Title: Myths of the Rhine

Author: X.-B. Saintine

Illustrator: Gustave Doré

Translator: M. Schele de Vere

Release date: December 14, 2013 [eBook #44430]

Most recently updated: February 21, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

DESCRIPTIVE TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Primitive Times.—The First Settlers on the Rhine.—Masters going to School.—Sanskrit and Breton.—An Idle God.—Microscopic Deities.—Tree Worship.—Birth-Trees and Death-Trees.....003

The Druids and their Creed.—Esus.—The Holy Oak.—The Pforzheim Lime Tree.—A Rival Plant.—The Mistletoe and the Anguinufh.—The Oracle at Do-dona.—Immaculate Horses.—The Druidesses.—A late Elector.—Philanthropic Institution of Human Sacrifices.—Second Druidical. Epoch.....027

A Visit to the Land of our Forefathers.—The Two Banks of the Rhine.—Druid Stones.—Weddings and Burials.—Night Service.—A Demigod Glacier.—Social Duels.—A Countrywoman of Aspasia.—Boudoir of a Celtic Lady.—The Bard’s Story.—Teutons and Titans.—Earthquake.....055

The Roman Gods invade Germany.—Drusus and the Dru-idess.—Ogmius, the Hercules of Gaul.—Great Philological Discovery concerning Tentâtes.—Transformations of every kind.—Irmensul.—The Rhine deified.—The Gods cross the River.—Druids of the Third Epoch.....091

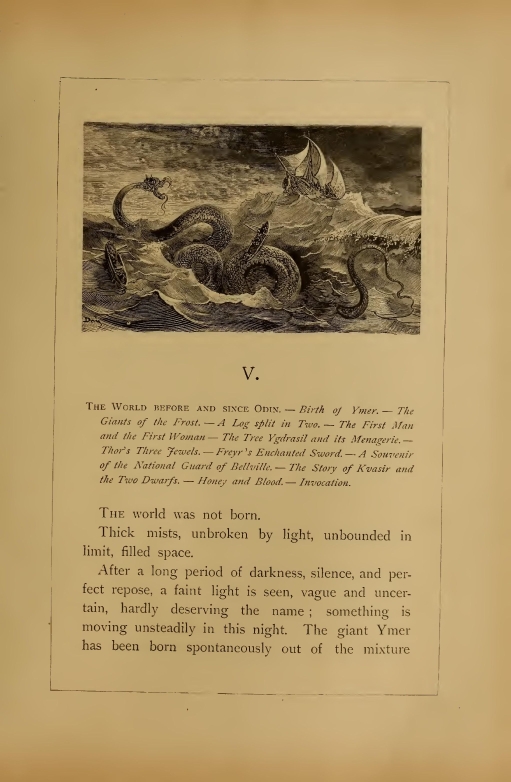

The World before and since Odin.—Birth of Ymer.—The Giants of the Frost.—A Log split in Two.—The First Man and the First Woman.—The Ash Ygdrasil and its Menagerie.—Thor’s Three Jewels.—Freyr’s Enchanted Sword.—A Souvenir of the National Guard of Belleville.—The Story of Kvasir and the Two Dwarfs.—Honey and Blood.—Invocation.....121

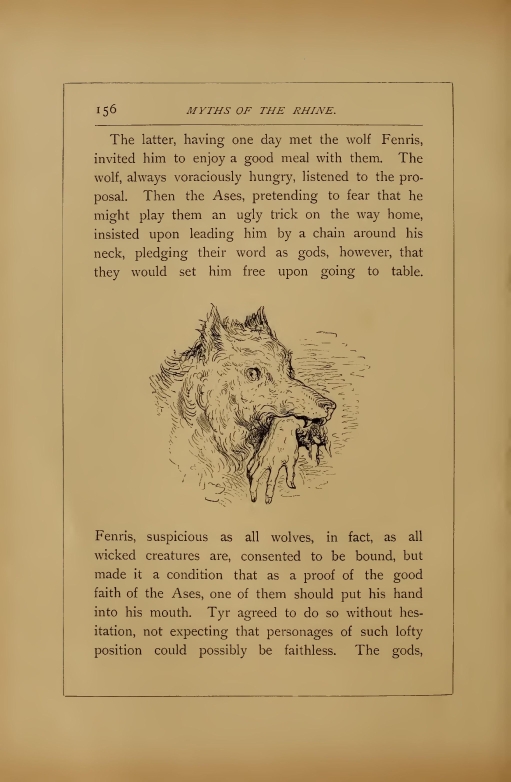

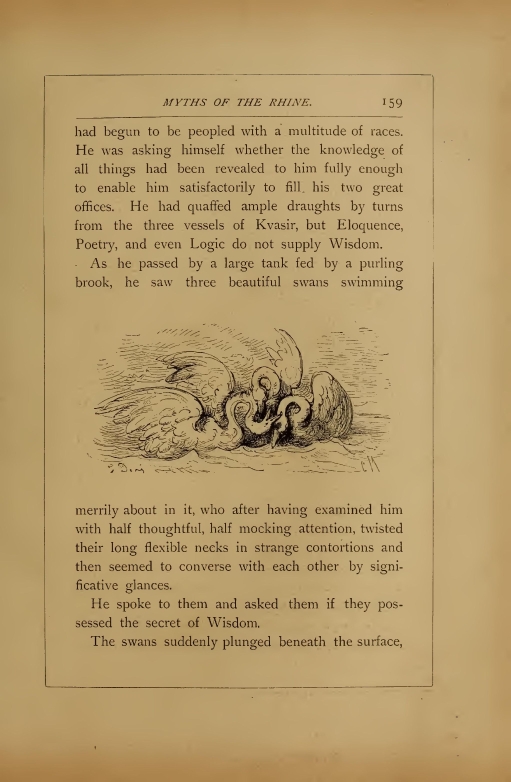

Short Biographies.—A Clairvoyant among the Gods.—A Bright God.—Tyr and the Wolf Fenris.—The Hospital at the Walhalla.—Why was Odin one-eyed.—The Three Norns.—Mimer the Sage.—A Goddess the Mother of Four Oxen.—The Love Affairs of Heimdall—The God with the Golden Teeth.....153

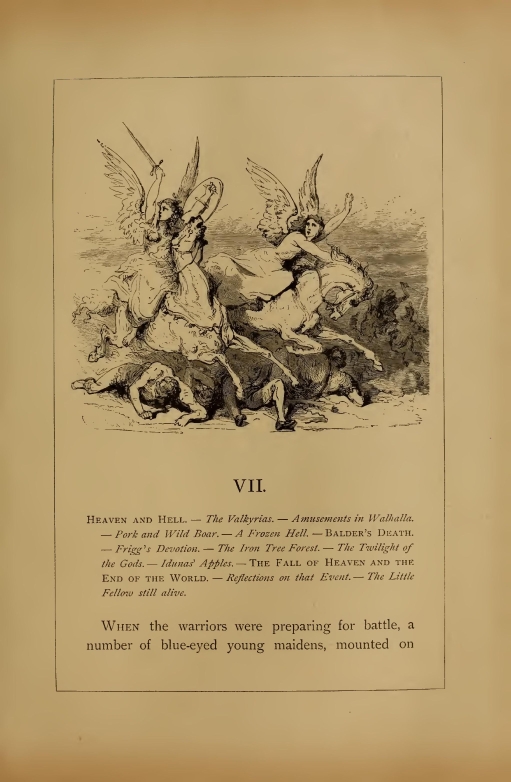

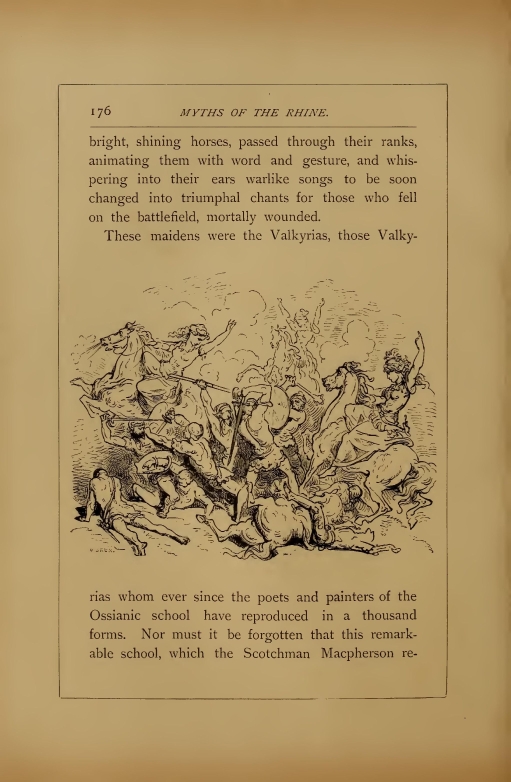

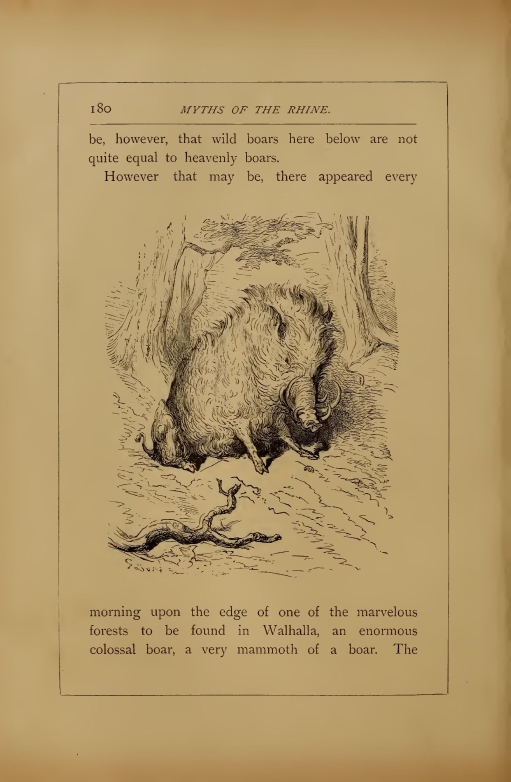

Heaven and Hell.—The Valkyrias.—Amusements in Walhalla.—Pork and Wild Boar.—A Frozen Hell.—Balder’s Death.—Frigg’s Devotion.—The Iron Tree Forest.—The Twilight of the Gods.—Iduna’s Apples.—The Fall of Heaven and the End of the World.—Reflections on that Event.—The Little Fellow still alive.....175

How the Gods of India live only for a Kalpa, that is, for the Time between one World and another.—How the God Vishnu was One-eyed.—How Celts and Scandinavians believed in Metempsychosis, like the Indians.—How Odin, with his Emanations, came forth from the God Buddha.—About Mahabarata and Ramavana.—Chronology.—The World’s Age.—Comparative Tables.—Quotations.—Supporting Evidence.—A Cenotaph.....211

Confederation of all the Northern Gods.—Freedom of Religion.—Christianity.—Miserere mei!—Homeric Enumeration.—Prussian, Slavic, and Finnish Deities.—The God of Cherries and the God of Bees.—A Silver Woman.—Ilmarinnen’s Wedding Song.—A Skeleton God.—Yaga-Baba’s Pestle and Mortar.—Preparation for Battle.—The Little Chapel on the Hill.—The Signal for the Attack.—Jesus and Mary.....217

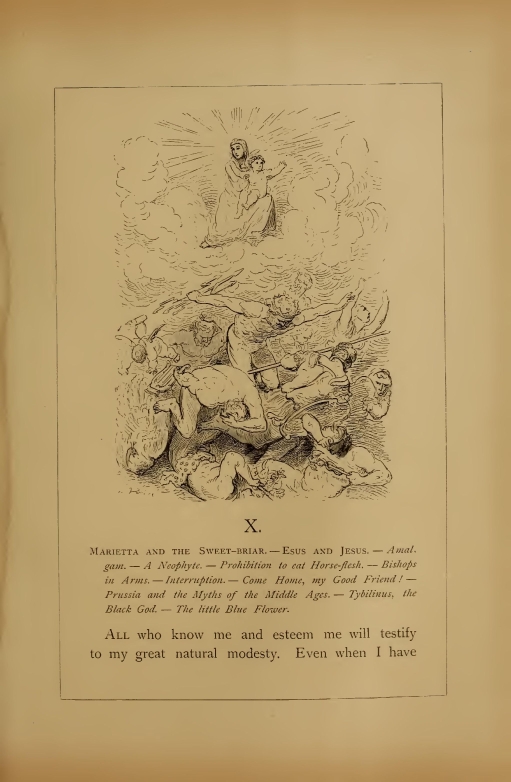

Marietta and the Sweet-briar.—Esus and Jesus.—Amalgam.—A Neophyte.—Prohibition to eat Horseflesh.—Bishops in Arms.—Interruption.—Come Home, my Good Friend!—Prussia and the Myths of the Middle Ages.—Tybilinus, the Black God.—The little Blue Flower.....245

