Title: The History of the British Post Office

Author: Joseph Clarence Hemmeon

Release date: June 18, 2013 [eBook #42983]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, Eric Skeet, The Philatelic

Digital Library Project at http://www.tpdlp.net and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber's Notes:

(1) Obvious spelling, punctuation, and typographical errors have been corrected. On page 99, footnote marker [6] is duplicated - it has been altered to [381] and the surrounding footnotes adjusted suitably. Footnote [616] has an uncorrectable duplication of "Ionian Isles".

(2) Table V in the Appendix has been divided into two parts (Scotland and Ireland), in view of its page width.

(3) All footnotes have been moved to the end of the book, with html links.

(4) The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

—————————

BY

J. C. HEMMEON, Ph.D.

PUBLISHED FROM THE INCOME OF THE

WILLIAM H. BALDWIN, JR., 1885, FUND

CAMBRIDGE

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

1912

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY THE PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published January 1912

In justice to those principles which influenced the policy of the Post Office before the introduction of penny postage, it is perhaps unnecessary to call attention to the fact that no opinion as to their desirability or otherwise is justifiable which does not take into consideration the conditions and prejudices which then prevailed. Some of the earlier writers on the Post Office have made the mistake of condemning everything which has not satisfied the measure of their own particular rule. If there is anything that the historical treatment of a subject teaches the investigator it is an appreciation of the fact that different conditions call for different methods of treatment. For example, the introduction of cheap postage was possibly delayed too long. But during the era of high postal rates a large net revenue was of primary importance, nor were those conditions present which would have made low rates a success.

The consideration of such debatable subjects as the telegraph system of the Postal Department and the department's attitude toward the telephone companies, as well as the intention of the Post Office to acquire the business of the latter, must necessarily give rise to controversy. Thanks to the magnificent net revenue obtained from letters in the United Kingdom the department has been able to lose a good deal of money by the extension of its activities into the realm of affairs not purely postal. Possibly a democratic type of government should, from the financial point of view, interfere least in the direct management of economic institutions, on account of the pressure which can easily be brought to bear upon it for the extension of such institutions on other than economic grounds. If non-economic principles are to be substituted in justifying the initiation or increase of government ownership, a popular form of government seems the least suitable for the presentation of such as shall be fair to all concerned, not to mention the difficult problem of dealing with those members of the civil service who do not hesitate to make use of their political power to enforce their demands upon the government.

In the treatment of a subject so complex as the history of the British Post Office it is not easy to decide how far its presentation should be strictly chronological or how far it should be mounted in "longitudinal sections," exposing its most salient features. Both methods have their advantages and their disadvantages. In order to obtain what is useful in both, I have described chronologically in the first four chapters the progress of the Post Office, while in the remaining chapters I have examined separately some of the more important aspects of postal development. But I am aware that by this compromise I have not entirely escaped the dangers of abrupt transitions from subject to subject and of the accumulation of dry details. I can only plead in extenuation, in the first place the nature of my subject, an institution with a long and varied history, characterized by the steady extension of its field of activity, and in the second place my desire to make my study as thorough as possible, even at the risk of some sacrifice of unity and interest of treatment.

The material for this sketch has been obtained from the Harvard University Library, the Boston Public Library, and the Canadian Parliamentary Library. Work was also done in the Library of the British Museum. I wish to acknowledge the help I have received from the advice and criticism of Professor Gay, under whose supervision the larger part of this history was prepared.

J. C. Hemmeon.

CHAPTER I

| The Postal Establishment supported directly by the State—Prior to 1635 | 3 |

| Methods of postal communication in vogue before the establishment of the Post Office. The first Postmaster-General and his duties. Alternative systems. The posts in Elizabeth's reign. Appointment of a Foreign Postmaster-General. Rivalry between the two Postmasters-General. Witherings as Foreign Postmaster-General. |

CHAPTER II

| The Postal Establishment a Source of Revenue to the State—1635-1711 | 13 |

| Condition of the postal establishment at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Witherings' project adopted. Disturbance produced in the Post Office by the struggle between the two Houses of Parliament. Rival claimants for the office of Postmaster-General. The Civil War and its effects upon the Post Office. The Post Office during the Commonwealth. Farming of the Post Office. Complaints about the delivery of letters after the Restoration. Condition of the postal establishment at the close of the seventeenth century. Dockwra's London Penny Post. Extension of the foreign postal service. Conditions in Ireland, Scotland, and the American Colonies. |

CHAPTER III

| The Postal Establishment an Instrument of Taxation—1711-1840 | 34 |

| The Post Office Act of 1711. The Post Office as a whole ceases to be farmed. Allen undertakes the farm of the bye and cross posts. Improvements in postal communications during the first half of the eighteenth century. Controversy over the delivery of letters. Competition from post coaches. Establishment of mail coaches by Palmer. Abuses in the Post Office and their reform. Opening and detention of letters. Franking of newspapers in certain cases and other privileges abolished. The Newspaper and Dead Letter Offices. Registration of letters. Money Order Office. Changes in the London Penny Post. Consolidation of different branches of the Post Office in London. Dublin and Edinburgh Penny Posts. Question of Sunday posts. Conditions under which mail coaches were supplied. Conveyance of mails by railways. Condition of the postal establishment during the first half of the nineteenth century. Irish Post Office and postal rates. Scotch Post Office. Sir Rowland Hill's plan. Investigation of postal affairs by a committee. Report of committee. Adoption of inland penny postage. |

CHAPTER IV

| The Postal Establishment an Instrument of Popular Communication—Since 1840 | 63 |

| Reductions in rates of postage, inland, colonial and foreign; and resultant increase in postal matter. Insurance and registration of letters. Failure of attempt to introduce compulsory prepayment of postage. Perforated postage stamps. Free and guaranteed delivery of letters in rural districts. Express or special delivery of letters. Newspaper postage rates. Book or Halfpenny Post. Pattern and Sample Post. Use of postcards. Parcel Post. Question of "cash on delivery." Postal notes. Their effect upon the number of money orders. Savings banks. Assurance and annuity privileges. Reform in these offices by Mr. Fawcett. Methods of conveyance of the mails. Condition of postal employees. Sunday labour. Dissatisfaction of employees with committee of 1858. Mr. Fawcett's reforms in 1881 and 1882. Mr. Raikes' concessions in 1888, 1890, and 1891. Appointment of Tweedmouth Committee in 1895 gives little satisfaction to the men. Appointment of a departmental committee. Grievances of the men. Report of committee accepted only in part by the Postmaster-General. Continued demand of the men for a select committee. Concessions granted to the men by Mr. Buxton, the Postmaster-General. Select committee appointed. Their report adopted by Mr. Buxton. Continued dissatisfaction among the men. |

CHAPTER V

| The Travellers' Post and Post Horses | 89 |

| Horses provided by the postmasters. Complaints concerning the letting of horses. Monopoly in letting horses granted to the postmasters. Reforms during Witherings' administration. Fees charged. Postmasters' monopoly abridged. Licences required and duties levied. These duties let out to farm. Licences and fees re-adjusted. |

CHAPTER VI

| Roads and Speed | 97 |

| Post roads in the sixteenth century. Speed at which mails were carried in the sixteenth century. Abuses during first part of the seventeenth century. New roads opened. Roads in Ireland and Scotland. First cross post road established in 1698. Improvement in speed. Delays in connection with Irish packet boats. Increased speed obtained from use of railways. |

CHAPTER VII

| Sailing Packets and Foreign Connections | 109 |

| Establishment of first regular sailing packets. Sailing packets in the seventeenth century. Difficulty with the Irish Office. Postal communications with the continent during the sixteenth century. Witherings improves the foreign service. Agreements with foreign postmasters-general. Expressions of dissatisfaction. Treaties with France. King William's interest in the Harwich sailing packets. Effect of the war with France. Postal communications with France improved. Dummer's West Indian packet boats. Other lines. Increase in number of sailing packets. Steam packets introduced by the Post Office. They are badly managed and prove a financial loss. Report against government ownership of the steam packets. Ship letter money. Question of carriage of goods. Trouble with custom's department adjusted. Methods of furnishing supplies for the packet boats. Abuses in the sailing packet service reformed. Expenses. Sailing packets transferred to the Admiralty. Committee reports against principle of government ownership of packet boats and payment of excessive sums to contractors. Abandonment of principle of government ownership. General view of packet services in existence at middle of the nineteenth century. Contracts with steamship companies. Controversy with the companies. General view of the packet service in 1907 with principles adopted in concluding contracts. Expenses of sailing packets. |

CHAPTER VIII

| Rates and Finance | 135 |

|

Foreign rates, 1626. First inland rates, 1635. Rates prescribed by

Council of State, 1652. Rates collected by the Farmers of the Posts.

