Title: The Arm-Chair at the Inn

Author: Francis Hopkinson Smith

Illustrator: Arthur Ignatius Keller

Herbert Ward

Release date: November 3, 2012 [eBook #41284]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander, The Internet Archive (TIA) and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

THE ARM-CHAIR AT THE INN

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

A. I. KELLER, HERBERT WARD

AND THE AUTHOR

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1912

Copyright, 1912, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published August, 1912

[v]

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

If I have dared to veil under a thin disguise some of the men whose talk and adventures fill these pages it is because of my profound belief that truth is infinitely more strange and infinitely more interesting than fiction. The characters around the table are all my personal friends; the incidents, each and every one, absolutely true, and the setting of the Marmouset, as well as the Inn itself, has been known to many hundreds of my readers, who have enjoyed for years the rare hospitality of its quaint and accomplished landlord.

F. H. S.

November, 1911

[vi]

[vii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Marmouset | 3 |

| II. | The Wood Fire and Its Friends | 18 |

| III. | With Special Reference to a Certain Colony of Penguins | 34 |

| IV. | The Arrival of a Lady of Quality | 60 |

| V. | In which the Difference Between a Cannibal and a Freebooter is Clearly Set Forth | 95 |

| VI. | Proving that the Course of True Love Never Did Run Smooth | 120 |

| VII. | In which Our Landlord Becomes Both Entertaining and Instructive | 144 |

| VIII.[viii] | Containing Several Experiences and Adventures Showing the Wide Contrasts in Life | 163 |

| IX. | In which Madame la Marquise Binds Up Broken Heads and Bleeding Hearts | 182 |

| X. | In which We Entertain a Jail-bird | 211 |

| XI. | In which the Habits of Certain Ghosts, Goblins, Bandits, and Other Objectionable Persons Are Duly Set Forth | 240 |

| XII. | Why Mignon Went to Market | 267 |

| XIII. | With a Dissertation on Round Pegs and Square Holes | 280 |

| XIV. | A Woman’s Way | 304 |

| XV. | Apple-blossoms and White Muslin | 335 |

[ix]

| Mignon | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Howls of derision welcomed him | 30 |

| Flooding the garden, the flowers, and the roofs | 60 |

| As her boy’s sagging, insensible body was brought clear of the wreck | 132 |

| Herbert caught up his sketch-book and ... transferred her dear old head ... to paper | 184 |

| Lemois crossed the room and began searching through the old fifteenth-century triptych | 240 |

| “Just think, monsieur, what does go on below Coco in the season” | 308 |

| First, of course, came the mayor—his worthy spouse on his left | 350 |

[x]

“How many did you say?” inquired Lemois, our landlord.

“Five for dinner, and perhaps one more. I will know when the train gets in. Have the fires started in the bedrooms and please tell Mignon and old Leà to put on their white caps.”

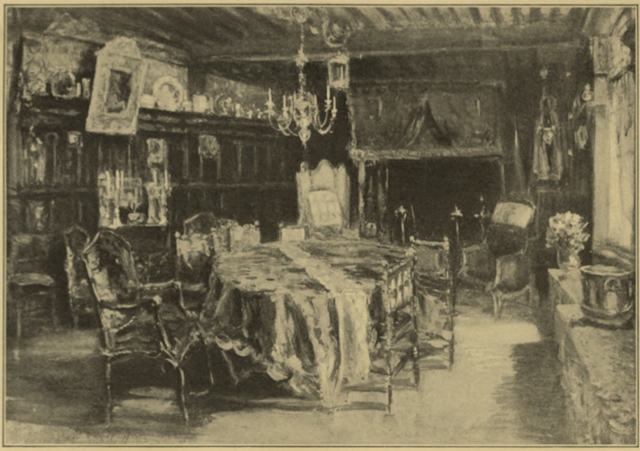

We were in the Marmouset at the moment—the most enchanting of all the rooms in this most enchanting of all Normandy inns. Lemois was busying himself about the table, selecting his best linen and china—an old Venetian altar cloth and some Nancy ware—replacing the candles in the hanging chandelier, and sorting the silver and glass. Every one of my expected guests was personally known to him; some of them for years. All had shared his hospitality, and each and every one appreciated its rare value. Nothing was too good for them, and nothing should be left undone which would add to their comfort.

I had just helped him light the first blaze in the big baronial fireplace, an occupation I revel in, for to me the kindling of a fire is the gathering of half a dozen friends together, each log nudging his neighbor, the cheer of good comradeship warming them all. And a roaring fire it was when I had piled high the logs, swept the hearth, and made it ready for the choice spirits who were to share it with me. For years we have had our outings—or rather our “in-tings” before it—red-letter days for us in which the swish of a petticoat is never heard, and we are free to enjoy a “man’s time” together; red-letter days, too, in the calendar of the Inn, when even Lemois, tired out with the whirl of the season, takes on a new lease of life.

His annual rejuvenation began at dawn to-day, when he disappeared in the direction of the market and returned an hour later with his procession of baskets filled with fish and lobsters fresh out of the sea a mile away (caught at daylight), some capons, a string of pigeons, and an armful of vegetables snatched in the nick of time from the early grave of an impending frost.

As for the more important items, the Chablis Moutonne and Roumanée Conti—rare Burgundies—they were still asleep in their cob[5]webs on a low Spanish bench that had once served as a temporary resting-place outside a cardinal’s door.

Until to-night Lemois and I have dined in the kitchen. You would too could you see it. Not by any manner of means the sort of an interior the name suggests, but one all shining brass, rare pottery, copper braziers, and resplendent pewter, reflecting the dancing blaze of a huge open hearth with a spit turned by the weight of a cannon ball fired by the British, and on which—the spit, not the ball—are roasted the joints, chickens, and game for which the Inn is famous, Pierre, the sole remaining chef—there are three in the season—ineffectually cudgelling his French pate under his short-cropped, shoe-brush hair for some dish better than the last.

Because, however, of the immediate gathering of the clan, I have abandoned the kitchen and have shifted my quarters to the Marmouset. Over it up a steep, twisted staircase with a dangling rope for banisters is my bedroom, the Chambre de Cure, next to the Chambre de Officier—where the gluttonous king tossed on his royal bed (a true story, I am told, with all the details set forth in the State Archives of[6] France). Mine has a high-poster with a half lambrequin, or bed curtain, that being all Lemois could find, and he being too honest an antiquary to piece it out with modern calico or chintz. My guests, of course, will take their pick of the adjoining rooms—Madame Sévigné’s, Grèvin’s, the Chambre du Roi, and the others—and may thank their stars that it is not a month back. Then, even if they had written ten days ahead, they would have been received with a shrug—one of Lemois’ most engaging shrugs tinged with grief—at his inability to provide better accommodation for their comfort, under which one could have seen a slight trace of suppressed glee at the prosperity of the season. They would then doubtless have been presented with a massive key unlocking the door of a box of a bedroom over the cake-shop, or above the apothecary’s, or next to the man who mends furniture—all in the village of Dives itself.

And now a word about the Inn itself—even before I tell you of the Arm-Chair or the man who sat in it or the others of the clan who listened and talked back.

Not the low-pitched, smothered-in-ivy Kings[7] Arms you knew on the Thames, with its swinging sign, horse-block, and the rest of it; nor the queer sixteenth-century tavern in that Dutch town on the Maas, with its high wainscoting, leaded window-panes, and porcelain stove set out with pewter flagons—not that kind of an inn at all.

This one bolsters up one corner of a quaint little town in Normandy; is faced by walls of sombre gray stone loop-holed with slits of windows, topped by a row of dormers, with here and there a chimney, and covers an area as large as a city block, the only break in its monotony being an arched gate-way in which swing a pair of big iron-bound doors. These are always open, giving the passer-by a glimpse of the court within.

You will be disappointed, of course, when you drive up to it on a summer’s day. You will think it some public building supported by the State—a hospital or orphan asylum—and, tourist-like, will search for the legend deep cut in the key-stone of the archway to reassure yourself of its identity. Nobody can blame you—hundreds have made that same mistake, I among them.

