Title: Jaufry the Knight and the Fair Brunissende: A Tale of the Times of King Arthur

Author: called Jean Bernard Lafon Mary-Lafon

Illustrator: Gustave Doré

Translator: Alfred Elwes

Release date: December 14, 2013 [eBook #44433]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE FRENCH VERSION.

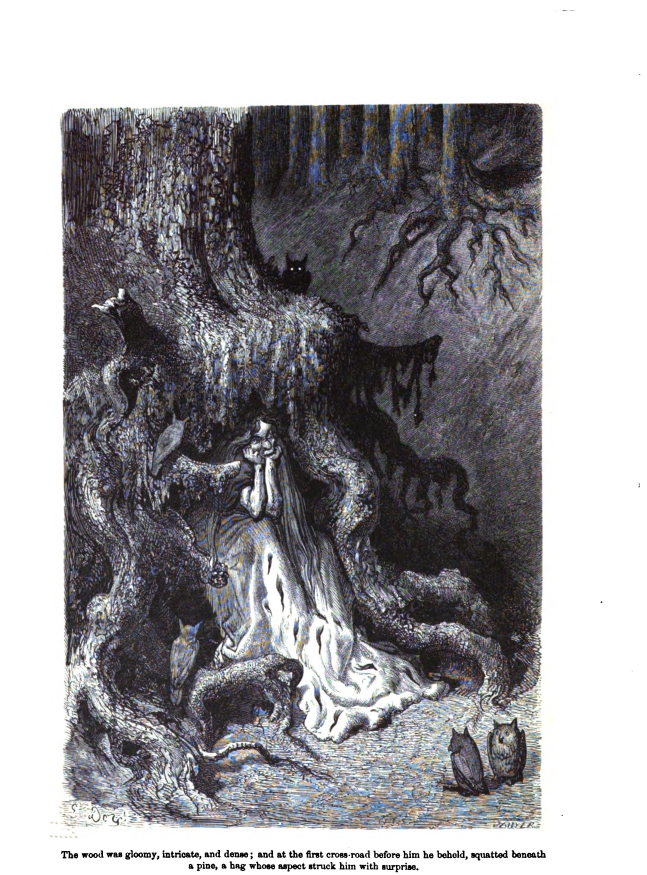

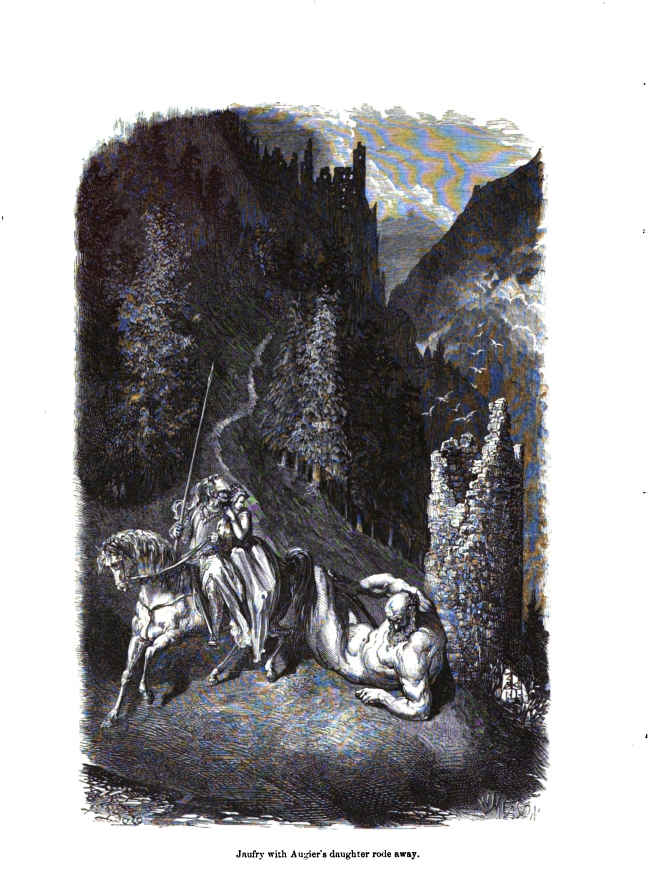

CHAPTER I. THE ADVENTURE OF THE FOREST.

CHAPTER II. ESTOUT DE VERFEIL.

CHAPTER III. THE DWARF AND THE LANCE.

CHAPTER V. THE CASTLE OF THE LEPER.

CHAPTER VI. THE ORCHARD OF BRUNISSENDE.

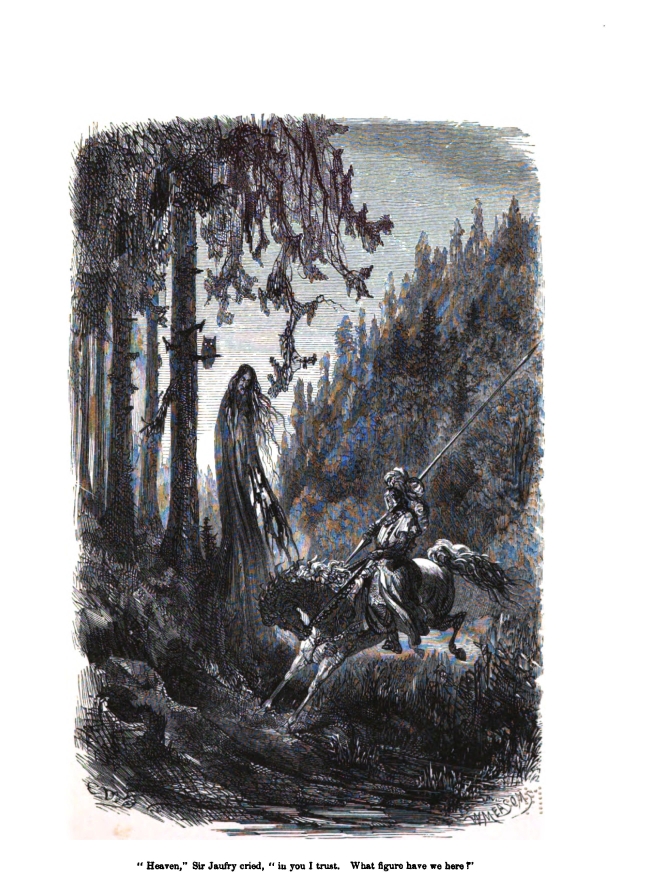

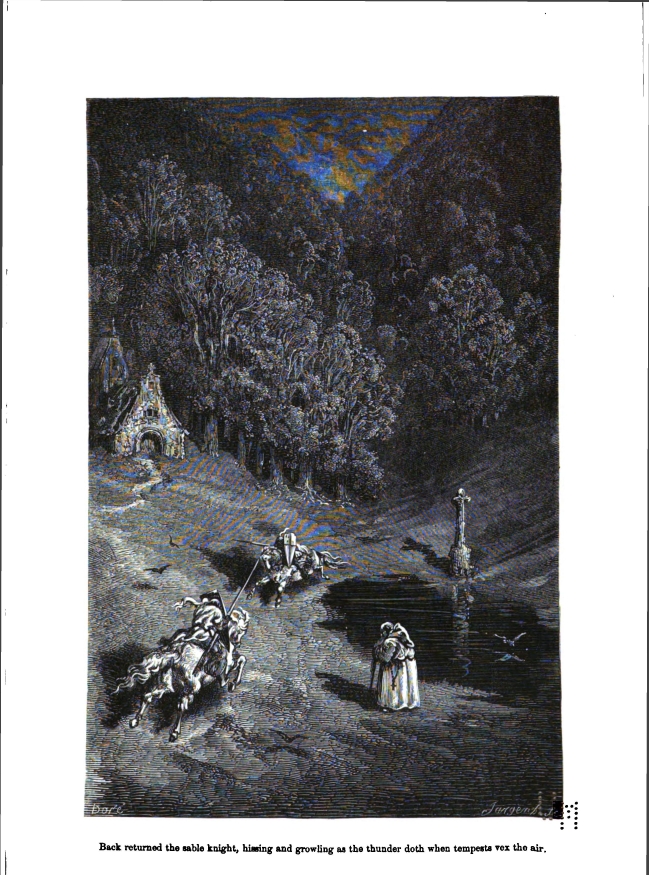

CHAPTER VII. THE BLACK KNIGHT.

CHAPTER VIII. TAULAT DE RUGUMON.

CHAPTER XI. THE COURT OF CARLISLE.

The description given by one of the authors of Jauvfry about the origin of the romance, and the evidence afforded by the French adapter concerning the Mss. wherein it is contained, make it unnecessary for me to dwell upon these particulars.

The veneration in which King Arthur's name is held by all lovers of the early romantic history of Britain will give the tale a strong recommendation in such eyes; while the personages with which it deals render the appearance of its characters in an English dress the more pleasing and appropriate.

As answerable for the fashion and material of the costume, I may be permitted to say a few words concerning the rule which has guided me in producing it. Keeping in view that the original romance is a poem in form and composition, I have endeavoured, in my translation, still to preserve the poetic character; and though compelled to base my work upon a prose version, I have tried, within certain limits, rather to restore its original shape, than allow it, by the second ordeal to which it is thus subjected, to lose it altogether. Whether such attempt, however honestly conceived, has been properly carried out, must be determined by my readers.

King's Arms,

Moorgate Street, London.

The literary world of France scarce knows the extent of its own riches. In the catacombs of its libraries and archives there is a heap of unknown jewels which would give a new and brighter lustre to its poetic wreath. The “great age” did not even suspect their existence; the eighteenth century passed over without bestowing on them, a glance; and if, in our days, a few of our learned brethren have conceived the idea of drawing them to light, the rumour of their labours, which moreover were both superficial and incomplete, never got beyond the doors of the Institute.

There still remains, then, more especially as regards the south, to open up the lode of this mine of gold,—a virgin mine as yet, inasmuch as Sainte-Palaye, Rochegude, Raynouard, and Fauriel, have but scraped Upon its surface,—and reanimate, in a poetic point of view, the middle ages, too easily sacrificed at the period of the renaissance, too severely proscribed by the University. Fed, in truth, from our entry into college with the literature of Greece and Rome, which, however admirable in form, is but sober in invention, we can have no conception of those works wherein the imagination of France, youthful, vigorous, and gay, blossomed in full freshness like a rose in spring. Some judgment may be formed of the value of the poems rhymed by the troubadours in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries by the romance which is now presented to the public. Dragged from the dust beneath which it has lain buried for six hundred years, the romance of Jaufry is translated for the first time; and when we consider the merit of the story, we may add, without fear of contradiction, that it deserved such honour long ago.

