Title: The Yellowstone National Park: Historical and Descriptive

Author: Hiram Martin Chittenden

Release date: February 17, 2013 [eBook #42112]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

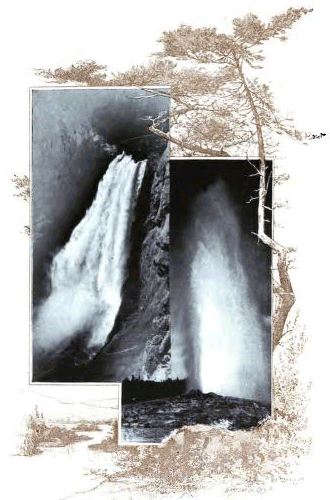

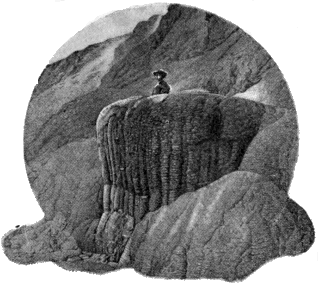

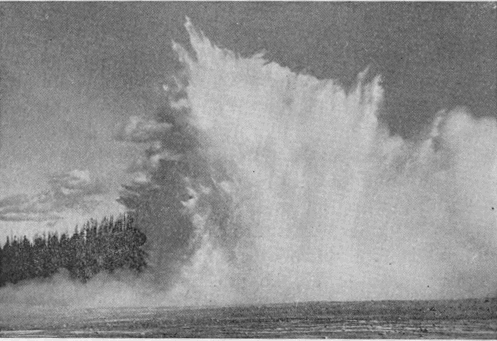

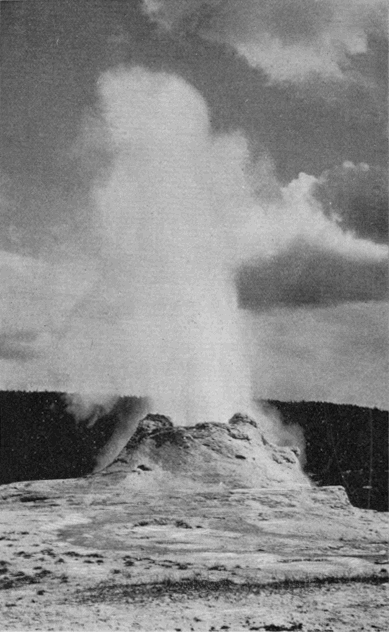

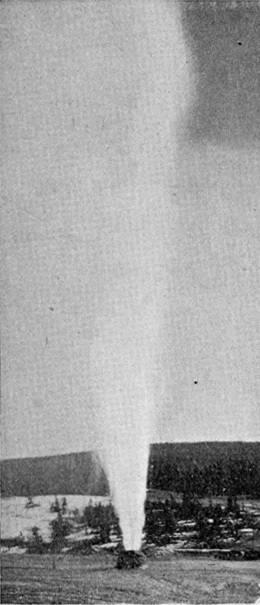

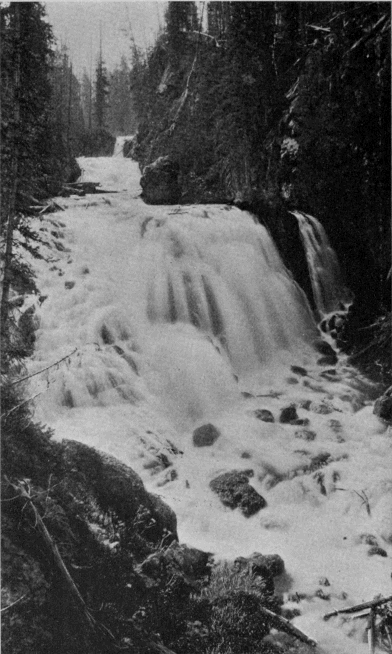

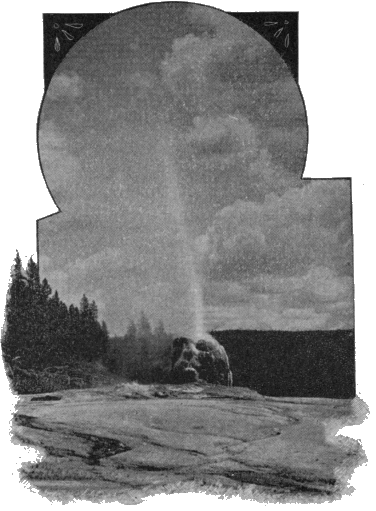

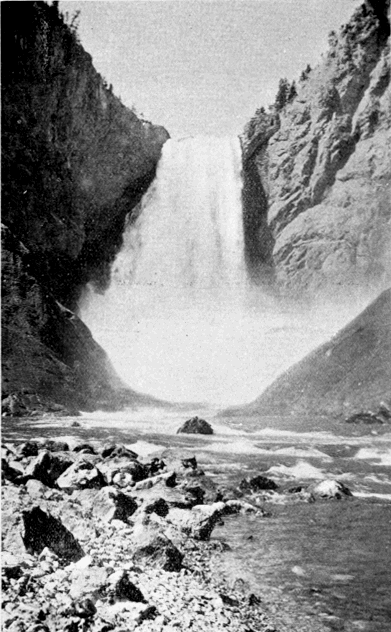

Grand Falls of the Yellowstone and Old Faithful Geyser.

THE

Yellowstone National Park

HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE

Illustrated with Maps, Views and Portraits

BY

Hiram Martin Chittenden

Captain, Corps of Engineers, United States Army

![]()

CINCINNATI

THE ROBERT CLARKE COMPANY

1895

Copyright, 1895,

By Hiram Martin Chittenden.

![]()

TO THE MEMORIES OF

![]()

AND

![]()

PIONEERS IN THE WONDERLAND

OF THE

![]()

Twenty-five years ago, this date, a company of gentlemen were encamped at the Forks of the Madison River in what is now the Yellowstone National Park. They had just finished the first complete tour of exploration ever made of that region. Fully realizing the importance of all they had seen, they asked what ought to be done to preserve so unique an assemblage of wonders to the uses for which Nature had evidently designed them. It required no argument to show that government protection alone was equal to the task, and it was agreed that a movement to secure such protection should be inaugurated at once. So rapidly did events develop along the line of this idea, that within the next eighteen months the “Act of Dedication” had become a law, and the Yellowstone National Park took its place in our country’s history.

The wide-spread interest which the discovery of this region created among civilized peoples has in no degree diminished with the lapse of time. In this country particularly the Park to-day stands on a firmer basis than ever before. The events of the past two [vi] years, in matters of legislation and administration, have increased many fold the assurances of its continued preservation, and have shown that even the petty local hostility, which has now and then menaced its existence, is yielding to a wiser spirit of patriotism.

The time therefore seems opportune, in passing so important an epoch in the history of the Park, and while many of the actors in its earlier scenes are still among us, to collect the essential facts, historical and descriptive, relating to this region, and to place them in form for permanent preservation. The present literature of the Park, although broad in scope and exhaustive in detail, is unfortunately widely scattered, somewhat difficult of access, and in matters of early history, notably deficient. To supply a work which shall form a complete and connected treatment of the subject, is the purpose of the present volume.

It deals first and principally with the history of the Upper Yellowstone from the days of Lewis and Clark to the present time. The main text is supplemented by a considerable amount of appendical matter, the most important features of which are a complete list of the geographical names of the Park, with their origin and signification; a few biographical sketches of the early explorers; and a bibliography of the literature pertaining to this region.

The descriptive portion of the work contains a succinct, [vii] though comprehensive, treatment of the various scientific and popular features of the Park. While it is sufficient for all the requirements of ordinary information, it purposely refrains from a minute discussion of those details which have been, or are now being, exhaustively treated by the scientific departments of the government.

In describing a region whose fame rests upon its natural wonders, the assistance of the illustrative art has naturally been resorted to. The various accompanying maps have all been prepared especially for this work and are intended to set forth not only present geography but historical features as well. The folded map embodies every thing to date from the latest geographical surveys. It will bear careful study, and this has been greatly simplified by a system of marginal references to be used with the list of names in Appendix A.

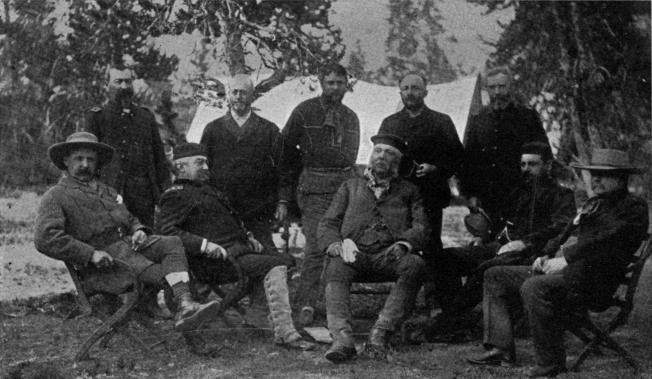

The illustrations cover every variety of subject in the Park and represent the best results of photographic work in that region. They are mostly from the studio of Mr. F. J. Haynes, of St. Paul, the well-known Park photographer, who has done so much by his art to disseminate a knowledge of the wonders of the Yellowstone. A considerable number are from views taken during the Hayden surveys by Mr. William H. Jackson, now of Denver, Colorado. A few excellent subjects are from the amateur work of Captain C. M. [viii] Gandy, Assistant Surgeon, U. S. A., who was stationed for some years on duty in the Park. The portraits are restricted to the few early explorers who visited the Upper Yellowstone prior to the creation of the Park.

To any one who is familiar with the recent history of the Park, a work like the present would seem incomplete without some reference to those influences which endanger its future existence. A brief discussion of this subject is accordingly presented, which, without considering particular schemes, exposes the dangerous tendencies underlying them all.

In the course of a somewhat extended correspondence connected with the preparation of this work, the author has become indebted for much information that could not be found in the existing literature of the Park. He desires in this place to return his sincere acknowledgments to all who have assisted him, and to refer in a special manner.

To the Hon. N. P. Langford, of St. Paul, whose long acquaintance with the Upper Yellowstone country has made him an authority upon its history.

To Dr. Elliott Coues, of Washington, D. C., who has contributed, besides much general assistance, the essential facts relating to the name “Yellowstone.”

