Title: Faux's Memorable Days in America, 1819-20; and Welby's Visit to North America, 1819-20, part 2 (1820)

Author: W. Faux

Adlard Welby

Editor: Reuben Gold Thwaites

Release date: March 18, 2013 [eBook #42364]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Early Western Travels

1748-1846

Volume XII

A Series of Annotated Reprints of some of the best

and rarest contemporary volumes of travel,

descriptive of the Aborigines and Social

and Economic Conditions in the Middle

and Far West, during the Period

of Early American Settlement

Edited with Notes, Introductions, Index, etc., by

Reuben Gold Thwaites, LL.D.

Editor of "The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents," "Original

Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition," "Hennepin's

New Discovery," etc.

Volume XII

Part II (1820) of Faux's Memorable Days in America, 1819-20;

and Welby's Visit to North America, 1819-20.

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1905

Copyright 1905, by

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

| I | ||

| Memorable Days in America: being a Journal of a Tour to the United States, etc. (Part II: January 1-July 21, 1820.) William Faux | 11 | |

II | ||

| A Visit to North America and the English Settlements in Illinois, with a Winter Residence at Philadelphia; solely to ascertain the actual prospects of the Emigrating Agriculturist, Mechanic, and Commercial Speculator. Adlard Welby | ||

| Author's Dedication | 145 | |

| Author's Preface | 147 | |

| Text | ||

| The Voyage | 151 | |

| Ship Cookery | 156 | |

| Situation of a Passenger on board ship | 156 | |

| Drive to the Falls of the Passaic River, Jersey State | 166 | |

| Philadelphia | 172 | |

| A Pensilvanian Innkeeper | 188 | |

| American Waiters | 196 | |

| Servants | 199 | |

| Black Population in Free Pensilvania | 200 | |

| Night | 200 | |

| Americans and Scots | 201 | |

| Virginia | 202 | |

| Wheeling | 204 | |

| State of Ohio | 205 | |

| Kentucky. Maysville or Limestone | 214 | |

| An Odd Mistake | 218 | |

| Lexington, Kentucky | 221 | |

| Frankfort[Pg 6] | 222 | |

| Louisville | 226 | |

| Indiana | 227 | |

| Vincennes (Indiana) | 236 | |

| A Visit to the English Settlement in the Illinois | 248 | |

| Harmony | 260 | |

| A Winter at Philadelphia | 294 | |

| Horrible Execution! | 309 | |

| Lectures on Anatomy | 314 | |

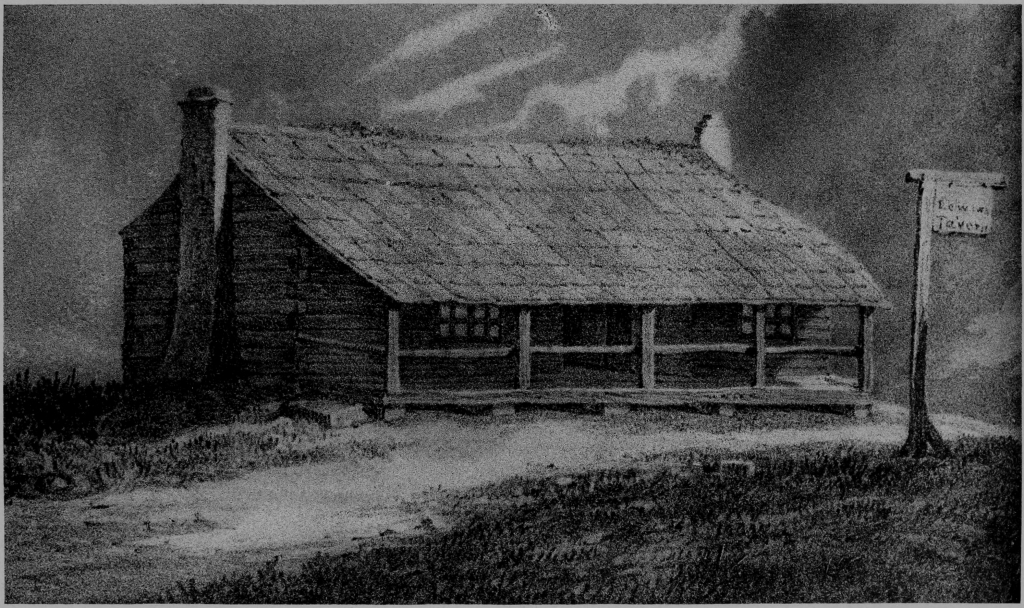

| "Log Tavern, Indiana" | 142 |

| Facsimile of title-page to Welby | 143 |

| "Little Brandywine, Pennsylvania" | 176 |

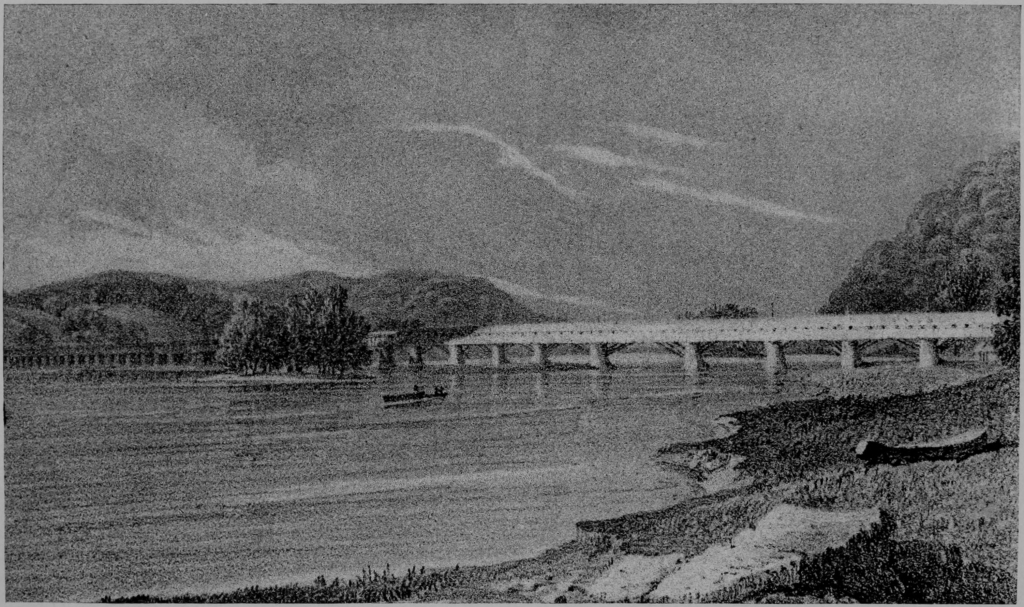

| "Bridge at Columbia, Pennsylvania" | 179 |

| "Susquehannah River at Columbia" | 184 |

| "Place of Worship & Burial Ground, at Ligonier Town, Pennsylvania" | 185 |

| "Widow McMurran's Tavern, Scrub Ridge" | 189 |

| "View on Scrub Ridge" | 193 |

| Wooden scoop (text cut) | 203 |

| "Ferry at Maysville, on the Ohio" | 209 |

| "Maysville, on the Ohio, Kentucky" | 215 |

| "Frankfort, Kentucky" | 224 |

| "The Church at Harmonie" | 264 |

| "Bridge at Zanesville, Ohio" | 277 |

| "View at Fort Cumberland, Maryland" | 281 |

| "View at Fort Cumberland, Maryland" | 286 |

Part II (1820) of Faux's Memorable Days in America

November 27, 1818-July 21, 1820

Reprint of the original edition: London, 1823. Part I is comprised

in Volume XI of our series

January 1st, 1820.—I left Princeton at ten o'clock, with Mr. Phillips and Mr. Wheeler; and here parted with my good and kind friend Ingle.

I met and spoke, ten miles off, with two hog-jobbing judges, Judge Prince and Judge Daniel,104 driving home twenty fat hogs, which they had just bought.

I reached, and rested at Petersburgh,105 consisting of fifteen houses. I passed good farms. Our landlord of this infant town, though having an [333] ostler, was compelled to groom, saddle, unsaddle, and to do all himself. Having fifty dollars owing to him, from a gentleman of Evansville, he arrested him, when he went into the bounds; then he sued one of the bondsmen, who also entered the bounds. The squire is next to be sued, who, it is expected, will do likewise.

Sunday, 2nd.—I rode thirty-one miles this day, and rested at Edmonstone, in a little cold log-hole, out of which I turned an officer's black cat, which jumped from the roof into our faces, while in bed; but she soon found her way in again, through a hole in the roof. The cat liked our fire. We got no coffee nor tea, but cold milk and pork, and corn cake.