Elementary Spirits of Air, Fire, and Water.—Sylphs, their Amusements and Domestic Arrangements.—Little Queen Mab.—Will-o’-the- Wisps.—White Elves and Black Elves.—True Causes of Natural Somnambulism.—The Wind’s Betrothed.—Fire-damp.—Master Haemmerling.—The Last of the Gnomes.....263

Elementary Spirits of the Water.—Petrarch at Cologne.—Divine Judgment by Water.—Nixen and Undines.—A Furlough till Ten o’clock.—The White footed Undine.—Mysteries on the Rhine.—The Court of the Great Nichus.—Nixcobt, the Messenger of the Dead.—His Funny Tricks.—I go in Search of an Undine.....283

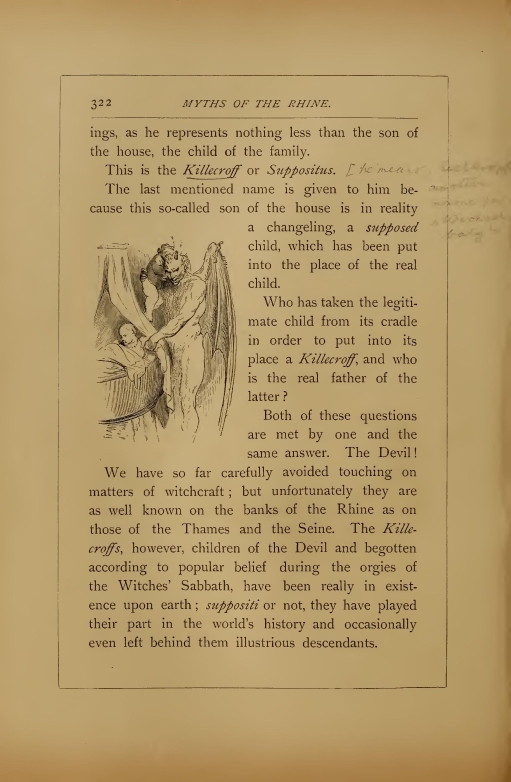

Familiar Spirits.—Butzemann.—The Good Frau Holle.—Kobolds.—A Kobold in the Cook’s Employ.—Zot-terais and the Little White Ladies.—The Killecroffs, the Devil’s Children.—White Angels.—Granted Wishes, a Fable.....309

Giants and Dwarfs.—Duel between Ephesim and Gromme-lund.—Court Dwarfs and Little Dwarfs.—Ymer’s Sons.—The Invisible Reapers.—Story of the Dwarf Kreiss and the Giant Quadragaat.—How the Giants came to serve the Dwarfs.....335

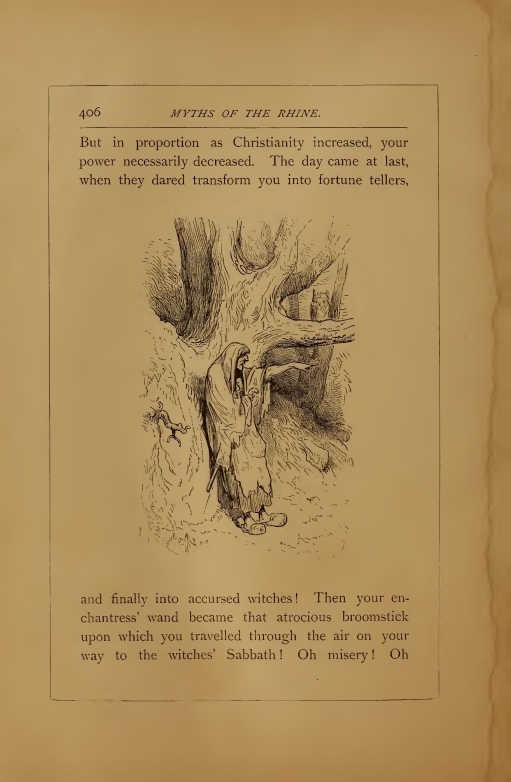

Wizards and the Bewitched.—The Journey of Asa-Thor and his Companions.—The Inn with the Five Passages.—Skrymner.—A Lost Glove found again.—Arrival at the Great City of Utgard.—Combat between Thor and the King’s Nurse.—Frederick Barbarossa and the Kyffhâuser.—Teutonia! Teutonia!—What became of the Ancient Gods.—Venus and the good Knight Tannhâuser.—Jupiter on Rabbit Island.—A Modern God.....371

Women as Missionaries, Women as Prophets, Strong Women, and Serpent Women.—Children’s Myths.—Godmothers.—Fairies.—The Magic Wand and the Broomstick.—The Lady of Kynast.—The World of the Dead, the World of Ghosts, and the World of Shadows.—Myths of Animals.....399

