Title: Old and New Paris: Its History, Its People, and Its Places, v. 1

Author: H. Sutherland Edwards

Release date: February 28, 2013 [eBook #42231]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

BY

H. SUTHERLAND EDWARDS

AUTHOR OF “IDOLS OF THE FRENCH STAGE” “THE GERMANS IN FRANCE” “THE

RUSSIANS AT HOME” ETC. ETC.

VOL. I

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

C A S S E L L AND C O M P A N Y LIMITED

LONDON PARIS & MELBOURNE

1893

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE | |

| PARIS: A GENERAL GLANCE. | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| THE EXPANSION OF PARIS | ||

Lutetia—La Cité—Lutetia taken by Labienus—The Visit of Julian the Apostate—Besieged by the Franks—The Norman Invasion—Gradual Expansion from the Île de la Cité to the Outer Boulevards—M. Thiers’s Line of Outworks | 6 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| THE LEFT BANK AND THE RIGHT. | ||

Paris and London—The Rive Gauche—The Quartier Latin—The Pantheon—The Luxemburg—The School of Medicine—The School of Fine Arts—The Bohemia of Paris—The Rive Droite—Paris Proper—The “West End” | 9 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| NOTRE DAME. | ||

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, a Temple to Jupiter—Cæsar and Napoleon—Relics in Notre Dame—Its History—Curious Legends—The “New Church”—Remarkable Religious Ceremonies—The Place de Grève—The Days of Sorcery—“Monsieur de Paris”—Dramatic Entertainments—Coronation of Napoleon | 12 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| SAINT-GERMAIN-L’AUXERROIS | ||

The Massacre of St. Bartholomew—The Events that preceded it—Catherine de Medicis—Admiral Coligny—“The King-Slayer”—The Signal for the Massacre—Marriage of the Duc de Joyeuse and Marguerite of Lorraine | 22 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| THE PONT-NEUF AND THE STATUE OF HENRI IV. | ||

The Oldest Bridge in Paris—Henri IV.—His Assassination by Ravaillac—Marguerite of Valois—The Statue of Henri IV.—The Institute—The Place de Grève | 30 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| THE BOULEVARDS. | ||

From the Bastille to the Madeleine—Boulevard Beaumarchais—Beaumarchais—The Marriage of Figaro—The Bastille—The Drama in Paris—Adrienne Lecouvreur—Vincennes—The Duc d’Enghien—Duelling—Louis XVI | 43 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| THE BOULEVARDS (continued). | ||

Hôtel Carnavalet—Hôtel Lamoignon—Place Royale—Boulevard du Temple—The Temple—Louis XVII—The Theatres—Astley’s Circus—Attempted Assassination of Louis Philippe—Trial of Fieschi—The Café Turc—The Cafés—The Folies Dramatiques—Louis XVI. and the Opera—Murder of the Duke of Berri | 67 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| THE BOULEVARDS (continued). | ||

The Porte Saint-Martin—Porte Saint-Denis—The Burial Place of the French Kings—Funeral of Louis XV.—Funeral of the Count de Chambord—Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle—Boulevard Poissonnière—Boulevard Montmartre—Frascati | 95 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

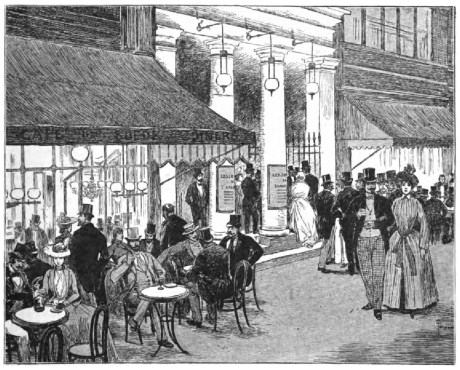

| BOULEVARD AND OTHER CAFÉS. | ||

The Café Littéraire—Café Procope—Café Foy—Bohemian Cafés—Café Momus—Death of Molière—New Year’s Gifts | 107 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| THE BOULEVARDS (continued). | ||

The Opéra Comique of Paris—I Gelosi—The Don Juan of Molière—Madame Favart—The Saint-Simonians | 115 | |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| THE BOULEVARDS (continued). | ||

La Maison Dorée—Librairie Nouvelle—Catherine II. and the Encyclopædia—The House of Madeleine Guimard | 122 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| PLACE DE LA CONCORDE. | ||

Its History—Louis XV.—Fireworks—The Catastrophe in 1770—Place de la Révolution—Louis XVI.—The Directory | 143 | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| THE PLACE VENDÔME. | ||

The Column of Austerlitz—The Various Statues of Napoleon Taken Down—The Church of Saint-Roch—Mlle. Raucourt—Joan of Arc | 155 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| THE JACOBIN CLUB. | ||

The Jacobins—Chateaubriand’s Opinion of Them—Arthur Young’s Descriptions—The New Club | 161 | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| THE PALAIS ROYAL. | ||

Richelieu’s Palace—The Regent of Orleans—The Duke of Orleans—Dissipation in the Palais Royal—The Palais National—The Birthplace of Revolutions | 166 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| THE COMÉDIE FRANÇAISE. | ||

Its History—The Roman Comique—Under Louis XV.—During the Revolution—Hernani | 172 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| THE NATIONAL LIBRARY AND THE BOURSE. | ||

The “King’s Library”—Francis I. and the Censorship—The Imperial Library—The Bourse | 187 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| THE LOUVRE AND THE TUILERIES. | ||

The Louvre—Origin of the Name—The Castle—Francis I.—Catherine de Medicis—The Queen’s Apartments—Louis XIV. and the Louvre—The Museum of the Louvre—The Picture Galleries—The Tuileries—The National Assembly—Marie Antoinette—The Palace of Napoleon III.—“Petite Provence” | 193 | |

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| THE CHAMPS ÉLYSÉES AND THE BOIS DE BOULOGNE. | ||

The Champs Élysées—The Élysée Palace—Longchamps—The Bois de Boulogne—The Château de Madrid—The Château de la Muette—The Place de l’Étoile | 218 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| THE CHAMP DE MARS AND PARIS EXHIBITIONS. | ||

The Royal Military School of Louis XV.—The National Assembly—The Patriotic Altar—The Festival of the Supreme Being—Other Festivals—Industrial Exhibitions—The Eiffel Tower—The Trocadéro | 229 | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

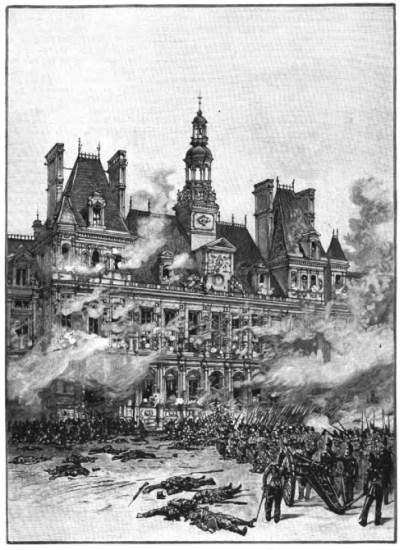

| THE HÔTEL DE VILLE AND CENTRAL PARIS. | ||

The Hôtel de Ville—Its History—In 1848—The Communards | 242 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| THE PALAIS DE JUSTICE. | ||

The Palais de Justice—Its Historical Associations—Disturbances in Paris—Successive Fires—During the Revolution—The Administration of Justice—The Sainte-Chapelle | 250 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| THE FIRE BRIGADE AND THE POLICE. | ||

The Sapeurs-pompiers—The Prefect of Police—The Garde Républicaine—The Spy System | 270 | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| THE PARIS HOSPITALS. | ||

The Place du Parvis—The Parvis of Notre Dame—The Hôtel-Dieu—Mercier’s Criticisms | 276 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| CENTRAL PARIS. | ||

The Hôtel de Ville—Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie—Rue Saint-Antoine—The Reformation | 281 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| CENTRAL PARIS (continued). | ||

Rue de Venise—Rachel—St.-Nicholas-in-the-Fields—The Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers—The Gaieté—Rue des Archives—The Mont de Piété—The National Printing Office—The Hôtel Lamoignon | 298 | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| CENTRAL PARIS (continued). | ||

The Rue Saint-Denis—Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles—George Cadoudal—Saint-Eustache—The Central Markets—The General Post Office | 311 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | ||

| THE “NATIONAL RAZOR.” | ||

The Rue de l’Arbre Sec—Dr. Guillotin—Dr. Louis—The Guillotine—The First Political Execution | 327 | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | ||

| THE EXECUTIONER. | ||

The Executioner—His Taxes and Privileges—Monsieur de Paris—Victor of Nîmes | 330 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | ||

| PÈRE-LACHAISE. | ||

The Cemeteries of Clamart and Picpus—Père-Lachaise—La Villette and Chaumont—The Conservatoire—Rue Laffitte—The Rothschilds—Montmartre—Clichy | 333 | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | ||

| PARIS DUELS. | ||

The Legal Institution of the Duel—The Congé de la Bataille—In the Sixteenth Century—Jarnac—Famous Duels | 345 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | ||

| THE STUDENTS OF PARIS. | ||

Paris Students—Their Character—In the Middle Ages—At the Revolution—Under the Directory—In 1814—In 1819—Lallemand—In the Revolution of 1830 | 355 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | ||

| THE RAG-PICKER OF PARIS. | ||

The Chiffonier or Rag-picker—His Methods and Hours of Work—His Character—A Diogenes—The Chiffonier de Paris | 360 | |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | ||

| THE BOHEMIAN OF PARIS. | ||

Béranger’s Bohemians—Balzac’s Definition—Two Generations—Henri Mürger | 365 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | ||

| THE PARIS WAITER. | ||

The Garçon—The Development of the Type—The Garçon’s Daily Routine—His Ambitions and Reverses | 369 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | ||

| THE PARIS COOK. | ||

Brillat Savarin on the Art of Cooking—The Cook and the Roaster—Cooking in the Seventeenth Century—Louis XV.—Mme. de Maintenon | 372 | |

[Illustrations have been moved from within paragraphs for ease of reading.

(note of e-text transcriber.)]