3rd.—Travelled all day, through the mud-holes formed by springs running from countless hills, covered with fine timber, to breakfast, at three o'clock, p. m. I supped and slept at Judge Chambers's, a comfortable house, and saw again the judge's mother, of eighty, whose activity and superior horsemanship, I have before mentioned. I smoked a segar with Mrs. Judge, while she smoked her pipe, (the first pipe I have seen here.) She, as well as the old lady, is a quaker. The judge was gone to the metropolitan town of Coridon, being a senator, on duty.106 The land which I passed over all this day, seemed poor, but full of wild turkeys and bears.

4th.—I reached Miller's to supper, but found no [334] coffee; cold milk only, as a substitute. The ride hither is interesting, through a fine rolling country. The wolves howled around us all night.

5th.—Passed the Silver Hills,107 from the summit of which is a fine, extensive prospect of Kentucky, the Ohio, and of Louisville, where we breakfasted. I called with Mr. Flower's letter to Archer, who was out. I received the present of a cow-hide whip, from a lady, and promised to treat the beast kindly, for her sake. Judge Waggoner recently shook hands at a whiskey-shop, with a man coming before him that day, to be tried for murder. He drank his health, and wished him well through.

I rode seven miles with an intelligent old Kentucky planter, having four children, who cultivate his farm,[Pg 13] without negroes. He says, "Kentucky is morally and physically ruined. We have been brought up to live without labour: all are demoralized. No man's word or judgment is to be taken for the guidance and government of another. Deception is a trade, and all are rogues. The west has the scum of all the earth. Long ago it was said, when a man left other States, he is gone to hell, or Kentucky. The people are none the better for a free, good government. The oldest first settlers are all gone or ruined. Your colt, sir, of one hundred dollars, is worth only fifteen dollars. At Louisville, as good a horse can be bought at ten dollars, or fifteen dollars. You are therefore cheated."

The Missouri territory boasts the best land in [335] the country, but is not watered by springs. Wells are, however, dug, abounding in good water, says our hearty landlord, just returned from viewing that country.

The bottom land is the finest in the world. Corn, from sixty to eighty bushels, and wheat, from forty to sixty bushels an acre. The best prairies are full of fine grass, flowers, and weeds, not coarse, benty, sticky grass, which denotes the worst of prairie land. Grass, of a short fine quality, fit for pasture or hay, every where abounds. The country is full of wild honey, some houses having made seven and eight barrels this season, taken out of the trees, which are cut down without killing the bees. These industrious insects do not sting, but are easily hived and made tame. Our landlord likes the Missouri, but not so well as Old Kentucky.

Two grim, gaunt-looking men burst into our room, at two, this morning; and by six, the landlord disturbed us by cow-hiding his negro, threatening to squeeze the life out of him.[Pg 14]

6th.—I rode all day through a country of fine plantations, and reached Frankfort to supper, with the legislative body, where I again met my gay fellow-traveller, Mr. Cowen. It was interesting to look down our table, and contemplate the many bright, intelligent faces around me: men who might honour any nation. As strangers, we were [336] invited by the landlord, (the best I have seen) to the first rush for a chance at the table's head.

7th.—I travelled this day through a fine country of rich pasture and tillage, to Lexington City, to Keen's excellent tavern. I drank wine with Mr. Lidiard, who is removing eastward, having spent 1,100l. in living, and travelling to and fro. Fine beef at three cents per lb. Fat fowls, one dollar per dozen. Who would not live in old Kentucky's first city?

8th.—Being a wet day, I rested all day and this night. Prairie flies bleed horses nearly to death. Smoke and fire is a refuge to these distressed animals. The Indian summer smoke reaches to the Isle of Madeira.

Visited the Athenæum. Viewed some fine horses, at two hundred dollars each.

Sunday, 9th.—I quitted Lexington, and one of the best taverns in America, for Paris, Kentucky, and a good, genteel farm-house, the General Washington, twenty-three miles from the city, belonging to Mr. Hit, who, though owning between four hundred and five hundred acres of the finest land in Kentucky, does not think it beneath him to entertain travellers and their horses, on the best fare and beds in the country. He has been offered sixty dollars, and could now have forty dollars an acre, for his land, which averages thirty bushels of wheat, and sixty bushels of corn per acre, and, in [337] natural or artificial grass, is the first in the world. Sheep, (fine stores) one[Pg 15] dollar per head; beef, fine, three cents per lb., and fowls, one dollar per dozen.

10th.—Rode all day in the rain and mud, and through the worst roads in the universe, frequently crossing creeks, belly deep of our horses. Passed the creek at Blue-lick, belly deep, with sulphurous water running from a sulphur spring, once a salt spring. The water stinks like the putrid stagnant water of an English horse-pond, full of animal dung. This is resorted to for health.

Five or six dirkings and stabbings took place, this fall, in Kentucky.

11th.—Breakfasted at Washington, (Kentucky) where we parted with Mr. Phillips, and met the Squire, and another gentleman, debating about law. Rested at Maysville, a good house, having chambers, and good beds, with curtains. The steam-boats pass this handsome river town, at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles an hour. To the passenger, the effect is beautiful, every minute presenting new objects of attraction.

12th.—Crossed the Ohio in a flat, submitting to Kentuckyan imposition of seventy-five cents a horse, instead of twenty-five, because we were supposed to be Yankees. "We will not," said the boat-man, "take you over, for less than a dollar each. We heard of you, yesterday. The gentleman in the cap (meaning me) looks as though he [338] could afford to pay, and besides, he is so slick with his tongue. The Yankees are the smartest of fellows, except the Kentuckyans." Sauciness and impudence are characteristic of these boat-men, who wished I would commence a bridge over the river.

Reached Union town, Ohio,108 and rested for the night.[Pg 16]

13th.—Breakfasted at Colonel Wood's. A fine breakfast on beef, pork-steaks, eggs, and coffee, and plenty for our horses, all for fifty cents each. Slept at Colonel Peril's, an old Virginian revolutionary soldier, living on 400 acres of fine land, in a good house, on an eminence, which he has held two years only. He now wishes to sell all at ten dollars an acre, less than it cost him, because he has a family who will all want as much land each, in the Missouri, at two dollars. He never had a negro. He knows us to be English from our dialect. We passed, this day, through two or three young villages.

14th.—Breakfasted at Bainbridge,109 where is good bottom land, at twenty to thirty dollars an acre, with improvements. The old Virginian complains of want of labourers. A farmer must do all himself. Received of our landlady a lump of Ohio wild sugar, of which some families make from six to ten barrels a-year, sweet and good enough.

Reached Chilicothé, on the Sciota river, to [339] sup and rest at the tavern of Mr. Madera, a sensible young man. Here I met Mr. Randolph, a gentleman of Philadelphia, from Missouri and Illinois, who thinks both sickly, and not to be preferred to the east, or others parts of the west. I saw three or four good houses, in the best street, abandoned, and the windows and doors rotting out for want of occupants.

15th.—I rode all day through a fine interesting country, abounding with every good thing, and full of springs and streams. Near Lancaster,110 I passed a large high ridge[Pg 17] of rocks, which nature has clothed in everlasting green, being beautified with the spruce, waving like feathers, on their bleak, barren tops. I reached Lancaster to rest; a handsome county seat, near which land is selling occasionally from sixteen dollars to twenty dollars. A fine farm of 170 acres, 100 being cleared, with all improvements, was sold lately by the sheriff, at sixteen dollars one cent an acre, much less than it cost. Labour is to be had at fifty cents and board, but as the produce is so low, it is thought farming, by hired hands, does not pay. Wheat, fifty cents; corn, 33½ cents; potatoes, 33 cents a bushel; beef, four dollars per cwt.; pork, three dollars; mutton none; sheep being kept only for the wool, and bought in common at 2s. 8d. per head.

Met Judge and General ——, who states that four millions of acres of land will this year [340] be offered to sale, bordering on the lakes. Why then should people go to the Missouri? It is not healthy near the lakes, on account of stagnant waters, made by sand bars, at the mouth of lake rivers. The regular periodical rising and falling of the lakes is not yet accounted for. There is no sensible diminution, or increase of the lake-waters. A grand canal is to be completed in five years, when boats will travel.111

Sunday, 16th.—I left Lancaster at peep of day, travelling through intense cold and icy roads to Somerset, eighteen miles, in five hours, to breakfast.112 Warmed at an old quarter-section man, a Dutch American, from Pennsylvania. He came here eleven years since, cleared seventy acres, has eight children, likes his land, but says, produce is too low to make it worth raising. People[Pg 18] comfortably settled in the east, on good farms, should stay, unless their children can come and work on the land. He and his young family do all the work. Has a fine stove below, warming the first, and all other floors, by a pipe passing through them.

