Title: The Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

Author: Sir James W. Barrett

P. E. Deane

Release date: January 24, 2013 [eBook #41911]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Moti Ben-Ari and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY

MEDICAL CORPS IN EGYPT

BY

JAMES W. BARRETT

K.B.E., C.M.G., M.D., M.S., F.R.C.S. (Eng.)

TEMPORARY LIEUT.-COL. R.A.M.C.

LATELY LIEUT.-COL. A.A.M.C. AND A.D.M.S. AUSTRALIAN FORCE IN EGYPT, CONSULTING

OCULIST TO THE FORCE IN EGYPT AND REGISTRAR FIRST AUSTRALIAN

GENERAL HOSPITAL; OPHTHALMOLOGIST TO THE MELBOURNE HOSPITAL, LECTURER

ON THE PHYSIOLOGY OF THE SPECIAL SENSES IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE

AND

LIEUT. P. E. DEANE, A.A.M.C.

QUARTERMASTER FIRST AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL, EGYPT

H. K. LEWIS & CO. LTD.

136 GOWER STREET, LONDON, W.C.1

1918

DEDICATED TO

SIR HENRY and LADY MacMAHON,

IN GRATEFUL RECOLLECTION

OF THE SERVICES RENDERED BY THEM

TO THE

AUSTRALIAN SICK AND WOUNDED

IN EGYPT

CHAPTER I

The Australian Army Medical Corps at the Outbreak of WarThe Call for Hospitals—Appeal to the Medical Profession, and the Response—Raising the Units

CHAPTER II

The Voyage of the "Kyarra"Lack of Adequate Preparation—Difficulties of Organisation—Ptomaine Poisoning

CHAPTER III

Arrival and Settlement in EgyptDisposal of the Hospital Units—Treatment of Camp Cases—The Acquisition of Many Buildings—Where the Thanks of Australia are Due

CHAPTER IV

The Rush of Wounded and Rapid Expansion of HospitalsSaving the Situation—Period of Improvisation—Shortage of Staff and Equipment—How the Expansion was effected—The Number of Sick and Wounded

[viii]CHAPTER V

Convalescent DepotsEvacuation of Convalescent Sick and Wounded from Congested Hospitals—Keeping the Hospitals Free—Libels on the Egyptian Climate—Discipline

CHAPTER VI

Evacuation of the UnfitRelieving the Pressure on the Hospitals and Convalescent Depots—Back to Duty or Australia—Methods adopted—Transport of Invalids by Sea and Train

CHAPTER VII

Sickness and Mortality amongst AustraliansThe Dangers of Camp Life—Steps taken to prevent Epidemics—Nature of Diseases contracted and Deaths resulting—Defective Examination of Recruits—Ophthalmic and Aural Work—The Fly Pest—Low Mortality—The Egyptian Climate again—Surgical Work and Sepsis—Cholera—Infectious Diseases

CHAPTER VIII

Venereal DiseasesThe Greatest Problem of Camp Life in Egypt—Conditions in Cairo—Methods taken to limit Infection—Military and Medical Precautions—Soldiers' Clubs

[ix]CHAPTER IX

The Red Cross WorkIts Value and Limitations—Origin in Australia—Report of Executive Officer in Egypt—Red Cross Policy—Defects of Civil and Advantages of Military Administration—What was actually done in Egypt

CHAPTER X

Suggested ReformsDefects which became Obvious in War-time—Recommendations to promote Efficiency—Dangers to be avoided—Conclusion

CHAPTER XI

PostscriptClosure of Australian Hospitals—The Fly Campaign—Venereal Diseases—Y.M.C.A. and Red Cross—Multiplicity of Funds—Prophylaxis—Condition of Recruits on Arrival—Hospital Organisation—The Help given by Anglo-Egyptians

APPENDIXES

I

Translation of Geneva Convention of July 6, 1906

II

Convention for the Adaptation of the Principles of the Geneva Convention to Maritime War

INDEX

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel, showing Rotunda and Piazzas | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Mena Camp | 6 |

| The s.s. "Kyarra" | 14 |

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel, showing Infectious Diseases Camp | 22 |

| Plan of Heliopolis Palace Hotel | 23 |

| The Main Hall, Heliopolis Palace Hotel | 24 |

| Surgical Ward, Heliopolis Palace Hotel | 25 |

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel: Isolation Tents | 26 |

| The Rink, Luna Park, Heliopolis | 27 |

| The Casino, Heliopolis: Infectious Diseases Hospital | 29 |

| The Pavilion, Luna Park, Heliopolis | 30 |

| The Atelier, Heliopolis | 37 |

| The Sporting Club, Heliopolis | 40 |

| The Fleet of Ambulances, Heliopolis | 42 |

| The Operating Room, Heliopolis Palace Hotel | 44 |

| Unloading the Hospital Train, Heliopolis Siding | 47 |

| The Lake, Luna Park, Heliopolis | 49 |

| The Sporting Club, Heliopolis | 51 |

| The Sporting Club, Heliopolis | 52 |

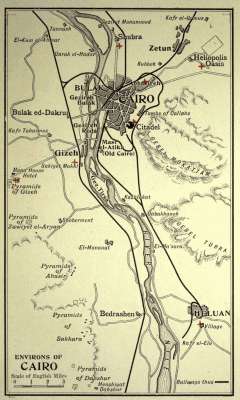

| Cairo and Neighbourhood | 58 |

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel: Convalescents on Piazza | 59 |

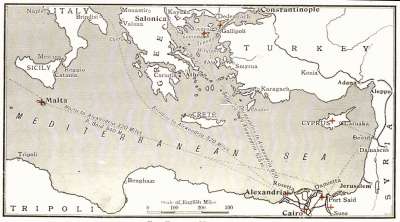

| The Eastern Mediterranean | 77 |

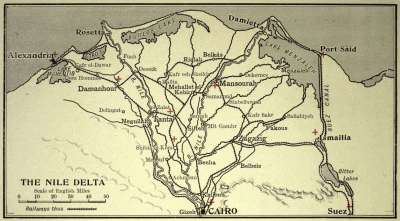

| Egypt, the Delta | 80 |

| [xii]Officers and Nurses, No. 1 Australian General Hospital | 86 |

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel: Rotunda and Piazzas | 97 |

| Venereal Diseases Hospital, Abbassia | 120 |

| Soldiers' Club, Esbekieh, Cairo | 133 |

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel | 141 |

| Interior Red Cross Store: Utilisation of Cases for Shelving | 144 |

| Red Cross Base Depot, Heliopolis | 148 |

| Heliopolis Siding: Arrival of Wounded | 166 |

| Matrons and Nurses, No. 1 Australian General Hospital | 169 |

| Soldiers' Club, Esbekieh, Cairo | 174 |

| N.C.O.s and Men, No. 1 Australian General Hospital | 197 |

| Palace of Prince Ibrahim Khalim (Nurses' Home) | 198 |

| Gordon House, Heliopolis (Nurses' Home) | 200 |

| Australian Convalescent Hospital, Al Hayat, Helouan | 204 |

The experience of the Australian Army Medical Service, since the outbreak of war, is probably unique in history. The hospitals sent out by the Australian Government were suddenly transferred from a position of anticipated idleness to a scene of intense activity, were expanded in capacity to an unprecedented extent, and probably saved the position of the entire medical service in Egypt.

The disasters following the landing at Gallipoli are now well known, and the following pages will show how well the A.A.M.C. responded to the call then made upon it.

When the facts are fully known, its achievements will be regarded as amongst the most effective and successful on the part of the Commonwealth forces.

In the following pages we have set out the problems which faced the A.A.M.C. in Egypt, regarding both Red Cross and hospital management, the necessities which forced one 520-bed hospital to expand to a capacity of approximately 10,500 beds, and the manner in which the work was done.

The experience gained during this critical period enables us to indicate a policy the adoption of which will enable similar undertakings in future to be developed with less difficulty.

We desire to acknowledge gratefully the permission to publish documents granted by General Sir William Birdwood and Dr. Ruffer of Alexandria, and also much valuable help given by Mr. Howard D'Egville.

The beautiful photographs which are reproduced were mostly taken by Private Frank Tate, to whom our best thanks are due.

In any reference to the work of the Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt it must never be forgotten that the expansion of No. 1 Australian General Hospital was effected under the personal direction of the officer commanding, Lieut.-Colonel Ramsay Smith, who was responsible for a development probably unequalled in the history of medicine.

The story told is the outcome of our personal experience and consequently relates largely to No. 1 Australian General Hospital, with which we were both connected.

THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY MEDICAL CORPS AT THE OUTBREAK OF WAR—THE CALL FOR HOSPITALS—APPEAL TO THE MEDICAL PROFESSION AND THE RESPONSE—RAISING THE UNITS.

