Title: The Incubator Baby

Author: Ellis Parker Butler

Illustrator: May Wilson Preston

Release date: November 18, 2013 [eBook #44219]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

If the Day Comes when She is Entered to Creep And Don't

Tied Her to the Head of The Crib

On his Hands and Knees Playing Peek-boo

On the sunniest slope of the garden of Paradise the trees stand in long, pleasant rows. The air is always balmy, and the trees are forever in bloom with pink and white blossoms. From a distance the trees look like apple trees, but, close at hand, you see that the pink and white blossoms are little bows and streamers of ribbon and that the boughs are swaying gently with the weight of many dimpled babies.

Walking up and down beneath the trees are kind old storks, and as they walk they turn their heads, looking upward to see where there may be a sweet pink and white baby ready to be carried away, out of the garden into the big, strange world. It is a vast garden, and there are many trees and many storks, and every moment there is a whirring of strong wings and a stork has passed out of the confines of the garden with the dearest gift that Heaven can give to woman.

The storks are very grave and very careful, but that is because only storks of mature age are allowed to carry the precious babies. The younger storks may stand on one leg and watch their elders, or they may hop awkwardly between the trees to amuse the babies, but they are never permitted to pick the babies from their leafy cradles, nor to attempt such a delicate undertaking as flying away with them into the outside world.

But one day the very youngest of the storks got into mischief and before its elders knew what it was about it had flown into one of the trees. It tried to lift one of the biggest, plumpest, prettiest of the babies, but it was such a small stork it could do no more than make the baby sway to and fro on its branch, so it picked the very smallest baby on the tree, and carried it straight to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Vernon Fielding, and left it there rather unexpectedly.

If ever there was a surprised baby it was Marjorie Fielding. She did not care for the Vernon Fielding home in the least. She vastly preferred Paradise; it was far more comfortable, and she had just made a decision to return there immediately, when a very remarkable thing happened. It seemed to Marjorie that the Fieldings cared as little for her as she cared for the atmosphere of their home, for she was rolled in soft cotton, wrapped again and again in flannel cloths, and a large man with soft hands carried her away.

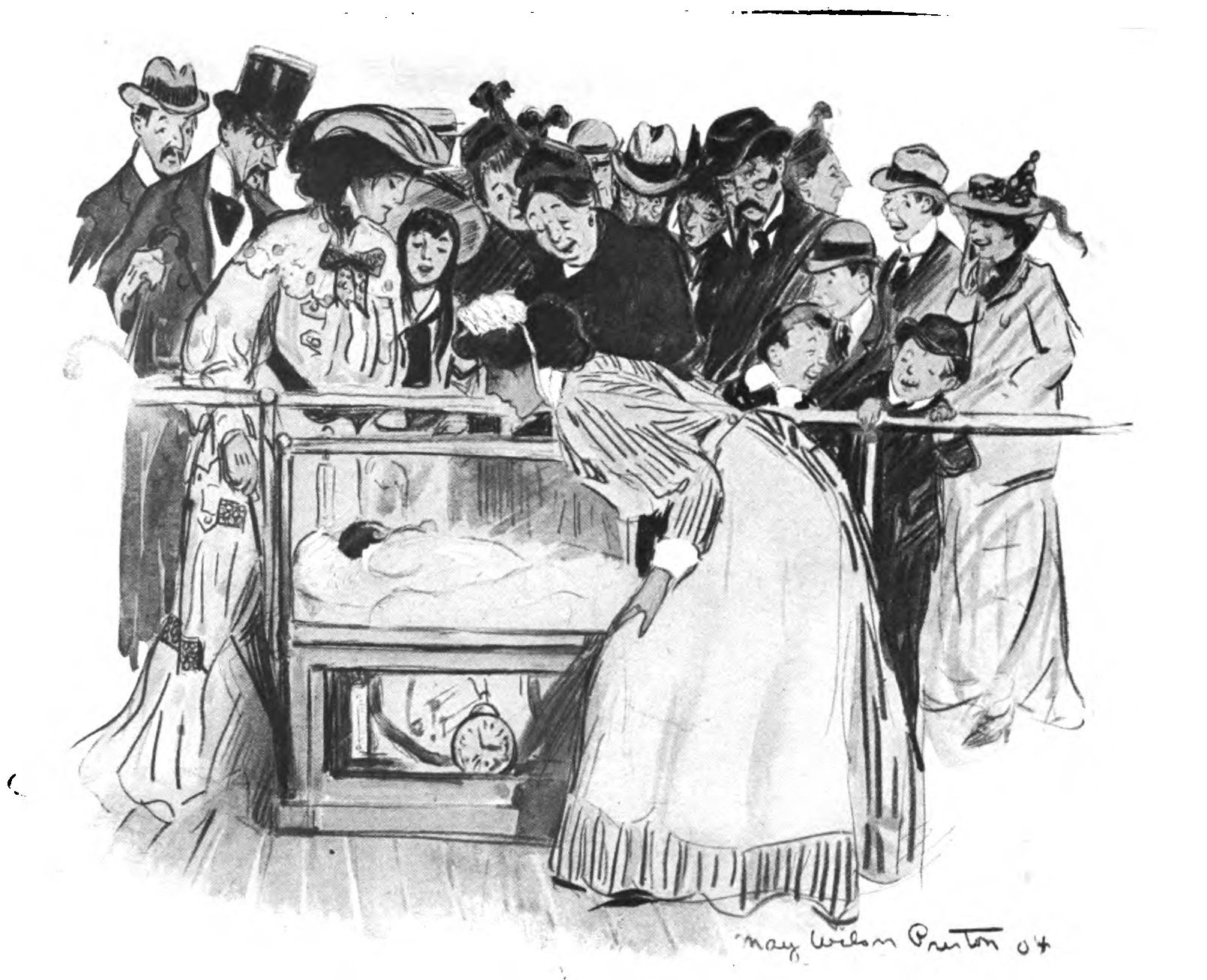

When she awoke she had an impression that she must be back on her own twig in the garden of Paradise. The air was soft and balmy and very warm, but when she opened her eyes everything was strange. There were no trees, no gently swaying branches, and no kindly old storks parading below her. Instead, she gazed into dozens of faces that peered at her curiously. They were faces of men and women, and those in the back rows tried, by twisting and turning and peering through small openings, to get as clear a view as those in the front row had. There were all sorts of faces and they showed all sorts of emotions. Some expressed the most violent curiosity, some were softened by kindly pity, some wore expressions of disappointment as if the show was not as interesting as they had expected, and some showed a certain weak disgust.

Marjorie wondered lazily why they were there. Probably they were some amusement contrived by a mistaken person for her entertainment. If so, she wished the amusement discontinued; it had too many eyes in it.

“Isn't it wonderful!” she heard one of the faces say. “Before the invention of incubators nearly every one of them died, and now they hardly lose one in ten;” and another said, disdainfully: “And to think I paid me decent money to see dis! I'm easy, I am. Come on, let's shoot the chutes;” but one face, a sweet face, said:

“Poor, dear, sweet little baby. It makes my heart ache,” and Marjorie liked that face. She fixed her eyes on it and for the first time in her very few hours of life something in her own heart pulled toward a face. She wanted that face to stay there; it was motherly. That was it, the face was motherly, and deep in the small heart of Marjorie there was a desire to be mothered and loved, but the face passed on and never came back again.

