Title: Live toys

or, Anecdotes of our four-legged and other pets

Author: Emma Davenport

Illustrator: Harrison Weir

Release date: June 14, 2013 [eBook #42946]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Sandra Eder and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (http://archive.org/details/americana) and Google Books Library Project (http://books.google.com)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Live Toys, by Emma Davenport

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/livetoysoranecdo00dave |

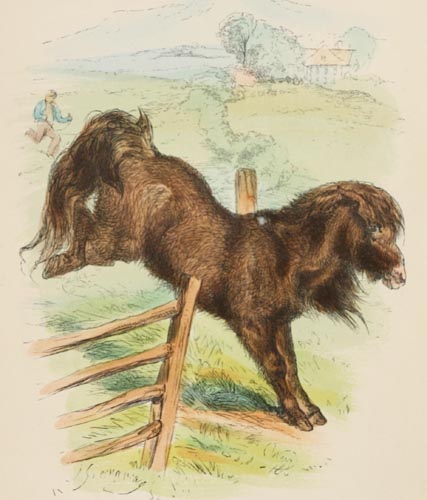

BLUEBEARD, THE SHETLAND PONY.

Page 85.

BY

EMMA DAVENPORT,

AUTHORESS OF

"JAMIE'S QUESTIONS," "WEAK AND WILFUL," ETC.

With Illustrations by Harrison Weir.

LONDON:

GRIFFITH AND FARRAN,

(SUCCESSORS TO NEWBERY AND HARRIS,)

CORNER OF ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD.

M DCCC LXII.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WERTHEIMER AND CO.,

CIRCUS PLACE, FINSBURY.

TO

LADY NEPEAN,

THIS

LITTLE VOLUME IS DEDICATED,

AS

CONTAINING TRUE ANECDOTES OF THE VARIOUS ANIMALS

THAT WERE IN THE POSSESSION OF A LITTLE BOY

AND GIRL, IN WHOM SHE HAS ALWAYS

SHEWN A KIND INTEREST.

| PAGE | |

| Moppy, the White Rabbit | 1 |

| The Two Birds, Goldie and Brownie | 4 |

| Poll Parrot | 10 |

| Neddy and the Rifle Donkey | 19 |

| Bunny, the Wild Rabbit | 31 |

| The Jackdaw | 38 |

| Pricker, the Hedgehog | 50 |

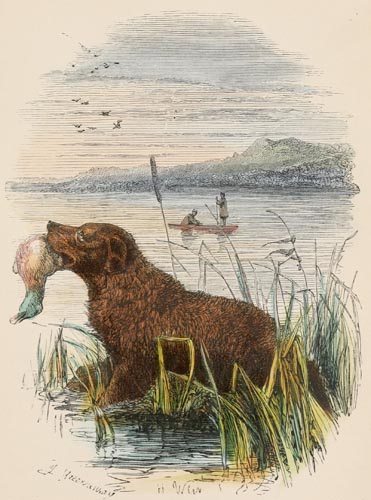

| Drake, the Retriever | 55 |

| Tawney, the Terrier | 60 |

| Puffer, the Pigeon | 70 |

| Dr. Battius, the Bat | 75 |

| The Chough | 80 |

| The Kittens, Blacky and Snowdrop | 83 |

| Bluebeard, the Shetland Pony | 85 |

| Joe, the German Dog | 96 |

LIVE TOYS;

OR

ANECDOTES OF OUR FOUR-LEGGED AND OTHER PETS.

The first Pet that we ever remember possessing was a large white rabbit. We were then very little children; and, being at the sea-side, we spent the greater part of the day on the shore, or rather on the broad esplanade, that stretched for full half-a-mile round the pretty bay. When we were quite tired of running there, or of picking up stones and weeds on the shingle below the esplanade wall, we were enabled to prolong our stay out of doors by means of the pretty little goat-carriages that were kept in readiness on the esplanade. Some of them were made with two seats; some were drawn by one goat, and some with two. There were reins and regular harness to these little goats, and we were indeed pleased, when our nurse allowed us to drive in one of the double-seated carriages. We took turns to sit in front and drive, and we tried hard to persuade our Mamma to let us have a goat, and a goat-carriage for ourselves. What a nice Pet that would have been! But Mamma said she could not take it about, as we travelled much, and also that a goat would butt at us and knock us down. Therefore we were obliged to be content with patting and coaxing the goats on the walk.

During one of our drives in the goat-carriage, we met with a boy carrying a beautiful white creature with pink eyes; "Look! look! nurse," we cried, "what is that?" "It is a rabbit," she said, "would you like to stroke it?" and she took it out of the boy's hands, and held it close to us; we kissed it and stroked it, and buried our faces in its long white hair, felt its curious long ears, and wondered at the strange colour of its eyes. The boy said that a sailor gave it to him; but that his mother wished him to sell it, as it was troublesome in her small cottage, and they had no yard to keep it in, and he asked nurse if she would buy it from him. We earnestly begged that we might have it; "Do buy it, Mary," we cried; "please buy it." And, after some talking, Mary gave sixpence to the boy for the rabbit, and, my sister giving up her front seat and her reins to me, went home with the pretty creature in her lap.

We called the rabbit Moppy; it was a source of great amusement to us. Mary contrived a bed for it in a large packing-box in an empty garret at the top of the house, and when we wished to play with it, it was brought down to the nursery. We always fed it from our hands. It became extremely tame, and would follow us about the room, and allow us to lift it and carry it in all sorts of strange ways; for we could not manage lifting it by the ears in the proper way. When it began to be tired of us, it used to get under the sofa, and when we dragged it out again it appeared angry and would kick with its hind legs, and make quite a loud knocking on the floor, with what we called its hind elbows. When this commenced, nurse usually carried it off to its box, fearing that it might bite, or else she covered it up in her lap, when it would remain asleep for some time.

Now and then we took it with us when we drove in the little carriage, and it lay so snugly on our knees and kept us so warm. Before we had become at all weary of our plaything, or indifferent to its welfare, we removed to Ireland; and going first to visit grand-mamma, it was thought impossible to take Moppy, so after much consultation, nurse spoke to one of the little boys who kept the goats, and seemed to be a gentle good-natured lad, and with many instructions and requests that he would be most kind and careful to the poor little animal, we kissed and stroked our pet, and, burying our faces in its long white hair for the last time, we made him a present of beautiful soft Moppy.

"Would you like to buy a bird, Sir?" said a poor woman to me one day when we were just setting out for our walk. She held in her hand a small cage with a beautiful goldfinch.

"I have one shilling and sixpence," I said, "will you give it to me for that?"

"I hoped to be able to sell it for half-a-crown," the woman said, "for I am very poor; I am leaving this place and want money for my journey, or I should not part with my bird."

"But I have a shilling," said my sister, "and that added to your money will make half-a-crown, and so we can buy it between us and it will belong to us both."

We gave our money to the poor woman, and she put the cage into my hand. The little bird was quite a beauty, his colours so bright, his plumage so glossy and thick, and his chirp so merry. After displaying him to Mamma, and to every body we met, we carried him to the nursery, and placed him on the broad window-seat; Mamma said she was afraid we should soon get tired of him, and neglect to feed him and to clean his cage. This, we thought, was quite unlikely. However, we promised very faithfully; and we commenced with feeding and petting him so much that he soon became extremely tame, would take seeds and crumbs from our fingers, chirp to us when we came near his cage, and sing without the least sign of fear.

One day we had carried him into the drawing-room; and, on opening the door of the cage to put in some sugar, he darted out. "Oh dear! oh dear! Goldie is out," we exclaimed; "what shall we do? We shall lose him." But Mamma quickly got up, and shut both the windows and begged us to be quiet, and not to frighten him by rushing after him and attempting to seize him. "If you leave him alone," said Mamma, "he will perhaps allow you quietly to take him in your hand when he has flown about as much as he wishes; but he will lose all his tameness if you terrify him." So we sat down to watch the little fellow, he darted about the room for some time, and presently alighted on the table, where the breakfast things remained. First he pecked at the bread, then tried the sugar, peeped into the cups, and seemed highly amused at the different articles which he was now examining for the first time. Then he flew on the top of the picture frames that hung on the wall, then on the curtain rods, and at last perched on Mamma's head, peeped at her hair, and looked as proud and happy as possible. And after he had looked at every thing in the room and well stretched his wings, he quietly returned to his cage, chirping at us, as if to say, "I have seen enough for one day, I'll come out again to-morrow." So afterwards we used to give him a fly every morning, taking care to shut all the windows before his door was opened. We paid so much attention to our bird; that he did not seem to find his life at all dull, but he obtained a companion in an unexpected manner.

