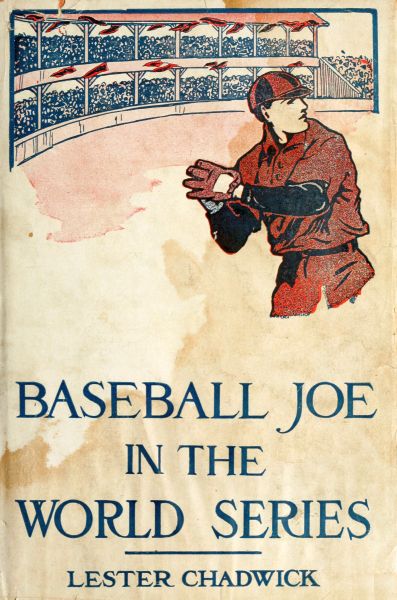

Title: Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship

Author: Lester Chadwick

Release date: August 12, 2013 [eBook #43455]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

OR

Pitching for the Championship

AUTHOR OF

“BASEBALL JOE OF THE SILVER STARS,” “BASEBALL

JOE IN THE BIG LEAGUE,” “THE RIVAL

PITCHERS,” “THE EIGHT-OARED

VICTORS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

BOOKS BY LESTER CHADWICK

THE BASEBALL JOE SERIES

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated

Price per volume, 75 Cents, postpaid

BASEBALL JOE OF THE SILVER STARS

BASEBALL JOE ON THE SCHOOL NINE

BASEBALL JOE AT YALE

BASEBALL JOE IN THE CENTRAL LEAGUE

BASEBALL JOE IN THE BIG LEAGUE

BASEBALL JOE ON THE GIANTS

BASEBALL JOE IN THE WORLD SERIES

(Other Volumes in Preparation)

THE COLLEGE SPORTS SERIES

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated

Price per volume, $1.00, postpaid

THE RIVAL PITCHERS

A QUARTERBACK’S PLUCK

BATTING TO WIN

THE WINNING TOUCHDOWN

THE EIGHT-OARED VICTORS

(Other Volumes in Preparation)

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY, New York

Copyright, 1917, by

Cupples & Leon Company

Baseball Joe in the World Series

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | An Insolent Intruder | 1 |

| II | Glowing Hopes | 12 |

| III | A Popular Hero | 20 |

| IV | The Spoils of War | 30 |

| V | Getting Ready for the Fray | 37 |

| VI | Joe Gives Fair Warning | 45 |

| VII | The Thousand Dollar Bankbill | 52 |

| VIII | Reckless Driving | 61 |

| IX | A Brutal Act | 69 |

| X | The Opening Gun | 77 |

| XI | Snatched From the Fire | 84 |

| XII | The Tables Turned | 92 |

| XIII | A Gallant Effort | 106 |

| XIV | More Hard Luck | 113 |

| XV | Fleming Turns Up Again | 121 |

| XVI | A Cad’s Punishment | 128 |

| XVII | Planning for Revenge | 134 |

| XVIII | The Plot | 140 |

| XIX | Weaving the Web | 147 |

| XX | A Stirring Battle | 155 |

| XXI | Evening Up the Score | 163 |

| XXII | A Hole in the Web | 169 |

| XXIII | Taking the Lead | 176 |

| XXIV | Plotting Mischief | 187 |

| XXV | A Random Clue | 193 |

| XXVI | A Bluff That Worked | 200 |

| XXVII | Stealing Signals | 212 |

| XXVIII | A Blow in the Dark | 217 |

| XXIX | Quick Work | 223 |

| XXX | A Glorious Victory | 232 |

“Here he comes!”

“Hurrah for Matson!”

“Great game, old man.”

“You stood the Chicagos on their heads that time, Joe.”

“That home run of yours was a dandy.”

“What’s the matter with Matson?”

“He’s all right!”

A wild uproar greeted the appearance of Joe Matson, the famous pitcher of the New York Giants, as he emerged from the clubhouse at the Polo Grounds after the great game in which he had pitched the Giants to the head of the National League and put them in line for the World Series with the champions of the American League.

It was no wonder that the crowd had gone crazy with excitement. All New York shared the[2] same madness. The race for the pennant had been one of the closest ever known. In the last few weeks it had narrowed down to a fight between the Giants and the Chicagos, and the two teams had come down the stretch, nose to nose, fighting for every inch, each straining every nerve to win. It had been a slap-dash, ding-dong finish, and the Giants had won “by a hair.”

Joe Matson—affectionately known as “Baseball Joe”—had pitched the deciding game, and to him above all others had gone the honors of the victory. Not only had he twirled a superb game, but it had been his home run in the ninth inning after two men were out that had brought the pennant to New York.

And just at this moment his name was on more tongues than that of any other man in the United States. Telegraph wires had flashed the news of his triumph to every city and village in the country, and the cables and wireless had borne it to every American colony in the world.

Joe’s hand had been shaken and his back pounded by exulting enthusiasts until he was lame and sore all over. It was with a feeling of relief that he had gained the shelter of the clubhouse with its refreshing shower and rubdown. Even here his mates had pawed and mauled him in their delight at the glorious victory, until he had laughingly threatened to thrash a few of them. And[3] now, as, after getting into his street clothes, he came out into the side street and viewed the crowd that waited for him, he saw that he was in for a new ordeal.

“Gee whiz!” he exclaimed to his friend and fellow player, Jim Barclay, who accompanied him. “Will they never let up on me?”

“It’s one of the penalties of fame, old man,” laughed Jim. “Don’t make out that you don’t like it, you old hypocrite.”

“Of course I like it,” admitted Joe with a grin. “All the same I don’t want to have this old wing of mine torn from its socket. I need it in my business.”

“You bet you do,” agreed Jim. “It’s going to come in mighty handy for the World Series. But we’ll be out of this in a minute.”

He held up his hand to signal a passing taxicab, and the cab edged its way to the curb.

The crowd swept in upon the players and they had all they could do to elbow their way through. They succeeded finally and slammed the door shut, while the chauffeur threw in the clutch and the taxicab darted off, pursued by the shouts and plaudits of the crowd.

Joe sank back on the cushions with a sigh of relief.

“The first free breath I’ve drawn since the game ended,” he remarked.

“It’s been a wonderful day for you, Joe,” said Jim, looking at his chum with ungrudging admiration. “That game will stand out in baseball history for years to come.”

“I’m mighty glad I won for my own sake,” answered Joe; “but I’m gladder still on account of the team. The boys backed me up in great shape—except in that fifth inning—and I’d have felt fearfully sore if I hadn’t been able to deliver the goods. But those Chicagos certainly made us fight to win.”

“They’re a great team,” admitted Jim; “and they put up a corking good game. But it was our day to win.”

“Did you see McRae and Robson after the game?” he went on, referring to the manager and the coach of the Giant team. “Whatever dignity they had, they lost it then. They fairly hugged each other and did the tango in front of the clubhouse.”

Joe grinned as the burly figures came before his mental vision.

“They’ve been under a fearful strain for the last few weeks,” he commented; “and I guess they had to let themselves go in some fashion or they’d have burst.”

“Do you realize what that home run of yours meant in money, to say nothing of the glory?” jubilated Jim.

“I haven’t had time to do much figuring yet,” smiled Joe.

“It meant at least fifty thousand dollars for the team,” pursued Jim. “We’ll get that much even if we lose the World Series, and a good deal more if we win. And if the Series goes to six or seven games the management will scoop in a big pot of money, too—anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand dollars.”

“That’s good,” replied Joe, a little absent-mindedly.

“Good?” echoed Jim, sharply. “It’s more than good—it’s great, it’s glorious! Wake up, man, and stop your dreaming.”

Joe came to himself with a little start.

“You’re—you’re right, Jim,” he stammered somewhat confusedly. “To tell the truth, I wasn’t thinking just then of money.”

Jim gave him a quick glance, and a sudden look of amused comprehension came into his eyes. Joe caught his glance and flushed.

“What are you blushing about?” demanded Jim with a grin.

“I wasn’t blushing,” defended Joe, stoutly. “It’s mighty warm in this cab.”

Jim laughed outright.

“Tell that to the King of Denmark,” he chuckled. “I’m on, old man. You told me in the clubhouse that you were going to the Marlborough[6] Hotel, and I know just who it is that’s stopping there.”

“My friend, Reggie Varley, is putting up there,” countered Joe, feebly.

“My friend Reggie Varley,” mimicked Jim, “to say nothing of his charming sister. Oh, I’m not blind, old fellow. I’ve seen for a long time how the wind was blowing. Well,” he continued, dropping his light tone for a more earnest one, “go in and win, Joe. I hope you have all the luck in the world.”

He reached over and slapped his friend cordially on the shoulder. Then he signaled for the chauffeur to stop.

“What are you getting out here for?” asked Joe. “We haven’t got to your street yet.”

“I know it,” answered Jim, preparing to jump out. “I want to give you a chance to think up what you’re going to say to the lady fair,” he added, mischievously.

He ducked the friendly thrust that Joe made toward him and went away laughing, while the cab started on.

Joe knew perfectly well what he intended to say when he should meet Mabel Varley. He had wanted to say it for a long time, and had determined that if his team won the pennant he would wait no longer.

He had met her for the first time two years before[7] under unusual circumstances. At that time he was playing in the Central League, and his team was training at Montville, North Carolina. He had saved Mabel from being carried over a cliff by a runaway horse, and the acquaintance thus formed had soon deepened into friendship. With Joe it had now become a much stronger feeling, and he had dared to hope that this was shared by Mabel.

Reggie Varley, Mabel’s brother, was a rather affected young man, who ran chiefly to clothes and automobiles and had an accent that he fondly supposed was English. Joe had met him at an earlier date than that at which he had formed Mabel’s acquaintance and under unpleasant conditions. Reggie had lost sight of his valise in a railway station, and had rashly accused Joe of taking it. He apologized later, however, and the young men had become the best of friends, for Reggie, despite some foolish little affectations, was at heart a thoroughly good fellow.

The brother and sister had come to New York to see the deciding games and were quartered at the Marlborough Hotel. Mabel had waved to Joe from a box at the Polo Grounds that afternoon, and her presence had nerved him to almost superhuman exertions. And he had won and won gloriously.

Would his good luck continue? He was asking[8] himself this question when the taxicab drew up at the curb, and he saw that he was at the door of the Marlborough.

He jumped out and thrust his hand in his pocket to get the money for his fare, but the chauffeur waved him back with a grin.

“Nuthin’ doin’,” he said. “This ride is on me.”

“What do you mean?” inquired Joe in surprise.

“Jest what I said,” returned the chauffeur. “The fellow that won the championship for the New Yorks can’t pay me any money. It’s enough for me to have Baseball Joe ride in my cab. I can crow over the other fellows that wasn’t so lucky.”

“Nonsense,” laughed Joe, as he took out a bankbill and tried to thrust it on him.

“No use, boss,” the man persisted. “Your money’s counterfeit with me.”

He started his car with a rush and a backward wave of his hand, and Joe, warned by a cheer or two that came from people near by who had recognized him, was forced to retreat into the hotel.

He did not send up a card, as he was a frequent caller and felt sure of his welcome. Besides, he was too impatient for any formalities. He wanted to be in the presence of Mabel, and even the elevator seemed slow, though it shot him with amazing speed to the fifth floor on which the Varley suite was located.

His heart was beating fast as he knocked at the parlor door, and it beat still faster when a familiar voice bade him enter.

He burst in with a rush that suddenly stopped short when he saw that he was not the only visitor. A young man had stepped back quickly from Mabel’s side and it was evident that he had just withdrawn his hand from hers.

For a moment Joe’s blood drummed in his ears and the demon of jealousy took possession of him. He glared at the visitor, who stared back at him with an air of insolence that to Joe at that moment was maddening.

The stranger was dressed in a degree of fashion that bordered on foppishness. He wore more jewelry than was dictated by good taste, even going so far as to carry a tiny wrist watch. His eyes were pale, his chin slightly retreating, and his face showed unmistakable marks of dissipation. His air was arrogant and supercilious as he took Joe slowly in from head to foot.

Mabel rushed forward eagerly as Joe entered.

“Oh, Joe!” she cried. “I’m so glad you’ve come! I never was so glad in all my life.”

Before the joyous warmth of that greeting, Joe’s jealousy receded. He could not question her sincerity. All her soul was in her eyes.

He took her hand tenderly in his and felt that it was trembling. Had she been frightened? He[10] turned her about so that he stood between her and the visitor.

“Tell me,” he commanded in a low voice. “Has this man offended you?”

“Yes, no, yes!” she whispered. “Oh, Joe, please don’t say anything now! Please, for my sake, Joe! It’s all right now. I’ll tell you about it afterward. He’s Reggie’s friend. Don’t make a scene, please, Joe!”

Joe’s muscles stiffened, and had it not been for Mabel’s earnest pleading, he would have thrown the other fellow out of the room. But Mabel’s name must not be mixed up in any brawl, and by a mighty effort he restrained himself.

The visitor during this brief colloquy had been moving about uneasily. He evidently wished himself anywhere else than where he was. Then, as the two turned toward him, he put on a mask of carelessness and drawled lazily:

“Won’t you introduce me to—ah—your friend, Miss Varley?”

Mabel, recalled to her duty as hostess, had no option but to comply.

“This is Mr. Beckworth Fleming, Joe,” she said. “Mr. Fleming, this is Mr. Matson.”

The two men bowed coldly but neither extended a hand.

“Mr. Fleming is a friend of Reggie’s,” Mabel explained to Joe.

“And of yours also, I hope, Miss Varley,” said Fleming with an ingratiating smile.

“I said a friend of Reggie’s,” returned Mabel, coldly.

It was a direct cut, and Fleming felt it as he would have felt the lash of a whip. He turned a dull red and was about to reply, when he caught the menacing look in Joe’s eyes and stopped. He muttered something about a pressing engagement, took up his hat and cane, and with a pretence of haughtiness that failed dismally of its effect, swaggered from the room.

“And now!” exclaimed Joe, as soon as the door had closed on the unwelcome visitor, “tell me, Mabel, what that fellow said or did, and I’ll hunt him up and thrash him within an inch of his life. I’ll make him wish he’d never been born.”

“Don’t do anything like that, Joe,” urged the girl. “He’s probably had his lesson, and it isn’t likely I’ll ever be troubled by him again. He’s just an acquaintance that Reggie picked up somewhere, and I’ve only seen him once before to-day. He called at the hotel to see Reggie, and when he found he wasn’t in, he stayed to talk with me. He started in by paying me a lot of compliments and then became familiar and impudent. He seized my hand, and when I sought to pull it away from him he wouldn’t let me. I was getting thoroughly frightened and was going to call out when your knock came at the door. Oh, Joe, I was so glad when I saw who it was!”

She was perilously near to tears, and her beautiful eyes were dewy as they looked into his. Joe’s[13] heart beat madly. The words he had been longing to say leaped to his lips, but he choked them back. He did not want to catch her off her guard, to take advantage of her emotions and of her shaken condition. Her acceptance of him at that moment might be due in part to gratitude and relief. He wanted more than that—the unconditional, unreserved surrender of her heart and life into his keeping, based only on affection.

So he held himself under control and recompensed himself for his selfdenial by an inward promise to make things interesting for Mr. Beckworth Fleming, if ever that cad’s path and his should cross.

“But come,” said Mabel more brightly, as she sank into a chair and motioned Joe to another, “let’s talk about something pleasant.”

“About you then,” smiled Joe, his eyes dwelling on her eloquently.

“Not poor little me,” she pouted in mock humility. “Who am I compared with the great Joseph Matson about whom all the world is talking—the man who won the championship for the Giants, the hero whose picture to-morrow will hold the place of honor in every newspaper in the country?”

“You’re chaffing me now,” laughed Joe.

“Not a bit,” she said demurely, her dimples coming and going in a way that drove him nearly[14] distracted. “I really feel as though I ought to salaam or kow-tow or whatever it is the Orientals do when they come before the Emperor. But, oh, Joe,” and here she dropped her bantering manner and leaned forward earnestly, “you were simply magnificent this afternoon. The way you kept your nerve and won that game was just wonderful. I was so excited at times that I thought my heart would leap out of my body. I was proud, oh, so proud that you were a friend of mine!”

Joe had heard many words of praise that day but none half so sweet as these.

“Will you let me tell you a secret?” he exclaimed, half rising from his chair. “Do you want to know who really won that game?”

“Why, you did,” she returned in some surprise. “Of course the rest of the team did, too, but if it hadn’t been for your pitching and batting——”

“No,” he interrupted, “it was you who won the game.”

He had risen now and had come swiftly to her side.

“Listen, Mabel,” he said, and before the note in his voice she felt her pulses leap. “You were in my mind from the start to the finish of that game. I looked up at you every time I went into the box. This little glove of yours”—he took it from his pocket with a hand that trembled—“lay close to my heart all through the game. Mabel——”

“Why, hello, Joe, old top!” came a voice from the door that had opened without their hearing it. “What good wind blew you here? I’m no end glad to see you, don’t you know. Congratulations, old man, on winning that game. You were simply rippin’, don’t you know.”

And Reggie Varley ambled in and shook Joe’s hand warmly, blandly unconscious of the lack of welcome from the two inmates of the room.

“How are you, Reggie?” Joe managed to blurt out, wishing viciously that at that moment his friend were at the very farthest corner of the world.

It is possible that Mabel’s feelings were most unsisterly, but she concealed them and rallied more readily than Joe from the shock caused by her brother’s inopportune coming.

“I was just telling Joe how proud we were of him,” she smiled. “But he’s so modest that he refuses to take any credit for what he has done. Insists that somebody else won the game.”

“Of course that’s all bally nonsense, don’t you know,” declared Reggie, looking puzzled. “The other fellows helped, of course, but Joe was the king pin. Those Chicagos were out for blood and Joe was the only one who could tame them.”

Joe listened moodily, and while he is recovering his composure it may be well, for the sake of those who have not followed the career of the famous[16] young pitcher, to mention the previous books of this series in which his exploits are recorded.

His diamond history opened in the first volume of the series, entitled: “Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; Or, The Rivals of Riverside.” Here he had his first experience in pitching. In that restricted circle he soon became widely known as one of the best of the amateur boxmen, but he had to earn that position by overcoming many difficulties.

In “Baseball Joe on the School Nine,” we find the same qualities of grit and determination shown in a different field. The situation here was complicated by the efforts of the bully of the school, who did everything in his power to frustrate Joe and bring him to disaster.

A little later on, Joe went to Yale, and his triumphs in the great university are told in the third volume of the series, entitled: “Baseball Joe at Yale; Or, Pitching for the College Championship.”

As may be imagined, with such redoubtable rivals as Harvard and Princeton, a very different class of baseball is required from that which will “get by” in academies and preparatory schools.

Joe got his chance to pitch against Princeton in an exciting game where the Yale “Bulldog” “put one over” on the Princeton “Tiger.”

But in spite of his athletic prowess and general popularity, Joe was not entirely happy at Yale.[17] His mother had set her heart on Joe’s studying for the ministry. But Joe himself did not feel any special call in that direction. While always a faithful student he was not a natural scholar, and outdoor life had a strong appeal for him. His success in athletics confirmed this natural bent, until at last he came to the conclusion that he ought to adopt professional baseball as his vocation.

His mother was, naturally, much disappointed, as she had had great hopes of seeing her only son in the pulpit. Moreover, she had the vague feeling that there was something almost disreputable in making baseball a profession. But Joe at last convinced her that whatever might have been true in the early days of the game did not apply now, when so many high-class men were turning toward it, and she yielded, though reluctantly.

Joe’s chance to break into the professional ranks was not long in coming. That last great game with Princeton had been noted by Jimmie Mack, manager of the Pittston team in the Central League. He made Joe an offer which the latter accepted, and the story of his first experience on the professional diamond is told in the fourth volume of the series entitled: “Baseball Joe in the Central League; Or, Making Good as a Professional Pitcher.”

But this was only the first step in his career. He[18] was too ambitious to be content with the Central League except as a stepping stone to something higher. His delight can be imagined, therefore, when he learned that he had been drafted into the St. Louis Club of the National League. He was no longer a “busher” but the “real thing.” He had to work hard and had many stirring adventures. How he succeeded in helping his team into the first division is told in the fifth volume of the series, entitled: “Baseball Joe in the Big League; Or, A Young Pitcher’s Hardest Struggles.”

But these hard struggles were at the same time victorious ones and attracted the attention of the baseball public, who are always on the lookout for a new star. Among others, McRae, the famous manager of the New York Giants, thought he saw in Joe a great chance to bolster up his pitching staff. Joe could hardly believe his eyes when he learned that he had been bought by New York. It brought a bigger reputation, a larger salary and a capital chance to get into the World Series. He worked like a Trojan all through the season, and, as we have already seen, came through with flying colors, winning from the Chicagos the final game that made the Giants the champions of the National League and put them in line for the championship of the world. The details of the stirring fight are told in the sixth volume of the[19] series, entitled: “Baseball Joe on the Giants; Or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis.”

“I say, old top,” remarked Reggie, breaking in on Joe’s rather resentful musings, “you’re going to stay and have dinner with us to-night, you know.”

Joe looked at Mabel for confirmation.

“You certainly must, Joe,” she said enthusiastically. “We won’t take no for an answer.”

As there was nothing else on earth that Joe wanted so much as to be with Mabel, he did not require much urging.

“And I’ll tell you what we’ll do,” suggested Mabel. “In fact, it’s the only thing we can do. We’ll have the dinner served right in here for the three of us. If you should go down in the public dining-room of the hotel to-night, Joe, you’d have a crowd around the table ten lines deep.”

“By Jove, you’re right,” chimed in Reggie. “They’d have to send out a call for reserves. I’ll go down and have a little talk with the head waiter, and I’ll have him send up a dinner fit for a king.”

“Fit for a queen,” corrected Joe, as he glanced at Mabel.

Reggie hurried away to order the meal that was to put the chef on his mettle, leaving Mabel and Joe once more in possession of the room.

Good-natured, blundering Reggie! Why had he not waited five minutes longer before breaking in on that momentous conversation?

To be sure they could have resumed it now, but Joe felt instinctively that it was not the time. Cupid is sensitive as to time and place, and the little blind god is only at his best when assured of leisure and privacy. His motto is that “two is company” while three or more are undeniably “a crowd.”

Reggie might be back at any moment, and then, too, the waiters would be coming in to spread the table. So Joe, though sorely against his will, was forced to wait till fate should be more kind.

But he was in the presence of his divinity anyway and could feast his eyes upon her as she chatted gaily, her color heightened by the scene through which they had just passed.

And Mabel was a very delightful object for the eyes to rest upon. Joe himself, of course, was not a competent witness. If any one had asked him to describe her, he would have answered that she was a combination of Cleopatra and Madame Recamier and all the other famous beauties of history. What the unbiased observer would have seen was a very charming girl, sweet and womanly, with lustrous brown eyes, wavy hair whose tendrils persisted in playing hide and seek about her ears, dimples that came and went in a maddening fashion and a flower-like mouth, revealing two rows of pearly teeth when she smiled, which was often.

Even Reggie was moved to compliment her when he came in again after his interview with the head waiter.

“My word, Sis, but you’re blooming to-night, don’t you know,” he remarked, as he went across the room and put his hand caressingly on her shoulder. “This little trip must be doing you good. You’ve got such a splendid color, don’t you know.”

“Just think of it! A compliment from a brother! Wonder of wonders!” she laughed merrily.

Perhaps if she had cared to, she might have enlightened the obtuse Reggie as to the cause of the heightened color that enhanced her loveliness. Joe, too, could have made a shrewd guess at it.

But now the waiters came bustling in and they talked of indifferent things until the table was spread. A sumptuous meal was brought in, and the three sat down to as merry a little dinner party as there was that night in the city of New York.

“How honored we are, Reggie,” exclaimed Mabel, “to have the great Mr. Matson as our guest! There are hundreds of people who would give their eyes for such a chance.”

She flashed a mocking glance at Joe who grew red, as she knew he would. The little witch delighted in making him blush. It made his bronzed face still more handsome, she thought.

“You’d better make the most of it,” Joe grinned in reply. “I may fall down in the World Series and be batted out of the box. Then you’ll be pretending that you don’t know me.”

“I’m not afraid of that,” returned Mabel. “After the way you pitched this afternoon, I’m sure there’s nothing in the American League you need to be afraid of.”

“That’s loyal, anyway,” laughed Joe. “Still you never can tell. It’s happened to me before and it may happen again. Then, too, you must remember that it’s a different proposition I’ll be up against.

“Take, for instance, the Chicagos to-day. I’ve pitched against them before and I knew their weak points. I knew the fellows who can’t hit a high[23] ball but are death on the low ones. I knew the ones who would try to wait me out and those who would lash out at any ball that came within reach. I knew the ones who would crowd the plate and those who would inch in to meet the ball. The whole problem was to feed them what they didn’t want.

“But it will be different when I come up against the American Leaguers. It will be some time before I catch on to their weak points. And while I’m learning, one of them may line out a three bagger or a home run that will win the game.”

“You speak of their weak points as though they all had them,” put in Reggie.

“They do,” replied Joe, promptly. “All of them have some weakness, and sooner or later you find it out. If there’s any exception to that rule at all, it’s Ty Cobb of Detroit. If he has any weakness, no one knows what it is. For the last seven years he’s led the American League in batting, base stealing and everything else worth while. All pitchers look alike to him. He’s a perfect terror to the twirlers.”

“Well, you won’t have to worry about him, anyway,” smiled Mabel. “It’s lucky that he’s on the Detroits instead of the Bostons. For I suppose it’s the Bostons you’ll have to face in the World Series.”

“I guess it will be,” answered Joe. “Their season[24] doesn’t end until Friday. They’ve had almost as tight a race in their league as we’ve had in ours, for the Athletics have been close on their heels. But the Bostons have to take only one game to clinch the flag while the Athletics will have to win every game. So it’s pretty nearly a sure thing for the Red Sox.”

“Which team would you rather have to fight against?” asked Reggie.

“Well, it’s pretty near a toss-up,” answered Joe, thoughtfully. “Either one will be a hard nut to crack. That one hundred thousand dollar infield of the Athletics is a stone wall, but I think the Boston outfield is stronger. That manager of the Athletics is in a class by himself, and what he doesn’t know about the game isn’t worth knowing. He’s liable to spring something on you at any time. Still the Boston manager is mighty foxy, too, and you have to keep your eyes open to circumvent him. Take it all in all, I’d just about as lief face one team as the other.”

“It will be a little shorter trip for you between the two cities, if you happen to have the Athletics for your opponents,” suggested Mabel.

“Yes,” assented Joe. “In that case we’d have a good long sleep in regular beds every night, while on the Boston trip we’d have to put up with sleeping cars. Still the jumps wouldn’t be big in either case, and it’s a mighty sight better than if[25] we had to go out West for the Chicagos or Detroits.

“From a money point of view the boys are rooting for Boston to win,” he went on.

“Why, what difference would that make?” asked Mabel in surprise.

“Because the Boston grounds hold more people than the Athletics’ park,” was the answer.

“That’s something new to me,” put in Reggie. “I’ve attended games at both grounds, and it didn’t seem to me there was much difference between them.”

“The answer is,” replied Joe, “that we’re not going to play at Fenway Park, the regular American League grounds in Boston, in case Boston is our opponent.”

“How is that?”

“Because Braves Field, the National League grounds there, will hold over forty-three thousand people, and the owners have put it at the disposal of the American League Club,” Joe answered.

“That’s a sportsmanlike thing to do,” commented Mabel, warmly.

“It certainly is,” echoed her brother.

“Oh, the days of the old cutthroat policy have gone by,” said Joe. “The National and American Leagues used to fight each other like a pair of Kilkenny cats, but they’ve found that there is[26] nothing in such a game. This act of the Boston people shows the new spirit. We saw it, too, when the grandstand was burned at the Polo Grounds. The ruins hadn’t got through smoking before the Yankee management offered the use of its grounds to McRae as long as he needed them. And then a little later when the Yankees lost their grounds because streets were going to be cut through them, McRae returned the favor by giving them the use of the Polo Grounds. It’s the right spirit. Fight like tigers to win games, but outside of that, let live and wish the other luck.”

“Tell me honestly, Joe, what you think the New York’s chances are, in case they have to stack up against Boston,” said Reggie.

“Well,” answered Joe, thoughtfully, toying with his spoon, “if you’d asked me that question a week ago, I’d have said that New York would win in a walk. But just now I wouldn’t be anywhere near so sure of that.”

“You mean the accident to Hughson?” put in Mabel.

“Exactly that. He was going like a house afire just before that. You saw what he did to Chicago in the first game. He had those fellows eating out of his hand. He was simply unhittable. That fadeaway of his was zipping along six inches under their bats. They didn’t have a Chinaman’s chance.

“Then, too, in addition to that splendid pitching his reputation helps a lot. The minute it is announced that Hughson is going to pitch, the other fellows begin to curl up. They’re half whipped before they start, because they feel that he has the Indian sign on them, and it’s of no use to try.”

“That’s so,” assented Reggie. “Besides, when he’s in the box his own team feel they’re in for a victory and they play like demons behind him.”

“It’s going to take away a lot of confidence from our boys,” said Joe, “and in a critical series like that, confidence is half the battle. We could have lost two or three other men and yet have a better chance than we will have with Hughson out of the game.”

“Isn’t there any chance of his recovering in time to take part in some of the games?” asked Mabel.

“A bare chance only,” Joe replied. “I saw the old boy yesterday, and he’s getting along surprisingly fast. You see, he always keeps himself in such splendid physical condition that he recovers more quickly than an ordinary man would. We’ve got over a week yet before the Series starts, and he may possibly be able to go in before the games are over. If he does, that will be an immense help. But McRae had figured on having him[28] pitch the first game, so as to get the jump on the other fellows at the very start. Then he could have gone in at least twice more, perhaps three times, and it would have been all over but the shouting.”

“It’s lucky that McRae has you at hand to step into Hughson’s shoes,” declared Reggie.

“Step into them!” exclaimed Joe. “Yes, and rattle around in them. Nobody can fill them.”

“I don’t believe a word of it,” cried Mabel warmly—so warmly in fact that her brother looked at her in some surprise.

“Yes,” she repeated, holding her ground valiantly, “I mean just what I say. It’s awfully generous of you, Joe, to praise Hughson to the skies, but there’s no use in underrating yourself. I don’t think Hughson can pitch one bit better than you can. Look at that game this afternoon. I heard lots of people around me say that they never saw such pitching in all their lives. And what you did to-day you can do again. So there!”—she caught herself up, smiling a little confusedly, as though she had betrayed herself, but finished defiantly—“if that be treason, make the most of it.”

Joe’s heart gave a great leap, not only at the tribute but at the tone and look that had gone with it. So this was what Mabel thought of him! This was how she believed in him!

His head was whirling, but in his happy confusion[29] one thought kept pounding away at his consciousness, a thought that never left him through all the tremendous test that lay before him:

“I’ve got to make good! I’ve got to make good!”

The rest of the evening flew by as though on wings, and Joe was startled when he looked at his watch and found that it was nearly eleven o’clock.

“I’ll have to go,” he said reluctantly. “I had no idea it was so late.”

“Why should you hurry?” asked Reggie. “The season’s over now in the National League, and the World Series won’t begin for a week or more. I should think you might have a little leeway in the matter of sitting up late.”

“I’ll have plenty of leeway before long,” laughed Joe. “But just now I want to keep in the very pink of condition. I’ll need every ounce of strength and vitality I’ve got before I get through the Series.”

He would have dearly loved a chance for a few words with Mabel in private before he went away, but Reggie failed to appreciate that fact, and he accompanied the pair even when they went out to the elevator. But Joe avenged himself by holding Mabel’s hand much longer and more[31] closely than he had ever dared do before, and the girl did not dream of calling for help.

But although Joe had been balked in saying what he had wanted to that night, he felt much surer of Mabel’s feelings toward him, and his heart was a tumult of joyous emotions as he made his way home to the rooms he shared with Jim.

He found Barclay sound asleep, at which he rejoiced. He was in no mood for chaff and banter. He wanted to go over in his mind every incident of that memorable evening—to recall the tones of Mabel’s voice, the look in Mabel’s eyes. It was a delightful occupation and took a good while, so that it was late when he dropped off to sleep.

He was awakened at a much later hour than usual the next morning by a vigorous tugging at the shoulder of his pajamas; and, opening one sleepy eye, saw Jim fully dressed standing at the side of his bed.

“Go away and let me sleep,” grumbled Joe, turning over on his pillow for another forty winks.

“For the love of Pete, man! how much sleep do you want?” snorted Jim. “What are you trying to do, forget your sorrows? Here it is after nine o’clock, and I’ve already had my breakfast and a shave. Get a wiggle on and see what it is to be a popular hero.”

“Stop your joshing,” muttered Joe, sleepily.

“Josh nothing,” Jim came back at him. “If[32] you’ll just open those liquid orbs of yours and give this room the once over, you’ll see whether I’m joshing or not.”

This stirred Joe’s curiosity and he sat up in bed with a jerk.

“Great Scott!” he exclaimed, as he saw the room littered with a mass of boxes and packages that covered every available spot on chairs and tables and overflowed to the floor. “Where did you get all this junk? Going to open a department store?”

“I guess you’ll be able to if they keep on coming,” returned Jim. “I’ve been signing receipts for express packages until I’ve got the writer’s cramp. And there’s a pile of letters and telegrams, and there’s a bunch of reporters down in the lobby waiting for an interview with your Royal Highness, and—but what’s the use? Get up, you lazy hulk, and get busy.”

“It surely looks as though it were going to be my busy day,” grinned Joe, as he jumped out of bed and rushed to the shower.

He shaved and dressed in a hurry and then ate a hasty breakfast, after which he saw the reporters.

Those clever and wideawake young men greeted him with enthusiasm and overwhelmed him with questions that ranged from the date of his birth to his opinion on the outcome of the World Series.[33] They knew that their papers would give them a free hand in the matter of space, and they were in search not of paragraphs but of columns from the idol of the hour.

“You look limp and wilted, Joe,” laughed Jim, as they went back to their rooms.

“It’s no wonder,” growled Joe. “Those fellows got the whole sad story of my life. They hunted out every fact and shook it as a terrier shakes a rat. They turned me inside out. The only thing they forgot to ask was when I got my first tooth and whether I’d ever had the measles. And, oh, yes, they didn’t find out what was my favorite breakfast food. But now let’s get busy on these parcels and see what’s in them.”

“What’s in them is plenty,” prophesied Jim, “and these are only the few drops before the shower.”

It was a varied collection of objects that they took from the packages. There were boxes of cigars galore, enough to keep the chums in “smokes” for a year to come. There were canes and silk shirts and neckties accompanied by requests from dealers to be permitted to call their product the “Matson.” There were bottles of wine and whiskey, which met with short welcome from these clean young athletes, who took them over to the bathroom, cracked their necks and poured the contents down the drain of the washbasin,[34] until, as Jim declared, the place smelled for all the world like a “booze parlor.”

“No merry mucilage for ours,” declared Joe, grimly. “We’ve seen what it did for Hartley, as clever a pitcher as ever twirled a ball.”

“Right you are,” affirmed Jim. “There’s none of us strong enough to down old John Barleycorn, and the only way to be safe is never to touch it.”

After they had gone through the lot and rung for a porter to carry away the litter of paper and boxes, they attacked the formidable pile of letters and telegrams.

Among the former were two offers from vaudeville managers, urging Joe to go on the stage the coming winter. They offered him a guarantee of five hundred dollars a week. They would prepare a monologue for him, or, if he preferred to pair up with a partner, they would have a sketch arranged for him.

“That sounds awfully tempting, Joe,” said Jim, as they looked up from the letters they had been reading together.

“It’s a heap of money,” agreed Joe, “and I do hate to pass it up. But I won’t accept. I’m not an actor and I know it and they know it. I’d simply be capitalizing my popularity. I’d feel like a freak in a dime museum.”

“How do you know you’re not an actor?” asked[35] Jim. “You might have it in you. You never know till you try.”

But Joe shook his head.

“No,” he said, “there’s no use kidding myself. And even if I could make good, I wouldn’t do it. You know what it did for Markwith the season after he made his record of nineteen straight. He never was the same pitcher after that. The late hours, the feverish atmosphere, the irregular life don’t do a ball player any good. They take all the vim and sand out of him. No vaudeville for yours truly.”

“Well,” said Jim, “you’re the doctor. And I guess you’re right. But it certainly seems hard to let that good money get away when it’s fairly begging you to take it.”

The telegrams came from all over the country. A lot were from Joe’s old team-mates on the St. Louis club, including Rad Chase and Campbell. Others were from newspaper publishers offering fancy prices if Joe would write some articles for them, describing the games in the forthcoming World Series. Joe knew perfectly well that this would entail no time or labor on his part. Some bright reporter would actually write the articles, and all Joe needed to do was to let his name be signed to them as the author. But the practice was beginning to be frowned upon by the baseball magnates, and it was in a certain sense a fraud[36] upon the public, so that Joe mentally decided in the negative.

One telegram was far more precious to Joe than all the others put together. It came from Clara, his only sister, to whom he was devotedly attached, and was sent in the name of all the little family at Riverside. Joe’s eyes were a little moist as he read:

“Dearest love from all of us, Joe. We are proud of you.”

For a long time Joe sat staring at the telegram, while Jim considerately buried himself in the newspaper descriptions of yesterday’s great game.

How dear the home folks were! How their hearts were wrapped up in him and his success! What a splendid, wholesome influence that cozy little village home had been in his life. He thought of his patient, hard-working father, his loving mother, his winsome sister. He thought of their quiet, circumscribed life, shut out from the great currents of the world with which he had become so familiar.

They were proud of him! Yet all they could do was to read of his triumphs. They had never seen him pitch.

He took a sudden resolution.

The home folks were in for one great, big, glorious fling!

“Come along, Jim!” cried Joe, jumping to his feet. “Put down that old paper and let’s go up to the Polo Grounds. You know we’ve got to meet McRae and the rest of the gang there at two o’clock, and it’s almost one now. We’ll just have time to get a bite of lunch before we go.”

“I’m with you,” responded Jim.

They hurried through their lunch and took the train at the nearest elevated station.

“Some difference to-day from the way we felt when we were going up yesterday, eh, Joe,” grinned Jim, as he stretched out his legs luxuriously and settled back in his seat.

“About a million miles,” assented Joe. “Then my heart was beating like a triphammer. Then the work was all to do. Now it’s done.”

“And well done, too, thanks to you,” returned Jim. “Say, Joe, suppose for a minute—just suppose that the Chicagos had copped that game yesterday.”

“Don’t,” protested Joe. “It gives me the cold shivers just to think of it.”

When they entered the clubhouse, a roar of welcome greeted them from the members of the team who were already there. They crowded round Baseball Joe in jubilation, and the air was filled with a hubbub of exclamations.

“Here’s the man to whom the team owes fifty thousand dollars!” shouted the irrepressible Larry Barrett, the second baseman, who had led the league that year in batting.

“All right,” laughed Joe. “If you owe it to me, hand it over and I’ll put it in the bank.”

In the laugh that ensued, McRae and Robson, the inseparable manager and trainer of the Giants, came hurrying up to Joe. Their faces were beaming and they looked years younger, now that the tremendous strain of the last few weeks of the league race had been taken from their shoulders.

They shook hands warmly.

“You’re the real thing, Joe,” cried Robson.

“You won the flag for us,” declared McRae. “That home run of yours was a life saver. It brought home the bacon.”

Joe flushed with pleasure. Praise from these veterans meant something.

“It took the whole nine to win for us,” he said modestly.

“Sure it did,” agreed McRae. “The boys put[39] up a corking good game. But your pitching held Brennan’s men down, and it was that scorching hit that put on the finishing touch.”

“It was the trump that took the trick,” supplemented Robson.

Denton, the third baseman and wag of the team, stepped up and gravely put his hands around Joe’s head as though measuring it.

“Not swelled a bit, boys,” he announced to his grinning mates. “He can wear the same size hat that he did yesterday.”

They were all so full of hilarity that it was hard to get down to serious business, and McRae, who was as happy as a boy, made no attempt at his usual rigid discipline.

But when they had at last quieted down a little, he gathered them about him for a talk about the forthcoming World Series.

“You’ve done well, boys,” he told them, “and I’m proud of you. You’ve played the game to the limit and made a splendid fight. I don’t believe there’s another team in the league that wouldn’t have gone to pieces if the same thing had happened to their crack pitcher that happened to Hughson. It was a knockout blow, and I don’t mind admitting to you now that for a time my own heart was in my boots. But you stood the gaff, and I want to thank you, both for the owners of the club and for myself.”

There was a gratified murmur among the players, and then Larry shouted:

“Three cheers for McRae, the best manager in the league!”

The cheers were given with a will and the veteran’s face grew red with pleasure.

“And three more for Robson, the king of trainers!” cried Jim.

They were given with equal heartiness, and Robson waved his hand to them with a grin.

“I’m glad we all feel that way,” resumed McRae, when the tumult had subsided. “If at times I’ve been a bit hasty with you lads and given you the rough side of my tongue, it’s been simply because I was wild with excitement and crazy to win. And now for the big fight that lies before us. It’s a great thing to be champions of the National League. But it’s a greater thing to be champions of the world.”

A rousing shout rose from the eager group.

“Sure, we’ve got it copped already,” cried Larry.

McRae smiled.

“That’s the right spirit to tackle the job with,” he replied, “but don’t let the idea run away with you that it’s going to be an easy thing to do. It isn’t. Those American Leaguers are tough birds, and any one who beats them will know he’s been in a fight.

“There used to be a time,” he went on, “when the bulk of the talent was in the National League. But it isn’t so any longer. They have just as good batting, just as good pitching and just as good fielding as we have.

“Of course, we don’t know yet just which team we’ll have to face, but we may know before night. If the Bostons win to-day that will settle it. Even if they lose, provided the Athletics lose, too, the Red Sox will be the champions. Of course, there’s nothing sure in baseball, but all the chances are in favor of the Bostons.

“In any case, it will be an Eastern club, and that cuts out the matter of the long jumps. But whichever one it happens to be, it’ll prove a hard nut to crack.”

“Nut-crackers is our middle name,” murmured Denton.

“You proved that yesterday,” laughed McRae, “and you’re going to have a good chance to prove it again.

“Just as soon as the American race is decided,” he continued, “and it’s known in what city we are to play, the National Commission will have a meeting to fix all the details of the World Series. If they follow precedent, as they probably will, the first game will be appointed for a week from this Friday. They’ll toss a coin to see whether it shall be here or in the other city. I’m rooting for it to[42] be here. It’ll give us a better chance to win the first game if we play it on the home grounds, and you know what it means to get the jump on the other fellows.”

“You bet we do!” went up in a chorus.

“Just as soon as it is decided who our opponents are to be,” the manager resumed, “I’m going to send some of you fellows out as scouts to see some of the practice games of the other fellows and get a line on their style of play. You can pick up a lot of useful information that way, and we’ve got so much at stake that we can’t afford to overlook a single point of the game.”

“How about our own practice?” asked Larry.

“I was coming to that,” replied McRae. “I’m going to get together just as husky a bunch of sluggers and fielders as can be found in the National League.”

He took a sheaf of telegrams from his pocket.

“I’ve got a lot of wires here from every club in the league, offering the services of any of their players I want,” he said. “We’ve had our own fight, and now that it’s over they’re all eager to help the National League to down the American. It means a good deal to each of them to have us come out winner. Even Brennan has offered to let me have some of the Chicagos to practise against. I saw him at the hotel last night, and, although of course he was sore that he didn’t win[43] yesterday, he told me I could call upon him for any men I wanted.”

“He’s a good sport,” ejaculated Jim.

“Sure he is,” confirmed McRae, heartily. “He’s a hard fighter but he’s as white as they make ’em.”

He consulted a list on which he had jotted down a few names in pencil.

“How will this do for an All National team to practise against,” he asked.

A murmur went up from the players.

“Some sweet hitters!” exclaimed Markwith.

“A bunch of fence breakers,” echoed Jim.

“They’ll give you mighty good practice,” grinned McRae. “If they can’t straighten out the curves of you twirlers, nobody can. I’ll have them all on here in a day or two, and then we’ll start in training.”

The conference lasted till late in the afternoon,[44] and just as it was breaking up, a telegraphic report was handed to McRae. He scanned it hastily.

“That settles it!” he exclaimed. “Boston won to-day, three to two. We’re up against the Red Sox in the World Series!”

Although the news only confirmed what had been all along expected, it was worth a great deal to the Giants to know certainly just whom they would have to fight. Their enemy now was detached from the crowd and out in the open. They could study him carefully and arrange a clear plan of campaign.

Joe and Jim were discussing the matter earnestly, as they passed out of the Polo Grounds to go downtown.

“Don’t let’s take the elevated,” suggested Joe. “We haven’t had much exercise, and I want to stretch my legs a little.”

“I’m agreeable,” replied Jim. “There’s a cool breeze and it’s a nice night for walking. We can go part of the way on foot, anyway, and if we feel like it we’ll hoof it for the whole distance.”

They soon got below the Harlem River and before long found themselves in the vicinity of Columbus Circle. They were passing one of the fashionable cafés that abound in that quarter when[46] the door opened and a man came out. Joe caught a good look at his face, and a grim look came into his eyes as he recognized Beckworth Fleming.

Fleming saw him at the same time, and the eyes of the two men met in a look of undisguised hostility. Then with an ugly sneer, Fleming remarked:

“Ah, Mr. Matson, I believe. Or was it Mr. Buttinski? I’m not very good at remembering names.”

“You’ll remember mine if I have to write it on you with my knuckles,” returned Joe, brought to a white heat by the insult and the remembrance of the occurrence of the day before.

“Now, my good fellow——” began Fleming, a look of alarm replacing his insolent expression.

“Don’t ‘good fellow’ me,” replied Joe. “I owe you a thrashing and I’m perfectly able to pay my debts. You’d have gotten it yesterday if we’d been alone.”

“I—I don’t understand you,” stammered Fleming, looking about him for some way of escape from the sinewy figure that confronted him.

“Well, I’m going to make myself so clear that even your limited intelligence can understand me,” said Joe, grimly. “You keep away from the Marlborough Hotel. Is that perfectly plain?”

Before the glow in Joe’s eyes, Fleming retreated a pace or two, but as he caught sight of a policeman[47] sauntering up toward them, his courage revived.

“I’ll do nothing of the kind,” he snarled.

“You will if you value that precious skin of yours. I’ve given you fair warning, and you’ll find that I keep my word.”

By this time the officer had come up close to them, and Fleming, immensely relieved, turned to him as an ally.

“Officer, this man has been threatening me with personal violence,” he complained.

The policeman sized him up quizzically. Then he looked at Joe and his face lighted up.

“Good evening, Mr. Matson. That was a great game you pitched yesterday,” he ejaculated in warm admiration.

“I tell you he threatened me,” repeated Fleming, loudly.

The officer smiled inquiringly at Joe.

“Just a trifling personal matter,” Joe explained quietly. “He insulted me and I called him down.”

The policeman turned to Fleming.

“Beat it,” he commanded briefly. “You’re blocking up the sidewalk.”

Fleming bristled up like a turkey cock.

“I’ll have your number,” he said importantly. “I’ll——”

“G’wan,” broke in the officer, “or I’ll fan you. Don’t make me tell you twice.”

He emphasized the command by a poke in the back with his club that took away the last shred of Fleming’s dignity, and he retreated, with one last malignant look at Joe.

“I know his kind,” said the officer, complacently. “One of them rich papa’s boys with more money than brains. Sorry he bothered you, Mr. Matson. Are youse boys goin’ to lick them Bostons?”

“We’re going to make a try at it,” laughed Joe.

“You will if you can pitch all the games,” rejoined the policeman, admiringly. “It cert’nly was a sin an’ a shame the way you trimmed them Chicagos. You own New York to-day, Mr. Matson.”

The chums bade him a laughing good-night and resumed their interrupted stroll.

“Who was that fellow, anyway?” asked Jim in curiosity.

“His name is Fleming,” answered Joe. “That’s about all I know of him.”

“How long have you known him?”

“Since yesterday.”

“What was the row all about, anyway?”

“Oh, nothing much,” evaded Joe. “I guess we just don’t like the color of each other’s eyes.”

Jim laughed and did not press the question. But he had heard the warning to keep away from the Marlborough Hotel, and could hazard a vague guess as to the cause of the quarrel.

At their hotel both Joe and Jim found a letter from the owners of the New York Club waiting for them. In addition to the informal thanks conveyed to the team in general by McRae, they had taken this means of thanking each player personally. It was a gracious and earnest letter, and wound up by inviting them to a big banquet and theatre party that was to be given by the management to the players in celebration of their great feat in winning the National League championship for New York.

But Joe’s letter also contained a little slip from the Treasurer, to which a crisp, blue, oblong paper was attached. Joe unfolded it in some wonderment and ran his eyes over it hastily.

It was a check for a thousand dollars, and on the accompanying slip was written:

“In payment of bonus as per contract for winning twenty games during the season.”

Joe grabbed Jim and waltzed him about the room, much to Barclay’s bewilderment.

“What are you trying to do?” he gasped. “Is it a new tango step or what?”

“Glory, hallelujah!” ejaculated Joe. “Yesterday and to-day are sure my lucky days.”

He thrust the check before his friend’s eyes.

“Great Scott!” exclaimed Jim. “It never rains[50] but it pours. If you fell overboard, you’d come up with a fish in your mouth.”

“It sure is like finding money,” chortled Joe. “Everything seems to be coming my way.”

