CLÉMENCE ROYER.

CLÉMENCE ROYER.

Title: Appletons' Popular Science Monthly, March 1899

Author: Various

Editor: William Jay Youmans

Release date: November 27, 2013 [eBook #44297]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Judith Wirawan, Greg Bergquist, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by Biodiversity Heritage Library.)

Established by Edward L. Youmans

EDITED BY

WILLIAM JAY YOUMANS

VOL. LIV

NOVEMBER, 1898, TO APRIL, 1899

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1899

Copyright, 1899,

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY.

Vol. LIV.Established by Edward L. Youmans.No. 5.

APPLETONS' POPULAR SCIENCE MONTHLY.

MARCH, 1899.

EDITED BY WILLIAM JAY YOUMANS.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Evolution of Colonies. VII. Social Evolution. By J. Collier. | 577 |

| II. | Politics as a Form of Civil War. By Franklin Smith. | 588 |

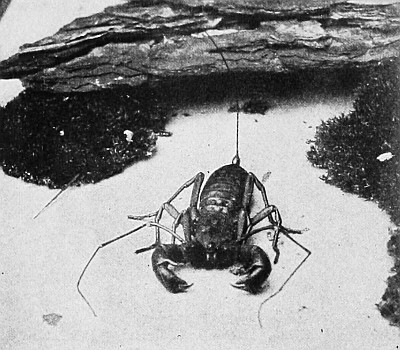

| III. | My Pet Scorpion. By Norman Robinson. (Illustrated.) | 605 |

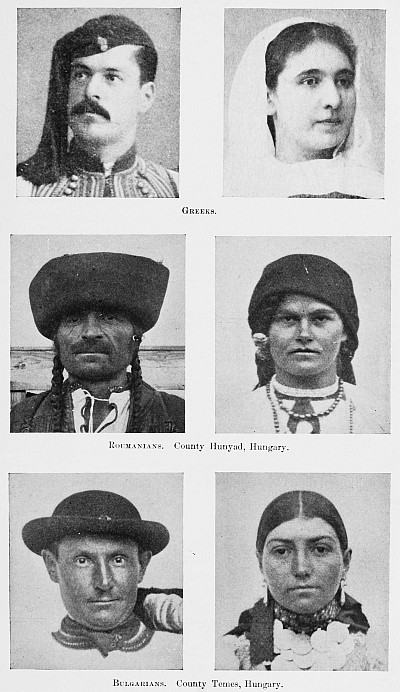

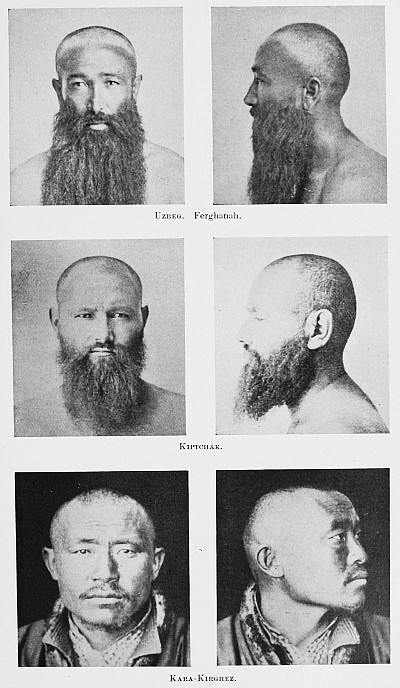

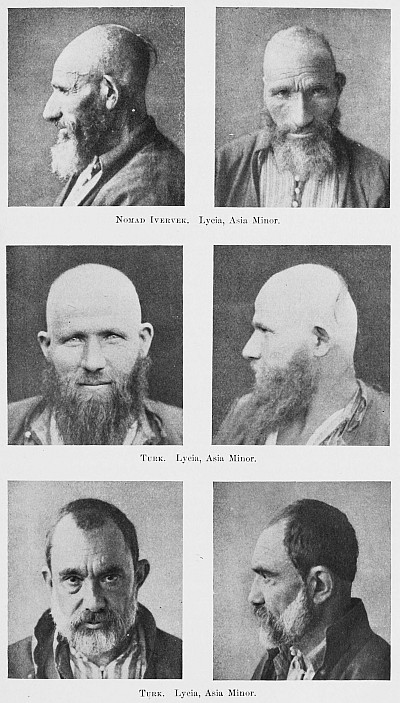

| IV. | The Peoples of the Balkan Peninsula—The Greek, the Slav, and the Turk. By Prof. William Z. Ripley. (Illustrated.) | 614 |

| V. | Marvelous Increase in Production of Gold. By Alexander E. Outerbridge, Jr. | 635 |

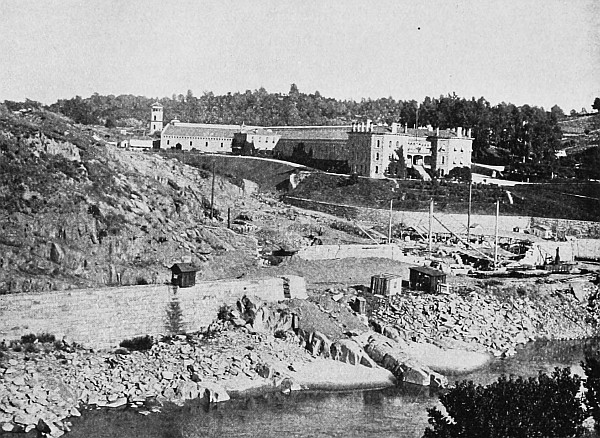

| VI. | The California Penal System. By Charles Howard Shinn. (Illus.) | 644 |

| VII. | The Scientific Expert and the Bering Sea Controversy. By George A. Clark. | 654 |

| VIII. | A School for the Study of Life under the Sea. By Eleanor Hodgens Patterson. | 668 |

| IX. | Science in Education. By Sir Archibald Geikie, F. R. S. | 672 |

| X. | Shall we Teach our Daughters the Value of Money? By Mrs. George Elmore Ide. | 686 |

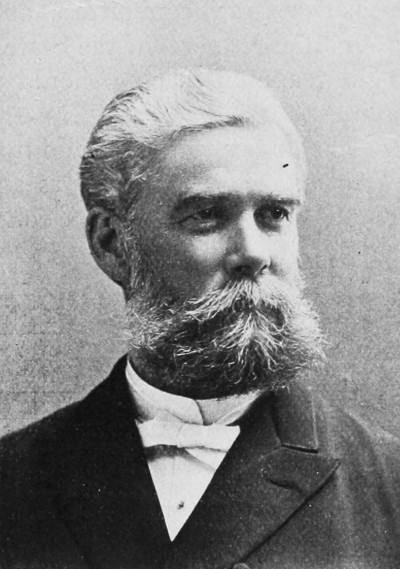

| XI. | Sketch of Clémence Royer. By M. Jacques Boyer. (With Portrait.) | 690 |

| XII. | Editor's Table: Words of a Master.—Fads and Frauds | 699 |

| XIII. | Scientific Literature | 704 |

| XIV. | Fragments of Science | 712 |

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY,

72 FIFTH AVENUE.

Single Number, 50 Cents.Yearly Subscription, $5.00.

Copyright, 1898, by D. APPLETON AND COMPANY.

Entered at the Post Office at New York, and admitted for transmission through the mails at second-class rates.

CLÉMENCE ROYER.

CLÉMENCE ROYER.

APPLETONS' POPULAR SCIENCE MONTHLY.

MARCH, 1899.

By JAMES COLLIER.

