Title: The Devil in Britain and America

Author: John Ashton

Release date: December 12, 2013 [eBook #44412]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

FACSIMILE OF THE ONLY KNOWN SPECIMEN OF THE DEVIL’S WRITING.

THE DEVIL IN BRITAIN

AND AMERICA

BY

JOHN ASHTON

AUTHOR OF

‘SOCIAL ENGLAND UNDER THE REGENCY,’ ‘SOCIAL LIFE IN THE REIGN

OF QUEEN ANNE,’ ‘VARIA,’ ETC.

‘Nam ut vere loquamur, superstitio fusa per gentes oppressit omnium fere animos, atque hominum imbecillitatem occupavit.’

Cicero—De Divin., Lib. ii. 72.

WITH FORTY-SEVEN ILLUSTRATIONS

WARD AND DOWNEY

Limited

12 YORK BUILDINGS, ADELPHI W.C.

1896.

[All rights reserved.]

To my thinking, all modern English books on the Devil and his works are unsatisfactory. They all run in the same groove, give the same cases of witchcraft, and, moreover, not one of them is illustrated. I have endeavoured to remedy this by localizing my facts, and by reproducing all the engravings I could find suitable to my purpose.

I have also tried to give a succinct account of demonology and witchcraft in England and America, by adducing authorities not usually given, and by a painstaking research into old cases, carefully taking everything from original sources, and bringing to light very many cases never before republished.

For the benefit of students, I have given—as an Appendix—a list of the books consulted in the preparation of this work, which, however, the student must remember is not an exhaustive bibliography on the subject, but only applies to this book, whose raison d’être is its localization.

The frontispiece is supposed to be the only specimen of Satanic caligraphy in existence, and is[Pg vi] taken from the ‘Introductio in Chaldaicam Linguam,’ etc., by Albonesi (Pavia, 1532). The author says that by the conjuration of Ludovico Spoletano the Devil was called up, and adjured to write a legible and clear answer to a question asked him. Some invisible power took the pen, which seemed suspended in the air, and rapidly wrote what is facsimiled. The writing was given to Albonesi (who, however, confesses that no one can decipher it), and his chief printer reproduced it very accurately. I am told by experts that in some of the characters may be found a trace of Amharic, a language spoken in its purity in the province of Amhara (Ethiopia), and which, according to a legend, was the primeval language spoken in Eden.

JOHN ASHTON.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Universal Belief in the Personality of the Devil, as portrayed by the British Artist—Arguments in Favour of his Personality—Ballad—‘Terrible and Seasonable Warning to Young Men’ | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| ‘Strange and True News from Westmoreland’—‘The Politic Wife’—‘How the Devill, though subtle, was guld by a Scold’—‘The Devil’s Oak’—Raising the Devil—Arguments in Favour of Devils—The Number of Devils | 13 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| ‘The Just Devil of Woodstock’—Metrical Version—Presumed Genuine History of ‘The Just Devil of Woodstock’ | 28 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| ‘The Dæmon of Tedworth’ | 47 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| ‘The Dæmon of Burton’—‘Strange and Wonderful News from Yowel, in Surrey’—The Story of Mrs. Jermin—A Case at Welton—‘The Relation of James Sherring’ | 60 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Demon in Gilbert Campbell’s Family—Case of Sir William York—Case of Ian Smagge—Disturbances at Stockwell | 72 |

| [Pg viii] | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Possession by, and casting out, Devils—The Church and Exorcisms—Earlier Exorcists—‘The Strange and Grievous Vexation by the Devil of 7 Persons in Lancashire’ | 85 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| James I. on Possession—The Vexation of Alexander Nyndge—‘Wonderful News from Buckinghamshire’—Sale of a Devil | 113 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Witch of Endor—The ‘Mulier Malefica’ of Berkeley—Northern Witches | 129 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Legal Witch—James I. on Witches—Reginald Scot on Witches—Addison on Witches | 139 |

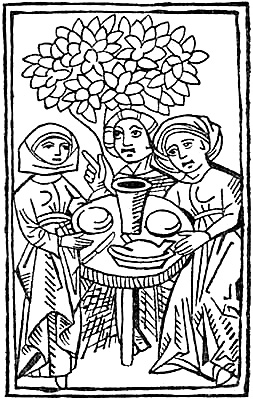

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| How a Witch was made—Her Compact with the Devil—Hell Broth—Homage and Feasting—The Witches’ Sabbat | 148 |

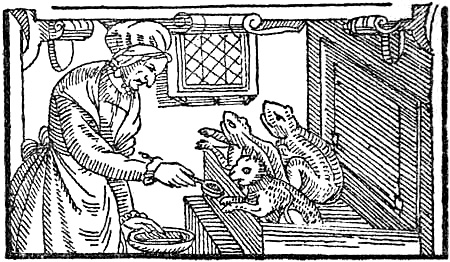

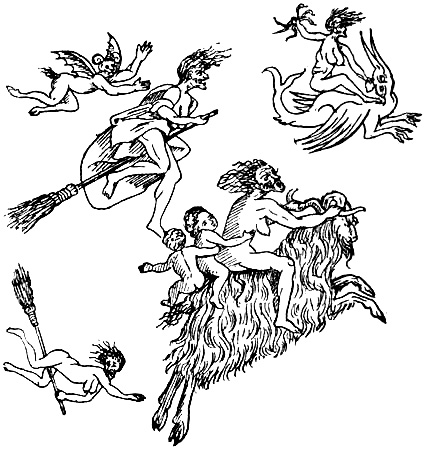

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Familiar Spirits—Matthew Hopkins, the ‘Witch-finder’—Prince Rupert’s dog Boy—Unguents used for transporting Witches from Place to Place—Their Festivities at the Sabbat | 157 |

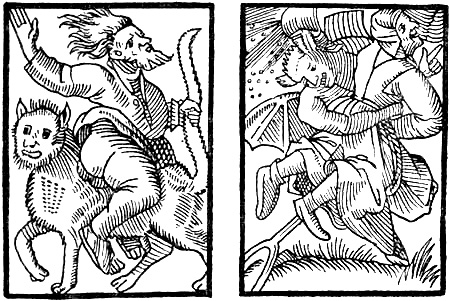

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Waxen Figures—Witches change into Animals—Witch Marks—Testimony against Witches—Tests for, and Examination of, Witches | 175 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Legislation against Witches—Punishment—Last Executions for Witchcraft—Inability to weep and sink—Modern Cases of Witchcraft | 191 |

| [Pg ix] | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Commencement of Witchcraft in England—Dame Eleanor Cobham—Jane Shore—Lord Huntingford—Cases from the Calendars of State Papers—Earliest Printed Case, that of John Walsh—Elizabeth Stile—Three Witches tried at Chelmsford—Witches of St. Osyth—Witches of Warboys—Witches of Northamptonshire | 199 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Lancashire Witches—Janet Preston—Margaret and Philip Flower—Anne Baker, Joane Willimot, and Ellen Greene—Elizabeth Sawyer—Mary Smith—Joan Williford, Joan Cariden, and Jane Hott | 220 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Confessions of Witches executed in Essex—The Witches of Huntingdon—‘Wonderful News from the North’—Trial of Six Witches at Maidstone—Trial of Four Witches at Worcester—A Lancashire Witch tried at Worcester—A Tewkesbury Witch | 234 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| A Case of Vomiting Stones, etc., at Evesham—Anne Bodenham—Julian Cox—Elizabeth Styles—Rose Cullender and Amy Duny | 246 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Case of Mary Hill of Beckington—The Confession of Alice Huson—Florence Newton of Youghal—Temperance Lloyd (or Floyd), Mary Trembles, and Susannah Edwards | 260 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Elizabeth Horner—Pardons for Witchcraft—A Witch taken in London—Sarah Mordike—An Impostor convicted—Case of Jane Wenham—The Last Witch hanged in England | 273 |

| [Pg x] | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Scotch Witches—Bessie Dunlop—Alesoun Peirson—Dr. John Fian—The Devil a Preacher—Examination of Agnes Sampson—Confession of Issobel Gowdie | 287 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Early Witchcraft in Scotland—Lady Glamys—Bessie Dunlop—Lady Foulis—Numerous Cases | 301 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Witchcraft in America—In Illinois: Moreau and Emmanuel—In Virginia: Case of Grace Sherwood—In Pennsylvania: Two Swedish Women—In South Carolina—In Connecticut: Many Cases—In Massachusetts: Margaret Jones; Mary Parsons; Ann Hibbins; Other Cases | 311 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Cotton and Increase Mather—The Case of Goodwin’s Daughter—That of Mr. Philip Smith—The Story of the Salem Witchcrafts—List of Victims—Release of Suspects—Reversal of Attainder, and Compensation | 326 |

| Appendix | 340 |

THE DEVIL IN BRITAIN AND AMERICA

Universal Belief in the Personality of the Devil, as portrayed by the British Artist—Arguments in Favour of his Personality—Ballad—‘Terrible and Seasonable Warning to Young Men.’