Our nursery window was standing open, Goldie was in his cage on the table, and we were playing on the floor; suddenly my sister exclaimed, pointing to the window, "Goldie is out! Goldie is out!" and there indeed, perched on the window-sill, was a little bird, which for a moment we believed to be our own little pet. We gently approached the window. "Oh that is a brown bird," said I, "and look! Goldie is safe in his cage." Nurse now advised us to draw back from the window, for that if not frightened, the little stranger might possibly be attracted by the bird in the cage, and might come inside the window; so we retreated to the opposite side of the room, and watched the little fellow. In he hopped very cautiously, now and then making a little chirrup, and twisting his head in all directions, as if to discover with his sharp black eyes, whether there was anything or anybody likely to hurt him; now he came on a chair-back, and then becoming bolder, ventured on the table. When Goldie saw him, he left his seed box at which he had been very busy, and hopping about his cage in a most excited mannere began to chirrup as loudly as he could, and shaking his tails up and down, he seemed to express his great joy at the sight of the little brown visitor. Nurse quietly passed round the room and shut the window, "Now we have him safe," we cried, dancing about. "Pray be still, my dears," said nurse, "until we get him into the cage." So we again became immoveable, and there was the brown stranger peeping at Goldie through the bars, perhaps wishing to partake of the seed and sugar, and fresh groundsel that Goldie had been enjoying. He was a delicately shaped thin little bird, all his feathers of a pretty dark brown, he did not appear to be much frightened when nurse approached, nor did he leave the table when she opened the door of the cage; but on the contrary, he peeped in, and receiving a very civil chirp of invitation from Goldie, he actually hopped in to our extreme delight.

We ran to display our treasure to Mamma. She was quite amused at our having caught him in so strange a manner, and said that she thought he was a linnet, or some such kind of bird. He was evidently a tame bird that had been much petted. He soon accommodated himself to all Goldie's habits, came regularly to breakfast, and took his fly afterwards, all about the room, resting occasionally on our heads or shoulders. Brownie would now hop on our fingers, when we wished to take him up from the floor; and this we had never been able to teach to Goldie.

The two birds were very good friends, excepting when an unusually nice bit of groundsel or plantain excited a quarrel between them; then they scolded, fluttered, and pecked at each other in a very savage manner. We had a sliding partition made to the cage, and when they began to dispute, we punished them by sliding in this partition and separating them for a short time. They used to look quite unhappy, moping in their solitude, until we made them happy again, by withdrawing the partition.

These little birds went many journeys with us, even crossed to England, and back again to Ireland, and lived with us for a long time; and I suppose we became rather careless about open windows and doors, knowing that the birds were so very tame, and had no wish to fly away.

We were the following summer in another place. There our rooms were confined and small; so we used to allow the birds to fly about on the staircase every morning, in order to give them a larger range for using their wings.

One bright summer morning, Goldie flew out on the landing; and as he had invariably come back again to his cage, we were not noticing him much, and never perceived that the servant had gone down stairs, leaving open the door at the bottom of the flight, just outside of which door, was an open window. Presently we went to see for him, and it was some moments before we spied him sitting on the ledge of this open window. If we had made no exclamation, and placed the cage on the stairs, most probably he would have returned; but perhaps we startled him by running down the stairs towards him. Out he went so rapidly and yet so gently, in the bright fresh air, as if he would say, "Liberty and sunshine, and freedom of flight in the summer sky, is too delightful to refuse, even for you, my dear little master and mistress." He perched on a high tree and looked at us for a while. In vain we strewed crumbs about the window, and called and whistled. In vain we set his cage on the ledge with his deserted companion in it, hoping that hearing Brownie's chirp would entice him to return. He never came back again, and Brownie occupied the cage for many months; our care of him being greater than ever, since we lost our other favourite.

But Brownie's end was much more tragic. We were going away on a visit for some weeks; and it was decided that Brownie was not to go, but that he should live in the kitchen until we returned. There was a huge cat living in the barracks. We always had been in dread of her, and had tried to make her afraid of entering our door; but whilst we were away, she one day found all the doors open, and peeping into the kitchen, and seeing no protecting servant there, she seized our dear little pet, and soon destroyed him. When we returned home, there was nothing but the empty cage.

We were staying for some months at a seaport town in France, many vessels used to come in from different parts of the world; and I suppose the sailors brought with them all sorts of animals and birds, for the houses looking on the quay where the vessels were moored were almost entirely shops of birds, monkeys, etc., etc. It was most amusing to walk along the quay, and look at all the live creatures that were there exposed for sale. Such a chattering of monkeys of all shapes and sizes, such a twittering and singing from every imaginable species of small birds, such a screaming and chattering from the parrots and macaws, and such fun in peeping into the cages of white mice and ferrets. We often wished very much to buy a monkey; but Mamma did not fancy it, and said they were uncertain ill-tempered beasts, and that we should be constantly bitten if we had one. First, we longed for this bird, then for that squirrel, then for a cage of white mice, and so on; indeed I believe we quite tormented Mamma with requests to walk along the quay of animals, as we called it. At last we set our affections upon a grey parrot, the smoothest and handsomest among the large number exposed for sale. We never heard her say anything, it is true; but we thought that an advantage, as she would not have learnt to swear and talk like the sailors, and we should teach her to say just what we pleased.

The price of the parrot was rather high, because of her size and beauty, and we longed for her many weeks before we were her masters; but at last she was placed in our possession as a new year's gift, and, in addition, a nice cage with a swing, and tin dishes for her food, all the wood work being carefully bound with tin, to secure it from her formidable beak.

Cage and parrot were carried with us on our return to England, and she soon became a great pet. She was not at first very tame; but by much petting, and by leaving the door of her cage constantly open, so that she did not feel herself a prisoner, she gradually became more friendly. The first sign of love to any of us was after my sister's short absence of a few days at a friend's house. When she returned, we were talking together in the hall, and Poll's cage being in an adjoining room, she heard her voice, and recognising it, she came down from her cage, and gave notice of her arrival at my sister's feet by her usual croak; she flapped her wings, and gave every sign of pleasure at seeing her again. She did not, however, extend her amiability to any one but myself, sister, and Mamma; she was still savage to strangers, and would bite fiercely if touched, but if we offered our wrists, she would step soberly on, allow us to scratch her head, stroke her back, push back her feathers to look at her curious little ears, and in return she would lay her beak against our cheeks, and make a clucking noise as if she meant to kiss us. She used to waddle all about the room with her turned-in toes, and climbed up tables and chairs just as she pleased. She would get upon Mamma's knee by scrambling up her dress, holding it tight in her beak. When we were writing or drawing, she enjoyed sitting on the table, though she meddled sadly with our things, biting our pencils in pieces, tearing paper, and so on, and once in particular, she terrified us for her own safety by opening every blade of a sharp penknife, and flourishing it about in her claws as if in triumph. We had some difficulty in getting it from her grasp without cutting ourselves or hurting her. She was a famous talker, called us all by name, whistled and barked when the dog came into the room; called "Puss, puss!" and mewed when the cat showed itself, sang several bits of songs, and asked for fruit and food of different sorts. We never could teach her to sing through a whole tune. I never heard a parrot get beyond a few bars; and I wonder what is the reason that they will learn the commencement of half-a-dozen different songs, but still cannot remember any whole. I do think a parrot's voice and utterance is one of the most extraordinary of things, for it always repeats a word in the peculiar voice of the person who taught it; and, instead of closing its beak or touching the roof of its mouth with its tongue, in order to articulate, it invariably opens its mouth wide when it speaks, and its tongue is never used at all; yet it will pronounce m's, b's, p's, and t's as plainly as any human being. We could always tell who had taught our Poll any word or song, from the similarity of voice that she adopted. Her sleeping-place was for some time on the top of a chair-back in my sister's bedroom. When we were leaving the sitting-room to go upstairs at night, Poll used to waddle down from the cage and come to my sister, who held her wrist down for her to mount, and having been conveyed upstairs and placed on the floor, she mounted of her own accord to her sleeping perch, gave all her feathers a good shake, and settled her head for the night.