Let the reader call up in his mind a pavilion of Smyrna or Granada, with columns of white marble light and graceful as those of the Alhambra, with elegant trellis-work, glass of varied hues, and filled with a pervading tone of warmth,—the warmth of a May sun,—and he will have some notion of the romance of Jaufry and the fair Brunissende:—few things being more piquant, more fresh, more fanciful, or which better reflect the charming caprices of a southern imagination in the middle ages. Feudal society revives therein entire, with all its fairy doings, its knightly fictions, its manners, and its grand lance-thrusts; and such is the interest of the tale, that we allow ourselves to be carried away by it with as much pleasure as our ancestors must have felt, when it was told to the sounds of the minstrers viol in the great castle-hall, or beneath the shadow of the tent.

Two peculiarities, which are not matter of indifference to history, enhance the value of this poetic gem: one is, the influence of Arabic ideas, of which it has a distant savour like the balmy oases of the East; and the other, the inspiration which it evidently lent to Cervantes. If, for instance, we discover therein the roc, the wishes, and the tent of the Fairy Paribanou, as traces of the Arabian Nights, we behold, on the other hand, that this romance of Jaufry has furnished the one-handed genius of Alcala with the first idea of the adventure of the galley-slaves (desdichados galeotes), the cavalier in green (cavallero del verde gavan), the braying of the regidors (rebuzno de los dos regidores), the Princess Micomicona, and the enchanted head. And in this respect we may be permitted to remark, that the romance of Jaufry offers matter of a piquant comparison with the work of Miguel Cervantes. Is it not strange, after the ingenious Don Quixote, to find ourselves reading with pleasure the adventures of a knight-errant?

We should still have much to say concerning this poem and our system of translating it; but as we are averse to useless dissertations, we will confine our further remarks within short space. This romance, which is written in the Provençal tongue of the twelfth century, is composed of eleven thousand one hundred and sixty verses of eight syllables. * It was begun by a troubadour, who heard the tale related at the court of the king of Aragon, and finished by a poet whose modesty caused him to conceal his own name and that of his colleague. In order to render the reading of their work more pleasant, while using our efforts to retain the southern character and genuine tone of colour, we have pared away some of the verbosity and tautologies which at times encumber while they retard the progress of the action. May this flower of the genius of our fathers retain in our modern tongue a part of that freshness and perfume which were its attributes in former days!

* The Imperial Library possesses two manuscript copies: one

in small folio, written in a minute round Italian hand, with

double columns of forty-five verses,—124 pages, classed

under No. 291, 2d French supplement; the other, a small

quarto, which will be found under No. 7988.

Now of a tale of chivalry, of proper fashion, great allurement, full of-wise and courteous instances, and wherein abound acts of great prowess, strange adventures, assaults, encounters, and dread battles, you may list the telling. An it amuse you, I will relate thereof all that I do know, or that it please you to give ear unto. Let me know only that which ye desire, and if ye be inclined to listen in good sooth. When the minstrel doth indeed recite, neither should hearers buy nor sell, nor in low voice hold council; for thus the recital is lost to him who speaketh, and they methinks who listen cannot find therein great pleasure.

I come, then, to recount to you tidings of the court of good King Arthur; he who was so worthy, so valiant, and so wise, that his name shall never die, but whereof shall eternally be spoken the mighty things he did; and the good knights, all for their prowess known, whom he did gather at his famed Round Table. In that court, the fairest and most loyal that ever shone beneath the stars, all men did find that counsel and that aid of which they stood in need. There triumphed right, and there were wrongs redressed.

There dames and damsels, widows and orphans attacked unjustly, or disinherited by force, ne'er failed to meet with champions. The oppressed of all conditions there did find a refuge, and none e'er sought protection there in vain. Give, then, sweet welcome to a poem the fruit of such good place, and deign to listen unto it in peace.

The troubadour who rhymed it never knew King Arthur; but he heard the entire story told at the court of the king of Aragon, the best of monarchs in this world. *

* Don Pedro III., killed in 1213 at the battle of Muret.

A worthy father and a famous son, lord of goodly fortunes, humble in heart, and frank in nature as in mind, the king of Aragon loveth God and feareth Him; he maintaineth faith and loyalty, peace and justice: thus God protecteth him, giveth him the victory when he raiseth his banner against the infidel, and placeth him above all those who are alike worthy and bold. Where shall we seek youthful brows wearing a crown which emitteth rays of greater splendour?

He giveth good gifts to minstrels and to knights, and his court is the resort of all those who are esteemed brave and courteous. It was before him the troubadour heard related, by a stranger-knight of kin to Arthur and Sir Gawain, the song he here hath rhymed; and whereof the first adventure occurred while the king of the Round Table held his court at Carlisle on the day of Pentecost.

'Twas 017on the day of Pentecost, a feast which to Carlisle had drawn a host of knights, that Arthur, King of Briton's isle, his crown placed on his brows, and to the old monastic church proceeded to hear mass. And with him went a brilliant train, the Knights of the Round Table. There were Sir Gawain, Lancelot du Lac, Tristrem, and Ivan bold, Eric frank of heart, and Quex the seneschal, Percival and Calogrant, Cliges the worthy, Coedis the handsome knight, and Caravis short i' the arm; the whole of his bright court, indeed, was there, and many more whose names I have forgot.

When mass was done, they to the palace home returned 'mid laughter and loud noise, the thoughts of each on pleasure only bent. Each on arrival gave his humour play. Some spoke of love, and some of chivalry; 018and some of ventures they were going to seek. Quex at this moment came into the hall, holding a branch of apple in his hand. All made room for him; for there were few who did not fear his tongue and the hard words which it was wont to utter. This baron bold held nothing in respect. E'en of the best he ever said the worst. But this apart, he was a brave stout knight, in council sage, a valiant man of war, and lord of lineage high; but this, his humour and his biting words took from him much that was of right his due.

He, going straightway to the king, thus said:

“Sire, an it please you, it is time to dine.”

“Quex,” replied Arthur, in an angry tone, “sure thou wast born but to awake my wrath, and out of season ever to discourse. Have I not told thee, ay, a thousand times, naught should induce me to partake of food, when thus my court had met, till some adventure had turned up, some knight were vanquished, or some maid set free. Go sit thee down at bottom of the hall.”

Quex went without a word among that joyous throng, where men of all conditions, knights and lords, minstrels and mountebanks, ceased not their tricks, their 019gay discourse, their laughter, till the hour of noon. At noon, King Arthur called Sir Gawain, and thus spoke:

“Fair nephew, cause our chargers to be brought; for since adventure cometh not to us, we must fain seek it in the open field; for should we longer stay, our knights, indeed, would have a right to think that it were time to dine.”

“Your will, my lord,” Sir Gawain said, “shall be obeyed.”

And at the instant he the squires bade to saddle horses and their armour bring. Soon were the steeds prepared, the nobles armed. The king then girded on his famous sword, and at the head of his bold barons placed, set out for Bressiland, a gloomy wood. Having along its deep and shady paths awhile proceeded, the good king drew rein, and 'mid the greatest silence bent his ear. A distant voice was then distinctly heard, calling at intervals for human help, and turn by turn invoking God and saints!

“I will ride yonder,” bold King Arthur cried; “but with no company save my good sword.”

“An it please you, my lord,” Sir Gawain said, “I fain would ride with you.”

“Not 020so, fair nephew,” the king made reply; “I need no company.”

“Since such your wish,” said Gawain, “have your will.”

Arthur called quickly for his shield and lance, and spurred right eagerly towards the spot whence came the plaintive voice. As he drew near, the cries the sharper grew. The king pricked on with greater speed, and stopped before a stream by which a mill was placed. Just at the door he saw a woman stand, who wept, and screamed, and wrung her trembling hands, while she her tresses tore in deep despair. The good king, moved to pity, asked her why she grieved.

“My lord,” she weepingly replied, “oh! help me, in God's name! a dreadful beast, come down from yonder mount, is there within devouring all my corn!”

Arthur approached, and saw the savage beast, which truly was most frightful to behold.

Larger than largest bull, it had a coat of long and russet fur, a whitish neck and head, which bristled with a pile of horns. Its eyes were large and round, its teeth of monstrous size; its jaws were shapeless, legs of massive build; its feet were broad and square. A giant elk were not of greater bulk. Arthur observed 021it for a certain time with wonder in his mind; crossing himself, he then got off his horse, drew forth his sword, and, covered with his shield, went straight into the mill. The beast, however, far from being scared, did not so much as even raise its head, but from the hopper still devoured the corn. Seeing it motionless, the king believed the beast was lack of spirit, and, to excite it, struck it on the back: but still the creature moved not. He then advanced, and standing right in front, lunged at the beast as though to run it through. It did not even seem to note the act. Arthur then cautiously laid down his shield, replaced his sword, and, being stout and strong, he seized it by the horns, and shook it with great force; natheless he could not make it leave the grain. In rage, he was about to raise his fist, so as to deal it on the head a blow; but lo! he could not then remove his hands,—they were as riveted unto its horns.

Soon as the beast perceived its foe was caught, it raised its head; and issued from the mill, bearing, pendant from its horns, the king, aghast, distracted, and yet wild with rage. It then regained the wood at easy pace; when Gawain, who, by good fortune, happed to ride before his Mends, beheld it thus his uncle 022carrying off,—a sight which half-deprived him of his wits.

“Knights!” he exclaimed aloud, “hie hither! help to our good lord! and may the laggard never sit at his Round Table more! We should indeed deserve dishonoured names were the king lost for want of timely aid.” As thus he spoke, he flew towards the beast, not waiting for the rest, and couched his lance as though to strike at it.

But the king, fearing harm would come to him, addressed him thus:

“Fair nephew, thanks; but e'en for my sake halt. If thou do touch it, I am surely lost; and if thou spare it, saved. I might have slain it, and yet did not so; something now tells me I held not my hand in vain. Let it, then, go its course; and keep my men from coming on too near.”

“My lord,” Sir Gawain answered him with tears, “must I, then, let you perish without help?”

“The best of help,” the king rejoined, “will be to do my bidding.”

