Title: Carlo Dolci

Author: George Hay

Editor: T. Leman Hare

Release date: January 13, 2013 [eBook #41836]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

On some devices, clicking an illustration will display it in a larger, higher-quality format.

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY

T. LEMAN HARE

| Artist. | Author. |

| VELAZQUEZ. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| REYNOLDS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| TURNER. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| ROMNEY. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| GREUZE. | Alys Eyre Macklin. |

| BOTTICELLI. | Henry B. Binns. |

| ROSSETTI. | Lucien Pissarro. |

| BELLINI. | George Hay. |

| FRA ANGELICO. | James Mason. |

| REMBRANDT. | Josef Israels. |

| LEIGHTON. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| RAPHAEL. | Paul G. Konody. |

| HOLMAN HUNT. | Mary E. Coleridge. |

| TITIAN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| MILLAIS. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| CARLO DOLCI. | George Hay. |

| GAINSBOROUGH. | Max Rothschild. |

| LUINI. | James Mason. |

| TINTORETTO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

Others in Preparation.

This work, which is the only one by Dolci in the National Gallery, represents the Virgin presenting flowers to the Divine Infant. In composition and drawing it is one of the most happy efforts of Dolci. A small canvas of 2 feet 6 inches, it came into the possession of the National Gallery in 1876 through the Wynn Ellis bequest.

| Page | ||

| I. | Introduction | 11 |

| II. | The Artist's Life | 22 |

| III. | The Artist's Work | 62 |

| Plate | ||

| I. | Virgin and Child | Frontispiece |

| National Gallery, London | ||

| Page | ||

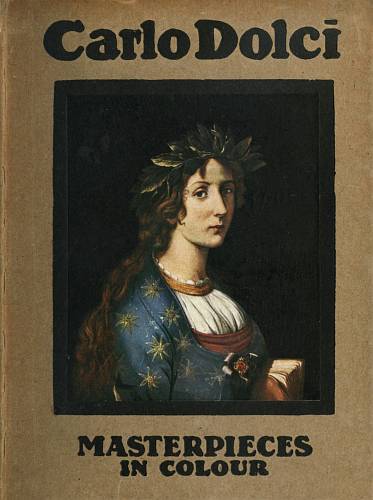

| II. | Poetry | 14 |

| In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence | ||

| III. | The Magdalen | 24 |

| In Florence | ||

| IV. | The Eternal Father | 34 |

| Part of an alter-piece in Fresco, Florence | ||

| V. | Angel of the Annunciation | 40 |

| In Florence | ||

| VI. | The Magdalen | 50 |

| In the Corsini Palace, Rome | ||

| VII. | Portrait of the Artist | 60 |

| In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence | ||

| VIII. | The Sleep of St. John | 70 |

| In the Pitti Palace, Florence |

IF, in dealing with the life and work of Carlo Dolci, a writer sets down an apology by way of preface, it is in recognition of the fact that the art form of this painter, for all that it is serious and beautiful,[12] is one of the first that we outgrow. There are artists in plenty, and their names are written large in the roll of fame, whose work makes no immediate appeal to us. Rembrandt, Velazquez, Tintoretto, one and all must be approached with an eye that has received some measure of training, and then the beauty of their work brings perennial enjoyment, though at first it could not be easily seen. Other men who lived and thought and wrought on quite a different plane appeal to the eye right away. Their work conceals nothing, its beauties are patent and entirely free from reticence or subtlety; such painters bear the same relation to the really great masters of the art as the writers of the songs sung at Ballad Concerts bear to the composers of the Pastoral, Unfinished or Pathetic Symphonies. Yet in their way it must be admitted that both the[14] writer of ballads, and the painter of pictures that please, do a certain service. They help the uninitiated along the path that leads to higher things; they are a support that the timid explorer may rely upon until he has learnt to walk alone. There comes a time when the painter of pretty pictures and the writer of pretty songs cease to please us; we have mastered what we are pleased to regard as the tricks of both, and feel a little contempt for them. Then, perhaps, some of us are even anxious to forget our former attitude towards the men who charmed our youthful fancy. We think we have become as gods, knowing good from evil, and in this mood we ignore the fine points of work we criticise. Carlo Dolci was in many ways a man who never grew up, but he had a keen and almost childish sense of beauty and of righteousness, and he sought to[16] express it on canvas, leaving the deeper truths of art, and the more important aspects of life, to be treated by those who cared to deal with them. Beauty obvious, palpable; sentimental virtue as broad and unblushing as that of Edmund Spenser's heroines, were the themes that the artist chose to dwell upon, and it would be in the last degree unwise to forget that such a message as his will make a strong appeal to the rising generation as long as the world endures, and that by the time those who have been pleased are pleased no longer, there will be others waiting to take their place. Moreover Carlo Dolci laboured with a certain measure of sincerity until the message he had chosen to deliver to his generation became as true to him as the visions that helped Fra Angelico while he laboured in the cells of St. Mark's Convent in Florence.[17] To-day in Florence and in Rome the younger generation seek the pictures of Carlo Dolci and find in them a realisation of certain ideals. We may be a little shocked or even contemptuous, but to recognise the claims of those who are coming on as well as the claims of those who are passing, is to keep a sane outlook on life. For the world was not made for the middle-aged and the experienced, any more than it was created for the immature enthusiasts. There is a place on this planet for us all.