But don’t lose heart—keep on through the[8] gate, take a dozen steps into the court-yard and look about, and if you have any red corpuscles left in your veins you will get a thrill that will take your breath away. Spread out before you lies a flower-choked yard flanked about on three sides by a chain of moss-encrusted, red-tiled, seesaw roofs, all out of plumb. Below, snug under the eaves, runs a long go-as-you-please corridor, dodging into a dozen or more bedrooms. Below this again, as if tired out with the weight, staggers a basement from which peer out windows of stained glass protected by Spanish grills of polished iron, their leaded panes blinking in the sunshine, while in and out, up the door-jambs, over the lintels, along the rain-spouts, even to the top of the ridge-poles of the wavy, red-tiled roofs, thousands of blossoms and tangled vines are running riot.

And this is not all. Close beside you stands a fuchsia-covered, shingle-hooded, Norman well, and a little way off a quaint kiosk roofed with flowering plants, and near by a great lichen-covered bust of Louis VI, to say nothing of dozens of white chairs and settees grouped against a background of flaring reds and brilliant greens. And then, with a gasp of joy, you follow the daring flight of a giant feather-blown[9] clematis in a clear leap from the ground, its topmost tendrils throttling the dormers.

Even then your surprises are not over. You have yet to come in touch with the real spirit of the Inn, and be introduced to our jewel of a dining-room, the “Marmouset,” opening flat to the ground and hidden behind a carved oaken door mounted in hammered iron: a low-ceilinged, Venetian-beamed room, with priceless furniture, tapestries, and fittings—chairs, tables, wainscoting of carved oak surmounted by Spanish leather; quaint andirons, mirrors, arms, cabinets, silver, glass, and china; all of them genuine and most of them rare, for Lemois, our landlord, has searched the Continent from end to end.

Yes!—a great inn this inn of William the Conqueror at Dives, and unique the world over. You will be ready now to believe all its legends and traditions, and you can quite understand why half the noted men of Europe have, at one time or another, been housed within its hospitable walls, including such exalted personages as Louis XI and Henry IV—the latter being the particular potentate who was laid low with a royal colic from a too free indulgence in the seductive oyster—not to men[10]tion such rare spirits as Molière, Dumas, George Sand, Daubigny, as well as most of the litterateurs, painters, and sculptors of France, including the immortal Grèvin, many of whose drawings decorate the walls of one of the garden kiosks, and whose apartment still bears his name.

And not only savants and men of rank and letters, but the frivolous world of to-day—the flotsam and jetsam of Trouville, Houlgate, and Cabourg—have gathered here in the afternoon for tea in the court-yard, their motors crowding the garage, and at night in the Marmouset when, under the soft glow of overhead candles falling on bare shoulders and ravishing toilettes, laughter and merry-making extend far into the small hours. At night, too, out in the gardens, what whisperings and love-makings in the soft, starry air!—what seductive laughter and little half-smothered screams! And then the long silences with only the light of telltale cigarettes to mark their hiding-places!

All summer this goes on until one fine morning the most knowing, or the most restless, or the poorest of these gay birds of passage (the Inn is not a benevolent institution) spreads its wings and the flight begins. The next day the[11] court is empty, as are all the roosting-places up and down the shore. Then everybody at the Inn takes a long breath—the first they have had for weeks.

About this time, too, the crisp autumn air, fresh from the sea, begins to blow, dulling the hunger for the open. The mad whirl of blossoms no longer intoxicates. Even the geraniums, which have flamed their bravest all summer, lose their snap and freshness; while the blue and pink hydrangeas hang their heads, tired out with nodding to so many passers-by: they, too, are paying the price; you can see it in their faces. Only the sturdy chrysanthemums are rejoicing in the first frost, while the more daring of the roses are unbuckling their petals ready to fight their way through the perils of an October bloom.

It is just at this blessed moment that I move in and settle down with my companions, for now that the rush is over, and the little Normandy maids and the older peasant women who have served the hungry and thirsty mob all summer, as well as two of the three French cooks, have gone back to their homes, we have Leà, Mignon, and Pierre all to ourselves.

I put dear old Leà first because it might as[12] well be said at once that without her loving care life at the Inn, with all its comforts, would be no life at all—none worth living. Louis, the running-water painter, known as the Man in High-Water Boots—one of the best beloved of our group—always insists that in the days gone by Leà occupied a pedestal at the main entrance of the twelfth-century church at the end of the street, and is out for a holiday. In proof he points out the empty pedestal set in a niche, and has even gone so far as to pencil her name on the rough stone.

Mignon, however, he admits, is a saint of another kind—a dainty, modest, captivating little maid, who looks at you with her wondering blue eyes, and who is as shy as a frightened gazelle. There is a young fisherman named Gaston, a weather-tanned, frank, fearless fellow who knows all about these eyes. He brings the fish to the Inn—those he catches himself—and Mignon generally manages to help in their unpacking. It is not a part of her duty. Her special business is to make everybody happy; to crack the great white sugar-loaf into bits with a pair of pincers—no machine-made dominoes for Lemois—and to turn the coffee-roaster—an old-fashioned,[13] sheet-iron drum swinging above a brazier of hot coals—and to cool its contents by tossing them in a pan—much as an Egyptian girl winnows wheat. It is a pity you never tasted her coffee, served in the garden—old Leà on the run with it boiling-hot to your table. You might better have stopped what you were doing and taken steamer for Havre and the Inn. You would never have regretted it.

Nor would you even at this late hour regret any one of the dishes made by Pierre, the chef. And now I think of it, it is but fair to tell you that if you repent the delay and show a fit appreciation of his efforts, or come properly endorsed (I’ll give you a letter), he may, perhaps, invite you into his kitchen which I have just vacated, a place of such various enticing smells from things baking, broiling, and frying; with unforgettable, appetizing whiffs of burnt sugar, garlic, fine herbs, and sherry, to say nothing of the flavors of bowls of mayonnaise, heaps of chopped onions, platters of cream—even a basket of eggs still warm from the nest—that the memory of it will linger with you for the rest of your days.

Best of all at this season, we have quite to ourselves that prince of major-domos, our land[14]lord, Lemois. For as this inn is no ordinary inn, this banquet room no ordinary room, and this kitchen no ordinary kitchen, so, too, is Monsieur Lemois no ordinary landlord. A small, gray, gently moving, low-voiced man with thoughtful, contented face, past the prime of life; a passionate lover of animals, flowers, and all beautiful things; quick of temper, but over in a moment; a poet withal, yet a man with so quaint a humor and of so odd a taste, and so completely absorbed in his pets, cuisine, garden, and collection, that it is easy to believe that when he is missed from his carnal body, he will be found wandering as a ghost among these very flower-beds or looking down from the walls of the Marmouset—doubtless an old haunt of his prior to this his latest incarnation. Only here would he be really happy, and only here, perhaps, among his treasures, would he be fully understood.

One of the rarest of these—a superb Florentine chair—the most important chair he owns, stood within reach of my hand as I sat listening to him before the crackling blaze.

“Unquestionably of the sixteenth century!” he exclaimed with his customary enthusiasm, as I admired it anew, for, although I had heard[15] most of it many times, I am always glad to listen, so quaint are his descriptions of everything he owns, and so sincerely does he believe in the personalities and lineage of each individual piece.

“I found it,” he continued, “in a little chapel in Ravenna. For years it had stood outside the cabinet of Alessandro, one of the Florentine dukes. Think of all the men and women who have sat in it, and of all the cruel and anxious thoughts that raced through their brains while they waited for an audience with the tyrant! Nothing like a chair for stirring up old memories and traditions. And do you see the carved heads on the top! I assure you they are alive! I have caught them smiling or frowning too often at the talk around my table not to know. Once when De Bouf, the great French clown was here, the head next you came near splitting itself in two over his grimaces, and when Marcot told one of his pathetic stories that other one wept such tears that I had to mop them up to keep the velvet from being spoilt. You don’t believe it?—you laugh! Ah!—that is just like you modern writers—you do not believe anything—you have no imagination! You must measure things with a rule! You must[16] have them drawn on the blackboard! It is because you do not see them as they are. You shut your eyes and ears to the real things of life; it is because you cannot understand that it is the soul of the chair that laughs and weeps. Monsieur Herbert will not think it funny. He understands these queer heads—and, let me tell you, they understand him. I have often caught them nodding and winking at each other when he says something that pleases them. He has himself seen things much more remarkable. That is the reason why he is the only one of all who enters this room worthy to sit in it.”

“You like Herbert, then?” I interrupted, knowing just what he would say.

