Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Letter" to "Lightfoot, John"

Author: Various

Release date: December 6, 2012 [eBook #41567]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

LETTER (through Fr. lettre from Lat. littera or litera, letter of the alphabet; the origin of the Latin word is obscure; it has probably no connexion with the root of linere, to smear, i.e. with wax, for an inscription with a stilus), a character or symbol expressing any one of the elementary sounds into which a spoken word may be analysed, one of the members of an alphabet. As applied to things written, the word follows mainly the meanings of the Latin plural litterae, the most common meaning attaching to the word being that of a written communication from one person to another, an epistle (q.v.). For the means adopted to secure the transmission of letters see Post and Postal Service. The word is also, particularly in the plural, applied to many legal and formal written documents, as in letters patent, letters rogatory and dismissory, &c. The Latin use of the plural is also followed in the employment of “letters” in the sense of literature (q.v.) or learning.

LETTERKENNY, a market town of Co. Donegal, Ireland, 23 m. W. by S. of Londonderry by the Londonderry and Lough Swilly and Letterkenny railway. Pop. (1901) 2370. It has a harbour at Port Ballyrane, 1 m. distant on Lough Swilly. In the market square a considerable trade in grain, flax and provisions is prosecuted. Rope-making and shirt-making are industries. The handsome Roman Catholic cathedral for the diocese of Raphoe occupies a commanding site, and cost a large sum, as it contains carving from Rome, glass from Munich and a pulpit of Irish and Carrara marble. It was consecrated in 1901. There is a Catholic college dedicated to St Ewnan. The town, which is governed by an urban district council, is a centre for visitors to the county. Its name signifies the “hill of the O’Cannanans,” a family who lorded over Tyrconnell before the rise of the O’Donnells.

LETTER OF CREDIT, a letter, open or sealed, from a banker or merchant, containing a request to some other person or firm to advance the bearer of the letter, or some other person named therein, upon the credit of the writer a particular or an unlimited sum of money. A letter of credit is either general or special. It is general when addressed to merchants or other persons in general, requesting an advance to a third person, and special when addressed to a particular person by name requesting him to make such an advance. A letter of credit is not a negotiable instrument. When a letter of credit is given for the purchase of goods, the letter of credit usually states the particulars of the merchandise against which bills are to be drawn, and shipping documents (bills of lading, invoices, insurance policies) are usually attached to the draft for acceptance.

LETTERS PATENT. It is a rule alike of common law and sound policy that grants of freehold interests, franchises, liberties, &c., by the sovereign to a subject should be made only after due consideration, and in a form readily accessible to the public. These ends are attained in England through the agency of that piece of constitutional machinery known as “letters patent.” It is here proposed to consider only the characteristics of letters patent generally. The law relating to letters patent for inventions is dealt with under the heading Patents.

Letters patent (litterae patentes) are letters addressed by the sovereign “to all to whom these presents shall come,” reciting the grant of some dignity, office, monopoly, franchise or other privilege to the patentee. They are not sealed up, but are left open (hence the term “patent”), and are recorded in the Patent Rolls in the Record Office, or in the case of very recent grants, in the Chancery Enrolment Office, so that all subjects of the realm may read and be bound by their contents. In this respect they differ from certain other letters of the sovereign directed to particular persons and for particular purposes, which, not being proper for public inspection, are closed up and sealed on the outside, and are thereupon called writs close (litterae clausae) and are recorded in the Close Rolls. Letters patent are used to put into commission various powers inherent in the crown—legislative powers, as when the sovereign entrusts to others the duty of opening parliament or assenting to bills; judicial powers, e.g. of gaol delivery; executive powers, as when the duties of Treasurer and Lord High Admiral are assigned to commissioners of the Treasury and Admiralty (Anson, Const. ii. 47). Letters patent are also used to incorporate bodies by charter—in the British colonies, this mode of legislation is frequently applied to joint stock companies (cf. Rev. Stats. Ontario, c. 191, s. 9)—to grant a congé d’élire to a dean and chapter to elect a bishop, or licence to convocation to amend canons; to grant pardon, and to confer certain offices and dignities. Among grants of offices, &c., made by letters patent the following may be enumerated: offices in the Heralds’ College; the dignities of a peer, baronet and knight bachelor; the appointments of lord-lieutenant, custos rotulorum of counties, judge of the High Court and Indian and Colonial judgeships, king’s counsel, crown livings; the offices of attorney- and solicitor-general, commander-in-chief, master of the horse, keeper of the privy seal, postmaster-general, king’s printer; grants of separate courts of quarter-sessions. The fees payable in respect of the grant of various forms of letters patent are fixed by orders of the lord chancellor, dated 20th of June 1871, 18th of July 1871 and 11th of Aug. 1881. (These orders are set out at length in the Statutory Rules and Orders Revised (ed. 1904), vol. ii. tit. “Clerk of the Crown in Chancery,” pp. i. et seq.) Formerly each colonial governor was appointed and commissioned by letters patent under the great seal of the United Kingdom. But since 1875, the practice has been to create the office of governor in each colony by letters patent, and then to make each appointment to the office by commission under the Royal Sign Manual and to give to the governor so appointed instructions in a uniform shape under the Royal Sign Manual. The letters patent, commission and instructions, are commonly described as the Governor’s Commission (see Jenkyns, British Rule and Jurisdiction beyond the Seas, p. 100; the forms now in use are printed in Appx. iv. Also the Statutory Rules and Codes Revised, ed. 1904, under the title of the colony to which they relate). The Colonial Letters Patent Act 1863 provides that letters patent shall not take effect in the colonies or possessions beyond the seas until their publication there by proclamation or otherwise (s. 2), and shall 502 be void unless so published within nine months in the case of colonies east of Bengal or west of Cape Horn, and within six months in any other case. Colonial officers and judges holding offices by patent for life or for a term certain, are removable by a special procedure—“amotion”—by the Governor and Council, subject to a right of appeal to the king in Council (Leave of Absence Act, formerly cited as “Burke’s Act” 1782; see Montagu v. Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, 1849, 6 Moo. P.C. 491; Willis v. Gipps, 1846, 6 St. Trials [N.S., 311]). The law of conquered or ceded colonies may be altered by the crown by letters patent under the Great Seal as well as by Proclamation or Order in Council (Jephson v. Riera, 1835, 3 Knapp, 130; 3 St. Trials [N.S.] 591).

Procedure.—Formerly letters patent were always granted under the Great Seal. But now, under the Crown Office Act 1877, and the Orders in Council made under it, many letters patent are sealed with the wafer great seal. Letters patent for inventions are issued under the seal of the Patent Office. The procedure by which letters patent are obtained is as follows: A warrant for the issue of letters patent is drawn up; and is signed by the lord chancellor; this is submitted to the law officers of the crown, who countersign it; finally, the warrant thus signed and countersigned is submitted to His Majesty, who affixes his signature. The warrant is then sent to the Crown Office and is filed, after it has been acted upon by the issue of letters patent under the great or under the wafer seal as the case may be. The letters patent are then delivered into the custody of those in whose favour they are granted.

Construction.—The construction of letters patent differs from that of other grants in certain particulars: (i.) Letters patent, contrary to the ordinary rule, are construed in a sense favourable to the grantor (viz. the crown) rather than to the grantee; although this rule is said not to apply so strictly where the grant is made for consideration, or where it purports to be made ex certâ scientiâ et mero motu. (ii.) When it appears from the face of the grant that the sovereign has been mistaken or deceived, either in matter of fact or in matter of law, as, e.g. by false suggestion on the part of the patentee, or by misrecital of former grants, or if the grant is contrary to law or uncertain, the letters patent are absolutely void, and may still, it would seem, be cancelled (except as regards letters patent for inventions, which are revoked by a special procedure, regulated by § 26 of the Patents Act 1883), by the procedure known as scire facias, an action brought against the patentee in the name of the crown with the fiat of the attorney-general.

As to letters patent generally, see Bacon’s Abridgment (“Prerogative,” F.); Chitty’s Prerogative; Hindmarsh on Patents (1846); Anson, Law and Custom of the Const. ii. (3rd ed., Oxford and London, 1907-1908).

