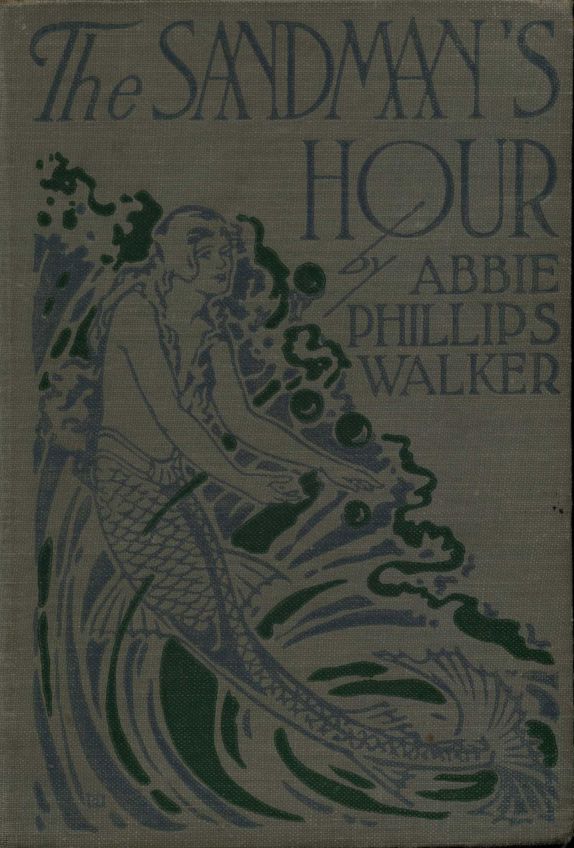

THE SANDMAN'S HOUR

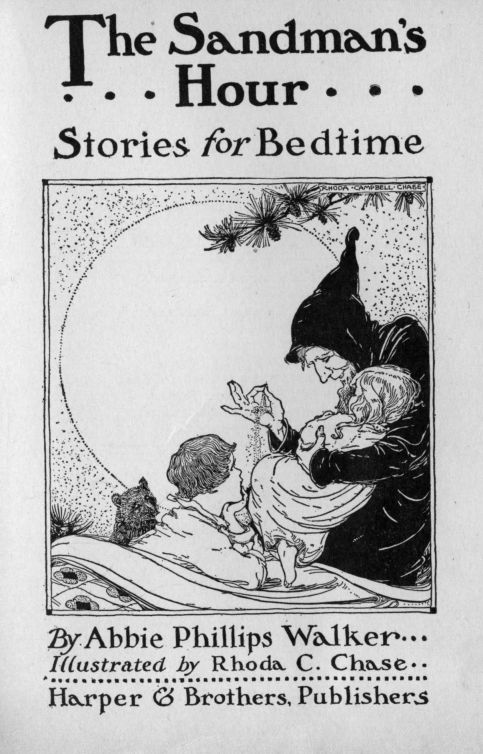

The Sandman's Hour

Stories for Bedtime

By Abbie Phillips Walker

Illustrated by Rhoda. C. Chase

Harper & Brothers, Publishers

The Sandman's Hour

Copyright, 1917, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Where the Sparks Go

The Good Sea Monster

Mother Turkey and Her Chicks

The Fairies and the Dandelion

Mr. 'Possum

The Rooster That Crowed Too Soon

Tearful

Hilda's Mermaid

The Mirror's Dream

The Contest

The Pink and Blue Eggs

Why the Morning-Glory Sleeps

Dorothy and the Portrait

Mistress Pussy's Mistake

Kid

The Shoemaker Rat

The Poppies

Little China Doll

The Disorderly Girl

The Wise Old Gander

Dinah Cat and the Witch

The Star and the Lily

Lazy Gray

The Old Gray Hen

The Worsted Doll

THE SANDMAN'S HOUR

WHERE THE SPARKS GO

One night when the wind was blowing and it was clear and cold out of doors, a cat and a dog, who were very good friends, sat dozing before a fire-place. The wood was snapping and crackling, making the sparks fly. Some flew up the chimney, others settled into coals in the bed of the fireplace, while others flew out on the hearth and slowly closed their eyes and went to sleep.

One spark ventured farther out upon the hearth and fell very near Pussy. This made her jump, which awakened the dog.

"That almost scorched your fur coat, Miss Pussy," said the dog.

"No, indeed," answered the cat. "I am far too quick to be caught by those silly sparks."

"Why do you call them silly?" asked the dog. "I think them very good to look at, and they help to keep us warm."

"Yes, that is all true," said the cat, "but those that fly up the chimney on a night like this certainly are silly, when they could be warm and comfortable inside; for my part, I cannot see why they fly up the chimney."

The spark that flew so near Pussy was still winking, and she blazed up a little when she heard the remark the cat made.

"If you knew our reason you would not call us silly," she said. "You cannot see what we do, but if you were to look up the chimney and see what happens if we are fortunate enough to get out at the top, you would not call us silly."

The dog and cat were very curious to know what happened, but the spark told them to look and see for themselves. Pussy was very cautious and told the dog to look first, so he stepped boldly up to the fireplace and thrust his head in. He quickly withdrew it, for his hair was singed, which made him cry and run to the other side of the room.

Miss Pussy smoothed her soft coat and was very glad she had been so wise; she walked over to the dog and urged him to come nearer the fire, but he realized why a burnt child dreads the fire, and remained at a safe distance.

Pussy walked back to the spark and continued to question it. "We cannot go into the fire," she said. "Now, pretty, bright spark, do tell us what becomes of you when you fly up the chimney. I am sure you only become soot and that cannot make you long to get to the top."

"Oh, you are very wrong," said the spark. "We are far from being black when we fly up the chimney, for once we reach the top, we live forever sparkling in the sky. You can see, if you look up the chimney, all of our brothers and sisters, who have been lucky and reached the top, winking at us almost every night. Sometimes the wind blows them away, I suppose, for there are nights when we cannot see the sparks shine."

"Who told you all that?" said the cat. "Did any of the sparks ever come back and tell you they could live forever?"

"Oh no!" said the spark; "but we can see them, can we not? And, of course, we all want to shine forever."

"I said you were silly," said the cat, "and now I know it; those are not sparks you see; they are stars in the sky."

"You can call them anything you like," replied the spark, "but we make the bright light you see."

"Well, if you take my advice," said the cat, "you will stay right in the fireplace, for once you reach the top of the chimney out of sight you go. The stars you see twinkling are far above the chimney, and you never could reach them." But the spark would not be convinced. Just then some one opened a door and the draught blew the spark back into the fireplace. In a few minutes it was flying with the others toward the top of the chimney.

Pussy watched the fire a minute and then looked at the dog.

"The spark may be right, after all," said the dog. "Let us go out and see if we can see it."

Pussy stretched herself and blinked. "Perhaps it is true," she replied; "anyway, I will go with you and look."

THE GOOD SEA MONSTER

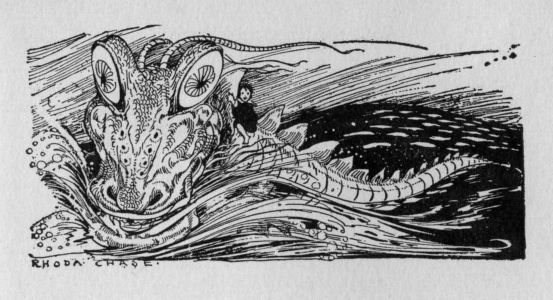

On an island of rocks out in the ocean lived a sea monster. His head was large, and when he opened his mouth it looked like a cave.

It had been said that he was so huge that he could swallow a ship, and that on stormy nights he sat on the rocks and the flashing of his eyes could be seen for miles around.

The sailors spoke of him with fear and trembling, but, as you can see, the sea monster had really been a friend to them, showing them the rock in the storm by flashing his eyes; but because he looked so hideous all who beheld him thought he must be a cruel monster.

One night there was a terrible storm, and the monster went out into the ocean to see if any ship was wrecked in the night, and, if possible, help any one that was floating about.

He found one little boy floating about on a plank. His name was Ko-Ko, and when he saw the monster he was afraid, but when Ko-Ko saw that the monster did not attempt to harm him he climbed on the monster's back and he took him to the rocky island. Then the monster went back into the sea and Ko-Ko wondered if he were to be left alone. But after a while the monster returned and opened his mouth very wide.

Ko-Ko ran when he saw the huge mouth, for he thought the monster intended to swallow him, but as he did not follow him Ko-Ko went back.

The monster opened his mouth again, and Ko-Ko asked, "Do you want me to go inside?" and the monster nodded his head.

"It must be for my own good," said Ko-Ko, "for he could easily swallow me if he wished, without waiting for me to walk in."

