Title: Indoor and Outdoor Recreations for Girls

Author: Lina Beard

Adelia B. Beard

Release date: April 16, 2013 [eBook #42549]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The publishers hereby give warning that the unauthorized printing of any portion of the text of this book, and the reproduction of any of the illustrations or diagrams, are expressly forbidden.

Since the publication of this volume two years ago as "Handicraft and Recreation for Girls," it has occurred to us that "Recreations" alone much more accurately defines the contents, for the handicrafts represented are only those that in effect are recreations. Therefore we have thought it best to drop the word Handicraft and issue the new edition under the more appropriate title, "Recreations for Girls."

September, 1906.

This book, like a girl's life, is divided into two parts: occupation and amusement, or handicraft and recreation.

It is not equally divided, for handicraft is so much more like play than work, and is so entertaining in itself, we find difficulty in drawing a distinct line between that and recreation. The one insists upon blending with the other and the book, after all, is a book of entertainment.

With the old handicrafts coming back into favor and new ones constantly being brought forward, a girl's life may be full of delightful employment. To work with joyous enthusiasm and self-reliant energy, as well as to play with light-hearted enjoyment, cannot fail to make her sensible, wholesome, and happy, and it is with this end in view that we have written and illustrated the book. Our wish is to help our girl friends to make the most of their girlhood and to enjoy it to its fullest extent.

We have had practical experience in the actual working out of all the various handicrafts and recreations, and therefore give only that which we know can be well and easily done by the average girl.

Thanks are due to the Delineator, Harper's Bazar, Woman's[vi] Home Companion, and Good Housekeeping, for their courtesy in promptly returning for this work the original drawings and material used in their respective magazines.

Flushing, August 2, 1904.

| PART I | |

| HANDICRAFT | |

CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

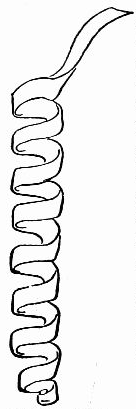

| Spinning | 3 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| Weaving on a Home-made Loom | 15 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| A Ball of Twine and What May Be Made of It | 27 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| An Armful of Shavings, and What to Do with Them | 36 |

| [viii] | |

CHAPTER V. | |

| Primitive Reed Curtains | 43 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| Things to Make of Common Grasses | 53 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| Possibilities of a Clothes Line | 62 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| How to Weave a Splint Basket | 68 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| Modelling in Tissue-Paper | 75 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| Nature Study with Tissue-Paper | 86 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

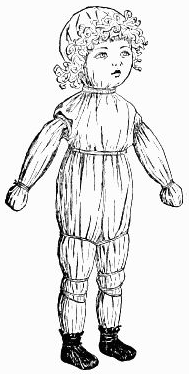

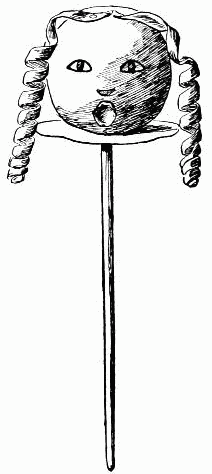

| A New Race of Dolls | 103 |

| [ix] | |

CHAPTER XII. | |

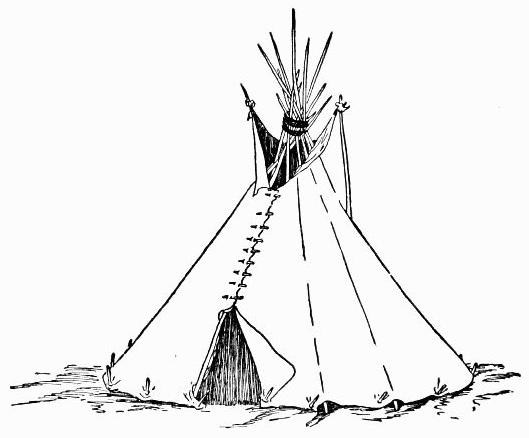

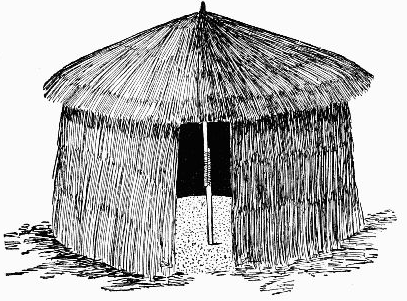

| An Indian Encampment on a Pastry-Board | 111 |

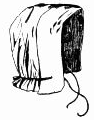

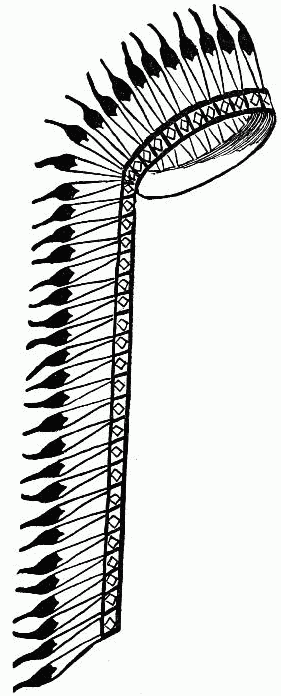

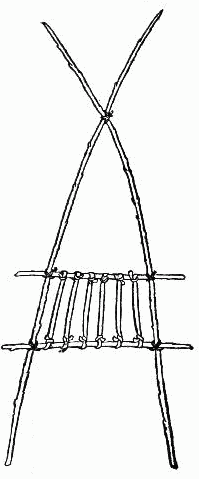

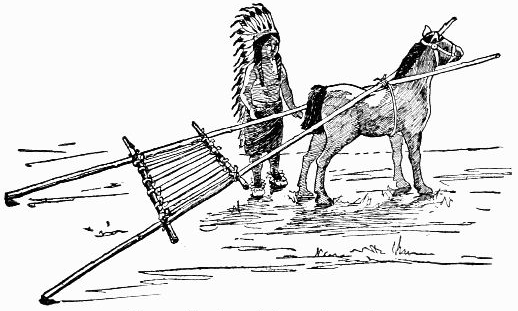

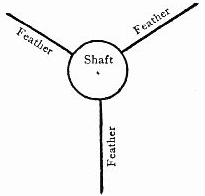

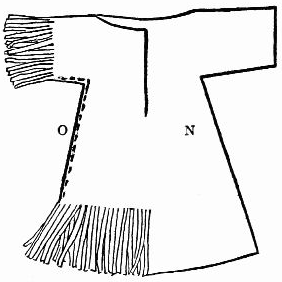

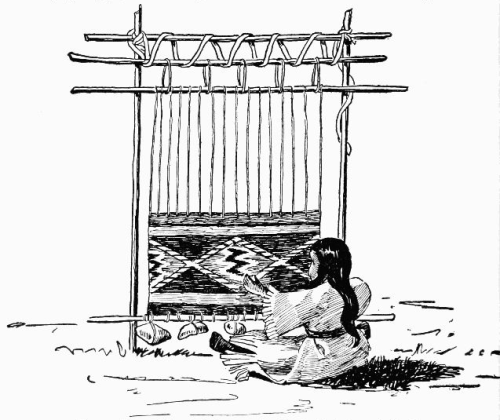

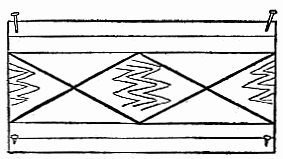

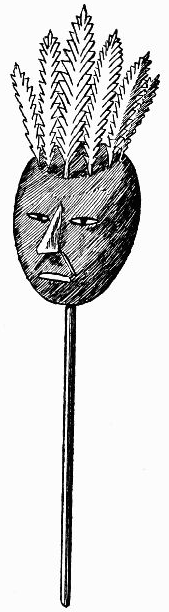

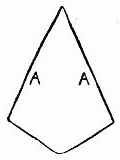

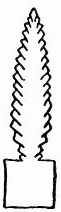

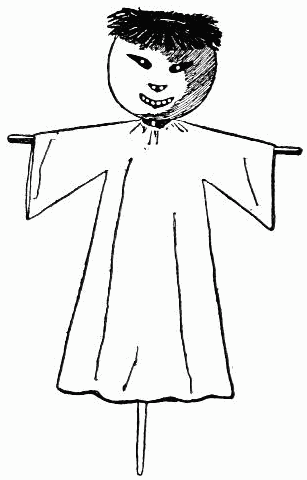

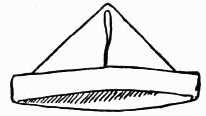

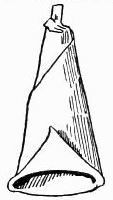

The Ground, 111; The Wigwam, 112; Decorating the Wigwam, 114; The Fire, 114; The Doll Indian, 115; The War Head-Dress, 116; A Travois, 118; Pipe of Peace, 119; A Perfect Little Tomahawk, 120; The Chieftain's Shield, 120; Arrow-Heads and Arrows, 122; A Bow That Will Shoot, 124; The Doll Squaw, 125; Squaw's Chamois Gown, 125; Primitive Loom and Navajo Blanket, 125; Papoose, 130; Cradle for Papoose, 130; Indian Money, 131; Wampum Necklace, 131. | |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

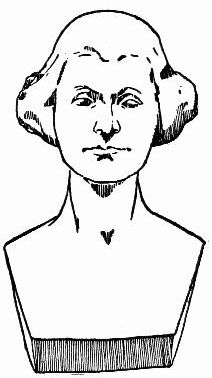

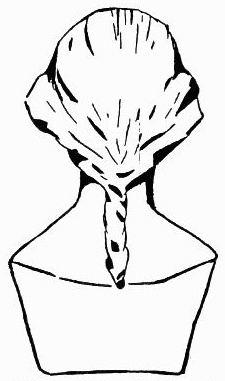

| A Toy Colonial Kitchen with Fac-simile Colonial Furnishings | 133 |

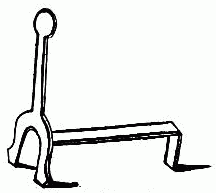

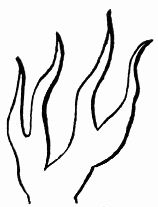

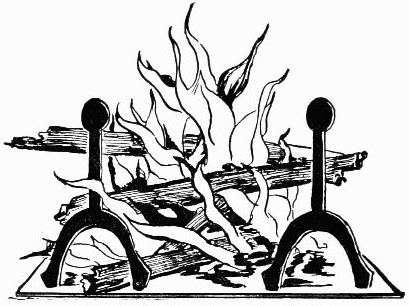

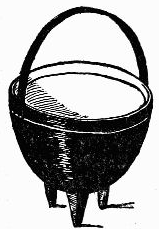

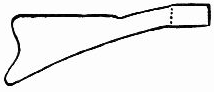

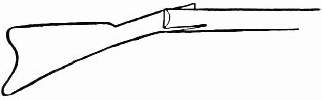

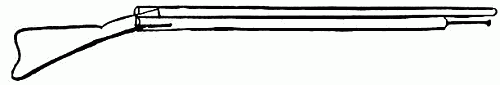

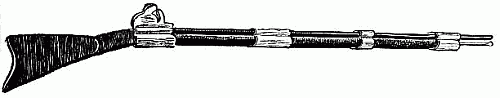

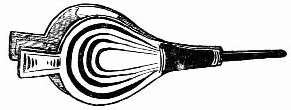

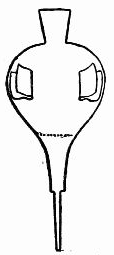

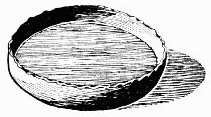

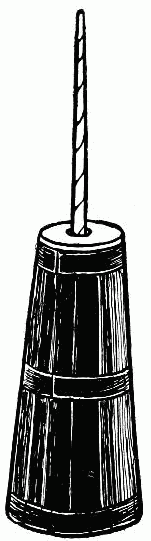

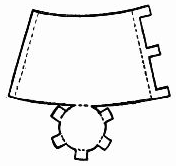

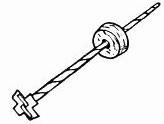

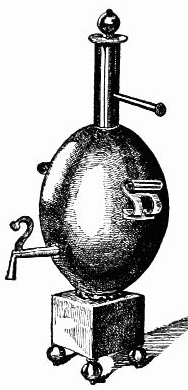

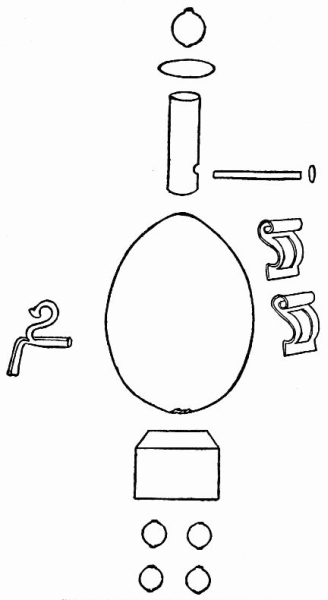

The Floor, 135; The Fireplace, 138; A Hair-pin Crane, 138; Little Dutch Oven, 139; Two Andirons, 141; The Fire, 142; Iron Pot, 143; The Peel, 144; The Toaster, 144; Pot-Hooks, 145; The Spinning-Wheel, 147; The Little Spinner, 150; The Costume, 150; Flint-Lock Rifle, 151; The Bellows, 153; Colonial Pewter Dish, 154; Grandfather's Clock, 155; Colonial Churn, 160. | |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

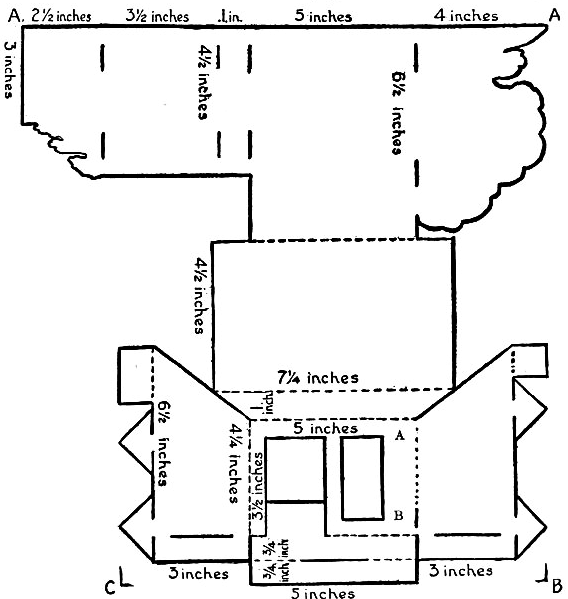

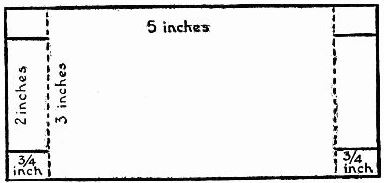

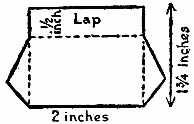

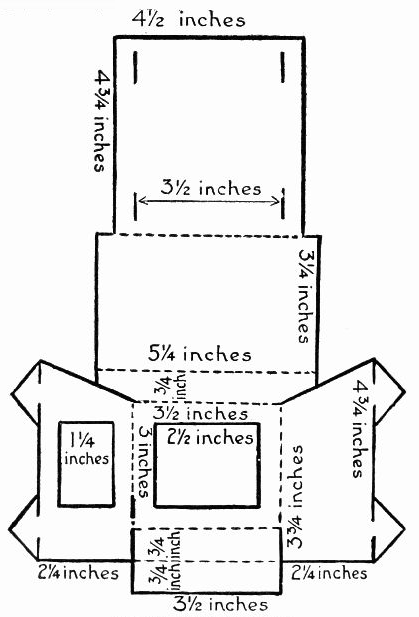

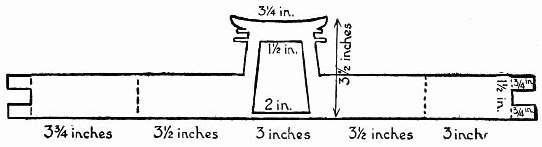

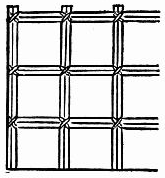

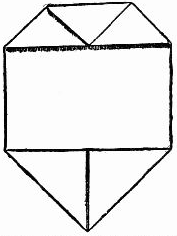

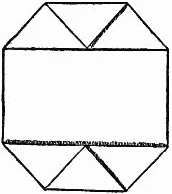

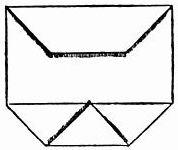

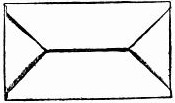

| Little Paper Houses of Japan | 162 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

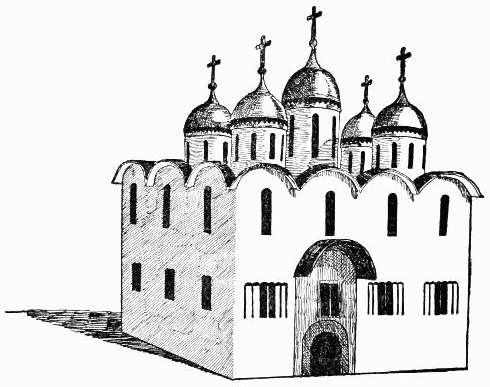

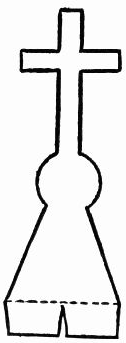

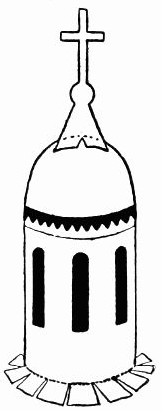

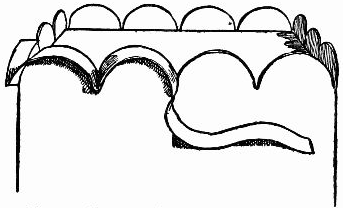

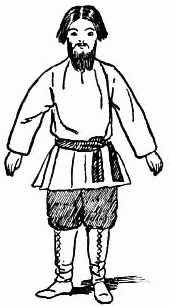

| Some Odd Things in Russia | 175 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Pottery Without a Potter's Wheel | 185 |

| [x] | |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

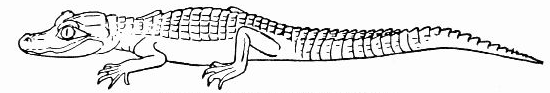

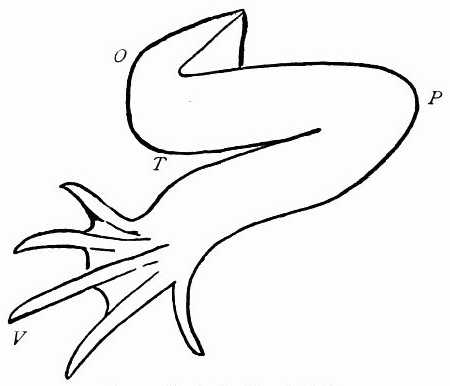

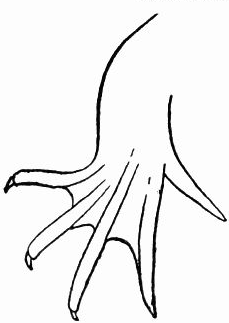

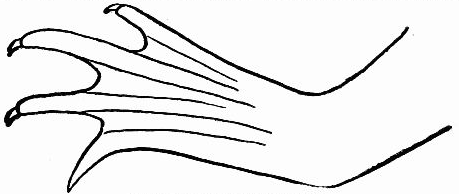

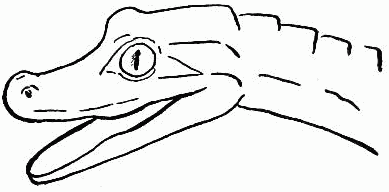

| Baby Alligators and Other Things of Clay | 193 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Funny Little Apple Toys | 206 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Marvel Pictures | 215 |

