Title: Seventy Years on the Frontier

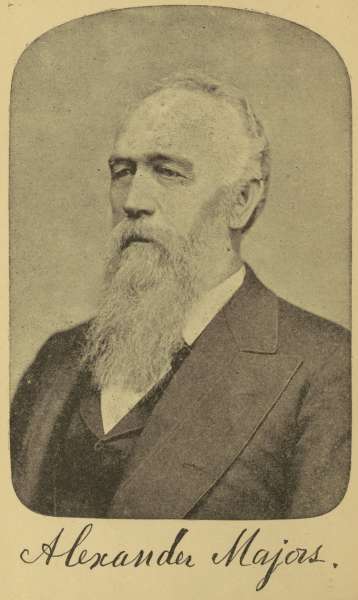

Author: Alexander Majors

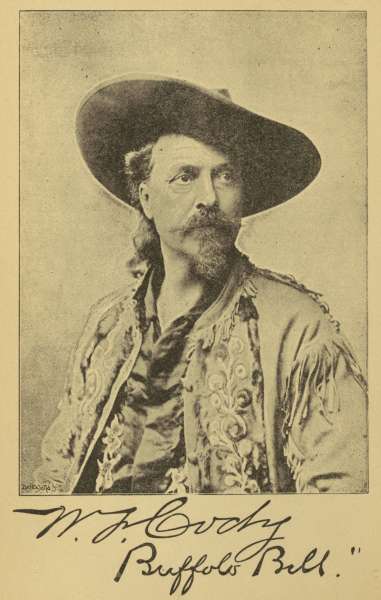

Author of introduction, etc.: Buffalo Bill

Editor: Prentiss Ingraham

Release date: February 25, 2013 [eBook #42195]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Moti Ben-Ari and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

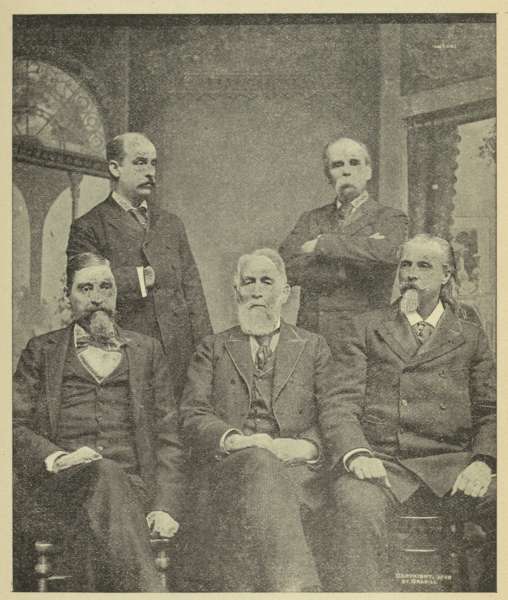

SEVENTY YEARS ON THE FRONTIER.

Alexander Majors.

Alexander Majors.

ALEXANDER MAJORS' MEMOIRS

OF A

Lifetime on the Border

WITH A PREFACE BY

"BUFFALO BILL" (GENERAL W. F. CODY)

EDITED BY

COLONEL PRENTISS INGRAHAM

CHICAGO AND NEW YORK

Rand, McNally & Company, Publishers

1893

Copyright, 1893, by Rand, McNally & Co.

Seventy Years on the Frontier

AS A TRIBUTE OF MY SINCERE REGARD FOR

W. F. CODY

AS BOY AND MAN, MY FRIEND FOR TWO SCORE YEARS,

I DEDICATE TO HIM

THIS BOOK OF BORDER LIFE.

Alexander Majors.

| PAGE. | ||

| Preface, by Buffalo Bill | 9 | |

| Note to Reader | 13 | |

| CHAPTER. | ||

| I. | Reminiscences of Youth | 15 |

| II. | Missouri in Its Wild and Uncultivated State | 25 |

| III. | A Silver Expedition | 32 |

| IV. | The Mormons | 43 |

| V. | The Mormons' Mecca | 63 |

| VI. | My First Venture | 71 |

| VII. | Faithful Friends | 78 |

| VIII. | Our War with Mexico | 85 |

| IX. | Doniphan's Expedition | 90 |

| X. | The Pioneer of Frontier Telegraphy | 99 |

| XI. | An Overland Outfit | 102 |

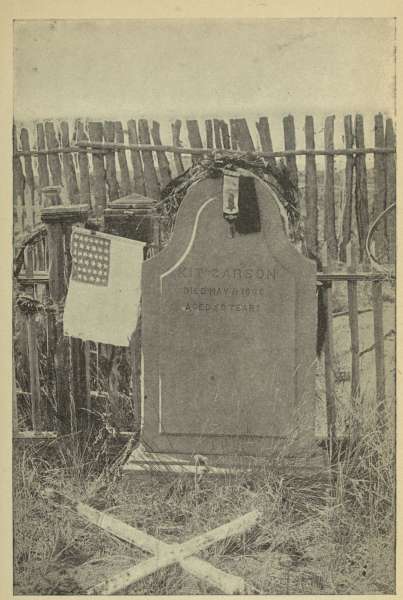

| XII. | Kit Carson | 107 |

| XIII. | Adventures of a Trapper | 119 |

| XIV. | Trapping | 125 |

| XV. | An Adventure with Indians | 128 |

| XVI. | Crossing the Plains | 137 |

| XVII. | "The Jayhawkers of 1849" | 150 |

| XVIII. | Mirages | 157 |

| XIX. | The First Stage into Denver | 164 |

| XX. | The Gold Fever | 168 |

| XXI. | The Overland Mail | 173 |

| XXII. | The Pony Express and Its Brave Riders | 182 |

| XXIII.[8] | The Battle of the Buffaloes | 194 |

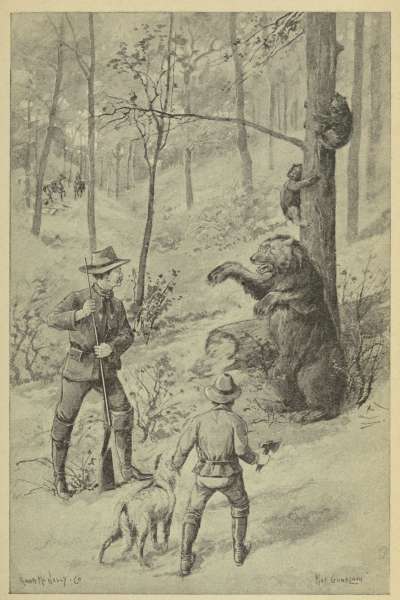

| XXIV. | The Black Bear | 201 |

| XXV. | The Beaver | 215 |

| XXVI. | A Boy's Trip Overland | 221 |

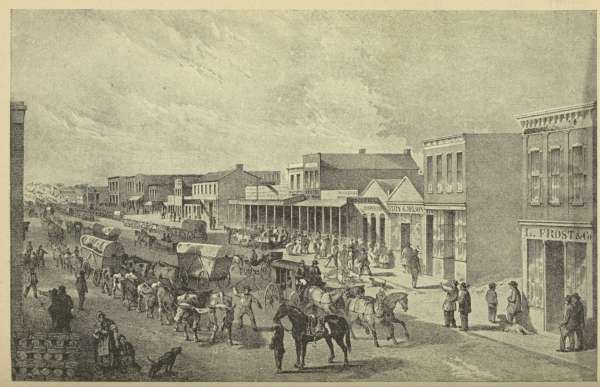

| XXVII. | The Denver of Early Days | 228 |

| XXVIII. | The Denver of To-day and Its Environs | 232 |

| XXIX. | Buffalo Bill from Boyhood to Fame | 243 |

| XXX. | The Platte Valley | 247 |

| XXXI. | Kansas City before the War | 253 |

| XXXII. | The Graves of Pioneers | 258 |

| XXXIII. | Silver Mining | 267 |

| XXXIV. | Wild West Fruits | 272 |

| XXXV. | How English Capitalists Got a Foothold | 277 |

| XXXVI. | Montana's Towns and Cities | 285 |

| XXXVII. | California's Great Trees | 290 |

| XXXVIII. | The Flowers of the Far West | 294 |

| XXXIX. | Colorado | 304 |

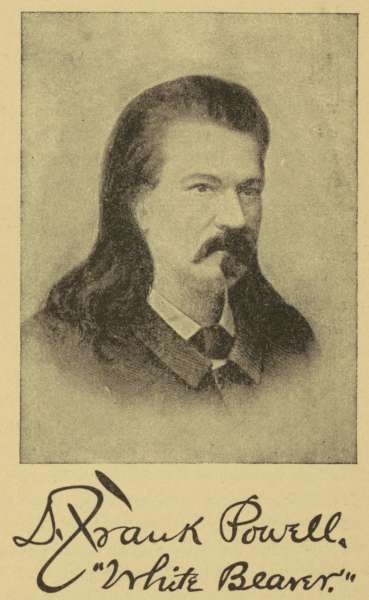

| XL. | The Surgeon Scout | 317 |

| Conclusion | 320 |

W. F. Cody

W. F. CodyAs there is no man living who is more thoroughly competent to write a book of the Wild West than my life-long friend and benefactor in my boyhood, Alexander Majors, there is no one to whose truthful words I would rather accept the honor of writing a preface.

