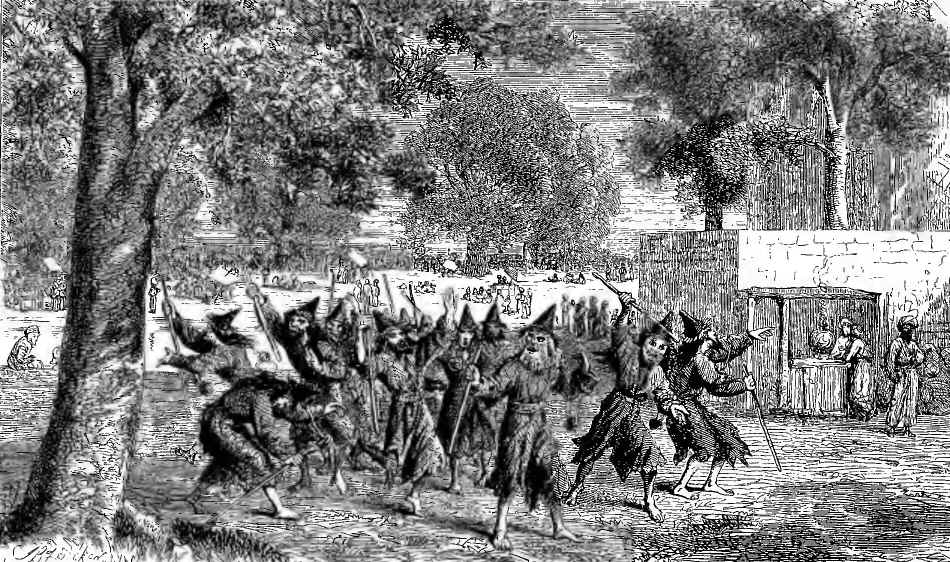

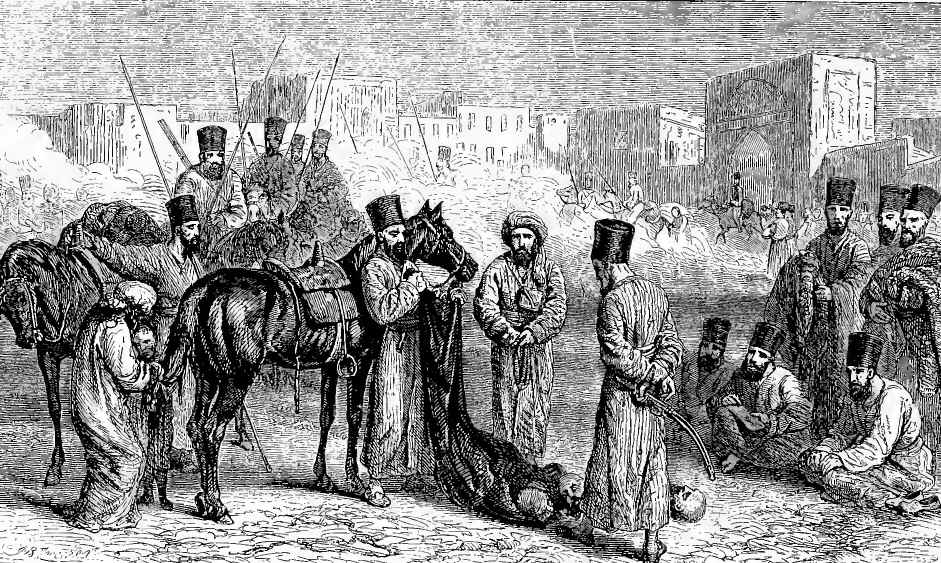

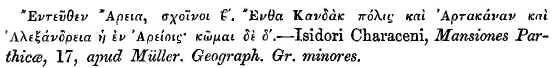

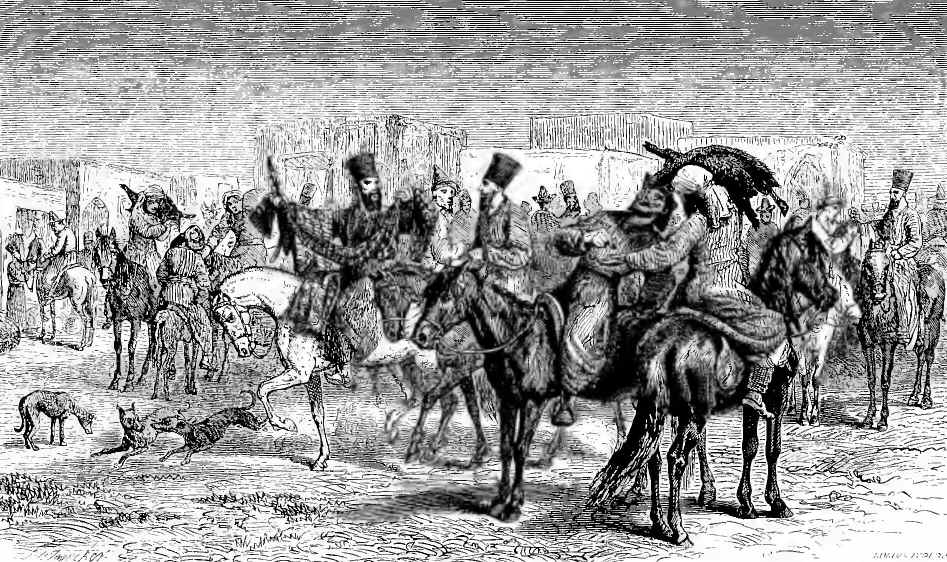

DERVISHES AT BOKHARA.

Title: Travels in Central Asia

Author: Ármin Vámbéry

Release date: January 1, 2013 [eBook #41751]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Don Kostuch

[Transcriber's note]

Page numbers in this book are indicated by numbers enclosed in curly

braces, e.g. {99}. They have been located where page breaks occurred

in the original book.

Section titles which appear with the odd page numbers in the

original text have been placed before the referenced paragraph in

square brackets.

[End transcriber's notes]

DERVISHES AT BOKHARA.

I was born in Hungary in 1832, in the small town of Duna Szerdahely, situated on one of the largest islands in the Danube. Impelled by a particular inclination to linguistic science, I had in early youth occupied myself with several languages of Europe and Asia. The various stores of Oriental and Western literature were in the first instance the object of my eager study. At a later period I began to interest myself in the reciprocal relations of the languages themselves; and here it is not surprising if I, in applying the proverb 'nosce teipsum,' directed my principal attention to the affinities and to the origin of my own mother-tongue.

That the Hungarian language belongs to the stock called Altaic is well known, but whether it is to be referred to the Finnish or the Tartaric branch is a question that still awaits decision. This enquiry, interesting [Footnote 1] to us Hungarians both in a scientific and {viii} a national point of view, was the principal and the moving cause of my journey to the East. I was desirous of ascertaining, by the practical study of the living languages, the positive degree of affinity which had at once struck me as existing between the Hungarian and the Turco-Tartaric dialects when contemplating them by the feeble light which theory supplied. I went first to Constantinople. Several years' residence in Turkish houses, and frequent visits to Islamite schools and libraries, soon transformed me into a Turk--nay, into an Efendi. The progress of my linguistic researches impelled me further towards the remote East; and when I proposed to carry out my views by actually undertaking a journey to Central Asia, I found it advisable to retain this character of Efendi, and to visit the East as an Oriental.

[Footnote 1: The opinion consequently that we Hungarians go to Asia to seek there those of our race who were left behind, is erroneous. Such an object, the carrying out of which, both from ethnographical as well as philological reasons, would be an impossibility, would render a man amenable to the charge of gross ignorance. We are desirous of knowing the etymological construction of our language, and therefore seek exact information from cognate idioms.]

The foregoing observations will explain the object which I proposed to myself in my wanderings from the Bosphorus to Samarcand. Geological or astronomical researches were out of my province, and had even become an impossibility from my assumption of the character of a Dervish. My attention was for the most part directed to the races inhabiting Central Asia, of whose social and political relations, character, usages, and customs I have striven, however imperfectly, to give a sketch in the following {ix} pages. Although, as far as circumstances and my previous avocations permitted, I allowed nothing that concerned geography and statistics to escape me, still I must regard the results of my philological researches as the principal fruits of my journey. These I am desirous, after maturer preparation, to lay before the scientific world. These researches, and not the facts recorded in the present pages, must ever be regarded by me as the real reward of a journey in which I wandered about for months and months with only a few rags as my covering, without necessary food, and in constant peril of perishing by a death of cruelty, if not of torture. I may be reproached with too much limiting my views, but where a certain object is proposed we should not lose sight of the principle, 'non omnia possumus omnes.'

A stranger on the field to which the publication of this narrative has introduced me, I feel my task doubly difficult in a land like England, where literature is so rich in books of travels. My design was to record plainly and simply what I heard and saw, whilst the impression still remained fresh on my mind. I doubt much whether I have succeeded, and beg the kind indulgence of the public. Readers and critics may find many errors, and the light that I may throw upon particular points may be accounted too small a compensation for the hardships I actually encountered; but I entreat them not to forget that I return from a country where to hear is regarded as impudence, to ask as crime, and to take notes as a deadly sin. {x}

So much for the grounds and purposes of my journey. With respect to the arrangement of these pages, in order that there may be no interruption, I have divided the book into two parts; the first containing the description of my journey from Teheran to Samarcand and back, the second devoted to notices concerning the geography, statistics, politics, and social relations of Central Asia. I hope that both will prove of equal interest to the reader; for whilst on the one hand I pursued routes hitherto untrodden by any European, my notices relate to subjects hitherto scarcely, if at all, touched on by writers upon Central Asia. And now let me perform the more pleasing task of expressing my warm acknowledgments to all those whose kind reception of me when I arrived in London has been a great furtherance and encouragement to the publication of the following narrative. Before all let me mention the names of SIR JUSTIN and LADY SHEIL. In their house I found English open-heartedness associated with Oriental hospitality; their kindness will never be forgotten by me. Nor are my obligations less to the Nestor of geological science, the President of the Royal Geographical Society, SIR RODERICK MURCHISON; to that great Oriental scholar, VISCOUNT STRANGFORD; and to MR. LAYARD, M.P., Under-Secretary of State. In Central Asia I bestowed blessing for kindness received; here I have but words, they are sincere and come from the heart.