PART II | |

RECREATION | |

CHAPTER XX. | |

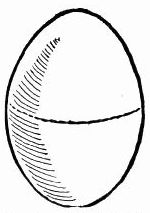

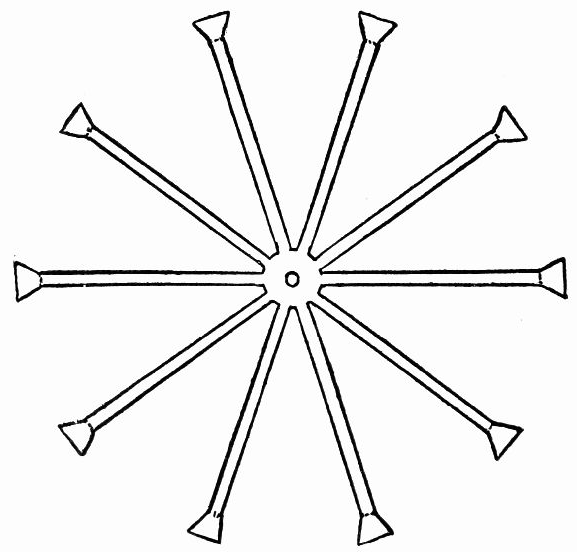

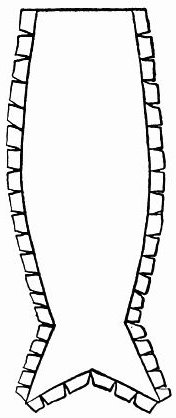

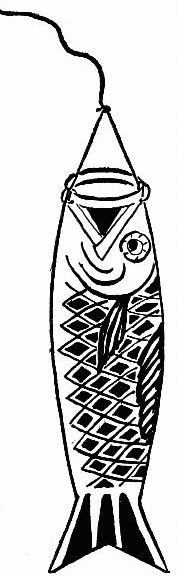

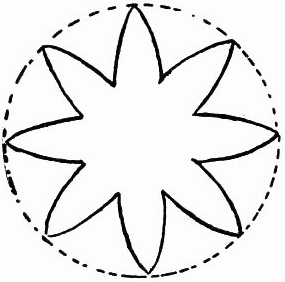

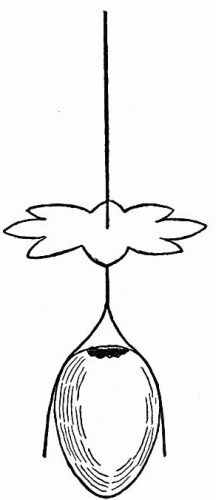

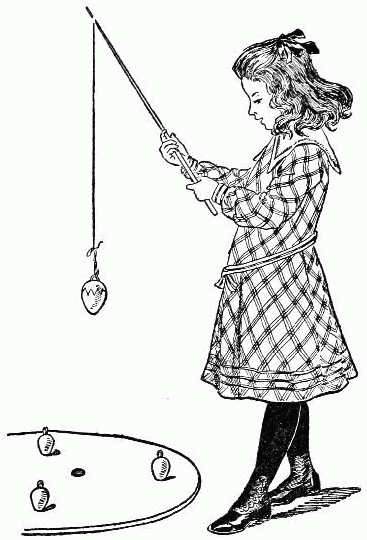

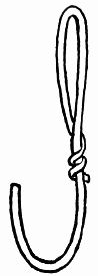

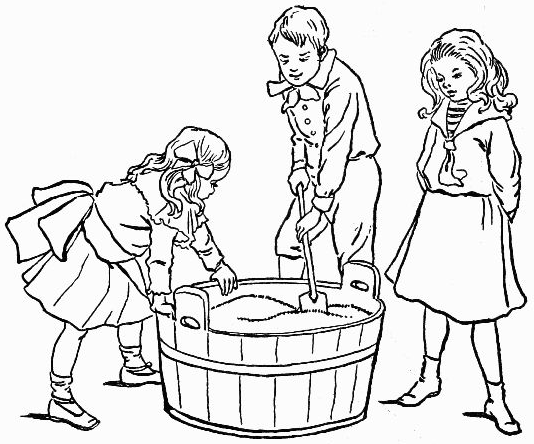

| Egg Games for the Easter Holidays | |

| Lifting for Pasch Eggs | 227 |

How to Prepare the Egg-Shells, 227; Hanging the Eggs, 228; The Players, 228; The Lifting, 229; The Egg Dance, 230; Placing the Eggs, 230; Dividing the Players, 230; The Dance, 230; The Reward, 231; Easter Angling, 231; Materials for the Game, 231; Fish-poles, 231; Eggs, 232; Rules of the Game, 234; Table Egg-Rolling, 235. | |

| [xi] | |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

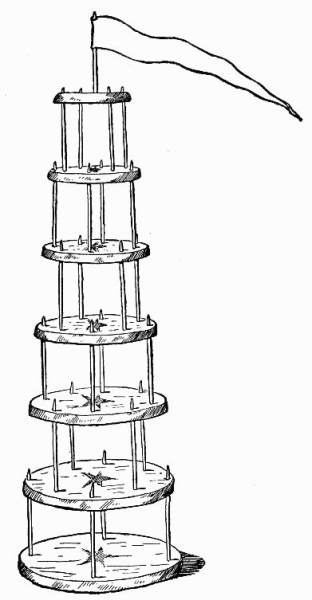

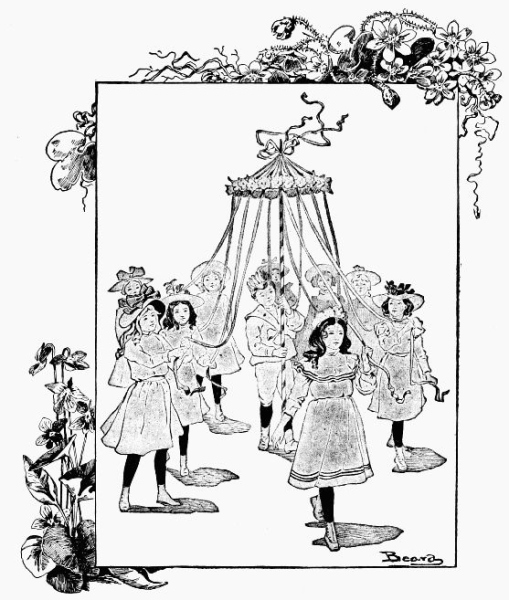

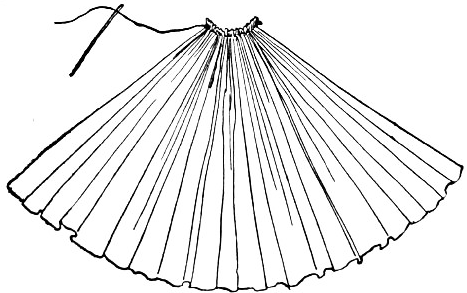

| May Day Amusements | 237 |

CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Hallowe'en Revels | 254 |

CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Magic Cloth and What It Will Do | 264 |

CHAPTER XXIV. | |

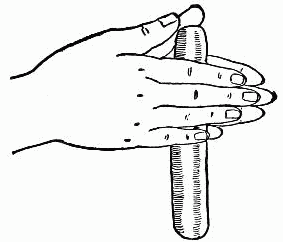

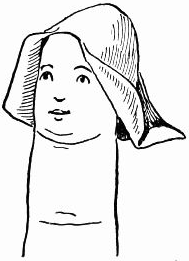

| Finger Plays for Little Folk | 273 |

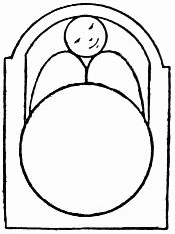

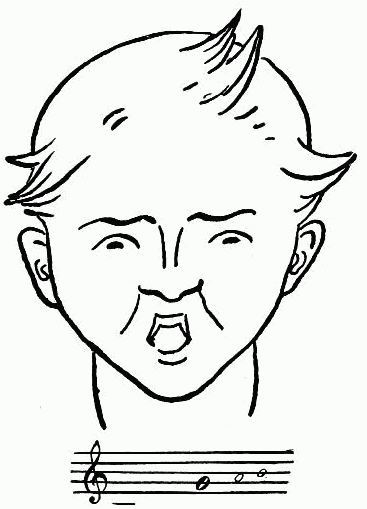

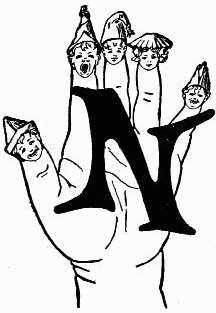

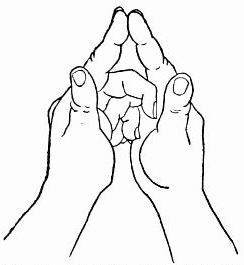

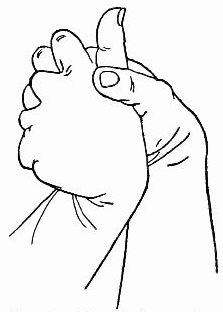

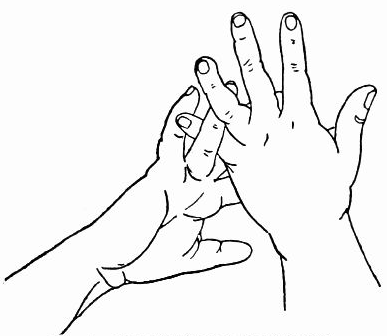

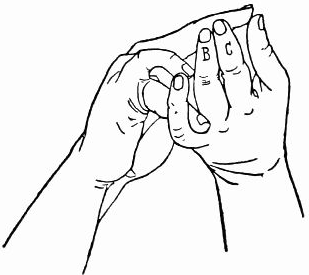

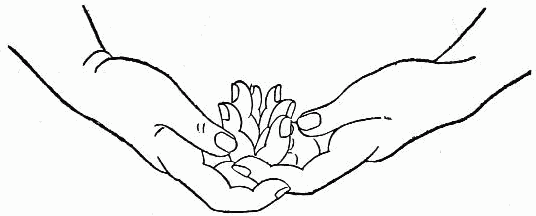

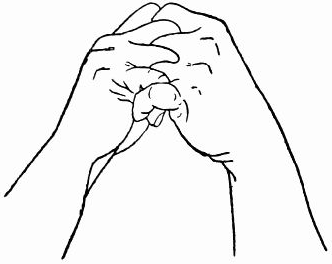

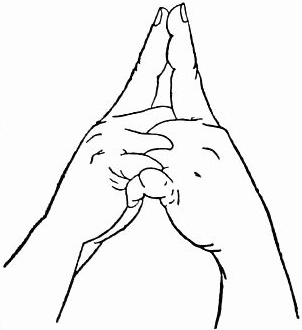

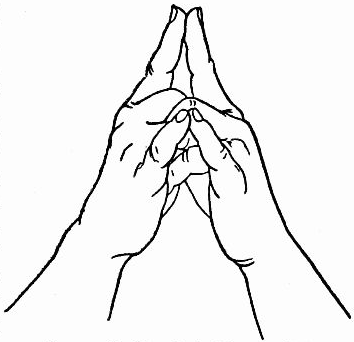

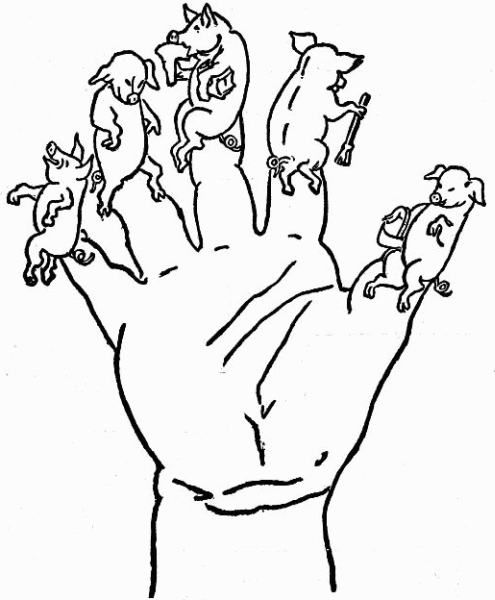

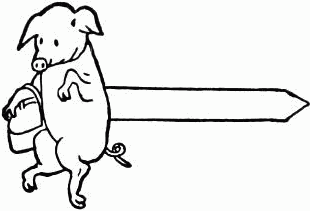

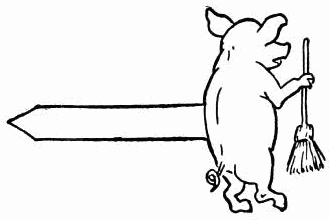

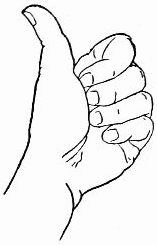

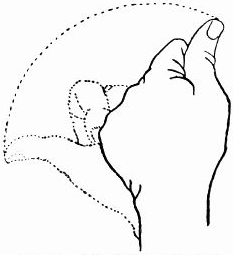

The Teeter, 273; Church, 275; Steeple, 275; Open Door, 276; The People, 276; The Preacher, 277; Man Chopping Wood, 277; My Mother's Knives and Forks, 279; My Father's Table, 280; My Sister's Looking-Glass, 280; The Little Black Birds, 280; The Baby's Cradle, 281; Chin Chopper Chin, 282; Build the Tower, 282; The Five Little Pigs, 285; Little Heads for Little Fingers, 285. | |

CHAPTER XXV. | |

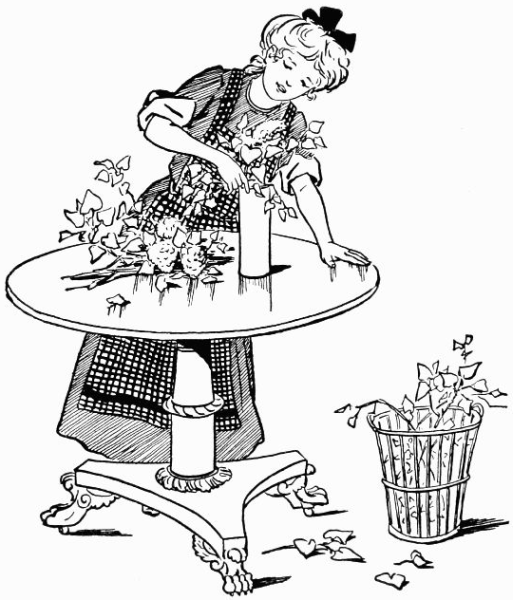

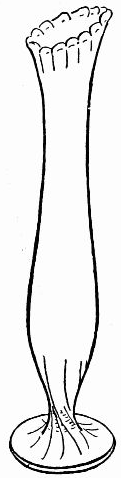

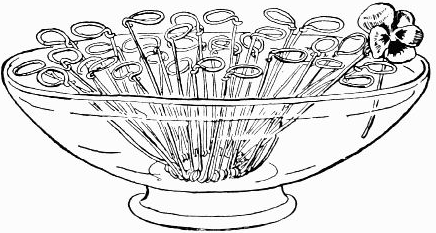

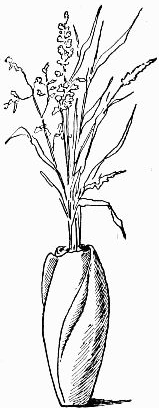

| How to Arrange Fresh Flowers | 289 |

| [xii] | |

CHAPTER XXVI. | |

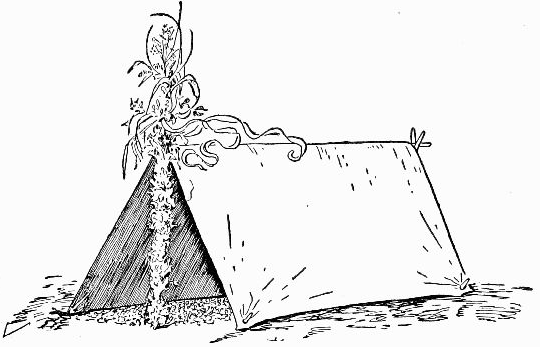

| Open Air Playhouses | 298 |

CHAPTER XXVII. | |

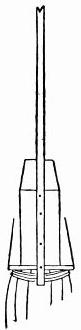

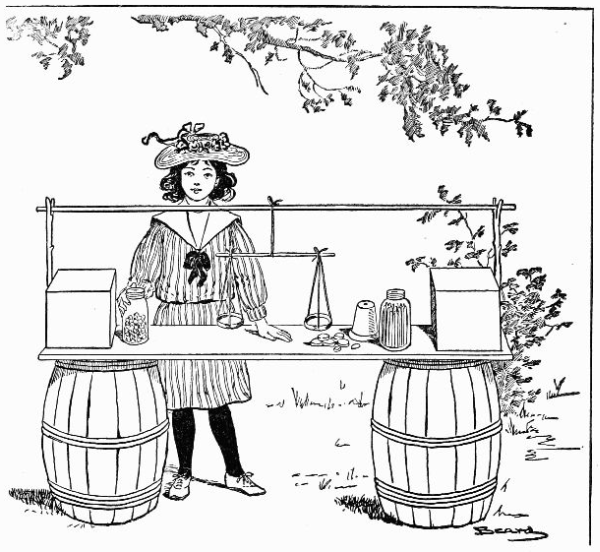

| Keeping Store | 308 |

CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

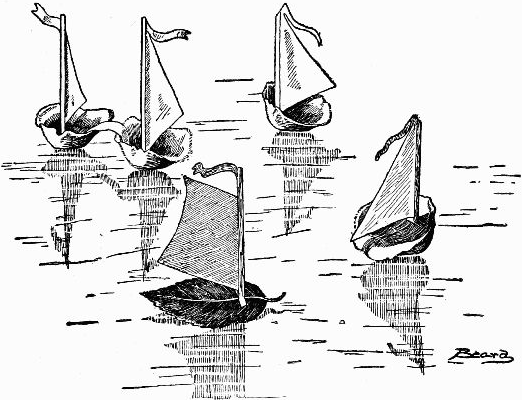

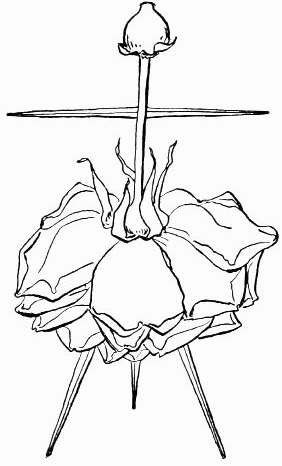

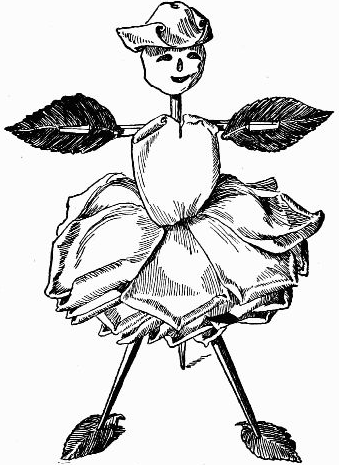

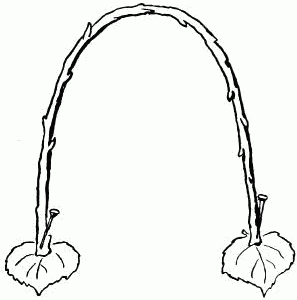

| A Frolic with the Roses | 320 |

CHAPTER XXIX. | |

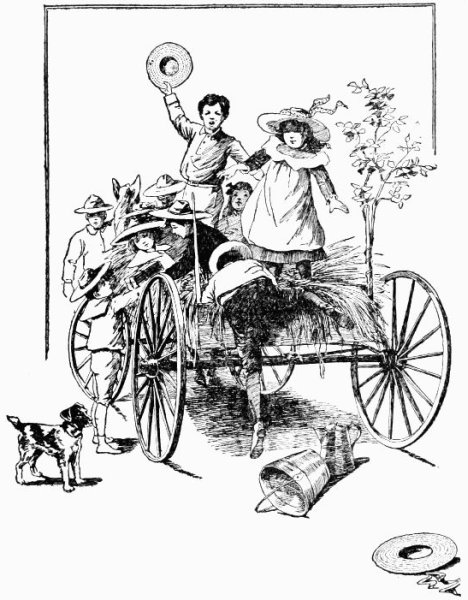

| A Straw Ride Picnic | 333 |

The Season, 333; Games for the Wagon, 333; Simon Says, 335; Bird Wish, 337; Lines to Be Recited Rapidly, 337; At the Grounds, 338; Chasing the Deer, 338; The Swing, 338; Teeter-Tarter, 338; The Dinner, 339; Dishes, 339; Camp-Fire, 342; After Luncheon, 342; Telling Stories, 343; Game of Menagerie, 343. | |