First rates established by act of Parliament, 1657. Slightly amended,

1660. Separate rates for Scotland, 1660. Scotch rates, 1695. Rates to

and within Jamaica. In American Colonies, 1698. Increased rates, inland,

colonial and foreign, 1711. Controversy over rates on enclosures. Slight

reductions in rates, 1765. Increases in 1784, 1796, 1801. In Ireland,

1803. For United Kingdom a further increase, 1805. Culminating point of

high rates, 1812. Changes in Irish rates, 1810, 1813, 1814. Rates on

"ships' letters," 1814. Irish rates to be collected in British currency,

1827. Reduction in rates between England and France, 1836. Consolidating

act of 1837. Rates by contractors' packet boats, 1837. Rates charged

according to weight in certain cases, 1839. Inland penny postage adopted

and basis of rate-charging changed to weight, 1840. Franking privilege,

1652. Abused. Attempt to curtail the use of franks only partially

successful. Curtailment so far as members of Parliament are concerned.

Estimated loss from franking. Enquiry into question of franking. Further

attempts to control the abuse prove fruitless. Extension of franking

privilege especially on newspapers. Abolition of franking privilege,

1840. Reductions in letter, newspaper, and book post rates. Re-directed

letter and registration fees. Inland parcel post established. Postcards

introduced. Concessions of 1884 and Jubilee concessions. Foreign and

colonial rates reduced. Reductions in money order and postal note rates.

Telegraph money order rates. Finances of the Post Office before the seventeenth century. From beginning of seventeenth century to Witherings' reforms. From 1635 to 1711. During the remainder of the eighteenth century. Finances of Scotch and Irish Posts. Of the London Penny Post. From bye and cross post letters. Finances of the Post Office from the beginning of the nineteenth century to 1840. Since the introduction of inland penny postage. |

CHAPTER IX

| The Question of Monopoly | 189 |

| Rival methods available for the conveyance of letters. Government's monopolistic proclamation the result of an attempt to discover treasonable correspondence. Competition diminishes under Witherings' efficient management. House of Commons declares itself favourable to competition. Changes its attitude when in control of the posts. Monopoly of government enforced more rigorously. Carriers' posts largely curtailed. London's illegal Half-penny Post. Attempts to evade the payment of postage very numerous during the first half of the nineteenth century. Different methods of evasion outlined. |

CHAPTER X

| The Telegraph System as a Branch of the Postal Department | 202 |

| The telegraph companies under private management. Proposals for government ownership and Mr. Scudamore's report. Conditions under which the telegraph companies were acquired. Public telegraph business of the railways. Cost of acquisition. Rates charged by the government. Reduction in rates in 1885. Guarantee obligations reduced. Underground lines constructed. Telegraphic relations with the continent. Position of the government with reference to the wireless telegraph companies. Attempts to place the government telegraphs on a paying basis do not prove a success. Financial aspect of the question. Reasons given for the lack of financial success. |

CHAPTER XI

| The Post Office and the Telephone Companies | 219 |

| Telephones introduced into England. Judicial decision in favour of the department. Restricted licences granted the companies. Feeble attempt on the part of the department to establish exchanges. Difficulties encountered by the companies. Popular discontent with the policy of the department leads to granting of unrestricted licences. Way-leave difficulties restrict efficiency of the companies. Agreement with National Telephone Company and acquisition of the trunk lines by the department. Demand for competition from some municipalities leads to granting of licences to a few cities and towns. The department itself establishes a competing exchange in London. History of the exchanges owned and operated by the municipalities. Struggle between the London County Council and the company's exchange in London. Relation between the company's and the department's London exchanges. Agreement with the company for the purchase of its exchanges in 1911. Financial aspect of the department's system. |

CHAPTER XII

| Conclusion | 237 |

APPENDIX

| Expenditure and Revenue Tables | 243 |

| Bibliography | 253 |

| Index | 259 |

| Acc. & P. | Accounts and Papers. |

| A. P. C. | Acts of the Privy Council. |

| Add. | Additional. |

| Cal. B. P. | Calendar of Border Papers. |

| Cal. S. P. | Calendar of State Papers. A. & W. I., Col., D., For., and Ire., added to Cal. S. P., indicate respectively to the America and West Indies, Colonial, Domestic, Foreign, and Ireland sections of this series. |

| Cal. T. B. | Calendar of Treasury Books. |

| Cal. T. P. | Calendar of Treasury Papers. |

| Cal. T. B. & P. | Calendar of Treasury Books and Papers. |

| D. N. B. | Dictionary National Biography. |

| Fin. Rep., 1797. | Finance Reports 1797-98. |

| Hist. MSS. Com. | Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. |

| Jo. H. C. | Journals of the House of Commons. |

| Jo. H. L. | Journals of the House of Lords. |

| Joyce. | Joyce, H. The History of the Post Office to 1836. |

| L. & P. Hen. VIII. | Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII. |

| Parl. Deb. | Hansard, Parliamentary Debates. |

| Parl. Papers. | Parliamentary Papers. |

| P. & O. P. C. | Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council. |

| Rep. Commrs. | Reports from Commissioners. |

| Rep. Com. | Reports from Committees. |

| Rep. P. G. | Reports of the Postmasters-General. |

| Scobell, Collect. | Scobell, H. A Collection of Acts and Ordinances made in the Parliament held 3 Nov., 1640 to 17 Sept., 1656. |

THE HISTORY OF

THE BRITISH POST OFFICE

THE POSTAL ESTABLISHMENT SUPPORTED DIRECTLY

BY THE STATE

The history of the British Post Office starts with the beginning of the sixteenth century. Long before this, however, a system of communication had been established both for the personal use of the King and for the conveyance of official letters and documents. These continued to be the principal functions of the royal posts until well on in the seventeenth century.

Before the sixteenth century, postal communications were carried on by royal messengers. These messengers either received stated wages or were paid according to the length of the journeys they made. We find them mentioned as early as the reign of King John under the name of nuncii or cursores; and payments to them form a large item in the Household and Wardrobe accounts of the King as early as these accounts exist.[1] They travelled the whole of the journey themselves and delivered their letters personally to the people to whom they were directed. A somewhat different style of postal service, a precursor of the modern method, was inaugurated by the fourth Edward. During the war with Scotland he found himself in need of a speedier and better system of communication between the seat of war and the seat of government. He accomplished this by placing horses at intervals of twenty miles along the great road between England and Scotland. By so doing his messengers were able to take up fresh horses along the way and his despatches were carried at the rate of a hundred miles a day.[2]

From an early period private letters were conveyed by carriers and travellers both within the kingdom and between it and the Continent. The Paston letters,[3] containing the correspondence of the different members of the Paston family, throw some light upon the manner in which letters were conveyed during the latter half of the fifteenth century. Judging from such references as we find in the letters themselves, they were generally carried by a servant,[4] a messenger,[5] or a friend.[6] The later letters of this series, written towards the close of the fifteenth century, show that regular messengers and carriers, who carried letters and parcels, travelled between London and Norwich and other parts of Norfolk.[7] From the fourteenth century down, we have instances of writs being issued to mayors, sheriffs, and bailiffs for the apprehension and examination of travellers, who were suspected of conveying treasonable correspondence between England and the Continent.[8] For the most part these letters were carried by servants, messengers, and merchants.[9]

Sir Brian Tuke is the first English Postmaster-General of whom we have any record. The King's "Book of Payments" for the year 1512 contains an order for the payment of £100 to Sir Brian for his use as Master of the Posts.[10] As the King's appointed Postmaster, he received a salary of £66 13s. 4d.[11] He named the postmen, or deputy postmasters as they were called later, and he was held responsible for the performance of their duties.[12] All letters carried by the royal postmen were delivered to him, and after being sorted by him personally were carried to their destination by the court messengers.[13] The wages of the postmen varied from 1s. to 2s. a day according to the number of horses provided, and they were paid by the Postmaster-General, who had authority to make all payments to those regularly employed.[14] If messages or letters were sent by special messengers, their payment entailed additional expense upon the state and the use of such messengers, when regular postmen were available, was strongly discouraged.[15]

In addition to his other duties Sir Brian was supposed to have a general supervision over the horses used for the conveyance of letters and of travellers riding on affairs of state. Of course on the regular roads there were always horses in readiness, provided by the postmen. Where there were no regular post roads, the townships were supposed to provide the necessary horses, and it was part of the Postmaster-General's duties to see that the townships were kept up to the mark.[16] It was largely on account of the fact that the same horses were used for conveying travellers and mails that the systems of postal and personal communication were so closely interwoven as well in England as in continental countries.[17]

The postmen along the old established routes and on the routes temporarily established for some definite purpose received a fixed daily wage. These men were called the ordinary posts.[18] If, however, letters should arrive in Dover after the ordinary post had left for London, they were generally sent on at once by a messenger hired for the occasion only. He was called a special post and was paid only for the work which he actually performed.[19] Those regular posts, who carried the royal and state letters between London and the place where the Court might be, were called "Court Posts."[20] During the sovereign's tours, posts were always stationed between him and London to carry his and the state's letters backward and forward. These were called extraordinary posts and received regular wages while so employed.[21] In addition there were always messengers employed to carry important despatches to foreign sovereigns. These received no fixed wages, but were paid according [6] to the distance travelled and the expenses incurred on the road.[22]

Apart from his regular duties as outlined above, the Postmaster-General had little initiative power. He could not on his own responsibility order new posts to be laid. Such decisions always originated with the King or the Council and Tuke simply executed their orders.[23] Any increase in the wages of the posts also required the consent of the King or Council.[24]

During the sixteenth century there were three ways to send letters between England and the Continent: by the Royal Post, the Foreigners' Post, and the Merchant Adventurers' Post, apart from such opportunities as occasional travellers and messengers offered. The Royal Posts were presumed to carry only state letters, and consequently the conveyance of a large part of the private letters fell to the other two. Owing to industrial and later to religious motives there had been a large emigration of foreigners from the Continent to England. Edward III had induced many Flemings to leave their native country in the middle of the fourteenth century.[25] Froude says, probably with exaggeration, that in 1527 there were 15,000 Flemings in London alone.[26] In the fifteenth century many Italian artisans came over to reside but not to settle.[27] They were a thrifty people, who did much to place the industrial life of England on a better footing, and were probably more intelligent and better educated than the majority of the English artisans among whom they settled. It seems therefore only natural that they should seek to establish a better system of communication between their adopted and native countries. Their business relations with the cloth markets of the continental cities made necessary a better and speedier postal system than was afforded by the Royal Posts. In addition to this, it was only by act of grace that private letters were carried [7]by Tuke's postmen. In the opening year of the sixteenth century, by permission of the state, the foreign merchants in London established a system of posts of their own between the English capital and the Continent. This was called the "Foreign or Strangers' Post," and was managed by a Postmaster-General, nominated by the Italians, Spanish, and Dutch and confirmed by the Council.[28] These posts were used largely by the English merchants in spite of considerable dissatisfaction on account of the poor service afforded and on political grounds. Their grievances were detailed in a petition to the Privy Council. They considered it unprecedented that so important a service as the carriage of letters should be in the hands of men who owed no allegiance to the King. Such a procedure was unheard of in any of the continental countries. "What check could there be over treasonable correspondence while the carriage of letters continued to be in the hands of foreigners and most of them Dutchmen?" In addition they were not treated so well as were their fellow merchants of foreign allegiance. Their letters were often retained for several days at a time, while all others were delivered as soon as they arrived. The foreign ambassadors could not complain if a change were made, for most of their correspondence was carried on by special messengers.[29] The "Strangers' Post" seems to have come to an end after the Proclamation of 1591 was issued, forbidding any but the Royal Posts from carrying letters to and from foreign countries.[30]

Sir Brian Tuke died in 1545 and was succeeded by Sir John Mason and Mr. Paget, who acted as joint Postmasters-General. Mr. Paget was the sleeping partner, and what little was done was by Mason.[31] They were succeeded in 1568 by Thomas Randolph.[32] He was occasionally sent as special ambassador to France and during his absence Gascoyne, a former court post, performed his duties. From Sir Brian's death until the end of Elizabeth's reign was a period of little advance in postal matters. The regular posts, and it [8]is with them that our chief interest lies, appear to have fallen into disuse. The payments for special messengers are much larger than they had been during Henry's reign. In 1549, a warrant was issued empowering Sir John Mason to pay £400 to the special messengers used during the summer. If anything was left, he was instructed to use it in paying arrears due the ordinary posts.[33] Elizabeth is generally credited with being economical to the extreme of parsimony so far as state expenses were concerned. However this may be, she is responsible for an order to discharge all the regular posts unless they would serve for half of their old wages.[34] The postmen did not receive their wages at all regularly. Randolph was accused by the Governor of Berwick of withholding all of their first year's wages, of receiving every year thereafter a percentage of their salaries, and of demanding certain fees from them, all for his personal use. The Governor considered that Randolph's extortions were largely the cause of the general inefficiency in the posts,[35] but the accusation may have been due to personal grudge. At any rate one measure of postal reform may be credited to Randolph. In 1582, orders were issued to all the London-Berwick posts to the following effect. Every post on the arrival of letters to or from the Queen or Council was to fasten a label to the packet. On this label he was to write the day and hour when the packet came into his hands and he was to make the same entry in a book kept for the purpose. He was also to keep two or three good horses in his stable for the speedier conveyance of such packets.[36]

In 1590, John Lord Stanhope was appointed Postmaster-General by order of the Queen. The office was given to him for his life and then was to go to his son for his son's life.[37] Both the Stanhopes were men of action, but they looked upon their position rather as a means of enriching themselves than as a trust for the good of the state. They proved a stumbling block to the advancement of better men and it was not for sixty years that they were finally swept away to make room for men of greater ability. In 1621, the elder Stanhope was succeeded by his son Charles according to the terms [9]of the original patent.[38] It had been the custom for the Postmasters-General to demand fees and percentages from their appointees. So lucrative were many of their positions from the monopoly in letting horses and the receipts from private letters that many applicants were willing to pay for appointments as deputy postmasters. The ordinary payments when Lord Charles was at the head of the posts amounted to 2s. in the pound as poundage and a fee of £2 from each man. These payments were considered so exorbitant that the Council ordered them to be reduced.[39] One, Hutchins, entered the lists as the champion of the postmasters. He himself was one of them and acted as their solicitor in the contest. Stanhope was glad to compound the case by the payment of £30. Hutchins gave the Council so much trouble that they gave orders that "turbulent Hutchins" should cease to act as the postmasters' solicitor and leave them in peace.[40] His object, however, seems to have been accomplished so far as Stanhope was concerned. The struggle with the Paymasters of the Posts was not so successful, for, supported by a report of the Treasurer, they continued to receive their shilling in the pound.[41]

By a Privy Council Proclamation issued in 1603, all posts receiving a daily fee were required to have two leather bags, lined with "bayes" or cotton, and the post himself was to sound a horn whenever he met any one on the road or four times in every mile. The packet of letters was not to be delayed more than fifteen minutes and was to be carried at a rate of seven miles an hour in summer and five in winter. The time at which it was delivered into a post's hands and the names and addresses of the people by whom and to whom it was sent were to be entered in a book kept for the purpose. All posts and their servants were exempted from being "pressed" and from attendance at assizes, sessions, inquests, and musters.[42]

It is doubtful how far the postmasters were held responsible for the delivery of letters to the persons to whom they were addressed. This did not become a burning question, however, until after the recognition of the fact that the letters of private individuals should receive as good treatment at the hands of the postmen as the letters of the state officials. Lord Stanhope in 1618 issued an order to the Justices of the Peace in Southwark to aid the postmaster of that place in the delivery of letters within six miles.[43] This was followed two years later by a general order to establish two or three foot-posts in every parish for the conveyance of letters.[44]

During the early part of the seventeenth century, Stanhope had employed a foreigner, de Quester, as one of the King's posts "beyond seas." He commended himself to the notice of his superiors by his promptitude in dealing with the foreign letters.[45] In 1619 James appointed him Postmaster-General for "foreign parts" and henceforth he was his own master.[46] This was followed four years later by a formal proclamation, confirming to de Quester and his son the position already granted to the father.[47] He was to have the sole monopoly of carrying foreign letters and was to appoint the necessary officials. All persons were formally prohibited from entrenching upon the privileges granted him in 1619. From this time until 1635, the foreign and inland posts were under separate management and the accounts were kept separate until long after the latter date. Stanhope was unwilling to submit to the curtailment of his profits, which necessarily followed the appointment of de Quester. There was much to be said for Stanhope's contention that the patent of 1623 was illegal for, ever since there had been a Postmaster-General, his duties had extended to the foreign as well as to the inland office. The question was referred to a committee, composed of the Lord Chamberlain, one of the Secretaries of State and the Attorney-General, who decided that Stanhope's patent extended only to the inland office.[48] The whole question was finally brought before the Court of King's Bench, which decided the case in favour of Stanhope.[49] This was in 1625, but de Quester seems to have paid no attention to the decision for it is certain that he continued to act as [11]Foreign Postmaster until 1629[50] and in 1632 he resigned his patent to Frizell and Witherings. It can be imagined what must have been the chaotic condition of the foreign post while this struggle was going on. The Merchant Adventurers established posts of their own between London and the Continent under Billingsley. The Council issued the most perplexing orders. First they forbade Billingsley from having anything to do with foreign letters.[51] Then they decided that the Adventurers might establish posts of their own and choose a Postmaster.[52] Then they extended the same privilege to all merchants. Next this was withdrawn and the Adventurers were allowed to send letters only to Antwerp, Delft and Hamburg or wherever the staple of cloth might be.[53] These orders do not seem to have been passed in full council for, in 1628, Secretary Coke in writing to Secretary Conway said that "Billingsley, a broker by trade, strives to draw over to the merchants that power over foreign letters which in all states is a branch of royal authority. The merchant's purse has swayed much in other matters but he has never heard that it encroached upon the King's prerogative until now." He adds "I confess it troubleth me to see the audacity of men in these times and especially that Billingsley." He enclosed a copy of an order "made at a full Council and under the Broad Seal," which in effect was a supersedeas of the place which de Quester enjoyed.[54] When de Quester resigned in favour of Frizell and Witherings, the resignation and new appointments were confirmed by the King.[55] Of these men Witherings was far the abler. He had a plan in view, which was eventually to place the foreign and inland systems on a basis unchanged until the time of penny postage. In the meantime he had to overcome the prejudices of the King and get rid of Frizell. In order to raise money for the promotion of his plan, Witherings mortgaged his place. Capital was obtained from the Earl of Arundel and others through John Hall, who held the mortgage. The King heard of this and ordered [12]the office to be sequestered to his old servant de Quester and commanded Hall to make over his interest to the same person.[56] There were now three claimants for the place, Frizell, Witherings, and de Quester. Frizell rushed off to Court, where he offered to pay off his part of the mortgage and asked to have sole charge of the Foreign Post. "Witherings," he said, "proposes to take charge of all packets of State if he may have the office, but being a home-bred shopkeeper, without languages, tainted of delinquency and in dislike with the foreign correspondents, he is no fit person to carry a trust of such secrecy and importance."[57] Coke knew better than this, however, and through his influence Witherings, who had in the meantime paid off the mortgage and satisfied Frizell's interest, was made sole Postmaster-General for Foreign Parts.[58] With Witherings' advent a new period of English postal history begins. His dominant idea was to make the posts self-supporting and no longer a charge to the state. It had been established as a service for the royal household and continued as an official necessity. The letters of private individuals had been carried by its messengers but the state had derived no revenue for their conveyance. The convenient activity of other agencies for the carriage of private letters was not only tolerated but officially recognized. The change to a revenue-paying basis tended naturally to emphasize the monopolistic character of the government service.[59]

THE POSTAL ESTABLISHMENT A SOURCE OF REVENUE

TO THE STATE

1633-1711

For some time there had been dissatisfaction with the services rendered by the inland posts. It was said that letters would arrive sooner from Spain and Italy than from remote parts of the kingdom of England.[60] The only alternative was to send them by express and this was not only expensive but was not looked upon with favour by the Postmaster-General. The five great roads from London to Edinburgh, Holyhead, Bristol, Plymouth, and Dover were in operation. From the Edinburgh Road there were branches to York and Carlisle, from the Dover Road to Margate, Gravesend, and Sandwich, and from the Plymouth Road to Falmouth, but the posts were slow and the rates for private letters uncertain.[61] In 1633, a project was advanced for the new arrangement of the Post Office. The plan was not entirely theoretical, for an attempt was made to show that it would prove a financial success. There were about 512 market towns in England. It was considered that each of these would send 50 letters a week to London and as many answers would be returned. At 4d. a day for each letter, this would amount to £426 a week. The charge for conveyance was estimated at £37 a week, leaving a weekly profit of £389, from which £1500 a year for the conveyance of state letters and despatches must be deducted. Letters on the northern road were to pay 2d. for a single and 4d. for a double letter, to Yorkshire and Northumberland 3d., and to Scotland 8d. a letter. The postmasters in the country were not to take any charge for a letter except one penny for carriage to the next market town.[62] It is probable that this project originated with Witherings. At any rate it resembles closely the plan which [14]was introduced by him two years later. He had already reformed the foreign post by appointing "stafetti" from London to Dover and through France and they had proved so efficient as to disarm the opposition even of the London merchants. His name is without doubt the most distinguished in the annals of the British Post Office. Convinced that the carriage of private letters must be placed upon a secure footing, he laid the foundation for the system of postal rates and regulations, which continued to the time of national penny postage. He introduced the first legal provision for the carriage of private letters at fixed rates, greatly increased the speed of the posts, and above all made the Post Office a financial success. In order to do this he saw that the proceeds from private letters must go to the state and not to the deputy postmasters.

His plan was entitled "A proposition for settling of Stafetti or pacquet posts betwixt London and all parts of His Majesty's Dominions. The profits to go to pay the postmasters, who now are paid by His Majesty at a cost of £3400 per annum." A general office or counting house was to be established in London for the reception of all letters coming to or leaving the capital. Letters leaving London on each of the great roads were to be enclosed in a leather "portmantle" and left at the post-towns on the way. Letters for any of the towns off the great roads were to be placed in smaller leather bags to be carried in the large portmantle. These leather bags were to be left at the post-towns nearest the country towns to which they were directed. They were then to be carried to their destination by foot-posts to a distance of six or eight miles and for each letter these foot-posts were to charge 2d., the same price that was charged by the country carriers. At the same time that the foot-posts delivered their letters, they were to collect letters to be sent to London and carry them back to the post-town from which they had started and there meet the portmantle on its way back from Edinburgh or Bristol or wherever the terminus of the road might be. The speed of the posts was to be at least 120 miles in twenty-four hours and they were to travel day and night. He concludes his proposition by saying that no harm would result to Stanhope by his plan "for neither Lord Stanhope nor anie[15] other, that ever enjoyed the Postmaster's place of England, had any benefit of the carrying and re-carrying of the subjects' letters."[63]

The question now was, Who was to see that these reforms were carried out? Stanhope was not the man for so important and revolutionary an undertaking. Witherings alone, the author of the proposition, should carry it into effect. Sir John Coke made no mistake in constituting himself the friend of the postal reformer. Witherings was already Foreign Postmaster-General and in 1635 he was charged with the reformation of the inland office on the basis of his projected scheme. In 1637 the inland and foreign offices were again united when he was made Foreign and Inland Postmaster-General.[64] His experiment was tried on the Northern Road first and was exceedingly successful. Letters were sent to Edinburgh and answers returned in six days. On the Northern Road bye-posts were established to Lincoln, Hull and other places.[65] Orders were given to extend the same arrangement to the other great roads, and by 1636 his reform was in full and profitable operation.

Witherings still continued to sell the positions of the postmasters, if we are to trust the complaints of non-successful applicants. One man said that he offered £100 for a position but Witherings sold it to another for £40.[66] The Postmaster at Ferrybridge asserted that he had paid Stanhope £200 and Witherings £35 and yet now fears that he will be ousted. Complaints of a reduction in wages were also made, and this was a serious matter, since the postmasters no longer obtained anything from private letters.[67] The old complaint, however, of failure to pay wages at all is not heard under Witherings' administration. He was punctual in his payments and held his employees to equally rigid account. Their arrears were not excused.[68] An absentee postmaster, who hired [16]deputies to perform his duties, was dismissed.[69] His ambition to establish a self-supporting postal system demanded rigid economy and strict administration, and with the then prevailing laxity of administrative methods, this was no mean achievement. From one occasional practice of the Post Office, that of tampering with private letters, he cannot perhaps wholly be absolved. It is hinted that he may have been guilty of opening letters, but the suggestion follows that this may have happened before they reached England, for the letters so opened were from abroad.[70]

In June of 1637, Coke and Windebank, the two Secretaries of State, were appointed Postmasters-General for their lives. The surviving one was to surrender his office to the King, who would then grant it to the Secretaries for the time being.[71] It does not appear that Witherings was altogether dismissed from the service, for his name continued to appear in connection with postal affairs.[72] Windebank later urged as reasons for the withdrawal of Witherings' patent, that he was not a sworn officer, that there was a suspicion that his patent had been obtained surreptitiously, and that the continental postmasters disdained to correspond with a man of his low birth. He concludes by saying that something may be given him, but that he is said to be worth £800 a year in land and to have enriched himself from his position.[73] At the time of his removal, in June, 1637, the London merchants petitioned for his continuance in office, as he had always given them satisfaction. When they heard who had been appointed in his stead, like loyal and fearful subjects, they hastened to add that they thought someone else was trying for the position but they had no doubt that it would be managed best by the Secretaries.[74] If they thought so they were mistaken, for the commander of the English army against Scotland found that his letters were opened,[75] the Lord High Admiral complained that his were delayed,[76] and Windebank promised an unknown [17]correspondent that the delay in his letters should be seen to at once and Witherings was the agent chosen for the investigation.[77] This, however, was not the worst, for only a month after Witherings had been degraded, orders were issued to the postmasters that no packets or letters were to be sent by post but such as should be directed "For His Majesty's Special Affairs" and were subscribed by certain officials connected with the Government.[78] It is fair to add that this check on private correspondence may have been a protective measure induced by the unsettled state of the kingdom.

In 1640 both the inland and foreign offices were sequestered into the hands of Philip Burlamachi, a wealthy London merchant who had lent money to the king. No reasons were given except that information had been received "of divers abuses and misdemeanours committed by Thomas Witherings."[79] Stanhope, who had resigned his patent in 1637, now came forward claiming that his resignation had been unfairly obtained by the Council, and at the same time he presented his bill for £1266, the arrears in his salary for nineteen years.[80] In reply to his demand it was said that shortly before he resigned he had assigned his rights in the Post Office to the Porters, father and son. The Attorney-General gave his opinion that whatever rights Stanhope and the Porters had, they certainly had no claim to the proceeds from the carriage of private letters.[81] Stanhope had offered to enter an appearance in a suit brought against him by the Porters but now he refused to do so.[82] Windebank was also looking out for money due to him while Coke and he were Postmasters-General.[83] The state had indeed entered upon troublous times and it was every man for himself before it was too late.

As long as Witherings had enjoyed the King's favour, the House of Commons had looked upon him with suspicion. They had ordered in 1640 "that a Sub-Committee of the Committee of Grievances should be made a House Committee to consider abuses in the [18]inland posts, to take into consideration the rates for letters and packets together with the abuses of Witherings and the rest of the postmasters."[84] As soon as Witherings was finally dismissed, the Commons took him up and resolutions were passed that the sequestration was illegal and ought to be repealed, that the proclamation for ousting him from his position ought not to be put into execution, and that he ought to be restored to his old position and be paid the mean profits which had been received since his nominal dismissal.[85] Protected by the authority of the House of Commons, Witherings continued to act as Postmaster-General.[86] Windebank, in Paris, was trying to collect evidence against him through Frizell, who, he said, had been forced out of his position by Witherings and Coke.[87] Coke himself was in disgrace and could do nothing. Parliament was now supreme. Witherings was ordered to send to a Committee of the Lords, acting with Sir Henry Vane, all letters coming into or going out of the kingdom for examination and search. Frequent orders to the same effect followed during the turbulent summer and autumn of 1641.[88] Among other letters opened were those of the Venetian Ambassador in England. He was so indignant that a Committee of the Lords was sent to him to ask his pardon.[89] The two Houses of Parliament united in condemning the sequestration to Burlamachi, but Witherings, who had become tired of the strife, assigned his position to the Earl of Warwick.[90] The Earl was supported by both Houses, but the Lower House played a double part, for, while openly supporting Warwick, they now secretly favoured Burlamachi, who had found an influential friend in Edmund Prideaux, former chairman of the committee appointed to investigate the condition of the posts and later Attorney-General under the Commonwealth.[91] Prideaux was a strong Parliamentarian, but was distrusted even by his own friends. But for the time being, as the representative of the Commons, he was supported by them. The [19]messenger of the Upper House made oath that he had delivered the Commons' resolution to Burlamachi, commanding him to hand over the Inland Letter Office to Warwick, but James Hicks had presented an order at the place appointed by Warwick for receiving letters, to deliver all letters to Prideaux. Burlamachi on being summoned before the Lords for contempt said that Prideaux had hired his house and now had charge of the mails. The fight went merrily on. Two servants of Warwick seized the Holyhead letters from Hicks, but were in turn stopped by five troopers, agents of Prideaux, who took the letters from them by order of the House of Commons. Prideaux also seized the Chester and Plymouth letters, one of his servants calling out "that an order of the House of Commons ought to be obeyed before an order of the House of Lords."[92] Hicks, who had been arrested by order of the Lords, was liberated by the Commons as a servant of a member of Parliament.[93] As between Lords and Commons, there could be no doubt as to which side would carry the day, and by the end of 1642 the Lower House was triumphant all along the line. Understanding that discretion was the better part of valour, the Lords freed Burlamachi and dropped the contest. Warwick now petitioned the Lords again, setting forth that he was the legal successor and assignee of Witherings. Stanhope put in a counter-petition to the effect that Witherings never had any right to the position which Warwick now claimed. The House of Lords felt its own weakness too much to interfere directly, but ordered the whole matter to trial.[94] Besides Stanhope and Warwick, the following put in claims before the Council of State: Henry Robinson, through the Porters, to whom Stanhope had assigned; Sir David Watkins in trust for Thomas Witherings, Jr., for the foreign office; Moore and Jessop through Watkins and Walter Warde. Billingsley also, the old Postmaster of the Merchant Adventurers, made a claim for the foreign office.[95]

The confusion in postal administration which naturally resulted from the struggle among the rival claimants was increased by the Civil War. In 1643 the Royal Court was moved to Oxford. The Secretaries of State acting as Postmasters-General sent James Hicks, the quondam servant of Prideaux, to collect arrears from the postmasters due to the Letter Office. In addition to collecting the money due, he was to require all postmasters on the road to Coventry to convey to and from the Court all letters and packets on His Majesty's service, to establish new stages, to forward the names of those willing to supply horses and guides, and to report those postmasters who were disobedient or disloyal.[96] During the most desperate period of the royal cause Hicks acted as special messenger for the King, and apparently had some exciting experiences in carrying the letters of his royal master. He lived to enjoy his reward when the second Charles had come to his own. Parliament, in the meantime, was establishing its control over the posts and reorganizing the service. In the early period of Parliamentary government, postal affairs were as a rule looked after by what was known as the "Committee of Both Kingdoms," and the orders which it issued were necessarily based upon political conditions. Later the Postmaster-General acted under the Council of State or under Cromwell himself. In 1644 the House of Commons issued an order that protection should be granted to the postmasters between London and Hull, to their servants, horses and goods.[97] The fact that it was necessary to re-settle posts on the old established London-Berwick road shows how demoralized conditions had been during the conflict.[98] Many of the loyal postmasters were dismissed. Their lukewarm conduct in supplying the messengers of the Commonwealth with horses produced a reprimand from the Committee and a sharp warning from Prideaux.[99] Posts were settled from London to Lyme Regis for better communication with the southwestern counties. In 1644 Edmund Prideaux was formally appointed Postmaster-General.[100] He was allowed to use as his office part of the [21]building occupied by the Committee of Accounts, formerly the house of a London alderman.[101] As long as the war continued it was necessary that a close watch should be kept over letters passing by post. Many of the new postmasters were military men and in addition others were appointed in each town under the heading of "persons to give intelligence."[102] With the return of normal conditions after 1649 Prideaux was ordered by the Council of State to make arrangements for establishing posts all over England as in the peaceful days before the war.[103] His report of the same year to the Council of State indicates the successful fulfilment of his instructions. He said that he had established a weekly conveyance of letters to all parts of the Commonwealth and that with the receipts from private letters he had paid all the postmasters except those on the Dover road.[104]

For the safety of the Commonwealth it was often found necessary to search the letters. Sometimes the posts were stopped and all the letters examined. When this was done, it was by order of the Council of State, which appointed certain officials to go through the correspondence.[105] Sir Kenelm Digby, writing to Lord Conway from Calais, asks him to direct his letters to that place, where they would find him, "if no curious overseer of the packets at the post break them open for the superscription's sake."[106] The Commonwealth did openly and is consequently blamed for what had been done more or less secretly by the Royal Government.

In 1651 the first proposal for farming the Post Office was submitted to the Council of State. The Council reported the question to Parliament but there is no evidence as to their attitude on the question at that time.[107] The next year Parliament ordered that the question of management, whether by contract or otherwise, should be re-committed to the Council,[108] and in 1653 it was decided that it would be better to let the posts out to farm. Prideaux had been quietly dropped by the Council after making, as it was reported, a [22]large fortune. When we remember that under his management there was an annual deficit of £600 besides the expenses of the Dover road and that in 1653 there was a net revenue of £10,000, it seems probable that there is some truth in the report. The conditions upon which the Post Office was farmed, were as follows:—

The farmers must be men of stability and good credit and must be selected from those contracting. Official letters and letters from and to members of Parliament must be carried free. All postage rates must be fixed by the Council and not changed without its consent. Finally all postmasters should be approved by the Council and Lord Protector.[109]

The policy of the Commonwealth in letting the posts out to farm had much in its favour. The evil usually resulting from farming is the temptation and the opportunity it offers for extortion from the people. But in the case of the posts no oppression was possible, for the farmer was limited in his charge to the rate fixed by the Government. More than this, private control over the post office business afforded what was most needed at the time, greater economy and stricter supervision over the deputy postmasters. It was upon the deputy postmasters alone that the farming system might exercise undue pressure, but from them there was no complaint of the withholding or reduction of wages until after Cromwell's death.[110]

John Manley was appointed "Farmer of the Posts" for two years at a yearly rent of £10,000. There were at least four higher tenders than his, and Manley contracted only for £8259. It was hinted that Manley and the Council had come to a private agreement concerning the rent to be paid.[111] In his orders to the postmasters, Manley [23]requested them to take particular care of government packets and to see that no one was allowed to ride in post unless by special warrant. All letters should be counted by them and the number certified in London. They were to keep a sharp eye upon people, especially travellers, and report any discontent or disaffection.[112] In 1654 Manley's title of Postmaster-General was confirmed by act of Parliament, the first act dealing directly with postal affairs.[113] He was unsuccessful in having his franchise extended beyond the original two years, and by order of the Council of State the management of the Posts was entrusted to Mr. Thurloe, Secretary of State, for £10,000 a year, the same amount which Manley had paid.[114]

Shortly after Thurloe had been appointed Postmaster-General, general orders were issued by Cromwell to all the postmasters. He forbade them to send by express any letters or packets except those sent by certain officials on affairs of state, all others to await the regular time for the departure of the mails. The old regulations for providing mail-bags, registration of the time of reception, and the like were repeated. The number of mails to and from London was increased from one to three a week each way, and to ensure higher speed, each postmaster was to provide a horse ready saddled and was not to detain the mail longer than half an hour under any consideration. He was ordered to deliver all letters in the country at or near his stage and was to collect the postage marked on the letter unless it was postpaid. The money so collected was to be returned to London every three months.[115]

In 1657 the first act of Parliament was passed which fixed rates for the conveyance of letters and established the system for the British Islands. The preamble stated: "That whereas it hath been found by experience that the writing and settling of one General Post Office ... is the best means not only to maintain certain intercourse of trade and commerce betwixt all the said places to the great benefit of the people of these nations, but also to convey the public despatches and to discover and prevent many dangerous and wicked designs, [24]which have been and are daily continued against the peace and welfare of this Commonwealth," it is enacted that there shall be one General Post Office called the Post Office of England, and one Postmaster-General nominated and appointed by the Protector for life or for a term of years not exceeding eleven.[116] In accordance with the terms of this act, Thurloe was appointed by Cromwell and continued to act as Postmaster-General until the downfall of the Commonwealth.[117]

After the Restoration most of the old claimants to the Post Office came to the front again. Stanhope besieged King and Parliament for restoration to his old place. He seems to have received some compensation, which he deserved for his pertinacity if for nothing else. The Porters were up in arms at once, for he had promised them to come to no agreement until they were satisfied.[118] The two daughters of Burlamachi pleaded for some mark of favour, on the ground that their father had ruined himself for the late King. Frizell was still very much alive, and a nephew of Witherings carried on the family feud.[119] In the meantime James Hicks was employed by the Secretary of State to ascertain how many of the old deputy postmasters were still eligible for positions. He reported that many of them were dead and that many of those who were applying for positions had been enemies of the King. For the time being it was decided that the present officials should remain in office until a settlement should be made.[120]

Henry Bishop was appointed by royal patent Postmaster-General of England for seven years at a rent of £21,500 a year. The King agreed to persuade Parliament to pass an act[121] settling the rates and terms under which Bishop was to exercise his duties. For the time being he was to charge the same rates as those in the [25]"pretended Act of 1657," to defray all postal expenses and to carry free all public letters and letters of members of Parliament during the present session. He agreed also to allow the Secretaries to examine letters and not to change old routes or set up new without their consent. He was to dismiss all officials whom they should object to on reasonable grounds. If his income should be lessened by war or plague or if this grant should prove ineffectual, the Secretaries agreed to allow such abatement in his farm as should seem reasonable to them.[122] Bishop's régime does not seem to have been popular with the postmasters, for a petition in behalf of 300 of them, representing themselves to be "all the postmasters in England, Scotland, and Ireland," was presented to Parliament in protest against the Postmaster-General's actions. They describe how Cromwell had let the Post Office out to farm. They credit him with respecting their rights and paying their wages. Lately, however, Bishop had been appointed farmer, and unless they submitted to his orders, they were dismissed at once. He had decreased their wages by more than one half, made them pay for their places again, and demanded bonds from them that they should not disclose any of these things.[123]

In 1633, Bishop resigned his grant to Daniel O'Neale for £8000. O'Neale offered £2000 and, in addition, promised £1000 a year, during the lease, to Bennet, Secretary of State, if he would have the assignment confirmed. He explained that this would not injure the Duke of York's interest, who could expect no increase until the expiration of the original contract, which still had four years and a quarter to run.[124] This refers to an act of Parliament which had just been passed, settling the £21,500 post revenue upon the Duke of York and his male heirs,[125] with the exception of some £5000 which had been assigned by the King to his mistresses and favourites. O'Neale having died before his lease expired, his wife, the Countess of Chesterfield, performed his duties until 1667.[126]

According to the grant made to O'Neale in 1663 no postmaster nor any other person except the one to whom it was directed or returned was to open any letter unless ordered so to do by an express warrant from one of the Secretaries of State. If any letter was overcharged, the excess was to be returned to the person to whom it was directed. Nothing was said about letters which were lost or stolen in the post. A certain John Pawlett complained that of sixteen letters which he had posted not one was ever delivered in London although the postage was prepaid.[127] Letters not prepaid were stamped with the postage due in the London Office when they were sent from London. Letters sent to London were charged by the receiving postmaster in the country and the charge verified at the London Office. An account was kept there of the amounts due and the postmasters were debited with them, less the sum for letters not delivered, which had also to be returned for verification.[128] All this meant losses to the postal revenue, but compulsory prepayment would have been impracticable at the time. The postmasters had nothing to gain by retaining letters not prepaid, but by neglecting to forward prepaid letters, they could keep the whole of the postage, for stamps were unknown. An incentive to the delivery of letters was provided by the penny payment which it was customary to give the postmasters for each letter delivered, over and above the regular postage. The postmasters were required to remit the postage collected to London every month and give bonds for the performance of their duties.[129]

The postal service was very much demoralized by the plague in 1665 and 1666 and the great fire which followed. Hicks, the clerk, said that the gains during this time would be very small. To prevent contagion the building was so "fumed" that they could hardly see each other.[130] The letters were aired over vinegar or in front of large fires and Hicks remarks that had the pestilence been carried by letters they would have been dead long ago. While the plague was still dangerous, the King's letters were not allowed to pass [27]through London.[131] After the fire the headquarters of the Post-Office in London were removed to Gresham College.

When O'Neale's lease had expired in 1667, Lord Arlington, Secretary of State, was appointed Postmaster-General.[132] The real head was Sir John Bennet, with whom Hicks was entirely out of sympathy. He accused Bennet of "scurviness" and condemned the changes initiated by him. These changes were in the shape of reductions in wages. The postmasters' salaries were to be reduced from £40 to £20 a year. In the London Office, the wages of the carriers and porters were also to be reduced.[133]

At the close of the seventeenth century there were forty-nine men employed in the Inland Department of the Post Office in London. The Postmaster-General, or Controller as he was sometimes called, was nominally responsible for the whole management although the accountant and treasurer were more or less independent. Then there were eight clerks of the roads. They had charge of the mails coming and going on the six great roads to Holyhead, Bristol, Plymouth, Edinburgh, Yarmouth, and Dover. The old veteran Hicks had been at their head until his resignation in 1670. The General Post Office building was in Lombard Street.[134] Letters might be posted there or at the receiving stations at Westminster, Charing Cross, Pall Mall, Covent Garden, and the Inns of Court. From these stations, letters were despatched to the General Office twice on mail nights. For this work thirty-two letter carriers were employed, but they did not deliver letters as their namesakes now do. The mails left London for all parts of the country on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday late at night or early the next morning. On these days all officials had to attend at 6 P.M. and were generally at work all night. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday when the mails arrived from all parts of England they had to be on hand at 4 or 5 A.M. The postage to be paid was stamped on the letters by the clerks of the roads. In addition three sorters and three window-men were employed. The window-men were the officials who stood at the window to receive the letters handed in and to collect [28]postage when it was prepaid. Then there were an alphabet-man, who posted the names of merchants for whom letters had arrived, a sorter of paid letters, and a clerk of undertaxed letters.[135] In the Foreign Office, there were a controller, two sorters, an alphabet-man, and eight letter receivers, of whom two were women. In addition the Foreign Office had a rebate man who saw that overcharged letters were corrected. Both offices seem to have shared the carriers in common.[136]

Before 1680 there was no post between one part of London and another. A Londoner having a letter for delivery had either to take it himself or send it by a special messenger. The houses were not numbered and were generally recognized by the signs they bore or their nearness to some public building. Such was the condition in the metropolis when William Dockwra organized his London Penny Post. On the first of April, 1680, London found itself in possession of a postal system which in some respects was superior to that of to-day. In the Penny Post Office as so established there were employed a controller, an accountant, a receiver, thirteen clerks in the six offices, and about a hundred messengers to collect and deliver letters. The six offices were:—

The General Office in Star Court, Cornhill;

St. Paul's Office in Queen's Head Alley, Newgate Street;

Temple Office in Colchester Rents in Chancery Lane;

Westminster Office, St. Martin's Lane;

Southwark Office near St. Mary Overy's Church;

Hermitage Office in Swedeland Court, East Smithfield.

There were in all about 179 places in London where letters might be posted. Shops and coffee-houses were used for this purpose in addition to the six offices, and in almost every street a table might be seen at some door or shop-window bearing in large letters the sign "Penny Post Letters and Parcels are taken in here." From these places letters were collected every hour and taken to the six main receiving-houses. There they were sorted and stamped by the thirteen clerks. The same messengers carried them from [29] the receiving-houses to the people to whom they were addressed. There were four deliveries a day to most parts of the city and six or eight to the business centres.

The postage fee for all letters or parcels to be delivered within the bills of mortality was one penny, payable in advance. The penny rate was uniform for all letters and parcels up to one pound in weight, which was the maximum allowed. Articles or money to the value of £10 might be sent and the penny payment insured their safe delivery. There was a daily delivery to places ten or fifteen miles from London and there was also a daily collection for such places. The charge of one penny in such cases paid only for conveyance to the post-house and an additional penny was paid on delivery. From such places to London, however, only one penny was demanded and there was no fee for delivery. The carriers in London travelled on foot, but in some of the neighbouring towns they rode on horseback.[137]

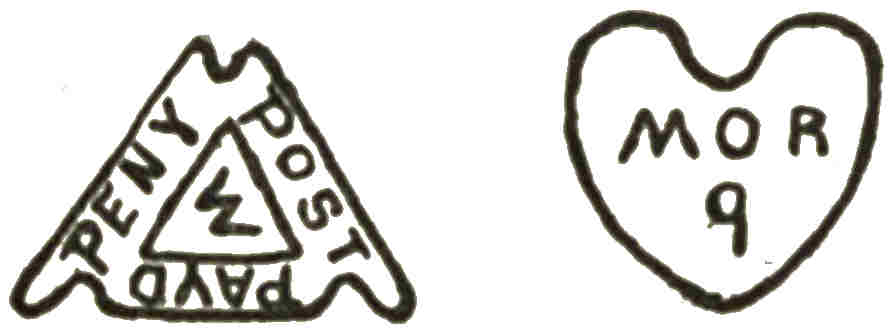

Dockwra is credited with being the first to make use of post-marks. All letters were stamped at the six principal receiving-offices with the name of the receiving-office and the hour of their reception. For instance, we have samples of letters post-marked thus:

The first figure shows that they were Penny Post letters and that they were prepaid. The "W" in the centre is the initial letter of the receiving-office, Westminster. The second figure shows the hour of arrival at the Westminster office, 9 A.M. The earliest instance of these marks is on a letter dated Dec. 9, 1681, written by the Bishop of London to the Lord Mayor.[138]

Whenever letters came from any part of the world by the General Post, directed to persons in London or in any of the towns where the Penny Post carriers went, they were handed over to these carriers to be delivered. In the same way, letters directed to any part of the world might be left at any of the receiving-offices of the Penny Post to be carried by its messengers to the General Office. This must have increased greatly the number of letters carried by the General Post. In the case of letters arriving by the General and delivered by the Penny Post, the postage was paid on delivery.[139] Over two hundred and thirty years ago then, London had for a time a system of postal delivery not only unrivalled until a short time ago, but in the matter of parcel rates and insurance not yet equalled.

What was Dockwra's reward for the boon which he had conferred? He himself says that it had been undertaken at his sole charge and had cost him £10,000. It had not paid for the first few months, and the friends who had associated themselves with him fell away.[140] As long as it produced no surplus, Dockwra was left to do as he pleased, for the General Post was gaining indirectly from it. As soon as it began to pay, the Duke of York cast his eye on it. In 1683 an action was brought against Dockwra for infringing upon the prerogative of His Royal Highness, and the Duke won the case. The Penny Post was incorporated in the General Post soon after.[141] After William and Mary had come to the throne, Dockwra was given a pension of £500 a year for seven years. At the end of that time he was appointed manager of the Penny Post Department of the General Post and his pension was continued for three years longer. In 1700 he was dismissed, charged with "forbidding the taking in of band-boxes (unless very small) and all parcels above one pound in weight, with stopping parcels, and opening and detaining letters."[142] Such was Dockwra's reward and such had been Witherings'. He who would reform the Post Office must be prepared to take his official life in his hands.

The transition between two reigns was usually a period of unrest and disquietude, and the Revolution which resulted in the expulsion of James was naturally accompanied by internal disorder. For a time the posts suffered quite severely. The Irish and Scotch mails were robbed several times and not even the "Black Box" escaped. This was the box in which were carried the despatches between Scotland and the Secretaries of State, the use of which was not discontinued until after the accession of the new King and Queen. After 1693 each Secretary was to send and receive his own despatches separately and all expenses were to be met from the proceeds of the London-Berwick post.[143] Major Wildman had been appointed to the oversight of the Post Office, but held office for a few months only, being succeeded in 1691 by Cotton and Frankland. The Postmasters-General were henceforth to act under the Lords of the Treasury.[144]

Important improvements in the frequency and extension of postal communication were inaugurated under the management of Cotton and Frankland. It was, however, for the extension of the foreign postal service and for that to Ireland and the plantations that their administration is most notable.

On Monday and Thursday letters went to France, Italy, and Spain, on Monday and Friday to the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark. On Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, mails left for all parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and there was a daily post to Kent and the Downs. Letters arrived in London from all parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, from Wales every Monday and from Kent and the Downs every day. Besides the establishment of the General Post in London, there were about 200 deputy postmasters employed in England and Scotland.[145] The Irish Post was supervised from London and during the Irish war its headquarters in Ireland [32]were transferred from Dublin to Belfast. It was directly managed by a Deputy Postmaster-General, aided by ten or a dozen officials and clerks. The net receipts were sent to England and the books were audited by a deputy sent over by the Auditor-General of the English Post.[146]

The Scotch Post Office was not in so good condition as the Irish. The time when every Scotchman could read and write was yet very far distant. The only post road of any importance was from Edinburgh to Berwick and this had been established by the English. For many years the vast majority of letters travelling over this road were official despatches. After the crowns of England and Scotland were united, it was necessary for the English Government to keep in close touch with Scotland and "Black Box" made frequent journeys between the two countries. The canny people in the north had discovered a rich country to the south waiting to be exploited, and the post horses between Edinburgh and London were kept busy carrying the lean and hungry northern folk to the land of milk and honey. Until 1695 the English and Scotch Post Offices had been united under the English Postmaster-General with an Edinburgh deputy; but by the Scotch act of 1695 the Post Office of Scotland was separated from that of England. The terms of this act were much the same as those of the English act of 1660, although the rates established were somewhat higher. There was to be a Postmaster-General living in Edinburgh, who was to have the monopoly of carrying all letters and packets where posts were settled.[147]

The first proposal for a postal establishment in the American colonies came from New England in 1638. The reason given was that a post office was "so useful and absolutely necessary."[148] Nothing was done by the home government until fifty years later when a proclamation was issued, ordering letter offices to be settled in convenient places on the North American continent. Rates were established for the continental colonies and Jamaica.[149] In 1691, acting upon a report of the Governors of the Post-Office, the Lords [33]of Trade and Plantations granted a patent to Thomas Neale to establish post offices in North America. About the same time an act was passed by the Colony of Massachusetts appointing Andrew Hamilton Postmaster-General. The Lords of Trade and Plantations called attention to the fact that this act was not subject to the patent granted to Neale. Matters were adjusted by Neale himself, who appointed Hamilton his deputy in North America.[150] In 1699 a report was made by Cotton and Frankland to the Lords of the Treasury based on a memorial from Neale and Hamilton. The latter had established a regular weekly post between Boston and New York and from New York to Newcastle in Pennsylvania. The receipts had increased every year and now covered all expenses except Hamilton's own salary, £200. Postmasters had been appointed in New York and Philadelphia, Hamilton himself being in Boston. The New York postmaster received a salary of £20 with an additional £90 for carrying the mail half-way to Boston. The Philadelphia postmaster was paid £10 a year.[151]

The business of the Post Office was rapidly increasing. The same decade that saw the establishment of the Board of Trade witnessed also the organization of the Colonial Post. The expansion of English commerce[152] necessarily reacted on communications both internal and foreign, while the linking of the country posts with the general system and the stimulus given by the London Penny Post showed itself in the increased postal revenue.[153] The way was prepared for the great expansion of the following century, an expansion turned to account as a source of taxation.

THE POSTAL ESTABLISHMENT AN INSTRUMENT OF TAXATION

1711-1840

The year 1711 is an important landmark in the history of the British Post Office. England and Scotland had united not only under one king but under one Parliament, the war with France made a larger revenue necessary, the growth of the Colonies required better communication with the mother country and each other, and it was highly expedient that certain changes in the policy of the Post Office should receive parliamentary sanction. The act of 1711 was intended to meet these conditions. The English and Scotch Post Offices were united under one Postmaster-General in London, where letters might be received from and sent to all parts of Great Britain, Ireland, the colonies and foreign countries. The postage rates were increased to meet the demand for a larger revenue. In addition to the General Office in London, chief letter offices were ordered to be set up in Edinburgh, Dublin, New York, the West Indies, and other American colonies, and deputies were appointed to take charge of them.