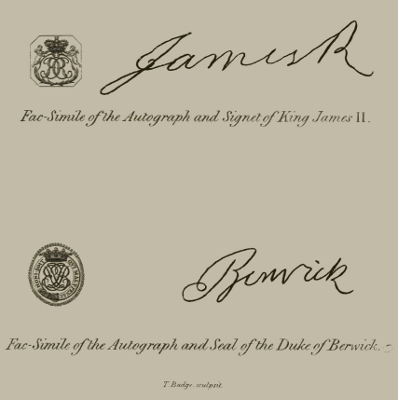

Fac-Simile of the Autograph and signet of King James

II.

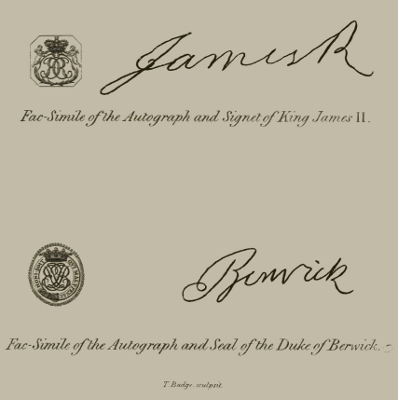

Fac-Simile of the Autograph and Seal of the Duke of Berwick.

T. Badge. sculpsit.

Title: The Eve of All-Hallows; Or, Adelaide of Tyrconnel, v. 3 of 3

Author: Matthew Weld Hartstonge

Release date: November 23, 2013 [eBook #44264]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Robert Cicconetti, Sue Fleming and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

IN THREE VOLUMES.

By MATTHEW WELD HARTSTONGE, Esq. M. R. I. A.

VOL. III.

LONDON:

FOR G. B. WHITTAKER, AVE MARIA LANE.

1825.

CONTENTS

THE

The banditti who made the fierce and fiery attack, as recounted in our last chapter, a few days subsequent to that sad event were arrested by the Gens d'Armes in Soignies wood. They had been composed, it appeared upon examination, of the daring and desperate of different nations, and that their leader was a Spaniard.

But it is indeed full time that we should return to the mansion of Tyrconnel, where [2]all was distress and dismay. But amid all this incidental confusion and alarm no time whatever had been lost in calling in surgical assistance; two surgeons of reputed eminence being instantly summoned—an English practitioner of the name of Leach, who long had been a resident at Brussels, and a Monsieur Bourreau, a French surgeon in considerable practice, likewise a resident of this ancient city, who immediately obeyed the summons.

Monsieur Bourreau was the first to arrive, who had a conference with Sir Patricius Placebo, understanding that he was a medical gentleman.

Monsieur Bourreau.—"Ah! serviteur, Monsieur.—Mais je demand votre pardon! car je pourrois dire, le Chevalier Aussi-bon!"

Sir Patricius Placebo.—"Hem, hem! Placebo, je dis Placebo!—Prononces comme il faut, si vous plais, Monsieur Chirurgien!"

Monsieur Bourreau.—"Oh, pardon encore, je demand tres humblement de votre mains. Je dis, Chevalier Placebo, que les blesseurs portées de les fusils sont toujours trop [3]dangereux; et pour moi, Chevalier Assebo, je prefere dix blesseurs de l'epée partout, à une diable blesseure de portée de fusil!—Mais, neanmoins, toujours chacun à son goût!"

Sir Patricius.—"Cette remarque, Monsieur Chirurgien, est trop vrai; et vous-avez sans doute beaucoup de raison certainment; car comme ils ont dit autrefois,

'De gustibus non disputandum!'

Hem, hem, ahem!"—having immediate recourse to his Carolus' snuff-box, which in the first instance he most politely handed to Monsieur Bourreau. And here the name of Surgeon Leach being announced, the two surgeons with due formality were conducted by the medical baronet to the sick man's chamber.

They found their patient suffering under much bodily pain, attended also with inflammation and a considerable degree of fever. They alternately felt his pulse, holding forth their watches, upon which they intently gazed; then looked at each other grave and portentous as the visages of two undertakers in their [4]vocation, and most sadly shook their sapient sconces.

However, it was not long before a very decided difference of opinion arose between the knights of the lance—to wit, M. Bourreau was for the immediate extraction of the ball, insisting most strenuously that such an operation was unavoidably necessary, thus to effect the enlargement of the wound, in order finally to extract the ball, which was the immediate and important consideration of the case, and thus finally to facilitate the cure; but at the same time with candour he acknowledged that the operation would not be unattended with pain. Meanwhile Mr. Leach was for leaving the bullet gradually to work out its own tranquil way in the quiet lapse of years and time, which result, he insisted pertinaciously, he had known to be the case in numerous instances, where bullets have remained innocuously lodged in several parts of the human body, until eventually, after a long lapse of years, they have worked forth a passage to the surface, and have been easily extracted. And other cases he knew, where individuals have retained with impu[5]nity bullets within their bodies, from a gun-shot or pistol wound, even to the closing hour of a protracted life.

Mr. Leach was likewise too of opinion that, as the wound was placed upon a joint, assuredly, that both knife and forceps should be put under due restraint, nor should any more opening be made than what was quite absolutely and imperatively necessary to meet the circumstances of the case.

It was considered incumbent by the duke, from this most serious difference of opinion, that a third surgeon should instantly be called in as umpire, and that his opinion in this intended consultation should be absolute.

Accordingly a Dutch surgeon, cognomine Mynheer Van Phlebodem, a practitioner of considerable repute, was called in, who, in conferring with his learned brethren, after a minute examination of the patient, whom he found labouring under a restless accession of fever, and having understood that Sir David Bruce had not sustained any loss of blood worth noticing, as issuing from the wound, the sage Mynheer considered it advisable to open a vein immediately, as he [6]was decidedly of opinion, from a course of long established practice, that repeated and copious bleedings, promptly and immediately adopted in the commencement, seldom or never fail of being attended with success. They prevented too, he said, much pain; kept down likewise inflammation, and diminished the assaults of fever, &c. &c.—This determination was accordingly carried into effect.

At one time, from long continued pain and continued loss of sleep, it was found necessary liberally to administer opium; at another period the medical attendants, fearing symptoms of mortification to appear, were not sparing in administering doses of Peruvian bark, with which they drenched their victim.

For the first fifteen or twenty days considerable apprehensions were entertained for the safety of the patient's life. We feel, however, most happy to state that none of those predicted evils ensued, although certainly circumstances existed to call forth such apprehensions—namely, the violent heat of [7]summer, the deadly pain of the wound, the irritation caused by fever, the inflamed state of the patient's blood; these certainly were conducive in exciting those melancholy forebodings. A constantly cooling regimen was rigidly enforced, and the patient kept quiet, free from noise or irritation. At another stage of the patient's confinement gangrene was again seriously indeed apprehended; however, from the external application of warm emolients, &c. &c., this apprehended danger was completely obviated, suppuration was successfully brought on, and the learned triumvirate freely acknowledged that the patient might now be pronounced as nearly out of danger; and in about ten days, or longer, the ball was cautiously and safely extracted, and with no other ill result, we are happy to state, than the operation having caused a considerable degree of torture in the shoulder of our wounded hero.

Nothing could exceed the manifold attentions which were shown, and the intense interest that was felt by every individual in the family of Tyrconnel, and that innumera[8]ble kindnesses were fully manifested from a certain quarter our readers will not be at a loss to guess, during the illness and progress of recovery of the wounded patient, whose convalescence, we are happy to state, had so far advanced that he was daily permitted to walk for an hour in the garden pertaining to the mansion of Tyrconnel.

One afternoon the dinner cloth had been just removed; and the family were seated at their wine, when lo! to the great amazement of the duke and duchess, a king's messenger was announced, bearing a despatch from the King of England, which, under envelope and direction of the Lord Privy Seal, was duly directed "For his Grace the Duke of Tyrconnel, these—Lonsdale P. S."

Upon opening and reading the contents of the despatch, the astonishment of the duke was no way abated. It contained the following:—

"I revoke the edict of your banishment; your attainture is taken off; your honours are restored; and you may now return in safety to your native land! You are a man [9]of honour—I will not desire you to act against your principle. Disturb not the government, and we shall be very good friends.

(l. s.) W. R."

This important and quite unexpected change in the mind of the English monarch, which now called forth in return the immediate gratitude and acknowledgments of him upon whom these favours had so graciously been bestowed, had happily been effected through the interest and intercession of the Elector Palatine, the firm friend and patron of Sir David Bruce; thus no doubt could possibly exist but that through the earnest representations, and at the especial request of the latter, this important and conciliatory measure was effectuated. Indeed this was fully corroborated by the same messenger bearing a despatch from the Elector Palatine, addressed to Sir David Bruce, which stated that the Elector felt most happy in having to acquaint him of the complete success of his interference with the King of England in the behalf of Sir David's exiled friends.

The immediate departure of the Duke and Duchess of Tyrconnel from Brussels, so soon as circumstances would permit, was fully determined upon. No obstacle, therefore, to preclude the union of Sir David Bruce and the Lady Adelaide remained, save the delay of their voyage and journey to Ireland, where, upon the event of their return to Tyrconnel Castle, it was agreed that the marriage was duly to be solemnized.

The day previous to their final departure from Brussels Adelaide devoted in bidding a fond and final farewell to those she sincerely regarded, and from whom were received numberless attentions during her sojourn. Adelaide took a parting look at scenes that were endeared to her by past associations and pleasing recollections.

"Farewell!" she mentally said, "thou fair and flourishing city!—patroness of the arts, the mistress of painting—thou queen of fountains, farewell! Ever rich and luxuriant be thy valleys, thy gardens, and thy groves; and long may the olive on thy undulating hills shadow this happy realm in peace!"

Then, with her accustomed enthusiasm, Adelaide wrote the following

farewell to belgium!

The Duchess of Tyrconnel wrote, according to promise, to Mrs. Cartwright, duly recording to her the happy turn that fortune had taken in their favour. A copy of this [12]epistle now lies before us; but as we are no admirers of unnecessary repetition, we must take the liberty of wholly suppressing the letter of her Grace.

Before we close this short, but eventful chapter, we have to observe that the Soignies banditti, who had been arrested, were tried, identified, and executed.

Not once nor twice was Sir Patricius Placebo overheard soliloquizing to himself thus: "I am," quoth the knight, "in sooth no longer a philosopher, who is desirous inter silvas foresti (non academi) quærere verum—no, no—horribile dictu! After this confounded rencontre in cursed Soignies wood, I shall for ever forego and forswear the eating of Ortolan or Perigord pies, while I live—ahem! except—that is to say, unless I can eat them with safety in the city! for there is no general rule or law without an exception; and indeed the long-robed gentry say as much—exceptio probat regulam—ahem!

"DOSS MOI, TANE STIGMEN!"

It was at the close of the last week in [13]August, which had now arrived, when the duke and family took their departure from Brussels, on their route for Ireland; and while they are on their way we shall conduct our readers in their transit to the succeeding chapter.

About two months had now passed over, which had been occupied in travelling to their long-wished for home, since the departure of the duke and his family from Brussels, the journey having commenced towards the close of August, and now had arrived the last week in October, which witnessed the due accomplishment and end of their travels, by their welcome return to their ancient and magnificent castle.

No occurrences whatever worthy of record having happened during the continental journey, the passage of two seas, or while occupied in their travels through England, Wales, and Ireland, all of which were performed in perfect safety; and moreover, the weather proved propitiously mild and serene.

While the travellers continued their route homeward, the duke thus expressed his sentiments to the duchess:—"My love, I am fully resolved for ever to abandon politics and party, to burn my grey goose quill of diplomacy; I am determined too to relinquish the ways and woes of war for the cultivation of the happy arts of peace; to desert a city life for a country life; to arise with the lark, and plough my paternal lands; to transmute my sword into a ploughshare, and my spear into a reaping-hook. My firm, fixed intention being decided for ever tranquilly to abide within my own domains, to pass our time in classic ease within the venerable towers of Tyrconnel Castle, and there eke out the remnant of my days until summoned by the cold and chilling call of death!"

The duchess said: "My Lord, I most highly approve of your wise determination, and trust that we yet have many years of happiness before us."

With these fixed resolves impressed upon his mind, the duke proceeded on his way. His journey was now nearly at an end, when the towers of his lordly, but long unfrequented castle, which bounded the horizon, arose to view, rich and red, glowing beneath the brilliant beams of the setting sun, and struck his vision with delight as gladly he approached his long deserted hereditary halls.

This long wished return was joyously and generously hailed by all ranks and descriptions of persons, from the proud peer down to the lowly peasant; bonfires crowned every surrounding mountain height, hill, peninsula, and promontory, while they beamed forth a brilliant welcome to the returned wanderer; the lofty windows of the wealthy, and the lowly lattices of the cottier, in the town of Tyrconnel, bespoke the general joy that burst around, and conjointly the wax taper and rush-light commingled their rays to manifest [17]the heart-yearning welcome that the duke's happy return had inspired.

The welcoming notes of the merry pipe and the national harp resounded blithely over hill and vale. Meanwhile the peasantry were all collected, and clad in their best and gayest attire; their honest, grateful, and joyful countenances bearing the impress of their gladdened hearts, told forth a welcome that was not to be mistaken nor misunderstood, for it affectionately hailed the much desired return of their beloved and long exiled benefactor! It was evening when this interesting scene took place, but all meet preparation had previously been arranged,—torch, flambeau, and fire-works, had been prepared, and blazed forth in all becoming brilliancy.

A triumphal arch, tastefully adorned with appropriate armorial escutcheons, emblems, and trophies, and crowned with wreaths and festoons of living shrubs and flowers, adorned the pass which led to the castellated gateway. Bouquets and coronals of flowers were flung along the way, while grateful shouts made the welkin ring as the ducal train [18]passed along. Groups of lovely damsels united their welcome song, and soon joined hands with the manly peasants in the national Irish dance of the Rinceadh-Fada.[1]

Once more the ducal standard floated on "the Raven Tower," the cannon on the terrace thundered forth a princely salvo, which boomed upon the buoyant waves of the deep Atlantic, and was re-echoed by the castle walls, while the loud continued shouts of a grateful and happy tenantry bore burden to the burst of joy.

It would be difficult to express the exul[19]tation and gladness that pervaded all ranks, and which the old domestics in particular displayed in no common way; Mrs. Judith Brangwain, the venerable old nurse of Lady Adelaide, seemed nearly crazed with joy at the long wished, but unhoped return of her dear Mavourneen, her best beloved young lady:—"Oh," she exclaimed, "at last have I survived, with these mine aged eyes, to witness this happy, happy day! Oh, never, never, did I expect so great a blessing; I am stricken in years, and nearly blind, yet the Lord be praised for these and all his mercies!"

Next the old crone sung with joy and delight, held up her garments in jig attitude, and capered about as if actually bitten by a tarantula; then seized and led out, per force, old Sandy Rakeweel, the Scotch gardener, with whom she danced an Irish reel, and that too with so much qui vive, as to demonstrate that the joys of her dancing days had not passed over. This frolic was performed on the green sward, and honest old Sandy, when the reel was completed, which, sooth [20]to say, he had undertaken nolens volens, vehemently exclaimed, "'Fore Saint Aundrewe, Mrs. Judith, wi' a' her whigmaleeries was ower pauky, to hap, step, an' loup wi' me; the gude woman is a' fou' and sae daft she ha' geck'd a' her wits into a creel, aiblins she hae been bit by a bogle. Ise naer be so jundied in a jig again; yet I'm not meikle fashed—nae, nae!"

There was, exclusive of the ancient Mrs. Judith, another venerable

follower of this noble family, in whom the general joy, so conspicuous

amongst all ranks, was not the less sincere and ardent, and this was

the aged and sightless minstrel, old Cormac, whose best suit was duly

assumed upon this happy occasion, to welcome home his kind and generous

master; his harp was newly strung, and carefully tuned aright; and

patiently, but anxiously, in the baronial hall he awaited the entrance

of the duke and family, upon whose welcome approach he thus poured

forth his strains of gratitude and affection upon his noble Lord's

return.

old cormac's welcome.

When the ancient and sightless bard had concluded this, his improviso welcome, he [22]appeared absolutely overpowered, and shed a copious torrent of tears, which flowed from eyes long indeed closed to the light, but not to intensity of feeling! But these were not tears of sorrow, they were effusions of grateful affection, that often speak the joyful feelings of the heart, while the tongue remains wholly silent. His was the unspeakable joy at his noble benefactor's happy return in health and peace, after so long an absence, to his ancient towers. The duke, duchess, Lady Adelaide, &c. &c. &c. in succession approached the aged minstrel to express severally their approbation of his song, and thanks for the feeling manner in which his welcome had been expressed. The duke obligingly and condescendingly said to him:—"My friend Cormac, although thy locks are more blenched and snowy than they were when last we parted, yet I am glad to find that your heart is not chilled by the frost of age, and that the chords of thy harp so sweetly still respond to a master's touch!"

Then addressing one of his pages, his Grace said, "Fill, fill the goblet high to the very brim, and present it to the bard!"

In sooth we need not say that sightless, honest Cormac retired to rest that night the happiest old man in the province of Ulster; his slumbers were sound and serene, and his dreams flattering as ever youthful poet dreamt.

The next morning, when breakfast was concluded, the duke said in a lively way:—"Come, come, Sir David, you have not travelled here for nothing, we must e'en show you the curiosities of the country. There lives, or rather vegetates, not far hence, a wight, the most eccentric being perhaps that ever existed—I pray you go see him. This personage is Squire Cornelius Kiltipper, of Crownagalera Castle, once the mighty Nimrod of these parts. You must, moreover, know, that from Squire Kiltipper's determined addiction to strong liquors, and likewise from the fatal consequence of a far-bruited boozing bout, in which he actually out-drank and out-lived his opponent in a long continued contest; (the defunct had been a gauger who thus succumbed in death, even at the base of the Squire's dinner-table;) in consequence of which Kiltipper was ever [24]afterwards called, in popular parlance, Squire Kil-Toper! For, Sir David, you must know that the lower class of my countrymen are feelingly sensible of the ridiculous, and extremely fond of soubriquets, or nick-names.—Indeed they are curious bodies! So I pray you proceed to see this curiosity, and my kind Sir Patricius Placebo shall, upon this occasion, be your conduttóre."

Acceding to this recommendation of the duke, Sir David Bruce, accompanied by Sir Patricius Placebo, proceeded onward in their walk; and, as a prétexte par hazard, they carried with them their fowling-pieces, and were accompanied with a couple of pointers, and an attendant terrier. They set out, and walked across the field-paths, in due direction for the castle of Crownagela, which was distant about two miles.

Upon their arrival they stoutly knocked at the hall-door, but the servant refused admittance. However, after some parlance, and the rank of the visitors having been announced, they were admitted. Here a loud and general exclamation vociferated from the [25]parlour, struck the ears of the visitors—"A song, a song!" The servant upon this observed, "Gentlemen, yees must have the goodness to wait just a bit till this same song is over, and then I will show yees to my master. If I dare go in now, to transdispose their musicals, the penalty would be, that I should be flung flat out of the window, and that, I am sartin, would not quite plaze yees."

While the visitors waited with what patience they might, before they

were admitted to an audience with the original whom they had come

to visit, the following bacchanalian song was conjointly sung; and

which rumour likewise reported to have been composed by the vocal

triumvirate, namely, Mr. Barrabbas Tithestang, the proctor, Mr. Simon

Swigg, the gauger, and Mr. Stephen Stavespoil, the parish clerk and

sexton: but the latter personage was strongly suspected to have had the

principal hand, or pen, in the precious composition.

song.

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

Squire Kiltipper, somewhat pleased, sung a semi-stave of the song:—

A very plain and palpable alternative truly, the drunkard fairly caught on the horns of the mathematician's dire dilemma, and then to flounder on the floor—ha, ha! Oh, lame and lamentable conclusion! Come lads, the health of the composer; hip, hip,—hurrah!"

This toast drank at mid-noon, however strange to tell, was loudly chorussed, with various manual accompaniments inflicted on the table, until the window panes and the very drinking-glasses again returned the echo; and amid this uproar the door was opened, and the visitors introduced, their names being duly announced. Squire Kiltipper was discovered seated in his bed, holding in his hand the MS. of the precious rant which had just been sung; he wore spectacles; his dark beard was unshorn; he wore on his head a cap made of otter skin; he was habited in a [28]scarlet waistcoat trimmed with rabbit skin, over which he wore a dressing-gown of purple camlet; his small clothes, which had been once white, but now stained with claret, reminded one rudely of the union of the rival roses of York and Lancaster! The Squire arose to receive his guests, but was preceded by his prime minister, Bounce, his favourite greyhound, who had been also snugly reposing under cover of the counterpane, which now rising to a portentous height, he and his master were safely delivered from the thraldom of the bed-clothes, and the Squire politely advancing, paid obeisance to his visitors, and invited them to luncheon.

The guests were, Mr. Simon Swigg, the gauger, Mr. Stephen Stavespoil, the parish clerk and sexton, and Mr. Barabbas Tithestang, the proctor, who began the world a beggar's brat, and barefooted withal; sans shoe, sans stocking, sans every thing, save a large and inexhaustible stock of confidence; but was now metamorphosed into a country justice; and this squire of mean degree enjoying the otium cum dignitate of four hundred pounds [29]per annum, besides the important privilege of daily entrè to the dinner-table of Squire Kiltipper, alias Kill-Toper!

These gentry were the squire's led captains, his most abject vassals, whose presence at his table contributed, by their native gross humour, to divert the tedious hours of the squire, and whose society had now become quite necessary to his existence. He had been well educated, and was not deficient in mental ability; but his sad propensity to the worship of Bacchus had nearly hebetated the powers of his mind, and had nearly likewise debilitated his powers of loco-motion by frequent confirmed attacks of gout, which had much undermined his constitution.

In the centre of the room was stationed a table, on which still stood some stout cheer, the remains of last night's banquet; here were to be seen the remnant of a huge venison pasty, cold roast beef, pickled oysters, cold roasted fowls, tongues, &c., and relics of exhausted bottles reposing like dead men upon the carpet. Upon the approach of the strangers, Vulcan and Hecate, his two fa[30]vourite cats, that had been busily employed in subdividing the venison pasty, at sight of the visitor's dogs most incontinently abandoned their plunder, loudly yelling, and retreating with precipitation, they scampered up the chimney; while the general panic, with effect of electricity, communicating its fearful effects to his favourite pigeons, who had been peaceably reposing, with their gentle heads under their wings, upon the tester of the bed; but now they sprang up in affright, as if pursued by falcon or eagle, and dashed themselves suddenly against the window-casement; the poor pigeons received some slight hurts, and the Squire was evidently discomfited. "D——n, I say, to Vulcan and Hecate; but I am indeed sorry for my pretty pets—my dear pigeons. You know, my worthy and venerated Sir Patricius, how much I am obligated to my late dear, dear, dear uncle Commodore Pigeon, of Capstern Hall in Yorkshire, who bequeathed me an estate to the tune of nearly two thousand pounds per annum; and therefore you can fully account for my warm attachment to the [31]pretty bird that bears his honoured name! I am now waxing old, and peradventure am not exempt from the follies of old age; I have long since become tired of the chace, my bugle-horn hangs silent in my hall, and my unkennelled hounds wander forth, to my cost, committing petty larcenies amid the peaceably disposed ducks and turkeys of the vicinage; my hunters I have turned abroad to increase and multiply exceedingly, and cats daily kitten in my quondam boots of the chase! But I have dwelt too long on myself and mine own concern—I give you a hearty congratulation upon your safe return to these parts, and also at the happy return of the duke to his ancient towers. I pray you that you both stop and dine with me; I can only promise you a yeoman's fare, but indeed you shall likewise have a friend's welcome! For, Sir Patricius, I do esteem thee, and I do consider thee, by yea and nay, a man of the most recondite taste and parlous judgment that I ever have encountered; withal resembling, methinks, most accurately what old Flaccus terms 'Homo ad unguem factus.'"

Sir Patricius politely thanked him for his too good opinion of him, which he feared was rather overrated, and apologized for the next to impossibility of accepting of his friendly invitation, which they begged to postpone to some more opportune time. And now having quite sufficiently amused themselves with the eccentric Squire of Crownagelera Castle, Sir David Bruce and Sir Patricius Placebo again returned thanks for the proffered hospitality of Squire Kiltoper, and having bade him good morning, set out on their return, "Non sine multo risu," as Sir Patricius expressed himself, for Tyrconnel Castle.

