure." Von Tirpitz had had his way with two German Chancellors, his nominal superiors, in succession. He never dreamt of allowing himself to be bowled over now by an amateur sailor from London, who, if he came to Kiel, would only come armed with a fresh bait designed to rob the Fatherland of its "future upon the water."

Until a bare two weeks before the date of the arrival of the British Squadron in German waters, nothing was publicly known either in London or Berlin of the projected trip of Mr. Churchill to Kiel. Von Tirpitz thereupon had resort to the weapon he wields almost as dexterously as the submarine--publicity--to depopularize the scheme of the misguided friends of Anglo-German peace. It was not the first time, of course, that the Grand-Admiral had deliberately crossed the avowed policy of the German Foreign Office. Von Tirpitz now caused the Churchill-Kiel enterprise to be "exposed" in the press, in the confident hope that premature announcement would effectually kill the entire plan. It did. Tirpitz diplomacy scored again, as it was wont to do. Whereof I speak in this highly pertinent connection I know, on the authority of one of von Tirpitz's most subtle and trusted henchmen. To the latter's eyes, I hope, these reminiscences may some day come. He, at least, will know that history, not fiction, is recited here.

CHAPTER II

THE FIRST ACT

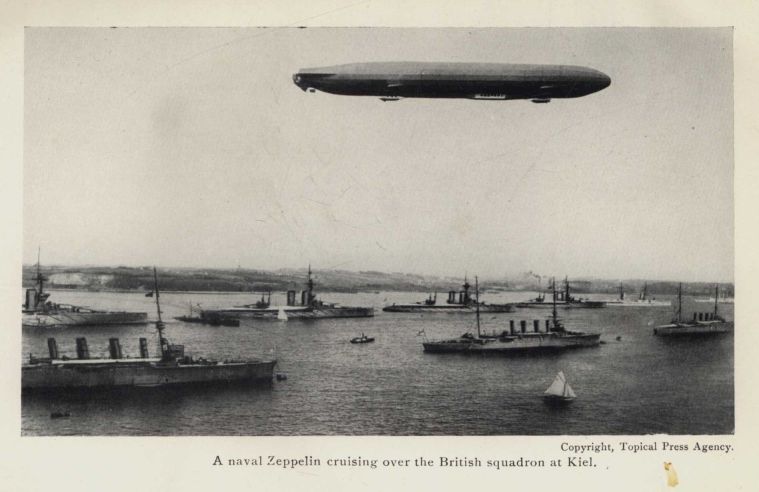

"I am simply in my element here!" exclaimed the Kaiser ecstatically to Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender, as the twain stood surveying the glittering array of steel-blue German and British men-of-war facing one another amicably on the unruffled bosom of Kiel harbor at high noon of June 25. From my perch of vantage abaft the forward thirteen-and-one-half-inch guns of His Britannic Majesty's superdreadnought battleship King George V, whither the quartette of London correspondents had been banished during William II's sojourn in the flagship, I could "see" him talking on the quarter-deck below, speaking with those nervous, jerky right-arm gestures which are as important a part of his staccato conversation as uttered words.

The Kaiser was inspecting his flagship, for when he boarded us, almost without notice, in accordance with his irrepressible love of a surprise, Sir George Warrender's flag came down and the emblem of the German Emperor's British naval rank, an Admiral of the Fleet, was hoisted atop all the British vessels in the port. For the nonce the Hohenzollern War Lord was Britannia's senior in command. Aboard the four great twenty-three-thousand-ton battleships, King George V, Audacious, Centurion and Ajax and the three fast "light cruisers" Birmingham, Southampton and Nottingham there was, for the better part of an hour, no man to say him nay. I wonder if he, or any of us at Kiel during that amazing week, let our imaginations run riot and conjure up the vision of the Birmingham in action against German warships off Heligoland within ten short weeks, or of the Audacious at the bottom of the Irish Sea, victim of a German mine, five months later?

Warrender's squadron had come to Kiel two days before. Another British squadron was at the same moment paying a similar visit of courtesy and friendship to the Russian Navy at Riga. The English said then, and insist now, that their ships were dispatched to greet the Kaiser and the Czar as sincere messengers of peace and good-will. The Germans, in the myopic view they have taken of all things since the war began, are convinced that the White Ensign which floated at Kiel six weeks before Great Britain and Germany went to war was the emblem of deceit and hypocrisy, sent there to flap in the Fatherland's guileless face while Perfidious Albion was crouching for the attack. They say that to-day, even in presence of the incongruous fact that Serajevo, which applied the match to the European powder-barrel, wrote its red name across history's page while the British squadron was still riding at anchor in Germany's war harbor.