I slept at a good tavern, the keeper of which is a farmer. All are farmers, and all the best farmers are tavern-keepers. Farms, therefore, on the road, sell from 50 to 100 per cent more than land lying back, though it is no better in quality, and for mere farming, worth no more. But on the road, a farm and frequented tavern is found to be [341] a very beneficial mode of using land; the produce selling for double and treble what it will bring at market, and also fetching ready money. Labour is not to be commanded, says our landlord.

17th.—Started at peep of day in a snow-storm, which had covered the ground six inches deep. Breakfasted at beautiful Zanesville, a town most delightfully situated amongst the hills. Twelve miles from this town, one Chandler, in boring for salt, hit upon silver; a mine, seven feet thick, 150 feet below the surface. It is very pure ore, and the proprietor has given up two acres of the land to persons who have applied to the legislature to be incorporated. He is to receive one-fifth of the net profits.

18th.—I rode all day through a fine hilly country, full of springs and fountains. The land is more adapted for good pasture than for cultivation. Our landlord, Mr. Gill, states that wheat at fifty cents is too low; but, even at that price, there is no market, nor at any other. In some former years, Orleans was a market, but now it gets supplied from countries more conveniently situated than Ohio, from which it costs one dollar, or one dollar[Pg 19] and a quarter per barrel, to send it. Boats carrying from 100 to 500 barrels, sell for only 16 dollars.

From a conversation, with an intelligent High Sheriff of this county, I learn that no common debtor has ever lain in prison longer than five [342] days. None need be longer in giving security for the surrender of all property.

19th.—Reached Wheeling late at night, passing through a romantic, broken, mountainous country, with many fine springs and creeks. Thus I left Ohio, which, thirty years ago, was a frontier state, full of Indians, without a white man's house, between Wheeling, Kaskasky, and St. Louis.

20th.—Reached Washington, Pennsylvania, to sleep, and found our tavern full of thirsty classics, from the seminary in this town.

21st.—Reached Pittsburgh, through a beautiful country of hills, fit only for pasture. I viewed the fine covered bridges over the two rivers Monongahela and Allegany, which cost 10,000 dollars each. The hills around the city shut it in, and make the descent into it frightfully precipitous. It is most eligibly situated amidst rocks, or rather hills, of coal, stone, and iron, the coals lying up to the surface, ready for use. One of these hills, or coal banks, has been long on fire, and resembles a volcano. Bountiful nature has done every thing for this rising Birmingham of America.

We slept at Wheeling, at the good hotel of Major Spriggs, one of General Washington's revolutionary officers, now near 80, a chronicle of years departed.113

22nd.—Bought a fine buffalo robe for five dollars. [343] The buffaloes, when Kentucky was first settled, were shot,[Pg 20] by the settlers, merely for their tongues; the carcase and skin being thought worth nothing, were left where the animal fell.

Left Pittsburgh for Greensburgh, travelling through a fine, cultivated, thickly settled country, full of neat, flourishing, and good farms, the occupants of which are said to be rich. Land, on the road, is worth from fifteen to thirty dollars; from it, five to fifteen dollars per acre. The hills and mountains seem full of coal-mines and stone-quarries, or rather banks of coal and stone ever open gratuitously to all. The people about here are economical and intelligent; qualities characteristic of Pennsylvania.

Sunday, 23d.—We agreed to rest here until the morrow; finding one of our best horses sick; and went to Pittsburgh church.

24th.—My fellow traveller finding his horse getting worse, gave him away for our tavern bill of two days, thus paying 175 dollars for two days board. While this fine animal remained ours, no doctor could be found, but as soon as he became our landlord's, one was discovered, who engaged to cure him in a week. Mr. Wheeler took my horse, and left me to come on in the stage, to meet again at Chambersburgh.

The country round about here is fine, but there is no market, except at Baltimore, at five dollars a barrel for flour. The carriage costs two and half [344] dollars. I saw two young ladies, Dutch farmers' daughters, smoking segars in our tavern, very freely, and made one of their party. Paid twelve dollars for fare to Chambersburgh.114

Invited to a sleying party of ten gentlemen, one of[Pg 21] whom was the venerable speaker (Brady) of the senate of this state. They were nearly all drunk with apple-toddy, a large bowl of which was handed to every drinker. One gentleman returned with a cracked skull.

25th.—Left this town, at three o'clock in the morning, in the stage, and met again at Bedford, and parted, perhaps, for ever, with my agreeable fellow-traveller, Mr. Wheeler, who passed on to New York. Passed the Laurel-hill, a huge mountain, covered with everlasting green, and a refuge for bears, one of which was recently killed with a pig of 150lbs. weight in his mouth.

26th.—Again mounted my horse, passing the lonely Allegany mountains, all day, in a blinding snow-storm, rendering the air as dense as a November fog in London. Previous to its coming on, I found my naked nose in danger. The noses of others were wrapped up in flannel bags, or cots, and masks for the eyes, which are liable to freeze into balls of ice.

Passed several flourishing villages. The people here seem more economical and simple, than in other states. Rested at M'Connell's town, 100 miles from Washington city.

[345] 27th.—Crossed the last of the huge Allegany mountains, called the North Mount, nine miles over, and very high. My horse was belly deep in snow.

Breakfasted at Mercersburgh, at the foot of the above mountain, and at the commencement of that fine and richest valley in the eastern states, in which Hagar's town stands, and which extends through Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, from 100 to 200 miles long, and from 30 to 40 broad. Land here, three years ago, sold at 100 to 120 dollars, although now at a forced sale, 160 acres sold for only 1,600 dollars, with improvements, in Penn[Pg 22]sylvania. And if, says my informant, the state makes no law to prevent it, much must come into the market, without money to buy, except at a ruinous depreciation.

Passed Hagar's town, to Boonsburgh, to rest all night, after 37 miles travel.

The old Pennsylvanian farmer, in answer to "How do you do without negroes?" said, "Better than with them. I occupy of my father 80 acres in this valley, and hire all my hands, and sell five loads of flour, while some of the Marylanders and Virginians cannot raise enough to maintain their negroes, who do but little work."

28th.—Breakfasted on the road; passed Middletown, with two fine spires, a good town; and also Frederick town, a noble inland town, and next to Lancaster, in Pennsylvania, and the first [346] in the United States. It has three beautiful spires. It is much like a second rate English town, but not so cleanly; something is dirty, or in ruins. It stands at the foot of the Blue Ridge, in the finest, largest vale in the world, running from the eastern sea to the Gulf of Mexico.

Rested at Windmiller's, a stage-house, thirty miles from Washington, distinguished only by infamous, ungenerous, extortion from travellers. Here I paid 75 cents for tea; 25 cents for a pint of beer, 9s. sterling for a bushel of oats and corn, and 50 cents for hay for the night. The horse cost 6s. 9d. in one night.

29th.—Rode from seven till eleven o'clock, sixteen miles to breakfast, at Montgomery-court-house, all drenched in rain. I reached Washington city, at six this evening. Here, for the first time, I met friend Joseph Lancaster, full of visionary schemes, which are unlikely to produce him bread.

Sunday, 30th.—Went to Congress-hall, and heard grave[Pg 23] senators wrangling about slavery. Governor Barbour spoke with eloquence.

Friend Lancaster's daily and familiar calls on the great, and on his Excellency, the President, about schooling the Indians, and his praises of the members, are likely to wear out all his former fame, already much in ruins. I was this day introduced by him to —— Parr, Esq., an English gentleman of fortune, from Boston, Lincolnshire, [347] who has just returned from a pedestrian pilgrimage to Birkbeck and the western country.

February 1st.—I again went to Congress, where I heard Mr. Randolph's good speech on the Missouri question. This sensible orator continually refers to English authors and orators, insomuch that all seemed English. These American statesmen cannot open their mouths without acknowledging their British origin and obligations.—I shall here insert some observations on the constitution and laws of this country, and on several of the most distinguished members of Congress, for which I am indebted to the pen of G. Waterstone, Esq., Congressional Librarian at Washington.115

Observations on the Constitution and Laws of the United States, with Sketches of some of the most prominent public Characters.