LETTRES DE CACHET. Considered solely as French documents, lettres de cachet may be defined as letters signed by the king of France, countersigned by one of his ministers, and closed with the royal seal (cachet). They contained an order—in principle, any order whatsoever—emanating directly from the king, and executory by himself. In the case of organized bodies lettres de cachet were issued for the purpose of enjoining members to assemble or to accomplish some definite act; the provincial estates were convoked in this manner, and it was by a lettre de cachet (called lettre de jussion) that the king ordered a parlement to register a law in the teeth of its own remonstrances. The best-known lettres de cachet, however, were those which may be called penal, by which the king sentenced a subject without trial and without an opportunity of defence to imprisonment in a state prison or an ordinary gaol, confinement in a convent or a hospital, transportation to the colonies, or relegation to a given place within the realm.

The power which the king exercised on these various occasions was a royal privilege recognized by old French law, and can be traced to a maxim which furnished a text of the Digest of Justinian: “Rex solutus est a legibus.” This signified particularly that when the king intervened directly in the administration proper, or in the administration of justice, by a special act of his will, he could decide without heeding the laws, and even in a sense contrary to the laws. This was an early conception, and in early times the order in question was simply verbal; thus some letters patent of Henry III. of France in 1576 (Isambert, Anciennes lois françaises, xiv. 278) state that François de Montmorency was “prisoner in our castle of the Bastille in Paris by verbal command” of the late king Charles IX. But in the 14th century the principle was introduced that the order should be written, and hence arose the lettre de cachet. The lettre de cachet belonged to the class of lettres closes, as opposed to lettres patentes, which contained the expression of the legal and permanent will of the king, and had to be furnished with the seal of state affixed by the chancellor. The lettres de cachet, on the contrary, were signed simply by a secretary of state (formerly known as secrétaire des commandements) for the king; they bore merely the imprint of the king’s privy seal, from which circumstance they were often called, in the 14th and 15th centuries, lettres de petit signet or lettres de petit cachet, and were entirely exempt from the control of the chancellor.

While serving the government as a silent weapon against political adversaries or dangerous writers and as a means of punishing culprits of high birth without the scandal of a suit at law, the lettres de cachet had many other uses. They were employed by the police in dealing with prostitutes, and on their authority lunatics were shut up in hospitals and sometimes in prisons. They were also often used by heads of families as a means of correction, e.g. for protecting the family honour from the disorderly or criminal conduct of sons; wives, too, took advantage of them to curb the profligacy of husbands and vice versa. They were issued by the intermediary on the advice of the intendants in the provinces and of the lieutenant of police in Paris. In reality, the secretary of state issued them in a completely arbitrary fashion, and in most cases the king was unaware of their issue. In the 18th century it is certain that the letters were often issued blank, i.e. without containing the name of the person against whom they were directed; the recipient, or mandatary, filled in the name in order to make the letter effective.

Protests against the lettres de cachet were made continually by the parlement of Paris and by the provincial parlements, and often also by the States-General. In 1648 the sovereign courts of Paris procured their momentary suppression in a kind of charter of liberties which they imposed upon the crown, but which was ephemeral. It was not until the reign of Louis XVI. that a reaction against this abuse became clearly perceptible. At the beginning of that reign Malesherbes during his short ministry endeavoured to infuse some measure of justice into the system, and in March 1784 the baron de Breteuil, a minister of the king’s household, addressed a circular to the intendants and the lieutenant of police with a view to preventing the crying abuses connected with the issue of lettres de cachet. In Paris, in 1779, the Cour des Aides demanded their suppression, and in March 1788 the parlement of Paris made some exceedingly energetic remonstrances, which are important for the light they throw upon old French public law. The crown, however, did not decide to lay aside this weapon, and in a declaration to the States-General in the royal session of the 23rd of June 1789 (art. 15) it did not renounce it absolutely. Lettres de cachet were abolished by the Constituent Assembly, but Napoleon re-established their equivalent by a political measure in the decree of the 9th of March 1801 on the state prisons. This was one of the acts brought up against him by the sénatus-consulte of the 3rd of April 1814, which pronounced his fall “considering that he has violated the constitutional laws by the decrees on the state prisons.”

See Honoré Mirabeau, Les Lettres de cachet et des prisons d’état (Hamburg, 1782), written in the dungeon at Vincennes into which his father had thrown him by a lettre de cachet, one of the ablest and most eloquent of his works, which had an immense circulation and was translated into English with a dedication to the duke of Norfolk in 1788; Frantz Funck-Brentano, Les Lettres de cachet à Paris (Paris, 1904); and André Chassaigne, Les Lettres de cachet sous l’ancien régime (Paris, 1903).

LETTUCE, known botanically as Lactuca sativa (nat. ord. Compositae), a hardy annual, highly esteemed as a salad plant. The London market-gardeners make preparation for the first main crop of Cos lettuces in the open ground early in August, a frame being set on a shallow hotbed, and, the stimulus of heat not being required, this is allowed to subside till the first week in October, when the soil, consisting of leaf-mould mixed with a little sand, is put on 6 or 7 in. thick, so that the surface is within 4½ in. of the sashes. The best time for sowing is found to be about the 11th of October, one of the best varieties being Lobjoits Green Cos. When the seeds begin to germinate the sashes are drawn quite off in favourable weather during the day, and put on, but tilted, at night in wet weather. Very little watering is required, and the aim should be to keep the plants gently moving till the days begin to lengthen. In January a more active growth is encouraged, and in mild winters a considerable extent of the planting out is done, but in private gardens the preferable time would be February. The ground should be light and rich, and well manured below, and the plants put out at 1 ft. apart each way with the dibble. Frequent stirring of the ground with the hoe greatly encourages the growth of the plants. A second sowing should be made about the 5th of November, and a third in frames about the end of January or beginning of February. In March a sowing may be made in some warm situation out of doors; successional sowings may be made in the open border about every third or fourth week till August, about the middle of which month a crop of Brown Cos, Hardy Hammersmith or Hardy White Cos should be sown, the latter being the most reliable in a severe winter. These plants may be put out early in October on the sides of ridges facing the south or at the front of a south wall, beyond the reach of drops from the copings, being planted 6 or 8 in. apart. Young lettuce plants should be thinned out in the seed-beds before they crowd or draw each other, and transplanted as soon as possible after two or three leaves are formed. Some cultivators prefer that the summer crops should not be transplanted, but sown where they are to stand, the plants being merely thinned out; but transplanting checks the running to seed, and makes the most of the ground.

For a winter supply by gentle forcing, the Hardy Hammersmith and Brown Dutch Cabbage lettuces, and the Brown Cos and Green Paris Cos lettuces, should be sown about the middle of August and in the beginning of September, in rich light soil, the plants being pricked out 3 in. apart in a prepared bed, as soon as the first two leaves are fully formed. About the middle of October the plants should be taken up carefully with balls attached to the roots, and should be placed in a mild hotbed of well-prepared dung (about 55°) covered about 1 ft. deep with a compost of sandy peat, leaf-mould and a little well-decomposed manure. The Cos and Brown Dutch varieties should be planted about 9 in. apart. Give plenty of air when the weather permits, and protect from frost. For winter work Stanstead Park Cabbage Lettuce is greatly favoured now by London market-gardeners, as it stands the winter well. Lee’s Immense is another good variety, while All the Year Round may be sown for almost any season, but is better perhaps for summer crops.

There are two races of the lettuce, the Cos lettuce, with erect oblong heads, and the Cabbage lettuce, with round or spreading heads,—the former generally crisp, the latter soft and flabby in texture. Some of the best lettuces for general purposes of the two classes are the following:—

Cos: White Paris Cos, best for summer; Green Paris Cos, hardier than the white; Brown Cos, Lobjoits Green Cos, one of the hardiest and best for winter; Hardy White Cos.

Cabbage: Hammersmith Hardy Green; Stanstead Park, very hardy, good for winter; Tom Thumb; Brown Dutch; Neapolitan, best for summer; All the Year Round; Golden Ball, good for forcing in private establishments.

Lactuca virosa, the strong-scented lettuce, contains an alkaloid which has the power of dilating the pupil and may possibly be identical with hyoscyamine, though this point is as yet not determined. No variety of lettuce is now used for any medicinal purpose, though there is probably some slight foundation for the belief that the lettuce has faint narcotic properties.

LEUCADIA, the ancient name of one of the Ionian Islands, now Santa Maura (q.v.), and of its chief town (Hamaxichi).