It was exactly ten years to the week since British warships had last been to Kiel. I happened to be there on that occasion, too, when King Edward VII, convoyed by a cruiser squadron, shed the luster of his vivacious presence on the gayest "Week" Kiel ever knew. Meantime the Anglo-German political atmosphere had remained too stubbornly clouded to make an interchange of naval amenities, of all things, either logical or possible. It was the era in which Germania was preparing her grim battle-toilet for "the Day"--for all the world to see, as she, justly enough, always insisted. They were the years in which her new dreadnought fleet sprang into being. It was the period in which offer after offer from England for an "understanding" on the question of naval armaments met nothing but the cold shoulder in Tirpitz-ruled Berlin. Not until the summer of 1914 had it seemed feasible for British and German warships to mingle in friendly contact. Doctor von Bethmann Hollweg quite legitimately accounted the arrangement of the Kiel love-feast as an achievement of no mean magnitude, viewed in the light of the ten acrimonious years which preceded it. The War Party, realizing its harmlessness, and, indeed, recognizing its value for the party's stealthy purposes, blandly tolerated it. Even Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz was on hand to do the honors, and no one performs them more suavely than Germany's fork-bearded sailor-statesman.

The day after Sir George Warrender's vessels crept majestically out of the Baltic past Friedrichsort, at the mouth of Kiel harbor, to be welcomed by twenty-one German guns from shore batteries, the symptomatic event of the "Week" was enacted--the formal opening of the reconstructed Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. I place that day, June 24, not far behind the sanguinary 28th of June, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand fell, in its direct relationship to the outbreak of the war. When the giant locks of Holtenau swung free, ready henceforth for the passage of William II's greatest warships, the moment of Germany's up-to-the-minute preparedness for Armageddon was signalized.

For ten plodding years tens of thousands of hands had been at work converting the waterway which links Baltic Germany with North Sea Germany (Kiel with Wilhelmshaven) into a channel wide and deep enough for navigation by battleships of the largest bulk. After an expenditure of more than fifty million dollars the canal, dedicated with pomp and ceremony in 1892 to the peaceful requirements of European shipping, was now become a war canal, pure and simple, raised to the war dimension and destined, as the German War Party knew, to play the role for which it was rebuilt almost before its newly-banked stone sides had settled in their foundations. When I watched proud William II, standing solemn and statue-like on the bridge of his Imperial yacht Hohenzollern, as her gleaming golden bow broke through the black-white-red strand of ribbon stretched across the locks, I recall distinctly an invincible feeling that I was witness of an historic moment. Germany's army, I said to myself, had long been ready. Now her fleet was ready, too. With an inland avenue of safe retreat, invulnerably fortified at either end, Teuton sea strategists had always insisted that the Fatherland's naval position would be well-nigh impregnable. That hour had arrived. There was the Kaiser, before my very eyes, leading the way through the War Canal for his twenty-seven-thousand-five-hundred-ton battleships and battle cruisers, and even for his thirty-five-thousand-ton or fifty-thousand-ton creations of some later day, for the War Canal was made over for to-morrow, as well as for to-day. The German war machine tightened up the last bolt when William of Hohenzollern emerged from Holtenau locks into the harbor of Kiel, spectacular symbol of the fact that German ironclads of any dimensions were now able to sally back and forth from the Baltic to the North Sea and hide for a year, as the world has meantime seen, even from the Mistress of the Seas. No wonder a British bluejacket, forming the link of an endless chain of his fellows dressing ship round the rail of the Centurion in honor of the War Lord, whispered audibly to a mate, as the Hohenzollern steamed down the line to her anchorage, "Say, Bill, don't he look jest like Gawd!" Perhaps the Divinely-Anointed felt that way, too.

When the Kaiser had left the King George V after a politely cursory "inspection"--the only real "understanding" effected between England and Germany at Kiel was a tacit agreement on the part of officers and men to do no amateur spying in one another's ships--Sir George Warrender summoned us from the turret and told us some details of the All-Highest visitation. The Emperor had been "delighted to make his first call in a British dreadnought aboard so magnificent a specimen as the King George V" (she and her sisters being at the time the most powerful battleships flying the Union Jack). He wanted the Vice-Admiral to assure the British Government what pleasure it had done the German Navy "in sending these fine ships to Kiel." He hoped nothing was being left undone to "complete the English sailors' happiness" in German waters. That extorted from Sir George Warrender the exclamation that German hospitality, like all else Teutonic, was seemingly thoroughness personified, for somebody had even been thoughtful enough to lay a submarine telephone cable from the Seebade-Anstalt Hotel to the Vice-Admiral's flagship, so that Lady Maude Warrender might talk from her apartments on shore directly to her husband's quarters afloat.