Very early in the morning, she used to commence her toilet. Such scratchings and smoothings of her feathers, such picking and cleaning of her feet and legs; and having arranged her dress for the day, she would come down, take a turn or two about the room, and then look at my sister to see if she were awake. If not stirring, Poll used to clamber up on the bed by means of the curtain or counterpane, get quietly on the pillow, and examine her eyes closely. If no wink was perceptible, Poll would gently and cautiously lift up an eyelid, pinching it softly in her beak, then go to the other eye and do the same; then she would wait a little bit, saying, "Hey? hey?" as if to ask whether her mistress was not yet properly roused. Then she would again work away at the eyelids, till my sister could no longer refrain from laughing. She used to feign being asleep every morning, in order to amuse herself with Poll's proceedings.

I wished to try having my eyelids opened by Poll in the same manner, and one night took the bird into my own room; but she did not approve of this change of quarters, and instead of going quietly to sleep, made such a croaking and grinding of teeth on her chair-back, that I was glad to carry her back to my sister's room. Indeed, although she was very friendly with me, she did not manifest the same attachment as towards my sister and mother, apparently preferring ladies' society.

While Poll was with us, we went another journey into France, and took the parrot with us in a basket. It was a stormy night when we crossed from Southampton, and Poll in her basket was placed at the foot of my sister's berth, and no further attention was paid her. The cabin was very full of people, and numbers had to lie on the floor, there not being sufficient berths or sofas. In the middle of the night, the inmates of the ladies' cabin were all startled by a scream from an old lady who was stretched on the floor.

"Stewardess! Here! Here! Some dreadful thing is biting me. I have received a shocking bite on the leg. Do search for the creature, whatever it is."

So the stewardess came and looked, and could find nothing.

My sister, who had looked out of her shelf at the old lady's cry, immediately divined what it was, seeing that Poll's basket had rolled off the berth to the floor, and she having gnawed a hole in the basket, had put out her beak and bitten the first thing with which it came in contact.

When the stewardess came to look for the monster, the basket had rolled, with the motion of the ship, to the other side of the cabin, and not finding a sea voyage pleasant, she put forth her beak again.

"Oh! bless me! What can that be?" cried another passenger. "Something bit me. Do find it, stewardess."

Then came another lurch, and away rolled Poll in her basket; and no one suspected a rather shabby old basket of containing anything but perhaps a pair of slippers, or a brush and comb, or some such articles. So poor Poll rolled about in her prison, inflicting bites on several legs and arms, my sister meanwhile in agonies of laughter on her shelf, and not daring to say who was the real offender, lest Poll should be turned out of the cabin.

At last the stewardess said that she supposed it must be rats, and she ran away at the entreaties of the poor victims on the floor to fetch the steward to search for the rats. Whilst she was gone, my sister slipped down from her berth, and took possession of Poll's basket. She had scarcely retreated with it in safety, when the stewardess returned with the steward; and rather an angry altercation ensued, the man insisting that there was not a rat in the ship, and the injured passengers insisting that sharp bites could not be made by nothing at all. However, after a long dispute, he begged them all to move from the floor, and made a regular search.

My sister was all the time in the greatest alarm, lest Poll should think proper to croak or sing "Nix my dolly," or otherwise to make known her presence. As luck would have it, however, Poll was either too sea-sick or too angry to say anything, and the steward announced that no live thing was in the cabin, and that the ladies had been dreaming.

"But bites in a dream, don't bleed," retorted an angry old lady, holding up to view a pocket handkerchief which indeed wore a murderous appearance.

This being unanswerable, the steward could only shrug his shoulders and retreat from the Babel of voices in the ladies' cabin; and soon after, my sister had the pleasure of landing, with Poll undiscovered and safe in her old basket, and we are ignorant whether the old lady ever found out what it was that had bitten her.

During our journey, Poll often caused great amusement, by suddenly shouting or singing as we were jogging along in a diligence or slowly steaming on a river, thereby astonishing and alarming our fellow passengers; nor did she forget, when occasion offered, to make good use of her strong beak.

At one place we were entering a town late at night, and the place being a frontier town, our luggage was all strictly examined by the custom-house officers before we were permitted to enter the gates. All having been passed and paid for, we remounted the diligence; my sister was the last. She had her foot on the step, when one of the men rudely pulled her back, asking why she had not shown her basket. She said there was nothing in it but a bird, but the man declared he must look; and seeing that my sister was unwilling to open it, he imagined there was something valuable and contraband in it, so roughly dragging it out of her hands, he tore open the lid, and thrust in his hand. Poll gave a loud croak, and the man rather quickly withdrew his hand, with a thousand vociferations at the bird and the basket and my sister. I must confess I was delighted to see that Poll had made her beak nearly meet in the surly fellow's finger.

When my sister had regained her basket, and we had left the gate, we lavished much praise on Poll for her discriminating conduct on this occasion. She would not have bitten my hand had I put it into the basket; how did she know that the hand was a stranger's?

When we arrived at our destination in the south of France, Poll enjoyed the novelty as much as any one. Now she revelled in the abundance of oranges and other fruits, eating just the best part, and flinging away the rest with lavish epicurism. And how she basked in the hot sun, and climbed about the cypress and olive trees in the garden, biting the bark and leaves, and almost I think believing that she was again in her wild birth-place, wherever that may have been! She accompanied us in safety on our homeward journey, went to Ireland with us; and whenever we travelled, Poll went too.

At one time she took an erroneous notion into her head, that she could fly; now this was an impossibility, for her wings were very short and small, and her body very large and heavy. Whether this had chanced from her unnatural life in a house, or from early cutting of her wings, I do not know, but she could not support herself in the air, even from the table to the ground. However, she thought she could, and on one occasion she tried to fly, when perched on the top bannister of a large well staircase of four flights. Down she came like a lump of lead on the floor below, and when we ran to pick her up, poor Poll was gasping, lying on her back, with her eyes rolling about in a fearful manner. We thought she would die, but we put some water in her mouth, blew in her face and did what we could to revive her, and gradually she recovered.

But this lesson was lost upon her. A few days after, she tried to fly out of a window on the first floor, and came down in the same heavy way, on the flagged pavement before the door. This time her head was wounded, and bled, and she seemed stupid for some days after; but she recovered and lived long after that. Probably these falls had injured her brain, for at last she began to tumble off her perch, as if giddy, and then her head swelled very much, and she died in a sort of fit.

I have seen other parrots who were better talkers than ours; but I never saw one so tame, and so fond of her own master and mistress, she used to come to meet us like a dog, when we came into the house, after being absent for walks or rides, knew our times for rising and going to bed, called us separately by our names, and really showed much intelligence.

Birds, in general, are, I think rather stupid, and do not understand anything, but what their own instinct tells them; but parrots seem to know the meaning of the words they learn: and if others do not, I am sure that our Poll did.

Our next pet was a very different creature. One of our aunts had sent us some money as a present; and I and my sister had many consultations as to what we should do with it. At last we hit upon an idea that charmed us both, and we ran to our Mamma. "Oh Mamma, we cried, do you think our money will buy a donkey? We saw the other day, a little boy and girl both riding upon a donkey, it trotted along so nicely with them, and the little boy at the other side of the square has a donkey, and we should like it so very much." Then Mamma said that a donkey would be of no use unless we could also buy a saddle and bridle; and besides that, she must enquire where he could graze, or whether there was any spare stall in which he could live. These things had not occurred to us; but we went to Papa, and begged him to find out where our donkey could live in case we had one.

Now there was a large sort of waste field adjoining the Barrack Square; a few sheep and some old worn-out horses were kept in it, but I believe it was not used for anything else. We sometimes ran and played there, and there was a pond in it, into which we were very fond of flinging large cobble stones. Papa found that he could easily obtain leave for our donkey to graze there, and it was of such extent, that it could find there quite sufficient food; so that difficulty was done away with.

Then we made enquiry about the price of donkeys. We talked one day to the nurse of the little boy and girl who rode together. She did not know what their donkey cost, but told us that she knew a little boy who bought a young donkey, when it was scarcely able to stand, and so small, that he had it in his nursery, where it lay on the rug before the fire, and was quite a playfellow to him.

We thought we should like a tiny donkey to play with in the house; but Mamma persuaded us that it would be much pleasanter to have one that we could ride. Papa heard of a donkey we could buy for one pound, it came to be looked at, and we liked its appearance much; it was in very good condition, its coat thick and smooth, and not rubbed in any place. Our other pound supplied us with a sort of soft padded saddle and bridle; the pommels took off, so that either of us could use the saddle, and happy indeed was the morning, when Neddy was brought to the door for us.

I had the first ride, and, owing to a peculiarity in Neddy's manners, I soon had my first tumble. We proceeded across the square very nicely, and were about to cross a large gutter, along which a good deal of water was rushing. I had no idea that Neddy would not quietly step over it; but he had an aversion to water, and coming close to the gutter, he made a great spring and leapt over it; the sudden jerk tossed me off his back, and Papa catching me by the collar of my dress, just prevented me from going headlong into the water. And we found that Neddy always jumped over a puddle, or any appearance of water; sometimes a damp swampy place in the road, was enough to set him springing. But when we knew that this was his custom, we were prepared for it, and had no more falls; we rode in turns, and sometimes I got on behind my sister, and many nice long rides we had all about the fields and lanes. When we returned home, we took off the saddle and bridle at the door, and gave Neddy a pat; away he scampered through the open gateway into the field, flinging up his heels with pleasure. We could see all over the field and the square from our windows, and soon found it extremely amusing to watch the proceedings of our Neddy and another donkey.

This donkey belonged to a little boy, who also lived in the square; he did not often ride upon it, but it followed him about more in the manner of a large dog. It had learned how to open the latches of the doors, and could go up and down stairs quite well.

Our Mamma went one day to see the little boy's Mamma, and when she opened the door of their house she was much surprised to find the donkey's face close to her's, and she was obliged to give him a good push to get past him. When we heard this, we used to watch for the donkey going in and out, and soon we saw him go into the field and make friends with Neddy. They held their heads near together and seemed to be whispering; then they would trot about a little while, then whisper again. We supposed that the strange donkey was telling Neddy what fun he had in going into the different houses and getting bits to eat from the inhabitants, and instructing him how to bray under such and such windows when cooking was going on. For Neddy soon began to follow his friend about, and to imitate everything that he did. We did not know the name of the other donkey, so we called him the Rifle donkey, because his little master's Papa belonged to a rifle regiment. Neddy was an apt pupil, for soon after the conversations between the two donkeys had begun, we were seated one evening at tea, when we heard an extraordinary clattering upon the staircase, we listened and wondered, as it became louder. The staircase came up to the end of a long passage, which led to our doors, and when the clattering reached the passage I exclaimed, "I do believe it is the donkey coming up stairs."

We rushed to the door, and looked out. Yes, indeed, the Rifle donkey and Neddy were quietly pacing along the passage. We were thoroughly charmed at Neddy's cleverness in mounting two long flights of stairs, and when we had given them each a piece of bread, and patted and coaxed them, they turned away to go down again, the Rifle donkey leading the way. He managed very well indeed, but Neddy made rather awkward work with his hind legs; however, he managed to reach the bottom without throwing himself down. Next they went under the windows of the adjoining house, and the Rifle donkey began to bray loudly, Neddy copied him in his most sonorous tones, and presently a window was opened and a variety of little bits of food were thrown out, which they ran to pick up. They came every morning to this window, and the officer who lived there always answered their call, by throwing something out to them. When he shut his window, they quietly went away, and about the middle of the day, when luncheons and dinners were going on, they would go to other windows about the square, and bray for food. Neddy always walked behind the other, and did not bray till he began. Sometimes there were clothes laid out to dry by the washer-women on a piece of grass, behind the houses. This supplied great amusement to the donkeys, for as soon as the women went away they would run to the grass, take up the clothes in their mouths, fling them up in the air, tread upon them, tear them, and even used to eat some of the smallest things, such as frills and pocket-handkerchiefs. But this was really too mischievous, as the poor women suffered for their fun.

No one would believe them, when they said that such a missing handkerchief had been eaten by donkeys, or that such a piece of lace or a collar had been bitten and torn by the same tiresome creatures. I well remember some of our shirts coming home half eaten, and our Mamma then advised the washer-women to have a boy, with a good thick stick, to watch the drying ground, and to desire him to belabour them well if they attempted to touch any of the clothes. This advice was followed, so that piece of fun was in future denied to the donkeys. But, I and my sister highly disapproved of this system; we thought that we would much rather have our shirts eaten, or indeed all our clothes torn than allow Neddy to be beaten with a stick, to say nothing of the great amusement it gave us, to see the two queer animals rushing about among the wet things, entangling their feet in them, and sometimes trotting off into the square with a night-cap or a stocking sticking on their noses. However, we still took great interest in their proceedings even without the poor washerwomen's clothes; for being deprived of that game, they began to plague the soldiers at the guard room. It had a sort of colonnade in front, supported by pillars, and the Rifle donkey found that it was very diverting to rush head first at the men who were standing under the colonnade. If they tried to strike him, he used to dodge round a pillar, and then rush at them again from the other side. Often he singled out one man for his attacks, and then Neddy assisted his friend, by biting at the same man from behind, but he was not nearly so active in evading punishment as the Rifle donkey, and received many a buffet and kick during these encounters. Sometimes the soldiers punished them by getting on their backs. This, however, was not to be borne, and cling as tightly as they could, the donkeys never failed to fling them off, when they would return to the charge with renewed vigour.

These games of bo-peep, and so forth, apparently amused the men quite as much as ourselves, and many a half-hour have we sat in our stair-case window-seat, watching the antics of the donkeys and the soldiers. Their play usually ended by the Rifle donkey receiving a harder rap on the nose than he deemed pleasant, then he would fling up his heels, and with a most unearthly yell, gallop off to the field, closely followed by the sympathising Neddy, who imitated in his best fashion both the yell and the fling of his heels.

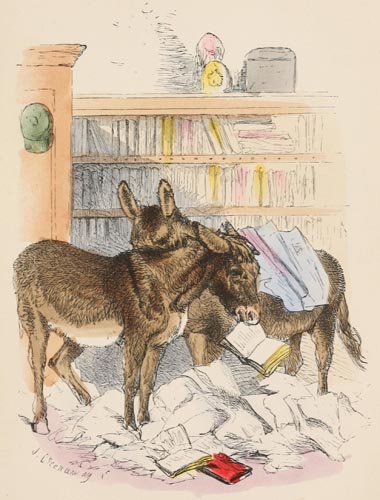

NEDDY, AND THE RIFLE DONKEY.

Page 25.

We were going to leave the barracks, and move to another part of Ireland; and just before we went, the two donkeys got into a terrible scrape. Indeed, it was very well that we did go away; for they were becoming so extremely mischievous and so cunning, that they would soon have become too tiresome; and although we were charmed with every trick they played, almost all the grown-up people thought them a great torment; and the Rifle-donkey had become a great deal more active and monkey-like, since Neddy had followed and copied him. I suppose he felt proud of being able to lead the other wherever he chose.

It was extremely hot weather, and all doors and windows were generally left standing open. Not that it would have made much difference to the Rifle-donkey had they been shut; for there was not a door in the place that he could not open. But very likely they were tempted to this work of destruction by the sight of the open door. Whilst the officers were dining, the two donkeys walked into the ante-room. The table there was covered with newspapers, magazines, and books; and perhaps the donkeys thought that these papers were some of their old friends the clothes, from the drying-green; so they pulled them off the table; tore the newspapers into little bits; munched the backs of some bound books; scattered the magazines about the room; upset an ink-bottle that stood on the table; dabbled their noses in the pond of ink, and having done their best to destroy and spoil everything there, our Neddy, I suppose, was so delighted at the mischief they had done, that he could not refrain from setting up a loud and prolonged bray of pleasure and exultation.

This brought in some of the officers, and there they found the Rifle-donkey trampling a heap of torn papers and books, with the remains of a blotted "Punch" in his mouth, and Neddy was looking on and expressing his admiration.

So they were ignominiously turned out with kicks and blows; and some of the officers were very angry, and said that both of the donkeys ought to be shot immediately; and the others said that, at any rate, they should be shut up, and not allowed to run at large about the barracks. But, luckily for Neddy, we went away in a day or two, and we never heard how they managed to keep the Rifle-donkey in order. Perhaps he was not so mischievous when he had lost his companion, having then no one to admire his proceedings. We only heard that when his regiment left, some months later, the donkey marched out with them just in front of the band.

As soon as we arrived at our new abode, our first thought was to find a field for Neddy. The fort in which we were to live was quite small; there was a street on one side, and the river close up to the wall on the other; the square, or rather the small space within the wall, was gravelled: no where could we see a blade of grass for our poor donkey, and there appeared to be nothing but brown bog anywhere round. Poor Neddy was put in a stall at the inn for the night; he must have been much surprised at the hay, and the luxurious bed of straw; for a bare field had hitherto been his only resting-place, and green grass the very best thing he had had to eat.

But the stall could not be continued; and as soon as our Papa had leisure, he looked about for a suitable place for Neddy.

There was another small fort about half-a-mile down the river: it consisted of a moat, and a low wall with a few guns. There was one little cottage inside for the gunner in charge; and the whole space inside the wall, consisting of a flat terrace, with sloping banks, and a good space in the middle, was covered with beautiful thick green grass. This was just the place for Neddy; he would not be able to get out, and there was nothing inside that he could hurt; for, of course, the gunner would soon teach him that he was not to poke his nose inside his neat little cottage; and there was plenty of space for him to run about, and fresh moist grass to eat, which I should think he would like better than dry hay in a hot stall. So Papa asked, and obtained leave, to keep our donkey there; and we rode upon him from the inn, and put him in possession of the little fort. He pricked up his ears, and seemed not quite to like the clatter of his hoofs, as he crossed the planks which formed a rude bridge over the moat. We thought nothing of this at the time, but we had to think a great deal of it the next day, when we came to take our ride—in happy ignorance that this would be the very last ride we should ever take on Neddy's back. We kept our saddle and bridle in our kitchen, and had to carry it with us to the fort; so I put it on my head and the bridle round my waist, and my sister drove me, and pretended I was a donkey. So we came very merrily to the fort, and having saddled and bridled Master Neddy, I was mounted, and we proceeded towards the plank bridge. But just at the edge, Neddy stopped short, laid back his ears, tried to turn round, and, in fact, refused to cross. In vain we patted and coaxed, tried to tempt him across with a biscuit, then tied a pocket handkerchief over his eyes, and attempted to cheat him into crossing without his seeing where he stepped.

In no way could we induce him to put his foot upon the plank. The gunner came to our aid; and we all worried ourselves to no purpose. There was no other way out of the fort, and we were ready to cry with vexation. At last, Nurse suggested that it would be best to return home, and ask Papa what we could do; and being at our wit's end, we took her advice and scampered back to the other fort. Papa, having heard our story, sent four of the men with us, telling them they were to bring Neddy out in the best way they could; but, that, come out, he must. When we returned, there stood Neddy, just where we had left him, staring stupidly at the bridge. At first, they wanted to whip him, only leaving open to him the way to the bridge; but we declared he should not be beaten; and the gunner agreed with us, that blows would only make him still more obstinate.

"Well, then," they said, "as he is to come out at all hazards, the only thing we can do is to carry him, one to each leg."

So they began to hoist up poor Neddy, who did not in the least approve of this mode of conveyance. He tried to bite and kick, and twisted himself about in all directions. How we did laugh to be sure! For when two of them had got his fore legs over their shoulders, he made darts at their hair and their faces with his mouth, so that they had to hold his nose with one hand and his leg with the other. Then getting up his hind-legs was worse still; for he jerked and kicked so, as almost to throw down the men; and we quite expected to see the whole four and the donkey roll into the moat together. At last, he was raised entirely on their shoulders, and they ran across the bridge and set him down on the other side.

"Are we to have this piece of fun every morning, Sir?" asked one of the soldiers, as they stood panting and laughing.

"I hope not," I said, "I dare say he will be glad to go in to the grass when we come back from our ride; and if he once crosses it, perhaps he will not be afraid tomorrow."

So we took our ride; Neddy behaved quite as well as usual; his fright did not appear at all to have disturbed his placidity; and in about two hours we again stood before the terrible bridge. The gunner came out to see how we should manage. We took off the saddle and bridle, and invited Neddy to enter. There was the nice fresh grass, and banks to roll upon, and to run up and down, looking very tempting through the gate; and on the other side of the road, there was nothing but heaps of stones and a great brown bog, stretching away as far as we could see, with nothing at all to eat upon it. But for all that, Neddy looked at the bridge; smelt it; and, resolutely turning his back to it, stared dismally at the bog, as if he were thinking,

"I don't see anything that I can eat there."

However, it was evident that although the fear of starvation was before him, he could not make up his mind to cross the ditch; and, in fact, had absolutely determined not to do so.

We were in despair; but feeling sure that it would not do to have him carried in and out every day; we disconsolately led him back to our home, and told our troubles to Papa, who ordered him back to the stall at the inn for the night.

Next day, we tried in all directions to find a field where Neddy could graze; but no such place could be found. So we had a grand consultation as to what must be done for him; and Papa said that he could not keep him in a stall, feeding with hay, for, perhaps, half-a-year or more, as he expected to remain where we were for a long time. So we made up our minds to part with our donkey; and we did not regret it quite so much at this time of year, as winter would soon come on, when, probably, we should not be able to ride much.

We sent Neddy to the nearest town, about ten miles off; and a little boy there became his master. And we kept his saddle and bridle, in hopes of supplying his place some day.

We were now living in England, in a country place—fields and woods and lanes all around. We took great pleasure in all the amusements of country life.

Our Papa had some ferrets, which he used to take out for rat-hunting in the corn stacks with a terrier we had, named Tawney, and other dogs; and now and then he went to a rabbit warren at some little distance. A boy one day brought from this warren a hat full of young rabbits for the ferrets to eat. They were all supposed to be dead; but when Papa was looking at them, he saw that one of the poor little things was alive, so he brought it into the house and gave it to me and my sister, saying that if we thought we could feed it we might keep it.

The poor little thing was so young, that it was a great chance whether we could bring it up; but we had a cook who was very fond of all animals, and she helped us to nurse it. She fed it with milk for a few days, and then it soon began to nibble at bran and vegetables, and in a week or two could eat quite as well as a full-grown rabbit.

The gardener made us a nice little house for it, by nailing some bars across the open side of an old box, and it slept in this by the side of the kitchen fire; but we never fastened it up so that it could not get out, and in the day-time it was seldom in its box, but running about the kitchen, and it soon found its way along the passage into the sitting-room, and then upstairs to the nursery, and into all the bed-rooms. It went up and down stairs quite easily, and seemed perfectly happy running about the house.

It was a very strange thing that our terrier Tawney, of whom I have much to tell afterwards, never thought of touching Bunny, for when out of doors he was most eager after any sort of animal, would run for miles after a rabbit or a hare, went perfectly crazy at the sight of a cat, and was famous for rat-hunting and all such things; but as soon as he entered the house, even if the saucy little Bunny bounded about just before his nose, he would quietly pass by, apparently without an idea that it was a thing to be hunted. In the evenings, when Tawney would lie asleep on the rug, Bunny used to run over him, sometimes nestling itself against his back or legs; then would pat his face with its fore paws, and take all manner of liberties with him, he never so much as growled or snapped at it, and seemed really to like the companionship of the poor little creature.

One very favourite hiding-place of Bunny's was behind the books on the dining-room shelves. These were quite low down to the floor, and if he could find a gap where a book was taken out, he squeezed himself in, and as the shelves were very wide, there was plenty of room for him to run about behind the books. I suppose he liked the darkness, and thought it was something like one of his native burrows, and if he could not remember them, it was his natural propensity to live in narrow dark passages, and therefore he preferred such places to the open daylight. It was very funny to see his little brown face peeping out between the books. Sometimes it happened that a book was replaced whilst Bunny was snugly hidden behind, and then we missed him when we went to put him to bed in his box for the night. First we went to look for him in all the rooms, and about the passages, and if he was not in the bookcase he would always come when we called, so when we saw nothing of the little animal, we went and took a book out of each shelf, and we were sure to see his bright eyes glistening in the dark, and then out came little Bunny with a bound. He did not seem to care for running into the garden or yard, which was odd; but as he grew older his taste for burrowing showed itself strongly.

As he used to follow the cook about everywhere, he had of course been often down to the cellar and larder. These were paved with small round stones, and there was an inner cellar, or rather a sort of receptacle for lumber of all sorts, which was not paved at all; it had a floor of earth. Old hampers and boxes were put away there, sometimes potatoes and carrots, etc., were spread on the floor there, and altogether the place had a very damp, earthy sort of smell, perhaps very like the inside of a rabbit burrow, and one day the cook came to ask Mamma to come and look at the litter Bunny had made in the cellar. We all ran down, and saw that Bunny had scratched up a quantity of earth from between the little stones with which the cellar was paved; in fact the cellar floor looked almost like a flower-bed, all earth. The door into the inner cellar happened to be shut, or most probably he would have commenced his operations where there were no stones to hinder him.

Mamma said that the gardener should press down the earth again between the stones, and tighten any that were loose, and that Bunny must not be allowed at any time to go down into the cellar. But it was very difficult to prevent his doing so. In summer, the meat and the milk were kept down there, as being the coolest place, and the beer barrels were there, and the coals, in different compartments; and to fetch all these different things somebody or other was perpetually opening the door at the top of the stairs. So Bunny frequently found opportunities for slipping in at the open door, and he came every day less and less into the sitting-rooms. One evening he had the cunning to hide himself behind some of the empty hampers in the inner cellar, and when we called him, and looked about for him in the evening, no Bunny appeared. In vain we took books out of all the shelves, hunted behind the curtains, under the sofas, and in all his usual hiding-places, we were obliged to give it up, and go to bed without finding him.

The next morning, we renewed our search, and seeing no sign of his work in the outer cellar, we determined to have a regular rummage in the inner one. After moving a great many bottles, baskets, boxes, and barrels, we found a great hole. The earth had evidently been just scratched out; for it was quite moist and fresh. The busy little fellow had made a long burrow during the night in the floor of the cellar. When he heard our voices, he came out of his newly-made retreat, and we took him up stairs and gave him some food; for he was quite ravenous after his hard work. Then we consulted with his friend the cook, how to manage about him in future. It would certainly never do to let him go on burrowing under the house; in time we should have all the walls undermined, and the house would come tumbling down upon us, burying us in the ruins. Terrible, indeed, was the catastrophe that we created in our imagination from the small foundation of Bunny's having scratched a hole in the cellar! And now that he had once tried and enjoyed the pleasures of burrowing, we could scarcely expect that he would relinquish it again.

We went to talk about it to Mamma; and we proposed that Bunny should live in the garden.

"But," said Mamma, "I shall have all my nice borders scratched into holes; and the roots of my beautiful rose-trees laid bare; and, in short, the whole flower-garden destroyed, to say nothing of the kitchen-garden, which would, of course, become a mere burrow."

"Well, then, Mamma," we said; "we must make him a much larger house, and keep him in it altogether. We will not let him have his liberty at all; and then it will be impossible for him to do any mischief."

But Mamma said, that although that plan would certainly prevent Bunny from burrowing; she thought that it would not be a very happy life for the poor little animal, who had been accustomed all his life to perfect liberty, and had never been confined to one place.

We could think of no other plan; so begged Mamma to tell us what she thought we had better do.

"Do you remember," said Mamma, "seeing a number of little brown rabbits, running about and darting in and out of their holes, in the wild part of the fir-woods, where we sometimes drive. There is a great deal of fern and grass about there, and nothing at all to prevent the rabbits from burrowing and enjoying their lives without any one to molest them. I advise you to take Bunny there, and to turn him loose in the fir-wood; he will very soon find some companion and make himself a home; and do you not think he will be far happier when leading that life of freedom, than if kept in a wooden house, or even if allowed to burrow in a cellar?"

After some deliberation, we agreed to follow Mamma's advice; and the next day we drove to the fir-wood, taking Bunny with us in a basket.

We drove slowly along the skirts of the wood, looking for a nice place to turn him out. At last, we came to an open space among the fir-trees; the ground was there thickly covered with long grass, ferns, and wild-flowers, and the banks beneath the firs were full of rabbit-holes; we saw many little heads popping in and out.

"This is just the place," we cried. "What a beautiful sweet fresh place to live in; and we got down and went a little way into the grass; then we placed the basket on the ground and opened it. Bunny soon put up his head, snuffed the sunny sweet air, and glanced about him in all directions. No doubt he was filled with wonder at the change from our kitchen or dark cellars, to this lovely wood; with a bright blue sky, instead of a ceiling; waving green trees, instead of white walls; and on the ground, in place of a bare stone floor; inexhaustible delights in the way of food; and soft earth for burrowing. Having admired all this, he jumped out of the basket; first he nibbled a little bit of grass, then ran a little way among the ferns.

"Do let us watch him till he runs into a rabbit hole," we said to Mamma.

And Mamma said she would drive up and down the road that skirted the firs, for about half-an-hour, and we might watch Bunny.

He wandered about for a long time among the grass and plants; and at last we lost sight of him in a thick mass of broom and ferns.

Mamma thought it was useless to search for him; there was no doubt that he would thoroughly appreciate the advantages of the fir-wood. So we gathered a large bunch of wild flowers, jumped into the carriage, and left Bunny in his beautiful new home.

One morning, my sister was sitting with Mamma at the dining-room window, when they saw me coming down the garden walk, with my head bent down, and something perched on my back.

"Look!" said Mamma, "What has your brother got on his back?"

Up started my sister.

"Oh!" cried she, "It is something alive; it is black: what can it be?"

And she darted out to look at my prize.

It was a fine glossy fully-fledged Jackdaw. The gardener, knowing my love for pets of all kinds, had rescued it from the hands of some boys, who had found a nest of jackdaws, and had presented it to me.

Although it was quite young, it looked like a solemn old man; the crown of its head was becoming very grey; and it put its head on one side, and examined us in such a funny manner, listening with a wise look when we spoke, as if considering what we were saying.

The gardener had cut one of his wings pretty close, and the remaining wing was not very large. We set him down in the garden, and watched him for some time, in order to be certain that he could not fly over the low wall that separated our garden from the road. And we soon saw that he could only flutter a few inches from the ground, and hop in a very awkward sidelong manner; there was no fear of his escaping.

Luckily, there was a large wicker cage, that had once been used for a thrush, in the coach-house. We fetched this out, cleaned it, and placed Jacky in it on the ground near some shady bushes. We left the door open, that he might hop in and out, and always kept a saucer of food for him in the cage.

He soon became very tame; would hop on our wrists and let us carry him about, and liked sitting on our shoulders, as we went about the garden. Near his cage was a large lilac-bush, and he found that he could hop nearly to the top by means of its branches; and he picked out for himself a nice perch there, in a sort of bower of lilac-leaves and flowers.

Finding this much pleasanter than the cage, he soon deserted that entirely; and at night, and whenever he was not hopping about the garden, or playing with us, he was to be found always on the same twig in the lilac bush.

We used to place his saucer of sopped bread, and his saucer of water at the foot of the bush.

When we passed, he used to shout "Jacky!" and soon began to try other words; and tried to imitate all sorts of sounds and noises.

In the heat of summer, when the bed-room windows were all opened at daylight, we used to hear him practising talking in his bush. He barked like the dogs; utterly failed in his attempt to sing like the canaries; mewed like pussy very well, indeed; and then kept up an indescribable kind of chattering, which we called saying his lessons; for we supposed that he intended it to imitate our repeating of lessons, which he heard every morning through the dining-room window.

Sometimes we heard more noise than he could possibly make alone; and we softly got out of our beds, and peeped through the window to discover what it was about. There must have been six or seven other jackdaws, running round and about his bush, hopping up and down into it; apparently trying how they liked his house, and having all sorts of fun and conversation with our Jacky.

Within a few fields of our garden walls, stood the old ruin of a hall or manor-house; it had once, doubtless, been large and handsome; nothing now remained of it but the outer wall, a few mullioned windows, and some remnants of stone-staircases. The walls being very thick and much broken, afforded excellent holes and corners for jackdaws'-nests; for owls and such things. Indeed, it was from one of these holes in the ruined hall, that Jacky had been taken. And the numerous feathered inhabitants of the "Old Hall," as it was called, having spied our pet, sitting in lonely state in his bower among the lilac leaves, doubtless thought he would be grateful for a little company, and the society of his equals; so kindly used to pay him a visit in the early morning, before children or gardener were likely to interfere.

We were rather afraid that the wild jackdaws might entice away our Jacky, by describing to him their own free life, and the mode of existence in the crumbling walls of their home. But when Mamma made us observe how very awkwardly he hopped about with his cropped wing, and how utterly impossible it was for him to fly across two or three fields, and to the top of the ruin, we were satisfied that his stay in our garden was compulsory; and we agreed that the "Old Hall" jackdaws might visit him as much as they pleased. But they never once came at any other time than very early in the morning.

I suppose Jacky thought that he had kept these visits a profound secret from us.

As he grew older, he became extremely mischievous. When Mamma was busy in the garden, he used to come down from his tree and follow her about from one border to another, watching earnestly whatever she was doing; and whilst she tied up the plants, or gathered away the dead leaves and flowers, he used to put his head on one side, and seemed to be considering for what purpose this or that was done.

Mamma was planting a quantity of sweet peas, in order to have a second and late crop, after the first had begun to fade. She planted them in circles, twelve peas in each, and a white marker was stuck in the centre of each patch. As it was fine warm weather, Mamma expected that these peas would very soon appear; but in a few days, when she went to look at them, she saw that all the white markers had been pulled up and thrown on one side.

So she called to us, "Children! I am afraid you have meddled with my seed markers; for they have all been taken out, and I stuck them firmly in the ground; some one must have touched them."

We assured Mamma that we were not the delinquents; indeed, we were too fond of all the beautiful flowers to injure them in any way.

When we looked closer, we saw that there was an empty hole in each place where Mamma had planted a pea. They had every one been picked out.

Whilst we were wondering who could have done this, the gardener passed, and Mamma showed him the empty holes, and the markers pulled up; and asked him who he thought likely to have done such a piece of mischief.

"I shouldn't wonder if it war he," said the gardener, pointing to Jacky, who, as usual, was close to Mamma, listening attentively to all we said.

"Jacky, Jacky!" shouted he, making some of his awkward jumps at the same time, and going close to the ring of little holes, he peeped down them, with his head on one side, as if to make sure that he had left nothing at the bottom.

We could not help laughing at the queer old-fashioned manner of the creature; but, at the same time, it was very annoying for Mamma to lose all the pretty and sweet flowers through Jacky's greediness.

She said she would plant some more immediately; and she sent my sister, with Jacky on her wrist, to the front of the house, with orders to stay there till the planting was finished, so that the mischievous bird might not watch the whole process, and would not know where the seeds were planted.

I staid to help Mamma; we planted rings of sweet peas in different places from the old ones; and instead of white markers, which might attract Jacky's notice, we stuck in a great many bramble-sticks, all round every patch, so closely that a much smaller bird than Jacky would have found it difficult to squeeze himself in between the rough prickly twigs. Then we thought that all was safe, and we let Jacky come back to his perch.

The next day he had not touched the brambles; but I suppose he had thought it necessary to do something in the way of gardening; so he had fetched up, from the farthest end of the kitchen garden, a roll of bass, or strips of old matting, that was used for tying plants and flowers to sticks. This he had pulled into little shreds, all about the lawn and the flower-beds, and a great deal of time and trouble he must have spent upon his work. How the gardener did scold! saying, that it would take the whole afternoon to clear away the litter, and that Jacky did more mischief than he was worth; and so on.

But Jacky was a privileged person, and did pretty much as he liked; so it was of no use to complain about him.

It was most amusing to see how he teased the gardener when mowing was going on; he would watch his opportunity, and when no one chanced to be looking, he would run away with a bit of carpet or piece of old flannel, that the gardener used to wipe his scythe; or else he would drag away the hone, or sharpening-stone, and hide it under his lilac-bush.

So gardener, finding him a great nuisance on mowing days, told us that he should certainly mow off Jacky's head or legs some day; for he would come hopping about among the cut grass; and if taken up and landed in his tree, he would immediately come down again, and thrust himself just in the way.

So for the future, we took care on mowing days to shut up Jacky in the nursery, or in the dining-room, where he used with a rueful countenance to watch all proceedings through the window, pecking now and then in a spiteful way at the glass.

THE SPARROW-HAWK AND CAT.

Page 45.

Whilst Jacky was in our possession, we had a sparrow-hawk for a short time. Papa brought him home one evening in a paper bag; he was a very handsome fellow, with such brilliant eyes, and such a beak! He was perfectly wild, and bit furiously at any hand that approached him; so we covered up his head in a pocket-handkerchief, whilst gardener fastened a small chain round his leg. Then we fixed a short stump in the grass, not far from Jacky's lilac, and fastened the end of the chain to the stump. So he could run and hop about for a yard or two round the stump; we intended to keep him there until he became a little tamer, and hoped that the example of his neighbour would teach him good manners. But instead of taking Jacky as a pattern, the new comer bullied him in a most dreadful way. We might have saved ourselves the trouble of chaining him, for he snapped the chain in two with his strong beak, and came down from his stump quite at liberty to roam about. Strange to say, he did not go away altogether, but walked in at the dining-room window. We were seated at tea, and not knowing that the hawk had liberated himself, we were quite startled at hearing a curious flapping in the corner of the room, but we soon saw the two brilliant eyes, and there sat Mr. Sparrow-hawk, on the top of the book-case. We took him out and confined him to his stump again. There he staid quietly all night; but next day we heard Jacky pitying himself in his bush, and we found him fidgetting about in the top of the lilac, and fearing to come down, because Mr. Sparrow-hawk was walking about at the bottom, and whenever poor Jacky ventured down, he was darted at by the new comer, and hastily scrambled up the bush again. This was done out of pure love of teasing, for the hawk would not condescend to touch Jacky's food, consisting of sopped bread; but yet he would not let the poor old grey-head come down to eat his own breakfast. Jacky was quite crest-fallen, and we procured a stronger chain which held Mr. Sparrow-hawk fast on his stump for several days, during which time Jacky regained his equanimity.

But then the chain was burst again, and this time the hawk took to chasing the cats as well as tormenting Jacky. We had two cats, they were very good friends with Jacky, and used wander about the garden a good deal; quite unconscious of what was in store for them; they commenced playing about Mr. Sparrow-hawk's stump, when down stepped the gentleman and nipped the tail of the nearest cat quite tightly in his sharp beak, poor pussy shrieked and mewed, and we had to go to her rescue. At last we left off chaining the hawk, as we found that he did not try to escape, but sat on his stump or else came into the house; and we often were startled by finding him perched on a table, or on the bannisters, but at the same time he would not become tame, and he so terrified and annoyed poor Jacky, that we soon sent him away; and certainly the cats and Jacky must have rejoiced, when they found the savage owner of the stump had disappeared. The only sign of civilization which Mr. Sparrow-hawk had shown, was one evening, when a gentleman who visited us, happened to be playing the flute in the drawing-room. The hawk never came into the room when any one was there, and had very often heard the piano and singing; but probably the peculiar sound of the flute had something very pleasing to the bird's ear, for although this room was full of people, he came to the open window, hopped in, and gradually approached the flute-player, till he perched himself on the end of the flute. When the music ceased, the hawk, quietly took himself out of the window again, and next day was as wild as ever.

