Title: Haunted London

Author: Walter Thornbury

Editor: Edward Walford

Illustrator: F. W. Fairholt

Release date: December 8, 2012 [eBook #41580]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

Dr. Johnson’s Opinions of London.—“It is not in the showy evolution of buildings, but in the multiplicity of human habitations, that the wonderful immensity of London consists.... The happiness of London is not to be conceived but by those who have been in it. I will venture to say there is more learning and science within the circumference of where we now sit than in all the rest of the kingdom.... A man stores his mind [in London] better than anywhere else.... No place cures a man’s vanity or arrogance so well as London, for no man is either great or good, per se, but as compared with others, not so good or great, and he is sure to find in the metropolis many his equals and some his superiors.... No man of letters leaves London without regret.... By seeing London I have seen as much of life as the world can show.... When a man is tired of London he is tired of life, for there is in London all life can afford, and [London] is the fountain of intelligence and pleasure.”—Boswell’s Life of Johnson.

Boswell’s Opinion of London.—“I have often amused myself with thinking how different a place London is to different people. They whose narrow minds are contracted to the consideration of some one particular pursuit, view it only through that medium, a politician thinks of it merely as the seat of government, etc.; but the intellectual man is struck with it as comprehending the whole of human life in all its variety, the contemplation of which is inexhaustible.”—Boswell’s Life of Johnson (Croker, 1848), p. 144.

HAUNTED LONDON

BY

WALTER THORNBURY

EDITED BY EDWARD WALFORD, M.A.

TEMPLE BAR, 1761.

ILLUSTRATED BY F. W. FAIRHOLT, F.S.A.

London

CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1880

This book deals less with the London of the ghost-stories, the scratching impostor in Cock Lane, or the apparition of Parson Ford at the Hummums, than with the London consecrated by manifold traditions—a city every street and alley of which teems with interesting associations, every paving-stone of which marks, as it were, the abiding-place of some ancient legend or biographical story; in short, this London of the present haunted by the memories of the past.

The slow changes of time, the swifter destructions of improvement, and the inevitable necessities of modern civilisation, are rapidly remodelling London.

It took centuries to turn the bright, swift little rivulet of the Fleet into a fœtid sewer, years to transform the palace at Bridewell into a prison; but events now move faster: the alliance of money with enterprise, and the absence of any organised resistance to needful though sometimes reckless improvements, all combine to hurry forward modern changes.

If an alderman of the last century could arise from his sleep, he would shudder to see the scars and wounds from which London is now suffering. Viaducts stalk over our chief roads; great square tubes of iron lie heavy as nightmares on the breast of Ludgate Hill. In Finsbury and Blackfriars there are now to be seen yawning chasms as large and ghastly as any that breaching cannon ever effected in[Pg vi] the walls of a besieged city. On every hand legendary houses, great men’s birthplaces, the haunts of poets, the scenes of martyrdoms, and the battle-fields of old factions, heave and totter around us. The tombs of great men, in the chinks of which the nettles have grown undisturbed ever since the Great Fire, are now being uprooted. Milton’s house has become part of the Punch office. A printing machine clanks where Chatterton was buried. Almost every moment some building worthy of record is shattered by the pickaxes of ruthless labourers. The noise of falling houses and uprooted streets even now in my ears tells me how busily Time, the Destroyer and the Improver, is working; erasing tombstones, blotting out names on street-doors, battering down narrow thoroughfares, and effacing one by one the memories of the good, the bad, the illustrious, and the infamous.

A sincere love of the subject, and a strong conviction of the importance of the preservation of such facts as I have dredged up from the Sea of Oblivion, have given me heart for my work. The gradual changes of Old London, and the progress of civilisation westward, are worth noting by all students of the social history of England. It will be found that many traits of character, many anecdotes of interest, as illustrating biography, are essentially connected with the habitations of the great men who have either been born in London, or have resorted to it as the centre of progress, art, commerce, government, learning, and culture. The fact of the residence of a poet, a painter, a lawyer, or even a rogue, at any definite date, will often serve to point out the social status he either aimed at or had acquired. It helps also to show the exact relative distinctions in fashion and popularity of different parts of London at particular epochs, and contributes to form an illustrated history of[Pg vii] London, proceeding not by mere progression of time, and dealing with the abstract city—the whole entity of London—but marching through street after street, and detailing local history by districts at a time.

A century after the martyrs of the Covenant had shed their blood for the good old cause, an aged man, mounted on a little rough pony, used periodically to make the tour of their graves; with a humble and pious care he would scrape out the damp green moss that filled up the letters once so sharp and clear, cut away the thorny arches of the brambles, tread down the thick, prickly undergrowth of nettles, and leave the brave names of the dead men open to the sunlight. It is something like this that I have sought to do with London traditions.

I have especially avoided, in every case, mixing truth with fiction. I have never failed to give, where it was practicable, the actual words of my authorities, rather than run the risk of warping or distorting a quotation even by accident, or losing the flavour and charm of original testimony. Aware of the paramount value of sound and verified facts, I have not stopped to play with words and colours, nor to sketch imaginary groups and processions. Such pictures are often false and only mislead; but a fact proved, illustrated, and rendered accessible by index and heading, is, however unpretentious, a contribution to history, and has with certain inquirers a value that no time can lesson.

In a comprehensive work, dealing with so many thousand dates, and introducing on the stage so many human beings, it is almost impossible to have escaped errors. I can only plead for myself that I have spared no pains to discover the truth. I have had but one object in view, that of rendering a walk through London a journey of interest and of pilgrimage to many shrines.

[Pg viii]In some cases I have intentionally passed over, or all but passed over, outlying streets that I thought belonged more especially to districts alien to my present plan. Maiden Lane, for example, with its memories of Voltaire, Marvell, and Turner, belongs rather to a chapter on Covent Garden, of which it is a palpable appanage; and Chancery Lane I have left till I come to Fleet Street.

I should be ungrateful indeed if, in conclusion, I did not thank Mr. Fairholt warmly for his careful and valuable drawings on wood. To that accomplished antiquary I am indebted, as my readers will see, for several original sketches of bygone places, and for many curious illustrations which I should certainly not have obtained without the aid of his learning and research.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Introduction | pp. 1-3 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| BAR. | |

| The Devil Tavern—London Bankers and Goldsmiths—A Whim of John Bushnell, the Sculptor—Irritating Processions—The Bonfire at Inner Temple Gate—A Barbarous Custom—Called to the Bar—A Curious Old Print of 1746—The White Cockades—An Execution on Kennington Common—Shenstone’s “Jemmy Dawson”—Counsellor Layer—Dr. Johnson in the Abbey—The Proclamation of the Peace of Amiens—The Dispersion of the Armada—City Pageants and Festivities—The Guildhall—The Guildhall Twin Giants—Proclamation of War—A Reflection | pp. 4-24 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE STRAND (SOUTH SIDE). | |

| Essex Street—Beheading a Bishop—Exeter Place—The Gipsy Earl—Running a-muck—Lettice Knollys—A Portrait of Essex—Robert, Earl of Essex, the Parliamentary General—The Poisoning of Overbury—An Epicurean Doctor—Clubable Men—The Grecian—The Templar’s Lounge—Tom’s Coffee-house—A Princely Collector—“The Long Strand”—“Honest Shippen”—Boswell’s Enthusiasm—Sale and the Koran—The Infamous Lord Mohun—A fine Rebuke—Jacob Tonson | pp. 25-55 |

| [Pg x] | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

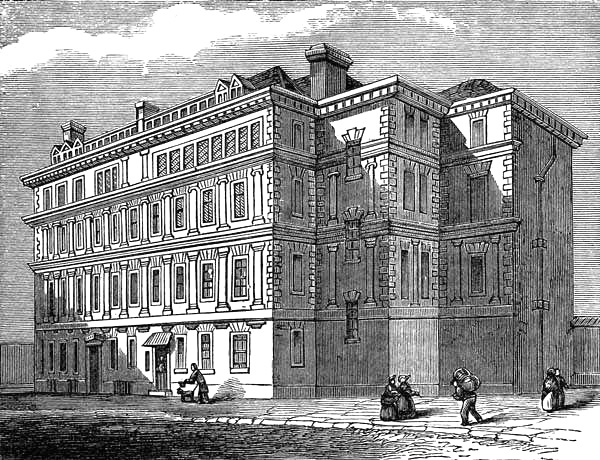

| SOMERSET HOUSE. | |

| The Protector Somerset—Denmark House—The Queen’s French Servants—The Lying-in-State of Cromwell—Scenes at Somerset House—Sir Edmondbury Godfrey—Old Somerset House—Erection of the Modern Building—Carlini’s Grandeur—A Hive of Red Tapists—Expensive Auditing—The Royal Society—The Geological and the Antiquarian Societies—A Legend of Somerset House—St. Martin’s Lane Academy—An Insult to Engravers—Rebecca’s Practical Jokes—A Fashionable Man actually Surprised—Lying in State | pp. 56-81 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE STRAND (SOUTH SIDE, CONTINUED). | |

| The Folly—Fountain Court and Tavern—The Coal-hole—The Kit-cat Club—Coutts’s Bank—The Eccentric Philosopher—Old Salisbury House—Robert the Devil—Little Salisbury House—Toby Matthew—Ivy Bridge—The Strand Exchange—Durham House—Poor Lady Jane—The Parochial Mind—A Strange Coalition—Garrick’s Haunt—Shipley’s School of Art—Barry’s Temper—The Celestial Bed—Sir William Curtis | pp. 82-105 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE SAVOY. | |

| The Earl of Savoy—John Wickliffe—A French King Prisoner—The Kentish Rebellion—John of Gaunt—The Hospital of St. John—Cowley’s Regrets—Secret Marriages—Conference between Church of England and Presbyterian Divines—An Illegal Sanctuary—A Lampooned General—A Fat Adonis—John Rennie—Waterloo Bridge—The Duchy of Lancaster | pp. 106-125 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| FROM THE SAVOY TO CHARING CROSS. | |

| York House—Lord Bacon—“To the Man with an Orchard give an Apple”—“Steenie”—Buckingham Street—Zimri—York Stairs—Pepys and Etty—Scenery on the Banks of the Thames—The London Lodging of Peter the Great—The Czar and the Quakers—The Hungerford Family—The Suspension Bridge—Grinling Gibbons—The Two Smiths—Cross Readings—Northumberland Street—Armed Clergymen | pp. 126-145 |

| [Pg xi] | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE NORTH SIDE OF THE STRAND (FROM TEMPLE BAR TO CHARING CROSS). | |

| Faithorne, the Engraver—The Stupendous Arch—The Murder of Miss Ray—One of Wren’s Churches—Thomas Rymer—Dr. Johnson at Church—Shallow’s Revelry—Low Comedy Preachers—New Inn—Alas! poor Yorick!—The first Hackney Coaches—Doyley—The Beef-steak Club—Beef and Liberty—Madame Vestris—Old Thomson—Irene in a Garret—Mathews at the Adelphi—The Bad Points of Mathew’s Acting—The Old Adelphi—A Riot in a Theatre—Dr. Johnson’s Eccentricities | pp. 146-189 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| CHARING CROSS. | |