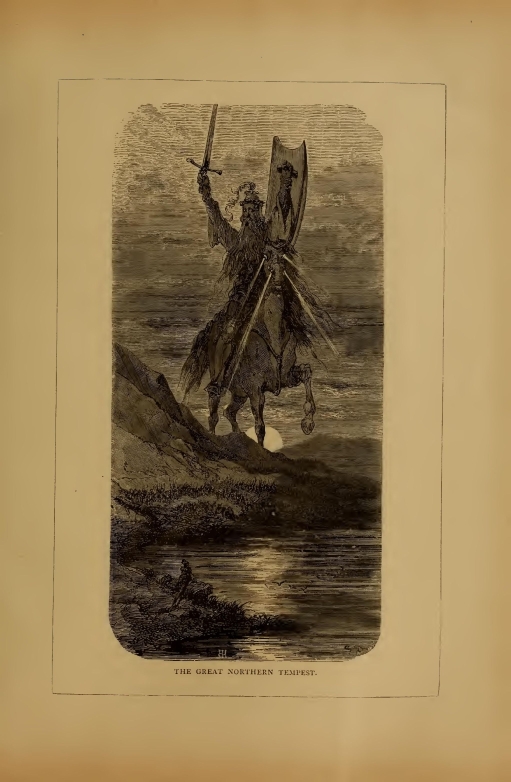

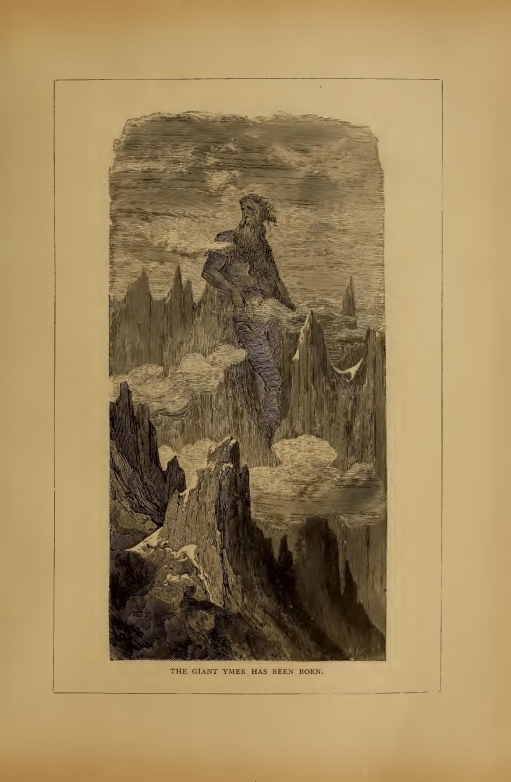

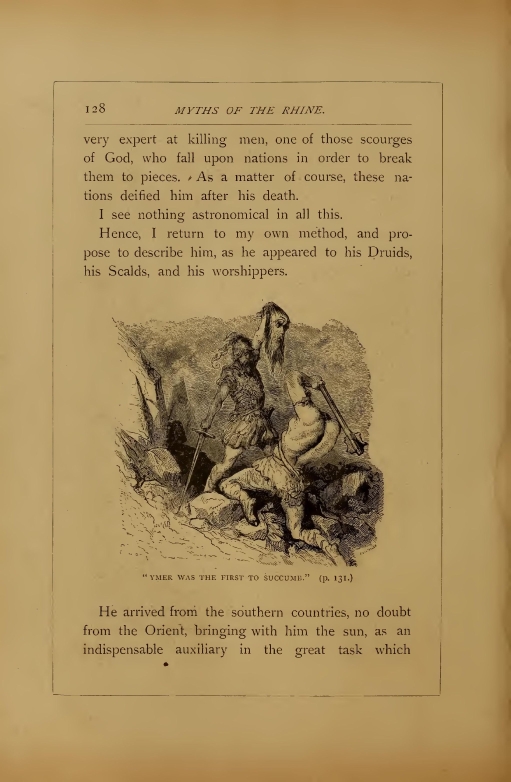

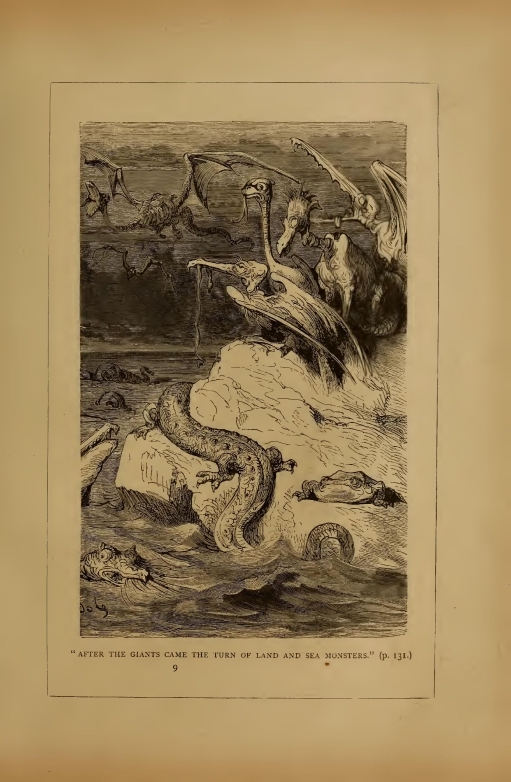

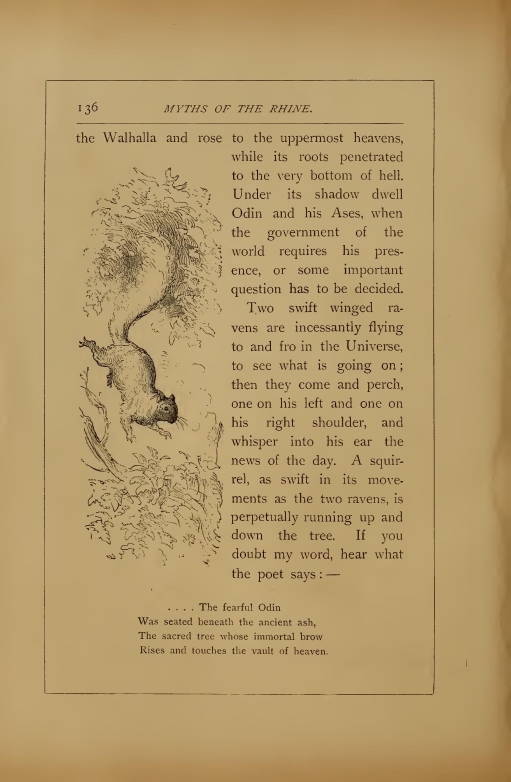

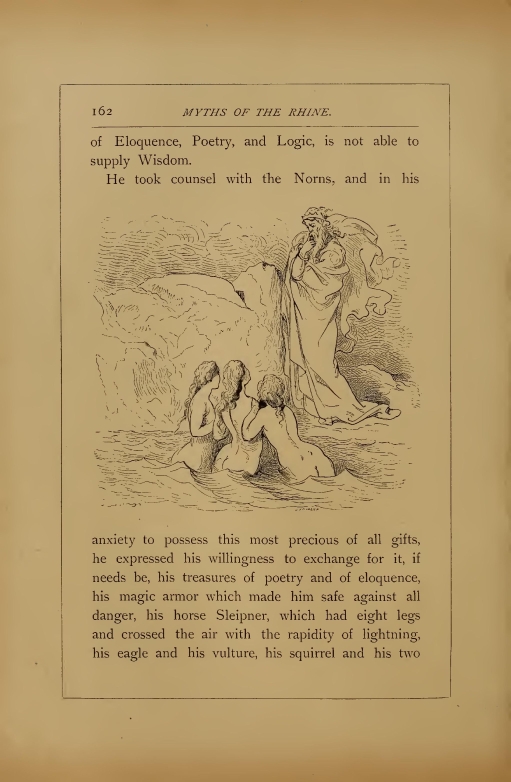

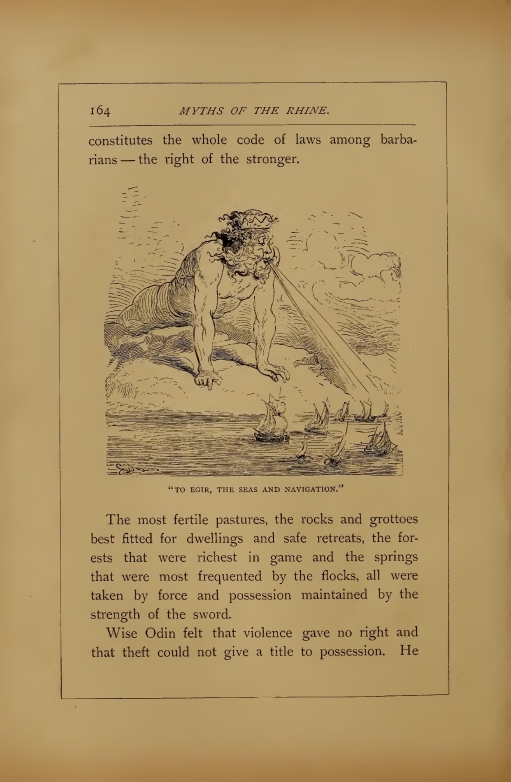

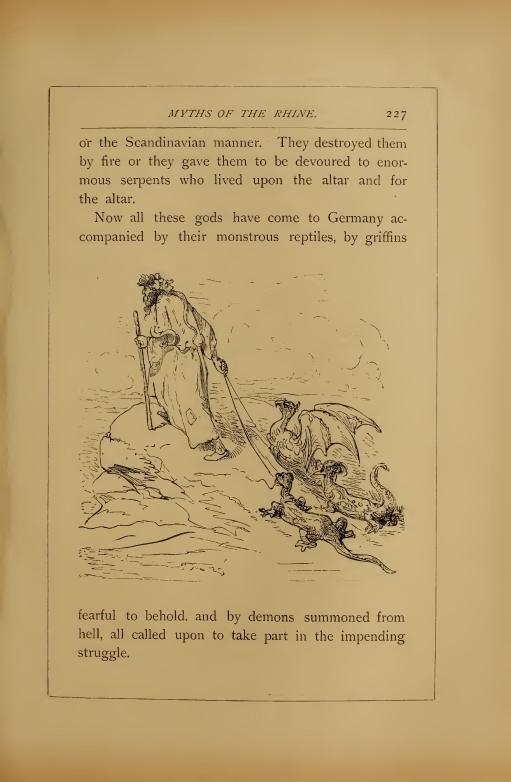

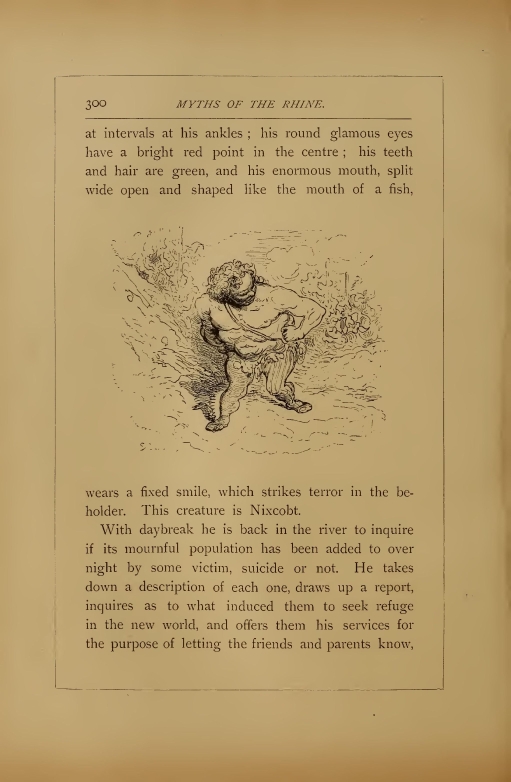

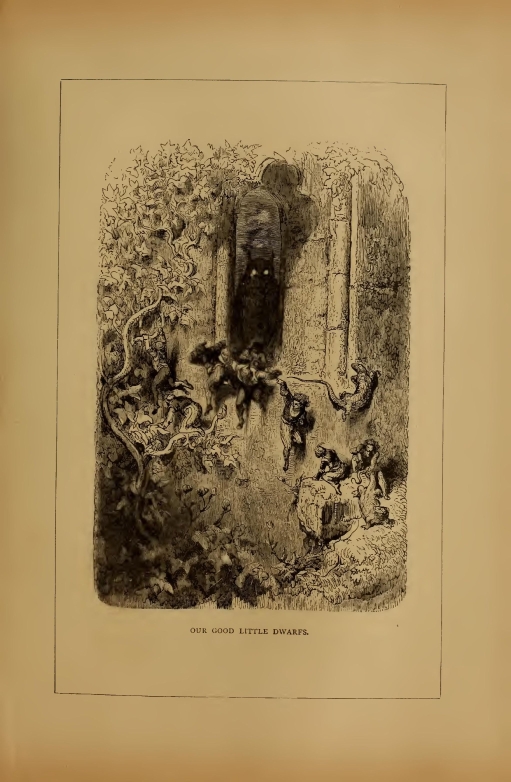

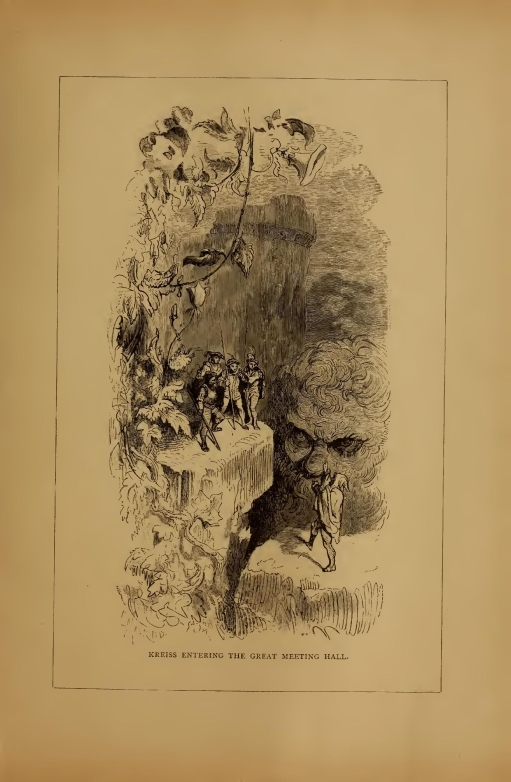

Father Rhine....................................................003 The impassive historian ........................................004 Vast forests as old as the world ...............................005 The first pioneers..............................................007 The Celts were a people from India..............................009 What happy people scholars are..................................010 A horrible custom...............................................019 Dead man’s trees................................................022 The Druids now appear for the first time in Germany.............023 The other chieftains were generally polygamists.................031 Courts of justice were always held under an elm tree............032 Attempt to murder the mayor ....................................033 Mistletoe an officinal and sacred plant.........................035 Gauls...........................................................037 Serpents’ knots.................................................038 Prophetic trembling and neighing................................041 A Druid teacher ................................................044 The Germans were in full flight ................................046 The bloody knife of the Druids .................................052 I turn my steps from the sacred precincts.......................055 Who are these other soldiers?...................................057 These laborers seem to suffer from some restraint...............058 I look around for a resting-place ..............................059 A shepherd......................................................060 The guard of a sword, which had been driven into the ground.....061 The shepherd,—as mournful as ever...............................063 Herds of swine are wallowing ...................................066 A young wife bearing the burden of united household.............067 Happiness consists in the fulfillment of duty ..................068 Such were the ways of our fathers: rejoice in facing death......069 The Druidical altars............................................070 As there is no window I peep through the trap-door..............072 One of the chief men of the country ............................075 She was a young Ionian girl, a country-woman of Aspasia.........080 The boudoir of a Celtic lady....................................082 The Druid-bard..................................................085 Death of Druids.................................................091 A Druidess endowed with the gift of prophecy ...................093 The victorious march of the Romans .............................094 Her deities personified nothing but vices ......................096 The Hercules—so called..........................................098 Mercury, the son of Jupiter ....................................099 “O Varus, Varus, bring me back my legions!”.....................103 Perhaps the old river remembered his grievances.................105 They made him a king, the King of German rivers.................106 He had already allowed Jupiter to cross.........................107 The vines began to adorn the banks of the river.................108 Once more caresses had their hoped-for effect...................109 He did his best to help everybody across........................110 Fnvolous and ill-mannered deities...............................110 The dauntless pirates will end by wearing white night-caps......113 The great Northern Tempest .....................................115 The German Druids gave way......................................117 Iormungondur, the great sea serpent.............................118 The giant Ymer has been born....................................123 The first men had been born with a telescope in their pocket?...127 Ymer was the first to succumb...................................128 After the giants came the turn of land and sea monsters.........129 The new creation was assuming a more pleasing appearance........132 Deer, eland, and aurochs were bounding in herds.................133 Incessantly a tiny squirrel comes and goes......................136 A vulture perching upon the loftiest top of the sacred tree.....137 Thor’s weighty hammer Mjoïner...................................139 The good Freyr seated at Odin’s table...........................141 Portrait of Freyr...............................................142 Bragi and the beautiful Freya ..................................147 Return of the eagle with the three precious vessels.............149 Balder, the bright god..........................................151 The wolf Fenris.................................................156 Converse with each other by significative glances...............159 They were the Norns.............................................160 He took counsel with the Norns..................................162 “To Egir, the seas and navigation”..............................164 Gefione took her four sons and changed them into oxen...........165 Jarl, the noble.................................................171 The Valkyrias ..................................................175 Beautiful nymphs of carnage.....................................176 A very mammoth of a boar........................................180 Feast in Scandinavian Paradise..................................181 Hela, the pale goddess..........................................185 “Balder, fair Balder, is going to die”..........................189 Loki succeeds in exhilarating even Odin himself.................191 Balder is amused by the game....................................192 When the mother told her pitiful tale the iron trees wept.......197 The three sacred cocks announcing the Twilight of Greatness.....202 The death of the gods...........................................208 My VIIIth chapter is thus changed into a cenotaph...............211 I like to glean a little where scholars have reaped.............214 The two religions face to face..................................217 Ovid reciting his “Metamorphoses”...............................219 Druidic worship suspended by the Romans.........................220 “Miserere mei, Jesu”............................................222 Perkunos, Pikollos, and Potrympos...............................224 Puscatus,—a kind-hearted god ...................................226 Monstrous reptiles accompany the gods to Germany................227 He let his heavy mace fall upon a little town...................238 The blacksmiths of Ilmarinnen...................................239 Marietta appeared in their midst................................245 “Do you think I am a man to be taken in ?”......................251 Horse-head, a la mode...........................................253 The Undines mingled with the Tritons and the Naiads.............258 Have transferred their Olympus to the Brocken...................259 The Olympus of the North........................................263 Able to see without being seen .................................266 Dance of the white fairies .....................................269 The black fairies personify Nightmare ..........................271 An important personage with a will of his own ..................272 Enormous toads are posted about.as watchmen.....................279 Elementary spirits of the water.................................283 Imaginary music ................................................288 The nix with the harp ..........................................289 Schoolmaster’s son who had fallen in love with one of them......291 He thought he saw a pale form arise from the waters.............294 He rose suddenly and fled to another room ......................295 The steward whispered some words in her ear ....................297 Niord, the Scandinavian god ....................................299 This creature is Nixcobt........................................300 The Vintner is hanged, and Nixcobt laughs heartily..............302 Four Prussian soldiers watching the water ......................305 The Zotterais protected sheep ..................................309 The master has nothing to do....................................315 Prefer to remember the Kobold a cheerful household companion....317 The Zotterais as fond of stables as the Kobolds of kitchens.....319 They are naturally easily tired ................................321 The Killecroffs are children of the Devil ......................322 His nurse has to be reinforced by two goats and a cow...........324 The great Reformer, Dr. Martin Luther ..........................326 The fall of Killecroff .........................................331 Giants and dwarfs...............................................335 The last of the giants..........................................337 Grommelund and Ephesim .........................................339 The humiliated giant............................................340 Our good little dwarfs .........................................341 He stood at first with his mouth wide open .....................346 A long and deep sigh of satisfaction............................348 Flight of the conspirators......................................353 Kreiss slipped boldly into this vast and spacious cavity........354 They fixed strong piles between the two rows of teeth...........355 In his hand he held not a club but a lantern....................357 Kreiss compelled to leave his position by torrents of tears.....359 The last two held each a long thorn in their hands..............361 Kreiss entering the great meeting hall..........................363 Putskuchen was in love..........................................364 Ouadragant vanquished...........................................367 The passing of the wizard ......................................371 Venus and Tannhàuser............................................390 His ex-colleague Jupiter .......................................396 The author pursues the subject .................................399 The conscientious collector of myths............................401 The Druidess transformed into an accursed witch.................406 To return was as impossible as to proceed.......................409 She had rejoined her victims ...................................413 He is the Lord Hackelberg.......................................417 These ghosts can imitate all the motions of men.................421 Farewell........................................................423

Primitive Times.—The First Settlers on the Rhine.—Masters going to School.—Sanskrit and Breton.—Ax Idle God.—Microscopic Deities.—Tree Worship.—Birth-Trees and Death-Trees.

