Title: May Iverson's Career

Author: Elizabeth Garver Jordan

Release date: November 9, 2012 [eBook #41328]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

BY

ELIZABETH JORDAN

AUTHOR OF

"MAY IVERSON—HER BOOK"

"MANY KINGDOMS" ETC.

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

TO

F. H. B.

WITH MEMORIES OF THE WISTFUL ADRIATIC

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | My First Assignment | 1 |

| II. | The Cry of the Pack | 24 |

| III. | The Girl in Gray | 43 |

| IV. | In Gay Bohemia | 68 |

| V. | The Case of Helen Brandow | 94 |

| VI. | The Last of the Morans | 120 |

| VII. | To the Rescue of Miss Morris | 140 |

| VIII. | Maria Annunciata | 162 |

| IX. | The Revolt of Tildy Mears | 184 |

| X. | A Message from Mother Elise | 206 |

| XI. | "T. B." Conducts a Rehearsal | 228 |

| XII. | The Rise of the Curtain | 256 |

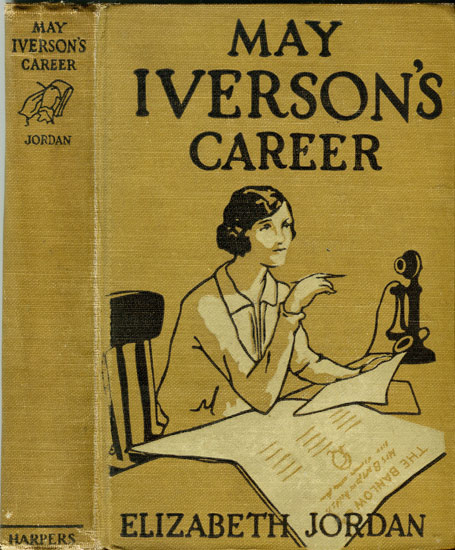

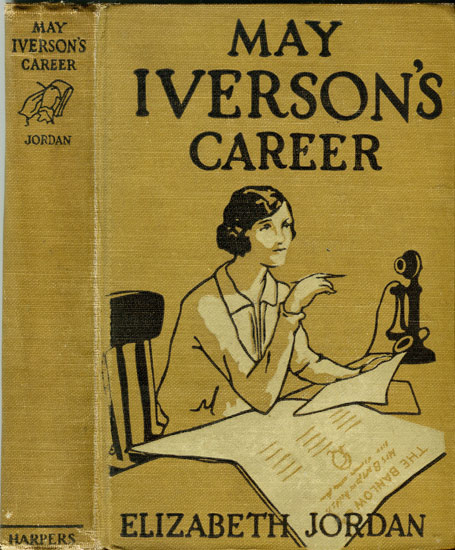

| May Iverson | Frontispiece | |

| "Don't Stand There Staring. I Know I'm Not a

Beauty," and She Cackled Like an Angry Hen. |

Facing p. | 12 |

| It Was Young "Shep," the Last of the Morans | 124 | |

| "D'ye Know the Woman?" He Said | 176 | |

MAY IVERSON'S CAREER

MAY IVERSON'S CAREER

1 The Commencement exercises at St. Catharine's were over, and everybody in the big assembly-hall was looking relieved and grateful. Mabel Muriel Murphy had welcomed our parents and friends to the convent shades in an extemporaneous speech we had overheard her practising for weeks; and the proud face of Mabel Muriel's father, beaming on her as she talked, illumined the front row like an electric globe. Maudie Joyce had read a beautiful essay, full of uplifting thoughts and rare flowers of rhetoric; Mabel Blossom had tried to deliver her address without the manuscript, and had forgotten it at a vital point; Adeline Thurston had recited an original poem; Kittie James had sung a solo; and Janet Trelawney had played the Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody on the piano.

Need I say who read the valedictory? It was I—May Iverson—winner of the Cross of Honor, winner 2 of the Crown, leader of the convent orchestra, and president of the senior class. If there are those who think I should not mention these honors I will merely ask who would do it if I did not—and pause for a reply. Besides, young as I am, I know full well that worldly ambitions and triumphs are as ashes on the lips; and already I was planning to cast mine aside. But at this particular minute the girls were crying on one another over our impending parting, and our parents were coming up to us and saying the same things again and again, while Sister Edna was telling Mabel Muriel Murphy, without being asked, that she was not ashamed of one of us.

I could see my father coming toward me through the crowd, stopping to shake hands with my classmates and tell them how wonderful they were; and I knew that when he reached me I must take him out into the convent garden and break his big, devoted heart. At the thought of it a great lump came into my throat, and while I was trying to swallow it I felt his arm flung over my shoulder.

He bent down and kissed me. "Well, my girl," he said, "I'm proud of you."

That was all. I knew it was all he would ever say; but it meant more than any one else could put into hours of talk. I did not try to answer, but I kissed him hard, and, taking his arm, led him down-stairs, through the long halls and out into the convent garden, lovely with the scent of roses and honeysuckle and mignonette. He had never seen the garden 3 before. He wanted to stroll through it and glance into the conservatories, to look at the fountain and visit the Grotto of Lourdes and stand gazing up at the huge cross that rises from a bed of passion-flowers. But at last I took him into a little arbor and made him sit down. I was almost glad my delicate mother had not been able to come to see me graduate. He would tell her what I had to say better than I could.

When I have anything before me that is very hard I always want to do it immediately and get it over. So now I stood with my back braced against the side of the arbor, and, looking my dear father straight in the eyes, I told him I had made up my mind to be a nun.

At first he looked as if he thought I must be joking. Then, all in a minute, he seemed to change from a gallant middle-aged officer into a crushed, disappointed old man. He bowed his head, his shoulders sagged down, and, turning his eyes as if to keep me from seeing what was in them, he stared out over the convent garden.

"Why, May!" he said; and then again, very quietly, "Why, May!"

I told him all that was in my mind, and he listened without a word. At the end he said he had thought I wanted to be a newspaper woman. I admitted that I had felt that desire a year ago—when I was only seventeen and my mind was immature. He sat up in his seat then and looked more comfortable—and younger. 4

"I'll put my answer in a nutshell," he said. "You're too young still to know your mind about anything. Give your family and the world a chance. I don't want you to be a nun. I don't want you to be a newspaper woman, either. But I'll compromise. Be a newspaper woman for three years."

I began to speak, but he stopped me. "It's an interesting life," he went on. "You'll like it. But if you come to us the day you are twenty-one and tell us you still want to be a nun I promise that your mother and I will consent. Give us a chance, May." And he added, gently, "Play fair."

Those two words hurt; but they conquered me. I agreed to do as he asked, and then we sat together, hand in hand, talking over plans, till the corners of the garden began to look mysterious in the twilight. Before we went back to the assembly-room it was understood that I was to go to New York in a week and begin my new career. Papa had friends there who would look after me. I was sure they would never have a chance; but I did not mention that to my dear father then, while he was still feeling the shock of decision.

When I was saying good-by to Sister Irmingarde six days later I asked her to give me some advice about my newspaper work. "Write of things as they are," she said, without hesitation, "and write of them as simply as you can."

I was a little disappointed. I had expected something inspiring—something in the nature of a trumpet-call. 5 I suppose she saw my face fall, for she smiled her beautiful smile.

"And when you write the sad stories you're so fond of, dear May," she said, "remember to let your readers shed their own tears."

I thought a great deal about those enigmatic words on my journey to New York, but after I reached it I forgot them. It was just as well, for no one associated with my work there had time to shed tears.

My editor was Mr. Nestor Hurd, of the Searchlight. He had promised to give me a trial because Kittie James's brother-in-law, George Morgan, who was his most intimate friend, said he must; but I don't think he really wanted to. When I reported to him he looked as if he had not eaten or slept for weeks, and as if seeing me was the one extra trouble he simply could not endure. There was a bottle of tablets on his desk, and every time he noticed it he stopped to swallow a tablet. He must have taken six while he was talking to me. He was a big man, with a round, smooth face, and dimples in his cheeks and chin. He talked out of one side of his mouth in a kind of low snarl, without looking at any one while he spoke.

