Title: Marion Berkley: A Story for Girls

Author: Elizabeth B. Comins

Release date: December 1, 2012 [eBook #41524]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

PHILADELPHIA

HENRY T. COATES & CO

Copyright, 1870, by A. K. Loring.

TO

MY TWIN SISTERS

This Book

IS MOST AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED.

"Come on, Mab! the carriage is round; only fifteen minutes to get to the depot."

"Yes, I am coming. O mamma! do fasten this carpet-bag for me. Dear me! there goes the button off my gloves. Was there ever any one in such a flutter?"

"Never mind, dear; it is too late to sew it on now. Here is your bag; come, we must not stop another moment; there is Fred calling again."

"I say, Mab," shouted the first speaker from the bottom of the stairs, "if you're coming, why don't you come? I shan't leave until you bid me good-by, and I know I shall lose the ball-match. You do keep a fellow waiting so eternally long!"

His sister was downstairs, and had her arms around his neck before he had finished speaking, and said to him, in a tone of mock gravity, "Now, Frederic, don't get excited; always follow my good example, and keep cool. There now!" she exclaimed, as she gave him a hearty kiss; "be off. I forgot all about your ball-match, and all the amends I can make is to hope the Isthmians will beat the Olympics all to pieces."

"Come, come," called Mrs. Berkley from the inside of the carriage, "we have not a moment to lose."

"Good-by, Hannah. One more kiss for Mab, Charlie. Good-by, all;" then to the coachman, as she whisked into the carriage, "Drive on, John, just as fast as you can."

The carriage-door was shut with a snap; off went the horses, and Mrs. Berkley and her daughter were soon at the Western depot, where the latter was to take the cars for B——, a little New England town, where she attended boarding-school. They were very late at the depot, and Mrs. Berkley had only time for a fond kiss and a "Write often, darling," when the bell rung, and she was forced to leave the car, feeling a little uneasy that her daughter was obliged to take her journey alone. Just as the cars were starting, Marion put her head out of a window, and called to her mother, "O mamma! Flo is here; isn't that jolly? No fear now of—" The last part of the sentence was unintelligible, and all Mrs. Berkley got was a bright smile, and a wave of the hand, as the train moved out of the depot.

"Now, Flo, I call this providential," exclaimed Marion; "for, I can tell you, I did not relish the prospect of my solitary ride. Just hand me your bag, and I'll put it in the rack with my budgets. This seat is empty; suppose we turn it over, and then we shall be perfectly comfortable. Now I say this is decidedly scrumptious;" and she settled herself back, with a sigh of satisfaction.

"Why, Mab, what made you so late? I had been here fifteen minutes before you came, all on the qui vive, hoping to see some one I knew; but I never dreamed you would be here. I thought you were going up yesterday with the Thayers."

"I did intend to; but Fred had a sort of spread last night for the Isthmians, so I stayed over. I expect Miss Stiefbach will give me one of her annihilators, but I guess I can stand it. I've been withered so many times, that the glances of those 'eagle eyes' have rather lost their effect."

"Well, I only wish I had a little more of your spirit of resistance. What a lovely hat you have! Just suits your style. Where did you get it?"

"Why, it's only my old sun-down dyed and pressed over, and bound with the velvet off my old brown rep. I trimmed it myself, and feel mighty proud of it."

"Trimmed it yourself!—really? Well, I never saw such a girl; you can do anything! I couldn't have done it to save my life. I only wish to gracious I could; it would be very convenient sometimes."

And so the two girls rattled on for some time, in true school-girl fashion; but at last they each took a book, and settled back into their respective corners. Before very long, however, Marion tossed her book on to the opposite seat; for they were coming to Lake Cochituate, and nothing could be lovelier than the view which was stretching itself before them. I do not think that half the people of Massachusetts realize how beautiful this piece of water is; but I believe, if they had seen it then, they surely must have appreciated its charms.

It was about the middle of September, and the leaves were just beginning to turn; indeed, some of them were already quite brilliant. The day was soft and hazy,—just such a one as we often have in early autumn, and the slight mist of the atmosphere served to soften and harmonize the various colors of the landscape. The lake itself was as clear and smooth as polished glass, and every tree on the borders was distinctly reflected on its clear bosom; while the delicate blue sky, with the few feathery clouds floating across it seemed to be far beneath the surface of the water.

Marion was at heart a true artist, and had all a true artist's intense love of nature; she now sat at the window, completely absorbed in the scene before her, her eye and mind taking in all the beauties of form, color, and reflection; and as the cars bore her too swiftly by she uttered a sigh of real regret.

Perhaps there will be no better time than the present for giving my young readers a description of my heroine. My tale will contain no thrilling incidents, no hairbreadth escapes, or any of those startling events with which ideas of heroism are generally associated. It will be a simple story of a school-girl's life; its fun and frolic; its temptations, trials, and victories.

Marion Berkley was a remarkably beautiful girl; but she owed her beauty chiefly to the singular contrast of her hair and eyes. The former was a beautiful golden color, while her eyes, eyebrows, and lashes were very dark. Her nose and mouth, though well formed, could not be considered in any way remarkable. When in conversation her face became animated, the expression changed with each inward emotion, and her eyes sparkled brilliantly; but when in repose they assumed a softer, dreamier look, which seemed to hint of a deeper nature beneath this gay and often frivolous exterior.

Mr. Berkley was very fond of his daughter. He had a large circle of acquaintances, many of whom were in the habit of dining, or passing the evening, at his house, and it pleased him very much to have them notice her. Marion was by no means a vain girl; yet these attentions from those so much older than herself were rather inclined to turn her head. Fortunately, her mother was a very lovely and sensible woman, whose good example and sound advice served to counteract those influences which might otherwise have proved very injurious.

And now that I have introduced my friends to Marion, it is no more than fair that I should present them to her companion. Florence Stevenson was a bright, pretty brunette, of sixteen. She and Marion had been friends ever since they made "mud pies" together in the Berkleys' back yard. They shared the same room at school, got into the same scrapes, kept each other's secrets, and were, in short, almost inseparable. Florence had lost her mother when she was very young, and her father's house was ruled over by a well-meaning, but disagreeable maiden-aunt, who, by her constant and oftentimes unnecessary fault-finding, made Florence so unhappy, that she had hailed with delight her father's proposition of going away to school. For three years Florence and Marion had been almost daily together, being only separated during vacations, when, as Florence lived five miles from Boston, it was impossible that they should see as much of each other as they would have liked.

About four in the afternoon, the girls reached their destination; rather tired out by their long ride, but, nevertheless, in excellent spirits. Miss Stiefbach, after a few remarks as to the propriety of being a day before, rather than an hour behind time, dismissed them to their rooms to prepare for supper, where for the present we will leave them.

Miss Stiefbach and her sister Christine, were two excellent German ladies who, owing to a sudden reverse of fortune, were obliged to leave their mother-country, hoping to find means of supporting themselves in America. They were most kindly received by the gentlemen to whom they brought letters of introduction, and with their assistance they had been able to open a school for young ladies; and now, at the end of seven years, they found themselves free from debt, and at the head of one of the best boarding-schools in the United States.

Miss Stiefbach, the head and director of the establishment, was a stern, cold, forbidding woman; acting on what she considered to be the most strictly conscientious principles, but never unbending in the slightest degree her frigid, repelling manner. To look at her was enough to have told you her character at once. She was above the medium height, excessively thin and angular in her figure, and was always dressed in some stiff material, which, as Marion Berkley expressed it, "looked as if it had been starched and frozen, and had never been thawed out."

Miss Christine was fifteen years her junior, and her exact opposite in appearance as well as in disposition: she was short and stout, and rosy-cheeked, not at all pretty; but having such a kind smile, such a thoroughly good-natured face, that the girls all thought she was really beautiful, and would feel more repentance at one of her grieved looks, than they would for forty of Miss Stiefbach's frigid reprimands. And well they might love her, for she certainly was a kind friend to them. Many a school-girl trick or frolic had she concealed, which, if it had come under the searching eyes of her sister, would have secured the perpetrators as stern a rebuke, and perhaps as severe a punishment, as if they had committed some great wrong.

Miss Stiefbach's school was by no means what is generally called a "fashionable school." The parents of the young girls who went there wished that their daughters should receive not only a sound education, but that they should be taught many useful things not always included in the list of a young lady's accomplishments.