The Rhine is born in Switzerland, in the Canton of Grisons; it skirts France and passes through it, and after a long and magnificent career it finally loses itself in the countless canals of Holland; and yet the Rhine is essentially a German river.

[004]Already in the earliest ages, long before towns were built on its banks, it saw all the Germanic races dwell here in tents, watch their flocks, and fight their interminable battles, although the clash of arms and the blast of trumpets never for a moment aroused the impassive historian from his deep slumbers.

His silence, long continued into later centuries, does not prevent us from supposing, however, that the Rhine was already at that time the great high-[005]road on which the Germanic races wandered to and fro, and other races came to their native land. It was the Rhine that brought to them commerce and civilization; but on the Rhine came also invasions of a very different kind. We can allude here only to those religious invasions which are connected with our subject.

In the earliest ages the South of Europe alone was inhabited, while the Northern part was covered with vast forests, as old as the world, and as yet[006]unbroken by the footsteps of men. Dark, dismal solitudes, consisting of ancient woods or wretched morasses, where trees struggled painfully for existence and only the strongest survived when they reached the light and the sun; densely wooded deserts, in which vast herds of wild beasts pursued each other incessantly, while in the deep shadow of impenetrable foliage flocks of timid, trembling birds sought a refuge against hosts of voracious birds of prey. Thus, even while Man was yet absent, War was already reigning supreme here, and in these vast regions the Great Destroyer seemed to revel in it, as if it had been a feast, a necessity, a glory!

Had never human eye yet looked upon these magnificent but unknown regions?

Then, one fine day a host of savages appeared here and settled down with their flocks. After them came another host of more warlike and better armed men, who drove out the first comers and took possession of the tilled ground.

After them another race, and then still another. Thus it went on for years and for centuries, and all these waves of immigration came down from the extreme North, marking each halting place by a bloody battle, while the conquered people, driven by the sharp edge of the sword to seek new homes, by turns pursued and pursuing, went and peopled those wild unsettled countries which afterwards be[007]came known as Belgium and France, as Bretagne and England. Continuing their march from thence southward, from the Rhine to the Mediterranean, they spread right and left, east and west, and crossed the Pyrenees and the Alps, making themselves masters on one side of Iberia, and on the other side of the plains of Lombardy, thus changing from fugitives into conquerors.

These conquered conquerors, driven from their own homes, and now driving other nations from their homes, these first pioneers who laid open one unknown country after another, were all children of one great family and all bore the same name of Celts.

But where was the first source from which this [008]flood of families, of peoples, of nations, broke forth, that now overflowed Europe and in successive waves spread over the greater part of the Old World? Whence came these vast multitudes of Northern visitors, unexpected and unknown, who broke the mournful silence that had so long reigned in Europe? Were the frozen regions of the North pole, at that early time, really so fertile in men? We call upon men of science to answer our question. The question is a serious one, perhaps an indiscreet one, for who can be appealed to on such a difficult point? History? It did not exist. Monuments, written or sculptured? The Celts had never dreamt yet of writings or of carvings. Does this universal silence put it out of the power of our learned men to give a reply? Must they confess that they are unable to do so? By no means. Learned men never condescend to make such confessions. The Celts have left as a monument, a language, a dialect, still largely used in certain parts of ancient Bretagne as well as in the Principality of Wales.

Illustrious academicians, mostly Germans, did not hesitate to go to school once more in order to learn Breton. The self-denial of which science is capable, deserves our admiration.

After long labors, devoted to the separation of what belonged to the primitive language from subsequent additions, our great scholars found them[009]selves once more face to face with Sanskrit, the sacred idiom of the Brahmins, the ancestor of the old German tongue, and of the old Celtic tongue, and thus of the Breton.

The matter was decided, scientifically and categorically, and no appeal allowed. The Celts were a people from India. Europeans are all descended from Indians, driven from home by some powerful pressure, a political or religious revolution, or one of those fearful famines which periodically devastate [010]that immense and inexhaustible storehouse of nations.

At first, we good people, artists, poets, or authors, who generally claim to possess some little knowledge, were rather surprised at such a decision. But the wise men had said so; Bengal and Bretagne had to fraternize; the Brahmins of Benares speak Breton and the Bretons of Bretagne speak Sanskrit. Bretagne is Indian and India is Breton.

Comparative Philology has taught the children of our day, that two syllables which are identical [011]in the idioms of two different races, prove the connection between two nations; hybridism means kinship.

What happy people scholars are! They can converse with people who have been dead these three thousand years, and the grave has no secrets for them! A single word bequeathed to us by an extinct people, enables them to reconstruct that whole race.

But I am bound to ask them another question, a question of much greater importance to myself. What were the religious convictions of these first inhabitants of Europe? I am answered by Mr. Simon Pelloutier, a minister of the Reformed Church in Berlin, of French descent, who has studied the primitive creed of the Celts most thoroughly and successfully. He tells us that these people, before they had Druids, worshipped, or rather held in honor the sun, the moon, and the stars, a kind of Sabaism, which, however, did not exclude the belief in a God, who was the creator, but not the ruler, of all things.

This god appears to me to have been very imperfect; he was heavy, sleepy, and shapeless, having neither eyes to see nor ears to hear; he was incapable of feeling pity or anger, and the prayers and vows of men were unable to reach him. Invisible, intangible, and incomprehensible, he was floating in space, which he filled, and which he [012]animated without bestowing a thought upon it; omnipotent and yet utterly inactive, creating islands and continents, and causing the sun and the stars to give light by his mere approach, this divine idler had created the world, but declined taking the trouble of governing his creation.

To whom had he confided the control over the stars in heaven? Mr. Pelloutier himself never could find out. As to the government of the earth, he had entrusted it to an infinite number of inferior deities, gods and sub-gods, of very small stature. They were as shapeless and as invisible as he was, but vastly more active, and endowed with all the energy which he had disdained to bestow upon himself. By their numbers and by their collective force they made up for their individual feebleness—and they must have been feeble indeed, since their extremely small size permitted a thousand of them to find a comfortable shelter under the leaf of a walnut tree!

Besides, they presided over the different departments which were assigned to them, not by hundreds, but by myriads, nay, by millions of myriads. Thus they rushed forth in vast hosts, stirring the air in lively currents, causing the rivers and brooks to flow onwards, watching over fields and forests, penetrating the soil to great depths, creeping in through every crack and crevice, and breaking out [013]again through the craters of volcanoes. They formed a belt from the Rhine to the Taunus mountains, dazzling the whole region for a moment by a shower of sparks, and falling back upon the plain in the form of columns of black smoke.

Science has, moreover, established this incontestable principle, that motion can only be produced in two ways here, below: either by the acts of living beings, or by the contact of these microscopic deities.

Whenever the waters rose or broke forth in cataracts, whenever the leaves trembled in the wind, or the flowers bent before a storm, it was these diminutive gods who, invisible and yet ever active, forced the waters to come down in torrents, drove the tempest through the branches, bent the flowers down to the ground, and chased the dust of the highroads in lofty columns up to the clouds. It was they who caused the golden hair of the maid to fall down upon her shoulders as she went to the well, who shook the earthenware pitcher she carried on her shoulder, who crackled in the fire on the hearth, and who roared in the storm, or the eruptions of fiery mountains.

When I think of this little world of tiny insect gods, who passed through the air in swarms, coming and going, turning to the left and to the right, struggling and striving above and beneath (I ask [014]their pardon for comparing these deities to humble insects, born in the mud and subject to infirmity and death like ourselves), I cannot help thinking of the beautiful lines by Lamartine, in which he so graphically describes life in Nature.

“Chaque fois que nos yeux, pénétrant dans ces ombres, De la nuit des rameaux éclairaient les dais sombres, Nous trouvions sous ces lits de feuille où dort l’été, Des mystères d’amour et de fécondité. Chaque fois que nos pieds tombaient dans la verdure Les herbes nous montaient jusques à la ceinture, Des flots d’air embaumé se répandaient sur nous, Des nuages ailés partaient de nos genoux; Insectes, papillons, essaims nageants de mouches, Oui d’un éther vivant semblaient former les couches, Ils’ montaient en colonne, en tourbillon flottant, Comblaient l’air, nous cachaient l’un à l’autre un instant, Comme dans les chemins la vague de poussière Se lève sous les pas et retombe en arrière. Ils roulaient; et sur l’eau, sur les prés, sur le foin, Ces poussières de vie allaient tomber plus loin; Et chacune semblait, d’existence ravie, Epuiser le bonheur dans sa goutte de vie, Et l’air qu’ils animaient de leurs frémissements N’était que mélodie et que bourdonnements.”

Such were the gods known to the first ingenuous dwellers on the banks of the Rhine—gods worthy of a society but just beginning. And still, I venture to make a suggestion, which Mr. Simon Pelloutier, my guide up to this point, has unfortunately neglected to make. It is this: I feel as if [015]there was hidden beneath this primitive and apparently puerile mythology a hideous monster, writhing in fearful threatenings and bitter mockery. This god Chaos, so careless and reckless, gifted with the power of creation but not with love for his work, seems to me nothing else but Matter, organizing itself. I have called these countless inferior deities microscopic. I should have called them molecular, for they are atoms, the monads of our science. There is evidently here a germ, not of a religious creed so much as of a philosophic system, a shadow of the materialism of a former civilization that is now degraded and nearly lost.

At first I doubted the correctness of the opinions of our learned men; but I begin to believe in them; yes, these early Celts had come, to us from distant India, from that ancient, decayed country, and in their knapsacks they had brought with them, by an accident, this fragment of their symbolic cosmogony, the sad meaning of which was, no doubt, a mystery to them also.

After some years, perhaps after some centuries, —for time does not count for much in those questions,—the Celts became weary of this selfish Deity, which was lost in the contemplation of its own being and dwelt in the centre of a cold and empty heaven, and they desired to establish some relations between him and themselves. Unable to appeal to [016]the Creator, they appealed to Creation, and asked for a mediator, who should hear their complaints or accept their thank-offerings and transmit them to the Supreme Power.

We have already seen that they turned first to sun and moon; but they were ill rewarded for their efforts. These heavenly bodies were either too far removed from their clients to hear their complaints, or they were too busy with their own daily duties; at all events they shared with their common master in his indifference towards men.

Our pious friends were offended by this want of consideration, and thought of looking for other intercessors, who might be less busy; whom they might not only see with their eyes but touch with their hands, and who would remain as much as possible in the same place, so as to be always on hand when they were needed.

They appealed to rivers and mountains; but the rivers had nothing permanent but their banks, and went their way like the sun and moon; while the mountains, besides being the home of wolves, bears, and serpents, and thus enjoying an evil reputation, were continually hid by snow and rain from the eyes of the petitioners.

At last they turned to the trees, and as it always happens, they now found out that they ought to have commenced where they ended. [017]A tree was an excellent mediator; standing between heaven and earth, it clung to the latter by its roots, while its trunk, shaped like an arrow, feathered with verdure, rose upwards as if to touch the sky.

The worship of trees was probably the first effect of sedentary life adopted by the Celts after their long, more or less forced wanderings; in a few years it prevailed on both sides of the river Rhine.

There was no lack of trees; every man had his own. As he could not carry it away with him, he became accustomed to live by its side.

Man could lean his hut against the trunk; the flock could sleep in its shade.

The birds came to it in numbers. If they were singing, it was a sign of joy to come; if they built their nests there, it was an invitation to marry.

The fruit-bearing tree suggested comfort, abundance, and enjoyment; it spoke of harvest feasts and cider-making, when friends gathered around it, holding in their hands large horns filled to overflowing with foaming drink.

Soon it became customary to plant at the birth of a child a tree which was to become a companion and a counsellor for life.

Thus in the course of time a copse represented a family.

The worship bestowed upon the tree consisted [018]in pruning it, in making it grow straight, in freeing its bark from parasitical growth and in keeping the roots free from ants, rats, snakes and all dangerous enemies. Such continuous care naturally led in the course of time to an improvement in cultivation.

The tree worshippers, however, did more than this. On certain hallowed days they hung bouquets of herbs and of flowers on its branches, they brought food and drink, and thus fetichism crept in gradually. Alas! That men have never been able to keep from extremes!