CHAPTER XXX. | |

| A Paper Chase | 345 |

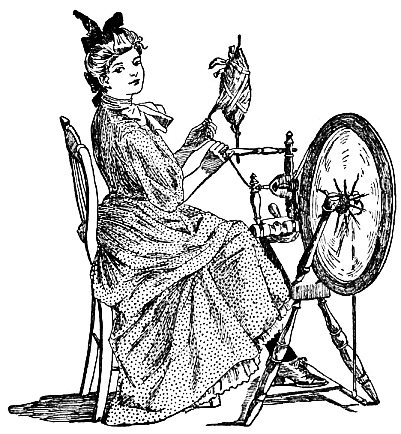

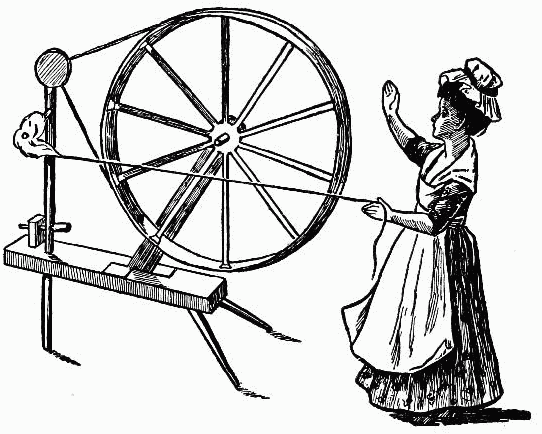

The spinning-wheel shall buzz and whirr.

The spinning-wheel shall buzz and whirr.

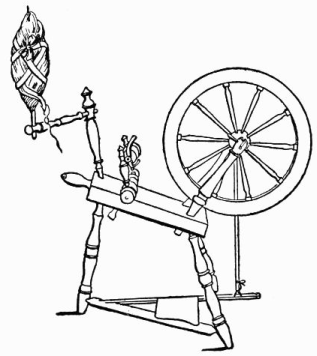

All the old handicrafts are coming back again, and ere long we shall be as proud as the maids in Revolutionary[4] times of our hand-spun and hand-woven fabrics. To be able to spin and weave is to be accomplished in the newest as well as the oldest of household arts.

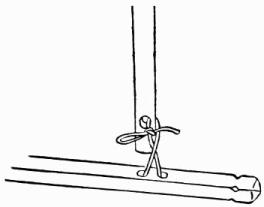

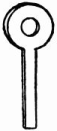

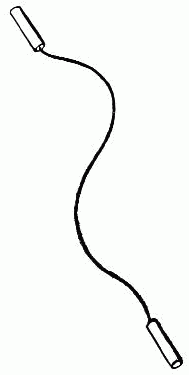

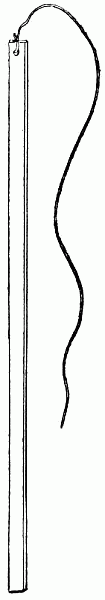

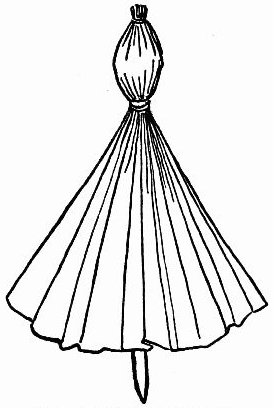

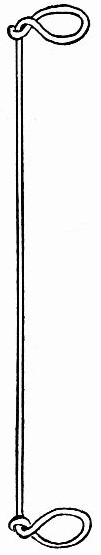

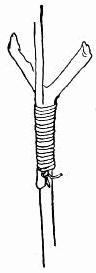

Fig. 1.—The slender rod tied at the lower end.

Fig. 1.—The slender rod tied at the lower end.

Fig. 2.—The looped upper

end of the rod.

Fig. 2.—The looped upper

end of the rod.

Is the old spinning-wheel in the attic, neglected and covered with dust, or in the parlor, decked in all its bravery of blue ribbons and snowy flax? Bring it out, wherever it may be, and for the first time in many years it shall buzz and whirr, while a girl's slender fingers part the flax and a girl's light foot rests upon the treadle. Look well to

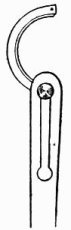

Fig. 3.—A little peg slipped through two holes.

Fig. 3.—A little peg slipped through two holes.

Fig. 4.—The leather rings.

Fig. 4.—The leather rings.

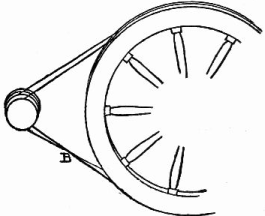

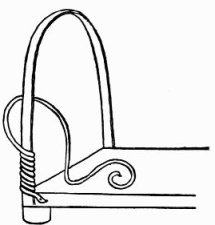

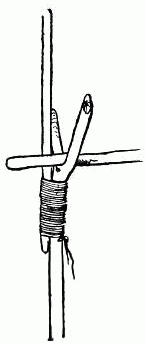

The two slanting uprights which hold the wheel in place are slotted at the upper ends, and in these slots rests the axle. A little peg, slipped through two holes in one of the uprights, keeps the axle from slipping out of place (Fig. 3).

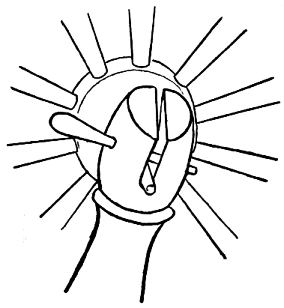

The frame that holds

Fig. 5.—One ring in each

upright.

Fig. 5.—One ring in each

upright.

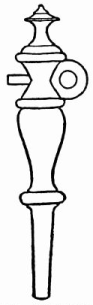

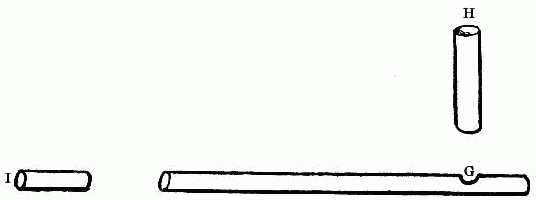

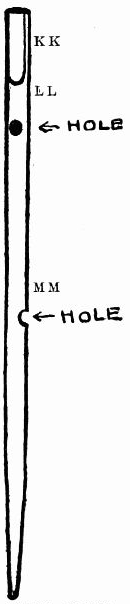

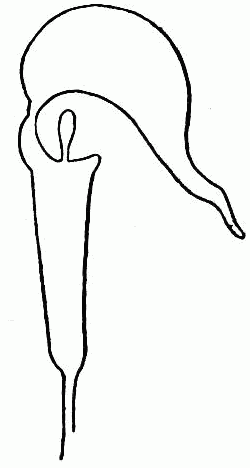

Fig. 6.—The spindle.

Fig. 6.—The spindle.

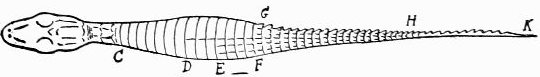

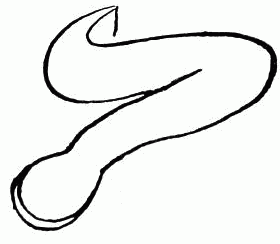

In the two uprights of the spindle-frame there must be[6] leather rings like Fig. 4, one ring in each upright. The narrow strip extending outward from the ring is pushed through the hole in the upright, and the edge of the ring fitted into the little grooves just above and below one of the holes (Fig. 5). These two leather rings hold the ends of the spindle, which can be easily taken out and put in by bending one of the rings backward or slightly turning one of the uprights. Fig. 6 shows the spindle with the spool, or bobbin, and the small, double-grooved wheel. The spindle proper is simply the metal rod and horseshoe-shaped piece of wood with its two rows of[7] little hooks or teeth. Besides the wheel and spindle there must be

Fig. 7.—The tip of your Christmas

tree for a distaff.

Fig. 7.—The tip of your Christmas

tree for a distaff.

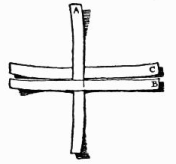

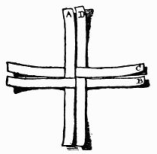

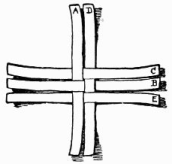

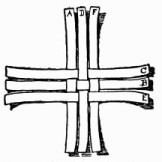

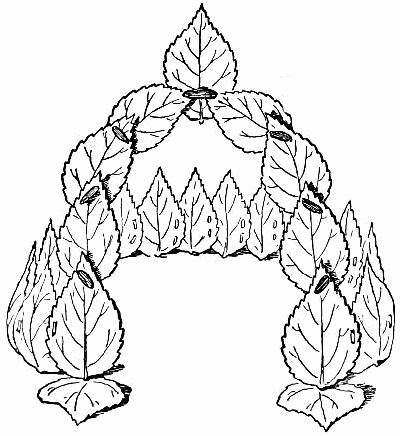

Fig. 8.—Bring the four branches

up and tie at the top.

Fig. 8.—Bring the four branches

up and tie at the top.

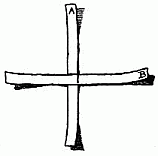

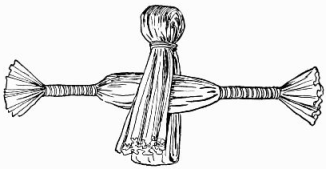

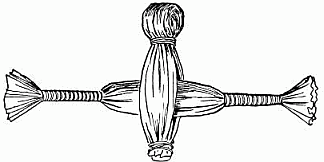

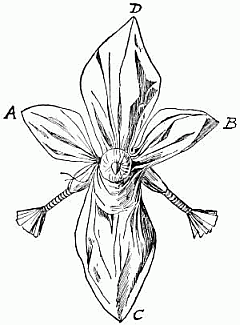

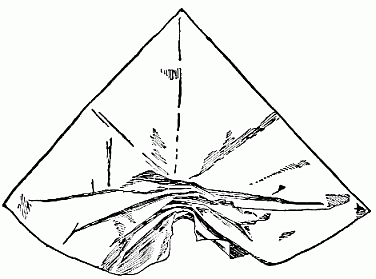

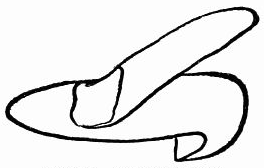

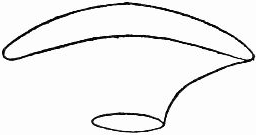

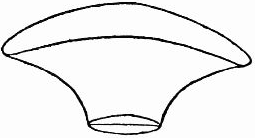

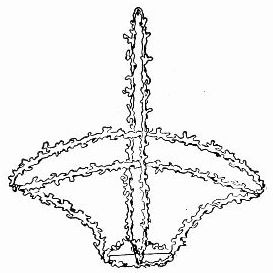

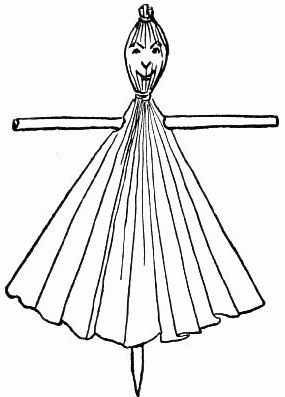

The distaff, which the mountaineers of Kentucky call the "rock," is a thing you can make for yourself if your wheel happens to have lost its own. Many are cut from the top points of pine-trees which grow like Fig. 7, and dogwood also is sometimes used. The tip of your Christmas tree will be just the thing. Strip off the bark, bring the four branches up, and tie at the top to the middle stem (Fig. 8). Let the lower end of the stem extend about four inches below the branches and whittle it down to fit in the hole in the distaff-arm.

These are all the parts of the spinning-wheel, but before[8] you can "see the wheels go round" every piece of metal must be

When the cleaning is finished, grease with lard the parts where there is any friction. The slots that hold the axle, the spindle-stem, and the metal arm, where the treadle-rod rests upon it, all need lubricating.

The best

Fig. 10.—Make a double loop.

Fig. 10.—Make a double loop.

Fig. 11.—The band will cross at the bottom.

Fig. 11.—The band will cross at the bottom.

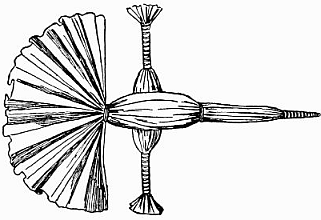

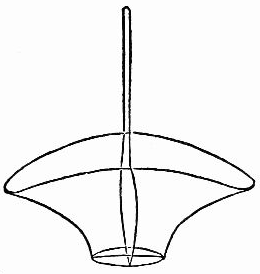

The spinning-wheel.

The spinning-wheel.

Open your hank of flax, take part of it, and spread thinly over the distaff, wrapping it around and around. Put on several layers, each almost as thin as a spider-web, extending it out widely and smoothly each time.

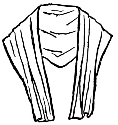

You may think the ribbon tied on the distaff of your parlor wheel is merely for ornament, but it is not. The bands hold the flax in place while it is being spun, and a crisp, dainty, pretty-colored ribbon is just as useful for the purpose as one that is old and faded, and it is far prettier to look upon. Wrap the ribbon around the flax on the distaff, beginning at the bottom, cross it, and tie as shown in illustration of the spinning-wheel.

Though everything is ready, before attempting to spin,

It seems a simple thing to work the treadle, but you will find that without previous practice you will forget to make your foot go in the absorbing interest of getting the flax ready to run on the spindle. Curb your impatience a little while therefore, and resolutely turn the distaff, with its pretty load, away from you. Place one foot on the treadle, give the large wheel a turn to the right, or away from the spindle, and try to keep a steady, even motion with your foot. The jerks caused by uneven pedalling will always break the thread, so you must learn to make the wheel turn smoothly and easily, without hurry and without stopping. Some spinners place only the toe of the foot on the treadle, others rest on it the heel also; it matters little which[12] method you adopt so long as the wheel turns evenly. When you are quite satisfied that you can keep the wheel going without giving it a thought you may begin

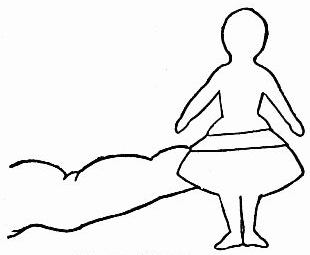

From the lowest ends of the flax draw down several strands and twist them with your fingers into a thread long enough to reach easily the bobbin on the spindle. Pass the end of the thread through the hole in the end of the spindle nearest to you (Letter A, Fig. 6), carry it across and over the upper row of teeth and tie to the bobbin (Fig. 6). Start your wheel going, and, forgetting the action of your foot, give your undivided attention to drawing out the flax. Hold the strands lightly with your left hand and with your right keep constantly pulling them down and at the same time twisting them slightly. See illustration on first page. All this time you must keep the flax from matting and tangling and the twist from running up into the mass of flax on the distaff. Only practice will make perfect in this work, though the knack may come suddenly and you will wonder at your first clumsy attempts. The little fluster and excitement one feels in beginning and the hurry to get the flax into shape for the spindle is a drawback that practice will also overcome.

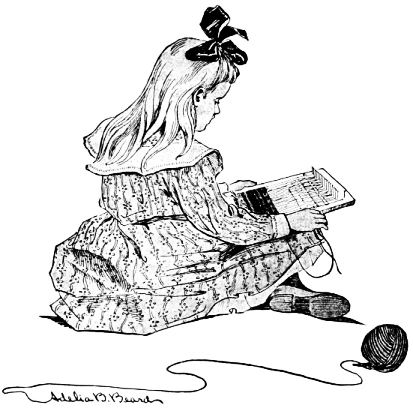

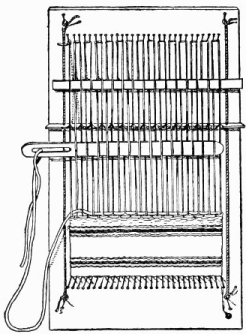

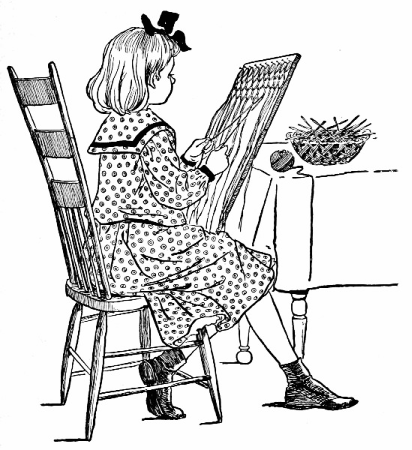

The little girl and the little loom.

The little girl and the little loom.