A. VÁMBÉRY.

London: September 28, 1864.

| Travelling in Persia |

| Sleep on Horseback |

| Teheran |

| Reception at the Turkish Embassy |

| Turkey and Persia |

| Ferrukh Khan's Visit to Europe |

| War between Dost Mohammed Khan and Sultan Ahmed Khan |

| Excursion to Shiraz |

| Return to Teheran |

| Relief of Sunnites, Dervishes, and Hadjis at the Turkish Embassy |

| Author becomes acquainted with a Karavan of Tartar Hadjis returning from Mecca |

| The different Routes |

| The Author determines to join the Hadjis |

| Hadji Bilal |

| Introduction of Author to his future Travelling Companions |

| Route through the Yomuts and the Great Desert decided upon |

| Departure from Teheran in North-easterly Direction |

| The Component Members of Karavan described |

| Ill-feeling of Shiites towards the Sunnite Hadjis |

| Mazendran |

| Zirab |

| Heften |

| Tigers and Jackals |

| Sari |

| Karatepe |

| Karatepe |

| Author entertained by an Afghan, Nur-Ullah |

| Suspicions as to his Dervish Character |

| Hadjis provision themselves for Journey through Desert |

| Afghan Colony |

| Nadir Shah |

| First View of the Caspian |

| Yacoub the Turkoman Boatman |

| Love Talisman |

| Embarkation for Ashourada |

| Voyage on the Caspian |

| Russian Part of Ashourada |

| Russian War Steamers in the Caspian |

| Turkoman Chief, in the Service of Russia |

| Apprehension of Discovery on the Author's part |

| Arrival at Gömüshtepe and at the Mouth of the Gorghen. |

| Arrival at Gömüshtepe, hospitable Reception of the Hadjis |

| Khandjan |

| Ancient Greek Wall |

| Influence of the Ulemas |

| First Brick Mosque of the Nomads |

| Tartar Raids |

| Persian Slaves |

| Excursion to the North-east of Gömüshtepe |

| Tartar Fiancée and Banquet, etc. |

| Preparation of the Khan of Khiva's Kervanbashi for the Journey through the Desert |

