Title: Unexplored Spain

Author: Abel Chapman

Walter John Buck

Illustrator: E. Caldwell

Joseph Crawhall

Release date: December 10, 2012 [eBook #41593]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

| Every attempt has been made to replicate the original book as printed. Some typographical errors have been corrected (see the list here). No attempt has been made to correct or normalize the printed accentuation or spelling of Spanish names or words. Click on any image to see it enlarged. (etext transcriber's note) |

UNEXPLORED SPAIN

ABEL CHAPMAN’S WORKS

BIRD-LIFE OF THE BORDERS. First Edition, 1889;

—— ——, Second Edition, 1907.

WILD SPAIN. (With W. J. B.) 1893.

WILD NORWAY. 1897.

ART OF WILDFOWLING. 1896.

ON SAFARI (In British East Africa). 1908.

UNEXPLORED SPAIN. (With W. J. B.) 1910.

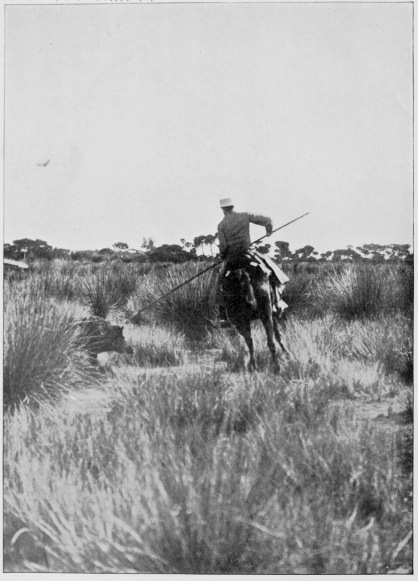

H.M. King Alfonso XIII spearing a boar.

BY

ABEL CHAPMAN

AUTHOR OF ‘WILD SPAIN,’ ‘WILD NORWAY,’ ‘ON SAFARI,’ ETC.

AND

WALTER J. BUCK

BRITISH VICE-CONSUL AT JEREZ

AUTHOR OF ‘WILD SPAIN’

WITH 209 ILLUSTRATIONS BY

JOSEPH CRAWHALL, E. CALDWELL, AND ABEL CHAPMAN

AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW YORK

LONGMANS, GREEN & CO.

LONDON: EDWARD ARNOLD

1910

INSCRIBED

BY GRACIOUS PERMISSION

TO THEIR MAJESTIES

KING ALFONSO XIII.

HIMSELF AN ACCOMPLISHED SPORTSMAN

AND

QUEEN VICTORIA EUGENIA OF SPAIN

WITH DEEP RESPECT

BY THEIR MAJESTIES’ GRATEFUL AND DEVOTED SERVANTS

THE AUTHORS

THE undertaking of a sequel to Wild Spain, we are warned, is dangerous. The implication gratifies, but the forecast alarms not. Admittedly, in the first instance, we occupied a virgin field, and naturally the almost boyish enthusiasm that characterised the earlier book—and probably assured its success—has in some degree abated. But it’s not all gone yet; and any such lack is compensated by longer experience (an aggregate, between us, of eighty years) of a land we love, and the sounder appreciation that arises therefrom. Our own resources, moreover, have been supplemented and reinforced by friends in Spain who represent the fountain-heads of special knowledge in that country.

No foreigners could have enjoyed greater opportunity, and we have done our best to exploit the advantage—so far, at least, as steady plodding work will avail; for we have spent more than two years in analysing, checking and sorting, selecting and eliminating from voluminous notes accumulated during forty years. The concentrated result represents, we are convinced, an accurate—though not, of course, a complete—exposition of the wild-life of one of the wildest of European countries.

No, for this book and its thoroughness neither doubt nor fear intrudes; but we admit to being, in two respects, out of touch with modern treatment of natural-history subjects. Possibly we are wrong in both; but it has not yet been demonstrated, by Euclid or other, that a minority even of two is necessarily so? Nature it is nowadays customary to portray in somewhat lurid and sensational colours—presumably to humour a “popular taste.” Reflection might suggest that nothing in Nature is, in fact, sensational, loud, or extravagant; but the lay public possess no such technical training as would enable them to discern the line where Nature stops and where fraud and “faking” begin. At any rate we frequently read purring approval of what appears to us meretricious imposture, and see writers lauded as constellations whom we should condemn as charlatans. Beyond the Atlantic President Roosevelt (as he then was) went bald-headed for the “Nature-fakers,” and in America the reader has been put upon his guard. If he still likes “sensations”—well, that’s what he likes. But he buys such fiction forewarned.

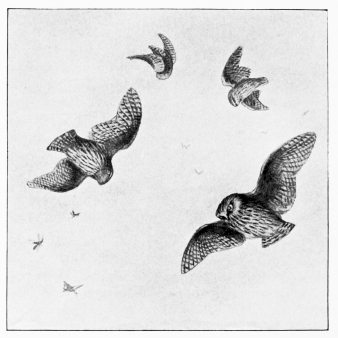

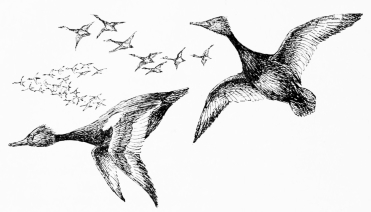

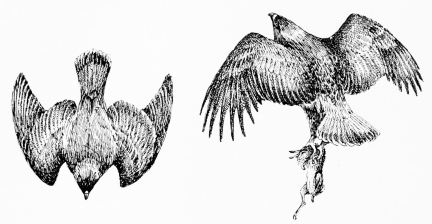

In the illustration of wild-life our views are also, in some degree, divergent from current ideas. Animal-photography has developed with such giant strides and has taught us such valuable lessons (for which none are more grateful than the Authors), that there is danger of coming to regard it, not as a means to an end but as the actual end itself. While photography promises uses the value of which it would be difficult to exaggerate, yet it has defects and limitations which should not be ignored. First as regards animals in motion; the camera sees too quick—so infinitely quicker than the human eye that attitudes and effects are portrayed which we do not, and cannot see. Witness a photograph of the finish for the Derby. Galloping horses do not figure so on the human retina—with all four legs jammed beneath the body like a dead beetle. No doubt the camera exhibits an unseen phase in the actual action and so reveals its process; but that phase is not what mortals see. Similarly with birds in flight, the human eye only catches the form during the instantaneous arrest of the wing at the end of each stroke—in many cases not even so much as that. But the camera snaps the whirling pinion at mid-stroke or at any intermediate point. The result is altogether admirable as an exposition of the mechanical processes of flight; but it fails as an illustration, inasmuch as it illustrates a pose which Nature has expressly concealed from our view.

Secondly, in relation to still life. Here the camera is not only too quick, but too faithful. A tiny ruffled plume, a feather caught up by the breeze with the momentary shadow it casts, even an intrusive bough or blade of grass—all are reproduced with such rigid faithfulness and conspicuous effect that what are in fact merest minute details assume a wholly false proportion, mislead the eye, and disguise the whole picture. True, these things are actually there; but the human eye enjoys a faculty (which the camera does not) of selecting its objective and ignoring, or reducing to its correct relative value each extrinsic detail; of looking, as it were, through obstacles and concentrating its power upon the one main subject of study.

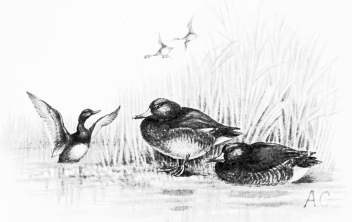

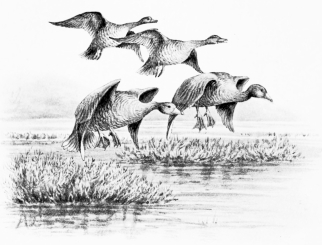

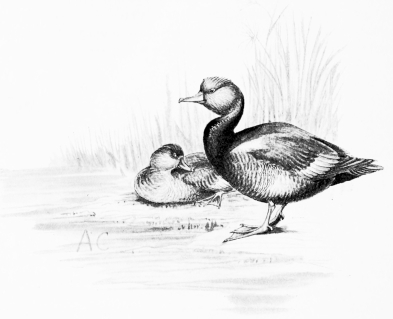

The portrayal of wildfowl presents a peculiar difficulty. This group differs in two essential characters from the rest of the bird-world. Though clad in feathers, yet those feathers are not “feathery.” Rather may they be described as a steely water-tight encasement, as distinct from the covering, say of game-birds as mackintosh differs from satin. Each plume possesses a compactness of web and firmness of texture that combine to produce a rigidity, and this, it so happens, both in form and colour. For in this group the colours, too, or patterns of colour, are clean-cut, the contrasts strong and sharply defined. The plumage of wild-fowl, in short, is characterised by lack of subdued tints and half-tones. That is its beauty and its glory; but the fact presents a stumbling-block to treatment, especially in colour.

The difficulty follows consequentially. Subjects of such character and crude coloration defy accustomed methods. That is not the fault of the artist; rather it reveals the limitations of Art. Just as in landscape distance ever demands an “atmosphere” more or less obliterative of distinctive detail afar (though such detail may be visible to non-artistic eyesight miles away), so in birds of sharply contrasted colouring the needed effect can only (it would appear) be attained by processes of softening which are not, in fact, correct, and which ruin the real picture as designed by Nature.

No wild bird (and wildfowl least of all) can be portrayed from captive specimens—still less from bedraggled corpses selected in Leadenhall market. In the latter every essential feature has disappeared. The ruffled remains resemble the beauty of their originals only as a dish-clout may recall some previous existence as a damask serviette. Living captives at least give form; but that is all. The loss of freedom, with all its contingent perils, involves the loss of character, the pride of life, and of independence. Once remove the first essential element—the sense of instant danger, with all that the stress and exigencies of wild-life import—and with these there vanish vigilance, carriage, sprightliness, dignity, sometimes even self-respect.

Not a man who has watched and studied wild beasts and wild birds in their native haunts, glorified and ennobled by self-conscious aptitude to prevail in the ceaseless “struggle for existence,” but instantly recognises with a pang the different demeanour of the same creatures in captivity, albeit carefully tended in the best zoological gardens of the world.

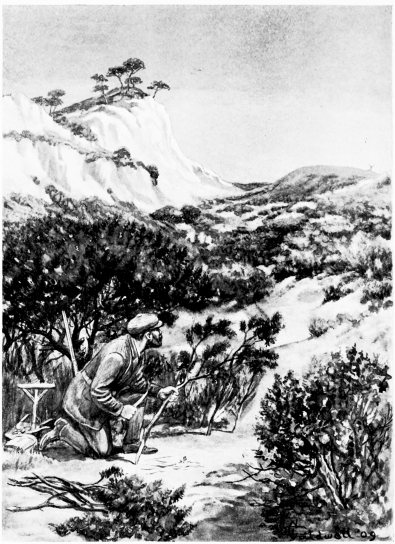

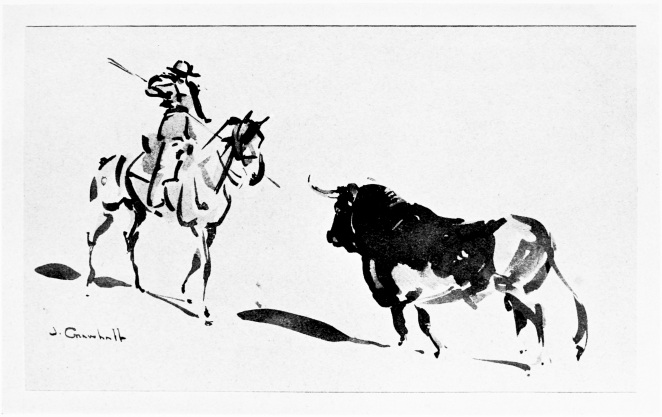

To Mr. Joseph Crawhall (cousin of one author) we and our readers are indebted for a series of drawings that speak for themselves.