An introduction to a book of Mountain and Plain by Mr. Majors certainly need hardly be written, unless it be to refer to the author in a way that his extreme modesty will not permit him to speak of himself, for he is not given to sounding his own praise, being a man of action rather than words, and yet whose life has its recollections of seventy years upon the frontier, dating to a period that tried men's souls to the fullest extent, and when daring deeds and thrilling adventures were of every-day occurrence. Remembrance of seventy years of life in the Far West and amid the Rocky Mountains!

What a world of thought this gives rise to, when we recall that a quarter of a century ago there was not a railroad west of the Missouri River, and every pound of freight, every emigrant, every letter, and every message had to be carried by wagon or on horseback, and at the risk of life and hardships untold.

The man who could in the face of all dangers and obstacles originate and carry to success a line of freighter wagons, a mail route from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and a Pony Express, flying at the utmost speed of a hare through the land, was no ordinary individual, as can be well[10] understood. And such a man Alexander Majors was. He won success; and to-day, on the verge of four score years, lives over again in his book the thrilling scenes in his own life and in the lives of others.

Family reverses after the killing of my father in the Kansas War, caused me to start out, though a mere boy, in 1855 to seek to aid in the support of my mother and sisters, and it was to Mr. Alexander Majors that I applied for a situation. He looked me over carefully in his kindly way, and after questioning me closely gave me the place of messenger boy, that was, one to ride with dispatches between the overland freighters—wagon trains going westward into the almost unknown wild dump of prairie and mountain.

That was my first meeting with Alexander Majors, and up to the present time our friendship has never had a break in it, and, I may add, never will through act of mine.

Having thus shown my claim to a thorough knowledge of my distinguished old friend, let me now state that his firm was known the country over as Majors, Russell & Woddell, but it was to Mr. Majors particularly that the heaviest duties of organizing and management fell, and he never shirked a duty or a danger, as I well remember.

Severe in discipline, he was yet never profane or harsh, and a Christian and temperance man through all; he governed his men kindly, and was wont to say that he would have no one under his control who would not promptly obey an order without it was emphasized with an oath. In fact, he had a contract with his men in which they pledged themselves not to use profanity, get drunk, gamble, or be cruel to animals under pain of dismissal, while good behavior was rewarded. Every man, from wagon-boss and teamster down to rustler and messenger-boy, seemed anxious to gain the good will of Alexander Majors and to hold[11] it, and to-day he has fewer foes than any one I know, in spite of his position as chief of what were certainly a wild and desperate lot of men, where the revolver settled all difficulties.

It was Mr. Majors' firm that originated and put in the Pony Express across the plains and made it the grand success it proved to be.

It was his firm that so long and successfully carried on the business of overland freighting in the face of every obstacle, and also the Overland Stage Drive between the Missouri River and Pacific Ocean, and in his long life on the border he has become known to all classes and conditions of men, so that in writing now his memoirs, no man knows better whereof he speaks than he does.

In each instance where he has written to his old-time comrades for data, he has taken only that which he knew could be verified, and has thrown out material sufficient to double his book in size, where he felt the slightest doubt that it could not be relied upon to the fullest extent.

His work, therefore, is a history of the Wild West, its pages authentic, and though many of its scenes are romantic and thrilling, it is what has hitherto been an unwritten story of facts, figures, and reality; and now, that in his old age he finds his occupation gone, I feel and hope that his memoirs will find a ready sale.

In preparing the material of my book, I desire here to give justice where justice is due, and express myself as under obligations for valuable data and letters, which I fully appreciate; and publicly thank for their kindness in this direction those whose names follow:

Col. W. F. Cody ("Buffalo Bill") of Nebraska.

Col. John B. Colton, Kansas City, Mo.

Mr. V. DeVinny, Denver, Colo.

Mr. E. L. Gallatin, Denver, Colo.

Judge Simonds, Denver, Colo.

Mr. John T. Rennick, Oak Grove, Mo.

Mr. Geo. W. Bryant, Kansas City, Mo.

Mr. George E. Simpson, Kansas City, Mo.

Mr. John Martin, Denver, Colo.

Mr. David Street, Denver, Colo.

Mrs. Nellie Carlisle, Berkeley, Cal.

Mr. A. Carlisle, Berkeley, Cal.

Mr. Green Majors, San Francisco, Cal.

Mr. Ergo Alex. Majors, Alameda, Cal.

Mr. Seth E. Ward, Westport, Mo.

Robert Ford, Great Falls, Mont.

Doctor Case, Kansas City, Mo.

Benj. C. Majors, May Bell P. O., Colo.

Prof. Robert Casey, Denver, Colo.

John Burroughs, Colorado.

Eugene Munn, Swift, Neb.

Rev. Dr. John R. Shannon, Denver, Colo.

Thos. D. Truett, Leadville, Colo.

Will C. Ferril.

Yours with respect,

ALEXANDER MAJORS.

My father, Benjamin Majors, was a farmer, born in the State of North Carolina in 1794, and brought when a boy by my grandfather, Alexander Majors, after whom I am named, to Kentucky about the year 1800. My grandfather was also a farmer, and one might say a manufacturer, for in those days nearly all the farmers in America were manufacturers, producing almost everything within their homes or with their own hands, tanning their own leather, making the shoes they wore, as well as clothing of all kinds.

My mother's maiden name was Laurania Kelly; her father, Beil Kelly, was a soldier in the Revolutionary War, and was wounded at the battle of Brandywine.

I was born in 1814, on the 4th day of October, near Franklin, Simpson County, Kentucky, being the eldest of the family, consisting of two boys and a girl. When I was about five years of age my father moved to Missouri, when that State was yet a Territory. I remember well many of the occurrences of the trip; one was that the horses ran away with the wagon in which my father, myself, and younger brothers were riding. My father threw us children out and jumped out himself, though crippled in one foot at the time. One wheel of the wagon was broken to pieces, which caused us a delay of two days.

After crossing the Ohio River, in going through the then Territory of Illinois, the settlements were from ten to twenty miles apart, the squatters living in log cabins, and along one stretch of the road the log cabin settlements were forty miles apart. When we arrived at the Okaw River, in the Territory of Illinois, we found a squatter in his little log cabin whose occupation was ferrying passengers across the river in a small flatboat which was propelled by a cable or large rope tied to a tree on each side of the river, it being a narrow but deep stream. The only thing attracting my special attention, as a boy, at that point was a pet bear chained to a stake just in front of the cabin where the family lived. He was constantly jumping over his chain, as is the habit of pet bears, especially when young.

From this place to St. Louis, a distance of about thirty-five miles, there was not a single settlement of any kind. When we arrived on the east bank of the Mississippi River, opposite the now city of St. Louis, we saw a little French village on the other side. The only means of crossing the river was a small flatboat, manned by three Frenchmen, one on each side about midway of the craft, each with an oar with which to propel the boat. The third one stood in the end with a steering oar, for the purpose of giving it the proper direction when the others propelled it. This ferry would carry four horses or a four-horse wagon with its load at one trip. These men were not engaged half their time in ferrying across the river all the emigrants, with their horses, cattle, sheep, and hogs, who were moving from the East to the West and crossing at St. Louis. Of course the current would carry the boat a considerable distance down the river in spite of the efforts of the boatmen to the contrary. However, when they reached the opposite bank the two who worked the side oars would lay down their[17] oars, go to her bow, where a long rope was attached, take it up, put it over their shoulders, and let it uncoil until it gave them several rods in front of the boat. Then they would start off in a little foot-path made at the water's edge and pull the boat to the place prepared for taking on or unloading, as the case might be. There they loaded what they wanted to ferry to the other side, and the same process would be gone through with as before. Reaching the west bank of the river we found the village of St. Louis, with 4,000 inhabitants, a large portion of whom were French, whose business it was to trade with the numerous tribes of Indians and the few white people who then inhabited that region of country, for furs of various kinds, buffalo robes and tongues, as this was the only traffic out of which money could be made at that time.

