Title: Dickensian Inns & Taverns

Author: B. W. Matz

Release date: June 10, 2013 [eBook #42908]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Dickensian Inns & Taverns, by B. W. (Bertram Waldrom) Matz, Illustrated by T. Onwhyn, Charles G. Harper, L. Walker, F. G. Kitton, and G. M. Brimelow

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/dickensianinnsta00matziala |

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

THE INNS AND TAVERNS OF PICKWICK

With thirty-one illustrations.

Large Crown 8vo. Second Edition.

10/6 net.

“The Inns and Taverns of Pickwick” has proved one of the most successful books of the season. The reviewers have been unanimous in its praise, and in speaking of its value and qualities have used such adjectives as famous, friendly, entertaining, delightful, well-informed, irresistible, valuable, fascinating, jolly, glowing, jovial, great, favourite, charming, congenial, and agreed that it is the “final authority and worthy of its mighty subject.”

LONDON: CECIL PALMER

JOHN BROWDIE AND FANNY SQUEERS ARRIVE

AT THE SARACEN’S HEAD

Drawn by T. Onwhyn

DICKENSIAN

INNS & TAVERNS

BY

B. W. MATZ

EDITOR OF “THE DICKENSIAN”

AUTHOR OF

“THE INNS AND TAVERNS OF PICKWICK”

ETC., ETC.

WITH THIRTY-NINE ILLUSTRATIONS BY T. ONWHYN,

CHARLES G. HARPER, L. WALKER, F. G. KITTON, G. M. BRIMELOW

AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS AND OLD ENGRAVINGS

LONDON

CECIL PALMER

OAKLEY HOUSE, BLOOMSBURY STREET, W.C. I

First

Edition

1922

Copyright

Printed in Great Britain by Burleigh Ltd. Bristol

TO

RIDGWELL CULLUM

| Chapter | Page | |

| Preface | 13 | |

| I | Dickens and Inns | 15 |

| II | Oliver Twist | 22 |

| III | Nicholas Nickleby: The Saracen’s Head | 32 |

| IV | Nicholas Nickleby (continued) | 49 |

| V | Barnaby Rudge: The Maypole | 72 |

| VI | Barnaby Rudge (continued) and The Old Curiosity Shop | 89 |

| VII | Martin Chuzzlewit | 105 |

| VIII | Dombey and Son | 132 |

| IX | David Copperfield | 144 |

| X | Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Hard Times | 169 |

| XI | A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations | 178 |

| XII | Our Mutual Friend | 191 |

| XIII | Edwin Drood, and The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices | 217 |

| XIV | Sketches by Boz, and The Uncommercial Traveller | 239 |

| XV | Christmas Stories and Minor Writings | 258 |

| John Browdie and Fanny Squeers arrive at the Saracen’s Head. Drawn by T. Onwhyn | Frontispiece | |

| The Red Lion, Barnet. Photo by T. W. Tyrell | Page | 24 |

| The Coach and Horses, Isleworth. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 26 |

| The Eight Bells, Hatfield. Drawn by F. G. Kitton | " | 29 |

| The Sign of the Saracen’s Head | " | 35 |

| The Saracen’s Head, Snow Hill. From an old print | " | 41 |

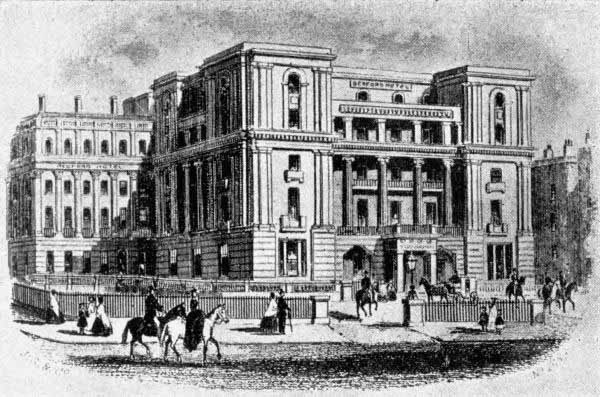

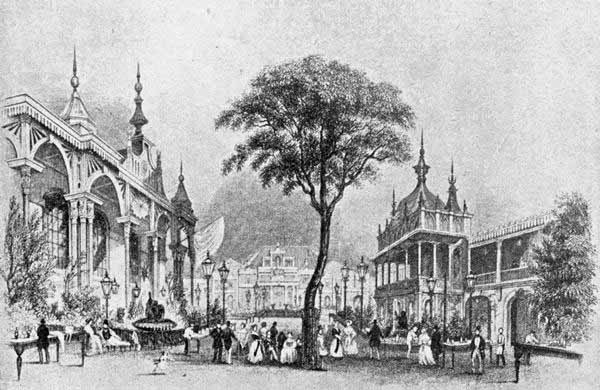

| The Peacock, Islington. From an old engraving | " | 50 |

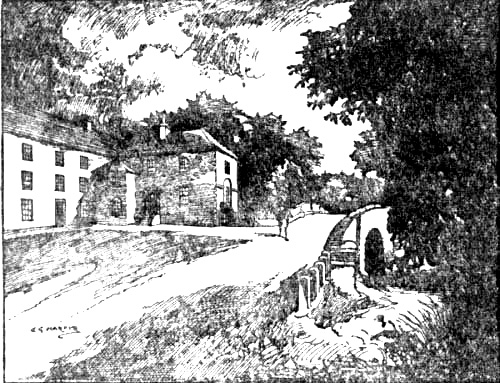

| The George Inn, Greta Bridge. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 57 |

| The King’s Head, Barnard Castle. Photo by T. W. Tyrrell | " | 60 |

| The Bottom Inn, near Petersfield. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 65 |

| The King’s Head, Chigwell. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 75 |

| The Chester Room, King’s Head. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 82 |

| The Old Boot Inn, 1780. From an old engraving | " | 91 |

| The Red Lion, Bevis Marks. Drawn by G. M. Brimelow | " | 99 |

| The George, Amesbury. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 111 |

| The George Inn, Salisbury. Photo by T. W. Tyrrell | " | 114 |

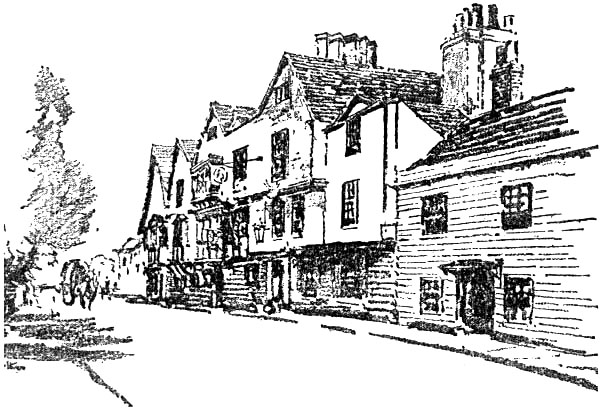

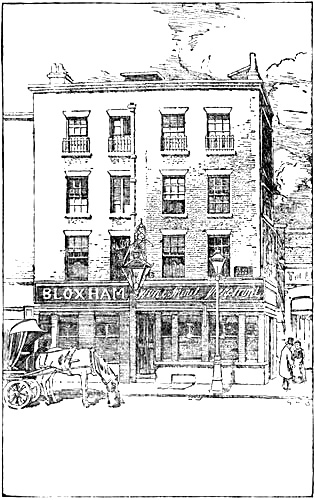

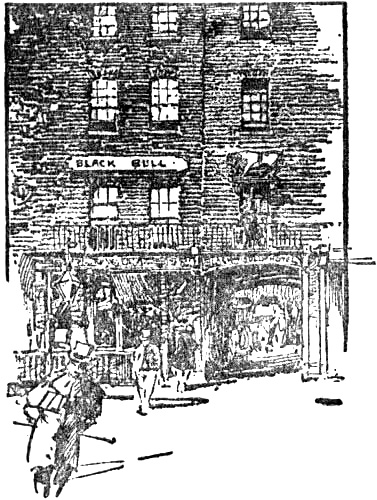

| The Black Bull, Holborn. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 121 |

| The Sign of the Black Bull. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 129 |

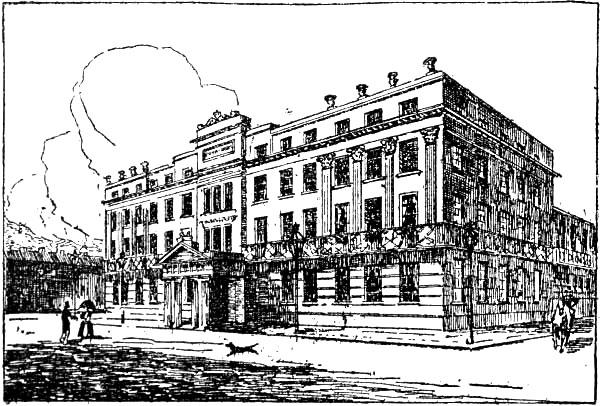

| The Bedford Hotel, Brighton. From an old engraving | " | 134 |

| The Royal Hotel, Leamington. From a lithograph | " | 134 |

| The Plough Inn, Blunderstone. Photo by T. W. Tyrrell | " | 146 |

| The Buck Inn, Yarmouth. Photo by T. W. Tyrrell | " | 146 |

| The Duke’s Head, Yarmouth. Photo by T. W. Tyrrell | " | 146 |

| The Little Inn, Canterbury. Drawn by F. G. Kitton | " | 157 |

| Jack Straw’s Castle. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 163 |

| The London Coffee House. From an old engraving | " | 172 |

| The Old Cheshire Cheese. From a photo | " | 180 |

| The Ship and Lobster, Gravesend. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 187 |