When the wind whispered in the leaves, the devout owner listened attentively, trying anxiously to interpret the mystic language of his cedar or his pear tree, and often a regular conversation ensued.

It was a bad omen when a rising storm shook the tree fiercely; if the tempest was strong enough to break a branch, the event foretold a great calamity, and if it was struck by lightning, the owner was warned of his approaching death. The latter was resigned; he felt quite proud at having at last compelled his indolent god to reveal himself to his devout worshipper.

When a child died, it was buried under its own tree, a mere sapling.. But it was not so when a man died.[019]

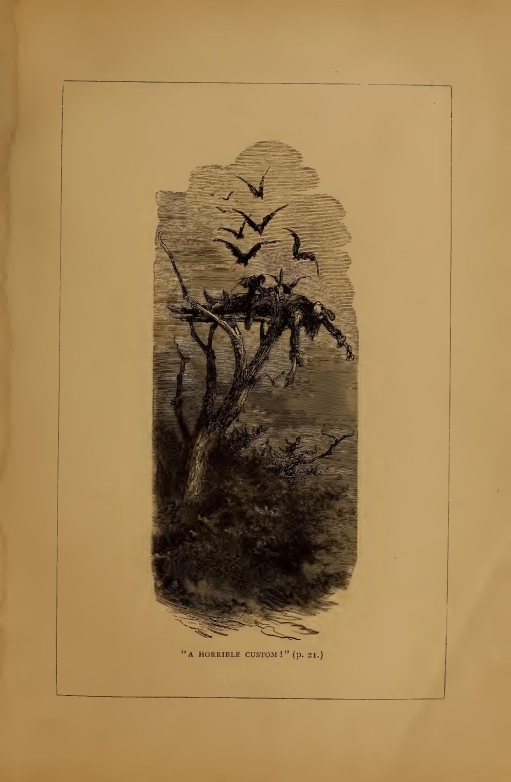

The Celts used various and strange means for the purpose of disposing of the remains of their [021]deceased friends. In some countries they were burnt, and their own tree furnished the fuel for the funeral pile; in other countries the Todtenbaum (Tree of the Dead), hollowed out with an axe, became the owner’s coffin. This coffin was interred, unless it was intrusted to the current of the river, to be carried God knows where! Finally, in certain localities there existed a custom—a horrible custom!—of exposing the body to the voracity of birds of prey, and the place of exposure was the top of the very tree which had been planted at the birth of the deceased, and which in this case, quite exceptionally, was not cut down.

Now, observe, that in these four distinct methods by which human remains were restored to the four elements of air and water, earth and fire, we meet again the four favorite ways of burial still practiced in India, as of old, by the followers of Brahma, Buddha, and Zoroaster. The fire-worshippers of Bombay are as familiar with them as the dervishes who drown children in the Ganges. Thus we have here four proofs, instead of one, of the Indian origin of our Celts. For my part at least, I confess I am convinced by this quadruple evidence.

It is to be presumed that the use of Dead Men’s Trees and of posthumous drownings continued for centuries in ancient Gaul as well as in ancient Germany. About 1560 some Dutch laborers found, [022]in examining a part of the Zuyder Zee, at a great depth, several trunks of trees which were marvelously well preserved and nearly petrified. Each one of these trunks had been occupied by a man, and contained some half-petrified fragments. It was evident that they had been carried down, trunk and man, by the Rhine, the Ganges of Germany.

As recently as 1837 such Todtenbaume or Dead Men’s Trees, well preserved by the peculiar nature of the soil, have been discovered in England, near Solby in Yorkshire, and still more recently, in 1848, on Mount Lupfen in the Grand Duchy of Baden.

In face of such well authenticated evidence of Dead Men’s Trees having been confided to the current of rivers or the bosom of the earth, it seems superfluous to ask for additional proof in support of the fact that cremation was practiced all over ancient Europe. Nor do I consider myself, as a collector of myths, bound to prove everything. I [023]do not mean to speak, therefore, any further of Birthday Trees, of Dead Men’s Trees, and of Fetich Trees,—which we shall moreover meet again presently,—and hasten on to other myths of far greater importance.

The Druids now appear for the first time in Gaul and in Germany.

[027]The Druids and their Creed.—Esus.—The Holy Oak.—The Pforzheim Lime Tree.—A Rival Plant.—The Mistletoe and the Ansfuinum.—The Oracle at Dodona.—Immaculate Horses.—The Druidesses.—A late Elector.—Philanthropic Institution of Human Sacrifices.—Second Druidical Epoch.

The Druids were the first to bring to the Gauls as well as to the Germans religious truths, but their creed can be appreciated from no dogma of theirs; it must be judged by their rites.

The first question is: Whence did the Druids [028]come? Were they disciples of the Magi, and did they come from Persia? Such an origin has been claimed for them: or had they been initiated by Isis in her ancient mysteries, and did they come from Egypt? This view also has its adherents. Or, finally, had they been driven towards Western Europe by one of the last waves of immigration, which left India under the pressure of some new calamity? Many think so.

As it seems to be difficult to decide between these three suggestions, it might be worth while to try and reconcile them with each other. It is a long way from India to Germany and to Gaul, and there might have been many stopping places between the country from which they started and their future home.

The Druids, like all other Celts, might very well have started from India, and choosing not the most direct way might have reached Europe only after making many a long halt in Persia and in Egypt.

'If that can be admitted, then there is no difficulty in assuming that the first Celts might very well have taken with them from the banks of the Indus and the Ganges only a few fragments of a sickly materialism taught by false teachers outside of the temple, while the Druids might have been initiated within the temple itself, thus learning to know the true nature of the Deity.

Their creed was founded upon a triple basis—one [029]God; the immortality of the soul; and rewards and punishments in a future life.

These sound doctrines, which are as old as the world and form the foundation of all human morality, had ever been maintained by their wise men.

At a later period the Greeks, proud as they were of their Platonic philosophy, had not hesitated to acknowledge that they had obtained the first germ of it from the Celts, the Galati, and consequently from the Druids. One of the Fathers of the Church, Clement of Alexandria, openly admits that these same Celts had been orthodox in their religion, at least as far as their dogmas were concerned.

By what name was the Supreme Being known to the Druids? They called it Esus, which means the Lord, or they gave it the simple designation of Teut (God). Through this Teut the German races became afterwards Teutons, the sons and followers of Teut, and even in our day they call themselves in their own language Teutsche or Deutsche.

Three marvelously brief maxims contain almost the whole catechism of the Druids: Serve God; Abstain from evil; Be brave!

The Druids, being warriors as well as priests, displayed in the performance of their warlike priesthood all the energy, the severity, and the authority which must needs accompany such a strange combination of powers. [030]Holding all the power of the state in their hands, and speaking in the name of God, commanding the army, controlling the public treasury, and acting not only as judges but also as physicians, they punished heresy and rebellion, and ended lawsuits as well as diseases, by the death of the person most interested.

Their laws, liberal and philanthropic in spite of their apparent severity, allowed a jury consisting of notables, to judge grave crimes; this fact of a jury suggests naturally the idea of extenuating circumstances, and thus the criminal, escaping more readily than the patient, frequently got off with a fine, if he was rich, or with banishment if he was poor.

Nevertheless all the efforts of the Druids did not succeed in thoroughly eradicating Tree worship; they were thus led to adopt one tree, to the exclusion of all others, which should rally around it the scattered adoration of all the nations. This official tree, a kind of green altar, on which God manifested himself to his priests, was an oak, a strong, vigorous oak, the king of the forests.

Thus the holy oak became known and honored; pious worshippers came by night, with torches in their hands, in long processions to present their offerings.

This usage soon became general among all Celtic nations. Around these oaks the Druids formed sacred precincts within which they lived with their families, for they were married; but they could have [031]only one wife, while the other chieftains were generally polygamists.

But the oak, although thus enjoying preeminence over all other trees, was by no means exclusively worshipped everywhere. Perhaps from religious antagonism, or perhaps merely from local usage, some provinces of Gaul and of Italy preferred the beech and the elm. In Gaul especially, the elm prevailed over the oak, and even Christian France still continued for a long time to plant an elm tree before every newly built church, so as to draw God’s blessing the more surely upon it; and down to the end of the Middle Ages courts of justice were always held under an elm tree. Hence the curious [032]French proverb, which did not always have the mocking sense in which it is used nowadays, wait for me under the elm tree! (Attendez-moi sous forme) What was then a formal summons to appear before a judge has now come to mean: Wait till doomsday.

The ash tree, also, had its worshippers among the dwellers in high northern latitudes, and it was under the dense branches of an enormous ash tree that terrible Odin and his following of deities appeared in a dark cloud.

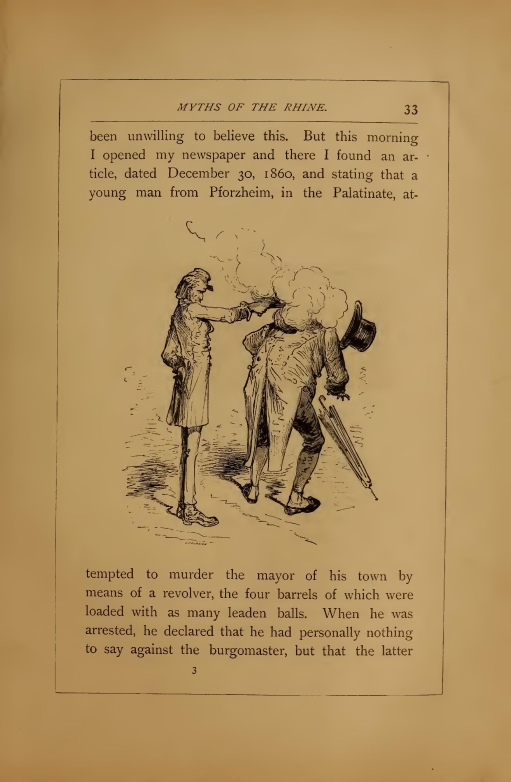

Thus Tree worship appeared once more. It has ever since continued to flourish more or less in Germany, and even now exists to a certain extent. But it is not the oaks, nor the beech, nor the elm, nor the ash tree, which in our day receives the worship of the young especially—but the lime tree. The admirers of the lime tree carry their fervor to fanaticism and their fanaticism to murder. I had [033]been unwilling to believe this.

But this morning I opened my newspaper and there I found an article, dated December 30, 1860, and stating that a young man from Pforzheim, in the Palatinate, attempted to murder the mayor of his town by means of a revolver, the four barrels of which were loaded with as many leaden balls. When he was arrested, he declared that he had personally nothing to say against the burgomaster, but that the latter [034]had recently ordered certain lime trees to be cut down, that the good people of Pforzheim idolized these trees, and that he had determined to punish him for such profanation.

The paper added: “This young man belongs to an honorable family, his antecedents are excellent, and he has never shown the slightest symptom of mental derangement.”

How, then does it come about that the lime tree should in our day, in the nineteenth century, call forth sentiments of such extreme violence? The reason is that Young Germany has proclaimed it to be the Tree of Love, because its leaves are shaped like hearts.

If I were not afraid of getting myself into trouble, having a natural horror of all firearms, and especially of four barrelled revolvers, I should mention here, that anatomists protest against this pretended resemblance of the leaf to the heart. In reality it looks much more like the ace of hearts, as it terminates below in a sharp point—but superstition prevails over anatomy, and teaches us once more that science ought not to meddle with things pertaining to love.

The Druids’ Oak, although less tempting to gallant comparisons, finally excited almost equal fanaticism. Processions and sacrifices became well nigh endless; young maidens adorned it with garlands of flowers, [035]interspersed with bracelets and necklaces, while warriors suspended in its branches the most precious spoil they brought home from their battles. If a storm arose, the other trees of the forest seemed in good faith, humbly to bow down before their chief.

And yet it had an enemy, a fierce, relentless enemy. An abject, little plant, unknown and miserable in appearance, came unceremoniously and made its home on its sacred branches and even on its august summit; there it lived on its life’s blood, feeding on its sap, absorbing its substance, threatening [036]to impede its natural growth, and finally carrying the impudence so far as to conceal the glossy leaves of the noble godlike tree under its own lustreless and viscous foliage. This hostile and impious plant was the Mistletoe, the mistletoe of the oak (Guythil).

Other people, less intelligent and less sagacious than the Druids, would have freed the tree from this unwelcome and obnoxious visitor, by simply climbing up and cutting off the parasite by means of a pruning bill. This would have been irreverent as well as impolitic. What would the people have thought? The people would most assuredly have reasoned, that the sacred tree had been rendered powerless, being unable to rid itself of its vermin.