"Yes," continued the Kaiser, who is a genial conversationalist and raconteur, "I am in my element in surroundings like these. I love the sea. I like to go to launchings of ships. I am passionately fond of yachting. You must sail with me to-morrow, Admiral, in my newest Meteor, the fifth of the name. I race only with German crews now. Time was when I had to have British skippers and British sailors. You see, my aim is to breed a race of German yachtsmen. As fast as I've trained a good crew in the Meteor, I let it go to the new owner of the boat. I am the loser by that system, but I have the satisfaction of knowing that I am promoting a good cause." The confab was approaching its end. "Oh, Admiral, before I forget, how is Lady ........ and the Duchess of ........? I know so many of your handsome Englishwomen."

Sir George Warrender's captains and the officers of the flagship were now grouped around him for a farewell salute to their Imperial senior officer. The Kaiser spied the King George V's chaplain, and leaning over to him inquired, gaily, "Chaplain, is there any swearing in this ship?" "Oh, never, Your Majesty, never any swearing in a British dreadnought!" The War Lord liked that, for we who had been in the Olympian heights for'd remembered his laughing aloud at this veracious tribute to Jack Tar's world-famed purity of diction.

Kiel Week thenceforward was an endless round of Anglo-German pleasantries. A Zeppelin, harbinger of coming events, hovered over the British squadron at intervals, her crew wagging cheery greetings to the ships while acquainting themselves at close range with the looks of English dreadnoughts from the sky. British sailormen paid fraternal visits to German dreadnoughts and German sailormen returned their calls. The crew of the Ajax gave a music-hall smoker in honor of the crew of the big battle-cruiser Seydlitz, the Teuton tars being no little awestruck by the complacency with which two heavyweight British boxers pummeled each other a sea-green for six rounds and then smilingly shook hands when it was all over. Germans never punch one another except in gory hate, and they seldom fight with their fists. The Kaiser was host nightly at splendid State dinners in the Hohenzollern and Vice-Admiral Warrender returned the fire with state banquets aboard the King George V. The atmosphere was fairly thick with brotherly love. It was not so much as ruffled even when the octogenarian Earl of Brassey, who wards off rheumatism by an early morning pull in his row-boat, was arrested by a German harbor-policeman as an "English spy" for approaching the forbidden waters of Kiel dockyard. German diplomacy was typically represented by Lord Brassey's zealous captor, for the master of the famous Sunbeam brought that venerable craft to Kiel to demonstrate that Englishmen of his class sincerely favored peace, and, if possible, friendship with Germany. Wilhelmstrasse tact was exemplified again when, by way of apology to Lord Brassey, the Kiel police explained that there was, of course, no intention of charging him with espionage. The policeman who arrested him merely thought he was nabbing a smuggler! At dinner that night in the Hohenzollern, the Kaiser chuckled jovially at Lord Brassey's expense. England's greatest living marine historian stole away from Kiel with the Sunbeam in the gray dawn of the next day, with new ideas of German courtesy to the stranger within the gate. He had intended to stay longer.

Of all the billing and cooing at Kiel there is photographed most indelibly on my memory the glorious jamboree of the sailors of the British and German squadrons in the big assembly hall at the Imperial dockyard on the Saturday night of the "Week." There were free beer, free tobacco, free provender for everybody, in typical German plenty. A ship's band blared rag-time and horn-pipes all night long. Only the supply of Kiel girls fell short of the demand, but that only made merrier fun for the bluejackets, who, lacking fair partners, danced with one another, and when the hour had become really hilarious, they tripped across the floor, when they were not rolling over it, embracing in threes, bunny-hugging, grotesquely tangoing, turkey-trotting and fish-walking more joyously than men ever reveled before.

There, I thought, was Anglo-German friendship in being--not an ideal, but an actuality. I am sure the British and German tars at Kiel that boisterous Saturday night which melted into the Sunday of Serajevo little dreamt that when next they would be locked in one another's arms, it would be at grips for life or death.

CHAPTER III

THE PLOT DEVELOPS

Von G. is a Junker. He is also Germany's ablest special correspondent. A Junker, let the uninitiated understand, is a Prussian land baron, or one of his descendants, who considers dominion over the earth and all its worms his by Divine Right. If, like von G., a Junker is an army officer besides, active or ausser Dienst, and had a grandfather who belonged to Moltke's headquarters in 1870-71, he is the superlatively real thing. So, as my mission in Germany was study of the Fatherland in its characteristic ramifications, I always felt myself richly favored by the friendship and professional comradeship of von G. He was Junkerism incarnate. Several years' residence in the United States had signally failed to corrode von G.'s Junker instincts. Indeed, it intensified them, for he was ever after a confirmed believer in the ignominious failure of Democracy. It was he who popularized "Dollarica" as a German nickname for "God's country."