This canvas was painted for the head of the Corsini Family in Rome, when Dolci was a young man. It is one of a series that included Hope, Patience, and Painting. It is now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Carlo Dolci painted, or over-painted, the romance of life. It was his misfortune that he always saw it in the same way. He was like a musician who, having all the keys of the piano at his disposal, regards anything more than the simplest modulation from tonic to dominant and back again as an extravagance to which he must not surrender. Nowadays[18] the horizon of art has widened very considerably; even in literature the obvious has passed out of fashion, but in the rather degenerate days when Carlo Dolci lived physical beauty was in a sense the keynote of all art work. No heroine could reach the last chapter of a romance in safety unless she chanced to be equipped with a measure of beauty that defied the assaults of time. Beauty other than physical was entirely overlooked, or was associated deliberately with good looks. Handsome sinners were as far removed from the public ken as ugly saints. In many senses the world was younger than it is to-day; indeed, it has aged more in the past two hundred years than in five hundred that went before. Consequently the living painter of prettiness stands now at a certain disadvantage. Perhaps he is more handicapped in the struggle for recognition now than he[19] will be a hundred years hence, because we have but recently taken possession of our heritage of culture and judgment and are a little anxious to forget that we have been young. It may be granted that while a large collection of the works of a painter who laboured for all time pleases our every mood, it would be hard to live in a room in which Dolci's pictures dominated the walls. Swinburne has expressed the position very simply in the first volume of his famous "Poems and Ballads": "A month or twain to live on honeycomb is pleasant; but one tires of scented time."

We suffer from the painter's excess of sweetness, from a sentiment that comes dangerously near to sentimentality, from a quality that is almost as cloying as saccharine; but taken in the proper proportions, relegated to their proper place, the pictures[20] of Carlo Dolci are bound to please, and we feel perhaps a little envious of the man who throughout his life could see nothing that was not gracious and pleasing, and moral and sweet. As we have said, he has his counterpart in literature and in music, and had he not been forced by circumstances he could not control into the immediate neighbourhood of men who had so much more to say than he, Dolci would have received more attention from his contemporaries and from succeeding generations. But, perhaps unfortunately for himself, Dolci is to be found only in the best artistic company of the world. His work hangs in Florence and in Rome cheek by jowl with that of the world's great masters; before the flame of their genius his light pales and becomes insignificant. Yet he is by no means to be despised, for he saw through his own little[21] window a view of the pageantry of life that must have made him happy, and was destined to stimulate generations that have passed and generations still unborn. His pictures do not lack sincerity, and do not fail to express the best that was in him. He saw Holy Families and saints and living sitters with an eye that insisted upon beauty and righteousness. He painted with exquisite finish, with delicate colouring, and with a measure of enthusiasm that the years have not dimmed. In short, though many men have done better, he did his best, and the pictures that are reproduced in these pages indicate very fairly the measure of his achievement, even while they do nothing to conceal his limitations. Moreover, while greater artists have had their biographers by the score, it is hard to find in the literature of Great Britain, France, or Italy any work dealing even in the simplest[22] fashion with this painter's life, though it does not deserve to be neglected. Dolci would seem to have been ignored altogether, and this attitude of contempt is quite unfair, because no man who has pleased so many simple minds is unworthy of our attention, and it is more reasonable to praise a man for the gifts that were his than to ignore him on account of what he lacked.

As was said on a previous page, few people seem to have been at pains to deal with the life and work of our painter, and while the curators of the Italian museums can tell you little about him, save the approximate dates of his life and death, and a few stories relating to events that would perhaps[24] have occurred if they could, the catalogue of the British Museum has no more than one reference to his name. Tracing the reference to its source, we find a little paper-covered pamphlet, written in the closing years of the seventeenth century and published in Florence some quarter of a century ago. In the British Museum library it is bound with two or three other booklets relating to totally different matters. The pamphlet that concerns us was written by Carlo Dolci's friend and patron, Signor Baldinucci, and has never been translated into English. Baldinucci was one of Dolci's intimates, evidently a good friend and an ardent admirer, a man who praises generously, but is rather reticent about the painter's artistic shortcomings, just as though reticence would avail to keep them hidden from the understanding eye. However, it is no bad thing for us that Signor Baldinucci[26] should have been an enthusiast, because without enthusiasm the bounteous harvest of facts to which we can turn would not have been gathered, and we should have been left in such a state of doubt with regard to the incidents of the painter's life as besets us in dealing with so many of the earlier and more notable men of his art and country.