| The Gunpowder Plot—Lord Herbert’s Chivalry—A Schoolboy Legend—Goldsmith’s Audience—Dobson Buried in a Garret—Charing—Queen Eleanor—A Brave Ending—Great-hearted Colonel Jones—King Charles at Charing Cross—A Turncoat—A Trick of Curll’s—The Cock Lane Ghost—Savage the Poet—The Mews—The Nelson Column—The Trafalgar Square Fountains—Want of Pictures of the English School—Turner’s Pictures—Mrs. Centlivre of Spring Gardens—Maginn’s Verses—The Hermitage at Charing Cross—Ben Jonson’s Grace—The Promised Land | pp. 190-238 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| ST. MARTIN’S LANE. | |

| A Certain Proof of Insanity—An Eccentric Character—Experimentum Crucis—St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields—Gibb’s Opportunity—St. Martin’s Church—Good Company—The Thames Watermen—Copper Holmes—Old Slaughter’s—Gardelle the Murderer—Hogarth’s Quack—St. Martin’s Lane Academy—Hayman’s Jokes—The Old Watch-house and Stocks—Garrick’s Tricks—An Encourager of Art—John Wilkes—The Royal Society of Literature—The Artist Quarter | pp. 239-261 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| LONG ACRE AND ITS TRIBUTARIES. | |

| The Plague—Great Queen Street—Burning Panama—Lord Herbert’s Poetry—Kneller’s Vanity—Conway House—Winchester House—Ryan the Actor—An Eminent Scholar and Antiquary—Miss Pope—The [Pg xii]Freemasons’ Hall—Gentleman Lewis—Franklin’s Self-denial—The Gordon Riots—Colonel Cromwell—An Eccentric Poetaster—Black Will’s Rough Repartee—Ned Ward—Prior’s Humble Cell—Stothard—The Mug-houses—Charles Lamb | pp. 262-286 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| DRURY LANE. | |

| Drury House—Donne’s Vision—Donne in his Shroud—The Queen of Bohemia—Brave Lord Craven—An Anecdote of Gondomar—Drury Lane Poets—Nell Gwynn—Zoffany—The King’s Company—Memoranda by Pepys—Anecdotes of Joe Haines—Mrs. Oldfield’s Good Sense—The Wonder of the Town—Quin and Garrick—Barry and Garrick—The Bellamy—The Siddons—Dicky Suett—Liston’s Hypochondria—The First Play—Elliston’s Tears—The End of a Man about Town—Edmund Kean—Grimaldi—Kelly and Malibran—Keeley and Harley—Scenes at Drury Lane—“Wicked Will Whiston”—Henley’s Butchers—“Il faut vivre”—Henley’s Sermons—The Leaden Seals | pp. 287-348 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| ST. GILES’S. | |

| The Lollards—Cobham’s Death—The Lazar House—Holborn First Paved—The Mud Deluge—French Protestants—The Plague Cart—The Plague Time—Brought to his Knees—The New Church—The Grave of Flaxman—The Thorntons—Hog Lane—The Tyburn Bowl—The Swan on the Hop—The Irish Deluge—Sham Abraham—Simon and his Dog—Hiring Babies—Pavement Chalkers—Monmouth Street | pp. 349-386 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS. | |

| The Earl of Lincoln’s Garden—The Headless Chancellor—Spelman a late Ripener—Denham and Wither—Lord Lyndhurst—Warburton and Heber—Ben Jonson the Bricklayer—A Murder in Whetstone Park—The Dangers of Lincoln’s Inn Fields—Shelter in St. John’s Wood—Lord William Russell—A Brave Wife—Pelham—The Caricature of a Duke—Wilde and Best—Lindsey House—The Dukes of Ancaster—Skeletons—Lady Fanshawe—Lord Kenyon’s Latin—The Belzoni Sarcophagus—Sir John Soane—Worthy Mrs. Chapone—The Duke’s House—Betterton—Mrs. Bracegirdle—A Riot—Rich’s Pantomime—The Jump | pp. 387-442 |

| Appendix | pp. 443-465 |

| Index | pp. 467-476 |

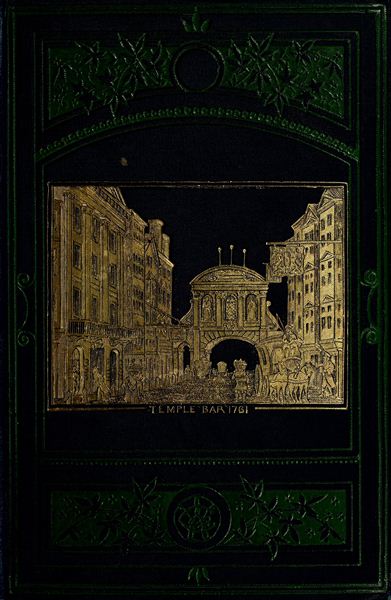

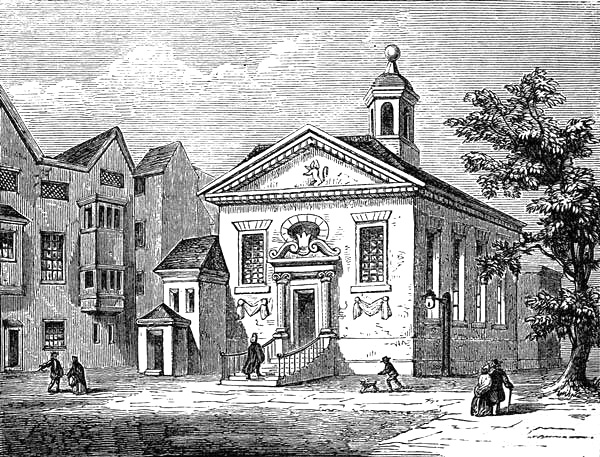

| Temple Bar, 1761, from a drawing by S. Wale. The view is taken from the City side of the Bar, looking through the arch to Butcher Row and St. Clement’s Church. The sign projecting from the house to the spectator’s left is that of the famous Devil Tavern | Vignette on Title |

| PAGE | |

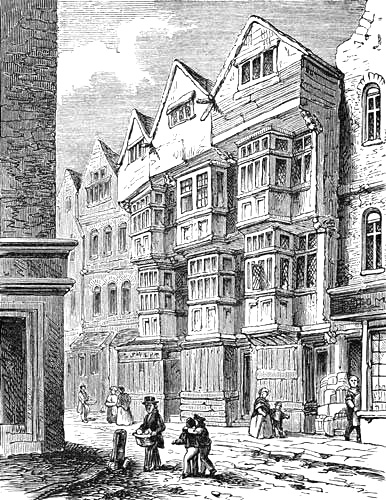

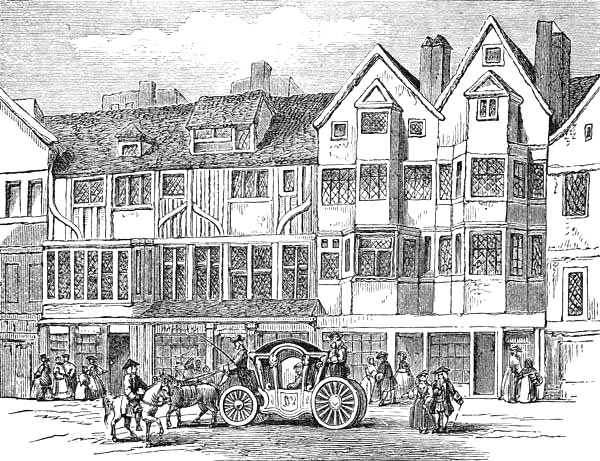

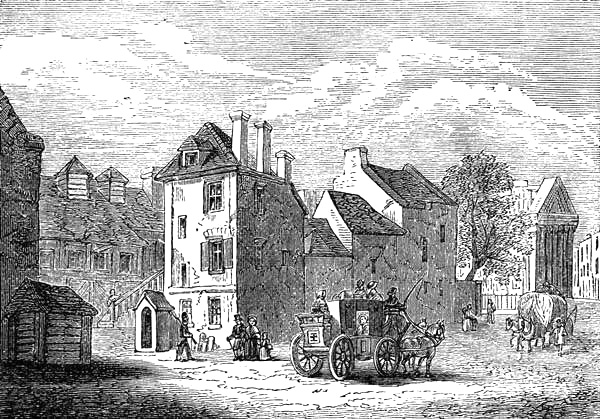

| Old Houses, Ship Yard, Temple Bar, circa 1761, from a plate in Wilkinson’s Londina Illustrata | 4 |

| The Lord Mayor’s Show. From the picture by Hogarth | 19 |

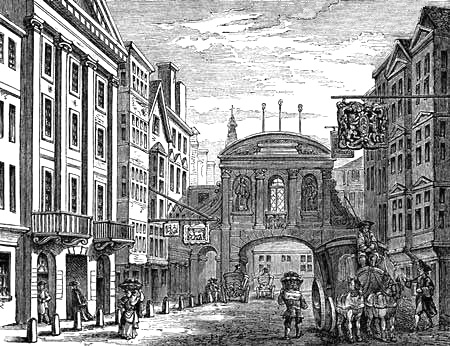

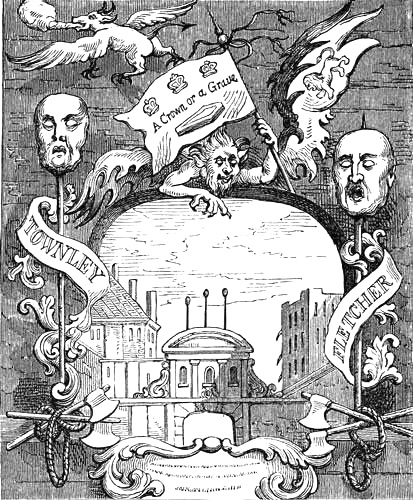

| Temple Bar, 1746, copied from an undated print published soon after the execution of the rebel adherents of the young Pretender. The view is surrounded by an emblematic framework, and contains representations of the heads of Townley and Fletcher, remarkable as the last so exposed; they remained there till 1772 | 23 |