Boulevard des Italiens | Frontispiece |

Place de la Concorde | 1 |

The Left Bank of the Seine, from Notre Dame | 4 |

Right Bank of the Seine, from Notre Dame | 5 |

On the Boulevards—Corner of Place de l’Opéra | 8 |

Théâtre Français | 9 |

A Street Scene | 11 |

Notre Dame | 12 |

The Choir Stalls, Notre Dame | 13 |

Rue du Cloitre | 16 |

Apsis of Notre Dame | 17 |

The Leaden Spire, Notre Dame | 20 |

Gargoyles in the Sacristy, Notre Dame | 21 |

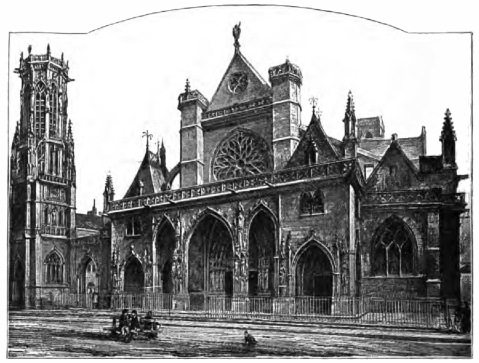

Church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois | 24 |

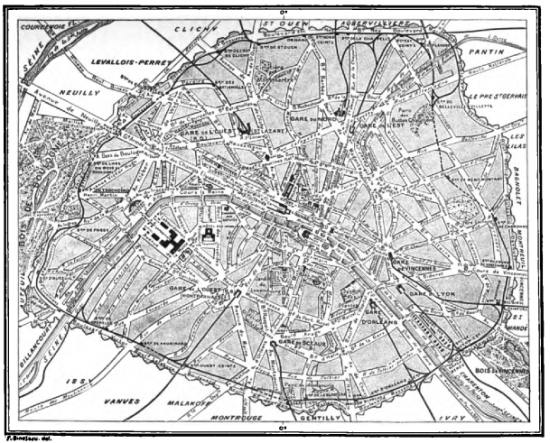

(Map) Principal Streets of Paris | 25 |

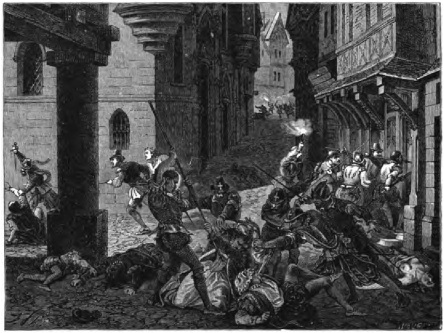

Scene during the Massacre of St. Bartholomew | 28 |

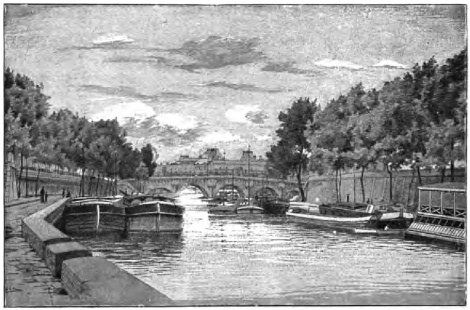

The Pont-Neuf and the Louvre, from the Quai des Augustins | 30 |

By the Pont-Neuf | 32 |

Seine Fishers | 32 |

View from the Pavilion de Flore | facing 33 |

The Pont-Neuf and the Mint | 33 |

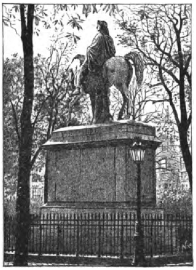

Statue of Henri IV. on the Pont-Neuf | 36 |

The Institute | 37 |

The Pont-Neuf from the Island | 40 |

View from the Western Point of the Île de la Cité | 41 |

Place de la Bastille and Column of July | 45 |

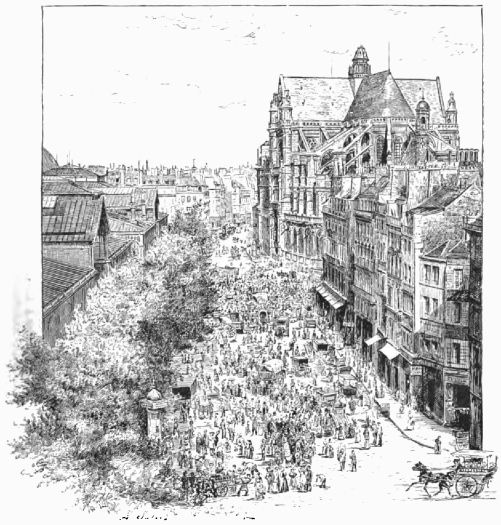

Junction of Grands Boulevards and Rue and Faubourg Montmartre | 48 |

The Bastille | 49 |

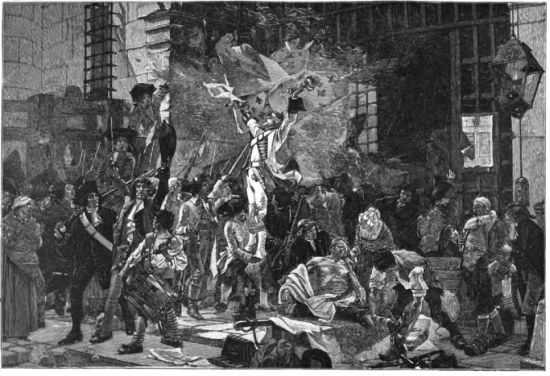

The Conquerors of the Bastille | 53 |

À la Robespierre | 56 |

A Lady of 1793 | 56 |

A Tricoteuse | 56 |

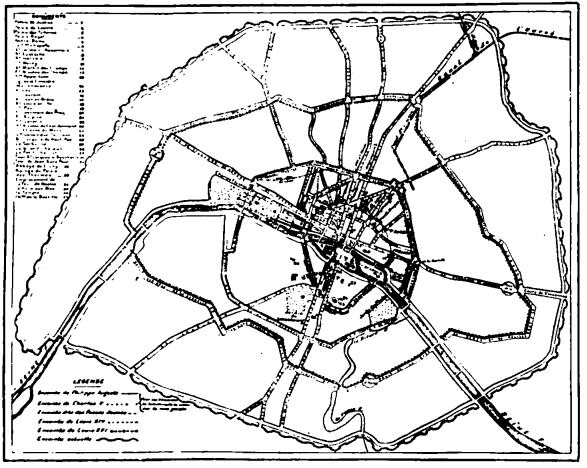

Map showing the Extension of Paris | 57 |

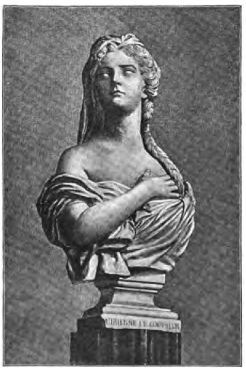

Adrienne Lecouvreur | 61 |

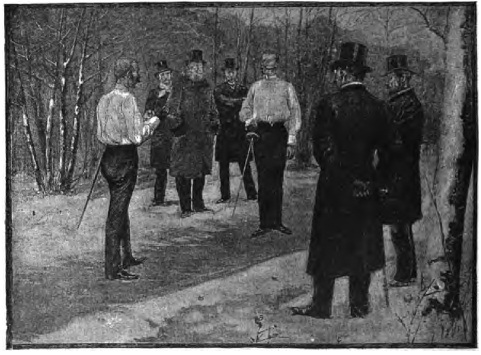

A Duel in the Bois de Boulogne | 64 |

The Seine from Notre Dame | facing 65 |

Recruits | 65 |

Hôtel Carnavalet | 68 |

Hôtel Lamoignon | 69 |

Statue of Louis XIII. in the Place des Vosges | 71 |

The Place des Vosges, formerly Place Royale | 72 |

The Arcade in the Place des Vosges | 73 |

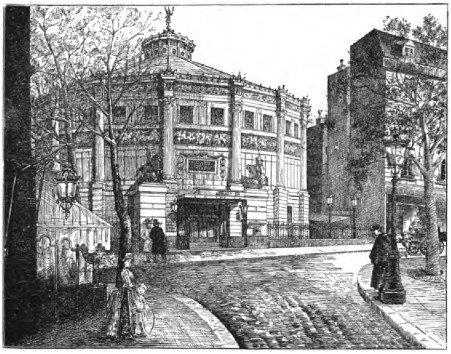

The Winter Circus in the Boulevard des Filles de Calvaire | 77 |

Louis Philippe | 80 |

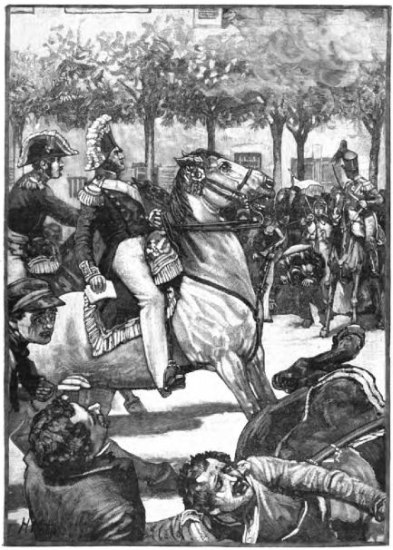

Attempted Assassination of Louis Philippe | 81 |

A Parisian Café | 84 |

Place de la République | 85 |

Frédéric Lemaître | 89 |

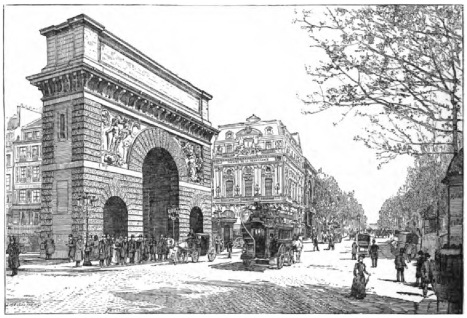

Porte Saint-Martin and the Renaissance Theatre | 92 |

Church of Saint-Méry, Rue Saint-Martin | 93 |

Apsis of Church of Saint-Méry, Rue Brisemiche | 96 |

Notre Dame | facing 97 |

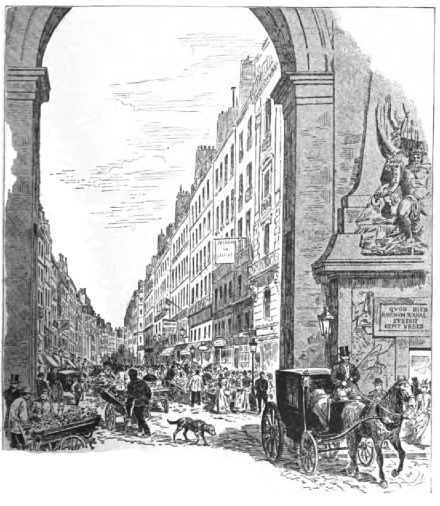

Entrance to the Faubourg Saint-Denis | 97 |

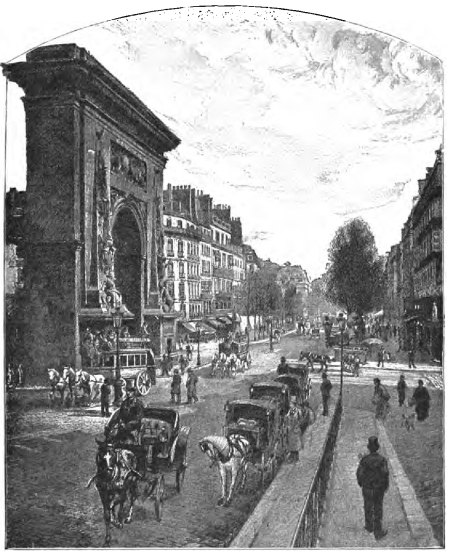

Boulevard and Porte Saint-Denis | 101 |

Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle and the Gymnase Theatre | 104 |