There were thirty scholars, ranging from the ages of seventeen to ten; two in each room. They were obliged to make their own beds, and take all the care of their rooms, except the sweeping. Every Saturday morning they all assembled in the school-room to darn their stockings, and do whatever other mending might be necessary. Formerly Miss Stiefbach herself had superintended their work, but for the last year she had put it under the charge of Miss Christine; an arrangement which was extremely pleasing to the girls, making for them a pleasant pastime of what had always been an irksome duty. After their mending was done, and their Bible lesson for the following Sabbath learned, the rest of the day was at their own disposal. Those who had friends in the neighborhood generally went to visit them; while the others took long walks, or occupied themselves in doing whatever best pleased them. There were of course some restrictions; but these were so slight, and so reasonable, that no one ever thought of complaining, and the day was almost always one of real enjoyment. Miss Stiefbach herself was an Episcopalian, and always required that every one, unless prevented by illness, should attend that church in the morning; but, in the afternoon, any girl who wished might go to any other church, first signifying her intention to one or the other of the sisters.

Some of Miss Stiefbach's ancestors had suffered from religious persecutions in Germany, and, although she felt it her duty to have her scholars attend what she considered to be the "true church," she could not have it on her conscience to be the means of preventing any one from worshipping God in whatever manner their hearts dictated.

It was the half-hour intermission at school; and Marion and Florence had taken Julia Thayer up into their room to give her a taste of some of the goodies they had brought from home with them. Their room was one of the largest in the house, having two deep windows; one in front, the other on the side. The side window faced the west, and in it the girls had placed a very pretty flower-stand filled with plants; an ivy was trained against the side, and a lovely mirandia hung from the top. The front window had a long seat fitted into it, and as it overlooked the street it was here that the girls almost always sat at their work or studies.

"Now, Julie," began Marion, "which will you have, sponge or currant?"

"Why, you are getting awfully stingy!" exclaimed Flo; "give her some of both."

"No, she can't have both; it is altogether too extravagant. This is my treat, and you need not make any comments."

"Well, if I can't have but one, I think I'll try sponge."

"Sensible girl! you knew it would not keep long. There, you shall have an Havana orange to pay you for your consideration."

"Please, ma'am," said Flo, in a voice of mock humility, "may I give her some of my French candies?"

"Yes, if you'll be a very good girl, and never interfere again when I am 'head-cook and bottle-washer.'"

The girls sat round the room chatting and eating; Flora and Julia were on the bed, when Marion, who was at the front window, jumped up on the seat, and called out: "O Flo! Julie! do come here! Just look at this man coming down the street. Such a swell!"

The two girls rushed precipitately to the window, and they all stood looking out with intense interest.

"I do declare, he is coming in here! Who in the world can he be? How he struts!" said Marion. "What a startling mustache! I do wonder who in the world he is."

"Allow me to see, young ladies; perhaps I can inform you," said a calm voice directly in their ears; and, turning, they beheld Miss Stiefbach. She had entered the room just as they began their comments, and now stood directly behind them. Florence and Julia fell back in dismay, and for a second a look of amazement passed over Marion's face; but it was only a second, for she instantly replied to Miss Stiefbach, in the same eager tone she had used when speaking to her companions: "Jump right up here; you can see him better, for he is underneath on the steps."

Miss Stiefbach looked at her aghast, and for once she was overpowered. She, the calm, the dignified, the stately Miss Stiefbach—jump! It was too much. If a glance could have transfixed her, Marion would have been immovable for life. Miss Stiefbach's usually pale face was flushed to a burning red, and her voice was choked with suppressed excitement, as she said, "Young ladies, you will go at once to the school-room. Miss Berkley, report to me in my study, immediately after the close of school;" and she sailed out of the room.

When she was gone, the girls stood and looked at each other, not exactly knowing whether to laugh or cry; but Marion decided for herself, by sitting down on the floor, and bursting into a fit of uncontrollable laughter. Florence held up her finger warningly, "Hush-sh-sh! Mab, she'll hop out from under the bed, like as not; do come downstairs."

"O girls! girls! that look!" shouted Marion. "Oh, I shall die! She was furious. Won't I catch it?"

"O Mab, how did you dare? It was awfully impudent."

"I know it, and I'm sure I don't know what made me say it. I never stopped to think; it just popped out, and I would not have lost that scene for anything;" and Marion went off again into one of her laughing-fits.

"O Mab, do stop!" said Julia, rather impatiently; "you'll get us into a pretty scrape."

"Well, I won't laugh another bit, if I can help it; come on!" and, jumping up, Marion ran downstairs, the others following her, into the school-room; when, what was their astonishment to see before them "the swell," who had been the cause of all their trouble, standing talking to Miss Stiefbach. They went quietly to their seats, wondering what would happen next. Marion whispered to Flo, "The new French teacher; a man, as I live, and not very old either. Won't we have fun?"

"Young ladies of the first class in French go into the anteroom, where M. Béranger will examine you. Miss Christine, accompany them, and preserve order." As Miss Stiefbach said this in her usual calm tones, Marion's recollections were almost too much for her; but she had a little laugh all to herself, behind the cover of her desk, as she took out her books.

The former French teacher had been a little, quiet woman, who had allowed herself to be ruled over by her pupils; but she had gone back to France, and Miss Stiefbach had secured the services of M. Béranger, who was recommended to her, both for his complete knowledge of his own language, and for his high moral character. The latter was indeed to be considered, for many foreigners, calling themselves professors, often prove to be mere worthless adventurers, knowing very little themselves of what they attempt to teach others, and being in other respects unfit for respectable society.

The young ladies were in quite a little flutter of expectation, as they took their seats, for Mr. Stein, their old music-teacher, was the only gentleman teacher of the establishment, and he was decidedly different from this rather elegant-looking Frenchman. M. Béranger came in, bowed in a dignified manner, took his chair, and at once began questioning the girls as to what they had studied, how far they were advanced, etc. Marion, who was ready for anything, and thought she might as well have a little more fun for the scolding that she knew was in store for her, tried hard to get up a little excitement; pretending not to understand when M. Béranger spoke to her; replying to all his questions in English, notwithstanding his repeated ejaculations of "Mademoiselle, je ne vous comprends pas du tout; parlez Français." But Marion would not "parlez Français," disregarding the beseeching looks of Miss Christine, and either made no reply, or obstinately spoke in English. For some time M. Béranger took no notice of her conduct, but went on questioning the rest of the class; assuring the timid by his polite, considerate patience, and quietly correcting the mistakes of the more confident. At last, however, as Marion asked him some trifling question, he looked her directly in the face, and simply replied, "M'lle Berkley, si vous parlez l'Anglais, il faut que je vous mette dans la classe des petites filles."

Marion looked at him a moment, in doubt whether he could be in earnest; but there was no mistaking that calm, determined look. Two things were before her: to rebel, and go down to the lower class in disgrace, or to yield gracefully to what she knew to be right. She chose the latter, and replied, "Monsieur, je pense que je resterai ici." As she said this, there was a slight flush of shame on her cheeks, and she bent her head with a little gesture, which seemed to beg pardon for her rudeness. At any rate, M. Béranger so understood it, and he ever afterwards entertained a secret respect and admiration for M'lle Berkley.

That night, in her own room, Marion thus explained her singular conduct: "You see, Flo, I wanted to find out, in the first place, what sort of stuff he was made of; whether he was to rule us, or we him, as we did poor little mademoiselle; and I found out pretty quickly. He came here to teach, not to be made game of. In two weeks, I expect to have the true Parisian accent, and to have entirely forgotten all the English I ever knew. Bonne nuit, ma chère;" and Marion turned over, and was asleep in five minutes.