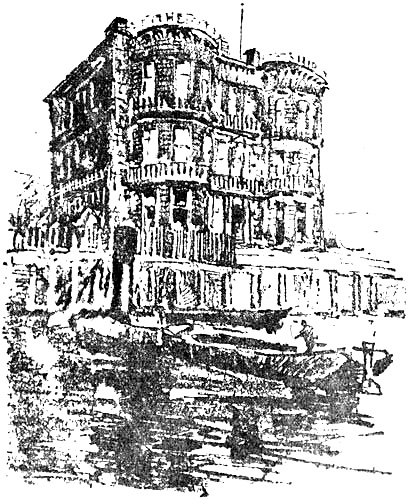

| [Pg 12]The Grapes Inn, Limehouse. Photo by T. W. Tyrrell | " | 194 |

| Limehouse Reach. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 199 |

| The Ship Hotel, Greenwich. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 207 |

| The Red Lion, Hampton. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 213 |

| Wood’s Hotel, Furnival’s Inn. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 223 |

| The King’s Arms, Lancaster. Drawn by L. Walker | " | 231 |

| The Eagle Tavern. From an old print | " | 242 |

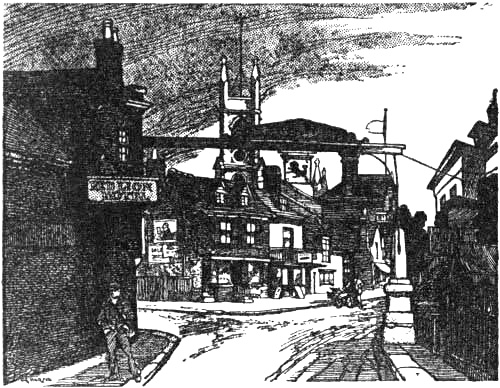

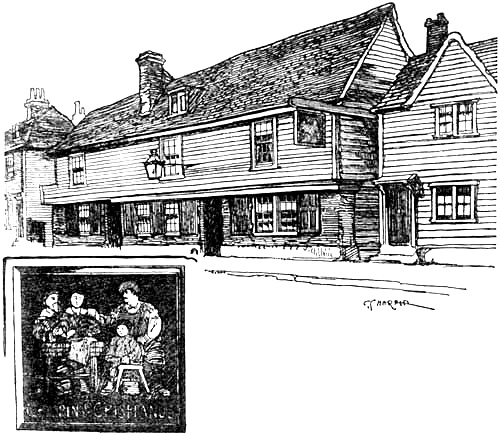

| The Crispin and Crispianus. Drawn by C. G. Harper | " | 255 |

| The Mitre Inn, Chatham. From an engraving | " | 259 |

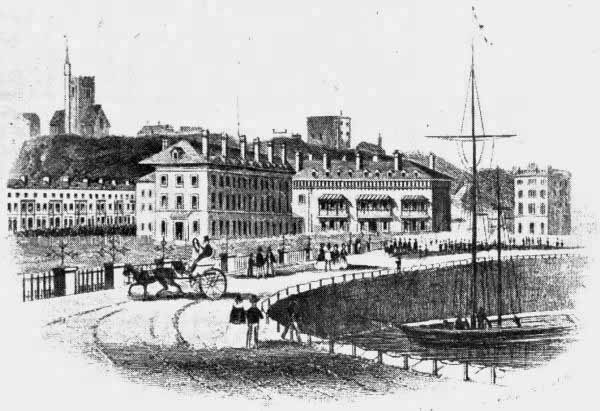

| The Lord Warden Hotel, Dover. From an engraving | " | 268 |

| The Pavilion Hotel, Folkestone. From an engraving | " | 268 |

The very friendly reception given to my previous book on the Inns and Taverns of Pickwick has encouraged me to pursue the subject through the other novels and writings of Dickens, and to compile the present volume.

I do not claim that it is encyclopædic in the sense that it will be found to supply a complete index to every inn mentioned in the novelist’s books. Many a reader will recall, I expect, a certain inn in his favourite story which has been overlooked; but, while my chief aim has been to deal with the famous and prominent ones, I have not ignored the minor ones which, in many cases, are also the most alluring, and often play an important part in the story.

The plan has been to take the long novels in something approximating to chronological order, followed by the shorter stories and sketches; and, where an inn is mentioned in more than one book, to deal with it fully in the chapter devoted to the story in which it was first alluded to.

Inns associated with the novelist’s own life find[Pg 14] no place in this volume, unless they have association also with his books.

In such a volume as this it is obviously necessary to quote freely from Dickens’s books, but, when one recalls the young person’s comment on lectures about Dickens that “she always loved them because of the quotations,” no apology or excuse is needed here.

I am greatly indebted to my friends T. W. Tyrrell and Charles G. Harper for much valuable advice and assistance in my task. The former has kindly loaned me prints from his unique collection of topographical photographs, and has also given me the advantage of his expert knowledge of the subject.

How much I owe to the latter goes without saying. No one can write of old inns, old coaches, or old coaching roads without acknowledging indebtedness to the score of books standing in Mr. Harper’s name, which are rich mines for any student of the subject quarrying for facts. He has not only permitted me to dig in his mines, but has allowed also the use of many of his charming drawings.

Acknowledgment is also made to Messrs. A. & C. Black, Messrs. Methuen & Co., and the proprietors of the Cheshire Cheese for the use of blocks on pages 24, 99 and 180 respectively.

B. W. MATZ.

DICKENSIAN INNS & TAVERNS

Dickens and Inns

In these days when life is, for the most part, and for most of us, a wearying process of bustle and “business,” it is comforting as well as pleasant to reflect that the old coaching inn still remains in all its quiet grandeur and the noble dignity which quaint customs and unbroken centuries of tradition have given to it. For a brief period in our recent history, it seemed that even so great a British institution as the old English inn, and its first cousin the tavern, were doomed to pass away. Indeed, the invention of railways, followed by the almost automatic suspension of the coach as a means of locomotion, did succeed actually in closing down many of them. But the subsequent invention of the motor-car reopened England’s highways and[Pg 16] by-ways so that to-day there are unmistakable indications that the old English inn is once more acquiring that atmosphere of friendly hospitality and utility with which it was endowed in the past, and which is so faithfully reflected in every book of Dickens.

No one can really believe that the palatial and gilded hotels that sprang up in the place of scores of the old coaching inns possessed the same snug cheerfulness, the same appeal to the traveller, as did the old hostelries of the coaching era. To-day, this is being realised more and more, and when the time comes, as we are told is not far off, when everyone will have his own motor-car, mine host of every wayside inn and county town hostelry will once again become the prominent figure that Dickens made him. The real romance of the coaching era may never return. Perhaps we have become too matter-of-fact for that. But something approximating to the spirit and glamour of those days is possible still for those who are content to undertake a motor journey minus the feverish ambition for breaking speed records. In many an old-world English village stands an old-world English inn, and when that hour before sunset arrives that all travellers of the open road know—the moment when a luxurious[Pg 17] and healthy weariness overcomes us—ah, well, be sure the right sort of inn awaits you if you deserve such good fortune, and, when the time comes to fill pipes and sit at ease before a blazing log-fire, what better subject for your dreams will you find than the glowing pages of a Dickens book?

In them you get not only the romance and the glamour of the journey from place to place, but also descriptive pictures of the various inns, of their picturesque outward appearances, of their interior comfort and customs, of their glorious and luscious array of wholesome food and wine, to say nothing of the wonderful description of the happy company assembled there, all told with that incomparable charm and grace and good humour of a writer of genius.

Dickens not only knew how to describe an inn and its comforts (and its discomforts, too, sometimes), but he seemed to revel in doing so, and became filled with delight when he was one of the guests within its walls.

He seems to have shared Dr. Johnson’s view that there was no private house in which people could enjoy themselves so well as at a good tavern, where there was general freedom from anxiety, and where you were sure of a welcome;[Pg 18] and to agree with him that there is nothing as yet contrived by man by which so much happiness is produced as in a good tavern or inn.

His books are full of the truth of this, and provide many such happy occasions when, after a cold coach drive, the hospitable host conducts the passengers to a large room made cosy with a roaring fire, and drawn curtains, and presenting an inviting spread of the good things of life, and a plentiful supply of the best wines or a bowl of steaming punch, for the jovial company. And the coach journey which brings one to these inns! Is there any described with so much exhilaration to be found elsewhere? Take the coach ride of Nicholas Nickleby along the Great North Road to his destination in Yorkshire. Here is reflected the real spirit of old-time travelling which brings us in touch with the old customs of the coaching age in a manner that no historian could possibly convey so realistically. Read again Tom Pinch’s ride to London. We not only encounter old inns and old houses with their cherished memories, their old rooms, each with its own romantic atmosphere and a tale to tell, but we traverse picturesque by-ways and highways, which in themselves recall the past as well as reveal unchanging scenes of glorious nature; we can[Pg 19] experience these feelings to-day in a way our fathers could not. The railroad, for a spell, made this impossible. To-day the road has come into its own again, and the motor-car brings back to us the glory of the road, the pleasure of the inn, and the enjoyment of the wonderful country which is England.

There seems to have been a positive allurement about an inn or tavern for Dickens which he could not resist. He lingered over the most decrepit and lowly public-house, such as the dirty Three Cripples, the resort of Bill Sikes, as he did over the sumptuous Pavilion Hotel at Folkestone. A wayside inn was as real a joy to him in its modest way as was the chief coaching hotel in a country town with its studied comfort.

When travelling about the country himself with his friends, some comment or pen-picture of the inn they stayed at creeps into his letters, as it would seem, by instinct. Even in his unpublished diary we see noted items about delightfully beautiful drives, coach offices, stage-coaches, and excellent inns. And, when he and Wilkie Collins went for their idle tour, it resolved itself into visiting the inns and coast corners in out-of-the-way places.

His knowledge of inns was stupendous. In[Pg 20] that Christmas story, “The Holly Tree,” there are scores of them recalled, each recollection no doubt reminiscent of experiences and association.

One gets a gleam of the joy he experiences at such times in the extract from a letter to an American friend, in 1842, after he had gone for a trip into Cornwall with some bright and merry companions:

“If you could but have seen one gleam of the bright fires by which we sat at night in the big rooms of the ancient inns, or smelt but one steam of the hot punch which came in every evening in a huge broad china bowl!”

But instances could be multiplied.

Dickens saw something different in every inn, and succeeded in conveying it to the reader. There were no two inns alike to him. Each had its own tale to tell, its own individuality to reveal, its own atmosphere and fare to present, whatever its grade or social environment. As for an inn sign, it transported him into his most whimsical and pleasant of moods.

In the following pages an attempt has been made to gather together the material from his books which shows how Dickens delighted in everything appertaining to inns, and how he extracted from association with them all that glow of[Pg 21] sentiment and joy which permeated their atmosphere in the old days, leaving their pictures in glowing words for all time.

There is nothing so calculated to make a place famous as mention of it in a classic story. It may have already had a past history by association with notable names and events, which gave it prominence in our annals for a time; but in the case of a building, when it is demolished, it soon passes out of memory. If, however, Dickens has drawn a pen-picture of it, or, in the case of an old inn, has used it for a scene in one of his books, it can never be forgotten; even when razed to the ground its fame survives, and the site becomes a Dickens landmark.

Oliver Twist

THE RED LION, BARNET—THE ANGEL, ISLINGTON—THE COACH AND HORSES, ISLEWORTH—THE THREE CRIPPLES—THE GEORGE INN—THE EIGHT BELLS, HATFIELD

There are not many inns that can be identified in Oliver Twist, and those that can play very little part in the enactment of the story, or have any notable history to relate in regard to them. The first one to attract attention is that at Barnet, where the Artful Dodger took Oliver Twist for breakfast on the morning they encountered each other on the latter’s tramp to London.

Although Dickens does not name this inn, we believe he had in mind the Red Lion, for it was one of those inns that was an objective when he and his friends went for a horse-ride out into the country. One such occasion was chosen when his eldest daughter, Mamie, was born, in March,[Pg 23] 1838. He invited Forster to celebrate the event by a ride “for a good long spell,” and they rode out fifteen miles on the Great North Road. After dining at the Red Lion, in Barnet, on their way home, they distinguished the already memorable day, as Forster tells us, by bringing in both hacks dead lame.

This trip along the Great North Road was a favourite one, and Dickens consequently became well acquainted with the highway. At the time of Forster’s specific reference to the Red Lion, Dickens was engaged on the early chapters of Oliver Twist, and we find him describing the district in those pages wherein particular mention is made of Barnet.

Tramping to London after leaving Mr. Sowerberry, the undertaker, Oliver, on the seventh morning, “limped slowly into the little town of Barnet,” we are told. “The windows,” Dickens proceeds, “were closed; the street was empty; not a soul was awakened to the business of the day.” Oliver, with bleeding feet, and covered with dust, sat upon a doorstep. For some time he wondered “at the great number of public houses (every other house in Barnet was a tavern, large or small), gazing listlessly at the coaches as they passed through.” Here he was[Pg 24] discovered by Jack Dawkins, otherwise the Artful Dodger, who, taking pity on him, assisted him to rise, escorted him to an adjacent chandler’s shop, purchased some ham and bread, and the two adjourned finally into a public-house tap-room, to regale themselves prior to continuing their journey to London. As the Red Lion was so familiar to Dickens, we may assume that this was the inn to which he referred.

The inn, no doubt, was the same from which Esther Summerson, in Bleak House, hired the carriage to drive to Mr. Jarndyce’s house, near St. Albans. Arriving at Barnet, Esther, Ada and Richard found horses waiting for them, “but, as they had only just been fed, we had to wait for them, too,” she said, “and got a long fresh walk over a common and an old battle-field, before the carriage came up.” Doubtless the posting-house where this change was made was the Red Lion, for Dickens had used it for posting his own horse many a time.

It is there to-day, and drives a busy trade, more as a suburban hostelry than as a posting-inn.

Continuing their walk to London, the Artful Dodger and Oliver gradually reached Islington, and entered the City together. Islington in days gone by was a starting point for the mail-coaches [Pg 25]going to the north, and as a consequence was famous for its old inns. Perhaps the most famous, particularly from the antiquarian standpoint, was the old Queen’s Head, a perfect specimen of ancient domestic architecture, which was destroyed in 1829. Another was, of course, the Angel; but the house bearing that name to-day can claim none of the romance or attractiveness of its ancient predecessor, and has recently been modernised on the lines adopted by a very modern firm of caterers. But the Angel of its palmy days was well-known to Dickens, and, although he does not make it the scene of any prominent incident in his books, it has mention in Oliver Twist in the chapter describing Oliver’s trudge to London. It was nearly eleven o’clock when he and the Artful Dodger reached the turnpike at Islington. They then crossed from the Angel into St. John’s Road, on their way to the house near Field Lane, where Oliver was dragged in and the door closed behind him.

THE RED LION, BARNET

Photograph by T. W. Tyrrell

The inn is mentioned again in the same book on the occasion when Noah Claypole and Charlotte traversed the same road. “Mr. Claypole,” we read, “went on, without halting, until he arrived at the Angel, at Islington, where he wisely judged, from the crowd of passengers and number of[Pg 26] vehicles, that London began in earnest.” He, too, led the way into St. John’s Road.

The Angel has been a London landmark for over two centuries. There have been at least three houses of the same name, but the one Dickens knew and referred to was apparently that built after the destruction in 1819 of the original.

In those days, it was the first halting-place, after leaving London, of coaches bound along the Holyhead and Great North Roads. The original house presented the usual features of a large old country inn, and “the inn yard, approached by a gateway in the centre, was nearly a quadrangle, with double galleries, supported by plain columns and carved pilasters, with caryatides and other figures.” Now, as we have said, it is merely a very ordinary, everyday modern refreshment house.

The low public-house in the “filthiest” part of Little Saffron Hill, in whose dark and gloomy den, known as the parlour, was frequently to be found Bill Sikes and his dog, Bull’s-Eye, probably was no particular public-house so far as the novelist was concerned, although he gave it the distinguishing name of the Three Cripples. At any rate, it has not been identified, and must be assumed to be typical of the many with which [Pg 27]this district at one time was infested. First referred to in Chapter XV, it is more minutely described in Chapter XXVI. “The room,” we are told, “was illuminated by two gas-lights, the glare of which was prevented by the barred shutters and closely drawn curtains of faded red from being visible outside. The ceiling was blackened, to prevent its colour from being injured by the flaring lamps; and the place was so full of dense tobacco smoke that at first it was scarcely possible to discern anything more. By degrees, however, as some of it cleared away, through the open door, an assemblage of heads, as confused as the voices that greeted the ear, might be made out; and, as the eye grew more accustomed to the scene, the spectators gradually became aware of the presence of a numerous company, male and female, crowded round a long table, at the upper end of which sat a showman with a hammer of office in his hands, while a professional gentleman with a bluish nose, and his face tied up for the benefit of a toothache, presided at a jingling piano in a remote corner.” That was a scene common to the “low public-house,” of which the Three Cripples was a notorious example, and the atmosphere depicted no doubt applied generally to most of them.

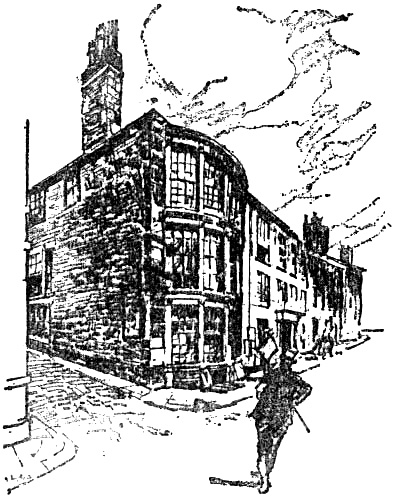

THE COACH AND HORSES, ISLEWORTH

Drawn by C. G. Harper

[Pg 28]On the other hand, the Coach and Horses, at Isleworth, where Bill Sikes and Oliver alighted from the cart they had “begged a lift” in, is no flight of Dickens’s imagination and can be discovered to-day exactly where he located it.

The tramp of the two from Spitalfields to Chertsey on the burglary expedition can easily be followed from Dickens’s clearly indicated itinerary. The point on the journey where they obtained their lift in a cart bound for Hounslow was near Knightsbridge. Having bargained with the driver to put them down at Isleworth, they at length alighted a little way beyond “a public-house called the Coach and Horses, which stood at the corner of a road just beyond Isleworth leading to Hampton.” They did not enter this public-house, but continued their journey. Mr. John Sayce Parr, in an article in The Dickensian, Vol. I, page 261, speaks of the topographical accuracy of Dickens in this instance: “The literary pilgrim,” he says, “sets out to follow the route he indicates, doubtful if he will find the places mentioned. There is, however, not the slightest excuse for making mistakes, for Dickens apparently visited the scenes and described them with the accuracy of a guide-book. Thus, one finds the Coach and Horses, sure enough, at the point where[Pg 29] Brentford ends and Isleworth begins, by the entrance to Sion Park, and near the spot where the road rambles off to the left.”

THE “EIGHT BELLS” Hatfield

Drawn by F. G. Kitton

The Coach and Horses, the same writer says, is not a picturesque inn. It is a huge four-square lump of a place, and wears, indeed, rather a dour and forbidding aspect. It is unquestionably the house of which Dickens speaks, and was built certainly not later than the dawn of the nineteenth century.

It still exists to-day, although the surroundings[Pg 30] have altered somewhat by the advent of the electric tramways and other “improvements.”

The George Inn, mentioned in Chapter XXXIII, where Oliver took the letter for Mr. Losberne to be sent by “an express on horseback to Chertsey,” cannot be identified, as the market-town in whose market-place it stood is not mentioned or hinted at. Mr. Percy FitzGerald claims that the description applies to Chertsey, but, as the letter had to be taken to Chertsey, something seems wrong in his deduction.

In the chapter describing the flight of Bill Sikes, we read that, on leaving London behind, he shaped his course for Hatfield. “It was nine o’clock at night when the man, quite tired out, and the dog, limping and lame from the unaccustomed exercise, turned down the hill by the church of the quiet village, and, plodding along the little street, crept into a small public-house whose scanty light had guided them to the spot. There was a fire in the tap-room, and some of the country labourers were drinking before it. They made room for the stranger, but he sat down in the farthest corner, and ate and drank alone, or rather with his dog, to whom he cast a morsel of food from time to time.” Here he met the pedlar with his infallible composition for removing[Pg 31] blood-stains. This particular public-house is no doubt the Eight Bells, a picturesque old house which still remains on the spot where Dickens accurately located it. It is a quaint little building with a red-tiled roof and dormer windows, and local tradition assigns it as that at which Bill Sikes sought refuge for a short time before continuing his journey to St. Albans, enabling Hatfield to claim it as a veritable Dickens landmark, together with that other, the churchyard, where Mrs. Lirriper’s husband was buried.

Nicholas Nickleby

THE SARACEN’S HEAD, SNOW HILL

The Saracen’s Head Inn, Snow Hill, long since demolished, is familiar to all readers of Nicholas Nickleby, because it was the hotel from which Squeers took coach with his boys for Dotheboys Hall; and, but for the fact, the name of Saracen’s Head would recall little or nothing to the ordinary Londoner.

It stood on Snow Hill or Snore Hill, as it was called in the very early days, and its exact location was two or three doors from St. Sepulchre’s Church, down the hill, and was one of London’s oldest and most historic inns, dating back to the 12th century. The first mention of it that we can find is in a volume by John Lydgate, the Benedictine monk who flourished in the early part of the 15th century, who is best remembered by his[Pg 33] poem, “The London Lyckpenny.” He tells the story of the origin of the name, which is interesting as fixing an early date at which the inn existed; even if it cannot be vouched for as correct in face of the fact that others have been suggested, it is at least as plausible.

It would appear that, when Richard Cœur-de-Lion returned from the Third Crusade in 1194, he approached the city of London and entered it by the New Gate, on the west. Being much fatigued by his long journey, the weary monarch, on arriving at Snow Hill, outside the gate, stopped at an inn there and called loudly to a tapster for refreshment. He drank rather freely, “untille ye hedde of ye Kinge did swimme ryghte royallie.” He then began laying about him right and left with a battle-axe, to the “astoundmente and dyscomfythure of ye courtierres.” Upon which one of the Barons said, “I wish hys majestie hadde ye hedde of a Saracen before hym juste now, for I trowe he woulde play ye deuce wyth itte.” Thereupon the King paid all the damage and gave permission that the inn should be called “Ye Saracen’s Hedde.”

It is a pretty story, and, as we have suggested, may or may not be true; but it gives us a starting point in the history of the inn. How long[Pg 34] before this incident the inn had existed and what its name was previously, we cannot say.

Lydgate refers to the inn’s name again in the following stanza of one of his poems:

Richarde hys sonne next by successyon,

Fyrst of that name—strong, hardy and abylle—

Was crowned Kinge, called Cuer de Lyon,

With Sarasenys hedde served at hys tabyelle.

The inn, by virtue of its situation, was in the centre of many an historic event enacted in the surrounding streets, and would naturally be the resort of those taking part in them. If records existed, many a thrilling tale could be gathered from their perusal; as it is, only meagre details can be furnished.

In 1522, Charles V of Germany, when on his visit to London, stayed at the inn, and his retinue occupied three hundred beds, whilst stabling for forty horses was needed also; evidence that it was no mean hostelry, in spite of the fact that Stow’s record of the inn’s existence in his “Survey of London” is confined to the following sentence:

“Hard by St. Sepulchre’s Church is a fayre and large inn for the receipt of travellers, and hath to signe the ‘Saracen’s Head.’”

A few years later (1617) we get another reference to the hostel, in Wm. Fennor’s “The Comptor’s[Pg 35] Commonwealth,” a book describing the troubles of an unfortunate debtor in the hands of serjeants and gaolers. Therein is an allusion to a serjeant “with a phisnomy much resembling the ‘Saracen’s Head,’ without Newgate,” alluding, of course, to the figurehead on the sign-board of the inn.

THE SIGN OF THE SARACEN’S HEAD

It goes without saying that the famous Pepys knew the house, and we have the following entry[Pg 36] in his diary as confirmation: “11 Nov. 1661. To the wardrobe with Mr. Townsend and Mr. Moore and then to the ‘Saracen’s Head’ to a barrel of oysters.” How Bob Sawyer and Benjamin Allen would have revelled in that occasion!

The inn and the church were both victims of the Great Fire in 1666, but both were rapidly rebuilt on the old sites. From the time the original inn was erected in the 12th century, until the last of its race on the same site was demolished in 1868, doubtless there had been more than one Saracen’s Head, and through this long stretch of years it was a favoured resort of all sorts and conditions of men.

In 1672, John Bunyan, after his release from Bedford Gaol, paid frequent visits to London by coach to the Saracen’s Head, and it is recorded that he spent several nights within its hospitable walls; and we are told that Dean Swift made the inn his headquarters in 1710, on his visits to London from Ireland. An even more famous man, in the person of Horatio Nelson, at the early age of twelve years, stayed a night there prior to making his first voyage in a merchant ship in 1770. Many years afterwards, when he had become world-famous as Lord Nelson, the[Pg 37] proprietor of the hostelry, in honour of the early event, named his smartest coach after the admiral.

These are a few bare facts worth recording of an inn which was the most prominent of the coaching inns of London, as it was one of the largest and most flourishing. At one period of its history, coaches started from it for almost every large town in England and Scotland, and over 200 horses were kept in readiness for the purpose.

During the years 1780-1868, the inn had been managed by three generations of the Mountain family, the most notable member of which, owing perhaps to the coaching era then being at its height, was Sarah Ann Mountain, who succeeded her husband in 1818. Innkeeping in those days was one of the most ancient and honourable of professions, and Mrs. Mountain was evidently an ornament to the calling. She was a keen competitor in the business of coach proprietors, and set the pace to other coach owners by putting on the first really fast coach to Birmingham, which did the journey of 109 miles in 11 hours. At that time thirty coaches left her inn daily, amongst them being the “Tally Ho!” the fast coach referred to, whose speed was, we are told, the cause of the furious racing on the St. Albans, Coventry and Birmingham roads up to 1838. At[Pg 38] the rear of the inn, Mrs. Mountain had a busy coach factory, and sold her vehicles to other coach proprietors. One of her advertisements announced that “Good, comfortable stage-coaches, with lamps,” could be purchased “at 110 to 120 guineas.”

It was at this period of its prosperity that Dickens made the Saracen’s Head a centre of interest in his novel, Nicholas Nickleby. Ralph Nickleby, being anxious to find employment for his nephew Nicholas, called upon him one day and produced the following advertisement in the newspaper:

“Education.—At Mr. Wackford Squeers’ Academy, Dotheboys Hall, at the delightful village of Dotheboys, near Greta Bridge, in Yorkshire, Youth are boarded, clothed, booked, furnished with pocket-money, provided with all necessaries, instructed in all languages living and dead, mathematics, orthography, geometry, astronomy, trigonometry, the use of globes, algebra, single stick (if required), writing, arithmetic, fortification, and every other branch of classical literature. Terms, twenty guineas per annum. No extras, no vacations, and diet unparalleled. Mr. Squeers is in town, and attends daily, from one till four, at the Saracen’s Head, Snow Hill. N.B.—An able[Pg 39] assistant wanted. Annual salary £5. A Master of Arts preferred.”

“There!” said Ralph, folding the paper again. “Let him get that situation, and his fortune is made.”

After some little discussion, Nicholas decided to try for the post, and the two men set forth together in quest of Mr. Squeers at the meeting place announced in the advertisement.

Before Nicholas and his uncle met Squeers, Dickens proceeded, in one of his very picturesque passages, to give a description, first of Snow Hill and then of the Saracen’s Head:

“Snow Hill! What kind of place can the quiet town’s-people who see the words emblazoned, in all the legibility of gilt letters and dark shading, on the north-country coaches, take Snow Hill to be? All people have some undefined and shadowy notion of a place whose name is frequently before their eyes, or often in their ears. What a vast number of random ideas there must be perpetually floating about regarding this same Snow Hill. The name is such a good one. Snow Hill—Snow Hill, too, coupled with a Saracen’s Head: picturing to us by a double association of ideas something stern and rugged! A bleak, desolate tract of country, open to piercing blasts[Pg 40] and fierce wintry storms—a dark, cold, gloomy heath, lonely by day and scarcely to be thought of by honest folks at night—a place which solitary wayfarers shun, and where desperate robbers congregate; this, or something like this, should be the prevalent notion of Snow Hill, in those remote and rustic parts, through which the Saracen’s Head, like some grim apparition, rushes each day and night with mysterious and ghost-like punctuality; holding its swift and headlong course in all weathers, and seeming to bid defiance to the very elements themselves.”

The reality, he goes on to say, was rather different, and presents the true picture of it as it really was, situated in the very core of London, surrounded by Newgate, Smithfield, the Compter and St. Sepulchre’s Church—

“and, just on that particular part of Snow Hill where omnibus horses going eastward seriously think of falling down on purpose, and where horses in hackney cabriolets going westward not unfrequently fall by accident, is the coach-yard of the Saracen’s Head inn; its portal guarded by two Saracens’ heads and shoulders—there they are, frowning upon you from each side of the gateway. The inn itself, garnished with another Saracen’s Head, frowns upon you from the top of[Pg 41] the yard; while from the door of the hind boot of all the red coaches that are standing therein there glares a small Saracen’s Head, with a twin expression to the large Saracen’s Head below, so that the general appearance of the pile is decidedly of the Saracenic order.

“When you walk up this yard, you will see the booking-office on your left, and the tower of St. Sepulchre’s Church, darting abruptly up into the[Pg 42] sky, on your right, and a gallery of bedrooms on both sides. Just before you, you will observe a long window with the words ‘coffee-room’ legibly painted above it; and, looking out of the window, you would have seen in addition, if you had gone at the right time, Mr. Wackford Squeers with his hands in his pockets.”

THE SARACEN’S HEAD, SNOW HILL

From an old Print

Here, Mr. Squeers was standing “in a box by one of the coffee-room fire-places, fitted with one such table as is usually seen in coffee-rooms, and two of extraordinary shapes and dimensions made to suit the angles of the partition,” waiting for fond parents and guardians to bring their little boys for his treatment. At the moment he had only secured one, but presently two more were added to the list, and, during the bargaining with their stepfather, Ralph Nickleby and his nephew arrived on the scene. The incident of Nicholas’s engagement for the post will be recalled by all and need not be repeated here. As the uncle and nephew emerged from the Saracen’s Head gateway, Ralph promised Nicholas he would return in the morning to see him “fairly off” by the coach.

Nicholas kept his appointment by arriving at the Saracen’s Head in good time, and went in search of Mr. Squeers in the coffee-room, where he[Pg 43] discovered him breakfasting with three little boys. The sound of the coach horn quickly brought the frugal repast to an end, and “the little boys had to be got up to the top of the coach and their boxes had to be brought out and put in.” All was animation in the coach-yard when Nicholas’s mother and sister and his uncle arrived to bid him good-bye.

“A minute’s bustle, a banging of the coach doors, a swaying of the vehicle to one side, as the heavy coachman, and still heavier guard, climbed into their seats; a cry of all right, a few notes from the horn, a hasty glance of two sorrowful faces below and the hard features of Mr. Ralph Nickleby—and the coach was gone too, and rattling over the stones of Smithfield.”

And so the Saracen’s Head is left behind, and is not referred to again until John Browdie comes to London with his newly wed wife, Tilda Price that was, and her friend, Fanny Squeers. Dismounting near the Post Office he called a hackney coach, and, placing the ladies and the luggage hurriedly in, commanded the driver to “Noo gang to the Sarah’s Head, mun.”

“To the were?” cried the coachman.

“Lawk, Mr. Browdie,” interrupted Miss Squeers. “The idea! Saracen’s Head.”

[Pg 44]“Surely,” said John, “I know’d it was something aboot Sarah’s Son’s Head. Dost thou know thot?”

“Oh ah! I know that,” replied the coachman gruffly, as he banged the door.

Arriving there safely they all retired to rest, and in the morning partook of a substantial breakfast in “a small private room upstairs, commanding an uninterrupted view of the stables.” Fanny Squeers made anxious enquiries for her father who had been in London some time seeking the lost Smike. She was under the impression that he made the Saracen’s Head his headquarters, but was woefully disillusioned when she was informed that he “was not stopping in the house, but that he came there every day, and that when he arrived he should be shown upstairs.” He shortly appeared, and the good-hearted John Browdie invited him to “pick a bit,” which he promptly did.

Mr. Squeers did not make the Saracen’s Head his abiding place; he was too mean for that; John Browdie, who was up for a holiday, stayed there the whole time he was in London, and some very merry, not to say solid meals he enjoyed during the period—for John liked a good meal.

On one such occasion, when Nicholas was a[Pg 45] guest, the conviviality was sadly marred by a terrible quarrel between Fanny Squeers and her father, and Mrs. and John Browdie—Nicholas incidentally coming in for some of the abuse. Very nasty and cutting things were said on both sides, and Mr. Squeers was summarily dismissed with a threat from John that he would “pound him to flour.”

After the excitement had subsided and the Squeers family had withdrawn in a perfect hurricane of rage, John calmly ordered of the waiter another “Sooper—very coomfortable and plenty o’ it at ten o’clock ... and ecod we’ll begin to spend the evening in earnest.”

The storm had long given place to a calm the most profound, and the evening pretty far advanced, when there occurred in the inn another incident more angry still, and reached a state of ferocity which could not have been surpassed, we are told, if there had actually been a Saracen’s Head then present in the establishment. Nicholas and John Browdie, following to where the noise came from, discovered coffee-room customers, coachmen and helpers congregating round the prostrate figure of a young man, with another young man standing in defiance over him. The latter was no other than Frank Cheeryble, who,[Pg 46] overhearing disrespectful and insolent remarks coming from his opponent in the fray, relative to a young lady, had taken the part of the latter by vigorously setting about the traducer, who was ultimately turned out of the inn. Frank Cheeryble was staying the night in the house, and so the four friends adjourned upstairs together and spent a pleasant half-hour with great satisfaction and mutual entertainment.

These are the chief associations the Saracen’s Head had in connection with Nicholas Nickleby, except that it might be mentioned that Mrs. Nickleby, as she would, confused its sign with that of another notable inn, by referring to it as the “Saracen with two necks.”

There are, however, two other references to the inn in Dickens’s books. In Our Mutual Friend, we read that:

“Mrs. Wilfer’s impressive countenance followed Bella with glaring eyes, presenting a combination of the once popular sign of the Saracen’s Head with a piece of Dutch clockwork”; and again, in one of his Uncommercial papers, Dickens, speaking of his wanderings about London and of having left behind him this and that historic spot, says he “had got past the Saracen’s Head (with an ignominious rash of posting bills[Pg 47] disfiguring his swarthy countenance) and had strolled up the yard of its ancient neighbour,” making clear that the old inn was a notable landmark to him. He knew it in the flourishing days of the coaching era and lived to see it demolished in 1868 to allow of the Metropolitan improvements in the neighbourhood.

But its name was not to be entirely erased from London’s annals, for another inn, although quite an unromantic one, was erected at the lower end of Snow Hill, only to wither in course of time into an unprofitable concern and to give up the ghost as a tavern. In 1912, this building was taken over by a firm of manufacturers of fancy leather goods and kindred articles of commerce, who recast the building for the purpose of their trade and its necessary business offices.

The proprietors have retained the old sign of the Saracen’s Head and have done much to keep up the association of the name with the most notable and living part of its history—that of its connection with Dickens’s story of Nicholas Nickleby.

Over the entrance they have placed a bust of Dickens mounted on a pedestal, flanked on each side by full-length figures of Nicholas and Squeers. Whilst on each side of the entrance porch is a[Pg 48] bas-relief of a scene from Nicholas Nickleby: one representing Nicholas, Squeers and the boys preparing to leave the inn by coach, and the other, the well-known scene in Dotheboys Hall, depicting Nicholas thrashing Squeers.

And so, from out of seven centuries of historical associations, the one that emerges and remains to-day is that created by Dickens.

Nicholas Nickleby (continued)

THE PEACOCK, ISLINGTON—THE WHITE HORSE, ETON SLOCOMBE—THE GEORGE, GRANTHAM—THE GEORGE AND NEW INN, GRETA BRIDGE—THE KING’S HEAD, BARNARD CASTLE—THE UNICORN, BOWES—THE INN ON THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD—THE LONDON TAVERN—AND OTHERS

The first stop of Nicholas’s coach after it had left the Saracen’s Head was at the Peacock, at Islington, an inn of immense popularity in those palmy days when the north-country mail-coaches made it their headquarters. It stood a little further north of the Angel, and was even more famous than that historic inn. Besides being the starting point for certain coaches, it was the house of call for nearly all others going in that direction out of London, and the busy and exciting[Pg 50] scenes which ensued outside its doors became more bewildering still by the ostlers calling out the name of each coach as it arrived.

Such a scene, no doubt, was witnessed by Nicholas, in whose charge Squeers had placed the scholars, when, “between the manual exertion and the mental anxiety attendant upon his task, he was not a little relieved when the coach stopped at the Peacock, Islington. He was still more relieved when a hearty-looking gentleman, with a very good-humoured face and a very fresh colour, got up behind, and proposed to take the other corner of the seat,” as he thought it would be safer for the youngsters if they were sandwiched between Nicholas and himself.

Everything and everybody being settled, off they went “amidst a loud flourish from the guard’s horn and the calm approval of all the judges of coaches and coach-horses congregated at the Peacock.”

That was in 1838; later (in 1855) Dickens refers again to the same inn. But on that occasion the scene must have been one of great tranquillity and calm, if not a little dismal.

This was when the bashful man, as related in the “first branch” of The Holly Tree, starts on his journey to the Holly Tree Inn. “There was no [Pg 51]Northern Railway at that time,” he says, “and in its place there were stage-coaches; which I occasionally find myself, in common with some other people, affecting to lament now, but which everybody dreaded as a very serious penance then. I had secured the box seat on the fastest of these, and my business in Fleet Street was to get into a cab with my portmanteau, so to make the best of my way to the Peacock at Islington, where I was to join this coach.... When I got to the Peacock, where I found everybody drinking hot purl, in self-preservation, I asked if there were an inside seat to spare. I then discovered that, inside or out, I was the only passenger. This gave me a still livelier idea of the great inclemency of the weather, since that coach always loaded particularly well. However, I took a little purl (which I found uncommonly good), and got into the coach. When I was seated they built me up with straw to the waist, and, conscious of making a rather ridiculous appearance, I began my journey. It was still dark when we left the Peacock.”

THE PEACOCK, ISLINGTON

From an old Engraving

A reference to the same inn is made in “Tom Brown’s Schooldays,” when Tom and his father stayed the night there in order to catch the “Tally-Ho” coach for Rugby the next morning.

[Pg 52]There is still a reminder of the old Peacock at 11 High Street, where a sign-board announces the date of its establishment in 1564, and a relic of the coaching days may be seen in the form of an iron hook upon a lamp-post opposite, to which horses were temporarily tethered.

Following Nicholas’s coach on its journey north we find it passing through the counties of Hertford and Bedford in bitterly and intensely cold weather. In due course it arrived at Eton Slocombe, where a halt was made for a good coach dinner, of which all passengers partook, “while the five little boys were put to thaw by the fire, and regaled with sandwiches.” Mr. Squeers, it may be noted in passing, had, in the interim, alighted at almost every stage to refresh himself, leaving his charges on the top of the coach to content themselves with what was left of their breakfast.

Eton Slocombe is Dickens’s thinly disguised name for Eaton Socon, a picturesque little village of one straggling street in Huntingdonshire. He does not mention the inn by name, but it may be rightly assumed that it was the White Horse, an attractive old road-side coaching-house, which, in those days, was the posting inn for the mail and other coaches passing through the county. In[Pg 53] later years it became the favourite resort of the North Road Cycling Club, and witnessed the beginning and ending of many a road race in the “’eighties” and “’nineties,” and is, no doubt, a welcome place of call for motorists to-day.

Leaving Eton Slocombe, the coach took the turnpike road via Stilton, as the night and the snow came on together. In the dismal weather the coach rambled on through the deserted streets of Stamford until twenty miles further on it arrived at the George at Grantham, where “two of the front outside passengers, wisely availing themselves of their arrival at one of the best inns in England, turned in for the night.” The remainder of the passengers, however, “wrapped themselves more closely in their coats and cloaks, and, leaving the light and the warmth of the town behind them, pillowed themselves against the luggage, and prepared, with many half-suppressed moans, again to encounter the piercing blast which swept across the open country.”

Grantham has the reputation of being a town of many and excellent inns, of which the honours seem to have been divided between the Angel and the George. When Dickens set out on his voyage in search of facts concerning the Yorkshire[Pg 54] schools prior to writing Nicholas Nickleby he took the same coach journey which he describes so realistically in his book, accompanied by his artist friend, Phiz. They slept the night at the George, like the two wise “front outsides” of the story; and in a letter to his wife Dickens said that the George was “the very best inn I have ever put up at,” and he repeats this encomium in his book.

The George was burnt down in 1780 and its beautiful mediæval structure replaced by a building not so picturesque, but none the less comfortable. It was a famous coaching inn and consequently always busy with the mail and stage coaches of the period. It is a square red-bricked building of the Georgian type, and, although its outward appearance is not so inviting from an antiquarian point of view as its predecessor, the testimony of travellers confirms its interior comfort.

The coach carrying Squeers and his party was little more than a stage out of Grantham, “or half-way between it and Newark,” to be precise, when the accident occurred which turned the vehicle over into the snow. After the bustle which ensued and after casualties had been attended to, all walked back to the nearest[Pg 55] public-house, described as a “lonely place, with no great accommodation in the way of apartments.” Here, having “washed off all effaceable marks of the late accident,” they settled down to the comfort of a warm room in patient anticipation of the arrival of another coach from Grantham. As this entailed a two hours’ wait the company amused themselves by listening to the narration of the story of “The Five Sisters of York” by the grey-haired gentleman, and of “The Baron of Grogzwig” by the merry-faced gentleman. Which was the “public-house” round whose fire these two famous stories were told, the chronicler does not say, nor has it been identified. At the conclusion of the last-named story the welcome announcement of the arrival of the new coach was made and the company resumed the journey. Nothing further of any note occurred until at six o’clock that night, when Nicholas, Squeers “and the little boys and their united luggage were all put down together at the George and New Inn, Greta Bridge.” The coach having traversed the road via Retford and Bawtry, crossed Yorkshire, via Doncaster and Borough Bridge to this inn “in the midst of a dreary moor,” as Dickens so described it.

Although Greta Bridge was but a small and[Pg 56] picturesque hamlet at the time Dickens visited and wrote of it, it nevertheless boasted at least two important inns doing a busy trade with the coaches and mail on the main coaching route to Glasgow. These were known as the George and the New Inn respectively, and were about half a mile apart. In his book the novelist combines the two names, perhaps to avoid identification; but there seems no doubt that the George was the inn Dickens and Phiz stayed at themselves, and therefore it may be assumed it was at that inn Nicholas and Squeers also alighted when their coach journey ended. The George stands near the bridge which spans the Greta river a little above its junction with the Tees. It is no longer an inn, having since been converted into a residential building known as “The Square” and let out in tenements. But it still shows unmistakable signs of its former calling. Its large square yard remains, although want of use has allowed grass to overgrow it; whilst its commodious stabling, empty and bare as it is, conjures up the busy scenes of excitement and animation the mail-coaches and travellers must have created in those far-off days.

The inn was the coaching centre of the district, received the mail as it arrived and despatched it[Pg 57] to the villages round about. Dickens was evidently very pleased with the hospitality he received on his arrival after a dreary journey, for when writing to his wife he said:

THE GEORGE INN, GRETA BRIDGE

Drawn by C. G. Harper

“At eleven we reached a bare place with a house standing alone in the midst of a dreary moor, which the guard informed me was Greta Bridge. I was in a perfect agony of apprehension, for it was fearfully cold, and there were no outward signs of anyone being up in the house; but to our great joy we discovered a comfortable room, with drawn curtains, and a most blazing fire. In[Pg 58] half an hour they gave us a smoking supper, and a bottle of mulled port, in which we drank your health, and then retired to a couple of capital bedrooms, in each of which there was a rousing fire half-way up the chimney. We had for breakfast toast, cakes, a Yorkshire pie, a piece of beef about the size and much the shape of my portmanteau, tea, coffee, ham, eggs; and are now going to look about us.”

Dickens seems to be a little misleading in saying the inn stood on the heath. It was actually in the village by the side of the road. But he apparently got this idea that the house stood “alone in the midst of a dreary moor” well into his mind, for, when using the inn again as the original of the Holly Tree Inn in the charming Christmas story with that name, we find that the bashful man is made to speak of it as being on a bleak wild solitude of the Yorkshire moor. He describes the interior in many whimsical details, perhaps at times a little exaggerated, as, for instance, when he says his bedroom was some quarter of a mile from his huge sitting-room. Next day it was still snowing, and, not knowing what to do, he, in desperation, invited the Boots “to take a chair—and something in a liquid form—and talk” to him. This he did and the[Pg 59] delightful story of Mr. and Mrs. Harry Walmers, junior, the chief incidents of which all took place in the same inn, was recalled by the Boots.

But to return to Squeers and his party:

Having run into the tavern to “stretch his legs,” he returned in a few minutes, as, at the same time, there emerged from the yard a rusty, pony-chaise, and a cart, driven by two labouring men. By these conveyances he transported his charges to “the delightful village of Dotheboys” about three miles away.

Nicholas was preparing for bed that evening when the letter Newman Noggs had given him in London fell out of his pocket unopened. This letter interests at the moment by reason of its postscript, which runs: “If you should go near Barnard Castle, there is good ale at the King’s Head. Say you know me, and I am sure they will not charge you for it. You may say Mr. Noggs there, for I was a gentleman then. I was indeed.”

It is not recorded that Nicholas had occasion to visit the King’s Head, Barnard Castle, but we know that Dickens went there after having explored the neighbourhood of Greta Bridge. He and Phiz made the journey in a post chaise, there to deliver the letter Mr. Charles Smithson,[Pg 60] the London solicitor, had given him by way of introduction to a certain person who would help him in his discoveries about the Yorkshire schools.

Barnard Castle is about four miles from Greta Bridge, and is in the county of Durham, just across the Yorkshire border. Arriving there Dickens made the King’s Head his headquarters. Since that date the inn has been enlarged somewhat, but much of the older portion remains the same as when he stayed there.

It was here the interview referred to above took place before a fire in one of the cosiest rooms in the building, and the person who furnished the information became the original of John Browdie.

Many legends about Dickens’s stay at the King’s Head have got into print, such as that he stayed there six weeks, that he wrote a great part of the book there, working hard at a table in front of the window all day, and that he spent the nights in the bar parlour gathering facts from the frequenters. Actually he only remained two nights, and wrote no more of his book there than a few brief notes, in the same way that Phiz made rough pictures in his sketch-book.

It was whilst on this short visit that Dickens made the acquaintance of Mr. Humphrey, who kept a watchmaker’s shop lower down the street. [Pg 61]This worthy conducted him to some of the schools in the neighbourhood, and from the friendly association sprang the title of Master Humphrey’s Clock, used by the novelist for his next serial. When Dickens first met Mr. Humphrey, who we believe was the source from which sprang all the legendary stories about Dickens and Barnard Castle, he exhibited no clock outside his shop. It was not until two years after Dickens’s visit that the old man, having moved opposite the inn, placed a clock above the door.

THE KING’S HEAD, BARNARD CASTLE

Photograph by T. W. Tyrrell

The King’s Head in those days was kept by two sisters, who were wont to inform customers that Dickens wrote a good deal of Nicholas Nickleby in their house. He was always writing, it was said, and they could show the ink-stand he used during the long stay he made. This is a little exaggeration which reflected glory engenders sometimes.

The inn is of the Georgian period and was built about the middle of the eighteenth century. It is situated in the market place, and the room Dickens occupied is still cared for and exhibited to visitors. The house is practically the same, with its intricate staircases, low ceilings, its old-world atmosphere, and old-fashioned appurtenances.

[Pg 62]Dotheboys Hall, Squeers’s academy, has been identified as being at Bowes, and at the Unicorn Inn there Dickens is said to have met Shaw, the original of Squeers. It was Squeers’s custom, we are told, “to drive over to the market town every evening, on pretence of urgent business, and stop till ten or eleven o’clock at a tavern he much affected,” and no doubt it was to the Unicorn that he repaired.

This ancient inn stands midway in the village and was at that time the most important inn between York and Carlisle. A dozen or more coaches changed every day in its yard, which was, and still is, with its abundant stabling, one of the largest of the ancient road-side hostelries surviving the old coaching days. It is still unspoiled, and we believe remains much the same as when Dickens and Phiz drew up there and partook of a substantial lunch, and ultimately interviewed the veritable Mr. Shaw, Squeers’s prototype.

The next inn carries us a good way into the story and brings us in company with Nicholas and Smike on their tramp to Portsmouth. Chapter XXII of the book describes how these two, having deserted Squeers, sally forth to seek their fortune at the naval port. On the first evening they arrived at Godalming, where they bargained[Pg 63] for two beds and slept soundly in them. On the second day, they reached the Devil’s Punch Bowl, at Hindhead, and Nicholas, having read to Smike the inscription upon the stone, together they passed on with steady purpose until they were within twelve miles of Portsmouth, just beyond Petersfield. Here they turned off the path to the door of a road-side inn, where they learned from the landlord that it was not only “twelve long miles” to their destination, but a very bad road. Following the advice of the innkeeper Nicholas decided to stay where he was for the night, and was led into the kitchen. Asked what they would have for supper “Nicholas suggested cold meat, but there was no cold meat—poached eggs, but there were no eggs—mutton chops, but there wasn’t a mutton chop within three miles, though there had been more last week than they knew what to do with, and would be an extraordinary supply the day after to-morrow.” Nicholas determined to leave the decision entirely to the landlord, who rejoined: “There’s a gentleman in the parlour that’s ordered a hot beefsteak pudding and potatoes at nine. There’s more of it than he can manage, and I have very little doubt that, if I ask leave, you can sup with him. I’ll do that in a minute.” In spite of Nicholas’s disinclination[Pg 64] to consent to do any such thing, the landlord hurried off and in a few minutes Nicholas was shown into the presence of Mr. Vincent Crummles, who was rehearsing his two sons in “what is called in play-bills a terrific combat” with broadswords.

After the rehearsal was finished Nicholas and Crummles drew round the fire and the conversation revealed the latter’s profession and business. The appearance of the beefsteak pudding put a stop to the discussion for the time being; but after Smike and the two young Crummleses had retired for the night Nicholas and Mr. Vincent Crummles continued their conversation over a bowl of punch, which sent forth “a most grateful and inviting fragrance.” Under the influence of this stimulant Mr. Vincent Crummles proposed that Nicholas should join his theatrical company.

“There’s genteel comedy in your walk and manner, juvenile tragedy in your eye, and touch-and-go farce in your laugh,” said Mr. Vincent Crummles. “You’ll do as well as if you had thought of nothing else but the lamps from your birth downwards.” After further flattery and persuasiveness, Nicholas agreed to try, and without more deliberation declared it was a bargain and gave Mr. Vincent Crummles his hand upon it.

[Pg 65]Next morning they all continued their journey to Portsmouth in Mr. Vincent Crummles’s “four-wheeled phaeton” drawn by his famous pony.

Dickens does not name the inn in which this incident took place, and beyond stating it was twelve miles from Portsmouth gives no other indication helpful in identifying it.

THE BOTTOM INN, NEAR PETERSFIELD

Drawn by C. G. Harper

Mr. Charles G. Harper however says from Dickens’s very accurate description there can be no question as to the identical spot the novelist had in mind, which is just below Petersfield. There is an inn, the Coach and Horses, standing by the wayside to-day, but according to Mr. Harper it did not exist at the time of the story,[Pg 66] so that the inn to which Dickens referred was the Bottom Inn, or Gravel Hill Inn, as it was sometimes called, which stood there in those days, and exists to-day as a gamekeeper’s cottage.

There are other inns in the book that are referred to without name and one or two which leave no doubt as to their identity.

The handsome hotel, for instance, where Nicholas accidentally overheard Sir Mulberry Hawk talking familiarly about his sister Kate, was situated, Dickens tells us, in one of the thoroughfares lying between Park Lane and Bond Street. It cannot, however, definitely be identified. It was in one of the boxes of the coffee-room that the incident took place and there were many such hotels at the time in the district whose coffee-rooms were partitioned off into such boxes as Dickens describes this one. It has been suggested that Mivart’s, afterwards Claridge’s—the old one, not the present building—was possibly the one Dickens meant. It stood in Brook Street and for that reason would perhaps answer the purpose. But this is mere conjecture.

This hotel may also be the one referred to in Chapter XVI of Book II of Little Dorrit, where we are told “The courier had not approved of Mr. Dorrit’s staying in the house of a friend, and[Pg 67] had preferred to take him to an hotel in Brook Street, Grosvenor Square.” He had just returned from the Continent and remained for a short time only. But it was the scene of two or three momentous interviews with Mr. Merdle, Flora Finching and young John Chivery.

The Crown public-house Newman Noggs used to frequent in the neighbourhood of Golden Square, London, and which he told Nicholas was “at the corner of Silver Street and James Street, with a bar door both ways,” has been rebuilt and greatly altered since those days. The names of the streets, too, have been changed to Upper James Street and Beak Street, but at the corner where they meet is to be found a Crown public-house occupying the site of Newman Noggs’s favoured house of call.

There is something more definite and real in the London Tavern referred to in the second chapter of the book, where the “United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company” was to hold its first meeting with Sir Matthew Pupker in the chair, which Company was being floated and engineered by Ralph Nickleby and his fellow conspirator, Mr. Bunney. Arriving in Bishopsgate Street Within, where the London Tavern was,[Pg 68] and still is situated, they found it in a great bustle. Half a dozen men were exciting themselves over the announcement of the meeting which was to petition Parliament in favour of the wonderful Company with a capital of five hundred thousand shares of ten pounds each. The two men elbowed their way into a room upstairs containing a business-looking table and several business-looking people. The report of that meeting is too long to quote, but, long as it is, not too long for the reader to relish every word of it if he will but turn again to the pages describing it. After the petition was agreed upon, Mr. Nickleby and the other directors adjourned to the office to lunch, and to remunerate themselves; “for which trouble (as the company was yet in its infancy) they only charged three guineas each man for every such attendance.”

The London Tavern where this meeting was held was opened in 1768. It was built on the Tontine principle, the name of the architect one Richard B. Jupp. The great dining-room was known as the “Pillar-room” and was “decorated with medallions and garlands, Corinthian columns and pilasters.” It had a ball-room running the whole length of the structure, which was also used for banquets, and was hung with paintings and[Pg 69] contained a large organ at one end. In those days the hotel was famous for its turtle soup, the turtles being kept alive in large tanks, and as many as two tons were seen swimming in the vat at one time. The cellars were filled with barrels of porter, pipes of port, butts of sherry, and endless other bottles and bins. The building was erected to provide a spacious and convenient place for public meetings, such as had drawn Ralph Nickleby and his friends on the occasion referred to above.

In Household Words in 1852 was a long article on the tavern to which we are indebted for some of the facts here recorded. Meetings of Mexican Bondholders were held on the second floor; of a Railway Assurance “upstairs, and first to the left”; of an asylum election at the end of the passage; and of the party on the “first floor to the right,” who had to consider “the union of the Gibbleton line of the Great-Trunk-Due-Eastern Junction”; all these functions brought persons in great excitement and agitation to its hospitable walls.

For these meetings the rooms were arranged with benches, and sumptuously Turkey-carpeted: the end being provided with a long table for the directors, with an imposing array of paper and pens.

[Pg 70]In a word, it was a city tavern for city men, and it still exists to-day to cater for the requirements of the same class of business men, although perhaps not so ostentatiously. Banquets are still held there; city companies hold their meetings there, and Masonic institutions their lodges.

Dickens knew the tavern very well, having given dinners there himself or taken the chair for some fund, as he did in June 1844, in aid of the “Sanatorium or Sick-house,” an institution for students, governesses and young artists who were above using hospitals and could not afford the expenses of home-nursing in their lodgings.

On another occasion (in 1851) Dickens presided there at the annual dinner held in aid of the General Theatrical Fund. The thought of this dinner may have come back to him when he was writing one of his short pieces entitled “Lying Awake,” (1852) in which, among the strange things which came to his mind on those occasions, he mentions that he found himself once thinking how he had “suffered unspeakable agitation of mind from taking the chair at a public dinner at the London Tavern in my night clothes, which not all the courtesy of my kind friend and host, Mr. Bathe, could persuade me were quite adapted to the occasion.”

[Pg 71]There are a few other inns not mentioned by name, or merely alluded to in passing, which, together with those we have dealt with, make Nicholas Nickleby almost as interesting from this point of view as Pickwick Papers.

Barnaby Rudge

THE MAYPOLE, CHIGWELL

Of all the inns with which Dickens’s books abound there is none that plays so important a part in any of his stories as the Maypole at Chigwell does in Barnaby Rudge. Other inns are just the scene of an incident or two, or are associated with certain characters or groups of characters; the Maypole is the actual pivot upon which the whole story of Barnaby Rudge revolves. It is associated in some way with every character that figures prominently in the narrative, and scene after scene is enacted either in it or near by. The story begins with a picturesque description of the inn and its frequenters, and ends with a delightful pen-picture of young Joe Willet comfortably settled there with Dolly as his wife, and a happy family growing up around them.

For these reasons it may therefore be said to[Pg 73] be the most important of all the Dickensian inns. It is also one of the few hostels Dickens describes in detail, and perhaps the only one he admittedly gave a fanciful name to, for its real name is the King’s Head. Ever since it has been an inn it has been so called, and is known by that name to-day, although it is never referred to in conversation or print without the corroborative appendage of “The Maypole of Barnaby Rudge,” nor does the sign-board omit this important fact. There are the remains of an inn near by at Chigwell Row, boasting the sign of the Maypole, and this may have suggested the name to Dickens, but that is all it can claim: the King’s Head is the inn and Chigwell is the place chosen by Dickens for the centre of some of the chief scenes in his story, and the few fanciful touches he gives to it and its surroundings are nothing but the licence allowed a novelist for rounding off and completing the details necessary for the presentment of his ideal. As long as the King’s Head exists, therefore, it will always remain famous as “the Maypole of Barnaby Rudge,” and reflect pleasant memories to all who know the book.

In 1841 Dickens, writing to his friend and biographer, John Forster, inviting him to take a trip to Chigwell, said: “Chigwell, my dear fellow, is[Pg 74] the greatest place in the world. Name your day for going. Such a delicious old inn, opposite the churchyard—such a lovely ride—such beautiful forest scenery—such an out-of-the-way, rural, place—such a sexton! I say again name your day.” In quoting this alluring invitation in his biography of the novelist, John Forster adds: “The day was named at once, and the whitest of stones marks it, in now sorrowful memory. Dickens’s promise was exceeded by our enjoyment; and his delight in the double recognition of himself and of Barnaby, by the landlord of the nice old inn, far exceeded any pride he would have taken in what the world thinks the highest sort of honour.”

As Barnaby Rudge had been published by this time, the novelist must have made many a trip to the King’s Head previously, for the early chapters of the story in which the inn is introduced had been written long before.

Time has played very few tricks either with the building or with Chigwell, for they are practically the same to-day as they were at the period in which Dickens was writing. The inn can still be said to be a delicious old one, and, if one rides to it as Dickens did, his description of the forest scenery and the nature of the out-of-the-way, rural[Pg 75] place will be found as true to-day as when he discovered it, nearly a century ago: facts which many a pilgrim to it since can substantiate.

THE KING’S HEAD, CHIGWELL

Drawn by L. Walker

The description of the Maypole in the opening chapter of Barnaby Rudge has been quoted often, but we make no apology for quoting it again, for no more enticing way of introducing it could be imagined. Besides which it incidentally suggests its past history as well as affirms its present picturesqueness:

“The Maypole was an old building, with more[Pg 76] gable ends than a lazy man would care to count on a sunny day; huge zigzag chimneys, out of which it seemed as though even smoke could not choose but come in more than naturally fantastic shapes, imparted to it in its tortuous progress; and vast stables, gloomy, ruinous, and empty. The place was said to have been built in the days of King Henry the Eighth; and there was a legend, not only that Queen Elizabeth had slept there one night while upon a hunting excursion, to wit, in a certain oak-panelled room with a deep bay window, but that next morning, while standing on a mounting-block before the door, with one foot in the stirrup, the Virgin Monarch had then and there boxed and cuffed an unlucky page for some neglect of duty.... Whether these, and many other stories of the like nature, were true or untrue, the Maypole was really an old house, a very old house, perhaps as old as it claimed to be, and perhaps older, which will sometimes happen with houses of an uncertain, as with ladies of a certain, age. Its windows were old diamond-pane lattices, its floors were sunken and uneven, its ceilings blacked by the hand of Time, and heavy with massive beams. Over the doorway was an ancient porch, quaintly and grotesquely carved; and here on Summer[Pg 77] evenings the more favoured customers smoked and drank—aye, and sang many a good song, too, sometimes—reposing in two grim-looking high-backed settles, which, like the twin dragons of some fairy tale, guarded the entrance to the mansion. In the chimneys of the disused rooms swallows had built their nests for many a long year, and, from earliest Spring to latest Autumn, whole colonies of sparrows chirped and twittered in the eaves. There were more pigeons about the dreary stable-yard and outbuildings than anybody but the landlord could reckon up. The wheeling and circling flights of runts, fantails, tumblers and pouters were perhaps not quite consistent with the grave and sober character of the building, but the monotonous cooing, which never ceased to be raised by some among them all day long, suited it exactly, and seemed to lull it to rest.

“With its overhanging stories, drowsy little panes of glass, and front bulging out and projecting over the pathway, the old house looked as if it were nodding in its sleep. Indeed, it needed no great stretch of fancy to detect in it other resemblances to humanity. The bricks of which it was built had originally been a deep dark red, but had grown yellow and discoloured like an old man’s[Pg 78] skin; the sturdy timbers had decayed like teeth; and here and there the ivy, like a warm garment to comfort it in its age, wrapt its green leaves closely round the time-worn walls.”

That is a charming pen-picture of the Maypole’s outward appearance, and beyond a little exaggeration as regards some details almost perfectly fits the “delicious” old inn to-day. Some topographers have seen fit to quarrel with the picture because the porch was never there as described by Dickens and because the gable ends could easily be counted without trouble, and because in their hurried visit they had failed to discover the old bricks and the warm garment of ivy wrapping its green leaves closely round the time-worn walls. But that is being meticulous, not to say pedantic, and if a visit is made to the back of the building this delightful simile can be thoroughly appreciated. Indeed, no more appropriate words could be found to describe its appearance to-day than those written by the novelist many years ago.

Cattermole, who drew a picture of the inn for the book, went woefully wrong. He did not even follow Dickens’s words, but drew a picture more representing an old English baronial mansion than an inn. Even granting that, before the Maypole[Pg 79] was an inn it was a mansion, Cattermole very much overstepped the mark. History tells us that about 1713 the King’s Head was used for sittings of the Court of Attachments, and that farther back in 1630 “the Bailiff of the Forests was directed to summon the Constables to appear before the Forest Officers, for the purposes of an election,” at the “house of Bibby,” which probably was no other than what became the King’s Head at Chigwell. “In this quaint and pleasant inn,” we are informed, “may still be seen the room in which the Court of Attachments was held.” This evidently is the Chester Room to which we shall refer later. The same writer also mentions “an arched recess in the cellar, made to hold the wine which served for the revels of the Officers of the Forest, after the graver labours of the day.”

Let us follow the story of Barnaby Rudge through, and see how everything in it focusses on the Maypole Inn.