You cannot surely have failed, some time or other, to

meet by chance some of those poor idiots, or innocents, whose utmost

wisdom scarcely serves to lead them as beggars from door to door in

quest of daily bread. One might almost fancy they were straying calves

who have lost their way home. They stare all round with open eyes and

mouth, as if in search of somewhat; but, alas, that they seek is not

plentiful enough in these parts to be found upon the highways—for

it is common sense.

Peronnik was one of these poor idiots, to whom the charity of

strangers had been in place [183]of father or of mother. He

wandered ever onwards unconscious whither; when he was thirsty, he

drank from wayside springs; when hungry, he begged stale crusts from

the women he saw standing at their doors; and when in need of sleep, he

looked out for a heap of straw, and hollowed himself out a nest in it

like a lizard.

As to any knowledge of a trade, Peronnik had, indeed, never learnt

one; but for all that he was skilful enough in many matters: he could

go on eating as long as you desired him to do so; he could outsleep any

one for any length of time; and he could imitate with his tongue the

song of larks. There is many a one now in these parts who cannot do so

much as this.

At the time of which I am telling you (that is, many a hundred years

ago and more), the land of White-Wheat was not altogether what you see

it nowadays. Since then many a gentleman has devoured his inheritance,

and cut up his forests into wooden shoes. Thus the forest of Paimpont

extended over more than twenty parishes; some say it even crossed the

river, and went as far as Elven. However that may be, Peronnik came one

day to a farm built upon the border of the wood; and as the

Benedicite bell had long since rung in his stomach, he drew near

to ask for food.

The farmer’s wife happened at that moment to be kneeling down

on the door-sill to scrape [184]the soup-bowl with her

flint-stone;2 but when she heard the idiot’s voice

asking for food in the name of God, she stopped and held the kettle

towards him.

“Here,” she cried, “poor fellow, eat these

scrapings, and say an ‘Our Father’ for our pigs, that

nothing on earth will fatten.”

Peronnik seated himself on the ground, put the kettle between his

knees, and began to scrape it with his nails; but it was little enough

he could succeed in finding, for all the spoons in the house had

already done their duty upon it. However, he licked his fingers, and

made an audible grunt of satisfaction, as if he had never tasted any

thing better.

“It is millet-flour,” said he, in a low

voice,—“millet-flour moistened with the black cow’s

milk,3 and by the best cook in the whole Low

Country.”

The farmer’s wife, who was going by, turned round

delighted.

“Poor innocent,” said she, “there is little enough

of it left; but I will add a scrap of rye-bread.” [185]

And she brought the lad the first cutting of a round loaf just out

of the oven. Peronnik bit into it like a wolf into a lamb’s leg,

and declared that it must have been kneaded by the baker to his

lordship the Bishop of Vannes.

The flattered peasant replied, that was nothing to the taste of it

when spread with fresh-churned butter; and to prove her words, she

brought him some in a little covered saucer. After taking this, the

idiot declared that this was living butter, not to be excelled

by butter of the White Week itself;4 and to give greater force

to his words, he poured over his crust all that the saucer contained.

But the satisfaction of the farmer’s wife prevented her from

noticing this; and she added to what she had already given him a lump

of dripping left from the Sunday soup.

Peronnik praised every mouthful more and more, and swallowed every

thing as if it had been water from a spring; for it was very long since

he had made so good a meal.

The farmer’s wife went and came, watching him as he ate, and

adding from time to time sundry scraps, which he took, making each time

the sign of the cross. [186]

Whilst thus employed in recruiting himself, behold a knight appeared

at the house-door, and addressing himself to the woman, asked her which

was the road to Kerglas castle.

“Heavens! good gentleman,” exclaimed the farmer’s

wife, “are you going there?”

“Yes,” replied the warrior; “and I have come from

a land so distant for this purpose, that I have been travelling night

and day these three months to get so far on my way.”

“And what are you come to seek at Kerglas?” asked the

Breton woman.

“I am come in quest of the golden basin and the diamond

lance.”

“These two are, then, very valuable things?” asked

Peronnik.

“They are of more value than all the crowns on earth,”

replied the stranger; “for not only will the golden basin produce

instantaneously all the dainties and the wealth one can desire, but it

suffices to drink therefrom to be healed of every malady; and the dead

themselves are raised to life by touching it with their lips. As to the

diamond lance, it kills and overthrows all that it touches.”

“And to whom do this diamond lance and golden basin

belong?” asked Peronnik, bewildered.