Further, we desire most heartily to thank H.R.H. the Duke of Orleans for notes and photographs illustrative both of Baetican scenery and of the wild camels of the marisma; also the many Spanish and Anglo-Spanish friends whose assistance is specifically acknowledged, passim, in the text.

Should some slight slip or repetition have escaped the final revision, may we crave indulgence of critics? ‘Tis not care that lacks, but sheer mnemonics. In a work of (we are told) 150,000 words the mass of manuscript appals, and to detect every single error may well prove beyond our power. We have lost, moreover, that guiding eye and pilot-like touch on the helm that helped to steer our earlier venture through the shoals and seething whirlpools that ever beset voyages into the unknown.

A. C.

W. J. B.

British Vice-Consulate, Jerez,

December 1910.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Unexplored Spain: Introductory | 1 |

| II. | " " " (Continued) | 17 |

| III. | The Coto Doñana: Our Historic Hunting-Ground (A Foreword by Sir Maurice de Bunsen, P.C., G.C.M.G., G.C.V.O., British Ambassador at Madrid) | 30 |

| IV. | The Coto Doñana: Notes on its Physical Formation, Fauna, and Red Deer | 35 |

| V. | Andalucia and its Big Game: Still-Hunting | 54 |

| VI. | " " "Wild-Boar | 70 |

| VII. | “Our Lady of the Dew”: The Pilgrimage to the Shrine Of Nuestra Señora del Rocío | 82 |

| VIII. | The Marismas of Guadalquivir | 88 |

| IX. | Wildfowl-Shooting in the Marismas | 105 |

| X. | Wild-Geese in Spain: Their Species, Haunts, and Habits | 114 |

| XI. | Wild-Geese on the Sand-Hills | 125 |

| XII. | Some Records in Spanish Wildfowling | 133 |

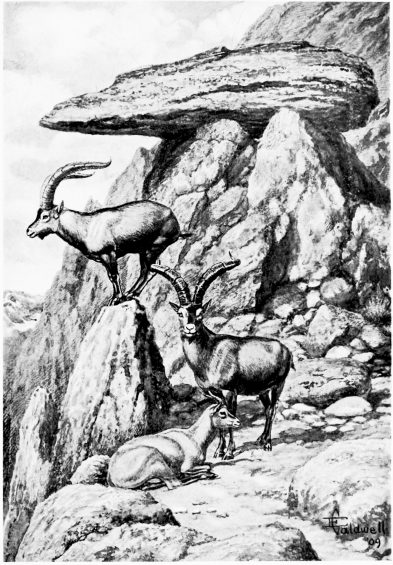

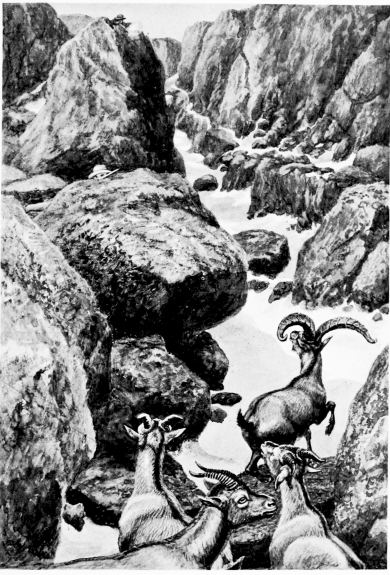

| XIII. | The Spanish Ibex | 139 |

| XIV. | Sierra Moréna: Ibex | 147 |

| XV. | " "Red Deer and Boar | 158 |

| XVI. | Pernales | 174 |

| XVII. | La Mancha | 183 |

| XVIII. | The Spanish Bull-Fight | 192 |

| XIX. | The Spanish Fighting-Bull | 200 |

| XX. | Sierra de Grédos | 208 |

| XXI. | " ": Ibex-Hunting | 216 |

| XXII. | An Abandoned Province: Estremadura | 225 |

| XXIII. | Las Hurdes (Estremadura) and the Savage Tribes that inhabit them | 234 |

| XXIV. | The Great Bustard | 242 |

| XXV. | " " (Continued) | 256 |

| XXVI. | Flamingoes | 265 |

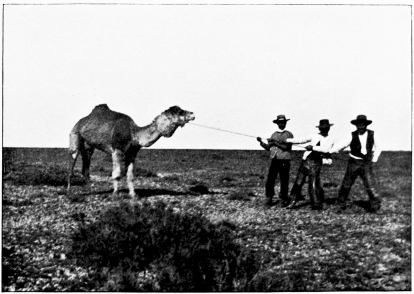

| XXVII. | Wild Camels | 275 |

| XXVIII. | After Chamois in the Asturias | 283 |

| XXIX. | Highlands of Asturias | 294 |

| XXX. | The Sierra Neváda | 301 |

| XXXI. | " " (Continued) | 311 |

| XXXII. | Valencia | 321 |

| XXXIII. | Small-Game Shooting in Spain | 328 |

| XXXIV. | Alimañas, or The Minor Beasts of Chase | 337 |

| XXXV. | Our “Home-Mountains”: The Serranía de Ronda | 347 |

| XXXVI. | " " " " (Continued) | 360 |

| XXXVII. | A Spanish System of Wildfowling: The “Cabresto” or Stalking-Horse | 371 |

| XXXVIII. | The “Corros”, or Massing of Wildfowl in Spring for their Northern Migration | 376 |

| XXXIX. | Spring-Time in the Marismas | 381 |

| XL. | Sketches of Spanish Bird-life | 392 |

| Appendix | 407 | |

| Index | 413 |

| List of Plates | |

|---|---|

| H.M. King Alfonso XIII. spearing a Boar | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Typical Landscape in Coto Doñana | 30 |

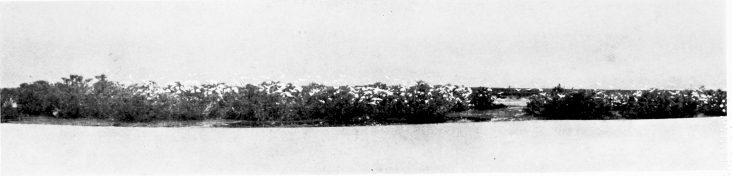

| Egret Heronry at Santolalla, Coto Doñana | 32 |

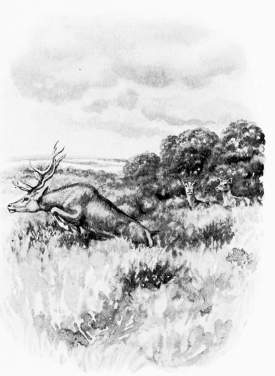

| Red Deer in Doñana. From a Drawing by Joseph Crawhall | 36 |

| Three Views in Coto Doñana: (1) Saharan Sand-Dunes; (2) Transport; (3) a Corral, Or Pinewood Enclosed by Sand | 40 |

