Title: Ruth of Boston: A Story of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Author: James Otis

Release date: November 3, 2013 [eBook #44100]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

A Story of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

BY

JAMES OTIS

NEW YORK -:- CINCINNATI -:- CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Copyright, 1910 by

JAMES OTIS KALER

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

The purpose of this series of stories is to show the children, and even those who have already taken up the study of history, the home life of the colonists with whom they meet in their books. To this end every effort has been made to avoid anything savoring of romance, and to deal only with facts, so far as that is possible, while describing the daily life of those people who conquered the wilderness whether for conscience sake or for gain.

That the stories may appeal more directly to the children, they are told from the viewpoint of a child, and purport to have been related by a child. Should any criticism be made regarding the seeming neglect to mention important historical facts, the answer would be that these books are not sent out as histories,—although it is believed that they will awaken a desire to learn more of the building of the nation,—and only such incidents as would be particularly noted by a child are used. 4

Surely it is entertaining as well as instructive for young people to read of the toil and privations in the homes of those who came into a new world to build up a country for themselves, and such homely facts are not to be found in the real histories of our land.

James Otis.

| PAGE | |

| A Proper Beginning | 9 |

| On the Broad Ocean | 11 |

| Making Ready for Battle | 13 |

| The Rest of the Voyage | 15 |

| The First View of America | 17 |

| The Town of Salem | 19 |

| Other Villages | 21 |

| Visiting Salem | 22 |

| Making Comparisons | 25 |

| An Indian Guest and Other Visitors | 27 |

| A Christening and a Dinner | 30 |

| Deciding upon a Home | 33 |

| A Sad Loss | 35 |

| Rejoicing Turned into Mourning | 36 |

| Thanksgiving Day in July | 38 |

| Leaving Salem for Charlestown | 39 |

| Our Neighbors | 40 |

| Getting Settled | 42 |

| The Great Sickness | 44 |

| Moving the Town | 46 |

| Master Graves Prohibits Swimming | 48 |

| Anna Foster's Party | 49 |

| The Town of Boston | 51 |

| Guarding against Fires | 53 |

| Our Own New Home | 54 6 |

| The Fashion of the Day | 56 |

| My Own Wardrobe | 59 |

| Master Johnson's Death | 60 |

| Many New Kinds of Food | 61 |

| The Supply of Food | 64 |

| The Sailing of the "Lyon" | 66 |

| The Famine | 67 |

| The Search for Food | 69 |

| The Starvation Time | 70 |

| A Day to Be Remembered | 73 |

| The Coming of the "Lyon" | 74 |

| Another Thanksgiving Day | 75 |

| A Defense for the Town | 78 |

| The Problem of Servants | 79 |

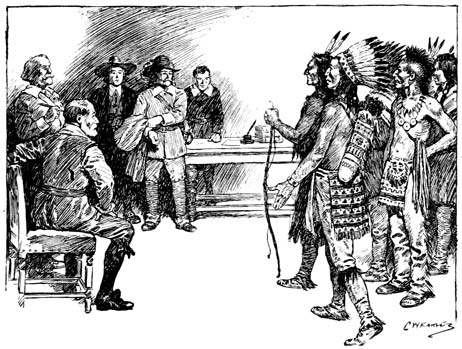

| Chickatabut | 80 |

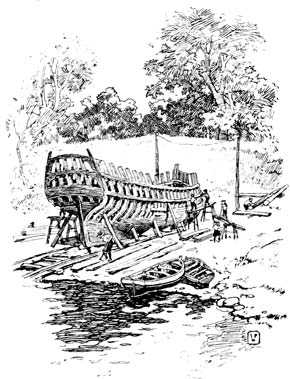

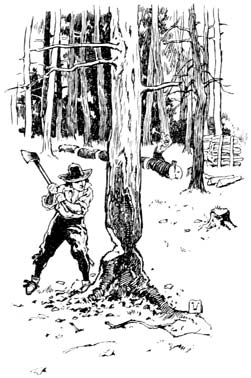

| Building a Ship | 82 |

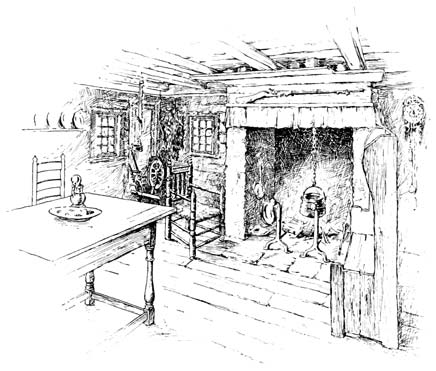

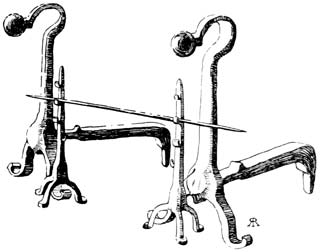

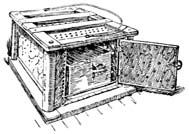

| Household Conveniences | 84 |

| How the Work is Divided | 86 |

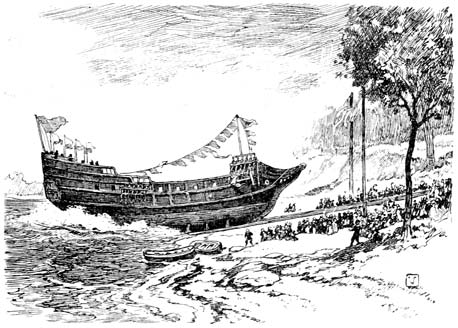

| Launching the Ship | 88 |

| Master Winthrop's Mishap | 90 |

| New Arrivals | 92 |

| Another Famine | 94 |

| Fine Clothing Forbidden | 96 |

| Our First Church | 97 |

| A Troublesome Person | 100 |

| The Village of Merry Mount | 101 |

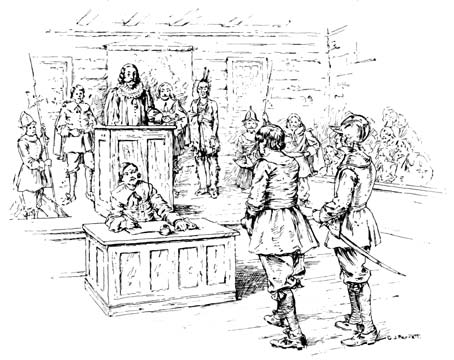

| Punishing Thomas Morton | 102 |

| Philip Ratcliff's Crime | 105 |

| In the Pillory | 107 |

| Stealing from the Indians | 108 |

| The Passing of New Laws | 110 7 |

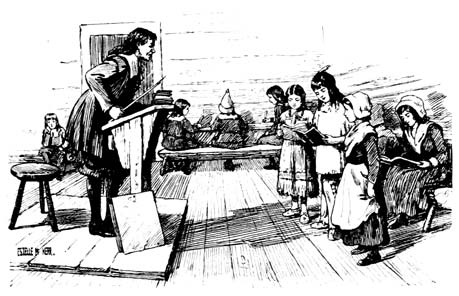

| Master Pormont's School | 112 |

| School Discipline | 114 |

| Other Tools of Torture | 116 |

| Difficult Lessons | 118 |

| Other Schools | 119 |

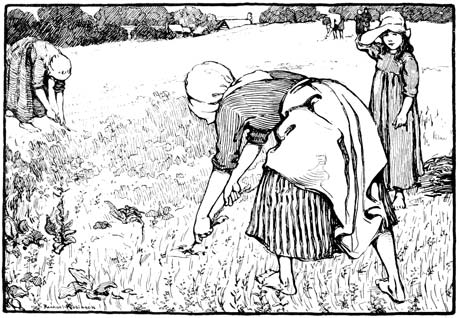

| Raising Flax | 121 |

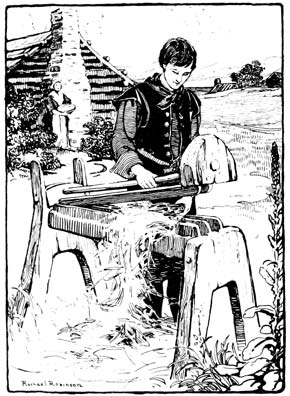

| Preparing Flax | 123 |

| Spinning, Bleaching, and Weaving Flax | 125 |

| What We Girls Do at Home | 127 |

| Making Soap | 129 |

| Soap from Bayberries | 132 |

| Goose-picking | 133 |

| A Change of Governors | 135 |

| The Flight of Roger Williams | 136 |

| Sir Harry Vane | 138 |

| Making Sugar | 140 |

| A "Sugaring Dinner" | 143 |

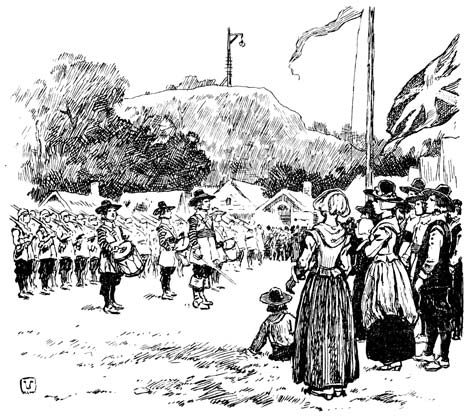

| Training Day | 146 |

| Shooting for a Prize | 149 |

| Lecture Day | 151 |

| Punishment for Evil-doers | 152 |

| The Murder of John Oldham | 154 |

| Savages on the War-path | 156 |

| Pequot Indians | 158 |

RUTH OF BOSTON

Truly it seems a great undertaking to journey from London into the land of America, yet I have done so, and because of there being very few girls only twelve years of age who are likely to make such a voyage, it seems to me well if I set down those things which I saw and did that might be interesting to myself in the future, when I shall have grown to be an old lady, if God permits, or to any other who may come upon this diary.

Of course I must first set down who I am, in case strangers should some day chance to find this book, and, growing interested in it—for who can say that I may not be able to tell a story which shall be entertaining, because of there being in it much which the people of England have never 10 seen—give me credit for having written a diary without a proper beginning.

You must know, then, that my name is Ruth. In the year of our Lord, 1630, when, as I have said, I was but twelve years of age, my father joined that company led by Master John Winthrop, whose intent it was to go into America to spread the gospel, and there also build up a town wherein should live only those who were one with them in the worship of God.

This company was made up of four classes of people. First there were those who paid a sum of money for their passage to America, and, because of having done so, were to be given a certain number of acres of land in the New World.

In the second class were those who, not having enough money to pay the full price for their passage, agreed to perform a sufficient amount of work, after arriving in America, to make up for the same.

In the third class were those called indentured servants, which is much the same as if I said apprentices.

The fourth and last class had in it those people who were to work for wages, at whatsoever trade or calling they were best fitted.

It needs not that I should say more by way of a beginning, for surely all the people in England, if they do not know it now, will soon come to understand why we, together with those who have gone before us, and 11 the companies that are to come after, have journeyed into America.

It was decided that my parents, and, of course, myself, should sail in the same ship with Master Winthrop, and the name of that vessel was the Arabella, she having been so called in honor of Lady Arabella Johnson, who journeyed with us.

My mother was sadly grieved because of Mistress Winthrop's deciding not to go on the voyage with her husband, but to join him in the New World later, and this decision was a disappointment to very many of the company. I am in doubt as to whether the Lady Arabella would have gone with us on this ship, had she not believed Mistress Winthrop also was to go.

It was on the twenty-second day of March, in that year which I have previously set down, that, having already journeyed from London to Southampton, we went aboard the Arabella, counting that the voyage would be begun without delay, and yet, because of unfriendly winds and cruel storms, our ship, with three others of the company, lay at anchor until the eighth day of April.

Then it was, after the captain of the ship had shot off three guns as a farewell, that we sailed out on the 12 broad ocean, where we were tossed by the waves and buffeted by the winds for nine long, dreary weeks.

Had it not been for Master Winthrop's discourses day after day, we should have been more gloomy than we were; but with such a devout man to remind us of the mercy and goodness of God, it would have been little short of a sin had we repined because of not being carried more speedily to that land where was to be our home.

There was one day during the voyage, when it seemed verily as if the Lord was not minded we should journey away from England.

We had not been out from the port many days, when on a certain morning eight ships were seen behind us, coming up as if counting to learn what we were like; and then it was that all the men of the company believed these were Spanish vessels bent on taking us prisoners, for, as you know, at that time England was at war with Spain. 13

It was most fearsome to all the children, but very much so to Susan, a girl very nearly my own age, with whom I made friends after coming aboard, and myself.

When Susan and I saw the men taking down the hammocks from that portion of the vessel which was called the gun deck, loading the cannon, and bringing out the powder-chests, truly were we alarmed.

Standing clasped in each other's arms, unheeded by our elders, all of whom were in a painful state of anxiety or fear, we watched intently all that forenoon the ships which we believed belonged to the enemy.

Then I heard one of the sailors say that the Spaniards were surely gaining on us, and the captain of the vessel, as well as Master Winthrop and my father, must have believed it true, for all preparations were made for a battle. 14

The small cabins, leading from the great one, were torn down that cannon might be used without hindrance, and the bedding, and all things that were likely to take fire, were thrown overboard. The boats were launched into the sea and towed alongside the ship so that when the worst came we might fly in them, and then that which was most fearsome of all, the women and children were sent down into the very middle of the vessel, where they might not be in danger when the Spaniards began to send iron balls among us, as it seemed certain they soon would.

While we were huddled together in the darkness, many weeping, some moaning, and a few women, among whom was my mother, silent in the agony of grief, Master Winthrop came down to pray with us, greatly to our comforting, after which, so I have been told since, he went up among the men where he performed the same office.

It was not until an hour after noon that our people discovered that those ships which we believed to be Spanish, were English vessels, from which we had nothing to fear.

Then word was sent down to us in that dark place that we might come up above, and once in the sunlight again, we found all the passengers rejoicing and making merry over the fears which had so lately beset them.

How bright the sun looked to Susan and me as we 15 stood near the rail of our ship, gazing at the vessels which only a few hours before were a fearsome sight, but now seemed so friendly! It was as if we had been very near to death, and were suddenly come into a place of safety.

From that time until St. George's Day, which you all know is the twenty-third of April, nothing happened deserving of being set down here. Then it was, however, that during the forenoon the captain moved our sails so that the ship would remain idle upon the waters, which is what sailors call "heaving to," and the captains of the other vessels, together with Master Pynchon and many more gentlemen, came on board for a feast.

Lady Arabella and the gentlewomen of our company had dinner in the great cabin, while the gentlemen partook of their good cheer in the roundhouse, as the sailors call it, which is a sort of cabin on the hindermost part of the quarter-deck.

By four o'clock in the afternoon the feast was at an end; the gentlemen who had come to visit us went on board their own ships, and again were the vessels headed for that country of America in which we counted to spend the remainder of our lives.

Susan and I were much together during this voyage, 16 for neither of us made very friendly with the other children, and I do not remember that anything of import happened until we were come, so the captain said, near to the New World.

It is not needed I should set down that again and again were there furious storms, when it seemed certain our ship would be sunk, for there was so much of such disagreeable weather during the nine weeks of voyaging, that if I were to make a record of each unpleasant day, this diary would be filled with little else.

I have set down, however, that on the seventh day of June, which was Monday, we had come, so Master Winthrop said, off "the Banks," where was good fishing to be found; but why this particular spot on the ocean should be called the Banks, neither Susan nor I could understand. The waves were much like those we had seen from day to day; but yet, in some way, the captain knew that we had come to the place where it would be possible to take fish in great numbers, and so we did. 17

It is not seemly a young girl should set down the fact, with much of satisfaction, that she enjoyed unduly the food before her, and yet I must confess that those fish tasted most delicious after we had been feeding upon pickled pork, or pickled beef, with never anything fresh to take from one's mouth the flavor of salt.

It was a feast, as Susan and I looked at the matter, far exceeding that which we had on St. George's Day, and surely more enjoyable to us, for what can be better pleasing to the mouth than a slice of fresh codfish, fried until it is so brown as to be almost beautiful, after one has had nothing save that which is pickled?

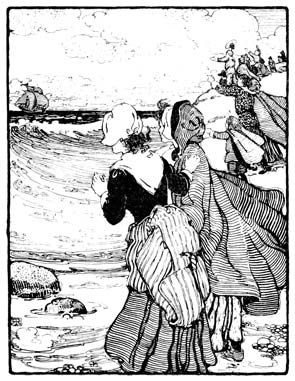

Five days later, which is the same as if I said on the twelfth day of June, early in the morning, when Susan and I came on deck, we saw spread out before us the land, and it needed not we should ask if this was the America where we were to live, for all the people roundabout us were talking excitedly of the skill which had been displayed by the master of the Arabella, in thus bringing us directly to the place where we had counted on coming.

It can well be fancied that Susan and I overhung the rail as the ship sailed nearer and nearer to the land, watching intently everything before us; yet seeing, 18 much to our surprise, little more than would have been seen had we come upon the coast of England.

I had foolishly believed that even the shores of this New World would be unlike anything to be found elsewhere, and yet they were much the same. The rocks rising high above the waters, with the waves beating against them, made up a picture such as we had before us even while we lay at anchor off Cowes. The trees were like unto the trees in our own land, and the grass was of no different color. Save that all this before us was a wilderness, we might have been off the coast of Cornwall.

I have said it was all the same, and yet because of the fears and the anxieties regarding the future, was it different.

This was the land to which we had come for the making of a new home; the place where our parents had pledged themselves to spread the gospel as the Lord would have it spread.

We knew, because of what had been written by our friends who had journeyed to this new world before us that here we were to find brown savages, many of whom, like wild beasts, would thirst to shed our blood. Here also could we expect to see fierce animals, such as might not be met with elsewhere in the world; and, in the way of blessings, we should meet those friends of ours who, for conscience sake and for the will to do God's bidding, 19 had come to prepare the land that it should be more friendly toward us.

I had not yet been able to discover any of the dwellings which marked the town of Naumkeag, or Salem, when all the cannon on board our vessel were set off with a great noise. Then, as we came around a point of land, there appeared before our eyes a goodly ship lying at anchor, and beyond her the town that was—much to my disappointment, for I had fancied something grander—made up of a few log houses which seemed rather to be quarters for servants than dwellings for gentlemen's families, although we had been told that the habitations would be rude indeed.

A boat was put into the water from our ship, and as the sailors rowed toward the vessel which was at anchor, I heard my father say to my mother that they were going in quest of Master William Pierce, a London friend of ours.

As we watched, I asked that question which had come often in my mind during the voyage, which was, why this new town that Master Endicott had built should have two names.

Mother told me that the Indians had called the place Naumkeag, and so also did those men who first settled here; but when some of our people came, and gathered around them several from the Plymouth Colony, together with a number of planters who had built themselves homes along the shore, it was decided to name the new town Salem, which means peace, for here it was they hoped to gain that peace which should be on this earth like unto the peace we read of in the Book, which passeth all understanding.

And now before I set down that which we saw, and while you are picturing our company on the deck of the Arabella looking shoreward, impatient to set their feet once more on the earth, let me tell you what I had heard, since we left England; regarding this town of peace, and those of our people, or of other faiths, who settled here two years or more ago. 21

Master Endicott, who was of our faith, had come to these shores in March of the year 1628, with a company of thirty or forty people, and, finding other men living at the head of this harbor which the Arabella had entered after her long voyage, decided to build his home at this place.

In the next year, Master Higginson, coming over with six vessels in which were eighteen women, twenty-six children, and three hundred men, joined the little colony. These last brought with them one hundred and forty head of cattle, and forty goats.

However, only two hundred of this last company remained at Salem, the others having chosen to build for themselves a new town, which they called Charlestown, on that large body of water which is set down on the maps as Massachusetts Bay.

In addition to these two villages, it was said that there were five or six houses at the place called Nantasket; that one Master Samuel Maverick was living on Noddles Island, and one Master William Blackstone on the Shawmut Peninsula.

I have set this down to the end that those who read it may understand we were not come into a wild country, in which lived none but savages, and I must also add 22 that not so many miles away was the town of Plymouth, where had been living, during ten years, a company of Englishmen who had worked bravely to make for themselves a home.

And now since I am done with explaining, and since the boat which put out from our vessel and which I left you watching, has come back from that other ship, bringing Master William Pierce, let me tell you what we did on the first day in this new world.

The gentlemen and ladies of our company were invited on shore to a feast of deer meat, while the servant women and maids were allowed to land on the other side of the harbor, where they feasted themselves on wild strawberries, which were exceeding large and sweet. 23

It would be untrue for me to say that deer meat made into a huge pie is not inviting, because of my having enjoyed it greatly, and yet I could not give so much attention to the dainty as I would have done at almost any other time, so intent was I upon seeing this village concerning which Master Endicott had written so many words of praise.

Had Susan and I come upon it within an hour after leaving the city of London, it would have looked exceedingly poor and mean; but now, when we were on the land after a voyage of nine long weeks, verily it seemed like a wondrous pleasant place in which to live.

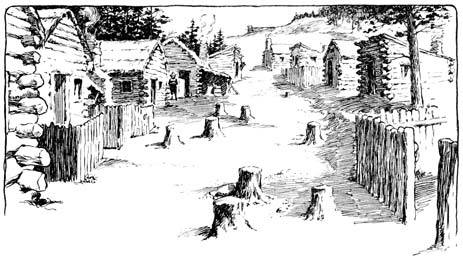

More than an hundred dwellings, so my father said, had been built. Some were of logs laid one on top of the other in a clumsy fashion, with the places where windows of glass should have been, covered with oiled paper, and doors that were so cumbersome and heavy it was a real task for Susan and me to open and close them, but yet they had a homely look.

Then there were what might be called sheds, made of logs, or the bark of trees, and, in two cases, dwellings of branches laid up loosely as a child would build a toy camp.

It was as if each man had built according to his inclination and willingness to labor, the more thrifty having log dwellings, and the indolent ones rude huts.

Even Susan and I could understand that whosoever 24 had decided upon the places where these homes should be built, had in mind the making of a large town; for paths, like unto streets, led here and there, while all around grew trees, not thickly, to be sure, but yet in such abundance as to show that all this had lately been a wilderness.

Even in these streets had been left the stumps of trees after the trunks were removed, which served to give an untidy look to the whole, making it seem as if one were in a place where had been built shelters only for a little time, and which would shortly be abandoned.

The welcome which was given us, however, was even warmer than we would have received at home in England, and little wonder that these gentlefolk whom we had known there, should be overjoyed to see us here.

Both Susan and I came to understand, not many 25 months afterward, how great can be the pleasure one has at seeing old friends whom he had feared never to meet again in this world.

It was a veritable feast which these good people of Salem set before us, and yet so strange was the cookery, that I am minded to describe later some of the dishes at risk of dwelling overly long upon matters of no importance.

Master Winthrop said, when we were going on board the ship again, that although it was nothing but peas, pudding, and fish, quite coarse as compared with what we would have had at home in England, save as to the venison pie, it all seemed sweet and wholesome to him.

When the day was come to an end, we went into the ship once more, for there were not spare beds enough in all the town to serve for half our party, and you may be very certain that once we were gathered again in the great cabin, all talked eagerly concerning what had been done; at least our parents did, for it would have been unseemly in us children to interrupt while our elders were talking.

Mother was not well satisfied with the houses, believing it would be possible to make dwellings more like those we left behind; but father bade her have 26 patience, saying that a shelter from the weather was the first matter to be thought of, and that the pleasing of the eye could well come later, after we had more with which to work.

She, thinking as was I at the moment, of the floor in the house where we ate the venison pie, declared stoutly that there would be no more of labor in laying down planks, at least in the living-room, than in beating the earth hard, as it seemingly had been where we visited.

Then, laughingly, he bade her rest content, nor set her mind so strongly upon the vanities of this world, saying that if God permitted him to raise a roof, so that his wife and child might be sheltered from the sun 27 and from the rain, he would be satisfied, even though the legs of his table stood upon the bare earth.

It was this conversation between my parents that caused the other women to talk of how they would have a home built, until Lady Arabella put an end to what was almost wrangling,—for each insisted that her plan for a dwelling in this New World was the best,—by saying that whatsoever God willed we should have, and that it would be more than we deserved.

Both Susan and I had gazed about us eagerly when we went on shore, hoping to see a savage. We were not bent on meeting him near at hand, where he might do us a mischief; but had the desire that a brown man might go past at a distance, and we were grievously disappointed at coming aboard the ship again without having seen one.

Therefore it is that you can well fancy how surprised and delighted we were next morning when, on going on deck just after breakfast to have another look at this new town, whom should we see walking to and fro on the quarter-deck with Master Winthrop, as if he had been one of the first gentlemen of the land, but a real Indian!

There were the feathers, of which we had heard, 28 encircling his head and ending in a long train behind. His skin was brown, or, perhaps, more the color of dulled copper. He wore a mantle of fur, with the skin tanned soft as cloth, and that which father said was deer hide cunningly treated until it was like to flannel, had been fashioned into a garment which answered in the stead of a doublet.

I cannot describe his appearance better than by saying it would not have surprised me, had I been told that one of our own people had painted and dressed himself in this fanciful fashion to take part in some revel, for truly, save in regard to the color of his skin, he was not unlike the gentlemen who were on the ship.

As Susan and I learned later, he was the king, or chief man, among those Indians who called themselves Agawams. Father said he was the sagamore, which, as I understand it, means that he was at the head of his people, and his name was Masconomo.

A very kindly savage was he, and in no wise bloodthirsty 29 looking as I had expected. He was a friend of Master Endicott as well as of all those who lived with him in this town of Salem, and had come to welcome our people to the new world, which, as it seemed to both Susan and me, was very thoughtful in one who was nothing less than a heathen.

The Indian sagamore stayed on board the ship all day, and our company, together with the people of Salem, were as careful to make him welcome as if he had been King James himself.

The reason for this, as father afterward explained to me, was because of its being of great importance that we make friends with the savages, else the time might come when they would set about taking our lives, being in far greater numbers than the white men.

Neither Susan nor I could believe that there was any danger that these people with brown skins would ever want to do us harm. Surely they must be pleased, we thought, at knowing we were willing to live among them, and, besides, if all the savages were as mild looking as this Masconomo, they would never be wicked enough to commit the awful crime of murder.

In the evening, after the Indian went ashore, the good people of Salem came on board in great numbers, and, seeing that it was a time when he might do good to their souls, Master Winthrop gathered 30 us on deck, where he talked in a godly strain not less than an hour and a half.

It was indeed wicked of Susan to say that she would have been better pleased had we been allowed to chat with the people concerning this new land, rather than listen to Master Winthrop, who, so mother says, is a most gifted preacher even though that is not his calling, yet way down in the bottom of my heart I felt much as did Susan, although, fortunately, I was not tempted to give words to the thought.

When another day came, we girls had a most delightful time, for there was to be a baby baptized in the house of logs where are held the meetings, and Mistress White, one of the gentlefolks who came here with the company of Master Higginson, was to give a dinner because of her young son's having lived to be christened. 31

To both these festivals Susan and I were bidden, and it surprised me not a little to see so much of gaiety in this New World, where I had supposed every one went around in fear and trembling lest the savages should come to take their lives.

The christening was attended to first, as a matter of course, and, because of his having so lately arrived from England, Master Winthrop was called upon to speak to the people, which he did at great length. Although the baby, in stiff dress and mittens of linen, with his cap of cotton wadded thickly with wool, must have been very uncomfortable on account of the heat, he made but little outcry during all this ceremony, or even when Master Higginson prayed a very long time.

We were not above two hours in the meetinghouse, and then went to the home of Mistress White, getting there just as she came down from the loft with her young son in her arms. 32

Mother was quite shocked because of the baby's having nothing in his hands, and while she is not given to placing undue weight in beliefs which savor of heathenism, declares that she never knew any good to come of taking a child up or down in the house without having first placed silver or gold between his fingers.

Of course it is not so venturesome to bring a child down stairs empty-handed; but to take him back for the first time without something of value in his little fist, is the same as saying that he will never rise in the world to the gathering of wealth.

The dinner was much enjoyed by both Susan and me, even though the baby, who seemed to be frightened because of seeing so many strange faces, cried a goodly part of the time.

We had wild turkey roasted, and it was as pleasing a morsel as ever I put in my mouth. Then there was a huge pie of deer meat, with baked and fried fish in abundance, and lobsters so large that there was not a trencher bowl on the board big enough to hold a whole one. We had whitpot, yokhegg, suquatash, and many other Indian dishes, the making of which shall be explained as soon as I have learned the methods.

It was a most enjoyable feast, and the good people of Salem were so friendly that when we went on board ship that night, Susan and I were emboldened to say 33 to my father, that we should be rejoiced when the time arrived for our company to build houses.

Then we learned for the first time that it had not been the plan of our people to settle in this pleasant place. It was not to the mind of Governor Winthrop, nor yet in accord with the belief of our people in England, that all of us who were to form what would be known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony, should build our homes in one spot.

Therefore it was that our people, meaning the elders among the men, set off through the forest to search for a spot where should be made a new town, and we children were allowed to roam around the village of Salem at will, many of us, among whom were 34 Susan and I, often spending the night in the houses of those people who were so well off in this world's goods as to have more than one bed.

Lady Arabella Johnson and her husband had gone on shore to live the second day after we arrived, for my lady was far from well when she left England, and the voyage across the ocean had not been of benefit to her.

Our fathers were not absent above three days in the search for a place to make our homes, and then Sarah and I were told that it had been decided we should live at Charlestown, where, as I have already told you, a year before our coming, Master Endicott had sent a company of fifty to build houses.

It pleased me to know that we were not going directly into the wilderness, as both Susan and I had feared; but that we should be able to find shelter with the people who had already settled there, until our own houses could be built.

It appeared that all the men of our company were not of Governor Winthrop's opinion, regarding the place for a home. Some of them, discontented with the town of Charles, went further afoot, deciding to settle on the banks of a river called the Mystic, while yet others crossed over that point of land opposite where we were to live, and found a pleasing place which they had already named Rocksbury. 35

Susan and I believed, on the night our fathers came back from their journey, that we would set off in the ship to this village of Charlestown without delay, and so we might have done but for my Lady Arabella, who was taken suddenly worse of her sickness; therefore it was decided to wait until she had gained her health.

But alas! the poor lady had come to this New World only to die, and it was a sad time indeed for Susan and me when the word was brought aboard ship that she had gone out from among us forever.

We had learned during the voyage to love her very dearly, and it seemed even more of a blow for God to take her from us in this wilderness, than if she had been at her home in England.

Although it is not right for me to say so, because, of course, our fathers know best, yet would my heart have been less sore if some word of farewell could have been said when we laid my Lady Arabella in the grave amid the thicket of fir trees.

Mother says, that she is but repeating the words of Governor Winthrop, that it is wrong to say prayers over the dead, or to utter words of grief or faith. Therefore it was in silence we followed my lady in the coffin made by the ship's carpenter, up the gentle slope to 36 the thicket of firs, the bell of the Arabella tolling all the while; and in silence we stood, while the body was being covered with earth, little thinking how soon should we be doing a like service for another who had come to aid in building up a new nation.

On the day after we left my Lady Arabella on the hillside, the ship Talbot, which was one of the vessels that should have sailed in company with the Arabella, arrived at Salem, and the grief which filled our hearts for the dead, was lightened somewhat by the joy in greeting the living who were come to join us.

Governor Winthrop was among those who seemingly had most cause for rejoicing, because of his son Henry's having arrived on the Talbot, bringing news of his mother and of the remainder of the family.

Good Master Winthrop had so much of business to 37 look after on this day, that he could not spend many moments in talking with his son, and mayhap he will never cease to regret that he did not give his first attention to the boy, for, during the afternoon, while his father was engaged with public affairs, Henry was moved by curiosity to visit some Indian wigwams which could be seen a long distance along the coast.

Not being of the mind to walk so far, he cast about for a boat of some kind, and, seeing a canoe across the creek, plunged into the water to swim over that he might get it.

Susan and I were watching the brave young man when he sprang so boldly and confidently into the water, never dreaming that harm might come to him, and yet before he was one quarter way across the creek, he suddenly flung up his arms with a stifled cry. Then he sank from our sight, to be seen no more alive.

He had been seized with a cramp, while swimming most-like 38 because of having gone into the cold water heated, so my father said, for the day was very warm; but however that may be, eight and forty hours later we walked, a mournful procession, up the hill, even as we had done behind the earthly clay of Lady Arabella, while the bells of the ships in the harbor tolled most dismally.

Verily Governor Winthrop's strength is in the Lord, as my mother said, for although his heart must have been near to bursting with grief, no one saw a sign of sorrow on his face, so set and stern, as he stood there listening to the clods of earth that were thrown upon the box in which lay the body of his son.

Susan, who is overly given to superstition, I am afraid, declared that it was an ill omen for us to have two die when we had but just come into the new country, and when I told her that it was wicked to place one's faith in signs, she reminded me that I found fault because of Mistress White's baby's being taken out of the room for the first time with neither gold nor silver in his hands.

The ship Success, which was also of our fleet, having been left behind when we sailed from England, came into the harbor on the sixth of July, and then it was, 39 although our hearts were bowed down with grief because of the death of Lady Arabella and the drowning of Henry Winthrop, that our people decided we should hold a service of thanksgiving to God because of His having permitted all our company to arrive in safety.

Word was sent to the people of Charlestown, and to those few men in the settlement which is called Dorchester, that they might join with us in the service of praise, and many came to Salem to hear the preaching of Master Endicott, Master Higginson, and Governor Winthrop.

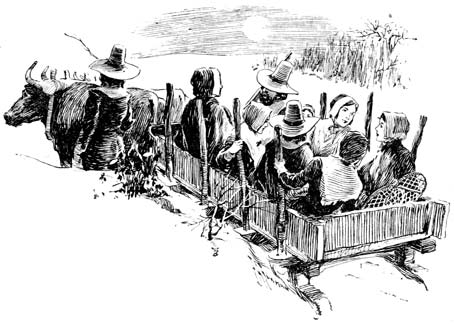

Four days later, which is the same as if I said on the twelfth of July, the fleet of ships sailed out of Salem harbor with those of our people on board who could not bear the fatigue of walking, to go up to the new village of Charlestown.

Before night was come, we were at anchor off that 40 place where we believed the remainder of our days on this earth would be spent.

Because of the labor performed by those men whom Master Endicott had sent to this place a year before, there were five or six log houses which could be used by some of our people, and the governor's dwelling, which of course would be the most lofty in the town, was partially set up; yet the greater number of us did not go on shore immediately to live.

Governor Winthrop remained on board the Arabella, as did my parents and Susan's, and now because there is little of interest to set down regarding the building of the village, am I minded to tell that which I heard our fathers talking about evening after evening, as we sat in the great cabin when the day's work was done.

To you who have never gone into the wilderness to make a home, the anxiety which people in our condition felt concerning their neighbors cannot be understood. To us, if all we heard regarding what the savages might do against us was true, it was of the greatest importance we should know who were settled near at hand, if it so came that we were driven out from our town.

Now you must know that many years before, which is much the same as if I had said in the year of our Lord, 41 1620, a number of English people who had been living in Holland because of their consciences not permitting them to worship God in a manner according to the Church of England, came over to this country, and built a town which was called Plymouth.

This town was not far by water from our settlement; indeed, one might have sailed there in a shallop, if he were so minded, and, in case the wind served well, perform the voyage between daylight and sunset.

It was, as I have said, settled ten years before we came to this new world, and the inhabitants now numbered about three hundred. There were sixty-eight dwelling houses, a fort well built with wood, earth and stone, and a fair watch tower. Entirely around the town was a stout palisade, by which I mean a fence made of logs that stand eight or ten feet above the surface, and placed so closely together that an enemy may not make his way between them, and in all respects was it a goodly village, so my father declared. 42

Near the mouth of the Neponset river Sir Christopher Gardner, who was not one of our friends in a religious way, had settled with a small company, and farther down the coast, many miles away, it was said were three other villages; but none among them could outshine Salem, either in numbers of people, or in dwellings.

When we were on the shore in Charlestown, looking straight out over the water toward the nearest land, we could see, not above two miles away, three hills which were standing close to each other, and Master Thomas Graves, who had taken charge of the people that first settled in the town of Charles, had named the place Trimountain; but the Indians called it Shawmut. There only one white man was living and his name was Master William Blackstone, as I have already told you.

It seemed to me a fairer land, because of the hills and dales, than was our settlement, and yet it would not have been seemly for me to say so much, after our fathers and mothers had decided this was the place where we were to live.

The days which followed our coming to Charlestown were busy ones, even to us women folks, for there 43 was much to be done in taking the belongings ashore, or in helping our neighbors to set to rights their new dwellings.

The Great House, in which Governor Winthrop would live, was finished first, and into this were moved as many of our people as it would hold.

Then again, there were others who, not content with staying on the Arabella after having remained on board of her so long, put up huts like unto the wigwams made by the Indians, which, while the weather continued to be so warm, served fairly well as places in which to live.

If I said that we made shift to get lodgings on shore in whatsoever manner came most convenient for the moment, I should only be stating the truth, for some indeed were lodged in an exceeding odd and interesting fashion.

Susan's father, going back some little distance from 44 the Great House, cut away the trees in such a manner as to leave four standing in the form of a square, and from one to another of these he nailed small logs, topped with a piece of sail cloth that had been brought on shore from the Talbot, finishing the sides with branches of trees, sticks, and even two of his wife's best bed quilts. Into this queer home Susan went with her mother, while my parents were content to use one of the rooms in the Great House until father could build for us a dwelling of logs.

It seemed much as if Susan was in the right, when she said that the deaths of Lady Arabella and Henry Winthrop were ill omens, because no sooner had all our people landed from the ships, or come up through the forest from Salem, than a great sickness raged among us.

Many had been ill during the voyage with what 45 Master Higginson called scurvy, which is a disease that attacks people who have lived long on salted food, and again many others took to their beds with a sickness caused by the lack of pure, fresh water.

Our fathers had but just begun to build up this new town when it was as if the hand of God had been laid heavily upon us, for, so it was said, not more than one out of every five of our people was able to perform any work whatsoever.

Those were long, dismal, dreadful days, when at each time of rising in the morning we learned that this friend or that neighbor had gone out from among us, and it seemed to Susan and me as if there were a constant succession of funerals, with not even the tolling of bells to mark the passage of a body from its poor home to its last resting place on earth, for by this time the ships had gone out of the harbor.

The graves on the side of the hill increased tenfold faster than did the dwellings, and all of us, even the children, felt that our only recourse now was to pray God that He would remove the curse, for of a verity did it seem as if one had been placed upon us.

Again and again did I hear men and women who had ever been devout and regular in their attendance upon the preaching, ask if we had not offended the Lord by breaking off from the English church, or if we might not have committed some sin in thus abandoning the land 46 of our birth, thinking to ourselves that we would build up a new nation in the world.

Therefore it was that even Susan and I felt a certain relief of mind, when Governor Winthrop set the thirtieth day of July as a day of fasting and of prayer; and in order that all the English people who had come into this portion of the New World might unite with us in begging God to remove the calamity from our midst, word was sent even as far as Plymouth, asking that every one meet on that day with words of devout petition.

I have no doubt, because of mother's having said so again and again, that the good Lord heard our fervent entreaties, although the sickness was not removed from among us for near to six weeks.

Then it was that Master William Blackstone came across from Trimountain, and told Governor Winthrop it was his belief we should do more toward aiding 47 ourselves than simply praying. He advised, because of there being plenty of good water in Trimountain, that we forsake this village of Charlestown, and go across to the opposite shore.

I might set down many words, repeating what I heard our fathers say concerning the wisdom of such a move, and yet this story which I am telling would not be improved thereby, for the day finally came when it was decided that, even at the cost of building new dwellings, we should take all our belongings across the water to the cove, back of which was a small hill, and, yet further behind, a circle of mountains.

The cove would make an agreeable harbor for our boats; the hill straight behind it would serve as a location for a fort, while here and there were pleasant streams, or gushing springs, whereas in Charlestown we had only the water of the river, or from the marsh.

That I may not weary you by much explaining, it is best I say that on the seventeenth of September, when the sun had risen, we gathered at the Great House to pray that God would bless us in this which was much the same as our second undertaking, for without delay, and before night had come, we were to go across the bay and make for ourselves other homes.

And now lest it seem as if I were telling the same story twice, I will not set down anything concerning the building of this second village, because of that which 48 we did in Trimountain being the same as had been done in Charlestown.

The Great House was taken apart and carried across the water, as were also the dwellings of logs, and while this was being done, the women and children stayed in Charlestown, where Master Thomas Graves had made, what seemed to Susan and me, odd rules and regulations.

He had been placed in command of the settlement by Master Endicott, and among his first acts was the appointment of tithing men, one of whose duties it was to prevent the boys from swimming in the water, as some lads of our company speedily learned when they would have enjoyed such sport.

They were arrested straightway, and but for the fact of being strangers, who were not acquainted with the rules of the settlement, would have been fined three shillings each.

Susan and I had no desire to spend our time swimming, even had it been seemly for girls so to do; but during very warm days it would have pleased us much to go down into the water, properly clad, in order to take a bath. Therefore did we believe Master Graves had done that which was almost cruel, and it surprised us 49 no little when, later, our own fathers passed the same law.

There were good friends of ours in England who believed that we had come into a wilderness where was to be found naught save savages and furious beasts, and it would have surprised them greatly, I believe, if they could have known how much of entertainment could already be found.

It was while we were waiting in Charlestown for the homes in Trimountain to be built, that Anna Foster, whose father is one of the tithing-men, invited all of us young girls who had come under Governor Winthrop's charge, to spend an evening with her, and we had much pleasure in playing hunt the whistle and thread the needle.

Anna was dressed in a yellow coat with black bib and apron, and she had black feathers on her head. 50 She wore both garnet and jet beads, with a locket, and no less than four rings. There was a black collar around her neck, black mitts on her hands, and a striped tucker and ruffles. Her shoes were of silk, and one would have said that she was dressed for some evening entertainment in London.

Neither Susan nor I wore our best, because of the candles here being made from a kind of tallow stewed out of bayberry plums, which give forth much smoke, and mother was afraid this would soil our clothing. We were also told that because of there not being candles enough, some parts of the house would be lighted with candle-wood, which last is taken from the pitch pine tree, and fastened to the walls with nails. This wood gives forth a fairly good light; but there drops from it so much of a black, greasy substance, that whosoever by accident should stand beneath these flames would be in danger of receiving a most disagreeable shower.

This entertainment was not the only one which was made for our pleasure while we remained in Charlestown; but because of the sickness everywhere around, very little in the way of merrymaking was indulged in, and it seemed almost a sin for us to be thus light-hearted while so many were in sore distress. 51

The first thing which was done by the governor and his advisors, after we had moved from Charlestown, was to change the name of Trimountain to that of Boston.

As you must remember, Boston in England was near to the home of Captain John Smith, who explored so much of this New World and planted in Jamestown a prosperous settlement. It was also in Boston that the Lady Arabella, and the preacher, John Cotton, who had promised to come here to us, had lived; therefore did it seem as if such were the proper name for a town which we hoped would one day, God willing, grow to be a city.

It is true our new village is built in a rocky place, where are many hollows and swamps, and it is almost an island, because the neck of land which leads from it to the main shore, is so narrow that very often does the tide wash completely over it; but yet, after that time of suffering in Charlestown, it seems to us a goodly spot.

Our dwellings, except the Great House, are made of logs, and the roofs thatched with dried marsh-grass, or with the bark of trees. That each man shall have so much of this thatching as he may need, the governor and 52 chief men of the village have set aside a certain portion of the salt marsh nearby, where any one may go to reap that which is needed for his own dwelling; but no more.

In time to come, so father says, we shall have chimneys built of brick or stone, for when our settlement is older grown some of the people will, in order to gain a livelihood, set about making bricks, and already has Governor Winthrop sent out men to search for limestone so we may get mortar. But until that time shall come, we have on the outside of our houses what are called chimneys, which are made of logs plastered with clay, or of woven reeds besmeared both as to the outside and the inside with mud, until they are five or six inches thick. 53

It needs not for me to say that these chimneys are most unsafe, for during our first winter in this new town of Boston, hardly a week passed but that one or another caught fire; and among the first laws which our people passed was one providing for the appointment of firewardens, who should have the right, and be obliged, to visit every kitchen, looking up into the chimneys to see if peradventure the plastering of clay had been burned away.

Because of the number of these fires, and the likelihood that they would continue to visit us frequently, another law was made, obliging every man who owned a dwelling of logs to keep a ladder standing nearby, so that it might be easy to get at the thatched roof if the flames fastened upon it; and, as soon as might be, iron hooks with large handles were made to be hung on the outside of the buildings, for the purpose of tearing off the thatch when it was burning.

It has also been decided that when we have a church, as we count on within a year, a goodly supply of ladders and buckets shall be kept therein for the use of the entire town, and then, when a fire springs out, our people will know where to go for tools with which to fight against it. 54

It must not be supposed that because of our dwellings being unsightly on the outside, they are rough within, for such is not the case. Many of the settlers, as did father, brought over glass for the windows, therefore we are not forced to put up with oiled paper, as are a great many people living in this New World.

It was partly the dampness inside our homes, so Governor Winthrop believed, which caused the sickness in Charlestown, and therefore it was that my father insisted we should have a floor of wood, instead of striving to get along with bare ground which had been beaten hard. Our floor is made of planks, roughly hewn, it is true, but nevertheless it serves to keep our feet from the ground. We have on the door real iron hinges, instead of leather, or the skins of animals, as we saw in Salem.

Save for the roughness of the floor and the walls, the inside of my father's house is much the same as we had in England, for he, like all of Governor Winthrop's company who were able to do so, brought over the furnishings of the old home, and while some of the things look sadly out of place here, they provide us with a certain comfort which would have passed unheeded in the other country, because there we were not 55 much better off in this world's goods than were our neighbors.

Here, when I see a table made only of rough boards spread upon trestles, I can get much pleasure out of the knowledge that we brought with us those tables which we had been using in England, and, when our dinner is spread, save for the difference in the food, I can well fancy myself in the old home. We have our ware of pewter and of copper, and our trencher bowls are of the best that can be hewn from maple knots.

In order that the walls and crevices, filled with moss and plastered over with clay, may not offend the eye, 56 mother has put up all the hangings which she brought with her, and these, with some skins my father bought at Salem, hide entirely that which is so unsightly in other dwellings.

Contrasting our home with many which we saw in Salem, or in Charlestown, I am come to believe my lines are truly cast in pleasant places, and I strive to be thankful to God for having given me the father which I have.

I am afraid it may be almost sinful for me so to set my mind upon the garments which one wears, and yet I cannot but contrast my father with some of the common men in the village.

The ruff which he wears around his neck is always well starched, clean, and stands out in beautiful proportions. On his low, peaked shoes, mother ever has fixed rosettes, or knots made of ribbon. His doublet, which is gathered around the waist with a silken belt, is slashed on the sleeves to show the snowy linen beneath. His trunk hose, meaning those which reach from his waist to his knees, are of the finest wool. His stockings, when he is dressed to meet with the Council, are of silk, while his mandilion, or cloak, is always of silk or velvet. 57

Perhaps one may think such attire hardly befitting a wild place like this, yet I know of nothing which serves to set off a man's figure, making him seem of importance in the world, better than that he be clad with due regard to the fashion of the day. Master Winthrop would not present the gentlemanly appearance which he does if he wore, as do the common people here, a band, or a flat collar with cord and tassels, breeches of leather, and a leather girdle around his waist. If he had, as do they, heavy shoes with heels of wood, or if his clothing were fastened together with hooks and eyes, instead of silken points, and if his hat were of leather, would we be pleased to call him Governor?

My mother often says that it is unseemly in a child like me to speak of the clothing worn by gentlemen, and yet I have noticed often and again, that she is as careful of my father's attire when he goes out of doors as she was at home in England, where all gentlemen were dressed becomingly. 58

Verily one need not go abroad in tatters, or oddities, simply because of having come into this New World, where much of work is required, and he who cares for his personal appearance, to my way of thinking, is to be given due credit.

Surely so the Massachusetts Bay Company thought, for they furnished to every man who came from England to settle here, save it be those who could afford such things for themselves, four pairs of shoes and the same number of stockings; four shirts; two suits of doublet, and hose of leather lined with oiled skin; a woolen suit, lined with leather, together with four bands and two handkerchiefs, a green cotton waistcoat, two pairs of gloves, a leather belt, a woolen cap and two red knit caps, a mandilion lined with cotton, and also an extra pair of breeches. Of course such an outfit was for the common people, not the gentlefolk.

In our company, the boys are clothed exactly as are their fathers, and many of them present a most attractive appearance, although my mother would not think it proper for me to say so, much less to put it down in writing. 59

It surely cannot be wrong for me to think of that which I wear, for if the good Lord has given me a comely body, why shall I not array it properly? Or if it be wrong, why did my father buy for me those things, a list of which I am here setting down, not from vanity, but simply to show how kind were my parents?

I had a cap ruffle and a tucker, the lace of which cost five shillings a yard; eight pairs of white kid gloves, with two pairs of colored gloves, two pairs of worsted hose and three pairs of thread, a pair of laced silk shoes, and a pair of morocco shoes, not to speak of four pairs of plain Spanish shoes, or two pairs made of calf-skin for every day use; a hoop coat and a mask to wear when the wind blows too roughly, and a fan for use when the sun is hot. Susan had two necklaces, one of garnet and one of jet; but I had only garnets. Then I have a girdle with a buckle of silver; a mantle and coat of lutestring; a piece of calico to be made up when mother has time; four yards of ribbon for knots or bows, and one and one-half yards of best cambric. All these were bought especially for me when we left home, and surely it can be no sin that I take pride in them. 60

It was shortly after coming to this town of Boston that we heard of the death of Master Johnson, Lady Arabella's husband. A friendly man was he, ever ready with a kindly word for us children, and we would have mourned his loss much more, but for knowing that it pleased him right well to go out of this world of sorrow, that he might join his wife in God's country.

Susan and I had hoped we should hear of no more deaths among those we cared for, after having come into this last place of abode, and the news of Master Johnson's taking away caused her superstitious fears to break out anew; but I reminded her that we were in God's keeping, whatsoever might befall, and that for us to look forward into the morrow, searching for evil, was the same as an injustice to our Maker, who would do toward us whatsoever seemed good in His sight.

As I look back now upon the time when our town of Boston first came into being, I can understand how well it is for us that we may not read the future. Had we at that time, when the winter was coming on, known how much of sorrow and of suffering was in store for us, before the earth would be freed from its bonds of ice, then I believe of a verity we must have given up in despair. 61

However, it is not for me to look ahead even in this poor attempt at setting down what we did in the new land. Rather let me go back to our home life, and tell somewhat concerning the odd dishes which were frequently set on our table.

There is little need for me to say that we had lobsters in abundance, and of such enormous size that one was put to it to lift them. I have heard it said that twenty-pound weight was not unusual, and whosoever might could catch, in traps made for the purpose, all the lobsters he would.

As for other fish, I can not set down on one page of this paper, the many kinds with which the housewife might provide herself for a trifling sum of money. We often had eels roasted, fried, or boiled, because of father's being very fond of them, and mother sometimes stuffed them with nutmegs and cloves, making a dish which was not to my liking, for it was hot to the tongue. 62

Some of the good wives in Salem had shown my mother how to prepare nassaump, which those who first came to Salem learned from the Indians how to make: It is nothing but corn beaten into small pieces, and boiled until soft, after which it is eaten hot, or cold, with milk or butter.

Nookick is to my mind more of a dainty than a substantial food, and yet father declares that on a very small quantity of it, say three great spoonfuls a day, a man may travel or work without loss of strength. It is made by parching the Indian corn in hot ashes, and then beating it to a powder. Save for the flavor lent to it by the roasting, I can see no difference between nookick, and the meal made from the ground corn.

Mother makes whitpot of oat meal, milk, sugar and spice, which is much to my taste, although father declares it is not unlike oatmeal porridge such as is eaten in some parts of England; but it hardly seems to me possible, because of one's not putting sugar and spice into porridge.

We often have bread made of pumpkins boiled soft, and mixed with the meal from Indian corn, and this father much prefers to the bread of rye with the meal of corn; but the manner of cooking pumpkins most to my liking, is to cut them into small pieces, when they are ripe, and stew during one whole day upon a gentle fire, adding fresh bits of pumpkin as the mass softens. If 63 this be steamed enough, it will look much like unto baked apples, and, dressed with a little vinegar and ginger, is to me a most tempting rarity. But we do not often have it upon the table because of so much labor being needed to prepare it.

Yokhegg is a pudding of which I am exceedingly fond, and yet it is made of meal from the same Indian corn that supplies the people hereabout with so much of their food. It is boiled in milk and chocolate, sweetened to suit one's taste after being put on the table, and while to English people, who are not accustomed to all the uses which we make of this wheat, it may not sound especially inviting, it most truly is a toothsome dainty.

The cost of setting one's table here is not great as compared with that in England, for we may get a quart of milk by paying a penny, or a dozen fat pigeons, in the season, for three pence, while father has more than once bought wild turkeys, to the weight of thirty pounds, 64 for two shillings, and wild geese are worth but eight pence.

The season had come when, if we had been in England, the people would have been gathering the harvest; but here we had none, having come so late in the year that there was no time to plant, and, consequently, we had no crops.

I had never before realized how necessary it is for people that the earth shall yield in abundance; but I came to know it now right well through hearing father, as he talked with mother regarding the fears which the chief men of the colony had concerning the supply of food.

Of course, girls such as Susan and I would not have been likely to learn anything of the kind, save that matters had come to such a pass as made the situation serious, in which case it was no more than natural we should hear our parents talking about it.

It seems, from what I learned, that a portion of the provisions brought from England were spoiled during the voyage, and also, that many of our people had taken with them no more than enough to sustain life for a month or two, believing that in this New World food of all kinds would be found in abundance. 65

Then again, many had bartered provisions, which they should have kept for the winter use, with the Indians in exchange for beaver skins, thinking thereby to make much money. So general had this traffic become, that early in September the Governor gave strict orders against it, and it was also ordered that no person in the town be allowed to carry out therefrom anything eatable.

But yet the store of food grew smaller and smaller, for there were many mouths to feed, and it seemed as if we children were more often hungry because of knowing that there was little to be had.

Susan reminded me of what she was pleased to call the "omen," when it was as if the first of our duties in the New World had been to bury two members of the company, and as the days wore on I began really to believe it a sin to harbor such thoughts.

As it had been in Charlestown, so did it come to be here in Boston, when the rains of autumn set in.

Many of the dwellings had not been built with due regard to sheltering those who were to live therein, and because of the dampness—although mother says it was owing quite as well to the homesickness and gloom which came upon us when the leaves in the forest turned brown, and yellow, and golden in token of the dying year—the people sickened.

However it was, much of sickness prevailed among 66 us in Boston, until the time came when my father and mother, to both of whom God had allowed good health, were absent from home day after day, nursing those of our neighbors who were unable to aid themselves.

It seemed at this time as if the Lord had set His face against the rearing of a nation in this new land, which he had given to the brown men for their homes, and Susan and I were not the only ones who came to believe we were offending Him in some way by thus having come here.

Then Governor Winthrop caused it to be known throughout the town that he had hired Captain Pierce, of the ship Lyon, which was then in Salem Harbor, to go with all haste to the nearest town in England, there to get for us as much of food as could be bought. 67

This news cheered the people somewhat, for now was the season when the winds blew strong, and it was believed the ship would have speedy passage. Indeed, some of the women declared she must return before the middle of October, and said so much concerning such possibility, that in time they came to believe it true. Therefore, when the month of October had nearly passed, their disappointment was great, and they were more despondent than at first.

Each day saw the store of provisions in the town grow smaller. Every family husbanded that which could be eaten, with greatest care, putting no more on the table than was absolutely necessary for a single meal, and those things which we had considered dainties, were no longer prepared. 68

Then came the Angel of Death, and man after man, woman after woman, laid themselves down to die, not from being starved, but, so Governor Winthrop declared, from having sickened through scurvy, which had come upon them during the voyage, after which, falling into discontent and giving way to home-sickness, they no longer struggled to live.

Before October had come to an end, food was so scarce in Boston that the poorer people had nothing save acorns, clams, and mussels to eat. During the summer it had seemed as if the sea were actually filled with fish, and yet now, when every boat that could be found in the town and nearby had been sent out, it was difficult for our men to take even fifty pounds weight in a day.

As Susan said, even the fish forsook us, as the clams and mussels would have done had they legs or fins.

The fowls of the forest also appeared to have departed, and by November the most any family could boast of was meal boiled in salt and water. In more happy days I would have turned up my nose at such food, and yet now it was like unto some sweet morsel, for so scanty had our store become that my mother would cook for each meal no more than half as much as we could have eaten.

I have heard father say that for a bushel of flour which had been brought from England, he paid in 69 those dark days fourteen shillings, and there was so little of it even at such price, that mother saved what store we had that it might be made into gruel, or something dainty, which the sick could keep upon their stomachs.

Then it was that our pinnace was made ready for a voyage, and with five of the strongest men on board, was sent along the coast to trade with those Indians who called themselves Narragansetts, taking with them everything in the way of trinkets which was in the general store, or could be gathered up from among the housewives.

Great was our rejoicing, five days later, when the men came back, bringing with them an hundred bushels of Indian corn. This seemed like a large amount of food, and yet, so many were the mouths to be fed from it, it was, so father said, scarce enough to hold life in our bodies three days, if so be it had been divided equally among all.

Father told us that three men, who were of the poorer people, had walked all the way from Boston town to Plymouth; but even there, where a harvest had been gathered, they could get no more than one half-bushel of meal made from Indian corn.

It was a time of famine such as I pray God we may never know again. In my home, until these dreary days, there had been no scarcity of food, and yet again and again did I save a crust of rye bread, thinking it a dainty to be nibbled upon slowly so that I might have longer the pleasure of eating.

It was as if the ship Lyon, on whose return a few weeks before we had counted so hopefully, was gone, never to come back.

Even the children watched the direction of the winds, saying on this day that it was a favoring one if the Lyon were on her course for Boston, and on 71 the morrow mourning because of the breeze being against her.

Yet she came not, nor did we hear aught concerning her, or any other from the world beyond us.

We were alone in what was much the same as a wilderness, and all those around upon whom we had counted to aid us in time of distress were in nearly the same dismal straits as were we.

Even the Indians declared that they were hard pressed for something to eat, and more than once did they come in twos or in threes to beg from us who were starving, something that could be eaten.

Susan and I, as we sat clasped in each other's arms hungry, and pining for the home over-seas which we had left, came to fancy that the famine which held possession of the land was like unto some terrible monster who hung above us as a cloud, settling slowly but surely day after day, until the hour would come when his terrible fangs would be securely fastened upon us.

During the month of January the deaths through scurvy, if that indeed were the cause, grew less; but all believed that in the stead of being removed by disease, our people were slowly perishing from starvation.

All the food in Boston was brought together, and portioned out, so that no one, whether he had of money, 72 or was penniless, should suffer more than another. And yet again and again in the night have I been awakened by the gnawing of hunger in my stomach.

With the beginning of January, Governor Winthrop appointed a day on which we should all fast and pray, as if indeed we had been doing other than fasting throughout the long, dreary winter. On this day every man, woman, and child in Boston town was to spend his or her time in praying to the Lord to deliver us from our affliction.

We no longer hoped for the coming of the Lyon. Surely she must have been destroyed by the tempest, 73 otherwise had we seen her before this, for nearly five months had gone by since she left Salem Harbor.

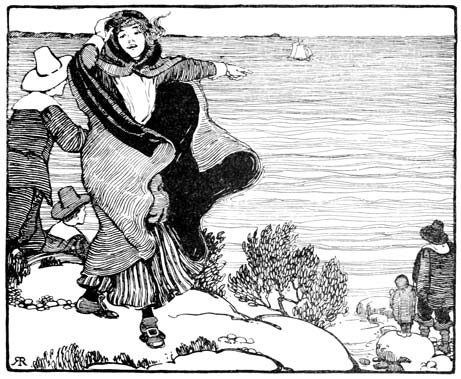

It was on the fifth day of February, which is the same as if I had said Saturday, and the fast was to be kept on the next Thursday. Susan had come to my home on Friday night to sleep in my bed with me, so that we might have such poor comfort as could be found in each other's company when we were nigh to starving.

She had awakened before the day dawned on this Saturday morning, which will be remembered by me so long as the Lord permits that I live, and moaned in distress because of the desire for food, until I opened my eyes, fretting because of not being allowed to sleep yet longer, for while I slumbered the pangs of hunger were not known.

Seeing me awake, Susan began to speak of the fast day on the following Thursday, saying that if we had no food whatsoever during the twenty-four hours, at a time when we were so near to starvation, surely would we die, and she was going back to what she called the omens, which came to us shortly after we arrived, when we were startled by a loud shouting in the street next beyond, where could be had a view of the sea. 74

Dimly, like one in a dream, for there was no thought in my mind this might be a signal that our time of trial was come to an end, I wondered how it was that any in this famine-stricken Boston of ours could raise their voices as if in joy, until I heard father cry out from the living-room below:

"The Lyon has arrived! The Lyon has arrived!"

It might be that I could give you, by the aid simply of words, some faint idea of how we suffered during the time of starvation, of sickness, and of death; but it is impossible for me to set down that which shall picture the heartfelt rejoicings and fervent thanksgiving that were ours at thus knowing we were soon to have enough with which to drive death from our doors. 75

It was a time of the wildest excitement. I hardly know what Susan and I did or said on that day, save that we dressed hurriedly, running down to the very shore of the cove, finding there nearly every person in Boston, and stood with the water lapping our feet as we watched the oncoming of the ship which was bringing relief.

Never before had I thought a vessel could be beautiful; but I have not seen a fairer sight than was the Lyon on that morning, and before night came, our stomachs, which had been crying out in distress because of lack of food, were groaning through being overly well filled.

The time of famine had passed, at least for this season, and it was as if the sick began to gain new life, and health, and strength, simply through knowing that we were no longer in such dire straits.

Governor Winthrop gave voice to his relief and pleasure by ordering, even before the Lyon had come to anchor, that the fast which had been appointed for the next Thursday should be a day of thanksgiving instead, and so we made it, with prayers all the more fervent because of our stomachs being well filled, and the fear of dying by starvation being put behind us. 76

The ship was loaded with such things as wheat, peas, oatmeal, pickled beef and pork, cheese and butter, and, with what my mother declared was of the greatest value, lemon juice, which is said to be a remedy for those who are suffering with scurvy.

It was not allowed that those who had money should buy plentifully of this cargo; but it was paid for by the town authorities, and divided equally among us all.

When the day for thanksgiving came, my mother allowed me to have an unusually hearty breakfast, for, she said, there was so much for which to be thankful, and so many who would be present to give thanks, that no one could say when we might be able to have dinner.

It was well she was thus thoughtful, for one of the preachers who came over with us, Master Wilson, preached, while Governor Winthrop treated us to a lecture, and Master Phillips was so blessed with the spirit that he prayed a full hour.

Susan and I feared we would have yet more preaching, for on the ship Lyon had come a young man whom my father said was gifted, and Susan's father believed he would make his influence felt among us. It was Master Roger Williams, and I am ashamed to say that I sat in fear and trembling lest Governor Winthrop should call upon him for a sermon, after we had already had much the same as two; but, fortunately, 77 so it seemed to me, Master Williams did not raise his voice during the service.

It was near to night before we were done with giving thanks, and then at each home was held a feast.

During Governor Winthrop's lecture on this thanksgiving day, he urged that all the people, children as well as grown folks, should take this time of famine as a lesson, reminding us that it would not be a long while before we could hope to reap a harvest, and in the meantime there was very much of labor to be performed.

He declared that even with the cargo of the Lyon, we had not enough to satisfy our wants until crops could be gathered; but it was certain other ships would come to Boston during the summer, with more stores. Yet 78 because of its being possible we might come to a time of suffering again, so must we be careful that not the smallest grain of wheat be wasted.

When the spring had come, and before it was time to put seed into the ground, our fathers set about building a defense for the town.

If you remember, I have already set down that this new village of ours was on a point, connected with the main coast only by a very narrow strip of land. Now to defend our town from an attack by enemies, save they should come by water, it was only necessary the defence be built on this narrow neck, or strip, and so it was built.

From one side to the other, extending even down into the water, was a palisade, or fence, of heavy logs, in the middle of which stood a gate to give entrance, and the law was that it should be shut at sunset, not to be opened again until day had dawned. 79

Since coming here we have seen so many Indians as to become acquainted with them, which is to say, that we no longer look upon them as savages, and have no fear to stand in the road when they pass. But those whom Susan and I had seen, up to the day when Chickatabut, the chief man of the Massachusetts tribe, came, were only common people, and such servants as are employed here in the town, for you must know that more than one family has a Narragansett Indian, or, mayhap, a Nipmuck, to work in the house.

Mother says that she would rather do all the work of the house alone, than have one of the brown women to help her, for they are not cleanly to look upon, but as for myself, I think I could stand the sight of one of them, especially when it comes to soap making, of which I will tell you later. 80

Of course there are times when housewives must have some one to aid them, and those girls or women among us who would go out to work in the house are not many in numbers, therefore one must put up with the Indians, which is unpleasant, or take those who are known as indentured servants, meaning the people who have agreed with the Massachusetts Bay Company to work for so many years, in order to pay for their passage over from England.