This is an early picture, painted for one of the Florentine religious houses, finished with the utmost care. It has preserved its colour remarkably, and is now to be seen in Florence.

Signor Baldinucci's work describes the artist's pictures in terms of quaint enthusiasm, and happily, too, it does not despise biographical details. This is as well, for, while there is no call for very subtle criticism in the case of Dolci, it is of great interest for us to discover what manner of man he was and how he came to paint so many pretty pictures all in the same key, why he never sought to enlarge the boundaries of his art, or to see "with dilated eye." Our biographer is generous; he gives us facts in plenty, and writes[27] just enough about art to enable us to understand that his knowledge and his enthusiasm stood in inverse ratio to one another. That the author had a following is proved by the fact that the little pamphlet is now out of print, and though the writer sought diligently throughout Florence to procure a copy, he was quite unsuccessful.

Carlo Dolci was born about the year 1616. His father was a highly respected tailor of Florence, Andrea Dolci by name, his mother a daughter of Pietro Marinari, a painter (says Baldinucci) of repute. Carlo's parents seem to have been an exemplary couple, who earned the esteem of all who knew them and raised a family of five children to follow the straight and narrow paths of probity. Carlo is said to have been born on the 25th of May 1616, a day devoted to the honour of St. Zenobius and Santa Maria Maddalena de[28] Pazzi. The elder Dolci died when Carlo was four years old, and his mother was left in straitened circumstances, with which she struggled bravely and not without success. Carlo seems to have been in every respect a model boy; in fact, if his biographer is strictly reliable, he was almost too good for the wicked world he lived in. It would be a relief to hear that he had moments when he was not on his best behaviour, that he robbed orchards, or played truant, or got into one or other of the scrapes that are associated with boyhood; but, alas, he did nothing of the kind. He was not even content to be good, but wanted all his schoolfellows to follow his example, and used to persuade them to tell their beads and say their prayers even when they were out walking.

At the early age of nine Carlo Dolci gave unmistakable signs of possessing an artist's[29] gifts, and was entrusted by his mother to the care of Jacopo Vignali and Matteo Rosselli. He worked very hard under these masters, and was so good that Mr. Barlow of "Sandford and Merton" fame would have been moved to tears of joy had he belonged to the seventeenth century and flourished in the neighbourhood of Florence, while Master Harry Sandford would have hidden a diminished head and confessed that he had found a greater saint than himself. At the age of eleven Carlo Dolci painted his first heads of Christ, one as a child, and the other crowned with thorns; he also painted a full-length figure of St. John. Then he painted a portrait of his mother, who was so pleased with the work that she took it to his master's studio, where, as good luck would have it, Pietro de Medici was in the habit of passing some of his idle hours. This patron of the[30] arts was so pleased with the boy's work that he ordered a portrait of himself and another of a friend, the musician Antonio Landini. He also took the pictures that little Carlo had just painted and showed them to the leaders of society in Florence, presenting the young artist to the duke, who could hardly believe that the work before him had been accomplished by one so young. In order to assure himself, he told the boy to sketch two heads in his presence, only to be so pleased with the work that he rewarded him handsomely for it.

Florence, of course, began to talk of the boy painter, for a prodigy is neither to be despised nor overlooked in any wealthy city. His reputation passed from palace to studio, gathering commissions on its travels, and in a very little time young Dolci had all the work he could do. He painted the portrait of the[31] head of the Bardi family, and that of his nephew John de Bardi. He painted a portrait of Raphael Ximenes. When he was not painting portraits he turned his attention to still life, painting some fruit and flower pictures for his Confessor, Canon Carpanti. His next work was for Lorenzo de Medici, an "Adoration," for which he asked twenty scudi and received forty, and then he painted the subject again on a rather larger canvas for one of the Genitori family, who paid seventy scudi. This picture was sold at the owner's death and realised just four times the sum that had been paid for it, while some pictures of the Evangelists painted by Dolci for one of his Confessors realised nearly twenty times as much as he had received.

It may be suggested without much fear of contradiction, that the success of the[32] painter's earliest work was not the best thing that could have happened to him. If he had been compelled to develop slowly and in the face of adverse circumstance, it is more likely that Carlo Dolci would have given the world work of more lasting merit, but circumstance forced him to paint for patrons at a time when he should have been studying for himself. The style and method of his labours were settled for him, his development was limited and circumscribed; with his native gifts he might have travelled far had he not been hampered by these early successes.

This plate, so characteristic of the sentiment of Dolci, is only part of an altar-piece in fresco, painted for one of the religious houses in the middle of the artist's career.