Perhaps there is no civilized institution to which, man has accommodated himself with so ill a grace as monogamy. Hardly a perversion of it has ever existed but may still be found. Polygamy is widely spread in the most advanced communities; temporary polyandrous ménages à trois are known to exist elsewhere than among the Nairs and Tibetans and ancient Britons; the matriarchate in one shape or another may be detected well outside the sixty peoples among whom Mr. Tylor has discovered it; and marriage by free choice is far from having superseded marriage by capture or by purchase. It is the less surprising that abnormal or ancient forms of the union should have been revived in colonies. In this relationship, as in most others, the colonist, like the sperm cell after its junction with the germ cell, sinks at once to a lower level, and the race has to begin life over again. The fall is inevitable. The earliest immigrants are all of them men. Everywhere finding indigenes in the newly settled country, they can usually count on the complaisance or the submissiveness of the tribesmen. Native women have a strange fascination for civilized men, even for those who have been intimate with the European aristocracies and have belonged to them. Adventurous Castins might find their account in a relationship that was in perfect keeping with the wild life they led. It is more strange that, enslaved by an appetite which sometimes rose to a collective if seldom to a personal passion, educated men, with a scientific or a public career flung open to them at their option, able men who have written the best books about the races they knew only too well, men[Pg 578] of great position whose heroic deeds and winning manners made them adored by women of their own race, should have spoiled their prime, or inextricably entangled themselves, or wrecked their own roof-tree and incurred lifelong desertion by the wife of their youth. The bluest blood of Spain was not contaminated by an alliance with the Incas, but just ten years ago the direct line of an ancient English earldom was extinguished among the Kaffirs. The truth seems to be that while a woman will not as a rule accept a man who is her inferior in rank or refinement, a man easily contents himself for the time with almost any female. The Bantu woman and the Australian zubra are not alluring, but they have never lacked suitors. Colonial women shrink (or profess to shrink) from the Chinaman; all colors—black, brown, red, and yellow—seem to be alike to the undiscriminating male appetite. Yet it has its preferences. The high official who stands unmoved before the cloudy attractions of the Zulu, surrenders at discretion to the soft-voiced, dark-eyed, plump-limbed daughters of Maoriland. In the last case a perverse theory (of the future amalgamation of the races) may have been "the light that led astray"; it certainly was used to justify their acts to the consciences of the doers. Romance had its share: Browning's Waring (who was premier as well as poet) threw a poetic glamour over the miscegenation, as another minister found in the race the Ossianesque attributes of his own Highlanders. It sometimes, even now, rises into passion: the colonial schoolmaster who marries a native girl will declare that his is a love match. But the chief reason at all times was "the custom of the country." "It was the regular thing," remarked an old legislator, looking ruefully back on his past. Nor is it to be harshly censured. Corresponding to the Roman slave-concubinage which Cato Major did not disdain to practice, it repeated a stage in the history of the mother country when the invading Angles allied themselves (as anthropology abundantly proves) with the native Britons. While making a kind of atonement to the indigenes, it was a solatium to the pioneer colonists for a life of hardship and privation.

A higher grade was the concubinage of convictism, which was with women of the same race and was capable of rising into normal marriage. In the early days of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land it seems to have been almost universal, and it lasted for many years. Not one in ten of the officials lived with his legally married wife. In the latter colony it was suppressed by the governor, who ordered them to marry the women by whom they had families. In the former, if Dr. Lang's account of his exertions is accepted, it was put down by the exposure of guilty parties. It was accompanied by other features of a low social state. The public and private sale of wives was not infrequent. The colonial equivalent for a wife, in the[Pg 579] currency of those days, was sometimes four gallons of rum, or five pounds sterling and a gallon, or twenty sheep and a gallon; one woman was sold for fifty sheep.

Around gold and silver mining encampments nondescript relationships of a slightly higher order arise. They are with free women, though the women are apt to be of the same class as Bret Harte's Duchess of Poker Flat, answering to the Doll Tearsheets of hardly more civilized communities. They often issue in marriage. In mining townships, and even in colonial towns, professional men are to be found married to unpresentable women.

In colonies of regular foundation normal marriages are contracted under difficulties. Few women at first go out, the emigrants intending to return when they have made their fortune. Women have accordingly to be sent. In the seventeenth century a number of girls of good repute were persuaded to emigrate to Virginia, a subscription being raised to defray the cost. In the following century wives were sent to settlers in French Louisiana on the same plan. To French Canada women were dispatched by shiploads. They were selected (according to Parkman) as butchers choose cattle: the plumpest were preferred, because they could stand the winter best and would stay at home. In Virginia women were offered for sale to eager colonists, who willingly paid one hundred pounds of tobacco for one, or as much as one hundred and fifty pounds for a very pretty girl; a debt incurred for the purchase of a wife being considered a debt of honor. In the early days of Canterbury, New Zealand, when a consignment of servant girls arrived, young farmers would ride over the Port hills and carry them off, though in the style rather of young Lochinvar than of the Sabine rape. Settlers have often requested the agent general for the colony or the mayor of their native town to send them out a wife. Wives so easily acquired are apt to be lightly parted with, and within the last few years, in colonial villages, amicable exchanges have been effected—one woman going with her children to the house of another man, whose wife and children made a reciprocal migration. Facts such as these (which might readily be multiplied) show how easily so-called civilized man sloughs off the conventions of ages and sinks to a primitive level. They soon disappear, however, and social colonial conditions rapidly assimilate themselves to those of the mother country. In most young colonies marriage is universal and it is early. After a few days' acquaintance couples rashly engage themselves, in utter ignorance of one another's character or of their own, and a precipitate marriage follows, with such results as might be expected. Statistics show that the age of marriage on the part of women is steadily rising. In the early days of each colony a girl was deemed passée if she did not get married before[Pg 580] she was twenty-one. In the decade that ended the first century of New South Wales the proportion of married women under that age fell from 28.17 to 23.55 per cent; in less prosperous Victoria, after only half a century, it fell from 21 to 17.4; in New Zealand there was a big drop from 29.4 to 19.7. The proportion of married women under twenty-five has also seriously declined. The decrease is noticeably correspondent with the increased number of young women who are gaining their own livelihood—largely as teachers and typewriters. On these lines the colonies are following the lead of the mother country. Long engagements, followed by late marriages with fewer children, take the place of short engagements with hasty marriages and larger families. Female celibacy is no longer dishonorable, and women are beginning to understand that they may be far happier single and self-supporting. The quality of marriage improves with its rarity. When an Australian M. A. marries an M. A., or the most brilliant of New Zealand professors marries one of his most distinguished students, we feel, as when a Dilke marries a Pattison, that the ideal of the union has been realized.

The growth of the colonial house follows the development of the family and repeats the history of the race. The immigrant procures his abode, as he afterward buys his clothes, ready made. The ancient troglodyte lives to-day in the Derbyshire cave dweller; the original Romanist settlers of Maryland were driven to take refuge in cave houses in Virginia; and the New Zealand hermit, like "great Pæan's son" at Lemnos, "weeps o'er his wound" of the heart in a cave by the resounding sea. Where they can not be found ready dug they can be excavated, as they were by some early Pennsylvania colonists. Others in Virginia, New York, and New England found it easier to dig holes in the ground, thus imitating the Germans of Tacitus, whose winter residences are also repeated in those basements which form the wholesome abode of the London domestic servant. The wattle-and-daub house of the Anglo-Saxon villager has been everywhere reproduced in the colonies, and may still be abundantly found.