The thirty-first day of October, sixteen hundred ninety and ——, being the birth-day of our heroine, was the morning appointed for the solemnization of the nuptials of Sir David Bruce and the Lady Adelaide Raymond. The young lady's consent, and that of her noble parents, having been previously obtained, and also that sine qua non preliminary of nuptial happiness—to wit, a marriage license, having been duly and properly procured, no obstacle to their happy union now remained. Preparations upon a grand [34]scale had been in a progressive state of forwardness for some weeks at Tyrconnel Castle, to crown the nuptial banquet, and every delicacy and luxury that taste could select, or that money could procure, were not wanting to furnish forth the splendid marriage feast. The Duke of Tyrconnel, in order to add to the pomp and circumstance of the event, had a new state coach built for the happy bridal day, selon des reglès, as then the fashion of the day controlled. The carriage was connected by massive crane necks, which in our modern days of fashion have crept down and shrunk into a slender perch; these were richly carved and gilt. The wheels were of a very circumscribed orbit; and the naves were gilt, as well as the spokes. The springs likewise were of burnished gold; while the ponderous massive body, with shape (if it could so be called) which much more, in sooth, resembled a city barge abducted from its natural element, and aided by wheels in its terrestrial progressions; or perhaps as cumbersome, although not as unsightly, as a French diligence—but assuredly not to be compared with the present modern turn-out [35]of a nobleman. Ducal coronets of brass, richly embossed and gilt, adorned and surrounded the four angles of the roof of the state carriage. A splendidly embroidered hammer-cloth mantled the coach-box, which was destined to glitter in the last rays of a brilliant October sun, upon this ever-memorable day, and to glance forth the rich emblazoned quarterings of the noble houses of Tyrconnel and O'Nial. The superb liveries of the domestics were neither overlooked nor forgotten upon this happy occasion; they were indeed truly magnificent; they were of rich green cloth, with gold embroidery and trimming.

Sir David Bruce had also duly in readiness a very handsome town chariot, which he had caused to be built for the occasion. This was drawn by four handsome horses, and guided by two postillions, preceded by two outriders, and in the rere followed by two footmen on horseback, their housings ornamented with the Bruce crest in embroidery, and from each holster peeped forth travelling pistols, mounted in chased silver, [36]and richly ornamented. The outriders had the additional appendage of belts slung from their shoulders, to each of which were attached small silver powder flasks, or priming horns. The same state attended upon the duke and duchess. Six running footmen, (the fashion of the day,) with ribbons streaming at their knees, and with long white walking-poles, entwined with ribbon and surmounted with favours, preceded the carriage of the duke, and as many were the precursors of the carriage in which were seated the duchess and the beauteous bride. Such was to be the pomp and procession destined for this illustrious bridal.

Old Cormac seemed resolutely determined that he at least should not be omitted in the dramatis personæ of this most memorable day. At an early hour, therefore, with due intention of the full performance of his resolve, he was seen flitting from alley green to the dark embowered wood, bearing his constant companion, his harp; and as the old gardener somewhat quaintly expressed [37]it, "he was for a' the warld like a hen on a het girdle!"

Old honest Cormac's intention could not long be mistaken or

misunderstood; for soon with right shoulder forward, and strong

intuitive confidence, he stoutly marched onward, nor did the veteran

halt until he had reached Lady Adelaide's flower garden, where he

was often accustomed to sit and play; where having arrived, he soon

seated himself upon a rustic chair, beneath the casement of the Lady

Adelaide's chamber, where anon he began to strum and tune his harp.

The moment that the sightless bard had begun his minstrelsy, vocal

and instrumental, it was with considerable delight and joy that he

distinctly heard the casement window of Lady Adelaide to be thrown

open. Meanwhile the lovely fair (in whose honest praise the poetic

raptures of the ancient minstrel were composed) looked down upon

her old, faithful, and favourite bard, while mirthfully he sung and

accompanied the following:—

nuptial song.

Here ceased the old sightless Cormac, while tears of deep and intense feeling and [39]affection trickled down his venerable, time-furrowed cheeks.

Adelaide descended from her chamber, and entering the garden, with great sweetness and condescension approached the old minstrel: "Thanks, many thanks, my kind and ancient bard, for this thy matin lay; and here too is a boon withal for the minstrel."—At the same time placing a gold doubloon in his hand.

"Oh, receive my warm, grateful thanks, my dear, kind—my noble young mistress—Cead millia failtha! May the benison of the sightless bard bless you and yours for ever and ever! Indeed I dare not refuse the bridal present, for it carries luck and happiness, and every thing that is kind, and noble, and good, along with it. God bless you, young lady, and may you be as happy as you deserve; this, young lady, is the warm and fervent prayer of poor blind old Cormac!"

The Lady Adelaide felt much affected with the respect and affection manifested by the ancient minstrel, and once more thanking him [40]for his verses, adjourned to the breakfast-room. While on her way she was met by Sir David Bruce at the garden door, and according to the fashion and reserve of that day, he ceremoniously led by the hand his lovely mistress. They now entered the breakfast parlour, where they found the duke with the family assembled, to whom they kindly bade good morrow.

The worthy and venerable Bishop Bonhomme and his lady had arrived, as also the bride's-maids, and the whole of the company who had been invited to the wedding. And the bridal breakfast having begun and ended, the splendid equipages of the noble party were ordered to approach the grand porch of the castle. And here that our fair readers may not "burst in ignorance" of the mode and manner in which a marriage in high life was conducted in those times by the gens de condition, we shall endeavour to give a report, albeit not copied verbatim from the court gazette of the day.

Bishop Bonhomme and his lady first departed from the castle, ascending their state [41]chariot, if indeed it could be called ascending a vehicle, the body of which was barely raised some inches above the carriage part, and which was all richly carved and gilt, and also attached by low massive crane-necks. The single step by which the ascent into the chariot was accomplished, was fastened perpendicularly at the outside: it was finely carved and gilt, and of the shape and form of the escalop shell, and two golden keys, interlaced and embossed, adorned its centre. In lieu of leather pannels at the sides and back, the body was ornamented all around with windows of rich plate glass, from the royal factory of Saint Idelphonso, by means of which a full view was clearly presented to the spectator of those within.

The bishop wore a full-dress orthodox peruke; he was arrayed in his robes and lawn sleeves; his white bridal gloves were trimmed with gold. He looked very episcopal and dignified. The pannels of the chariot were emblazoned with their due quantity of mitres; a rich bordure of the crozier, interlaced with foliations of the shamrock, adorn[42]ed the sides and angles. The state chariot was drawn by six sleek, stately, coalblack steeds, whose long and bushy tails nearly swept the ground. It was driven by an old, fat, jolly-looking coachman, who displayed fully to every beholder that he was not stinted in his meals at the palace, to which his portentous paunch bore full attestation. He was assisted by two postillions, arrayed in rich purple jackets and purple velvet caps. Six footmen, in their episcopal state liveries, stood behind. Next in the procession came on the state coach and six of the duke, in which were seated his Grace and two of his Reverend chaplains. Then followed the state coach and six which contained the duchess and her lovely daughter, and Lady Adelaide's two bride's-maids. Next came on the chariot and four of Sir David Bruce, which contained the Baronet and Sir Patricius Placebo. These were followed by numerous carriages of the surrounding nobility and gentry; the servants all decorated with silver favours; while numerous parties of the tenants and peasants, "dressed in all their best," some [43]on horseback and others on foot, closed the extended cavalcade.

The joyful pealing of the sacred chimes now cheerily rang forth from the cathedral tower, to salute the natal morn of Lady Adelaide.

Meanwhile a number of female peasants were seen advancing, arrayed in white, their heads garlanded with living flowers. They danced before the bride's carriage; and so soon as the cavalcade had reached the cathedral porch, as the bride entered, they strewed the way before with rosemary, gilliflowers, and marygolds; the mystery and signification of which was this—the first stood for remembrance, the second for gentleness, and the last for marriage, being an alliteration between the name of the flower and that of the thing signified.

Old Bellrope, the sexton and verger, who, "man and boy," had witnessed many nuptials celebrated in the venerable cathedral, solemnly asseverated that he had never before set eye upon so beautiful a couple! To do due honours to the ceremony, he had [44]newly purchased a verger's gown, and wore a purple cloth coat, waistcoat, and indispensables, which had appertained in the olden time to some pious bishop of defunct celebrity. His wig was very commendably frizzed, thanks to the skill and indefatigability of Madam Bellrope, and looked unusually gay, from a judicious distribution of a successful foray made upon the drudging-box by the said thrifty dame, so that it provoked a remark from Sandy Rakeweel, the gardener at the castle, an honest old Caledonian devoid of guile:—"That indeed auld Bellrope's peruke for a' the warld remeended him o' aine of his awn kale plants in fu' flower in the middle o' August."

The noble procession entered the cathedral porch, where being duly marshalled in meet heraldic pomp, rank, and file, the distinguished persons proceeded along the venerable nave. Lady Adelaide was arrayed in a silver tissue, a splendid tiara of pearls, in form of a shamrock-wreath, encircled her noble brow, with ear-rings of the same, and [45]on her lovely neck she wore "a rich and orient carcanet."[2]

Sir David Bruce, with firm and dignified step and gesture, advanced, leading onward by the hand to the bridal altar the lovely Lady Adelaide, her eye beaming with all the radiance of intelligence and of genius, while the deep glow of health and the blush of modesty mantled her beauteous cheek as she approached the sacred altar, the gaze, delight, and admiration of all, high and low, who beheld her. Her graceful, but bashful step, and her modest mien, reminded the spectator of Milton's fine description of Eve, when

"Onward she came, led by her heav'nly Maker," &c.