From his youth Carlo Dolci had been devout, the rules of the brotherhood of St. Benedict appealed to him very strongly. He passed much of his scanty leisure within the walls of the brethren in Florence, and, probably under the influence of his advisers[34] there, made a firm resolve to paint nothing but religious subjects, or those that illustrated some one of the cardinal virtues. At the back of each canvas it was his custom to write the date upon which he had started the work and the name of the saint to whom the day was dedicated. In Holy Week his brush was devoted entirely to subjects relating to the Passion.

One of his greatest early successes was a picture of the Madonna with the Infant Christ and St. John, painted for Signor Grazzini. This work added so much to his commissions that he could no longer stay in Vignali's studio, finding it more convenient to work at home, where there was more accommodation in his mother's house. Here he painted his beautiful picture of St. Paul for one of the family of Strozzi, and his picture of St. Girolamo writing, and the penitence[36] of Mary Magdalen. He also painted the picture of Christ blessing the bread, a head of St. Philip of Neri, and the picture of St. Francis and St. George. For one of his Corsican patrons he painted a woman with weights and scales in her hand as Justice, and for one of the Corsini he painted the Hope, Patience, Poetry, and Painting, of which series the Poetry is reproduced here.

In 1648 Carlo Dolci was elected a member of the Florentine Academy, and, in accordance with the custom that prevailed, was required to present one of his pictures to the Academy on election. Not unnaturally, perhaps, his thoughts turned to the man with whose art he sympathised most, Fra Angelico of Fiesole—the man whose exquisite work has made the Florentine Convent of St. Mark a place of pilgrimage to this day. Oddly enough there was no portrait of Fra Angelico[37] in the Academy. It was necessary to send to Rome to procure a drawing from which the portrait could be painted.

The public demand for Carlo Dolci's work at this time was very greatly in excess of the supply, but the painter was hardly a man who sought or obtained the highest price for his labours. A very little would seem to have contented him; cases might be multiplied in which his work was re-sold at far higher prices than he received for it. For example, he painted a picture of Mary Magdalen washing the feet of Christ, and sold the work to his doctor for 160 scudi. The Marquis Niccolini offered the doctor 1200 scudi for it, but could not tempt him to give it up.

By this time the fame of Carlo Dolci had spread well beyond the boundaries of Florence; he was known and taken seriously in art circles of Italy, and his work had[38] special attractions for the religious houses whose heads saw that its influence was bound to be beneficial. We find the monks of the Italian Monastery dedicated to Santa Lucia of Vienna commissioning him to copy one of their pictures of the Virgin. He made several drawings and started work on the picture, but did not finish it for a long time, and some eight years later he sold it to some distinguished visitors to Florence for 160 scudi. Dolci was never idle, and his brush was always busy on canvas or wood, always setting out some sacred story or seeking to glorify some virtue. Among the important pictures belonging to this period are one of the Martyrdom of St. Andrew, which was taken to Venice, and one of the Flight into Egypt, painted for Andrea Rosselli, a rather graceful if not original composition, in which the Virgin is seen riding[40] with the Infant Christ in her arms. The same subject was commissioned by Lord Exeter and sent to England.

This was painted about 1656 for the house of the Benedictines in Florence. It is one of the most popular of the artist's work, and has been widely reproduced.

The picture of an angel pointing out to Christian souls the road to Heaven attracted great comment and praise when it was painted; so too did two oval pictures, one of the Archbishop of Florence, and the other of St. Philip of Neri. A half-length figure of St. Catherine was another of the painter's notable works that may be referred to his middle life. He had acquired the art of giving to his canvas the high finish of a miniature, and his colours were very fresh and glowing. Indeed, it may be said of Carlo Dolci's work that it has preserved its freshness to a very remarkable extent; some of the pictures painted more than 250 years ago are still glowing with colour, while the work of many men who came after Dolci has lost[42] all its original brightness and has become muddy. This suggests that Dolci had found time to study the composition of paint with great care, and that some of the secrets of glazing surfaces had been revealed to him. Belonging to the middle period is the picture of St. Andrew embracing the Cross and the picture in octagon shape called Charity, presenting a beautiful woman nursing a sleeping babe, and holding a flaming heart in her right hand. A small picture of Hagar and Ishmael belongs to these years.

In 1655 Carlo Dolci's teacher, Rosselli, passed away, and in the following year the artist completed the painting of a standard that his master had begun. The subject is St. Benedict on a cloud in a blue sky, and Dolci is said to have made studies of it from a picture that was already in possession of another brotherhood. Composition was[43] never his strong point. He painted another standard for the Benedictines, to their great delight, and in the following year a St. Dominic on wood, and the famous Angel of the Lily.