LEUCIPPUS, Greek philosopher, born at Miletus (or Elea), founder of the Atomistic theory, contemporary of Zeno, Empedocles and Anaxagoras. His fame was so completely overshadowed by that of Democritus, who subsequently developed the theory into a system, that his very existence was denied by Epicurus (Diog. Laërt. x. 7), followed in modern times by E. Rohde. Epicurus, however, distinguishes Leucippus from Democritus, and Aristotle and Theophrastus expressly credit him with the invention of Atomism. There seems, therefore, no reason to doubt his existence, although nothing is known of his life, and even his birthplace is uncertain. Between Leucippus and Democritus there is an interval of at least forty years; accordingly, while the beginnings of Atomism are closely connected with the doctrines of the Eleatics, the system as developed by Democritus is conditioned by the sophistical views of his time, especially those of Protagoras. While Leucippus’s notion of Being agreed generally with that of the Eleatics, he postulated its plurality (atoms) and motion, and the reality of not-Being (the void) in which his atoms moved.

See Democritus. On the Rohde-Diels controversy as to the existence of Leucippus, see F. Lortzing in Bursian’s Jahresbericht, vol. cxvi. (1904); also J. Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy (1892).

|

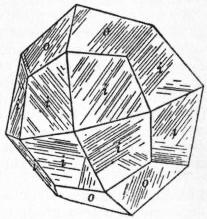

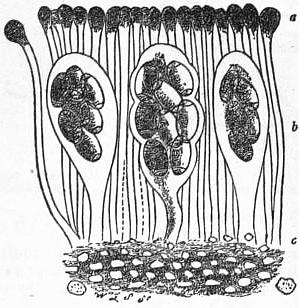

LEUCITE, a rock-forming mineral composed of potassium and aluminium metasilicate KAl(SiO3)2. Crystals have the form of cubic icositetrahedra {211}, but, as first observed by Sir David Brewster in 1821, they are not optically isotropic, and are therefore pseudo-cubic. Goniometric measurements made by G. vom Rath in 1873 led him to refer the crystals to the tetragonal system, the faces o being distinct from those lettered i in the adjoining figure. Optical investigations have since proved the crystals to be still more complex in character, and to consist of several orthorhombic or monoclinic individuals, which are optically biaxial and repeatedly twinned, giving rise to twin-lamellae and to striations on the faces. When the crystals are raised to a temperature of about 500° C. they become optically isotropic, the twin-lamellae and striations disappearing, reappearing, however, when the crystals are again cooled. This pseudo-cubic character of leucite is exactly the same as that of the mineral boracite (q.v.).

The crystals are white (hence the name suggested by A. G. Werner in 1791, from λευκός) or ash-grey in colour, and are usually dull and opaque, but sometimes transparent and glassy; they are brittle and break with a conchoidal fracture. The hardness is 5.5, and the specific gravity 2.5. Enclosures of other minerals, arranged in concentric zones, are frequently present in the crystals. On account of the colour and form of the crystals the mineral was early known as “white garnet.” French authors employ R. J. Haüy’s name “amphigène.”

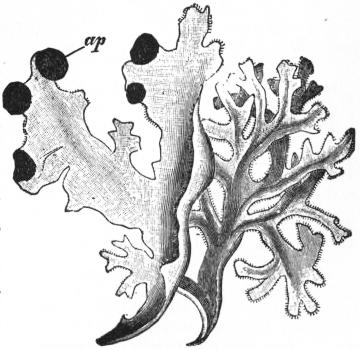

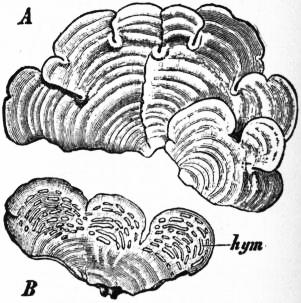

Leucite Rocks.—Although rocks containing leucite are numerically scarce, many countries such as England being entirely without them, yet they are of wide distribution, occurring in every quarter of the globe. Taken collectively, they exhibit a considerable variety of types and are of great interest petrographically. For the presence of this mineral it is necessary that the silica percentage of the rock should not be high, for leucite never occurs in presence of free quartz. It is most common in lavas of recent and Tertiary age, which have a fair amount of potash, or at any rate have potash equal to or greater than soda; if soda preponderates nepheline occurs rather than leucite. In pre-Tertiary rocks leucite is uncommon, since it readily decomposes and changes to zeolites, analcite and other secondary minerals. Leucite also is rare in plutonic rocks and dike rocks, but leucite-syenite and leucite-tinguaite bear witness to the possibility that it may occur in this manner. The rounded shape of its crystals, their white or grey colour, and rough cleavage, make the presence of leucite easily determinable in many of these rocks by simple inspection, especially when the crystals are large. “Pseudo-leucites” are rounded areas consisting of felspar, nepheline, analcite, 504 &c., which have the shape, composition and sometimes even the crystalline forms of leucite; they are probably pseudomorphs or paramorphs, which have developed from leucite because this mineral, in its isometric crystals, is not stable at ordinary temperatures and may be expected under favourable conditions to undergo spontaneous change into an aggregate of other minerals. Leucite is very often accompanied by nepheline, sodalite or nosean; other minerals which make their appearance with some frequency are melanite, garnet and melilite.

The plutonic leucite-bearing rocks are leucite-syenite and missourite. Of these the former consists of orthoclase, nepheline, sodalite, diopside and aegirine, biotite and sphene. Two occurrences are known, one in Arkansas, the other in Sutherlandshire, Scotland. The Scottish rock has been called borolanite. Both examples show large rounded spots in the hand specimens; they are pseudo-leucites and under the microscope prove to consist of orthoclase, nepheline, sodalite and decomposition products. These have a radiate arrangement externally, but are of irregular structure at their centres; it is interesting to note that in both rocks melanite is an important accessory. The missourites are more basic and consist of leucite, olivine, augite and biotite; the leucite is partly fresh, partly altered to analcite, and the rock has a spotted character recalling that of the leucite-syenites. It has been found only in the Highwood Mountains of Montana.

The leucite-bearing dike-rocks are members of the tinguaite and monchiquite groups. The leucite-tinguaites are usually pale grey or greenish in colour and consist principally of nepheline, alkali-felspar and aegirine. The latter forms bright green moss-like patches and growths of indefinite shape, or in other cases scattered acicular prisms, among the felspars and nephelines of the ground mass. Where leucite occurs, it is always eumorphic in small, rounded, many-sided crystals in the ground mass, or in larger masses which have the same characters as the pseudo-leucites. Biotite occurs in some of these rocks, and melanite also is present. Nepheline appears to decrease in amount as leucite increases. Rocks of this group are known from Rio de Janeiro, Arkansas, Kola (in Finland), Montana and a few other places. In Greenland there are leucite-tinguaites with much arfvedsonite (hornblende) and eudyalite. Wherever they occur they accompany leucite- and nepheline-syenites. Leucite-monchiquites are fine-grained dark rocks consisting of olivine, titaniferous augite and iron oxides, with a glassy ground mass in which small rounded crystals of leucite are scattered. They have been described from Bohemia.

By far the greater number of the rocks which contain leucite are lavas of Tertiary or recent geological age. They are never acid rocks which contain quartz, but felspar is usually present, though there are certain groups of leucite lavas which are non-felspathic. Many of them also contain nepheline, sodalite, hauyne and nosean; the much rarer mineral melilite appears also in some examples. The commonest ferromagnesian mineral is augite (sometimes rich in soda), with olivine in the more basic varieties. Hornblende and biotite occur also, but are less common. Melanite is found in some of the lavas, as in the leucite-syenites.

The rocks in which orthoclase (or sanidine) is present in considerable amount are leucite-trachytes, leucite-phonolites and leucitophyres. Of these groups the two former, which are not sharply distinguished from one another by most authors, are common in the neighbourhood of Rome (L. Bracciano, L. Bolsena). They are of trachytic appearance, containing phenocysts of sanidine, leucite, augite and biotite. Sodalite or hauyne may also be present, but nepheline is typically absent. Rocks of this class occur also in the tuffs of the Phlegraean Fields, near Naples. The leucitophyres are rare rocks which have been described from various parts of the volcanic district of the Rhine (Olbrück, Laacher See, &c.) and from Monte Vulture in Italy. They are rich in leucite, but contain also some sanidine and often much nepheline with hauyne or nosean. Their pyroxene is principally aegirine or aegirine augite; some of them are rich in melanite. Microscopic sections of some of these rocks are of great interest on account of their beauty and the variety of felspathoid minerals which they contain. In Brazil leucitophyres have been found which belong to the Carboniferous period.