To Captain George S. Anderson, 6th U. S. Cavalry, Superintendent of the Park, for the use of his extensive collection of Park literature.

To Prof. Arnold Hague, and others, of the U. S. Geological Survey, for many important favors.

To Prof. J. D. Butler, of Madison, Wis., for biographical data relating to James Bridger.

To Dr. R. Ellsworth Call, of Cincinnati, Ohio, for valuable assistance pertaining to the entire work.

To the Hon. D. M. Browning, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, for important data relating to the Indian tribes in the vicinity of the Yellowstone Park.

To the officers of the War and Interior Departments, the U. S. Fish Commission, the U. S. Bureau of Ethnology, and of the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, for public documents and other information of great value.

To R. T. Durrett, LL.D., of Louisville, Ky.; Mr. J. G. Morrison, of the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C.; Mr. J. D. Losecamp, of Billings, Mont.; Mr. George Bird Grinnell, of Forest and Stream, New York City; Major James F. Gregory, Corps of Engineers, U. S. A.; Lieutenant Wm. H. Bean, Second Cavalry, U. S. A.; Hon. David E. Folsom, White Sulphur Springs, Mont.; Washington Mathews, Major and Surgeon, U. S. A.; Dr. A. C. Peale, of Philadelphia, Pa.; William Hallett Phillips, of Washington, D. C.; Dr. Lyman B. Sperry, of Bellevue, O.; Mrs. Matilda Cope Stevenson, of Washington, D. C.; Mrs. Sirena J. Washburn, of Greencastle, Ind.; Miss Isabel Jelke, of Cincinnati, O.; Mr. O. B. Wheeler, [x] of St. Louis, Mo.; Mr. O. D. Wheeler, of St. Paul, Minn.; Mr. J. H. Baronett, of Livingston, Mont.; Mr. W. T. Hamilton, of Columbus, Mont.; Mr. Richard Leigh, of Wilford, Idaho; Mr. Edwin L. Berthoud, of Golden, Colo.; and Miss Laura S. Brown, of Columbus, O. H. M. C.

Columbus, Ohio, September 19, 1895.

PART I.—HISTORICAL.

| Chapter I.—“Yellowstone” | 1 |

| Chapter II.—Indian Occupancy of the Upper Yellowstone | 8 |

| Chapter III.—John Colter | 20 |

| Chapter IV.—The Trader and Trapper | 32 |

| Chapter V.—Early knowledge of the Yellowstone | 40 |

| Chapter VI.—James Bridger | 51 |

| Chapter VII.—Raynolds Expedition | 58 |

| Chapter VIII.—Gold in Montana | 65 |

| Chapter IX.—Discovery | 72 |

| Chapter X.—The National Park Idea—Its Origin and Realization | 87 |

| Chapter XI.—Why So Long Unknown | 98 |

| Chapter XII.—Later Explorations | 103 |

| Chapter XIII.—An Indian Campaign through the National | 111 |

| Chapter XIV.—Administrative History of the Park | 127 |

| Chapter XV.—The National Park Protective Act | 142 |

PART II.—DESCRIPTIVE.

| Chapter I.—Boundaries and Topography | 148 |

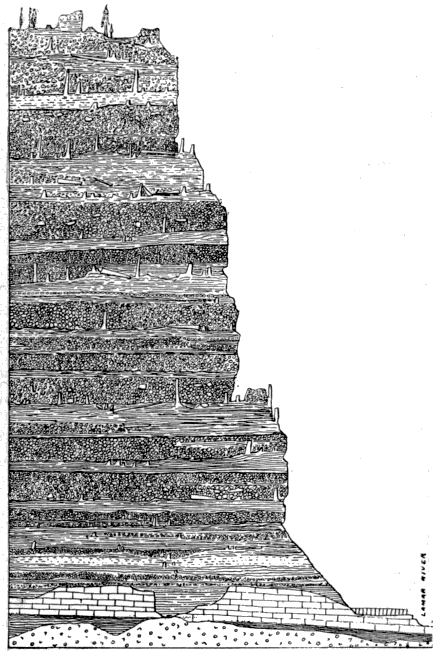

| Chapter II.—Geology of the Park | 156 |

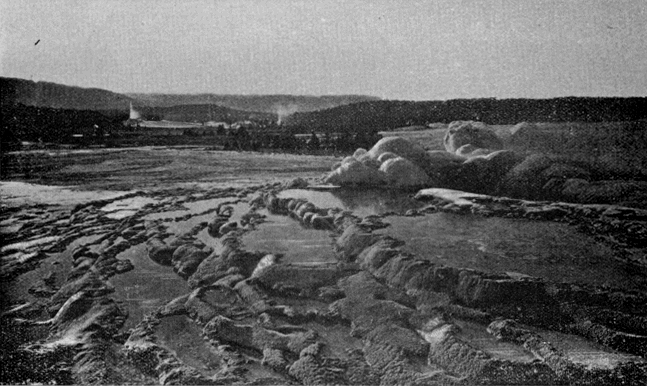

| Chapter III.—Geysers | 162 |

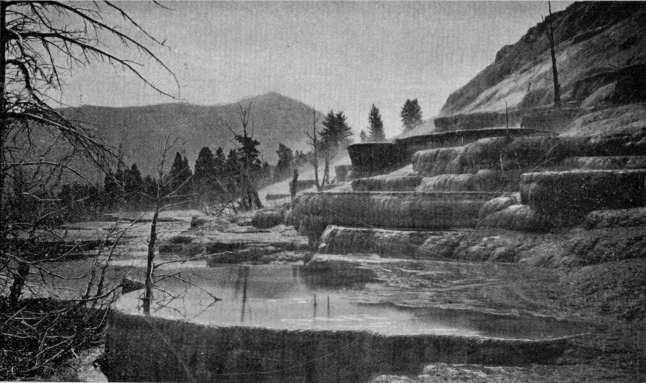

| Chapter IV.—Hot Springs | 172 |

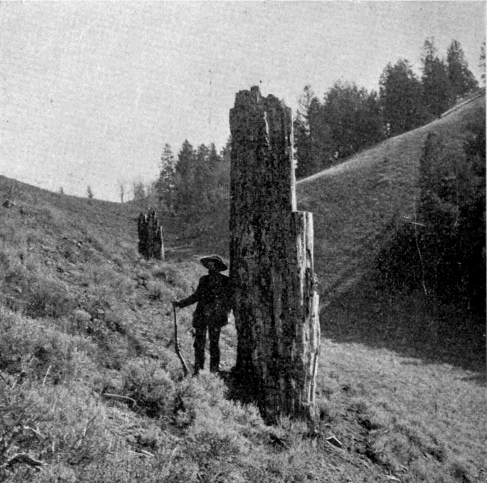

| Chapter V.—Fossil Forests of the Yellowstone | 175 |

| Chapter VI.—Fauna of the Yellowstone | 181[xii] |

| Chapter VII.—Flora of the Yellowstone | 187 |

| Chapter VIII.—The Park as a Health Resort | 193 |

| Chapter IX.—The Park in Winter | 198 |

| Chapter X.—Roads, Hotels, and Transportation | 201 |

| Chapter XI.—Administration of the Park | 206 |

| Chapter XII.—A Tour of the Park—Preliminary | 209 |

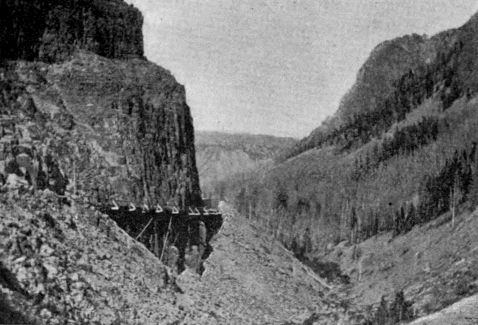

| Chapter XIII.—A Tour of the Park—North Boundary to Mammoth Hot Springs | 211 |

| Chapter XIV.—A Tour of the Park—Mammoth Hot Springs to Norris Geyser Basin | 217 |

| Chapter XV.—A Tour of the Park—Norris Geyser Basin to Lower Geyser Basin | 221 |

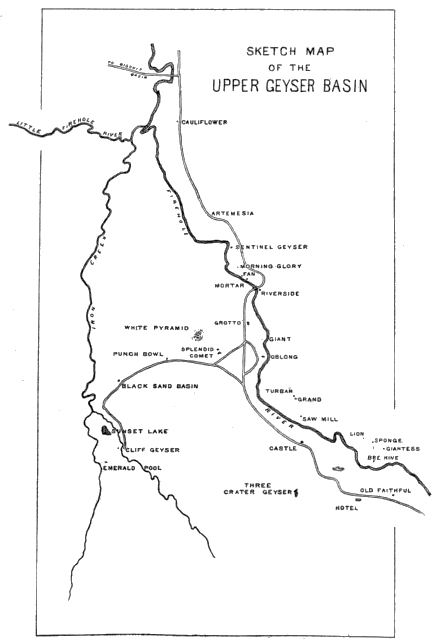

| Chapter XVI.—A Tour of the Park—Lower Geyser Basin to Upper Geyser Basin | 228 |

| Chapter XVII.—A Tour of the Park—Upper Geyser Basin to Yellowstone Lake | 237 |

| Chapter XVIII.—A Tour of the Park—Yellowstone Lake to the Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone | 248 |

| Chapter XIX.—A Tour of the Park—Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone to Junction Valley | 260 |

PART III.—THE FUTURE.

| Chapter I.—Hostility to the Park | 267 |

| Chapter II.—Railroad Encroachment and Change of Boundary | 270 |

| Chapter III.—Conclusion | 281 |

APPENDIX A.

| Geographical Names in the Yellowstone National Park | 285 | |

| I. | —Introductory | 285 |

| II. | —Mountain Peaks | 289 |

| III. | —Streams | 313 |

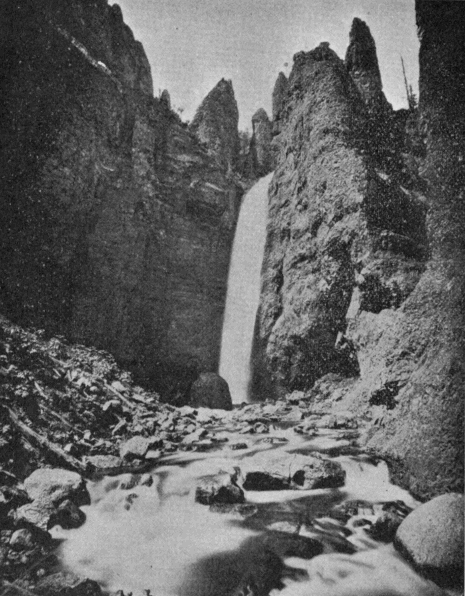

| IV. | —Water-falls | 324 [xiii] |

| V. | —Lakes | 327 |

| VI. | —Miscellaneous Features | 338 |

| VII. | —Geysers | 342 |

APPENDIX B.

| Legislation and Regulations now in Force affecting the Yellowstone National Park | 345 |

APPENDIX C.

| Appropriations on Account of the Yellowstone National Park | 357 |

APPENDIX D.

| List of Superintendents of the Yellowstone National Park | 359 |

APPENDIX E.

| Bibliography of the Yellowstone National Park | 361 |

The Yellowstone National Park.