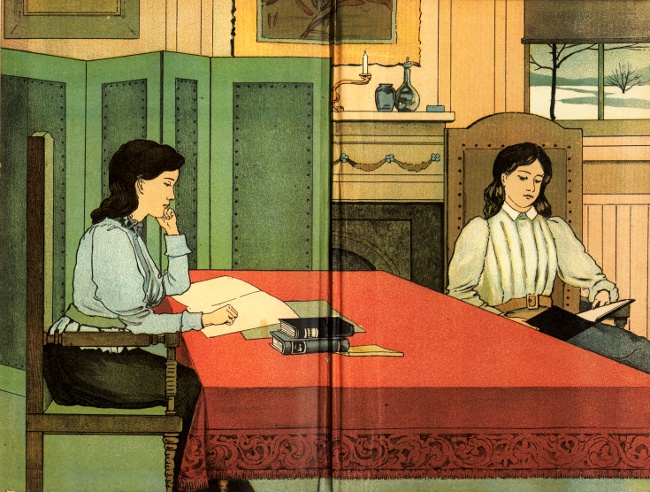

Immediately after the close of school Marion betook herself to the private study of Miss Stiefbach. This was a small room back of the drawing-room, fitted up very cosily and comfortably, and which no one but the sisters ever entered, except on state occasions, or under circumstances like the present. It must be confessed that Marion did not feel very comfortable as the door closed behind her, and Miss Stiefbach, who was sitting at her desk, turned round, motioning her to be seated. Marion knew she had done very wrong, and was really sorry for it, for, although none of the scholars could be said to have much affection for Miss Stiefbach, they all held her in the most profound respect, and no such direct attack upon her dignity had ever been made within the memory of any of the present pupils.

Miss Stiefbach cleared her throat, and commenced speaking in her most impressive and awful voice. "Miss Berkley" (the fact that she addressed Marion in this very distant manner proved at once that she was very angry), "your conduct to me this day has been such as I have never seen in any young lady since I became the head of this establishment, and I consider it deserves a severe punishment. The remarks which I overheard this morning, as I entered your room, were enough in themselves to have merited a stern rebuke, even if they had not been followed by a direct insult to myself. I am surprised indeed, that any young ladies brought up in refined society should have made use of such expressions as 'swell' and—and—other words of a like nature." It was evidently so hard for Miss Stiefbach to pronounce the word, even in a tone of intense disapproval, that Marion, despite her uneasiness, could not help being amused; but no trace of her feelings could be seen in her face; she sat before her teacher perfectly quiet,—so quiet, that Miss Stiefbach could not tell whether she was deeply repentant or supremely indifferent.

"I have decided," resumed Miss Stiefbach, "that as M. Béranger was indirectly connected with the affair, you shall apologize to me before the whole school, and in his presence, on the next French day, which will be Friday. I should not have subjected you to this mortification, if you had shown any willingness to apologize to me here; but as you seem entirely insensible of the impropriety of your conduct, I consider that the punishment is perfectly just."

Marion rose; for one second her eyes had flashed ominously when her sentence was delivered, but it was the only sign she gave of being surprised or otherwise moved. Perceiving that Miss Stiefbach had nothing more to say, she left the room as quietly as she had entered it. Several of the girls were standing at the study door waiting for her to come out, for the whole story had by this time become pretty freely circulated, and every one was impatient to know the result of the interview. Marion passed them without a glance, and without speaking, but with the most perfect sang froid, and went directly upstairs to her room. But once there her forced composure gave way, and, throwing herself on the bed, she burst into a passion of tears.

Florence, who had been anxiously waiting for Marion to come up, knelt down beside her, smoothing her hair, calling her by all their fond, pet names, and doing everything she could to soothe and quiet her, but never once asking the questions that were uppermost in her own mind, for she knew that, as soon as this first hysterical fit of weeping was over, her friend would tell her all. She waited some time, until she became almost frightened, for Marion's sobs shook her from head to foot, and she seemed unable to control herself.

Suddenly Marion sprang up, and exclaimed in the most excited, passionate tones, "Florence! Florence! what do you think she is going to make me do? Think of the most humiliating thing you can!"

"Indeed, my darling, I cannot guess," replied Flo, while she had hard work to restrain her own tears.

"I have got to apologize to her before the whole school, and before M. Béranger next Friday. Oh! I think it is abominable. She wouldn't have made any other girl do it, but she knows how proud I am, and she thinks now she'll humble me. Oh, it is too hard, too hard to bear!" and Marion threw herself back on the pillow, and sobbed aloud.

Poor Florence was completely overpowered. Distressed as she was for her friend, and furiously indignant with Miss Stiefbach, she hardly dared to comfort and sympathize with her, except by caresses, for fear of increasing her excitement, and she could only throw her arms round Marion's neck, kissing her repeatedly, and exclaiming again and again, "I wish I could help you!—I wish I could help you!"

But after a while the violence of Marion's grief and anger subsided, but left its traces in a severe headache; her temples throbbed fearfully, and her face and hands were burning hot.

Florence wet a cloth in cold water, and laid it on her head, and, knowing that Marion would prefer to be alone, she kissed her quietly, and as her eyes were closed was about to leave the room without speaking, when Marion called her back, exclaiming, "Don't tell the girls anything about it; they'll find it out soon enough."

"No, dear, I won't mention it, if I can help it. You lie still and try to get to sleep. Don't come downstairs to supper. I will excuse you to Miss Christine, and bring you up a cup of tea."

"No! no! no!" excitedly repeated Marion; "do no such thing. I wouldn't stay up from supper, if it killed me to go down; it would only prove to old Stiffback how deep she has cut, and I mean she shall find it will take more than she can do to humble me. Be sure and let me know when the bell rings. I don't think there is much danger of my going to sleep; but for fear I should, you come up before tea,—won't you?"

Flo promised, and giving her another kiss, and advising her again to lie still and go to sleep,—a thing which she knew it was impossible for Marion to do,—she left the room.

Left to herself Marion became a prey to her own varying emotions. Pride, anger, and mortification were rankling in her breast. When she thought of the coming disgrace which she was to endure, she sobbed and wept as if her heart would break; and then the image of Miss Stiefbach, with her calm, cool face, and deliberate manner, seeming so much as if she enjoyed giving such pain, rose before her mind, and she clenched her hands, and shut her teeth together, looking as she felt, willing to do almost anything to revenge herself.

In her inmost heart she had been truly sorry for having spoken so impertinently to her teacher, and she had gone to the study fully prepared to acknowledge that she had done wrong, and to ask pardon for her fault. But Miss Stiefbach, by presupposing that she felt no regret for her conduct, or any desire to apologize, had frozen all such feelings, and roused all the rebellious part of the girl's nature.

For some time Marion tossed restlessly from side to side; but at last, finding it impossible to quiet herself, much less to sleep, she got up, bathed her face, and prepared to arrange her disordered hair.

To her excited imagination, it seemed almost as if she could hear the girls downstairs discussing the whole matter. Every laugh she heard she believed to be at her expense, and she dreaded meeting her companions, knowing full well that her looks and actions would be the subject of general comment.

Throughout the school Marion was not a general favorite; almost all the girls admired her, but there were few who felt that they really knew her.

She was acknowledged by almost all her companions to be the brightest and prettiest girl in the school, and was apparently on good terms with all of them; but that was all. Many who would have liked to know her better, and who would have been glad to make advances of intimate friendship, felt themselves held back from doing so, by a certain haughty, reserved manner, which she at times assumed, and by her own evident disinclination for anything more than an amicable school-girl acquaintance.

Marion was quick to perceive the petty weaknesses and follies of these around her, and her keen sense of the ludicrous, combined with a habit of saying sharp, sarcastic things, often led her to draw out these foibles, and show them up in their most absurd light.

No one knew her faults better than Marion herself, and she was constantly struggling to overcome them; but her pride and strong will led her to conceal her real feelings, and often when she was at heart angry with herself, and ashamed of her wilful, perhaps unkind, behavior, she would assume an aspect of supreme indifference, effectually deceiving every one as to what was really passing in her mind.

She kept her struggles to herself. No one but her friend Florence and Miss Christine knew how sincerely she longed to conquer her faults, and how severe these struggles were.

The knowledge of them had come to Miss Christine by accident. One day Marion had said something unusually sharp and cutting to one of her companions, but had appeared perfectly unconscious of having done anything unkind, and had gone to her own room humming a tune, with the most perfect nonchalance.

Miss Christine shortly after followed her, wishing to talk with her, and show her the folly and wickedness of persisting in such conduct. She had found her door closed, and, knocking softly and receiving no answer, she gently opened it, when what was her astonishment to find Marion stretched upon the floor, weeping violently. She went to her, and, kneeling down beside her, called her by name. Marion, thus surprised, could not conceal her grief, or summon her cold, indifferent manner, and, leaning her head on Miss Christine's shoulder, she sobbed out her sorrow, shame, and repentance.