The belief in a good and evil influence has existed from the earliest ages, in every nation having a religion. The Egyptians had their Typho, the Assyrians their Ti-a-mat (the Serpent), the Hebrews their Beelzebub, or Prince of Flies,[1] and the Scandinavians their Loki. And many religions teach that the evil influence has a stronger hold upon mankind than the good influence—so great, indeed, as to nullify it in a large degree. Christianity especially teaches this: ‘Enter ye by the narrow gate; for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many be they that enter in thereby. For narrow is the gate, and straitened the way, that leadeth unto life, and few be they that find it.’ This doctrine of the great power of the Devil, or evil[Pg 2] influence over man, is preached from every pulpit, under every form of Christianity, throughout the world; and although at the present time it is only confined to the greater moral power of the Devil over man, at an earlier period it was an article of belief that he was able to exercise a greater physical power.

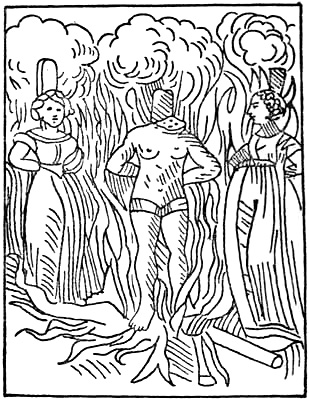

This was coincident with a belief in his personality; and it is only in modern times that that personality takes an alluring form. In the olden days the Devil was always depicted as ugly and repulsive as the artist could represent him, and yet he could have learned a great deal from the modern Chinese and Japanese. The ‘great God Pan,’ although he was dead, was resuscitated in order to furnish a type for ‘the Prince of Darkness’; and, accordingly, he was portrayed with horns, tail and cloven feet, making him an animal, according to a mot attributed to Cuvier, ‘graminivorous, and decidedly ruminant’; while, to complete his classical ensemble, he was invested with the forked sceptre of Pluto, only supplemented with another tine.

The British artist thus depicted him, but occasionally he drew him as a ‘fearful wild fowl’ of a totally different type—yet always as hideous as his imagination could[Pg 3] conceive, or his pencil execute.

That the Devil could show himself to man, in a tangible form, was, for many centuries, an article of firm belief, but, when it came to be argued out logically, it was difficult of proof. The only evidence that could be adduced which could carry conviction was from the Bible, which, of course, was taken as the ipsissima verba of God, and, on that, the old writers based all their proof. One of the most lucid of them, Gyfford or Gifford, writing in the sixteenth century, evidently feels this difficulty. Trying to prove that ‘Diuels can appeare in a bodily shape, and use speeche and conference with men,’ he says:[2]

‘Our Saviour Christ saith that a spirite hath neither flesh nor bones. A spirite hath a substance, but yet such as is invisible, whereupon it must[Pg 4] needes be graunted, that Diuels in their owne nature have no bodilye shape, nor visible forme; moreover, it is against the truth, and against pietie to believe that Diuels can create, or make bodies, or change one body into another, for those things are proper to God. It followeth, therefore, that whensoever they appeare in a visible forme, it is no more but an apparition and counterfeit shewe of a bodie, unless a body be at any time lent them.’

And further on he thus speaks of the incarnation of Satan, as recorded in the Bible.

‘The Deuill did speake unto Eua out of the Serpent. A thing manifest to proue that Deuils can speake, unlesse we imagine that age hath made him forgetfull and tongue tyde. Some holde that there was no visible Serpent before Eua, but an invisible thing described after that manner, that we might be capable thereof.... But to let those goe, this is the chiefe and principall, for the matter which I have undertaken, to shewe euen by the very storye that there was not onely the Deuill, but, also, a very corporall beaste. If this question bee demaunded did Eua knowe there was anye Deuill, or any wicked reprobate Angels. What man of knowledge will say that she did? She did not as yet knowe good and euill. She knewe not the authour of euill. When the Lorde sayde unto hir, What is this which thou hast done? she answereth by and by, The serpent deceiued me. Shee saw there was one which had deceiued hir, shee nameth him a serpent; whence had she that name for the deuill whome shee had not imagined to bee? It is plaine that she[Pg 5] speaketh of a thing which had, before this, receiued his name.

‘It is yet more euident by that she sayth, yonder serpent, or that serpent, for she noteth him out as pointing to a thing visible: for she useth the demonstratiue particle He in the Hebrew language, which seuereth him from other. Anie man of a sound mind may easilie see that Eua nameth and pointeth at a visible beast, which was nombred among the beastes of the fielde.’

The Devil seems, with the exception of his entering into persons, not to have used his power of appearing corporeally until people became too holy for him to put up with, and many are the records in the Lives of the Saints of his appearance to these detestably good people—St. Anthony, to wit. Of course he always came off baffled and beaten, and, in the case of St. Dunstan, suffered acute bodily pain, his nose being pinched by the goldsmith-saint’s red-hot tongs. Yet even that did not deter him from again becoming visible, until, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of our era, he became absolutely familiar on this earth.

But, according to all the records that we possess, his mission no longer was to seduce the saints from their allegiance, and, having become more democratic, he mixed familiarly with the people, under different guises. Of course, his object was to secure the reversion of their souls at their decease, his bait usually being the promise of wealth in this life, or the gratification of some passion.

[Pg 6]He found many victims, but yet he met with failures—two of which are recorded here.

A NEW BALLAD.

SHEWING THE GREAT MISERY SUSTAINED BY A POORE MAN IN ESSEX, HIS WIFE AND CHILDREN, WITH OTHER STRANGE THINGS DONE BY THE DEVILL.

A poore Essex man

that was in great distresse,

Most bitterly made his complaint,

in griefe and heavinesse:

Through scarcity and want,

he was oppressed sore,

He could not find his children bread,

he was so extreme poore.

His silly Wife, God wot,

being lately brought to bed,

With her poore Infants at her brest

[Pg 7]had neither drinke nor bread.

A wofull lying in

was this, the Lord doth know,

God keep all honest vertuous wives

from feeling of such woe.

My Husband deare, she said,

for want of food I die,

Some succour doe for me provide,

to ease my misery.

The man with many a teare,

most pittiously replyde,

We have no means to buy us bread;

with that, the Children cry’d.

They came about him round,

upon his coat they hung:

And pittiously they made their mone,

their little hands they wrung.

Be still, my boyes, said he,

And I’le goe to the Wood,

And bring some Acornes for to rost,

and you shall have some food.

Forth went the Wofull Man,

a Cord he tooke with him,

Wherewith to bind the broken wood,

that he should homewards bring:

And by the way as he went,

met Farmers two or three,

Desiring them for Christ his sake,

to helpe his misery.

Oh lend to me (he said)

one loafe of Barley-bread,

One pint of milke for my poore wife,

in Child-bed almost dead:

Thinke on my extreme need,

to lend me have no doubt,

I have no money for to pay,

but I will worke it out.

But they in churlish sort,

did one by one reply,

We have already lent you more

than we can well come by.

This answere strooke his heart

as cold as any stone;

Unto the Wood from thence he went,

[Pg 8]with many a grievous groane.

Where at the length (behold)

a tall man did him meet

And cole-black were his garments all

from head unto his feet.

Thou wretched man, said he,

why dost thou weep so sore?

What is the cause thou mak’st this mone,

tell me, and sigh no more.

Alas, good Sir (he said)

the lacke of some reliefe,

For my poore wife and children small,

’tis cause of all my griefe.

They lie all like to starve,

for want of bread (saith he);

Good Sir, vouchsafe therefore to give

one peny unto me.

Hereby this wretched man

committed wondrous evill,

He beg’d an almes, and did not know

he ask’t it of the Devill.

But straight the hellish Fiend,

to him reply’d againe,

An odious sinner art thou then

that dost such want sustaine.

Alack (the poore man said)

this thing for truth I know,

That Job was just, yet never Man

endured greater woe.

The godly oft doe want,

and need doth pinch them sore,

Yet God will not forsake them quite,

but doth their states restore.

If thou so faithfull bee,

why goest thou begging then?

Thou shalt be fed as Daniel was

within the Lyon’s den.

If thus thou doe abide,

the Ravens shall bring thee food,

As they unto Elias did

that wandred in the Wood.

Mocke not a wofull man,

good Sir, the poore man said,

Redouble not my sorrows so,

[Pg 9]that are upon me laid.