Like the Minerva of the ancients, the American people have sprung, at once, into full and vigorous maturity, with[Pg 24]out the imbecility of infancy, or the tedious process of gradual progression. They possess none of the thoughtless liberality and inconsiderate confidence of youth; but are, already, distinguished by the cold and cautious policy of declining life, rendered suspicious by a long acquaintance with the deceptions and the vices of the world.

Practitioners of jurisprudence have become [348] almost innumerable, and the great end of all laws, the security and protection of the citizen, is in some degree defeated. It is to the multiplicity and ambiguity of the laws of his age, that Tacitus has ascribed most of the miseries which were then experienced; and this evil will always be felt where they are ambiguous and too numerous. In vain do the Americans urge that their laws have been founded on those of England, the wisdom and excellence of which have been so highly and extravagantly eulogized. The difference, as Mably correctly observes, between the situation of this country and that is prodigious;116 the government of one having been formed in an age of refinement and civilization, and that of the other, amidst the darkness and barbarism of feudal ignorance. In most of the states the civil and criminal code is defective; and the latter, like that of Draco, is often written in blood. Why should not each state form a code of laws for itself, and cast off this slavish dependence on Great Britain, whom they pretend so much to dislike?

With a view of explaining more perfectly the nature of this constitution, I will briefly exhibit the points in which the British and American governments differ [349].[Pg 25]

| In England. | In America. |

| I. The king possesses imperial dignity. | There is no king; the president acts as the chief magistrate of the nation only. |

| II. This imperial dignity is hereditary and perpetual. | The presidency lasts only four years. |

| III. The king has the sole power of making war and peace, and of forming treaties with foreign powers. | The president can do neither, without the consent of Congress. |

| IV. The king alone can levy troops, build fortresses, and equip fleets. | The president has no such power: this is vested in Congress. |

| V. He is the source of all judicial power, and the head of all the tribunals of the nation. | The executive has only the appointment of judges, with the consent of the senate, and is not connected with the judiciary. |

| VI. He is the fountain of all honour, office, and privilege; can create peers, and distribute titles and dignities. | The president has no such power. There are no titles, and he can only appoint to office, by and with the consent of the senate. |

| VII. He is at the head of the national church, and has supreme control over it. | There is no established church. |

| VIII. He is the superintendent of commerce; regulates the weights and measures, and can alone coin money and give currency to foreign coin. | The president has no such power. |

| IX. He is the universal proprietor of the kingdom. | The president has nothing to do with the property of the United States [350]. |

| X. The king's person is sacred and inviolate; he is accountable to no human power, and can do no wrong. | The president is nothing more than an individual, is amenable like all civil officers, and considered as capable of doing wrong as any other citizen. |

| XI. The British legislature contains a house of lords, 300 nobles, whose seats, honours, and privileges are hereditary. | There are no nobles, and both houses of Congress are elected. |

It may, perhaps, be unnecessary to adduce more points of difference to illustrate the nature of the American government. These are amply sufficient to demonstrate the entire democratic tendency of the constitution of the United States, and the error under which those persons labour, who believe that but few differences, and those immaterial and unimportant, exist between these two governments. They have, indeed, in common the Habeas Corpus and the Trial by Jury, the great bulwarks of civil liberty, but in almost every other particular they disagree.

The second branch of this government is the legislature. This consists of a Senate and House of Representatives; the members of the latter are chosen every two years by the people; and those of the former, every six years by the legislatures of the different states. It is in this branch that the American government differs from the republics of ancient and modern times; it is this which [351] makes it not a pure, but a representative democracy; and it is this which gives it such a decided superiority over all the governments in the world. Experience has demonstrated the impracticability of assembling a numerous collection of people to frame laws, and their incompetency, when assembled, for judicious deliberation and prompt and unbiassed decision. The passions of illiterate and unthinking men are easily roused into action and inflamed to madness. Artful and designing demagogues are too apt to take advantage of those imbecilities of our nature, and to convert them to the basest purposes.

The qualifications of representatives are very simple. It is only required that they should be citizens of the United States, and have attained the age of twenty-five. The moment their period of service expires, they are again,[Pg 27] unless re-elected, reduced to the rank and condition of citizens. If they should have acted in opposition to the wishes and interests of their constituents, while performing the functions of legislation, the people possess the remedy and can exercise it without endangering the peace and harmony of society; the offending member is dropped, and his place supplied by another, more worthy of confidence. This consciousness of responsibility, on the part of the representatives, operates as a perpetual guarantee to the people, and protects and secures them in the enjoyment of their political and civil liberties.

[352] It must be admitted that the Americans have attained the Ultima Thulé in representative legislation, and that they enjoy this inestimable blessing to a much greater extent than the people of Great Britain. Of the three distinct and independent branches of that government, one only owes its existence to the free suffrages of the people, and this, from the inequality of representation, the long intervals between the periods of election, and the liability of members, from this circumstance, to be corrupted, is not so important and useful a branch as might otherwise be expected. Imperfect, however, as it is, the people, without it, would indeed be slaves, and the government nothing more than a pure monarchy.

The American walks abroad in the majesty of freedom; if he be innocent, he shrinks not from the gaze of upstart and insignificant wealth, nor sinks beneath the oppression of his fellow-man. Conscious of his rights and of the security he enjoys, by the liberal institutions of his country, independence beams in his eye, and humanity glows in his heart. Has he done wrong? He knows the limits of his punishment, and the character of his judges. Is he innocent? He feels that no power on earth can crush[Pg 28] him. What a condition is this, compared with that of the subjects of almost all the European nations!

As long as it is preserved, the security of the citizen and the union of the states, will be guaranteed, [353] and the country thus governed, will become the home of the free, the retreat of misery, and the asylum of persecuted humanity. As a written compact, it is a phenomenon in politics, an unprecedented and perfect example of representative democracy, to which the attention of mankind is now enthusiastically directed. Most happily and exquisitely organized, the American constitution is, in truth, at once "a monument of genius, and an edifice of strength and majesty." The union of its parts forms its solidity, and the harmony of its proportions constitutes its beauty. May it always be preserved inviolate by the gallant and highminded people of America, and may they never forget that its destruction will be the inevitable death-blow of liberty, and the probable passport to universal despotism!

The speaker of the House of Representatives is Mr. Clay, a delegate from Kentucky, and who, not long ago, acted a conspicuous part, as one of the American commissioners at Ghent.117 He is a tall, thin, and not very muscular man; his gait is stately, but swinging; and his countenance, while it indicates genius, denotes dissipation. As an orator, Mr. Clay stands high in the estimation of his countrymen, but he does not possess much gracefulness or elegance of manner; his eloquence is impetuous and vehement; it rolls like a torrent, but like a torrent which is sometimes irregular, and occasionally obstructed. Though there is a [354] want of rapidity and fluency in his elocu[Pg 29]tion, yet he has a great deal of fire and vigour in his expression. When he speaks he is full of animation and earnestness; his face brightens, his eye beams with additional lustre, and his whole figure indicates that he is entirely occupied with the subject on which his eloquence is employed. In action, on which Demosthenes laid such peculiar emphasis, and which was so highly esteemed among the ancients, Mr. Clay is neither very graceful nor very imposing. He does not, in the language of Shakespear, "so suit the word to the action, and the action to the word, as not to o'erstep the modesty of nature." In his gesticulation and attitudes, there is sometimes an uniformity and awkwardness that lessen his merit as an orator, and in some measure destroy the impression and effect his eloquence would otherwise produce. Mr. Clay does not seem to have studied rhetoric as a science, or to have paid much attention to those artificial divisions and rhetorical graces and ornaments on which the orators of antiquity so strongly insist. Indeed, oratory as an art is but little studied in this country. Public speakers here trust almost entirely to the efficacy of their own native powers for success in the different fields of eloquence, and search not for the extrinsic embellishments and facilities of art. It is but rarely they unite the Attic and Rhodian manner, and still more rarely do they devote their attention to the acquisition [355] of those accomplishments which were, in the refined ages of Greece and Rome, considered so essential to the completion of an orator. Mr. Clay, however, is an eloquent speaker; and notwithstanding the defects I have mentioned, very seldom fails to please and convince. His mind is so organized that he overcomes the difficulties of abstruse and complicated subjects, apparently without the toil of investigation or the labour[Pg 30] of profound research. It is rich, and active, and rapid, grasping at one glance, connections the most distant, and consequences the most remote, and breaking down the trammels of error and the cobwebs of sophistry. When he rises to speak he always commands attention, and almost always satisfies the mind on which his eloquence is intended to operate. The warmth and fervor of his feelings, and the natural impetuosity of his character, which seem to be common to the Kentuckians, often indeed lead him to the adoption of opinions, which are not, at all times, consistent with the dictates of sound policy. Though ambitious and persevering, his intentions are good and his heart is pure; he is propelled by a love of country, but yet is solicitous of distinction; he wishes to attain the pinnacle of greatness without infringing the liberties, or marring the prosperity of that land of which it seems to be his glory to be a native.

