Title: The Awakening of the Desert

Author: Julius Charles Birge

Release date: November 9, 2012 [eBook #41333]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

With Illustrations

RICHARD G. BADGER

THE GORHAM PRESS

BOSTON

Copyright 1912 by Richard G. Badger

All Rights Reserved

The Gorham Press, Boston, U. S. A.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | A Call to the Wilderness | 11 |

| II | "Roll Out" | 18 |

| III | The Advancing Wave of Civilization | 24 |

| IV | A River Town of the Day | 38 |

| V | Our Introduction to the Great Plains | 52 |

| VI | The Oregon Trail | 64 |

| VII | Society in the Wilderness | 76 |

| VIII | Jack Morrow's Ranch | 88 |

| IX | Men of the Western Twilight | 102 |

| X | Dan, the Doctor | 118 |

| XI | Fording the Platte in High Water | 133 |

| XII | The Phantom Liar of Greasewood Desert | 142 |

| XIII | The Mystery of Scott's Bluffs | 156 |

| XIV | The Peace Pipe at Laramie | 167 |

| XV | Red Cloud on the War Path | 186 |

| XVI | The Mormon Trail | 196 |

| XVII | Wild Midnight Revelry in the Caspar Hills | 211 |

| XVIII | A Night at Red Buttes | 223 |

| XIX | Camp Fire Yarns at Three Crossings | 237 |

| XX | A Spectacular Buffalo Chase | 252 |

| XXI | The Parting of the Ways | 267 |

| XXII | The Banditti of Ham's Fork | 281 |

| XXIII | Through the Wasatch Mountains | 290 |

| XXIV | Why a Fair City Arose in a Desert | 303 |

| XXV | Some Inside Glimpses of Mormon Affairs | 324 |

| XXVI | Mormon Homes and Social Life | 342 |

| XXVII | The Boarding House Train | 359 |

| XXVIII | Some Episodes in Stock Hunting | 380 |

| XXIX | Adventures of an Amateur Detective | 393 |

| XXX | The Overland Stage Line | 409 |

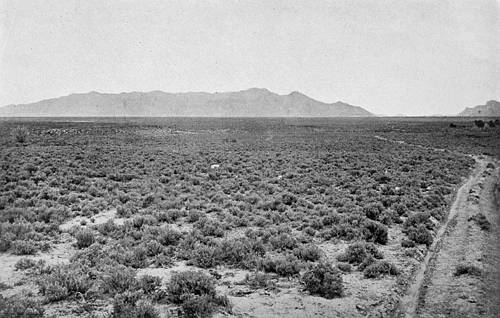

| Trail Through Salt Lake Desert | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | |

| Elk | 16 |

| Wild Cat | 48 |

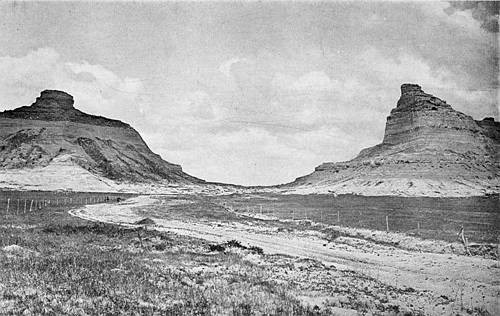

| The Oregon Trail, Through Mitchell Pass | 64 |

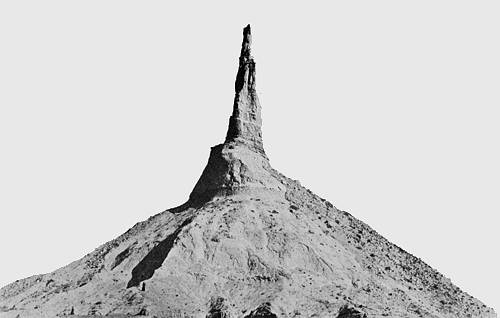

| Chimney Rock, One of the Old Landmarks of the '49 Trail | 74 |

| Grizzly Bear | 96 |

| Cougar | 112 |

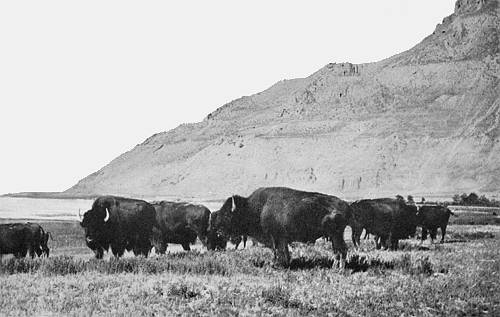

| Buffalos | 130 |

| Jail Rock and Court House Rock | 148 |

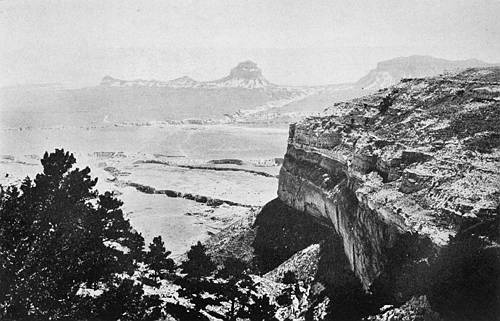

| Scott's Bluff, Showing Dome Rock in the Distance | 155 |

| The Old Company Quarters at Fort Laramie | 184 |

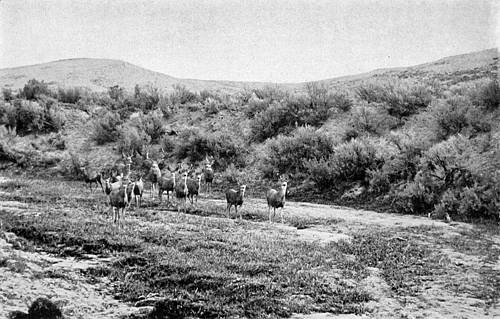

| Sage Brush Growth | 202 |

| The Rockies | 252 |

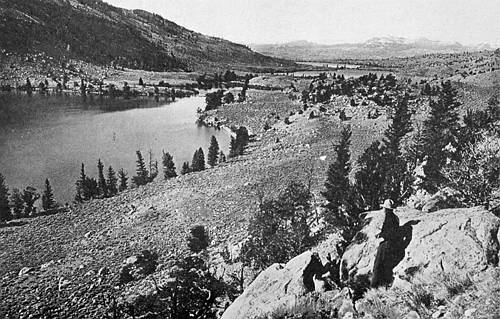

| Fremont Peak and Island Lake on the West Slope of the Wind River Range | 268 |

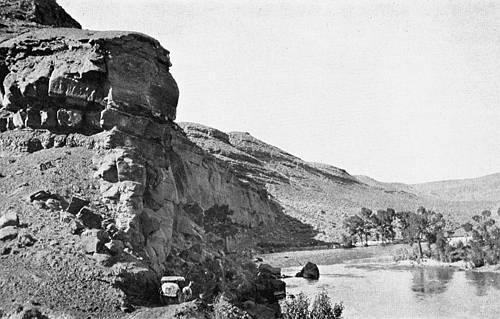

| Red Sandstone Cliffs, on Wind River | 280 |

| Weber River, Mouth of Echo Canyon | 294 |

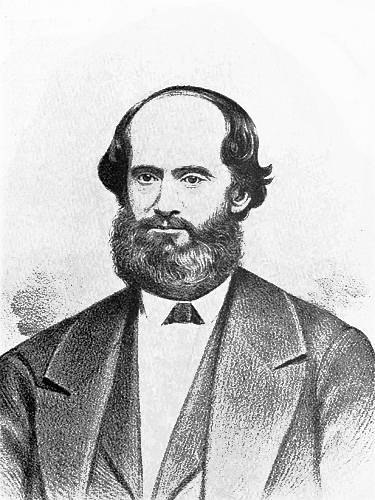

| Joseph Smith | 304 |

| The King of Beaver Island | 308 |

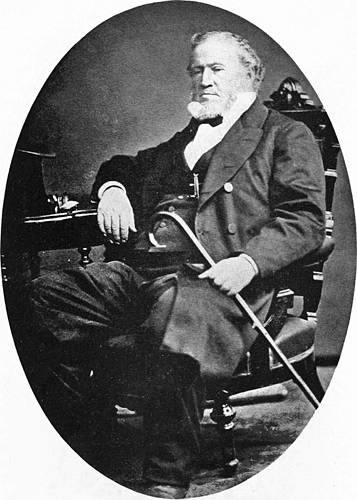

| Brigham Young | 316 |

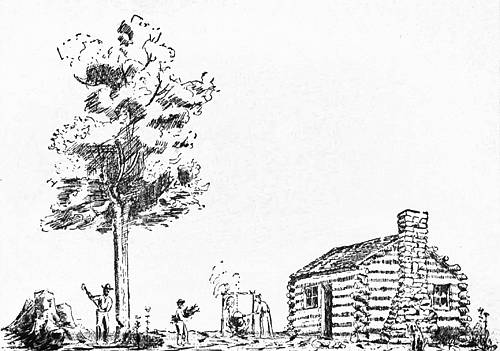

| First House Built in Salt Lake City | 330 |

| Great Salt Lake | 346 |

| Through the Wasatch | 360 |

| Dead Man's Falls, Little Cottonwood, Utah | 386 |

| Sutter's Fort Before Restoration, Sacramento, Calif | 406 |

| First House in Denver | 420 |

TRAIL THROUGH SALT LAKE DESERT

TRAIL THROUGH SALT LAKE DESERT

WILL you join us in a camping trip to the Pacific Coast?" This alluring invitation was addressed to the writer one cold, drizzly night in the early spring of 1866 by Captain Hill Whitmore, one of a party of six men who by prearrangement had gathered round a cheerful wood fire in a village store in Whitewater, Wisconsin.

The regular business of the establishment had ended for the day; the tight wooden shutters had been placed upon the doors and windows of the store as was the custom in those times; and the key was now turned in the lock to prevent intrusions. All the lights had been turned off, except that of a single kerosene lamp, suspended from the ceiling near the stove; the gentle glow revealed within a small arc on either side of the room the lines of shelving filled with bolts of dry goods, but toward the front and the rear of the long room it was lost in the darkness. The conditions were favorable for a quiet, undisturbed discussion of a proposed enterprise, for even Ray, the clerk, after ramming a maple log into the fire, had quietly stretched himself out upon one of the long counters near the stove, resting his head upon a bolt of blue denim.

Tipping back in a big wooden chair against the opposite[12] counter, at the Captain's side, with his feet on the rail by the stove, sat big John Wilson. John had made a trip across the plains with Whitmore the preceding year, and was now arranging to become his partner in a similar venture on a larger scale. Trader and adventurer by instinct, Wilson, as his record had shown, would promptly accept a brickyard or a grocery in exchange for live stock or a farm, and preferred any new enterprise to a business with which he was familiar.

Fred Day, an interesting young man of twenty years, was a consumptive. He and I sat side by side at the front of the stove, while nervous little Paul Beemer, when not pacing back and forth between the counters behind us, sat astride a small chair, resting his arms on its back, and listening with close attention.

Stalwart Dan Trippe sat in a big arm chair near Paul. He had already been informed in a general way that a transcontinental expedition was being planned. Dan also was ever ready to consider any new venture. He had once crossed the plains to Pike's Peak, and had no present vocation. Running his fingers through his curly hair, as was his habit in serious moments, he launched a question toward the opposite side of the stove.

"Well, John, what's the proposition? What's the scheme?"

Dropping his chair forward upon its four legs, and knocking the ashes from his pipe, John proceeded to outline the tentative plan then in mind. Briefly stated, the project was to fit out a wagon train with the view of freighting from the Missouri River to the Coast. In the preceding year the rates for transportation to Salt Lake had been from twenty to thirty cents per pound, affording a fine profit if the train should go through safe.

[13] Hill Whitmore, a vigorous, compactly built man, then in the prime of life, and who since the discovery of gold in California had more than once piloted such trains across the wide stretch of plains and mountains to the Pacific Coast, would be a partner in the enterprise and the Captain of the expedition. We had known him long and well.

An opportunity was now offered for the investment of more capital which, if no mishap should befall the train, would pay 'big money.'

A few young fellows could also accompany the outfit and obtain a great experience at a moderate cost. Being myself a convalescent from a serious attack of typhoid fever, and having temporarily withdrawn from business at the recommendation of physicians, Fred's condition commanded my serious consideration. I gently pulled his coat-sleeve as a signal for him to follow me, and we leisurely sauntered down into the shadows near the front of the store where, backing up against a counter, we were soon seated together on its top. We both knew, without exchanging a word, that we had some interests in common. Ordinarily, he was a genial and affable companion, but we both remained silent then, for we were absorbed in thinking—and doubtless along the same lines. The mere suggestion of the trip at once brought vividly to my mind all the little I then knew of the West. Like all Gaul in the days of Caesar, it seemed in some vague way to be divided into three parts, the plains, the mountains, and the region beyond.

The indefiniteness of the old western maps of the day left much to the imagination of the young student of geography and suggested the idea of something new to be discovered. The great American Desert was represented as extending hundreds of miles along the eastern slope of the[14] mountains. Other deserts were shown in the unoccupied spaces beyond, and

so here and there on our maps of the western territories was inserted the name of some Indian tribe which was supposed to lead its wild, nomadic life in the district indicated. A few rivers and mountain peaks which had received the names of early explorers, Great Salt Lake to which the Mormons had been led, and other objects to which had been applied the breezy, not to say blood-curdling, appellations peculiar to the nomenclature of the West, all were perhaps more familiar to the average American schoolboy than were the classic names which have lived through twenty centuries of history. In the imagination of youth, "Smoky Hill Fork," "Devil's Slide," and "Rattlesnake Hills" figured as pretty nearly what such terms naturally suggest. Along the first-mentioned stream—then far away from civilization—the soft haze and smoke of an ideal Indian summer was supposed to rest perpetually, and it was believed that in days of long ago, weird demons were really wont to disport themselves on the mountain slope called Devil's Slide. The far West seemed to be a mystic land always and everywhere wooing to interesting adventure.

"Do you think that Ben would go?" asked Fred in an earnest tone.

"That's a bright thought, Fred. With Ben, we would be a harmonious triumvirate; but let's hear more of the program." So we returned to our seats by the stove.

Whitmore was outlining some of the details and indicating the provisions which it would be necessary to make, in[15] view of the fact that no railroad had as yet been laid even across Iowa, much less between the Missouri and the Pacific.

"Now boys, you must understand that we're cutting loose from all established settlements. There won't be any stores to drop into to buy anything that you have forgotten to bring along. Anybody that wants lemonade will have to bring along his lemons and his squeezer. After we get beyond the Missouri River you will find no white peoples' homes until you strike the Mormon settlement in Utah, so we'll have to take along enough grub to feed us for several months;—of course we ought to kill some game on the way, which will help out. Our stock must live wholly upon such pasturage as can be found along the way. The men must also be well armed with rifles; wagons must be built; and the cattle must be purchased. There is a lot to do to get ready, and we must start in on it at once."

During the preceding year, as was well known, the Indians in the West had been unusually hostile. Many parties of freighters, among them Whitmore's train, had been attacked, and a great number of travelers had been massacred. That year and the one to be described, are still mentioned in the annals of the West, as "the bloody years on the plains." This state of affairs was fully considered and discussed, not solely from the standpoint of personal safety, but also with reference to the success of the enterprise.

Having been reared among the Indian tribes of Southern Wisconsin, and within a mile of the spot where Abraham Lincoln disbanded his company at the close of the Black Hawk War, I was disposed to believe that I was not entirely unfamiliar with the manners and customs of the aborigines. Searches for arrows and spearheads in prehistoric Aztalan and in other places, visits to Bad Axe and[16] to other scenes of conflict with Indians had been to me sources of keen delight. Over these battlefields there seemed to rest a halo of glory. They were invested with interest profound as that which, in later years, stimulated my imagination when I looked upon more notable battlefields of the Old World, where the destinies of nations had been decided. But at this time the experiences of my youth were fresh in my mind and the suggestion of a western trip found in me an eager welcome.

It was not indeed the lure of wealth, nor entirely a search for health that attracted the younger members of the party to a consideration of the project, nor in contemplating such an expedition was there enkindled any burning desire for warfare; it was the fascination of the wild life in prospect that tempted us most powerfully to share the fortunes of the other boys who had been our companions in earlier years and whom we fervently hoped would join the party. Fred undoubtedly expressed our sentiments when he said:

"My enthusiasm might take a big slump if a raid of those red devils should swoop down upon us, but if I go, I shall feel as if I didn't get my money's worth, if we don't see some of the real life of the Wild West."

We had all been accustomed to the use of firearms and could picture in our imagination how, from behind an ample rock, with the aid of good long-range rifles, we would valiantly defend ourselves against an enemy armed with bows and arrows, we being far beyond the range of such primitive weapons.