The Boulevard Montmartre | 105 |

Entrance to the Théâtre des Variétés, Boulevard Montmartre | 109 |

Cafés on the Boulevard Montmartre | 112 |

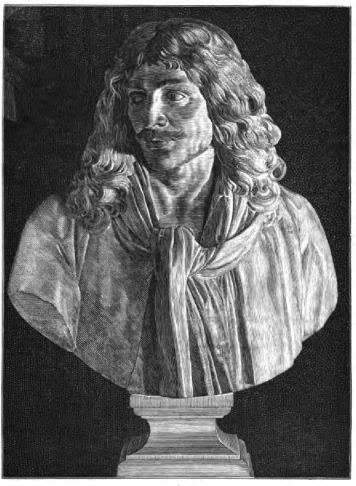

Molière | 113 |

Street Coffee Stall | 114 |

Boulevard des Italiens | 116 |

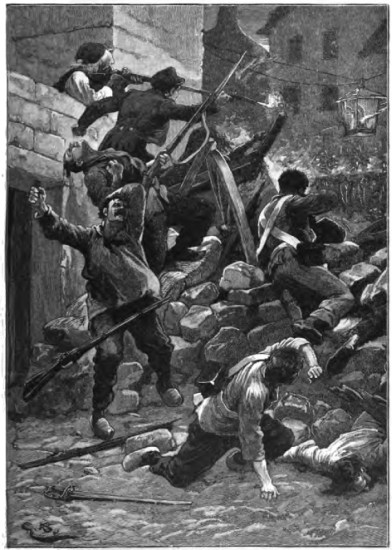

The 6th of June; the Last of the Insurrection | 121 |

Marivaux | 124 |

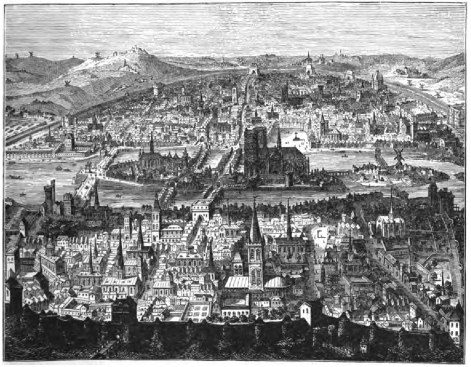

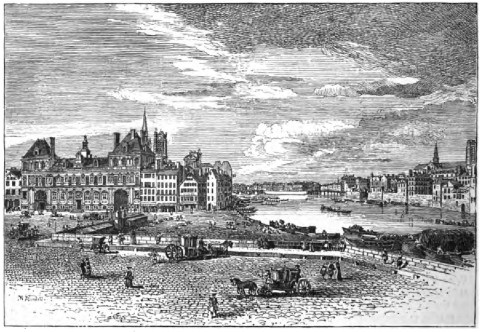

Paris in the Seventeenth Century | 125 |

Rue de la Chaussée d’Antin | 128 |

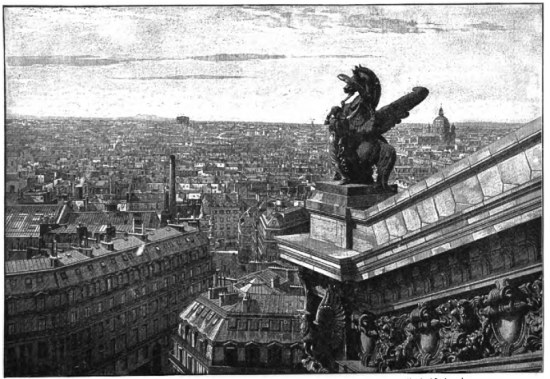

View from the Roof of the Opera House | facing 129 |

Mlle. Clairon | 129 |

View from the Balcony of the Opera | 132 |

Avenue de l’Opéra | 133 |

One of the Domes of the Opera House | 135 |

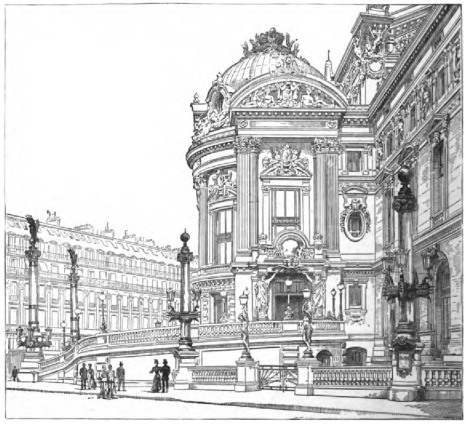

Eastern Pavilion, Opera House | 136 |

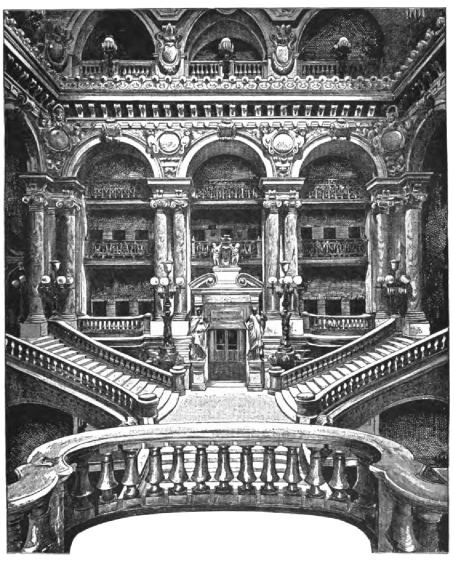

The Public Foyer, Opera House | 137 |

Western Pavilion, Opera House | 140 |

The Staircase of the Opera House | 141 |

The Madeleine | 144 |

Interior of the Madeleine | 145 |

Place de la Concorde | 149 |

Place de la Concorde, from the Terrace of the Tuileries | 152 |

Trial of Louis XVI | 153 |

Top of the Vendôme Column | 155 |

The Place Vendôme | 157 |

Rue Castiglione | 160 |

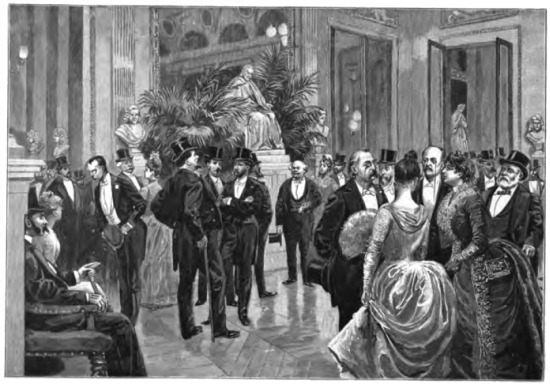

A First Night at the Comédie Française—The Foyer | facing 161 |

Mirabeau | 161 |

Robespierre | 164 |

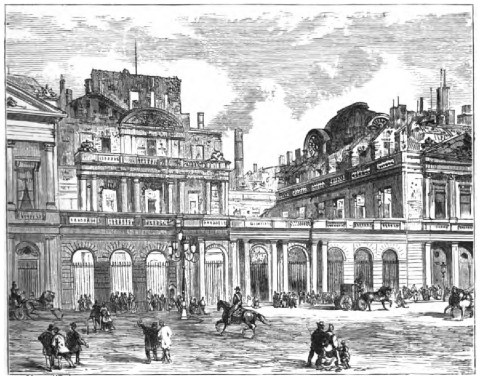

The Palais Royal | 165 |

Gardens of the Palais Royal | 168 |

The Palais Royal after the Siege | 169 |

The Montpensier Gallery, Palais Royal | 170 |

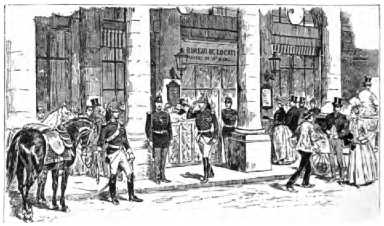

Entrance to the Comédie Française | 172 |

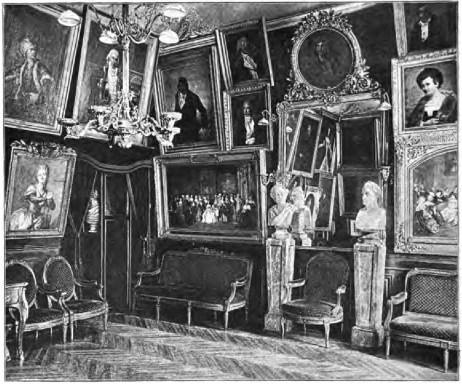

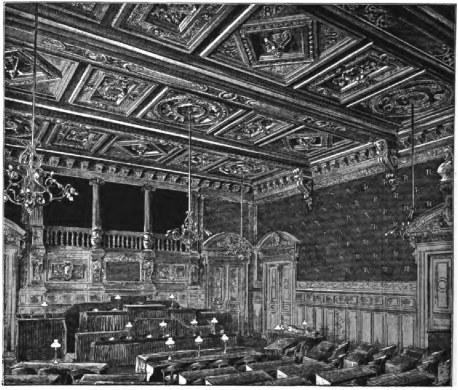

The Public Foyer, Comédie Française | 173 |

The Green Room, Comédie Française | 176 |

Molière | 177 |

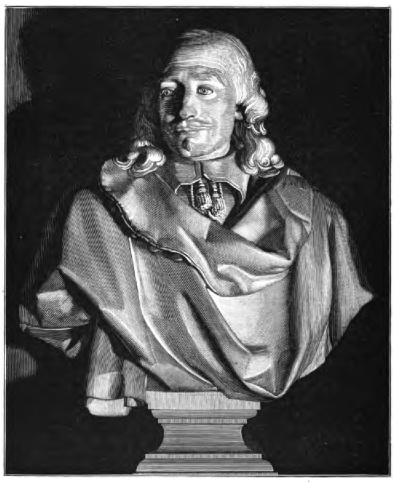

Corneille | 180 |

Voltaire | 181 |

The Committee of the Comédie Française: Alexandre Dumas (the younger) Reading a Play | 185 |