If the occupation of caves and the burrowing of holes suggests man's distant affinity to the carnivora and lower quadrupeds, his simian origin is confirmed by the use he makes of the tree. In the infant city of Philadelphia there were "few mansions but hollow trees." A rude form of tent is the next stage, the canvas consisting (as may still be seen among the poorer campers-out) of clothes or rags. Then, as in the early days of Sydney, the tents were covered in with bushes and thatched over. Next (as may to-day be observed in the neighborhood of Coolgardie) a framework of branches is employed to support the canvas, and the tent is converted into a cabin.[Pg 581] A stride toward the house is taken when the branches are replaced by a regular woodwork, with doors and windows; the envelope being still sometimes canvas, which is soon replaced by corrugated iron. The Brazilian country house where Darwin lodged sixty years ago was built of upright posts with interwoven boughs. Another line of development starts from the trunk of the tree. The early American colonists made bark wigwams. The Australian pastoralist "erected a temporary house, generally of large sheets of bark, in the first instance." In countries where the winter is more severe or the bark less substantial, the backwoodsman builds, as the early colonist built, a rude cabin of round logs. Then the logs are hewn, or they are split or sawn into planks, and built into the weatherboard houses still common in the rural parts of Australia, and general even in New Zealand towns. In their earliest stages they are still without a floor and are roofed with thatch or shingle. Towns often thus remain like early Sydney, "a mere assemblage of paltry erections intermediate between the hut and the house." The architecture is of the simplest. A "butt" and a "ben," with a "lean-to," form the prevailing type. As the family grows or its wealth increases, new portions are added, till many colonial houses look for all the world as if they had "come out in penny numbers." Even with a few stately structures—luxurious mansions, extensive government offices, Gothic parliamentary buildings—a wooden city has an indefinable meanness of appearance. It is improved out of existence by the dread agency of fire. Like Charles's London, New Orleans and many another colonial town have thus had an Augustan renewal. Houses are now built of brick, stone, or concrete; tile, slate, and iron replaced thatch and shingle; two stories were ventured on; chimneys were smaller but safer. They became susceptible of architecture: Spanish features were introduced into those of New Orleans; the more northern colonies copied the English country house, with modifications to suit the hotter or colder climate; and in New South Wales a taste for mansion-building came into vogue along with splendid equipages, liveried servants, and pedigrees. Such houses were at first arranged in all degrees of irregularity and confusion. The street is a modern invention. The cows returning from pasture laid out Boston, and the bullock teams climbing up from the harbor charted Sydney. Towns in manufactured colonies, as Savannah, Augusta, most South American cities, Christchurch and Invercargill in New Zealand, were planned before settlement and have their streets at right angles.

A hundred years ago Talleyrand, exiled in the United States, described the journey from one of these cities to the interior as successively exhibiting all past stages of the human habitation from the[Pg 582] mansion to the tent, and just a century later one of Talleyrand's countrymen, M. Pierre Leroy-Beaulieu, traveling in the reverse direction, from "the bush" to Coolgardie, witnessed the gradual transformation of the tent into the two-storied hotel. A great part of the history of the race in the matter of habitations is thus museumed in the space of a few miles.

If the temple rises out of the tomb, is modeled on that, and remains to the last pre-eminently a place of sacrifice, the church is an enlarged dwelling house. It is the house of the god, as the fetichist called it—the house of God, as we still reverently call it; and in Romanist countries to this day it is in a manner the abode of two divine personages, who figure as dizened and painted dolls that are named respectively God and the Mother of God! Both lines of development are rapidly recapitulated in colonies. The temple appears as the cathedral, which has modest beginnings, but gradually assumes the architecture and proportions of Gothic cathedrals, losing relation to the primary wants of the worshipers—comfort and audibility—ministering mainly to their higher needs, and if used for preaching at all, reserved for such occasional and sensational pulpit oratory as that of Dominican monks like Lacordaire at Notre Dame in Paris, or of a Protestant Dominican like the late Canon Liddon at St. Paul's in London. The church, chapel, or meeting house may be found in colonial villages in its most rudimentary form, scarcely distinguishable in style from a dwelling house. According to the sect it belongs to, it develops in one of two opposite directions. The age of cathedrals is past, even in Roman Catholic countries, but the tendency of Anglican and allied churches is to simulate the old cathedral; high ritualistic sections mimic the gorgeous Madeleine. The more liberal denominations, on the other hand, develop downward; the colonial Baptist tabernacle is on the lines of Spurgeon's great building at Newington, but the ancient pulpit is widened into a platform and the seats slope upward as in a concert hall; it is a mere auditorium, in which the preacher is all. The development in this direction finds its extreme in the secularist hall, which is a mere concert room, with a piano in place of an organ. The ceremonial development is on the same lines—toward the gradual adoption of ancient rites by the older churches, toward more freedom in the younger sects. Many a colonial clergyman has wrecked himself or his congregation through too much ritualism; a few have injured themselves through an excess of liberalism.

A parallel evolution takes place in church government. Where an organized settlement is made on political principles, congregations carry their minister with them, or rather the ministers carry their congregations. Where the colony is normally founded and grows up[Pg 583] as the mother country grew, the first ministers, like the first preachers of Christianity itself, are often laymen. In an interior county of Virginia Morris read every Lord's day to his neighbors from the writings of Luther and Bunyan, and a meeting house was at length built for him; it is a typical instance of the beginnings of most churches. The part of laymen remains long prominent in colonies. The Anglican lay reader is everywhere a feature of colonial church life. In the more flexible churches a storekeeper or retired sea captain will read Spurgeon's sermons or preach excellent sermons of his own in an Otago village or the Australian bush. Where missionaries have been sent out to convert the heathen in a country afterward colonized, many of them remain as ministers, as did Augustin and his monks in England. The Presbyterian catechist likewise becomes a settled minister. Others arrive. Men of independent character, like Dr. Lang, of Sydney, resolve not to wait for any dead man's shoes in the kirk, but sail beyond the seas to colonies where there is no minister of their own denomination. Heretics, incompatibles, men who have failed, men whose health has given way, emigrate in increasing numbers. Still, the supply is long deficient. Clergymen were scarce in New York. A bounty was offered to immigrants in Virginia. Six years after the establishment of the Church of England in North Carolina there was only one clergyman in the country. The few there are repeat the history of the first Christian bishops and the early English monks in serving a circuit of two, three, or more churches. The state comes to the rescue by providing for their support. In England contributions were at first voluntary; by the eighth century tithes were levied, folk-land was granted, and private endowments were made. Just so was the Church of England established and endowed in New York, Virginia, and North Carolina; in Maryland a poll tax of forty pounds of tobacco was levied for its support. In Connecticut and Massachusetts a church was set up in each parish on Congregationalist principles by a vote of the people, who elected the minister and voted his salary. So uncertain was the tenure that in several States even the Anglican minister was hired from year to year; and quite lately an Anglican church in a British colony engaged its incumbent, as it might have engaged its organist, for a term. In 1791 the Church of England in Canada was partially established, and its clergy endowed with grants of land. The Australasian colonies have pursued a very various policy. By the Constitution Act of 1791 one seventh of the ungranted lands in New South Wales was set apart for the support of a Protestant clergy. An attempt to endow the Anglican Church in South Australia in the early forties was defeated by a radical governor. A recrudescence of the ecclesiastical principle[Pg 584] permitted the church settlements of Otago and Canterbury in New Zealand to appropriate a portion of the funds derived from the sale of lands for the endowment of the Presbyterian and Anglican churches respectively. So far the colonies followed, latterly with halting steps, the history of the mother country. As in political, so in ecclesiastical government, they have anticipated that history. The American state churches did not survive the Revolution. In Canada the Presbyterians and other sects successfully asserted their claims to a share in the church endowments, which between 1840 and 1853 were distributed among the municipalities, all semblance of a connection between church and state being thus destroyed. New South Wales passed through a period of religious equality with concurrent endowment of the four most numerous denominations, and a long struggle against the principle of establishment was ended in 1879, when the reserves were devoted to the purposes of education. The practice of confiscating for the church a portion of the proceeds of the land sales was gradually dropped in Otago and Canterbury, probably more for commercial reasons than in consequence of the opposition of the democratic governor aforesaid, who spoked the wheel of the South Australians. Yielding to Nonconformist pressure, the liberal Government in 1869 enforced the principle of religious equality throughout the crown colonies, which were thus, willingly or not, made to follow the lead of the movement in Ireland. The internal organization of the colonial church is also anticipative. Fifty-two years ago Sir George Grey bestowed on the Anglican Church in New Zealand, then governed by him, a constitution modeled on that of the corresponding church in the United States, as the political constitution he drafted for the colony was modeled on the Constitution of the United States; and it has been imitated in other Australasian colonies, which have thus declared themselves independent of the mother church, while the colony is still politically dependent on the mother country. In yet another point the daughters have outstripped the parent. Three Presbyterian denominations still fissure the old home of Presbyterianism; only two have ever existed in the colonies, and for thirty years these two have been one. The four chief Methodist sects in Australia are also said to be on the point of amalgamating.