But, rather, doe extend

unto my need, and give

One peny for to buy some bread,

my Children poore may live.

With that he opened straight

the fairest purse in sight

That ever mortal eye beheld,

fild up with crownes full bright.

Unto the wofull man

the same he wholly gave,

Who very earnestly did pray

that Christ his life might save.

Well, (quoth the damn’d Spirit)

goe, ease thy Children’s sorrow,

And, if thou wantest anything,

come, meet me here to-morrow.

Then home the poore man went,

with cheerfull heart and mind,

And comforted his woful wife

with words that were most kind.

Take Comfort, Wife, he said,

I have a purse of Gold,

Now given by a Gentleman,

most faire for to behold.

And thinking for to pull

his purse from bosome out,

He found nothing but Oken leaves,

bound in a filthy Clout.

Which, when he did behold,

with sorrowe pale and wan,

In desperate sort to seeke the purse,

unto the Wood he ran,

Supposing in his mind,

that he had lost it there;

He could not tell then what to think,

he was ’twixt hope and feare.

He had no sooner come

into the shady Grove,

The Devil met with him againe,

as he in fancy strove.

What seek’st thou here? he said,

the purse (quoth he) you gave,

Thus Fortune she hath crossed me,

[Pg 10]and then the Devill said

Where didst thou put the Purse?

tell me, and do not lye,

Within my bosome, said the man,

where no man did come nigh.

Looke there againe, (quoth he)

then said the Man, I shall,

And found his bosome full of Toads,

as thicke as they could crawle.

The poore man at this sight,

to speak had not the power,

See (q’d the Devill) vengeance doth

pursue thee every hour.

Goe, cursed wretch, (quoth he)

and rid away thy life,

But murther first thy children young,

and miserable Wife.

The poore man, raging mad,

ran home incontinent,

Intending for to kill them all,

but God did him prevent.

For why, the chiefest man

that in the Parish dwelt,

With meat and money thither came,

which liberally he dealt.

Who, seeing the poore man

come home in such a rage,

Was faine to bind him in his bed,

his fury to asswage.

Where long he lay full sicke,

still crying for his Gold,

But, being well, this whole discourse

he to his neighbours told.

From all temptations,

Lord, keep both Great and Small,

And let no man, O heavenly God,

for want of succour fall.

But put their speciall trust

in God for evermore,

Who will, no doubt, from misery

each faithfull man restore.

‘A TERRIBLE AND SEASONABLE WARNING TO YOUNG MEN.

‘Being a very particular and True Relation of one Abraham Joiner, a young man about 17 or 18 Years of Age, living in Shakesby’s Walks in Shadwell, being a Ballast Man by Profession, who, on Saturday Night last, pick’d up a leud Woman, and spent what money he had about him in Treating her, saying afterwards, if she wou’d have any more he must go to the Devil for it, and, slipping out of her Company, he went to the Cock and Lyon in King Street, the Devil appear’d to him, and gave him a Pistole, telling him he shou’d never want for Money, appointing to meet him the next Night, at the World’s End at Stepney; Also how his Brother persuaded him to throw the Money away, which he did; but was suddenly taken in a very strange manner, so that they were fain to send for the Reverend Mr. Constable and other Ministers to pray[Pg 12] with him; he appearing now to be very Penitent; with an Account of the Prayers and Expressions he makes use of under his Affliction, and the Prayers that were made for him, to free him from this violent Temptation.

‘The Truth of which is sufficiently attested in the Neighbourhood, he lying now at his Mother’s house,’ etc.

Stepney seems to have been a favourite haunt of the Devil, for there is a tract published at Edinburgh, 1721, entitled ‘A timely Warning to Rash and Disobedient Children. Being a strange and wonderful Relation of a young Gentleman in the Parish of Stepheny, in the Suburbs of London, that sold himself to the Devil for 12 Years, to have the Power of being revenged on his Father and Mother, and how, his Time being expired, he lay in a sad and deplorable Condition, to the Amazement of all Spectators.’

‘Strange and True News from Westmoreland’—‘The Politic Wife’—‘How the Devill, though subtle, was guld by a Scold’—‘The Devil’s Oak’—Raising the Devil—Arguments in Favour of Devils—The Numbers of Devils.

In the foregoing examples we have seen the Devil in human form, and properly apparelled, but occasionally he showed himself in his supposed proper shape—when, of course, his intentions were at once perceived; and on one occasion we find him called upon by an Angel, to execute justice on a bad man. It is in

STRANGE AND TRUE NEWS FROM WESTMORELAND.

Attend good Christian people all,

Mark what I say, both old and young,

Unto the general Judgment day,

I think it is not very long.

A Wonder strange I shall relate,

I think the like was never shown,

In Westmoreland at Tredenton,

Of such a thing was never known.

[Pg 14]

One Gabriel Harding liv’d of late,

As may to all men just appear,

Whose yearly Rent, by just account,

Came to five hundred pound a year.

This man he had a Virtuous Wife,

In Godly ways her mind did give:

Yet he, as rude a wicked wretch,

As in this sinful Land did live.

Much news of him I will relate,

The like no Mortal man did hear;

’Tis very new, and also true,

Therefore, good Christians, all give ear.

One time this man he came home drunk,

As he us’d, which made his wife to weep,

Who straightway took him by the hand,

Saying, Dear Husband, lye down and sleepe.

She lovingly took him by the arms,

Thinking in safety him to guide,

A blow he struck her on the breast,

The woman straight sank down and dy’d.

The Children with Mournful Cries

They ran into the open Street,

They wept, they wail’d, they wrung their hands,

To all good Christians they did meet.

The people then, they all ran forth,

Saying, Children, why make you such moan?

O, make you haste unto our house,

Our dear mother is dead and gone.

Our Father hath our Mother kill’d,

The Children they cryed then.

The people then they all made haste

And laid their hands upon the man.

He presently denied the same,

Said from Guilty Murder I am free,

If I did that wicked deed, he said,

Some example I wish to be seen by me.

Thus he forswore the wicked deed,

Of his dear Wife’s untimely end.

Quoth the people, Let’s conclude with speed,

That for the Coroner we may send.

[Pg 15]

Mark what I say, the door’s fast shut,

The People the Children did deplore,

But straight they heard a Man to speak,

And one stood knocking at the door.

One in the house to the door made haste,

Hearing a Man to Knock and Call,

The door was opened presently,

And in he came amongst them all.

By your leave, good people, then he said,

May a stranger with you have some talk?

A dead woman I am come to see;

Into the room, I pray, Sir, walk.

His eyes like to the Stars did shine,

He was clothed in a bright grass green,

His cheeks were of a crimson red,

For such a man was seldome seen.

Unto the people then he spoke,

Mark well these words which I shall say,

For no Coroner shall you send,

I’m Judge and Jury here this day.

Bring hither the Man that did the deed,

And firmly hath denied the same.

They brought him into the room with speed,

To answer to this deed with shame.

Now come, O wretched Man, quoth he,

With shame before thy neighbours all,

Thy body thou hast brought to Misery,

Thy soul into a deeper thrall.

Thy Chiefest delight was drunkeness,

And lewd women, O, cursed sin,

Blasphemous Oaths and Curses Vile

A long time thou hast wallowed in.

The Neighbours thou wouldst set at strife,

And alwaies griping of the poor,

Besides, thou hast murdered thy wife,

A fearful death thou dy’st therefore.

Fear nothing, good people, then he said,

A sight will presently appear,

Let all your trust be in the Lord,

No harm shall be while I am here.

[Pg 16]

Then in the Room the Devil appear’d,

Like a brave Gentleman did stand,

Satan (quoth he that was the Judge)

Do no more than thou hast command.

The Devil then he straight laid hold

On him that had murdered his wife,

His neck in Sunder then he broke,

And thus did end his wretched life.

The Devil then he vanished

Quite from the People in the Hall,

Which made the people much afraid,

Yet no one had no hurt at all.

Then straight a pleasant Melody

Of Musick straight was heard to sound,

It ravisht the hearts of those stood by,

So sweet the Musick did abound.

Now, (quoth this gallant Man in green)

With you I can no longer stay,

My love I leave, my leave I take,

The time is come, I must away.

Be sure to love each other well,

Keep in your breast what I do say.

It is the way to go to Heaven,

When you shall rise at Judgment day.

The people to their homes did go,

Which had this mighty wonder seen,

And said, it was an Angel sure

That thus was clothed all in green.

And thus the News from Westmoreland

I have related to you o’er,

I think it is as strange a thing,

As ever man did hear before.