Carlo Dolci was now a married man, for in 1654, apparently on the advice of his friends, he married the Signora Teresa di Giovanni. The suggestion that Carlo Dolci married to order is supported to some extent by the incidents of the marriage day. Baldinucci tells us that the painter's friends and family, together with the friends and family of his wife, were all gathered together, but Carlo did not keep his appointment, and messengers were despatched all over the city to find him. He was not at home, he was not with the Benedicts, he was not in the churches he favoured most, and dinner-time had come round when some happy searcher[44] found the painter in a church that the others had overlooked. Having scolded him for forgetting his appointment, the bride forgave her absent-minded partner, and the marriage took place. It was a very happy one.

Some time after this alliance, and when he had passed his fortieth year, Carlo Dolci turned his attention to fresco, and painted a figure of God the Father, the Holy Ghost, and four archangels. We learn that one of his pupils painted in the other angels, and this little fact is worth noting, because it shows that Carlo Dolci had reached the period of his life in which the demands for his work could not be satisfied without assistance, and he had been forced to follow the example of great predecessors. We know that Titian and Tintoretto and other masters of the Renaissance period in Italy never scrupled to avail themselves of the[45] services of clever pupils, and many a picture that left the studio with the master's name upon it did not receive more than the slightest touch of the master's brush. This scandal, for so we must describe it, has been common to nearly every period in the development of art, and was perhaps justified to some small extent in days when artists were not rewarded on a generous scale. While their commissions came from patrons who would not brook delay, and were quite well able to make their anger effective, it was unwise to be too scrupulous about the means to an end. For the preparation of a canvas and the painting in of draperies for portraits the use of pupils may escape adverse criticism, but when the pressure of commission became very serious, too many great artists have succumbed to the temptation of leaving the bulk of the work[46] to be painted by a pupil, trusting to a few skilled touches to give the completed canvas the stamp of their own individuality. We have no means of saying how far Carlo Dolci indulged in a custom that was common to his time. We are quite sure that had he thought it an immoral one he would have abandoned it without hesitation.

After turning his attention to fresco work the painter sent a St. Agatha to Venice, together with a portrait of St. John the Evangelist, and a picture entitled Sincerity, a woman garlanded with lilies. For another picture sent to Venice, representing Christ crowned with flowers and sitting at the entrance of a garden, Dolci received 200 scudi, a rather considerable sum when it is compared with those that were generally paid for his pictures. This picture was so successful that he painted another version[47] of it in 1675 for a daughter of the Archduke Ferdinand and Anna de Medici. For this he received no less than 300 scudi, and the Marquis Runecini paid the same price for a picture of St. John, in which the saint sees in a vision a lady trampling a dragon under foot. Among other works belonging to this period are a St. Girolamo, a St. Luke, and a St. Benedict, all commissioned by his doctor, Signor Lorenzo.

For one of the Corsini family Dolci painted St. Anthony with a skull in his hand, and for Signor Corbinelli the full-length life-size canvas of the figure of St. Peter. For the Scalzi Brotherhood he painted the picture of the Eternal Father that was placed over the high altar, and a picture of Herodiade with the head of St. John the Baptist. A David with the head of Goliath was painted for the Marquis Runecini, and a copy was[48] made for the English ambassador in Florence. This picture created a sensation when it was sent to England, and brought the painter many commissions for the portraits of Englishmen. The head of the Corsini house had given Dolci certain commissions, and they were so well executed that requests followed for another St. John, and a picture of King Casimir of Poland. The St. Cecilia playing the organ, which was sent to Poland, was painted shortly afterwards.

This picture, painted for a Roman patron, is at present to be in the Corsini Palace, Rome. It has, however, not been so well preserved as some of the best work from the same hand.

About this time Sustermans, a painter some of whose work may be seen and admired in Florence to-day, was commissioned to paint a portrait of Claudia, daughter of the Grand-duke Ferdinand and Anna de Medici, on the occasion of her marriage with the Emperor Leopold. But Sustermans on account of his great age could not accept the commission, and it was then offered to[50] Carlo Dolci, who, although he had lived so long, and had achieved so large a measure of renown, had never travelled beyond the walls of Florence. However, he did not hesitate, but started out for Innsbrück in the spring of the year. He arrived in Holy Week, when, according to his rule of life, he would not paint secular subjects, but as soon as Easter had come to an end he began the portrait commissioned, and was then asked by the Duke to paint a second one of the same subject in a different pose. At Innsbrück Dolci received another commission of the sort that throws a strong light upon the ethics of the art world of his time. He was asked to repaint or touch up several devotional pictures by great masters who had passed away, and he does not seem to have hesitated. It was sufficient for him that the pictures were of[52] a kind that met his approval; he asked nothing more, but set to work on the canvases of other men without a qualm. He was the guest at Innsbrück of the Abbé Viviani, and by way of expressing his gratitude for his host's unvarying attention and kindness he painted a beautiful head of St. Philip of Neri and gave it to him. Dolci remained at Innsbrück from April until the end of August, and received in addition to a considerable sum of money a gift of valuable jewels from his grateful patrons.