| St. Clement’s Church and the Strand in 1753, from a print by I. Maurer | 25 |

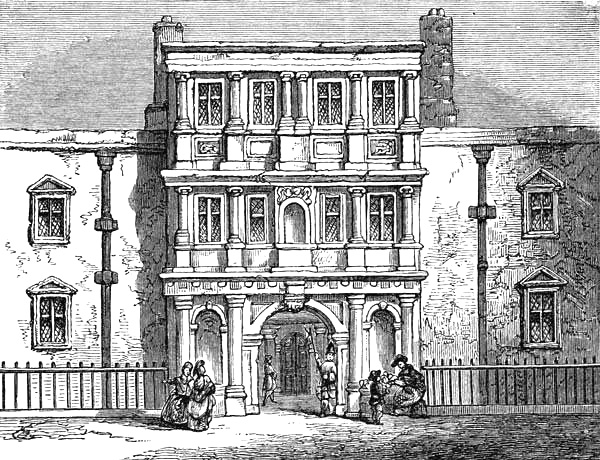

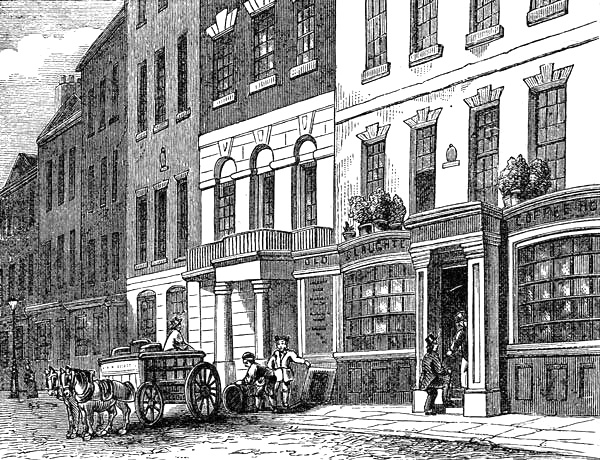

| Two Views of Arundel House, 1646, after Hollar. These views, unique of their kind, are particularly valuable for the clear idea they give of a noble London mansion of the period. Arundel House retains many ancient features, particularly in its dining-hall, which, with the brick residence for the noble owner, is the only dignified portion of the building. The rest has the character of an inn-yard—a mere collection of ill-connected outhouses and stabling. The shed with the tall square window in the roof was the depository of the famous collection of pictures and antiques made by the renowned Earl, part of which still forms the Arundel Collection at Oxford | 40, 41 |

| Penn’s House, Norfolk Street, 1749, from a view by J. Buck. The view is taken from the river, looking up Norfolk Street to a range of old houses, still standing, in the Strand. Penn’s house was the last on the west side of the street (to the spectator’s left), overlooking the water | 55 |

| [Pg xiv] | |

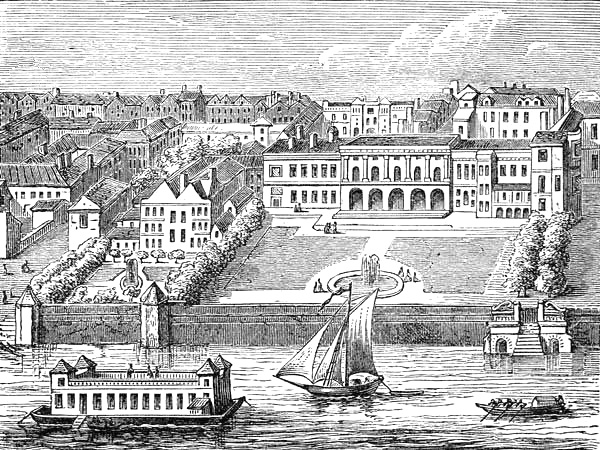

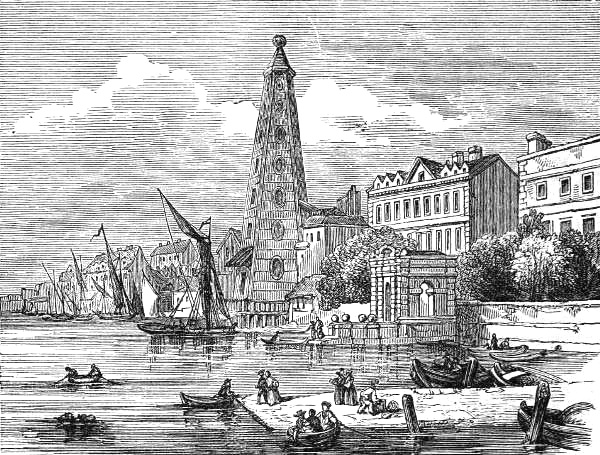

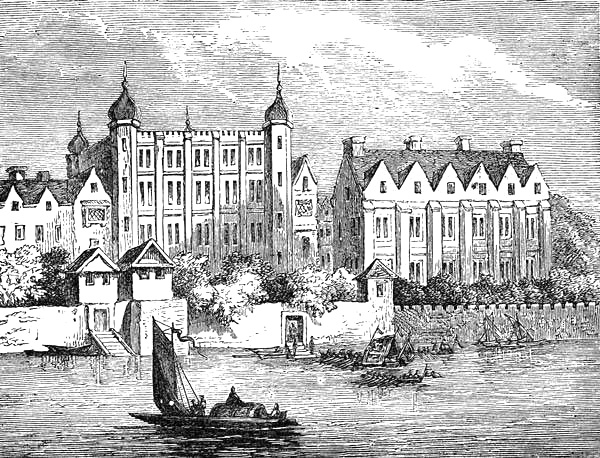

| Somerset House from the River, 1746, from an engraving by I. Knyff. Upon a barge moored in the river is seen the famous coffee-house known as “The Folly,” which, originally used as a musical summer-house, ended in being the resort of depravity | 56 |

| Strand Front of Somerset House, 1777, from a large engraving after I. Moss | 80 |

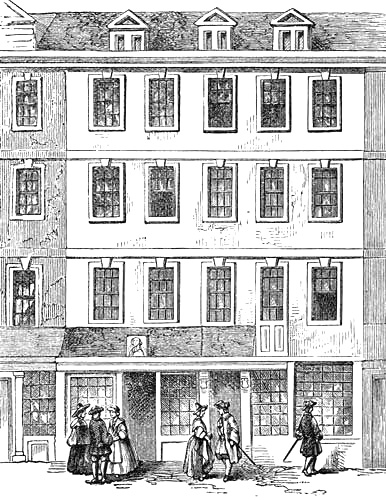

| Jacob Tonson’s Book-shop, 1742, from an etching by Benoist. The shop of this famous bibliopole was opposite Catherine Street. The view is obtained from the background of the print representing a burlesque procession of Masons, got up by some humourist in ridicule of the craft | 82 |

| Old Houses in the Strand, 1742, copied from the same print as the preceding view. These houses stood on the site of the present Wellington Street | 104 |

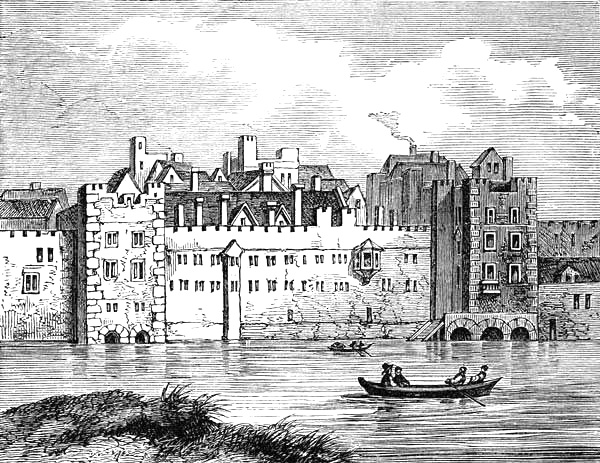

| The Savoy, from the Thames, in 1650, after Hollar | 106 |

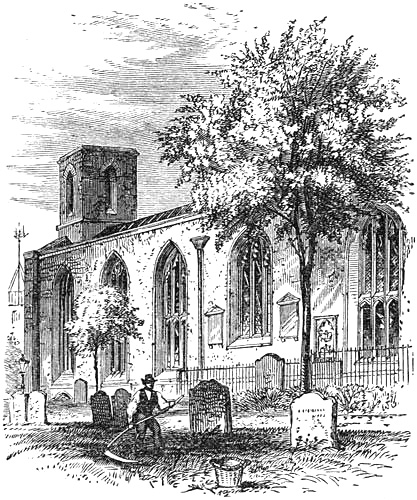

| The Savoy Chapel, from an original drawing | 119 |

| The Savoy Prison, 1793, from an etching by J. T. Smith | 125 |

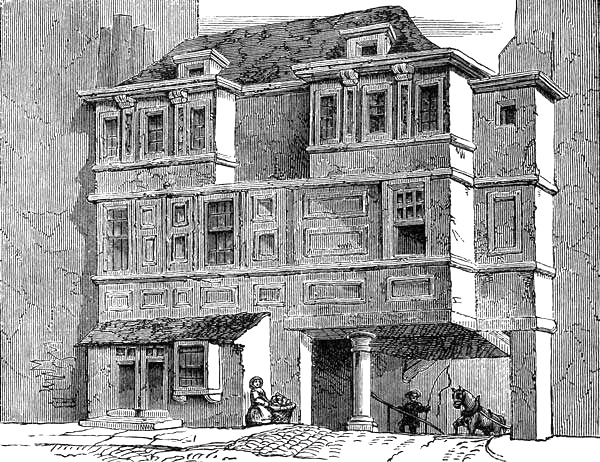

| Durham House, 1790, from an etching by J. T. Smith | 126 |

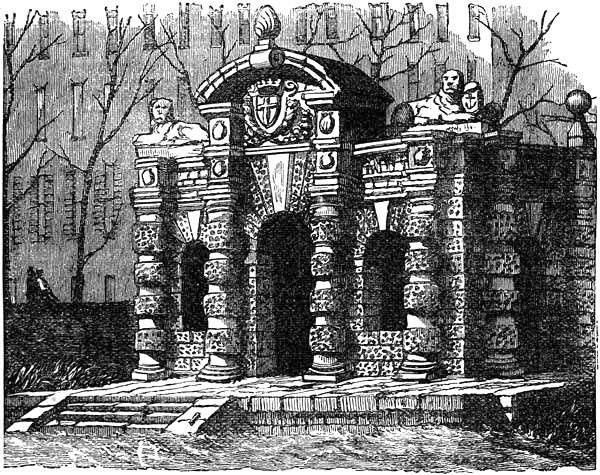

| The Water Gate, 1860, from a Sketch | 133 |

| York Stairs and surrounding Buildings, circa 1745, after an original drawing by Canaletti in the British Museum. This is one of the few interesting views of Old London sketched by Canaletti during his short stay in England. It comprises the famous water-gate designed by Inigo Jones, and the tall wooden tower of the York Buildings Water Company. The large mansion behind this (at the south-west corner of Buckingham Street) was that inhabited by Pepys from 1684, and in which he entertained the members of the Royal Society during his presidency. The house at the opposite corner (seen above the trees) is that in which the Czar Peter the Great resided for some time, when he visited England for instruction in shipbuilding | 144 |

| Crockford’s Fish-shop, from an original sketch | 146 |

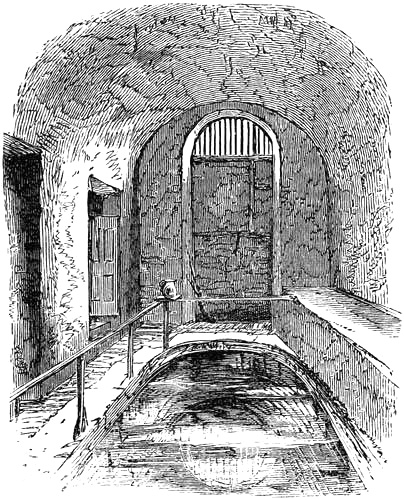

| The Old Roman Bath, from a drawing | 169 |

| Exeter Change, 1821, from an etching by Cooke | 188 |

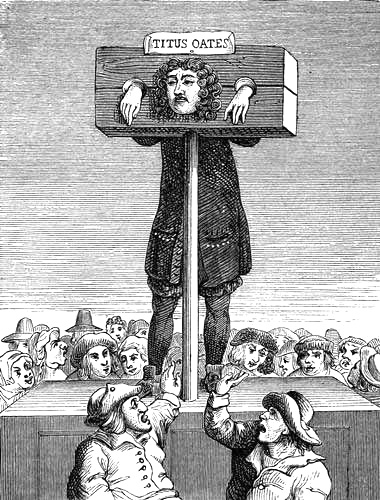

| Titus Oates in the Pillory, from an anonymous contemporary Dutch engraving | 190 |