“To a magician called Rogéar, who lives in [187]the

castle of Kerglas,” answered the farmer’s wife. “He

is to be seen any day near the forest pathway, riding along upon his

black mare followed by a colt of three months’ old; but no one

dares to attack him, for he holds the fearful lance in his

hand.”

“Yes,” replied the stranger; “but the command of

God forbids him to make use of it within the castle of Kerglas. So soon

as he arrives there, the lance and the basin are deposited at the

bottom of a dark cave, which no key will open; therefore, it is in that

place I propose to attack the magician.”

“Alas, you will never succeed, my good sir,” replied the

peasant woman. “More than a hundred gentlemen have already

attempted it; but not one amongst them has returned.”

“I know that, my good woman,” answered the knight;

“but they had not been instructed as I have by the Hermit of

Blavet.”

“And what did the Hermit tell you?” asked Peronnik.

“He warned me of all that I shall have to do,” replied

the stranger. “First of all, I shall have to cross an enchanted

wood, wherein every kind of magic will be put in force to terrify and

bewilder me from my way. The greater number of my predecessors have

lost themselves, and there died of cold, hunger, or fatigue.”

[188]

“And if you succeed in crossing it?” said the idiot.

“If I get safely through it,” continued the gentleman,

“I shall meet a Korigan armed with a fiery sword, which lays all

it touches in ashes. This Korigan keeps watch beside an apple-tree,

from which it is necessary that I should gather one apple.”

“And then?” said Peronnik.

“Then I shall discover the laughing flower, and this is

guarded by a lion whose mane is made of vipers. This flower I must also

gather; after which I must cross the lake of dragons to fight the black

man, who flings an iron bowl that ever hits its mark and returns to its

master of its own accord. Then I shall enter on the valley of delights,

where every thing that can tempt and stay the feet of a Christian will

be arrayed before me, and shall reach a river with one single ford.

There I shall meet a lady clad in sable whom I shall take upon my

horse’s crupper, and she will tell me all that remains to be

done.”

The farmer’s wife did her best to persuade the stranger that

it would be impossible for him to go through so many trials; but he

replied that women were incapable of judging in so weighty a matter;

and after ascertaining correctly the forest entrance, he set off at

full gallop, and was soon lost among the trees. [189]

The farmer’s wife heaved a deep sigh, declaring that here was

another soul going before our Lord for judgment; then giving some more

crusts to Peronnik, she bade him go on his way.

He was about to follow her advice, when the farmer came in from the

fields. He had just been turning off the lad who looked after his cows

at the wood-side, and was revolving in his mind how his place should be

supplied.

The sight of the idiot was to him as a ray of light; he thought he

had happened on the very thing he sought, and after putting a few

questions to Peronnik, he asked him bluntly if he would stay at the

farm to look after the cattle. Peronnik would have preferred having no

one but himself to look after, for no one had a greater aptitude than

he for doing nothing; but the taste of the lard, the fresh butter, the

rye-bread, and the millet-flour hung still sweet upon his lips; so he

suffered himself to be tempted, and accepted the farmer’s

proposal.

The good man forthwith conducted him to the edge of the forest,

counted aloud all the cows, not forgetting the heifers, cut him a

hazel-switch to drive them with, and bade him bring them safely home at

set of sun.

Behold Peronnik now established as a keeper of cattle, watching over

them to see they did no mischief, and running from the black to the

red, [190]and from the red to the white, to keep them from

straying out of the appointed boundary.

Now whilst he was thus running from side to side, he heard suddenly

the sound of horse’s hoofs, and saw in one of the forest-paths

the giant Rogéar seated on his mare, followed by her

three-months’ colt. He carried from his neck the golden basin,

and in his hand the diamond lance, which glittered like flame.

Peronnik, terrified, hid himself behind a bush; the giant passed close

by him and went on his way. As soon as he was gone by, the idiot came

out of his hiding-place, and looked down in the direction he had taken,

but without being able to see which path he had followed.

Well, armed knights came on unceasingly in quest of the castle of

Kerglas, and not one was ever seen to return. The giant, on the

contrary, took his airing every day as usual. The idiot, who had at

length grown bolder, no longer thought of concealing himself when he

passed, but looked after him as long as he was in sight with envious

eyes; for the desire of possessing the golden basin and the diamond

lance grew stronger every day within his heart. But these things, alas,

were more easily desired than obtained.

One day, when Peronnik was all alone in the pasture-land as usual,

he saw a man with a white beard pausing at the entrance of the

forest-path. [191]The idiot took him for some fresh adventurer,

and inquired if he did not seek the road to Kerglas.

“I seek it not, since I already know it,” replied the

stranger.

“You have been there, and the magician has not killed

you?” exclaimed the idiot.

“Because he has nothing to fear from me,” replied the

white-bearded old man. “I am called the sorcerer Bryak, and am

Rogéar’s elder brother. When I wish to pay him a visit I

come here, and as, in spite of all my power, I cannot cross the

enchanted wood without losing my way, I call the black colt to carry

me.”

With these words, he traced three circles with his finger in the

dust, repeated in a low tone such words as demons teach to sorcerers,

and then cried,

“Colt, wild, unbroken, and with footstep

free,—

Colt, I am here; come quick, I wait for

thee.”

The little horse speedily made his appearance. Bryak

put him on a halter, shackled his feet, and then mounting on his back,

allowed him to return into the forest.

Peronnik said nothing of this adventure to any one; but he now

understood that the first step towards visiting Kerglas was to secure

the colt that knew the way. Unfortunately he knew neither how to trace

the three circles, nor to pronounce [192]the magic words

necessary for the colt to hear the summons. Some other method,

therefore, must be hit upon for making himself master of it, and, when

once it was captured, of gathering the apple, plucking the laughing

flower, escaping the black man’s bowl, and of crossing the valley

of delights.

Peronnik thought it all over for a long time, and at last he fancied

himself able to succeed. Those who are strong go forth clad in their

strength to meet danger, and too often perish in it; but the weak

compass their ends sideways. Having no hope of braving the giant, the

idiot resolved to try craft and cunning. As to difficulties, he

suffered them not to scare him: he knew that medlars are hard as

flint-stones when first gathered, and that a little straw and much

patience softens them at length.

So he made all his preparations against the time when the giant

usually appeared in the forest-path. First he made a halter and a

horse-shackle of black hemp; a springe for taking woodcocks, moistening

the hairs of it in holy water; a cloth-bag full of birdlime and

lark’s feathers; a rosary, an elder-whistle, and a bit of crust

rubbed with rancid lard. This done, he crumbled the bread given him for

breakfast along the pathway in which Rogéar, his mare, and three

months’ colt would shortly pass. [193]

They all three appeared at the usual hour, and crossed the pasture

as on other days; but the colt, which was walking with hanging head,

snuffing the ground, smelt out the crumbs of bread, and stopped to eat

them, so that it was soon left alone out of the giant’s sight.

Then Peronnik drew gently near, threw his halter over it, fastened the

shackle on two of its feet, jumped upon its back, and left it free to

follow its own course, certain that the colt, which knew its way, would

carry him to the castle of Kerglas.

And so it came to pass; for the young horse took unhesitatingly one

of the wildest paths, and went on as rapidly as the shackle would

permit.

Peronnik trembled like a leaf; for all the witchery of the forest

was at work to scare him. One moment it seemed as if a bottomless pit

yawned suddenly before his steed; the next all the trees appeared on

fire, and he found himself surrounded by flames; often whilst in the

act of crossing a brook, it became as a torrent, and threatened to

carry him away; at other times, whilst following a little footway

beneath a gentle slope, he saw huge rocks on the point of rolling down

and crushing him to pieces.

In vain he assured himself these were but magical delusions, he felt

his very marrow grow cold with dread. At last he resolutely pulled his

[194]hat down over his eyes, and let the colt carry

him blindly onwards.

Thus they both came safely to a plain where all enchantment ceased,

and Peronnik pushed up his cap and looked about him.

It was a barren spot, and gloomier than a cemetery. Here and there

might be seen the skeletons of gentlemen who had come in quest of

Kerglas Castle. There they lay, stretched beside their horses, and the

gray wolves still gnawing at their bones.

At length the idiot entered a meadow entirely overshadowed by one

single apple-tree; and this was so heavily laden with fruit, that the

branches hung to the ground. Before this tree the Korigan kept watch,

grasping in his hand the fiery sword which would lay all it touched in

ashes.

At sight of Peronnik, he uttered a cry like that of a wild bird, and

raised his weapon; but, without betraying any emotion, the lad simply

touched his hat politely, and said,

“Don’t disturb yourself, my little prince; I am only

passing by on my way to Kerglas, according to an appointment the Lord

Rogéar has made with me.”

“With you?” replied the dwarf; “and who, then, may

you be?”

“I am our master’s new servant,” said the idiot;

“you know, the one he is expecting.” [195]

“I know nothing of it,” replied the dwarf; “and

you look to me uncommonly like a cheat.”

“Excuse me,” returned Peronnik, “such is by no

means my profession; I am only a catcher and trainer of birds. But, for

God’s sake, don’t keep me now; for his lordship, the

magician, is expecting me this very moment; and has even lent me his

own colt, as you see, that I may the sooner reach the

castle.”

The Korigan saw, in fact, that Peronnik rode the magician’s

young horse, and began to consider whether he might not really be

speaking truth. Besides, the idiot had so simple an air, that it was

not possible to suspect him of inventing such a story. However, he

still felt mistrust; and asked what need the magician had of a

bird-catcher?

“The greatest need, it seems,” said Peronnik;

“for, according to his account, all that ripens, whether seed or

fruit, in the garden at Kerglas, is just now eaten up by

birds.”

“And what can you do to hinder them?” asked the

dwarf.

Peronnik showed the little snare which he had manufactured, and

declared that no bird would be able to escape it.

“That is just what I will make sure of,” said the

Korigan. “My apple-tree is ravaged just as much by the blackbirds

and thrushes. Set your [196]snare; and if you can catch them,

I will let you pass.”

To this Peronnik agreed; he fastened his colt to a bush, and going

up to the apple-tree, fixed therein one end of the snare, calling to

the Korigan to hold the other whilst he got the skewers ready. He did

as the idiot requested; and Peronnik hastily drawing the running noose,

the dwarf found himself caught like a bird.

He uttered a cry of rage, and struggled to get free; but the

springe, having been well steeped in holy water, bade defiance to all

his efforts.

The idiot had time enough to run to the tree, pluck an apple from

it, and remount his colt, which continued its onward course.

And so they came out of the plain; and behold, there lay a thicket

before them, formed of the very loveliest plants. There were to be seen

roses of every hue, Spanish brooms, rose-coloured honeysuckles, and,

towering above all, the mysterious laughing flower; but round about the

thicket stalked a lion, with a mane of vipers, rolling his eyes, and

with his teeth grinding like a couple of new mill-stones.

Peronnik stopped, and bowed over and over again; for he knew that in

the presence of the powerful a hat is more serviceable in the hand than

on the head. He wished all sorts of prosperities to the lion and his

family; and requested to [197]know if he was without mistake

upon the road to Kerglas.

“And what are you going to do at Kerglas?” cried the

ferocious beast with a terrible air.

“May it please your worship,” replied the idiot timidly,

“I am in the service of a lady who is a great friend of Lord

Rogéar, and she has sent him something as a present to make a

lark-pasty of.”

“Larks!” repeated the lion, licking his moustache;

“it is an age since I have tasted them. How many have you

got?”

“This bagful, your lordship,” replied Peronnik, showing

the cloth-bag which he had stuffed with feathers and birdlime.

And in order to verify his words, he began to counterfeit the

warbling of larks.

This song aggravated the lion’s appetite.

“Let me see,” said he, drawing near; “show me your

birds; I should like to know if they are large enough to be served up

at our master’s table.”

“I desire nothing so much,” replied the idiot;

“but if I open the bag, I am afraid they will fly

away.”

“Half open it, just to let me peep in,” said the greedy

monster.

This desire fulfilled Peronnik’s highest hopes; he offered the

bag to the lion, who poked in his [198]head to seize the larks, and

found himself smothered in feathers and birdlime. The idiot hastily

drew the strings of the bag tight round his neck, making the sign of

the cross over the knot, to keep it inviolable; then, rushing to the

laughing flower, he gathered it, and set off as fast as the colt could

go.

But it was not long before he came to the dragons’ lake, which

he must needs cross by swimming; and scarcely had he plunged in, when

they came towards him from every side to devour him.

This time Peronnik troubled not himself to pull off his hat, but he

began to throw out to them the beads of his rosary, as one would

scatter black wheat to ducks; and at every bead swallowed one of the

dragons turned over on its back and expired; so that he at length

reached the opposite shore unharmed.

The valley guarded by the black man had now to be crossed. Peronnik

soon perceived him, chained by one foot to the rock, and holding in his

hand an iron bowl, which ever returned, of its own accord, so soon as

it had struck the appointed mark. He had six eyes, ranged round his

head, which generally took turns in keeping watch; but at this moment

it so chanced that they were every one open. Peronnik, knowing that if

seen he should be struck by the iron bowl before he had [199]the

opportunity of speaking a word, resolved to creep along the brushwood.

And by this means, hiding himself carefully behind the bushes, he soon

found himself within a few steps of the black man, who had just sat

down, and closed two of his eyes in repose. Peronnik, guessing that he

was sleepy, began to chant in a drowsy voice the beginning of the High

Mass. The black man at first, taken by surprise, started, and raised

his head; but, as the murmur took effect upon him, a third eye closed.