"Oh," was his greeting to me, "you're the convent girl? Ready for work? All right. I'll try you on this."

He turned to the other person in the office—a thin young man at a desk near him. Neither of them had risen when I entered. 6

"Here, Morris," he said. "Put Miss Iverson down for the Ferncliff story."

The young man called Morris dropped a big pencil and looked very much surprised.

"But—" he said. "Why, say, she'll have to stay out in that house alone—all night."

Mr. Hurd said shortly that I couldn't be in a safer place. "Are you afraid of ghosts?" he asked, without looking at me. I said I was not, and waited for him to explain the joke; but he didn't.

"Here's the story," he said. "Listen, and get it straight. Ferncliff is a big country house out on Long Island, about three miles from Sound View. It's said to be haunted. Its nearest neighbor is a quarter of a mile away. It was empty for three years until this spring. Last month Mrs. Wallace Vanderveer, a New York society woman, took a year's lease of it and moved in with a lot of servants. Last week she moved out. Servants wouldn't stay. Said they heard noises and saw ghosts. She heard noises, too. Now the owner of Ferncliff, a Miss Watts, is suing Mrs. Vanderveer for a year's rent. Nice little story in it. See it?"

I didn't, exactly. That is, I didn't see what he wanted me to do about it, and I said so.

"I want you to take the next train for Sound View," he snarled, impatiently, and pulled the left side of his mouth down to his chin. "When you get there, drive out and look at Ferncliff to see what it's like in the daytime. Then go to the Sound 7 View Hotel and have your dinner. About ten o'clock go back to Ferncliff, and stay there all night. Sit up. If you see any ghosts, write about 'em. If you don't, write about how it felt to stay there and wait for 'em. Come back to town to-morrow morning and turn in your story. If it's good we'll run it. If it isn't," he added, grimly, "we'll throw it out. See now?" I saw now.

"Here's the key of the house," he said. "We got it from the agent." He turned and began to talk to Mr. Morris about something else—and I knew that our interview was over.

I went to Sound View on the first train, and drove straight from the station to Ferncliff. It was almost five o'clock, and a big storm was coming up. The rain was like a wet, gray veil, and the wind snarled in the tops of the pine-trees in a way that made me think of Mr. Hurd. I didn't like the look of the house. It was a huge, gloomy, vine-covered place, perched on a bluff overlooking the Sound, and set far back from the road. An avenue of pines led up to it, and a high box-hedge along the front cut off the grounds from the road and the near-by fields. When we drove away my cabman kept glancing back over his shoulder as if he expected to see the ghosts.

I was glad to get into the hotel and have a few hours for thought. I was already perfectly sure that I was not going to like being a newspaper woman, and I made up my mind to write to papa 8 the next morning and tell him so. I thought of the convent and of Sister Irmingarde, who was probably at vespers now in the chapel, and the idea of that assignment became more unpleasant every minute. Not that I was afraid—I, an Iverson, and the daughter of a general in the army! But the thing seemed silly and unworthy of a convent girl, and lonesome work besides. As I thought of the convent it suddenly seemed so near that I could almost hear its vesper bell, and that comforted me.

I went back to Ferncliff at ten o'clock. By that time the storm was really wild. It might have been a night in November instead of in July. The house looked very bleak and lonely, and the way my driver lashed his horse and hurried away from the neighborhood did not make it easier for me to unlock the front door and go in. But I forced myself to do it.

I had filled a basket with candles and matches and some books and a good luncheon, which the landlady at the hotel had put up for me. I hurriedly lighted two candles and locked the front door. Then I took the candles into the living-room at the left of the hall, and set them on a table. They made two little blurs of light in which the linen-covered furniture assumed queer, ghostly shapes that seemed to move as the flames flickered. I did not like the effect, so I lighted some more candles.

I was sure the first duty of a reporter was to search the house. So I took a candle in each hand and went 9 into every room, up stairs and down, spending a great deal of time in each, for it was strangely comforting to be busy. I heard all sorts of sounds—mice in the walls, old boards cracking under my feet, and a death-tick that began to get on my nerves, though I knew what it was. But there was nothing more than might be heard in any other old house.

When I returned to the living-room I looked at my luncheon-basket—not that I was hungry, but I wanted something more to do, and eating would have filled the time so pleasantly. But if I ate, there would be nothing to look forward to but the ghost, so I decided to wait. Outside, the screeching wind seemed to be sweeping the rain before it in a rising fury. It was half past eleven. Twelve is the hour when ghosts are said to come, I remembered.

I took up a book and began to read. I had almost forgotten my surroundings when a noise sounded on the veranda, a noise that made me stop reading to listen. Something was out there—something that tried the knob of the door and pushed against the panels; something that scampered over to the window-blinds and pulled at them; something that opened the shutters and tried to peer in.

I laid down my book. The feet scampered back to the door. I stopped breathing. There followed a knocking at the door, the knocking of weak hands, which soon began to beat against the panels with closed fists; and next I heard a high, shrill voice. It seemed to be calling, uttering words, but above the 10 shriek of the storm I could not make out what they were.

Creeping along the floor to the window, I pulled back one of the heavy curtains and raised the green shade under it half an inch. For a moment I could see nothing but the twisting pines. But at last I was able to distinguish something moving near the door—something no larger than a child, but with white hair floating round its head. It was not a ghost. It was not an animal. It could not be a human being. I had no idea what it was. While I looked it turned and came toward the window where I was crouching, as if it felt my eyes upon it. And this time I heard its words.

"Let me in!" it shrieked. "Let me in! Let me in!" And in a kind of fury it scampered back and dashed itself against the door.

Then I was afraid—not merely nervous—afraid—with a degrading fear that made my teeth chatter. If only I had known what it was; if only I could think of something normal that was a cross between a little child and an old woman! I went to the door and noiselessly turned the key. I meant to open it an inch and ask what was there. But almost before the door had moved on its hinges the thing outside saw it. It gave a quick spring and a little screech and threw itself against the panels. The next instant I went back and down, and the thing that had been outside was inside.

I got up slowly and looked at it. It seemed to be 11 a witch—a little old, humpbacked witch—not more than four feet high, with white hair that hung in wet locks around a shriveled brown face, and black eyes gleaming at me in the dark hall like an angry cat's.

"You little fool!" she hissed. "Why didn't you let me in? I'm soaked through. And why didn't that bell ring? What's been done to the wire?"

I could not speak, and after looking at me a moment more the little old creature locked the hall door and walked into the living-room, motioning to me to follow. She was panting with anger or exhaustion, or both. When we had entered the room she turned and grinned at me like a malicious monkey.

"Scared you, didn't I?" she chuckled, in her high, cracked voice. "Serves you right. Keeping me out on that veranda fifteen minutes!"

She began to gather up the loose locks of her white hair and fasten them at the back of her head. "Wind blew me to pieces," she muttered.

She took off her long black coat, threw it over a chair, and straightened the hat that hung over one ear. She was a human being, after all; a terribly deformed human being, whose great, hunched back now showed distinctly through her plain black dress. There was a bit of lace at her throat, and when she took off her gloves handsome rings glittered on her claw-like fingers.

"Well, well," she said, irritably, "don't stand there staring. I know I'm not a beauty," and she cackled like an angry hen. 12

But it was reassuring, at least, to know she was human, and I felt myself getting warm again. Then, as she seemed to expect me to say something, I explained that I had not intended to let anybody in, because I thought nobody had any right in the house.

"Humph," she said. "I've got a better right here than you have, young lady. I am the owner of this house and everything in it—I am Miss Watts. And I'll tell you one thing"—she suddenly began to trot around the room—"I've stood this newspaper nonsense about ghosts just as long as I'm going to. It's ruining the value of my property. I live in Brooklyn, but when my agent telephoned me to-night that a reporter was out here working up another lying yarn I took the first train and came here to protect my interests."

She grumbled something about having sent her cab away at the gate and having mislaid her keys. I asked her if she meant to stay till morning, and she glared at me and snapped that she certainly did. Then, taking a candle, she wandered off by herself for a while, and I heard her scampering around on the upper floors. When she came back she seemed very much surprised to hear that I was not going to bed.

