Title: The Bird

Author: Jules Michelet

Illustrator: Hector Giacomelli

Release date: July 28, 2013 [eBook #43341]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Sonya Schermann and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Notes:

Some presumed printer's errors were corrected. The following is a list of changes made from the original. The first line shows the original text; the second line is the corrected text as it appears in this e-book.

A. E p. viii

A. E.

and. thou p. 105

and, thou

resemblance p.126

resemblance.

Page 14 p. 315

Page 74

Don Jean Footnote 29

Don Juan

THE BIRD.

BY

JULES MICHELET.

WITH 210 ILLUSTRATIONS BY GIACOMELLI.

LONDON:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

1868.

I dedicate to thee what is really thine own: three books of the fireside, sprung from our sweet evening talk,—

THE BIRD—THE INSECT—THE SEA.

Thou alone didst inspire them. Without thee I should have pursued, ever in my own track, the rude path of human history.

Thou alone didst prepare them. I received from thy hands the rich harvest of Nature.

And thou alone didst crown them, placing on the accomplished work the sacred flower which blesses them.

J. MICHELET.

"L'Oiseau," or "The Bird," was first published in 1856. It has since been followed by "L'Insecte" and "La Mer;" the three works forming a trilogy which few writers have surpassed in grace of style, beauty of description, and suggestiveness of sentiment. "L'Oiseau" may be briefly described as an eloquent defence of the Bird in its relation to man, and a poetical exposition of the attractiveness of Natural History. It is animated by a fine and tender spirit, and written with an inimitable charm of language.

In submitting the following translation to the English public, I am conscious of an urgent need that I should apologize for its shortcomings. It is no easy matter to do justice to Michelet in English; yet, if I have failed to convey a just idea of his beauties of expression, if I have suffered most of the undefinable aroma of his style to escape, I believe I have rendered his meaning faithfully, without exaggeration or diminution. I have endeavoured to preserve, as far as possible, his more characteristic peculiarities, and even mannerisms, carrying the literalness of my version to an extent which some critics, perhaps, will be disposed to censure. But in copying the masterpiece [Pg viii] of a great artist, what we ask of the copyist is, that he will reproduce every effect of light and shade with the severest accuracy; and, in the translation of a noble work from one language to another, the public have a right to demand the same exact adherence to the original. They want to see as much of the author as they can, and as little as may be of the translator.

The present version is from the eighth edition of "L'Oiseau," and is adorned with all the original Illustrations.

A. E.

| INTRODUCTION. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Page | ||

| HOW THE AUTHOR WAS LED TO THE STUDY OF NATURE, | 13 | |

| PART FIRST. | ||

| THE EGG, | 63 | |

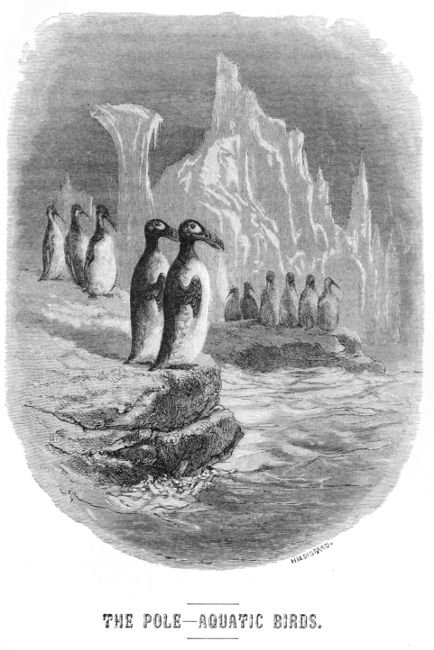

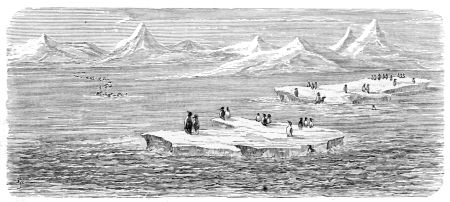

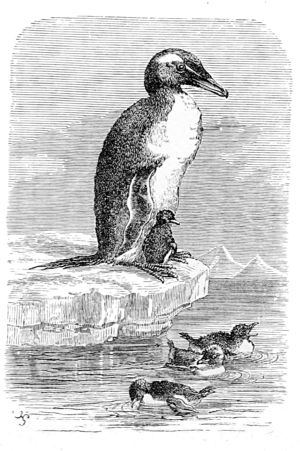

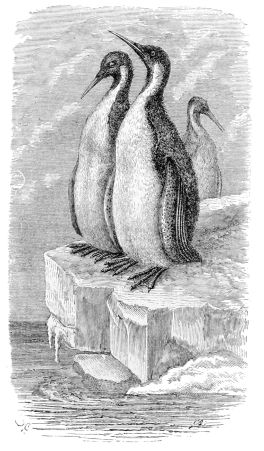

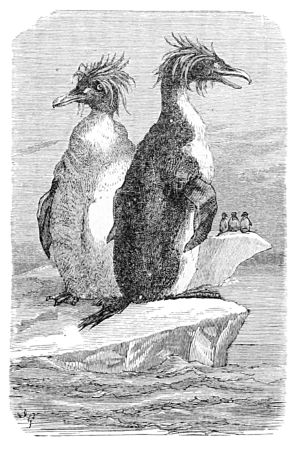

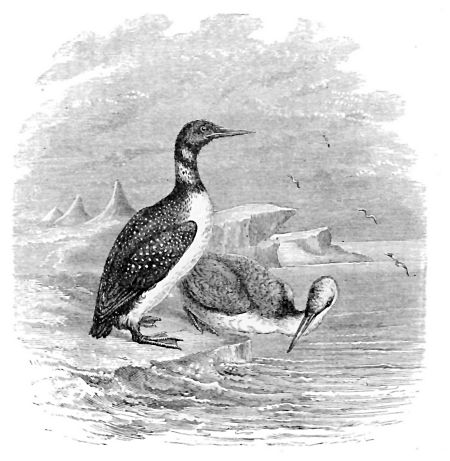

| THE POLE—AQUATIC BIRDS, | 71 | |

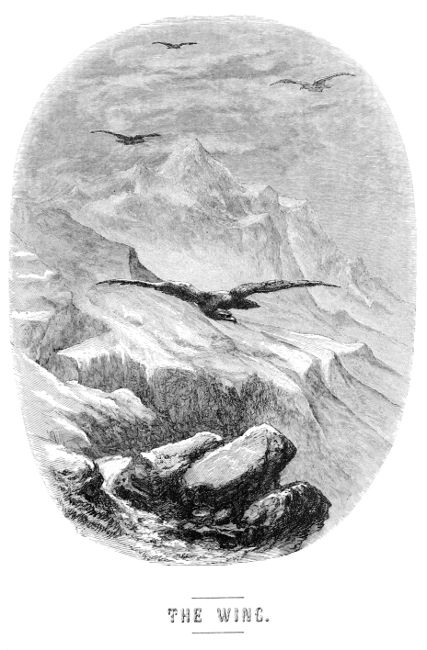

| THE WING, | 81 | |

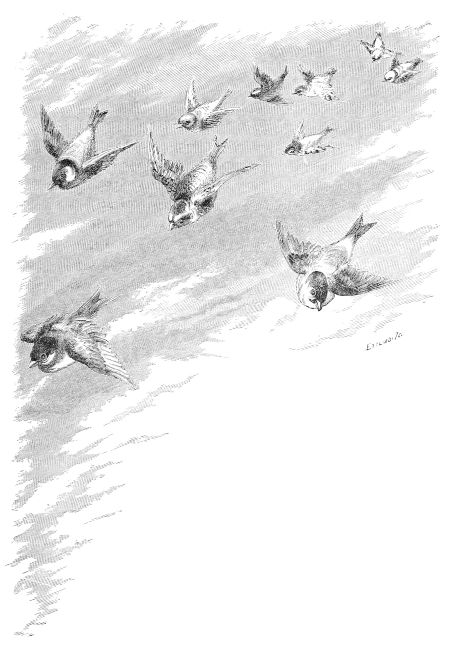

| THE FIRST FLUTTERINGS OF THE WING, | 91 | |

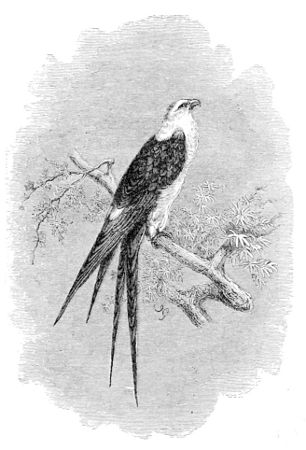

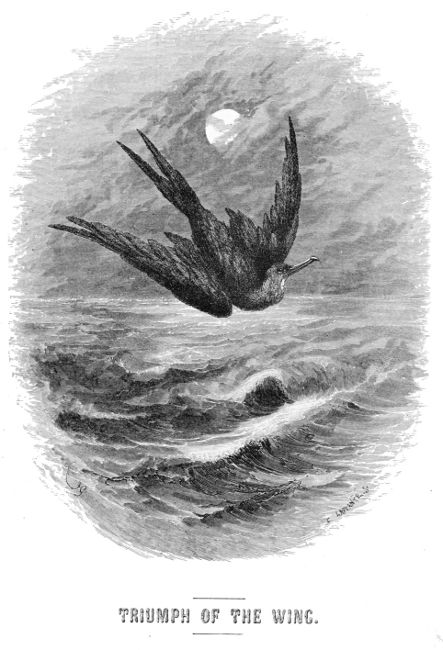

| TRIUMPH OF THE WING—THE FRIGATE BIRD, | 101 | |

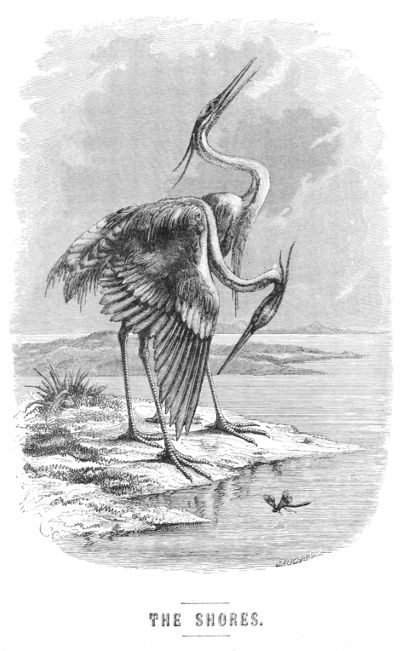

| THE SHORES—DECAY OF CERTAIN SPECIES, | 111 | |

| THE HERONRIES OF AMERICA—WILSON, THE ORNITHOLOGIST, | 121 | |

| THE COMBAT—THE TROPICAL REGIONS, | 131 | |

| PURIFICATION, | 143 | |

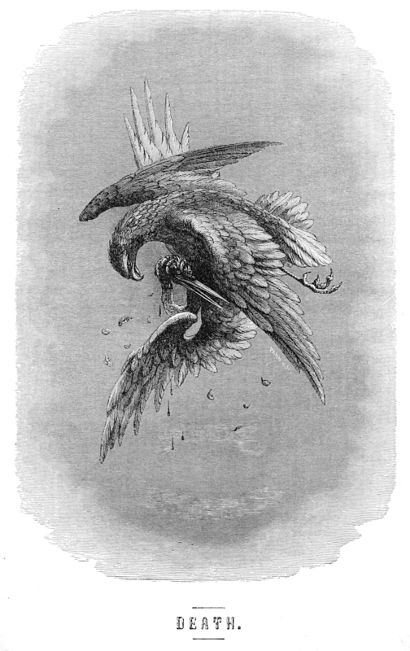

| DEATH—BIRDS OF PREY (THE RAPTORES), | 153 | |

| PART SECOND. | ||

| THE LIGHT—THE NIGHT, | 171 | |

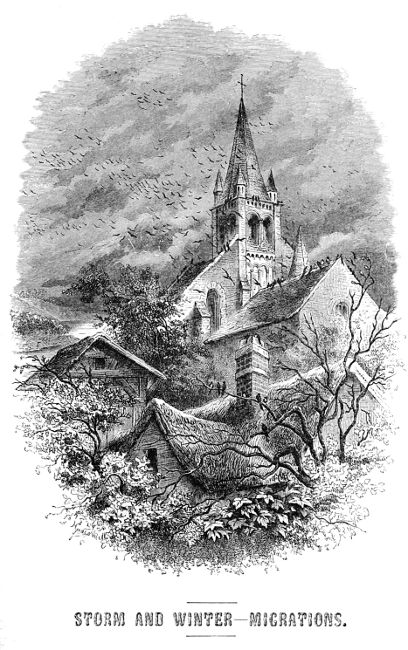

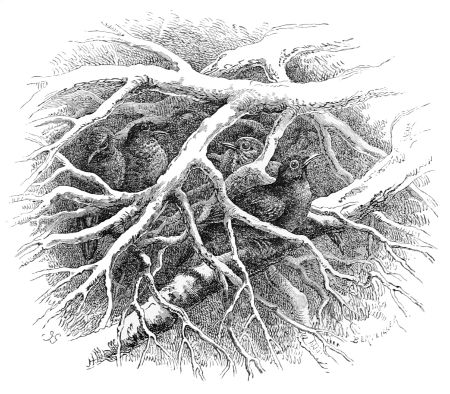

| STORM AND WINTER—MIGRATIONS, | 181 | |

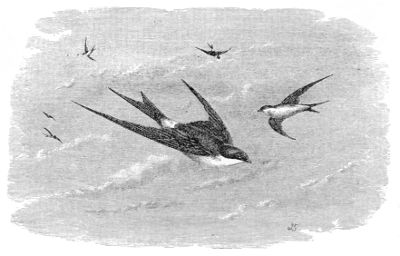

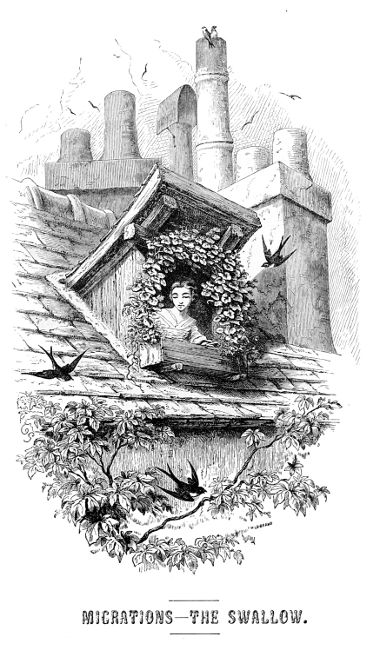

| MIGRATIONS, Continued—THE SWALLOW, | 193 | |

| HARMONIES OF THE TEMPERATE ZONE, | 205 | |

| THE BIRD AS THE LABOURER OF MAN, | 213 | |

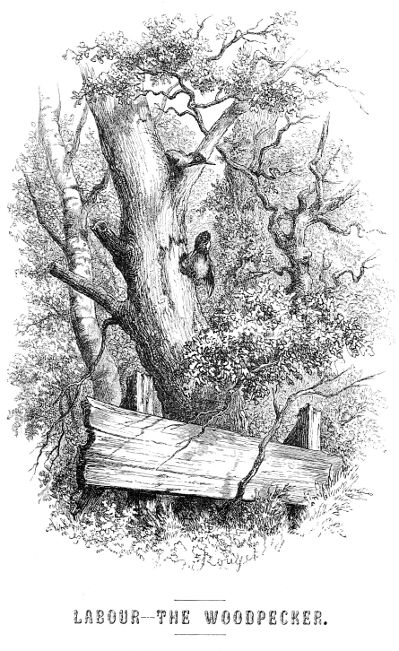

| LABOUR—THE WOODPECKER, | 223 | [Pg x] |

| THE SONG, | 235 | |

| THE NEST—ARCHITECTURE OF BIRDS, | 247 | |

| THE COMMUNITIES OF BIRDS—ESSAYS AT A REPUBLIC, | 257 | |

| EDUCATION, | 265 | |

| THE NIGHTINGALE—ART AND THE INFINITE, | 277 | |

| THE NIGHTINGALE, Continued, | 287 | |

| CONCLUSION, | 297 | |

| ILLUSTRATIVE NOTES, | 311 |

HOW THE AUTHOR WAS LED

TO

THE STUDY OF NATURE.

THE BIRD.

To my faithful friend, the Public, who has listened to me for so long a period without disfavour, I owe a confession of the peculiar circumstances which, while not leading me altogether astray from history, have induced me to devote myself to the natural sciences.

The book which I now publish may be described as the offspring of the domestic circle and the home fireside. It is from our hours of rest, our afternoon conversations, our winter readings, our summer gossips, that this book, if it be a book, has been gradually evolved.

Two studious persons, naturally reunited after a day's toil, put together their gleanings, and refreshed their hearts by this closing evening feast.

Am I saying that we have had no other assistance? To make [Pg 14] such a statement would be unjust, ungrateful. The domesticated swallows which lodged under our roof mingled in our conversation. The homely robin, fluttering around me, interjected his tender notes, and sometimes the nightingale suspended it by her solemn music.

The burden of the time, life, labour, the violent fluctuations of our era, the dispersion of a world of intelligence in which we lived, and to which nothing has succeeded, weighed heavily upon me. The arduous toils of history found occasional relaxation in friendly instruction. These pauses, however, are only periods of silence. Where shall we seek repose or moral invigoration, if not of nature?

The mighty eighteenth century, which included a thousand years of struggle, rested at its setting on the amiable and consoling, though scientifically feeble book of Bernardin de St. Pierre.[1] It ended with that pathetic speech of Ramond's: "So many irreparable losses lamented in the bosom of nature!"

We, whatever we had lost, asked of solitude something more than tears, something more than the dittany[2] which softens wounded hearts. We sought in it a panacea for continual progress, a draught from inexhaustible fountains, a new strength, and—wings.

This work, whatever its character, possesses at least the distinction of having entered upon life under the usual conditions of existence. It results from the intimate communion of two souls; and is in all[Pg 15] things itself uniform and harmonious because the offspring of two different principles.

Of the two souls to which it owes its existence, one was the more powerfully attracted to natural studies by the fact that, in a certain sense, it had been born among them, and had ever preserved their fragrance and sweet savour. The other was so much the more strongly impelled towards them because it had always been separated by circumstances, and detained in the rugged ways of human history.

History never releases its slave. He who has once drunk of its sharp strong wine will drink thereof till his death. I could not wrench myself from it even in days of suffering. When the sorrows of the past blended with those of the present, and when on the ruins of our fortunes I inscribed "ninety-three," my health might fail, but not my soul, my will. All day I applied myself to this last duty, and pressed forward among the thorns. In the evening I listened—at first not without effort—to the peaceful narrative of some naturalist or traveller. I listened and I admired, unable as yet to console myself, or to escape from my thoughts, but, at all events, keeping them under control, and preventing any anxieties and any mental storms from disturbing this innocent tranquillity.

Not that I was insensible to the sublime legends of those heroic men whose labours and enterprise have so largely benefited humanity. The great national patriots whose history I was relating were the nearest of kindred to these cosmopolitan patriots, these citizens of the world.

For myself, I had long hailed, with all my heart, the great French Revolution which had occurred in the Natural Sciences—the era of Lamarck and of Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire,[3] so fertile in method, the mighty restorers of all science. With what happiness I traced their features in their legitimate sons—those ingenious children who have inherited their intellect!

At their head let me name the amiable and original author of the "Monde des Oiseaux,"[4] whom the world has long recognized as one of the most solid, if not also the most amusing, of naturalists. I shall refer to him more than once; but I hasten, on the threshold of my book, to pay this preliminary homage to a truly great observer, who, in all that concerns his own observations, is as weighty, as special, as Wilson or Audubon.

He has wronged himself by saying that, in his noble work, "he has only sought a pretext for a discourse on man." On the contrary, numerous pages demonstrate that, apart from all analogy, he has loved and studied the Bird for its own sake. And it is for this reason that he has surrounded it with so many legends, with such vivid and profound personifications. Each bird which Toussenel treats of is now, and will for ever remain, a person.

Nevertheless, the book now before the reader starts from a point of view which differs in all things from that of our illustrious master.

A point of view by no means contrary, yet symmetrically opposed, to his.

For I, as much as possible, seeking only the bird in the bird, avoid the human analogy. With the exception of two chapters, I have written as if only the bird existed, as if man had never been.

Man! we have already met with him sufficiently often in other places. Here, on the contrary, we have sought an alibi from the human world, from the profound solitude and desolation of ancient days.

Man could not have lived without the bird, which alone could save him from the insect and the reptile; but the bird had lived without man.

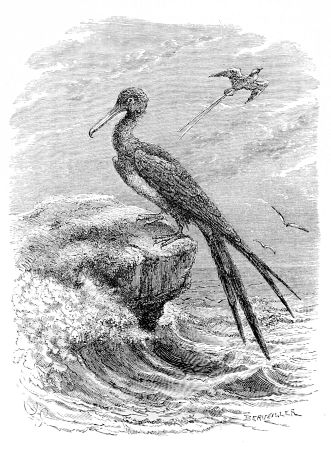

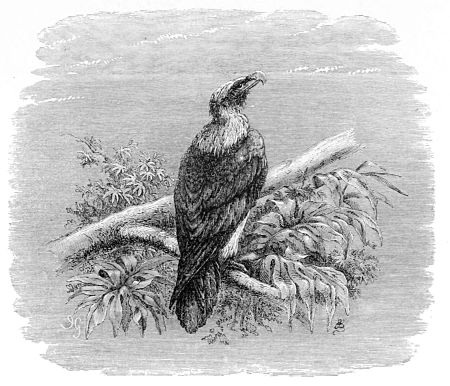

Man or no man, the eagle had reigned on his Alpine throne. The swallow would not the less have performed her yearly migration. The frigate bird,[5] unseen by human eyes, had still hovered over the [Pg 18] lonely ocean-waters. Without waiting for human listeners, and with all the greater security, the nightingale had still chanted in the forest his sublime hymn. And for whom? For her whom he loves, for his offspring, for the woodlands, and, finally, for himself, his most fastidious auditor.

Another difference between this book and that of Toussenel's is, that, harmonious as he is, and a disciple of the gentle Fourier, he is not the less a sportsman. In every page the military calling of the Lorraine is clearly visible.

My book, on the contrary, is a book of peace, written specifically in hatred of sport.

Hunt the eagle and the lion, if you will; but do not hunt the weak.

The devout faith which we cherish at heart, and which we teach in these pages, is, that man will peaceably subdue the whole earth, when he shall gradually perceive that every adopted animal, accustomed to a domesticated life, or at least to that degree of friendship or neighbourliness of which its nature is capable, will be a hundred times more useful to him than if he had simply cut its throat.

Man will not be truly man—we return to this topic at the close of our volume—until he shall labour seriously to accomplish the mission which the earth expects of him:

The pacification and harmonious communion of all living nature.

"A woman's dreams!" you exclaim. What matters that?

Since a woman's heart breathes in this book, I see no reason to reject the reproach. We accept it as an eulogy. Patience and gentleness, tenderness and pity, and maternal warmth—these are the things which beget, preserve, develop a living creation.

May this, in due time, become not a book, but a reality! Then, haply, it shall prove suggestive, and others derive from it their inspiration.

The reader, au reste, will better understand the character of the work, if he will take the trouble to read the few pages which follow, and which I transcribe word for word. [The succeeding section, as the reader will perceive, is written by Madame Michelet.]

"I was born in the country, where I have passed two-thirds of my life-time. I feel myself constantly recalled to it, both by the charm of early habits, by natural sensibilities, and also, undoubtedly, by the dear memories of my father, who bred me among its shades, and was the object of my life's worship.

"Owing to my mother's illness, I was nursed for a considerable period by some honest peasants, who loved me as their own child. I was, in truth, their daughter; and my brothers, struck by my rustic ways, called me the Shepherdess.

"My father resided at no great distance from the town, in a very pleasant mansion, which he had purchased, built, and surrounded by plantations, in the hope that the charms of the spot might console his young wife for the sublime American nature she had recently quitted. The house, well exposed on the east and south, saw the morning sun rise on a vine-clad slope, and turn, before its meridian heats, towards the [Pg 21] remote summits of the Pyrenees, which were visible in clear weather. The young elm-trees of our own France, mingled with American acacias, rose-laurels, and young cypresses, interrupted its full flood of light, and transmitted to us a softened radiance.

"On our right, a thicket of oaks, inclosed with a dense hedge, sheltered us from the north, and from the keen wind of the Cantal. Far away, on the left, swept the green meadows and the corn-fields. Through the broom, and in the shade of some tall trees, flowed a brooklet—a thin thread of limpid water, defined against the evening horizon by a small belt of haze which ran along its border.

"The climate is intermediate. In the valley, which is that of the Tarn, and which shares the mildness of the Garonne and the severity of Auvergne, we find none of those southern products common everywhere around Bordeaux. But the mulberry, and the melting perfumed peach, the juicy grape, the sugared fig, and the melon, growing in the open air, testify that we are in the south. Fruits superabounded with us; one portion of the estate was an immense vineyard.

"Memory vividly recalls to me all the charms of this locality, and its varied character. It was never otherwise than grave and melancholy in itself, and it impressed these feelings on all about it. My father, though lively and agreeable, was a man already aged, and of uncertain health. My mother, young, beautiful, austere, had the queenly bearing of the North American, with a prudence and an active economy very rare in Creoles. The estate which we occupied formerly belonged [Pg 22] to a Protestant family, and after passing through many hands before it fell into ours, still retained the graves of its ancient owners—simple hillocks of turf, where the proscribed had enshrined their dead under a thick grove of oaks. I need hardly say, that these trees and these tombs, consecrated by their very oblivion, were religiously respected by my father. Each grave was marked out by rose-bushes, which his own hands had planted. These sweet odours, these bright blossoms, concealed the gloom of death, while suffering, nevertheless, something of its melancholy to remain. Thither, then, we were drawn, and as it were in spite of ourselves, at evening time. Overcome by emotion, we often mourned over the departed; and, at each falling star, exclaimed, 'It is a soul which passes!'[6]

"In this living country-side, among alternate joys and pains, I lived for ten years—from four to fourteen. I had no comrades. My sister, five years older than myself, was the companion of my mother when I was still but a little girl. My brothers, numerous enough to play among themselves without my help, often left me all alone in the hours of recreation. If they ran off to the fields, I could only follow them with my eyes. I passed, then, many solitary hours in wandering near the house, and in the long garden alleys. There I acquired, in spite of a natural vivacity, habits of contemplation. [Pg 23] At the bottom of my dreams I began to feel the Infinite: I had glimpses of God, of the paternal divinity of nature, which regards with equal tenderness the blade of grass and the star. In this I found the chief source of consolation; nay, more, let me say, of happiness.

"Our abode would have offered to an observant mind a very agreeable field of study. All creatures under its benevolent protection seemed to find an asylum. We had a fine fish-pond near the house, but no dove-cot; for my parents could not endure the idea of dooming creatures to slavery whose life is all movement and freedom. Dogs, cats, rabbits, guinea-pigs, lived together in concord. The tame chickens, the pigeons, followed my mother everywhere, and fed from her hand. The sparrows built their nests among us; the swallows even brooded under our barns; they flew into our very chambers, and returned with each succeeding spring to the shelter of our roof.

"How often, too, have I found, in the goldfinches' nests torn from our cypress-trees by rude autumnal winds, fragments of my summer-robes buried in the sand! Beloved birds, which I then sheltered all unwittingly in a fold of my vestment, ye have to-day a surer shelter in my heart, but ye know it not!

"Our nightingales, less domesticated, wove their nests in the lonely hedge-rows; but, confident of a generous welcome, they came to our threshold a hundred times a-day, and besought from my mother, for themselves and their family, the silk-worms which had perished.

"In the depths of the wood the woodpecker laboured obstinately at the venerable trunks; one might hear him at his task when all other sounds had ceased. We listened in trembling silence to the mysterious blows of that indefatigable workman mingling with the owl's slow and lamentable voice.

"It was my highest ambition to have a bird all to myself—a turtle-dove. Those of my mother's—so familiar, so plaintive, so tenderly resigned at breeding-time—attracted me strongly towards them. If a young girl feels like a mother for the doll which she dresses, how much more so for a living creature which responds to her caresses! I would have given everything for this treasure. But it was not to be so; and the dove was not my first love.

"The first was a flower, whose name I do not know.

"I had a small garden, situated under an enormous fig-tree, whose humid shades rendered useless all my cultivation. Feeling very sad and sorely discouraged, I descried one morning, on a pale-green stem, a beautiful little golden blossom. Very little, trembling at the lightest breath, its feeble stalk issued from a small basin excavated by the rains. Seeing it there, and always trembling, I supposed it was cold, and provided it with a canopy of leaves. How shall I express the transports which this discovery awakened? I alone knew of its existence; I alone possessed it. All day we could do nothing but gaze at each other. In the evening I glided to its side, my heart full of emotion. We spoke little, for fear of betraying ourselves. But ah! what [Pg 25] tender kisses before the last adieu! These joys endured but three days. One afternoon my flower folded itself up slowly, never again to re-open. There was an end to its love.

"I kept to myself my keen regret, as I had kept my happiness. No other flower could have consoled me; a life more full of life was needed to restore the freedom of my soul.

"Every year my good nurse came to see me, invariably bringing some little present. On one occasion, with a mysterious air, she said to me, 'Put thy hand in my basket.' I did so, expecting to find some fruit, but felt a silken fur, and something trembling. Ah! it is a rabbit! Seizing it, I ran in all directions to announce the news. I hugged the poor animal with a convulsive joy, which nearly proved fatal to it. My head was troubled with giddiness. I could not eat. My sleep was disturbed by painful dreams. I saw my rabbit dying; I was unable to move a single step to succour it. Oh! how beautiful it was, my rabbit, with its pink nose, and its fur as polished as a mirror! Its large pearled ears, which were constantly in motion, its fantastic gambols, had, I confess, a share of my admiration. As soon as the morning dawned, I escaped from my mother's bed to visit my favourite, and carry it a green leaf or two. There it sat, and gravely ate the leaves, casting upon me protracted glances, which I thought full of affection; then, erecting itself on its hind paws, it turned to the sun its little snow-white belly, and sleeked its fine whiskers with marvellous dexterity.

"Nevertheless, slander was busy in its detraction; its face was too small, said its enemies, and it was very gluttonous. To-day, I might subscribe to these assertions; but at seven years of age I fought for the honour of my rabbit! Alas! there was no need to make it the subject of dispute, it lived so short a time. One Sunday, my mother having set out for the town with my sister and eldest brother, we were wandering—we, the little ones—in the enclosure, when a sudden report broke over our heads. A strange cry, like an infant's first moan, followed it close at hand. My rabbit had been wounded by a flash of fire. The unfortunate beast had transgressed beyond the vineyard-hedge, and a neighbour, having nothing better to do, had amused himself with shooting at it.

"I was in time to see it rise up, bleeding. So great was my grief that I almost choked, utterly unable to sob out a single word. But for my father, who received me in his arms, and by gentle words gave my full heart relief, I should have fainted. My limbs yielded under me. Pardon the tears which this recollection still calls forth.

"For the first time, and in early youth, I had a revelation of death, abandonment, desolation. The house, the garden, appeared to me empty and bare. Do not laugh: my grief was bitter, and all the deeper because concentrated in myself.

"Thenceforth, having learned the meaning of death, I began to watch my father with wistful eyes. I saw, not without terror, that his face was very pale and his hair white. He would quit us; he would go [Pg 27] 'whither the village-bell summoned him,' to use his oft-repeated phrase. I had not the strength to conceal my thoughts. Sometimes I flung my arms around his neck, exclaiming: 'Papa, do not die! oh, never die!' He embraced me, without replying; but his fine large black eyes were troubled as they gazed on me.

"I was attached to him by a thousand ties, by a thousand intimate relations. I was the daughter of his mature age, of his shattered health, of his affections. I had not that happy equilibrium which his other children derived from my mother. My father was transmitted in me (passé en moi). He said so himself: 'How I feel that thou art my daughter!'

"Years and life's trials had deprived him of nothing; to his last hour he retained the vivacity, the aspirations, and even the charm of youth. Every one felt it without being able to account for it, and all flocked around him of their own accord—women, children, men. I still see him in his little study, seated before his small black table, relating his Odyssey, his long journeys in America, his life in the colonies; one never grew weary of his stories. A maiden of twenty years, in the last stage of a pulmonary disease, heard him shortly before her end: she would fain have listened to him always; implored him to visit her, for while he was discoursing she forgot her sufferings and her decay, even the approach of death.

"This charm I speak of was not that of a clever talker only; it was due to the great goodness so plainly visible in him. The trials, the life of adventure and misfortune, which harden so many hearts, [Pg 28] had, on the contrary, but softened his. No man in this generation—a generation so much agitated, tossed to and fro by so many waves—had undergone such painful experiences. His father, an Auvergnat, the principal of a college, then juge consulaire in our most southern city, and finally summoned to the Assembly of Notables in '88, had all the hard austerity of his country and his functions, of the school and the tribunals. The education of that era was cruel, a perpetual chastisement; the more wit, the more character, the more strength, the more did this education tend to shatter them, to break them down. My father, of a delicate and tender nature, could never have survived it, and only escaped by flying to America, where one of his brothers had previously established himself. A change of linen was his only fortune, except his youth, his confidence, his golden dreams of freedom. Thenceforth he always cherished a peculiar tenderness for that land of liberty; he often revisited it, and earnestly wished to die there.

"Called by the needs of business to St. Domingo, he was present in that island at the great crisis of the reign of Toussaint L'Ouverture. This truly extraordinary man, who up to his fiftieth year had been a slave, who comprehended and foresaw everything, did not know how to write, or to give expression to his ideas. His genius succeeded better in great actions than in fine speeches. He lacked a hand, a pen, and more—the young bold heart which shall teach the hero the heroic language, the words in harmony with the moment and the situation. Toussaint, at his age, could only utter [Pg 29] this noble appeal: 'The First of the Blacks to the First of the Whites!'[7] Permit me to doubt if it were his. At least, if he conceived it, it was my father who gave expression to the idea.

"He loved my father warmly; he perceived his frankness, and he trusted him—he, so profoundly mistrustful, dumb with his long slavery, and secret as the tomb! But who can die without having one day unlocked his heart? It was my father's misfortune that at certain moments Toussaint broke his silence, and made him the confidant of dangerous mysteries. Thenceforth, all was over; he became afraid of the young man, and felt himself dependent upon him—a new servitude, which could only end with my father's death. Toussaint threw him into prison, and then, with a fresh access of fear, would have sacrificed him. Fortunately, the prisoner was guarded by gratitude; he had been bountiful to many of the blacks; a negress whom he had protected, warned him of his peril, and assisted him to escape from it. All his life long he sought that woman, to show his gratitude towards her; he did not discover her until some fourteen years afterwards, on his last voyage; she was then living in the United States.

"To return: though out of prison, he was not saved. Wandering astray in the forest, at night, without a guide, he had cause to dread the Maroons, those implacable enemies of the whites, who would have killed him, in ignorance that they were murdering the best [Pg 30] friend of their race. Fortune is the boon of youth; he escaped every danger. Having discovered a good horse, whenever the blacks issued from their hiding-places, one touch of the spear, a wave of the hat, a cry: 'Advanced guard of General Toussaint!' and this was enough. At that formidable name all took to flight, and disappeared as if by enchantment.

"Such was the tenderness of my father's soul, that he did not withdraw his regard from the great man who had misunderstood him. When, at a later period, he saw him in France, abandoned by everybody, a wretched prisoner in a fort of the Jura, where he perished of cold and misery,[8] he alone was faithful to him. Despite his errors, despite the deeds of violence inseparable from the grand and terrible part which that man had played, he revered in him the daring pioneer of a race, the creator of a world. He corresponded with him until his death, and afterwards with his family.

"A singular chance ordained that my father should be engaged in the isle of Elba when the First of the Whites, dethroned in his turn, arrived to take possession of his miniature kingdom. Heart and imagination, my father fell captive to this wonderful romance. An American, and imbued with Republican ideas, he became on this occasion, and for the second time, the courtier of misfortune. He was the most intimate of [Pg 31] the servants of the Emperor, of his children, of that accomplished and adored lady who was the charm and happiness of his exile. He undertook to convey her back to France in the perilous return of March 1815. This attraction, had there been no obstacle, would have led him even to St. Helena. As it was, he could not endure the restoration of the Bourbons, and returned to his beloved America.

"The New World was not ungrateful, and made the happiness of his life. He had resigned every official capacity in order to abandon himself wholly to the more independent career of tuition. He taught in Louisiana. That colonial France, isolated, sundered by the events of her mother-land's history, and mingling so many diverse elements of population, breathes ever the breath of France. Among my father's pupils was an orphan, of English and German extraction. She came to him when very young, to learn the first elements of knowledge; she grew under his hands, and loved him more and more; she found a second family, a second father; she sympathized with the paternal heart, with a charm of youthful vivacity which our French of the south preserve in their mature age. She had but three faults: wealth, beauty, extreme youth—for she was at least thirty years younger than my father; but neither of them perceived it, and they never reminded themselves of it. My mother has been inconsolable for my father's death, and has ever since worn mourning.

"My mother longed to see France, and my father, in his pride of her, was delighted to show to the Old World the brilliant flower he had gathered in the New. [Pg 32] But anxious as he was to maintain this young Creole lady in the position and with the fortune which she had always enjoyed, he would not embark until he had accomplished, with her consent, a religious and holy act. This was the manumission of his slaves—of those, at least, above the age of twenty-one; the young, whom he was prevented by the American law from setting free, received from him their future liberty, and, on attaining their majority, were to rejoin their parents. He never lost sight of them. They were always before his eyes; he knew their names, their ages, and their appointed hour of liberty. In his French home, he took note of these epochs, and would say, with a glow of happiness, 'To-day, such an one becomes free!'

"See my father now in his native country, happy in a residence near his birth-place—building, planting, bringing up his family, the centre of a young world in which everything sprung from him: the house, the garden, were his creation; even his wife, whom he had reared and trained, and whom everybody thought to be his daughter. My mother was so young that her eldest daughter seemed to be her sister. Five other children followed, almost in as many successive years, promptly enwreathing my father with a living garland, which was his special pride. Few families exhibited a greater variety of tastes and temperaments; the two worlds were distinctly represented in ours: the French of the south with the sparkling vivacity of Languedoc—the grave colonists of Louisiana marked from their birth with the phlegmatic idiosyncrasies of the American character.

"It was ordered, however, that, with the exception of the eldest, who was already my mother's companion and shared with her the management of the household, the five youngest should receive their education in common from one master—my father. Notwithstanding his age, he undertook the duties of preceptor and schoolmaster. He gave up to us his whole day, from six in the morning until six in the evening. He reserved for his correspondence, his favourite studies, only the first hours of morning, or, more truly speaking, the last hours of night. Retiring to rest very early, he rose every day at three o'clock, without taking any heed of his pulmonary weakness. First of all, he threw wide his door, and there, before the stars or the dawn, according to the season, he blessed God; and God also blessed that venerable head, silvered by the experiences of life, not by the passions of humanity. In summer time, after his devotions, he took a short walk in the garden, and watched the insects and the plants awake. His knowledge of them was wonderful; and very often, after breakfast, taking me by the hand, he would describe the nature of each flower, would point out where each little animal that he had surprised at dawn took refuge. One of these was a snake, which the sight of my father did not in the least disconcert; each time that he seated himself near its domicile, it never failed to put forth its head and peer at him curiously. He alone knew that it was there, and he told none but me of its retirement; it remained a secret between us.

"In those morning-hours everything he met with [Pg 34] became a fertile text for his religious effusions. Without formal phrases, and inspired by true feeling, he spoke to me of the goodness of God, for whom there is neither great nor small, but all are brothers in His eyes, and all are equals.

"Associated with my brothers in their labours, I also took a part in those of my mother and my sister. When I put aside my grammar and arithmetic, it was to take up the needle.

"Happily for me, our life, naturally blending with that of the fields, was, whether we willed it or not, frequently varied by charming incidents which broke the chains of habit. Study has commenced; we apply ourselves with eagerness to our books; but what now? See, a storm is coming! the hay will be spoiled. Quick, we must gather it in! Everybody sets to work; the very children hasten thither; study is adjourned; we toil courageously, and the day goes by. It is a pity, for the rain does not fall; the storm has lingered on the Bordeaux side; it will come to-morrow.

"At harvest-time we frequently diverted ourselves with gleaning. In those grand moments of fruition, at once a labour and a festival, all sedentary application is impossible; one's thoughts are in the fields. We were constantly escaping out-of-doors, with the lark's swiftness; we disappeared among the furrows—we little ones concealed by the tall corn, hidden among the forest of ripe ears.

"It was well understood that during the vintage there was no time to think of study: much needed [Pg 35] labourers, we lived among the vines; it was our right. But before the grape ripened, we had numerous other vintages, those of the fruit-trees—cherries, apricots, peaches. Even at a later period, the apples and the pears imposed upon us new and severe labours, in which it was a matter of conscience that our hands should be employed. And thus, even in winter, these necessities returned—to act, to laugh, and to do nothing. The last tasks, occurring in mid-November, were perhaps the most delightful; a light mist then enfolded everything; I have seen nothing like it elsewhere; it was a dream, an enchantment. All objects were transfigured under the wavy folds of the vast pearl-gray canopy which, at the breath of the warm autumn, lovingly alighted hither and thither, like a farewell kiss.

"The dignified hospitality of my mother, my father's charm of manner and piquant conversation, drew upon us also the unforeseen distractions of visitors from the town, constraining suspensions of our studies, at which we did not weep. But the great and unceasing visit was from the poor, who well knew the house and the hand inexhaustibly opened by charity. All participated in its benefits, even the very animals; and it was a curious and diverting thing to see the dogs of the neighbourhood, patiently, silently seated on their hind legs, waiting until my father should raise his eyes from his book: they felt assured that he would not resist the mute eloquence of their prayer. My mother, more reasonable, was inclined to drive away these indiscreet guests who came at their own invitation. My father felt that he was wrong, and yet he never [Pg 36] failed to throw them stealthily some fragments, which sent them away satisfied.

"This they knew perfectly well. One day, a new guest, lean, bristling, unprepossessing, something between a dog and a wolf, arrived; he was, in fact, a half-breed of the two species, born in the forests of the Gresigne. He was very ferocious, very irascible, and bore much too close a resemblance to his wolfish mother. But, besides this, he was intelligent, and gifted with a very keen instinct. From the first he gave himself wholly up to my father, and neither words nor rough usage could induce him to quit his side. For us he had but little love; and we repaid him in kind, seizing every opportunity of playing him a hundred tricks. He ground and gnashed his teeth, though, out of regard for my father, he abstained from devouring us. To the poor he was furious, implacable, very dangerous; which decided us on suffering him to be lost. But there was no such chance. He always came back again. His new masters would chain him to a post; chains and post, he carried them all off, and brought them into our house. It was too much for my father; he would never forsake him.

"But the cats enjoyed even more of his good graces than the dogs. This was due to his early education, to the cruel years spent at college; his brother and himself, beaten and repulsed, between the harshness of their home and the severities of their school, had found a consolation in a couple of cats. This predilection was transmitted to his family—each of us, in childhood, possessed our cat. The gathering at the fireside was [Pg 37] a beautiful spectacle; all the grimalkins, in furred dignity, sitting majestically under the chairs of their young masters. One alone was missing from the circle—a poor wretch, too ugly to figure among the others; he knew his unworthiness, and held himself aloof, in a wild timidity which nothing was able to conquer. As in every assembly (such is the piteous malignity of our nature!) there must be a butt, a scapegoat, who receives all the blows, he, in ours, filled this unthankful rôle. If there were no blows, at least there were abundant mockeries: we named him Moquo. Weak, and scantily provided with fur, he stood in more need than the others of the genial hearth; but we children filled him with fear: even his comrades, better clothed in their warm ermine, appeared to esteem him but lightly, and to look at him askant. Of course, therefore, my father turned to him, and fondled him; the grateful animal lay down under that beloved hand, and gained confidence. Wrapped up in his coat, and revived by its warmth, he would frequently be brought, unseen, to the fireside. We quickly caught sight of him; and if he showed a hair, or the tip of an ear, our laughter and our glances threatened him, in spite of my father. I can still see that shadow gathering itself up—melting, so to speak—in its protector's bosom, closing its eyes, annihilating itself, well content to see nothing.

"All that I have read of the Hindus, and their tenderness for nature, reminds me of my father. He was a Brahmin. More even than the Brahmins did he love every living thing. He had lived in a time of blood and war—he had been an eye-witness of the [Pg 38] most terrible slaughters of men that had ever disgraced history; and it seemed as if that frightful lavishness of the irrecoverable good, which is life, had given him a respect for all life, an insurmountable aversion to all destruction.

"This had in time arrived at such an extreme, that he would have willingly lived upon vegetable food alone. He would have no viands of blood; they excited his horror. A morsel of chicken, or, more often, an egg or two, served for his dinner. And frequently he dined standing.

"Such a regimen, however, could not strengthen him. Nor did he economize his strength, expending it largely in lessons, in conversations, and in the habitual overflow of a too benevolent heart, which lived in all things, interested itself in all. Age came, and with it anxieties: family anxieties? no, but from jealous neighbours or unfaithful debtors. The crisis of the American banks dealt a severe blow to his fortune. He came to the extreme resolution, in spite of his ill health and his years, of once more visiting America, in the belief that his personal activity and his industry might re-establish affairs, and secure the fortune of his wife and children.

"This departure was terrible. It was preceded for me by another blow. I had quitted the mansion and the country; I had entered a boarding-school in the town. Cruel servitude, which deprived me of all that made my life—of air and respiration! Everywhere, walls! I should have died, but for the frequent visits of my mother, and the rarer visits of my father, to which I [Pg 39] looked forward with a delirious impatience that perhaps love has never known. But now that my father himself was leaving us—heaven, earth, everything seemed undone. With whatever hope of reunion he might endeavour to cheer me, an internal voice, distinct and terrible, such as one hears in great trials, told me that he would return no more.

"The house was sold, and the plantations laid out by our hands, the trees which belonged to the family, were abandoned. Our animals were plainly inconsolable at my father's departure. The dog—I forget for how many successive days—seated himself on the road which he had taken at his departure, howled, and returned. The most disinherited of all, the cat Moquo, no longer confided in any person, though he still came to regard with furtive glances the empty place. Then he took his resolution, and fled to the woods, from which we could never call him back; he resumed his early life, miserable and savage.

"And I, too, I quitted the paternal roof, the hearth of my young years, with a heart for ever wounded. My mother, my sister, my brothers, the sweet friendships of infancy, disappeared behind me. I entered upon a life of trial and isolation. At Bayonne, however, where I first resided, the sea of Biarritz spoke to me of my father; the waves which break on its shore, from America to Europe, repeated the story of his death; the snow-white ocean birds seemed to say, 'We have seen him.'

"What remained to me? My climate, my birth-land, my language. But even these I lost. I was [Pg 40] compelled to go to the North, to an unknown tongue and a hostile sky, where the earth for half a year wears mourning weeds. During these long seasons of frost, my failing health extinguishing imagination, I could scarcely re-create for myself my ideal South. A dog might have somewhat consoled me: in default, I made two little friends, who resembled, I fancied, my mother's turtle-doves. They knew me, loved me, sported by my fireside; I gave to them the summer which my heart had not.

"Seriously affected, I fell very ill, and thought I should soon touch the other shore. However studious and tender towards me might be the hospitality of the stranger, it was needful I should return to France. It was long before carefulness of affection, and a marriage in which I found again a father's heart and arms, could restore my health. I had seen death from so near a view-point—let us rather say, I had entered so far upon it—that nature herself, living nature, that first love and rapture of my young years, had for a long time little hold upon me, and she alone had any. Nothing had supplied her place. History, and the recital of the pathetic stirring human drama, moved me but lightly; nothing seized firmly on my mind but the unchangeable, God and Nature.

"Nature is immovable and yet mobile; that is her eternal charm. Her unwearied activity, her ever-shifting phantasmagoria, do not weary, do not disturb; this harmonious motion bears in itself a profound repose.

"I was recalled to her by the flowers—by the cares [Pg 41] which they demand, and the species of maternity which they solicit. My imperceptible garden of twelve trees and three beds did not fail to remind me of the great fertile vineyard where I was born; and I found, too, some degree of happiness, by the side of an ardent intellect, which toiled athirst in the dreary ways and wastes of human history, in cherishing for him these living waters and the charm of a few flowers."

I resume.

See me now torn from the city by this loving inquietude, by my fears for an invalid whom it was essential to restore to the conditions of her early life and the free air of the country. I quitted Paris, my city, which I had never left before; that city which comprises the three worlds; that cradle of Art and Thought.

I returned there daily for my duties and occupations; but I hastened to get quit of it. Its noise, its distant hum, the ebb and flow of abortive revolutions, impelled me to wander afar. It was with much pleasure that, in the spring of 1852, I broke through all the ties of old habits; I closed my library with a bitter joy, I put under lock and key my books, the companions of my life, which had assuredly thought to hold me bound for ever. I travelled so long as earth supported me, and only halted at Nantes, close to the sea, on a hill which overlooks the yellow streams of Brittany as they flow onward to mingle, in the Loire, with the gray waters of La Vendée.

We established ourselves in a large country mansion, completely isolated, in the midst of the constant rains with which our western fields are inundated at this season. At such a distance from the ocean, one does not feel its briny influence; the rains are tempests of fresh water. The house, in the Louis Quinze style, had been uninhabited for a considerable period, and at first sight seemed a little gloomy. Situated on elevated ground, it was rendered not the less sombre by thick hedges on the one side, on the other by tall trees and by an untold number of unpruned cherry-trees. The whole, on a greensward, which the undrained waters preserved, even in summer, in a beautifully fresh condition.

I adore neglected gardens, and this one reminded me of the great abandoned vineyards of the Italian villas; but it possessed, what these villas lack, a charming medley of vegetables and plants of a thousand different species—all the herbs of the St. John, and each herb tall and vigorous. The forest of cherry-trees, bending under their burden of scarlet fruit, gave also the idea of inexhaustible abundance.

It was not the sweet austerity (soave austero) of Italy; it was a soft and overflowing profusion, under a warm, mild, and moist sky.

Nothing appeared in sight, though a large town was close at hand, and a little river, the Erdre, wound under the hill, and from thence dragged itself towards the Loire. But this vegetable prodigality, this virgin forest of fruit trees, completely shut in the view. For a prospect, one must mount into a species of turret, whence the landscape began to reveal itself in a certain grandeur, with its woods and its meadows, its distant monuments, its towers. Even from this observatory the view was still limited, the city only appearing imperfectly, and not allowing you to catch sight of its mighty river, its island, its stir of commerce and navigation. A few paces from its great harbour, of whose existence there was no sign, one might believe oneself in a desert, in the landes of Brittany, or the clearings of La Vendée.

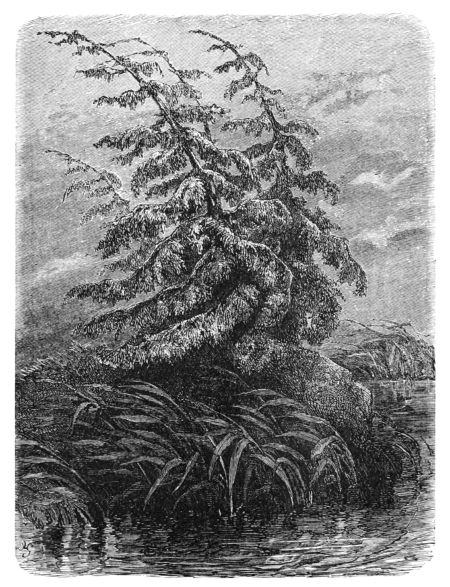

Two things were of a lofty character, and detached themselves [Pg 44] from this sombre orchard. Penetrating the ancient hedges and chestnut-alleys, you found yourself in a nook of barren argillaceous soil, where, among thyme-laurels and other strong, rude trees, rose an enormous cedar, a veritable leafy cathedral, of such stature that a cypress already grown very tall was choked by it, and lost. This cedar, bare and stripped below, was living and vigorous where it received the light; its immense arms, at thirty feet from the ground, clothed themselves with strange and pointed leaves; then the canopy thickened; the trunk attained an elevation of eighty feet. You saw, about three leagues distant, the fields opposite the banks of the Sèvre and the woods of La Vendée. Our home, low and sheltered on the side of this giant, was not less distinguished by it [Pg 45] throughout an immense circuit, and perhaps owed to it its name, the High Forest.

At the other end of the enclosure, from a deep sheet of water, rose a small ascent, crowned with a garland of pines. These fine trees, incessantly beaten by the sea-breezes, and shaken by the adverse winds which follow the currents of the great river and its two tributaries, groaned in the struggle, and day and night filled the profound silence of the place with a melancholy harmony. At times, you might have thought yourself by the sea; they so imitated the noise of the waves, of the ebbing and flowing tide.

By degrees, as the season became a little drier, this sojourn exhibited itself to me in its real character; serious, indeed, but more varied than one would have supposed at the first glance, and beautiful with a touching beauty which went home to the soul. Austere, as became the gate of Brittany, it had all the luxuriant verdure of the Vendean coast.

I could have thought, when I saw the pomegranates blooming in the open air, robust and loaded with flowers, that I was in the south. The magnolia, no dwarf, as we see it elsewhere, but splendid and magnificent, and full-grown, like a great tree, perfumed all my garden with its huge white blossoms, which contain in their thick chalices an abundance of I know not what kind of oil, an oil sweet and penetrating, whose odour follows you everywhere; you are enveloped in it.

We found ourselves this time in possession of a true garden, a large establishment, a thousand domestic occupations with which we had previously dispensed. A wild Breton girl rendered help only in the coarser tasks. Save one weekly journey to the town, we were very lonely, but in an extremely busy solitude; rising very early in the morning, at the first awakening of the birds, and even before the day. It is true that we retired to rest at a good hour, and almost at the same time as the birds.

This profusion of fruits, vegetables, and plants of every kind, enabled us to keep numerous domestic animals: only the difficulty was, that nourishing them, knowing each of them, and well-known by [Pg 46] them, we could not make up our minds to eat them. We planted, and here we met with quite a distinct kind of inconvenience—our plantations were nearly always devoured beforehand.

This earth, fertile in vegetables, was equally or more prolific of destructive animals; enormous capacious snails, devouring insects. In the morning we collected a great tubful of snails. The next day you would never have thought so. There still seemed to be the full complement.

Our hens did their best. But how much more effective would have been the skilful and prudent stork, the admirable scavenger of Holland and all marshy districts, which some Western lands ought at all costs to adopt. Everybody knows the affectionate respect in which this excellent bird is held by the Dutch. In their markets you may see him standing peacefully on one foot, dreaming in the midst of the crowd, and feeling as safe as in the heart of the deepest deserts. It is a fantastic but well-assured fact, that the Dutch peasant who has had the misfortune to wound his stork and to break his leg, provides him with one of wood.

To return: our residence near Nantes would have possessed an infinite charm for a less absorbed mind. This beautiful spot, this great liberty of work, this solitude, so sweet in such society, formed a rare harmony, such as one but seldom meets with in life. Its sweetness contrasted strongly with the thoughts of the present, with the gloomy [Pg 47] past which then occupied my pen. I was writing of '93. Its heroic primeval history enveloped, possessed, shall I say consumed, me. All the elements of happiness which surrounded me, which I sacrificed to work, adjourning them for a time that, according to all appearances, might never be mine, I regretted daily, and incessantly cast back upon them a look of sorrow. It was a daily battle of affection and nature, against the sombre thoughts of the human world.

That battle for me will be always a powerful souvenir. The scene has remained sacred in my thought. Elsewhere it no longer exists. The house is destroyed—another built on its site. And it is for this reason that I have dallied here a little. My cedar, however, has survived; a notable thing, for architects now-a-days hate trees.

When, however, I drew near the end of my task, some glimpses of light enlivened the wild darkness. My sorrows were less keen, when I felt sure that I should thenceforth enjoy this memorial of a cruel but fertile experience. Once more I began to hear the voices [Pg 48] of solitude, and more plainly I believe than at any other age, but slowly and with unaccustomed ear, like one who shall have been some time dead, and have returned from the other world.

In my youth, before I was taken captive by this implacable History, I had sympathized with nature, but with a blind warmth, with a heart less tender than ardent. At a later period, when residing in the suburb of Paris, I had again felt that emotion of love. I watched with interest my sickly flowers in that arid soil, so sensible every evening of the joy of refreshing waterings, so plainly grateful. How much more at Nantes, surrounded by a nature ever powerful and prolific, seeing the herbage shoot upward hour after hour, and all animal life multiplying around me, ought I not, I too, to expand and revive with this new sentiment!

If there were aught that could have re-inspired my mind and broken the sombre spell that lay upon it, it would have been a book which we frequently read in the evening, the "Birds of France," by Toussenel, a charming and felicitous transition from the thought of country to that of nature.

So long as France exists, his Lark and his Redbreast, his Bullfinch, his Swallow, will be incessantly read, re-read, re-told. And if there were no longer a France, in its ingenious pages we should re-discover all which it owned of good, the true breath of that country, the Gallic sense, the French esprit, the very soul of our fatherland.

The formulæ of a system which it bears, however, very lightly, its [Pg 49] forced comparisons (which sometimes make us think of those too spirituel animals of Granville), do not prevent the French genius, gay, good, serene, and courageous, young as an April sun, from illuminating the entire book. It possesses numerous passages enlivened with the joyousness, the elasticity, the gushing song of the lark in the first day of spring.

Add a thing of great beauty, which does not spring from youth. The author, a child of the Meuse and of a land of hunters, himself in his early years an ardent and impassioned sportsman, appears altered in character by his book. He wavers visibly between the first habits of slaughterous youth, and his new sentiment, his tenderness for those pathetic lives which he unveils—for these souls, these beings recognized by his soul. I dare to say that thenceforth he will no more hunt without remorse. Father and second creator of this world of love and innocence, he will find interposed between them and him a barrier of compassion. And what barrier? His own work, the book in which he gives them life.

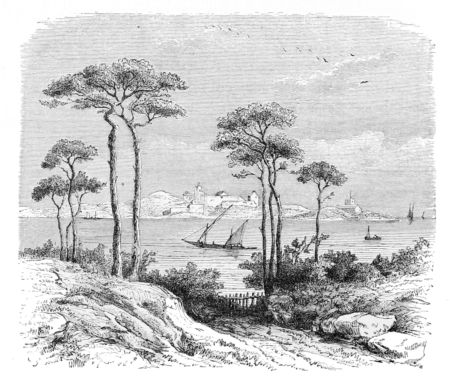

I had scarcely begun my book, when it became necessary for me to leave Nantes. I, too, was ill. The dampness of the climate, the hard continuous labour, and still more keenly, without doubt, the conflict of my thoughts, seemed to have struck home to that vital nerve of which nothing had ever before taken hold. The road which our swallows tracked for us, we followed; we proceeded southward. We fixed our transitory nest in a fold of the Apennines, two leagues from Genoa.

An admirable situation, a secure and well-defended shelter, which, in the variable climate of that coast, enjoys the astonishing boon of an equable temperature. Although one could not entirely dispense with fires, the winter sun, warm in January, encouraged the lizard and the invalid to think it was spring. Shall I confess it, however? These oranges, these citrons, harmonizing in their changeless foliage with the changeless blue of heaven were not without monotony. Animated life was very rare. There were few or no small birds; no sea birds. The fish, limited in numbers, did not fill with life those [Pg 50] translucent waters. My glance pierced them to a great depth, and saw nothing but solitude, and the white and black rocks which form the bed of that gulf of marble.

The littoral, exceedingly narrow, is nothing but a small cornice, an extremely confined border, a mere eyebrow (sourcil) of the mountains, as the Latins would have said. To ascend the ladder and overlook the gulf is, even for the most robust, a violent gymnastic effort. My sole promenade was a little quay, or rather a rugged circular road, which wound, with a breadth of about three feet, between ancient garden walls, rocks, and precipices.

Deep was the silence, sparkling the sea, but all lonesome and monotonous, except for the passage of a few distant barks. Work was prohibited to me; for the first time for thirty years, I was separated from my pen, and had escaped from that paper and ink existence in which I had previously lived. This pause, which I thought so [Pg 51] barren, in reality proved to me very fertile. I watched, I observed. Unknown voices awoke within me.

At some distance from Genoa, and the excellent friends whom we knew there, our only society was the small people of the lizards, which run over the rocks, played, and slumbered in the sun. Charming, innocent animals, which every noon, when we dined, and the quay was absolutely deserted, amused me with their vivacious and graceful evolutions. At the outset my presence had appeared to disquiet them; but a week had not passed before all, even the youngest, knew me, and knew they had nothing to fear from the peaceful dreamer.

Such the animal, and such the man. The abstemious life of my lizards, for which a fly was an ample banquet, differed in nothing from that of the povera gente of the coast. Many lived wholly on herbs. But herbs were not abundant in the barren and gaunt mountain. The destitution of the country exceeded all belief. I was not grieved at daring it, at finding myself sympathizing with the woes of Italy, my glorious nurse, who has nourished France, and me more than any Frenchman.

A nurse? That was she ever, so far as was possible in her poverty of resources, in the poverty of nature to which my health reduced me. Incapable of food, I still received from her the only nourishment which I could support, the vivifying air and the light—the sun, which frequently permitted us, in one of the severest winters of the century, to keep the windows open in January.

In the lazy, lizard-like life which I lived upon that shore, I wholly occupied myself with the surrounding country, with the apparent antiquity of the Apennines and the mountains which girdle the Mediterranean. Is there then no remedy? Or rather, in their leafless declivities shall we not discover the fountains which may renew their life? Such was the idea which absorbed me. I no longer thought of my illness; I troubled myself no more about recovering. I had made what is truly great progress for an invalid: I had forgotten myself. My business henceforward was to resuscitate that mighty patient, the Apennines. And as by degrees I became [Pg 52] aware that the case was not hopeless—that the waters were hidden, not lost—that by their discovery we might restore vegetable life, and eventually animal life,—I felt myself much stronger, refreshed, renewed. For each spring that revealed itself, I grew less athirst; I felt its waters rise within my soul.

Ever fertile is Italy. She proved so to me through her very barrenness and poverty. The ruggedness of the bald Apennines, the lean Ligurian coast, did but the more awaken, by contrast, the recollection of that genial nature which cherishes the luxuriant richness of our western France. I missed the animal life; I felt its absence. From the mute foliage of sombre orange-gardens I demanded the woodland birds. For the first time I perceived the seriousness of human existence when it is no longer surrounded by the grand society of innocent beings whose movements, voices, and sports are, so to speak, the smile of creation.

A revolution took place in me which I shall, perhaps, some day relate. I returned, with all the strength of my ailing existence, to the thoughts which I had uttered, in 1846, in my book of "The People," to that City of God where the humble and simple, peasants and artisans, the ignorant and unlettered, barbarians and savages, children, and those other children, too, which we call animals, are all citizens under different titles, have all their privileges and their laws, their places at the great civic banquet. "I protest, for my part, that if any one remains in the rear whom the City still rejects and does not shelter with her rights, I myself will not enter in, but will halt upon her threshold."

Thus, all natural history I had begun to regard as a branch of the political. Every living species came, each in its humble right, striking at the gate and demanding admittance to the bosom of Democracy. Why should their elder brothers repulse them beyond the pale of those laws which the universal Father harmonizes with the law of the world?

Such, then, was my renovation, this tardy new life (vita nuova), which led me, step by step, to the natural sciences. Italy, whose [Pg 53] influence over my destiny has always been great, was its scene, its occasion, just as, thirty years before, it had lit for me, through Vico, the first spark of the historic fire.

Beloved and beneficent nurse! Because I had for one moment shared her sorrows, suffered, dreamed with her, she bestowed on me a priceless gift, worth more than all the diamonds of Golconda. What gift? A profound sympathy of spirit, a fruitful interchange of the most intimate ideas, a perfect home-harmony in the thought of Nature.

We arrived at this goal by two paths: I, by my love of the City, by the effort of completing it through an association of self with all other beings; my wife, by religious feeling and by her filial reverence for the fatherhood of God.

Henceforth we were able, every evening, to enjoy a mutual feast.

I have already explained how this work, unknown to ourselves, grew rich, was rendered fruitful, was impelled forward, by our modest auxiliaries. They have almost always dictated it.

Our Parisian flowers prepared what our birds of Nantes accomplished. A certain nightingale of which I speak at the close of the book crowned the work.

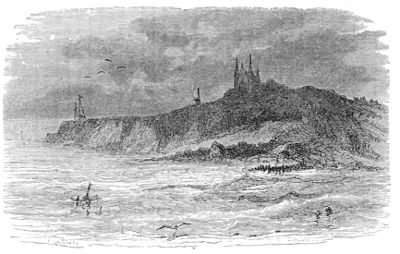

These divers impressions blended and melted together, on our return to France, and especially here, in the presence of the ocean. At the promontory of La Hève, under the venerable elms which overshadow it, this revelation completed itself. The gulls, gannets, and guillemots of the coast, the small birds of the groves, could say nothing which was not understood. All things found an echo in our hearts, like so many internal voices.

The Pharos, the huge cliff, from three to four hundred feet in height,[9] which from so lofty an elevation overlooks the vast embouchure of the Seine, the Calvados, and the ocean, was the customary goal of our promenades, and our resting-point. We usually climbed to it by a deep covered road, full of freshness and shadow, which suddenly opened upon this immense lighthouse. Sometimes we ascended the [Pg 54] colossal staircase which, without surprises, in the full sunlight, and always facing the mighty sea, leads by three flights to the summit, each flight covering upwards of a hundred feet. You cannot accomplish this ascent at one breath; at the second stage, you breathe, you seat yourself for a few moments by the monument which the widow of one of France's greatest soldiers has raised to his memory, in the hope that its pyramid might prove a beacon to the mariner, and guard him from shipwreck.

This cliff, of a very sandy soil, loses a little every winter.[10] It is not, however, the sea which gnaws at it; the heavy rains wash it away, carrying off the débris, which, at first bare and shapeless, bear eloquent witness to their downfall. But tender and gracious Nature does not long suffer this. She speedily attires them, bestows upon them greensward, herbs, shrubs, briers, which in due time become miniature oases on the declivity, Liliput landscapes suspended on the vast cliff, consoling its gloomy barrenness with their sweet youth.

Thus the Beautiful and the Sublime here embrace, a thing of rarity. [Pg 55] The storm-beaten mountain relates to you the epopea of earth, its rude dramatic history, and shows its bones in evidence of its truth. But these young children of chance, who spring up on its arid flank, prove that she is still fertile, that her débris contain the elements of a new organization, that all death is a life begun.

So these ruins have never caused us any sadness. We have conversed among them freely of destiny, providence, death, the life to come. I, whom age and toil have given a right to die—she, whose brow is already bent by the trials of infancy and a wisdom beyond her years, we have not lived the less for a grand inspiration of soul, for the rejuvenescent breath of that much-loved mother, Nature.[11]

Sprung from her at so great a distance from one another, so united in her to-day, we would fain have rendered eternal this rare moment of existence, "have cast anchor on the island of time." And how could we better realize our idea than by this work of tenderness, of universal brotherhood, of adoption of all life!

My wife incessantly recalled me to it, enlarging my sentiments of individual tenderness by her facile, bright, emotional interpretation of the spirit of the country and the voices of solitude.

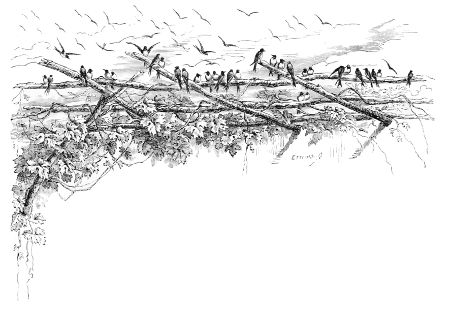

It was then, among other things, that I learned to understand birds which, like the swallows, sing little, but talk much—prattling of the fine weather, of the chase, of scanty or abundant food, of their approaching departure; in fact, of all their affairs. I had listened to them at Nantes in October, at Turin in June. Their September causeries were more intelligible at La Hève. We translated them easily in all their fond vivacity, all their joyousness of youth and good-humour, free from ostentation or satire, in accord with the happy moderation of a bird so free and so wise, which appears not ungratefully to recognize that he has received from God a lot of such signal felicity.

Alas! even the swallow is not spared in that senseless warfare [Pg 56] which we wage against nature. We destroy the very birds that protect our crops—our guardians, our honest labourers—which, following close upon the plough, seize the future pest, which the heedless peasant disturbs only to replace in the earth.

Whole races, valuable and interesting, perish. Those lords of ocean, those wild and sagacious creatures which Nature has endowed with blood and milk—I speak of the cetacea—to what number are they reduced! Many great quadrupeds have vanished from the globe. Many animals of every kind, without utterly disappearing, have recoiled before man; brutalized (ensauvagés) they fly, they lose their natural arts, and relapse into barbarism. The heron, whose prudence and address were remarked by Aristotle, is now, at least in Europe, a misanthropical, narrow-minded, half-foolish animal. The beaver, which, in America, in its peaceful solitudes, had become a great architect and engineer, has grown discouraged;[12] to-day it has scarcely the heart to excavate a burrow in the earth. The hare, so gentle, so handsome, distinguished by its fur, its swiftness, its wonderful delicacy of ear, will soon have disappeared; the few of its kind which remain are positively embruted. And yet the [Pg 57] poor animal is still docile and teachable: in careful hands it might be taught the things most antagonistic to its nature, even those which need a display of courage.[13]

These thoughts, which others have expressed in far better language, we cherished at heart. They had been our aliment, our habitual dream, over which we had brooded for two years, in Brittany, in Italy; it is here that they have developed into—what shall I say—a book? a living fruit? At La Hève it appeared to us in its genial idea, that of the primitive alliance which God has ordained for all his creatures, of the love-bond which the universal mother has sealed between her children.

The winged order—the loftiest, the tenderest, the most sympathetic with man—is that which man now-a-days pursues most cruelly.

What is required for its protection? To reveal the bird as soul, to show that it is a person.

The bird, then, a single bird—that is all my book; but the bird in all the variations of its destiny, as it accommodates itself to the thousand conditions of earth, to the thousand vocations of the winged life. Without any knowledge of the more or less ingenious systems of transformations, the heart gives oneness to its object; it neither allows itself to be arrested by the external differences of species, nor by that death which seems to sever the thread. Death, rude and cruel, intervenes in this book, in the full current of life, but as a passing accident only; life does not the less continue.

The agents of death, the murdering species, so glorified by man, who recognizes in them his image, are here replaced very low in the hierarchy, remitted to the rank which is rightly theirs. They are the most deficient in the two special qualifications of the bird—nest-making and song. Sad instruments of the fatal passage, they appear in the midst of this book as the blind ministers of nature's hardest necessity.

But the lofty light of life—art in its earliest dawn—shines only [Pg 58] in the smallest. With the small birds, unostentatious as they are, modestly and seriously clad, art begins, and, on certain points, rises higher than the sphere of man. Far from equalling the nightingale, we have been unable to express or to render an account of his sublime song.

The eagle, then, is in these pages dethroned; the nightingale reigns in his stead. In that moral crescendo, where the bird continuously advances in self-culture, the apex and the supreme point are naturally discovered, not in brutal strength, so easily overpassed by man, but in a puissance of art, of soul, and of aspiration which man has not attained, and which, beyond this world, transports him in a moment to the further spheres.

High justice and true, because it is clear-visioned and tender! Feeble on too many points, I doubt not, this book is strong in tenderness and faith. It is one, constant and faithful. Nothing makes it divaricate. Above death and its false divorce, through life and the masks which disguise its unity, it flies, it loves to hover, from nest to nest, from egg to egg, from love to the love of God.

La Hève, near Havre, September 21, 1855.

Part First.

THE EGG

The wise ignorance, the clear-seeing instinct of our forefathers gave utterance to this oracle: "Everything springs from the egg; it is the world's cradle."

Even our original, but especially the diversity of our destiny, is due to the mother. She acts and she foresees, she loves with a stronger or a weaker love, she is more or less the mother. The more she is so, the higher mounts her offspring; each degree in existence depends on the degree of her love.

What can the mother effect in the mobile existence of the fish? Nothing, but trust her birth to the ocean. What in the insect world, where she generally dies as soon as she has produced the egg? To obtain for it before dying a secure asylum, where it may come to light, and live.

In the case of the superior animal, the quadruped, where the [Pg 64] warm blood should surely stir up love, where the mother's womb is so long the rest and home of her young, the cares of maternity are also of minor import. The offspring is born fully formed, clothed in all things like its mother; and its food awaits it. And in many species its education is accomplished without any further care on the part of the mother than she bestowed when it grew in her bosom.

Far otherwise is the destiny of the bird. It would die if it were not loved.

Loved! Every mother loves, from the ocean to the stars. I should rather say anxiously tended, surrounded by infinite love, enfolded in the warmth of the maternal magnetism.

Even in the egg, where you see it protected by a calcareous shell, it feels so keenly the access of air, that every chilled point in the egg is a member the less for the future bird. Hence the prolonged and disquieted labour of incubation, the self-inflicted captivity, the motionlessness of the most mobile of beings. And all this so very pitiful! A stone pressed so long to the heart, to the flesh—often the live flesh!

It is born, but born naked. While the baby-quadruped, even from his first day of life, is clothed, and crawls, and already walks, the young bird (especially in the higher species) lies motionless upon its back, without the protection of any feathers. It is not only while hatching it, but in anxiously rubbing it, that the mother maintains and stimulates warmth. The colt can readily suckle and nourish itself; the young bird must wait while the mother seeks, selects, and prepares its food. She cannot leave it; the father must here supply her place; behold the real, veritable family, faithfulness in love, and the first moral enlightenment.

I will say nothing here of a protracted, very peculiar, and very hazardous education—that of flight. And nothing here of that of song, so refined among the feathered artists. The quadruped soon knows all that he will ever know: he gallops when born; and if he experiences an occasional fall, is it the same thing, tell me, to slide without danger among the herbage, as to drop headlong from the skies?

Let us take the egg in our hands. This elliptical form, at once the most easy of comprehension, the most beautiful, and presenting the fewest salient points to external attack, gives one the idea of a complete miniature world, of a perfect harmony, from which nothing can be taken away, and to which nothing can be added. No inorganic matter adopts this perfect form. I conceive that, under its apparent inertness, it holds a high mystery of life and some accomplished work of God.

What is it, and what should issue from it? I know not. But she knows well—yonder trembling creature who, with outstretched wings, embraces it and matures it with her warmth; she who, until now the free queen of the air, lived at her own wild will, but, suddenly fettered, sits motionless on that mute object which one would call a stone, and which as yet gives no revelation.

Do not speak of blind instinct. Facts demonstrate how that clear-sighted instinct modifies itself according to surrounding conditions; in other words, how that rudimentary reason differs in its nature from the lofty human reason.

Yes; that mother knows and sees distinctly by means of the penetration [Pg 66] and clairvoyance of love. Through the thick calcareous shell, where your rude hand perceives nothing, she feels by a delicate tact the mysterious being which she nourishes and forms. It is this feeling which sustains her during the arduous labour of incubation, during her protracted captivity. She sees it delicate and charming in its soft down of infancy, and she predicts with the vision of hope that it will be vigorous and bold, when, with outspread wings, it shall eye the sun and breast the storm.

Let us profit by these days. Let us hasten nothing. Let us contemplate at our leisure this delightful image of the maternal reverie—of that second childbirth by which she completes the invisible object of her love—the unknown offspring of desire.

A delightful spectacle, but even more sublime than delightful. Let us be modest here. With us the mother loves that which stirs in her bosom—that which she touches, clasps, enfolds in assured possession; she loves the reality, certain, agitated and moving, which responds to her own movements. But this one loves the future and unknown; her heart beats alone, and nothing as yet responds to it. Yet is not her love the less intense; she devotes herself and suffers; she will suffer unto death for her dream and her faith.

A faith powerful and efficacious! It produces a world, and one of the most wonderful of worlds. Speak not to me of suns, of the elementary chemistry of globes. The marvel of a humming-bird's egg transcends the Milky Way.

Understand that this little point which to you seems imperceptible, is an entire ocean—the sea of milk where floats in embryo the well-beloved of heaven. It floats; fears no shipwreck; it is held suspended by the most delicate ligaments; it is saved from jar and shock. It swims all gently in the warm element, as it will swim hereafter in the atmosphere. A profound serenity, a perfect state in the bosom of a nourishing habitation! And how superior to all suckling (allaitement)!

But see how, in this divine sleep, it has perceived its mother and her magnetic warmth. And it, too, begins to dream. Its dream is of motion; it imitates, it conforms to its mother; its first act, the act of an obscure love, is to resemble her.

And as soon as it resembles her, it will seek to join her. It inclines, it presses more closely against the shell, which thenceforth is the sole barrier between it and its mother. Then, then she listens! Sometimes she is blessed by hearing already its first tender piping. It will remain a prisoner no longer. Grown daring, it will take its own part. It has a beak, and makes use of it. It strikes, it cracks, it cleaves its prison wall. It has feet, and brings them to its assistance. See now the work begun! Its reward is deliverance; it enters into liberty.

To tell the rapture, the agitation, the prodigious inquietude, the mother's many cares, is beyond our province here; of the difficulties of its education we have already spoken.