Title: On the Mexican Highlands, with a Passing Glimpse of Cuba

Author: William Seymour Edwards

Release date: February 8, 2013 [eBook #42000]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

CINCINNATI

PRESS OF JENNINGS AND GRAHAM

Copyright, 1906, by

William Seymour Edwards

THE SIX COMRADES OF CAMP FLAP-JACK—1881

To

Julius H. Seymour, Otto Ulrich von Schrader,

Edmund Seymour, and Rudolph Matz,

Companions, Comrades, and

Fellow-Travellers of

“CAMP FLAP-JACK”

These pages are affectionately dedicated.

These pages contain the impressions of a casual traveller—a few letters written to my friends.

Upon the temperate Highlands of Mexico, a mile and more above the sea, I was astonished and delighted at the salubrity of climate, the fertility of soil, the luxuriance of tree and plant, the splendor and beauty of the cities, the intelligence and progressiveness of the people, the orderliness and beneficence of the governmental rule.

In Cuba I caught the newborn sentiment for liberty and order, and at the same time came curiously into touch with restive leaders, who even then boldly announced the intention to plot and wreck that liberty and order by sinister revolution, if their wild spirits should find no other way to seize and hold command.

If there shall be aught among these letters to interest the reader, I shall welcome another to the little circle for whose perusal they were originally penned.

Charleston-Kanawha, West Virginia,

November 1, 1906.

ON THE MEXICAN HIGHLANDS

A VISTA OF MEXICO

New Orleans, Louisiana,

November 15th.

When the New York and Cincinnati Flyer (the “F. F. V. Limited”) came into Charleston yesterday, it was an hour late and quite a crowd was waiting to get aboard. Going with me as far as Kenova were D, H, and eight or ten of “the boys.” They all carried Winchesters and were bound on a trip to the mountains of Mingo and McDowell, on the Kentucky line, to capture a moonshine still which was reported to be doing a fine business selling to the mines. D wanted me to go along, and offered me a rifle or a shotgun, as I chose. They are big men, all of them, and love a scrap, which means the give and take of death, and have no fear except of ambush. I still carry in my pocket the flat-nosed bullet D took from the rifle of Johnse Hatfield two years ago, when he caught him lying-in-wait behind a rock watching for Doc. Ellis to come forth from[Pg 16] his front door. Johnse was afterward hanged in Pikeville for other crimes. Then, a few months later, his brother “Lias,” just to get even, picked off Doc. Ellis as he was getting out of a Pullman car. Now “Lias” is said to be looking for D, also, but D says he’s as handy with his gun as “Lias” is, if only he can get a fair show. D is captain of this raid and promises to bring me tokens of a successful haul, but I am apprehensive that, one of these days, he or some other of “the boys” will not come back to Charleston.

At Ashland my Louisville car was attached to the Lexington train, and we turned to the left up the long grade and soon plunged into the hill country of eastern Kentucky. Here is a rough, harsh land, a poor, yellow soil, underlying miles of forest from which the big timber has long since been felled. Here and there small clearings contain log cabins, shack barns, and soil which must always produce crops as mean as the men who till it. We were traversing the land of the vendettas. At the little stations, long, lank, angular men were gathered, quite frequently with a rifle or a Winchester shotgun in their bony hands. It was only two or three years ago that one of these passenger trains was “held up,” by a rifle-armed gang, who found the man they were looking for crouching in the end of the smoker, and shot him to death[Pg 17] right then and there—but not before he had killed two or three of the assassins.

I had gone forward into the smoking car, for it is in the day coaches where one meets the people of the countryside when traveling. I had seated myself beside a tall, white-haired old man who was silently smoking a stogie, such as is made by the local tobacco growers of this hill country. He had about him the air of a man of importance. He was dressed in homespun jeans and wore the usual slouch felt hat. He had a strong, commanding face, with broad, square chin and a blue eye which bespoke friendliness, and yet hinted of inexorable sternness. I gave him my name and told him where I lived, and whither I was going, introducing myself as one always must when talking to these mountain people. He was a republican, like myself, he said, and had several times been sheriff of his county; but that was many years ago and he declared himself to be now “a man of peace.” We talked of the vendettas and he told me of a number of these tragedies. When I made bold to ask him whether he had ever had any “trouble” himself, he replied, “No, not for right smart o’ yearn;” and then he slowly drew from his trousers pocket, a little buckskin bag, and unwound the leathern thong with which it was fast tied. Having opened it he took out three misshapen[Pg 18] pieces of lead and handed them to me, remarking, “‘T was many yearn ago I cut them thar pieces of lead, and four more of the same kind, from this h’yar leg of mine,” slapping his hand upon his right thigh. “But where are the other four?” I queried. For an instant the blue eyes dilated and glittered as he replied, “I melted ’em up into bullets agen, and sent ’em back whar they cum from.” “Did you kill him?” I asked. The square jaws broadened grimly, and he said, “Wall, I don’t say I killed him, but he ain’t been seen aboot thar sence.” I offered him one of my best cigars, and turned to the subject of the horses of Kentucky. He was going to Lexington, he said, to attend the horse sales the coming week and he begged me to “light off with him,” for he was sure I would there “find a beast” I would delight to own. I promised to visit him some day when I should return, and he has vouched to receive me with all the hospitality for which Kentucky mountaineers, as well as blue grass gentlemen, are famed.

When we had come quite through the hill region, we rolled out into a country with better soil, and land more generally cleared, and much in grass. It was the renowned blue grass section of Kentucky, and at dark we were in Lexington. Twinkling lights were all that I could see of the noted town. The people who were about the sta[Pg 19]tion platform were well dressed and looked well fed, and a number of big men climbed aboard.

LOG CABIN OF KENTUCKY MOUNTAINEER

We arrived at Louisville half an hour late. This was fortunate, for we had to wait only an hour for the train to Memphis, via Paducah. Two ladies, who sat behind me when I entered the car at Charleston, stood beside me when I secured my ticket in the Memphis sleeper and took the section next to mine. It had been my intention to change trains at Memphis, take the Yazoo Valley Railway and go via Vicksburg, thinking that I might see something of the Mississippi River; but in the morning I met a young engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad, who told me that this route had a very bad track, the cars were poor, the trains slow, while the line itself lay ten or twelve miles back from the river so that I should never see it; therefore, I decided to stick to the through fast train on which I had started, and go on to New Orleans by the direct route down through central Mississippi.

When I awoke we were speeding southward through the wide, flat country of western Tennessee. We passed through acres of cornstalks from which the roughness (the leaves of the corn) and ears had been plucked, through broad reaches of tobacco stumps, and here and there rolled by a field white with cotton.

In the toilet room of the sleeper I found myself alone with a huge, black-bearded, curly-headed planter, who was alternately taking nips from a gigantic silver flask and ferociously denouncing the Governor of Indiana for refusing to surrender Ex-governor Taylor to the myrmidons of Kentucky law, to be there tried by a packed jury for the assassination of Governor Goebel. I finally felt unable to keep silent longer, and told him that I did not see the justice of his position, and reminded him that the Governors of the neighboring States of West Virginia, Ohio and Illinois had publicly expressed their approval of the Governor of Indiana, and their disapproval of the political methods then prevailing in Kentucky. He looked steadily at me with an air of some surprise, then stretching out his flask begged me to take a drink with him. He thereafter said no more on politics, but talked for half an hour of the tobacco and cotton crops of western Tennessee.

We arrived in Memphis at about ten o’clock of the morning and stopped there some time. In the big and dirty railway station I felt myself already in a country other than West Virginia.

Memphis, the little I saw of it, appeared to be a straggling, shabby town, with wide, dusty streets, and many rambling dilapidated buildings. The people had lost the rosy, hearty look of the blue [Pg 21]grass country, and were pale and sallow, while increasingly numerous everywhere were the ebony-hued negroes. We were passing from the latitude of the mulattoes to that of the jet-blacks, the pure blooded Africans.

PICKING COTTON—MISSISSIPPI

Leaving Memphis, we turned southeastward and then due south, through the central portions of the state of Mississippi. Here spreads a flat country, with thin, yellow soil in corn and cotton. Everywhere were multitudes of negroes, all black as night. Negro women and children were picking cotton in the fields. There were wide stretches of apparently abandoned land, once under cultivation, much of it now growing up in underbrush and much of it white with ripened seedling cotton. In many places the blacks were gathering this cotton, apparently for themselves. There were a few small towns, at long intervals. Everywhere bales of cotton were piled on the railway station platforms; generally the big, old-fashioned bales, occasionally the small bale made by the modern compress. This is the shipping season, and we frequently passed teams of four and six mules, hauling large wagons piled high with cotton bales coming toward the railway stations. We passed through great forests of the long-leaved yellow pine, interspersed with much cottonwood and magnolia, while the leaves of the sumach marked with[Pg 22] vivid red the divisions of the clearings and the fields. The day was dull and cloudy and a chill lingered in the air. The two lady travelers sat all day long with their curtains down and never left their books. The scenery and life of Mississippi held no interest for them.

In the late afternoon we passed through Mississippi’s capital, Jackson, and could see in the distance the rising walls of the new statehouse, to be a white stone building of some pretentions. Here a number of Italians and Jews, well dressed and evidently well-to-do, entered our sleeper en route to New Orleans. The country trade of Mississippi is said to be now almost altogether in the hands of Jews and of Italians. The latter coming up from New Orleans, are acquiring many of the plantations in both Mississippi and Louisiana, as well as, in many cases, pushing out the blacks from the work on the plantations by reason of their superior intelligence, industry and thrift. A lull in Italian immigration followed the New Orleans massacre of the Mafia plotters some years ago, but that tragedy is now quite forgotten, and a steady influx of Italians of a better type has set in.

In the dining car, I sat at midday lunch with a round-faced, pleasant mannered man some forty years of age, with whom I fell into table chat. He was a writer on the staff of a western monthly[Pg 23] magazine and was well acquainted with the country we were traversing. He pointed out places of local interest as we hurried southward, while many incidents of history were awakened in my own mind. All of this land of swamp and bayou and cotton field had been marched and fought over by the contending armies during the Civil War. Here Grant skirmished with Johnston and won his first great triumphs of strategy in the capture of Vicksburg. Here the cotton planters in “ye olden time” lived like lords and applauded their senators in Congress for declaring in public speech that “Mississippi and Louisiana wanted no public roads.” Here Spain and France contended for supremacy and finally yielded to the irresistible advance of the English-speaking American pioneer, pressing southwestward from Georgia, Carolina and Tennessee.

It was still the same flat country when, near dusk, we entered Louisiana. At the first station where we stopped an old man was offering for sale jugs of “new molasses” and sticks of sugar cane—the first hint that we were surely below the latitude of the frosts.

It was a murky night, no stars were out, only a flash of distant electric lights told us that we were approaching New Orleans. We were in the city before I was aware. Quickly passing many[Pg 24] unlighted streets, we were suddenly among dimly lighted houses, and then drew into an old-time depot, a wooden building yet more dilapidated than that of Memphis. We were instantly surrounded by a swarm of negroes. There were acres of them with scarcely a white face to be seen. I made out one of the swarthy blacks to be the porter of the new St. Charles Hotel. Giving him my bags, I was piloted to an old-fashioned ’bus and was soon driving over well asphalted streets amidst electric lights, and found myself in the thoroughfares of a really great city. From broad Canal Street we turned down a narrow alley and drew up in front of a fine modern hotel. This is an edifice of iron, stone and tile, with seemingly no wood in its structure, large, spacious and filled with guests, the chief hostelry of New Orleans, and worthy of the modern conditions now prevailing in this Spanish-French-American metropolis of the Gulf States.

New Orleans, Louisiana,

November 16th.

After a well-served dinner in the spacious dining-room of the hotel, where palms and orange trees yellow with ripened fruit and exhaling the fragrance of living growth were set about in great pots, I lighted my cigar and strolled out upon narrow St. Charles street. Following the tide of travel I soon found myself upon that chief artery of the city’s life,—boulevard, avenue and business thoroughfare all in one—stately Canal street. It was crowded with a slowly moving multitude, which flowed and ebbed and eddied, enjoying the soft warm air beneath the electric lights and stars. I quickly became a part of it, taking pleasure in its leisurely sauntering company.

The typical countenance about me was of the dark, swarthy Latin south, and tall men were rarely met. Among the gossiping, good natured promenaders of Canal street there is none of the haste which marks New York’s lively “Rialto;”[Pg 26] none of the scurry and jam which jostles you in brusque Chicago. In New Orleans there is an air of contented ease in the movement of the most poorly clad. Even the beggars lack the energy to be importunate.

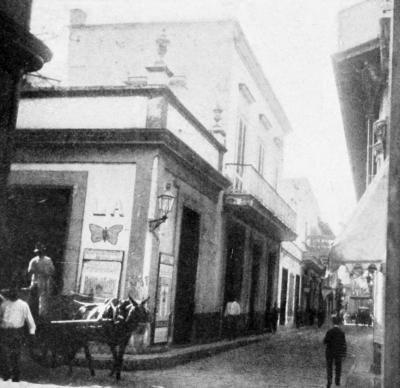

At a later hour, crossing the wide thoroughfare, I was at once among narrow streets, the rues of the Vieux Carré, the Quartier Francais,—the Quartier now, but once all that there was of New Orleans. The transition was sharp. The buildings hinted of Quebec and Montreal, and of Old France. Balconies clung to second stories, high adoby and stucco walls were entered by narrow, close-barred doorways, latticed windows looked down upon the passer-by, and now and then, I fancied behind their jalousies the flash of dark eyes. My ear, too, caught softly sonorous accents which are foreign to the harsher palatals and sibilants of English. Beneath a glaring electric arc two swarthy pickaninnies were pitching coppers and eagerly ejaculating in curious, soft French. A man and a woman were chaffering at a corner meat shop, seller and buyer both vociferating in an unfamiliar tongue. I was hearing, for the first time, the Creole patois of old New Orleans.

Along one narrow rue—all streets are rues and all rues are narrow here—were many brilliant lights. It was the rue —— where cafés and wine[Pg 27] shops and quiet restaurants abound. When last in New York M B, had posted me and said, “If ever you shall be in New Orleans, go to the Café ——. Go there and if you care to taste a pompano before you die, a pompano cooked as only one mortal on this earth can do the job, go there and whisper to the chef that ‘I’m your friend.’” So I went and found the chef and ever since have dreamed about that fish. The room was large; its floor was sanded and scrupulously clean. Many little tables were set along the walls. Pangs of hunger griped me the instant I peered within that door. I grew hungrier as I sat and watched the zest and relish with which those about me stowed away each dainty fragment. I was ready for that pompano when at last it came. I have eaten this fish in New York, in Baltimore, in Washington and in Richmond, and ever as I came further south did the delicacy of its flesh and flavor grow. Now, the long leap to New Orleans has given me this gourmet’s joy fresh taken from the waters of the Gulf. I ate with slow and leisurely delight, letting my enamored palate revel in the symphony of flavor, sipping my claret, and watching the strange company which filled the room. The men were mostly in evening dress—lawyers, bankers and business men. They had come in from the theatre or, perhaps, had spent[Pg 28] the evening over cards. At some of the tables were only men, at others ladies were present, young, comely and, many of them, elegantly gowned. Black eyes were dominant among these belles, and here and there I fancied that I caught the echo, in some of their complexions, of that warmer splendor of the tropics which just a dash of African blood when mixed with white, so often gives, and which has made the octoroon demoiselles of New Orleans famous for brilliant beauty the world around. It was a gay company, full of chat and laughter and gracious manner—the graciousness of well-bred Latin blood.

When, at last, my pompano was vanished, and the claret gone, and I regretfully quitted the shelter of La —— it was long past the stroke of twelve, yet the café was still crowded and the Vieux Carré was alight and astir as though it were early in the night. Again crossing Canal street, I found the American city dark and silent. I hurriedly went my way to the hotel, my footsteps echoing with that strange, reverberating hollowness which marks the tread upon the deserted, midnight city street.

In the morning I was up betimes, taking a cup of coffee and a roll, and then making my way down St. Charles street and crossing Canal to the rue Royale, passing the open gates of the old convent garden of the Ursulines, now the Archbishop’s palace, and turning into the rue St. Petre, then into Jackson Square. The air was cool. The world had not quite waked up. The gardeners with their water carts were giving the morning bath to the lawns and flowers of the park. A friendly mannered policeman had just disturbed two tramps from their nightly slumber, bidding them move on. I sat down upon a stone bench near where they had slept and looked across at the old Spanish-French Cathedral of St. Louis and the municipal buildings of the courts, the Cabildo and Hotel de Ville—architectural monuments of an already shadowy past. The chimes were ringing to matins and the devout were entering to the early mass.

JACKSON STATUE—NEW ORLEANS

I watched the hurrying groups, musing the while upon the picture

before me. Here, the Canadian de Bienville, and Cadillac and Aubry and

their French compeers, as well as the Spanish Captains General, from

Don Juan de Ulloa to Don Manuel Salcedo had offered up their thanks

for safe arrival from dangerous voyages across uncharted seas. Here,

Don Antonio O’Rielly, Havana’s murderous Irish Governor, had ordered

his Spanish musketeers to shoot to death the Creole patriots,

Lafreniere, Milhet, Noyant, Marquis, Caresse, that devoted band who

refused to believe[Pg 29]

[Pg 30] that Monsieur le Duc de Choiseul and his Majesty,

Louis XV, le bien aimé—had secretly made cold-blooded sale of the

fair Province of Louisiana to Spain. Here, Citizen Laussat, by order

of Napoleon, had surrendered the great Louisiana Province to General

Wilkinson and Governor Claiborne, the Commissioners of Thomas

Jefferson, who thereby added an empire to the dominion of the young

government of the United States. Here, also, had been celebrated with

so much pomp and trumpet fanfare the victory of Andrew Jackson’s

border riflemen over Pakenham’s Peninsular veterans. The historic

Place d’Armes has been rechristened Jackson Square, and “Old Hickory”

now rides his big horse in the midst of a lovely municipal garden. In

later years, here also had Confederate Mayor and Federal General

posted their decrees and proclamations, among the latter that famous

“General Order No. 28,” wherein the doughty General presumed to teach

good manners to the dames and demoiselles of New Orleans, and gained

thereby the sobriquet “Beast Butler.”

The worshipers were returning from the mass. My reverie was at an end. I arose and, crossing the square, strolled over to Decatur Place toward the old French market by the river side. There I found much that reminded me of the greater Marché Central which I had visited one early [Pg 31]morning in Paris. There were the same daintiness and care in arranging and displaying the vegetables, the same taste and skill in showing the flowers, which are everywhere the glory of New Orleans. There were bushels of roses—the Marechal Neil, the gorgeous Cloth of Gold among the more splendid. Here also the butchers were carrying the meats upon their heads, just as they did in France, and the fish and game were as temptingly displayed. But the people of the market, though speaking the French tongue, were widely different. The swarthy tints of the tropics were here in evidence. Negresses black as night made me bonjour! The venders and porters were ebony or mulatto, and even the buyers were largely tinctured with African blood, while the French they talked was a speech I could with difficulty comprehend. The sharp nasal twang of Paris was greatly softened, and their “u” had lost that certain difficult liquidity which English and American mouths find it almost impossible to attain. Curious two-wheeled carts loaded with brass milk cans were starting on their morning rounds, and lesser two-wheeled wagons were being loaded with vegetables, meats and fish for the day’s peddling throughout the city. Burdens were not so generally borne upon the backs and shoulders as in France, although some of the women and a few[Pg 32] men were carrying their wares and goods upon the head with easy balance.

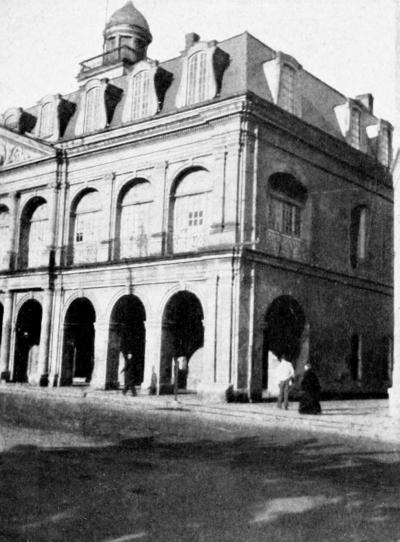

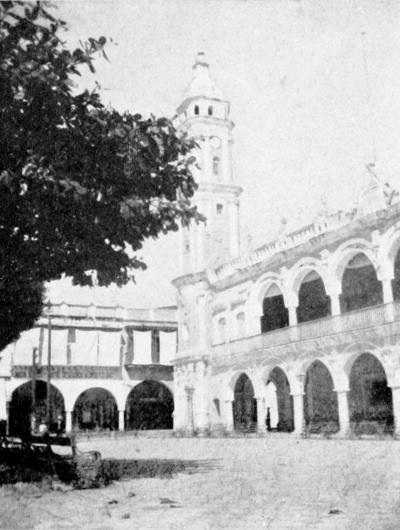

THE CABILDO—NEW ORLEANS

The Vieux Carré has in it to me a certain note of sadness. As you wander along its rues and ways you feel that, somehow or other, the days of its importance and its power are forever gone. Mansions, once the imposing homes of the affluent, are now cracked and marred, and there seem to be none to put them into good repair. Dilapidation broods over the Vieux Carré. You feel that the good old Creole days are surely fled. You realize that as the language of La Belle France is disappearing, so the leisurely customs and easy habits of French New Orleans, before many years, will be submerged by the direct speech and commercial brusqueness of modern America.

In the afternoon I rode many miles upon the trolley cars through and about the city, and particularly along by the levees and through the fine avenue St. Charles, and the upper modern section. Low, very low, lies New Orleans, the greater part of it only a few feet above the water, really below the level of the Mississippi in times of flood. Many streets are now asphalted and kept comparatively clean, but the greater portion of the city is yet unpaved, or, when there is pavement at all, is still laid with the huge French blocks of granite (a foot or eighteen inches square) put down two [Pg 33]centuries ago. The city lies too close to perpetual dead water to permit of modern drainage and there are few or no underground sewers. The houses drain into deep, open gutters along the streets between the sidewalks and the thoroughfares over which you must step; fresh water is pumped into these gutters and, combining with the inflowing sewerage, is pumped out again into the Mississippi. It is in this crude and unsanitary manner that New Orleans strives to keep measurably clean.