In the old days the Devil was used as a butt at which people shot their little arrows of wit. In the miracle plays, when introduced, he filled the part of the pantaloon in our pantomimes, and was accompanied by a ‘Vice,’ who played practical jokes with him, slapping him with his wooden sword, jumping[Pg 17] on his back, etc.; and in the carvings of our abbeys and cathedrals, especially in the Miserere seats in the choir, he was frequently depicted in comic situations, as also in the illuminations of manuscripts. He was often written about as being sadly deficient in brains, and many are the instances recorded of him being outwitted by a shrewd human being, as we may see by the following ballad.

THE POLITIC WIFE;

or, The Devil outwitted by a Woman.

Of all the plagues upon the earth,

That e’er poor man befal,

It’s hunger and a scolding wife,

These are the worst of all:

There was a poor man in our country

Of a poor and low degree,

And with both these plagues he was troubled,

And the worst of luck had he.

He had seven children by one wife,

And the times were poor and hard,

And his poor toil was grown so bad,

He scarce could get him bread:

Being discontented in his mind,

One day his house he left,

And wandered down by a forest side,

Of his senses quite bereft.

As he was wandering up and down,

Betwixt hope and despair,

The Devil started out of a bush,

And appeared unto him there:

O what is the matter, the Devil he said,

You look so discontent?

Sure you want some money to buy some bread,

Or to pay your landlord’s rent.

Indeed, kind sir, you read me right,

And the grounds of my disease,

Then what is your name, said the poor man,

[Pg 18]Pray, tell me, if you please?

My name is Dumkin the Devil, quoth he,

And the truth to you I do tell,

Altho’ you see me wandering here,

Yet my dwelling it is in hell.

Then what will you give me, said the Devil,

To ease you of your want,

And you shall have corn and cattle enough,

And never partake of scant?

I have nothing to give you, said the poor man,

Nor nothing here in hand,

But all the service that I can do,

Shall be at your command.

Then, upon the condition of seven long years,

A bargain with you I will frame,

You shall bring me a beast unto this place,

That I cannot tell his name:

But, if I tell its name full right,

Then mark what to you I tell,

Then you must go along with me

Directly unto Hell.

This poor man went home joyfully,

And thrifty he grew therefore,

For he had corn and cattle enough,

And every thing good store.

His neighbours who did live around,

Did wonder at him much,

And thought he had robb’d or stole,

He was grown so wondrous rich.

Then for the space of seven long years

He lived in good cheer,

But when the time of his indenture grew near,

He began to fear:

O what is the matter, said his wife,

You look so discontent?

Sure you have got some maid with child,

And now you begin to repent.

Indeed, kind wife, you judge me wrong,

To censure so hard of me,

Was it for getting a maid with child,

That would be no felony:

But I have made a league with the Devil,

For seven long years, no more,

That I should have corn and cattle enough,

And everything good store.

[Pg 19]

Then for the space of seven long years

A bargain I did frame,

I should bring him a beast unto that place,

He could not tell its name:

But if he tell his name full right,

Then mark what to you I tell,

Then I must go along with him,

Directly unto Hell.

Go, get you gone, you silly old man,

Your cattle go tend and feed,

For a woman’s wit is far better than a man’s,

If us’d in time of need:

Go fetch me down all the birdlime you have,

And set it down on the floor,

And when I have pulled my cloathes all off,

You shall anoint me all o’er.

Now when he had anointed her

From the head unto the heel,

Zounds! said the man, methinks you look

Just like the very De’el.

Go, fetch me down all the feathers thou hast,

And lay them down by me,

And I will roll myself therein,

’Till never a place go free.

Come, tie a string about my neck,

And lead me to this place,

And I will save you from the Devil,

If I have but so much grace.

The Devil, he stood roaring out,

And looked both fierce and bold;

Thou hast brought me a beast unto this place,

And the bargain thou dost hold.

Come, shew me the face of this beast, said the Devil,

Come, shew it me in a short space;

Then he shewed him his wife’s buttocks,

And swore it was her face:

She has monstrous cheeks, the Devil he said,

As she now stands at length,

You’d take her for some monstrous beast

Taken by Man’s main strength.

How many more of these beasts, said the Devil,

How many more of this kind?

I have seven more such, said the poor man,

[Pg 20]But have left them all behind.

If you have seven more such, said the Devil,

The truth unto you I tell,

You have beasts enough to cheat me

And all the Devils in Hell.

Here, take thy bond and indenture both,

I’ll have nothing to do with thee:

So the man and his wife went joyfully home

And lived full merrily.

O, God send us good merry long lives,

Without any sorrow or woe,

Now here’s a health to all such wives

Who can cheat the Devil so.

There is

‘A Pleasant new Ballad you here may behold

How the Devill, though subtle, was guld by a Scold.’

The story of this ballad is, that the Devil, being much amused with this scolding wife, went to fetch her. Taking the form of a horse, he called upon her husband, and told him to set her on his back. This was easily accomplished by telling her to lead the horse to the stable, which she refused to do.

‘Goe leade, sir Knave, quoth she,

and wherefore not, Goe ride?

She took the Devill by the reines,

and up she goes astride.’

[Pg 21]And once on the Devil, she rode him; she kicked him, beat him, slit his ears, and kept him galloping all through Hell, until he could go no longer, when he concluded to take her home again to her husband.

‘Here, take her (quoth the Devill)

to keep her here be bold,

For Hell would not be troubled

with such an earthly scold.

When I come home, I may

to all my fellowes tell,

I lost my labour and my bloud,

to bring a scold to Hell.’

In another ballad, called ‘The Devil’s Oak,’ he is made out to be a very poor thing; the last verse says:

‘That shall be try’d, the Devil then he cry’d,

then up the Devil he did start,

Then the Tinker threw his staff about,

and he made the Devil to smart:

There against a gate, he did break his pate,

and both his horns he broke;

And ever since that time, I will make up my rhime,

it was called “The Devil’s Oak.”’

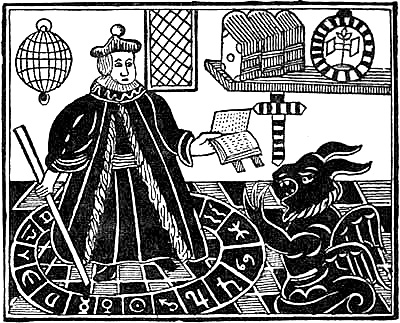

But popular belief credited to certain men the power of being able to produce the Devil in a visible form, and these were called necromancers, sorcerers, magicians, etc. Of them Roger Bacon was said to have been one, and Johann Faust, whom Goethe has immortalized, and whose idealism is such a favourite on the lyric stage. But Johann Faust was not at all the Faust of Goethe. He was the son of poor parents, and born at Knittlingen, in Würtemberg, at the end of the fifteenth century. He was educated at the University of Cracow,[Pg 22] thanks to a legacy left him by an uncle, and he seems to have been nothing better than a common cheat, called by Melancthon ‘an abominable beast, a sewer of many devils,’ and by Conrad Muth, who was a friend both of Melancthon and Luther, ‘a braggart and a fool who affects magic.’ However, he was very popular in England, and not only did Marlowe write a play about him, but there are many so-called lives of him in English, especially among the chap-books—in which he is fully credited with the power of producing the Devil in a tangible form by means of his magic art.

But the spirits supposed to be raised by these magicians were not always maleficent; they were more demons than devils. It will therefore be as well if we quote a competent and learned authority on the subject of devils.

Says Gyfford: ‘The Devils being the principall[Pg 23] agents, and chiefe practisers in witchcrafts and sorceryes, it is much to the purpose to descrybe them and set them forth whereby wee shall bee the better instructed to see what he is able to do, in what maner, and to what ende and purpose. At the beginning (as God’s word doth teach us) they were created holy Angels, full of power and glory. They sinned, they were cast down from heauen, they were utterly depriued of glory, and preserued for iudgement. This therefore, and this change of theirs, did not destroy nor take away their former faculties; but utterly corrupt, peruert, and depraue the same: the essence of spirits remayned, and not onely, but also power and understanding, such as is in the Angels: ye heavenly Angels are very mighty and strong, far above all earthly creatures in the whole world. The infernall Angels are, for their strength called principalityes and powers: those blessed ones applye all their might to set up and aduaunce the glory of God, to defend and succour his children: the deuils bend all their force against God, agaynst his glory, his truth and his people. And this is done with such fiercenes, rage and cruelty, that the holy ghost paynteth them out under the figure of a great red or fiery dragon, and roaring lyon, in very deed anything comparable to them. He hath such power and autority indeede, that hee is called the God of the world. His Kingdome is bound and inclosed within certayne limits, for he is ye prince but of darknes; but yet within his sayd dominion (which is in ignorance of God) he exerciseth a mighty[Pg 24] tyranny, our Saviour compareth him to a strong man armed which kepeth his castle.

‘And what shall we saie for the wisedome and understanding of Angels, which was giuen them in their creation, was it not far aboue that which men can reach unto? When they became diuels (euen those reprobate angels) their understanding was not taken awaie, but turned into malicious craft and subtiltie. He neuer doth any thing but of an euill purpose, and yet he can set such a colour, that the Apostle saith he doth change himselfe into the likenesse of an angell of light. For the same cause he is called the old serpent, he was subtill at the beginning, but he is now growne much more subtill by long experience, and continuall practise, he hath searched out and knoweth all the waies that may be to deceiue. So that, if God should not chaine him up, as it is set forth, Revel. 20, his power and subtiltie ioined together would overcome and seduce the whole world.

‘There be great multitudes of infernall spirits, as the holy scriptures doe euerie where shew, but yet they doe so ioine together in one, that they be called the divell in the singular number. They doe all ioine together (as our Saviour teacheth) to uphold one kingdome. For though they cannot loue one another indeede, yet the hatred they beare against God, is as a band that doth tye them together. The holie angels are ministring spirits, sent foorth for their sakes which shall inherit the promise. They haue no bodilie shape of themselues, but to set[Pg 25] foorth their speedinesse, the scripture applieth itselfe unto our rude capacitie, and painteth them out with wings.

‘When they are to rescue and succour the seruants of God, they can straight waie from the high heauens, which are thousands of thousands of miles distant from the earth, bee present with them. Such quicknesse is also in the diuels; for their nature being spirituall, and not loden with any heauie matter as our bodies are, doth afford unto them such a nimblenes as we cannot conceiue. By this, they flie through the world over sea and land, and espie out al aduantages and occasions to doe euill.’[3]

Indeed, ‘there be great multitudes of infernall spirits,’ if we can believe so eminent an authority upon the subject as Reginald Scott, who gives ‘An inuentarie of the names, shapes, powers, gouernement, and effects of diuels and spirits, of their seuerall segniories and degrees: a strange discourse woorth the reading.

‘Their first and principall King (which is of the power of the east) is called Baëll; who, when he is conjured up, appeareth with three heads; the first, like a tode; the second, like a man; the third, like a cat. He speaketh with a hoarse voice, he maketh a man go invisible, he hath under his obedience and rule sixtie and six legions of divels.’[4]

[Pg 26]All the other diabolical chiefs are described at the same length, but I only give their names, and the number of legions they command.

| Agares | 31 | |

| Marbas or Barbas | 36 | |

| Amon or Aamon | 40 | |

| Barbatos | 30 | |

| Buer | 50 | |

| Gusoin | 40 | |

| Botis or Otis | 60 | |

| Bathin or Mathinn | 30 | |

| Purson or Curson | 22 | |

| Eligor or Abigor | 60 | |

| Leraie or Oray | 30 | |

| Valefar or Malefar | 10 | |

| Morax or Foraij | 36 | |

| Ipos or Ayporos | 36 | |

| Naberius or Cerberus | 19 | |

| Glasya Labolas or Caacrinolaas | 36 | |

| Zepar | 26 | |

| Bileth | 85 | |

| Sitri or Bitru | 60 | |

| Paimon | 20 | |

| Belial | none | |

| Bune | 30 | |

| Forneus | 29 | |

| Ronoue | 19 | |

| Berith | 26 | |

| Astaroth | 40 | |

| Foras or Forcas | 29 | |

| Furfur | 26 | |

| Marchosias | 30 | |

| Malphas | 40 | |

| Vepar or Separ | 29 | |

| Sabnacke or Salmac | 50 | |

| Sidonay or Asmoday | 72 | |

| Gaap or Tap | 36 | |

| Shax or Scox | 30 | |

| Procell | 48 | |

| Furcas | 20 | |

| Murmur | 30 | |

| Caim | 30 | |

| Raum or Raim | 30 | |

| Halphas | 26 | |

| Focalor | 3 | |

| Vine | none | |

| Bifrons | 26 | |

| Gamigin | 30 | |

| Zagan | 33 | |

| Orias | 30 | |

| Valac | 30 | |

| Gomory | 26 | |

| Decarabia or Carabia | 30 | |

| Amduscias | 29 | |

| Andras | 30 | |

| Andrealphus | 30 | |

| Ose | none | |

| Aym or Haborim | 26 | |

| Orobas | 20 | |

| Vapula | 36 | |

| Cimeries | 20 | |

| Amy | 36 | |

| Flauros | 20 | |

| Balam | 40 | |

| Allocer | 36 | |

| Vuall | 37 | |

| Saleos | none | |

| Haagenti | 33 | |

| Phœnix | 20 | |

| Stolas | 26 |

‘Note that a legion is 6666, and now by multiplication count how manie legions doo arise out of euerie particular,’

Or a grand total of 14,198,580 devils, not including their commanders.

How many of these fall to the share of England? I know not, but they were very active in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, especially in the seventeenth. They seem to us, nowadays, to have frittered away their energies in attending on witches, in entering into divers[Pg 27] persons and tormenting them, and in making senseless uproars and playing practical jokes. Let us take about half a dozen of these latter. Say, for argument sake, that they are not very abstruse or intellectual reading; at all events, they are as good as the modern stories of spiritual manifestations, and are as trustworthy.

‘The Just Devil of Woodstock’—Metrical Version—Presumed Genuine History of ‘The Just Devil of Woodstock.’

THE JUST DEVIL OF WOODSTOCK.[5]

‘The 16 day of October in the year of our Lord 1649, The Commissioners for surveying and valuing his Majesties Mannor House, Parks, Woods, Deer, Demesnes, and all things thereunto belonging, by Name Captain Crook, Capt. Hart, Capt. Cockaine, Capt. Carelesse, and Capt. Roe their Messenger, with Mr. Brown their Secretary, and two or three servants, went from Woodstock town (where they had lain some nights before) and took up their lodgings in his Majesties House, after this manner: The Bedchamber and withdrawing room, they both lodged in, and made their Kitchin; the Presence Chamber their room for dispatch of business with all commers: of the Councel Hall, their Brewhouse, as of the Dining room, their Woodhouse, where they laid in the clefts, of that antient standard in the High-Park, for many ages beyond memory,[Pg 29] known by the Name of the Kings Oak, which they had chosen out, and caused to be dug up by the Roots.

‘Octob. 17. About the middle of the night, these new guests were first awaked, by a knocking at the Presence Chamber door, which they also conceived did open, and something to enter, which came through the room, and also walkt through the withdrawing room into the Bed chamber, and there walkt about that room with a heavy step during half an hour; then crept under the bed where Captain Hart, and Capt. Carelesse lay, where it did seeme (as it were) to bite and gnaw the Mat and Bed-coards, as if it would tear and rend the feather beds, which having done a while, then would they heave a while, and rest; then heave them up again in the bed more high than it did before, sometime on the one side, sometime on the other, as if it had tried which Captain was heaviest; thus having heaved for some half an hour, from thence it walkt out, and went under the servants’ bed, and did the like to them; thence it walkt into a withdrawing room, and there did the same to all who lodged there: Thus having welcomed them for more than two hours space, it walked out as it came in, and shut the outer door again, but with a clap of some mightie force; these guests were in a sweat all this while, but out of it falling into a sleep again, it became morning first before they spoke their minds, then would they have it to be a Dog, yet they described it more to the likenesse of a great Bear, so fell to examining under the Beds, where finding[Pg 30] only the Mats scratcht, but the Bed-coards whole, and the quarters of Beef which lay on the floor untoucht, they entertained other thoughts.

‘Octob. 18. They were all awaked, as the night before, and now conceived that they heard all the great clefts of the Kings Oak brought into the Presence Chamber, and there thumpt down, and, after, roul about the room; they could hear their chairs and stools tost from one side of the room unto the other; and then (as it were) altogether jostled; thus having done an hour together, it walkt into the withdrawing room, where lodged the two Captains, the Secretary, and two servants; here stopt the thing a while, as if it did take breath, but raised a hideous tone, then walkt into the Bed-chamber, where lay those as before, and under the Bed it went, where it did heave, and heave again, that now they in bed were put to catch hold upon Bed-posts, and sometimes one of the other, to prevent their being tumbled out upon the ground; then coming out as from under the bed, and taking hold upon the bed-posts, it would shake the whole bed, almost as if a cradle rocked; Thus, having done here for half an hour, it went into the withdrawing room, where first it came and stood at the bed’s feet, and heaving up the bed’s feet, flopt down again a while, until at last it heaved the feet so high, that those in bed thought to have been set upon their heads, and having thus for two hours entertained them, went out as in the night before, but with a great noise.