So Ko-Ko walked into the big mouth and down a dark passage, but what the monster wanted him to do he could not think. He could see very faintly now, and after a while he saw a stove, a chair, and a table. "I will take these out," said Ko-Ko, "for I am sure I can use them."

He took them to a cave on the island, and when he returned the monster was gone; but he soon returned, and again he opened his mouth.

Ko-Ko walked in this time without waiting, and he found boxes and barrels of food, which he stored away in the cave. When Ko-Ko had removed everything the monster lay down and went to sleep.

Ko-Ko cooked his dinner and then he awoke the monster and said, "Dinner is ready," but the monster shook his head and plunged into the ocean. He soon returned with his mouth full of fish. Then Ko-Ko knew that the monster had brought all the things from the sunken ship for him, and he began to wish that the monster could talk, for he no longer feared him.

"I wish you could talk," he said.

"I can," the monster replied. "No one ever wished it before. An old witch changed me into a monster and put me on this island, where no one could reach me, and the only way I can be restored to my original form is for some one to wish it."

"I wish it," said Ko-Ko.

"You have had your wish," said the monster, "and I can talk; but for me to become a man some one else must wish it."

The monster and Ko-Ko lived for a long time on the island. He took Ko-Ko for long rides on his back, and when the waves were too high and Ko-Ko was afraid the monster would open his mouth and Ko-Ko would crawl inside and be brought back safe to the island.

One night, after a storm, Ko-Ko saw something floating on the water, and he jumped on the monster's back and they swam out to it.

It proved to be a little girl, about Ko-Ko's age, who had been on one of the wrecked vessels, and they brought her to the island.

At first she was afraid of the monster, but when she learned that he had saved Ko-Ko as well as her and brought them all their food she became as fond of him as Ko-Ko was.

"I wish he were a man," she said one day, as she sat on his back with Ko-Ko, ready for a sail. Splash went both children into the water, and there in place of the monster was an old man. He caught the children in his arms and brought them to the shore.

"But what will we do for food, now that you are a man?" asked Ko-Ko.

"We shall want for nothing now," replied the old man. "I am a sea-god and can do many things, now that I have my own form again. We will change this island into a beautiful garden, and when the little girl and you are grown up and married you shall have a castle, and all the sea-gods and nymphs will care for you. You will never want for anything again.

"I will take you out on the ocean on the backs of my dolphins."

Ko-Ko and the little girl lived on the enchanted island, and all the things that the old sea-god promised came true.

MOTHER TURKEY AND HER CHICKS

Mother Turkey believed in the old adage taught to her by her grandmother, "The early bird catches the worm," and every night when the sun set she took her little chicks to the highest branch they could reach in an old apple-tree and sang them to sleep with this lullaby:

"Close your eyes, my little turkey chicks;Hide your heads, don't peep.Mother knows the bogy fox's tricks,And she'll watch while you sleep."

Mother Turkey had told them about the bogy fox that lived in a hole on the other side of the hill, and it did not need more than the mention of that name to make them obey.

"I do wish we could get just a look at him," said one chick, as his mother came to the end of the verse. "I should not know him if I met him."

"Oh yes, you would," replied his mother. "He has a very long tail, and a sharp nose, and his teeth! Oh, dear me!" she exclaimed, as she flapped her wings at the thought of them.

"Will you wake us if he comes to-night?" asked another chick.

"I shall not need to do that," replied Mother Turkey; "you will hear us talking. He is a very sly fellow, and always very polite and says nice things. But you cover your heads; it is getting late," and she began to sing:

"Close your eyes, my little turkey chicks;Hide your heads, don't peep.Mother knows the bogy fox's tricks,And she'll watch while you sleep."

By the time Mother Turkey reached the end of the verse this time all the chicks were fast asleep.

Mother Turkey stretched out her wings once or twice and turned her head in all directions, and then she settled herself for a nap.

The moon was shining brightly when she awoke, and she saw not far off what looked like a large black dog walking cautiously toward the tree. Mother Turkey took another look and saw the bushy tail, and she perched herself more firmly on the limb and looked to see if her children were safe on there, too, for she knew that the bogy fox had come to take one of her chicks back to his hole if he could.

"Good evening, Mr. Fox," she said, as the fox came near enough to hear her. "I was sure that I knew your splendid figure; you certainly make a most remarkable picture in the moonlight."

Mr. Fox was somewhat taken aback at this compliment paid him in such a pleasant manner, for usually he was the one to make remarks and the turkeys listened, not daring to move or speak.

He recovered from his surprise by the time he was under the tree, and said: "You are most flattering, Mistress Turkey, and I can only return the compliment by telling you that you are a picture yourself in the moonlight, sitting so stately on that limb, but if you would enjoy to the full extent this beautiful evening you must come from the tree and take a walk over the hill."

"No doubt you are right," replied Mrs. Turkey, "but I could not think of leaving my children alone."

"I should be very glad to take care of the little dears while you are gone," said Mr. Fox, "and if you will have them come down beside me I will tell them a story which I am sure will keep them interested until you return."

By this time the turkey chicks were awake and listening to what the fox was saying. He seemed so nice and polite that they quite forgot to be afraid, and when he spoke of telling them a story one of them said: "Oh, please do go, mother, and let him tell us a story. We'll be very good if you will."

"You see, my dear madam," said the fox, "the little dears are quite willing to stay with me. Do go and enjoy the moonlight."

Mother Turkey looked at her children in a way that plainly said to them, "Be quiet," and then she said to Mr. Fox: "I appreciate your kind offer, and were my children well should be very glad to leave them with you, but they have been sick, and are so lean that I have to be very careful that they sleep and eat well, or they will not be fat by next Thanksgiving, and that would be a disgrace, you know."

When the fox heard this he was not so anxious to have the chicks come down, so he said, "I know just how anxious you must feel, Mistress Turkey, and if you will come down where I can talk with you without being heard I will tell you the very thing to give them to make them fat."

"If he cannot get the chicks he will take me," thought Mrs. Turkey, "but I am too old a bird to be caught even by this sly fellow."

Mrs. Turkey did not reply to this last remark. She was thinking of a trap she saw her master set the day before. "I wish you would walk around a little so my children can see what a beautiful bushy tail you have," she said. "They have never seen so handsome a fellow as you are."

Mr. Fox was very proud of his tail, so he walked out from the shade of the tree and strutted about.

"Tell him how handsome he is," whispered Mother Turkey to her chicks.

"Oh, isn't he handsome!" said one, and another said, "I wish we had such bushy tails, instead of these straight feathers," while Mrs. Turkey said, "You are quite the handsomest creature I have ever seen, and I have seen many in my time."

By this time the fox was so pleased with their admiration that he was ready to do anything to display his charms, so when Mrs. Turkey said, "I wish you would run and show them how you can run and jump," he asked what he could jump on to show his nimbleness.

"The top of that hogshead would be a good place," said Mrs. Turkey, knowing well that the cask had no head and that it was nearly full of water.

Away ran Mr. Fox, and splash he went into the hogshead. He tried to get out, but it was no use; the cask was too high, and then the farmer, hearing the noise, came out and soon put an end to Mr. Fox.

The little turkeys sat wide-awake and trembling beside their mother, but when the farmer went into the house she began to sing:

"Close your eyes, my little turkey chicks;Hide your heads, don't peep.Mother knows the bogy fox's tricks,And she'll watch while you sleep."

And in a few minutes all was quiet again in the yard.

THE FAIRIES AND THE DANDELION

The Fairies say that a long time ago the dandelion did not have a yellow blossom or the fluffy white cap it wears after the yellow has been taken off.

They tell the story that one night, a long time ago, while they were holding one of their revels in a field, sounds of weeping and moaning were heard.

The Fairy Queen stopped the dance and listened. "It comes from the ground," she said, "down among the grasses. Hurry, all of you; find out who is in trouble and come back and tell me."

Away went the Fairies into the fields and gardens and lanes. Darting in and out among the blades of grass, they found queer-looking weeds with leaves resembling a lion's tooth. They were crying and chanting a sing-song tune:

"Here we grow so bright and green,The color of grass, and can't be seen.O bitter woe, but we'll not stopTill the Fairies give us a yellow top."

Back flew the Fairies to their Queen and told her what they had heard.

"If only they had asked for some other color!" she said. "There are so many yellow blossoms now. The buttercup, the goldenglow, and the goldenrod will all be jealous if another yellow flower enters their bright circle. Go back and ask them if they will be quiet if we give them a white top."

The Fairies danced away to the crying dandelions with the Queen's message.

"The Queen will give you a white top," they said.

"No, no!" they cried. "Yellow is the color we should wear with our green leaves. It is the color of the sun and we wish to be as near like him as we can," and they all began to cry:

"O bitter woe, we will not stopTill the Fairies give us a yellow top."

They made such a noise that the Fairies put their fingers in their ears as they flew back to the Queen.

The grass-blades stood up higher and looked about. "Do quiet those noisy weeds," they said to the Queen; "give them the yellow top for which they are crying, and let us go to sleep. We have been kept awake since sunset and it will soon be sunrise."

"What shall we do?" said the Queen. "I do not know where to get the yellow they want."

"If we could get some sunbeams," said one Fairy, "we could have just the color they are crying for. Of course, we cannot venture into such a strong light, but the Elves might gather them for us."

So they went to the Elves and asked them to gather the sunbeams for the next day, and bring them to the valley the next night.

The Elves were very willing to help them, but the sun shone very little the next day, and they were able to gather only a few basketfuls of the bright golden color.

When the Queen saw the quantity she was in despair. "This will never go around," she said, "and those that are left without a yellow top will cry louder than ever."

"Why not divide it among them?" said one Fairy. "It will last for a little while and we can give them our fluffy white caps when that is gone. We shall take them off soon and the dandelions can wear them the rest of the season."

The face of the Queen brightened. "The very thing," she said, "if only the noisy little weeds will agree. Go to them and say they can wear yellow of the very shade they most desire half the season if they are willing to accept our fluffy white caps for the other half."

The Fairies hurried to the dandelions and told them what the Queen had said. The dandelions stopped crying and said they would be satisfied, and the Queen rode through the meadows, fields, gardens, and lanes, dropping gold upon each weed as she passed along.

In the morning when the sun beheld his own bright color looking up at him he was so surprised that he almost stood still.

The Fairies kept their promise, and when it was time to take off their fluffy white caps they went among the dandelions and hung a cap on each stem.

The dandelions did not cry again, and the grass sleeps on from sunset to sunrise, undisturbed.

MR. 'POSSUM

Mr. 'Possum lived in a tree in the woods where Mr. Bear lived, and one morning just before spring Mr. 'Possum awoke very hungry.

He ran around to Mr. Squirrel's house and tried to get an invitation to breakfast, but Mr. Squirrel had only enough for himself. He knew that Mr. 'Possum always lived on his neighbors when he could, so he said: "Of course you have been to breakfast long ago, Mr. 'Possum, you are such a smart fellow, so I will not offer you any."

Mr. 'Possum of course said he had, and that he only dropped in to make a call; he was on his way to Mr. Rabbit's house.

But he met with no better success at Mr. Rabbit's, for he only put his nose out of the door, and when he saw who was there, said: "I am as busy as I can be getting ready for my spring planting. Will you come in and help sort seeds?"

Mr. Rabbit knew the easiest way to be rid of Mr. 'Possum was to ask him to work.

"I would gladly help you," replied Mr. 'Possum, "but I am in a great hurry this morning. I have some important business with Mr. Bear and I only stopped to say how-do-you-do."

"Mr. Bear, I am afraid, will not be receiving to-day," said Mr. Rabbit. "It is rather early for him to be up, isn't it?"

"I thought as the sun was nice and warm he might venture out, and I thought it would please him to have me there to welcome him," said Mr. 'Possum. "Besides that, I wish to see him on business."

Now, Mr. 'Possum knew well enough that Mr. Bear would not be up, and he wanted to find him sleeping, and soundly, too.

He went to the door and knocked softly, then he waited, and as he did not hear any moving inside he went to a window and looked in. There was Mr. Bear's chair and pipe just as he left them when he went to bed. He looked in the bedroom window and he could see in the bed a big heap of bedclothes, and just the tiniest tip of Mr. Bear's nose.

Mr. 'Possum listened, and he trembled a little, for he could hear Mr. Bear breathing very loud, and it sounded anything but pleasant.

"Oh, he is sound asleep for another week!" said Mr. 'Possum. "What is the use of being afraid?" He walked around the house until he came to the pantry window; then he stopped and raised the sash.

He put in one foot and sat on the sill and listened. All was still, so he slid off to the floor. Mr. 'Possum looked around Mr. Bear's well-filled pantry. He did not know where to begin, he was so hungry.

He became so interested and was so greedy that he forgot all about that he was in Mr. Bear's pantry, and he stayed on and on and ate and ate.

Then he fell asleep, and the first thing he knew a pair of shining eyes were looking in the window and a big head with a red mouth full of long white teeth was poked into the pantry.

Mr. 'Possum thought his time had come, so he just closed his eyes and pretended he was dead, but he peeked a little so as to see what happened.

The big head was followed by a body, and when it was on the sill Mr. 'Possum saw it was Mr. Fox, and the next thing he knew Mr. Fox came off the sill with a bang and hit a pan of beans and then knocked over a jar of preserves.

The noise was enough to awaken all the bears for miles around, and Mr. 'Possum was frightened nearly to death, for he heard Mr. Bear growling in the next room.

While Mr. Fox was on the floor and trying to get up on his feet Mr. 'Possum jumped up and was out of the window like a flash. Mr. Fox saw something, but he did not know what, and before he could make his escape the door of the pantry opened and there stood Mr. Bear with a candle in his hand, looking in.

"Oh, oh!" he growled, "so you are trying to rob me while I'm taking my sleep," and he sprang at Mr. Fox.

"Wait, wait," said Mr. Fox. "Let me explain, my dear Mr. Bear. You are mistaken; I was trying to protect your home. I saw your window open and knew you were asleep, and when I got in the window the thief attacked me and nearly killed me and now you are blaming me for it. You are most ungrateful. I shall know another time what to do."

Mr. Bear looked at him. His mouth did not show any signs of food, and Mr. Fox opened his mouth and told him to look.

"I wonder who it could have been?" he said, when he was satisfied that Mr. Fox was not the thief. "It may have been that 'Possum fellow. I'll go over to his house in the morning."

The next morning Mr. Bear called on Mr. 'Possum. He found him sleeping soundly, and when he at last opened the door he was rubbing his eyes as though he was not half awake.

"Why, how do you do?" he said, when he saw Mr. Bear. "I did not suppose you were up yet."

"You didn't?" asked Mr. Bear, and then he stared at Mr. 'Possum's coat. "What is the matter with your coat?" he asked. "You have white hairs sticking out all over you, and the rest of your coat is almost white, too."

Now Mr. 'Possum had a black coat before, and he ran to the mirror and looked at himself. It was true; he was almost white. He knew what had happened. He was so frightened when he was caught in Mr. Bear's pantry by Mr. Fox, and heard Mr. Bear growl, that he had turned nearly white with fright.

"I have been terribly ill," he told Mr. Bear, going back to the door. "And I have been here all alone this winter. It was a terrible sickness; I guess that is what has caused it."

Mr. Bear went away, shaking his head. "That fellow is crafty," he said. "I feel sure he was the thief, and yet he certainly does look sick."

After that all the opossums were of dull white color, with long, white hairs scattered here and there over their fur. They were never able to outgrow the mark the thieving Mr. 'Possum left upon his race.

THE ROOSTER THAT CROWED TOO SOON

Red Rooster felt it was time he showed the new drake that had come to live in the barnyard that he was a very brave rooster, as well as the ruler of the barnyard.

So the next time he saw the drake he said: "I suppose you have been in many battles, and no doubt the home you have just come from will miss your protection as well as your company.'

"No," replied the drake; "I never was in a battle. I do not quarrel with any one. I believe in living in peace with all around me."

"Oh, well, that is all very well for you, perhaps," said the rooster; "but for me, it is a different matter. I have to protect all the hens and chickens and I also protect myself. I can whip any rooster around here, and no one dares come into my yard."

The drake did not reply, for just then a strange rooster came into the yard, and Red Rooster ran at him with sweeping wings.

He pecked at the intruder and spurred him until he was glad to run away.

"There, what did I tell you?" said Red Rooster, coming back to the drake. "I am the greatest fighter around this part of the country. I am not afraid of anything."

"Oh, don't talk so much about it," said the dog from his house near-by. "I think there are a few things even you are afraid of, Mr. Rooster. I guess you would run from a fox."

"I am not afraid of a fox," said Red Rooster. "I can scare him by crowing loudly. Master knows when I make a great noise it is time for him to find the cause. Oh, I am very brave and can take care of myself."

Red Rooster felt so brave that he thought the highest place he could get on the wall would be a good place to talk about his bravery, so he flew up on the wall by the gate, and then to the top of the hen-house.

Madam Pig was in her pen on the other side. "Madam Pig," he said, "did you see me whip that impudent rooster that came through our yard?"

Madam Pig grunted that she did not, as she could not see over the wall.

"You surely missed a great sight," said the rooster, stretching his neck and strutting along the roof. "I am a brave fellow. I never allow any one to come around here that does not belong here. I have just been telling the new drake about my prowess and bravery.

"Mr. Drake," he called, as the new drake and his family waddled past the hen-house, "if you need protection at any time do not hesitate to call upon me."

A robin perched upon the roof not far from him, and Red Rooster flew at him. "Go away," he said. "I am very fierce and brave, and if you were as large as a cow I should attack you just the same. I am not afraid of anything."

Red Rooster strutted up and down, crowing and thinking how brave he was, and so intent was he upon his greatness that he did not heed the warning cries that came from the fowls in the yard below him.

In a moment more a big hawk swooped down and held Red Rooster in his claws. He started to fly just as the shot from a gun sounded, and Red Rooster fell to the ground.

He jumped up and shook himself, and looked in time to see his master pick up the dead hawk.

"I guess that hawk won't show himself around here again," he said. "That was a very hard fight, but I won, even if I did get a tumble."

"Well, if you are not a conceited fellow!" laughed the dog; "but I was not the only one that saw the hawk start off with you, and we all know that if master had not shot it you would not be here to crow to-morrow morning."

"No," piped the robin from a tree; "you were telling me how brave you were, and the hawk was not half as large as a cow. You were not very brave when he came upon you. You did not do a thing. Oh, dear! it was so funny to hear you crowing about your bravery and then to see you caught up so soon by a hawk that is only a little larger than you."

The drake and all his family were listening, and Madam Pig had put her head over the wall to listen. Poor Red Rooster felt that it was no time to crow about his bravery, so he walked away with all the dignity he could muster.

"He crowed too soon," said the drake.

"He crowed too much," said the dog.

"He crowed too loud," said the robin, "or he would have heard the warning cries from the hens and chickens."

TEARFUL

Once upon a time there was a little girl named Tearful, because she cried so often.

If she could not have her own way, she cried; if she could not have everything for which she wished, she cried.

Her mother told her one day that she would melt away in tears if she cried so often. "You are like the boy who cried for the moon," she told her, "and if it had been given to him it would not have made him happy, for what possible use could the moon be to any one out of its proper place? And that is the way with you; half the things for which you cry would be of no use to you if you got them."

Tearful did not take warning or heed her mother's words of wisdom, and kept on crying just the same.

One morning she was crying as she walked along to school, because she wanted to stay at home, when she noticed a frog hopping along beside her.

"Why are you following me?" she asked, looking at him through her tears.

"Because you will soon form a pond around you with your tears," replied the frog, "and I have always wanted a pond all to myself."

"I shall not make any pond for you," said Tearful, "and I do not want you following me, either."

The frog continued to hop along beside her, and Tearful stopped crying and began to run, but the frog hopped faster, and she could not get away from him, so she began to cry again.

"Go away, you horrid green frog!" she said.

At last she was so tired she sat on a stone by the roadside, crying all the time.

"Now," replied the frog, "I shall soon have my pond."

Tearful cried harder than ever, then; she could not see, her tears fell so fast, and by and by she heard a splashing sound. She opened her eyes and saw water all around her.

She was on a small island in the middle of the pond; the frog hopped out of the pond, making a terrible grimace as he sat down beside her.

"I hope you are satisfied," said Tearful. "You have your pond; why don't you stay in it?"

"Alas!" replied the frog, "I have wished for something which I cannot use now that I have it. Your tears are salt and my pond which I have all by myself is so salt that I cannot enjoy it. If only your tears had been fresh I should have been a most fortunate fellow."

"You needn't stay if you do not like it," said Tearful, "and you needn't find fault with my tears, either," she said, beginning to cry again.

"Stop! stop!" cried the frog, hopping about excitedly; "you will have a flood if you keep on crying."

Tearful saw the water rising around her, so she stopped a minute. "What shall I do?" she asked. "I cannot swim, and I will die if I have to stay here," and then she began to cry again.

The frog hopped up and down in front of her, waving his front legs and telling her to hush. "If you would only stop crying," he said, "I might be able to help you, but I cannot do a thing if you cover me with your salt tears."

Tearful listened, and promised she would not cry if he would get her away from the island.

"There is only one way that I know of," said the frog; "you must smile; that will dry the pond and we can escape."

"But I do not feel like smiling," said Tearful, and her eyes filled with tears again.

"Look out!" said the frog; "you will surely be drowned in your own tears if you cry again."

Tearful began to laugh. "That would be queer, wouldn't it, to be drowned in my own tears?" she said.

"That is right, keep on smiling," said the frog; "the pond is smaller already." And he stood up on his hind legs and began to dance for joy.

Tearful laughed again. "Oh, you are so funny!" she said. "I wish I had your picture. I never saw a frog dance before."

"You have a slate under your arm," said the frog. "Why don't you draw a picture of me?" The frog picked up a stick and stuck it in the ground, and then he leaned on it with one arm, or front leg, and, crossing his feet, he stood very still.

Tearful drew him in that position, and then he kicked up his legs as if he were dancing, and she tried to draw him that way, but it was not a very good likeness.

"Do you like that?" she asked the frog when she held the slate for him to see. He looked so surprised that Tearful laughed again. "You did not think you were handsome, did you?" she asked.

"I had never thought I looked as bad as those pictures," replied the frog. "Let me try drawing your picture," he said.

"Now look pleasant," he said, as he seated himself in front of Tearful, "and do smile."

Tearful did as he requested, and in a few minutes he handed her the slate. "Where is my nose?" asked Tearful, laughing.

"Oh, I forgot the nose!" said the frog. "But don't you think your eyes are nice and large, and your mouth, too?"

"They are certainly big in this picture," said Tearful. "I hope I do not look just like that."

"I do not think either of us are artists," replied the frog.

Tearful looked around her. "Why, where is the pond?" she asked. "It is gone."

"I thought it would dry up if you would only smile," said the frog; "and I think both of us have learned a lesson. I shall never again wish for a pond of my own. I should be lonely without my companions, and then, it might be salt, just as this one was. And you surely will never cry over little things again, for you see what might happen to you, and then you look so much prettier smiling."

"Perhaps I do," said Tearful, "but your pictures of me make me doubt it. However, I feel much happier smiling, and I do not want to be on an island again, even with such a pleasant companion as you were."

"Look out for the tears, then," said the frog as he hopped away.

HILDA'S MERMAID

Little Hilda's father was a sailor and went away on long voyages. Hilda lived in a little cottage on the shore and used to spin and knit while her father was away, for her mother was dead and she had to be the housekeeper. Some days she would go out in her boat and fish, for Hilda was fond of the water. She was born and had always lived on the shore. When the water was very calm Hilda would look down into the blue depths and try to see a mermaid. She was very anxious to see one, she had heard her father tell such wonderful stories about them--how they sang, and combed their beautiful long hair.

One night when the wind was blowing and the rain was beating hard upon her window Hilda could hear the horn warning the sailors off the rocks. Hilda lighted her father's big lantern and ran down to the shore and hung it on the mast of a wreck which lay there, so the sailors would not run their ships upon it. Little Hilda was not afraid, for she had seen many such storms. When she returned to her cottage she found the door was unlatched, but thought the wind had blown it open. When she entered she found a little girl with beautiful hair sitting on the floor. She was a little frightened at first, for the girl wore a green dress and it was wound around her body in the strangest manner.

"I saw your light," said the child, "and came in. The wind blew me far up on shore. I should not have come up on a night like this, but a big wave looked so tempting I thought I would jump on it and have a nice ride, but it was nearer the shore than I thought it, and it landed me right near your door."

"Oh, my!" How Hilda's heart beat, for she knew this child must be a mermaid. Then she saw what she had thought a green dress was really her body and tail curled up on the floor, and it was beautiful as the lamp fell upon it and made it glisten.

"Will you have some of my supper?" asked Hilda, for she wanted to be hospitable, although she had not the least idea what mermaids ate.

"Thank you," answered the mermaid. "I am not very hungry, but if you could give me a seaweed sandwich I should like it."

Poor Hilda did not know what to do, but she went to the closet and brought out some bread, which she spread with nice fresh butter, and filled a glass with milk. She told her she was sorry, but she did not have any seaweed sandwiches, but she hoped she would like what she had prepared. The little mermaid ate it and Hilda was pleased.

"Do you live here all the time?" she asked Hilda. "I should think you would be very warm and want to be in the water part of the time."

Hilda told her she could not live in the water as she did, because her body was not like hers.

"Oh, I am so sorry!" replied the mermaid. "I hoped you would visit me some time; we have such good times, my sisters and I, under the sea."

"Tell me about your home," said Hilda.

"Come and sit beside me and I will," she replied.

Hilda sat upon the floor by her side. The mermaid felt of Hilda's clothes and thought it must be a bother to have so many clothes.

"How can you swim?" she asked.

Hilda told her she put on a bathing-suit, but the mermaid thought that a nuisance.

"I will tell you about our house first," she began. "Our father, Neptune, lives in a beautiful castle at the bottom of the sea. It is built of mother-of-pearl. All around the castle grow beautiful green things, and it has fine white sand around it also. All my sisters live there, and we are always glad to get home after we have been at the top of the ocean, it is so nice and cool in our home. The wind never blows there and the rain does not reach us."

"You do not mind being wet by the rain, do you?" asked Hilda.

"Oh no!" said the mermaid, "but the rain hurts us. It falls in little sharp points and feels like pebbles."

"How do you know how pebbles feel?" Hilda asked.

"Oh, sometimes the nereids come and bother us; they throw pebbles and stir up the water so we cannot see."

"Who are the nereids?" asked Hilda.

"They are the sea-nymphs; but we make the dogfish drive them away. We are sirens, and they are very jealous of us because we are more beautiful than they," said the mermaid.

Hilda thought she was rather conceited, but the little mermaid seemed to be quite unconscious she had conveyed that impression.

"How do you find your way home after you have been at the top of the ocean?" asked Hilda.

"Oh, when Father Neptune counts us and finds any missing he sends a whale to spout; sometimes he sends more than one, and we know where to dive when we see that."

"What do you eat besides seaweed sandwiches?" asked Hilda.

"Fish eggs, and very little fish," answered the mermaid. "When we have a party we have cake."

Hilda opened her eyes. "Where do you get cake?" she asked.

"We make it. We grind coral into flour and mix it with fish eggs; then we put it in a shell and send a mermaid to the top of the ocean with it and she holds it in the sun until it bakes. We go to the Gulf Stream and gather grapes and we have sea-foam and lemonade to drink."

"Lemonade?" said Hilda. "Where do you get your lemons?"

"Why, the sea-lemon!" replied the mermaid; "that is a small mussel-fish the color of a lemon."

"What do you do at your parties--you cannot dance?" said Hilda.

"We swim to the music, circle around and dive and glide."

"But the music--where do you get musicians?" Hilda continued.

"We have plenty of music," replied the mermaid. "The sea-elephant trumpets for us; then there is the pipefish, the swordfish runs the scales of the sea-adder with his sword, the sea-shells blob, and altogether we have splendid music. But it is late, and we must not talk any more."

So the little mermaid curled herself up and soon they were asleep.

The sun shining in the window awakened Hilda next morning and she looked about her. The mermaid was not there, but Hilda was sure it had not been a dream, for she found pieces of seaweed on the floor, and every time she goes out in her boat she looks for her friend, and when the whales spout she knows they are telling the mermaids to come home.

THE MIRROR'S DREAM

"The very idea of putting me in the attic!" said the little old-fashioned table, as it spread out both leaves in a gesture of despair. "I have stood in the parlor down-stairs for fifty years, and now I am consigned to the rubbish-room," and it dropped its leaves at its side with a sigh.

"I was there longer than that," said the sofa. "Many a courtship I have helped along."

"What do you think of me?" asked an old mirror that stood on the floor, leaning against the wall. "To be brought to the attic after reflecting generation after generation. All the famous beauties have looked into my face; it is a degradation from which I can never recover. This young mistress who has come here to live does not seem to understand the dignity of our position. Why, I was in the family when her husband's grandmother was a girl and she has doomed me to a dusty attic to dream out the rest of my days."

The shadows deepened in the room and gradually the discarded mirror ceased to complain. It had fallen asleep, but later the moonlight streamed in through the window and showed that its dreams were pleasant ones, for it dreamed of the old and happy days.

The door opened softly and a young girl entered. Her hair was dark and hung in curls over her white shoulders. Her dark eyes wandered over the room until she saw the old mirror.

She ran across the room and stood in front of it. She wore a hoop-skirt over which hung her dress of pale gray, with tiny pink ruffles that began at her slender waist and ended at the bottom of her wide skirt.

Tiny pink rosebuds were dotted over the waist and skirt, and she also wore them in her dark curls, where one stray blossom bolder than the others rested against her soft cheek.

She stood before the mirror and gazed at her reflection a minute; then she curtsied, and said, with a laugh, "I think you will do; he must speak to-night."

She seemed to fade away in the moonlight, and the door opened again and a lady entered, and with her came five handsome children.

They went to the mirror, and one little girl with dark curls and pink cheeks went close and touched it with her finger. "Look," she said to the others, "I look just like the picture of mother when she was a girl." And as they stood there a gentleman appeared beside them and put his arm around the lady and the children gathered around them. They seemed to walk along the moonlight path and disappear through the window.

Softly the door opened again and an old lady entered, leaning on the arm of an old gentleman. They walked to the mirror and he put his arms around her and kissed her withered cheek.

"You are always young and fair to me," he said, and her face smiled into the depths of the old mirror.

The moonlight made a halo around their heads as they faded away.

The morning light streamed in through the window and the mirror's dream was ended.

By and by the door opened and a young girl came in the room. Her dark hair was piled high on her head, and her dark eyes looked over the room until they fell upon a chest in the corner. She went to it and opened it and took out a pale-gray dress with pink ruffles. She put it on; then she let down her hair, which fell in curls over her shoulders.

She ran to the old mirror and looked at herself. "I do look like grandmother," she said. "I will wear this to the old folks' party to-night. Grandfather proposed to grandmother the night she wore this dress." Her cheeks turned very pink as she said this, and she ran out of the room.

Then one day the door opened again and a bride entered, leaning on the arm of her young husband. There were tears in her eyes, although she was smiling. She led him in front of the old mirror. "This old mirror," she said, "has seen all the brides in our family for generations, and I am going far away and may never look into it again. My brother's wife does not want it down-stairs, and I may be the last bride it will ever see," and she passed her hand over its frame caressingly.

And then she went away and the old mirror was left to its dreams for many years. Then one day the door opened again and a lady entered; with her was a young girl.

The lady looked around the attic room until she saw the mirror. "There it is," she said. "Come and look in it, dear." The young girl followed her. "The last time I looked into this dear old mirror," the lady said, "was the day your father and I were married. I never expected to have it for my own then. But your uncle's wife wants to remodel the house, and these things are in the way; she does not want old-fashioned things, and they are willing I should have them."

"Oh, mother, they are beautiful!" said the girl, looking around the room. "We will never part with them; we will take them to our home and make them forget they were ever discarded."

And so the mirror and the sofa and the table and many other pieces of bygone days went to live where they were loved, and the old mirror still reflects dark-haired girls and ladies, who smile into its depths and see its beauty as well as their own.

THE CONTEST

The old white rooster was dead.

The hens stood in groups of threes and fours all around the yard, the turkeys were gathered around the big gobbler and seemed to be talking very earnestly.

The ducks stood around the old drake, who was shaking his head emphatically as he talked.

The geese were listening very attentively to the gander, and he was stretching his neck and seemed to be trying to impress them with its length.

"I see no reason now why I should not be king of the yard," he was saying. "White Rooster is dead and there is no other rooster to take his place. I am going to see the hens and ask them what they think.

"White Rooster is dead," he said to them, "and I think I should be king of the yard. My neck is very long and I can see over the heads of all the fowls; I see no reason why I should not take the place of White Rooster."

The turkeys and the geese, seeing the gander approach the hens, ran as fast as they could to hear what he was saying.

The turkey gobbler, hearing the last part of the gander's remark, said: "How can you say that you can see over all heads? Have you forgotten me and my height? And as for being king," he said, "the rooster never should have been cock of the walk. I am a much more majestic-looking bird than any rooster. No, indeed, you should never think of ruling, Sir Gander. I should be king of the yard."

The gobbler walked away, spreading out his wings and letting them drag on the ground and gobbling very loudly.

The ducks and the drake stood listening to all this talk, and as the gobbler walked away the drake said: "I cannot understand why any one should think of being king when I know so much of the world. I am the one to rule, for I have been all around the pond, and it is very large; because of my knowledge I think I should be king."

"He must not be king," whispered one old hen to another; "he would make us go in the water, and we will all be drowned."

They had talked a long time without reaching any decision, when the dog happened along. "What is the matter?" he asked.

"The old white rooster is dead," said the gobbler, who had returned with his family to hear the discussion, "and I think I should be king, and the drake and the gander think they should, but, of course, you can see that I am best suited to rule the yard."

"You can settle that very easily," said the dog. "You can all take a turn at being king, and in that way you will know who is best suited to rule." And so it was decided, and the gobbler was the first one to go on trial. The poor hens tagged along after the turkeys, for the gobbler insisted upon parading all around the yard. The gander and the drake would not follow behind, so the gander and his family walked on one side of the gobbler, and the drake and his family on the other.

The poor hens wept as they followed behind. "I never was so humiliated in my life," said one old hen, "and it is not right."

The next day there was so much dissatisfaction because of the gobbler's overbearing way that the dog decided that the drake must take his turn.

"Everybody must learn to swim," said the drake as soon as he was appointed ruler. "Come down to the pond," and off he started, his family waddling after him.

"What did I tell you?" said the old hen. "This will be the end of us."

The geese did not mind being in the water part of the time, but the turkeys set up such a gobble and the hens cackled so loudly that the dog had to decide right there that the drake was not a suitable king.

The gander, knowing that his time had come, stretched his neck and looked very important.

"You need not go near the pond," he said to the hens, "but you must learn to fly," and he spread out his wings as he spoke and flew over the fence, the geese following him.

The turkeys flew to the top of the fence and roosted there, but the hens and ducks stood on the ground, looking up at them in the most discouraged way, and at the gobbler, who gobbled at them, saying, "You are to be pitied, for you do not see all the sights we do and you never can fly to the top of this fence.

"There is the master," he said. "He is coming down the road and he has something under his arm. I'll tell you what it is when he gets nearer."

The hens were trying to look under the fence and through the holes.

The gobbler looked for a minute, and then he said: "I do believe--" then he stopped. "Yes, it is," he continued, looking again; "it's a rooster."

The gobbler flew down and the turkeys followed and the master drove the gander and his family back to the yard. "You will get your wings clipped to-morrow," he said, and then from under his arm he released a big yellow-and-black rooster, which flew to the ground, looked about, spread his wings and crowed in a way that plainly said: "I am cock of this walk and king of this yard. Let none dispute my rights."

The drake collected his family and started for the pond, and the gander and geese followed along behind.

The turkey spread his wings and held his head high as he strutted away with his family. But he did not impress the new rooster; he was ruler and he knew it.

"Now the sun will know when to rise," said one hen, "and we shall know when to awake."

"Yes," said another, "and we have had a narrow escape; it looked for a while as if our family were to lose its social standing, but now that we have a new king we can hold up our heads again and look down on the others, if we have to go to the top of the wood-pile to do it."

The dog laughed to himself as he walked away. "I knew all the time," he said, "that the new rooster was coming, but I thought it would do them good to know they were only fitted to care for their own flock."

THE PINK AND BLUE EGGS

"I tell you I saw them with my own eyes," said old White Hen, standing on one foot with her neck outstretched and her bill wide open. "One was pink and the other was blue. They were just like any other egg as far as size, but the color--think of it--pink and blue eggs. Whoever could have laid them?" Old White Hen looked from one to the other of the group of hens and chickens as they stood around her.

"Well, I know that I didn't," said Speckled Hen.

"You needn't look at me," said Brown Hen. "I lay large white eggs, and you know it, every one of you. They are the best eggs in the yard, if I do say it."

"Oh, I would not say that," said White Hen. "You seem to forget that the largest egg ever seen in this yard was laid by me, and it was a little on the brown color; white eggs are all well enough, but give me a brown tone for quality."

"You never laid such a large egg as that but once," replied Brown Hen, "and everybody thought it was a freak egg, so the least said about it the better, it seems to me."

"It is plain to understand how you feel about that egg," said White Hen, "but it does not help us to find out who laid the blue and pink eggs."

"Where did you see them?" asked Speckled Hen.

"On the table, by the window of the farm-house," said old White Hen. "I flew up on a barrel that stood under the window, and then I stretched my neck and looked in the window, and there on the table, in a little basket, I saw those strange-looking eggs."

"Perhaps the master had bought them for some one of us to sit on and hatch out," said Brown Hen.

"Well, I, for one, refuse to do it," said White Hen. "I think it would be an insult to put those gaudy things into our nests."

"I am sure I will not hatch them," said Speckled Hen. "I would look funny hiking around here with a blue chick and a pink chick beside me, and I a speckled hen. No! I will not mother fancy-colored chicks; the master can find another hen to do that."

"You do not think for a minute that I would do such a thing, I hope," said Brown Hen. "I only mentioned the fact that the master might have such an idea, but as for mixing up colors, I guess not. My little yellow darlings shall not be disgraced by a blue and a pink chick running with them."

"Perhaps White Hen is color-blind," said Speckled Hen. "The eggs she saw may be white, after all."

"If you doubt my word or my sight go and look for yourselves," said White Hen, holding her head high. "You will find a blue and a pink egg, just as I told you."

Off ran Speckled Hen and Brown Hen, followed by many others, and all the chicks in the yard.

One after another they flew to the top of the barrel and looked in the window at the eggs White Hen had told them of. It was all too true; the eggs were blue and pink.

"Peep, peep, peep, peep, we want to see the blue and pink eggs, too," cried the chickens. "We never saw any and we want to look at them."

"Oh dear! why did I talk before them?" said Brown Hen. "They will not be quiet unless they see, and how in the world shall I get them up to that window?"

"Did it ever occur to you not to give them everything they cry for?" said White Hen. "Say 'No' once in a while; it will save you a lot of trouble."

"I cannot bear to deny the little darlings anything," said Brown Hen, clucking her little brood and trying to quiet them.

"Well, you better begin now, for this is one of the things you will not be able to do." said White Hen, strutting over to the dog-house to tell the story of the blue and pink eggs to Towser.

"Wouldn't it be just too awful if the master puts those eggs in one of our nests?" asked White Hen, when she had finished her story.

"Oh--oh!" laughed Towser, "that is a good joke on you; don't know your own eggs when you see them."

"Don't tell me I laid those fancy-colored eggs," said White Hen, looking around to see if any of her companions were within hearing distance. "I know I never did."

"But you did," said Towser, laughing again. "I heard the master say to my little mistress, 'If you want eggs to color for Easter take the ones that White Hen laid; they are not so large as the others, and I cannot sell them so well.'"

"Towser, if you will never mention what you have just told me I will tell you where I saw a great big bone this morning," said White Hen. "I was saving it for myself. I like to pick at one once in a while, but you shall have it if you promise to keep secret what you just told me."

Towser promised, and White Hen showed where it was hidden.

A few days after Brown Hen said: "I wonder when master is going to bring out those fancy eggs. If he leaves them in the house much longer no one will be able to hatch them."

"Oh! I forgot to tell you that those eggs were not real eggs, after all," said White Hen, "but only Easter eggs for the master's little girl to play with, so we had all our worry for nothing. Towser told me, but don't say a word to him, for I did not let on that we were worried and didn't know they were only make-believe eggs; he thinks he is so wise, you know, it would never do to let him know how we were fooled."

WHY THE MORNING-GLORY SLEEPS

One day the flowers got into a very angry discussion over the sun, of whom they were very fond.

"Surely you all must know that he loves me best," said the rose. "He shines upon me and makes me sweeter than any of you, and he gives me the colors that are most admired by man."

"I do not see how you can say that," said the dahlia. "You may give forth more fragrance than I can, but you cannot think for a second that you are more beautiful. Why, my colors are richer than yours and last much longer! The sun certainly loves me the best."

The modest lily looked at the dahlia and said in a low, sweet voice, "I do not wish to be bold, but I feel that the sun loves me and that I should let you know that he gives to me more fragrance than to any of you."

"Oh, oh! Hear lily!" said the others in chorus. "She thinks the king of day loves her best."

The lily hung her head and said no more, for the other flowers quite frightened her with their taunts.

"How can any of you think you are the best beloved of the sun?" said goldenglow. "When you behold my glowing color which the sun bestows on me, do any of you look so much like him as I do? No, indeed; he loves me best."

The hollyhock looked down on the others with pitying glances. "It is plain to be seen that you have never noticed that the sun shines on me with more warmth than on you, and now I must tell you he loves me best and gives me the tenderest of his smiles. See how tall I am and how gorgeous are my colors. He loves me best."

"When it comes to sweetness, I am sure you have forgotten me," said the honeysuckle. "Why, the king of day loves me best, you may be sure! He makes me give forth more sweetness than any of you."

"You may be very sweet," said the pansy, "but surely you know that my pet name is heart's-ease and that the sun loves me best. To none of you does he give such velvet beauty as to me. I am nearest his heart and his best beloved."

The morning-glory listened to all this with envy in her heart. She did not give forth sweetness, as many of the others, neither did she possess the beauty of the rose or the pansy.

"If only I could get him to notice me," she thought. "I am dainty and frail, and I am sure he would admire me if only he could behold me; but the others are always here and in such glowing colors that poor little me is overshadowed by their beauty."

All day morning-glory thought of the sun and wondered how she could attract his attention to herself, and at night she smiled, for she had thought of a plan. She would get up early in the morning and greet him before the other flowers were awake.

She went to bed early that night so that she might not oversleep in the morning, and when the first streak of dawn showed in the sky morning-glory opened her eyes and shook out her delicate folds. The dew was on her and she turned her face toward the sun.

As soon as she peeped into the garden the sun beheld her. "How dainty and lovely you are!" he said. "I have never noticed before the beauty of your colors, morning-glory," and he let his warm glances fall and linger upon her.

The sunflower all this time was watching with jealous eyes, for she was the one who had always welcomed the sun, and this morning he seemed to have entirely forgotten her.

Still sunflower kept her gaze upon them and wondered what she could do to win back her king from the delicate little morning-glory.

But as she looked she saw the morning-glory sway and nod her head. "She is going to sleep," said the sunflower; "his warm breath makes her drowsy, or else she was up so early that she cannot keep awake."

While the sunflower watched, sure enough the morning-glory nodded and closed her eyes. She was fast asleep, and the fickle sun, seeing that she no longer looked upon him, looked away and beheld the sunflower looking toward him with longing eyes.

"Good morning, King," she said, as she caught his eye, and she was wise enough not to let him know she had seen him before. So the sun smiled and turned his face upon them all, and the sunflower kept to herself what she had seen, knowing full well that she was the one who knew best how to keep his first and last glances.

A little later one of the flowers called out: "Look at morning-glory; she is still sleeping. Let us tell her it is time to awaken."

"Morning-glory! morning-glory!" they called, but she did not answer. She was sound asleep.

"That is strange," said the rose. "I wonder if she has gone to sleep never to awake. I have heard of such things happening."

After two or three mornings the other flowers ceased to notice morning-glory, for they thought she had ceased to be one of them, but the wise sunflower kept her own counsel. She knew that morning-glory had to sleep all day in order that she might not miss the sun; but, as I told you, she was wise enough not to complain, and she kept his love for her by so doing.

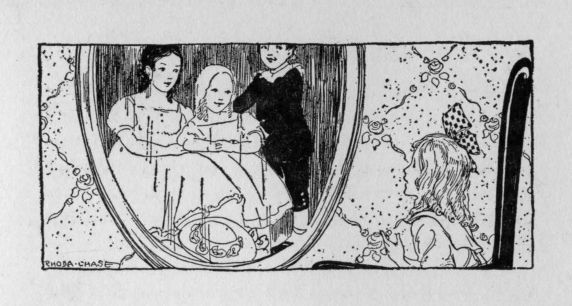

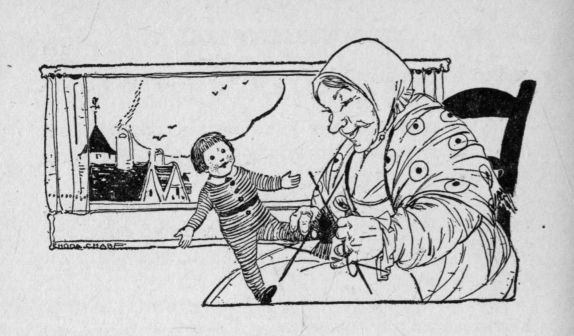

DOROTHY AND THE PORTRAIT

Dorothy was very fond of her grandmother and grandfather, and liked to visit them, but there were no little girls to play with, and sometimes she was lonely for some one her own age. She would wander about the house looking for the queer things that grandmothers always have in their homes. The hall clock interested Dorothy very much. It stood on the landing at the top of the stairs, and she used to sit and listen to its queer tick-tock and watch the hands, which moved with little nervous jumps. Then there were on its face the stars and the moon and the sun, and they all were very wonderful to Dorothy. One day she went into the big parlor, where there were pictures of her grandfather and grandmother, and her great-grandfather and great-grandmother, also.

Dorothy thought the "greats" looked very sedate, and she felt sure they must have been very old to have been the parents of her grandfather. But the picture that interested her the most was a large painting of three children, one a little girl about her own age, and one other older, and a boy, who wore queer-looking trousers, cut off below the knee. His suit was of black velvet, and he wore white stockings and black shoes. The little girls were dressed in white, and their dresses had short sleeves and low necks. The older girl had black hair, but the one that Dorothy thought was her age had long, golden curls like hers, only the girl in the picture wore her hair parted, and the curls hung all about her face.

Dorothy climbed into a big chair and sat looking at them. "I wish they could play with me," she thought, and she smiled at the little golden-haired girl. And then, wonderful to tell, the girl in the picture smiled at Dorothy.

"Oh! are you alive?" asked Dorothy.

"Of course I am," the little girl replied. "I will come down, if you would like to have me, and visit with you."

"Oh, I should be so glad to have you!" Dorothy answered.

Then the boy stepped to the edge of the frame, and from there to the top of a big chair which stood under the picture, and stood in the chair seat. He held out his hand to the little girls and helped them to the floor in the most courtly manner. Dorothy got out of her chair and asked them to be seated, and the boy placed chairs for them beside her.

"What is your name?" asked the golden-haired girl, for she was the only one who spoke.

"That was my name," she said, when Dorothy told her. "I lived in this house," she continued, "and we used to have such good times. This is my sister and my brother." The little girl and boy smiled, but they let their sister do all the talking. "We used to roast chestnuts in the fireplace," she said, "and once we had a party in this room, and played all sorts of games."

Dorothy could not imagine that quiet room filled with children.

"Do you remember how we frightened poor old Uncle Zack in this room?" she said to her brother and sister, and then they all laughed.

"Do tell me about it," said Dorothy.

"These glass doors by the fireplace did not have curtains in our day," said the little girl, "and there were shells and other things from the ocean in one cupboard, and in the other there were a sword and a helmet and a pair of gauntlets. My brother wrapped a sheet around him and put on the helmet and the gauntlets, and, taking the sword in his hand, he climbed into the cupboard and sat down. We girls closed the doors and hid behind the sofa. Uncle Zack came in to fix the fire, and my brother beckoned to him. Poor Zack dropped the wood he was carrying and fell on his knees, trembling with fright. The door was not fastened and my brother pushed it open and pointed the sword at poor Uncle Zack.

"'Don' hurt a po' ol' nigger,' said Zack, very faintly. 'I 'ain' don' noffin', 'deed I 'ain'.'

"'You told about the jam the children ate,' said my brother, in a deep voice, 'and you know you drank the last drop of rum Mammy Sue had for her rheumatism, and for this you must be punished,' and he brought the sword down on the floor of the cupboard with a bang.

"Poor Uncle Zack fell on his face with fright. This was too much for my sister and me, and we laughed out.

"You never saw any one change so quickly as Uncle Zack. He jumped up and we ran, but my brother had to get out of his disguise, and Uncle Zack caught him. He agreed not to tell our father if we did not tell about his fright, and so we escaped being punished."

"Tell me more about your life in this old house," said Dorothy, when the little girl finished her story. But just then the picture of Dorothy's great-grandmother moved and out she stepped from her frame. She walked with a very stately air toward the children and put her hand on the shoulder of the little girl who had been telling the story, and said: "You better go back to your frame now."

"Oh dear!" said the little girl. "I did so dislike being grown up, and I had forgotten all about it, when my grown-up self reminds me. That is the trouble when you are in the room with your grown-up picture," she told Dorothy. "You see, I had to be so sedate after I married that I never even dared to think of my girlhood, but you come in here again some day and I will tell you more about the good times we had."

The boy mounted the chair first and helped his sisters back into the frame. Dorothy looked for her great-grandmother, but she, too, was back in her frame, looking as sedate as ever. The next day Dorothy asked her grandmother who the children were in the big picture.

"This one," she said, pointing to the little golden-haired girl, "was your great-grandmother; you were named for her; and the other little girl and boy were your grandfather's aunt and uncle. They were your great-great-aunt and uncle."

Dorothy did not quite understand the "great-great" part of it, but she was glad to know that her stately-looking great-grandmother had once been a little girl like her, and some day, when the great-grandmother's picture is not looking, she expects to hear more about the fun the children had in the days long ago.

MISTRESS PUSSY'S MISTAKE

A very kind gentleman, who lived in a big house which was in the midst of a beautiful park, had a handsome cat of which he was very fond. While he felt sure Pussy was fond of him, he knew very well she would hurt the birds, so he put a pretty ribbon around Pussy's neck, and on it a little silver bell which tinkled whenever she moved and this warned the birds that she was near.

Pussy resented this, but pretended she did not care. One day a thrush was singing very sweetly on the bough of a tree which overhung a small lake. Pussy walked along under the tree, and, looking up at the thrush, said: "Madam Thrush, you have a most beautiful voice, and you are a very handsome bird. I do wish I were nearer to you, for I am not so young as I was once, and I cannot hear so well."

The thrush trilled a laugh at Pussy, and said: "Yes, Miss Puss, I can well believe you wish me nearer, but not to see or hear me better, but that you might grasp me."

Pussy pretended not to hear the last remark, but said: "My beautiful Thrush, will you not come down where I can hear you better? I cannot get about as nimbly as I used to when I was young, or I would go to you."

"I cannot sing so well on the ground," replied the thrush. "You can come up here, even if you are not so spry as you were. But tell me, do you not find the bell you wear very trying to your nerves?"

"Oh no," answered sly Pussy. "It is so pretty that I'm glad to wear it, and my master thinks I am so handsome that he likes to see me dressed well. And then he can always find me when he hears the bell. That is why I wear it."

"I understand," answered the thrush, "and we birds are always glad to hear it, too." And she trilled another laugh at Pussy and added, "You are certainly a very handsome creature, Miss Puss."

Pussy all this time had very slowly climbed the tree, for she wanted the thrush to think she was old and slow, but the bird had her bright eyes upon her. When Pussy reached the branch the thrush was on she stopped and seated herself.

"Now, my pretty little friend, do sing to me your loudest song."

She hoped it would be loud enough to drown the tinkle of the bell. The thrush began and was soon singing very sweetly. Pussy took a very cautious step and then remained quiet. The thrush stopped singing and spread her wings.

"Oh, do not stop!" said Puss. "Your song was so soothing I was in a doze; do sing again." And she moved a little closer.

The thrush took a step nearer to the end of the bough and said: "I am glad you like my voice. I will sing again if it pleases you so much."

She began her song, but she kept her eyes on Puss, and as Puss drew nearer she moved closer to the end of the swinging bough.

She had reached a very high note when Puss gave a spring, but the thrush was too quick; she flew out of Pussy's reach, and splash went Pussy into the lake, for she had not noticed that the thrush was moving to the end of the bough, so intent was she on the thought of catching her.

Poor Pussy was very wet when she scrambled to the bank of the lake, and the birds were chirping and making a great noise.

"How did you like your bath, Miss Puss?" the thrush called to her. "You should never lay traps for others, for often you fall into them yourself."

KID

Kid was one of those little boys who seemed to have grown up on the streets of the big city where he lived.

He never remembered a mother or a father, and no one ever took care of him. His first remembrance was of an old woman who gave him a crust of bread, and he slept in the corner of her room. One day they carried her away, and since then Kid had slept in a doorway or an alley.

By selling papers he managed to get enough to eat, and if he did not have the money he stole to satisfy his hunger.

He was often cold and hungry, but he saw many other children that were in the same condition, and he did not suppose that any one ever had enough to eat or a warm place to sleep every night.

Kid went in to the Salvation Army meetings, when they held them in his neighborhood, because it was a place where the wind did not blow, and while there he heard them sing and talk about Some One who loved everybody and would help you if only you would ask Him. Kid was never able to find out just where this Person lived, and, therefore, he could not ask for help.

One day Kid saw a lady who was too well dressed to belong in his part of the city, and he followed her, thinking that she might have a pocket-book he could take. The opportunity did not offer itself, however, and before Kid realized it he was in a part of the city he had never seen before.

The buildings were tall and the streets much cleaner than where he lived. Kid walked along, looking in windows of the stores, when he noticed a lady standing beside him with a jeweled watch hanging from her belt.

He had never seen anything so beautiful or so easy to take, and he waited for a few more people to gather around the window, and then he carefully reached for the watch, and with one pull off came the trinket, and away ran Kid, like a deer, with the watch clasped firmly in his begrimed little hand.

On and on he ran, not knowing where he was going--nor caring, for that matter--and it seemed to Kid that the whole world was crying, "Stop, thief!" and was chasing him.

After a while the noise grew fainter and fainter and he stopped and looked back. There was not a person in sight.

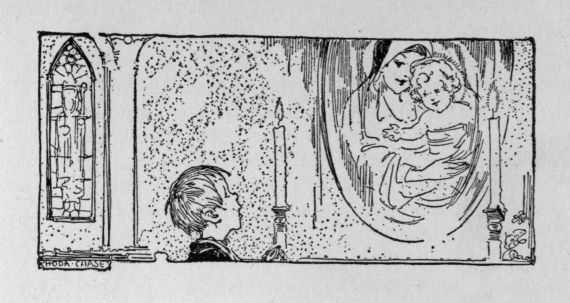

Kid looked around him. All the houses were large with clean stone steps in front of them. Kid sat down on the bottom step of one of these houses and looked at his treasure.

He held it to his ear and heard its soft tick, then he looked at the sparkling stones on the case. He opened it and watched the little hands move, then he opened the back part, and there was the picture of a baby, a little boy, Kid thought. Around its chubby face were curls, and its eyes were large and earnest-looking. Kid sat gazing at it for some minutes, wondering who it was. When he looked up he saw a large building across the street with a steeple on it, and on the top of that a cross.

The door of the building was open, and after a while Kid walked across the street and up the long, wide steps. He went in and looked cautiously about. It was still and no one was to be seen.

There were two doors, and Kid went to one of them and pushed it open. He thought for a minute he was dreaming, for he did not suppose that anything so grand could be real.

There were rows and rows of seats, and at the very end of the big room Kid saw a light. He walked down one of the aisles to where the little flame was burning, and stood in front of the altar.

Kid looked at everything with a feeling of awe, but he had not the slightest idea of what it all meant, and he wondered who lived in this beautiful house, and thought it strange that no one appeared and told him to go out.

There were pictures on the wall and Kid came to one of a sweet-faced lady who was holding a little child. Kid started and stepped back as he looked at it. "It is the baby in the watch," he said. "This must be where he lives and that is his mother." Some one was coming. He was caught at last, he felt sure. He slid into a pew and crawled under the seat and kept very still--so still, in fact, that he fell asleep. When he awoke a light was burning in the church and its rays fell across the picture of the mother and child in such a way that the eyes of the mother seemed to be looking straight at Kid under the seat.

For the first time in his life he felt like crying. "I wish I had a mother," he thought, "and I should like to have her hold me in her arms just as that little boy's mother is holding him. I would tell her about this watch and perhaps she would tell me how to get it back to the lady."

Kid crept from under the seat and stood up, and coming toward him down the aisle was a man. Kid thought he wore a queer-looking costume, and he dodged back of the seat; but the man had seen him and there was no use in trying to run away; besides that, Kid was not at all sure that he wished to get away.

"Is this your house?" asked Kid, when the man came up to him.

"No, my son," he replied; "this is the house of God."

Kid's heart leaped for joy; that was the name of the One the Salvation Army people told him about, who loved everybody and helped you.

"If you please," said Kid, "I should like to see Him."

The good man looked at Kid very earnestly, and then he said, "If you will tell me what you wish to see Him about, I am sure I can help you."

Kid told him about the watch and that he felt sure the lady lived there, as the baby in the big picture was very much like the picture in the watch. "And if this is God's house," said Kid, "I thought He might be the father and forgive me. I am very sorry that I took it."

The good man took Kid by the hand. "Come with me," he said; "you are forgiven, I am sure."

Kid was given a good supper, and for the first time in his life he slept in a real bed.

The next day the good man found the owner of the watch, and when she heard Kid's story she forgave him.

Kid was placed in a school, where he learned to be a good boy, as well as to be studious, and he soon forgot the old life. He grew to be a man of whom any mother could have been proud. But the only mother Kid ever knew was the mother of the little boy in the picture, which he cherishes as a thing sacred in his life.

THE SHOEMAKER RAT

One day a rat gnawed his way into a pantry, and after he had eaten all he wanted he grew bold and went into the kitchen.

There the cook saw him and chased him with a broom, but, not being able to hit him as he ran out of the door, she picked up a pair of shoes that were standing near and threw them after him.

The rat picked them up and put them on. On his way home he met a cat. "What have you on your feet?" he asked the rat.

"Can you not see, my dear Tom?" said the rat. "They are shoes. I am a shoemaker, and, of course, must wear my own product."

"Make me a pair," said the cat, "and I will spare your life."

"Very well," replied the rat, "but first you must bring me some leather."

So the cat ran away and brought back two hides.

When the rat saw the amount of leather he was struck with an idea. "My dear Tom," he said, "I can make you a suit of clothes and a pair of gloves as well as the shoes, and you will be the envy of all the other cats."

Tom was delighted and told the rat to hurry and make the outfit.