“You’ll be lending money to Rockefeller if this sort of thing keeps on,” Jim grinned. “But after all it can’t be such a surprise. You must have known that you had won twenty games.”

“That’s just it,” explained Joe. “I wasn’t sure of it at all. I figured that with yesterday’s game I had nineteen. But there was that game in August, you remember, when I relieved Markwith in the sixth inning. We won the game, but there were some fine points in it which made it doubtful whether it should be credited to Markwith or me. I had a tip that the official scorers were inclined to give it to Markwith, and so I had kissed the game good-bye. But it must be that they’ve decided in my favor after all and notified the New York Club to that effect.”

“That’s bully, old man,” cried Jim, enthusiastically. “And you can’t say that they’ve lost any time in getting it to you.”

“No,” replied Joe. “Ordinarily, they’d settle with me on the regular salary day. But I suppose they feel so good over getting the pennant that they take this means of showing it.”

“They can well afford to do it,” said Jim. “Your pitching has brought it into the box office[51] twenty times over. Still it’s nice and white of them just the same to be so prompt. That’s one thing that you have to hand to the Giant management. There isn’t a club in the league that treats its players better.”

“You’re just right,” assented Joe, warmly, “and it makes me feel as though I’d pitch my head off to win, not only for my own sake but for theirs.”

“You certainly have had a dandy year,” mused Jim. “With your regular salary of forty-five hundred and this check in addition you’ve grabbed fifty-five hundred so far. And you’ll get anywhere from two to four thousand more in the World Series.”

“I haven’t any kick coming,” agreed Joe. “It was a lucky day for me when I joined the Giants.”

“I suppose you’ll soak that away in the bank to-morrow, you bloated plutocrat,” laughed Jim.

“Not a bit of it,” Joe answered promptly. “To-morrow night that money will be on its way to Riverside as fast as the train can carry it.”

The little town of Riverside had been buzzing with excitement ever since the news had flashed over the wires that the Giants had won the championship of the National League. On a miniature scale, it was as much stirred up as New York itself had been at the glorious victory.

For was not Joe Matson, who had twirled that last thrilling game, a son of Riverside? Had he not grown up among the friends and neighbors who took such pride and interest in his career? Had he not, as Sol Cramer, the village oracle and the owner of the hotel, declared, “put Riverside on the map?”

There had been a big crowd at the telegraph office in the little town on the day that the final game had been played, and cheer after cheer had gone up as each inning showed that Joe was holding the Chicagos down. And when in that fateful ninth his home run had “sewed up” the victory, the enthusiasm had broken all bounds.

An impromptu procession had been formed, the[53] village band had been pressed into service, the stores had been cleared out of all the fireworks left over after the Fourth of July, and practically the whole population of the town had gathered on the street in front of the Matson house where they held a hilarious celebration.

The quiet little family found itself suddenly in the limelight, and were almost as much embarrassed as they were delighted by the glory that Joe’s achievement had brought to them.

The crowd dispersed at a late hour, promising that this was not a circumstance to what would happen when Joe himself should come home after the end of the World Series.

Had any one suggested that possibly the Giants would lose out in that Series, he would have stood a good chance of being mobbed. To that crowd of shouting enthusiasts, the games were already stowed in the New York bat bag. How could they lose when Joe Matson was on their team?

In the Matson household joy reigned supreme. Joe had always been their pride and idol. He had been a good son and brother, and his weekly letters home had kept them in touch with every step of his career. They had followed with breathless interest his upward march in his profession during this year with the Giants, but had hardly dared to hope that his season would wind up in such a blaze of glory.

Now they were happy beyond all words. They fairly devoured the papers that for the next day or two were full of Joe’s exploits. They could not stir out of the house without being overwhelmed with congratulations and questions. Clara, Joe’s sister, a pretty, winsome girl, declared laughingly that there could hardly have been more fuss made if Joe had been elected President of the United States.

“I’m sure he’d make a very good one if he had,” said Mrs. Matson, complacently, as she bit off a thread of her sewing.

“You dear, conceited Momsey,” said Clara, kissing her.

Mr. Matson smiled over his pipe. He was a quiet, undemonstrative man, but in his heart he was intensely proud of this stalwart son of his.

“How I wish we could have seen that game!” remarked Clara, wistfully. “Just think, Momsey, of sitting in a box at the Polo Grounds and seeing that enormous crowd go crazy over Joe, our Joe.”

“I’m afraid my heart would almost break with pride and happiness,” replied her mother, taking off her glasses and wiping her eyes.

“Of course it’s great, reading all about it in the papers and seeing the pictures,” continued Clara, “but that isn’t like actually being there and hearing the shouts and all that. But I’m a very wicked[55] girl to want anything more than I’ve got,” she went on brightly. “Now I’m going to run down to the post-office. The mail must be in by this time and I shouldn’t wonder if I’d find a letter from Joe.”

She put on her hat and left the house. Mrs. Matson looked inquiringly at her husband.

“You heard what Clara said, dear,” she observed. “I don’t suppose there’s any way in the world we could manage it, is there?”

“I’m afraid not,” returned Mr. Matson. “I’ve had to spend more money than I expected in perfecting that invention of mine. But there’s nothing in the world that I would like more than to see Joe pitch, if it were only a single game.”

Clara soon reached the little post-office and asked for the Matson mail. There were several letters in their box, but none from Joe.

She was much disappointed, as in Joe’s last telegram he had told her that a letter was on the way and to look out for it.

She had turned away and was going out of the office, when the postmaster called her back.

“Just wait a minute,” he said. “I see I’ve got something for you here in the registered mail.”

He handed her a letter which Clara joyfully saw was addressed in Joe’s handwriting.

“It’s directed to your mother,” the postmaster[56] went on, “but of course it will be all right if you sign for it.”

Clara eagerly signed the official receipt and hurried home with her precious letter.

“Did you get one from Joe?” asked her mother, eagerly.

“There wasn’t anything from him in the box,” said Clara, trying to look glum. Then as she saw her mother’s face fall, she added gaily: “But here’s one that the postmaster handed me. It came in the registered mail.”

She handed it over to her mother, who took it eagerly.

“Hurry up and open it, Momsey!” cried Clara, fairly dancing with eagerness. “I’m just dying to know what Joe has to say.”

Mr. Matson laid aside his pipe and came over to his wife. She tore open the letter with fingers that trembled.

Something crisp and yellow fluttered out and fell on the table. Clara’s nimble fingers swooped down upon it.

“Why, it’s a bankbill!” she exclaimed as she unfolded it. “A ten dollar bill it looks like. No,” as her eyes grew larger, “it’s more than that. It’s a hundred—Why, why,” she stammered, “it’s a thousand dollar bill!”

“Goodness sakes!” exclaimed her mother. “It can’t be. There aren’t any bills as big as that.”

Mr. Matson took it and scrutinized it closely.

“That’s what it is,” he pronounced in a voice that trembled a little. “It’s a thousand dollar bill.”

The members of the little family stared at each other. None of them had ever seen a bill like that before. They could hardly believe their eyes. They thought that they were dreaming.

Mrs. Matson began to cry.

“That blessed, blessed boy!” she sobbed. “That blessed, darling boy!”

Clara’s eyes, too, were full of tears, and Mr. Matson blew his nose with astonishing vigor.

But they were happy tears that did not scald or sting, and in a few minutes they had recovered their equanimity to some degree.

“What on earth can it all mean?” asked Mrs. Matson, as she put on her glasses again.

“Let’s read the letter and find out,” urged Clara.

“You read it, Clara,” said her mother. “I’m such a big baby to-day that I couldn’t get through with it.”

Clara obeyed.

The letter was not very long, for Joe had had to dash it off hurriedly, but they read a good deal more between the lines than was written.

“Dearest Momsey,” the communication ran, “I am writing this letter in a rush, as I’m fearfully busy just now, getting ready for the World Series. Of course, you’ve read by this time all about the last game that won us the pennant. I had good luck and the boys supported me well so that I pulled through all right.

“Now don’t think, Momsey, when you see the enclosed bill that I’ve been cracking a bank or making counterfeit money. I send the money in a single bill so that it won’t make the registered letter too bulky. Dad can get it changed into small bills at the bank.

“You remember the clause in my contract by which I was to get a thousand dollars extra if I won twenty games during the season? Well, that last game just made the twentieth, and the club handed the money over in a hurry. And in just as much of a hurry I’m handing it over to the dearest mother any fellow ever had.

“Now, Momsey, I want you and Dad and Clara to shut up the house, jump into some good clothes and hustle on here to New York just as fast as steam will bring you. You’re going to see the World Series, take in the sights of New York and Boston, and have the time of your life. You’re going to have one big ga-lorious spree!

“Now notice what I’ve said, Momsey—spree. Don’t begin to figure on how little money you can do it with. You’ve been trying to save money all[59] your life. This one time I want you to spend it. Doll yourself up without thinking of expense, and see that that pretty sister of mine has the best clothes that money can buy. Don’t put up lunches to eat on the way. Live on the fat of the land in the dining cars. Don’t come in day coaches, but get lower berths in the Pullmans. Make the Queen of Sheba look like thirty cents. I want you, Momsey dear, to have an experience that you can look back upon for all your life.

“I’ve engaged a suite of rooms for you in the Marlborough Hotel—a living room, two bedrooms and a private bath. Reggie Varley and Mabel are stopping there now, and they’ll be delighted to see you. They often speak of the good times they had with you when they were at Riverside. And you know how fond Clara and Mabel are of each other.

“Tell Sis that Jim Barclay, my chum, has seen her picture and is crazy to meet her. He’s a Princeton man, a splendid fellow, and I wouldn’t mind a bit having him for a brother-in-law.”

“The idea!” exclaimed Clara, tossing her pretty head and blushing like a rose, but looking not a bit displeased, nevertheless.

“Now don’t lose a minute, Momsey, for the time is short and the Series begins next week.[60] You’ll have to do some tall hustling. Wire me what train you’ll take, and I’ll be there with bells on to meet you and take you to the hotel.

“Am feeling fine. Best love to Dad and Sis and lots for yourself from

“Your loving son,

“Joe.”

There was silence in the room for a moment after Clara finished reading. They looked at each other with hearts beating fast and eyes shining.

“New York, Boston, the World Series!” Clara gasped in delight. “Pinch me, Dad, to see if I’m dreaming! Oh, Momsey!” she exclaimed as she danced around the room, “Joe put it just right. It’s going to be a ‘ga-lorious spree!’”

In New York, the preparation for the World Series was rapidly taking form. Little else was thought or spoken of. Pictures of the teams and players usurped the front pages of the newspapers, crowding all other news into the background. For the time being the ballplayer was king.

It was generally agreed by the experts that the contest would be close. Neither side could look for a walkover. The fight would be for blood from the very start.

On paper the teams seemed pretty evenly matched. If the Red Sox were a little quicker in fielding, the Giants seemed to have “the edge” on their opponents in batting. It was felt that the final decision would be made in the pitcher’s box.

And here the “dope” favored the Red Sox. This was due chiefly to the accident that had befallen Hughson. Had that splendid veteran been in his usual shape, it was conceded that New York[62] ought to win and win handsomely. For Boston could not show a pair to equal Hughson and Matson, although the general excellence of their staff was very high.

But with Hughson out of the Series, it looked as though Joe’s shoulders would have to bear the major part of the pitching burden; and though those shoulders were sturdy, no one man could carry so heavy a load as that would be.

Thus the problem of New York’s success seemed to resolve itself into this: Would Hughson have so far recovered as to take part in the games? And behind this was still another question: Even if he should take part, would he be up to his usual form after the severe ordeal through which he had passed?

So great was the anxiety on this score that almost every new edition of the afternoon papers made a point of publishing the very latest news of the great pitcher’s condition. Most of these were reassuring, for Hughson really was making remarkable progress, and it goes without saying that, regardless of cost, he was receiving the very best attention from the most skilful specialists that could be secured.

In the meantime the National Commission—the supreme court in baseball—had met in conclave at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. They really had little to do, except to reaffirm[63] the rules which had governed previous Series and had been found to work well in practice.

The Series was to consist of seven games, to be played alternately on succeeding days in the two cities. The place where the games were to start would be decided by the toss of a coin. If rain interfered with any of the games, the game was to be played in the same city on the first fair day.

The Series was to finish when either of the teams had won four games. Only in the first four games played were the players to share in the money paid to see them. This provision was made so that there should be no temptation for the players to “spin out” the Series in order to share additional receipts. It was up to each team to win four straight games if it could.

Of the money taken in at these first four games, ten per cent. was to go to the National Commission and ten per cent. into the clubs’ treasuries. The balance was to be divided between the two teams in the proportion of sixty per cent. to the winner and forty per cent. to the loser.

The players had no financial interest whatever in any money taken in at other games, which went to the clubs themselves, less the percentage of the National Commission.

“Hurrah!” cried Jim Barclay in delight, as he broke into the rooms occupied by Joe and himself.

“What’s the matter?” asked Joe, looking up. “Dropped into a fortune? Got money from home?”

“We’ve won the toss of the coin!” ejaculated Jim. “New York gets the first game.”

“Bully!” cried Joe. “That’s all to the good. That’s the first break in the game and it’s come our way. Let’s hope that luck will stay with us all through.”

“And just as we supposed, the first game will start on Friday,” continued Jim. “So that we’ll have about a week for practice before we have to buckle to the real work.”

“McRae told me this morning that he had almost all the practice team together now, and that we’d start to playing against them on Monday,” said Joe.

“It’s up to us to make the most of this little breathing spell, then,” returned Jim. “I think I’ll take a little run down to the beach to-morrow. Care to come along?”

“I’ve got an engagement myself to-morrow,” Joe replied. “I’m going for an automobile ride with Reggie Varley and Miss Varley. By the way, Jim, why don’t you come along with us? Reggie told me to bring along a friend if I cared to. There’s plenty of room, and he has a dandy auto. Flies like a bird. Come along.”

“Where are you going?”

“Out on Long Island somewhere. Probably stop at Long Beach for dinner.”

“Sure, I’ll come,” said Jim readily. “But don’t think I’m not on to your curves, you old rascal. You want me to engage Reggie in conversation so that you can have Miss Varley all to yourself.”

“Nonsense!” disclaimed Joe, flushing a trifle.

“Well, then,” said the astute Jim, “I’ll let you have the front seat with Reggie, while I sit back in the tonneau.”

“Not on your life you won’t!” said Joe, driven out into the open.

“All right,” grinned Jim resignedly. “I’ll be the goat. When do we start?”

“Reggie will have the car up in front of the Marlborough at about ten, he said. We’ll have a good early start and make a day of it.”

“All right,” said Jim. “Let’s root for good weather.”

They could not have hoped for a finer day than that which greeted them on the following morning. The sun shone brightly, but there was just enough fall crispness to make the air fresh and delicious.

Reggie was on time, nor did Mabel avail herself of the privilege of her sex and keep them waiting. The girl looked bewitching in her new fall costume and the latest thing in auto toggery, and her rosy cheeks and sparkling eyes drew Joe[66] more deeply than ever into the toils. Jim’s mischievous glance at them as they settled back in the tonneau while he took his seat beside Reggie, left no doubt in his own mind how matters stood between them.

Whatever else Reggie lacked, he was a master hand at the wheel, and he wound his way in and out of the thronging traffic with the eye and hand of an expert. They soon reached and crossed the Queensboro Bridge, and then Reggie put on increased speed and the swift machine darted like a swallow along one of the magnificent roads in which the island abounds. Beautiful Long Island lay before them, dotted with charming homes and rich estates, fertile beyond description, swept by ocean breezes, redolent of the balsam of the pines, “fair as a garden of the Lord.”

Jim, like the good fellow and true friend that he was, absorbed Reggie’s attention—that is, as much of it as could be taken from the road that unrolled like a ribbon beneath the flying car—and Joe and Mabel were almost as much alone as though they had had the car to themselves. And it was very evident that neither was bored with the other’s society. Joe’s hand may have brushed against Mabel’s occasionally, but that was doubtless due to the swaying of the car. At any rate, Mabel did not seem to mind.

At the rate at which they were going, it was[67] only a little while before they heard the sound of the breakers, and the great hotel at Long Beach loomed up before them.

Reggie put up his car and they spent a glorious hour on the beach, watching the white-capped waves as they rushed in like race horses with crested manes and thundered on the sands. Then they had a choice and carefully selected dinner served in full view of the sea.

“Some hotel, this,” remarked Reggie as he gazed about him. “Make a dent in a man’s pocketbook to live here right along.”

“Yes,” agreed Jim. “They give you the best there is, but you have to pay the price. Reminds me of a story that used to be told of a famous hotel in Washington. The proprietor was known among statesmen all over the country for the way he served beefsteak smothered in onions. One man who had tried the dish advised his friend to do the same the next time he went to Washington.”