‘Octob. 19. This night they awaked, not until the midst of the night, they perceived the room to shake,[Pg 31] with something that walkt about the bed-chamber, which, having done so for a while, it walkt into a withdrawing room, where it took up a Brasse warming-pan, and returning with it into the bed-chamber, therein made so loud a noise, in these Captains’ own words, it was as loud and scurvie as a ring of five untuned Bells rang backward, but the Captains, not to seem afraid, next day made mirth of what had past, and jested at the Devil in the pan.

‘Octob. 20. These Captains and their Company, still lodging as before, were wakened in this night with some things flying about the rooms, and out of one room into the other, as thrown with some great force: Captain Hart being in a slumber, was taken by the shoulder and shaked until he did sit up in his bed, thinking that it had been by one of his fellows, when suddenly he was taken on the Pate with a Trencher, that it made him shrink down into the bed-clothes, and all of them, in both rooms, kept their heads, at least, within their sheets, so fiercely did three dozen of Trenchers, fly about the rooms; yet Captain Hart ventured again to peep out to see what was the matter, and what it was that threw, but then the Trenchers came so fast and neer about his ears, that he was fain to couch again: In the morning they found all their Trenchers, Pots and Spits, upon and about the rooms; this night there was also in several parts of the room, and outer rooms, such noises of beating at doors, and on the Walls, as if that several Smiths had been at work; and yet our Captains shrunk not from their[Pg 32] work, but went on in that, and lodged as they had done before.

‘Octob. 21. About midnight, they heard great knocking at every door, after a while, the doors flew open, and into the withdrawing room entred something, as of a very mighty proportion, the figure of it they knew not how to describe; this walkt a while about the room, shaking the floor at every step, then came it close to the bed side, where lay Captains Crook and Carelesse; and, after a little pause, as it were, The bed-curtains, both at sides and feet, were drawn up and down, slowly, then faster again for a quarter of an hour, then from end to end as fast as imagination could fancie the running of the rings, then shaked it the beds, as if the joints thereof had crackt; then walkt the thing into the bed-chamber, and so plaied with those beds there: Then took up eight Pewter-dishes, and bouled them about the room, and over the servants in the truckle beds; then sometimes were the dishes taken up, and throwne crosse the high beds, and against the walls, and so much battered; but there were more dishes wherein was meat in the same room, that were not at all removed: During this, in the Presence Chamber there was stranger noise of weightie things thrown down, and as they supposed, the clefts of the King’s Oak did roul about the room, yet at the wonted hour went away, and left them to take rest, such as they could.

‘October 22. Hath mist of being set down, the Officers imployed in their work farther off, came not that day to Woodstock.

[Pg 33]‘October 23. Those that lodged in the withdrawing room, in the midst of the night were awakened with the cracking of fire, as if it had been with thorns and sparks of fire burning, whereupon they supposed that the bed chamber had taken fire, and, listening to it farther, they heard their fellows in bed sadly groan, which gave them to suppose they might be suffocated, wherefore they call’d upon their servants to make all possible hast to help them; when the two servants were come in, they found all asleep, and so brought back word, but that there were no bedclothes upon them, wherefore they were sent back to cover them, and to stir up and mend the fire; when the servants had covered them, and were come to the chimney, in the corners they found their wearing apparel, boots and stockings, but they had no sooner toucht the Embers, when the firebrands flew about their ears so fast, that away ran they into the other room, for the shelter of their cover-lids, then after them walkt something that stampt about the room, as if it had been exceeding angry, and likewise threw about the Trenchers, Platters, and all such things in the room; after two hours went out, yet stampt again over their heads.

‘October 24. They lodged all abroad.

‘October 25. This afternoon came unto them Mr. Richard Crook, the Lawyer, brother to Captain Crook, and now Deputy-Steward of the Mannor, unto Captain Parsons, and Major Butler, who had put out Mr. Hyans his Majesties Officer: To entertain this new guest the Commissioners caused a very great[Pg 34] fire to be made, of neere the chimney full of wood, of the King’s Oak, and he was lodged in the withdrawing room with his brother, and his servant in the same room: about the midst of the night a wonderful knocking was heard, and into the room something did rush, which, coming to the chimney side, dasht out the fire, as with the stamp of some prodigious foot, then threw down such weighty stuffe, what ere it was (they took it to be the residue of the clefts and roots of the King’s Oak) close by the bed side, that the house and bed shook with it. Captain Cockain and his fellow arose and took their swords to go unto the Crooks, the noise ceased at their rising, so that they came to the door, and called; the two brothers, though fully awaked, and heard them call, were so amazed, that they made no answer, untill Captain Cockaine had recovered the boldness to call very loud, and came unto their bed-side; then, faintly first, after some more assurance, they came to understand one another, and comforted the lawyer: Whilst this was thus, no noise was heard, which made them think the time was past of that nights troubles, so that, after some little conference, they applied themselves to take some rest. When Captain Cockaine was come to his own bed, which he had left open, he found it closely covered, which he much wondered at, but turning the clothes down, and opening it to get in, he found the lower sheet strewed over with trenchers, their whole three dozens of trenchers were orderly disposed between his sheets, which he and his fellow endeavouring to cast out, such noise arose about the room, that they[Pg 35] were glad to get into bed with some of the trenchers; the noise lasted a full half hour after this. This entertainment so ill did like the Lawyer, and being not so well studied in the point, as to resolve this the Devil’s Law-case, that he, next day, resolved to begone, but, not having dispatcht all that he came for, profit and perswasions prevailed with him to stay the other hearing, so that he lodged as he did the night before.

‘Octob. 26. This night each room was better furnished with fire and candle than before; yet about twelve at night came something in, that dasht all out, then did walk about the room, making a noise, not to be set forth by the comparison with any other thing, sometimes came it to the bed-sides, and drew the Curtains to and fro, then twerle them, then walk about again, and return to the bed-posts, shake them with all the bed, so that they in bed were put to hold one upon the other; then walk about the room again, and come to the servants bed, and gnaw the wainscot head—and shake altogether in that room; at the time of this being in doing, they in the bed-chamber heard such strange dropping down from the roof of the room, that they supposed ’twas like the fall of money by the sound. Captain Cockaine not frighted with so small a noise (and lying near the chimney) stept out, and made shift to light a candle, by the light of which he perceived the room strewed over with broken glass, green, and some as it were pieces of broken bottles. He had not long been considering what it was, when suddainly his candle was hit out, and glass flew[Pg 36] about the room, that he made haste to the protection of the Coverlets, the noise of thundering rose more hideous than at any time before; yet, at a certain time, all vanisht into calmness. The morning after, was the glass about the room, which the maid, that was to make clean the rooms, swept up into a corner, and many came to see it. But Mr. Richard Crooke would stay no longer, yet as he stopt, going through Woodstock Town, he was there heard to say, that he would not lodge amongst them another night, for a Fee of £500.

‘Octob. 27. The Commissioners had not yet done their work, wherefore they must stay, and, being all men of the sword, they must not seem afraid to encounter with anything, though it be the Devill, therefore, with pistols charged, and drawn swords laied by their bed sides, they applied themselves to take some rest, when something, in the midst of night, so opened and shut the window casements, with such claps, that it awakened all that slept; some of them peeping out to look what was the matter with the windows, stones flew about the rooms as if hurled with many hands; some hit the walls, and some the bed’s head close above the pillows; the dints of which were then, and yet (it is conceived) are to be seen, thus sometime throwing stones; and sometime making thundering noise; for two hours space it ceast, and all was quiet till the morn. After their rising, and the maid come in to make the fire, they looked about the rooms; they found fourscore stones brought in that night, and, going to lay them together, in the corner,[Pg 37] where the glass (before mentioned) had been swept up, they found that every piece of glass had been carried away that night: many people came next day to see the stones, and all observed that they were not of such kind of stones as are naturall in the countrey thereabout; with these were noises like claps of thunder, or report of Cannon planted against the rooms; heard by all that lodged in the outer courts, to their astonishment; and at Woodstock Town, taken to be thunder.