As pure and spotless Adelaide stepped to the holy altar. But it was impossible to withhold the veneration and admiration called forth by the appearance, voice, manner, and noble countenance of the good bishop, who, indeed, more than seemed "the beauty of [46]holiness," while with a clear, distinct, and dignified intonation of voice, he read the sacred service.

The ceremony concluded, the bridal party went forth in the same order in which it had commenced, save that Sir David Bruce and his fair bride rode in the same carriage from the cathedral. Sir Patricius Placebo returned in the duke's carriage. The remainder of the morning was occupied until dinner time in various rides and drives to view the beauties of the surrounding country; some went out on a boating excursion on the beautiful lake of Loch-Neagh, others drove out in low phaetons, or cabriolets; and some went on a walking excursion to view the lawns and woods of Tyrconnel, thus to occupy the time until dinner. The elder folks sat down to the green field of the card-table, playing at primero, cribbage, ombre, &c., jusque à diner.

The dinner was splendidly superb. The services of richly chased and embossed plate which this day decorated the nuptial table, were truly magnificent. One service was of gold, two others were of silver.

In the evening there was a grand ball, which was opened by Sir David Bruce and his beauteous bride; they were followed by the Duke and Duchess of Tyrconnel, who, (ah, good old-fashioned times!) upon this occasion, tripped it on the light fantastic toe; they were soon followed by a large group, who danced down the contrè-danse with great spirit; a smile of joy was evidently seen in the benevolent face of Bishop Bonhomme, and he was even seen to beat time with his head and foot.

Brilliant illuminations were observable throughout the domain, various coloured lamps were garlanded from tree to tree, and likewise across different avenues in the lawn.

A banquet was spread for the duke's tenantry, where most excellent and substantial fare was presented in abundance to all; and there was no lack of strong beer, which flowed forth in streams. Fire-works of various kinds were played off. And the duke's band of French horns, stationed in different parts of the park, played various tunes, which were sweetly echoed by the adjoining woods, and the responding waters of the Eske.

The tenants and peasantry did not omit the Irish dance, the Rinceadh-Fada, which was danced with great spirit and grace in front of the windows of the baronial hall. Old Cormac was now summoned to assist at the ceremonies and the gaiety of the hall. Upon command to attend, his remark was—"Weel, weel, 'twas anely as I expected!" He immediately hastened to the festive scene, and brought with him a Scotch harper, old Donald, who had been a retainer in the family of Bruce, and whom the intelligence of the nuptials that were that day to be solemnized had brought into the neighbourhood. Here a polite and courteous contest arose between the minstrels, each standing upon etiquette, and quite ready to award to the other the right of precedence; however, this posing point, d'embarras, was at length finally settled by Donald's declaring, that "he wad na pla' at a' afore maister Cormac." So, volens, nolens, old Cormac seized his harp, and thus began, accompanying his instrument with the following verses:—

Cormac sung the foregoing simple lines in order that he might be

entitled to call upon old Donald; who now being left without an

apology, and endeavouring to recollect a song, after a short pause the

Scottish minstrel struck his harp, and thus began:—

i thought on distant hame!

Donald received applause upon the conclusion of his pathetic song; who, in return, bowed low and respectfully to the company. [51]Here the minstrels tuned their pipes with a refreshing draught of Innishowen and water, of which commixture the first ingredient was, doubtless, the most predominant.

It now came to Cormac's turn to strike his harp. When about to proceed the duke observed: "I fear, old friend Cormac, that it now waxes late, and we shall not have much time for any lengthened production, for you are aware that when the great hall-clock shall strike the ninth hour we proceed to supper. This rule at our castle is as peremptory and inviolable as the ancient laws of the Medes and Persians; so remember, good Cormac!"

"Never fear, your Grace's honour, I shall not fail to obey you."

Then turning to Lady Adelaide Bruce, he said: "I will sing the loves

of Sir Trystan and the beautiful Isoud! they were young and noble;

they were likewise comely too, lovely lady: but they were unfortunate

in their loves. Grant, O heaven, that such a fate may never betide the

Lady Adelaide or Sir David!" He then commenced—

the romaunt

OF SIR TRYSTAN AND LA BELLE ISOUD.

Just at the conclusion of the above, to the horror, confusion, and surprise of old Cormac, the German clock in the baronial hall chimed musically forth the ninth hour. But it was no music to the ear of Cormac, who in dumb despair somewhat sullenly laid down his harp, knowing that remonstrance would not be heard, and that solicitation was all in vain. But the duke was loud in his commendations, in which he was duly echoed by his guests, and Cormac was assured that the company should certainly be gratified upon the succeeding night, and at an earlier hour, with the remainder of the Romaunt of Trystan and Isoud.

The company now descended to the great supper-room, where a most superb banquet was spread for the noble guests. The wassail-bowl was duly and meetly placed in the [55]centre of the table upon a magnificent gold plateau. The bowl was decorated with artificial flowers, festoons of "true-lover's knots," "rose-buds," "heart's-ease," "forget me not," and the bow and arrow of Cupid were not omitted.

"The spiced wassail-bowl,"[6] duly impregnated with love philtres, was composed of Muscadel,[7] principally, in which, inter alia, the following ingredients were mixed in this mystic beverage: namely, angelica, adianthum, eggs, eringo, orchis, &c. The concoction was made with great caution, measure, and propriety, according to the avoirdupois weight, as duly laid down in the family receipt book. The bride and bridegroom, of course, were the first to quaff from this charmed potion, and then those who chose to follow their example.

The song, the jest, and the cup, detained the company until the eleventh hour, a time in that primitive period which was considered late; when mutually pleasing and pleased, the [57]noble guests arose to separate; and all retired to their respective chambers to repose, pleased and delighted with the hospitalities of this happy and most memorable day.

It was on a serene autumnal morning succeeding the day of Lady Adelaide's nuptials, the sun had brilliantly arisen, dispelling the misty gloom and dews of night, and shed around his broad refracted rays; unruffled by a passing cloud, a clear and lofty sky spread forth its mighty canopy of mild aërial blue; the twittering swallows hovered around, and circled in mid-air, while clustering, they chattered their parting lullaby. The solitary redbreast too joined in nature's chorus, and thrilled forth his matin song. Every mountain lake shone forth a glassy mirror, and the [59]waves of the mighty Atlantic hushed to repose, slumbered amid their coral caves; what time the minister of the gospel of peace, the Reverend Doctor M'Kenzie, returned to the castle of his noble and generous patron, after a long protracted absence of many years.

His return had been provokingly delayed by long continued ill health, and besides by various vexatious detainers, such as bad roads, bad drivers, the cumbersome, ill-constructed vehicles of those days, and having encountered various disastrous chances of many "moving accidents" by sea and land, which had all concurred with direful combination to retard his journey, and prevent his being present upon the auspicious day when the lovely heiress of the noble duke was to bestow her hand in marriage.

His Reverence received a kind and hearty welcome from the duke and duchess, and all the inmates of the castle were rejoiced to behold his return, and to find that his health was quite re-established, so as to have permitted him to undertake such a long and [60]fatiguing journey. His health and spirits were indeed much recruited through the beneficial effects of the waters of Pyrmont, which, like those of fabled Lethe, seemed to cause a total oblivion of all the perils inflicted amid the deep, and the dangers and difficulties sustained upon land.

Matters went on at the castle this day pretty much alike to what they had upon the preceding ever memorable yesterday, which witnessed the happy union of Sir David Bruce and the Lady Adelaide. A large company assembled at the castle, and sat down to a splendid dinner in the great hall of state. The desert could boast fruits collected from every quarter of the globe, and every rich, rare, and generous wine, sparkled on the board, and were poured forth in hospitable libations—

In the evening there was a concert of instrumental music, which was performed on the terrace; cards and supper succeeded; every [61]thing was conducted and served up in a style at once splendid and superb.

The company had all departed to their homes, and the guests had retired to their chambers; but the duke and duchess, and the bride and bridegroom, still tarried, engaged in pleasant discourse; when at length the noble host and hostess also took leave, and embracing their beloved daughter, and cordially shaking Sir David by the hand, they bade good night, and ascended to their chamber. The bridal pair now also remained some few moments engaged in sweet converse, when he said:—"My love, retire to your chamber, and soon I shall follow thee; I have a letter or two to write, and despatch by the messenger, who at dawn of day departs to deposit them in the general post. I have too a few letters to read; these being despatched, quickly I shall retire anon to our chamber. The night is a cold autumnal one, but I know that I shall find a blazing fire—a heart still warmer than that fire, and sweet smiles withal, to welcome me when I shall [62]rejoin thee.—Go, go, my love!" he said, and affectionately embraced her.

He sat for some time reading and writing, for the papers were of importance. He now arose from his chair, and was about to retire to his happy chamber, when a loud and hollow knock was heard at the portal gates; the watch dogs were aroused, and loudly and deeply barked. The old porter cautiously and slowly opened the lattice peep-hole of the gate to ask, who at this unseasonable hour of the night it was that would fain demand admittance? The answer given was, that he was a king's messenger bearing despatches of importance for Sir David Bruce, and as the glimmering lamp was held forth, he showed the silver badge, the insignia of his office. The wicket-gate was instantly unbarred, and he was accordingly admitted. The messenger was shown into the servants' hall, where supper and refreshments were immediately brought him; and while he was regaling upon the hospitable cheer of the castle, a bed was put in readiness for him. [63]Sir David Bruce having seen that all was as it should be, retired to his chamber.

It was midnight, the fire in the bridal chamber brightly blazed, and the wax-lights shot forth their brilliant beams. Sir David seated himself on a chair beside the bed, and having gently drawn aside the curtain, he affectionately embraced his bride, while he kindly said, "My dear Adelaide, I always have been of opinion that no secret nor mystery should ever exist between man and wife. I know, my love, that your understanding ranks too high, your love for me is too great, and your opinion of my character is too elevated ever to induce you, in any shape or form, to pry into what I may not think necessary to disclose. For indeed you do not aspire to that superior wisdom which some of your sex rather somewhat too confidently and arrogantly assume; the true term and appellation of which properly should be called not wisdom, but superior curiosity! But, my dear love, in strictest verity I may say of thee, before our happy union, in foreign realms, and in perilous tracts over land and ocean, [64]that I have ever witnessed thy equanimity of temper, and always have found thee one and the same;—ever unchanged and unchangeable! and indeed I know no one (not even your noble and highly gifted mother) who could, with more propriety than yourself, assume the motto of the virgin queen—

'Semper eadem!'"

"Oh, my dear husband!" rejoined Adelaide, "although delighted ever to hear your praise, yet when you would overstep the due and meet boundaries of discretion, and, forsooth, make of me an ideal goddess, it is meet and due time, that stepping down from the lofty pedestal whereon thou hast been graciously pleased to rear thy fond idol, for me to intrude a word or two, if it were but to dispel the charm which fascinates thee, recall thy wandering thoughts from paradise to earth, and convince thee, at least, that I am but a mere mortal; and, moreover, a woman to boot, with all a woman's faults—yea, too, my love, with all a woman's fondness, and the love that no tongue can utter; and [65]thus I swear it upon thy beloved lips, my first, my only love!"

"Oh, my adorable Adelaide," he said, while he met the fond embrace, "let this blessed moment be ever sacred in our recollection! dawning with hope and promised joy on all our future days. Oh, my Adelaide, imperishable let this happy, too happy hour remain, and ever marked and stamped by a holy communion of heart and mind! Your taste shall be mine, your liking shall be my liking, your joy be my joy, and your sorrows (if ever they come) shall be all mine own!—thy disgrace would become my disgrace, and mine would be attended with yours! But now I only look upon the happy obverse of the medal, when I pause on your beauty, your accomplishments, your virtue, and your religion! for without the latter a woman is a monster, and man little less than a demon. You must now permit me to say, that you are the theme of every tongue, the charm of every eye, the idol of every heart, and the bright ornament of every circle, that might fairly, at thy throne,

'Bid kings come bow to it!'"

"Oh, my dear Bruce, you will turn my brain—no more of hyperbole!"

"Nay, Adelaide, nay! can I think on all these, and yet not feel the thrill of transport throbbing at my heart?—quite impossible!—it could not be so, my love! Between us then let there ever exist a holy communion of soul that shall support and bear us onward throughout the trials of this stormy world, gilding the days of health and happiness, and not deserting us when years increase, and health declines; for even then the Hymenial torch shall brightly burn, although it may be with a mild, yet steady light, and only expire upon the tomb! Believe me the true and indissoluble bond of conjugal affection is no other than an unreserved and reciprocal interchange of every thought, plan, purpose, and design. Enduring, meanwhile, a contented participation of fortune, whether it be prosperous or adverse; possessing only one will, one mind, and one heart, thus harmoniously resembling a finely performed air of [67]music, where three voices melodiously melt into one, and close in full and perfect diapason. Oh, my dear love, if this conjugal—this perfect harmony, were, as it ought to be, always preserved, what follies might not be avoided!—what heart-burnings would ever exist!—what horrible vice might not be shunned!—and what dread and horrid disgrace might not be prevented! When oft, my love, at evening time retired in our tranquil solitude, I shall there retrace the events and transactions of the day that has gone by, then, then, shall I tell thee of aught perchance which I may have observed in thy conduct or deportment to censure or to praise. Oh, with what delight I shall dwell upon all that I approve, while with gentleness I pass over what I may discommend. And the same sincerity, sweet love, I shall expect from thee; thou shalt, as in a tablet, set down all my faults and misdemeanors. It is thus that we shall best fulfil the holy compact which we entered into yesterday—of abiding by each other in sickness, sorrow, or in health, in adversity, or in prosperity! And now let me seal this sa[68]cred bond by this warm pressure on thy lips. Thus, my Adelaide, we ratify this deed of co-partnership!"

He then added playfully, "Certes I ever have been of opinion that, although corporeally speaking, man and wife are two bodies, yet am I at the same time of opinion that they should have between them but one mind. However, I am altogether not unreasonable withal, and therefore feel not disinclined to allow them the firm of TWO hearts; but I ever must protest against dissolution of partnership!"

Then sweetly smiling, he said, "Here, my love, I bear in my hand despatches of high importance, and brought by a king's messenger; I needs must cut their silken tressure ere I can peruse the contents thereof; pray you therefore direct me, my dearest love, where I may find your etui, or work-box, as I now stand in need of a penknife, or your ladyship's shears, to cut the silky-gordian knot of this important packet?"

Adelaide replied, "Truly, my dearest love, I do not know where to direct you, the [69]events of yesterday have quite caused me to forget; but open yonder cabinet of ebon, inlaid with ivory, which stands in yonder recess, search it, perhaps there a penknife or shears may be found."

"May find! Adelaide, nay now, thou art what truly I did not suspect that thou wert, a most unthrifty housewife!"

Sir David Bruce approached the cabinet; it contained many curious and secret drawers; at length sprung forth one opened by a spring, which unconsciously he had touched, when the drawer fell from the cabinet, and lo! forth was flung from it, and, to his infinite horror and surprise, he saw, and scarce could believe his eyes, a whinger! [i. e. a Scottish knife or poniard, answering for both purposes,] which trundled on the floor with a foreboding sound. The handle was of silver, richly wrought; it bore the crest of Bruce, namely, a dexter hand and arm cased in armour, wielding a royal sceptre, and supported on a cap of maintenance; and beneath was engraved the motto of The Bruce, Fuimus! While, oh! horrible to tell, deeply were im[70]printed "on the blade and dudgeon gouts of blood," and which seemed to have been there "long before," rusted and corroded as they were by time. Oh, when this was done it was

Maddened with furious rage, he frantic raised the gory poniard from the ground, and rushing with dreadful impetuosity to the bed-side, he presented the fatal dagger at Adelaide's heart.

"Oh strike—strike Sir David, and by thy hand let me die! But indeed, indeed, I am innocent!"

"Thou, innocent!—hah, hah, hah!" with a violent hysteric expression he repeated—"Innocent!—thou witch, fiend, sorceress, devil!——Thou innocent!—no, no!—thou hast held unholy converse and communion with the arch-fiend, and with all the demons of darkness and of hell! But tell!—come, [71]this instant tell! or on this spot—aye, thy bridal bed, thou surely shalt die—this moment thou shalt die! Tell at once then, how, where, and when, from whom didst thou receive?—No, no deceit, no prevarication will be allowed nor tolerated. Tell, oh tell, thou devil, although moulded in an angel's form! Tell, I conjure thee tell!"

"Oh, spare—spare me, and I shall tell thee all!—each particular shalt thou know. It——It was upon the Eve of All-Hallows, some ten years ago—I forget the year—when foolishly, with some young friends, upon my birth-day, of which it was the fatal anniversary, I impiously dared to tempt my fate, or try my fortune, by one of those mystic accursed tricks that are too oft resorted to—"

"Come, come, less words, lady, and more facts! I demand expedition, for my impatience cannot brook delay; so come, continue thy accursed tale——quickly proceed!"

"Oh, terrible to recollect, and still more terrible to tell. It was midnight! and, true to his compact, the phantom, whom I had charmed, appeared in my chamber at the [72]same time of night as now. I had caused a collation to be served, consisting of viands, fruits, confections, and wine; which were placed upon a table in the centre of the room; a chair was placed near it, between the table and the fire; upon another table was displayed the toilette, where were placed a silver basin, napkin, and a golden ewer, which was filled with rose-water, and bestrewed with flowers. The fire blazed brilliantly bright, and wax-lights shed their lustre on the collation. Meanwhile, trembling fearfully, I lay in my bed, with my back to the light; upon the counterpane I had stationed a large mirror, (with a trembling hand and a palpitating heart,) in order that I might behold distinctly reflected on its polished surface the image of whatever object might place itself at either of the tables, which, from the position in which I was placed, I could not fail to see. Thus stationed, was heard a fearful rumbling sound, as if issuing down the chamber chimney; then followed a noise, loud and like to the electric shock of a thunderbolt, which sounded as if it had burst through the chim[73]ney-flue, and from whence was forcibly flung, with an astounding crash, upon the hearth-stone of this very chamber, that same dread and fearful instrument which you now uphold! Sad, sorrowful, and dreadful is the recollection. Yet still I had the courage to look upon the mirror which I held, when I instantly and fearfully saw reflected in it a cloud of blue flame, which illuminated within its cloud of fire, exposed suddenly a tall and manly chieftain, whose figure boldly emanating from the mist which surrounded it, seemed clad in a Tartan plaid; his head was covered, or crowned, with a Scottish bonnet, adorned with plumes, and surmounted by the Scottish thistle, which sparkled in gold embroidery. The figure, or spectre, or whatever that unsightly vision might be, held forth to me his hands, which were bloody; he then sat down to the banquet; he tasted, but eat not; sipped, but he did not drink: and then on the sudden arose from his seat, slightly dipped his hands in rose-water, and applied the napkin. This at the time did virtually all appear a vision, dreadfully reflected within [74]the glass which I held on my couch. Yea, you look amazed! but I did see it all, and am too well convinced it was no vision!—for still horribly, even now through the lapse of years, I see it still! fresh in my memory, and never, never to be forgotten! While thus, all terrified and petrified, I looked upon the awful form, or spectre; frightfully and passionately it grinned upon me a demon's smile, and said in deep sepulchral voice:

The phantom then, or whatever it was, fiercely took up the dagger, and dashed it horribly against the mirror I held, which it shivered into pieces. Then the bloody instrument fell upon the floor, and the spectre vanished: while I fell into a dreadful trance, which lasted for hours, and from which I grieve that ever I did waken to witness this most wretched night! While the phantom vanished, the heavens loudly thundered, and the vivid lightning illumed this fatal chamber. Oh, the crash of the mirror I never [75]can forget, nor the ominous fall of the blood-stained dagger as it fearfully trundled upon the oaken floor!—these two ominous circumstances too surely manifested that this was no dream! Oh no, they pierced my heart to conviction! That dread and awful moment of my life I never can forget!—only to be equalled, and only to be outdone, by the agonies which now I so severely undergo in this unhappy hour! Oh, Sir David, in pity at once kill me, and end my sorrow and my suffering together!—you hold the bloody instrument, oh then strike!—strike, there's my bosom!—I fear not to die—oh kill me, I beseech thee!—in mercy, at once destroy me! But, oh, do not—do not look thus again!—It was thus the awful spectre looked, while thus the fire flashed from his visage!—Thus! it was thus he frowned! and like thee he spoke! Oh—oh, I never saw thee look thus before!—never, never! Ah! THOU!—thou! thyself wert that spectre!!"

"No, no, Adelaide, no! I looked not thus; it was the infernal fiend, from the lowest depth of hell, that looked thus, and [76]then assumed my shape and form! At that moment I was on ship-board, Dr. M'Kenzie was my fellow-voyager, who can vouch for the same; we had then left the Scottish shore, and the destination of the vessel was for Ireland. This weapon, which now I hold, I then flung into the hissing waves, when unearthly voices and unearthly music met mine ear, and smote my heart!—Oh, it was then that I suffered the deep-thrilling agonizing horrors of the damned. The arch-fiend, I felt, was working in my bosom; and strongly, desperately, was I tempted to fling myself into the same remorseless element into which I had flung this blood-besprent instrument—the damned testimony of my crime; and by so doing end at once my earthly misery! But even then I lifted up my humble supplication to heaven, although with crimsoned hands! I fell into a trance, and lay to all appearance lifeless upon the deck.——You seem to doubt!"

"Oh, yes, yes; I see it all!—that frown—that look! Oh, thou, thou, wert that horrible spectre!"

Having thus replied, poor Adelaide, with a piteous, heart-rending scream, and to all appearance as if life had fled, sunk down, pale and ghastly as a corse, upon her pillow. It was indeed some time before Sir David could bring her to herself. When the hapless Adelaide recovered from her faint, he said: "My reproaches now are at an end. For you now are the object of my compassion and of my pity, not of my wrath. It is however true, that although infernal agents have given you a husband, yet know they have not the power to cause me to remain with you one hour more!—There I am a free agent. No, no!—not Lucifer himself shall detain me here!—no, nor all thy witchery! Within a short hour, or less, I depart from hence, and never, never more to return; and I shall be no more seen!"

With a desperate grasp, then stooping, he seized and held up the fatal dagger, the deadly record of his grief—the sævi monumentum doloris—the bloody pledge of his crime—the avengeful instrument of his rage, stamped with the crimsoned tears of unabated [78]and unabatable grief!... "Yet before I go, look, lady, upon that dagger!—whose blood, think you, it is with which it is imbued?—You shall hear!... That once was noble blood—it was valiant blood—the proudest blood of Caledon—the blood of her royal race of kings! And, oh, wretch that I am!—it was the blood of my brother—my only brother!—yea, and my elder born! rashly, madly, wickedly shed by me!—yes!... Oh, still gaze upon it—turn not thine eyes away. It was blood nearly, deeply, none nearer, allied to me, and beloved. But, but this—all this was forgot in the moment of delirium—of madness! It was the blood of my elder brother—yea, an only brother!... Oh, Adelaide, look not thus again!—my weary, sickening heart, condemns me enough——enough. Well, well, we lived in the same home, we partook of the same board, we slept in the same bed.... Oh, oh my brain, how it maddens! and my heart would fain burst!... Yet, yet, yet I slew him—in rage, madness, I did!—I did, I did—monster that I am!... Lady, be[79]hold I weep!—Ah, I did not weep when my poor brother died!—and when this I plunged into his beloved breast!—No, no, no! But it is just, it is truly just, that heaven's vengeance should make this base instrument of my crime, this fratricidal dagger, the fatal cause which now separates me from all happiness upon earth; and divorces me, body and soul, from thee—oh, whom I loved better—yea, beyond life itself! But time advances, and I must depart from hence—oh, and for ever! One parting look, and then I am gone. Oh, thou precious mischief!—so young, so fascinating, so beautiful! Oh, my very heart shall burst!... Yet, yet—oh, must it be!—and must we part?... Lady, from hence I go, and shall be no more seen; peradventure too no more be remembered. Well, well, let justice have its vengeance and its victim too! Yes, yes, let it be so."

Here, pallid as death, and woe-stricken, he gave one sad, one last, agonizing look upon that face that he had so well beloved—the face of one with whom to part were [80]worse than death itself. Then sad and sorrowful, in a dejected tone, he said:—"Oh, Adelaide, we have loved as others yet have never loved; now heart-broken and sorrow-stricken I here must bid a sad and solemn farewell. Yet, oh, must we part?—Yes, we must part—oh, and for ever! Never, never again in this wide world to meet!—again, never! Oh, farewell—one sad, one sorrowful farewell, and hence I go.... Farewell! forgive and forget, if thou canst forget (to forgive were impossible) that such a wretched outcast exists as David Bruce!"

Here he sobbed like a child, while he slowly and silently withdrew, gently closing after him the chamber door. But suddenly he returned, and approaching the bed-side, he thus addressed Adelaide: "It were best that the mournful tale which now I have disclosed to thee, as well too as thine own, should be kept inviolably secret, and remain for ever unknown. Divulge not then thine own criminal weakness; neither expose the enormity of my guilt. Oh, how often and often have I wished, have I longed for, aye, [81]and have courted death;—yea often too have I keenly sought him in flood and field. But in vain. It almost seemed as if I had borne a charmed life. Often I

in anxious hope that it might strike a guilty fratricide dead!——Now, now, you must say, and swear too, upon this blood-stained poniard!—swear never—no, never! to reveal what this sad and eventful night has developed; save it be upon your death-bed alone that you may divulge it. Come, I demand thy oath; I must have thy solemn oath—thy sanctified oath of secrecy! But I will not place that horrid instrument to thy lips, to swear by! No, no! I could not do it—I would not. Oh, no—if even past joys and hopes again were to return—no! But there—there, place thy hand upon that horrible instrument of my deep damnation! Swear upon it!—solemnly swear upon that blood-[82]besprent dagger. Swear!—I charge thee, swear!——Oh, yet weep not, my poor Adelaide! Oh, no!—weep not thus, my Adelaide, or I forego my purpose; and soon, then, this dagger shall be plunged into mine own guilty bosom!——Thou hast heard me——my love! Oh, yes, yes, my love; for still, oh, still art thou dear to me—dearer than life—ay, or even the blessed hopes of ******!—although we never may meet again!——There, I beseech thee! yet there place thy hand upon that instrument of my torture—of my unspeakable woe—and of my deep and deadly crime.—Swear!

Adelaide firmly clasped the fatal instrument, and then exclaimed: "I swear, I solemnly swear, to observe to the very letter all thou hast now enjoined!"

"Oh," replied he, dejected and overcome, "how cold, how deadly cold, is thy hand, my poor, poor Adelaide!—frozen as are all my hopes, and chilled, chilled—deadly chilled as is my own wretched heart's blood. Oh, I shall lose my reason! Oh God, what an hour is this? But pardon me, [83]thou Almighty power. It was I, the impassioned wretch, that flew forth in thy defiance, like another branded criminal—the blood-besprinkled Cain, whose mark, I fear, is stamped upon my forehead and in my heart. But, oh, great and dread Omnipotent, thou art truly just—and I am guilty. Most justly do I confess that I am punished as I ought to be, by thy retributive justice, even upon earth—the irreparable loss of her whom no earthly power upon this habitable spot of earth can ever alleviate or redeem!—never, never, never!"

While Sir David Bruce impassionately and woefully said this, he fell prostrate, and cold, and lifeless, upon the floor of the bridal chamber.

To describe the emotions of Adelaide, would be to attempt indeed an impracticable task. It was so truly horrifying and affecting, that it must wholly be left to the imagination of the feeling reader. It was some time before Sir David recovered from this overpowering blow of affliction. When he did recover, he said mournfully:—

"Sorrow has paralyzed me; and I who often have cleft in twain the helmet of the foeman, now shrink and bend before thee, my much-injured love. A guilty conscience hath unmanned me quite. But oh, my poor Adelaide, time presses onward; the night wears apace, and I must now conclude the few words which I have to say to thee. You must tell the duke and duchess—boldly, as it is true, to account for the rapidity of my departure—that the import of the despatches received, which are from the Elector Palatine of Brandenburgh, in whose service I fought at the battle of the Boyne, bear with them life or death, and I must instantly depart. Thus summoned so suddenly, say to them, and kindly say, that I could not await their arising for the slow ceremony of leave-taking, but that I was forced to hasten forthwith, even amidst the cold and darkness of midnight, with all the expedition I might. And ... when hence I am gone, and thou shalt silently sit in judgment on my passion, and upon my crime, and shalt pronounce condemnation on the destroyer of a brother's [85]life, and of a wife's happiness—oh, even then still think how fervently, how affectionately, how devotedly, I loved thee;—yea, and in my very heart's core!... And now a long farewell—for ever farewell. Mayst thou obtain that peace that is to me denied and lost in this world for ever!"

Having thus said, sad, sorrowful, and slow, he descended from the bridal chamber, the tears streaming adown his manly cheeks. Meantime he had lighted a lamp which lay in the recess, and bearing it in his hand, with cautious and silent step, he descended the staircase; and having gone out at the postern, he proceeded to the stables, where, having called up his faithful servant, he ordered his horses instantly to be saddled, and in less than half an hour all was in readiness for his departure,—servant, horses, travelling valise, &c. &c. And now Sir David, and his faithful servant Malcolm, who had attended him at the battle of the Boyne, proceeded beneath the embattled portal of Tyrconnel Castle, never again to return. The solitary bittern mournfully boomed as they rode [86]along the lonely marsh, and the startled eagle from his lofty eirie-crag loudly shrieked, awakened by the tramp of the horse-hoofs, which were deeply re-echoed through this stilly solitude, in the dark and dismal hour of midnight.

Oh, what pen can write, what tongue can tell, what heart can feel, save the heart which deeply hath felt it, how bitter are the pangs of a wounded spirit, when love becomes horribly transformed into rancorous and deadly hate! Oh, happy it were then that "the silver cord were loosened, and the golden bowl were broken," what time the sweet bond of harmony snapt suddenly in twain, dissevered by a rude and discordant crash, when two fond, faithful, and affectionate hearts, are changed in one short, sad, and eventful moment—becoming, alas, fatally and irrevocably estranged and separated for ever.

We must now go still further back into our history, and give some account of Sir David Bruce, and the unhappy causes that led to so unexpected and so speedy a termination of a connexion honourable and enviable in every respect, and indeed every way deserving of happier results.

In the parish of Kirkoswald, in Ayrshire, is situated the ancient and the celebrated castle of Turnberry, stationed upon the north-west point of a rocky angle of the coast, extending towards Girvan. This cas[88]tle belonged to Sir Robert Bruce, Laird of Annandale. The situation of the castle of Turnberry is extremely delightful, commanding a full view of the Frith of Clyde, and its indented shores. Upon the land side it overlooks a richly extended plain, bounded by distant hills, which rise around in gradual and beautiful undulations, and adorned to their very summits with woods of mountain-ash, oak, and the most graceful of all trees, in glen, plain, valley, or mountain, the weeping birch.

The lord of this castle—we should say "the laird"—was Sir Robert Bruce, and with him resided his twin-brother, Sir David Bruce, the hero of this eventful tale. This castle had belonged in the olden time to Alexander Earl of Carrick, who died nobly fighting, as a true and valiant Red-Cross Knight, in the Holy Land; who left an only daughter, named Martha Countess of Carrick. This noble lady having accidentally met Robert Bruce, (the ancestor of our hero,) Laird of Annandale in Scotland, and Baron Cleveland in England, while he was occu[89]pied in a hunting party near her castle, his manners, deportment, and person, pleased the countess; she invited him to the castle of Turnberry, and they were speedily married.

From this illustrious marriage sprung the kings of Scotland of the royal race of Stuart;—and hence the successors of Bruce, until they ascended the throne of Scotland, were styled Earls of Carrick; and this title still appertains to the heir apparent to the throne of England, one of the titles of the Prince of Wales being "Earl of Carrick and Lord of the Isles."

Robert was the ancestor of David, who married a lady of the noble house of Moray. Sir David Bruce, Laird of Annandale, died when young, leaving two sons, Robert and David, (the latter the subject of these memoirs,) and appointing, by his last will and testament, his lady and the Reverend George Wardlaw, D. D., as guardians to his sons. His death was soon followed by that of his lady. And the young men, now grown up, having received a due preparatory education [90]from the Reverend Doctor, whilom fellow of St. Andrew's College, were there shortly matriculated as students. But Robert soon got tired of his Reverend tutor and the grave and ponderous tomes of Saint Andrew's, which were soon exchanged for the academy of nature, the wooded banks of the Doon, and the rocky, romantic shores of Ayrshire.

David, on the contrary, pursued his academic studies with much perseverance, and with very considerable credit, calling forth the approbation and praise of his Reverend tutor and the heads of that learned seminary.

While in the university he formed an intimacy with Thomas Lord Maxwell, which was soon cemented into friendship. They were chums; their studies, pursuits, and tastes coincided, and they were inseparable companions.

Upon one occasion Lord Maxwell saved the life of Sir David Bruce. They were one day, during college vacation, amusing themselves in fishing for pike and perch in a small row-boat on the Loch of Lindores; when [91]suddenly a squall of wind coming on, the boat overset. Bruce, not knowing how to swim, would certainly have been drowned; but Lord Maxwell said: "Be calm, and I will save you;—be firm, and fear not!—Closely lock your arms around my waist; but do not by any means impede my exertions, and trust me I shall bring you safe to shore."