Never since had Miss Christine in any way alluded to the event, or by any means tried to force herself into Marion's confidence; but this glimpse into her heart had showed her what she might otherwise never have known, that Marion saw and regretted her own faults and failings, and was resolved to conquer them. From that time a secret bond of sympathy was established between pupil and scholar, and though no word was spoken, a mild, reproachful glance from Miss Christine, or her hand laid gently on Marion's shoulder, had often checked a rising exclamation, or cutting sarcasm, which, no matter how sharply it might have struck its victim, would have rebounded with greater and deeper pain to the very heart of Marion.

At home Marion had little or nothing to call forth the disagreeable qualities of her disposition. Surrounded by love and admiration on every side, the darling of her mother, and the pride and glory of her father, to whom she appeared almost faultless, it was no wonder that she found it hard to get on smoothly when thrown among a number of girls her own age, many of whom, jealous of her superior beauty and intelligence, would have been glad of any opportunity of getting her into trouble.

Then it was that the worst side of her nature showed itself; and she was shocked when she discovered how many faults she had which she had never thought of before.

Her sharp, sarcastic speeches gave her father infinite amusement when she was at home; but there her remarks rarely wounded any one; but at school she made her words tell, and she knew that her tongue was her greatest enemy.

But towards the younger girls Marion was always kind and good-natured. No one ever told such delightful stories, or made such pretty paper-dolls, or drew them such lovely pictures as Marion Berkley, and it was always a mystery to them why the "big girls" did not all love her.

Downstairs poor Florence had been having a hard time. When she first made her appearance in the library there had been a general rush towards her, and she was greeted with a perfect volley of questions, which it needed her utmost ingenuity to parry.

She knew Julia Thayer had a right to know all, for she had been personally concerned in the matter, besides being, next to Flo, Marion's dearest friend; but she saw that she could not tell her without further exciting the curiosity of the other girls, and she was forced to take her book, and appear to be deeply interested in her studies. But, although her lips monotonously whispered page after page of history, she knew no more about her lesson than if she had been reading Hindoostanee.

What was her astonishment when she heard close beside her Marion's voice, asking, in a perfectly natural tone, "Did Miss Christine say six pages of English History, or seven?"

Florence gave a quick glance at Marion's face, and saw that, although she was a little pale, she showed no signs of the storm that had so lately disturbed her. Neither did she throughout the evening appear other than bright and cheerful, effectually silencing by her own apparent ease any surmises or questions in which her companions might have indulged, and they all supposed that she had received a severe reprimand, and that there the matter would end.

But all agreed with Sarah Brown, who exclaimed, "How Miss Stiefbach had ever swallowed that pill so easily was a perfect mystery!"

"Well, Flo, I've hit it!" exclaimed Marion to Florence, as they were sitting together in their room Thursday afternoon.

"What do you mean?—hit what?"

"Why, I mean I've hit upon a plan; no, not exactly a plan;—I have decided what my apology shall be."

"Oh!" said Florence, "do you know just what you are going to say?"

"No, not precisely; that is, I have not yet settled upon any exact form of words, but I have got my ideas together, and I really think it will be something quite out of the common line."

Florence looked up inquisitively, for Marion's face or voice by no means expressed the repugnance which she had heretofore shown whenever she had spoken of the coming apology. In fact she looked rather triumphant, and a little, amused smile played about the corners of her mouth, as she bent over her work.

"Now, Mab," exclaimed Florence, "I know you are up to something! Do tell me what it is that evidently amuses you so much?"

"Oh, nothing particular," replied Marion; but in a tone which said plainly enough that there was something very particular indeed.

"Now, Mab, you needn't tell me!"

"That is exactly what I don't mean to do," provokingly replied Marion.

"Oh, don't be disagreeable! You know I am positively dying with curiosity; so out with it!" and Florence tossed her own work on to the bed, and, catching hold of Marion's canvas, threw it behind her, as she established herself on her friend's lap.

"Well, I'm sorry, my dear; but if your life depends on my telling you anything particular to-day, I am afraid you will come to an early grave."

Florence laid her hands on Marion's shoulders, and looked steadily into her eyes. Marion met the look with a confident, amused smile, and exclaimed, "Well, Flo, you look as sober as a judge. I really believe you think I meditate murder; but I assure you Miss Stiefbach's life is in no danger from my hands."

"I'll tell you just what I do think, Marion. I believe you are going to refuse to apologize, and if you do, you will be worse off than you've been yet;" and Florence really looked as serious as if she were trying a case in court.

"No, Flo, you needn't trouble yourself on that score. I mean to apologize before the whole school, and M. Béranger to boot,—just as old Stiffy ordered."

"Well, I am glad of it! Not glad that it must be done, you know; but I was afraid you would try to get rid of it in some way; and I know that would make matters worse."

"No, I don't mean to get rid of it; I shall do it in the most approved style. Come, get up, miss; you're awfully heavy!"

Florence jumped up, considerably relieved, but still a little suspicious of her friend's intentions. At that moment Julia Thayer came into the room.

"O girls! you here?" she exclaimed. "I've been hunting for you everywhere."

"Well, I don't think you hunted much; we've been here ever since lessons were done," replied Marion.

"Take a seat, Miss Thayer, and make yourself at home," said Florence.

"Thank you, I was only waiting to be asked. Now, Marion, do tell me; have you decided what you are going to say to-morrow?"

"It is no use asking her; you can't get anything out of her. I've just tried my best."

"What! don't you mean to tell us, beforehand?"

"No."

"Not a word? not a syllable? Well, I do declare! I tell you what it is, Flo, she means to astonish us all by some wonderful production."

"I suppose most of the girls will be astonished, for I don't believe they know there is to be any apology at all."

"No, I don't think they suspect it," said Julia. "So much for knowing how to hold one's tongue."

"Well, Julia, I guess this is the first time you could be accused of that," laughingly replied Flo.

"That is a libel! Who held their tongue about Aunt Bettie's doughnuts, I should like to know?"

"Another rare instance," mischievously put in Marion; "put it down, Julia, you'll never have another chance."

"But, girls, what do you mean?" cried Julia, in a deprecating tone. "Do you think I run and tell everything I know?"

"No, dear, not a bit of it," replied Flo; "you are not quite so reserved as Marion, but I never heard any one accuse you of telling what you ought to keep to yourself, or, as the boys say, of 'peaching.'"

"There, Julia, don't look so forlorn, for mercy's sake!" exclaimed Marion. "You are so delightfully easy to tease; but I confess it was a very poor reward for your silence of the past two days, which (she added with a mischievous twinkle in her eyes) I know must have almost killed you."

Julia and Florence both laughed outright at this rather equivocal consolation, and at that moment the supper-bell rang.

Friday morning every girl was in her seat precisely as the clock struck nine; for it was French day, and consequently only the second appearance of M. Béranger, and the novelty of having him there at all had by no means worn off.

He entered the room, shortly after, and, having politely wished Miss Stiefbach and her sister good-morning, was about to pass into the anteroom, when Miss Stiefbach detained him.

"Excuse me, M. Béranger, but I must trouble you to remain here a few moments."

M. Béranger bowed with his usual grace, and Miss Stiefbach continued:—

"I regret to say (she did not look as if she regretted it at all) that a circumstance of a most painful nature has lately taken place in this school. One of my young ladies has done that which makes me deem it necessary to exact a public apology from her. As you were indirectly concerned in the matter, I think it proper that the apology should be made before you. Miss—"

"But, madame," hastily interrupted the astonished Frenchman, "I cannot imagine; there must be a meestake—I am a perfect stranger; if you will have the goodness to excuse me, I shall be one tousand times obliged;" and the poor man looked as if he himself was the culprit.

"It is impossible, monsieur," decidedly replied Miss Stiefbach; "one particular clause of her punishment was, that it should be made in your presence. Miss Berkley, you will please come forward."

During the above conversation a most profound silence had reigned throughout the room; the girls, with the exception of the initiated three, had looked from one to another, and then at the group on the platform, with faces expressive of the most intense astonishment, proving how wholly unsuspicious they had been; but as Marion's name was pronounced a light broke in upon every one, and all eyes were turned upon her as she left her seat.