The development of doctrine runs a fourth parallel to those of buildings, cult, and organization, and in a brief space it recapitulates a long history. In early colonial communities religious dogma is found in a state of "albuminous simplicity." "A healthy man," says Thoreau, "with steady employment, as wood-chopping at fifty cents a cord, and a camp in the woods, will not be a good subject for Christianity." Nor will a bush-faller, at twenty-five shillings the[Pg 585] acre. Distant from a church and a minister, he gets out of the way of attending the rare services brought within his reach, and forgets the religion in which he was nurtured. It does not mingle with his life. He is usually married at a registrar's. His children are unbaptized. His parents die unshriven. The dull crises of his mean existence come and go, and religion stands dumb before them. The inner spiritual realities fade from his view as their outward symbols disappear, and bit by bit the whole theological vesture woven by nineteen Christian centuries drops off him like Rip Van Winkle's rotten garments when he woke from his long sleep. In the matter of religion, as in almost all else, the colonist has to begin life again poor.

As population grows and people come nearer to one another, two things happen. The churches push their skirmishers into the interior, plant stations, and have regular services. Gradually the old doctrines strike root in the new soil, and at length a creed answering to Evangelicalism is commonly held, thus repeating the first stage in the history of Christianity in Asia as in England. On the other hand, many of those whom neglect had softened into indifference or hardened into contempt assume a more decided attitude. With the spirit of independence which colonial life so readily begets, and stimulated by the skeptical literature of the day, they take ground against the renascent religion. Secularism, which denies what Evangelicalism affirms and is on a level with that, is born. It organizes itself, has halls and Sunday meetings, catechisms and children's teaching, newspapers, and a propaganda. For a while it is triumphant, openly contemptuous of the current religious mythology, and menacing toward its exponents. The Secularist leaders make their way to the bench and the legislature, the cabinet and the premiership. It is here the hitch arises. Some (by no means all) of these leaders are found to prefer power to principle, and prudently let their secularism go by the board when a wave of popular odium threatens to swamp the ship. Financial distress spreads. The movement loses éclat. As Bradlaugh's Hall of Science in London has been sold to the Salvation Army, the Freethought Hall in Sydney has been purchased by the Methodists, and in other colonial towns the cause has collapsed. But it always remains, whether patent or latent, as a needed counterpoise to the crudities of Evangelicalism, and it is the core of that increasing mass of religious indifferentism which strikes those who have been brought up in the old country. Statistics are said to prove that Australia is more addicted to church-going than England. If they prove any such thing, then statistics (as Mr. Bumble irreverently said of the British Constitution) are hasses and hidiots. You may sit down on any Sunday morning at a colonial table[Pg 586] with a dozen highly respectable persons of both sexes and all ages, not one of whom has any thought of going to church that day. Such an experience would be impossible in England. The mistake has arisen from comparing England as a whole, which has classes below the line of church-going or indeed of civilization, with Australia as a whole, where such classes hardly exist. Compare Australia in this respect with the English middle classes, and the fallacy will be manifest.

When a colony has hived off from the parent state at a time of religious excitement, and especially when it has religion for its raison d'être, it starts fully equipped on lines of its own, the earlier naturalistic stages being dropped. English theology and Puritan religion emigrated to North America in the seventeenth century, and there for two centuries they for the most part remained. Ever since, in New England and the States of the middle belt, religion has played the same high part as it did in old England under Oliver. There has, therefore, been a theological development in the United States to which, till fifty years ago, there was no antecedent parallel in the mother country. While it has produced no theologian or pulpit orator of the first rank—no Calvin, but only Jonathan Edwards; no Bossuet or Chalmers, but only Channing and Beecher—its theological literature compares favorably with that of England during the same period, and its preachers are acknowledged to be the best in Christendom. States and colonies that have grown up more normally get at length on the same lines, and as they put on civilization the tendency is to adopt ever more of the dogmatic system long inseparable from it. By a well-understood sociological law it generates its contradictory and corrective, and there springs up a higher type of denial than secularism—what Huxley felicitously named Agnosticism—the position of those who know nothing about the matters which theological dogma defines, not the position of those who say that nothing can be known. As the Evangelical develops into the High Churchman and he into the Catholic, the Secularist refines into the Agnostic and rarefies into the Unknowabilist.

The literature of colonies is at first theological, as the literature of all countries is at first hieratic; the priest alone can write. But it is long before the stage of original production is reached, and books have to be imported before they can be written. The daughter must go to school with the mother, who supplies her with hornbooks. The continuity of the spiritual germ-plasm is insured by the transmission of books. Rome was thus initiated by Greece in every theoretical branch of knowledge. Rome thus educated early Europe. Chests of manuscripts from Thessalonica, Byzantium, and Crete were the precursors of the Renaissance. Books brought by Benedict[Pg 587] to England formed the first English library. So is it long with all new countries. To this day the book circulation of the United States is largely English; in contemporary colonies it is overwhelmingly English, almost wholly Spanish, exclusively French or Dutch. The second stage also repeats the literary history of the mother countries. Colonial literature is a prolongation of the parental literature and is at first commentative and imitative of that. In a school at Canterbury founded by two foreign monks English written literature took its birth. The literature of mediæval Europe was a continuation of Roman literature. This stage may last long. Seventy or eighty years after the Declaration of Independence the literature of New England was still English literature of a subtler strain—perhaps lacking the strength of the old home-brew, but with a finer flavor. Naturally, in far younger Australia even popular poetry is still imitative—the hand is that of Gordon or of Kendall, but the voice is Swinburne's. The beginnings of a truly national literature are humble. They are never scholastic, but always popular. As chap-books, ballads, and songs were the sources of the æsthetic literature of modern Europe, the beginnings of general literature in the United States have been traced to the old almanacs which, besides medical recipes and advice to the farmer, contained some of the best productions of American authors. It is further evidence of the popular origin of native literature that some of its early specimens are works of humor. The most distinctive work of early Canadian and American authors is humorous, from Sam Slick to ——; but it would be rash to say who is the last avatar of the genius of humor. If an alien may say so without offense, Walt Whitman's poems, with their profound intuitions and artless metre, seem to be the start of a new æsthetic, and recall ancient Beowulf. Australian literature, after a much shorter apprenticeship, has lately, in both fiction and verse, again of a popular character, made a new departure that is instinct with life and grace and full of promise.

Literature and art have no independent value, but are merely the phonographic record of mental states, and would practically cease to exist (as they did during the middle ages) if these disappeared. The grand achievement of new, as of old, countries is man-making, and every colony creates a new variety. The chief agent is natural selection, of which the seamy side appears in vicissitudes of fortune. Here again the law prevails. These recapitulate those vicissitudes in early European societies which make picturesque the pages of Gregory of Tours. There are the same sudden rises, giddy prosperities, and inevitable falls. In the simple communities of ancient Greece the distance between antecedent and consequent was short, and the course of causation plain. Hence in myth and legend, in early historians[Pg 588] like Herodotus, early poets like Pindar, early dramatists like Æschylus, we find a deep sense of the fateful working of the laws of life. The history of colonies is a sermon on the same text. Goodness is speedily rewarded; retribution no longer limps claudo pede, like Vulcan, but flies like Mercury with winged feet. In Europe a high-handed wrongdoer like Napoleon may pursue his career unchecked for fifteen years, or a high-handed rightdoer like Bismarck for five-and-twenty years; a would-be colonial Bismarck or Napoleon is commonly laid by the heels in the short duration of a colonial parliament. The vision of providential government, or the reign of law, in old countries is hard, because its course is long and intricate; in a colony it is so comparatively simple that all may understand it and find it (as Carlyle found it) "worthy of horror and worship." From witnessing the ending of a world Augustine constructed a theodicy, and so justified the ways of God to man. We may discover in the beginnings of a world materials for a cosmodicy which shall exhibit the self-operating justice inherent in the laws of the universe.