CHAPTER I

Prior to the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Australian Army Medical Corps consisted of one whole-time medical officer, the Director-General of Medical Services, Surgeon-General Williams, C.B., a part-time principal medical officer in each of the six States (New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania), and a number of regimental officers. With the exception of the Director-General, all the medical officers were engaged in civil practice, which absorbed the greater portion of their energy.

The system of compulsory military training which came into operation in 1911 was creating a new medical service, by the appointment of Area Medical Officers, whose functions were to render the necessary medical services in given areas, apart from camp work. These also were mostly men in civil practice, to whom the military service was a supplementary means of livelihood.

Camps were formed at periodical intervals for the training of the troops, the duration of the camps rarely exceeding a week. At these camps a certain number of regimental medical officers were in attendance, and were exercised in ambulance and field-dressing work.

In common with the members of other portions of the British Empire, few medical practitioners in Australia had regarded the prospect of war seriously, and in consequence the most active and influential members of the profession, with some notable exceptions, held aloof from army medical service.

In 1907, however, owing to the representations of Surgeon-General Williams, and to the obvious risk with which the Empire was threatened, senior members of the profession volunteered and joined the Army Medical Reserve, so that they would be available for service in time of war. The surgeons and physicians to the principal hospitals received the rank of Major in the reserve, and the assistant surgeons and assistant physicians the rank of Captain. Some attempt was made to give these officers instruction by the P.M.O's, but the response was not enthusiastic, and little came of it.

At the same time there were a number of medical officers in the Australian Army Medical Corps who possessed valuable experience of war, notably the Director-General, whose capacity for organisation evidenced in South Africa and elsewhere made for him a lasting reputation. The Principal Medical Officer for Victoria, Colonel Charles Ryan, had served with distinction in the war with Serbia in 1876, and in the war between Russia and Turkey in 1877. A fair number of the regimental officers had seen service in South Africa. The bulk of the medical practitioners concerned, however, had not only no knowledge of military duty, but certainly no conception whatever of military organisation and discipline; and what was still more serious, no real and adequate realisation of the extraordinary part[5] that can be played in war by an efficient medical service by prophylaxis.

Such, then, was the position when war was declared.

The response from the people throughout Australia was, as Australians expected, practically unanimous. They determined to throw in their lot with Great Britain and do everything that was possible to aid. This determination found immediate expression in the decision of the Government of Mr. Joseph Cook, endorsed later by the Government of Mr. Fisher, to raise and equip a division of 18,000 men and send it to the front as fast as possible. The system of compulsory military service entails no obligation on the trainee to leave Australia, and in any event, the system having been introduced so late as 1911, the trainees were not available. The expedition consequently became a volunteer expedition from the outset. Volunteers were rapidly forthcoming, camps were established in the various States and training was actively begun.

Of the difficulty and delays consequent on the raising of such a force—of men mostly civilians, of all classes of society, without clothing, or with insufficient clothing and equipment of all kinds—little need be said. The difficulties were slowly overcome, and the force gradually became somewhat efficient. As both officers and men were learning their business together, the difficulties may well be imagined. In fairness, however, it should be said that from the physical and from the mental point of view the material was probably the finest that could be obtained.

We are, however, only concerned here with the medical aspect of the movement. The medical establishment[6] was modelled on that of Great Britain, and consisted of regimental medical officers and of three field ambulances. The Director-General accompanied the expedition as Director of Medical Services, and Colonel Chas. Ryan, the Principal Medical Officer of the State of Victoria, accompanied the expedition as A.D.M.S. on the staff of General Bridges, the Commander of the Division. Colonel Fetherston took General Williams's place as Acting Director-General of Medical Services, and Colonel Cuscaden the place of Colonel Ryan as Principal Medical Officer of the State of Victoria.

The expedition left in October, a considerable delay having taken place owing to the necessity of finding suitable convoy, a number of German cruisers being still afloat and active. It reached Egypt without serious mishap in December, and at once encamped near the Pyramids at Mena.

There were some difficulties in transit. There was a most extensive outbreak of ptomaine poisoning on one ship, and measles, bronchitis, and pneumonia were much in evidence. The mortality was, however, small. The division on arrival settled down to hard training.

At once difficulties caused by the absence of Lines of Communication Medical Units became obvious. The amount of sickness surprised those who had not profited by previous experience. To meet the difficulty Mena House Hotel was improvised as a hospital and staffed by regimental and field ambulance officers.

At this stage, however, we can leave the division and return to the further development of medical necessities in Australia.

Steps were at once taken in Australia to raise a second division, and subsequently a third and other divisions in the same manner as the preceding. As time passed on, the unsuitability of some of the camps and the lack of medical military knowledge told their tale, and a number of serious outbreaks of disease took place. It is impossible to give accurate statistical evidence, but the Australian public seems to have been shocked that young, healthy, and well-fed men should in camp life have been so seriously damaged and destroyed. The causes as usual were measles, bronchitis, pneumonia, tonsillitis, and later on a serious outbreak of infective cerebro-spinal meningitis which was stamped out with difficulty and took toll (inter alia) in the shape of the lives of three medical men. The sanitation of the Broadmeadows Camp near Melbourne was not such as to provoke respect or admiration. The camp was ultimately regarded as unsuitable, and moved to Seymour, pending the necessary improvements.

It is instructive to note in passing that the Australian public received a shock when they were first informed of the amount of disease among the troops in Egypt. Yet it was apparently nothing like so great as that which existed in Australia, where the usual death-rate is so low. And yet, had the Service really profited by the lessons of the Russo-Japanese war, much of the trouble might have been avoided. The truth of course is that camp life, except under rigorous discipline as regards hygiene, and the loyal observance of that discipline by each soldier, is much more dangerous than the great majority of people seem to imagine. The benefit of the open-air life and of exercise is[8] counteracted by the chances of infection due to crowding, defective tent ventilation, the absence of the toothbrush, and other causes.

In September, however, the Imperial Government notified the Australian Government that Lines of Communication Medical Units were required, and for the first time the majority of members of the Australian Army Medical Corps became aware of the nature of Lines of Communication Medical Units. The Government decided to equip and staff a Casualty Clearing Station, then called the Clearing Hospital, two Stationary Hospitals (200 beds each), and two Base Hospitals (each 520 beds). They were organised on the R.A.M.C. pattern, and the total staff required was approximately eighty medical officers. Even at this juncture the matter was not taken very seriously, and there was some doubt as to the nature of the response. The Director of Medical Services was anxious that the base hospitals should be commanded and staffed by men of weight and experience, and accordingly a number of the senior medical consultants in the Australian cities decided to volunteer. The example was infectious and there were over-applications for the positions.

The First Casualty Clearing Station was to a great extent raised and equipped in Tasmania. The First Stationary Hospital was raised and equipped in South Australia, the Second Stationary Hospital in Western Australia, and the Second General Hospital in New South Wales. An exception to this sound territorial arrangement was, however, made in the case of the First Australian General Hospital—an exception which proved unfortunate. The commanding officer, a senior lieutenant-colonel,[9] was resident in South Australia. The hospital itself was recruited from Queensland, but as the Queensland medical profession was hardly strong enough to supply the whole of the medical personnel, most of the consultants, including all the lieutenant-colonels, were recruited in Victoria. Now Brisbane, the capital of Queensland, is some 1,200 miles by rail from Melbourne, and Melbourne about 400 miles by rail from Adelaide, the capital of South Australia. The result of these arrangements was that the captains and some of the majors were recruited in Queensland, together with the bulk of the rank and file and many of the nurses; whilst most of the senior medical officers, the matron, and a number of nurses were recruited in Melbourne, and the commanding officer (Lt.-Colonel Ramsay Smith) from South Australia. He brought with him some seven or eight clerks and orderlies. Furthermore a number of medical students and educated men joined in Melbourne. The bulk of the staff was, however, based in Queensland. This arrangement led to untold difficulties in the way of recruiting, and it is remarkable that the result should have been as satisfactory as it was. The equipment was provided partly from Melbourne, partly from Brisbane, and partly from South Australia. As the commanding officer was in South Australia, as the registrar and secretary was in Melbourne, and as the orderly officer was in Brisbane, some idea of the difficulties can well be imagined—particularly when it is remembered that with the exception of the commanding officer and a few officers, the members of the staff had no experience whatsoever of military matters. Nevertheless an[10] earnest effort was made to secure the necessary equipment and personnel. In Melbourne great trouble was taken to secure as many medical students and educated men as could possibly be obtained.

On the whole the response to the call was more than satisfactory, and Australian people were of the opinion that a stronger staff could not have been secured.

It was at first intimated that specialists were not required, but ultimately after discussion the Government agreed to find the salary of one specialist. Consequently a radiographer was appointed with the rank of Major, and another officer was appointed oculist to the hospital with the rank of honorary Major. Subsequently he was appointed as secretary and registrar in addition, but without salary or allowances.