“YELLOWSTONE.”

Lewis and Clark passed the first winter of their famous trans-continental expedition among the Mandan Indians, on the Missouri River, sixty-six miles above the present capital of North Dakota. When about to resume their journey in the spring of 1805, they sent back to President Jefferson a report of progress and a map of the western country based upon information derived from the Indians. In this report and upon this map appear for the first time, in any official document, the words “Yellow Stone” as the name of the principal tributary of the Missouri.

It seems, however, that Lewis and Clark were not the first actually to use the name. David Thompson, the celebrated explorer and geographer, prominently identified with the British fur trade in the North-west, was among the Mandan Indians on the Missouri River from December 29, 1797, to January 10, 1798. While there he secured data, mostly from the natives, from which he estimated the latitude and [2] longitude of the source of the Yellowstone River. In his original manuscript journal and field note-books, containing the record of his determinations, the words “Yellow Stone” appear precisely as used by Lewis and Clark in 1805. This is, perhaps, the first use of the name in its Anglicised form, and it is certainly the first attempt to determine accurately the geographical location of the source of the stream. [A]

[A] Thompson’s estimate:

Latitude, 43° 39’ 45” north.

Longitude, 109° 43’ 17” west.

Yount Peak, source of the Yellowstone (Hayden):

Latitude, 43° 57’ north.

Longitude, 109° 52’ west.

Thompson’s error:

In latitude, 17’ 15”.

In longitude, 8’ 43”, or about 21 miles.

Neither Thompson nor Lewis and Clark were originators of the name. They gave us only the English translation of a name already long in use. “This river,” say Lewis and Clark, in their journal for the day of their arrival at the mouth of the now noted stream, “had been known to the French as the Roche Jaune, or, as we have called it, the Yellow Stone.” The French name was, in fact, already firmly established among the traders and trappers of the North-west Fur Company, when Lewis and Clark met them among the Mandans. Even by the members of the expedition it seems to have been more generally used than the new English form; and the spellings, “Rejone,” “Rejhone,” “Rochejone,” “Rochejohn,” and “Rochejhone,” are among their various attempts to render orthographically the French pronunciation.

Probably the name would have been adopted unchanged, as so many other French names in our geography have been, except for the recent cession of Louisiana to the United States. The policy which led the government promptly to explore, and take formal possession of, its extensive acquisition, led it also, as part of the process of rapid Americanization, to give English names to all of the more prominent geographical features. In the case of the name here under consideration, this was no easy matter. The French form had already obtained wide currency, and it was reluctantly set aside for its less familiar translation. As late as 1817, it still appeared in newly English-printed books, [B] while among the traders and trappers of the mountains, it survived to a much later period.

[B] Bradbury’s “Travels in the Interior of America.” See Appendix E.

By whom the name Roche Jaune, or its equivalent form Pierre Jaune, was first used, it would be extremely interesting to know; but it is impossible to determine at this late day. Like their successor, “Yellow Stone,” these names were not originals, but only translations. The Indian tribes along the Yellowstone and upper Missouri rivers had names for the tributary stream signifying “yellow rock,” [C] and the French had doubtless adopted them long before any of their number saw the stream itself.

[C] The name “Elk River” was also used among the Crow Indians.

The first explorations of the country comprised within the present limits of the State of Montana are matters of great historic uncertainty. By one account it appears that, between the years 1738 and 1753, [4] Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, the Sieur de la Verendrye, and his sons, particularly the Chevalier de la Verendrye, conducted parties of explorers westward, from Lake Superior to the Assinnaboine River, thence south to the Mandan country, and thence to the very sources of the Missouri. Even the date, January 12, 1743, is given for their first ascent of the Rocky Mountains. But such is the dearth of satisfactory evidence relating to these explorations, that positive inferences concerning them are impossible. The most that can be said is, that if De la Verendrye visited these regions, as is generally believed, to him doubtless belongs the honor of having adopted from original sources the name of the Yellowstone River.

The goal of De la Verendrye’s explorations was the Pacific Ocean; but the French and Indian war which robbed France of her dominion in America, prevented his ever reaching it. Following him, at the distance of nearly half a century, came the traders and trappers of the North-west Fur Company. As already noted, they were among the Mandans as early as 1797, and the name Roche Jaune was in common use among them in 1804. They appear to have been wholly ignorant of the work of De la Verendrye, and it is quite certain that, prior to 1805, none of them had reached the Yellowstone River. Lewis and Clark particularly record the fact, while yet some distance below the junction of this river with the Missouri, that they had already passed the utmost limit of previous adventure by white men. Whatever, therefore, was at this time known of the Yellowstone could have come to these traders only from Indian sources. [D]

[D] An interesting reference to the name “Yellowstone,” in an entirely different quarter, occurs on Pike’s map of the “Internal Provinces of Spain,” published in 1810. It is a corrupt Spanish translation in the form of “Rio de Piedro Amaretto del Missouri,” (intended of course to be Rio de la Piedra Amarilla del Missouri) river of the Yellow Stone of the Missouri. No clue has been discovered of the source from which Pike received this name; but the fact of its existence need occasion no surprise. The Spanish had long traded as far north as the Shoshone country, and had mingled with the French traders along the lower Missouri. Lewis and Clark found articles of their manufacture among the Shoshones in 1805. There is also limited evidence of early intercourse between them and the Crow nation. That the name of so important a stream as the Yellowstone should have become known to these traders is therefore not at all remarkable. There is, however, no reason to suppose that the Spanish translation antedates the French. It certainly plays no part in the descent of the name from the original to the English form, and it is of interest in this connection mainly as showing that, even at this early day, the name had found its way to the provinces of the south.

We thus find that the name, which has now become so celebrated, descends to us, through two translations, from those native races whose immemorial dwelling-place had been along the stream which it describes. What it was that led them to use the name is easily discoverable. The Yellowstone River is pre-eminently a river with banks of yellow rock. Along its lower course “the flood plain is bordered by high bluffs of yellow sandstone.” Near the mouth of the Bighorn River stands the noted landmark, Pompey’s Pillar, “a high isolated rock” of the same material. Still further up, beyond the mouth of Clark’s fork, is an extensive ridge of yellow rock, the “sheer, vertical sides” of which, according to one writer, “gleam in the sunlight like massive gold.” All along the lower river, in fact, from its mouth to [6] the Great Bend at Livingston, this characteristic is more or less strikingly present.

Whether it forms a sufficiently prominent feature of the landscape to justify christening the river from it, may appear to be open to doubt. At any rate the various descriptions of this valley by early explorers rarely refer to the same locality as being conspicuous from the presence of yellow rock. Some mention it in one place, some in another. Nowhere does it seem to have been so striking as to attract the attention of all observers. For this reason we shall go further in search of the true origin of the name, to a locality about which there can be no doubt, no difference of opinion.

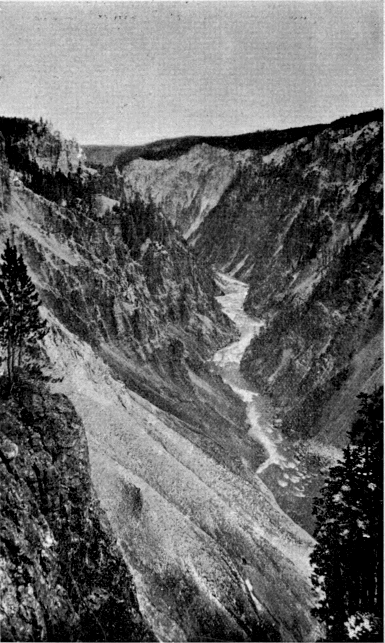

Seventy-five miles below the ultimate source of the river lies the Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone, distinguished among the notable cañons of the globe by the marvelous coloring of its walls. Conspicuous among its innumerable tints is yellow. Every shade, from the brilliant plumage of the yellow bird to the rich saffron of the orange, greets the eye in bewildering profusion. There is indeed other color, unparalleled in variety and abundance, but the ever-present background of all is the beautiful fifth color of the spectrum.

So prominent is this feature that it never fails to attract attention, and all descriptions of the Cañon abound in references to it. Lieutenant Doane (1870) notes the “brilliant yellow color” of the rocks. Captain Barlow and Doctor Hayden (1871) refer, in almost the same words, to the “yellow, nearly vertical walls.” Raymond (1871) speaks of the “bright yellow of the sulphury clay.” Captain Jones (1873) says that "about [7] and in the Grand Cañon the rocks are nearly all tinged a brilliant yellow." These early impressions might be repeated from the writings of every subsequent visitor who has described the scenery of the Yellowstone.

That a characteristic which so deeply moves the modern beholder should have made a profound impression on the mind of the Indian, need hardly be premised. This region was by no means unknown to him; and from the remote, although uncertain, period of his first acquaintance with it, the name of the river has undoubtedly descended.

Going back, then, to this obscure fountain-head, the original designation is found to have been

Mi tsi a-da-zi,

[E] Rock Yellow River.

And this, in the French tongue, became

Roche Jaune and Pierre Jaune;

and in English,

Yellow Rock and Yellow Stone.

Established usage now writes it

Yellowstone.

INDIAN OCCUPANCY OF THE UPPER YELLOWSTONE.