By FRANKLIN SMITH.

Why is it that, in spite of exhortation and execration, the disinclination of people in all the great democracies of the world to take part in politics is becoming greater and greater? Why is it that persons of fine character, scholarly tastes, and noble aims, in particular, seek in other ways than association and co-operation with politicians to better the lot of their fellows? Why is it, finally, that with the enormous extension of political rights and privileges during the past fifty years, there has occurred a social, political, and industrial degeneration that fills with alarm the thoughtful minds of all countries? Aside from the demoralization due to the destructive wars fought since the Crimean, the answer to these questions is to be found in the fact that at bottom politics is a form of civil war, that politicians are a species of condottieri, and that to both may be traced all the ethics and evils of a state of chronic war itself. In the light of this truth, never so glaring as at present in the United States, the peril to civilization is divested of mystery; it is the peril that always flows from anarchy, and the refusal of enlightened men to-day to engage in politics is as natural as the refusal of enlightened men in other days to become brigands.

The analogy between war and politics is not new. The very language in common use implies it. When people speak of "leaders,"[Pg 589] "rank and file," "party loyalty," "campaigns," "spoils of victory," etc., which figure so conspicuously and incessantly in political discussion, there is only a fit appropriation of the militant terms invented by one set of fighters to describe with vividness and precision the conduct of another set. What is new about the matter is the failure of thoughtful persons to perceive and to act upon their perception that in politics, as in war, vast economic, social, and political evils are involved. To be sure, lives are not often sacrificed, as in a battle, nor property destroyed, as in a siege or an invasion. But even here the analogy is not imperfect. Political riots have occurred that have brought out as completely as any struggle over a redoubt or barricade the savage traits of human nature. People were maimed and killed, and houses wrecked and burned. Especially was that the case in this country during the antislavery struggle and the period of reconstruction. Even in these days of more calm, political contests as fatal as the Ross-Shea émeute in Troy are reported from time to time. Owing, however, to the advance in civilization since the sack of Antwerp and the siege of Saragossa, the devastation wrought by political warfare has assumed forms less deplorable. But in the long run they will be found to be just as fatal to everything that constitutes civilization, and just as productive of everything that constitutes barbarism. "Lawless ruffianism," says Carl Schurz, pointing out in his Life of Henry Clay the demoralizing effects of the fierce political struggles during Jackson's administrations, "has perhaps never been so rampant in this country as in those days. 'Many of the people of the United States are out of joint,' wrote Niles in August, 1835. 'A spirit of riot and a disposition to "take the law in their own hand" prevails in every quarter.' Mobs, riots, burnings, lynchings, shootings, tarrings, duels, and all sorts of violent excesses, perpetrated by all sorts of persons upon all sorts of occasions, seemed to be the order of the day.... Alarmingly great was the number of people who appeared to believe that they had the right to put down by force and violence all who displeased them by act or speech or belief in politics, or religion, or business, or in social life." It is only familiarity with such fruits of violent political activity, only a vision impaired by preconceived notions of the nature of politics, that blinds the public to their existence.

To see why politics must be regarded as a form of civil war rather than as a method of business, as a system of spoliation rather than as a science to be studied in the public schools,[1] it is but needful to grasp the fundamental purpose of government as generally understood. It is not too much to say that nothing in sociology is regarded as more indicative of an unsound mind or of a mean and selfish[Pg 590] disposition than the conception of government as a power designed to prevent aggression at home and abroad. Such a conception has been contemptuously called "the police conception." "Who would ever fight or die for a policeman?" cried an opponent of it, trying to reduce an adversary to ignominious silence. It was not sufficient to reply with the counter question, "Who would not die for justice?" and thus expose the fallacy of the crushing interrogation. "No one," came the retort, "could care for a country that only protected him against swindlers, robbers, and murderers. To merit his allegiance and to fire his devotion, she must do more than that; she must help to make his life easier, pleasanter, and nobler." Accordingly, the Government undertakes for him a thousand duties that it has no business with. It builds schools and asylums for him; it protects him against disease, and, if needful, furnishes him with physicians and medicines; it sees that he has good beef and pork, pure milk, and sound fruit; it refuses to permit him to drink what he pleases, though it be only the cheaper grades of tea, nor to eat chemical substitutes for butter and cheese, except they bear authorized marks; it transports his mails, supplies him with garden seeds, instructs him in the care of fowls, cattle, and horses, shows him how to build roads, and tells him what the weather will be; it insures him not only against incompetent plumbers, barbers, undertakers, horseshoers, accountants, and physicians, but also against the competition of the pauper labor of foreign countries; it creates innumerable offices and commissions to look after the management of his affairs, particularly to stand between him and the "rapacity" of the corporations organized to supply the necessaries of life at the lowest cost; it builds fleets of cruisers and vast coast fortifications to frighten away enemies that never think of assailing him, and to inspire them with the same respect for "the flag" that he is supposed to feel. Indeed, there is hardly a thing, except simple justice, cheap and speedy, that it does not provide to fill him with a love of his country, and to make him ready to immolate himself upon her altars.

But I can not repeat with too much emphasis that every expenditure beyond that required to maintain order and to enforce justice, and every limitation of freedom beyond that needful to preserve equal freedom, is an aggression. In no wise except in method does it differ from the aggressions of war. In war the property of an enemy is taken or destroyed without his consent. In case of his capture his conduct is shaped in disregard of his wishes. The seizure of a citizen's property in the form of taxes for a purpose that he does not approve, and the regulation of any part of his conduct not violative of the rights of his neighbors, are precisely the same. If he is forbidden to carry the mails and thus earn a living, his freedom[Pg 591] is restricted. If he can patronize no letter carrier but the Government, to which he must pay a certain rate, no matter how excessive, he has to a degree become a slave. The same is true if he can not employ whomever he pleases to cut his hair, or to fix his plumbing, or to prescribe for his health. Still truer is it if he is obliged to contribute to a system of public education which he condemns, or to public charities which he knows to be schools of pauperism, or to any institution or enterprise that voluntary effort does not sustain. In whatever way the Government may pounce upon him to force him to work for some one besides himself and to square his conduct with notions not his own, he is still a victim of aggression, and the aggression is none the less real and demoralizing because it is not committed amid the roar of cannon and the groans of the dying.

To what extent the American people have become victims of this kind of aggression can not be determined with precision. Still, an idea may be had from the volume of laws enacted at every legislative session, and the amount of money appropriated to enforce them. A commonplace little appreciated is that every one of them, no matter what its ostensible object, either restricts or contributes to individual freedom. The examination of any statute-book will soon make painfully apparent the melancholy fact that the protection of individual freedom figures to the smallest extent in the considerations of the wise and benevolent legislator. Of the eight hundred enactments of the Legislature of the State of New York in 1897, for example, I could find only fifty-eight that had this supreme object in view. If we apply the same ratio to the work of all the legislatures of the country, and, allowing for biennial sessions, make it cover a period of two years—namely, 1896 and 1897—the astonishing result will be that, of the 14,718 laws passed, all but 1,030 aim, not to the liberation but to the enslavement of the individual. But to this restrictive legislation must be added the thousands of acts and ordinances of town, city, and county legislatures that are more destructive of freedom even than the State and Federal legislation. If not more numerous, they are certainly more minute, meddlesome, and exasperating.

As to the amount of plunder passing through the hands of the modern condottieri, that is susceptible of an estimate much more accurate. If we take the expenditures of all the governments of the United States, Federal, State, municipal, county, and town, for a similar period of two years, they reach the enormous total of two billion dollars, equal to more than two thirds of the national debt at the close of the civil war.[2] Of this sum only about one hundred[Pg 592] and twenty million dollars, or six per cent, are devoted to the legitimate functions of government—namely, the maintenance of police and courts—and one hundred and forty million dollars to the support of the military establishment.[3] All the rest is expenditure that should no more be intrusted to the Government—that is, subject to the application of political instead of business methods—than the expenditure of a household, or a farm, or a cotton mill, or an iron foundry. Even if it were a legitimate expenditure of the Government, it could not be collected nor expended without injustice. Tax laws have never been and never will be framed that will not permit some one to escape his share of the burdens of the community; and the heavier those burdens are, as they are constantly becoming to an alarming degree, the more desperate will be the effort to shirk them—the more lightly will they rest upon the dishonest and unworthy, and the more heavily upon the honest and worthy. Moreover, it has never been possible, and it never will be possible, to expend money by political methods without either waste or fraud, and most usually without both.

Such a volume of legislation and taxation permits of the easy detection of the vital difference between the theory and practice of politics. According to the text-books and professors, politics is the science of government. In countries like the United States, where popular institutions prevail, the purpose of its study is the discovery and the application of the methods that shall enable all citizens, rich and poor, to share alike in the inestimable privilege of saying what laws they shall have, and bear in proportion to their means the burdens it entails. Such a privilege is supposed to confer innumerable benefits. Every one is assured of scrupulous justice. He is made to feel profound gratitude for his happy deliverance from the odious tyranny and discrimination of a monarchy or an aristocracy. The participation of everybody in the important and beneficent work of government possesses a rare educational value. It leads the ignorant and indifferent to take a deep interest in public questions, and to attempt, as their strength and ability allow, the promotion of the welfare of their beloved country. Thus they escape the deplorable fate of burial in the sordid and selfish pursuit of their own affairs, and the consequent dwarfing of their minds and emotions. Rising to broader views of life and duty, they become patriots, statesmen, and philanthropists.

Enchanting as this picture is, one that can be found in the speeches of every demagogue, male and female, as well as in the works of every political philosopher of the orthodox faith, it has no[Pg 593] sanction in the practice of politics. As long as the greater part of legislation and taxation has nothing whatever to do with government, properly speaking, politics can have no kinship with any pursuit held in esteem by men truly civilized. What it consists of may be reduced to a desperate and disgraceful struggle between powerful organizations, sometimes united, like the Italian condottieri and the Spanish brigands, in the form of "rings," to get control of the annual collection and distribution of one billion dollars, and to reap the benefits that grow out of the concession of privileges. The legislation placing this vast power in the hands of the successful combatants is only an incident of their work. It simply enables them under the form of law to seize the taxpayer, bind him like another Gulliver with rules and regulations, and to take from him whatever they please to promote their political ambition and private interests. From this point of view it is easy to see that politics has no more kinship with science or justice than pillage. Nor is it likely to make people more patriotic, high-minded, and benevolent than the rapacity of Robin Hood or Fra Diavolo.

However startling or repugnant may be this view, it is the only one that furnishes an adequate explanation of the practice of government as carried on in every democratic country in the world. The work of private business and philanthropy, the work in which modern democracies have come to be chiefly engaged, is not in itself productive of the ethics and evils of war. Contrary to the common belief, industrial competition, which is conducted by voluntary co-operation, tends to the supremacy of excellence, moral and material. In societies where civilization has made headway, a merchant or manufacturer does not seek to crush rivals by misrepresenting them or assailing them in other ways. His natural and constant aim is to have his goods so cheap and excellent that the public will patronize him rather than them. To be sure, the ethics of war often prevail in industrialism. They are not, however, one of its products; they are the fruits of militant ages and activities. But in political competition, which is coercive, the policy pursued is precisely the reverse. Not by proof of moral and material excellence does the politician establish his worth. Not by the superiority of his services or by his fidelity to obligations does he gain the esteem and patronage of the public. It is by the infliction of injury upon his rivals. He misrepresents them; he deceives them; he assails them in every way within his reach. When he triumphs over them he uses his power, not primarily for the benefit of the people whom he is supposed to serve, but to maintain his supremacy in order to pillage them. "Those who make war," says Machiavelli, whose famous book is a vade mecum for a modern politician as well as for an unscrupulous[Pg 594] and a tyrannical prince, "have always and very naturally designed to enrich themselves and impoverish the enemy. Neither is victory sought nor conquest desirable except to strengthen themselves and weaken the enemy."

In the light of this truth the organization of powerful political parties becomes natural and inevitable. It is just as natural and inevitable that the more numerous the duties intrusted to the State—that is, the greater the spoil to be fought for in caucus and convention and on the floors of legislatures—the more powerful, dangerous, and demoralizing they are certain to be. Were these duties confined to the maintenance of order and the enforcement of justice, it would be an easy matter for the busiest citizen to give them the attention they required. So simple would they be that he could understand them, and so important that he would insist upon their proper performance. But when they become vast and complex, including such special and difficult work as the education of children; the care of idiots, lunatics, and epileptics; the supervision of the liquor traffic, the insurance business, and railroad transportation, and the regulation of the amount of currency needed in an industrial community, it is beyond the powers of any man, however able, to understand them all, and, no matter how much time he may have, to look after them as he ought. When to these duties are added the management of agricultural stations; the inspection of all kinds of food; the extirpation of injurious insects, noxious weeds, and contagious diseases; the licensing of various trades and professions; the suppression of quacks, fortune-tellers, and gamblers; the production and sale of sterilized milk, and the multitude of other duties now intrusted to the Government, it is no wonder that he finds himself obliged to neglect public questions and to devote himself more closely to his own affairs in order to meet the ever-increasing burdens of taxation. Neither is it any wonder that there springs up a class of men to look after the duties he neglects, and to make such work a means of subsistence. The very law of evolution requires such a differentiation of social functions and organs. The politician is not, therefore, the product of his own love of spoliation solely, but of the necessities of a vicious extension of the duties of the State. There is nothing more abnormal or reprehensible about his existence under the present régime than there is about the physician or lawyer where disease and contention prevail. As long as the conditions are maintained that created him, so long will he ply his profession. When they are abolished he will be abolished. No number of citizens' unions, or nonpartisan movements, or other devices of hopeful but misguided reformers to abolish him, can modify or reverse this immutable decree of social science.

Politics tends to bring to the front the same kind of men that other social disorders do. A study of political leaders in the democratic societies of the world discloses portraits that differ only in degree from those that hang in the galleries of history in Italy in the fifteenth century, in Germany during the Thirty Years' War, and in France at the height of the French Revolution. Although the men they represent may not be as barbarous as Galeazzo or Wallenstein or Robespierre, they are just as unscrupulous and despicable. Like their prototypes, some of them are of high birth; others are of humble origin; still others belong to the criminal class. They do not, of course, capture cities and towns and hold them for ransom, or threaten to burn fields of wheat and corn unless bribed to desist; still they practice methods of spoliation not less efficient. By blackmailing corporations and wealthy individuals, they obtain sums of money that would have filled with bitter envy the leaders of the famous or rather infamous "companies of adventurers." With the booty thus obtained they gather about them numerous and powerful bands of followers. In every district where their supremacy is acknowledged they have their lieutenants and sublieutenants that obey as implicitly as the subordinates in an army. Thus equipped like any of the great brigands of history, they carry caucuses and conventions, shape the party policy, and control the legislation proposed and enacted.

To be sure, the economic devastation of politics is not as conspicuous as that of war. It does not take the tragic form of burning houses, trampled fields of grain, tumbling walls of cities, and vast unproductive consumption by great bodies of armed men. Yet it is none the less real. Not infrequently it is hardly less extensive when measured in dollars and cents. Seldom does an election occur, certainly not a heated congressional or presidential election, that the complaint of serious interference with business is not universal. So great has the evil become that, long before the meeting of the national conventions in 1896, a concerted movement on the part of the industrial interests of the country was started to secure an abbreviation of the period given up to political turmoil. Even more serious is the economic disturbance due to legislatures. As no one knows what stupendous piece of folly they may commit at any moment, there is constant apprehension. "The country," said the Philadelphia Ledger, a year ago, referring to the disturbance provoked by the Teller repudiation resolution in the Senate and the violent Cuban debate in the House, "has got Congress on its hands, and, after their respective fashions, Senate and House are putting enormous weight of disturbing doubts and fears upon it.... To a greater or less degree a meeting of Congress has been during recent years anticipated[Pg 596] by the community of business with timidity which in some instances has amounted to trepidation." The State legislatures are hardly better. No great industry has any assurance that it will not find itself threatened with a violent and ruinous assault in some bill that a rapacious politician or misguided philanthropist has introduced. In New York the attacks of these modern brigands have become so frequent and so serious that many of the larger corporations have had to take refuge in adjacent States,[4] where they can enjoy greater, if not complete immunity. In a less degree the same is true of the minor legislatures—town, county, and municipal. Ordinances for pavements or sewers or in concession of valuable privileges keep the taxpayers in a state of constant anxiety. At the same time vast harm comes from the neglect of more important matters. The time of legislators is spent in intriguing and wrangling, and the millions of dollars that the sessions cost are as completely destroyed as though burned by invaders.