Those leucite rocks which contain abundant essential plagioclase felspar are known as leucite-tephrites and leucite-basanites. The former consist mainly of plagioclase, leucite and augite, while the latter contain olivine in addition. The leucite is often present in two sets of crystals, both porphyritic and as an ingredient of the ground mass. It is always idiomorphic with rounded outlines. The felspar ranges from bytownite to oligoclase, being usually a variety of labradorite; orthoclase is scarce. The augite varies a good deal in character, being green, brown or violet, but aegirine (the dark green pleochroic soda-iron-augite) is seldom present. Among the accessory minerals biotite, brown hornblende, hauyne, iron oxides and apatite are the commonest; melanite and nepheline may also occur. The ground mass of these rocks is only occasionally rich in glass. The leucite-tephrites and leucite-basanites of Vesuvius and Somma are familiar examples of this class of rocks. They are black or ashy-grey in colour, often vesicular, and may contain many large grey phenocysts of leucite. Their black augite and yellow green olivine are also easily detected in hand specimens. From Volcanello, Sardinia and Roccamonfina similar rocks are obtained; they occur also in Bohemia, in Java, Celebes, Kilimanjaro (Africa) and near Trebizond in Asia Minor.

Leucite lavas from which felspar is absent are divided into the leucitites and leucite basalts. The latter contain olivine, the former do not. Pyroxene is the usual ferromagnesian mineral, and resembles that of the tephrites and basanites. Sanidine, melanite, hauyne and perofskite are frequent accessory minerals in these rocks, and many of them contain melilite in some quantity. The well-known leucitite of the Capo di Bove, near Rome, is rich in this mineral, which forms irregular plates, yellow in the hand specimen, enclosing many small rounded crystals of leucite. Bracciano and Roccamonfina are other Italian localities for leucitite, and in Java, Montana, Celebes and New South Wales similar rocks occur. The leucite-basalts belong to more basic types and are rich in olivine and augite. They occur in great numbers in the Rhenish volcanic district (Eifel, Laacher See) and in Bohemia, and accompany tephrites or leucitites in Java, Montana, Celebes and Sardinia. The “peperino” of the neighbourhood of Rome is a leucitite tuff.

LEUCTRA, a village of Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae, chiefly noticeable for the battle fought in its neighbourhood in 371 B.C. between the Thebans and the Spartans and their allies. A Peloponnesian army, about 10,000 strong, which had invaded Boeotia from Phocis, was here confronted by a Boeotian levy of perhaps 6000 soldiers under Epaminondas (q.v.). In spite of inferior numbers and the doubtful loyalty of his Boeotian allies, Epaminondas offered battle on the plain before the town. Massing his cavalry and the 50-deep column of Theban infantry on his left wing, he sent forward this body in advance of his centre and right wing. After a cavalry engagement in which the Thebans drove their enemies off the field, the decisive issue was fought out between the Theban and Spartan foot. The latter, though fighting well, could not sustain in their 12-deep formation the heavy impact of their opponents’ column, and were hurled back with a loss of about 2000 men, of whom 700 were Spartan citizens, including the king Cleombrotus. Seeing their right wing beaten, the rest of the Peloponnesians retired and left the enemy in possession of the field. Owing to the arrival of a Thessalian army under Jason of Pherae, whose friendship they did not trust, the Thebans were unable to exploit their victory. But the battle is none the less of great significance in Greek history. It marks a revolution in military tactics, affording the first known instance of a deliberate concentration of attack upon the vital point of the enemy’s line. Its political effects were equally far-reaching, for the loss in material strength and prestige which the Spartans here sustained deprived them for ever of their supremacy in Greece.

Authorities.—Xenophon, Hellenica, vi. 4. 3-15; Diodorus xi. 53-56; Plutarch, Pelopidas, chs. 20-23; Pausanias ix. 13. 2-10; G. B. Grundy, The Topography of the Battle of Plataea (London, 1894), pp. 73-76; H. Delbrück, Geschichte der Kriegskunst (Berlin, 1900), i. 130 ff.

LEUK (Fr. Loèche Ville), an ancient and very picturesque little town in the Swiss canton of the Valais. It is built above the right bank of the Rhone, and is about 1 m. from the Leuk-Susten station (15½ m. east of Sion and 17½ m. west of Brieg) on the Simplon railway. In 1900 it had 1592 inhabitants, all but wholly German-speaking and Romanists. About 10½ m. by a winding carriage road N. of Leuk, and near the head of the Dala valley, at a height of 4629 ft. above the sea-level, and overshadowed by the cliffs of the Gemmi Pass (7641 ft.; q.v.) leading over to the Bernese Oberland, are the Baths of Leuk (Leukerbad, or Loèche les Bains). They have only 613 permanent inhabitants, but are much frequented in summer by visitors (largely French and Swiss) attracted by the hot mineral springs. These are 22 in number, and are very abundant. The principal is that of St Laurence, the water of which has a temperature of 124° F. The season lasts from June to September. The village in winter is long deprived of sunshine, and is much exposed to avalanches, by which it was destroyed in 1518, 1719 and 1756, but it is now protected by a strong embankment from a similar catastrophe.

LEUTHEN, a village of Prussian Silesia, 10 m. W. of Breslau, memorable as the scene of Frederick the Great’s victory over the Austrians on December 5, 1757. The high road from Breslau to Lüben crosses the marshy Schweidnitz Water at Lissa, and immediately enters the rolling country about Neumarkt. 505 Leuthen itself stands some 4000 paces south of the road, and a similar distance south again lies Sagschütz, while Nypern, on the northern edge of the hill country, is 5000 paces from the road. On Frederick’s approach the Austrians took up a line of battle resting on the two last-named villages. Their whole position was strongly garrisoned and protected by obstacles, and their artillery was numerous though of light calibre. A strong outpost of Saxon cavalry was in Borne to the westward. Frederick had the previous day surprised the Austrian bakeries at Neumarkt, and his Prussians, 33,000 to the enemy’s 82,000, moved towards Borne and Leuthen early on the 5th. The Saxon outpost was rushed at in the morning mist, and, covered by their advanced guard on the heights beyond, the Prussians wheeled to their right. Prince Charles of Lorraine, the Austrian commander-in-chief, on Leuthen Church tower, could make nothing of Frederick’s movements, and the commander of his right wing (Lucchesi) sent him message after message from Nypem and Gocklerwitz asking for help, which was eventually despatched. But the real blow was to fall on the left under Nadasdy. While the Austrian commander was thus wasting time, the Prussians were marching against Nadasdy in two columns, which preserved their distances with an exactitude which has excited the wonder of modern generations of soldiers; at the due place they wheeled into line of battle obliquely to the Austrian front, and in one great échelon,—the cavalry of the right wing foremost, and that of the left “refused,”—Frederick advanced on Sagschütz. Nadasdy, surprised, put a bold face on the matter and made a good defence, but he was speedily routed, and, as the Prussians advanced, battalion after battalion was rolled up towards Leuthen until the Austrians faced almost due south. The fighting in Leuthen itself was furious; the Austrians stood, in places, 100 deep, but the disciplined valour of the Prussians carried the village. For a moment the victory was endangered when Lucchesi came down upon the Prussian left wing from the north, but Driesen’s cavalry, till then refused, charged him in flank and scattered his troopers in wild rout. This stroke ended the battle. The retreat on Breslau became a rout almost comparable to that of Waterloo, and Prince Charles rallied, in Bohemia, barely 37,000 out of his 82,000. Ten thousand Austrians were left on the field, 21,000 taken prisoners (besides 17,000 in Breslau a little later), with 51 colours and 116 cannon. The Prussian loss in all was under 5500. It was not until 1854 that a memorial of this astonishing victory was erected on the battlefield.

See Carlyle, Frederick, bk. xviii. cap. x.; V. Ollech, Friedrich der Grosse von Kolin bis Leuthen (Berlin, 1858); Kutzen, Schlacht bei Leuthen (Breslau, 1851 ); and bibliography under Seven Years’ War.

LEUTZE, EMANUEL (1816-1868), American artist, was born at Gmünd, Württemberg, on the 24th of May 1816, and as a child was taken by his parents to Philadelphia, where he early displayed talent as an artist. At the age of twenty-five he had earned enough to take him to Düsseldorf for a course of art study at the royal academy. Almost immediately he began the painting of historical subjects, his first work, “Columbus before the Council of Salamanca,” being purchased by the Düsseldorf Art Union. In 1860 he was commissioned by the United States Congress to decorate a stairway in the Capitol at Washington, for which he painted a large composition, “Westward the Star of Empire takes its Way.” His best-known work, popular through engraving, is “Washington crossing the Delaware,” a large canvas containing a score of life-sized figures; it is now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. He became a member of the National Academy of Design in 1860, and died at Washington, D.C., on the 18th of July 1868.