It is a singular fact in the history of the Yellowstone National Park that no knowledge of that country seems to have been derived from the Indians. The explanation ordinarily advanced is that the Indians had a superstitious fear of the geyser regions and always avoided them. How far this theory is supported by the results of modern research is an interesting inquiry.

Three great families of Indians, the Siouan, the Algonquian, and the Shoshonean, originally occupied the country around the sources of the Yellowstone. Of these three families the following tribes are alone of interest in this connection: The Crows (Absaroka) of the Siouan family; the Blackfeet (Siksika) of the Algonquian family; and the Bannocks (Panai’hti), the Eastern Shoshones, and the Sheepeaters (Tukuarika) of the Shoshonean family.

The home of the Crows was in the Valley of the Yellowstone below the mountains where they have dwelt since the white man’s earliest knowledge of them. Their territory extended to the mountains which bound the Yellowstone Park on the north and east; but they never occupied or claimed any of the country beyond. Their well-known tribal characteristics were an insatiable love of horse-stealing and a wandering and predatory habit which caused them to roam over all the West from the Black Hills to the Bitter Root Mountains and from the British Possessions to the Spanish Provinces. [9] They were generally, although by no means always, friendly to the whites, but enemies of the neighboring Blackfeet and Shoshones. Physically, they were a stalwart, handsome race, fine horsemen and daring hunters. They were every-where encountered by the trapper and prospector who generally feared them more on account of their thievish habits than for reasons of personal safety.

The Blackfeet dwelt in the country drained by the headwaters of the Missouri. Their territory was roughly defined by the Crow territory on the east and the Rocky Mountains on the west. Its southern limit was the range of mountains along the present north-west border of the Park and it extended thence to the British line. The distinguishing historic trait of these Indians was their settled hostility to their neighbors whether white or Indian. They were a tribe of perpetual fighters, justly characterized as the Ishmaelites of their race. From the day in 1806, when Captain Lewis slew one of their number, down to their final subjection by the advancing power of the whites, they never buried the hatchet. They were the terror of the trapper and miner, and hundreds of the pioneers perished at their hands. Like the Crows they were a well-developed race, good horsemen and great rovers, but, in fight, given to subterfuge and stratagem rather than to open boldness of action.

In marked contrast with these warlike and wandering tribes were those of the great Shoshonean family who occupied the country around the southern, eastern, and western borders of the Park, including also that of the Park itself. The Shoshones as a family [10] were an inferior race. They seem to have been the victims of some great misfortune which had driven them to precarious methods of subsistence and had made them the prey of their powerful and merciless neighbors. The names “Fish-eaters,” “Root-diggers,” and other opprobrious epithets, indicate the contempt in which they were commonly held. For the most part they had no horses, and obtained a livelihood only by the most abject means. Some of the tribes, however, rose above this degraded condition, owned horses, hunted buffalo, and met their enemies in open conflict. Such were the Bannocks and the Eastern Shoshones—tribes closely connected with the history of the Park, one occupying the country to the south-west near the Teton Mountains, and the other that to the south-east in the valley of Wind River. The Shoshones were generally friendly to the whites, and for this reason they figure less prominently in the books of early adventure than do the Crows and Blackfeet whose acts of “sanguinary violence” were a staple article for the Indian romancer.

It was an humble branch of the Shoshonean family which alone is known to have permanently occupied what is now the Yellowstone Park. They were called Tukuarika, or, more commonly, Sheepeaters. They were found in the Park country at the time of its discovery and had doubtless long been there. These hermits of the mountains, whom the French trappers called “les dignes de pitié,” have engaged the sympathy or contempt of explorers since our earliest knowledge of them. Utterly unfit for warlike contention, they seem to have sought immunity from their dangerous neighbors by dwelling among the inaccessible fastnesses of the mountains. They were destitute of even savage comforts. Their food, as their name indicates, was principally the flesh of the mountain sheep. Their clothing was composed of skins. They had no horses and were armed only with bows and arrows. They captured game by driving it into brush inclosures. Their rigorous existence left its mark on their physical nature. They were feeble in mind, diminutive in stature, and are always described as a “timid, harmless race.” They may have been longer resident in this region than is commonly supposed, for there was a tradition among them, apparently connected with some remote period of geological disturbance, that most of their race were once destroyed by a terrible convulsion of nature.

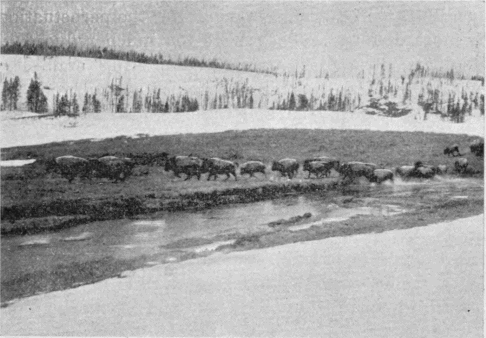

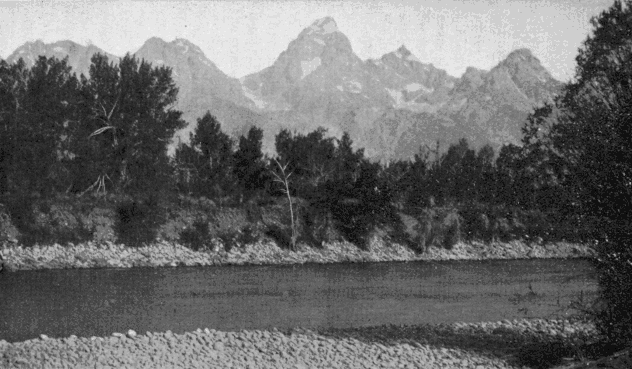

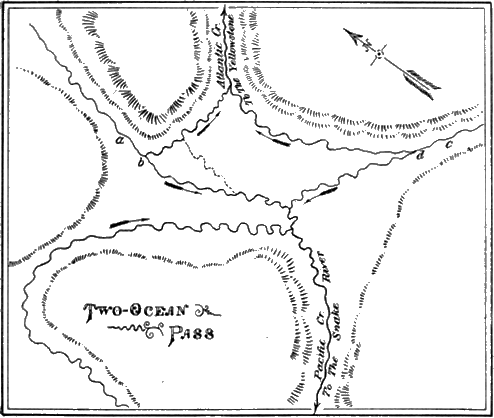

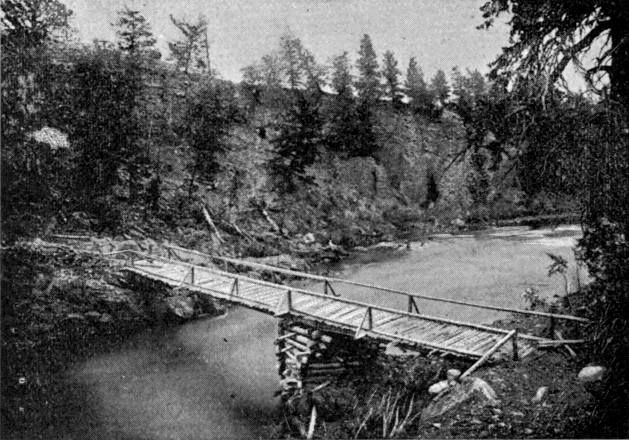

Such were the Indian tribes who formerly dwelt within or near the country now embraced in the Yellowstone National Park. That the Sheepeaters actually occupied this country, and that wandering bands from other tribes occasionally visited it, there is abundant and conclusive proof. Indian trails, [F] though generally indistinct, were every-where found by the early explorers, mostly on lines since occupied by the tourist routes. One of these followed the Yellowstone Valley entirely across the Park from north to south. It divided at Yellowstone Lake, the principal branch following the east shore, crossing Two-Ocean-Pass, and intersecting a great trail which connected the Snake and Wind River Valleys. The other branch passed along the west shore of the lake and over the divide to the valleys of Snake River and [12] Jackson Lake. This trail was intersected by an important one in the vicinity of Conant Creek leading from the Upper Snake Valley to that of Henry Fork. Other intersecting trails connected the Yellowstone River trail with the Madison and Firehole Basins on the west and with the Bighorn Valley on the east.

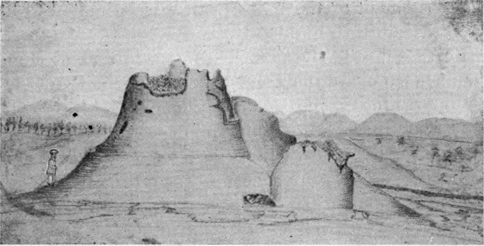

[F] See historical chart, opposite.

The most important Indian trail in the Park, however, was that known as the Great Bannock Trail. It extended from Henry Lake across the Gallatin Range to Mammoth Hot Springs, where it was joined by another coming up the valley of the Gardiner. Thence it led across the Black-tail Deer plateau to the ford above Tower Falls; and thence up the Lamar Valley, forking at Soda Butte, and reaching the Bighorn Valley by way of Clark’s Fork and the Stinkingwater River. This trail was certainly a very ancient and much-traveled one. It had become a deep furrow in the grassy slopes, and it is still distinctly visible in places, though unused for a quarter of a century.

Additional evidence in the same direction may be seen in the wide-spread distribution of implements peculiar to Indian use. Arrows and spear heads have been found in considerable numbers. Obsidian Cliff was an important quarry, and the open country near the outlet of Yellowstone Lake a favorite camping-ground. Certain implements, such as pipes, hammers, and stone vessels, indicating the former presence of a more civilized people, have been found to a limited extent; and some explorers have thought that a symmetrical mound in the valley of the Snake River, below the mouth of Hart River, is of artificial origin. Reference will later be made to the discovery of a [13] rude granite structure near the top of the Grand Teton, which is unquestionably of very ancient date.