From the first day the incubator people were proud of Marjorie. She was the smallest baby of all those in the long row of incubators; “one pound and eight ounces when born,” the placard above her incubator said; but she grew rapidly. When she was sixteen days old she weighed two pounds, and after that you could see her grow. She slept a great deal, and was fed constantly and her crystal palace was like a little hothouse.

For several days, shortly after her arrival, she was greatly worried by a man who seemed to have a desire to flirt with her. He stood near at hand all day, and hardly took his eyes off her, and then only to examine the thermostat that regulated the heat in her nest. He seemed to be more anxious than the nurse that Marjorie should not be baked too brown, and from time to time he made ridiculous passes at her with his hands or screwed his face into peculiar shapes that sought to be amusing. It was most disconcerting.

Marjorie tried to appear unconscious of all his antics. When she could not avoid looking at him she stared at him coldly, but that did not seem to dishearten him. Even a cold glance filled him with joy, and once, when she was preparing a little cry and had screwed her face into the prescribed shape, he grasped the attendant by the arm and exclaimed: “She's smiling! Isn't she smiling?” Marjorie was quite ashamed, he was so idiotically ecstatic. She learned later that he was her father, and that for some reason fathers have a right to do that sort of thing. In fact, it is rather nice when one gets used to it.

But the great day was the day of her mother's coming. The nurse had prepared Mar jorie for it. “Little girl, your mother is coming to-day.”

Marjorie watched closely for her mother all that day. She scanned the faces that came and went, picking out those she thought might be her mother, but she could not be sure, for they all passed by. All the faces she chose were kind young faces, and she was rather surprised when her mother finally came. She did not recognize her for quite a while.

A tall lady came to the incubator in company with the nurse. She examined the incubator carefully, and asked a great many questions about temperature, the sanitation, alimentation and digestion and other scientific things. She examined the record chart carefully, and asked the nurse if Marjorie's weight was not increasing less than the proper average, and when the nurse assured her that Marjorie was surpassing the average she objected to that and said that she had no desire for her to grow so rapidly she would be soft and pulpy. Then she examined the nurse carefully and critically regarding her experience with babies, and all the while she made notes in a small memorandum book. She copied everything on the record chart, and asked to have Marjorie weighed, and put the weight down in the little memorandum book.

“I wish to be very careful and exact,” she said, “for I am her mother, and if I do not look after these things no one will,” and Marjorie knew this was her mother. She waited patiently for the preliminaries to be completed so that the real mother business could begin, but her mother must have been very busy that day, for she went away without being really introduced to Marjorie.

Marjorie was disappointed. She had become used to being regarded as an entertainment for the faces that passed by, and she had become accustomed to have the incubator people regard her as a Case—a most interesting Case, to be sure, but still a Case—but she did not like to have her mother look upon her merely as a Statistic.

Her mother came after that, almost daily for a week, and then not so frequently. It was not necessary, for the statistics showed that Marjorie was making progress favorably, and Mrs. Fielding was a very busy woman. She believed in the broad life for women, and a woman broadens her life by stepping out of the home occasionally. The home is better for it. When the woman is not a slave to the home, the home becomes an ennobled place, and the woman who can step out and bring back culture and knowledge, and broader views of life and things, is the only woman who can raise the home to the level of the man's life. Science and system work wonders in the home, as well as in the office of the business man.

Mrs. Fielding was not a slave to the home. I would sign her certificate of freedom myself. Neither did she look upon Marjorie as a necessary evil. She was glad and proud to be a mother, and she loved Marjorie, and wished to do all that is in a mother's power for her, but she knew that many of the old notions about babies were mistaken ideas. The incubator itself proved that. Science and system are far more efficacious than much of the old-fashioned granny's twaddle. With the help of educated minds Mrs. Fielding meant to give Marjorie an ideal mother's care.

Marjorie didn't care much for the broader life herself. She was incorrigibly like other babies. She wanted to be fed when she was hungry, to sleep when she was sleepy, and to be loved and mothered and petted whenever she was not hungry nor sleepy, and whatever a nickel-plated incubator may be able to do, it is not an adept at kissing. It may exude balmy temperature better than an old-style open fireplace, but it is a failure at wrapping its warm, soft arms around a baby, and pressing its cheek against a tiny, satin cheek. The very cast-ironness of its construction prevents it from lifting the infant high in the air until coos and crows of baby laughter tell of unsystematic, unscientific joy. So Marjorie adopted the fly.

The fly came one day and alighted on the glass door of her crystal case and winked its wings at her, and she blinked her eyes at it, and after that they understood each other perfectly. It knew she wanted to be amused, and it knew it was an amusing fellow. It had a clever trick of shaking hands with itself under its coat tails, and as long as she knew it, it never mentioned a statistic, and altho it walked all over the thermostat, it disdained to look at the figures. Marjorie and the fly became good friends. There was something very human about the fly, far more than about the constantly passing faces of the sightseers, or the prim, statistical nurse, or even the systematic, broadened Mrs. Fielding, and one day it slipped into the incubator and alighted on Marjorie's lips, and kissed her. Shortly after the scandalized nurse assassinated the fly, and Marjorie would have mourned deeply but for a new companion she discovered a little while afterward.

It was shortly before she was sufficiently incubated to leave her glass prison, and she was fine and plump, and had begun to roll over and bump her head against the glass, surprising herself greatly, for she could not see the glass. If she had stayed a little longer she would have been afraid to move at all, for wherever there was nothing to be seen there might be that hard, smooth wall that hurt her.

She was lying flat on her downy pillow one morning, watching the faces, when something stirred at the foot of the pillow. She raised her head a very little but could see nothing, but as soon as her head fell back the thing moved again. She was sure it moved, and she waited quietly, and again it moved. This time there seemed to be two of the things. It was puzzling, for the nurse never allowed anything interesting inside the case.

Marjorie lay low, and presently, up, up, into her range of vision crept a little pink and white affair with five short, plump branches, and just behind it arose another. She cooed with pleasure.

The things seemed quite tame and unafraid, and they came nearer until they stood quite upright on plump white branches. Marjorie reached out her dimpled hands, which wandered a little uncertainly in the air, wavering to and fro, until one came in contact with one of the plump, mysterious things. She grasped it firmly, and it was soft and pleasant to the touch.

The crowd of faces paused and increased in number. They seemed greatly interested as she tried to catch the thing, and one old man offered to bet she would catch it. He was immensely tickled when she did and grinned delightedly. Marjorie held fast to her captive.

She pondered what she should do with it, and finally decided that it must be edible. She drew it closer to her face, and it resisted and tugged to get away, but she dragged it on relentlessly.

It was a hard fight. The old man coached her, cheering her on to fresh endeavors, and, thus encouraged, she made one great final effort and pulled the soft pink thing into her lips, and the old man laughed long and loud and wiped his eyes.

“Look at her!” he cried. “Just look at her! Ain't she a picter for you? I knowed she'd get it, she's grit clean through.” A small boy, excited by the size of the crowd, pushed his way to the front and looked, and then turned away, indignant. “Huh!” he exclaimed scornfully, “'tain't nut'in' but a kid got its toe in its mout'!” During her last days in the incubator Marjorie and her feet became fast friends. All the long period of her loneliness was forgotten in this new companionship. Never were there more accommodating playmates than those two gentle twins, for they seemed to be twins, they were so much alike in size and appearance. They never forced themselves forward. When Marjorie wanted to sleep the feet lay quietly at the foot of the pillow, but the moment she felt like playing they crept upward and stood enticingly in her sight. Sometimes she played with one, and sometimes with the other, and whichever was not needed curled up snugly out of sight and waited patiently until it was needed.

They had glorious times together. Usually she had no trouble in catching a foot when she wanted it, but sometimes they played a little game with her, and dodged about just beyond her reach, coaxing her to catch them, and eluding her hands by the smallest part of an inch, but this only made the fun more riotous, and one of them always ended the game by letting itself be captured.

But one day a wonderful thing happened to Marjorie. The nurse and the manager came to Marjorie's incubator, and consulted the chart, and weighed Marjorie and pinched her arms and legs to see whether they were firm and solid, and after that the air in the incubator lost a little of its warmth every day, until it was as cool as the air of the great outside world.

Marjorie was playing the foot game when the end came. She had not the least idea that anything of the sort was going to happen. No one thought of consulting her convenience in the matter.

First her father and mother appeared, and she might have known that something unusual was on foot if she had thought about it, for they had never before visited Marjorie simultaneously, but Marjorie was too deeply in the foot game to pay attention to parents. Parents were a necessity, but the foot game was a joy.

The nurse, who often did unaccountable things to Marjorie, did the most unaccountable of all. She took Marjorie from her bed on the soft, pillow and dressed her in stiff new garments, and enfolded her in blankets and capes until she was like a bundle of soft cloths, with only a little peephole for her eyes, and then, with cruelty unthought of, she handed her bodily to Mrs. Fielding. Marjorie objected. She foresaw some trick in all this. She raised her voice and protested, but they covered her face with a soft white veil. Marjorie indignantly went to....

When she awoke the world had changed. She was in a strange foreign land, where the walls were of white and blue tiles, and the ceiling was white, and the floor was covered with soft rugs. It may have been beautiful but it was not home. There was no incubator.

There were charts and sterilizers and scales and thermometers and everything necessary for a highly systematized and scientific nursery, but there was no incubator, and there was no long line of impertinent, curious faces, constantly passing and constantly changing. Marjorie was homesick.

Mrs. Fielding made the first entry on a brand-new chart, with triumphant satisfaction. She epitomized Marjorie in an array of dates and figures. To Mrs. Fielding and Chiswick, the new nurse, all was well so long as the chart was normal. When the figures on the chart were abnormal they considered that the baby in the crib had transgressed the laws of system and science, and they paid her little attentions in the way of small powders administered in a teaspoon.

Marjorie missed the nickel-plated trimmings of her incubator and she longed to see the procession of faces that she had seen so often. She would have given two degrees of temperature and three respirations just to have a fat, greasy East Side washlady beam upon her as in the incubator days. Even the occasional visits of her father became a joy. She hoped he would be sufficiently weak-minded to take her in his arms, but he was afraid to do anything that might affect the beautifully correct procession of figures on the chart. She tried to soften Chiswick with smiles, and betray her father with gurgles, and she even attempted to astonish her mother by assuming a high temperature and a low pulse, but all she got was a disreputable chart record and a dose of white powder.

She lay back and puckered up her chin and yelled a good, healthy baby yell. Chiswick entered it on the chart. She added a disparaging remark to the effect that the cry was for “no apparent reason.” It was an insult, and Marjorie considered it one.

Where were the pink and white playfellows? A ripple shook the white of her lace-decked skirt; two lumps arose in it; they pushed upward higher and higher until the skirt slid back, and peeping over its edge came ten rosy toes that twinkled at her mischievously. Marjorie held out her hand appealingly, and the two plump feet, that had not dared to venture into the atmosphere of the scientific nursery, cast aside their hesitation, and met the waiting hands half way.

“Sakes alive!” exclaimed Chiswick, “if the child isn't trying to put both its feet in its mouth!”

Marjorie lay in blissful content; she had found human companionship.

It must be said, to the credit of incubators and science, that Marjorie was a beautifully normal baby. Mrs. Fielding took the greatest possible satisfaction in that. She was always ready to show Marjorie's record charts to visitors, and it was touching to see with what motherly pride she exhibited them. There was not another baby in the town that had maintained such an even temperature, such a steady respiration, or such a reliably even pulse.

Mr. Fielding was no less proud of the record. He bragged about it at the club and tried to induce his married friends to allow their babies to enter temperature matches with Marjorie, offering to wager two to one that Marjorie could maintain a normal temperature for a longer time than any baby of her age and weight.

When Marjorie reached six months Mr. Fielding decided that she deserved a reward of merit, and he made her a present of an oak filing cabinet of sixteen drawers, together with three thousand index cards. There was the food drawer, with cards for every day of the year, and places on each card to note the time of every feeding, the ounces of food taken, the minutes Marjorie required to take the food, the formula of the food, and the average cost of food per hour.

There was the clothing drawer, with cards on which to record the weight of clothing worn, the temperature of the air, the number of pieces of clothing worn, the method by which the garments were washed, and for remarks on the comparative good effects of cotton, wool, silk, and linen garments.

There were cards for sleep records, weight records, temperature, respiration, and pulse records—in fact Marjorie was analyzed and specified until one could tell at a glance just how many thousandths of an ounce of food she consumed for each beat of her heart, or how many times she breathed per pound of clothing worn.

Unfortunately, the nurse, Chiswick, objected. She threatened to leave. She said her professional training had not included card systems, and that even if she had had a modern business education, she had no time to keep such multitudinous records. Mr. Fielding promptly engaged a private secretary for Marjorie. Miss Vickers knew all about card index systems. She loved two things passionately—card systems and babies.

And then, just when a record card had been allotted to every function of Marjorie's pink and white body, a complication arose. Marjorie developed a will and a temper.

She decided that she had reached the age when she ought to sit alone. She looked upon the world and saw Chiswick sitting upright and Miss Vickers sitting upright and she longed to sit upright too. For six months she had reposed docilely upon her back or her stomach, with occasional variations of lying on one side or the other, and she felt that she had had enough of it. It was time to have a backbone and to take her place as a sitter. She told Chiswick so plainly enough. When Chiswick laid her on her back she yelled and raised her head. When Chiswick laid her on her stomach she turned over upon her back and raised her head and yelled. A little more and she would have been able to sit up without aid. Her head and her neck sat up—as far as they could. At least they flopped forward and tossed from side to side, but her backbone would not follow. It continued to repose in placid flatness on the pillow. Marjorie was very angry with her backbone. She got quite purple in the face about it at times, and choked.