Immense herds of buffalo and other large game were also known to range over the plains from the Canadian border to the Gulf of Mexico, and these at times might receive proper attention. Yea, there were some present who even expressed a desire to capture a grizzly bear in the[17] mountains—of course under sane and safe conditions—though none up to that time had seen the real thing.

A former schoolmate, Billy Comstock, best known as "Wild Bill," who rode the first pony express from Atchison, and had often been called upon by our Government to act as Indian interpreter, was said to be somewhere on the plains. This was encouraging, for William would be able to give us some interesting pointers.

"We will meet here again after the store closes tomorrow night" was the word that passed round as we went out into the sleet and rain, and the door closed behind us.

At the earliest opportunity our friend, Ben Frees, who had recently returned from the war, was interviewed with favorable results.

"Yes, I will go with the boys," was my decision finally reached after a full discussion of the subject at home.

And the three boys went.

WHITMORE and Wilson, who were the leading spirits in our expedition, urged that twenty-five Henry repeating rifles (which had recently been invented) and thirty Colt's revolvers should be secured for our party; this in view of their experience on the plains in the preceding year and of recent reports from the West. If any trifling precaution of that nature would in any way contribute to the safety and comfort of those gentlemen, it would certainly meet with my approval. They were to leave families behind them and should go fully protected. In fact certain stories that had been related in my hearing had excited even within my breast a strong prejudice against the impolite and boorish manner in which Indians sometimes scalped their captives. Orders were accordingly transmitted for the arms to be shipped from Hartford. The sixty wagons were built specially for the purpose in question and thirty-six vigorous young men, the most of whom had seen service in the Civil War just ended, were secured to manage the teams.

Under the new white canvas cover of each wagon lay at least one rifle. The men had practiced more or less the[19] use of the peculiar whip that seemed necessary for the long teams. It consisted of a very short stock and an exceedingly long lash, which the expert can throw to its utmost length so as to reach the flank of a leader with accuracy, and without injury to the beast, producing a report rivaling in sharpness the explosion of a firecracker. The loudness of its snap was the measure of the skill with which the whip had been wielded.

The afternoon of Wednesday, April 18th, beheld a lively scene on the streets of the old town. Three hundred and sixty oxen, strong and healthy, but in some instances refractory, (as might have been expected), were carefully distributed and yoked up in their assigned positions. With the wagons they were lined out in the long street, the train extending about three-fifths of a mile, while the men in position awaited the command to move. In addition to the crowds of children and other curious onlookers, there were gathered at each wagon many friends, relatives, and, in some cases, sweethearts of the young men in charge of the several teams, to speak the tender words of farewell. It may sound strange now to say that many tears were shed. In this day of safe and swift travel, it is not easy to find occasion that would justify such a demonstration. It must be remembered, however, that the trip, even to Salt Lake City, on which this train was about to set out, would consume more time than now would be necessary to circle the globe. Moreover, the war, during which partings had come to be serious occasions, had but just ended. After leaving the Missouri River by the route contemplated, communication with friends at home would be suspended or uncertain for many months. The alarming indications of trouble with Indians on the plains were also in every mind, but were doubtless viewed less seriously by the[20] strong young men now departing than by those who were left behind, even by such as would not be apt "to fear for the fearless were they companions in their danger."

The appointed hour of four o'clock having arrived, the command "roll out," which afterwards became very familiar, was given. Under vigorous and incessant cracking of the new whips, the long train began to move on its journey westward. Expressions of kind wishes blended with cheers and the voices of the drivers, who were as yet not familiar with the great teams which they were to manage.

The undignified conduct of some of the young, untrained oxen, which occasionally persisted in an endeavor to strike off for themselves (possibly to seek their former masters' cribs), and the efforts of inexperienced drivers to bring them under subjection, were the cause of much amusement, especially when one long team, inspired by some sudden impulse, swung round its driver and doubled up in a confused mass, while a lone but unobserved country woman in a buggy was endeavoring to drive by. His years of experience in a country store were then of little avail to the young whipmaster who was less expert in wielding a long lash than in measuring calico for maidens. While raising his voice to its highest pitch, he was also striving to demonstrate his skill in manipulating the formidable thong by landing its resounding tip on the flank of an unruly steer full fifty feet away. As the long cord whirled swiftly in its broad circuit behind him it completely enwrapped the body of the woman. A terrific scream was the first intimation which came to our busy driver telling him the nature of the obstruction against which he was tugging. Her horse at once joined in the mêlee, and, starting, dragged the whip behind the buggy, until assistance was given and apologies were made. The woman pleasantly[21] remarked that she would not feel safe on her farm with many such drivers around.

Before sunset the train reached Harrington's Pond, the objective point of the first night's camp. The cooks at once pitched their tent, while the teamsters, having corralled the wagons into a circle, prepared to turn the cattle loose to feed upon the range. Before they were released, Whitmore shouted to the driver inside the circle:

"Now boys, everybody must look at his oxen mighty careful so as to know them and know where they belong in the teams, because if you don't you'll have a tussle in the morning picking out your stock and yoking them right when they'll be mixed up with four hundred other oxen."

Hearing this admonition, Gus Scoville, who had long been a store clerk, stood beside his oxen in a state of doubt and dire perplexity and finally opened his heart:

"Say Jule, these oxen all look just alike to me. How in thunder is a fellow going to know them in the morning; it's hard enough to know some people."

"Why Gus, they have lots of expression in their faces, and know each other mighty well. Say, I'll tell you how to work it, get a black rag and tear it into long strings and tie a strip around the tail of each ox."

I don't know from whose old coat Gus tore the black lining, but the oxen were soon decorated with emblems of mourning. The guards to watch the stock having been assigned, the men came down to the realities of camp life: no more china plates set by dainty hands on white linen tablecloths; no more delicate tidbits such as a housewife in a comfortable home so often serves; no easy chairs in which to rest in comfort, and no cleanly beds in which to pass the night,—yet no one was disappointed, and good spirits prevailed. The tin plates with bacon and hot[22] bread, and the big tin cups of coffee, without milk, were disposed of with evident relish, born of exercise and good digestion.

After the earlier evening hours had been whiled away with song and jest, one by one the pilgrims retired to their respective covered wagons, wrapped their blankets round them and maybe with boots beneath their heads for a pillow, sought the peace of sleep. Now and then the voice of some exuberant youth yet untamed would break the stillness of the night with an old song inappropriate to the hour, and from out some remote wagon another would join in the refrain.

As the mariner on the first glimpse of the morning light looks out toward the sky to see what are the signs for the coming day, so on their first morning in camp the boys, hearing the murmur of raindrops on their wagon covers or tents, looked out to take an observation, and discovered indications of an approaching storm. After the first preliminary gusts, the weather settled down into a steady rain, which continued thirty-six hours. It was deemed inexpedient so early in the trip to subject the men to unnecessary exposure, and the party was continued in camp. There were many duties to perform. The guard for the stock was changed periodically, but the boys in general devoted their energies to keeping dry and to drying out what had become wet. This was no easy matter, because the camp became surrounded by a sea of mud, and little comfort could be derived from an open, out-of-door bonfire, upon which the heavens were sending a drenching rain. The meals were served largely in the wagons, in some of which a number of the party would gather for mutual comfort and warmth, the food being conveyed to them by self-sacrificing young men, who with a pail of hot coffee[23] in one hand and tinware in the other, braved the elements for the common good.

They were already beginning to learn who were the good fellows, ready to do service, and who were the "gentlemen," too selfish or indifferent to share fully with others the responsibilities and sacrifices of this mode of life. Travel of the kind upon which they were embarking brings out the inward characteristics of men more quickly and thoroughly than can anything else. The spirit of Burns' Grace before Meat is consoling when all does not go smoothly:

The gloomy day was followed by a night of inky blackness, during which the April wind made the wagon covers flap incessantly, while the rain steadily rattled on the sheets and the air was chilly and penetrating. The conditions were not favorable to hilarity, and there was little noise except that caused by the elements; so until noon of the following day everyone sought to make the best of existing conditions, believing that, as had always been their observation, there never was a night so dark, nor a storm so severe that it was not followed by a sunburst.

HAVE you ever carefully watched the movements or caught the earnest spirit of the immigrant who, after traveling many hundreds of miles along the difficult roads through an unbroken country to a strange land, there seeks a spot where he may build a home for his family? Many of the young men in our party were on such a mission. That we may better understand the motives which inspired them and the movement of which they became a part, a retrospective glance seems almost necessary.