The Druids did much better. They treated the mistletoe very much as we, in our day, treat a formidable member of the opposition; they gave it a place in the sanctuary. The mistletoe was proclaimed to be an official and sacred plant, and became an essential part of their worship. When it was to be detached from the tree, this was not done stealthily and by a mean iron bill-hook, but in the presence of all, amid public rejoicings and accompanied by solemn chants. The instrument was a golden reaping hook, and with it the Guythil was carefully cut off at the base and gathered in [037]linen veils. These veils became henceforth sacred, and were not allowed to be used for ordinary purposes.

The Teutons who lived on the Rhine, obtained from the mistletoe a kind of glue, which they looked upon as a panacea against the sterility of women, the ravages of diseases, the effects of witchcraft,—and also as a means to catch birds.

The Gauls, on the other hand, dried it carefully and put the dust into pretty little scent-bags, which they presented to each other as New Year’s Gifts on the first day of the year. Hence, in t some provinces of France, the cry is still heard, “Aguilanneuf” (au gui l’an neuf), “Mistletoe for New Year!”

Modern science treats mistletoe simply as a purgative, and thus attempts to prove that our ancestors showed their affection to each other by exchanging presents of violent purgatives.

The introduction of this parasite plant into the [038]sanctuary became, however, very soon a public benefit. For the oak-mistletoe obtained ere long considerable commercial value, and at once counterfeiters (for even under the Druids there existed such men) went to work and gathered it from other trees also, from apple trees and pear trees, from nut trees and lime trees, from beeches, elms, and even larches. The consequence was, that owners of orchards as well as owners of forests, rejoiced in the trick, at which the Druids discreetly winked; for they took advantage of the lesson.

At one time venomous reptiles had become so numerous in the regions of the Rhine, that they caused continually serious accidents among the [039]people, the majority of whom lived all day long in the open air, and did not always sleep under shelter. During their winter sleep, these reptiles rolled themselves up into vast balls, and became apparently glued to each other by a kind of viscous ooze. In this state they were called by the Celts Serpents Eggs, or rather Serpents’ Knots, while the Romans called them anguimim.

These strange balls were used medicinally by the Druids like the mistletoe; they employed them even in their religious ceremonies, and soon they became so rare, that only the wealthiest people could procure them, by paying their weight in gold. If the Druids had really at first been misled so as to adopt superstitious customs, which they repented of in their hearts, they soon found means to make these same superstitious rites beneficial to the people.

Unfortunately serpents’ knots, oaks, and their parasites, did not long satisfy a people ever desirous of new things. It is a well-known fact that innovations, however small may have been their first beginning, are sure to go on enlarging and increasing from day to day.

The old party of Tree worshippers, still numerous and very active as all old parties are, complained of the suppression of their companion-trees, the ancient family oracles, for the purpose of favoring [040]one single oak tree,—a tree which yet was not able, in spite of all the privileges it enjoyed, to put them into communication with Estes, the god of heaven.

This complaint was certainly not unfounded;—it had to be answered.

The Druids consisted of three classes:—

The Druids proper (Eubages, they were called in Gaul) were philosophers as well as scholars, perhaps even magicians, for magic was at that time nothing more than the outward form of science. They were charged with the maintenance of the principles of morality, and had to study the secrets of nature. The Prophets, on the other hand, knew how to interpret in the slightest breath of wind, the language of the holy oak, which spoke to them in the rustling of its leaves, in the soughing of the branches, in the low cracking heard within the trunk, and even in the earlier or later appearance of the foliage. There were, finally, the Bards, poets bound to the altar.

While the bards were singing around the oak, the prophets caused it to render its oracles. These oracles soon increased largely not only in Europe, but also in Asia Minor, where a Celtic colony, according to Herodotus, established in the land they had conquered the oracle of Dodona. Early Greece worshipped an oak tree, which Strabo, however, assures [041]us was a beech. There is no disputing about trees any more than about colors; but Homer calls it an oak, and an oak it must remain for us.

This new movement, grafted upon the simple worship of the Druids, did not stop here. After having for some time been accustomed to converse with Teut by means of a tree, the Celts were naturally surprised at seeing that, while trees could speak, living creatures remained silent, and were apparently deprived of the power of foretelling the future. Certain chieftains, especially, felt aggrieved, [042]upon setting out on a great campaign, that they were not allowed to carry the holy oak along with them, and in their intense devotion, fell upon the idea of consulting the nervous trembling of their horses and their sudden neighing in moments of surprise or terror,—for in order to be of prophetic nature the movements of the animals had to be involuntary and spontaneous. As this creed began to spread gradually, every man who was setting out on a journey or a warlike expedition mounted his horse in the firm conviction that he would be able to consult his four-footed prophet at any time during his absence from home, provided he was able to submit the omens to the learned interpretations of a soothsayer.

The Druid priests were not long in becoming seriously alarmed at these travelling oracles, liable as they naturally were to contradict each other.

As they had before chosen a single tree to be the sacred tree, so they now accepted as genuine omens only the symptoms noticed in certain horses which were bred within the sacred precincts and under their own eyes.

These horses, of immaculate whiteness and raised at public expense, were not employed for any work, and never had to submit to saddle or bridle. Wild and untamed, they roamed with fluttering manes in perfect liberty through the lofty forests. The freedom [043]of their movements gave naturally a safer character to their omens, and thus these prophetic horses, which formed almost a part of the druidical clergy, enjoyed for a long time the highest authority in all Celtic countries, when suddenly one fine day new rivals arose.

Other living creatures entered into competition with them, and these rivals of the horses were—shall I say it?—were women. These women discovered, all of a sudden, that they also were endowed, and in the very highest degree, with the gifts of second sight, of inspiration, intuition, and divination.

When public opinion appealed to the Druids to give their views on this claim, they admitted, according to the statement of Tacitus, that women had something more instinctive and more divine in them than men, nay, even than horses. Their sensitive organization predisposed them to receive the gift of prophecy, and hence “women indeed act more readily from natural impulse, without reflection, than from thought or reason.”

This last explanation, improper in the highest degree, does not come from Tacitus, nor from myself, God forbid! It is the exclusive property of the aforementioned Mr. Simon Pelloutier. Let every one be responsible for his own work!

The Druids treated the women just as they had [044]treated the horses, the mistletoe, and the trees. They acknowledged as true prophetesses only those who were already under the direct influence of the holy place and the sacred oak; that is to say, their wives and their daughters.

The principle of centralization of power is evidently not of modern origin.

Thus, there were now Druidesses, as there had been Druids before. The latter became the teachers of the young men; they taught their pupils the motions of the stars, the shape and extent of the earth, the divers products of nature, the history of their ancestors written in the form of poems which the bards recited; in fact, they taught them everything except reading and writing. Memory was as yet sufficient for all things. The priestesses, on the other hand, opened schools for the young girls; they taught them to sing and to sew, they initiated them into religious ceremonies and confided to them the knowledge of simples; nor was poetry neglected, as they had to learn by heart certain poems which were specially composed for their benefit. These verses, of somewhat doubtful [045]lyrical character, probably taught them how to make bread, how to brew beer, and other small details of the kitchen and the house.

The Druidesses practiced also medicine. This threefold prerogative of being physicians, prophets, and preceptors, finally raised them so high in the estimation of the nation, that when the priests of Teut were compelled to abandon their sanctuaries, they did not hesitate to confide them to their guardianship. They even presided in their own right, at certain ceremonies.

If one of them excelled by the frequency, the lucidity, and the reliability of her inspirations, as was the case at different times with the illustrious Aurinia, Velleda, and Ganna, whom the Roman emperors even deigned to consult through their ambassadors, the proud Druids placed her with humble submission, at the head of their own college of priests. During this female dictatorship, she became the arbiter of the destiny of nations, decided on peace and war, and controlled all the movements of great armies.

Caesar tells us that he once asked one of his German captives, why Ariovistus, their chieftain, had never yet dared to meet him in battle, and was told in reply, that the Druidesses, after a careful examination of the eddies and whirlpools of the Rhine, had forbid his engaging in action till the [046]time of the new moon. As a matter of course, the shrewd general profited by this information, and when the new moon appeared, the Germans were in full flight.

But the Rhine has not yet given its oracles, and the time has not yet come, when Ganna Velleda, and Aurinia condescend to grant audiences to Roman ambassadors.

We only wished to trace in a few outlines the future development of this institution of Druidesses, which we shall meet again in the days of its decline. [047]In the mean time, however, their influence and their power were daily growing. Were the Teutons at last satisfied? By no means. In spite of all the skill displayed by their diviners and the Druid-esses, they came to the conclusion, that neither the trembling foliage of the holy oak, nor the sudden starts, the wild leaps, and the more or less prolonged, loud neighings of the horses, afforded them sufficient excitement and perfectly reliable revelations. It occurred to them next, to consult animals, not in their outward manifestations, but in their still quivering entrails. This new ceremony could not fail to give to their religious worship a more serious aspect, and a certain savor of murder, which no doubt had its charms for a warlike people.

The Druids yielded once more, but they felt discouraged. What had become of that grand philosophic religion, which was content with prayer and meditation, and which they once—too fondly, perhaps—had hoped to be able to adapt to the nature of these barbarians?

They first consented to slay at the foot of the sacred oak, so long kept free from blood, a number of noxious beasts, like wolves, lynxes, and bears; but the turn of domestic animals came ere long, and they began to sacrifice sheep, goats, and finally man’s best companion in war, the horse. Not even the spotless white horses, heretofore looked upon [048]with such profound and superstitious reverence, were spared any longer.

And at each step forward in this bloody career, the Druids, always resisting, and always compelled to yield, made their last and their very last concession, vainly hoping that they might thus retain for a little while longer the power, which they felt was fast slipping from their grasp.

Encouraged by success, the reformers finally came to the question, whether the most acceptable offering to be presented to God, was not the blood of man? Is not man, of all created beings, the most noble and the most perfect? Perhaps they were inclined to carry the argument still farther, and to reason that among all men the most worthy to be chosen and the most likely to be acceptable to God, were the Druids themselves? But they took care not to ask too much at once. They held this final consequence of a great principle in reserve, requiring for the present nothing more than a common victim, anything that might come in the way, provided it was a human being.

It might have been expected, that when this abominable demand was made to hallow murder by committing it in the name of Heaven, the descendants and heirs of the ancient sages would have remembered their noble ancestors who had put an end to the first and quite inoffensive superstitions [049]of the early Celts. They ought to have veiled their faces, drawn back with horror, and recovering for once their former energy, appealed by means of the holy oak, the spotless horses, the soothsayers and the Druidesses, nay of heaven and earth itself, to the whole nation, calling upon them to anathematize the infamous petitioners. But they did no such thing. On the contrary they hastened to legalize such savage bloodshed by their holy consent. One might almost be led to suspect that they had themselves, underhand, suggested the horrible idea.

O ye hypocritical priests, ye false philosophers, ye tigers disguised as shepherds of the people!.... But we must check our indignation. For who knows, but they may have been swayed not so much by an instinct of cruelty as by a lofty political, or even philanthropic principle? Philanthropic? Yes, indeed; we will explain.

Among the Celts human life counted for little; it was lavished in battles, it was cast away in duels. At the time when the Gauls held large national assemblies, they tried to secure punctual attendance by simply putting to death the man who was the last to come; he paid for all the tardy ones. I do not mean to propose such a plan at the present day; but after all it was an infallible and economical measure. [050]The Teutons, on the other hand, bloodless in their national assemblies, after a battle in which they had been victorious, delighted in massacring all their prisoners.

These massacres ceased from the time when the Druids claimed for themselves the exclusive right of human sacrifices.

The good Esus, having become bloodthirsty, demanded all the captives to be slain in expiation at his altar, and woe to him who dared to anticipate him in his wrath. He was excluded from the sacred precincts; he was declared an impious, sacrilegious person, who could no longer take his place among the citizens; and he ran great risk of being forced to offer his own life in compensation for that which by his fault was wanting at the holocaust.

When this custom became once fully established, the prisoners of war were all delivered up to the high-priest, who chose from among them one or more to be slain as an offering. The victim was generally one of the captive chieftains, and he was slain together with his war horse, so as to add to the impressiveness of the ceremony and to reconcile the spectators by the abundance of blood that was shed to the small number of victims.

After having carefully examined the opened bodies of man and animal, the sacrificing priest, his [051]beard and clothes saturated with blood, raised his bloody right hand to heaven and, reeking with murder and breathing carnage, he proclaimed that his god was satisfied. The remainder of the prisoners were kept for another day, but that other day never came.

Thus a new office had been created: that of a sacrificing priest. On both banks of the Rhine, in Germany as well as in Gaul, the Druids reserved this office for themselves; in other Celtic countries, in Scandinavia and among the Scythians, women performed the terrible duty; we all remember as a proof of it, Iphigenia of Tauris.

