Title: The Mother of Washington and Her Times

Author: Sara Agnes Rice Pryor

Release date: August 27, 2013 [eBook #43571]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Melissa McDaniel, Julia Neufeld, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Mother of Washington and Her Times, by Sara Agnes Rice Pryor

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/motherofwashingt00pryo |

The Mother of Washington

And Her Times

SUPPOSED PORTRAIT OF MARY WASHINGTON.

BY

"That one who breaks the way with tears

Many shall follow with a song"

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1903

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1903,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up, electrotyped, and published October, 1903

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

To the Hon. Roger A. Pryor, LL.D.

IN WHOM LIVES ALL THAT WAS BEST

IN OLD VIRGINIA

PART I

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Mary Washington's English Ancestry | 11 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Ball Family in Virginia | 15 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Coat Armor and the Right to bear it | 20 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Traditions of Mary Ball's Early Life | 25 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Revelations of an Old Will | 32 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Mary Ball's Childhood | 37 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Good Times in Old Virginia | 47 |

| [viii]CHAPTER IX | |

| Mary Ball's Guardian and her Girlhood | 55 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Young Men and Maidens of the Old Dominion | 58 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Toast of the Gallants of her Day | 62 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Her Marriage and Early Life | 69 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

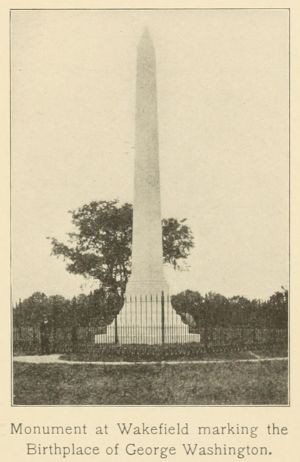

| Birthplace of George Washington | 75 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| The Cherry Tree and Little Hatchet | 85 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Young Widow and her Family | 90 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Betty Washington, and Weddings in Old Virginia | 102 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Defeat in War: Success in Love | 114 |

| [ix]CHAPTER XVIII | |

| In and Around Fredericksburg | 127 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| Social Characteristics, Manners, and Customs | 143 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| A True Portrait of Mary Washington | 167 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| Noon in the Golden Age | 186 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| Dinners, Dress, Dances, Horse-races | 197 |

PART II

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Little Cloud | 231 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Storm | 245 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Mary Washington in the Hour of Peril | 251 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Old Revolutionary Letters | 262 |

| [x]CHAPTER V | |

| The Battle-ground | 279 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| France in the Revolution | 289 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| "On with the Dance, let Joy be unconfined" | 304 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Lafayette and our French Allies | 312 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| In Camp and at Mount Vernon | 317 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Mrs. Adams at the Court of St. James | 327 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The First Winter at Mount Vernon | 332 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| The President and his Last Visit to his Mother | 340 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Mary Washington's Will; her Illness and Death | 347 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Tributes of her Countrymen | 353 |

| Supposed Portrait of Mary Washington | Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | ||

| An Old Doll | 39 | |

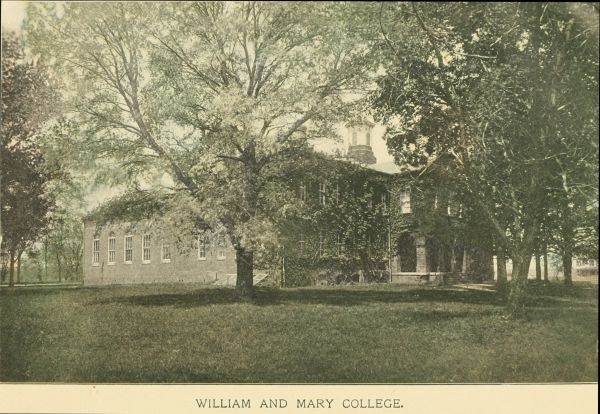

| Horn-book | 41 | |

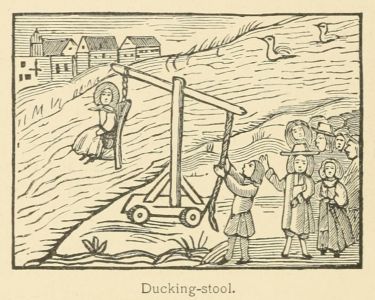

| Ducking-stool | 44 | |

| The Old Stone House | 45 | |

| William and Mary College | Facing | 59 |

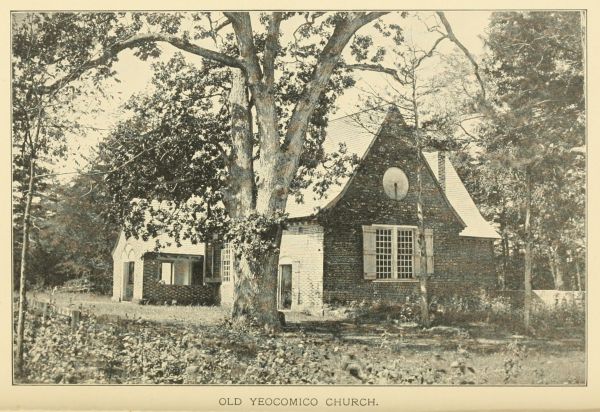

| Old Yeocomico Church | " | 63 |

| Monument at Wakefield marking the Birthplace of George Washington | 75 | |

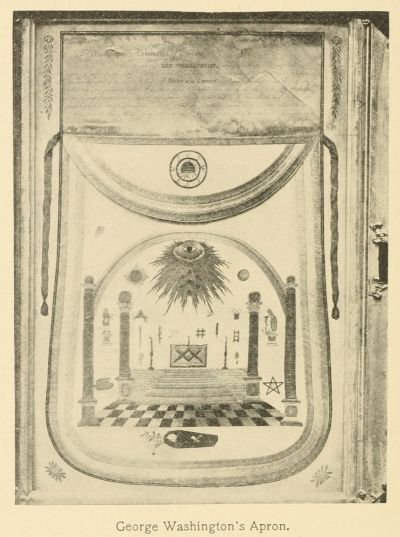

| George Washington's Apron | 82 | |

| Bewdley | Facing | 83 |

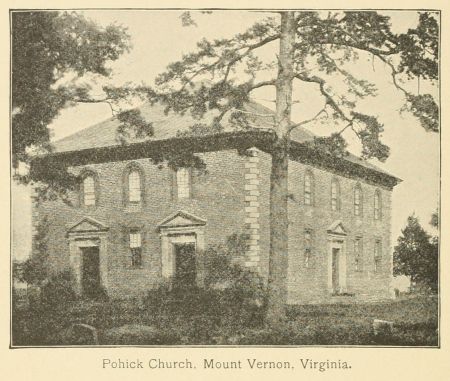

| Pohick Church, Mount Vernon, Virginia | 86 | |

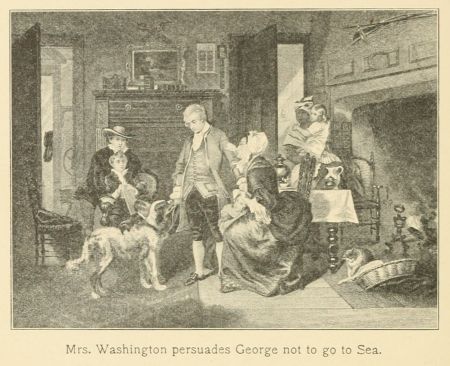

| Mrs. Washington persuades George not to go to Sea | 100 | |

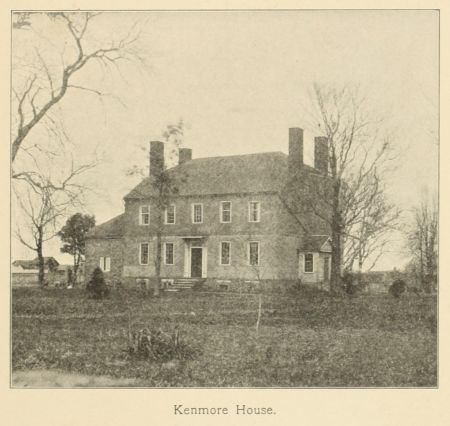

| Kenmore House | 103 | |

| The Hall at Kenmore, showing the Clock which belonged to Mary Washington | 111 | |

| Nellie Custis | Facing | 112 |

| George Washington as Major | 115 | |

| General Braddock | 118 | |

| Mount Vernon | Facing | 120 |

| St. Peter's Church, in which George Washington was married | 123 | |

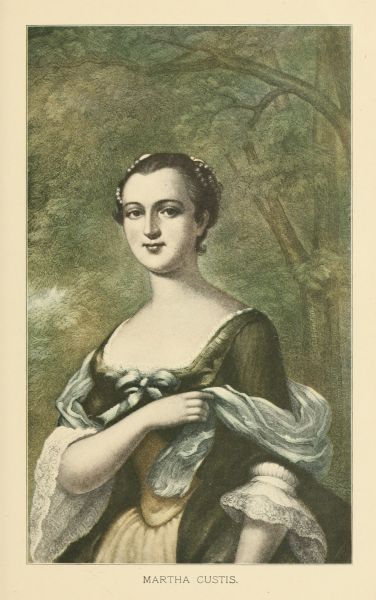

| [xii]Martha Custis | Facing | 124 |

| Williamsburg | 124 | |

| "Light-horse Harry" Lee | 133 | |

| Governor Spotswood | 134 | |

| Prince Murat | 140 | |

| Colonel Byrd | 147 | |

| Westover | Facing | 150 |

| The Kitchen of Mount Vernon | 156 | |

| James Monroe | 165 | |

| Mrs. Charles Carter | 177 | |

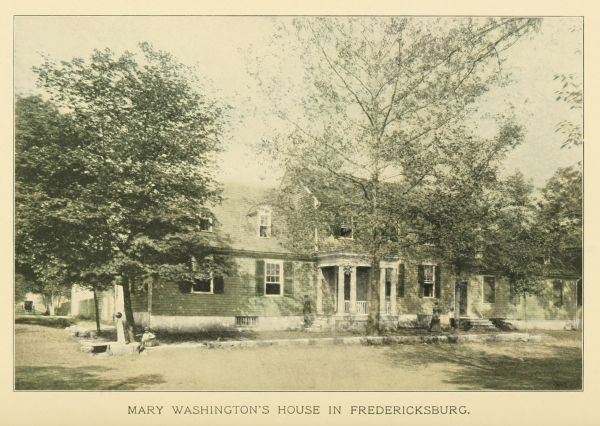

| Mary Washington's House in Fredericksburg | Facing | 183 |

| Monticello. The Home of Thomas Jefferson | 188 | |

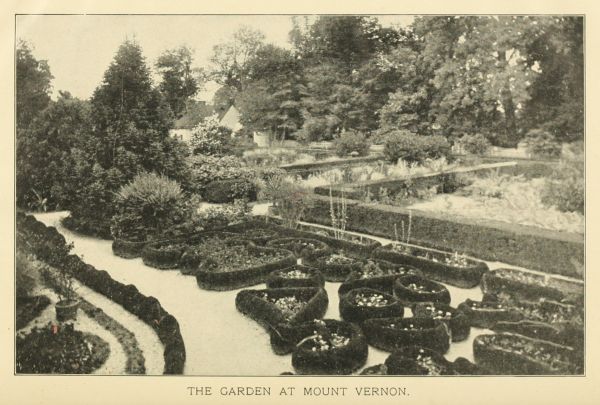

| The Garden at Mount Vernon | Facing | 189 |

| Elsing Green | 192 | |

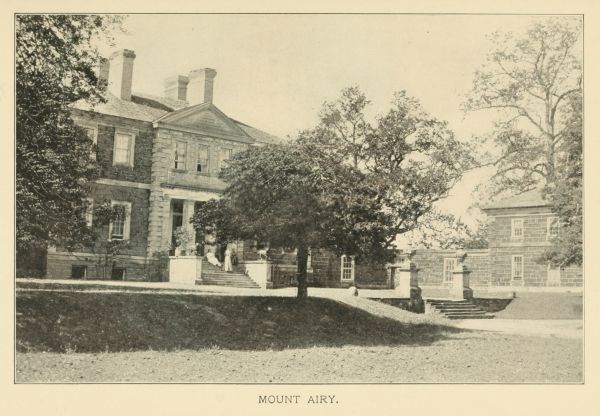

| Mount Airy | Facing | 192 |

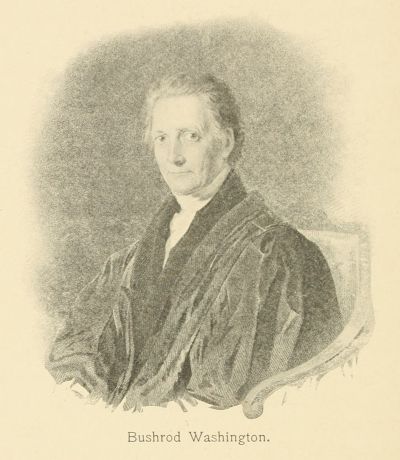

| Bushrod Washington | 206 | |

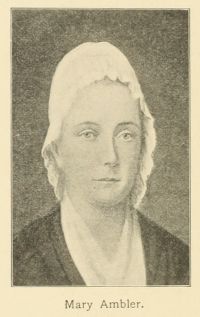

| Mary Ambler | 210 | |

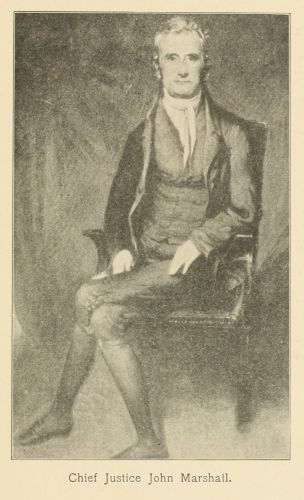

| Chief Justice John Marshall | 211 | |

| Lord Dunmore | 237 | |

| Robert Carter of Nomini Hall | 241 | |

| Abigail Adams | 248 | |

| Oratory Rock | 260 | |

| Sir William Howe | 265 | |

| Major André | 270 | |

| Arthur Lee | 274 | |

| Vergennes | 289 | |

| Beaumarchais | 290 | |

| Silas Deane | 291 | |

| [xiii]Benjamin Franklin | 292 | |

| General Burgoyne | 295 | |

| Rochambeau | 297 | |

| De Grasse | 298 | |

| Lord Cornwallis | 300 | |

| Greenway Court | Facing | 302 |

| George Washington Parke Custis | 306 | |

| The Chair used by George Washington when Master of Fredericksburg Lodge | 307 | |

| General Lafayette | Facing | 313 |

| John Adams | 328 | |

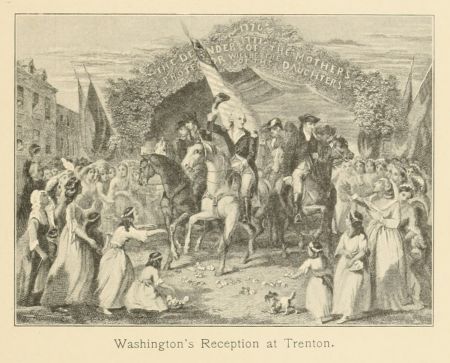

| Washington's Reception at Trenton | 343 | |

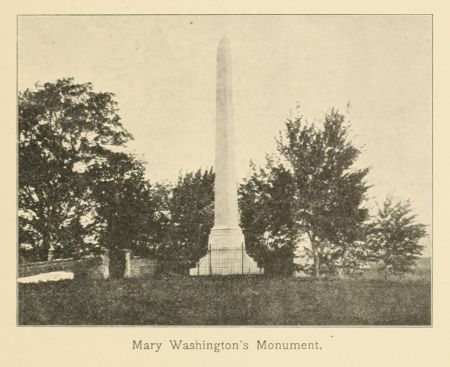

| Mary Washington's Monument | 357 | |

| The Avenue of Poplars at Nomini Hall | 363 |

Virginia Historical Magazine.

William and Mary Quarterly.

Virginia Historical Register.

Meade's Old Churches and Families of Virginia.

Campbell's History of Virginia.

Irving's Life of Washington.

Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington. By George Washington Parke Custis.

Cooke's Virginia.

The Bland Papers. By Campbell.

Howe's Virginia.

Journal of Philip Vickars Fithian.

Towers's Lafayette.

Creasy's Fifteen Decisive Battles.

Morse's Franklin.

Lecky's England in the Eighteenth Century.

Fiske's American Revolution.

Sparks's Diplomatic Correspondence.

Washington's Works.

Bancroft's History of the United States.

Life and Letters of George Mason. By Kate Mason Rowland.

[xvi]Beaumarchais and his Times.

Edwardes's Translations of Lemonie.

Lives of the Chief Justices of England.

Twining's Travels in America.

Burnaby's Travels.

The Story of Mary Washington. By Marion Harland.

Randall's Life of Jefferson.

Worthies of England. By Thomas Fuller.

Foote's Sketches of Virginia.

Parton's Franklin.

A Study in the Warwickshire Dialect. By Appleton Morgan, A.M., LL.B.

Maternal Ancestry of Washington. By G. W. Ball.

The mothers of famous men survive only in their sons. This is a rule almost as invariable as a law of nature. Whatever the aspirations and energies of the mother, memorable achievement is not for her. No memoir has been written in this country of the women who bore, fostered, and trained our great men. What do we know of the mother of Daniel Webster, or John Adams, or Patrick Henry, or Andrew Jackson, or of the mothers of our Revolutionary generals?

When the American boy studies the history of his country, his soul soars within him as he reads of his own forefathers: how they rescued a wilderness from the savage and caused it to bloom into fruitful fields and gardens, how they won its independence through eight years of hardship and struggle, how they assured its prosperity by a wise Constitution and firm laws. But he may look in[2] vain for some tribute to the mothers who trained his heroes. In his Roman history he finds Cornelia, Virginia, Lucretia, and Veturia on the same pages with Horatius, Regulus, Brutus, and Cincinnatus. If he be a boy of some thought and perception, he will see that the early seventeenth century women of his own land must have borne a similar relation to their country as these women to the Roman Republic. But our histories as utterly ignore them as if they never existed. The heroes of our Revolution might have sprung armed from the head of Jove for aught the American boy can find to the contrary.

Thus American history defrauds these noble mothers of their crown—not self-won, but won by their sons.

Letitia Romolino was known to few, while the fame of "Madame Mère" is as universal as the glory of Napoleon himself. But Madame Mère had her historian. The pioneer woman of America, who "broke the way with tears," retires into darkness and oblivion; while "many follow with a song" the son to whom she gave her life and her keen intelligence born of her strong faith and love.

Biographers have occasionally seemed to feel that something is due the mothers of their heroes. Women have some rights after all! And so we can usually find, tucked away somewhere, a short[3] perfunctory phrase of courtesy, "He is said to have inherited many of his qualities from his mother," reminding us of "The Ladies—God bless 'em," after everybody else has been toasted at a banquet, and just before the toasters are ripe for the song, "We won't go home till morning!"

But—if we are willing to be appeased by such a douceur—there is literature galore anent the women who have amused "great" men: Helen of Troy, Madame de Pompadour, Madame du Barry, Lady Hamilton, the Countess Guicciola, and such. We may comfort ourselves for this humiliating fact only by reflecting that the world craves novelty, and that these dames are interesting to the reading public, solely because they are exceptional, while the noble, unselfish woman, being the rule of motherhood, is familiar to every one of us and needs no historian.

It is the noble, unselfish woman who must shine, if she shine at all, by the light reflected from her son. Her life, for the most part, must be hidden by the obscurity of domestic duties. While herself thus inactive and retired, her son is developed for glory, and the world is his arena. It is only when he reaches renown that she becomes an object of attention, but it is then too late to take her measure in the plenitude of her powers. Emitting at best but a feeble ray, her genius is soon lost in the splendor of his meridian.

Nay more, her reputation is often the sport of a[4] love of contrast, and her simplicity and his magnificence the paradox of a gossiping public.

Mary Washington presents no exception to this picture. As the mother of the man who has hitherto done most for the good and glory of humanity, the details of her life are now of world-wide and enduring interest. Those details were lost in the seclusion and obscurity of her earlier years or else absorbed in the splendor of her later career. It is not deniable, too, that in the absence of authentic information, tradition has made free with her name, and has imputed to her motives and habits altogether foreign to her real character. The mother of Washington was in no sense a commonplace woman. Still less was she hard, uncultured, undignified, unrefined.

The writer hopes to trace the disparaging traditions, and to refute them by showing that all the known actions of her life were the emanations of a noble heart, high courage, and sound understanding.

"Characters," said the great Englishman who lived in her time, "should never be given by an historian unless he knew the people whom he describes, or copies from those who knew them." "A hard saying for picturesque writers of history," says Mr. Augustine Birrell, who knows so well how to be picturesque and yet faithful to the truth. Even he laments how little we can know of a dead man we never saw. "His books, if he wrote books, will tell us something; his letters, if he wrote any, and[5] they are preserved, may perchance fling a shadow on the sheet for a moment or two; a portrait if painted in a lucky hour may lend a show of substance to our dim surmisings; the things he did must carefully be taken into account, but as a man is much more than the mere sum of his actions even these cannot be relied upon with great confidence. For the purpose, therefore, of getting at any one's character, the testimony of those who knew the living man is of all the material likely to be within our reach the most useful."

How truly the words of this brilliant writer apply to the ensuing pages will be apparent to every intelligent reader. No temptation has availed with the compiler to accept any, the most attractive, theory or tradition. The testimony of those who knew Mary Washington is the groundwork of the picture, and controls its every detail.

A few years ago an episode of interest was awakened in Mary Washington's life. There was a decided Mary Washington Renaissance. She passed this way—as Joan of Arc—as Napoleon Bonaparte, Burns, Emerson, and others pass. A society of women banded themselves together into a Mary Washington Memorial Association. Silver and gold medals bearing her gentle, imagined face were struck off, and when the demand for them was at its height, their number was restricted to six hundred, to be bequeathed for all time from mother to daughter,[6] the pledge being a perpetual vigil over the tomb of Mary Washington, thus forming a Guard of Honor of six hundred American women. The Princess Eulalia of Spain, and Maria Pilar Colon, a descendant of Christopher Columbus, were admitted into this Guard of Honor, and wear its insignia.

This "Renaissance" grew out of an advertisement in the Washington papers to the effect that the "Grave of Mary, the Mother of General Washington," was to be "sold at Public Auction, the same to be offered at Public Outcry," under the shadow of the monument erected in her son's honor, and in the city planned by him and bearing his name.

A number of the descendants of Mary Washington's old Fredericksburg neighbors assembled the next summer at the White Sulphur Springs in Virginia. It was decided that a ball be given at the watering-place to aid the noble efforts of the widow of Chief Justice Waite to avert the disaster, purchase the park, and erect a monument over the ashes of the mother of Washington. One of the guests was selected to personate her: General Fitzhugh Lee to represent her son George.

A thousand patrons assured the success of the ball. They wore Mary Washington's colors—blue and white—and assumed the picturesque garb of pre-Revolutionary days. The bachelor governor of New York, learning what was toward with these fair ladies, sent his own state flag to grace the occasion,[7] and its snow-white folds mingled with the blue of the state banner contributed by the governor of Virginia.

The gowns of the Virginia beauties were yellow with age, and wrinkled from having been hastily exhumed from the lavender-scented chests; for when lovely Juliet Carter chose the identical gown of her great, great grandmother,—blue brocade, looped over a white satin quilted petticoat,—the genuine example was followed by all the rest. The Madam Washington of the hour was strictly taken in hand by the Fredericksburg contingent. Her kerchief had been worn at the Fredericksburg Peace Ball, her mob cap was cut by a pattern preserved by Mary Washington's old neighbors. There were mittens, a reticule, and a fan made of the bronze feathers of the wild turkey of Virginia. Standing with her son George in the midst of the old-time assembly, old-time music in the air, old-time pictures on the walls, Madam Washington received her guests and presented them to her son, whose miniature she wore on her bosom. "I am glad to meet your son, Madam Washington!" said pretty Ellen Lee, as she dropped her courtesy; "I always heard he was a truthful child!"

The lawn and cloister-like corridors of the large hotel were crowded at an early hour with the country people, arriving on foot, on horseback, and in every vehicle known to the mountain roads.[8] These rustic folk—weather-beaten, unkempt old trappers and huntsmen, with their sons and daughters, wives and little children—gathered in the verandas and filled the windows of the ball-room. When the procession made the rounds of the room the comments of the holders of the window-boxes were not altogether flattering. The quaint dress of "the tea-cup time of hoop and hood" was disappointing. They had expected a glimpse of the latest fashions of the metropolis.

"I don't think much of that Mrs. Washington," said one.

"Well," drawled another, a wiry old graybeard, "she looks quiet and peaceable! The ole one was a turrible ole woman! My grandfather's father used to live close to ole Mrs. Washington. The ole man used to say she would mount a stool to rap her man on the head with the smoke-'ouse key! She was that little, an' hot-tempered."

"That was Martha Washington, grandfather," corrected a girl who had been to school in Lewisburg. "She was the short one."

"Well, Martha or Mary, it makes no differ," grimly answered the graybeard. "They was much of a muchness to my thinkin'," and this was the first of the irreverent traditions which caught the ear of the writer, and led to investigation. They cropped up fast enough from many a dark corner!

About this time many balls and costume entertainments were given to aid the monument fund. There were charming garden parties to

"Bring back the hour

Of glory in the grass and splendor in the flower,"

when the Mother of Washington was beautiful, young, and happy. A notable theatrical entertainment, the "Mary Washington matinée," was arranged by Mrs. Charles Avery Doremus, the clever New York playwright. The theatre was hung with colors lent by the Secretary of the Navy, the order therefor signed by "George Dewey." Everybody wore the Mary Washington colors—as did Adelina Patti, who flashed from her box the perennial smile we are yet to see again. Despite the hydra-headed traditions the Mother of Washington had her apotheosis.

Brought face to face with my reader, and devoutly praying I may hold his interest to the end, I wish I could spare him every twice-told tale—every dull word.

But "we are made of the shreds and patches of many ancestors." What we are we owe to them. God forbid we should inherit and repeat all their actions! The courage, the fortitude, the persistence, are what we inherit—not the deeds through which they were expressed. A successful housebreaker's courage may blossom in the valor of a descendant[10] on the field who has been trained in a better school than his ancestor.

Dull as the public is prone to regard genealogical data, the faithful biographer is bound to give them.

And therefore the reader must submit to an introduction to the Ball family, otherwise he cannot understand the Mother of Washington or Washington himself. One of them, perhaps the one most deserving eminence through her own beneficence, we cannot place exactly in our records. She was an English "Dinah Morris," and her name was Hannah Ball. She was the originator of Sunday-schools, holding her own school in 1772, twelve years before the reputed founder, Robert Raikes, established Sunday-schools in England.

The family of Ball from which Mary, the mother of Washington, descended, can be traced in direct line only as far back as the year 1480. They came originally from "Barkham, anciently 'Boercham'; noted as the spot at which William the Conqueror paused on his devastating march from the bloody field of Hastings:[1] 'wasting ye land, burning ye towns and sleaing (sic) ye people till he came to Boerchum where he stayed his ruthless hand.'"

In the "History of the Ball family of Barkham, Comitatis Berks, taken from the Visitation Booke of London marked O. 24, in the College of Arms," we find that "William Ball, Lord of the Manor of Barkham, Com. Berks, died in the year 1480." From this William Ball, George Washington was eighth in direct descent.

The entry in the old visitation book sounds imposing, but Barkham was probably a small town nestled amid the green hills of Berkshire, whose beauty possibly so reminded the Conqueror of his[12] Normandy that "he stayed his ruthless hand." A century ago it was a village of some fifty houses attached to the estate of the Levison Gowers.

There is no reason to suppose that the intervening Balls in the line,—Robert, William, two Johns,—all of whom lived in Barkham, or the William of Lincoln's Inn, who became "attorney in the Office of Pleas in the Exchequer," were men of wealth or rank. The "getting of gear was never," said one of their descendants, "a family trait, nor even the ability to hold it when gotten"; but nowhere is it recorded that they ever wronged man or woman in the getting. They won their worldly goods honorably, used them beneficently, and laid them down cheerfully when duty to king or country demanded the sacrifice, and when it pleased God to call them out of the world. They were simply men "doing their duty in their day and generation and deserving well of their fellows."

They belonged to the Landed Gentry of England. This does not presuppose their estates to have been extensive. A few starved acres of land sufficed to class them among the Landed Gentry, distinguishing them from laborers. As such they may have been entitled to the distinction of "Gentleman," the title in England next lowest to "Yeoman." No one of them had ever bowed his shoulders to the royal accolade, nor held even the position of esquire to a baronet. But the title[13] "Gentleman" was a social distinction of value. "Ordinarily the King," says Sir Thomas Smith, "doth only make Knights and create Barons or higher degrees; as for gentlemen, they be made good cheap in this Kingdom; for whosoever studieth the laws of the realm, who studieth in the universities, who professeth the liberal sciences, he shall be taken for a gentleman; for gentlemen be those whom their blood and race doth make noble and known." By "a gentleman born" was usually understood the son of a gentleman by birth, and grandson of a gentleman by position. "It takes three generations to make a gentleman," we say to-day, and this seems to have been an ancient rule in England.

The Balls might well be proud to belong to old England's middle classes—her landed, untitled Gentry. A few great minds—Lord Francis Verulam, for instance—came from her nobility; and some gifted writers—the inspired dreamer, for instance—from her tinkers and tradesmen; but the mighty host of her scholars, poets, and philosophers belonged to her middle classes. They sent from their ranks Shakespeare and Milton, Locke and Sir Isaac Newton, Gibbon, Dryden, "old Sam Johnson," Pope, Macaulay, Stuart Mill, Huxley, Darwin, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Burke, Disraeli, Cowper, Sir William Blackstone, and nearly all of the Chief Justices of England. These are but a few of the[14] great names that shine along the ranks of England's middle classes.

Many of these men were called to the foot of the throne by a grateful sovereign to receive some distinction,—so paltry by comparison with glory of their own earning,—and among them came one day an ancestor of the mother of George Washington. Who he was we know not, nor yet what had been his service to his country; but he was deemed worthy to bear upon his shield a lion rampant, the most honorable emblem of heraldry, and the lion's paws held aloft a ball! This much we know of him,—that in addition to his valor and fidelity he possessed a poet's soul. He chose for the motto, the cri de guerre of his clan, a suggestive phrase from these lines of Ovid:—

"He gave to man a noble countenance and commanded him to gaze upon the heavens, and to carry his looks upward to the stars."

WILLIAM AND MARY COLLEGE.

The first of the family of Ball to come to Virginia was William Ball, who settled in Lancaster County in 1650. He was the son of the attorney of Lincoln's Inn. He emigrated, with other cavaliers because of the overthrow of the royal house and the persecution of its adherents.

Before this time one John Washington, an Englishman and a loyalist, had settled in Westmoreland. He became a man of influence in the colony, rising rapidly from major to colonel, justice of Westmoreland, and member of the House of Burgesses; accepting positions under the Commonwealth, as did others of King Charles's adherents; doing their duty under the present conditions, and consoling themselves by calling everything—towns, counties, rivers, and their own sons—after the "Martyred Monarch"; and in rearing mulberry trees and silkworms to spin the coronation robe of purple for the surely coming time of the Restoration.

John Washington married three times,—two Annes and one Frances,—and, innocently unconscious[16] of the tremendous importance to future historians of his every action, he neglected to place on record the date of these events. In his day a woman appeared before the public only three times,—at her baptism, marriage, and death. But one of Colonel Washington's wives emerges bravely from obscurity. A bold sinner and hard swearer, having been arraigned before her husband, she was minded to improve her opportunity; and the Westmoreland record hath it that "Madam Washington said to ye prisoner, 'if you were advised by yr wife, you need not acome to this passe,' and he answered, having the courage of his convictions, '—— —— my wife! If it were to doe, I would do it againe.'"

And so no more of Madam Washington! This trouble had grown out of what was characterized as "ye horrid, traiterous, and rebellious practices" of a young Englishman on the James River, whose only fault lay in the unfortunate circumstance of his having been born a hundred years too soon. Bacon's cause had been just, and he was eloquent enough and young and handsome enough to draw all men's hearts to himself, but his own was stilled in death before he could right his neighbors' wrongs.

And now, the Fates that move the pieces on the chess-board of life ordained that two prophetic names should appear together to suppress the first rebellion against the English government. When the Grand Assembly cast about for loyal men and true to lay[17] "a Levy in ye Northern Necke for ye charges in Raisinge ye forces thereof for suppressing ye late Rebellion," the lot fell on "Coll. John Washington and Coll: Wm. Ball," the latter journeying up from his home in Lancaster to meet Colonel Washington at Mr. Beale's, in Westmoreland.

Colonel Ball's Lancaster home was near the old White Chapel church, around which are clustered a large number of strong, heavy tombstones which betoken to-day "a deep regard of the living for the dead."

Almost all of them are inscribed with the name of Ball. In their old vestry books are stern records. A man was fined five thousand pounds of tobacco for profane swearing; unlucky John Clinton, for some unmentioned misdemeanor, was required four times to appear on bended knees and four times to ask pardon. As late as 1727 men were presented for drunkenness, for being absent one month from church, for swearing, for selling crawfish and posting accounts on Sunday. "And in addition to above," adds Bishop Meade, "the family of Ball was very active in promoting good things," as well as zealous in the punishment of evil. Overt acts—swearing, fishing on Sunday, absence from church—could easily be detected and punished. But how about drunkenness? There are degrees of intoxication. At what point was it punishable?

An old Book of Instructions settled the matter.[18] "Where ye same legges which carry a Man into a house cannot bring him out againe, it is Sufficient Sign of Drunkennesse."

The descendants of William Ball held good positions in the social life of the colony. Their names appear in Bishop Meade's list of vestrymen, as founders and patrons of the Indian schools, and fourteen times in the House of Burgesses. They intermarried with the leading families in Virginia; and the Balls, in great numbers, settled the counties of Lancaster, Northumberland, Westmoreland, and Stafford. They are not quoted as eminent in the councils of the time, or as distinguished in letters. That they were good citizens is more to their credit than that they should have filled prominent official positions; for high offices have been held by men who were not loyal to their trusts, and even genius—that beacon of light in the hands of true men—has been a torch of destruction in those of the unworthy.

They, like their English ancestors, bore for their arms a lion rampant holding a ball, and for their motto Cælumque tueri, taken, as we have said, from these lines of Ovid:—

The rampant lion holding the ball appears on an armorial document belonging to the first emigrant.[19] On the back of this document are the following words, written in the round, large script of those days, which, whatever it left undone, permitted no possible doubt of the meaning it meant to convey:—

"The Coat of Arms of Colonel William Ball, who came from England about the year 1650, leaving two sons—William of Millenbeck [the paternal seat] and Joseph of Epping Forest—and one daughter, Hannah, who married Daniel Fox.... Joseph's male issue is extinct."[2]

George Washington was the grandson of this Joseph Ball through his youngest daughter Mary. She was born at Epping Forest, in Lancaster, Virginia, in 1708, and "not as is persistently stated by careless writers on Nov: 30th 1706—a year before her parents were married."

Bishop Meade says of William Ball's coat of arms: "There is much that is bold about it: as a lion rampant with a globe in his paw, with helmet, shield and visor, and other things betokening strength and courage, but none these things suit of my work! There is, however, one thing that does. On a scroll are these words, Cælum tueri! May it be a memento to all his posterity to look upward and seek the things which are above!"

The Bishop attached, probably, more importance to the heraldic distinction than did the mother of Washington. Virginia families used the arms to which they had a right with no thought of ostentation—simply as something belonging to them, as a matter of course. They sealed their deeds and contracts with their family crest and motto, displayed their arms on the panels of their coaches, carved them on their gate-posts and on the tombstones of their people; for such had been the custom in the old country which they fondly called "home."

The pedigrees and coats of arms of the families, from which Mary Ball and her illustrious son descended, have been much discussed by historians. "Truly has it been said that all the glories of ancestral escutcheons are so overshadowed by the deeds of Washington that they fade into insignificance; that a just democracy, scornful of honors not self-won, pays its tribute solely to the man, the woman, and the deed; that George Washington was great because he stood for the freedom of his people, and Mary Washington was great because she implanted in his youthful breast righteous indignation against wrong, which must ever be the inspiration of the hero. And yet the insignia of a noble name, handed down from generation to generation, and held up as an incentive to integrity and valor, may well be cherished." The significance of the shield granted as reward, and the sentiment chosen as the family motto, are not to be ignored. The shield witnesses a sovereign's appreciation; the motto affords a key-note to the aspirations of the man who chose it. Not of the women! for only under limitations could women use the shield; the motto they were forbidden to use at all. Mottoes often expressed lofty sentiments. Witness a few taken from Virginia families of English descent: Malo mori quam fœdari. Sperate et Virite Fortes (Bland), Sine Deo Cares (Cary), Ostendo non ostento (Isham), Rêve et Révéle (Atkinson), etc.

At the present moment the distinction of a coat of arms is highly esteemed in this country. Families of English descent can always find a shield or crest on some branch, more or less remote, of the Family Tree. The title to these arms may have long been extinct—but who will take the trouble to investigate? The American cousin scorns and defies rules of heraldry! To be sure, he would prefer assuming a shield once borne by some ancestor, but if that be impossible, he is quite capable of marshalling his arms to suit himself. Is not "a shield of pretence" arms which a lord claims and which he adds to his own? Thus it comes to pass that the crest, hard won in deadly conflict, and the motto once the challenging battle-cry, find themselves embalmed in the perfume of a fine lady's tinted billet, or proudly displayed on the panels of her park equipage. Thus is many a hard-won crest and proud escutcheon of old England made to suffer the extreme penalty of the English law, "drawn and quartered," and dragged captive in boastful triumph at the chariot wheels of the Great Obscure! They can be made to order by any engraver. They are used, unchallenged, by any and every body willing to pay for them.

It may, therefore, be instructive to turn the pages of old Thomas Fuller's "Worthies of England," and learn the rigid laws governing the use of arms by these "Worthies."

The "fixing of hereditary arms in England was a hundred years ancienter than Richard the Second"—in 1277, therefore. Before his second invasion into France, Henry V issued a proclamation to the sheriffs to this effect: "Because there are divers men who have assumed to themselves arms and coat-armours where neither they nor their ancestors in times past used such arms or coat-armours, all such shall show cause on the day of muster why he useth arms and by virtue of whose gift he enjoyeth the same: those only excepted who carried arms with us at the battle of Agincourt;" and all detected frauds were to be punished "with the loss of wages, as also the rasing out and breaking off of said arms called coat-armours—and this," adds his Majesty, with emphasis, "you shall in no case omit."

By a later order there was a more searching investigation into the right to bear arms. A high heraldic officer, usually one of the kings-at-arms, was sent into all the counties to examine the pedigrees of the landed gentry, with a view of ascertaining whether the arms borne by them were unwarrantably assumed. The king-at-arms was accompanied on such occasions by secretaries or draftsmen. The "Herald's Visitations," as they were termed, were regularly held as early as 1433, and until between 1686 and 1700. Their object was by no means to create coats of arms but to[24] reject the unauthorized, and confirm and verify those that were authentic. Thus the arms of the Ball and Washington families had been subjected to strict scrutiny before being registered in the Heralds' College. They could not have been unlawfully assumed by the first immigrant, nor would he, while living in England, have been allowed to mark his property or seal his papers with those arms nor use them in any British colony.

Of the ancestry of Mary Washington's mother nothing is known. She was the "Widow Johnson," said to have descended from the Montagus of England, and supposed to have been a housekeeper in Joseph Ball's family, and married to him after the death of his first wife. Members of the Ball family, after Mary Washington's death, instituted diligent search to discover something of her mother's birth and lineage. Their inquiries availed to show that she was an Englishwoman. No connection of hers could be found in Virginia. Since then, eminent historians and genealogists, notably Mr. Hayden and Mr. Moncure Conway, have given time and research "to the most important problem in Virginia genealogy,—Who and whence was Mary Johnson, widow, mother of Mary Washington?" The Montagu family has claimed her and discovered that the griffin of the house of Montagu sometimes displaced the raven in General Washington's crest; and it was asserted that the griffin had been discovered perched upon the tomb of one Katharine Washington, at Piankatnk.[26] To verify this, the editor of the William and Mary Quarterly journeyed to the tomb of Katharine, and found the crest to be neither a raven or a griffin but a wolf's head!

It matters little whether or no the mother of Washington came of noble English blood; for while an honorable ancestry is a gift of the gods, and should be regarded as such by those who possess it, an honorable ancestry is not merely a titled ancestry. Descent from nobles may be interesting, but it can only be honorable when the strawberry leaves have crowned a wise head and the ermine warmed a true heart. Three hundred years ago an English wit declared that "Noblemen have seldom anything in print save their clothes."

Knowing that Mary Johnson was an Englishwoman, we might, had we learned her maiden name, have rejoiced in tracing her to some family of position, learning, or wealth; for position and learning are desirable gifts, and wealth has been, and ever will be, a synonym of power. It can buy the title and command genius. It can win friendship, pour sunshine into dark places, cause the desert to bloom. It can prolong and sweeten life, and alleviate the pangs of death.

These brilliant settings, for the woman we would fain honor, are denied us. That she was a jewel in herself, there can be no doubt. We must judge of her as we judge of a tree by its fruits; as we[27] judge a fountain by the streams issuing therefrom. She was the mother of a great woman "whose precepts and discipline in the education of her illustrious son, himself acknowledged to have been the foundation of his fortune and fame:—a woman who possessed not the ambitions which are common to meaner minds." This was said of her by one who knew Mary, the mother of Washington,—Mary, the daughter of the obscure Widow Johnson.

Indeed, she was so obscure that the only clew we have to her identity as Joseph Ball's wife is found in a clause of his will written June 25, 1711, a few weeks before his death, where he mentions "Eliza Johnson, daughter of my beloved wife."

Until a few months ago it was supposed that Mary Ball spent her childhood and girlhood at Epping Forest, in Lancaster County; that she had no schooling outside her home circle until her seventeenth year; that she visited Williamsburg with her mother about that time; that in 1728 her mother died, and she went to England to visit her brother Joseph, a wealthy barrister in London. Her biographers accepted these supposed facts and wove around them an enthusiastic romance. They indulged in fancies of her social triumphs in Williamsburg, the gay capital of the colony; of her beauty, her lovers; how she was the "Rose of Epping Forest," the "Toast of the Gallants of[28] her Day." They followed her to England,—whence also Augustine Washington was declared to have followed her,—sat with her for her portrait, and brought her back either the bride, or soon to become the bride, of Augustine Washington; brought back also the portrait, and challenged the world to disprove the fact that it must be genuine and a capital likeness, for had it not "George Washington's cast of countenance"?

The search-light of investigation had been turned in vain upon the county records of Lancaster. There she had not left even a fairy footprint. What joy then to learn the truth from an accidental discovery by a Union soldier of a bundle of old letters in an abandoned house in Yorktown at the close of the Civil War! These letters seemed to lift the veil of obscurity from the youthful unmarried years of Mary, the mother of Washington. The first letter is from Williamsburg, 1722:—

"Dear Sukey—Madam Ball of Lancaster and her sweet Molly have gone Hom. Mama thinks Molly the Comliest Maiden She Knows. She is about 16 yrs. old, is taller than Me, is verry Sensable, Modest and Loving. Her Hair is like unto Flax. Her Eyes are the colour of Yours, and her Chekes are like May blossoms. I wish You could see Her."

A letter was also found purporting to have been written by Mary herself to her brother in England;[29] defective in orthography, to be sure, but written in a plain, round hand:—

"We have not had a schoolmaster in our neighborhood until now in five years. We have now a young minister living with us who was educated at Oxford, took orders and came over as assistant to Rev. Kemp at Gloucester. That parish is too poor to keep both, and he teaches school for his board. He teaches Sister Susie and me, and Madam Carter's boy and two girls. I am now learning pretty fast. Mama and Susie and all send love to you and Mary. This from your loving sister,

"Mary Ball."

The fragment of another letter was found by the Union soldier. This letter is signed "Lizzie Burwell" and written to "Nelly Car——," but here, alas! the paper is torn. Only a part of a sentence can be deciphered. "... understand Molly Ball is going Home with her Brother, a lawyer who lives in England. Her Mother is dead three months ago." The date is "May ye 15th, 1728," and Mary Ball is now twenty years old.

Could any admiring biographer ask more? Flaxen hair, May blossoms—delightful suggestion of Virginia peach-blooms, flowering almond, hedge roses! "Sensible, Modest, and Loving!" What an enchanting picture of the girlhood of the most eminent of American women! The flying steeds of imagination were given free rein. Away they went! They bore her to the gay life in Williamsburg, then[30] the provincial capital and centre of fashionable society in the Old Dominion. There she rode in the heavy coaches drawn by four horses, lumbering through the dusty streets: or she paid her morning visits in the sedan-chairs, with tops hitherto flat but now beginning to arch to admit the lofty head-dresses of the dames within. She met, perhaps, the haughty soldier ex-Governor, who could show a ball which had passed through his coat at Blenheim: and also her Serene Highness, Lady Spotswood, immortalized by William Byrd as "gracious, moderate, and good-humored." Who had not heard of her pier glasses broken by the tame deer and how he fell back upon a table laden with rare bric-a-brac to the great damage thereof! Along with the records of the habeas corpus, tiffs with the burgesses, the smelting of iron, the doughty deeds of the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe, invariable mention had been made of this disaster, and of the fact that the gracious Lady Spotswood "bore it with moderation and good-humor." This sublime example might have had some influence in moulding the manners of Mary Ball—one of whose crowning characteristics was a calm self-control, never shaken by the most startling events!

And then we took ship and sailed away with our heroine to England—Augustine Washington, as became an ardent lover, following ere long. Anon, we bore her, a happy bride, home again, bringing[31] with her a great treasure,—a portrait true to the life, every feature bearing the stamp of genuineness. Through how many pages did we gladly amplify this, chilled somewhat by fruitless searches for "Sister Susie"! "Never," said an eminent genealogist, "never reject or lose tradition. Keep it, value it, record it as tradition;" but surely this was not tradition. It was documentary evidence, but evidence rudely overthrown by another document,—a dry old yellow will lately found by the Rev. G. W. Beale in the archives of Northumberland County, in Virginia.

The old will proves beyond all question that Mary Ball's girlhood was not passed in Lancaster, that she had ample opportunity for education, and was, therefore, not untaught until she was sixteen. She, probably, never visited Williamsburg when seventeen,—certainly never with her mother. There never was a Sister Susie! At the time the Williamsburg letter announced the recent death of her mother, that mother had for many years been sleeping quietly in her grave. Moreover, the letter of Mary herself had done a great injustice to Gloucester parish, which was not a "poor parish" at all—with an impecunious curate working for his board—but a parish erecting at that moment so fine a church that Bishop Meade's pious humility suffered in describing it.

From Dr. Beale's researches we learn that the "Rose of Epping Forest" was a tiny bud indeed when her father died; that before her fifth birthday her mother had married Captain Richard Hewes, a vestryman of St. Stephen's parish, Northumberland, and removed to that parish with her three[33] children, John and Elizabeth Johnson, and our own little Mary Ball.

In 1713, Captain Hewes died, and his inventory was filed by his "widow, Mary Hewes," who also died in the summer of 1721. "It is seldom," says Dr. Beale,[3] commenting upon her last will and testament, "that in a document of this kind, maternal affection—having other and older children to share its bequests—so concentrates itself upon a youngest daughter, and she a child of thirteen summers. Perhaps of all the tributes laid at the feet of Mary Washington, none has been more heart-felt or significant of her worth than legacies of her mother's last will and testament, written as they were, all unconsciously of her future distinction." The will discovered by the Rev. G. W. Beale settles all controversies. For the benefit of those who must see in order to believe, we copy it verbatim.

"In the name of God Amen, the seventeenth Day December in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and twenty."

"I Mary Hewes of St. Stephen's Parish, Northumberland County, widow, being sick and weak in body but of sound and perfect memory, thanks be to Almighty God for the same, and calling to mind the uncertain state of this transitory life, and that the flesh must yield unto Death, when it shall please God to call, do make and ordain this my last will and Testament.

"First, I give and bequeath my soul (to God) that gave it me, and my body to the Earth to be buried in Decent Christian burial at the discretion of my executors in these presents nominated. And as touching such Worldly estate which it hath pleased God to bestow upon me, I give, devise and dispose of in the following manner and form. Imprimis, I give and devise unto my Daughter Mary Ball one young likely negro woman to be purchased for her out of my Estate by my Executors and to be delivered unto her the said Mary Ball at the age of Eighteen years, but, my will is that if the said Mary Ball should dye without Issue lawfully begotten of her body that the said negro woman with her increase shall return to my loving son John Johnson to him, his heirs and assigns forever.

"Item. I give and bequeath unto my said Daughter Mary Ball two gold rings, the one being a large hoop and the other a stoned ring.

"Item. I give unto my said Daughter Mary Ball one young mare and her increase which said mare I formerly gave her by word of mouth.

"Item. I give and bequeath unto my said Daughter Mary Ball sufficient furniture for the bed her father Joseph Ball left her, vizt: One suit of good curtains and fallens, one Rugg, one Quilt, one pair Blankets.

"Item. I give and bequeath unto my said Daughter Mary Ball two Diaper Table clothes marked M. B. with inck, and one Dozen of Diaper napkins, two towels, six plates, two pewter dishes, two basins, one large iron pott, one Frying pan, one old trunk.

"Item. I give and bequeath unto my said Daughter Mary Ball, one good young Paceing horse together with a good silk plush side saddle to be purchased by my Executors out of my Estate.

"Item. I give and bequeath unto my Daughter Elizabeth Bonum one suit of white and black callico, being part of my own wearing apparel.

"Item. All the rest of my wearing apparel I give and bequeath unto my said Daughter Mary Ball, and I do hereby appoint her (to) be under Tutiledge and government of Capt. George Eskridge during her minority.

"Item. My will is I do hereby oblige my Executors to pay to the proprietor or his agent for the securing of my said Daughter Mary Ball her land Twelve pounds if so much (be) due.

"Item. All the rest of my Estate real and personal whatsoever and wheresoever I give and devise unto my son John Johnson, and to his heirs lawfully to be begotten of his body, and for default of such Issue I give and devise the said Estate unto my Daughter Elizabeth Bonum, her heirs and assigns forever.

"Item. I do hereby appoint my son John Johnson and my trusty and well beloved friend George Eskridge Executors of this my last will and Testament and also revoke and Disannul all other former wills or Testaments by me heretofore made or caused to be made either by word or writing, ratifying and confirming this to be my last Will and Testament and no other.

"In witness whereof I have hereunto sett my hand and seal the Day and Date at first above written.

"The mark and seal of Mary III Hewes. Sig. (Seal) Signed, Sealed and Published and Declared by Mary Hewes to be her last Will and Testament in presence of us.

"The mark of Robert × Bradley.

"The mark of Ralph × Smithurst

"David Stranghan."

The chief witness to this will was a teacher of no mean repute who lived near Mrs. Hewes, "And," says Dr. Beale, "others might be named who followed the same calling in Mary Ball's girlhood and near her home."

The son, John Johnson, named as joint executor in his mother's will, died very soon after her. His will and hers were recorded on the same day. The first bequest reveals his affection for his little half-sister.

"Imprimis. I give and bequeath unto my sister Mary Ball all my land in Stafford which my father-in-law Richard Hewes gave me, to the said Mary Ball and her heirs lawfully to be begotten of her body forever."

The will of Samuel Bonum, husband of the "Elizabeth" mentioned in Mrs. Hewes's will, was probated in Westmoreland, Feb. 22, 1726, and contains an item bequeathing "to my sister-in-law Mary Ball, my young dapple gray riding horse." Mary Ball was then eighteen years old.

So it appears that the mother of Washington, although not rich, according to the standard of that day or this, was fairly well endowed with Virginia real estate. Also that she owned three or more riding-horses, her own maid, a few jewels, and house plenishing sufficient for the station of a lady in her day and generation.

It is easy to imagine the childhood of Mary Ball. Children in her day escaped from the nursery at an early age. They were not hidden away in convents or sent to finishing schools. There were no ostentatious débuts, no "coming-out teas." As soon as a girl was fairly in her "teens" she was marriageable.

Little girls, from early babyhood, became the constant companions of their mothers, and were treated with respect. Washington writes gravely of "Miss Custis," six years old. They worked samplers, learned to edge handkerchiefs with a wonderful imitation of needle-point, plaited lace-strings for stays, twisted the fine cords that drew into proper bounds the stiff bodices, knitted garters and long hose, took lessons on the harpsichord, danced the minuet, and lent their little hands to "clap muslins" on the great clearstarching days, when the lace "steenkirk," and ruffled bosoms, and ample kerchiefs, were "gotten up" and crimped into prescribed shape. No lounging, idleness, or loss of time was permitted. The social customs of the day[38] enforced habits of self-control. For long hours the little Mary was expected to sit upon high chairs, with no relenting pillows or cushions, making her manners as became a gentleman's daughter throughout the stated "dining days," when guests arrived in the morning and remained until evening. Nor was her upright figure, clad in silk coat and mittens, capuchin and neckatees, ever absent from the front seat of the yellow chariot as it swung heavily through the sands to return these stately visits, or to take her mother and sister to old St. Stephen's church. Arriving at the latter, she might possibly have had a glimpse now and then of other little girls as she paced the gallery on her way to the high-backed family pew, with its "railing of brass rods with damask curtains to prevent the family from gazing around when sitting or kneeling." Swallowed up in the great square pew she could see nothing.

An Old Doll.

From the viewpoint of a twentieth-century child, her small feet were set in a hard, if not thorny, path. The limits of an early colonial house allowed no space for the nursery devoted exclusively to a child, and filled with every conceivable appliance for her instruction and amusement. There were no wonderful mechanical animals, lifelike in form and color, and capable of exercising many of their functions. One stiff-jointed, staring, wooden effigy was the only prophecy of the enchanting doll family,—the blue-eyed, brown-eyed,[39] flaxen-curled, sleeping, talking, walking, and dimpled darlings of latter-day children,—and the wooden-handled board, faced with horn and bound with brass, the sole representative of the child's picture-book of to-day. No children's books were printed in England until the middle of the eighteenth century; but one Thomas Flint, a Boston printer, appreciating the rhymes that his mother-in-law, Mrs. Goose, sang to his children, published them in book form and gave them a name than which none is more sure of immortality. This, however, was in 1719—too late for our little Mary Ball. She had only the horn-book as resource in the long, dark days when the fairest of all books lay hidden beneath the snows of winter—the horn-book, immortalized by Thomas Tickell as far back as 1636:—

The "sword and lance" were in allusion to the one illustration of the horn-book. When the blue eyes wearied over the alphabet, Lord's prayer, and nine digits, they might be refreshed with a picture of St. George and the Dragon, rudely carved on the wooden back. The "instructed handle" clasped the whole and kept it together.

Horn-book.

All orphans and poor children in colonial Virginia were provided with public schools under the care of the vestries of the parishes—"litle houses," says Hugh Jones in 1722, "built on purpose where are taught English, writing, etc." Parents were compelled to send their children to these schools, and masters to whom children were bound were required to give them schooling until "ye years of twelfe or thereabout" without distinction of race or sex. For instance, in the vestry book of Petsworth Parish, in Gloucester County, is an indenture dated Oct. 30, 1716, of Ralph Bevis to give George Petsworth, "a molattoe boy of the age of 2 years, 3 years' schooling; and carefully to instruct him afterwards that he may read well any part of the Bible." Having mastered the Bible,[41] all literary possibilities were open to the said George. The gentry, however, employed private tutors in their own families,—Scotchmen or Englishmen fresh from the universities, or young curates from Princeton or Fagg's Manor in Pennsylvania. Others secured teachers by indenture.[42] "In Virginia," says the London Magazine, "a clever servant is often indentured to some master as a schoolmaster." John Carter of Lancaster directed in his will that his son Robert should have "a youth servant bought for him to teach him in his books in English or Latin." Early advertisements in the Virginia Gazette assured all "single men capable of teaching children to Read English, write or Cypher or Greek Latin and Mathematicks—also all Dancing Masters," that they "would meet with good encouragement" in certain neighborhoods.

But this was after Mary Ball's childhood. Days of silent listening to the talk of older people were probably her early school days. In Virginia there were books, true, but the large libraries of thirty years later had not yet been brought over. There was already a fine library at Stratford in Westmoreland. Colonel Byrd's library was considered vast when it attained to "3600 titles." Books were unfashionable at court in England. No power in heaven or earth has been yet found to keep the wise and witty from writing them, but in the first years of the eighteenth century it was very bad form to talk about them. Later, even, the first gentleman in England was always furious at the sight of books. Old ladies used to declare that "Books were not fit articles for drawing-rooms." "Books!" said Sarah Marlborough; "prithee,[43] don't talk to me about books! The only books I know are men and cards."

But there were earnest talkers in Virginia, and the liveliest interest in all kinds of affairs. It was a picturesque time in the life of the colony. Things of interest were always happening. We know this of the little Mary,—she was observant and wise, quiet and reflective. She had early opinions, doubtless, upon the powers of the vestries, the African slave-trade, the right of a Virginia assembly to the privileges of parliament, and other grave questions of her time. Nor was the time without its vivid romances. Although no witch was ever burnt in Virginia, Grace Sherwood, who must have been young and comely, was arrested "under suspetion of witchcraft," condemned by a jury of old women because of a birth-mark on her body, and sentenced to a seat in the famous ducking-stool, which had been, in the wisdom of the burgesses, provided to still the tongues of "brabbling women,"—a sentence never inflicted, for a few glances at her tearful eyes won from the relenting justice the order that this ducking was to be "in no wise without her consent, or if the day should be rainy, or in any way to endanger her health!"

Ducking-stool.

Stories were told around the fireside on winter nights, when the wooden shutters rattled—for rarely before 1720 were "windows sasht with crystal glass." The express, bringing mails from the[44] north, had been scalped by Indians. Four times in one year had homeward-bound ships been sunk by pirates. Men, returning to England to receive an inheritance, were waylaid on the high seas, robbed, and murdered. In Virginia waters the dreaded "Blackbeard" had it all his own way for a while. Finally, his grim head is brought home on the bowsprit of a Virginia ship, and a drinking-cup, rimmed with silver, made of the skull that held his wicked brains. Of course, it could not be expected that he could rest in his grave under these circumstances, and so, until fifty years ago (when possibly the drinking-cup was reclaimed by his restless spirit), his phantom sloop might be seen spreading its ghostly sails in the moonlight on the York River and putting into Ware Creek to hide ill-gotten gains in the Old Stone House. Only a few years before had[45] the dreadful Tuscaroras risen with fire and tomahawk in the neighbor colony of North Carolina.

The Old Stone House.

Nearer home, in her own neighborhood, in fact, were many suggestive localities which a child's fears might people with supernatural spirits. Although there were no haunted castles with dungeon, moat, and tower, there were deserted houses in lonely places, with open windows like hollow eyes, graveyards half hidden by tangled creepers and wept over by ancient willows. About these there sometimes hung a mysterious, fitful light which little Mary, when a belated traveller in the family coach, passed with bated breath, lest warlocks or witches should issue therefrom, to say nothing of the interminable stretches of dark forests, skirting ravines fringed[46] with poisonous vines, and haunted by the deadly rattlesnake. People talked of strange, unreal lights peeping through the tiny port-holes of the old Stone House on York River—that mysterious fortress believed to have been built by John Smith—while, flitting across the doorway, had been seen the dusky form of Pocahontas, clad in her buckskin robe, with a white plume in her hair: keeping tryst, doubtless, with Captain Smith, with none to hinder, now that the dull, puritanic John Rolfe was dead and buried; and, as we have said, Blackbeard's sloop would come glimmering down the river, and the bloody horror of a headless body would land and wend its way to the little fortress which held his stolen treasure. Moreover, Nathaniel Bacon had risen from his grave in York River, and been seen in the Stone House with his compatriots, Drummond, Bland, and Hansford.

Doubtless such stories inspired many of little Mary's early dreams, and caused her to tremble as she lay in her trundle-bed,—kept all day beneath the great four poster, and drawn out at night,—unless, indeed, her loving mother allowed her to climb the four steps leading to the feather sanctuary behind the heavy curtains, and held her safe and warm in her own bosom.

Despite the perils and perplexities of the time; the irreverence and profanity of the clergy; the solemn warning of the missionary Presbyterians; the death of good Queen Anne, the last of the Stuarts, so dear to the hearts of loyal Virginians; the forebodings on the accession to the throne of the untried Guelphs; the total lack of many of the comforts and conveniences of life, Virginians love to write of the early years of the century as "the golden age of Virginia." These were the days known as the "good old times in old Virginia," when men managed to live without telegraphs, railways, and electric lights. "It was a happy era!" says Esten Cooke. "Care seemed to keep away and stand out of its sunshine. There was a great deal to enjoy. Social intercourse was on the most friendly footing. The plantation house was the scene of a round of enjoyments. The planter in his manor house, surrounded by his family and retainers, was a feudal patriarch ruling everybody; drank wholesome wine—sherry or canary—of his own importation; entertained every one; held great[48] festivities at Christmas, with huge log fires in the great fireplaces, around which the family clan gathered. It was the life of the family, not of the world, and produced that intense attachment for the soil which has become proverbial. Everybody was happy! Life was not rapid, but it was satisfactory. The portraits of the time show us faces without those lines which care furrows in the faces of the men of to-day. That old society succeeded in working out the problem of living happily to an extent which we find few examples of to-day."

"The Virginians of 1720," according to Henry Randall, "lived in baronial splendor; their spacious grounds were bravely ornamented; their tables were loaded with plate and with the luxuries of the old and new world; they travelled in state, their coaches dragged by six horses driven by three postilions. When the Virginia gentleman went forth with his household his cavalcade consisted of the mounted white males of the family, the coach and six lumbering through the sands, and a retinue of mounted servants and led horses bringing up the rear. In their general tone of character the aristocracy of Virginia resembled the landed gentry of the mother country. Numbers of them were highly educated and accomplished by foreign study and travel. As a class they were intelligent, polished in manners, high toned, and hospitable, sturdy in their loyalty and in their adherence to the national church."

Another historian, writing from Virginia in 1720, says: "Several gentlemen have built themselves large brick houses of many rooms on a floor, but they don't covet to make them lofty, having extent enough of ground to build upon, and now and then they are visited by winds which incommode a towering fabric. Of late they have sasht their windows with crystal glass; adorning their apartments with rich furniture. They have their graziers, seedsmen, brewers, gardeners, bakers, butchers and cooks within themselves, and have a great plenty and variety of provisions for their table; and as for spicery and things the country don't produce, they have constant supplies of 'em from England. The gentry pretend to have their victuals served up as nicely as the best tables in England."

A quaint old Englishman, Peter Collinson, writes in 1737 to his friend Bartram when he was about taking Virginia in his field of botanical explorations: "One thing I must desire of thee, and do insist that thee oblige me therein: that thou make up that drugget clothes to go to Virginia in, and not appear to disgrace thyself and me; for these Virginians are a very gentle, well-dressed people, and look, perhaps, more at a man's outside than his inside. For these and other reasons pray go very clean, neat and handsomely dressed to Virginia. Never mind thy clothes: I will send more another year."

Those were not troublous days of ever changing fashion. Garments were, for many years, cut after the same patterns, varying mainly in accordance with the purses of their wearers. "The petticoats of sarcenet, with black, broad lace printed on the bottom and before; the flowered satin and plain satin, laced with rich lace at the bottom," descended from mother to daughter with no change in the looping of the train or decoration of bodice and ruff. There were no mails to bring troublesome letters to be answered when writing was so difficult and spelling so uncertain. Not that there was the smallest disgrace in bad spelling! Trouble on that head was altogether unnecessary.

There is not the least doubt that life, notwithstanding its dangers and limitations and political anxieties, passed happily to these early planters of Virginia. The lady of the manor had occupation enough and to spare in managing English servants and negroes, and in purveying for a table of large proportions. Nor was she without accomplishments. She could dance well, embroider, play upon the harpsichord or spinet, and wear with grace her clocked stockings, rosetted, high-heeled shoes and brave gown of "taffeta and moyre" looped over her satin quilt.

There was no society column in newspapers to vex her simple soul by awakening unwholesome ambitions. There was no newspaper until 1736. She had small knowledge of any world better than her[51] own, of bluer skies, kinder friends, or gayer society. She managed well her large household, loved her husband, and reared kindly but firmly her many sons and daughters. If homage could compensate for the cares of premature marriage, the girl-wife had her reward. She lived in the age and in the land of chivalry, and her "amiable qualities of mind and heart" received generous praise. As a matron she was adored by her husband and her friends. When she said, "Until death do us part," she meant it. Divorce was unknown; its possibility undreamed of. However and wherever her lot was cast she endured to the end; fully assured that when she went to sleep behind the marble slab in the garden an enumeration of her virtues would adorn her tombstone.

In the light of the ambitions of the present day, the scornful indifference of the colonists to rank, even among those entitled to it, is curious. Very rare were the instances in which young knights and baronets elected to surrender the free life in Virginia and return to England to enjoy their titles and possible preferment. One such embryo nobleman is quoted as having answered to an invitation from the court, "I prefer my land here with plentiful food for my family to becoming a starvling at court."

Governor Page wrote of his father, Mason Page of Gloucester, born 1718, "He was urged to pay court to Sir Gregory Page whose heir he was supposed[52] to be but he despised title as much as I do; and would have nothing to say to the rich, silly knight, who finally died, leaving his estate to a sillier man than himself—one Turner, who, by act of parliament, took the name and title of Gregory Page."

Everything was apparently settled upon a firm, permanent basis. Social lines were sharply drawn, understood, and recognized. The court "at home" across the seas influenced the mimic court at Williamsburg. Games that had been fashionable in the days of the cavaliers were popular in Virginia. Horse-racing, cock-fighting, cards, and feasting, with much excess in eating and drinking, marked the social life of the subjects of the Georges in Virginia as in the mother country. It was an English colony,—wearing English garments, with English manners, speech, customs, and fashions. They had changed their skies only.

Cœlum, non animum, qui trans mare currunt.

It is difficult to understand that, while custom and outward observance, friendship, lineage, and close commercial ties bound the colony to England, forces, of which neither was conscious, were silently at work to separate them forever. And this without the stimulus of discontent arising from poverty or want. It was a time of the most affluent abundance. The common people lived in the greatest comfort, as far as food was concerned. Fish and flesh, game, fruits,[53] and flowers, were poured at their feet from a liberal horn-of-plenty. Deer, coming down from the mountains to feed upon the mosses that grew on the rocks in the rivers, were shot for the sake of their skins only, until laws had to be enforced lest the decaying flesh pollute the air. Painful and hazardous as were the journeys, the traveller always encumbered himself with abundant provision for the inner man.

When the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe accomplished the perilous feat of reaching the summit of the Blue Ridge Mountains, they had the honor of drinking King George's health in "Virginia red wine, champagne, brandy, shrub, cider, canary, cherry punch, white wine, Irish usquebaugh, and two kinds of rum,"—all of which they had managed to carry along, keeping a sharp lookout all day for Indians, and sleeping on their arms at night. A few years later we find Peter Jefferson ordering from Henry Wetherburn, innkeeper, the biggest bowl of arrack punch ever made, and trading the same with William Randolph for two hundred acres of land.

We are not surprised to find that life was a brief enjoyment. Little Mary Ball, demurely reading from the tombstones in the old St. Stephen's church, had small occasion for arithmetic beyond the numbers of thirty or forty years—at which age, having "Piously lived and comfortably died, leaving the sweet perfume of a good reputation," these light-hearted good livers went to sleep behind their monuments.

Of course the guardians of the infant colony spent many an anxious hour evolving schemes for the control of excessive feasting and junketing. The clergy were forced to ignore excesses, not daring to reprove them for fear of losing a good living. Their brethren across the seas cast longing eyes upon Virginia. It was an age of intemperance. The brightest wits of England, her poets and statesmen, were "hard drinkers." "All my hopes terminate," said Dean Swift in 1709, "in being made Bishop of Virginia." There the Dean, had he been so inclined, could hope for the high living and hard drinking which were in fashion. There, too, in the tolerant atmosphere of a new country, he might—who knows?—have felt free to avow his marriage with the unhappy Stella.

In Virginia the responsibility of curbing the fun-loving community devolved upon the good burgesses, travelling down in their sloops to hold session at Williamsburg. We find them making laws restraining the jolly planters. A man could be presented for gaming, swearing, drunkenness, selling crawfish on Sunday, becoming engaged to more than one woman at a time, and, as we have said, there was always the ducking-stool for "brabbling women who go about from house to house slandering their neighbors:—a melancholy proof that even in those Arcadian days the tongue required control."

Except for the bequest in her brother-in-law's will, nothing whatever is known of Mary Ball for nine years—indeed, until her marriage with Augustine Washington in 1730. The traditions of these years are all based upon the letters found by the Union soldier,—genuine letters, no doubt, but relating to some other Mary Ball who, in addition to the flaxen hair and May-blossom cheeks, has had the honor of masquerading, for nearly forty years, as the mother of Washington, and of having her story and her letters placed reverently beneath the corner-stone of the Mary Washington monument.

Mary Ball, only thirteen years old when her mother died, would naturally be taken to the Westmoreland home of her sister Elizabeth, wife of Samuel Bonum and only survivor, besides herself, of her mother's children. Elizabeth was married and living in her own house seven years before Mrs. Hewes died. The Bonum residence was but a few miles distant from that of Mrs. Hewes, and a mile and a half from Sandy Point, where lived the[56] "well-beloved and trusty friend George Eskridge." Major Eskridge "seated" Sandy Point in Westmoreland about 1720. The old house was standing until eight years ago, when it was destroyed by fire. He had seven children; the fifth child, Sarah, a year older than Mary Ball and doubtless her friend and companion.

Under the "tutelage and government" of a man of wealth, eminent in his profession of the law, the two little girls would naturally be well and faithfully instructed. We can safely assume, considering all these circumstances, that Mary Ball's girlhood was spent in the "Northern Neck of Virginia," and at the homes of Major Eskridge and her only sister; and that these faithful guardians provided her with as liberal an education as her station demanded and the times permitted there cannot be the least doubt. Her own affectionate regard for them is emphatically proven by the fact that she gave to her first-born son the name of George Eskridge, to another son that of Samuel Bonum, and to her only daughter that of her sister Elizabeth.

Tradition tells us that in the latter part of the seventeenth century, George Eskridge, who was a young law student, while walking along the shore on the north coast of Wales, studying a law-book, was suddenly seized by the Press Gang, carried aboard ship and brought to the colony of Virginia.[57] As the custom was, he was sold to a planter for a term of eight years. During that time, he was not allowed to communicate with his friends at home. He was treated very harshly, and made to lodge in the kitchen, where he slept, because of the cold, upon the hearth.

On the day that his term of service expired he rose early, and with his mattock dislodged the stones of the hearth. Upon his master's remonstrance, he said, "The bed of a departing guest must always be made over for his successor;" and throwing down his mattock he strode out of the house, taking with him the law-book which had been his constant companion during his years of slavery.

He returned to England, completed his law studies, was admitted to the bar, and, returning to Virginia, was granted many thousand acres of land, held several colonial positions, and became eminent among the distinguished citizens of the "Northern Neck,"—the long, narrow strip of land included between the Potomac and the Rappahannock rivers. His daughter, Sarah, married Willoughby Newton, and lived near Bonum Creek in Westmoreland. The family intermarried, also, with the Lee, Washington, and other distinguished families in the Northern Neck.

The social setting for Mary Ball—now a young lady—is easily defined. It matters little whether she did or did not visit her brother in England. She certainly belonged to the society of Westmoreland, "the finest," says Bishop Meade, "for culture and sound patriotism in the Colony." Around her lived the families of Mason, Taliaferro, Mountjoy, Travers, Moncure, Mercer, Tayloe, Ludwell, Fitzhugh, Lee, Newton, Washington, and others well known as society leaders in 1730. If she was, as her descendants claim for her, "The Toast of the Gallants of Her Day," these were the "Gallants,"—many of them the fathers of men who afterward shone like stars in the galaxy of revolutionary heroes.

The gallants doubtless knew and visited their tide-water friends,—the Randolphs, Blands, Harrisons, Byrds, Nelsons, and Carters,—and, like them, followed the gay fashions of the day. They wrote sonnets and acrostics and valentines to their Belindas, Florellas, Fidelias, and Myrtyllas—the real names of Molly, Patsy, Ann, and Mary being[59] reckoned too homespun for the court of Cupid. These gallants wore velvet and much silk; the long vests that Charles the Second had invented as "a fashion for gentlemen of all time"; curled, powdered wigs, silver and gold lace; silken hose and brilliant buckles. Many of them had been educated abroad, or at William and Mary College,—where they had been rather a refractory set, whose enormities must be winked at,—even going so far as to "keep race-horses at ye college, and bet at ye billiard and other gaming tables." Whatever their sins or shortcomings, they were warm-hearted and honorable, and most chivalrous to women. It was fashionable to present locks of hair tied in true-lovers' knots, to tame cardinal-birds and mocking-birds for the colonial damsels, to serenade them with songs and stringed instruments under their windows on moonlight nights, to manufacture valentines of thinnest cut paper in intricate foldings, with tender sentiments tucked shyly under a bird's wing or the petal of a flower.

With the youthful dames themselves, in hoop, and stiff bodice, powder and "craped" tresses, who cut watch-papers and worked book-marks for the gallants, we are on terms of intimacy. We know all their "tricks and manners," through the laughing Englishman, and their own letters. An unpublished manuscript still circulates from hand to hand in Virginia, under oath of secrecy, for it[60] contains a tragic secret, which reveals the true character of the mothers of Revolutionary patriots. These letters express high sentiment in strong, vigorous English, burning with patriotism and ardent devotion to the interests of the united colonies—not alone to Virginia. The spelling, and absurdly plentiful capitals, were those of the period, and should provoke no criticism. Ruskin says, "no beauty of execution can outweigh one grain or fragment of thought." Beauty of execution and good spelling, according to modern standards, do not appear in the letters of Mary Ball and her friends, but they are seasoned with many a grain of good sense and thought.