Having late in the thirties become the first scion of the pioneers in the country where I was born, I ought to be qualified to throw some light upon the experiences of the frontiersman, because primeval Wisconsin, as it lay untouched by civilization, and the inflow of its population as I saw it, left upon my mind vivid impressions. There was a blending of pathos and humor in the arduous lives of these builders of the nation.

Without then comprehending its significance, I had observed from time to time the arrival of sturdy and intelligent home-seekers from New England and New York, transporting their household effects in country wagons along the old, but almost impassable territorial road. I was[25] once led to accompany two other children, who, with their parents, were on such a pilgrimage. In their two-horse wagon were tightly packed a little furniture and a few boxes. The wagon cover had been turned that the view might be unobstructed. At one time the immigrants paused as they forded a running brook; they looked up and down the green valley; then they drove out from the road to the summit of a nearby knoll, where their horses were again rested. Here the father rose to his feet; he turned his eyes earnestly and intently now in one direction and now in another across the inviting stretches of unoccupied territory. An entrancing panorama of small valleys and vistas of groves, all clothed in soft verdure of June, was spread out before him; not a thing of man's construction, nor even a domestic animal, was visible on the landscape, except their faithful dog, which was scurrying among the hazel bushes.

To me there seemed a long delay. The father finally lifted his little, young wife so that she stood upon the wagon seat, supporting her with an encircling arm, his two boys standing before him. The children looked with wondering eyes, as he pointed to a far-away green meadow traversed by a brook, from near which rose a wooded slope. He asked if that would be a good place for a home. A simple but expressive nod, a tear in her eye, and a kiss on her husband's cheek, were the only signs of approval that the sick and weary wife was able to give. In later years, when I had learned their history, I knew better the meaning of the mother's emotion. The father drove down the bushy slope to the meadow, then taking his axe he crossed to the woodland, and there he blazed a tree as an evidence of his claim. Returning to the shelter of another settler's home, he was welcomed, as were all comers, by the pioneers, and[26] one little room was for many days the home of the two families once accustomed to eastern comforts. There they remained until the father could drive fifty miles to the Government land office, there perfect his title, and return to "roll up" his log cabin.

Such was the beginning of that colonization. I watched the first wagon train that later heralded the coming tide of thrifty Norwegians, and many of their trains that followed. I had never before seen a foreigner. They all followed round the Great Lakes in sailing vessels to Milwaukee. There they piled high their great wooden chests upon farmers' wagons by the side of which in strange, short-waisted, long-skirted woolen coats and blue caps, and with their women and children at their side, they plodded along on foot, first through the forests, then over the openings along the same territorial road. Both men and women often slept at night under the loaded wagons. I have observed them at their meals by the wayside where nothing was eaten but dry sheets of rye bread little thicker than blotting paper, and much like it in appearance. A few villages had then sprung up. From these the Norwegians scattered, chiefly among the hills, and there built little homes and left their impress upon the country.

But westward, and farther westward, the tide continued to flow. As some of the young men in our train were emigrating to the West to establish a home in the new country which they had never seen, I now found myself to be a part of this wonderful westward movement and was again to share in its peculiar vicissitudes and experiences; however, as a participant, favored with special opportunities, observing others also borne forward in the flux of nations.

As our train was traversing the first five-hundred-mile[27] lap to the Missouri River, we discovered that the homes beyond a certain point in Central Iowa seemed suddenly as it were to be few and far apart, leaving increasing stretches of unoccupied land between them. The population rapidly thinned out, until its last ripples were reached in the western part of the state, where the serenity of nature was hardly disturbed by the approaching flood of immigration.

There was already a line of small towns along the west bank of the Missouri, which were the starting points for transcontinental traffic, where freight was transferred from river steamers to wagons. Beyond the Missouri and a narrow strip of arable land along its western shore, lay the vast territory believed to be fit only for savages, wild beasts, and fur traders, a wide, inhospitable waste, which men were compelled to cross who would reach the Eldorado on the Pacific, or the mines in the mountains.

The line of demarcation between the fertile and the arid country was supposed to be well defined. On one side Nature responded to the spring and summer showers with luxuriant verdure; on the western side the sterile soil lay dormant under rainless skies. It was believed that immigration would certainly be checked at this line as the ocean tide faints upon a sandy shore; but it had now begun to flow along a narrow trail across the desert to a more generous land beyond. To this trail our course was now directed.

It would be an exceedingly dull company of emigrants and ox drivers which while traveling together even through a somewhat settled country, and sharing with each other the free life of the camp, would not have among its members a few whose thoughts and activities would at times break out from the narrow grooves of prescribed duties.[28] Our life of migration through the inhabited country was intensely interesting, furnishing many peculiar experiences, all flavored to some extent by the character and temper of the persons concerned. As the eagerness of the men to emancipate themselves from the restraints of civilization increased, they began soon to adopt the manners of frontiersmen, and to resort to every possible device within the range of their inventive powers for diversion.

Young Moore, who hoped to reach Oregon, was an exuberant fellow preferring any unconstrained activities to regular duties. In former days he had distinguished himself in "speaking pieces" in the district school. This training led him often to quote poetry very freely and dramatically. It was Moore who sighted the first game worthy of mention, when he observed two beautiful animals at the moment that they glided into a copse of bushes nearly half a mile from the train. Transferring the care of his team to another, he hastened for his gun and started upon the first interesting hunt of the trip. This being really his maiden experience in the fascinating sport, he was desirous of winning for himself the first laurels of victory in the chase. Not knowing the nature of the animals to be encountered, he approached as closely as possible to the coveted game, penetrating the thicket where the animals were concealed. The first discharge of his gun probably wounded one of the animals which, by the way, had a means of defense that baffles the attacks of the most powerful foe. The more experienced drivers soon knew that he had encountered the malodorous Mephites Americana, commonly known as skunk. Both of the animals and possibly some unseen confederates of the same family, must have invoked their combined resources in the conflict with Moore, for the all-pervasive pungent odor loaded the air and was wafted[29] toward us, seemingly dense enough to be felt. Moore retreated into the open and ran toward the train for assistance, but he was no longer a desirable companion. While it might be truly said that he was a sight, it might better be said that he was a smell.

The train moved on in search of pure air, and Moore followed, bearing with him the reminder of his unfortunate experience. Wheresoever he went he left behind him an invisible trail of odor which had the suggestion of contagion, and from which his fellows fled in dismay or disgust.

In the calm stillness of the next evening, when voices were easily heard at a distance, and when through the soft air of spring, perfumes were transmitted in their greatest perfection, Moore stood alone, far away from the camp, and delivered an eloquent but pathetic monologue, concluding with the servant's words to Pistol, "I would give all my fame for a pot of ale and safety." Then across the intervening space he calmly discussed with his friends the advisability of burying his clothes for a week to deodorize them, a custom said to be common among farmers who have suffered a like experience. It was finally conceded that he should hold himself in quarantine for the night, and not less than a mile from the train, and that during the ensuing days his garments might be hung in the open air on the rear of the hind wagon. The sequel to this hunt was approximately forty miles long, for the train covered more than that distance before it ceased to leave in its trail the fragrant reminder of Moore's first essay in hunting.

On a Saturday the long train rolled through the comparatively old town of Milton, a little village settled in the forties by a colony of Seventh Day Baptists. As is well known, these people honor the seventh day, or Saturday,[30] as their Sabbath, or day of rest. We filed through the quiet, sleepy town while the worshippers were going to their church. It seemed as if we had either lost our reckoning of time, or were flagrantly dishonoring the Lord's Day.

After we had passed through to the open country beyond, some of the boys who had been riding together in the rear and had been discussing the Sunday question brought to mind by this trifling occurrence, decided to interview our highest authority upon the subject, and accordingly rode alongside of Captain Whitmore, who had been riding in advance. "Captain," said one of the party, in a dignified and serious manner, "we know that your recent life has been spent very much in the mountains and that you have not been a regular attendant at church, although we believe your wife to be a good Methodist. What has been your practice in this kind of travel with reference to Sabbath observance?"

