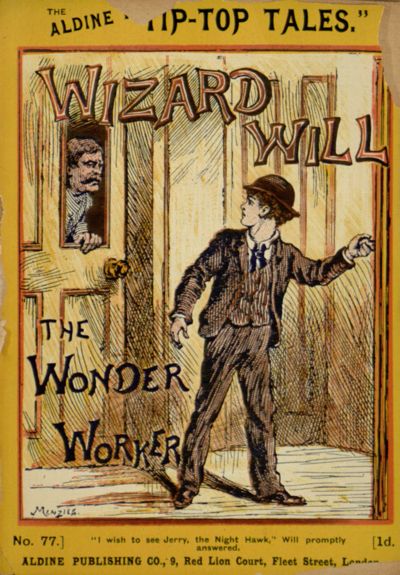

Title: Wizard Will, the Wonder Worker

Author: Prentiss Ingraham

Release date: July 26, 2013 [eBook #43301]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

CHAPTER I.—The Boy Messenger.

CHAPTER II.—An Oath to Win, a Vow to Avenge.

CHAPTER III.—Tracked to His Lair.

CHAPTER IV.—The Meeting.

CHAPTER V.—The Boy Protector.

CHAPTER VI.—The Reward for a Convict.

CHAPTER VII.—The Lost Gold Piece.

CHAPTER VIII.—The Dashing Dragoon.

CHAPTER IX.—Phantoms of the Past.

CHAPTER X.—Deserted.

CHAPTER XI.—A Rebuff.

CHAPTER XII.—The Boy Captive.

CHAPTER XIII.—Put to the Test.

CHAPTER XIV.—Will Plays his little Game.

CHAPTER XV.—The Boy Guide.

CHAPTER XVI.—The Raid.

CHAPTER XVII.—On Secret Service.

CHAPTER XVIII.—Headed Off.

CHAPTER XIX.—Unknown Kindred Ties.

CHAPTER XX.—The Grave on the Prairie.

CHAPTER XXI.—Retribution at Last.

CHAPTER XXII.—Insnared by a Watch.

CHAPTER XXIII.—Wizard Will's Luck.

CHAPTER XXIV.—Conclusion.

ALDINE PUBLISHING CO., 9, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street, London.

THE

This is the largest (containing more good reading), the Cheapest and BEST TWOPENNY LIBRARY IN THE WORLD.

Each carefully written volume is guaranteed to be a work of absorbing interest and of the highest Literary Merit.

VOLUMES NOW READY.

1. Buffalo Bill. His Life and Adventures in the Wild West

2. The Comrade Scout of Buffalo Bill

3. The Cabin-Boy of the "Polly Ann"; or, the Gardens of Paradise

4. Mexican Joe. His wonderful Life, Exploits, and Adventures

5. The Sailor Castaways; or, the Buried Treasure of Phantom Island

6. The Death's Head Cuirassiers; or, Brave of all Braves

7. The Boy Wonder; or, the Star of the Circus

8. Joe Phœnix, the Police Spy

9. Billy Boots, the Jockey, and Colonel Plunger

10. The Mystery of the Satin-wood Box

11. The Armourer's Apprentice. A Story of "The Battle and the Breeze."

12. The Red Rajah; or, the Scourge of the Indies

13. The Whitest Man in the Mines, and Charley Jones, the "Angel" of Dogtown

14. The Mad Hussars; or, the O's and the Macs. A Story of Four Irish Soldiers of Fortune

15. "One Eye," the Cannoneer; or, Marshal Ney's Last Legacy

16. The "Deep One;" or, the Puzzled Detective

17. Larry Locke; or, A Fight for Fortune

18. "Parson Jim," King of the Cowboys

19. Little Charlie and Pug Billy. A Mystery of the Thames

20. The Skipper of the Seagull; or, the Fog Fiend of Newfoundland

21. Life and Adventures of Barnum, the Emperor of Showmen

22. Joe Phœnix's Great Man Hunt; or, the Captain of the Wolves

23. The Irish Captain. A Tale of the Fight at Fontenoy

24. Nemo, King of the Tramps; or, a Romany Girl's Vengeance

25. The Saucy Jane, Privateer

26. Journeyman John, the Champion

27. The Maverick Hunters; or, the Night Riders of Satanta County

28. The Man in Red; or, the Ghost of the Old Guard

29. Top Notch Tom, the Cowboy Outlaw

30. The Marshal of Satanstown; or, the League of the Cattle-lifters.

31. Lance and Lasso; or, Adventures on the Pampas

32. The Three Frigates, and the Peerless Privateer

33. The Russian Spy; or, the Brothers of the Starry Cross

34. The Demon Duellist; or, the League of Steel

35. The Wild Ranger; or, the Crack Shot of the West

36. The Mutineer. A Romance of Sunny Lands and Blue Waters

37. Captain "Freelance," the Buccaneer

38. Montezuma the Merciless; or, the Eagle and Serpent

39. Overland Kit; or, the Idyl of White Pine

Continued on page 2 of cover.

O, my boy! do you wish to make a dollar?"

"I do, sir—indeed I do."

"What is your name?"

"Will, sir."

"Well, Will, can you keep your mouth shut?"

"Yes, sir."

"Can you be blind, if need be?"

"You mean not to see anything that is not intended for me to see, sir?"

"Yes."

"I understand, sir."

"Well, it is important that this letter reaches a friend of mine, as I cannot go myself, so you take it to the number; can you read?"

"Yes."

"Well, take it to the number on the envelope, and ring the bell sharply three times; then ask for Jerry, the Night Hawk; will you remember the name?"

"Yes, sir—Jerry, the Night Hawk."

"Yes, that's it; and you must give him the letter in person."

"Suppose he is not there, sir?"

"Then find out when he will be, and keep the letter for him; and see, I write on the back here for him to give you a couple of dollars, after which go your way, and forget all about what you have done."

"Yes, sir;" and the boy took the note and turned to depart to the address on the envelope, when he was called back, while the man stood in silent thought.

He was a gentlemanly looking person, with a face, however stamped with dissipation.

In the neighbourhood where he had met the boy, he appeared to be out of place.

For half a moment he stood, gazing at the face of the youngster, and then he said:

"My boy, do you remember to have seen me before?"

"No, sir; and yet it seems as if I had."

"It so seems to me, and your face comes to me like a dream of the past which I cannot recall; but—never mind; go and do as I have told you, and you will get your pay," and the man walked on down the street; but before he had gone far he sprang into a hack, which had evidently been waiting for him, and was driven away.

The boy thus intrusted with what was evidently an important note, was an urchin of twelve; but he looked older, and there was that in his bright, handsome face which denoted both courage of a high order and intelligence beyond his years.

He was poorly, very poorly clad, but his clothing was clean, and he evidently took pride in appearing at his best.

The locality he was in was a hard one, one of the worst localities in the city of New York, and rude, rough characters—men, women and children—were in the streets.

But the lad went on his way without noticing any one, and, as though acquainted with his surroundings, turned into a wretched street that was little more than an alleyway.

He stopped at a certain number and seized the bell knob, which appeared to belong to a bygone age, and in fact the house was a quaint old structure that had long been the abode of poverty.

His three sharp rings, as he had been directed to give, were answered by the door opening, seemingly without human agency, while a gruff voice demanded:

"Well, step inside and tell me what you want?"

The messenger stepped into a small hallway, and saw before him, a few feet distant, another door, while, through an open panel in it peered a man's face.

"I wish to see Jerry, the Night Hawk," explained the youngster.

"What do you want with him?"

"I have a letter for him."

"Give it to me."

"No, sir, for I have orders from my boss to give it only to Jerry."

"All right, you can go up and see him, top floor, right hand side front room," was the reply, and as the man spoke the other door closed behind the boy, the one in his front opened, and he found he was in a hallway, into which no doors opened, except the one through which he had passed, and in the rear was only a pair of stairs occupying the entire width of the narrow passageway.

A dim light came from above somewhere, and the messenger ascended the stairs to the second floor, where he saw doors upon either side.

Ascending to the third floor, he sought the door to which he had been directed, and knocked.

No answer came, and he waited a while and again knocked.

Still no answer, and then his eyes fell upon a small knob, which he pulled and found to be a bell.

Still no response, and the thought came to him to ring it three times, as he had the bell below stairs.

This he did, and instantly he heard a voice behind him.

"Well, youngster, what is it you are after?"

He was startled, and turning saw a man's face at a panel in the door.

"I wish to see Jerry, the Night Hawk," answered Will, promptly.

"Who sent you?"

"That I will tell him," was the cool reply.

"Well, I'm Jerry, the Night Hawk."

The boy looked incredulous, and the man opened the door, and called to him to enter.

This he did, and found himself in a hallway that was perfectly square, and the light came into it from above through a skylight.

There was no door in this hall, except the one by which he had entered, but the man said:

"Is there an answer?"

"Yes, sir," said the boy, when he had meant to say 'no,' but he did not correct himself, and instantly the man tapped three times upon the wooden wall of the hallway.

To the new surprise of the boy one side of it was at once run upward, revealing a small room, and into this the two stepped, the man telling the youngster to follow.

In the room was a cot-bed, a table, and a rough-looking individual stood in one corner, holding a rope in his hand, and which he now let go, the wooden partition, under which they had passed, immediately sliding back into place again.

"Now, lad, the letter," said the man who had entered the room with him.

"Are you Jerry, the Night Hawk?" and the boy looked the man straight in the eyes.

"Yes."

The boy took out the letter and handed it to him, and glancing at the address he broke open the envelope.

What was written within was to the point, and very short, for the man at once said:

"Yes, you are just the boy we want, as the captain says," and he gazed into the handsome, fearless young face before him.

"What do you want me for?" asked the lad.

"That you shall soon know, and if you serve us well, you will be well treated; but if not, then you will have to die, that is all," was the ominous reply of the man, as he seized the boy by the shoulder and dragged him through a door into a large room where were a dozen men, whose scowling faces were turned upon the lad with a look that was wicked and threatening. As he recalled the words of Jerry, the Night Hawk, and beheld the wild, evil looking men about him, the heart of the brave boy shrank with fear, for it needed no words to tell him that he had been led into some trap from which there seemed little chance of escape.

HE scene of my story shifts from the city to the country. A young man, evidently city bred, was standing beneath the shelter of a woodman's shanty, while the rain poured in torrents, and sent little brooks surging like miniature rivers adown the hillsides.

It was in one of the most beautiful localities of the State of Maryland, where forest, stream, woodland and vale stretched away in picturesque attractiveness for miles, and where the broad fields of well-to-do farmers were filled with the golden grain.

The young man was clad in sporting garb, carried a gun, which he shielded from the dampness, and at his feet crouched a dog, while the game-bag hanging on a limb near-by proved the sportsman's skill.

It was approaching sunset time, and the storm had been raging for a couple of hours, the rain-fall being so heavy as to deluge the country, and make foaming torrents of mere rivulets.

"It is clearing now, and I will venture, for I would not like to be caught in the wood by darkness, as I would have to remain all night," and the sportsman gazed up anxiously at the clouds, breaking away in the westward.

He was a man of twenty-six perhaps, and his erect form, elegant manners and handsome face had won many a girl's heart.

A Philadelphian, and the ideal of society, he had run away from dissipation and comrades for a few days shooting in Maryland, and his first day of sport had been checked by the storm.

As the rain ceased falling he threw his game bag over his shoulder and started out upon his return to the little Cross-Roads Inn where he was stopping.

He had to pick his way carefully, and often, as it was, he went into water nearly up to the top of his boots.

At last he came to a rustic bridge, across a brook; but the brook was now surging beyond its banks, and driving furiously along.

"Ho, don't cross there!" cried a voice from the other side.

But the hunter heeded not the warning and sprang upon the bridge.

It was tottering, for its foundations had become undermined; but he hastened on; it trembled, swerved, rocked, and he sprang quickly toward the other shore, but too late, as before and behind him the spans were torn away, and the centre one, upon which he stood must go next.

"Ah! I cannot swim, and am lost!" he cried, in a tone of horror.

"I will save you," shouted the same voice from the shore.

Then followed the words: "Throw your gun and game-bag away, and spring clear of the wreck when I call to you."

The hunter tossed his fine gun and game-bag from him and nerved himself for the ordeal.

He saw the one who had called to him—a tall, fearless-faced young[Pg 5] man—throw aside his coat and hat and plunge into the whirling waters, some distance above the bridge.

As he came sweeping down the bold swimmer called out:

"Now jump!"

The hunter obeyed, and sank beneath the foaming current; but, as he arose, his arm was seized by the swimmer, and at the same instant the tottering centre of the bridge gave way, and was swept after them.

"Don't be alarmed, but keep cool, and I'll work toward the bank with you."

"There, put your hands on my shoulders! That's right, and you are as serene as a May morn; so all will be well;" and the swimmer struck out for the bank, and at last caught the bough of an overhanging tree.

It blistered his hands to hold on; but he did so, and the hunter, who was perfectly self-possessed, also grasped the tree, and both clambered up the bank.

"I owe you my life, my man, and you have but to name your price," said the sportsman.

"Thank you, stranger, but I am not a professional life-saver, and money would not have tempted me to have gone to the aid of one who could not swim."

"But come, I was on my way to Miller Raymond's, and I can make bold to take you there, as I'm about one of the family, I may say, for I soon will be."

"The miller will send you over to the inn in his spring waggon, for I guess you're the city gentleman I heard was stopping there."

The sportsman saw that his bold rescuer, evidently a farmer, was one who had pride, and merited the treatment of a gentleman.

"I beg pardon for offering you money, but it could never repay the service, so we'll be friends.

"My name is Schuyler Cluett, and that I appreciate your saving my life you must know."

The young farmer, for such he was, grasped the outstretched hand, and said:

"My name is Kent Lomax, and I'm glad you begged my pardon, for it proves you to be the man I thought you when I saw your pluck in the water. You were as cool as an icicle. But let us move on, for we'll get cold staying here."

So on they went along the road bordering the stream, and just at dark, came in view of an old mill standing upon the bank, the water-wheel turning furiously, while up on the hillside was a handsome country house, that had the look of being the abode of one who enjoyed living.

"Well, Kent, you and your friend have been caught in the storm, that's certain," said an honest-faced old man, meeting them at the door.

"We've been caught in the creek, Miller Raymond; and this is Mr. Schuyler Cluett, a city gentleman, stopping at the Cross-Roads Inn, for a few days shooting, and I told him you would send him over."

"I am glad to meet you, sir; but I guess you'd better stay with us to-night, for we can rig you out, as well as Kent, and I've got a little apple brandy that will do you both good."

"I thank you, sir;" and then Schuyler Cluett added: "But let me say that my modest friend here failed to tell you that he saved my life, as the bridge went in with me, and I cannot swim a stroke."

"Ah! that is just like Kent; but here is my daughter, and he saved her life years ago in this same stream, when they were children together. Ruby, this is Mr. Cluett, whose life Kent has just saved; but hasten to lay out some of my clothes in the spare rooms, and tell your mother that we have guests to supper.

"Come, Mr. Cluett, you and Kent need a little internal warming up after your ducking," and the two young men dashed off a glass of apple brandy of the miller's own making, and then sought their respective rooms to change their clothes, for, after his eyes had fallen upon Ruby Raymond, the young sportsman had decided to remain all night at the miller's.

He felt that he did not look his best, in a corduroy suit of the miller's and a broad shirt collar; but he had to make the best of it, and so descended to the parlour.

Kent was already there, as was Miller Raymond, his wife, and Ruby, and the young sportsman was introduced, and again told the story of his rescue by Kent.

Then supper was served, and such a supper Schuyler Cluett had never sat down to before, he said, and with truth, for Mistress Raymond was noted for her housekeeping the country over.

During the evening Ruby sang, in a sweet soprano voice, played the piano with a skill that surprised the city-bred gentleman, and he found her to be lovely in face and form, with large, dark-blue eyes, golden hair, and a smile of the most fascinating sweetness, while her refinement of manner was as much a surprise to him as were her accomplishments.

Mr. Schuyler Cluett also learned a secret from the miller, and that was the fact of Ruby's engagement to Kent Lomax.

"Kent is a fine fellow, Mr. Cluett," volunteered the miller, "and we have known him from boyhood.

"His father married a crossed-grained woman after his first wife's death, and she made it so warm for the boy he ran away and went to sea.

"He was gone six years, and returned one day to find his step-mother dead, so he remained at home, took care of his father until his death, and now owns the farm, a mile from here, and a good one it is.

"He and Ruby have loved each other always, and they are to be married, come Christmas."

Schuyler Cluett went to his room that night, pondering over all he had heard, and at last he said half aloud:

"That beautiful girl marry that common fellow? Never! she shall be mine, and I swear it!"

And Schuyler Cluett kept his treacherous oath against the man who had saved his life, for the very eve of her wedding-day with Kent[Pg 7] Lomax, Ruby Raymond stole out of her pleasant room, unlocked the front door, and glided across the lawn to the foot of the hill, where in a buggy, with a pair of spirited horses, sat a young man awaiting her.

"Come, hasten, Ruby," he said in a low tone.

"Oh, Schuyler, I have given up all for you, my parents, my happy home, and poor Kent.

"It will break his heart; but then it would have broken my heart to become his wife loving you as I do."

And away sped the fleet horses, while the night wore on, the dawn came, Christmas morn, and Mrs. Raymond hastened to her daughter's room, to wish her only child a happy Christmas, a happy wedding day.

A shriek that broke from her lips, followed by a heavy fall, brought the miller to the room.

His wife lay unconscious on the floor, an open letter in her hand.

He read it, and his heart grew cold at the words:

"Forgive me, mother, father, forgive me; but I could not marry Kent, as I do not love him, my heart being another's.

"Finding out the secret of my heart, I would not perjure myself by marrying Kent Lomax, and so I fly to-night with the one whose wife I am to be.

"Some day, when you feel more kindly toward me, I will come back and plead for your forgiveness.

"Now good-bye, and Heaven bless you and poor Kent, whom my heart bleeds for in the sorrow I know he will feel.

"Your ever loving daughter,

"Ruby."

Loud and stern rang the miller's voice, calling for aid, and one servant was dispatched for the village doctor, for Mrs. Raymond still lay in a swoon, and another for Kent Lomax.

They arrived together, and Kent Lomax looked like a corpse as the miller read his daughter's letter, for the eyes of the deserted lover were blinded with grief and all seemed blurred before him.

"Miller Raymond," said the doctor softly, as he bent over the form of the mother.

"Well."

"Nerve yourself for another bitter blow."

"Oh Heaven! another?"

"Your wife is dead," was the low response, and the miller groaned, as he sank upon his knees by the body of his wife and grasping her hand buried his face in the pillow by the side of the one who had for twenty years borne his name, the mother of his child who had struck the death-blow.

"Dead! dead!" shouted Kent Lomax with wild eyes and writhing face.

"That man did this deed, for he fascinated poor Ruby, won her from me, from home, from all, and by the eternal Heaven I will track him to the death for this!

"I saved his life once, but now I will take away that life; I vow it, so help me Heaven!"

HERE was no handsomer bachelor rooms in the city of Philadelphia, than were those of Schuyler Cluett, the handsome young gallant and "man about town."

Society said he was very rich, that he had been left a large fortune by an uncle, and many were the young ladies who sought to win favour in his eyes.

His rooms consisted of a suite of five, for there was his parlour, combined with sitting-room, his bed-chamber, a spare one for a belated guest, a snug little kitchen, that was also used as a breakfast-room, and a sleeping place for a servant.

All were delightfully furnished, and the young bachelor was wont to take his breakfast at ten, his valet getting the meals for him, while his dinners and suppers he always took at the fashionable True Blue Club, of which he was a popular member.

At a stable near he kept his coupe and riding-horse, with a coachman, so that he lived in very great comfort; in fact, it amounted to luxury.

His bills were always promptly paid at the end of the month; he dressed with elegance, took the best seat at the opera and theatres, was able to take a run around to Long Branch, Cape May, Newport, Saratoga and the White Mountains in the summer, and having spare money always with him to lend a friend an X or a XX, he was rated a good fellow among the men.

One night, about one, a.m., Schuyler Cluett was preparing to retire, and a friend who had accompanied him home had been shown to the spare room, which also opened into the parlour, so that the two talked as they undressed.

"That deuced valet of mine is always away when I need him most," growled the young bachelor.

"Now, here he is off at a ball, and why servants must have balls I cannot understand, and both you and I, Rayford, are half drunk, and need him to look after our comfort."

"It's too bad!" sang out Rayford from his room.

"I'd discharge him, Schuyler."

"I will, and I do. I discharge him every day, but I hire him over again before he gets off, and that spoils him; so I'll discharge him some time for a week, and it will teach him a lesson—ah! there he is now, and I'll have to go out in the hall and let him in, for he's forgotten his night key," and Schuyler Cluett went to the door to answer a ring.

As the door opened, he began to berate his valet, as he supposed it was, but was considerably taken aback at beholding a stranger enter the hall.

He failed to recognise him at first, but suddenly beheld him in the full light of the parlour, whither the stranger had strode with the remark:

"I wish to see you, Mr. Schuyler Cluett."

"Ho, Lomax, my dear fellow, I did not know you; but you look ill and something has surely happened, for you are as haggard as though after a long illness," and Schuyler Cluett held out his hand.

"No, Cluett, I do not take the hand of a villain," was the stern reply of the young farmer.

"By Heaven! are you drunk? What do you mean?" and the eyes of the young aristocrat flashed, while his friend Rayford, half-dressed, peered out of his door, startled at the turn affairs had taken.

"I mean, Schuyler Cluett, that you, like a snake that you are, fascinated poor little Ruby Raymond, she that was to have been my wife.

"We were happy until you came, and she was all my own; but one unlucky day I dragged you away from death, and I took you to her home, and from that moment you began to win her from me.

"I saw it all, I felt it all, for she became unhappy, and she told me she thought we should be as sister and brother, for she loved me, but not as a wife should.

"She saw how it hurt me to hear her say so, and so she said she did not mean it; but she deceived me, for she did mean it, and one week ago, on the very eve of our wedding-day, you came like a thief in the night and stole her from me."

"Good Heaven! Lomax, I am not guilty of this, and you wrong me, indeed you do!" cried Schuyler Cluett, his face the picture of amazement.

Kent Lomax seemed astounded, and asked, sternly:

"Do you deny it?"

"I do. Upon my honour, yes!"

"You deny that you ran off with Ruby Raymond from her father's house, at twelve o'clock on the night of Christmas Eve?"

"I do."

"You lie in your false throat, man!" shouted the farmer, and at his words Schuyler Cluett sprang toward him; but quick as a flash, a pistol met him, the muzzle in his face, while the young farmer said sternly:

"Back! I did not come here unprepared, and I would kill you, oh! how gladly!"

"I tell you I am falsely accused; and being unarmed, and knowing your great strength, I am forced to hear you accuse me and submit to your insults, Kent Lomax."

"Schuyler Cluett, I know that you are guilty, for I tracked you in your villainy."

"Yet you find me here in my bachelor rooms, and there is a friend who is with me, and can vouch for my words."

"I can, indeed, sir, for I know that my friend Cluett has been but two days absent from the city the week past," and Randal Rayford stepped out of his room into the parlour, he having hastily dressed as he saw that a tragedy was threatening.

"Ah! he was two days absent, then?

"They are the two days in which he committed the crime of kidnapping and murder—"

"Murder? Great Heaven! of what else will you accuse me, Lomax?"

"Yes, of murder; for when poor Mrs. Raymond read the note left by Ruby, she fell in a faint, and she never came to herself again, but died, and four days ago I went to see her buried over in the village graveyard.

"Then I took your track, Schuyler Cluett, and I found out where you hired your team of fast horses, and where you drove to catch the train.

"There you bought two tickets for Baltimore, and I lost trace of you after I arrived in that city."

"You have tracked some other man, Lomax, for your sweetheart did not run off with me."

"And I say that I saw the man of whom you hired your horses, and he described you."

"Other men look like me, Lomax."

"And I saw the station-agent where you took the train for Baltimore, and he described you, and Ruby, also."

"An accidental resemblance."

"A man met you at that station, to drive the horses back to the town where you hired them."

"That proves nothing."

"Does this?" and Kent Lomax drew from his pocket a handkerchief.

"That is a lady's handkerchief, I believe," was the cool reply.

"It was left by Ruby Raymond in the waiting-room of the railroad station, and it bears her name."

"That proves that she did run off with someone; but who, Lomax, for I am not the guilty one?"

"Does this prove anything?" and the young farmer held up the gold head of a walking-stick.

Schuyler Cluett again started forward, as though to grasp it; but the pistol's muzzle once more confronted him, while Kent Lomax fairly hissed forth the words:

"This I found in the buggy, and there is the stick—see, it fits!" and stepping to a corner, he picked up a headless walking-stick of snake-root.

"You will not deny your guilt now, for this gold head bears your name, and it came off in the buggy, and you doubtless thought you had dropped it along the road."

"I say that I am not guilty," was the sullen reply.

"Well, sir, I say that you are, and I came here to kill you; but I will not be a coward and shoot down an unarmed man. Yet I will not allow you to escape, for I intend to right the wrong I believe you have done poor Ruby, and I have vowed, over the dead body of Mrs. Raymond, to avenge her death."

"What is your intention, Lomax, for this scene is growing monotonous to me?"

"My intention is to demand that you meet me face to face, arms in our hands, and as one gentleman should meet another, though I do not consider you worthy the name you have dishonoured."

"By the Lord Harry! but this is too much, and I will meet you were you the lowest of the low; so name your friend, and Mr. Rayford here will arrange with him!" hotly said Schuyler Cluett.

"I have no friend, but that gentleman will do, and he is all we need.

"I will meet you at sunrise, at any place you may state, for I do not know this city, and our weapons will be revolvers, the distance ten paces, that gentleman to give the word to fire, and to keep it up until one or both are killed."

"That will suit me," was the cool reply, and turning to his friend, he continued:

"You will act for us, Rayford, in this affair this mad fool has forced upon me?"

"Certainly, and there is a pretty spot, on the banks of the Schuylkill river we can select, for I know it well, and I will give this gentleman written instructions how to reach there.

"At sunrise you say?" and he turned to Kent Lomax.

"Yes, and sooner if it could be so."

"That is soon enough, and here is your directions to reach the spot," and he jotted down a few notes upon a paper.

"Thank you; and Schuyler Cluett if you prove yourself a coward and do not come, I will prove merciless and kill you at sight, as I would a snake," and Kent Lomax left the rooms.

NTIL the time for him to seek some means of reaching the spot, selected for the meeting, that he intended should be fatal to one of them, Kent Lomax walked the streets of the city, brooding deeply over his sorrows, and his determination to avenge Ruby, whom he looked upon with pity rather than anger, and her mother, whose death had been brought on by the act of Schuyler Cluett.

At daylight he sought a livery stable, and asked for a horse to ride out to the rendezvous.

"You can get a horse, sir, but you are unknown to us, and we must ask a deposit of his value," said the man.

"Ah! that is it, you fear I am a horse-thief; well, hitch a carriage for me and send a driver, one who knows how to reach this place," and he gave the directions where he wished to go.

Soon after he sprang into the vehicle and was driven away at a rapid pace, and in an hour's time was set down at a lonely spot on the riverbank.

Up the stream some distance he saw another vehicle draw up, and out of it sprang Schuyler Cluett and Rayford, and he walked hastily toward them.

"I am glad to see that you are not a coward," said Kent Lomax, addressing Schuyler Cluett.

"You are all wrong in this, Lomax, much as appearances are against me," said Cluett.

"I know I am right, for I have not had my eyes shut the past two months.

"Are you ready?"

"I am."

"I have brought a pair of weapons belonging to Mr. Cluett, sir, and you can take your choice," said Rayford, opened a box in which were a pair of handsome revolvers.

"I have a weapon, sir."

"It is best that they be alike."

"Very well, I will take one of these."

"Take your choice."

Kent Lomax selected one without an instant of hesitation, and said:

"This will do."

Rayford took the revolver and carefully loaded it, and then took up the other and did likewise.

Then he paced off ten paces, gave the men the choice of positions by tossing up a dollar, and Kent Lomax won.

Both took their positions, Schuyler Cluett with a quiet smile of confidence upon his face, and Kent Lomax calm, cold, but haggard, stern and determined.

The sun was now up, gilding the tree-tops and causing the dew to sparkle like diamonds upon the grass.

It was a pretty scene, and yet one that had been selected to be desecrated by a tragedy.

Each man took his position, revolver in hand, and standing to one side, Rayford said:

"Gentlemen, I am to give the word as follows:

"One, two, three, fire!

"Between the words three and fire, you are to pull trigger, and you can keep firing until one or the other falls, or you empty your weapons.

"Now, are you ready?"

Both nodded in the affirmative, and then in a loud voice came the fatal words:

"One! two! three—"

There was no need of uttering the word fire, for the revolver of each flashed at three.

And the result?

Schuyler Cluett staggered backward, his hand to his head, while Kent Lomax dropped as though a bullet had pierced his brain.

"Shot through the heart," said Rayford coolly, and then turning to his friend he added:

"I think that should cancel my indebtedness to you, Schuyler."

"What?"

"I put a ball of putty, wrapped with tin-foil, in his pistol, and even with it he left his mark in the dead centre of your forehead, for it is bruised; but had it been lead, you would have been a dead man."

"Great Heavens! did you do that?" asked Schuyler Cluett.

"I did."

"Rayford, I know not what to say; but as you have saved my life,[Pg 13] I will call the debt square between us; but see, he is not dead, and I will put him in his carriage and send him to a hospital, for we must look to our own safety now."

This was done; the body of the wounded, unconscious man was placed in the carriage that had brought him out, and the driver ordered to take him to a hospital.

Then the two friends entered their own carriage, and were driven, by another road, rapidly back to the city.

The next morning the following notice of the affair appeared in the morning papers:

"A MYSTERIOUS DUEL.

"At dawn yesterday morning a young gentleman evidently from the country, judging from his dress and appearance, went to Nailor's livery stable and sought to hire a saddle-horse for a few hours; but, upon the price of the animal being demanded, as he was an utter stranger to the foreman, he called for a carriage and driver, and ordered the latter to drive him to a spot on the Schuylkill river, between the Laurel Hill Cemetery and the Wissahickon creek, and to lose no time in getting there.

"Upon reaching the spot he left the vehicle, just as another carriage drove up in the distance, and from it alighted two gentlemen.

"There the stranger walked on and met them, reports his driver, and the three conversed together for a moment; then two of them threw off their overcoats, while the third paced off a certain distance and, after loading two weapons taken from a case, handed them to the duelists.

"Word was then given, the driver supposes—for he was too far off to hear—and the pistols flashed together, one man staggering, as though wounded, the other falling as though dead.

"The driver was then called, and the one who lay prostrate was raised and placed in the vehicle which was ordered to drive with all speed to the Hospital, the others entering the other carriage and driving rapidly off in another direction.

"Upon being questioned by our reporter, the driver of the stranger said that the other duelist was a young society man about town, but he did not, or pretended not to know his name.

"He said the stranger's bullet had wounded him in the head, as he wore a handkerchief about it, but there was no blood-stain visible.

"The comrade of the alleged society-man was also a young gentleman of this city, but whom the driver pretended not to know.

"Going to the Hospital our reporter discovered that the stranger was there.

"He had a watch, chain, seal-ring, and sleeve buttons all of good value, and a pocket book containing several hundred dollars in bank-bills, but not a slip of paper, or anything to solve his identity.

"He was shot just over the heart, and the surgeons feared to probe the wound, which they say will doubtless prove fatal though there is the slightest chance for his recovery, as he possesses a fine physique and the appearance of an iron constitution.

"Reporters and detectives are busy trying to solve the mystery, and our readers will be informed if aught is discovered regarding this strange affair."

GAIN to the crowded metropolis my story shifts, and to a part of the grand city where dwell those of the humbler walks in life.

Here are no brown-stone fronts, no elegant homes, but the imprint of poverty is upon all.

Long years before the place was a fashionable locality; but the rapid growth of the city forced the wealthy residents up town, and into their homes, not then as now, superb structures, palatial in their fittings, the poorer classes moved, to again give place to those of a still lower strata of the society that goes to make up the world to be found in metropolitan life.

In a tenement-flat, on the fourth floor of a dingy-looking building, a woman sat alone, a piece of embroidery in her hands.

The flat consisted of four rooms, one large one in the front, with a hall-room adjoining, and the same in the rear.

Those in the front were used as sitting-room and bed-room; those in the rear, the larger one for a kitchen and dining-room combined, the smaller for a sleeping-chamber, for there was a cot in it.

The furniture was very scant, and cheap-looking, there being nothing more than was actually necessary for use.

But an air of cleanliness was upon all, and the woman who sat alone in the front room had the appearance of one reared in refinement, one who had seen better days ere she had come to feel the pinching of poverty.

She was neatly clad in a black cashmere dress that was a trifle seedy, and which appeared to have been often brushed.

Her form was slender, very graceful, and her face was beautiful yet sad, while her large eyes were sunken and inflamed as though from weeping.

The work she was engaged upon ill accorded with the rooms and surroundings, for she was embroidering a silk scarf of a rare and costly pattern, and she kept it folded closely in a clean towel, excepting the part upon which her slender, skilful fingers worked.

An easel stood near her with a box of paints and brushes, and a half-finished painting was before her, a landscape scene, with a cosy country house, an old mill, a brook, and a valley stretching away in the distance.

Suddenly her eyes were raised from her work, and rested upon the canvas.

"Dear, dear old Brookside! how I long to see you once again, and yet I dare not go, even though I should have to beg my bread.

"Not one word in all these long, weary, wretched years have I heard from those whom I love so dearly, and deserted to become the wife of—a scoundrel!

"Heaven forgive me that rash act; and forgive me for bringing sorrow upon my parents and poor Kent; but I was fascinated by that wretch—yes, fascinated, as though by a snake, for it was not love I felt, as now I hate him—no, no, I should not say that of the dead, of the father of my children," and she dropped her face in her hands and burst into tears.

Thirteen years have passed away since the reader last beheld her[Pg 15] who sits there sobbing like a child, and the once beautiful girl of eighteen, pretty Ruby Raymond, the miller's daughter, has sadly changed in all that time.

Almost from the moment that she left her lovely, happy home, deserting her parents, and flying from the love of honest, brave Kent Lomax, her miseries had begun; and, too proud to return to dear old Brookside, though deserted by her husband, whom she afterward had heard was dead, she struggled on to support herself and her two children.

Not a word had she heard from her parents, and she would not write to them, fearing a rebuff.

Not a word had she heard from Kent Lomax, and, after all that she had done to break his heart, she would not seek his aid in her distress.

She had sewed, embroidered, and then taken up painting as a means of support; but her income was small, and she had to live very humbly.

Her children she sent to the public school, and she clothed them as well as she could.

"Oh! if I could only get a little money saved up, that, in disguise, I could go down to Brookside and see them all there, though they know me not!

"I could leave my children with good hearted Mrs. Lucas, next door, and be gone but a few days, for I only wish to see the dear old home, to gaze upon the faces of my parents, to see Kent, and then come back to my wretchedness and toil; but I feel I could work the better if I could go.

"Still, I cannot, for it would take nearly fifty dollars to go and return, and I have but ten saved up, and it would not be right, if I had the money to spend it thus, for what if I should be taken sick, what would my little ones do?"

Again she buried her face in her hands and wept, to start suddenly, hastily drying her eyes, and, as a second knock came at the door, to call out:

"Come in!"

The door opened and a man entered.

He was a most unprepossessing looking person, one to dread, for he looked like a tramp in dress, and a scoundrel in his face.

The woman arose quickly, and asked as firmly as she could:

"Well, sir, what do you wish here?"

"I've come on business, missus, so don't go to squealin', fer I doesn't mean ter harm yer ef yer puts up ther chink as I tells you," was the reply in a sullen voice.

The woman saw that she was in the man's power, for to scream would bring no aid, as it would scarcely be heard above the din of the city.

Her children were at school, and there was no one to call upon.

The face of the man showed his evil heart, and in dread she said:

"I have but a few dollars in the world, and would you take that?"

"I would, you bet! fer I needs money, and I'll git it, ef I has ter make trouble, so out with it."

The poor woman stepped to a little half-desk, half-table, the place where she kept the few souvenirs of the past, and took therefrom a silk purse.

Out of this she took the money, eleven dollars in all.

"Let me keep one dollar," she pleaded, adding:

"I need it so much."

"Not a copper cent, missus, so hand it over."

"Here it is, eleven dollars."

"It is not enough, for I need more."

"It is all I have."

"You've got jewellery."

"I've a little, souvenirs of my girlhood."

"Durn yer girlhood! Yer should forgit it; so hand it over."

"I will not!" she said firmly.

"Then I chokes that neck o' yours ontil yer can't preach, and takes all."

"Mercy you can have all," and she handed out a small box containing a few trinklets of little intrinsic value, but which she prized most highly.

"You've got some rings there."

"My wedding ring, and one other."

"They are worth somethin'."

"They are worth a great deal to me, for one tells me of a happy past, the other of only sorrow."

"One was given by a lover, I guesses, and t'other by your husband."

"You are right."

"Well, I wants 'em."

"No! no! no! You would not take these."

"Come, I hain't no time to lose, for I'm wanted by the perlice, and to pertect mysel', I'll jist tie you up, and put a bandage on that music-box o' yourn, so you sha'n't shout when I gets out."

As he spoke he advanced toward her, and with a spring he grasped her arm, stifling a cry with his huge right hand.

At the same moment he fell like a log upon the floor, struck down by an iron poker held in the hand of a boy of twelve, who unseen by the robber or his victim, had glided into the room from the back chamber, closely followed by a little girl of ten.

With a bound the woman sprang away from the man as he fell, while she cried in a voice of anguish:

"Oh, Will, my son, you have killed him!"

"I have but protected you, mother," was the reply of the brave boy, who stood over the prostrate form, the iron, which he had used as a weapon, still grasped in his hand.

HE boy who had entered the room and dealt what appeared a death-blow to the robber, was a handsome little fellow of twelve, well-grown for his age, with an agile, athletic form, and a face that would win attention anywhere.

He was poorly clad, yet his clothes were neat, and he had the look of one who had been reared in refinement, in spite of his humble and poverty-stamped surroundings.

Behind him, holding in her little hands her own and her brother's books, for the two had just come from school, was a little, fairy-like form of ten years.

Her face was bright, sparkling and lovely, with a look of wisdom and feeling above her years, while her attire was neat, fashionably-made, though of very cheap material, and there was a certain style about her that many a millionaire's daughter on Fifth Avenue would give much to possess.

"My son, you have killed him," repeated the mother, in a tone of horror.

"No—no, mother, for I did not hit him that hard; I don't think I did, at least, though I was very angry at seeing him spring at you, and I am so glad we came.

"We got a half-holiday this afternoon, and came in the back door to surprise you, when we heard that man talking, and I picked up the kitchen poker and—"

"But, Will, something must be done, and—"

The words ended in a startled cry, for the man suddenly rose up to a sitting posture.

But Will was equal to the situation, and raising his poker he cried out sternly:

"Lie down, sir! quick, or I will kill you!"

The half-dazed wretch saw that the boy held him at his mercy, and he dropped back again in a recumbent position.

"Run, Pearl, and get a policeman to come!" cried Will, and the young girl darted away, while the robber started to rise, with the remark:

"No perlice for me, boy—Oh!"

Back he fell, as the poker descended upon his head with a force that again stunned him.

"Oh, Will!" groaned the poor woman.

"I had to do it, mother, or he would have killed us both to get away, for he's a desperate fellow."

And the fearless boy stood over his prisoner with the air of one who meant to stand no trifling, and knew very well that he was master of the situation.

The man soon revived again, but a motion of the poker held over him, and a stern order, kept him on his back, for he had twice felt the weight of the boy's blow, and, bleeding from two scalp-wounds and with aching head, he concluded to remain quiet.

It seemed an age to the mother and son that Pearl was gone; but she had fairly flown to the nearest police station, and came dashing into the room breathlessly, crying:

"They are coming!"

Again the man moved uneasily, but the boy said sternly:

"Don't make me hit you again; but I will if you don't keep quiet."

"I'll even up on yer some day, boy, if I go to prison for ten years!" growled the man; and as he spoke, there came steps upon the stairs without, and a sergeant and two policemen entered, as Pearl threw open the door.

The sergeant bowed politely, for the appearance of the lady commanded respect, and he said:

"Well done, my little man—ha! it is you is it, Black Brick?" and he turned his attention to the prisoner, who already was in irons, as the two officers had lost no time in getting the handcuffs upon him and placing him upon his feet.

"Yes, it's me, Sergeant Daly, and you put a cool thousand in your pocket by my capture," was the sullen reply, and then he added:

"I s'pose you won't share it with me fer givin' myself up?"

"My boy, this fellow you have caught is an escaped convict, and there's a thousand dollars' reward offered for his capture, which you can get by making an application for it."

"Thank you, sir, but neither my son or myself would accept money thus earned, poor as we are," said the lady quickly.

"You know best, madam," said the surprised sergeant, while the two officers also looked amazed.

"What is your name, my lad?" asked Sergeant Daly, taking out a note-book.

"Will Raymond, sir."

"And your name, madam, in full, please?" and the sergeant turned to the mother.

She choked up at the question, her face flashed and then paled; but after an effort at self-control she responded:

"My name was Ruby Raymond, and since my husband's death I retain the name for my children.

"Is it necessary that I should give another?"

"No madam, the name of Raymond will do; but you will not surely refuse the reward allowed for the capture of that rascal there!"

"I cannot allow my son to accept it, sir."

"Pardon me if I say I believe you need the money."

"I need it, sir, true; but not blood money, for I could not look upon it in any other way."

The sergeant bowed, gave a hasty glance about the rooms, and said to Will:

"Come and see me, my boy, and should you need a friend at any time call on me," and the sergeant followed his men and their prisoner, after bowing politely to Mrs. Raymond.

As the door closed behind the officer, Mrs. Raymond sprang toward her son, and throwing her arms about him, she cried earnestly:

"Oh, Willie, my noble boy, you have saved me more than you can ever[Pg 19] know, for poor as I am I would not take a fortune for this ring," and she held up a solid gold band before his eyes; but it was not her wedding ring.

EVERAL months have passed away since the daring attempt of the escaped convict to rob Mrs. Raymond in her humble home, and a change has come that has brought gloom upon the mother and her two children.

It may have been the shock she had, when threatened by the intruder, that caused her to break down and take to her bed ill; but certain it is that she was forced to give up her work, she said for a day or two, and keep her children home from school.

Little Pearl was a good cook, however, and Will made the fires and did what little marketing there was, so that their mother did not suffer for want of attention.

Still she fretted, and a fever followed, and Will went after a doctor on his own responsibility, and placed his mother in his care.

The man of medicine made three visits, and his pay took two-thirds of the little money the poor woman had, and she determined to get up and go to work to earn more.

But she could do but little, and, weak and wretched, she gained strength very slowly.

Then Will went out to see what he could get to do, and each night he came in with a few pence, earned by blacking boots, running errands or selling papers, and this helped to eke out a subsistence for all three.

Mrs. Raymond did not seem to suffer pain, she had no fever, but her ailment appeared to be heart trouble, and night after night she lay awake brooding over her sorrows.

Surprised, as the days passed, that Will seemed to be bringing in more money each day, she wondered at it, and questioned him, but he merely said that he picked it up in odd jobs.

"But, Will, you are looking pale and haggard, and you are working too hard," seeing that he did look wan and white.

"No, mother, I'm all right," he answered, and so the conversation ended.

But that night Mrs. Raymond could not sleep, and growing strangely nervous, she went to wake her son to talk to her for awhile.

To her surprise he was not in his little rear room adjoining the kitchen, and the bed had not been slept in.

She awakened Pearl and asked her about her brother.

"Oh, mamma, don't scold him, for he is at work," said Pearl anxiously.

"Your brother at work, and at night?"

"Yes, mamma, for he has a place as night messenger in a telegraph office; he goes on at ten o'clock and gets off at six," explained Pearl.

"My poor boy! and this accounts for his being so hard to wake up every morning.

"Yes, mamma; but he sleeps in the daytime when he can, and you know he goes to bed early, but I always wake him up at half-past nine o'clock; and, oh, mamma! Will gets six dollars a week, only think of that."

"And he's killing himself, he don't get half the sleep he should have.

"He must give it up, Pearl, for I will not allow him to ruin his health and slave his young life away as he is doing."

"But, mamma, you are sick, and Will makes so much, and you ought not to work."

But Mrs. Raymond was firm in her resolve, and when Will came creeping into his little room in the early morning, he was astonished at finding his mother lying in his bed, awaiting him.

In vain he argued; she would not hear of his continuing his night-work, and so Will Raymond left his place and looked for something else to do.

But nothing came in his way; times were hard, and but a few pennies a day were all the mother and her children had to live on.

Will seldom ate at home, saying that he got plenty at the lunch-counters during the day, and he left the scanty food for his mother and sister; but this his mother soon began to disbelieve, as the boy looked really ill and was growing thin.

"To-day is Thanksgiving Day, Will, so we must have a good dinner," said Mrs. Raymond, with a forced smile, one morning, after a most meagre breakfast.

"Oh, mamma!" said Will, and his heart was too full to say more.

"My son, I have a gold-piece—a three-dollar piece given me years ago, and which I have held on to until now, never counting it in thinking of my finances; but I wish you to take it and go to some good market and invest a dollar at least in a good dinner;" and the poor mother turned away to hide her tears, for the faces of her children told her plainly that they were hungry—yes, very hungry, as she was herself.

Will took the piece of gold, when his mother had taken it from its hiding-place, and placed it carefully in his pocket.

Then he started out upon his errand.

He was anxious to make his money go as far as possible, and yet secure the best, so he wended his way to a market, which had often attracted his attention.

Arriving at the market he feasted his eyes upon bunches of crisp, white celery, selected some fine sweet-potatoes, picked out a fine chicken, and then felt in his pocket for his money.

The marketman saw him turn pale as death, and then say, in a whisper, which he knew was not feigned:

"My gold-piece is gone!"

"Have you lost your money, my little man?" he asked, in a kindly way.

"Yes, sir; and it is all we have in the world.

"Ah! here is a hole in my pocket, and it has rolled out, for it was a three-dollar gold-piece.

"But maybe I can find it, sir," and the tears were in the boy's eyes.

"If you do not come back, I will trust you for your Thanksgiving dinner, for I know you will pay me when you can."

"Oh, thank you, sir! You are so kind!" and Will bounded away to look for his gold-piece.

But then he remembered that if he went at a rapid pace it might escape his eye; he walked slowly, searching the ground at every step of the way.

Presently he walked bolt up against a gentleman who had been watching his approach for half a block.

"Oh, pardon me, sir!" he said.

"Certainly, my boy; but you appear to be searching for something that you have lost?"

The face of the man was full of kindness, though stern, and his voice had a sympathetic tone in it that touched the boy, who told his misfortune to the stranger, adding:

"It was all we had, sir, and poor mother's heart will break, I know."

The man looked like one who had seen the world, and he dressed as one who had a plethoric pocket-book.

He was a reader of human nature, and saw that it was no begging for sympathy that the boy told his story for.

A man of fifty, perhaps, he was well preserved, and yet there was that in his face that seemed to indicate that his life had not been all made up of sunshine.

"My boy, I found your gold-piece, and—"

"Oh, sir!" cried Will, in delight.

"Yes, and I took it as an omen of good luck, this Thanksgiving day, and I meant to devote many times its amount to charity, of which I might not have thought but for my finding this gold-piece.

"No, I cannot give you my 'luck-piece,' as I must keep it; but I will give you more than its value, so let us go to the market and get the things you ordered, and then, if you will ask me home with you, I will go, for somehow I look upon you as a lucky find, my boy.

"Come, now, to the market."

"But, sir, our home is a flat on the top floor of a tenement-house, and it is so humble, and we are so poor, you would not like to go there."

"I will go, unless you refuse to take me, my boy."

"No, sir, I could not refuse one who is so kind to me," was the answer, and Will led the way back to the market.

"Did you find your money, my lad?" asked the man.

"Yes, sir, or rather this gentleman found it for me."

"Yes, sir, and I wish you to put up your best turkey, and other things that I will order, and send at once to the address that my young friend here will give you."

Will stood aghast, as he heard the orders, for flour, tea, coffee, sugar, hams and other things were on the list until he seemed to feel that his kind friend was going to provision the flat for a year to come.

"Now, Will, we must take a carriage, for I am a trifle lame, from the effects of an old wound when I was a soldier in the Mexican war," and a passing hack was called, and the two entered it.

Arriving at the tenement-house the gentleman bade the driver wait, and then he followed Will up the dingy flights of stairs to the top floor.

Opening the door of the sitting-room, Will ushered his guest in, and Mrs. Raymond arose from her easy-chair at sight of a stranger.

She looked pale and thin, but very beautiful, and her face slightly flushed as she saw her son with the visitor.

"This is my mother, Mr. Ivey, and this, my little sister Pearl.

"Mother, this gentleman has been most kind to me," and Will introduced his visitor with the ease of one double his years.

The visitor seemed amazed at the lovely woman he beheld before him, and instinctively he knew that he was in the presence of a lady.

He bowed low, and advancing held out his hand, while he said:

"You must pardon my intrusion, Mrs. Raymond; but I was so fortunate this morning as to find a three-dollar gold-piece.

"It caught my eye, as it glittered upon the pavement, and picking it up I saw that it had a hole in it, so attached it to my watch-chain.

"A moment after I beheld one I recognized as the owner coming in search of it, and thus I made the acquaintance of your noble boy, and hence took the occasion to also meet you and his sister."

Mrs. Raymond was touched by the words of the visitor, and there was that in his face that seemed to impress her, and she said:

"You are very welcome, sir, though ours is but a poor home for visitors, and I have been an invalid for some little time; but may I ask, as my son introduced you as Mr. Ivey, if you are not Colonel Richard Ivey, who was known as Dashing Dick Ivey of the Dragoons in the Mexican war?"

"Why yes, madam, that was my name, when years ago I was a cavalry officer; but have we met before that you recognize me?"

"No, sir, but when a girl I kept a scrap-book, and yours was among the pictures that I took from a paper and put in it, and often have I looked over the book and your face has but little changed, so I recalled it upon hearing your name."

"You are very kind, my dear madam, and this is another link of friendship between us that you should remember me as a soldier, and I hope you will look upon me from this day as an old friend, one who knows your sufferings and your needs, for I have heard all from Will, and I intend to do for you just what I would have done for a sister of mine were she in distress," and into the hearts of the mother and her children came a joy that they had not known for many a long day, and all through Will Raymond's losing his three-dollar gold-piece on Thanksgiving Day.

OLONEL DICK IVEY was a bachelor and a man of vast wealth.

He had been an only son, and the idol of his boyhood life had been his sister, two years his junior.

Their parents had been wealthy, and they dated their ancestry back for many generations, and the father of the young Richard had been anxious to have his son become a soldier, and so got for him a cadetship at West Point.

A handsome, dashing youth, generous to a fault, Dick Ivey had won the hearts of professors and comrades alike, and none of the latter had envied him the first honours of his class when he had graduated, while the instructors had said they were well won and deserved.

There were four persons present at the graduating exercises that Dick was most desirous of pleasing, and these were his parents, his sister, and her best friend, the young cadet's lady-love.

But, in spite of his honours won, the fickle young lady-love had flirted with the honoured cadet, refused his proffered love, and became infatuated, as it were, with a brother cadet of her old lover.

It cut Dick Ivey to the heart, but he nursed his sorrow in silence, uttered no complaint, and went to the border with his regiment, to soon win distinction as a daring officer.

The fickle maiden meanwhile married the successful rival, and two years after died, it was said, of a broken heart.

The news came to Dick Ivey that his sister was to marry, and when he heard whom it was that was to be her husband, he obtained a furlough and started for his home to warn her against the man who had broken the heart of his old lady-love.

But, wounded on the way, in a fight with Indians, he was laid up for weeks, and arrived too late, for his sister had married the man whom he now hated with all his soul.

Soon after the Mexican war broke out, and as the American army crossed the Rio Grande, Dick Ivey met his old rival, and learned of his sister's death.

Soon after a letter came to him, written by his sister, and given to some faithful servant to mail.

It told of her sorrows, her sufferings, the cruelties of the man she had loved, and that she too was dying of a broken heart.

At once did Dick Ivey seek the man who had wrecked the lives of two whom he had so dearly loved, and what he said was terse, to the point, and in deadly earnest. It was:

"You know my cause of quarrel with you, sir, and that now is no time to settle it, for we belong to our country.

"But, the day this war ends, if you and I are alive, you shall meet me on the field of honour, and but one of us shall ever leave it alive."

And all through the war did Dick Ivey win fame, and he became a hero in the eyes of his gallant comrades.

At last the war ended, the City of Mexico was in the hands of General Scott, and the Daring Dragoons, commanded by Colonel Ivey, were ordered home.

Instantly, he sought his rival, and reminded him of his words at the breaking out of hostilities, and the two met in personal combat upon the duelling field.

It was a duel with swords, and each man meant that it should be to the death, that no mercy should be shown, and it could end in but one way—the death of one, or both.

It was fought through to the bitter end, and Dick Ivey left his hated enemy dead upon the field.

Resigning his commission, he returned to his home in the State of Mississippi, and yet he remained there but a short while, for the spirit of unrest was upon him, and the papers teeming with stories of his career, he sailed for foreign lands and remained abroad for years.

Again, he returned to America and settled in an elegant bachelor-home upon a fashionable avenue in New York city, a man of noble impulses, yet one upon whose life a shadow had fallen, and who carried in his heart a skeleton of bitter memories.

Such was the man who had found Will Raymond's lost gold-piece, and his career, from a cadet at West Point, to his living a luxurious bachelor life in New York, Mrs. Raymond read to her children that Thanksgiving night after he had left; for the distinguished soldier had begged an invitation to eat his Thanksgiving turkey that day in the humble home of the woman he had so strangely met, and who, by some strange accident, had pasted in her scrap-book his picture, as a young soldier, and the scraps of his life history as she had then read them, never dreaming that she would meet the hero with the dark, handsome face, dressed in his gorgeous Dragoon uniform.

To her children then, that Thanksgiving night, after he had departed, Mrs. Raymond read the history of the Dashing Dragoon, and he became to Will and Pearl a hero also in their eyes, and warm was the welcome that he received when he came the next day to tell Mrs. Raymond that he had adopted all of them as protegées, and meant to take them to a pleasant home and send the children to school.

This promise he kept, for he would not be said nay, and Mrs. Raymond, grown almost happy-faced with the change, moved to a pleasant little home in the upper part of the city, and Will and Pearl daily attended the most fashionable schools in the metropolis.

Months thus passed away, Colonel Ivey taking his Sunday dinner with the mother and her children at first, and then calling oftener and oftener, until one night he called Will and Pearl to him and told them that he had asked their mother to become his wife, and that she had said that she would.

It made them happy, for they were glad to see joy in the face of their dearly loved mother, and soon after Mrs. Ruby Raymond became Mrs. Richard Ivey.

It was a quiet wedding in the cosey home, and then into the grand mansion of Colonel Ivey the mother and her children moved, and sunshine seemed to brighten all their pathway through life; but alas! who can see into the future, who can tell how far beyond the sunshine[Pg 25] lie the shadows that must fall upon our lives, shutting out all brightness, encircling them with gloom as black as the grave, and far more cruel.

T was a pleasant night and Mrs. Richard Ivey sat alone in the handsome library of her elegant country house on the sea-shore, for it was the summer time.

Her face had lost its look of haunting care, and her cheeks glowed with health, and she appeared to be happy once more.

Still there were phantoms of the past that would rise before her and they would not go down at her bidding.

She recalled her first love, noble-hearted, honest Kent Lomax, from whom she had fled to become the wife of a man who had proved himself a wretch, a villain.

She recalled her happy home, her loving parents, and wondered if they had ever forgiven her, for she had not heard one word from them since her flight, and she knew not the scene that had followed, when Kent Lomax had met Schuyler Cluett upon the field of honour, and had fallen before the bullet of the man she had married.

She had told Colonel Ivey all before she had married him, and he had but loved her the more for her confession and the sorrows she had known.

He had told her, too, that in the pleasant fall of the year, they would all go down to Maryland on a visit, and see the old home and her parents, and ask that she might be forgiven.

As she sat alone in her home she was pondering over the past.

Her husband had gone off on a business trip to the far West, Will was away upon a yachting cruise, for he had become a skilful and devoted yachtsman, his step-father having presented him with a beautiful craft, and Pearl was spending the night with a little playmate who lived near.

Presently a footfall was heard in the hallway, and Mrs. Ivey supposed it was the butler, about to close up the house for the night, so that it did not disturb her, but she started when the words fell upon her ears:

"Mrs. Ivey, I believe?"

"Oh, Mercy!"

The cry came like a groan of anguish from the lips of the woman, as she turned and beheld the form of a man standing before her.

He had entered the mansion unseen, had walked into the library unannounced, and was within a few paces of her.

His appearance was that of a gentleman, and yet one whose life was a fast one.

He was well dressed, in fact almost flashily attired, wore a diamond in his front shirt, another upon the little finger of his left hand, and a heavy watch chain crossed his vest front.

He appeared to be a man of forty, and his face was handsome, his[Pg 26] eyes piercing, yet a certain cold look, added to recklessness and a cynical smile were not prepossessing.

"You did not expect to see me again, Ruby?" he said in a voice that was tinged with a sneer.

"I believed you dead," she whispered, for she seemed scarcely able to articulate.

"Yes, for so I sent you word."

"You sent me word," she said repeating his words.

"Yes, I got a pal of mine to come and see you, and tell you how I had been smashed up in a railway accident.

"The smash-up was true, and I had my leg broken, and lay for weeks in agony; but I got well, and here I am."

"Oh why did you do me this cruel wrong?" she groaned.

"To accomplish just what you have done."

"And that is—"

"That, believing me dead you might marry, for I knew your beauty would turn the head of some old millionaire fool as it has done."

"And this was your plot?"

"Certainly," and he took a seat near her.

"What is your purpose?" she asked in a voice scarcely audible.

"Not to claim my wife, I assure you."

"I would die before I would again live with you; but it breaks my heart to feel that I have committed this crime against the noble man that made me, as he supposed, his wife, for we both felt that you were dead."

"And wished me so?" he said with a sneer.

"Indeed I did, though Heaven forgive me for telling the truth."

"Well, you see I am by no means a dead man, and as I have no desire to die of starvation I have come to you."

"To me?"

"Yes."

"And why?"

"You are rich."

"I am worth nothing, only such as my husband gives me."

"Well, you'll have to strike him for a loan on my account."

"What do you mean?"

"I need money."

"I can't help you."

"You must."

"I will not."

"Listen to me, Ruby, and don't be silly.

"You have broken the laws of the land, in marrying Colonel Ivey when you had a husband living."

"I believed you dead."

"That does not excuse you, and besides, I can bring up witnesses to swear that you knew me to be alive!"

"Oh, monster!"

"I can do it, and that will prove your guilt, so you see, you are wholly in my power."

"What do you wish of me?"

"I wish, as I said, some money, and I will give you a reasonable time to get it for me.

"If I get it I will go far away and never appear again to disturb you; but, if I do not receive it, I will simply make my presence known to your husband and destroy you."

"It will but drive me again into poverty and wretchedness, for I will not live a lie to that good man, and shall tell him all."

"You are a fool, Ruby."

"I was a fool when I became your wife.

"I did not love you, though I believed that I did, and I soon found out that it was but a fascination, such as a serpent has over a bird.

"I fled from my happy home, I deserted a true, honourable man, and became your wife, not to be acknowledged as such, for you hid me away in a little village, while you led a life of dissipation in Philadelphia, still believed to be a bachelor by your friends.

"In that lonely life I lived, and my children were born, and, with no friend near, mine was a wretched existence.

"Deserted by you, with my children, I went to New York to earn my living, and thither you followed me, and I had to give you all that I had saved up, and you gambled it away.

"Again deserted by you, I sought to hide away where you could not find me, and I became prosperous, in a small way, by selling the work of my hands; but again you found me, took my little earnings and went West, and soon after I heard of your death.

"Believe me, Schuyler Cluett, wicked as it was, I rejoiced that I was free, for I believed that I was.

"And now you come again, when I felt that my life was not all shadow, and you demand that I rob my husband to help you."

"I am your husband, Ruby, and I need help, and will have it."

"Not from me, sir."

"Yes, from you."

"I say no!—for I will tell all, and defy you."

"I will first see him, tell him who I am, and he will pay me to keep quiet, for the man loves you.

"For the sake of yourself, and of your children, you had best decide to give me the money, I ask."

She was silent, and lost in deep thought for full a minute, while he watched her face narrowly.

At last she said:

"Schuyler Cluett, you know that I would give much to have you never cross my path again; but your coming has unnerved me, and I am not myself.

"If I give you money, without telling my husband all, it would but be robbing him to pay you.

"If I tell him, I believe he would pay you as you demand; but yet, with you alive, and he knowing it, I could not remain here as his wife.

"So go from me, and I will decide when I can collect my thoughts."

"I will give you just one week."

"It is long enough, for I will not need so much time; but do not come here."

"No, I will give you an address in the city that will reach me, and you can appoint a place of meeting when you can give me the money."

"If I decide to do so."

"Oh, no fear about that, for you will decide in my favour, and for your children for it would be a big scandal, you know, to come out; that—but I'll not remind you, so here is my address, and I'll bid you goodnight, Mrs. Ivey," and he left the room as silently as he had entered it, and the poor woman was again alone with the phantoms of the past.

OLONEL RICHARD IVEY came back to his elegant home, from his trip to the West.

He had telegraphed to have the carriage meet him at the railway station, but to his surprise it was not there, and so he sprang into a village hack and drove homeward.

It was dark ere he reached the mansion and his surprise was greater when he saw no lights to greet him.

"Why Ruby must have gone up to the city; but she wrote nothing of intending to do so, in her last letter," he said, as he sprang out of the vehicle and paid the driver.

Ascending to the piazza he rang the bell, and soon a light flashed within the hallway, and the butler opened the door.

"Well, Richard, what is the matter, that I receive such a bleak welcome?" he said.

"The madam is away, sir, and has been for some days; but she left a letter for you, sir, and it's on your table with the mail.

"I'll have lights, sir, at once."

The mansion was soon lighted up, and supper ordered for the master, who went into his library and took up the numerous letters that had arrived for him during his absence of several weeks.

All were thrown aside excepting one.

That one bore no stamp or post-mark, and was from his wife.

Hastily he broke the seal, and seeing that it was several pages in length, he threw himself into his easy-chair beneath the lamp.

As he read, he uttered a sound very like a moan, and, strong man though he was, his hands trembled as he held the letter.

When he had finished he slowly re-read it, and then bending his head upon his hands he sat thus, the picture of silent, manly grief.

What he read was as follows:

"Dare I, in this letter that I now write you, address you as my heart would dictate and call you my own dear Richard?—for such you are to me and ever will be, though a cruel blow causes me to fly from you.

"The other night I sat alone in your library in your pet chair.

"Will was away in his yacht, on a cruise for a few days, and Pearl was spending the night with a little girl friend.

"Suddenly a visitor entered the library.

"To my horror, it was one I deemed dead, years ago!

"But no not dead, alas! but alive, cynical, sneering, cold-hearted, cruel he stood before me.

"Dressed well, wearing diamonds, yet a begger for gold.

"Need I tell you that it was my husband?

"Need I tell you that he had deceived me in his death, and told me that he had purposely done so, that I might, by my beauty—such were his words—win a rich husband and then he could force from me gold to keep my secret?

"Such was his mission to me, and he demanded a large sum that he might dissipate it in his luxurious life.

"He promised to go from me, and never return if I gave him the sum he demanded.

"If I refused, he said that he would go to you, and you, for honour's sake, to save scandal, would buy him off.

"Again, he said he would tell you that I knew he was alive and yet married you.

"So, in my grief, I begged him to give me time for thought, though I then knew what my course would be.

"He gave me a week to consider, and, confident that I would yield, he left.

"He judged me by his own guilty heart and felt safe in his threats to divulge the secret of his being still alive.

"When he was gone I fell into a swoon upon the floor, and there Richards found me when he came to put out the lights.

"The maid revived me, and I passed a night of bitter agony; but I was decided as to what I should do, and I told the servants that I had heard bad news, and must go away, perhaps to be gone a long time.

"I did not care to say more, that I would never return, for your sake.

"Then I began to get ready, and that day Pearl returned home.

"The next day Will came back from his cruise and I told my children that we must go.

"I told them that it was no quarrel, no wrong of one of us against the other, only duty forced me away.