“How absurd, my dear friend! You like a filet, and a gown on a woman—but you don’t like a man. You love him—when he is a man!—and Monsieur Herbert is all that. It is the English in him which counts. Since he was fourteen years of age he has been roaming around the world doing everything a man could to make his bread—and he a gentleman born, with his father’s house to go home to if he pleased. Yet he has been farm-hand, acrobat, hostler, sailor before the mast, newspaper reporter, next four years in Africa among[17] the natives; then painter, and now, at forty-five, after only six years’ practice, one of the great sculptors of France, with his work in the Luxembourg and the ribbon of the Legion in his button-hole! Have I not the right to say that he is a man? And one thing more: not for one moment has he ever lost the good heart and the fine manner of the gentleman. Ah! that is most extraordinary of all, when you think of the adventures and hair-breadth escapes and sufferings he has gone through! Did he ever tell you of his stealing a ride in Australia on a locomotive tender to get to Sydney, two hundred miles away?”

I shook my head.

“Well—get him to tell you. You will be so sorry for him, even now, that you cannot keep the tears from your eyes. Listen! There goes the scream of his horn—and I wager you, too, that he brings that delightful wild man, Monsieur Louis, with him.”

Two men burst in.

Herbert, compact, wellknit, ruddy, simple in his bearing and manner; Louis, broad-shouldered, strong as a bull, and bubbling over with unrepressed merriment. Both were muffled to their chins—Herbert in his fur motor-coat, his cap drawn close over his steady gray eyes; Louis in his big sketching-cloak and hood and a pair of goggles which gave him so owlish a look that both Mignon and Leà broke out laughing at the sight.

“Fifty miles an hour, High-Muck” (I am High-Muck) “this brute of a Herbert kept up. Everything went by in a blur; but for these gig-lamps I’d be stone blind.”

The brace and the snap of the crisp autumn air clinging to their clothes suddenly permeated the room as with electricity. Even slow-moving Lemois felt its vivifying current as he hurriedly dragged the Florentine nearer the fire.

“See, Monsieur Herbert, the chair has been[19] waiting for you. I have kept even Monsieur High-Muck out of it.”

“That’s very good of you, Lemois,” returned the sculptor as he handed Leà his coat and gloves and settled himself in its depths. “I’m glad to get back to it. What the chair thinks about it is another thing—make it tell you some time.”

“But it has—only last night one of the heads was saying——”

“None of that, Lemois,” laughed Louis, abreast of the fireplace now, his fingers outspread to the blaze. “Too many wooden heads talking around here as it is. I don’t, of course, object to Herbert’s wobbling around in its upholstered magnificence, but he can’t play doge and monopolize everything. Shove your high-backed pulpit with its grinning cherubs to one side, I tell you, Herbert, and let me warm up”—and off came the cloak and goggles, his broad shoulders and massive arms coming into view. Then tossing them to Mignon, he turned to me.

“There’s one thing you’re good for, High-Muck-a-Muck, if nothing else, and that is to keep a fire going. If I wanted to find you, and there was a chimney within a mile, I’d be sure you were sitting in front of the hearth with[20] the tongs in your hand”—here he kicked a big log into place bringing to life a swarm of sparks that blazed out a welcome and then went laughing up the chimney. “By thunder!—isn’t this glorious! Crowd up, all of you—this is the best yet! Lemois, won’t you please shove just a plain, little chair this way for me? No—come to think of it, I’ll take half of Herbert’s royal throne,” and he squeezed in beside the sculptor, one leg dangling over the arm of the Florentine.

Herbert packed himself the closer and the talk ran on: the races at Cabourg and Trouville; the big flight of wild geese which had come a month earlier than usual, and last, the season which had just closed with the rush of fashion and folly, in which chatter Lemois had joined.

“And the same old crowd, of course, Lemois?” suggested Herbert; “and always doing the same things—coffee at nine, breakfast at twelve, tea at five, dinner at eight, and bridge till midnight! Extraordinary, isn’t it! I’d rather pound oakum in a country jail.”

“Some of them will,” remarked Louis with a ruminating smile. “And it was a good season, you say, Lemois?” he continued; “lots of[21] people shedding shekels and lots of tips for dear old Leà? That’s the best part of it. And did they really order good things—the beggars?—or had you cleaned them out of their last franc on their first visit? Come now—how many Pêche-Flambées, for instance, have you served, Lemois, to the mob since July—and how many demoiselles de Cherbourg—those lovely little girl lobsters without claws?”

“Do you mean the on-shore species—those you find in the hotels at Trouville?” returned Lemois, rubbing his hands together, his thoughtful face alight with humor. “We have two varieties, you know, Monsieur Louis—the on-shore—the Trouville kind who always bring their claws with them—you can feel them under their kid gloves.”

“Oh, let up!—let up!” retorted Louis. “I mean the kind we devour; not the kind who devour us.”

“Same thing,” remarked Herbert in his low, even tones from the depths of the chair, as he stretched a benumbed hand toward the fire. “It generally ends in a broil, whether it’s a woman or a lobster.”

Louis twisted his body and caught the sculptor by the lapel of his coat.[22]

“None of your cheap wit, Herbert! Marc, the lunatic, would have said that and thought it funny—you can’t afford to. Move up, I tell you, you bloated mud-dauber, and give me more room; you’d spread yourself over two chairs with four heads on their corners if you could fill them.”

Whereupon there followed one of those good-natured rough-and-tumble dog-plays which the two had kept up through their whole friendship. Indeed, a wrestling match started it. Herbert, then known to the world as an explorer and writer, was studying at Julien’s at the time. Louis, who was also a pupil, was off in Holland painting. Their fellow students, noting Herbert’s compact physique, had bided the hour until the two men should meet, and it was when the room looked as if a cyclone had struck it—with Herbert on top one moment and Louis the next—that the friendship began. The big-hearted Louis, too, was the first to recognize his comrade’s genius as a sculptor. Herbert had a wad of clay sent home from which he modelled an elephant. This was finally tossed into a corner. There it lay a shapeless mass until his conscience smote him and the whole was transformed into a Congo[23] boy. Louis insisted it should be sent to the Salon, and thus the explorer, writer, and painter became the sculptor. And so the friendship grew and strengthened with the years. Since then both men had won their gold medals at the Salon—Louis two and Herbert two.

The same old dog-play was now going on before the cheery fire, Louis scrouging and pushing, Herbert extending his muscles and standing pat—either of them could have held the other clear of the floor at arm’s length—Herbert, all his sinews in place, ready for any move of his antagonist; Louis, a Hercules in build, breathing health and strength at every pore.

Suddenly the tussle in the chair ceased and the young painter, wrenching himself loose, sprang to his feet.

“By thunder!” he cried, “I forgot all about it! Have you heard the news? Hats off and dead silence while I tell it! Lemois, stop that confounded racket with your dishes and listen! Let me present you to His Royal Highness, Monsieur Herbert, the Gold Medallist—his second!” and he made a low salaam to the sculptor stretched out in the Florentine. He was never so happy as when extolling Herbert’s achievements.[24]

“Oh, I know all about it!” laughed back Lemois. “Le Blanc was here before breakfast the next morning with the Figaro. It was your African—am I not right, Monsieur Herbert?—the big black man with the dagger—the one I saw in the clay? Fine!—no dryads, no satyrs nor demons—just the ego of the savage. And why should you not have won the medal?” he added in serious tones that commanded instant attention. “Who among our sculptors—men who make the clay obey them—know the savage as you do? And to think, too, of your being here after your triumph, under the roof of my Marmouset. Do you know that its patron saint is another African explorer—the first man who ever set foot on its western shores—none other than the great Bethencourt himself? He was either from Picardy or Normandy—the record is not clear—and on one of his voyages—this, remember, was in the fifteenth century, the same period in which the stone chimney over your heads was built—he captured and brought home with him some little black dwarfs who became very fashionable. You see them often later on in the prints and paintings of the time, following behind the balloon petticoats and high headdresses of the great ladies. After a time[25] they became a regular article of trade, these marmots, and there is still a street in Paris called ‘The Marmouset.’ So popular were they that Charles VI is said to have had a ministry composed of five of these little rascals. So, when you first showed me your clay sketch of your African, I said—‘Ah! here is the spirit of Bethencourt! This Monsieur Herbert is Norman, not English; he has brought the savage of old to light, the same savage that Bethencourt saw—the savage that lived and fought and died before our cultivated moderns vulgarized him.’ That was a glorious thing to do, messieurs, if you will think about it”—and he looked around the circle, his eyes sparkling, his small body alive with enthusiasm.