Miss Stiefbach stood with her hands folded over each other in her usual stately attitude. M. Béranger looked infinitely annoyed and distressed, and twirled his watch-chain in a very nervous manner. Miss Christine had retired to the extreme end of the platform, and was trying to appear interested in a book; but her face had a sad, pained look, which showed how fully her sympathies were with her pupil.

Florence Stevenson buried her face in her hands; she could not bear to witness her friend's disgrace. Marion advanced quietly up between the rows of desks, and as she stepped upon the platform turned so as to face the school.

She never looked lovelier in her life; a bright color burned in her cheeks, and her eyes, always wonderfully beautiful, glowed with a strange light; but the expression of her face would have baffled the most scrutinizing observer. Calm, quiet, perfectly self-possessed, but without a particle of self-assurance, she stood, the centre of general observation.

Presently she spoke in a full, clear voice: "Miss Stiefbach, as M. Béranger evidently does not know how he is concerned in this matter, perhaps I had better explain the circumstances to him."

Miss Stiefbach bowed her consent, and Marion, turning towards the bewildered Frenchman, thus addressed him:—

"M. Béranger, last Wednesday morning, as I, with two of my companions, was in my room, which is in the front of the house, my attention was attracted towards a gentleman who was coming down the street, and I immediately called my two friends to the window that they might get a good view of him. Our interest was of course doubly increased when we saw the gentleman enter this garden. His whole appearance was so decidedly elegant (here M. Béranger, who began to see that he was the subject of her remarks, colored up to the roots of his hair) that we could not help giving our opinions of him, and I applied to him the word 'swell,' which in itself I acknowledge to be very inelegant; but my only excuse for using it is, that in this case it was so very expressive."

M. Béranger, despite his embarassment, could hardly conceal a smile, while a suppressed murmur of amusement ran round the room. Miss Stiefbach looked hard at Marion, but her face was composed, and her manner quietly polite; she was apparently perfectly unconscious of having said anything to cause this diversion.

"While we were talking of him, Miss Stiefbach entered the room, and must have, unintentionally of course, overheard our comments, for the first intimation we had of her presence was this remark, which she made standing directly behind us: 'Young ladies, allow me to see; perhaps I can inform you.' And now occurred the remark which it was so exceedingly improper in me to make, and which justly gave so much offence to Miss Stiefbach." (Here Marion turned towards her teacher, who, as if to encourage her to proceed, bowed quite graciously.) "I was standing on the seat in the window, and consequently had the best view of the gentleman. In the excitement of the moment, regardless of the difference in our ages, and only remembering that we were impelled by one common object, I asked her to jump on to the seat beside me. Miss Stiefbach, for that rudeness I most sincerely ask your pardon. It was wrong, very wrong of me; I should have stepped aside, thus giving you an excellent opportunity of gratifying your desire to look at what is rarely seen here,—a handsome man."

The perfect absurdity of Miss Stiefbach's jumping up in a window with a party of wild school-girls, for the sake of looking at a handsome man, or indeed for her to look at a man at any time with any degree of interest, could only be appreciated by those who were daily witnesses of her prim, stately ways. It certainly was too much for the gravity of the inhabitants of that school-room.

M. Béranger bit his lip fiercely under his mustache; Miss Christine became suddenly very much interested in something out in the back yard; and the school-girls were obliged to resort to open books and desk-covers to conceal their amusement.

Marion alone remained cool and collected, looking at Miss Stiefbach as if to ask if she had said enough.

Miss Stiefbach's face was scarlet, and she shut her teeth tightly together, striving for her usual composure. The sudden turn of Marion's apology, which placed her in such a ridiculous light, had completely disconcerted her, and she knew not what to do or say.

If Marion's eyes had twinkled with mischief; if there had been the slightest tinge of sarcasm in her tone, or of triumph in her manner, Miss Stiefbach would have thought she intended a fresh insult; but throughout the whole her bearing had been unusually quiet, ladylike, and polite. There was no tangible point for her teacher to fasten on, and, commanding herself sufficiently to speak, Miss Stiefbach merely said, "It is enough; you may go to your seat."

Even then, if Marion's self-possession had given way, she would have been called back and severely reprimanded. But it did not; she passed all her school-mates, whose faces were turned towards her brimming with laughter and a keen appreciation of the affair, with a sort of preoccupied air, and, taking her books from her desk, followed M. Béranger into the anteroom.

At recess the girls with one impulse flocked round her, exclaiming, "Oh! it was too good; just the richest scene I ever saw."

"What do you mean?" coolly replied Marion.

"Why!" exclaimed Sarah Brown, an unencouraged admirer of Marion's, "the way you turned the tables on Miss Stiefbach."

"Indeed, Sarah, you are very much mistaken; I simply apologized to her for a great piece of rudeness."

And Marion turned away and ran upstairs to her own room, where Florence and Julia were already giving vent to their long pent-up feelings in only half-suppressed bursts of laughter.

As Marion made her appearance it was the signal for another shout; but she only replied by a quiet smile, which caused Julia to ejaculate in her most earnest manner, "I declare, Marion, you don't look a bit elated! If I had done such a bright thing as you have, I should be beaming with satisfaction."

"Well, Julia, I don't think I have done anything so very smart. To be sure I have had my revenge, and the only satisfaction I've got out of it is to feel thoroughly and heartily ashamed of myself."

"Marion Berkley, you certainly are the queerest girl I ever did see," exclaimed Julia.

But Florence, who knew her friend best, said nothing, for she understood her feelings, and admired her the more for them.

Marion had been determined to make her apology such as would reflect more absurdity on her teacher than on herself, and in that way to have her revenge for what she rightly considered her very unjust punishment. She had succeeded; but now that her momentary triumph was over, she sincerely wished that it had never occurred.

The next day she went to Miss Christine, and told her just how she felt about it, and that, if she advised her to do so, she would go to Miss Stiefbach and ask her forgiveness. But Miss Christine told her, that, although she heartily disapproved of her conduct, she thought nothing more had better be said about it, for Miss Stiefbach had only been half inclined to believe that Marion could intend a fresh impertinence.

And so there the matter ended; but Marion could never fully satisfy her own conscience on the subject.

She wrote a long letter to her mother, telling her the whole thing from beginning to end; and received one in reply, gently, but firmly, rebuking her for her conduct.

But the next day came four pages from her father, full of his amusement and enjoyment of the whole matter, and highly complimenting her on what he called "her brilliant coup d'état."

No wonder Marion's better nature was sometimes crushed, when the inward fires which she longed to extinguish were kindled by a father's hand.

"O girls, the new scholar has come!" shouted little Fannie Thayer, as she bounced into the library one afternoon, where some of the older girls were studying.

"Do hush, Fannie!" exclaimed her sister Julia; "you do make such an awful noise! Of course you've left the door open, and it's cold enough to freeze one. Run away, child."

"But, Julia," remonstrated Fannie, as her sister went on reading without taking any notice of her communication, "you didn't hear what I said,—the new scholar has come."

"What new scholar?" inquired Florence Stevenson, looking up from her book. "This is the first I have heard of any."

"Why, don't you know?" answered little Fannie, glad to have a listener. "Her name is—is—Well, I can't remember what it is,—something odd; but she comes from ever so far off, and she's real pretty, kind of sad-looking, you know."

"What in the world is the child talking about?" broke in Marion. "Who ever heard of Miss Stiefbach's taking a scholar after the term had begun?"

"I remember hearing something about it, now," said Julia. "The girl was to have come at the beginning of the quarter; but she has been sick, or something or other happened to prevent. I believe she comes from St. Louis."

"I wonder who she'll room with; she can't come in with us, that's certain," said Marion, with a very decided air.

"Why, of course she won't," replied Florence; "we never have but two girls in a room. Oh! I know, she will go in with little Rose May; see if she doesn't!"

"Well, I tell you, I am sorry she's come!" ejaculated Marion. "I hate new scholars; they always put on airs, and consider themselves sort of privileged characters. I for one shall not take much notice of her."

"Why, Marion," exclaimed Grace Minton, "I should think you would be ashamed to talk so! She may be a very nice girl indeed. You don't know anything about her."

"I don't care if she is a nice girl. She ought to have come before. It will just upset all our plans; the classes are all arranged, and everything is going on nicely. There are just enough of us, and I say it is a perfect bother!"