One of Jacky's great pleasures during the summer, was bathing or washing at the sink in the back kitchen. We always took care that he was provided with a large saucer of water, which stood beneath his lilac bush, but this did not appear to be sufficient. One day when the cook was pumping water out of the sink-pump, Jacky jumped up, and put his head under the stream, shouting and fluttering, with expressions of the greatest delight; and after this he generally came every day into the back kitchen, and called and hopped about until cook came and pumped over him. Such a miserable half drowned creature as he looked, with all his feathers sticking close to his body; then he used to repair to the kitchen and sit before the fire, till he became dry. Sometimes he got upon the fender, and when the fire was large, it made his feathers appear quite to smoke, by so rapidly drawing out the water. Once he was actually singeing, when the cook snatched him up and put him out of the window, and it was strange that he seemed to like the roasting at the fire, quite as well as the cold water.

He soon discovered the time that tea was prepared in the kitchen, and regularly came to the window to ask for tea and bread and butter; so a saucer of tea and a piece of bread and butter were placed on the window-sill for him, as punctually as the cook's own tea was prepared; and Jacky sipped his tea, and ate his bread and butter like any old washerwoman. But whilst sitting at the kitchen window he spied all sorts of things on cook's little work-table that strongly tempted his thieving propensities, and coming cautiously one morning, when the cook was absent, he pretty well cleared the table; very many journeys in and out must it have cost him, for when the poor cook returned to her kitchen, she began exclaiming. "Who has been meddling with my work and all my things?" and she called to me and my sister, and asked if we had hidden her work materials to plague her. "No indeed," we said, "we have not been here this morning at all."

"Well then," said she, "what has become of my thimble, my scissors, and reels of cotton, my work, that I laid upon the table, and there was also an account-book of your Mamma's, and a pen; I don't see one of them!" We hunted about for the missing articles. The kitchen window looked out on a plantation, not far from Jacky's bush. My sister looked out. "Oh!" cried she, "there is one leaf of your account-book on the border." "And I declare," exclaimed cook, who had run to the window, "there is one of my new reels twisted round and round yon rose tree; I do believe it's that mischeevous bird." We were delighted. We both sprang out of the window—"There's your thimble," I shouted, "full of wet mould!" "And here are your scissors," cried my sister, "in Jacky's drinking saucer! And there is your half-made shirt, hanging on the rose bush beneath the window!" Poor cook could not forbear laughing. "Well," said she, "he must have been right-down busy to take off all these things in about five minutes. Gather up my things for me, like good bairns." So we ran about picking up the things; the cotton reels were restored with about half their supply of cotton, as he had twisted them all round about the stems of different plants; the pen was stuck into the earth, and as for the account-book, the leaves were all about the garden, some he had even carried down to the cucumber frame, quite at the other end. But he was such a favourite, that even this sort of trick was allowed to pass unpunished. He furnished us with much amusement; and I am now coming to his sad end.

The wall which separated our garden from the road, was very rough and old, full of holes and crumbling mortar. Once or twice, when sitting at the windows, we had seen a small animal run across the gravel walk; we could not discern whether it was most like a rat or a weasel, and probably it came in through one of the holes in the wall. We did think of Jacky; but knowing that he always roosted at the top of the lilac bush, we supposed that he was quite out of the reach of rat or weasel. One morning quite early, our Papa whose window was open, heard a very strange sort of chattering from poor Jacky, so unlike his usual language, that he got up and looked out of his window. Seeing nothing, and hearing no more, he went to bed again; but when Mamma went as usual to give Jacky his breakfast, no call of pleasure came from the bush, no Jacky was there, and he was no where to be seen.

"Then a weasel has taken him," said Papa, when we told him; "the singular cry he made this morning, was doubtless when the weasel seized him." And when we searched about the garden, there we found on a grass bank, at some distance, the remains of our poor pet. The weasel had bitten him behind the ear, and sucked the blood; his feathers were a good deal ruffled, but no other bite had been made. We blamed ourselves much, for not having safely fastened him in a cage every night in the house. But now we could do nothing but bury the body of poor Jacky.

Shortly after poor Jacky's death, Papa called us into the garden.

"Children!" he said, "Here is something for you in my handkerchief. Guess what it is; but don't touch."

The handkerchief looked as if something very heavy was in it; and we guessed all sorts of things, but in vain.

At last Papa let us feel, and my sister grasped it rather roughly; but withdrew her hand quickly, with five or six sharp pricks.

"Oh! it is a nasty hedgehog," cried she; "look how my fingers are bleeding!"

"Not a nasty hedgehog," I said, "but a curious nice creature; where did you get it, Papa?"

"It was given to me this morning for you," he replied; "It will live in the garden; and you must sometimes give it a little milk, and it will do very well; and perhaps become quite tame."

The little creature, when placed on the grass, did not curl itself up and appear affrighted, but looked about him, and ran quickly to and fro. We brought some milk out in a saucer, but he could not manage to get his nose over the side; so we made a little pond of the milk on the grass, and he dipped his black snout into it, and then sucked it up greedily.

This hedgehog soon became very tame; when we took him up in our hands, he did not curl up in afright, but let us look at his feet, and touch and pat his curious little pig's face. He helped himself to what he liked best in the garden; and we never found that he rooted up anything, or did the slightest damage; he liked the milk which we gave him daily; and when we were playing on the grass, he used to run about us, as if he liked our company.

We had been told that we should never be able to keep a hedgehog; that they always climbed over the walls, and escaped to the fields and hedges.

But although we did not in any way confine Pricker, he never attempted to leave us, being apparently quite content with his run of the kitchen garden, flower garden and house; for we sometimes carried him into the kitchen, and up stairs into the nursery, where he would roll himself up into some snug corner, and remain apparently asleep for an hour or more.

When we had had Pricker for some weeks, we received a present of a second hedgehog. He was larger, but never became so tame as our first friend; he did not like to be taken up in our hands, and we never could obtain a good look at his black face and legs, as he rolled up on the slightest touch; and when Pricker was running about on the grass, his shy companion used to remain hidden beneath the leaves and plants.

We had, at this time, a very favourite dog; and at the first coming of the hedgehogs, we were in some fear that Tawney would kill them, for he was a most eager hunter of rats, weasels, rabbits, cats; in short, of anything that would run from him.

But every one assured us that a dog would not kill a hedgehog, on account of his sharp prickles; and the first time that we showed Pricker to Tawney, he made a sort of dart at him, and received, of course, a violent prick on the nose; at this he retreated, barking and licking his lips, and dancing round poor Pricker, with every desire to attack again; but hoping to find a spot unprotected by the formidable spikes.

Pricker, however, having tightly rolled himself up, such a spot was not to be found; and, after a great deal of noise and excitement, Tawney retired, and we never observed him to venture again.

When Pricker was running on the grass, or when we were feeding him with milk, Tawney used to play about without condescending to take the slightest notice of the little animal; in short, he pretended not to see him. So that we felt quite easy about the safety of Pricker and his comrade.

What it was that induced Tawney not only to see Pricker, but to attack him again, we do not know, as nobody was witness of the catastrophe.

On going into the garden one brilliant morning, Tawney made his appearance in a very excited state, bounding about our feet with a short delighted bark, that was not usually his morning salutation; and on looking more closely at him, we saw that his nose was bleeding; indeed, his whole head and ears were much ruffled and marked.

We did not at first think of Pricker; but on wiping Tawney's face with a wet towel, we found that he was bleeding from many wounds.

"The hedgehog!" we exclaimed, "He must have killed poor Pricker."

So we commenced a grand hunt through the garden, looking under all the cabbage-plants, and in all the usual haunts.

Behind the cucumber frame we found our hedgehog; but as he curled up the moment we looked at him, we knew that it was not Pricker; and on further search we discovered the mangled remains of the poor animal, whose natural armour had not been sufficient to protect him from so brave and plucky a little dog as our Tawney, who must really have suffered greatly from the deep thrusts into his face and head before he could have inflicted a mortal bite.