"You're a fool," she said, rudely, "but I suppose you've got to do what the other fools tell you to."

After that I didn't feel much like sharing my supper with her, but I did, and she seemed to enjoy it. 13 Then she curled herself up on a big divan in the corner and grinned at me again. I liked her face better when she was angry.

"I'm going to take a nap," she said. "Call me if any ghosts come."

I opened my book again and read for half an hour. Then suddenly, from somewhere under the house, I heard a queer, muffled sound. "Tap, tap, tap," it went. And again, "Tap, tap, tap."

At first it didn't interest me much. But after a minute I realized that it was different from anything I had heard that night. And soon another noise mingled with it—a kind of buzz, like the whir of an electric fan, only louder. I looked at Miss Watts. She was asleep.

I picked up a candle and followed the noise—through the hall, down the cellar steps, and along a bricked passage. There the sound stopped. I stood still and waited. While I was staring at the bricks in front of me I noticed one that seemed to have a light behind it. I lowered my candle and examined it. Some plaster had been knocked out, and through a hole the size of a penny I saw another passage cutting through the earth like a little catacomb, with a light at the far end of it. While I was staring, amazed, the tapping began again, much nearer now; and I heard men's voices.

There were men under that house, in a secret cellar!

In half a minute I was standing beside Miss Watts, 14 shaking her arm and trying to wake her. Almost before I was able to make her understand what I had seen she was through the front door and half-way down the avenue, dragging me with her.

"Where are we going?" I gasped.

"To the next house, idiot, to telephone to the police," she said. "Do you think we could stay there and do it?"

We left the avenue and came into the road, and as we ran on, stumbling into mud-holes and whipped by wind and rain, she panted out that the men were probably escaped convicts from some prison or patients from some asylum. I ran faster after that, though I hadn't thought I could. I wondered if I were having a bad dream. Several times I pinched myself, but I didn't wake up. Instead, I kept on running and stumbling and gasping, until I felt sure I had been running and stumbling and gasping for years and must keep on doing it for eons more. But at last we came to a house set far back in big grounds, and we raced side by side up the driveway that led to the front door. Late as it was, there were lights everywhere, and through the long windows opening on the veranda we could see people moving about.

Miss Watts gave the bell a terrific pull; some one opened the door, and we stumbled in. After that everything was a mixture of questions and answers and excitement and telephoning, followed by a long wait for the police. A man led Miss Watts and 15 me into a room where a fire was burning, and left us to get warm and dry. When we were alone I asked Miss Watts if she thought they would keep us overnight. She stared at me.

"You won't have much time for sleep," she answered, almost kindly. "It will take you an hour or two to write your story."

It was my turn to stare, and I did it. "My story?" I asked her. "To-night? What do you mean?"

She swung round in her chair and stared at me harder than ever. Then she cackled in her nastiest way. "And this is a New York reporter!" she said. "Why, you little dunce, you know you've got a story, don't you?"

"Yes," I answered, doubtfully. "But I'm to write it to-morrow, after I talk to Mr. Hurd."

Miss Watts uttered a squawk and then a squeal. "I don't know what fool sent you here," she snapped, "or what infant-class you've escaped from. But one thing I do know: You came here to write a Sunday 'thriller,' I suppose, which would have destroyed what little value my property has left. By bull-headed luck you've stumbled on the truth; and it's a good news story. It will please your editor, and it will save my property. Now, here's my point." She pushed her horrible little face close to mine and kept it there while she finished. "That story is coming out in the Searchlight to-morrow morning. I'd do it if I could, but I'm not a writer. So you're 16 going to write it and telephone it in to the Searchlight office within the next hour. Have I made myself clear?"

She had. I felt my face getting red and hot when I realized that I had a big story and had not known it. I wondered if I could ever live that down. I felt so humble that I was almost willing to let Miss Watts see it.

But before I could answer her there was the noise of many feet in the hall, with the voices of men. Then our door was flung open, and a young man came in, wearing a rain-coat, thick boots covered with mud, and a wide grin. He was saving time by shaking the rain off his soft hat as he crossed the room to us. His eyes touched me, then passed on to Miss Watts as if I hadn't been there.

"Miss Watts," he said, "the police are here, and I'm going back to the house with them to see the capture. I'm Gibson, of the Searchlight."

Miss Watts actually smiled at him. Then she held out her skinny little claw of a hand. "A real reporter!" she said. "Thank Heaven! You know what it means to me to have this thing put straight. But how do you happen to be here?"

"Hurd sent me to look after Miss Iverson," he explained, glancing at me again. "He couldn't put her in a haunted house without a watch-dog, but, to do her justice, she didn't know she had one. I was in a summer-house on the grounds. I saw you leave and followed you here. Then I went up the road to meet the police." 17

He grinned at me, and I smiled a very little smile in return. I wasn't going to give him a whole smile until I found out how he was going to act about my story. Miss Watts started for the door.

"Come on," she said, with her hand on the knob.

The real reporter's eyes grew big. "Are you going along?" he gasped.

"Certainly I'm going along," snapped Miss Watts. "I'm going to see this thing through. And I'll tell you one thing right now, young man," she ended, "if you don't put the facts into your story I'm going to sue your newspaper for twenty-five thousand dollars."

He did not answer. His attention seemed to be diverted to me. I was standing beside Miss Watts, buttoning my rain-coat and pulling my hat over my eyes again, preparatory to going out.

"Say, kid," said the real reporter, "you go back and sit down. You're not in this, you know. We'll come and get you and take you to the hotel after it's all over."

I gave him a cold and dignified glance. Then I buttoned the last button of my coat and went out into the hall. It was full of men. The real reporter hurried after me. He seemed to expect me to say something. So finally I did.

"Mr. Hurd told me to write this story," I explained, in level tones, "and I'm going to try to write it. And I can't write it unless I see everything that happens." 18

I looked at him and Miss Watts out of the corner of my eye as I spoke, and I distinctly saw them give each other a significant glance. Miss Watts shrugged her shoulders as if she didn't care what I did; but the real reporter looked worried.

"Oh, well, all right," he said, at last. "I suppose it isn't fair not to let you in on your own assignment. There's one good thing—you can't get any wetter and muddier than you are." That thought seemed to comfort him.

We had a hard time going back, but it was easier because there were more of us to suffer. Besides, the real reporter helped Miss Watts and me a little when we stumbled or when the wind blew us against a tree or a fence. When we got near the house everybody moved very quietly, keeping close to the high hedge. We all went around to the back entrance. There the chief constable began to give his men orders, and the real reporter led Miss Watts and me into a grape-arbor, about fifty feet from the house.

"This is where we've got to stay," he whispered, pulling us inside and closing the door. "We can see them come out, and get the other details from Conroy, who's in charge."

The police were creeping closer to the house. Three of them took places outside while the rest went forward. First there was a long silence; then a sudden rush and crash—shouts and words that we didn't catch. Gleams of light flashed up for a 19 minute—then disappeared. The men stationed outside the house ran toward the cellar. There was the flashing of more light, and at last the police came out with their prisoners—and the whole thing was over. There had not been a pistol-shot.

I was as warm as toast in my wet clothes, but my teeth were chattering with excitement, and I knew Miss Watts was excited, too, by the grip of her hand on my shoulder. The men came toward us through the rain on their way to the gate, and Mr. Conroy's voice sounded as if he had been running a race. But he hadn't. He had been right there.

"Well, Miss Watts, we've got 'em," he crowed. "A nice little gang of amachur counterfeiters. They've been visitin' you for 'most a year, snug and cozy; but I guess this is the end of your troubles."

Miss Watts walked out into the rain and, taking a policeman's electric bull's-eye, looked at the prisoners one by one. I followed her and looked, too, while the real reporter talked to Mr. Conroy. There were three counterfeiters, and they were all handcuffed and looked young. It could not have been very hard for six policemen to take them. One of them had blood on his face, and another was covered with mud, as if he had been rolled in it. Miss Watts asked the bloody one, who was also the biggest one, if his gang had really worked in a secret cellar at Ferncliff for a year. He said it had been there about ten months.

"Then you were there all winter?" Miss Watts 20 asked him. "And you were so safe and comfortable that when the tenants moved in and you found they were all women, except a stupid butler, you decided to scare them away and stay right along?"