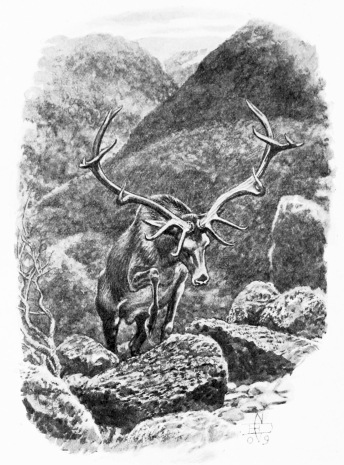

| Red Deer. From Drawings by Joseph Crawhall | 46 |

| Inspiring Moments | 51 |

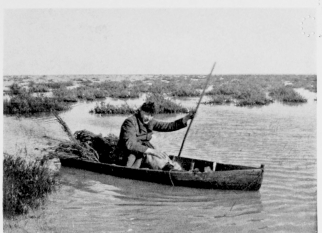

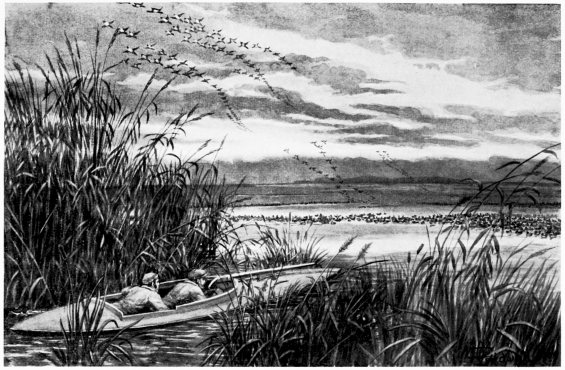

| Gunning-Punt in the Marisma | 90 |

| Wild-Goose Shooting on the Sand-hills | 90 |

| Vasquez approaching Wildfowl with Cabresto-Pony | 90 |

| Stancheon-Gun in the Marisma—Dawn | 106 |

| Wild-Geese in the Marisma | 122 |

| Spanish Ibex in Sierra de Grédos | 140 |

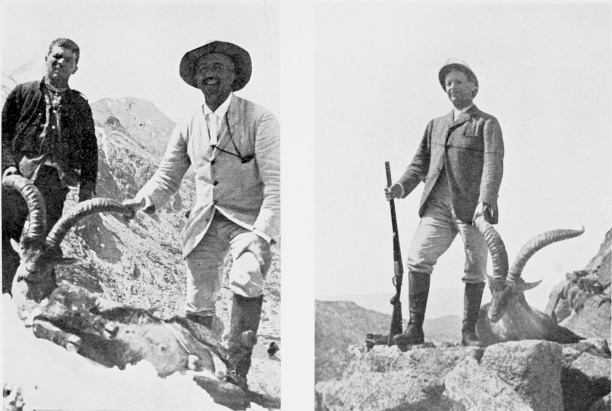

| Heads of Spanish Ibex | 152 |

| Red-Deer Heads, Sierra Moréna | 156 |

| Wolf shot in Sierra Moréna, March 1909 | 158 |

| Huntsman with Caracola, Sierra Moréna | 158 |

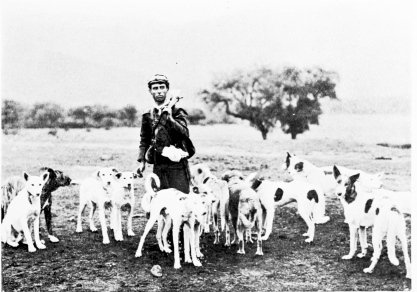

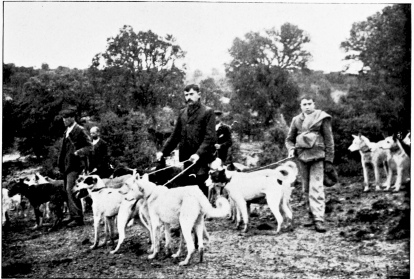

| Pack of Podencos, Sierra Moréna | 158 |

| Wild-Boar, weighing 200 Lbs. | 162 |

| The Record Head (Red Deer), Sierra Moréna | 162 |

| Red Deer. From Drawings by Joseph Crawhall | 166 |

| Red Deer. From Drawings by Joseph Crawhall | 170 |

| Wild-Boar. From Drawings by Joseph Crawhall | 170 |

| Red-Deer Heads, Sierra Moréna | 172 |

| Bull-Fighting. From a Drawing by Joseph Crawhall | 194 |

| Bull-Fighting. From a Drawing by Joseph Crawhall | 198 |

| After the Stroke. From a Drawing by Joseph Crawhall | 202 |

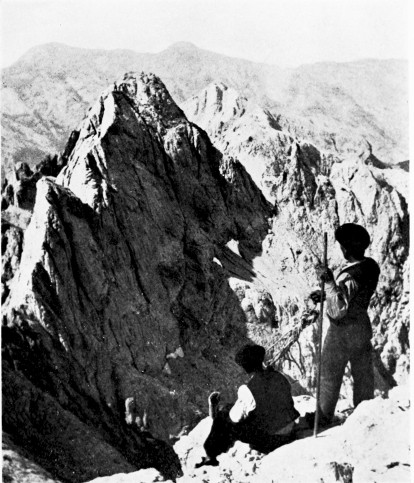

| Scenes in Sierra de Grédos | 212 |

| “At the Apex of all the Spains” | 216 |

| Two Spanish Ibex shot in Sierra de Grédos, July 1910 | 220 |

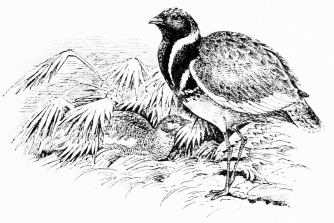

| Great Bustard | 250 |

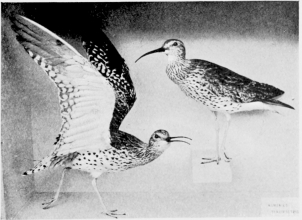

| Slender-billed Curlew | 250 |

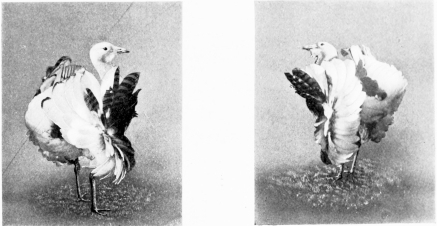

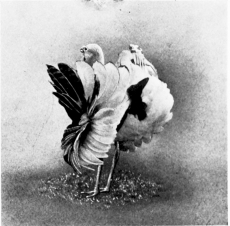

| Great Bustard “showing off” | 260 |

| Flamingoes on their Nests | 272 |

| Wild Camels | 276 |

| Capturing a Wild Camel in the Marisma | 280 |

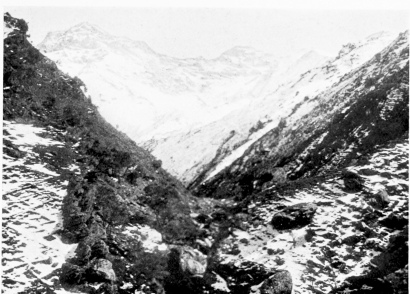

| The Home of the Chamois | 286 |

| Peaks of Sierra Neváda | 306 |

| Nest of Griffon | 306 |

| Royal Shooting at the Pardo, near Madrid | 334 |

| Illustrations in the Text | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Lammergeyer (Gypaëtus barbatus) | 3 |