Herbert extended his palms in protest, muttering something about parts of the statue not satisfying him and its being pretty bad in spots, if Lemois did but know it, thanking him at the same time for comparing him to so great a man as Bethencourt; but his undaunted admirer kept on without a pause, his voice quivering with pride: “The primitive man demanding of civilization his right to live! Ah! that is a new motive in art, my friends!”

“Hear him go on!” cried Louis, settling[26] himself again on the arm of Herbert’s chair; “talks like a critic. Gentlemen, the distinguished Monsieur Lemois will now address you on——”

Lemois turned and bowed profoundly.

“Better than a critic, Monsieur Louis. They only see the outside of things. Pray don’t rob Monsieur Herbert of his just rights or try to lean on him; take a whole chair to yourself and keep still a moment. You are like your running water—you——”

“Not a bit like it,” broke in Herbert, glad to turn the talk away from himself. “His water sometimes reflects—he never does.”

“Ah!—but he does reflect,” protested Lemois with a comical shrug; “but it is always upsidedown. When you stand upsidedown your money is apt to run out of your pockets; when you think upsidedown your brains run out in the same way.”

“But what would you have me do, Lemois?” expostulated Louis, regaining his feet that he might the better parry the thrust. “Get out into your garden and mount a pedestal?”

“Not at this season, you dear Monsieur Louis; it is too cold. Oh!—never would I be willing to shock any of my beautiful statues in[27] that way. You would look very ugly on a pedestal; your shoulders are too big and your arms are like a blacksmith’s, and then you would smash all my flowers getting up. No—I would have you do nothing and be nothing but your delightful and charming self. This room of mine, the ‘Little Dwarf,’ is built for laughter, and you have plenty of it. And now, gentlemen”—he was the landlord once more—both elbows uptilted in a shrug, his shoulders level with his ears—“at what time shall we serve dinner?”

“Not until Brierley comes,” I interposed after we were through laughing at Louis’ discomfiture. “He is due now—the Wigwag train from Pont du Sable ought to be in any minute.”

“Is Marc coming with him?” asked Herbert, pushing his chair back from the crackling blaze.

“No—Marc can’t get here until late. He’s fallen in love for the hundredth time. Some countess or duchess, I understand—he is staying at her château, or was. Not far from here, so he told Le Blanc.”

“Was walking past her garden gate,” broke in Louis, “squinting at her flowers, no doubt, when she asked him in to tea—or is it another Fontainebleau affair?[28]”

“That’s one love affair of Marc’s I never heard of,” remarked Herbert, with one of his meaning smiles, which always remind me of the lambent light flashed by a glowworm, irradiating but never creasing the surface as they play over his features.

“Well, that wasn’t Marc’s fault—you would have heard of it had he been around. He talked of nothing else. The idiot left Paris one morning, put ten francs in his pocket—about all he had—and went over to Fontainebleau for the day. Posted up at that railroad station was a notice, signed by a woman, describing a lost dog. Later on Marc came across a piece of rope with the dog on one end and a boy on the other. An hour later he presented himself at madame’s villa, the dog at his heels. There was a cry of joy as her arms clasped the prodigal. Then came a deluge of thanks. The gratitude of the poor lady so overcame Marc that he spent every sou he had in his clothes for flowers, sent them to her with his compliments and walked back to Paris, and for a month after every franc he scraped together went the same way. He never called—never wrote her any letters—just kept on sending flowers; never getting any thanks either, for he never gave[29] her his address. Oh, he’s a Cap and Bells when there’s a woman around!”

A shout outside sent every man to his feet; the door was flung back and a setter dog bounded in followed by the laughing face of a man who looked twenty-five of his forty years. He was clad in a leather shooting-jacket and leggings, spattered to his hips with mud, and carried a double-barrelled breech-loading gun. Howls of derision welcomed him.

“Oh!—what a spectacle!” cried Louis. “Don’t let Brierley sit down, High-Muck, until he’s scrubbed! Go and scrape yourself, you ruffian—you are the worst looking dog of the two.”

The Man from the Latin Quarter, as he is often called, clutched his gun like a club, made a mock movement as if to brain the speaker, then rested it tenderly and with the greatest care against one corner of the fireplace.

“Sorry, High-Muck, but I couldn’t help it. I’d have missed your dinner if I had gone back to my bungalow for clothes. I’ve been out on the marsh since sunup and got cut off by the tide. Down with you, Peter! Let him thaw out a little, Herbert; he’s worked like a beaver all day, and all we got were three plover[30] and a becassine. I left them with Pierre as I came in. Didn’t see a duck—haven’t seen one for a week. Wait until I get rid of this,” and he stripped off his outer jacket and flung it at Louis, who caught it with one hand and, picking up the tongs, held the garment from him until he had deposited it in the far corner of the room.

Howls of derision welcomed him

Howls of derision welcomed him

“Haven’t had hold of you, Herbert, since the gold medal,” the hunter resumed. “Shake!” and the two pressed each other’s hands. “I thought ‘The Savage’ would win—ripping stuff up and down the back, and the muscles of the legs, and he stands well. I think it’s your high-water mark—thought so when I saw it in the clay. By Jove!—I’m glad to get here! The wind has hauled to the eastward and it’s getting colder every minute.”

“Cold, are you, old man!” condoled Louis. “Why don’t you look out for your fire, High-Muck? Little Brierley’s half frozen, he says. Hold on!—stay where you are; I’ll put on another log. Of course, you’re half frozen! When I went by your marsh a little while ago the gulls were flying close inshore as if they were hunting for a stove. Not a fisherman fool enough to dig bait as far as I could see.”

Brierley nodded assent, loosened his under coat of corduroy, searched in an inside pocket for a pipe, and drew his chair nearer, his knees to the blaze.

“I don’t blame them,” he shivered; “mighty sensible bait-diggers. The only two fools on the beach were Peter and I; we’ve been on a sand spit for five hours in a hole I dug at daylight, and it was all we could do to keep each other warm—wasn’t it, old boy?” (Peter, coiled up at his feet, cocked an ear in confirmation.) “Where’s Marc, Le Blanc, and the others—upstairs?”

“Not yet,” replied Herbert. “Marc expects to turn up, so he wired High-Muck, but I’ll believe it when he gets here. Another case of Romeo and Juliet, so Louis says. Le Blanc promises to turn up after dinner. Louis, you are nearest—get a fresh glass and move that decanter this way,—Brierley is as cold as a frog.”

“No—stay where you are, Louis,” cried the hunter. “I’ll wait until I get something to eat—hot soup is what I want, not cognac. I say, High-Muck, when are we going to have dinner? I’m concave from my chin to my waistband; haven’t had a crumb since I tumbled out of bed this morning in the pitch dark.[32]”

“Expect it every minute. Here comes Leà now with the soup and Mignon with hot plates.”

Louis caught sight of the two women, backed himself against the jamb of the fireplace, and opened wide his arms.

“Make way, gentlemen!” he cried. “Behold the lost saint—our Lady of the Sabots!—and the adorable Mademoiselle Mignon! I kiss the tips of your fingers, mademoiselle. And now tell me where that fisher-boy is—that handsome young fellow Gaston I heard about when I was last here. What have you done with him? Has he drowned himself because you wouldn’t be called in church, or is he saving up his sous to put a new straw thatch on his mother’s house so there will be room for two more?”

Pretty Mignon blushed scarlet and kept straight on to the serving-table without daring to answer—Gaston was a tender subject to her, almost as tender as Mignon was to Gaston—but Leà, after depositing the tureen at the top of the table, made a little bob of a curtsy, first to Herbert and then to Louis and Brierley—thanking them for coming, and adding, in her quaint Normandy French, that[33] she would have gone home a month since had not the master told her of our coming.

“And have broken our hearts, you lovely old gargoyle!” laughed Louis. “Don’t you dare leave the Inn. They are getting on very well at the church without you. Come, Herbert, down with you in the old Florentine. I’ll sit next so I can keep all three wooden heads in order,” and he wheeled the chair into place.

“Now, Leà—the soup!”

Lemois, as was his custom, came in with the coffee. He serves it himself, and always with the same little ceremony, which, while apparently unimportant, marks that indefinable, mysterious line which he and his ancestry—innkeepers before him—have invariably maintained between those who wait and those who are waited upon. First, a small spider-legged mahogany table is wheeled up between the circle and the fire, on which Leà places a silver coffee-pot of Mignon’s best; then some tiny cups and saucers, and a sugar-dish of odd design—they said it belonged to Marie Antoinette—is laid beside them. Thereupon Lemois gravely seats himself and the rite begins, he talking all the time—one of us and yet aloof—much as would a neighbor across a fence who makes himself agreeable but who has not been given the run of your house.