The furs bought of the Indians were carried from St. Louis to New Orleans in pirogues or flatboats, which were carried along solely by the current, for at that time steam power had never been applied to the waters of the Mississippi River. Sixty-seven years later, in 1886, I visited St. Louis and went down to the wharf or steamboat landing, and looking across to East St. Louis, which in 1818 was nothing but a wilderness, beheld the river spanned by one of the finest bridges in the world, over which from 100 to 150 locomotives with trains attached were daily passing. Three big steam ferryboats above and three below the bridge were constantly employed in transferring freight of one kind or another. What a change had taken place within the memory of one man! While looking in amazement at the great and mighty change, a nicely dressed and intelligent man passed by; I said to him:

"Sir, I stood on the other bank of this river when a little boy, in the month of October, 1818, when there was no[18] improvement whatever over there" (pointing to the east shore). I also stated to him that a little flatboat, manned by three Frenchmen, was the only means for crossing the river at that time. The gentleman took his pencil and a piece of paper and figured for a few moments, and then turning to me said: "Do you know, sir, those three Frenchmen, with their boat, who did all the work of ferrying, and were not employed half the time, could not, with the facilities you speak of, in 100 years do what is now being done in one day with our present means of transportation."

Since that time, which was six years ago, another bridge has been built to meet the necessities of the increasing business of that city, which shows that progress and increase of wealth and development are still on the rapid march.

The next thing of note, after passing St. Louis, occurred one evening after we camped. My mother stepped on the wagon-tongue to get the cooking utensils, when her foot slipped and she fell, striking her side and receiving injuries which resulted in her death eighteen months later.

On that journey my father traveled westward, crossing the Missouri River at St. Charles, Mo., following up the river from that point to where Glasgow is now situated, and there crossed the river to the south side, and wintered in the big bottoms. In the spring of 1819 he moved to what afterward became La Fayette County, and took up a location near the Big Snye Bear River.

In February, the winter following, my dear mother died from the injuries she received from the accident previously alluded to. The Rev. Simon Cockrell, a baptist preacher, who at that time was over eighty years of age, preached her funeral sermon. He was the first preacher I had ever seen stand up before a congregation with a book in his[19] hand. Although my mother died when I was little more than six years of age, my memory of her is apparently as fresh and endearing as though her death had occurred but a few days ago. Many acts I saw her do, and things I heard her say, impressed me with her courage and goodness, and their memory has been a help to me throughout the whole career of my long life. No mother ever gave birth to a son who loved her more, or whose tender recollections have been more endearing or lasting than mine.

I have never encountered any difficulty so great, no matter how threatening, that I have not been able to overcome fearlessly when the recollection of my dear mother and the spirit by which she was animated came to me. Even to this day, and I am an old man in my eightieth year, I can not dwell long in conversation about her without tears coming to my eyes. There are no words in the English language to express my estimate and appreciation of the dear mother who gave me birth and nourishment. I would that all men loved and held the memories of their mothers more sacred than I think many of them do. One of the greatest safeguards to man throughout the meanderings of his life is the love of a father, mother, brother and sister, children and friends; it is a great solace and anchor to right-thinking men when they may be hundreds and thousands of miles away. Love of family begets true patriotism in his bosom, for, in my opinion, there is no such thing as true patriotism without love of family.

Returning to the events of 1821, we had in the neighborhood of the Snye Bear River a great Indian scare. This happened in the month of August, when I was in my seventh year, after my father had built a log cabin for himself in that part of the country which afterward became Lafayette County, Mo. My mother had died the winter[20] before, leaving myself, the eldest, a brother next, and a sister little more than two years old.

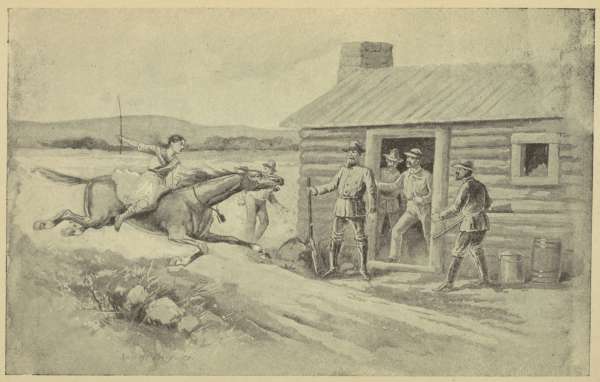

Mrs. Ferrin, a settler who lived on the outskirts of the little settlement of pioneers, was alone, except for a baby a year old. She left the child and went to the spring for water. When she had filled her bucket and rose to the top of the bank, she imagined she saw Indians. She dropped her bucket, ran to the cabin, took the child in her arms, and fled with all her might to Thomas Hopper's, the nearest neighbor. As soon as she came near enough to be heard, she shouted "Indians" at the top of her voice. Polly Hopper, a young girl of seventeen, hearing Mrs. Ferrin shouting "Indians," seized a bridle and ran to a herd of horses that were near by in the shade of some trees, caught a flea-bitten gray bell mare, the leader of the herd, she being gentle and easier to catch than the others, mounted the animal without saddle, riding after the fashion of men, and started to alarm the settlement.

My father was lying in bed taking a sweat to abate a bilious fever. A family living near by were caring for us children, and nursing my father in his sickness. My brother and I were playing a little distance from the cabin when we heard the screams of the woman, shouting "Indians" with every jump the horse made, her hair streaming out behind like a banner in the wind. We were on the very outside boundary of the settlement, and some signs of Indians had been discovered a few days previous by some neighbors who were out hunting for deer. This fact had been made known to the little settlement, and the day this scare took place had been selected for the men to meet at Henry Rennick's to discuss ways and means for building a stockade for the protection of their families in case the Indians should make an attempt of a hostile nature. So the first thoughts of the families at home were to start for[21] Rennick's, where the men were. This accounts for the young woman going by our house, as she had to pass our cabin to reach that place. My father, sick as he was, jumped out of bed when she passed giving the alarm, took a heavy gun from the rack, hung his shot pouch over his shoulder, took my little sister in his arms, and, like the rest, started for Rennick's, my little brother and I toddling along behind him.

A family living near by, consisting of the mother, Mrs. Turner, two daughters, a son, and a little grandson, also started for Rennick's. They would run for a short distance, and then stop and hide in the high weeds until they could get their breath. The old lady had a small dog she called Ging. He was on hand, of course, and just as much excited as all the rest of the dogs in the neighborhood, and the people themselves. The screams of the girl Polly Hopper, and the ringing of the bell on the animal she was riding, aroused the dogs to the highest pitch of excitement. In those days dogs were a necessity to the frontiersman for his protection, and as much of a necessity on that account as any other animal he possessed, and consequently every settler owned from three to five dogs, and some more. They were the watch-guards against Indians and prowling beasts, both by night and day, and could not have been dispensed with in the settling of the frontier.

To return to our trip to Rennick's: When the old lady and her flock would run into the weeds to hide and regain their breath, this little dog Ging could not be controlled, for bark he would. The old lady when angry would use "cuss words," and she used them on this dog, and would jump out of her hiding-place and start on the trail again. Of course when the dog barked he exposed her hiding-place. They would run a little farther, and when their breath would fail, they would make another hiding in the weeds,[22] but would scarcely get settled when the dog would begin his barking again. The old lady, with another string of "cuss words," would jump out of the weeds and try the trail again a short distance. This was repeated until they reached Rennick's almost prostrate, as the distance was considerably over a mile, and the day an exceedingly hot one about noon. My father, though sick, was more fortunate with his little group of children. When he felt about to faint, he would turn with us into the high weeds and sit there quietly, and, not having any dog with us to report our whereabouts, we were completely hidden by the high weeds, and had a hundred Indians passed they would not have discovered our hiding-place.

In due time we arrived safe at Rennick's, and strange to say, my father was a well man, and did not go to bed again on account of the fever.

When Polly Hopper reached Rennick's and ran into the crowd, she was in a fainting condition. The men took her off the horse, laid her on the ground, and administered cold water and other restoratives. She soon regained consciousness and strength, and of course was regarded as a heroine in the neighborhood after that memorable day. One can well imagine the excitement among the men whose families were at home and exposed, as they thought, to the mercies of the savages. They scattered immediately toward their homes as rapidly as their horses would carry them, fearing they might find their families murdered. For hours after we reached Rennick's there continued to be arrivals of women and children, many times in a fainting condition, and all exhausted from the fright, the heat, and the speed at which they had run.