‘Octob. 28. This night, both strange and differing noise from the former, first wakened Captain Hart who lodged in the bed-chamber, who hearing Roe and Brown to groan, called out to Cockaine and Crooke to come and help them, for Hart could not now stir himself. Cockaine would faine have answered, but he could not, or look about, something he thought, stopt both his breath and held down his eye lids. Amazed thus, he struggled and kickt about, till he had awaked Captain Crook, who, half asleep, grew very angry at his kicks, and multiplied words till it grew to an appointment in the field: but this fully recovered Cockaine to remember that Captain Hart had called for help, wherefore to them he ran in the other room, whom he found sadly groaning: where scraping in the chimney he found a candle and fire to light it; but had not gone two steps, when something blew the candle out, and threw him in the chair by the bed side, when presently cried out Captain Careless, with a most pittiful voice, Come hither, O come hither, brother Cockaine, the thing’s gone off me. Cockaine scarce[Pg 38] yet himself, helpt to set him up in his bed, and, after, Captain Hart; and having scarce done that to them, and also to the other two, they heard Captain Crook crying out, as if something had been killing him; Cockaine snacht up the sword that lay by their bed, and ran into the room to save Crook, but was in much more likelyhood to kill him, for at his coming the thing that pressed Crook, went off him, at which Crook started out of his bed, when Cockaine thought a spirit made at him, at which Crook cried out Lord help, Lord save me; Cockaine let fall his hand, and Crook embracing Cockaine desired his reconcilement: giving him many thanks for his deliverance, then rose they all and came together, discoursed sometimes godly, and sometimes praied, for all this while was there such stamping over the roof of the house, as if 1,000 horse had there been trotting. This night, all the stones brought in the night before, and laid up in the withdrawing room, were all carried away again by that which brought them in, which at the wonted time, left off, and, as it were, went out, and so away.

‘Octob. 29. Their businesse having now received so much forwardnesse, as to be neer dispatcht, they encouraged one the other, and resolved to try further, therefore they provided more lights and fires, and further, for their assistance, prevailed with their Ordinary Keeper to lodge amongst them, and bring his Mastive Bitch, and it was so this night with them, that they had no disturbance at all.

‘Octob. 30. So well had they past the night before, that this night they went to bed confident[Pg 39] and carelesse, untill, about 12 of the clock, something knockt at the door as with a smith’s great hammer, but with such force as if it had cleft the door; then entred something like a Bear, but seem’d to swell more big and walkt about the room, and out of one room into the other; treading so heavily, as the floore had not been strong enough to bear it; when it came to the bed chamber, it dasht against the beds heads some kind of glasse vessell, that broke in sundry pieces; and, sometimes, it would take up those pieces, and hurle them about the room, and into the other room; and when it did not hurle the glasse at their heads, it did strike upon the tables as if many smiths, with their greatest hammers, had been laying on as upon an anvill: sometimes it thumpt against the walls, as if it would beat a hole through; then upon their heads such stamping, as if the roof of the house were beating down upon their heads, and, having done thus during the space (as was conjectured) of two hours, it ceased and vanished, but with a more fierce shutting of the doors than at any time before. In the morning they found the pieces of glass about the room, and observed that it was much differing from that glasse, brought in three nights before, this being of a much thicker substance, which severall persons which came in carried away some pieces of. The Commissioners were in debate of lodging there no more, but all their businesse was not done, and some of them were so conceited as to believe, and to attribute the rest they enjoyed the night before this last unto the Mastive bitch; wherefore they resolved to get more[Pg 40] company, and the Mastive bitch, and try another night.

‘Octob. 31. This night, the fires and lights prepared, the Ordinary Keeper and his bitch, with another man persuaded by him, they all took their beds, and fell asleep. But, about 12 at night, such rapping was on all sides of them, that it wakened all of them. As the doors did seem to open, the Mastive bitch fell fearfully a yelling, and presently ran fiercely into the bed to them in the truckle bed. As the thing came by the table, it struck so fierce a blow on that, as that it made the frame to crack; then took the warming pan from off the table and stroke it against the walls with so much force as that it was beat flat together, lid and bottom; now were they hit as they lay covered over head and ears within the bedclothes; Captain Carelesse was taken a sound blow on the head with the shoulder blade-bone of a dead Horse (before, they had been but thrown at when they peept up, and mist,) Brown had a shrewd blow on the leg with the back bone, and another on the head; and everyone of them felt severall blows of bones and stones through the bed clothes, for now these things were thrown as from an angry hand that meant further mischief; the stones flew in at the window as if shot out of a Gun, nor was the bursts lesse (as from without) than of a Cannon, and all the windows broken down. Now, as the hurling of the things did cease, and the thing walkt up and down, Captains Cockaine and Hart cried out, In the Name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, What are you? what would you have? what[Pg 41] have we done that you disturb us thus? No voice replied (as the Captains said, yet some of their servants have said otherwise) and the noise ceast. Hereupon Captains Hart and Cockaine rose, who lay in the Bed-chamber, renewed the fire and lights, and one great candle in a candlestick they placed in the door, that might be seen by them in both the rooms; no sooner were they got to bed, but the noise arose on all sides more loud and hideous than at any time before, in so much (as to use the Captain’s own words) it returned and brought seven Devils worse than itself; and, presently, they saw the candle and candlestick in the passage of the door, dasht up to the roof of the room, by a kick of the hinder parts of a Horse, and after, with the Hoof trod out the snuffe, and so dasht out the Fire in the Chimnies. As this was done, there fell, as from the sieling, upon them in the Truckle beds, such quantities of water, as if it had been poured out of Buckets, which stunk worse than any earthly stink could make. And, as this was in doing, something crept under the High Beds, tost them up to the roof of the House, with the Commissioners in them, until the Testers of the Beds were beaten down upon them, and the Bedsted-frames broke under them. And here, some pause being made, they all, as if with one consent, started up, and ran down the stairs until they came into the Counsel-Hall, where two sate up a Brewing, but were now fallen asleep; those they scared much with wakening of them, having been much perplext before with the strange noise, which commonly was taken by them abroad[Pg 42] for thunder, sometimes for rumbling wind; here the Captains and their company got fire and candle, and everyone carrying something of either, they returned into the Presence-Chamber, where some applied themselves to make the fire, whilst others fell to Prayers, and, having got some clothes about them, they spent the residue of the night in singing Psalms and Prayers; during which, no noise was in that room, but most hideously round about, as at some distance.

‘It should have been told before, how that when Captain Hare first rose this night (who lay in the Bed-Chamber next the fire) he found their Book of valuations crosse the embers smoaking, which he snacht up, and cast upon the Table there, which, the night before, was left upon the Table in the presence, amongst their other papers. This Book was, in the morning, found a handful burnt, and had burnt the Table where it lay; Brown the Clerk said, he would not for a 100 and a 100l. that it had been burnt a handful further.

‘This night it happened that there were six Cony-stealers, who were come with their Nets and Ferrets to the Cony-burrows by Rosamond’s Well, but with the noise this night from the Mannor-house, they were so terrified, that, like men distracted, away they ran, and left their Haies all ready pitched, ready up, and the Ferrets in the Cony-burrows.

‘Now the Commissioners, more sensible of their danger, considered more seriously of their safety, and agreed to go and confer with Mr. Hoffman, the Minister of Wotton (a man not of the meanest note[Pg 43] for life or learning, by some esteemed more high) to desire his advice, together with his company and prayers. Mr. Hoffman held it too high a point to resolve on suddenly and by himself, wherefore, desired time to consider upon it, which, being agreed unto, he forthwith rode to Mr. Jenkinson and Mr. Wheat, the two next Justices of Peace, to try what Warrant they could give him for it. They both (as ’tis said from themselves) encouraged him to be assisting to the Commissioners, according to his calling.

‘But certain it is, that when they came to fetch him to go with them, Mr. Hoffman answered, That he would not lodge there one night, for £500, and being askt to pray with them, he held up his hands, and said, That he would not meddle upon any terms.

‘Mr. Hoffman refusing to undertake the quarrel, the Commissioners held it not safe to lodge where they had been thus entertained, any longer, but caused all things to be removed into the Chambers over the Gatehouse, where they staid but one night, and what rest they enjoyed there, we have but an uncertain relation of, for they went away early the next morning; but if it may be held fit to set down what hath been delivered by the report of others, they were also the same night much affrighted with dreadful apparitions; but, observing that these passages spread much in discourse, to be also in particulars taken notice of, and that the nature of it made not for their cause, they agreed to the concealing[Pg 44] of the things for the future; yet this is well known and certain, that the Gate-keeper’s wife was in so strange an agony in her bed, and in her bed-chamber such noise (whilst her husband was above with the Commissioners) that two maids in the next room to her durst not venture to assist her, but, affrighted, ran out to call company, and their Master, and found the woman (at their coming in) gasping for breath: and the next day said that she saw and suffered that, which, for all the world, she would not be hired to again.