Von G. and I roomed together at Kiel, sharing apartments and a bath in the harbormaster's flat above the Imperial Yacht Club postoffice, whose two stories of brick and stucco serve as "annex" to the always overcrowded and palatial Krupp hotel, the Seebade-Anstalt, at the other end of the flowered club grounds. That bath, which I mention in no spirit of ablutionary arrogance, has to do with the story of von G., for it was to bring me on a day destined to be historic in violent conflict with Junkerism. Von G. and I regulated the bath situation at Kiel by leaving word on our landlady's slate the night before which of us would bathe first next morning and at what hour. The bath happened to adjoin my sleeping quarters and von G. could not reach it except by crossing my bedroom, which he always entered without knocking. On Sunday, June 28, fateful day, von G. was timed to bathe at eight A.M., I at nine--so read the schedule inscribed by our respective hands on the good Frau Hafenmcistcr's tablet. At seven-thirty I was roused from my feathered slumbers by her soft footsteps--the softest steps of German harbormasters' wives are quite audible--as she trundled across the room to arrange Herr von G.'s eight o'clock dip. Junkers are punctual people, but that morning mine was late. Eight, eight-thirty, eighty-forty-five passed, and there was no sign of him. When nine o'clock came, I thought I might reasonably conclude, in my rude, inconsiderate American way, that von G. had overslept or postponed his bath, so I made for the tub at the hour I had intended to. I was just stepping one foot into it when--it was nine-ten now--von G., rubbing his eyes, bolted in.

"What do you mean by taking my bath?" he yelled at me. "That's some of your damned American impudence!"

Whereupon, imperturbably pouring the rest of me into the bath, I ventured to suggest to Field-Marshal von G., that if he would drop the barrack-yard tone and remember that I was neither a Dachshund nor a Pomeranian recruit, I would deign to hold converse on the point under debate. I am not sure I spoke as calmly as that sounds, for to gain a conversational lap on a German you must outshout him. At any rate, von G., abandoning abuse, stalked whimperingly from the room, fired some rearguard shrapnel about "just like an American's 'nerve'," and bathed later in the day.

I did not see him again until about five o'clock that afternoon. He bolted into my room this time, too, but in excitement, not anger.

"The Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife have been assassinated," he exclaimed.

"Good God!" I rejoined, stupefied.

"It's a good thing," said von G. quietly.

For many days and nights I wondered what the Junker meant. I think I know now. He meant that the War Party (of which he was a very potent and zealous member) had at length found a pretext for forcing upon Europe the struggle for which the German War Lords regarded themselves vastly more ready than any possible combination of foes. The first year of the war has amply demonstrated the accuracy of their calculations. Germany's triumphs in the opening twelvemonth of Armageddon were the triumphs of the superlatively prepared. If Serajevo had not come along when it did--with the German military establishment just built up to a peace-footing of nearly one million officers and men and re-armed at a cost of two hundred and fifty million dollars; with von Tirpitz's Fleet at the acme of its efficiency; with the Kiel Canal reconstructed for the passage of super-dreadnought ironclads--Germany's readiness for war might have been fatally inferior to that of her enemies-to-be. The Fatherland was ready, armed to the teeth, as nation never was before. The psychological moment had dawned.

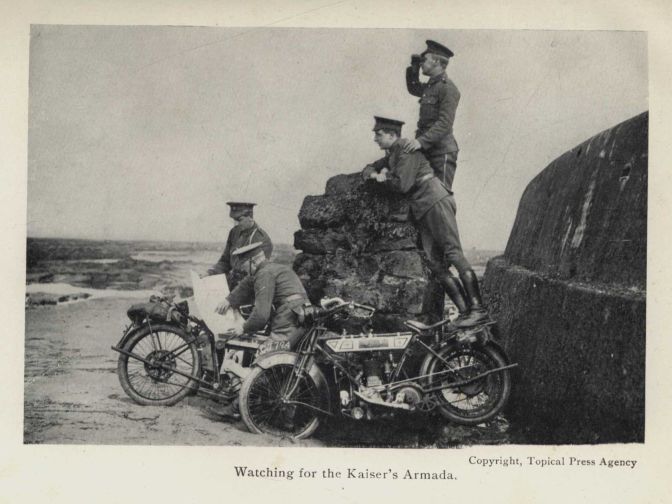

This was the reassuring state of affairs at home. What did the War Party see when it put its mailed hand to the vizor and looked abroad, across to England, west over the Rhine to France, and toward Russia? It saw Great Britain on what truly enough looked to most of the world like the brink of revolution in Ireland. It saw a France, of which a great Senator had only a few days before said that her forts were defective, her guns short of ammunition and her army lacking in even such rudimentary war sinews as sufficient boots for the troops. It saw a Russia stirred by industrial strife which seemed to need only the threat of grave foreign complications to inflame her always rebellious proletariat into revolt. Serajevo had all the earmarks of providential timeliness.