| Woodchat Shrike (Lanius pomeranus) | 7 |

| Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus) | 9 |

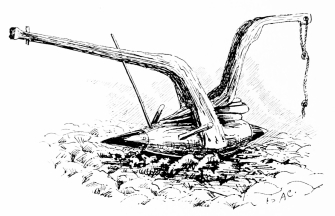

| Wooden Plough-share | 12 |

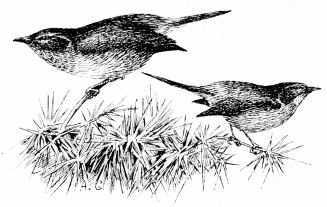

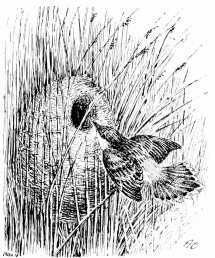

| Cetti’s Warbler (Sylvia cettii) | 14 |

| Dartford Warbler (Sylvia undata) | 16 |

| Fantail Warbler (Cisticola cursitans) | 17 |

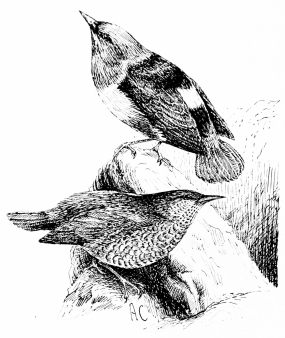

| Rock-Thrush (Petrocincla saxatilis) | 18 |

| A Village Posada | 20 |

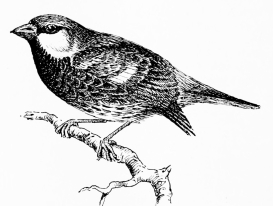

| Serin (Serinus hortulanus) | 23 |

| Bonelli’s Eagle (Aquila bonellii) | 26 |

| Black Vulture (Vultur monachus) | 27 |

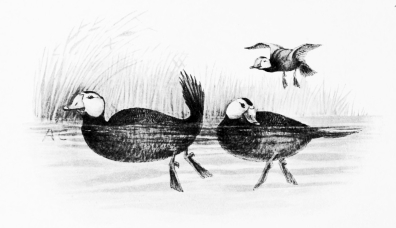

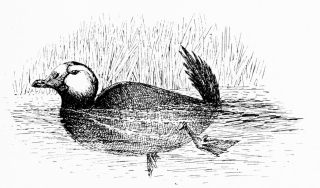

| White-Faced Duck (Erismatura leucocephala) | 28 |

| Spanish Imperial Eagle | 31 |

| Spanish Lynx | 33 |

| Greenshank (Totanus canescens) | 34 |

| Sketch-Map of Delta of Guadalquivir | 35 |

| Marsh-Harrier (Circus aeruginosus) | 38 |

| “Silent Songsters” | 39 |

| Blackstart (Ruticilla titys) | 39 |

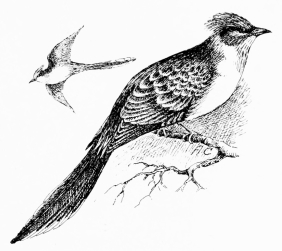

| Great Spotted Cuckoo (Oxylophus glandarius) | 41 |

| “Globe-Spanners” | 42 |

| “Confidence” | 43 |

| Abnormal Cast Antler | 44 |

| Egret | 45 |

| “Suspicion” | 49 |

| Altabaca (Scrofularia) | 51 |

| Tomillo de Arena | 51 |

| “What’s This?” | 52 |

| Antlers | 56 |

| Stag “taking the Wind” | 57 |

| Sylvia melanocephala | 60 |

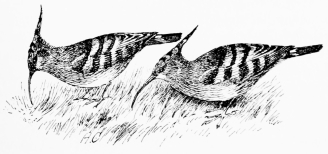

| Reed-Climbers | 61 |

| Great Grey Shrike (Lanius meridionalis) | 62 |

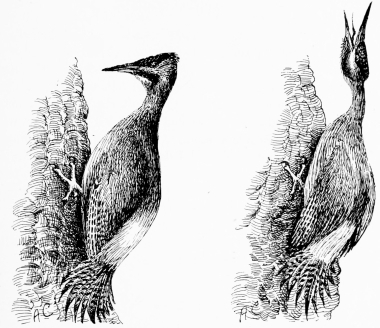

| Spanish Green Woodpecker (Gecinus sharpei) | 63 |

| Tarantula | 64 |

| Stag—as he fell | 67 |

| Hoopoes at Jerez, March 19, 1910 | 69 |

| “Room for Two” | 71 |

| Wild-Boar—at bay | 73 |

| Wild-Boar—“Bolted past” | 79 |

| Wild-Boar | 81 |

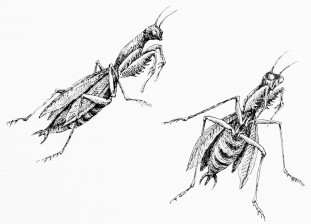

| Praying Mantis | 87 |

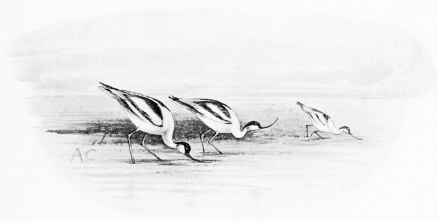

| Avocet | 88 |

| Samphire | 90 |

| Greylag Geese | 92 |

| White-Eyed Pochard (Fuligula nyroca) | 94 |

| “Flamingoes over” | 95 |

| Pochard (Fuligula ferina) | 96 |

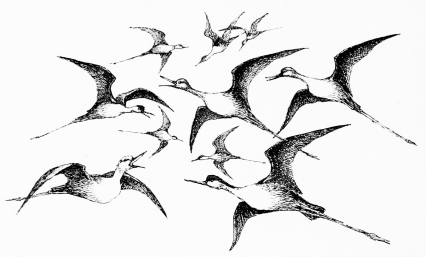

| Flight of Flamingoes | 97 |

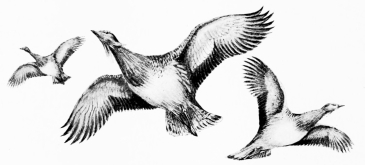

| Wild-Geese alighting | 98 |

| Wildfowl in the Marisma | 101 |

| Flamingoes | 102 |

| Stilt | 105 |

| Godwits | 113 |

| Root of Spear-Grass | 115 |

| System of driving Wild-Geese | 117 |

| Shelters for driving Wild-Geese | 118 |

| Godwits | 124 |

| Wild-Geese alighting on Sand-Hills | 129 |

| Wild-Geese | 133 |

| Godwits | 134 |

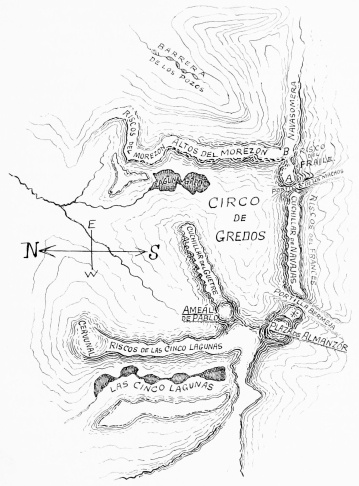

| Sketch-Map of the Nucléo Central of Grédos | 141 |

| Grey Shrike | 162 |

| Azure-Winged Magpie | 163 |

| Sardinian Warbler | 164 |

| Griffon Vulture | 166 |

| Pair of Antlers | 167 |

| Stag—“picking his way up a Rock-Staircase” | 168 |

| “The Hart bounced, full-broadside, over the Pass” | 169 |

| Pernales | 175 |

| Sparrow-Owls (Athene noctua) and Moths | 182 |

| Hoopoes | 183 |

| Woodchat Shrike and its “Shambles” | 184 |

| Desert-loving Wheatears | 185 |

| Red-crested Pochard (Fuligula rufila) | 186 |

| Red-crested Pochards | 190 |

| “Minor Game” | 210 |

| Southern Grey Shrike | 212 |

| Griffon Vulture and Nest | 215 |

| “The Way of an Eagle in the Air” (Lammergeyer) | 218 |

| Black Vulture (Vultur monachus) | 222 |

| Roller (Coracias garrula) | 226 |

| Trujillo | 227 |

| “Scavengers” | 228 |

| Wolf-proof Dog-Collar | 231 |

| Woodlark | 232 |

| Sketch-Map of Las Hurdes | 234 |

| White Wagtail | 238 |

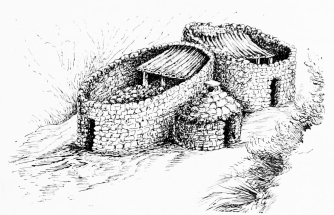

| Wolf-proof Sheepfold | 239 |

| The Great Bustard | 243 |

| Well on Andalucian Plain | 244 |

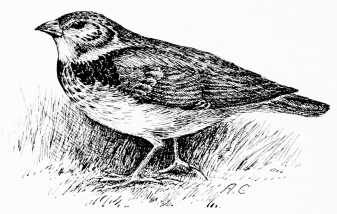

| Calandra Lark | 246 |

| Spanish Thistle and Stonechat | 248 |

| Bustards—“Swerve aside” | 252 |

| Bustards passing full broadside | 254 |

| Imperial Eagle—“Hurtling through Space” | 258 |

| Draw-Well with Cross-Bar | 259 |

| “Hechando la Rueda” | 260 |

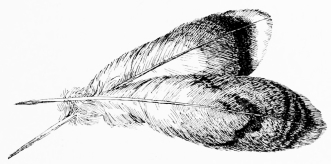

| Tail-Feathers of Great Bustard | 261 |

| Little Bustard | 263 |

| Stilts in the Marisma | 265 |

| Flamingoes | 266 |

| Stilts disturbed at Nesting-Place | 268 |

| Flamingoes and their Nests | 269 |

| Flight of Flamingoes | 270-1 |

| Head of Flamingo | 273 |

| Little Gull and Tern | 274 |

| Flamingoes | 277 |

| “The Camels a-coming” | 281 |

| Chamois | 283 |

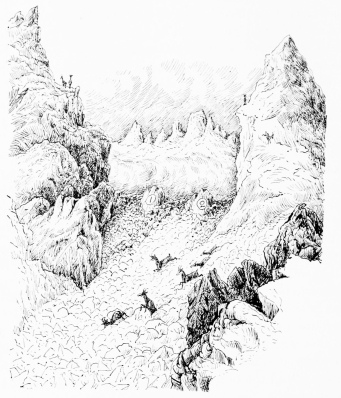

| A Chamois Drive—Picos de Europa | 288 |

| Hoopoe | 293 |

| Lammergeyer (Gypaëtus barbatus) | 303 |

| “Unemployed”: Bee-eaters on a Wet Morning | 311 |

| Woodlark (Alauda arborea) | 313 |

| Lammergeyer | 314 |

| Soaring Vulture | 315 |

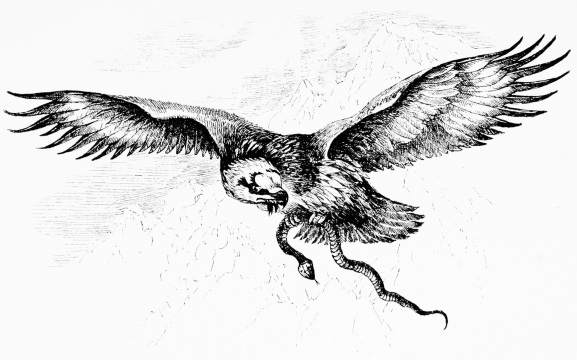

| Golden Eagle Hunting | 317 |

| Rock-Thrush | 318 |

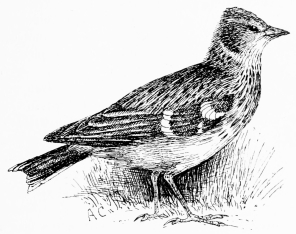

| Spanish Sparrow | 320 |

| Imperial Eagle Passing Overhead | 342 |

| Pinsápo Pine (Abies pinsapo) | 347 |

| Rock-Bunting (Emberiza cia) | 348 |

| Pinsápo Pines | 350 |

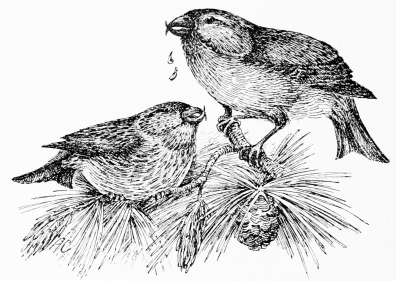

| Crossbill | 351 |

| Lammergeyer Overhead | 353 |

| Golden Eagle Hunting | 354 |

| Vultures | 356 |

| Lammergeyer entering Eyrie | 358 |

| Lammergeyer | 361 |

| Griffon Vultures | 368 |

| Reed-Bunting | 378 |

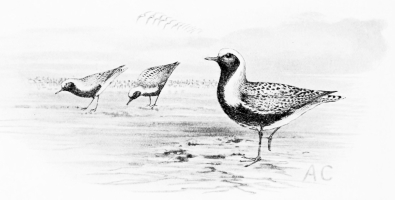

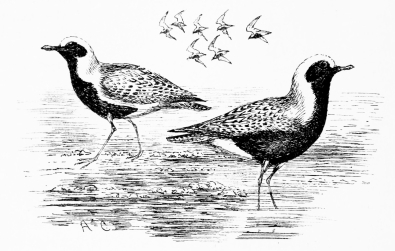

| Grey Plover | 381 |

| Head of Crested Coot | 384 |

| Avocets Feeding | 385 |

| White-Faced Duck (Erismatura leucocephala) | 387 |

| Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea) | 389 |

| Grey Plovers | 390 |

| Orphean Warbler | 391 |

| Savi’s Warbler (Sylvia savii) | 393 |

| Unknown Insect | 394 |

| Bonelli’s Eagles | 395 |

| Great Spotted Cuckoo (Oxylophus glandarius) | 400 |

| Crossbills (Loxia curvirostra) | 402 |

THE Spain that we love and of which we write is not the Spain of tourist or globe-trotter. These hold main routes, the highways from city to city; few so much as venture upon the bye-ways. Our Spain begins where bye-ways end. We write of her pathless solitudes, of desolate steppe and prairie, of marsh and mountain-land—of her majestic sierras, some well-nigh inaccessible, and, in many an instance, untrodden by British foot save our own. Lonely scenes these, yet glorified by primeval beauty and wealth of wild-life. As naturalists—that is, merely as born lovers of all that is wild, and big, and pristine—we thank the guiding destiny that early directed our steps towards a land that is probably the wildest and certainly the least known of all in Europe—a land worthy of better cicerones than ourselves.

Do not let us appear to disparage the other Spain. The tourist enjoys another land overflowing with historic and artistic interest—with memorials of mediæval romance, and of stirring times when wave after wave of successive conquest swept the Peninsula. Such subjects, however, fall wholly outside the province of this book: nor do they lack historians a thousand-fold better qualified to tell their tale.

The first cause that differentiates Spain from other European countries of equal area is her high general elevation. This fact must jump to the eye of every observant traveller who books his seat by the Sûd-express to the Mediterranean. Better still, for our purpose, let him commence his journey, say at the Tweed. From Berwick southwards through the heart of England to London: from London to Paris, and right across France—all the way he traverses low-lying levels; fat pastures, fertile and tilled to the last acre. His aneroid tells him he has seldom risen above sea-level by more than a few hundred feet; and never once has his train passed through mountains—hardly even through hills; he can scarce be said to have had a real mountain within the range of his vision in all these 1200 miles.

Now he crosses the Bidassoa ... the whole world changes! At once his train plunges into interminable Pyrenees, and ere it clears these, he has ascended to a permanent highland level—a tawny treeless steppe that averages 2000-feet altitude, and sometimes approaches 3000, traversed by range after range of rugged mountains that arise all around him to four, five, or six thousand feet. Railways, moreover, avoid mountains (so far as they can). Our traveller, therefore, must bear in mind that what he actually sees is but the mildest and tamest version of Spanish sierras. There are bits here and there that he may have thought anything but tame—only tame by comparison with those grander scenes to which we propose guiding him.

For the next 500 miles he never quits that austere highland altitude nor ever quite loses sight of jagged peaks that pierce the skies—peaks of that hoary cinder-grey that shows up almost white against an azure background. Never does he descend till, after leaving behind him three kingdoms—Arragon, Navarre, and Castile—his train plunges through the Sierra Moréna, down the gorges of Despeñaperros, and at length on the third day enters upon the smiling lowlands of Andalucia. Here the aneroid rises once more to rational readings, and fertile vegas spread away to the horizon. But our traveller is not even now quite clear of mountains. Whether he be booked to Malaga or to Algeciras, he will presently find himself enveloped once more amidst some fairly stupendous rocks—the Gaëtánes or Serranía de Ronda respectively.

Spain is, in fact, largely an elevated table-land, 400 miles square, and traversed by four main mountain-ranges, all (like her great rivers) running east and west. The only considerable areas of lowland are found in Andalucia and Valencia.

Naturally such physical features result in marked variations of climate and scene, which in turn react upon their productions and denizens, whether human or of savage breed. We take three examples.

![Types of Spanish Bird-Life LAMMERGEYER (Gypaëtus barbatus) Whose home is in the wildest Sierras—a weird dragon-like bird-form; expanse, 9 feet. [Formerly reputed to carry off babies to its eyrie.]](images/ill_001_sml.jpg)

Types of Spanish Bird-Life

LAMMERGEYER (Gypaëtus barbatus)

Whose home is in the wildest Sierras—a weird dragon-like bird-form;

expanse, 9 feet.

[Formerly reputed to carry off babies to its eyrie.]

The central table-lands, subject all summer to solar rays that burn, in winter shelterless from biting blasts off snow-clad sierras, present precisely that landscape of desperate desolation that always results from a maximum of sunshine combined with a minimum of rainfall. A desiccated downland, khaki-colour or calcareous by turn, but bare (save for a few weeks in spring) of green thing, naked of bush or shrub, innocent even of grass. Not a tree grows so far as eye can reach, not a watercourse but is stone-dry and leaves the impress that it has been so since time began. Oh, it is an unlovely landscape, that central plateau. ‘Twere ungrateful, nevertheless (and unjust too), to forget that here we are journeying in a glory of atmosphere, brilliant in aggressive radiance that annihilates distance and revels in space. Though patches of vine-growth be lost in the monotony of tawny expanse, mud-built hamlet and village church indistinguishable amidst a universal khaki, yet this is, in truth, a kingdom of the sun. The great bustard maintains a foothold on these arid uplands, but the fauna is best exemplified by the desert-loving sand-grouse (Pterocles arenarius).