The equipment of the hospital was on the R.A.M.C. pattern, and was supposed to be complete. Furthermore, the Australian branch of the British Red Cross Society set aside for the use of the hospital one hundred cubic tons of Red Cross goods which were specially prepared and labelled at Government House, Melbourne.

THE VOYAGE OF THE "KYARRA"—LACK OF ADEQUATE PREPARATION—DIFFICULTIES OF ORGANISATION—PTOMAINE POISONING.

CHAPTER II

The mode of conveyance of the hospitals to the front next engaged the attention of the authorities, and negotiations were entered into with various steamship companies. It was desirable that the hospitals should be conveyed under the protection of the regulations of the Geneva Convention.

After some negotiation and the rejection of larger and more suitable steamers, a coastal steamer, the Kyarra, was selected and was fitted to carry the hospital staff and equipment. The steamer is of about 7,000 tons burden. There were on board approximately 83 medical officers, 180 nurses, and about 500 rank and file, or a total of nearly 800 souls. The cargo space was supposed to be ample, and 100 tons of space were promised for the Red Cross stores.

When ready, the Kyarra proceeded to Brisbane and embarked a portion of the First Australian General Hospital. She then proceeded to Sydney, embarked the Second Australian General Hospital with its stores, equipment, and Red Cross goods, and then left for Melbourne, where she was to embark the remainder of the First Australian General Hospital, the First Stationary Hospital, and the Casualty Clearing Station.

On arrival at Melbourne, however, it was found[14] that she was carrying ordinary cargo, that she was not lighted as required by the rules of the Convention, and that she was already fully loaded. Consequently the whole of the cargo was taken out of her, the ordinary cargo was removed, and she was reloaded. It was found, however, that there was no room for the Red Cross goods belonging to the First Australian General Hospital. Furthermore, a portion of the equipment which subsequently turned out to be invaluable, namely 130 extra beds donated to the hospital by a firm in Adelaide, was nearly left behind. It was only by the exercise of personal pressure that space was found for this valuable addition at the last minute. The importance of this donation will be mentioned later in the story.

Finally, after many delays, the Kyarra left Melbourne on December 5 amidst the goodwill and the blessings of the people, and made her way to Fremantle, there to embark the Second Australian Stationary Hospital and its equipment. She finally left Fremantle with this additional hospital, and made her way across the Indian Ocean.

Lieut.-Col. Martin, Commanding Officer of the No. 2 Australian General Hospital, was promoted to the rank of Colonel for the voyage only. He was promoted for the purpose of placing him in command of the troopship.

The voyage of the Kyarra involved calls at Colombo, Aden, Suez, Port Said, and Alexandria. Those on board believed in the first instance they were proceeding to France, and when they arrived at Alexandria, and found they were all destined for Egypt, many expressed feelings of keen disappointment on the ground that they would have no work to do. They were soon, however, to be undeceived.

The voyage itself does not call for lengthy comment. The ship was unsuitable for the purpose for which she had been chartered. She was small, overcrowded, and not as clean or sanitary as she might have been. Her speed seemed to decrease, and was scarcely respectable at any time; there were apparently breakdowns of the engines; and the food supplied to the officers and nurses was not infrequently inferior in quality and in preparation. In consequence an outbreak of ptomaine poisoning took place, and twenty-two officers and others were infected, two of them seriously.

The arrangements at the men's canteen had not been fully thought out, and in the Tropics it was not possible to obtain fruit of any description. Fresh or tinned fruits were not kept in stock. There was some tinned meat and fish, but the men could obtain nothing to drink except a mixture made from Colombo limes and water.

There was a certain amount of illness apart from ptomaine poisoning, and amongst the cases treated were bronchitis, influenza, tonsillitis, and eye disease. Five cases reacted severely to anti-typhoid inoculation, and required rest in hospital.

On the whole, officers, nurses, and men took the voyage seriously, and did their best to learn something of their work. The officers were drilled, the nurses gave lessons to the orderlies, and systematic lectures were given by the officers. An electric lantern had been provided by the O.C., and lantern lectures were given regularly during the voyage.

The quarters provided in the fore part of the ship[16] for the men were certainly insanitary, and to an extent dangerous. Towards the end of the voyage many cases of rotten potatoes were thrown overboard, having been removed from beneath the quarters occupied by the men. With Red Cross aid, however, provided by the Queensland branch, fans had been installed, and an attempt made to render these quarters more sanitary and habitable. A portion of the deck could not be used because of leaky engines, and neither request nor remonstrance enabled those concerned to get these leaks stopped.

The following measurements show what trouble so simple a fault can cause. In the tropics the wet portion of the deck could not of course be used for sleeping purposes.

| sq. ft. | |

| Approximate deck space available | 1,920 |

| Space obtainable on hatches | 288 |

| —— | |

| 2,208 | |

| Space permanently wet through leaking engines | 648 |

| —— | |

| Approximate net | 1,560 |

As the number of men occupying these quarters[17] (including sergeants and warrant officers) was about 300, the space available approximated 5 sq. ft. per man.

Notwithstanding these conditions, the usual peculiarity of Anglo-Saxon human nature showed itself when at the end of the voyage the officers were required to sign the necessary certificates stating that the catering had been satisfactory. Only three refused to sign; the remainder signed, mostly with qualifications.

The manner in which the average Australian makes light of his misfortunes was strikingly illustrated on one occasion. A long, mournful procession of privates slowly walked around the deck. In front, with bowed head, was a soldier in clerical garb, an open book in his hand. Immediately behind him were four solemn pall-bearers, carrying the day's meat ration, which is stated to have been "very dead." Apparently the entire ship's company acted as mourners. The procession wended its way to the stern, where an appropriate burial service was read; the ship's bugler sounded the "last post," and the remains were committed to the deep. Needless to say the usual formality of stopping the ship during the burial service was not observed on this occasion. An attempt to repeat the performance was fortunately stopped by those in authority, and all subsequent "burials" were strictly unceremonious.

Those who go to war must expect to rough it, but on a peaceful ocean, secure from the enemy, and in a modern passenger ship, it should be possible to provide food which does not imperil those who consume it, and also to ensure reasonable comfort.

With reference to the defects of the ship it[18] should be said that when the Kyarra was chartered Australians had not realised the colossal nature of the war, and had not begun to think on a large scale, and those responsible had neither tradition nor experience to guide them. Furthermore the commander and officers of the Kyarra courteously did their best, but it was evident they understood the difficulty of transforming a coastal steamer into a Hospital Transport.

The Geneva Convention does not seem to be fully understood, and experience shows what complicated conditions arise, and how easy it is to commit an unintentional breach of the Regulations. But in war there can be no excuses.

ARRIVAL AND SETTLEMENT IN EGYPT—DISPOSAL OF THE HOSPITAL UNITS—TREATMENT OF CAMP CASES—THE ACQUISITION OF MANY BUILDINGS—WHERE THE THANKS OF AUSTRALIA ARE DUE.

CHAPTER III

On arrival at Alexandria, there seemed to be no great hurry in disembarking, and many of the older medical officers were fully persuaded that the units were not wanted in France; that there was very little to do in Egypt; and that if their services were not required it would be fairer to inform them of the fact, and let them go home again. They were soon to be undeceived. A message was received asking the O.C.s of the various units to visit Cairo, where they waited on Surgeon-General Ford, Director of Medical Services to the Force in Egypt. They were informed that there was more than enough work for all these Lines of Communication Medical Units in Egypt.

The First Australian General Hospital was to be placed in the Heliopolis Palace Hotel at Heliopolis. The Second Australian General Hospital was to take over Mena House and release the regimental medical officers and officers of the Field Ambulances from the hospital work they were doing. The First Stationary Hospital was to be placed with the military camp at Maadi, and the Second Australian Stationary Hospital was to go into camp at Mena and undertake the treatment of cases of venereal diseases. The First Casualty Station was temporarily lodged in Heliopolis, and then sent to Port Said to form a small hospital there in view of the imminent[22] fighting on the Canal. These dispositions were made as soon as possible.

It should be noted at this juncture that the bulk of the Australian Forces, namely the First Division, was camped at Mena. A certain quantity of Light Horse was encamped at Maadi, whilst the Second Division, composed chiefly of New Zealanders, was encamped near Heliopolis. New Zealand had not provided any Lines of Communication Units, but her sick had been accommodated at the British Military Hospital, Citadel, Cairo, and also at the Egyptian Army Hospital, Abbassia.

The First and Second Stationary Hospitals used their tents for the respective purposes. The Casualty Clearing Station utilised a building assigned to it in Port Said.

Some description is required, however, of the Heliopolis Palace Hotel. This, as the photograph shows, is a huge hotel de luxe, consisting of a basement and four stories.