| Line of Camels |

| Ilias Beg, the Hirer of Camels |

| Arrangements with Khulkhan |

| Turkoman Expedition to steal Horses in Persia |

| Its Return. |

| Departure from Gömüshtepe |

| Character of our late Host |

| Turkoman Mounds or Tombs |

| Disagreeable Adventure with Wild Boars |

| Plateau to the North of Gömüshtepe |

| Nomad Habits |

| Turkoman Hospitality |

| The last Goat |

| Persian Slave |

| Commencement of the Desert |

| A Turkoman Wife and Slave |

| Etrek |

| Persian Slaves |

| Russian Sailor Slave |

| Proposed Alliance between Yomuts and Tekke |

| Rendezvous with the Kervanbashi |

| Tribe Kem |

| Adieu to Etrek |

| Afghan makes Mischief |

| Description of Karavan. |

| Kervanbashi insists that Author should take no Notes |

| Eid Mehemmed and his Brother's noble Conduct |

| Guide loses his Way |

| Körentaghi, Ancient Ruins, probably Greek |

| Little and Great Balkan |

| Ancient Bed of the Oxus |

| Vendetta |

| Sufferings from Thirst. |

| Thunder |

| Gazelles and Wild Asses |

| Arrival at the Plateau Kaftankir |

| Ancient Bed of Oxus |

| Friendly Encampment |

| Approach of Horsemen |

| Gazavat |

| Entry into Khiva |

| Malicious Charge by Afghan |

| Interview with Khan |

| Author required to give Specimen of Turkish Penmanship |

| Robes of Honour estimated by Human Heads |

| Horrible Execution of Prisoners |

| Peculiar Execution of Women |

| Kungrat |

| Author's last Benediction of the Khan. |

| Departure from Khiva for Bokhara |

| Ferry across the Oxus |

| Great Heat |

| Shurakhan |

| Market |

| Singular Dialogue with Kirghis Woman on Nomadic Life |

| Tünüklü |

| Alaman of the Tekke |

| Karavan alarmed returns to Tünüklü |

| Forced to throw itself into the Desert, 'Destroyer of Life' |

| Thirst |

| Death of Camels |

| Death of a Hadji |

| Stormy Wind |

| Precarious State of Author |

| Hospitable Reception amongst Persian Slaves |

| First Impression of Bokhara the Noble. |

| Bokhara |

| Reception at the Tekkie, the Chief Nest of Islamism |

| Rahmet Bi |

| Bazaars |

| Baha-ed-din, Great Saint of Turkestan |

| Spies set upon Author |

| Fate of recent Travellers in Bokhara |

| Book Bazaar |

| The Worm (Rishte) |

| Water Supply |

| Late and present Emirs |

| Harem, Government, Family of Reigning Emir |

| Slave Depot and Trade |

| Departure from Bokhara, and Visit to the Tomb of Baha-ed-din. |

| Bokhara to Samarcand |

| Little Desert of Chöl Melik |

| Animation of Road owing to War |

| First View of Samarcand |

| Haszreti Shah Zinde |

| Mosque of Timour |

| Citadel (Ark) |

| Reception Hall of Timour |

| Köktash or Timour's Throne |

| Singular Footstool |

| Timour's Sepulchre and that of his Preceptor |

| Author visits the actual Tomb of Timour in the Souterrain |

| Folio Koran ascribed to Osman, Mohammed's Secretary |

| Colleges |

| Ancient Observatory |

| Greek Armenian Library not, as pretended, carried off by Timour |

| Architecture of Public Buildings not Chinese but Persian |

| Modern Samarcand |

| Its Population |

| Dehbid |

| Author decides to return |

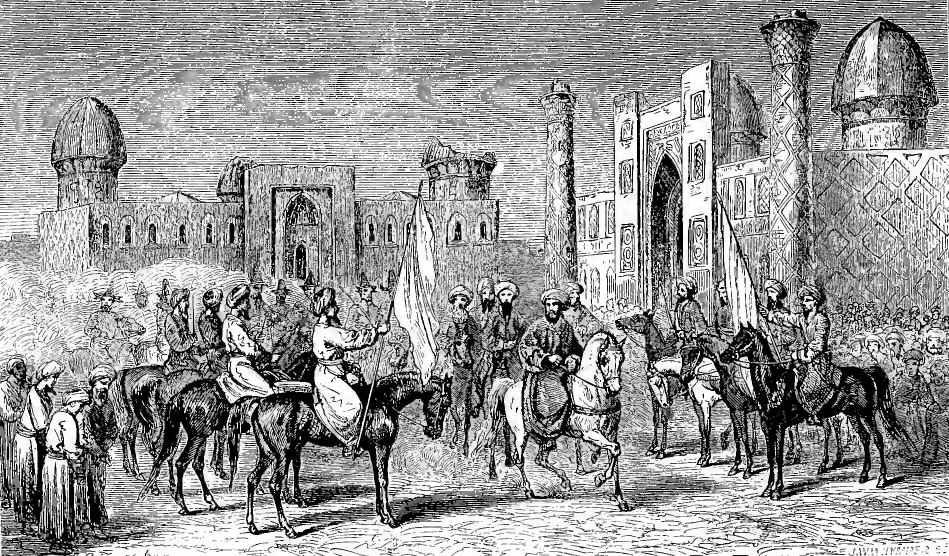

| Arrival of Emir |

| Author's Interview with him |

| Parting from the Hadjis, and Departure from Samarcand. |

| Samarcand to Karshi through Desert |

| Nomads |

| Karshi, the Ancient Nakhseb |

| Trade and Manufacture |

| Kerki |

| Oxus |

| Author charged with being runaway Slave |

| Ersari Turkomans |

| Mezari Sherif |

| Belkh |

| Author joins Karavan from Bokhara |

| Slavery |

| Zeid |

| Andkhuy |

| Yeketut |

| Khairabad |

| Maymene |

| Akkale. |

| Maymene |

| Its Political Position and Importance |

| Reigning Prince |

| Rivalry of Bokhara and Kabul |

| Dost Mohammed Khan |

| Ishan Eyub and Mollah Khalmurad |

| Khanat and Fortress of Maymene |

| Escaped Russian Offenders |

| Murgab River and Bala Murgab |

| Djemshidi and Afghan |

| Ruinous Taxes on Merchandise |

| Kalè No |

| Hezare |

| Afghan Exactions and Maladministration. |

| Herat |

| Its Ruinous State |

| Bazaar |

| Author's Destitute Condition |

| The Serdar Mehemmed Yakoub Khan |

| Parade of Afghan Troops |

| Interview with Serdar |

| Conduct of Afghans on storming Herat |

| Nazir Naim the Vizir |

| Embarrassed State of Revenue |

| Major Todd |

| Mosalla, and Tomb of Sultan Husein Mirza |

| Tomb of Khodja Abdullah Ansari, and of Dost Mohammed Khan. |

| Author joins Karavan for Meshed |

| Kuhsun, last Afghan Town |

| False Alarm from Wild Asses |

| Debatable Ground between Afghan and Persian Territory |

| Bifurcation of Route |

| Yusuf Khan Hezareh |

| Ferimon |

| Colonel Dolmage |

| Prince Sultan Murad Mirza |

| Author avows who he is to the Serdar of Herat |

| Shahrud |

| Teheran, and Welcome there by the Turkish Charge d' Affaires, Ismael Efendi |

| Kind Reception by Mr. Alison and the English Embassy |

| Interview with the Shah |

| The Kavvan ud Dowlet and the Defeat at Merv |

| Return by Trebisond and Constantinople to Pesth |

| Author leaves the Khiva Mollah behind him at Pesth and proceeds to London |

| His Welcome in the last-named City. |

| Boundaries and Division of Tribes |

| Neither Rulers nor Subjects |

| Deb |

| Islam |

| Change introduced by latter only external |

| Influence of Mollahs |

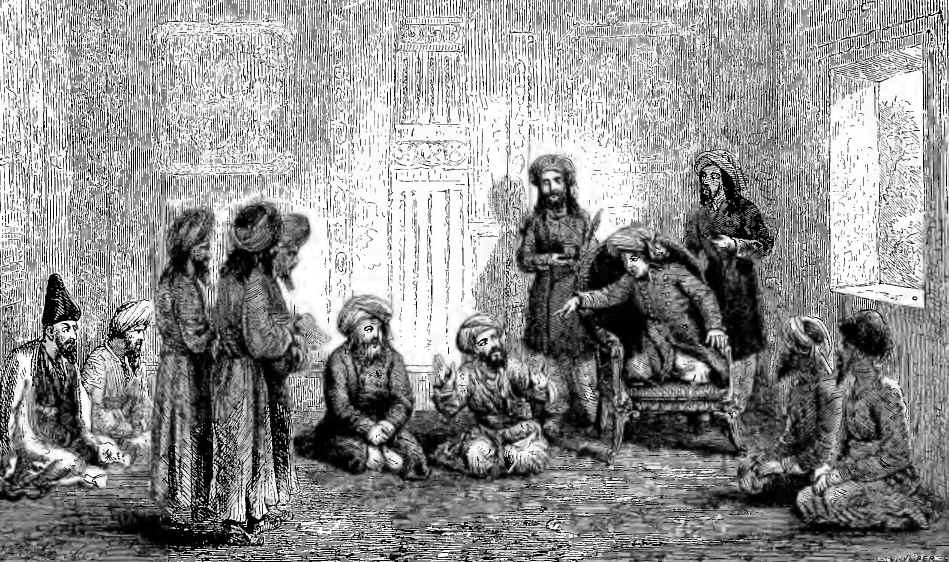

| Construction of Nomad Tents |

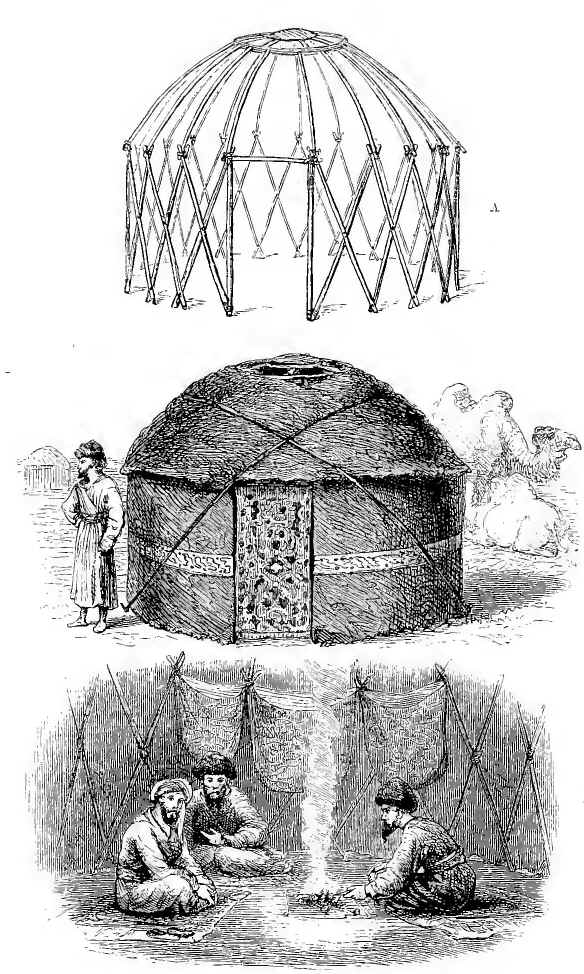

| Alaman, how conducted |

| Persian Cowardice |

| Turkoman Poets |

| Troubadours |

| Simple Marriage Ceremonies |

| Horses |

| Mounds, how and when formed |

| Mourning for Dead |

| Turkoman Descent |

| General Points connected with the History of the Turkomans |

| Their present Political and Geographical Importance. |

| Khiva, the Capital |

| Principal Divisions, Gates, and Quarters of the City |

| Bazaars |

| Mosques |

| Medresse or Colleges; how founded, organised, and endowed |

| Police |

| Khan and his Government |

| Taxes |

| Tribunals |

| Khanat |

| Canals |

| Political Divisions |

| Produce |

| Manufactures and Trade |

| Particular Routes |

| Khanat, how peopled |

| Ozbegs |

| Turkomans |

| Karakalpak |

| Kasak (Kirghis) |

| Sart |

| Persians |

| History of Khiva in Fifteenth Century |

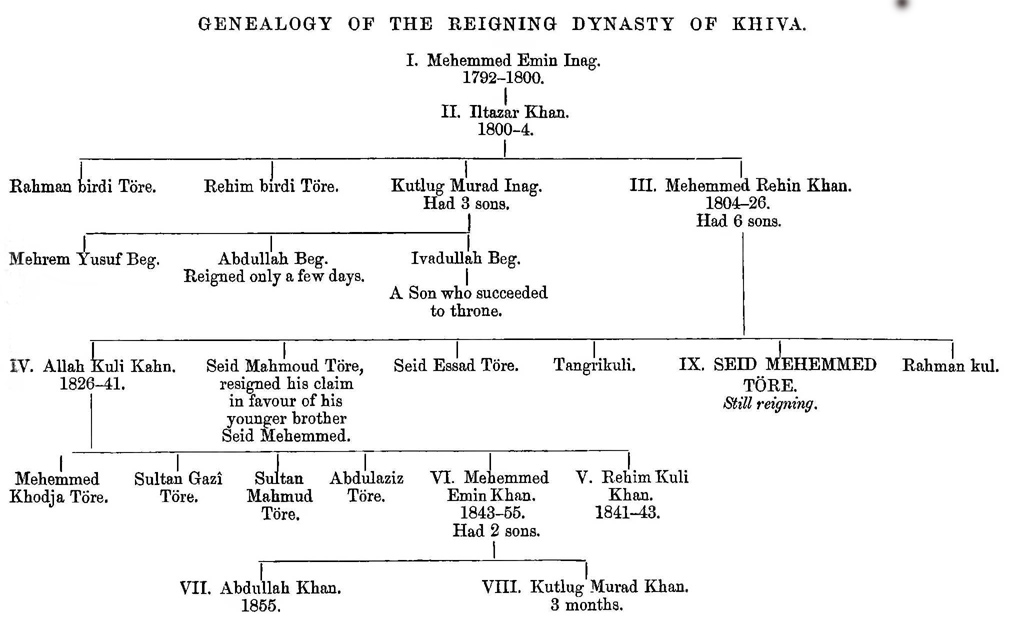

| Khans and their Genealogy. |

| City of Bokhara, its Gates, Quarters, Mosques, Colleges |

| One founded by Czarina Catherine |

| Founded as Seminaries not of Learning but Fanaticism |

| Bazaars |

| Police System severer than elsewhere in Asia |

| The Khanat of Bokhara |

| Inhabitants: Ozbegs, Tadjiks, Kirghis, Arabs, Mervi, Persians, Hindoos, Jews |

| Government |

| Different Officials |

| Political Divisions |

| Army |

| Summary of the History of Bokhara. |

| Inhabitants |

| Division |

| Khokand Tashkend |

| Khodjend |

| Morgolan Endidjan |

| Hazreti Turkestana |

| Oosh |

| Political Position |

| Recent Wars. |

| Approach from West |

| Administration |

| Inhabitants--Cities. |

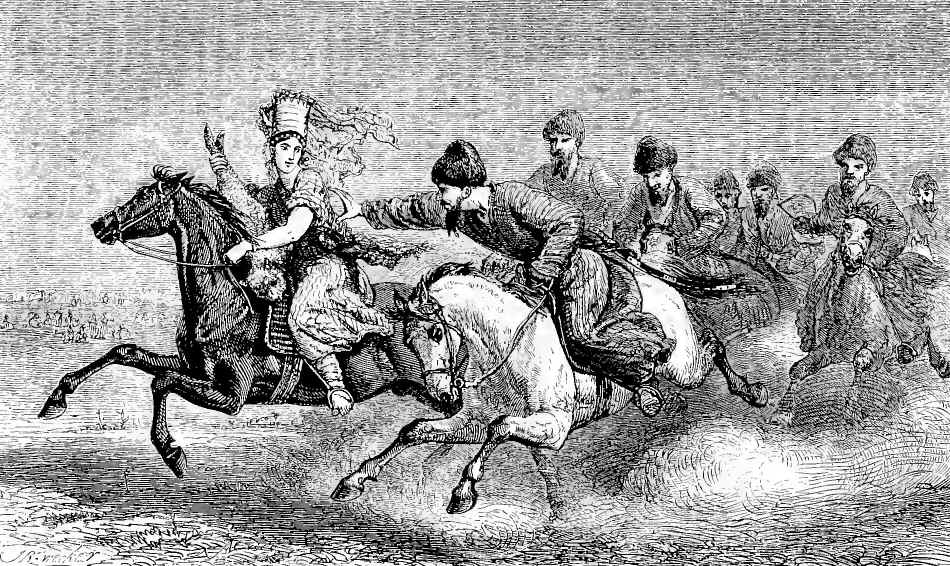

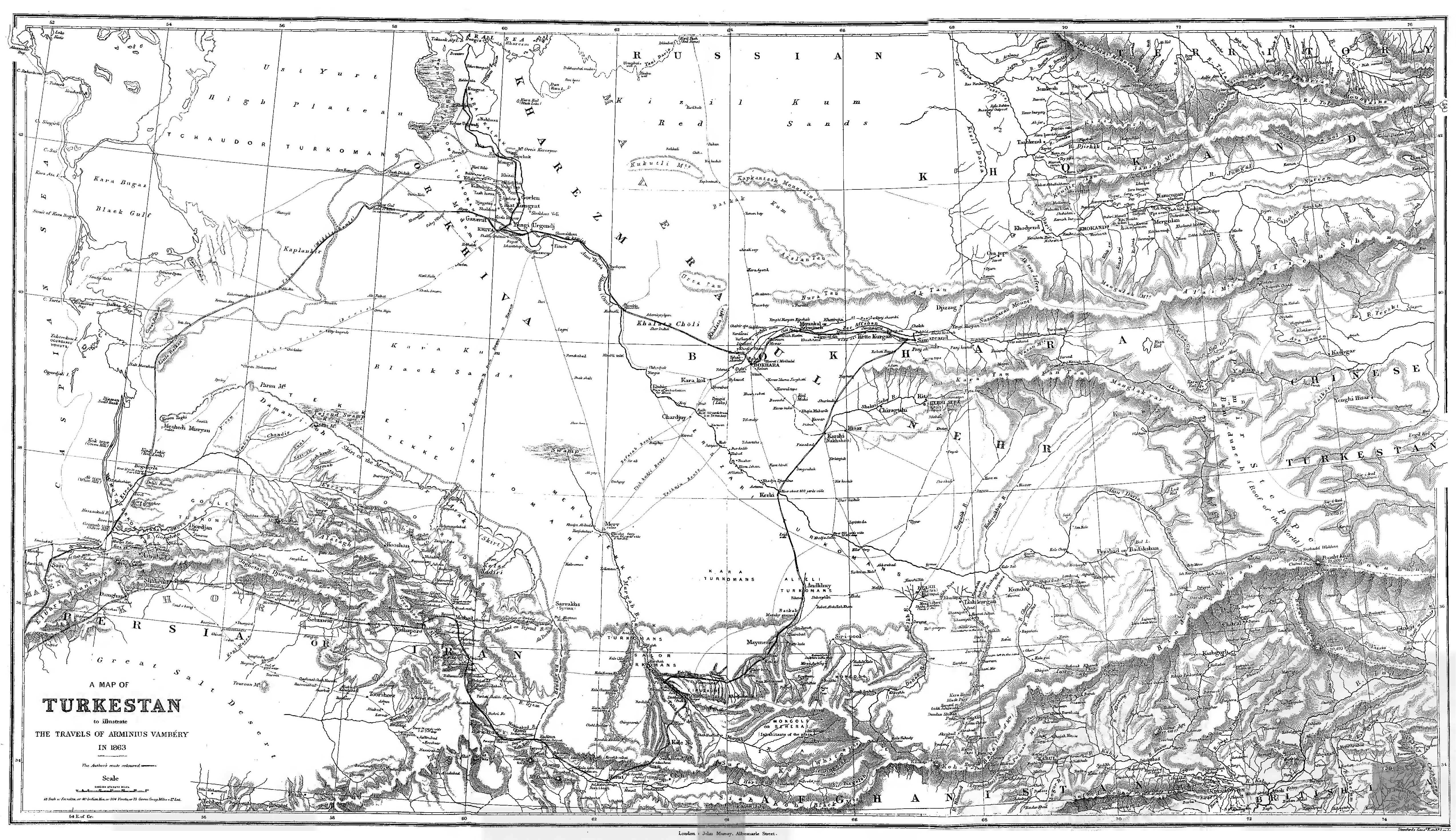

| Communication of Central Asia with Russia, Persia, and India |

| Routes in the three Khanats and Chinese Tartary. |

| Agriculture |

| Different kinds of Horses |

| Sheep |

| Camels |

| Asses |

| Manufactures, Principal Seats of Trade |

| Commercial Ascendancy of Russia in Central Asia. |

| Internal Relations between Bokhara, Khiva, and Khokand |

| External Relations with Turkey, Persia, China, and Russia. |

| Attitude of Russia and England towards Central Asia |