The man muttered something that seemed to mean that she was right. The real reporter interrupted, looking busy and worried again. "Miss Watts," he said, quickly, "can't we go right into your house and send this story to the Searchlight over your telephone? It's a quarter to one, and there isn't a minute to lose. The Searchlight goes to press in an hour. I've got all the facts," he added, in a peaceful tone.

Miss Watts said we could, and led the way into the house, while the counterfeiters and the police tramped off through the mud and rain. When we got inside, Miss Watts took us to the library and lit the electric lights, while the real reporter bustled about, looking busier than any one I ever saw before. I watched him for a minute. Then I told Miss Watts I wanted to go into a quiet room and write my story. She and the real reporter looked at each other again. I was getting tired of their looks. The real reporter spoke to me very kindly, like a Sunday-school superintendent addressing his class.

"Now, see here, Miss Iverson," he said; "you've had a big, new experience and lots of excitement. You discovered the counterfeiters. You'll get full credit for it. Let it go at that, and I'll write the story. It's got to be a real story, not a kindergarten special." 21

If he hadn't said that about the kindergarten special I might have let him write the story, for I was cold and tired and scared. But at those fatal words I felt myself stiffen all over.

"It's my story," I said, with icy determination. "And I'm going to write it."

The real reporter looked annoyed. "But can you?" he protested. "We haven't time for experiments."

"Of course I can," I said. And I'm afraid I spoke crossly, for I was getting annoyed. "I'll write it exactly the way Sister Irmingarde told me to."

I sat down at the table as I spoke. I heard a bump and something that sounded like a groan. The real reporter had fallen into a chair. "Good Lord!" he said; and then for a long time he didn't say anything. Finally he began to fuss with his paper, as if he meant to write the story anyway. I wrote three pages and forgot about him. At last he muttered, "Here, let me see those," and his voice sounded like a dove's when it mourns under the eaves. I pushed the sheets toward him with my left hand and went on writing. Suddenly I heard a gasp and a chuckle. In another second the real reporter was standing beside me, grinning his widest grin.

"Why, say, you little May Iverson kid," he almost shouted, "this story is going to be good!"

I could hear Miss Watts straighten up in the chair from which she was watching us. She snatched at 22 my pages, and he let her have them. I wanted to draw myself up to my full height and look at him coldly, but I didn't—there wasn't time. Besides, far down inside of me I was delighted by his praise.

"Of course it's going to be good," was all I said. "Sister Irmingarde told me to write about things as they are, and very simply."

He had my pages back in his hands now and was running over them quickly, putting in a few words here and there with a pencil. I could see he was not changing much. Then he started on a jump for the next room, where the telephone was, but stopped at the door. There was a queer look in his eyes.

"Sister Irmingarde's a daisy!" he muttered.

Then I heard him calling New York. "Gimme the Searchlight," he called. "Gimme the city desk. Hurry up! Say, Jack, this is Gibson, at Sound View. We've got a crackerjack of a story out here. No—the Iverson kid is doing it. It's all right, too. Get Hammond busy there and let him take it on the typewriter as fast as I read it. Ready? Here goes."

He began to read my first page.

Miss Watts got up and shut the door, and I bowed my thanks to her. The storm was worse than ever, but I hardly heard it. For a second his words had made me think of Sister Irmingarde. I felt sorry for her. She would never have a chance like this—to write a real news story for a great newspaper. The convent seemed like a place I had heard of, long ago. 23

Then I settled down to work, and for the next hour there was no sound in the room but the whisper of my busy pen and the respectful footsteps of Miss Watts as she reverently carried my story, page by page, to the chastened "real reporter."

24 Mr. Nestor Hurd, our "feature" editor, was in a bad humor. We all knew he was, and everybody knew why, except Mr. Nestor Hurd himself. He thought it was because he had not a competent writer on his whole dash-blinged staff, and he was explaining this to space in words that stung like active gnats. Really it was because his wife had just called at his office and drawn his month's salary in advance to go to Atlantic City.

Over the little partition that separated his private office from the square pen where his reporters had their desks Mr. Hurd's words flew and lit upon us. Occasionally we heard the murmur of Mr. Morris's voice, patting the air like a soothing hand; and at last our chief got tired and stopped, and an office boy came into the outer room and said he wanted to see me.

I went in with steady knees. I was no longer afraid of Mr. Hurd. I had been on the Searchlight a whole week, and I had written one big "story" and three small ones, and they had all been printed. I knew my style was improving every day—growing 25 more mature. I had dropped a great many amateur expressions, and I had learned to stop when I reached the end of my story instead of going right on. Besides, I was no longer the newest of the "cub reporters." The latest one had been taken on that morning—a scared-looking girl who told me in a trembling voice that she had to write a special column every day for women. It was plain that she had not studied life as we girls had in the convent. She made me feel a thousand years old instead of only eighteen. I had received so much advice during the week that some of it was spilling over, and I freely and gladly gave the surplus to her. I had a desk, too, by this time, in a corner near a window where I could look out on City Hall Park and see the newsboys stealing baths in the fountain. And I was going to be a nun in three years, so who cared, anyway? I went to Mr. Hurd with my head high and the light of confidence in my eyes.

"'S that?" remarked Mr. Hurd, when he heard my soft footfalls approaching his desk. He was too busy to look up and see. He was bending over a great heap of newspaper clippings, and the veins bulged out on his brow from the violence of his mental efforts. Mr. Morris, the thin young editor who had a desk near his, told him it was Miss Iverson. Mr. Morris had a muscular bulge on each jaw-bone, which Mr. Gibson had told me was caused by the strain of keeping back the things he wanted to say to Mr. Hurd. Mr. Hurd twisted the right corner 26 of his mouth at me, which was his way of showing that he knew that the person he was talking to stood at his right side.

"'S Iverson," he began (he hadn't time to say Miss Iverson), "got 'ny money?"

I thought he wanted to borrow some. I had seen a great deal of borrowing going on during the week; everybody's money seemed to belong to everybody else. I was glad to let him have it, of course, but a little surprised. I told him that I had some money, for when I left home papa had given me—

He interrupted me rudely. "Don't want to know how much papa gave you," he snapped. "Want to know where 'tis."

I told him coldly that it was in a savings-bank, for papa thought—

He interrupted again. I had never been interrupted when I was in the convent. There the girls hung on my words with suspended breath.

"'S all right, then," Mr. Hurd said. "Here's your story. Go and see half a dozen of our biggest millionaires in Wall Street—Drake, Carter, Hayden—you know the list. Tell 'em you're a stranger in town, come to study music or painting. Got a little money to see you through—'nough for a year. Ask 'em what to do with it—how to invest it—and write what happens. Good story, eh?" He turned to Morris for approval, and all his dimples showed, making him look like a six-months-old baby. He immediately regretted this moment of weakness and frowned at me. 27

"'S all," he said; and I went away.

I will now pause for a moment to describe an interesting phenomenon that ran through my whole journalistic career. I always went into an editor's room to take an assignment with perfect confidence, and I usually came out of it in black despair. The confidence was caused by the memory that I had got my past stories; the despair was caused by the conviction that I could not possibly get the present one. Each assignment Mr. Hurd had given me during the week seemed not only harder than the last, but less worthy the dignity of a general's daughter. Besides, a new and terrible thing was happening to me. I was becoming afraid—not of work, but of men. I never had been afraid of anything before. From the time we were laid in our cradles my father taught my brother Jack and me not to be afraid. The worst of my fear now was that I didn't know exactly why I felt it, and there was no one I could go to and ask about it. All the men I met seemed to be divided into two classes. In the first class were those who were not kind at all—men like Mr. Hurd, who treated me as if I were a machine, and ignored me altogether or looked over my head or past the side of my face when they spoke to me. They seemed rude at first, and I did not like them; but I liked them better and better as time went on. In the second class were the men who were too kind—who sprawled over my desk and wasted my time and grinned at me and said things I didn't understand 28 and wanted to take me to Coney Island. Most of them were merely silly, but two or three of them were horrible. When they came near me they made me feel queer and sick. After they had left I wanted to throw open all the doors and windows and air the room. There was one I used to dream of when I was overworked, which was usually. He was always a snake in the dream—a fat, disgusting, lazy snake, slowly squirming over the ground near me, with his bulging green eyes on my face. There were times when I was afraid to go to sleep for fear of dreaming of that snake; and when during the day he came into the room and over to my desk I would hardly have been surprised to see him crawl instead of walk. Indeed, his walk was a kind of crawl.