Precisely the reverse of all this is Cantabria—the Basque provinces of the north, with Galicia and the Asturias. There, bordering on the Biscayan Sea, you find a region absolutely Scandinavian in type—pinnacled peaks, precipitous beyond all rivals even in Spain, with deep-rifted valleys between, rushing salmon-rivers and mountain-torrents abounding in trout. Here the fauna is alpine, if not subarctic, and includes the brown bear and chamois, the ptarmigan, hazel-grouse, and capercaillie.

Cantabria is a region of rock, snow, and mist-wraith; of birch and pine-forest—the very antithesis of the third region, that next concerns us, the smiling plains of Andalucia and Valencia nestling on Mediterranean shore. Here for eight months out of the twelve one lives in a paradise; but the summer is African in its burden of heat and discomfort. Every green thing outside the vineyard and irrigated garden is burnt up by a fiery sun, a sun that changes not, but, day following day, grips the land in a blistering embrace. Climatic conditions such as these reacting on a race already infused with Arab blood naturally conduce to Oriental modes of life. Yet even here we have examples of the curious contradictions that characterise this pays de l’imprévu. Thus within sight of one another, there flourish on the vega below the date-palm and sugar-cane, while the ice-defying edelweiss embellishes the snows above—arctic and tropic in one.

Such extremes of climate react, as suggested, upon the character of the human inhabitants of a land which includes within its boundaries nearly all the physical conditions of Europe and North Africa. From the north, as might be expected, comes the worker—the sturdy laborious Galician, disdained and despised by his Andalucian brother, regarded as lacking in dignity—the very name Gallego is a term of reproach. But he is a happy and contented hewer of wood and drawer of water, that Gallego: throughout Spain he carries the baskets, bears the burdens, cleans the floors; and finally returns, a rich man, to his barren hills of Galicia.

The Andalucian will condescend to tend your cattle or garden, to drive your horses or ponies: and such offices he will perform well; but anything menial, or what he might regard as derogatory, he prefers—instinctively, not offensively—to leave to the Galician. From Castile and Navarre comes a different caste, stately and aristocratic by nature, yet with fiery temperament concealed beneath subdued exterior—honestly, we prefer both the preceding exemplars. The Catalan comes next, pushing and effervescent, all for his own little corner, his factories and his trade—impregnated, every man, with a sort of cinematograph of advanced views on social and political questions of the day—borrowed mostly from his up-to-date neighbours beyond the Pyrenees, yet grafted on to old-world fueros, or franchises, that date back to the times of the Counts of Barcelona.[1] Perhaps the most perfect example of contemporary natural nobility is afforded by the peasant-proprietor of pastoral León; then there is the Basque of Biscay, Tartar-sprung or Turanian, Finnic, or surviving aboriginal—let philologists decide. Among Spain’s manifold human types, we suggest to ethnologists (and suggested before, twenty years ago) the study of a surviving remnant that still clings secreted, lonely as lepers, in the far-away mountains of Northern Estremadura—the Hurdes. These wild tribes of unknown origin (presumed to be Gothic) live apart from Spain, four thousand of them, a root-grubbing race of homo sylvestris, squatted in a land without written history or record, where all is traditional even to the holding of the soil. Not a title-deed or other document exists; yet this is a region of considerable extent—say fifty miles by thirty. A recent pilgrimage to these forgotten glens enables us to give, in another chapter, some contemporary facts about “Las Hurdes.”

Throughout Spain the people of the “lower orders”—the peasantry—strike those who leave the beaten tracks by their independence and manly bearing. North or south, east or west, an infinite variety of races differing in habit and character, even in tongue, yet all agreeing in their solid manliness, in straight-forward honesty, in what the Romans entitled virtus—fine types save where contaminated by empléomania, call that “officialdom” (one of the twin curses of Spain). Largely there exists here ground-work for the rebuilding of Spanish greatness—such a land awaits but the wand of a magician to recall its people to front rank. Neither by despotic methods nor by the power that is only demonstrated by violence will the change be brought about, but by the enlightenment that has learnt to leave unimitated the follies of the past, and unused the forces of coercion.

Such a leader, we believe, to-day wields that wand. May he be spared to restore the destinies of his country.

It was in Spain, remember, that, more than 2000 years ago, the fate of Carthage and, later, that of Rome was decided. To the latter Imperial city Spain had given poets, philosophers, and emperors. It was in Spain that there dawned the earlier glimmerings of popular liberties, as such are now understood. Self-government with municipal rights were recognised by the Cortes of León previous to our Magna Charta. Individual guarantees, freedom of person and contract, and the inviolability of the home were granted by the Cortes of Zaragoza in 1348—more than three centuries before our Habeas Corpus was signed in 1679. A land with such traditions and achievements, with its twenty millions of inhabitants, cannot long be held back outside the trend of liberal expansion.

The pursuit of game, alike with other aspects of Spanish things, is not exempt from startling surprises. A ramble through the cistus-scrub, with no more exciting object than shooting a few redlegs, may result in bagging a lynx; or a handful of snipe from some cane-brake be augmented by the addition of a wild-boar. It is not that game abounds, but that the country is wide and wild, abandoned to natural state and combining conditions congenial to animal-life. Of the big-game that is obtained or of its habitats, there is no approximate estimate, nor do precise knowledge or records exist. Each village in the sierra or higher mountain-region lives its own life apart. Communication with other places is rare and difficult, nor is it sought. One must go oneself to the spot to ascertain with any sort of accuracy what game has been, or may be obtained thereat. This means finding out every fact at first-hand, for no reliance can be placed on reports or hearsay evidence. Nor does this remark apply to game alone: it applies universally in wilder Spain. The Englishman straying in these lone scenes finds himself amongst a kindly but independent people where sympathy and a knowledge of the language carry him further than money. Where all are Caballeros, neither titles nor wealth impress or subdue. The wanderer is free to join his new-made friends in the chase, taking equal chance with keen sportsmen and on terms of equality. He will find his nationality a passport to their liking, and soon discover that Arab hospitality has left an abiding impress in these wild regions; as, indeed, Moorish domination has done on every Spanish thing.

That last sentence sums up an ever-present and essential factor. In any description of this country, however superficial, this Oriental heritage must always be borne in mind as an influence of first importance. Previous to the Arab inrush, Spain had enjoyed practically no organic national existence. The Peninsula was occupied by a cluster of separate kingdoms, not united nor even homogeneous, and usually one or another at war with its neighbour. Neither Roman nor Goth had fused the Spanish races into a concrete whole during their eight centuries of overlordship. In A.D. 711 occurred a decisive day. Then, on Guadalete’s plain, below the walls of Jerez, that impetuous Arab chieftain Tarik overthrew the Gothic King Roderick and with him the power of Spain. Like an overwhelming flood, the Arabs swept across the land. Within two years (by 713) the insignia of the Crescent floated above every castle and tower, and Moslem rule was absolute throughout the country—excepting only in the wild northern mountains of Asturias, whence the tenacity of the mountaineers, guided by the genius of Pelayo, flung back the tide of war.

Spanish history for the next seven centuries (711-1492) records “Moorish domination.” Now history, as such, lies outside our scope; but we become concerned where Arab systems, and their methods of colonisation, have altered the face of the earth and left enduring marks on wilder Spain. And we may, beyond that, be allowed to interpolate a remark or two in elucidation of what sometimes appear popular misconceptions on these and subsequent events. Thus, during the period denominated “domination,” the Arab conquerors enjoyed no peaceful or undisputed possession. During all those centuries there continued one long succession of wars—intermittent attempts, successful and the reverse, at reconquest by the Christian power. Here a patch of ground, a city, or a province was regained; presently, perhaps, to be lost a second or a third time. Never for long was there a final acceptance of the major force. But during the interludes, the periods of rest between struggles, the two contending races lived in more or less friendly intercourse, exchanging courtesies and even maintaining a stout rivalry in those warlike forms of sport which in mediæval times formed but a substitute for war. It was thence that the custom of bull-fighting took its rise. If not fighting Arabs, fight bulls, and so prepare for the more strenuous contest. Such conditions could not but have tended towards greater coherence among the various elements on the Christian side, except for the incessant internecine rivalries between the Christians themselves. A Spanish knight or kinglet would invoke the aid of his nation’s foe to consolidate or establish his own petty estate. Christians with Moslem auxiliaries fought Moslems reinforced by Christian renegades.

The Moorish invader had to fight for his possession—every yard of it. Yet despite that, this energetic race found time to colonise, to develop and enrich the subjugated region with a thoroughness the evidence of which faces us to-day. We do not refer to their cities or to such monuments in stone as the Mezquita or Alhambra, but to their introduction into rural Spain of much of what to-day constitutes chief sources of the country’s wealth, and which might have been enormously increased had Moorish methods been followed up. The Koran expressly ordains and directs the introduction of all available fruits or plants suitable to soil that came, or comes, under Moslem dominion. “The man who plants or sows the seed of anything which, with the fruit thereof, gives sustenance to man, bird or beast does an action as commendable as charity”—so wrote one of their philosophers. “He who builds a house and plants trees and who oppresses no one, nor lacks justice, will receive abundant reward from the Almighty.” There you have the religion both of the good man and the good colonist. These precepts the Moors habitually and energetically carried out to the letter. Arboriculture was universal: the provinces of Valencia, Cordoba, and Toledo they filled with trees—fruit-trees and timber. In the warm valleys of the coast and in the sheltered glens of the mountains they acclimatised exotic fruits, plants, and vegetables hitherto restricted to the more benign climes of the East or to Afric’s scorching strand. Sugar-cane flourished in such luxuriance as to leave available a heavy margin for export. The fig-tree and carob, quince and date-palm, the cotton-plant and orange, with other aromatic and medicinal herbs, together with aloes and the anachronous-looking prickly-pear (Cactus), its amorphous lobes reminiscent of the Pleistocene, were all brought over for the use and benefit, the delight and profit of Europe. Of these, the orange to-day forms one of Spain’s most valuable exports, representing some three millions sterling per annum.

Types of Spanish Bird-Life

GRIFFON VULTURE (Gyps fulvus)

Abounds all over Spain: sketched while drying his wings after a

thunderstorm, in the Sierra de San Cristobal, Jerez.

Silk and its manufacture represented another immense source of wealth and industry introduced into Spain—to-day extinct. The Moors covered Andalucia with mulberry-groves: in Granada alone ran 5000 looms for the weaving of the fibre, and the streets of the Zacatin and the Alcarcería became world-markets, where every variety of costly stuffs were bought and sold—tafetans, velvets, and richest textures that surpassed in quality and brilliancy of tint even the far-famed products of Piza, Florence, and the Levantine cities which since Roman days had monopolised the silk-supply of the world. These now found their wares displaced by Spanish silks; even the sumptuous “creations” of Persia and China met with a dangerous rivalry.