Sir Gawain was at this so much incensed, he cast down lance and shield, he tore his cloak and handfuls from his hair.

Just 023at this time Ivan and Tristrem came, with lances lowered, and at top of speed; Gawain threw up his hands, and loudly cried:

“Strike not, my lords, for his, King Arthur's sake; he's a dead man if you but touch the beast.”

“What, then, are we to do?” inquired they.

“We'll follow it,” quoth Gawain: “if the king be hurt, the beast shall die.”

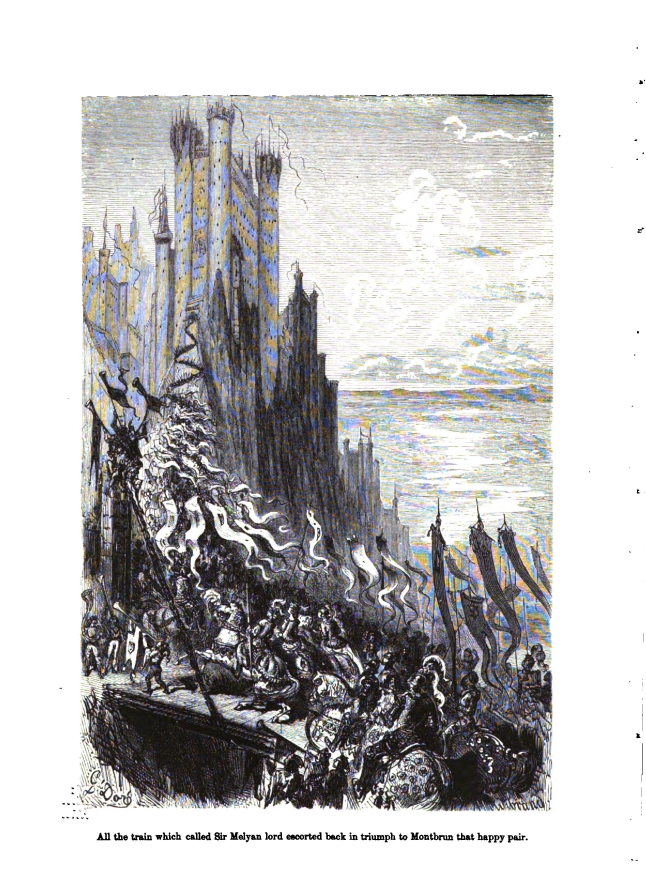

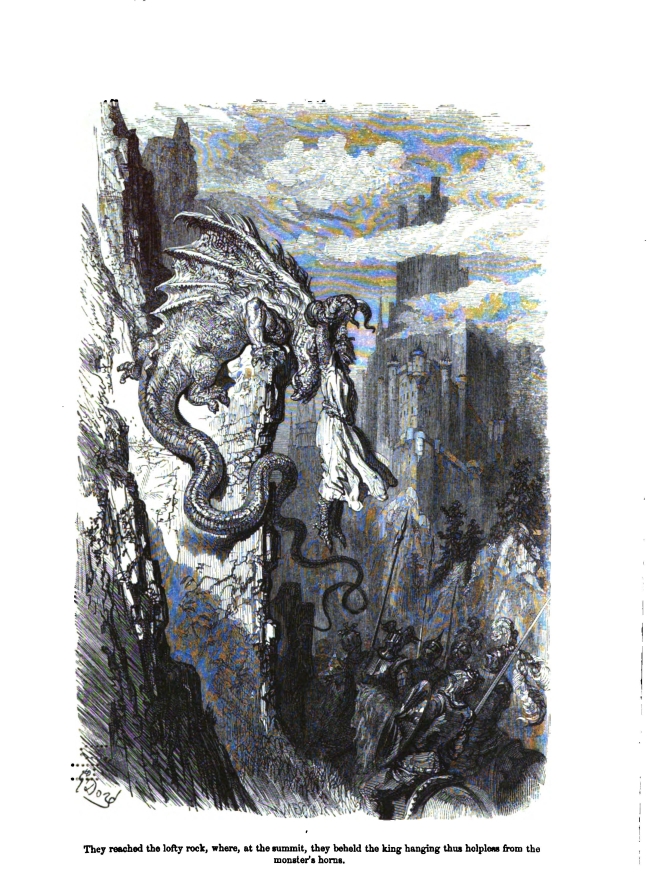

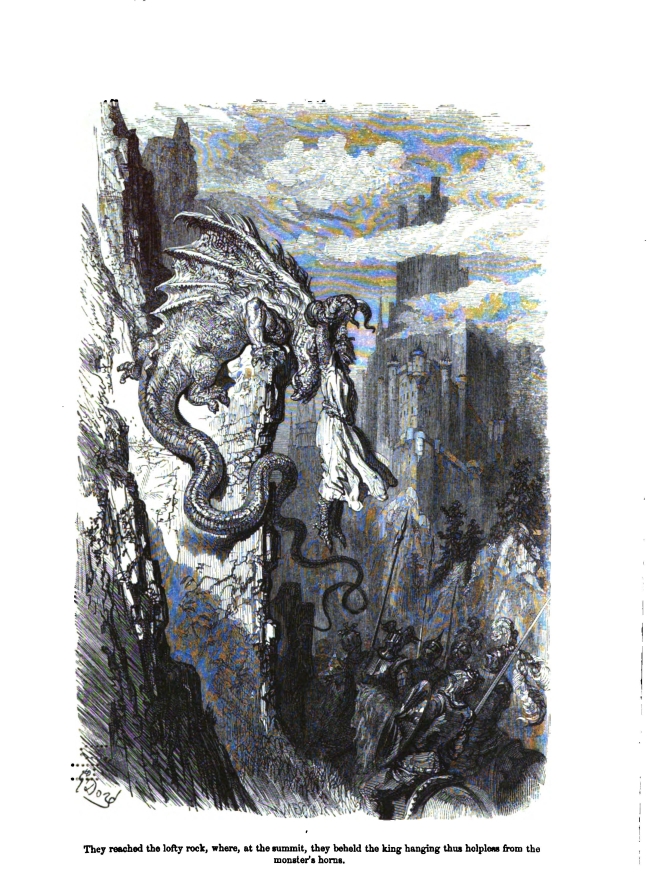

The monster still kept on its even way, not seeming to remark the knights, until a rock it reached, lofty and round and high. It scaled it, as a swallow, rapidly; and Gawain and his friends, who at a distance followed, sad and full of thought, saw it, when thus the summit was attained, crawl straight towards a peak which overhung. There, stretching out its head, it held the king suspended o'er the abyss. Judge the alarm of Gawain and his friends, who each beside was almost wild with rage! Hearing their cries, they who remained behind came up full spur, and reached the lofty rock, where, at the summit, they beheld the king hanging thus helpless from the monster's horns. They then gave loose to the most doleful cries that ever had been heard. I cannot picture to you their despair. Brave knights and pages then you might have 024seen tearing their hair and rending their attire, that wood reviling and the strange adventure which they had come to seek. And Quex exclaimed, by way of final stroke:

“Alas! fair chivalry, how hard thy lot! this day to cause the death of our good king, and lose thy valour when 'twas needed most!”

Saying these words he sank upon the ground. The king, however, still remained suspended in mid air, the beast meanwhile not offering to stir. The monarch feared to drop in that abyss; and in low voice he prayed the saints and God to save him from this pass. Then Gawain, Tristrem, and I know not who beside, took counsel how they might heap up their robes, so as to break the brave King Arthur's fall. Gawain had scarce proposed it to the crowd than each one doffed his garments speedily.

In haste they brought their cloaks and mantles gay; stripped off with eagerness their doublets, hose; and in an instant every knight was bare: such was the heap of garments 'neath that rock, the king had fallen without deadly risk. When this the beast beheld, it stirred as though it would draw back, and slightly shook its head. The crowd below, alarmed, at 025once upraised a cry; and on their bended knees prayed Heaven to guard the king, and bear him safe and sound. The beast with mighty spring then leaped below; and setting Arthur free, itself it changed into a handsome knight, in scarlet richly dad from head to heel. This noble bent his knee before the king, and smiling said:

“My liege, command your men their garments to resume; they now may dine in peace; though somewhat late, the adventure has been found.”

Arthur amazed, nay, half-distraught at this adventure strange, now recognised the knight,—a courtly guest, esteemed among the brave, the courteous, and the sage.

Adroit in arms, gay, graceful, and beloved; among the first in strife, yet kind and modest too,—this lord was master of the seven arts, and in all spells was versed. For some time past between him and the king a compact stood, whereby it was agreed, if he himself transformed when all the court was met, he should as guerdon three good gifts receive—a cup of gold, a charger of great price, and from the fairest damsel a sweet kiss.

Gawain at once ran up, fearing his uncle in his fell 026was crushed; and you may safely judge of his surprise—finding him thus, in high good humour, stand loud laughing with the beast.

“In faith, fair friend,” quoth he, “you can indeed enchant poor folks, and force even barons to throw off their clothes.”

“You may resume them, good my lord,” said the enchanter in the same gay tone; “for lo! the king no longer needs their use.”

They did indeed soon put them on again, nor stayed to pick or choose; the court at once returned to fair Carlisle, the monarch and Sir Gawain riding on a-head. The palace-walls soon echoed with their joy. The pages brought them wherewithal to wash, and soon the knights were placed about the board. Grand was that court, and rich and brave and good; many a puissant name, full many a king, and many a duke and count, were seated there. Gawain the valiant knight and Ivan the well-bred, each holding the queen's arm, then led her in, where, at the table, sat she 'neath the king. Gawain then placed himself the other side, and Ivan by the queen: at once with laughter they began to tell of the enchanter's skill; and when Queen Guenever, and they, the knights who were 027not in the wood, had learned the doings there, they were indeed surprised; and soon loud laughed and chatted with the rest. Meanwhile Sir Quex before the king and fair Queen Ghieneyer the golden dishes placed; he then sat down to eat his own good meal, for he did boast a famous appetite, while ready pages served the other knights. Nothing was wanting at that banquet high: the roebuck, kid, and succulent wild-boar; the crane, the bustard, capons, swans, wild-geese; peacocks, and fine fat hens and partridges; white bread and purest wine,—of all good things the best was there beheld. Served by a host of graceful youths beside, the guests did honour to the feast.