Peronnik then went on to intone the Kyrie eleison, in the tone

of one possessed by the sleepy demon.5 The black

man closed a fourth eye, and half the fifth. Peronnik then began

Vespers; but before he had reached the Magnificat, the black man

slept soundly.

Then the youth, taking the colt by the bridle, led it softly over

mossy places; and so, passing close by the slumbering guardian, he came

into the valley of delights.

This was the most-to-be-dreaded place of all; for it was no longer a

question of avoiding positive danger, but of fleeing from temptation.

Peronnik called all the saints of Brittany to his aid.

The valley through which he was now passing [200]bore

every appearance of a garden richly filled with fruits, with flowers,

and with fountains; but the fountains were of wines and delicious

drinks, the flowers sang with voices as sweet as those of cherubim in

Paradise, and the fruits came of their own accord and offered

themselves to the hand. Then at every turning of the path Peronnik

beheld huge tables, spread as for a king, could scent the tempting

odour of pastry drawn fresh from the oven, and see the valets

apparently expecting him; whilst further off were beautiful maidens

coming to dance upon the turf, who called him by his name to come and

lead the ball.

In vain the idiot made the sign of the cross, insensibly he

slackened the pace of his colt, involuntarily he raised his face to

snuff up the delicious odour of the smoking dishes, and to gaze more

fixedly upon the lovely maidens; he would possibly have stopped

altogether, and there would have been an end of him, if the

recollection of the golden basin and the diamond lance had not all at

once crossed his mind. Then he instantly began to blow his

elder-whistle, that he might hear no more those soft appeals; to eat

his bread well rubbed with rancid dripping, to deaden the odour of the

dainty meats; and to stare fixedly on his horse’s ears, that the

lovely dancers might no more attract his eyes.

And so he came to the end of the garden quite [201]safely, and caught sight at last of Kerglas

Castle. But the river of which he had been told still lay between it

and him, and he knew that this river could only be forded in one place.

Happily the colt was familiar with this ford, and prepared to enter at

the right spot.

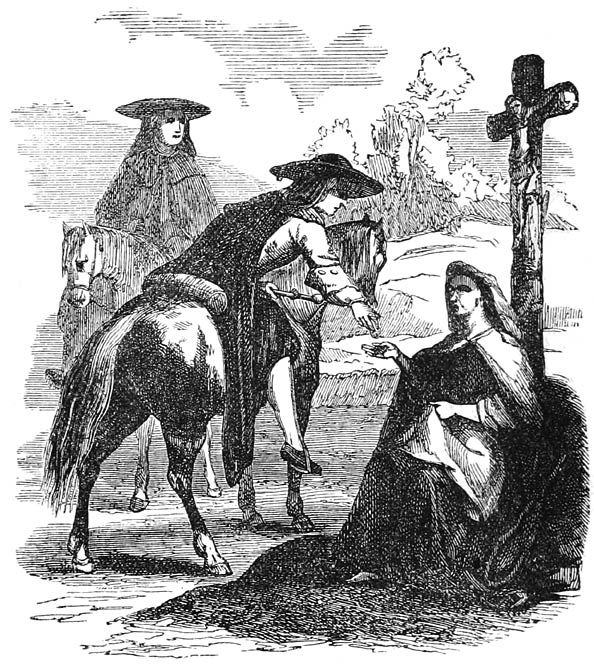

Then Peronnik looked around him in quest of the lady who was to be

his guide to the castle; and soon perceived her seated on a rock, clad

in black satin, and her countenance as yellow as a Moor’s.

The idiot pulled off his hat, and asked if it was her pleasure to

cross the river.

“I expected thee for that very purpose,” replied the

lady; “draw near, that I may seat myself behind thee.”

Peronnik approached, took her on his horse’s crupper, and

began to cross the ford. He had almost reached the middle of it, when

the lady said to him,

“Knowest thou who I am, poor innocent?”

“I beg your pardon,” replied Peronnik, “but from

your dress I clearly see that you are a noble and powerful

lady.”

“As to noble, I ought to be,” replied the lady,

“for I can trace back my origin to the first sin; and powerful I

certainly am, for all nations give way before me.” [202]

“Then what is your name, may it please you, madam?”

asked Peronnik.

“I am called the Plague,” replied the yellow woman.

The idiot made a spring as if he would have thrown himself from his

horse into the water; but the Plague said to him,

“Rest easy, poor innocent, thou hast nothing to fear from me;

on the contrary, I can be of service to thee.”

“Is it possible that you will be so benevolent, Madam

Plague?” said Peronnik, taking his hat off, this time for good;

“by the by, I now remember that it is you who are to teach me how

to rid myself of the magician Rogéar.”