Mr. Gibson, Hurd's star reporter, whose desk was next to mine, spoke to me about him one day, and his grin was not as wide as usual.

"Is Yawkins annoying you?" he asked. "I've seen you actually shudder when he came to your desk. If the cad had any sense he'd see it, too. Has he said anything? Done anything?"

I said he hadn't, exactly, but that I felt a strange feeling of horror every time he came near me; and Gibson raised his eyebrows and said he guessed he knew why, and that he would attend to it. He must have attended to it, for Yawkins stopped coming to my desk, and after a few months he was discharged for letting himself be "thrown down" on a big story, and I never saw him again. But at the time Mr. 29 Hurd gave me his Wall Street assignment I was beginning to be horribly afraid to approach strangers, which is no way for a reporter to feel; and when I had to meet strange men I always found myself wondering whether they would be the Hurd type or the Yawkins type. I hardly dared to hope they would be like Mr. Gibson, who was like the men at home—kind and casual and friendly; but of course some of them were.

Once Mrs. Hoppen, a woman reporter on the Searchlight, came and spoke to me about them. She was forty and slender and black-eyed, and her work was as clever as any man's, but it seemed to have made her very hard. She seemed to believe in no one. She made me feel as if she had dived so deep in life that she had come out into a place where there wasn't anything. She came to me one day when Yawkins was coiled over my desk. He crawled away as soon as he saw her, for he hated her. After he went she stood looking down at me and hesitating. It was not like her to hesitate about anything.

"Look here," she said at last; "I earn a good income by attending to my own business, and I usually let other people's business alone. Besides, I'm not cut out for a Star of Bethlehem. But I just want to tell you not to worry about that kind of thing." She looked after Yawkins, who had crawled through the door.

I tried to say that I wasn't worrying, but I couldn't, for it wasn't true. And someway, though I didn't 30 know why, I couldn't talk to her about it. She didn't wait for me, however, but went right on.

"You're very young," she said, "and a long way from home. You haven't been in New York long enough to make influential friends or create a background for yourself; so you seem fair game, and the wolves are on the trail. But you can be sure of one thing—they'll never get you; so don't worry."

I thanked her, and she patted my shoulder and went away. I wasn't sure just what she meant, but I knew she had tried to be kind.

The day I started down to Wall Street to see the multimillionaires I was very thoughtful. I didn't know then, as I did later, how guarded they were in their offices, and how hard it was for a stranger to get near them. What I simply hated was having them look at me and grin at me, and seeing them under false pretenses and having to tell them lies. I knew Sister Irmingarde would not have approved of it—but there were so many things in newspaper work that Sister Irmingarde wouldn't approve of. I was beginning to wonder if there was anything at all she would approve; and later, of course, I found there was. But I discovered many, many other things long before that.

I went to Mr. Drake's office first. He was the one Mr. Hurd had mentioned first, and while I was at school I had heard about him and read that he was very old and very kind and very pious. I thought perhaps he would be kind enough to see a strange 31 girl for a few minutes and give her some advice, even if his time was worth a thousand dollars a minute, as they said it was. So I went straight to his office and asked for him, and gave my card to a buttoned boy who seemed strangely loath to take it. He was perfectly sure Mr. Drake hadn't time to see me, and he wanted the whole story of my life before he gave the card to any one; but I was not yet afraid of office boys, and he finally took the card and went away with dragging steps.

Then my card began to circulate like a love story among the girls at St. Catharine's. Men in little cages and at mahogany desks read it, and stared at me and passed it on to other men. Finally it disappeared in an inner room, and a young man came out holding it in his hand and spoke to me in a very cold and direct manner. The card had my real name on it, but no address or newspaper, and it didn't mean anything at all to the direct young man. He wanted to know who I was and what I wanted of Mr. Drake, and I told him what Mr. Hurd had told me to say. The young man hesitated. Then he smiled, and at last he said he would see what he could do and walked away. In five or six minutes he came back again, still smiling, but in a pleasanter and more friendly manner, and said Mr. Drake would see me if I could wait half an hour.

I thanked him and settled back in my seat to wait. It was a very comfortable seat—a deep, leather-covered chair with big wide arms, and there was 32 enough going on around me to keep me interested. All sorts of men came and went while I sat there; young men and old men, and happy men and wretched men, and prosperous men and poor men; but there was one thing in which they were all alike. Every man was in a hurry, and every man had in his eyes the set, eager look my brother Jack's eyes hold when he is running a college race and sees the goal ahead of him. A few of them glanced at me, but none seemed interested or surprised to see me there. Probably they thought, if they thought of it at all, that I was a stenographer trying to get a situation.

The half-hour passed, and then another half-hour, and at last the direct young man came out again. He did not apologize for keeping me waiting twice as long as he had said it would be.

"Mr. Drake will see you now," he said.

I followed him through several offices full of clerks and typewriters, and then into an office where a little old man sat alone. It was a very large office, with old rugs on the floor, and heavy curtains and beautiful furniture, and the little old man seemed almost lost in it. He was a very thin old man, and he sat at a great mahogany desk facing the door. The light in his office came from windows behind and beside him, but it fell on my face, as I sat opposite him, and left his in shadow. I could see, though, that his hair was very white, and that his face was like an oval billiard-ball, the thin skin of it drawn tightly over bones that showed. He might have been fifty 33 years old or a hundred—I didn't know which—but he was dressed very carefully in gray clothes almost as light in color as his face and hair, and he wore a gray tie with a star-sapphire pin in it. That pale-blue stone, and the pale blue of his eyes, which had the same sort of odd, moving light in them the sapphire had, were the only colors about him. He sat back, very much at his ease, his small figure deep in his great swivel-chair, the finger-tips of both hands close together, and stared at me with his pale-blue eyes that showed their queer sparks under his white eyebrows.

"Well, young woman," he said, "what can I do for you?"

And then I knew how old he was, for in the cracked tones of his voice the clock of time seemed to be striking eighty. It made me feel comfortable and almost happy to know that he was so old. I wasn't afraid of him any more. I poured out my little story, which I had rehearsed with his clerk, and he listened without a word, never taking his narrow blue eyes from my face. When I stopped he asked me what instrument I was studying, and I told him the piano, which was true enough, for I was still keeping up the music I had worked on so hard with Sister Cecilia ever since I was eight years old. He asked me what music I liked best, and when I told him my favorite composers were Beethoven and Debussy he smiled and murmured that it was a strange combination. It was, too, and well I knew it. 34 Sister Cecilia said once that it made her understand why I wanted to be both a nun and a newspaper woman.

In a few minutes I was talking to Mr. Drake as easily as I could talk to George Morgan or to my father. He asked who my teachers had been, and I told him all about the convent and my years of study there, and how much better Janet Trelawney played than I did, and how severe Sister Cecilia was with us both, and how much I liked church music. I was so glad to be telling him the truth that I told him a great deal more than I needed to. I told him almost everything there was to tell, except that I was a newspaper reporter. I remembered not to tell him that.

He seemed to like to hear about school and the girls. Several times he laughed, but very kindly, and with me, you know, not at me. Once he said it had been a long time since any young girl had told him about her school pranks, but he did not sigh over it or look sentimental, as a man would in a book. He merely mentioned it. We talked and talked. Twice the direct young secretary opened the door and put his head in; but each time he took it out again because nobody seemed to want it to stay there. At last I remembered that Mr. Drake was a busy man, and that his time was worth a thousand dollars a minute, and that I had taken about forty thousand dollars' worth of it already, so I gasped and apologized and got up. I said I had forgotten all 35 about time; and he said he had, too, and that I must sit down again because we hadn't even touched upon our business talk.