[356] The prominent traits of Mr. Clay's mind are quickness, penetration, and acuteness; a fertile invention, discriminating judgment, and good memory. His attention does not seem to have been much devoted to literary or scientific pursuits, unconnected with his profession; but fertile in resources, and abounding in expedients, he is seldom at a loss, and if he is not at all times able to amplify and embellish, he but rarely fails to do justice to the subject which has called forth his eloquence. On the most complicated questions, his observations made immediately and on the spur of the occasion, are generally such as would be suggested by long and deep reflection. In short, Mr. Clay has been gifted by nature with great intellectual superiority, which will always give him a decided influence in whatever sphere it may be his destiny to revolve.[Pg 31]

Mr. Clay's manners are plain and easy. He has nothing in him of that reserve which checks confidence, and which some politicians assume; his views of mankind are enlarged and liberal; and his conduct as a politician and a statesman has been marked with the same enlarged and liberal policy. As Speaker of the House of Representatives, he presides generally with great dignity, and decides on questions of order, sometimes, indeed, with too much precipitation, but almost always correctly. It is but seldom his decisions are disputed, [357] and when they are, they are not often reversed.118

"A Statesman," says Mirabeau, "presents to the mind the idea of a vast genius improved by experience, capable of embracing the mass of social interests, and of perceiving how to maintain true harmony among the individuals of which society is composed, and an extent of information which may give substance and union to the different operations of government."

Mr. Pinkney119 is between fifty and sixty years of age; his form is sufficiently elevated and compact to be graceful, and his countenance, though marked by the lines of dissi[Pg 32]pation, and rather too heavy, is not unprepossessing or repulsive. His eye is rapid in its motion, and beams with the animation of genius; but his lips are too thick, and his cheeks too fleshy and loose for beauty; there is too a degree of foppery, and sometimes of splendor, manifested in the decoration of his person, which is not perfectly reconcileable to our [358] ideas of mental superiority, and an appearance of voluptuousness about him which cannot surely be a source of pride or of gratification to one whose mind is so capacious and elegant. It is not improbable, however, that this character is assumed merely for the purpose of exciting a higher admiration of his powers, by inducing a belief that, without the labour of study or the toil of investigation, he can attain the object of his wishes and become eminent, without deigning to resort to that painful drudgery by which meaner minds and inferior intellects are enabled to arrive at excellence and distinction. At the first glance, you would imagine Mr. Pinkney was one of those butterflies of fashion, a dandy, known by their extravagant eccentricities of dress, and peculiarities of manners; and no one could believe, from his external appearance, that he was, in the least degree, intellectually superior to his fellow men. But Mr. Pinkney is indeed a wonderful man, and one of those beings whom the lover of human nature feels a delight in contemplating. His mind is of the very first order; quick, expanded, fervid, and powerful. The hearer is at a loss which most to admire, the vigour of his judgment, the fertility of his invention, the strength of his memory, or the power of his imagination. Each of these faculties he possesses in an equal degree of perfection, and each is displayed in its full maturity, when the [359] magnitude of the subject on which he descants renders its operation necessary. This[Pg 33] singular union of the rare and precious gifts of nature, has received all the strength which education could afford, and all the polish and splendour which art could bestow. Under the cloak of dissipation and voluptuousness his application has been indefatigable, and his studies unintermitted: the oil of the midnight lamp has been exhausted, and the labyrinths of knowledge have been explored.

Mr. Pinkney is never unprepared, and never off his guard. He encounters his subject with a mind rich in all the gifts of nature, and fraught with all the resources of art and study. He enters the list with his antagonist, armed, like the ancient cavalier, cap-a-pee; and is alike prepared to wield the lance, or to handle the sword, as occasion may require. In cases which embrace all the complications and intricacies of law, where reason seems to be lost in the chaos of technical perplexity, and obscurity and darkness assume the dignified character of science, he displays an extent of research, a range of investigation, a lucidness of reasoning, and a fervor and brilliancy of thought, that excite our wonder, and elicit our admiration. On the driest, most abstract, and uninteresting questions of law, when no mind can anticipate such an occurrence, he occasionally blazes forth in all the enchanting exuberance of a chastened, but rich [360] and vivid imagination, and paints in a manner as classical as it is splendid, and as polished as it is brilliant. In the higher grades of eloquence, where the passions and feelings of our nature are roused to action, or lulled to tranquillity, Mr. Pinkney is still the great magician, whose power is resistless, and whose touch is fascination. His eloquence becomes sublime and impassioned, majestic and overwhelming. In calmer moments, when these passions are[Pg 34] hushed, and more tempered feelings have assumed the place of agitation and disorder, he weaves around you the fairy circles of fancy, and calls up the golden palaces and magnificent scenes of enchantment. You listen with rapture as he rolls along: his defects vanish, and you are not conscious of any thing but what he pleases to infuse. From his tongue, like that of Nestor, "language more sweet than honey flows;" and the attention is constantly rivetted by the successive operation of the different faculties of the mind. There are no awkward pauses, no hesitation for want of words or of arguments: he moves forward with a pace sometimes majestic, sometimes graceful, but always captivating and elegant. His order is lucid, his reasoning logical, his diction select, magnificent, and appropriate, and his style, flowing, oratorical, and beautiful. The most laboured and finished composition could not be better than that which he seems to utter [361] spontaneously and without effort. His judgment, invention, memory, and imagination, all conspire to furnish him at once with whatever he may require to enforce, embellish, or illustrate his subject. On the dullest topic he is never dry: and no one leaves him without feeling an admiration of his powers, that borders on enthusiasm. His satire is keen, but delicate, and his wit is scintillating and brilliant. His treasure is exhaustless, possessing the most extensive and varied information. He never feels at a loss; and he ornaments and illustrates every subject he touches. Nihil quod tetigit, non ornavit. He is never the same; he uses no common place artifice to excite a momentary thrill of admiration. He is not obliged to patch up and embellish a few ordinary thoughts, or set off a few meagre and uninteresting facts. His resources seem to be as unlimited as those of nature; and fresh powers, and new[Pg 35] beauties are exhibited, whenever his eloquence is employed. A singular copiousness and felicity of thought and expression, united to a magnificence of amplification, and a purity and chastity of ornament, give to his eloquence a sort of enchantment which it is difficult to describe.

Mr. Pinkney's mind is in a high degree poetical; it sometimes wantons in the luxuriance of its own creations; but these creations never violate the purity of classical taste and elegance. He [362] loves to paint when there is no occasion to reason; and addresses the imagination and passions, when the judgment has been satisfied and enlightened. I speak of Mr. Pinkney at present as a forensic orator. His career was too short to afford an opportunity of judging of his parliamentary eloquence; and, perhaps, like Curran, he might have failed in a field in which it was anticipated he would excel, or, at least, retain his usual pre-eminence. Mr. Pinkney, I think, bears a stronger resemblance to Burke than to Pitt; but, in some particulars, he unites the excellences of both. He has the fancy and erudition of the former, and the point, rapidity, and elocution of the latter. Compared with his countrymen, he wants the vigour and striking majesty of Clay, the originality and ingenuity of Calhoun; but, as a rhetorician, he surpasses both. In his action, Mr. Pinkney has, unfortunately, acquired a manner, borrowed, no doubt, from some illustrious model, which is eminently uncouth and inelegant. It consists in raising one leg on a bench or chair before him, and in thrusting his right arm in a horizontal line from his side to its full length in front. This action is uniform, and never varies or changes in the most tranquil flow of sentiment, or the grandest burst of impassioned eloquence. His voice, though not naturally good, has been disciplined to modulation by art;[Pg 36] and, if it is not always musical, it is [363] never very harsh or offensive. Such is Mr. Pinkney as an orator; as a diplomatist but little can be said that will add to his reputation. In his official notes there is too much flippancy, and too great diffuseness, for beauty or elegance of composition. It is but seldom that the orator possesses the requisites of the writer; and the fame which is acquired by the tongue sometimes evaporates through the pen. As a writer he is inferior to the present Attorney-General,120 who unites the powers of both in a high degree, and thus in his own person illustrates the position which he has laid down, as to the universality of genius.