Mr. Rennick, who was one of the first pioneers, soon had more visitors than he knew what to do with, and more than his log cabin could shelter. These people remained in[23] and around the cabin for two days, and until the men rode the country over and found the alarm had been a false one and there were no Indians in the neighborhood.

One of the first occurrences of note in the early settlement of the West was the visitation of grasshoppers, in September, 1820, an occurrence which had never been known by the oldest inhabitants of the Mississippi Valley. They came in such numbers as to appear when in the heavens as thin clouds of vapor, casting a faint shadow upon the earth. In twenty-four hours after their appearance every green thing, in the nature of farm product, that they could eat or devour was destroyed. It so happened, however, that they came so late in the season that the early corn had ripened, so they could not damage that, otherwise a famine would have resulted. The next appearance of these pests was over forty years later, in Western Missouri, Nebraska, and Kansas, which all well remember, as there were two or three seasons in close proximity to each other in the sixties when Western farmers suffered to a great extent from their ravages.

For five years, from 1821 to 1826, nothing worthy of note occurred, but everything moved along as calmly as a sunny day.

In the month of April, 1826, a terrible cyclone passed through that section of the country, leaving nothing standing in its track. Fortunately the country was but sparsely settled, and no lives were lost. It passed from a southwesterly direction to the northeast, tearing to pieces a belt of timber about half-a-mile wide, in that part of the country which became Jackson County, and near where Independence was afterward located, passing a little to the west of that point.

The next cyclone that visited that country was in 1847; this also passed from the southwest to the northeast, passing across the outskirts of Westport, which is now a suburb[24] of Kansas City. The third and last cyclone that visited that section of the country, about eight years ago, blew down several houses in Kansas City, and killed a number of children who were attending the High School, the building being demolished by the storm.

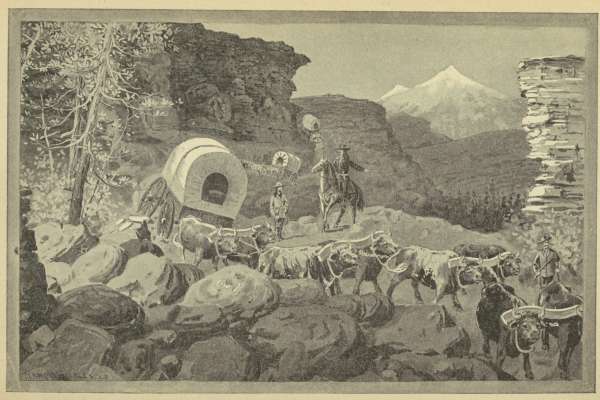

POLLY'S WARNING.

POLLY'S WARNING.

There was about one-fourth of the entire territory of Missouri that was covered with timber, and three-fourths in prairie land, with an annual growth of sage-grass, as it was called, about one and one-half feet high, and as thick as it could well grow; in fact the prairie lands in the commencement of its settlement were one vast meadow, where the farmer could cut good hay suitable for the wintering of his stock almost without regard to the selection of the spot; in other words, it was meadow everywhere outside of the timber lands. This condition of things would apply also to the States of Illinois, Iowa, and some of the other Western States, with the exception of Missouri, which had a greater proportion of timber than either of the others mentioned. The timber in all these States grew in belts along the rivers and their tributaries, the prairie covering the high rolling lands between the streams that made up the water channels of those States.

Many of the streams in the first settling of these States were bold, clear running water, and many of them in Missouri were sufficiently strong almost the year round to afford good water power for running machinery, and it was the prediction in the commencement of the settlement of these States by the best-informed people, that the water would increase, for the reason that the swampy portions in the bottom lands, and where there were small lakes, would, by the settlement of the country, become diverted, its force to run directly into and strengthen the larger streams for[26] all time to come. And to show how practical results overthrow theories, the fact proved to be exactly the reverse of their predictions. There has been a continuous slow decline in the natural flow of water-supply from the first settlement of the country. Many places that I can now remember that were ponds or small lakes, or in other words little reservoirs, which held the water for months while it would be slowly passing out and feeding the streams, have now become fields and plowed ground. Roads and ditches have been made that let the water off at once after a rainfall. The result has been that streams that used to turn machinery have become not much more than outlets for the heavy rainfalls that occur in the rainy season, and if twenty of those streams, each one of which had water enough to run machinery seventy years ago, were all put together now into one stream, there would not be sufficient power to run a good plant of machinery. The numerous springs that could be found on every forty or eighty acres of land in the beginning, have very many of them entirely failed.

The wells of twenty or thirty feet in depth that used to afford any quantity of water for family uses, many of them in order to get water supplies have to be sunk to a much greater depth. Little streams that used to afford any quantity of water for the stock have dried up, giving no water supply, only in times of abundance of rain. All the first settlers in the State located along the timber belts, without an exception, and cultivated the timber lands to produce their grain and vegetables. It was many years after the forest lands were settled before prairie lands were cultivated to any extent, and it was found later that the prairie lands were more fertile than they gave them credit for being before real tests in the way of farming were made with them. The sage grass had the tenacity to stand a great deal of grazing and tramping over, and still grow to considerable[27] perfection. It required years of grazing upon the prairie before the wild grass, which was universal in the beginning, gave way, but in the timber portions the vegetation that was found in the first settling of the land gave way almost at once. In two years from the time a farmer moved upon a new spot and turned his stock loose upon it, the original wild herbs that were found there disappeared and other vegetation took its place. The land being exceedingly fertile, never failed to produce a crop of vegetation, and when one variety did appear and cover the entire surface as thick as it could grow for a few years, it seemed to exhaust the quality of the soil that produced that kind, and that variety would give way and something new come up.

The older the country has become, as a rule, the more obnoxious has been the vegetation that the soil has produced of its own accord. But there has been in my recollection, which goes back more than seventy years, a great many changes in the crops of vegetation on those lands, showing to my satisfaction that there is an inherent potency in nature, in rich soil that will cover itself every year with a growth of some kind. If it is not cultivated and made to produce fruit, vegetables, and cereals, it will nevertheless produce a crop of some kind.

The first settlers in the Mississippi Valley were as a rule poor people, who were industrious, economizing, and self-sustaining. From ninety-five to ninety-seven per cent of the entire population manufactured at home almost everything necessary for good living. A great many of them when they were crossing the Ohio and Mississippi to their new homes would barely have money enough to pay their ferriage across the rivers, and one of the points in selling out whatever they had to spare when they made up their minds to emigrate was to be sure to have cash enough with them to pay their ferriage. They generally carried with[28] them a pair of chickens, ducks, geese, and if possible a pair of pigs, their cattle and horses. The wife took her spinning wheel, a bunch of cotton or flax, and was ready to go to spinning as soon as she landed on the premises, often having her cards and wheel at work before her husband could build a log cabin. Going into a land, as it was then, that flowed with milk and honey they were enabled by the use of their own hands and brains to make an independent and good living. There was any quantity of game, bear, elk, deer, wild turkeys, and wild honey to be found in the woods, so that no man with a family, who had pluck and energy enough about him to stir around, ever need to be without a supply of food. At that time nature afforded the finest of pasture, both summer and winter, for his stock.

While the people as a rule were not educated, many of them very illiterate as far as education was concerned, they were thoroughly self-sustaining when it came to the knowledge required to do things that brought about a plentiful supply of the necessities of life. In those times all were on an equality, for each man and his family had to produce what was required to live upon, and when one man was a little better dressed than another there could be no complaint from his neighbor, for each one had the same means in his hands to bring about like results, and he could not say his neighbor was better dressed than he was because he had cheated some other neighbor out of something, and bought the dress; for at that time the goods all had to come to them in the same way—by their own industry. There was but little stealing or cheating among them. There was no money to steal, and if a man stole a piece of jeans or cloth of any kind he would be apprehended at once. Society at that time was homogeneous and simple, and opportunities for vice were very rare. There were[29] very few old bachelors and old maids, for about the only thing a young man could do when he became twenty-one, and his mother quit making his clothes and doing his washing, was to marry one of his neighbor's daughters. The two would then work together, as was the universal custom, and soon produce with their own hands abundance of supplies to live upon.