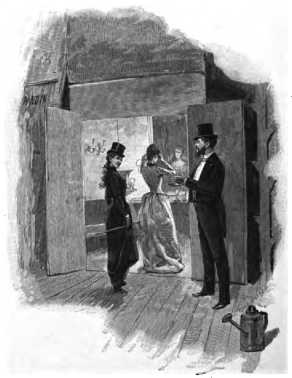

Behind the Scenes, Comédie Française | 186 |

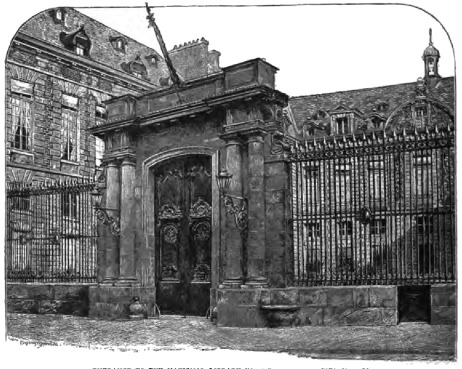

Entrance to the National Library in the Rue des Petits Champs | 188 |

The Bourse | 189 |

The Apollo Gallery—The Louvre | facing 193 |

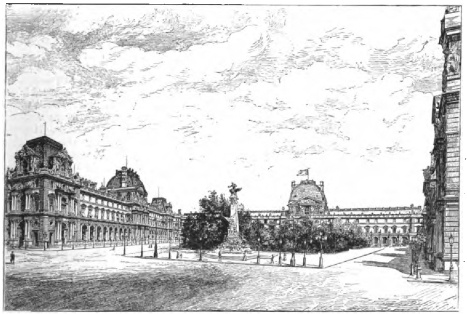

The Louvre, from the Place du Carrousel | 193 |

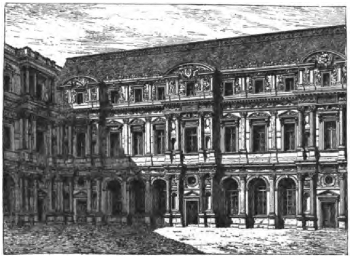

The Old Louvre (Pierre Lescot’s Façade) | 195 |

The Colonnade of the Louvre | 196 |

Portion of the Façade of Henri IV.’s Gallery, Louvre | 197 |

Top of the Marsan Pavilion, Louvre | 200 |

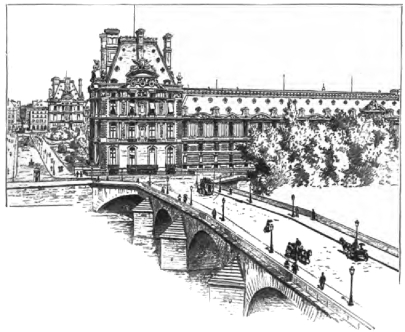

The Marsan and Flora Pavilions, Louvre, from the Pont-Royal | 201 |

The Richelieu Pavilion | 205 |

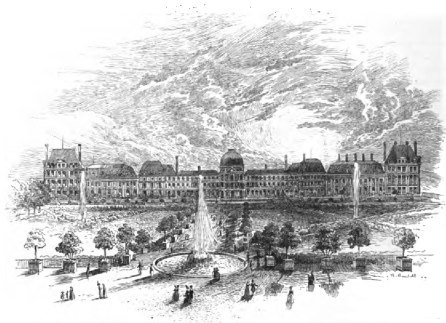

The Tuileries in the Eighteenth Century | 208 |

The Terrace, Tuileries Gardens | 209 |

The Tuileries Gardens | 209 |

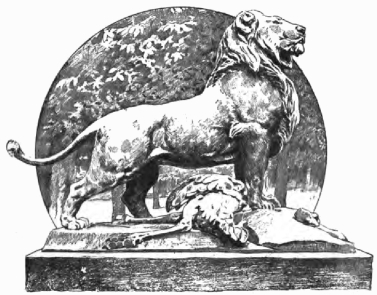

Lion in the Tuileries Gardens | 211 |

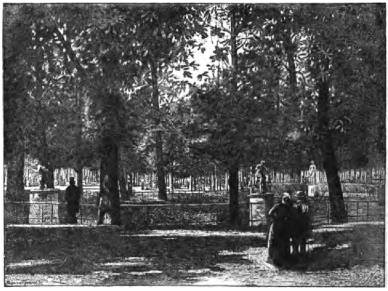

The Chestnuts of the Tuileries | 212 |

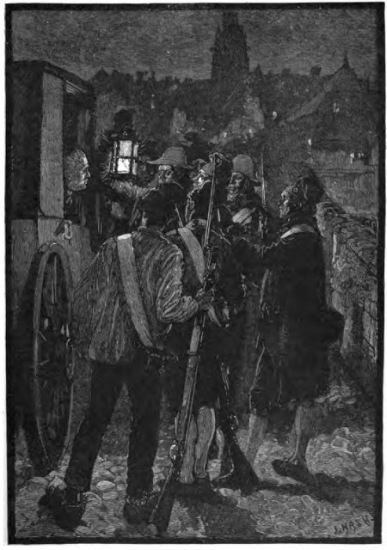

Louis XVI. Stopped at Varennes by Drouet | 213 |

The Royal Family at Varennes | 216 |

Monument to Gambetta, Place du Carrousel | 217 |

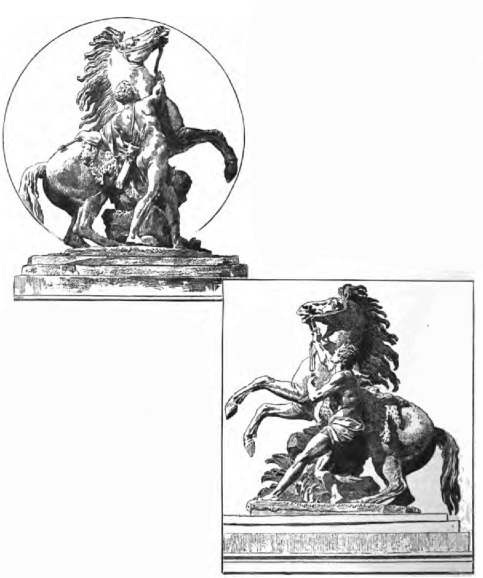

The Horses of Marly, Champs Élysées | 220 |

The Elysée | 221 |

Saint-Philippe du Roule | 221 |

The Great Lake, Bois de Boulogne | 223 |

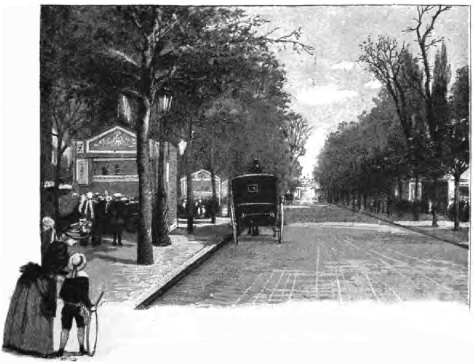

Avenue du Bois de Boulogne | 224 |

Arc de Triomphe | facing 225 |

Avenue des Champs Élysées | 225 |

Avenue Marigny, Champs Élysées | 227 |

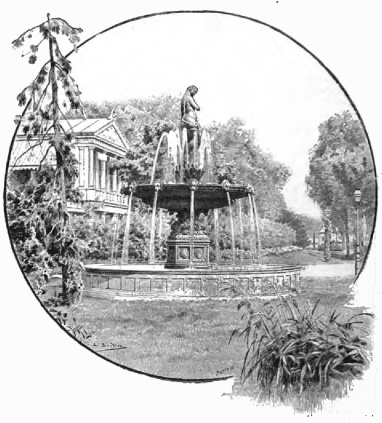

Fountain in the Champs Élysées | 228 |

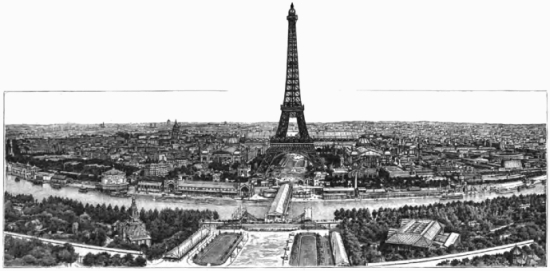

The Champ de Mars, 1889 | 229 |

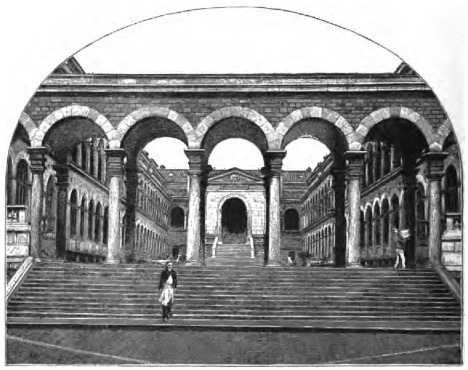

The Military School, Champ de Mars | 232 |

General La Fayette | 233 |

The Palais de l’Industrie, Champs Élysées | 236 |

View Showing Exhibition of 1889 | 237 |

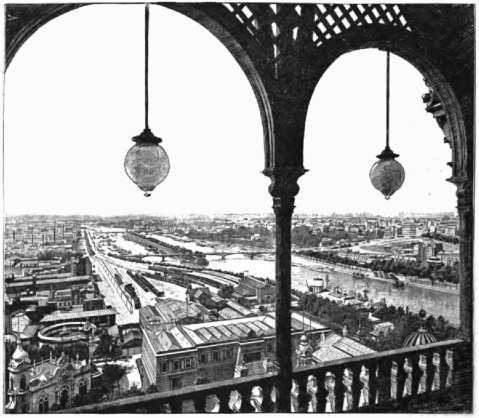

View from the First Platform of the Eiffel Tower | 240 |

The Trocadéro | 241 |

Hôtel de Ville in the Fifteenth Century | 244 |

Attack on the Hôtel de Ville, 1830 | 245 |

Statue of Étienne Marcel on the Quai Hôtel de Ville | 246 |

The Municipal Council Chamber, Hôtel de Ville | 248 |

Île St. Louis | 249 |

The Quai de l’Horloge | 252 |

Pont au Change and Palais de Justice | 253 |

The Clock of the Palais de Justice | 255 |

Entrance to the Court of Assize | 256 |

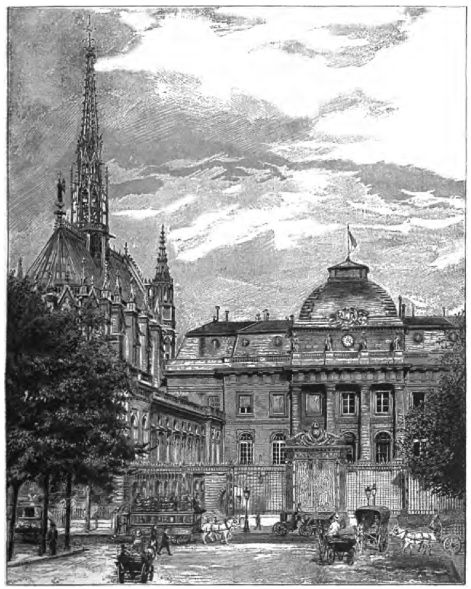

The Palais de Justice | facing 257 |

The Palais de Justice and Sainte-Chapelle | 257 |

The Façade of the Old Palais de Justice | 260 |

The Salle des Pas Perdus | 261 |

Police Carriages | 263 |

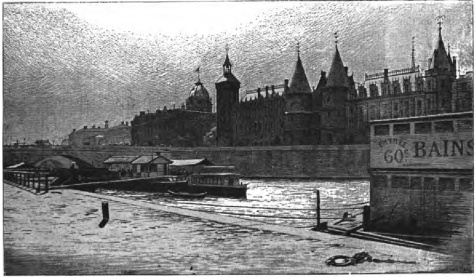

The Conciergerie, Palais de Justice | 264 |

The Sainte-Chapelle | 265 |

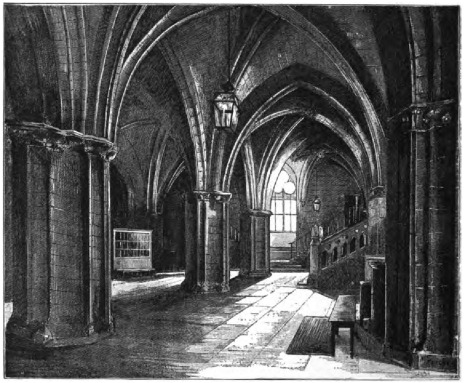

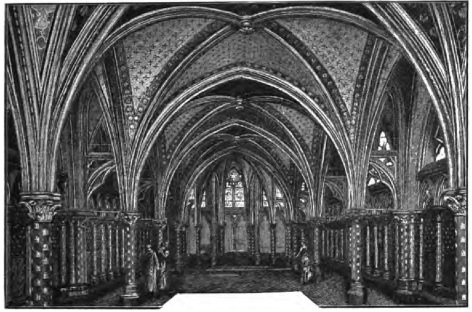

The Lower Chapel of the Sainte-Chapelle | 267 |

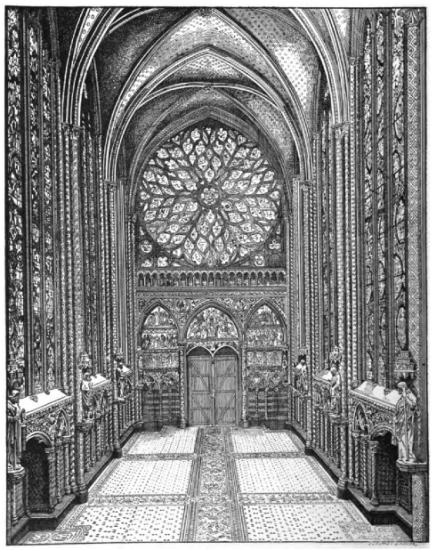

The Upper Chapel of the Sainte-Chapelle | 268 |

The Tribunal of Commerce | 269 |

A Pompier | 272 |

A Guardian of the Peace | 273 |

An Orderly of the Garde de Paris | 274 |

A Gendarme | 277 |

Principal Court of the Hôtel-Dieu | 280 |

Rue de Rivoli | 281 |

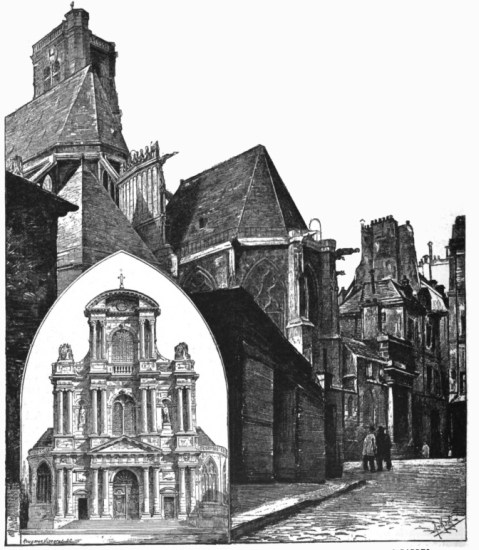

Façade of the Church of St. Gervais and St. Protais; and the Apsis, from the Rue des Barres | 284 |

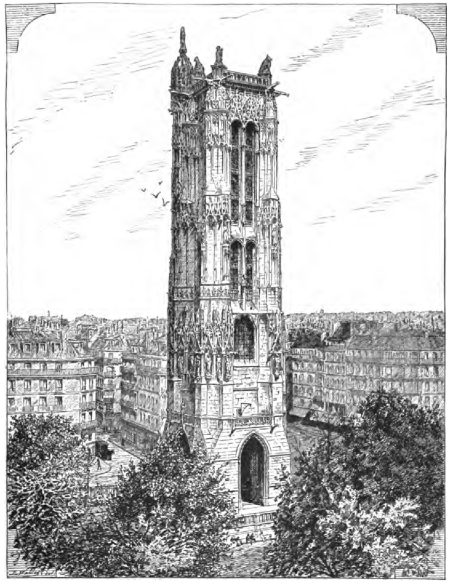

Tower of Saint-Jacques-la-Boucherie | 285 |

Hôtel de Beauvais | 286 |

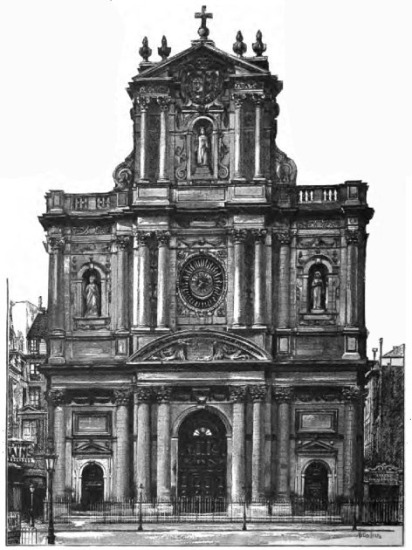

Church of St. Louis and St. Paul | 288 |

Rue de Rivoli and Hôtel de Ville | facing 289 |

Rue Grenier-sur-l’eau | 289 |

The Pont-Marie | 292 |

Rue Saint Louis-en-l’Île | 293 |

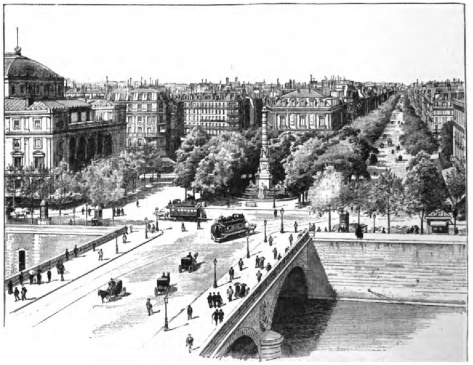

Pont au Change, Place du Châtelet, and Boulevard de Sebastopol | 296 |

The Palmier Fountain, Place du Châtelet | 297 |

Rue de Venise | 299 |

St. Nicholas-in-the-Fields | 300 |

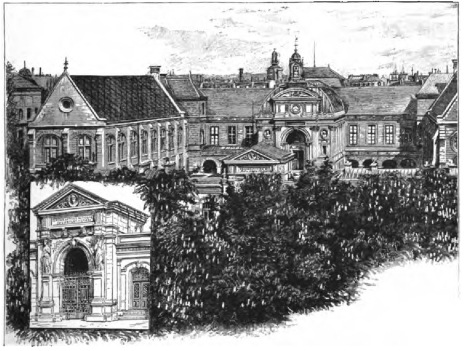

The Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers | 301 |

The Vertbois Tower and Fountain | 303 |

The Gaieté Theatre | 304 |

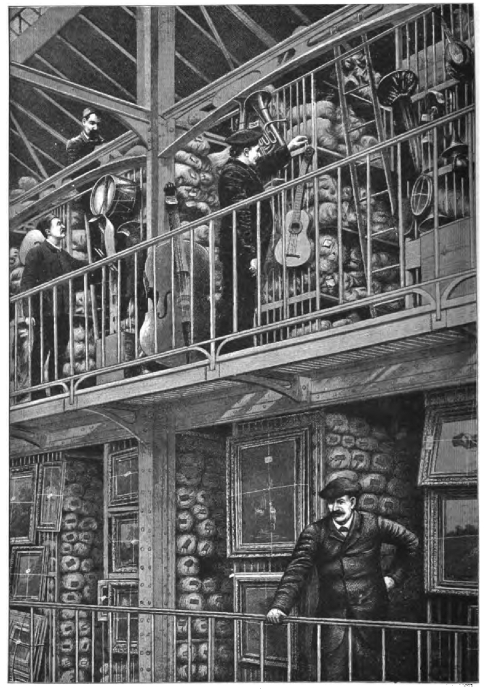

In the Temple Market | 305 |

The Temple Market | 305 |

Sixteenth Century Cloisters, Rue des Billettes | 307 |

Palace of the National Archives | 308 |

Hôtel de Hollande | 309 |

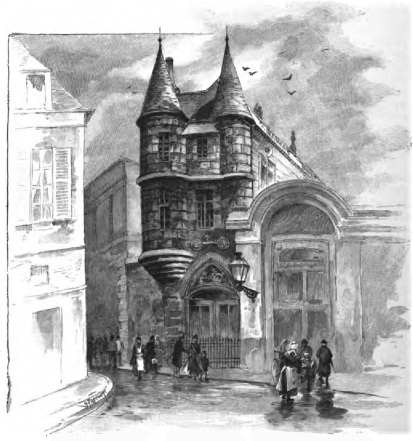

Turret at Corner of Rues Vieille du Temple and Francs Bourgeois | 309 |

Rue de Birague, leading to the Place des Vosges | 311 |

Fountain of the Innocents | 312 |

Saint-Eustache | 313 |

A Market Scene | 315 |

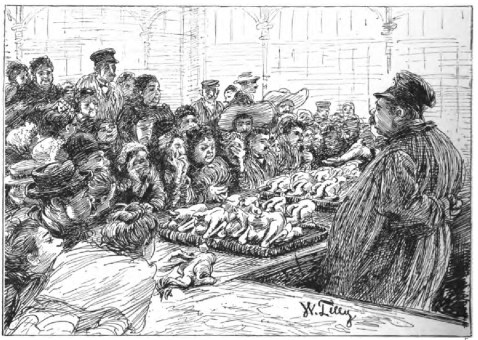

An Auction Sale of Poultry in the Central Market | 316 |

Rue Rambuteau in the Early Morning | 317 |

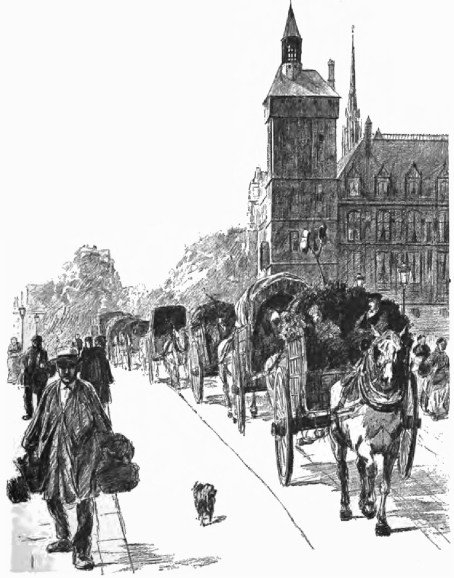

On the Way to the Central Markets | 319 |

The Fish Market | 320 |

Interior of the Mont de Piété, Rue Capron | facing 321 |

The General Post Office | 321 |

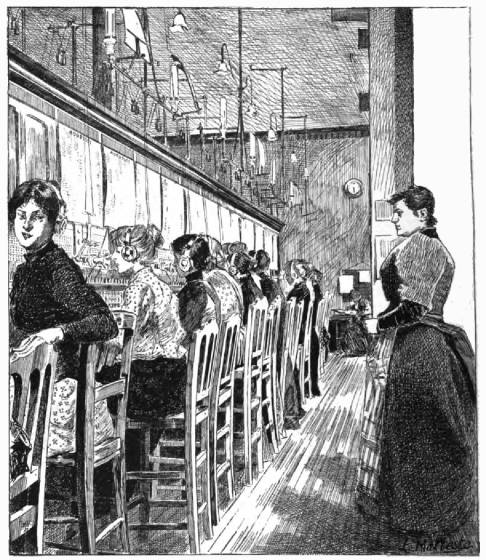

The Poste Restante | 321 |

The Public Hall, General Post Office | 323 |

The Telephone Room at the General Post Office | 324 |

Place des Victoires | 325 |

Rue de la Vrillière | 328 |

In Père-Lachaise | 333 |

Parc des Buttes Chaumont | 336 |

Montmartre | 340 |

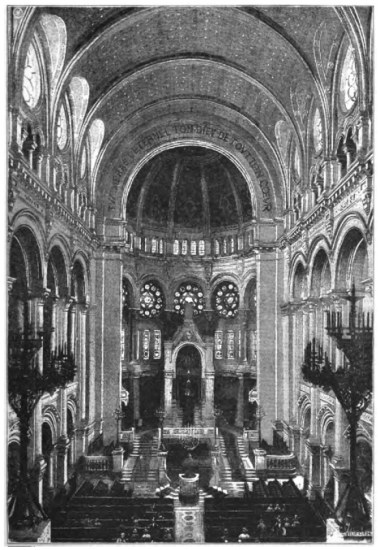

The Synagogue in the Rue de la Victoire | 341 |

St. Peter’s Church, Montmartre | 343 |

The Bells of St. Peter’s | 343 |

The New Municipal Reservoir and the Church of the Sacred Heart, Montmartre | 344 |