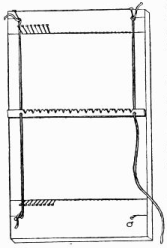

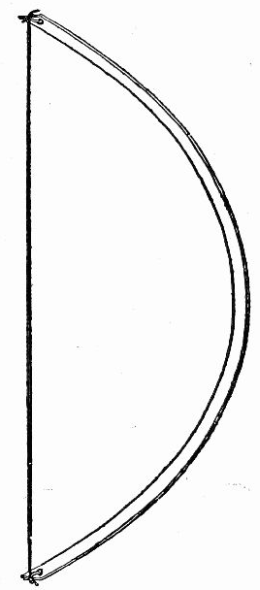

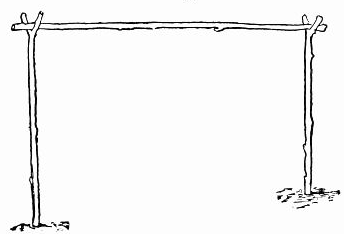

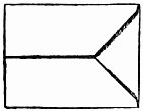

Fig. 12.—The frame for the loom.

Fig. 12.—The frame for the loom.

If it is natural to weave, it should also be natural to make one's own loom, and

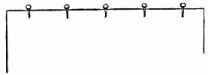

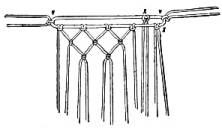

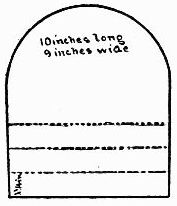

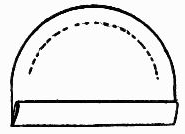

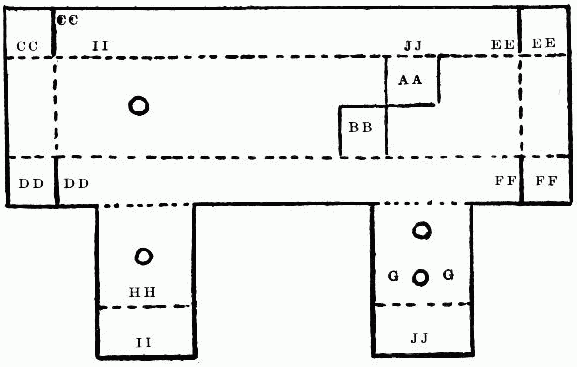

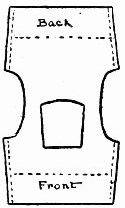

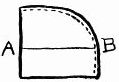

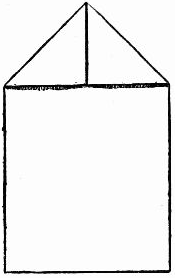

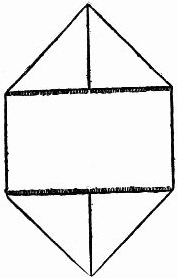

Make the frame for the loom of a smooth piece of soft pine-board, fifteen inches long by nine inches wide (Fig. 12). Make the heddles of two flat sticks, nine inches long, half an inch wide, and one-eighth of an inch thick (Figs. 13 and 14). From another flat stick of the same thickness, nine inches long by one inch wide, make the shuttle (Fig. 15).

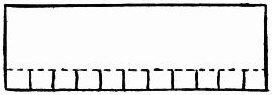

With a pencil and ruler draw two straight lines across the board, the first one inch and a half from the top edge, the other two inches and a half from the bottom edge. This will make the lines just eleven inches apart. On these lines, beginning one inch from the side edge of the board, make a row of dots exactly one-quarter of an inch apart, twenty-nine dots on each line, as in Fig. 12. At each corner of the board, one inch above the upper line and one inch below the lower line, draw a short line, and on[17] each short line, three-quarters of an inch from the side edge, make one dot.

With a small tack-hammer drive a pin in each of the twenty-nine dots on each long line, and in each single dot on the four short lines (Fig. 12). When driving in the pins let them all slant evenly outward, the ones on the top lines slanting toward the upper edge of the board, those on the lower lines slanting toward the bottom edge, as in Fig. 16. Now lay your board aside where nothing will be placed on top of it, and make your heddles.

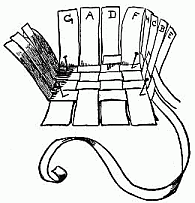

Along the entire length of one of the sticks rule a line dividing it exactly in the middle (Fig. 17). On this line, beginning three-quarters of an inch from the end of the stick, mark off spaces one-quarter of an inch apart, making thirty-one dots. At the upper edge of the stick mark off the same number of spaces exactly opposite those on the line. Then draw straight lines connecting the upper and lower dots, extending the first and last lines entirely across the stick (Fig. 17.) At a point on the upper edge, exactly[18] in the middle between the first two lines, start a slanting line and bring it down to meet the second line where it touches the long line. Between the second and third lines draw another slanting line to meet the first at the bottom, forming a V. Leave the third line, and make another V at the fourth, and so go the length of the heddle, drawing a V at every other short line. At the top between the V's make smaller V's, as in Fig. 17. With a sharp knife cut out these notches, bringing the large ones quite down to the middle line (Fig. 17). On the end lines just below the middle line bore a hole with a small gimlet or a hat-pin heated red-hot at Letter A in Fig. 17. Indeed the notches, too, may be made with a hat-pin by laying the red-hot end across the edge of the stick at the top of the line, and pressing it down while rubbing it back and forth. If you are unused to handling a knife, burning the notches will be the easier way. You can shape and trim them off afterward with the knife.

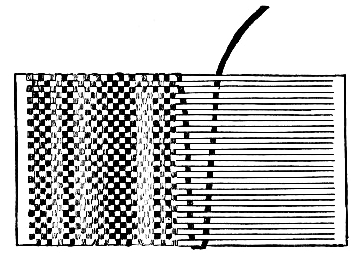

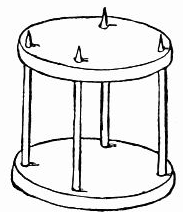

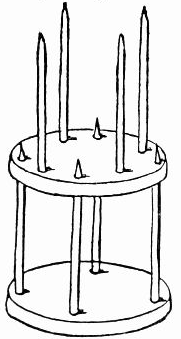

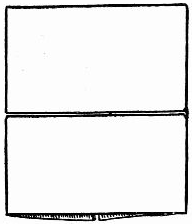

The complete pin loom.

The complete pin loom.

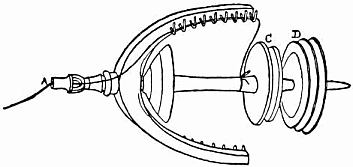

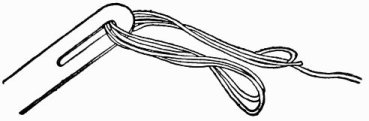

Of the third flat stick make

Curve the corners at each end as in Fig. 15. Sharpen one end down to a thin edge and in the other end cut an eye two inches long and one-quarter of an inch wide (Fig. 15). Cut your yard of colored cord in half, pass the end of one piece through one of the holes in the notched heddle, the end of the other piece through the hole in the opposite end of the heddle, and tie each end of the cords to one of the pins at the four corners of the board, drawing the cords taut. This will fasten the heddle in its place across the loom (Fig. 12).

Near the bottom of the board, directly below the last pin at the right on the long line, drive the carpet-tack to serve as a cleat for fastening the end of the warp. All that now remains to be done is

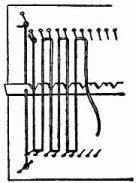

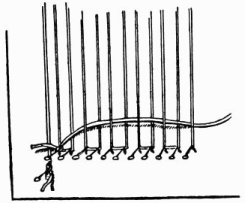

Fig. 18.—Adjusting the warp.

Fig. 18.—Adjusting the warp.

Tie the end of the warp securely to the first pin on the long line at the upper left-hand corner of the loom (Fig. 18). Bring the string down and around the first two pins on the lower line, up again and around the second and third pins on the upper line, and then down and around the third and fourth pins on the lower line. Up[20] again, down again, crossing two pins each time, back and forth until the last pin on the lower line has been reached. Wrap the warp around this pin several times, and then around the tack, tying it here so that it cannot slip. The warp must lie flat on the board where it passes around the pins, and in stringing up it must be drawn rather tight, though not with sufficient force to pull the pins out of place.

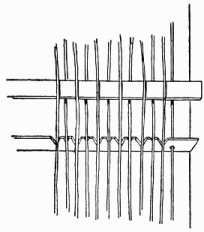

Fig. 19.—Putting in the second heddle.

Fig. 19.—Putting in the second heddle.

Turn the heddle on edge, the notches up, and slip the threads of the warp into the notches, one thread in each notch. This, you will see, divides the warp into upper and lower threads, and forms what is called the shed. While the threads are separated take the other heddle and darn it in and out above the first heddle, taking up the lower threads and bringing the heddle over the upper ones as in Fig. 19.

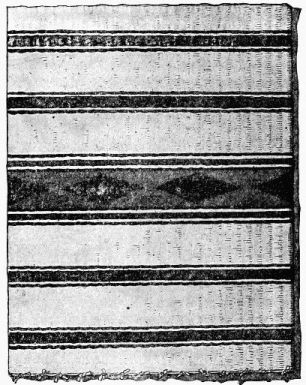

A Miniature Navajo Blanket.

A Miniature Navajo Blanket.

This is

Fig. 20.—The threaded shuttle.

Fig. 20.—The threaded shuttle.

Tie the long end of the wool to the first pin at the lower left-hand corner of the loom, on the long line, making a tight knot and pushing it down close to the board (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21.—Starting the woof.

Fig. 21.—Starting the woof.

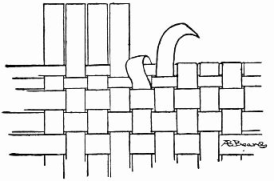

With the notched heddle on edge push the shuttle through the shed—that is, between the upper and lower threads of the warp. Draw it out on the other side, then turn the heddle down, notched edge toward you, and stand the plain heddle on edge. This will lift the lower threads of the warp above the others and make them the upper ones. Push the shuttle back through the shed, lay the plain heddle[23] flat, and stand up the notched heddle. Weaving from the left, the notched heddle always stands, while the plain one lies flat. Weaving from the right, the plain heddle stands, and the notched one is turned down.

Do not draw the woof tight across the warp. When you have passed the shuttle through, leave the thread like Fig. 21, and then push it down firmly with your finger-tips until it lies close to the pins.

Weave back and forth until all the wool in the shuttle is used. If the end of the woof extends beyond the last thread of the warp on either side, turn it back and weave it under and over several threads, and start a new piece with the end just lapping the old. The ends of the woof must never be allowed to extend beyond the warp at the sides. It is not necessary to tie the new piece of woof; the tight packing will hold it in place.

In this case the new woof must be of the red wool. Weave it across twice, or once over and back, making a very narrow red stripe, then cut it off and thread the shuttle with white. Weave the white twice across, then change to black and weave a stripe one-quarter of an inch wide. Above the black weave another narrow white stripe and another narrow red one. Put a long thread of white wool[24] in the shuttle, and weave a white stripe one inch wide. You will have to thread the shuttle twice for this, as too long a thread will make so large a bunch that it will be difficult to pass it through the shed. After the white stripe weave another black, white, and red stripe like the first, then another inch-wide white stripe. Once more weave a black, a white, and a red stripe. Begin with the narrow black, follow with the narrow white, and then weave a wider red stripe, taking the thread four times across. After the red the narrow white, and then the narrow black stripe.

This last stripe is the lower border of

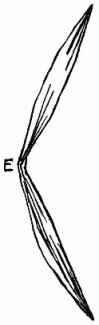

Thread the shuttle with a long piece of red wool and weave it once across from the left, turn back and weave through five threads of the warp, draw the shuttle out and weave back again to the edge; again weave through the five threads, then back as shown at B in Fig. 22. Turn here and do not take up the last thread of the warp; pass the shuttle under three threads, turn on the next thread, and bring it back under four threads (C, Fig. 22), once more under the three threads, turning on the next as before, but passing back under two threads only. Turn on the next thread (D), and pass under three.[25] Back under two threads (E), turn as before on the next thread under two, turn, back under two (F), turn, under one, turn on the next, under two (G), turn, under one, turn on the next, back under two, and unthread the shuttle, leaving the woof hanging.

Begin with a new piece of red wool, follow the same direction, and weave another red point on the next five threads, then a third one which will take in the last warp-thread on the left. You will notice in the diagram that the woof always turns twice on the same thread of warp.

When the three red points are finished fill in the spaces between with black (Fig. 23), then continue to weave the black up into points as you did the red, making two whole and two half black diamonds. Leave the woof quite loose when you make a turn in weaving, and the space left between the red and black will fill up in packing.

Take up the end of the red wool left at the top of the first red point, and weave in the space between the half and first black diamond, then break off. Take the next red end and fill in between the two whole diamonds, then the next, and fill in between the whole and the last half diamond. This will give you a pattern of black diamonds on a red ground. Weave the last of the red woof once across, then break off and weave a black, white, and red stripe like the one forming the lower border of the pattern. Finish the blanket with the wide white stripes and narrow colored ones like those first woven.

To take the work from the loom, cut the threads between the pins at the top of the loom, and with quick but gentle jerks pull it off the lower row of pins. Tie together the first and third loose ends of the warp close to the edge of the blanket, then the second and fourth threads, and so on across, then cut the ends off rather close to the knots.

The little Navajo blanket woven in this way will closely resemble the real Indian blanket in texture, pattern, and colors.

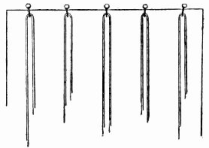

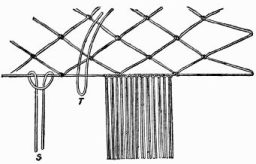

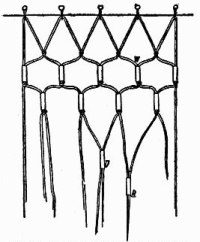

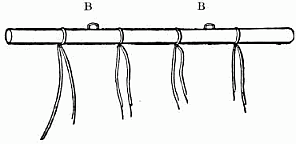

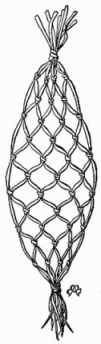

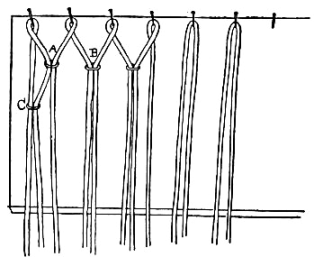

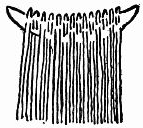

Drive twelve large tacks in a straight line across the top edge of the board; place the tacks one inch and a half apart (Fig. 25), and with a pencil draw lightly a line across the board from side to side, one inch and a half below the tacks.[28] This will guide you in keeping the knots even. Be sure that the line is perfectly straight; then draw another line one inch and a half below the first and continue making lines until the board is covered with them, at equal distances apart and running across from side to side. Over each tack on the top of the board hang a piece of string about two yards long (Fig. 26). Being doubled, each string makes two lengths of one yard each.

Fig. 25.—Tacks in top of board.

Fig. 25.—Tacks in top of board.

Fig. 26.—Over each tack hang a piece of

string.

Fig. 26.—Over each tack hang a piece of

string.

Bring the two ends of each strand down evenly together that all the strings may hang exactly the same in length. Fig. 26 is intended only to show how to hang the strings and gives but a section of the work.

Fig. 27.—With strong pins fasten the first and fourth strings

to the board.

Fig. 27.—With strong pins fasten the first and fourth strings

to the board.

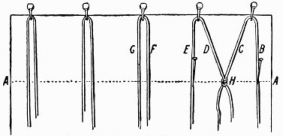

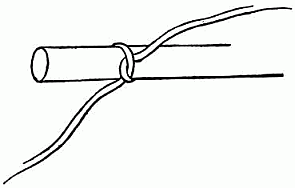

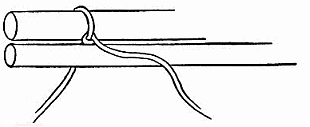

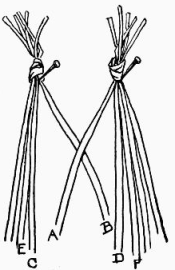

With strong pins fasten the first and fourth strings down tight to the board (see B and E, Fig. 27); then tie the second and third strings together (C, D, Fig. 27), making the knot H (Fig. 27).

Fig. 28.—When knot H is secure stick pin in string G.

Fig. 28.—When knot H is secure stick pin in string G.

Fig. 29.—Tying the knot.

Fig. 29.—Tying the knot.

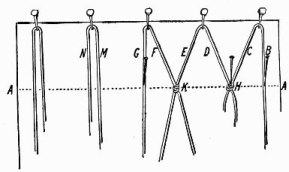

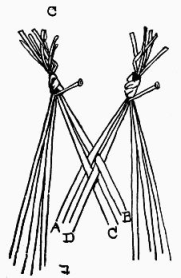

When the first knot (H, Fig. 27) is tied, take the pin out of the string E and stick it in the string G, according to[30] Fig. 28. Fasten down the knot H with another pin, and you will have the knot H and the string G firm and tight to the board while you tie the two loose strings F and E together, forming the knot K. Pin this down to the board and remove the pin from the string G and place it in the string N, leaving M and G free to be knotted together.

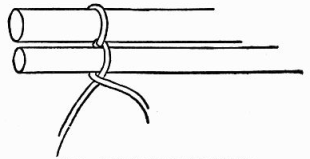

Continue tying the strings in this way until you have made the first row of knots across the board, always using pins to hold the boundary-strings securely to the board on each side of the two you are tying. As each knot is formed, pin it to the board and allow the pins to remain in the first row until the second row of knots has been made.

Fig. 29 shows the beginning of the third row of knots in the knot P, the pin being taken from the first knot, H, ready to be placed in the knot P. Form row after row of meshes by knotting the strings until the netting comes too near the bottom of the board to work comfortably, then slip the top loops off from the tacks and hang a portion of the net over the top of the board, allowing a lower row of meshes to hang on the tacks.

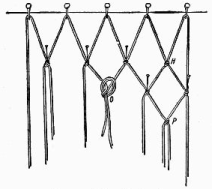

Fasten the last row of the knots carefully, binding with strong strings the short loose ends of the strands securely to the string forming the mesh each side of the knot. Remove the net from the board and make

Fig. 30.—Making the fringe.

Fig. 30.—Making the fringe.

Fig. 31.—Heavy

cord through loops

on end of hammock.

Fig. 31.—Heavy

cord through loops

on end of hammock.