The country was new, and when a young man got married his father and brothers, and his wife's father and brothers, often would turn out and help him put up a log cabin, which work required only a few days, and he and his spouse would move into it at once. They would go to work in the same way as their fathers had done, and in a few years would be just as independent as the old people. The young ladies most invariably spun and wove, and made their bridal dresses. At that time there were millions of acres of land that a man could go and squat on, build his cabin, and sometimes live for years upon it before the land would come into market, and with the prosperity attending such undertakings, as a general thing would manage in some way, when the land did come into market, to pay $1.25 per acre for as much as he required for the maintenance of his family.

Men in those days who came to Missouri and looked at the land often declined to select a home in the State on account of their having no market for their products, as above stated, everybody producing all that was needed for home consumption and often a surplus, but were so far away from any of the large cities of the country, without transportation of either steamboats or railroads, for it was before the time of steamboats, much less railroads—for neither of them in my early recollections were in existence—to make them channels of business and trade. Men in the[30] early settlement often wondered if the rich land of the State would ever be worth $5 per acre.

Missouri at that time was considered the western confines of civilization, and it was believed then that there never would be in the future any white settlements of civilized people existing between the western borders of Missouri and the Pacific Coast, unless it might be the strip between the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the Pacific Ocean, which the people at that time knew but little or nothing about.

In 1820 and 1830 there were a great many peaceable tribes of Indians, located by the Government all along the western boundary of Missouri, in what was then called the Indian Territory, and has since then become the States of Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma Territory. I remember the names of many of the tribes who were our nearest neighbors across the line, and among them were the Shawnees, Delawares, Wyandottes, Kickapoos, Miamis, Sacs, Foxes, Osages, Peorias, and Iowas, all of whom were perfectly friendly and docile, and lived for a great many years in close proximity to the white settlers, even coming among them to trade without any outbreaks or trespassing upon the rights of the white people in any way or manner worth mentioning.

There was a long period existing from 1825 to 1860 of perfect harmony between these tribes and the white people, and in fact even to this day there is no disturbance between these tribes and their neighbors, the whites. The Indian troubles have been among the Sioux, Arapahoes, Cheyennes, Apaches, Utes, and some other minor tribes, all of which, at the present time, seem to have submitted to their fate in whatever direction it may lie. There is one remark that I will venture here, and it is this, that while the white people were in the power of the Indians and[31] understood it, we got along with the Indian a great deal better than when the change to the white people took place. In the early days white men respected the Indian's rights thoroughly, and would not be the aggressors, and often they were at the mercy of the Indians, but as soon as they began to feel that they could do as they pleased, became more aggressive and had less regard for what the Indian considered his rights. Then in the early days Indians were paid their annuities in an honest way, and there was no feeling among them that they were mistreated by the agent whose duty it was to pay them this annuity.

I was acquainted with one Indian agent by the name of Major Cummings, who for a long time was a citizen of Jackson County, and for a great many years agent for a number of the tribes living along the borders of Missouri. There never was a complaint or even a suspicion, to the best of my knowledge, that he or his clerks ever took one cent of the annuities that belonged to the Indians. The money was paid to them in silver, either in whole or half dollars, and the head of every family received every cent of his quota. Therefore we had a long period of quiet and peace with our red brethren. It is only since the late war that there has been so much complaint from the Indians with reference to the scanty allowances and poor food and blankets.

In the summer of 1827 my father, Benjamin Majors, with twenty-four other men, formed a party to go to the Rocky Mountains in search of a silver mine that had been discovered by James Cockrell,[1] while on a beaver-trapping expedition some four years previous.

At that time, men attempting to cross the plains had no means of carrying food supplies to last more than a week, or ten days at the outside. When their scanty supply of provisions was exhausted, they depended solely upon the game they might chance to kill, invariably eating this without salt. These twenty-five men elected James Cockrell their captain, as he was the only man of the party who had crossed the plains. Being the discoverer of what he claimed was a rich silver mine, they relied solely upon him to pilot them to the spot. The only facilities for transportation were one horse each. Their scant amount of bedding, with the rider, was all the horse could carry. Each man had to be armed with a good gun, and powder and ball enough to last him during the entire trip, for the territory through which they had to pass was inhabited by hostile Indians. No cooking vessels were taken with them, as they depended entirely upon roasting or broiling their meat upon the fire. When they could not find deer, antelope, elk, or buffalo they had to do without food, unless they were driven to kill and eat a wolf they might chance to get. When they reached the buffalo belt, however, 200 miles farther west, there was no scarcity of meat. The country where they[33] roamed was 400 miles across, reaching to the base of the Rocky Mountains, and extending from Texas more than 3,000 miles, very far north of the Canadian line. The buffalo were numbered by the millions. It often occurred in traveling through this district that there would be days together when one would never be out of sight of great herds of these animals. They stayed in the most open portion of the plains they could find, for the country was one vast plain, or level prairie. The grass called buffalo grass did not grow more than one and one-half to two inches high, but grew almost as thick in many places as the hair on a dog's back. Other grasses that were found in this locality grew much taller, but one would invariably find the buffalo grazing upon the short kind, especially so in the winter, as the high winds blew the snow away from where this grass grew. There were millions of acres of this grass. The buffalo's teeth and under jaw were so arranged by nature that he could bite this short grass to the earth; in fact no small animal, such as a sheep, goat, or antelope, could cut the grass more closely than the largest buffalo. Strange to say this short grass of the prairie is rapidly disappearing, as the buffaloes have done. In crossing the plains with our oxen in later years we found it impossible for them to get a living by grazing on the portions of the plains where this grass grew.

The party in question soon reached the Raton Mountains not far from Trinidad, now on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fé Railroad. It is proper to state that after leaving their homes in Jackson and Lafayette counties, Mo., they traveled across the prairie, bearing a little south of west, until they reached the Big Bend, or Great Bend, as it is lately called, of the Arkansas River. At this point they found innumerable herds of buffalo, and no trouble in finding[34] grass and water in plenty, as well as meat. They followed the margin of the river until they reached the foot-hills of the Rocky Mountains; then their captain told them he was in the region where he had discovered the mine. He found some difficulty in locating the spot, and after many days spent in searching, some of the party grew restless and distrustful, doubting as to whether he ever discovered silver ore, or if so, if he was willing to show them the location, and became very threatening in their attitude toward him. He finally found what he and they had supposed was silver ore. This fact pacified the party and perhaps saved his life, as it was a long way for men to travel through peril and hardships only to be disappointed, or, as they expressed it, "to be fooled." They were disappointed, however, when they found nothing but dirty-looking rock, with now and then a bright speck of metal in it. Not one of them had ever seen silver ore, nor did they know anything about manipulating the rock in order to get the silver out of it. Many of them expected to find the silver in metallic form, and thought they could cut it out with their tomahawks and pack home a good portion of wealth upon their horses. They thought they could walk and lead their horses if they could get a load of precious metal to carry, as their captain had done a few years before, when he sold his beaver skins in St. Louis, took his pay in silver dollars, put them in a sack, bought a horse to carry it, and led him 300 miles to his home.