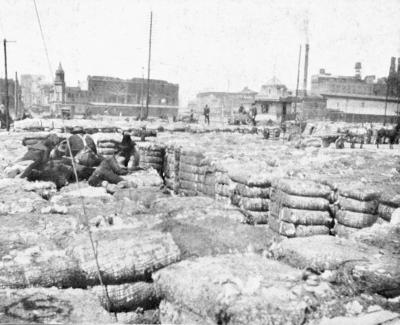

HAULING COTTON—NEW ORLEANS

The residence section, in the American city, contains many handsome mansions with wide lawns and a profusion of semitropical trees, and everywhere are gardens—flower gardens that are riotous masses of roses and jasmines and splendid blooms. Just as the glory of England is her flowers, where no home is too humble for a window box, so, too, is it in New Orleans. However dirty she may be, however slovenly and slipshod, you must yet love the city for her flowers. Even the laborer’s most humble cottage glows with its mass of color.

New Orleans has no parks to boast of—Audubon Park is a mere ribbon of green—but the cemeteries on her borders are really her parks. The live oaks in them hang with masses of drooping moss, and blossoming magnolias and shrubs are[Pg 34] everywhere. So near is the water to the surface, however, that there can be no burials within the earth, and the cemeteries are therefore filled with tombs built above the ground. Many of these are costly works of art.

The city clings to the river where the Mississippi makes a great bend, like a half moon, to the southwest, whence its name, the “Crescent City.” Only the big embankments, fourteen to fifteen feet in height, prevent the homes and gardens, as well as the entire business portion of the city, from being sometimes submerged by the angry waters of the great river. I found it strange, from a steamer’s deck, lying at the levee, to be looking down into the city, ten or twenty feet below. It reminded me of Holland and of Rotterdam, except that there the waters are the dead and quiet pools of Dutch canals, while here they are the swelling restless tide of the more than mile-wide Mississippi.

Along the levees were many ocean liners loading with molasses, sugar and cotton, chiefly cotton, in which there is an enormous and constantly increasing trade. The biggest ships now come up right alongside the wooden wharves of the levees, and for several miles lie there bow to stern.

The theatres and business blocks, the customhouse, and city hall and other public buildings of [Pg 35]New Orleans are none of them modern, but appear to have been built long years ago, yet, notwithstanding their marks of antiquity, the business part of the city is animate with stir and action. There is hope in men’s faces in New Orleans, and the younger men are finding in the city’s waxing commerce opportunity for achievement which their forefathers never knew. With the completion of the Panama Canal, New Orleans will become one of the greatest of commercial ports.

ALONG THE LEVEE—NEW ORLEANS

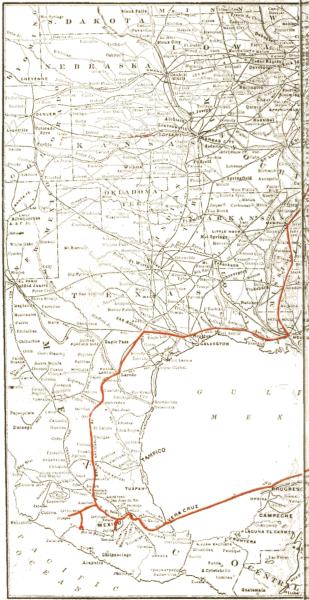

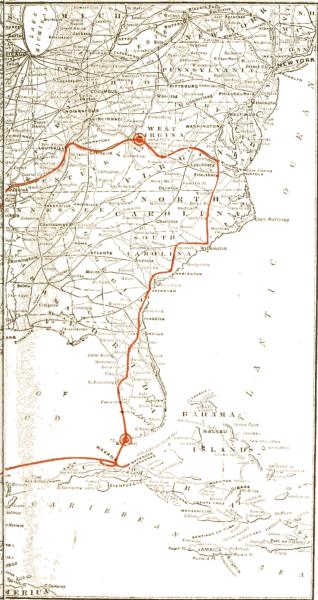

From New Orleans I shall go via the Southern Pacific Railway, crossing the Mississippi and traveling westward through Louisiana and Texas to San Antonio, Texas, and then I shall go south into Mexico.

(Written on the train and mailed at Laredo, Texas.)

November 16th.

The journey from New Orleans was somewhat tedious, but yet so crowded with new sights that the time passed quite too quickly for me even to glance at the copy of Lew Wallace’s Fair God, which I had bought in New Orleans for reading on the way.

At 9:45 A. M. I left the Hotel St. Charles and took the ’bus for the Southern Pacific Station, which is a shabby, weatherworn wooden building down by the water side, in the French quarter of the city. A large, ill-kept waiting room was crowded with emigrants—chiefly “crackers” and “po’ white trash” from the cotton states. A wide gangway led to the clumsy puffing ferryboat which took us across the Mississippi to a series of long, low, wooden sheds where our transcontinental train awaited us.

The ferry crosses the Mississippi from near the[Pg 37] center of the bow, where the river sweeps in a giant curve against the crescent shore. The current is swift, and whether the waters be high or low, the river always hurries on with relentless eagerness toward the Gulf of Mexico, one hundred miles away.

As I stood upon the boat and my eye swept up and down the river, the city stretched before me black and sombre beneath a heavy pall of smoke, flat and uninteresting, only here and there a spire or steeple lifting itself solitarily above the level monotony. But along the miles of levees there was activity and life. Ocean steamers were taking on cargo, and multitudes of river steamboats were discharging freights of cotton bales and other upstream products, brought from the coal mines and wheat fields and plantations of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee, of Wisconsin and Minnesota and Iowa, even from the Dakotas and Nebraska and Kansas, and from Missouri and Arkansas and Mississippi and Louisiana, for here converges the vast interior water-traffic of the continent. (The enormous traffic of the Great Lakes is now urging Congress to give them ship canals and unimpeded access to New Orleans.)

It is a prodigious traffic that steadily increases notwithstanding the competition of the railways[Pg 38] which are now penetrating everywhere, even into the rich plantation country. For some years after the Civil War, New Orleans seemed to be losing her one-time pre-eminence as a port. The railways to the north threatened to cut off her trade from above, the silting up of the Mississippi’s mouths threatened to destroy her access to the sea. Then came the strong, wise hand of Uncle Sam, who built the magnificent jetty system contrived by Captain Eads, and New Orleans began to wake up. Her trade increased by leaps and bounds, the river traffic revived, and she became the mistress of a water commerce far exceeding what she had known before. Now not merely are her suburbs extending along the river, but her trade and commerce have crossed to the western shore, where a new and supplemental city is rapidly growing up. There, the Southern Pacific Railway and other western lines have erected their shops and factories, laid out extensive yards and built great warehouses. There they unload and store the freight which Louisiana, Texas and the farther West send eastward for distribution to the eastern railway connections which carry it to the Gulf and Atlantic seaboard ports for export, and for delivery to domestic consumption by inland water carriage.

We were to take the through San Francisco [Pg 39]Express, and I had anticipated a fine transcontinental train, something like our own “F. F. V.” which takes us from Kanawha to Cincinnati, or New York. But I was disappointed. The “Sunset Limited,” as it is called, consisted of two sleepers, hitched behind a number of shabby immigrant cars and old-fashioned passenger day coaches. None of these were vestibuled, and there was no dining car attached. I had secured, fortunately, several days in advance, a lower berth as far as San Antonio; but many passengers applied who could obtain no berths, and were allowed to crowd into the sleepers for lack of accommodation in the day coaches, into which the swarming immigrants had overflowed.

ANCIENT FRENCH PAVEMENTS

We were late in starting; we were late at every station along the road; we were an hour late when we arrived next morning at San Antonio; a poor beginning, surely, for a train that must journey four long days and nights to the Pacific coast.

We traversed a flat land, with many ditches and canals and pools of stagnant water lying a few feet below the level of the surface. The soil was black and rich. We crossed acres and acres, thousands of acres, of sugar-cane, and we saw many large mills, all using modern machinery for grinding cane and making sugar. Then there were fewer ditches, fewer canals, the land was higher,[Pg 40] slightly, and there were miles of cotton fields, the cotton yet in the boll, ripe for the picking. Then it was a land with many little ditches, and little dykes; there were rice fields to be flooded; and there were rice mills,—representing a large and rapidly increasing interest. Every extent of forest we passed hung heavy with gray moss and parasitic vines. There were many live oaks and palmettoes and some cypress. The land was still gradually rising, finally becoming drier, grass-covered and grazed by herds of cattle and horses; but it was flat, always flat.

Toward dusk we passed through Beaumont, the famous oil town. This is the fateful place where millions of dollars have been made and lost within a few months. Ten years ago a group of our own Kanawha tenderfeet drilled here a four-hundred-foot dry hole, and abandoned the project, finding no oil within a stone’s throw of the spot where, a few years later, Dan Lucas drilled down eight hundred feet, and struck his seventy-thousand-barrel gusher. There was an excited “boom” throng at the station, and the travelers entering our car fairly buzzed thrilling talk of oil. Among them were a number of ladies, more bediamonded, bejeweled and begolded than any group of femininity I ever saw before. The men, too, wore flashing jewels and bore that dis[Pg 41]tinct stamp which marks those who, with nonchalance, win or lose a fortune in a night. They were by all odds the toughest-looking lot of elegantly clad men and women I ever yet beheld.

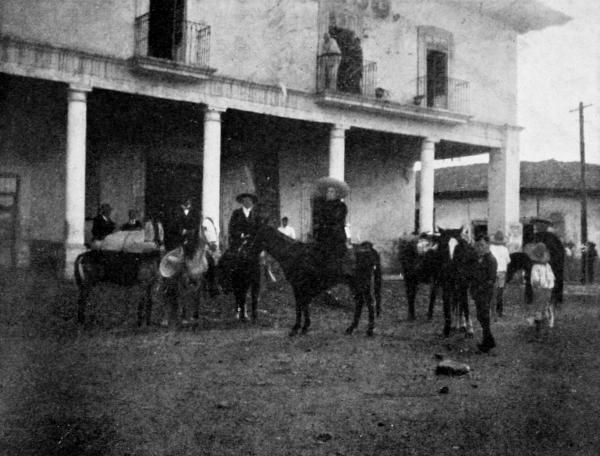

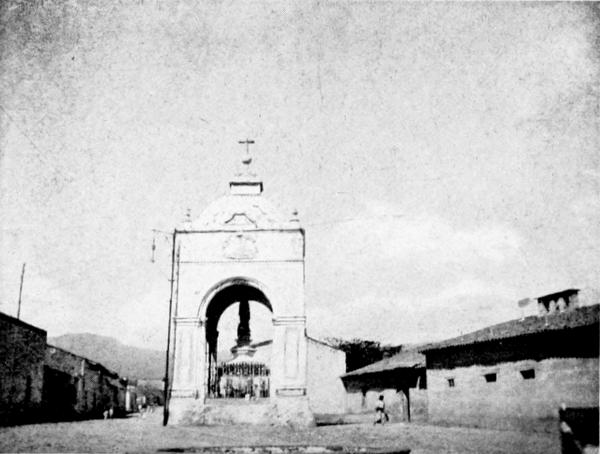

THE ALAMO

We passed Houston near midnight, and in the morning by eight o’clock were at San Antonio, a city of wide streets, and spacious parks adorned everywhere with palms and palmettoes and semitropical shrubs. We entered a ’bus and drove a mile to the station of the International and Great Northern Railway, which comes down from St. Louis and runs south seventy miles to Laredo, on the Rio Grande and the Mexican border. We passed the bullet-battered walls of the famous Alamo, the hallowed shrine of every loyal Texan, then a large Roman Catholic Cathedral with Spanish roof and bell tower, a huge convent and several stately public buildings. San Antonio is a city of forty thousand people and the last American town of magnitude north of Mexico. At the station, where we waited half an hour, I saw my first Mexican greasers, in their prodigious sombreros and began to feel myself nearing a strange land.

Our train from the North drew in at nine o’clock, on time, all vestibuled, lighted with electricity, with a dining car attached, and all its equipment greatly superior to that of the Southern[Pg 42] Pacific. It was one of the Gould trains from St. Louis to the far South.

Leaving San Antonio, we traversed a country still flat, always flat, covered with sand and mesquit for miles and miles and miles. As far as the eye could see in every direction, hour after hour stretched this illimitable monotonous wilderness. The mesquit trees looked like ill-grown peach trees. To my unaccustomed eye, we seemed to be passing through endless barren orchards, the trees standing generally thirty or forty feet apart. Here is the home of the jack rabbit, and toward the Mexican border and within reach of the waters of the Rio Grande, deer abound. Quail are also common, but of other life there is little or none. Here and there the mesquit trees were cut away, and wide, sandy fields were planted with cotton. Cattle also were cropping the short, dry native grass. As we traveled south the grass diminished, the sand increased and the prickly cactus became increasingly plentiful. At one of the stations where we stopped for the engine to take water, I talked with a tall white-bearded planter, who stood holding his horse, the horse accoutered with Mexican saddle and lariat, the man in high Mexican sombrero. “The labor hereabouts is all Mexican,” he said. “Mexican peons you can import in unlimited numbers, who are glad to work for thirty cents per day and board themselves. Hence there are no negroes south of San Antonio, for no negro will work and live on such small pay. Moreover, the soil is so poor and water is so scarce that neither cotton nor cattle could here be raised with profit, if it were not for the low wage the Mexican is glad to accept.”

OLD SPANISH CONVENT

We reached Laredo, a city of some five thousand inhabitants, about six o’clock, P. M., where I sent the following telegram, “Cane, cotton, cattle, mesquit, sand and cactus, O. K.,” which, though brief, sums up the country I have been traversing for the last two days. Laredo is upon the American side of the Rio Grande, which is crossed by a long bridge to Nuevo Laredo, in the State of Nuevo Leon. Here smartly uniformed Mexican customs officers examined my baggage and passed me through.

Mexico City, Mexico,

November 18th.

He llegado en esta ciudad, hoy, cerca las ocho de la mañana! The moment we crossed the Rio Grande we changed instantly from American twentieth century civilization to mediæval Latin-Indian. The Mexican town of Nuevo Laredo, the buildings, the women, the men, the boys, the donkeys, all were different. I felt as though I had waked up in another world. As we approached the station of the Mexican city, I noticed an old man riding upon his donkey. His saddle was fastened over the hips just above the beast’s tail, his feet trailed upon the ground. He sat there with immense dignity and self-possession, viewing with curiosity the gringos, who had come down from the land of the distant North. He silently watched us for some moments and then rode solemnly away, while I wondered by what hand of Providence it was he did not slide off behind.

From Nuevo Laredo to Monterey, which we reached at half past ten P. M., was all one flat mesquit and cactus-covered plain; sand, mesquit and cactus; cactus, sand and mesquit, mile after mile, till darkness fell upon us, when we could see no more. Monterey is the center of Mexico’s steel and iron industries, of large tobacco manufactories, of extensive breweries. It is the chief manufacturing city of modern Mexico. Our stay was brief, and I caught only a glimpse of a cloaked and high-sombreroed crowd, hurrying beneath the glare of electric lamps, and then we passed on toward the great interior plateau of the Mexican Highlands.

During the night it grew cold. I awoke shivering and called for blankets. In San Antonio the morning had been warm and, all day, south to Laredo and on to Monterey, the heat had been oppressive. It was cold when I left Kanawha, but the chilly air had not followed me beyond New Orleans, and I had there packed into my trunk all my warm clothing and checked it through to Mexico. Passing westward through Louisiana and Texas, the mild air was delightful and I was comfortable in my thinnest summer garments. Thus dreaming of orange groves and sunny tropics I fell asleep. Now I was shivering with a deadly chill, and the thin keen air cut like[Pg 46] a scimiter. I pulled on my overcoat, which I fortunately still had with me, and slept fitfully till the day.

We crossed, during the night, the first great mountain range which shuts out the inland plateau of central Mexico from the lowland plains stretching eastward toward the Gulf and into Texas. We climbed many thousands of feet to Saltillo, where the mercury almost registered frost. Now we were descending the inner slopes of the barrier mountains, passing near the battle field of Buena Vista, where Zachary Taylor smote Santa Anna and his dark-skinned horde, and gained the fame which made him President of the United States. We were entering that vast desolate inland plain which stretches so many hundreds of miles south to Acambaro, where we should begin to climb again yet higher ranges, crossing them at last—at an altitude of eleven thousand feet,—before we should finally descend into the high cool valley of Anahuac to the City of Mexico.

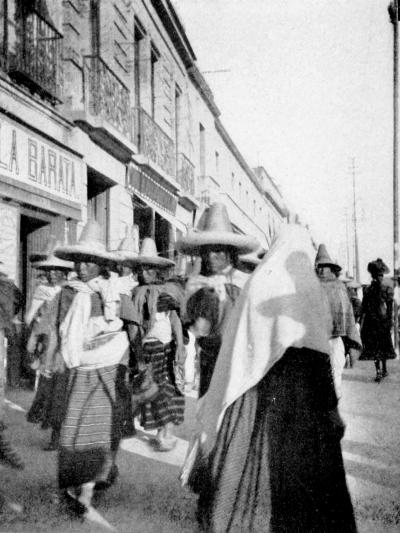

About nine o’clock, we drew up at a wayside station for breakfast (almuerzo). If I had known it, I might have obtained my desayuno coffee and roll at an earlier hour upon the train. We were now upon a wide-stretching sandy level. A cold mist hung over us. The scorching sun was trying to penetrate this barrier. A band of [Pg 47]Indians wrapped to their eyes in brilliant colored blankets of native make (zerapes), their high-peaked sombreros pulled over their eyes, with folded arms, silent as statues, stood watching us. I deliberately took their photograph. They did not smile or move. A group of Indian women sitting on the ground near these men were not so placid. They regarded the kodak as an evil mystery and hid their faces in their rebozos when I pointed my lens at them. The strange instrument smacked of witchcraft, and they would none of it. With rebozos still drawn, they got upon their feet and fled.

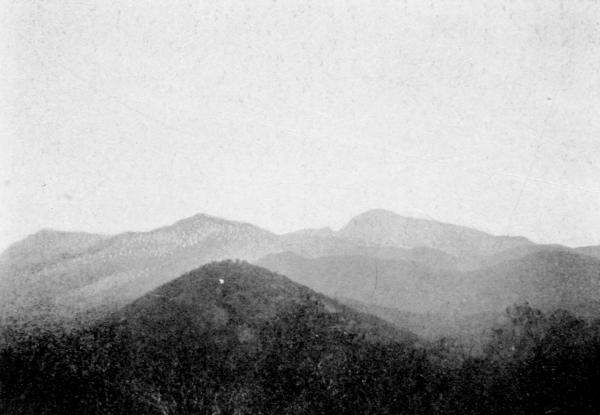

THE DESOLATE PLAINS

In another hour the bright white sun dissipated the mists. The sky was blue and cloudless. The track ran straight, with rarely a curve, mile after mile into the South. The land lay flat as a table, an arid plain, shut in by towering, verdureless mountains, ranging along the horizon on east and west. All day we thus sped south through illimitable wastes of sand, and sage brush and cactus, and a curious stunted palm, which lifted up a naked trunk with a single tuft of green at the very end. The landscape gave no sign of ever having been blessed by a drop of water, the barren prospect extending upon all sides in apparently unending monotony.

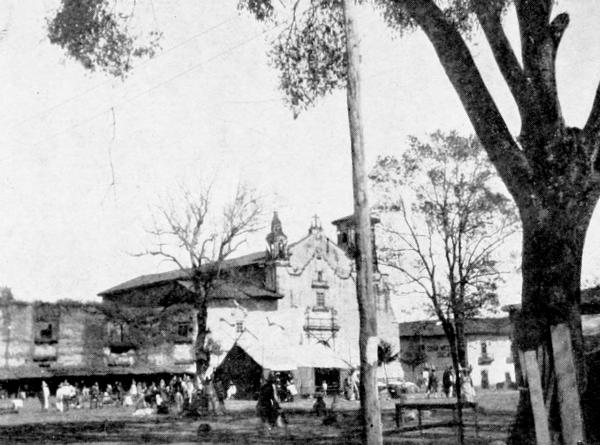

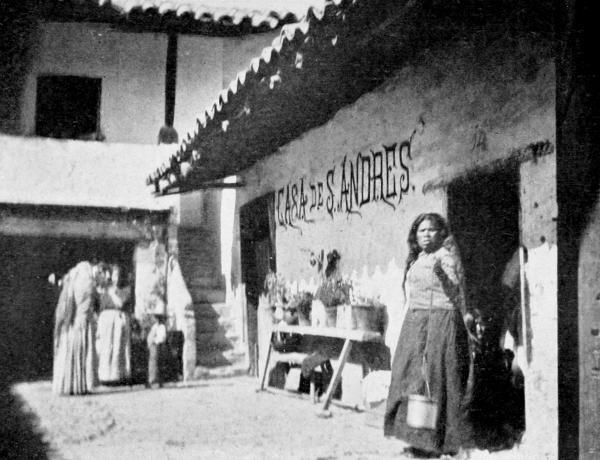

Now and then we passed a small station made[Pg 48] of adoby brick. Now and then, a cluster of adoby dwellings centered about a low-roofed adoby church. At one place a half wild rancherro raced along beside the train on his broncho, vainly trying to keep the pace and wildly waving his sombrero as he fell behind. At the stations were always women and children, and the ever silent men standing like statues. They never moved, they never spoke, they never smiled; they gazed at us with blank astonishment. As we came further and further south, the extreme aridness of the landscape began to lessen. Cattle began to appear upon the plain, adoby villages became more frequent, the swarthy dark brown population became more numerous. Toward midafternoon, the towers, the high walls, the red tiled roofs of a great church, a cathedral, and a town of magnitude grew large before us. We drew up at a fine, commodious station, built of red sandstone. There, gathered to meet the train, were curious two-wheeled carts and antique carriages with high wheels, drawn by mules; many donkeys bearing burdens, some with men sitting upon their hips; a multitude of dark-faced Latins, men in high sombreros, the women with heads enveloped in rebozos or mantillas. We were at the station built a mile distant from the important city of San Louis Potosí, one of the great ore-smelting centers [Pg 49]of Mexico, and a city of sixty thousand inhabitants. In the station we dined, and I ate my first Mexican fruits, one a sort of custard apple, and all delicious.

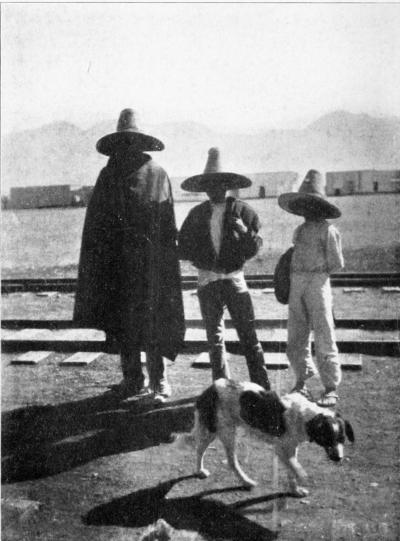

AWAITING OUR TRAIN

In the car with me sat a Mexican youth, who had evidently been studying and traveling in the States. He was dressed in the height of American fashion, and bore himself as a young gentleman of means. As he stepped from the train he was enveloped in the arms of another youth of about his own age. They clasped their right hands and patted each other on the small of the back with their left hands, and kissed each other’s cheeks, and then he was similarly embraced by a big stately man, over six feet in height, with a long gray beard, who carried himself with great dignity. The two were dressed in full Mexican costume, with tight-fitting pantaloones flaring at the bottom and laced with silver cording on the sides, short velvet jackets embroidered with gold lace, high felt hats with gold cords and tassels, and their monograms six inches high in burnished metal fastened on the side of the crown. Several peons seized the young man’s bags and American suit-case, and the party moved toward a six-mule carryall, set high on enormous wheels. The traveler was evidently the son of one of the great haciendados, whose estates lay perhaps fifty miles[Pg 50] away. Only grandees of the first magnitude travel by carriage in Mexico.

Our colored porter, black as jet, was also in a happy mood. The first of his series of Mexican sweethearts had come to greet him, bringing him a basket of fruit. She was comely, with fine dark eyes, her long hair coiled beneath her purple rebozo. There is no color line in Mexico and Sam proved himself to be a great beau among the Mexican muchachas.

Sitting in the smoking compartment of my car, during the morning, I found myself in company with three Mexican gentlemen who entered at Monterey. They could speak no English. My Spanish was limited. But as we sat there I became conscious of a most friendly interchange of sentiment between us. They were demonstratively gracious. One of them offered me a fine cigar, the other insisted that I accept of his cigarettos, and they would accept none of mine until I first took one from them. They sent the porter for beer, and insisted that I share with them. They even got out at one of the way stations and bought fragrant light skinned oranges, and pressed me to share the fruit. I could not speak to them, nor they to me, but I became aware that they were members of the Masonic order. I wore my Master Mason’s badge. They displayed no outward [Pg 51]tokens, but their glances and friendliness revealed their fraternal sentiments. They treated me with distinguished courtesy through all the journey to Mexico City, and at last said good-bye with evident regret. At a later time, I learned that a Mexican of the Masonic Fraternity wears no outward sign of his membership, owing to the hostility of the yet dominant Roman Church, while the Masonic bond is of peculiar strength by very reason of that animosity.

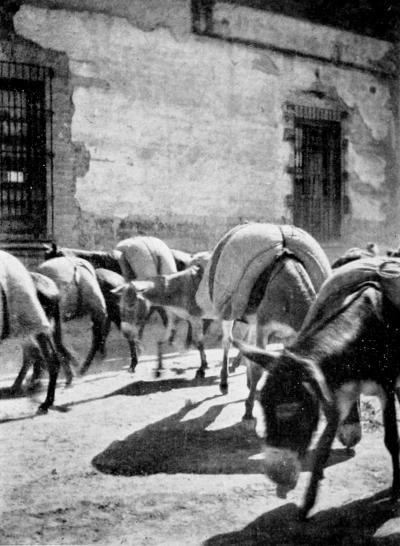

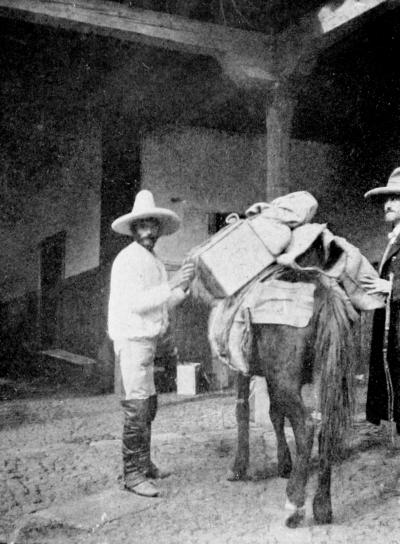

MULES CARRYING CORN

After leaving San Louis Potosí, the great inland plain which we had all day been traversing grew more and more broken. We came among small hills, with here and there deep ravines, and we began turning slightly toward the west and climbing by easy grades toward distant, towering mountains far upon the horizon to the south. Water now became more plentiful. We followed the course of a stream, wide, between high banks, where were long reaches of sand interspersed with well filled pools. There were adoby villages in increasing numbers, and here and there were little churches or chapels, each surmounted with a large cross. I counted more than a hundred of these chapels in the course of a few miles. It was as though the whole population had for centuries devoted its time to building these shrines. Some were dilapidated and in ill repair, others looked[Pg 52] as though recently constructed. Each has its Madonna, and each is venerated and cared for by the family who may have erected it. It was eight o’clock and dark when we reached Acambaro where a good supper awaited us in the commodious station.

Just as the train was starting, I asked some questions of the American conductor and, after a little conversation with him, was surprised to find that he was a West Virginian from Kanawha. “Señor Brooks,” he said, who had grown up near “Coal’s Mouth,” now St. Albans. He was delighted to learn from me of Charleston and the Kanawha Valley, and hoped some day to return and see the home of his childhood. He now loved Mexico. Its dry and sunny climate had given him life, when in the colder latitude of West Virginia he would have perished.

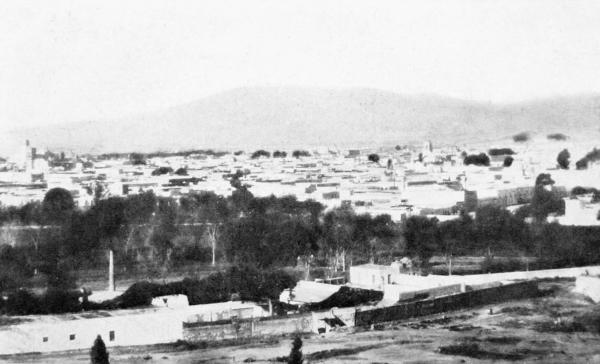

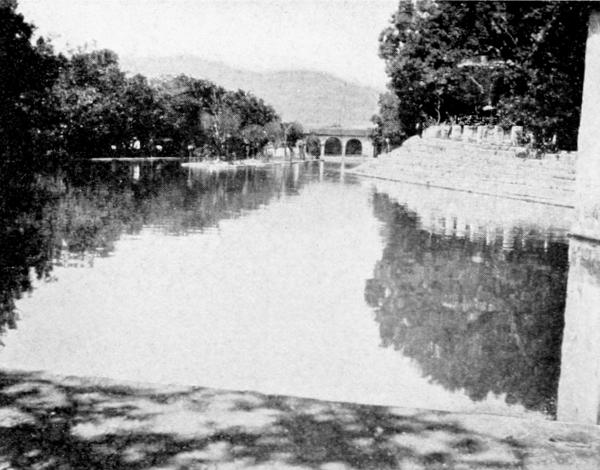

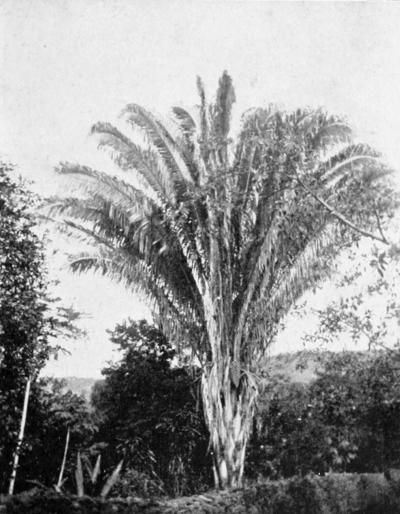

During the night, while crossing the summit of the Sierra, at La Cima,—nearly eleven thousand feet above the sea,—it became intensely cold again, even colder than when we crossed the mountains near Saltillo. The chill again awoke me, when I discovered that we were rolling down into the valley of Anahuac toward the City of Mexico. We were soon below the mists and beneath a cloudless sky, yet I felt no undue heat, but rather, a quickening exhilaration in the pure, dry air. As [Pg 53]we curved and twisted and descended the sharp grades, many vistas of exceeding beauty burst upon the eye. We were entering a wide valley of great fertility surrounded by lofty mountains, and to the far south, fifty miles away, the burnished domes of Popocatepetl and Ixtacciuhatl, lifted their ice crests into space, eighteen thousand feet above the level of the sea. Far beneath us glittered and glinted the waters of Lakes Tezcoco, Xochimilco and Chalco, once joined, but now separated, by the rescued land on which stood Tenochtitlan, the mighty capital of Montezuma, even yet to-day a city exceeding four hundred thousand souls (when Cortez conquered it, it is said to have held more than a million). Everywhere the eye rested upon fruitful land, tilled under irrigation, containing plantations of maguey, orchards of oranges and limes, and pomegranates, and groves of figs and olives—all forming a landscape where spring is perpetually enthroned.

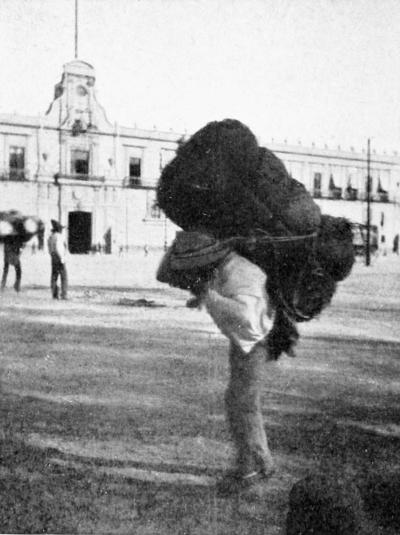

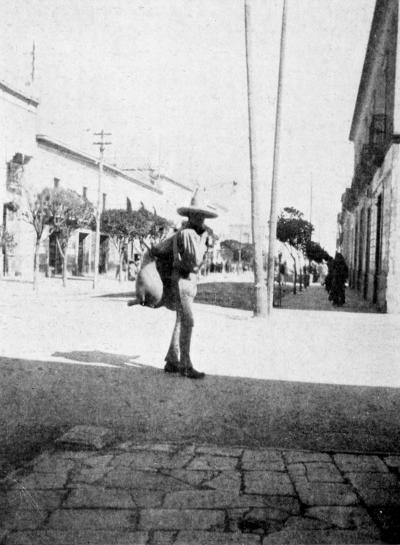

A CARGADORE BEARING VEGETABLES

Along the roads, trains of pack mules and burros, heavily laden, were toiling toward the great city, and many footfarers were bearing upon their backs enormous packs, the weight resting on the shoulders, and held in place by a strap about the forehead. When the Aztecs were lords of Mexico and Montezuma ruled, the horse, the ox, the ass, the sheep were unknown upon the Amer[Pg 54]ican continent. All burdens and all freight were then carried upon the backs and shoulders of the Indians, who from their forefathers had inherited the hardy muscles and the right to bear the traffic of the land. And from these ancestors the Indian cargadores of to-day have received the astonishing strength, enabling them to bear these great loads with apparent ease; the Indian, with his jog-trot gait, carrying a hundred pounds upon his back a distance of fifty miles a day. A large part of the fruit, vegetables and tropical products displayed each day in the markets of the city are thus brought up from distant lowland plantations upon the backs of men. As we approached the city, nearer and nearer, the highways we ran beside or cut across were filled more and more with these pack trains and cargadores, and with men and women faring cityward.

We finally drew into a large newly-built station of white sandstone. Pandemonium reigned upon the platform alongside which we stopped. Men were embracing each other, slapping each other’s backs and kissing either cheek. Women flew into each other’s arms and children kissed their elders’ hands. We passed along through wide gateways and into a paved semicircular courtyard, where were drawn up carriages with bands of yellow or red or blue across the door. Those [Pg 55]with yellow bands are cheap and dirty, those with blue bands mean a double fare and those with red bands are clean and make a reasonable charge, all of which is regulated by the Federal government. I entered one of the red-banded vehicles. The driver called two cargadores, who seized my steamer trunks, loaded them on their backs and ran along beside us. The horses started on a half gallop and when we reached the hotel, the cargadores, with the trunks upon their backs were there as well, less out of breath than the panting team, and each was gratified with a Mexican quarter for his pay (equal to an American dime), while my cochero swore in profuse Spanish because I did not pay him five times his legal fare.

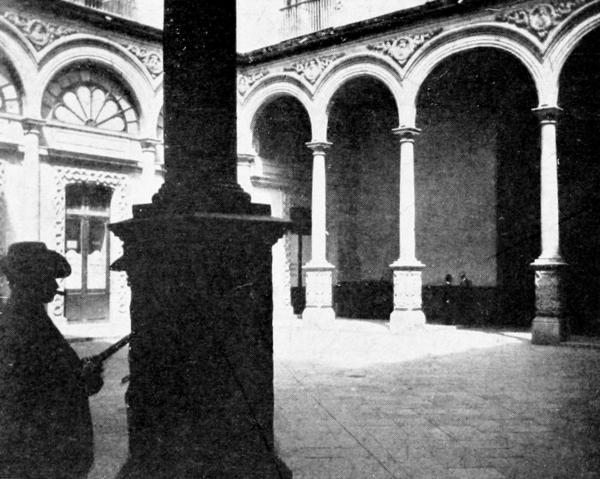

PATIO—HOTEL ITURBIDE

I was come to the one-time palace of the Emperor Iturbide, and was welcomed by the American speaking Administrador, in softly accented Louisianian speech.

Hotel Iturbide,

November 20th.

When I awoke this morning, the bare stone walls of my chamber, the stone-paved floor, the thin morning air drifting in through the wide-open casements, all combined to give me that sensation of nipping chilliness, which may perhaps only be met in altitudes as high as these. I am a mile and a quarter in the air above the city of Charleston-Kanawha, a mile and half above the city of New York. By the time I had made my hasty toilet, my fingers were numb with the cold. I put on my winter clothes, which I had brought with me for use when returning to Virginia in January. I also put on my overcoat.

Leaving my vault-like chamber, I passed along the stone-flagged hallways, down the stone flights of stairs, into the stone-paved court, passed out through the narrow porter’s door and found myself among the footfarers on the Calle de San Francisco. It was early. The street was still in the morning shadows. The passers-by, whom I met, were warmly wrapped up. The rebozos of the women were wound about the head and mouth. The zerapes of the men were held closely about the shoulders and covered the lower face. Overcoats were everywhere in evidence, and scarfs shielded the mouths of the Frenchly uniformed police. All these were precautions against the dread pneumonia, the most feared and fatal ailment of Mexico.

CARGADORES TOTING CASKS

I entered a restaurant kept by an Irishman speaking with a Limerick

brogue, but calling himself a citizen of the United States. I came

into a high, square room with stone walls, stone floor, windows

without glass, with many little tables accommodating three and four.

Here were a few Americans with their hats off, and many Mexicans with

their hats on. A dish of strawberries was my first course, the berries

not very large, a pale pink in color, very faint in flavor. These are

gathered every day in the year from the gardens in the neighborhood of

the city. My coffee was con leche (with milk). I asked for rolls and

a couple of blanquillos (eggs) passados por agua (passed through

the water, i. e. soft boiled). For a tip, cinco centavos (five cents

in Mexican, equal to two cents in United States) was regarded as

liberal by the Indian waiter. Upon leaving the[Pg 57]

[Pg 58] wide entrance, I found

the shadows fled and the sunshine flooding its white rays upon the

street.

Leaving my overcoat in the hotel, I took my way toward the lovely Alameda Park, where, choosing a seat beneath a splendid cypress, I sat in the delicious sunshine and watched the moving crowds. Many droves of mules, laden with products of the soil, were coming into the city. Later in the day, these same carriers of freight go out again, laden with merchandise for distribution to all the cities and villages of the mountain hinterlands.

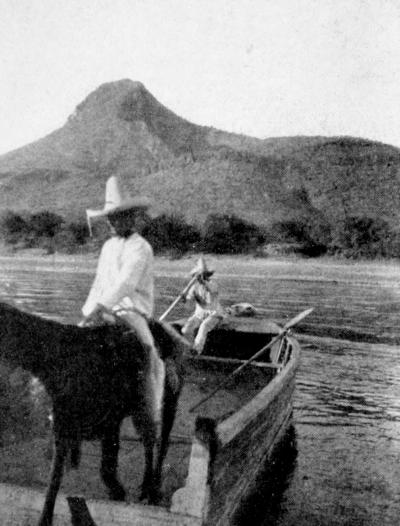

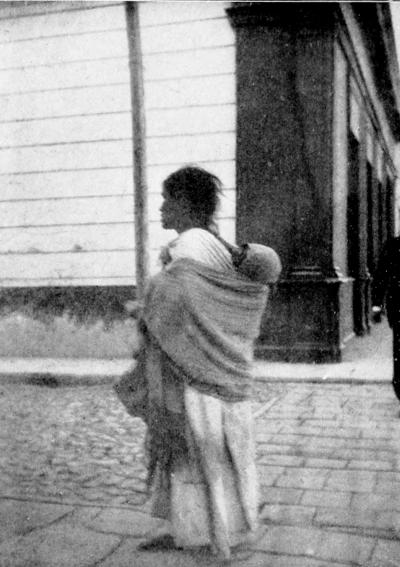

An Indian mother passes by, her baby caught in the folds of her rebozo. I toss her a centavo, and she allows me to kodak herself and child.

A SNAP-SHOT FOR A CENTAVO

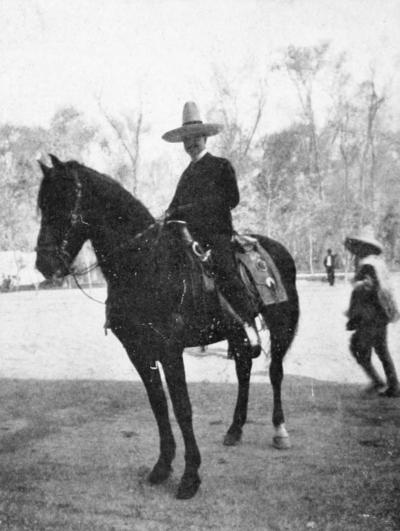

A handsome man riding a fine, black horse, pauses a moment at the curb. He is gratified that I should admire the splendid animal. He reins him in, and I capture a view.

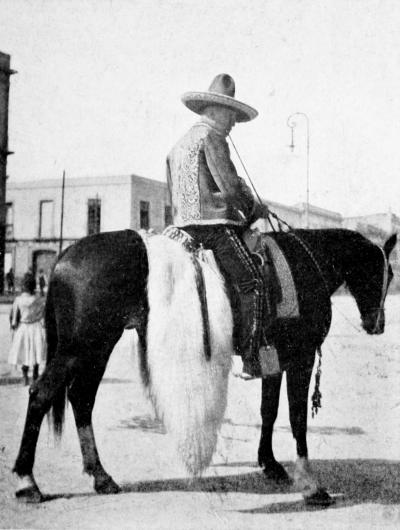

A rancherro in all the gaudy splendor of gilt braid, silver-laced pantaloones, and costly saddle, behung with ornaments of trailing angora goat’s wool, draws near me. He permits me to photograph his fine sorrel horse, but will never allow me to take himself face to face. He halts, that his animal may be admired by the passing throngs; he chats with friends who linger by his side, but whenever I try to catch his face he wheels about.

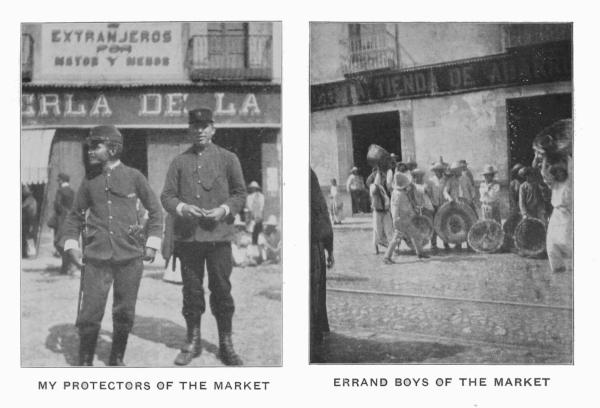

MY PROTECTORS OF THE MARKET & ERRAND BOYS OF THE MARKET

The dulce sellers bearing sweets in trays upon their heads; the flower venders carrying baskets piled high, such roses as only veritable trees may yield, come also within the vision of my kodak.

Later, I take my way to the Plaza Grande, fronting the Cathedral, and there again catch glimpses of the life of the city. Here are men bearing upon their shoulders casks, apparently filled, bales of garden produce, crates of chickens. Every sort of portable thing is here borne upon the human back. Now and then one or another seats himself upon the stone and iron benches and engages in gossip. Of these, also, my camera makes note.

Later in the morning, I saunter through many streets, inquiring my way

to one of the great markets. Here I linger, going about from stall to

stall and taking a picture as my fancy urges. A policeman, uniformed

like a Paris gendarme, eyes me curiously, comprehends the power of

my camera, and comes up to me smiling. He drives back the crowd, calls

up his companion-in-arms and stands at attention, begging me to send

him a copy of the picture. A group of errand boys, who carry large

flat baskets, and will take anything home you buy, attracted by the

mysterious black box, line up and motion that their pictures also be

taken. The instantaneous movement of[Pg 59]

[Pg 60] the shutter strikes them with

wonder, when, throwing a few centavos among them, I catch them now

struggling for the coin. I have become the center of attraction. The

swarming street crowd crushes about me, all eager to face the magic

instrument, till I am fain to call upon my policemen friends to fend

them off.

Standing there, joking with my guardians and keeping the good will of the increasing mob, I am accosted by a tall, thin-bearded gentleman in rusty though once fashionable black. He speaks to me in French. He is from Paris, he says; and Ah! have I really been there in Paris! Très jolie Paris! He also enjoys coming to the markets, and wandering among the stalls, and watching the people, and noting their habits and their ways. He guides me about among the different sections, commenting on the fruits and vegetables and wares. When we have spent an interesting hour, he invites me to share a bottle of French wine, a delicious claret, and then, lifting his hat, bids me adieu and is lost forever among the swarming multitudes.

There is so much to see in this ancient city, so much to feel! It is so filled with historical romance! As I wander about it, my mind and imagination are continually going back to the pages of Prescott and Arthur Helps, whose histories of Spanish invasion and conquest I used to pore over when a boy, and to the tragedies which Rider Haggard and Lew Wallace so graphically portray. I scarcely dare take up my pen, so afraid am I of retelling what you already know. I am ever seeing the house tops swarming with the dark hosts of Montezuma, hurling the rocks and raining the arrows upon the steel-clad ranks of Cortez and his Christian bandits as they fight for life and for dominion in these very streets below.

A RANCHERRO DUDE

I stood, this morning, within the splendid cathedral, built upon the very spot where once towered the gigantic pyramid on whose summit the Aztec priests sacrificed their human victims to their gods, while down in the dungeons beneath my feet, the Holy Inquisition, a few years later, had also tortured men to their death, human victims sacrificed to the glory of the Roman Church. An Aztec pagan, a Spanish Christian, both sped the soul to Paradise through blood and pain, and I wondered, as I watched an Indian mother kneel in humble penitence before an effigy of the Virgin, and fix a lighted taper upon the altar before the shrine, whether she, too, felt clustering about her, in the sombre shadows of the semi-twilight, memories of these tragedies which have so oppressed her race.

On these pavements, also, I review in fancy[Pg 61]

[Pg 62] the serried regiments of

France and Austria marshaled in the attempt to thrust Maximillian upon

a cis-Atlantic Imperial throne. In this day, one recalls almost with

incredulity the insolence of this conspiracy by European Monarchy to

steal a march on Western liberty, when it was thought that democracy

was forever smitten to the death by civil war. But the bold scheme was

done to death by Juarez, the Aztec, without Sheridan’s having to come

further south than the Rio Grande.

All these pictures of the past, and many more, crowd thick upon me as I walk the streets and avenues of this now splendid modern city.

I have also tried to see what I could of the churches,—the more important of them—which here abound, but my brain is all in a whirl, and saints and Madonnas troop by me in confused and interminable train.

Ever since Cortez roasted Guatemozin upon a bed of coals, to hasten his conversion to the Roman faith and quicken his memory as to the location of Montezuma’s hidden treasure, the Spanish conquerors have been building churches, shrines and chapels to the glory of the Virgin, the salvation of their own souls and the profit of their private purse. Whenever a Spaniard got in a tight place, he vowed a church, a chapel or a shrine to the Virgin or a saint. If luck was with him, he hadn’t the nerve to back down, but made some show of keeping his vow and, the work once started, there were enough other vowing sinners to push the job along. Mexican genius has found its highest expression in its many and beautiful churches, and perhaps it has been a good thing for genius that so many sinners have been ready to gamble on a vow.

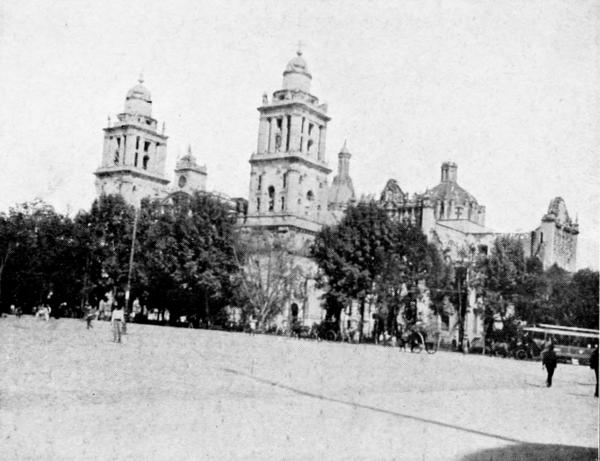

THE CATHEDRAL—MEXICO CITY

When Juarez shot Maximillian he also smote the Roman Church. The Archbishop of Mexico, and the church of which he was virtual primate, had backed the Austrian invader. Even Pope Pius IX had shed benedictions on the plot. When the Republic crushed the conspirators, the Roman Church was at once deprived of all visible power. Every foot of land, every church edifice, every monastery, every convent the church owned in all Mexico was confiscated by the Republic. The lands and many buildings were sold and the money put in the National Treasury. Monks and nuns were banished. Priests were prohibited from wearing any but ordinary garb. The Roman Church was forbidden ever again to own a rod of stone or a foot of land.

So now it is, that the priest wears a “bee-gum” hat and Glengarry

coat, and the state takes whatever church-edifices it wants for public

use. The church of San Augustin is a public library. Many[Pg 63]

[Pg 64] churches

have been converted into schools. Others have been pulled down, and

modern buildings erected in their stead. The cloisters and chapel of

the monastery of the Franciscans are leased to laymen, and have become

the hotel Jardin. What churches the Republic did not need to use, it

has been willing to rent to the Roman hierarchy for the religious uses

of the people. So many have been these edifices that, despite the

government’s appropriations and private occupations, there yet remain

church buildings innumerable where the pious may worship and the

priesthood celebrate the mass. But the Roman hierarchy has no longer

the wealth and will to keep these buildings in repair and in all of

those I visited there was much dilapidation.

While it is true that the stern laws of the Republic debar the Roman Church from owning land, yet, it is said, this law is now evaded by a system of subrosa trusteeships, whereby secret trustees already hold vast accumulations of land and money to its use. And although the church cannot go into court to enforce the trust, yet the threat of dire pains in Purgatory is seemingly so effective that there is said to have been extraordinary little loss by stealing. The promise of easy passage to Paradise also makes easy the evasion of human law.

LA CASA DE AZULEJOS, NOW JOCKEY CLUB

Hotel Iturbide, Mexico,

November 22d.

This limpid atmosphere, this vivifying sun,—how they redden the blood and exhilarate the spirit! This is a sunshine which never brings the sweat. But yet, however hot the sun may be, it is cold in the shadow, and at this I am perpetually surprised.

The custom of the hotels in this Latin land is to let rooms upon the “European” plan, leaving the guest free to dine in the separate café of the hotel itself, or to take his meals wherever he may choose among the city’s multitude of lunch rooms and restaurants. Thus I may take my desayuno in an “American” restaurant, where the dishes are of the American type, and my almuerzo, the midmorning meal, in an Italian restaurant where the dishes of sunny Italy are served; while for my comida, I stroll through a narrow doorway between sky blue pillars, and enter a long, [Pg 66]stone-flagged chamber, where neat tables are set about and where the Creole French of Louisiana is the speech of the proprietor. Here are served the most delicious meals I have yet discovered. If you want fish, a swarthy Indian waiter presents before you a large silver salver on which are arranged different sorts of fish fresh from the sea, for these are daily received in the city. Or, perhaps, you desire game, when a tray upon which are spread ducks and snipe and plover, the heads and wings yet feathered, is presented to you. Or a platter of beefsteaks, chops and cutlets is held before you. From these you select what you may wish. If you like, you may accompany the waiter who hands your choice to the cook, and you may stand and see the fish or duck or chop done to a turn, as you shall approve, upon the fire before your eyes. You are asked to take nothing for granted, but having ascertained to your own satisfaction that the food is fresh, you may verify its preparation, and eat it contentedly without misgiving. In this autumn season, flocks of ducks come to spend their winters upon the lakes surrounding the city. At a cost of thirty cents, our money, you may have a delicious broiled teal with fresh peas and lettuce, and as much fragrant coffee as you will drink. The food is cheap, wholesome and abundant. And what is time to a cook [Pg 67]whose wages may be ten or fifteen centavos a day, although his skill be of the greatest!

PLEASED WITH MY CAMERA

The city is full of fine big shops whose large windows present lavish displays of sumptuous fabrics. There is great wealth in Mexico. There is also abject poverty. The income of the rich comes to them without toil from their vast estates, often inherited in direct descent from the Royal Grants of Ferdinand and Isabella to the Conquestadores of Cortez, when the fruitful lands of the conquered Aztecs were parceled out among the hungry Spanish compañeros of the Conqueror. Some of these farms or haciendas, as they are called, contain as many as a million acres.

Mexico is to all intents and purposes a free trade country, and the fabrics and goods of Europe mostly supply the needs and fancies of the Mexicans. The dry goods stores are in the hands of the French, with here and there a Spaniard from old Spain; the drug stores are kept by Germans, who all speak fluent Spanish, and the cheap cutlery and hardware are generally of German make. The wholesale and retail grocers have been Spaniards, but this trade is now drifting to the Americans. There are some fine jewelry stores, and gems and gold work are displayed in their windows calculated to dazzle even an American. The Mexican delights in jewels, and men[Pg 68] and women love to have their fingers ablaze with sparkling diamonds, and their fronts behung with many chains of gold. And opals! Everyone will sell you opals!

In leather work, the Mexican is a master artist. He has inherited the art from the clever artificers among the ancient Moors. Coats and pantaloons (I use purposely the word pantaloons) and hats are made of leather, soft, light and elastic as woven fibre. And as for saddles and bridles, all the accoutrements of the caballero are here made more sumptuously than anywhere in all the world.

The shops are opened early in the morning and remain open until noon, when most of them are closed until three o’clock, while the clerks are allowed to take their siesta, the midday rest. Then in the cool hours of the evening they stay open until late.

Over on one side of a small park, under the projecting loggia of a long, low building, I noticed, to-day, a dozen or more little tables, by each of which sat a dignified, solemn-looking man. Some were waiting for customers, others were writing at the dictation of their clients; several were evidently composing love letters for the shy, brown muchachas who whispered to them. Of the thirteen millions constituting the population of [Pg 69]the Mexican Republic, less than two millions can read and write. Hence it is, that this profession of scribe is one of influence and profit.

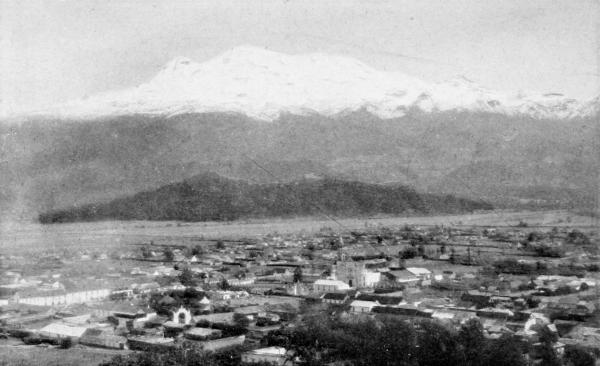

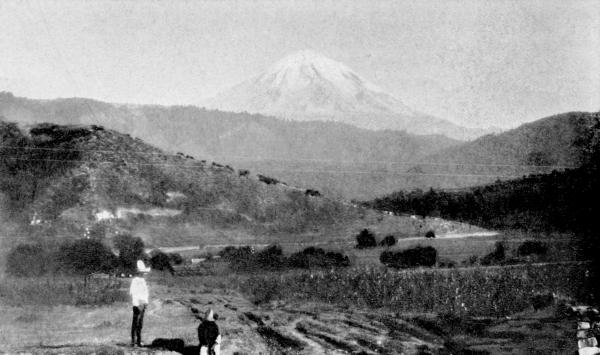

VOLCANO DE POPOCATEPETL

I have once more visited the famous cathedral which faces the Plaza Grande. From the north tower of it, to the top of which I climbed by a wonderful convoluted staircase, ninety-two spiral steps without a core, I gained a view of the city. North and south and east and west it spread out several miles in extent. It lies beneath the view, a city of flat roofs, covering structures rarely more than two stories high, of stone and sun-dried brick, and painted sky blue, pink and yellow, or else remaining as white and clean as when first built, who knows how many hundreds of years ago? For here are no chimneys, no smoke and no soot! To the south I could descry the glistening surface of Lake Tezcoco, and to the west, at a greater distance, Lakes Chalco and Xochomilco. Never a cloud flecked the dark blue dome of the sky. Only, overhead, I noted one burst of refulgent whiteness. It was with difficulty that I could compel my comprehension to grasp the fact that this was nothing less than the snow summit of mighty Popocatepetl, so distant that tree and earth and rock along its base, even in this pellucid atmosphere, were hid in perpetual haze.

It is said that peoples differ from one another[Pg 70] not merely in color, in form and in manners, but equally so in their peculiar and individual odors. The Chinese are said to find the European offensive to their olfactory nerves because he smells so much like a sheep. The Englishman vows the Italian reeks with the scent of garlic. The Frenchman declares the German unpleasant because his presence suggests the fumes of beer. Just so, have I been told that the great cities of the world may be distinguished by their odors. Paris is said to exhale absinthe. London is said to smell of ale and stale tobacco, and Mexico City, I think, may be said to be enwrapped with the scent of pulque (Pool-Kay). “Pulque, blessed pulque,” says the Mexican! Pulque, the great national drink of the ancient Aztec, which has been readily adopted by the Spanish conqueror, and which is to-day the favorite intoxicating beverage of every bibulating Mexican. At the railway stations, as we descended into the great valley wherein Mexico City lies, Indian women handed up little brown pitchers of pulque, fresh pulque new tapped. Sweet and cool and delicious it was, as mild as lemonade (in this unfermented condition it is called agua miel, honey water). The thirsty passengers reached out of the car windows and gladly paid the cinco centavos (five cents) and drank it at leisure as the train rolled on. Through miles and miles we [Pg 71]traversed plantations of the maguey plant from which the pulque is extracted. For pulque is merely the sap of the maguey or “century plant,” which accumulates at the base of the flower stalk, just before it begins to shoot up. The pulque-gatherer thrusts a long, hollow reed into the stalk, sucks it full to the mouth, using the tongue for a stopper, and then blows it into a pigskin sack which he carries on his back. When the pigskin is full of juice, it is emptied into a tub, and when the tub is filled with liquor it is poured into a cask, and the cask is shipped to the nearest market. Itinerant peddlars tramp through the towns and villages, bearing a pigskin of pulque on their shoulders and selling drinks to whosoever is thirsty and may have the uno centavo (one cent) to pay for it. When fresh, the drink is delightful and innocuous. But when the liquid has begun to ferment, it is said to generate narcotic qualities which make it the finest thing for a steady, long-continuing and thorough-going drunk which Providence has yet put within the reach of man. Thousands of gallons of pulque are consumed in Mexico City every twenty-four hours, and the government has enacted stringent laws providing against the sale of pulque which shall be more than twenty-four hours old. The older it grows the greater the drunk, and the less you need drink to become intoxicated,[Pg 72] hence, it is the aim of every thirsty Mexican to procure the oldest pulque he can get. In every pulque shop, where only the mild, sweet agua miel, fresh and innocuous, is supposed to be sold, there is, as a matter of fact, always on hand a well fermented supply, a few nips of which will knock out the most confirmed drinker almost as soon as he can swallow it.

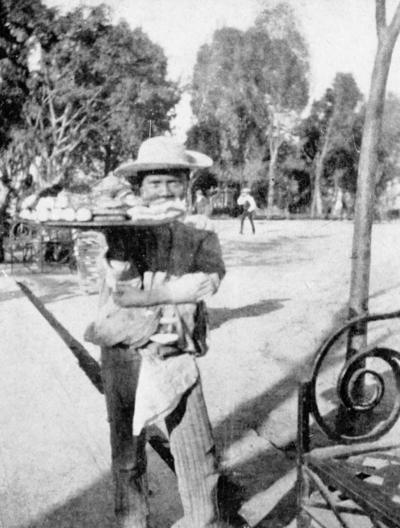

A PULQUE PEDDLER

I was passing a pulque shop this afternoon when I noticed a tall, brawny Indian coming out. He walked steadily and soberly half way across the street, when all of a sudden the fermented brew within him took effect and he doubled up like a jackknife, then and there. Two men thereupon came out of the self same doorway, picked him up head and heels, and I saw them sling him, like a sack of meal, into the far corner of the shop, there to lie, perhaps twenty-four hours, till he would come out of his narcotic stupor.

Riding out to the shrine of Guadeloupe the other afternoon, I passed many Indians leaving the city for their homes. Some were bearing burdens upon their backs, some were driving donkeys loaded with goods. Upon the back of one donkey was tied a pulque drunkard. His legs were tied about the donkey’s neck and his body was lashed fast to the donkey’s back. His eyes and mouth were open. His head wagged from side to side with the burro’s trot. He was apparently dead. He had swallowed too much fermented pulque. His compañeros were taking him home to save him from the city jail.

A FRIEND OF MY KODAK

The Mexicans have a legend about the origin of their pulque. It runs thus: One of their mighty emperors, long before the days of Montezuma’s rule, when on a war raid to the south, lost his heart to the daughter of a conquered chief and brought her back to Tenochtitlan as his bride. Her name was Xochitl and she gained extraordinary power over her lord, brewing with her fair, brown hands a drink for which he acquired a prodigious thirst. He never could imbibe enough and, when tanked full, contentedly resigned to her the right to rule. Other Aztec ladies perceiving its soothing soporific influence upon the emperor, acquired the secret of its make and secured domestic peace by also administering it to their lords. Thus pulque became the drink adored by every Aztec. The acquisitive Spaniard soon “caught on” and has never yet let go.

DULCE VENDER

The one redeeming feature about the pulque is that he who gets drunk on it becomes torpid and is incapable of fight. Hence, while it is so widely drunk, there comes little violence from those who drink it.

But not so is it with mescal, a brandy distilled[Pg 73]

[Pg 74] from the lower

leaves and roasted roots of the maguey plant. It is the more high

priced and less generally tasted liquor. Men who drink it become mad

and, when filled with it, sharpen their long knives and start to get

even with some real or imaginary foe. Fortunately, mescal has few

persistent patrons. It is pulque, the soporific pulque that is the

honored and national beverage of the Mexican.

VOLCANO DE IZTACCIHUATL

Mexico City,

Sunday, November 24th.

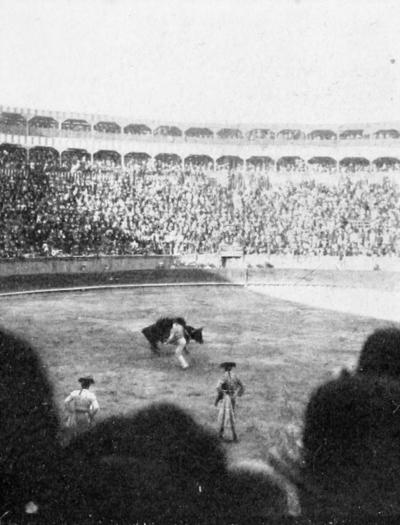

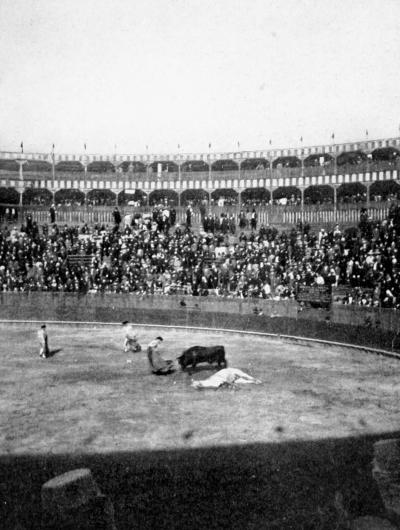

A feeling first of disgust and then of anger came over me this

afternoon. I was sitting right between two pretty Spanish women, young

and comely. One of them as she came in was greeted by the name

Hermosa Paracita (beautiful little parrot), by eight or ten sprucely

dressed young Spaniards just back of me. The spectators with ten

thousand vociferous throats had just been cheering a picador. He had

done a valiant deed. He had ridden his blindfolded horse around the

ring twice, lifting his cap to the cheering multitude. He was

applauded because he had managed to have the belly of his horse so

skillfully ripped open by the maddened black bull, that all its vitals

and entrails were dragging on the ground while he rode it, under the

stimulus of his cruel spurs and wicked bit, twice around the ring

before it fell, to be dragged out, dying, by mules, gaily-capari[Pg 75]

[Pg 76]soned

in trappings of red and gold, tugging at its heels! Paracita clapped

her pretty bejeweled hands and cried “bravo!” And so did the scores

of other pretty women; women on the reserved seats, elegant ladies and

pretty children in the high-priced boxes on the upper tiers! The

howling mob of thousands also applauded the gallant picador! Would

he be equally fortunate and clever and succeed in having the next

horse ripped open so completely, all at one thrust of the bull’s

horns? Quien sabe?

The city of four hundred thousand inhabitants, capital of the Mexican Republic, had been profoundly stirred all the week over the arrival from Spain of the renowned Manzanillo and his band of toreadors (bullfighters). Their first appearance would be the opening event of the bullfighting season.

Manzanillo, the most renowned Toreador of old Spain! And bulls, six of them, of the most famous strains of Mexico and of Andalusia! Señor Limantour, Secretary of State for Mexico, spoken of as the successor to President Diaz, had just delighted the jeunesse dorée by publicly announcing his acceptance of the honor of the Presidency of the newly founded “Bullfighting Club.” Spanish society and the Sociadad Española had publicly serenaded Don Manzanillo at his hotel! A dinner would be given in his honor after the event! Men and women were selling tickets on the streets. Reserved tickets at five dollars each, could only be obtained at certain cigar stores. The rush would be so great that, to secure a ticket at all, one must buy early. I secured mine on Thursday, and was none too soon. The spectacle would come off Sunday afternoon at three o’clock, by which hour all the churches would have finished their services, and the ladies would have had their almuerzo, and time to put on afternoon costume.

SETTING A BANDERILLA