Whatever we may think of this bloody innovation, it certainly benefited the prisoners, but the Druids obtained from it, after all, the greatest advantage. Their power, which had been seriously undermined, step by step, was once more firmly established. The opposition, which had paid no attention to their remonstrances or their prayers, shrunk from their knives.

From this moment begins the Second Period of the Druids.

The bloody knife of the Druids remained long all powerful, but we need not follow its later fate. Cæsar had conquered and pacified Gaul, and the successors of Augustus fulminated their Imperial [052]decrees against the Druids, as slayers of men, while the same knife continued to shed the blood of the Germans.

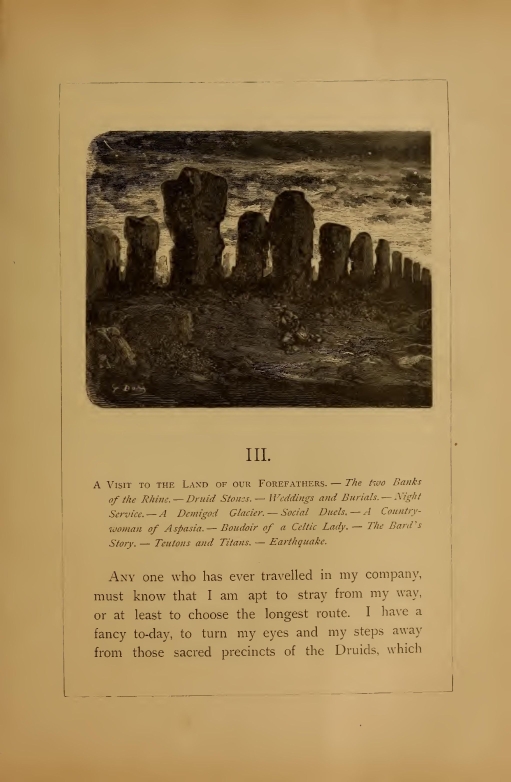

[055]A Visit to the Land of our Forefathers.—The two Banks of the Rhine.—Druid Stones.—Weddings and Burials.—Xight Service.—A Dentigod Glacier.—Social Duels. A Countrywoman of Aspasia.—Boudoir of a Celtic Lady.—The Bard’s Story.—Teutons and Titans.—Earthquake.

Any one who has ever travelled in my company, must know that I am apt to stray from my way, or at least to choose the longest route. I have a fancy to-day, to turn my eyes and my steps away from those sacred precincts of the Druids, which [056]had become slaughter-houses and in which the hand that blessed was also the hand that killed.

I desire to breathe an air less filled with the perfumes, or rather the fetid odor of sacrifices. Up there, on that hill-top, where the setting sun lights up the bright summit, I shall breathe more freely.

Here I am.

Beneath me the Rhine spreads out its two banks, not united yet by any bridge, and even without a ferry to bring the one nearer to the other.

But on both sides, half hid under dense willow thickets and gigantic reeds, there lie, in many a shallow little bay, large numbers of tiny barks. These cunning looking boats belong to harmless fishermen in the daytime; but at night they are filled with robbers and corsairs, who form in bands, cross over to the other side in search of booty, and even venture, if needs be, out into the Northern Sea. Just now nothing stirs; the fishermen have gone home, the corsairs have not come forth. I look farther out.

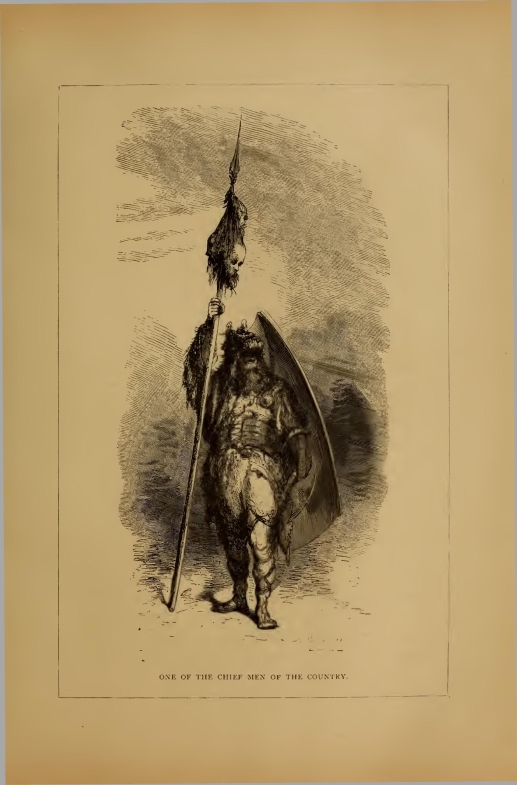

On the left bank there are some Gallic Celts encamped, with blue eyes, white skin, and abundant golden tresses. Almost naked, their principal garment seems to be that immense shield, almost as long as their body, which shelters them on the march as well as when they are at rest, and which protects [057]them against the sun and the enemy alike. All of a sudden I hear them, with lips held close to one of the edges of their shields, utter sharp cries, which are taken up and repeated, from distance to distance, all the way down the river. To these cries, which no doubt represent their telegraphic system, there comes an answer from far sounding trumpets.

Who are these other soldiers with the black hair and the bronzed complexions? Carefully arrayed in symmetrical lines they advance steadily, clad in brilliant armor, and carrying banners surmounted by golden eagles with half open wings. Has Cæsar really succeeded, after ten years’ warfare, in making himself master of Gaul as far as the banks of the Rhine? I cannot doubt it; for at their [058]approach, the Gauls lower their lance-heads, in token of their peaceful disposition, and allow them to pass.

When they reach the river, the small Roman army pauses; under the protection of this armed force a few men, dressed in simple tunics, with no arms but tablets, a style, and ropes for measuring the ground, go to work preparing a plan, perhaps for a bridge, perhaps for a town.

German sentinels, take care!

From the height of my hill I look down upon a [059]narrow strip of land on the right bank of the river, and here I see several groups of men, scattered here and there in the woods and on the plain, who work under the superintendence of a Druid. Some are digging up the roots of trees which overshadow and impoverish the ground; others draw long furrows with the iron of their ploughs. These laborers seem all to suffer from some restraint which impedes their movements, but of which at this distance I can discover no cause.

In order to meditate on this strange sight, I look around for a resting place. Half way up the hill I notice a small stone bench. As I draw nearer, the object grows in size and rises to such a height, that I should need a ladder if I wished to take possession of my seat.

This apparent bench is a monument, a Druidical monument, and consists of two upright stones, on which rests a third, horizontal stone. In France, in England, and in Germany there are still found [060]such Druidical altars, cromlechs or dolmens; these menhyrs astonished already Alexander of Macedonia when he marched through Scythia. In Bretagne, at Carnac, some of these stones, consisting of a single rock, rise by the wayside, as if to tell the traveller the story of the past, or they range themselves before his eyes in long lines, forming on the ground endless circles of emblematic meaning, as it is supposed. But the traveller can no longer understand their language. Was this an altar, or was it an idol, or perhaps only a simple monument raised over a grave. If they were altars, Carnac would be Olympus; if they were tombstones, it would be a cemetery.

I was going all around the mystic three stones to examine them more closely, when I noticed close by a flock of sheep, and then a shepherd.

This shepherd, covered with a ragged sagum, had on his feet leather sandals, a half open wound on his forehead, which had not yet had time to close, enhanced the fierceness of his appearance. His burning [061]glances fell now upon the Druidical stone and now upon another object which I had not noticed before. This was the guard of a sword which had been driven into the ground.

Could it be that this stone resting upon two supports, were new concessions made by the politic Druids?

As according to their spiritualistic views God could not render himself visible in a shape resembling our own, they had represented him as well as they could by a symbol. It appeared thus that human sacrifices were already no longer sufficient to maintain their creed.

While I was examining with growing curiosity this strange keeper of sheep, fair, with bare neck and bare feet, was busy watching on the same side of the hill another flock, and at the same time gathering herbs for medicinal purposes. When she was about to leave, she offered the shepherd to attend to his wound, sword handle, and this [062]but he refused haughtily; she ran away laughing, and threw a flower into his face.

He did not pick up that flower; he did not salute that pretty girl as she left him. He looked at her with disdain.

Ah! I can doubt it no longer; this unhappy man is like the wood-cutter in the forest, and the laborers in the field, one of those prisoners taken in war, whom the Druids have spared, and now render useful. His closely shorn hair, his open wound, and the heavy wooden yoke which he has to carry on his neck, all betray his sad fate. He has made no reply to the half pitiful, half coquettish advances of the pretty gatherer of simples, because she has only awakened in his heart painful memories of his distant love, or of his wife, whom he is never to see again! He has cast glances of fierce hatred and burning revenge at the Druidical altar and the handle of the sword, because both of these objects point out the place of bloody sacrifices. Does he think he is himself destined to be slain? or was perhaps the warrior whom they slew yesterday, a man of his own tribe, his best friend, his own brother?

But I have taken refuge here in order to escape from these painful thoughts of blood and murder. I propose to seek new objects of interest.

Farther down, nearly at the foot of the hill, I [063]see a few huts, or rather a few low, almost crushed roofs, which seem hardly to rise from the ground. Are they houses, or stables, or caves?

On the left bank Gauls and Romans have alike disappeared in the mists rising from the river. On the right bank the wood-cutters and the field-laborors are resting upon their axes or their ploughs, and seem to ask the sun if the day is not drawing to an end.

A breeze is springing up, the shepherd gathers his flock and, as mournful as ever, he slowly takes [064]the footpath that leads down the hill towards the village.

I follow him without knowing what mysterious power draws me in that direction.

Perhaps some Druid magician holds me under a potent spell, which enables me to forget who I am, whence I come, and even to what century I belong, and to witness these strange scenes, which, well nigh forgotten by all living beings, I alone am permitted to watch? Let me try, at all events, to profit by this rare piece of good fortune.

I reach the low village and find it occupied by a colony of Salic Franks, who live scattered all along the Rhine. With their eyes fixed upon the left bank, they are just now far more occupied with the invasion of Germany by the Romans, than with the thought of invading Gaul themselves.—I feel suddenly a deep interest in these people. What Frenchman of this nineteenth century can feel sure that the blood in his veins is not the same that once gave life and strength to these terrible warriors from the North, Franks or Gauls? We are all natives of one or the other bank of this great river Rhine, and feel towards each other, whether we live on the right or the left bank, very much like school-boys whose friendship is cemented by many a battle royal.

Being a Frenchman, I feel that I am about to [065]pay a visit to my paternal ancestors—for the Franks have given us our name. No wonder that I feel deeply moved.

I examine the low huts of the village, if village it can be called, and find that they are separated from each other by commons and by fields, and that they finally lose themselves in the open country. Where now these scattered huts are standing, there may be one of these days a Mayence or a Cologne, and yet they will occupy no larger space with all their suburbs included.

On both sides of the road extend orchards, fenced in with reeds and all aglow with blooming apple trees; dark, sombre pine forests and swamps, the greenish waters of which are confined within slight dams; here and there the live rock crops out from the ground and interrupts the road, or huge trees are lying across, recently cut down and but just deprived of their branches. In the open pasture grounds huge buffaloes are lying about snorting and panting with fatigue, for they have worked all day in the plough; the neighing of horses is heard from one end of the country to the other, and gradually dies out as the sun sinks below the horizon; lean heifers, with long, spiral horns, push here and there their heads through the fence of the orchards to have a last bite at the tender foliage of the reeds, and small oxen of an [066]inferior breed return to their quarters at the same time with the sheep, quite content to browse on the grass by the wayside, while herds of swine are wallowing in the mire of the low grounds.

The landscape resembles parts of Bretagne and of Normandy; but these provinces have no such huts. To see a human habitation, you have to rise high above the fences and hedges and then look down upon the ground.

At a place where two roads meet, the cracking of a whip is heard; hogs, sheep, and small oxen are driven aside to make way for a kind of procession, consisting of grave and solemn men and women, who almost all wear a look of consternation.

It is a wedding.

Two young people have just had their union blessed by the priests under the sacred oak. The bride is dressed in black, and wears a wreath of dark leaves on her head; she walks in the midst [067]of her friends, bent double, as if weighed down by overwhelming thoughts. A matron, who walks on her left, holds before her eyes a white cloth; it is a shroud, the shroud in which she will be buried one of these days. On her right, a Druid intones a chant, in which he enumerates, in solemn rhythm, all the troubles and all the anxieties which await her in wedded life.

“From this day, young wife, thou alone wilt have to bear all the burden of your united household.

“You will have to attend the baking oven, to provide fuel, and to go in search of food; you will have to prepare the resinous torch and the lamp.

“You will wash the linen at the fountain, and you will make up all the clothing;

“You will attend to the cow, and even to the horse if your husband requires it;

“Always full of respect, you will wait upon him, standing behind him, at his meals;

“If he chooses to take more wives, you will receive your new companions with sweetness; [068]"If needs be, you will even offer to nurse the children of these favorites, and all from obedience to your karl (master);

“If he is angry against you and strikes you, you will pray to Esus, the only God, but you will never blame your husband, who cannot do wrong.

“If he expresses a wish to take you with him to war, you will accompany him to carry his baggage, to keep his arms in good condition, and to nurse him if he should be sick or wounded.

“Happiness consists in the fulfillment of duty. Be happy, my child!”

When I heard this dolorous wedding song, which in some parts of France is to this day addressed to brides by local minstrels, when I saw this winding-sheet, [069]the mournful costumes and the whole funereal wedding procession, I felt overcome with sadness. Just then, cries and joyous acclamations were heard at some little distance.

Another procession came from the opposite direction to the cross-roads; there all the faces were smiling and full of joyousness.

This was a funeral.

Such were the ways of our fathers; they rejoiced in facing death, which relieves man from all his sufferings; they had nothing but tears for man when he entered upon his trials.

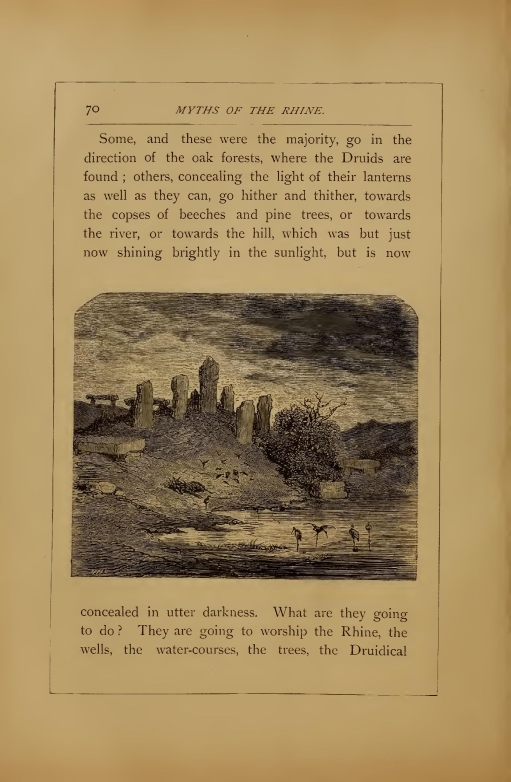

In the meantime the twilight had passed into darkness. Small lights, looking like will-o’-the-wisps, were flitting to and fro in field and forest, going in all directions. Devout worshippers, carrying torches or lanterns in their hands, were going to consecrated places, to hold public worship or to recite private prayers. [070]Some, and these were the majority, go in the direction of the oak forests, where the Druids are found; others, concealing the light of their lanterns as well as they can, go hither and thither, towards the copses of beeches and pine trees, or towards the river, or towards the hill, which was but just now shining brightly in the sunlight, but is now concealed in utter darkness.

What are they going to do? They are going to worship the Rhine, the wells, the water-courses, the trees, the Druidical [071]altars, and the sword-guards. For no creed yet but has had its schisms.

Orthodox or not, German or Gallic, the Franks have always shown a preference for nocturnal worship; they divide the year into moons, and count the moons not by days but by nights. And yet they have been suspected of worshipping the sun! And I had nearly fallen into the same error! How well it was that I came to see for myself!

As I am just now more interested in watching manners than in studying mythology, I pursue my investigations, especially as I know very well that we must know the lives which people lead in order to be able fully to appreciate the objects of their worship.

While all these small lights are flashing, like shooting stars, here and there through the landscape, certain specially bright lights seem to become stationary and permanent. These are the lighted-up windows of human habitations. I called the latter just now stables, or caves, and excepting a few of them, I must still call them such.

They are dug out of the ground, damp and dark; their ceiling is on a level with the surface of the earth, and their roof consists of layers of turf, or of dry thatch covered with moss. The only door resembles the lid of a snuff-box, and is set in the roof on a level with the ground. The dwelling [072]has no light but such as enters through these trapdoors; consequently they are utterly dark during the whole rainy season and during winter, that is to say, for three fourths of the year! Darkness reigns supreme here; that darkness which is the enemy of all healthfulness, of enjoyment, of every comfort. No windows! No glass! O divine Apollo,—

“Thou of the silver bow, god of Claros, hear!”

I never had any objection to the doctrine which made of you, the brilliant personification of the sun, a first class divinity; but I think like honors ought to have been bestowed upon the unknown man who first invented windows and window-panes, the [073]first glazier in fine. He ought at least to have been made a demigod, and if he had to remain a simple mortal, they ought surely to have remembered his name! Alas! that high honors are as unfairly distributed in heaven as upon earth!

As there is no window, I peep through the trapdoor to see how these subterranean dwellings look inside. The aspect is far from being as wretched as I had expected. I find that the walls are hung with mattings and the floor is beaten hard; by the side of the smoking lamp which is suspended from the main beam of the ceiling, there are hanging, on hooks, a hindquarter of venison, baskets filled with provisions, and implements for fishing and hunting. Besides, I notice long strings of medicinal herbs, such as we see in the shops of herb-doctors, and among these plants the mistletoe occupies, as a matter of course, the place of honor.

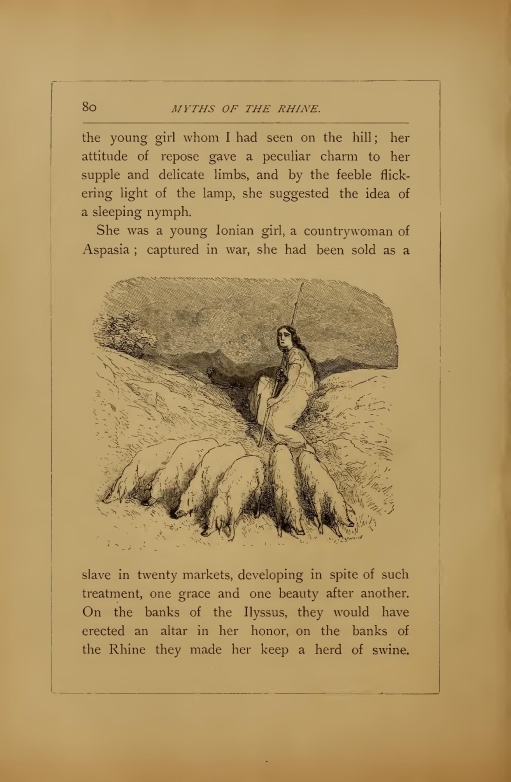

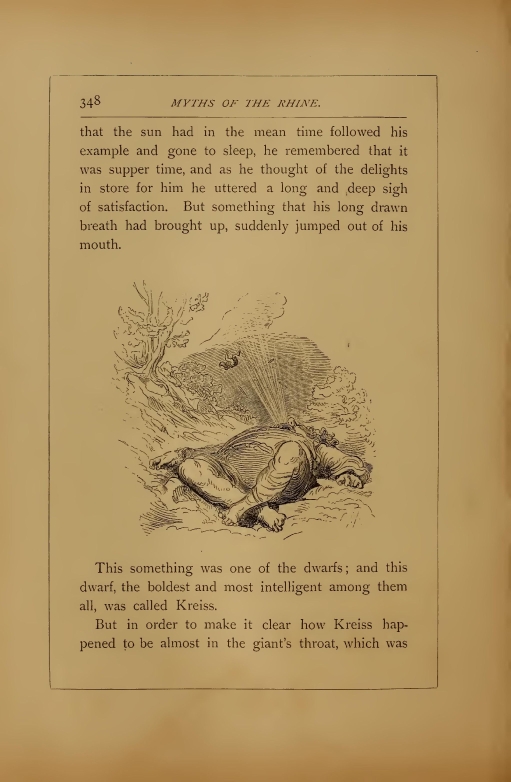

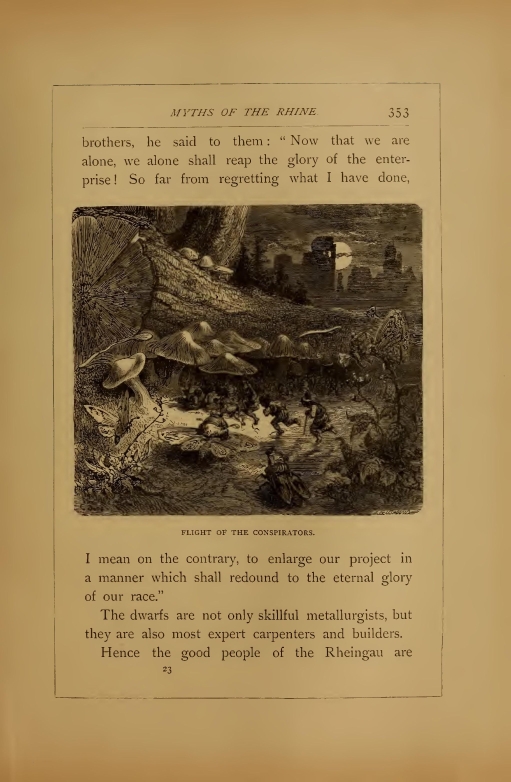

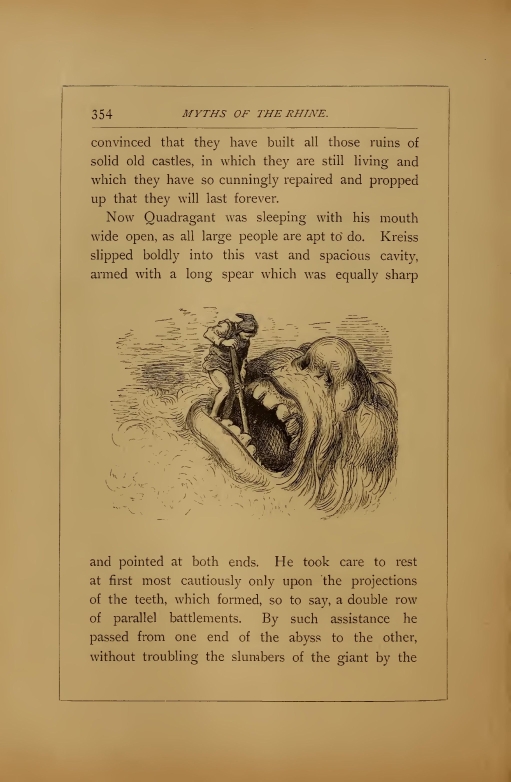

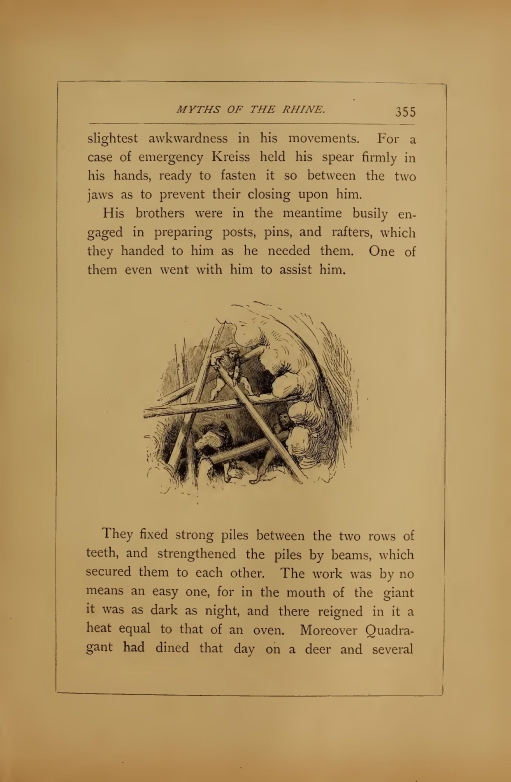

In another underground hut there appear actually some traces of luxury. Here the walls are incrusted with pebbles from the Rhine, of many colors and skillfully arranged; here and there weapons are arranged in various shapes; javelins with sharp hooks; framees, such as the ancient Franks were using; hatchets of stone or iron; “morning stars,” with sharp points, were pleasantly mingled with huge bucklers; large leather quivers and long arrows feathered at one end and with jagged teeth [074]at the other. At first sight it looks as if for the purpose of softening somewhat the threatening aspect of these panoplies, the Celtic lady of the house had added some of her jewels to these weapons. But it is not so; these gold chains, these necklaces set with onyx and rubies, are worn by the grim warriors on the day of battle, quite as much in the nature of ornaments as for the purpose of protection. One of our sober, I may say, most sober historians, ascribes to this custom of our forefathers, the Franks, the gorget, worn still by officers in some European armies. Here also I see straw mats, but here they are trod under foot; they are used as carpets, not as hangings.