It must be remembered that this was the first prospecting party to look for silver that ever left the western borders of Missouri for the Rocky Mountains. After finding what they supposed was a silver mine, each one selected some of the best specimens and left for their homes. Everything moved along well with them until they arrived at about the point on the Arkansas River where Dodge City[35] now stands. They camped one evening at the close of a day's travel, ate a hearty supper of buffalo meat, put their guard around their horses, and went to bed. Two men at a time guarded the horses, making a change every three hours during the night. This precaution was necessary to keep the Indians, who were in great numbers and hostile, from running off their horses. But on that fatal night the Indians succeeded in crawling on their bellies where the grass was tall enough to conceal them from the guard. It was only along the river bottoms and water courses that the grass grew tall. When they got between the guard and the horses, they suddenly rose, firing their guns, shaking buffalo robes, and with war-whoops and yells succeeded in frightening the horses to an intense degree. Then the Indians who were in reserve, mounted on ponies, ran the horses off where their owners never heard of or saw them afterward. Part of the Indians, at the same time, turned their guns upon the men that were lying upon the bank of the river. They jumped out of their beds, over the bank and into the water knee-deep. The men, by stooping under the bank, which was four feet perpendicular, were protected from the arrows and bullets of the enemy. There they stood for the remainder of that cold October night. One of the party, a man named Mark Foster, when they jumped over the bank, did not stop, but ran as fast as he could go for the other side. The water was shallow, not being more than knee-deep anywhere, and in some places not half that depth. The bottom was sandy, and at that place the river was some 400 yards wide. In running in the dark of the night, with the uneven bottom of the river, Mr. Foster fell several times. Each time it drew a yell from the Indians, who thought they had killed him, for they were shooting at him as he ran. After being three times ducked, he reached the other side and dry land.[36] His clothes were thoroughly drenched, and his gun, which was a flint-lock and muzzle-loader, entirely useless. Just think of a man in that condition—his gun disabled, apparently a thousand wolves howling around him in all directions, the darkness of the night, the yelling of the Indians on the other side, and 400 miles from home; the only living white man, unless some of his comrades happened not to be killed. He remained there shivering with the cold the rest of the night. When daylight appeared he started to cross the river to the camp to find out whether his comrades were dead or alive. He reached the middle of the river and halted, his object being to see, if possible, whether it was the Indians or his party that he could see through the slight fog that was rising and slowly moving westward and up the river. His comrades, who fortunately were alive, could hear, in the still of the morning, every step he made in the water. After standing a short time he decided that the men he saw moving about were Indians, and he was confirmed in the belief that all his party were killed, so he ran back to where he had spent such a doleful part of the night and there remained until the fog entirely cleared away. He then could see that the men at the camp from where he fled were his comrades. He returned within about sixty yards from where they were, stopped and called to my father, who answered him, after some persuasion from the rest of the party, for they all felt ugly toward him, thinking he had acted the coward in doing as he did. When my father answered his call, he asked if they would allow him to join them. After holding a consultation it was agreed that he might come. He walked firmly up to them and remarked:

"I have something to say to you, gentlemen. It is this: I know you think I have acted the d—d coward, and I do not blame you under the circumstances. When you all[37] jumped over the bank I thought you were going to run to the other side, and I did not know any better until I had got so far out I was in greater danger to return than to go ahead. For, as you know, the Indians were sending volleys of bullets and arrows after me, and really thought they had killed me every time I fell. Now, to end this question, there is one of two things you must do. The first is that you take your guns and kill me now, or if you do not comply with this, that every one of you agree upon your sacred honor that you will never allude, in any way, or throw up to me the unfortunate occurrences of last night. Now, gentlemen, mark what I say. If you do not kill me, but allow me to travel with you to our homes, should one of you ever be so thoughtless or forgetful of the promise you must now make as to throw it up to me, I pledge myself before you all that I will take the life of the man who does it. Now, I have presented the situation fairly, and you must accept one or the other before you leave this spot."

The party with one accord, after hearing his story, agreed never to allude to it in any way in his presence, and gave him a cordial welcome to their midst. They treated him as one of them from that time on, for he was a brave man after all. Think of the awful experience the poor fellow had during the night, and in the morning, to reach an amicable understanding with his party. One can readily see that he was a man of very great courage and physical endurance, or he could not have survived the pressure upon him. It was a sad time for those twenty-five brave men for more reasons than one. Knowing that they were 400 miles from home, late in the fall, without a road or path to follow, no stopping place of any kind between them and their homes on the borders of the Missouri, which was as far as civilization had reached westward. The thought that impressed them most deeply was in reference to one[38] of their comrades by the name of Clark Davis, whom they all loved and honored. He was a man weighing 300 pounds, but not of large frame, his weight consisting more of fat than bone. It was the universal verdict of the party that it would be impossible for him to walk home and carry his gun and ammunition as they all had to do. They would go aside in little groups, so he would not hear them, and deplore the situation. They thought they would have to leave him sitting in the prairie for the wolves to devour, or hazard the lives of all the rest of the party. Some actually wept over the thought of the loss of such a dear comrade and noble-hearted man. Should they chance to reach their own homes, for they were all men with families, the idea of telling his family that they were obliged to leave him was more than they felt their nerves could endure. In my opinion there never was a more brave and heroic group of men thrown together than were those twenty-five frontiersmen. All were fine specimens of manhood, physically speaking, between thirty and forty years of age, and with perfect health and daring to do whatever their convictions dictated.

They went to work and burned their saddles, bridles, blankets, in fact everything they had in camp that they could not carry with them on their backs. This they did to prevent the Indians from getting any more "booty." After all their arrangements were made for leaving their unfortunate camping-place, they started once more for their homes. They traveled at the rate of twenty to twenty-five miles per day. They could have gone farther, but for the fact that they had no trail to walk in. The grass in some places, and the drifting sand in others, made it exceedingly irksome for footmen.

My father was frequently asked after his return:

"Was there no road you could follow?"

He would answer:

"No, from the fact that the drifting sand soon filled every track of a passing caravan and no trace was left of a trail a few hours afterward."

A few years later on this shifting of sand discontinued, and grass and small shrubbery soon began to grow and cover many places that were then perfectly bare. One-half of the distance they had to walk was covered with herds of buffalo, the other half was through desolate prairie country, where game of any kind was seldom seen. It was on this part of their journey that they came near starvation. It only took them a few days after leaving the buffalo belt to consume what meat they had carried on their backs, as men become very hungry and consume a great deal of meat when they have long and tiresome walks to make. In the first week of their march their convictions in regard to Clark Davis were confirmed, as they thought, for his feet blistered in a terrible manner, his fat limbs became exceedingly raw and sore, so he of necessity would lag. Then they would detail of a morning when they started, a guard of five or six men to remain with him for protection from the Indians. The rest of the party would walk on to some point they would designate for camping the next night, and he with his little guard would arrive some three or four hours later. This went on for seven or eight days in succession, each day they expecting the news from the guard that he had given up the hope of going any farther. But in time his feet began to improve, in fact his condition every way, and he would reach camp sooner each day after the arrival of the party. After they had passed the buffalo belt, where meat was abundant, and struck the starvation belt in their travels, Mr. Davis' fat proved a blessing and of great service. When fatigue and want were to be endured at the same time, he began to take the lead instead[40] of the rear of the party. Several days before they reached home they would have perished, but for the fact that he alone had sufficient activity and strength to attempt to hunt for game, for they had seen none after leaving the buffalo. They had reached a place called Council Grove—now a city of that name—in the State of Kansas, about one hundred and thirty miles from their homes. After so many weeks of hard marching they thought they could go no farther, and some dropped on the ground, thinking it useless to make the attempt. At this juncture Clark Davis said:

"Boys, I will go and kill a deer."

My father said the very word was tantalizing to a lot of men who were almost dying of hunger. They did not know there was a deer in the country, or anything else that could be eaten, not even a snake, for cold weather was so near even they had disappeared. Davis, however, determined on his hunt, left his comrades, and had traveled only a few hundred yards until he saw two fine deer standing near. Directly the men in the camp heard the report of his gun, and as soon as he could reload they heard a second report, and then a shout, "Come here, boys! there is meat in plenty." You may imagine it was not long until every one joined him. They drank every drop of blood that was in the two deer, ate the livers without cooking, and saved every particle, even taking the marrow out of their legs. This meat tided them over until they were able to reach other food.

Never before in the history of the past, nor since that time, did 150 pounds of surplus fat—so considered until starvation overtook them—prove to be of such great value, and was worth more to them than all the gold and silver in the Rocky Mountains. When the test came, it was found to be one of nature's reservoirs that could be drawn upon[41] to save the lives of twenty-five brave men when all else failed them. Mr. Davis, as well as the rest of the party, no doubt often wished it could be dispensed with, as after losing his horse he carried it with great suffering and fatigue, before they learned its use, and that it was to be the salvation of the party. We often hear it said that truth is stranger than fiction, and this certainly was one of the cases where it proved to be so.

They finally reached home without losing one of their party; but they all gave the man whom they expected to leave to the wolves in the start the credit of saving their lives. When Mr. Davis reached his family the first thing his wife did was to set him a good meal. When he sat down to the table he said, "Jane, there is to be a new law for the future of our lives at our table." She said, "What is it, Clark?" He answered, "It is this. I never want to hear you or one of my children say bread again." "What then must we call it?" asked his wife. "Call it bready," said he, "for when I was starving on the plains it came to me that the word bread was too short and coarse a name to call such sweet, precious, and good a thing, and whoever eats it should use this pet name and be thankful to God who gives it, for I assure you, wife, the ordeal I have passed through will forever cause me to appreciate life and the good things that uphold it."

The outcome of this trip was drawing the party together, like one family, and they could not be kept long apart. It is a fact that mutual suffering begets an endearment stronger than ties of blood. It was interesting to me as a boy to hear them relate their experiences in reference to their hard trials and forebodings that were undergone, with no beneficial results. Some of them sent their specimens to St. Louis to be tested for silver, but received discouraging accounts of its value. If a very rich mine had been found[42] at that time it would not have been of any practical value, for they were more than thirty years ahead of the time when silver-mining could be carried on, from an American standpoint, with success. There was no one west of the Alleghanies with capital and skill enough to carry on such an enterprise, and there were no means whatever for transporting machinery to the Rocky Mountains.

Nothing of very great note occurred in the county of Jackson, after the cyclone of 1826, until the year 1830, when five Mormon elders made their appearance in the county and commenced preaching, stating to their audiences that they were chosen by the priesthood which had been organized by the prophet Joseph Smith, who had met an angel and received a revelation from God, who had also revealed to him and his adherents the whereabouts of a book written upon golden plates and deposited in the earth. This book was found in a hill called Cumorah, at Manchester, in the State of New York. They selected a place near Independence, Jackson County, Mo., in the early part of the year 1831, which they named Temple Lot, a beautiful spot of ground on a high eminence. They there stuck down their Jacob's staff, as they called it, and said: "This spot is the center of the earth. This is the place where the Garden of Eden, in which Adam and Eve resided, was located, and we are sent here according to the directions of the angel that appeared to our prophet, Joseph Smith, and told him this is the spot of ground on which the New Jerusalem is to be built, and, when finished, Christ Jesus is to make his reappearance and dwell in this city of New Jerusalem with the saints for a thousand years, at the end of which time there will be a new deal with reference to the nations of the earth, and the final wind-up of the career of the human family." They claimed to have all the spiritual gifts and understanding of the works of the Almighty that[44] belonged to the Apostles who were chosen by Christ when on his mission to this earth. They claim the gift of tongues and interpretation of tongues or languages spoken in an unknown tongue. In their silent meetings, the one who had received the gift of an unknown tongue knew nothing of its interpretation whatever, but after some silence some one in the audience would rise and claim to have the gift of interpretation, and would interpret what the brother or sister had previously spoken. They also claimed to have the gift of healing by anointing the sick with oil and laying on of hands, and some claimed that they could raise the dead; in fact, they laid claim to every gift that belonged to the Apostolic day or age. They established their headquarters at Independence, where some of their leading elders were located. There they set up a printing office, the first that was established within 150 miles of Independence, and commenced printing their church literature, which was very distasteful to the members and leaders of other religious denominations, the community being composed of Methodists, Baptists of two different orders, Presbyterians of two different orders, and Catholics, and a denomination calling themselves Christians. In that day and age it was regarded as blasphemous or sacrilegious for any one to claim that they had met angels and received from them new revelations, and the religious portion of the community, especially, was very much incensed and aroused at the audacity of any person claiming such interviews from the invisible world. Of course the Mormon elders denounced the elders and preachers of the other denominations above mentioned, and said they were the blind leading the blind, and that they would all go into the ditch together. An elder by the name of Rigdon preached in the court house one Sunday in 1832, in which he said that he had been to the third heaven, and had talked face to face[45] with God Almighty. The preachers in the community the next day went en masse to call upon him. He repeated what he had said the day before, telling them they had not the truth, and were the blind leading the blind.

The conduct of the Mormons for the three years that they remained there was that of good citizens, beyond their tantalizing talks to outsiders. They, of course, were clannish, traded together, worked together, and carried with them a melancholy look that one acquainted with them could tell a Mormon when he met him by the look upon his face almost as well as if he had been of different color. They claimed that God had given them that locality, and whoever joined the Mormons, and helped prepare for the next coming of the Lord Jesus Christ, would be accepted and all right; but if they did not go into the fold of the Latter Day Saints, that it was only a matter of time when they would be crushed out, for that was the promised land and they had come to possess it. The Lord had sent them there and would protect them against any odds in the way of numbers. Finally the citizens, and particularly the religious portion of them, made up their minds that it was wrong to allow them to be printing their literature and preaching, as it might have a bad effect upon the rising generation; and on the 4th of July, 1833, there was quite a gathering of the citizens, and a mob was formed to tear down their printing office. While the mob was forming, many of the elders stood and looked on, predicting that the first man who touched the building would be paralyzed and fall dead upon the ground. The mob, however, paid no attention to their predictions and prayers for God to come and slay them, but with one accord seized hold of the implements necessary to destroy the house, and within the quickest time imaginable had it torn to the ground, and scattered their type and literature to the four winds. This,[46] of course, created an intense feeling of anger on the part of the Mormons against the citizens. At this time there were but a few hundred Mormons in the county against many times their number of other citizens. I presume there was not exceeding 600 Mormons in the county.

Immediately after they tore down the printing office they sent to the store of Elder Partridge and Mr. Allen, who was also an elder in the church, and took them by force to the public square, stripped them to their waists, and poured on them a sufficient amount of tar to cover their bodies well, and then took feathers and rubbed them well into the tar, making the two elders look like a fright. One of their names being Partridge, many began to whistle like a cock partridge, in derision. Now, be it remembered that the people who were doing this were not what is termed "rabble" of a community, but many among them were respectable citizens and law-abiding in every other respect, but who actually thought they were doing God's service to destroy, if possible, and obliterate Mormonism. In all my experience I never saw a more law-abiding people than those who lived where this occurred. There is nothing, however, that they could have done that would have proved more effectual in building up and strengthening the faith of the people so treated as this and similar performances proved to do. For if there is anything under the sun that will strengthen people in their beliefs or faith, no matter whether it is error or truth, if they have adopted it as true, it is to abuse and punish them for their avowed belief in whatever they espouse as religion or politics.

A few months after the tearing down of the building, a dozen or two Mormons made their appearance one day on the county road west of the Big Blue and not far from the premises of Moses G. Wilson. Wilson's boy rode out to drive up the milk cows in the morning, and saw[47] this group of Mormons and had some conversation with them, and they used some very violent language to the boy. He went back and told his father, and it happened that there were several of the neighbors in at the time, as he kept a little county store; and in those days men generally carried their guns with them, in case they should have a chance to shoot a deer or turkey as they went from one neighbor's to another. It so happened that several of them had their guns with them; those who did not picked up a club of some kind, and they all followed the boy, who showed them where they were. When they got in close proximity to where the Mormons were grouped, seeing the men approaching with guns, the Mormons opened fire upon them, and the Gentiles, as they were called by the Mormons, returned the fire. There was a lawyer on the Gentile side by the name of Brazeel, who was shot dead; another man by the name of Lindsay was shot in the jaw and was thought to be fatally wounded, but recovered. Wilson's boy was also shot in the body, but not fatally. There were only one or two Mormons killed. Of course, after this occurrence, it aroused an intense feeling of hate and revenge in the citizens, and the Mormons would not have been so bold had it not been for their elders claiming that under all circumstances and at all times they would be sustained by the Almighty's power, and that a few of them would be able to put their enemies to flight. The available Mormon men then formed themselves into an organization for fighting the battles of the Lord, and started to Independence, about ten miles away, to take possession of the town. On their way, and when they were within about a mile of Independence, they marched with all the faith and fervor imaginable for fanatics to possess, encouraging each other with the words, "God will be with us and deliver our enemies into our hands." At this point they met a gentleman whom I well knew, by the name of Rube[48] Collins, a citizen of the place, who was leaving the town in a gallop to go home and get more help to defend the town from the Mormon invasion. He shouted out as he passed them, "You are a d—d set of fools to go there now; there are armed men enough there to exterminate you in a minute." They were acquainted with Collins, and supposed he had told them the truth; however, at that time they could have taken the town had they pressed on, but his words intimidated them somewhat, and they filed off from the big road and hid themselves in the brush until they could hold a council, and I presume pray for light to be guided by. During this time there were runners going in all directions, notifying the citizens that the Mormons were coming to the town to take it, and every citizen, as soon as he could run bullets and fill his powder horn with powder, gathered his gun and made for the town; and in a few hours men enough had gathered to exterminate them had they approached. In their council that they held they decided not to approach until they sent spies ahead to see whether Collins had told them the truth or not. They supposed he had, from the fact that they found the public square almost covered with men, and others arriving every minute. As quickly as the citizens had organized themselves into companies (my father, Benjamin Majors, being captain of one of them), they then sent a message by two or three citizens to the Mormons, where they were still secreted in the paw-paw brush, and told them that if they did not come and surrender immediately, the whole party that was waiting for them in the town would come out and exterminate them. This message sent terror to their hearts, with all their claims that God would go before them and fight their battles for them. After holding another council they decided the best thing they could do was to go and surrender themselves to their enemies, which[49] they did. I never saw a more pale-faced, terror-stricken set of men banded together than these seventy-five Mormons, for it was all the officers could do to keep the citizens from shooting them down, even when they were surrendering. However, they succeeded in keeping the men quiet, and no one was hurt. They stacked all their arms around a big white-oak stump that was perhaps four feet in diameter, and at that time was standing in the public square. Afterward the guns were put in the jail house for safe keeping, and were eaten up with rust, and never to my knowledge delivered to them. They then stipulated that every man, woman, and child should leave the county within three weeks. This was a tremendous hardship upon the Mormons, as it was late in the fall, and there were no markets for their crops or anything else that they had. The quickest way to get out of the county was to cross the river into Clay, as the river was the line between the two counties. They had to leave their homes, their crops, and in fact every visible thing they had to live upon. Many of their houses were burned, their fences thrown down, and the neighbors' stock would go in and eat and destroy the crop.