Such was the technical skill and success of the Moors in agriculture and acclimatisation that, on the eventual conquest and final expulsion of their race from Spain, overtures were made with a view of inducing a certain proportion to remain, lest Spain might lose every expert she possessed in these essential pursuits. Six families in every hundred were promised amnesty on condition of remaining, but none accepted the offer. Deep as was their love for Spain—so deep that the departing Moors are related to have knelt and kissed its strand ere embarking, broken-hearted, for Africa—yet not a man of them but refused to remain as vassals where, for centuries, they had lived as lords.

Such were the Moors—strong in war, yet equally strong in all the arts and enterprises of peace, filled with energy, an industrious and a practical race. It is safe to say that under their regime the resources of this difficult land were being developed to their utmost capacity.[2]

Of the final expulsion of the Moors (and that of the Jews was analogous) ‘tis not for us to write. Yet, for Spain, both events proved momentous, and, along with the antecedent practices of the Moriscos, provide side-lights on history that are worth consideration.[3]

The subjoined statistics give the state of Spanish agriculture at the present day, the total acreage being taken as 50,451,688 hectares (2½ acres each):—

| Hectares. | ||

| Cultivated | 21,702,880 | |

| Uncultivated:— | ||

| Pasture, scrub, and wood | 24,055,547 | |

| Unproductive | 4,693,261 | |

| Total | 28,748,808 | |

| Grand Total | 50,451,688 |

These figures demonstrate precisely the extent of the authors’ condominium in Spain—well over one-half the country! With the area under cultivation (say 43 per cent), we have but one concern—the Great Bustard. The remaining 57 per cent pertain absolutely to our province—Wilder Spain. The term scrub or brushwood (in Spanish monte), though by a sort of courtesy it may be ranked as “pasture”—and parts of it do support herds of sheep and goats—implies as a rule the wildest of rough covert and jungle, rougher far than a Scottish deer-forest; and this monte clothes well-nigh one-half of Spain.

Such figures may appear to infer considerable apathy and lack of effort as regards agriculture. ‘Twere, nevertheless, a false assumption to conclude that Spanish mountaineers are an idle race—quite the reverse, as is repeatedly demonstrated in this book. In the hills every acre of available soil is utilised, often at what appears excessive labour—maybe it is a patch so tiny as hardly to seem worth the tilling, or so terribly steep that none save a serrano could keep a foothold, much less plough, sow, and reap.

The main explanation of the immense percentage of waste lies in the fact first set forth—the high general elevation of Spain; and, secondly, in her mountainous character.

Whether these or any other extenuating circumstances apply to the corn-lands, we are not sufficiently expert in such subjects as to express a confident opinion. But we think not. So antiquated, wasteful, and utterly inefficient have been Spanish methods of agriculture, that a land which might be one of the granaries of Europe is actually to some extent dependent on foreign grain, and that despite an import-duty! A distinct movement is, nevertheless, perceptible in the direction of employing modern agricultural machinery, chemical manures, and such-like. Irrigation in a land whose head-waters can be tapped at 2000 feet and upwards could be carried out on a larger scale and at cheaper rates than in any other European country—yet it is practically neglected; no considerable extension has been made to the two million acres of irrigated lands that existed when we last wrote, twenty years ago, although the ruined aqueducts of Roman, Goth, and Moor are ever present to suggest the silent lesson of former foresight and prosperity.

WOODEN PLOUGH-SHARE

(As still commonly used.)

One incidental circumstance of rural Spain, the fatal effects of which are all-penetrating (though it will never be altered), is absenteeism on the part of landowners. Not even a tenant-farmer will live on his holding. No, he must have his town-house, and employ an administrator or agent to superintend the farm, only visiting it himself at rare intervals. Oh! that hideous nightmare, the hireling, how his dead-weight of apathy and dishonesty at secondhand crushes out every spark of interest and enterprise, and breeds in their stead a rampant crop of all the petty vices and frauds that prey on industry. But that evil can hardly be eradicated.

What we British understand by the expression “country life” totally fails to commend itself to the more gregarious peoples of the south. Rich and poor alike, from grandee to day-labourer, the Spanish ignore and disdain the joys of the country. They call it the campo and the campo they detest. Each nightfall must see every man of them, irrespective of class, assembled within the walls of their beloved town or city, irresistibly attracted to street-girt abode—be it humblest cot or sumptuous palace (and one stands next door to the other). Even suburban existence is eschewed. There are no outer fringes to a Spanish town. No straggling “villa residences,” no Laburnum Lodge or River-View “ornament” the extramural solitude. Back at dusk all hie, crowding to the paséo, to club or casino, to social gathering and games of chance or (more rarely) of skill. That ubiquitous term “animacion,” which may be translated gossip, chatter, light-hearted intercourse, fulfils the ideals of life. Its more serious side—reading, study, scientific pursuit—have little place; seldom does one see a library in any Spanish home, urban or rural.

None can accuse the authors of desiring to use a comparison (proverbially odious) to the detriment of our Spanish friends. The above is merely a record of patent facts that must quickly become obvious to the least observant. It is but a definition of divergent idiosyncrasies as between different human genera. And remember that we in England have recently been told that our rural system is fraught with unseen and unsuspected evil. Into those wider questions we have no intention of entering. But at least our impressions are based upon personal experience of both lines of life, while much of the vituperation recently poured upon rural England is derived from a view of but one, and not a very clear view at that.

Where the owner—big or little, but the more of them the better—lives on the land, that land and the country at large benefit to a degree that is demonstrated with singular clearness by seeing the converse system as it is practised in Spain to-day. Here no one, owner or tenant—still less the hireling—takes any living interest (to say nothing of pride) in his possession or occupation beyond that very short-sighted “interest” of squeezing the utmost out of it from day to day. Ancient forests are cut down and burnt into charcoal, and rarely a tree replanted or a thought given to the resulting effects on rainfall or climate. As to beauty of landscape—what matter such æsthetic notions when the owner lives a hundred miles away? The collateral fact that, to a great extent, nature’s beauty and nature’s gifts are analogous and interdependent is ignored. Such simple issues are too insignificant, and too little understood, for frothy rhetoricians to reflect upon: the latter, moreover, like Gallio (and Pontius Pilate) care for none of these things.

A characteristic that differentiates the Spaniard, north or south, from other (more modern) nationalities, is a comparative indifference in money matters. Now a Spaniard requires money for his daily needs as much as the others; yet he never sinks to the level of total absorption in his pursuit of the dollar. Put that down to apathy, if you will—or to pride; at least there is dignity in the attribute. The leading Spanish newspapers quote the various market fluctuations and changes in value from day to day. Sometimes, possibly, the report may read sin operaciones, but never will you see conspicuously protruded, as a main item in the morning’s news, the headline “Wall Street.” There is (or was) dignity in commerce, and there may yet be readers in England who silently wish that such matters were relegated to their proper position—the monetary columns.

Types of Spanish Bird-Life

CETTI’S WARBLER (Sylvia cettii)

A winter songster, abundant but rarely seen, skulking in densest

brakes.

The chief financial flutter that interests is the Government lottery which is held every fortnight, and at which all classes lose their money; but the National Treasury profits to the tune of three millions sterling yearly. Spain is the home of “chance”: that element appeals to Spanish character. Thus in bull-fighting (the one popular pastime) the name applied to each of its formulated exploits is suerte—chance.

SPAIN is frequently accused of being a land of mañana. Hardly can we call to mind a book on the country in which some play on that word does not figure. But procrastination is not confined to any one country, and in this case the accusers are quite as likely to be guilty as the accused. A characteristic that strikes us as more applicable is rather the reverse—that of taking no thought for the morrow. Let us take an example or two. It is not the custom to repair roads. When, from long use, a road has gradually passed from bad to worse, till at length it has virtually ceased to exist, then it is “reconstruction” that is the remedy. Annual repairs, one may presume, would cost, say half the amount, would preserve continuous utility, and avoid that slowly aggravated destruction that ends finally in a hiatus. But that is not the Spanish way. “Reconstruction” is preferred. The ruthless cutting down of her forests without replanting a single tree has already been quoted. Next take an example or two of the things that lie most directly under the authors’ special view, such as game. The ibex—a unique asset, restricted to Spain, and of which any other country would be proud—has been callously shot down without thought for to-morrow, extirpated for ever in a dozen of its former habitats. The redleg—under the murderous system of shooting, year in and year out, over decoy-birds—would be exterminated within three or four years in any other country save this. It is merely the incredible fecundity of the bird and the vast area of waste lands that preserves the breed. Partridge in Spain are like rabbits in Australia—indestructible. The trout affords another example. Everywhere else on earth the trout is prized as one of nature’s valued gifts—hard to over-appreciate. Fully one-half of Spain is expressly adapted to its requirements. Trout were intended by nature to abound over the northern half of Spain—say down to the latitude of Madrid, and even in the extreme south where conditions are favourable, as in the Sierra Neváda. Trout might abound in Spain to the full as they abound in Scotland or Norway, adding value to every river and a grace to country life. But what is the treatment meted out to the trout in Spain? No sooner is its presence detected than the whole stock—big and little alike, even the spawn—is blown out of existence with dynamite, poisoned by quicklime, or captured wholesale (regardless of season or condition) in nets, cruives, funnel-traps, and every other abomination. Kill and eat, big or little, breeding female or immature—it matters not; kill all you can to-day and leave the morrow to itself. True, there are game-laws and close-seasons, but none observe them.[4]

Types of Spanish Bird-Life

DARTFORD WARBLER (Sylvia undata)

Resident. Frequents deep furze-coverts, seldom seen (as we are

constrained to represent it) in separate outline.

We have selected these examples because we know and can speak with absolute authority. Presumption and analogy will naturally suggest that the same intelligence, the same blind improvidence will apply equally in other and far more important matters. Not one of our Spanish friends with whom we have discussed these subjects time and again but agrees to the letter with the above conclusions and most bitterly regrets them.

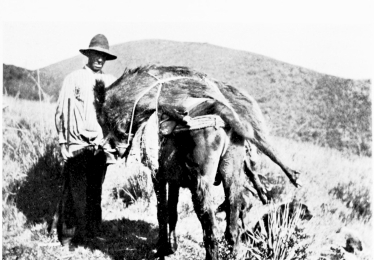

TRAVEL in all the wilder regions of Spain implies the saddle. Our Spain begins, as premised, where roads end. For us railways exist merely to help us one degree nearer to the final plunge into the unknown; and not railways only, but roads and bridges soon “petter out” into trackless waste, and leave the explorer face to face with open wilds—despoblados, that is, uninhabited regions—with a route-map in his pocket that is quite unreliable, and a trusty local guide who is just the reverse.

Riding light, with the “irreducible minimum” stowed in the saddle-bags, one may traverse Spain from end to end. But it is only a hasty and superficial view that is thus obtainable, and except for those who love roughing it for roughness’ sake, even the freedom of the saddle presents grave drawbacks in a land where none live in the country and none travel off stated tracks. In the campo, nothing—neither food for man nor beast—can be obtained, and no provision exists for travellers where travellers never come. The little rural hostelry of northern lands has no place; there is instead a venta or posada which may too often be likened to a stable for beasts with an extra stall for their riders. It is a characteristic of pastoral countries everywhere that their rude inhabitants discriminate little between the needs of man and beast.

But even towns of quite considerable size—when far removed from the track—are totally devoid of inns in our sense. Inns are not needed. The few Spanish travellers who, greatly daring, venture so far afield, usually bespeak beforehand the hospitality of some local friend or acquaintance.

Incidentally it may be added that a visit to one of these out-of-the-world cities—asleep most of them for the last few centuries—is a pleasing and restful change amidst the racket of exploration. One breathes a mediæval atmosphere and marvels at the revelation, enjoying prehistoric peeps in lost cities replete for the antiquary with historic memorial and long-forgotten lore. No one cares.

Yet in those bygone days of Spain’s world-power these somnolent spots produced the right stuff,—a minority, no doubt, belonged to the type satirised by Cervantes,—but many more strong in mind as in muscle, who went forth, knights-errant, Paladins and Crusaders, to conquer and to shape the course of history. Is the old spirit extinct? Our own impression is that the material is there all right ready to spring to life like the stones of Deucalion, so soon as Spain shall have shaken off her incubus of lethargy and the tyranny that clogs the wheels of progress. Nor need the interval be long.

That sound human material continues to exist in rural Spain we have had recent evidence during the calling-out of levies of young troops ordered abroad to serve their country in Morocco. None could witness the entrainment at some remote station of a detachment of these fine lads without being struck by their bearing, their set purpose, and above all their patriotism. With such material, with a well cared-for, contented, and loyal army and a broadening of view, wisely graduated but equally resolute, Spain moves forward. Alfonso XIII. is a soldier first—No! Above that he is a king by nature, but his care for his army and its well-being has already borne fruits that are making and will make for the honour, safety, and advancement of his country.

To resume our interrupted note on travel: whether you are riding across bush-clad hills, over far-spread prairie, or through the defiles of the sierra, as shadows lengthen the problem of a night’s lodging obtrudes. There is a variety of solutions. At a pinch—as when belated or benighted—one may, in desperate resort, seek shelter in a choza. Now a choza is the reed-thatched hut which forms the rural peasant’s lonely home. Assuredly you will be made welcome, and that with a grace and a courtesy—aye, a courtliness—that characterises even the humblest in Spain. The best there is will be at your disposal; yet—if permissible to say so in face of such splendid hospitality (and in the hope that these good leather-clad friends of ours may not read this book)—the open air is preferable. There exists in a choza absolutely no accommodation—not a separate room; a low settee running round the interior, or a withy frame, forms the bed; those kindly folk live all together, along with their domestic animals—and pigs are reckoned such in Spain. Let us gratefully pay this due tribute to our peasant friends—but let us sleep outside.

At each village will usually be found a posada. These differ in degree, mostly from bad downwards. The lowlier sort—little better than the choza—is but a long, low, one-storeyed barn which you share with fellow-wayfarers, and your own and their beasts, or any others that may come in, barely separated by a thatched partition that is neither noise-proof nor scent-proof. We can call instances to mind when even that small luxury was lacking, and all, human and other, shared alike. There are no windows—merely wooden hatches. If shut, both light and air are excluded; if open, hens, dogs, and cats will enter with the dawn—the former to finish what remains of supper. The cats will at least disperse the regiment of rats which, during the night, have scurried across your sleeping form.

Here we relate, as a specific example, a night we spent this last spring in northern Estremadura:—

Owing to a miscalculation of distance, it was an hour after sundown ere we reached our destination, a lonely hamlet among the hills. Our good little Galician ponies were dead-beat, for we had been in the saddle since 5 A.M., and it was past eight ere we toiled up that last steep, rock-terraced slope. We were a party of three, with a local guide and our own Sancho Panza—faithful companion, friend, and servant of many years’ standing. At a dilapidated hovel, the last in the village and perched on a crag, we drew rein, and after repeated knocks the door was opened by a girl—she had set down a five-year-old child among the donkeys while she drew the bolt, the ground-floor being (as usual) a stable. To our inquiry as to food—and the hunger of the lost was upon us—our hostess merely shrugged her shoulders, and with an expressive gesture of open hands, answered “Nada”—nothing! Sancho, however, was equal to the occasion. Within two minutes, while we yet stood disconsolate, he returned with a cackling cockerel in his arms. “Stew him quick before he crows,” he adjured the girl, and turned to unload the ponies.

What an age a cockerel takes to cook! It was midnight ere he smoked on the board and, hunger satisfied, we could turn in. In an upper den were two alcoves with beds, or rather stone ledges, ordinarily used by the family, and which were assigned to us, the luckless No. 3 by lot having to make shift (in preference to sleeping on a filthy floor) with three cranky tables of varying heights, and whose united lengths proved a foot too short at either end!

Oh, the joy of the morning’s dawn and delicious freshness of the mountain air, as we turned out at five o’clock for yet another ten-league spell to our next destination. Two nights later we slept in the gilded luxury of Madrid! But how we abused our previous neglect in not having brought a camp-outfit.

The above, however, presents the gloomier side of the picture, and there is a reverse, even in posadas. We cannot better describe the latter side than in our own words from Wild Spain:—

A Night at a Posada (Andalucia)

The wayfarer has been travelling all day across the scrub-clad wastes, fragrant with rosemary and wild thyme, without perhaps seeing a human being beyond a stray shepherd or a band of nomad gypsies encamped amidst the green palmettos. Towards night he reaches some small village where he seeks the rude posada. He sees his horse provided with a good feed of barley and as much broken straw as he can eat. He is himself regaled with one dish—probably the olla or a guiso (stew) of kid, either of them, as a rule, of a rich red-brick hue, from the colour of the red pepper or capsicum in the chorizo or sausage, which is an important (and potent) component of most Spanish dishes. The steaming olla will presently be set on a table before the large wood-fire, and with the best of crisp white bread and wine, the traveller enjoys his meal in company with any other guest that may have arrived at the time—be he muleteer or hidalgo. What a fund of information may be picked up during that promiscuous supper! There will be the housewife, the barber, and the padre of the village, perhaps a goatherd come down from the mountains, a muleteer, and a charcoal-burner or two, each ready to tell his own tale, or to enter into friendly discussion with the “Ingles.” Then, as you light your breva, a note or two struck on the guitar falls on ears predisposed to be pleased.

How well one knows those first few opening notes: no occasion to ask that it may go on: it will all come in time, and one knows there is a merry evening in prospect. One by one the villagers drop in, and an ever-widening circle is formed around the open hearth, rows of children collect, even the dogs draw around to look on. The player and the company gradually warm up till couplet after couplet of pathetic malagueñas follow in quick succession. These songs are generally topical, and almost always extempore; and as most Spaniards can—or rather are anxious to—sing, one enjoys many verses that are very prettily as well as wittily conceived.

But girls must dance, and find no difficulty in getting partners to join them. The malagueñas cease, and one or perhaps two couples stand up, and a pretty sight they afford! Seldom does one see girl-faces so full of fun and so supremely happy as they adjust the castanets, and one damsel steps aside to whisper something sly to a sister or friend. And now the dance begins; observe there is no slurring or attempt to save themselves in any movement. Each step and figure is carefully executed, but with easy, spontaneous grace and precision both by the girl and her partner.

Though two or more pairs may be dancing at once, each is quite independent of the others, and only dance to themselves; nor do the partners ever touch each other.[5] The steps are difficult and somewhat intricate, and there is plenty of scope for individual skill, though grace of movement and supple pliancy of limb and body are almost universal, and are strong points in dancing both the fandango and minuet. Presently the climax of the dance approaches. The notes of the guitar grow faster and faster; the man—a stalwart shepherd-lad—leaps and bounds around his pirouetting partner, and the steps, though still well ordered and in time, grow so fast that one can hardly follow their movements.

Now others rise and take the places of the first dancers, and so the evening passes; perhaps a few glasses of aguardiente are handed round—certainly much tobacco is smoked—the older folks keep time to the music with hand-clapping, and all is good nature and merriment.

What is it that makes the recollection of such evenings so pleasant? Is it merely the fascinating simplicity and freedom of the dance, or the spectacle of those weird, picturesque groups, bronze-visaged men and dark-eyed maidens, all lit up by the blaze of the great wood-fire on the hearth, and low-burning oil-lamps suspended from the rafters? Perhaps it is only the remembrance of many happy evenings spent among these people since our boyhood. This we can truly say, that when at last you turn in to sleep you feel happy and secure among a peasantry with whom politeness and sympathy are the only passports required to secure to you both friendship and protection if required. Nor is there a pleasanter means of forming acquaintance with Spanish country life and customs than a few evenings spent thus at a farm-house or village inn in any retired district of laughter-loving Andalucia.

For rough living we are of course prepared, and accept the necessity without demur or second thought while travelling. But when more serious objects are in hand—say big-game or the study of nature, objects which demand more leisurely progress, or actually encamping for a week or more at selected points—then we prefer to assure complete independence of all local assistance and shelter.

An expedition on this scale involves an amount of care and forethought that only those who have experienced it would credit. For in Spain it is an unknown undertaking, and to engineer something new is always difficult. Quite an extensive camping-trip can be organised in Africa, where the system is understood, with less than a hundredth part of the care needed for a comparatively short trip in Spain where it is not. The necessary bulk of camp-outfit and equipment requires a considerable cavalcade, and this mule-transport (since no provender is obtainable in the country) involves carrying along all the food for the animals—the heaviest item of all. Naturally the cost of such expeditions works out to nearly double that of simple riding.

But, after all, it is worth it! Compare some of the miseries we have above but lightly touched upon—the dirt and squalor, the nameless horrors of choza or posada—with the sense of joyous exhilaration felt when encamped by the banks of some babbling trout-stream or in the glorious freedom of the open hill. Casting back in mental reverie over a lengthening vista of years, we certainly count as among the happiest days of life those spent thus under canvas—whether on the sierras and marismas of Spain, on high field or dark forest in Scandinavia, or on Afric’s blazing veld.

Should some remarks (here or elsewhere in this book) appear self-contradictory the reason will be found rather in our inadequate expression than in any confusion of idea. We love Spain primarily because she is wild and waste; but, loving her, are naturally desirous that she should advance to that position among nations that is her due. Such material development, nevertheless, need not—and will not—imply the total destruction of her wild beauties. Development on those lines would not consist with the peculiar genius of the Spanish race, and, while we trust the development will come, we fear no such collateral results. Take, for instance, the corn-lands. There the great bustard is alike the index and the price of vast, unwieldy farms unfenced and but half tilled, remote from rail, road, or market. That condition we neither expect nor hope to see exchanged for smug fields with a network of railways. For “three acres and a cow” is not the line of Spanish regeneration; it is rather a claptrap catch-word of politicians—a murrain on the lot of them!

True, the plan seems to answer in Denmark, and if the Danes are satisfied, well and good—that is no business of ours. But no such mathematical and Procrustean restriction of vital energies and ambitions will subserve our British race, nor the Spanish. In Spanish sierra may the howl of the wolf at dawn never be replaced by blast from factory siren, nor the curling blue smoke of the charcoal-burner in primeval forest be abolished in favour of black clouds belching from bristling chimneys that pierce a murky sky. Either in such circumstance would be misplaced.

Similarly, when the engineer shall have been turned loose in the Spanish marismas, he can, beyond all doubt, destroy them for ever. His straight lines and intersecting canals, hideous in utilitarian rectitude, would right soon demolish that glory of lonely desolation—those leagues of marshland, samphire, and glittering lucio. And all for nothing! Since the desecration will not “pay” financially—the reason we give in detail elsewhere—and you sacrifice for a shadow some of the grandest bits of wild nature that yet survive—the finest length and breadth of utter abandonment that still enrich a humdrum Europe. Should “progress” only advance on these lines no scrap of that continent will be left to wanderer in the wilds—no spot where clanging skeins of wild-geese serry the skies, and the swish of ten thousand wigeon be heard overhead; or that marvellous iridescence—as of triple flame—the passing of a flight of flamingoes, be enjoyed.[6]

That national progress and development may come, for Spain’s sake, we earnestly pray. But does there exist inherent reason why progress, in itself, should always come to ruin natural and racial beauties? Progress seems nowadays to be misunderstood as a synonym for uniformity—and uniformity to a single type. Disciples of the cult of insensate haste, of self-assertion and advertisement, have pretty well conquered the civilised world; but in Spain they find no foothold, and we glory to think they never will. Spain will never be “dragooned” into a servile uniformity. There remain many, among whom we count our humble selves, who bow no knee to the modern Baal, and who (while conceding to the “hustling” crowd not one iota of their pretensions to fuller efficiency in any shape or form) are proud to find fascination in simplicity, a solace in honest purpose and in old-world styles of life—right down (if you will) to its inertia.

Yes, may progress come, yet leave unchanged the innate courtesy, the dignity and independence of rural Spain—unspoilt her sierras and glorious heaths aromatic of myrtle and mimosa, alternating with natural woods of ilex and cork-oak—self-sown and park-like, carpeted between in spring-time with wondrous wealth of wild flowers. There is nothing incongruous in such aspiration. Incongruity rather comes in with misappreciation of the fitness of things, as when a coal-mine is planked down in the midst of sylvan beauties, to save some hypothetic penny-a-ton (as per Prospectus); where pellucid streams are polluted with chemical filth and vegetation blasted by noisome fumes; or where God’s fairest landscapes are ruined by forests of hideous smoke-stacks.

If vandalisms such as these be progress then we prefer Spain as she is.

A Note on the Spanish Fauna

After all, it is less with the human element that this book is concerned than with the wild Fauna of Spain; a brief introductory notice thereof cannot, therefore, be omitted.

BONELLI’S EAGLE (Aquila bonellii)

A pair disturbed at their eyrie.

As head of the list must stand the Spanish Ibex (Capra hispánica), a game-animal of quite first rank, peculiar to the Iberian Peninsula, and whose nearest relative—the Bharal (Capra cylindricornis)—lives 2500 miles away in the far Caucasus. In Spain the ibex inhabits six great mountain-ranges, each covering a vast area but all widely separated. After a crisis that five years ago threatened extermination, this grand species is now happily increasing under a measure of protection and the ægis of King Alfonso. Next—a notable neighbour of the ibex (and practically extinct in central Europe)—we place the lone and lordly Lammergeyer. A memorable spectacle it is to watch the huge Gypaëtus sweeping through space o’er glens and corries of the sierra in striking similitude to some weird flying dragon of Miocene age—a vision of blood-red irides set on a cruel head with bristly black beard, of hoary grey plumage and golden breast. Watch him for half an hour—for half a day—yet never will you discern a sign of force exerted by those 3-yard pinions. With slightly reflexed wings he sinks 1000 feet; then, shifting course, rises 2000, 3000 feet till lost to sight over some appalling skyline. You have seen the long cuneate tail deflected ever so slightly—more gently than a well-handled helm—but the wide lavender wings remain rigid, not an effort that indicates force have you descried. Yet the power (so defined as “horse-power”) required to raise a deadweight of 20 lbs. through such altitudes can be calculated by engineers to a nicety—how is it exerted? That the power is there is conspicuous enough, and at least it serves to explain fabled traditions of giant lammergeyers hurling ibex-hunter from perilous hand-hold on the crag, to feast on the remains below; or, in idler moment, bearing off untended babes to their eyries—alas! that the duty of nature-students involves dissipating all such romance.

Types of Spanish Bird-Life

BLACK VULTURE (Vultur monachus)

Nests in the mountain-forests of Central Spain, and winters in

Andalucia. Sketched in Cote Doñana—“Getting under way.”

Spain, as geologically designed, being, as to one-half of her superficies, either a desert wilderness or a mountain solitude, naturally lends congenial conditions of life to the predatory forms that rely on hooked bill, on tooth and claw, fang and talon, to ravage their more gentle neighbours. Savage raptores, furred and feathered, characterise her wilder scenes. Wherever one may travel, a day’s ride will surely reveal huge vultures and eagles circling aloft, intent on blood. Throughout the wooded plains the majestic Imperial Eagle is overlord—you know him afar in sable uniform, offset by snow-white epaulets. Among the sierras a like condominium is shared by the Golden and Bonelli’s Eagles—and they have half-a-dozen rivals, to say nothing of lynxes and fierce wolves (we give a photo of one, the gape of whose jaws exceeds by one-half that of an African hyaena). Then there patrol the wastes a horde of savage night-rovers, denominated in Spanish Alimañas, to which a special chapter is devoted.

Types of Spanish Bird-Life

WHITE-FACED DUCK (Erismatura leucocephala)

Bill much dilated, waxy-blue in colour. Wings extremely short; a sheeny

grebe-like plumage, and long stiff tail, often carried erect.

In Estremadura, where man is a negligible quantity, and along the wild wooded valley of the Tagus, roams the Fallow-deer in aboriginal purity of blood—whether any other European country can so claim it, the authors have been unable to ascertain. In Cantabria and the Pyrenees the Chamois abounds.

Of the big game (the list includes red, roe, and fallow-deer, wild-boar, ibex, chamois, brown bear, etc.), we treat in full detail hereafter.

As regards winged game, this south-western corner of Europe, is singularly weak. There exists but a single resident species of true game-bird—the redleg. Compare this with northern Europe, where, in a Scandinavian elk-forest, we have shot five kinds of grouse within five miles; while southwards, in Africa, francolins and guinea-fowl are counted in dozens of species. True, there are ptarmigan in the Pyrenees, capercaillie, hazel-grouse, and grey partridge in Cantabria, but all these are confined to the Biscayan area. Nor are we overlooking the grandest game-bird of all, the Great Bustard, chiefest ornament of Spanish steppe, and there are others—the lesser bustard, quail, sand-grouse, etc.—but these hardly fall within our definition. As for the teeming hosts of wildfowl and waterfowl that throng the Spanish marismas (some coming from Africa in spring, the bulk fleeing hither from the Arctic winter), all these are so fully treated elsewhere as to need no further notice here.

Spain boasts several distinct species peculiar to her limits. Among such (besides the ibex) are that curious amphibian, the Pyrenean musk-rat (Myogale pyrenaica), not again to be met with nearer than the eastern confines of Europe. Birds afford an even more striking instance. The Spanish azure-winged magpie (Cyanopica cooki) abounds in Castile, Estremadura, and the Sierra Moréna, but its like is seen nowhere else on earth till you reach China and Japan!

A Foreword by Sir Maurice de Bunsen, G.C.M.G., British Ambassador at Madrid.

Among my recollections of Spain none will be more vivid and delightful than those of my visits to the Coto Doñana. From beginning to end, climate, scenery, sport, and hospitable entertainment combine, in that happy region, to make the hours all too short for the joys they bring. Equipped with Paradox-gun or rifle, and some variety of ammunition, to suit the shifting requirements of deer and boar, lynx, partridge, wild-geese and ducks, snipe, rabbit and hare, nay, perhaps a chance shot at flamingo, vulture, or eagle, the favoured visitor steps from the Bonanza pier into the broad wherry waiting to carry him across the Guadalquivir, a few miles only from its outflow into the Atlantic. In its hold the first of many enticing bocadillos is spread before him. Table utensils are superfluous luxuries, but, armed with hunting blade and a formidable appetite, he plays havoc with the red mullet, tortilla, and carne de membrillo, washed down with a tumbler of sherry which has ripened through many a year in a not far distant bodega.

In half an hour he is in the saddle. Distances and sandy soil prohibit much walking in the Coto Doñana.

Landscape in Coto Doñana, with Marisma in background.

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY H.R.H. PHILIPPE, DUKE OF ORLEANS.

Marshalled by our host, the soul of the party, the cavalcade canters lightly up the sandy beach of the river. Thence it strikes to the left into the pine-coverts, leading in five hours more to the friendly roof of the “Palacio.” A picturesque group it is with Vazquez, Caraballo, and other well-known figures in the van, packhorses loaded with luggage and implements of the chase, and lean, hungry podencos hunting hither and thither for a stray rabbit on the way. The views are not to be forgotten, the distant Ronda mountains seen through a framework of stone-pines, across seventy miles of sandy dunes, marismas, and intervening plains. After a couple of hours we skirt the famous sandhills, innocent of the slightest dash of green, which for some inscrutable reason attract, morning after morning, at the first tinge of dawn, countless greylag geese to their barren expanse and on which, si Dios quiere, toll shall be levied ere long. The marismas and long lagoons are covered here and there with black patches crawling with myriads of waterfowl, to be described after supper by the careful Vazquez as muy pocos, un salpicon—a mere sprinkling. Their names and habits, are they not written, with the most competent of pens, in this very volume? We stop, perhaps, for a first deer-drive on our line of march. How thrilling that sudden rustle in the brushwood! Stag is it, or hind, or grisly porker? As we approach the “Palacio” we see the spreading oak on which perched, contemptuous and unsuspecting, the imperial eagle, honoured this year by a bullet from King Alfonso’s unerring rifle. As we ride through the scrub the whirr of the red-legged partridge sends an involuntary hand to the gun. They may await another day. At dusk we ride into the whitewashed patio, just in time to sally forth and get a flighting woodcock between gun and lingering glow of the setting sun.

For no precious hours are wasted in the Coto Doñana. Next day at early dawn, maybe, if the lagoon be our destination, or at any rate after a timely breakfast, off starts again the eager cavalcade, be it in quest of red deer or less noble quarry. Then all day in the saddle, from drive to drive, dismounting only to lie in wait for a stag, or trudge through the sage-bushes after partridge, or flounder through the boggy soto, beloved of snipe, with intervening oases for the unforgotten bocadillo.

If Vazquez be kind, he will take you one day to crouch with him behind his well-trained stalking-horse, drawing craftily nearer and nearer to where the duck sit thickest, till, straightening your aching back, you have leave to put in your two barrels, as Vazquez lays low some twenty couples with one booming shot from his four-bore, into the brown.

Egret-Heronry at Santolalla, Coto Doñana.

(THE FOREGROUND IS SAND.)

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY H. R. H. PHILIPPE, DUKE OF ORLEANS.