“The magician must die,” said the yellow lady.

“I should like nothing better,” replied Peronnik;

“but he is immortal.”

“Listen, and try to understand,” said the Plague.

“The apple-tree guarded by the Korigan is a slip from the tree of

good and evil, set in the earthly Paradise by God Himself. Its fruit,

like that which was eaten by Adam and Eve, renders immortals

susceptible of death. Try, then, to induce the magician to taste the

apple, and from that moment he need only be touched by me to sink in

death.” [203]

“I will try,” said Peronnik; “but even if I

succeed, how can I obtain the golden basin and the diamond lance, since

they lie hidden in a gloomy cave, which cannot be opened by any key yet

forged?”

“The laughing flower will open every door,” replied the

Plague, “and can illuminate the darkest night.”

As she spoke these words they reached the further bank of the river,

and the idiot went onwards to the castle.

Now there was before the entrance-hall a huge canopy, like that

which is carried over his lordship the Bishop of Vannes at the

processions of the Fête Dieu. Beneath this sat the giant,

sheltered from the heat of the sun, his legs crossed, like a proprietor

who has gathered in his harvest, and smoking a tobacco-pipe of virgin

gold. On perceiving the colt, on which sat Peronnik and the lady clad

in black satin, he lifted up his head, and cried in a voice which

roared like thunder,

“Why this idiot is mounted on my three-months’

colt!”

“The very same, O greatest of all magicians,” replied

Peronnik.

“And how did you get possession of him?” asked

Rogéar.

“I repeated what your brother Bryak taught [204]me,” replied the idiot. “On reaching

the forest border I said,

‘Colt, wild, unbroken, and with footstep

free,—

Colt, I am here; come quick, I wait for

thee.’

and the little horse came at once.”

“Then you know my brother?” said the giant.

“As one knows his master,” replied the youth.

“And what has he sent you here for?”

“To bring you a present of two curiosities he has just

received from the country of the Moors,—this apple of delight,

and the female slave whom you see there. If you eat the first, you will

always have a heart as much at rest as that of a poor man who has found

a purse of a hundred crowns in his wooden shoe; and if you take the

second into your service, you will have nothing left you to desire in

the world.”

“Give me then the apple, and make the Moorish woman

dismount,” replied Rogéar.

The idiot obeyed; but the instant the giant had set his teeth into

the fruit, the yellow lady laid her hand upon him, and he fell to the

ground like a bullock in the slaughter-house.

Then Peronnik entered the palace, holding the laughing flower in his

hand. He traversed more than fifty halls, one after the other, and came

at length before the cavern with the silver door. This opened of its

own accord before the flower, [205]which also gave the idiot

sufficient light to find the golden basin and the diamond lance.

But scarcely had he seized them when the earth shook under his feet;

a terrible clap of thunder was heard; the palace disappeared; and

Peronnik found himself once more in the midst of the forest, holding

his two talismans, with which he set forward instantly to the court of

the King of Brittany.

He only delayed long enough at Vannes to buy the richest costume he

could find there, and the finest horse that was for sale in the diocese

of White-Wheat.

Now when he came to Nantes, this town was besieged by the Franks,

who had so mercilessly ravaged the surrounding country, that there were

scarcely more trees left than would serve a single goat for forage; and

more than that, famine was in the city; and those soldiers died of

hunger whose wounds had spared their lives. And on the very day of

Peronnik’s arrival, a trumpeter proclaimed aloud in every street

that the King of Brittany would adopt that man as his heir who could

deliver the city, and drive the enemy out of the country.

Hearing this promise, Peronnik said to the trumpeter,

“Proclaim no more, but lead me to the king; for I am able to

do all he asks.” [206]

“Thou!” said the herald, seeing him so young and small;

“go on thy way, fine goldfinch;6 the king has

now no time for taking little birds from cottage-roofs.”7

By way of reply, Peronnik touched the soldier with his lance; and

that very instant he fell dead, to the infinite terror of the crowd who

looked on, and would have fled away; but the idiot cried,

“You have just seen what I can do against my enemies; know now

what is in my power for my friends.”

And having touched with his golden basin the dead man’s lips,

he rose up instantly, restored to life.

The king being informed of this wonder, gave Peronnik command of all

the soldiers he had left; and as with his diamond lance the idiot

killed thousands of the Franks, and with his golden basin restored to

life the Bretons who were slain, a very few days sufficed him for

putting an end to the enemy’s army, and taking possession of all

their camp contained.

