Title: Immortal Songs of Camp and Field

Author: Louis Albert Banks

Release date: August 22, 2013 [eBook #43539]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by K Nordquist, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

| Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed. Some illustrations

have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading. (etext transcriber's note) |

IMMORTAL SONGS

OF

CAMP AND FIELD

BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL

(From the celebrated painting by Trumbull)

Copyright, 1898

by

The Burrows Brothers Co.

———

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Imperial Press

CLEVELAND

To my sister

Lacibel Ainsworth Wood

this volume is lovingly and gratefully

dedicated by the author

| Page | |

| Thomas à Becket | 76 |

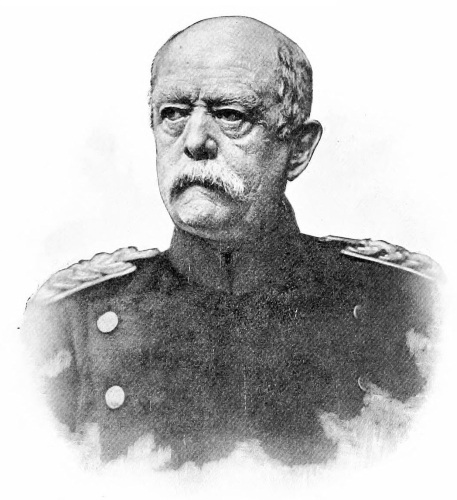

| Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen | 258 |

| John Brown | 96 |

| Joseph Rodman Drake | 16 |

| Daniel Decatur Emmett | 108 |

| Francis Miles Finch | 236 |

| Stephen Collins Foster | 226 |

| Ulysses Simpson Grant | 216 |

| Joseph Hopkinson | 66 |

| Julia Ward Howe | 158 |

| John Wallace Hutchinson | 148 |

| Francis Scott Key | 52 |

| Rudyard Kipling | 290 |

| La Fayette | 268 |

| Robert Edward Lee | 204 |

| Abraham Lincoln | 124 |

| George Pope Morris | 86 |

| Robert Treat Paine | 26 |

| Albert Pike | 118 |

| George Frederick Root | 170 |

| Charles Carroll Sawyer | 180 |

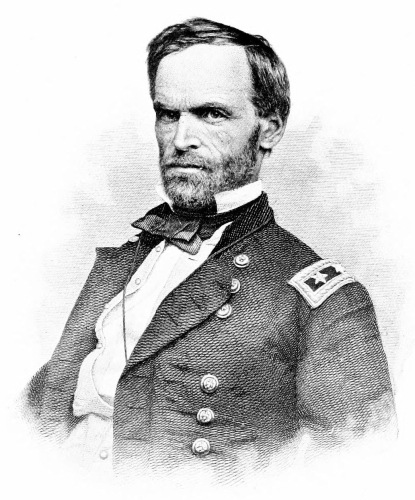

| William Tecumseh Sherman | 192 |

| Charles Edward Stuart, the Pretender | 278 |

| James Thomson | 248 |

| George Washington | 40 |

| Henry Clay Work | 136 |

| Page | |

| Battle of Bunker Hill | Frontispiece |

| Bunker Hill Monument | xii |

| Washington Monument | xiv |

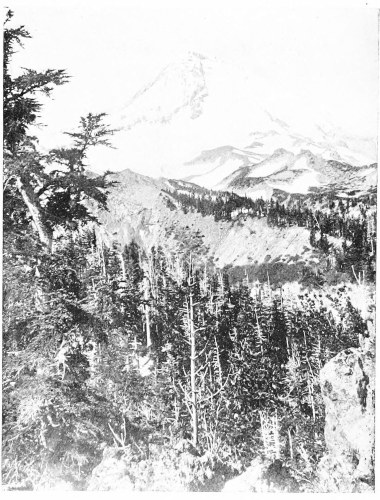

| Mount Hood | 22 |

| Statue of the Minuteman at Concord, Massachusetts | 32 |

| Liberty Bell | 37 |

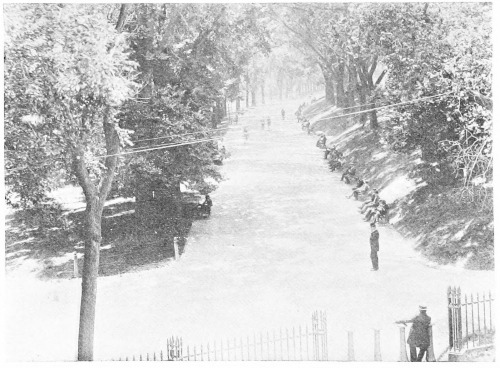

| Boston Common | 46 |

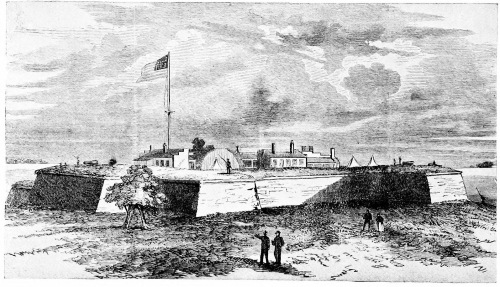

| Fort McHenry | 58 |

| The Capitol | 72 |

| Statue of Liberty | 80 |

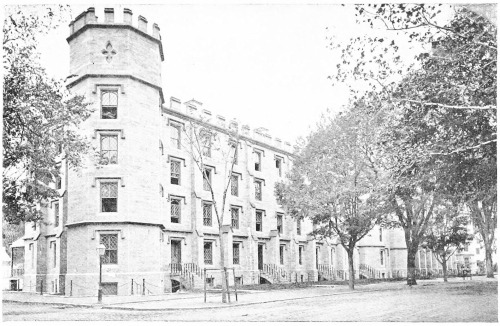

| West Point Military Academy | 90 |

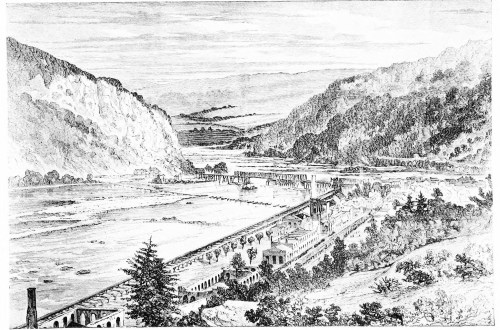

| Harper’s Ferry | 102 |

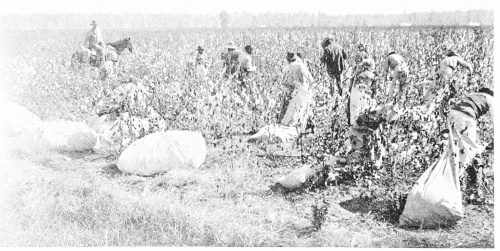

| Picking Cotton | 112 |

| Fort Sumter | 130 |

| The White House | 142 |

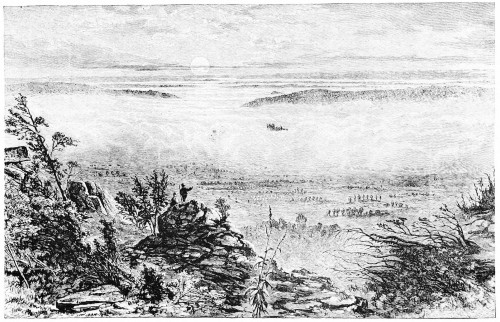

| Moccasin Bend | 152 |

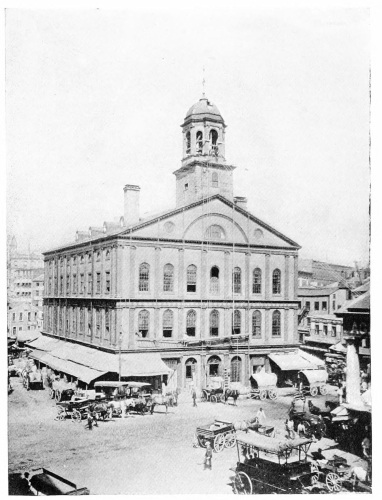

| Faneuil Hall | 164 |

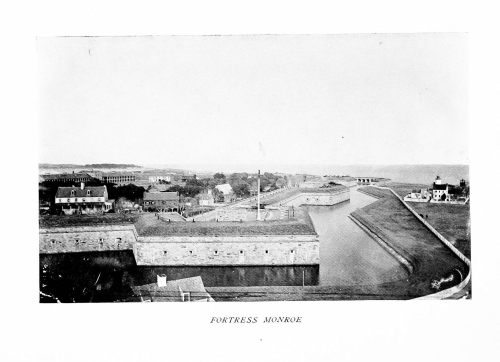

| Fortress Monroe | 176 |

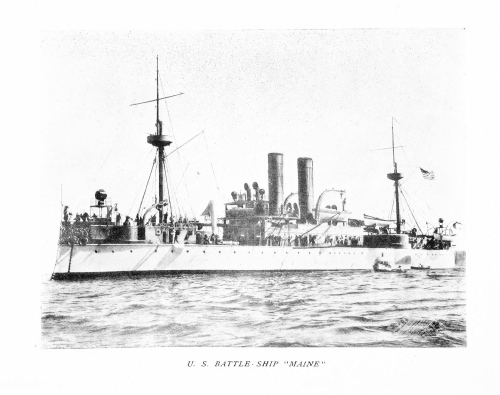

| U. S. Battle-Ship “Maine” | 186 |

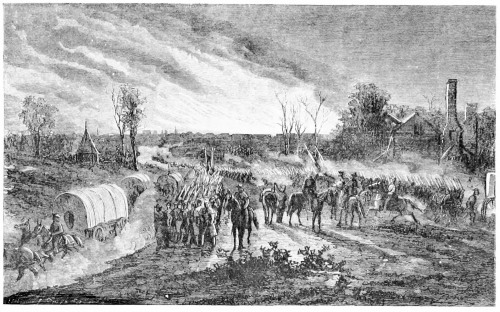

| Sherman burns Atlanta and marches toward the sea | 198 |

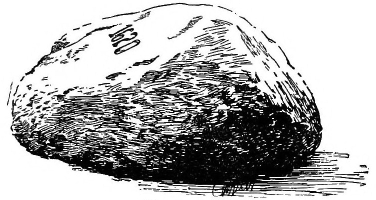

| Plymouth Rock | 202 |

| The Invasion of Maryland | 210 |

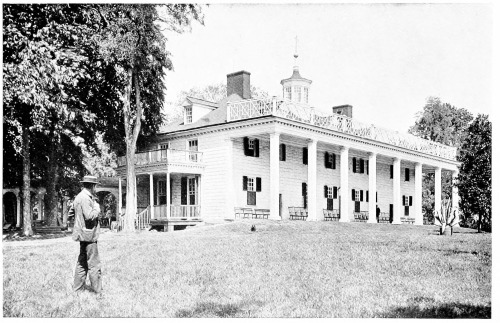

| Mount Vernon | 222 |

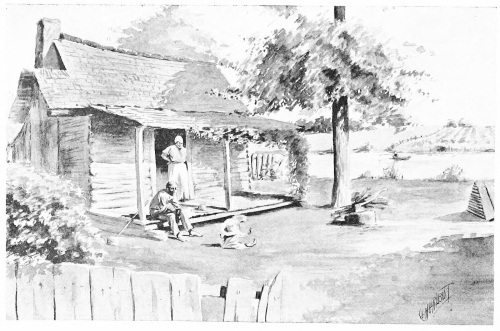

| “Still longin’ for de old plantation, And for de old folks at home” | 232 |

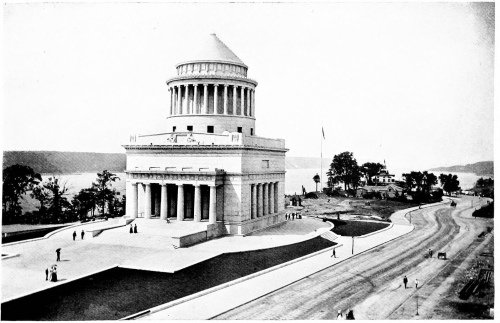

| Grant’s Monument | 242 |

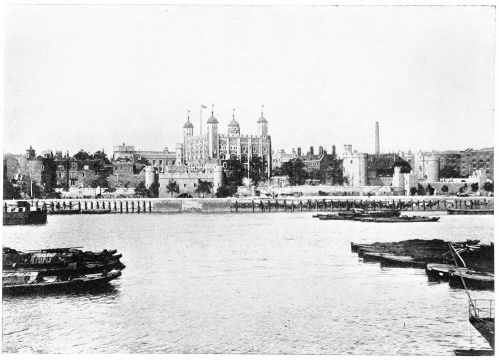

| The Tower of London | 254 |

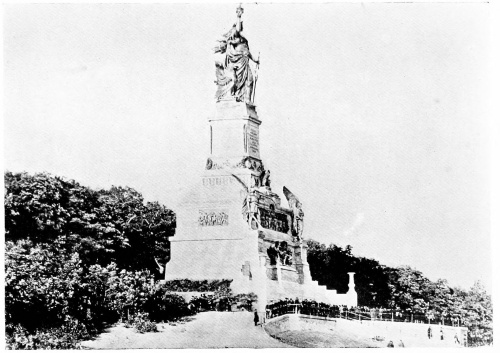

| National Monument, Niederwald | 264 |

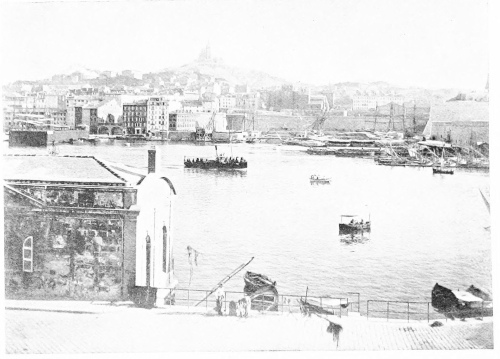

| Vieux Port, Marseilles | 274 |

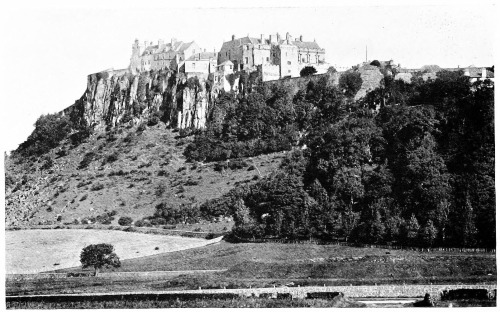

| Stirling Castle | 284 |

| Houses of Parliament | 296 |

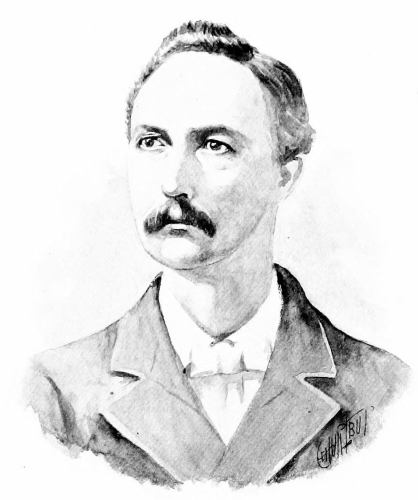

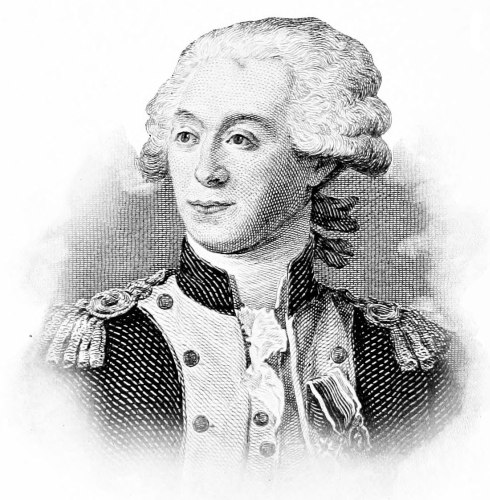

JOSEPH RODMAN DRAKE

The author of The American Flag was born to poverty, but by hard work he obtained a good education, and studied medicine under Dr. Nicholas Romayne, by whom he was greatly beloved. He obtained his degree and shortly afterward, in October, 1816, he was married to Sarah Eckford, who brought him a good deal of wealth. Two years later, his health failing, he visited New Orleans for the winter, hoping for its recovery. He returned to New York in the spring, only to die in the following autumn, September, 1820, at the age of twenty-five. He is buried at Hunt’s Point, in Westchester County, New York, where he spent some of the years of his boyhood. On his monument are these lines, written by his friend, Fitz-Green Halleck,—

Drake was a poet from his childhood. The anecdotes preserved of his early youth show the fertility of his imagination. His first rhymes were a conundrum which he perpetrated when he was but five years old. He was one day, for some childish offense, punished by imprisonment in a portion of the garret shut off by some wooden bars. His sisters stole up to witness his suffering condition, and found him pacing the room, with something like a sword on his shoulder, watching an incongruous heap on the floor, in the character of Don Quixote at his vigils over the armor in the church. He called a boy of his acquaintance, named Oscar, “Little Fingal;” his ideas from books thus early seeking embodiment in living shapes. In the same spirit the child listened with great delight to the stories of an old neighbor lady about the Revolution. He would identify himself with the scene, and once, when he had given her a very energetic account of a ballad which he had read, upon her remarking that it was a tough story, he quickly replied, with a deep sigh: “Ah! we had it tough enough that day, ma’am.”

Drake wrote The Mocking-Bird, one of his poems which has lived and will live, when a mere boy. It shows not only a happy facility but an unusual knowledge of the imitative faculty in the young poets of his time.

MOUNT HOOD

The American Flag was written in May, 1819, when the author was not quite twenty-four. It has remained unchanged except the last four lines. It originally concluded:—

These lines were very unsatisfactory to Drake, and he said to Fitz-Green Halleck, “Fitz, can’t you suggest a better stanza?” Whereupon the brilliant author of Marco Bozzaris sat down and wrote in a glowing burst of inspiration the four concluding lines:—

Drake immediately agreed that these were a splendid improvement on the former ending, and incorporated them into his one poem that is certain of immortality. It was first published in the New York Evening Post, in a series known as the Croaker Pieces, The American Flag being the last one of the series.

The young poet was entirely free from vanity and affectation, and had no morbid seeking for popular applause. When he was on his deathbed, at his wife’s request, Doctor DeKay collected and copied all his poems which could be found and took them to him. “See, Joe,” said he to him, “what I have done.” “Burn them,” he replied; “they are valueless.”

Drake’s impulsive nature, as well as the spirit and force, yet simplicity, of expression, with his artless manner, gained him many friends. He had that native politeness which springs from benevolence—that would stop to pick up the hat or the crutch of an old servant, or fly to the relief of a child. His acquaintance with Fitz-Green Halleck arose in a romantic incident on the Battery one day when, in a retiring shower, the heavens were spanned by a rainbow. DeKay and Drake were together, and Halleck, a new acquaintance, was talking with them; the conversation taking the turn of some passing expression of the wishes of the moment, Halleck whimsically remarked that it would be heaven for him, just then, to ride on that rainbow and read Campbell. The idea was very pleasing to Drake. He seized Halleck by the hand and from that moment until his untimely death they were bosom friends.

ROBERT TREAT PAINE

STATUE OF THE MINUTEMAN AT CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS

The father of the author of Adams and Liberty, or as it has been more usually entitled in later days, Ye Sons of Columbia, was the Robert Treat Paine who was one of the immortal signers of the Declaration of Independence. The author of this hymn was given by his parents the name of Thomas, but on account of that being the name of a notorious infidel of his time, he appealed to the legislature of Massachusetts to give him a Christian name; thereafter he took the name of his father, Robert Treat Paine.

He was a very precocious and brilliant youth. When he was seven years of age his family removed from Taunton, where he was born, to Boston, and there he prepared for Harvard College at one of the public schools, entering the freshman class in his fifteenth year. One of his classmates wrote a squib on him in verse on the college wall, and Paine, on consultation with his friends, being advised to retaliate in kind, did so, and thus became aware of the poetic faculty of which he afterward made such liberal use. He wrote nearly all his college compositions in verse, with such success that he was assigned the post of poet at the College Exhibition in the autumn of 1791, and at the Commencement in the following year. After receiving his diploma, he entered the counting-room of Mr. James Tisdale, but soon proved that his tastes did not lie in that direction. He would often be carried away by day-dreams and make entries in his day-book in poetry. On one occasion when he was sent to the bank with a check for five hundred dollars, he met some literary acquaintances on the way and went off with them to Cambridge, and spent a week in the enjoyment of “the feast of reason and the flow of soul,” returning to his duties with the cash at the end of that period.

In 1792 young Paine fell deeply in love with an actress, a Miss Baker, aged sixteen, who was one of the first players to appear in Boston. Their performances were at first called dramatic recitations to avoid a collision with a law forbidding “stage plays.” He married Miss Baker in 1794, and was promptly turned out of doors by his father.

The next year, on taking his degree of A.M. at Cambridge, he delivered a poem entitled The Invention of Letters. There was a great deal of excitement over this poem at the time, as it contained some lines referring to Jacobinism, which the college authorities crossed out, but which he delivered as written. The poem was greatly admired, and Washington wrote him a letter in appreciation of its merits. It was immediately published and large editions sold, the author receiving fifteen hundred dollars as his share of the profits, which was no doubt a very grateful return to a poet with a young wife and an obdurate father. The breach with his family, however, was afterward healed.

Mr. Paine was also the author of a poem entitled The Ruling Passion, for which he received twelve hundred dollars. Still another famous poem of his was called The Steeds of Apollo.

In 1794 he produced his earliest ode, Rise, Columbia, which, perhaps, was the seed thought from which later sprang the more extended hymn,—

His most famous song, Adams and Liberty,—which is sung to the same tune as Key’s Star-Spangled Banner, or Anacreon in Heaven,—was written four years later at the request of the Massachusetts Charitable Fire Society. Its sale yielded him a profit of more than seven hundred and fifty dollars. These receipts show an immediate popularity which has seldom been achieved by patriotic songs. In 1799 he delivered an oration on the first anniversary of the dissolution of the alliance with France which was a great oratorical triumph. The author sent a copy, after its publication, to Washington, and received a reply in which the General says: “You will be assured that I am never more gratified than when I see the effusions of genius from some of the rising generation, which promises to secure our national rank in the literary world; as I trust their firm, manly, and patriotic conduct will ever maintain it with dignity in the political.”

The next to the last stanza of Adams and Liberty was not in the song as originally written. Paine was dining with Major Benjamin Russell, when he was reminded that his song had made no mention of Washington. The host said he could not fill his glass until the error had been corrected, whereupon the author, after a moment’s thinking, scratched off the lines which pay such a graceful tribute to the First American:—

Instead of being added to the hymn it was inserted as it here appears. The second, fourth, and fifth stanzas have been usually omitted in recent publications of the hymn.

The brilliant genius of Paine was sadly eclipsed by strong drink, that dire foe of many men of bright literary promise. His sun, which had risen so proudly, found an untimely setting about the beginning of the war of 1812.

Liberty Bell

GEORGE WASHINGTON

It is certainly the tune of Yankee Doodle, and not the words of this old song, which captured the fancy of the country and held its sway in America for nearly a hundred and fifty years.

The tune, however, is much older than that. It has been claimed in many lands. When Kossuth was in this country making his plea for liberty for Hungary, he informed a writer of the Boston Post that, when the Hungarians that accompanied him first heard Yankee Doodle on a Mississippi River steamer, they immediately recognized it as one of the old national airs of their native land, one played in the dances of that country, and they began to caper and dance as they had been accustomed to do in Hungary.

It has been claimed also in Holland as an old harvest song. It is said that when the laborers received for wages “as much buttermilk as they could drink, and a tenth of the grain,” they used to sing as they reaped, to the tune of Yankee Doodle, the words,—

BOSTON COMMON

(Beacon Street Mall)

From Spain, also, comes a claim. The American Secretary of Legation, Mr. Buckingham Smith, wrote from Madrid under date of June 3, 1858: “The tune of Yankee Doodle, from the first of my showing it here, has been acknowledged, by persons acquainted with music, to bear a strong resemblance to the popular airs of Biscay; and yesterday, a professor from the north recognized it as being much like the ancient sword-dance played on solemn occasions by the people of San Sebastian. He says the tune varies in those provinces. The first strains are identically those of the heroic Danza Esparta of brave old Biscay.”

France puts in a claim, and declares that Yankee Doodle is an old vintage song from the southern part of that land of grapes; while Italy, too, claims Yankee Doodle for her own.

The probabilities are that it was introduced into England from Holland.

Yankee Doodle became an American institution in June, 1755. General Braddock, of melancholy fate, was gathering the colonists to an encampment near Albany for an attack on the French and Indians at Niagara. The countrymen came into camp in a medley of costumes, from the buckskins and furs of the American Indian to some quaint old-fashioned military heirloom of a century past. The British soldiers made great sport of their ragged clothes and the quaint music to which they marched. There was among these regular troops from England a certain Dr. Richard Shuckburg, who could not only patch up human bodies, but had a great facility in patching up tunes as well. As these grotesque countrymen marched into camp, this quick-witted doctor recalled the old air which was sung by the cavaliers in ridicule of Cromwell, who was said to have ridden into Oxford on a small horse with his single plume fastened into a sort of knot which was derisively called a “macaroni.” The words were,—

Doctor Shuckburg at once began to plan a joke upon the uncouth newcomers. He set down the notes of Yankee Doodle, wrote along with them the lively travesty upon Cromwell, and gave them to the militia musicians as the latest martial music of England. The band quickly caught the simple and contagious air which would play itself, and in a few hours it was sounding through the camp amid the laughter of the British soldiers. It was a very prophetic piece of fun, however, which became significant a few years later. When the battles of Concord and Lexington began the Revolutionary War, the English, when proudly advancing, played along the road God save the King; but after they had been routed, and were making their disastrous retreat, the Americans followed them with the taunting Yankee Doodle.

It was only twenty-five years after Doctor Shuckburg’s joke when Lord Cornwallis marched into the lines of these same old ragged Continentals to surrender his army and his sword to the tune of Yankee Doodle.

Francis Hopkinson, of Philadelphia, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and the father of Joseph Hopkinson, the author of Hail Columbia, adapted the words of his famous song The Battle of the Kegs, to the tune of Yankee Doodle. David Bushnell, the inventor of the torpedo, in December, 1777, had set adrift at night a large number of kegs charged with gunpowder, which were designed to explode on coming in contact with the British vessels in the Delaware. They failed in their object, but, exploding in the vicinity, created intense alarm in the fleet, which kept up for hours a continuous discharge of cannon and small arms at every object in the river. This was “the battle of the kegs.”

Verses without number have been sung to the tune of Yankee Doodle, but the ballad given here is the one that was best known and most frequently sung during the war for independence. They are said to have been written by a gentleman of Connecticut whose name has not survived. The exact date of their first publication is not known, but as these verses were sung at the Battle of Bunker Hill it must have been as early as 1775.

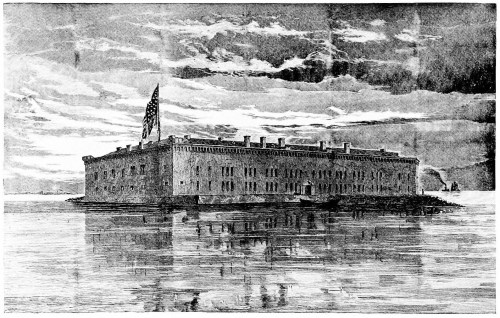

FRANCIS SCOTT KEY

No song could have had a more inspiring source of creation than did this. Its author, Mr. Francis Scott Key, was a young lawyer who left Baltimore in September, 1814, while the war of 1812 was yet going on, and under a flag of truce visited the British fleet for the purpose of obtaining the release of a friend of his, a certain Doctor Beanes, who had been captured at Marlborough. After his arrival at the fleet he was compelled to remain with it during the bombardment of Fort McHenry, as the officers were afraid to permit him to land lest he should disclose the purposes of the British. Mr. Key remained on deck all night, watching every shell from the moment it was fired until it fell, and listening with breathless interest to hear if an explosion followed. The firing suddenly ceased before day, but from the position of the ship he could not discover whether the fort had surrendered or the attack had been abandoned. He paced the deck for the remainder of the night in painful suspense, watching with intense anxiety for the return of day, and looking every few minutes at his watch to see how long he must wait for it; and as soon as it dawned, and before it was light enough to see objects at a distance, his glass was turned to the fort, uncertain whether he should see there the Stars and Stripes or the flag of the enemy. At length the light came, and he saw that “our flag was still there;” and as the day advanced he discovered from the movement of the boats between the shore and the fleet that the English troops had been defeated, and that many wounded men were being carried to the ships. At length Mr. Key was informed that the attack on Baltimore had failed, and he with his friend was permitted to return home, while the hostile fleet sailed away, leaving the Star-Spangled Banner still waving from Fort McHenry.

During the intense anxiety of waiting for dawn, Mr. Key had conceived the idea of the song and had written some lines, or brief notes that would aid him in calling them to mind, upon the back of a letter which he happened to have in his pocket. He finished the poem in the boat on his way to the shore, and finally corrected it, leaving it as it now stands, at the hotel, on the night he reached Baltimore, and immediately after he arrived. The next morning he took it to Judge Nicholson, the chief justice of Maryland, to ask him what he thought of it; and he was so pleased with it that he immediately sent it to the printer, Benjamin Edes, and directed copies to be struck off in handbill form. In less than an hour after it was placed in the hands of the printer it was all over the town, and hailed with enthusiasm, and at once took its place in the national songs. The first newspaper that printed it was the American, of Baltimore.