Mr. R. King is a senator from the State of New York, and was formerly the resident minister at the court of St. James's.121 He is now about sixty years of age, above the middle size, and somewhat inclined to corpulency. His countenance, when serious and thoughtful, possesses a great deal of austerity and rigour; but at other moments it is marked with placidity and benevolence. Among his friends he is facetious and easy; but when with strangers, reserved and distant; apparently indisposed to conversation, and inclined to taciturnity; but when called out, his colloquial powers are of no ordinary character, and his conversation becomes peculiarly instructive, fascinating, and humourous. Mr. King has read and reflected much; and though long in public life, his attention [364] has[Pg 37] not been exclusively devoted to the political sciences; for his information on other subjects is equally matured and extensive. His resources are numerous and multiplied, and can easily be called into operation. In his parliamentary addresses he always displays a deep and intimate knowledge of the subject under discussion, and never fails to edify and instruct if he ceases to delight. He has read history to become a statesman, and not for the mere gratification it affords. He applies the experience of ages, which the historical muse exhibits, to the general purposes of government, and thus reduces to practice the mass of knowledge with which his mind is fraught and embellished. As a legislator he is, perhaps, inferior to no man in this country. The faculty of close and accurate observation by which he is distinguished has enabled him to remark and treasure up every fact of political importance, that has occurred since the organization of the American government; and the citizen, as well as the stranger, is often surprised at the minuteness of his historical details, and the facility with which they are applied. With the various subjects immediately connected with politics, he has made himself well acquainted; and such is the strength of his memory, and the extent of his information, that the accuracy of his statements is never disputed. Mr. King, however, is somewhat of an [365] enthusiast, and his feelings sometimes propel him to do that which his judgment cannot sanction. When parties existed in this country, he belonged to, and was considered to be the leader of what was denominated the federal phalanx; and he has often, perhaps, been induced, from the influence of party feeling, and the violence of party animosity, to countenance measures that must have wounded his moral sensibilities; and that now, when reason is suffered to dictate,[Pg 38] cannot but be deeply regretted. From a rapid survey of his political and parliamentary career, it would appear that the fury of party has betrayed him into the expression of sentiments, and the support of measures, that were, in their character, revolting to his feelings; but whatever he may have been charged with, his intentions, at least, were pure, and his exertions, as he conceived, calculated for the public good. He was indeed cried down by a class of emigrants from the mother country, who have far too great a sway in the political transactions of the United States; and though, unquestionably, an ornament to the nation which has given him birth, his countrymen, averse to him from party considerations, joined in the cry, and he became a victim, perhaps, to the duty he owed, and the love he bore to his country. Prejudice, however, does not always continue, and the American people, with that good sense which forms so prominent a feature of their character, are beginning justly to appreciate those [366] virtues and talents, they once so much decried. Mr. King has a sound and discriminating mind, a memory uncommonly tenacious, and a judgment, vigorous, prompt, and decisive. He either wants imagination, or is unwilling to employ a faculty that he conceives only calculated to flatter and delight. His object is more to convince and persuade, by the force of reason, than to amuse the mind by the fantastic embroidery and gaudy festoonings of fancy. His style of eloquence is plain, but bold and manly; replete with argument, and full of intelligence; neither impetuous nor vehement, but flowing and persuasive. His mind, like that of Fox, is historical; it embraces consequences the most distant with rapidity and ease. Facts form the basis of his reasoning. Without these his analysis is de[Pg 39]fective, and his combinations and deductions are often incorrect. His logic is not artificial, but natural: he abandons its formal divisions, non-essentials, moods, and figures, to weaker minds, and adheres to the substantials of natural reason. Of Mr. King's moral character I can say nothing from my own personal knowledge, as my acquaintance with him has not been long and intimate enough to enable me to judge correctly. I have not, however, heard any thing alleged against it calculated to lessen his reputation as an honourable statesman, or a virtuous member of society. He is wealthy, and has, no doubt, something of pride and hauteur in his manner, [367] offensive to the spirit of republicanism, and inconsistent with the nature of equality; but, as a father, husband, and friend, I have not yet heard him charged with any dereliction of duty, or any violation of those principles which tend to harmonize society, and to unite man to man by the bonds of affection and virtue. I must now beg permission to despatch the portrait of Mr. King, in order to submit to your inspection an imperfect likeness of another member of the same body. This is not the country to look for the blazonry and trappings of ancestry; merit alone claims and receives distinction; and none but the fool or the simpleton, ever pretends to boast of his ancestry and noble blood, or to offer it as a claim to respect or preferment. The people alone form the tribunal to which every aspirant for fame or honour must submit; and they are too enlightened and too independent to favour insignificance, though surrounded by the splendour of wealth, or to countenance stupidity, though descended from those who were once illustrious and great.

James Barbour is a senator from Virginia, his native[Pg 40] state.122 He was in his youth a deputy sheriff of the county in which he was born, and received an education which was merely intended to fit him for an ordinary station in life. He felt, however, superior to his condition, and stimulated by that love of fame which often characterizes genius, he devoted himself to study, and became [368] a practitioner of the law. He rose rapidly in his profession, and soon acquired both wealth and reputation. Like most of the barristers of this country, he conceived that to be a lawyer was necessarily to be a politician, and he rushed forward into public life to extend his fame and enlarge his sphere of action. From a member of the house of delegates he was elevated to the gubernatorial chair of Virginia, and received the highest honour his native state could confer. Gratified thus far in the wishes he had formed, he became desirous to enter on a more enlarged theatre, where his talents would have a greater field of action, and his eloquence a wider range and better effect, and he accepted the situation of senator of the United States.

Mr. Barbour commenced his career with a speech against the establishment of the national bank, which was then in agitation. He had come fraught with prejudices against this mammoth institution, and in the fervor of the moment gave vent to those prejudices in a manner certainly very eloquent, but not very judicious. When he had soberly weighed the good and evil with which it might be attended, the peculiar condition of his country, and the[Pg 41] necessity of adopting some scheme by which the difficulties of government should be obviated, and its financial embarrassment relieved, he very candidly confessed the error into which his feelings had betrayed him, and [369] in a speech, conceived and uttered in the very spirit of true eloquence, supported the measure.

Mr. Barbour is, in person, muscular and vigorous, and rather inclined to corpulency. His eyebrows are thick and bushy, which gives to his countenance a little too much the appearance of ferocity, but this is counterbalanced by a peculiar expression in his visage, that conveys a sentiment of mildness and humanity. He seems to be above forty years of age, and is about five feet ten inches high. Of his mind, the prominent characters are brilliancy and fervor. He has more imagination than judgment, and more splendor than solidity. His memory is not very retentive, because it has never been much employed, except to treasure up poetical images, and to preserve the spangles and tinsel of oratory. As an orator, Mr. Barbour has some great defects. His style is too artificial and verbose, and he seems always more solicitous to shine and dazzle than convince or persuade. He labours after splendid images, and strives to fill the ear more with sound than sense. His sentences are sometimes involved and complicated, replete with sesquipedalia verba, and too much charged with "guns, trumpets, blunderbuss, and thunder." He has unfortunately laid down to himself a model, which, with reverence be it spoken, is not the best that could have been adopted. Curran has gone a great way to corrupt the taste of the present age. His powers [370] were certainly very extraordinary, but his taste was bad, and by yielding too much to the impulse of a highly poetical imagination, he filled the mind[Pg 42] of his hearer with fine paintings indeed, and left it at last glowing, but vacant, delighted, but unconvinced. Too many of the youths of this country seem to be smitten with the model which he has thus given, and which is certainly calculated to fire an ardent mind, and lead it astray from the principles of correct taste and genuine oratory. Mr. Barbour, however, is frequently not only very fluent but very persuasive, and he often employs his full flowing oratorical style to great advantage in setting off his argument, and in decorating and enforcing his reasoning. From the want of opportunities, his reading, like that of most of the politicians of this country, has been confined, and his range of thought, from the absence of that knowledge which books afford, is necessarily limited. He has, indeed, derived advantages from an association with men of literary and scientific attainments, but he has still much to acquire to render him eminent as a statesman. The contributions, which, from this circumstance, he is compelled to levy on his own unaided native resources, have, however, tended to sharpen his intellectual powers, and to give them vivacity and quickness. Mr. Barbour seldom thinks deeply, but he is always rapid; and though his observations are sometimes trite and ordinary, there is almost always something [371] new and gratifying in the manner in which they are uttered. His mind does not appear organized for long continued investigation, and nature has formed him more for a poet than a mathematician. He is rather too anxious to be thought a great orator, and this over-ruling propensity is manifested even in common conversation; when, instead of ease, simplicity, and conciseness, he discovers the formal elocution of the public speaker, on the most unimportant and incidental subjects. In private circles, Mr. Barbour is always very[Pg 43] pleasant, and exhibits a politeness, which, flowing from the heart rather than the head, delights all who have the pleasure of his acquaintance, and renders him an acceptable guest, and an agreeable companion.