"Well, now, my boy," replied the Captain, "I have never cared very much for Sunday or for churches, but you must know that when we get out on the plains we can't afford to stop all our stock to starve on a desert where there is no feed or water just because it is Sunday. Sometimes there may be grass enough on a little bottom for a night, but it will be cropped close before the stock lies down. To remain another night would mean starvation to the stock, which would be roaming in every direction. Of course I don't know the ranges as well as the buffaloes do, but there are a few places, and I know pretty near where to find them, where in most seasons stock can feed a second day, unless others have too recently pastured it. When I find such a place I lie over for a day and don't care if it is Saturday, Sunday or Monday. But," he added, with earn[31]estness, "I want to tell you one thing. I have crossed the plains to the coast many times, and I can take a train of oxen or mules and turn them out one whole day every sixth or seventh day, free to range for twenty-four hours, and I can make this trip in less time and bring my stock through to the Pacific in better condition than any fool can who drives them even a little every day."

"Now, Cap," said one, "you are getting right down to the philosophy of Sabbath observance. Why can you drive farther by resting full days rather than to rest your stock a little more each day?"

"Well, I don't know, except that I have tried both ways. Animals and men seem to be built that way. Now, here's these Seventh Day Baptists whose Sunday comes on Saturday. They're all right, but they would be just as correct if they would regularly use any other day as the Sabbath, and I believe the Lord knew what we ought to have when he got out the fourth commandment. I know 'em all as well as you do. I think Mrs. Whitmore is right in going to church on Sunday, and in making me put on a clean shirt when at home, even though I do not go with her. It would be better for me if I would go with her, but I have roughed it so much that I have got out of the way of it."

Thus was announced the Captain's policy for our quasi weekly days of rest, and the affair was conducted accordingly.

As our train crawled across Rock River, whose banks were once the favorite hunting grounds of the Winnebagoes and Pottawattamies, I recalled a final gathering of the remnant of the latter tribe, which I witnessed, when, for the last time, they turned from their beautiful home and started in single file on their[32] long, sad trail toward the setting sun, to the reservation set apart for them forever. We shall note more of this type of historical incident as we pass beyond the Missouri, for the white man was pushing the Indian year by year farther back into the wild and arid lands then supposed to be of no use for cultivation.

The overshadowing events of more recent years cause us almost to forget that Zachary Taylor, Winfield Scott, Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame, and other men who became distinguished in American affairs, were once engaged in pursuing the Sacs and Foxes up these streams which we crossed while on our journey to the land of the yet unsubdued Sioux and Cheyennes.

Passing beyond the Mississippi, and to the western limit of railroad transportation, I was joined at Monticello by my old friends, Ben Frees and Fred Day.

Walking back six miles from the frontier station we struck the camp in time for a late supper. The dark evening hours were brightened by a rousing bonfire that the boys had built. The shadows of night had long since settled down upon the camp, and, there being no apparent occasion for us to retire immediately, Ben, Fred and I wandered together out into the gloom far away from the now flickering camp fire, which like some fevered lives, was soon to leave nothing but gray ashes or blackened, dying embers. We had just come together after our separation, and we conversed long concerning the unknown future that lay before us, for no definite plans for our trip, nor even the route that we were to take, had been perfected, and this was the second of May.

Our footsteps led us toward a rural cemetery, some miles east of the town of Monticello, in which we had already[33] observed a few white grave stones, indicating that the grim reaper had found an early harvest in this new settlement. Our attention was soon attracted to a dim light slowly floating around the ground in a remote ravine within the enclosure. A lonely graveyard at night had never appealed to me as a place of especial interest, yet I had heard of one unfortunate, who in his natural life had done a great wrong; when consigned to the tomb, his spirit, unable to rise, was held to earth, and yearly on certain nights it hovered over the grave where his own body had gone to dust.

"Boys," said Fred, "that light is certainly mysterious; it is not the light of a candle." A slight chill ran up my spinal column, concerning which I made no comment. It was at once suggested that there was nothing we were able to do about it; moreover our diffidence and modesty naturally inclined us to avoid mixing up in the private, sub-mundane affairs of the departed, especially those with whom we had had no acquaintance, or whose character was uncertain. If, instead of this strange light, the appearance had been something of flesh and blood, we, being as we believed, quite courageous, would have proceeded at once to investigate its nature. Curiosity, however, led us to advance cautiously forward. Ben, being a trifle shorter than I, was permitted to move in advance, as I did not wish to obstruct his view. The phosphorescence, or whatever it was, soon ceased to move, and rested near a little gravestone, the form of which we could faintly discern in outline. Quietly drawing nearer, we caught the subdued sound of something like a human voice coming, as we believed (and as was truly the fact), from the earth; the words, as nearly as we could understand, were, "help me out." Surely this was a spirit struggling to escape, and our[34] approach was recognized. At that moment we were startled to discover an arm reaching upward from the earth. Another dark form, emerging from the shadow of a nearby copse of bushes, in the dim light could be seen approaching toward the extended hand, which it appeared to grasp, and a body was lifted to the surface, from which came the words of kind assurance, "It's all right, Mike." "Sure," said Ben, "that is an Irishman, and I think Irishmen are generally good fellows, but I believe they are robbing a grave."

Drawing still nearer we discovered that the light which we had observed was an old-fashioned tin lantern, suspended from a small tree, and its feeble rays now brought to our view a plain, wooden coffin resting upon the ground. Inspired by a better knowledge of the situation, we quickly came to the front, and, as if vested with some authority for inquiring concerning this desecration, we demanded an explanation, for it was now past midnight.

"And wad ye have all the facts?" asked the Irishman, as we looked into the open grave. We firmly urged that we must understand the whole situation. The two men glanced at each other. "Well," said one, "this man in this coffin ferninst ye, died last night of smallpox, and we were hired to bury him before morning, because ye wouldn't have a smallpox stiff around in the day time, wad ye?" The path out of the graveyard was tortuous and dark; in fact, we found no path through the dense underbrush, but we reached the road in safety. Unseen and immaterial things are usually more feared than are visible and tangible objects. The combination of smallpox and spirits departed verges visibly on the uncanny.

On a tributary of the Des Moines River we found the first Indians thus far seen, possibly two score of miserable,[35] degraded beings who were camping there. They had little of the free, dignified bearing of representatives of the tribes with which I had once been familiar. A little contact with civilization and a little support from the Government had made them the idle, aimless wanderers that nearly all savages become when under such influence. Keokuk, the successor of Black Hawk, and Wapello, became chiefs of the united tribes of the Sacs and Foxes, and along with Appanoose, a Fox chief, received reservations along these streams. Wapello was buried at Indian Agency near Ottutumwa, beside the body of his friend and protector, General Street.

Our men had not yet reached a state of savagery in which there was not occasional longing for the good things commonly enjoyed by civilized beings. Among these was milk. On the day that we met the Indians, and at some distance from the camp, a solitary cow was seen feeding on the prairie. Several days had passed since our men had been permitted to enjoy the luxury of milk for coffee. It occurred to Brant that a golden opportunity was presented, which if seized upon would place the camp under lasting obligations to him. He struck across the country and gradually approaching the animal succeeded so thoroughly in securing her confidence that he soon returned with a pail of the precious liquid. The question arose as to whether or not Brant could set up a valid defense against a charge of larceny in case the owner of the cow, having proof that he had extracted the milk, should prefer charges against him. The case was argued at the evening session, and I preserved a record of the proceedings. Evidence was adduced to show that at the time the milk was taken, the cow was feeding upon the public domain, or what is known as Government land; that the grass and water[36] which were taken for its support and nourishment were obtained by the said cow from public lands without payment therefor; that a portion of said grass taken by said cow and not required for nourishment did, through the processes of nature, become milk; that the said milk at the time of its extraction had not become either constructively or prospectively an essential part of said cow, nor could any title thereto become exclusively vested in the owner of said cow, except such milk as said cow should have within her when she should enter upon the premises of her owner. It was admitted that the milk was obtained from said cow under false pretences, by virtue of the fact that Brant's manner in approaching her was such as was calculated to cause any cow of ordinary intelligence to believe that he was duly authorized to take said milk. It was assumed, however, that under the statutes of Iowa there was no law by which said cow could become a plaintiff in a case, even through the intervention of a nearest friend.

As the milk was to be served freely to all the boys for breakfast, and as we were desirous that all questions of justice and equity should be fairly settled before any property should be appropriated to our use which might have been unlawfully acquired, the jury, after prayerful consideration decided that as the food taken by said cow to produce said milk was public property, the milk also was the property of the public. We, therefore, used the milk in our coffee for breakfast. It was also the last obtained by the men for many months.

At this juncture I was to be sent upon a mission. There had been transported in the Captain's wagon a little more than $8,000.00 in currency to be used in the purchase of supplies. Whitmore was anxious that this currency, which was quite a large sum for that day, should be de[37]posited in some bank in Nebraska City. Improvising a belt in which the money was placed, I started out alone for that town, and soon encountered heavy storms, which delayed progress. On one day in which I made a continuous ride of seventy-eight miles, one stretch of twenty-four miles was passed along which no house was visible. This indicated the tapering out of civilization and the proximity of the western limit of population in that territory.