"It's a good thing," said the sententious von G.

The "trippers" from Hamburg and nearer-by points in Schleswig-Holstein, whom the Sunday of Kiel Week attracts by the thousand, were far more stunned than von G. by the news from Bosnia, which put so tragic an end to their seaside holiday. The esplanade, which had been throbbing with bustle and glittering with color, did not know at first why all the ships in the harbor, British as well as German, had suddenly lowered their pennants to half-mast, or why the Austrian royal standard had suddenly broken out, also at the mourning altitude. The Kaiser was racing in the Baltic. "Old Franz Josef," some said, "has died. He's been going for many a day." Presently the truth percolated through the awestruck crowds. The sleek white naval dispatch-boat Sleipner tore through the Bay, Baltic-bound. She carries news to William II when he governs Germany from the quarter-deck of the Hohenzollern. Sleipner dodged eel-like, through the lines of British and German men-of-war, ocean liners, pleasure-craft and racing-yachts anchored here, there and everywhere. In fifteen minutes she was alongside the Emperor's fleet schooner, Meteor V, which had broken off her race on receipt of wireless tidings of the Archducal couple's murderous fate. The Hohenzollern had already "wirelessed" for the fastest torpedo-boat in port to fetch the Kaiser and his staff off the Meteor, and the destroyer and Sleipner snorted up, foam-bespattered, almost simultaneously. The Emperor clambered into the torpedo-boat and started for the harbor.

It was the face of a William II, blanched ashen-gray, which turned from the bridge of the destroyer to acknowledge, in solemn gravity, the salutes of the officers and crew of the British flagship, as the Kaiser's craft raced past the King George V. Always stern of mien, the Emperor now looked severity personified. His staff stood apart. He seemed to wish to be alone, absolutely, with the overwhelming thoughts of the moment. Three minutes later, and he stepped aboard the Hohenzollern. Now another pennant showed at the mainmast of the Imperial yacht--the blue and yellow signal flag which means: "His Majesty is aboard, but preoccupied." I wonder if posterity will ever know what monumental reflections flitted through the Kaiser's mind in that first hour after Serajevo? Did he, like von G., think it was "a good thing," too? I suppose the first stars and stripes to be half-masted anywhere in the world that dread sundown were those which drooped from the stern of Utowana, Mr. Allison Vincent Armour's steam-yacht, anchored in the Bay off Kiel Naval Academy. A puffing little launch took me out to the Utowana as soon as I had gathered some coherent facts, which I wanted to present to Mr. Armour and his guests, American Ambassador and Mrs. James W. Gerard, of Berlin, who had motored to Kiel the day before. Mrs. Gerard's sister, Countess Sigray, is the wife of a Hungarian nobleman, and the Ambassador's wife, if my memory serves me correctly, once told me of her sister's acquaintance with both of the assassinated Royalties. We Americans discussed the immediate consequences of the day's event--how the Kaiser would take it, how it would affect poor old Emperor Francis Joseph. William II and Admiral von Tirpitz had been the Archduke's guests at Konopischt in Bohemia only a few weeks before. The Kaiser and the future ruler of Austria-Hungary had become great friends. They were not always that. There had been a good deal of the William II in Franz Ferdinand himself. People often said it was a case of Greek meet Greek, and that two such insistent personalities were inevitably bound to clash. Others said that the Archduke, inspired by his brilliantly clever consort, always insisted that German overlordship in Vienna would cease when he came to the throne. Still others knew that despite antipathies and antagonisms, the two men had at length come to be genuinely fond of each other, and that their ideas and ideals for the greater glory of Germanic Europe coincided.

These things we chatted and canvassed, irresponsibly, on Utowana's immaculate deck. All of us were persuaded of the imminency of a crisis in Austrian-Serbian relations in consequence of Princip's crime. But I am quite sure not a soul of us held himself capable of imagining that, because of that remote felony, Great Britain and Germany would be at war five weeks later. Beyond us spread the peaceful panorama of British and German war-craft, anchored side by side, and the thought would have perished at birth.