FORT McHENRY

The tune, which has helped so much to make it famous, also had an interesting selection. Two brothers, Charles and Ferdinand Durang, were actors at the Holliday Street Theater in Baltimore, but were also soldiers. A copy of Francis Key’s poem came to them in camp; it was read aloud to a company of the soldiers, among whom were the Durang brothers. All were inspired by the pathetic eloquence of the song and Ferdinand Durang at once put his wits to work to find a tune for it. Hunting up a volume of flute music which was in one of the tents, he impatiently whistled snatches of tune after tune, just as they caught his quick eye. One, called Anacreon in Heaven, struck his fancy and riveted his attention. Note after note fell from his puckered lips until, with a leap and shout, he exclaimed, “Boys, I’ve hit it!” And fitting the tune to the words, there rang out for the first time the song of The Star-Spangled Banner. How the men shouted and clapped; for there never was a wedding of poetry to music made under more inspiring influences! Getting a brief furlough, the Durang brothers sang it in public soon after. It was caught up in the camps, and sung around the bivouac fires, and whistled in the streets, and when peace was declared, and the soldiers went back to their homes, they carried this song in their hearts as the most precious souvenir of the war of 1812.

The song bears evidence of the special incident to which it owes its creation, and is not suited to all times and occasions on that account. To supply this want, additional stanzas have, from time to time, been written. Perhaps the most notable of all these is the following stanza, which was written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, at the request of a lady, during our civil war, there being no verse alluding to treasonable attempts against the flag. It was originally printed in the Boston Evening Transcript.

The air selected under such interesting circumstances as we have described—Anacreon in Heaven,—is that of an old English song. In the second half of the eighteenth century a jovial society, called the “Anacreontic,” held its festive and musical meetings at the “Crown and Anchor” in the Strand. It is now the “Whittington Club;” but in the last century it was frequented by Doctor Johnson, Boswell, Sir Joshua Reynolds and others. One Ralph Tomlinson, Esq., was at that time president of the Anacreontic Society, and wrote the words of the song adopted by the club, and John Stafford Smith set them to music, it is claimed to an old French air. The song was published by the composer, and was sold at his house, 7 Warwick Street, Spring Garden, London, between the years 1770-75. Thus the source of the music so long identified with this inspiring song is swallowed up in the mystery of the name of Smith.

The flag of Fort McHenry, which inspired the song, still exists in a fair state of preservation. It is at this time thirty-two feet long and of twenty-nine feet hoist. In its original dimensions it was probably forty feet long; the shells of the enemy, and the work of curiosity hunters, have combined to decrease its length. Its great width is due to its having fifteen instead of thirteen stripes, each nearly two feet wide. It has, or rather had, fifteen five-pointed stars, each two feet from point to point, and arranged in five indented parallel lines, three stars in each horizontal line. The Union rests in the ninth, which is a red stripe, instead of the eighth, a white stripe, as in our present flag. There can be no doubt as to the authenticity of this flag. It was preserved by Colonel Armstead, and bears upon its stripes, in his autograph, his name and the date of the bombardment. It has always remained in his family and in 1861 his widow bequeathed it to their youngest daughter, Mrs. William Stuart Appleton, who, some time after the bombardment, was born in Fort McHenry under its folds. She was named Georgians Armstead for her father, and the precious flag was hoisted on its staff in honor of her birth. Mrs. Appleton died in New York, July 25, 1878, and bequeathed the flag to her son, Mr. Eben Appleton, of Yonkers, New York, who now holds it.

The Star-Spangled Banner has come out of the Spanish War baptized with imperishable glory. Throughout the war it has been above all others, in camp or on the battlefield, the song that has aroused the highest enthusiasm. During the bombardment of Manila the band on a British cruiser, lying near the American fleet, played The Star-Spangled Banner, thus showing in an unmistakable way their sympathy with the American cause. In the trenches before Santiago it was sung again and again by our soldiers and helped, more than anything else, to inspire them to deeds of heroic valor. Once when the army moved forward in the charge, the man who played the E-flat horn in the band left his place and rushed forward with the soldiers in the attacking column. Of course the band’s place is in the rear. But this man, unmindful of everything, broke away and went far up the hill with the charge, carrying his horn over his shoulder, slung with a strap. For a time he went along unobserved, until one of the officers happened to see him. And he said to him, “What are you doing here? You can’t do anything; you can’t fight; you haven’t any gun or sword. This is no place for you. Get down behind that rock.” The soldier fell back for a minute, half dazed, and feeling the pull of the strap on his shoulder cried out in agony: “I can’t do anything, I can’t fight.” And so he got down behind the rock. But almost instantly he raised his horn and began to play The Star-Spangled Banner. They heard him down in the valley, and immediately the band took it up, and in the midst of those inspiring strains the army charged to victory.

JOSEPH HOPKINSON

Joseph Hopkinson, like Francis Scott Key, the author of The Star-Spangled Banner, was also a lawyer. He commenced the practice of law in Easton, Pennsylvania, but soon removed to Philadelphia, where he acquired high distinction at the bar. He was four years a member of Congress, and was afterward appointed judge of the United States District Court, an office held by his grandfather under the British Crown before the Revolutionary War, and to which his father had been chosen on the organization of the United States Judiciary in 1789. He retained this office until his death in 1842.

Mr. Hopkinson was still a young man, only twenty-eight years of age, when he wrote the song which will make his name honored as long as American liberty is remembered. It was in the summer of 1798, when a war with France was thought to be inevitable. Congress was in session in Philadelphia, discussing the advisability of a declaration of war, and many acts of hostility had actually occurred. England and France were at war already, and the people of the United States were divided into factions for the one side or the other. One party argued that policy and duty required Americans to take part with republican France; the other section urged the wisdom of connecting ourselves with England, under the belief that she was the great conservator of modern civilization, and that her triumph meant the rule of good principles and safe government. Both belligerents had been careless of our rights, and seemed to be forcing us from the just and wise policy of Washington, which was to maintain a strict and impartial neutrality between them. The prospect of a rupture with France was exceedingly offensive to that portion of the people who hoped for her success, and the violence of party spirit ran to the highest extreme.

Just at this time a young singer who was very popular in Philadelphia was to be given a benefit at one of the theaters. This young man was a school friend of Joseph Hopkinson. They had kept up their acquaintance after their school-days had passed, and one Saturday afternoon he called on Hopkinson to talk over with him his benefit which was announced for the following Monday. He said he had every prospect of suffering a loss instead of receiving a benefit from the performance; but that if he could get a patriotic song adapted to the tune of the President’s March, then the popular air, he would no doubt have a full house. The poor fellow was almost in despair about it, as the poets of the theatrical corps had been trying to accomplish it, and had come to the conclusion that no words could be composed to suit the music of that march. The young lawyer told his friend that he would try what he could do for him. He came the next afternoon, and the song, Hail Columbia, was ready for him. It was announced on Monday morning, and the theater was crowded to overflowing, and so continued, night after night, for the rest of the season. The excitement about it grew so great that the song was not only encored but had to be repeated many times each night, the audience joining in the chorus. It was also sung at night in the streets by large crowds of citizens, which often included members of Congress and other distinguished public officials. The enthusiasm spread to other cities and the song was caught up and reëchoed at all kinds of public gatherings throughout the United States.

THE CAPITOL

The object of Mr. Hopkinson in writing the song, in addition to doing a kind deed for his friend and schoolmate, was to arouse an American spirit which should be independent of and above the interests, passions, and policy of both belligerents, and look and feel exclusively for our own honor and rights. For this reason no allusion was made to France or England, or to the war which was raging between them, or to our indignation as to their treatment of us. It was this prudence which gave the song its universal popularity. It found equal favor with both parties, for neither could disown the loyal sentiments it inculcated. It was so purely American, and nothing else, that the patriotic feelings of every American heart responded to it.

The President’s March, for which the poem was specially written and to which it was easily adapted, was composed in honor of President Washington, who then resided at 190 High Street, Philadelphia. The composer of the popular air was Philip Roth, a teacher of music. Not a great deal is left on record about him, but it is declared that he was a very eccentric character, familiarly known as “Old Roat.” It is also said that he took snuff immoderately. A claim has been set up for Professor Phyla, of Philadelphia, but the evidence favors Roth.

During the centennial year an autograph copy of Hail Columbia was displayed in the museum at Independence Hall, Philadelphia. This copy was written from memory, February 22, 1828, and presented to George M. Kein, Esq., of Reading, in compliance with a request made by him. This interesting manuscript has marginal notes, one of which informs us that the lines:—

refer to John Adams, who was President of the United States at the time Hail Columbia was written. Mr. Hopkinson also presented General Washington with an autograph copy of his poem, and received from him a complimentary letter of thanks, which is now in possession of his descendants.

THOMAS À BECKET

This splendid song, as popular, perhaps, as any of America’s patriotic hymns, was written in 1843 by a young actor named Thomas à Becket. He was engaged at that time at the Chestnut Street Theater, in Philadelphia. He was waited upon by a Mr. D. T. Shaw, an acquaintance, who was also an actor, with the request that he would write him a song for his benefit night. Mr. Shaw had been trying to write one for himself, but had made a sad failure of it. He produced some patriotic lines, and asked Mr. À Becket’s opinion on them; he found them ungrammatical and so deficient in measure as to be totally unfit to be set to music. They went to the house of a mutual friend, and there À Becket wrote the two first verses in pencil, and sitting down at a piano in the room of the friend’s house, he composed the melody. On reaching home that evening he added the third verse, wrote the symphonies and arrangements, made a fair copy in ink, and gave it to Mr. Shaw, requesting him not to give or sell a copy to any one.

STATUE OF LIBERTY

A few weeks afterward Mr. À Becket left for New Orleans, and a little while later was greatly astonished to see a published copy of his song entitled, “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean, written, composed, and sung by David T. Shaw, and arranged by T. à Becket, Esq.” On his return to Philadelphia he sought out Mr. Willig, the publisher, who told him he had purchased the song from Mr. Shaw. Mr. À Becket produced the original copy in pencil, and claimed the copyright, which Mr. Willig admitted, making some severe remarks upon Shaw’s conduct in the affair. A week later it appeared under its proper title, “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean, written and composed by T. à Becket, and sung by D. T. Shaw.” The song has been often printed under the title The Red, White, and Blue, and is very familiarly known as “The Army and Navy Song,” from being peculiarly adapted to reunions of the two wings of the military department of the government.

Mr. E. L. Davenport, an eminent actor, sung the song nightly in London for many weeks, where it became very popular. It was printed there under the title Britannia, the Pride of the Ocean. On this account some people have supposed the English version to be the original, and ours merely an adaptation of it. That part of its title, “The Gem of the Ocean,” belongs to the Emerald Isle, rather than to Columbia, and seems more appropriate to designate an island power like Great Britain than a continental power like the United States. However, it is beginning to look as though we might have islands of our own in abundance.

While red, white, and blue have for a long time been the ranking order of the colors of British national ensigns, with us blue—the blue of the union, the firmament of our constellation of stars—claims the first place on our colors, red the second, and white the third; so that for us the song should read,—

“When borne by the blue, red, and white,”

instead of,—

“When borne by the red, white, and blue.”

These lapses are explained by the fact that the author was an Englishman by birth, and it was very natural that he should make them. Though written by a native-born Englishman, the song was thoroughly American in its inception and origin. In the English version, already referred to, the first line is altered to read,—

In these days of kindly fellowship with England, Americans are perfectly willing to share their song of “red, white, and blue” with their cousins across the water.

GEORGE POPE MORRIS

The author of The Flag of our Union was one of the most distinguished journalists of the early half of the nineteenth century in America. He was for many years the editor of the Mirror, which was in its time the best literary magazine in the country. Such men as William Cullen Bryant, Fitz-Green Halleck, Nathaniel P. Willis, Theodore S. Fay, and Epes Sargent found in its pages a chance to express the poetry, romance, and philosophy which flowed from their brilliant and graceful pens.

Morris was the author of many songs and poems that have become household words throughout the land. Who does not recall,—

And these other lines from My Mother’s Bible, equally well known,—

WEST POINT MILITARY ACADEMY

(N. E. corner of cadets’ barracks)

And what schoolboy of twenty-five years ago does not remember the song of The Whip-poor-will, the first verses of which always aroused his sympathetic interest?—

Morris had traveled abroad rather widely for that day, but instead of its weaning him from his native land, it made it all the more dear to him. He set this forth in a well-known song entitled, I’m with You once Again, which so accurately voices the feelings of thousands of loyal American travelers that it is worth repeating here:—

In this song we see the spirit in which was written The Flag of our Union. Ten years before the War of the Rebellion, when the mutterings of the coming storm were already in the air, this poet and traveler, who had found his country’s flag such an inspiration when roving in foreign lands, poured out his heart in this hymn to the Flag. It was set to music by William Vincent Wallace, and was very popular in war times. It is worthy of popularity so long as the Flag of the Union shall wave.

JOHN BROWN

No prophet is ever able to foretell what will catch the popular ear. The original John Brown song, written by Miss Edna Dean Proctor, is certainly far more coherent and intelligible than the lines which have formed the marching song for over a million men, and have held their own through a generation. It is well worth repeating here:—

The more popular, if not more worthy, song of John Brown’s Body seems to have been of Massachusetts origin at the commencement of the Civil War. It was first sung in 1861. When the Massachusetts Volunteers, commanded by Colonel Fletcher Webster, a son of the famous Daniel Webster, were camped on one of the islands in Boston Harbor, some of the soldiers amused themselves by adapting the words,—

to a certain air. Mr. Charles Sprague Hall, who is the author of the lines as finally sung, says that when the soldiers first began to sing it the first verse was the only one known. He wrote the other verses, but did not know where the first one came from.

The way was opened for this song through a campaign song heard from the lips of the Douglas, and the Bell, and the Everett Campaign Clubs, who, in order to spite Governor John A. Andrew, the famous war governor of Massachusetts, sang the following lines as they were marching through the streets of Boston, with their torches in hand,—

These lines are supposed to have been an imitation of the doggerel,—

Great stress having been laid by the opponents of Governor Andrew upon the fact that John Brown was dead, the authors of the song spoken of took good care to assert that, while

HARPER’S FERRY

This was the answer of those that sympathized with John Brown, a song which they flung at those who seemed to take delight in the fact that he was dead.

Thane Miller, of Cincinnati, heard the melody, which is perhaps the most popular martial melody in America, in a colored Presbyterian church in Charleston, South Carolina, about 1859, and soon after introduced it at a convention of the Young Men’s Christian Association in Albany, New York, with the words,—

Professor James E. Greenleaf, organist of the Harvard Church in Charlestown, found the music in the archives of that church, and fitted it to the first stanza of the present song. It has since been claimed that the Millerites, in 1843, used the same tune to a hymn, one verse of which is as follows,—

Whatever may have been the origin of the melody, when fitted by Greenleaf to the first stanza of John Brown’s Body, it became so great a favorite with the Glee Club of the Boston Light Infantry that they asked Mr. Hall to write the additional stanzas.

As has been the case with popular tunes in every age, verses have been often added to it to meet the occasion. While the words are not of a classical order, the air is of that popular kind which strikes the heart of the average man. During the Civil War it served to cheer and inspire the Union soldiers in their camps and on the march, and was sung at home at every popular gathering in town or country. It seemed to be just what the soldiers needed at the time, and served its purpose far better than would choicer words or more artistic music. No song during all the war fired the popular heart as did John Brown’s Body. It crossed the sea and became the popular street song in London. The Pall Mall Gazette of October 14, 1865, said: “The street boys of London have decided in favor of John Brown’s Body, against My Maryland, and The Bonnie Blue Flag. The somewhat lugubrious refrain has excited their admiration to a wonderful degree, and threatens to extinguish that hard-worked, exquisite effort of modern minstrelsy, Slap Bang.”

After the original song had gained world-wide notoriety, the following words were written by Henry Howard Brownell, who died at Hartford, Connecticut, October 31, 1872, aged fifty-two. Mr. Brownell entitled his poem, “Words that can be sung to the Hallelujah Chorus,” and says: “If people will sing about Old John Brown, there is no reason why they shouldn’t have words with a little meaning and rhythm in them.”

But Mr. Brownell has shared the same fate with Miss Proctor, and his song and hers are only curiosities to-day, which show how arbitrary the popular will is when once the heart or the imagination is really captured. Mr. Richard Henry Dana, Jr., writing to Mr. James T. Fields, the famous Boston litterateur, said: “It would have been past belief had we been told that the almost undistinguishable name of John Brown should be whispered among four millions of slaves, and sung wherever the English language is spoken, and incorporated into an anthem to whose solemn cadences men should march to battle by the tens of thousands.”

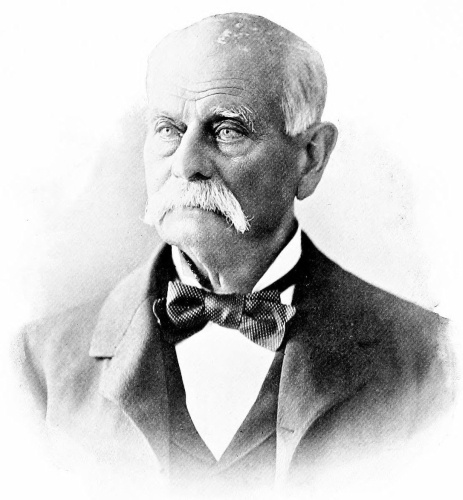

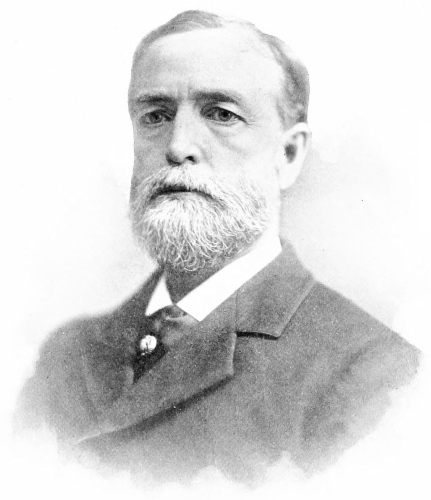

DANIEL DECATUR EMMETT

PICKING COTTON

Dan Emmett, who wrote the original Dixie, which has been paraphrased and changed and adapted nearly as frequently as Yankee Doodle was born at Mount Vernon, Ohio, in 1815. He came from a family all of whose members had a local reputation, still traditional in that part of the country, as musicians. In his own case this talent, if given a fair chance for development, would have amounted to genius. He began life as a printer, but soon abandoned his trade to join the band of musicians connected with a circus company. He was not long in discovering that he could compose songs of the kind in use by clowns; one of the most popular of these was Old Dan Tucker. Its success was so great that Emmett followed it with many others. They were all negro melodies, and many of them won great popularity. Finally he took to negro impersonations, singing his own songs in the ring, while he accompanied himself on the banjo. He made a specialty of old men, and he declares with pride that when he had blackened his face, and donned his wig of kinky white hair, he was “the best old negro that ever lived.” He became such a favorite with the patrons of the circus in the South and West, that at last—partly by chance, and partly through intention—he became a full-fledged actor. This was in 1842, at the old Chatham Theater in New York City, when with two companions he gave a mixed performance, made up largely of songs and dances typical of slave life and character. The little troupe was billed as “The Virginia Minstrels,” and their popularity with the public was instantaneous.

This was the beginning of negro minstrelsy, which was destined to have such a wide popularity in America. From New York the pioneer company went to Boston, and later on sailed for England, leaving the newly-discovered field to the host of imitators who were rapidly dividing their success with them. Emmett had great success in the British Isles, and remained abroad for several years. When he returned to New York, he joined the Dan Bryant Minstrel Company, which then held sway in Bryant’s Theater on lower Broadway, which was at that time one of the most popular resorts in New York City. Emmett was engaged to write songs and walk-arounds and take part in the nightly performances. It was while he was with Bryant that Dixie was composed.

Emmett is still living and resides at Mount Vernon, Ohio, where he hopes to end his days. The old man is a picturesque figure on the streets. In his prime he was one of the mid-century dandies of New York City, but now, with calm indifference to the conventional, he usually carries a long staff and wears his coat fastened in at the waist by a bit of rope. His home is a little cottage on the edge of town, where he lives entirely alone. On almost any warm afternoon he can be found seated before his door reading, but he is ready enough to talk with the chance visitor whose curiosity to meet the composer of one of the National Songs of America, has brought him thither. A newspaper man who recently went to talk with the old minstrel found him seated in the shade by his house with a book open before him. As he went up the path, he said, for he had some doubt in his own mind,—

“Are you Dan Emmett, who wrote Dixie?”

“Well, I have heard of the fellow; sit down,” and Emmett motioned to the steps.

“Won’t you tell me how the song was written?”

“Like most everything else I ever did,” said Emmett, “it was written because it had to be done. One Saturday night, in 1859, as I was leaving Bryant’s Theater, where I was playing, Bryant called after me, ‘I want a walk-’round for Monday, Dan.’

“The next day it rained and I stayed indoors. At first when I went at the song I couldn’t get anything. But a line,

kept repeating itself in my mind, and I finally took it for my start. The rest wasn’t long in coming. And that’s the story of how Dixie was written.

“It made a hit at once, and before the end of the week everybody in New York was whistling it. Then the South took it up and claimed it for its own. I sold the copyright for five hundred dollars, which was all I ever made from it. I’ll show you my first copy.”

He went into the house and returned in a moment with a yellow, worn-looking manuscript in his hand.

“That’s Dixie,” he said, holding it up for inspection. “I am going to give it to some historical society in the South, one of these days, for though I was born here in Ohio, I count myself a Southerner, as my father was a Virginian.”

Dixie Land was without question the most famous of all the Southern war songs. But it was the tune, as in the case of Yankee Doodle, and not the words that gave it its great power to fire the heart. It is claimed that Emmett appropriated the tune from an old negro air, which is quite probable.

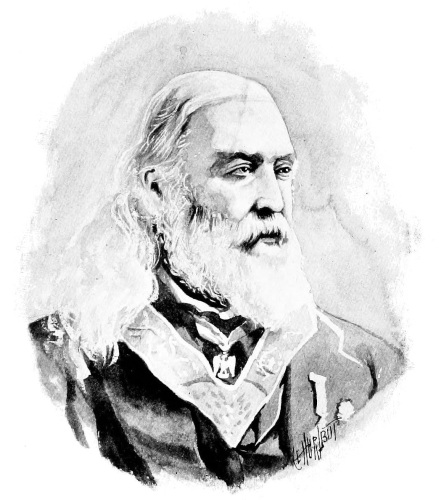

The only poem set to the famous air of Dixie which has any literary merit is one that was written by General Albert Pike. Some one has said that it is worthy of notice that the finest Puritan lyric we have was written by an Englishwoman, Mrs. Felicia Hemans, and the most popular Southern war song was written by a Yankee, a native of Massachusetts. Albert Pike was born in Boston, December 29, 1809, but most of his boyhood was spent in Newburyport. He became a teacher, but in 1831 visited what was then the wild region of the Southwest with a party of trappers. He afterward edited a paper at Little Rock, and studied law. He served in the Mexican War with distinction, and on the breaking out of the Rebellion enlisted, on the Confederate side, a force of Cherokee Indians, whom he led at the battle of Pea Ridge. After the war he edited the Memphis Appeal till 1868, when he settled in Washington as a lawyer. He has written a number of fine poems, and retired from the profession of law in 1880, to devote himself to literature and Freemasonry. Mr. Pike’s version of Dixie is as follows,—

ALBERT PIKE

Since the war Dixie has been as favorite a tune with bands of music throughout the North as has Yankee Doodle. Abraham Lincoln set the example for this. A war correspondent recalls an incident which occurred only a night or two before Mr. Lincoln was assassinated. The President had returned from Richmond, and a crowd called with a band to tender congratulations and a serenade. The great man who was so soon to be the victim of the assassin’s bullet appeared in response to calls and thanked his audience for the compliment. Several members of his Cabinet surrounded him, and it was a very interesting and dramatic occasion. Just as he was closing his brief remarks, Mr. Lincoln said: “I see you have a band with you. I should like to hear it play Dixie. I have consulted the Attorney-General, who is here by my side, and he is of the opinion that Dixie belongs to us. Now play it.” The band struck up the old tune, and played it heartily. As the strains of the music rang out upon the air, cheer after cheer went up from the throats of the hundreds of happy men who had called to congratulate Mr. Lincoln upon the return of peace. It was that great soul’s olive branch which he held out to the South.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

This inspiring rallying song was written by George F. Root, to whom we are indebted for so many songs of camp and field. Mr. Root also composed the music. Perhaps no hymn of battle in America has been sung under so many interesting circumstances as this. It was written in 1861, on President Lincoln’s second call for troops, and was first sung at a popular meeting in Chicago and next at a great mass meeting in Union Square, New York, where those famous singers, the Hutchinson Family, sounded it forth like a trump of jubilee to the ears of thousands of loyal listeners.

It was always a great favorite with the soldiers. Dr. Jesse Bowman Young, of St. Louis, the author of What a Boy Saw in the Army, relates a very affecting and pathetic incident which occurred while a portion of the Army of the Potomac was marching across Maryland. A young officer and his company were in the lead, and just behind them came one of the regimental bands, while ahead of them rode General Humphreys and his staff. As the division marched along, they passed by a country schoolhouse in a little grove at a crossroad. The teacher, hearing the music of the band at a distance, and expecting the arrival of the troops, had dismissed the school to give them a sight of the soldiers. Before the troops came in sight the boys and girls had gathered bunches of wild flowers, platted garlands of leaves, and secured several tiny flags, and as General Humphreys rode up in front of the schoolhouse, a little girl came forth and presented him with a bouquet, which he acknowledged with gracious courtesy. Then the group of assembled pupils began to sing, as they waved their flags and garlands in the air. That song made a tumult in every soldier’s heart. Many strong men wept as they looked on the scene and thought of their own loved ones far away in their Northern homes, and were inspired with newborn courage and patriotism by the sight and the song. This is the chorus which rang forth that day from the country schoolhouse, and which soon afterward echoed through the battle in many a soldier’s ear and heart, miles away, on the bloody field of Gettysburg:—

The first company that passed responded to their captain with a will as he shouted, “Boys, give them three cheers and a tiger!” and the example was imitated by the regiments that followed; so that amid the singing of the children and the cheers of the soldiers, and the beating of the drums, the occasion was made memorable to all concerned.

Richard Wentworth Browne relates that a day or two after Lee’s surrender in April, 1865, he visited Richmond, in company with some other Union officers. After a day of sight-seeing, the party adjourned to Mr. Browne’s rooms for dinner. After dinner one of the officers who played well opened the piano, saying, “Boys, we have our old quartette here, let’s have a song.” As the house opposite was occupied by paroled Confederate officers, no patriotic songs were sung. Soon the lady of the house handed Mr. Browne this note: “Compliments of General —— and staff. Will the gentlemen kindly allow us to come over and hear them sing?” Consent was readily given and they came. As the General entered the room, the Union officers recognized instantly the face and figure of an officer who had stood very high in the Confederacy. After introductions, and the usual interchange of civilities, the quartette sang for them glees and college songs, until at last the General said, “Excuse me, gentlemen, you sing delightfully, but what we want to hear is your army songs.” Then they gave them the army songs with unction: The Battle Hymn of the Republic; John Brown’s Body; We’re coming, Father Abraham; Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys are Marching; and so on through the whole catalogue to the Star-Spangled Banner,—to which the Confederate feet beat time as if they had never stepped to any but the music of the Union,—and closed their concert with Root’s inspiring Battle Cry of Freedom.

FORT SUMTER

When the applause had subsided, a tall, fine-looking young fellow in a major’s uniform exclaimed, “Gentlemen, if we’d had your songs we’d have licked you out of your boots! Who couldn’t have marched or fought with such songs? while we had nothing, absolutely nothing, except a bastard Marseillaise, The Bonny Blue Flag, and Dixie, which were nothing but jigs. Maryland, my Maryland was a splendid song, but the tune, old Lauriger Horatius, was about as inspiring as the Dead March in Saul, while every one of these Yankee songs is full of marching and fighting spirit.”

Then turning to the General he said, “I shall never forget the first time I heard that chorus, ‘Rally round the Flag.’ It was a nasty night during the Seven Days’ fight, and if I remember rightly, it was raining. I was on picket, when just before ‘taps’ some fellow on the other side struck up The Battle Cry of Freedom and others joined in the chorus until it seemed to me that the whole Yankee army was singing. A comrade who was with me sang out, ‘Good heavens, Cap, what are those fellows made of, anyway? Here we’ve licked them six days running, and now, on the eve of the seventh, they’re singing “Rally round the Flag?”’ I am not naturally superstitious, but I tell you that song sounded to me like the knell of doom; my heart went down into my boots; and though I’ve tried to do my duty, it has been an uphill fight with me ever since that night.”

Perhaps the most romantic and inspiring occasion on which The Battle Cry of Freedom was ever sung was at the raising of the flag over Fort Sumter on the 14th of April, 1865, that being the fourth anniversary of the day when Major Anderson had evacuated the fort after his brave defense. A large number of citizens went from New York in excursion steamers, to assist in the celebration. Colonel Stewart L. Woodford, recently the United States minister to Spain, was master of ceremonies. The oration was delivered by the eloquent Henry Ward Beecher, but the supreme moment of interest came when Major-General Anderson, who had added General to the Major in the past four years, after a touching and tender address, received from Sergeant Hart a bag containing the precious old flag which had waved in the breeze through those days of fierce bombardment, the din of which had been heard around the world. The flag had been saved for such a time as this, and now, by order of Abraham Lincoln, it was brought back to wave again over Fort Sumter. It was attached to the halyards, and General Anderson hoisted it to the head of the flagstaff amid loud huzzas. One can imagine the inspiration of the occasion, as William B. Bradbury led the singing of The Battle Cry of Freedom. How the tears ran down the cheeks, and hearts overflowed with thanksgiving as they shouted the chorus underneath the folds of the very flag that had received the first baptism of fire at the beginning of the Rebellion:—

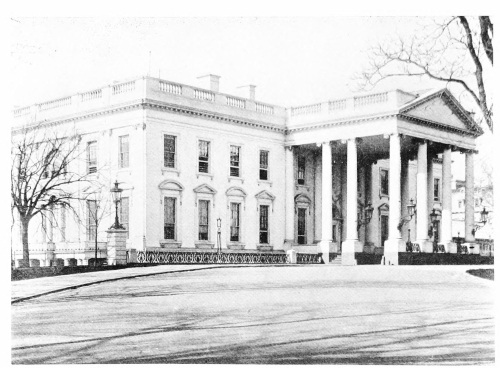

HENRY CLAY WORK

Henry Clay Work was born in Middletown, Connecticut, October 1, 1832. The family came originally from Scotland, and the name is thought to have come from a castle, “Auld Wark, upon the Tweed,” famed in the border wars in the times made immortal by Sir Walter Scott. He inherited his love of liberty and hatred of slavery from his father, who suffered much for conscience’ sake. While quite young, his family moved to Illinois, near Quincy, and he passed his boyhood in the most abject poverty, his father having been taken from home and imprisoned because of his strong anti-slavery views and active work in the struggles of those enthusiastic and devoted reformers. In 1845, Henry’s father was pardoned on condition that he would leave the State of Illinois. The family then returned to Connecticut. After a few months’ attendance at school in Middletown, our future song writer was apprenticed to Elisha Geer, of Hartford, to learn the printer’s trade. He learned to write over the printer’s case in much the same way as did Benjamin Franklin. He never had any music lessons except a short term of instruction in a church singing school. The poetic temperament, and his musical gifts as well, were his inheritance. He began writing very early, and many of his unambitious little poems found their way into the newspapers during his apprenticeship.

Work’s first song was written in Hartford and entitled, We’re coming, Sister Mary. He sold this song to George Christie, of Christie’s minstrels, and it made a decided hit. In 1855 he removed to Chicago, where he continued his trade as a printer. The following year he married Miss Sarah Parker, of Hubbardston, Massachusetts, and settled at Hyde Park. In 1860 he wrote Lost on the “Lady Elgin,” a song commemorating the terrible disaster to a Lake Michigan steamer, which became widely known.

Kingdom Coming was Work’s first war song, and was written in 1861. Now that it has been so successful, it seems strange that he should have had trouble to find a publisher for it; yet such was the case. But its success was immediate as soon as published. It is perhaps the most popular of all the darkey songs which deal directly with the question of the freedom of the slaves. It set the whole world laughing, but there was about it a vein of political wisdom as well as of poetic justice that commended it to strong men. The music is full of life and is as popular as the words. It became the song of the newsboys of the home towns and cities as well as of the soldiers in the camp and on the march. It portrays the practical situation on the Southern plantation as perhaps no other poem brought out by the war:—

THE WHITE HOUSE

Another most popular slave song which had a tremendous sale was entitled Wake Nicodemus, the first verse of which is,—

While Marching through Georgia is, without doubt, Mr. Work’s most renowned war song, his Song of a Thousand Years has about it a rise and swell, and a sublimity both in expression and melody, that surpasses anything else that he has written. The chorus is peculiarly fine both in words and music.

Work’s songs brought him a considerable fortune. After the close of the war he made an extended tour through Europe, and while on the sea wrote a song which became very famous, entitled The Ship that Never Returned. During the later years of his life he wrote Come Home, Father, and King Bibbler’s Army—both famous temperance songs.

After his return from Europe, Work invested his fortune in a fruit-growing enterprise in Vineland, New Jersey. He was also a somewhat remarkable inventor, and a patented knitting machine, a walking doll, and a rotary engine are among his numerous achievements. These years were saddened by financial and domestic misfortunes. His wife became insane, and died in an asylum in 1883. He survived her only a year, dying suddenly of heart disease on June 8, 1884, at Hartford, Connecticut. His ashes rest in Spring Grove Cemetery in that city, and on Decoration Day the Grand Army of the Republic never fail to strew flowers on the grave of the singer whose words and melodies led many an army to deeds of heroism. May a grateful people keep his memory green, and cause his grave to blossom for “A Thousand Years!”

JOHN WALLACE HUTCHINSON

Walter Kittredge was born in Merrimac, New Hampshire, October 8, 1832. His father was a farmer, and though New Hampshire farms are proverbial for their stony hillsides, they were fertile for the production of large families in those days, and Walter was the tenth of eleven children. His education was received at the village school. Like most other writers of war songs, Kittredge had an ear for music from the very first. All of his knowledge of music, however, he picked up for himself, as he never had an opportunity of attending music schools, or being under a teacher. He writes: “My father bought one of the first seraphines [a species of melodeon] made in Concord, New Hampshire, and well do I remember when the man came to put it up. To hear him play a simple melody was a rich treat, and this event was an important epoch in my child life.”

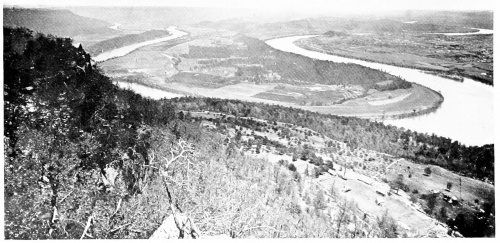

MOCCASIN BEND

(From Lookout Mountain)

Tenting on the Old Camp Ground, more than any other of our American war songs, had in it the heart experience of the man who wrote it. In 1863 Kittredge was drafted into the army. That night he went to bed the prey of many conflicting emotions. He was loyal to the heart’s core, but was full of grief at the thought of leaving his home, and his rather poetic and timid nature revolted against war. In the middle of the night he awoke from a troubled sleep with the burden of dread still on his mind. In the solemnity and stillness of the night the sad and pathetic fancies of the battle field filled his thought. He reflected on how many of the dear boys had already gone over to the unseen shore, killed in battle, or dead from disease in the camps. He thought of the unknown graves, of the sorrowful homes; of the weary waiting for the end of the cruel strife, of the trials and hardships of the tented field where the brave soldier boys waited for the coming battle, which might be their last. Suddenly these reflections began to take form in his mind. He arose and began to write. The first verse reveals his purpose not only to give cheer to others, but to comfort his own heart:—

That verse was like a prayer to God for comfort and the prayer was heard and answered.

Being a musician, a tune for the song easily came to Kittredge’s mind, and after copying both words and music he went at once to Lynn, Massachusetts, to visit his friend, Asa Hutchinson, one of the famous Hutchinson family, who then lived at Bird’s Nest Cottage, at High Rock. After they had looked it over together, they called in John Hutchinson, who still lives, the “last of the Hutchinsons,” to sing the solo. Asa Hutchinson sang the bass, and the children joined in the chorus. Kittredge at once made a contract with Asa Hutchinson to properly arrange and publish the song for one-half the profits.

The Hutchinson family were just then giving a series of torchlight concerts on the crest of old High Rock, with the tickets at the exceedingly popular price of five cents. The people from all the towns about turned out en masse. They had half a dozen or more ticket sellers and takers stationed at the various approaches to the rock. During the day they would wind balls of old cloth and soak them in oil. These, placed in pans on the top of posts at intervals, would burn quite steadily for an hour or more, and boys stood ready to replace them when they burned out. The audience gathered in thousands every night during this remarkable series of concerts, and on the very night of the day Kittredge had brought his new hymn, Tenting on the Old Camp Ground was sung for the first time from the crest of High Rock.

Like so many other afterward famous songs, it was hard to find a publisher at first, but the immense popularity which sprang up from the singing of the hymn about Boston soon led a Boston publisher to hire some one to write another song with a similar title, and a few weeks later the veteran music publisher, Ditson, brought out the original. Its sale reached many hundreds of thousands of copies during the war, and since then it has retained its popularity perhaps as completely as any of our war lyrics. It has been specially popular at reunions of soldiers, and every Grand Army assembly calls for it. Many a time I have seen the old veteran wiping away the tears as he listened to the singing of the second verse:—

JULIA WARD HOWE

This is, perhaps, the most elevated and lofty strain of American patriotism. Julia Ward Howe is a worthy author of such a hymn. She was the daughter of Samuel Ward, a solid New York banker of his time. Her mother, Julia Rush Ward, was herself a poet of good ability. Mrs. Howe received a very fine education, and, in addition to ordinary college culture, speaks fluently Italian, French, and Greek. In her girlhood she was a devout student of Kant, Hegel, Spinoza, Comte, and Fichte. Her literary work had given her considerable prominence before her marriage to Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, of Boston, just then famous for his self-sacrificing services in association with Lord Byron in behalf of the liberty of the Greeks, and henceforth to become forever immortal for his life-long devotion to the cause of the blind. America never produced a more daring and benevolent man than Doctor Howe.

The Battle Hymn of the Republic had its birth-throes amid the storms of war. In December, 1861, Mrs. Howe, in company with her husband, Governor and Mrs. John A. Andrew, Rev. Dr. James Freeman Clarke, and other friends, made a journey to Washington. They arrived in the night. As their train sped on through the darkness, they saw in vivid contrast the camp fires of the pickets set to guard the line of the railroad. The troops lay encamped around the Capital City, their lines extending to a considerable distance. At the hotel where the Boston party were entertained, officers and their orderlies were conspicuous, and army ambulances were constantly arriving and departing. The gallop of horsemen, the tramp of foot soldiers, the noise of drum, fife, and bugle were heard continually. The two great powers were holding each other in check, and the very air seemed tense with expectancy. The one absorbing thought in Washington was the army, and the time of the visitors was generally employed in visits to the camps and hospitals.

One day during this visit a party which included Doctor and Mrs. Howe and Doctor Clarke attended a review of the Union troops at a distance of several miles from the city. The maneuvers were interrupted by a sudden attack of the enemy, and instead of the spectacle promised them, they saw some reinforcements of cavalry gallop hastily to the aid of a small force of Federal troops which had been surprised and surrounded. They returned to the city as soon as possible, but their progress was much impeded by marching troops who nearly filled the highway. As they had to drive very slowly, in order to beguile the time they began to sing army songs, among which the John Brown song soon came to mind. This caught the ear of the soldiers and they joined in the inspiring chorus, and made it ring and ring again. Mrs. Howe was greatly impressed by the long lines of soldiers and the devotion and enthusiasm which they evinced, as they sung while they marched, John Brown’s Body. James Freeman Clarke, seeing Mrs. Howe’s deep emotion which was mirrored in her intense face, said:

“You ought to write some new words to go with that tune.”

“I will,” she earnestly replied.

FANEUIL HALL

She went back to Washington, went to bed, and finally fell asleep. She awoke in the night to find her now famous hymn beginning to form itself in her brain. As she lay still in the dark room, line after line and verse after verse shaped themselves. When she had thought out the last of these, she felt that she dared not go to sleep again lest they should be effaced by a morning nap. She sprang out of bed and groped about in the dim December twilight to find a bit of paper and the stump of a pencil with which she had been writing the evening before. Having found these articles, and having long been accustomed to jot down stray thoughts with scarcely any light in a room made dark for the repose of her infant children, she very soon completed her writing, went back to bed, and fell fast asleep.

What sublime and splendid words she had written! There is in them the spirit of the old prophets. Nothing could be grander than the first line:—

In the second verse one sees through her eyes the vivid picture she had witnessed in her afternoon’s visit to the army:—

In the third and fourth verses there is a triumphant note of daring faith and prophecy that was wonderfully contagious, and millions of men and women took heart again as they read or sang and caught its optimistic note:—

On returning to Boston, Mrs. Howe carried her hymn to James T. Fields, at that time the editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and it was first published in that magazine. The title, The Battle Hymn of the Republic, was the work of Mr. Fields.

Strange to say, when it first appeared the song aroused no special attention. Though it was destined to have such world-wide appreciation, it won its first victory in Libby Prison. Nearly a year after its publication, a copy of a newspaper containing it was smuggled into the prison, where many hundreds of Northern officers and soldiers were confined, among them being the brilliant Chaplain, now Bishop, Charles C. McCabe. The Chaplain could sing anything and make music out of it, but he seized on this splendid battle hymn with enthusiastic delight. It makes the blood in one’s veins boil again with patriotic fervor to hear him tell how the tears rained down strong men’s cheeks as they sang in the Southern prison, far away from home and friends, those wonderful closing lines:—

It was Chaplain McCabe who had the privilege and honor of calling public attention to the song after his release. He came to Washington and in his lecture (that has come to be almost as famous as the battle hymn) on “The Bright Side of Life in Libby Prison,” he described the singing of the hymn by himself and his companions in that dismal place of confinement. People now began to ask who had written the hymn, and the author’s name was easily established by a reference to the magazine.

GEORGE FREDERICK ROOT

George F. Root was born in Sheffield, Massachusetts, in 1820. He has perhaps written more popular war songs than any other American. His songs have carried his name to the ends of the earth. He was a musician from childhood. He began as a boy by getting hold of every musical instrument he could find and attempting to master it. When about eighteen years of age, he left his father’s farm in the beautiful Housatonic Valley, and went to Boston to obtain instruction in music, which he had already determined to make his life-work. He was very fortunate in finding employment with a Boston teacher named A. B. Johnson, who also took the young countryman into his own home and manifested the warmest interest in his superior musical gifts. It was not long before young Root became a partner in Mr. Johnson’s school. He was ambitious and industrious, and was soon acting as leader for a number of church choirs. There are several churches in Boston to-day which recall as one of the legends of their history that George F. Root used to lead their music. His reputation as a teacher spread so rapidly that he was sought after to give special instruction in other institutions. Later he went to New York and became the principal of the Abbott Institute.

Mr. Root was not satisfied to make anything less than the best out of himself, and so went to Europe in 1850 and spent a year in special work improving his musical talent. About this time he began writing songs, in which he had success from the start. These won him such wide recognition that Mason and Bradbury, the great musical publishers of that day, secured his aid in the making of church music books. He now retired from the field of teaching and devoted himself to composing music and the holding of great musical conventions.

On the breaking out of the war, Dr. Root was in Chicago, and from that Western center of patriotic fire and enthusiasm he sent forth scores of songs that thrilled the heart of the country. While the Battle Cry of Freedom was perhaps his most famous song, there are a number of others that keep, even to this day, close company with it in popularity. The old veterans who still linger on the scene, as well as those who were but boys and girls in those days, well remember the martial enthusiasm that was evoked by his prison song, Tramp, Tramp, Tramp! The mingled pathos and hopefulness of it has been rarely, if ever, surpassed:—

To appreciate the pathos of that song one needs to hear a company of Grand Army Veterans tell about singing it in Andersonville or Libby Prisons.

FORTRESS MONROE

Just Before the Battle, Mother appealed to the tender side of those who remained at home, and made it a very popular song not only for public gatherings, but in drawing-rooms, and camps in the twilight of the evening. The sequel to it, Just After the Battle, was equally as popular and retains its popularity though a generation has passed away since it was written. It, too, has the vein of optimism in it which runs through all of Doctor Root’s work. Perhaps that is one of the secrets of his great power over the human heart. While he makes us weep with the tenderness of the sentiment, there is always a rainbow on his cloud, a rainbow with promises of a brighter to-morrow. Just After the Battle has that rainbow in it, in the hope expressed by the singer that he shall still see his mother again in the old home:—

CHARLES CARROLL SAWYER

Charles Carroll Sawyer was born in Mystic, Connecticut, in 1833. His father, Captain Joshua Sawyer, was an old-fashioned Yankee sea captain. The family moved to New York when Charles was quite young, and he obtained his education in that city. The poetic instinct was marked in his youth, and at the age of twelve he wrote several sonnets which attracted a good deal of attention among his acquaintances. At the breaking out of the war he began to write war songs, and in a few months was recognized everywhere as one of the most successful musical composers of the day. His most popular songs were Who will Care for Mother Now? Mother would Comfort Me, and the one we have selected—When this Cruel War is Over. Each of these three songs named reached a sale of over a million copies before the close of the war, and were sung in almost every mansion and farmhouse and cabin from the Atlantic to the Pacific throughout all the northern part of the Union, as well as in every camp where soldiers waited for battle.

His song, Mother would Comfort Me, was suggested, as indeed were most of his songs, by a war incident. A soldier in one of the New York regiments had been wounded and was taken prisoner at Gettysburg. He was placed in a Southern hospital, and when the doctor told him that nothing more could be done for him, his dying words were: “Mother would comfort me if she were here.” When Sawyer learned of the incident, he wrote the song, the first verse of which runs as follows:—

This song captured the country at once, and spread its author’s fame everywhere.

On another occasion a telegram came to a Brooklyn wife concerning her husband who was killed on the battlefield. The last words of the despatch read: “He was not afraid to die.” Sawyer caught up that note in the telegram, and wrote his splendid song beginning,—

Another of his greatest creations found its inspiration in a similar way. During one of the battles, among the many noble men that fell was a young man who had been the only support of an aged and invalid mother for years. Overhearing the doctor tell those who were near him that he could not live, he placed his hands across his forehead, and with a trembling voice said, while burning tears ran down his cheeks: “Who will care for mother, now?” Sawyer took up these words which voiced the generous heart of the dying youth, and made them the title and theme of one of his noblest songs. The first verse is full of pathos,—

U. S. BATTLE-SHIP “MAINE”

At that time, when every community throughout the North as well as the South had more than one mother whose sole dependence for the future days of weakness and old age was the strong arm of some soldier boy at the front, this song struck a chord that was very tender, and it was sung and whistled and played in street and theater and drawing-room throughout the entire country.

Sawyer’s songs were unique in that they were popular in both armies. They never contained a word of malice, and appealed to the universal human heart. At the close of the war a newspaper published at Milledgeville, Georgia, said of Sawyer’s songs, “His sentiments are fraught with the greatest tenderness, and never one word has he written about the South or the war that could wound the sore chords of a Southern heart.”

The most universally famous of all Sawyer’s songs was When this Cruel War is Over. As the long years of carnage dragged on, the fascination for the glamour and glory of war disappeared, and its horrid cruelty impressed people, North and South, more and more. Loving hearts in the army and at home caught up this song as an appropriate expression of the hunger for peace that was in their souls. A popular Southern song, When upon the Field of Glory, the words of which were written by J. H. Hewitt and the music by H. L. Schreiner, was an answer to this song of Sawyer’s. As it is one of the best of the songs of the Confederacy, it is worth repetition here:—

WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN

Among Mr. Work’s famous war songs, none have captured so wide an audience, or held their own so well since the war, as Marching through Georgia. I think it is the foraging idea, so happily expressed, that, more than anything else except the contagious music which starts the most rheumatic foot to keeping time, has given this song its popular sway. There was something so reckless and romantic in Sherman’s cutting loose from his base of supplies and depending on the country through which he marched for food for his army, that the song which expressed this seized the imagination of the people.

General Sherman in his Memoirs says: “The skill and success of the men in collecting forage was one of the features of this march. Each brigade commander had authority to detail a company of foragers, usually about fifty men with one or two commissioned officers, selected for their boldness and enterprise. This party would be despatched before daylight with a knowledge of the intended day’s march and camp, would proceed on foot five or six miles from the route traveled by their brigade, and then visit every plantation and farm within range. They would usually procure a wagon, or family carriage, load it with bacon, cornmeal, turkeys, chickens, ducks, and everything that could be used as food or forage, and would then regain the main road, usually in advance of their train. When this came up, they would deliver to the brigade commissary the supplies thus gathered by the way. Often would I pass these foraging parties at the roadside, waiting for their wagons to come up, and was amused at their strange collections—mules, horses, even cattle, packed with old saddles and loaded with hams, bacon, bags of cornmeal, and poultry of every character and description. Although this foraging was attended with great danger and hard work, there seemed to be a charm about it that attracted the soldiers, and it was a privilege to be detailed on such a party. Daily they returned mounted on all sorts of beasts, which were at once taken from them and appropriated to the general use; but the next day they would start out again on foot, only to repeat the experience of the day before.”