On the 22d of May I crossed the Missouri River by a ferry, after fording a long stretch of flooded bottom lands to the landing, five days after leaving our train, and reached Nebraska City, then an outfitting point for transcontinental travel.

FROM the western boundary of the state that bears its name, the attenuated channel of the Missouri River stretched itself far out into the unsettled Northwest, projecting its long antennae-like tributaries into the distant mountains, where year after year the fur traders awaited the annual arrival of the small river steamers, which in one trip each summer brought thither supplies from St. Louis and returned with rich cargoes of furs and peltries. On the western bank of that turbid, fickle stream were half a dozen towns, known chiefly as out-fitting places, which owed their existence to the river transportation from St. Louis, whereby supplies consigned to the mountains, or to the Pacific Coast, could be carried hundreds of miles further west and nearer to the mining districts and the ocean than by any other economical mode of transit. These towns had, therefore, become the base of operations for commerce and travel between the East and the far West, and so remained until the transcontinental railroads spanned the wilderness beyond.

Nebraska City was a fair type of those singular towns, which possibly have no counterpart at the present time. Like many western settlements, Nebraska City was christened a city when in its cradle, possibly because of the pre[39]vailing optimism of all western town-site boomers, who would make their town a city at least in name, with the hope that in time it would become a city in fact. The visitor to one of those towns at the present day is sure to be impressed with the remarkable metamorphosis wrought in five decades, if he stops to recall the hurly-burly and bustle of ante-railroad days when the great wagon trains were preparing for their spring migration.

It was at noon on the day of my arrival in Nebraska City when I debarked from the ferryboat and rode my horse up the one street of the embryo city until I discovered the primitive caravansary known as the Seymour House, which provided entertainment not only for man and beast but incidentally also for various other living creatures. The house seemed to be crowded, but with the suave assurance characteristic of successful hotel managers, the host encouraged me to cherish the hope that I might be provided with a bed at night, which would be assigned me later. After taking a hasty meal, being as yet undespoiled of the funds I had transported, I entered a bank, and with little knowledge concerning its solvency, gladly relieved myself of the burden of currency which I had borne for many days and nights. Then I strolled out upon the busy highway to see the town.

Rain had been falling intermittently for several days, leaving portions of the roadway covered with a thick solution of clay, but there were sidewalks which the numerous pedestrians followed. A panoramic view of the streets could not fail to remind one of the country fairs in olden times. Huge covered wagons, drawn by four or five yoke of oxen, or as many mules, moved slowly up and down that thoroughfare. Mingled with these were wagons of more moderate size, loaded with household goods, the property of[40] emigrants. I learned that the greater number of these were taking on supplies for their western journey. Many men, some mounted upon horses and others upon mules, were riding hurriedly up and down the street, as if speeding upon some important mission. All these riders seemed to have adopted a free and easy style of horsemanship entirely unlike that which is religiously taught by riding masters and practiced by gentlemen in our city parks. Their dress was invariably some rough garb peculiar to the West, consisting in part of a soft hat, a flannel shirt, and "pants" tucked tightly into long-legged boots, which were generally worn in those days. To these were added the indispensable leather belt, from which in many cases a revolver hung suspended. Men of the same type thronged the sidewalks; many of them with spurs rattling at their heels were young, lusty-looking fellows, evidently abounding in vigor and enthusiasm.

I conversed with many of them, and learned that the greater number were young farmers or villagers from the western and southern states. Some of them were wearing the uniform of the Northern or the Southern army. Assembled in and around the wide-open saloons there were also coteries of men whose actions and words indicated that they were quite at home in the worst life of the frontier. Hardly one of these men then upon the streets, as far as I could discover, was a resident of the city; all seemed to be planning to join some train bound for the West. Such were some of the factors destined to waken into life the slumbering resources of the broad, undeveloped regions beyond the Missouri.

Wandering further up the street, my steps were attracted toward a band of Pawnee Indians, who had entered the town, and, standing in a compact group, were gazing with[41] silent, stolid solemnity upon the busy scene. As was the custom with that tribe, their stiff black hair was cut so as to leave a crest standing erect over their heads. Their blankets, wrapped tightly around their bodies, partly exposed their bare limbs and moccasined feet, their primitive bows and their quivers of arrows. They had not yet degenerated into the mongrel caricatures of the noble red man that are often seen in later days, garbed in old straw hats and a few castaway articles of the white man's dress, combined with paint and feathers; but they stood there as strong representatives of the last generation of one of the proudest and most warlike tribes of America, the most uncompromising enemy of the Sioux, and as yet apparently unaffected by contact with civilization.

Led by a natural desire to learn what were the thoughts then uppermost in their minds, I cordially addressed them with the formal salutation "How," a word almost universally understood and used in friendly greeting to Indians of any tribe. A guttural "How" was uttered in return, but all further efforts to awaken their interest were fruitless. I was not surprised to discover that no language at my command could convey to them a single idea. The subject of their revery, therefore, remains a secret.

I well knew, however, that we were then standing on a part of their former hunting grounds and that lodges of their tribe had often stood on that very bluff. Had I seen my home of many years thus occupied by unwelcome invaders, I, too, might have spurned any greeting from a member of the encroaching race. Those Pawnees certainly heard their doom in the din and rattle upon that street where the busy white man was arming to go forward through the Indian's country. They soon turned their[42] backs on the scene and I saw them file again slowly westward toward the setting sun.

The time having arrived to return to the hotel, and, if possible to perfect my arrangement for a room, I retraced my steps. The hotel at night naturally became the rendezvous for all classes of people, if it can be properly said that there was more than one class. Most conspicuous were the rough freighters, stock traders, and prospective miners; and the few rooms were crowded to overflowing. Any request for a private room was regarded as an indication of pride or fastidiousness on the part of the applicant, and was almost an open breach of the democratic customs of the West. But I passed the night without serious discomfort and doubtless slept as peacefully as did my companions.

There were, however, other houses in Nebraska City for the entertainment of guests. It was another hospitable tavern and another well remembered night, to which I would now briefly refer. Accompanied by an older companion, I repaired to this hostelry, because of our previous acquaintance with the proprietor, who had formerly been a genial old farmer near my native town and was known as Uncle Prude. He promised to "fix us up all right" after supper. Accordingly we stepped out under a spreading oak tree, where, upon a bench, were set two tin washbasins and a cake of yellow soap, while from a shed nearby a long towel depended, gliding on a roller and thoroughly wet from frequent and continued service,—all of which instruments of ablution and detergence we exploited to the greatest advantage possible. Sitting a little later at one of the long, well-filled supper tables, we wondered how Uncle Prude would dispose of the great number of people in and around his hostelry. At an early hour we signified our in[43]clination to retire, and by the light of a tallow candle were escorted to a large room known as the ball room, so called because on great occasions, like the Fourth of July and New Year's night, it was used by the country swains and their lasses for dances. It was now filled with beds, with only narrow passages between them. A wooden shoe box, upon which was a tin washbasin and pitcher, stood near the end of the room. A single towel and a well-used horn comb still boasting a number of teeth, were suspended by strings. These, with four or five small chairs, constituted the furnishings. Some of the beds were already occupied by two persons, in some cases doubtless the result of natural selection. We took possession of the designated bed, blew out the light, and soon fell fast asleep. Later in the night we were awakened by the arrival of a belated guest, who was ushered in by the landlord's assistant. Taking a careful survey of the long row of beds, the assistant pointed to the one next to that which we were occupying and said, "You had better turn in with that fellow. I see it's the only place left." Gratified by his good fortune in securing accommodations, the guest thanked his escort, sat down on a chair and with his foot behind his other leg proceeded to remove his long boots. The noise of his grunts, or the falling of his boots upon the bare floor, awoke his prospective companion, who, slowly coming to consciousness, addressed the newcomer with the remark in kindly accents, accompanied with a yawn, "Are ye thinking about coming in here with me, stranger?" "Wa'll yes," he replied, "Prude sent me up. He said you and I had about all that's left. Pretty much crowded here tonight, they tell me," and he was soon nearly ready to blow out the light. The man in the bed, apparently revolving in his mind some serious proposition, added, "I think it's noth[44]ing more than fair, stranger, to tell you that I've got the itch, and maybe you wouldn't like to be with me." As a fact that undesirable contagion was known to be somewhat prevalent in those parts. The announcement, however, failed to produce the expected result. The newcomer, apparently unconcerned, calmly replied, "If you've got the itch any worse than I have, I am sorry for you. I guess we can get along together all right," and then proceeded to turn down his side of the bed. The occupant jumped to the floor, hastily gathered up his wearing apparel and suddenly bolted out the door. With no word of comment, the last comer blew out the light, turned into the vacant bed, and enjoyed its luxury the rest of the night. We were unable to identify the strangers on the following morning, but there were many questionings among the guests concerning the manner in which a certain affection may be transmitted.

On the following morning I had little choice but to follow the example of other transients and join the throng upon the street. It was not difficult to determine what thoughts were uppermost in the minds of the many men whom I met along that thoroughfare. I heard negotiations for the purchase of mules and oxen, and contracts for freight, often ratified with Stygian sanctity by the invitation to "go in and have something to drink." I was brought in contact with many men from Missouri and Kentucky. In negotiating for a small purchase, the price named by the seller was two bits. "What is two bits?" I asked. The gentleman from Pike County, Missouri, appeared to be surprised when my ignorance was revealed. After he had enlightened me, I found him to be equally dense when I proposed to give two shillings for the article,[45] the shilling of twelve and a half cents being then a common measure of value in my own state.

The signs over many of the stores of the town appealed to the requirements of a migratory people, "Harness Shop," "Wagon Repairing," "Outfitting Supplies," being among those frequently observed. The legend "Waggins for Sail" was of more doubtful and varied significance. The symbols, "Mammoth Corral," "Elephant Corral," and other corrals, indicated stables with capacious yards for stock, with rude conveniences which the freighter temporarily needs until he is out on the plains. The term "corral" was applied in the West to any enclosure for keeping stock and supplies, as well as to the circle formed by arranging the wagons of a train, as is the custom of freighters at night, for their protection and for other obvious reasons. In these regions the significance of the term widened so as to include any place where food or drink is meted out to men, instead of to mules, and signs bearing the word "Corral" were very common on resorts of that class. The sign "Bull Whackers Wanted," posted in many conspicuous places, was well understood by the élite of the profession to be a call for drivers.

The demand for firearms and knives seemed to be very active. The majority of men who had recently arrived from the East seemed to regard a revolver as quite indispensable, even in Nebraska City. As a fact, however, they were equipping for the plains. The local residents who were busy in their stores selling supplies apparently had no use for revolvers, except to sell them as fast as possible.

Near the foot of the street is the levee, where at that season of the year many steamers arrived and departed, their freight being discharged and transported to ware[46]houses, whence the greater part of it was reshipped by wagon trains to the far West. I went aboard one of the steamers and looked down upon the scene of feverish activity. The merchandise was being rushed ashore, that the boat might be hurried back to St. Louis, whence all freight to these towns was then brought. The busy season was brief, and time was money.

A mate stood near the head of the gangplank urging the colored deck hands to move more rapidly. The fervent curses that he hurled at the men seemed to tumble over each other in the exuberance of his utterance. While thus engaged, a coatless man walked rapidly up the gangplank and with clenched fists approached the officer thus busied with his exhortations. In threatening tones and manner and with an oath he notified the mate that he had been waiting for him and now ——. The mate, anticipating the man's evident purpose, instantly caught the spirit of the occasion and without awaiting the full delivery of the threat, himself delivered a powerful blow between the intruder's eyes, which unceremoniously tumbled him into an open hatchway nearby. Casting a brief glance through it into the hold, he asked the visitor if there was any one else around there that he had been waiting for. The mate then turned on the deck hands and cursed them for stopping to see the sport. The "niggers" displayed their teeth and smiled, knowing that the mate would have been inconsolable had there been no witnesses to his encounter.

On the 30th of May, eight days after my arrival at Nebraska City, our train arrived on the opposite side of the river, and I went over to assist in the crossing. The stream had overflowed its banks and night and day on its bosom a mighty drift of logs and trees went sweeping by.

There was, however, no tint on the rushing, rolling waters of the chocolate-colored Missouri that could remind one of the ocean blue.

The diary of a journey such as we embarked upon is probably of more interest in those features that deal with early western life under then existing conditions than in geological or archaeological observations. With this idea in mind, I venture to narrate an incident as it was told me on meeting our outfit at the river. The train had come to a halt in the village of Churchville, Iowa. Just before the order to "Roll out," was given, a youth apparently fifteen or sixteen years of age, approached and expressed a desire to see the proprietor of the expedition. Captain Whitmore was indicated as that person. The youth requested permission to accompany the train to Nebraska City, to find an uncle. The Captain cast glances at the boy, whose fine, clear complexion, delicate form, and quiet, unassuming manners indicated that he was probably unaccustomed to a life of exposure and was hardly fitted to enjoy the rough experience of an ox driver. "Young man," said the Captain, "I guess this will be a little too severe for you; I hardly think you will like this kind of travel." On being assured that no fears need be entertained in this matter, but that the boy was not able to pay the high rate of stage fare, the permission was finally granted. The impression really made upon the Captain was similar to that made by Viola on Malvolio, as given in Twelfth Night, where he is made to say:

"Not yet old enough for a man nor young enough for a boy! as a squash is before 'tis a peascod, or a codling when[48] 'tis almost an apple; 'tis with him in standing water between boy and man. He is very well-favored and he speaks very shrewishly."

The boy immediately, as if by instinct or delicacy, took a position in the train with Mrs. Brown, the cook's wife. As an assistant the youth did not assume the fresh manners expected from the average boy who is gifted with attractive features and fine temperament, but rode quietly along from day to day. In the course of time the Captain was led to entertain a suspicion concerning the youngster, which was finally embodied in a question concerning his sex. Without hesitation the boy frankly admitted that he was a girl. Being exposed so suddenly and among so large a number of men, she burst into tears, a very natural mode of expression among women.

Her story was short. It was a story of wrongs suffered at the hands of a step-father, and of desire to find an uncle in the West, which she had taken this method of accomplishing. "But where's her hame and what's her name, she didna choose to tell." She admitted having her proper apparel in her satchel, which was substituted for her male attire in the house of a farmer nearby. She then returned to the train and finished her journey, keeping herself in close company with Mrs. Brown. I saw the young woman soon after meeting the train. She was certainly a handsome, refined, modest-looking village girl, not more than nineteen years of age. We may catch another glimpse of the young girl's life later.

There have been but few writers who have laid the scenes of their romances in the far West, but there are numerous bits of history, supplied by the social life of the pioneers, like this truthfully-related incident, which the pen of a ready writer might turn into a tale as beautiful[49] and interesting as that of Viola, who in the role of page enacted her part and "never told her love."

On Saturday, June 2nd, additional crowds of people were attracted to the town by its first election, at which an opportunity was offered the people of the territory to vote upon the question of "State or no State." We learned later, that the vote of the people as might have been expected was in the affirmative, but on President Johnson's failing to approve the measure, statehood was for a time denied them.

Our train passed on through Nebraska City and camped six miles westward. We discovered later that the congestion of travel on the one thoroughfare of the town was really the result of the lack of business. The amount of freight to be moved from the river towns was less than had been expected, and the shippers being unwilling to pay the rates that had prevailed in former years, the freighters were refusing to carry the merchandise and were lingering in the towns expecting better prices.

In the course of a few days some expected friends arrived from Wisconsin with special merchandise and horse teams, and without waiting for the ox train, it was decided that a few from our party should separate from the others and with horse teams proceed westward at once. Negotiations with reference to a common interest in the mercantile venture were finally perfected. We purchased the supplies of provisions for our journey, and after supper, on June 8th, pulled out five miles from the town to our first Nebraskan camp. The sun had hardly set, closing the long June day, when our party, now brought together for the first time on this expedition, found its members all rounded on the grass in a prairie valley and half reclining upon boxes and bags, discussing the future.

[50] There was Peter Wintermute, a powerful, athletic young man; he was six feet and three inches in height, and his long legs were stretched out upon the grass. He was an experienced horseman, and had a team of four fine animals with a modest wagon load of merchandise of some value, which it was proposed to retail somewhere in the West. Paul Beemer, his wagon companion, interested in the venture, was a small, nervous, untiring fellow, and a fine shot with a rifle. This Peter and Paul had few of the characteristics of the Apostles whose names they bore. It is written of Peter, the Disciple, that on one occasion he swore and repented. I fail to recall the occasion when our Peter did not swear—and that is only one of many points of dissimilarity.