| Progress of Russia on the Jaxartes. |

| Dervishes at Bokhara | Frontispiece |

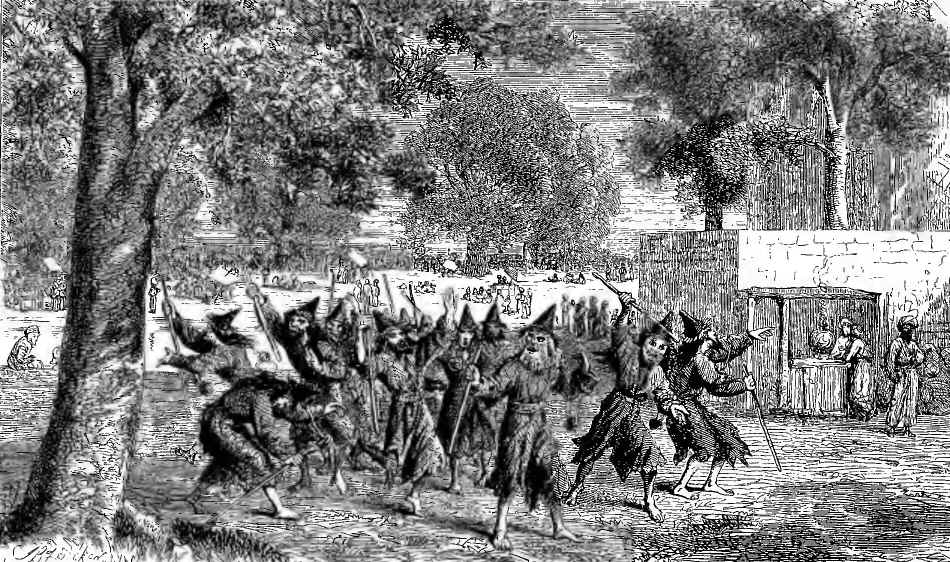

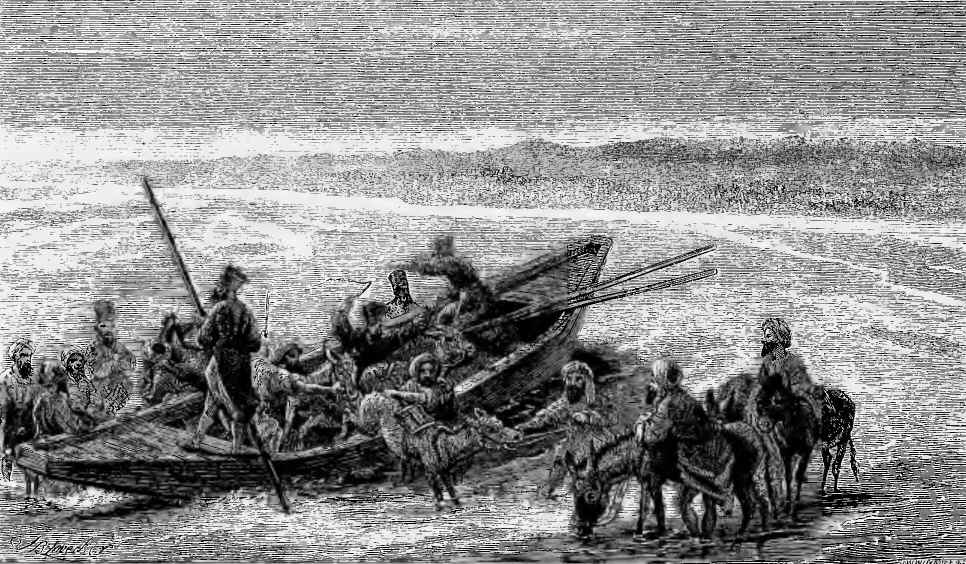

| Reception by Turkoman Chief on the Caspian Shore | 45 |

| Intruding upon the Haunts of the Wild Boar | 72 |

| Wild Man in the Desert | 108 |

| Receiving Payment for Human Heads--Khiva | 140 |

| The Ferry across the Oxus | 149 |

| Tebbad--Sand Storm in the Desert | 161 |

| Entry of the Emir into Samarcand | 216 |

| 'I swear you are an Englishman!' | 278 |

| Tent in Central Asia | 316 |

| Tartar Horse Race--Pursuit of a Bride (Kokburi) | 323 |

| Market on Horseback--Amongst the Özbegs | 345 |

| Map of Central Asia, showing Author's Route | At the end |

| TRAVELLING IN PERSIA |

| SLEEP ON HORSEBACK |

| TEHERAN |

| RECEPTION AT THE TURKISH EMBASSY |

| TURKEY AND PERSIA FERRUKH KHAN'S VISIT TO EUROPE |

| WAR BETWEEN DOST MOHAMMED KHAN AND SULTAN AHMED KHAN |

| EXCURSION TO SHIRAZ. |

Je marchais, et mes compagnons flottaient comme des branches par l'effet du sommeil.--Victor Hugo, from Omaïah ben Aiëdz.

Whoever has travelled through Persia in the middle of July will sympathise with me when I say how glad I felt at having got through the district that extends from Tabris to Teheran. It is a distance of only fifteen, or perhaps we may rather say of only thirteen karavan stations: still, it is fearfully fatiguing, when circumstances compel one to toil slowly from station to station under a scorching sun, mounted upon a laden mule, and condemned to see nothing but such drought and barrenness as characterise almost the whole of Persia. How bitter the disappointment to him who has studied Persia only in Saadi, Khakani, and Hafiz; {2} or, still worse, who has received his dreamy impressions of the East from the beautiful imaginings of Goethe's 'Ost-Westlicher Divan,' or Victor Hugo's 'Orientales,' or the magnificent picturings of Tom Moore!

It was not until we were about two stations from Teheran, that the idea struck our Djilodar [Footnote 2] to change our march by day into night marches. But even this expedient had its inconveniences: for the coolness of the night in Persia is a great disposer to slumber; the slow pace of the animals has a composing effect, and one must really firmly cling to them, or sometimes even suffer oneself to be bound on by cords, to avoid being precipitated during one's sleep down upon the sharp flint stones below. The Oriental, habituated to this constant torment, sleeps sweetly enough, whatever may be the kind of saddle, whether it be upon horse, camel, mule, or ass; and it gave me many a moment of merry enjoyment, as I contemplated the tall, lanky, long-robed Persians, lying outstretched with their feet nearly touching the ground, and their heads supported upon the necks of the patient beasts. In this position the Persians take their nap quite tranquilly, whilst they unconsciously pass many stations. But, at that time, Necessity, the mother of invention, had not yet imparted to me the necessary experience; and whilst the greater part of my travelling companions near me, in spite of their soft slumbers, were still riding on, I was left undisturbed to the studious contemplation of the Kervankusch and Pervins (Pleïades); and I looked with inexpressible longing to that quarter where the Suheil (Canopus) {3} and the Sitarei Subh (morning star) emerging, should announce the dawn of day, the proximity of the station, and the end of our torments. What wonder that I was somewhat in the condition of a half-boiled fish, when on the 13th July, 1862, I approached the capital of Persia? We stopped at a distance of a couple of English miles on the banks of a stream, to let our beasts drink. The halt awakened my companions, who, still sleepily rubbing their eyes, pointed out to me how Teheran was there lying before us to the north-east. I looked about me, and perceived in that direction a blue smoke rising and lengthening in long columns upwards, permitting me, however, here and there to distinguish the outline of a glittering dome, till at last, the vaporous veil having gradually disappeared, I had the enjoyment, as Persians express themselves, of beholding before me, in all her naked wretchedness, the Darül Khilafe, or Seat of Sovereignty.

[Footnote 2: The same as Kervanbashi; one who hires the camels, mules, asses, etc.]

I made my entry through the Dervaze (gate) No, and shall certainly not soon forget the obstacles amidst which I had to force my way. Asses, camels, and mules laden with barley straw, and bales of Persian or European merchandise, were all pressing on in the most fearful confusion, at the very entrance of the gate. Drawing up my legs under me upon the saddle, and screaming out as lustily as my neighbours, 'Khaberdar, Khaberdar' (Take care), I at last succeeded in getting into the city, though with no little trouble. I traversed the bazaar, and finally reached the palace of the Turkish Embassy, without having received any serious wound either by squeeze, blow, or cut.

A native of Hungary, sent by the Hungarian Academy upon a scientific mission to Central Asia, what had I to do at the Turkish Embassy? This will appear from the Preface, to which I respectfully request my readers' attention, in spite of the prejudice condemning such introductions as tiresome and unnecessary.

With Haydar Efendi, who then represented the Porte at the Persian Court, I had been already acquainted at Constantinople. He had previously filled similar functions at St. Petersburg and at Paris. But, notwithstanding my being personally known to him, I was bearer also of letters from his most esteemed friends; and, counting upon the oft-proved hospitality of the Turks, I felt sure of meeting with a good reception. I consequently regarded the residence of the Turkish Embassy as my future abode; and as these gentlemen had resorted already to their yailar or summer seat at Djizer (eight English miles from Teheran), I only changed my clothes, and after indulging in a few hours' repose to atone for my recent sleepless nights, I mounted an ass, hired for an excursion into the country, and in two hours found myself in the presence of the Efendis, who, in a magnificent tent of silk, were just about to commence a dinner possessing in my eyes still superior magnificence and attraction.

My reception, both by the ambassador and the secretaries, was of the most friendly description: room was soon found for me at the table, and in a few moments we were in deep conversation, respecting Stamboul and her beautiful views, the Sultan and his mode of government. Ah! how refreshing in Teheran is the recollection of the Bosphorus!

What wonder if, in the course of the conversation, frequent comparisons were instituted between the Persian and the Turkish manner of living?

If one too hastily gives way to first impressions, Iran, the theme of so much poetic enthusiasm, is, after all, nothing but a frightful waste; whereas Turkey is really an earthly paradise. I accord to the Persian all the politeness of manners, and all the readiness and vivacity of wit, that are wanting to the Osmanli; but in the latter the absence of these qualities is more than compensated by an integrity and an honourable frankness not possessed by his rival. The Persian can boast a poetic organisation and an ancient civilisation. The superiority of the Osmanli results from the attention he is paying to the languages of Europe, and his disposition gradually to acquaint himself with the progress that European savans have made in chemistry, physics, and history.