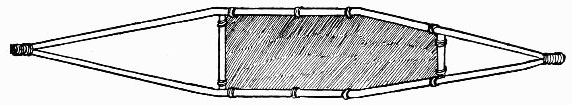

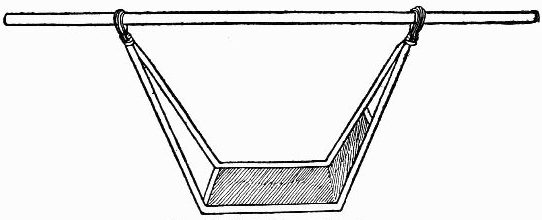

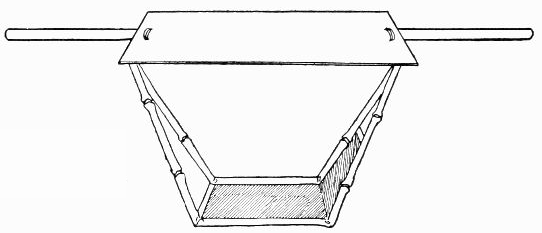

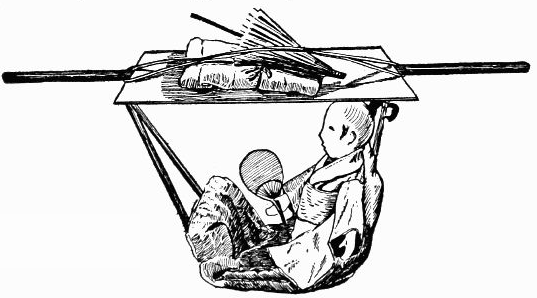

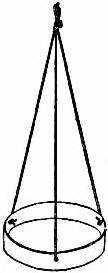

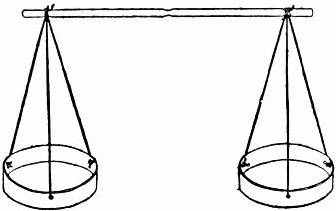

When you have made the fringe, thread a separate heavy cord through the loops on each side of the hammock (Fig. 31). Tie the loops together (Fig. 32) and fasten together the two ends of each cord, making these two extra last loops long enough to allow of a free swing for the little hammock, or you can thread a cord of the same as that used in the hammock through every loop, tying the ends of each piece together through a brass ring, and instead of one long loop a number will support the hammock.

Fig. 32.—Tie

loops together.

Fig. 32.—Tie

loops together.

Making a sash-curtain for her room.

Making a sash-curtain for her room.

Fig. 33 shows a strong, serviceable little

Fig. 33—Your school-bag made of string.

Fig. 33—Your school-bag made of string.

Having finished the bag, untie the strings attached to the two ends and make two handles of heavy cord or slender rope. Fasten the handles on their respective sides of the bag. Loop the ends of the handles under the cord forming the top of the bag, and bring each end up against its own side of the handle. Sew each of the two ends of the two handles securely to the handle proper; then bind the sewed portions neatly together with fine cord as in Fig. 33.

Fig. 34—Making the school-bag.

Fig. 34—Making the school-bag.

With some firm straws and more string we will make

Fig. 35 shows how to manage the work. It is almost exactly like that of the hammock, the only difference being the threading on of the straws which hold the strings in place without a knot at the top (see W in Fig. 35). Let the bottom of the net end in a fringe. Take the loops off from the tacks when the curtain is finished, and slide them on a straight, slender stick, which you can fasten to the window by resting the ends of the stick through loops of tape tacked on the sides of the window-frame at the right distance up from the ledge of the window.

Fig. 35.—Sliding straws on strings for

curtain.

Fig. 35.—Sliding straws on strings for

curtain.

If possible, let all the net-work be made of pliable, soft material; it is easier to handle, and the results are much prettier.

Make the curtains of any color you may fancy.

It is great fun, yet there is still more entertainment to be found in these pretty shavings.

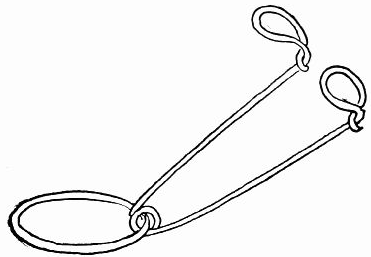

Gather an armful, then, choosing the most perfect ones, not too thin, with firm, smooth edges, and you shall weave them into

The soft little basket made of shavings.

The soft little basket made of shavings.

Fig. 37—So that the upper edge of B

will touch the dividing line of A.

Fig. 37—So that the upper edge of B

will touch the dividing line of A.

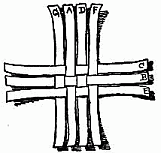

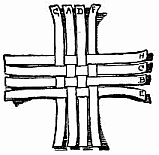

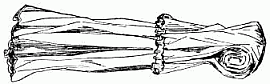

Pine-shavings are the best to use, as they are less brittle than those of harder woods. Select a number and put them to soak in cold water to make them soft and pliable. Then, lifting out those of an even width, place them before you[37] on a lap-board or table, and after passing them between your fingers several times to take the curl out, cut eight pieces eleven inches long. Directly across the centre of two of the strips draw a straight line, as in Fig. 36. Place one of these strips, A, flat on the table and lay the other, B, across it so that the upper edge of B will touch the dividing line of A and the mark on B will be on a line with right-hand edge of A, Fig. 37. Under A slide another strip, C, Fig. 38. Over B and under C slide[38] the strip D, Fig. 39. Over D and under A pass the strip E, Fig. 40. Under E, over B and under C weave the strip F, Fig. 41. Under E, over B, and under C weave the strip G, Fig. 42. Over F, under D, over A, and under G weave the strip H, Fig. 43. This forms a square for the bottom of the basket.

Fig. 38.—Under A slide the strip C.

Fig. 38.—Under A slide the strip C.

Fig. 39.—Over B and under C slip

the strip D.

Fig. 39.—Over B and under C slip

the strip D.

Fig. 40.—Over D and under A pass E.

Fig. 40.—Over D and under A pass E.

Fig. 41.—Under E, over B and under

C weave F.

Fig. 41.—Under E, over B and under

C weave F.

Bend up the ends and

Fig. 42.—Under E, over B and

under C weave G.

Fig. 42.—Under E, over B and

under C weave G.

Fig. 43.—This forms the bottom of

the basket.

Fig. 43.—This forms the bottom of

the basket.

If you find any difficulty in keeping in place the part you have woven, pin it to the board or table with several pins, as in Fig. 44. Bring the sides up close to the edges of the bottom, then start your weaver at D, on the inside of the basket (Fig. 44).

Fig. 44.—Bend up the ends now and weave

the sides.

Fig. 44.—Bend up the ends now and weave

the sides.

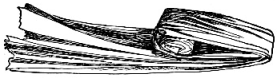

Weave all the way around, turning the corners sharply, until the weaver meets the first end; lap it over this, cut it off and tuck the last end under H. Start the next weaver at C, weave it around and tuck under E. Weave five weavers around the sides of the basket, beginning each time[40] in a new place that the joints may not all come together, then bend the upright shavings over the edge of the top weaver, tucking the ends of each under the third weaver, one inside, the next outside, as they may come inside or outside the basket (Fig. 45).

Fig. 45—Bend the upright shavings over

the top edge.

Fig. 45—Bend the upright shavings over

the top edge.

Fig. 46.—Bind the edge with two

binders.

Fig. 46.—Bind the edge with two

binders.

Cut two strips the width of your side weavers for

Loop the handle diagonally over the basket and fasten the other end on the second weaver on the side. Secure the ends of the long strip on the third weaver, allowing it to cross the other side of the handle at the[41] top, then bind the two pieces together at the middle by wrapping with a shaving of the same width over and over. Split this wrapper at the last end and tuck the two ends in at the sides. Fig. 48 shows the under part of the handle with one end of the wrapper tucked in.

Fig. 48.—Tuck the two ends in at the

sides.

Fig. 48.—Tuck the two ends in at the

sides.

You can make table-mats, charming little handkerchief-cases, and a number of other things of the dainty shavings, all on the same principle as that of the basket.

To make

The handkerchief case.

The handkerchief case.

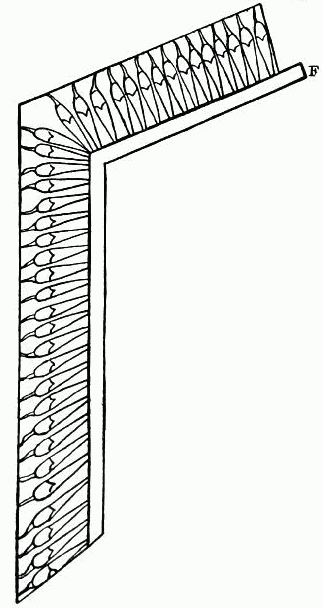

Fig. 49.—Beginning a primitive curtain.

Fig. 49.—Beginning a primitive curtain.

Fig. 50.—Centre of twine tied

on long stick.

Fig. 50.—Centre of twine tied

on long stick.

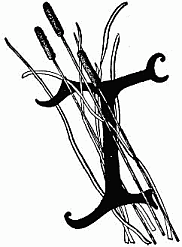

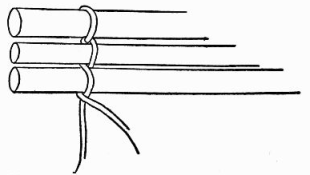

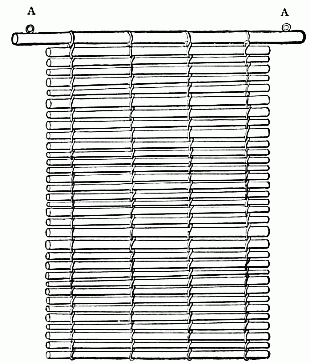

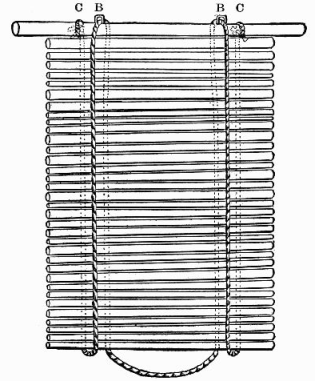

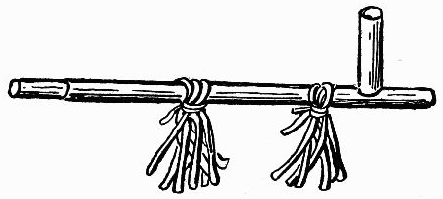

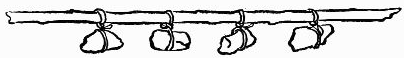

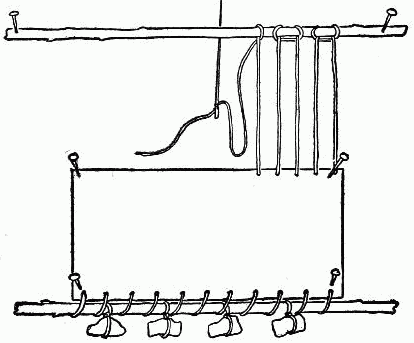

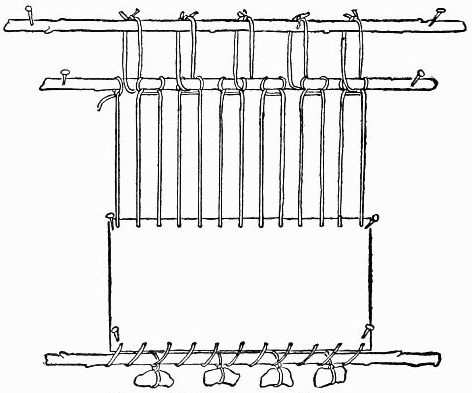

An old bamboo fishing-rod, a length of handle from a long-handled dusting or window brush, or any kind of a long, slender, smooth, round stick will do for the top curtain-pole from which to hang the reeds. Lay the pole across a table in front of and parallel to you; then tie the centres of four pieces of cord of even lengths on it at equal distances from each other (Fig. 49). Detail of the work is given in Fig. 50. Place a cat-tail reed up against the four ties, allowing one string from each tie to come over and the other under the cat-tail (Fig. 51). Cross the two lengths of each cord over the last cat-tail, bringing the lower string up and the upper string down (Fig. 52); then lay another reed up against the crossed strings, carrying the strings in turn over this reed (Fig. 53). Again bring the lower strings up and the upper down before[45] placing in another cat-tail, and always alternate the large and small ends of the reeds as in Fig. 54, in order to have them equally balanced and to avoid bringing all the small ends on one side and the large ones on the other side of the curtain.

Fig. 51.—Allow one string to come over and the other under

the cat-tail.

Fig. 51.—Allow one string to come over and the other under

the cat-tail.

Fig. 52.—Cross the two lengths of twine.

Fig. 52.—Cross the two lengths of twine.

Fig. 53.—Lay another cat-tail up against the crossed strings.

Fig. 53.—Lay another cat-tail up against the crossed strings.

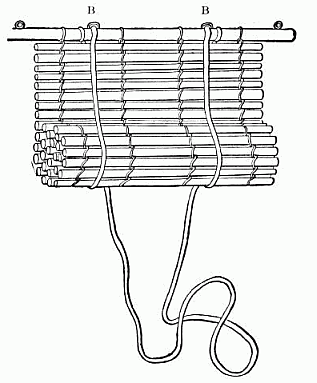

Fig. 55—Primitive curtain of reeds and twine stitch.

Fig. 55—Primitive curtain of reeds and twine stitch.

Fig. 56.—Staple nail in top pole of curtain.

Fig. 56.—Staple nail in top pole of curtain.

Fig. 57.—Cord fastened on top pole for rolling up curtain.

Fig. 57.—Cord fastened on top pole for rolling up curtain.

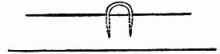

The girls and boys could readily make a number of hangings[49] in one afternoon, and while weaving the reeds together they would weave into the work all sorts of bright speeches and gay laughter, so that ever after the curtains would be filled with delightful associations of the charming summer afternoon. Reed curtains can be fashioned in any width. If very narrow hangings are in demand, cut your reeds to measure the length needed for the curtain-width and weave them together with the same twine cross-weave used in Fig. 55.

Fig. 58.—Cat-tail curtain

raised by loop

from bottom.

Fig. 58.—Cat-tail curtain

raised by loop

from bottom.

Fig. 60.—Large end of another.

Fig. 60.—Large end of another.

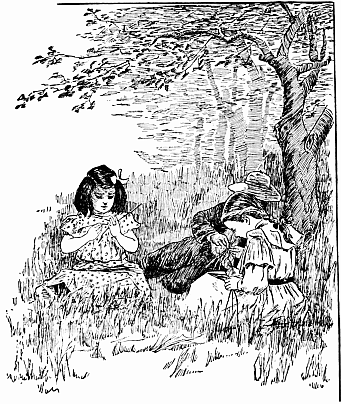

Sitting in the orchard

Sitting in the orchard

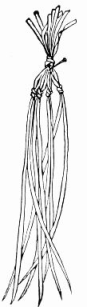

"Go 'long, chile, I done got 'nough to do 'thout makin' no hoppergrass-houses."

"Please, mammy, only one, and then I can make them for myself. I'll watch you just as close. Won't you, mammy?"

"Pick me some grasses, then; I 'low I has to, but don't yo' come pesterin' me no more after this time.

"Seed-top grasses, honey, seed-top grasses; don't git me none of them blade kind. Ketch hol' near the top and pull 'em up slow like, then they'll come out nice and smooth, an' leave they ole rough skins behind, just like a eel does when you skins him. That's it, you got 'nough now; bring 'em 'long here an' we'll make the hoppergrass-house.

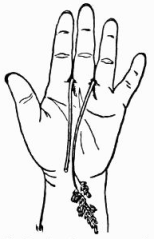

"Hol' your own hand, honey, you'll learn best that-a-way. Can't forgit the feelin' of it once you build it on yo' fingers.

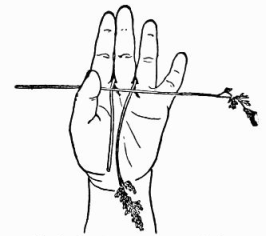

Fig. 62.—Put the grass around your middle finger with the end inside.

Fig. 62.—Put the grass around your middle finger with the end inside.

|

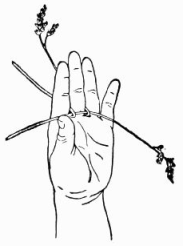

Fig. 63.—Lay the next grass across the first.

Fig. 63.—Lay the next grass across the first.

|

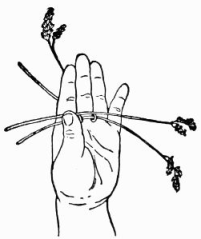

Fig. 64.—Bend back the ends of the first grass.

Fig. 64.—Bend back the ends of the first grass.

|

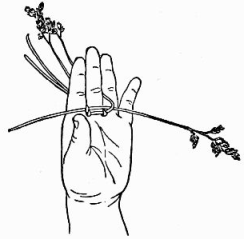

Fig. 65.—Put the next grass across your hand.

Fig. 65.—Put the next grass across your hand.

|

Fig. 66.—Bend back the second grass

ends like the first.

Fig. 66.—Bend back the second grass

ends like the first.

"Take one piece o' grass an' put it round yo' middle

finger with the ends inside like this (Fig. 62). Now lay the

next piece right across the first (Fig. 63), an' bend back the[54]

[55]

ends of the first grass

over the tother an' tuck

'em 'tween yo' fingers just

like that (Fig. 64). Put

the next grass across yo'

hand (Fig. 65), an' take up

the second grass-ends,

bendin' 'em back to keep

company with first grass-ends.

That makes another

bar (Fig. 66). Now

yo' do it an' let mammy

see how yo' git along.

That's right, lay the grass

across an' put

the under ends

back ev'ry time. How

many bars has yo' got

now? Six? That's 'nough

fo' any hoppergrass, an'

is as many as yo' little

hand can hol' anyway.

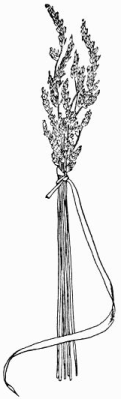

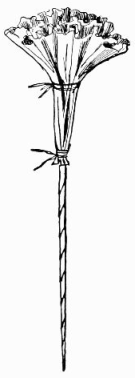

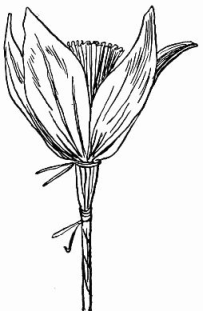

"Now slip it offen yo' fingers, bring the ends together an' tie with a blade o' grass just above these here blossom ends (see illustration). There now, yo' done made a hoppergrass-house, an' don' yo' come askin' yo' ole mammy to stop her work no more."

That is the way the little girls and boys in the South are taught to make the grasshopper-houses, by the old colored "mammies." They are funny little cages, and, of course, will not hold a grasshopper or any other insect, but we like to imagine they will.

The

grasshopper-house

The

grasshopper-house

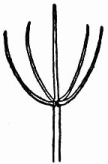

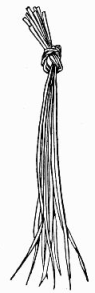

There are other things to make of grasses, any one of them requiring only a few moments' work, and it is a pretty, quiet occupation for restless little fingers. Sitting in the orchard, nestling like little partridges amid the tall grasses, all your materials are close at hand. Reach out and gather some of the long-bladed grass, and we will make

Fig. 67.—Tie them together

at the root ends.