Eating and drinking then engaged each thought; when straight there entered, mounting a fleet horse, with spotted robe, a youthful squire, tall and of noble mien. Never, do I believe, was man more finely-shaped. His shoulders were at least two cubits broad, his features regular, his eyes were sparkling, full of love and mirth; his hair was shining as the brightest gold, his arms were large and square, his teeth as ivory white. His frame, which tapered at the waist, was well developed, and displayed his strength. His legs were long and straight, and feet high-arched.

His 028violet and well-cut robe rested in graceful folds on hose of the same hue. A garland of fresh flowers crowned his brows, to which the sun had given a deeper tint, heightening the colour of his ruddy cheeks.

Entering the hall, he alighted from his horse, and came with quick and joyous step to kneel at the good monarch's feet. He then his purpose opened with these words:

“May He who made this world and all it holds; He who no suzerain hath,—now save the king, and all that 's his!”

“Friend,” replied Arthur, “thank thee for those words; if thou dost seek a boon, it shall be thine.”

“My liege, I am a squire, come from far unto your court, because I knew so doing I should meet the best of kings; and I conjure you for St. Mary's sake, if you so please, to arm me now a knight.”

“Friend,” said the king, “arise, and take thy seat; it shall be done thee even as thou wilt.”

“Never, my liege, if you permit, will I uprise from hence till you have granted me the boon I ask.”

“It is conceded,” then exclaimed the king.

The squire arose as these fair words were said, and went 029to take his place at that rich board. But scarcely was this done, than lo! the guests beheld a knight, well armed, and on a charger fleet, come riding in. Crossing the hall, he with his lance did strike a lord upon the breast, and stretched him dying just before the queen. He then rode out, exclaiming as he went:

“This have I done to shame thee, wicked king. If it do grieve thee, and thy boasted knights should care to follow, I am Taulat Lord of Rugimon; and each passing year, on this same day, will I return to do thee the like scorn.”

Good Arthur drooped his head, enraged, yet sad; but then the squire rose, and knelt before the king:

“Sire,” he said, “now give me knightly arms, that I may follow up that haughty lord who casts dishonour on this royal court.”

“Friend,” exclaimed Quex at this, “your courage will be higher when you're drunk. Sit yourself down again, and drink another bout; the heart will be the merrier, and you can better floor a knight with wine than with a sharp-edged sword, however stout!”

The squire to this responded not a word, out of his duty for the worthy king; but for such cause, Quex had 030for his speech paid dear. Arthur, however, gave his anger vent, and thus exclaimed:

“Wilt thou, then, Quex, ne'er hold that biting tongue until I've driven thee from out my court? What has emboldened thee to speak thus vilely, and to a stranger who a suit prefers? Canst thou not keep within thee all the spite, the envy, wicked words, and slanderous thoughts with which thou art swelling o'er?”

“My lord,” the squire said, “pray let him have his say; little heed I the flings of his forked tongue, for which I will a noble vengeance seek. Vile word ne'er sullieth honour. Let me rather have a suit of arms, to follow him who now has issued hence; for I do feel I shall not eat at ease till he and I have met in deadly fight.”

The monarch courteously replied:

“My friend, I willingly will give thee steed, good arms, and knightly spurs; for thou dost ask these gifts as squire of gentle birth. But thou art all too young to fight with him who now has left this hall. Not four among the knights of my Hound Table can dare to meet his blows, or touch him in the field. Leave, then, this care to others; I should grieve to lose at once so stout and brave a squire.”

“Since, 031sire, you think me stout, and call me brave, 'tis wrongfully or but to jeer you wish to stay my fighting; but in that you'll not succeed save you refuse to grant the boon erewhile you promised me;—and should a king forget his promise made, gone are his lustre and his courtesy.”

The monarch answered:

“Friend, I yield me to thy ardent wish; thou shalt be armed a knight.”

He then commanded two attendant squires at once go seek his armour, lance, a fine and tempered shield, the casque, the sharp-edged sword, the spurs, and horse of price in full caparison; then, when they brought the arms and horse, he caused the squire to put the hauberk on, he buckled his right spur, girded his sword upon the youth's left flank, and having kissed him gently on the mouth, he asked of him his name.

“Sire, in the land where I was born my name is Jaufry, son of Dovon.”

The king, on hearing him speak thus, sighed heavily, and said, while tears were in his eye:

“Ah! what a knight and lord of mark was this same Dovon! He was of my table and my court. A 032brave knight and a learned: never had he superior in arms. None were held stouter or more dread in fight. May God, if He so will it, grant him grace; since for my sake he died! An archer pierced his heart with a steel bolt, while he a keep held out on my domain in Normandy.”

Meanwhile a squire brought Jaufry a bay steed. The young knight placed his hand upon the bow, and leaped upon the horse, all armed as he then stood, without the use of stirrup; then called he for his shield and lance, consigned the king to God, and having taken leave of all the rest, he galloped from that hall.

The 033charger, which was fleet and fair to view, started off like an arrow from its bow. So that, as Jaufry left the castle-gates, he hoped he yet should overtake the knight; and therefore cried aloud to two men on the way:

“Good fellows, if you can, tell me the road just taken by the lord who left the castle yonder even now. If naught prevent you, point me out the way.”

One of those men replied:

“Speak you of him whose armour was so bright?”

“The same,” quoth Jaufry.

“He is on before; you start too late, sir knight, to catch him up.”

“By Heaven!” murmured Jaufry, much aggrieved, “he cannot flee so far, or sink so deep, but I will reach 034him. I'll seek him the world through, where land and sea are found, and will discover his retreat even beneath the earth!”

This said, he held his course; and spurring, came to a broad causeway where fresh prints of horses' hoofs appeared upon the dust.

“Methinks,” said Jaufry, “that a knight ere-while hath passed this way: so I will follow up this selfsame road while thus the trail is seen.”

Putting his horse into an ambling pace, he rode on all that day without a town or castle being met. At eventide he still continued on, when a loud cry, followed by din of arms and clash of steel on helm, suddenly rose from out the heavy shade.

Jaufry spurred readily towards the spot, and cried:

“Who are ye, lords, who at this hour do fight? Reply, since eyes of man cannot behold you.”

But no one replied; and when, as fits a bold and venturous man, he reached the place whence came the clashing noise, the fight was over and the din had ceased. Whilst then he listened, seeing naught, and at the silence wondering, there rose from out the shade deep sighs and moans; when, stooping forward, he made out 035a knight so sadly hurt the soil was bathed in blood.

“Knight,” cried Jaufry to the corpse, “it grieves me not to know thy slayer, or whether thou wert wrong or whether right: thou art now dead; but if I can, I even will learn why, and by whose hand.

“Knight,” he exclaimed, “speak, and inform me for what, and by whom, thou hast been so sorely used.” The wounded man could not e'en stir his lips or move a limb; his arms grew stiff; and, with two fearful groans, he yielded up the ghost.

“Knight,” then cried Jaufry to the corpse, “it grieves me not to know thy slayer, or whether thou wert wrong or whether right: thou now art dead; but if I can, I even will learn why and by whose hand.” He then departed, and resumed his way, now on the trot and now at ambling pace, stopping at intervals to bend his ear and give a look around. For some time nothing met his ear or eye; but, after having ridden for a space, a noise of battle once again assailed him. Steel, wood, and iron met with such dread force, it seemed as though the thunder vexed the air, and that this din proclaimed the bursting storm. At once, then, to the side from whence it came Sir Jaufry turned his horse; and, with his shield about his neck, his lance in rest prepared, he spurred with ardour on, for, in his mood, it seemed as though he ne'er should learn who slew the knight and who were they that fought. On, then, to 036that affray he hotly came; but to behold, stretched stiff upon the ground, a knight all armed, whose casque and head beside had by a single blow been cloven to the teeth, while his steel hauberk was all red with gore. Jaufry his visor raised, and touched him with his lance; but, seeing no life was there, exclaimed with grief:

“Heaven! shall I, then, never know whose hand hath slain these knights?”

Full of impatience he resumed his course; and when he far had ridden, lit upon another knight, whose body was so shattered with his hurts that blood and life were oozing fast away. Moved deeply at his cries and sad laments, Jaufry drew near, and kindly asked what hand had dealt such measure to himself and the two others slain, and which side was moreover in the wrong?

“Alas!” the wounded man made answer with a sigh, “I will explain to you the simple truth. It is Estout, the master of Verfeil, who has reduced us to the state you see, to feed his pride. This knight is known so quarrelsome and fierce, that without mercy and without a cause he doth assault all comers far and near.”

“Tell 037me,” said Jaufry, “was he wrong in this?”

“I will, my lord, with Heaven's help, and that without e'en lying by a word. I and my friends were going to our rest, when Estout to my castle-gates, hard by, rode up, and bade us high defiance. Had it been day, we should have tarried long ere venturing forth; for we did know him master of such skill, that few as yet could e'er make head against him,—so merciless beside, as never in his lifetime ever known to grant his foeman grace: seeing him not, the bridge was lowered, and at once was passed. He, having drawn us far upon the road,—the better for the treacherous ends he had,—suddenly stopped, and turning, with lance couched on him who pressed him nearest, stretched him dead upon the earth.

“By this time we had recognised Estout, and turned our horses' heads; but he with threatening words pursued us close, and reaching my companion, slew him with a blow. He then his rage concentrated on me, and with such fierceness, thinking my end come, I missed my aim, the lance just glancing from his shield; but he with one stroke bore me from my horse, and three times struck me as I helpless lay, so that, 038good faith, he little life hath left. This, my good lord, is how the thing hath happed.”

“Know you,” asked Jaufry, full of thought, “the road he took, and where he may be met?”

“My lord, I cannot tell; but little do I doubt that you will find him earlier than you wish. Haste, then, to fly such presence; for believe, you cannot gain thereby aught else but iron: an you take my advice, you'll change your route.”

“Change my route, say ye?” quoth Sir Jaufry; “no, by my troth; nay more, I will but follow him the closer up; and, should I catch this lord, we part not, he may rest assured, without a struggle; and without learning, too, which of us twain doth bear the stouter heart, the stronger arm, or wield the better sword.”

He took his leave, with these words, of the knight; the latter prayed him to pass by his keep and send him aid from thence.

“I will not fail,” said Jaufry.

Towards the manor of the dying man he took his way, and after some brief space he saw high towers and two squires well armed, who mounted guard before a raised drawbridge.

“Friends,” 039he exclaimed to them, “God save you both!”

“And you, my lord, from every harm,” they said.