It was arranged that the kitchens, stores, and accommodation for rank and file should be placed in the basement. The first floor was allotted to offices and officers' quarters; a wing of the third floor provided accommodation for nurses, and the only portions of the building used at first for patients were the large restaurant and dining-room, and the billiard recesses, i.e. the Rotundas and Great Hall.

The hospital when fully developed required a large staff. The two large wards in the Rotundas and Central Hall could be administered easily enough, but the rest of the hotel consisted of rooms holding from three to six beds. The doors were removed. There were fortunately many bathrooms and lavatories. The rooms are very lofty, and provided with very large windows, but there are no fanlights over the doors, so that if doors were left in place ventilation was inadequate. A good deal of difficulty was experienced in providing suitable slop hoppers and sinks, places for cleaning bed-pans and the like, but little by little suitable arrangements were made.

The Arab servants, employed to ease the pressure on the staff, were housed in tents in one part of the grounds, and some of the rank and file in tents in another part. Others, for a short period, slept on the roof. The accommodation in general of the rank and file was excellent. The kitchens were a source of difficulty as the ranges were so elaborate; the hot-water service was unsatisfactory because of failure of fuel due to war conditions. Still, by one device and another, smooth running was ultimately secured.

When full value is given to all adverse criticism, it must be admitted that few better surgical hospitals could have been obtained.

The Officer Commanding the hospital (Lt.-Colonel Ramsay Smith) visited it with the Registrar, and made the preliminary arrangements. He then returned to Alexandria to supervise the disembarkation. Meanwhile the Registrar spent his time interviewing the proprietors, the D.M.S., and others concerned.

Only those who, knowing nothing of military organisation, tackle a job of the kind can fully appreciate the bewilderment caused by the mystic letters A.D. of S. and T., D.A.A. and Q.M.G., and the like, with all they connote. The Imperial officers[24] saw the difficulties and were kindly and helpful to a remarkable degree.

The hospital was opened on January 25, with provision for 200 patients. The first patient to be admitted was suffering from eye disease. An ophthalmic department was opened on the first floor, providing accommodation for out-patients as well as in-patients. As there were few oculists and aurists in Egypt at this juncture other than those at this hospital, the department rapidly assumed formidable proportions. The solid floors, lofty rooms, shuttered windows, and provision of electric light lent themselves to the creation of an excellent ophthalmic department.

The number of soldiers within easy distance of Heliopolis was not very great. Nevertheless patients, mostly medical cases, made their appearance in steadily increasing numbers, especially as Mena House was soon filled, and was limited in its accommodation.

With the arrival of the Second Australian Division in Egypt, and of subsequent reinforcements, the pressure on the First Australian General Hospital intensified, since these new arrivals went into camp at or near Heliopolis. The hotel rooms were filled with valuable furniture, including large carpets. From the outset it was arranged that neither carpets nor curtains were to be retained, and that the only hotel furniture which was to be used was beds and bedding for the officers and nurses. Everything else was stored away in various rooms. Up to this period the belief in official circles was that the First Australian General Hospital would soon be moved to France, and that it was consequently unwise to expand further, or to spend any considerable sum of money. The pressure, however, steadily continued, and when the Dardanelles campaign commenced, orders were given for the immediate expansion of the hospital to meet the ever-growing requirements of the troops. In order to effect this development the whole of the hotel furniture was moved into corridors of the building. Subsequently it was taken from the building and stored elsewhere, a difficult proceeding involving a great deal of labour.

On February 7 a New Zealand Field Ambulance which had taken charge of the venereal cases in camp, nearly 250 in number, was summarily ordered to the Suez Canal. Orders were given on that evening at 9 p.m. that the tent equipment of the First Australian General Hospital was to be erected at the Aerodrome Camp (about three-quarters of a mile distant), and that the hospital was to staff and equip a Venereal Diseases Camp by 2 p.m. the following day. By this time, too, large numbers of cases of measles had made their appearance, and it was quite clear that some provision must be made for these and other infectious cases. Accordingly another camp was pitched alongside the Venereal Camp for the accommodation of those suffering from infectious diseases. By direction of the D.M.S. Egypt, a senior surgeon was appointed to command the camp, and was given the services of two medical officers, one in connection with[26] the venereal cases, and one in connection with the infectious cases. Definite orders were given that such cases were not to be admitted into the General Hospital.

The camp was no sooner pitched than it was filled, and the demand on the accommodation for venereal and other cases rose until upwards of 400 venereal cases, and 100 infectious cases—chiefly measles—were provided for. A good deal of difficulty was experienced in suitably providing for the serious measles cases in camp, and accordingly a limited number of tents were erected in the hospital grounds, and a small camp was formed in that position, and placed under the charge of a nursing sister. To this camp all serious cases of infectious disease, and all cases with complications, were immediately transferred. It may be said in passing that the cases treated in this way did exceedingly well.

The number of venereal cases would have wholly out-stepped the accommodation had it not been for the policy adopted by the D.M.S. Egypt. All venereal cases not likely to recover rapidly were sent back to Australia, or (on one occasion) to Malta.

The hospital, then, at this juncture consisted of the main building, in which the accommodation was being steadily extended by the utilisation of all the rooms, and of the venereal and infectious diseases camp.

The first khamsin, however, which blew warned every one concerned that patients could not be treated satisfactorily in tents in midsummer. At the request of the medical officer in charge, two rooms in one wing of the main building were given over to bad infectious cases, and the camp in the grounds was abolished. The arrangement was unsatisfactory. The cases did not do as well as might have been desired, though this was attributed to an alteration in their type; and renewed efforts were made to devise a better arrangement. Finally a portion of the Abbassia barracks was obtained, and converted into an excellent venereal diseases hospital to which the venereal cases were transferred.

The Mena camp had been struck, and the troops sent to the Dardanelles; the First and Second Stationary hospitals had moved to Mudros; and the First Casualty Clearing Station had been transferred to the Dardanelles. Consequently the pressure fell almost entirely on the First General Hospital, and the Venereal Diseases Hospital thus became the only Venereal Diseases Hospital in Egypt.

Close to the Palace Hotel there was a large pleasure resort, known as the Luna Park, at one end of which was a large wooden skating-rink, enclosed by a balcony on four sides. This building was obtained, and was railed off from the rest of Luna Park by a fence 13 feet high. The infectious cases from the camp were then transferred to it. A camp kitchen was built, and an admirable open-air infectious diseases hospital was obtained. It became obvious, however, that the skating-rink, which with the balcony could accommodate, if necessary, 750 patients, might better serve as an overflow hospital in case of emergency, and accordingly efforts were made to[28] obtain another infectious diseases hospital in the vicinity.

Eventually a fine building known as the Race Course Casino, a few hundred yards from the Heliopolis Palace, was obtained and converted into an infectious diseases hospital providing for the accommodation of about 200 patients. With its ample piazzas and excellent ventilation it formed an ideal hospital, and was reluctantly abandoned at a later date owing to the development of structural defects which threatened its stability.

The position, then, at this stage was that the First Australian General Hospital consisted of (1) the Palace Hotel, ever increasing in its accommodation as the furniture was steadily removed and space economised, its magnificent piazzas utilised, and tents erected in the grounds for the accommodation of the staff; of (2) the rink at Luna Park, which was now empty and ready for the reception of light cases overflowing from the Palace; of (3) the Casino next door to Luna Park, which had now become an infectious diseases hospital; and of (4) the Venereal Diseases Hospital at Abbassia, which soon became an independent command though still staffed from No. 1 General Hospital.

At or shortly before this period, however, the authorities had become aware that wounded might be received from the Dardanelles at some future date in considerable numbers, which could not, however, be accurately estimated. Accordingly a consultation was held between Surgeon-General Ford and Surgeon-General Williams (who arrived in Egypt in February), Colonel Sellheim, who was the officer commanding the newly formed Australian Intermediate Base, the O.C. of the First Australian General Hospital, Lieut.-Col. Ramsay Smith, and Lieut.-Col. Barrett. It was decided to authorise the expenditure of a considerable sum of money in making the necessary preparation, on the ground that if the wounded did not arrive the Australian Government would justify this action, and that if the wounded did arrive a reasonable attempt would have been made to meet the difficulty. Instructions were accordingly given to buy up beds, bedding, and equipment, which would inter alia provide at least another 150 beds in the Infectious Diseases Hospital and 750 in the rink. At first iron beds were purchased, but it was impossible to obtain deliveries of iron beds at a rate exceeding 120 a week, and there were (practically) none ready made in Egypt. It was during this period of expansion that the donation of 130 beds made to Lieut.-Col. Ramsay Smith in Adelaide proved to be so useful.