| [Pg xv] | |

| The King’s Mews, 1750, from a print by I. Maurer. This building, erected in 1732 at the expense of King George II., was pulled down in 1830. In the foreground of this view the King is represented returning to his carriage after inspecting his horses | 238 |

| Barrack and Old Houses on the site of Trafalgar Square in 1826, from an original sketch by F. W. Fairholt. The view is taken from St. Martin’s Church, looking toward Pall Mall; the building in the distance, to the left, is the College of Physicians | 239 |

| Old Slaughter’s Coffee-house, 1826, from an original sketch by F. W. Fairholt | 260 |

| Salisbury and Worcester Houses in 1630, from a drawing by Hollar in the Pepysian Library, Cambridge | 262 |

| Lyon’s Inn, 1804, from an engraving in Herbert’s History of the Inns of Court | 286 |

| Craven House, 1790, from an original drawing in the British Museum | 287 |

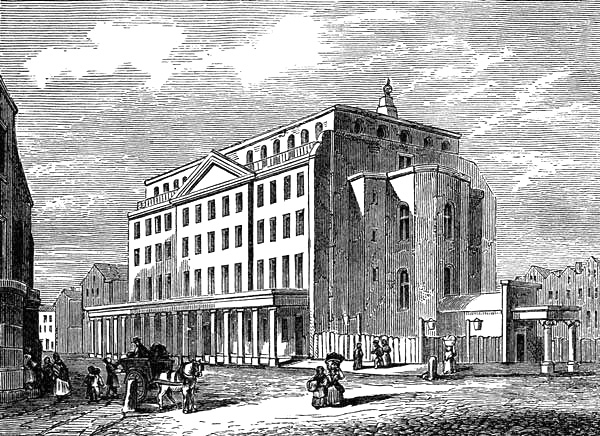

| Drury Lane Theatre, 1806, from an original drawing by Pugin. This was the third theatre, succeeding Garrick’s. It was built by Henry Holland, opened March 12, 1794, and burnt down Feb. 24, 1809. It was never properly finished on the side toward Catherine Street, where this view was taken | 347 |

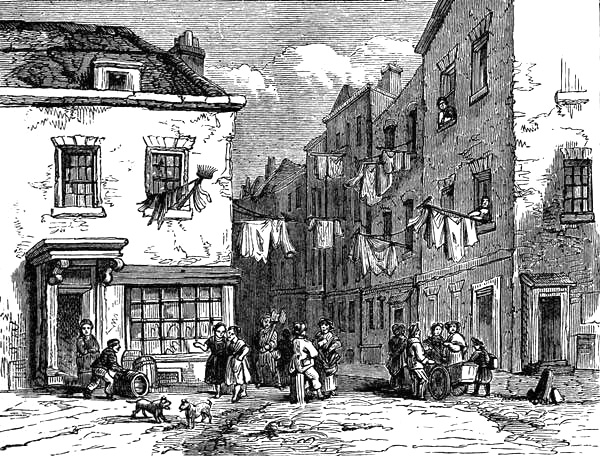

| Church Lane and Dyot Street, from an original sketch by F. W. Fairholt | 349 |

| The Seven Dials, from an original sketch by F. W. Fairholt | 386 |

| Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre in 1821, from an original sketch by F. W. Fairholt | 387 |

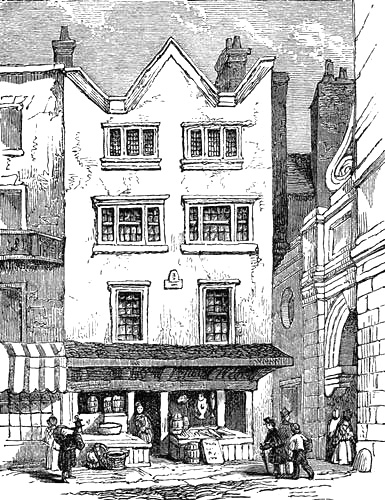

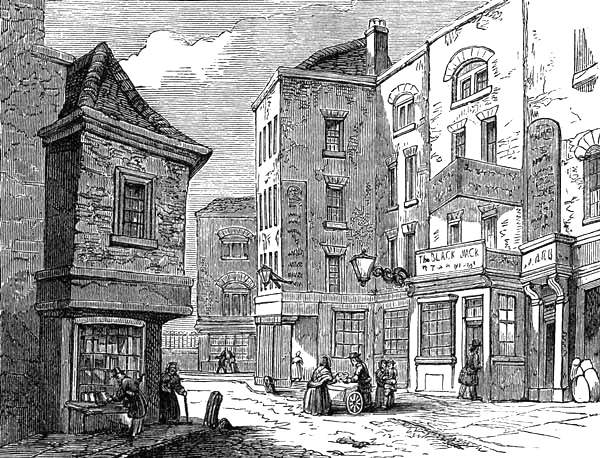

| The Black Jack, Portsmouth Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, from an original sketch by F. W. Fairholt. This public-house was the resort of the actors from the theatre, and among them Joe Miller, who was buried in the graveyard close by, where the hospital now stands. The house was also frequented by Jack Sheppard, and was sometimes termed “The Jump,” from the circumstance of his having once jumped from one of the first-floor windows to escape from officers of justice | 441 |

HAUNTED LONDON.

INTRODUCTION.

One day when Fuseli and Haydon were walking together, they reached the summit of a hill whence they could catch a glimpse of St. Paul’s.

There was the grey dome looming out by fits through rolling drifts of murky smoke. The two little lion-like men stood watching “the sublime canopy that shrouds the city of the world.”[1] Now it spread and seethed like the incense from Moloch’s furnace; now it lifted and thinned into the purer blue, like the waft of some great sacrifice, or settled down to deeper and gloomier grandeur over “the vastness of modern Babylon.” That brown cloud hid a huge ants’ nest teeming with three millions of people. That dome, with its golden coronet and cross, rose like the globe in an emperor’s hand—a type of the civilisation, and power, and Christianity of England.

The hearts of the two men beat faster at the great sight.

“Be George!” said Fuseli, shaking his white hair and stamping his little foot, “be George! sir, it’s like the smoke of the Israelites making bricks for the Egyptians.”

“It is grander, Fuseli,” said Haydon, “for it is the smoke of a people who would have made the Egyptians make bricks for them.”

It is of the multitudinous streets of this more than[Pg 2] Egyptian city, their traditions, and their past and present inhabitants, that I would now write. I shall not pass by many houses where any eminent men dwell or dwelt, without some biographical anecdote, some epigram, some illustration; yet I will not stop long at any door, because so many others await me. I have “set down,” I hope, “nought in malice.” Truth I trust has been, and truth alone shall be, my object. I shall stay at Charing Cross to point out the heroism of the dying regicides; I shall pause at Whitehall to narrate some redeeming traits even in the character of a wilful king.

The growth of London, and its conquest of suburb after suburb, has roused the imagination of poets and essayists ever since the days of Queen Elizabeth.

When James I. forbade the building of fresh houses outside London walls, he little foresaw the time when the City would become almost impassable; when practical men would burrow roads under ground, or make subterranean railways to drain off the choking traffic; when cool-headed people would seriously propose to have flying bridges thrown over the chief thoroughfares; when new manners and customs, new diseases, new follies, new social complications would arise, from the fact of three millions of men silently agreeing to live together on only eleven square miles of land; when fish would cease to inhabit the poisoned river; when the roar of the traffic would render it almost impossible to converse; when, in fact, London would grow too large for comfort, safety, pleasure, or even social intercourse.

It is difficult to select from what centre to commence a pilgrimage. For old Roman London we might start from the Exchange or the Tower; for mediæval London from Chepe or Aldermanbury; for fashionable London from Charing Cross; for Shaksperean London from the Globe or Blackfriars. Even then our tours would be circuitous, and sometimes retrograde, and we should turn and double like hares before the hounds.

I have for several reasons, therefore, and after some consideration, decided to start from Temple Bar, and walk[Pg 3] westward along the Strand to Charing Cross; then to turn up St. Martin’s Lane, and return by Longacre and Drury Lane to Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields.

That walk embraces the long line of palaces which once adorned the Strand, or river-bank street, the countless haunts of artists in St. Martin’s Lane, the legends of Longacre, the theatrical reminiscences of Drury Lane, and the old noblemen’s houses in Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields. It comprises a period not so remote as East London, and not so modern as that of the West End. It brings us acquainted not only with many of the contemporaries of Shakspere and Dryden, but also with many celebrities of Garrick’s time and of Dr. Johnson’s age.

If this is not the best point of departure, it has at least much to be said in its favour, as the loop I have drawn includes nothing intramural, and comprises a part of London inhabited by persons who lived more within the times of memoir-writing than those in the farther East,—a district, too, more within the range of the antiquary than the newer region of the West.

I trust that in these remarks I have in some degree explained why I have spent so much time in pouring “old wine into new bottles.”

A preface is too often a pillory made by an author, in which he exposes himself to a shower of the most unsavoury missiles. I trust that mine may be considered only as a wayside stone on which I stand to offer a fitting apology for what I trust is a venial fault.

It is the glory of my old foster-mother, London, I would celebrate; it is her virtues and her crimes I would record. Her miles of red-tiled roofs, her quiet green squares, her vast black mountain of a cathedral, her silver belt of a river, her acres and acres of stony terraces, her beautiful parks, her tributary fleets, seem to me as so many episodes in one great epic, the true delineation of which would form a new chapter in the History of Mankind.

SHIP YARD, TEMPLE BAR, 1761.

TEMPLE BAR.

Temple Bar, that old dingy gateway of blackened Portland stone which separates the Strand from Fleet Street, the City from the Shire, and the Freedom of the City of London from the Liberty of the City of Westminster, was built by[Pg 5] Sir Christopher Wren in the year 1670, four years after the Great Fire, and ten after the Restoration.

In earlier days there were at this spot only posts, rails, and a chain, as at Holborn, Smithfield, and Whitechapel. In later times, however, a house of timber was erected, with a narrow gateway and one passage on the south side.[2]

The original Bar seems to have crossed Fleet Street, several yards farther to the east of its successor. In the time of James I. it consisted of an iron railing with a gate in the middle. A man sat on the spot for many years after the erection of the new gate, to take toll from all carts which had not the City arms painted on them.

Temple Bar, if described now in an architect’s catalogue, would be noted as pierced with two side posterns for foot passengers, and having a central flattened archway for carriages. In the upper story is an apartment with semicircular arched windows on the eastern and western sides, and the whole is crowned with a sweeping pediment.

