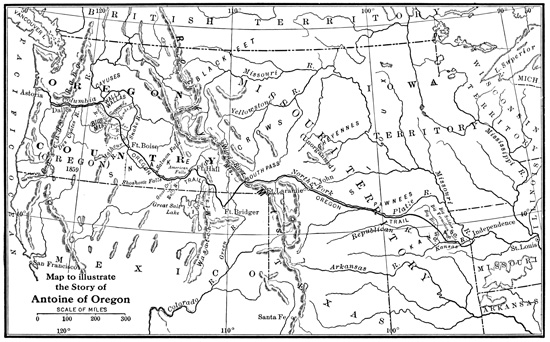

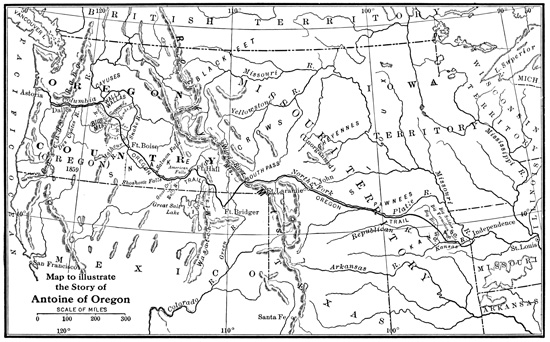

Map to illustrate the Story of Antoine of Oregon

Title: Antoine of Oregon: A Story of the Oregon Trail

Author: James Otis

Release date: October 5, 2013 [eBook #43897]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

Map to illustrate the Story of Antoine of Oregon

A Story of the Oregon Trail

BY

JAMES OTIS

NEW YORK -:- CINCINNATI -:- CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Copyright, 1912, by

JAMES OTIS KALER.

Copyright, 1912, in Great Britain.

ANTOINE OF OREGON.

W. P. I

The author of this series of stories for children has endeavored simply to show why and how the descendants of the early colonists fought their way through the wilderness in search of new homes. The several narratives deal with the struggles of those adventurous people who forced their way westward, ever westward, whether in hope of gain or in answer to "the call of the wild," and who, in so doing, wrote their names with their blood across this country of ours from the Ohio to the Columbia.

To excite in the hearts of the young people of this land a desire to know more regarding the building up of this great nation, and at the same time to entertain in such a manner as may stimulate to noble deeds, is the real aim of these stories. In them there is nothing of romance, but only a careful, truthful record of the part played by children in the great battles with those forces, human as well as natural, which, for so long a time, held a vast 4 portion of this broad land against the advance of home seekers.

With the knowledge of what has been done by our own people in our own land, surely there is no reason why one should resort to fiction in order to depict scenes of heroism, daring, and sublime disregard of suffering in nearly every form.

JAMES OTIS.

| PAGE | |

| The Fur Traders | 9 |

| Why I am not a Fur Trader | 11 |

| Striving to Plan for the Future | 13 |

| An Inquisitive Stranger | 15 |

| An Unexpected Proposition | 16 |

| I set Out as a Guide | 18 |

| John Mitchell's Outfit | 20 |

| Making the Bargain | 23 |

| We Leave St. Louis | 25 |

| The Hardships to be Encountered | 26 |

| The Camp at Independence | 28 |

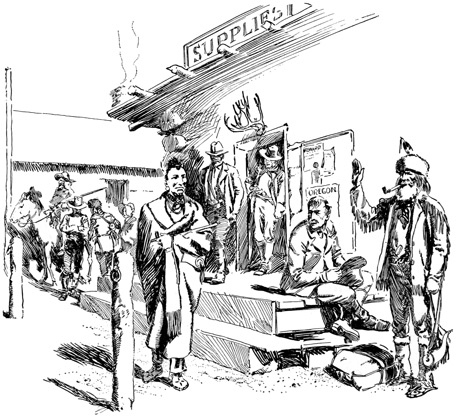

| A Frontier Town | 30 |

| The Start from Independence | 33 |

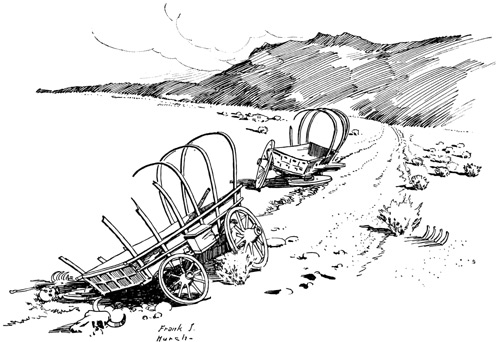

| Careless Travelers | 35 |

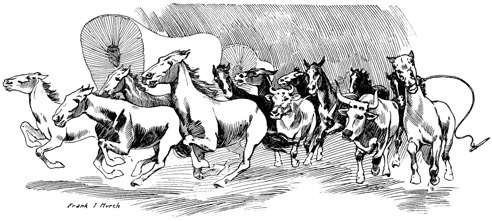

| Overrun by Wild Horses | 38 |

| Searching for the Live Stock | 40 |

| Abandoning the Missing Animals | 42 |

| Meeting with Other Emigrants | 43 |

| A Tempest | 46 |

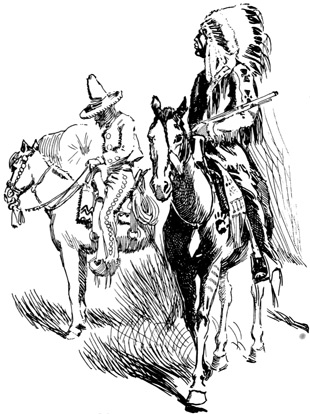

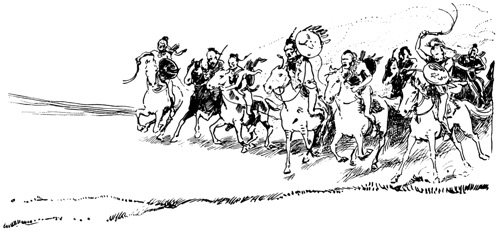

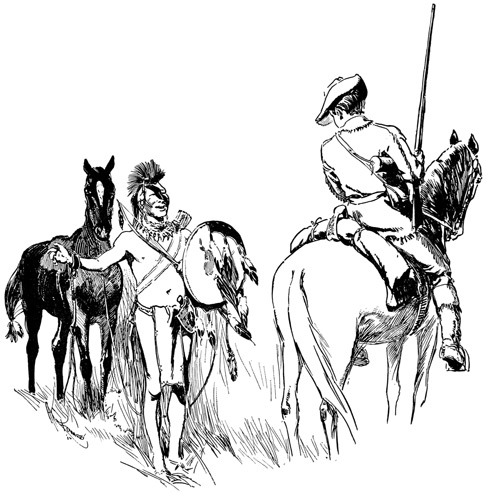

| Facing the Indians | 49 |

| Teaching the Pawnees a Lesson | 51 |

| The Pawnee Village | 53 |

| A Bold Demand | 54 6 |

| I Gain Credit as a Guide | 56 |

| A Difficult Crossing | 58 |

| Wash Day | 60 |

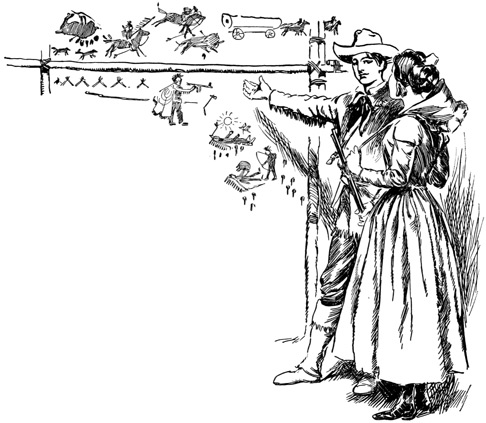

| Indian Pictures | 62 |

| A Plague of Wood Ticks | 64 |

| Another Tempest | 66 |

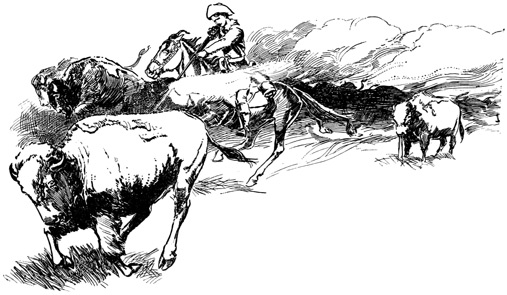

| The Cattle Stampeded Again | 68 |

| Difficult Traveling | 69 |

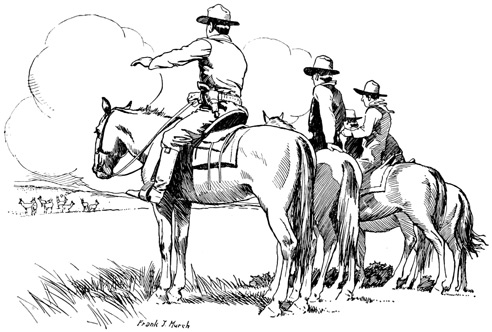

| Colonel Kearny's Dragoons | 71 |

| Disagreeable Visitors | 73 |

| Driving away the Indians | 75 |

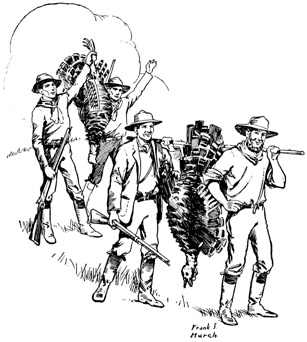

| Turkey Hunting | 76 |

| Eager Hunters | 77 |

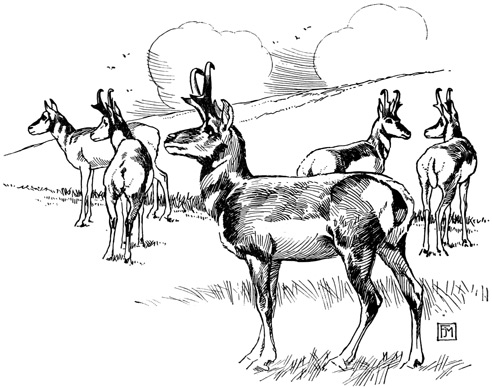

| Antelope Country | 79 |

| Shooting Antelopes | 81 |

| A Pawnee Visitor | 83 |

| The Pawnees try to Frighten Us | 85 |

| Defending Ourselves | 87 |

| Scarcity of Fuel, and Discomfort | 89 |

| Lame Oxen | 91 |

| An Army of Emigrants | 92 |

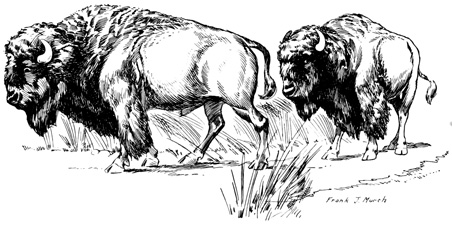

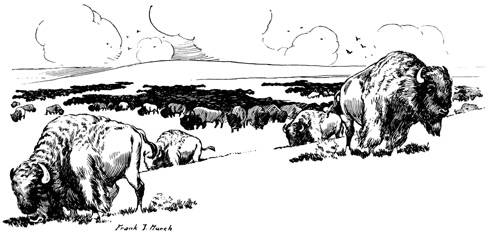

| The Buffalo Country | 95 |

| Hunting Buffaloes | 97 |

| My Mother's Advice | 99 |

| Ash Hollow Post Office | 100 |

| New Comrades | 102 |

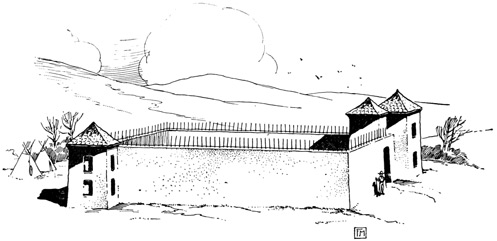

| Fort Laramie | 103 |

| A Sioux Encampment | 106 7 |

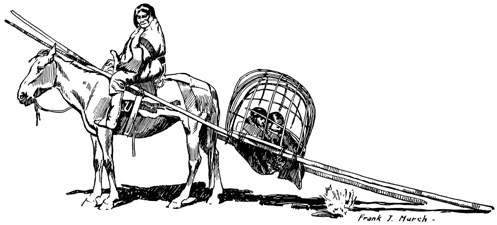

| Indians on the March | 107 |

| The Fourth of July | 109 |

| Multitudes of Buffaloes | 111 |

| We Meet Colonel Kearny Again | 113 |

| Across the Divide | 115 |

| Fort Bridger | 117 |

| Trading at Fort Hall | 122 |

| Thievish Snakes | 123 |

| The Hot Springs | 124 |

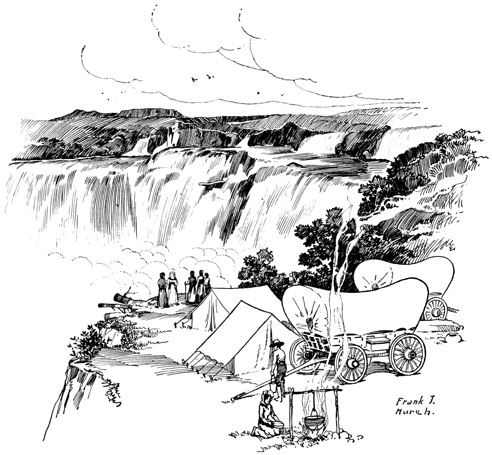

| The Falls of the Snake River | 126 |

| Signs of the Indians | 128 |

| Beset with Danger | 129 |

| Hunger and Thirst | 131 |

| Nearly Exhausted | 133 |

| Arrival at Fort Boise | 135 |

| On the Trail Once More | 137 |

| Cayuse Indians | 139 |

| The Columbia River | 140 |

| An Indian Ferry | 141 |

| The Dalles of the Columbia | 143 |

| Our Live Stock | 144 |

| My Work as Guide Ended | 145 |

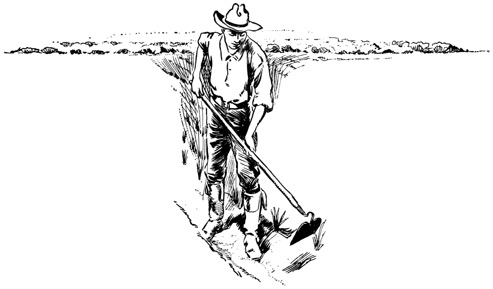

| I Become a Farmer | 146 |

ANTOINE OF OREGON

There is ever much pride in my heart when I hear it said that all the trails leading from the Missouri River into the Great West were pointed out to the white people by fur buyers, for my father was well known, and in a friendly way, as one of the most successful of the free traders who had their headquarters at St. Louis.

It is not for me to say, nor for you to believe, that the fur traders were really the first to travel over these trails, for, as a matter of fact, they were marked out 10 in the early days by the countless numbers of buffaloes, deer, and other animals that always took the most direct road from their feeding places to where water could be found.

Then came the Indians, seeking a trail from one part of the country to another, and they followed in the footsteps of the animals, knowing full well that thereby they would not lack for water, the one thing needful to those who go to and fro in the wilderness.

Thus it was that the animals and the Indians combined to mark out the most direct roads that could be made, with due regard to the bodily needs of those who traveled from one part of the Great West to another.

As the traders in furs journeyed from tribe to tribe of the Indians, or sought the most favored places for trapping, they learned how white men could go westward from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean without fear of dying from hunger or thirst.

My father, Pierre Laclede, was, as I have said, a free trader, which means that he went out into the wilderness with his crew of boatmen and trappers, free from any bargains or duties to the great fur trading companies, such as the Hudson's Bay, the Northwest, and the X. Y.

There were regular battles fought between the hunters and trappers of these great companies in the olden 11 days, when St. Louis was under Spanish rule and had become a famous gathering place for the fur traders.

There were many like my father, who, hiring men to help them, carried into the wilderness goods to be exchanged with the Indians for furs, and, failing in this, set about trapping fur-bearing animals throughout the winter season.

Wonderful sport these same traders had, as I know full well, having been more than once with my father over that trail leading from the Missouri River to the Oregon country.

Then there was the home-coming to St. Louis, when every man forgot the days on which he had been cold or hungry, and no longer heeded the half-healed wounds received in Indian attacks, when he had been forced to defend with his life the furs he had gathered.

Once in St. Louis, what rare times of feasting and making merry, while the furs were being shipped to New Orleans, or bartered to the big companies that were ever on the watch for the return of the free traders!

I, Antoine Laclede, would have followed in the footsteps of my father, becoming myself a free trader after the treacherous Blackfeet Indians killed him, had it not been that my mother, with her arms around my neck, pleaded that I remain at home with her. 12

Therefore, instead of carrying on my father's business as a lad of fifteen should have done, I strove to content myself at St. Louis, to the pleasure of my dear mother.

However much affection there might be between us, it remained that we must be supplied with food, and that my mother should have the things necessary for her comfort.

But if I did not take up my father's business after he had lost, with his life, the store of furs which he had been eight months in gathering, as well as what remained of the goods he had carried into the wilderness for trading, then how could I rightly fill the position as head of the family, when all I had in this world were my two hands and the desire to make my mother happy?

We lived on a street near the old cathedral, and it may be that our small home was not the most pleasing to look upon of all the houses in St. Louis; but in it I was born. My father had built it, paying for 13 every timber with furs he had gathered at risk of his life, and I would not have yielded it in exchange for the finest house in the land.

The evil days fell upon us, meaning my mother and me, very shortly after the news of my father's murder was brought to St. Louis, for we soon came to know that we had neither goods nor furs enough to keep us one full year.

Then it was that I went out one day alone to the river bank, where I might have solitude and think how I could care for my mother as the only son of a widow should care for that person whom he most loves.

I had lived fifteen years. There was no trapper in the Northwest Company who could take more furs than I could. To ride and shoot were my pleasures, and my unhappiness was in being forced to set down words with a pen, or to puzzle my poor brain over long rows of figures which must have been invented only for the sorrow of Antoine Laclede.

My rifle and Napoleon, a small spotted pony that could outkick any beast this side the Rocky Mountains, made up all I owned of value, and yet with them I must earn enough to support my mother and make her comfortable. 14

The truth is, I might have joined with some free trader who had known my father, working for a small wage, which would not be more than enough to supply my mother with food and clothes such as had been provided by my father; but I must earn more than that, lest the day should come when, from wounds or sickness, I could not hold up my end with my companions on the trail or with the traps.

All this made my heart heavy as I sat there on the river bank asking myself what there was a lad like me could do.

Just at that time, when I was most downhearted, a man, tall of stature and spare in flesh, came up close beside me, and, as it seemed, looked down with much mirth in his heart, perhaps because I carried such a woebegone expression on my face. 15

Then, much to my surprise, he said, speaking in what seemed an odd tone, much as though he had a cold in his head:—

"Are you the son of Laclede, the free trader who was killed by the Blackfeet Indians not so long ago?"

I was ever proud to own that I was my father's son, and speedily gave the stranger an answer, although at the same time asking myself whether there was any good reason for such a question, or if he was intending to make sport of me.

"I am told that you have been over the trail 'twixt here and the Oregon country with your father, lad?"

"I have been twice into the land of the Walla Wallas, but no farther than that, although it would have pleased me well could I have seen the great ocean."

"Now I am not so certain where the country of what you call the Walla Wallas may be," the man said with a puzzled expression upon his face, whereupon I answered quickly, proud because of being able to tell:—

"It is this side the Cascade Range, the other side of the Blue Mountains, near where the Columbia River takes a sharp turn to the westward."

"The Columbia River, eh?" the man repeated, as 16 if satisfied with my reply. "Then you surely must have traveled near to the Pacific Ocean?"

"I have been so near that one might go down the river to it in a canoe, if he were so disposed; but there is a station of the Hudson's Bay Company near the coast and we free traders who deal with the Northwest Company have no desire for traffic with those who would shut us out from St. Louis, fearing lest we may cut into their trade."

The man seated himself by my side as if satisfied that I was the one whom he sought, and began his business by saying:—

"My name is John Mitchell. I am at the head of a party of thirty men, women, and children who are bound for the Oregon country. We are taking with us forty head of oxen, twenty horses, ten mules, and thirty cows, to say nothing of the remainder of the outfit. I counted on meeting here at St. Louis a man who would guide us across, but find 17 that he has left us in the lurch, likely because of getting a better offer from some other company of settlers. Now I have been told that you could serve us as guide; that you are what may be called a fairly good hunter; and, although you look a bit too young for the business, there are those here in St. Louis who say you may be depended upon. What about guiding my party across? We are willing to pay considerably more than fair wages—"

"It may not be for me to do any such thing," I replied quickly, although at the same time wishing I could go once more into the Oregon country and do a man's work as guide. "I have here my mother, who has no other to depend upon, and I must stand by her, as a son should."

"Well said, lad, well said. It does you credit to think first of your mother; but we are willing to pay considerable money to one who can guide us, because this kind of traveling is new to all my party. Already in coming up from Indiana we have had trouble with the cattle and with the teams. Now say three hundred dollars for the trip, and if you are minded to take your mother with you we stand ready to let her share in whatsoever we have."

There is no reason why I should set down all we said, for we sat there on the river bank until an hour had passed, talking all the while. 18

Each moment I grew more and more eager for the adventure, until it seemed to me I had never had but one desire in life, and that to go into the Oregon country and make there a home for my mother.

I promised to meet the man again that evening and went straight away home to lay the matter before my mother. It surprised me not a little that she seemed to be in favor of going to the Oregon country, and I have since been led to believe that her willingness to abandon the home in St. Louis came from the wish to make a change and to leave that place where everything must needs remind her of my father.

Before seeking out John Mitchell, whose company was encamped on the opposite side of the river, I visited a neighbor who had once offered to buy our home. With him I agreed that for a certain sum of money he should take possession of the house, using it as his own until my mother and I came back, or, in case we remained in the Oregon country, then he was to pay us as many dollars as we agreed upon.

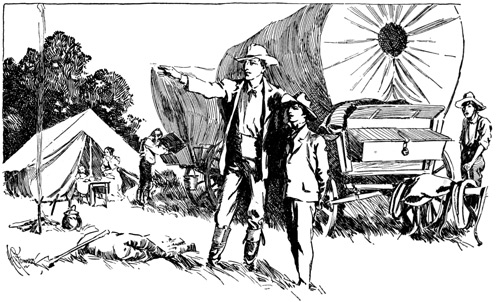

That afternoon, an hour before sunset, I paddled across the river to where John Mitchell's company was encamped, and for the first time I questioned whether it might be possible for me, a lad only fifteen years of age, to guide all these people, who seemingly 19 had no more idea of what was to be encountered in a journey to the Oregon country, than if they had never heard of such a place.

I dare venture to say there could not have been found in St. Louis a lad over ten years old who would have shown so much ignorance in forming a camp, as did John Mitchell, who held himself commander of the company.

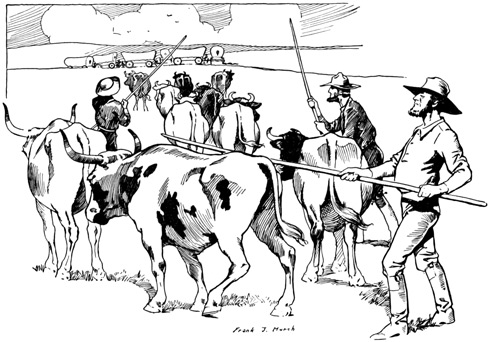

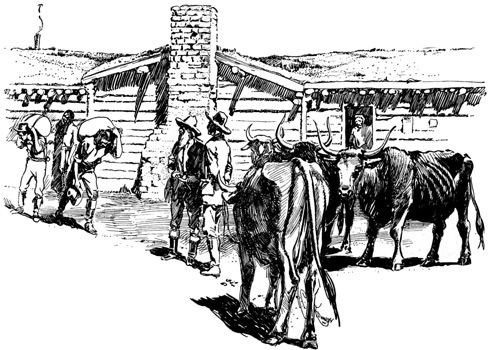

True, there was no reason why they need guard themselves as if in the country of an enemy. Yet 20 if they were careless at the start, heeding not the common precautions against the stampeding of their cattle, or the possibility that prowling Indians might steal whatever lay carelessly around, then surely when in a place where danger lurked, they could not be depended upon to care for themselves in a sensible manner.

Somewhat of this I said to John Mitchell while looking around the encampment, and that he himself was ignorant of what might be met with on a journey to the Oregon country, was shown when he asked:—

"And are you reckoning, lad, that we may come upon much danger?"

"Ay, sir, and plenty of it," I replied. "Just now the Indians are quiet, so I have heard it said by the traders; but even when there is no disturbance of any account, you are likely to come upon roving bands that will make trouble. Even though they may do no worse, you can set it down as a fact that from the time of leaving the settlement of Independence, where the journey really begins, until you have come into the Walla Walla country, there will be hardly a day, or, I should say, a night, when you are not in danger of losing your stock through these red thieves."

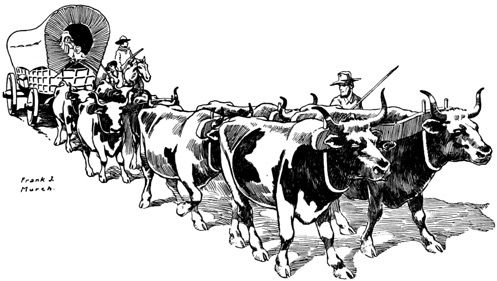

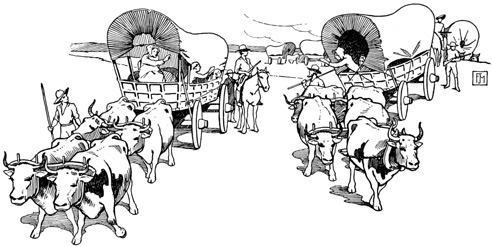

There was one thing in favor of John Mitchell, as I looked at the matter, which was that his outfit was 21 most complete. He had five well-made carts with straight bodies, and sideboards from fourteen to sixteen inches wide running outward four or five inches; in other words, what are called "Mormon wagons," and to three of these he counted on putting four yoke of cattle apiece. I was not so well satisfied with this, for the beasts had been raised in Indiana, and therefore were not accustomed to eating prairie grass, which would be the greater portion of their food during the journey.

I had always heard it said that Illinois or Missouri cattle could stand the journey to the Oregon country better than any others, although then I did not know it from my own experience.

The ten mules were to be used for the hauling of the two remaining wagons. To one of these would be harnessed six of the animals, and the other, in which many of the women and children were to ride, was to be drawn by four. The horses were to be used under the saddle. 22

I was forced to admit that Mitchell had not been niggardly in outfitting his company.

He had no less than five sheet-iron stoves with boilers, one being carried on a small platform at the rear end of each wagon. There were tents in abundance for all the company, while for cooking utensils, there were plates and cups and basins of tinware, half a dozen or more churns, an ample supply of water kegs, and farming tools almost without number.

I had little or no interest in this part of the outfit, but took good care to make certain there were ropes and hobble straps in plenty for tying up the horses and fettering those that were likely to stray, because I knew from experience how much of such supplies might be lost or stolen during the long journey. 23

The weapons carried by the men were of heavier caliber than I would have suggested, unless they counted on using them wholly for buffalo shooting. John Mitchell took no little pride in showing me his rifled gun which carried thirty-two bullets to the pound, when to my mind fifty-six would have served him better for general work; but that was really no concern of mine.

We talked over the matter fairly and at great length, all the men of the company and some of the women taking part in the parley. The bargain, as I understood it, was that I was hired for no other service than to guide this company, and also to make suggestions as to the best places for camping, as well as how we could keep the people supplied with fresh meat.

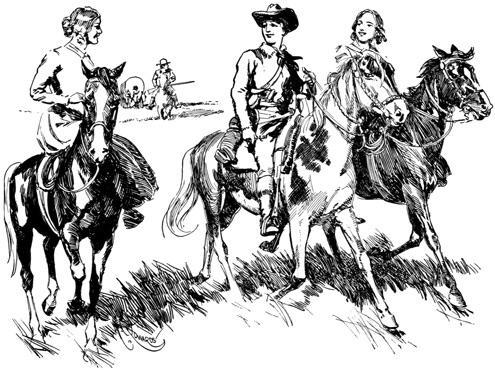

It was agreed that my mother should ride in the four-mule wagon with John Mitchell's family, which consisted of his wife, a girl about my own age by name of Susan, and three awkward-looking boys. The oldest of these lads was not more than ten, I should think, and all of them were so clumsy that it seemed almost impossible for them to avoid treading on their own feet. About mounting a horse or rounding up cattle, they knew no more than my Napoleon knew about good manners. 24

Susan, however, was a sprightly girl, who, as it seemed to me, had more good sense in her little finger than might be found in all the rest of the family. Before my visit was at an end, she came to ask concerning this or that which we might meet with on the way, and I believed I had found one who would be a most desirable comrade.

Unless I mistook her entirely, she was a girl to be depended upon in the time of trouble, and when one would travel from the Missouri River to the Oregon country, it is of the greatest importance to have with him only those who can be relied on to a certainty when danger lurks at hand, as it surely does, so I have heard my father say, from the time the voyager leaves the Kansas River until he has come to the Columbia.

It was agreed that my mother and I should have a day in which to make ready for this journey, which, if we met with no serious mishaps, would require not less than five months to make; therefore it can well be understood that we had little time to spend in sleep, 25 if we would present ourselves to John Mitchell at the hour agreed upon.

It is my desire never to make a promise which I do not, or cannot keep; consequently there were many things left undone in St. Louis when mother and I crossed the river; but it was better thus than that I should disappoint ever so slightly those with whom I had made a positive agreement.

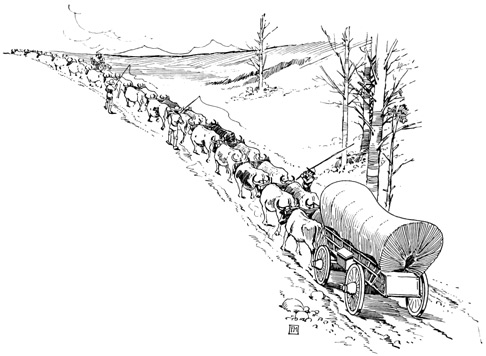

In order that one may the better understand how much of a journey it is from the Missouri River to the Oregon country, I set down here the fact that at eleven o'clock in the forenoon, on the twenty-fifth day of April, in the year 1845, we, meaning John Mitchell's company, my mother, and I, set off on that long march. The real journey would not begin until we had passed that settlement on the Missouri known as Independence, which is the point of departure for those who count on traversing the Oregon or the Santa Fe trail.

Therefore concerning this portion of our march I shall content myself simply with saying that we arrived at Independence on the morning of May 6th, and made camp two miles beyond, on the bank of a small creek, where there was plenty of grass for the cattle.

It must be understood that up to this time we had been traveling through one settlement and another 26 in a portion of the country where were to be found as many people as lived, mayhap, in the neighborhood from which John Mitchell had come. Yet so awkward were the men and boys, that while we were traversing beaten roads they found it exceedingly difficult to keep the cows from straying or the oxen from stampeding even while they were yoked and hitched to the heavy wagons.

I do not claim to have had any experience at driving oxen or herding cattle, and therefore I held myself aloof, saying it were better these people from Indiana should learn their lesson when there were but few difficulties in the way and no dangers, so that after we should come where the real labor began, they might at least have some slight idea of what was expected of them.

But for the fact that Susan Mitchell, riding upon a small black, wiry-looking horse, held herself well by my side, I would have been disheartened even before we had really begun the journey, because I was looking forward to what we must encounter, and saying to myself that unless these people could pull themselves together in better fashion, we were certain to come to grief.

When a company fails to herd thirty cows, over 27 what might well be called a beaten highway, what would you expect when in a country where the Indians are doing all they can to stampede and run off cattle as well as horses?

I soon saw that Susan was a girl of good understanding, for without a word having been spoken, she seemed to realize those fears which had come into my mind, and said again and again as if to strengthen my courage:—

"They will know more about this kind of traveling when we reach Independence."

I could not refrain from saying in reply that unless they learned more speedily it would be well we waited a full year at Independence, rather than attempt a journey where so much danger and hardship awaited us.

I venture to say that there was not one among John Mitchell's company who could have put a pack upon a horse in such a manner that it would hold in 28 place half an hour over rough traveling; and as for handling a mule team, the driver of that wagon in which my mother rode had no more idea of how the beasts should be treated than if he had so many sheep in harness.

To show how ignorant these people were regarding the country, I have only to say that from the moment we left St. Louis one or another was continually asking me whether we were likely to come upon buffaloes before the night had set. The idea of buffaloes between St. Louis and Independence, save perchance we came upon some old bull that had been driven away from the herd by the hunters!

It was by my advice that John Mitchell decided to overhaul his outfit at Independence in order to learn whether there might be anything needed, for after having left the settlement we would find no opportunity of replenishing our stores save at some one of the forts, and then it was a question, serious indeed, whether we could get what might be needed.

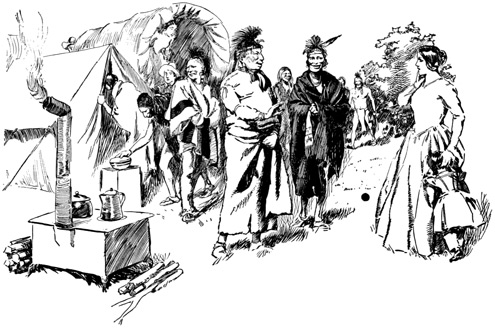

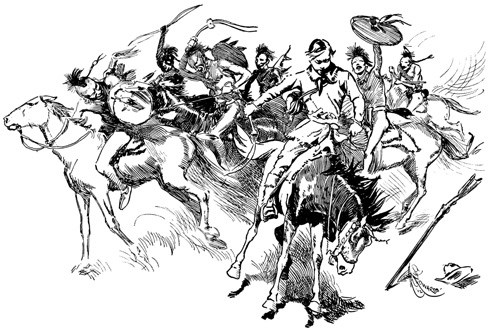

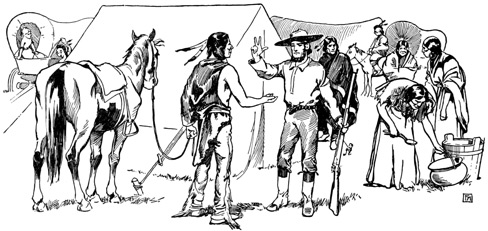

The tents were hardly more than set up, and the women had but just got about their cooking, for the breakfast had been a hasty meal owing to our being so near the settlement, when we were visited by a dozen or more Kansas Indians, who are about as disreputable 29 a looking lot as can be found in the country—dirty, ill-favored red men with ragged blankets cast about them, and seeming more like beggars than anything else.

To tell the truth, I would rather have seen around the camp a Blackfoot, a Cheyenne, or a Sioux, knowing that any of them would murder me if he had a fair opportunity, than those beggarly Kansas savages.

It was the first time any of the women of our company, save my mother, had seen an Indian near his own village, and straightway all of them, with the exception of Susan, were in a panic of fear, believing harm would be done.

Even John Mitchell was undecided as to how he should treat them, until I told him that any attempt 30 to drive the creatures away would be useless, and that if his people were so disposed they might give them some food; but it was in the highest degree necessary that sharp watch be kept, else we would find much of our outfit missing after the visitors had taken their departure.

The men and the boys of our company were so disquieted because of having come thus suddenly upon the Indians, that they kept good watch over the camp during this first day, and it would have been well for all of us if they had continued to stand as honest guard over their belongings.

It was found that we were needing extra bows for the wagons, meaning those bent hoops over which the canvas covering is stretched, that the supply of shoes for the horses and mules was not sufficient, and, in fact, there were half a hundred little things required which the women believed necessary to their comfort.

Therefore John Mitchell and I went into the settlement to get what was wanted, and, like the good comrade she gave promise of being, Susan insisted on going with us.

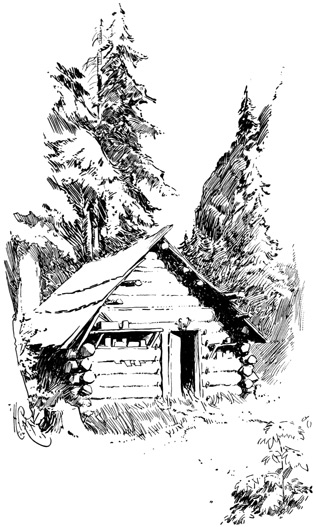

Independence was much like a trading post, save that there were no blockhouses; but the log tavern had the appearance of a building put up to resist an attack, and the brick houses surrounding it were made 31 with heavy walls in which were more than one loophole for defense.

The idea that the settlement was a frontier post was heightened by the number of Indians to be seen, while their scrawny ponies were tied here and there in every available place.

There were the wretched Kansas, only half covered with their greasy, torn blankets, Shawnees, decked out in calicoes and fanciful stuff, Foxes, with their shaved heads and painted faces, and here and there a Cheyenne sporting his war bonnet of feathers.

The scene was not new to me, and so did not invite my attention; but Susan, who seemingly believed that she had suddenly come into the very heart of the Indian country, was so interested that I went with her here and there, while her father was bartering in the shops, and before an hour had passed her idea of an Indian was far different from what it had been before she left her home in Indiana. 32

I had nothing to say against the savages more than can be set down when I speak of the murder of my father, and save for the fact that Susan was so eager to see all she might, and that everything was so strange to her, I would not have lingered in the settlement a single minute longer than was necessary to complete our outfit.

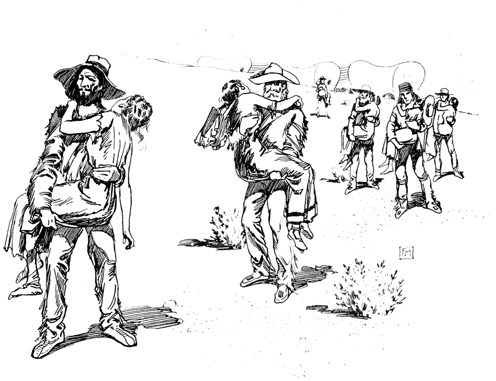

There were here Santa Fe traders in Mexican costume; French trappers from the mountains, with their long hair and buckskin clothing; groups of 33 Spaniards, who were evidently bound down the Santa Fe trail; and here and there and everywhere as it seemed, were people from the States, emigrants like those who followed John Mitchell, to the number, I should say, of not less than two hundred, all expecting to make homes in the Oregon country.

It saddened me to think of what was before these people. To gain the banks of the Columbia River they must travel more than two thousand miles, in part over sandy plains, where would be found little or no water for themselves and scanty feed for their animals. There were rivers to be crossed where the current ran so swiftly that a single misstep might mean death. Mountain ranges were to be climbed when even the strongest would find it difficult to make progress, and all the while danger from wild beasts or wilder men.

And it was I who must show these men when and where to camp, how to bring down the game which would be necessary for their very existence, and lead them, in fact, as one might lead children.

We remained in camp by the creek until next morning, and then our way lay over the rolling prairies, where was grass on every hand and water in abundance, yet we made only fifteen miles between eight 34 o'clock in the morning and within an hour of sunset, owing to the awkwardness of those who were striving to drive our few head of cattle.

Then came the first real camp, meaning the first time we had halted where it was necessary to guard everything we owned against the Indians, for we knew full well there were plenty in the vicinity of Independence, and I strove my best to show these people how an encampment should be formed on the prairie.

It was difficult to persuade John Mitchell that it would be better to give the horses and mules a side hobble, than to take chances of securing them by picket ropes. I had always heard that by buckling a strap around the fore and hind legs, on the same side, taking due care not to chafe the animal's legs, he could not 35 move away faster than a walk, while if he was hobbled by the forefeet only, it would be possible for him to gallop after some practice.

There were many in our party who claimed it was a useless precaution to hobble the horses, and insisted on fastening them to picket pins, doing so in such a slovenly manner that I knew if the animals were stampeded they could easily make their escape.

Before morning came we had good proof that carelessness in looking after the live stock at such a time is much the same as a crime.

When I proposed that watch be set around the encampment during the night, every man, even including John Mitchell, protested, saying it was a needless precaution, that they were all needing sleep, and there was no reason why any should stand guard when they could look around on every hand and make certain there was no one near to do them harm.

One of the women asked me if there might be any danger from wild beasts, and when I told her we had not yet come into that part of the country where such game were found, every member of the company believed I was only trying to show myself as the commander.

I heard one of the men say grumblingly to another, 36 that he was not minded to put himself under the orders of a boy who took pleasure in displaying his authority even to the extent of making them stand needless watch.

Never had I seen my father make camp, even though no more than two miles from a fort or a settlement, without carefully hobbling his horses, rounding up the cattle, if he had any, and stationing a picket guard, insisting that those on duty remain awake during every hour of the night.

Now, however, these people from Indiana, who knew nothing whatsoever of traveling in the wilderness, claimed to have a better idea of how camp should be guarded than did I, who had already traversed the Oregon trail twice, and I so far lost my temper as to make no reply, saying to myself that if they were inclined to take desperate chances, the loss would be theirs, not mine.

Mayhap if we had been farther along the trail among the mountains, where the danger would be greater if we lost all our animals, then for my mother's 37 sake I might have insisted strongly that the orders which I gave should be obeyed.

As I have said, however, I held my peace, while those foolish people lay down to sleep in their tents, or in the wagon bodies, believing they were safe beyond any possible chance of danger simply because of being no more than seventeen miles from Independence.

I must say to John Mitchell's credit that he outfitted me as he would have done an older guide, and set apart for my especial use one of the small canvas tents.

Believing that my mother would have more comfort by herself than if she shared a bed in one of the larger tents, or in one of the wagons where so many must sleep, I proposed that she use my camp, and we two laid ourselves down that night feeling uncomfortable in mind, for she understood quite as well as did I that we were taking great chances at the outset of the journey.

I had hobbled Napoleon securely, as you can well fancy. In addition to that I had made him fast to a picket pin firmly driven into the ground so there might be no danger of his straying too far away.

It was not a simple matter to enjoy the resting time, because of the weight of responsibility which was upon me.

Even though John Mitchell's people were not inclined to obey such orders as I saw fit to give, yet I 38 knew that in event of trouble they would cast all the blame on my shoulders, and not until a full hour had passed were my eyes closed in slumber.

It seemed as if I had hardly more than lost myself in sleep when I was aroused by a noise like distant thunder, and springing to my feet, as I had been taught to do by my father at the first suspicious sound, I stood at the door of the tent while one might have counted ten, before realizing that a herd of those wild ponies which are to be found now and then on the prairies was coming upon us.

Once before in my life had I seen horses and cattle stampeded by a herd of those little animals, and without loss of time I rushed into the open air, shouting loudly for the men to bear a hand, at the same time discharging all the chambers of my weapon. 39

Unfortunately, however, I was too late to avert the evil. If we had had a single man on guard he could have given warning in time for us to have checked the rush; but as it was the ponies were within the encampment before I had emptied my weapon.

John Mitchell had not brushed the slumber from his eyelids before the ponies overran the camp and passed on at full speed, taking with them every horse, mule, ox, and cow we had among us, save only Napoleon, who would have joined in the flight had it been possible for him to do so.

"What has happened? What was it?" John Mitchell cried as he came running toward my tent with half a dozen of the other men at his heels, and I replied with no little bitterness in my tone:—

"A herd of wild ponies has stampeded every head of stock, except Napoleon."

"But my horse was made fast," one man cried, as if, because he had left the animal with his leading rope around a picket pin loosely driven, it would have been impossible for him to get away.

The driver of the four-mule team declared that his stock could not have been run off because he had seen to it that each animal was hitched securely, while a third insisted that we must have been visited by the Indians, who had frightened the beasts in order the better to carry them away. 40

I could not refrain from saying what was true:—

"If we had had but one man on guard this could not have happened. I tell you that the disturbance this night was caused by a herd of wild ponies."

"Then why do we not go in search of the stock?" John Mitchell cried, and I replied:—

"That you may do, if it please you; but I have never yet seen the man who, on foot, could come up with a horse that had joined the wild of his kind. When the morning dawns, I will do all I can to aid in gathering up the stock, but until then there is nothing to be done."

Then, with much anger in my heart because this thing had happened through sheer carelessness, I went back into my tent, nor would I have more to say to any member of the company, although no less than half a dozen men stood outside asking this question or that, all of which simply served to show their folly.

When day broke John Mitchell was man enough to meet me as I came out of my tent, and say in what he intended should be a soothing tone:—

"I am willing to admit, lad, that we showed ourselves foolish in not obeying your orders. From now on you can make certain every man jack of us will 41 do whatsoever you say. Now tell us how we had best set off in search of the stock."

"There is no haste. The horses and mules will run with the ponies until they are tired and need food, therefore we may eat our breakfast leisurely. My advice is that the company get under way, moving a few miles across the prairie to the next creek, while all, save those needed to drive the teams, go with me."

"But we can't start a single wheel. There is no ox, horse, or mule in the encampment," John Mitchell cried, and then my face flushed with shame because I had forgotten for the instant that we had no means of breaking camp.

There is little need why I should spend many words 42 in telling of what we did during that day. Within an hour we found one of the mules and succeeded in getting hold of his leading rope. Before noon we had overtaken all the cows and eight of the oxen, bringing them back to camp while the wild ponies circled around the prairie within seven or eight miles of us, as if laughing to scorn our poor attempts to catch the horses which they had stolen.

The afternoon was not yet half spent when we succeeded in gathering up all our stock save two horses and two mules, and then I insisted we should go on without them.

"Between here and the Columbia River we shall lose more stock than that," I said, "and if we are to reach the Oregon country before winter sets in, such misadventures as this must not be allowed to delay us."

I noted that more than one of the men wore a dissatisfied look, as if believing we should remain at this camp until all the stock had been found; but mayhap they remembered that the loss was caused by their not listening to me, and not a word was said in protest.

Next day, without giving further heed to the horses and mules that were with the pony herd, we pushed forward toward the Oregon country once more, traveling 43 twenty-two miles and in the meanwhile crossing the Wakarusa River.

Then came a stretch of prairie land, and after that, near nightfall, we arrived at the Kansas River, where camp was made.

This time you may set it down as certain that when I claimed we ought to set a picket guard, there were none to say me nay. Even more, I noticed that every man carefully hobbled his horses or his mules, as I hobbled Napoleon, and when I went into my tent I said to myself that we need have no fear of trouble that night.

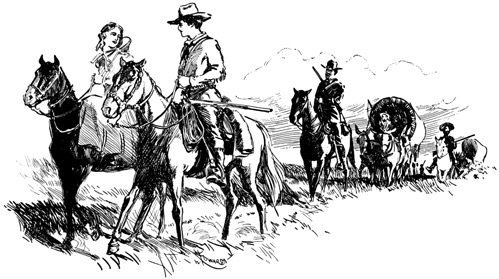

When we started out next day, Susan Mitchell insisted on riding by my side. She held her place there until we made camp, although it was no slight task, for while the company was passing over twenty miles of distance, I had ridden from the front to the rear of the train mayhap twelve times, thereby almost doubling the length of the journey.

Not once did the plucky girl show signs of faltering, even though a good half of the day's march was up the side of a ridge and along the top of it, where the way was hard even for those of us who were riding light.

We were traveling within two or three miles of the Kansas River, not yet having come to the ford, when 44 at about four o'clock in the afternoon we overtook a company of people who were bound for the Oregon country, having in their train twenty-eight wagons.

At first John Mitchell was eager to join the strangers as they suggested; but he lost much of the desire on being told that two miles in advance was another party having nearly a hundred wagons. I really believe the man grew confused when he learned there were so many people on the Oregon trail.

When he asked my advice as to joining the larger company, I told him that my father had ever said if he could travel independently of any one else, it was profitable for him to do so, for then he was forced neither to go faster than he desired, nor remain idle when it pleased him to push on.

I asked John Mitchell how much he could gain by forming a small part of such a large company, unless, 45 perhaps, he intended to dismiss me as guide, whereupon he assured me heartily that he had no such idea, but it seemed to him we might join the strangers for mutual assistance.

It was not for me to do more than offer advice, and I told him that unless we came upon hostile Indians, we had best continue on by ourselves, for the time was coming, and not very far in the future, when we should be put to it to find grass for the cattle and fuel with which to cook our food. At such times the smaller the company, the less chance for suffering.

It was Susan who settled the matter, for she said very decidedly that I, who had already traveled over the Oregon trail twice, ought to know more about such affairs than any other in the company.

When she had spoken, her father held his peace as if convinced that her words were wise.

We did not overtake the company of a hundred wagons that night, but camped near a small brook about four miles from the Kansas River, I having led the people off the trail a mile or more so that we might not be joined by those emigrants in the rear.

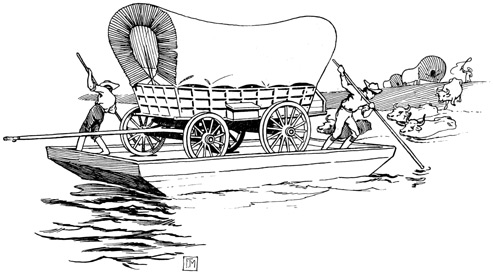

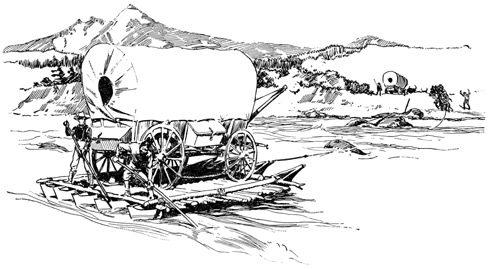

Next morning we traveled four miles to the river ford, and there found the water already so high that there was nothing to do but to ferry our wagons over in a flatboat owned by a man named Choteau whom I had already known in St. Louis. 46

He was no relative of that famous Choteau of the fur company, but a very obliging Frenchman indeed, who, because of his acquaintance with me, did all he could to hasten our movements. It was necessary we have a friend in such work, for it was a hard task to make the journey back and forth across that muddy stream, which was at least two hundred and fifty yards wide, when we could carry only one unloaded wagon at a time.

It was nearly nightfall before we were all across with our outfit and cattle, and then I gave the word that we should encamp within a mile of the stream, for I was not pleased with the appearance of dark clouds which were rolling up from the west.

It would have been better had I halted the company 47 when we first crossed, for before we could get the tents up and the wagons in place, a terrific storm of thunder and lightning was upon us.

Instantly, as it seemed, our oxen and cows were stampeded, rushing off across the prairie like wild things, and although I did my best to round them up, all efforts were vain.

There was nothing for it but to let them go, and seek shelter from the downpour of water, which was so heavy that at times one could hardly stand against it.

Susan Mitchell had followed my mother into the tent which I had taken care to set up immediately we halted, and because there was no other shelter save the overcrowded wagons, the girl was there when I 48 entered. It made my heart ache to see the evidences of her fright. Well was it for her that she was with my mother, for I truly believe none could have soothed her fears so readily.

I left the two together while the storm was at its height, and sought shelter in one of the wagons, believing the tempest would continue to rage throughout the night.

Next morning, before day had fully come, I aroused all the men. We saddled our horses and set out in search of the cattle, John Mitchell saying in a grumbling tone as he rode forward, that it seemed to him as if he was "doing more in the way of running down oxen and cows, than in making any progress toward the Oregon country."

Hardly realizing how true my words might prove to be, I told him laughingly that we were likely to get more of such work as the days wore on, rather than less, and another four and twenty hours had not passed before he came to believe that I was a true prophet.

Not until noon did we succeed in getting all the live stock rounded up, and I believed we were exceedingly fortunate in not losing a single animal, for it seldom happens, as I have heard, that cattle can be stampeded during the night and every one brought into camp next morning. 49

It was my belief that we ought to travel rapidly during the afternoon and until a reasonably late hour in the night, in order to make up the time we had lost; but it is one thing to say and quite another matter to accomplish.

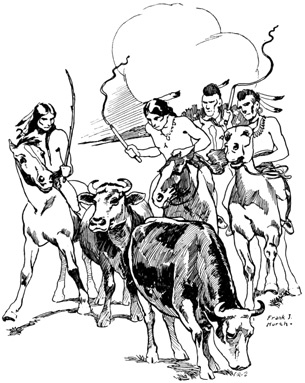

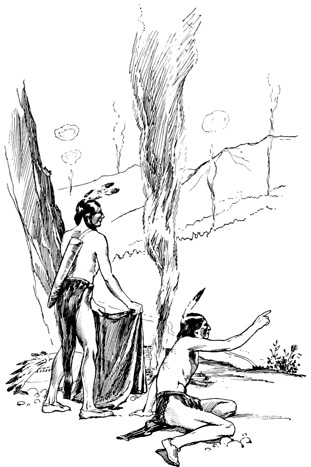

After traveling no more than three miles we arrived at Big Soldier Creek. As Susan and I were riding on in advance to make certain the ford was safe for heavy wagons, I saw coming down over a slight incline a band of mounted Indians, who immediately, on seeing our company, came forward at full speed, brandishing bows and arrows, or guns, accordingly as they were armed, and yelling furiously.

Susan Mitchell screamed with fear, as well she might; but I had already seen just such an Indian maneuver and knew what it meant. I hurriedly told her to ride back and join the company, while I held Napoleon steady.

Their intention was to stampede the cattle, as I well knew, and although it would have been unwise for me to have sent a bullet among them, it was my purpose to do so if I failed in checking their advance otherwise.

Then Napoleon took the matter into his own hands, 50 or, I should say, his own feet, for when the Indians were perhaps thirty yards away he wheeled about, flinging up his heels as if he counted on kicking the entire band over the ridge.

Do what I might I could not get the stubborn animal wheeled around before the savages had rushed by me, whooping and yelling in such a manner as caused a panic among our company and a stampede of the beasts.

The oxen wheeled around in the yokes until they were so mixed up that the most expert would have found it difficult to untangle them, while the cows, their tails straight up in the air, fled back over the trail, bellowing with fright. 51

By the time all this mischief had been done, Napoleon was ready to attend to his own business once more, and I rode among the company to find the people in such a state of panic and fear as one would hardly credit.

"Get your rifles and follow me!" I shouted as I rushed forward, and it is quite certain that more than one of the men cried after me to come back, for all were so terrified that they would have suffered the loss of the stock rather than make any attempt at reclaiming it.

It must not be supposed that I am trying to make it appear as if I was wondrously brave in thus giving chase. I knew from the experience gained while with my father, that there is but one way to treat these savages, and that is to put on a bold front. 52

After doing any mischief the Indians would go farther and farther, until having accomplished all their desires, if their victims made no attempt to defend themselves; therefore it was necessary that we make a decided stand.

I knew full well that if we pursued, these Pawnees, as I judged them to be, would speedily be brought to their senses. Whereas if we remained idle in camp they would run off all the stock, and for us to lose that herd of cows at the very outset of the journey would indeed have been disastrous.

It was fortunate for those under my charge that they followed as I commanded, even though they did not do so willingly. When we had ridden at our best pace six miles or more, we came upon all except three of the cows who, wearied with their mad race, were now feeding; but not a feather of an Indian could be seen.

That the Pawnees knew we were coming in pursuit, there could be no doubt, and because they were not in war paint I understood that they must have an encampment near by.

Therefore, as soon as we had rounded up the cattle, I told John Mitchell it was our duty to search for the Indian camp, and there demand that they return to us, or aid us in searching for, the cows we failed to find. 53

The man looked at me uncertainly an instant, as if questioning whether we had the pluck, as the Easterners say, to ride into an Indian encampment. Then he said grimly, almost as if doubting his own judgment:—

"I shall do as you say, boy; but if mischief comes of it, remember that I hold you responsible."

"Mischief will surely come of it if we fail to put on a bold front," I replied hotly, and then wheeling Napoleon around, I sent him ahead under the whip, which he richly deserved because, but for his foolish trick of kicking, all this mischief might have been spared us.

We rode through our encampment, for by this time the lads and the women had set up some of the tents, while one of the men who had remained behind was straightening out the oxen, and from there on a distance of about three miles, when we found that for which we were searching.

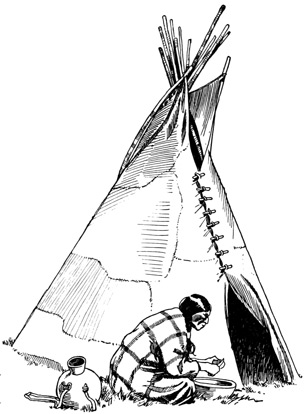

It was a Pawnee village, and in it there might have been forty men, women, and children, occupying say, ten tepees, or lodges, while there were so many ponies and dogs that one would hardly have had the patience to count them.

We could see no signs of our cattle, nor did I expect 54 to find them there; but, riding directly into the center of the village, I brought Napoleon to a standstill, at the same time demanding in the Pawnee language, or such smattering of it as I could command, to be brought to the chief.

Within a minute he came out from one of the lodges, and it gave me more courage when I noted the fact that he was looking disturbed in mind.

I demanded that he, or some of his tribe, return to us the cows which had been driven away.

If there had ever been such a being as an honest Indian, then I might have believed we had come upon him, for this chief, knowing there were men enough in our company to wipe out his entire band, declared 55 again and again, with no little show of innocence, that neither he nor his young men had had anything to do with our cattle.

Straightway I pointed here to one fellow and there to another, as two whom I recognized among those who had ridden over the ridge, and called the attention of the chief to the ponies at the farther end of the village, which were yet covered with perspiration.

Instead of staying there to parley with the fellows, I insisted that the cows be brought to us before another 56 day had passed, and made many threats as to what would happen in case my demands were not complied with.

Then we rode out of the village. When we were some distance away, John Mitchell asked in a bantering tone if I really expected to see the cows again, whereupon I told him we would not move from the present encampment, save to punish the rascally Pawnees, until every head of the three had been brought to us.

Because he laughed I saw that he believed that he never would see his cattle again; but I was better acquainted with the Pawnees than he.

Because of all that had happened I found no reason to complain of the manner in which watch was kept over the encampment that night, and at a fairly early hour next morning, even before I had begun to expect them, the Indians came into camp with two of the cows. They talked much about their innocence so far as causing a stampede and claimed that it was not possible to find the third beast.

The Pawnee who acted as spokesman would have tried to make me believe they were simply in sport when they overrode our camp; but I let him know that I was acquainted with such thievish tricks, and 57 threatened them as to the future, much as though I had a company of soldiers at my back.

It may be that the Indians were not greatly frightened by what I said; but certain it is that the members of John Mitchell's company began to believe that I was to be treated less like a boy, and more after the manner of one who knew somewhat regarding the work in which we were engaged.

They gave more heed to my words from that time on, and Susan Mitchell seemed to think I had done some wondrously brave deed when I frightened the cowardly red men, or attempted to; but we never again saw that third cow.

I believe that the Pawnees had hidden her, intending to have a great feast after we had gone away; but I dared not go any farther in the way of threats lest they openly defy me, when I would have been powerless because the men of our company were not equal to fighting the savages.

I could have told Susan that if we had come across 58 a party on the warpath, then my words would have been laughed at, and I might have found myself in serious trouble through making threats which could not be carried into execution.

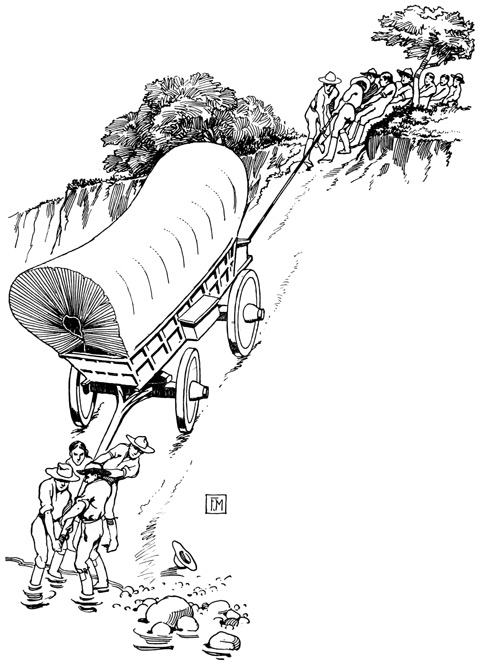

Because of having been thus delayed by waiting for the cattle, we traveled only five miles on this day, which, if I remember rightly, was the 14th of May. Then we arrived where Big Soldier Creek must be crossed, an undertaking I had been looking forward to with no little anxiety because the banks of the creek are very steep and it is impossible to drive either 59 mules or oxen down to the bed of the stream while attached to the wagons.

We were forced to unyoke the oxen and unharness the mules, after which we let the wagons down by means of ropes, with four men to steer the tongue of each cart.

The ford was shallow, but on the other side the banks loomed in front of us like the sides of a cliff. In order to get even the lightest wagon to the top we had to yoke all the oxen in one team, and even then every man of us put his shoulder to the tailboard, pushing and straining as we forced the heavy vehicle straight into the air, as one might say.

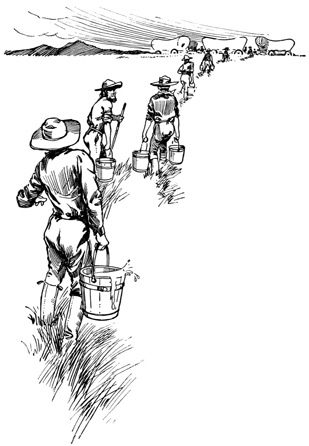

One entire day was spent in crossing, and within an hour of sunset we pitched our tents on the high banks, where we let down buckets by ropes in order to get water for cooking,—this method being easier than scrambling up and down the steep incline.

Before night had come a party of about sixty from the Ohio country joined us, having fifteen wagons.

They were unaccustomed to such traveling, as I understood after seeing them make camp. When the leader came up to John Mitchell, proposing that we journey together from then onward, claiming that by thus increasing the numbers each company would be in greater security from the Indians, I gave my employer a look which I intended should say that we would travel as we had started, independently. 60

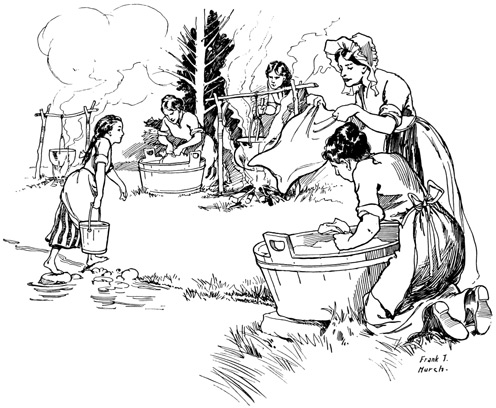

From this point on to the Little Vermilion Creek was eighteen miles over high, rolling prairie, and I believed we ought to make it in one day's travel, which we did.

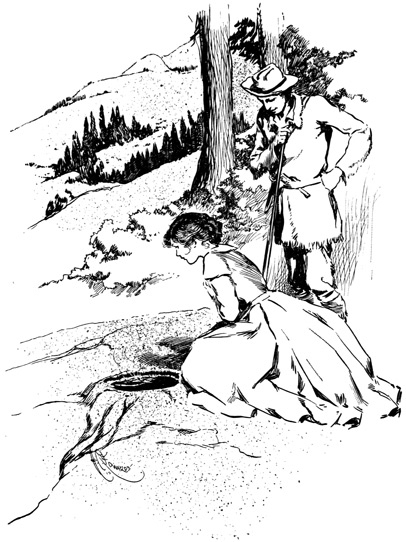

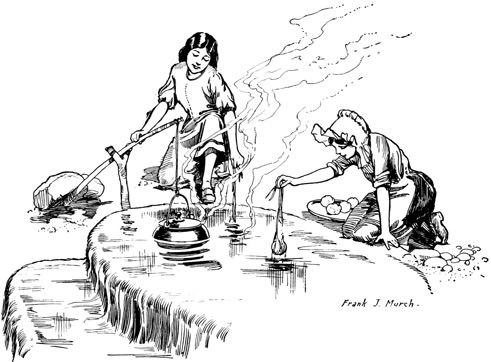

We arrived at the creek about four o'lock in the afternoon, and within thirty minutes it seemed as if the banks of that small stream were literally lined with fires, over each of which was suspended a kettle filled with water. Tubs were brought out from all the wagons, for the women of our company had decided 61 on making a "wash day" of the three or four hours remaining before sunset.

On seeing that Susan Mitchell was not taking part in this labor, I proposed that we ride five or six miles onward, where I knew would be found quite a large village of Kansas Indians. She was only too well pleased with the proposition, even though having been in the saddle since early morning.

To me one Indian village is much like another; but before we had come to the end of our journey Susan could point out the difference between a Kansas, a Pawnee, a Cheyenne, or a Sioux tepee.

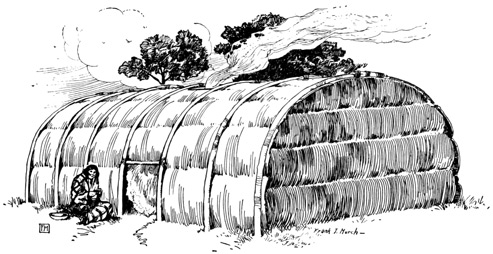

The Kansas Indians make their houses about thirty feet in length by fifteen feet wide, and build them by sticking hickory saplings firmly into the ground in the shape of the lodge desired. These are bent to form an arch eight to ten feet in height, when the tops 62 of the saplings are bound together by willow twigs. This forms the inner framework, which is covered with bark taken from linden trees; over this is another frame of saplings, also tied with willows, to bind the whole together securely and prevent the coverings from being blown away during a high wind.

Each of these lodges has one small door about four feet in height and three feet wide, while at the top of the hut is an opening for the smoke to pass out, when a fire is built in the center of the floor during cold or stormy weather.

There were in the village when we arrived but few women and children, with here and there an old man, all the hunters having gone out, as I learned, hoping to find antelopes near at hand.

Understanding by this information that there would be no attempt made to hinder us from gratifying our curiosity, I led Susan into one of the largest of the empty lodges. She was filled with wonder because of the pictures, drawn with charcoal and colored with various paints, which were to be seen on the inside of the bark walls.

There were mounted men fighting with bows and arrows, horses hauling wagons, figures of beasts and reptiles, all done as one can well fancy in a rude way; 63 but to Susan they afforded no little amusement, and she would have remained studying them until after nightfall, had I not insisted that we must return to camp before darkness.

It was an odd picture which our encampment presented when we rode in just at twilight. The women had finished their washing, and, having no ropes on which to stretch their clothes, had hung them on wagon wheels and the tongues of the carts, in fact, on everything available, until the entire place had much the appearance of a gigantic, ragged ghost.

Because so much time was spent next morning in gathering up these garments and packing them away, we traveled only twelve miles, arriving at the bank of a small stream with all the animals, save the saddle horses, showing signs of weariness. 64

I insisted we should take a day for resting the cattle, although John Mitchell would have pushed on, regardless of their condition; but I knew we must keep them in good shape, else when we arrived at the more difficult portion of the journey they would fail us entirely. Perhaps because of our experience with the Indians, the men failed to grumble at the delay.

Every member of the party was not only willing, but eager, to set out after our long halt, for we had a most disagreeable experience with wood ticks, little insects much like those that worry sheep. They covered every bush as with a veil and lay like a carpet over the ground as far as one could see.

I have never come upon them in such numbers, and before we lay down to rest I wished a dozen times that I had delayed the halt another day.

These ticks fasten themselves to a person's skin so tightly that, in picking them off, the heads are often left embedded in the flesh, and unless carefully removed, cause most painful sores. It was like one of the Plagues of Egypt such as I have heard my mother read about, and so much did our people suffer that John Mitchell came to me in the middle of the night, urging that we break camp at once rather than remain there to be tortured. 65

I soon convinced him that we could not hope to drive the cattle in the darkness, without danger of losing one or more, therefore he ceased to urge; but before the sun had risen, all our company were astir making preparations for the day's journey.

Early though it was when we set off, only fourteen miles were traveled, owing to the difficulty in crossing the Big Vermilion River.

The banks of the stream were steep and the channel muddy, affording such difficult footing for the animals that we were forced to hew down many small trees and lop off large quantities of branches to fill up the 66 bed of the river before the wagons could be hauled across. All this occupied so much time that after arriving at the opposite bank we traveled only one mile before it was necessary to make camp.

On this night we were not troubled by wood ticks, yet I had the camp astir early next morning, knowing that before nightfall we must cross the Bee and the Big Blue Creeks, therefore much time would be spent in making the passages.

The difficulties which I had anticipated in crossing the creeks were not realized. We got over in fairly good shape, being forced on Bee Creek to double up the teams in order to pull the wagons across, and when night came we were two and a half miles west of Big Blue.

There I believed we should make a long halt, for the country was covered with oak, walnut, and hickory trees, and, if I remembered rightly, this would be the last time we could procure timber for wagon tongues, axletrees, and such other things as might be needed in case of accidents.

It was well we came to a halt early, for the tents were no more than up and the wagons not yet drawn in a circle to form a corral for the horses, before the 67 most terrific storm of rain I ever experienced burst upon us.

The women had but just begun to cook supper. The first downpour from the clouds quenched the fires, making literal soup of the bread dough, and it was only by building a small blaze under one of the wagons, where it would be partly sheltered from the storm, that we could get sufficient heat to make coffee.

Before this was done—and nearly all us men took part in it, for the storm was so furious that the women could not be expected to remain exposed to its full fury—no less than two hours were spent, and I had almost forgotten that the encampment and all within it were under my charge. 68

Each moment the storm increased, and had I been attending to my duties instead of trying to play the part of cook in order to enjoy a cup of coffee, I would have noticed that the cattle were growing uneasy. After standing with their tails to the storm for a while, they began milling, that is running around in a circle, and by the time I gathered my wits every animal was galloping off across the plain.

Fortunately the horses and mules were properly hobbled, and, in fact, some of the saddle beasts had been brought into the corral formed by the wagons; therefore when John Mitchell would have set off in pursuit of the oxen and cows despite the terrific storm, I insisted that he take such ease in camp as was possible because on the following morning we, mounted, would quickly round up the stampeded cattle.

It was a most dismal night, and for the first time since leaving their homes these people, who were setting their faces toward the Oregon country, had a fair taste of what hardships awaited them.

So furious was the wind that the rain found entrance to every camp and beneath each wagon cover, until beds and bedding were saturated.

Welcome indeed was the morning to my mother and me, for our tent stood in a tiny pond when the 69 day broke, and we waded out to a higher bit of ground, where the gentle summer breeze, now that the storm had cleared away, might dry our water-soaked clothing.

Without waiting for breakfast I saddled Napoleon, calling upon the men to follow me, and within four hours we had rounded up and brought into camp the missing animals.

Then came a hasty meal, and I gave the word to break camp, whereupon John Mitchell reminded me that we were to take in a store of oak and hickory timber for future needs; but I insisted that we push on a short distance, knowing that this wooded country extended ten or twelve miles farther westward, where I hoped to find higher ground, so we might be able to camp with some comfort.

The trail was heavy. The rain had so softened the ground that the wagon wheels sank several inches into it, and many times before nightfall we were forced to hew trees and cut large quantities of brush, in order to fill up the depressions in the way where the water stood deep and the bottom was much like a bog.

Again and again we found it necessary to double up the teams in order to haul the heavy wagons over the spongy soil, and after we had traveled eight miles 70 with more labor than on the previous day we had expended in going twice that distance, we decided to encamp.

We were on reasonably high ground, or, in other words, we were not in a quagmire, and after camp had been made I counted that we would spend the following day in getting as much hickory and oak timber as we might need when we came to the mountain ranges, where axletrees, wagon tops, and even the wheels themselves, were likely to be splintered because of the roughness of the way.

Next morning while the men were hewing trees and shaping them roughly into such forms as might 71 come convenient, the women took advantage of the opportunity to churn, and at noon we had fresh butter on our bread, which was indeed a luxury.

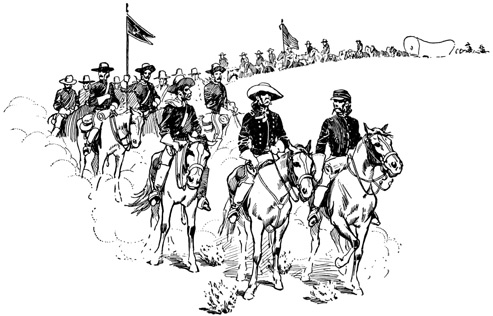

We were yet eating slowly in order the better to enjoy the butter, when we saw in the distance, coming toward us, what appeared to be a large body of soldiers and emigrants.

Among the foremost of the horsemen who came up and halted near us, was Colonel Stephen W. Kearny who, with three hundred dragoons, nineteen wagons drawn by mules, fifty head of cattle, and twenty-five 72 sheep, was making the first military campaign into the Far West, in order properly to impress the Indians with the strength and power of the Great Father at Washington.

Colonel Kearny would not permit his train to halt where we were encamped, but he remained with us a full half hour, taking his due share of the newly made butter, and eating heartily of our poor store.

It was a most pleasing break in the journey, and to me it was indeed something to be remembered, for never before had I seen or heard of such a number of soldiers so far away from the frontier.

When we set off again all our teamsters pressed forward eagerly, hoping to overtake the dragoons, who had already no less than two hours' start of us.

Perhaps I ought to have checked them, knowing they were forcing our stock at too rapid a pace; but yet I did not, and when next we halted thirty-two miles had been traversed since morning. This, though the way was smooth and the crossings easy, I allowed was a good day's work.

It was on the twenty-sixth day of May, after we had traveled ten miles, that we came to the bank of Little Sandy River, where was already encamped a company of emigrants bound for the Oregon country. They had thirty-two wagons, and, in addition to the 73 other stock, ninety cows, having started from Independence with a hundred.

Susan Mitchell laughed with glee when we arrived at this camp and, when I asked the reason for her high spirits, told me our people could spend the evening visiting these strangers even as they visited their neighbors at home. Indeed, I saw that all the members of the company were prinking and pluming like a party of savages making ready for a war dance.

Men whose clothing had been well-nigh in rags suddenly appeared decked out in finery, and as for the women and the girls, a garden of flowers could hardly have compared with them for variety of colors.

However, our company did not spend the evening visiting the strangers; on the contrary, they were forced to entertain others, for before supper had been cooked and eaten about three hundred Kansas Indians, men, women, and children, some walking, some riding, came into camp.

The emigrants whom our people had intended to visit were overrun even as we were, and during two hours or more the beggars remained watching for an opportunity to steal something, or striving to trade their skeleton-like ponies for our horses and mules. 74

Some of the visitors were clad in buckskin, others had leggings of elk hide, with buffalo skins over their shoulders, while many wore only greasy, ragged blankets and leggings so besmeared with blood and dirt that one could not tell what the material might be.

Many of the men had long hair, while the heads of others were shaved close to the skin, save for a tuft extending from the forehead over the crown and down to the neck, much like the comb of a rooster.

Some had their faces painted in a fanciful manner with red, while others had only their eyelids and lips colored. Again, there were those with various colored noses or ears, and I failed to see any two who were decked out, either with garments or by paint, in the same manner.

The costumes and decorations of the women were as varied as those of the men, and equally filthy. 75 All, from the smallest papoose to the oldest brave, were repulsive, at least to me, because of their uncleanliness.

How long those representatives of the Kansas tribe would have remained with us awaiting an opportunity to steal whatever they might, I cannot say; but at about eight o'clock John Mitchell urged that I drive them away, if indeed I dared. This last suggestion caused me to smile, for what fellow would not dare anything among the Kansas Indians, who know no more of courage than they do of cleanliness?

I speedily sent them out of the camp, and when, next morning, the whole tribe returned begging this or that, I threatened punishment to any who should dare linger around.

Again we had an opportunity to join forces with another company, for those emigrants whom we met at Little Sandy River were eager to journey with us, but intended to remain one full day on the bank of the stream in order to rest their stock.

I urged that we push on, lest they should travel with us whether we wished or not, and so we set off at an early hour across the prairie, arriving next day at the Republican Fork of the Blue River.

It was on the last day of May that we came to 76 where the trail turns abruptly away from the stream, stretching out twenty-five miles or more to the Platte River.

Then we advanced in wild, fertile bottoms, where wild peas abounded, and we were among the last of the oak and hickory trees that we would see for many a long day.

Here I knew we might find game, and said to those men who had been eagerly inquiring day after day as to when we would come upon buffaloes, that now was the time when they could display their skill in bringing down wild turkeys.

I had supposed that these people knew somewhat about hunting; but when one of the men turned upon me sharply, asking how I knew turkeys could be found near about, I nearly laughed in his face. For it seemed to me that a child should have known we were come at last to where game of some sort might be taken easily.

I had no idea of hunting turkeys, for I knew that 77 within the next few hours there should be a possibility of bringing down as many antelopes as Napoleon would be willing to carry.

Therefore I remained in camp, and saw those eager hunters striding off amid the timber, making noise enough to warn every fowl or beast of their coming.

The wonder of it was that the fellows brought in a feather; yet at night they returned triumphant and excited, with two turkeys, and one would have believed, from the way the game was displayed, that they had shown great skill.

When Susan Mitchell asked why I did not go out in search of game, I told her it was not for me to spend my time in such sport, but that before many days had passed I would show her what a hunter could and should do in this country.

It may be she thought I was boasting, and I fancied I read as much on her face; but I contented myself in silence, knowing that she soon would see what kind of hunting those, who have crossed from the Missouri River into the Oregon country twice, could do.

Next day every man and boy in our company was looking eagerly forward for signs of game, and when, the afternoon being nearly spent, they saw large herds of antelopes in the distance, it was only with 78 difficulty I could force the teamsters to remain on their wagons.

Every horseman would have set off at that time in the afternoon with weary steeds, when there was no possibility of running down the game, had it not been for John Mitchell, who, after talking with me, insisted that no man should leave the company until we had made camp.

The Platte River was to be crossed before we halted, and we needed every man with us, for I knew that the bottom of the stream was soft, and the chances many that we would be forced to double up our teams.

However, we gained the opposite bank without much difficulty and were hardly more than ready to encamp, after having traveled eighteen or nineteen 79 miles, when it began to rain once more, and then the men were glad that they had not set off to hunt at nightfall.

We camped where it would be possible for us to get water without too much labor, and set about gathering fuel before everything was soaked by the rain, and darkness was upon us.

Then the men began to treat me as if I was of their own age. They came into my tent by twos and threes, asking when it would be possible for them to hunt antelopes, and when I would go with them to bring in fresh meat.

I told them that on the next day they should have all the hunting that would satisfy them and their horses, and this caused them to wonder how I knew antelopes might be near at hand.

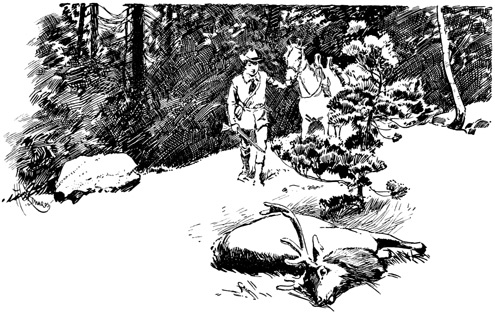

Next morning, when we had traveled no more than six miles, any hunter could see that we were in a game country, and because our people were really in need of fresh meat, to say nothing of the desire of the men for sport, I gave the word to halt and make camp.

John Mitchell angrily demanded why I had halted the company before the forenoon was half spent.

When I told him that here was our opportunity to 80 get antelope steaks for supper, he looked at me as if he believed I was talking of something wholly beyond my knowledge. I have an idea he would have countermanded my order to form camp, insisting that we move on, had not his wife suggested that now we were so near the river, where the bank was shelving instead of steep, it would be a good time for the women to finish washing their clothing.

After she had spoken he said to me:—

"Very well, lad, you may show the other men your antelopes. I have no desire for a wild-goose chase across the prairie."

I gave little heed to his banter, and those who had been so eager for the hunt were right willing to follow 81 me on the chance that they might come upon something that could be killed; John Mitchell finally consented to go with us, in order, as he said, to hear what sort of excuse I would make for not finding game.

We rode straight away from the river, and within half an hour came upon a herd of from twenty to thirty antelopes feeding less than three miles away, whereupon every member of the company would have started off singly, taking the poor chances of getting a shot, had I not insisted they should hold themselves under my orders, lest there be no possibility of bringing in fresh meat that day.

"You made a good guess, lad," John Mitchell said to me, as if he was disappointed because we had brought the game to view, and I replied:—

"Any one familiar with this country may say with reasonable certainty that he will find deer in such and such a place without first having seen any signs. With buffaloes it is different. But on feeding grounds like this, one can declare positively that he will come upon some kind of deer without riding very far."

Then I gave the word for the men to divide into two parties, one going to the right and the other to the left toward the herd, in order to come up with them on both sides at the same moment, and the 82 silly animals did not note our approach until we were within half a mile.

Then they showed how rapidly they could run.

I have never seen antelopes in full flight without thinking how nearly alike they are to swallows, both for swiftness and the manner in which they bound over the ground without seeming to touch it. There are not many horses that can come up with this game once the fleet animals have been aroused; but I knew my pony could gain upon them in a chase of five miles or less, and straightway urged him on, shouting for the others to follow.

It was like horses accustomed to the plow striving to keep the pace with a blooded racer, when we struck off across the plains, and before two miles had been traversed, my companions were left so far in the rear that there was little chance they could take any part in this sport. 83

I urged Napoleon on until we were in fairly good range, when, firing rapidly, I brought two of the beautiful creatures to the ground.

There was no possibility of overtaking the herd, once having halted, so swinging the game across the saddle in front of me, I let my pony walk leisurely back to where the men waited, each of them looking with envious eyes at the result of the chase.

Within half an hour after our return to camp, five or six fires had been built, and our people were busily engaged in cooking the fresh meat, which was so welcome to them, giving little or no heed to anything save the preparations for a feast. Suddenly a single Indian of the Pawnee tribe stood before us, having ridden up without attracting the attention of any member of the company.

It was the first time such a thing had ever occurred while I was supposed to be on duty, and I said to myself that until we had come into the Oregon country and I had said good-by to these people, I should never again be caught off guard.

The Indian who had thus surprised me was as fine a specimen of a Pawnee as I have ever seen. He was tall, had a good figure, and rode a handsome pony which was really fat,—something seldom come upon, 84 for the Indians do not generally allow their horses to take on very much flesh.

He wore a calico shirt, buckskin leggings, and fancifully decorated moccasins. It would seem as if he had set himself up as a trader in footgear, for he carried with him half a dozen or more pairs of moccasins, some of them well worn, which he wanted to trade for meat.