“I have sad message for you,” added Jaufry, “and bad news. Your lord is lying yonder sorely hurt; and his two comrades are both slain. Estout de Verfeil has misused them thus. So hasten to your lord, who wants your help.”

He then commended them to God, and parted in all haste. Jaufry resumed his way, now trotting hard and now at ambling pace, until he reached a valley deep and dark. There he beheld the blaze of a great fire, round which were met a numerous company. Trusting he might get tidings there of Estout and of Taulat,—for truly counted he on fighting both,—he straightway rode to where the fire was, and found there figures that awaked surprise. Lords in rich vestments roasted a wild-boar; meanwhile, by dwarfs, stunted and out of shape, the spit was turned.

“Good sirs,” said Jaufry civilly, “could I but learn from some of you where I may meet a lord I have followed this night through?”

“Friend,” exclaimed one in answer, “it may be we can tell you when we know his name.”

“I 040seek,” said Jaufry, “Estout de Verfeil, and Taulat called the Lord of Rugimon.”

“Friend,” said the knight with courtesy, “from hence depart, and that with greatest speed; for should Estout but chance to meet you here thus armed, I would not give a denier for your life. He is so valiant and so stout of limb, that never yet hath he encountered foe who could make head against him. All these you see around are knights of proof, and can meet sturdy blows; natheless he hath subdued us all, and we are forced to follow him on foot wherever choice or venture leads him on. We're now engaged preparing him his food; so I advise you to depart at once.”

“Not so, indeed,” said Jaufry; “I came not here to flee. Before I turn my face, my shield shall be destroyed, my hauberk riven, and my arm so bruised it cannot wield a blade.”

Whilst thus they held discourse, behold Estout arrived full spur, and, at the sight of Jaufry, cried aloud: “Who art thou, vassal, who thus dar'st to come and meddle with my men?”

“And who are you,” said Jaufry in reply, “who use such pleasant words?”

“Thou shalt know that anon.”

“Are 041you Estout?”

“I am, indeed.”

“Full long have I been seeking you throughout this weary night, without e'er stopping in my course or closing eye.”

“And for what end hast thou thus sought me out?”

“For that I wish to know why thou hast slain the three knights on the road; which act I take to be a sin and wrong.”

“And is it for this that thou art hither come? Thou wouldst have better done to stay behind, for to thy ruin do I meet thee here; thou shalt this instant lose that head of thine, or follow me on foot like yonder knights who patter humbly at my horse's heels. Deliver, therefore, up to me thy shield, thy breastplate, and thy sword, and the bay horse that brought thy body here.”

“My care shall be to guard them with my life,” quoth Jaufry. “'Twas the good king bestowed this courser on me when he armed me knight. As to the shield, thou shalt not have it whole; nor e'en the hauberk, without rent or stain. Thou tak'st me for a child, whom thy poor threats can frighten: the shield, the hauberk, and the horse, are not yet thine; but if they 042please thee, try a bout to win them. As to thy threats, I scorn them: 'threats,' saith the proverb, 'often cover fear.'”

Estout drew off his horse at these bold words, and Jaufry nerved him to sustain the shock; then ran they at each other with their utmost speed. Estout struck Jaufry on the shield's bright boss, and with such mighty strength, that through the riven metal went the lance, breaking the mail which guarded his broad chest, and grazing e'en the skin. Jaufry meanwhile had struck his foe in turn, and with so just an aim, he lost at once his stirrups and his seat, and rolled halfstunned upon the ground.

He rose again full quickly, pale with rage, and came with upraised sword towards Jaufry. The latter, wishing his good horse to spare, at once leapt on the sod and raised his shield. 'Twas just in time: Estout, in his fierce rage, brandished his sword with both his hands, and made it thunder down with such effect the shield was cloven to the arm.

“St. Peter!” murmured Jaufry, “thou dost covet this poor shield; still, if naught stay me, it shall cost thee dear.”

Suiting to such words the act, upon Estout's bright casque 043he then let fly so fierce a downward stroke, that fire issued therefrom. But the good helm of proof was not a whit the worse. With gathering fury Estout came again, and with one stroke pared from Sir Jaufry's shield the double rim, full half a palm of mail, and the left spur, which was cut through as the blade reached the ground.

Wondering at the vigour of his dreadful foe, Jaufry, on his side, struck a second time his burnished helm; and with such force, his sword in twain was broken, yet left it not upon the trusty steel even the slightest dent.

“Heaven!” thought Jaufry, “what doth this portend? confounded be the hand that helmet wrought, whereon my blade hath spent itself in vain!”

Then Estout, uttering a fearful cry as he beheld Sir Jaufry's sword in two, flew straight towards him, and in his turn struck the son of Dovon on the helm, smashing the visor as the blow came down. Had he not raised in time the remnant of his shield, which that fell stroke for aye destroyed, the combat had been done.

“Knight,” said Sir Jaufry, “thou dost press me sore; and I, good sooth, must be indeed bewitched; strike 044as I will upon that helm of thine, I cannot crack its shell.”

As thus he spoke, he launched a desperate blow with what was left him of his blade; which, falling on the casque of his stout foe like hammer on an anvil, for the time deprived him both of sight and sound. With dizzy eye and tottering step, Estout, thinking to strike at Jaufry, whom he would have cloven to the heel had he received the blow, let fall his sword with such unbounded rage, it struck into the ground, and buried half its blade. Before he could withdraw it, the young knight, casting aside the battered shield and broken sword, seized with both arms Estout about the waist, and that with such good-will, his very ribs were heard to crack within. To cast him to the ground, undo his helm, and seize his sword to strike off his foe's head, were but an instant's work.

Estout, who moved not, cried with feeble voice:

“Mercy, good knight! O, slay me not, but take of me such ransom as thou wilt; I own that thou hast vanquished me.”

“Thou shalt have mercy,” Jaufry then replied, “an thou do'st that which I shall now command.”

“It 045shall be done most willingly, my lord; thou canst not ask a thing I will not do.”

“In the first place,” said Jaufry, “thou shalt go and yield thyself a captive to King Arthur, with all these knights, to whom thou must restore what thou hast ta'en from them; and thou shalt then relate to that good king how I have thus o'ercome thee in the fight.”

“I will do so full willingly, by Heaven!” Estout replied.

“And now,” said Jaufry, “give to me thine arms; for mine have been all hacked and hewed by thee.”

“Agreed, my lord. Give me your hand: the bargain shall be kept; and well can I aver, without a lie, that ne'er did knight boast armour such as mine. Many's the blow may fall upon this helm, yet never pass it through; no lance can dim this shield or pierce this mail; and for this sword, so hard is it of temper, iron nor bronze nor steel resists its edge.”

Jaufry then donned these valuable arms; and whilst he buckled on the shining helm and burnished shield and girded the good sword, the captives of Estout came up to do him homage. They were two score in number, all of price and lofty lineage, who addressed him, 'mid warm smiles of joy:

“Fair 046lord, what answer will ye that we make when good King Arthur asks the name of him who sets us free?”

“You will reply that Jaufry is his name,—Jaufry the son of Dovon.”

This said, he ordered that his horse be led; for still he burned to overtake Taulat. And though Estout and all the knights pressed him awhile to tarry, yet he stayed neither to eat nor take the least repose: from squires' hands receiving shield and lance, he took his leave, and wandered on his way.

The day came on both clear and beautiful; a bright sun rose on fields humect with dew; charmed with the spring-tide and the matin hour, the birds sang merrily beneath the verdant shade and conned their latin notes. * Jaufry, natheless, went straight upon his road, still bent on finding Taulat; for to him nor peace nor rest nor pleasure can e'er come till that proud lord be met.

* E l'jom e clars e bel gentz

E l'solelz leva respondents

Lo matin que span la rosada,

E l's auzels per la matinada

E per lo temps qn'es en dousor,

Chantan desobre la verdor

E s'alegron en or latin....

After 047Sir Jaufry had rode on his way, Estout his promise kept, and to each knight restored both horse and arms. That evening he set out for Arthur's court, which he resolved to reach before the jousts and games and banquetings were o'er. Eight days had they been holden in those halls when he arrived there with his company. 'Twas after dinner, as the king was seated with his lords, lending an ear to minstrels' tales and the discourse of knights, who told of acts of lofty prowess done, that Estout came with that armed troop of knights. Having alighted at the palace-gates, they soon were led before the worthy king; when, kneeling at his feet, Estout expressed himself in terms like these:

“Sure, may that high King who made and fashioned 048all things, He, the Lord of every sovereign, who hath nor peer nor mate, now save us in your company!”

“Friend,” the king replied, “God save you, and your friends beside! Who are ye, and what come ye here to seek?”

“My lord, I will recount you the whole truth: from Jaufry, son of Dovon, come we, to proclaim ourselves your captives, and submit to your just law. Sir Jaufry hath delivered all these knights, whom I had captured one by one, and who were bound to follow me on foot,—for they had mercy only on such terms; now he hath conquered me by force of arms.”

“And when thou last beheldst him,” asked the king, “by that true faith thou ow'st to gracious Heaven, say, was he well in health?”

“Yea, sire, by the troth I owe to you, believe, that eight days since, arise to-morrow's sun, I left him sound, robust, and full of fire. He would not even tarry to break bread; for he declared no food should pass his lips, no joy, no pleasure, no repose be his, until the knight named Taulat he had found. He now is on his track; and I engage, that if he meet him, and a chance do get to measure sword with sword, it will be strange 049an he not force him to cry grace; for I do not believe the world doth own a braver knight, or one more strong in arms. I speak from proof, who dearly know his force.”

“O Heaven, in which I trust,” cried Arthur, as he clasped his hands, “grant me my prayer, that Jaufry fry safe and sound may back return! Already is he known a doughty knight, and noble are the gifts he hither sends.”

Leave we now bold Estout to tell his tale, and turn we to our knight. I have related how Sir Jaufry still went on seeking his foe by valley and by mount; yet neither spied nor heard he living man to give him tidings. He rode on thus, nor met he man or beast till the high noon was passed. The sun had now become intensely hot, and hardly could he bear its burning ray; still, neither sun, nor hunger, thirst, nor aught beside, could cow his spirit. Determined not to stop upon his road till he had Taulat met, he still progressed, though ne'er a soul was seen.

As he pressed hotly on, some hours' riding found the youthful knight close by a gentle hill shaded by one of nature's finest trees. Pendent there hung from an outstretching bough a fair white lance of ash with point 050of burnished steel. Thinking a knight perchance was resting near, Jaufry in that direction turned his horse, and galloped towards the spot. When he had reached the bottom of the hill, he nimbly leapt him down, and walked to the high tree; but, to his great surprise, no soul was there, naught save the lance suspended to the bough. With wonder then—asking of himself why arm so stout and good, the point of which like virgin silver shone, should there be placed—he took it down, and his own resting gainst the mossy trunk, handled and brandished this new dainty lance, which he discovered to be good as fair.

“Good faith,” quoth he, “I will e'en keep this arm, and leave mine own behind.”

Whilst making this exchange, a dwarf of frightful shape suddenly rushed from out a neighbouring grove. Stunted and broad and fat, he had a monstrous head, from which straight hair streamed down and crossed his back; long eyebrows hid his eyes; his nose was large and shapeless; nostrils so immense they would have held your fists; and thick and bluish lips rested on large and crooked fangs; a stiff moustache surrounded this huge mouth; and to his very girdle flowed 051his beard; he measured scarce a foot from waist to heel; his head was sunken in his shoulders high; and his arms seemed so short, that useless would have been the attempt to bind them at his back. As to his hands, they were like paws of toads, so broad and webbed.

“Knight,” cried this monster, “woe befals the man who meddles with that lance! Thou wilt receive thy dues, and dangle on our tree; come, then, give up thy shield.”

Sir Jaufry eyed the dwarf, and angrily replied:

“What mean you by such tale, misshapen wretch?” At this the dwarf set up so loud a cry that all the vale resounded; and at once a knight well armed, mounted upon a steed in iron cased, came, with high threats upon his lips exclaiming:

“Woe to the man who hath dared touch the lance!”

Having the hill attained, he Jaufry saw; and thereupon he said:

“By Heaven, sir knight! to do what thou hast done is proof thou carest little for thy life.”

“And why so, lord?” Sir Jaufry calmly asked.

“Thou shalt soon learn. No man doth touch that lance 052and get him hence without a fight with me. If I unhorse the knight so bold as dare to touch it, and conquer him by arms, no ransom saves his life,—I hang him by the neck; and on my gallows which thou seest from here full three-and-thirty dangle in mid air.”

“Tell me now faithfully,” Sir Jaufry said,—“can he who sues for mercy gain it at thy hands?”

“Yea, but on one condition I have firmly fixed; which is, that never in his life he cross a horse; ne'er cut his hair or pare his nails; ne'er eat of wheaten bread, or taste of wine; and never on his back wear other dress than what his hands have woven. Should he such terms accept before the fight, he may perchance find grace; but naught can save the man who once hath fought.”

“And if he know not how to weave such dress?” asked Jaufry.

“The art to weave, to shape the doth, and sew, must then be learned,” the knight replied. “Say, then, if thou consent; or if thou choose this hour to be thy last.”

“I'll not do so,” quoth Jaufry; “for too hard the labour seems.”

“Thou'lt do it well before five years are fled; for thou art tall and strong.”

“No, 053by my troth, I'd rather chance the fight, since 'twould appear I've no alternative.”

“Take my defiance, then!” cried out the knight; “and bear in mind, the combat 's to the death.”

“So be it!” said Sir Jaufry; “I'll defend myself.”

They drew apart some space with such-like words, each thinking on his side a victim soon would fall. Then the knight came and thundered at his foe. In shivers flew the lance; but Jaufry bore the shock unmoved. Not so the knight; for Jaufry, his weapon planting at his shield, broke it right through; the hauberk too beside, and wood and iron, for a cubit's length, pierced through the shoulder.

He fell: Jaufry with naked blade was by his side; but as he saw him thus, so poorly sped,—

“Knight,” he exclaimed, “methinks thy hanging-trade is done.”

“Lord,” cried the wounded man, “unhappily 'tis true. Thou hast too well performed thy work for safety henceforth to be banished hence.”

“I will not trust to that,” quoth Jaufry; “or at least, it shan't prevent my hanging thee.”

“In Heaven's name, my lord, I crave thy grace!”

“And by what claim canst thou obtain it, thou who 054never yet hast granted it to man? Thou shalt find pity, such as those yonder found who once begged grace of thee.”

“If, good my lord, my head have erred, my heart been black and habits villanous, guard thee from following in my steps. I ask for mercy—that should I receive. Wilt thou, a man of lofty virtue, choose that ever the reproach should come to thee of hanging up a brave and courteous knight, such as I once did bear the title of?”

“Thou liest in thy throat,” Sir Jaufry said; “never couldst thou be prized a proper knight, but rather, I believe, an arrant knave. Who doth a villain's act doth forfeit rank and chivalry alike. In vain thy suit; no pardon shalt thou find.”

Undoing his steel helmet as he spoke, he seized a rope and placed it round his neck; then, dragging him beneath the dismal tree, he well and fairly hung him up thereto.

“Good friend,” he then apostrophised the knight, “the passage now may be considered safe, and travellers need fear little more from thee.”

Leaving him hanging upon such adieu, he rode towards the dwarf, as with intent to kill. But when the latter 055saw him thus return, crossing his arms full quickly on his breast,—

“Fair sir,” he cried, “I yield to you and Heaven; but grant me, pray, your pity. Of myself no evil have I done; since, had I disobeyed the knight, I should have lost my life. Maugre myself, for fourteen years I've watched this lance, which twice a-day I burnished. Woe had betided me if I had bilked such task, or failed by signal to advise my lord when it was touched by knight. This, fair my lord, hath been my only crime.”

“Thou mayst have mercy,” Jaufry said, “an thou dost that which I shall now command.”

“Speak, good my lord; and God confound me if I lose a word!”

“Rise, then, and hie thee to King Arthur's court. Tell to that king the son of Dovon sends thee, and presents this lance which he hath won, the fairest weapon eye hath e'er beheld. Recount to him beside thy lord's ill-deeds, how that so many worthy knights he'd hung, and how in his turn like meed was given unto him.”

“My lord,” exclaimed the dwarf, “all this I promise you.”

And Jaufry made reply, “Well then, begone!”

It 056was one Monday eye that this fell out, just at the setting sun. The night came shortly on serene and fair, and the full moon shone out as bright as day. Jaufry pursued his road,—for naught could change his purpose,—and the dwarf prepared to execute his trust. At peep of morn he started for Carlisle, where, after certain time, he safely came. The king was breaking up his court, which for two weeks he there had held, and knights and barons all were going their way content and glad, bearing rich guerdons from their noble lord, when curiosity their steps detained at sight of a strange dwarf, who in his hand a handsome lance did hold. This dwarf pushed forward to the palace-hall, where each with eager eye observed his shape; for never till that day had they beheld such wondrous man; but he, passing the gaping crowd without remark, straight to the monarch's throne his steps pursued; and there he said:

“May God, most noble sire, grant you weal! Albeit my form is strange, yet, please you, hear, for I do come a messenger from far.”

“Dwarf,” said the king, “God save thee too! for thou methinks art honest. Speak without fear, and do thy message featly.”

The 057dwarf preluded with a sigh, and thus began:

“Sire, from Dovon's son I bear to you this lance, which has been cause of mourning dire and great. Proud of his valour and his strength, a knight had hung it to a tree upon a hill, where I have watched it, burnished it beside twice every day, for fourteen weary years. If a knight touched it, I by my cry aroused my lord, who then, all armed, would rush upon the stranger; being vanquished, he was quickly seized and by the neck incontinently hung. 'Twas thus that three-and-thirty met their fate; when that the knight, whose messenger I am, conquered this lord and won the lance, hanging in turn its owner for his deeds. This is the lance that now he sends to you; and here am I, your vassal and your slave.”

“'Tis well,” the king replied; “but, dwarf, now give me, on thy faith, some news of brave Sir Jaufry: without a lie, say when thou saw'st him last.”

“'Twas Monday evening, please you, my good lord; I left him when the fray was o'er and he had finished hanging up the knight.”

“And was his health then good?”

“Yea, sire, with God's help, and well disposed and gay.”

“Good 058Lord divine and full of glory,” cried the king with clasped hands, “grant of your grace that I behold him safe; for scant my pleasure and my joys will be till I have held him in these arms again!”

We 059now return to Jaufry, who still wanders on, resolving not to stay for food or sleep before he meets with Taulat; for in his ears incessantly do ring the biting words of Quex: “Your courage will be higher when you're drunk,”—and he yet trusts to prove that lord did lie by beating Taulat fasting. Onward he therefore pricked till midnight hour, when he attained a narrow and dark gorge shut in on either side by mountains high. No other passage was there but this one. Sir Jaufry gave his horse the spur; when, at the very mouth of the defile, before him stood a yeoman, active, of stout build and large of limb, who held within his grasp three pointed darts that were as razors 060sharp. A large knife pended from his girdle, which enclosed an outer garment of good form and fashion.

“Halt, knight,” he cried; “I'll have a word with thee.”

Jaufry drew rein, and said:

“And what's thy quest, good friend?”

“Thou must give up thy horse and knightly arms; for upon such condition only mayst thou pass.”

“Indeed,” quoth Jaufry; “dost thou mean to say an armed and mounted knight must not pass through this strait?”

“He might do so, but for the toll I've levied.”

“To the foul fiend such toll! Never will I give up my horse or arms, till strength's denied me to defend them both.”

“An that thou yield'st them not with gentle grace,” the yeoman said, “I must use force to take them.”

“And wherefore so? what harm have I e'er wrought thee?'

“Dost thou not wish to pass this gorge, and bilk the toll that's due save I use force to get it?”

“And what's the force thou'lt use?”

“That 061thou shalt briefly see; meantime I bid thee 'ware my hand!”

“I will do so,” quoth Jaufry.

The yeoman now prepared himself for fight, and seized his dart as though in act to strike; but Jaufry, fearing for his horse, awaited not the blow, but gal-loped off amain. As o'er the road he sped, the man let fly the missile with just aim; it hit the shield, and that with force so great, red fire and flame forth issued at the stroke, which did not pierce it through. The sharpened point curled upwards on the steel, and the wood flew in shivers.

Sir Jaufry turned his steed at once and bore down on his foe, counting full surely that the fight was done; but, lo, at that instant he had leapt aside, and in the act discharged a second dart, which lighted on his helm; so fierce the stroke, the casque seemed all on fire; yet it resisted, though its lord was stunned.

The yeoman, seeing his second blow had failed, was as a man possessed; so dread his rage as neither to have hurt the knight or broken his bright arms. Jaufry, whose senses had now back returned, thought only of his horse, which he rode here and there to guard it from the blow of the third dart. Not this, however, was his foe's 062intent, for he still thought to take the beast alive; like lightning swift he came, and whirling round the dart, launched the fell weapon with these haughty words:

“By Heaven, slave, thou now shalt leave the horse, nor shall thy hauberk, helm, or shield protect thyself!” Jaufry wheeled round his horse at this stem threat; and as the dart came hissing to its prey, he deftly bowed him down; it harmed him not, but striking on his mail, tore from the goodly arms a palm away, then bounded out of view.

“And now,” cried Jaufry, the third dart being flung, “my lance's point shall give me my revenge.” With lowered lance he flew towards the man, trusting this time to pierce him through and through; but he was nimble as a roe or deer, and leapt from place to place to such effect, that Jaufry missed his aim; and as he passed, the yeoman seized a rock and hurled it at the knight, who, but for his shield, must fain have bit the ground. The mass in atoms flew; but such the force with which the blow was struck, it battered-in the shield. Jaufry, enraged at following such a foe, now doubly maddened at this fresh attack, in wrath exclaimed:

“God, 063thou all-glorious King! how shall I meet this fiend? The world I'll hold not at a denier's price till he doth sue for grace!”

Then wielding his long lance,—

“This time,” he loudly to the yeoman cried, “or thou or I shall fall.”

The yeoman from his girdle plucked his knife, and made reply:

“Ere that thou leave this spot thou'lt pay the toll!”

“Ay, that will I,” quoth Jaufry, “take my promise on't; before we part, thou shalt have toll enough!”

He once again renewed a brisk attack, but still the other dodged; and ere that Jaufry could draw-in the rein, with mighty spring upon the horse he leapt and round Sir Jaufry's body twined his arms.

“Stir not, sir knight,” he cried, “unless thou wish for death.”

When Jaufry felt himself thus rudely seized, his mind was in a maze, and for a time incapable of thought. The yeoman held him with such strait embrace he could not stir a limb, while in his ear he hissed his future fate: how that a prison should his 060body hold, where tortures, griefs, unheard-of pains, should vex him evermore. Till break of day his arms were round him clasped; but when the stars were gone, then Jaufry communed with himself and said:

“Better to die for God, who made this earth, than let my body be a dungeon's prey. We'll see what can be done.”

Reflecting thus, he let his lance drop down, and as the yeoman's right arm pressed him most with energy he clutched it in his grasp; so vigorous the attack, so nerved his strength, he forced the hand to loose the gleaming knife: then, when he saw the arm was paralysed and drooped inertly down, he fixed with both hands on the yeoman's left, which he then twisted till he caused such pain, its owner reeled in groaning to the ground. Dismounting from his horse, Jaufry drew near his foe, who lay quite motionless crying for mercy in his agony.

“By Heaven! which I adore,” quoth Jaufry, “ne'er will I pity show to wretch like thee.”

And at the words he cut off both his feet.

“I prithee, now,” he said, “run not, nor leap, nor battle more with knights. Take to another trade; for far too long hath this one been thy choice.”

He 065gathered up his lance and shield, and, mounting on his horse, prepared him quietly to go his way.

'Twas on a Tuesday, early in the morn, that Jaufry held this speech; but as he turned him from his footless foe,—

“I have not yet inquired,” he observed, “if thou perchance hold'st knights within thy walls?”

“My lord,” the man replied, “full five-and-twenty are there held in chains beyond the mount where stands my dwelling-place.”

“O, O!” said Jaufry, “these I must set free; it likes me not that thou shouldst guard such prize.” Without delay he hied him to the house, whose massive portals were thrown open wide; and to a dwarf who stood before the gates he cried:

“Where lie the imprison'd knights?”

Replied the dwarf:

“Methinks you're all too rash to venture here. 'Tis more indeed than rashness,—downright folly. You wake my pity; therefore take advice, and get you gone before my lord returns, save that you covet an inglorious death, or torments even worse.”

Jaufry with smiles replied:

“Nay, 066friend, I want the knights; quickly lead on, that I may break their chains.”

“An I mistake not, you will join their ranks ere you deliver them; and I must hold you as a fool distraught, not to have hied you hence; for should my lord chance meet you by the way, deeply you'll grieve that e'er you ventured here.”

“Thy lord will ne'er return; I have deprived him of his nimble feet, and near his end he lies. The knights shall now be free, and thou, my prisoner, their place shalt take, save that thou goest where my bidding sends; then peradventure brief shall be thy thrall.”

“Sir knight,” the dwarf replied, “since, then, my lord is thus so poorly sped, I, by my faith, will follow your commands, and from great pain will draw those suffering knights, whose language is but moans; this featly will I do, who by constraint and fear was here detained. Truly, to God and you we should give thanks, and joyfully obey what you ordain.”

“First, then,” said Jaufry, “lead me to the knights.”

The dwarf most gladly acted as his guide; and pacing on before, conveyed him to a hall where five-and-twenty knights were rudely chained, as each by turns 067had been the yeoman's prey. Jaufry on entering made them a salute, to which not one replied; nay, they began to weep, and mutter in their teeth:

“Accurs'd the day that yeoman was e'er born, who thus hath overcome so good a knight!”

But Jaufry, as he gaily drew him nigh:

“Why weep, fair knights?” he said, with courtesy. “Go, madman, go,” did one of them reply; “for sure thy senses must have left thee quite, to ask us why we weep, when walls like these rise up on ev'ry side. There is not one of us who doth not grieve to see the yeoman's prisoner in thee. Unhappy was the day that saw thy birth. In person thou art tall and fair to view, yet soon like ours will torments be thy lot.” Quoth Jaufry, “Great is God; easy to Him can your deliverance be. Through Him my sword hath 'venged you on your foe, and now the yeoman lies deprived of feet. If, then, you see me in this weary spot, 'tis but to break your chains.”

Scarce had the words escaped from out his mouth, when loudly did they call:

“Happy the day which dawned upon thy birth; for thou hast saved us all, and swept our pain and martyrdom away!”

Then 068Jaufry bade the dwarf set free the knights; the manikin obeyed, and with a hammer broke in bits their chains. They all arose, and bowed their heads in token of submission, whilst they said:

“Lord, we are thy serfs; do with us as thou please, be it for good or evil, as is fit.”

“Good knights,” Sir Jaufry said, “whate'er of evil may henceforth betide you, none shall come from me. All that I ask of you is simply this, that ye betake you to King Arthur's court, and tell him all you know.”

“My lord,” they all exclaimed, “full willingly shall thy behest be done; but to the service rendered, add one more by telling us thy name.”

“Barons,” said Jaufry then, “tell him the son of Dovon burst your chains. Now quickly set ye out; and, mark, my friendship ne'er shall be bestowed, if that ye fail to tell the king each word.”

The dwarf meanwhile had gone to seek the arms and fetch the steeds to furnish forth the knights. Each donned his hauberk, mounted his good horse, and then with Jaufry parted from that spot. He led them to the great highway, and in their company rode full a league. In passing by, he pointed to the place where, cold and motionless, the yeoman lay: they stayed an instant 069to observe their foe, then went upon their road. A little further Jaufry got him down, and tightened more his goodly charger's girths; then, his impatience to fall in with Taulat reviving in full force:

“God speed you, sirs,” he said; “I can delay no more; already have I wasted too much time.”

“My lord,” replied the knights, as they presented him his shield and lance, “accept again our thanks: where'er we be, the service thou hast done in this great fight shall widely be proclaimed.”

When that the band had watched him out of sight, they went their way until they reached Carlisle. They found King Arthur in his flowery mead with five-and-twenty of his primest knights. There, kneeling at his feet, one of the troop was spokesman for the rest; and thus he fearlessly and sagely said:

“Sire, so please it the true God, who knoweth all that every creature doth, give you good luck, and guard from pain and ill the greatest king this world doth now contain!”

“Friend,” the good king replied, “God and St. Mary keep thee and thy mates! Speak without fear, and tell me what thou wilt.”

“Sire, 070we come to yield ourselves to thee, from Jaufry, Dovon's son; he hath delivered us from durance vile.”

“Good sir, give me at once your tidings. Is't long since you and he have parted company?”

“We left him, sire, on Tuesday morning last, both safe and sound, ardent and full of strength, tracking a lord with whom he seeks to fight, and to avenge thy cause.”

“O Lord, thou glorious Sire,” said the king, with joined hands, “grant I may Jaufry see unchecked, unscathed; for, an I hold him not within six months, I'll prize my fortunes as of nothing worth!”

Whilst that the dwarf in turn begins his speech, to tell the king how this adventure happed, we will go back to follow Jaufry's steps, who still, unwearied, presses stoutly on.

The 071knight had rode for great part of the day beneath the rays of a most burning sun, and horse and rider both alike fatigued, when he beheld a young and handsome squire running towards him at his greatest speed. Rent was his garment even to his waist; and on he came, with madness in his looks, tearing by handfuls his fair curling hair.

Scarce did he make out Jaufry from afar when he exclaimed:

“Fly, fly, brave knight, fly quickly from this spot, an that thou choosest not to lose thy life!”

“And wherefore so, fair friend?” asked Dovon's son.

“Fly, for the love of God, say I; nor lose thou further time.”

“Art 072thou, then, shorn of sense,” exclaimed the knight, “such counsel to propose, when I behold no foe?”

“Ah!” cried the squire then, “he comes; he's there; nor think I in a year to cure the fright that he hath caused me! He hath slain my lord,—a knight of price, who was conducting to his castle-home his lady-wife, a Norman count's most noble daughter. This wretch hath seized the bride; and to myself has caused such dire fear, that ev'ry limb still trembles at the shock.”

“And is't because thou fearest,” asked Sir Jaufry, red with rage, “thou counsell'st flight to me? By holy faith, I hold thee fool, and worse.”