On the western or Westminster side there are two niches, in which are placed mean statues of Charles I. and Charles II. in fluttering Roman robes, and on the east or Fleet Street side there are statues of James I. and Queen Elizabeth. They are all remarkable for their small feeble heads, their affected and crinkled drapery, and the piebald look produced by their projecting hands and feet being washed white by years of rain, while the rest of their bodies remains a sooty black.

The upper room is held of the City by the partners of the very ancient firm of Messrs. Child, bankers. There they store their books and records, as in an old muniment-chamber. The north side ground floor, next to Shire Lane, was occupied as a barber’s shop from the days of Steele and the Tatler.

The centre slab on the east side of Temple Bar once contained the following inscription, now all but obliterated:—“Erected in the year 1670, Sir Samuel Sterling, Mayor; continued in the year 1671, Sir Richard Ford, Lord Mayor;[Pg 6] and finished in the year 1672, Sir George Waterman, Lord Mayor.” It is probable that the corresponding western slab, and also the smaller one over the postern, once bore inscriptions.

Temple Bar was doomed to destruction by the City as early as 1790, through the exertions of Alderman Picket. “Threatened men live long,” says an old Italian proverb. Temple Bar still stands[3] a narrow neck to an immense decanter; an impeder of traffic, a venerable nuisance, with nothing interesting but its associations and its dirt. But then let us remember that as Holborn Hill has tormented horses and drivers ever since the Conquest, and its steepness is not yet in any way mitigated,[4] we must not expect hasty reforms in London.

It does not enter into my purpose (unless I walked like a crab, backwards) to give the history of Child’s bank. Suffice it for me to say that it stands on part of the site of the old Devil Tavern, kept by old Simon Wadloe, where Ben Jonson held his club. It was taken down in 1788, and Child’s Place built in its stead.[5] Alderman Backwell, who was ruined by the shutting up of the Exchequer in the reign of Charles II., and became a partner in this, the oldest banking-house in London, was the agent for Government in the sale of Dunkirk to the French.

Pepys makes frequent allusions to his friend Child, probably one of the founders of this bank. The Duke of York opposed his interference in Admiralty matters, and had a quarrel with a gentleman who declared that whoever impugned Child’s honesty must be a knave. Child wrote an enlightened work on Indian trade, supporting the interests of the East India Company.

Apollo Court, exactly opposite the bank, marks a passage that once faced the Apollo room, from whose windows Ben Jonson must have often glowered and Herrick laughed.

Archenholz says that in his day there were forty-eight[Pg 7] bankers in London. “The Duke of Marlborough,” writes the Prussian traveller, “had some years ago in the hands of Child the banker, a fund of ten, fifteen, or twenty thousand pounds. Drummond had often in his hands several hundred thousand pounds at one time belonging to the Government.”[6]

In the earliest London Directory (1677),[7] among “the goldsmiths that keep running cashes,” we find “Richard Blanchard and Child, at the Marygold in Fleet Street.” The huge marigold (really a sun in full shine), above four feet high, the original street-sign of the old goldsmiths at Temple Bar, is still preserved in one of the rooms of Child’s bank.

John Bushnell, the sculptor who executed the statues on Temple Bar, being compelled by his master, Burman, of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields, to marry a discarded servant-maid, went to Italy, and resided in Rome and Venice, and in the latter place executed a monument to a Procuratore, representing a naval engagement between the Venetians and the Turks. His best works are Cowley’s monument, that of Sir Palmes Fairborne in Westminster Abbey, and Lord Mordaunt’s statue in Fulham church. He also executed the statues of Charles I., Charles II., and Sir Thomas Gresham for the Royal Exchange. He had agreed to complete the set of kings, but Cibber being also engaged, Bushnell would not finish the six or seven he had begun. Being told by rival sculptors that he could carve only drapery, and not the naked figure, he produced a very despicable Alexander the Great.

The next whim of this vain, fantastic, and crazy man, was to prove that the Trojan Horse could really have been constructed.[8] He therefore had a wooden horse built with huge timbers, which he proposed to cover with stucco. The head held twelve men and a table; the eyes served as windows. Before it was half completed, however, it was[Pg 8] demolished by a storm of wind, and no entreaties of the two vintners who had contracted to use the horse for a drinking booth could induce the mortified projector to rebuild the monster, which had already cost him £500. A wiser plan of his, that of bringing coal to London by sea, also miscarried; and the loss of an estate in Kent, through an unsuccessful lawsuit, completed the overthrow of Bushnell’s never very well-balanced brain. He died in 1701, and was buried at Paddington. His two sons (to one of whom he left £100 a year, and to the other £60) became recluses, moping in an unfinished house of their father’s, facing Hyde Park, in the lane leading from Piccadilly to Tyburn, now Park Lane. This strange abode had neither staircase nor doors, but there they brooded, sordid and impracticable, saying that the world had not been worthy of their father. Vertue, in 1728, describes a visit to the house, which was then choked with unfinished statues and pictures. There was a ruined cast of an intended brass equestrian statue of Charles II.: an Alexander and other unfinished kings completed the disconsolate brotherhood. Against the wall leant a great picture of a classic triumph, almost obliterated; and on the floor lay a bar of iron, as thick as a man’s wrist, that had been broken by some forgotten invention of Bushnell’s.

After the discovery of the absurd Meal-Tub Plot, in 1679, the 17th of November, the anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth was kept, according to custom, as a high Protestant festival, and celebrated by an extraordinary procession, at the expense of the Green-Ribbon Club, a few citizens, and some gentlemen of the Temple. The bells began to ring out at three o’clock in the morning; at dusk the procession began at Moorgate, and passed through Cheapside and Fleet Street, where it ended with a huge bonfire, “just over against the Inner Temple gate.”[9]

The stormy procession was thus constituted:—

1. Six whifflers, in pioneer caps and red waistcoats, who[Pg 9] cleared the way. 2. A bellman, ringing his bell, and with a doleful voice crying, “Remember Justice Godfrey.” 3. A dead body, representing the wood-merchant of Hartshorne Lane (Sir E. Godfrey), in a decent black habit, white gloves, and the cravat wherewith he was murdered about his neck, with spots of blood on his wrists, breast, and shirt. This figure was held on a white horse by a man representing one of the murderers. 4. A priest in a surplice and cope, embroidered with bones, skulls, and skeletons. He handed pardons to all who would meritoriously murder Protestants. 5. A priest, bearing a great silver cross. 6. Four Carmelite friars, in white and black robes. 7. Four Grey Friars. 8. Six Jesuits with bloody daggers. 9. The waits, playing all the way. 10. Four bishops in purple, with lawn sleeves, golden crosses on their breasts, and croziers in their hands. 11. Four other bishops, in full pontificals (copes and surplices), wearing gilt mitres. 12. Six cardinals, in scarlet robes and caps. 13. The Pope’s chief physician, with Jesuits’ powder and other still more grotesque badges of his office. 14. Two priests in surplices, bearing golden crosses. 15. Then came the centre of all this pageant, the Pope himself, sitting in a scarlet and gilt fringed chair of state. His feet were on a cushion, supported by two boys in surplices, with censers and white silk banners, painted with red crosses and bloody consecrated daggers. His Holiness wore a scarlet gown, lined with ermine and daubed with gold and silver lace. On his head he had the triple tiara, and round his neck a gilt collar, strung with precious stones, beads, Agnus Dei’s, and St. Peter’s keys. At the back of his chair climbed and whispered the devil, who hugged and caressed him, and sometimes urged him aloud to kill King Charles, or to forge a Protestant plot and to fire the city again, for which purpose he kept a torch ready lit.

The number of spectators in the balconies and windows was computed at two hundred thousand. A hundred and fifty flambeaux followed the procession by order, and as many more came as volunteers.

Roger North also describes a fellow with a stentorophonic[Pg 10] tube (a speaking-trumpet), who kept bellowing out—“Abhorrers! abhorrers!”[10]

Lastly came a complaisant, civil gentleman, who was meant to represent either Sir Roger l’Estrange, or the King of France, or the Duke of York. “Taking all in good part, he went on his way to the fire.”

At Temple Bar some of the mob had crowned the statue of Elizabeth with gilt laurel, and placed in her hand a gilt shield with the motto, “The Protestant Religion and Magna Charta.” A spear leant against her arm, and the niche was lit with candles and flambeaux, so that, as North said, she looked like the goddess Pallas, the object of some solemn worship and sacrifice.

All this time perpetual battles and skirmishes went on between the Whigs and Tories at the different windows, and thousands of volleys of squibs were discharged.

When the pope was at last toppled into the fire a prodigious shout was raised, that spread as far as Somerset House, where the queen then was, and, as a pamphleteer of the time says, before it ceased, reached Scotland, France, and even Rome.

From these processions the word MOB (mobile vulgus) became introduced into our language.[11] In 1682, Charles II. tried to prohibit this annual festival, but it continued nevertheless till the reign of Queen Anne, or even later.[12]

At Temple Bar, where the houses seemed turned into mountains of heads, and many fireworks were let off, a man representing the English cardinal (Philip Howard, brother of the Duke of Norfolk) sang a rude part-song with other men who personated the people of England. The cardinal first began:—

“From York to London town we come

To talk of Popish ire,

To reconcile you all to Rome,

And prevent Smithfield fire.”

[Pg 11]To which the people replied, valorously:—

“Cease, cease, thou Norfolk cardinal,

See! yonder stands Queen Bess,

Who saved our souls from Popish thrall:

Oh, Bess! Queen Bess! Queen Bess!

“Your Popish plot, and Smithfield threat,

We do not fear at all,

For, lo! beneath Queen Bess’s feet,

You fall! you fall! you fall!

“’Tis true our king’s on t’other side,

A looking t’wards Whitehall,

But could we bring him round about,

He’d counterplot you all.

“Then down with James and up with Charles,

On good Queen Bess’s side,

That all true commons, lords, and earls

May wish him a fruitful bride.

“Now God preserve great Charles our king,

And eke all honest men,

And traitors all to justice bring:

Amen! Amen! Amen!”

It was formerly the barbarous and brutal custom to place the heads and quarters of traitors upon Temple Bar as scarecrows to all persons who did not consider William of Orange, or the Elector of Hanover, the rightful possessors of the English crown.

Sir Thomas Armstrong was the first to help to deck Wren’s new arch. When Shaftesbury fled in 1683, and the Court had partly discovered his intrigues with Monmouth and the Duke of Argyle, the more desperate men of the Exclusion Party plotted to stop the king’s coach as he returned from Newmarket to London, at the Rye House, a lonely mansion near Hoddesden. The plot was discovered, and Monmouth escaped to Holland. In the meantime the informers dragged Russell and Sydney into the scheme, for which they were falsely put to death. Sir Thomas Armstrong, who had been taken at Leyden and delivered up to the English Ambassador at the Hague, claimed a trial as a[Pg 12] surrendered outlaw, according to the 6th Edward VI. But Judge Jeffreys refused him his request, as he had not surrendered voluntarily, but had been brought by force. Armstrong still claiming the benefit of the law, the brutal judge replied:—“And the benefit of the law you shall have, by the grace of God. See that execution be done on Friday next, according to law.”

Armstrong had sinned deeply against the king. He had sold himself to the French ambassador, he had urged Monmouth on in his undutiful conduct to his father, and he had been an active agent in the Rye House Plot. Charles would listen to no voice in his favour. On the scaffold he denied any intention of assassinating the king or changing the form of government.[13]

Sir William Perkins and Sir John Friend were the next unfortunate gentlemen who lent their heads to crown the Bar. They were rash, hot-headed Jacobites, who, too eagerly adopting the “ultima ratio” of political partisans, had planned, in 1696, to stop King William’s coach in a deep lane between Brentford and Turnham Green, as he returned from hunting at Richmond. Sir John Friend was a person who had acquired wealth and credit from mean beginnings, but Perkins was a man of fortune, violently attached to King James, though as one of the six clerks of Chancery he had taken the oath to the new Government. Friend owned that he had been at a treasonable meeting at the King’s Head Tavern in Leadenhall Street, but denied connivance in the assassination-plot. Perkins made an artful and vigorous defence, but the judge acted as counsel for the Crown and guided the jury. They both suffered at Tyburn, three nonjuring clergymen absolving them, much to the indignation of the loyal bystanders.[14]

John Evelyn calls the sight of Temple Bar “a dismal sight.”[15] Thank God, this revolting spectacle of traitors’ heads will never be seen here again.

In 1716 Colonel Henry Oxburgh’s head was added to[Pg 13] the quarters of Sir John Friend (a brewer) and the skull of Sir William Perkins. Oxburgh was a Lancashire gentleman, who had served in the French army. General Foster (who escaped from Newgate, in 1716) had made him colonel directly he joined the Pretender’s army. To him, too, had been entrusted the humiliating task of proposing capitulation to the king’s troops at Preston, when the Highlanders, frenzied with despair, were eager to sally out and cut their way through the enemy’s dragoons. He met death with a serene temper. A fellow-prisoner described his words as coming “like a gleam from God. You received comfort,” he says, “from the man you came to comfort.” Oxburgh was executed at Tyburn, May 14; his body was buried at St. Giles’, all but his head, and that was placed on Temple Bar two days afterwards.

A curious print of 1746 represents Temple Bar with the three heads raised on tall poles or iron rods. The devil looks down in triumph and waves the rebel banner, on which are three crowns and a coffin, with the motto, “A crown or a grave.” Underneath are written these wretched verses:

“Observe the banner which would all enslave,

Which ruined traytors did so proudly wave.

The devil seems the project to despise;

A fiend confused from off the trophy flies.

“While trembling rebels at the fabrick gaze,

And dread their fate with horror and amaze,

Let Briton’s sons the emblematick view,

And plainly see what to rebellion’s due.”

A curious little book “by a member of the Inner Temple,” which has preserved this print, has also embalmed the following stupid and cold-blooded impromptu on the heads of Oxburgh, Townley, and Fletcher:—

“Three heads here I spy,

Which the glass did draw nigh,

The better to have a good sight;

Triangle they’re placed,

Old, bald, and barefaced,

Not one of them e’er was upright.”[16]

[Pg 14]The heads of Fletcher and Townley were put up on Temple Bar August 2, 1746. On August 16, Walpole writes to Montague to say that he had “passed under the new heads at Temple Bar, where people made a trade of letting spying-glasses at a halfpenny a look.”

Townley was a young officer about thirty-eight years of age, born at Wigan, and of a good family. His uncle had been out in 1715, but was acquitted on his trial. Townley had been fifteen years abroad in the French army, and was close to the Duke of Berwick when the duke’s head was shot off at the siege of Philipsburgh. When the Highlanders came into England he met them near Preston, and received from the young Pretender a commission to raise a regiment of foot. He had been also commandant at Carlisle, and directed the sallies from thence.

Fletcher, a young linen chapman at Salford, had been seen pulling off his hat and shouting when a sergeant and a drummer were beating up for volunteers at the Manchester Exchange. He had been seen also at Carlisle, dressed as an officer, with a white cockade in his hat and a plaid sash round his waist.[17]

Seven other Jacobites were executed on Kennington Common with Fletcher and Townley. They were unchained from the floor of their room in Southwark new gaol early in the morning, and having taken coffee, had their irons knocked off. They were then, at about ten o’clock, put into three sledges, each drawn by three horses. The executioner, with a drawn scimitar, sat in the first sledge with Townley; a party of dragoons and a detachment of foot-guards conducted him to the gallows, near which a pile of faggots and a block had been placed. While the prisoners were stepping from their sledges into a cart drawn up beneath a tree, the wood was set on fire, and the guards formed a circle round the place of execution. The prisoners had no clergyman, but Mr. Morgan, one of their number, put on his spectacles and read prayers to them, which they listened and responded to with devoutness. This lasted above an hour. Each one then[Pg 15] threw his prayer-book and some written papers among the spectators; they also delivered notes to the sheriff, and then flung their hats into the crowd. “Six of the hats,” says the quaint contemporary account, “were laced with gold,—all of these prisoners having been genteelly dressed.” Immediately after, the executioner took a white cap from each man’s pocket and drew it over his eyes; then they were turned off. When they had hung about three minutes, the executioner pulled off their shoes, white stockings, and breeches, a butcher removing their other clothes. The body of Mr. Townley was then cut down and laid upon a block, and the butcher seeing some signs of life remaining, struck it on the breast, then took out the bowels and the heart, and threw them into the fire. Afterwards, with a cleaver, they severed the head and placed it with the body in the coffin. When the last heart, which was Mr. Dawson’s, was tossed into the fire, the executioner cried, “God save King George!” and the immense multitude gave a great shout. The heads and bodies were then removed to Southwark gaol to await the king’s pleasure.

According to another account the bodies were cloven into quarters; and as the butcher held up each heart he cried, “Behold the heart of a traitor!”

Mr. James Dawson, one of the unhappy men thus cruelly punished, was a young Lancashire gentleman of fortune, just engaged to be married. The unhappy lady followed his sledge to the place of execution, and approached near enough to see the fire kindled and all the other dreadful preparations. She bore it well till she heard her lover was no more, but then drew her head back into the coach, and crying out, “My dear, I follow thee!—I follow thee! Sweet Jesus, receive our souls together!” fell on the neck of a companion and expired. Shenstone commemorated this occurrence in a plaintive ballad called “Jemmy Dawson.”

Mr. Dawson is described as “a mighty gay gentleman, who frequented much the company of the ladies, and was well respected by all his acquaintance of either sex for his genteel deportment. He was as strenuous for their vile cause[Pg 16] as any one in the rebel army. When he was condemned and double fettered, he said he did not care if they were to put a ton weight of iron on him; it would not in the least daunt his resolution.”[18]

On January 20 (between 2 and 3 A.M.), 1766, a man was taken up for discharging musket-bullets from a steel crossbow at the two remaining heads upon Temple Bar. On being examined he affected a disorder in his senses, and said his reason for doing so was “his strong attachment to the present Government, and that he thought it was not sufficient that a traitor should merely suffer death; that this provoked his indignation, and that it had been his constant practice for three nights past to amuse himself in the same manner. And it is much to be feared,” says the recorder of the event, “that he is a near relation to one of the unhappy sufferers.”[19] Upon searching this man, about fifty musket-bullets were found on him, wrapped up in a paper with a motto—“Eripuit ille vitam.”

“Yesterday,” says a news-writer of the 1st of April, 1772, “one of the rebel heads on Temple Bar fell down. There is only one head now remaining.”

The head that fell was probably that of Councillor Layer, executed for high treason in 1723. The blackened head was blown off the spike during a violent storm. It was picked up by Mr. John Pearce, an attorney, one of the Nonjurors of the neighbourhood, who showed it to some friends at a public-house, under the floor of which it was buried. In the meanwhile Dr. Rawlinson, a Jacobite antiquarian, having begged for the relic, was imposed on with another. In his will the doctor desired to be buried with this head in his right hand,[20] and the request was complied with.

This Dr. Rawlinson, one of the first promoters of the Society of Antiquaries, and son of a lord mayor of London, died in 1755. His body was buried in St. Giles’ churchyard, Oxford, and his heart in St. John’s College. The sale of his effects lasted several days, and produced £1164. He left[Pg 17] upwards of 20,000 pamphlets; his coins he bequeathed to Oxford.

The last of the iron poles or spikes on which the heads of the unfortunate Jacobite gentlemen were fixed, was removed only at the commencement of the present century.[21]

The above-named Christopher Layer was a barrister, living in Old Southampton Buildings, who had engaged in a plot to seize the Bank and the Tower, to arm the Minters in Southwark, to seize the king, Walpole, and Lord Cadogan, to place cannon on the terrace of Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields gardens, and to draw a force of armed men together at the Exchange. The prisoner had received blank promissory-notes signed in the Pretender’s own hand, and also treasonable letters full of cant words of the party in disguised names—such as Mr. Atkins for the Pretender, Mrs. Barbara Smith for the army, and Mr. Fountaine for himself.

It was proved that, at an audience in Rome, Layer had assured the Pretender that the South Sea losses had done good to his cause; and the Pretender and the Pretender’s wife (through their proxies, Lord North and Grey, and the Duchess of Ormond) had stood as godfather and godmother to his (Layer’s) daughter’s child.

He was executed at Tyburn in May 1723, and avowed his principles even under the gallows. His head was taken to Newgate, and the next day fixed upon Temple Bar; but his quarters were delivered to his relations to be decently interred.

In April 1773 Boswell dined at Mr. Beauclerk’s with Dr. Johnson, Lord Charlemont, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and some other members of the Literary Club—it being the evening when Boswell was to be balloted for as candidate for admission into that distinguished society.[22] The conversation turned on Westminster Abbey, and on the new and commendable practice of erecting monuments to great men in St. Paul’s; upon which the doctor observed—

“I remember once being with Goldsmith in Westminster[Pg 18] Abbey. While we surveyed the Poets’ Corner, I said to him—

‘Forsitan et nostrum nomen miscebitur illis.’

When we got to Temple Bar he stopped me, pointed to the heads upon it, and slily whispered—

‘Forsitan et nostrum nomen miscebitur istis.’”[23]

This walk must have taken place a year or two before 1773, for in 1772, as we have seen, the last head but one fell.

O’Keefe, the dramatist, who arrived in England on August 12, 1762, the day on which the Prince of Wales (afterwards George IV.) was born, describes the heads of poor Townley and Fletcher as stuck up on high poles, not over the central archway, but over the side posterns. Parenthetically he mentions that he had also seen the walls of Cork gaol garnished with heads, like the ramparts of the seraglio at Constantinople.[24]

O’Keefe tells us that he heard the unpopular peace of 1763 proclaimed at Temple Bar, and witnessed the heralds in the Strand knock at the city gate. The duke of Nivernois, the French ambassador on that occasion, was a very little man, who wore a coat of richly-embroidered blue velvet, and a small chapeau, which set the fashion of the Nivernois hat.[25]

At the proclamation of the short peace of Amiens, the king’s marshal, with his officers, having ridden down the Strand from Westminster, stopped at Temple Bar, which was kept shut to show that there commenced the Lord Mayor’s jurisdiction. The herald’s trumpets were blown thrice; the junior officer then tapped at the gate with his cane, upon which the City marshal, in the most unconscious way possible, answered, “Who is there?” The herald replied, “The officers-of-arms, who seek entrance into the City to publish his majesty’s proclamation of peace.” On[Pg 19] this the gates were flung open, and the herald alone was admitted, and conducted to the Lord Mayor. The latter then read the royal warrant, and returning it to the bearer, ordered the City marshal to open the gate for the whole procession. The Lord Mayor and aldermen then joined it, and proceeded to the Royal Exchange, where the proclamation, that was to bid the cannon cease and chain up the dogs of war, was read for the last time.