Chiswick was very dense. Marjorie's head and neck explained again and again what they wanted to do, but Chiswick could not understand them. She did not appreciate that it was ambition—she thought it was colic. She pepperminted Marjorie until the sight of the peppermint spoon made Marjorie tremble with rage, and when Marjorie had absorbed ounces and ounces of peppermint water, Chiswick decided that Marjorie was past the colic age, anyway.

Miss Vickers discovered what Marjorie wanted.

“I believe,” she said, “that the child wants to sit up,” and then she tried it. That is why Marjorie loved Miss Vickers and hated Chiswick—and peppermint—from that day onward.

It would have all ended there if Marjorie had been willing to compromise, but she was not willing. The first day she might have been willing, but when a person has cried steadily for three days and has fought such a good fight, she feels it her right to dictate terms. She would not compromise on an angle of forty-five degrees. She refused to be satisfied with a plump, downy pillow at her back. She would sit upright and alone, or yell.

Not that it mattered that she sat upright and unsupported, except that she could not. Miss Vickers would seat her so and steady her for a moment, but when the protecting hands were removed Marjorie unfailingly collapsed. Sometimes she sank backward upon her pillow waving her arms impotently, but usually she doubled disgracefully forward until her nose bumped against her knee, or toppled to one side or the other like a pulpy fallen idol. Her backbone was irritatingly pliable—somewhat like a wet rag in stiffness. It was a poor affair, as backbones go. She might quite as well not have had any. It made Marjorie remarkably angry.

She spent three entire days in a continuous round of being set up and crumpling down again into the various bunchy shapes, and each day her temper grew more violent. For the first time in her life she cried real tears.

Mrs. Fielding was usually busy. Her club life was engrossing, but when, for three days in succession, the index cards bore the words “Cried all day,” she felt it her duty to investigate. She went to the nursery, indignant.

“Well, mam,” said Chiswick, “I don't know how to stop her. My opinion is that it's temper. She will sit up, mam, and she can't. We set her up, like she wants, and then she topples down and hollers. She hollers if we do and she hollers if we don't. You can do a thing or you can leave it undone, and there ain't nothing else you can do. There ain't anything between them two ways. If there was we might suit her.”

“You should distract her attention,” said Mrs. Fielding.

“She won't distract,” declared Chiswick. “She made up her mind to sit up alone—which she can't—and she gets in a temper over it, and her temper's getting worse right along.”

Mrs. Fielding looked at her daughter doubtfully.

“Perhaps she needs a little punishment,” she suggested, “but I am not sure that the latest authorities approve of punishment. I will let you know. I should like to consult others before acting.”

Mrs. Fielding laid the matter before the Mothers' club at its next meeting. She found the Mothers' club to be frankly and openly divided on the question. Mothers who had at first held the most modern ideas had fallen into laxly illogical methods, and instead of taking broad views of the infant as a theoretical subject, had become rank individualists. Mrs. Jones could talk only of Johnny Jones and Mrs. Smith argued all questions to and from Susie Smith. Mrs. Fielding found no satisfaction there and at length appealed to the monthly convocation of the local federation of Women's clubs, which included the best intellect of all the women of the city. When the federation had finished considering the question, Mrs. Fielding found that she was one of a committee of four appointed to direct the growth of Marjorie in mind, body, and soul. The federation had undertaken to guide Marjorie through the pitfalls of infancy.

Miss Martha Wiles, of the Browning club, was made chairman of the committee; Miss Vesey, of the Higher Life circle, and Miss Loring, of the Physical Good guild, were members of it, and Mrs. Fielding was added at the last moment to represent the Mothers' club because the other members of the Mothers' club said they had enough to do to look after their own babies.

When the committee convened in the Fielding nursery to consider Marjorie's temper, Marjorie greeted it with a sweet smile. The committee sat on the sofa and Marjorie sat in her crib. She had conquered her backbone and was on good terms with it and the world again.

The committee entered upon its duties enthusiastically. It began by studying the records of Marjorie. It met daily to adopt rules and regulations and spent hours over the card cabinet until it became thoroughly acquainted with Marjorie's averages. Then it made out a schedule of normal development for mind and body.

Chiswick viewed the schedule skeptically.

“It's a nice schedule, mam, I'll say that much for it,” she said, “but if the day comes when she's entered to creep, and she don't creep, what am I going to do about it?”

“It is your duty to see that she does creep,” said Miss Wiles.

“Very well, mam,” said Chiswick, “but may I ask one question?”

“You may. It is your duty to ask questions. Refer all your doubts to the committee,” replied Miss Wiles.

“Then,” said Chiswick, “answer me this. On page six of the records of the committee it says: 'Whereas, the lower strata of air in a room are the abiding places of millions of germs; and whereas, children playing upon the floor must breathe the said air; and whereas, children playing upon the floor take into their mouths and convey thence to their stomachs the said germs, as well as pins, lint, needles, buttons, and other indigestible and highly injurious substances. Therefore, be it resolved, that the said Marjorie Fielding shall never be allowed to sit, lie, recline, or rest upon the floor, nor upon any rug, blanket, or other covering upon the said floor.' What I want to know is, how the child is to learn to creep if she isn't to be allowed on the floor.”

The committee looked at itself questioningly. Miss Loring giggled. Miss Wiles alone saved the day.

“You will, of course,” she said, haughtily, “give the child her lessons in creeping upon a table. Mrs. Fielding will see that one is provided.”

When the committee was gone Chiswick walked over to the crib where Marjorie lay and looked at her doubtfully. According to the schedule a creep was due from Marjorie in six weeks and Marjorie had only learned the art of sitting alone. Sitting alone at seven months is not bad progress for an incubator baby and Marjorie was rather proud of it.

“Well,” said Chiswick, “you've got to do it, and if you've got to do it you might as well begin to learn now.”

Marjorie was lifted and deposited upon her rotund little stomach, which protruded so much that she rocked back and forth upon it like a helpless hobby horse. She looked up at Chiswick appealingly but saw only a stern taskmistress.

“Lie that way a while,” said Chiswick coldly. “Get used to it,” and she went away.

Marjorie laid her cheek on the cool sheet and thought. It was a rather pleasant position. It gave her a comfortable compressed sensation below the waist. She liked it but she could not afford to be idle. She raised her head and peered around, as a tortoise peers, lengthening her neck. A foot beyond her reach she saw her rattle. She stretched her hands for it and only succeeded in bringing her pudgy little nose flat against the sheet. She kicked with her feet, but even that did not bring the rattle within reach; it only served to rock her gently to and fro on her stomach. Marjorie needed the rattle. She had still several hundred shakes to give it before her day's work would be complete. And the rattle needed Marjorie; it looked forlorn and lonely. Even as she considered the matter Marjorie found that she was raising her body on her plump little arms. They were acting like little posts to elevate her shoulders and head. Then, in a most phenomenal way, one knee doubled itself and drew up under her body, and the other followed it, and she was on her hands and knees.

From this frightfully elevated position the rattle appeared quite near, so near that it seemed as if she could touch it. She put out a hand, and lo! the whole fabric of herself that she had reared, collapsed, and she was sprawled flat on the sheet.

But the rattle certainly seemed nearer. She tried it again, and this time she put her hand forward only a little way, and followed it with the other, but she was firmly anchored at the rear, and there was no elasticity in her body. It would not stretch another inch. She thought of her legs reproachfully. But for them she might even now have the rattle. Her legs felt the reproach and wiggled with shame. They knew they were in disgrace and they longed to come closer and nestle lovingly against Marjorie. One of them moved forward slowly and paused. Its fellow, fearing it was being deserted, moved up beside it, but cruel Marjorie moved her hands forward again.

She could almost touch the rattle! One more forward movement of her legs and—

Chiswick, turning, saw it just in time. She was beside the crib in one bound, and her right hand pressed down upon Marjorie and squeezed her deep into the softness of the crib, and held her there kicking and squealing.

“Land sakes!” cried Chiswick. “You're breaking the schedule! You can't creep now. The idea! What will that there committee say! What will they say of you to that federation of clubs! You and me won't have no reputation left. Don't you ever creep till I say so. Never!”

She picked up the offended Marjorie and set her upright in the end of the crib. Marjorie rolled over upon her hands and knees. She wanted the rattle. She scoffed at schedules. Chiswick held her down with one hand and reached for the rattle with the other.

“Now I've got to watch you day and night,” she grumbled, “or we'll be having resolutions made about us, and things voted, and land knows what! You'd break the whole constitution and by-laws, you would.”

Marjorie smiled gleefully, and struggled to free herself. Chiswick tied her to the head of the crib with a strip of antiseptic bandage; and entered in the day book: “Tried to creep; restrained by nurse.”

When the committee met again they passed a resolution of thanks to Chiswick for her prompt action, and Marjorie's private secretary entered it on the records. As she wrote the last word she looked at Marjorie and winked, and Marjorie smiled wickedly.

There were hours when Chiswick was off duty, and then the private secretary was left alone in charge of Marjorie, and those were hours of riotous living. The private secretary was scientific—as a bookkeeper—but as a nurse she was ignorantly human.

She scoffed at the Higher Life for Women; she ate candy and avoided as much as possible her physical good. She refused to be emancipated. She had an idea it meant something in the way of doing without lacing and wearing shoes a size too large for one.

So when she was left alone with Marjorie they had a good time. They sat on the floor and imbibed germs, and they did all sorts of unscientific, retrogressive things. Perhaps that was why Marjorie remained a sweet, cheerful baby instead of becoming a sour little old woman.

One evening when Chiswick was away the private secretary and Marjorie were having a romp on the floor of the nursery. It was a handicap race, a creeping match, and the private secretary was handicapped by her skirts. The two were so interested that they did not hear the nursery door open. When Marjorie had won the twenty-foot dash the private secretary turned, and blushed with confusion and guilt. Mr. Fielding stood in the doorway! A frown darkened his brow and he looked at the private secretary with severity.

Miss Vickers sprang to her feet hastily and brushed out the folds of her skirt.

“Well!” exclaimed Mr. Fielding. “So this is how you behave! This is what you may be expected to do when you are trusted alone with the child! What do you suppose Mrs. Fielding and the committee would say?”

The private secretary laughed. Marjorie laughed and clapped her hands. Mr. Fielding frowned and picked Marjorie up. He put her in the crib, and Marjorie, rudely taken from her playmate by this stern man, lifted up her voice and wailed. She turned red in the face and howled. There was a swish of silk skirts—which never should be worn in the nursery—a rush of feet, and a hand pushed Mr. Fielding aside. With one sweep of her arms the private secretary gathered Marjorie to her breast.

“What did you do to her?” she cried. “Much you know about babies, and all your silly committees!”

Mr. Fielding paused irresolute. Marjorie cooed gently in her protector's arms, and her father looked at her curiously.

“You—you don't believe in scientific motherhood?” he said to Miss Vickers. He seemed to be asking for information; seeking light on a question that had already raised itself in his mind.

“'Scientific' doesn't hurt any, but it needs some mother with it,” she replied. “See her smile!” Mr. Fielding leaned forward cautiously.

“She does, doesn't she?” he said, with curiosity. “I never saw that before. It is quite interesting.”

“It's great!” exclaimed the private secretary. “You take her a minute and I'll show you something else.”

Mr. Fielding took her, carefully.

The private secretary clapped her hands and Marjorie looked toward her.

“Two hands, baby,” she said, and the two pink arms reached out to her.

“Well!” exclaimed Mr. Fielding, “How human!”

“See if she will do it for you,” suggested the girl.

Mr. Fielding clapped his hands. “Two hands!” he said.

Marjorie looked at him good naturedly. If he was willing to play she could forgive everything. She reached out her hands, and jumped toward her father. Before he knew how it happened, he had pressed his lips to her soft cheek and her hands were entangled in his hair.

When the doorbell rang, half an hour later, Mr. Fielding was on his hands and knees playing “peek-boo!” with Marjorie. Miss Vickers swept her into her crib and helped him to arise hastily. Then she pushed him toward the door.

“It is Chiswick!” she whispered. “Hurry!”

“Yes!” he whispered in return. “We—we will keep this matter private? It is not necessary to inform any one.”

The private secretary watched him nervously while he gave Marjorie a last, long kiss, and then she pushed him gently from the nursery. She really had to push him out.

When Mrs. Fielding was appointed to read a paper on Scientific Motherhood at the annual convention of the national federation of Women's clubs, she accepted the task with due modesty but not without a sense of complete fitness. Her mere presence in the distant convention city would in itself be a proof of the correctness of her theories. Under what other system could a mother leave her young baby and devote a week's absence to club duties? She felt quite at ease, however, for the three remaining members of the committee of four were in charge of Marjorie's welfare, and back of the committee was the entire federation of her city. She took the train with a grateful sense of freedom.

It was the opportunity Marjorie had been awaiting. No sooner had Mrs. Fielding left the city than Marjorie raised her temperature two degrees, just as an experiment. It was wonderfully successful. It made Chiswick scurry around the nursery with distracted concern. Marjorie raised her temperature a few degrees more and Chiswick telephoned for the committee.

The committee came, consulted and wondered what to do. It decided to await developments, and went away again.

As Mrs. Fielding sped toward the place where she was to exercise the noble functions of her mind, Marjorie, in the nursery, lay in the private secretary's arms, at times sleeping and at times with wide-open, glassy, bright eyes. The private secretary was staying overtime, but she did not mind it. She was glad to stay because Marjorie was fretful and would not let Chiswick touch her.

Marjorie moved about restlessly in Miss Vickers's arms, trying fresh positions each moment, and tossing her hot head from side to side. Her cheeks glowed red, and the same red overspread her forehead and gleamed through the tossed gold of her hair. Where her head touched it the private secretary's arm burned as under a hot iron.