To the group’s delight, however, he was as[35] much a part of the coterie as if he had taken the fifth chair, left vacant for the always late Marc, who had not yet put in an appearance, and a place we would have insisted upon his occupying, despite his intended isolation, but for a certain look in the calm eyes and a certain dignity of manner which forbade any such encroachments on his reserve.

To-night he was especially welcome. Thanks to his watchful care we had dined well—Pierre having outdone himself in a pigeon pie—and that quiet, restful contentment which follows a good dinner, beside a warm fire and under the glow of slow-burning candles, had taken possession of us.

“A wonderful pie, Lemois—a sublime, never-to-be-forgotten pie!” exclaimed Louis, voicing our sentiments. “Every one of those pigeons went straight to heaven when they died.”

“Ah!—it pleased you then, Monsieur Louis? I will tell Pierre—he will be so happy.”

“Pleased!” persisted the enthusiastic painter. “Why, I can think of no better end—no higher ambition—for a well-brought-up pigeon than being served hot in one of Pierre’s pies. Tell him so for me—I am speaking as a pigeon, of course.[36]”

“What do you think the pigeon himself would have said to Pierre before his neck was wrung?” asked Herbert, leaning back in his big chair. “Thank you—only one lump, Lemois.”

“By Jove!—why didn’t I ask the bird?—it might have been illuminating—and I speak a little pigeon-English, you know. Doubtless he would have told me he preferred being riddled with shot at a match and crawling away under a hedge to die, to being treated as a common criminal—the neck-twisting part, I mean. Why do you want to know, Herbert?”

“Oh, nothing; only I sometimes think—if you will forgive me for being serious—that there is another side to the whole question; though I must also send my thanks to Pierre for the pie.”

That one of their old good-natured passages at arms was coming became instantly apparent—tilts that every one enjoyed, for Herbert talked as he modelled—never any fumbling about for a word; never any uncertainty nor vagueness—always a direct and convincing sureness of either opinion or facts, and always the exact and precise truth. He would no sooner have exaggerated a statement than he would have added a hair’s-breadth of clay to a[37] muscle. Louis, on the other hand, talked as he painted—with the same breeze and verve and the same wholesome cheer and sanity which have made both himself and his brush so beloved. When Herbert, therefore, took up the cudgels for the cooked pigeon, none of us were surprised to hear the hilarious painter break out with:

“Stop talking such infernal rot, Herbert, and move the matches this way. How could there be another side? What do you suppose beef and mutton were put into the world for except to feed the higher animal, man?”

“But is man higher?” returned Herbert quietly, in his low, incisive voice, passing Louis the box. “I know I’m the last fellow in the world, with my record as a hunter—and I’m sometimes ashamed of it—to advance any such theory, but as I grow older I see things in a different light, and the animal’s point of view is one of them.”

“Pity you didn’t come to that conclusion before you plastered your studio with the skins of the poor devils you murdered,” he chuckled, winking at Lemois.

“That was because I didn’t know any better—or, rather, because I didn’t think any bet[38]ter,” retorted Herbert. “When we are young, we delude ourselves with all sorts of fallacies, saying that things have always been as they are since the day of Nimrod; but isn’t it about time to let our sympathies have wider play, and to look at the brute’s side of the question? Take a captive polar bear, for instance. It must seem to him to be the height of injustice to be hunted down like a man-eating tiger, sold into slavery, and condemned to live in a steel cage and in a climate that murders by slow suffocation. The poor fellow never injured anybody; has always lived out of everybody’s way; preyed on nothing that robbed any man of a meal, and was as nearly harmless, unless attacked, as any beast of his size the world over. I know a case in point, and often go to see him. He didn’t tell me his story—his keeper did—though he might have done so had I understood bear-talk as well as Louis understands pigeon-English,” and a challenging smile played over the speaker’s face.

“You ought to have stepped inside and passed the time of day with him. They wouldn’t have fed him on anything but raw sculptor for a month.”

Herbert fanned his fingers toward Louis in[39] good-humored protest, and kept on, his voice becoming unusually grave.

“They wanted, it seems, a polar bear at the Zoo, because all zoos have them, and this one must keep up with the procession. It would be inspiring and educating for the little children on Sunday afternoons—and so the thirty pieces of silver were raised. The chase began among the icebergs in a steam-launch. The father and mother in their soft white overcoats—the two baby bears in powder-puff furs—were having a frolic on a cake of floating ice when the strange craft surprised them. The mother bear tucked the babies behind her and pulled herself together to defend them with her life—and did—until she was bowled over by a rifle ball which went crashing through her skull. The father bear fought on as long as he could, dodging the lasso, encouraging the babies to hurry—sweeping them ahead of him into the water, swimming behind, urging them on, until the three reached the next cake. But the churning devil of a steam launch kept after them—two armed men in the bow, one behind with the lariat. Another plunge—only one baby now—a staggering lope along the edge of the floe, the little tot tumbling, scuf[40]fling to its feet; crying in terror at being left behind—doing the best it could to keep up. Then only the gaunt, panic-stricken, shambling father bear—slower and slower—the breath almost out of him. Another plunge—a shriek of the siren—a twist of the rudder—the lasso curls in the air, the launch backs water, the line tautens, there is a great swirl of foam broken by lumps of rocking ice, and the dull, heavy crawl back to the ship begins, the bear in tow, his head just above the water. Then the tackle is strapped about his girth, the ‘Lively now, my lads!’ rings out in the Arctic air, and he is hauled up the side and dumped half dead on deck, his tongue out, his eyes shot with blood.

“You can see him any day at the Zoo—the little children’s noses pressed against the iron bars of his cage. They call him ‘dear old Teddy bear,’ and throw him cakes and candies, which he sniffs at and turns over with his great paw. As for me, I confess that whenever I stand before his cage I always wonder what he thinks of the two-legged beasts who are responsible for it all—his conscience being clear and neither crime, injustice, nor treachery being charged against him. Yes, there are two sides[41] to this question, although, as Louis has said, it might have been just as well to have thought about it before. Speak up, Lemois, am I right or wrong? You have something on your mind; I see it in your eyes.”

“It’s more likely on his stomach,” interrupted Louis; “the pigeon may have set too heavy.”

“You are more than right, Monsieur Herbert,” Lemois answered in measured tones, ignoring the painter’s aside. He was stirring his cup as he spoke, the light of the fire making a silhouette of his body from where I sat. “For your father bear, as you call him, I have every sympathy; but I do not have to go to the North Pole to express what we owe to animals. I bring the matter to my very door, and I tell you from my heart that if I had my way there would never be anything served in my house which suffered in the killing—not even a pigeon.”

Everybody looked up in astonishment, wondering where the joke came in, but our landlord was gravity itself. “In fact,” he went on, “I believe the day will come when nothing will be killed for food—not even your dear demoiselle de Cherbourg, Monsieur Louis. Adam and[42] Eve got on very well without cutlets or broiled squab, and yet we must admit they raised a goodly race. I, myself, look forward to the time when nothing but vegetables and fruit, with cheese, milk, and eggs, will be eaten by men and women of refinement. When that time comes the butcher will go as entirely out of fashion as has the witch-burner and, in many parts of the world, the hangman.”

“But what are you going to do with Brierley, who can’t enjoy his morning coffee until he has bagged half a dozen ducks on his beloved marsh?” cried Louis, tossing the stump of his cigar into the fire.

“But Monsieur Brierley is half converted already, my dear Monsieur Louis; he told me the last time I was at his bungalow that he would never kill another deer. He was before his fireplace under the head of a doe at the time—one he had shot and had stuffed. Am I not right, Monsieur Brierley?” and Lemois inclined his head toward the hunter.

Brierley nodded in assent.

“Same old game,” muttered Louis. “Had his fun first.”

“I have been a cook all my life,” continued the undaunted Lemois, “and half the time[43] train my own chefs in my kitchen, and yet I say to you that I could feed my whole clientele sumptuously without ever spilling a drop of blood. I live in that way myself as far as I can, and so would you if you had thought about it.”

“Skimmed milk and hard-boiled eggs for breakfast, I suppose!” roared Louis in derision, “with a lettuce sandwich and a cold turnip for luncheon.”