He then proposed to conquer all the neighbouring countries, such as

Anjou, Poitou, and Normandy, which cost him but very little trouble;

[207]and finally, when all were in obedience to the

king, he declared his intention of setting out to deliver the Holy

Land, and embarked from Nantes in a magnificent fleet, with the first

nobility of the land.

On reaching Palestine, he performed great deeds of valour, compelled

many Saracens to be baptised, and married a fair maiden, by whom he had

many sons and daughters, to each of whom he gave wealth and lands. Some

even say that, thanks to the golden basin, he and his sons are living

still, and reign in this land; but others maintain that

Rogéar’s brother, the magician Bryak, has succeeded in

regaining possession of the two talismans, and that those who wish for

them have only—to seek them out.

[Contents]

Note on the Tale of “Peronnik the

Idiot.”

It seems almost impossible not to recognise in the

story of Peronnik the Idiot traces of that tradition which has given

birth to one of the epic romances of the Round Table. Disfigured and

overlaid with modern details as is the Breton version, the primitive

idea of the Quest of the Holy Graal may still be found there pure and

entire.

Some explanation must be given of this. So early as the sixth

century, the Gallic bards speak of a magic vase which bestows a

knowledge of the future, and universal science, on its owner; in later

times a popular fable tells of a golden vase possessed by Bran the

Blessed, which healed all wounds, and even restored the dead to life.

Other [208]tales are told of a basin in which every desired

delicacy instantly appeared. In time all these fictions become fused,

and the several properties of these different vases are found united in

one; the possession of which is of course naturally sought after by all

great adventurers.

There is still extant a Gallic poem, composed in the beginning of

the twelfth century, of which the whole burden is this quest. The hero,

named Perédur, goes to war with giants, lions, serpents,

sea-monsters, sorcerers, and finally becomes conqueror of the basin and

the lance, which is here added to the primitive tradition.

Now there can be no doubt that this Gallic legend, which found its

way throughout Europe, as is proved by the attempts at imitation which

have been made in every language, must have been known in Brittany

above all, united as it is to Gaul by a common origin and language. It

must have become popular in the very form it wore when taught by the

bards to the Armoricans.

But besides the successive alterations which are the speedy result

of oral transmission, French imitations by degrees incorporated

themselves with all the primitive versions. M. de la Villemarqué

has in fact observed, in his learned work on the Popular Tales of

the Ancient Bretons, that when the Gallic legends were developed by

the French poets, they appeared so beautified in their new costume,

that the Gauls themselves abandoned the originals in favour of the

imitations. Now that which is true of them is equally so of the

Armoricans; and it seems to us beyond a doubt that the tradition of

Perédur, which they had originally received, must have been

seriously modified by the later poem of Christian of Troyes.

In order to elucidate our idea, we will give a hasty analysis of

this poem, which is little known, being only extant in

manuscript.8 [209]

Perceval, the last remaining son of a poor widow, whom the miseries

of war had left destitute, is simple, ignorant, and boorish. His mother

carefully conceals from his sight every thing that might turn his

attention to the idea of war; but one day the lad meets King

Arthur’s knights, learns the secret so long hidden from him, and,

his mind filled with nothing now but tournaments and battles, abandons

his maternal roof and sets off for Arthur’s court. On the way he

sees a pavilion, which, taking in his simplicity for a church, he

enters. There he eats two roebuck pasties, and drinks a large flagon of

wine; after which he goes once more upon his way, and soon arrives at

Cardeuil, ill-clad, ill-armed, and ill-mounted. He finds Arthur buried

in profound meditation, a treacherous knight having just carried off

his golden cup, defying any warrior to take it from him again. Perceval

accepts the challenge, pursues the thief, kills him, recovers the cup,

and seizes on the slain knight’s armour. He is at length admitted

into the order of chivalry.

But the recollection of his mother haunts him every where. What is

he in quest of? He himself knows not; he wanders at random and without

a purpose wherever his wild courser carries him. Thus one day he

reaches a castle, and enters. A sick old man reposes there upon a bed;

a servant appears with a lance from which flows one drop of blood, and

then a damsel bearing a graal, or basin, of pure gold. Perceval

longs to know the meaning of what he sees, but dares not ask. The

following day, on leaving the castle, he is informed that the sick old

man is called the fisher-king, and that he has been wounded in the

thigh; Perceval is at the same time reproached for not having

questioned him.

He continues onwards, meeting by chance Arthur, whom he follows to

court; but the day after his arrival a lady [210]clad

in black appears to him, and warmly blames him for being the cause of

the fisher-king’s sufferings.

“His wound,” said she, “has become incurable,

because thou didst not question him.”

The knight, wishing to repair his fault, seeks in vain to find once

more the king’s palace; he is repulsed as by an invisible hand,

until the moment when he resolves to go and find a saintly hermit, to

whom he makes his confession. The priest shows him that all his errors

are owing to his ingratitude towards his mother, and that sin held his

tongue in bondage when he ought to have inquired the meaning of the

graal; he imposes a penance on him, gives him advice, reveals to

him a mysterious prayer containing certain terrible words, which he

forbids him from making known; and then Perceval, absolved from his

sins, fasts, adores the Cross, hears Mass, receives Holy Communion, and

returns to a new life.

He now sets forth in quest of the graal, and meets with a

thousand obstacles. A woman, whom he has loved, White-Flower, appears,

and endeavours to detain him; but he escapes from her. He fastens his

horse to the golden ring of a pillar rising on a mountain called the

Mount of Misery, arrives at length at the castle for which he sought,

and this time fails not to inquire into the history of the lance and

the graal. He is told that the lance is that with which Longus

pierced the side of Christ, and that the graal is the basin in

which Joseph of Arimathea received His divine blood. This has come down

by inheritance to the fisher-king, who is descended from Joseph, and is

Perceval’s uncle. It procures all good things, both spiritual and

temporal, heals all wounds, and even restores life to the dead, besides

becoming filled with the most delicious dainties at its owner’s

desire.

After the lance and the graal, they bring out a broken

[211]sword; the fisher-king presents it to his

nephew, begging him to reunite the fragments; in which he succeeds. The

king then tells him that, according to prophecies, the bravest and most

pious knight in the whole world was to perform this act; that he

himself had attempted to weld the pieces together, but had been

chastised for his rashness by receiving a wound in the thigh. “I

shall be healed,” he added, “on the same day that sees the

knight Pertiniax perish,—that treacherous knight who broke this

wonderful sword in slaying my brother.”

Perceval kills Pertiniax, thanks to the aid of the holy

graal, cuts off his head, and brings it to the fisher-king, who

gets well, and abdicates in favour of his nephew.

The points of accordance between this poem and the Breton story are

not very difficult to trace. In the two recitals we hear of the

conquest of a basin and a lance, the possession of which ensures

corresponding advantages; the heroes both of the French and Armorican

version are subjected to dangers and temptations, and success assures

to them alike—a crown. Some points of resemblance may even

perhaps be discovered between the idiot Peronnik, going ever onwards he

knows not whither, and extracting from the farmer’s wife his

rye-bread, his fresh-churned butter, and his Sunday dripping; and this

Perceval, simple, ignorant, boorish, who begins by eating two

roebuck pasties, and drinking a great flagon of wine.

Certainly the different details, and the trials imposed on Peronnik,

are not in general much like the probation to which Perceval was

subjected; but, on the other hand, they closely resemble those to which

Perédur, the hero of the Gallic tradition, was exposed. It would

seem, therefore, that this Armorican story has drunk successively from

the two fountains of French and Breton legendary lore. Born of the

Gallic tradition, modified by the French version, and finally

accommodated to the popular genius of our province, it has become such

as we have it at this day. [212]

Peronnik the idiot seems, moreover, to us worthy of being studied by

those who seek, above all else in tradition, for traces of the popular

genius. Idiotism, amongst all tribes of Celtic race, was never looked

on as a degradation, but rather as a peculiar condition wherein

individuals could attain to certain perceptions unknown to the vulgar;

and the Celts were led to imagine that they had an acquaintance with

the invisible world not permitted to other men. Thus the words of the

idiot were looked on as prophetic; a hidden meaning was sought for in

his acts; he was, in fact, considered, in the energetic language of an

old poet, as having his feet in this world, and his eyes in the

other.

Brittany has preserved in part this ancient reverence for persons of

weak mind. It is by no means unusual in the farms of Léon to see

some of these unfortunates, clad, whatever may be their age, in a long

dress with bone buttons, and holding a white wand in their hands. They

are tenderly cared for, and only spoken of under the endearing title of

dear innocents, unless in their absence, when they are called

diskyant, that is to say, without knowledge.

They stay at home with the women and little children; they are never

called upon to perform any labour; and when they die, they are wept

over by their relations.

I remember meeting with one of these idiots one day, in the

neighbourhood of Morlaix; he was seated before a farm-house door, and

his sister, a young girl, was feeding him. Her caressing kindness

struck me.

“Then you are very fond of this poor innocent?” I

asked, in Breton.

“It is God who gave him to us,” she replied.

Words full of meaning, which hold the key to all this pious

tenderness for creatures useless in themselves, but precious for His

sake by whom they were confided to our care. [1]