So I sat down again, and he looked at me more closely than ever, as if he had noticed how hot and red my face had suddenly got and couldn't understand why it looked that way. Of course he couldn't, either; for I had just remembered that, though I had been a reporter for a whole week, I had forgotten my assignment! It seemed as if I would never learn to be a real newspaper woman. My heart went way down, and I suppose the corners of my mouth did, too; they usually went down at the same time. He asked very kindly what was the matter, and the tone of his voice was beautiful—old and friendly and understanding. I said it was because I was so silly and stupid and young and unbusiness-like. He started to say something and stopped, then sat up and began to talk in a very business-like way. He asked where my money was, and I told him the name of the bank. He looked at his watch and frowned. I didn't know why; but I thought perhaps it was because he wanted me to take it out of there right away and it was too late. It was almost four o'clock. Then he put the tips of his fingers together again, and talked to me the way the cashier at the bank had talked when I put my money in.

He said that the savings-bank was a good place for a girl's money—under ordinary conditions it was the best place. The interest would be small, but 36 sure. Certain investments would, of course, bring higher interest, but no woman should try to invest her money unless she had business training or a very wise, experienced adviser back of her. Then he stopped for a minute, and it seemed hard for him to go on. I did not speak, for I saw that he was thinking something over, and of course I knew better than to interrupt him. At last he said that ordinarily, of course, he never paid any attention to small accounts, but that he liked me very much and wanted to help me and that, if I wished, he would invest my money for me in a way that would bring in a great deal more interest than the savings-bank would pay. And he asked if I understood what he meant.

I said I did—that he was offering to take entirely too much trouble for a stranger, and that he was just as kind as he could be, but that I couldn't think of letting him do it, and I was sure papa wouldn't want me to. He seemed annoyed all of a sudden, and his manner changed. He asked why I had come if I felt that way, and I began to see how silly it looked to him, for of course he didn't know I was a reporter getting a story on investments for women. I didn't know what to say or what to do about the money, either, for Mr. Hurd hadn't told me how to meet any offer of that kind.

While I was thinking and hesitating Mr. Drake sat still and looked at me queerly; the blue sparks in his eyes actually seemed to shoot out at me. 37 They frightened me a little; and, without stopping to think any more, I said I was very grateful to him and that I would bring the money to his office the next day. Then I stood up and he stood up, too; and I gave him my hand and told him he was the kindest man I had met in New York—and the next minute I was gasping and struggling and pushing him away with all my strength, and he stumbled and went backward into his big chair, knocking over an inkstand full of ink, which crawled to the edge of his desk in little black streams and fell on his gray clothes.

For a minute he sat staring straight ahead of him and let them fall. Then he brushed his hand across his head and picked up the inkstand and soaked up the ink with a blotter, and finally turned and looked at me. I stared back at him as if I were in a nightmare. I was opposite him and against the wall, with my back to it, and for a moment I couldn't move. But now I began to creep toward the door, with my eyes on him. I felt some way that I dared not take them off. As I moved he got up; he was much nearer the door than I was, and, though I sprang for it, he reached it first and stood there quietly, holding the knob in his hand. Neither of us had uttered a sound; but now he spoke, and his voice was very low and steady.

"Wait a minute," he said. "I want to tell you something you need to know. Then you may go." And he added, grimly, "Straighten your hat!" 38

I put up my hands and straightened it. Still I did not take my eyes off his. His eyes seemed like those of Yawkins and the great snake in my dreams, but as I looked into them they fell.

"For God's sake, child," he said, irritably, "don't look at me as if I were an anaconda! Don't you know it was all a trick?" He came up closer to me and gave me his next words eye to eye and very slowly, as if to force me to listen and believe.

"I did that, Miss Iverson," he said, "to show you what happens to beautiful girls in New York when they go into men's offices asking for advice about money. Some one had to do it. I thought the lesson might come better from me than from a younger man."

His words came to me from some place far away. A bit of my bit of Greek came, too—something about Homeric laughter. Then next instant I went to pieces and crumpled up in the big chair, and when he tried to help me I wouldn't let him come near me. But little by little, when I could speak, I told him what I thought of him and men like him, and of what I had gone through since I came to New York, and of how he had made me feel degraded and unclean for ever. At first he listened without a word; then he began to ask a few questions.

"So you don't believe me," he said once. "That's too bad. I ought to have thought of that."

He even wrung from me at last the thing that was worst of all—the thing I had not dared to tell Mrs. 39 Hoppen—the thing I had sworn to myself no one should ever know—the deep-down, paralyzing fear that there must be something wrong in me that brought these things upon me, that perhaps I, too, was to blame. That seemed to stir him in a queer fashion. He put out his hand as if to push the idea away.

"No," he said, emphatically. "No, no! Never think that." He went on more quietly. "That's not it. It's only that you're a lamb among the wolves."

He seemed to forget me, then to remember me again. "But remember this, child," he went on. "Some men are bad clear through; some are only half bad. Some aren't wolves at all; they'll help to keep you from the others. Don't you get to thinking that every mother's son runs in the pack; and don't forget that it's mighty hard for any of us to believe that you're as unsophisticated as you seem. You'll learn how to handle wolves. That's a woman's primer lesson in life. And in the mean time here's something to comfort you: Though you don't know it, you have a talisman. You've got something in your eyes that will never let them come too close. Now good-by."

It was six o'clock when I got back to the Searchlight office. I had gone down to the Battery to let the clean sea-air sweep over me. I had dropped into a little chapel, too, and when I came out the world had righted itself again and I could look my 40 fellow human beings in the eyes. Even Mr. Drake had said my experience was not my fault and that I had a talisman. I knew now what the talisman was.

Mr. Hurd, still bunched over his desk, was drinking a bottle of ginger-ale and eating a sandwich when I entered. Morris, at his desk, was editing copy. The outer pen, where the rest of us sat, was deserted by every one except Gibson, who was so busy that he did not look up.

"Got your story?" asked Hurd, looking straight at me for the third time since I had taken my place on his staff. He spoke with his mouth full. "Hello," he added. "What's the matter with your eyes?"

I sat down by his desk and told him. The sandwich dropped from his fingers. His young-old, dimpled face turned white with anger. He waited without a word until I had finished.

"By God, I'll make him sweat for that!" he hissed. "I'll show him up! The old hypocrite! The whited sepulcher! I'll make this town ring with that story. I'll make it too hot to hold him!"

Morris got up, crossed to us, and stood beside him, looking down at him. The bunches on his jaw-bones were very large.

"What's the use of talking like that, Hurd?" he asked, quietly. "You know perfectly well you won't print that story. You don't dare. And you know that you're as much to blame as Drake is for what's happened. When you sent Miss Iverson out 41 on that assignment you knew just what was coming to her."

Hurd's face went purple. "I didn't," he protested, furiously. "I swear I didn't. I thought she'd be able to get to them because she's so pretty. But that's as far as my mind worked on it." He turned to me. "You believe me, don't you?" he asked, gently. "Please say you do."

I nodded.

"Then it's all right," he said. "And I promise you one thing now: I'll never put you up against a proposition like that again."

He picked up his sandwich and dropped the matter from his mind. Morris stood still a minute longer, started to speak, stopped, and at last brought out what he had to say.

"And you won't think every man you meet is a beast, will you, Miss Iverson?" he asked.

I shook my head. I didn't seem to be able to say much. But it seemed queer that both he and Mr. Drake had said almost the same thing.

"Because," said Morris, "in his heart, you know, every man wants to be decent."

I filed that idea for future reference, as librarians say. Then I asked them the question I had been asking myself for hours. "Do you think Mr. Drake really was teaching me a—a terrible lesson?" I stammered.

The two men exchanged a look. Each seemed to wait for the other to speak. It was Gibson who 42 answered me. He had opened the door, and was watching us with no sign of his usual wide and cheerful grin.

"The way you tell it," he said, "it's a toss-up. But I'll tell you how it strikes me. Just to be on the safe side, and whether he lied to you or not, I'd like to give Henry F. Drake the all-firedest licking he ever got in his life."

"You bet," muttered Hurd, through the last mouthful of his sandwich. Mr. Morris didn't say anything, but the bunches on his jaw-bones seemed larger than ever as he turned to his desk.