The private secretary—who really had no voice at all—chanted:

“Ma-mie had a lit-tle lamb, Little lamb, Little lamb, Ma-mie had a lit-tle lamb, Its fleece was white as snow.”

Marjorie fretted. She did not want to be sung to. She did not know what she wanted. She was not used to being abnormal in temperature, it made her peevish, but she was lovable even so, for through the peevishness stray smiles would creep—sick little “please—excuse—Marjorie”—smiles, to show she had no hard feelings, but just one great uncomfortable feeling.

“You dear, dear, dear baby!” the private secretary exclaimed, and bent and kissed the hot cheek.

It was a hard night for the private secretary but it was a treasured night. It was blessed to feel the little hot baby resting in her arms and to be able to give up sleep and comfort and everything for the sleepless child.

When the sun arose Marjorie had fallen asleep, but tossed restlessly, and on her white skin, from which the fever had retreated, thousands of bright red spots glowed and glowed. Marjorie had the measles.

Chiswick suggested sending a hurry call for the committee, but while she was sending it the private secretary routed Mr. Fielding from his bed. He came to the nursery in bath robe and slippers, and dashed out again to set the telephone bell clamoring.

Before the committee had its pompadours well under way the good old bulky doctor was bending over Marjorie's crib.

“Very severe attack,” he said, “but not necessarily dangerous. Keep her (and so on), give her (and so on). I'll drop in after noon.”

When the committee arrived an hour later it had nothing to do but approve or disapprove of what had already been done. It decided to send Mrs. Fielding bulletins. Nothing weak or exciting; just cool, calm statements of facts. Things in the manner of reports to a fellow committee woman.

Mrs. Fielding received the first as she was in the hands of the reception committee.

“Marjorie has measles. No cause for alarm,” it said. She frowned. Why should they bother her with trifles.

About noon she received another message. It read: “Patient's condition unchanged. No cause for alarm.”

She crumpled it in her hand and threw it on the floor. It had interrupted an inspiring conversation on the Higher Life.

When the doctor visited Marjorie about noon he sat fully five minutes with her, which was unusually long for such a busy man, and as he left he gravely remarked that he would drop in during the evening.

He did not like the way those red spots were fading.

When he returned he frowned. Mr. Fielding was sitting on the cribside holding one of Marjorie's hot hands and gently passing his fingers over her brow. The private secretary was on her knees at the other side of the crib. But the doctor did not frown at either of these.

“I don't like her condition, at all,” he said. “Not at all. But I'll try to pull her through. Telephone my wife I'll not be home to-night, will you?” Marjorie lay in open-eyed listlessness, staring upward at nothing. Her breath was short and rapid, and her heart beat like the quick strokes of a trip hammer.

She wondered vaguely why this strange thing was happening to her, and when the private secretary touched her she tried to smile, and only succeeded in making white lines about her drawn, dry lips.

It was nine o'clock when Mrs. Fielding arose to read her paper before the national convention, and as she arose she was handed a telegram. It was from the committee.

“Patient seriously ill. Best possible medical attendance. Do not worry.”

Mrs. Fielding read it and walked to the rostrum. “President and ladies,” her paper began, “my child is an example of the benefits of scientific motherhood,” but she did not read it so. As she stood facing her audience, her paper trembled in her hand, and as she looked at the lines written upon it they said but one thing—“Patient seriously ill.”

“President and ladies,” she began, “my child is—my child is—” The lines vanished and she faltered. “My child,” she said, “is—is very ill to-night. I must go, of course. You must excuse me,” and she turned and fled.

It was rather odd that the first articulate word that Marjorie said in her life was uttered about that time. She had grown more irritable and had pushed away her father's hand and the drink that the private secretary offered her.

“What do you want, little girl?” Miss Vickers asked, and Marjorie, whole weeks ahead of her schedule, said, “Ma-ma.”

For an incubator baby, Marjorie handled the measles remarkably well. After a first reluctant period when she seemed to prefer death to disfigurement, she blossomed into exceeding spotfulness and rioted in soda baths, and then she gently faded into her usual pink-and-white-ness. The effect on her system was excellent, but to Chiswick, her faithful nurse, it brought distress.

The world bows down before a sick baby, but a convalescent baby puts its foot on the neck of the prostrate world and then pushes. Marjorie ruled. She demanded many things. She insisted on being rocked to sleep, and sung to, and being held while awake, and all manner of things that her governing committee considered debilitating and antiquated, and Mrs. Field-ing, glowing with newly found mother love, decided that Marjorie must have them. She felt that a little petting would not harm the child, but she was afraid of Chiswick.

Chiswick, like an incorruptible guard, was always present, and back of Chiswick was the governing committee, and back of the committee was the Federation of Women's Clubs, and back of that was all the great theory of scientific motherhood and the greater theory of the Higher and Better Life for Women. Mrs. Fielding felt that the eye of the world was upon her, and that Chiswick was that eye. The only way to secure freedom was to put the eye out, so she put it out. She gave Chiswick an afternoon off.

Chiswick went reluctantly. She was a lover of duty, and she had but one desire in life, to see Marjorie keep to her schedule.

Mrs. Fielding and Marjorie had a good time that afternoon. Marjorie learned to put her arms around her mother's neck and to lay her face close against her mother's face, but Chiswick wandered up and down before the house disconsolately.

When she was let in she threw off her hat and dashed at Marjorie greedily. She took her pulse eight times in succession and refused supper because she wanted to get so many respirations and temperatures that she had no time to eat.

She was just settling down to a nicely scientific evening when Mr. Fielding entered the nursery. Mr. Fielding feared Chiswick as much as he feared Mrs. Fielding. He cast one glance at Marjorie, sweet and clean in her nightgown, and another at the door, and then smiled at Chiswick. It was a guileful smile.

“Chiswick,” he said, “it is a beautiful evening.”

“Is it, sir?” she asked, coldly.

“Beautiful,” he returned with great enthusiasm. “Beautiful! I never saw a finer night—outside.”

“You don't say!” she remarked, but her voice expressed the deepest unconcern for the weather. Mr. Fielding moved toward Marjorie. Chiswick quietly slipped between them.

“My!” Mr. Fielding exclaimed. “You are not looking at all well yourself, Chiswick. You are overworking. I don't know what Mrs. Fielding can be thinking about to let you wear yourself out so. You are so faithful, so—”

Chiswick shook her head.

“I don't want no outing,” she said, sullenly. “I've had one. I don't need no more. I'm well.”

“Really,” said Mr. Fielding, “a little run in this fresh evening air would do wonders for you; wonders! It would quite set you up again. You must think of your health, Chiswick.” He eyed Marjorie longingly.

“No, thank you,” said Chiswick. “I'll try to get along.”

“Chiswick!” said Mr. Fielding. “I insist. You may neglect your health if you wish, but I cannot. What would Marjorie do if you should get sick—and die? I insist that you must go out for a little constitutional. Say for two hours, or three, if you wish.”

Chiswick balked and Mr. Fielding gently put his hand against her shoulder and pushed her to the door. She gave a last longing glance backward into the nursery and went. For two hours she sat desolately on the horse block and then sadly entered the house with a cold in her head.

Marjorie was asleep, but when she heard Chiswick's tread she sighed and held up one soft hand. Chiswick clasped it—and took her pulse.

The next morning Miss Vickers looked up from her task of filling in the record cards for the previous day and smiled at Chiswick. It was unusual, for they were not the best of friends, and Chiswick hardened instantly.

“I'm looking sick, ain't I?” she said, defiantly. “I need air, don't I? I'll lose my complexion if I don't go out and sit a few hours on that stone horse block, won't I? Huh! Not for you! No, mam, I'll out in the afternoon for Mrs. Fielding, and I'll out in the evening for Mr. Fielding, if I have to, but I won't out in no morning for no private secretary. Not much?”

“I only thought,” said Miss Vickers, sweetly, “that perhaps you'd like to take a little fresh air. I don't mind tending Marjorie, if you would.”

“I wouldn't,” said Chiswick, shortly.

“Oh!” said Miss Vickers. She wrote rapidly for a few moments. “By the way,” she said, between cards. “I forgot to tell you—” she wrote in a temperature—“that the committee”—another card—“said that a new sterilizer is needed”—another record written—“and said to tell you to get one”—another card—“this morning.”

Chiswick threw the baby clothes she held in her hand upon the crib with more than necessary violence. She jammed her hat on her head and stuck a hat pin through it vindictively. She ran all the way to the druggist's and back, and as she entered the house she glanced at the horse block spitefully. Mrs. Fielding met her at the door.

“Chiswick,” she said, “I'm going to let you have another afternoon out to-day.”

Marjorie enjoyed Chiswick's outings. She found herself in a world where people did nice things to her, and her appetite for petting became a vice. When entertainment stopped she doubled up her fists, closed her eyes and yelled. Sometimes, if her demands went long unanswered, she held her breath until she was purple in the face. Against such a plea only Chiswick could remain obdurate. She seemed absolutely incorruptible, but she was not. Every woman has her price.

It was an afternoon of the meeting of the federation and Mrs. Fielding was out. Miss Vickers was out, too, and Chiswick was happy. She did not have to take an outing.

Marjorie sat on the sterilized floor and planned the downfall of Chiswick. She wanted to be rocked asleep, and that, like Mary's little lamb, was against the rule. Scientific babies are laid in the crib and go to sleep without rocking. Marjorie wept.

She began by rubbing her eyes with the back of her chubby fists and yawning until her mouth was a little pink circle. That was to tell Chiswick she was sleepy. Chiswick put her in the crib.

Marjorie sat up and whimpered, pausing from time to time to look at Chiswick. Chiswick remained calm and indifferent. Marjorie lay back, stiffened her limbs and yelled. Chiswick was not affected. Marjorie rolled over on one side, raised her voice an octave, and shrieked, beating the side of her crib with her fists. She became purple in the face. Chiswick paid no attention.

Marjorie, disgusted, became suddenly quiet. She feigned meekness. She sat up in her crib and smiled. She pretended that sleep and rocking were farthest from her thoughts. She coaxed to be put on the floor. Chiswick yielded so far, as a reward of merit.

Without an instant's hesitation Marjorie crept to the rocking chair that stood in one corner of the room and tried her latest and most famous trick. It was a trick of which she was justly proud. When she had done it for her mother she had been deliciously hugged, and it never failed to win a kiss from her father. True, she had always performed it with the assistance of a crib leg, but the rocking chair looked serene. Marjorie could stand on her own legs, with something to hold to, and she was going to do it for Chiswick.

She raised herself on her knees by the chair, and grasped it firmly by the seat. Cautiously she drew a foot up under her and tested her knee strength. It was good. She raised herself carefully and slid the other foot beside its companion, stiffened her knees and was standing upright! It was glorious! She turned her head to see how Chiswick was taking it. The chair failed her basely. It swung forward in an unaccountable manner and developed a strange instability. Marjorie grasped it firmly and it reared up in front and then dived down again. She cast an agonized glance at Chiswick, staggered, grasped widely in the air for a firmer support, gasped, and sat down so suddenly that the bottles in the sterilizer on the table rattled.

The chair, released, nodded at her sagely once or twice and settled into a motionless and fraudulent appearance of stability.

Marjorie was not to be fooled twice by the same chair. She tried it cautiously. She put her hand on it and it swayed. She took her hand off and it became still. It was a remarkable mechanism. She crawled around to one side and tried it there. It was much better so. She upended herself again, and the chair, altho it wabbled distractingly, did not cast her off.

Chiswick was not duly impressed. She seemed to consider standing upright quite an everyday matter. Marjorie hesitated, looked at her appealingly, and then, to overwhelm her, released one hand and stood alone, supported by one hand only.

Suddenly the deceitful chair began to rock again. It fell sickeningly beneath her hand, and arose again, only to fall once more. Marjorie trembled. If all the world should develop this instability! If cribs and floors and walls should take to sinking and rising.

She lost faith in the inanimate. Nothing was firm and secure but strong, warm arms, holding one firmly. She cast off her remaining clasp on the chair and in her excitement forgot that she was standing. She had but one thought, Chiswick and safety!

Steadying herself for a moment she reached out her arms and took a step toward Chiswick. She swayed backward, threatening to sit down again, and then in a rush she took three quick steps, bent forward and fell flat on her face.

Chiswick darted toward her, but too late. Her forehead struck the hard floor just before Chiswick reached her, and she screamed with fright. It was true! Even the floor had proved false and had risen to strike her. Her heart broke, and then, before she knew how, she was wrapped in Chiswick's arms and was being rocked tumultuously. Chiswick had fallen from scientific grace.

After that it was only a question of who could do the most to spoil Marjorie. There was Mrs. Fielding, who was sure no one suspected her; and Mr. Fielding, who carefully avoided publicity in his ministrations; and Chiswick, who was severely correct when observed and weakly indulgent when alone; and Miss Vickers, who was shamelessly indifferent to rules. Between them Marjorie had quite a normal babyhood, and the members of the committee were blissfully unaware of it. They regularly reported her progress, and bragged of her scientific upbringing.

When Marjorie reached the age of two years she had cut all her teeth and was saying words of one and one-half syllables, and stringing them together to form sentences that no one but her loving intimates could by any chance understand. By the direction of her governing committee she wore frocks cut on a scientific plan that had originated in the mind of some person who had a chronic aversion to ruffles and whose firm belief seemed to be that only the ugly was hygienic. Marjorie wore health garments that looked like misfit flour sacks, and health shoes that made people stop and stare at her feet. Her garb was so highly healthful that Marjorie should have bloomed like a rose, but she began to droop visibly. She became pale and peevish and would not eat her bran mash and Infant's Delight puddings. By day she was listless and by night she slept fitfully and awakened with screams. She had no appetite. Every one was sorry for her and did little things to please her—on the sly.