Fig. 67.—Tie them together

at the root ends.

|

Fig. 68.—Lift two of

the grasses and tie

them together.

Fig. 68.—Lift two of

the grasses and tie

them together.

|

Fig. 69.—Tie them all

in pairs.

Fig. 69.—Tie them all

in pairs.

|

Fig. 70.—Make the knots

of the second row one

inch below the first row.

Fig. 70.—Make the knots

of the second row one

inch below the first row.

|

The grass hammock.

The grass hammock.

Some of this grass measures twenty-five inches in length. It does not grow on stalks, but the blade appears to spring directly from the root, and it is smooth and pliable. You may find orchard-grass almost any where, generally in neglected corners and close to fences where the scythe does not reach.

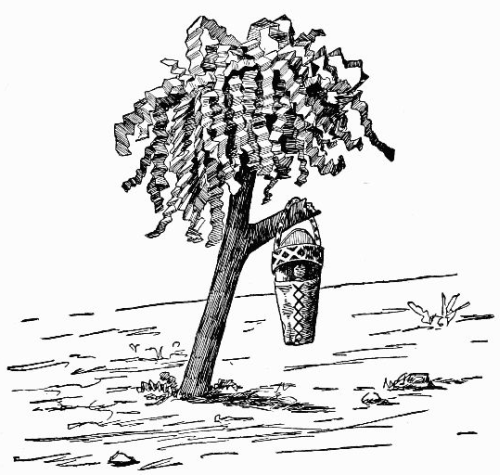

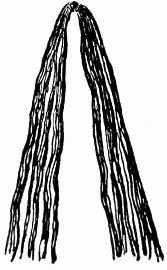

Take eight or ten of the blades of this grass and tie them together at the root-ends as in Fig. 67, drawing the knot tight as in Fig. 68. Stick a pin through just below the knot and fasten to your knee; then lift two of the grasses at the right-hand side, and tie[57] them together about one inch below the pin (Fig. 68). Tie the next two grasses together in the same manner, the next, and the next, until you have tied them all in pairs (Fig. 69). Make the second row by separating the pairs of the first and tying one grass of one pair to the neighboring grass of the next pair, making the knots one inch below the first row. This leaves the first and last grasses hanging loose (Fig. 70). On the third row the first and last grasses are tied in once more (Fig. 70). On the fourth they are left again, and so they alternate until the hammock is finished. Keep the rows of knots at even distances apart, and make the hammock as long as the length of the grass will allow. Leave about three inches of the grass below the last row of knots, and then tie the ends together as in the illustration. Swing the little hammock between the low-hanging branches of a tree; put your dolly in it and let the summer breezes rock her to sleep while you sing:

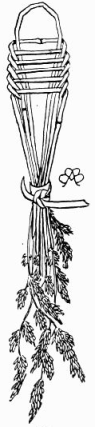

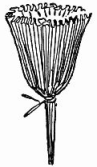

A very pretty

Bouquet-holder made

of seed-grass.

Bouquet-holder made

of seed-grass.

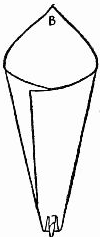

|  Fig. 71.—Bunch together

the seed-grass stalks.

Fig. 71.—Bunch together

the seed-grass stalks.

|

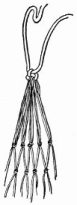

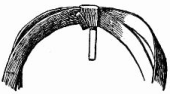

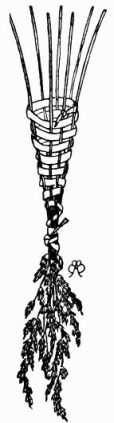

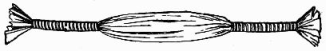

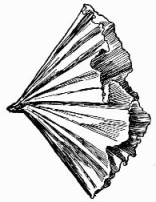

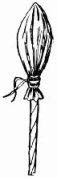

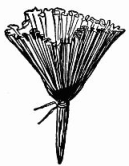

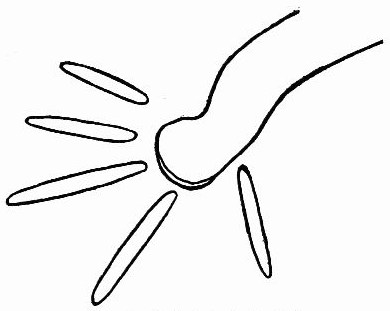

Bunch together seven fine, strong seed-grass stalks and tie just below the blossoms, with the root-end of your long-blade grass (Fig. 71). The stems of the seed-grasses are the spokes, the long grass the weaver. Turn the blossom-ends down, the stem-ends up, and close to where it is tied, begin to weave the long grass in and out, under one spoke, over the next, under the third, over the fourth, going around and around spirally until the end of the weaver is reached, then tie it to one of the spokes. Keep forcing the spokes farther and farther apart as you weave until the holder is shaped like a cone. As you see in the illustration, the weaver never passes over one of the spokes twice in succession. In one row it goes over a spoke, in the next[59] row under it, in the third over again, and so on. In order that it may always come this way you must have an uneven number of spokes. Four will not do, nor six, nor eight, but five, seven, or nine spokes will bring the weave out all right.

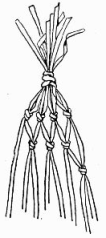

Grass napkin-ring.

Grass napkin-ring.

Fig. 72.—Take one blade from each bunch and cross them.

Fig. 72.—Take one blade from each bunch and cross them.

|  Fig. 73.—Bring C over A and D under B and over C.

Fig. 73.—Bring C over A and D under B and over C.

|

Select ten fine long blades of grass, divide them into two bunches of five each, put the root-ends together, and tie them as when making the hammock. Pin these two bunches to your knee about two inches apart, and taking one blade from each bunch, cross them as in[60] Fig. 72, the right-hand grass A on top of the left-hand grass B. Now bring the left-hand grass C over A, and the right-hand grass D under B and over C (Fig. 73). Next weave the left-hand grass E under A and over D, then the right-hand grass F over B, under C, and over E. Weave the remaining four grasses in the same way, taking first from one side, then from the other. When your work has reached the stage shown in Fig. 74, take the grass A, turn it under and weave it in and out as in Fig. 76, then the grass B, turn it over and weave until it crosses A (Fig. 76). D comes next, to be woven until it crosses B, then C, which will cross D. On the left hand always turn the grasses under before beginning to weave, on the right hand turn them over before beginning to weave.

Fig. 74—Weave the remaining grasses in

the same way.

Fig. 74—Weave the remaining grasses in

the same way.

|  Fig. 76.—Turn the grass A under,

and weave it in and out.

Fig. 76.—Turn the grass A under,

and weave it in and out.

|

Fig. 77.—Tie the opposite ends

together.

Fig. 77.—Tie the opposite ends

together.

Do not use rough or saw-edged grasses for any of this work, for they sometimes cut the hands, and the seed-top grasses must not be old enough to shed their seeds into your eyes. When dry most grass is quite brittle and will break if you attempt to bend it. The fresh, green, soft and pliable grasses are the kind you need and these you may always find in season.

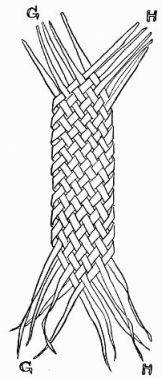

Hemp rope and cotton, large rope and small, down to the ordinary heavy twine, all lend themselves to this work.

It requires a rather heavy clothes-line, one considerably lighter, called by some rope-cord, and a piece of strong twine for the

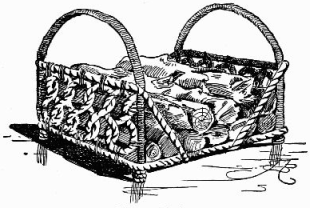

The wood-basket.

The wood-basket.

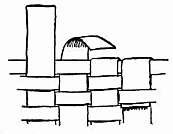

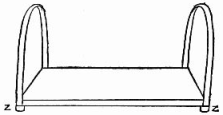

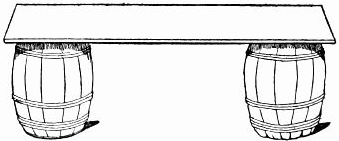

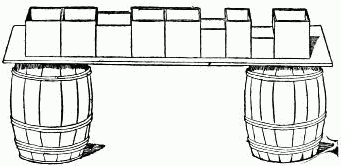

Make the bottom of a board two feet long and sixteen inches wide, and on each end of the board nail securely one-half of a barrel-hoop (Fig. 78). From an old broom-stick cut four rounds one inch thick for the feet (Fig. 79), and fasten one round to each corner underneath the board with strong screws or wire nails (Fig. 78, Z Z).[63] This is all the wood you will need for the basket, the rest is to be made entirely of rope.

Fig. 78—On each end nail one-half of a barrel-hoop.

Fig. 78—On each end nail one-half of a barrel-hoop.

Fig. 79—For

the feet.

Fig. 79—For

the feet.

Take your small rope and nail one end of it to the edge of the bottom, close to one end of one of the barrel-hoops (Fig. 80), then wrap the hoop with the rope, one row close to another until it is completely covered. Cut off the rope when it reaches the end of the hoop and nail it down as you did the first end of the rope in beginning. Fasten a piece of the heavy rope entirely around the edge of the board, nailing it at intervals along each side, but leaving loose that at the end edges until later. Make the

Fig. 80.—Nail one end of the small rope to

the edge of the bottom.

Fig. 80.—Nail one end of the small rope to

the edge of the bottom.

Eight inches from the end of the bottom, underneath but near the side edge, nail one end of your heavy rope; bring it up slantingly and wrap and tie it to the hoop just above and touching the top edge of the loops, stretch the rope tightly across the hoop and tie at the other side, then carry the end down and fasten underneath the bottom eight inches from the end of the board (see illustration). Wrap and tie the top loops of the end piece to the top rope as shown in illustration. Finish the other end of the basket in the same manner, not forgetting to nail in place the rope left loose at the end edges. Give the completed wood-basket several coats of dark varnish. The varnish not only produces a nice finish, smoothing down both wood and rope, but also stiffens and helps to hold the rope in place.

Fig. 81.—Make the end pieces like this.

Fig. 81.—Make the end pieces like this.

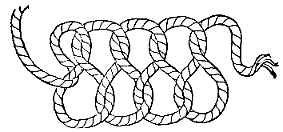

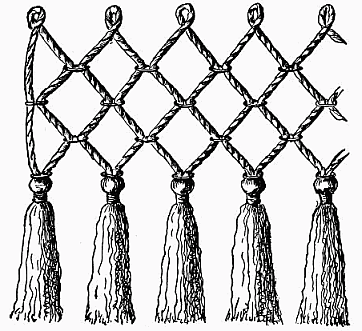

This netting may be made of heavy rope for a grille in an open doorway, or of lighter rope for fringe. In either case the method is the same.

In a board, at regular distances apart, along a straight line, drive a row of wire nails. It depends upon the size of the rope how far apart the nails should be placed. For a heavy rope there must be at least four inches between, and this distance should lessen as the rope decreases in size.

Fig. 82.—A Rope netting.

Fig. 82.—A Rope netting.

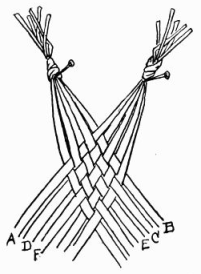

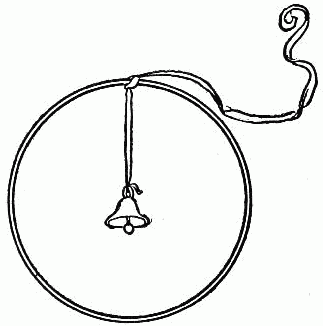

Cut your rope into pieces four feet in length if it is heavy, not so long if it is light rope. Loop one piece of rope over each nail and let it hang down evenly, then[66] bring the first and fourth strands together and slip on them a small brass curtain or embroidery ring (Letter A, Fig. 83). Push the ring up to within four inches of the line of nails if the nails are four inches apart. If the distance between the nails is three inches the ring must be three inches below the line. Catch the ring to each strand of rope with needle and thread to hold it in place. Bring the third and sixth strands together and slip on a ring (Letter B, Fig. 83). Then the fifth and seventh, and so across the board.

Fig. 83.—Slip on a small brass curtain ring.

Fig. 83.—Slip on a small brass curtain ring.

Begin the next row by slipping a ring on the first and second strands, placing it the same distance below the first row of rings that the first row of rings is below the line of nails (Letter C, Fig. 83). Bring the third and fourth strands together with a ring, the fifth and sixth, continuing the original pairing of the strands until the row is complete. The third row of rings brings together again the second and fourth strands, the third and sixth, as in the first row, and the fourth row of rings goes back to pairing the first and second, third and fourth strands.

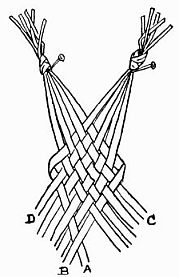

Below the last row of rings wrap and tie the strands together, then untwist the ends of the rope up to where it[67] is tied and fray it out until it becomes fluffy. Make the head of the tassel by wrapping closely with twine a short distance below the ring, or you may slip on several of the brass rings as a finish.

The board on which you make your netting need not be any longer than is convenient to handle, for when one part of the netting is finished it can be taken off the nails and new strands added to carry on the work.

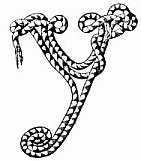

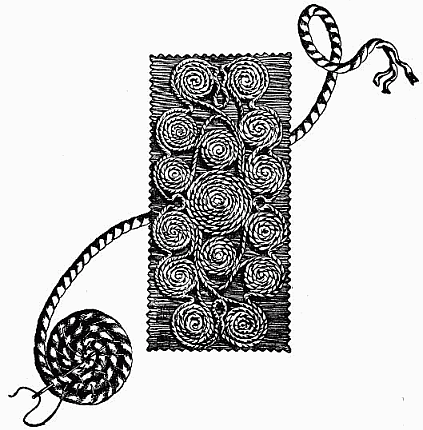

Fig. 84 is an ornamental design suitable for decorating a wooden chest or, if sewed on cloth, for a hanging. By studying the design you can easily reproduce it without the aid of description or other diagram.

Fig. 84.—Ornamental design.

Fig. 84.—Ornamental design.

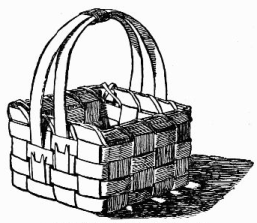

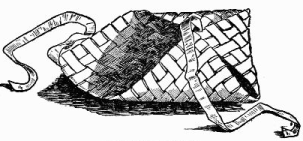

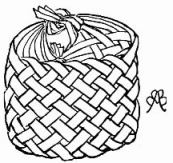

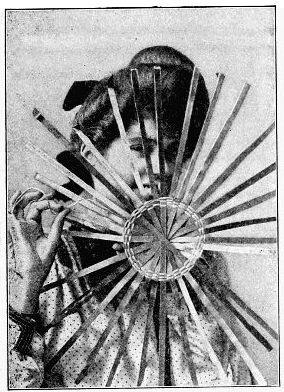

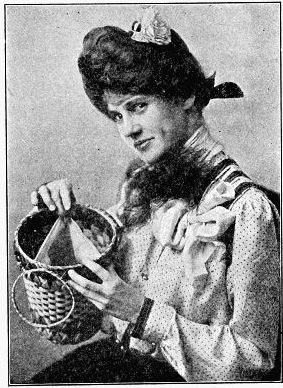

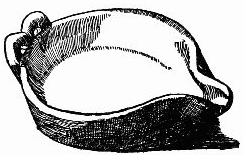

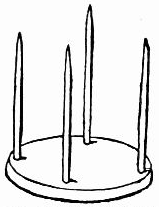

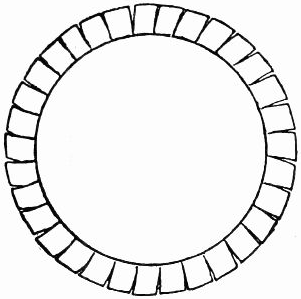

A basket measuring about six inches in diameter and three inches in height is a convenient size on which to learn.

Weaving the sides of basket with long weaver.

Weaving the sides of basket with long weaver.

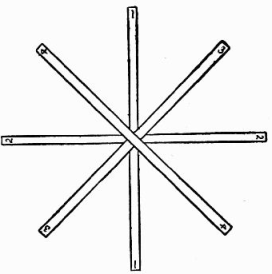

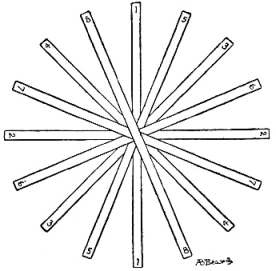

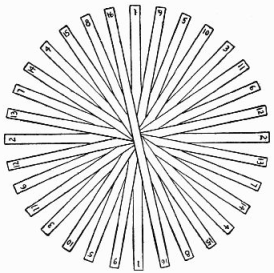

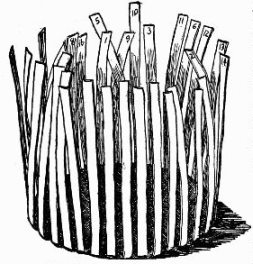

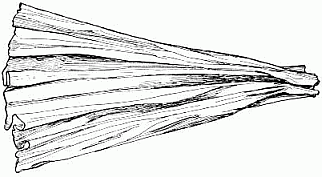

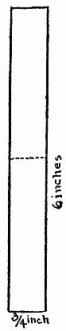

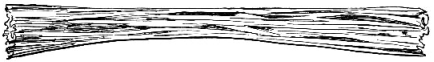

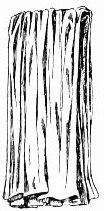

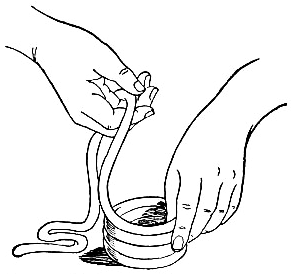

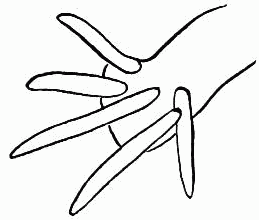

Wipe the dripping water from the splint, and cut off six pieces nineteen inches long; then cut these into sixteen strips one-half inch wide, for the spokes of the basket. Do not attempt to tear the splint, for it will not tear evenly. From the other piece of splint cut four strips for weavers, making the first one-half of an inch wide, the next one-fourth of an inch wide, another one-eighth of an inch wide, and the last one-sixteenth of an inch wide. Place all the weavers in the water and leave them until you are ready to begin weaving.

Fig. 85.—The first four spokes.

Fig. 85.—The first four spokes.

Fig. 86.—Eight spokes in place.

Fig. 86.—Eight spokes in place.

For instance, the

ninth spoke should

come between No. 1 and No. 5, the tenth spoke between

No. 5 and No. 3, the eleventh spoke between No. 3 and

No. 6, and so on around the circle (Fig. 87). Be sure the

lower end of a spoke fits between the same numbers as the

upper end. When all the spokes are placed hammer a[69]

[70]

strong pin directly through the centre where they are

crossed, to hold them together while you begin.