There is a native openness and benevolence in his character, which excite the love of all who know him, and which powerfully attract the stranger as well as the friend. He seems superior to the grovelling intrigues of party, and always expresses his feelings, in the bold and lofty language of conscious independence and freedom. There is a marked difference between this gentleman and his brother, Mr. Philip P. Barbour,123 a member of the House of Representatives, in the respective faculties of their mind; the latter is more logical, and also more laborious and indefatigable. He seems to have a peculiar tact for those constitutional and legal questions which [372] are involved and obscure, and possesses that clearness and vigor of mind necessary to unfold what is complicated, and illuminate what is dark. He casts on such subjects so powerful a light, that we wonder we should ever have doubted, and behold at once the truth, stripped of all its obscurity. The former seldom attempts an analysis of such questions. He reasons, but his reasoning is not so much that of a mathematician, as of an advocate who labours to surprise by his novelty, and to fascinate by the ingenuity of his deductions, and the ease and beauty of his elocution. He has more genius than his brother, but less judgment; more refinement and elegance, but less vigor and energy. It appears to me that there is a vast deal of what may be denominated law mind in this coun[Pg 44]try, which will ultimately reach a point of excellence that must astonish the world. The fondness for the profession of the law, at present, is wonderful; almost every man, whatever be his means of support, or grade in society, if he have children, endeavours to make one of them, at least, a disciple of Coke, or a "fomentor of village vexation," and you cannot enter a court-house, without being astonished at the number of young men, who are either studying or practising the law. This, however, is not a matter of surprise, when we consider the facility with which this profession leads to preferment and distinction, and the ease with which it seems to be acquired. Amidst such [373] a mass of law mind, therefore, as exists here, excellence must hereafter be attained, if it has not now reached its climax; and the Cokes, the Mansfields, and Ellenboroughs of England are, or will soon be, equalled in this country. The future destinies of this republic cannot be fully anticipated; the march of mind is progressive and resistless, and intellectual pre-eminence must be attained where so many inducements are offered to effect, and so few impediments exist to prevent it. Mind is often regulated by the circumstance in which it is placed, and fashioned by the objects by which it is surrounded. This country is, therefore, peculiarly favorable for the expansion and development of the intellectual powers. Physical, as well as moral causes, operate to this end. The eye of an American is perpetually presented with an outline of wonderful magnificence and grandeur; every work of nature is here on a vast and expansive scale; the mountains, and lakes, and rivers, and forests, appear in a wild sublimity of grandeur, which renders the mountains, lakes, and rivers of Europe, mere pigmies in comparison. The political and religious freedom, too, which[Pg 45] is here experienced, removes all shackles, and gives an elasticity, a loftiness, and an impetus to the mind that cannot but propel it to greatness. Thus operated upon by moral and physical causes, what must be the ultimate destiny of the people of this country, and the range and expansion of intellect which they [374] will possess? Devoted as they are for the most part to studies and professions, which have a tendency to enlarge and liberalize the mind, and influenced by the causes I have mentioned, it would be worse than stupidity to suppose they could long remain an inferior people, or possibly avoid reaching that point of elevation of which mankind are capable. The law mind of this country has now attained a high degree of splendor, and is in rapid progress to still greater excellence. There are many men, in this country, though so much calumniated by British writers, who would shed a lustre on the bench of that nation, and not suffer by a comparison with some of the brightest luminaries of English jurisprudence.

Before I quit this body of American worthies, I must introduce to your acquaintance, as succinctly as possible, another member of the senate, who, though not so conspicuous as the two former, in the walks of public life, is not inferior to any in this country, in all that constitutes and dignifies the patriot and the statesman. Mr. Roberts is from Pennsylvania.124 He is a plain farmer, and was, once, I understand, a mechanic. Though he cannot boast of a liberal education, yet nature has given him a mind, which, with early improvement, would have made him prominent in any sphere in life. It is vigorous and powerful in no ordinary degree, and the sophistry of art,[Pg 46] and the dexterity of learning, are often foiled and defeated [375] by the unaided and spontaneous efforts of his native good sense. But he has that which is of more sterling advantage, both to himself and his country,—immoveable political and moral integrity. It is gratifying, in this age of corruption and voluptuousness, to contemplate men like Aristides, Fabricius, and Cato. They exhibit to us the true dignity of man, and hold out examples that we must feel delighted to imitate. They show us to what pitch of excellence man is capable of attaining, and rescue the exalted condition of human nature from that odium and disgrace which profligacy and corruption have heaped upon it. No spectacle can be more sublime or more elevating than he, who, in the hour of public danger and trial, and amidst the allurements and fascinations of vice, stands like a rock in the ocean, placid and immoveable, and endures the dangers that surround, and braves the storms and tempests that beat upon him, with undeviating firmness, for the safety of his country and the glory of his God! The mind rests upon such a character as the eye upon a spot of fertility, amidst deserts of sand, and we rise from the blood-stained page of history, and the corruptions of the living world, with a heart filled with love, admiration, and reverence, by the contemplation of the few who have shed an imperishable lustre on the exalted character of man. This description is not exaggerated; it is drawn from nature and truth, and [376] fancy has nothing to do with the picture. But I must now hasten to finish my portraits of American characters.

Mr. Bagot,125 the English minister to this government,[Pg 47] appears to be about thirty-five years of age. He is tall, elegant, and rather graceful in his person, with a countenance open and ingenuous, an English complexion, and eyes mild though dark. He has ingratiated himself with the Americans, by the real or affected simplicity of his manners, and by assimilating himself to their usages and customs. He has thrown aside the reserve and hauteur of the English character, as not at all suited to the meridian of this country, and attends to all with equal courtesy and politeness. I can say nothing of the powers of his mind, but they do not appear to be more than ordinary. It has always seemed to me very strange policy on the part of the British cabinet, to appoint ministers to this country of inferior capacity and inconsiderable reputation, while the Americans send to our court only their most prominent and leading men, who have distinguished themselves by their ability and their eloquence.

The French minister, M. Hyde de Neuville,126 is a "fat, portly gentleman," with a broad chest, big head, and short neck, which he seems almost incapable of turning ad libitum. He is full of [377] Bourbon importance and French vivacity; has petits soupers every Saturday evening during the winter, and spends his summer at the springs, or his country residence, in extolling the virtues of his beloved Louis le desiré. I do not think that M. Neuville, though an amiable, and, I understand, a benevolent man, has that kind of talent which would qualify him for the station he holds, or that, in the event of any difficulty arising between this country and France, he could counteract the intrigues of diplomatic ingenuity, or benefit his nation, by inducing the American cabinet, though I believe he is[Pg 48] highly esteemed, to adopt any measure not manifestly advantageous to the United States. He has been many years a resident of this country, and was driven from France by the persecutions of Buonaparte. He is said to have evinced for his exiled countrymen much feeling and interest, and to have given them, while strangers and unknown in a foreign land, all the aid he could afford. His acts of benevolence certainly redound to the credit of his heart, and I should be sorry to say any thing that would disparage the qualities of his head. He is too much occupied with his own, or other people's concerns, to attend to the little or the complicated intrigues of courts, and though he resides here as a representative, yet he now represents a cypher.

[378] 4th.—To tea with J. C. Wright, Esq., to meet a young man, Mr. Dawson, who is giving up a school here to go as "Teacher to the Cherokee nation of Indians." Much enthusiasm takes him there; little will be needed to bring him back again. Since my return, Washington has been visited by some very distant and interesting tribes of Indians, with the following account of whom I have been favoured by a friend residing there.

Some account of the Indians who visited all the Chief Cities in the Eastern States, and made a long stay in Washington in the winter of 1821.

These Indians were the chiefs and half-chiefs of tribes from the most western part of this continent with which we are at all acquainted, and came under the guid[Pg 49]ance of Major O'Fallan127 from the Counsel Bluffs.128 All of them were men of large stature, very muscular, having fine open countenances, with the real noble Roman nose, dignified in their manners, and peaceful and quiet in their habits. There was no instance of drunkenness among them during their stay here. The circumstances which led to their visit were singular. A missionary, who had been amongst them a few years back, on renewing his visit recently, found an old chief, with whom he was acquainted, degraded from his rank, and another appointed in his place. This led to inquiries after the cause, which proved to be that this chief having, during a considerable [379] absence from his tribe, visited some of the cities of the whites, carried back such a report of their houses, ships, numbers, wealth, and power, that they disbelieved his account, and degraded him as a man unworthy of being longer their chief. They inquired of their missionaries, who confirmed the statement, and they met in council with other tribes, and resolved that a deputation should, in company with the representative of the great father, "see if things were so," and if they were, the chief should be reinstated. They have returned, saying the "half was not told them." Red Jacket129 (of whom you[Pg 50] have heard) used to say, that "the great spirit was too great a being to overlook red men; that he listened to the talk of red men as well as to the talk of white men;" but these natives of the forest thought the great spirit favoured white men more than red. An anecdote is related of one of the chiefs (a Pawnee) which is a well authenticated fact, and recorded by Dr. Morse in his account of visits to the western regions.130 The tribe of the Pawnees had taken a woman prisoner from a neighbouring tribe with whom they were at war, and, as was their custom, they made every preparation to offer her a sacrifice to the great spirit. Every thing was prepared, the wood, the green withes, and the fire, and the victim, when this chief suddenly flew and seized her, carried her under his arm to a neighbouring thicket, where [380] he had prepared horses for her and himself, and riding away at speed, he, after three days' travelling through the woods, returned her in safety to her tribe and friends. This event was considered by the Pawnee tribe as an interference of the great spirit in her favour, and on the return of the chief no questions were asked him on that subject, nor has a woman been offered a sacrifice by that tribe since. As a compliment justly due to his gallant exploit, a number of ladies in this city had a medal made, and presented to him in due form, in the presence of all the Indians; on one side of which[Pg 51] was represented the preparation for the sacrifice, and on the reverse the chief running off with a woman under his arm, and two horses stationed at a short distance, surmounted by this inscription, "To the bravest of the Braves," (the Pawnees are also called the Braves). These Indians excited so much interest from their dignified personal appearance, and from their peaceful manner, that they received a great number of rich presents, sufficient to fill six large boxes in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington; these were forwarded before they left us. Their portraits, which are gone with them, were taken in oil by Mr. King in their native costume, buffalo skins, with the hair inside, turned back at the neck and breast, which looked very handsome, like fur collars. Eight, however, the chiefs and [381] the squaw, Mr. King copied and keeps himself.131 He received 400 dollars from Uncle Sam for it. There was a notice in the papers that the Indians would dance and display their feats in front of the President's house on a certain day, which they did to at least 6,000 persons. They shewed their manner of sitting in council, their dances, their war whoop, with the noises, gesticulations, &c. of the centinels on the sight of an approaching enemy. They were in a state of perfect nudity, except a piece of red flannel round the waist and passing between the legs. They afterwards performed at the house of his Excellency M. Hyde de Neuville. They were painted horribly, and exhibited the operation of scalping and tomahawking in fine style.[Pg 52]

The Otta half-chief132 and his squaw have taken tea with and frequently visited us. She was a very good natured, mild woman, and he shewed great readiness in acquiring our language, being inquisitive, retaining any thing that he was once informed, and imitating admirably the tones of every word. He spent the evening with us before they finally left the city. I took himself and squaw into Dr. Barber's room, and opened gently the skeleton case. He looked slyly in, and the wife wanted to look, but he put himself in an attitude to represent a dead person, and said, "no good, no good." She still wanted to see, but he would [382] not let her. Three others came afterwards wanting to see it, who, when I opened it, raised themselves up in a dignified manner and said, "very good," one of them taking hold of the hand said, "how you do."133 The Otta half-chief and squaw afterwards saw it together and were very well pleased. Our children were all full of play with them, and the squaw nursed the younger ones. Margaret wanted to go with them. The calumet134 of peace (the tomahawk pipe and their own sumach tobacco) frequently went round, and they expressed a wish to see us again.

I have recorded much of the vocabulary of these Indians, and would transcribe it, but have not room. They count by tens as we do, for instance, noah, two; taurny, three; crabraugh, ten; crabraugh noah, twenty; crabraugh taurny, thirty, &c. They hold polygamy as honourable; one wife, no good; three, good; four, very good. In their talks with the residents they shew no wish to adopt our habits.[Pg 53]

5th.—To dine with Dr. Dawes at his poor, worn out farm, of which he is already tired. The Doctor seems one of the best Englishmen I have met in America.

Sunday, 6th.—Dr. Rice135 preaching this day in Congress-hall before the senate, and representatives, [383] called the assembly, polite, just, respected, respectable, and deemed it unnecessary to mention sin and human depravity.

American husbands abound in outward politeness and respect to their wives; and gentlemen, in general, are excessively attentive to the fair sex, rising and leaving their seats, even at church, to accommodate the late coming ladies. I gave much offence, on a recent occasion, by my want of gallantry in this particular. The meanest white woman is here addressed by the title of Madam.

It may also be mentioned, as a proof of superior civilization and refinement in manners, that a stranger cannot, in this country, enter and join a party or social circle, without being publicly presented by name, and exchanging names and hearty shakes of the hand with all present. Should he, however, happen to enter and take his seat without submitting to this indispensable ceremony, he must remain dumb and unnoticed, as an intruder, or as a person whose character renders him unfit for introduction, and for the acquaintance of any. But, on the other hand, when properly presented, he is instantly at home; and ever after, at any distance of time and place, acknowl[Pg 54]edged as entitled to the goodwill and friendship of all who thus met him. Friendships are thus formed and propagated, and the boundaries of society in the new world extended. It would hence be impracticable for me to be half an hour, as has happened to me in England, [384] unknowingly present with a person of distinction; and many unpleasant mistakes and misunderstandings are thus obviated.

8th.—I heard Mr. Speaker Clay deliver a splendid speech of four hours long on the Missouri slave-question. His voice fills the house; his action is good and generally graceful.

I met this evening Mr. Smith, a young gentleman from Lincolnshire, the fellow-traveller of Mr. Parr, who walked through the west, and admired all! He is not determined on continuing here; he has a good farm in England. He and Mr. Parr have been introduced by a member of Congress to the President, who sat half an hour familiarly talking with them, in a plain, domestic, business-like manner.

Sunday, 13th.—From the Speaker's chair in Congress-hall, I heard the young, learned, and reverend professor Everett, of Cambridge University, (aged 29) preach most eloquently to the President and legislature of this great empire.136 His voice, bewitchingly melodious, yet manly, filled the house, and made every word tell, and every ear hear. "Time is short," was the subject. His discourse was full of high praise of this land, it being, he said, (in my own language) "the only resting place for liberty, who, when driven hence, must ascend in her pure, white robes to heaven. No more new continents will be discovered[Pg 55] for her reception, and therefore let this nation wisely [385] keep her asylum here." He then spoke very warmly against kings, lords, and priests, and what he called the toleration of man and his rights. "In England they tolerate liberty; and what is liberty there? A shadow! But here, a substance! There her existence is only nominal. She is mocked by her very name." Independent of its moral instruction, this sermon was a fine specimen of oratory, and greatly interested the members of both houses, who very cordially shook the preacher by the hand. Though not forgetting slavery in his discourse, the professor seemed too partial to it.

This gentleman had just returned from his tour through Europe, where he visited Sir Walter Scott, and other distinguished literati, and preached in London.

I met Mr. Lowndes, the Howard of America, at Mr. Elliott's. He says, that "Harmony presents much moral philosophy in practice. Flesh and blood had hard work at first, but now they have but few desires to gratify. Nature seems under the hatches, and they have little to wish, want, or fear. But theirs is a stagnant life."

14th.—Read Mr. John Wright's pamphlet on Slavery, in which he uses my name in reference to my negro letter, and shows very clearly the evil effects of slavery on the character of this country, and proves the unalterable nature of the black man's right to liberty, and its benefits.

[386] Mr. Rufus King, a member for New York, a gentlemanly English-like speaker, confines himself to business, and to the grand fundamental principles of every political question, and the consequences likely to result from extending slavery over the continent. "In time," says he, "you will enable the blacks to enslave the whites.[Pg 56] Why, therefore, should we of the free, be compelled to suffer with you of the slave states?"