It was, therefore, quite certain that full provision could not be made in time if iron beds were to be used, and accordingly large purchases of palm beds were made. These are very strong, stoutly constructed beds, made of palm wood. They are quite comfortable and last for several months. The drawback is that they are liable ultimately to become vermin-infected and that their sharp projecting struts are very apt to catch the dresses of those who pass by. We were able, however, to obtain them with mattresses at a rate exceeding 100 a day.[30] They were ordered in practically unlimited numbers, so that shortly there was accommodation for the 900 patients referred to. In addition a large reserve of beds and mattresses had been created so that they could be placed in the corridors if it became necessary.

At an earlier date the project of taking the whole of Luna Park and using the upper portion of it, the Pavilion, as well as the lower portion, the Rink, had been under contemplation, but had been rejected on the ground of expense. The rental demanded was high, owing to the fact that the park must perforce be closed as a pleasure resort if used as a hospital.

The conveyance of sick and wounded from Cairo to Heliopolis next engaged attention, and on April 26 it was found possible to run trains from Cairo on the tram-lines to Heliopolis Palace Hotel. A trial run was made about midnight on the 27th. The first train containing sick from Mudros arrived on the evening of the 28th, and on the 29th and 30th without warning the wounded poured into Heliopolis.

As soon as the nature of the engagement at the Dardanelles became known, the D.M.S. Egypt ordered that the whole of Luna Park be taken over and immediately equipped. The pavilion was made ready for the reception of the wounded within a very few hours, and in a few days Luna Park was so equipped with baths, latrines, beds, bedding, etc., that it could accommodate 1,650 patients.

Never before in history were precautions better justified. Had the expenditure not been incurred, had the representative of the Australian Government held up the execution of the policy of preparation by waiting for instructions, a disaster would have occurred, and many wounded would have been treated in tents in the sand of the desert. Yet so strangely constituted is a minor section of humanity that instead of satisfaction being expressed that the best possible had been done, some criticism was levelled at the undertaking on the ground that it was not at the outset technically perfect, and that it showed the initial defects inseparable from rapid improvisation. The Australian people should be profoundly grateful to Surgeon-General Williams and Colonel Sellheim, whose decisive promptitude enabled the position to be saved.

THE RUSH OF WOUNDED AND RAPID EXPANSION OF HOSPITALS—SAVING THE SITUATION—PERIOD OF IMPROVISATION—SHORTAGE OF STAFF AND EQUIPMENT—HOW THE EXPANSION WAS EFFECTED—THE NUMBER OF SICK AND WOUNDED.

CHAPTER IV

During the first ten days of the crisis approximately 16,000 wounded men entered Egypt, of whom the greater number were sent to Cairo, and during those ten days an acute competition ensued between the supply of beds and the influx of patients. Fortunately the supply kept ahead of the demand, the pressure being eased by the immediate provision at Al Hayat, Helouan, of a convalescent hospital capable of accommodating 1,000 and in an emergency even 1,500 patients.

At the end of the ten days referred to, the position was as follows:

Heliopolis Palace Hotel had expanded to 1,000 beds, Luna Park accommodated 1,650 patients, the Casino would accommodate 250, the Convalescent Hospital, Al Hayat, Helouan, was accommodating 700, and if need be could accommodate 1,500 patients, and the Venereal Diseases Hospital could receive 500 patients.

In the meantime No. 2 General Hospital had been transferred to Ghezira Palace Hotel, which was rapidly equipped, and at a later date became capable of receiving as many as 900 patients. Mena House remained an overflow hospital, bearing the same relation to No. 2 General Hospital as the Auxiliary Hospitals at Heliopolis bore to No. 1 General Hospital.

It was quite evident, however, that the accommodation was still insufficient, and a further search was made for other buildings. At this juncture a building opposite Luna Park known as the Atelier was offered by a Belgian firm for the use of the sick and wounded. It consisted of a very large brick building, with a stone floor and a lofty roof, which had been used as a joinery factory. At first the idea was entertained of creating a purely medical hospital, and of keeping the Heliopolis Palace for heavy surgery, with the auxiliaries for lighter cases. This policy was found to be impracticable, and the Atelier was converted into a 400-bed auxiliary hospital similar in character to Luna Park.

It was open for the reception of patients on June 10, and on the 11th was practically full of wounded.

As it was evident that the accommodation was still insufficient, a further search was made, and the Sporting Club pavilion, a building in the vicinity of the Heliopolis Palace, was taken over, and converted into a hospital of 250 beds. It was at first intended to use it as an infectious diseases hospital. As, however, it possessed great possibilities of expansion if suitable hutting could be erected, another infectious diseases hospital was sought elsewhere, and wooden shelters were erected. The accommodation of the Sporting Club was raised by this means to 1,250 beds.

The heat of summer was coming on, and the necessity for providing seaside accommodation for the convalescents from Cairo became obvious. Consequently the Ras el Tin school at Alexandria was taken by No. 1 General Hospital, and turned into an excellent convalescent hospital for 500 patients. It consisted of a very large courtyard, surrounded by (mostly) one-story buildings, and was about 400 yards from the sea. In the courtyard a Recreation Tent, provided by the British Red Cross Australian Branch, was erected by the Y.M.C.A. The whole formed an admirable seaside convalescent hospital.

But even now the accommodation was not sufficient, and by direction the Grand Hotel, Helouan, was acquired, and converted into an additional convalescent hospital for 500 patients. This institution, however, was shortly afterwards transferred to the Imperial authorities and used for British troops.

The structural defects in the Casino or Infectious Diseases Hospital, and the undesirability of using the Sporting Club for this purpose, necessitated the erection of an Infectious Diseases Hospital elsewhere. A beautifully constructed private hospital, the Austrian Hospital at Choubra, was commandeered and staffed by the First Australian General Hospital, and provided 250 beds. This hospital also was, however, soon transferred to the Imperial authorities, and administered as a British hospital.

As the demand for accommodation for infectious cases increased, the artillery barracks at Abbassia were taken over by the Australian authorities, and converted into an Infectious Diseases Hospital which ultimately accommodated 1,250 patients.

The needs continuing to press, the Montazah Palace at Alexandria was offered by His Highness the Sultan to Lady Graham as a convalescent hospital. The offer was gratefully accepted by the combined British and Australian Branches of the Red Cross[38] Society. It is the only hospital in Egypt in the administration of which the Australian Red Cross takes part.

In addition to these major activities, there were many other minor changes. The introduction of cholera from Gallipoli was feared, and in the grounds of the Casino a cholera hospital was erected in anticipated need, under the direction of the Board of Public Health, Egypt. Fortunately it was never required, but it was ready for use, and would have been staffed by the First Australian General Hospital.

The final result, then, of all these expansions was as follows. The 520-bed hospital which landed in Egypt on January 25 had expanded into:

| Beds | |

| Heliopolis Palace Hotel | 1,000 |

| Luna Park | 1,650 |

| Atelier | 450 |

| Sporting Club | 1,250 |

| Choubra Infectious | 250 |

| Abbassia Infectious | 1,250 |

| Venereal Diseases, Abbassia | 2,000 |

| Al Hayat, Helouan (Convalescent) | 1,250 |

| Ras el Tin (Convalescent) | 500 |

| Montazah Palace (Convalescent, Australian moiety) | 500 |

| Grand Hotel, Helouan | 500 |

| ——— | |

| (Approximately) 10,600 | |

| ====== |

Almost the whole of this work was undertaken by the staff originally intended to manage a 520-bed hospital, at all events until the latest developments. Reinforcements did not arrive until June 15, and even then they were not long available.

To house the reinforcements of nurses two other buildings were taken at Heliopolis: Gordon House, opposite Luna Park, and the Palace of Prince Ibrahim Khalim, on the outskirts of Heliopolis.

It will be noted that the greater part of the expansion took place in the immediate vicinity of the Palace Hotel. This step was alike deliberate and necessary, for reasons that will be explained hereafter.

The methods adopted in organising these hospitals varied. In the first instance Lieut.-Col. Barrett was deputed by the D.M.S. Egypt to seek for the necessary buildings, and when these were approved to negotiate with the owners respecting the rent. This proceeding proved very tedious and difficult, and in pursuance of a General Army Order another and simpler plan was adopted by the appointment of an arbitration commission under the chairmanship of Sir Alexander Baird. To this commission the determination of rent and compensation was referred when the acquisition of the buildings received the sanction of the Commander-in-Chief. It need hardly be said that a good deal of tact was necessary in these proceedings, and every attempt was made to meet the wishes of owners with regard to the buildings commandeered.

Up till June 15 the number of nurses available was small, and it became quite obvious that, owing to the rush of sick and wounded, and the hot weather, some of the nurses would experience a breakdown. Lieut.-Col. Barrett accordingly visited Alexandria, and arranged with the Australian and Egyptian branches of the British Red Cross Society[40] to take over and equip two buildings as Rest Homes. These houses had been generously offered for this purpose to Her Excellency Lady MacMahon, wife of the High Commissioner for Egypt. One of these buildings was a large house belonging to a distinguished Egyptian and was situated in Ramleh, not very far from the beach, and the other was about eight miles from Alexandria at Aboukir Bay, the site of Nelson's victory. The latter consisted of a large seaside bungalow owned by Mr. Alderson, with an excellently fitted house-boat anchored some little distance from the shore.