The Caulaincourt Bridge, Montmartre | 344 |

In the Parc Monceau | 345 |

Diana of Poitiers | 348 |

Marshal Ney | 352 |

The Race-course, Longchamps | facing 353 |

Camille Desmoulins | 356 |

The Polytechnic School | 357 |

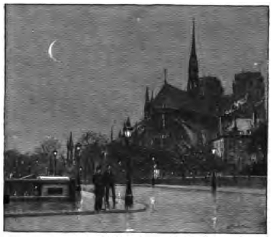

Notre Dame from the Pont Saint-Louis | 360 |

A Rag-picker | 361 |

A Rag-picker | 364 |

The Boulevard Poissonière | 368 |

Selling Goats | 369 |

The Bird Market | 373 |

Madame de Maintenon | 375 |

“PARIS,” said Heinrich Heine, “is not simply the capital of France, but of the whole civilised world, and the rendezvous of its most brilliant intellects.” The art and literature of Europe were at that time represented in Paris by such men as Ary Scheffer, the Dutch painter, Rossini, the Italian composer, the cosmopolitan Meyerbeer, and Heine himself. Towards the close of the eighteenth century most of the European Courts, with those of Catherine II. and Frederick the Great prominent among them, were regularly supplied with letters on Parisian affairs by Grimm, Diderot, and other writers of the first distinction, who, in their serious moments, contributed articles to the Encyclopédie. At a much remoter period Paris was already one of the most famous literary capitals of Europe; nor was it renowned for its literature alone. Its art, pictorial and sculptural, was also celebrated, and still more so its art manufactures; while of recent years the country of Auber and Gounod, of Bizet, Massenet and Saint-Saëns, has played a leading part in the world of music. Paris, too, has from the earliest times been a centre of science and philosophy. Here Abélard lectured, and here the first hospitals were established. Then, again, Paris has a military history of singular interest and variety. It has been oftener torn within its walls by civic conflicts, and attacked from without by the invader, than any other European city; while none has undergone so many regular sieges as the capital of the country of which Frederick the Great used to say that, if he ruled it, not a shot should be fired in Europe without his permission.

Paris is at once the most ancient and the most modern capital in Europe. Great are the changes it has undergone since it first took form, eighteen centuries ago, as a fortress or walled town on an island in the middle of the Seine; and at every period of its history we find some chronicler dwelling on the disappearance of ancient landmarks. Whole quarters are known to have been pulled down and rebuilt under the second Empire. But ever since the Revolution of 1789, under each successive form of government and in almost every district, straggling lanes have been giving way gradually to wide streets and stately boulevards, and suburb after suburb has been merged into the great city.

The Chaussée d’Antin was at the end of the last century a chaussée in fact as well as in name: a mere high-road, that is to say; and there were people living under the government of Louis-Philippe who claimed to have shot rabbits on the now densely populated Boulevard Montmartre.

The greatest changes, however, in the general physiognomy of Paris date from the Revolution, when, in the first place, as if by way of symbol, the hated fortress was demolished in which so many victims of despotism had languished. “Athens,” says Victor Hugo, “built the Parthenon, but Paris destroyed the Bastille.” In the days when the great State {2} prison was still standing, the broad, well-built Rue Saint-Antoine, in its immediate neighbourhood, used to be pointed to by antiquarians as covering the ground where King Henry II. was mortally wounded in a tournament by Montgomery, an officer in the Scottish Guard. It was there, too, that, after the death of their protector, the “minions” of Henry II. slaughtered one another.

The now thickly inhabited Place des Victoires, where stands the statue of Louis XIV., lasting monument of kingly pride and popular adulation, was at one time the most dangerous part of the capital. In the open space now enclosed by lordly mansions and commodious warehouses thieves and murderers held their nightly assemblies, or even in the face of day committed depredations on the passers-by. “Could a better site have been chosen,” asks an historian of the last century, “for the effigy of that royal robber, born for the ruin of his subjects and the disturbance of Europe: who aimed at universal monarchy and sacrificed the wealth and happiness of a whole kingdom to pursue an empty shadow; who lived a tyrant and died an idiot?”

Not far distant, the Halles, or general markets, stand on the spot where Charles V. made a famous speech against Charles, surnamed the Mischievous, King of Navarre; when the former was hissed and hooted by the mob because he had neither the good looks, the eloquence, nor the reasoning power of his antagonist. It was here, too, that the first dramas were acted in France; and here, significantly enough, that Molière was born.

At the Butte Saint-Roch, now remembered chiefly by the church of the same name, the Maid of Orleans was wounded during the siege of Paris, then in the hands of the English. Joan of Arc was not at this time—not, at least, with the Parisians—the popular heroine she has since become. Detesting Charles VII. and all his supporters, they could not love the inspired girl whose example had restored the courage of the king’s troops. A Parisian of that day, who had witnessed the siege, describes her as a “fiend in woman’s guise.”

The bell may still be heard of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois; the very bell, it is asserted, that called the faithful to the massacre of St. Bartholomew. Near the church from which the tragic signal rang forth stands the palace from whose windows Charles IX. fired upon the unhappy Huguenots as they sought safety by swimming across the Seine; and close at hand used to be pointed out another window from which money was thrown to an agitated crowd in order to keep it from attending Molière’s funeral, at which the mob proposed, not to honour the remains of the illustrious dramatist, but to insult them.

It was in the old Rue du Temple that the Duke of Burgundy fell by the hand of his assassin, the Duke of Orleans, only brother of Charles VI., who, though a madman and an idiot, was suffered to remain on the throne; and it was in this same Rue du Temple that Louis XVI. and Marie-Antoinette were confined before being taken to the guillotine. What scenes has not the Place de Grève witnessed! from the burning of witches to the torture of Damiens, and from the atrocious cruelties inflicted upon this would-be regicide to the first executions under the Revolution, when the cry of “A la lanterne!” (to the lamp-post, that is to say, of the Place de Grève) was so frequently heard.

But the most revolutionary spot in this, the most revolutionary capital in the world, is to be found in the gardens of the Palais Royal; those gardens from whose trees Camille Desmoulins plucked the leaves which the besiegers of the Bastille were to have worn in their hats as rallying signals. Here, too, assembled the journeymen printers, who, their newspapers having been suppressed by Charles X., determined, under the guidance of the journalists—their natural leaders on such an occasion—to reply by force to the armed censorship of the Government. Again, in 1848, the Palais Royal Gardens witnessed the first manifestations of discontent, though it was a pistol-shot fired on a fashionable part of the boulevard that precipitated the collision between the insurgents and the troops. The next morning, at breakfast, Louis-Philippe was told that he had better abdicate; and an hour afterwards an old gentleman, with a portfolio under his arm, was {3} seen to take a cab on the Place de la Concorde, and drive off in the direction of Saint-Cloud, whence he reached the coast of Normandy, and in due time the shores of England.

Paris possesses one of the most ancient and one of the most characteristically modern churches in Europe—the venerable Notre-Dame, and in sharp contrast, the fashionable Madeleine, celebrated for the splendour of its essentially mundane architecture, the luxurious attire of its female frequenters, the beauty of its music, and the eloquence of its preachers. The first stone of Notre-Dame was laid, as Victor Hugo puts it, by Tiberius, who, recognising the site of the future cathedral as well-fitted for a temple, began by erecting an altar “to the god Cerennos and to the bull Esus.” In like manner, on the hill of Sainte-Geneviève, where now stands the edifice known as the Pantheon, Mercury was at one time worshipped.

So rich is Paris in historical associations that often the same street, the same spot, recalls two widely different events. Thus the statue of Henri IV. on the Pont-Neuf commemorates the glory of the best and greatest of the French kings, and at the same time marks the very ground where, in the fourteenth century, Jacques de Molay, the Templar, was infamously burned. At No. 14 in the Rue de Béthisy Admiral Coligny died and Sophie Arnould was born. At a house in the Rue des Marais Racine wrote “Bajazet” and “Britannicus” in the room where, fifty years later, the Duchess de Bouillon is said to have poisoned Adrienne Lecouvreur. There was a time when, at the corner of the Rue du Marché des Innocents, a marble slab, inscribed with letters of gold, associated the important year of 1685 with three notable events: the arrival of an embassy from Siam, a visit from the Doge of Genoa, and the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. This strange record has disappeared, together with many other interesting memorials of various shapes and kinds: such, for example, as the iron cauldron in the Cour des Miracles, where, in the name of a whole series of kings who had played tricks with the national currency, and more than once produced national bankruptcy, coiners used to be boiled alive.

As we go further back in the history of Paris, lawlessness on the part of the inhabitants, and cruelty on that of the rulers, seem constantly to increase. Until the reign of Louis XI., Paris was without police, though laws were nominally in force, especially against stealing. Theft was punished much on the principle laid down in the inscription of the sixth century which adorned one of the walls of Lutetia, the Paris of the Romans: “If a thief is caught in the act he must, in the case of a noble, be brought to trial; in the case of a peasant, be hanged on the spot.” The capitular of Charlemagne forbade ecclesiastics to take human life: which did not prevent the abbés of different monasteries from besieging one another or crossing swords when, with their followers, they chanced to meet outside the fortified monasterial walls, whether in the plain or in the public street. The right of private warfare existed in France until 1235.

Paris has undergone atrocious sufferings through war, famine, pestilence, and calamities of all kinds. The Normans, after burning one half of Paris, allowed the remainder to be ransomed with an enormous sum of money. In one of the famines by which Paris in its early days was so often visited, people cast lots as to which should be eaten. The taxes were so excessive that many pretended to be lepers, in order to profit by the exemption accorded in such cases. But it was sometimes not well to be a leper, real or pretended; for it was proclaimed one day to the sound of horn and trumpet that lepers throughout the kingdom should be exterminated: “in consequence of a mixture of herbs and human blood, with which, rolling it up in a linen cloth and tying it to a stone, they poison the wells and rivers.”

How terrible, and often how ridiculous, were the proclamations issued in those days! In front of the Grand-Châtelet six heralds of France, clothed in white velvet, and rod in hand, were wont to announce after a plague, a war, or a famine that there was nothing more to be feared, and that the king would be graciously pleased to receive taxes as before. In the centre of the so-called “town”—Paris in general, that is to say, as distinct from the city—was “la Maubuée” (derived, according to Victor Hugo, from mauvaise fumée), where Jews innumerable were roasted over fires of pitch and green wood to punish what a chronicler of the time terms their “anthropomancy”; and what the Counsellor de l’Ancre further describes as “the marvellous cruelty they have always shown towards Christians, their mode of life, their synagogue, so displeasing to God, their uncleanliness, and their stench.” The unhappy Jews, however, were not the only victims. Close by, at the corner of the Rue du Gros-Chenet, was the place where sorcerers used to be burned. Torture, moreover, in {4} its most hideous forms was practised upon criminals even until the time of the Revolution; which, while introducing the guillotine, abolished, in addition to a variety of other torments, breaking on the wheel, and the beating of criminals to death with the iron bar.

Many of the names, still extant, of the old Paris streets recall the ferocity and the superstition of past times. The Rue de l’Arbre Sec was the Street of the Gibbet, with “Dry Tree” as its familiar name. The Rue d’Enfer, or Hell Street, was so called from a belief that this thoroughfare on the outskirts of Paris, just beyond the Luxemburg Gardens, was haunted by the fiend. In order to put an end to the scandal by which the whole neighbourhood was alarmed, it occurred to the authorities to make over the street to the Order of Capuchins who, they thought, would know how to deal with their inveterate enemy. The Capuchins accepted, with gratitude, the valuable trust; and thenceforth, whether as the result of some exorcising process or because public confidence had been restored, no more was heard of the visitor from below.

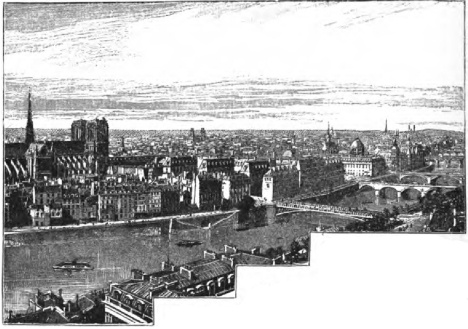

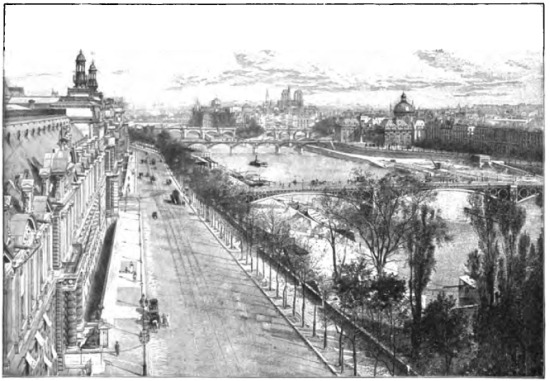

THE LEFT BANK OF THE SEINE, FROM NOTRE-DAME.

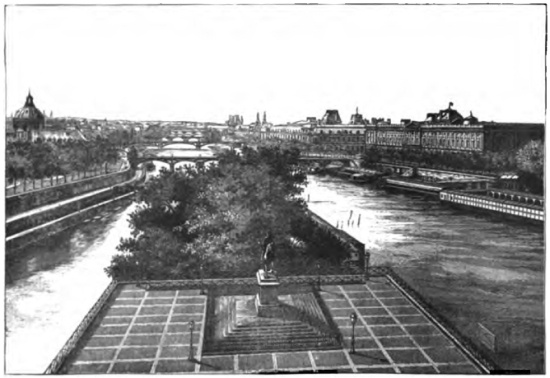

To get a complete idea of the vastness and variety of Paris, it should be seen from the towers of Notre-Dame, the Pantheon, the July Column of the Place de la Bastille, the tower of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie, the Vendôme Column, the Triumphal Arch, and, finally, the Eiffel Tower. From these different points panoramic views may be obtained which together would form a complete picture of Paris.

The shape of Paris is oval. The longest diameter—east to west—would be drawn from the Gate of Vincennes to the Gate of Auteuil; and the shorter—north to south—from the Gate of Clignancourt to the Gate of Italy.

Paris is divided longitudinally by the course of the Seine, whose windings are scarcely noticed by the observer taking a bird’s-eye view. The river looks like a silver thread between two borders of green. These are the plantations of the quays, whose trees, during the last five-and-twenty years, have become as remarkable for their luxuriant growth as for their beauty of form. From the height of our observatory we see the Island of the City, looking like a ship at anchor, with its prow towards the west.

On all sides the summits of religious edifices present themselves: the towers of Notre-Dame, the dome of the Pantheon, the turrets of Saint-Sulpice, the steeple of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the gilded cupola of the Invalides, and the lofty isolated belfry of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie.

Following the course of the Seine with careful eye, one may see its {5} twenty-one “ports”—eleven on the right bank, and ten on the left—from Bercy to the Tuileries; also, like slender bars thrown across the river, the twenty-seven bridges connecting the two banks, from the Pont-National to the viaduct of the Point du Jour.

The double line of quays—quadruple, where the islands of St. Louis and of the City divide the river in two—presents an incomparable series of stately structures; such as the Hôtel de Ville, the Palais de Justice, the Louvre, the Mint, the Institute, the Palais Bourbon, and a number of magnificent private mansions.

RIGHT BANK OF THE SEINE, FROM NOTRE-DAME.

From the Gothic steeple of the Sainte Chapelle the eye wanders to innumerable domes, built under the influence of the Renaissance; for while the domes have endured, the steeples, so numerous in ancient Paris, have, for the most part, succumbed either to fire or to the vandalism of the renovating architect. It must be remembered, too, that under the reign of Louis XIV. Gothic architecture was proscribed, as recalling “the age of barbarism.” Every new edifice was constructed in the Italian or Italo-Byzantine style. The finest, if not the most ancient, dome that Paris could ever boast was the one which crowned the central pavilion of the Tuileries Palace. The cupola of St. Peter’s was the model adopted in the early part of the sixteenth century by all French architects who had studied in Italy, or Italian architects who had settled in France; and the masterpiece of Michael Angelo at Rome was not yet finished when the first stone of the impressive and picturesque Church of Saint-Eustace was laid in 1532 at Paris. Only a few years afterwards the French architect, Philibert de l’Orme, attached to the service of Pope Paul III., returned to Paris, and, beneath the delighted eyes of Queen Catherine de Medicis, worked out the designs which he had formed under the inspiration of Michael Angelo and of Bramante. The dome, however, of Philibert de l’Orme was destined to lose its beauty through the additions made to it by other architects.

Of late years it has been the rule in Paris not to destroy but to preserve the ancient architecture of the city. “Demolish the tower of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie?” asked Victor Hugo, when, during the reconstruction and prolongation of the Rue Rivoli, the question of keeping it standing or pulling it down was under general discussion: “Demolish the tower of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie? No! Demolish the architect who suggests such a thing? Yes!” {6}

Lutetia—La Cité—Lutetia taken by Labienus—The Visit of Julian the Apostate—Besieged by the Franks—The Norman Invasion—Gradual Expansion from the Ile de la Cité to the Outer Boulevards—M. Thiers’s Line of Outworks.

LUTETIA, the ancient Paris, or Lutetia Parisiorum, as it was called by the Romans, stood in the midst of marshes. The name, derived, suggestively enough, from lutum, the Latin for mud, has been invested with a peculiar significance by those stern moralists who see in Paris nothing but a sink of iniquity. Balzac called it a “wen”; and Blucher, when some ferocious member of his staff suggested the destruction of Paris, exclaimed: “Leave it alone; Paris will destroy all France!” By a critic of less severe temperament Paris has been contemptuously described as “the tavern of Europe”—le cabaret de l’Europe. Lutetia, however, can afford to smile alike at the slurs of moralists and the sneers of cynics; and the etymology of her name need by no means alarm those of her admirers who will reflect that lilies may spring from mud, and that the richest corn is produced from the blackest soil.

The development of the Lutetia of Cæsar’s time into the Paris of our own has occupied many eventful centuries; and the centre of the development may still be seen in that little island of the so-called City—l’Ile de la Cité—once known as the Island of Lutetia. As to the dimensions of the ancient Lutetia, neither historians nor geographers are wholly agreed. The germ of Paris is, in any case, to be found in that part of the French capital which has long been known as la Cité, and which is the dullest and sleepiest part of Paris, just as inversely our “city,” distinctively so called, is the most active and energetic part of London.

The Parisians have always been given to insurrection; and their first rising was made against a ruler who was likely enough to put it down—Julius Cæsar, that is to say. Finding his power defied, Cæsar sent against the Parisians a body of troops, under the command of Labienus, who crushed the rebels in the first battle. Historians give different versions of the engagement, but modern writers are content for the most part to rely on a tradition related by an author of the fourteenth century, Raoul de Presles, who published a French version of Cæsar’s account of the Battle of Paris, enriched by notes and comments from his own pen. Labienus, according to Cæsar and Raoul de Presles, was arrested in his first attack by an impassable marsh. Then, simulating a retreat along the left bank of the Seine, he was pursued by the Gauls, in spite of Camulogenes, their cautious leader; who, unable to restrain them, fell with them at last into an ambuscade, in which chief and followers all perished.

Raoul de Presles gives some interesting details about the marsh which Labienus, on making his advance against Paris, was unable to cross. Some identify it with the Marshes of the Temple, which formed, on the north of Paris, a continuous semicircle; but Raoul de Presles seems to hold that the marsh which stopped the advance of Labienus protected Lutetia itself: that Lutetia of the Island which sprang from the mud as Venus sprang from the sea. The city of Lutetia was at that time so strong, so entirely shut in by water, that Julius Cæsar himself speaks of the difficulty of reaching it. “But since then,” says Raoul de Presles, “there has been much solidification through gravel, sand, and all kinds of rubbish being cast into it.”

After the victory of Labienus, Lutetia, which the conqueror had destroyed, was quickly re-built; and it was then governed as a Roman town. This, however, was in Cæsar’s time; and the first description of Lutetia as a city was given by Strabo some fifty years later. Thus it may safely be said that of the original Lutetia nothing whatever is known.

It is certain, nevertheless, that in the new Lutetia, built by the Romans, the most important edifices stood at the western end of the island, including a palace, on whose site was afterwards to be erected the Palace of the French Kings; while at the eastern end the most striking object was a Temple to Jupiter, in due time to be replaced by the Cathedral of Notre-Dame.

As early as the fourth century Lutetia found favour in the eyes of illustrious visitors; and the Emperor Julian, known as the “Apostate,” when, after defeating seven German kings near Strasburg, he retired to Lutetia for winter quarters, spoke of it, then and for ever afterwards, {7} as his “dear Lutetia.”

“Lutetia lætitia!”—Paris is my joy!—he might, with a certain modern writer, have exclaimed.

Julian is not the only man who, going to Paris for a few months, has stayed there several years; and Julian’s winter quarters of the year 355 so much pleased him that he remained in them until 360. Encouraged, no doubt, by what Julian, in his enthusiasm, told them about the already attractive capital of Gaul, a whole series of Roman emperors visited the city, including Valentinian I., Valentinian II., and Gratian, who left Paris in 379, never to return.

From this date Paris ceased practically to form part of the Roman Empire.

More than a century before (in 245) St. Denis had undergone martyrdom on the banks of the Seine, walking about after decapitation with his head under his arm. This strange tradition had probably its origin in a picture by some simple-minded painter, who had represented St. Denis carrying his own head like a parcel, because he could think of no more ingenious way of indicating the fate that had befallen the first apostle of Christianity in Gaul; just as St. Bartholomew has often been painted with his skin hanging across his arm like a loose overcoat.

After the defeat and death of Gratian, the government of Lutetia passed into the hands of her bishops, who often defended the city against the incursions of the barbarians.

In 476 Lutetia was besieged by the Franks, when Childeric gained possession of it, and destroyed for ever all traces of the Roman power. It now became a Frank or French town; and, “Lutetia Parisiorum” being too long a name for the unlettered Goths, was shortened by them first into “Parisius,” and ultimately, by the suppression of the two last syllables, into “Paris.”

In the ninth century Paris underwent the usual Norman invasion, by which so many European countries, from Russia to England, and from England to Sicily—not to speak of the Norman or Varangian Guard of Constantinople—were sooner or later to be visited. The “hardy Norsemen”—or Norman pirates, as the unhappy Parisians doubtless called them—started from the island of Oissel, near Rouen, where they had established themselves in force; and, moving with a numerous fleet towards Paris, laid siege to it, and, on its surrender, first pillaged it and then burnt it to the ground. Three churches alone—those of Saint-Étienne, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and Saint-Denis, near Paris—were saved, through the payment of a heavy ransom. Sixteen years later, after a sufficient interval to allow of a reconstruction, the Normans again returned, when once more the unhappy city was plundered and burnt. For twenty successive years Paris was the constant prey of the Norman pirates who held beneath their power the whole course of the Seine.

At last, however, a powerful fleet, led by a chief whom the French call “Siegfroi,” but whose real name was doubtless “Siegfried,” sustained a crushing defeat; and, simultaneously with the Norman invaders, the Carlovingian Dynasty passed away.

With the advent of the Capet Dynasty a continuous history began for Paris—in due time to become the capital of all France. Ancient Paris was three times burnt to the ground: the Paris which dates from the ninth century has often been conquered, but never burnt.

Ancient Paris, the Lutetia of the Romans, was an island enclosed between two branches of the Seine. But the river overflowed north and south, and it became necessary to construct large ditches or moats, which at once widened the boundaries of the “city.” Gradually the population spread out in every direction; and when, under Louis XIV., the line of boulevards was traced, the extreme limits of the capital were marked by this new enclosure. Then under Louis XVI., the Farmers-General, levying dues (the so-called octroi) on imports into the town, established for their own convenience certain “barriers,” at which persons bringing in food or drink were stopped until they had acquitted themselves of the appointed tax; and, connecting these “barriers,” they thus formed the line of outer boulevards.

Paris extended in time even to these outer boulevards. Then, under Louis-Philippe, at the instigation of his Minister, M. Thiers, a line of fortifications was constructed around Paris; which, proving insufficient in 1870 and 1871 to save the capital from bombardment, has in its turn been surrounded by a circle of outlying detached forts intercommunicating with one another.

The fortifications of Paris have had a strange history. At the time of their being planned, opinions in France were divided as to whether they were intended to oppose a foreign invasion or to control an internal revolt. In all probability they were meant, according to the occasion, to serve either purpose. They were not only designed by M. Thiers, but executed under his orders; and this statesman, who had made a careful {8} study of military science, lived to see them powerless against the German army of investment, and successful against the Paris Commune.

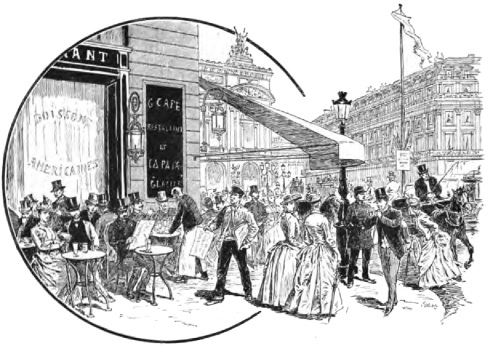

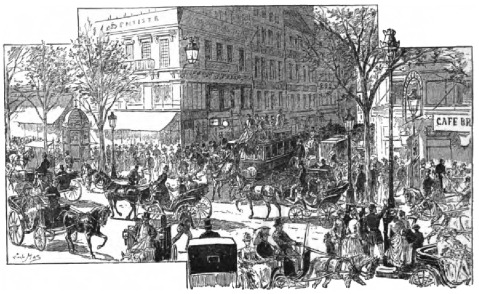

ON THE BOULEVARDS—CORNER OF PLACE DE L’OPÉRA.

Paris had been invaded and occupied in 1814, and again in 1815. On the other hand, domestic government had been upset in 1830 by a popular insurrection, which, with adequate military force to oppose it, might at once have been suppressed. Was it as patriot, people asked, or as minister of a would-be despotic king, that M. Thiers proposed to raise around Paris a new and formidable wall?

M. Thiers’s circular line of outworks played no part in connection with the successful insurrection of February, 1848, nor with the unsuccessful one of June in the same year. Nor was a single shot fired from the fortifications in connection with the coup d’État of 1851. They did not in 1871 prevent the French capital from falling into the hands of the Germans: but they delayed for a considerable time the fatal moment of surrender; and if the army of Metz could have held out a few weeks longer—if, above all, the inhabitants of the inactive south, who practically took no part in the war, had been prepared, to fight with something like the energy displayed by the Confederates against the Federals during the American Civil War—then the fortifications would have justified the views of those who had chiefly regarded them as a valuable defence against foreign invasion.

The fortifications erected by M. Thiers have since been pulled down: partly because the constantly expanding city wanted fresh building ground, partly because, in view of new plans of defence, and of the new artillery of offence, it was considered desirable to protect Paris by a system of outlying but inter-protecting forts, at a sufficient distance from the houses of the capital to render reduction by what is called “simple bombardment” impossible. In time Lutetia, with fresh developments, may require yet another new girdle. {9}

Paris and London—The Rive Gauche—The Quartier Latin—The Pantheon—The Luxemburg—The School of Medicine—The School of Fine Arts—The Bohemia of Paris—The Rive Droite—Paris Proper—“The West End.”

AN effective contrast might be drawn between London and Paris. But, unlike as they are in so many features, physical, moral, and historical, they differ most widely, perhaps, by the relative parts they have played in the history of their respective countries.

The history of Paris is the history of France itself. The decisive battles which brought the great civil and religious wars of the country to an end were fought outside or in the very streets of Paris. It was in Paris that the massacre of St. Bartholomew—darkest blot on the French annals—was perpetrated. The Revolution of 1789, again, was prepared and accomplished in the French capital; and, thenceforth, all those revolutions and coups d’état by which the government of the country was periodically to be changed had Paris for their scene. In England, on the other hand, London had little or nothing to do with the battles of the great Rebellion, the Revolution, or the two insurrections by which the Revolution was followed.

But the English visitor to Paris is in the first place struck by external points of dissimilarity. As regards the difference in the structural physiognomy of the two great capitals (less pronounced now than at one time, though Paris is still loftily, and London for the most part dwarfishly, built), it was ingeniously remarked, some fifty years ago, that the architecture of one city seemed vertical, of the other horizontal.

To pass from the houses to their inhabitants, the population of Paris is as remarkable for variety as that of London for uniformity of costume. For in Paris almost every class has its own distinctive dress. In England, and especially in London, the employer and his workmen, the millionaire and the crossing-sweeper, wear coats of the same pattern. In London, again, every work-girl, every market-woman, wears a bonnet imitated more or less perfectly from those worn by ladies of fashion.

When Gavarni first visited London, he was astonished and amused to see an old woman in a bonnet carrying a flower-pot on her head, and {10} made this grotesque figure the subject of a humorous design, with the following inscription beneath it: “On porte cette année beaucoup de fleurs sur les chapeaux.”

Shop-girls and work-girls in Paris wear neat white caps instead of ill-made, or, it may be, dilapidated bonnets; though the more aspiring among them reserve the right of appearing in a bonnet on Sundays and holidays. The French workman wears a blouse and a cap, and looks upon the hat as a sign, if not of superiority, at least of pretension.

was the burden of a song very popular with the working classes during the revolutionary days of 1848 to 1851.

Owing to the varieties of dress already touched upon, a crowd in Paris presents a less gloomy, less monotonous appearance than the black-coated mobs of London; and in harmony with the greater relief afforded by the different colours of the costumes are the animated gestures of the persons composing the crowd. Observe, indeed, a mere group of persons conversing on no matter what commonplace subject, or idly chatting as they sip their coffee together on the boulevards, and they appear to be engaged in some violent dispute.

To mention yet another point on which Paris differs from London: the most interesting part of Paris lies on the right bank of the Seine, whereas all that is interesting in London lies on the left bank of the Thames.

The left bank of the Seine possesses, however, buildings and streets of historical interest. Here, too, is the quarter of the schools: the Quartier Latin, as it is still called, not by reason of its Roman antiquities, which, except at the Hotel Cluny, would be sought for in vain, but because, in the mediæval period whence the schools for the most part date, even to comparatively modern times, Latin was the language of the student. On the “left bank,” moreover, stand the Institute, the Pantheon or Church of Ste. Geneviève, as, according to the predominance of religion or irreligion, it is alternately called; the Ste. Geneviève Library, the Luxemburg Palace, with its magnificent picture gallery, the School of Medicine, and the School of Fine Arts. Many of the great painters, too, have their studios—often little academies in themselves—on the left bank of the river; while among the famous streets on the “left bank” is that Rue du Bac so often referred to in the chronicles and memoirs of the eighteenth century. The famous Café Procope, again, literary headquarters of the encyclopædists, stands on what is now considered the wrong side of the water. So too does the Odéon Theatre, once the Théàtre Français, where, in modern as well as ancient times, so many dramatic masterpieces have been produced.

On the other hand, there is scarcely on the left bank one good hotel: certainly not one that could put forward the slightest pretension to being fashionable. Nor, except in the case of professional men connected with the hospitals or the schools, would anyone mixing in fashionable society care to give his address anywhere on the left bank.

Jules Janin, one of the most distinguished writers of his time, and one of the most popular men in the great world of Paris from the reign of Louis Philippe until that of Napoleon III., did, it is true, live for years in a house close to the Luxemburg Gardens. But Janin possessed a certain originality, and thought more of what suited himself than of what pleased others. On one occasion, having engaged to fight a duel, he failed to put in an appearance by reason of the inclemency of the weather and his disinclination to get out of bed at the early hour for which the meeting had been fixed. Such a man would not be ashamed to live on the left bank if he happened to have found a place there which harmonised with his tastes.

Apart, however, from all question of inclination and fashion, it is really inconvenient to anyone who mingles in Parisian life to live on the left bank of the Seine, remote as it is from the boulevards, the Champs Élysées, the best hotels, the best restaurants, the best cafés, and the best theatres.

At the same time, no sort of comparison can be established between the transpontine districts of Paris and those of London. In London, no one who is anyone would dream of living “on the other side of the water,” where neither picture galleries, nor public gardens, nor artists’ studios, nor famous streets, nor great houses of business, nor even magnificent shops are to be met with. Even Jules Janin, had he been an Englishman, would have declined to live in the region of Blackfriars or the Waterloo Road.

On the right bank of the Seine—the Paris West End, and something more—we find much greater concentration than in the West End of {11} London. Here, indeed, all that is most important in the artistic, financial, and fashionable life of the capital may be found within a small compass.

The Théàtre Français is close to the Bourse, and the Bourse to the Boulevard des Italiens, which leads to the Opera by a line along which stand the finest hotels, the best restaurants in Paris. From the Opera it is no far cry to the Champs Élysées, the Hyde Park of Paris; while, going along the boulevards in the opposite direction, one comes step by step to a seemingly endless series of famous theatres. All the best clubs, too, all the best book-shops and music-shops, are to be found on the most fashionable part of the boulevard, extending from the Boulevard des Italiens, past the Opera House, to the adjacent Church of the Madeleine: architecturally a repetition of the Bourse, as though commerce and religion demanded temples of the same character.

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, a Temple to Jupiter—Cæsar and Napoleon—Relics in Notre Dame—Its History—Curious Legends—“The New Church”—Remarkable Religious Ceremonies—The Place de Grève—The Days of Sorcery—Monsieur de Paris—Dramatic Entertainments—Coronation of Napoleon

THERE is no monument of ancient Paris so interesting, by its architecture and its historical associations, as the Cathedral of Notre Dame; which, standing on the site of a Temple to Jupiter, carries us back to the time of the Roman domination and of Julius Cæsar. Here, eighteen centuries later, took place the most magnificent ceremony ever seen within the walls of the actual edifice: the coronation, that is to say, of the modern Cæsar, the conqueror who ascended the Imperial throne of France on the 2nd of December, 1804.

Meanwhile, the strangest as well as the most significant things have been witnessed inside the ancient metropolitan church of Paris.

Among the curious objects deposited from time to time on the altar of Notre Dame may be mentioned a wand which Louis VII. inscribed with the confession of a fault he was alleged to have committed against the Church. Journeying towards Paris, the king had been surprised by the darkness of night, and had supped and slept at Créteil, on the invitation of the inhabitants. The village, inhabitants and all, belonged to the Chapter of Notre Dame; and the canons were much irritated at the king’s having presumed to accept hospitality indirectly at their cost. When, next day, Louis, arriving at Paris, went, after his custom, to the cathedral in order to render thanks for his safe journey, he was astonished to find the gates of Notre Dame closed. He asked for an explanation, whereupon the canons informed him that {13} since, in defiance of the privileges and sacred traditions of the Church, he had dared at Créteil to sup, free of cost to himself and at the expense of the flock of Notre Dame, he must now consider himself outside the pale of Christianity. At this terrible announcement the king groaned, sighed, wept, and begged forgiveness, humbly protesting that but for the gloom of night and the spontaneous hospitality of the inhabitants—so courteous that a refusal on his part would have been most uncivil—he would never have touched that fatal supper. In vain did the bishop intercede on his behalf, offering to guarantee to the canons the execution of any promise which the king might make in expiation of his crime; it was not until the prelate placed in their hands a couple of silver candlesticks as a pledge of the monarch’s sincerity that they would open to him the cathedral doors; and even then his Majesty had to pay the cost of his supper at Créteil, and by way of confession, to deposit on the altar of Notre Dame the now historical wand.

Louis XI., more devout even than the devout Louis VII., was equally unable to inspire his clergy with confidence. Before the discovery of printing, in 1421, manuscript books at Paris, as elsewhere, were so rare and so dear that students had much trouble in procuring even those which were absolutely necessary for their instruction. Accordingly, when Louis XI. wished to borrow from the Faculty of Medicine the writings of Rhases, an Arabian physician, he was required, before taking the book away, to deposit a considerable quantity of plate, besides the signature of a powerful nobleman, who bound himself to see that his Majesty restored the volume.

Among the many legends told in connection with Notre Dame is a peculiarly fantastic one, according to which the funeral service of a canon named Raimond Diocre, famed for his sanctity, was being celebrated by St. Bruno, when, at a point where the clergy chanted the words: Responde mihi quantas habes iniquitates? the dead man raised his head in the coffin, and replied: Justo Dei judicio accusatus sum. At this utterance all present took flight, and the ceremony was not resumed till the next day, when for the second time the clergy chanted forth: {14} Responde mihi, etc., on which the corpse again raised its head, and this time answered: Justo Dei judicio judicatus sum. Once more there was a panic and general flight. The scene, with yet another variation, was repeated on the third day, when the dead, who had already declared himself to have been “accused” and “judged” by Heaven, announced that he had been condemned: Justo Dei judicio condamnatus sum. Witness of this terrible scene, St. Bruno renounced the world, did penance, became a monk, and founded the Order of Les Chartreux.

The incident has been depicted by Lesueur, who received a commission to record on canvas the principal events in the life of the saint.

It is looked upon as certain by the historians of Paris that the Cathedral of Notre Dame stands on the site formerly occupied by a heathen temple. But how and when the transformation took place is not known, though the period is marked more or less precisely by the date of the introduction of Christianity into France. Little confidence, however, is to be placed in those authors who declare that the Paris cathedral was founded in the middle of the third century by St. Denis, the first apostle of Christianity in France; for at the very time when St. Denis was preaching the Gospel to the Parisians the severest edicts were still in force against Christians. It cannot, then, be supposed that the officials of the Roman Empire would have tolerated the erection of a Christian church. It can be shown, however, that under the episcopacy of Bishop Marcellus, about the year 375, there already existed a Christian church in the city of Paris, on the borders of the Seine and on the eastern point of the island, where a Roman temple had formerly stood. Towards the end of the sixth century the cathedral was composed of two edifices, close together, but quite distinct. One of these was dedicated to the Virgin, the other to St. Stephen the Martyr. Gradually, however, the Church of our Lady was extended and developed until it touched and embraced the Church of St. Stephen. The Church of St. Mary, as many called it, was the admiration of its time. Its vaulted roofs were supported by columns of marble, and Venantius Fortunatus, Bishop of Poitiers, declares that this was the first church which received the rays of the sun through glass windows. More than once it is said to have been burnt during the incursions of the Normans. But this is a matter of mere tradition, and the destruction of the cathedral by fire, whether it ever occurred or not, is held in any case to have been only partial.

In the twelfth century Notre Dame was, it is true, known as the “New Church.” This appellation, however, served only to distinguish it from the smaller Church of St. Stephen (St. Etienne), which had been left in its original state, without addition or renovation.