Returned to the terrace of the Seebade-Anstalt, one found the atmosphere heavily charged with suppressed excitement. Immaculately-groomed young diplomats, down from Berlin for the Sunday, were twirling their walking-sticks and yellow gloves which were not, after all, to accompany them to Grand-Admiral Prince Henry of Prussia's garden-party. That, like everything else connected with Kiel Week, had suddenly been called off.

A party of Americans flocked together at the entrance to the hotel to exchange low-spoken views on the all-pervading topic. There was big Lieutenant-Commander Walter R. Gherardi, our wide-awake Berlin Naval Attaché, resplendent in gala gold-braided uniform, and Mrs. Gherardi, who had motored me around the environs of Kiel that morning; Albert Billings Ruddock, Third Secretary of the Embassy, and his pretty and clever wife; and Lanier Winslow, Ambassador Gerard's private secretary, his effervescent good nature repressed for the first time I ever remembered observing it in that unbecoming and unnatural condition. Secretary Ruddock's father, Mr. Charles H. Ruddock, of New York, completed the group.

I met Mr. Ruddock, Sr., six months later in New York. "Do you remember what you told me that afternoon at Kiel, when we were discussing Serajevo?" he asked. I pleaded a lapse of recollection. "You said," he reminded me, "'this means war.'"

The aspect of Kiel became in the twinkling of an eye as funereal as Serajevo and Vienna themselves must have been in that blood-bespattered hour. Bands stopped playing, flags not lowered to half-mast were hauled down altogether, and beer-gardens emptied. "Hohenzollern weather," Teuton synonym for invincible sunshine, vanished in keeping with the drooping spirits of everybody and everything, and bleak thunder-showers intermingled with flashes of heat-lightning to complete the mise en scène. A week of gaiety unsurpassed evaporated into gloom and foreboding.

For myself it had been a week crowded with great recollections. Special correspondents telegraphing to influential foreign newspapers, particularly if they were English and American newspapers, were always persona gratissima with German dignitaries, even of the blood royal. The group of us on duty at what, alas! was to be the last Kiel Week, at least of the old sort, for many a year, were the recipients, as usual, of that scientific hospitality which foreign newspapermen always receive at German official hands. Before we were at Kiel twenty-four hours we were deluged with invitations to garden-parties at the Commanding Admiral's, to soirees innumerable ashore and afloat, to luncheons at the Town Hall, to the grand balls at the Naval Academy, and to functions of lesser magnitude for the bluejackets. Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz had left his card at my lodgings and so had Admiral von Rebeur-Paschwitz, the Chief of Staff of the Baltic Station, who will be pleasantly remembered by friends of Washington days when he was German Naval Attaché there. Captain Lohlein, the courteous chief of the Press Bureau of the Navy Department at Berlin, had equipped me with credentials which practically made me a freeman of Kiel harbor for the time being. In no single direction was effort lacking, on the part of the authorities who have the most practical conception of any Government in the world of the value of advertising, to enable special correspondents at Kiel to practise their profession comfortably and successfully. I must not forget to mention the visit paid me by Baron von Stumm, chief of the Anglo-American division of the German Foreign Office; for Stumm's opinion of me underwent a kaleidoscopic and mysterious change a few weeks later. Treasured conspicuously in my memories of Kiel, too, will long remain the call I received from Herr Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach's private secretary, and the message he brought me from the Master of Essen. It seems less cryptic to me now than then. I sought an interview from the Cannon Queen's consort about the visit he and his staff of experts had just paid to the great arsenals and dockyards of Great Britain.

"Herr Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach presents his compliments," said the secretary, "and asks me to say how much he regrets he can not grant an interview, as the matters which took him to England are not such as he cares to discuss in public."

I wonder how many American newspaper readers, in the hurly-burly of the fast-marching events which preceded and ushered in the war, ever knew of the little army of eminent and expert "investigators" who honored England with their company on the very threshold of hostilities? June saw the presence in London, ostensibly for "the season," of Herr Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, accompanied not only by his plutocratic wife, but by his chief technical expert, Doctor Ehrensberger of Essen, an old-time friend of American steel men like Mr. Schwab and ex-Ambassador Leishman, and by Herr von Bülow, a kinsman of the ex-Imperial Chancellor, who was the Krupp general representative in England. With a naïveté which Britons themselves now regard almost incomprehensible, the Krupp party was shown over practically all of England's greatest weapons-of-war works at Birkenhead, Barrow-in-Furness, Glasgow, Newcastle-on-Tyne and Sheffield. They saw the world-famed plants of Firth, Cammell-Laird, Vickers-Maxim, Brown, Armstrong-Whitworth and Hadfield. Not with the eyes of Cook tourists, but with the practised gaze of specialists, they were privileged to look upon sights which must have sent them away with a vivid, up-to-date and accurate impression of Britain's capabilities in the all-vital realm of production of war materials for both army and navy. It was from this personally conducted junket through the zone of British war industry that Herr Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach returned--not to Essen, but to Kiel (where he has his summer home) and to the Kaiser and von Tirpitz. It was to them his report was made. I think I understand better now why he could not see his way to letting me tell the British public what he saw and learned in England. I was guileless when I sought the interview. Let this be my apology to Herr Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach for attempting to penetrate into matters obviously not fit "to discuss in public."

During July England entertained three other important German emissaries, each a specialist, as befitted the country of his origin and the object of his mission. Doctor Dernburg came over. He spent ten strenuous days "in touch" with financial and economic circles and subjects. No man could be relied upon to bring back to Berlin a shrewder estimate of the British commercial situation. A few days later Herr Ballin, the German shipping king, crossed the channel. I recall telegraphing a Berlin newspaper notice which explained that the astute managing director of the Hamburg-American line went to England to "look into the question of fuel-oil supplies." Herr Ballin, like Doctor Dernburg, also kept "in touch" with the British circles most important and interesting to himself and the Fatherland. He must have dabbled in high politics a bit, too, for only the other day Lord Haldane revealed that he arranged for Herr Ballin to "meet a few friends" at his lordship's hospitable home at Queen Anne's Gate. Germans always felt a proprietary right to seek the hospitality of the Scotch statesman who acknowledged that his spiritual domicile was in the Fatherland.

Then, finally, came another German, far more august than Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Dernburg and Ballin--Grand-Admiral Prince Henry of Prussia. His visit fell within a week of Germany's declaration of war against France and Russia. The Prince, who enjoyed many warm friendships in England and visited the country at frequent intervals, also spent a busy week in London. He saw the King, called on with Prince Louis of Battenberg, the then First Sea Lord, and paid his respects to Mr. Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. Englishmen only conjecture how he put in the rest of his time.

Perhaps an episode in the trial of Karl Lody, the German naval spy who was executed at the Tower of London on November 6, has its place in the unrecorded history of Prince Henry of Prussia's epochal visit to the British Isles. Lody confessed to his military judges at Middlesex Guildhall that he received his orders to report on British naval preparations from "a distinguished personage."

"Give us his name," commanded Lord Cheylesmore, presiding officer of the court.

"I would rather not tell it in open court," pleaded the prisoner, whom Scotland Yard, the day before, had asked me to look at, with a view to possible identification with certain Berlin affiliations.

"I will write his name on a piece of paper for the court's confidential information," Lody added. His request was granted.

When we were officially notified that the Kaiser would proceed next morning by special train to Berlin, we made our own preparations to depart. The British squadron had still a day and a half of its scheduled visit to complete, and Vice-Admiral Warrender told us he would remain accordingly. The German Admiralty had extended him the hospitality of the new War Canal for the cruise of his fleet into the North Sea, but he decided to send only the light cruisers by that route and take his battleships home, as they had come, by the roundabout route of the Baltic.

On Monday noon, June 29, I went back to Berlin, to live through five weeks of finishing touches for the grand world blood-bath.

CHAPTER IV

THE STAGE MANAGERS

Armageddon was plotted, prepared for and precipitated by the German War Party. It was not the work of the German people. What is the "War Party"? Let me begin by explaining what it is not. It is not a party in the sense of President Wilson's organization or Colonel Roosevelt's Bull Moosers. It maintains no permanent headquarters or National Committee, and holds no conventions. The only barbecue it ever organized is the one which plunged the world into gore and tears in August, 1914, though its attempts to drench Europe with blood are decade-old. You would search the German city directories in vain for the War Party's address or telephone number. No German would ever acknowledge that he belonged to Europe's largest Black Hand league. You could, indeed, hardly find anybody in Germany willing even to acknowledge that the War Party even existed. Yet, unseen and sinister, its grip was fastened so heavily upon the machinery of State that when it deemed the moment for its sanguinary purposes at length ripe, the War Party was able to tear the whole nation from its peaceful pursuits and fling it, armed to the teeth, against a Europe so flagrantly unready that more than a year of strife finds Germany not only unbeaten but at a zenith of fighting efficiency which her foes have only begun to approach.

When the German War Party pressed the button for the Great Massacre, the Fatherland had, roundly, sixty-seven million five hundred thousand inhabitants within its thriving walls. At a liberal estimate, no one can ever convince me that more than one million five hundred thousand Germans really wanted war. They were the "War Party." Sixty-six millions of the Kaiser's subjects, immersed in the most abundant prosperity any European country of modern times had been vouchsafed, longed only for the continuance of the conditions which had brought about this state of unparalleled national weal. I do not believe that William II, deep down in his heart, craved for war. I can vouch for the literal accuracy of a hitherto unrecorded piece of ante-bellum history which bears out my doubts of the Kaiser's immediate responsibility for the war, though it does not acquit him of supine acquiescence in, and to that extent abetting, the War Party's plot.

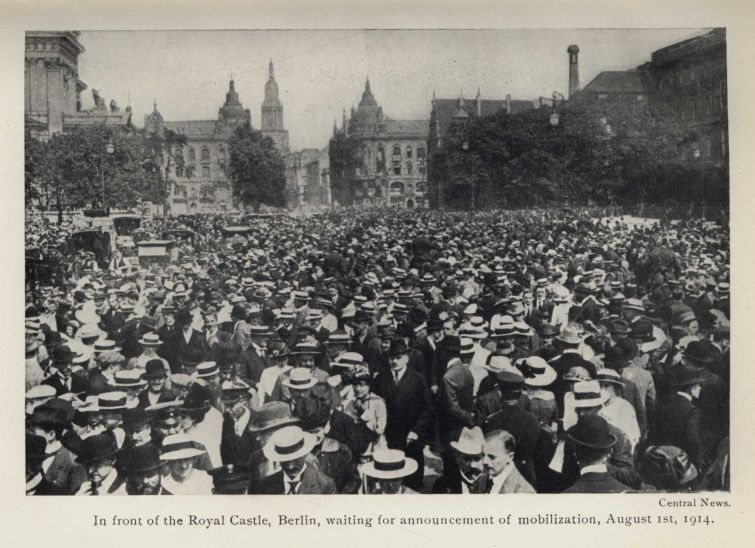

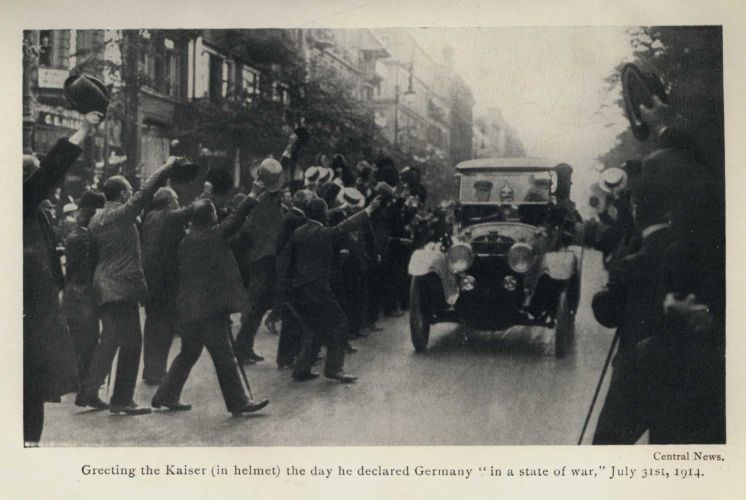

On the afternoon of Saturday, August 1, 1914, the wife of Lieutenant-General Helmuth von Moltke, then Chief of the Great German General Staff, paid a visit to a certain home in Berlin, which shall be nameless. The Frau Generalstabschef was in a state of obvious mental excitement.

"Ach, what a day I've been through, Kinder!" she began. "My husband came home just before I left. Dog-tired, he threw himself on to the couch, a total wreck, explaining to me that he had finally accomplished the three days' hardest work he had ever done in his whole life--he had helped to induce the Kaiser to sign the mobilization order!"

There is the evidence, disclosed in the homeliest, yet the most direct, fashion, of the German War Party's unescapable culpability for the supreme crime against humanity. The "sword" had, indeed, been "forced" into the Kaiser's hand. This is no brief for the Kaiser's innocence. No man did more than William II himself, during twenty-six years of explosive reign, to stimulate the military clique in the belief that when the dread hour came the Supreme War Lord would be "with my Army." Yet German officers, in those occasional moments when conviviality bred loquacity, were fond of averring, as more than one of them has averred to me, that "the Kaiser lacked the moral courage to sign a mobilization order." Die Post, a leading War Party organ, said as much during the Morocco imbroglio in 1911. Perhaps that is why General von Moltke had to force the pen, which for the nonce was mightier than the sword, into the reluctant hand of William II.