Title: The Comic English Grammar: A New and Facetious Introduction to the English Tongue

Author: Percival Leigh

Illustrator: John Leech

Release date: August 4, 2013 [eBook #43397]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

LONDON:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY,

Bangor House, Shoe Lane.

THE COMIC

ENGLISH GRAMMAR;

A NEW AND FACETIOUS

Introduction to the English Tongue.

BY THE AUTHOR OF THE COMIC LATIN GRAMMAR.

EMBELLISHED

WITH UPWARDS OF FIFTY CHARACTERISTIC ILLUSTRATIONS BY J. LEECH.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET.

1840.

TO MR. GEORGE ROBINS,

A Writer unrivalled in this or any other Age for

AN ORIGINALITY OF STYLE,

(if the expression may be pardoned) quite unique, and a Dexterity in the Use

of Metaphor unparalleled; whose multifarious and sublime—it would not

be too much to say

talented—Compositions would, it may be fearlessly

asserted, afford any

ENTERPRISING PUBLISHER

a not-every-day-to-be-met-with, and not in-a-hurry-to-be-relinquished opportunity

for an

ELIGIBLE INVESTMENT OF CAPITAL,

forming a Property which, under judicious management, would soon become

entitled to the well-merited appellation of a

PRINCELY DOMAIN!

which, without exciting a blush in the mind of veracity, might be said (in a

literary point of view) to be fertilised by a meandering rivulet of Poetry,

comparable for Beauty and Picturesque Effect to

THE SILVERY STREAM OF THE ISIS;

whose richness (equalled only by his fidelity) of description, presenting a refreshing

contrast to the style of his various compeers, precludes the attempt

to perpetrate a panegyric, otherwise than by assuming the responsibility and

risk of applying to him the words of our

IMMORTAL BARD:

“Take him for all in all

We ne’er shall see his like again.”

This little Treatise on

COMIC ENGLISH

is, with the most profound Veneration, Admiration, nay, even with

Respect (and the term is used “advisedly”)

humbly dedicated

by

HIS MOST OBLIGED AND MOST

OBEDIENT SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR.

It may be considered a strange wish on the part of an Author, to have his preface compared to a donkey’s gallop. We are nevertheless desirous that our own should be considered both short and sweet. For our part, indeed, we would have every preface as short as an orator’s cough, to which, in purpose, it is so nearly like; but Fashion requires, and like the rest of her sex, requires because she requires, that before a writer begins the business of his book, he should give an account to the world of his reasons for producing it; and therefore, to avoid singularity, we shall proceed with the statement of our own, excepting only a few private ones, which are neither here nor there.

[Pg viii]To advance the interests of mankind by promoting the cause of Education; to ameliorate the conversation of the masses; to cultivate Taste, and diffuse Refinement; these are the objects which we have in view in submitting a Comic English Grammar to the patronage of a discerning Public. Nor have we been actuated by philanthropic motives alone, but also by a regard to Patriotism, which, as it has been pronounced on high authority to be the last refuge of a scoundrel, must necessarily be the first concern of an aspiring and disinterested mind. We felt ourselves called upon to do as much, at least, for Modern England as we had before done for Ancient Rome; and having been considered by competent judges to have infused a little liveliness into a dead language, we were bold enough to hope that we might extract some amusement from a living one.

Few persons there are, whose ears are so extremely obtuse, as not to be frequently annoyed at the violations of Grammar by which they are so often assailed. It is really painful to be forced, in walking along the streets, to hear such phrases as, “That ’ere homnibus.” “Where’ve you bin.”[Pg ix] “Vot’s the hodds?” and the like. Very dreadful expressions are also used by draymen and others in addressing their horses. What can possibly induce a human being to say “Gee woot!” “’Mather way!” or “Woa?” not to mention the atrocious “Kim aup!” of the ignorant and degraded costermonger. We once actually heard a fellow threaten to “pitch into” his dog! meaning, we believe, to beat the animal.

It is notorious that the above and greater enormities are perpetrated in spite of the number of Grammars already before the world. This fact sufficiently excuses the present addition to the stock; and as serious English Grammars have hitherto failed to effect the desired reformation, we are induced to attempt it by means of a Comic one.

With regard to the moral tendency of our labours, we may here be permitted to remark, that they will tend, if successful, to the suppression of evil speaking.

We shall only add, that as the Spartans used to exhibit a tipsy slave to their children with a view to disgust them with drunkenness, so we, by giving a few examples here and there, of[Pg x] incorrect phraseology, shall expose, in their naked deformity, the vices of speech to the ingenuous reader.

| Page | |

| FRONTISPIECE. | Frontispiece |

| MINERVA TEACHING | x |

| JOHN BULL | 12 |

| THE “PRODIGY” | 14 |

| “JANE YOU KNOW WHO” | 18 |

| MUTES AND LIQUIDS | 23 |

| AWKWARD LOUT | 24 |

| HA! HA! HA! HO! HO! HO! HE! HE! HE! | 27 |

| “O!, WHAT, A, LARK!—HERE, WE, ARE!” | 28 |

| ALDIBORONTIPHOSCOPHORMIO AND CHRONONHOTONTHOLOGOS | 34 |

| SINGLE BLESSEDNESS | 40 |

| APPLE SAUCE | 45 |

| MATILDA | 48 |

| A SOCIALIST | 50 |

| “SHAN’T I SHINE TO NIGHT, DEAR?” | 51 |

| JULIA | 57 |

| A VERY BAD CASE | 59 |

| A SELECT VESTRY | 69 |

| SELF-ESTEEM | 78 |

| “FACT, MADAM!”—“GRACIOUS, MAJOR!” | 82 |

| YEARS OF DISCRETION | 89 |

| “I SHALL GIVE YOU A DRUBBING!” | 97 |

| [Pg xii]A COMICAL CONJUNCTION | 106 |

| “AS WELL AS CAN BE EXPECTED” | 108 |

| “HOW’S YOUR INSPECTOR?” | 119 |

| “WHAT A DUCK OF A MAN!” | 120 |

| THE FLIRT | 122 |

| THE CAPTAIN | 128 |

| THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON | 131 |

| “OH! YOU GOOD-FOR-NOTHING MAN!” | 137 |

| THE YOUNG GENTLEMAN | 139 |

| “VIRTUE’S REWARD” | 142 |

| “NOT TO MINCE MATTERS, MISS, I LOVE YOU” | 145 |

| THE FRENCH MARQUIS | 149 |

| “THE ENGAGED ONES” | 153 |

| “THE LADIES!” | 156 |

| “HIT ONE OF YOUR OWN SIZE!” | 158 |

| ALL FOR LOVE | 169 |

| “TALE OF A TUB” | 170 |

| “A RESPECTABLE MAN” | 177 |

| DOING WHAT YOU LIKE WITH YOUR OWN | 180 |

| “WHAT A LITTLE DEAR!” | 183 |

| BRUTUS | 187 |

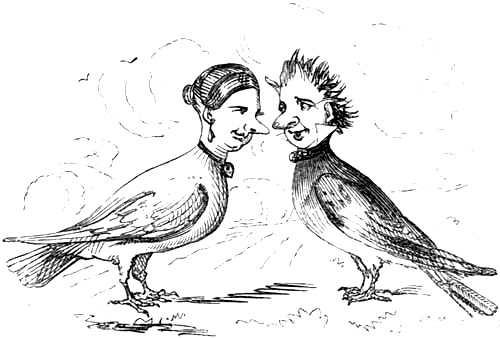

| THE TWO DOVES | 190 |

| “THE NASTY LITTLE SQUALLING BRAT” | 205 |

| “OH, JEMIMA!” | 214 |

| LOVE AND MURDER | 216 |

| STANDING ON POINTS | 218 |

| “WHERE GOT’ST THOU THAT GOOSE?” | 219 |

Our native country having been, from time immemorial, entitled Merry England, it is clear that, provided it has been called by a right name, a Comic Grammar will afford the most hopeful means of teaching its inhabitants their language.

That the epithet in question has been correctly applied, it will therefore be our business to show.

If we can only prove that things which foreigners regard in the most serious point of view, and which, perhaps, ought in reality to be so considered, afford the modern Minotaur John Bull, merely matter of amusement, we shall go far towards the establishment of our position. We hope to do this and more also.

Births, marriages, and deaths, especially the latter, must be allowed to be matters of some consequence. Every one knows what jokes are[Pg 2] made upon the two first subjects. Those which the remaining one affords, we shall proceed to consider.

Suicide, for instance, is looked upon by Mr. Bull with a very different eye from that with which his neighbours regard it. As to an abortive attempt thereat, it excites in his mind unmitigated ridicule, instead of interest and sympathy. In Paris a foolish fellow, discontented with the world, or, more probably, failing in some attempt to make himself conspicuous, ties a brickbat to his neck, and jumps, at twelve o’clock of the day, into the Seine. He thereby excites great admiration in the minds of the bystanders; but were he to play the same trick on London Bridge, as soon as he had been pulled out of the water he would only be laughed at for his pains.

There was a certain gentleman, an officer in the navy, one Lieutenant Luff; at least we have never heard the fact of his existence disputed; who used to spend all his time in drinking grog; and at last, when he could get no more, thought proper to shoot himself through the chest. In France he would have been buried in Père La Chaise, or some such place, and would have had an ode written to his memory. As his native country, however, was the scene of his exploit,[Pg 3] he was interred, for the affair happened some years ago, in a cross-road; and his fate has been made the subject of a comic song.

That our countrymen regard Death as a jest, no one who considers their bravery in war or their appetite in peace, can possibly doubt. And the expressions, “to hop the twig,” “to kick the bucket,” “to go off the hooks,” “to turn up the toes,” and so on, vernacularly used as synonymous with “to expire,” sufficiently show the jocular light in which the last act of the farce of Life is viewed in Her Majesty’s dominions.

An execution is looked upon abroad as a serious affair; but with us it is quite another matter. Capital punishments, whatever they may be to the sufferers, are to the spectators, if we may judge from their behaviour, little else than capital jokes. The terms which, in common discourse, are used by the humble classes to denote the pensile state, namely, “dancing on nothing,” “having a drop too much,” or “being troubled with a line,” are quite playful, and the “Last Dying Speech” of the criminal is usually a species of composition which might well be called “An Entertaining Narrative illustrated with Humourous Designs.”

The play of George Barnwell, in which a[Pg 4] deluded linendraper’s apprentice commits a horrid murder on the body of a pious uncle, excites, whenever it is represented, as much amusement as if it were a comedy; and there is also a ballad detailing the same circumstances, which, when sung at convivial meetings, is productive of much merriment. Billy Taylor, too, another ballad of the same sort, celebrates, in jocund strains, an act of unjustifiable homicide.

Even the terrors of the other world are converted, in Great Britain, into the drolleries of this. The awful apparitions of the unfortunate Miss Bailey, and the equally unfortunate Mr. Giles Scroggins, have each of them furnished the materials of a comical ditty; and the terrific appearance of the Ghost of a Sheep’s Head to one William White,—a prodigy which would be considered in Germany as fearful in the extreme, has been applied, by some popular but anonymous writer, to the same purpose. The bodily ablation of an unprincipled exciseman by the Prince of Darkness, a circumstance in itself certainly of a serious nature, has been recorded by one of our greatest poets in strains by no means remarkable for gravity. The appellation, “Old Nick,” applied by the vulgar to the Prince in question, is, in every sense of the words, a[Pg 5] nickname; and the aliases by which, like many of his subjects, he is also called and known, such as “Old Scratch,” “Old Harry,” or “The Old Gentleman,” are, to say the very least of them, terms that border on the familiar.

In the popular drama of Punch,[1] we observe a[Pg 6] perfect climax of atrocities and horrors. Victim after victim falls prostrate beneath the cudgel of the deformed and barbarous monster; the very first who feels his tyranny being the wife of his bosom. He, meanwhile, behaves in the most heartless manner, actually singing and capering among the mangled carcases. Benevolence is shocked, Justice is derided, Law is set at nought, and Constables are slain. The fate to which he had been consigned by a Jury of his Country is eluded; and the Avenger of Crime is circumvented by the wily assassin. Lastly, to crown the whole, Retribution herself is mocked; and the very Arch Fiend is dismissed to his own dominions with a fractured skull. And at every stage of these frightful proceedings shouts of uproarious laughter attest the delight of the beholders, increasing in violence with every additional terror, and swelling at the concluding one to an almost inextinguishable peal.

Indeed there is scarcely any shocking thing out of which we can extract no amusement, except the loss of money, wherein, at least when it is our own, we cannot see anything to laugh at.

Some will say that we make it a principle to convert whatever frightens other people into a jest, in order that we may imbibe a contempt[Pg 7] for danger; and that our superiority (universally admitted) over all nations in courage and prowess, is, in fact, owing to the way which we have acquired of laughing all terrors, natural and supernatural, utterly to scorn. With these, however, we do not agree. Our national laughter is, in our opinion, as little based on principle as our national actions have of late years been. We laugh from impulse, or, as we do everything else, because we choose. And we shall find, on examination, that we have contrived, amongst us, to render a great many things exceedingly droll and absurd, without having the slightest reason to assign for so doing.

For example, there is nothing in the office of a Parish Clerk that makes it desirable that he should be a ludicrous person. There is no reason why he should have a cracked voice; an inability to use, or a tendency to omit, the aspirate; a stupid countenance; or a pompous manner. Nor do we clearly see why he should be unable to pronounce proper names; should say Snatchacrab for Sennacherib, or Leftenant for Leviathan. Such, nevertheless, are the peculiarities by which he is commonly distinguished.

We are likewise at a loss to divine why so studiously ridiculous a costume has been made to[Pg 8] enhance the natural absurdity of a Beadle; for we can hardly believe that his singular style of dress was really intended to inspire small children with veneration and awe.

It can scarcely be supposed that a Lord Mayor’s Show was instituted only to be laughed at; yet who would contend that it is of any other use? Nor could the office of the Chief Magistrate of a Corporation, nor that of an Alderman, have been created for the amusement of the Public: there is, however, no purpose which both of them so frequently serve.

If the wig and robes of a Judge were meant to excite the respect of the community in general, and the fear of the unconscientious part of it, we cannot but think that the design has been unsuccessful. That the ministers of justice are not, in fact, so reverently held, by any means, as from the nature of their functions they might be expected to be, is certain. A magistrate, to go no further, is universally known, if not designated, by the jocose appellation of “Beak.”

Butchers, bakers, cobblers, tinkers, costermongers, and tailors; to say nothing of footmen, waiters, dancing-masters, and barbers have become the subjects of ridicule to an extent not warranted by their avocations, simply considered.

[Pg 9]But the comical mind, like the jaundiced eye, views everything through a coloured medium. Such a mind is that of the generality of Britons. We distinguish even the nearest ties of relationship by facetious names. A father is called “Dad,” or “The Governor;” an uncle, “Nunkey;” and a wife, “a rib,” or more pleasantly still, as in the advertisements, an “encumbrance.” Almost every being or thing, indeed, has in English two words to express it, an ordinary and an odd one; and so greatly has the number of expressions of the kind last mentioned increased of late, that, as it appears to us, a new edition of Johnson’s Dictionary, enriched with modern additions, is imperatively called for. When we talk of odd words, we have no fear that our meaning will be misunderstood. It is true that there are some few individuals who complain that they do not see any wit in calling a sheep’s-head a “jemmy,” legs “bandies,” or a hand a “mawley;” and it is also true that there was once a mathematician, who, after reading through Milton’s Paradise Lost, wanted to know what it all proved?

And now that we are speaking of names, we may mention a few which are certainly of a curious nature, and which no foreigner could possibly have invented; unless, which would be likely enough,[Pg 10] he meant to apply them seriously. The names we allude to are names of places—and pretty places they are too; as, “Mount Pleasant,” “Paradise Row,” “Golden Lane.”

Then there are a great many whimsical things that we do:—

When a man cannot pay his debts, and has no prospect of being able to do so except by working, we shut him up in gaol, and humorously describe his condition as that of being in Quod.

We will not allow a man to give an old woman a dose of rhubarb if he have not acquired at least half a dozen sciences; but we permit a quack to sell as much poison as he pleases, with no other diploma than what he gets from the “College of Health.”

When a thief pleads “Guilty” to an indictment, he is advised by the Judge to recall his plea; as if a trial were a matter of sport, and the culprit, like a fox, gave no amusement unless regularly run down. This perhaps is the reason why allowing an animal to start some little time before the pursuit is commenced, is called giving him law.

When one man runs away with another’s wife, and, being on that account challenged to fight a duel, shoots the aggrieved party through the head, the latter is said to receive satisfaction.

[Pg 11]We never take a glass of wine at dinner without getting somebody else to do the same, as if we wanted encouragement; and then, before we venture to drink, we bow to each other across the table, preserving all the while a most wonderful gravity. This, however, it may be said, is the natural result of endeavouring to keep one another in countenance.

The way in which we imitate foreign manners and customs is very amusing. Savages stick fish-bones through their noses; our fair countrywomen have hoops of metal poked through their ears. The Caribs flatten the forehead; the Chinese compress the foot; and we possess similar contrivances for reducing the figure of a young lady to a resemblance to an hour-glass or a devil-on-two-sticks.

There being no other assignable motive for these and the like proceedings, it is reasonable to suppose that they are adopted, as schoolboys say, “for fun.”

We could go on, were it necessary, adducing facts to an almost unlimited extent; but we consider that enough has now been said in proof of the comic character of the national mind. And in conclusion, if any foreign author can be produced, equal in point of wit, humour, and drollery, to[Pg 12] Swift, Sterne, or Butler, we hereby engage to eat him; albeit we have no pretensions to the character of a “helluo librorum.”

THE

COMIC ENGLISH GRAMMAR.

“English Grammar,” according to Lindley Murray, “is the art of speaking and writing the English language with propriety.”

The English language, written and spoken with propriety, is commonly called the King’s English.

A monarch, who, three or four generations back, occupied the English throne, is reported to have said, “If beebles will be boets, they must sdarve.” This was a rather curious specimen of “King’s English.” It is, however, a maxim of our law, that “the King can do no wrong.” Whatever bad English, therefore, may proceed from the royal mouth, is not “King’s English,” but “Minister’s English,” for which they alone are responsible. For illustrations of this kind of “English” we beg to refer the reader to the celebrated English Grammar which was written by the late Mr. Cobbett.

King’s English (or, perhaps, under existing circumstances we should say, Queen’s English) is the[Pg 14] current coin of conversation, to mutilate which, and unlawfully to utter the same, is called clipping the King’s English; a high crime and misdemeanour.

Clipped English, or bad English, is one variety of Comic English, of which we shall adduce instances hereafter.

He’s only a little “prodigy” of mine, Doctor.

Slipslop, or the erroneous substitution of one word for another, as “prodigy” for “protégée,”[Pg 15] “derangement” for “arrangement,” “exasperate” for “aspirate,” and the like, is another.

Slang, which consists in cant words and phrases, as “dodge” for “sly trick,” “no go” for “failure,” and “carney” “to flatter,” may be considered a third.

Latinised English, or Fine English, sometimes assumes the character of Comic English, especially when applied to the purposes of common discourse; as “Extinguish the luminary,” “Agitate the communicator,” “Are your corporeal functions in a condition of salubrity?” “A sable visual orb,” “A sanguinary nasal protuberance.”

American English is Comic English in a “pretty particular considerable tarnation” degree.

Among the various kinds of Comic English it would be “tout-à-fait” inexcusable, were we to “manquer” to mention one which has, so to speak, quite “bouleversé’d” the old-fashioned style of conversation; French-English, that is what “nous voulons dire.” “Avec un poco” of the “Italiano,” this forms what is also called the Mosaic dialect.

English Grammar is divided into four parts—Orthography, Etymology, Syntax, and Prosody; and as these are points that a good grammarian always stands upon, he, particularly when a pedant, and consequently somewhat flat, may very properly be compared to a table.

OF THE NATURE OF THE LETTERS, AND OF A COMIC ALPHABET.

Orthography is like a junior usher, or instructor of youth. It teaches us the nature and powers of letters and the right method of spelling words.

Note.—In a public school, the person corresponding to an usher is called a master. As it is sometimes his duty to flog, we propose that he should henceforth be called the “Usher of the Birch Rod.”

Comic Orthography teaches us the oddity and absurdities of letters, and the wrong method of spelling words. The following is an example of Comic Orthography:—

islinton foteenth of

febuary 1840.

my Deer jemes

wen fust i sawed yu doun the middle and up agin att Vite condick ouse i maid Up my Mind to skure you for my hone for i Felt at once that my appiness was at Steak, and a sensashun in my Bussum I coudent no ways accompt For. And i [Pg 17]said to mary at missis Igginses said i theres the Mann for my money o ses Shee i nose a Sweeter Yung Man than that Air Do you sez i Agin then there we Agree To Differ, and we was sittin by the window and we wos wery Neer fallin Out. my deer gemes Sins that Nite i Havent slept a Wink and Wot is moor to the Porpus i Have quit Lost my Happy tight and am gettin wus and wus witch i Think yu ort to pitty Mee. i am Tolled every Day that ime Gettin Thinner and a Jipsy sed that nothin wood Cure me But a Ring.

i wos a Long time makin my Mind Up to right to You for of Coarse i Says jemes will think me too forrad but this bein Leep yere i thout ide Make a Plunge speshialy as her grashius madjesty as Set the Exampel of Popin the queshton, leastways to all Them as dont Want to Bee old Mades all their blessed lives. so my Deer Jemes if yow want a Pardoner for Better or for wus nows Your Time dont think i Behave despicable for tis my Luv for yu as makes Me take this Stepp.

please to Burn this Letter when Red and excuse the scralls and Blotches witch is Caused by my Teers i remain

till deth Yure on Happy

Vallentine

jane you No who.

[Pg 18]poscrip

nex Sunday Is my sunday out And i shall be Att the corner of Wite lion Street pentonvil at a quawter pas Sevn.

Wen This U. C.

remember Mee

j. g.

[Pg 19]Now, to proceed with Orthography, we may remark, that

A letter is the least part of a word.

Of a comic letter an instance has already been given.

Dr. Johnson’s letter to Lord Chesterfield is a capital letter.

The letters of the Alphabet are the representatives of articulate sounds.

The Alphabet is a Republic of Letters.

There are many things in this world erroneously as well as vulgarly compared to “bricks.” In the case of the letters of the Alphabet, however, the comparison is just; they constitute the fabric of a language, and grammar is the mortar. The wonder is that there should be so few of them. The English letters are twenty-six in number. There is nothing like beginning at the beginning; and we shall now therefore enumerate them, with the view also of rendering their insertion subsidiary to mythological instruction, in conformity with the plan on which some account of the Heathen Deities and ancient heroes is prefixed or subjoined to a Dictionary. We present the reader with a form of Alphabet composed in humble imitation of that famous one, which, while appreciable by the dullest[Pg 20] taste, and level to the meanest capacity, is nevertheless that by which the greatest minds have been agreeably inducted into knowledge.

THE ALPHABET.

A was Apollo, the god of the carol,

B stood for Bacchus, astride on his barrel;

C for good Ceres, the goddess of grist,

D was Diana, that wouldn’t be kiss’d;

E was nymph Echo, that pined to a sound,

F was sweet Flora, with buttercups crown’d;

G was Jove’s pot-boy, young Ganymede hight,

H was fair Hebe, his barmaid so tight;

I, little Io, turn’d into a cow,

J, jealous Juno, that spiteful old sow;

K was Kitty, more lovely than goddess or muse;

L, Lacooon—I wouldn’t have been in his shoes!

M was blue-eyed Minerva, with stockings to match,

N was Nestor, with grey beard and silvery thatch;

O was lofty Olympus, King Jupiter’s shop,

P, Parnassus, Apollo hung out on its top;

Q stood for Quirites, the Romans, to wit;

R, for rantipole Roscius, that made such a hit;

S, for Sappho, so famous for felo-de-se,

T, for Thales the wise, F.R.S. and M.D.:

[Pg 21]U was crafty Ulysses, so artful a dodger,

V was hop-a-kick Vulcan, that limping old codger;

Wenus—Venus I mean—with a W begins,

(Vell, if I ham a Cockney, wot need of your grins?)

X was Xantippe, the scratch-cat and shrew,

Y, I don’t know what Y was, whack me if I do!

Z was Zeno the Stoic, Zenobia the clever,

And Zoilus the critic, Victoria for ever!

Letters are divided into Vowels and Consonants.

The vowels are capable of being perfectly uttered by themselves. They are, as it were, independent members of the Alphabet, and like independent members elsewhere form a small minority. The vowels are a, e, i, o, u, and sometimes w and y.

An I. O. U. is a more pleasant thing to have, than it is to give.

A blow in the stomach is very likely to W up.

W is a consonant when it begins a word, as “Wicked Will Wiggins whacked his wife with a whip;” but in every other place it is a vowel, as crawling, drawling, sawney, screwing, Jew. Y follows the same rule.

A consonant is an articulate sound; but, like an old bachelor, if it exist alone it exists to no[Pg 22] purpose. It cannot be perfectly uttered without the aid of a vowel; and even then the vowel has the greatest share in the production of the sound. Thus a vowel joined to a consonant becomes, so to speak, a “better half:” or at all events very strongly resembles one.

Consonants are divided into mutes and semi-vowels.

The mutes cannot be sounded at all without the aid of a vowel. Like young ladies just “come out,” they are silent as long as you let them alone. Some have compared them, on account of their name, to the “Original Good Woman;” but how joining her to anything except to her head again would have cured her of her dumbness, it is not easy to see. B, p, t, d, k, and c and g hard, are the letters called mutes, or, as some have denominated them, black letters.

The semi-vowels, which are f, l, m, n, r, v, s, x, z, and c and g soft, have an imperfect sound of themselves. Well! half a loaf is better than no bread.

L, m, n, r, are further distinguished by the name of liquids. Like certain other liquids they are good for mixing, that is to say, they readily unite with other consonants; and flow, as it were, into their sounds.

[Pg 23]The specific gravity of liquids can only be rendered amusing by comical figures. The gravity, too, of a solid is generally the more ludicrous.

MUTES AND LIQUIDS.

[Pg 24]A diphthong is the union of two vowels in one sound, as ea in heavy, eu in Meux, ou in stout.

A triphthong is a similar union of three vowels, as eau in the word beau; a term applied to dandies, and addressed to geese: probably because they are birds of a feather.

A proper diphthong is that in which the sound is formed by both the vowels: as, aw in awkward, ou in lout.

[Pg 25]An improper diphthong is that in which the sound is formed by one of the vowels only, as ea in heartless, oa in hoax.

According to our notions there are a great many improper diphthongs in common use. By improper diphthongs we mean vowels unwarrantably dilated into diphthongs, and diphthongs mispronounced, in defiance of good English, and against our Sovereign Lady the Queen, her crown and dignity.

For instance, the rustics say,—

“Loor! whaut a foine gaal! Moy oy!”

“Whaut a precious soight of crows!”

“As I was a comin’ whoam through the corn fiddles (fields) I met Willum Jones.”

After this manner cockneys express themselves:—

“I sor (saw) him.”

“Dror (draw) it out.”

“Hold your jor (jaw).”

“I caun’t. You shaun’t. How’s your Maw and Paw? Do you like taut (tart)?”

We have heard young ladies remark,—

“Oh, my! What a naice young man!”

“What a bee—eautiful day!”

“I’m so fond of dayncing!”

Dandies frequently exclaim,—

[Pg 26]“I’m postively tiawed (tired).”

“What a sweet tempaw! (temper).”

“How daughty (dirty) the streets au!”

And they also call,—

Literature, “literetchah.”

Perfectly, “pawfacly.”

Disgusted, “disgasted.”

Sky (theatrical dandies do this chiefly) “ske-eye.”

Blue, “ble—ew.”

We might here insert a few remarks on the nature of the human voice, and of the mechanism by means of which articulation is performed; but besides our dislike to prolixity, we are afraid of getting down in the mouth, and thereby going the wrong way to please our readers. We may nevertheless venture to invite attention to a few comical peculiarities in connection with articulate sounds.

Ahem! at the commencement of a speech, is a sound agreeably droll.

The vocal comicalities of the infant in arms are exceedingly laughable, but we are unfortunately unable to spell them.

The articulation of the Jew is peculiarly ridiculous. The “peoplesh” are badly spoken of, and not well spoken.

[Pg 27]Bawling, croaking, hissing, whistling, and grunting, are elegant vocal accomplishments.

Lisping, as, “thweet, Dthooliur, thawming, kweechau,” is by some considered interesting, by others absurd.

Stammering is sometimes productive of amusement.

Humming and hawing are ludicrous embellishments to a discourse. Crowing like a cock, braying like a donkey, quacking like a duck, and hooting like an owl, are modes of exerting the voice which are usually regarded as diverting.

But of all the sounds which proceed from the human mouth, by far the funniest are Ha! ha! ha!—Ho! ho! ho! and He! he! he!

OF SYLLABLES.

Syllable is a nice word, it sounds so much like syllabub!

A syllable, whether it constitute a word or part of a word, is a sound, either simple or compound, produced by one effort of the voice, as, “O!, what, a, lark!—Here, we, are!”

[Pg 29]Spelling is the art of putting together the letters which compose a syllable, or the syllables which compose a word.

Comic spelling is usually the work of imagination. The chief rule to be observed in this kind of spelling, is, to spell every word as it is pronounced; though the rule is not universally observed by comic spellers. The following example, for the genuineness of which we can vouch, is one so singularly apposite, that although we have already submitted a similar specimen of orthography to the reader, we are irresistibly tempted to make a second experiment on his indulgence. The epistolary curiosity, then, which we shall now proceed to transcribe, was addressed by a patient to his medical adviser.

“Sir,

“My Granmother wos very much trubeld With the Gout and dide with it my father wos also and dide with it when i was 14 years of age i wos in the habbet of Gettin whet feet Every Night by pumping water out of a Celler Wich Cas me to have the tipes fever wich Cas my Defness when i was 23 of age i fell in the Water betwen the ice and i have Bin in the habbet of [Pg 30]Getting wet when traviling i have Bin trubbeld with Gout for seven years

“Your most humbel

“Servent

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . .

Clearkenwell”

Chelsea College has been supposed by foreigners to be an institution for the teaching of orthography; probably in consequence of a passage in the well known song in “The Waterman,”

“Never more at Chelsea Ferry,

Shall your Thomas take a spell.”

Q. Why is a dunce no conjuror?

A. Because he cannot spell.

Among the various kinds of spelling may be enumerated spelling for a favour; or giving what is called a broad hint.

Certain rules for the division of words into syllables are laid down in some grammars, and we should be very glad to follow the established usage, but, limited as we are by considerations of comicality and space, we cannot afford to give more than two very general directions. If you[Pg 31] do not know how to spell a word, look it out in the dictionary, and if you have no dictionary by you, write the word in such a way, that, while it may be guessed at, it shall not be legible.

OF WORDS IN GENERAL.

There is no one question that we are aware of more puzzling than this, “What is your opinion of things in general?” Words in general are, fortunately for us, a subject on which the formation of an opinion is somewhat more easy. Words stand for things: they are a sort of counters, checks, bank-notes, and sometimes, indeed, they are notes for which people get a great deal of money. Such words, however, are, alas! not English words, or words sterling. Strange! that so much should be given for a mere song. It is quite clear that the givers, whatever may be their pretensions to a refined or literary taste, must be entirely unacquainted with Wordsworth.

Fine words are oily enough, and he who uses them is vulgarly said to “cut it fat;” but for all that it is well known that they will not butter parsnips.

Some say that words are but wind: for this reason, when people are having words, it is often said, that “the wind’s up.”

[Pg 33]Different words please different people. Philosophers are fond of hard words; pedants of tough words, long words, and crackjaw words; bullies, of rough words; boasters, of big words; the rising generation, of slang words; fashionable people, of French words; wits, of sharp words and smart words; and ladies, of nice words, sweet words, soft words, and soothing words; and, indeed, of words in general.

Words (when spoken) are articulate sounds used by common consent as signs of our ideas.

A word of one syllable is called a Monosyllable: as, you, are, a, great, oaf.

A word of two syllables is named a Dissyllable; as, cat-gut, mu-sic.

A word of three syllables is termed a Trisyllable; as, Mag-net-ism, Mum-mer-y.

A word of four or more syllables is entitled a Polysyllable; as, in-ter-mi-na-ble, cir-cum-lo-cu-ti-on, ex-as-pe-ra-ted, func-ti-o-na-ry, met-ro-po-li-tan, ro-tun-di-ty.

Words of more syllables than one are sometimes comically contracted into one syllable; as, in s’pose for suppose, b’lieve for believe, and ’scuse for excuse: here, perhaps, ’buss, abbreviated from omnibus, deserves to be mentioned.

In like manner, many long words are elegantly trimmed and shortened; as, ornary for ordinary,[Pg 34] ’strornary for extraordinary, and curosity for curiosity; to which mysterus for mysterious may also be added.

Polysyllables are an essential element in the sublime, both in poetry and in prose; but especially in that species of the sublime which borders very closely on the ridiculous; as,

“Aldiborontiphoscophormio,

Where left’st thou Chrononhotonthologos?”

[Pg 35]All words are either primitive or derivative. A primitive word is that which cannot be reduced to any simpler word in the language; as, brass, York, knave. A derivative word, under the head of which compound words are also included, is that which may be reduced to another and a more simple word in the English language; as, brazen, Yorkshire, knavery, mud-lark, lighterman.

Broadbrim is a derivative word; but it is one often applied to a very primitive kind of person.

A COMICAL VIEW OF THE PARTS OF SPEECH.

Etymology teaches the varieties, modifications, and derivation of words.

The derivation of words means that which they come from as words; for what they come from as sounds, is another matter. Some words come from the heart, and then they are pathetic; others from the nose, in which case they are ludicrous. The funniest place, however, from which words can come, is the stomach. By the way, the Lord Mayor would do well to keep a ventriloquist, from whom, at a moment’s notice, he might ascertain the voice of the corporation.

Comic Etymology teaches us the varieties, modifications, and derivation, of words invested with a comic character.

Grammatically speaking, we say that there are, in English, as many sorts of words as a cat is said[Pg 37] to have lives, nine; namely, the Article, the Substantive or Noun, the Adjective, the Pronoun, the Verb, the Adverb, the Preposition, the Conjunction, and the Interjection.

Comically speaking, there are a great many sorts of words which we have not room enough to particularise individually. We can therefore only afford to classify them. For instance; there are words which are spoken in the Low Countries, and are High Dutch to persons of quality; as in Billingsgate, Whitechapel, and St. Giles’s.

Words in use amongst all those who have to do with horses.

Words that pass between rival cab-men.

Words peculiar to the P. R. where the order of the day is generally a word and a blow.

Words spoken in a state of intoxication.

Words uttered under excitement.

Words of endearment, addressed to children in arms.

Similar words, sometimes called burning, tender, soft, and broken words, addressed to young ladies, and whispered, lisped, sighed, or drawled, according to circumstances.

Words of honour; as, tailors’ words and shoemakers’ words; which, like the above-mentioned, or lovers’ words, are very often broken.

[Pg 38]With many other sorts of words, which will be readily suggested by the reader’s fancy.

But now let us go on with the parts of speech.

1. An Article is a word prefixed to substantives to point them out, and to show the extent of their meaning; as, a dandy, an ape, the simpleton.

One kind of comic article is otherwise denominated an oddity, or queer article.

Another kind of comic article is often to be met with in Bentley’s Miscellany.

2. A Substantive or Noun is the name of anything that exists, or of which we have any notion; as, tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, apothecary, ploughboy, thief.

Now the above definition of a substantive is Lindley Murray’s, not ours. We mention this, because we have an objection, though, not, perhaps, a serious one, to urge against it; for, in the first place, we have “no notion” of impudence, and yet impudence is a substantive; and, in the second, we invite attention to the following piece of Logic,

A substantive is something,

But nothing is a substantive;

Therefore, nothing is something.

A substantive may generally be known by its taking an article before it, and by its making sense of itself: as, a treat, the mulligrubs, an ache.

3. An Adjective is a word joined to a substantive[Pg 39] to denote its quality; as a ragged regiment, an odd set.

You may distinguish an adjective by its making sense with the word thing: as, a poor thing, a sweet thing, a cool thing; or with any particular substantive, as a ticklish position, an awkward mistake, a strange step.

4. A Pronoun is a word used in lieu of a noun, in order to avoid tautology: as, “The man wants calves; he is a lath; he is a walking-stick.”

5. A Verb is a word which signifies to be, to do, or to suffer: as, I am; I calculate; I am fixed.

A verb may usually be distinguished by its making sense with a personal pronoun, or with the word to before it: as I yell, he grins, they caper; or to drink, to smoke, to chew.

Fashionable accomplishments!

Certain substantives are, with peculiar elegance, and by persons who call themselves genteel, converted into verbs: as, “Do you wine?” “Will you malt?” “Let me persuade you to cheese?”

6. An Adverb is a part of speech which, joined to a verb, an adjective, or another adverb, serves to express some quality or circumstance concerning it: as, “She swears dreadfully; she is incorrigibly lazy; and she is almost continually in liquor.”

7. An adverb is generally characterised by answering to the question, How? how much? when?[Pg 40] or where? as in the verse, “Merrily danced the Quaker’s wife,” the answer to the question, How did she dance? is, merrily.

8. Prepositions serve to connect words together, and to show the relation between them: as,

“Off with his head, so much for Buckingham!”

9. A Conjunction is used to connect not only words, but sentences also: as, Smith and Jones are happy because they are single. A miss is as good as a mile.

SINGLE BLESSEDNESS.

[Pg 41]10. An Interjection is a short word denoting passion or emotion: as, “Oh, Sophonisba! Sophonisba, oh!” Pshaw! Pish! Pooh! Bah! Ah! Au! Eughph! Yah! Hum! Ha! Lauk! La! Lor! Heigho! Well! There! &c.

Among the foregoing interjections there may, perhaps, be some unhonoured by the adoption of genius, and unknown in the domains of literature. For the present notice of them some apology may be required, but little will be given; their insertion may excite astonishment, but their omission would have provoked complaint: though unprovided with a Johnsonian title to a place in the English vocabulary, they have long been recognised by the popular voice; and let it be remembered, that as custom supplies the defects of legislation, so that which is not sanctioned by magisterial authority may nevertheless be justified by vernacular usage.

OF THE ARTICLES.

The Articles in English are two, a and the; a becomes an before a vowel, and before an h which is not sounded: as, an exquisite, an hour-glass. But if the h be pronounced, the a only is used: as, a homicide, a homœopathist, a hum.

This rule is reversed in what is termed the Cockney dialect: as, a inspector, a officer, a object, a omnibus, a individual, a alderman, a honour, an horse, or rather, a norse, an hound, an hunter, &c.

It is usual in the same dialect, when the article an should, in strict propriety, precede a word, to omit the letter n, and further, for the sake of euphony and elegance, to place the aspirate h before the word; as, a hegg, a haccident, a hadverb, a hox. But sometimes, when a word begins with an h, and has the article a before it, the aspirate is omitted, the letter a remaining unchanged: as, a ’ogg, a ’edge, a ’emisphere, a ’ouse.

[Pg 43]The slight liberties which it is the privilege of the people to take with the article and aspirate become always most evident in the expression of excited feeling, when the stress which is laid upon certain words is heightened by the peculiarity of the pronunciation: as, “You hignorant hupstart! you hilliterate ’og! ’ow dare you to hoffer such a hinsult to my hunderstanding?—You are a hobject of contempt, you hare, and a hinsolent wagobond! your mother was nothing but a happle-woman, and your father was an ’uckster!”

Note.—In the above example, the ordinary rules of language relative to the article and aspirate (to say nothing of the maxims of politeness) are completely set at nought; but it must be remembered, that in common discourse the modification of the article, and the omission or use of the aspirate, are determined by the Cockneys according to the ease with which particular words are pronounced; as, “Though himpudent, he warn’t as impudent as Bill wur.” Here the word impudent, following a vowel-sound, is most easily pronounced as himpudent, while the same word, coming after a consonant, even in the same sentence, is uttered with greater facility in the usual way.

A or an is called the indefinite article, because it is used, in a vague sense, to point out some one[Pg 44] thing belonging to a certain kind, but in other respects indeterminate; as,

“A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”

So say grammarians. Eating-house keepers tell a different story. A cheese, in common discourse, means an object of a certain shape, size, weight, and so on, entire and perfect; so that to call half a cheese a cheese, would constitute a flaw in an indictment against a thief who had stolen one. But a waiter will term a fraction, or a modicum of cheese, a cheese; a plate-full of pudding, a pudding; and a stick of celery, a celery, or rather, a salary. Nay, he will even apply the article a to a word which does not stand for an individual object at all; as a bread, a butter, a bacon. Here we are reminded of the famous exclamation of one of these gentry:—“Master! master! there’s two teas and a brandy-and-water just hopped over the palings!”

The is termed the definite article, inasmuch as it denotes what particular thing or things are meant; as,

“The miller he stole corn,

The weaver he stole yarn,

And the little tailòr he stole broad-cloth

To keep the three rogues warm.”

[Pg 45]A substantive to which no article is prefixed is taken in a general sense; as, “Apple sauce is proper for goose;” that is, for all geese.

APPLE-SAUCE.

A few additional remarks may advantageously be made with respect to the articles. The mere substitution of the definite for the indefinite article is capable of changing entirely the meaning of a[Pg 46] sentence. “That is a ticket” is the assertion of a certain fact; but “That is the ticket!” means something which is quite different.

The article is not prefixed to a proper name; as, Stubbs, Wiggins, Chubb, or Hobson, except for the sake of distinguishing a particular family, or description of persons; as, He is a Burke; that is, one of the Burkes, or a person resembling Burke. The article is sometimes also prefixed to a proper name, to point out some distinguished individual; as, The Burke, or the great politician, or the resurrectionist, Burke.

Who is the Smith?

The indefinite article is joined to substantives in the singular number only. We have heard people say, however, “He keeps a wine-vaults;” or, to quote more correctly—waltz. The definite article may be joined to plurals also.

The definite article is frequently used with adverbs in the comparative and superlative degree: as, “The longer I live, the broader I grow;” or, as we have all heard the showman say, “This here, gentlemen and ladies, is the vonderful heagle of the sun; the ’otterer it grows, the higherer he flies!”

SECTION I.

OF SUBSTANTIVES IN GENERAL.

Substantives are either proper or common.

Proper names, or substantives, are the names belonging to individuals: as William, Birmingham.

These are sometimes converted into nicknames, or improper names: as Bill, Brummagem.

Common names, or substantives, denote kinds containing many sorts, or sorts containing many individuals under them: as brute, beast, bumpkin, cherub, infant, goblin, &c.

Proper names, when an article is prefixed to them, are employed as common names: as, “They thought him a perfect Chesterfield; he quite astonished the Browns.”

Common names, on the other hand, are made to denote individuals, by the addition of articles or pronouns: as,

“There was a little man, and he had a little gun.”

“That boy will be the death of me!”

[Pg 48]Substantives are considered according to gender, number, and case; they are all of the third person when spoken of, and of the second when spoken to: as,

Matilda, fairest maid, who art

In countless bumpers toasted,

O let thy pity baste the heart

Thy fatal charms have roasted!

SECTION II.

OF GENDER.

The distinction between nouns with regard to sex is called Gender. There are three genders; the Masculine, the Feminine, and the Neuter.

The masculine gender belongs to animals of the male kind: as, a fop, a jackass, a boar, a poet, a lion.

The feminine gender is peculiar to animals of the female kind: as, a poetess, a lioness, a goose.

The neuter gender is that of objects which are neither males nor females: as, a toast, a tankard, a pot, a pipe, a pudding, a pie, a sausage, a roll, a muffin, a crumpet, a puff, a cheesecake, a bun, an apricot, an orange, a lollipop, a cream, an ice, a jelly, &c. &c. &c.

We might go on to enumerate an infinity of objects of the neuter gender, of all sorts and kinds; but in the selection of the foregoing examples we have been guided by two considerations:—

1. The desire of exciting agreeable emotions in the mind of the reader.

2. The wish to illustrate the following proposition, “That almost everything nice is also neuter.”

Except, however, a nice young lady, a nice duck,[Pg 50] and one or two other nice things, which we do not at present remember.

Some neuter substantives are by a figure of speech converted into the masculine or feminine gender: thus we say of the sun, that when he shines upon a Socialist, he shines upon a thief; and of the moon, that she affects the minds of lovers.

A SOCIALIST.

There are certain nouns with which notions of strength, vigour, and the like qualities, are more particularly connected; and these are the neuter substantives which are figuratively rendered masculine. On the other hand, beauty, amiability, and[Pg 51] so forth, are held to invest words with a feminine character. Thus the sun is said to be masculine, and the moon feminine. But for our own part, and our view is confirmed by the discoveries of astronomy, we believe that the sun is called masculine from his supporting and sustaining the moon, and finding her the wherewithal to shine away as she does of a night, when all quiet people are in bed; and from his being obliged to keep such a family of stars besides. The moon, we think, is accounted feminine, because she is thus maintained and kept up in her splendour, like a fine lady, by her husband the sun. Furthermore, the moon is continually changing; on which account alone she might be referred to the feminine gender. The earth is feminine, tricked out, as she is, with gems and flowers. Cities and towns are likewise feminine, because there are as many windings, turnings, and little odd corners in them as there are in the female mind. A ship is feminine, inasmuch as she is blown about by every wind. Virtue is feminine by courtesy. Fortune and misfortune, like mother and daughter, are both feminine. The Church is feminine, because she is married to the state; or married to the state because she is feminine—we do not know which. Time is masculine, because he is so trifled with by the ladies.

“Shan’t I shine to-night, dear?”

The English language distinguishes the sex in three manners; namely,

1. By different words; as,

| MALE. | FEMALE. | |

| Bachelor | Maid. | |

| Boar | Sow. | |

| [Pg 53]Boy | Girl. | |

| Bull | Cow. | |

| Brother | Sister. | |

| Buck | Doe. | |

| Bullock | Heifer. | |

| Hart | Roe. | |

| Cock | Hen. | |

| Dog | Bitch. | |

| Drake | Duck. | |

| Wizard | Witch. | |

| Earl | Countess. | |

| Father | Mother. | |

| Friar | Nun. |

And several other

Words we don’t mention,

(Pray pardon the crime,)

Worth your attention,

But wanting in rhyme.

2. By a difference of termination; as,

| MALE. | FEMALE. | |

| Poet | Poetess. | |

| Lion | Lioness, &c. |

3. By a noun, pronoun, or adjective being prefixed to the substantive; as,

| MALE. | FEMALE. | |

| A cock-lobster | A hen-lobster. | |

| A jack-ass | A jenny-ass (vernacular). | |

| A man-servant, or flunkey. | A maid-servant, or Abigail. | |

| A he-bear (like King Harry). | A she-bear (like Queen Bess). | |

| A male flirt (a rare animal). | A female flirt (a common animal). |

We have heard it said, that every Jack has his Jill. That may be; but it is by no means true that every cock has his hen; for there is a

Cock-swain, but no Hen-swain.

Cock-eye, but no Hen-eye.

Cock-ade, but no Hen-ade.

Cock-atrice, but no Hen-atrice.

Cock-horse, but no Hen-horse.

Cock-ney, but no Hen-ney.

Then we have a weather-cock, but no weather-hen; a turn-cock, but no turn-hen; and many a jolly cock, but not one jolly hen; unless we except some of those by whom their mates are pecked.

Some words; as, parent, child, cousin, friend, neighbour, servant, and several others, are either male or female, according to circumstances. The word blue (used as a substantive) is one of this class.

It is a great pity that our language is so poor in the terminations that denote gender. Were we to[Pg 55] say of a woman, that she is a rogue, a knave, a scamp, or a vagabond, we feel that we should use, not only strong but improper expressions. Yet we have no corresponding terms to apply, in case of necessity, to the female. Why is this? Doubtless because we never want them. For the same reason, our forefathers transmitted to us the words, philosopher, astronomer, philologer, and so forth, without any feminine equivalent. Alas! for the wisdom of our ancestors! They never calculated on the March of Intellect.

We understand that it is in contemplation to coin a new word, memberess; it being confidently expected that by the time the new Houses of Parliament are finished, the progress of civilisation will have furnished us with female representatives.

In that case the House will be an assembly of Speakers.

But if all the old women are to be turned out of St. Stephen’s, and their places to be filled with young ones, the nation will hardly be a loser by the change.

SECTION III.

OF NUMBER.

Number is the consideration of an object as one or more; as, one poet, two, three, four, five poets; and so on, ad infinitum.

[Pg 56]Other countries may reckon up as many poets as they please; England has one more.

The singular number expresses one object only; as, a towel, a viper.

The plural signifies more objects than one; as, towels, vipers.

Some nouns are used only in the singular number; dirt, pitch, tallow, grease, filth, butter, asparagus, &c.; others only in the plural; as, galligaskins, breeches, &c.

Some words are the same in both numbers; as, sheep, swine, and some others.

“A doctor, both to sheep and swine,”

Said Mrs. Glass, “I am;

For legs of mutton I can dress,

And shine in curing ham.”

The plural number of nouns is usually formed by adding s to the singular; as, dove, doves, love, loves, &c.

Julia, dove returns to dove,

Quid pro quo, and love for love;

Happy in our mutual loves,

Let us live like turtle doves!

When, however, the substantive singular ends in x, ch soft, sh, ss, or s, we add es in the plural.

But remember, though box

In the plural makes boxes,

That the plural of ox

Should be oxen, not oxes.

[Pg 58]A few Singular Plurals, or Plurals popularly varied, are as follow:—

| SINGULAR. | PLURAL. | |

| Beast | Beastes, beastices. | |

| Crust | Crustes. | |

| Gust | Gustes. | |

| Ghost | Ghostes. | |

| Host | Hostes. | |

| Joist | Joistes. | |

| Mist | Mistes. | |

| Nest | Nestes. | |

| Post, &c. | Postes, postices, &c. |

Note.—The singular is often used, by a kind of licence conceded to persons of refinement, for the plural; as, “May I trouble you for a bean?” “Will you assist Miss Spriggins to a pea?” So also people say, “A few green.” “Two or three radish,” &c.

SECTION IV.

OF CASE.

There is nearly as much difference between Latin and English substantives, with respect to the number of cases pertaining to each, as there is between a quack-doctor and a physician; for while in Latin substantives have six cases, in English they have but three. But the analogy should not[Pg 59] be strained too far; for the fools in the world (who furnish the quack with his cases) more than double the number of the wise.

A VERY BAD CASE.

The cases of substantives are these: the Nominative, the Possessive or Genitive, and the Objective or Accusative.

The Nominative Case merely expresses the name of a thing, or the subject of the verb: as, “The doctors differ;”—“The patient dies!”

[Pg 60]Possession, which is nine points of the law, is what is signified by the Possessive Case. This case is distinguished by an apostrophe, with the letter s subjoined to it: as, “My soul’s idol!”—“A pudding’s end.”

But when the plural ends in s, the apostrophe only is retained, and the other s is omitted: as, “The Ministers’ Step;”—“The Rogues’ March;”—“Crocodiles’ tears;”—“Butchers’ mourning.”

When the singular terminates in ss, the letter s is sometimes, in like manner, dispensed with: as, “For goodness’ sake!”—“For righteousness’ sake!” Nevertheless, we have no objection to “Guinness’s” Stout.

The Objective Case follows a verb active, and expresses the object of an action, or of a relation: as, “Spring beat Bill;” that is, Bill or “William Neate.” Hence, perhaps, the American phrase, “I’ll lick you elegant.”

By the by, it seems to us, that when the Americans revolted from the authority of England, they determined also to revolutionise their language.

The Objective Case is also used with a preposition: as, “You are in a mess.”

English substantives may be declined in the following manner:—

SINGULAR.

What is the nominative case

Of her who used to wash your face,

Your hair to comb, your boots to lace?

A mother!

What the possessive? Whose the slap

That taught you not to spill your pap,

Or to avoid a like mishap?

A mother’s!

And shall I the objective show?

What do I hear where’er I go?

How is your?—whom they mean I know,

My mother!

PLURAL.

Who are the anxious watchers o’er

The slumbers of a little bore,

That screams whene’er it doesn’t snore?

Why, mothers!

Whose pity wipes its piping eyes,

And stills maturer childhood’s cries,

Stopping its mouth with cakes and pies?

Oh! mothers’!

And whom, when master, fierce and fell,

Dusts truant varlets’ jackets well,

Whom do they, roaring, run and tell?

Their mothers!

OF ADJECTIVES.

SECTION I.

OF THE NATURE OF ADJECTIVES AND THE DEGREES OF COMPARISON.

An English Adjective, whatever may be its gender, number, or case, like a rusty weathercock, never varies. Thus we say, “A certain cabinet; certain rogues.”

But as a rusty weathercock may vary in being more or less rusty, so an adjective varies in the degrees of comparison.

The degrees of comparison, like the genders, the Graces, the Fates, the Kings of Cologne, the Weird Sisters, the Jolly Postboys, and many other things, are three; the Positive, the Comparative, and the Superlative.

The Positive state simply expresses the quality of an object; as, fat, ugly, foolish.

[Pg 63]The Comparative degree increases or lessens the signification of the positive; as, fatter, uglier, more foolish, less foolish.

The Superlative degree increases or lessens the positive to the highest or lowest degree; as, fattest, ugliest, most foolish, least foolish.

Amongst the ancients, Ulysses was the fattest, because nobody could compass him.

Aristides the Just was the ugliest, because he was so very plain.

The most foolish, undoubtedly, was Homer; for who was more natural than he?

The positive becomes the comparative by the addition of r or er; and the superlative by the addition of st or est to the end of it; as, brown, browner, brownest; stout, stouter, stoutest; heavy, heavier, heaviest; wet, wetter, wettest. The adverbs more and most, prefixed to the adjective, also form the superlative degree; as, heavy, more heavy, most heavy.

Most heavy is the drink of draymen: hence, perhaps, the weight of those important personages. More of this, however, in our forthcoming work on Phrenology.

Monosyllables are usually compared by er and est, and dissyllables by more and most; except dissyllables ending in y or in le before a mute, or those[Pg 64] which are accented on the last syllable; for these, like monosyllables, easily admit of er and est. But these terminations are scarcely ever used in comparing words of more than two syllables.

We have some words, which, from custom, are irregular in respect of comparison; as, good, better, best; bad, worse, worst, &c. Much amusement may be derived from the comparisons of adjectives, as made by natural grammarians; a class of beings who generally inhabit the kitchen or stable, but may sometimes be met with in more elevated regions. A few examples will not be out of place. We are not speaking of servants, but of degrees of comparison; as,

| POSITIVE. | COMPARATIVE. | SUPERLATIVE. | ||

| Good | More better, betterer or more betterer. |

Most best, bestest. | ||

| Tight | More tighter, tighterer or more tighterer. |

Most tightest. | ||

| Bad | Wuss or wusser. | Wust or wussest. | ||

| Handsome | More handsomer like. | Most handsomest. | ||

| Extravagant | Extravaganter, more extravaganter. |

Extravagantest, most extravagantest. | ||

| Stupid | Stupider, more stupider. |

Stupidest, most stupidest. | ||

| Little | Littler, more littler. | Littlest, most littlest. |

With many others.

[Pg 65]Here also may be adduced the Yankee’s “notion” of comparison; “My uncle’s a tarnation rogue; but I’m a tarnationer.”

SECTION II.

A FEW REMARKS ON THE SUBJECT OF COMPARISON.

Comparisons appear to have been strongly disapproved of by Dr. Johnson. “Sir,” said he, “the Whigs make comparisons.” It must be confessed that the Doctor’s meaning is not quite so evident here as it is in general; but that may be the fault of his biographer. Perhaps some of the Whigs had been making comparisons at his expense, or impertinent comparisons, which his temper, being positive, may have tempted them to indulge in. Or they may have been out in making their comparisons, which, in that case, must of course have been bad. But a truce to speculations of this kind, on the saying of one, another of whose dogmas was, that “the man who could make a pun would also pick a pocket.” We only hope, that such comparisons as we may make, will no more vex his spirit now than they would once have aroused his bile.

Lindley Murray judiciously observes, that “if we consider the subject of comparison attentively,[Pg 66] we shall perceive that the degrees of it are infinite in number, or at least indefinite:” and he proceeds to say, “A mountain is larger than a mite; by how many degrees? How much bigger is the earth than a grain of sand? By how many degrees was Socrates wiser than Alcibiades? or by how many is snow whiter than this paper? It is plain,” quoth Lindley, “that to these and the like questions no definite answers can be returned.”

No; but an impertinent one may. Ask the first charity-boy you meet any one of them, and see if he does not immediately respond, “Ax my eye;” or, “As much again as half.”

But when quantity can be exactly measured, the degrees of excess may be exactly ascertained. A foot is just twelve times as long as an inch; a tailor is nine times less than a man.

Moreover, to compensate for the indefiniteness of the degrees of comparison, we use certain adverbs and words of like import, whereby we render our meaning tolerably intelligible; as, “Byron was a much greater poet than Muggins.” “Honey is a great deal sweeter than wax.” “Sugar is considerably more pleasant than the cane.” “Maria says, that Dick the butcher is by far the most killing young man she knows.”

The words very, exceedingly, and the like, placed[Pg 67] before the positive, give it the force of the superlative; and this is called by some the superlative of eminence, as distinguished from the superlative of comparison. Thus, Very Reverend is termed the superlative of eminence, although it is the title of a dean, not of a cardinal; and Most Reverend, the appellation of an Archbishop, is called the superlative of comparison.

A Bishop, in our opinion, is Most Excellent.

The comparative is sometimes so employed as to express the same pre-eminence or inferiority as the superlative. For instance; the sentence, “Of all the cultivators of science, the botanist is the most crafty,” has the same meaning as the following “The botanist is more crafty than any other cultivator of science.”

Why? some of our readers will ask—

Because he is acquainted with all sorts of plants.

OF PRONOUNS.

Pronouns or proxy-nouns are of three kinds; namely, the Personal, the Relative, and the Adjective Pronouns.

Note.—That when we said, some few pages back, that a pronoun was a word used instead of a noun, we did not mean to call such words as thingumibob, whatsiname, what-d’ye-call-it, and the like, pronouns.

And that, although we shall proceed to treat of the pronouns in the English language, we shall have nothing to do, at present, with what some people please to call pronoun-ciation.

SECTION I.

OF THE PERSONAL PRONOUNS.

“Mr. Haddams, don’t be personal, Sir!”

“I’m not, Sir.”

“You har, Sir!”

“What did I say, Sir?—tell me that.”

[Pg 69]“You reflected on my perfession, Sir; you said, as there was some people as always stuck up for the cloth; and you insinnivated that certain parties dined off goose by means of cabbaging from the parish. I ask any gentleman in the westry, if that an’t personal?”

A SELECT VESTRY.

[Pg 70]“Vell, Sir, vot I says I’ll stick to.”

“Yes, Sir, like vax, as the saying is.”

“Wot d’ye mean by that, Sir?”

“Wot I say, Sir!”

“You’re a individual, Sir!”

“You’re another, Sir!”

“You’re no gentleman, Sir!”

“You’re a humbug, Sir!”

“You’re a knave, Sir!”

“You’re a rogue, Sir!”

“You’re a wagabond, Sir!”

“You’re a willain, Sir!”

“You’re a tailor, Sir!”

“You’re a cobbler, Sir!” (Order! order! chair! chair! &c.)

The above is what is called personal language. How many different things one word serves to express in English! A pronoun may be as personal as possible, and yet nobody will take offence at it.

There are five Personal Pronouns; namely, I, thou, he, she, it; with their plurals, we, ye or you, they.

Personal Pronouns admit of person, number, gender, and case.

Pronouns have three persons in each number.

[Pg 71]In the Singular;

I, is the first person.

Thou, is the second person.

He, she, or it, is the third person.

In the plural;

We, is the first person.

Ye or you, is the second person.

They, is the third person.

This account of persons will be very intelligible when the following Pastoral Fragment is reflected on:—

HE.

I love thee, Susan, on my life:

Thou art the maiden for a wife.

He who lives single is an ass;

She who ne’er weds a luckless lass.

It’s tiresome work to live alone;

So come with me, and be my own.

SHE.

We maids are oft by men deceived;

Ye don’t deserve to be believed;

You don’t—but there’s my hand—heigho!

They tell us, women can’t say no!

The speaker or speakers are of the first person; those spoken to, of the second; and those spoken of, of the third.

[Pg 72]Of the three persons, the first is the most universally admired.

The second is the object of much adulation and flattery, and now and then of a little abuse.

The third person is generally made small account of; and, amongst other grievances, suffers a great deal from being frequently bitten about the back.

The Numbers of pronouns, like those of substantives, are, as we have already seen, two; the singular and the plural.

In addressing yourself to anybody, it is customary to use the second person plural instead of the singular. This practice most probably arose from a notion, that to be thought twice the man that the speaker was, gratified the vanity of the person addressed. Thus, the French put a double Monsieur on the backs of their letters.

Editors say “We,” instead of “I,” out of modesty.

The Quakers continue to say “thee” and “thou,” in the use of which pronouns, as well as in the wearing of broad-brimmed hats and of stand-up collars, they perceive a peculiar sanctity.

Gender has to do only with the third person singular of the pronouns, he, she, it. He is masculine; she is feminine; it is neuter.

[Pg 73]Pronouns have the like cases with substantives; the nominative, the possessive, and the objective.

Would that they were the hardest cases to be met with in this country!

The personal pronouns are thus declined:—

| CASE. | FIRST PERSON SINGULAR. |

FIRST PERSON PLURAL. | ||

| Nom. | I | We. | ||

| Poss. | Mine | Ours. | ||

| Obj. | Me | Us. |

Pronouns, you see, are declined without fuss.

| CASE. | SECOND PERSON. | SECOND PERSON. | ||

| Nom. | Thou | Ye or you. | ||

| Poss. | Thine | Yours. | ||

| Obj. | Thee | You. |

How glad I shall be when my task I’ve got through!

Now the third person singular, as we before observed, has genders; and we shall therefore decline it in a different way. Variety is charming.

THIRD PERSON SINGULAR.

| CASE. | MASC. | FEM. | NEUT. | |||

| Nom. | He | She | It. | |||

| Well | done | Kit! | ||||

| Poss. | His. | Hers | Its. | |||

| Now | Tom’s | quits. | ||||

| [Pg 74]Obj. | Him | Her | It. | |||

| Deuce | a | bit! |

| CASE. | PLURAL. | |

| Nom. | They | |

| Poss. | Theirs. | |

| Obj. | Them. |

Reader, Mem.

We beg to inform thee, that the third person plural has no distinction of gender.

SECTION II.

OF THE RELATIVE PRONOUNS.

The Pronouns called Relative are such as relate, for the most part, to some word or phrase, called the antecedent, on account of its going before: they are, who, which, and that: as, “The man who does not drink enough when he can get it, is a fool; but he that drinks too much is a beast.”

What is usually equivalent to that which, and is, therefore, a kind of compound relative, containing both the antecedent and the relative; as, “You want what you’ll very soon have!” that is to say, the thing which you will very soon have.

[Pg 75]Who is applied to persons, which to animals and things without life; as, “He is a gentleman who keeps a horse and lives respectably.” “To the dog which pinned the old woman, they cried, ‘Cæsar!’” “This is the tree which Larkins called a helm.”

Larkins.—I say, Nibbs, ven is a helm box like a asthmatical chest?

Nibbs.—Ven it’s a coffin.

That, as a relative, is used to prevent the too frequent repetition of who and which, and is applied both to persons and things; as, “He that stops the bottle is a Cork man.” “This is the house that Jack built.”

Who is of both numbers; and so is an Editor; for, according to what we observed just now, he is both singular and plural. Who, we repeat, is of both numbers, and is thus declined:—

SINGULAR AND PLURAL.

| Nominative. | Who | |

| Is the maiden to woo? | ||

| Genitive. | Whose | |

| Hand shall I choose? | ||

| Accusative. | Whom | |

| To despair shall I doom? | ||

Which, that, and what are indeclinable; except[Pg 76] that whose is sometimes used as the possessive case of which; as,

“The roe, poor dear, laments amain,

Whose sweet hart was by hunter slain.”

Thus whose is substituted for of which, in the following example:—

“There is a blacking famed, of which

The sale made Day and Martin rich;

There is another blacking, whose

Compounder patronised the Muse.”[2]

Who, which, and what, when they are used in asking questions, are called Interrogatives; as, “Who is Mr. Walker?” “Which is the left side of a round plum-pudding?” “What is the damage?”

Those who have made popular phraseology their study, will have found that which is sometimes used for whereas, and words of like signification; as in Dean Swift’s “Mary the Cookmaid’s Letter to Dr. Sheridan”:—

“And now I know whereby you would fain make an excuse,

[Pg 77]Because my master one day in anger call’d you a goose;

Which, and I am sure I have been his servant since October,

And he never called me worse than sweetheart, drunk or sober.”

What, or, to speak more improperly, wot, is generally substituted by cabmen and costermongers for who; as, “The donkey wot wouldn’t go.” “The man wot sweeps the crossing.”

That, likewise, is very frequently rejected by the vulgar, who use as in its place; as, “Them as asks shan’t have any; and them as don’t ask don’t want any.”

SECTION III.

OF THE ADJECTIVE PRONOUNS.

Adjective pronouns partake of the nature of both pronouns and adjectives. They may be subdivided into four sorts: the possessive, the distributive, the demonstrative, and the indefinite.

The possessive pronouns are those which imply possession or property. Of these there are seven; namely, my, thy, his, her, our, your, their.

The word self is added to possessives; as, myself, yourself, “Says I to myself, says I.” Self is[Pg 78] also sometimes used with personal pronouns; as, himself, itself, themselves. His self is a common, but not a proper expression.

SELF-ESTEEM.

The distributive are three: each, every, either; they denote the individual persons or things separately, which, when taken together, make up a number.

Each is used when two or more persons or[Pg 79] things are mentioned singly; as, “each of the Catos;” “each of the Browns.”

Every relates to one out of several; as, “Every mare is a horse, but every horse is not a mare.”

Either refers to one out of two; as,

“When I between two jockeys ride,

I have a knave on either side.”

Neither signifies “not either;” as “Neither of the Bacons was related to Hogg.”

The demonstrative pronouns precisely point out the subjects to which they relate; such are this and that, with their plurals these and those; as, “This is a foreign Prince; that is an English Peer.”

This refers to the nearest person or thing, and to the latter or last mentioned; that to the most distant, and to the former or first mentioned; as, “This is a man; that is a nondescript.” “At the period of the Reformation in Scotland, a curious contrast between the ancient and modern ecclesiastical systems was observed; for while that had been always maintained by a Bull, this was now supported by a Knox.”

The indefinite are those which express their subjects in an indefinite or general manner; as, some, other, any, one, all, such, &c.

[Pg 80]When the definite article the comes before the word other, those who do not know better, are accustomed to strike out the he in the, and to say, t’other.

The same persons also use other in the comparative degree; for sometimes, instead of saying quite the reverse, or perhaps rewerse, they avail themselves of the expression, more t’other.

So much for the Pronouns.

OF VERBS.

SECTION I.

OF THE NATURE OF VERBS IN GENERAL.

The nature of Verbs in general, and that in all languages, is, that they are the most difficult things in the Grammar.

Verbs are divided into Active, Passive, and Neuter; and also into Regular, Irregular, and Defective. To these divisions we beg to add another; Verbs Comic.

A Verb Active implies an agent, and an object acted upon; as, to love; “I love Wilhelmina Stubbs.” Here, I am the agent; that is, the lover; and Wilhelmina Stubbs is the object acted upon, or the beloved object.

A Verb Passive expresses the suffering, feeling, or undergoing of something; and therefore implies an object acted upon, and an agent by which it is acted upon; as, to be loved; “Wilhelmina Stubbs is loved by me.”

[Pg 82]A Verb Neuter expresses neither action nor passion, but a state of being; as, I bounce, I lie.

“Fact, Madam!”

“Gracious, Major!”

Of Verbs Regular, Irregular, and Defective, we shall have somewhat to say hereafter.

Verbs Comic are, for the most part, verbs which cannot be found in the dictionary, and are used to[Pg 83] express ordinary actions in a jocular manner; as, to “morris,” to “bolt,” to “mizzle,” which signify to go or to depart; to “bone,” to “prig,” that is to say, to steal; to “collar,” which means to seize, an expression probably derived from the mode of prehension, or rather apprehension characteristic of the New Police, as it is one very much in the mouths of those who most frequently come in contact with that body: to “lush,” or drink; to “grub,” or eat; to “sell,” or deceive, &c.