The Australian Government undertook to pay for the maintenance of the nurses in these homes, which were placed under the management of a joint committee of the two branches of the Red Cross Society, under the presidency of Lady MacMahon. Nurses were then sent to these homes for a week at a time, and derived great benefit from the sea-bathing. These vacations formed a welcome and healthy break in work of excessive severity.

The following table indicates the dates of the principal changes which took place in the First Australian General Hospital.

January 14.—Arrived at Alexandria.

January 24.—Arrived at Heliopolis.

February 7.—Established Aerodrome Camp.

April 6.—Luna Park taken over.

April 19.—Established Venereal Hospital, Abbassia.

April 26.—The Casino taken over.

April 29.—Arrival of wounded.

May 1.—Prince Ibrahim Khalim's Palace taken over.

May 5.—Al Hayat Hotel taken over.

May 26.—The Atelier taken over.

May 27.—Gordon House taken over.

June 10.—Sporting Club taken over.

It has frequently been said in criticism of the Auxiliary Hospitals that it would have been better to have taken over Shepheard's Hotel, or the Savoy. Neither Shepheard's nor the Savoy (particularly the former) is very suitable for hospital purposes, since hotels containing a large number of small rooms involve much labour, and consequently a large staff, and the authorities were faced with the fact that there was no staff available. Surgeon-General Williams had cabled to Australia for reinforcements long before the crisis, but the reinforcements did not arrive until the middle of June. Clearly the sound policy was to obtain buildings as close to Heliopolis as possible, to administer them with a small staff, and to use them as overflow hospitals. Shepheard's or the Savoy would have required a very large staff, and it was not existent. Even at Helouan the employment of civilians as officers was necessary in order to carry on. Arab servants were extensively employed by reason of the shortage of staff. They acted as menservants, sweepers, and the like.

When the Kyarra arrived in Egypt the British authorities did not possess any motor transport. There were some motor ambulances belonging to the[42] New Zealand authorities and a few motor ambulances which accompanied the hospitals on the Kyarra, and which had been allotted to special units. It became obvious, however, that units might be placed in circumstances in which they did not require their ambulances, and others in circumstances in which they required more than their share; and accordingly Surgeon-General Williams decided to park the whole of these motor ambulances in two garages, a major one at Heliopolis and a smaller one at Ghezira, near No. 2 General Hospital. The garage at Heliopolis held at least thirty motor ambulances. It belonged to the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, and was equipped and furnished with a repairing plant at the expense of the Australian branch of the British Red Cross. The Ghezira garage was dealt with in like manner, and in addition the rent was paid in the first instance by the Australian branch of the British Red Cross. The organisation of these garages involved considerable difficulty. The drivers employed were not recruited by the Commonwealth Government as belonging to the motor transport, since there was not any motor ambulance establishment, and they consequently only received the ordinary private's pay. Furthermore promotions were very difficult to effect. Nevertheless they saved the position. For a long while Egypt was absolutely dependent on these motor fleets for the removal of the sick and wounded, British or Australian. The work was excessive but the drivers responded splendidly. Difficulties arose through different units endeavouring to commandeer motor ambulances for their own use. This was met by a decision of the D.M.S. Egypt that ambulances were to be kept in the garages, and telephoned for when necessary. From the outset, the lack of runabout motors was severely felt, and ambulances were frequently employed for purposes which would have been better effected by runabouts.

The end of April was reached. The bulk of the forces had disappeared from Egypt, and their position was only known by rumour; the hospital was gradually emptied of patients; Mena Camp had been abandoned, and Maadi Camp was reduced to small proportions. The weather was beautiful, and any one might have been easily lulled into a sense of false security. On April 28, however, a train-load of sick arrived. Its contents were not known until it arrived at the Heliopolis siding. The patients had come from Mudros, and numbered over 200 sick, including some 60 venereal cases, a matter of some interest in the light of subsequent events.

On the following day, however, without notice or warning of any description, wounded began to arrive in appalling numbers. On April 30 and May 1 and 2 no less than 1,352 cases were admitted at Heliopolis.

The expansion already indicated at Luna Park was at once effected, and some relief was obtained by transferring the lighter cases to Mena House—some seventeen miles distant. The last train-load of wounded arrived in the early morning of May 2, and deserves special notice, as many of the men were very seriously injured. There were about 100 cases; the train arrived at midnight, and was emptied by 4 o'clock in the morning. The bearing[44] of the men badly injured was past praise. At 4 a.m. the main operating-room of the hospital bore eloquent testimony to the gravity of the work, which had been going on for many hours, and the exhausted condition of the staff further demonstrated what had occurred. The staff at the hospital was quite inadequate to cope with the rush, notwithstanding the willingness of every one concerned, and accordingly volunteers from some of the Field Ambulances, and from the Light Horse units which were still in Egypt, were called for and readily obtained. With the aid of the volunteers and by dint of universal devotion to duty the work was done, and on the whole done well.

The following table shows the staff available from April 2 to August 18, and the work required of it:

| Date. | Officers. | Nurses. | Rank and | Patients. | No. of | |

| File. | Beds. | |||||

| April | 25 | 28 | 92 | 163 | 495 | 893 |

| 26 | 29 | 92 | 187 | 504 | 893 | |

| 27 | 28 | 92 | 184 | 479 | 897 | |

| 28 | 28 | 92 | 184 | 479 | 895 | |

| 29 | 28 | 92 | 197 | 631 | 925 | |

| 30 | 28 | 92 | 204 | 1,082 | 1,100[1] | |

| Date. | Officers. | Nurses. | Rank and | Patients. | No. of | ||

| File. | Beds. | ||||||

| May | 1 | 26 | 92 | 216 | 1,324 | 1,100 | |

| 2 | 26 | 92 | 236 | 1,465 | |||

| 3 | 32 | 92 | 236 | 1,425 | |||

| 4 | 28 | 109 | 221 | 1,427 | |||

| 5 | 30 | 107 | 221 | 1,389 | |||

| 6 | 30 | 107 | 209 | 1,362 | 2,108 | ||

| 7 | 30 | 107 | 198 | 1,353 | |||

| 8 | 30 | 107 | 198 | 1,454 | |||

| 9 | 29 | 107 | 201 | 1,432 | |||

| 10 | 26 | 107 | 201 | 1,485 | |||

| 11 | 26 | 107 | 209 | 1,618 | 2,493 | ||

| 12 | 26 | 107 | 209 | 1,846 | 2,487[45] | ||

| 13 | 28 | 107 | 249 | 2,293 | 2,592 | ||

| 14 | 29 | 107 | 244 | 2,302 | 2,726 | ||

| 15 | 29 | 107 | 244 | 2,218 | 2,705 | ||

| 16 | 32 | 107 | 261 | 2,208 | 2,679 | ||

| 17 | 30 | 107 | 259 | 2,165 | 2,646 | ||

| 18 | 30 | 107 | 252 | 2,187 | 2,940 | ||

| 19 | 30 | 107 | 274 | 1,911 | |||

| 20 | 30 | 107 | 302 | 1,904 | |||

| 21 | 29 | 107 | 290 | 1,889 | |||

| 22 | 29 | 107 | 287 | 1,856 | |||

| 23 | 29 | 107 | 287 | 1,812 | |||

| 24 | 29 | 104 | 287 | 1,811 | |||

| 25 | 32 | 104 | 299 | 1,777 | |||

| 26 | 32 | 104 | 295 | 1,768 | |||

| 27 | 32 | 104 | 295 | 1,805 | |||

| 28 | 32 | 104 | 317 | 1,781 | |||

| 29 | 35 | 143 | 319 | 1,931 | |||

| 30 | 35 | 143 | 322 | 1,918 | |||

| 31 | 35 | 143 | 322 | 1,820 | |||

| Date. | Officers. | Nurses. | Rank and | Patients. | No. of | |

| File. | Beds. | |||||

| June | 1 | 35 | 143 | 322 | 1,876 | |

| 2 | 35 | 143 | 315 | 1,873 | ||

| 3 | 36 | 143 | 314 | 1,869 | ||

| 4 | 36 | 147 | 277 | 1,866 | ||

| 5 | 35 | 147 | 277 | 1,872 | ||

| 6 | 36 | 147 | 264 | 1,786 | ||

| 7 | 36 | 147 | 264 | 1,627 | ||

| 8 | 34 | 147 | 253 | 1,709 | ||

| 9 | 34 | 147 | 253 | 2,474 | 2,805 | |

| 10 | 32 | 133 | 247 | 2,211 | ||

| 11 | 32 | 133 | 247 | 2,605 | ||

| 12 | 32 | 133 | 262 | 2,375 | ||

| 13 | 32 | 133 | 263 | 2,384 | ||

| 14 | 34 | 133 | 264 | 2,324 | ||

| 15 | 34 | 133 | 264 | 2,324 | ||

| 16 | 54[2] | 171[3] | 463[4] | 2,269 | ||

| 17 | 54 | 171 | 463 | 2,328 | ||

| 18 | 55 | 165 | 462 | 2,259 | ||

| 19 | 55 | 165 | 449 | 2,266 | ||

| 20 | 55 | 165 | 443 | 2,339 | ||

| 21 | 55 | 165 | 439 | 2,335 | ||

| 22 | 55 | 165 | 439 | 2,357 | ||

| 23 | 55 | 165 | 439 | 2,159[46] | ||

| 24 | 55 | 165 | 438 | 2,157 | ||

| 25 | 55 | 163 | 438 | 2,003 | ||

| 26 | 55 | 163 | 429 | 1,926 | ||

| 27 | 55 | 163 | 429 | 1,887 | ||

| 28 | 55 | 163 | 429 | 2,121 | ||

| 29 | 54 | 163 | 429 | 2,150 | ||

| 30 | 55 | 163 | 429 | 2,135 | ||

| Date. | Officers. | Nurses. | Rank and | Patients. | No. of | |

| File. | Beds. | |||||

| July | 1 | 55 | 163 | 430 | 2,332 | 2,956 |

| 2 | 58 | 163 | 430 | 2,305 | ||

| 3 | 58 | 163 | 405 | 2,187 | ||

| 4 | 55 | 163 | 403 | 2,131 | ||

| 5 | 55 | 163 | 395 | 2,131 | ||

| 6 | 55 | 157 | 325 | 2,032 | ||

| 7 | 55 | 157 | 395 | 1,982 | ||

| 8 | 56 | 157 | 395 | 2,107 | ||

| 9 | 55 | 157 | 397 | 2,120 | ||

| 10 | 56 | 157 | 393 | 2,145 | ||

| 11 | 56 | 157 | 399 | 2,115 | ||

| 12 | 52 | 157 | 399 | 2,072 | ||

| 13 | 52 | 155 | 394 | 2,130 | ||

| 14 | 52 | 155 | 394 | 2,087 | ||

| 15 | 52 | 155 | 391 | 2,101 | ||

| 16 | 52 | 153 | 407 | 1,930 | ||

| 17 | 51 | 155 | 410 | 1,885 | ||

| 18 | 51 | 153 | 561 | 1,785 | ||

| 19 | 73 | 234 | 616 | 1,713 | ||

| 20 | 73 | 234 | 616 | 1,782 | ||

| 21 | 79 | 231 | 565 | 1,716 | ||

| 22 | 79 | 231 | 374 | 1,487 | ||

| 23 | 78 | 223 | 570 | 1,450 | ||

| 24 | 75 | 226 | 568 | 1,476 | ||

| 25 | 75 | 226 | 548 | 1,438 | ||

| 26 | 75 | 226 | 548 | 1,447 | ||

| 27 | 74 | 226 | 555 | 1,434 | ||

| 28 | 74 | 226 | 555 | 1,692 | ||

| 29 | 75 | 226 | 544 | 1,695 | ||

| 30 | 75 | 224 | 449 | 1,452 | ||

| 31 | 70 | 224 | 457 | 1,362 | ||

| Date. | Officers. | Nurses. | Rank and | Patients. | No. of | |

| File. | Beds. | |||||

| Aug. | 1 | 70 | 224 | 457 | 1,588 | 2,876 |

| 2 | 70 | 224 | 457 | 1,610 | ||

| 3 | 71 | 224 | 447 | 1,652 | ||

| 4 | 71 | 224 | 447 | 1,631 | ||

| 5 | 61 | 224 | 447 | 1,759 | ||

| 6 | 60 | 224 | 456 | 1,731 | ||

| 7 | 60 | 224 | 456 | 1,793[47] | ||

| 8 | 60 | 224 | 424 | 1,927 | ||

| 9 | 59 | 224 | 432 | 1,902 | ||

| 10 | 58 | 224 | 432 | 339[5] | ||

| 11 | 357 | |||||

| 12 | 542 | |||||

| 13 | 42 | 216 | 416 | 454 | ||

| 14 | 47 | 216 | 462 | 504 | ||

| 15 | 45 | 216 | 462 | 535 | ||

| 16 | 45 | 216 | 480 | 587 | ||

| 17 | 47 | 216 | 484 | 485 | ||

| 18 | 48 | 216 | 460 | 470 | ||

[1] Including Luna Park.

[2] 20 Reinforcements.

[3] 38 Reinforcements.

[4] 195 Reinforcements.

[5] Auxiliaries separated and made independent.

The proceeding adopted on arrival of the train was as follows: Two officers were on duty on the platform in control of guard and stretcher squad. The officer in charge of the train handed in a list of the number of wounded on the train, classified into lying-down and sitting-up cases, those of gravity being specially marked. The train was then emptied carriage by carriage of the sitting-up patients, who walked to the hospital or were driven by the motor ambulances as the case might be, tally being kept at the door of the carriage. As soon as the train had been emptied of the sitting-up cases, the cot patients were removed by the stretcher squad to the motor ambulances, each of which carried a load of two patients. In serious cases an officer was sent with the patient, and as the distance was less than a quarter of a mile, the transfer was fairly rapid.

The Egyptian ambulance trains were on the whole good, and were equipped with necessaries and comforts by the Australian Branch British Red Cross. The Australian military authorities also provided nurses for the trains. The stretcher squads soon learned and did their work exceedingly well; but however well the work may be done, the removal of a gravely injured man from a mattress in a wooden bunk to a stretcher offers some difficulty and may cause distress. The construction of the wooden bunks left something to be desired. There is no doubt that it is desirable to devise a carriage of such a nature that stretchers can be inserted without difficulty under every patient, and his removal effected without disturbance.

The patients on arrival in the front hall of the hospital were provided with hot chocolate and biscuits, or with lime juice, and were at once drafted to various portions of the hospital. The lighter cases were sent to the auxiliary hospitals, and the more severe cases transferred to wards in the Palace building. Four sets of admitting medical officers with staffs were in readiness, and 200 patients could be disposed of in an hour. Promptitude was essential, as the trains sometimes followed on one another quickly. On admission the patients were bathed and given clean pyjamas. Their clothes and kit were sent to the Thresh Disinfector to be sterilised before being passed into the pack store.

Every patient on entering the hospital was provided with pyjamas, shirt, two handkerchiefs, socks, plate, knife, fork, spoon, mug, and slippers. The Red Cross Society provided him with writing-paper and envelopes, pencil, chocolate, nail brush, soap, cigarettes, tooth powder, and tooth brush.

As the equipment of additional beds involved the supply of all these articles, in addition to mattresses, blankets, linen, towels, kitchens, cooking-utensils, stoves, bedside tables, ward utensils, instruments, drugs, and bandages, the strain on the Quartermaster's department during this period of expansion was very great. The supply and distribution of food to the auxiliary hospitals occasioned considerable difficulty at the beginning of the crisis, but was satisfactorily adjusted.

As the patients became convalescent they were moved to one of the auxiliary hospitals, and from the auxiliary hospitals to one of the convalescent hospitals at Helouan or Alexandria, and thence either invalided or discharged to duty. As the patients during transference to the auxiliaries were conveyed in a motor ambulance, and when transferred to Helouan or Alexandria were motored to Cairo railway station under charge of a N.C.O., some idea of the work thrown on the motor ambulance corps and on the staff can be imagined.

So far all the auxiliary hospitals were regarded as wards of the main hospital, and administered from the main building—the only possible method of administration at this juncture. It was generally believed that the Dardanelles campaign would be of short duration, and that Luna Park and the other auxiliary hospitals would soon be closed. Consequently the expenditure of much money on these auxiliaries was deprecated. When, however, it became obvious that the operations at Gallipoli might last a very long time, and that in any event the troops pouring into Egypt from Australia and elsewhere[50] would require hospital accommodation, an entirely new view of the matter was taken, and active steps were taken to permanently equip the auxiliary hospitals for more serious work. Of this equipment something must now be said in detail.

At Luna Park the central lake was emptied and drained, and was covered by an enormous shelter shed provided by the Australian Red Cross. The shelter with a modern kitchen provided by the authorities formed the dining-room for the patients, nearly all of whom were able to leave their beds. In addition an excellent operating-room was built in brick, barbers' shops were organised, and a canteen, store, and numerous comforts in the way of blinds, sunshades, punkahs, were provided. Ample bath and latrine accommodation was added. As time passed, the palm beds were gradually replaced by metal beds, and the total number reduced to 1,000. In the event of another emergency, beds can be again provided, to the number of 1,650, but such a step will only be taken in the presence of necessity.