In the circle sat Daniel Trippe, another giant in strength and activity, cultured and well informed on current and general topics, a man of fine presence and wonderfully attractive in manner and appearance. Noah Gillespie was financially interested with Dan in a proposed manufacturing project in Idaho. Our Daniel, like his great prototype, was something of a prophet and seer, indeed also something of a philosopher, and his pronouncements were frequently invited. The similarity between our Noah and the great navigator of diluvian days lay chiefly in the fact that Gillespie also had met with much success in navigation—while propelling a canoe in duck hunting on the Wisconsin lakes. Moreover, so far as reported, the patriarch drank too much wine on but one occasion, whereas our Noah excelled greatly in tarrying too often at the wine cup; but he was a good fellow and a valuable companion in time of peril. Noah and Dan had a fine team.

A grand old man was Deacon Simeon E. Cobb, who now sat in the circle upon an empty cracker box, which he fre[51]quently used throughout the trip. He was trying the life on the plains in the hope of relieving himself of dyspepsia. He had a team and a light wagon with personal supplies, including a small tent. Henry Rundle and Aleck Freeman were also in the circle. They were vigorous, hardy and reliable men and they too had a team. The especial companions of the writer were Ben Frees and Fred Day. Ben was a compactly-built fellow of elephantine strength, and although only twenty years of age, had been a first-lieutenant in a Wisconsin regiment before Richmond at the surrender. Fred, who was still younger, was delicate but vivacious and buoyant and abounded in all those qualities that make for good fellowship.

And now spoke Dan, saying, "Boys, it's all right where we are now, but only last summer on the Big Blue, only a little west of us, the Indians were raiding and destroyed nearly all the stations from there on, beyond and along the Platte. Keep your rifles in their proper places, loaded and in perfect order." "All right, Dan," said Fred, "we'll keep 'em loaded until we fire 'em off." Each of the party had in his wagon a Henry repeating rifle and plenty of ammunition. Our supplies consisted chiefly of bacon, flour, coffee and sugar, no available canned goods then being on the market. With these preparations, we continued in the morning out upon the broad plains.

IT was in the gray light of the quiet early dawn, when all members of the camp except one were in peaceful slumber, that these familiar lines of Longfellow's heartening lyric were suddenly howled forth from the interior of Fred's tent. Coupled with the ill-mated refrain,

that dignified stanza had been often sung by boys like Fred, who persistently turned the serious things of life to levity. Because of frequent showers it had been really decided to make an early morning start, if conditions should prove favorable. Ordinarily Fred did not aspire to catch the worm, and in fact, after rousing the camp he lapsed back into his blanket and was the last man out for further service, in remarkable fulfillment of the famous Scripture. He had brought his companion, Ben, to his feet, who inflicted on him some harmless punishment for his breach of the peace.

Aroused by Fred's ill-timed outburst, I poked my head[53] outside my wagon cover and surveyed the situation. The white-covered prairie schooners were parked in a row, as they had been on the preceding night. The two little tents, one of which sheltered the venerable deacon, stood side by side. Not far distant our horses were picketed by ropes. At this first indication of human activity, the faithful animals one by one scrambled to their feet, shook their manes, and doubtless expected the usual supply of morning oats, in which expectation they were doomed to disappointment, for hereafter they had to make an honest living by foraging on the country. There was sufficient light to reveal the sparkling of the heavy dew upon the grass. Fred's matin song had accomplished its purpose, and many good-natured but vigorous epithets were thundered toward his tent by members of the party as they emerged from their wagons, and he himself was finally pulled forth from his lair.

It seems needless to state that to some members of our party who were early pioneers of Wisconsin, a primeval forest, or a broad, virgin prairie was not an unfamiliar sight. Nevertheless, there was something in the expanse of the Nebraska plains as they then were, before the farmer had desecrated them, that was wonderfully impressive. The almost boundless stretch of undulating green extended in every direction to the horizon, at times unrelieved by a single tree or shrub, and only now and then we observed the winding course of some little stream indicated by a narrow line of small timber half hidden in the valley, whose inclined and stunted growth told of the sweeping winds that had rocked them. Even those thin green lines were few and far between.

Bryant beautifully described this type of scenery when he wrote of the prairies:

We finally reached a little, solitary sod hut, which a pioneer had recently constructed. Not another work of man was visible in any direction. If Cowper sighing "for a lodge in some vast wilderness" had been placed in control of this sequestered cabin, his ardent desire would have been fully realized. It seemed as if it might well afford to any one grown weary of the wrong and outrage with which earth is filled, a spot where he might spend his remaining days in unbroken peace and quietude. But no! this cabin was but a little speck in advance of the on-coming tide of human life whose silent flow we had seen slowly but steadily creeping westward across the Iowa prairies. Thousands of men released from service in the army were turning to the West for homes, and the tens of thousands of foreigners landing at the Atlantic ports were then as now spreading over the country, adding volume and momentum to the westward movement.

The following night found us beside a little brook, on the banks of which wild strawberries were abundant. Our horses were picketed on the range, each being tied with a rope fifty feet in length, attached to an iron pin driven into the ground, as was the usual custom. Aleck Freeman, however, concluded to tie the lariat of one of his horses to the head of a nearby skeleton of an ox. In fact, Aleck commented duly upon his own sagacity in conceiving that idea. All went well until the horse in pulling upon the rope, detached the skull from the remaining vertebrae. The ani[55]mal seemed to be mystified on observing the head approach him as he receded, and for a moment regarded it thoughtfully and inquiringly. Backing still further away, he gazed with growing apprehension at the white skull, which continued to pursue him at a uniform distance. The horse evidently was unable to comprehend the cause of this strange proceeding and, like a child frightened at an apparition which it does not understand, his first impulse was to escape. He therefore gave a vigorous snort, wheeled, and with head high in the air, suddenly started southward toward the Gulf of Mexico. The faster the horse ran, the louder rattled the skull behind him. An occasional backward glance of the flying animal revealed to him the same white skull still pursuing, and at times leaping threateningly into the air as it was pulled over any slight obstruction; and thus they sped wildly away until they disappeared from sight. Aleck watched the affair from afar with dismay. What could stop the flight of this Pegasus but sheer exhaustion? It was soon many miles away. Securing another steed and starting in pursuit, he too was soon lost to view. In the late hours of the night he returned to camp leading the tired runaway, and himself too tired and hungry to tell his story until morning. It seems that about seven or eight miles away the skull had caught in a cottonwood bush, which was fortunately on an upward grade and the speed of the horse was temporarily slackened. The animal doubtless believed that the skull for the moment had stopped its pursuit, that it also was very weary. The horse when reached was well fastened and easily captured. Aleck urged that the Government authorities should have cottonwood bushes set out on all the hills of Nebraska, and that the heads of all carcasses on the prairie should be securely tied to the rest of the skeleton.

[56] Violent storms of wind and driving rain, accompanied by terrific lightning, forced us at noon to camp in the mud beside a swollen brook. We endeavored to build a fire in the wet grass, for we sighed for coffee. The combined skill of our best hunters failed to start a blaze. We were wet to the skin, and our saturated boots with trousers inside, down which the water ran in streams, were loaded with black Nebraskan mud; for every man had been out in the storm to picket his horses securely, as they were uneasy during the tempest. The few chunks of tough bread culled from the remnant found in the mess box served but little that night to fill the aching voids.

Not far away on a hill slope was an unoccupied frame house not yet completed. This building, which was about twenty-five miles west from Nebraska City, was the last farmhouse that we passed, but even here there was no sign of cultivation. To this, as the day was closing, we plowed our way through the mud, for the storms continued. Its partly finished roof furnished us a welcome protection through the following stormy night. A peck of shavings more or less was equitably distributed among the party for bedding, but there were no facilities for building a fire without igniting the structure itself. On the floor we endeavored, with our internal heat, to steam our garments dry. We had previously observed a few huts built of sod, with roofs of the same material laid upon poles. I ascertained that at least one of those structures was strengthened by a framework of logs, but the scarcity of timber and the expense of transporting it from where it was produced, led to the use of the more available material. The huts were similar in appearance to many that I have seen in Ireland, though the fibrous Irish sod cut from the bogs of the Emerald Isle is more durable—like all else that is Irish!

[57] A few ducks and plover had fallen before the Noachian and were gladly appropriated in the mess department, but we were on the qui vive for bigger game. We had been tantalized daily by dubious reports of antelope alleged to have been seen in the distance, and had been anxiously watching for an opportunity to test our Henry rifles on this elusive game.