I looked at them, and in that moment I learned the lesson that follows the primer lesson. At least one thing Mr. Drake had told me was true—all men were not wolves.

43 Nine typewriters were stuttering over nine news stories; four electric fans were singing their siren songs of coolness; two telephone bells were ringing; one office boy, new to his job, was hurtling through the air on his way to the night city editor's desk, and the night city editor was discharging him because he was not coming faster; the managing editor was "calling down" a copy-reader; the editor-in-chief was telling the foreign editor he wished he could find an intelligent man to take the foreign desk; Mr. Nestor Hurd was swearing at Mr. Godfrey Morris. In other words, it was nearly midnight in the offices of the Searchlight.

I was sitting at my desk, feeling very low in my mind. That day, for the first time in my three weeks' experience as a reporter, Mr. Hurd had not given me an assignment. This was neither his fault nor mine. I had written a dozen good stories for him, besides many more that were at least up to the average. My assignments had taken me to all sorts of places strangely unlike the convent from which I had graduated only a month before—morgues, hospitals, police stations, the Tombs, the Chinese 44 quarter—and I had always brought back something, even, as Mr. Gibson had once muttered, if it were merely a few typhoid germs. Mr. Gibson did not approve of sending me to all those places. Only that morning I had heard my chief tell Mr. Morris the Iverson kid was holding down her job so hard that the job was yelling for help. This was a compliment, for Mr. Hurd never joked about any one who worked less than eighteen hours a day.

I knew he hated to see me idle now, even for a few hours, and I did not like it myself. But we both had to bear it, for this had been one of the July days when nothing happened in New York. Individuals were born, and married, and died, and were run over by automobiles, as usual; but, as Mr. Hurd said, "the element of human interest was lacking." At such times the newspapers fill their space with symposiums on "Can a Couple Live on Eight Dollars a Week?" or "Is Suicide a Sin?" Or they have a moral spasm over some play and send the police to suppress it. The night before Mr. Hurd had sent Gibson, his star reporter, with a police inspector, to see a play he hoped the Searchlight could have a moral spasm over. Mr. Gibson reported that the police inspector had left the theater wiping his eyes and saying he meant to look after his daughters better hereafter; so the Searchlight could not have a spasm that time, and Mr. Hurd swore for five minutes without repeating once. He was wonderful that way, but not so gifted as Col. John 45 Cartwell, the editor-in-chief, who used to check himself between the syllables of his words to drop little oaths in. Such conversation was new and terrible to me. I had never heard any one swear before, and at first it deeply offended me. I thought a convent girl should not hear such things, especially a girl who intended to be a nun when she was twenty-one. But after a week or two I discovered that the editors never meant anything by their rude words; they were merely part of their breath.

To kill time that evening I wrote a letter to my mother—the first long one I had sent her since I left my Western home. I wrote it on one side of my copy paper, underlining my "u's" and overlining my "n's," and putting little circles around all my periods, to show the family I was a real newspaper woman at last. When I finished the letter I put it in an office envelope with a picture of the Searchlight building on the outside, and began to think of going home. But I did not feel happy. I realized by this time that in newspaper work what one did yesterday does not matter at all; it is what one does to-day that counts. In the convent we could bask for a fortnight in the afterglow of a good recitation, and the memory of a brilliant essay would abide, as it were, for months. But full well I knew that if I gave Mr. Hurd the biggest "story" of the week on Thursday, and did nothing on Friday, he would go to bed Friday night with hurt, grieved feelings in his heart. This was Friday. 46

However, there was no sense in waiting round the office any longer, so I put on my hat and left the Searchlight building, walking across City Hall Park to Broadway, where I took an open car up-town. I was getting used to being out alone late at night; but I had not ceased to feel an exultant thrill whenever I realized that I, May Iverson, just out of the convent and only eighteen, was actually part of the night life of great, wonderful, mysterious New York. Almost every man and woman I saw interested me because of the story I knew was hidden in each human heart; so to-night, as usual, I studied closely those around me. But my three fellow-passengers did not look as if they had any stories in them. They were merely tired, sleepy, perspiring men going home after a day of hard work. I envied them. I had not done a day's work, and I felt that I hardly deserved to rest. This thought was still in my mind when I left the car at Twenty-fifth Street and walked across Madison Square toward the house where I had rooms.

It was after midnight and very hot. The benches in the park still held many men—most of them the kind that stay there because they have no place else to go. There were a dozen tramps, some stretched at full length and sound asleep, others talking together. There were men out of work, trying to read the newspaper advertisements by the electric light from the globes far above them. Over the park hung a yellow mist that looked like fog but was merely heat, 47 and from every side came the deep mutter of a great city on a summer night. The men around me were the types I had seen every time I crossed the Square, and, though I was always sorry for them, they no longer made me feel sick with sympathy, as they did at first.

But on a bench a little apart from the rest sat a girl who interested me at once. I noticed her first because she was young and alone, and then because she seemed to be in trouble. She was drooping forward in her seat, with her elbows on her knees and her chin in her hands, staring hard at a spot on the ground in front of her. I could not see what it was. It looked like an ordinary brown stain. I usually walked very fast when I was alone at night, but now I slackened my pace and strolled toward the girl as slowly as I dared, studying her as I went. I could not see much of her face, which was in the hollow of her joined hands, but the way she was sitting—all bunched up—showed me that she was sick or discouraged, or both. She wore a gray dress with a very narrow skirt, and a wide, plain lace collar on the jacket. The suit had a discouraged air, as if it had started out to be smart and knew it had failed. Her hat was a cheap straw with a quill on it that had once been stiff but was now limp as an unstarched collar, and the coil of hair under it was neat and brown and wavy. Her plain lingerie blouse was cut low at the neck and fastened with a big black bow, and when I was closer to her I saw that both her 48 shoes were broken at the sides. Altogether, she looked very sick and very poor, and when she changed her position a little to glance at a man who was passing, something about her profile made me think of one of my classmates at St. Catharine's.

I had tried to pass her, but now my feet would not take me. It was simply impossible to ignore a girl who looked like Janet Trelawney and who seemed to be in trouble. I saw when I got nearer that she was not Janet, but she might have been—and, anyway, she was a young girl like myself. We were taught at the convent that to intrude on another person's grief, uninvited, is worse than to intrude at any other time. Mere sympathy does not excuse it. But this looked like a special case, for there was no one else around to do anything for the girl in gray if she needed help. However, I did not speak to her at once. I merely sat down on the bench beside her and waited to see if she would speak to me.

She raised her head the minute she felt me there, and sat up and stared at me with eyes that were big and dark and had a queer, desperate expression in them. It seemed to startle her to know that some one was so near her, but after she had looked at me her surprise changed to annoyance, and she moved as if she meant to get up and go away. That full glance at her had shown me what she was like. She was not pretty. Her face was dreadfully pale, her nose was ordinary in shape, and her firmly set, thin lips made her mouth look like a straight line. 49 I did not see how I could have thought of Janet Trelawney in connection with her. However, I felt that I could not drive her away from her seat, so I stopped her and begged her pardon and asked if she was ill or had hurt herself in any way, and if I could help her.

At first she did not answer me. She merely sat still and looked me over slowly, as if she were trying to make up her mind about me. The longer she looked the more puzzled she seemed to be. It had been raining when I left home in the morning, so I had on a mackintosh and a little soft rainy-day hat. I knew I did not look impressive, and it was plain that the girl in gray did not think much of me. At last she asked what I wanted, and her voice sounded hard and indifferent—even rude. I was disappointed in that, too, as well as in her face. It would have been more interesting, of course, to help a refined, educated girl. There was no doubt, however, that she needed help of some kind, so I merely repeated in different words what I had said to her at first. She laughed then—a laugh I did not like at all—and stared at me again in her queer way, as if she could not make me out. She seemed to be more puzzled over me than I was over her.