LEVALLOIS-PERRET, a north-western suburb of Paris, on the right bank of the Seine, 2½ m. from the centre of the city. Pop. (1906) 61,419. It carries on the manufacture of motor-cars and accessories, carriages, groceries, liqueurs, perfumery, soap, &c., and has a port on the Seine.

LEVANT (from the French use of the participle of lever, to rise, for the east, the orient), the name applied widely to the coastlands of the eastern Mediterranean Sea from Greece to Egypt, or, in a more restricted and commoner sense, to the Mediterranean coastlands of Asia Minor and Syria. In the 16th and 17th centuries the term “High Levant” was used of the Far East. The phrase “to levant,” meaning to abscond, especially of one who runs away leaving debts unpaid, particularly of a betting man or gambler, is taken from the Span. levantar, to lift or break up, in such phrases as levantar la casa, to break up a household, or el campo, to break camp.

LEVASSEUR, PIERRE EMILE (1828- ), French economist, was born in Paris on the 8th of December 1828. Educated in Paris, he began to teach in the lycée at Alençon in 1852, and in 1857 was chosen professor of rhetoric at Besançon. He returned to Paris to become professor at the lycée Saint Louis, and in 1868 he was chosen a member of the academy of moral and political sciences. In 1872 he was appointed professor of geography, history and statistics in the Collège de France, and subsequently became also professor at the Conservatoire des arts et métiers and at the École libre des sciences politiques. Levasseur was one of the founders of the study of commercial geography, and became a member of the Council of Public Instruction, president of the French society of political economy and honorary president of the French geographical society.

His numerous writings include: Histoire des classes ouvrières en France depuis la conquête de Jules César jusqu’à la Révolution (1859); Histoire des classes ouvrières en France depuis la Révolution jusqu’à nos jours (1867); L’Étude et l’enseignement de la géographie (1871); La Population française (1889-1892); L’Agriculture aux États-Unis (1894); L’Enseignement primaire dans les pays civilisés (1897); L’Ouvrier américain (1898); Questions ouvrières et industrielles sous la troisième République (1907); and Histoire des classes ouvrières et de l’industrie en France de 1789 à 1870 (1903-1904). He also published a Grand Atlas de géographie physique et politique (1890-1892).

LEVECHE, the name given to the dry hot sirocco wind in Spain; often incorrectly called the “solano.” The direction of the Leveche is mostly from S.E., S. or S.W., and it occurs along the coast from Cabo de Gata to Cabo de Nao, and even beyond Malaga for a distance of some 10 m. inland.

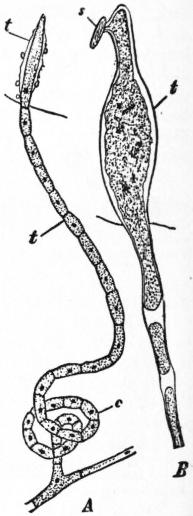

LEVÉE (from Fr. lever, to raise), an embankment which keeps a river in its channel. A river such as the Mississippi (q.v.), draining a large area, carries a great amount of sediment from its swifter head-streams to the lower ground. As soon as a stream’s velocity is checked, it drops a portion of its load of sediment and spreads an alluvial fan in the lower part of its course. This deposition of material takes place particularly at the sides of the stream where the velocity is least, and the banks are in consequence raised above the main channel, so that the river becomes lifted bodily upwards in its bed, and flows above the level of the surrounding country. In flood-time the muddy water flows over the river’s banks, where its velocity is at once checked as it flows gently down the outer side, causing more material to be deposited there, and a long alluvial ridge, called a natural levée, to be built up on either side of the stream. These ridges may be wide or narrow, but they slope from the stream’s outer banks to the plain below, and in consequence require careful watching, for if the levée is broken by a “crevasse,” the whole body of the river may pour through and flood the country below. In 1890 the Mississippi near New Orleans broke through the Nita crevasse and flowed eastward with a current of 15 m. an hour, spreading destruction in its path. The Hwang-ho river in China is peculiarly liable to these inundations. The word levée is also sometimes used to denote a riverside quay or landing-place.

LEVEE (from the French substantival use of lever, to rise; there is no French substantival use of levée in the English sense), a reception or assembly held by the British sovereign or his representative, in Ireland by the lord-lieutenant, in India by the viceroy, in the forenoon or early afternoon, at which men only are present in distinction from a “drawing-room,” at which ladies also are presented or received. Under the ancien règime in France the lever of the king was regulated, especially under Louis XIV., by elaborate etiquette, and the various divisions of the ceremonial followed the stages of the king’s rising from bed, from which it gained its name. The petit lever began when the 506 king had washed and said his daily offices; to this were admitted the princes of the blood, certain high officers of the household and those to whom a special permit had been granted; then followed the première entrée, to which came the secretaries and other officials and those having the entrée; these were received by the king in his dressing-gown. Finally, at the grand lever, the remainder of the household, the nobles and gentlemen of the court were received; the king by that time was shaved, had changed his linen and was in his wig. In the United States the term “levee” was formerly used of the public receptions held by the president.

LEVELLERS, the name given to an important political party in England during the period of the Civil War and the Commonwealth. The germ of the Levelling movement must be sought for among the Agitators (q.v.), men of strong republican views, and the name Leveller first appears in a letter of the 1st of November 1647, although it was undoubtedly in existence as a nickname before this date (Gardiner, Great Civil War, iii. 380). This letter refers to these extremists thus: “They have given themselves a new name, viz. Levellers, for they intend to sett all things straight, and rayse a parity and community in the kingdom.”

The Levellers first became prominent in 1647 during the protracted and unsatisfactory negotiations between the king and the parliament, and while the relations between the latter and the army were very strained. Like the Agitators they were mainly found among the soldiers; they were opposed to the existence of kingship, and they feared that Cromwell and the other parliamentary leaders were too complaisant in their dealings with Charles; in fact they doubted their sincerity in this matter. Led by John Lilburne (q.v.) they presented a manifesto, The Case of the Army truly stated, to the commander-in-chief, Lord Fairfax, in October 1647. In this they demanded a dissolution of parliament within a year and substantial changes in the constitution of future parliaments, which were to be regulated by an unalterable “law paramount.” In a second document, The Agreement of the People, they expanded these ideas, which were discussed by Cromwell, Ireton and other officers on the one side, and by John Wildman, Thomas Rainsborough and Edward Sexby for the Levellers on the other. But no settlement was made; some of the Levellers clamoured for the king’s death, and in November 1647, just after his flight from Hampton Court to Carisbrooke, they were responsible for a mutiny which broke out in two regiments at Corkbush Field, near Ware. This, however, was promptly suppressed by Cromwell. During the twelve months which immediately preceded the execution of the king the Levellers conducted a lively agitation in favour of the ideas expressed in the Agreement of the people, and in January 1648 Lilburne was arrested for using seditious language at a meeting in London. But no success attended these and similar efforts, and their only result was that the Levellers regarded Cromwell with still greater suspicion.

Early in 1649, just after the death of the king, the Levellers renewed their activity. They were both numerous and dangerous, and they stood up, says Gardiner, “for an exaggeration of the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy.” In a pamphlet, England’s New Chains, Lilburne asked for the dissolution of the council of state and for a new and reformed parliament. He followed this up with the Second Part of England’s New Chains; his writings were declared treasonable by parliament, and in March 1649 he and three other leading Levellers, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and Prince were arrested. The discontent which was spreading in the army was fanned when certain regiments were ordered to proceed to Ireland, and in April 1649 there was a meeting in London; but this was quickly put down by Fairfax and Cromwell, and its leader, Robert Lockyer, was shot. Risings at Burford and at Banbury were also suppressed without any serious difficulty, and the trouble with the Levellers was practically over. Gradually they became less prominent, but under the Commonwealth they made frequent advances to the exiled king Charles II., and there was some danger from them early in 1655 when Wildman was arrested and Sexby escaped from England. The distinguishing mark of the Leveller was a sea-green ribbon.

Another but more harmless form of the same movement was the assembling of about fifty men on St George’s Hill near Oatlands in Surrey. In April 1649 these “True Levellers” or “Diggers,” as they were called, took possession of some unoccupied ground which they began to cultivate. They were, however, soon dispersed, and their leaders were arrested and brought before Fairfax, when they took the opportunity of denouncing landowners. It is interesting to note that Lilburne and his colleagues objected to being designated Levellers, as they had no desire to take away “the proper right and title that every man has to what is his own.”