THE LORD MAYOR’S SHOW. AFTER HOGARTH.

The timber work and doors of Temple Bar have been often renewed since 1672. New doors were hung for Nelson’s funeral, when the Bar was to be closed; and again at the funeral of Wellington, when the plumes and trophies had to be removed in order that the car might pass through the gate, which was covered with dull theatrical finery.[26]

[Pg 20]The old, black, mud-splashed gates of Temple Bar are also shut whenever the sovereign has occasion to enter the City. This is an old custom, a tradition of the times when the city was proud of its privileges, and sometimes even jealous of royalty. When the cavalcade approaches, a herald, in his tabard of crimson and gold lace, sounds a trumpet before the portal of the City; another herald knocks; a parley ensues; the gates are then thrown open, and the Lord Mayor appearing, kneels and hands the sword of the city to his sovereign, who graciously returns it.

Stow describes a scene like this in the old days of the “timber house,” when Queen Elizabeth was on her way to old St. Paul’s to return thanks to God for the discomfiture of the Armada. The City waits fluted, trumpeted, and fiddled from the roof of the gate; while below, the Lord Mayor and his brethren, in scarlet gowns, received and welcomed their brave queen, delivering up the sword which, after certain speeches, she re-delivered to the mayor, who, then taking horse, rode onward to St. Paul’s bearing it in its shining sheath before her.[27]

In the June after the execution of Charles I., when Cromwell had dispersed the mutinous regiments with his horse, and pistolled or hanged their leaders, a day of thanksgiving was appointed, and the Parliament, the Council of State, and the Council of the Army, after endless sermons, dined together at Grocers’ Hall; on that day Lenthall, the Speaker, received the sword of state from the mayor at the Bar, and assumed the functions of royalty.

The same ceremony took place when Queen Anne went to St. Paul’s to return thanks for the Duke of Marlborough’s victories, and again when George III. came to return thanks for a recovery from his fit of insanity, and when Queen Victoria passed on her way to Cornhill to open the Royal Exchange.

Temple Bar naturally does not figure much in the early City pageants, because, after proceeding to Westminster[Pg 21] by water, the mayor and aldermen usually landed at St. Paul’s Stairs.

It is, we believe, first mentioned in the great festivities when the City brought poor Anne Boleyn, in 1533, from Greenwich to the Tower, and on the second day after conducted her through the chief streets and honoured her with shows. On that day the Fleet Street conduit ran claret, and Temple Bar was newly painted and repaired; there also stood singing men and children, till the company rode on to Westminster Hall. The next day was the coronation.[28]

On the 19th of February 1546-7 the young King Edward VI. passed through London, the day before his coronation. At the Fleet Street conduit two hogsheads of wine were given to the people. The gate at Temple Bar was also painted and fashioned with varicoloured battlements and buttresses, richly hung with cloth of arras, and garnished with fourteen standards. There were eight French trumpeters blowing their best, besides a pair of “regals,” with children singing to the same.[29]

In September 1553 Queen Mary rode through London, the day before her coronation, in a chariot covered with cloth of tissue, and drawn by six horses draped with the same. Minstrels played at Ludgate, and the Temple Bar was newly painted and hung.[30]

But even a greater time came for the old City boundary in January 1558-9, when Queen Elizabeth went from the Tower to Westminster. Temple Bar was “finely dressed” up with the two giants—Gog and Magog (now in the Guildhall)—who held between them a poetical recapitulation of all the other pageantries, both in Latin and English. On the south side was a noise of singing children, one of whom, richly attired as a poet, gave the queen farewell in the name of the whole city.[31]

In 1603 King James, Queen Anne of Denmark, and Prince Henry Frederick passed through “the honourable[Pg 22] City and Chamber” of London, and were welcomed with pageants. The last arch, that of Temple Bar, represented a temple of Janus. The principal character was Peace, with War grovelling at her feet; by her stood Wealth; below sat the four handmaids of Peace,—Quiet treading on Tumult, Liberty on Servitude, Safety on Danger, and Felicity on Unhappiness. There was then recited a poetical dialogue by the Flamen Martialis and the Genius Urbis, written by Ben Jonson.

Here, hitherto, the pageantry had always ceased, but the Strand suburbs having now greatly increased, there was an additional pageant beyond Temple Bar, which had been thought of and perfected in only twelve days. The invention was a rainbow; and the moon, sun, and pleiades advanced between two magnificent pyramids seventy feet high, on which were drawn out the king’s pedigrees through both the English and the Scottish monarchs. A speech composed by Ben Jonson was delivered by Electra.[32]

When Charles II. came through London, according to custom, the day before his coronation, I suspect that “the fourth arch in Fleet Street” was close to Temple Bar. It was of the Doric and Ionic orders, and was dedicated to Plenty, who made a speech, surrounded by Bacchus, Ceres, Flora, Pomona, and the Winds; but whether the latter were alive or only dummies, I cannot say.

The London Gazette of February 8, 1665-6, announces the proclamation of war against France; and Pepys mentions this as also the day on which they went into mourning at court for the King of Spain. War was proclaimed by the herald-at-arms and two of his brethren, his majesty’s sergeants-at-arms, and trumpeters, with the other usual officers before Whitehall, and afterwards (the Lord Mayor and his brethren assisting) at Temple Bar, and in other usual parts of the City.

James II., in 1687, honoured Sir John Shorter as Lord Mayor with his presence at an inaugurative banquet at Guildhall. The king was accompanied by Prince George[Pg 23] of Denmark, and was met by the two sheriffs at Temple Bar.

TEMPLE BAR, 1746.

On Lord Mayor’s Day, 1689, when King William and Queen Mary came to the City to see the show, the City militia regiments lined the street as far as Temple Bar, and beyond came the red and blue regiments of Middlesex and Westminster; the soldiers, at regulated distances, holding lighted flambeaux in their hands, and all the houses being illuminated.[33]

In 1697, when Macaulay’s hero, William III., made a[Pg 24] triumphant entry into London to celebrate the conclusion of the peace of Ryswick, the procession included fourscore state coaches, each with six horses; the three City regiments guarded Temple Bar, and beyond them came the liveries of the several companies, with their banners and ensigns displayed.[34]

George III. in his day, and Queen Victoria in her and our own, passed through Temple Bar in state more than once, on their way into the City; the last occasion was on February 1872, when the Queen proceeded to St. Paul’s to offer thanks for the recovery of her son the Prince of Wales. Through it also the bodies of Nelson and of Wellington were borne to their last resting place in St. Paul’s.

On the auspicious entrance into London of the fair Princess Alexandra, the old gate was hung with tapestry of gold tissue, powdered with crimson hearts; and very mediæval and gorgeous it looked; but the real days of pageants are gone by. We shall never again see fountains running wine, nor maidens blowing gold-leaf into the air, as in the luxurious days of our Plantagenet kings.

There are many portals in the world loftier and more beautiful than our dull, black arch of Temple Bar. The Vatican has grander doorways, the Louvre more stately entrances, but through no gateway in the world have surely passed onwards to death so many millions of wise and brave men, or so many thinkers who have urged forward learning and civilisation, and carried the standard of struggling humanity farther into space.

ST. CLEMENT’S CHURCH IN THE STRAND, 1753.

THE STRAND (SOUTH SIDE).

Essex Street was formerly part of the Outer Temple, the western wing of the Knight Templars’ quarter. The outer district of these proud and wealthy Crusaders stretched as far as the present Devereux Court; those gentler spoilers, the mediæval lawyers, having extended their frontiers quite as far as their rooted-out predecessors. From the Prior and Canons of the Holy Sepulchre[35] it was transferred, in the reign of Edward II. to the Bishops of Exeter, who built a palace here and occupied it till the reign of Henry VII. or Henry VIII.

[Pg 26]The first tenant of Exeter House was the ill-fated Walter Stapleton, Lord Treasurer of England, a firm adherent to the luckless Edward II., against his queen and the turbulent barons. In 1326, when Isabella landed from France to chase the Spensers from her husband’s side, and advanced on London, the weak king and his evil counsellors fled to the Welsh frontier; but the bishop held out stoutly for his king, and, as custos of the City of London, demanded the keys from the Lord Mayor, Hammond Chickwell, to prevent the treachery of the disaffected city. The watchful populace, roused by Isabella’s proclamation that had been hung on the new cross in Cheapside, rose in arms, seized the vacillating mayor, and took the keys. They next ran to Exeter House, then newly erected, fired the gates, and burnt all the plate, jewels, money, and goods. The bishop, at that time in the fields, being almost too proud to show fear, rode straight to the northern door of St. Paul’s to take sanctuary. There the mob tore him from his horse, stripped him of his armour, and dragging him to Cheapside, proclaimed him a traitor, a seducer of the king, and an enemy of their liberties, and lopping off his head, set it on a pole. The corpse was buried without funeral service in an old churchyard of the Pied Friars.[36] His brother and some servants were also beheaded, and their bleeding and naked bodies thrown on a heap of rubbish by the river side.

Exeter Place was shortly afterwards rebuilt, but the new house seemed a doomed place, and brought no better fortune to its new owners. Lord Paget, who changed its name to Paget House, fought at Boulogne under the poet Earl of Surrey, was ambassador at the court of Charles V., and on his return obtained a peerage and the garter. He fell with the Protector Somerset, being accused of having planned the assassination of the Duke of Northumberland at Paget House. Released from the Tower, he was deprived of the garter upon the malicious pretence that he was not a gentleman by blood. Queen Mary, however, restored the fallen man to honour, made him Lord Privy Seal, and sent him on an embassy.

[Pg 27]The next occupier of the unlucky house, Thomas Howard, fourth Duke of Norfolk, and son of the poet Earl of Surrey, maintained in its chambers an almost royal magnificence. It was here he was arrested for conspiring, with the aid of Mary Queen of Scots, the Pope, and the King of Spain, to marry Mary and restore the Popish religion.

The duke’s ambition and treason were fully proved by his own intercepted letters; indeed, he himself confessed his guilt, though he had denounced Mary to Elizabeth as a “notorious adulteress and murderer.” To crown his rashness, meanness, and treason, he wrote from the Tower the most abject letters to Elizabeth, imploring her clemency. He was privately beheaded in 1572, but his estates were restored to his children.[37] It was under the mat, hard by a window in the entry towards the duke’s bedchamber, that the celebrated alphabet in cipher[38] was hidden, which the duke afterwards concealed under a roof tile, where it was found, unmasking all his plans.