"I really don't see why you need trouble yourself so much," broke in Georgie Graham, who was always jealous of Marion, and never lost an opportunity of differing with her, though in a quiet way that was terribly aggravating. "I don't believe you will be called upon to make any arrangements, and I don't see how one, more or less, can make much difference any way."

The entrance of Miss Christine prevented Marion's reply, and she immediately took up her book and became apparently absorbed in her studies.

"O Miss Christine," they all exclaimed at once, "do tell us about the new scholar." "Is she pretty?" "Will she be kind to us little girls?" "How old is she?" and many other questions of a like nature, all asked in nearly the same breath.

"If you will be quiet, and not all speak at once, I will try and tell you all you want to know. The name of the new scholar is Rachel Drayton. She is about sixteen, and I think she is very pretty, although I do not know as you will agree with me. She seems to have a very lovely disposition, and I should think that after a while she might be very lively, and a pleasant companion for you all; but at present she is very delicate, as she has just recovered from a very severe illness brought on by her great grief at the death of her father. They were all the world to each other, and she was perfectly devoted to him. She cannot yet reconcile herself to her loss. He has been dead about eight weeks. Her mother died when she was a baby, and the nearest relation she has is her father's brother, who is now in Europe. Poor child! she is all alone in the world; my heart aches for her."

Miss Christine's usually cheery voice was very low and sad, and the tear that glistened in her eye proved that her expressions of sympathy were perfectly sincere; if, indeed, any one could have doubted that kind, loving face. As she ceased speaking, there was a perfect silence throughout the room, and those who had felt somewhat inclined to side with Marion felt very much conscience-stricken.

Marion, however, continued studying, not showing the slightest signs of having had her sympathies aroused.

Miss Christine continued: "I hope, girls, you will be particularly kind to Miss Drayton. She must naturally feel lonely, and perhaps diffident, among so many strangers, and I want you all to do everything in your power to make it pleasant for her. You in particular, Marion, having been here longer than any of the others, will be able to make her feel quite at home."

"Indeed, Miss Christine, you must excuse me. You know taking up new friends at a moment's notice, and becoming desperately intimate with them, is not my forte."

"Marion," replied Miss Christine, in a quiet, but reproving tone, "I do not ask you to become desperately intimate with her, as you call it, or anything of the kind. I merely wish you to show her that courtesy which is certainly due from one school-girl to another."

Marion made no reply, and Miss Christine sat down and commenced talking to the girls in her usual pleasant manner. It was her evident interest in everything which concerned them, that made her so beloved by her pupils.

They all knew that they could find in her a patient listener, and a willing helper, whenever they chose to seek her advice; whether it was about an important, or a very trifling matter.

There was some little bustle and confusion as the girls laid aside their books, and clustered round Miss Christine with their fancy-work, or leaned back in their chairs, glad to have nothing in particular to do.

"Miss Christine!" exclaimed little Rose May, "I do wish you would show me how to 'bind off.' I keep putting my thread over and over, and, instead of taking off stitches, it makes more every time. I think these sleeves are a perfect nuisance. I wish I hadn't begun 'em!"

"Why, you poor child," laughingly replied her teacher, "what are you doing? You might knit forever and your sleeves would not be 'bound off,' if you do nothing but put your worsted over. Who told you to do that?"

"Julia Thayer did; she said knit two and then put over, and knit two and then put over, all the time, and it would come all right."

"Now, Rose, I didn't!" exclaimed Julia. "I said put your stitch over, you silly child! I should think you might have known that putting your worsted over would widen it."

"I know you didn't say put your stitch over," retorted Rose; "you just said put over, and how was I going to know by that? I think you're real mean; you never take any pains with us little ones; I don't—"

"Hush, hush, Rose! You must not speak so," said Miss Christine, laying her hands on the child's lips; then, turning to Julia, she said, "If you had taken more pains with Rose, and tried to explain to her how she ought to have done her work, it would have been much better for both of you."

"Well, Miss Christine, she came just as I was thinking up for my composition, and I didn't want to be bothered by any one. As it was, she put all my ideas out of my head."

Miss Christine's only reply was a shake of the head and an incredulous smile, which made Julia wish she had shown a little more patience with the child.

"There, Rose," said Miss Christine, as the little girl put the finishing touch to her sleeves, "next time you will not have to ask any one to show you how to 'bind off.' Your sleeves are very pretty, and I know your mother will be glad her daughter took so much pains to please her."

Rose glanced up at her teacher with a bright smile, and went skipping off, ready for fun and frolic, now that those troublesome sleeves were finished. But she had hardly reached the hall when she came running back, saying, in a most mysterious sort of stage-whisper, "She's coming! she's coming downstairs with Miss Stiefbach! Rebecca what's-her-name; you know!"

The girls looked up as Miss Stiefbach entered the room, and, although they were too well-bred to actually stare at her companion, it must be confessed that their faces betrayed considerable interest.

Rachel Drayton, the "new scholar," was between sixteen and seventeen; tall and very slight; her eyes were very dark; her face intensely pale, but one saw at once it was the pallor of recent illness, or acute mental suffering, not of continued ill-health.

She was dressed in the deepest mourning, in a style somewhat older than that generally worn by girls of her age. Her jet-black hair, which grew very low on her forehead, was brushed loosely back, and gathered into a rough knot behind, as if the owner was too indifferent to her personal appearance to try to arrange it carefully.

As she stood now, fully conscious of the glances that were surreptitiously cast upon her, she appeared frightened and bewildered. Her eyes were cast down, but if any one had looked under their long lashes, they would have seen them dimmed with tears.

Accustomed all her life to the society of older persons, no one who has not experienced the same feeling can imagine how great an ordeal it was for her to enter that room full of girls of her own age. To notice the sudden hush that fell upon all as she came in; to feel that each one was mentally making comments upon her, was almost more than she could bear. If they had been persons many years older than herself, she would have gone in perfectly at her ease; chatted first with this one, then with that, and would have made herself at home immediately.

Unfortunately the only young persons in whose society she had been thrown were some young ladies she had met while travelling through the West with her father. They had been coarse, foolish creatures, making flippant remarks upon all whom they saw, in a rude, unladylike manner, and from whom she had shrunk with an irresistible feeling of repugnance. No wonder her heart had sunk within her when she thought that perhaps her future companions might be of the same stamp.

Miss Christine noticed her embarrassment at once, and kindly went forward to meet her, saying as she did so, "Well, my dear, I am glad to see you down here; I am not going to introduce you to your companions now, you will get acquainted with them all in time; first I want you to come into the school-room with me and see how you like it."

And she took her hand and led her through the open door into the school-room beyond; talking pleasantly all the time, calling her attention to the view from the windows, the arrangement of the desks, and various other things, until at last she saw her face light up with something like interest, and the timid, frightened look almost entirely disappear; then she took her back into the library.

As they went in, Florence Stevenson, who stood near the fireplace, made room for them, remarking as she did so, "It is very chilly; you must be cold; come here and warm yourself. How do you like our school-room?"

"Very much; that is, I think I shall. It seems very pleasant."

"Yes, it is pleasant. It's so much nicer for being papered with that pretty paper than if it had had dark, horrid walls like some I've seen. What sort of a school did you use to go to?"

"I never went to school before; I always studied at home;" and poor Rachel's voice trembled as she thought of the one who had always directed her studies; but Florence went bravely on, determined to do her part towards making the new scholar feel at home.

"Well, I'm afraid you will find it hard to get used to us, if you have never been thrown with girls before. I don't believe but what you thought we were almost savages; now honestly, didn't you feel afraid to meet us?"

"It was hard," replied Rachel; but as she glanced up at the bright, animated face before her, she thought that if all her future companions were like this one she should have no great fears for the future.

Most of the scholars had left the room; the few who remained were chatting together apparently unconscious of the stranger's presence, and as Rachel stood before the fire, with her back to the rest of the room, and Florence beside her talking animatedly, she was surprised to find herself becoming interested and at ease, and before Miss Christine left them the two girls were comparing notes on their studies, and gave promise of soon becoming very good friends.