Our conversation was prolonged far into night. The following days were devoted to my presentation at the other European embassies. I found Count Gobineau, the Imperial ambassador, under a small tent in a garden like a caldron, where the heat was awful. Mr. Alison was more comfortably quartered in his garden at Gulahek, purchased for him by his Government. He was very friendly. I had often the opportunity, at his hospitable table, of studying the question why the English envoys everywhere distinguish themselves amongst their diplomatic brethren, by the comfortableness as well as the splendour of their establishments. In addition to the diplomatic corps of Europe, I found at that time at Teheran many officers, French or Italian; an Austrian officer, too, of the engineers, R. von Gasteiger; all of them in the service of the Shah, with liberal allowances. {6} These gentlemen, as I heard, were disposed to render themselves very serviceable, possessing all the requisite qualifications; but any benefit that might have resulted was entirely neutralised by the systematic want of system that existed in Persia, and by the low intrigues of the Persians.

The object of Ferrukh Khan's diplomatic journeys in Europe was in reality to show our cabinets how much Iran had it at heart to obtain admittance into the comity of States. He begged aid everywhere, that his country might have the wondrous elixir of civilisation imparted to it as rapidly as possible. All Europe thought that Persia was really upon the point of adopting every European custom and principle. As Ferrukh Khan has a long beard, wears long robes and a high hat, which give him a very earnest look, our ministers were kind enough to attach to him unlimited credit. Wishing to honour a regular Government in Persia, troops of officers, artists, and artisans flocked to him. They went still further, and hastened to return the visits of the Envoy Extraordinary of the Shah. In consequence we saw Belgium, at no small expense, forwarding an ambassador to Persia to study commercial relations, to make treaties of commerce, and to give effect to numberless other strokes of policy. He arrived, and I can scarcely imagine that his first report home could have begun with 'Veni, vidi, vici,' or that he could have felt the slightest desire to pay a second visit to 'la belle Perse.' Next to Belgium came Prussia. The learned diplomatist Baron von Minutoli, to whom the mission was entrusted, devoted his life to it. His thirst after science impelled him to proceed to South Persia; and at only two days' journey from 'heavenly Shiraz,' as the Persians call it, he fell a sacrifice to the pestilential air, and now {7} reposes in the place last mentioned, a few paces from Hafiz, and behind the Baghi Takht.

A few days after I came, the embassy of the new kingdom of Italy arrived also, consisting of twenty persons, divided into diplomatic, military, and scientific sections. The object they had in view has remained always a mystery to me. I have much to recount respecting their reception, but prefer to keep these details for a better occasion, and to busy myself more especially with the preparations I then made for my own journey.

By the kind offices of my friends at the Turkish Embassy, I was in a condition very little suited to the character of a mendicant Dervish which I was about to assume: the comforts I was enjoying were heartily distasteful to me, and I should have preferred, after my ten days' repose at Teheran, to proceed at once to Meshed and Herat, had not obstacles, long dreaded, interfered with my design. Even before the date of my leaving Constantinople, I had heard, by the daily press, of the war declared by Dost Mohammed Khan against his son-in-law and former vassal at Herat, Sultan Ahmed Khan, because the latter had broken his fealty to him, and had placed himself under the suzerainty of the Shah of Persia. Our European papers seemed to me to exaggerate the whole matter, and the story failed to excite in me the apprehensions it really ought to have done. I regarded the difficulties as unreal, and began my journey. Nevertheless, here in Teheran, at a distance of only thirty-two days' journey from the seat of war, I learnt from undeniable sources, to my very great regret, that the war in those parts had really broken off all communications, and that since the siege had begun, no karavan, still less any solitary {8} traveller, could pass either from or to Herat. Persians themselves dared not venture their wares or their lives; but there would have been far more cause for apprehension in the case of a European whose foreign lineaments would, in those savage Asiatic districts, even in periods of peace, be regarded by an Oriental with mistrust, and must singularly displease him in time of war. The chances, indeed, seemed to be, if I ventured thither, that I should be unceremoniously massacred by the Afghans. I began to realise my actual position, and convinced myself of the impossibility, for the moment, of prosecuting my journey under such circumstances; and in order not to reach, during the wintry season, Bokhara, in the wastes of Central Asia, I immediately determined to postpone my journey till next March, when I should have the finest season of the year before me; and, perhaps, in the meantime the existing political relations, which barricaded Herat, the gate of Central Asia, from all approach, might have ceased. It was not till the beginning of September that I became reconciled to this necessity. It will be readily understood how unpleasant it was for me to have to spend five or six months in a country possessing for me only secondary interest, and respecting which so many excellent accounts have already appeared. Not, then, with any serious intention of studying Persia, but rather to withdraw myself from a state of inactivity calculated to be prejudicial to my future purposes, I quitted, in a semi-dervish character, my hospitable Turkish friends, and proceeded at once by Ispahan to Shiraz, and so obtained the enjoyment of visiting the oft-described monuments of ancient Iran civilisation.

| RETURN TO TEHERAN |

| RELIEF OF SUNNITES, DERVISHES, AND HADJIS AT THE TURKISH EMBASSY |

| AUTHOR BECOMES ACQUAINTED WITH A KARAVAN OF TARTAR HADJIS RETURNING FROM MECCA |

| THE DIFFERENT ROUTES |

| THE AUTHOR DETERMINES TO JOIN THE HADJIS |

| HADJI BILAL |

| INTRODUCTION OF AUTHOR TO HIS FUTURE TRAVELLING COMPANIONS |

| ROUTE THROUGH THE YOMUTS AND THE GREAT DESERT DECIDED UPON. |

The Parthians held it as a maxim to accord no passage over their territory to any stranger.--Heeren, Manual of Ancient History.

Towards the middle of January 1863, I found myself back in Teheran, and again sharing the hospitality of my Turkish benefactors. A change came over me; my hesitation was at an end, my decision was made, my preparations hastened. I resolved, even at the greatest sacrifice, to carry out my design. It is an old custom of the Turkish Embassy to accord a small subsidy to the Hadjis and Dervishes, who every year are in the habit of passing in considerable numbers through Persia towards the Turkish Empire. This is a real act of benevolence for the poor Sunnitish mendicants in Persia, who do not obtain a farthing from the Shiitish Persians. The consequence was, that the Hotel of the Embassy received guests from the most remote parts of Turkestan. I felt the greatest pleasure whenever I saw these ragged wild Tartars enter my apartment. They had it in their power to give {10} much real information respecting their country, and their conversations were of extreme importance for my philological studies. They, on their part, were astonished at my affability, having naturally no idea of the objects which I had in view. The report was soon circulated in the karavanserai, to which they resorted in their passage through, that Haydar Efendi, the ambassador of the Sultan, has a generous heart; that Reshid Efendi (this was the name I had assumed) treats the Dervishes as his brethren; that he is probably himself a Dervish in disguise. As people entertained those notions, it was no matter of surprise to me that the Dervishes who reached Teheran came first to me, and then to the minister; for access to the latter was not always attainable, and now, through me, they found a ready means of obtaining their obolus, or the satisfaction of their other wishes.

It was thus that in the morning of the 20th March four Hadjis came to me with the request that I would present them to the Sultan's envoy, as they wished to prefer a complaint against the Persians who, on their return from Mecca, at Hamadan, had exacted from them the Sunni tribute--an exaction not only displeasing to the Shah of Persia, but long since forbidden by the Sultan. For here it must be remarked, that the good Tartars think that the whole world ought to obey the chief of their religion, the Sultan. [Footnote 3]

[Footnote 3: In the eyes of all the Sunnites, the lawful khalife (successor) of Mahomet is he who is in possession of the precious heritage, which comprises--1st, all the relics preserved in Stamboul, in the Hirkai Seadet, e.g. the cloak, beard, and teeth of the Prophet, lost by him in a combat; articles of clothing, Korans, and weapons which belonged to the first four khalifs, 2ndly, the possession of Mecca and Medina, Jerusalem, and other places of pilgrimage resorted to by the Islamite.]

'We desire,' they say, 'from his excellency the ambassador, no money: we pray only, that for the future our Sunnitish brethren may visit the holy places without molestation.' Words so unselfish proceeding from the mouth of an Oriental much surprised me. I scrutinised the wild features of my guests, and must avow that, barbarous as they seemed, wretched as was their clothing, I was yet able to discover in them a something of nobility, and from the first moment was prepossessed in their favour. I had a long conversation with them, to inform myself more fully respecting their companions, and the route which they had selected to go to Mecca, and the one which they thought of taking after leaving Teheran. The spokesman of the party was, for the most part, a Hadji from Chinese Tartary (called also Little Bokhara), who had concealed his ragged dress under a new green Djubbe (over-dress), and wore on his head a colossal white turban, and, by his fiery glance and quick eye, showed his superiority over the whole body of his associates. After having represented himself as the Court Imam of the Vang (Chinese Governor) of Aksu (a province in Chinese Tartary), who had twice visited the Holy Sepulchre--hence being twofold a Hadji--he made me acquainted with his friend seated near him, and gave me to understand that the persons present were to be regarded as the chiefs of the small Hadji karavan, amounting to twenty-four in all. 'Our company,' said their orator, 'consists of young and old, rich and poor, men of piety, learned men and laity; still we live together with the greatest simplicity, since we are all from Khokand and Kashgar, and have amongst us no Bokhariot, no viper of that race.' The hostility of the Özbeg (Tartar) tribes of Central {12} Asia to the Tadjiks (the ancient Persian inhabitants) had been long previously known to me: I listened, therefore, without making any comment, and preferred informing myself of the plan of their journey onwards. 'From Teheran to our homes,' the Tartars explained, 'we have four roads: viz., first, by Astrakhan, Orenburg, and Bokhara; secondly, by Meshed, Herat, and Bokhara; thirdly, by Meshed, Merv, and Bokhara; fourthly, through the Turkoman wilderness, Khiva, and Bokhara. The first two are too costly, and the war at Herat is also a great obstacle; the last two, it is true, are very dangerous routes. We must, nevertheless, select one of these, and we wish, therefore, to ask your friendly counsel.'

We had now been nearly an hour in conversation. It was impossible not to like their frankness, and in spite of the singular lineaments marking their foreign origin, their wretched clothing, and the numerous traces left behind by their long and fatiguing journeys--all which lent a something forbidding to their appearance--I could not refrain from the thought. What if I journeyed with these pilgrims into Central Asia? As natives, they might prove my best Mentors: besides, they already know me as the Dervish Reshid Efendi, and have seen me playing that part at the Turkish Embassy, and are themselves on the best understanding with Bokhara, the only city in Central Asia that I really feared from having learnt the unhappy lot of the travellers who had preceded me thither. Without much hesitation, my resolution was formed. I knew I should be questioned as to the motives that actuated me in undertaking such a journey. I knew that to an Oriental 'pure sang' it was impossible to assign a scientific {13} object. They would have considered it ridiculous, perhaps even suspicious, for an Efendi--that is, for a gentleman with a mere abstract object in view--to expose himself to so many dangers and annoyances. The Oriental does not understand the thirst for knowledge, and does not believe much in its existence. It would have been the height of impolicy to shock these fanatical Musselmans in their ideas. The necessity of my position, therefore, obliged me to resort to a measure of policy, of deception, which I should otherwise have scrupled to adopt. It was at once flattering to my companions, and calculated to promote the design I had in view. I told them, for instance, that I had long silently, but earnestly, desired to visit Turkestan (Central Asia), not merely to see the only source of Islamite virtue that still remained undefiled, but to behold the saints of Khiva, Bokhara, and Samarcand. It was this idea, I assured them, that had brought me hither out of Roum (Turkey). I had now been waiting a year in Persia, and I thanked God for having at last granted me fellow-travellers, such as they were (and I here pointed to the Tartars), with whom I might proceed on my way and accomplish my wish.'

When I had finished my speech, the good Tartars seemed really surprised, but they soon recovered from their amazement, and remarked that they were now perfectly certain of what they before only suspected, my being a Dervish. It gave them, they said, infinite pleasure that I should regard them as worthy of the friendship that the undertaking so distant and perilous a journey in their company implied. 'We are all ready not only to become your friends, but your servants,' said Hadji Bilal (such was the name of their {14} orator above mentioned); 'but we must still draw your attention to the fact that the routes in Turkestan are not as commodious nor as safe as those in Persia and in Turkey. On that which we shall take, travellers meet often for weeks with no house, no bread, not even a drop of water to drink; they incur, besides, the risk of being killed, or taken prisoners and sold, or of being buried alive under storms of sand. Ponder well, Efendi, the step! You may have occasion later to rue it, and we would by no means wish to be regarded as the cause of your misfortune. Before all things, you must not forget that our countrymen at home are far behind us in experience and worldly knowledge, and that, in spite of all their hospitality, they invariably regard strangers from afar with suspicion: and how, besides, will you be able without us and alone to perform that great return journey?' That these words produced a great impression it is easy to imagine, but they did not shake me in my purpose. I made light of the apprehensions of my friends, recounted to them how I had borne former fatigues, how I felt averse to all earthly comforts, and particularly to those Frankish articles of attire of which we would have to make a sacrifice. 'I know,' I said, 'that this world on earth resembles an hotel, [Footnote 4] in which we merely take up our quarters for a few days, and whence we soon move away to make room for others, and I laugh at the Musselmans of the present time who take heed not merely for the moment but for ten years of onward existence. Yes, dear friend, take me with you; I must hasten away from this horrid kingdom of Error, for I am too weary of it.'

[Footnote 4: Mihmankhanei pendjruzi, 'a five days' hostelry,' is the name employed by the philosophers of the East to signify this earthly abode.]

My entreaties prevailed; they could not resist me: I was consequently immediately chosen by the chiefs of the Dervish karavan as a fellow-traveller: we embraced and kissed. In performing this ceremony, I had, it is true, some feeling of aversion to struggle against. I did not like such close contact with those clothes and bodies impregnated with all kinds of odours. Still, my affair was settled. It only now remained for me to see my benefactor, Haydar Efendi, to communicate to him my intentions, ask him for his recommendation to the Hadjis, whom I proposed immediately to present to him.

I counted, of course, at first upon meeting with great opposition, and accordingly I was styled a lunatic who wanted to journey to a place from which few who had preceded me had returned; nor was I, they said, content with that, but I must take for my guides men who for the smallest coin would destroy me. Then they drew me the most terrifying pictures; but, seeing that all efforts to divert me from my plans were fruitless, they began to counsel me, and in earnest to consider how they could be of service in my enterprise. Haydar Efendi received the Hadjis, spoke to them of my design in the same style as I had used, and recommended me to their hospitality, with the remark that they might look for a return for any service rendered by them to an Efendi, a servant of the Sultan, now entrusted to their charge. At this interview I was not present, but I was informed that they promised the faithful performance of their engagement.

The reader will see how well my worthy friends kept their promise, and how the protection of the excellent Envoy of Turkey was the means of saving my life so often threatened, and that it was always the good faith of my pilgrim companions that rescued me from the most critical positions. In the course of conversation, I was told that Haydar Efendi, when Bokhara came under discussion, expressed his disapprobation of the policy of the Emir. [Footnote 5] He afterwards demanded the entire list of all the poor travellers, to whom he gave about fifteen ducats--a magnificent donation to these people, who sought no greater luxury in the world than bread and water.

[Footnote 5: Emir is a title given to the sovereign of Bokhara, whereas the princes of Khiva and Khokand are styled Khans. ]

It was fixed that we should begin our journey a week later. In the interval, Hadji Bilal alone visited me, which he did very frequently, presenting to me his countrymen from Aksu Yarkend and Kashgar. They looked to me, indeed, rather like adventurers, dreadfully disfigured, than pious pilgrims. He expressed especial interest in his adopted son, Abdul Kadér, a bumpkin of the age of twenty-five years, whom he recommended to me as 'famulus.' 'He is,' said Hadji Bilal, 'a faithful fellow: although awkward, he may learn much from you; make use of him during your journey; he will bake bread and make tea for you, occupations that he very well understands.' Hadji Bilal's real object, however, was not merely that he should bake my bread, but help me to eat it; for he had with him a second adopted son on the journey, and the two, with appetites sharpened by their wanderings on foot, were too heavy a burthen upon the resources of my friend. I promised to accede to their request, and they were accordingly delighted. To {17} say the truth, the frequent visits of Hadji Bilal had made me a little suspicious: for I readily thought this man supposes that in me he has had a good catch, he takes a great deal of trouble to get me with him; he dreads my not carrying out my intentions. But no, I dare not, I will not think ill of him; and so to convince him of my unbounded confidence, I showed the little sum of money that I was taking with me for the expenses of the journey, and begged him to instruct me as to what mien, dress, and manners I ought to assume to make myself as much as possible like my travelling companions, in order that by doing so I might escape unceasing observation. This request of mine was very agreeable to him, and it is easy to conceive how singular a schooling I then received.

Before all things he counselled me to shave my head, and exchange my then Turkish-European costume for one of Bokhara; as far as possible to dispense with bedclothes, linen, and all such articles of luxury. I followed exactly his direction, and my equipment, being of a very modest nature, was very soon made; and three days before the appointed day I stood ready prepared for my great adventure.

In the meantime I went one day to the karavanserai, where my travelling companions were quartered, to return their visit. They occupied two little cells; in one were fourteen, in the other ten persons. They seemed to me dens filled with filth and misery. That impression will never leave me. Few had adequate means to proceed with their journey; for the majority their beggar's staff was the sole resource. I found them engaged in an occupation of the toilette which I will not offend the reader by recording, although {18} the necessity of the case obliged me myself later to resort to it.

They gave me the heartiest reception, offered me green tea, and I had to go through the torture of drinking without sugar a large Bokhariot bowl of the greenish water. Worse still, they wished to insist upon my swallowing a second; but I begged to be excused. I was now permitted even to embrace my new associates; by each I was saluted as a brother; and after having broken bread with them individually, we sat down in a circle in order to take counsel as to the route to be chosen. As I before remarked, we had the choice between two; both perilous, and traversing the desert home of the Turkomans, the only difference being that of the tribes through which they pass. The way by Meshed, Merv, and Bokhara was the shortest, but would entail the necessity of proceeding through the midst of the Tekke tribes, the most savage of all the Turkomans, who spare no man, and who would not hesitate to sell into slavery the Prophet himself, did he fall into their hands. On the other route are the Yomut Turkomans, an honest, hospitable people. Still that would necessitate a passage of forty stations through the desert, without a single spring of sweet drinking water. After some observations had been made, the route through the Yomuts, the Great Desert, Khiva, and Bokhara was selected. 'It is better, my friends, to battle against the wickedness of the elements than against that of men. God is gracious, we are on His way; He will certainly not abandon us.' To seal their determination, Hadji Bilal invoked a blessing, and whilst he was speaking we all raised our hands in the air, and when he came to an end every one seized his beard and said aloud, 'Amen!' We rose from {19} our seats, and they told me to make my appearance there two days after, early in the morning, to take our departure together. I returned home, and during these two days I had a severe and a violent struggle with myself. I thought of the dangers that encircled my way, of the fruits that my travels might produce. I sought to probe the motives that actuated me, and to judge whether they justified my daring; but I was like one bewitched and incapable of reflection. In vain did men try to persuade me that the mask they bore alone prevented me from perceiving the real depravity of my new associates; in vain did they seek to deter me by the unfortunate fate of Conolly, Stoddart, and Moorcroft, with the more recent mishaps of Blôcqueville, who fell into the hands of the Turkomans, and who was only redeemed from slavery by the payment of 10,000 ducats: their cases I only regarded as accidental, and they inspired me with little apprehension. I had only one misgiving, whether I had enough physical strength to endure the hardships arising from the elements, unaccustomed food, bad clothing, without the shelter of a roof, and without any change of attire by night; and how then should I with my lameness be able to journey on foot, I, who was liable to be tired so soon? and here for me was the chief hazard and risk of my adventure. Need I say which side in this mental struggle gained the victory?

The evening previous I bade adieu to my friends at the Turkish Embassy; the secret of the journey was entrusted but to two; and whereas the European residents believed I was going to Meshed, I left Teheran to continue my course in the direction of Astrabad and the Caspian Sea.

| DEPARTURE FROM TEHERAN IN NORTH-EASTERLY DIRECTION |

| THE COMPONENT MEMBERS OF KARAVAN DESCRIBED |

| ILL-FEELING OF SHIITES TOWARDS THE SUNNITISH HADJIS |

| MAZENDRAN |

| ZIRAB |

| HEFTEN |

| TIGERS AND JACKALS |

| SARI |

| KARATEPE. |

Beyond the Caspian's iron gates. --Moore.

On the morning of the 28th March, 1863, at an early hour, I proceeded to our appointed rendezvous, the karavanserai. Those of my friends whose means permitted them to hire a mule or an ass as far as the Persian frontiers were ready booted and spurred for their journey; those who had to toil forwards on foot had on already their jaruk (a covering for the feet appropriate for infantry), and seemed, with their date-wood staves in their hands, to await with great impatience the signal for departure. To my great amazement, I saw that the wretched clothing which they wore at Teheran was really their city, that is, their best holiday costume. This they did not use on ordinary occasions; every one had now substituted his real travelling dress, consisting of a thousand rags fastened round the loins by a cord. Yesterday I regarded myself in my clothing as a beggar; to-day, in the midst of them, I was a king in his royal robes. At last Hadji Bilal raised his hand for the parting benediction; {21} and hardly had every one seized his beard to say 'Amen,' when the pedestrians rushed out of the gate, hastening with rapid strides to get the start of us who were mounted. Our march was directed towards the north-east from Teheran to Sari, which we were to reach in eight stations. We turned therefore towards Djadjerud and Firuzkuh, leaving Taushantepe, the little hunting-seat of the king, on our left; and were, in an hour, at the entrance of the mountainous pass where one loses sight of the plain and city of Teheran. By an irresistible impulse I turned round. The sun was already, to use an Oriental expression, a lance high; and its beams illuminated, not Teheran alone, but the distant gilded dome of Shah Abdul Azim. At this season of the year, Nature in Teheran already assumes all her green luxuriance; and I must confess that the city, which the year before had made so disagreeable an impression upon me, appeared to me now dazzlingly beautiful. This glance of mine was an adieu to the last outpost of European civilisation. I had now to confront the extremes of savageness and barbarism. I felt deeply moved; and that my companions might not remark my emotion, I turned my horse aside into the mountainous defile.