In the Tower the unhappy plotter had written affecting letters to his son Philip, bidding him worship God, avoid courts, and beware of ambition.[39] The warning of the man whose eyes had been opened too late is touching. The writer, speaking of court life, remarks, “It hath no certainty. Either a man, by following thereof, hath too much worldly pomp, which in the end throws him down headlong, or else he liveth there unsatisfied, either that he cannot obtain to himself that he would, or else that he cannot do for his friends as his heart desireth.”

Poor Philip did not benefit much by these lessons, but remained simple Earl of Arundel, was repeatedly committed to the Tower, as by necessity an ill-wisher to Elizabeth, and eventually died there after ten weary years of imprisonment. His initials are still to be found on the walls of one of the chambers in the Beauchamp Tower.

Fools never learn the lessons which Time tries so hard to beat into them. Plotter succeeds plotter, and the rough[Pg 28] lesson of the headsman seldom teaches the conspirator’s successor to cease from conspiring.

To the Norfolks succeeded Dudley, the false Earl of Leicester, the black or gipsy earl, as he was called from his swarthy Italian complexion. Leicester, like the duke before him, plotted with Mary’s Jesuits and assassins, and at the same time contrived to keep in favour with his own jealous queen, in spite of all his failures and schemings in Holland, and his suspected assassinations of his enemies in England. Leicester died of fever the year of the Armada (1588), on his return from the camp at Tilbury, leaving Leicester Place to Robert Devereux, his step-son, the Earl of Essex,[40] who succeeded to his favour at court, but was doomed to an untimely death.

It was to the great Lord of Kenilworth—that dark, mysterious man, who perhaps deserved more praise than historians usually give him—that Spenser dedicated his poem of “Virgil’s Gnat.” In his beautiful “Prothalamion” on the marriage of Lady Elizabeth and Lady Catherine Somerset, he speaks somewhat abjectly of Leicester, ingeniously contriving to remind Essex of his father-in-law’s bounty. “Near to the Temple,” the needy poet says,

“Stands a stately place,

Where I gayned giftes and the goodly grace

Of that great lord who there was wont to dwell,

Whose want too well now feels my friendless case;

But, ah! here fits not well

Old woes.”

Then the poet goes on to eulogise Essex, who, however, it is supposed, after all allowed him to die in want. But there is a mystery about Spenser’s death. He returned from Ireland, beggared and almost broken-hearted, in October or November 1599, and died in the January following, just as Essex was preparing to start to Ireland. In that whirl of ambition, the poor poet may perhaps have been rather overlooked than wilfully slighted. This at least is certain, that he was buried in Westminster Abbey, near Chaucer’s[Pg 29] tomb, the Earl of Essex defraying the expenses of his public funeral.

It was in his prison-house near the Temple that the hair-brained Earl of Essex shut himself sulkily up, when Queen Elizabeth had given him a box on the ears, after a dispute about the new deputy for Ireland, in which the earl had shown a petulant violence unworthy of the pupil of Burleigh.

Far too much sympathy has been shown with this rash, imperious, and unbearable young noble. He was sent to Ireland, and there concluded a disgraceful, wilful, and traitorous treaty with one of England’s most inveterate and dangerous enemies. He returned from that “cursedest of all islands,” as he called it, against express command, and was with difficulty dissuaded from landing in open rebellion. Generous and frank he may have been, but his submission to the mild and well-deserved punishment of confinement to his own house was as base and abject as it was false and hypocritical.

Alarmed, mortified, and enraged at the duration of his banishment from court, and at the refusal of a renewed grant for the monopoly of sweet wines, Essex betook himself to open rebellion, urged on by ill-advisers and his own reckless impatient spirit. He invited the Puritan preachers to prayers and sermons; he plotted with the King of Scotland. It was arranged at secret meetings at Drury House (then Sir Charles Daver’s) to seize Whitehall and compel the queen to dismiss Cecil and other ministers hostile to Essex.

Sir Christopher Blount was to seize the palace gates, Davies the hall, Davers the guard-room and presence-chamber, while Essex, rushing in from the Mews with some hundred and twenty adherents, was to compel the queen to assemble a parliament to dismiss his enemies, and to fix the succession. All these plans were proposed to Essex in writing—the arch-conspirator was never himself present.

The delay of letters from Scotland led to the premature outbreak of the plot. An order was at once sent summoning[Pg 30] Essex to the council, and the palace guards were doubled.

On Sunday, February 7, 1601, Essex, fearing instant arrest, assembled his friends, and determined to arm and sally forth to St. Paul’s Cross, where the Lord Mayor and aldermen were hearing the sermon, and urge them to follow him to the palace. On the Lord Keeper and other noblemen coming to the house to know the cause of the assembly, Essex locked them into a back parlour, guarded by musketeers, and followed by two hundred gentlemen, drew his sword and rushed into the street like a madman “running a-muck.”

Temple Bar was opened for him; but at St. Paul’s Cross he found no meeting. The citizens crowded round him, but did not join his band. When he reached the house of Sheriff Smith, the crafty Sheriff had stolen away.

In the meantime Lord Burleigh and the Earl of Cumberland, with a herald, had entered the City and proclaimed Essex a traitor; a thousand pounds being offered for his apprehension. Despairing of success, the mad earl then turned towards his own house, and finding Ludgate barricaded by a strong party of citizens under Sir John Levison, attempted to force his way, killing two or three citizens, and losing Tracy, a young friend of his own. Then striking down to Queenhithe, the earl and some fifty followers who were left took boat for Essex Gardens.

On entering his house, he found that his treacherous confidant, Sir Ferdinand Gorges, had made terms with the court and released the hostages. Essex then, by the advice of Lord Sandys, resolved to fortify the place, hold out to the last extremity, and die sword in hand. In a few minutes, however, the Lord Admiral’s troops surrounded the building. A parley ensued between Sir Robert Sidney in the garden, and Essex and his rash ally, Shakspere’s patron, the Earl of Southampton, who were on the roof. The earl’s demands were proudly refused, but a respite of two hours was given him, that the ladies and female servants might[Pg 31] retire. About six the battering train arrived from the Tower, and Essex then wisely surrendered at discretion.[41]

The night being very dark, and the tide not serving to pass the dangers of London Bridge, Essex and Southampton were taken by boat to Lambeth Palace, and the next morning to the Tower.

Essex had fully deserved death. He was executed privately, by his own request, at the Tower, February 25, 1601. Meyrick, his steward, and Cuffe, his secretary, were hanged and quartered at Tyburn. Sir Charles Davers and Sir Christopher Blount perished on Tower Hill. Other prisoners were fined and imprisoned, and the Earl of Southampton pined in durance till the accession of James I. (1603).

Among the even older tenants of Essex House, we must not forget that unhappy woman, the earl’s mother, who, first as Lettice Knollys, then as Countess of Essex, afterwards as Lady Leicester, and next as wife of Sir Christopher Blount, was a barb in Elizabeth’s side for thirty years. Married as a girl to a noble husband, she gave up her honour to a seducer, and there is reason to think that she consented to the taking of his life. While Devereux lived, she deceived the queen by a scandalous amour, and, after his death, by a clandestine marriage with the Earl of Leicester. While Dudley lived, she wallowed in licentious love with Christopher Blount, his groom of the horse. When her second husband expired in agony at Cornbury, not an hour’s gallop from the place in which Amy Robsart died, she again mortified the queen by a secret union with her last seducer, Blount. Her children rioted in the same vices. Essex himself, with his ring of favourites, was not more profligate than his sister Penelope, Lady Rich.[42]

This sister was the (Platonic?) mistress of Sydney, whose stolen love for her is pictured in his most voluptuous verse. On his death at Zütphen, she lived with Lord Montjoy, though her husband, Lord Rich, was still alive. Nor was[Pg 32] her sister Dorothy one whit better. After marrying one husband secretly and against the canon, she wedded Percy, the wizard Earl of Northumberland, whom she led the life of a dog, until he indignantly turned her out of doors.[43] It is not easy, observes Mr. Dixon, except in Italian story, to find a group of women so depraved and so detestable as the mother and sisters of the Earl of Essex.

Essex, the rash noble, who died at the untimely age of thirty-three, had a dangerous, ill-tempered face, if we may judge by More’s portrait of him. He stooped in walking, danced badly, and was slovenly in his dress;[44] yet being a generous, frank friend, an impetuous and chivalrous if not wise soldier, and an enemy of Spain and the Cecils, he became a favourite of the people. The legend of the ring sent by Essex to the queen,[45] and maliciously detained by the Countess of Nottingham, we shall presently discuss. No applications for mercy by Essex (and he made many during his trial) affect the question of his deserving death. That the queen consented with regret to the death of Essex, on the other hand, needs no doubtful legend to serve as proof.

Elizabeth had forgiven the earl’s joining the Cadiz fleet against her wish, she forgave his secret marriage, she forgave his shameful abandonment of his Irish command and even his dishonourable treaty with Tyrone, but she could not forgive an open and flagrant rebellion at a time when she was so surrounded by enemies.

An historical writer, gifted with an eminently analytical mind, Mr. Hepworth Dixon, has lately, with great ingenuity, endeavoured to refute the charges of ingratitude brought against Bacon for his time serving and (to say the least) undue eagerness in aggravating the crimes of his old and generous friend. There can be, however, no doubt that Bacon too soon abandoned the unfortunate Essex, and, moreover, threw the weight of much misapplied learning[Pg 33] into the scale against the prisoner. No minimising of the favours received by him from Essex can in my mind remove this stain from Bacon’s reputation.

In Essex House was born a less brilliant but a happier and a more prudent man—Robert, Earl of Essex, afterwards the well-known Parliamentary general. A child when his father died on the scaffold, he was placed under the care of his grandmother, Lady Walsingham, and was afterwards at Eton under the severe Saville. A good, worthy, heavy lad, brought up a Presbyterian, he was betrothed when only fourteen to Lady Frances Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk, who was herself only thirteen.

The earl travelled on the Continent for four years, and on his return was married at Essex House. It was for this inauspicious marriage that Ben Jonson wrote one of his most beautiful and gorgeous masques, Inigo Jones contributing the machinery, and Ferrabosco the music. The rough-grained poet seems to have been delighted with the success of the entertainment, for he says, “Nor was there wanting whatsoever might give to the furniture a complement, either in riches or strangeness of the habits, delicacy of dances, magnificence of the scene, or divine rapture of music.”[46]

The countess was already, even at this time, the mistress of Robert Carr, the handsome minion of James I. She obtained a divorce from her husband in 1613, and espoused her infamous lover. The cruel poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury for opposing the new marriage followed; and the earl and countess, found guilty, but spared by the weak king, lingered out their lives in mutual reproaches and contempt, loathed and neglected by all. Fate often runs in sequences—the earl was unhappy with his second wife, from whom he also was divorced.

Essex emerged from a country retirement to turn general for the Parliament. Just, affable, and prudent, he was a popular man till he became marked as a moderatist desirous for peace, and was ousted by the artful “Self-denying Ordinance.” If he had lived it is probable he would either[Pg 34] have lost his head or have fled to France and turned cavalier. His death during the time that Charles I. remained a prisoner with the Scotch army at Newcastle saved him from either fate. With him the Presbyterian moderatists and the House of Peers finally lost even their little remaining power.