It was characteristic of the man that on his return to his native city and before he took the picture he had painted to the Palace of the Medici, he went to the church in Florence at which he was accustomed to pray, and returned thanks for the happy termination of his travels. Then he was instructed by the Medici family to finish the[53] portrait, so that it might stand for Santa Galla Placidia, the Empress whose famous tomb may be seen in Ravenna to this day, and, indeed, is one of the show-places of that quaint old city. Dolci then painted a very charming picture reproduced in these pages, the sleeping St. John with St. Zacharias and St. Elizabeth, and following the painting of this picture is associated the great misfortune of a life that had hitherto been pleasant and peaceful. The religious feelings that had been with him since the days when he was a little boy busily instructing his schoolfellows to turn from profane to sacred thoughts now degenerated into melancholy, and Dolci suffered from the true melancholia which baffles physicians to-day, and was then, of course, quite beyond the reach of palliative or cure. He could not speak without deep sighs; he was convinced that he had[54] lost all his ability as a painter, and that the world had no more use for him. His wife, who gave up much of her time and attention to him, suffered in health from the premature birth of a child, and then Baldinucci, who wrote the little biography of the artist that was printed in Florence in the early 'eighties, and is the foundation of our knowledge of the artist's life, took the painter away from Florence to the country to the house of one Domenico Valdinotti. This man, an artist, had one or two pictures in his studio commissioned for wealthy patrons. He took up a palette with colours mixed, and gave it to Dolci, commanding him in sternest tones to finish a veil on one of the pictures of the Virgin. The painter obeyed, and succeeded so well in his task that all the doubt and fear that had clouded his life for the greater part of a year vanished in an hour, and he returned[55] to Florence with a perfectly healthy mind to finish the Santa Galla Placidia, and one or two altar-pieces, including one for the Church of San Francesco.

Dolci then received a commission from the Empress Claude to paint a canvas for the Imperial Palace, but as she died in the following April this work was not completed. But he painted a fine martyrdom of St. Lorenzo and a striking picture of St. Francis of Assisi for the Duke. Then came more commissions from Venice, and the painter worked at half-a-dozen well-known pictures for that city. These pictures showed, perhaps, even more finish than those that had gone before, because concentration seems to have been the keynote of the painter's life, and while other men in all ages have used art as a means to an end, and have been unable to avoid the social[56] temptations that have beset them in the day of their success, Carlo Dolci, like Tintoretto before him, had no care for anything save his work. So long as health was good he desired nothing better than to devote the whole day to labour, and his closest and most complete attention to what he had in hand. Of course, one only compares Dolci with Tintoretto in point of industry; all the developments that the great Venetian had made, all the truths he had discovered, were either unknown to Dolci or ignored by him. He was painting for a public that knew very little about art, and regarded exquisite finish as the surest sign of artistic accomplishment. Consequently the painter did not seek to develop along lines of independent thought; he had no pressing need to do so while everything he could reasonably require in the way of patronage and commission was at his command.

[57] In 1682 Luca Giordano came to Florence to paint frescoes in the Chapel of the Corsini Palace. He admired Carlo Dolci's work very much, but used to rally him about the time he spent on it. "You do beautiful work, my Carlo," he said; "but how can you make it pay when you give hours and hours to that close finish? When I think of the 150,000 scudi I have earned since I took up the brush, I begin to fear that you will die hungry."

This is one of the collection of portraits of artists painted, each by his own hand. As may be seen from the canvas, Dolci executed it in 1674 when he was approaching his sixtieth year. The canvas hangs in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

It was perhaps a little unwise to talk in this fashion to a man who had been suffering from some form of brain disease, but it is certain that the words, though they were only spoken in jest, made a very deep impression upon the painter. Dolci had just finished an Adoration of the Magi, and had sent it to the Palace of the Duchess Vittoria. Receiving a summons from the Palace, he[58] went there and heard the Duchess express herself to him in terms of high praise. Then she sent his Adoration back to its wall and ordered one of Giordano's pictures to be brought to her. "What do you think of this," she said to Dolci; "is it not a wonderful piece of work? Can you believe that it was really painted in such a short time?" and she named the dates of its commission and completion. This unlucky remark brought back all the painter's forebodings. His friend and biographer tells us that the Duchess did not mean to hurt his feelings, she had admired his work for the qualities it possessed, and in praising Giordano's she had commented upon what had struck her most about it—that is, the rapidity with which it had been executed. From that hour the painter went about silent and miserable, he was seldom heard to speak, and then to add[60] to his troubles, his wife, to whom he had been devoted so passionately, died. His melancholy returned, and his Confessor, remembering how successfully he had been treated in the country beyond Florence, ordered him to turn to a picture of St. Ludovic and paint the vestments of one of the figures on the canvas. Dolci did as he was told, but this time the effort was in vain. Doubtless his brain had been weakened by the first attack of melancholia, and fears for the future, coupled with the shock of a beloved wife's death, were altogether too much for the enfeebled constitution of a man of seventy. He took to his bed, and died on the 17th of January 1686, leaving a family of seven daughters and one son. Dolci was buried in the family vault in the Church of the Santissima Nunziata, where he had worshipped so long, and where one of his[62] friends had found him on his marriage day when he should have been with his bride. He did not leave much money behind him, but quite a large number of pictures that doubtless served his family in lieu of legacies at a time when the painter's work would be in greater demand than ever, because the limit of his output had been reached.

When we turn from a résumé of the chief events of the painter's comparatively uneventful life to an endeavour to estimate the place he takes in the history of his country's art we have, in the first place, to consider the season in which he was born. Looking at the art history of Florence we see that Dolci came very late into the[63] world. From the close of the fourteenth century, when Fra Angelico was born, down to the late years of the sixteenth century, when the last of the great masters seemed to pass away, Florence had enjoyed the services of a long series of distinguished artists. Lippo Lippi, Botticelli, Ghirlandajo, da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Lorenzo di Credi, Andrea del Sarto, Bronzino, Cigoli, all these and many others whose names can hardly be recalled without delight flourished in Florence, and while they lived there the city's reputation filled all the rest of Italy with envy. But neither a man nor his influence is everlasting; the great ones passed and left no successors; when Carlo Dolci appeared upon the scene the last trace of their influence had disappeared. Consequently he brought his gifts to a city from which inspiration[64] had departed. The great achievements of the art world were no more than echoes. Florence had excelled herself in all directions. Painting had served her greatest men as no more than one form of expression. The greatest of them had sought to give their message to the world through the medium of more arts than one, and consequently, he who was a simpler painter was of comparatively small account. When Carlo Dolci was born, the time of great men having passed, no great forces were at work in his native city. He did not have the advantage of travel, he was never called upon to struggle hard and anxiously for the necessities of life. In some ways he was regarded as an infant prodigy and treated as such, and it would be hard to say that the premature development of gifts however great has ever served their possessor[65] in the long run. No man's work can be judged properly save in relation to his circumstances and his time, and, in order that we may avoid the danger of underrating Carlo Dolci's achievement and dismissing for obvious faults what we should praise for merit, we are forced to consider the case carefully lest we treat a deserving man with injustice. Bearing time, place, and limitations in mind, it is possible then to consider the painter without the prejudice that the most glaring defects of his art are calculated to arouse.

We have seen in the course of our necessarily short survey that Carlo Dolci lived to the established age of man, and started his work before he was in his teens, that no long journeys or extended sojourns in foreign countries withdrew him from the area of his normal activities; we have seen[66] that he never left Florence save on one occasion. And, as he was working throughout his life, his output would have been uncomfortably large but for the fact that he never allowed a canvas to leave his studio until every stroke that his brain could suggest, and his hand execute, had been added to it. His conscientiousness alone availed to check his output, and so intent was he upon expressing himself as well as he could within the obvious limitations of his gift that he never attempted to grapple with the problems that beset bigger men.

In composition, for example, Carlo Dolci was distinctly deficient; there is no more serious charge against him as an artist than that he could not compose a large figure picture. If he had to devote himself to one, under the terms of some commission from a wealthy patron, he would not hesitate[67] to go to other masters in search of a composition that would suit his purpose. It may be put to his credit that he did these things openly, he does not seem to have claimed for himself the work that he borrowed from his contemporaries. In fact, it is quite probable that he knew his gifts did not lie in the direction of composition; he regarded it as something that did not matter very much, and was quite content with the praises that his single figure subjects received. One cannot help thinking that he would have been very successful as a painter of miniatures.

Dolci impresses us to-day with the feeling that he was a man who struggled valiantly and conscientiously with a very considerable gift, which he had neither the time nor the will to develop along the lines that lead from mediocrity to remarkable[68] achievement. Then again we must remember that the fates were not auspicious, he was not taken in the early days to the studio of a first-class master, he did not have the inspiration of great work. By the time the seventeenth century had travelled over a third of its appointed course Florentine art, as we have seen, was hardly in a very flourishing condition. The days of great experiments and earnest striving had passed, and, although Venice is comparatively close to Florence, and was full even in Carlo Dolci's days of some of the world's most inspiring work, although the Venetians were delighted by Carlo Dolci's rich vivid colouring, and commissioned many pictures from his brush, there is no evidence to show that he ever visited the great city of the Adriatic, or that he found the time or the inclination to learn any of the lessons she has to teach.

This is one of the last efforts of Dolci. It was painted after his return from Innsbrück, just before he was taken ill. It hangs in the Pitti Palace, Florence.

[71] We cannot, then, look upon Carlo Dolci's life or work as being complete. He seems to afford an example of what talent will do when it lacks adequate direction, and we see too the danger into which the art of the painter falls when his inclinations are too literary. For it was no part of Carlo Dolci's aim in life to express harmonies in colour and line, although such expression may be taken to be the beginning and end of all that is greatest in painting. Dolci was always keen on telling a story, always intent upon preaching a sermon in paint, always forgetful that the provinces of art and literature have a very wide boundary line. It is rather interesting to compare the lives of Carlo Dolci and Fra Angelico of Fiesole, because each was a man who sought to express moral principles, sentiments, and belief on canvas, and, while the[72] one succeeded beyond all possibility of doubt, the other has met with only a modified success. Beato Angelico was influenced by the Dominicans as Dolci was by the Benedictines; each gave his life work to the service of the Church and the pursuit of virtues that the Church teaches man to practise. One laboured in the cloister and the other outside it, but oddly enough, he who came first and decorated the walls of St. Mark's Convent knew the more about life and more about art, more about perspective and more about composition, than his successor, who followed so many years later. The truth is, perhaps, that when Fra Angelico came to the convent of the Dominicans the Renaissance was just blossoming in Italy. It was a season of great inspiration. Man and Learning were being discovered, and although some aspects of the discovery[73] were hidden from the good brother of St. Dominic, all the attendant enthusiasms came to him. Moreover, Angelico travelled and mingled freely with scholars and great artists, so that we can divide his life work into three stages, of which the second is better than the first, and the last is best of all.

On the other hand, when Dolci came on the scene the Renaissance had blossomed and budded and filled the face of the earth with fruit, but the fruit was already overripe. The great stimulus had passed; degeneration had set in, not only in the world of art. The mere fact that Carlo Dolci's gifts found an immediate acceptance shows that the times were not distinguished, and we do not find in Baldinucci's life of his friend one solitary suggestion that any of the great rulers who employed his brush ever turned to him with the request that he[74] should enter into competition with those who had gone before, that he should take a course of study and learning to strengthen the weak points of his work, sacrificing a little of its sweetness to gain some small measure of strength. At the same time we must not underrate Carlo Dolci's work because we have outgrown it, since, as was suggested on an early page of this little essay, his charm in certain aspects is perennial, and although its powers to hold us must pass when we have turned to higher things, those who are following us will find pleasure and inspiration in the painter's art when they visit for the first time the galleries of Italy. They will travel by easy degrees from pictures that please to those that call in the first place for study, and then for admiration and the recognition of masterpieces.

[75] Carlo Dolci's place in art is not altogether unlike that of some of his living countrymen in the world of music. There are Italian musicians known to all of us who have such a gift of sweetness that we cannot endure their melodies for long. A song now and again, or some sparkling little work for piano or violin, gives us a passing thrill of pleasure, and then we turn with complete content to the clearer atmosphere and more serene moods of the great masters whose works endure for all time. So it is with Carlo Dolci; we go to him now and again, if only for a little while, conscious that sweetness as well as strength has its place in the world of art as in the world of music and letters. And we know, too, that criticism can say nothing worse about Carlo Dolci's gifts than that he was never able to turn them to the best account, that the rough diamond of his[76] talent was never in the hands of a competent lapidary. His life is not one we are called upon to overlook, for his achievement, though it has little variety, is marked by certain definite qualities that call for recognition, even though these qualities are often moral rather than artistic.

Dolci was eminently a sentimentalist; he had no redeeming vices; a little of the devilry of a Benvenuto Cellini would have been invaluable to him and to his art. But it is futile to complain of a man for being as Nature made him, and if we will turn to Carlo Dolci's pictures for pretty, agreeable, and highly finished interpretations of moral ideas in terms of paint, we shall find no small amount of momentary satisfaction.

We must not forget that the world at large had suffered not a little when Carlo Dolci came upon the scene from the excessive[77] daring and superb initiative of the Renaissance. Its eyes were a little dimmed by the splendour of the great men who had gone before, and had travelled to heights beyond the ken of the average citizen. Carlo Dolci helped to bring his greatly dazzled fellow-countrymen back to earth, pleasantly and in fashion that flattered their vanity. In the eyes of hundreds of his contemporaries the devout, God-fearing, conscientious Florentine must have been regarded as the greatest artist Italy had ever seen, and if such a thought pleases some of the unsophisticated among their descendants, who should desire to complain? Let us rather put to Dolci's credit the facts that he did not pose as a heaven-born genius, that he was not greedy or grasping, that he did not seek to found a school. The portrait he painted of himself suggests that he was not altogether[78] deficient in humour; perhaps there were hours when he laughed with himself at those who praised him for the gifts he lacked. If we could but be sure that he laughed now and again at himself and his pictures, recognising the limitations that are so patent to us to-day, the most superior critic could refuse no longer to have some regard for Carlo Dolci.

The plates are printed by Bemrose Dalziel, Ltd., Watford

The text at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh