Title: Life of Mozart, Vol. 3 (of 3)

Author: Otto Jahn

Commentator: George Grove

Translator: Pauline D. Townsend

Release date: August 7, 2013 [eBook #43413]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

| Volume I. | Volume II. |

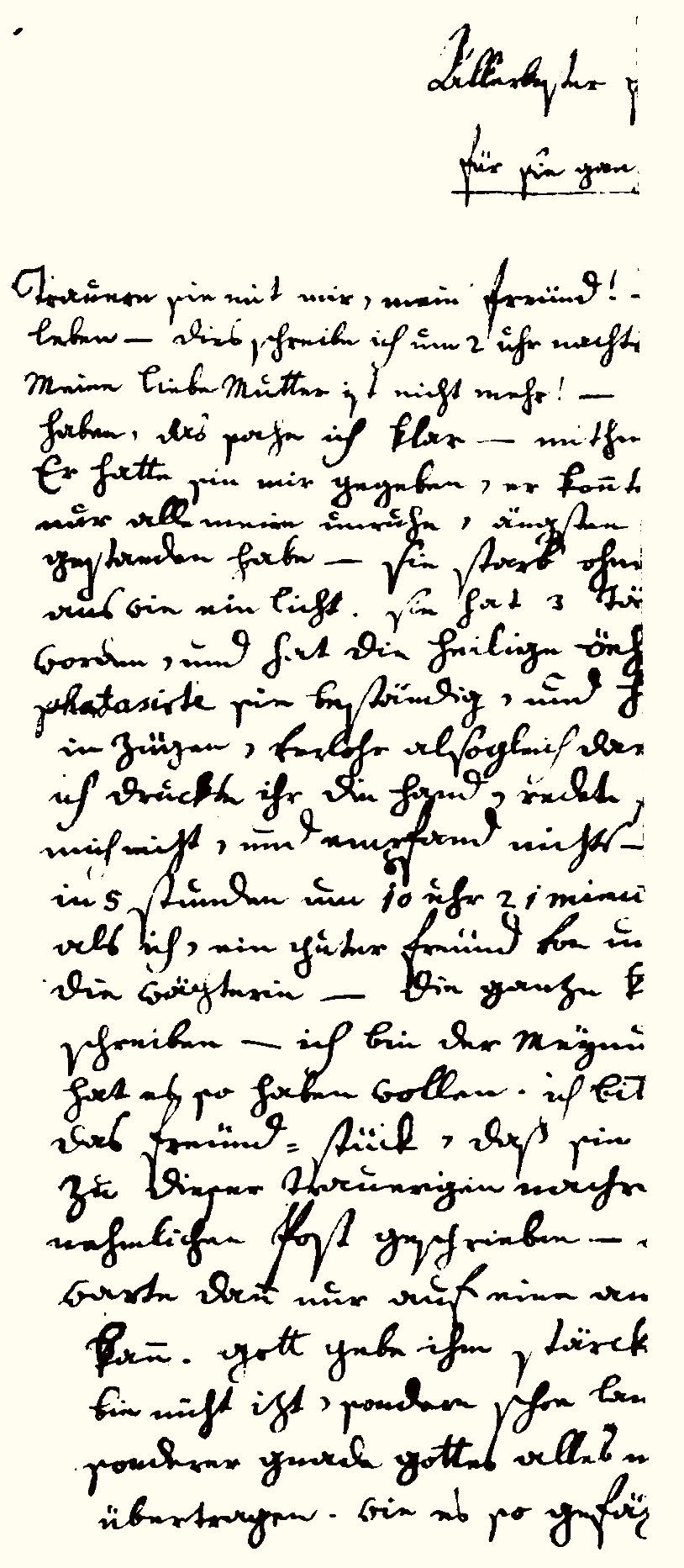

Fac-similé No. 1 is of Mozart's letter to Bullinger from Paris, after the death of his mother (see Vol. II., p. 53).

Fac-simile No. 2 is of the original MS. of "Das Veil-chen," now in the possession of Mr. Speyer, of Herne Hill (see Vol. II., p. 373).

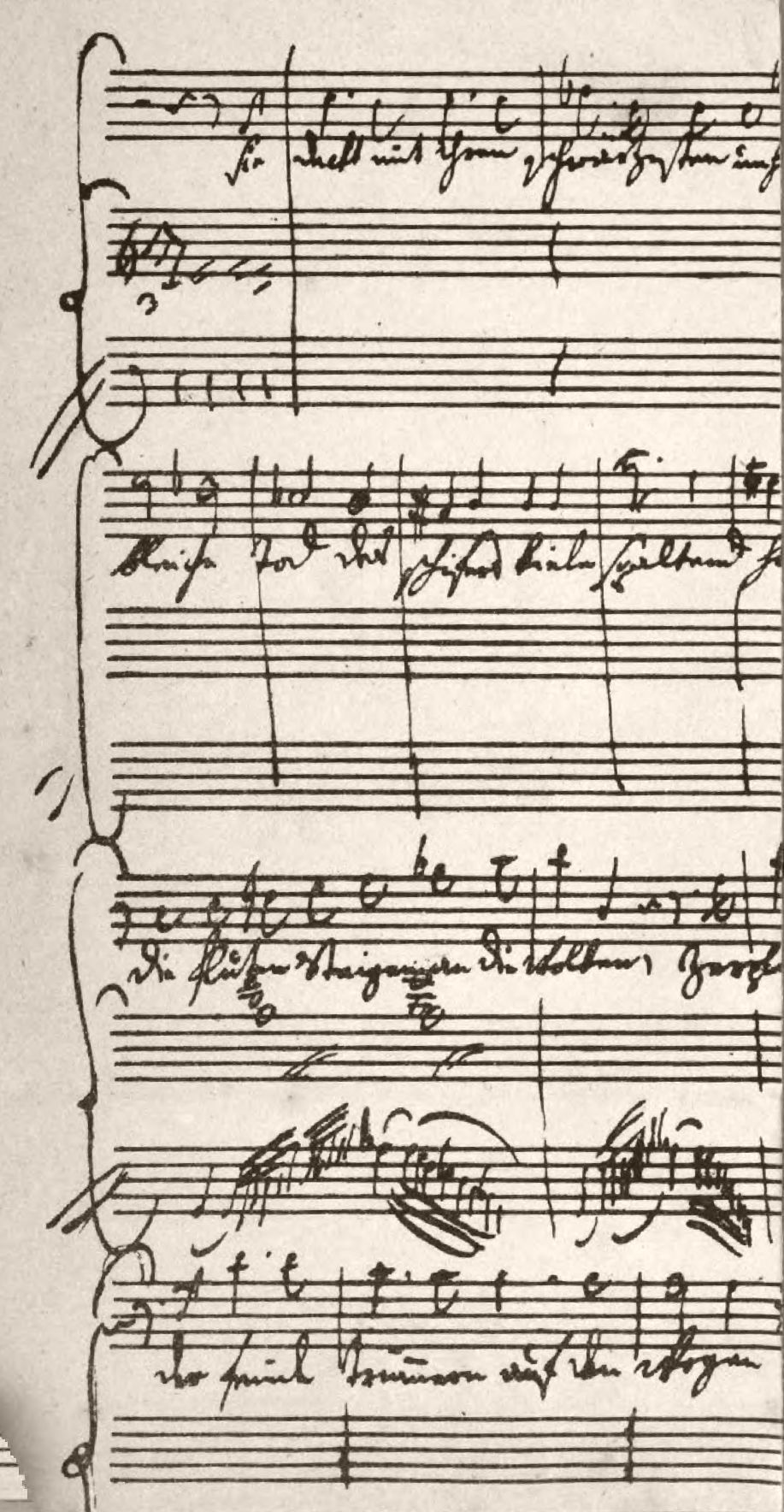

Fac-similes Nos. 3 and 4 are sketches illustrative of Mozart's method of composing. Sketch I. is described in Vol. II., p. 425. Sketch II. is of part of Denis's Ode, the words of which are given below; it is noticed in Vol. II., pp. 370, 424:

O Calpe! dir donnerts am Fusse,

Doch blickt dein tausendjähriger

Gipfel Ruhig auf Welten umher.

Siehe dort wölkt es sich auf

Ueber die westlichen Wogen her,

Wölket sich breiter und ahnender auf,—

Es flattert, O Calpe! Segelgewolk!

Flügel der Hülfe! Wie prachtig

Wallet die Fahne Brittaniens

Deiner getreuen Verheisserin!

Calpe! Sie walltl Aber die Nacht sinkt,

Sie deckt mit ihren schwàrzesten,

Unholdesten Rabenfittigen Gebirge,

Flàchen, Meer und Bucht Und Klippen, wo der bleiche

Tod Des Schiffers, Kiele spaltend, sitzt.

Hinan!

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XXXIV. MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC.

CHAPTER XXXV. MOZART AS AN OPERA COMPOSER.

CHAPTER XXXVI. "LE NOZZE DI FIGARO."

CHAPTER XXXVII. MOZART IN PRAGUE.

CHAPTER XXXVIII. "DON GIOVANNI."

CHAPTER XXXIX. OFFICIAL AND OCCASIONAL WORKS.

CHAPTER XL. A PROFESSIONAL TOUR.

CHAPTER XLI. "COSÌ FAN TUTTE,"

CHAPTER XLII. LABOUR AND POVERTY.

CHAPTER XLIII. "DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE"

CHAPTER XLIV. ILLNESS AND DEATH.

APPENDIX II. ARRANGEMENTS OF MOZART'S CHURCH MUSIC.

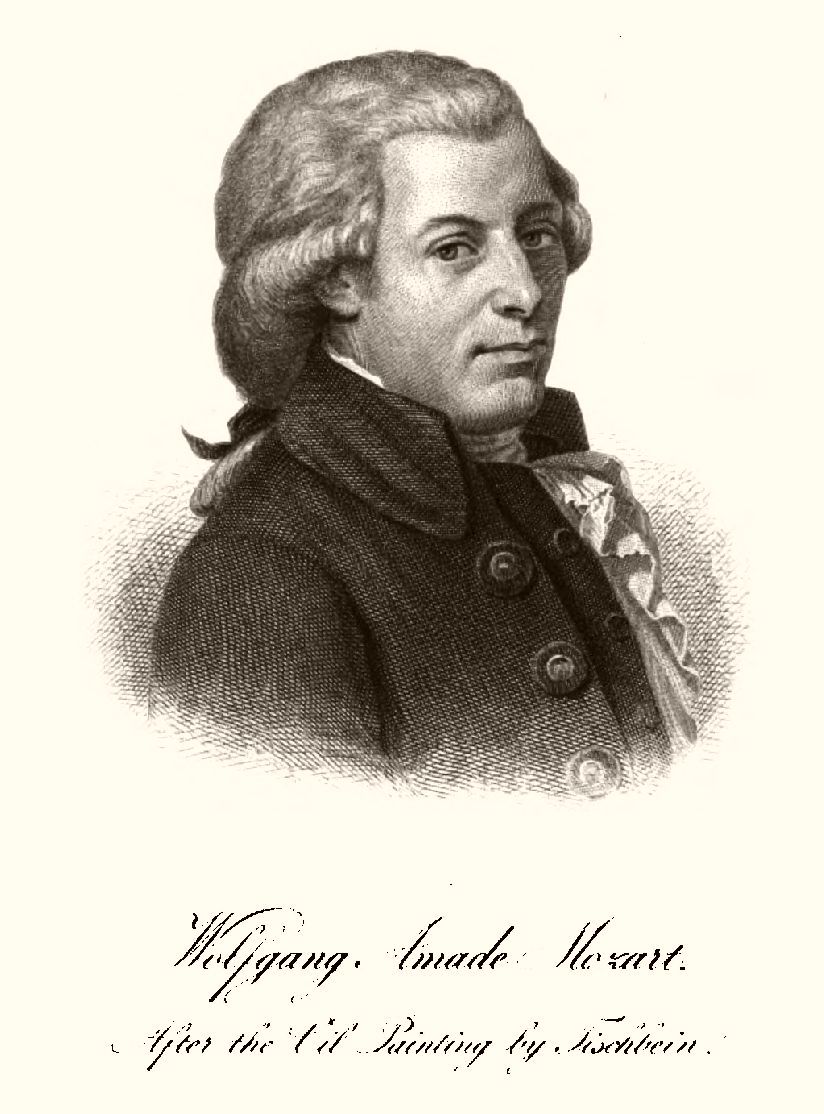

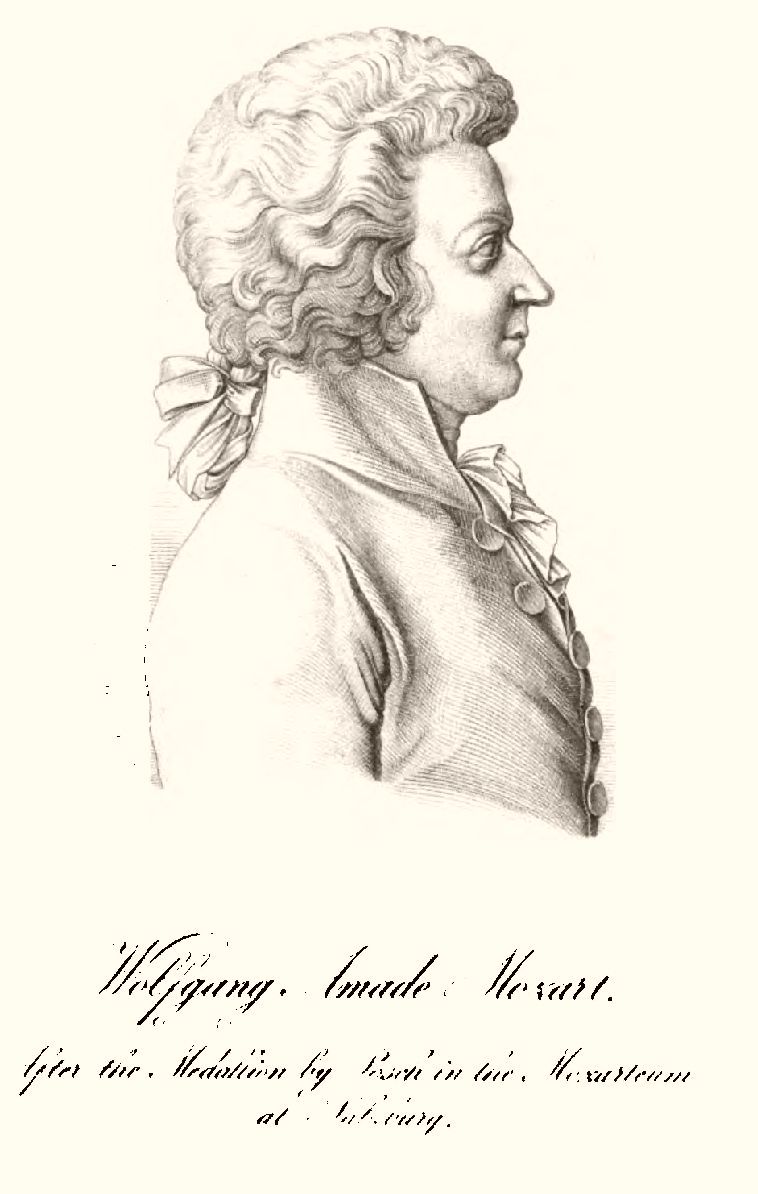

APPENDIX III. PORTRAITS OF MOZART.

APPENDIX IV. LIST OF WORKS and INDEX

NEXT to pianoforte music for amateur musical entertainments, the quartet for stringed instruments was the favourite form of chamber music. The performers were occasionally highly cultivated amateurs, but more often professional musicians, thus giving scope for more pretentious compositions. The comparatively small expense involved enabled others besides noblemen, even those of the citizen class who were so inclined, to include quartet-playing among their regular entertainments. 1 Jos. Haydn was, as is well known, the musician who gave to the quartet its characteristic form and development. 2 Other composers had written works for four stringed instruments, but the string quartet in its well-defined and henceforth stationary constitution was his creation, the result of his life-work. It is seldom that an artist has been so successful in discovering the fittest outcome for his individual productiveness; the quartet was Haydn's natural expression of his musical nature. The freshness and life, the cheerful joviality, which are the main characteristics of his compositions, gained ready and universal acceptance for them. Connoisseurs and critics, it is true, were at first suspicious, and even contemptuous, of this new kind of music; and it was only gradually that they became aware that depth and earnestness of feeling, as well as knowledge and skill, existed together with humour in Haydn's quartets. He went on his way, however, untroubled MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [2] by the critics, and secured the favour and adherence of the public by an unbroken series of works: whoever ventured on the same field was obliged to serve under his banner.

The widespread popularity of quartet music in Vienna could not fail to impel Mozart to try his forces in this direction. His master was also his attached friend and fellow-artist, with whom he stood in the position, not of a scholar, but of an independent artist in noble emulation. The first six quartets belong to the comparatively less numerous works which Mozart wrote for his own pleasure, without any special external impulse. They are, as he says in the dedication to Haydn, the fruit of long and earnest application, and extended over a space of several years. The first, in G major (387 K.), was, according to a note on the autograph manuscript, written on December 31, 1782; the second, in D minor (421 K.), in June, 1783, during Constanze's confinement (Vol. II., p. 423); and the third, in E flat major (428 K.), belongs to the same year. After a somewhat lengthy pause he returned with new zeal to the composition of the quartets; the fourth, in B flat major (458 K.), was written November 9, 1784; the fifth, in A major (464 K.), on January 10; and the last, in C major (465 K.), on January 14, 1785. It was in February of this year that Leopold Mozart paid his visit to Vienna. He knew the first three quartets, Wolfgang having sent them to him according to custom; and he heard the others at a musical party where Haydn was also present; the warmly expressed approbation of the latter may have been the immediate cause of Mozart's graceful dedication, when he published the quartets during the autumn of 1785 (Op. ü). 3

The popular judgment is usually founded on comparison, and a comparison with Haydn's quartets was even more obvious than usual on this occasion. The Emperor Joseph, who objected to Haydn's "tricks and nonsense" (Vol. II., MOZART AND KLOPSTOCK. [3] p. 204), requested Dittersdorf in 1786 to draw a parallel between Haydn's and Mozart's chamber music. Dittersdorf answered by requesting the Emperor in his turn to draw a parallel between Klopstock and Gellert; whereupon Joseph replied that both were great poets, but that Klopstock must be read repeatedly in order to understand his beauties, whereas Gellert's beauties lay plainly exposed to the first glance. Dittersdorf's analogy of Mozart with Klopstock, Haydn with Gellert (!), was readily accepted by the Emperor, who further compared Mozart's compositions to a snuffbox of Parisian manufacture, Haydn's to one manufactured in London. 4 The Emperor looked at nothing deeper than the respective degrees of taste displayed by the two musicians, and could find no better comparison for works of art than articles of passing fancy; whereas the composer had regard to the inner essence of the works, and placed them on the same footing as those of the (in his opinion) greatest poets of Germany. However odd may appear to us—admiring as we do, above all things in Mozart, his clearness and purity of form—Dittersdorf s comparison of him with Klopstock, it is nevertheless instructive, as showing that his contemporaries prized his grandeur and dignity, and the force and boldness of his expression, as his highest and most distinguishing qualities. L. Mozart used also to say, that his son was in music what Klopstock was in poetry; 5 no doubt because Klopstock was to him the type of all that was deep and grand. But the public did not regard the new phenomenon in the same light; the quality they esteemed most highly in Haydn's quartets was their animated cheerfulness; and his successors, Dittersdorf, Pichl, Pleyel, had accustomed them even to lighter enjoyments. "It is a pity," says a favourable critic, in a letter from Vienna (January, 1787), "that in his truly artistic and beautiful compositions Mozart should carry his effort after originality too far, to the detriment of the sentiment and heart of his works. His new quartets, dedicated to Haydn, are much too highly spiced to be palatable for any length

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [4]

of time." 6 Prince Grassalcovicz, a musical connoisseur of rank in Vienna, 7 had the quartets performed, as Mozart's widow relates, 8 and was so enraged at finding that the discords played by the musicians were really in the parts, that he tore them all to pieces—but Gyrowetz's symphonies pleased him very much. From Italy also the parts were sent back to the publisher, as being full of printer's errors, and even Sarti undertook to prove, in a violent criticism, that some of the music in these quartets was insupportable from its wilful offences against rule and euphony. The chief stumbling-block is the well-known introduction of the C major quartet—[See Page Image]

the harshness of which irritates the expectant ear. Its grammatical justification has been repeatedly given in learned analyses. 9 Haydn is said to have declared, during a dispute over this passage, that if Mozart wrote it so, he must have had his reasons for doing it 10 —a somewhat QUARTETS, 1785. [5] ambiguous remark. Ulibicheff 11 undertook to correct the passage with the aid of Fétis, 12 and then considered it both fine and pleasing; and Lenz 13 declared that Mozart in "this delightful expression of the doctrine of necessary evil, founded on the insufficiency of all finite things" had produced a piquant, but not an incorrect passage. It is certain, at least, that Mozart intended to write the passage as it stands, and his meaning in so doing, let the grammatical construction be what it will, will not be obscure to sympathetic hearers. The C major quartet, the last of this first set, is the only one with an introduction. The frame of mind expressed in it is a noble, manly cheerfulness, rising in the andante to an almost supernatural serenity—the kind of cheerfulness which, in life or in art, appears only as the result of previous pain and strife. The sharp accents of the first and second movements, the struggling agony of the trio to the minuet, the wonderful depth of beauty in the subject of the finale, startling us by its entry, first in E flat and then in A flat major, are perhaps the most striking illustrations of this, but the introduction stands forth as the element which gives birth to all the happy serenity of the work. The contrast between the troubled, depressed phrase—[See Page Images]

has a direct effect upon the hearer; both phrases have one solution:—

and the shrill agitated one—[See Page Images]

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [6]

The manner in which they are opposed to each other, and the devices by which their opposition is thrown into strong relief, are of unusual, but by no means unjustifiable, harshness. But the goal is not reached by one bound; no sooner does serenity seem to be attained than the recurrence of the b draws the clouds together again, and peace and the power of breathing and moving freely are only won by slow and painful degrees. 14

Any difference of opinion as to this work at the present day can only exist with regard to minor details, and it will scarcely now be asserted by any one that "a piece may be recognised as Mozart's by its rapid succession of daring transitions." 15 We are accustomed to take our standard from Beethoven, and it seems to us almost incredible that a contemporary of Mozart's, the Stuttgart Hofmusicus, Schaul (who acknowledged, it is true, that he belonged to a time when nothing was heard but Italian operas and musicians), should exclaim: 16 —

What a gulf between a Mozart and a Boccherini! The former leads us over rugged rocks on to a waste, sparsely strewn with flowers; the latter through smiling country, flowery meadows, and by the side of rippling streams.

Apart from all differences of opinion or analogies with other works, it may safely be asserted that these quartets are the clear and perfect expression of Mozart's nature; nothing less is to be expected from a work upon which he put forth all his powers in order to accomplish something that would redound to his master Haydn's honour as well as his own. The form had already, in all its essential points, been determined by Haydn; it is the sonata form, already described, with the addition of the minuet—in this application a creation of Haydn's. Mozart appropriated these main MOZART'S AND HAYDN'S QUARTETS. [7] features, without feeling it incumbent on him even to alter them. Following a deeply rooted impulse of his nature, he renounced the light and fanciful style in which Haydn had treated them, seized upon their legitimate points, and gave a firmer and more delicate construction to the whole fabric. To say of Mozart's quartets in their general features that, in comparison with Haydn's, they are of deeper and fuller expression, more refined beauty, and broader conception of form, 17 is only to distinguish these as Mozart's individual characteristics, in contrast with Haydn's inexhaustible fund of original and humorous productive power. Any summary comparison of the two masters must result in undue depreciation of one or the other, for nothing but a detailed examination would do full justice to them both and explain their admiration of each other. Two circumstances must not be left out of account. Mozart's quartets are few in number compared with the long list of Haydn's. Every point that is of interest in Mozart may be paralleled in Haydn; hence it follows that certain peculiarities found in Haydn's music are predominating elements in Mozart's. Again, Haydn was a much older man, and is therefore usually regarded as Mozart's predecessor; but the compositions on which his fame chiefly rests belong for the most part to the period of Mozart's activity in Vienna, and were not without important influence on the latter. This mutual reaction, so generously acknowledged by both musicians, must be taken into account in forming a judgment upon them.

The string quartet offers the most favourable conditions for the development of instrumental music, both as to expression and technical construction, giving free play to the composer in every direction, provided only that he keep within the limits imposed by the nature of his art. Each of the four combined instruments is capable of the greatest variety of melodic construction; they have the advantage over the piano in their power of sustaining the vibrations of the notes, so as to produce song-like effects; nor are they inferior MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [8] in their power of rapid movement. Their union enables them to fulfil the demands of complete harmonies, and to compensate by increase of freedom and fulness for the advantages which the pianoforte possesses as a solo instrument. The quartet is therefore particularly well adapted both for the polyphonic and the homophonie style of composition. The varieties of tone of the instruments among each other, and of each in different keys, further increases their capacity for expression, the nuances of tone-colouring appearing to belong to the nature of stringed instruments. Thus the material sound elements of the string quartet are singularly uniform, at the same time that they allow free scope to the individual movement of the component parts. The beginning of the andante of the E flat major quartet (428 K.) will suffice to show how entirely different an effect is given by a mere difference in the position of the parts. The value which Mozart set upon the uniformity of the naturally beautiful sound effects of stringed instruments may be inferred from the fact that he seldom attempted interference with it as a device for pleasing the ear. Pizzicato passages occur only three times—in the trio of the D minor quartet (421 K.), of the C major quintet (515 K.), and of the clarinet quintet (581 K.)—and each time as the gentlest form of accompaniment to a tender melody. He was not prone either to emphasise bass passages by pizzicato, and has done so only in the second adagio of the G minor quintet (516 K.) and in the first movement of the horn quintet (407 K.). Nor is the muting, formerly so frequent, made use of except in the first adagio of the G minor quartet and in the larghetto of the clarinet quintet. It need scarcely be said that an equal amount of technical execution and musical proficiency was presupposed in each of the performers. This is especially noticeable in the treatment of the violoncello. It is not only put on a level with the other instruments as to execution, but its many-sided character receives due recognition, and it is raised from the limited sphere of a bass part into one of complete independence.

The favourite comparison of the quartet with a conversation between four intellectual persons holds good in some MOZART'S STRING QUARTETS. [9] degree, if it is kept in mind that the intellectual participation and sympathy of the interlocutors, although not necessarily languishing in conversation, are only audibly expressed by turns, whereas the musical embodiment of ideas must be continuous and simultaneous. The comparison is intended to illustrate the essential point that every component part of the quartet stands out independently, according to its character, but so diffidently that all co-operate to produce a whole which is never at any moment out of view; an effect so massive as to absorb altogether the individual parts would be as much out of place as the undue emphasising of any one part and the subordination of the others to it. The object to be kept continually in view is the blending of the homophonie or melodious, and the polyphonic or formal elements of composition to form a new and living creation. Neither is neglected; but neither is allowed to assert itself too prominently. Even when a melody is delivered by one instrument alone, the others do not readily confine themselves to a merely harmonic accompaniment, but preserve their independence of movement. Infallible signs of a master-hand are visible in the free and ingenious adaptation of the bass and the middle parts to the melodies; and, as a rule, the characteristic disposition of the parts gives occasion for a host of interesting harmonic details. The severer forms of counterpoint only appear in exceptional cases, such as the last movement of the first quartet, in G major (387 K.). The intention is not to work out a subject in a given form, but to play freely with it, presenting it from various interesting points of view by means of combinations, analysis, construction, and connection with fresh contrasting elements. But since this free play can only be accepted as artistic by virtue of the internal coherency of its component parts, it follows that the same laws which govern strict forms must lie at the root of the freer construction. In the same way a conversation—even though severe logical disputation may be studiously avoided—adheres to the laws of logic while letting fall here a main proposition, there a subordinate idea, and connecting apparent incongruities by means of association of ideas. A similar freedom in the grouping and MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [10] development of the different subjects exists in the quartet, limited only by the unity of artistic conception, and by the main principles of rhythmic and harmonic structure, and of the forms of counterpoint. This is most observable when an apparently unimportant phrase is taken up, and by its interesting development formed into an essential element of the whole, as in the first movement of the third quartet, in B flat major (458 K.), where a figure—[See Page Image]

at the close of a lengthy subject is first repeated by the instruments separately, with a mocking sort of air, and afterwards retained and treated as the germ of numerous freely developed images.

In publishing these six quartets together Mozart certainly did not intend them to be regarded in all their parts as one whole; his object was to bring to view the many-sidedness of expression and technical treatment of which this species of music was capable. The first quartet, in G major (387 K.), and the fourth, in E flat major (428 K.), have a certain relationship in their earnest and sustained tone; but how different is the expression of energetic decision in the first from that of contemplative reserve in the fourth; a difference most noticeable in the andantes of the two quartets. Again, in the third and fifth quartets, in B flat (458 K.) and A major (464 K.), the likeness in their general character is individualised by the difference in treatment throughout. The second quartet, in D minor (421 K.), and the sixth, in C major (465 K.), stand alone; the former by its affecting expression of melancholy, the latter by its revelation of that higher peace to which a noble mind attains through strife and suffering.

An equal wealth of characterisation and technical elaboration meets us in a comparison of the separate movements. The ground-plan of the first movement is the usual one, and the centre of gravity is always the working-out at the beginning of the second part, which is therefore distinguished by its length as a principal portion of the movement. The working-out of each quartet is peculiar to itself. In the two SIX QUARTETS, 1785. [11] first the principal subject is made the groundwork, and combined with the subordinate subject closing the first part, but quite differently worked-out. In the G major quartet the first subject is spun out into a florid figure, which is turned hither and thither, broken off by the entry of the second subject, again resumed, only to be again broken off in order, by an easy play on the closing bar—[See Page Images]

to lead back again to the theme. In the D minor quartet, on the other hand, only the first characteristic division—[See Page Images]

of the broad theme is worked out as a motif; the next division somewhat modified—[See Page Images]

is imitated and adorned by the final figure:—[See Page Images]

The first part of the third quartet, in B flat major, has not the usual sharply accented second subject; the second part makes up for this in a measure by at once introducing a new and perfectly formed melody, followed by an easy play with a connecting passage—

this is invaded by the analogous motif of the first part—[See Page Images]

which brings about the return to the first part. The peculiar structure of the movement occasions the repetition of the second part, whereupon a third part introduces the chief subject anew, and leads to the conclusion in an independent MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [12] way. In the E flat major quartet the interest depends upon the harmonic treatment of an expressive triplet passage connected with the principal subject. The first subject of the fifth quartet, in A major, is indicated from the very beginning as a suitable one for imitative treatment, and very freely developed in the working-out section. In the last quartet in C major also, the treatment of the principal subject is indicated at once, but the importance of the modest theme is only made apparent by the harmonic and contrapuntal art of its working-out, leading to the expressive climax of the coda and the conclusion.

The slow movements of the quartets are the mature fruit of deep feeling and masterly skill. With fine discrimination the consolatory andante of the melancholy D minor quartet is made easy, but so managed as to express the character of ardent longing, both in the ascending passage—[See Page Image]

and in the tendency to fall into the minor key. The andante of the fourth quartet, in E flat major, forms a complete contrast to this. Its incessant harmonic movement only allows of pregnant suggestions of melodies, and is expressive of a self-concentrated mood, rousing itself with difficulty from mental abstraction. But the crown of them all in delicacy of form and depth of expression is the andante of the last quartet, in C major; it belongs to those wonderful manifestations of genius which are only of the earth in so far as they take effect upon human minds; which soar aloft into a region of blessedness where suffering and passion are transfigured.

The minuets are characteristic of Mozart's tendencies as opposed to Haydn's. The inexhaustible humour, the delight in startling and whimsical fancy, which form the essence of Haydn's minuets, occur only here and there in Mozart's. SIX QUARTETS, 1785. [13] They are cast in a nobler mould, their distinguishing characteristics being grace and delicacy, and they are equally capable of expressing merry drollery and strong, even painful, emotion. Haydn's minuets are the product of a laughter-loving national life, Mozart's give the tone of good society. Especially well-defined in character are the minuets of the D minor and C major quartets—the former bold and defiant, the latter fresh and vigorous. Delicate detail in the disposition of the parts is common to almost all of them, keeping the interest tense and high, and there are some striking peculiarities of rhythmical construction. Among such we may notice the juxtaposition of groups of eight and ten bars, so that two bars are either played prematurely, as in the minuet of the first quartet, or inserted, as in the trio of the B flat major quartet. 18 The ten-bar group in the minuet of the D minor quartet is more complicated, because more intimately blended, and still more so is the rhythm of the minuet in the fourth quartet, where the detached unequal groups are curiously interlaced. 19 Very characteristic is also the sharp contrast between minuet and trio—as, for instance, the almost harshly passionate minor trios of the first and last quartets, and the still more striking major trio of the D minor quartet, light and glittering, like a smile in the midst of tears.

The finales have more meaning and emphasis than has hitherto been the case in Mozart's instrumental compositions. Three of them are in rondo form (those of the B flat, E flat, and C major quartet), quick, easy-flowing movements, rich in graceful motifs and interesting features in the working-out. The merriment in them is tempered by 1 a deeper vein of humour, and we are sometimes startled by a display of pathos, as in the finale of the C major quartet. The more cheerful passages are distinctly German in tone; and echoes of the "Zauberflote" may be heard in many of the melodies and turns of expression.

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [14]

The last movement of the G major quartet is written in strict form, and highly interesting by reason of the elegance of its counterpoint; the finale of the A major quartet is freer and easier, but nevertheless polyphonic in treatment. 20 The D minor quartet concludes with variations, the original and long-drawn theme having the rhythmical and sharply accented harmonic form of the siciliana. It is in imitation of a national song, and is sometimes like a slow gigue, sometimes like a pastorale. The rhythm of the 6-8 time is somewhat peculiar, in that the first of three quavers is dotted throughout; the tone is soft and tender. There is a very similar siciliana in Gluck's ballet "Don Juan" (No. 2), showing how marked the typical character is. 21 The variations, which are as charming from their grace and delicacy of form as from their singular mixture of melancholy and mirth, bring this wonderful quartet to a close in a very original manner.

The middle movement of the A major quartet is also in variations—more earnest and careful on the whole—the precursor of the variations in Haydn's "Kaiser" and Beethoven's A major quartets. These quartet variations far surpass the pianoforte variations in character and workmanship; they consist not merely of a graceful play of passages, but of a characteristic development of new motifs springing from the theme.

The success of the quartets, on which Mozart put forth all his best powers, was scarcely sufficient to encourage him to make further attempts in the same direction; not until August, 1786, do we find him again occupied with a quartet (D major, 499 K.), in which may be traced an attempt to LATER QUARTETS, 1786-1790. [15] meet the taste of the public without sacrificing the dignity of the quartet style. It is not inferior to the others in any essential point. The technical work is careful and interesting, the design broad—in many respects freer than formerly—the tone cheerful and forcible throughout, with the sentimental element in the background, as compared with the first quartets. The last movement approaches nearest to Haydn's humorous turn of thought, following his manner also in the contrapuntal elaboration of a lightly suggested motif into a running stream of merry humour. Nevertheless, this quartet remained without any immediate successor; it would appear that it met with no very general approval on its first appearance. "A short serenade, consisting of an allegro, romance, minuet and trio, and finale" in G major, composed August 10, 1787 (525 K.), does not belong to quartet music proper. The direction for violoncello, contrabasso, points to a fuller setting, which is confirmed by the whole arrangement, especially in the treatment of the middle parts. It is an easy, precisely worked-out occasional piece.

During his stay in Berlin and Potsdam in the spring of 1789 Mozart was repeatedly summoned to the private concerts of Frederick William II. of Prussia, in which the monarch himself took part as a violoncellist. He was a clever and enthusiastic pupil of Graziani and Duport, and he commissioned Mozart to write quartets for him, as he had previously commissioned Haydn 22 and Boccherini, 23 rewarding them with princely liberality. In June of this year Mozart completed the first of three quartets, composed for and dedicated to the King of Prussia, in D major (575 K.); the second, in B flat major (589 K.), and the third, in F major (590 K.), were composed in May and June, 1790. From letters to Puchberg, we know MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [16] that this was a time of bitter care and poverty, which made it a painful effort to work at the quartets, but there is even less trace of effort in them than in the earlier ones. The instrument appropriated to his royal patron is brought to the front, and made into a solo instrument, giving out the melodies in its higher notes. This obliges the viola frequently to take the bass part, altering the whole tone-colouring of the piece, and the instruments are altogether set higher than usual, the more so as the first violin constantly alternates with the violoncello. By this means the tone of the whole becomes more brilliant and brighter, but atones for this in an occasional loss of vigour and force. In other respects also, out of deference no doubt to the King's taste, there is more stress laid upon elegance and clearness than upon depth and warmth of tone. Mozart was too much of an artist to allow any solo part in a quartet to predominate unduly over the others; the first violin and violoncello leave the other two instruments their independent power of expression, but the motifs and working-out portions are less important, and here and there they run into a fanciful play of passages. It is singular that in the quartets in D and F major the last movements are the most important. When once the composer has thrown himself into the elaboration of his trifling motifs he grows warm, and, setting to work in good earnest, the solo instrument is made to fall into rank and file; the artist appears, and has no more thought of his presentation at court. The middle movements are very fine as to form and effect, but are without any great depth of feeling. The charming allegro of the second quartet, in F major, is easy and graceful in tone, and interesting from the elegance of its elaboration. In short, these quartets completely maintain Mozart's reputation for inventive powers, sense of proportion, and mastery of form, but they lack that absolute devotion to the highest ideal of art characteristic of the earlier ones.

Mozart's partiality for quartet-writing may be inferred from the many sketches which remain (68-75, Anh., K.), some of them of considerable length, such as that fragment of a lively movement in A major (68, 72, Anh., K.) consisting of 169 bars.

TRIO IN E FLAT, 1788. [17]

Duets and trios for stringed instruments were naturally held in less esteem than string quartets. Mozart composed in Vienna (September 27, 1788), for some unspecified occasion, a trio for violin, viola, and violoncello, in £ flat major (563 K.), which consists of six movements, after the manner of a divertimento—allegro, adagio, minuet, andante with variations, minuet, rondo. The omission of the one instrument increases the difficulty of composing a piece full in sound and characteristic in movement, more than could have been imagined; the invention and skill of the composer are taxed to the utmost. It is evident that this only gave the work an additional charm to Mozart. Each of the six movements is broadly designed and carried out with equal care and devotion, making this trio unquestionably one of Mozart's finest works. No one performer is preferred before the other, but each, if he does his duty, may distinguish himself in his own province. With wonderful discrimination, too, every technical device is employed which can give an impulse to any happy original idea. How beautifully, for instance, is the simple violoncello passage which ushers in the adagio—[See Page Images]

transformed into the emphatic one for the violin—

coined in due time, with climacteric effect, by the viola and violoncello. The violin-jumps in the same adagio—

are effective only in their proper position; and all the resources at command are made subservient to the art which is to produce the living work.

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [18]

The variations demand special attention. The theme is suggestive of a national melody, and its effect is heightened by the different treatment of each part when repeated, which also gives fulness and variety to the variations. Each of these is artistically worked out in detail and of distinctly individual character; the last is especially remarkable, in which the viola, to a very lively figure, carries out the theme in its simplest enunciation as a true Cantus firmus. The whole impression is one of freshness and beauty of conception, elevated and enlivened by the difficulties which offered themselves. Nothing more charming can be imagined than the first trio of the second minuet; its tender purity charms us like that of a flower gleaming through the grass.

Haydn seems to have made no use of the increased resources offered by the quintet, although other musicians—Boccherini, for instance—cultivated this branch. It would appear to have been for some particular occasions that Mozart composed four great string quintets, in which he followed the track laid out in the first quartets. Two were composed in the spring of 1787, after his return from Prague— 24

C major, composed April 19, 1787 (515 K.).

G major, composed May 16, 1787 (516 K.).—

the other two—

D major, composed December, 1790 (593 K.).

E flat major, composed April 12, 1791 (614 K.).—

at short intervals, "at the earnest solicitation of a musical friend," as the publisher's announcement declares. 25

Mozart doubles the viola 26 —not like Boccherini in his 155 quintets, the violoncello 27 —whereby little alteration in tone, colour, or structure is effected. The doubling of the violoncello gives it a predominance which its very charm of tone THE QUINTET. [19] renders all the more dangerous: whereas the strengthening of the less strongly accentuated middle parts by the addition of a viola gives freer scope for a lengthy composition. The additional instrument gives increase of freedom in the formation of melodies and their harmonic development, but it also lays on the composer the obligation of providing independent occupation for the enlarged parts. A chief consideration is the grouping of the parts in their numerous possible combinations. The first viola corresponds to the first violin as leader of melodies, while the second viola leaves the violoncello greater freedom of action; these parts share the melodies in twos or threes, either alternately or in imitative interweaving; the division of a motif as question and answer among different instruments is especially facilitated thereby. Again, two divisions may be placed in effective contrast, the violins being supported by a viola, or the violas by the violoncello. But the device first used by Haydn in his quartets, of giving two parts in octaves, is perhaps the most effective in the quintets, a threefold augmentation being even employed in the trio of the E flat major quintet (614 K.). Finally, it is easier to strengthen the violoncello by the viola here than it is in the quartet. It is not that all these resources are out of reach for the quartet, but that they find freer and fuller scope in the quintet. The effect of the quintet is not massive; it rests on the characteristic movement of the individual parts, and demands greater freedom in order that this movement of manifold and differing forces may be well ordered and instinct with living power. The increased forces require greater space for their activity, if only on account of the increased mass of sound. If the middle parts are to move freely without pressing on each other, the outer parts must be farther apart, and this has a decided influence on the melodies and the sound effects, the general impression becoming more forcible and brilliant. The dimensions must also be increased in other directions. A theme, to be divided among five parts, and a working-out which is to give each of them fair play, must be planned from the first. The original motif of the first Allegro of the C major quintet (515 K.)—[See Page Image] MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [20] involves of necessity the continuation of the idea enunciated; and only after a third repetition with modifications is it allowed to proceed to a conclusion. It has thus become too far developed to allow of a repetition of the whole theme; it starts again in C minor, is further developed by harmonic inflections; and after a short by-play on a tributary, it is again taken up and leads on to the second theme; we have thus a complete organic development of the first motif. The second theme is then of course carried out, and finally we have the broadly designed motif which brings the part to a conclusion in a gradually increasing crescendo for all the parts; the whole movement thus gains considerably in dimensions.

The motif of the first movement of the E flat major quintet (614 K.)—[See Page Image]

is precisely rendered. But it is the germ whence the whole movement is to spring; all beyond itself is suggested by this motif, and is important only in relation thereto. The unfettered cheerfulness which runs through the whole of the movement is expressed in these few bars, given by the violas like a call to the merry chase. The opening of the C major quintet prepares us in an equally decided manner for what is to follow. The decision and thoughtfulness which form the ground-tone of the whole movement, in spite of its lively agitation, are calmly and clearly expressed in the first few bars.

The G minor quintet begins very differently, with a complete melody of eight bars, repeated in a different key. Few MOZART'S G MINOR QUINTET. [21] instrumental compositions express a mood of passionate excitement with such energy as this G minor quintet. We feel our pity stirred in the first movement by a pain which moans, sighs, weeps; is conscious in its ravings only of itself, refuses to take note of anything but itself, and finds its only consolation in unreasoning outbreaks of emotion, until it ends exhausted by the struggle. But the struggle begins anew in the minuet, and now there is mingled with it a feeling of defiant resentment, showing that there is some healthy force still remaining; in the second part a memory of happy times involuntarily breaks in, but is overcome by the present pain; then the trio bursts forth irresistibly, as if by a higher power, proclaiming the blessed certainty that happiness is still to be attained. One of those apparently obvious touches, requiring nevertheless the piercing glance of true genius, occurs when, after closing the minuet in the most sorrowful minor accents—[See Page Image]

Mozart introduces the trio with the same inflection in the major—

and proceeds to carry it out in such a manner that only a whispered longing may be detected underlying the gently dying sounds of peace. This turn of expression decides the further course of the development. The next movement, "Adagio ma non troppo, con sordini," gives us an insight into a mind deeply wounded, tormented with self-questionings; earnest reflection, doubt, resolve, outbreaks of smothered pain alternate with each other, until a yearning MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [22] cry for comfort arises, tempered by the confident hope of an answer to its appeal; and so the movement ends in the calm of a joyful peace instead of, as the first, in the silence of exhaustion. The conquered pain breaks out again in the introduction to the last movement, but its sting is broken—it dies away to make room for another feeling. The new émotion is not merely resignation, but joy—the passionate consciousness of bliss, just as inspired, just as restlessly excited as the previous pain. But the exultant dithyramb has not the same engrossing interest for the hearers; man is readier to sympathise with the sorrows of others than with their joys, although he would rather bear his sorrow alone than his joy. This complete change of mood may well excite a suspicion of fickleness, but it is not the less true that the anguish of the first movement, and the exultation of the last, belong to one and the same nature, and are rendered with absolute truth of artistic expression.

We turn involuntarily from the artist to the man after such a psychological revelation as this, and find traces of Mozart's nature unmistakably impressed on his work. But we may seek in vain for any suggestion of the work in his actual daily life. At the time when he wrote this quintet his circumstances were favourable, he had only lately returned from Prague covered with honour and substantial rewards, and he was enjoying an intercourse with the Jacquin family which must have been altogether pleasurable to him. It is true that he lost his father soon after (May 26), but a recollection of the letter which he addressed to him with the possibility of his death in view (Vol. II., p. 323), Mozart being at the time engaged on the C major quintet, will prevent our imagining that the mood of the G minor quintet was clouded by the thought of his father's approaching decease. The springs of artistic production flow too deep to be awakened by any of the accidents of life. The artist, indeed, can only give what is in him and what he, has himself experienced; but Goethe's saying holds good of the musician as well as of the poet or painter; he reveals nothing that he has not felt, but nothing as he felt it.

The main characteristics of the other quintets are calmer MOZART'S QUINTETS. [23] and more cheerful, but they are not altogether wanting in energetic expression of passion. The sharper characterisation made necessary by the division of the music among a greater number of instruments was only possible by means of the agitation and restless movement of the parts, even when the tone of the whole was quiet and contained. We find therefore various sharp or even harsh details giving zest to the whole—such, for instance, as the use of the minor ninth and the comparatively frequent successions of ninths in a circle of fifths; and the quintets have apparently been a mine of wealth to later composers, who have made exaggerated use of these dangerous stimulants. Greater freedom of motion stands in close connection with the better defined characterisation of the quintets. Polyphony is their vital element; the forms of counterpoint became more appropriate as the number of parts increased. The finales to the Quintets in D and E flat Major (573, 614, K.) showed that Mozart was able to make use of the very strictest forms upon occasion. Both movements begin in innocent light-heartedness, but severe musical combinations are developed out of the airy play of fancy; ideas which have only been, as it were, suggested are taken up and worked out, severe forms alternate with laxer ones—one leads to the other naturally and fluently, and sometimes they are both made use of at the same time. The disposition of the parts is free, without any preconceived or definitive form, and its many delicate details of taste and originality give an individual charm to each separate part. The homophonie style of composition is not altogether disregarded for the polyphonic, but it is never made the determining element. Even a melody such as the second subject of the first movement of the G minor quintet, complete in itself as any melody can be, is made use of as a motif for polyphonic development. The freest and most elastic treatment of form is that of the last movements. The other movements are fully developed, and sometimes carried out at great length, but the main features are always distinct and well preserved; the outline of the finales is less firm, and capable of a lighter and more varied treatment.

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [24]

Another branch of concerted music high in favour in Mozart's day was the so-called "Harmoniemusik," written exclusively for wind instruments, and for performance at table or as serenades. Families of rank frequently retained the services of a band for "Harmoniemusik" instead of a complete orchestra. 28 The Emperor Joseph selected eight distinguished virtuosi 29 for the Imperial "Harmonie," who played during meals, especially when these took place in the imperial pleasure-gardens. The performances included operatic arrangements as well as pieces composed expressly for this object. 30 Reichardt dwells on the enjoyment afforded him in 1783 by the Harmoniemusik of the Emperor and the Archduke Maximilian. "Tone, delivery, everything was pure and harmonious; some movements by Mozart were lovely; but unluckily nothing of Haydn's was performed." 31 First-class taverns supported their own "Harmonie" bands, in order that the guests might not be deprived of this favourite accompaniment to their meals. 32

Besides the great serenades, intended for public performance, the old custom was still practised of writing "Standchen," 33 for performance under the window of the person who was to be thus celebrated; and the general desire that such pieces should be new and original provided composers with almost constant employment on them. 34 Wind instruments were most in vogue for this "night-music." The instruments were usually limited to six—two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons, strengthened SERENADES FOR WIND INSTRUMENTS. [25] sometimes by two oboes. Such eight-part harmonies sufficed both the Emperor and the Elector of Cologne as table-music and for serenades; and at a court festival at Berlin in 1791 the music during the banquet was thus appointed. 35 The "Standchen," in "Cosi fan Tutte" (21), and the table-music, in the second finale of "Don Giovanni," are imitations of reality.

Mozart did not neglect the opportunities thus afforded him of making himself known during his residence in Vienna. He writes to his father (November 3, 1781):—

I must apologise for not writing by the last post; it fell just on my birthday (October 31), and the early part of the day was given to my devotions. Afterwards, when I should have written, a shower of congratulations came and prevented me. At twelve o'clock I drove to the Leopoldstadt, to the Baroness Waldstädten, where I spent the day. At eleven o'clock at night I was greeted by a serenade for two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons, of my own composition. I had composed it on St. Theresa's day (October 15) for the sister of Frau von Hickl (the portrait-painter's wife), and it was then performed for the first time. The six gentlemen who execute such pieces are poor fellows, but they play very well together, especially the first clarinet and the two horns. The chief reason I wrote it was to let Herr von Strack (who goes there daily) hear something of mine, and on this account I made it rather serious. It was very much admired. It was played in three different places on St. Theresa's night. When people had had enough of it in one place they went to another, and got paid over again.

This "rather serious" composition is the Serenade in E flat major (375 K.), which Mozart increased by the addition of two oboes, no doubt in June, 1782, when he also wrote the Serenade in C minor for eight wind instruments (388 K., s.). He had at that time more than one occasion for works of this kind. The attention both of the Emperor and the Archduke Maximilian was directed towards him (Vol. II., p. 197); and since Reichardt heard compositions by Mozart at court in 1783, his attempt to gain Strack's good offices must have been successful. In the year 1782 Prince Liechtenstein was in treaty with Mozart concerning the arrangement of a Harmoniemusik (Vol. II., p. 206), and he MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [26] had undertaken with Martin the conduct of the Augarten concerts, which involved the production of four great public serenades (Vol. II., p. 283).

Both the serenades already mentioned are striking compositions, far above the ordinary level of their kind, and may be considered, both as to style and treatment, the precursors of modern chamber music. The first movement of the Serenade in E flat major had originally two parts, which Mozart afterwards condensed into one, giving it greater precision by the omission of lengthy repetitions. The addition of the oboes gives it greater fulness and variety; but it is easy to detect that they are additions to a finished work. The whole piece is of genuine serenade character. After a brilliant introductory phrase, a plaintive melody makes its unexpected appearance, dying away in a sort of sigh, but only to reassert itself with greater fervour. The amorous tone of the "Entführung" may be distinctly traced in the adagio, and through all its mazy intertwining of parts we seem to catch the tender dialogue of two lovers. The closing rondo is full of fresh, healthy joy; the suggestion of a national air in no way interferes with the interesting harmonic and contrapuntal working-out. 36 The Serenade in C minor is far from leaving the same impression of cheerful homage. The seriousness of its tone is not that of sorrow or melancholy, but, especially in the first movement, of strong resolution. The second theme is especially indicative of this, its expressive melody being further noteworthy by reason of its rhythmical structure. It consists of two six-bar phrases, of which the first is formed of two sections of three bars each:—[See Page Image]

After the repetition of this, the second phrase follows, formed from the same melodic elements, but in three sections of two bars each—[See Page Image] SERENADE IN C MINOR. [27] and also repeated. On its first occurrence it forms a fine contrast to the passionate commencement, and lays the foundation for the lively and forcible conclusion of the first part, while in the second part its transposition into the minor prepares the way for the gloomy and agitated conclusion of the movement. The calmer mood of the andante preserves the serious character of the whole, without too great softness or languor of expression.

Mozart has perpetrated a contrapuntal joke in the minuet. The oboes and bassoons lead a two-part canon in octave, while the clarinets and horns are used as tutti parts. In the four-part trio the oboes and bassoons again carry out a two-part canon (al rovescio) in which the answering part exactly renders the rhythm and intervals, the latter, however, inverted:—[See Page Image]

Tricks of this kind should always come as this does, without apparent thought or effort, as if they were thrown together by a happy chance, the difficulties of form serving only to give a special flavour to the euphonious effect. The last movement, variations, passes gradually from a disquieted anxious mood into a calmer one, and closes by a recurrence to the subject in the major, with freshness and force.

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [28]

This serenade is best known in the form of a quintet for stringed instruments, to which Mozart adapted it apparently before 1784 (506 K.). Nothing essential is altered—only the middle parts, accompaniment passages, &c., are somewhat modified. Some of the passages and movements, however, especially the andante and finale, have lost considerably by the altered tone-colouring.

Various divertimenti for wind instruments, which have been published under Mozart's name, have neither external nor internal signs of authenticity. 37 An Adagio in B flat major for two clarinets and three basset-horns (411 K.), concerning which little is known, stands alone of its kind. 38 The combination of instruments points here as elsewhere (Vol. II., pp. 361, 410) to some special, perhaps masonic occasion, the more so as a detached and independent adagio could only have been written with a definite object in view. The juxtaposition of instruments so nearly related, with their full, soft, and, in their deeper notes, sepulchral tones, produces an impression of solemnity, which is in accordance with the general facter of peace after conflict expressed by the adagio.

Mozart's works for wind instruments are distinguished by delicacy of treatment apart from virtuoso-like effects. Considering them, however, in the light of studies for the treatment of wind instruments as essential elements of the full orchestra, they afford no mean conception of the performances of instrumentalists from whom so much mastery of technical difficulties, delicacy of detail, and expressive delivery might be expected. Instrumental music had risen to great importance in Vienna at that time. A great number of available, and even distinguished musicians had settled there. Besides the two admirably appointed imperial orchestras, and the private bands attached to families of rank, there were various societies of musicians ready to form large or small orchestras when required; and public and private concerts were, as we have seen, of very frequent occurrence.

THE VIENNA ORCHESTRA. [29]

The appointment was, as a rule, weak, when judged by the standard of the present day. The opera orchestra contained one of each wind instrument, six of each violin, with four violas, three violoncelli, and three basses. 39 On particular occasions the orchestra was strengthened (Vol. II., p. 173), but most of the orchestral compositions betray by their treatment that they were not intended for large orchestras. The purity and equality of tone and the animated delivery of the Vienna orchestra is extolled by a contemporary, who seems to have been no connoisseur, but to have faithfully rendered the public opinion of the day. 40 Of greater weight is the praise of Nicolai, a careful observer, who compared the performances of the Vienna orchestra with those of other bands. 41 He asserted, when he heard the Munich orchestra soon after, that it had far surpassed his highly wrought expectations of Mannheim, and that he had been perfectly astonished at the commencement of an allegro. 42 It was not a matter of small importance, therefore, that Mozart should have learnt all that could be learnt from the orchestras of Mannheim, Munich, and Paris, and then found in Vienna the forces at command wherewith to perfect this branch of his art. In this respect he had a great advantage over Haydn, who had only the Esterhazy band at his disposal, and never heard great instrumental performances except during his short stays in Vienna.

Mozart had much to do with raising the Vienna orchestra, particularly in the wind instruments, to its highest pitch of perfection. Among contemporary composers, who strove to turn to the best account the advantages of a fuller instrumentation,

Haydn undoubtedly claims the first rank. It is his incontestable merit to have opened the way in his symphonies to the free expression of artistic individuality in instrumental music, to have defined its forms, and developed MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [30] them with the many-sidedness of genius; he did not, how-I ever, bequeath to Mozart, but rather received from him the well-appointed, fully organised, and finely proportioned orchestra of our day. In his old age Haydn once complained to Kalkbrenner that death should call man away before he has accomplished his life-long desires: "I have only learnt the proper use of wind instruments in my old age, and now I must pass away without turning my knowledge to account." 43

The first of the seven Vienna symphonies is in D major (part 5, 384 K. (likely 385 K. DW)), and was composed by Mozart, at his father's wish, for a Salzburg fête in the summer of 1782. He wrote it under the pressure of numerous engagements in less than a fortnight, sending the movements as they were ready to his father (Vol. II., p. 211). No wonder that when he saw it again he was "quite surprised," not "remembering a word of it." For performance in Vienna (March 3, 1783) he reduced it to the usual four movements by the omission of the march and of one of the minuets, and strengthened the wind instruments very effectively in the first and last movement by flutes and clarinets.

A lively, festive style was called for by the occasion, and in the treatment of the different movements the influence of the old serenade form is still visible. The first allegro has only one main subject, with which it begins; this subject enters with a bold leap—[See Page Image]

and keeps its place to the end with a life and energy enhanced by harsh dissonances of wonderful freshness and vigour. The whole movement is a continuous treatment of this subject, no other independent motif occurring at all. The first part is therefore not repeated, the working-out section is short, and the whole movement differs considerably from the usual form of a first symphony movement. The andante is in the simplest lyric form, pretty and refined, but nothing more; the minuet is fresh and brilliant (Vol. I., p. 219).

THE D MAJOR SYMPHONY. [31]

The tolerably long drawn-out concluding rondo is lively and brilliant, and far from insignificant, though not equal to the first movement in force and fire.

A second symphony was written by Mozart in great haste on his journey through Linz in November, 1783; it was apparently that in C major (part 6, 425 K.), which with another short symphony in G major (part 6, 444 K.), bears clear traces of Haydn's influence, direct and indirect. (Note: By M. Haydn—the Introduction only by Mozart. DW)

Several years lie between these symphonies and the next in D major (part 1, 504 K.). This was written for the winter concerts on December 6, 1786, and met with extraordinary approbation, especially in Prague, where Mozart performed it in January, 1787 44 The first glance at the symphony shows an altered treatment of the orchestra; it is now fully organised, and both in combination and detail shows individual independence. The instrumentation is very clear and brilliant—here and there perhaps a little sharp—but this tone is purposely selected as the suitable one. Traces of Haydn's influence may be found in the prefixing of a solemn introduction to the first allegro, as well as in separate features of the andante; such, for instance, as the epigrammatic close; but in all essential points we have nothing but Mozart. The adagio is an appropriate preface for the allegro, which expresses in its whole character a lively but earnest struggle. In this allegro the form of a great symphony movement lies open before us. The chief subject is completely expressed at the beginning—[See Page Image] MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [32] and recurs after a half-close on the dominant with a characteristic figure—[See Page Image]

thus allowing of the independent development of section B. Then, after a complete close on the dominant, there enters the very characteristic and originally treated second subject; the close of the part is introduced by the figure, D, so that a member of the chief subject, A, is again touched upon. The working-out in the second part is founded on the third section of the chief subject, C. These two bars, which there formed only an intermediate passage, are here treated imitatively as an independent motif; first B, then D, are added as counter-subjects, all three are worked-out together, tributary subjects reappear from the first part, until the chief subject, A, enters on the dominant in D minor, leading the way for the other motifs, which press in simultaneously, and glide upon a long organ point gradually back to the first subject, with which the modified repetition of the first part begins. In this lengthy working-out every part of the main idea is fully developed. The simple enunciations of the first part appear, after the elaboration of their different elements like utterances of a higher power, bringing conviction and satisfaction to all who hear. The springlike charm of the andante, with all its tender grace, never degenerates into effeminacy; its peculiar character is given by the short, interrupted subject—[See Page Image]

which is given in unison or imitation by the treble part and the bass, and runs through the whole, different harmonic turns giving it a tone, sometimes of mockery, sometimes of thoughtful reserve. The last movement (for this symphony has no minuet) displays the greatest agitation and vivacity SYMPHONIES, 1788. [33] without any license; in this it accords with the restraint which characterises the other movements. It illustrates the moderation of most of Mozart's great works, which, as Ambros ("Granzen der Musik und Poesie," p. 56) remarks, "is not a proof of inability to soar into a higher sphere, but a noble and majestic proportioning of all his forces, that so they may hold each other in equilibrium." The essence of the work, to borrow the aesthetic expression of the ancients, is ethic rather than pathetic; character, decision, stability find expression there rather than passion or fleeting excitement.

A year and a half passed before Mozart again turned his attention to the composition of symphonies; then, in the summer of 1788, within two months, he composed the three symphonies in E flat major (June 26), G minor (July 25), and C major (August 10)—the compositions which most readily occur to us when Mozart's orchestral works come under discussion. The production of such widely differing and important works within so short a space of time affords another proof that the mind of an artist works and creates undisturbed by the changing impressions of daily life, and that the threads are spun in secret which are to form the weft and woof of a work of art. The symphonies display Mozart's perfected power of making the orchestra, by means of free movement and songlike delivery, into the organ of his artistic mood. As Richard Wagner says:—

The longing sigh of the great human voice, drawn to him by the loving power of his genius, breathes from his instruments. He leads the irresistible stream of richest harmony into the heart of his melody, as though with anxious care he sought to give it, by way of compensation for its delivery by mere instruments, the depth of feeling and ardour which lies at the source of the human voice as the expression of the unfathomable depths of the heart. 45

MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [34]

This result can only be attained by the most delicate appreciation of the various capacities of each individual instrument. The very diversity of tone-colouring which characterises these symphonies shows the masterly hand with which Mozart chooses and blends his tones, so that every detail shall come to full effect. It would not be easy to find places in which the sound-effect does not correspond with the intention; as he imagined it and willed it, so it sounds, and the same certainty, the same moderation, is apparent in every part of the artistic construction.

The Symphony in E flat major (543 K., part 3) is a veritable triumph of euphony. Mozart has employed clarinets here, and their union with the horns and bassoons produces that full, mellow tone which is so important an element in the modern orchestra; the addition of flutes gives it clearness and light, and trumpets endow it with brilliancy and freshness. It will suffice to remind the reader of the beautiful passage in the andante, where the wind instruments enter in imitation, or of the charming trio to the minuet, to make manifest the importance of the choice of tone-colouring in giving characteristic expression. We find the expression of perfect happiness in the exuberant charm of euphony, the brilliancy of maturest beauty in which these symphonies are, as it were, steeped, leaving such an impression as that made on the eye by the dazzling colours of a glorious summer day. How seldom is this unalloyed happiness and joy in living granted to mankind, how seldom does art succeed in reproducing it entire and pure, as it is in this symphony! The feeling of pride in the consciousness of power shines through the magnificent introduction, while the allegro expresses purest pleasure, now in frolicsome joy, now in active excitement, and now in noble and dignified composure. Some shadows appear, it is true, in the andante, but they only serve to throw into stronger relief the mild serenity of a G MINOR SYMPHONY, 1788. [35] mind that communes with itself and rejoices in the peace which fills it. This is the true source of the cheerful transport which rules the last movement, rejoicing in its own strength and in the joy of being. The last movement in especial is full of a mocking joviality more frequent with Haydn than Mozart, but it does not lose its hold on the more refined and elevated tone of the preceding movements. This movement receives its peculiar stamp from its startling harmonic and rhythmical surprises. Thus it has an extremely comic effect when the wind instruments try to continue the subject begun by the violins, but because these pursue their way unheeding, are thrown out as it were, and break off in the middle. This mocking tone is kept up to the conclusion, which appears to Nägeli ("Vorlesungen," p. 158) "so noisily inconclusive" (so stillos unschliessend), "such a bang, that the unsuspecting hearer does not know what has happened to him." 46

The G minor symphony affords a complete contrast to all this (550 K., part 2). Sorrow and complaining take the place of joy and gladness. The pianoforte quartet (composed August, 1785) and the Quintet (composed May 16, 1787) in G minor are allied in tone, but their sorrow passes in the end to gladness or calm, whereas here it rises in a continuous climax to a wild merriment, as if seeking to stifle care. The agitated first movement begins with a low plaintiveness, which is scarcely interrupted by the calmer mood of the second subject; 47 the working-out of the second part intensifies the gentle murmur—[See Page Image] MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [36] into a piercing cry of anguish; but, strive and struggle as it may, the strength of the resistance sinks again into the murmur with which the movement closes. The andante, on the contrary, is consolatory in tone; not reposing on the consciousness of an inner peace, but striving after it with an earnest composure which even attempts to be cheerful. 48 The minuet introduces a new turn of expression. A resolute resistance is opposed to the foe, but in vain, and again the effort sinks to a moan. Even the tender comfort of the trio, softer and sweeter than the andante, fails to bring lasting peace; again the combat is renewed, and again it dies away, complaining. The last movement brings no peace, only a wild merriment that seeks to drown sorrow, and goes on its course in restless excitement. This is the most passionate of all Mozart's symphonies; but even in this he has not forgotten that "music, when expressing horrors, must still be music" (Vol. II., p. 239). 49 Goethe's words concerning the Laocoon are applicable here ("Werke" XXIV., p. 233): "We may boldly assert that this work exhausts its subject, and fulfils every condition of art. It teaches us that though the artist's feeling for beauty may be stirred by calm and simple subjects, it is only displayed in its highest grandeur and dignity when it proves its power of depicting varieties of character, and of throwing moderation and control into its representations of outbreaks of human passion." And in the same sense in which Goethe ventured to call the Laocoon graceful, none can deny the grace of this symphony, in spite of much harshness and C MAJOR SYMPHONY. [37] keenness of expression. 50 The nature of the case demands the employment of quite other means to those of the E flat major symphony. The outlines are more sharply defined and contrasted, without the abundant filling-in of detail which are of such excellent effect in the earlier work, the result being a greater clearness, combined with a certain amount of severity and harshness. The instrumentation agrees with it; it is kept within confined limits, and has a sharp, abrupt character. The addition of clarinets for a later performance gave the tone-colouring greater intensity and fulness. Mozart has taken an extra sheet of paper, and has rearranged the original oboe parts, giving characteristic passages to the clarinets, others to the oboes alone, and frequently combining the two. No clarinets were added to the minuet. Again, of a totally distinct character is the last symphony, in C major (551 K., part 4), in more than one respect the greatest and best, although neither so full of passion as the G minor symphony, nor so full of charm as the E flat major. 51 Most striking is the dignity and solemnity of the whole work, manifested in the brilliant pomp in the first movement, with its evident delight in splendid sound-effects.:

It has no passionate excitement, but its tender grace is heightened by a serenity which shines forth most unmistakably in the subject already alluded to (Vol. II., p. 455, cf. p. 334), which occurs unexpectedly at the close of the first part. The andante reveals the very depths of feeling, with traces in its calm beauty of the passionate agitation and strife from which it proceeds; the impression it leaves is one of moral strength, MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [38] perfected to a noble gentleness. The minuet recalls to mind the cheerful subject of the first movement. There is an elastic spring in its motion, sustained with a delicacy and refinement which transports the hearer into a purer element, where he seems to exist without effort, like the Homeric gods. The finale is that masterpiece of marvellous contrapuntal art, which leaves even upon the uninitiated the impression of a magnificent princely pageant, to prepare the mind for which has been the office of the previous movements. We recognise in the principal subject which opens the movement—[See Page Images]

the motif of which Mozart made frequent use even in his youth (Vol. I., p. 259); here he seems anxious to bid it a final farewell. He takes it again as a fugue subject, and again inverted:—

Then other motifs join in. One, in pregnant rhythm—

asserting itself with sharp accents in all sorts of different ways, and connected with a third motif as a concluding section:—

All these subjects are interwoven or worked out with other subordinate ideas, both as independent elements for SYMPHONIES. [39] contrapuntal elaboration, and in two, three, or fourfold combinations, bringing to pass harmonic inflections of great force and boldness, sometimes even of biting harshness. There is scarcely a phrase, however insignificant, which does not make good its independent existence. 52 A searching analysis is out of the question in this place; such an analysis would serve, however, to increase our admiration of the genius which makes of strictest form the vehicle for a flow of fiery eloquence, and spreads abroad glory and beauty without stint. 53

The perfection of the art of counterpoint is not the distinguishing characteristic of this symphony alone, but of them all. The enthralling interest of the development of each movement in its necessary connection and continuity consists chiefly in the free and liberal use of the manifold resources of counterpoint. The ease and certainty of this mode of expression makes it seem fittest for what the composer has to say. Freedom of treatment penetrates every component part of the whole, producing the independent, natural motion of each. The then novel art of employing the wind instruments in separate and combined effects was especially admired by Mozart's contemporaries. His treatment of the stringed instruments showed a progress not less advanced, as, for instance, in the free treatment of the basses, as characteristic as it was melodious. The highest quality of the symphonies, however, is their harmony of tone-colour, the healthy combination of orchestral sound, which is not to be replaced by any separate effects, however charming. In this combination consists the art of making the orchestra as a living organism express the artistic idea which gives the creative impulse to the work, and controls the forces which are always ready to be set in motion. An unerring conception of the capacities for development MOZART'S INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. [40] contained in each subject, of the relations of contrasting and conflicting elements, of the proportions of the parts composing the different movements, 54 and of the proportions of the movements to the whole work; finally, of the proper division and blending of the tone-colours—such are the essential conditions for the production of a work of art which is to be effective in all its parts.

Few persons will wish to dispute the fact that Mozart's great symphonies display the happiest union of invention and knowledge, of feeling and taste. We have endeavoured also to show in brief outline that they are the characteristic expression of a mind tuned to artistic production, whence their entire organisation of necessity proceeds. But language, incapable of rendering the impressions made by the formative arts, is still more impotent in seeking to reproduce the substance of a musical work. 55 Points that can be readily apprehended are emphasised disproportionately; and the subjectivity of the speaker or writer intrudes itself upon the consideration of the music. It has been lately questioned, for instance, whether Mozart's compositions were the absolute and necessary results of certain definite frames of mind, and a comparison has been made between him and Beethoven upon this point. If it is intended by this to draw attention to Beethoven's art, as proceeding from his spiritual being (Geist), in contrast to that of earlier composers—of Mozart especially—which came from the mind (Seele), 56 an important point is indicated. But if this distinction is made exhaustive, or essentially qualitative, the right point of view is thereby disturbed. There can be no doubt that Beethoven has struck chords in the human mind which none before him had touched—that THE RIGHT MEANING OF THE SYMPHONIES. [41] he employs the means at his command with a power and energy of expression unheard before; that by him—the true son of his time—the strife of passions and the struggle for individual freedom are more powerfully and unhesitatingly expressed than by any of his predecessors. But human nature remains the same, and the genuine impulses of artistic creation proceed from universal and unalterable laws; the artist does but impress his individual stamp upon the composing elements of his work; and if, under certain circumstances, this should fail to be comprehended, it does not therefore follow that the work has no meaning. 57 For neither can the form and the substance of a veritable work of art be divided or substituted the one for the other, nor can such a work take effect as a whole when it is not accepted and grasped in all its parts. 58 It is this wholeness, this oneness, which brings the mind of the artist most clearly before us. Let it be remembered that Mozart's contemporaries dis-; covered an exaggerated expression of emotion and an incomprehensible depth of characterisation in those very compositions in which our age recognises dignified moderation, pure harmony, perfect beauty, and a graceful treatment of form sometimes even to the loss of intrinsic force; and it will be acknowledged that much which was supposed to depend on the construction of the work lies really in the changing point of view of the hearers. Those only who come to the consideration of the work with a clear and unbiased mind, taking their standard from the universal and unchangeable laws of art—those only who are capable of grasping the individuality of an artistic nature, will not go astray either in their appreciation or their criticism.

THE unexampled success of the "Entführung," which brought fame to the composer and pecuniary gain[42] to the theatrical management, justified Mozart in his expectation that the Emperor, having called German opera into existence, 1 would commission him to further its prosperous career. He was indeed offered an opera, but the libretto, ''Welches ist die beste Nation?" was such miserable trash, that Mozart would not waste his music on it. Umlauf composed it, but it was hissed off the stage; and Mozart wrote to his father (December 21, 1782) that he did not know whether the poet or the composer were most deserving of the condemnation the work received. In fact, the impulse given to German opera seemed only too likely to die away without lasting result. Stephanie the younger 2 contrived by his intrigues to obtain the dismissal of Müller as conductor of the opera, and the appointment of a committee, whose jealousies and party feelings he turned so skilfully to account that they were all speedily satisfied to leave the actual power in his hands. The incessant disagreements which were the consequence, the hostility between composers, actors, and musicians, disgusted Kienmayer and Rosenberg, the managers of the opera, and the Emperor himself. Nor were the repeated experiments made with the works of mediocre THE OPERA IN VIENNA. [43] composers (which so enraged Mozart that he purposed writing a critique on them with examples) likely to find favour with the Emperor. Add to this that his immediate musical surroundings, Salieri at the head of them, were at least passively opposed to German opera, and it will not be thought surprising that the Emperor Joseph angrily renounced German opera, and followed his own taste in the reinstalment of the Italian. Chance brought this determination to a point. A French company of considerable merit, both in opera and the drama, was performing at the Kamthnerthortheater, and was patronised by the Emperor. 3 He sent for the performers to Schönbrunn in the summer of

1782, and entertained them in the castle during their stay. They were dissatisfied with the hospitality they there received, and one of the actors had the ill-breeding, during a meal at which the Emperor happened to come in, to offer him a glass of wine, with the request that he would try it, and say whether such wretched Burgundy was good enough for them to drink. The Emperor drank the wine, and answered that it was good enough for him, but he had no doubt they would find better wine in France. 4