From Woodstock the Commissioners removed unto Euelme, and some of them returned to Woodstock, the Sunday sennight after (the Book of Valuations wanting something that was, for haste, left imperfect), but lodged not in any of those rooms where they had lain before, and yet were not unvisited (as they confess themselves) by the Devil, whom they called their nightly guest. Captain Crooke came not untill Tuesday night, and how he sped that night, the gate-keeper’s wife can tell, if she dareth; but, what she hath whispered to her gossips, shall not be made a part of this our Narrative, nor any more particulars which have fallen from the Commissioners themselves, and their servants to other persons; they are all, or most of them alive, and may add to it when they please, and, surely, have not a better way to be revenged of him who troubled them, than according to the Proverb, tell truth and shame the Devil.

There remains this observation to be added, that on a Wednesday morning, all these Officers went away;[Pg 45] And that, since then, diverse persons of severall qualities, have lodged often and sometimes long in the same rooms both in the presence, withdrawing room and bed Chamber belonging unto his Sacred Majesty, yet none have had the least disturbance, or heard the smallest noise, for which the cause was not as ordinary, as apparent; except the Commissioners and their company, who came in order to the alienating and pulling down the house, which is well nigh performed.’

As to the authenticity of the above, we are told in the Preface: ‘And now, as to the Penman of this Narrative, know that he was a Divine, and, at the time of those things acted, which are here related, the Minister and Schoolmaster of Woodstock, a person learned and discreet, nor byassed with factious humours, his name Widows, who, each day, put in writing what he heard from their mouthes, (and such things as they told to have befallen them the night before), therein keeping to their own words.’

There was also a metrical account[6] of these strange doings, printed in the year in which they occurred; but although it exactly tallies with the prose as above, it is not written in so refined a strain.

The British Magazine for April, 1747 (vol. ii., p. 156) professes to give ‘The genuine history of the good devil of Woodstock, famous in the world[Pg 46] in the year 1649, and never accounted for, or at all understood to this time.’ It is by an anonymous writer, who says he found it in some original papers which had lately fallen into his hands, ‘under the name of authentick memoirs of the memorable Joseph Collins of Oxford, commonly known by the name of funny Joe,’ and it puts forth that this said Joe, under the name of Giles Sharp, entered the service of the Commissioners as a servant, and with the help of two friends, an unknown trap-door in the ceiling of the bedchamber, and some fulminating mercury, played the part of the Devil; but as the document is not known to be in existence, and is only mentioned in the pages of a magazine a hundred years afterwards, the reader may attach whatever credit he pleases to it. At all events, it proves that something very extraordinary, according to popular rumour, did take place at Woodstock during the Commissioners’ occupation.

‘The Dæmon of Tedworth.’

‘THE DÆMON OF TEDWORTH.[7]

‘Master John Mompesson, of Tedworth in Wiltshire, being about the middle of March, in the year 1661, at a neighbouring Town, called Ludgarshal, heard a Drum beat there, and being concerned as a Commission Officer in the Militia, he enquired of the Bayliffe of the Town, at whose House he then was, what it meant. The Bayliffe told him that they had for some dayes been troubled by that Idle Drummer, who demanded money of the Constable, by virtue of a pretended pass, which he thought was counterfeit. Upon this Information Master Mompesson sent for the fellow, and ask’d him by what Authority he went up and down the Countrey in that manner, demanding money, and keeping a clutter with his Drum? The Drummer answered he had good Authority, and produced his pass, with a warrant under the hands of Sir William Cawly and Colonel Ayliffe of Gretenham. These papers[Pg 48] discover’d the knavery, for M. Mompesson knowing those Gentlemen’s hands, found that his pass and warrant were forgeries; and upon the discovery, commanded the vagrant to put off his Drum, and charged the Constable to carry him to the next Justice of Peace, to punish him according to the desert of his Insolence and Roguery. The fellow then confest the cheat, and begg’d earnestly for his Drum. But M. Mompesson told him that if he understood from Colonel Ayliffe, whose Drummer he pretended to be, that he had been an honest man, he should have it again; but in the interim he would secure it. So he left the Drum with the Bayliffe, and the Drummer in the Constable’s hands; who, it seems, after, upon intreaty, let him go.

‘About the midst of April following, when M. M. was preparing for a Journey to London, the Bayliffe sent the Drum to his house; and, being returned, his wife told him that they had been much affrighted in the night by Thieves, during his absence; and that the House had like to have been broken up. He had not been at home above three nights, when the same noise returned that had disturbed his Family when he was abroad. It was a very great knocking at his Doors, and the out side of his House. M. M. arose, and with a brace of Pistols in his hands, went up and down searching for the cause of the Disturbance. He open’d the door, where the great knocking was, and presently the noise was at another. He opened that also, and went forth, rounding his House, but could discover nothing; only he still heard a strange noise and[Pg 49] hollow sound; but could not perceive what was the occasion of it. When he was returned to his Bed, the noise was a Thumping and Drumming on the top of his House, which continued a good space, and then by degrees went off into the Air.

‘After this It would come 5 nights together, and absent itself 3. Knocking very hard at the out-sides of the House, which is most of it, of Board. This It did, constantly, as they were going to sleep, either early or late. After a month’s racket without, It came into the room where the Drum lay, where It would be 4 or 5 nights in 7, making great hollow sounds, and sensibly shaking the Beds and Windows. It would come within half an hour after they were in Bed, and stay almost two. The sign of Its approach was an hurling in the Air over the House; and at Its recess they should hear a Drum beat, like the breaking up of a Guard. It continued in this Room for the space of two months; the Gentleman himself lying there to observe It: and though It was very troublesome in the fore part of the night, yet, after two hours disturbance, It would desist, and leave all in quietness: At which time perhaps the Laws of the Black Society required Its presence at the general Rendezvous elsewhere.

‘About this time the Gentleman’s Wife was brought to Bed; the noise came a little that night she was in Travail, but then forbore for three weeks till she had recover’d strength. After this civil cessation, it return’d in a ruder manner than before, applying wholly to the younger children; whose Bedsteads It would beat with that violence that all[Pg 50] present would expect, when they would fall in pieces. Those that laid their hands upon them, could feel no blows, but perceived them to shake exceedingly. It would for an hour together beat, what they Call Roundheads and Cuckolds—the Tattoo, and several other Points of Warre, and that as dextrously as any Drummer. After which It would get under the Bed, and scratch there as if It had Iron Tallons. It would lift the children up in their Beds, follow them from one room to another; and, for a while, applied to none particularly but them.

‘There was a Cock-loft in the House which had been observed hitherto to be untroubled; thither they removed their children, putting them to bed while it was fair day: and yet they were no sooner covered, but the unwelcome Visitant was come, and played his tricks as before.

‘On the 5th of Novemb. 1662. It kept a mighty noise, and one of the Gentleman’s Servants observing two Boards in the children’s room that seemed to move, he bade It give him one of them, and presently the Board came within a yard of him. The Fellow added, Nay, let me have it in my hand: upon which it was shuft quite home. The man thrust it back, and the Dæmon returned it to him, and so from one to another at least 20 times together, till the Gentleman forbad his servant such Familiarities. That morning It left a Sulphurous smell behind It, very displeasant and offensive.... At night the Minister of the place, Mr. Cragge, and many of the Neighbours came to the House—and went to prayer at the Children’s Bed-side, where, at that time It was[Pg 51] very troublesome and loud. During the time of Prayer It with-drew into the Cock-Loft, but, the Service being ended, It returned; and in the sight and presence of the company, the Chairs walked about the Room, the Children’s Shooes were thrown over their heads, and every loose thing moved about the Chamber; also a Bed staffe was thrown at the Minister, which hit him on the Leg, but so favourably, that a lock of Wooll could not have fallen more softly. And a circumstance more was observed, viz., that it never in the least roul’d, nor mov’d from the place where it lighted.

‘The Gentleman perceiving that It so much persecuted the little Children, lodg’d them out at a Neighbour’s House, and took his eldest daughter, who was about 10 years of Age, into his own Chamber, where It had not been in a month before. But no sooner was she in Bed, but the troublesome Guest was with her, and continued his unquiet visits for the space of three weeks, during which time It would beat the Drum, and exactly answer any Tune that was knock’d, or called for. The House where the Gentleman had lodged his Children, being full of Strangers, he was forced to take them home again; and, because they had never observed any disturbance in the Parlor, he laid them there, where also their old Visitant found them; but, at this time, troubled them no otherwise than by plucking them by the hair and night-cloathes.

‘It would sometimes lift up the Servants with their Beds, and lay them down again gently, without any more prejudice than the fright of being[Pg 52] carried to the Drummer’s quarters. And at other times It would lie like a great weight upon their Feet.

‘’Twas observed, that when the noise was loudest, and came with the most suddain and surprizing violence, yet no Dog would move. The Knocking was oft so boysterous and rude, that it hath been heard at a considerable distance in the Fields, and awakened the Neighbours in the Village, none of which live very near this house.