When Marion left the library, she went directly to her room, locked the door, and threw herself on the seat in the window in a tumult of emotion. Paramount over all other feelings stood shame. She could not excuse herself for her strange behavior, and she felt unhappy; almost miserable. "Why did I speak so?" she asked herself. "Why should I feel such an unaccountable prejudice against a person I never even heard of before? I thought I had conquered all these old, hateful feelings, and here they are all coming back again. I don't know what is the matter with me. It is not jealousy; for how can I be jealous of a person I never saw or heard of before in my life? I don't know what it is, and I don't much care; there aren't four girls in the school that like me, and only one I really love, and that's dear old Flo. She's as good as gold, and if any one should ever come between us I pity her! I'll bet anything though, that she is downstairs making friends with that girl this minute."

This thought was not calculated to calm Marion's ruffled feelings, and she sat brooding by the window in anything but an enviable mood.

She was still in this state of mind when the tea-bell rang, and hastily smoothing her hair she went downstairs.

It chanced that just as she entered the dining-room Rachel Drayton and Florence came in by the opposite door. Florence was evidently giving Rachel an account of some of their school frolics, though in an undertone, so that Marion could not catch the words, and her companion was listening, her face beaming with interest. No circumstance could have occurred which would have been more unfavorable for changing Marion's wayward mood.

Coming downstairs she had been picturing to herself the unhappiness and loneliness of the poor orphan, and she had almost made up her mind to go forward, introduce herself, and try by being kind and agreeable to make amends for her former injustice; for although she knew Miss Drayton must be entirely unconscious of it, she could not in her own heart feel at rest until she had made some atonement.

No one could have presented themselves to a perfect stranger,—a thing which it is not easy for most persons to do,—with more grace and loveliness than Marion, if she had been so inclined, for there was at times a certain fascination about her voice and manner that few could resist.

She had expected to see a pale, sickly, utterly miserable-looking girl, towards whom she felt it would be impossible to steel her heart; and she saw one, who, although she was certainly pale enough, seemed to be anything but miserable, and above all was evidently fast becoming on intimate terms with her own dear friend Florence.

That was enough; resolutely crushing down all kindly feelings that were struggling for utterance, she took her seat at the table as if unconscious of the stranger's existence. Miss Stiefbach sat at the head of one very long table, and Miss Christine at another, having most of the little girls at her end; while Marion sat directly opposite with Florence on her right. Without changing this long-established order of things, Miss Christine could not make room for Rachel by the side of Florence as she would have liked, and the only place for her seemed to be on Marion's left, as there were not so many girls on that side of the table. Hoping that such close proximity would force Marion to unbend the reserved manner which she saw she was fast assuming, Miss Christine, before taking her own seat, went to that end of the table and introduced Marion to Rachel, laughingly remarking that as they were the oldest young ladies there, they would have to sustain the dignity of the table.

This jesting command was certainly carried out to the very letter of the law by Marion.

She was intensely polite throughout the meal, but perfectly frigid in the dignity of her manner, which so acted upon poor Rachel, that the bright smiles which Florence had called forth were effectually dispelled, and throughout the rest of the evening she was the same sad, frightened girl who had first made her appearance in the library.

When Marion knelt that night to pray, her lips refused to utter her accustomed prayers. It seemed hypocrisy for her, who had so resolutely made another unhappy, to ask God's blessings on her head, and she remained kneeling long after Florence had got into bed, communing with herself, her only inward cry being, "God forgive me!"

But how could she expect God would forgive her, when day after day she knowingly committed the same faults?

Sick at heart, she rose from her knees, turned out the gas, and went to bed, but not to sleep; far into the night she lay awake viewing her past conduct.

She did not try to excuse herself, or to look at her faults in any other than their true light; but, repentant and sorrowful though she might be, she could not as yet sufficiently conquer her pride to ask pardon of those she had openly wounded, or to contradict an expressed opinion even after she regretted ever having formed it.

Poor child! she thought she had struggled long and fiercely with herself; she had yet to learn that the battle was but just begun.

"Oh, dear!" yawned Grace Minton, "how I do hate stormy Saturdays!"

"So do I!" exclaimed Georgie Graham; "they are a perfect nuisance, and we were going up to Aunt Bettie's this afternoon."

"Who's we?"

"Oh, 'her royal highness' for one, and your humble servant for another; Sarah Brown, Flo Stevenson, and Rachel Drayton, of course. By the way, how terribly intimate those two have grown! I don't believe 'her highness' relishes their being so dreadfully thick."

"What in the world makes you call Marion 'her highness'?" said Grace.

"Oh, because she is so high and mighty; she walks round here sometimes as if she were queen and we her subjects."

"No such thing, Georgie Graham!" exclaimed Sarah Brown, who came in just as the last remark was made, and knew very well to whom it alluded; "she doesn't trouble herself about us at all."

"That's just it; she thinks herself superior to us poor plebeians."

"Stuff and nonsense! You know you're jealous of her, and always have been."

"Oh, no!" replied Georgie, who, no matter how much she might be provoked, always spoke to any one in a soft purring voice. "Oh, no! I'm not jealous of her; there is no reason why I should be. But really, Sarah, I don't see why you need take up the cudgel for her so fiercely; she always snubs you every chance she gets."

Sarah tossed her head, blushing scarlet; for the remark certainly had a good deal of truth in it, and was none the less cutting for being made in a particularly mild tone.

"Well, at any rate," said Grace Minton, for the sake of changing the subject, "I think Rachel Drayton is lovely."

"Lovely!" exclaimed Georgie, "she's a perfect stick! I don't see what there is lovely about her, and for my part I wish she had never come here."

"Seems to me the tune has changed," broke in Sarah. "I thought you were one of the ones who were so down on Marion Berkley for saying the same thing."

"Oh, that was before I had seen her," replied Georgie, not at all disconcerted.

"In other words, you said it just so as to have an opportunity to differ with Marion," retorted Sarah. "I really believe you hate her!"

"Sarah, how can you get so excited? it is so very unbecoming, you know," purred Georgie. Sarah flounced out of the room too indignant for speech, and just as she was going through the hall met Marion, who was in an unusually pleasant mood.

"See, Sarah, it is clearing off; we shall have a chance for our walk, I guess, after all."

"Do you think so? It will be awful sloppy though, won't it?"

"No, I don't believe it will; besides who cares for that? We are not made of sugar or salt."

"How many are going?" asked Sarah.

"I don't know exactly; let me see." And Marion counted off on her fingers. "You for one, and I for another; that's two. Miss Drayton and Florence are four. Grace Minton, if she wants to go, five; and Georgie Graham six."

At the mention of the last name, Sarah gave her head a toss, which was so very expressive that Marion could not help laughing, and exclaimed, "Oh, yes! you know 'her royal highness' must allow some of the plebeians among her subjects to follow in her train."

Sarah laughed softly. "Did you hear?" she whispered.

Marion nodded, and just at that moment Georgie came out of the room where she had been sitting. "What was that you said, Marion, about 'her highness'?" she asked. "Did you think that the title applied to yourself?"

"I shouldn't have thought of such a thing, Georgie, if I hadn't overheard your remarks, and of course I could not but feel gratified at the honorable distinction."

"How do you know it was meant for an honorable distinction?"

"How can I doubt it, Georgie, when it was bestowed upon me by such an amiable young lady as yourself? Now if it had been Sarah, I might have thought she said it out of spite; but of course when Georgie Graham said it, I knew it was intended as a tribute to my superiority;" and Marion made a provokingly graceful courtesy.

"There is nothing like having a good opinion of one's self," replied Georgie.

"But you see you are mistaken there, Georgie; it was you who seemed to have such a high opinion of me. You know I didn't claim the greatness,—it was 'thrust upon me;'" and Marion, satisfied with that shaft, turned on her heel, and opening the front door went out on to the piazza, followed by Sarah, who had been a silent but appreciative witness of the scene.

Georgie Graham shut her teeth, muttering in anything but her usual soft tones, and with an expression in her eyes which was anything but pleasant to see, "Oh, how I hate you! But I'll be even with you yet!"

The shower which had so disconcerted the whole school was evidently clearing off, and there was every prospect that the proposed plan of walking to Aunt Bettie's directly after dinner might be carried into execution.

Aunt Bettie, as all the school-girls called her, was a farmer's wife, who supplied the school with eggs, butter, and cheese, and during the summer with fresh vegetables and berries.

She lived about two or three miles from the school, on the same road, and the girls often went to see her. She was fond of them all, although she had her favorites, among whom was Marion; and she always kept a good supply of doughnuts, for which she was quite famous, on hand for them whenever they might come.