“No, you upsidedown man! Cheese souffles, omelets in a dozen different ways, stuffed peppers, tomatoes fried, stewed, and fricasseed, oysters, clams——”

“And crabs and lobsters?” added Louis.

“Ah! but crabs and lobsters suffer like any other thing which has the power to move; what I am trying to do is to live so that nothing will suffer because of my appetite.”

“And go round looking like a skeleton in a doctor’s office! How could you get these up on boiled cabbage?” and he patted Herbert’s biceps.

“No, my dear Monsieur Louis,” persisted Lemois gravely, still refusing to be side-tracked by the young painter’s onslaughts. “If we loved the things we kill for food as Monsieur[44] Brierley loves his dog Peter, there would never be another Chateaubriand cooked in the world. What would you say if I offered you one of that dear fellow’s ribs for breakfast? It would be quite easy—the butcher is only around the corner and Pierre would broil it to a turn. But that would not do for you gourmets. You must have liver or sweetbreads cut from an animal you never saw and of which, of course, you know nothing. If the poor animal had been a playmate of Mignon’s—and she once had a pet lamb—you could no sooner cut its throat than you could Peter’s.”

Before Louis could again explode, Brierley, who, at mention of Peter’s name had leaned over to stroke the dog’s ears, now broke in, a dry smile on his face.

“There’s another side of this question which you fellows don’t seem to see, and which interests me a lot. You talk about cruelty to animals, but I tell you that most of the cruelty to-day is served out to the man with the gun. The odds are really against him. The birds down my way have got so almighty cunning that they club together and laugh at us. I hear them many a time when Peter and I are dragging ourselves home empty-handed. They[45] know too when I start out and when I give up and make for cover.”

“Go slow, Brierley; go slow!”

“Of course they know, Louis!” retorted Brierley in mock dejection. “Doesn’t a crow keep a watch out for the flock? Can you get near one of them with a gun unless you are lucky enough to shoot the sentry first? You can call it instinct if you choose—I call it reason—the same kind of mental process that compels you to look out for an automobile before you cross the street, with your eyes both ways at once. When you talk of their helplessness and want of common sense, and inability to look out for themselves, you had better lie under a hedge as I have done, the briars scraping your neck, or scrunched down in a duckblind, with your feet in ice water, and study these simple-minded creatures. Explain this if you can. Some years ago, in America, I spent the autumn on the Housatonic River. The ducks come in from Long Island Sound to feed on the shore stuff, and I could sometimes get five—once I got eleven—between dawn and sunrise. The constant banging away soon made them so shy that if I got five in a week I was lucky. On the first of the month and for the first time in[46] the State a new law came into force making it cost a month’s wages for any pot-hunter to kill a duck or even have one in his possession. The law, as is customary, was duly advertised. Not only was it published in the papers but stuck up in bar-rooms and county post-offices, and at last became common gossip around the feeding-ground of the ducks. At first they didn’t believe it, for they still kept out of sight, flying high—and few at that. But when they found the law was obeyed and that all firing had ceased, not a gun being heard on the river, they tumbled to the game as quick as did the pot-hunters. When the shooting season opened the following year, hardly a duck showed up. Those that came were evidently stragglers who rested for a day on their long flight south; but the Long Island Sound ducks—the well-posted ducks—stayed away altogether until, with the first of the month, the law for their protection came into force again. Then, so the old farmer, a very truthful man with whom I used to put up, wrote me, they came back by thousands; the shore was black with them.”

“And you really believe it, Brierley?” Louis’ head was shaking in a commiserating way.

“Of course I believe it, and I can show the[47] farmer’s letter to back it,” he answered, with a wink at me behind his hand; “and so would you if you had been humbugged by them as many times as I have. Ask Peter—he’ll tell you the same thing. And I’ll tell you something else. On the edge of that same village was a jumble of shanties inhabited by a lot of Italians who had come up from New York to work a quarry near by. On Sundays and holidays these fellows went gunning for the small birds, especially cedar birds and flickers, hiding in the big woods a mile away. After these birds had stood it for a while they put their dear little innocent heads together and thought it all out. Women and children did not shoot, therefore the safest place for nesting and skylarking was among these very women and children. After that the woods were empty; the birds just made fools of the pot-hunters and swarmed to the gardens and yards and village trees. No one had ever seen them before in such quantities, and—would you believe it?—they never went back to the woods again until the Italians had left for New York.”

Lemois, having also missed the humor in Brierley’s tone, rose from his place beside the coffee-table, leaned over the young writer, and,[48] with a characteristic gesture, patted him on the arm, exclaiming:

“How admirably you have put it, my dear Monsieur Brierley; I have to thank you most sincerely. Ah! you Americans are always clear and to the point. May I add one more word? That which made these birds so cunning was the fact that you were out to kill them.” Here he straightened up, his back to the fire, and stood with the light of its blaze tingeing his gray beard. “It’s a foolish fancy, I know, but I would have liked to have lived, if only for one day, with the man Adam, just to see how he and Madame Eve and the Noah’s ark family got on before they began quarrelling and Cain made a hole in the head of the other monsieur. I have an idea that the lion and the lamb ate out of the same trough, with the birds on their backs for company—all the world at peace. My Coco rubs his beak against my cheek, not because I feed him, but because he trusts me; he would, I am sure, bite a piece out of Monsieur Louis’ because he does not trust him—and with reason,” and the old man smiled good-naturedly. “But why don’t they all trust us?”

Herbert, who had also for some reason en[49]tirely missed Brierley’s humor, fumbled for an instant with the end of a match he had picked from the cloth, and then, tossing it quickly from him as if he had at last framed the sentence he was about to utter, said in a thoughtful tone:

“I have often wondered what the world would be like if all fear of every kind was abolished—of punishment, of bodily hurt, and of pain? Everything that swims, flies, or walks is afraid of something else—women of men, men of each other. The first thing an infant does is to cry out—not from the pain, but from fright—just as a small dog or the cub of a bear hides under its mother’s coat before its eyes are open. It is the ogre, Fear, that begins with the milk and ends with the last breath in terror over the unknown, and it is our fault. Half the children in the world—perhaps three-fourths of them—have been brought up by fear and not by love.”

“How about the lambasting your father gave you, Herbert, when you hooked it from school? ‘Spare the rod and spoil the—’ You know the rest of it. Did you deserve it?”

“Probably I did,” laughed Herbert. “But, all the same, Louis, that foolish line has done[50] more harm in the world than any line ever written. Many a brute of a father—not mine, for he did what he thought was right—has found excuse in those half-dozen words for his temper when he beat his boy.”

“Oh, come, let us get back to dry ground, gentlemen,” broke in Brierley. “We commenced on birds and we’ve brought up on moral suasion with the help of a birch-rod. Nobody has yet answered my argument: What about the birds and the way they play it on Peter and me?” and again Brierley winked at me.

“It’s because you tricked them first, Brierley,” returned Herbert in all seriousness and in all sincerity. “They got suspicious and outwitted you, and they will every time. A beast never forgets treachery. I know of a dozen instances to prove it.”

“Now I think of it, I know of one case, too,” remarked Louis gravely, in the voice of a savant uncovering a matter of great weight; “that is, if I may be allowed to tell it in the presence of the big Nimrod of the Congo—he of a hundred pairs of tusks, to say nothing of skins galore.”

Herbert nodded assent and with an air of[51] surprise leaned forward to listen. That the jovial painter had ever met the savage beast in any part of the world was news to him.

“A most extraordinary and remarkable instance, gentlemen, showing both the acumen, the mental equipment, and the pure cussedness, if I may be permitted the expression, of the brute beast of the field. The incident, as told to me, made a profound impression on my early life, and was largely instrumental in my abandoning the pursuit and destruction of game of that class. I refer to the well-known case of the boy who gave the elephant a quid of tobacco for a cake, and was buried the following year by his relatives when the circus came again to his town—he unfortunately having occupied a front seat. Yes, you are right, the beast forgives anything but treachery. But go on, Professor Herbert; your treatment of this extremely novel view of animal life is most exhilarating. I shall, at the next meeting of the Academy of Sciences, introduce a——”

Brierley’s hand set firmly on Louis’ mouth, who sputtered out he would be good, would have ended the discussion had not Lemois moved into an empty chair beside Herbert, and, resting his hand on the sculptor’s shoulder, ex[52]claimed in so absorbed a tone as to command every one’s attention:

“Please do not stop, Monsieur Herbert, and please do not mind this wild man, who has two mouths in his face—one with which he eats and the other with which he interrupts. I am very much interested. You were speaking of the ogre, Fear. Please go on. One of the things I want to know is whether it existed in the Garden of Eden. Now if you gentlemen will all keep still”—here he fixed his eyes on Louis—“we may hear something worth listening to.”