In the meantime my companions were beginning to recite aloud passages from the Koran, and to chant telkins (hymns), as is seemly for genuine pilgrims to do. They excused me from taking part in these, as they knew that the Roumis (Osmanli) were not so strictly and religiously educated as the people in Turkestan; and they besides hoped that I should receive the necessary inspiration by contact with their society. I followed them at a slow pace, and will {22} now endeavour to give a description of them, for the double motive that we are to travel so long together and that they are in reality the most honest people I shall ever meet with in those parts. There were, then,

1. Hadji Bilal, from Aksu (Chinese Tartary), and Court Iman of the Chinese Musselman Governor of the same province: with him were his adopted sons,

2. Hadji Isa, a lad in his sixteenth year; and

3. Hadji Abdul Kader, before mentioned, in the company, and so to say under the protection, of Hadji Bilal. There were besides,

4. Hadji Yusuf, a rich Chinese Tartar peasant; with his nephew,

5. Hadji Ali, a lad in his tenth year, with little, diminutive, Kirghish eyes. The last two had eighty ducats for their travelling expenses, and, therefore, were styled rich; still this was kept a secret: they hired a horse for joint use, and when one was riding the other walked.

6. Hadji Amed, a poor Mollah, who performed his pilgrimage leaning upon his beggar's staff. Similar in character and position was

7. Hadji Hasan, whose father had died on the journey, and who was returning home an orphan;

8. Hadji Yakoub, a mendicant by profession, a profession inherited by him from his father;

9. Hadji Kurban (senior), a peasant by birth, who as a knife-grinder had traversed the whole of Asia, had been as far as Constantinople and Mecca, had visited upon occasions Thibet and Calcutta, and twice the Kirghish Steppes, to Orenburg and Taganrok;

10. Hadji Kurban, who also had lost his father and brother on the journey;

11. Hadji Said; and

12. Hadji Abdur Rahman, an infirm lad of the age of fourteen years, whose feet were badly frozen in the snow of Hamadan, and who suffered fearfully the whole way to Samarcand.

The above-named pilgrims were from Khokand, Yarkend, and Aksu, two adjacent districts; consequently they were Chinese Tartars, belonging to the suite of Hadji Bilal, who was besides upon friendly terms with

13. Hadji Sheikh Sultan Mahmoud from Kashgar, a young enthusiastic Tartar, belonging to the family of a renowned saint, Hazreti Afak, whose tomb is in Kashgar. The father of my friend Sheikh Sultan Mahmoud was a poet; Mecca was in imagination his child: after the sufferings of long years he reached the holy city, where he died. His son had consequently a double object in his pilgrimage: he proceeded as pilgrim alike to the tombs of his prophet and his father. With him were

14. Hadji Husein, his relative; and

15. Hadji Ahmed, formerly a Chinese soldier belonging to the regiment Shiiva that bears muskets and consists of Musselmans.

From the Khanat Khokand were

16. Hadji Salih Khalifed, candidate for the Ishan, which signifies the title of Sheikh, consequently belonging to a semi-religious order; an excellent man of whom we shall have often occasion to speak. He was attended by his son,

17. Hadji Abdul Baki, and his brother

18. Hadji Abdul Kader the Medjzub, which means, 'impelled by the love of God,' and who, whenever he has shouted two thousand times 'Allah,' foams at the mouth and falls into a state of ecstatic blessedness (Europeans name this state epilepsy).

19. Hadji Kari Messud (Kari has the same signification in Turkey as Hafiz, one who knows the whole Koran by heart). He was with his son,

20. Hadji Gayaseddin;

21. Hadji Mirza Ali; and

22.Hadji Ahrarkuli; the bags of the two last-named pilgrims still contained some of their travelling provision in money, and they had a beast hired between them.

23. Hadji Nur Mohammed, a merchant who had been twice to Mecca; but not on his own account, only as representing another.

We advanced up the slopes of the chain of the Elburs mountains, which rose higher and higher. The depression of spirits in which I was, was remarked by my friends, who did all in their power to comfort me. It was, however, particularly Hadji Salih who encouraged me with the assurance that 'they would all feel for me the love of brothers, and the hope that, by the aid of God, we should soon be at liberty beyond the limits of the Shiite heretics, and be able to live comfortably in lands subject to the Sunnite Turkomans, who are followers of the same faith.' A pleasant prospect certainly, thought I; and I rode more quickly on in order to mix with the poor travellers who were preceding us on foot. Half an hour later I came up with them. I noticed how cheerfully they wended their way; men who had journeyed on foot from the remotest Turkestan to Mecca, and back again on foot. Whilst many were singing merry songs, which had great resemblance to those of Hungary, others were recounting the adventures they had gone through in the course of their wanderings; a conversation which occasioned {25} me great pleasure, as it served to make me acquainted with the modes of thought of those distant tribes, so that at the very moment of my departure from Teheran I found myself, so to say, in the midst of Central Asiatic life.

During the daytime it was tolerably warm, but it froze hard in the early morning hours, particularly in the mountainous districts. I could not support the cold in my thin clothing on horseback, so I was forced to dismount to warm myself. I handed my horse over to one of the pedestrian pilgrims. He gave me his stick in exchange, and so I accompanied them a long way on foot, hearing the most animated descriptions of their homes; and when their enthusiasm had been sufficiently stimulated by reminiscences of the gardens of Mergolan, Namengan, and Khokand, they all began with one accord to sing a telkin (hymn), in which I myself took part by screaming out as loud as I was able, 'Allah, ya Allah!'

Every such approximation to their sentiments and actions on my part was recounted by the young travellers to the older pilgrims, to the great delight of the latter, who never ceased repeating 'Hadji Reshid (my name amongst my companions) is a genuine Dervish; one can make anything out of him.'

After a rather long day's march, on the fourth day we reached Firuzkuh, which hes rather high, and is approached by a very bad road. The city is at the foot of a mountain, which is crowned by an ancient fortification, now in ruins; a city of some importance from the fact that there the province Arak Adjemi ends, and Mazendran begins. The next morning our way passed in quite a northerly direction, and we had scarcely proceeded three or four hours when we {26} reached the mouth of the great defile, properly called Mazendran, which extends as far as the shores of the Caspian. Scarcely does the traveller move a few steps forwards from the karavanserai on the top of the mountain, when the bare dry district changes, as by enchantment, into a country of extraordinary richness and luxuriance. One forgets that one is in Persia, on seeing around everywhere the splendour of those primaeval forests and that magnificent green. But why linger over Mazendran and all its beauties, rendered so familiar to us by the masterly sketches of Frazer, Conolly, and Burnes?

On our passage Mazendran was in its gala attire of spring. Its witchery made the last spark of trouble disappear from my thoughts. I reflected no more on the perils of my undertaking, but allowed imagination to dwell only upon sweet dreams of the regions through which lay my onward path, visions of the various races of men, customs, and usages which I was now to see. I must expect to behold, it is true, scenes a perfect contrast to these; I must anticipate immense and fearful deserts--plains whose limits are not distinguishable to the human eye, and where I should have for days long to suffer from want of water. The enjoyment of that spot was doubly agreeable, as I was so soon to bid adieu to all sylvan scenes.

Mazendran had its charms even for my companions. Their feelings found expression in regrets that this lovely Djennet (paradise) should have become the possession of the heretical Shiites. 'How singular,' said Hadji Bilal, 'that all the beautiful spots in nature should have fallen into the hands of the unbelievers! The Prophet had reason to say, "This world is the prison of the believers, and the paradise of the unbelievers.'" [Footnote 6]

[Footnote 6: 'Ed dünya sidjn ül mumenin, ve djennet ül kafirin.']

In proof, he cited Hindoostan, where the 'Inghiliz' reign, the beauties of Russia which he had seen, and Frenghistan, that had been described to him as an earthly paradise. Hadji Sultan sought to console the company by a reference to the mountainous districts that lie between Oosh (boundaries of Khokand) and Kashgar. He represented that place to me as far more lovely than Mazendran, but I can hardly believe it.

At the station Zirab we came to the northern extremity of the mountainous pass of Mazendran. Here the immense woods begin, which mark the limits of the shore of the Caspian Sea. We pass along a causeway made by Shah Abbas, but which is fast decaying. Our night quarters--we reached them betimes--was Heften, in the middle of a beautiful forest of boxwood. Our young people started off in quest of a good spring of water for our tea; but all at once we heard a fearful cry of distress. They came flying back, and recounted to us that they had seen animals at the source, which sprang away with long bounds when they approached them. At first I thought they must be lions, and I seized a rusty sword, and found, in the direction they had described, but at a good distance off, two splendid tigers, whose beautifully-striped forms made themselves visible occasionally from the thickets. In this forest the peasants told me that there were numbers of wild beasts, but they very rarely attacked human beings. At all events, we were not molested by the jackals, who even dread a stick, but which are here so numerous that we cannot drive them away. There are jackals throughout {28} all Persia; they are not uncommon even in Teheran, where their howling is heard in the evenings. But still, they did not there approach men, as they did here. They disturbed me the whole night long. I was obliged, in self-defence, to use both hands and feet to prevent their making off with bread-sack or a shoe.

The next day we had to reach Sari, the capital of Mazendran. Not far from the wayside lies Sheikh Tabersi, a place long defended by the Babis (religious enthusiasts who denied Mohammed and preached socialism). They made themselves the terror of the neighbourhood. Here also are beautiful gardens, producing in exuberance crops of oranges and lemons. Their fruit, tinted with yellow and red, presented an enchanting contrast with the green of the trees. Sari itself has no beauty to recommend it, but is said to carry on an important trade. As we traversed the bazaar of this last Persian city, we received also the last flood of every possible imprecation and abuse; nor did I leave their insolence without rebuke, although I judged it better not to repeat my threatening movements of stick or sword in the centre of a bazaar and amid hundreds of Shiites.

We only remained in Sari long enough to find horses to hire for a day's journey to the sea-shore. The road passes through many marshes and morasses. It is impossible to perform the journey here on foot. From this point there are many ways by which we can reach the shore of the Caspian, e. g. by Ferahabad (Parabad, as it is called by the Turkomans), Gez, and Karatepe. We preferred, however, the last route, because it would lead us to a Sunnite colony, where we were certain of a hospitable reception, having already had opportunities of becoming acquainted with many of these colonists at Sari, and having found them good people.

After a rest of two days in Sari we started for Karatepe. It was not until evening, after a laborious journey of nine hours, that we arrived. Here it is that the Turkomans first become objects of terror. Piratical hordes of them hide their vessels along the coast, whence extending their expeditions to a distance of a few leagues into the interior, they often return to the shore, dragging a Persian or so in bonds.

| KAEATEPE |

| AUTHOR ENTERTAINED BY AN AFGHAN, NUR-ULLAH |

| SUSPICIONS AS TO HIS DERVISH CHARACTER |

| HADJIS PROVISION THEMSELVES FOR JOURNEY THROUGH DESERT |

| AFGHAN COLONY |

| NADIR SHAH |

| FIRST VIEW OF THE CASPIAN |

| YACOUB THE TURKOMAN BOATMAN |

| LOVE TALISMAN |

| EMBARKATION FOR ASHODRADA |

| VOYAGE ON THE CASPIAN |

| RUSSIAN PART OF ASHOURADA |

| RUSSIAN WAR STEAMERS IN THE CASPIAN |

| TURKOMAN CHIEF, IN THE SERVICE OF RUSSIA |

| APPREHENSION OF DISCOVERY ON THE AUTHOR'S PART |

| ARRIVAL AT GÖMÜSHTEPE AND AT THE MOUTH OF THE GORGHEN. |

| </p> |

Ultra Caspium sinum quidnam esset, ambiguum aliquamcliu fuit. --Pomponius Mela, De Situ Orbis.