The plan of the cathedral has, like that of other cathedrals, been changed from century to century; but in spite of innumerable modifications, the original plan asserts itself. From the fourteenth to the seventeenth century the Church of Notre Dame was left nearly untouched. Then, however, in obedience to the wishes of Louis XIII., it was subjected to a whole series of pretended embellishments, for which “mutilations” would be a fitter word. In the eighteenth century, between the years 1773 and 1787, damaging “improvements,” and “restorations” of the most destructive kind, were introduced; until at the time of the Revolution the idea was entertained of depriving the venerable edifice altogether of its religious character. The outside statues were first threatened, but Chaumette saved them by dwelling upon their supposed astronomical and mythological importance. He declared before the Council of the Commune that the astronomer Dupuis (author of “L’origine de tous les Cultes”) had founded his planetary system on the figures adorning one of the lateral doors of the church. In conformity with Chaumette’s representations, the Commune spared all those images to which a symbolic significance might be attached, but pulled down and condemned the statues of the French kings which ornamented the gallery and the principal façade. The cathedral at the same time lost its name. Temple of Reason it was now, until the re-establishment of public worship, to be called. Then new mutilations were constantly perpetrated, until at last, in 1845, the work of restoring the cathedral was placed in competent hands, when, thanks to the learning, the labour, and the taste of MM. Lassus and Viollet-Leduc, Notre Dame was made what it still remains—one of the most magnificent specimens of mediæval architecture to be found in Europe. Why describe the ancient monument, when it is so much simpler to represent through drawings and engravings its most characteristic features?

Some of the most interesting, most curious facts of its history may, however, be appropriately related. The Count of Toulouse, Raymond VII., accused of having supported the Albigenses by his arms and of sharing {15} their errors, was absolved in Notre Dame from the crime of heresy after he had formally done penance in his shirt, with naked arms and feet, before the altar.

An attempt was made by a thief to steal from the altar of Notre Dame its candlesticks. After concealing himself in the roof, the man, aided by other members of his band, let down ropes, and, encircling the silver ornaments, drew them upwards to his hiding-place. In performing this exploit, however, he set fire to the hangings of the church, by which much damage was caused.

The interior of Notre Dame has in different centuries been turned to the most diverse purposes. Here at one time, in view of Church festivals, vendors of fruits and flowers held market. At other times religious mysteries, and even mundane plays, have been performed; while in the thirteenth century the Paris cathedral was the recognised asylum of all who suffered in mind or body.

A particular part of the building was reserved for patients, who were attended by physicians in holy orders. It was provided by a special edict that this hospital within a church should be kept lighted at night by ten lamps. All attempts, however, to keep order were in vain; and in consequence of the noise made by the invalids while religious service was going on, they were, one and all, excluded from the cathedral.

During the troubles caused by the captivity of King John the citizens of Paris made a vow to offer every year to Our Lady a wax candle as long as the boundary-line of the city. Every year the municipal body carried the winding taper, with much pomp, to the Church of Notre Dame, where it was received by the bishop and the canons in solemn assembly. The pious vow was kept for five hundred and fifty years, but ceased to be fulfilled at the time of the religious wars and of the League. In 1603 Paris had gained such dimensions that the ancient vow could scarcely be renewed, and in place of it, François Miron, the celebrated Provost of the Merchants, offered a silver lamp, made in the form of a ship (principal object in the arms of Paris), which he pledged himself to keep burning night and day. In Notre Dame, too, were suspended the principal flags taken from the enemy, though it was only during war time that they were thus exhibited. When peace returned, the flags were put carefully out of sight. Notre Dame, while honouring peace, was itself the scene of frequent disturbances, caused by quarrels between high religious functionaries on questions of precedence. These disputes often occurred when the representatives of foreign Powers wished to take a higher position than in the opinion of their hosts was due to them. It must be noted, too, that at Notre Dame King Henry VI. of England, then ten years old, was crowned King of France.

Under the Regency the cathedral of Paris was the scene of one of the most daring exploits performed by Cartouche’s too audacious band. A number of the robbers had entered the church in the early morning, and had succeeded in climbing up and concealing themselves behind the tapestry of the roof. Their pockets were filled with stones, and at a pre-concerted signal, just as the priest began to read the first verse of the second Psalm in the service of Vespers, they shouted in a loud voice, threw their missiles among the congregation, and cried out that the roof was falling in. A frightful panic ensued, during which the confederates of the thieves overhead helped themselves to watches, purses, and whatever valuables they could find on the persons of the terrified worshippers.

It was at Notre Dame, on the 10th of November, 1793, that the Feast of Reason was celebrated, the Goddess of Reason being impersonated by a well-known actress, the beautiful Mlle. Maillard.

The space in front of Notre Dame was at one time the scene of as many executions as the Place de Grève, which afterwards became and for some centuries remained the recognised execution ground of the French capital.

It was on the Place de Grève that Victor Hugo’s heroine, the charming Esmeralda, suffered death, while the odious monk, Claude Frollo, gazed upon her with cruel delight, till the bell-ringer, Quasimodo, who, in his own humbler and purer way, loved the unhappy gipsy girl, seized him with his powerful arms, and flung him down headlong to the flags at the foot of the cathedral.

In 1587, under the reign of Henry IV., Dominique Miraille, an Italian, and a lady of Étampes, his mother-in-law, were condemned to be hanged and afterwards burnt in front of Notre Dame for the crime of magic. The Parisians were astonished at the execution: “for,” says L’Étoile, in his Journal, “this sort of vermin have always remained free and without punishment, especially at the Court, where those who dabble in magic are called philosophers and astrologers.” With such impunity was the black art practised at this period, that Paris contained in 1572, according {16} to the confession of their chief, some 30,000 magicians.

The popularity of sorcery in Paris towards the end of the sixteenth century is easily accounted for by the fact that kings, queens, and nobles habitually consulted astrologers. Catherine de Medicis was one of the chief believers in all kinds of superstitious practices; and a column used to be shown in the flower-market from which she observed at night the course of the stars. This credulous and cruel queen wore round her waist a skin of vellum, or, as some maintained, the skin of a child, inscribed with figures, letters, and other characters in different colours, as well as a talisman, prepared for her by the astrologer Regnier, an engraving of which may be found in the Journal of Henry III. By this talisman, composed as it was of human blood, goats’ blood, and several kinds of metals melted and mixed together, under certain constellations associated with her birth, Catherine imagined that she could rule the present and foresee the future.

Magic was employed not only for self-preservation, but with the most murderous intentions. When it was used to destroy an enemy, his effigy was prepared in wax; and the thrusts and stabs inflicted upon the figure were supposed to be felt by the original. A gentleman named Lamalle, having been executed on the Place de Grève in 1574, and a wax image, made by the magician Cosmo Ruggieri, having been found upon him, Catherine de Medicis, who patronised this charlatan, feared that the wax figure might have been designed against the life of Charles IX., and that Ruggieri would therefore be condemned to death. Lamalle had maintained that the figure was meant to represent the “Great Princess”: Queen Marguerite, that is to say. But Cosmo Ruggieri was condemned, all the same, to the galleys; though his sentence—thanks, no doubt, to the personal influence of Catherine de Medicis—was never executed. Nicholas Pasquier, who gives a long account of Ruggieri in his Public Letters, declares that he died “a very wicked man, an atheist, and a great magician,” adding that he made another wax figure, on which he poured all kinds of venoms and poisons in order to bring about the death of “our great Henry.” But he was unable to attain his end; and the king, “in his sweet clemency, forgave him.”

When, after the Barricades, Henry III. left Paris, the priests of the League erased his name from the prayers of the Church, and framed new prayers for those princes who had become chiefs of the League. They prepared at the same time images of wax, which they placed on many of the altars of Paris, and then celebrated forty masses during forty hours. At each successive mass the priest, uttering certain mystic words, pricked the wax image, until finally, at the fortieth mass, he {17} pierced it to the heart, in order to bring about the death of the king. Thirteen years later, under the reign of Henry IV., the Duke de Biron, who had his head cut off in the Bastille, publicly accused Laffin, his confidant and denunciator, of being in league with the devil, and of possessing wax figures which spoke. Marie de Medicis employed, even whilst in exile, a magician named Fabroni, much hated by Richelieu, for whom Fabroni had predicted a speedy death.

It was in front of Notre Dame that by order of the princes, dukes, peers, and marshals of France, assembled in the Grand Chamber of Parliament, Damiens was condemned to do penance before being tortured and torn to pieces. He was to be tormented, by methods no matter how barbarous, until he revealed his accomplices, and was also required to make the amende honorable before the principal door of Notre Dame. Thither, in his shirt, he was conveyed on a sledge, with a lighted wax candle in his hand weighing two pounds; and there he went down on his knees, and confessed that “wickedly and traitorously he had perpetrated the most detestable act of wounding the king in the right side with the stab of a knife”; that he repented of the deed, and asked pardon for it of God, of the king, and of justice. After this he was to be carried on the sledge to the Place de Grève, where, on the scaffold, he was to undergo a variety of tortures, copied from those appointed for the punishment of Ravaillac. Finally, his goods were to be confiscated, the house where he was born pulled down, and his name stigmatised as infamous, and for ever forbidden thenceforth, under the severest penalties, to be borne by any French subject.

Damiens had been educated far above his rank. His moral character, however, was peculiarly bad. His life had been one perpetual {18} oscillation between debauchery and fanaticism. His changeableness of disposition was noticed during his imprisonment at Versailles. Sometimes he seemed thoroughly composed, as though he had suffered nothing and had nothing to suffer; at other times he burst into sudden and vehement passions, and attempted to kill himself against the walls of his dungeon or with the chains on his feet. As in one of his furious fits he had tried to bite off his tongue, his teeth were all drawn, in accordance with an official order.

When the sentence was read to him, Damiens simply remarked, “La journée sera rude.” Every kind of torture was applied to him to extort confessions. His guards remained at his side night and day, taking note of the cries and exclamations which escaped him in the midst of his sufferings. But Damiens had nothing to confess, and on the 28th of January he was carried, with his flesh lacerated and charred by fire, his bones broken, to the place of execution.

Immediately after his self-accusation in front of Notre Dame he was taken to the Place de Grève, where the hand which had held the knife was burnt with the flames of sulphur. Then he was torn with pincers in the arms and legs, the thighs and the breast, and into his wounds were poured red hot lead and boiling oil, with pitch, wax, and sulphur melted and mixed. The sufferer endured these tortures with surprising energy. He cried out from time to time, “Lord, give me patience and strength.” “But he did not blaspheme,” says Barbier, in his narrative of the scene, “nor mention any names.”

The end of the hideous tragedy was the dismemberment. The four traditional horses were not enough. Two more were added, and still the operation did not advance. Then the executioner, filled with horror, went to the neighbouring Hôtel de Ville to ask permission to use “the axe at the joints.” He was, according to Barbier, sharply rebuked by the king’s attendants, though in an account of the tragedy contributed at the time to the Gentleman’s Magazine (and derived from the gazettes published in Holland, where there was no censorship), the executioner was blamed for having delayed the employment of the axe so long.

There are conflicting accounts, too, as to the burning of the prisoner’s calves. It was said on the one hand that the garde des sceaux, Machault, caused red hot pincers to be applied in his presence to Damiens’ legs at the preliminary examination; but another version declares this to be a mistake, and ascribes the burning of his legs to the king’s attendants, who, seeing their master stabbed, are represented as punishing the assassin by the unlikely method of applying torches to his calves.

The torture of Damiens lasted many hours, and it was not till midnight, when both his legs and one of his arms had been torn off, that his remaining arm was dragged from the socket. The life of the poor wretch could scarcely have lasted so long as did the execution of the sentence passed upon him. A report of the trial was published by the Registrar of the Parliament; but the original record being destroyed, it is impossible to test the authenticity of this report. It fills four small volumes, and is entitled “Pièces Originales et Procèdures du Procès fait à Robert François Damiens, Paris, 1757.”

Ivan the Terrible, when his digestion was out of order, and he felt unequal to the effort of breakfasting, used to revive his jaded appetite by visiting the prisons and seeing criminals tortured. George Selwyn claimed to have made amends for his want of feeling in attending to see Lord Lovat’s head cut off by going to the undertaker’s to see it sewn on again, when, in presence of the decapitated corpse, he exclaimed with strange humour, and in imitation of the voice and manner of the Lord Chancellor at the trial:—“My Lord Lovat, your lordship may rise.” This dilettante in the sufferings of others is known to have paid a visit to Paris for the express purpose of seeing Damiens torn in pieces. On the day of the execution, according to Mr. Jesse (“George Augustus Selwyn and his contemporaries”), “he mingled with the crowd in a plain undress and bob wig,” when a French nobleman, observing the deep interest he took in the scene, and supposing from the simplicity of his attire that he was a person of the humbler ranks in life, chose to imagine that the stranger must infallibly be an executioner. “Eh, bien, monsieur,” he said, “êtes-vous arrivé pour voir ce spectacle?” “Oui, monsieur.” “Vous êtes bourreau?” “Non, non, monsieur, je n’ai pas cet honneur; je ne suis qu’un amateur.”

Wraxall tells the story somewhat differently. “Selwyn’s nervous irritability,” he says, “and anxious curiosity to observe the effect of dissolution on men, exposed him to much ridicule, not unaccompanied with censure. He was accused of attending all executions, disguised sometimes, to elude notice, in female attire. I have been assured that in 1756 (or 1757) he went over to Paris expressly for the purpose of witnessing the last moments of Damiens, who expired in the most acute {19} tortures for having attempted the life of Louis XV. Being among the crowd, and attempting to approach too near the scaffold, he was at first repulsed by one of the executioners, but having explained that he had made the journey from London solely with a view to be present at the punishment and death of Damiens, the man immediately caused the people to make way, exclaiming at the same time:—‘Faites place pour monsieur; c’est un Anglais et un amateur.’”

According to yet another story on this doleful subject, for which Horace Walpole is answerable, the Paris executioner, styled “Monsieur de Paris,” was surrounded by a number of provincial executioners, “Monsieur de Rouen,” “Monsieur de Bordeaux,” and so on. Selwyn joined the group, and on explaining to the Paris functionary that he was from London, was saluted with the exclamation, “Ah, monsieur de Londres!”