Furthermore in the case of Luna Park and the other auxiliary hospitals, the D.M.S. Egypt decided that the feeding of patients should be effected by contract, and the matter was therefore left in the hands of a well-known caterer. A large amount of Red Cross money was expended on the shelter sheds and on a recreation hut managed by the Y.M.C.A., and Luna Park became an excellent open-air hospital. It is the more necessary to draw attention to this fact by reason of the adverse criticisms which have been passed by those who have only a superficial acquaintance with it. It will be sufficient to say that up to November 1, 5,500 patients had passed through it, and there had been only one death, and that from anæsthetic. This remarkable result was not altogether due to the fact that mild cases were admitted, for latterly many major operations had been performed, for appendectomy, etc., and according to Colonel Ryan, Consulting Surgeon to the Force in Egypt, all the operation cases had healed by first intention. In fact Luna Park really represents the triumph of the open-air method of treating patients in a rainless country. The patients preferred it because of the freedom the gardens gave them, but they showed one peculiarity which could never have been foreseen. The Australian soldier was not very fond of chairs. He did not want to stay in the shelter sheds, but preferred to spend much of his day lying in bed, and had to be ordered away from it to effect any change. It is not unnatural that men who have been doing excessive physical work should prefer physical rest when they can get it.

At No. 2 Auxiliary Hospital, the Atelier, similar changes were made. The Red Cross provided shelter sheds and a number of comforts. The Atelier was certainly the easiest of the buildings to adapt, by reason of the relatively small number of patients and its spacious surroundings.

At No. 3 Auxiliary Hospital the building could not accommodate more than 250 patients in any circumstances, but two large tennis courts were covered with matting and provided with a louvred roof. This proceeding was followed by the erection of wooden huts each of which constituted a ward of 50 beds. These huts were placed in convenient relationship to a central kitchen and other conveniences. The Sporting Club thus became an excellent outdoor hospital.

The creation of the Infectious Diseases Hospital at Abbassia is another instance of the importance of prevision. It was organised by Major Brown (who had already organised Luna Park and the Atelier) as a hospital of 250 beds. By successive squeezes, and by the erection of tents, the accommodation was rapidly increased to 1,250 beds, and was then insufficient although typhoid cases were not admitted.

The work of extension was at first difficult, but soon became quite simple because a considerable number of officers and men became experienced in the methods of effecting desirable results, and in the art of adapting means in sight to the end desired.

Finally it became obvious that the mechanism was becoming too complicated, i.e. that the administration of all these hospitals from the Palace Hotel, and the keeping of the records at the Palace Hotel, had become impossible. It was accordingly decided to separate them and make them independent commands. This arrangement was completed about the middle of August, but it involved a fresh crop of difficulties. It was quite necessary that some one should meet the trains and allot the patients to the various hospitals. That was a comparatively simple matter. It was necessary that the hospitals should be properly staffed, and that those who administered them should receive proper rank, in other words that there should be a definite establishment. This necessitated a reference to the Australian Government, and consequently difficulties and delays.

The valuable and almost essential part played by the Australian Branch British Red Cross, in effecting the expansion and in preventing a disaster, will be referred to in the chapter on the Red Cross.

The following table indicates the nature of the increasing demand on the hospital accommodation:

| Venereal and | |||

| Infectious Cases | |||

| Feb. 13 | 186 | cases | 358 cases |

| Feb. 15 | 200 | cases (39 Ophthalmic and aural cases) | 351 " |

| Feb. 25 | 324 | cases (including 51 special cases) | 422 " |

| March 1 | 477 | cases, 46 special cases | 404 " |

| March 15 | 532 | " 57 " " | 476 " |

| April 1 | 596 | " 64 " " | 283 " |

| April 15 | 567 | " 52 " " | 429 " |

| April 28 | 479 | " 57 " " | 433 " |

| April 29 | 631 | " 57 " " | 478 " |

| April 30 | 1,082 | " 49 " " | 469 " |

| May 1 | 1,324 | (286 patients discharged) | 456 " |

| May 2 | 1,465 | (213 patients discharged) | 462 " |

| May 3 | 1,492 | 453 " | |

| Patients admitted to July 31, 1915 | 13,325 | ||

| Deaths | 102 | = 0·76 per cent. | |

Largest number of patients admitted on any one day (June 8, 1915):

| Australians | 408 | |

| New Zealanders | 85 | |

| British | 325 | |

| Officers | 10 | |

| —— | ||

| 828 | ||

| —— | ||

| June 9 | 219 | |

| —— | ||

| 1,047 | in two days. | |

| ===== |

Sick and wounded received at the First Australian General Hospital at the end of April:

| April 28 | 195 |

| April 29 | 469 |

| April 30 | 529 |

| May 1 | 354 |

| —— | |

| Total | 1,547 |

| —— |

Surveying in retrospect this anxious and troublesome period, the outstanding feature is the mistake made in the constant assumption that the hospital expansion was temporary. It was stated that Luna Park would only be wanted for a few weeks; the Dardanelles campaign would soon be over, Luna Park would not then be wanted, and could be closed, consequently heavy expenditure on it was deprecated. Furthermore the experience gained makes it obvious that in war the Service cannot include too many medical officers—preferably juniors. The demand for their services here and there is practically unlimited. They should be young and unattached to any particular unit—in fact a junior reserve on the spot.

It should be remembered that the expansion of No. 1 Australian General Hospital was effected under the personal direction of the officer commanding, Lieut.-Colonel Ramsay Smith, who inspected all new buildings, gave his approval or disapproval, and was responsible for their efficient equipment when converted into hospitals.

CONVALESCENT DEPOTS—EVACUATION OF CONVALESCENT SICK AND WOUNDED FROM CONGESTED HOSPITALS—KEEPING THE HOSPITALS FREE—LIBELS ON THE EGYPTIAN CLIMATE—DISCIPLINE.

CHAPTER V

It will be remembered that so far as the Australian troops were concerned, provision had been made for three convalescent hospitals or homes. The magnificent hotel of Al Hayat at Helouan was taken over on May 5, emptied of hotel furniture, fitted with palm beds and mattresses, and converted into a convalescent hospital. As there was no staff in Egypt available, it was placed under the direction of a military commandant and a principal medical officer who was a civilian practitioner resident at Helouan. A few non-commissioned officers and orderlies were transferred to it from the convalescent camp in the desert at Zeitoun, which was very properly terminated. The cooking was effected by arrangement with a professional caterer at a charge of 5s. a day for officers, and 3s. a day for men. These charges ultimately included the provision of cooking and eating utensils. This convalescent hospital both in its general character and with respect to the food supplied represents in all probability the most successful effort made in Egypt. In fact it has been suggested that the hospital was almost too attractive, and that there was consequently a good deal of disinclination to leave it. In favour of the principle involved in installing a military commandant to administer a convalescent hospital there is much to be said, as the administration is one man's work.

| Jan. | Feb. | March. | April. | May. | June. | |

| Alexandria | 53.4 | 54 | 56.5 | 60 | 64.2 | 71.2 |

| Heliopolis | 51.8 | 52.7 | 57 | 59.7 | 64.9 | 72.3 |

| Helouan | 50 | 50 | 53.8 | 57.4 | 61 | 67.3 |

| July. | August. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | |

| Alexandria | 73.4 | 73.8 | 69 | 66 | 61.2 | 56.9 |

| Heliopolis | 73 | 74 | 70.2 | 65.7 | 60.1 | 54.7 |

| Helouan | 68.9 | 69.2 | 68.2 | 62.4 | 57.6 | 52.7 |

| Maximum at Helouan, 77.3. | Minimum at Helouan, 36.7. | |||||

Those who know Helouan and the hotel will not be surprised at the success of the Hospital, but it may surprise even those who know Egypt to learn that Helouan is considerably cooler than Cairo, notwithstanding the fact that it is situated on the edge of the desert. Owing to dryness the Wet Bulb temperature is considerably lower than at Cairo in midsummer and the nights are always cool.

It must be remembered that the figures in the attached table give means only, and that any registration over 75°F. Wet Bulb is high, and that at 80°F. Wet Bulb work becomes difficult. At 90°F. Wet Bulb the danger point is reached, and all work must cease on pain of death from heat apoplexy.

It will be seen, then, that Egypt is not especially hot, even from May till October, and that Helouan is particularly cool. These conclusions coincide with the feelings of those who live there. Alexandria is pleasant by day, because of the sea breezes, but at night most people prefer Heliopolis, which is drier and where they are more likely to enjoy a breeze.

These observations apply to the weather after May. From March to May the khamsin may blow for several days. The temperature then is high, but the air very dry. Khamsins usually cease in May.