In any other child the doctor would at once have suspected a wrong diet, but Marjorie's committee had arranged her diet and it was beyond criticism. The doctor suggested that perhaps incubator babies were subject to such declines. One of the strictest rules of the committee-arranged diet was “no sweets.” Candy was absolutely forbidden. On this point the committee was most positive.

Miss Vickers considered this a shocking cruelty. She lived largely on chocolate creams and considered a candyless world pathetic. She pitied Marjorie, and occasionally, when no one was looking, she smuggled a fat chocolate into Marjorie's willing mouth. Miss Vickers believed that a little candy was good for a child, but she was careful not to give Marjorie more than she thought was good for her.

Mr. Fielding was of the same opinion. He could not imagine an unsweetened childhood, and whenever he visited the nursery he smuggled in a few soft bonbons—the kind that dissolve in the mouth and leave no clews. Marjorie approved. She had a capacity for candy that was phenomenal. One morning she and her mother were taking a little toddle down the street when they passed one of those seductive candy shops in which the basely knowing proprietor has the show windows cut so low that the tempting display is very near the level of a two-year-old's mouth.

Marjorie stopped. She pushed her nose into flatness against the window and gloated. She edged back and forth from one side, where there were chocolate creams, to the other, where there were pink bonbons, and her nose in its course made a clean streak on the dusty window glass. She paused hesitatingly before the floury marshmallows, passed the cakes of flat chocolate without qualms, and settled firmly and finally before the pink bonbons.

She refused to leave the beautiful spot. When Mrs. Fielding tried to draw her away, her nose remained against the glass and she screamed. Mrs. Fielding glanced up and down the street guiltily. Not a committee member was in sight. The street was untroubled by the feet of members of the Federation of Women's Clubs. Mrs. Fielding vanished into the candy shop. It was quite safe to leave Marjorie outside; she would remain with her nose, and her nose seemed permanently affixed to the window.

But when Mrs. Fielding emerged with a small paper bag in her hand Marjorie turned. The sight of one of the delicious pink lumps of sweetness being lifted from the bag drew her away from the window, and when the bonbon was dropped into her open mouth she was conquered. She followed her mother gladly. Wherever that paper bag might go, Marjorie would follow. The last bonbon disappeared before they reached home, but Mrs. Fielding continued to carry the empty bag, and Marjorie followed it.

“Miss Vickers,” said Mrs. Fielding, as she turned Marjorie over to her, “you must never, never allow any one to give Marjorie candy. It would not be good for her.” Thus she tried to secure a monopoly of Marjorie's love, and forestall any ill effects, but she did not know the depths to which Chiswick had sunk. Concealed in her loose shirt waist was something that rustled suspiciously like paper and that made her once care-free conscience cringe at every rustle.

Naturally, Marjorie got too much candy. Whenever she was alone with one of her family she found candy appearing from unsuspected places about their persons, and she began to like confidential little parties of two.

It was truly joyful to see Marjorie eat candy. She was not greedy. At least, she did not look greedy. She looked surprised and pleased. She never seemed so soulful and sinless as at the moment when her pink lips closed over a bonbon. At such a moment she seemed to forget the world and to live in a more blessed sphere. The committee was particularly strict about candy. It made the most positive rules against candy and had them pasted on the walls of the nursery, and then during its calls, each of its members skirmished to be the last to leave. The last out of the room usually dropped a piece of candy into Marjorie's mouth.

Her indisposition was a glorious opportunity for the candy givers. Everybody had a good excuse for going to the nursery as often as possible, and she was in a constant glow of cherubic bliss, until the day of reckoning came. She lay on her cot and was crudely, simply sick. Her eyes were sunken and her cheeks varied from pale yellow to feverish red. For the first time in her life she refused candy.

Her family and attendants and her governing committee wandered about the nursery, each with one closed fist hiding a candy, seeking opportunities to bend over the crib, and offer the candy to Marjorie, unseen by the others. They made quite a procession. Someone was bending over the crib every moment. Finally the doctor came and bent over the crib, too, and then all the others joined him.

“That child is sick,” said the doctor, taking her from the crib and concocting a potion.

“We knew that, doctor,” said Miss Vickers. “We knew she was quite ill.”

“Ill!” he said. “Ill! I said sick. Dog sick. She's overfed. Too much candy.”

“Oh!” they all exclaimed. “Candy! Impossible!”

“The rules of the committee—” began the chairman.

“Did she eat 'em?” asked the doctor savagely. “If she did she ought to be sick. It makes me sick to look at 'em.” He glared at the assembly. “Which of you gave her candy?” he asked. There was no reply. He turned to Marjorie.

“Like candy?” he asked.

“Yeth,” said Marjorie.

“Who gives you candy?” he inquired. Marjorie looked at the faces above her. She selected Chiswick.

“Chithy,” she declared.

Chiswick blushed. The others looked at her in pained surprise.

“Who else gives you candy?” demanded the doctor.

“Papa,” said Marjorie.

Mr. Fielding crimsoned and avoided the eyes that frowned at him.

Miss Vickers alone spared him. She tossed her head defiantly.

“I gave her candy. Lots of it. It's good for her,” she declared.

“Who else?” demanded the doctor.

“Mamma,” said Marjorie.

Mrs. Fielding put her handkerchief to her eyes. She was afraid of the committee and hid weakly behind her tears, knowing that they would not attack her there, but the committee was not considering an attack. It was preparing a graceful retreat and it oozed away before Marjorie made its baseness known.

“Doctor,” said Mr. Fielding unsteadily, “do you think you can pull her through?”

The doctor rumbled deep in his throat.

“Pull her through!” he growled. “Pull her through! Why don't you ask me?” he snapped at Mrs. Fielding. Mrs. Fielding wiped her eyes.

“Will she get well?” she asked.

The doctor grew scarlet.

“You ask me?” he exclaimed at Chiswick, but Chiswick only looked mutely miserable, and the doctor turned and faced them.

“Pull her through!” he growled. “Yes, I'll pull her through. She's about as ill as I am, but she's as sick as a dog. Stuffed with candy. I'll prescribe—”

He turned, and, walking to the wall, tore down the rules and schedule so carefully prepared by the committee. When he faced Mr. Fielding again he seemed happier.

“How's your mother?” he asked.

Mr. Fielding gasped.

“My mother!” he stammered. “Why—why, she's dead.”

“How's your mother, then?” the doctor asked, turning to Mrs. Fielding.

“Mother is well, thank you.” she said.

“Good!” the doctor cried. “I prescribe one grandmother, one good, old-fashioned grandmother. And see that she isn't any new-fangled affair, either, or I'll turn her out and go out on the street and pick one to suit me.”

Marjorie, pale and big-eyed, looked at him wonderingly.

“An incubator is all right when a mother won't do,” he said, “and a mother is all right when you can't get a grandmother, but hang your committees and your rules! The only good thing about rules is to find exceptions to them. What this baby needs more than anything else is a course of good, old-style grandmothering.”

He buttoned his coat and paused to pinch Marjorie's cheek.

“We know what you want don't we?” he said, and Marjorie smiled a thin, pale smile.

“Want piece candy,” she replied. “Want piece candy,” she replied.