The sun kept his promise, and before dinner-time the girls were all out on the piazza, getting up an appetite they said, although that was not often wanting with any of them.

The party for Aunt Bettie's numbered eight,—Rose May and Fannie Thayer having begged Marion to ask permission for them to go,—and they all set out for their walk in high spirits. Although Marion treated Rachel with a certain degree of politeness, she never spoke to her unless it was absolutely necessary, and then always addressed her as Miss Drayton, although every other girl in school had, by this time, become accustomed to familiarly call her Rachel. Florence had done everything in her power to draw Marion into their conversation at table, but seeing that she was determined not to change her manner, she thought it best to take no more notice of it, as by doing so it only made it the more apparent to Rachel that Marion had no intention of becoming better acquainted with her.

Rachel had been there but a short time, and already Marion began to feel that Florence was turning from her for a new friend. This was not really the case, and Florence, who knew Marion's feelings, was secretly very much troubled.

She loved Marion as deeply and truly as ever; but she could not turn away from that motherless girl, between whom and herself an instinctive sympathy seem to have been established, arising from the loss which they had each felt, and which naturally drew them closer to each other. Florence had never known her mother, but the loss was none the less great to her; she felt that there was a place in the heart that none but a mother's love could ever have filled, and no matter how bright and happy she might feel, there was at times a sense of utter loneliness about her which she found hard to dispel.

Rachel seemed to turn to her as her only friend among that crowd of strangers, and she could not refuse to give her her friendship in return, even at the risk of seeing Marion for a time estranged from her; for she trusted to Marion's better nature, hoping that in the future she would not be misjudged, and that all might be made pleasant and happy again.

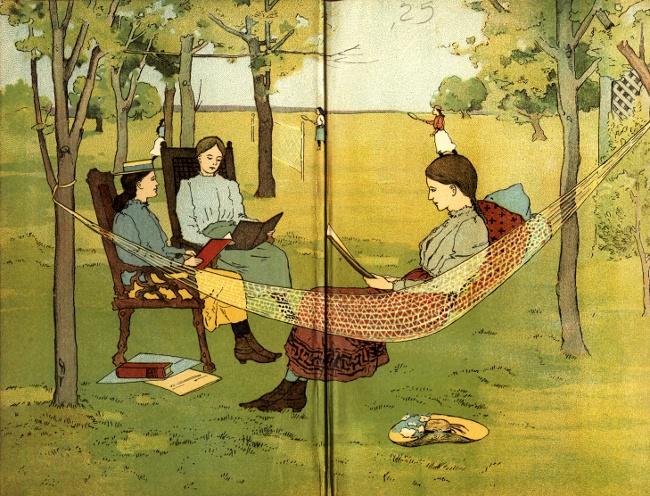

And so to-day for the first time since they had been to school together, Florence and Marion were taking their Saturday afternoon walk with separate companions. Marion had Rose May by the hand, while she told Sarah Brown to take care of little Fannie. Florence and Rachel were directly in front of her, and she knew that they would have been happy to have had her join in their conversation. In fact, they spoke so that she could hear every word they said; but she occupied herself by telling Rose a story of such remarkable length and interest as to perfectly enchant the child, who exclaimed as they reached the farm-house, "O Marion, you do tell the best stories; I really think you ought to write a book!" Marion laughed, but had no chance to answer, for at that moment the door opened and Aunt Bettie appeared upon the threshold.

"Wall, gals, I be glad to see ye; this is a sight good for old eyes!"

"Did you expect us, auntie?" asked Marion.

"Spect yer, child! why, I been a-lookin' for yer these three Saturdays past! What you been a-doin' that's kept yer so long?"

"Well, nothing in particular; but you see the term has only just begun, and we've hardly got settled."

"Oh, yes, honey, I know; I haint laid it up agin yer. But who's this new one?—yer haint introduced me."

As Marion showed no inclination to perform the ceremony Florence presented Rachel, remarking that she was a new scholar from the West. But Aunt Bettie's keen eyes took in at a glance the deep mourning apparel, and her kind heart at once divined its cause; and she exclaimed with great heartiness as she took Rachel's hands in her own rough palms, "Wall, child, you couldn't 'a come to a better place than Miss Stiffback's, and you couldn't 'a got in with a better lot o' girls; take em as they come, they're about as good a set as I knows on!"

"O Aunt Bettie!" exclaimed Florence; "flattering, as I live! I wouldn't have believed it of you."

"Not a bit of it, child; just plain speakin', a thing that never hurt anybody yet, according to my notion. But come in, gals; come in, you must be tired after your long walk, and the tin box is most a-bustin' its sides, I crammed it so full."

The girls laughed, for they all knew what the tin box contained, and were only too ready to be called upon to empty it.

They all seated themselves in the large, old-fashioned kitchen, with its low ceiling and tremendous open fireplace, surmounted by a narrow shelf, on which was displayed a huge Bible, and a china shepherdess in a green skirt and pink bodice, smiling tenderly over two glass lamps and a Britannia teapot, at a china shepherd in a yellow jacket and sky-blue smalls; being, I suppose, exact representations of the sheep-tenders of that part of the country.

Aunt Bettie bustled in and out of the huge pantry, bringing out a large tin box filled to the top with delicious brown, spicy doughnuts, and a large earthen pitcher of new milk.

"There, gals," as she put a tray of tumblers on the table, "jest help yerselves, and the more yer eat, why the better I shall be suited."

"Suppose we should go through the box and not leave any for Jabe; what should you say to that?" asked Marion.

"Never you mind Jabe; trust him for getting his fill. Eat all yer want, and then stuff the rest in yer pockets."

"Oh, that wouldn't do at all!" exclaimed Marion; "you don't know what a fuss we had about those Julia Thayer carried home last year! Miss Stiefbach didn't like it at all; she said it was bad enough bringing boxes from home, but going round the neighborhood picking up cake was disgraceful. She never knew exactly who took them to school, for Julia kept mum; but I don't think it would do to try it again."

"Wall, I think that was too bad of Miss Stiffback; she knows nothin' pleases me so much as to have you come here and eat my doughnuts, and if you choose to carry some on 'em to school, what harm did it do? She ought to remember that she was a gal once herself."

"Oh, mercy! auntie, I don't believe she ever was," ejaculated Marion. "She was born Miss Stiefbach, and I wouldn't be at all surprised if she wore the same stiff dresses, and had the same I'm-a-little-better-than-any-body-else look when she was a baby."

"Wall, child, she's a good woman after all. You know there aint any of us perfect; we all hev our faults; if it aint one thing it's another; it's pretty much the same the world over."

"You do make the best doughnuts, Aunt Bettie, I ever eat," declared Fannie Thayer, who was leaning with both elbows on the table, a piece of a doughnut in one hand, and a whole one in the other as a reserve force.

"Wall, child, I ginerally kalkerlate I ken match any one going on doughnuts; but 't seemed to me these weren't 's good as common. I had something on my mind that worrited me when I was mixin' 'em, and I 'spose I wasn't quite as keerful as usual."

"If you don't call these good, I do!" ejaculated Miss Fannie. "Why, I just wish you could have seen some Julia made last summer. She took a cooking-fit, and tried most everything; mother said she wasted more eggs and butter than she was worth, and her doughnuts!—Ugh! heavy, greasy things!"

"She must 'a let 'em soak fat!" exclaimed Aunt Bettie, who was always interested in the cookery question; "that's the great trouble with doughnuts; some folks think everything's in the mixin', but I say more'n half depends on the fryin'. You must hev yer fat hot, and stand over 'em all the time. I allers watch mine pretty close and turn 'em offen with a fork, and then I hev a cullender ready to put 'em right in so't the fat ken dreen off. I find it pays t' be pertickeler;" and Aunt Bettie smoothed her apron, and leaned back in her chair with the air of one who had said something of benefit to mankind in general.

"But where is Julia?" she asked after a short pause. "Why didn't she come?"

"Oh, I forgot!" exclaimed Fannie; "she sent her love to you, and told me to tell you not to let us eat up all your doughnuts this time, because she'll be up before long and want some. She had a sore throat, and Miss Stiefbach thought she had better not go out."

"I'm sorry for that," replied Aunt Bettie; "I hope she aint a-goin' to be sick."