NATURE'S TABERNACLE.

NATURE'S TABERNACLE.

It has been claimed by people who were highly colored in their prejudice against the Mormons that they were bad citizens; that they stole whatever they could get their hands on and were not law-abiding. This is not true with reference to their citizenship in Jackson County, where they got their first kick, and as severe a one as they ever received, if not the most severe. There was not an officer among them, all the offices of the county being in the hands of their enemies, and if one had stolen a chicken he could and would have been brought to grief for doing so; but it is my opinion there is nothing in the county records[50] to show where a Mormon was ever charged with any misdemeanor in the way of violation of the laws for the protection of property. The cause of all this trouble was solely from the claim that they had a new revelation direct from the Almighty, making them the chosen instruments to go forward, let it please or displease whom it might, to build the New Jerusalem on the spot above referred to, Temple Lot. And, as above stated, whoever did not join in this must sooner or later give way to those who would.

I met a Presbyterian preacher, Rev. Mr. McNice, in Salt Lake City a number of years ago at the dinner table of a mutual friend, Doctor Douglas. It was on the Sabbath after hearing him preach a very bitter sermon against the Mormons, denouncing their doctrines and doings in a severe manner, and while we were at the dinner table, the subject of the Mormons came up, and I told him that I was thoroughly versed in their first troubles in Missouri, and he asked me what the trouble was. I told him frankly that it grew out of the fact that they claimed to have seen an angel, and to have received a new revelation from God which was not in accord with the religious denominations that existed in the community at that time. He hooted at the idea and told me he had read the history of their troubles there, and that they were bad citizens with reference to being outlaws, thieves, etc., who would pick up their neighbors' property and the like. He insisted that he had read their history, and showed a disposition to discredit my statements. I then told him I was history, and knew as much about it as any living man could know, and that there were no charges of that kind against them; they were industrious, hard-working people, and worked for whatever they wanted to live upon, obtaining it by their industry, and not by stealing it from their neighbors. He then scouted at the idea that people would receive such treatment as[51] they did merely because they claimed to have seen angels and talked with God and claimed to have a new revelation. I then referred him to the fact that fifty or sixty years previous to that time the public mind in America lacked a great deal of being so tolerant as it was at the time of our conversation; that not more than one hundred years ago some of the American people were so superstitious that they could burn witches at the stake and drag Quakers through the streets of Boston on their backs, with a jack hitched to their heels; that the Mormons to-day could go to Jackson County, Mo., and preach the same doctrines that they did then, and the result would be that they would be laughed at instead of mobbed as they were sixty years ago.

I was sitting in a cabin with my father's miller, a Mr. Newman, a Mormon, at the time of this trouble. Mr. Newman's mother-in-law, who lived with him, was named Bentley; she had a son in the company that surrendered at Independence, and who walked six miles that evening and came home. The young man walked in and looked as sad as death, and when asked what the news was he stood there and related what had taken place that day at the surrender. They all sat in breathless silence and listened to the story, and when he was through with his statement and said the Mormons had agreed to leave the county within three weeks, the old lady, who sat by the table sewing, raised her hand and brought it down upon the table with a tremendous thud, and said:

"So sure as this is a world there will be a New Jerusalem built."

I relate this little incident to show that even after they had met with such a galling defeat how zealous even the old women were with reference to their future success. But it is my opinion that the more often a fanatic is kicked and abused, the stronger is his faith in his cause, for then[52] they would take up the Scriptures and read the sentences expressed by Christ:

"But before all these they shall lay their hands on you and persecute you, delivering you up to the synagogues and into prisons, being brought before kings and rulers for my name's sake." "But take heed to yourselves, for they shall deliver you up to councils, and in the synagogues ye shall be beaten; and ye shall be brought before rulers and kings for my sake for a testimony against them."

From such passages they have always drawn the greatest consolation, and one would ask one another, "Where are the people the blessed Lord had reference to?" Another brother, with all the sanctity and confidence imaginable for a fanatic to feel, would answer, "Well, brother, if you do not find them among the Latter Day Saints you can not find them upon the face of this green earth, for we have suffered all the abuses the blessed Lord refers to in the Scripture you have just quoted."

I have said before that the Mormons all crossed the Missouri into Clay County, where they wintered in tents and log cabins hastily thrown together, and lived on mast, corn, and meat that they would procure from the citizens for whom they worked in clearing ground and splitting rails, and other work of a like character.

In the spring they were determined to return to their homes, although they were so badly destroyed, and claimed again as before that God would vindicate them and put to flight their enemies. The people of Jackson County, however, watched for their return, and gathered, at the appointed time, in a large body, on the opposite side of the river to where the Mormons, were expected to congregate and cross back into the county. Their spies came to the river, and seeing camps of the citizens, who had gathered to the number of four or five hundred strong (I being one of[53] the number) to prevent their crossing, then changed their purpose and sent some of their leading men to locate in some other part of the State, for the time being, with the full understanding, however, that at the Lord's appointed time they would all be returned to Jackson County, and complete their mission in building the city of the New Jerusalem. The delegation they sent out selected Davis and Colwell counties as the portion of the State where they would make their temporary rally until they became strong enough for the Lord to restore them to their former location.

During that spring the citizens of Jackson County, feeling that there had been, in many cases, great outrages perpetrated upon the Mormons, held a public meeting at Independence and appointed five commissioners, whose duty it was to meet some of the leading elders of the Mormons at Liberty, the seat of Clay County, and make some reparation for the damages that had been done to their property the fall before in Jackson County. They met, but failed to agree, as the elders asked more and perhaps wanted to retain the titles they had to the lands, as they thought it would be sacrilege to part with them, for that was the chosen spot for the New Jerusalem. During the time that elapsed between the commissioners crossing the river in the morning and returning in the evening, the ferryman (Bradbury), whom I have often met, a man with a very large and finely developed physique, a great swimmer, was supposed to be bribed by the Mormons to bore large auger-holes through the gunwales of his flatboat just at the water's edge. The boat having a floor in it some inches above the bottom, there could be no detection of the flow of the water until it was sufficiently deep to cover the inner floor. The commissioners went upon the boat with their horses, and had not proceeded very far from the shore until they found the water coming up in the second floor and the boat rapidly[54] sinking. This, of course, produced great consternation, for the river was very high and turbulent. Bradbury, the owner of the ferry, said to his two men:

"Boys, we will jump off and swim back to the shore."

As above stated, he was a great swimmer, and had been known to swim the Missouri upon his back several times not long before this occurred. When the water rose in the boat so that it was necessary for the commissioners to leave it, three of them caught hold of their horses' tails, after throwing off as much clothing as they could before the boat went down with them. The other two men who could swim attempted to swim alone, but the current was so turbulent that they were overcome and were drowned. Those who hung on to the tails of their horses were brought safely to shore. One of the men drowned was a neighbor of my father's and as fine a gentleman and good fellow as ever lived. His name was David Lynch.

I remember well their names, and was well acquainted with two of the men who were pulled through by their horses, S. Noland and Sam C. Owens, the foremost merchant of the county, a man who stood high in every sense, and of marked ability.

This occurrence put the quietus on any further attempt to try to settle for the damages done the Mormons when driven from the county, for it caused in the whole population the most intense feeling against them, and they never were remunerated.

When Bradbury jumped off the boat he swam for the shore, but was afterward found dead, with one of his hands grasping the root of a cottonwood tree, so there was no opportunity for trying him for the crime, or finding out how it was brought about. It was supposed that he was bribed, as no one knew of any enmity he had against the commissioners.