Though seldom or never recognized, politics has the same structural effect upon society as war. The militant forces of the one, like the militant forces of the other, tend to the destruction of social mobility and the creation of social rigidity, making further social evolution difficult or impossible. There is a repression of the spirit of individual initiative, which calls into existence just such institutions as may be required at any moment and permits them to pass away as soon as they have served their purpose. There is an encouragement of the class and parasitic spirit, which produces institutions based upon artificial distinctions, and, like those in China, so tenacious of life as to defy either reform or abolition. To provide place and pelf for followers, political leaders, aided by the misdirected labors of social reformers, favor constantly the extension of the sphere of government in every direction. In New York, for example, during the past eighteen years, thirty-six additions to State offices and commissions have been made. Simultaneously, the expenditures on their account have grown from less than four thousand dollars a year to nearly seven million. This feudal tendency toward the bureaucracy that exists in France and Germany, and in every country cursed with the social structure produced by war, is not only the same in the other States, but in the Federal Government as well. Its latest manifestation is the amazing extension of the powers of the interstate commerce commission demanded in the Cullom bill, and the proposed establishment of a department of commerce to promote trade with foreign countries. As in New York, there has been an enormous increase in Federal expenditures. In the agricultural department it[Pg 597] has been from $3,283,000 in 1887 to $23,480,000 in 1897. In other departments the increase has ranged from nineteen per cent in the legislative and twenty-three in the diplomatic and consular to seventy in the Indian, seventy-seven in the post office and river and harbor, and one hundred and thirty-three in the pension. Another manifestation is the pressing demand for the extension of the pension system to civil officials. Already the system has been extended to policemen and firemen. In some States the teachers in the public schools receive pensions, and in others the clamor for this form of taxation is loud and persistent. At the present time a powerful movement is in progress to pension the civil servants of the Government. Still another manifestation is the passage of laws in revival of the old trade and professional corporations. For a long time those in protection of the legal and medical professions have been on the statute-books, if not always in force. But, as always happens, these bad precedents have been used as arguments in favor of the plumbers, barbers, dentists, druggists, and other trades and professions. But the most absurd manifestation is the social classification of Government employees in accordance with the size of their salaries, a form of folly particularly apparent in Washington, and the establishment of patriotic and other societies, like the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution, the Baronial Order of Runnymede, and the Royal Order of the Crown, that create social distinctions based, not upon character and ability, but upon heredity. Could anything be more un-American, to use the current word, or hostile to the spirit of a free democracy?

In the intellectual domain politics works a greater havoc than in the social. Politicians can no more tolerate independence in thought and action than Charles V or Louis XIV or Napoleon I. "I have never had confidence in political movements which pretend to be free from politics," said the Governor of New York at the close of the campaign that restored Tammany Hall to power in the metropolis, showing that the intolerance of this form of warfare does not differ from that of any other. "A creed that is worth maintaining at all," he added, using an argument made familiar by the agents of bigotry everywhere, "is worth maintaining all the time.... Do not put your faith in those that hide behind the pretense of nonpartisanship," he continued, striking a deadly blow at all party traitors; "it is a device to trap the thoughtless and unsuspecting." As was shown during the Blaine-Cleveland campaign of 1884, politicians treat dissent as proof of unmistakable moral and intellectual baseness. Only the progress of civilization prevents them from pouncing upon such men as George William Curtis, Carl Schurz, and Wayne McVeagh with the ferocity of the familiars of the Inquisition. As it is, they are[Pg 598] regarded with more abhorrence than the members of the opposition; they are treated with a greater wealth of contempt and hatred, and often pursued with the malignant vindictiveness of the cruelest savages. "I submit," said Mr. Wanamaker in one of his speeches against the Quay machine, "that the service of self-respecting men is lost to the Republican party by vile misrepresentations of reputable people, employment of bogus detectives, venomous falsifiers, a subsidized press, and conspirators who dare any plot or defilement, able to exert political control, and by protecting legislation and by domination of legal appointees of district attorneys and others not in elective but appointive offices." During the memorable campaign of 1896, when political bitterness and intolerance reached perhaps the highest point in the history of the United States, thousands of voters, driven by the scourge of "party regularity," either concealed or disavowed their convictions, and marched under banners that meant repudiation of public and private obligations. Even one of Mr. Cleveland's Cabinet officers, who had stood up bravely for the gold standard, succumbed to party discipline and became an apostate. The intolerant spirit of politics extends to dictation of instruction of students. The prolonged assaults of the protectionists upon Professor Perry and Professor Sumner are well known. The same spirit inspired the attack upon President Andrews, of Brown University, the dismissal of the anti-Populist professors in the Agricultural College of Kansas, and the populistic clamor against certain professors in the universities of Missouri and Texas. That politics produces the same contempt for culture and capacity that war does, evidence is not lacking. "There is," said Senator Grady, of Tammany Hall, apologizing for the appointment of some illiterate to office in New York city, "a class of persons, chiefly the educated, who thinks that if a man begins a sentence with a small letter, or uses a small 'i' in referring to himself, or misspells common words, that he is unfit for public office. Nothing could be further from the truth," he continues, using an argument that the barbarians that overran Europe might have made; "it is an idea that only the aristocracy of culture could hold.... We do not want the people ruled by men," he adds, giving a demagogic twist to his reasoning, "who are above them, or who fancy they are because they have wealth or learning or blood, nor by men who are below them, but we want them ruled in a genuine democracy by men who are the representatives in all their ways of thinking, feeling, speaking, and acting, of the average man." What is wanted, in other words, is not men anxious to acquit themselves with ability and fidelity to the public interests, but men that will look after the interests of their organization and do the other work of political condottieri. It can, of course, be a matter of no[Pg 599] consequence whether such men spell or speak correctly, or whether they conduct themselves like boors and ruffians.[5]

As implied in all that has been said, it is, however, upon morals that the effect of politics is the most deplorable. From the beginning of the discussion of the party platform and the nomination of the candidates to the induction of the successful combatants into office, the principles applied to the transaction of business play the smallest possible part. The principles observed are those of war. All the tactics needful to achieve success in the one are indispensable to success in the other. First, there is, as I have already said, an attempt to misrepresent and injure political opponents, and, next, to confuse, befool, and pillage the public. I shall not, however, describe the factional conflicts that precede a convention—the intrigue, the bribery, the circulation of false stories, and even the forgery of telegrams like the one that brought about the nomination and defeat of Secretary Folger. They exhibit only on a small scale the ethics of party warfare in general. More needful is it to illustrate these, and to make clear the vanity of any hope of moral reform through politics, or through any other agency, either religious, philanthropic, or pedagogic, as long as it remains a dominant activity of social life.

"If Mr. Gage had been a politician as well as a banker," said Senator Frye, criticising the secretary's honesty and courage at a time when both were urgently needed, "he would not have insisted upon a declaration in favor of a single gold standard. It was all right for him to submit his scheme of finance, but hardly politic to be so specific about the gold standard." Always adjusted to this low and debased conception of duty, a party platform is seldom or never framed in accordance with the highest convictions of the most intelligent and upright men in the party. The object is not the proclamation of the exact truth, as they see it, but to capture the greatest number of votes. If there is a vital question about which a difference of opinion exists, the work of putting it into a form palatable to everybody is intrusted to some cunning expert in verbal juggling. A money plank, for instance, is drawn up in such a way that the candidate standing upon it may be represented by editors and orators of easy consciences as either for or against the gold standard. The same was true for years of the slave and tariff questions; it is still true of the temperance question, the question of civil-service reform,[Pg 600] and of every other question that threatens the slightest party division. Again, questions are kept to the front that have no more vitality than the dust of Cæsar. Long after the civil war the issues of that contest formed the stock in trade of the politicians and enabled them to win many a battle that should have been fought on other grounds. If need be, the grossest falsehoods are embodied in the platform, and proclaimed as the most sacred tenets of party faith.

When the campaign opens, the ethics of the platform assume a more violent and reprehensible shape. Not only are its hypocrisies and falsehoods repeated with endless iteration, but they are multiplied like the sands of the beach. Very few, if any, editors or orators pretend to discuss questions or candidates with perfect candor and honesty. Indeed, very few of them are competent to discuss them. Hence sophistry and vilification take the place of knowledge and reason. Were one party to adopt the Decalogue for a platform, the other would find nothing in it to praise; it would be an embodiment of socialism, or anarchism, or some other form of diabolism. If one party were to nominate a saint, the other would paint him in colors that Satan himself would hardly recognize. Not even such men as Washington and Lincoln are immune to the assaults of political hatred and mendacity. As the campaign draws to a close, we have a rapidly increasing manifestation of all the worst traits of human nature. In times of quiet, a confessed knave would scarcely be guilty of them. False or garbled quotations from foreign newspapers are issued. The old Cobden Club, just ready to give up the ghost, is galvanized into the most vigorous life, and made to do valiant service as a rich and powerful organization devoted to the subversion of American institutions. Stories like Clay's sale of the presidency are invented, and letters, like the Morey letter, are forged, and, despite the most specific denials of their truth, they are given the widest currency. Other forms of trickery, like the Murchison letter, written by the British minister during Mr. Cleveland's second campaign, are devised with devilish ingenuity, and made to contribute to the pressing and patriotic work of rescuing the country from its enemies.

But this observation of the ethics of war does not stop with the close of the polls, where bribery, intimidation, and fraud are practiced, and the honest or dishonest count of the ballots that have been cast; it is continued with the same infernal industry in the work of legislation and administration. Upon the meeting of the statesmen that the people have chosen under "the most perfect system of government ever devised by man," what is the first thing that arrests their attention and absorbs their energies? More intriguing, bargaining, and bribery in a hundred forms, more or less subtle, to secure election and appointment to positions within the gift of the legislature.[Pg 601] Little or no heed is given to the primary question of capacity and public interests. Political considerations—that is, ability to help or to harm some one—control all elections and appointments. What is the next thing done? It is the preparation, introduction, discussion, and passage of the measures thought to be essential to the preservation of civilization. Here again political considerations control action. Such measures are introduced as will strengthen members with their constituents, or promote "the general welfare" of the party. Very rarely have they "the general welfare" of the public in view. Sometimes they seek to change district boundaries in such a way as to keep the opposition in a perpetual minority. Sometimes they have no other motive than the extortion of blackmail from individuals or corporations. Sometimes their object is to throw "sop to Cerberus"—that is, to pacify troublesome reformers within the party, like the prohibitionists and the civil-service reformers. Sometimes they authorize investigations into a department or a municipality with the hope that discoveries will be made that will assist the party in power or injure the party out of power; it happens not infrequently that they are undertaken to smother some scandal, like the mismanagement of the Pennsylvania treasury, or to whitewash some rascal. Sometimes they create commissions, superintendents, or inspectors, or other offices to provide rewards for party hacks and heelers. Finally, there are the appropriation bills. Only a person ignorant of the ways of legislators could be so simple-minded as to imagine that they are miracles of economy, or that they are anything else but the products of that clumsy but effective system of pillaging known as log-rolling, which enables each to get what he wants with the smallest regard for the interests of the taxpayer.

It is, however, during the debates over these wise and patriotic measures that the public is favored with the most edifying exhibition of the universal contempt of the legislator for its interests. They disclose all the scandalous practices of a political campaign. There are misrepresentations, recriminations, and not infrequently, as in the case of Sumner, personal assaults. A perverse inclination always exists toward those discussions that will put some one "in a hole," or enable some one to arouse party passion. For this purpose nothing is so effective as a foreign question, like a Cuban belligerency resolution, or a treaty for the annexation of Hawaii, or a domestic question, like responsibility for the crime of 1873, or the panic of 1893, or a comparison of party devotion to the interests of the "old soldier." Not the slightest heed, as has been shown on several occasions during the past few years, is paid to the shock that may be given to business or to the disturbance of pacific relations with foreign powers. In fact, the greater the danger involved in the discussion of a delicate[Pg 602] question, the more prone are the demagogues to mouth it. To such questions as bankruptcy, railroad pooling, and currency reform will they give their time and wisdom only when business interests have almost risen in insurrection and compelled attention to them.

The same policy of hypocrisy, deception, favoritism, and proscription is a dominant trait of the administration of the Government. The object almost invariably in mind is the welfare or injury of some party, or faction, or politician. The interests of the public are the last thing thought of, if thought of at all. Take dismissals and appointments. They may, as has been known to occur even in the United States, be made to better the public service. Even then a careful study of motive will disclose the characteristic purpose of the politician. In a choice between two men of equal ability, or rather of equal inability, which is more commonly the case, preference is given to the one with the stronger "pull." Often, as has been shown within the past year or two, convicted rascals are appointed at the behest of Congressmen and in defiance of the wishes of the business community, and, in spite of the civil-service laws, officials are dismissed because of their politics alone. In the letting of contracts it is not difficult to detect the observance of the same judicious rule. The virtuous formality of letting to the lowest bidder may be gone through with, and the public may be greatly pleased with this exhibition of official deference to its interests. Yet an examination of the work done under the supervision of complaisant inspectors, who may be blinded in various ways to the defects of that of a political friend, or made supernaturally alert to the defects of that of a political enemy, will reveal a trail that does not belong to scrupulous integrity. That is why dry docks, like that in Brooklyn, why harbor works, like those in Charleston, turn out defective; why the Government has to pay more for the transportation of the mails than a private corporation; why the cost of the improvement of the Erie Canal was concealed until nearly all the money voted for the folly had been expended; why of the money expended one million dollars was wasted, if not stolen; why so much of the State Capitol at Albany has been built over again; why the City Hall in Philadelphia has been an interminable job; why the supplies of prisons, asylums, and other public institutions are constantly proving to be inferior to those paid for—why, in a word, everything done by political methods is vitiated by the ethics of war. In the enforcement of laws very little justice or honesty can be found. As a rule, they bear much more harshly on the poor and weak, that is, those with small political influence, than on the rich and strong, that is, those with much political influence. Take the enforcement of liquor laws, health laws, factory laws, and compulsory school laws. If a man with political influence wishes[Pg 603] to keep his children at home for any purpose, no truant officer is indiscreet enough to trouble him; if, however, a poor woman, just made a widow, wishes to have her oldest son work in disregard of the statute, in order to keep her and her younger children out of the poor-house, his official zeal is above criticism. Politics poisons even the fountains of justice. Criminals that have sufficient political influence can escape prosecution or obtain pardon after conviction. Prosecuting officers are importuned incessantly, even by "leading citizens," to abandon prosecution of them or to "let them off easily." In the appointment of receivers and referees, judges are much more inclined to give preference to political friends than to political enemies. Finally, if political exigencies require it, there is no hesitation to invoke the latent savagery of a nation. In proof, recall the Venezuelan message of Mr. Cleveland, which "dished" the Republican jingoes, and the German emperor's assault upon Hayti and China to secure the adoption of his naval bill. To make the record complete, I ought to add that for a purpose more odious—namely, the increase of sales—newspapers, always the ready recipients of political patronage, commit the same atrocious crime against civilization.