Cromwell attacked the Levellers in his speech to parliament in September 1654 (Carlyle, Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches, Speech II.). He said: “A nobleman, a gentleman, a yeoman; the distinction of these; that is a good interest of the nation, and a great one. The ‘natural’ magistracy of the nation, was it not almost trampled under foot, under despite and contempt, by men of Levelling principles? I beseech you, for the orders of men and ranks of men, did not that Levelling principle tend to the reducing of all to an equality? Did it ‘consciously’ think to do so; or did it ‘only unconsciously’ practise towards that for property and interest? ‘At all events,’ what was the purport of it but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord? Which, I think, if obtained, would not have lasted long.”

In 1724 there was a rising against enclosures in Galloway, and a number of men who took part therein were called Levellers or Dyke-breakers (A. Lang, History of Scotland, vol. iv.). The word was also used in Ireland during the 18th century to describe a secret revolutionary society similar to the Whiteboys.

LEVEN, ALEXANDER LESLIE, 1st Earl of (c. 1580-1661), Scottish general, was the son of George Leslie, captain of Blair-in-Athol, and a member of the family of Leslie of Balquhain. After a scanty education he sought his fortune abroad, and became a soldier, first under Sir Horace Vere in the Low Countries, and afterwards (1605) under Charles IX. and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, in whose service he remained for many years and fought in many campaigns with honour. In 1626 Leslie had risen by merit to the rank of lieutenant-general, and had been knighted by Gustavus. In 1628 he distinguished himself by his constancy and energy in the defence of Stralsund against Wallenstein, and in 1630 seized the island of Rügen in the name of the king of Sweden. In the same year he returned to Scotland to assist in recruiting and organizing the corps of Scottish volunteers which James, 3rd marquis of Hamilton, brought over to Gustavus in 1631. Leslie received a severe wound in the following winter, but was able nevertheless to be present at Gustavus’s last battle at Lützen. Like many others of the soldiers of fortune who served under Gustavus, Leslie cherished his old commander’s memory to the day of his death, and he kept with particular care a jewel and miniature presented to him by the king. He continued as a general officer in the Swedish army for some years, was promoted in 1636 to the rank of field marshal, and continued in the field until 1638, when events recalled him to his own country. He had married long before this—in 1637 his eldest son was made a colonel in the Swedish army—and he had managed to keep in touch with Scottish affairs.

As the foremost Scottish soldier of his day he was naturally nominated to command the Scottish army in the impending war with England, a post which, resigning his Swedish command, he accepted with a glad heart, for he was an ardent Covenanter and had caused “a great number of our commanders in Germany subscryve our covenant” (Baillie’s Letters). On leaving Sweden he brought back his arrears of pay in the form of cannon and muskets for his new army. For some months he busied himself with the organization and training of the new levies, and with inducing Scottish officers abroad to do their duty to their country by returning to lead them. Diminutive in size and somewhat deformed in person as he was, his reputation and his shrewdness 507 and simple tact, combined with the respect for his office of lord general that he enforced on all ranks, brought even the unruly nobles to subordination. He had by now amassed a considerable fortune and was able to live in a manner befitting a commander-in-chief, even when in the field. One of his first exploits was to take the castle of Edinburgh by surprise, without the loss of a man. He commanded the Scottish army at Dunse Law in May of that year, and in 1640 he invaded England, and defeated the king’s troops at Newburn on the Tyne, which gave him possession of Newcastle and of the open country as far as the Tees. At the treaty with the king at Ripon, Leslie was one of the commissioners of the Scottish parliament, and when Charles visited Edinburgh Leslie entertained him magnificently and accompanied him when he drove through the streets. His affirmations of loyalty to the crown, which later events caused to be remembered against him, were sincere enough, but the complicated politics of the time made it difficult for Leslie, the lord general of the Scottish army, to maintain a perfectly consistent attitude. However, his influence was exercised chiefly to put an end to, even to hush up, the troubles, and he is found, now giving a private warning to plotters against the king to enable them to escape, now guarding the Scottish parliament against a royalist coup d’état, and now securing for an old comrade of the German wars, Patrick Ruthven, Lord Ettrick, indemnity for having held Edinburgh Castle for the king against the parliament. Charles created him, by patent dated Holyrood, October 11, 1641, earl of Leven and Lord Balgonie, and made him captain of Edinburgh Castle and a privy councillor. The parliament recognized his services by a grant, and, on his resigning the lord generalship, appointed him commander of the permanent forces. A little later, Leven, who was a member of the committee of the estates which exercised executive powers during the recess of parliament, used his great influence in support of a proposal to raise a Scottish army to help the elector palatine in Germany, but the Ulster massacres gave this force, when raised, a fresh direction and Leven himself accompanied it to Ireland as lord general. He did not remain there long, for the Great Rebellion (q.v.) had begun in England, and negotiations were opened between the English and the Scottish parliaments for mutual armed assistance. Leven accepted the command of the new forces raised for the invasion of England, and was in consequence freely accused of having broken his personal oath to Charles, but he could hardly have acted otherwise than he did, and at that time, and so far as the Scots were concerned, to the end of the struggle, the parliaments were in arms, professedly and to some extent actually, to rescue his majesty from the influence of evil counsellors.

The military operations preceding Marston Moor are described under Great Rebellion, and the battle itself under its own heading. Leven’s great reputation, wisdom and tact made him an ideal commander for the allied army formed by the junction of Leven’s, Fairfax’s and Manchester’s in Yorkshire. After the battle the allied forces separated, Leven bringing the siege of Newcastle to an end by storming it. In 1645 the Scots were less successful, though their operations ranged from Westmorland to Hereford, and Leven himself had many administrative and political difficulties to contend with. These difficulties became more pronounced when in 1646 Charles took refuge with the Scottish army. The king remained with Leven until he was handed over to the English parliament in 1647, and Leven constantly urged him to take the covenant and to make peace. Presbyterians and Independents had now parted, and with no more concession than the guarantee of the covenant the Scottish and English Presbyterians were ready to lay down their arms, or to turn them against the “sectaries.” Leven was now old and infirm, and though retained as nominal commander-in-chief saw no further active service. He acted with Argyll and the “godly” party in the discussions preceding the second invasion of England, and remained at his post as long as possible in the hope of preventing the Scots becoming merely a royalist instrument for the conquest of the English Independents. But be was induced in the end to resign, though he was appointed lord general of all new forces that might be raised for the defence of Scotland. The occasion soon came, for Cromwell annihilated the Scottish invaders at Preston and Uttoxeter, and thereupon Argyll assumed political and Leven military control at Edinburgh. But he was now over seventy years of age, and willingly resigned the effective command to his subordinate David Leslie (see Newark, Lord), in whom he had entire confidence. After the execution of Charles I. the war broke out afresh, and this time the “godly” party acted with the royalists. In the new war, and in the disastrous campaign of Dunbar, Leven took but a nominal part, though attempts were afterwards made to hold him responsible. But once more the parliament refused to accept his resignation. Leven at last fell into the hands of a party of English dragoons in August 1651, and with some others was sent to London. He remained incarcerated in the Tower for some time, till released on finding securities for £20,000, upon which he retired to his residence in Northumberland. While on a visit to London he was again arrested, for a technical breach of his engagement, but by the intercession of the queen of Sweden he obtained his liberty. He was freed from his engagements in 1654, and retired to his seat at Balgonie in Fifeshire, where he died at an advanced age in 1661. He acquired considerable landed property, particularly Inchmartin in the Carse of Gowrie, which he called Inchleslie.

See Leven and Melville, Earls of, below.