She kept on staring at me a long time with her singular eyes, that had dark circles under them. At last she asked me if I was a "society agent" or anything of that sort, and when I said I was not she asked how I happened to be out so late, and what I 50 was doing. Her voice was as queer as her eyes—low and husky. I did not like her manner. It almost seemed as if she thought I had no right to be there, so I told her rather coldly that I was a reporter on the Searchlight and that I was on my way home from the office. As soon as I said that her whole manner changed. I have noticed this quick change in others when they hear that I am a newspaper woman. Some are pleased and some are not, but few remain cold and detached. The girl in gray actually looked relieved about something. She laughed again, a husky, throaty laugh that sounded, however, much nicer and more human than before, and gave me a good-natured little push.

"Oh," she said, "all right. Better beat it now. So-long." And she waved me away as if she owned the park bench. I hesitated. I was sorry now that I had stopped, and I wanted to go; but it seemed impossible to leave her there. I sat still for a moment, thinking it over, and suddenly she leaned toward me and advised me very earnestly not to linger till the roundsman came to take my pedigree. She said he was letting her alone because he knew she was only out of the hospital two days and up against it, but the healthy thing for me was to move on while the walking was good.

I was sorry she used so much slang, but of course the fact that she was unrefined and uneducated made her situation harder, and demanded even more sympathy from those better off. What she had said 51 about the hospital and being "up against it" proved that I had done right to stop.

I told her I was going home in a few minutes, but that I wanted to talk to her first if she did not mind, and that there was no reason why I could not sit in the park if she could. She looked at me and laughed again as if I had made a joke, and the laugh brought on an attack of coughing which kept her busy for a full minute. When she had stopped I pointed out my home to her. It was on the opposite side of the Square, but we could see it quite plainly from where we sat. We could even see the windows of my rooms, which faced the park. The girl in gray looked up at them a long time.

"Gee!" she said, "you're lucky. Think of havin' a joint to fall into, and not knowin' enough to go to it when you got a chance." She added, "It wouldn't take me long to hop there if I owned the latch-key."

I asked her where she lived, and she laughed again and swung one knee over the other as we were taught in the convent not to do, and muttered that her present address was Madison Square Park, but she hoped it would not be permanent. Then she got up and said, "So-long," and started to go. I got up, too, and caught her arm. Her last words had simply thrilled me. I had read about girls being sick and out of work and being dismissed from the hospital with no money and no place to go to. But to read of them in books is one thing, and to see one 52 with your own eyes, to have one actually beside you, is another thing—and very different. My heart swelled till it hurt; so did my throat. The girl shook off my hand.

"Say," she said, and her voice was rude and cross again—"say, kid, what's the matter with you? You ain't got nothin' on me. Beat it, will you, or let me beat it. I can't set here and chin."

I held her arm. I knew what was the matter. She was too proud to ask for help. I knew another thing, too. There was a story in her, the story of what happens to the penniless girl in New York; and I could get it from her and write it and put the matter on a business basis that would mean as much to her as to me. Then I would have my story, the story I had not got to-day, and she would have a room and shelter, for of course I would give her some money in advance. My mind worked like lightning. I saw exactly how the thing could be done.

"Wait a minute," I said. "Forgive me—but you're hungry, aren't you?"

She stared at me again with that queer look of hers. Then she answered with simple truth. "You bet I am," she muttered.

"Very well," I said, and I put all the will-power I had in my voice. "Come with me and get something to eat. Then tell me what has happened to you. Perhaps I can make a newspaper story of it. If I can, we'll divide the space rates."

The girl in gray hung back. I could see that she 53 wanted to go with me, but that for some reason she was afraid.

"Say," she said at last, "you're kidding ain't you? You don't look like a reporter nor act like one. Honest, you got me guessin'."

I did not like that very much, but I could not blame her. I knew it required more than three weeks to make one look like a real newspaper woman. I opened my hand-bag and took out one of the new cards I had had engraved, with The New York Searchlight down in the left-hand corner. It looked beautiful. I could see that at last the girl in gray was impressed. She stood with the card in her hand, staring down at it and thinking. Finally she shrugged her shoulders and clapped me on the back with a force that hurt me.

"Al-l-l right!" she said, drawling out the first word and shooting the second at me like a bullet from a pistol. "I got the goods. I'm just out of Bellevue. I'll give you a spiel about the way those guys treated me. I'll tell you about the House of Detention, too, and the judges and the police. Oh, I got a story, all right, all right. I'll give it to you straight."

She was pulling me along the street as she talked. She seemed to be in a great hurry all of a sudden, and in good spirits, but I realized how weak she was when I saw that even to walk half a block made her breath come in little gasps.

"It's the eats first, ain't it?" she asked; and I told her it certainly was. Then I asked her where we 54 were going, for it was clear that she was headed for some definite place.

"Owl-wagon," she told me, and saved her breath for the walk. I said we would take a car, but she pointed to the "owl-wagon" standing against the curb only a square away. The sight of it seemed to give her fresh strength. She made for it like a carrier-pigeon going home. When we reached it she sat down on the curbstone and nodded affably to the man inside the wagon. He nodded back at her and then came through the door and down the wagon steps to stare at me.

"Hello," he said to the girl in gray. "Heard you was sick. Glad to see you round again. What'll you eat?"

She did not waste breath on him, but made a gesture toward me. For a moment I think she could not speak.

"Give her a large glass of milk first," I told the man—"not too cold." When I handed it to her I advised her to drink it slowly, but she did not. It vanished in one long gulp. While the man was filling another glass for her I asked her what she wanted for supper. Eating at the "owl" was a new experience to me. I began to enjoy it, and to examine the different kinds of food that stood on the little shelves around the sides of the wagon. The girl in gray looked at me over the rim of her glass.

"What'll you stand for?" she asked.

I laughed and told her to choose for herself; she 55 could have everything in the wagon if she wanted it. Before the words were past my lips she was on the top step, selecting sandwiches and pie and ordering the man around as if she owned the outfit. She took three sandwiches, one of every kind he had, and two pieces of pie, and some doughnuts. When she had all she wanted she got down from the wagon and backed carefully to the curb, balancing the food in her hands. Then she sat down again and smiled at me for the first time. Something about that smile made me want to cry; but she seemed almost happy.

"Ain't this a bit of all right?" she asked, with her mouth full. She told the proprietor that his pies had less sawdust in them than last year and that he must have put some real lemon in one of them by mistake. While they talked I continued to inspect the inside of the wagon, but I heard the owl-man ask her a question in a whisper that must have reached across the street. "Say, Mollie, who's your friend?" he wanted to know.

The girl in gray told him it was none of his business. Her speech sounded strangely like that of Mr. Hurd. There were several of his favorite words in it. I sighed. She was a dreadfully disappointing girl, but she had been starving, and I had only to look at her face and her poor torn shoes to feel sympathy surge up in me again. When she was finishing her last piece of pie she beckoned to me to come and sit beside her on the curb. 56

"Now for the spiel," she said, and her husky voice sounded actually gay. "You got the key. Wind me up. I'll run 's long's I can."

I looked around. The street was deserted except for two men who stood beside the owl-wagon munching sandwiches. They stared hard at us, but did not come near us. There was a light in the wagon, too, by which I might have made some notes. But I did not want to get my story at one o'clock in the morning out on a public avenue. I wanted a room and a reading-lamp and chairs and a table. Six months later I could write any story on the side of a steam-engine while the engine was in motion, but this was not then. Besides, while the girl was eating I had had an inspiration. I asked her if she had really meant what she said about having no place to go but the park; and when she answered that she had, I asked her where she would have gone that night if I had not come along. She looked at me, hesitated a moment, and then turned sulky.

"Aw, what's the use?" she said. "Get busy. Do I give you the story, or don't I?"

I told her she did. Then I produced my inspiration. "Aren't there homes for the friendless," I asked her, "where girls are taken in for a night when they have no money?"

The girl in gray said there were, and sat eyeing me with her lower jaw lax and a weary, discouraged air.

"All right," I said, briskly; "let's go to one." 57

It took her a long time to understand what I meant. I had to explain over and over that I wanted to go with her and see exactly how girls were received and treated in such places and what sort of rooms and food they got, and that I must play the part of a penniless and friendless girl myself to get the facts; for of course if the people in the "refuge" knew I was a reporter everything would be colored for me. At last my companion seemed to grasp my meaning. She got up, wabbling a little on her weak knees, and started toward Twenty-third Street.