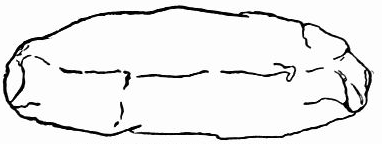

Bottom of basket completed.

Bottom of basket completed.

|

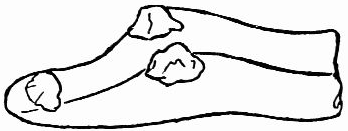

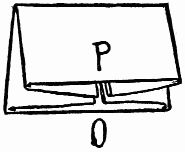

Material for weaving basket.

Material for weaving basket.

|

Small basket with two rows of trimming on

different colored weaver between.

Small basket with two rows of trimming on

different colored weaver between.

|

Lining the basket.

Lining the basket.

|

Fig. 87.—All of the spokes in place.

Fig. 87.—All of the spokes in place.

With the spokes lying in the position shown in diagram (Fig. 87), take the eighth-inch weaver, and begin to weave it in and out of the spokes. Start it under spoke No. 1 about two and one-half inches from the centre, bring it over No. 9, under No. 5, over No. 10, under No. 3, over, under, over, under, until it has crossed spoke No. 16; then skip No. 1, bring the weaver under No. 9, and weave another row. You will find it necessary to skip one spoke at the beginning of each row, in order to make a continuous under-and-over weave. Weave five rows with the eighth-inch weaver, then slide the end under the last row, lapping it an inch or so and running it under several spokes, to hide the joint. Slip the first end under a spoke also. During this part of the work your main endeavor must be to weave in a perfect circle. The illustration shows the bottom of the basket completed.

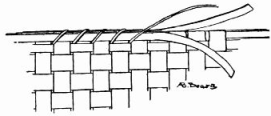

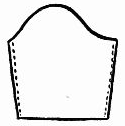

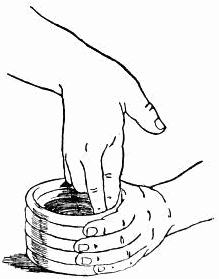

Before bending the spokes for the sides of the basket, let them soak in the water a few minutes, then place the work on the lap-board, the same side up as when started, and carefully bend the spokes up at right-angles with the bottom (Fig. 88). Start a half-inch weaver inside the basket, close to the bottom, and weave under and over until the row is complete; then, allowing for a lap of about three inches, cut the weaver off and slide the end under the first end of the weaver, making the invisible joint by tucking each end under a spoke. Start the next row a little beyond the joint of the first row, that the joining may not all come in one place. Weave five rows of the half-inch weaver, then two rows of the fourth-inch weaver and then bind off (Fig. 89).

Fig. 88.—Bend the spokes up.

Fig. 88.—Bend the spokes up.

Cut the spokes off evenly,

leaving about two inches extending

above the top of the[71]

[72]

basket, then put the basket in the water, spokes down,

and soak until pliable. Bend each spoke down snugly over

the top weaver, and

slip the end through

the next weaver,

pushing it down

until its end is hidden

under one of

the weavers. Bend

one spoke inside,

the next outside the

basket, according as

they come inside or

outside of the top

weaver (Fig. 89).

Fig. 89.—Binding off.

Fig. 89.—Binding off.

This binding off holds the top weaver in place and makes the basket very firm; but the spokes must be protected from wear where they are bent, and it is necessary to put a double band around the edge. For this band cut two pieces of the fourth-inch weaver which will go around the basket and lap about an inch. Place one piece along the inside edge, the other along the outside edge of the basket, and with the sixteenth-inch weaver bind them to the top weaver, as shown in Diagram 90. Fasten the end by taking several cross-stitches with the narrow weaver, passing it under the inside band only, and tucking the end under the same band.

Fig. 90.—Putting on the band.

Fig. 90.—Putting on the band.

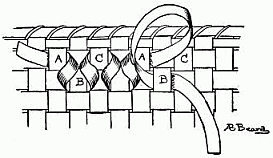

Many splint baskets are trimmed with twisted loops of the same material. For this trimming take one of the half-inch weavers and cut a thread's width off its edge, making it just a trifle narrower than the other weaver. Insert the end of this weaver under a spoke at the top of the basket (letter A, Diagram 91), give a twist to the left, and pass it beneath the next spoke, as shown in Diagram 91, letter B. Pull the loop down and flatten it a little with your thumb, then twist the weaver again, this time to the right, and slip the end under the next spoke, letter C. Continue this around the basket, and make the joint of the trimming as you did the other joints, by lapping the ends and slipping them under the spokes, which makes the last loop of double thickness.

Fig. 91.—Making the trimming.

Fig. 91.—Making the trimming.

The small basket shown in the illustration has two rows of trimming, and between them is run a weaver of another color pulled out into loops at the sides.

The illustration on the first page of this chapter shows a large basket with four rows of trimming and handles. The handles are made of the fourth-inch weaver, which is brought around twice, making a ring of double thickness. The ring is then wrapped with the eighth-inch weaver, and fastened to the basket with loops of the same. The weaving of this large basket differs from the smaller one, in that the weaver is not cut at the end of each row, but is continued[74] around row after row. For a large basket the half-inch weaver can be used in this way, but in a small basket the slant of the weaver as it runs around is too apparent. If a long weaver is used in a small basket it must not be more than one-eighth of an inch in width.

While baskets of the natural white splint are extremely dainty, color certainly gives variety and adds interest to the work, and the splints will take dye readily. You might also line your basket with silk of a color to harmonize with the splint.

The white-ash splint one and one-half inches wide comes in rolls of twenty-five yards, and a roll will make several medium-sized baskets. The material may be obtained of almost any kindergarten supply firm.

You must select paper of the necessary color, and fold, roll, fold, squeeze, fold, tie, with here a little pull and there a little pat, a spreading out, a pinching in; that is all. There is no sewing, no pasting, no pinning, merely modelling and tying, using only tissue-paper and string.

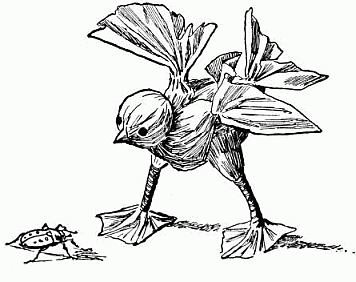

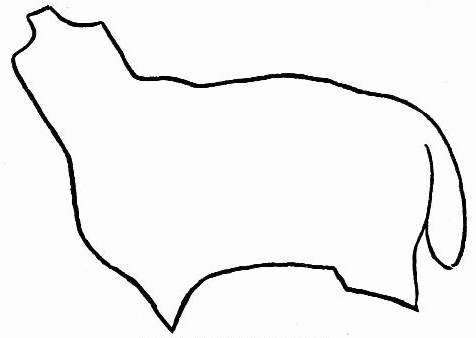

These animals are very substantial and unique. They are not at all thin or flat, but well rounded out and lifelike, with character and independence enough to stand alone—just the kind your little brother and sister will be delighted with, for they may play with the toys free from all danger of hurts or bruises. To

Fig. 92.—The beginning of the paper chicken.

Fig. 92.—The beginning of the paper chicken.

Fig. 93—Second step in modelling chicken.

Fig. 93—Second step in modelling chicken.

Fig. 94.—Third step in modelling chicken.

Fig. 94.—Third step in modelling chicken.

Fig. 95.—Fourth step in modelling chicken.

Fig. 95.—Fourth step in modelling chicken.

Fig. 98.—Modelling the chicken's legs.

Fig. 98.—Modelling the chicken's legs.

Roll a separate piece of paper into a little wad and lay it on the creased strip (Fig. 93) about one-fourth of the distance from one end. Bend the short end of the strip over the wad of paper, as in Fig. 94; then fold up the strip[77] where the end of the short fold lies, bend this over the first fold (Fig. 95) and bring the loose end on the bottom of the three layers. Fig. 96 shows a wad of paper inserted at one end of a strip of creased paper folded over and over three times, making four layers, two on top and two on the bottom of the paper wad. Wind a string around the paper tight up to the wad and tie it securely to form the head (Fig. 97). You now have the body and head of the chicken. Make the legs and feet of a strip of paper about sixteen inches long and seven and one-half wide. Gather up the two long sides with your fingers as you did the paper in Fig. 93; crease the paper, then wind each leg with string, leaving one inch free at each end to form the feet (Fig. 98). Lift up the free end of the folded paper (Fig. 97) and place the centre of the legs (Fig. 98) midway under the last fold as in Fig. 99. Tie the end of the loose layer of the body securely[78] on the body, and you will have the foundation ready for the beak, wings, and tail (Fig. 100).

Fig. 99.—Modelling body and legs of chicken.

Fig. 99.—Modelling body and legs of chicken.

Fig. 100.—Partially modelled ready for beak, wings and tail.

Fig. 100.—Partially modelled ready for beak, wings and tail.

Fig. 101.—The beak of chicken.

Fig. 101.—The beak of chicken.

Fig. 102.—Modelling beak on chicken.

Fig. 102.—Modelling beak on chicken.

Fig. 103.—Paper chicken

nearly finished.

Fig. 103.—Paper chicken

nearly finished.

Fig. 104.—Hungry little paper

chicken.

Fig. 104.—Hungry little paper

chicken.

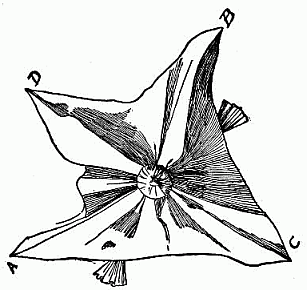

Cut a square of the same kind of tissue paper, measuring

nine and one-half inches on all four sides; fold diagonally

twice across the square as when making a paper pin-wheel.

The centre of the square is exactly where the

diagonal lines meet and cross; pinch the centre portion up

into a beak and tie it with a string (Fig. 101); then fit the

beak over the centre of the chicken's head, bringing the

paper entirely over the head on all sides; tie the square

around the chicken's neck close up to the head (Fig. 102).[79]

[80]

The two points A

and B of the square

must form the wings,

while C is carried

backward over the

under portion of the

body and D back

over the upper part,

the two ends C and

D being brought

together and tied tight

up to the body to form

the tail. In Fig. 103 you

will see exactly how to

pinch up the wing if you

notice particularly the

upper part of the wing

B, next to the body. The

wing A on Fig. 103 shows

how the two wings must

be tied close to, but not

on, the body. When each

wing is tied, make the

tail of C and D by tying

the extensions together

as explained above; that

done, bend down the legs,

spread out the wings and[81]

tail, open out and flatten the feet, then stand the little

chicken on a level surface (Fig. 104). Remember always

to crease the tissue-paper

with the grain of

the paper; if you attempt

to cross the grain

the paper will be very

apt to tear.

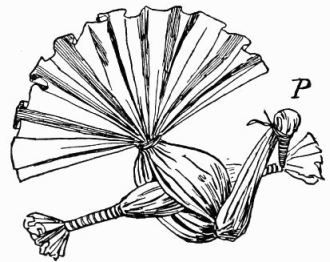

Fig. 105.—The astonished paper turkey.

Fig. 105.—The astonished paper turkey.

Fig. 106.—Modelling turkey's body.

Fig. 106.—Modelling turkey's body.

Fig. 107.—Legs and feet of turkey.

Fig. 107.—Legs and feet of turkey.

Fig. 108.—Head modelled on turkey.

Fig. 108.—Head modelled on turkey.

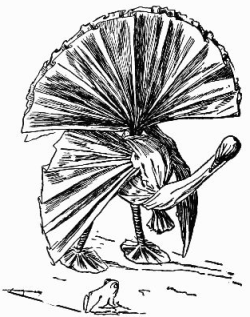

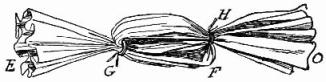

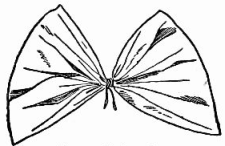

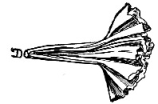

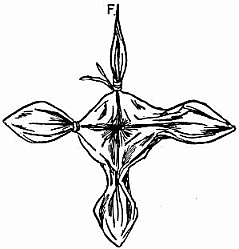

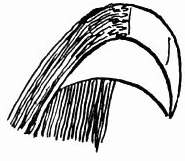

Fig. 109.—Paper for turkey wings.

Fig. 109.—Paper for turkey wings.

(Fig. 105) is also modelled from half a sheet of tissue-paper as near the general color of a turkey as can be found. Make Fig. 92 and Fig. 93 of the paper; then fold Fig. 93 five and three-quarter inches from one end (Fig. 106, F). Three inches from this end tie the two layers together (Fig. 106, G). Fold the strips back and tie a string through the lower loop up over the loose top layer (Fig. 106, H). Wind the extreme end of the paper (Fig. 106, O), with string to form[82] the beak (Fig. 107), bend the beak down and tie it to the neck to form the top of the head (Fig. 108, P). Make the legs and feet as you did those for the chicken (Fig. 98) and slide them through the body so that one fold of the body will be above and two beneath the legs (Fig. 107). Cut the wings from a separate piece of tissue-paper (Fig. 109). Let the paper measure seven inches on the widest side, five on the opposite side, and four and one-half on each of the other sides. Pinch the paper together through[83] the centre and tie (Fig. 110). Gather up one wing, so that it will not tear, and slip it through the body, immediately over the legs, with the widest side toward the front (Fig. 105), leaving the other wing out free on the other side of the turkey. Bend down the legs, spread the tail out fan shape and bend it up; open out the wings and drop them downward and forward (Fig. 105). Flatten out the feet and stand up the turkey (Fig. 105).

Fig. 110.—Turkey wings.

Fig. 110.—Turkey wings.

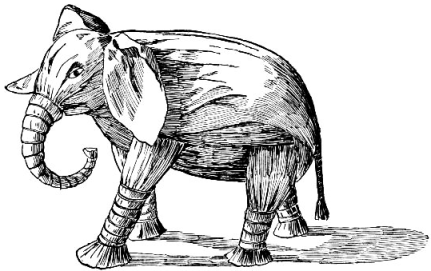

Fig. 111.—Elephant modelled of tissue-paper.

Fig. 111.—Elephant modelled of tissue-paper.

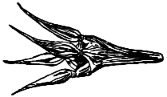

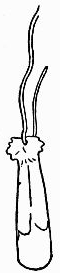

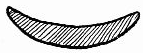

(Fig. 111) will require two sheets of brown tissue-paper for its body, head, and trunk, which are all made of a single strip of paper. Unfold, spread out and fit the two sheets of[84] tissue-paper together; then gather up one side, as in Fig. 92, crease and gather up the other side (Fig. 93). Bind one end with black thread to the distance of four and one-half inches to form the trunk; then fold the remainder of the strip into four layers, beginning with the free end of the paper; fold over and over three times. This gives the body and head. Bind black thread around the folds next to the trunk to form the head. Make four legs of two pieces of paper in the same way you formed those of the chicken (Fig. 98), only the elephant's legs must be very much thicker. Slide the legs through the body between the two layers of paper, shove the front legs forward and the hind legs backward. For the tail use a small strip of the brown tissue-paper. Wrap it around and around with black thread to within an inch of the bottom and cut this end up into fringe. Fasten the tail on the elephant with black thread,[85] pass the thread between the first and second layers of paper forming the back of the body of the animal and tie the tail on the outside threads which cross from side to side of the elephant; bend the top of the tail over the thread, as you would hang a garment on a clothes-line, and tie the bent-over end down on to the tail proper. Shape the ears like Fig. 112, pinch together the end S and tuck it under the thread which separates the head from the body. Allow the long side, M, to form the front of the ears. You can add white ivory tusks if desired. Roll up two white writing-paper lighters and push an end of each up in the head under the trunk, forming one tusk on each side.

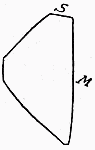

Fig. 112.—Elephant's

ear.

Fig. 112.—Elephant's

ear.

In making these little creatures do not forget that you must do some modelling, bending and shaping them with your fingers, squeezing up the paper where it stands out too far, and gently pulling it out in places where it flattens too much. The heads can be turned to suit the fancy, the bodies inclined this or that way, or they may stand stiff and erect. You might model a number of chickens, of different-colored paper, some yellow, some white, and others black, like real chickens; or make several turkeys and two or three elephants, some of the latter with tusks and others without. The toys when finished will cause exclamations of delight and approval. They are simple and easy to put together, something which will not cost much and yet be worth many times the amount expended for the necessary material to manufacture. The little animals are attractive, substantial toys, entirely different from the common ones which any girl or boy with sufficient pocket money may purchase.

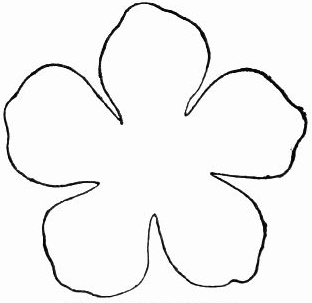

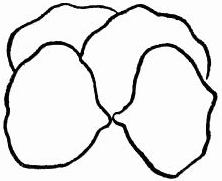

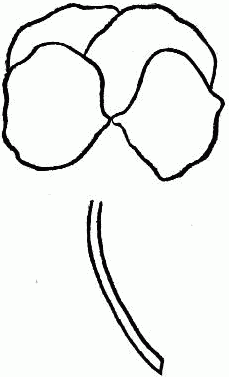

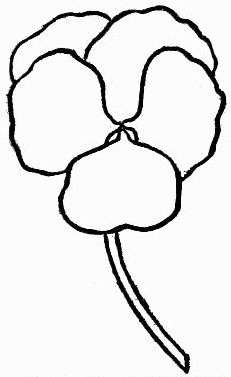

There are no patterns, only circles and squares and strips of paper which you gather here, spread out there, wrap and tie some place else and, with deft fingers, model into almost exact reproductions of the natural flower before you.

With its unfamiliar terms to be committed to memory and the many parts of the flower to be distinguished, botany is apt to prove dry and tiresome to the little child, but to study nature by copying the flowers in this marvellously adaptable material is only a beautiful game which every child, and indeed many grown people, will delight in. The form of the flower, its name and color, may, by this means, be indelibly stamped upon the memory, and a good foundation laid for further study.

Ordinary garden flowers and those most easily procured make the best models. The carnation-pink, the morning-glory, and the rarer blossoms of the hibiscus, are well[87] adapted to the work, also the daffodil and some of the wonderful orchids.

Carnations modelled from tissue-paper.

Carnations modelled from tissue-paper.

Even holly with its sharp-spiked leaves and scarlet berries and the white-berried, pale-green mistletoe may be closely copied. All these and many more are made on the same principle and in so simple a manner even quite a little child may succeed in producing very good copies from Nature.

Buy a sheet of light pink tissue-paper, another of darker pink, and one of the darkest red you can find. Then a sheet of light yellow-green and one of dark green. Have a table "cleared for action" and place your paper on the right-hand side, adding a pair of scissors and a spool of coarse thread, or, better still, of soft darning-cotton.

With all this you are to copy the

Lay your natural flower down on the left-hand side of the table, away from your material but quite within easy reach, for it must be consulted frequently. Seat yourself comfortably and don't work hurriedly.

Fig. 113.—Fold the square diagonally through

the centre.

Fig. 113.—Fold the square diagonally through

the centre.

The first thing necessary in this system of squares and circles is to know

Fig. 114.—The first triangle.

Fig. 114.—The first triangle.

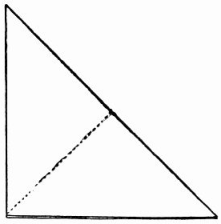

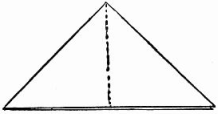

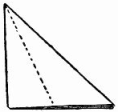

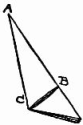

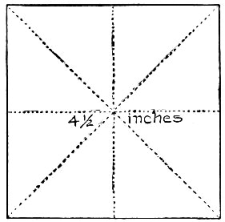

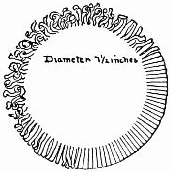

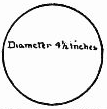

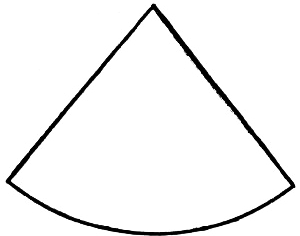

Cut a square the size you wish to make your circle. That is, if you want a circle with a diameter of four inches cut a four-inch square (Fig. 113). Fold the square diagonally through the centre according to the dotted line on Fig. 113, and you have the triangle (Fig. 114). Fold this at the dotted line and it will make another triangle (Fig. 115). Again fold through the middle and you have the third triangle (Fig. 116). Fold once more and Fig. 117 is the result. Measure[89] the distance from the edge, B, to the centre A in Fig. 117 and mark the same distance on the other side of the angle shown by the dot, C (Fig. 117). With your scissors cut across from C to B, curving the edge slightly, as shown by the dotted line from C to B (Fig. 118). Fig. 119 is the circle still in its folds. Fig. 120 is the circle opened, the dotted lines indicating where it has been folded.

Fig. 115.—Second triangle.

Fig. 115.—Second triangle.

Fig. 116.—Third triangle.

Fig. 116.—Third triangle.

Your eye will soon become sufficiently accurate to enable you to gauge the distance from A to B, and you can then cut from C to B without measuring.

Fig. 117.—Fold

once more.

Fig. 117.—Fold

once more.

|  Fig. 118.—Cut

from C to B, curving

the edge.

Fig. 118.—Cut

from C to B, curving

the edge.

|  Fig. 119.—The

circle still in its

folds.

Fig. 119.—The

circle still in its

folds.

|

Now hold the pink off at arm's length. The separateness of the petals disappears and you see them only as a mass; the points on the edges are not noticeable except as they give the flower a crimped appearance, and the edge of the calyx looks almost straight. It is this last appearance or the impression of the flower that you are to produce rather than its many and separate little parts. So now to work.

Fig. 122.—Crimp the edge with

your fingers.

Fig. 122.—Crimp the edge with

your fingers.

|

Fig. 123.—Draw these through

your hand to bring them

closely together.

Fig. 123.—Draw these through

your hand to bring them

closely together.

|

Fig. 126.—The calyx.

Fig. 126.—The calyx.

Fig. 125.—Wrap and tie at the bottom

and where the petals spread.

Fig. 125.—Wrap and tie at the bottom

and where the petals spread.

|  Fig. 127.—Wrap the paper spirally around

the stem.

Fig. 127.—Wrap the paper spirally around

the stem.

|

Fig. 128.—The leaves.

Fig. 128.—The leaves.

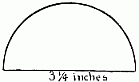

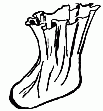

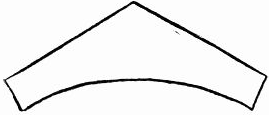

From your light-green paper cut a circle measuring three and one-quarter inches through its diameter and cut it in two to make the half circle for the calyx (Fig. 126). Remove the thread that holds the flower just below its petals and wrap the calyx closely around the lower part, tying it at the bottom;[93] then cut a narrow strip of dark-green paper and wrap it spirally around the stem, beginning at the top (Fig. 127). Let the wrapper extend a little below the lighter and twist the end to hold it in place. Spread the petals of your flower as much like the natural blossom as possible.

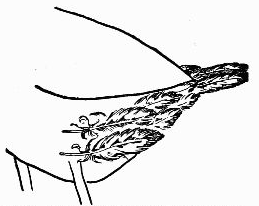

For the leaves cut a strip of dark-green paper six inches long and three-quarters of an inch wide (Fig. 128). Find the centre by folding the paper end to end and making the crease shown by dotted line in Fig. 128. Gather it along this line, not with needle and thread—we use no needle in this work—but with your fingers, and pinch it together; then twist each end into a point (Fig. 129). With the sharp point of your scissors punch a hole directly through the centre (E, Fig. 129), and push the point of the stem through the hole, bringing the leaves as far up on the stem as you find them on the natural flower; then wrap and tie them in place.

Fig. 129.—Twist each

end into a point.

Fig. 129.—Twist each

end into a point.

It is wonderful how very natural these blossoms appear. At a short distance no one would think they are not the real, old and familiar pinks. Only the fragrance is missing, and that may also be supplied and a spicy odor given by enclosing a whole clove in the heart of each flower.

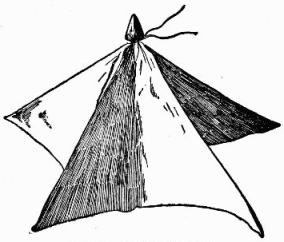

From your pale-pink paper you can make the delicately beautiful morning-glory. Have the natural flower with its stem and leaves to copy from, even if the blossom is not the color you want. As with the pink, it is the general form and appearance we strive for in the morning-glory, not the detail.

Fig. 132.—Slip

the bag over

the head of a

lighter.

Fig. 132.—Slip

the bag over

the head of a

lighter.

Make your pink circles with a diameter of about seven inches. It is always better to have your flowers a trifle larger than the natural ones, rather than smaller.

But one circle is required for each morning-glory. Crimp this in your fingers and draw through your hand as you did the circles for the pinks; then, pinching it together to within one and one-half inches of the edge, hold it in your left hand and flatten out the top as in Fig. 133. See that the fulness is evenly distributed, and pull and straighten out the edges until you are satisfied with its appearance.

Morning-glory modelled from tissue-paper.

Morning-glory modelled from tissue-paper.

Fig. 133.—Flatten out the top of the flower.

Fig. 133.—Flatten out the top of the flower.

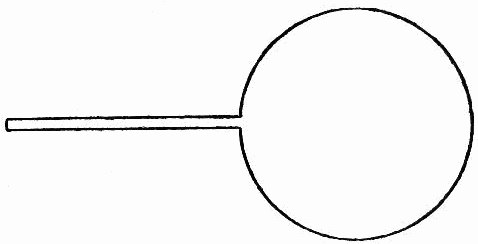

A piece of bonnet-wire makes the best stem if you wish to give the true viney effect of the growth. If it is only the blossom you are making, a paper lighter will answer. When you use the wire bend one end over to form a small loop; this is to keep the stem from slipping through the flower. Pass the[96] straight end of the wire through the centre of the flower and draw it down until the loop is hidden.

Fig. 134.—Green square for calyx.

Fig. 134.—Green square for calyx.

Make

Fig. 137.—Twist each corner into a point.

Fig. 137.—Twist each corner into a point.

Fig. 138.—Bring the points together.

Fig. 138.—Bring the points together.

Make several buds of the pink paper, following the directions given for the green bud of the pink; then twist each bud at the point and add a calyx.

The wilted flower shown in the illustration is made by taking one of the morning-glories you have just finished and actually wilting it by drawing the flower together and creasing and pressing it to resemble the partially closed and drooping natural blossom.

Fig. 139.—Gather along one of the creases.

Fig. 139.—Gather along one of the creases.

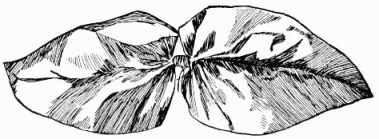

Only a piece of dark-green paper six inches square is required to model two almost perfectly shaped morning-glory leaves.

Fig. 140.—The morning-glory leaves.

Fig. 140.—The morning-glory leaves.

Daffodils modelled from

tissue-paper.

Daffodils modelled from

tissue-paper.

Fold the square twice diagonally across from corner to corner to find its centre; then begin at one corner and[98] gather along one of the creases until you reach the centre (Fig. 139). Start again at the opposite corner, gather along the crease to the centre, then wrap and tie (Fig. 140). Pinch each leaf from underneath along the crease in the middle, to give the depression at the midrib. Straighten the leaf out a little at its widest part and you will find you[99] have made a pair of leaves which are surprisingly natural. Wrap and tie these to the stem and make as many more as you think are needed.

Fig. 141.—For the two extra petals.

Fig. 141.—For the two extra petals.

Fig. 143.—Bring together

the fan of

paper below the

petal.

Fig. 143.—Bring together

the fan of

paper below the

petal.

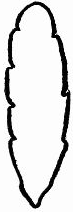

Match the tint of your natural daffodil in yellow tissue-paper as nearly as possible, and then cut two squares for each flower measuring about five and one-half inches. Fold the squares crosswise and diagonally through the centre as you did for the calyx of the morning-glory (Fig. 134), and cut one square in half along one of its diagonal folds[100] (Fig. 141). Gather the square two and a quarter inches below each corner and tie as in Fig. 137, but do not twist the points. This gives you four petals, but as the daffodil has six, you must make two more from the triangular halves of the square you have just cut. Gather each triangle across from side to side, according to the dotted line in Fig. 141, and pinch and tie in place as in Fig. 142, making sure the petal is of exactly the same size as those on the square. Bring together the fan of paper left below the petal and wrap and tie as in Fig. 143, then cut off the ragged end (Fig. 144).[101] Draw the petals of the square together as you did the calyx, and insert the stem made of a paper lighter. Put in place the two extra petals, pushing the wrapped ends down into the heart of the flower; fit each loose petal between two of the others and tie (Fig. 145).

Fig. 146.—Pinch the cup together.

Fig. 146.—Pinch the cup together.

|

Fig. 147.—Slip the cup on your

finger like a thimble.

Fig. 147.—Slip the cup on your

finger like a thimble.

|

Fig. 148.—Insert the stem of the cup into

the centre of the flower.

Fig. 148.—Insert the stem of the cup into

the centre of the flower.

|

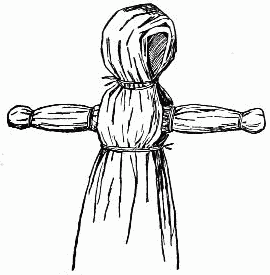

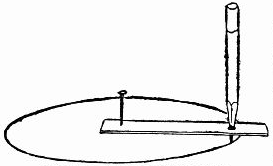

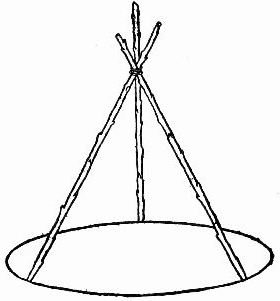

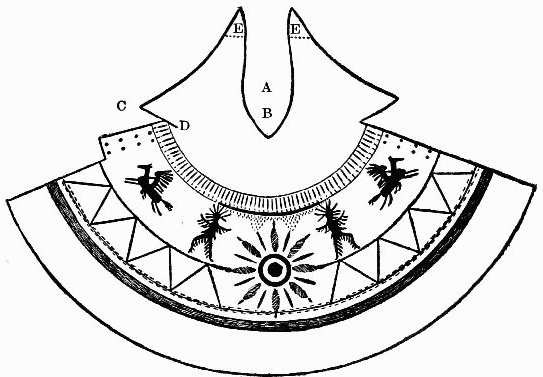

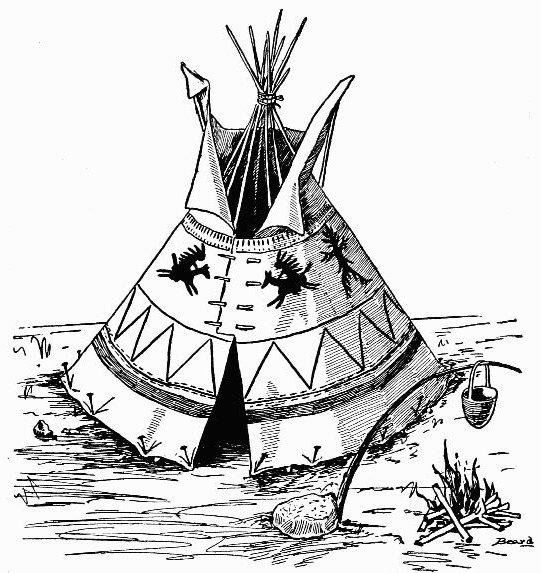

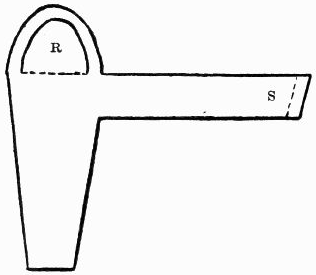

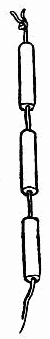

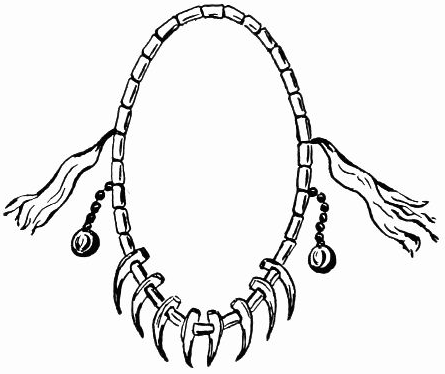

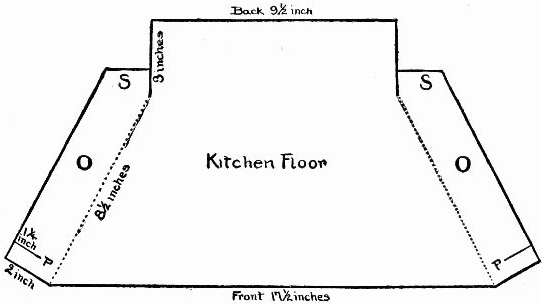

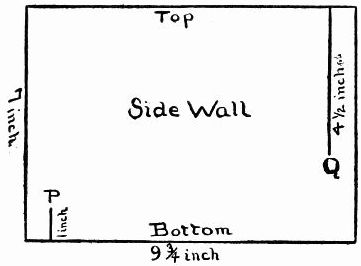

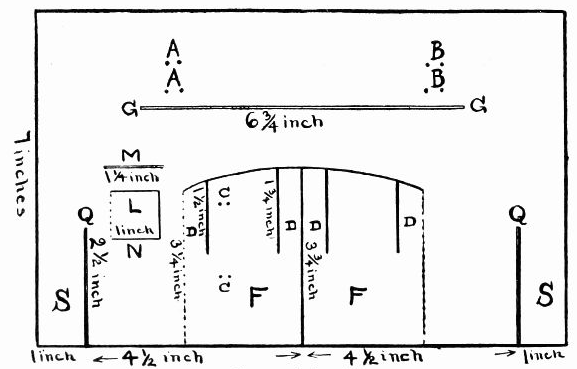

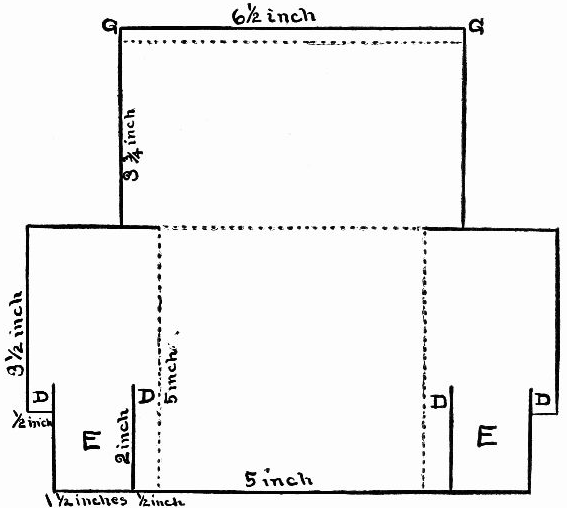

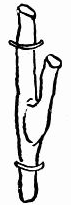

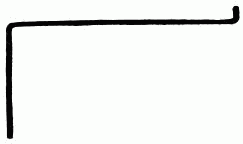

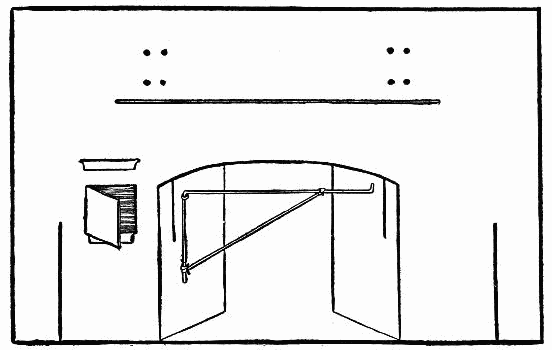

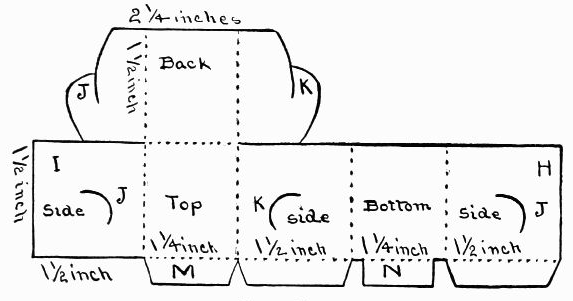

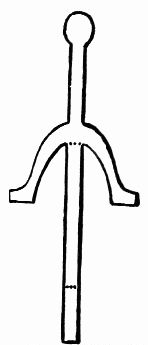

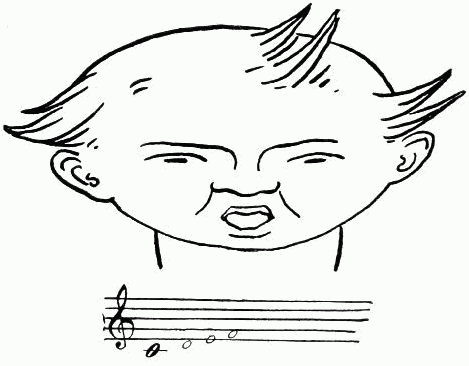

Turn back to the bud of the pink (Fig. 130), and from a circle of the yellow paper, with a diameter of four inches, make the cup (Fig. 131), using the scissors to give a fine crimp to the edges. Pinch the cup together at the bottom almost half-way up and tie (Fig. 146); slip it on your finger like a thimble and press it into shape like Fig. 147. Insert the point or stem of the cup into the centre of the[102] flower and tie in place just below the petals (Fig. 148).