LEVEN, a police burgh of Fifeshire, Scotland. Pop. (1901) 5577. It is situated on the Firth of Forth, at the mouth of the Leven, 5¾ m. E. by N. of Thornton Junction by the North British railway. The public buildings include the town hall, public hall and people’s institute, in the grounds of which the old town cross has been erected. The industries are numerous, comprising flax-spinning, brewing, linen-weaving, paper-making, seed-crushing and rope-making, besides salt-works, a foundry, saw-mill and brick-works. The wet dock is not much used, owing to the constant accumulation of sand. The golf-links extending for 2 m. to Lundin are among the best in Scotland. Two miles N.E. is Lundin Mill and Drumochie, usually called Lundin (pop. 570), at the mouth of Kiel Burn, with a station on the Links. The three famous standing stones are supposed to be either of “Druidical” origin or to mark the site of a battle with the Danes. In the vicinity are the remains of an old house of the Lundins, dating from the reign of David II. To the N.W. of Leven lies the parish of Kennoway (pop. 870). In Captain Seton’s house, which still stands in the village of Kennoway, Archbishop Sharp spent the night before his assassination (1679). One mile east of Lundin lies Largo (pop. of parish 2046), consisting of Upper Largo, or Kirkton of Largo, and Lower Largo. The public buildings include Simpson institute, with a public hall, library, reading-room, bowling-green and lawn-tennis court, and John Wood’s hospital, founded in 1659 for poor persons bearing his name. A statue of Alexander Selkirk, or Selcraig (1676-1721), the prototype of “Robinson Crusoe,” who was born here, was erected in 1886. Sir John Leslie (1766-1832), the natural philosopher, was also a native. Largo claims two famous sailors, Admiral Sir Philip Durham (1763-1845), commander-in-chief at Portsmouth from 1836 to 1839, and Sir Andrew Wood (d. 1515), the trusted servant of James III. and James IV., who sailed the “Great Michael,” the largest ship of its time. When he was past active service he had a canal cut from his house to the parish church, to which he was rowed every Sunday in an eight-oared barge. Largo House was granted to him by James III., and the tower of the original structure still exists. About 1½ m. from the coast rises the height of Largo Law (948 ft.). Kellie Law lies some 5½ m. to the east.

LEVEN, LOCH, a lake of Kinross-shire, Scotland. It has an oval shape, the longer axis running from N.W. to S.E., has a length of 32⁄3 m., and a breadth of 22⁄3 m. and is situated near the south and east boundaries of the shire. It lies at a height of 350 ft. above the sea. The mean depth is less than 15 ft., with a maximum of 83 ft., the lake being thus one of the shallowest in Scotland. Reclamation works carried on from 1826 to 1836 reduced its area by one quarter, but it still possesses a surface 508 area of 5½ sq. m. It drains the county and is itself drained by the Leven. It is famous for the Loch Leven trout (Salmo levenensis, considered by some a variety of S. trutta), which are remarkable for size and quality. The fishings are controlled by the Loch Leven Angling Association, which organizes competitions attracting anglers from far and near. The loch contains seven islands. Upon St Serf’s, the largest, which commemorates the patron saint of Fifeshire, are the ruins of the Priory of Portmoak—so named from St Moak, the first abbot—the oldest Culdee establishment in Scotland. Some time before 961 it was made over to the bishop of St Andrews, and shortly after 1144 a body of canons regular was established on it in connexion with the priory of canons regular founded in that year at St Andrews. The second largest island, Castle Island, possesses remains of even greater interest. The first stronghold is supposed to have been erected by Congal, son of Dongart, king of the Picts. The present castle dates from the 13th century and was occasionally used as a royal residence. It is said to have been in the hands of the English for a time, from whom it was delivered by Wallace. It successfully withstood Edward Baliol’s siege in 1335, and was granted by Robert II. to Sir William Douglas of Lugton. It became the prison at various periods of Robert II.; of Alexander Stuart, earl of Buchan, “the Wolf of Badenoch”; Archibald, earl of Douglas (1429); Patrick Graham, archbishop of St Andrews (who died, still in bondage, on St Serf’s Island in 1478), and of Mary, queen of Scots. The queen had visited it more than once before her detention, and had had a presence chamber built in it. Conveyed hither in June 1567 after her surrender at Carberry, she signed her abdication within its walls on the 4th of July and effected her escape on the 2nd of May 1568. The keys of the castle, which were thrown into the loch during her flight, were found and are preserved at Dalmahoy in Midlothian. Support of Mary’s cause had involved Thomas Percy, 7th earl of Northumberland (b. 1528). He too was lodged in the castle in 1569, and after three years’ imprisonment was handed over to the English, by whom he was beheaded at York in 1572. The proverb that “Those never got luck who came to Loch Leven” sums up the history of the castle. The causeway connecting the isle with the mainland was long submerged too deeply for use, but the reclamation operations already referred to almost brought it into view again.

LEVEN AND MELVILLE, EARLS OF. The family of Melville which now holds these two earldoms is descended from Sir John Melville of Raith in Fifeshire. Sir John, who was a member of the reforming party in Scotland, was put to death for high treason on the 13th of December 1548; he left with other children a son Robert (1527-1621), who in 1616 was created a lord of parliament as Lord Melville of Monymaill. Before his elevation to the Scottish peerage Melville had been a stout partisan of Mary, queen of Scots, whom he represented at the English court, and he had filled several important offices in Scotland under her son James VI. The fourth holder of the lordship of Melville was George (c. 1634-1707), a son of John, the 3rd lord (d. 1643), and a descendant of Sir John Melville. Implicated in the Rye House plot against Charles II., George took refuge in the Netherlands in 1683, but he returned to England after the revolution of 1688 and was appointed secretary for Scotland by William III. in 1689, being created earl of Melville in the following year. He was made president of the Scottish privy council in 1696, but he was deprived of his office when Anne became queen in 1702, and he died on the 20th of May 1707. His son David, 2nd earl of Melville (1660-1728), fled to Holland with his father in 1683; after serving in the army of the elector of Brandenburg he accompanied William of Orange to England in 1688. At the head of a regiment raised by himself he fought for William at Killiecrankie and elsewhere, and as commander-in-chief of the troops in Scotland he dealt promptly and effectively with the attempted Jacobite rising of 1708. In 1712, however, his office was taken from him and he died on the 6th of June 1728.

Alexander Leslie, 1st earl of Leven (q.v.), was succeeded in his earldom by his grandson Alexander, who died without sons in July 1664. The younger Alexander’s two daughters were then in turn countesses of Leven in their own right; and after the death of the second of these two ladies in 1676 a dispute arose over the succession to the earldom between John Leslie, earl (afterwards duke) of Rothes, and David Melville, 2nd earl of Melville, mentioned above. In 1681, however, Rothes died, and Melville, who was a great-grandson of the 1st earl of Leven, assumed the title, calling himself earl of Leven and Melville after he succeeded his father as earl of Melville in May 1707. Since 1805 the family has borne the name of Leslie-Melville. In 1906 John David Leslie-Melville (b. 1886) became 12th earl of Leven and 11th earl of Melville.

See Sir W. Fraser, The Melvilles, Earls of Melville, and the Leslies, Earls of Leven (1890); and the Leven and Melville Papers, edited by the Hon. W. H. Leslie-Melville for the Bannatyne Club (1843).

LEVER, CHARLES JAMES (1806-1872), Irish novelist, second son of James Lever, a Dublin architect and builder, was born in the Irish capital on the 31st of August 1806. His descent was purely English. He was educated in private schools, where he wore a ring, smoked, read novels, was a ringleader in every breach of discipline, and behaved generally like a boy destined for the navy in one of Captain Marryat’s novels. His escapades at Trinity College, Dublin (1823-1828), whence he took the degree of M.B. in 1831, form the basis of that vast cellarage of anecdote from which all the best vintages in his novels are derived. The inimitable Frank Webber in Charles O’Malley (spiritual ancestor of Foker and Mr Bouncer) was a college friend, Robert Boyle, later on an Irish parson. Lever and Boyle sang ballads of their own composing in the streets of Dublin, after the manner of Fergusson or Goldsmith, filled their caps with coppers and played many other pranks embellished in the pages of O’Malley, Con Cregan and Lord Kilgobbin. Before seriously embarking upon the medical studies for which he was designed, Lever visited Canada as an unqualified surgeon on an emigrant ship, and has drawn upon some of his experiences in Con Cregan, Arthur O’Leary and Roland Cashel. Arrived in Canada he plunged into the backwoods, was affiliated to a tribe of Indians and had to escape at the risk of his life, like his own Bagenal Daly.

Back in Europe, he travelled in the guise of a student from Göttingen to Weimar (where he saw Goethe), thence to Vienna; he loved the German student life with its beer, its fighting and its fun, and several of his merry songs, such as “The Pope he loved a merry life” (greatly envied by Titmarsh), are on Student-lied models. His medical degree admitted him to an appointment from the Board of Health in Co. Clare and then as dispensary doctor at Port Stewart, but the liveliness of his diversions as a country doctor seems to have prejudiced the authorities against him. In 1833 he married his first love, Catherine Baker, and in February 1837, after varied experiences, he began running The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer through the pages of the recently established Dublin University Magazine. During the previous seven years the popular taste had declared strongly in favour of the service novel as exemplified by Frank Mildmay, Tom Cringle, The Subaltern, Cyril Thornton, Stories of Waterloo, Ben Brace and The Bivouac; and Lever himself had met William Hamilton Maxwell, the titular founder of the genre. Before Harry Lorrequer appeared in volume form (1839), Lever had settled on the strength of a slight diplomatic connexion as a fashionable physician in Brussels (16, Rue Ducale). Lorrequer was merely a string of Irish and other stories good, bad and indifferent, but mostly rollicking, and Lever, who strung together his anecdotes late at night after the serious business of the day was done, was astonished at its success. “If this sort of thing amuses them, I can go on for ever.” Brussels was indeed a superb place for the observation of half-pay officers, such as Major Monsoon (Commissioner Meade), Captain Bubbleton and the like, who terrorized the tavernes of the place with their endless peninsular stories, and of English society a little damaged, which it became the specialty of Lever to depict. He sketched with a free hand, wrote, as he lived, from hand to mouth, and the chief difficulty he experienced was that of getting rid of his 509 characters who “hung about him like those tiresome people who never can make up their minds to bid you good night.” Lever had never taken part in a battle himself, but his next three books, Charles O’Malley (1841), Jack Hinton and Tom Burke of Ours (1843), written under the spur of the writer’s chronic extravagance, contain some splendid military writing and some of the most animated battle-pieces on record. In pages of O’Malley and Tom Burke Lever anticipates not a few of the best effects of Marbot, Thiébaut, Lejeune, Griois, Seruzier, Burgoyne and the like. His account of the Douro need hardly fear comparison, it has been said, with Napier’s. Condemned by the critics, Lever had completely won the general reader from the Iron Duke himself downwards.

In 1842 he returned to Dublin to edit the Dublin University Magazine, and gathered round him a typical coterie of Irish wits (including one or two hornets) such as the O’Sullivans, Archer Butler, W. Carleton, Sir William Wilde, Canon Hayman, D. F. McCarthy, McGlashan, Dr Kenealy and many others. In June 1842 he welcomed at Templeogue, 4 m. south-west of Dublin, the author of the Snob Papers on his Irish tour (the Sketch Book was, later, dedicated to Lever). Thackeray recognized the fund of Irish sadness beneath the surface merriment. “The author’s character is not humour but sentiment. The spirits are mostly artificial, the fond is sadness, as appears to me to be that of most Irish writing and people.” The Waterloo episode in Vanity Fair was in part an outcome of the talk between the two novelists. But the “Galway pace,” the display he found it necessary to maintain at Templeogue, the stable full of horses, the cards, the friends to entertain, the quarrels to compose and the enormous rapidity with which he had to complete Tom Burke, The O’Donoghue and Arthur O’Leary (1845), made his native land an impossible place for Lever to continue in. Templeogue would soon have proved another Abbotsford. Thackeray suggested London. But Lever required a new field of literary observation and anecdote. His sève originel was exhausted and he decided to renew it on the continent. In 1845 he resigned his editorship and went back to Brussels, whence he started upon an unlimited tour of central Europe in a family coach. Now and again he halted for a few months, and entertained to the limit of his resources in some ducal castle or other which he hired for an off season. Thus at Riedenburg, near Bregenz, in August 1846, he entertained Charles Dickens and his wife and other well-known people. Like his own Daltons or Dodd Family Abroad he travelled continentally, from Carlsruhe to Como, from Como to Florence, from Florence to the Baths of Lucca and so on, and his letters home are the litany of the literary remittance man, his ambition now limited to driving a pair of novels abreast without a diminution of his standard price for serial work (“twenty pounds a sheet”). In the Knight of Gwynne, a story of the Union (1847), Con Cregan (1849), Roland Cashel (1850) and Maurice Tiernay (1852) we still have traces of his old manner; but he was beginning to lose his original joy in composition. His fond of sadness began to cloud the animal joyousness of his temperament. Formerly he had written for the happy world which is young and curly and merry; now he grew fat and bald and grave. “After 38 or so what has life to offer but one universal declension. Let the crew pump as hard as they like, the leak gains every hour.” But, depressed in spirit as he was, his wit was unextinguished; he was still the delight of the salons with his stories, and in 1867, after a few years’ experience of a similar kind at Spezia, he was cheered by a letter from Lord Derby offering him the more lucrative consulship of Trieste. “Here is six hundred a year for doing nothing, and you are just the man to do it.” The six hundred could not atone to Lever for the lassitude of prolonged exile. Trieste, at first “all that I could desire,” became with characteristic abruptness “detestable and damnable.” “Nothing to eat, nothing to drink, no one to speak to.” “Of all the dreary places it has been my lot to sojourn in this is the worst” (some references to Trieste will be found in That Boy of Norcott’s, 1869). He could never be alone and was almost morbidly dependent upon literary encouragement. Fortunately, like Scott, he had unscrupulous friends who assured him that his last efforts were his best. They include The Fortunes of Glencore (1857), Tony Butler (1865), Luttrell of Arran (1865), Sir Brooke Fosbrooke (1866), Lord Kilgobbin (1872) and the table-talk of Cornelius O’Dowd, originally contributed to Blackwood. His depression, partly due to incipient heart disease, partly to the growing conviction that he was the victim of literary and critical conspiracy, was confirmed by the death of his wife (23rd April 1870), to whom he was tenderly attached. He visited Ireland in the following year and seemed alternately in very high and very low spirits. Death had already given him one or two runaway knocks, and, after his return to Trieste, he failed gradually, dying suddenly, however, and almost painlessly, from failure of the heart’s action on the 1st of June 1872. His daughters, one of whom, Sydney, is believed to have been the real author of The Rent in a Cloud (1869), were well provided for.

Trollope praised Lever’s novels highly when he said that they were just like his conversation. He was a born raconteur, and had in perfection that easy flow of light description which without tedium or hurry leads up to the point of the good stories of which in earlier days his supply seemed inexhaustible. With little respect for unity of action or conventional novel structure, his brightest books, such as Lorrequer, O’Malley and Tom Burke, are in fact little more than recitals of scenes in the life of a particular “hero,” unconnected by any continuous intrigue. The type of character he depicted is for the most part elementary. His women are mostly rouées, romps or Xanthippes; his heroes have too much of the Pickle temper about them and fall an easy prey to the serious attacks of Poe or to the more playful gibes of Thackeray in Phil Fogarty or Bret Harte in Terence Deuville. This last is a perfect bit of burlesque. Terence exchanges nineteen shots with the Hon. Captain Henry Somerset in the glen. “At each fire I shot away a button from his uniform. As my last bullet shot off the last button from his sleeve, I remarked quietly, ‘You seem now, my lord, to be almost as ragged as the gentry you sneered at,’ and rode haughtily away.” And yet these careless sketches contain such haunting creations as Frank Webber, Major Monsoon and Micky Free, “the Sam Weller of Ireland.” Falstaff is alone in the literature of the world; but if ever there came a later Falstaff, Monsoon was the man. As for Baby Blake, is she not an Irish Di Vernon? The critics may praise Lever’s thoughtful and careful later novels as they will, but Charles O’Malley will always be the pattern of a military romance.

Superior, it is sometimes claimed, in construction and style, the later books approximate it may be thought to the good ordinary novel of commerce, but they lack the extraordinary qualities, the incommunicable “go” of the early books—the élan of Lever’s untamed youth. Artless and almost formless these productions may be, but they represent to us, as very few other books can, that pathetic ejaculation of Lever’s own—“Give us back the wild freshness of the morning!” We know the novelist’s teachers, Maxwell, Napier, the old-fashioned compilation known as Victoires, conquêtes et désastres des Français (1835), and the old buffers at Brussels who emptied the room by uttering the word “Badajos.” But where else shall we find the equals of the military scenes in O’Malley and Tom Burke, or the military episodes in Jack Hinton, Arthur O’Leary (the story of Aubuisson) or Maurice Tiernay (nothing he ever did is finer than the chapter introducing “A remnant of Fontenoy”)? It is here that his true genius lies, even more than in his talent for conviviality and fun, which makes an early copy of an early Lever (with Phiz’s illustrations) seem literally to exhale an atmosphere of past and present entertainment. It is here that he is a true romancist, not for boys only, but also for men.

Lever’s lack of artistry and of sympathy with the deeper traits of the Irish character have been stumbling-blocks to his reputation among the critics. Except to some extent in The Martins of Cro’ Martin (1856) it may be admitted that his portraits of Irish are drawn too exclusively from the type depicted in Sir Jonah Barrington’s Memoirs and already well known on 510 the English stage. He certainly had no deliberate intention of “lowering the national character.” Quite the reverse. Yet his posthumous reputation seems to have suffered in consequence, in spite of all his Gallic sympathies and not unsuccessful endeavours to apotheosize the “Irish Brigade.”