Louis threw up both hands in submission, begging Lemois not to shoot, and Herbert, having made him swear by all that was holy not to open either of his mouths until his story was told to the end, emptied his glass of Burgundy and faced the expectant group.

“We don’t need to go back to the Garden of Eden to decide the question, Lemois. As to who is responsible for the existence of this ogre, Fear, I can answer best by telling you what happened only four years ago on a German expedition to the South Pole. It was told me by the commander himself, who had been specially selected by Emperor William as the best man to take charge. When I met him he was[53] captain of one of the great North Atlantic liners—a calm, self-contained man of fifty, with a smile that always gave way to a laugh, and a sincerity, courage, and capacity that made you turn over in your berth for another nap no matter how hard it blew.

“We were in his cabin near the bridge at the time, the walls of which were covered with photographs of the Antarctic, most of which he had taken himself, showing huge icebergs, vast stretches of hummock ice, black, clear-etched shore lines, and wastes of snow that swept up to high mountains, their tops lost in the fog. He was the first human being, so he told me, to land on that coast. He had left the ship in the outside pack and with his first mate and one of the scientists had forced a way through the floating floes, their object being to make the ascent of a range of low rolling mountains seen in one of the photographs. This was pure white from base to summit except for a dark shadow one-third the slope, which he knew must be caused by an overhanging ledge with possibly a cave beneath. If any explorers had ever reached this part of the Antarctic, this cave, he knew, would be the place of all others in which to search for records and remains.[54]

“He had hardly gone a dozen yards toward it when his first mate touched his arm and pointed straight ahead. Advancing over the crest of the snow came the strangest procession he had ever seen. Thirty or more penguins of enormous size, half as high as a man, were marching straight toward them in single file, the leader ahead. When within a few feet of them the penguins stopped, bunched themselves together, looked the invaders over, bending their heads in a curious way—walking round and round as if to get a better view—and then waddled back to a ridge a few rods off, where they evidently discussed their strange guests.

“The captain and the first mate, leaving the scientist, walked up among them, patted their heads, caressed their necks—the captain at last slipping his hand under one flipper of the largest penguin, the mate taking the other—the two conducting the bird slowly and with great solemnity and dignity back to the boat, its companions following as a matter of course. None of them exhibited the slightest fear; did not start or crane their heads in suspicion, but were just as friendly as so many tame birds waiting to be fed. The boat seemed to interest them as much as the men had done. One[55] by one, or by twos and threes, they came waddling gravely down to where it lay, examined it all over and as gravely waddled back, looking up into the explorers’ faces as if for some explanation of the meaning and purpose of the strange craft. They had, too, a queer way of extending their necks, rubbing their cheeks softly against the men’s furs, as if it felt good to them. The only thing they seemed disappointed in were the ship’s rations—these they would not touch.

“Leaving the whole flock grouped about the boat, the party pushed on to the dark shadow up the white slope. It was, as he had supposed, an overhanging cliff, its abrupt edge and slant forming a shallow cave protected from the glaciers and endless snows. As he approached nearer he could make out the whirling flight of birds, and when he reached the edge he found it inhabited by thousands upon thousands of sea fowl—a gray and white species common to these latitudes. But there was no commotion nor excitement of any kind—no screams of alarm or running to cover. On the contrary, when the party came to a halt and looked up at the strange sight, two birds stopped in their flight to perch on the mate’s shoulder,[56] and one hopped toward the captain with a movement as if politely asking his business. He even lifted the young birds from under their mother’s wings without protest of any kind—not even a peck of their beaks—one of the older birds really stepped into his hand and settled herself as unconcerned as if his warm palm was exactly the kind of nest she had been waiting for. He could, he told me, have carried the whole family away without protest of any kind so long as he kept them together.

“The following week he again visited the shore. This time he found not only the friendly penguins, who met him with even more than their former welcome, but a huge seal which had sprawled itself out on the rock and whose only acknowledgment of their presence was a lazy lift of the head followed by a sleepy stare. So perfectly undisturbed was he by their coming, that both the captain and the first mate sat down on his back, the mate remaining long enough to light his pipe. Even then the seal moved only far enough to stretch himself, as if saying, ‘Try that and you will find it more comfortable.’

“On this visit, however, something occurred[57] which, he told me, he should never cease to regret as long as he lives. That morning as they pushed off from the ship, one of the dogs had made a clear spring from the deck and had landed in the boat. It was rather difficult to send him back without loss of time, and so he put him in charge of the mate, with orders not to take his eyes off him and, as a further precaution, to chain him to the seat when he went ashore. So fascinated were the penguins by the dog that for some minutes they kept walking round and round him, taking in his every movement. In some way, when the mate was not looking, the dog slipped his chain and disappeared. Whether he had gone back to the vessel or was doing some exploring on his own account nobody knew; anyhow, he must be found.

“It then transpired that one of the penguins had also taken a notion to go on a still hunt of its own, and alone. Whether the dog followed the penguin, or the penguin the dog, he said he never knew; but as soon as both were out of sight the dog pounced upon the bird and strangled it. They found it flat on its back, the black-webbed feet, palms up, as in dumb protest, the plump white body glis[58]tening in the snow. From its throat trickled a stream of blood: they had come just in time to save any further mutilation. To hide all traces of the outrage, the captain and his men not only carried the dead penguin and the live dog to the boat, but carefully scraped up every particle of the stained snow, which was also carried to the boat and finally to the ship. What he wanted, he told me, was to save his face with the birds. He knew that not one of them had seen the tragedy, and he was determined that none of them should find it out. So careful was he that no smell of blood would be wafted toward them, that he had the boat brought to windward before he embarked the load; in this way, too, he could avoid bidding both them and the seal good-by.

“The following spring he again landed on the shore. He had completed the survey, and the coast lay on their homeward track. There were doubters in the crew, who had heard the captain’s story of the penguins walking arm and arm with him, so he landed some of the ship’s company to convince them by ocular demonstration of its truth. But no penguins were in sight, nor did any other living thing put in an appearance. One of his men—there were[59] six this time—caught a glimpse of a row of heads peering at them over a ridge of snow a long way off, but that was all. When he reached the cave the birds flew out in alarm, screaming and circling as if to protect their young.”

Herbert paused, moved his cup nearer the arm of his chair, and for a moment stirred it gently.

Lemois, whose grave eyes had never wandered from Herbert, broke the silence.

“I should have learned their language and have stayed on until they did understand,” he murmured softly. “It wouldn’t have taken very long.”

“The captain did try, Lemois,” returned Herbert, “first by signs and gentle approaches, and then by keeping perfectly still, to pacify them; but it was of no use. They had lost all confidence in human kind. The peace of the everlasting ages had come to an end. Fear had entered into their world!”

One of the delights of dressing by our open windows at this season is to catch the aroma of Mignon’s roasting coffee. This morning it is particularly delicious. The dry smell of the soil that gave it birth is fast merging into that marvellous perfume which makes it immortal. The psychological moment is arriving; in common parlance it is just on the “burn”—another turn and the fire will have its revenge. But Mignon’s vigil has never ceased—into the air it goes, the soft breeze catching and cooling it, and then there pours out, flooding the garden, the flowers, and the roofs, its new aroma and with it its new life.

Flooding the garden, the flowers, and the roofs

Flooding the garden, the flowers, and the roofs

And the memories it calls up—this pungent, fragrant, spicy perfume: memories of the cup I drank in that old posada outside the gate of Valencia and the girl who served it, and the matador who stood by the window and scowled; memories of my own toy copper [61] coffee-pot, with its tiny blue cup and saucer which Luigi, my gondolier, brings and pours himself; memories of the thimblefuls in shallow china cups hardly bigger than an acorn shell, that Yusef, my dragoman, laid beside my easel in the patio of the Pigeon Mosque in Stamboul, when the priests forbade me to paint.

Yes!—a wonderful aroma this which our pretty, joyous Mignon is scattering broadcast over the court-yard, hastening every man’s toilette that he may get down the earlier where Leà is waiting for him with the big cups, the crescents, the pats of freshly churned butter, and the pitcher of milk boiling-hot from Pierre’s fire.

Another of the pleasures of the open window is being able to hear what goes on in the court-yard. To-day the ever-spontaneous and delightful Louis, as usual, is monopolizing all the talk, with Lemois and Mignon for audience, he having insisted on the open garden for his early cup, which the good Leà has brought, her scuffling sabots marking a track across the well-raked gravel. The conversation is at long range—Louis sitting immediately under my window and Lemois, within reach of the kitchen[62] door at the other side of the court, busying himself with his larder spread out on a table.

“Monsieur Lemois! Oh, Monsieur Lemois!” Louis called; “will you be good enough to pay attention! What about eggs?—can I have a couple of soft-boiled?”

“Why, of course you can have eggs! Leà, tell Pierre to——”

“Yes, I know, but will it endanger the life of the chickens inside? After your sermon last night, and Herbert’s penguin yarn, I don’t intend that any living thing shall suffer because of my appetite—not if I can help it.”

Lemois shrugged his shoulders in laughter, and kept on with his work, painting a still-life picture on his table-top—a string of silver onions for high lights and a brace of pheasants with a background of green turnip-tops for darks. To see Lemois spread his marketing thus deliberately on his canvas of a kitchen table is a lesson in color and composition. You get, too, some idea as to why he was able to reproduce in real paint the “Bayeux” tapestry on the walls of the “Gallerie” and arrange the Marmouset as he has done.

My ear next became aware of a certain silence in the direction of the coffee-roaster[63] which had ceased its rhythm—the coffee is roasted fresh every morning. I glanced out and discovered our Mignon standing erect beside her roaster with flushed cheeks and dancing eyes. Next I caught sight of young Gaston, his bronze, weather-beaten face turned toward the girl, his eyes roaming around the court-yard. In his sunburned hand he clutched a letter. He was evidently inquiring of Mignon as to whom he should give it.

“Who’s it for?” shouted Louis, who, as godfather to Mignon’s romance, had also been watching the little comedy in delight. “All private correspondence read by the cruel parent! I am the cruel parent—bring it over here! What!—not for me? Oh!—for the High-Muck-a-Muck.” The shout now came over his left shoulder. “Here’s a letter for you, High-Muck, from Marc, so this piscatorial Romeo announces. Shall I send it up?”

“No—open and read it,” I shouted back.

Louis slit the envelope with his thumb-nail and absorbed its contents.

“Well!—I’ll be—No, I won’t, but Marc ought. What do you think he’s been and gone and done, the idiot!”

“Give it up![64]”

“Invited a friend of his—a young—the Marquise de la Caux—to dine with us to-night. Says she’s the real thing and the most wonderful woman he knows. Doesn’t that make your hair curl up backward! He’s coming down with her in her motor—be here at seven precisely. A marquise! Well!—if that doesn’t take the cake! I’ll bet she’s Marc’s latest mash!”

Herbert put his head out of an adjoining window. “What’s the matter?”

“Matter! Why that lunatic Marc is going to bring a woman down to dinner—one of those fine things from St. Germain. She’s got a château above Buezval. Marc stayed there last night instead of showing up here.”

“Very glad of it, why not?” called Herbert, drawing in his head.

Lemois, who had heard the entire outbreak, nodded to himself as if in assent, looked at Gaston for a moment, and, without adding a word of any kind, disappeared in the kitchen. What he thought of it all nobody knew.

There was no doubt as to the seriousness of the impending catastrophe. Marc, in his enthusiasm, had lost all sense of propriety, and was about to introduce among us an element[65] we had hitherto avoided. Indeed, one of the enticing comforts at the Inn was its entire freedom from petticoat government of any kind. A woman of quality, raised as she had been, would mean dress-coats and white ties for dinner and the restraint that comes with the mingling of the sexes, and we disliked both—that is, when on our outings.

By this time the news had penetrated to the other rooms, producing various comments. Herbert, with his head again out of the window, advanced the opinion that the hospitality of madame la marquise had been so overwhelming, and her beauty and charm so compelling, that Marc’s only way out was to introduce her among us. Louis kept his nose in the air. Brierley, from the opposite side of the court, indulged in a running fire of good-natured criticism in which Marc was described as the prize imbecile who needed a keeper. As for me, sitting on the window-sill watching the by-plays going on below—especially Louis, who demanded an immediate answer for Gaston—there was nothing left, of course, but a—“Why certainly, Louis, any friend of Marc’s will be most welcome, and say that we dine at seven.”

And yet before the day was over—so subtly[66] does the feminine make its appeal—that despite our assumed disgust, each and every man of us had resolved to do his prettiest to make the distinguished lady’s visit a happy one. As a woman of the world she would, of course, overlook the crudities of our toilettes. And then, as we soon reasoned to ourselves, why shouldn’t our bachelor reunions be enlivened, at least for once, by a charming woman of twenty-five—Marc never bothered himself with any older—who would bring with her all the perfume, dash, and chic of the upper world and whose toilette in contrast with our own dull clothes would be all the more entrancing? This, now that we thought about it, was really the touch the Marmouset needed.

It was funny to see how everybody set to work without a word to his fellow. Herbert made a special raid through the garden and nipped off the choicest October roses—buds mostly—as befitted our guest. Louis, succumbing to the general expectancy, occupied himself in painting the menus on which Watteau cupids swinging from garlands were most pronounced. Brierley, pretending it was for himself, spent half the morning tuning up the spinet with a bed-key, in case this rarest of[67] women could sing, or should want any one else to, while Lemois, with that same dry smile which his face always wears when his mind is occupied with something that amuses him, ordered Pierre to begin at once the preparation of his most famous dish, Poulet Vallée d’Auge, spending the rest of the morning in putting a final polish on his entire George III coffee service—something he never did except for persons, as he remarked, of “exceptional quality.”

Not to be outdone in courtesy I unhooked the great iron key of the wine-cellar from its nail in Pierre’s kitchen, and swinging back the old door on its rusty hinges, drew from among the cobwebs a bottle of Chablis, our heavier Burgundies being, of course, too heating for so dainty a creature. This I carried in my own hands to the Marmouset, preserving its long-time horizontal so as not to arouse a grain of the sediment of years, tucking it at last into a crib of a basket for a short nap, only to be again awakened when my lady’s glass was ready.

When the glad hour arrived and we were drawn up to receive her—every man in his best outfit—best he had—with a rosebud in his button-hole—and she emerged from the darkness and stood in the light of the overhead can[68]dles—long, lank Marc bowing and scraping at her side, there escaped from each one of us, all but Lemois, a half-smothered groan which sounded like a faint wail.

What we saw was not a paragon of delicate beauty, nor a vision of surpassing loveliness, but a parallelogram stood up on end, fifty or more years of age, one unbroken perpendicular line from her shoulders to her feet—or rather to a brown velvet, close-fitting skirt that reached to her shoe-tops—which were stout as a man’s and apparently as big. About her shoulders was a reefing jacket, also of brown velvet, fastened with big horn buttons; above this came a loose cherry-red scarf of finest silk in perfect harmony with the brown of the velvet; above this again was a head surmounted by a mass of fluffy, partly gray hair, parted on one side—as Rosa Bonheur wore hers. Then came two brilliant agate eyes, two ruddy cheeks, and a sunny, happy mouth filled with pearl-white teeth.

One smile—and it came with the radiance of a flashlight—and all misgivings vanished. There was no question of her charm, of her refinement, or of her birth. Neither was there any question as to her thorough knowledge of the world.[69]

“I knew you were all down here for a good time,” she began in soft, low, musical tones, when the introductions were over, “and would understand if I came just as I was. I have been hunting all day—tramping the fields with my dogs—and I would not even stop to rearrange my hair. It was so good of you to let me come; and I love this room—its atmosphere is so well bred, and it is never so charming as when the firelight dances about it. Ah, Monsieur Lemois! I see some new things. Where did you get that duck of a sauce-boat?—and another Italian mirror! But then there is no use trying to keep up with you. My agent offered what I thought was three times its value for that bit of Satsuma, and I nearly broke my heart over it—and here it is! You really should be locked up as a public nuisance!”

We turned instinctively toward Lemois, remembering his queer, dry smile when he referred to her coming, but his only reply to her comment was a low bow to the woman of rank, with the customary commonplace, that all of his curios were at her disposal if she would permit him to send them to her, and with this left the room.