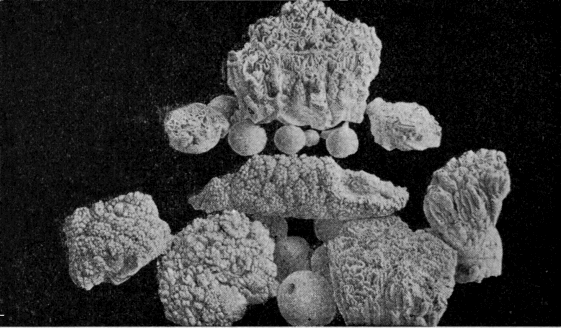

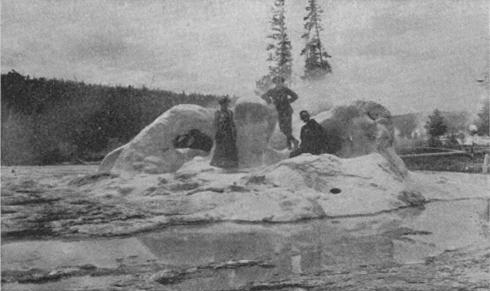

Dr. A. C. Peale, prominently connected with the early geological explorations of this region, states that the Rustic Geyser in the Hart Lake Geyser Basin is “bordered by logs which are coated with a crystalline, semi-translucent deposit of geyserite. These logs were evidently placed around the geyser by either Indians or white men a number of years ago, as the coating is thick and the logs firmly attached to the surrounding deposit.” [G]

[G] Page 298, Twelfth Annual Report of Dr. Hayden. See Appendix E. It is more than probable that this was the work of trappers.

More recent and perishable proofs of the presence of Indians in the Park were found by the early explorers in the rude wick-e-ups, brush inclosures, and similar contrivances of the lonely Sheepeaters; and it is not improbable that many of the arrow and spear heads were the work of these Indians.

The real question of doubt in regard to Indian occupancy of, or visits to, the Park, is therefore not one of fact, but of degree. The Sheepeaters certainly dwelt there; but as to other tribes, their acquaintance with it seems to have been very limited. No word of information about the geyser regions ever fell from their lips, except that the surrounding country was known to them as the Burning Mountains. With one or two exceptions, the old trails were very indistinct, requiring an experienced eye to distinguish them from game trails. Their undeveloped condition indicated infrequent use. Old trappers who have known this region for fifty years say that the great [14] majority of Indians never saw it. Able Indian guides in the surrounding country became lost when they entered the Park, and the Nez Percés were forced to impress a white man as guide when they crossed the Park in 1877.

An unknown writer, to whom extended reference will be made in a later chapter, visited the Upper Geyser Basin in 1832, accompanied by two Pend d’Oreilles Indians. Neither of these Indians had ever seen or apparently heard of the geysers, and “were quite appalled” at the sight of them, believing them to be “supernatural” and the “production of the Evil Spirit.”

Lieutenant Doane, who commanded the military escort to the Yellowstone Expedition of 1870, says in his report: [H]

“Appearances indicated that the basin [of the Yellowstone Lake] had been almost entirely abandoned by the sons of the forest. A few lodges of Sheepeaters, a branch remnant of the Snake tribe, wretched beasts who run from the sight of a white man, or from any other tribe of Indians, are said to inhabit the fastnesses of the mountains around the lakes, poorly armed and dismounted, obtaining a precarious subsistence, and in a defenseless condition. We saw, however, no recent traces of them. The larger tribes never enter the basin, restrained by superstitious ideas in connection with the thermal springs.”

[H] Page 26, “Yellowstone Expedition of 1870.” See Appendix E.

In 1880, Col. P. W. Norris, Second Superintendent of the Park, had a long interview on the shore of the [15] Yellowstone Lake with We-Saw, “an old but remarkably intelligent Indian” of the Shoshone tribe, who was then acting as guide to an exploring party under Governor Hoyt, of Wyoming, and who had previously passed through the Park with the expedition of 1873 under Captain W. A. Jones, U. S. A. He had also been in the Park region on former occasions. Colonel Norris records the following facts from this Indian’s conversation: [I]

“We-Saw states that he had neither knowledge nor tradition of any permanent occupants of the Park save the timid Sheepeaters…. He said that his people (Shoshones) the Bannocks and the Crows, occasionally visited the Yellowstone Lake and River portions of the Park, but very seldom the geyser regions, which he declared were ‘heap, heap, bad,’ and never wintered there, as white men sometimes did with horses.”

[I] Page 38, Annual Report of Superintendent of the Park for 1881.

It seems that even the resident Sheepeaters knew little of the geyser basins. General Sheridan, who entered the Park from the south in 1882, makes this record in his report of the expedition: [J]

“We had with us five Sheep Eating Indians as guides, and, strange to say, although these Indians had lived for years and years about Mounts Sheridan and Hancock, and the high mountains south-east of the Yellowstone Lake, they knew nothing about the Firehole Geyser Basin, and they exhibited more astonishment and wonder than any of us.”

[J] Page 11, Report on Explorations of Parts of Wyoming, Idaho and Montana, 1882. See Appendix E.

Evidence like the foregoing clearly indicates that this country was terra incognita to the vast body of Indians who dwelt around it, and again this singular fact presents itself for explanation. Was it, as is generally supposed, a “superstitious fear” that kept them away? The incidents just related give some color to such a theory; but if it were really true we should expect to find well authenticated Indian traditions of so marvelous a country. Unfortunately history records none. It is not meant by this to imply that reputed traditions concerning the Yellowstone are unknown. For instance, it is related that the Crows always refused to tell the whites of the geysers because they believed that whoever visited them became endowed with supernatural powers, and they wished to retain a monopoly of this knowledge. But traditions of this sort, like most Indian curiosities now offered for sale, are evidently of spurious origin. Only in the names “Yellowstone” and “Burning Mountains” do we find any original evidence that this land of wonders appealed in the least degree to the native imagination.

The real explanation of this remarkable ignorance appears to us to rest on grounds essentially practical. There was nothing to induce the Indians to visit the Park country. For three-fourths of the year that country is inaccessible on account of snow. It is covered with dense forests, which in most places are so filled with fallen timber and tangled underbrush as to be practically impassable. As a game country in those early days it could not compare with the lower surrounding valleys. As a highway of communication between the valleys of the Missouri, Snake, Yellowstone, [17] and Bighorn Rivers, it was no thoroughfare. The great routes, except the Bannock trail already described, lay on the outside. All the conditions, therefore, which might attract the Indians to this region were wanting. Even those sentimental influences, such as a love of sublime scenery and a curiosity to see the strange freaks of nature, evidently had less weight with them than with their pale-face brethren.

Summarizing the results of such knowledge, confessedly meager, as exists upon this subject, it appears:

(1.) That the country now embraced in the Yellowstone National Park was occupied, at the time of its discovery, by small bands of Sheepeater Indians, probably not exceeding in number one hundred and fifty souls. They dwelt in the neighborhood of the Washburn and Absaroka Ranges, and among the mountains around the sources of the Snake. They were not familiar with the geyser regions.

(2.) Wandering bands from other tribes occasionally visited this country, but generally along the line of the Yellowstone River or the Great Bannock Trail. Their knowledge of the geyser regions was extremely limited, and very few had ever seen or heard of them. It is probable that the Indians visited this country more frequently in earlier times than since the advent of the white man.

(3.) The Indians avoided the region of the Upper Yellowstone from practical, rather than from sentimental, considerations.

The legal processes by which the vast territory of these various tribes passed to the United States, are full of incongruities resulting from a general ignorance of the country in question. By the Treaty of Fort Laramie, dated September 17, 1851, between the United States on the one hand, and the Crows, Blackfeet and other northern tribes on the other, the Crows were given, as part of their territory, all that portion of the Park country which lies east of the Yellowstone River; and the Blackfeet, all that portion lying between the Yellowstone River and the Continental Divide. This was before any thing whatever was known of the country so given away. None of the Shoshone tribes were party to the treaty, and the rights of the Sheepeaters were utterly ignored. That neither the Blackfeet nor the Crows had any real claim to these extravagant grants is evidenced by their prompt relinquishment of them in the first subsequent treaties. Thus, by treaty of October 17, 1855, the Blackfeet agreed that all of their portion of the Park country, with much other territory, should be and remain a common hunting ground for certain designated tribes; and by treaty of May 17, 1868, the Crows relinquished all of their territory south of the Montana boundary line.

That portion of the Park country drained by the Snake River was always considered Shoshone territory, although apparently never formally recognized in any public treaty. By an unratified treaty, dated September 24, 1868, the provisions of which seem to have been the basis of subsequent arrangements with the Shoshonean tribes, all this territory and much besides was [19] ceded to the United States, and the tribes were located upon small reservations.

It thus appears that at the time the Park was created, March 1, 1872, all the territory included in its limits had been ceded to the United States except the hunting ground above referred to, and the narrow strip of Crow territory east of the Yellowstone where the north boundary of the Park lies two or three miles north of the Montana line. The “hunting ground” arrangement was abrogated by statute of April 15, 1874, and the strip of Crow territory was purchased under an agreement with the Crows, dated June 12, 1880, and ratified by Congress, April 11, 1882, thus extinguishing the last remaining Indian title to any portion of the Yellowstone Park.

JOHN COLTER.

Lewis and Clark passed the second winter of their expedition at the mouth of the Columbia River. In the spring and summer of 1806 they accomplished their return to St. Louis. Upon their arrival at the site of their former winter quarters among the Mandans, an incident occurred which forms the initial point in the history of the Yellowstone National Park. It is thus recorded in the journal of the expedition under date of August 14 and 15, 1806: [K]

“In the evening we were applied to by one of our men, Colter, who was desirous of joining the two trappers who had accompanied us, and who now proposed an expedition up the river, in which they were to find traps and give him a share of the profits. The offer was a very advantageous one, and, as he had always performed his duty, and his services might be dispensed with, we agreed that he might go provided none of the rest would ask or expect a similar indulgence. To this they cheerfully answered that they wished Colter every success and would not apply for liberty to separate before we reached St. Louis. We therefore supplied him, as did his comrades also, with powder, lead, and a variety of articles which might be useful to him, and he left us the next day.”

[K] Pages 1181-2, Coues' “Lewis and Clark.” See Appendix E.

To our explorers, just returning from a two years' [21] sojourn in the wilderness, Colter’s decision seemed too remarkable to be passed over in silence. The journal continues:

“The example of this man shows us how easily men may be weaned from the habits of civilized life to the ruder but scarcely less fascinating manners of the woods. This hunter has now been absent for many years from the frontiers, and might naturally be presumed to have some anxiety, or some curiosity at least, to return to his friends and his country; yet just at the moment when he is approaching the frontiers, he is tempted by a hunting scheme to give up those delightful prospects, and go back without the least reluctance to the solitude of the woods.”

Colter seems to have stood well in the esteem of his officers. Besides the fair character given him in his discharge, the record of the expedition shows that he was frequently selected when one or two men were required for important special duty. That he had a good eye for topography may be inferred from the fact that Captain Clark, several years after the expedition was over, placed upon his map certain important information on the strength of Colter’s statements, who alone had traversed the region in question. In another instance, when Bradbury, the English naturalist, was about to leave St. Louis to join the Astorians in the spring of 1811, Clark referred him to Colter, who had returned from the mountains, as a person who could conduct him to a certain natural curiosity on the Missouri some distance above St. Charles. Colter had not seen the place for six years. In the Missouri Gazette, for April 18, 1811, he is referred to as a “celebrated hunter and woodsman.” These glimpses of his [22] record, and a remarkable incident to be related further on, clearly indicate that he was a man of superior mettle to that of the average hunter and trapper.

Colter’s whereabouts during the three years following his discharge are difficult to fix upon. It may, however, be set down as certain that he and his companions ascended the Yellowstone River, not the Missouri. Captain Clark’s return journey down the first-mentioned stream had made known to them that it was better beaver country than the Missouri, and Colter’s subsequent wanderings clearly indicate that his base of operations was in the valley of the Yellowstone near the mouth of the Bighorn, Pryor’s Fork, or other tributary stream.

In the summer of 1807, he made an expedition, apparently alone, although probably in company with Indians, which has given him title to a place in the history of the Yellowstone Park, and which was destined in later years to assume an importance little enough suspected by him at the time. His route appears upon Lewis and Clark’s map of 1814, and is there called “Colter’s route in 1807.” There is no note or explanation, and we are left to retrace, on the basis of a dotted line, a few names, and a date, one of those singular individual wanderings through the wilderness which now and then find a permanent place in history.

The “route,” as traced on the map, starts from a point on Pryor’s Fork, the first considerable tributary of the Yellowstone above the mouth of the Bighorn. Colter’s intention seems to have been to skirt the eastern base of the Absaroka Range until he should reach an accessible pass across the mountains of which the Indians had probably told him; then to cross over to the headwaters of Pacific or gulf-flowing streams; and then to return by way of the Upper Yellowstone.

Accordingly, after he had passed through Pryor’s Gap, he took a south-westerly direction as far as Clark’s Fork, which stream he ascended for some distance, and then crossed over to the Stinkingwater. Here he discovered a large boiling spring, strongly impregnated with tar and sulphur, the odor of which, perceptible for a great distance around, has given the stream its “unhappy name.”

From this point Colter continued along the eastern flank of the Absaroka Range, fording the several tributaries of the Bighorn River which flow down from that range, and finally came to the upper course of the main stream now known as Wind River. He ascended this stream to its source, crossing the divide in the vicinity of Lincoln or Union Pass, and found himself upon the Pacific slope. The map clearly shows that at this point he had reached what the Indians called the “summit of the world” near by the sources of all great streams of the west. That he discovered one of the easy passes between Wind River and the Pacific slope, is evident from the reference in the Missouri Gazette already alluded to and here reproduced for the first time. It is from the pen of a Mr. H. M. Brackenridge, a contemporary writer of note on topics of western adventure. It reads:

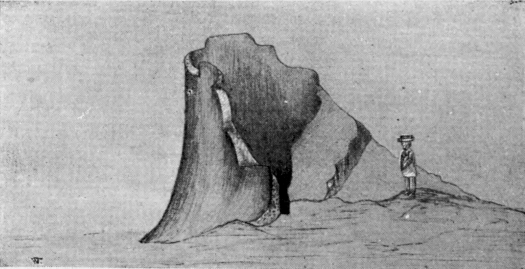

"At the head of the Gallatin Fork, and of the Grosse Corne of the Yellowstone [the Bighorn River], from discoveries since the voyage of Lewis and Clark, it is found less difficult to cross than the Allegheny [24] Mountains. Coulter, a celebrated hunter and woodsman, informed me that a loaded wagon would find no obstruction in passing."

The “discoveries” are of course those of Colter, for no other white man at this time had been in those parts.

From the summit of the mountains he descended to the westward; crossed the Snake River and Teton Pass to Pierre’s Hole, and then turned north, recrossing the Teton Range by the Indian trail in the valley of what is now Conant Creek, just north of Jackson Lake. [L] Thence he continued his course until he reached Yellowstone Lake,[L] at some point along its south-western shore. He passed around the west shore to the northernmost point of the Thumb, and then resumed his northerly course over the hills arriving at the Yellowstone River in the valley of Alum Creek. He followed the left bank of the river to the ford just above Tower Falls, where the great Bannock Trail used to cross, and then followed this trail to its junction with his outward route on Clark’s Fork. From this point he re-crossed to the Stinkingwater, possibly in order to re-visit the strange phenomena there, but more probably to explore new trapping territory on his way back. He descended the Stinkingwater until about south of Pryor’s Gap, when he turned north and shortly after arrived at his starting point.

[L] For the names given by Captain Clark to these bodies of water, see Appendix A, “Jackson Lake” and “Yellowstone Lake.”

The direction of Colter’s progress, as here indicated, and the identification of certain geographical features [25] noted by him, differ somewhat from the ordinary interpretation of that adventure. But, while it would be absurd to dogmatize upon so uncertain a subject, it is believed that the theory adopted is fairly well supported by the facts as now known. It must in the first place be assumed that Colter exercised ordinary common sense upon this journey and availed himself of all information that could facilitate his progress. It is probable that he was under the guidance of Indians who knew the country; but if not, he frequently stopped, like any traveler in an unknown region, to inquire his way. He sought the established trails, low mountain passes, and well-known fords, and did not, as the map suggests, take a direction that would carry him through the very roughest and most impassable mountain country on the continent. It is necessary to orient his map so as to make both his outgoing and return routes extend nearly due north and south, instead of north-east and south-west, in order to reconcile his geography at all with the modern maps. With these precautions some of the difficulty of the situation disappears.

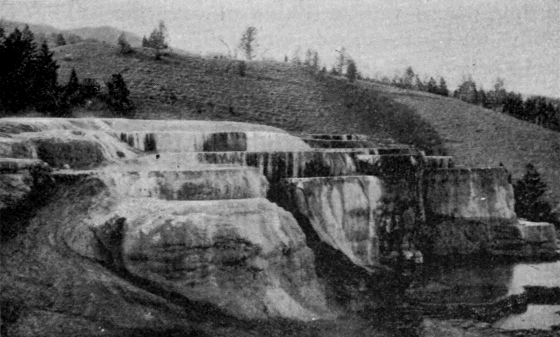

Colter, it is therefore assumed, followed the great trail along the Absarokas to the Wind River Valley, and crossed the divide by one of the easy passes at its head. His two crossings of the Teton range were along established trails. He evidently lost his bearings somewhat in the vicinity of the Yellowstone Lake, but as soon as he arrived at the river below the lake he kept along the trail until he reached the important crossing at Tower Falls. If he was in company with Indians who had ever been through that [26] country before, he learned that it would be no advantage to cross at Mud Geyser, inasmuch as he would strike the great Bannock Trail at the next ford below. Moreover, the distance below the lake to the point where Colter touched the Yellowstone is clearly greater than that to the Mud Geyser Ford. The bend in the river at the Great Falls, and the close proximity of the Washburn Range to the river, are distinctly indicated. The locality noted on the map as “Hot Springs Brimstone” is evidently not that near the Mud Geyser, as generally assumed, but instead, that of the now world-renowned Mammoth Hot Springs. As will be seen from the map, it is nearer the Gallatin River than it is to the Yellowstone where Colter crossed. If Colter visited the Springs from Tower Falls, as is not unlikely, a clue is supplied to the otherwise perplexing reference to the Gallatin River in the above extract from the Missouri Gazette, for it would thus appear that he was near the sources of both the Grosse Corne and of the Gallatin.

The essential difficulties in the way of this theory (and they exist with any possible theory that can be advanced) are the following: (1.) There is no stream on the map that can stand for the Snake River either above or below Jackson Lake, although Colter must have crossed it in each place. “Colter’s River” comes nearest the first location, and may possibly be intended to represent that stream; but Clark’s evident purpose to drain Jackson Lake into the Bighorn River doubtless led to a distortion of the map in this locality. (2.) The erroneous shape given to the Yellowstone Lake will be readily understood by any one who has visited its western shore. The jutting [27] promontories to the eastward entirely conceal from view the great body of the lake and give it a form not unlike that upon Clark’s map. (3.) The absence of the Great Falls from the map is not easily accounted for, although the location and trend of the Grand Cañon are shown with remarkable accuracy. (4.) The absence of the many hot springs districts, through which Colter passed, particularly that at the west end of the Yellowstone Lake, may be explained by the same spirit of incredulity which led to the rejection of all similar accounts for a period of more than sixty years. It is probable that Clark was not willing to recognize Colter’s statements on this subject further than to note on his map the location of the most wonderful of the hot springs groups mentioned by him.

The direction in which Colter traveled is a matter of no essential importance, and that here adopted is based solely upon the consideration that the doubling of the trail upon itself between Clark’s Fork and the Stinkingwater River, and the erratic course of the route around Yellowstone Lake, can not be well accounted for on the contrary hypothesis. [M]

[M] In adopting, as Colter’s point of crossing the Yellowstone, the ford at Tower Creek, the author has followed the Hon. N. P. Langford, in his reprint of Folsom’s “Valley of the Upper Yellowstone.” (See Appendix E.) All other writers who have touched upon the subject have assumed the ford to be that near the Mud Geyser.

Such, in the main, is “Colter’s route in 1807.” That he was the discoverer of Yellowstone Lake, and the foremost herald of the strange phenomena of that region, may be accepted as beyond question. He did [28] not, as is generally supposed, see the Firehole Geyser Basins. But he saw too much for his reputation as a man of veracity. No author or map-maker would jeopardize the success of his work by incorporating in it such incredible material as Colter furnished. His stories were not believed; their author became the subject of jest and ridicule; and the region of his adventures was long derisively known as “Colter’s Hell.” [N]

[N] This name early came to be restricted to the locality where Colter discovered the tar spring on the Stinkingwater, probably because few trappers ever saw the other similar localities visited by him. But Colter’s descriptions, so well summed up by Irving in his “Captain Bonneville,” undoubtedly refer in large part to what he saw in the Yellowstone and Snake River Valleys.

The story of Colter’s subsequent experience before he returned to St. Louis is thrilling in the extreme. Although it has no direct bearing upon this narrative, still, since it is part of the biography of the discoverer of the Upper Yellowstone, it can not be omitted. The detailed account we owe to the naturalist Bradbury, already referred to. He saw Colter above St. Louis in the spring of 1811, one year after his return from the mountains, and received the story directly from him. All other accounts are variations from Bradbury. Irving, who has made this story an Indian classic, borrows it in toto. Perhaps in all the records of Indian adventure there is not another instance of such a miraculous escape, in which the details are throughout so clearly within the range of possibility. It is a consistent narrative from beginning to end. In briefest outline it is as follows:

When Colter returned from his expedition of 1807, [29] he found Manuel Lisa, of the Missouri Fur Company, already in the country, where he had just arrived from St. Louis. With him was one Potts, believed to be the same person who had been a private in the party of Lewis and Clark. In the spring of 1808, Colter and his old companion in arms set out to the headwaters of the Missouri on a trapping expedition. It was on a branch of Jefferson Fork that they went to work, and here they met with their disastrous experience.

One morning while they were in a canoe examining their traps they were surprised by a large party of Blackfeet Indians. Potts attempted resistance and was slain on the spot. Colter, with more presence of mind, gave himself up as the only possible chance of avoiding immediate death. The Indians then consulted as to how they should kill him in order to yield themselves the greatest amount of amusement. Colter, upon being questioned as to his fleetness of foot, sagaciously replied that he was a poor runner (though in fact very swift), and the Indians, believing that it would be a safe experiment, decided that he should run for his life. Accordingly he was stripped naked and was led by the chief to a point three or four hundred yards in advance of the main body of the Indians. Here he was told “to save himself if he could,” and the race began—one man against five hundred.

The Indians quickly saw how they had been outwitted, for Colter flew away from them as if upon the wings of the wind. But his speed cost him dear. The exertion caused the blood to stream from his mouth and nostrils, and run down over his naked form. The prickly pear and the rough ground lacerated [30] his feet. Six miles away across a level plain was a fringe of cottonwood on the banks of the Jefferson River. Short of that lay not a shadow of chance of concealment. It was a long race, but life hung upon the issue. The Indians had not counted on such prodigious running. Gradually they fell off, and when Colter ventured for the first time to glance back, only a small number were in his wake. Encouragement was now added to hope, and he ran even faster than before.

But there was one Indian who was too much for him. He was steadily shortening the distance between them, and at last had arrived within a spear’s throw. Was Colter to be slain by a single Indian after having distanced five hundred? He would see. Suddenly whirling about, he confronted the Indian, who was astounded at the sudden move and at Colter’s bloody appearance. He tried to hurl his spear but stumbled and broke it as he fell. Colter seized the pointed portion and pinned the Indian to the earth.

Again he resumed his flight. He reached the Jefferson, and discovered, some distance below, a raft of driftwood against the head of an island. He dived under this raft and found a place where he could get his head above water. There, in painful suspense, he awaited developments. The Indians explored the island and examined the raft, but Colter’s audacious spirit was beyond their comprehension. It did not occur to them that he was all the time surveying their movements from his hiding place under the timber, and they finally abandoned the search and withdrew. Colter had saved himself. When evening came he swam several miles down the river and then went [31] ashore. For seven days he wandered naked and unarmed, over stones, cacti, and the prickly pear, scorched by the heat of noon and chilled by the frost of night, finding his sole subsistence in such roots as he might dig, until at last he reached Lisa’s trading post on the Bighorn River.

Even this terrible adventure could not dismay the dauntless Colter, and he remained still another year in the mountains. Finally, in the spring of 1810, he got into a canoe and dropped down the river, “three thousand miles in thirty days,” reaching St. Louis, May 1st, after an absence of six years.

Colter remained in St. Louis for a time giving Clark what information he could concerning the places he had seen, and evidently talking a great deal about his adventures. Finally he retired to the country some distance up the Missouri, and married. Here we again catch a glimpse of him when the Astorians were on their way up the river. As Colter saw the well appointed expedition setting out for the mountains, the old fever seized him again and he was upon the point of joining the party. But what the hardships of the wilderness and the pleasures of civilization could not dissuade him from doing, the charms of a newly-married wife easily accomplished. Colter remained behind; and here the curtain of oblivion falls upon the discoverer of the Yellowstone. It is not without genuine satisfaction that, having followed him through the incredible mazes of “Colter’s Hell,” we bid him adieu amid surroundings of so different a character.

THE TRADER AND TRAPPER.

For sixty years after Lewis and Clark returned from their expedition, the headwaters of the Yellowstone remained unexplored except by the trader and trapper. The traffic in peltries it was that first induced extensive exploration of the west. Concerning the precious metals, the people seem to have had little faith in their abundant existence in the west, and no organized search for them was made in the earlier years of the century. But that country, even in its unsettled state, had other and important sources of wealth. Myriads of beaver inhabited the streams and innumerable buffalo roamed the valleys. The buffalo furnished the trapper with means of subsistence, and beaver furs were better than mines of gold. Far in advance of the tide of settlement the lonely trapper, and after him the trader, penetrated the unknown west. Gradually the enterprise of individuals crystallized around a few important nuclei and there grew up those great fur-trading companies which for many years exercised a kind of paternal sway over the Indians and the scarcely more civilized trappers. A brief resumé of the history of these companies will show how important a place they occupy in the early history of the Upper Yellowstone.

The climax of the western fur business may be placed at about the year 1830. At that time three great companies operated in territories whose converging [33] lines of separation centered in the region about Yellowstone Lake. The oldest and most important of them, and the one destined to outlive the others, was the world-renowned Hudson’s Bay Company. It was at that time more than a century and a half old. Its earlier history was in marked contrast with that of later years. Secure in the monopoly which its extensive charter rights guaranteed, it had been content with substantial profits and had never pushed its business far into new territory nor managed it with aggressive vigor. It was not until forced to action by the encroachments of a dangerous rival, that it became the prodigious power of later times.

This rival was the great North-west Fur Company of Montreal: It had grown up since the French and Indian War, partly as a result of that conflict, and finally took corporate form in 1787. It had none of the important territorial rights of the Hudson’s Bay Company, but its lack of monopoly was more than made up by the enterprise of its promoters. With its bands of Canadian frontiersmen, it boldly penetrated the north-west and paid little respect to those territorial rights which its venerable rival was powerless to enforce. It rapidly extended its operations far into the unexplored interior. Lewis and Clark found its traders among the Mandans in 1804. In 1811 the Astorians saw its first party descend the Columbia to the sea. Two years later the American traders on the Pacific Coast were forced to succumb to their British rivals.

A long and bitter strife now ensued between the two British companies. It even assumed the magnitude of civil war, and finally resulted in a frightful [34] massacre of unoffending colonists. The British government interfered and forced the rivals into court, where they were brought to the verge of ruin by protracted litigation. A compromise was at last effected in 1821 by an amalgamation of the two companies under the name of the older rival.

But in the meantime a large part of their best fur country had been lost. In 1815 the government of the United States excluded British traders from its territory east of the Rocky Mountains. To the west of this limit, however, the amalgamated company easily forced all its rivals from the field. No American fur company ever attained the splendid organization, nor the influence over the Indians, possessed by the Hudson’s Bay Company. At the time of which we write it was master of the trade in the Columbia River valley, and the eastern limit of its operations within the territory of the United States was nearly coincident with the present western boundary of the Yellowstone Park.

The second of the great companies to which reference has been made was the American Fur Company. It was the final outcome of John Jacob Astor’s various attempts to control the fur trade of the United States. Although it was incorporated in 1809, it was for a time overshadowed by the more brilliant enterprises known as the Pacific Fur Company and the Southwest Fur Company. The history of Mr. Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, the dismal experiences of the Astorians, and the deplorable failure of the whole undertaking, are matters familiar to all readers of Irving’s “Astoria.”

The other project gave for a time more substantial [35] promise of success. A British company of considerable importance, under the name of the Mackinaw Company, with headquarters at Michilimacinac, had for some time operated in the country about the headwaters of the Mississippi now included in the states of Wisconsin and Minnesota. Astor succeeded in forming a new company, partly with American and partly with Canadian capital. This company bought out the Mackinaw Company, and changed the name to South-west Fur Company. But scarcely had its promising career begun when it was cut short by the War of 1812.

The failure of these two attempts caused Mr. Astor to turn to the old American Fur Company. The exclusion Act of 1815 enabled him to buy at his own price the North-west Fur Company’s posts on the upper rivers, and the American Company rapidly extended its trade over all the country, from Lake Superior to the Rocky Mountains. Its posts multiplied in every direction, and at an early date steamboats began to do its business up the Missouri River from St. Louis. It gradually absorbed lesser concerns, such as the Missouri Fur Company, and the Columbia Fur Company, and in 1823 was reorganized under the name of The North American Fur Company. In 1834, Astor sold his interests to Chouteau, Valle and Company, of St. Louis, and retired from the business. At this time the general western limit of the territory operated in by this formidable company was the northern and eastern slope of the mountains which bound the Yellowstone Park on the north and east. Its line of operations was down the river to St. Louis, [36] and its great trading posts were located at frequent intervals between.

The third of the great rival companies was the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, which originated in St. Louis in 1822, and received its full organization in 1826 under the direction of Jedediah Smith, David Jackson and William Sublette. Among the leading spirits, who at one time or another guided its affairs, was the famous mountaineer James Bridger to whom frequent reference will be made.

This company had its general center of operations on the head waters of Green River to the west of South Pass. Unlike the other companies, it had no navigable stream along which it could establish posts and conduct its operations. By the necessities of its exclusively mountain trade it developed a new feature of the fur business. The voyageur, with his canoe and oar, gave way to the mountaineer, with his saddle and rifle. The trading post was replaced by the annual rendezvous, which was in many points the forerunner of the later cattle “roundups” of the plains. These rendezvous were agreed upon each year at localities best suited for the convenience of the trade. Hither in the spring came from the east convoys of supplies for the season’s use. Hither repaired also the various parties of hunters and trappers and such bands of Indians as roamed in the vicinity. These meetings were great occasions, both in the transaction of business and in the round of festivities that always prevailed. After the traffic of the occasion was over, and the plans for the ensuing year were agreed upon, the convoys returned to the States and the trappers to their retreats in the mountains. The field of operations of [37] this company was very extensive and included about all of the West not controlled by the Hudson’s Bay and American Fur Companies.

Thus was the territory of the great West practically parceled out among these three companies. [O] It must not be supposed that there was any agreement, tacit or open, that each company should keep within certain limits. There were, indeed, a few temporary arrangements of this sort, but for the most part each company maintained the right to work in any territory it saw fit, and there was constant invasion by each of the proper territories of the other. But the practical necessities of the business kept them, broadly speaking, within the limits which we have noted. The roving bands of “free trappers” and “lone traders,” and individual expeditions like those of Captain Bonneville and Nathaniel J. Wyeth, acknowledged allegiance to none of the great organizations, but wandered where they chose, dealing by turns with each of the companies.

[O] A singular and striking coincidence at once discloses itself to any one who compares maps showing the territories operated in by these three companies, and those which belonged to the three great families of Indians mentioned in a preceding chapter. By far the larger part of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territory, as far west as the main range of the Rocky Mountains, was Algonquian. The American Fur Company’s territory was almost entirely Siouan, and that of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, Shoshonean.

Nor did any company maintain an exclusive monopoly of its peculiar methods of conducting business. The American Fur Company frequently held rendezvous at points remote from its trading posts; and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in later years resorted [38] to the Missouri River as its line of supplies. In fact, the interests of the two companies finally became to such an extent dependent upon each other that a union was effected, in 1839, under the firm name of P. Chouteau, Jr.

The records of those early days abound in references to the fierce competition in trade which existed between these great organizations. It led to every manner of device or subterfuge which might deceive a rival as to routes, conceal from him important trapping grounds, undermine the loyalty of his employes or excite the hostility of the Indians against him. It often led to deeds of violence, and made the presence of a rival band of trappers more dreaded than a war party of the implacable Blackfeet.

The vigor and enterprise of these traders caused their business to penetrate the remotest and most inaccessible corners of the land. Silliman’s Journal for January, 1834, declares that—

“The mountains and forests, from the Arctic Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, are threaded through every maze by the hunter. Every river and tributary stream, from the Columbia to the Rio del Norte, and from the Mackenzie to the Colorado of the West, from their head waters to their junctions, are searched and trapped for beaver.”

That a business of such all-pervading character should have left a region like our present Yellowstone Park unexplored would seem extremely doubtful. That region lay, a sort of neutral ground, between the territories of the rival fur companies. Its streams abounded with beaver; and, although hemmed in by vast mountains, and snow-bound most of the year, it [39] could not have escaped discovery. In fact, every part of it was repeatedly visited by trappers. Rendezvous were held on every side of it, and once, it is believed, in Hayden Valley, just north of Yellowstone Lake. Had the fur business been more enduring, the geyser regions would have become known at least a generation sooner.

But a business carried on with such relentless vigor naturally soon taxed the resources of nature beyond its capacity for reproduction. In regions under the control of a single organization, as in the vast domains of the Hudson’s Bay Company, great care was taken to preserve the fur-bearing animals from extinction; but in United States territory, the exigencies of competition made any such provision impossible. The poor beaver, as at a later day the buffalo, quickly succumbed to his ubiquitous enemies. There was no spot remote enough for him to build his dam in peace, and the once innumerable multitude speedily dwindled away. The few years immediately preceding and following 1830 were the halcyon days of the fur trade in the United States. Thenceforward it rapidly declined, and by 1850 had shrunk to a mere shadow of its former greatness. With its disappearance the early knowledge of the Upper Yellowstone also disappeared. Subsequent events—the Mormon emigration, the war with Mexico, and the discovery of gold—drew attention, both private and official, in other directions; and the great wonderland became again almost as much unknown as in the days of Lewis and Clark.

EARLY KNOWLEDGE OF THE YELLOWSTONE.

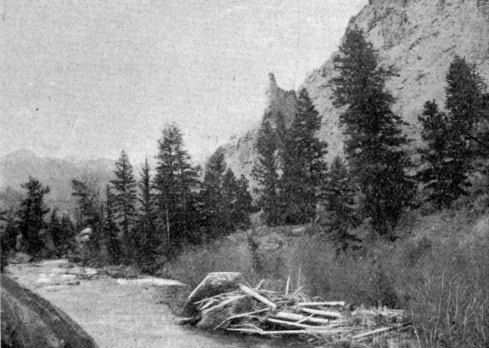

On the west bank of the Yellowstone River, a quarter of a mile above the Upper Falls, in a ravine now crossed by a lofty wooden bridge, stands a pine tree, on which is the oldest record, except that of Colter, of the presence of white men within the present limits of the Park. It is an inscription, giving the initials of a name and the date when inscribed. It was discovered in 1880 by Col. P. W. Norris, then Superintendent of the Park. It is now practically illegible from overgrowth, although some of the characters can still be made out. Col. Norris, who saw it fifteen years ago, claims to have successfully deciphered it. He verified the date by counting the annual rings on another tree near by, which bore hatchet marks, presumably of the same date. The time that had elapsed since these cuts were made corresponded well with the inscribed date. The inscription was:

J O R

Aug 19 1819

Efforts have been made to trace this inscription to some of the early noted trappers, but the attempt can hardly succeed. Even if an identity of initials were established, the identity of individuals would still remain in doubt. Nothing short of some authentic record of such a visit as must have taken place can satisfy the requirements of the case. In the absence [41] of any such record, the most that can be said is that the inscription is proof positive that the Park country was visited by white men, after Colter’s time, fully fifty years before its final discovery.

Col. Norris' researches disclosed other similar evidence, although in no other instance with so plain a clue as to date. Near Beaver Lake and Obsidian Cliff, he found, in 1878, a cache of marten traps of an old pattern used by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trappers fifty years before. He also examined the ruins of an ancient block-house discovered by Frederick Bottler at the base of Mt. Washburn, near the Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone. Its decayed condition indicated great age. In other places, the stumps of trees, old logs used to cross streams, and many similar proofs, were brought to light by that inveterate ranger of the wilderness.

The Washburn party, in 1870, discovered on the east bank of the Yellowstone, just above Mud Geyser, the remains of a pit, probably once used for concealment in shooting water fowl.

In 1882, there was still living in Montana, at the advanced age of one hundred and two years, a Frenchman by the name of Baptiste Ducharne. This man spent the summers of 1824 and 1826 on the Upper Yellowstone River trapping for beaver. He saw the Grand Cañon and Falls of the Yellowstone and the Yellowstone Lake. He passed through the geyser regions, and could accurately describe them more than half a century after he had seen them.

A book called “The River of the West,” [P] published [42] in 1871, but copyrighted in 1869, before the publication of any modern account of the geyser regions, contains the record of an adventure in the Yellowstone three years after those of Ducharne. The book is a biography of one Joseph Meek, a trapper and pioneer of considerable note. The adventure to which reference is made took place in 1829, and was the result of a decision by the Rocky Mountain Fur Company to retire from competition with the Hudson’s Bay Company in the Snake River Valley. In leaving the country, Captain William Sublette, the chief partner, led his party up Henry Fork, across the Madison and Gallatin Rivers, to the high ridge overlooking the Yellowstone, at some point near the present Cinnabar Mountain. Here the party was dispersed by a band of Blackfeet, and Meek, one of its members, became separated from his companions. He had lost his horse and most of his equipment and in this condition he wandered for several days, without food or shelter, until he was found by two of his companions. His route lay in a southerly direction, to the eastward of the Yellowstone, at some distance back from the river. On the morning of the fifth day he had the following experience:

"Being desirous to learn something of the progress he had made, he ascended a low mountain in the neighborhood of his camp, and behold! the whole country beyond was smoking with vapor from boiling springs, and burning with gases issuing from small craters, each of which was emitting a sharp, whistling sound. When the first surprise of this astonishing scene had passed, Joe began to admire its effect from an artistic point of view. The morning being clear, [43] with a sharp frost, he thought himself reminded of the City of Pittsburg, as he had beheld it on a winter morning, a couple of years before. This, however, related only to the rising smoke and vapor; for the extent of the volcanic region was immense, reaching far out of sight. The general face of the country was smooth and rolling, being a level plain, dotted with cone-shaped mounds. On the summit of these mounds were small craters from four to eight feet in diameter. Interspersed among these on the level plain were larger craters, some of them from four to six miles across. Out of these craters, issued blue flames and molten brimstone." [Q]

[P] See Appendix E.

[Q] Page 75, “River of the West.”

Making some allowance for the trapper’s tendency to exaggeration, we recognize in this description the familiar picture of the hot springs districts. The precise location is difficult to determine; but Meek’s previous wanderings, and the subsequent route of himself and his companions whom he met here, show conclusively that it was one of the numerous districts east of the Yellowstone, which were possibly then more active than now.

This book affords much other evidence of early knowledge of the country immediately bordering the present Park. The Great Bend of the Yellowstone where Livingston now stands, was already a famous rendezvous. The Gardiner and Firehole Rivers were well known to trappers; and a much-used trail led from the Madison across the Gallatin Range to the Gardiner, and thence up the Yellowstone and East Fork across the mountains to the Bighorn Valley.

In Vol. I, No. 17, August 13, 1842, of The Wasp, a Mormon paper published at Nauvoo, Ill., occurs the first, as it is by far the best, of all early accounts of the geyser regions prior to 1870. It is an extract from an unpublished work, entitled Life in the Rocky Mountains. Who was the author will probably never be known; but that he was a man of culture and education, altogether beyond the average trader, is evident from the passing glimpse which we have of his work. He apparently made his visit from some point in the valley of Henry Fork not far west of the Firehole River, for, at the utmost allowance, he traveled only about sixty or seventy miles to reach the geyser basins. The evidence is conclusive that the scene of this visit was the Upper Geyser Basin. It fits perfectly with the description, while numerous insuperable discrepancies render identification with the Lower Basin, which some have sought to establish, impossible. Following is this writer’s narrative: