Painting by Frank Stick

A Soldier of the Soil

Title: Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume XII

The Great Results of the War

Editor: Wilson Lloyd Bevan

Author of introduction, etc.: Irving Fisher

Editor: Hugo Christian Martin Wendel

Release date: November 17, 2013 [eBook #44213]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Martin Mayer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Words marked with a dotted underline are changes made by the transcriber. To view the published words, mouse-over the underlined words. There is a table of all words changed by the transcriber at the end of the book. The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

In Twelve Volumes

Profusely Illustrated

VOLUME XII

THE GREAT RESULTS OF THE WAR

Economics and Finance, The Peace Treaty, The League of Nations. Index

In Twelve Volumes

Profusely Illustrated

FOREWORD BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, PhD.

President Emeritus, Harvard University

VOLUME XII

The Great Results of the War

Economics and Finance, The Treaty of Versailles and League of Nations——Index

WITH INTRODUCTION BY PROFESSOR IRVING FISHER, YALE UNIVERSITY

Edited by

DR. W. L. BEVAN, KENYON COLLEGE

and

DR. HUGO C. M. WENDEL, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY

GENERAL EDITORIAL BOARD

Prof. Albert Bushnell Hart,

Harvard University

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, U.S.A.,

Chief of Staff, 42nd Division

Admiral Albert Gleaves,

U.S. Navy

Prof. W. O. Stevens,

U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis

Gen. Ulysses G. McAlexander,

U.S. Army

John Grier Hibben,

President of Princeton University

J. B. W. Gardiner,

Military Expert, New York Times

Commander C. C. Gill, U.S.N.,

Lecturer at Annapolis and aide to Admiral Gleaves

Henry Noble MacCracken,

President of Vassar College

Prof. E. R. A. Seligman,

Columbia University

Dr. Theodore F. Jones,

Professor of History, New York University

Carl Snyder

Prof. John Spencer Bassett,

Professor of History, Smith College

Major C. A. King, Jr.,

History Department, West Point

Harper & Brothers Publishers

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Established 1817

Vol. 12—Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War

Copyright, 1920, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

M-U

Department of Political Economy, Yale University

In various ways, as this volume shows, the war has profoundly affected our economic and political life. War has ever been a disturber and innovator, always leaving after it a different world from that which existed previous to it. On account of our tremendously complex economic organization—the specialization of industry among nations, and the network of commerce—war today causes more profound changes than ever before. There can not be a human being in the world today whose life is not altered by the war through which we have just passed.

In trying, now that the war is over, to stop drifting, and to think our way out of the bent (or broken) remains of the ante bellum life, the world is confronted by a maze of problems and a still greater maze of proffered solutions.

Many of these proposals are, unfortunately, of the nature of treatment directed not at fundamental conditions, but merely at symptoms. We should be past the stage, in our social science, as we are in medicine, where we treat symptoms without a thorough diagnosis of the fundamental causes.

And yet it is just this thorough diagnosis that we lack.

What, then, are the changes brought about by the war which most deeply affect "the body politic," and by meeting which the most far reaching improvements can be made?

I can not take up, or even touch on, all of them; but to one of them I wish to call especial attention—the High Cost of Living or, more generally, the high level of prices, which is the most striking economic effect of the war throughout the world. It is, as I see it, hard to over-emphasize the need for attacking this problem of the price level as a preliminary to attacking the other economic problems which the war has left us.

We need only glance at a newspaper today, or step into a corner grocery, or fall into conversation with our neighbor in the train to have this topic come out as foremost in interest. It is, I believe, responsible for much more of our present uncertainty and confusion than is usually realized. In its ramifications it is chiefly this phase of the war's effects which, as I suggested above, touches every one of us at every point of our lives. A member of the Federal Reserve Board has called the price level problem the central economic problem of reconstruction.

Professor William Graham Sumner, who has inspired so many to the scientific study of social conditions, used to say: "In taking up the study of any social situation, divide your study into four questions—(1) What is it? (2) Why is it? (3) What of it? (4) What are you going to do about it?"

Let us follow this outline, and look first at the facts of the case; secondly at their causes; thirdly at the evils involved; and lastly at the remedies.

We now possess a device for measuring the average change in prices. This is what is known as an "index number."

Thus, if one commodity has risen 4 per cent. since last month and another, 10 per cent., the average rise of the two is midway between the sum of 4 per cent., and 10 per cent., or 7 per cent. It is

4 + 10

———— = 7

2

If we call the price level of the two articles last month 100 per cent., then 107 per cent. is the "index number" for the prices of the two articles this month. The same principle, of course, applies to any number of commodities.

The index number of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, the best index number we have, shows an average price level in 1918 of 196 for wholesale prices and 168 for retail prices of food on the basis of 100 per cent. for 1913, the year before the war; showing that wholesale prices, on the average, almost exactly doubled. The latest index number for wholesale prices (May, 1919) is 206, and for retail (July, 1919), 190.

A look at the history of prices shows the interesting fact that, while prices have sometimes fallen, they have generally risen. The high cost of living has been for centuries a source of complaint. In the 16th century, people objected to the price of wheat, which was three to ten times what it cost during the preceding 300 years.

Where, through ignorance of monetary science, irredeemable paper money was used, prices have sometimes gone up quite "out of sight." This was the case with the famous assignats of the French Revolution, and the "Continental" paper money of our own Revolution. After the Revolution a barber in Philadelphia is said to have covered the walls of his shop with continental paper money, calling it the cheapest wallpaper he could get! Jokes were also heard of a housewife taking a market-basket full of this "money" to the butcher's shop and bringing home the meat in her purse! This money became a hissing and a byword; and, even to this day, one of the favorite expressions for worthlessness is "not worth a Continental." We see the same situation repeated again today with Russian paper money.

But our first scientific measurement of price movements began with 1782, the beginning of Jevons' index number of wholesale prices in England.

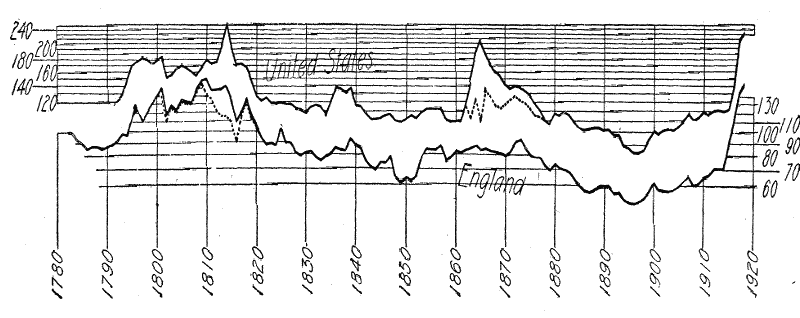

Figure 1 shows the course of prices in England from that date, and also, for comparison, that in the U.S.

Figure 1 - Price Movements of the United States and England from the Earliest Index Numbers Through the First Years of the World War

Showing, in general, a close similarity. England was on a paper basis, 1801—1820; and the United States, 1862—78. The dotted lines for these periods show the prices as translated back into gold.

The conspicuous feature of these curves is their great irregularity. Practically never are they for any length of time at all horizontal. Sometimes, even in time of peace, a variation of over 10 per cent. is shown in one year. The curve for the U. S. shows, at the time of the Civil War, a very considerable rise (especially as measured in terms of paper), followed by a decline beginning in 1873 and continuing to 1896. The fall in the first part of this period was accentuated by the return from a paper to a gold standard. From an index number of 100 in 1873, the index number dropped to 51 in 1896. This decline resulted politically in the famous Bryan "Free Silver" campaign.

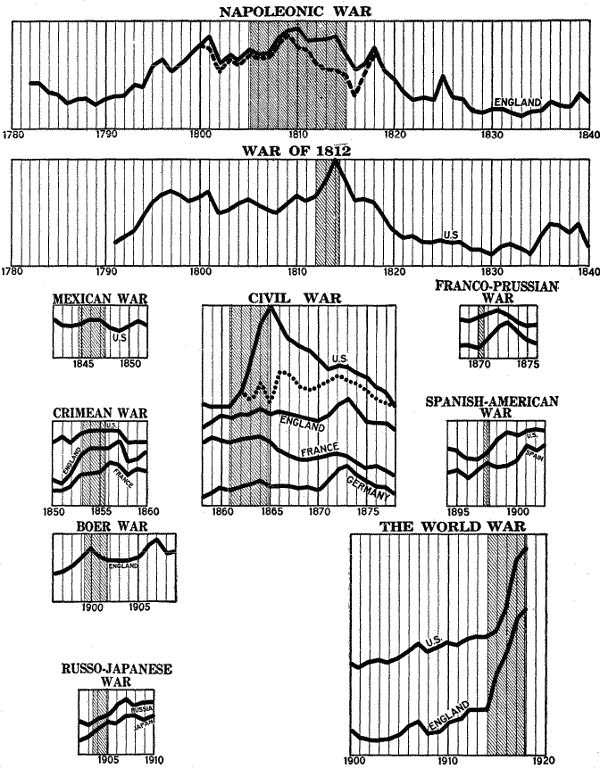

Figure 2 - Trend of Prices Before and After the Great Wars of History

Since that time, however, the course of prices has been steadily upward. Between 1896 and the outbreak of the war, the index number of the U. S. rose about 50 per cent. Substantially the same increase took place in Canada, while in the United Kingdom there was a rise of 35 per cent. This rise before the war amounted, in the United States, to about one-fifth of one per cent. per month. During the war, however, the rise amounted in this country to 1½ per cent. per month, and abroad to much more—in Germany and Austria to 3 per cent. per month, and in Russia, apparently, to 4 or 5 per cent. per month. In the light of the excitement caused up to 1914 by the comparatively moderate increase in this country, we can better understand the Russian economic unrest when a far steeper ascent of prices got under way.

The total effect can be summed up as follows: between 1914, before the war, and November, 1918, the price level in this country (as indicated by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics retail food index number) rose 79 per cent.; that in England (according to the Statist index number), 133 per cent.; that in France, approximately 140 per cent.; that in western Europe probably at least three-fold; and in Russia perhaps ten or twenty-fold.

The price level of the United States today is over three-fold that of 1896. Expressing the same fact in terms of the purchasing power of money, our dollar of today is worth only 30 cents of the money in 1896, so that as contrasted with the dollar of 1896 our dollar literally "looks like thirty cents."

Now it is a common belief, and one which seems to be borne out by the present situation, that war raises prices whereas peace lowers them. The matter is, however, not so simple. Each case must be considered on its own merits. Figure 2 shows price curves for the various wars.

In general prices have risen during wars. But there has not been any such uniformity of movement after wars. Moreover in most cases the price disturbances both during and after the wars had scarcely anything to do with the coming and going of the war. In only four of the cases on the chart is the rise of prices during the war really and clearly due to the war. In the Napoleonic Wars, the war of 1812, the Civil War, and the World War the rise of prices during the war was largely due to war inflation.

As to the after effects on prices there are likewise only four clear cases. The fall of paper prices relatively to gold after the Napoleonic Wars, and the Civil War was, in each case, clearly due to resumption of specie payments. The fall of prices in the United States after the War of 1812 was doubtless due in large measure to the resumption of foreign trade. In one case there was a rise of prices as an aftermath; the war of 1871, which gave Germany a billion dollars of indemnity, created inflation in Germany and prices rose there between 1871 and 1873 faster than in any other country. This doubtless accentuated the crash in the crisis of 1873.

In the other cases in the diagram the many instances of rise of prices after the wars were due primarily at least, to other causes, although the cessation of war and the undue optimism and spirit of speculation which often follow may, in several instances, have contributed to the boom period and the crisis which so often came a few years later, viz., that of 1857 after the Crimean War, that of 1866 after the Civil War, as well as that of 1873 just mentioned.

The only safe generalizations seem to be the following two: The first is that in so far as a war has been costly, i. e., has strained the economic resources of the belligerents, there has been recourse to inflation in some form and prices have risen. Besides the examples in the chart are those of the French Revolution, the American Colonial wars, the American Revolution and many others. The second generalization is that after a costly war the price level is affected up or down by the fiscal policy of the governments concerned.

Most cherish the belief that high war prices today represent war scarcity. In the case of some countries like Belgium and some commodities like paper this is true and in such cases scarcity serves as a partial explanation of high prices. But in the case of most countries and most commodities there has been no general scarcity. The almost universal rise of prices cannot be ascribed to scarcity. Prices have risen of many goods not affected by the war or in countries remotest from the war.

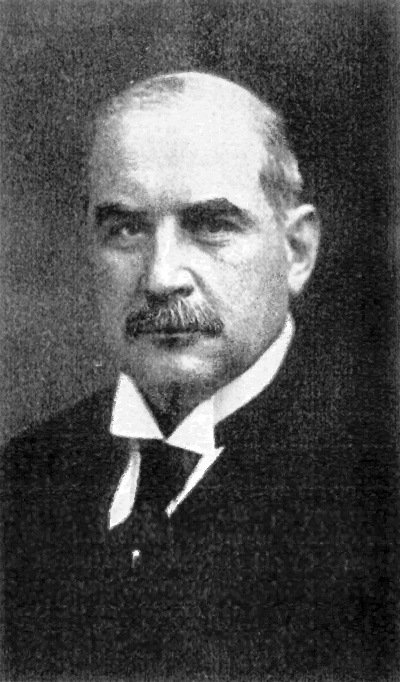

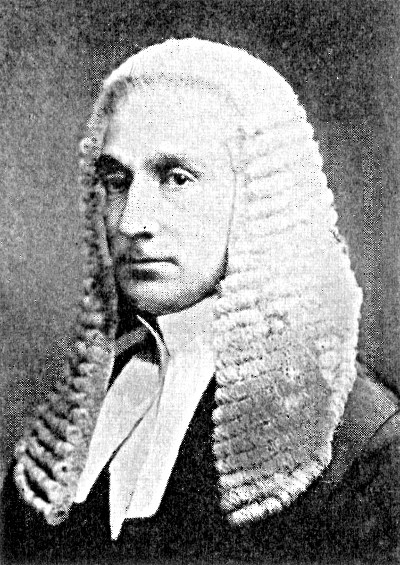

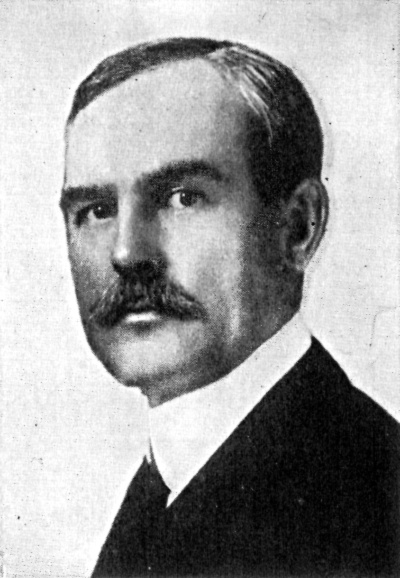

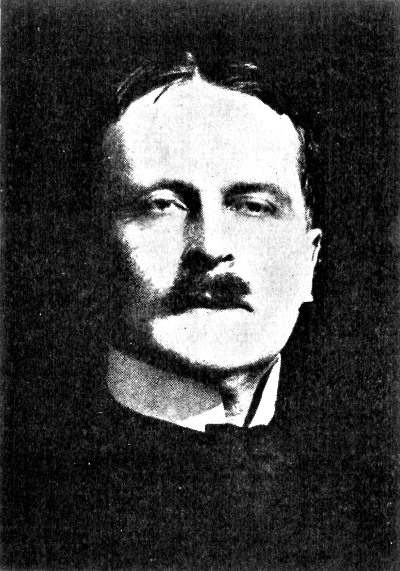

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood

William McAdoo

Secretary of the Treasury during the World War and Director-General of the Railroads.

As Mr. O. P. Austin, statistician of the National City Bank, has said:

"Raw silk, for example, for which the war made no special demand and which was produced on the side of the globe opposite that in which the hostilities were occurring, advanced from $3.00 per pound in the country of production in 1913 to $4.50 per pound in 1917, and over $6.00 per pound in the closing months of the war. Manila hemp, also produced on the opposite side of the globe and not a war requirement, advanced in the country of production from $180 per ton in 1915 to $437 per ton in 1918. Goat skins, from China, India, Mexico and South America, advanced from 25 cents per pound in 1914 to over 50 cents per pound in 1918; and yet goat skins were in no sense a special requirement of the war. Sisal grass produced in Yucatan advanced from $100 per ton in 1914 at the place of production to nearly $400 per ton in 1918; and Egyptian cotton, a high-priced product and thus not used for war purposes, jumped from 14 cents per pound in Egypt in 1914 to 35 cents per pound in 1918. Even the product of the diamond mines of South Africa advanced from 60 to 100 per cent. in price per karat when compared with prices existing in the opening months of the war.

"The prices are in all cases those in the markets of the country in which the articles were produced and in most cases at points on the globe far distant from that in which the war was being waged. They are the product of countries having plentiful supply of cheap labor and upon which there has been no demand for men for service in the war. The advance in the prices quoted is in no sense due to the high cost of ocean transportation since they are those demanded and obtained in the markets of the country of production.

"Why is it that the product of the labor of women and children who care for silk worms in China and Japan, of the Filipino laborer who produces the Manila hemp, the Egyptian fellah who grows the high grade cotton, the native workman in the diamond mines of South Africa, the Mexican peon in the sisal field of Yucatan, the Chinese coolie in the tin mines of Malay, or the goatherd on the plains of China, India, Mexico or South America has doubled in price during the war period?"

Mr. Austin goes on to show that the scarcity or "increased demand" for war goods has been greatly exaggerated. It is true that some 40 million men were at one time fighting in the war. But this is less than 2½ per cent. of the world's population and it must not be forgotten that these 40 million were also consumers before the war. Their withdrawal from industry did not really create a vacuum of even 1 per cent. of the world's productive power; as women, boys and old men took their places and others worked harder than in peace time.

In addition to the 40 million soldiers, some 150 million people have been required to work on "war work" at home but they have simply been "switched" from other forms of production which have been correspondingly reduced. War supplies were demanded but these also largely "switched" the demand from former and industrial uses. Lord D'Abernon found that in England those objects of luxury "which would seem to be influenced not at all or only very remotely and to a very small degree by increased cost of labor and materials," such as old books, prints and coins, had, nevertheless, advanced, roughly speaking 50 per cent., during the war. Thus "scarcity" and especial "war demands" do not go far toward explaining the high price level even in Europe and not at all, I believe, in this country.

In the United States while certain things have become scarce, including certain foods, the general mass of goods has been actually increased as a consequence of war.

The raw materials used in the United States in 1918 were 16 per cent. more than in 1913 and 2 per cent. more than in 1917. The physical volume of trade is estimated variously to be in 1918 from 22 per cent. to 41 per cent. above that in 1913 and 8 per cent. above that in 1917.

President Wilson, in his address to Congress, August 8, 1919, on the high cost of living, gave other impressive examples as to foods, especially eggs, frozen fowls, creamery butter, salt beef, and canned corn, showing that scarcity is not the cause of high prices.

The truth is that the chief causes of the rise of prices in war time are monetary causes.

It is almost invariably true that the great price movements of history are chiefly monetary. This is shown, in the first place by the fact that countries of like monetary standards have like price movements. Thus—to consider gold-standard countries—there has usually been a remarkable family resemblance between the curves representing the rise and fall of the index numbers of the United States, Canada, England, France, Belgium, Holland, Scandinavia, Germany, Austria and Italy. Again, the price movements in silver countries show a strong likeness, as in India and China between 1873 and 1893.

On the other hand, we find a great contrast between gold and silver countries or between any countries which have different monetary standards. In the World War the data are still too meager to enable us to express all the relations in exact figures, but we may arrange the different countries in the approximate order in which their prices have risen. The order of the nations corresponds, in general, with the order in which the currency in those nations has been inflated by paper as well as with the order in which their monetary units have depreciated in the foreign exchange markets.

This order—of ascending prices and of inflated currency—is as follows, beginning with the least rise and inflation: India, Australia, New Zealand, United States, Canada, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, Italy, Holland, England, Norway, France, Germany, Austria and Russia.

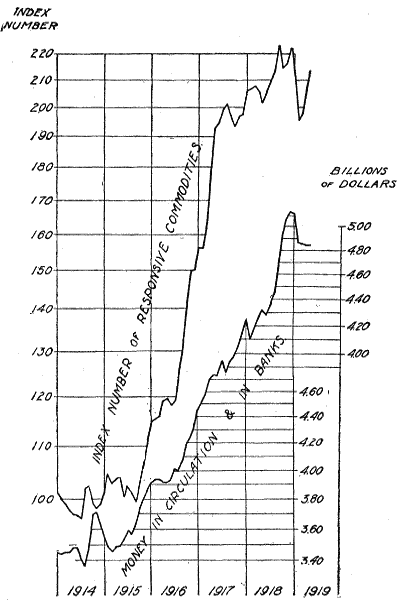

Figure 3. - Money and the Price Level

Showing a correspondence between the quantity of money and the level of prices. Since the middle of 1915, when the quantity of money in the United States began to be greatly affected by the war, the correspondence has been close, changes in the price level seeming usually to follow changes in the quantity of money one to three months later.

The ups and downs of prices correspond with the ups and downs of the money supply. Throughout all history this has been so. For this general statement there is sufficient evidence even where we lack the index numbers [Pg xiii] by which to make accurate measurements. Whenever there have been new discoveries of gold and rapid outpourings from mines, prices have gone up with corresponding rapidity. This was observed in the 16th century, after great quantities of the precious metals had been brought to Europe from the Americas; and again in the 19th century, after the Californian and Australian gold finds of the fifties; and still again, in the same century after the South African, Alaskan and Cripple Creek mining of the nineties.

Likewise when other causes than mining, such as paper money issues, produce violent changes in the quantity or quality of money, violent changes in the price level usually follow.

The World War furnishes important examples of this. In the United States the curve for the quantity of money in circulation and the curve for the index number of prices run continuously parallel, the price curve following the money curve after a lag of one to three months. It was in August, 1915, that the quantity of money in the United States began its rapid increase. One month later prices began to shoot upward, keeping almost exact pace with the quantity of money. In February, 1916, money suddenly stopped increasing, and two or three months later prices stopped likewise. As figure 3 shows, similar striking correspondences have continued to occur with an average lag between the money cause and the price effect of apparently about one and three-quarters months.

On the whole, the money in circulation in the United States rose from three and one-third billions in 1913 to five and a half billions in 1918, and bank deposits from thirteen to twenty-five billions, both approximately corresponding to the rise in prices.

Taking a world-wide view, the money in circulation in the world outside of Russia has increased during the war from fifteen billions to forty-five billions and the bank deposits in fifteen principal countries from twenty-seven billions to seventy-five billions. That is both money and deposits have trebled; and prices, on the average have perhaps trebled also.

The Bolsheviki are a law unto themselves. They have issued eighty billion dollars of paper money, or more than in all the rest of the world put together. Consequently prices in Russia have doubtless reached the sky, though no exact measure of them, since the Bolshevist régime, is at hand.

The increase of over thirty billions in the money of the world (outside of Russia) is as Austin says "more, in its face value, than all the gold and all the silver turned out by all the mines of all the world in 427 years since the discovery of America."

The conclusion toward which the foregoing and other arguments lead is that, in this war as in general in the past, the great outstanding disturber of the price level has always been money. If this is the case, how fruitless, except as treatments of symptoms, are price-fixing, or campaigns aimed at profiteers! The cry of profiteering may hinder a real solution of the difficulty by diverting attention from the real issue and fanning and giving up an object to the spirit of revolt. Money is so much an accepted convenience in practice that it has become a great stumbling block in theory. Since we talk always in terms of money and live in a money atmosphere, as it were, we become as unconscious of it as we do of the air we breathe.

We have now considered the cost of living situation under the two questions "What is it?" and "Why is it?"

The third question, "What of it?"—i. e., what are the evils connected with it—is more easily answered today, when it comes home to all of us, that it might have been 10 years ago.

If, for each one of us, the rise of income were to keep up exactly with the rise in cost of living, then the high cost of living would have no terrors; it would be merely on paper. But no such perfect adjustment ever occurs or can occur. Outstanding contracts and understandings in terms of money make this out of the question. The salaried men and the wage earners suffer—that is, the cost is borne by those with relatively "fixed" incomes.

The truth is, the war was largely paid for, not by taxes or loans but by the High Cost of Living. The result is that the effort to avoid [Pg xiv] discontent of tax payers has created or rather aggravated the discontent over high prices. Every rise in the cost of living brings new recruits to the labor malcontents who feel victimized by society and have come to hate society. They cite, in their indictment, the high price of necessities and the high profits of certain great corporations both of which they attribute, not to the aberrations of our monetary yardstick but to deliberate plundering by "profiteers" or a social system of "exploitation." They grow continually more suspicious and nurse an imaginary grudge against the world. We are being threatened by more quack remedies—revolutionary socialism, syndicalism, and Bolshevism. Radicalism rides on the wave of high prices.

As a matter of fact, the real wages in 1918, that is, their purchasing power, were only 80 per cent. of the real wages of 1913. That is, while the retail prices of food advanced 68 per cent., wages in money advanced only 30 per cent. The real wages of 1913 were in turn less than in earlier years.

Lord D'Abernon, in a recent speech in the House of Lords said: "I am convinced and cannot state too strongly my belief that 80 per cent. of our present industrial troubles and our Bolshevism which is so great a menace to Europe are due to this enormous displacement in the value of money." In fact, before the war, rising costs of living were manufacturing socialists all over the world, including Germany, and the German Government may have weighed, as one of the expected dynastic advantages of war, the suppression of the growing internal class struggle which this high cost of living was bringing on apace.

We are now ready for the question, "What can be done about it?" So far as the past is concerned, comparatively little. Bygones must largely be bygones. So far as wages and salaries are concerned, the remedy must be to raise them rather than to lower the high cost of living. While some kinds of work have had excessive wages during the war, this has not been true in general, public opinion to the contrary notwithstanding. I quite agree with Mr. Gompers that the wage level should not be lowered even if it could be. On the contrary it should be raised to catch up with prices, just as was done after the Civil War. But in regard to contracts little relief for past injuries can be expected. We would best use the past as a lesson for the future. That is what I understand by "reconstruction."

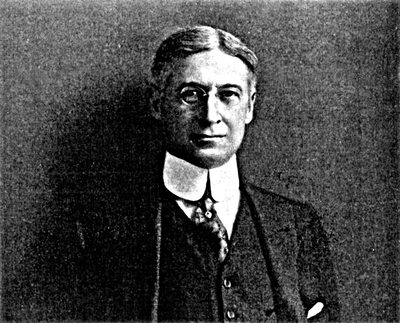

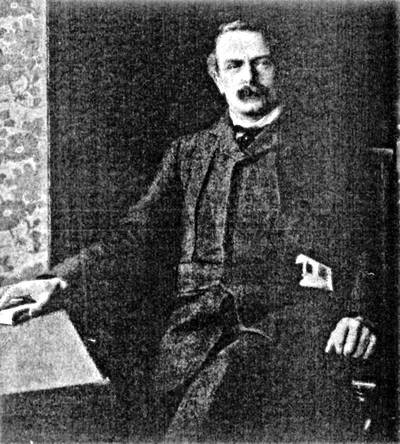

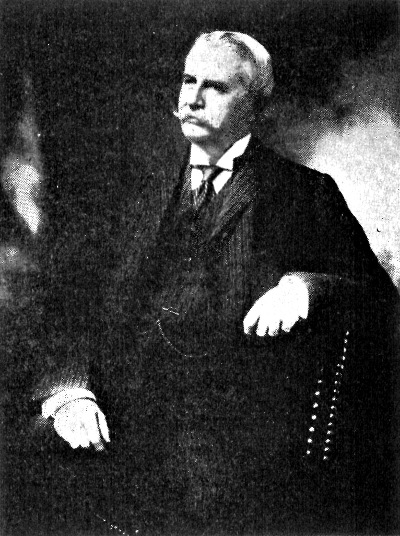

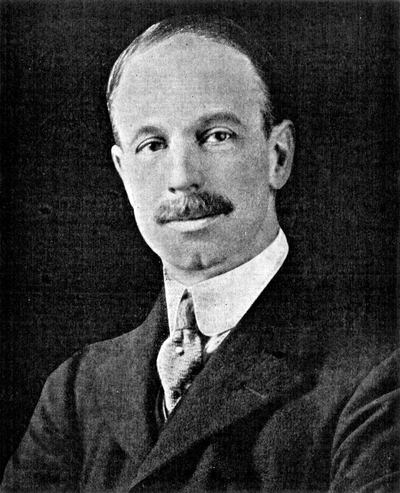

John Pierpont Morgan

The banking house of Morgan was closely identified with international finance throughout the World War.

Many impracticable plans have been proposed. Secretary Redfield undertook to stabilize prices by arbitrarily fixing them. He failed, necessarily. We might as well try to fix the sea level by pressing on the ocean. The same, as I stated above, is true of a campaign against profiteers though proposed by so high an authority as President Wilson.

The plan I shall here outline has received the approval of a large number of leading economists, business men, and organizations, [Pg xv] including President Hadley of Yale; a committee of economists appointed to consider the purchasing power of money in relation to the war; Frank A. Vanderlip, president of the National City Bank of New York; George Foster Peabody, Federal Reserve banker of New York; John Perrin, Federal Reserve Agent of San Francisco; Henry L. Higginson, the veteran banker of Boston; Roger W. Babson, statistician; John Hays Hammond, mining engineer; John V. Farwell, of Chicago; Leo S. Rowe, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury: United States Senator, Robert L. Owen, one of the authors of the Federal Reserve Act; Ex-Senator Shafroth; the late Senator Newlands; Sir David Barbour, one of the originators of the Indian gold exchange standard; the Society of Polish Engineers; the New England Purchasing Agents' Association; and a few Chambers of Commerce.

Our dollar is now simply a fixed weight of gold—a unit of weight, masquerading as a unit of value. It is almost as absurd to define a unit of value, or general purchasing power, in terms of weight as to define a unit of length in terms of weight. What good does it do us to be assured that our dollar weighs just as much as ever? We want a dollar which will always buy the same aggregate quantity of bread, butter, beef, bacon, beans, sugar, clothing, fuel, and the other essential things that we spend it for. What is needed is to stabilize or standardize the dollar just as we have already standardized the yardstick, the pound weight, the bushel basket, the pint cup, the horsepower, the volt, and, indeed, all the units of commerce except the dollar.

Money today has two great functions. It is a medium of exchange and it is a standard of value. Gold was chosen because it was a good medium, not because it was a good standard. And so, because our ancestors found a good medium of exchange, we now find ourselves saddled with a bad standard of value!

The problem before us is to retain gold as a good medium and yet to make it into a good standard; not to abandon the gold standard but to rectify it; not to rid ourselves of the gold dollar but to make it conform in purchasing power to the composite or goods-dollar. The method of rectifying the gold standard consists in suitably varying the weight of the gold dollar. The gold dollar is now fixed in weight and therefore variable in purchasing power. What we need is a gold dollar fixed in purchasing power and therefore variable in weight. I do not think that any sane man, whether or not he accepts the theory of money which I accept, will deny that the weight of gold in a dollar has a great deal to do with its purchasing power. More gold will buy more goods. Therefore more gold than 25.8 grains will, barring counteracting causes, buy more goods than 25.8 grains itself will buy. If today the dollar, instead of being 25.8 grains or about one-twentieth of an ounce of gold, were an ounce or a pound or a ton of gold it would surely buy more than it does now, which is the same thing as saying that the price level would be lower than it is now.

A Mexican gold dollar weighs about half as much as ours and has less purchasing power. If Mexico should adopt the same dollar that we have and that Canada has, no one could doubt that its purchasing power would rise—that is, the price level in Mexico would fall. Since, then, the heavier or the lighter the gold dollar is the more or the less is its purchasing power, it follows that, if we add new grains of gold to the dollar just fast enough to compensate for the loss in the purchasing power of each grain, or vice versa take away gold to compensate for a gain, we shall have a fully "compensated dollar," a stationary instead of fluctuating dollar, when judged by its purchasing power.

But how, it will be asked, is it possible, in practice, to change the weight of the gold dollar? The feat is certainly not impossible, for it has often been accomplished. We ourselves have changed the weight of our gold dollar twice—once in 1834, when the gold in the dollar was reduced 7 per cent., and again in 1837, when it was increased one-tenth of 1 per cent. If we can change it once or twice a century, we can change it once or twice a month!

In actual fact, gold now circulates almost entirely through "yellowbacks," or gold certificates. The gold itself, often not [Pg xvi] in the form of coins at all but of "bar gold," lies in the government vaults. The abolition of gold coin would make no material change in the present situation.

If gold thus circulated only in the form of paper representatives it would evidently be possible to vary at will the weight of the gold dollar without any such annoyance or complication as would arise from the existence of coins. The government would simply vary the quantity of gold bullion which it would exchange for a paper dollar—the quantity it would give or take at a given time. As readily as a grocer can vary the amount of sugar he will give for a dollar, the government could vary the amount of gold it would give for a dollar.

But, it will now be asked, what criterion is to guide the government in making these changes in the dollar's weight? Am I proposing that some government official should be authorized to mark the dollar up or down according to his own caprice? Most certainly not. A definite and simple criterion for the required adjustments is at hand—the now familiar "index number" of prices.

If, for instance, the index number is found to be 1 per cent. above the ideal par, this fact will indicate that the purchasing power of the dollar has gone down; and this fact will be the signal and authorization for an increase of 1 per cent. in the weight of the gold dollar. What is thereby added to the purchasing power of the gold dollar will be automatically registered in the purchasing power of its circulating certificate. If the correction is not enough, or if it is too much, the index number next month will tell the story.

Absolutely perfect correction is impossible, but any imperfection will continue to reappear and so cannot escape ultimate correction. Suppose, for instance, that next month the index number is found to remain unchanged at 101. Then the dollar is at once loaded an additional 1 per cent. And if, next month, the index number is, let us say, 100½ (that is, one half of 1 per cent above par) this one-half of 1 per cent. will call for a third addition to the dollar's weight, this time of one-half of one per cent. And so, as long as the index number persists in staying even a little above par, the dollar will continue to be loaded each month, until, if necessary, it weighs an ounce—or a ton, for that matter. But, of course, long before it can become so heavy, the additional weight will become sufficient; so that the index number will be pushed back to par—that is, the circulating certificate will have its purchasing power restored. Or suppose the index number falls below par, say 1 per cent. below. This fact will indicate that the purchasing power of the dollar has gone up. Accordingly, the gold dollar will be reduced in weight 1 per cent., and each month that the index number remains below par the now too heavy dollar will be unloaded and the purchasing power of the certificate brought down to par.

Thus by ballast thrown overboard or taken on, our dollar is kept from drifting far from the proper level. The result is that the price level would oscillate only slightly. Instead of there being any great price convulsions, such as we find throughout history, the index number would run, say 101, 100½, 101, 100, 102, 101½, 100, 98, 99, 99, 99½, 100, etc., seldom getting off the line more than 1 or 2 per cent.

With the question now before us, it is evident that the problem of our monetary standards has much more than theoretical significance. It is a practical problem, and, I submit, the most pressing which the war has left us. I do not offer the solution described above as the only answer to the problem. It is, however, a working basis, a starting point, from which we may be able to work out a better plan. Some scientifically sound plan is essential, or we shall be the victims of quack remedies.

Finally, now is the time to take up the matter. Public interest is now focused on the cost of living and is very largely educated to the fact that the high prices have a monetary basis. Furthermore, the world is looking to us, as never before, for leadership. It is our golden opportunity to set world standards. If we adopt a stable standard of value, it seems certain that other nations, as fast as they [Pg xvii] can straighten out their affairs, resume specie payments, and secure again stable pars of exchange, will follow our example.

Let us, then, who realize the situation, act upon our knowledge; and secure a boon for all future generations, a true standard for contracts, a stabilized dollar.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood

President Wilson and Rear Admiral Grayson Passing the Palace of the King in Brussels

The paramount position of War Finance was brought vividly and continuously before the whole people of the United States by the Liberty Loan campaigns. This lesson was an old one though it was enforced by all the improved methods of modern publicity. To Napoleon Bonaparte is attributed the statement that three things are necessary to wage a successful war: money, more money, and still more money.

It has been well said that:

"Perhaps the greatest surprise of the war to most people, even to those who had studied political economy, has been the enormous expenditure of money which a nation can incur, and the length of time which it can go on fighting without complete exhaustion. This should not have been in reality a surprise to anyone who had studied past history, for all experience shows that lack of money itself has never prevented a nation from continuing to fight, if it were determined to fight. The financial condition of Revolutionary France at the commencement of Napoleon's career was wretched in the extreme, yet France went on fighting for nearly twenty years after that. The Balkan States can hardly be said ever to have had great financial resources, and yet they fought, one after the other, two severe wars, and are now fighting a third still more severe and prolonged. The Boers in South Africa found no difficulty in fighting the British Empire for three years with practically no financial resources. The Mexicans recently managed to fight one another for a good many years in the same way. Lastly, the Southern states in our own Civil War fought for years a desperate and losing fight and were ultimately beaten to the ground, not so much by a lack of money, as by an actual lack of things to live on and fight with. In fact, all history proves, and this war proves over again, that if what the Germans call 'the will to fight' exists lack of money will never stop a nation's fighting, provided it possesses or can obtain its absolutely minimum requirements of food, clothing, and munitions of war. It was Bismarck who said: 'If you will give me a printing press, I will find you the money.' In finding the money required for an exhausting war a nation is driven to all sorts of desperate financial expedients which may very seriously affect its economic life, but if a nation wants to continue fighting and can produce, or be induced to produce, the things that are absolutely necessary for life and warfare, the government will get hold of those things somehow. If it cannot get them in any other way, ultimately it will take them."

When the war opened England was in the strongest position of any of the Allies. She was the greatest creditor nation in the world. That is, she was able to purchase goods from foreign countries on easier terms than her associates. Russia and Italy were debtor nations and had to borrow even before the war in order to balance their foreign accounts. So these members of the Entente had to be assisted in making purchases abroad. England was able for a long time to keep up her exchange rate in New York. This was done by the shipment of gold and by inducing the holders of American securities in England to sell or lend such securities to their government.

England was forced to act as the agent of other Powers who were fighting with her. Until the United States came in, it was the greatest industrial arsenal among the Allies. Large imports were naturally a feature of this policy. The United States soon began to feel the result of the changes in international credit. Exports almost doubled between 1912 and 1917, the figures being in millions, $2,399,000,000 and $6,231,000,000, respectively.

Another side of the United States trade account to the world is indicated by the following classified list of loans to January, 1917: [Pg 2]

"Between August 1, 1914, and December 31, 1916, the loans raised in the United States by foreign countries were estimated to reach $2,325,900,000, of which $175,000,000 had been repaid. The net indebtedness on January 1, 1917, was therefore $2,150,900,000. The loans may be classified geographically as follows:

| Europe | $1,893,400,000 |

| Canada | 270,500,000 |

| Latin America | 157,000,000 |

| China | 5,000,000 |

| ——————— | |

| Total foreign loans | $2,325,900,000 |

| Less amount paid, | 175,000,000 |

| ——————— | |

| Net foreign indebtedness | $2,150,900,000 |

"The loans of the belligerent countries which were floated in the United States up to the close of 1916 are divided as follows:

| Great Britain | $908,400,000 | |

| France | 695,000,000 | |

| Russia | 160,000,000 | |

| Germany | 45,000,000 | [1] |

| Canada | 270,500,000 | |

| ———————— | ||

| Total | $2,078,900,000 | [2] |

[1]Estimated.

[2] Nearly $1,900,000,000 of this constituted war loans.

A new pace in war finance was set by the United States when it became a belligerent. It had to provide for an increase of taxation ascending from the point of $3,000,000,000 in 1917 to over $8,000,000,000 in 1918. The largest source of estimated revenue was from taxes on excess profits, including war profits of $3,100,000,000, and the next was from taxes on incomes, $1,482,186,000 from individuals, and $828,000,000 from corporations. The New York Journal of Commerce shows by the following table the difference between the old and the new system of taxation. Exemptions under the new law were the same as under the old: $1,000 for single persons and $2,000 for married, $200 additional allowed for each dependent child under eighteen years of age:

| Incomes | Tax Under | |

|---|---|---|

| Old | New | |

| Law | Law | |

| $2,500 | $10 | $30 |

| 3,000 | 20 | 60 |

| 3,500 | 30 | 90 |

| 4,000 | 40 | 120 |

| 4,500 | 60 | 150 |

| 5,000 | 80 | 180 |

| 5,500 | 105 | 220 |

| 6,000 | 130 | 260 |

| 6,500 | 155 | 330 |

| 7,000 | 180 | 400 |

| 7,500 | 205 | 470 |

| 8,000 | 235 | 545 |

| 8,500 | 265 | 620 |

| 9,000 | 295 | 695 |

| 9,500 | 325 | 770 |

| 10,000 | 355 | 845 |

| 12,500 | 530 | 1,320 |

| 15,000 | 730 | 1,795 |

| 20,000 | 1,180 | 2,895 |

| 25,000 | 1,780 | 4,240 |

| 30,000 | 2,380 | 5,595 |

| 35,000 | 2,980 | 7,195 |

| 40,000 | 3,580 | 8,795 |

| 45,000 | 4,380 | 10,645 |

| 50,000 | 5,180 | 12,495 |

| 55,000 | 5,980 | 14,695 |

| 60,000 | 6,780 | 16,895 |

| 70,000 | 8,880 | 21,895 |

| 80,000 | 10,980 | 27,295 |

| 100,000 | 16,180 | 39,095 |

| 150,000 | 31,680 | 70,095 |

| 200,000 | 49,180 | 101,095 |

| 300,000 | 92,680 | 165,095 |

| 500,000 | 192,680 | 207,095 |

| 1,000,000 | 475,180 | 647,095 |

| 5,000,000 | 3,140,180 | 3,527,095 |

The following estimated yield from other sources is given by the same authority:

"Transportation—Freight, $75,000,000; express, $20,000,000; passenger fares, $60,000,000; seats and berths, $5,000,000; oil by pipe lines, $4,550,000.

"Beverages (liquors and soft drinks), $1,137,600,000; stamp taxes, $32,000,000; tobacco cigars, $61,364,000; cigarettes, $165,240,000; tobacco, 104,000,000; snuff, $9,100,000; papers and tubes, $1,500,000.

"Special Taxes.—Capital stock, $70,000,000; brokers, $1,765,000; theaters, etc., $2,143,000; mail order sales, $5,000,000; bowling alleys, billiard and pool tables, $2,200,000; shooting galleries, $400,000; riding academies, $50,000; business license tax, $10,000,000; manufacturers of tobacco, $69,000; manufacturers of cigars, $850,000; manufacturers of cigarettes, $240,000; use of automobiles and motor cycles, $72,920,000.

"Telegraph and telephone messages, $15,000,000; insurance, $12,000,000; admissions (theaters, circuses, etc.), $100,000,000; club dues, $9,000,000.

"Excise Taxes.—Automobiles, etc., $123,750,000; jewelry, sporting goods, etc., $80,000,000; other taxes on luxuries at 10 percent., $88,760,000; other taxes on luxuries (apparel, etc., above certain prescribed prices), at 20 percent., $181,095,000.

"Gasoline, $40,000,000; yachts and pleasure boats, $1,000,000."

"The income tax law levies on all citizens or residents of the United States a normal tax of 12 percent. upon the amount of income in excess of exemptions, except that on the first $4,000 of the taxable amount the rate shall be 6 percent. The law also increases the surtaxes all along the line. The advances by grades compared with the percentage under the old law are: $5,000 to $7,500 incomes, increased from 1 to 2 percent.; $7,500 to $10,000, from 2 to 3 percent.; $10,000 to $12,500, from 3 to 7 percent.; $12,500 to $15,000, from 4 to 7 percent.; $15,000 to $20,000, from 5 to 10 percent.; $20,000 to $30,000, from 8 to 15 percent.; $30,000 to $40,000, from 8 to 20 percent.; $40,000 to $50,000, from 12 to 25 percent.; $50,000 to $60,000, from 12 to 32 percent.; $60,000 to $70,000, from 17 to 38 percent.; $70,000 to $80,000, from 17 to 42 percent.; $80,000 to $90,000, from 22 to 46 percent.; $90,000 to $100,000, from 22 to 46 percent.; $100,000 to $150,000, from 27 [Pg 3] to 50 percent.; $150,000 to $200,000, from 31 to 50 percent.; $200,000 to $250,000, from 37 to 52 percent.; $250,000 to $300,000, from 42 to 55 percent. The rate continues to increase, but on incomes of over $5,000,000 the increase is only from 63 percent., under former law to 65 percent."

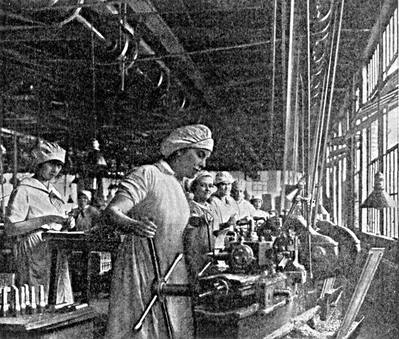

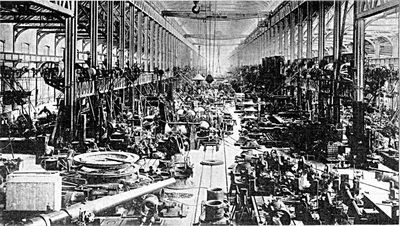

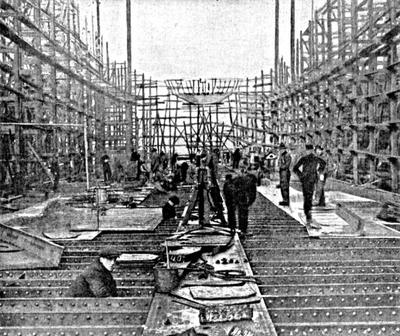

Copyright by International Film Service

Women Munition Workers in the International Fuse and Arms Works

Before entering the war, the United States was the great arsenal of the Allies. After our entry, production of munitions increased, while the man power in the industry diminished through enlistments and the draft. Women took up the work and showed surprising ability.

According to a calculation published in the New York World the war revenue bill imposed a war tax of $80 on every man, woman and child in the United States, or approximately $400 for each family. The amount expected to be derived from each item is given in the following table:

| Individual income tax | $1,482,186,000 |

| Corporation income tax | 894,000,000 |

| Excess and war profits | 3,200,000,000 |

| Estate tax | 110,000,000 |

| Transportation | 164,550,000 |

| Telegraph and telephone | 16,000,000 |

| Insurance | 12,000,000 |

| Admissions | 100,000,000 |

| Club dues | 9,000,000 |

| Excise, luxury, and semi-luxury | 518,305,000 |

| Beverages | 1,137,600,000 |

| Stamp taxes—chiefly documentary | 32,000,000 |

| Tobacco and products | 341,204,000 |

| Special business and automobile-user's Taxes | 165,607,000 |

| ——————— | |

| Total | $8,182,452,000 |

With the operation of this tax the people of the United States found it no longer possible to speak in terms of opprobrium of the tax-ridden people of Europe. The American income tax has a higher rate on large incomes than that provided for under the English system. A man in the United States with an income of $5,000,000 is taxed nearly 50 [Pg 4] percent., more than in England. The New York Tribune published tables printed below comparing the income tax rates of the United States with those existing in France and in Great Britain.

A compilation made for the Wall Street Journal shows that the United States income tax even with the increases made in 1918 was still far lower than the English income tax:

"The great bulk, numerically, of incomes taxed in 1917 was in the field reached by the lowering of the exemption in the 1917 law.... It is a fact, however, that no one of these new taxpayers was called on to contribute more than $40 to the government, as the rate was only 2 percent., while all other incomes paid a basic normal tax of 4 percent. The lowest rate for normal tax in Great Britain is 2 shillings and 3 pence on the pound, or 11¼ percent., and the exemption is only $600. The basic normal tax under the new English law is 6 shillings on the pound, or 30 percent., on all incomes over $25,000.

| ————— United States————— | United Kingdom | France | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Law | New Law | Rate (per cent.) | |||||

| Income | Amount | Rate (per cent.) | Amount | Rate (per cent.) | Unearned | Earned | Rate (per cent.) |

| $2,500 | $10 | .40 | $30 | 1.20 | 11.25 | 8.44 | 1.25 |

| 3,000 | 20 | .67 | 60 | 2.00 | 14.84 | 11.87 | 1.67 |

| 3,500 | 30 | .86 | 90 | 2.57 | 16.24 | 12.96 | 2.07 |

| 4,000 | 46 | 1.00 | 120 | 3.00 | 18.16 | 14.53 | 2.44 |

| 4,500 | 60 | 1.33 | 150 | 3.33 | 18.75 | 15.00 | 2.86 |

| 5,000 | 80 | 1.60 | 180 | 3.60 | 18.75 | 15.00 | 3.20 |

| 5,500 | 105 | 1.91 | 220 | 4.00 | 22.50 | 18.75 | 3.48 |

| 6,000 | 130 | 2.16 | 260 | 4.33 | 22.50 | 18.75 | 3.71 |

| 6,500 | 155 | 2.38 | 330 | 5.08 | 22.50 | 18.75 | 3.90 |

| 7,000 | 180 | 2.57 | 400 | 5.71 | 22.50 | 18.75 | 4.07 |

| 7,500 | 205 | 2.73 | 470 | 6.27 | 22.50 | 18.75 | 4.21 |

| 8,000 | 235 | 2.93 | 545 | 6.81 | 26.25 | 22.50 | 4.34 |

| 8,500 | 265 | 3.12 | 620 | 7.29 | 26.25 | 22.50 | 4.53 |

| 9,000 | 295 | 3.28 | 695 | 7.72 | 26.25 | 22.50 | 4.69 |

| 9,500 | 325 | 3.42 | 770 | 8.11 | 26.25 | 22.50 | 4.84 |

| 10,000 | 355 | 3.55 | 845 | 8.45 | 26.25 | 22.50 | 4.98 |

| 12,500 | 530 | 4.24 | 1,320 | 10.56 | 30.00 | 26.25 | 5.53 |

| 15,000 | 730 | 4.87 | 1,795 | 11.97 | 32.08 | 32.08 | 6.07 |

| 20,000 | 1,180 | 5.90 | 2,895 | 14.48 | 34.06 | 34.06 | 6.99 |

| 25,000 | 1,780 | 7.12 | 4,245 | 16.98 | 35.75 | 35.75 | 7.84 |

| 30,000 | 2,380 | 7.93 | 5,595 | 18.65 | 37.29 | 37.29 | 8.41 |

| 35,000 | 2,980 | 8.51 | 7,195 | 20.56 | 38.75 | 38.75 | 8.99 |

| 40,000 | 3,580 | 8.95 | 8,795 | 21.99 | 39.84 | 39.84 | 9.43 |

| 45,000 | 4,380 | 9.73 | 10,645 | 23.66 | 40.97 | 40.97 | 9.77 |

| 50,000 | 5,180 | 10.36 | 12,495 | 24.99 | 41.88 | 41.88 | 10.05 |

| 55,000 | 5,980 | 10.87 | 14,695 | 26.72 | 42.84 | 42.84 | 10.27 |

| 60,000 | 6,780 | 11.30 | 16,895 | 28.16 | 43.65 | 43.65 | 10.45 |

| 70,000 | 8,880 | 12.69 | 21,895 | 31.26 | 44.91 | 44.91 | 10.75 |

| 80,000 | 10,980 | 13.72 | 27,295 | 34.12 | 45.86 | 45.86 | 10.96 |

| 100,000 | 16,180 | 16.18 | 39,095 | 39.10 | 47.19 | 47.19 | 11.27 |

| 150,000 | 31,680 | 21.12 | 70,095 | 46.73 | 48.96 | 48.96 | 11.68 |

| 200,000 | 49,180 | 24.59 | 101,095 | 50.55 | 49.84 | 49.84 | 11.89 |

| 300,000 | 92,680 | 30.89 | 165,095 | 55.03 | 50.73 | 50.73 | 12.09 |

| 500,000 | 192,680 | 38.54 | 297,095 | 59.42 | 51.44 | 51.44 | 12.25 |

| 1,000,000 | 475,180 | 47.52 | 647,095 | 64.71 | 51.97 | 51.97 | 12.38 |

| 5,000,000 | 3,140,000 | 62.80 | 3,527,095 | 70.54 | 52.39 | 52.39 | 12.48 |

"If the new normal tax in the United States were made uniformly 12 percent.—wiping out the 2 percent. discrimination of the 1917 law—a single man in this country with a salary of $1,500 a year would be called on to pay $60 in income tax, as against an English tax of $101.25. Assuming that the normal tax were raised to 12 percent. and the surtax and excess tax were left as at present, an unmarried American with a salary of $10,000 would pay $1,430.20, while the unmarried Englishman would pay $2,250. If the Englishman derived his $10,000 income from rentals, his tax would be increased to $2,625, while the American tax would be reduced to $1,165—an Irish dividend on effort.

"According to a level where the British surtax becomes effective, take a salary of $20,000. The English normal tax on this would be $6,000 and the surtax $812.50 (figuring $5 to the pound), a total of $6,812.50. At the suggested rate of 12 percent., the American's normal tax would be $2,145.60 (rate applying to $20,000, less $1,000 exemption and $1,120 excess tax); the surtax would be $444 and the excess tax $1,120; a total of $3,709.60. If the American cut non-tax-free coupons for his income instead of working for it, his tax would be reduced to $2,780, making it more than $600, less than one-half the English tax. This, be it remembered, is figuring the American normal tax at the supposititious rate of 12 percent.

"Going abruptly to an income of $1,000,000, the American normal tax at 12 percent., would be $119,880, against an English normal tax of $300,000. The increase in the American normal tax would be $79,960 over present rates. The American surtax at present rates would be $435,300, as against a British surtax of $217,915; total American, $555,180, English, $519,687.50. No account is taken in this computation of any excess tax on the American income. With an income of $3,000,000. the American normal tax at 12 percent. would be $359,880, an increase of $239,960 over present rates. The surtax at present rates would be $1,680,300, a total of $2,040,180, or nearly 70 percent., the rate on the last $1,000,000 being at 75 percent. The corresponding British tax is, normal, $900,000, and surtax $669,685; total, $1,569,685, or nearly 52 percent., the actual maximum rate being 52½ percent. on all excess over $50,000.

"Expressed in tabular form, comparative results from a normal tax of 12 percent., combined with present surtax rates and assuming all income up to $50,000 to be earned income for a single man, would be as follows:

| Income | U.S. Tax | Per Cent. | British Tax | Per Cent. |

| $1,500 | $60.00 | 4.00 | $101.25 | 6.75 |

| 3,000 | 240.00 | 8.00 | 375.00 | 12.50 |

| 5,000 | 480.00 | 9.60 | 750.00 | 15.00 |

| 7,500 | 789.40 | 10.52 | 1,406.25 | 18.75 |

| 10,000 | 1,430.20 | 14.30 | 2,250.00 | 22.50 |

| 15,000 | 2,534.80 | 16.90 | 4,812.50 | 32.08 |

| 20,000 | 3,709.60 | 18.55 | 6,812.50 | 34.06 |

| 30,000 | 6,336.00 | 21.12 | 11,187.50 | 37.29 |

| 40,000 | 8,956.00 | 22.39 | 15,937.50 | 39.84 |

| 50,000 | 11,855.20 | 23.71 | 20,937.50 | 40.18 |

| 75,000 | 18,605.20 | 24.81 | 34,062.50 | 45.42 |

| 100,000 | 26,855.20 | 26.80 | 47,187.50 | 47.19 |

| 150,000 | 46,355.20 | 30.90 | 73,437.50 | 48.96 |

| 250,000 | 92,355.20 | 36.94 | 125,937.50 | 50.37 |

| 500,000 | 235,355.20 | 47.07 | 257,187.50 | 51.44 |

| 700,000 | 359,355.20 | 51.33 | 362,187.50 | 51.74 |

| 750,000 | 390,355.20 | 52.05 | 388,437.50 | 51.79 |

| 1,000,000 | 557,855.20 | 55.78 | 519,687.50 | 51.97 |

| 3,000,000 | 2,042,855.20 | 68.09 | 1,569,687.50 | 52.32 |

| 10,000,000 | 7,292,855.20 | 72.93 | 5,244,687.50 | 52.45 |

"With additional exemption of $1,000 for heads of families and $200 each for dependent children, the United States figures in the table would be reduced by $120 for the $1,000 exemption and $24 for each child. There are similar deductions to be made in the English figures. Furthermore, for incomes above $50,000, deduction for the excess tax has not been figured exactly in order to avoid long computations. This would slightly reduce the figure on the large incomes. But for demonstrative purposes, the table gives a fairly accurate general comparison of the range of taxes under the proposed English law and a tentative 12 percent. normal rate under our law.

"It will be noticed that the rates would come together just below $750,000. It is in the range between $5,000 and $500,000 incomes that greatest divergence in rates occurs. The British tax takes its largest jump between $10,000 and $15,000, where the surtax begins to operate. The United States gradations are erratic and irregular, showing the haphazard manner in which the steps of the surtax were applied."

The passing of the war tax bill was not altogether easy sailing; there was plenty of criticism from the press throughout the country. Republican editors and congressmen wondered why the bill did not contain a tax on cotton, and one Pennsylvania congressman thought that the tax levy should be at the rate of three dollars a bale. Senator Smoot of Utah attacked the bill as a bunglesome measure.

The New York Jourial

Journal of Commerce called attention to the

discrimination between those whose income is in the form of services or

property and those who get it in cash:

"Take the case, for instance, of the salaried employee of a bank or factory who receives $5,000 a year, out of which he pays his house rent and his usual costs of living; contrast him with the case of a farmer who owns his land and obtains the bulk of what he needs, both in food, fuel, and other essentials, for himself and family in [Pg 6] produce or in goods obtained by trade at the neighboring village; the situation becomes clear and shows why it is that the farming class pays only a microscopic proportion of the income tax at the present time."

And the Democratic New York World agreed that the farmer "is not carrying his share of the load of war taxation," and observes:

"An analysis of income tax returns for the fiscal year 1916, recently published, shows that, although farmers are the most numerous class of Americans engaged in gainful occupations, they were at the foot of the list proportionately among income tax payers. Outside of the notorious war profiteers, no element of our population has advantaged so greatly by war as agriculturists; yet in the year of which we speak only one farmer in four hundred paid a farthing's tax upon income. In this respect preachers and teachers showed a higher percentage."

There was some demand for extending the income tax downwards to cover smaller incomes, for example, we find the Council Bluffs' Nonpareil contending:

"The men of more moderate income should be required to pay at least a nominal income tax. This is a common country. It belongs to common people. And common people will esteem it a privilege to contribute their mites. One dollar per hundred on a thousand-dollar income would be both reasonable and just."

The attitude of the New York press is indicated by the Evening Sun and the Times. The New York Evening Sun (Rep.) said the committee "left so many rough edges upon their work." In the opinion of this newspaper, Mr. Kitchin "has given us a measure of class-taxation highly accentuated, and yet has failed to suit the McAdoo group, the most clear-minded adherents of the conscription-of-wealth idea. He has produced a confused series of taxes beyond the practical power of the ordinary busy citizen to master or comprehend, but has not combined these into a harmonious system." The morning Sun even went so far as to remark that "nothing that the Senate could do could make the Kitchin measure worse than it is." Yet it by no means criticized all the features of the bill. It objected to the proposed taxes on oil producers as discouraging the production of oil, and styled the plan to tax distributed corporation earnings at twelve percent. and undistributed earnings at eighteen percent. "simply a fool tax," which "will help to lock the wheels of every great industry in this country."

The foundation mistake of the bill, in the opinion of the New York Times (Ind. Dem.) was the "attempt to assess taxes upon the smallest possible number of persons and businesses, leaving a great majority of the people free from a levy direct or indirect." The Times thought that this policy was dictated by the desire "to leave the mass of voters free from grounds of complaint against the party in power." It insisted that there should be a consumption tax levying "upon the breakfast table and upon the purchases of a great mass of people." Such necessities as tea, coffee, cocoa, sugar, should bear a tax, in the opinion of this and other newspapers. The number of those taxed was also kept comparatively small by the retention of the old income exemption limits, namely, $1,000 for bachelors and $2,000 for married men, with the normal tax rate placed at only six percent. on incomes up to $5,000.

An outline of what was expected from the people of the country as a financial contribution was given by Mr. Wilson in his May (1918) address to Congress, when he decided to ask its members to remain in Washington and prepare a new revenue bill. Mr. Wilson's call for immediate action in behalf of both the public and the Treasury Department was a summons to a universal duty in language which, it is remarked, "was never before used in a tax speech." He said in part:

"We can not in fairness wait until the end of the fiscal year is at hand to apprize our people of the taxes they must pay on their earnings of the present calendar year, whose accountings and expenditures will then be closed.

"We can not get increased taxes unless the country knows what they are to be and practices the necessary economy to make them available. Definiteness, early definiteness, as to what its tasks are to be is absolutely necessary for the successful administration of the treasury....

"The present tax laws are marred, moreover, by inequities which ought to be remedied....

"Only fair, equitably distributed taxation of the widest incidence, drawing chiefly from the sources which would be likely to demoralize credit by their very abundance, can prevent inflation and keep our industrial system free of speculation and waste. [Pg 7]

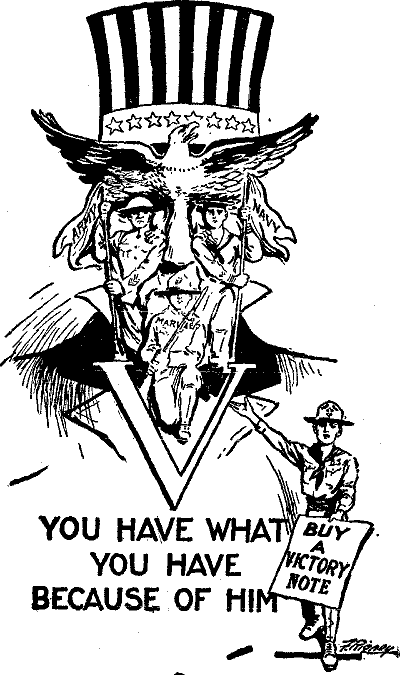

Poster for Boy Scouts Who Worked for the Victory Loan

"We shall naturally turn, therefore, I suppose, to war profits and incomes and luxuries for the additional taxes. But the war profits and incomes upon which the increased taxes will be levied will be the profits and incomes of the calendar year 1918. It would be manifestly unfair to wait until the early months of 1919 to say what they are to be....

"Moreover, taxes of that sort will not be paid until the June of next year, and the treasury must anticipate them....

"In the autumn a much larger sale of long-time bonds must be effected than has yet been attempted....

"And how are investors to approach the purchase of bonds with any sort of confidence or knowledge of their own affairs if they do not know what taxes they are to pay and what economies and adjustments of their business they must effect? I can not assure the country of a successful administration of the treasury in 1918 if the question of further taxation is to be left undecided until 1919."

Mr. Wilson's appeal for the practice of personal economy met with widespread approval in England, as it did in the United States. The Economist considered that his manifesto to the American people on this subject was among the greatest documents that the war has produced. National self-sacrifice had gone far, but not far enough. To attain Mr. Wilson's standard of individual patriotism much was still needed, the Economist says:

"We still have a very long way to go before we can attain to President Wilson's standard of individual patriotism. From the outbreak of war to the end of last year the small investor in this country has lent £118,179,000 to the government. Moreover, in the first two months of 1917 as much as £40,000,000 was contributed to war loans in one form or another in the shape of small savings. That result represents a great deal of patriotic saving, and reflects the highest credit on the committee, as well as upon the Montagu committee, which devised so suitable a form of investment as the 15s 6d certificate. But far more is required. During the war loan campaign, war savings certificates brought in £3,000,000 in a single week. That effort was, perhaps, too great to be kept up; but it is hardly satisfactory that, in spite of the hard work of the committee, and an enormous growth in the number of active war savings associations all over the country, the weekly receipts from the 15s 6d certificates have fallen back to the £800,000 to £900,000 level which was reached last December. This relapse may be partially accounted for by the late increase in the cost of living, but there can be no doubt that much more might yet be done by the masses of people of moderate means to whom the small certificates appeal. Nor is there any evidence that the wealthier classes, generally speaking, have done nearly as much, in the matter of war self denial, as they might have done."

When it came to a question of taxing luxuries, the difficulty was to decide what was a luxury. The situation perplexed Congress, for we find one congressman in Pennsylvania who held that collar buttons and cuff buttons were a necessity, while a representative from Texas asserted that Texas could get along without either collar buttons and cuff buttons and still be patriotic. A congressman from Oklahoma thought that all kinds of buttons could be done away with, adding, "Before I came to Congress I could use nails for my suspenders." Congressman from [Pg 8] agricultural states considered that automobiles and gasoline were not luxuries but were really necessities, especially for farmers.

Many newspapers opposed anything like a luxury tax. We find the New York Times advising the imposition of taxes on tea, sugar, coffee and cocoa. These are good revenue producers but few politicians care to interfere with the free breakfast table. The Wall Street Journal approved of luxury taxes because they would be a means of enforcing thrift. The Treasury's plan for imposing these taxes may be gathered from the following condensed summary:

"Fifty percent. on the retail price of jewelry, including watches and clocks, except those sold to army officers.

"Twenty percent. on automobiles, trailers and truck units, motor cycles, bicycles automobile, motor cycle, and bicycle tires, and musical instruments.

"A tax on all men's suits selling for more than $30, hats over $4, shirts over $2, pajamas over $2, hosiery over 35 cents, shoes over $5, gloves over $2, underwear over $3, and all neckwear and canes.

"On women's suits over $40, coats over $30, ready-made dresses over $35, skirts over $15, hats over $10, shoes over $6, lingerie over $5, corsets over $5. Dress goods—silk over $1.50 a square yard; cotton over 50 cents a square yard, and wool over $2 per square yard. All furs, boas and fans.

"On children's clothing—on children's suits over $15, cotton dresses over $3, linen dresses over $5, silk and wool dresses over $8, hats $5, shoes $4, and gloves $2.

"On house furnishings, all ornamental lamps and fixtures, all table linen, cutlery and silverware, china and cut glass; all furniture in sets for which $5 or more is paid for each piece; on curtains over $2 per yard, and on tapestries, rugs, and carpets over $5 per square yard.

"On all purses, pocketbooks, handbags, brushes, combs and toilet articles, and all mirrors over $2.

"Ten percent. on the collections from the sales of vending machines.

"Ten percent. on all hotel bills amounting to more than $2.50 per person per day. Also the present 10 percent. tax on cabaret bills is made to apply to the entire restaurant or café bill.

"Ten cents a gallon on all gasoline to be paid by the wholesale dealers.

"Ten percent. tax on wire leases.

"Graduated taxes on soft drinks. Mineral now taxed 1 cent a gallon to pay 16 cents. Chewing gum now taxed 2 percent. of the selling price, to pay 1 cent on each 5-cent package.

"Motion-picture shows and films: abolish the foot tax of ¼ and ½-cent a foot and substitute a tax of 5 percent. on the rentals received by the producer, and double the tax rate on admissions.

"Double the present taxes on alcoholic beverages, tobacco and cigarettes.

"Automobiles—a license tax on passenger automobiles graduated according to horsepower.

"Double club membership dues.

"Household servants, made 25 percent. of the wages of one servant up to 100 percent. of the combined wages of four or more. Female servants, each family exempted from tax on one servant. All additional servants (female) from 10 to 100 percent. on all over four."

Heavy taxes on luxuries were anticipated but until these taxes were considered it was hardly realized how much of the consumption in America was concerned with articles that could be considered luxuries; for example, the country imported $6,000,000 worth of foreign cigarette papers. Pictures, statuary and other works of art were brought into the country to the extent of $17,000,000. Over $2,000,000 worth of ivory was imported every year; over $2,000,000 worth of mother-of-pearl and more than $2,500,000 worth of bulbs and roots. Higher taxes were urged by the financial experts, so we see a writer in Financial America emphasizing the connection between the importation of luxuries and the need of shipping:

"America can not spare ships to bring costly garments and furnishings thousands of miles across the sea. For the war period these articles can be replaced at home with materials that cost less labor and less money. The money spent for domestic goods remains in America and maintains our working population and our business and banking resources.

"We lack a sufficient market for our cotton crop, owing to the lack of ships. Americans should wear more cotton. The money spent upon it maintains the Southern planter and his family. Modern processes give it the appearance of silk. It serves very well as carpets, curtains, hangings, and furniture coverings. It should answer present needs for such fabrics. A heavier tax on imports of these goods is indicated as a means of revenue and war economy.

"Imported wearing apparel of silk pays 60 percent. duty and of wool 44 cents a pound and 60 percent. ad valorem. There is a graduated rate on dress goods of these materials. Despite the tax, America spent [Pg 9] more on imported manufactures of silk in 1917 than ever, the total being nearly $40,000,000. The same was true of woolen goods, amounting to $23,000,000.

"Our imports of woolen carpets and rugs, most of them brought half way round the world from oriental lands, were also larger. They cost us $3,740,000, though America is a large producer of carpets and rugs, fine as well as coarse. These imports paid ten cents a square foot and 40 percent. ad valorem. Evidently, it was not enough.

"We also spent $53,000,000 for imported cotton manufactures, including cloth, laces, curtains, handkerchiefs, veils, and wearing apparel, though America is the world's chief producer of cotton. A higher tariff is indicated as a tax on those who insist on the foreign product.

"America has a large tobacco industry at home. We import tobacco in vast quantities from every producing land to satisfy the whimsical and varying tastes of connoisseurs. Our own tobacco is discouraged by those who smoke it under the name of Turkish, Egyptian, Cuban, Dutch, Spanish, and other foreign products, and pay a heavy price for the critical taste which their vanity causes them to imagine they possess. Last year these imports of leaf tobacco alone were valued at $26,000,000, or $10,000,000 more than in 1915. The war tax is five cents a pound added to eight cents paid under the internal revenue act, or thirteen cents altogether. There is also a duty of $1.85 to $2.50 a pound. To increase the tax would encourage the industry in Kentucky, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and other states, while saving our resources in ships and keeping our money at home.

"In addition, America spent $7,000,000 for foreign-made cigars and cigarettes last year. These purchases support foreign factories, although our own factories use the same raw material which they import. They have jumped nearly $3,000,000 in two years. Until the war is ended, Americans should be satisfied with cigars 'made in America.' The present war tax ranges from one tenth of a cent to one cent on each cigar, according to value, in addition to a duty of $4.50 a pound and 25 percent. ad valorem. A higher tax would deprive the smoker of nothing but a craving for the foreign label on his cigar box, unless he chose to pay well for it. He can even get a Spanish name on his American-made cigar.

"America spent $41,000,000 in 1917 to import diamonds, pearls, and other precious stones and imitations, not set. They paid a war tax of only 3 percent. when made into jewelry. America could be content with beauty less adorned to keep this $40,000,000 at home, or those who insist on sending their money to African mine owners and Dutch cutters should pay a larger tax.

"America last year had a tremendous bill for hides and skins of $209,000,000, nearly two and a half times that of 1915. Much of it was for the great necessities of the army. A good proportion of the rest was unnecessary. These imports of raw material are free of duty and there is no war tax on leather goods. Substitutes have been devised for many of them. These should be encouraged by a tax on the unnecessary use of leather in furnishings, decorations, toilet articles, hand bags, trunks, high shoes, belts, hatbands, and many small articles. Substitutes for these will be provided quickly enough if leather is lacking. A heavy tax would help the movement. The tremendous military and other legitimate demands for leather goods will keep the industry in thriving condition without so much waste.

"For imported millinery materials America spent nearly $13,000,000 last year, and we also spent $3,000,000 for mere feathers, tributes to feminine vanity that filled up many ships needed for war use. The greater part of this stuff came 10,000 miles from China and Japan. There are plenty of substitutes that a high war tax would encourage, including those provided by the American hen.

"Our imported glassware, on which there is no war tax, cost nearly $2,000,000. It occupies large space aboard ship, owing to voluminous packing that is necessary. Imported china, porcelain, earthenware, and crockery cost America nearly $6,500,000."

In spite of the enormous cost of war operations, roseate views were taken of the ability of the country to surmount the unusual difficulties. Unprecedented taxes were being paid, heavy subscriptions to the Liberty Loans were being collected and yet the business of the country seemed to show a high degree of prosperity. This optimistic outlook marks the following comment found in a circular published by the First National Bank in Boston, after it had called attention to the small number of failures reported throughout the country for August, 1918. No such low record had been reached since July, 1901:

"The steps that have been taken to curtail credits have resulted in greater conservatism, and have had a beneficent effect, which is likely to continue for some time after the present necessity disappears. The business foundation is extremely sound. Figures of resources of savings banks show that the subscriptions to the Liberty Loans have [Pg 10] brought only a trifling decrease in savings deposits. Evidently subscribers are buying bonds with their current income rather than with their savings. In other words, the Liberty Loans represent additions to the savings of the country, and not merely transfers of investments."

It was prophesied that in spite of the enormous financial obligations assumed by the United States normal conditions would soon be restored. History shows, the circular goes on to say, that financial recovery from devastation has been prompt and complete. Even the railway conditions at this time were viewed optimistically. Such a competent authority as the Wall Street Journal did not anticipate the financial troubles that soon overtook railway administration under government control. It thought that, by the end of the year, the existing debits on current operations would probably be wiped out:

"Aggregate railroad earnings and expenses for July of all the important roads in the country are in line with the individual statements of the different roads already published in showing large increases in both gross and net revenues. They also indicate, so far as one month's operating results may be used to generalize from, that the railroads are now on a self-supporting basis, if they are not actually returning a profit to the government on current operation.

"Net operating income of these roads for the month of July (1918) was $137,845,425 as compared with $92,599,620 in the same month of 1917. In a recent statement from the Director-General's office the compensation payable to the railroad companies for the use of their property by the government was estimated at $650,000,000 for the first eight months of the year, or at the rate of $81,250,000 a month. The net operating income of the Class 1 roads as mentioned above exceeds this monthly rental figure by $56,595,000."

Although called by other names, the United States has had issues of Liberty Bonds on several occasions during a period of one hundred and twenty-nine years, notably in the first years of the Republic and in the Civil War. The first was floated in 1789, the year when the Federal Government was established. Alexander Hamilton was Secretary of the Treasury and on him devolved the duty of raising funds for the government.

"Conditions being pressing, Hamilton, in raising the necessary money, at first did not wait even for the approval of Congress, but went to the Bank of New York, which he had helped to found in 1784—the second bank in the United States and the first in New York City—to raise the first necessary money. At a meeting of the board of directors the new secretary of the treasury asked for a loan of $200,000. It was promptly and unanimously granted, the money to be advanced in five installments of $20,000 each and ten of $10,000 each, at 6 percent. On the following day Hamilton sent to the bank the first bond ever issued by the United States Treasury—a bond of $20,000—on receipt of which the money was paid over, so that the United States Treasury could show $20,000 cash on hand. In The Investor's Magazine, where these facts were recently brought to light, we are further told that the bond then issued is still carefully preserved by the bank which bought it. Quite unlike the now familiar Liberty Bonds of 1917 and 1918, it was executed with an ordinary quill pen, such as was in use in those times, and signed in ink by the secretary. With its seal somewhat yellow with age, the bond is still in an excellent state of preservation."

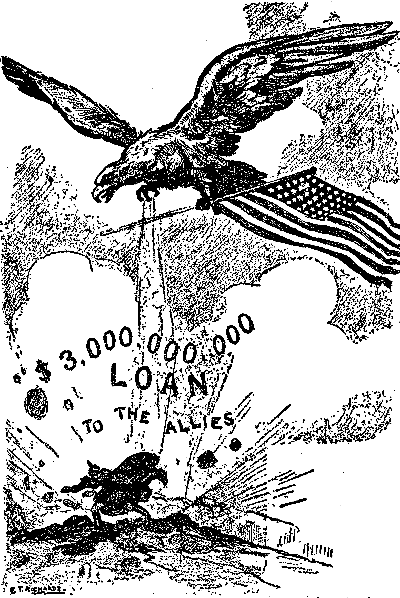

Richards in the Phila. North American

Dropping the First Bomb