Nur-Ullah, an Afghan of distinction, whose acquaintance I had already formed at Sari, conducted me to his house on my arrival at Karatepe; and as I objected to be separated from all my friends, he included Hadji Bilal also in his invitation, and did not rest until I had accepted his hospitality. At first I could not divine the motive of his extraordinary kindness, but I observed a little later that he had heard of the footing upon which I stood at the Turkish Embassy in Teheran, and he wished me to repay his kindness by a letter of recommendation, which I promised, and very willingly gave him before we parted.

I had hardly taken possession of my new abode when the room filled with visitors, who squatted down in a row all round against the walls, first staring at me with their eyes wide open, then communicating to each other the results of their observations, and then uttering aloud their judgment upon the object of my travelling. 'A Dervish,' said the majority, 'he is not, his appearance is anything but that of a Dervish; for the wretchedness of his dress contrasts too plainly with his features and his complexion. As the Hadjis told us, he must be a relative of the ambassador, who represents our Sultan at Teheran,' and here all stood up. 'Allah only knows what a man who issues from so high an origin has to do amongst the Turkomans in Khiva and Bokhara.'

This impudence amazed me not a little. At the first glance they wanted to tear the mask from my face; in the meantime I was acting the genuine part of an Oriental, sat seemingly buried in thought, with the air of one who heard nothing. As I took no part in the conversation, they turned to Hadji Bilal, who told them I was really an Efendi, a functionary of the Sultan, but had withdrawn myself, in pursuance of a Divine inspiration, from the deceptions of the world, and was now engaged with Ziaret (a pilgrimage to the tombs of the saints); whereupon many shook their heads, nor could this subject any more be broached. The true Musselman must never express a doubt when he is told of Divine inspiration (Ilham); and however speaker or listener may be convinced that there is imposture, they are still bound to express their admiration by a 'Mashallah! Mashallah! 'This first scene had, however, clearly unfolded to me that, although still on Persian soil, I had nevertheless at last gained the frontiers of Central Asia; for on hearing the distrustful enquiries of these few Sunnites-- enquiries never made in any part of Persia--I could {32} easily picture to myself the splendid future in store for me further on in the very nest of this people. It was not until two hours had elapsed, spent in chattering and questioning, that these visitors retired and we prepared tea, and then betook ourselves to repose. I was trying to sleep when a man in a Turkoman dress, whom I regarded as a member of the family, came near me, and began to tell me, in strict confidence, that he had travelled the last fifteen years on business matters to and from Khiva; that he was born at Khandahar; but that he had a perfect knowledge of the country of Özbeg and Bokhara; and then proposed that we should be friends, and make the journey together through the Great Desert. I replied, 'All believers are brethren,' [Footnote 7] and thanked him for his friendliness, with the observation that as a Dervish I was very much attached to my travelling companions. He seemed desirous to continue the conversation; but as I let him perceive how inclined I was to sleep, he left me to my slumbers.

[Footnote 7: 'Kulli mumenin ihvetun.']

Next morning Nur-Ullah informed me that this man was a Tiryaki (opium-eater), a scapegrace, whom I should, as much as possible, avoid. At the same time he warned me that Karatepe was the only place for procuring our stock of flour for a journey of two months, as even the Turkomans themselves got their provisions in this place; and that at all events we must furnish ourselves with bread to last as far as Khiva. I left this to Hadji Bilal to manage for me, and ascended in the meantime the black hill which is situated in the village, and from which it derives its name, Karatepe. One side is peopled by Persians, {33} the other by 125 or 150 Afghan families. It is said that this Afghan colony was at the beginning of this century of far more importance than at present, and was founded by the last great conqueror of the Asiatic world, Nadir Shah, who, as is well known, accomplished his most heroic actions at the head of the Afghans and Turkomans. Here also was pointed out to me the spot on the hill where he sat when he passed in review the thousands of wild horsemen who flocked from the farthest recesses of the desert, with their good horses and thirsty swords, under his banners. On these occasions Nadir is described as always having been in a good humour; so Karatepe had its holidays. The precise object of the transplantation of this Sunnite colony is unknown to me, but its existence has been found to be of the greatest service, as the Afghans serve as negotiators between Turkomans and Persians, and without them many a Persian would languish for months in Turkoman bonds, without any medium existing by which his ransom could be effected. On the east of Persia similar services are rendered by the Sunnites of Khaf, Djam, and Bakhyrz, but these have to deal with the Tekke, a far more dangerous tribe than the Yomuts.

From the summit of the black hill I was able to gain a view of the Caspian Sea. It is not the main sea which is here visible, but rather that portion of it shut in by the tongue of land which ends at Ashourada: it is termed the Dead Sea. This tongue of land looks at a distance like a thin strip on the water, whence shoots up a single line of trees, which the eye can follow a long, long way. The sight of this, with its bleak solitary beach, was anything but inspiriting. I burnt with desire to behold its eastern shore, and I {34} hurried back to my abode to ascertain how far our preparations were in a forward state for any embarkation in quest of the Turkoman coast. Nur-Ullah had taken upon himself to make all necessary preparations. The evening before we had been told that for a kran (franc) per head we might be taken to Ashourada by an Afghan vessel employed in supplying the Russians with provisions, and that thence we might, with the aid of Turkomans, reach Gömüshtepe in a few hours. 'In Ashourada itself,' they said, 'there is Khidr Khan, a Turkoman chieftain in the service of Russia, who gives assistance to poor Hadjis, and whom we may also visit.' We were all delighted to learn this, and greeted the intelligence with acclamation. How great then was my astonishment when I learnt that this Afghan was ready for the voyage, that he would allow the Hadjis to accompany him, but that he objected to my highness, whom he regarded as a secret emissary of the sultan; fearing lest he might lose his means of subsistence from the Russians should he venture to take such an individual on board his vessel. His resolution surprised me not a little. I was glad to hear my companions declare that if he did not take me they would not go, but would prefer to wait another occasion. So I heard, in an accent of peculiar emphasis, from the opium-smoker, Emir Mehemmed. Later, however, came the Afghan himself (his name was Anakhan), expressing his regret, promising secresy, and begging me to give him a letter of recommendation to Haydar Efendi. I considered it good policy not to say a syllable calculated to quiet his apprehensions, laughed heartily at his ideas, and promised to leave for him with Nur-Ullah some lines for Teheran, a promise {35} which I did not forget. I felt it quite necessary to leave my real character enveloped in a veil of doubt or mystery. The Oriental, and particularly the Islamite, bred up in lies and treachery, always believes the very contrary of what a man shows particular earnestness in convincing him of, and the slightest protestation on my part would have served to confirm their suspicions. No further allusion was made to the subject, and that very evening we heard that a Turkoman who plies to Gömüshtepe was prepared, from feelings of mere piety, without remuneration, to take all the Hadjis with him; that we had but to station ourselves early in the morning on the seashore, to profit by a tolerably favourable wind. Hadji Bilal, Hadji Salih, and myself, the recognised triumvirate of the mendicant karavan, immediately paid a visit to the Turkoman, whose name was Yakoub; he was a young man, with an uncommonly bold look; he embraced each of us, and did not object to wait a day that we might complete our provisioning. He received beforehand his benediction from Hadji Bilal and Hadji Salih. We had already risen to go, when he called me aside, and tried to get me to tarry a few moments with him. I remained behind. He then, with a certain timidity, told me that he had long entertained an unhappy unreturned affection for a girl of his own race, and that a Jew, an accomplished magician, who for the moment was staying in Karatepe, had promised to prepare an efficacious Nuskha (talisman) if he would but procure thirty drops of attar of roses fresh from Mecca, as this could not be dispensed with in the formula.

'We know,' said Yakoub, 'that the Hadjis bring back with them out of the holy city essences of roses {36} and other sweet perfumes; and as you are the youngest of their chiefs, I apply to you, and hope you will listen to my entreaty.'

The superstition of this son of the desert did not so much astonish me as the trust he had reposed in the words of the cunning Israelite, and as my travelling friends had really brought with them such attar of roses his wish was soon gratified. The joy that he displayed was almost childish. The second day afterwards, early in the morning, we all assembled on the sea-shore, each furnished, besides his mendicant equipment, with a sack of flour. We lost considerable time before the boat (called Teïmil), which was formed out of a hollow tree, set us alongside the little vessel, or skiff, called by Turks 'mauna.' This, on account of the shallowness of the water near the shore, was lying out at sea at a distance of about an English mile. Never shall I forget the mode in which we embarked. The small tree, in the hollow of which passengers were stowed away, together with flour and other effects, in the most diversified confusion, threatened each instant to go to the bottom. We had to bless our good fortune that we arrived on board all dry. The Turkomans have three kinds of vessels--

(1) Keseboy, furnished with a mast and two sails, one large and one small, principally for carrying cargoes;

(2) Kayuk, with a simple sail, generally used on their predatory expeditions; and

(3) The Teïmil, or skiff, already mentioned.

The vessel provided for our use by Yakoub was a keseboy, that had conveyed a cargo of naphtha, pitch, and salt to the Persian coast from the island Tchereken, and was now homeward-bound with corn on board.

As the vessel had no deck, and consequently had no distinction of place, every one suited himself, and sat down where he wished as he entered. Yakoub, however, observing that this would disturb the trim and management of the vessel, we each seized our bundle and our provisions, and were closely packed in two rows near each other like salted herrings, so that the centre of the boat remained free for the crew to pass backwards and forwards. Our position then was none of the most agreeable. During the daytime it was supportable, but at night it was awful, when sleep threw the sitters from their perpendicular position to the right and left, and I was forced to submit for hours to the sweet burthen of a snoring Hadji. Frequently a sleeper on my right and another on my left fell one over the other upon me: I dared not wake them, for that would have been a heinous sin, to be atoned by never-ending suffering.

It was mid-day on the 10th April, 1863, when a favourable wind distended our sails, driving the little vessel before it like an arrow. On the left side we had the small tongue of land; on the right, thickly covered with wood, extending down to the very sea, stood the mountain upon which rose the Palace Eshref, built by Shah Abbas, the greatest of the Persian kings. The charm of our Argonautic expedition was augmented by the beautiful spring weather; and in spite of the small space within which I was pent up, I was in very good spirits. The thought might have suggested itself to me that I had to-day left the Persian coast; that at last I had reached a point from which there was no drawing back, and {38} where regrets were useless. But no! at that moment no such idea occurred to me. I was firmly convinced that my travelling friends, whose wild appearance had at first rendered them objects of alarm, were really faithful to me, and that under their guidance I might face the greatest dangers.