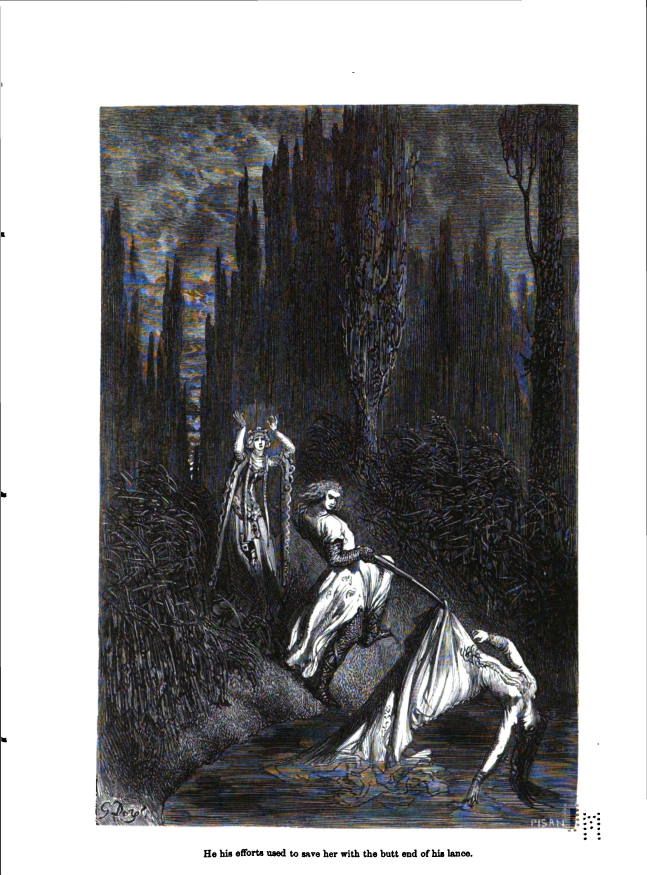

As he spoke thus, a leper came in sight, who sped along, a child within his arms. Its wretched mother, with dishevelled hair, followed with piercing cries. When she beheld the knight, she knelt down at his feet, and in a tone of agony exclaimed:

“Mercy, my lord; O, mercy! For the love of Heaven, grant me help, and get me back the child yon leper bears.”

“Woman,” responded Jaufry, “wherefore takes he it?”

“My 073lord, because it is his wicked will.”

“Had he no other cause?”

“No, by your glorious sire!”

“Since it is thus,” quoth Jaufry, “he is wrong; and I will try to win it back for you.”

He spurred at once his horse, she following; and cried aloud, with all the strength he had:

“Halt, leprous, wicked wretch! and bring thou back the child!”

The leper turned his head and raised his hand, making the mark of scorn; which so enraged the knight, he swore the insult deeply to avenge. The hideous leper answered with a laugh; for he had reached the threshold of his door. He darted in for refuge, followed full speed by Jaufry; who, dismounting from his horse, which with his lance he left to the poor dame, dashed through the castle-gate with sword in hand and shield upon his arm.

As he was traversing the castle through, which he found vast and sumptuous to the view, he came into a hall where a huge leper, frightful to behold, had cast upon a couch a damsel in first youth, whose beauty in that age could scarce be matched. Her cheek was fresher than an opening rose at break of day, and her torn 074vesture half-betrayed a bosom snowy white. Her eyes were bathed in tears; her words, despair, and sobs, moved Jaufry's soul: but when the leper rose and seized his club, such feelings changed to horror and surprise.

He was in height more tall than knightly lance, and at the shoulders was two fathoms broad: his arms and hands were huge, his fingers crookt and full of knots, his cheeks were spread with pustules and with scales; a broken pupil, eyes without lids but with vermilion edged, blue lips, and yellow teeth, made up the portrait of this monster dread. Fiercer than living coal he flew on Jaufry, bidding him straight to yield.

“No, certes,' the knight replied.

“Say, who in evil hour sent thee here?”

“No one.”

“And pray what seekest thou?”

“A child, that from its mother hath been torn by lep'rous hands, which must give up their prey.”

“Vain fool, 'tis I forbid,—I, by whose mace thy fate shall now be sealed; better for thee thou hadst not risen the morn, since thou shalt now for ever lay thee down.”

His club he raised in uttering these words, and on the 075shield of Jaufry then let fall so fierce a blow, the knight went reeling to the ground. Again that club was raised; but Jaufry rose and fled. Certes he had cause to flee the stroke he saw impending; for that huge mass of iron as it fell made the vast hall to tremble. Then Jaufry, with a bound, before the leper stood, and with firm hand dealt him in turn a blow which took a palm from off his raiment and the flesh behind. Seeing his blood, which fast began to stream, the giant uttered first a fearful cry, then ran at Jaufry, raising his knotted club with both his hands.

Scarce could the youthful knight evade the stroke and leap behind a column; the monster struck it with such dire strength, the massive iron crushed the marble plinth, and all the castle groaned.

Meanwhile the damsel fervently prayed Heaven, as humbly on the blood-stained stones she knelt:

“O, mighty Lord, who in Thy image didst great Adam make; Thou who hast done so much to save us all,—now save me from this wretch, and let yon knight withdraw me from his hands!”

Her orison scarce o'er, Jaufry stepped out, and ere the giant could again his heavy club let fall, he with his trenchant blade had severed his right arm. Being thus 076lopped, the monster in his wrath and agony so loudly groaned, the palace trembled to its very base and shook the outer air. In vain did Jaufry dodge his falling mace, it struck him to the ground; so that from nostrils, eyes, and mouth, the purple stream burst forth. The mace, in falling on the marble flags, now brake in twain, which Jaufry seeing, he uprose in haste, and newly struck the leper; at the knee-joint he aimed; the monster reeled, then fell like some great tree.

Prone as the leper lay, Jaufry ran up, his sword in air, and said:

“Methinks that peace will soon be made 'twixt you and me.”

Then letting fall his sword with both his hands, he clove the monster's head e'en to the teeth. In the convulsions of his agony still fiercely strove the wretch, and with his foot hurled him so madly 'gainst the distant wall, Sir Jaufry fell deprived of sound and sight. His trembling hand no longer clutched his sword; like ruby wine, from nostrils and from mouth burst forth his blood, and motion made he none.*

* E l'mezel a si repennat,

Que tal cop l'a del pe donat,

For 077an instant's space the damsel thought her champion was gone. In grief she hastened to undo the straps which bound his polished casque. The freshness drawing from his breast a sigh, she ran for water, and his face she bathed. His senses half-re-turned, he staggered up, and thinking still to hold his trusty blade, he struck the damsel,—deeming her the foe,—to such effect that both rolled on the ground. Like madman then he sped around the hall, and ran behind a column, where he crouched and trembled 'neath his shield.

'Twas there the damsel came; and in a voice of dulcet tone, she said:

“Brave knight, come, ope again those manly eyes, and see who 'tis that speaks. Forget ye what is due to chivalry, of which you are a lord? your courage and your fame? Recall yourself, and lower that bright shield; behold, the leper's dead!”

C'a ana part, lo fas anar

E si ab la paret urtar

Que l'auzer li tolc e l'vezer

Et anet à terra cazer

E l'sanc tot yin clar e vermeil

I eis per lo nas e la bocha.....

Ms. fol. 28 verso, verse 2461.

Jaufry 078recovered at this heart'ning speech, and finding his head bare,—

“Damsel,” he asked, “who hath removed my casque, and taken my good sword?”

“Myself, good lord, whilst you were in a swoon.”

“The giant, what doth he?”

“Bathed in his blood and at your feet he lies.” Jaufry looked up, and when the corpse he saw thus shattered and quite still, he slowly rose, and sat him on a bench until his senses were again restored; then, when the dizziness had fled his brain, he thought upon the mother and the child, and straightway ran from hall to hall to search the infant out. But though he sought and ran and called aloud, neither the leper nor the child appeared.

“I will yet search and search,” he then exclaimed; “or here or out the door they must be found; for I'll not hold me at a denier's worth till to the mother her poor child's restored, and I've had vengeance for that leper's scorn.”

With such resolve, he strode towards the door; but though the portal was thrown open wide, he could not pass it through. Spite of his will, his efforts, and his strength, 079his feet seemed stopped before an unseen bar.

“Good Heaven,” he said, “what! am I then entranced?”

He drew him back, and gathering for a spring, with wond'rous force he bounded to the door. Still all was vain, he could not cross the sill. Again and yet again he tried, till deep discouragement iced o'er his heart. Then tears broke from his eyes, and murmuring:

“Alas, good Lord,” he said, “Thou gav'st me strength to kill yon wicked wretch; what boots it, if I here must captive be?”

'Twas as he thus bemoaned his adverse fate, there broke upon his ear from some nigh place a sound of infant tongues, which sadly cried:

“Save us, O, save us, mighty lord!”

Swift at the sound he roused his spirit up, and running, found at one end of a hall a close-shut door fast bolted from within. Jaufry called out, and struck it with great noise; yet answer none was made: enraged at this, he burst it in with force, and with his naked blade entered a gloomy vault. There was the leper found, with knife in hand, who seven infants had just put 080to death. Some thirty more there still remained alive, whose bitter cries went through the softened soul.

Touched at the frightful sight, Jaufry struck down the wretch, who called his master's help; and then in wrath exclaimed:

“Thy master, villain, can no answer make; his soul this earth hath fled: and thou, for erstwhile making mock of me, shalt now thy meed receive.”

Raising meanwhile his arm, the leper's hand he severed at a blow. The wretch upon the blood-stained pavement rolled; then crawling to his feet, he humbly cried:

“Mercy, good knight; in God's name, pity me, and take not quite my life! 'Twas by constraint and force I killed these babes. My lord, who sought to cure his leprosy, bade me, with awful threats, each day prepare a bath of human blood.”

“Thy life I'll grant,” quoth Jaufry to him then, “an that thou give me means to leave this place.”

“I can,” the leper said; “but had you now deprived me of my life, not knowing of the spell, a hundred thousand years had rolled their course, and yet not seen you free.”

“Haste 081thee, then, now,” quoth Jaufry, eagerly. “Sir knight,” the man with shining face replied, “you still have much to bear. Such is the fashion of this castle's spell, my lord alone could power grant to such as hither came to cross the threshold; but never did they pass it in return save dead or maimed.”

“How, then, wilt thou succeed?” said Jaufry.

“Spy you, on top of yonder casement high, a marble head?”

“Yea, by my faith! And then?”

“Lo, reach it down; and break it fair in twain; you'll thus destroy the charm: but first your armour carefully put on; for when the spell is o'er, these castle-walls will crumble into dust.”

Trusting not wholly to the lep'rous wretch, Jaufry then bound him by the feet and arms, and to the damsel thus confided him: